Консервативная партия (Великобритания)

Консервативная и юнионистская партия , обычно Консервативная партия и в разговорной речи, известную как Тори , [ 18 ] является одной из двух основных политических партий в Соединенном Королевстве вместе с лейбористской партией . Это была официальная оппозиция с тех пор, как была побеждена на всеобщих выборах 2024 года . Вечеринка сидит на правом [ 16 ] Центр -право [ 27 ] политического спектра. Он охватывает различные идеологические фракции, включая консерваторы из одной нации , Тэтчериты и традиционалистские консерваторы . Было двадцать консервативных премьер -министров .

Консервативная партия была основана в 1834 году от партии Тори и была одной из двух доминирующих политических партий в 19 веке вместе с Либеральной партией . При Бенджамине Дисраэли он сыграл выдающуюся роль в политике в разгар Британской империи . В 1912 году Либеральная профсоюзная партия объединилась с партией, чтобы сформировать консервативную и юнионистскую партию. Соперничество с лейбористской партией сформировало современную британскую политику в течение прошлого века. Дэвид Кэмерон попытался модернизировать консерваторов после своих выборов в качестве лидера в 2005 году, и партия с 2010 по 2024 год управляла пятью премьер -министрами, в последнее время Риши Сунак .

Партия, как правило, приняла либеральную экономическую политику в пользу свободных рынков с 1980 -х годов, хотя исторически она выступала за протекционизм . Партия - британский юнионист , выступающий против Объединенной Ирландии , а также независимости шотландской и валлийской независимости , и она критиковала передачу . Исторически, партия поддержала продолжение и обслуживание Британской империи . Партия приняла различные подходы к Европейскому союзу (ЕС), с евроскептикой и, в уменьшении, проевропейские фракции внутри него. Исторически, партия приняла социально консервативный подход. [ 28 ] [ 29 ] В политике обороны он поддерживает независимую программу ядерного оружия и приверженность членству НАТО .

Для большей части современной британской политической истории Соединенное Королевство демонстрировало широкую городскую и сельскую политическую разрыв ; [ 30 ] голосования и финансовой поддержки Консервативной партии База исторически состояла в основном из домовладельцев , владельцев бизнеса , фермеров , застройщиков недвижимости и избирателей среднего класса , особенно в сельских и пригородных районах Англии . [ 31 ] [ 32 ] [ 33 ] [ 34 ] [ 35 ] Однако после референдума ЕС в 2016 году консерваторы нацелены на избирателей рабочего класса из традиционных оплотов труда. [ 36 ] [ 37 ] [ 38 ] [ 39 ] Доминирование консерваторов в британской политике в течение 20 -го века сделало его одной из самых успешных политических партий в западном мире . [ 40 ] [ 41 ] [ 42 ] [ 43 ] Самый последний период консервативного правительства был отмечен необычайной политической суматохой. [ 44 ]

История

Происхождение

Некоторые писатели прослеживают происхождение вечеринки до вечеринки тори , которую она вскоре заменила. Другие историки указывают на фракцию, основанную на партии вигов 18 -го века , которая объединилась вокруг Уильяма Питта младшего в 1780 -х годах. Они были известны как «независимые виги», « Друзья мистера Питта » или «Pittites» и никогда не использовали такие термины, как «тори» или «консерватор». Примерно с 1812 года название «Тори» обычно использовалось для новой партии, которая, по словам историка Роберта Блейка, «предки консерватизма». Блейк добавляет, что преемники Питта после 1812 года «ни в каком смысле не были стандартными носителями« истинного торизма »». [ 45 ]

Термин «Тори» был оскорблением, который вступил в английскую политику во время кризиса законопроекта об исключении в 1678–1681 гг., Который получен из Среднего Ирландского слова TORAIDHE (Modern Irish : Tóraí ), означающий Outlaw или Forber , который, в свою очередь, происходит от ирландского слова TOIR , значение Погоня , поскольку преступники были «преследованными мужчинами». [ 46 ] [ 47 ]

Термин « консерватор » был предложен в качестве названия партии в статье Дж. Уилсона Крокера, опубликованной в ежеквартальном обзоре в 1830 году. [ 48 ] Название сразу же завоевало и было официально принято под эгидой Роберта Пила около 1834 года. Пил признан основателем Консервативной партии, которую он создал с объявлением о манифесте Тамворта . Термин «консервативная партия», а не тори, был доминирующим использованием к 1845 году. [ 49 ] [ 50 ]

1867–1914: консерваторы и профсоюзные активы

Расширение избирательной франшизы в 19-м веке заставило Консервативную партию популяризировать его подход при Эдварде Смит-Стэнли, 14-м графе Дерби и Бенджамина Дисраэли , которые переносили через их собственное расширение франшизы с Законом о реформах 1867 года . Первоначально партия была против дальнейшего расширения электората, но в конечном итоге позволила принять Закон о реформе Гладстона в 1884 году . В 1886 году партия сформировала альянс со Спенсером Кавендишем и Джозефа Чемберлена новой либеральной юнионистской партией , а при государственных деятелях Роберт Гаскайн-Цецил и Артур Бальфур держали власть для всех, кроме трех из следующих двадцати лет, прежде чем пострадать от тяжелого поражения в 1906, когда он расстался из -за вопроса свободной торговли .

Молодой Уинстон Черчилль осудил атаку Чемберлена на свободную торговлю и помог организовать оппозицию в профсоюзной/консервативной партии. Тем не менее, Balfour, как лидер партии, представил протекционистское законодательство. [ 51 ] Черчилль пересек пол и официально присоединился к Либеральной партии (он присоединился к консерваторам в 1925 году). В декабре Бальфур потерял контроль над своей партией, когда дефекты умножились. Он был заменен либеральным премьер-министром Генри Кэмпбеллом-Баннерманом , который назвал выборы в январе 1906 года , что оказало огромную либеральную победу. Либеральный премьер -министр HH Asquith принял много законодательства о реформе, но профсоюзные деятели усердно работали над организацией на низовом уровне. Два всеобщих выбора были проведены в 1910 году, в январе и в декабре . Две основные партии теперь были почти мертвы на местах, но либералы держали контроль с коалицией с ирландской парламентской партией . [ 52 ] [ 53 ]

В 1912 году либеральные юнионисты объединились с Консервативной партией. В Ирландии альянс ирландского юниониста в 1891 году был сформирован , который объединил юнионистов, которые были против ирландского самоуправления в одно политическое движение. Его депутаты взяли консервативный кнут в Вестминстере, по существу, формируя ирландское крыло партии до 1922 года. В Британии Консервативная партия была известна как Юнистская партия из -за ее противодействия домашнему правлению. [ 54 ] [ 55 ] Под руководством Bonar Law в 1911–1914 годах партийный моральный дух улучшился, было содержалось «радикальное правое» крыло, а партийная механизм укреплялся. Это добилось некоторого прогресса в разработке конструктивной социальной политики. [ 56 ]

Первая мировая война

В то время как либералы были в основном против войны до вторжения в Бельгию, консервативные лидеры решили помощь Франции и остановки Германии. Либеральная партия полностью контролировала правительство до его неумелого управления военными усилиями в рамках кризиса Shell сильно повредить его репутации. Всепартийное коалиционное правительство было сформировано в мае 1915 года. В конце 1916 года либеральный Дэвид Ллойд Джордж стал премьер-министром, но вскоре либералы расстались, и консерваторы доминировали в правительстве, особенно после их оползня на выборах 1918 года . Либеральная партия так и не выздоровела, но лейбористы набрали силу после 1920 года. [ 57 ]

Найджел Кеохане обнаруживает, что консерваторы были горько разделены до 1914 года, но война собрала партию вместе, позволив ей подчеркнуть патриотизм, поскольку она нашла новое руководство, и разработала свои позиции по ирландскому вопросу, социализму, избирательной реформе и вопросу о вмешательстве в экономика. Новым акцентом на антисоциализм был его реакция на растущую силу лейбористской партии. Когда избирательная реформа была проблемой, она сработала, чтобы защитить их базу в сельской Англии. [ 58 ] В 1920 -х годах он агрессивно искал женщин -избирателей, часто полагаясь на патриотические темы. [ 59 ]

1920–1945

В 1922 году Бонар Лоу и Стэнли Болдуин возглавляли распад коалиции, и консерваторы, управляемые до 1923 года, когда правительство лейбористов меньшинства во главе с Рамсей Макдональдом к власти приходилось к власти . Консерваторы восстановили власть в 1924 году, но были побеждены в 1929 году, когда правительство по труду меньшинства вступило в должность. В 1931 году, после краха правительства трудового меньшинства, он вошел в другую коалицию, в которой доминировали консерваторы с некоторой поддержкой фракций как Либеральной партии, так и лейбористской партии ( национальный труд и национальные либералы ). [ 60 ] В мае 1940 года была сформирована более сбалансированная коалиция [ 60 ] - Национальное правительство , которое под руководством Уинстона Черчилля увидела Великобританию в течение Второй мировой войны. Тем не менее, партия проиграла всеобщие выборы 1945 года в оползне возрождающейся лейбористской партии. [ 61 ] [ 62 ]

Концепция «Демократии-владельца собственности» была придумана Ноэлем Скелтоном в 1923 году и стала основным принципом партии. [ 63 ]

1945–1975 гг.: Послевоенный консенсус

Популярное неудовлетворенность

Служа в оппозиции в конце 1940 -х годов, консервативная партия эксплуатировала и подстрекала растущий общественный гнев при нормировании пищевых продуктов , дефиците, контроле, жесткой экономии и государственной бюрократии. Он использовал неудовлетворенность социалистической и эгалитарной политикой лейбористской партии, чтобы сплотить сторонников среднего класса и построить политическое возвращение, которое выиграло их на всеобщих выборах 1951 года . [ 64 ]

Модернизация вечеринки

В 1947 году партия опубликовала свою промышленную хартию , которая ознаменовала его принятие « послевоенного консенсуса » в области смешанной экономики и трудовых прав . [ 65 ] Дэвид Максвелл Файф возглавлял комитет в организации консервативной партии, в результате которого доклад Maxwell Fyfe (1948–49). В докладе требуется, чтобы партия выполняла больше сбора средств, запрещая ассоциациям избирательных округов требовать крупных пожертвований со стороны кандидатов с намерением расширить разнообразие депутатов . На практике, возможно, это могло привести к предоставлению большей власти партиям избирателей и сделало кандидаты более однородными. [ 66 ] Уинстон Черчилль , лидер партии, привлек председателя партии для модернизации партии: Фредерик Маркиз, 1 -й граф Вултон, перестроил местные организации с акцентом на членство, деньги и единую национальную пропагандистскую привлекательность по критическим вопросам. [ 67 ]

С узкой победой на всеобщих выборах 1951 года , несмотря на то, что Черчилль вернулся в власть. Помимо нормирования, который был закончен в 1954 году, большая часть государства всеобщего благосостояния была принята консерваторами и стала частью «послевоенного консенсуса», который был сатирирован как бутуреллизм и продолжался до 1970-х годов. [ 68 ] [ 69 ] Консерваторы были примирительны по отношению к профсоюзам, но в 1953 году они приватилировали сталелитейную и дорожную промышленность. [ 70 ] В течение тринадцатилетнего пребывания консерваторов в должности пенсии выросли на 49% в реальных условиях, пособий по болезни и безработице на 76% в реальном выражении, а дополнительные выгоды-на 46% в реальном выражении. Тем не менее, семейные пособия упали на 15% в реальном выражении. [ 71 ] «Тринадцать потраченных впустую лет» был популярным лозунгом, нападающим на консервативную запись, в первую очередь из -за труда. Кроме того, были атаки правого крыла самой консервативной партии за ее терпимость к социалистической политике и нежелание обуздать юридические полномочия профсоюзов.

Консерваторы были переизбраны в 1955 и 1959 годах с большим большинством. Консервативные премьер-министры Черчилль, Энтони Иден , Гарольд Макмиллан и Алек Дуглас-Хом продвигали относительно либеральные торговые правила и меньше участия государства в течение 1950-х и начала 1960-х годов. Суэцкий кризис 1956 года был унизительным поражением премьер -министра Идена, но его преемник Макмиллан сводил к минимуму ущерб и сосредоточил внимание на внутренних вопросах и процветании. После противоречия по поводу выбора Гарольда Макмиллана и Алека Дугласа-Хом в процессе консультации, известного как «Волшебный круг», [ 72 ] [ 73 ] Был создан официальный процесс выборов, и первые выборы лидерских выборов были проведены в 1965 году, выигравших Эдвардом Хитом. [ 74 ]

1965–1975 гг.: Эдвард Хит

Правительство Эдварда Хита гг 1970–74 . рецессия 1973–75 гг . С момента вступления в ЕЭС, который превратился в ЕС, британское членство было источником горячих дебатов в партии.

Хит пришел к власти в июне 1970 года , и последняя возможная дата для следующих всеобщих выборов была не в середине 1975 года. [ 75 ] были проведены всеобщие выборы Однако в феврале 1974 года в попытке завоевать общественную поддержку во время национальной чрезвычайной ситуации, вызванной забастовкой шахтеров. Попытка Хита выиграть второй срок на этих «смазанных» выборах потерпел неудачу, поскольку результат тупика не оставил никакой стороны с общим большинством . Хит подал в отставку в течение нескольких дней, после того, как не смог получить поддержку Либеральной партии, чтобы сформировать коалиционное правительство. Лейбористская партия выиграла выборы в октябре 1974 года с общим большинством трех мест. [ 76 ]

1975–1990: Маргарет Тэтчер

Потеря власти ослабила контроль Хита над партией, и Маргарет Тэтчер свергла его на лидерских выборах 1975 года . Тэтчер привела свою партию к победе на всеобщих выборах 1979 года с манифестом, который сосредоточился на философии партии. [ 77 ]

Будучи премьер-министром, Тэтчер сосредоточился на том, чтобы отклонить легкий либерализм послевоенного консенсуса , который терпел или поощрял национализацию, сильные профсоюзы, тяжелые регулирование и высокие налоги. [ 78 ] Она не оспаривала Национальную службу здравоохранения и поддерживала политику консенсуса в холодной войне, но в противном случае попыталась демонтировать и делегитимизировать ее. Она построила правую политическую идеологию, которая стала известна как тэтчеризм , основанный на социальных и экономических идеях британских и американских интеллектуалов, таких как Фридрих Хайек и Милтон Фридман . Тэтчер полагала, что слишком много социально-демократической государственной политики привела к долгосрочному снижению в британской экономике. В результате ее правительство преследовало программу экономического либерализма , приняв свободный рыночный подход к государственным услугам на основе продажи государственных отраслей и коммунальных предприятий, а также сокращения профсоюзной власти.

Один из крупнейших и наиболее успешных политик, которые помогли доме Совета, в государственном жилищном строительстве помогли приобрести свои дома по благоприятным ставкам. «Право на покупку» появилось в конце 1940-х годов, но было слишком великим вызовом послевоенного консенсуса, чтобы выиграть консервативное одобрение. Тэтчер предпочитал эту идею, потому что это приведет к «собственной демократии», важной идеи, возникшей в 1920-х годах. [ 63 ] В конце 1960-х годов некоторые местные консервативные советы приняли прибыльные местные схемы продаж. К 1970-м годам многие люди из рабочего класса могли позволить себе покупать дома, и с радостью приняли приглашение Тэтчер приобрести свои дома со значительной скидкой. Новые владельцы с большей вероятностью проголосуют за консервативного, как надеялся Тэтчер. [ 79 ] [ 80 ]

Тэтчер привела консерваторов к двум победам на выборах в 1983 и 1987 годах . Она была глубоко непопулярна в некоторых частях общества из -за высокой безработицы и ее ответа на удар шахтеров . Безработица удвоилась между 1979 и 1982 годами, в основном из -за монетаристской битвы Тэтчер с инфляцией. [ 81 ] [ 82 ] Во время всеобщих выборов 1979 года инфляция составляла 9% или младше за предыдущий год, а затем увеличилась до более чем 20% в первые два года после министерства Тэтчер, но она снова упала до 5,8% к началу 1983. [ 83 ]

Период непопулярности консерваторов в начале 1980 -х годов совпал с кризисом в лейбористской партии, который затем сформировал основную оппозицию. Победа в войне Фолклендс в июне 1982 года вместе с восстановительной британской экономикой увидела, как консерваторы быстро вернулись на вершину опросов мнений и победили на всеобщих выборах 1983 года с оползневым большинством из -за разделительного голосования оппозиции. [ 81 ] К моменту всеобщих выборов в июне 1987 года экономика была сильнее, с более низкой инфляцией и падением безработицы, а Тэтчер обеспечила свою третью последовательную победу на выборах. [ 84 ]

Внедрение обвинения сообщества (известное его противниками в качестве налога на опрос ) в 1989 году часто упоминается как способствуя ее политическому падению. Внутренняя партийная напряженность привела к вызову лидерства со стороны консервативного депутата Майкла Хеселтина , и она подала в отставку 28 ноября 1990 года. [ 85 ]

1990–1997 гг.: Джон Майор

Джон Мейджор выиграл выборы на руководство партии 27 ноября 1990 года, и его назначение привело к почти немедленному повышению в состояниях Консервативной партии. [ 86 ] Выборы состоялись 9 апреля 1992 года, и консерваторы одержали четвертую последовательную победу на выборах, вопреки прогнозам из опросов общественного мнения. [ 87 ] [ 88 ] Консерваторы стали первой стороной, которая привлекла 14 миллионов голосов на всеобщих выборах. [ 89 ] [ 90 ]

16 сентября 1992 года правительство приостановило членство в Великобритании по европейскому механизму обменного курса (ERM) после того, как фунт упал ниже, чем его минимальный уровень в ERM, день после этого называется черной средой . [ 91 ] Вскоре после этого примерно миллион домовладельцев столкнулись с повторением их домов во время рецессии, в которой наблюдался резкий рост безработицы, взяв его около 3 миллионов человек. [ 92 ] Впоследствии партия потеряла большую часть своей репутации за хорошее финансовое управление. Конец рецессии был объявлен в апреле 1993 года. [ 93 ] [ 92 ] С 1994 по 1997 год, крупные приватизированные британские железные дороги .

Партия страдала от внутреннего подразделения и борьбы, в основном из -за роли Великобритании в Европейском Союзе . крыло партии Евроскептическое , представленное депутатами, такими как Джон Редвуд , выступило против дальнейшей интеграции ЕС, в то время как проевропейское крыло партии, представленное такими, как канцлер казначейства Кеннет Кларк , было в целом поддерживающим. Проблема создания одной европейской валюты также воспалана напряженность. [ 94 ] Майор пережил вызов лидерства в 1995 году Редвудом, но Редвуд получил 89 голосов, еще больше подрывая влияние майора. [ 95 ]

Консервативное правительство все больше обвинялось в средствах массовой информации в « Слайзе ». Их поддержка достигла самой низкой приливы в конце 1994 года. В течение следующих двух лет консерваторы получили некоторый кредит за сильное восстановление экономики и упасть в безработицу. [ 96 ] Но эффективная оппозиционная кампания лейбористской партии завершилась поражением оползня для консерваторов в 1997 году , их худшее поражение после всеобщих выборов 1906 года . Выборы 1997 года оставили Консервативную партию в качестве партии только в Англии, причем все шотландские и валлийские места были потеряны, и нигде не было завоевано ни одного нового места.

1997–2010: политическая дикая местность

Майор подал в отставку с поста лидера партии, и его сменил Уильям Хаг . [ 97 ] привели Всеобщие выборы в 2001 году к чистому прибыли от одного места для консервативной партии и вернули в основном невредительную лейбористскую партию обратно в правительство. [ 98 ] Все это произошло через несколько месяцев после того, как протесты топлива в сентябре 2000 года в результате консерваторов ненадолго взяли на себя узкий лидерство над лейбористом в опросах. [ 99 ]

В 2001 году Иэн Дункан Смит был избран лидером партии. [ 97 ] Хотя Дункан Смит был сильным евроскептиком , [ 100 ] В течение своего пребывания в должности Европа перестала быть проблемой отделения в партии, поскольку она объединилась за призывы на референдум по предлагаемой конституции Европейского Союза . [ 101 ] Однако, прежде чем он сможет привести партию на всеобщие выборы, Дункан Смит потерял голосование по ходатайству депутатов. [ 102 ] Это было несмотря на то, что консервативная поддержка, равная поддержанию труда в месяцы, предшествовавшие его отъезду из руководства. [ 96 ]

Майкл Ховард тогда выступил за лидерство, не сопровождаемое 6 ноября 2003 года. [ 103 ] Под руководством Говарда на всеобщих выборах 2005 года консервативная партия увеличила свою общую долю голосов и, что значительно больше, - их количество парламентских мест, сократив большинство лейбористов. [ 104 ] На следующий день после выборов Говард подал в отставку.

Дэвид Кэмерон выиграл лидерские выборы в 2005 году . [ 105 ] Затем он объявил о своем намерении реформировать и перестроить консерваторов. [ 106 ] [ 107 ] В течение большей части 2006 года и первой половины 2007 года опросы показали лиды по труду для консерваторов. [ 108 ] Опросы стали более нестабильными летом 2007 года с вступлением Гордона Брауна в качестве премьер -министра. Консерваторы получили контроль над мэрией впервые Лондона в 2008 году после того, как Борис Джонсон победил действующего лейбориста Кена Ливингстона . [ 109 ]

2010–2024 гг.

В мае 2010 года консервативная партия пришла в правительство, сначала под коалицией с либеральными демократами, а затем в качестве серии большинства и правительств меньшинств. В этот период было пять консервативных премьер -министров: Дэвид Кэмерон, Тереза Мэй, Борис Джонсон, Лиз Трусс и Риши Сунак. Первоначальный период этого времени, в первую очередь под премьер -лигой Дэвида Кэмерона, был отмечен постоянным последствиями финансового кризиса 2007–2008 гг. И реализацией мер экономической экономии в ответ. С 2015 года преобладающим политическим событием стало референдум Brexit и процесс реализации решения покинуть торговый блок.

Время консерваторов в должности было отмечено несколькими противоречиями. Присутствие исламофобии в консервативной партии , включая обвинения в отношении ее политики, полос и структуры, часто находилось в глазах общественности. К ним относятся обвинения против старших политиков, таких как Борис Джонсон , Майкл Гоув , Тереза Мэй и Зак Голдсмит .

В период Кэмерона [ 110 ] [ 111 ] [ 112 ] и правительства Джонсона, [ 113 ] Ряд консервативных депутатов были обвинены или осуждены за сексуальные проступки, в том числе случаи потребления порнографии в парламенте, изнасилование, нащупание и сексуальные домогательства. [ 114 ] [ 115 ] [ 116 ] В 2017 году просочился список из 36 сидящих консервативных депутатов, обвиняемых в неподходящем сексуальном поведении. Считается, что этот список был составлен партийным персоналом. [ 117 ] После обвинений в нескольких случаях изнасилования против неназванного депутата Тори в 2023 году [ 118 ] и обвинения в сокрытии, [ 119 ] [ 120 ] Баронесса Варси , который занимал должность сопредседателя партии под руководством Дэвида Кэмерона, заявила, что у консервативной партии возникла проблема с жалобами на сексуальные проступки против членов надлежащим образом. [ 121 ]

2010–2016: Дэвид Кэмерон

Выборы 2010 года привели к тому, что у консерваторов больше мест у консерваторов было наибольшее количество мест. [ 122 ] После отставки Гордона Брауна Кэмерон был назначен премьер -министром, и консерваторы поступили в правительство в коалицию с либеральными демократами - первым послевоенным коалиционным правительством . [ 123 ] [ 124 ]

Премьерство Кэмерона было отмечено постоянным последствиями финансового кризиса 2007–2008 гг .; Они включали большой дефицит в государственных финансах, который его правительство стремилось сократить посредством противоречивых мер экономии . [ 125 ] [ 126 ] В сентябре 2014 года профсоюзная сторона, отстаиваемая лейбористской партией, а также Консервативной партией и либеральными демократами, выиграла на референдуме по независимости Шотландии на 55% нет до 45% Да по вопросу «должна ли Шотландия быть независимой страной». [ 127 ] [ 128 ]

На всеобщих выборах 2015 года консерваторы сформировали правительство большинства в соответствии с Кэмероном. [ 129 ] После спекуляций о референдуме о членстве в Великобритании в ЕС на протяжении всего его премьер -министра, в июне 2016 года было объявлено голосование, когда Камерон прошел кампанию, чтобы остаться в ЕС. [ 130 ] [ 131 ] 24 июня 2016 года Кэмерон объявил о своем намерении уйти в отставку с поста премьер -министра, после того как он не смог убедить британскую публику остаться в Европейском союзе . [ 132 ]

2016–2019: Тереза Мэй

11 июля 2016 года Тереза Мэй стала лидером консервативной партии. [ 133 ] Мэй обещал социальную реформу и более центристскую политическую перспективу для консервативной партии и ее правительства. [ 134 ] Ранние назначения в кабинете кабинета Мэй были истолкованы как попытка воссоединить партию после голосования Великобритании по выходу из Европейского Союза . [ 135 ]

Она начала процесс отказа от Великобритании из Европейского Союза в марте 2017 года. [ 136 ] В апреле 2017 года кабинет министров согласился провести всеобщие выборы 8 июня. [ 137 ] В результате шока выборы привели к подвешенному парламенту , когда Консервативная партия нуждалась в договоренности о доверии и предложении с DUP , чтобы поддержать правительство меньшинства. [ 138 ] [ 139 ]

В премьерстве Мэй доминировали Брексит, когда она проводила переговоры с Европейским союзом, придерживаясь плана шашек , что привело к ее проекту соглашения о выводе Brexit . [ 140 ] Мэй пережила два голоса без доверия в декабре 2018 года и январе 2019 года, но после того, как версии ее договора о выходе из проекта были отклонены парламентом три раза , май объявила о своей отставке 24 мая 2019 года. [ 141 ]

После голосования на референдуме ЕС и в течение премьер -министров мая Борис Джонсон и их преемники партия сместилась прямо на политическом спектре. [ 16 ]

2019–2022: Борис Джонсон

В июле 2019 года Борис Джонсон стал лидером партии. [ 142 ] На следующий день он стал премьер -министром. Джонсон снял среду из ЕС к 31 октября «без IFS, Buts или Maybes» ключевым обещанием во время его кампании за партийное лидерство . [ 143 ]

Джонсон потерял свое рабочее большинство в Палате общин 3 сентября 2019 года. [ 144 ] Позже в тот же день 21 консервативный депутат снял консервативный кнут после голосования с оппозицией предоставить Палату общин контроль над своей статьей. [ 145 ] Джонсон позже остановит законопроект о соглашении о выводе , призывая к всеобщим выборам. [ 146 ]

Всеобщие выборы 2019 года привели к тому, что консерваторы выиграли большинство, крупнейшую партию с 1987 года . [ 147 ] Партия выиграла несколько избирательных округов, особенно в ранее традиционных трудовых местах . [ 36 ] [ 37 ] 20 декабря 2019 года депутаты приняли соглашение о выходе из ЕС; Соединенное Королевство официально осталось 31 января 2020 года. [ 148 ] [ 149 ]

Джонсон руководил реакцией Великобритании на пандемию Covid-19 . [ 150 ] С конца 2021 года Джонсон получил огромную негативную реакцию для скандала с партией , в котором сотрудники и старшие члены правительства были изображены, проводящие собрания во время блокировки вопреки правительству. [ 151 ] Столичная полиция в конечном итоге оштрафовала Джонсона за нарушение правил блокировки в апреле 2022 года. [ 152 ] В июле 2022 года Джонсон признался, что назначил Криса Пинчера заместителем главного кнута, в то же время осознав обвинения в сексуальном насилии против него. [ 153 ] Это, наряду с PartyGate и растущей критикой в отношении справки Джонсона в отношении кризиса о стоимости жизни, спровоцировало государственный кризис после потери в доверии и почти 60 отставке со стороны правительственных чиновников, в конечном итоге приведя к тому, что Джонсон объявил о своей отставке 7 июля. [ 154 ] [ 155 ]

2022: Лиз Трусс

Преемник Бориса Джонсона в качестве лидера был подтвержден как Лиз Трусс 5 сентября после выборов на руководство . [ 156 ] В стратегии с надписью на трассейне она ввела политику в ответ на стоимость живого кризиса , [ 157 ] в том числе ограничивание цен на счета за электроэнергию и правительство помогает им платить. [ 158 ] Минипудрус , 23 сентября, с тяжелой критикой, и рынки отреагировали плохо; [ 159 ] Фунт упал до рекордного минимума 1,03 по отношению к доллару, а доходность правительства Великобритании выросла до 4,3 процента, что побудило Банк Англии запустить программу покупки чрезвычайных ситуаций. [ 160 ] [ 161 ] После осуждения со стороны общественности, лейбористской партии и ее собственной партии, Трусс изменил некоторые аспекты мини-бюджета, включая отмену высшей ставки подоходного налога. [ 162 ] [ 163 ] После государственной кризисной фермы объявила о своей отставке в качестве премьер -министра 20 октября [ 164 ] После 44 дней пребывания в должности самое короткое премьер -лиги в британской истории. [ 164 ] [ 165 ] Трусс также курировал худший опрос, который когда -либо получали консерваторы, при этом трудовые опросы на 36 процентов выше консерваторов среди кризиса. [ 166 ]

2022–2024: Риши Сунак

24 октября 2022 года Риши Сунак был объявлен лидером, первым британским азиатским лидером консерваторов и первым британским премьер -министром Азии. 22 мая Сунак объявил о всеобщих выборах, которые пройдут 4 июля 2024 года. [ 167 ]

Во время всеобщих выборов 2024 года общественное мнение в пользу изменения в правительстве было отражено плохим опросом Консервативной партии, когда реформа Великобритания добилась значительных результатов опроса. [ 168 ] Консервативный манифест был сосредоточен на экономике, налогах, благосостоянии, расширении свободного ухода за детьми, образования, здравоохранения, окружающей среды, энергии, транспорта и преступности. [ 169 ] [ 170 ] Он пообещал снизить налоги, увеличить образование и расходы на NHS, доставлять еще 92 000 медсестер и еще 28 000 докторов, внедряет новую модель национальной службы и для отслеживания морской мощности в Великобритании и поддержать солнечную энергию. [ 171 ] [ 172 ] Окончательным результатом стал самый низкий уровень места на всеобщих выборах в истории консервативной партии, причем значительно ниже предыдущего рекордного минимума 156 мест, выигранных на всеобщих выборах 1906 года . [ 173 ]

Политики

Экономическая политика

| Эта статья является частью серии на |

| Консерватизм в Великобритании |

|---|

|

Консервативная партия считает, что свободный рынок и индивидуальные достижения являются основными факторами экономического процветания. Ведущей экономической теорией, отстаиваемой консерваторами, является экономика на стороне предложения , которая утверждает, что снижение ставок подоходного налога увеличивает рост и предприятие (хотя снижение дефицита бюджета иногда приоритетно приоритетном сокращению налогов). [ 174 ] Партия фокусируется на экономике социального рынка , продвигая свободный рынок для конкуренции с социальным балансом для создания справедливости. Это включало реформу образования, реформу профессиональных навыков, расширение свободного ухода за детьми , ограничения в банковском секторе, корпоративные зоны для возрождения регионов в Великобритании, а также грандиозные и обширные инфраструктурные проекты, такие как высокоскоростная железная дорога. [ 175 ] [ 176 ]

Одна конкретная экономическая политика последних лет была противостоящей европейской единой валюте, евро . С растущим евроскептицизмом в своей партии Джон Майор договорился о британском отказах в договоре о Маастрихте 1992 года , который позволил Великобритании остаться в Европейском Союзе без принятия единой валюты. Все последующие консервативные лидеры твердо определили партию против принятия евро .

Высшая ставка подоходного налога на 50% была снижена до 45% коалицией консервативно -либеральных демократов. [ 177 ] Наряду с сокращением налогов и обязательств по поддержанию налогообложения низкой, консервативная партия значительно сократила государственные расходы благодаря программе экономии , которая началась в 2010 году, после финансового кризиса 2007–2008 годов . В 2019 году и во время избирательной кампании в том же году Борис Джонсон дал представление о том, что он устроил жесткую экономию с увеличением государственных расходов, в таких областях, как здравоохранение, образование, транспорт, социальное обеспечение и полицию. [ 178 ] [ 179 ]

Социальная политика

Социально консервативная политика, такая как налоговые льготы для супружеских пар, возможно, сыграли свою роль в снижении избирательных избирателей партии в 1990 -х и начале 2000 -х годов, и поэтому партия попыталась найти новое направление. В рамках своей коалиции с либеральными демократами консервативное правительство поддерживало введение равных прав брака для лиц ЛГБТ+ в 2010 году, хотя 139 консервативных депутатов, большинство, проголосовали против Закона о однополых браках 2013 года . Таким образом, степень, в которой эта политика представляет собой более либеральную консервативную партию, была оспорена. [ 186 ]

С 1997 года дебаты происходили в партии между «модернизаторами», такими как Алан Дункан , [ 187 ] кто считает, что консерваторы должны изменить свои государственные позиции по социальным вопросам и «традиционалистам», такие как Лиам Фокс [ 188 ] [ 189 ] и Оуэн Патерсон , [ 190 ] кто считает, что партия должна оставаться верной своей традиционной консервативной платформе. В предыдущем парламенте модернизирующие силы были представлены депутатами, такими как Нил О'Брайен , который утверждал, что партия должна обновить свою политику и имидж, и, как говорят, вдохновляется центристской политикой Макрона . [ 191 ] Рут Дэвидсон также рассматривается как фигура по реформированию. Многие из первоначальных «традиционалистов остаются влиятельными, хотя влияние Дункана Смита с точки зрения вкладов общего пользования уменьшилось. [ 192 ]

Партия сильно критиковала то, что она описывает как «государственный мультикультурализм » лейбористов. [ 193 ] Секретарь «Теневой дома Доминик Грив» заявил в 2008 году, что государственная политика мультикультурализма создала «ужасное» наследие «культурного отчаяния» и дислокации, которое поощряло поддержку «экстремистов» по обеим сторонам дебатов. [ 194 ] Дэвид Кэмерон отреагировал на комментарии Грива, согласившись с тем, что политика «государственного мультикультурализма», которая рассматривает социальные группы как отдельные, например, политику, которая «относится к британским мусульманам как к мусульманам, а не как к британским гражданам», ошибочны. Тем не менее, он выразил поддержку предпосылке мультикультурализма в целом. [ 194 ]

в ЕС и не в ЕС Официальная статистика показала, что иммиграция , а также приложения для просмотра убежища , все значительно увеличилось в течение срока полномочий Камерона в должности. [ 195 ] [ 196 ] [ 197 ] Тем не менее, это было не только в результате преднамеренной государственной политики - в течение этого периода в Великобритании наблюдались значительные потоки беженцев и повышенный уровень заявлений о предоставлении убежища из -за конфликта и преследования во всем мире. [ 198 ] [ 199 ] В 2019 году бывший консервативный министр внутренних дел Прити Патель объявил, что правительство проведет более строгие иммиграционные реформы, нарушит нелегальную иммиграцию и откладывает свободу движения с Европейским Союзом после завершения Brexit . [ 200 ] В течение четырех лет после этого объявления чистая миграция увеличивалась ежегодно, в значительной степени из -за количества работников здравоохранения и их иждивенцев, которые были приглашены в страну из -за проблем набора персонала, вызванных Brexit и пандемией. [ 201 ] [ 202 ] Число лиц, ищущих убежища, сократилось как доля общей чистой мигрантов, тогда как число людей, приезжающих в Великобританию для изучения, увеличилось в течение этого периода времени. [ 203 ]

Внешняя политика

На протяжении большей части 20 -го века Консервативная партия занимала широкую атлантическую позицию в отношениях с Соединенными Штатами , членами ЕС и НАТО , в пользу тесных связей с Соединенными Штатами и такими же людьми, как Канада , Австралия , Новая Зеландия , Южная Африка , Корея , Тайвань , Сингапур и Япония . Консерваторы, как правило, предпочитают широкий спектр международных альянсов, от Северной Атлантической организации (НАТО) до Содружества наций . Консерваторы предложили панафриканскую зону свободной торговли , которая, по ее словам, может помочь предпринимательскому динамизму африканского народа. [ 204 ] Консерваторы пообещали увеличить расходы на помощь до 0,7% национального дохода к 2013 году. [ 204 ] Они выполнили это обещание в 2014 году, когда расходы на помощь достигли 0,72% ВВП, и приверженность была закреплена в законе Великобритании в 2015 году. [ 205 ]

Близкие англо-американские отношения были элементом консервативной внешней политики со времен Второй мировой войны. Хотя англо -американские отношения в иностранных делах часто называют « особыми отношениями », термин, придуманное Уинстоном Черчиллем , это часто наблюдалось наиболее четко, когда лидеры в каждой стране имеют аналогичную политическую полосу. Дэвид Кэмерон стремился дистанцироваться от бывшего президента США Буша и его неоконсервативной внешней политики. [ 206 ] Несмотря на традиционные связи между британскими консерваторами и республиканцами США , мэр Лондона Борис Джонсон , консерватор, одобрил Барака Обаму на выборах 2008 года. [ 207 ] Однако, став премьер -министром, Джонсон установил тесные отношения с республиканцев президентом Дональдом Трампом . [ 208 ] [ 209 ] [ 210 ] Это также было описано как восстановление особых отношений с Соединенными Штатами после ухода Британии из Европейского Союза , а также возвращения к связям между консерваторами и республиканской партией. [ 211 ] Помимо отношений с Соединенными Штатами, Содружества и ЕС , Консервативная партия, как правило, поддержала профессиональную свободную политику в рамках международных дел.

Хотя позиции изменились с последовательным лидерством, современная консервативная партия, как правило, поддерживает сотрудничество и поддержание дружеских отношений с Израилем . Исторические консервативные государственные деятели, такие как Артур Бальфур и Уинстон Черчилль, поддержали идею национального дома для еврейского народа. При консервативной поддержке Маргарет Тэтчер поддержка Израиля кристаллизуется. [ 212 ] [ 213 ] Поддержка Израиля возросла под руководством Терезы Мэй и Бориса Джонсона , с выдающимися консервативными деятелями в министерствах мая и Джонсона, которые решительно одобряют Израиль. В 2016 году Тереза Мэй публично опровергла заявления, сделанные государственным секретарем США Джоном Керри из -за состава правительства Израиля. [ 214 ] [ 215 ] В 2018 году партия пообещала запретить все крылья ливанской боевой группы Hezbollah , и это было принято в качестве политики в Великобритании в 2019 году. [ 216 ] [ 217 ] В 2019 году консервативное правительство под руководством Бориса Джонсона объявило о планах остановить влияние движения бойкота, отказа и санкций на местную политику, которое включало запрещение местным советам бойкотировать израильские продукты. [ 218 ] [ 219 ] [ 220 ]

Оборонная политика

После террористических атак 11 сентября 2001 года Консервативная партия поддержала военные действия коалиции в Афганистане . Консервативная партия полагала, что успех в Афганистане будет определен с точки зрения афганцев, достигающих возможности поддерживать свою собственную внутреннюю и внешнюю безопасность. Они неоднократно раскритиковали бывшее лейбористское правительство за то, что они не смогли адекватно оборудовать британские силы в предыдущие дни в кампании, особенно подчеркивая нехватку вертолетов для британских сил, возникающих в результате сокращения Гордона Брауна на 1,4 млрд фунтов стерлингов до бюджета вертолета в 2004 году. [ 221 ]

Консервативная партия считает, что в 21 -м веке защита и безопасность взаимосвязаны. Он пообещал отказаться от проведения традиционного обзора стратегической обороны и приверженности проведению более комплексного стратегического обзора обороны и безопасности (SDSR). [ 222 ] Помимо SDSR, консервативная партия в 2010 году пообещала провести фундаментальный и далеко идущий обзор процесса закупок и того, как оборудование предоставляется в Великобритании и увеличить долю Великобритании на мировом рынке обороны в качестве государственной политики. [ 223 ]

Консервативная партия поддерживает мнение о том, что НАТО остается и должна оставаться наиболее важным альянсом безопасности для Великобритании. [ 224 ] Он выступал за создание более справедливого механизма финансирования для экспедиционных операций НАТО и призвал всех стран НАТО удовлетворить свои необходимые расходы на оборону 2% ВВП. Некоторые консерваторы считают, что есть возможности для расширения статьи V НАТО, чтобы включить новые угрозы, такие как кибербезопасность .

Консервативная партия стремится построить расширенные двусторонние оборонные отношения с ключевыми европейскими партнерами и считает, что в национальных интересах Британии в полной мере сотрудничать со всеми своими европейскими соседями. Он пообещал гарантировать, что любые военные возможности ЕС должны были дополнять, а не вытеснять британскую национальную оборону и НАТО , и что это не в британском интересах передать безопасность какого -либо наднационального органа. [ 225 ]

Консерваторы считают это приоритетом, чтобы побудить всех членов Европейского союза делать больше с точки зрения приверженности европейской безопасности дома и за рубежом. Что касается роли обороны Европейского союза, консерваторы пообещали пересмотреть некоторые из обязательств в Великобритании в ЕС по определению их практичности и полезности; В частности, для пересмотра положений об участии Великобритании, таких как постоянное структурированное сотрудничество, Европейское оборонительное агентство и битвы ЕС, чтобы определить, есть ли какая -либо ценность в участии Британии.

Консерваторы поддерживают владение ядерным оружием Великобритании в рамках ядерной программы Trident . [ 225 ]

Политика в области здравоохранения и наркотиков

В 1945 году консерваторы объявили поддержку универсальным здравоохранением. [ 226 ] Они ввели Закон о здравоохранении и социальной помощи 2012 года , составляющий самую большую реформацию, которую когда -либо предпринял NHS. [ 227 ]

Консервативная партия поддерживает запрет на наркотики . [ 228 ] Тем не менее, взгляды на наркотики варьируются среди некоторых депутатов в партии. Некоторые консервативные политики придерживаются либертарианского подхода, что индивидуальная свобода и экономическая свобода промышленности и торговли следует уважать по сравнению с запретом. Другие консервативные политики, несмотря на то, что они экономически либеральны , в пользу полного запрета на наркотики. Легализация каннабиса для медицинского использования предполагается некоторыми консервативными политиками. [ 229 ] Сторона отклонила как декриминализацию лекарств для личного использования, так и создание мест безопасного потребления . [ 230 ] В 2024 году консерваторы запретили курить для будущих поколений, с целью сделать Англию свободной от дыма к 2030 году. [ 231 ]

Образование и исследования

В образовании консерваторы пообещали рассмотреть национальную учебную программу , представить английский бакалавриат и реформировать GCSE , A-уровни , другие национальные квалификации, ученичество и обучение. [ 232 ] Восстановление дисциплины также было выделено, так как они хотят, чтобы ученикам было проще искать контрабанды, предоставление анонимности учителям, обвиняемым ученикам, и запрет изгнанных учеников, возвращаемых в школы через апелляционные панели.

В высшем образовании консерваторы увеличили плату за обучение до 9 250 фунтов стерлингов в год, однако гарантировали, что это никому не будет выплачено, пока они не заработают более 25 000 фунтов стерлингов. Шотландские консерваторы также поддерживают повторное введение платы за обучение в Шотландии. В 2016 году консервативное правительство расширило доступ к студенческим кредитам в Англии на студенты аспирантов, чтобы помочь улучшить доступ к образованию. [ 233 ]

В рамках ЕС Великобритания была одним из крупнейших получателей финансирования исследований в Европейском Союзе , получив 7 миллиардов фунтов стерлингов в период с 2007 по 2015 год, который инвестирует в университеты и исследовательские предприятия. [ 234 ] После голосования по выходу из ЕС премьер -министр Тереза может гарантировать, что консервативное правительство защитит финансирование для существующих проектов исследований и разработок в Великобритании. [ 235 ] В 2017 году консерваторы ввели квалификацию уровня Т , направленную на улучшение обучения и управления техническим образованием. [ 236 ]

Семейная политика

Будучи премьер -министром, Дэвид Кэмерон хотел «поддержать семейную жизнь в Британии» и поставить семьи в центр внутренней социальной политики. [ 237 ] В 2014 году он заявил, что в консервативной миссии «Строительное общество снизу вверх» не было «лучшего места», чем семья, которая отвечала за индивидуальное благосостояние и благополучие задолго до того, как государство всеобщего благосостояния вступило в игру. [ 237 ] Он также утверждал, что «семья и политика неразрывно связаны». [ 237 ] И Кэмерон, и Тереза Мэй нацелились на то, чтобы помочь семьям достичь баланса домохозяйства и ранее предложили предложить всем родителям 12 месяцев отпуска по вопросам родителей, которые родители разделяют по мере их выбора. [ 238 ] Эта политика в настоящее время действует, предлагая общий отпуск по уходу за ребенком на 50 недель, из которых 37 недель оплачивается отпуск, который можно разделить между обоими родителями. [ 239 ]

Другие политики включали удвоение свободных часов ухода за детьми для рабочих родителей от трех и четырехлетних детей с 15 часов до 30 часов в неделю в течение срока действия, хотя родители могут сократить количество часов в неделю и распространяться по 52 годам. недели года. Правительство также ввело политику по финансированию 15 часов в неделю бесплатного образования и ухода за детьми для 2-летних детей в Англии, если родители получают определенные государственные льготы, или у ребенка есть заявление или диагноз SE в SEN на сумму 2500 фунтов стерлингов в год на ребенка. [ 240 ] [ 241 ]

Политика рабочих мест и социального обеспечения

Одна из ключевых политических целей консерваторов в 2010 году состояла в том, чтобы сократить количество безработных людей и увеличить количество людей в рабочей силе, укрепляя ученичество, навыки и трудоустройство. [ 242 ] В период с 2010 по 2014 год все заявители о пособии по неспособности были перенесены на новую схему пособий, пособие по трудоустройству и поддержке , которая затем была включена в универсальную кредитную систему наряду с другими преимуществами социального обеспечения в 2018 году. [ 243 ] [ 244 ] [ 245 ] Универсальная кредитная система попала под огромный анализ после ее введения. Вскоре после назначения в Департамент на работу и пенсии тогдашний секретарь Амбер Радд признала, что существуют реальные проблемы с универсальной кредитной системой, особенно время ожидания для первоначальных платежей и аспекта жилищных платежей. [ 246 ] Рудд пообещал специально рассмотреть и рассмотреть неравномерное влияние универсального реализации кредитов на экономически неблагоприятного женщин, что было предметом многочисленных отчетов Радио 4, программа « Вы» и «Программа» и другие. [ 246 ]

До 1999 года консерваторы выступали против создания национальной минимальной заработной платы , поскольку, по их мнению, это будет стоить рабочие места, и предприятия неохотно начинают бизнес в Великобритании от страха перед высокими затратами на рабочую силу. [ 247 ] Однако с тех пор партия пообещала поддержку, и в бюджете в июле 2015 года канцлер Джордж Осборн объявил о национальной заработной плате в 9 фунтов стерлингов в час. [ 248 ] Национальная минимальная заработная плата в 2024 году составила 11,44 фунтов стерлингов для тех, кто старше 21 года. [ 249 ] Поддержка партии и реализация, восстановление связи между пенсиями и доходами, и стремиться к повышению пенсионного возраста с 65 до 67 к 2028 году. [ 250 ]

Политика в области энергетики и изменения климата

Дэвид Кэмерон выдвинул несколько « зеленых » проблем на передний план своей кампании 2010 года. Они включали предложения, предназначенные для налога на парковочные места на рабочем месте, остановку роста в аэропорту, налог на автомобили с исключительно плохим пробезом бензина и ограничениями на автомобильную рекламу. Многие из этих политик были реализованы в коалиции, включая « зеленую сделку ». [ 251 ] В 2019 году был принят закон о том, что к 2050 году выбросы парниковых газов в Великобритании будут чистыми . [ 252 ] Великобритания была первой крупной экономикой, которая приняла юридическое обязательство по достижению чистого нулевого выбросов углерода. [ 253 ]

В 2019 году консерваторы стали первым национальным правительством в мире, которое официально объявило о чрезвычайной ситуации в климате (второе место в Великобритании после SNP ) . [ 252 ] В ноябре 2020 года консерваторы объявили о 10-балльном плане «зеленой промышленной революции», с зелеными предприятиями , что является окончанием продажи бензиновых и дизельных автомобилей, что в четыре раза увеличило количество мощности морской ветры в течение десятилетия, финансируйте разнообразие предложений по выбросам, и отвергнутую предложенное зеленое пост-ковид-19 восстановление . [ 254 ] В 2021 году консерваторы объявили о планах сократить выбросы углерода на 78% к 2035 году. [ 255 ]

Политика правосудия, преступления и безопасности

В 2010 году консерваторы провели кампанию по сокращению предполагаемой бюрократии современных полицейских сил и пообещали большую правовую защиту людей, осужденных за защиту себя от злоумышленников.

The party has also campaigned for the creation of a UK Bill of Rights to replace the Human Rights Act 1998, but this was vetoed by their coalition partners the Liberal Democrats.[256] The Conservatives' 2017 manifesto pledged to create a national infrastructure police force, subsuming the existing British Transport Police; Civil Nuclear Constabulary; and Ministry of Defence Police "to improve the protection of critical infrastructure such as nuclear sites, railways and the strategic road network".[257]

Transport and infrastructure policy

The Conservatives have invested in public transport and infrastructure, aimed to promoting economic growth.[258] This has included rail (including high-speed rail), electric vehicles, bus networks, and active transport.[259]

In 2020, new funding for active travel infrastructure was announced by the Conservatives.[260] The party's stated aim was for England to be a "great walking and cycling nation" and for half of all journeys in towns and cities being walked or cycled by 2030. The plan was accompanied by £2 billion in additional funding over the following five years for cycling and walking. The plan also introduced new inspectorate, known as Active Travel England.[261][262]

In 2021, the Conservatives announced a white paper that would transform the operation of the railways. The rail network will be partly renationalised, with infrastructure and operations brought together under the state-owned public body Great British Railways.[263] On 18 November 2021, the government announced the biggest ever public investment in Britain's rail network costing £96 billion and promising quicker and more frequent rail connections in the North and Midlands: the Integrated Rail Plan includes substantially improved connections North-South as well as East-West and includes three new high speed lines.[264][265]

European Union policy

No subject has proved more divisive in the Conservative Party in recent history than the role of the United Kingdom within the European Union. Though the principal architect of the UK's entry into the European Communities (which became the European Union) was Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath, most contemporary Conservative opinion is opposed to closer economic and particularly political union with the EU. This is a noticeable shift in British politics, as in the 1960s and 1970s the Conservatives were more pro-Europe than the Labour Party: for example, in the 1971 House of Commons vote on whether the UK should join the European Economic Community, only 39 of the then 330 Conservative MPs were opposed.[266][267]

The Conservative Party has members with varying opinions of the EU, with pro-European Conservatives joining the affiliate Conservative Group for Europe, while some Eurosceptics left the party to join the United Kingdom Independence Party. Whilst the vast majority of Conservatives in recent decades have been Eurosceptics, views among this group regarding the UK's relationship with the EU have been polarised between moderate, soft Eurosceptics who support continued British membership but oppose further harmonisation of regulations affecting business and accept participation in a multi-speed Europe, and a more radical, economically libertarian faction who oppose policy initiatives from Brussels, support the rolling back of integration measures from the Maastricht Treaty onwards, and have become increasingly supportive of a complete withdrawal.[266]

Constitutional policy

Traditionally the Conservative Party has supported the uncodified constitution of the United Kingdom and its traditional Westminster system of politics. The party opposed many of Tony Blair's reforms, such as the removal of the hereditary peers,[268] the incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into British law, and the 2009 creation of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, a function formerly carried out by the House of Lords.

There was also a split on whether to introduce a British Bill of Rights that would replace the Human Rights Act 1998; David Cameron expressed support, but party grandee Ken Clarke described it as "xenophobic and legal nonsense".[269]

In 2019, the Conservatives' manifesto committed to a broad constitutional review in a line which read "after Brexit we also need to look at the broader aspects of our constitution: the relationship between the government, parliament and the courts".[270]

Organisation

Party structure

The Conservative Party comprises the voluntary party, parliamentary party (sometimes called the political party) and the professional party.

Members of the public join the party by becoming part of a local constituency Conservative Association.[271] The country is also divided into regions, with each region containing a number of areas, both having a similar structure to constituency associations. The National Conservative Convention sets the voluntary party's direction. It is composed of all association chairs, officers from areas and regions, and 42 representatives and the Conservative Women's Organisation.[272] The Convention meets twice a year. Its Annual General Meeting is usually held at Spring Forum, with another meeting usually held at the Conservative Party Conference. In the organisation of the Conservative Party, constituency associations dominate selection of local candidates, and some associations have organised open parliamentary primaries.

The 1922 Committee consists of backbench MPs, meeting weekly while parliament is sitting. Frontbench MPs have an open invitation to attend. The 1922 Committee plays a crucial role in the selection of party leaders. All Conservative MPs are members of the 1922 Committee by default. There are 20 executive members of the committee, agreed by consensus among backbench MPs.

The Conservative Campaign Headquarters (CCHQ) is effectively head of the Professional Party and leads financing, organisation of elections and drafting of policy.

The Conservative Party Board is the party's ultimate decision-making body, responsible for all operational matters (including fundraising, membership and candidates) and is made up of representatives from each (voluntary, political and professional) section of the Party.[272] The Party Board meets about once a month and works closely with CCHQ, elected representatives and the voluntary membership mainly through a number of management sub-committees (such as membership, candidates and conferences).

Membership

Membership peaked in the mid-1950s at approximately 3 million, before declining steadily through the second half of the 20th century.[275] Despite an initial boost shortly after David Cameron's election as leader in December 2005, membership resumed its decline in 2006 to a lower level than when he was elected. In 2010, the Conservative Party had about 177,000 members according to activist Tim Montgomerie,[276] and in 2013 membership was estimated by the party itself at 134,000.[277] The Conservative Party had a membership of 124,000 in March 2018.[278] In May 2019, its membership was thought to be around 160,000, with over half of its members being over 55.[279][280] Its membership rose to 200,000 in March 2021.[281] In July 2022 it had 172,437 members.[4]

The membership fee for the Conservative Party is £25, or £5 if the member is under the age of 23.

Prospective parliamentary candidates

Associations select their constituency's candidates.[271][282] Some associations have organised open parliamentary primaries. A constituency Association must choose a candidate using the rules approved by, and (in England, Wales and Northern Ireland) from a list established by, the Committee on Candidates of the Board of the Conservative Party.[283] Prospective candidates apply to the Conservative Central Office to be included on the approved list of candidates, some candidates will be given the option of applying for any seat they choose, while others may be restricted to certain constituencies.[284][285] A Conservative MP can only be deselected at a special general meeting of the local Conservative association, which can only be organised if backed by a petition of more than fifty members.[284]

Young Conservatives

Young Conservatives is the youth wing of the Conservative Party for members aged 25 and under. The organisation aims to increase youth ownership and engagement in local associations.[286] From 1998 to 2015, the youth wing was called Conservative Future, and had branches at universities and at parliamentary constituency level. It was shut down in 2015 after allegations that bullying by Mark Clarke had caused the suicide of Elliot Johnson, a 21-year-old party activist.[287][288][289] The current incarnation was launched in March 2018.

Conferences

The major annual party events are the Spring Forum and the Conservative Party Conference, which takes place in Autumn in alternately Manchester or Birmingham. This is when the National Conservative Convention holds meetings.

Funding

In the first decade of the 21st century, half the party's funding came from a cluster of fifty "donor groups", and a third of it from only fifteen.[290] In the year after the 2010 general election, half the Conservatives' funding came from the financial sector.[291]

For 2013, the Conservative Party had an income of £25.4 million, of which £749,000 came from membership subscriptions.[292] In 2015, according to accounts filed with the Electoral Commission, the party had an income of about £41.8 million and expenditures of about £41 million.[293]

Construction businesses, including the Wates Group and JCB, have also been significant donors to the party, contributing £430,000 and £8.1m respectively between 2007 and 2017.[294]

The Advisory Board of the party represents donors who have given significant sums to the party, typically in excess of £250,000.[295]

In December 2022 The Guardian reported 10% of Conservative peers were large party donors and gave nearly £50m in total. 27 out of the party's 274 peers had given over £100,000 to the Conservatives. At least 6 large donor peers got government jobs in the 10 years to 2022.[296]

Financial ties to Russian oligarchs

The Conservative Party has received funding from Russian oligarchs, beginning in the early 2000s, for which it has been criticised.[297][298] Scrutiny became more prominent after alleged interference in the 2016 Brexit referendum by the Kremlin to support the Vote Leave campaign, and increased after the Intelligence and Security Committee Russia report into Russian interference in British politics was published in July 2020. Concerns over Conservative Party funds have become increasingly controversial due to Vladimir Putin's human rights abuses and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[299]

One of the first was Lubov Chernukhin, wife of former deputy finance minister and investment company VEB.RF founder Vladmir Chernukhin, who had donated north of £2.2 million as of the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[300][301] Donations to British political parties is only legal for citizens; the individuals who donated to the party had dual UK-Russian citizenship, and the donations were legal and properly declared.[302] However, an investigation conducted by The New York Times shortly after the invasion of Ukraine determined that a £399,810 donation made by British-Israeli businessman Ehud Sheleg in 2018 was in fact given directly to him by his father-in-law, Russian oligarch Sergei Kopytov. Kopytov, a former minister in Russian-occupied Crimea, has strong ties to Vladimir Putin's government.[297] Barclays Bank reported that in January 2021, they "[traced] a clear line back from this donation to its ultimate source", and reported it accordingly to the National Crime Agency.[297]

An investigation by the Good Law Project found that in spite of Johnson's claims that donations from those with links to the Russian government was to stop,[299] since the start of the war, the Conservatives have accepted at least £243,000 from Russia and Kremlin-associated donors.[303] In February 2022, the Labour Party used Electoral Commission information to calculate that donors who had made money from Russia or Russians had given £1.93m to either the Conservative party or constituency associations since Boris Johnson's premiership began.[304] Then-party leader Liz Truss said that the donations would not be returned, stating that they had been "properly declared".[305]

International organisations

The Conservative Party is a member of a number of international organisations, most notably the International Democracy Union which unites right-wing parties including the United States Republican Party, the Liberal Party of Australia, the Conservative Party of Canada and the South Korean People Power Party.

At a European level, the Conservatives are members of the European Conservatives and Reformists Party (ECR Party), which unites conservative parties in opposition to a federal European Union, through which the Conservatives have ties to the Ulster Unionist Party and the governing parties of Israel and Turkey, Likud and the Justice and Development Party respectively. In the European Parliament, the Conservative Party's MEPs sat in the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR Group), which is affiliated to the ACRE. Party leader David Cameron pushed the foundation of the ECR, which was launched in 2009, along with the Czech Civic Democratic Party and the Polish Law and Justice, before which the Conservative Party's MEPs sat in the European Democrats, which had become a subgroup of the European People's Party in the 1990s. Since the 2014 European election, the ECR Group has been the third-largest group, with the largest members being the Conservatives (nineteen MEPs), Law and Justice (eighteen MEPs), the Liberal Conservative Reformers (five MEPs), and the Danish People's Party and New Flemish Alliance (four MEPs each). In June 2009, The Conservatives required a further four partners apart from the Polish and Czech supports to qualify for official fraction status in the parliament; the rules state that a European parliamentary caucus requires at least 25 MEPs from at least seven of the 27 EU member states.[306] In forming the caucus, the party broke with two decades of co-operation by the UK's Conservative Party with the mainstream European Christian Democrats and conservatives in the European parliament, the European People's Party (EPP). It did so on the grounds that it is dominated by European federalists and supporters of the Lisbon treaty, which the Conservatives were generally highly critical of.[306]

Logo

When Sir Christopher Lawson was appointed as a marketing director at Conservative Central Office in 1981, he developed a logo design based on the Olympic flame in the colours of the Union Jack,[307] which was intended to represent leadership, striving to win, dedication, and a sense of community.[308] The emblem was adopted for the 1983 general election.[307] In 1989, the party's director of communications, Brendan Bruce, found through market research that recognition of the symbol was low and that people found it old fashioned and uninspiring. Using a design company headed by Michael Peters, an image of a hand carrying a torch was developed, which referenced the Statue of Liberty.[309]

In 2006, there was a rebranding exercise to emphasise the Conservatives' commitment to environmentalism; a project costing £40,000 resulted in a sketched silhouette of an oak tree, a national symbol, which was said to represent "strength, endurance, renewal and growth".[310] A change from green to the traditional Conservative blue colour appeared in 2007,[311] followed by a version with the Union Jack superimposed in 2010.[312] An alternative version featuring the colours of the Rainbow flag was unveiled for an LGBT event at the 2009 conference in Manchester.[313]

Party factions

The Conservative Party has a variety of internal factions or ideologies, including one-nation conservatism,[314][315] Christian democracy,[316] social conservatism, Thatcherism, traditional conservatism, neoconservatism,[317][318] Euroscepticism,[319] and, since 2016, right-wing populism.[20][320]

One-nation Conservatives

| Part of the Conservatism series |

| One-nation conservatism |

|---|

One-nation conservatism was the party's dominant ideology in the 20th century until the rise of Thatcherism in the 1970s. It has included in its ranks Conservative Prime Ministers such as Stanley Baldwin, Harold Macmillan and Edward Heath.[321] One-nation Conservatives in the contemporary party include former First Secretary of State Damian Green, the current chair of the One Nation Conservatives caucus.

The name itself comes from a famous phrase of Disraeli. Ideologically, one-nation conservatism identifies itself with a broad paternalistic conservative stance. One-nation Conservatives are often associated with the Tory Reform Group and the Bow Group. Adherents believe in social cohesion and support social institutions that maintain harmony between different interest groups, classes, and—more recently—different races or religions. These institutions have typically included the welfare state, the BBC, and local government.

One-nation Conservatives often invoke Edmund Burke and his emphasis on civil society ("little platoons") as the foundations of society, as well as his opposition to radical politics of all types. The Red Tory theory of Phillip Blond is a strand of the one-nation school of thought; prominent Red Tories include former Cabinet Ministers Iain Duncan Smith and Eric Pickles and Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State Jesse Norman.[322] There is a difference of opinion among supporters regarding the European Union. Some support it perhaps stemming from an extension of the cohesion principle to the international level, though others are strongly against the EU (such as Peter Tapsell).

Free-market Conservatives

The "free-market wing" of economic liberals achieved dominance after the election of Margaret Thatcher as party leader in 1975. Their goal was to reduce the role of the government in the economy and to this end, they supported cuts in direct taxation, the privatisation of nationalised industries and a reduction in the size and scope of the welfare state. Supporters of the "free-market wing" have been labelled as "Thatcherites". The group has disparate views of social policy: Thatcher herself was socially conservative and a practising Anglican but the free-market wing in the Conservative Party harbour a range of social opinions from the civil libertarian views of Michael Portillo, Daniel Hannan, and David Davis to the traditional conservatism of former party leaders William Hague and Iain Duncan Smith. The Thatcherite wing is also associated with the concept of a "classless society".[323]

Whilst a number of party members are pro-European, some free-marketeers are Eurosceptic, perceiving most EU regulations as interference in the free market and/or a threat to British sovereignty. EU centralisation also conflicts with the localist ideals that have grown in prominence within the party in recent years. Rare Thatcherite Europhiles included Leon Brittan. Many take inspiration from Thatcher's Bruges speech in 1988, in which she declared that "we have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain only to see them reimposed at a European level". A number of free-market Conservatives have signed the Better Off Out pledge to leave the EU.[324] Thatcherites and economic liberals in the party tend to support Atlanticism, something exhibited between Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

Thatcher herself claimed philosophical inspiration from the works of Burke and Friedrich Hayek for her defence of liberal economics. Groups associated with this tradition include the No Turning Back Group and Conservative Way Forward, whilst Enoch Powell and Keith Joseph are usually cited as early influences in the movement.[325] Some free-market supporters and Christian Democrats within the party tend to advocate the Social Market Economy, which supports free markets alongside social and environmental responsibility, as well a welfare state. Joseph was the first to introduce the model idea into British politics, writing the publication: Why Britain needs a Social Market Economy.

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Toryism |

|---|

|

Traditionalist Conservatives

This socially conservative right-wing grouping is currently associated with the Cornerstone Group (or Faith, Flag and Family), and is the oldest tradition within the Conservative Party, closely associated with High Toryism. The name stems from its support for three social institutions: the Church of England, the unitary British state and the family. To this end, it emphasises the country's Anglican heritage, oppose any transfer of power away from the United Kingdom—either downwards to the nations and regions or upwards to the European Union—and seek to place greater emphasis on traditional family structures to repair what it sees as a broken society in the UK. It is a strong advocate of marriage and believes the Conservative Party should back the institution with tax breaks and have opposed the alleged assaults on both traditional family structures and fatherhood.[326]

Prominent MPs from this wing of the party include Andrew Rosindell, Edward Leigh and Jacob Rees-Mogg—the latter two being prominent Roman Catholics, notable in a faction marked out by its support for the established Church of England.

Relationships between the factions

Sometimes two groupings have united to oppose the third. Both Thatcherite and traditionalist Conservatives rebelled over Europe (and in particular Maastricht) during John Major's premiership; and traditionalist and One Nation MPs united to inflict Margaret Thatcher's only major defeat in Parliament, over Sunday trading.

Not all Conservative MPs can be easily placed within one of the above groupings. For example, John Major was the ostensibly "Thatcherite" candidate during the 1990 leadership election, but he consistently promoted One-Nation Conservatives to the higher reaches of his cabinet during his time as Prime Minister. These included Kenneth Clarke as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Michael Heseltine as Deputy Prime Minister.[327]

Electoral performance and campaigns

National campaigning within the Conservative Party is fundamentally managed by the CCHQ campaigning team, which is part of its central office[328] However, it also delegates local responsibility to Conservative associations in the area, usually to a team of Conservative activists and volunteers[328] in that area, but campaigns are still deployed from and thus managed by CCHQ National campaigning sometimes occurs in-house by volunteers and staff at CCHQ in Westminster.[329]

The Voter Communications Department is line-managed by the Conservative Director of Communications who upholds overall responsibility, though she has many staff supporting her, and the whole of CCHQ at election time, her department being one of the most predominant at this time, including project managers, executive assistants, politicians, and volunteers.[330] The Conservative Party also has regional call centres and VoteSource do-it-from-home accounts.

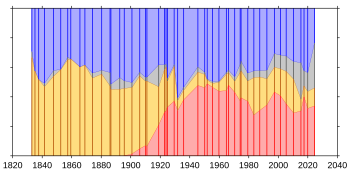

UK general election results

This chart shows the electoral performance of the Conservative Party in each general election since 1835.[331][332]

For all election results, including: devolved elections, London elections, Police and Crime Commissioner elections, combined authority elections and European Parliament elections see: Electoral history of the Conservative Party (UK)

For results of the Tories, the party's predecessor, see here.

| Election | Leader | Votes | Seats | Position | Government | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Share | No. | ± | Share | ||||

| 1835 | Robert Peel | 261,269 | 40.8% | 273 / 658

|

41.5% | Whig | ||

| 1837 | 379,694 | 48.3% | 314 / 658

|

47.7% | Whig | |||

| 1841 | 379,694 | 56.9% | 367 / 658

|

55.8% | Conservative[a] | |||

| 1847 | Earl of Derby | 205,481 | 42.7% | 325 / 656 [b]

|

49.5% | Whig[c] | ||

| 1852 | 311,481 | 41.9% | 330 / 654 [b]

|

50.5% | Conservative minority[d] | |||

| 1857 | 239,712 | 34.0% | 264 / 654

|

40.4% | Whig[e] | |||

| 1859 | 193,232 | 34.3% | 298 / 654

|

45.6% | Conservative minority[f] | |||

| 1865 | 346,035 | 40.5% | 289 / 658

|

43.9% | Liberal[g] | |||

| 1868[fn 1] | Benjamin Disraeli | 903,318 | 38.4% | 271 / 658

|

41.2% | Liberal | ||

| 1874 | 1,091,708 | 44.3% | 350 / 652

|

53.7% | Conservative | |||

| 1880 | 1,462,351 | 42.5% | 237 / 652

|

36.3% | Liberal[h] | |||

| 1885[fn 2] | Marquess of Salisbury | 1,869,560 | 43.4% | 247 / 670

|

36.9% | Conservative minority[i] | ||

| 1886 | 1,417,627 | 51.4% | 393 / 670

|

58.7% | Conservative–Liberal Unionist | |||

| 1892 | 2,028,586 | 47.0% | 314 / 670

|

46.9% | Conservative minority[j] | |||

| 1895 | 1,759,484 | 49.3% | 411 / 670

|

61.3% | Conservative–Liberal Unionist | |||

| 1900 | 1,637,683 | 50.2% | 402 / 670

|

60.0% | Conservative–Liberal Unionist[k] | |||

| 1906 | Arthur Balfour | 2,278,076 | 43.4% | 156 / 670

|

23.3% | Liberal | ||

| January 1910 | 2,919,236 | 46.8% | 272 / 670

|

40.6% | Liberal minority | |||

| December 1910 | 2,270,753 | 46.6% | 271 / 670

|

40.5% | Liberal minority | |||

| Merged with Liberal Unionist Party in 1912 to become the Conservative and Unionist Party | ||||||||

| 1918[fn 3] | Bonar Law | 4,003,848 | 38.4% | 379 / 707 332 elected with Coupon

|

53.6% | Coalition Liberal–Conservative | ||

| 1922 | 5,294,465 | 38.5% | 344 / 615

|

55.9% | Conservative | |||

| 1923 | Stanley Baldwin | 5,286,159 | 38.0% | 258 / 625

|

41.3% | Conservative minority[l] | ||

| 1924 | 7,418,983 | 46.8% | 412 / 615

|

67.0% | Conservative | |||

| 1929[fn 4] | 8,252,527 | 38.1% | 260 / 615

|

42.3% | Labour minority | |||

| 1931 | 11,377,022 | 55.0% | 470 / 615

|

76.4% | Conservative–Liberal–National Labour | |||

| 1935 | 10,025,083 | 47.8% | 386 / 615

|

62.8% | Conservative–Liberal National–National Labour | |||

| 1945 | Winston Churchill | 8,716,211 | 36.2% | 197 / 640

|

30.8% | Labour | ||

| 1950 | 11,507,061 | 40.0% | 282 / 625

|

45.1% | Labour | |||

| 1951 | 13,724,418 | 48.0% | 302 / 625

|

48.3% | Conservative–National Liberal | |||

| 1955 | Anthony Eden | 13,310,891 | 49.7% | 324 / 630

|

51.4% | Conservative–National Liberal | ||

| 1959 | Harold Macmillan | 13,750,875 | 49.4% | 345 / 630

|

54.8% | Conservative–National Liberal | ||

| 1964 | Alec Douglas-Home | 12,002,642 | 43.4% | 298 / 630

|

47.3% | Labour | ||

| 1966 | Edward Heath | 11,418,455 | 41.9% | 250 / 630

|

39.7% | Labour | ||

| 1970[fn 5] | 13,145,123 | 46.4% | 330 / 630

|

52.4% | Conservative | |||

| February 1974 | 11,872,180 | 37.9% | 297 / 635

|

46.8% | Labour minority | |||

| October 1974 | 10,462,565 | 35.8% | 277 / 635

|

43.6% | Labour | |||

| 1979 | Margaret Thatcher | 13,697,923 | 43.9% | 339 / 635

|

53.4% | Conservative | ||

| 1983 | 13,012,316 | 42.4% | 397 / 650

|

61.1% | Conservative | |||

| 1987 | 13,760,935 | 42.2% | 376 / 650

|

57.8% | Conservative | |||

| 1992 | John Major | 14,093,007 | 41.9% | 336 / 651

|

51.6% | Conservative | ||

| 1997 | 9,600,943 | 30.7% | 165 / 659

|

25.0% | Labour | |||

| 2001 | William Hague | 8,357,615 | 31.7% | 166 / 659

|

25.2% | Labour | ||

| 2005 | Michael Howard | 8,785,941 | 32.4% | 198 / 646

|

30.7% | Labour | ||

| 2010 | David Cameron | 10,704,647 | 36.1% | 306 / 650

|

47.1% | Conservative–Liberal Democrats | ||

| 2015 | 11,334,920 | 36.9% | 330 / 650

|

50.8% | Conservative | |||

| 2017 | Theresa May | 13,632,914 | 42.3% | 317 / 650

|

48.8% | Conservative minority with DUP confidence and supply | ||

| 2019 | Boris Johnson | 13,966,451 | 43.6% | 365 / 650

|

56.2% | Conservative | ||

| 2024 | Rishi Sunak | 6,814,650 | 23.7% | 121 / 650

|

18.6% | Labour | ||

Notes

- ^ Majority government (1841-1846); Opposition (1846-1847).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Includes Peelites