Франция в средние века

Эта статья имеет несколько вопросов. Пожалуйста, помогите улучшить его или обсудить эти вопросы на странице разговоров . ( Узнайте, как и когда удалить эти сообщения )

|

Королевство Франции Reaume de France Роялме де Франс | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

Motto:

| |||||||||

The Kingdom of France in 1000 | |||||||||

The Kingdom of France in 1190. The bright green area was controlled by the so-called Angevin Empire. | |||||||||

| Capital | Paris | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||

| King of France | |||||||||

| Legislature | Estates General (since 1302) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Beginning of Capetian dynasty | 987 | ||||||||

| 1337–1453 1422 | |||||||||

| c. 15th century | |||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | FR | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Topics |

|

|

Королевство Франция в средние века (примерно с 10 -го века до середины 15 -го века) было отмечено фрагментацией Каролианской империи и Вест Франции (843–987); Расширение Королевского контроля Домом Капет (987–1328), включая их борьбу с практически независимыми княжествами (герцогствами и округами, такими как нормандские и ангевинские регионы), а также создание и расширение административного/государственного контроля (особенно Под Филиппом II Августом и Луи IX ) в 13 веке; и рост Дома Валуа (1328–1589), включая длительный династический кризис против Палаты Плантагенета и их империи Ангевина , кульминацией которого стал сотнялетняя война (1337–1453) (составлена катастрофической черной смертью в 1348 году (1337–1453 ), которые уложили семена для более централизованного и расширенного состояния в ранний современный период и создание чувства французской идентичности.

Up to the 12th century, the period saw the elaboration and extension of the seigneurial economic system (including the attachment of peasants to the land through serfdom); the extension of the Feudal system of political rights and obligations between lords and vassals; the so-called "feudal revolution" of the 11th century during which ever smaller lords took control of local lands in many regions; and the appropriation by regional/local seigneurs of various administrative, fiscal and judicial rights for themselves. From the 13th century on, the state slowly regained control of a number of these lost powers. The crises of the 13th and 14th centuries led to the convening of an advisory assembly, the Estates General, and also to an effective end to serfdom.

From the 12th and 13th centuries on, France was at the center of a vibrant cultural production that extended across much of western Europe, including the transition from Romanesque architecture to Gothic architecture and Gothic art; the foundation of medieval universities (such as the universities of Paris (recognized in 1150), Montpellier (1220), Toulouse (1229), and Orleans (1235)) and the so-called "Renaissance of the 12th century"; a growing body of secular vernacular literature (including the chanson de geste, chivalric romance, troubadour and trouvère poetry, etc.) and medieval music (such as the flowering of the Notre Dame school of polyphony).

Geography

[edit]From the Middle Ages onward, French rulers believed their kingdoms had natural borders: the Pyrenees, the Alps and the Rhine. This was used as a pretext for an aggressive policy and repeated invasions.[1] The belief, however, had mere basis in reality for not all of these territories were part of the Kingdom and the authority of the King within his kingdom would be quite fluctuant. The lands that composed the Kingdom of France showed great geographical diversity; the northern and central parts enjoyed a temperate climate while the southern part was closer to the Mediterranean climate. While there were great differences between the northern and southern parts of the kingdom there were equally important differences depending on the distance of mountains: mainly the Alps, the Pyrenees and the Massif Central. France had important rivers that were used as waterways: the Loire, the Rhône, the Seine as well as the Garonne. These rivers were settled earlier than the rest and important cities were founded on their banks but they were separated by large forests, marsh, and other rough terrains.[1]

Before the Romans conquered Gaul, the Gauls lived in villages organised in wider tribes. The Romans referred to the smallest of these groups as pagi and the widest ones as civitates.[1] These pagi and civitates were often taken as a basis for the imperial administration and would survive up to the middle-ages when their capitals became centres of bishoprics. These religious provinces would survive until the French revolution.[1] During the Roman Empire, southern Gaul was more heavily populated and because of this more episcopal sees were present there at first while in northern France they shrank greatly in size because of the barbarian invasions and became heavily fortified to resist the invaders.[1]

Discussion of the size of France in the Middle Ages is complicated by distinctions between lands personally held by the king (the "domaine royal") and lands held in homage by another lord. The notion of res publica inherited from the Roman province of Gaul was not fully maintained by the Frankish kingdom and the Carolingian Empire, and by the early years of the Direct Capetians, the French kingdom was more or less a fiction. The "domaine royal" of the Capetians was limited to the regions around Paris, Bourges and Sens. The great majority of French territory was part of Aquitaine, the Duchy of Normandy, the Duchy of Brittany, the Comté of Champagne, the Duchy of Burgundy, the County of Flanders and other territories (for a map, see Provinces of France). In principle, the lords of these lands owed homage to the French king for their possession, but in reality the king in Paris had little control over these lands, and this was to be confounded by the uniting of Normandy, Aquitaine and England under the Plantagenet dynasty in the 12th century.

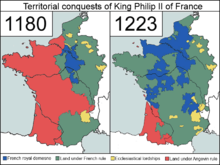

Philip II Augustus undertook a massive French expansion in the 13th century, but most of these acquisitions were lost both by the royal system of "apanage" (the giving of regions to members of the royal family to be administered) and through losses in the Hundred Years' War. Only in the 15th century would Charles VII and Louis XI gain control of most of modern-day France (except for Brittany, Navarre, and parts of eastern and northern France).

The weather in France and Europe in the Middle Ages was significantly milder than during the periods preceding or following it. Historians refer to this as the "Medieval Warm Period", lasting from about the 10th century to about the 14th century. Part of the French population growth in this period (see below) is directly linked to this temperate weather and its effect on crops and livestock.

Demography

[edit]At the end of the Middle Ages, France was the most populous region[clarification needed] in Europe—having overtaken Spain and Italy by 1340.[2] In the 14th century, before the arrival of the Black Death, the total population of the area covered by modern-day France has been estimated at 16 million.[3] The population of Paris is controversial.[4] Josiah Russell argued for about 80,000 in the early 14th century, although he noted that some other scholars suggested 200,000.[4] The higher count would make it by far the largest city in western Europe; the lower count would put it behind Venice with 100,000 and Florence with 96,000.[5] The Black Death killed an estimated one-third of the population from its appearance in 1348. The concurrent Hundred Years' War slowed recovery. It would be the mid-16th century before the population recovered to mid-fourteenth century levels.[6]

In the early Middle Ages, France was a center of Jewish learning, but increasing persecution, and a series of expulsions in the 14th century, caused considerable suffering for French Jews; see History of the Jews in France.

Languages and literacy

[edit]During the Middle Ages in France, Medieval Latin was the primary medium of scholarly exchange as well as the liturgical language of the Catholic Church; it was also the language of science, literature, law, and administration. From 1200 on, vernacular languages began to be used in administrative work and the law courts,[7] but Latin would remain an administrative and legal language until the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts (1539) prescribed the use of French in all judicial acts, notarized contracts, and official legislation.

The vast majority of the population, however, spoke a variety of vernacular languages derived from vulgar Latin, the common spoken language of the Western Roman Empire. The medieval Italian poet Dante, in his Latin De vulgari eloquentia, classified the Romance languages into three groups by their respective words for "yes": Nam alii oc, alii si, alii vero dicunt oil ("For some say oc, others say si, others say oïl"). The oïl languages – from Latin hoc ille, "that is it" – were spoken primarily in northern France, the oc languages – from Latin hoc, "that" – in southern France, and the si languages – from Latin sic, "thus" – on the Italian and Iberian peninsulas. Modern linguists typically add a third group within France around Lyon, the "Arpitan" or "Franco-Provençal language", whose modern word for "yes" is ouè.

The Gallo-Romance group in the north of France, consisting of langues d'oïl such as Picard, Walloon, and Francien, were influenced by Germanic languages spoken by the earliest Frankish invaders. From the time of Clovis I on, the Franks expanded their rule over northern Gaul. Over time, the French language developed from either the Oïl languages found around Paris and Île-de-France (the Francien theory) or from a standard administrative language based on common characteristics found in all Oïl languages (the lingua franca theory).

The langue d'oc, consisting of the languages which use oc or òc for "yes", was the language group spoken in the south of France and northeastern Spain. These languages, such as Gascon and Provençal, have relatively little Frankish influence.

The Middle Ages also saw the influence of other linguistic groups on the dialects spoken in France. From the 4th to 7th centuries, Brythonic-speaking peoples from Cornwall, Devon, and Wales travelled across the English Channel, both for reasons of trade and of flight from the Anglo-Saxon invasions of England, and established themselves in Armorica in northwest France. Their dialect evolved into the Breton language in more recent centuries, and they gave their name to the peninsula they inhabited: Brittany.

Attested since the time of Julius Caesar, a non-Celtic people who spoke a Basque-related language inhabited the Novempopulania (Aquitania Tertia) in southwestern France, though the language gradually lost ground to the expanding Romance during a period spanning most of the Early Middle Ages. This Proto-Basque influenced the emerging Latin-based language spoken in the area between the Garonne and the Pyrenees, eventually resulting in the dialect of Occitan called Gascon.

Scandinavian Vikings invaded France from the 9th century onwards and established themselves mostly in what would come to be called Normandy. The Normans took up the langue d'oïl spoken there, although Norman French remained heavily influenced by Old Norse and its dialects. They also contributed many words to French related to sailing and farming. After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the Normans' language developed into Anglo-Norman. Anglo-Norman served as the language of the ruling classes and commerce in England from the time of the conquest until the Hundred Years' War,[8] by which time the use of French-influenced English had spread throughout English society.

Also around this time period, many words from the Arabic language entered French, mainly indirectly through Medieval Latin, Italian and Spanish. There are words for luxury goods (élixir, orange), spices (camphre, safran), trade goods (alcool, bougie, coton), sciences (alchimie, hasard), and mathematics (algèbre, algorithme).

While education and literacy had been important components of aristocratic service in the Carolingian period,[9] by the 11th century and continuing into the 13th century, the lay (secular) public in France—both nobles and peasants—was largely illiterate,[10] except for (at least to the end of the 12th century) members of the great courts and, in the south, smaller noble families.[11] This situation began to change in the 13th century, where we find highly literate members of the French nobility like Guillaume de Lorris, Geoffrey of Villehardouin (sometimes referred to as Villehardouin), and Jean de Joinville (sometimes referred to as Joinville).[12] Similarly, due to the outpouring of French vernacular literature from the 12th century on (chanson de geste, chivalric romance, troubadour and trouvère poetry, etc.), French eventually became the "international language of the aristocracy".[12]

Society and government

[edit]Peasants

[edit]In the Middle Ages in France, the vast majority of the population—between 80 and 90 percent—were peasants.[13]

Traditional categories inherited from the Roman and Merovingian period (distinctions between free and unfree peasants, between tenants and peasants who owned their own land, etc.) underwent significant changes up to the 11th century. The traditional rights of "free" peasants—such as service in royal armies (they had been able to serve in the royal armies as late as Charlemagne's reign) and participation in public assemblies and law courts—were lost through the 9th to the 10th centuries, and they were increasingly made dependents of nobles, churches and large landholders.[14] The mid-8th century to 1000 also saw a steady increase of aristocratic and monastic control of the land, at the expense of landowning peasants.[15] At the same time, the traditional notion of "unfree" dependents and the distinction between "unfree" and "free" tenants was eroded as the concept of serfdom (see also History of serfdom) came to dominate.[16]

From the mid-8th century on, particularly in the north, the relationship between peasants and the land became increasingly characterized by the extension of the new "bipartite estate" system (manorialism), in which peasants (who were bound to the land) held tenant holdings from a lord or monastery (for which they paid rent), but were also required to work the lord's own "demesne"; in the north, some of these estates could be quite substantial.[17] This system remained a standard part of lord-tenant relations into the 12th century.[18]

The economic and demographic crises of the 14th–15th centuries (agricultural expansion had lost many of the gains made in the 12th and 13th centuries[19]) reversed this trend: landlords offered serfs their freedom in exchange for working abandoned lands, ecclesiastical and royal authorities created new "free" cities (villefranches) or granted freedom to existing cities, etc. By the end of the 15th century, serfdom was largely extinct;[20] henceforth "free" peasants paid rents for their own lands, and the lord's demesne was worked by hired labor.[21] This liberated the peasantry to a certain degree, but also made their lives more precarious in times of economic uncertainty.[21] For lords who rented out more and more of their holdings for fixed rents, the initial benefits were positive, but over time they found themselves increasingly cash-strapped as inflationary pressures reduced their incomes.[22]

Cities and towns

[edit]Much of the Gallo-Roman urban network of cities survived (albeit much changed) into the Middle Ages as regional centers and capitals: certain cities had been chosen as centers of bishoprics by the church[23] (for example, Paris, Reims, Aix, Tours, Carcassonne and Narbonne, Auch, Albi, Bourges, Lyon, etc.), others as seats of local (county, duchy) administrative power (such as Angers, Blois, Poitiers, Toulouse). In many cases (such as with Poitiers) cities were seats of both episcopal and administrative power.

From the 10th to the 11th centuries, the urban development of the country expanded (particularly on the northern coasts): new ports appeared and dukes and counts encouraged and created new towns.[24] In other areas, urban growth was slower and centered on the monastic houses.[25] In many regions, market towns (burgs) with limited privileges were established by local lords. In the late 11th century, "communes", governing assemblies, began to develop in towns.[24] Starting sporadically in the late 10th, and increasingly in the 12th century, many towns and villages were able to gain economic, social or judicial privileges and franchises from their lords (exemptions from tolls and dues, rights to clear land or hold fairs, some judicial or administrative independence, etc.).[25][26] The seigneurial reaction to expanding urbanism and enfranchisement was mixed; some lords fought against the changes, but some lords gained financial and political advantages from the communal movement and growing trade.[27]

The 13th to 14th centuries were a period of significant urbanization. Paris was the largest city in the realm, and indeed one of the largest cities in Europe, with an estimated population of 200,000 or more at the end of the century. The second-largest city was Rouen; the other major cities (with populations over 10,000) were Orléans, Tours, Bordeaux, Lyon, Dijon, and Reims. In addition to these, there also existed zones with an extended urban network of medium to small cities, as in the south and the Mediterranean coast (from Toulouse to Marseille, including Narbonne and Montpellier) and in the north (Beauvais, Laon, Amiens, Arras, Bruges, etc.).[28] Market towns increased in size and many were able to gain privileges and franchises including transformation into free cities (villes franches); rural populations from the countrysides moved to the cities and burgs.[29] This was also a period of urban building: the extension of walls around the entirety of the urban space, the vast construction of Gothic cathedrals (starting in the 12th century), urban fortresses, castles (such as Philip II Augustus' Louvre around 1200) and bridges.[30]

Aristocracy, nobles, knights

[edit]In the Carolingian period, the "aristocracy" (nobilis in the Latin documents) was by no means a legally defined category.[31] With traditions going back to the Romans; one was "noble" if he or she possessed significant land holdings, had access to the king and royal court, could receive honores and benefices for service (such as being named count or duke).[31] Their access to political power in the Carolingian period might also necessitate a need for education.[32] Their wealth and power was also evident in their lifestyle and purchase of luxury goods, and in their maintenance of an armed entourage of fideles (men who had sworn oaths to serve them).

From the late 9th to the late 10th century, the nature of the noble class changed significantly. First off, the aristocracy increasingly focused on establishing strong regional bases of landholdings,[33] on taking hereditary control of the counties and duchies,[34] and eventually on erecting these into veritable independent principalities[35] and privatizing various privileges and rights of the state. (By 1025, the area north of the Loire was dominated by six or seven of these virtually independent states.[36]) After 1000, these counties in turn began to break down into smaller lordships, as smaller lords wrest control of local lands in the so-called "feudal revolution"[37] and seized control over many elements of comital powers (see vassal/feudal below).

Secondly, from the 9th century on, military ability was increasingly seen as conferring special status, and professional soldiers or milites, generally in the entourage of sworn lords, began to establish themselves in the ranks of the aristocracy (acquiring local lands, building private castles, seizing elements of justice), thereby transforming into the military noble class historians refer to as "knights".[38]

Vassalage and feudal land

[edit]The Merovingians and Carolingians maintained relations of power with their aristocracy through the use of clientele systems and the granting of honores and benefices, including land, a practice which grew out of Late Antiquity. This practice would develop into the system of vassalage and feudalism in the Middle Ages. Originally, vassalage did not imply the giving or receiving of landholdings (which were granted only as a reward for loyalty), but by the eighth century the giving of a landholding was becoming standard.[39] The granting of a landholding to a vassal did not relinquish the lord's property rights, but only the use of the lands and their income; the granting lord retained ultimate ownership of the fee and could, technically, recover the lands in case of disloyalty or death.[39]

In the 8th-century Frankish empire, Charles Martel was the first to make large scale and systematic use (the practice had remained until then sporadic) of the remuneration of vassals by the concession of the usufruct of lands (a beneficatium or "benefice" in the documents) for the lifetime of the vassal, or, sometimes extending to the second or third generation.[40] By the middle of the 10th century, feudal land grants (fee, fiefs) had largely become hereditary.[41] The eldest son of a deceased vassal would inherit, but first he had to do homage and fealty to the lord and pay a "relief" for the land (a monetary recognition of the lord's continuing proprietary rights over the property). By the 11th century, the bonds of vassalage and the granting of fiefs had spread throughout much of French society, but it was in no ways universal in France: in the south, feudal grants of land or of rights were unknown.[42]

In its origin, the feudal grant had been seen in terms of a personal bond between lord and vassal, but with time and the transformation of fiefs into hereditary holdings, the nature of the system came to be seen as a form of "politics of land" (an expression used by the historian Marc Bloch). The 11th century in France saw what has been called by historians a "feudal revolution" or "mutation" and a "fragmentation of powers" (Bloch) that was unlike the development of feudalism in England or Italy or Germany in the same period or later:[43] counties and duchies began to break down into smaller holdings as castellans and lesser seigneurs took control of local lands, and (as comital families had done before them) lesser lords usurped/privatized a wide range of prerogatives and rights of the state, most importantly the highly profitable rights of justice, but also travel dues, market dues, fees for using woodlands, obligations to use the lord's mill, etc.[44] (what Georges Duby called collectively the "seigneurie banale"[45]). Power in this period became more personal[46] and it would take centuries for the state to fully reimpose its control over local justice and fiscal administration (by the 15th century, much of the seigneur's legal purview had been given to the bailliages, leaving them only affairs concerning seigneurial dues and duties, and small affairs of local justice)

This "fragmentation of powers" was not however systematic throughout France, and in certain counties (such as Flanders, Normandy, Anjou, Toulouse), counts were able to maintain control of their lands into the 12th century or later.[47] Thus, in some regions (like Normandy and Flanders), the vassal/feudal system was an effective tool for ducal and comital control, linking vassals to their lords; but in other regions, the system led to significant confusion, all the more so as vassals could and frequently did pledge themselves to two or more lords. In response to this, the idea of a "liege lord" was developed (where the obligations to one lord are regarded as superior) in the 12th century.[48]

Peerage

[edit]Medieval French kings conferred the dignity of peerage upon certain of his preëminent vassals, both clerical and lay. Some historians consider Louis VII (1137–1180) to have created the French system of peers.[49]

Peerage was attached to a specific territorial jurisdiction, either an episcopal see for episcopal peerages or a fief for secular. Peerages attached to fiefs were transmissible or inheritable with the fief, and these fiefs are often designated as pairie-duché (for duchies) and pairie-comté (for counties).

By 1216 there were nine peers:

- Archbishop of Reims who had the distinction of anointing and crowning the king

- Bishop of Langres

- Bishop of Beauvais

- Bishop of Châlons

- Bishop of Noyon

- Duke of Normandy

- Duke of Burgundy

- Duke of Aquitaine also called Duke of Guyenne

- Count of Champagne

A few years later and before 1228 three peers were added to make the total of twelve peers:

These twelve peerages are known as the ancient peerage or pairie ancienne, and the number twelve is sometimes said to have been chosen to mirror the 12 paladins of Charlemagne in the Chanson de geste (see below). Parallels may also be seen with mythical Knights of the Round Table under King Arthur. So popular was this notion, that for a long time people thought peerage had originated in the reign of Charlemagne, who was considered the model king and shining example for knighthood and nobility.

The dozen pairs played a role in the royal sacre or consecration, during the liturgy of the coronation of the king, attested to as early as 1179, symbolically upholding his crown, and each original peer had a specific role, often with an attribute. Since the peers were never twelve during the coronation in early periods, due to the fact that most lay peerages were forfeited to or merged in the crown, delegates were chosen by the king, mainly from the princes of the blood. In later periods peers also held up by poles a baldaquin or cloth of honour over the king during much of the ceremony.

In 1204 the Duchy of Normandy was absorbed by the French crown, and later in the 13th century two more of the lay peerages were absorbed by the crown (Toulouse 1271, Champagne 1284), so in 1297 three new peerages were created, the County of Artois, the Duchy of Anjou and the Duchy of Brittany, to compensate for the three peerages that had disappeared.

Thus, beginning in 1297 the practice started of creating new peerages by letters patent, specifying the fief to which the peerage was attached, and the conditions under which the fief could be transmitted (e.g. only male heirs) for princes of the blood who held an apanage. By 1328 all apanagists would be peers.

The number of lay peerages increased over time from 7 in 1297 to 26 in 1400, 21 in 1505, and 24 in 1588.

Monarchy and regional powers

[edit]France was a very decentralised state during the Middle Ages. At the time, Lorraine and Provence were states of the Holy Roman Empire and not a part of France. North of the Loire, the King of France at times fought or allied with one of the great principalities of Normandy, Anjou, Blois-Champagne, Flanders and Burgundy. The duke of Normandy was overlord of the duke of Brittany. South of the Loire were the principalities of Aquitaine, Toulouse and Barcelona. Normandy became the strongest power in the north, while Barcelona became the strongest in the south. The rulers of both fiefs eventually became kings, the former by the conquest of England, and the latter by the succession to Aragon. French suzerainty over Barcelona was only formally relinquished by Saint Louis in 1258.

Initially, West Frankish kings were elected by the secular and ecclesiastic magnates, but the regular coronation of the eldest son of the reigning king during his father's lifetime established the principle of male primogeniture, later popularized as the Salic law. The authority of the king was more religious than administrative. The 11th century in France marked the apogee of princely power at the expense of the king when states like Normandy, Flanders or Languedoc enjoyed a local authority comparable to kingdoms in all but name. The Capetians, as they were descended from the Robertians, were formerly powerful princes themselves who had successfully unseated the weak and unfortunate Carolingian kings.[50]

The Carolingian kings had nothing more than a royal title when the Capetian kings added their principality to that title. The Capetians, in a way, held a dual status of King and Prince; as king they held the Crown of Charlemagne and as Count of Paris they held their personal fiefdom, best known as Île-de-France.[50]

The fact that the Capetians both held lands as Prince as well as in the title of King gave them a complicated status. Thus they were involved in the struggle for power within France as princes but they also had a religious authority over Roman Catholicism in France as King. However, and despite the fact that the Capetian kings often treated other princes more as enemies and allies than as subordinates, their royal title was often recognised yet not often respected. The royal authority was so weak in some remote places that bandits were the effective power.[50]

Some of the king's vassals would grow sufficiently powerful that they would become some of the strongest rulers of western Europe. The Normans, the Plantagenets, the Lusignans, the Hautevilles, the Ramnulfids, and the House of Toulouse successfully carved lands outside France for themselves. The most important of these conquests for French history was the Norman Conquest by William the Conqueror, following the Battle of Hastings and immortalised in the Bayeux Tapestry, because it linked England to France through Normandy. Although the Normans were now both vassals of the French kings and their equals as kings of England, their zone of political activity remained centered in France.[51]

An important part of the French aristocracy also involved itself in the crusades, and French knights founded and ruled the Crusader states. An example of the legacy left in the Middle East by these nobles is the Krak des Chevaliers' enlargement by the Counts of Tripoli and Toulouse.

The history of the monarchy is how it overcame the powerful barons over ensuing centuries, and established absolute sovereignty over France in the 16th century. A number of factors contributed to the rise of the French monarchy. The dynasty established by Hugh Capet continued uninterrupted until 1328, and the laws of primogeniture ensured orderly successions of power. Secondly, the successors of Capet came to be recognised as members of an illustrious and ancient royal house and therefore socially superior to their politically and economically superior rivals. Thirdly, the Capetians had the support of the Church, which favoured a strong central government in France. This alliance with the Church was one of the great enduring legacies of the Capetians. The First Crusade was composed almost entirely of Frankish Princes. As time went on the power of the King was expanded by conquests, seizures and successful feudal political battles.[52]

French power in the Middle Ages

[edit]Vassals and cadets of the King of France made several foreign acquisitions during the Middle Ages:

- William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy (1066): conquered the Kingdom of England

- The success of the First Crusade led to the creation of a Frankish kingdom in the Levant in 1099

- Norman knights settled in Sicily, which was raised to a kingdom in 1130

- Fulk V, Count of Anjou (1131): became King of Jerusalem by marriage

- Afonso I of Portugal (1139): great-grandson of Robert I, Duke of Burgundy, and founder of the Kingdom of Portugal

- Henry II of England (1154): ruled England and much of Western France (The Angevin Empire)

- Alfonso II of Aragon, Count of Barcelona (1164): first Count of Barcelona to become King of Aragon in his own right

- Theobald I of Navarre, Count of Champagne (1234): inherited the Kingdom of Navarre from his uncle

- Charles I of Naples, Count of Anjou (1266): youngest son of Louis VIII of France, conquered the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily, proclaimed himself King of Albania

- Charles I of Hungary (1301): scion of the Capetian House of Anjou, King of Hungary and Croatia

- Henry VII, Holy Roman Emperor: became a vassal of Philip IV of France while Count of Luxembourg. Philip IV advanced the candidacy of his brother Charles of Valois for the imperial throne, but the German electors were unwilling to expand French influence even further. Henry was elected King of Germany in 1308 as a compromise candidate, and became emperor in 1312.

- John of Bohemia (1310): son of Emperor Henry VII, he became of King of Bohemia by marriage. John was raised in Paris, and died fighting for the French in the Battle of Crécy

- Philip III of Navarre, Count of Évreux (1328): became King of Navarre by marriage

- Louis I of Hungary (1342): son of Charles I of Hungary, eventually became King of Poland in addition to the realms inherited from his father

- Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor (1346): son of John of Bohemia, he received French education and resided in the French court for seven years. His close connection to the House of France facilitated the sale of Dauphiné, an imperial fief, in 1349, and its eventual transfer into the French crown.

- Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (1363): with his appanage of Burgundy and his marriage to the heiress of Flanders, he founded the House of Valois-Burgundy, the most powerful dynasty of the Middle Ages which is not of royal rank

The power of the French monarchy grew at a slower rate at the beginning:

- The early Capetians ruled much longer than their contemporaries, but had little power. They did not have the will, or the resources, to coerce their vassals into obedience.

- Louis VI began an aggressive policy of demanding obedience from his vassals in the Ile-de-France backed by military force

- Louis VII's marriage with Eleanor of Aquitaine brought the French monarchy's influence to southern France, but the annulment of their marriage brought about the rise of the Angevin dynasty, the most formidable rival of the French monarchy

- Philip II made the French king the foremost power within his own kingdom, destroying Angevin power in France through the conquest of Normandy and Anjou

- Louis VIII embarked on the Albigensian Crusade, which brought northern France to war against the south

- Louis IX brought the prestige of the French monarchy at its height. Even the Mongol leader Hulagu, who had been under the impression that the Pope was the ruler of all Christians, realized that the true power rested in the King of France and sought an alliance with him. His crusading ventures, however, were unsuccessful

- Philip III inherited Toulouse and married his son to the heiress of Navarre and Champagne

- Philip IV was the most absolutist of the medieval French kings, but his costly policies brought him into conflict with the pope and the persecution of the Templars in order to obtain their resources.

- The orderly succession of French kings for more than 300 years, combined with an abrupt dynastic crisis in 1316 led to the adoption of a succession law that prevented the kingship from going out of the Capetian dynasty. The successive deaths of the sons of Philip IV in a short period of time led to the rise of the House of Valois

- Philip VI was an initially promising ruler, having brought Flanders into submission early in his reign. At the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War France was the foremost power in Western Europe, but this did not prevent his overwhelming defeat at Crécy.

- John II brought the French monarchy at its lowest with another overwhelming defeat in Poitiers.

- Charles V recovered most of the territories lost during the war

- The madness of Charles VI multiplied the woes of France, as the princes of the royal house split into factions in order to obtain power. France suffered another defeat at Agincourt, and the king was forced to disinherit his own son in favor of Henry V of England

- Charles VII was apathetic during the early years of his reign, but his fortunes changed with the rise of Joan of Arc in 1429 and his reconciliation with the Duke of Burgundy in 1435. The French were victorious at the end of the war in 1453, and the King of France was once again the most powerful monarch in Europe, with the first standing army since Roman times.

Royal administration

[edit]King's Council

[edit]The kings of France traditionally always sought the advice of their entourage (vassals, clerics, etc.) before making important decisions. In the early Middle Ages, the entourage around the king was sometimes called the familia; later the expression "hôtel du roi" or the "maison du roi" (the "royal household") was used for people attached directly to the person of the king, while (in the 12th century), those who were called upon to counsel the king in his administration of the realm took the form of a specific (and separate) institution called the King's Court (Latin: the "Curia Regis", later the Conseil du Roi)), although by the middle of the 13th century distinctions between "hôtel du roi" and curia regis were less clear.[53]

In addition to the King's Council, the consultative governing of the country also depended on other intermittent and permanent institutions, such as the States General, the Parlements and the Provincial Estates. The Parliament of Paris – as indeed all of the sovereign courts of the realm – was itself born out of the King's Council: originally a consultative body of the Curia Regis, later (in the thirteenth century) endowed with judicial functions, the Parliament was separated from the King's Council in 1254.

The King's Court functioned as an advisory body under the early Capetian kings.[54] It was composed of a number of the king's trusted advisers but only a few traveled with the king at any time.[54] By the later twelfth century it had become a judicial body with a few branching off to remain the king's council.[54] By the fourteenth century the term curia regis was no longer used.[54] However, it had served as a predecessor to later sovereign assemblies; the Parlement which was a judiciary body, the Chamber of Accounts which was a financial body and King's Council.[55]

The composition of the King's Council changed constantly over the centuries and according to the needs and desires of the king. Medieval councils frequently excluded:

- the queen (both as queen consort or as queen mother) – the influence of the queen lost direct political control as early as the 13th century, except in periods of regency; the queen thus only exceptionally attended the Council.

- close relations to the king, including younger sons, grandsons and princes of the royal bloodline ("prince du sang") from junior branches of the family – these individuals were often suspected of political ambition and of plotting.

On the other hand, medieval councils generally included:

- the crown prince (the "dauphin") – if he was of age to attend the council

- the "grands" – the most powerful members of the church and of the nobility.

The feudal aristocracy would maintain great control over the king's council up until the 14th and 15th centuries. The most important positions in the court were those of the Great Officers of the Crown of France, headed by the connétable (chief military officer of the realm; established by King Philip I in 1060) and the chancellor. Other positions included the Grand Chambrier who managed the Royal Treasury along with the Grand Bouteiller (Grand Butler), before being supplanted of these functions by the Chamber of Accounts (Chambre des comptes, created by King Philip IV) and the position of Surintendant des finances (created in 1311). Certain kings were unable to reduce the importance of the feudal aristocracy (Louis X, Philip VI, John II, Charles VI), while others were more successful (Charles V, Louis XI).

Over the centuries, the number of jurists (or "légistes"), generally educated by the université de Paris, steadily increased as the technical aspects of the matters studied in the council mandated specialized counsellers. Coming from the lesser nobility or the bourgeoisie, these jurists (whose positions sometimes gave them or their heirs nobility, as the so-called "noblesse de robe" or chancellor nobles) helped in preparing and putting into legal form the king's decisions, and they formed the early elements of a true civil service and royal administration which would – because of their permanence – provide a sense of stability and continuity to the royal council, despite its many reorganizations. In their attempts at greater efficiency, the kings tried to reduce the number of counsellors or to convoke "reduced councils". Charles V had a council of 12 members.

The Council had only a consultational role: the final decision was always the king's. Although jurists frequented praised (especially later in the 16th century) the advantages of consultative government (with the agreement of his counsellors, the king could more easily impose the most severe of his decisions, or he could have his most unpopular decisions blamed on his counsellors), mainstream legal opinion never held that the king was bound by the decisions of his council; the opposite was however put forward by the States General of 1355–1358.

The Council's purview concerned all matters pertaining to government and royal administration, both in times of war and of peace. In his council, the king received ambassadors, signed treaties, appointed administrators and gave them instructions (called, from the 12th century on, mandements), elaborated on the laws of the realm (called ordonnances). The council also served as a supreme court and rendered royal justice on those matters that the king reserved for himself (so-called "justice retenue") or decided to discuss personally.

Council meetings, initially irregular, took on a regular schedule which became daily from the middle of the 15th century.

Royal finances

[edit]The king was expected to survive on the revenues of the "domaine royal", or lands that belonged to him directly. In times of need, the taille, an "exceptional" tax could be imposed and collected; this resource was increasingly required during the protracted wars of the 14th–15th centuries and the taille became permanent in 1439, when the right to collect taxes in support of a standing army was granted to Charles VII of France during the Hundred Years' War.

To oversee the Kingdom's revenues and expenditure, the French King first relied solely on the Curia Regis. However, by the mid-12th century, the Crown entrusted its finances to the Knights Templar, who maintained a banking establishment in Paris. The royal Treasury was henceforth organized like a bank and salaries and revenues were transferred between accounts. Royal accounting officers in the field, who sent revenues to the Temple, were audited by the King's Court, which had special clerks assigned to work at the Temple. These financial specialists came to be called the Curia in Compotis and sat in special sessions of the King's Court for dealing with financial business. From 1297, accounts were audited twice yearly after Midsummer Day (24 June) and Christmas. In time, what was once a simple Exchequer of Receipts developed into a central auditing agency, branched off, and eventually specialized into a full-time court.

In 1256, Saint Louis issued a decree ordering all mayors, burghesses, and town councilmen to appear before the King's sovereign auditors of the Exchequer (French gens des comptes) in Paris to render their final accounts. The King's Court's general secretariat had members who specialized in finance and accountancy and could receive accounts. A number of maîtres lais were commissioned to sit as the King's Exchequer (comptes du Roi).

In or around 1303, the Paris Court of Accounts was established in the Palais de la Cité. Its auditors were responsible for overseeing revenue from Crown estates and checking public spending. It audited the royal household, inspectors, royal commissioners, provosts, baillifs, and seneschals. In 1307, the Philip IV definitively removed royal funds from the Temple and placed them in the fortress of the Louvre. Thereafter, the financial specialists received accounts for audit in a room of the royal palace that became known as the Camera compotorum or Chambre des comptes, and they began to be collectively identified under the same name, although still only a subcommission of the King's Court, consisting of about sixteen people.

The Vivier-en-Brie Ordinance of 1320, issued by Philip V, required the Chambre to audit accounts, judge cases arising from accountability, and maintain registers of financial documents; it also laid out the basic composition of financial courts: three (later four) cleric masters of accounts (maîtres-clercs) to act as chief auditors and three maîtres-lais familiers du Roi empowered to hear and adjudge ("oyer and terminer") audit accounts. They were assisted by eleven clerks (petis clercs, later clercs des comptes) who acted as auditors of the prests. This complement grew by 50 percent in the next two decades but was reduced to seven masters and twelve clerks in 1346. The office of président was created by the Ordinance of 1381, and a second lay Chief Baron was appointed in 1400. Clerks of court were eventually added to the court's composition. Examiners (correcteurs) were created to assist the maitres. Other court officers (conseillers) appointed by the King were created to act alongside the maîtres ordinaires. Lastly, the Ordinance of 26 February 1464 named the Court of Accounts as the "sovereign, primary, supreme, and sole court of last resort in all things financial".[56]

While gaining in stability in the later 14th century, the court lost its central role in royal finances. First, currency was moved to a separate body (Chambre des monnaies), then the increasingly regular "extraordinary" taxes (aide, tallage, gabelle) became the responsibility of the généraux of the Cour des aides (created in 1390). The Crown's domainal revenues, still retained by the Court of Accounts, fell in importance and value. By 1400, the Court's role had been much reduced. However, with the gradual enlargement of the realm through conquest, the need for the court remained secure.

Parlements

[edit]The Parliament of Paris, born out of the king's council in 1307, and sitting inside the medieval royal palace on the Île de la Cité, still the site of the Paris Hall of Justice. The jurisdiction of the Parliament of Paris covered the entire kingdom as it was in the fourteenth century, but did not automatically advance in step with the enlarging personal dominions of the kings. In 1443, following the turmoil of the Hundred Years' War, King Charles VII of France granted Languedoc its own parlement by establishing the Parlement of Toulouse, the first parlement outside of Paris; its jurisdiction extended over most of southern France.

Several other parlements were created in various provinces of France in the Middle Ages: Dauphiné (Grenoble 1453), Guyenne and Gascony (Bordeaux 1462), Burgundy (Dijon 1477), Normandy (Rouen 1499/1515). All of them were administrative capitals of regions with strong historical traditions of independence before they were incorporated into France.

Estates General

[edit]In 1302, expanding French royal power led to a general assembly consisting of the chief lords, both lay and ecclesiastical, and the representatives of the principal privileged towns, which were like distinct lordships. Certain precedents paved the way for this institution: representatives of principal towns had several times been convoked by the king, and under Philip III there had been assemblies of nobles and ecclesiastics in which the two orders deliberated separately. It was the dispute between Philip the Fair and Pope Boniface VIII which led to the States-General of 1302; the king of France desired that, in addition to the Great Officers of the Crown of France, he receive the counsel from the three estates in this serious crisis. The letters summoning the assembly of 1302 are published by M. Georges Picot in his collection of Documents inédits pour servir à l'histoire de France. During the same reign they were subsequently assembled several times to give him aid by granting subsidies. Over time subsidies came to be the most frequent motive for their convocation.

The Estates-General included representatives of the First Estate (clergy), Second Estate (the nobility), and Third Estate (commoners: all others), and monarchs always summoned them either to grant subsidies or to advise the Crown, to give aid and counsel. In their primitive form in the 14th and the first half of the 15th centuries, the Estates-General had only a limited elective element. The lay lords and the ecclesiastical lords (bishops and other high clergy) who made up the Estates-General were not elected by their peers, but directly chosen and summoned by the king. In the order of the clergy, however, since certain ecclesiastical bodies, e.g. abbeys and chapters of cathedrals, were also summoned to the assembly, and as these bodies, being persons in the moral but not in the physical sense, could not appear in person, their representative had to be chosen by the monks of the convent or the canons of the chapter. It was only the representation of the Third Estate which was furnished by election. Originally, moreover, the latter was not called upon as a whole to seek representation in the estates. It was only the bonnes villes, the privileged towns, which were called upon. They were represented by elected procureurs, who were frequently the municipal officials of the town, but deputies were often elected for the purpose. The country districts, the plat pays, were not represented. Even within the bonnes villes, the franchise was quite narrow.

Prévôts, baillages

[edit]The prévôts were the first-level judges created by the Capetian monarchy around the 11th century who administered the scattered parts of the royal domain. Provosts replaced viscounts wherever a viscounty had not been made a fief, and it is likely that the provost position imitated and was styled after the corresponding ecclesiastical provost of cathedral chapters. Provosts were entrusted with and carried out local royal power, including the collection of the Crown's domainal revenues and all taxes and duties owed the King within a provostship's jurisdiction. They were also responsible for military defense such as raising local contingents for royal armies. The provosts also administered justice though with limited jurisdiction.

В 11 -м веке проректоры все чаще делали свои позиции наследственными и, следовательно, стали более трудными для контроля. Один из великих офицеров короля, великий Сеншал, стал их руководителем. В 12 -м веке офис проректора был назначен на торгов, а затем проректоры были фермерами доходов. Таким образом, проректор получил спекулятивное право набрать доходы Короля в рамках своего провинции. Это оставалось его основной ролью.

Чтобы контролировать производительность и сокращение злоупотреблений Prévôts или их эквивалент (в Нормандии Vicomte из , в некоторых частях северной Франции или , на юге, Viguier A Bayle ), Филипп II Август, способный и гениальный администратор, который основал многие Центральные институты, на которых будет основана система власти французской монархии, созданы странствующие судьи, известные как Baillis («судебный пристав»), основанный на Средневековые финансовые и налоговые подразделения, которые использовались более ранними суверенными принцами (такими как герцог Нормандия). [ 57 ] был Таким образом , Байли административным представителем короля в северной части Франции, ответственным за применение справедливости и контроля администрации и местных финансов в его Baillage (на юге Франции эквивалентным постом был «Sénéchal, Sénéchaussé»).

Со временем роль Baillages будет значительно расширена как расширение королевской власти, администрации и справедливости. С офисом Великого Сеншала, вакантной после 1191 года, Бейли стали неподвижными и зарекомендовали себя как влиятельные должностные лица, превосходящие проректора. В округе Бейли был около полудюжины провинций. Когда Корона была проведена апелляции, апелляция проректора, ранее невозможная, теперь лежала с Бейли. Более того, в 14 -м веке проректоры больше не отвечали за сбор доменных доходов, за исключением сельскохозяйственных проректора, вместо этого он взял на себя эту ответственность перед королевскими приемниками (преобразователи Royaux). Повышение контингентов местной армии (запрет и арриер-бань) также перешли в Бейли. Таким образом, проректоры сохранили единственную функцию низших судей над вассалами с первоначальной юрисдикцией, одновременно с Бейли, из -за претензий против дворян и действий, зарезервированных для королевских судов ( Cas Royaux ). Это последовало за прецедентом, установленным в главных феодальных судах в 13 и 14 -м веках, в которых судебные иски проректора были отличены от торжественных сессий.

Политическая история

[ редактировать ]Каролинговое наследие

[ редактировать ]В более поздние годы пожилого Карла Великого правления викинги достигли авансов вдоль северного и западного периметра его королевства. После смерти Карла Великого в 814 году его наследники не смогли поддерживать политическое единство, и империя начала рушиться. 843 Верден -договор года разделил Империю Каролингов, а Чарльз Ледос управлял над Вест -Франциной , примерно соответствующей территории современной Франции.

Достижения викинга были разрешены эскалаться, и их страшные длинные лондоны плыли по рекам Луары и Сене и другим внутренним водным путям, нанося хаос и распространяли террор. В 843 году викинговые захватчики убили епископа Нантеса , и через несколько лет они сожгли церковь святого Мартина в турах , а в 845 году викинги уволили Париж . [ Цитация необходима ] Во время правления Чарльза «Простые» (898–922) норманны под Ролло были заселены в районе по обе стороны от Сенера, вниз по течению от Парижа , которая должна была стать Нормандией .

Впоследствии Каролингцы , герцог Франции и графу Парижа, создано на поделились судьбой своих предшественников: после прерывистой борьбы за власть между двумя семьями вступление (987) Хью Капет престоле династия Капетсяна , которая с его Валуа И бурбонские оффруты должны были управлять Францией более 800 лет.

В эпохе Каролинга наблюдалась постепенное появление учреждений, которые должны были привести к развитию Франции на протяжении веков: признание в короне административной власти дворян царства на их территориях в обмен на их (иногда слабую) преданность и военную поддержку, Феномен, легко видимый в росте капетиан и в некоторой степени предвещал собственным подъемом каролигов.

Первые капетицы (940–1108)

[ редактировать ]

История средневековой Франции начинается с выборов Хью Кейпет (940–996) собранием, вызванным в Реймсе в 987 году. Ранее Кейпет был «герцог Франк», а затем стал «королем Франков» (Рекс Франкурм). Земли Хью немного простирались за парижским бассейном; Его политическая неважность весила против могущественных баронов, которые избрали его. Многие из вассалов короля (которые долгое время включали короли Англии) управляли территориями намного больше его собственных. [ 52 ] Он был записан как признанный королем галлами , бретонами , датчанами , аквитанцами , готами , испанскими и газонами . [ 58 ] Новая династия находилась под непосредственным контролем над Средней Сеной и прилегающими территориями, в то время как могущественные территориальные лорды, такие как количество 10-го и 11-го века Блуа, накопили свои собственные большие домены через брак и через частные договоренности с меньшими дворянами для защиты и поддержка.

Граф Борелл из Барселоны призвал к помощи Хью в отношении исламских рейдов, но даже если Хью намеревался помочь Бореллу, он был занят в борьбе с Карлом Лорейн . Затем последовала потеря других испанских принципов, поскольку испанские марши становились все более и более независимыми. [ 58 ] Хью Кейпет, первый капетский король, не является хорошо задокументированной фигурой, и его величайшее достижение, безусловно, состоит в том, чтобы выжить как король и победить заявителя Каролинга, что позволяет ему установить, что станет одним из самых могущественных домов царей Европы. [ 58 ]

Сын Хью - Роберт благочестивый - был коронован королем Франков до кончины Капета. Хью Кейпет решил так, чтобы его преемственность была обеспечена. Роберт II, как король Франкса, встретил императора Священного Римского Генриха II в 1023 году на границе. Они согласились положить конец всем претензиям в сфере друг друга, установив новый этап капетских и Оттонианских отношений. Несмотря на то, что король слабы, усилия Роберта II были значительными. Его выжившие хартиры подразумевают, что он сильно полагался на церковь, чтобы править Францией, так же, как и его отец. Хотя он жил с любовницей - Бертой из Бургундии - и был отлучен из -за этого, его считали моделью благочестия для монахов (отсюда и его прозвище, Роберт благочестивый). [ 58 ] Царствование Роберта II было довольно важным, потому что оно включало мир и перемирие Бога (начиная с 989 года) и реформы Cluniac . [ 58 ]

Роберт II увенчал своего сына - Хью Магнус - в качестве короля Франков в 10 лет, чтобы обеспечить преемственность, но Хью Магнус восстал против своего отца и умер, сражаясь с ним в 1025 году.

Следующим королем Франков был следующий сын Роберта II, Генрих I (правят 1027–1060). Как и Хью Магнус, Генри был коронован как коаллера со своим отцом (1027), в капетской традиции, но у него было мало власти или влияния как младший король, пока его отец все еще жил. Генри, я был коронован после смерти Роберта в 1031 году, что довольно исключительно для французского короля The Times. Генри, я был одним из самых слабых королей Франков, и его правление увидела рост некоторых очень сильных дворян, таких как Уильям -Завоеватель. [ 58 ] Самым большим источником забот Генриха был его брат - Роберт I из Бургундии , которого мать подтолкнула к конфликту. Роберт из Бургундии был сделан герцогом Бургундии королем Генрихом I и должен был быть доволен этим названием. От Генриха I и дальше, герцоги Бургундии были родственниками короля Франков до самого конца герцогства.

Король Филипп I , названная его киеговой матерью с типично восточно -европейским именем, не повезло, чем его предшественник [ 58 ] Хотя королевство действительно наслаждалось скромным выздоровлением во время своего чрезвычайно длительного правления (1060–1108). Его правление также привело к запуску первого крестового похода , чтобы восстановить Святую Землю , которая в значительной степени связала с его семью, хотя он лично не поддерживал экспедицию.

Район вокруг нижнейцы, уступившихся скандинавским захватчикам как герцогство Нормандии в 911 году, стала источником особой беспокойства, когда герцог Уильям завладел Королевством Англии в нормандском завоевании 1066 года, делая себя и своих наследников равными королем За пределами Франции (где он все еще был номинально подвергнут короне).

Луи VI и Луи VII (1108–1180)

[ редактировать ]Именно от Луи VI (царствованного 1108–1137)), что королевская власть стала более принятой. Людовик VI был скорее солдатом и воодушевляющим королем, чем ученым. То, как король собрал деньги от своих вассалов, сделало его совершенно непопулярным; Он был описан как жадный и амбициозный, и это подтверждается записями того времени. Его регулярные атаки на его вассалы, хотя и наносят ущерб королевскому образу, усилил королевскую власть. С 1127 года Луи имел помощь опытного религиозного государственного деятеля, аббата Сугера . Аббат был сыном несовершеннолетней семьи рыцарей, но его политический совет был чрезвычайно ценным для короля. Луи VI успешно победил, как военные, так и политически, многие из баронов -грабителей . Луи VI часто вызывал свои вассалы в суд, и те, кто не появлялся, часто конфисковали их земельные владения, а военные кампании противостояли им. Эта радикальная политика явно навязала некоторых королевских властей в Париж и его окрестностях. Когда Людовик VI умер в 1137 году, был достигнут большой прогресс в направлении укрепления капетского авторитета. [ 58 ]

Благодаря политическому совету аббата Сугера король Луи VII (младший король 1131–1137, старший король 1137–1180) пользовался большей моральной властью над Францией, чем его предшественники. Мощные вассалы отдали дань уважения французскому королю. [ 59 ] Эббот Сугер договорился о браке 1137 года между Людовиком VII и Элеонорой Аквитании в Бордо, который сделал Луи VII герцога Аквитании и дал ему значительную власть. Тем не менее, пара не согласилась из -за сжигания более тысячи человек в конфликте во время конфликта с графиком шампанского. [ 60 ]

Король Людовик VII был глубоко в ужасе от этого события и искал покаяние, отправившись на Святую Землю . Позже он привлек королевство Франции во втором крестовом походе, но его отношения с Элеонорой не улучшились. Брак в конечном итоге был аннулирован папой под предлогом кровного родства, и Элеонора вскоре вышла замуж за герцога Нормандии - Генри Фитцемпресс , который станет королем Англии как Генрих II два года спустя. [ 60 ] Людовик VII когда -то был очень могущественным монархом и теперь сталкивался с гораздо более сильным вассалом, который был его равным как король Англии и его самым сильным принцем как герцог Нормандии и Авитайн.

(Генри унаследовал герцогство Нормандии через свою мать, Матильду Англии и графство Анжу от своего отца, Джеффри из Анжу , и в 1152 году он женился на недавно разведенном Франции, Элеоноре Аквити , который правил много Юго -западного . Франции В тюрьму, сделал герцог Бриттани своим вассалом и фактически управлял западной половиной Франции как большую силу, чем французский престол . с Филиппом II позволила Филиппу II восстановить влияние на большую часть этой территории Ссора . сохранил власть только в юго -западном герцогстве Гайенн .)

Видение Аббата Сугера стало тем, что теперь известно как готическая архитектура . Этот стиль стал стандартным для большинства европейских соборов, построенных в позднем средневековье . [ 60 ]

Поздние прямые капетские короли были значительно более сильными и влиятельными, чем самые ранние. В то время как Филипп я едва мог контролировать его парижские бароны, Филипп IV мог диктовать папы и императоров. Поздние капетисты, хотя они часто правили в течение более короткого времени, чем их более ранние сверстники, часто были гораздо более влиятельными. В этом периоде также наблюдался рост сложной системы международных альянсов и конфликтов против династий, королей Франции и Англии и Императора Священной Римской им.

Филипп II и Луи VIII (1180–1226)

[ редактировать ]Правление Филиппа II Августа (младший король 1179–1180, старший король 1180–1223) ознаменовало важный шаг в истории французской монархии. Его правление увидела французский королевский домен и значительно влияет. Он установил контекст для роста власти гораздо более могущественным монархам, таким как Сент -Луис и Филипп Ярмарку.

Филипп II провел важную часть своего правления, борясь с так называемой империей Ангевина , которая, вероятно, была самой большой угрозой для царя Франции с момента роста династии Капетиан. Во время первой части своего правления Филипп II пытался использовать Генрих II из сына Англии против него. Он соблюдал себя с герцогом Аквитании и сыном Генриха II - Ричарда Лиовинового Сердца - и вместе они начали решающую атаку на замок Генри и дом Чинона и убрали его из власти.

Ричард заменил своего отца в качестве короля Англии впоследствии. Затем два короля пошли в крестовые походы во время третьего крестового похода ; Тем не менее, их альянс и дружба сломались во время крестового похода. Двое мужчин снова были в противоречии и сражались друг с другом во Франции, пока Ричард не нахожусь на грани полного победы над Филиппом II.

В дополнение к их битвам во Франции Короли Франции и Англии пытались установить своих соответствующих союзников во главе Священной Римской империи . Если Филипп II Август поддержал Филиппа из Свабии , члена Палаты Хохенстауфена , то Ричард Льонхарт поддержал Отто IV , члена Дома ВЕЛА . Филипп Свабии одержал верх, но его преждевременная смерть сделала Отто IV Священной римской императором. Корона Франции была спасена кончиной Ричарда после раны, которую он получил, сражаясь с собственными вассалами в лимузине .

Джон Лакленд , преемник Ричарда, отказался приехать в французский суд на судебное разбирательство против Лузигнов , и, как часто делал Луи VI для своих мятежных вассалов, Филипп II конфисковал имущество Джона во Франции. Поражение Джона было быстро, и его попытки вернуть его французскому владению в решающей битве при Бувин (1214) привели к полной неудаче. Аннексия Нормандии и Анжу была подтверждена, что графы Булони и Фландрии были захвачены, и император Отто IV был свергнут союзником Филиппа Фредерика II . Аквитайн и Гаскони пережили французское завоевание, поскольку герцогиня Элеонора все еще жила. Филипп II из Франции имел решающее значение при упорядочении западной европейской политики как в Англии, так и в Франции.

Филипп Август основал Сорбонн и сделал Париж городом для ученых.

Принц Луи (будущий Людовик VIII, правящий 1223–1226) был вовлечен в последующую гражданскую войну английского языка как французские и английские (или, скорее, англо-норманские) аристократии когда-то были едины и теперь были разделены между приверженностью. В то время как французские цари боролись против Плантагенетов, Церковь призвала к альбигенскому крестовому крестовому крестовому . Южная Франция была тогда в значительной степени поглощена в королевских областях.

Сент -Луис (1226–1270)

[ редактировать ]

Франция стала по -настоящему централизованным королевством при Луи IX (царствовано 1226–1270). Сент-Луис часто изображается как одномерный персонаж, безупречный пример веры и административного реформатора, который заботился о управляемых. Тем не менее, его правление было далеко не идеальным для всех: он совершил неудачные крестовые походы, его расширяющиеся администрации подняли оппозицию, и он сжигал еврейские книги по настоянию Папы. [ 61 ] Его суждения не часто были практичными, хотя по стандартам того времени они казались справедливыми. Похоже, у Луи было сильное чувство справедливости, и всегда хотелось судить людей, прежде чем применить какое -либо приговор. Это было сказано о том, что Луи и французское духовенство просят отлучить отлучения о вассалах Луи: [ 62 ]

Ибо это было бы против Бога и вопреки праву и справедливости, если бы он заставил любого человека искать отпущения, когда духовенство делало его неправильно.

Луи IX было всего двенадцать лет, когда он стал королем Франции. Его мать - Бланш из Кастилии - была эффективной силой как регента (хотя она официально не использовала название). Власть Бланш была решительно противопоставлена французскими баронами, но она сохранила свою позицию, пока Луи не стал достаточно взрослым, чтобы править сам.

В 1229 году король должен был бороться с длительным ударом в Парижском университете . Латинский квартал был сильно пострадал от этих ударов.

Королевство было уязвимым: в графстве Тулузы все еще происходила война, а Королевская армия была оккупирована боевым сопротивлением в Лангедоке. Граф Раймонд VII из Тулузы, наконец, подписал Парижский договор в 1229 году, в котором он сохранил большую часть своих земель на всю жизнь, но его дочь, замужем за графом Альфонсо из Пуиу , не принесла ему наследника, и поэтому графство Тулуза пошла к королю Франции.

Король Генрих III из Англии еще не признал Капетское Повелитель над Аквитанией и все еще надеялся восстановить Нормандию и Анжу и реформировать империю Ангевина. Он приземлился в 1230 году в Сен-Мало с огромной силой. Союзники Генриха III в Бриттани и Нормандии упали, потому что они не осмеливались сражаться с их королем, который сам возглавил контрштрик. Это превратилось в войну в Сейнтонге (1242).

В конечном счете, Генрих III потерпел поражение и должен был признать повелитель Луи IX, хотя король Франции не захватил Авитайн у Генриха III. Луи IX был теперь самым важным землевладельцем Франции, добавив к своему королевскому титулу. Было некоторое противодействие его правлению в Нормандии, но это оказалось удивительно легко править, особенно по сравнению с графством Тулузы, который был жестоко завоеван. Conseil du Roi , который будет развиваться в партию , был основан в эти времена.

После своего конфликта с королем Генрихом III из Англии Луи установил сердечные отношения с королем Plantagenet. Генриха III Забавный анекдот - это о посещении французского парламента , как герцог Аквитейн; Тем не менее, король Англии всегда опоздал, потому что он любил останавливаться каждый раз, когда он встречал священника, чтобы услышать мессу, поэтому Луи позаботился о том, чтобы ни один священник не был на пути Генриха III. Генрих III и Луи IX затем начали долгий конкурс о том, кто был самым верным; Это развивалось до такой степени, что никто никогда не прибыл вовремя к парке, которому тогда было разрешено обсудить в их отсутствие. [ 63 ]

Сент -Луис также поддержал новые формы искусства, такие как готическая архитектура ; Его Сэйнте-Шапель стала очень известным готическим зданием, и ему также приписывают за Библию Моргана .

Королевство было вовлечено в два крестовых похода при Сент -Луисе: седьмой крестовый поход и восьмой крестовый поход . Оба оказались полными неудачами для французского короля. Он умер в восьмом крестовом походе, а Филипп III стал королем.

13-й век должен был принести корону важные выгоды также на юге, где папский крестовый поход против Альбигенсийских или Катарских еретиков региона (1209) привел к включению в Королевский домен Нижнего (1229) и Верхнего (1271) LAMMEDOC Полем (1300) Филиппа IV Приступ Фландрии был менее успешным, закончившись два года спустя в разгроме его рыцарей силами фламандских городов в битве при Золотых Шпор недалеко от Кортрия (Куртри).

Philip III и Philip IV (1270–1314)

[ редактировать ]После того, как Луи IX умер от бубонной чумы в Тунисе в 1270 году, его сын Филипп III (1270–1285) и внук Филипп IV (1285–1314) последовали за ним. Филипп III был назван «жирным шрифтом» на основе его способностей в бою и верхом на лошадях, а не из -за его характера или правящих способностей. Филипп III принял участие в еще одной катастрофе Crusading: арагонский крестовый поход , который стоил ему его жизни в 1285 году.

Филипп III продолжил устойчивое расширение Королевского домена. Он унаследовал Тулузу в 1271 году от своего дядю и женился на своем сыне и наследнике наследнице Шампанского и Наварры.

Приняв трон, Филипп III почувствовал себя обязанным продолжить, по -видимому, солидную дипломатию своего отца, несмотря на то, что обстоятельства изменились. В 1282 году неправильное обращение Чарльза Анжу в Сицилии вынудило население острова восстать в пользу короля Петра III из Арагона . Когда Папа Мартин IV был близким союзником Филиппа, он сразу же отлучил Питера и предложил свой трон одному из сыновей французского короля. С тех пор, как Филипп Ярмарка уже должна была унаследовать Наварре, весь испанский марш казался созревшим для восстановления Франции. Тем не менее, попытка Филиппа III по совершению крестового похода против Арагона, явно политического романа, закончилась катастрофой как эпидемия, поразившая его армию, которая затем была обоснованно побеждена араготными войсками в Col de Panissars. Униженный король умер вскоре после этого в Перпиньяне, за которым следуют Чарльз Анжу и Мартин IV.

Из более поздних капетских правителей Филипп IV был величайшим, принося королевскую власть до самого сильного уровня, которого она достигнет в средние века, но отчуждает очень много людей и, как правило, оставляла Францию измотанной. Таким образом, его сыновья были вынуждены следовать более сдержанному курсу, не отказавшись от амбиций своего отца. Филипп IV по большей части проигнорировал Средиземноморье и вместо этого сосредоточил свои усилия по внешней политике на северных границах Франции. Некоторые из них были сделаны за счет императоров Священной Римской, но самые агрессивные действия царя были против Англии. Споры по поводу Аквитании были ячейкой раздора в течение многих лет, и, наконец, в 1294 году началась война. Французские армии въехали глубоко в Гаскони, что привело к тому, что Эдвард I из Англии объединяет усилия с Фландрией и другими союзниками на северных границах Франции. Союзные войска были обоснованно избиты в 1297 году французской армией во главе с Робертом Артуа, и было согласовано перемирия, что привело к сохранению статус -кво Анте Беллум Полем В рамках мирового соглашения Эдвард женился на сестре Филиппа, а сын и дочь обоих королей должны были жениться.

Фландрия оставалась упорно мятежным и непобирным. Хотя их счет был заключен в тюрьму Филиппом, это не помешало фламандским бургерам подняться против французских войск, размещенных там, нанеся сенсационное поражение на них в битве за Куртри 1302 . В конце концов, однако, король начал новое наступление во Фландрию, и в 1305 году был согласован мир, который, однако, все еще не смог успокоить фламандских горожан.

Кроме того, Philip IV расширил королевскую юрисдикцию договором на церковные территории Виверс, Кахорс, Менде и Ле Пуй. Со всем этим король теперь мог бы отстаивать власть практически в любой точке Франции, но еще предстоит еще много работы, а французские правители продолжались без Бриттани, Бургундии и многочисленных меньших территорий, хотя они законодали для всей царства. Правительственная администрация во Франции в течение этого периода стала более бюрократической и изощренной наряду с устойчивым расширением королевской власти. Несмотря на это, капетские короли не должны восприниматься как произвольные тираны, поскольку феодальный обычай и традиции все еще действовали в качестве ограничений на них.

Если политика Филиппа вызвала враждебность и жалобы, это было потому, что они не предпочитали, в частности, занятия. Политика царя в отношении городов оставалась довольно традиционной, но это не так с церковью. Когда он хотел налогодить французское духовенство для финансирования военных кампаний, он столкнулся с возражением Папы Бонифации VIII . Папа получил ряд жалоб от французского и английского духовенства на уставные налоги и, таким образом, издал быка Clericis Lacios в 1296 году, заявив, что для этого необходимо папское согласие. Филипп, однако, разозлился и выпустил громкие аргументы в соответствии с его действиями, оставив духовенство разделиться над этим вопросом. В конце концов папа снял свое возражение.

В 1301 году король епископа Памира был обвинен свежими проблемами, когда епископ Памир был обвинен в том, что церковная собственность не может быть конфискована без разрешения Рима, и все христианские правители были подчинены папской власти. Папа вызвал французское духовенство в Ватикан, чтобы обсудить реформу королевства. Еще раз прелаты были оставлены разделенными между верностью своей стране и верностью церкви. Те, кто взял на себя сторону Филиппа, встретились на большом собрании в Париже вместе с другими сегментами французского общества, критикуя папу, который ответил от церкви, отлучая короля и все духовенство, которые его поддерживали. В следующем году Филипп отбился от мести. Прелаты, преданные короне, сформировали схему, чтобы привести Бонифации в суд, и папа был в итоге арестован в Анагни в сентябре. Он был избит его тюремщиками и угрожал казни, если он не ушел в отставку, но он отказался. 68-летний папа был освобожден из плена всего через несколько дней и умер через несколько недель.

Филипп гарантировал, что у него больше никогда не будет проблем с церковью, продвигая Рэймонда Бертран Дей, архиепископа Бордо, как следующий папа. Папский конклав был равномерно разделен между французскими и итальянскими кардиналами, но последний согласился, и де Пот стал папой Климентом V. Таким образом, Филипп успешно установил послушную французскую марионетку в папство, которое было перенесено в Авиньон .

был проведен больше административных реформ Филипп IV , также называемых Ярмаркой Филиппа (правящий 1285–1314). Этот король подписал Альянс Аулд и создал Парлмен Париж .

Одним из самых странных эпизодов правления Филиппа было его участие в разрушении тамплиеров рыцарей . Тамплиеры были основаны во время крестовых походов более чем столетие ранее, но в настоящее время состояли из старых людей, чей престиж был значительно уменьшен после падения Святой Земли и, казалось, больше не служил какой -либо полезной цели, стоящей их привилегии. Не в состоянии найти подходящие доказательства проступков тамплиерами, чтобы оправдать распоряжение приказа, Филипп должен был прибегнуть к массовому собранию в Тур в 1308 году, чтобы сплотить поддержку. Наконец, в 1312 году Климент V, несмотря на его опасения, выпустил быка, приказывая их роспуск. Имущество тамплиеров было передано рыцарским госпиталерам, а оставшиеся члены заключили в тюрьму или казнены за ересь.

Louis X, Philip V и Charles IV (1314–1328)

[ редактировать ]В 1314 году Филипп IV внезапно скончался в результате аварии на охоте в возрасте 47 лет, и трон перешел к своему сыну Луи X (1314–1316). Краткое правление Луи привело к дальнейшим неудачным попыткам отстаивать контроль над Фландрией, поскольку король мобилизовал армию вдоль границы, но проблемы с поставками вызвали усилия, чтобы сломаться. Луи умер летом 1316 года только у 26 от неизвестной болезни (возможно, гастроэнтерита ) после того, как поглотил большое количество охлажденного вина после игры в теннис в чрезвычайно жаркий день. Жена короля была тогда беременна и родила сына Джона в ноябре, но он умер через неделю, и трон перешел к своему брату Филиппу.

Philip V (1316–1322) заключил мир с Фландрией через брачный компакт со своим графом Робертом III и столкнулся с постоянными ссорами с Эдвардом II из Англии над Гасконом. Он планировал новый крестовый поход, чтобы облегчить армянское королевство Килиции, но ситуация Фландрии оставалась нестабильной, и попытка военно -морской экспедиции Франции на Ближнем Востоке была разрушена от Генуи в 1319 году. На данный момент крестьяне и солдаты изначально намеревались вторгнуться на фланды. поднялся в другом самопровозглашенном крестовом походе (Pastoreux), который снова превратился в нападение на дворянство, сборщики налогов и евреев. Папа Иоанн XXII осудил восстание, и Филипп был вынужден отправлять войска, чтобы разорвать его.