Колумбийский университет

Эту статью необходимо отредактировать, чтобы Википедии она соответствовала Руководству по стилю . ( Апрель 2024 г. ) |

Эта статья может содержать неправомерное использование несвободных материалов. ( Апрель 2024 г. ) |

| |

| Латынь : Колумбийский университет | |

Прежние имена | Королевский колледж (1754–1784) Columbia College (1784–1896) |

|---|---|

| Motto | In lumine Tuo videbimus lumen (Latin) |

Motto in English | "In Thy light shall we see light"[1] |

| Type | Private, research university |

| Established | May 25, 1754 |

| Accreditation | MSCHE |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $13.6 billion (2023)[2]: 23 |

| Budget | $5.9 billion (2023)[2]: 5 |

| President | Minouche Shafik |

| Provost | Angela Olinto |

Academic staff | 4,628[3] |

| Students | 36,649[4] |

| Undergraduates | 9,761[4] |

| Postgraduates | 26,888[4] |

| Location | , , United States 40°48′27″N 73°57′43″W / 40.80750°N 73.96194°W |

| Campus | Large city, 299 acres (1.21 km2) |

| Newspaper | Columbia Daily Spectator |

| Colors | Columbia blue and white[5] |

| Nickname | Lions |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Roar-ee the Lion |

| Website | www |

Колумбийский университет , официально Колумбийский университет в городе Нью-Йорке , [6] — частный исследовательский Лиги плюща университет в Нью - Йорке . Основанный в 1754 году как Королевский колледж на территории церкви Троицы на Манхэттене , это старейшее высшее учебное заведение в Нью-Йорке и пятое старейшее в Соединенных Штатах .

Колумбия была основана как колониальный колледж при королевской хартией Георге II Великобритании . Он был переименован в Колумбийский колледж в 1784 году после американской революции , а в 1787 году был передан в ведение частного попечительского совета, возглавляемого бывшими студентами Александром Гамильтоном и Джоном Джеем . В 1896 году кампус был перенесен на нынешнее место в Морнингсайд-Хайтс и переименован в Колумбийский университет.

Columbia is organized into twenty schools, including four undergraduate schools and 16 graduate schools. The university's research efforts include the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory, the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and accelerator laboratories with Big Tech firms such as Amazon and IBM.[7][8] Columbia is a founding member of the Association of American Universities and was the first school in the United States to grant the MD degree.[9] The university also administers and annually awards the Pulitzer Prize.

Columbia scientists and scholars have played a pivotal role in scientific breakthroughs including brain–computer interface; the laser and maser;[10][11] nuclear magnetic resonance;[12] the first nuclear pile; the first nuclear fission reaction in the Americas; the first evidence for plate tectonics and continental drift;[13][14][15] and much of the initial research and planning for the Manhattan Project during World War II.

As of December 2021[update], its alumni, faculty, and staff have included seven of the Founding Fathers of the United States of America;[n 1] four U.S. presidents;[n 2] 34 foreign heads of state or government;[n 3] two secretaries-general of the United Nations;[n 4] ten justices of the United States Supreme Court; 103 Nobel laureates; 125 National Academy of Sciences members;[57] 53 living billionaires;[58] 23 Olympic medalists;[59] 33 Academy Award winners; and 125 Pulitzer Prize recipients.

History

18th century

Discussions regarding the founding of a college in the Province of New York began as early as 1704, at which time Colonel Lewis Morris wrote to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, the missionary arm of the Church of England, persuading the society that New York City was an ideal community in which to establish a college.[60] However, it was not until the founding of the College of New Jersey (renamed Princeton) across the Hudson River in New Jersey that the City of New York seriously considered founding a college.[60] In 1746, an act was passed by the general assembly of New York to raise funds for the foundation of a new college. In 1751, the assembly appointed a commission of ten New York residents, seven of whom were members of the Church of England, to direct the funds accrued by the state lottery towards the foundation of a college.[61]

Classes were initially held in July 1754 and were presided over by the college's first president, Samuel Johnson.[62]: 8–10 Johnson was the only instructor of the college's first class, which consisted of a mere eight students. Instruction was held in a new schoolhouse adjoining Trinity Church, located on what is now lower Broadway in Manhattan.[63]: 3 The college was officially founded on October 31, 1754, as King's College by royal charter of George II,[64][65] making it the oldest institution of higher learning in the State of New York and the fifth oldest in the United States.[9]

In 1763, Johnson was succeeded in the presidency by Myles Cooper, a graduate of The Queen's College, Oxford, and an ardent Tory. In the charged political climate of the American Revolution, his chief opponent in discussions at the college was an undergraduate of the class of 1777, Alexander Hamilton.[63]: 3 The Irish anatomist, Samuel Clossy, was appointed professor of natural philosophy in October 1765 and later the college's first professor of anatomy in 1767.[66] The American Revolutionary War broke out in 1776, and was catastrophic for the operation of King's College, which suspended instruction for eight years beginning in 1776 with the arrival of the Continental Army. The suspension continued through the military occupation of New York City by British troops until their departure in 1783. The college's library was looted and its sole building requisitioned for use as a military hospital first by American and then British forces.[67][68]

After the Revolutionary War, the college turned to the State of New York in order to restore its vitality, promising to make whatever changes to the school's charter the state might demand.[62]: 59 The legislature agreed to assist the college, and on May 1, 1784, it passed "an Act for granting certain privileges to the College heretofore called King's College".[62] The Act created a board of regents to oversee the resuscitation of King's College, and, in an effort to demonstrate its support for the new Republic, the legislature stipulated that "the College within the City of New York heretofore called King's College be forever hereafter called and known by the name of Columbia College",[62] a reference to Columbia, an alternative name for America which in turn comes from the name of Christopher Columbus. The Regents finally became aware of the college's defective constitution in February 1787 and appointed a revision committee, which was headed by John Jay and Alexander Hamilton. In April of that same year, a new charter was adopted for the college granted the power to a separate board of 24 trustees.[69]: 65–70

On May 21, 1787, William Samuel Johnson, the son of Samuel Johnson, was unanimously elected president of Columbia College. Prior to serving at the university, Johnson had participated in the First Continental Congress and been chosen as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention.[70] For a period in the 1790s, with New York City as the federal and state capital and the country under successive Federalist governments, a revived Columbia thrived under the auspices of Federalists such as Hamilton and Jay. President George Washington and Vice President John Adams, in addition to both houses of Congress attended the college's commencement on May 6, 1789, as a tribute of honor to the many alumni of the school who had been involved in the American Revolution.[62]: 74

19th century

In November 1813, the college agreed to incorporate its medical school with The College of Physicians and Surgeons, a new school created by the Regents of New York, forming Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.[69]: 53–60 The college's enrollment, structure, and academics stagnated for the majority of the 19th century, with many of the college presidents doing little to change the way that the college functioned. In 1857, the college moved from the King's College campus at Park Place to a primarily Gothic Revival campus on 49th Street and Madison Avenue, where it remained for the next forty years.

During the last half of the 19th century, under the presidency of Frederick A. P. Barnard, for whom Barnard College is named, the institution rapidly assumed the shape of a modern university. Barnard College was created in 1889 as a response to the university's refusal to accept women.[71] By this time, the college's investments in New York real estate became a primary source of steady income for the school, mainly owing to the city's expanding population.[63]: 5–8

In 1896, university president Seth Low moved the campus from 49th Street to its present location, a more spacious campus in the developing neighborhood of Morningside Heights.[62][72] Under the leadership of Low's successor, Nicholas Murray Butler, who served for over four decades, Columbia rapidly became the nation's major institution for research, setting the multiversity model that later universities would adopt.[9] Prior to becoming the president of Columbia University, Butler founded Teachers College, as a school to prepare home economists and manual art teachers for the children of the poor, with philanthropist Grace Hoadley Dodge.[60] Teachers College is currently affiliated as the university's Graduate School of Education.[73]

20th century

In the 1940s, research into the atom by faculty members John R. Dunning, I. I. Rabi, Enrico Fermi and Polykarp Kusch placed Columbia's physics department in the international spotlight after the first nuclear pile was built to start what became the Manhattan Project.[74]

In 1928, Seth Low Junior College was established by Columbia University in order to mitigate the number of Jewish applicants to Columbia College.[60][75] The college was closed in 1936 due to the adverse effects of the Great Depression and its students were subsequently taught at Morningside Heights, although they did not belong to any college but to the university at large.[76][77] There was an evening school called University Extension, which taught night classes, for a fee, to anyone willing to attend.

In 1947, the program was reorganized as an undergraduate college and designated the School of General Studies in response to the return of GIs after World War II.[78] In 1995, the School of General Studies was again reorganized as a full-fledged liberal arts college for non-traditional students (those who have had an academic break of one year or more, or are pursuing dual-degrees) and was fully integrated into Columbia's traditional undergraduate curriculum.[79] The same year, the Division of Special Programs, later called the School of Continuing Education and now the School of Professional Studies, was established to reprise the former role of University Extension.[80] While the School of Professional Studies only offered non-degree programs for lifelong learners and high school students in its earliest stages, it now offers degree programs in a diverse range of professional and inter-disciplinary fields.[81]

In the aftermath of World War II, the discipline of international relations became a major scholarly focus of the university, and in response, the School of International and Public Affairs was founded in 1946, drawing upon the resources of the faculties of political science, economics, and history.[82] The Columbia University Bicentennial was celebrated in 1954.[83]

During the 1960s, student activism reached a climax with protests in the spring of 1968, when hundreds of students occupied buildings on campus. The incident forced the resignation of Columbia's president, Grayson Kirk, and the establishment of the University Senate.[84][85]

Though several schools in the university had admitted women for years, Columbia College first admitted women in the fall of 1983,[86] after a decade of failed negotiations with Barnard College, the all-female institution affiliated with the university, to merge the two schools.[87] Barnard College still remains affiliated with Columbia, and all Barnard graduates are issued diplomas signed by the presidents of Columbia University and Barnard College.[88]

During the late 20th century, the university underwent significant academic, structural, and administrative changes as it developed into a major research university. For much of the 19th century, the university consisted of decentralized and separate faculties specializing in Political Science, Philosophy, and Pure Science. In 1979, these faculties were merged into the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.[89] In 1991, the faculties of Columbia College, the School of General Studies, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the School of the Arts, and the School of Professional Studies were merged into the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, leading to the academic integration and centralized governance of these schools.

21st century

In 2010, the School of International and Public Affairs, which was previously a part of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, became an independent faculty.[90]

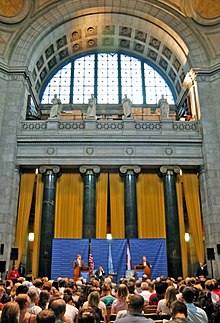

In fall of 2023, pro-Palestine student activists organized protests in response to the Israel–Hamas war, with counter-protests from pro-Israel activists.[91] On April 17, 2024, Columbia president Minouche Shafik was questioned by the House Committee on Education and the Workforce on the topic of antisemitism on campus. Shafik's comments regarding the student activists sparked renewed protests that same day,[92][93] leading to what CNN described as a "full-blown crisis" over tensions stemming from a pro-Palestinian campus occupation.[94] In response, the university moved in-person classes online on Monday, April 22.[95][96]

Columbia University called New York Police Department officers in riot gear to remove those demonstrators who seized Hamilton Hall, dozens of whom were arrested.[97]

Campus

Morningside Heights

The majority of Columbia's graduate and undergraduate studies are conducted in the Upper Manhattan neighborhood of Morningside Heights on Seth Low's late-19th century vision of a university campus where all disciplines could be taught at one location. The campus was designed along Beaux-Arts planning principles by the architects McKim, Mead & White. Columbia's main campus occupies more than six city blocks, or 32 acres (13 ha), in [Morningside Heights, New York City, a neighborhood that contains a number of academic institutions. The university owns over 7,800 apartments in Morningside Heights, housing faculty, graduate students, and staff. Almost two dozen undergraduate dormitories (purpose-built or converted) are located on campus or in Morningside Heights. Columbia University has an extensive tunnel system, more than a century old, with the oldest portions predating the present campus. Some of these remain accessible to the public, while others have been cordoned off.[98]

Butler Library is the largest in the Columbia University Libraries system and one of the largest buildings on the campus. Proposed as "South Hall" by the university's former president Nicholas Murray Butler as expansion plans for Low Memorial Library stalled, the new library was funded by Edward Harkness, benefactor of Yale University's residential college system, and designed by his favorite architect, James Gamble Rogers. It was completed in 1934 and renamed for Butler in 1946. The library design is neo-classical in style. Its facade features a row of columns in the Ionic order above which are inscribed the names of great writers, philosophers, and thinkers, most of whom are read by students engaged in the Core Curriculum of Columbia College.[99] As of 2020[update], Columbia's library system includes over 15.0 million volumes, making it the eighth largest library system and fifth largest collegiate library system in the United States.[100]

Several buildings on the Morningside Heights campus are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Low Memorial Library, a National Historic Landmark and the centerpiece of the campus, is listed for its architectural significance. Philosophy Hall is listed as the site of the invention of FM radio.[101] Also listed is Pupin Hall, another National Historic Landmark, which houses the physics and astronomy departments. Here the first experiments on the fission of uranium were conducted by Enrico Fermi. The uranium atom was split there ten days after the world's first atom-splitting in [[Copenhagen][, Denmark.[102][103] Other buildings listed include Casa Italiana, the Delta Psi, Alpha Chapter building of St. Anthony Hall, Earl Hall, and the buildings of the affiliated Union Theological Seminary.[104][105][106][107]

A statue by sculptor Daniel Chester French called Alma Mater is centered on the front steps of Low Memorial Library. McKim, Mead & White invited French to build the sculpture in order to harmonize with the larger composition of the court and library in the center of the campus. Draped in an academic gown, the female figure of Alma Mater wears a crown of laurels and sits on a throne. The scroll-like arms of the throne end in lamps, representing sapientia and doctrina. A book signifying knowledge, balances on her lap, and an owl, the attribute of wisdom, is hidden in the folds of her gown. Her right hand holds a scepter composed of four sprays of wheat, terminating with a crown of King's College which refers to Columbia's origin as a royal charter institution in 1754. A local actress named Mary Lawton was said to have posed for parts of the sculpture. The statue was dedicated on September 23, 1903, as a gift of Mr. & Mrs. Robert Goelet, and was originally covered in golden leaf. During the Columbia University protests of 1968 a bomb damaged the sculpture, but it has since been repaired.[108] The small hidden owl on the sculpture is also the subject of many Columbia legends, the main legend being that the first student in the freshmen class to find the hidden owl on the statue will be valedictorian, and that any subsequent Columbia male who finds it will marry a Barnard student, given that Barnard is a women's college.[109][110]

"The Steps", alternatively known as "Low Steps" or the "Urban Beach", are a popular meeting area for Columbia students. The term refers to the long series of granite steps leading from the lower part of campus (South Field) to its upper terrace. With a design inspired by the City Beautiful movement, the steps of Low Library provides Columbia University and Barnard College students, faculty, and staff with a comfortable outdoor platform and space for informal gatherings, events, and ceremonies. McKim's classical facade epitomizes late 19th-century new-classical designs, with its columns and portico marking the entrance to an important structure.[111]

Other campuses

In April 2007, the university purchased more than two-thirds of a 17 acres (6.9 ha) site for a new campus in Manhattanville, an industrial neighborhood to the north of the Morningside Heights campus. Stretching from 125th Street to 133rd Street, Columbia Manhattanville houses buildings for Columbia's Business School, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia School of the Arts, and the Jerome L. Greene Center for Mind, Brain, and Behavior, where research will occur on neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's.[112][113] The $7 billion expansion plan included demolishing all buildings, except three that are historically significant (the Studebaker Building, Prentis Hall, and the Nash Building), eliminating the existing light industry and storage warehouses, and relocating tenants in 132 apartments. Replacing these buildings created 6.8 million square feet (630,000 m2) of space for the university. Community activist groups in West Harlem fought the expansion for reasons ranging from property protection and fair exchange for land, to residents' rights.[114][115] Subsequent public hearings drew neighborhood opposition. As of December 2008[update], the State of New York's Empire State Development Corporation approved use of eminent domain, which, through declaration of Manhattanville's "blighted" status, gives governmental bodies the right to appropriate private property for public use.[116] On May 20, 2009, the New York State Public Authorities Control Board approved the Manhanttanville expansion plan.[117]

NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital is affiliated with the medical schools of both Columbia University and Cornell University. According to U.S. News & World Report's "2020–21 Best Hospitals Honor Roll and Medical Specialties Rankings", it is ranked fourth overall and second among university hospitals.[118] Columbia's medical school has a strategic partnership with New York State Psychiatric Institute, and is affiliated with 19 other hospitals in the U.S. and four hospitals in other countries. Health-related schools are located at the Columbia University Medical Center, a 20-acre (8.1 ha) campus located in the neighborhood of Washington Heights, fifty blocks uptown. Other teaching hospitals affiliated with Columbia through the NewYork-Presbyterian network include the Payne Whitney Clinic in Manhattan, and the Payne Whitney Westchester, a psychiatric institute located in White Plains, New York.[119] On the northern tip of Manhattan island (in the neighborhood of Inwood), Columbia owns the 26-acre (11 ha) Baker Field, which includes the Lawrence A. Wien Stadium as well as facilities for field sports, outdoor track, and tennis. There is a third campus on the west bank of the Hudson River, the 157-acre (64 ha) Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory and Earth Institute in Palisades, New York. A fourth is the 60-acre (24 ha) Nevis Laboratories in Irvington, New York, for the study of particle and motion physics. A satellite site in Paris holds classes at Reid Hall.[9]

Sustainability

In 2006, the university established the Office of Environmental Stewardship to initiate, coordinate and implement programs to reduce the university's environmental footprint. The U.S. Green Building Council selected the university's Manhattanville plan for the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Neighborhood Design pilot program. The plan commits to incorporating smart growth, new urbanism and "green" building design principles.[120] Columbia is one of the 2030 Challenge Partners, a group of nine universities in the city of New York that have pledged to reduce their greenhouse emissions by 30% within the next ten years. Columbia University adopts LEED standards for all new construction and major renovations. The university requires a minimum of Silver, but through its design and review process seeks to achieve higher levels. This is especially challenging for lab and research buildings with their intensive energy use; however, the university also uses lab design guidelines that seek to maximize energy efficiency while protecting the safety of researchers.[121]

Every Thursday and Sunday of the month, Columbia hosts a greenmarket where local farmers can sell their produce to residents of the city. In addition, from April to November Hodgson's farm, a local New York gardening center, joins the market bringing a large selection of plants and blooming flowers. The market is one of the many operated at different points throughout the city by the non-profit group GrowNYC.[122] Dining services at Columbia spends 36 percent of its food budget on local products, in addition to serving sustainably harvested seafood and fair trade coffee on campus.[123] Columbia has been rated "B+" by the 2011 College Sustainability Report Card for its environmental and sustainability initiatives.[124]

According to the A. W. Kuchler U.S. potential natural vegetation types, Columbia University would have a dominant vegetation type of Appalachian Oak (104) with a dominant vegetation form of Eastern Hardwood Forest (25).[125]

Transportation

Columbia Transportation is the bus service of the university, operated by Academy Bus Lines. The buses are open to all Columbia faculty, students, Dodge Fitness Center members, and anyone else who holds a Columbia ID card. In addition, all TSC students can ride the buses.[126]

In the New York City Subway, the ![]() train serves the university at 116th Street-Columbia University. The M4, M104 and M60 buses stop on Broadway while the M11 stops on Amsterdam Avenue.

train serves the university at 116th Street-Columbia University. The M4, M104 and M60 buses stop on Broadway while the M11 stops on Amsterdam Avenue.

The main campus is primarily boxed off by the streets of Amsterdam Avenue, Broadway, 114th street, and 120th street, with some buildings, including Barnard College, located just outside the area. The nearest major highway is the Henry Hudson Parkway (NY 9A) to the west of the campus. It is located 3.4 miles (5.5 km) south of the George Washington Bridge.

Academics

Undergraduate admissions and financial aid

| Undergraduate admissions statistics | |

|---|---|

| Admit rate | 3.9% ( |

| Yield rate | 66.5% ( |

| Test scores middle 50% | |

| SAT Total | 1510–1560 ( |

Columbia University received 60,551 applications for the class of 2025 (entering 2021) and a total of around 2,218 were admitted to the two schools for an overall acceptance rate of 3.66%.[129] Columbia is a racially diverse school, with approximately 52% of all students identifying themselves as persons of color. Additionally, 50% of all undergraduates received grants from Columbia. The average grant size awarded to these students is $46,516.[130] In 2015–2016, annual undergraduate tuition at Columbia was $50,526 with a total cost of attendance of $65,860 (including room and board).[131] The college is need-blind for domestic applicants.[132]

Annual gifts, fund-raising, and an increase in spending from the university's endowment have allowed Columbia to extend generous financial aid packages to qualifying students. On April 11, 2007, Columbia University announced a $400 million donation from media billionaire alumnus John Kluge to be used exclusively for undergraduate financial aid. The donation is among the largest single gifts to higher education.[133] As of 2008[update], undergraduates from families with incomes as high as $60,000 a year will have the projected cost of attending the university, including room, board, and academic fees, fully paid for by the university. That same year, the university ended loans for incoming and then-current students who were on financial aid, replacing loans that were traditionally part of aid packages with grants from the university. However, this does not apply to international students, transfer students, visiting students, or students in the School of General Studies.[134] In the fall of 2010, admission to Columbia's undergraduate colleges Columbia College and the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (also known as SEAS or Columbia Engineering) began accepting the Common Application. The policy change made Columbia one of the last major academic institutions and the last Ivy League university to switch to the Common Application.[135]

Scholarships are also given to undergraduate students by the admissions committee. Designations include John W. Kluge Scholars, John Jay Scholars, C. Prescott Davis Scholars, Global Scholars, Egleston Scholars, and Science Research Fellows. Named scholars are selected by the admission committee from first-year applicants. According to Columbia, the first four designated scholars "distinguish themselves for their remarkable academic and personal achievements, dynamism, intellectual curiosity, the originality and independence of their thinking, and the diversity that stems from their different cultures and their varied educational experiences".[136]

In 1919, Columbia established a student application process characterized by The New York Times as "the first modern college application". The application required a photograph of the applicant, the maiden name of the applicant's mother, and the applicant's religious background.[137]

Organization

| Columbia Graduate/Professional Schools[138] | |

|---|---|

| College/school | Year founded |

| Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons | 1767 |

| College of Dental Medicine | 1916 |

| Columbia Law School | 1858 |

| Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science | 1864 |

| Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences | 1880 |

| Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation | 1881 |

| Teachers College, Columbia University (affiliate) | 1887 |

| Columbia University School of Nursing | 1892 |

| Columbia University School of Social Work | 1898 |

| Graduate School of Journalism | 1912 |

| Columbia Business School | 1916 |

| Mailman School of Public Health | 1922 |

| Union Theological Seminary (affiliate) | 1836, affiliate since 1928 |

| School of International and Public Affairs | 1946 |

| School of the Arts | 1965 |

| School of Professional Studies | 1995 |

| Columbia Climate School | 2020 |

| Columbia Undergraduate Schools[138] | |

|---|---|

| College/school | Year founded |

| Columbia College | 1754 |

| Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science | 1864 |

| Barnard College (affiliate) | 1889 |

| Jewish Theological Seminary of America (affiliate) | 1886 |

| Columbia University School of General Studies | 1947 |

Columbia University is an independent, privately supported, nonsectarian and not-for-profit institution of higher education.[139] Its official corporate name is Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York.

In 1754, the university's first charter was granted King George II; however, its modern charter was first enacted in 1787 and last amended in 1810 by the New York State Legislature. The university is governed by 24 trustees, customarily including the president, who serves ex officio. The trustees themselves are responsible for choosing their successors. Six of the 24 are nominated from a pool of candidates recommended by the Columbia Alumni Association. Another six are nominated by the board in consultation with the executive committee of the University Senate. The remaining 12, including the president, are nominated by the trustees themselves through their internal processes. The term of office for trustees is six years. Generally, they serve for no more than two consecutive terms. The trustees appoint the president and other senior administrative officers of the university, and review and confirm faculty appointments as required. They determine the university's financial and investment policies, authorize the budget, supervise the endowment, direct the management of the university's real estate and other assets, and otherwise oversee the administration and management of the university.[140]

The University Senate was established by the trustees after a university-wide referendum in 1969. It succeeded to the powers of the University Council, which was created in 1890 as a body of faculty, deans, and other administrators to regulate inter-Faculty affairs and consider issues of university-wide concern. The University Senate is a unicameral body consisting of 107 members drawn from all constituencies of the university. These include the president of the university, the provost, the deans of Columbia College and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, all of whom serve ex officio, and five additional representatives, appointed by the president, from the university's administration. The president serves as the Senate's presiding officer. The Senate is charged with reviewing the educational policies, physical development, budget, and external relations of the university. It oversees the welfare and academic freedom of the faculty and the welfare of students.[141][142][143]

The president of Columbia University, who is selected by the trustees in consultation with the executive committee of the University Senate and who serves at the trustees' pleasure, is the chief executive officer of the university. Assisting the president in administering the university are the provost, the senior executive vice president, the executive vice president for health and biomedical sciences, several other vice presidents, the general counsel, the secretary of the university, and the deans of the faculties, all of whom are appointed by the trustees on the nomination of the president and serve at their pleasure.[140] Minouche Shafik became the 20th president of Columbia University on July 1, 2023.

Columbia has four official undergraduate colleges: Columbia College, the liberal arts college offering the Bachelor of Arts degree; the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (also known as SEAS or Columbia Engineering), the engineering and applied science school offering the Bachelor of Science degree; the School of General Studies, the liberal arts college offering the Bachelor of Arts degree to non-traditional students undertaking full- or part-time study; and Barnard College.[144][145] Barnard College is a women's liberal arts college and an academic affiliate in which students receive a Bachelor of Arts degree from Columbia University. Their degrees are signed by the presidents of Columbia University and Barnard College.[146][147] Barnard students are also eligible to cross-register classes that are available through the Barnard Catalogue and alumnae can join the Columbia Alumni Association.[148]

Joint degree programs are available through Union Theological Seminary, the Jewish Theological Seminary of America,[149] and the Juilliard School.[150][151] Teachers College and Barnard College are official faculties of the university; both colleges' presidents are deans under the university governance structure.[152] The Columbia University Senate includes faculty and student representatives from Teachers College and Barnard College who serve two-year terms; all senators are accorded full voting privileges regarding matters impacting the entire university. Teachers College is an affiliated, financially independent graduate school with their own board of trustees.[142][143] Pursuant to an affiliation agreement, Columbia is given the authority to confer "degrees and diplomas" to the graduates of Teachers College. The degrees are signed by presidents of Teachers College and Columbia University in a manner analogous to the university's other graduate schools.[153][154][152] Columbia's General Studies school also has joint undergraduate programs available through University College London,[155] Sciences Po,[156] City University of Hong Kong,[157] Trinity College Dublin,[158] and the Juilliard School.[159]

The university also has several Columbia Global Centers, in Amman, Beijing, Istanbul, Mumbai, Nairobi, Paris, Rio de Janeiro, Santiago, and Tunis.[160]

International partnerships

Columbia students can study abroad for a semester or a year at partner institutions such as Sciences Po,[161] École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS), École normale supérieure (ENS), Panthéon-Sorbonne University, King's College London, London School of Economics, University College London and the University of Warwick. Select students can study at either the University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge for a year if approved by both Columbia and either Oxford or Cambridge.[162] Columbia also has a dual MA program with the Aga Khan University in London.

Rankings

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Columbia University is ranked 12th in the United States and seventh globally for 2023–2024 by U.S. News & World Report. QS University Rankings listed Columbia as fifth in the United States. Ranked 15th among U.S. colleges for 2020 by The Wall Street Journal and Times Higher Education, in recent years it has been ranked as high as second. Individual colleges and schools were also nationally ranked by U.S. News & World Report for its 2021 edition. Columbia Law School was ranked fourth, the Mailman School of Public Health fourth, the School of Social Work tied for third, Columbia Business School eighth, the College of Physicians and Surgeons tied for sixth for research (and tied for 31st for primary care), the School of Nursing tied for 11th in the master's program and tied for first in the doctorate nursing program, and the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (graduate) was ranked tied for 14th.

In 2021, Columbia was ranked seventh in the world (sixth in the United States) by Academic Ranking of World Universities, sixth in the world by U.S. News & World Report, 19th in the world by QS World University Rankings, and 11th globally by Times Higher Education World University Rankings. It was ranked in the first tier of American research universities, along with Harvard, MIT, and Stanford, in the 2019 report from the Center for Measuring University Performance. Columbia's Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation was ranked the second most admired graduate program by Architectural Record in 2020.

In 2011, the Mines ParisTech: Professional Ranking of World Universities ranked Columbia third best university for forming CEOs in the US and 12th worldwide.

Controversies

In 2022, Columbia's reporting of metrics used for university ranking was criticized by Professor of Mathematics Michael Thaddeus, who argued key data supporting the ranking was "inaccurate, dubious or highly misleading."[174][175] Subsequently, U.S. News & World Report "unranked" Columbia from its 2022 list of Best Colleges saying that it could not verify the data submitted by the university.[176] In June 2023, Columbia University announced their undergraduate schools would no longer participate in U.S. News & World Report's rankings, following the lead of its law, medical and nursing schools. A press release cited concerns that such rankings unduly influence applicants and "distill a university's profile into a composite of data categories."[177]

Research

Columbia is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[179] Columbia was the first North American site where the uranium atom was split. The College of Physicians and Surgeons played a central role in developing the modern understanding of neuroscience with the publication of Principles of Neural Science, described by historian of science Katja Huenther as the "neuroscience 'bible' ".[180] The book was written by a team of Columbia researchers that included Nobel Prize winner Eric Kandel, James H. Schwartz, and Thomas Jessell. Columbia was the birthplace of FM radio and the laser.[181] The first brain-computer interface capable of translating brain signals into speech was developed by neuroengineers at Columbia.[182][183][184] The MPEG-2 algorithm of transmitting high quality audio and video over limited bandwidth was developed by Dimitris Anastassiou, a Columbia professor of electrical engineering. Biologist Martin Chalfie was the first to introduce the use of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) in labeling cells in intact organisms.[185] Other inventions and products related to Columbia include Sequential Lateral Solidification (SLS) technology for making LCDs, System Management Arts (SMARTS), Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) (which is used for audio, video, chat, instant messaging and whiteboarding), pharmacopeia, Macromodel (software for computational chemistry), a new and better recipe for glass concrete, Blue LEDs, and Beamprop (used in photonics).[186]

Columbia scientists have been credited with about 175 new inventions in the health sciences each year.[186] More than 30 pharmaceutical products based on discoveries and inventions made at Columbia reached the market. These include Remicade (for arthritis), Reopro (for blood clot complications), Xalatan (for glaucoma), Benefix, Latanoprost (a glaucoma treatment), shoulder prosthesis, homocysteine (testing for cardiovascular disease), and Zolinza (for cancer therapy).[187] Columbia Technology Ventures (formerly Science and Technology Ventures), as of 2008[update], manages some 600 patents and more than 250 active license agreements.[187] Patent-related deals earned Columbia more than $230 million in the 2006 fiscal year, according to the university, more than any university in the world.[188] Columbia owns many unique research facilities, such as the Columbia Institute for Tele-Information dedicated to telecommunications and the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, which is an astronomical observatory affiliated with NASA.

Military and veteran enrollment

Columbia is a long-standing participant of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Yellow Ribbon Program, allowing eligible veterans to pursue a Columbia undergraduate degree regardless of socioeconomic status for over 70 years.[189] As a part of the Eisenhower Leader Development Program (ELDP) in partnership with the United States Military Academy at West Point, Columbia is the only school in the Ivy League to offer a graduate degree program in organizational psychology to aid military officers in tactical decision making and strategic management.[190]

Awards

Several prestigious awards are administered by Columbia University, most notably the Pulitzer Prize and the Bancroft Prize in history.[191][192] Other prizes, which are awarded by the Graduate School of Journalism, include the Alfred I. duPont–Columbia University Award, the National Magazine Awards, the Maria Moors Cabot Prizes, the John Chancellor Award, and the Lukas Prizes, which include the J. Anthony Lukas Book Prize and Mark Lynton History Prize.[193] The university also administers the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize, which is considered an important precursor to the Nobel Prize, 51 of its 101 recipients having gone on to win either a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine or Nobel Prize in Chemistry as of October 2018;[194] the W. Alden Spencer Award;[195] the Vetlesen Prize, which is known as the Nobel Prize of geology;[196] the Japan-U.S. Friendship Commission Prize for the Translation of Japanese Literature, the oldest such award;[197] the Edwin Howard Armstrong award;[198] the Calderone Prize in public health;[199] and the Ditson Conductor's Award.[200]

Student life

| Race and ethnicity[201] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 33% | ||

| Foreign national | 18% | ||

| Asian | 17% | ||

| Hispanic | 15% | ||

| Other[a] | 10% | ||

| Black | 7% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 19% | ||

| Affluent[c] | 81% | ||

In 2020, Columbia University's student population was 31,455 (8,842 students in undergraduate programs and 22,613 in postgraduate programs), with 45% of the student population identifying themselves as a minority.[202] Twenty-six percent of students at Columbia have family incomes below $60,000. 16% of students at Columbia receive Federal Pell Grants,[203] which mostly go to students whose family incomes are below $40,000. Seventeen percent of students are the first member of their family to attend a four-year college.[204]

On-campus housing is guaranteed for all four years as an undergraduate. Columbia College and the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (also known as SEAS or Columbia Engineering) share housing in the on-campus residence halls. First-year students usually live in one of the large residence halls situated around South Lawn: Carman Hall, Furnald Hall, Hartley Hall, John Jay Hall, or Wallach Hall (originally Livingston Hall). Upperclassmen participate in a room selection process, wherein students can pick to live in a mix of either corridor- or apartment-style housing with their friends. The Columbia University School of General Studies, Barnard College and graduate schools have their own apartment-style housing in the surrounding neighborhood.[205]

Columbia University is home to many fraternities, sororities, and co-educational Greek organizations. Approximately 10–15% of undergraduate students are associated with Greek life.[206] Many Barnard women also join Columbia sororities. There has been a Greek presence on campus since the establishment in 1836 of the Delta chapter of Alpha Delta Phi.[207] The InterGreek Council is the self-governing student organization that provides guidelines and support to its member organizations within each of the three councils at Columbia, the Interfraternity Council, Panhellenic Council, and Multicultural Greek Council. The three council presidents bring their affiliated chapters together once a month to meet as one Greek community. The InterGreek Council meetings provide opportunity for member organizations to learn from each other, work together and advocate for community needs.[208]

Publications

The Columbia Daily Spectator is the nation's second-oldest continuously operating daily student newspaper.[209] The Blue and White[210] is a monthly literary magazine established in 1890 that discusses campus life and local politics. Bwog,[211] originally an offshoot of The Blue and White but now fully independent, is an online campus news and entertainment source. The Morningside Post is a student-run multimedia news publication.

Political publications include The Current, a journal of politics, culture and Jewish Affairs;[212] the Columbia Political Review, the multi-partisan political magazine of the Columbia Political Union;[213] and AdHoc, which denotes itself as the "progressive" campus magazine and deals largely with local political issues and arts events.[214]

Columbia Magazine is the alumni magazine of Columbia, serving all 340,000+ of the university's alumni. Arts and literary publications include The Columbia Review, the nation's oldest college literary magazine;[215] Surgam, the literary magazine of The Philolexian Society;[216] Quarto, Columbia University's official undergraduate literary magazine;[217] 4x4, a student-run alternative to Quarto;[218] Columbia, a nationally regarded literary journal; the Columbia Journal of Literary Criticism;[219] and The Mobius Strip, an online arts and literary magazine.[220] Inside New York is an annual guidebook to New York City, written, edited, and published by Columbia undergraduates. Through a distribution agreement with Columbia University Press, the book is sold at major retailers and independent bookstores.[221]

Columbia is home to numerous undergraduate academic publications. The Columbia Undergraduate Science Journal prints original science research in its two annual publications.[222] The Journal of Politics & Society is a journal of undergraduate research in the social sciences;[223] Publius is an undergraduate journal of politics established in 2008 and published biannually;[224] the Columbia East Asia Review allows undergraduates throughout the world to publish original work on China, Japan, Korea, Tibet, and Vietnam and is supported by the Weatherhead East Asian Institute;[225] The Birch is an undergraduate journal of Eastern European and Eurasian culture that is the first national student-run journal of its kind;[226] the Columbia Economics Review is the undergraduate economic journal on research and policy supported by the Columbia Economics Department; and the Columbia Science Review is a science magazine that prints general interest articles and faculty profiles.[227]

Humor publications on Columbia's campus include The Fed, a triweekly satire and investigative newspaper, and the Jester of Columbia.[228][229] Other publications include The Columbian, the undergraduate colleges' annually published yearbook;[230] the Gadfly, a biannual journal of popular philosophy produced by undergraduates;[231] and Rhapsody in Blue, an undergraduate urban studies magazine.[232] Professional journals published by academic departments at Columbia University include Current Musicology and The Journal of Philosophy.[233][234] During the spring semester, graduate students in the Journalism School publish The Bronx Beat, a bi-weekly newspaper covering the South Bronx.

Founded in 1961 under the auspices of Columbia University's Graduate School of Journalism, the Columbia Journalism Review (CJR) examines day-to-day press performance as well as the forces that affect that performance. The magazine is published six times a year.[235]

Former publications include the Columbia University Forum, a review of literature and cultural affairs distributed for free to alumni.[236][237]

Broadcasting

Columbia is home to two pioneers in undergraduate campus radio broadcasting, WKCR-FM and CTV. Many undergraduates are also involved with Barnard's radio station, WBAR. WKCR, the student run radio station that broadcasts to the Tri-state area, claims to be the oldest FM radio station in the world, owing to the university's affiliation with Major Edwin Armstrong. The station went operational on July 18, 1939, from a 400-foot antenna tower in Alpine, New Jersey, broadcasting the first FM transmission in the world. Initially, WKCR was not a radio station, but an organization concerned with the technology of radio communications. As membership grew, however, the nascent club turned its efforts to broadcasting. Armstrong helped the students in their early efforts, donating a microphone and turntables when they designed their first makeshift studio in a dorm room.[238] The station has its studios on the second floor of Alfred Lerner Hall on the Morningside campus with its main transmitter tower at 4 Times Square in Midtown Manhattan. Columbia Television (CTV) is the nation's second oldest student television station and the home of CTV News, a weekly live news program produced by undergraduate students.[239][240]

Debate and Model UN

The Philolexian Society is a literary and debating club founded in 1802, making it the oldest student group at Columbia, as well as the third oldest collegiate literary society in the country.[241] The society annually administers the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Bad Poetry Contest.[242] The Columbia Parliamentary Debate Team competes in tournaments around the country as part of the American Parliamentary Debate Association, and hosts both high school and college tournaments on Columbia's campus, as well as public debates on issues affecting the university.[243]

The Columbia International Relations Council and Association (CIRCA), oversees Columbia's Model United Nations activities. CIRCA hosts college and high school Model UN conferences, hosts speakers influential in international politics to speak on campus, and trains students from underprivileged schools in New York in Model UN.[244]

Technology and entrepreneurship

Columbia is a top supplier of young engineering entrepreneurs for New York City. Over the past 20 years, graduates of Columbia established over 100 technology companies.[245]

The Columbia University Organization of Rising Entrepreneurs (CORE) was founded in 1999. The student-run group aims to foster entrepreneurship on campus. Each year CORE hosts dozens of events, including talks, #StartupColumbia, a conference and venture competition for $250,000, and Ignite@CU, a weekend for undergrads interested in design, engineering, and entrepreneurship. Notable speakers include Peter Thiel, Jack Dorsey,[246] Alexis Ohanian, Drew Houston, and Mark Cuban. As of 2006, CORE had awarded graduate and undergraduate students over $100,000 in seed capital.

CampusNetwork, an on-campus social networking site called Campus Network that preceded Facebook, was created and popularized by Columbia engineering student Adam Goldberg in 2003. Mark Zuckerberg later asked Goldberg to join him in Palo Alto to work on Facebook, but Goldberg declined the offer.[247] The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science offers a minor in Technical Entrepreneurship through its Center for Technology, Innovation, and Community Engagement. SEAS' entrepreneurship activities focus on community building initiatives in New York and worldwide, made possible through partners such as Microsoft Corporation.[248]

On June 14, 2010, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg launched the NYC Media Lab to promote innovations in New York's media industry. Situated at the New York University Tandon School of Engineering, the lab is a consortium of Columbia University, New York University, and New York City Economic Development Corporation acting to connect companies with universities in new technology research. The Lab is modeled after similar ones at MIT and Stanford, and was established with a $250,000 grant from the New York City Economic Development Corporation.[249]

World Leaders Forum

Established in 2003 by university president Lee C. Bollinger, the World Leaders Forum at Columbia University provides the opportunity for students and faculty to listen to world leaders in government, religion, industry, finance, and academia.[250]

Past forum speakers include former president of the United States Bill Clinton, the prime minister of India Atal Bihari Vajpayee, former president of Ghana John Agyekum Kufuor, president of Afghanistan Hamid Karzai, prime minister of Russia Vladimir Putin, president of the Republic of Mozambique Joaquim Alberto Chissano, president of the Republic of Bolivia Carlos Diego Mesa Gisbert, president of the Republic of Romania Ion Iliescu, president of the Republic of Latvia Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga, the first female president of Finland Tarja Halonen, President Yudhoyono of Indonesia, President Pervez Musharraf of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Iraq President Jalal Talabani, the 14th Dalai Lama, president of the Islamic Republic of Iran Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, financier George Soros, Mayor of New York City Michael R. Bloomberg, President Václav Klaus of the Czech Republic, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner of Argentina, former Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan, and Al Gore.[251]

Other

The Columbia University Orchestra was founded by composer Edward MacDowell in 1896, and is the oldest continually operating university orchestra in the United States. Undergraduate student composers at Columbia may choose to become involved with Columbia New Music, which sponsors concerts of music written by undergraduate students from all of Columbia's schools.[252] The Notes and Keys, the oldest a cappella group at Columbia, was founded in 1909.[253] There are a number of performing arts groups at Columbia dedicated to producing student theater, including the Columbia Players, King's Crown Shakespeare Troupe (KCST), Columbia Musical Theater Society (CMTS), NOMADS (New and Original Material Authored and Directed by Students), LateNite Theatre, Columbia University Performing Arts League (CUPAL), Black Theatre Ensemble (BTE), sketch comedy group Chowdah, and improvisational troupes Alfred and Fruit Paunch.[254]

The Columbia Queer Alliance is the central Columbia student organization that represents the bisexual, lesbian, gay, transgender, and questioning student population. It is the oldest gay student organization in the world, founded as the Student Homophile League in 1967 by students including lifelong activist Stephen Donaldson.[255][256]

Columbia University campus military groups include the U.S. Military Veterans of Columbia University and Advocates for Columbia ROTC. In the 2005–06 academic year, the Columbia Military Society, Columbia's student group for ROTC cadets and Marine officer candidates, was renamed the Hamilton Society for "students who aspire to serve their nation through the military in the tradition of Alexander Hamilton".[257]

The largest student service organization at Columbia is Community Impact (CI). Founded in 1981, CI provides food, clothing, shelter, education, job training, and companionship for residents in its surrounding communities. CI consists of about 950 Columbia University student volunteers participating in 25 community service programs, which serve more than 8,000 people each year.[258]

Columbia has several secret societies, including St. Anthony Hall, which was founded at the university in 1847, and two senior societies, the Nacoms and Sachems.[259][260]

Athletics

A member institution of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in Division I FCS, Columbia fields varsity teams in 29 sports and is a member of the Ivy League. The football Lions play home games at the 17,000-seat Robert K. Kraft Field at Lawrence A. Wien Stadium. The Baker Athletics Complex also includes facilities for baseball, softball, soccer, lacrosse, field hockey, tennis, track, and rowing, as well as the new Campbell Sports Center, which opened in January 2013. The basketball, fencing, swimming & diving, volleyball, and wrestling programs are based at the Dodge Physical Fitness Center on the main campus.[261]

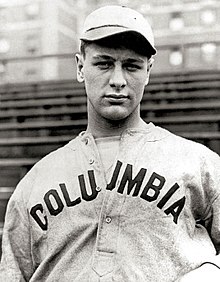

Former students include Baseball Hall of Famers Lou Gehrig and Eddie Collins, football Hall of Famer Sid Luckman, Marcellus Wiley, and world champion women's weightlifter Karyn Marshall.[262][263] On May 17, 1939, fledgling NBC broadcast a doubleheader between the Columbia Lions and the Princeton Tigers at Columbia's Baker Field, making it the first televised regular athletic event in history.[264][265]

Columbia University athletics has a long history, with many accomplishments in athletic fields. In 1870, Columbia played against Rutgers University in the second intercollegiate rugby football game in the history of the sport. Eight years later, Columbia crew won the famed Henley Royal Regatta in the first-ever defeat for an English crew rowing in English waters. In 1900, Olympian and Columbia College student Maxie Long set the first official world record in the 400 meters with a time of 47.8 seconds. In 1983, Columbia men's soccer went 18–0 and was ranked first in the nation, but lost to Indiana 1–0 in double overtime in the NCAA championship game; nevertheless, the team went further toward the NCAA title than any Ivy League soccer team in history.[266] The football program unfortunately is best known for its record of futility set during the 1980s: between 1983 and 1988, the team lost 44 games in a row, which is still the record for the NCAA Football Championship Subdivision. The streak was broken on October 8, 1988, with a 16–13 victory over arch-rival Princeton University. That was the Lions' first victory at Wien Stadium, which had been opened during the losing streak and was already four years old.[267] A new tradition has developed with the Liberty Cup. The Liberty Cup is awarded annually to the winner of the football game between Fordham and Columbia Universities, two of the only three NCAA Division I football teams in New York City.[268]

Traditions

The Varsity Show

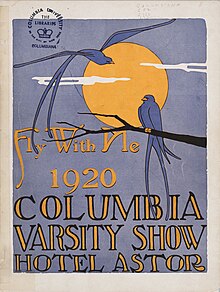

The Varsity Show is one of the oldest traditions at Columbia. Founded in 1893 as a fundraiser for the university's fledgling athletic teams, the Varsity Show now draws together the entire Columbia undergraduate community for a series of performances every April. Dedicated to producing a unique full-length musical that skewers and satirizes many dubious aspects of life at Columbia, the Varsity Show is written and performed exclusively by university undergraduates. Various renowned playwrights, composers, authors, directors, and actors have contributed to the Varsity Show, either as writers or performers, while students at Columbia, including Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II, Lorenz Hart, Herman J. Mankiewicz, I. A. L. Diamond, Herman Wouk, Greta Gerwig, and Kate McKinnon.[269]

Notable past shows include Fly With Me (1920), The Streets of New York (1948), The Sky's the Limit (1954), and Angels at Columbia (1994). In particular, Streets of New York, after having been revived three times, opened off-Broadway in 1963 and was awarded a 1964 Drama Desk Award. The Mischief Maker (1903), written by Edgar Allan Woolf and Cassius Freeborn, premiered at Madison Square Garden in 1906 as Mam'zelle Champagne.[269][270]

Tree Lighting and Yule Log ceremonies

The campus Tree Lighting ceremony was inaugurated in 1998. It celebrates the illumination of the medium-sized trees lining College Walk in front of Kent Hall and Hamilton Hall on the east end and Dodge Hall and Pulitzer Hall on the west, just before finals week in early December. The lights remain on until February 28. Students meet at the sundial for free hot chocolate, performances by a cappella groups, and speeches by the university president and a guest.[271]

Immediately following the College Walk festivities is one of Columbia's older holiday traditions, the lighting of the Yule Log. The Christmas ceremony dates to a period prior to the American Revolutionary War, but lapsed before being revived by President Nicholas Murray Butler in 1910. A troop of students dressed as Continental Army soldiers carry the eponymous log from the sundial to the lounge of John Jay Hall, where it is lit amid the singing of seasonal carols. The Christmas ceremony is accompanied by a reading of A Visit From St. Nicholas by Clement Clarke Moore and Yes, Virginia, There is a Santa Claus by Francis Pharcellus Church.[272]

Notable people

Alumni

This section contains an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. |

The university has graduated many notable alumni, including five Founding Fathers of the United States, an author of the United States Constitution and a member of the Committee of Five. Three United States presidents have attended Columbia,[273] as well as ten Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States, including three Chief Justices. As of 2011[update], 125 Pulitzer Prize winners and 39 Oscar winners have attended Columbia.[274] As of 2006[update], there were 101 National Academy members who were alumni.[275]

In a 2016 ranking of universities worldwide with respect to living graduates who are billionaires, Columbia ranked second, after Harvard.[276][277]

Former U.S. Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Delano Roosevelt attended the law school. Other political figures educated at Columbia include former U.S. President Barack Obama,[278] Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Ruth Bader Ginsburg,[279] former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright,[280] former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank Alan Greenspan,[281] U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, and U.S. Solicitor General Donald Verrilli Jr.[282] The university has also educated 29 foreign heads of state, including president of Georgia Mikheil Saakashvili, president of East Timor José Ramos-Horta, president of Estonia Toomas Hendrik Ilves and other historical figures such as Wellington Koo, Radovan Karadžić, Gaston Eyskens, and T. V. Soong. One of the architects of the Constitution of India, B. R. Ambedkar, was an alumnus.[283]

Alumni of Columbia have occupied top positions in Wall Street and the rest of the business world. Notable members of the Astor family[284][285] attended Columbia, while other business graduates include investor Warren Buffett,[286] former CEO of PBS and NBC Lawrence K. Grossman,[287] chairman of Walmart S. Robson Walton,[288] Bain Capital Co-Managing Partner, Jonathan Lavine,[289][290] Thomson Reuters CEO Tom Glocer,[291][292] New York Stock Exchange president Lynn Martin,[293] and AllianceBernstein Chairman and CEO Lewis A. Sanders.[294] CEO's of top Fortune 500 companies include James P. Gorman of Morgan Stanley,[295] Robert J. Stevens of Lockheed Martin,[296] Philippe Dauman of Viacom,[297] Robert Bakish of Paramount Global,[298][299] Ursula Burns of Xerox,[300] Devin Wenig of EBay,[301] Vikram Pandit of Citigroup,[302] Ralph Izzo of Public Service Enterprise Group,[303][304] Gail Koziara Boudreaux of Anthem,[305] and Frank Blake of The Home Depot.[306] Notable labor organizer and women's educator Louise Leonard McLaren received her degree of Master of Arts from Columbia.[307]

In science and technology, Columbia alumni include: founder of IBM Herman Hollerith;[308] inventor of FM radio Edwin Armstrong;[309] Francis Mechner; integral in development of the nuclear submarine Hyman Rickover;[310] founder of Google China Kai-Fu Lee;[311] scientists Stephen Jay Gould,[312] Robert Millikan,[313] Helium–neon laser inventor Ali Javan and Mihajlo Pupin;[314] chief-engineer of the New York City Subway, William Barclay Parsons;[315] philosophers Irwin Edman[316] and Robert Nozick;[317] economist Milton Friedman;[318] psychologist Harriet Babcock;[319] archaeologist Josephine Platner Shear;[320] and sociologists Lewis A. Coser and Rose Laub Coser.[321][322]

Many Columbia alumni have gone on to renowned careers in the arts, including composers Richard Rodgers,[323] Oscar Hammerstein II,[324] Lorenz Hart,[325] and Art Garfunkel;[326] and painter Georgia O'Keeffe.[327] Five United States Poet Laureates received their degrees from Columbia. Columbia alumni have made an indelible mark in the field of American poetry and literature, with such people as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, pioneers of the Beat Generation;[328] and Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, seminal figures in the Harlem Renaissance,[329][330] all having attended the university. Other notable writers who attended Columbia include authors Isaac Asimov,[331] J.D. Salinger,[332] Upton Sinclair,[333] Ursula K. Le Guin,[334] Danielle Valore Evans,[335] and Hunter S. Thompson.[336] In architecture, William Lee Stoddart, a prolific architect of U.S. East Coast hotels, is an alumnus.[337]

University alumni have also been very prominent in the film industry, with 33 alumni and former students winning a combined 43 Academy Awards (as of 2011[update]).[274] Some notable Columbia alumni that have gone on to work in film include directors Sidney Lumet (12 Angry Men)[338] and Kathryn Bigelow (The Hurt Locker),[339] screenwriters Howard Koch (Casablanca)[340] and Joseph L. Mankiewicz (All About Eve),[341] and actors James Cagney,[342] Ed Harris and Timothée Chalamet.[343]

- Notable Columbia University alumni include:

- Alexander Hamilton: Founding Father of the United States; author of The Federalist Papers; first United States Secretary of the Treasury — King's College

- John Jay: Founding Father of the United States; author of The Federalist Papers; first Chief Justice of the United States; second Governor of New York — King's College

- Robert R. Livingston: Founding Father of the United States; drafter of the Declaration of Independence; first United States Secretary of Foreign Affairs — King's College

- Gouverneur Morris: Founding Father of the United States; author of the United States Constitution; United States Senator from New York — King's College

- DeWitt Clinton: United States Senator from New York; sixth Governor of New York; responsible for construction of Erie Canal — Columbia College

- Barack Obama: 44th President of the United States; United States Senator from Illinois; Nobel laureate — Columbia College

- Franklin D. Roosevelt: 32nd President of the United States; 44th Governor of New York — Columbia Law School

- Theodore Roosevelt: 26th President of the United States; 25th Vice President of the United States; 33rd Governor of New York; Nobel laureate – Columbia Law School

- Wellington Koo: acting President of the Republic of China; judge of the International Court of Justice — Columbia College, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- B. R. Ambedkar: Founding Father of India; architect of the Constitution of India; First Minister of Law and Justice — Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States — Columbia Law School

- Neil Gorsuch: Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States — Columbia College

- Charles Evans Hughes: 11th Chief Justice of the United States; 44th United States Secretary of State; 35th Governor of New York — Columbia Law School

- Harlan Fiske Stone: 12th Chief Justice of the United States; 52nd United States Attorney General — Columbia Law School

- William Barr: 77th and 85th United States Attorney General – Columbia College, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Hamilton Fish: 26th United States Secretary of State; United States Senator from New York; 16th Governor of New York — Columbia College

- Madeleine Albright: 64th United States Secretary of State; first female Secretary of State — School of International and Public Affairs

- Frances Perkins: fourth United States Secretary of Labor; first female member of any U.S. Cabinet — Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Robert A. Millikan: Nobel laureate; measured the elementary electric charge — Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Isidor Isaac Rabi: Nobel Laureate; discovered nuclear magnetic resonance — Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Julian S. Schwinger: Nobel laureate; pioneer of quantum field theory — Columbia College, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Milton Friedman: Nobel laureate, leading member of the Chicago school of economics — Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Simon Kuznets: Nobel laureate; invented concept of GDP; Milton Friedman's doctoral advisor — School of General Studies, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Alan Greenspan: 13th Chair of the Federal Reserve — Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Warren Buffett: CEO of Berkshire Hathaway; one of the world's wealthiest people — Columbia Business School

- Herman Hollerith: inventor; co-founder of IBM – School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

- Robert Kraft: billionaire; owner of the New England Patriots; chairman and CEO of the Kraft Group — Columbia College

- Richard Rodgers: legendary Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony award-winning composer; Pulitzer Prize winner — Columbia College

- Langston Hughes: Harlem Renaissance poet, novelist, and playwright — School of Engineering and Applied Science

- Zora Neale Hurston: Harlem Renaissance author, anthropologist, and filmmaker — Barnard College, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Allen Ginsberg: poet; founder of the Beat Generation — Columbia College

- Jack Kerouac: poet; founder of the Beat Generation — Columbia College

- Isaac Asimov: science fiction writer; biochemist — School of General Studies, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- J. D. Salinger: novelist, The Catcher in the Rye — School of General Studies

- Amelia Earhart: first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean — School of General Studies

- Jake Gyllenhaal: actor and film producer — Columbia College

Faculty

As of 2021, Columbia employs 4,381 faculty, including 70 members of the National Academy of Sciences,[344] 178 members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences,[345] and 65 members of the National Academy of Medicine.[346] In total, the Columbia faculty has included 52 Nobel laureates, 12 National Medal of Science recipients,[347] and 32 National Academy of Engineering members.[348]

Columbia University faculty played particularly important roles during World War II and the creation of the New Deal under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who attended Columbia Law School. The three core members of Roosevelt's Brain Trust: Adolf A. Berle, Raymond Moley, and Rexford Tugwell, were law professors at Columbia.[349] The Statistical Research Group, which used statistics to analyze military problems during World War II, was composed of Columbia researchers and faculty including George Stigler and Milton Friedman.[350] Columbia faculty and researchers, including Enrico Fermi, Leo Szilard, Eugene T. Booth, John R. Dunning, George B. Pegram, Walter Zinn, Chien-Shiung Wu, Francis G. Slack, Harold Urey, Herbert L. Anderson, and Isidor Isaac Rabi, also played a significant role during the early phases of the Manhattan Project.[351]

Following the rise of Nazi Germany, the exiled Institute for Social Research at Goethe University Frankfurt would affiliate itself with Columbia from 1934 to 1950.[352] It was during this period that thinkers including Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse wrote and published some of the most seminal works of the Frankfurt School, including Reason and Revolution, Dialectic of Enlightenment, and Eclipse of Reason.[353] Professors Edward Said, author of Orientalism, and Gayatri Spivak are generally considered as founders of the field of postcolonialism;[354][355] other professors that have significantly contributed to the field include Hamid Dabashi and Joseph Massad.[356][357] The works of professors Kimberlé Crenshaw, Patricia J. Williams, and Kendall Thomas were foundational to the field of critical race theory.[358]

Columbia and its affiliated faculty have also made significant contributions to the study of religion. The affiliated Union Theological Seminary is a center of liberal Christianity in the United States, having served as the birthplace of Black theology through the efforts of faculty including James H. Cone and Cornel West,[359][360] and Womanist theology, through the works of Katie Cannon, Emilie Townes, and Delores S. Williams.[361][362][363] Likewise, the Jewish Theological Seminary of America was the birthplace of Conservative Judaism movement in the United States, which was founded and led by faculty members including Solomon Schechter, Alexander Kohut, and Louis Ginzberg in the early 20th century, and is a major center for Jewish studies in general.[364]

Other schools of thought in the humanities Columbia professors made significant contributions toward include the Dunning School, founded by William Archibald Dunning;[365][366] the anthropological schools of historical particularism and cultural relativism, founded by Franz Boas;[367] and functional psychology, whose founders and proponents include John Dewey, James McKeen Cattell, Edward L. Thorndike, and Robert S. Woodworth.[368]

Notable figures that have served as the president of Columbia University include 34th President of the United States Dwight D. Eisenhower, 4th Vice President of the United States George Clinton, Founding Father and U.S. Senator from Connecticut William Samuel Johnson, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Nicholas Murray Butler, and First Amendment scholar Lee Bollinger.[22]

Notable Columbia University faculty include Zbigniew Brzezinski, Sonia Sotomayor, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Lee Bollinger, Franz Boas, Margaret Mead, Edward Sapir, John Dewey, Charles A. Beard, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Edward Said, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Orhan Pamuk, Edwin Howard Armstrong, Enrico Fermi, Chien-Shiung Wu, Tsung-Dao Lee, Jack Steinberger, Joachim Frank, Joseph Stiglitz, Jeffrey Sachs, Robert Mundell, Thomas Hunt Morgan, Eric Kandel, Richard Axel, and Andrei Okounkov.

See also

- Columbia Encyclopedia

- Columbia Glacier, a glacier in Alaska, U.S., named for Columbia University

- Columbia MM, a text-based mail client developed at Columbia University

- Columbia Non-neutral Torus, a small stellarator at the Columbia University Plasma Physics Laboratory

- Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, an album of electronic music released in 1961

- Columbia Revolt, a black-and-white 1968 documentary film

- Columbia Scholastic Press Association

- Columbia School of Linguistics

- Columbia Spelling Board, a historic etymological organization

- Columbia Unbecoming controversy

- Columbia University in popular culture

- Columbia University Partnership for International Development

- Mount Columbia, a mountain in Colorado, U.S., named for Columbia University

- Nutellagate, a controversy surrounding high Nutella consumption at Columbia University

- The Strawberry Statement, a non-fiction account of the 1968 protests

- 2024 Columbia University pro-Palestinian campus occupations

Notes

- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

Citations

- ^ Founding Fathers include five alumni: Alexander Hamilton,[16] John Jay,[17] Robert R. Livingston,[18] Egbert Benson,[19] and Gouverneur Morris.[20] Additionally, Founding Fathers George Clinton[21] and William Samuel Johnson[22] served as presidents of the university.

- ^ Three presidents have attended Columbia: Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Barack Obama. Dwight D. Eisenhower served as the president of the university from 1948 to 1953.

- ^ Alumni who served as foreign heads of state or government include: Muhammad Fadhel al-Jamali (Iraq, 1953–54),[23] Kassim al-Rimawi (Jordan, 1980),[24] Giuliano Amato (Italy, 1992–1993 and 2000–2001),[25] Hafizullah Amin (Afghanistan, 1979),[26] Nahas Angula (Namibia, 2005–12),[27] Marek Belka (Poland, 2004–05),[28] Chen Gongbo (China, 1944–45),[29] Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz (Poland, 1996–97),[30] Gaston Eyskens (Belgium, 1949–50, 1958–61 and 1968–73),[31] Mark Eyskens (Belgium, 1981),[32] Ashraf Ghani (Afghanistan, 2014–21),[33] José Ramos-Horta (East Timor, 2007–12 and 2022– ),[34] Toomas Hendrik Ilves (Estonia, 2006–16),[35] Wellington Koo (China 1926–27),[36] Lee Huan (Taiwan, 1989–90),[37] Benjamin Mkapa (Tanzania, 1995–2005),[38] Mohammad Musa Shafiq (Afghanistan, 1972–73),[39] Nwafor Orizu (Nigeria, 1965–6),[40] Santiago Peña (Paraguay, 2023–present),[41] Mikheil Saakashvili (Georgia, 2004–13),[42] Juan Bautista Sacasa (Nicaragua, 1933–36),[43] Salim Ahmed Salim (Tanzania, 1984–85),[44] Ernesto Samper (Colombia, 1994–98),[45] T. V. Soong (China, 1945–47),[46] Sun Fo (China, 1932; Taiwan, 1948–49),[47] C. R. Swart (South Africa, 1959–67),[48] Tang Shaoyi (China, 1912),[49] Abdul Zahir (Afghanistan, 1971–72),[45] and Zhou Ziqi (China, 1922).[50] Faculty and fellows include Fernando Henrique Cardoso (Brazil, 1995–2002),[51] Alfred Gusenbauer (Austria, 2007–2008),[52] Václav Havel (Czechoslovakia, 1989–1992; Czech Republic, 1993–2003),[53] Lucas Papademos (Greece, 2011–2012),[54] Mary Robinson (Ireland, 1990–1997).[55]

- ^ Boutros Boutros-Ghali taught as a Fulbright Research Scholar from 1954 to 1955.[56] Kofi Annan was a global fellow at SIPA from 2009 to 2018.[52]

References

- ^ Psalms 36:9