Возобновляемая энергия

| Part of a series on |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

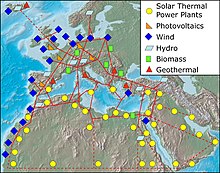

Возобновляемая энергия (или зеленая энергия ) - это энергия от возобновляемых природных ресурсов , которые пополняются на человеческом масштабе . Наиболее широко используемыми типами возобновляемых источников энергии являются солнечная энергия , энергия ветра и гидроэнергетика . Биоэнергетика и геотермальная власть также значительны в некоторых странах. Некоторые также считают ядерную энергию возобновляемым источником энергии , хотя это противоречиво. Установки возобновляемой энергии могут быть большими или небольшими и подходят как для городских, так и для сельских районов. Возобновляемая энергия часто развертывается вместе с дальнейшей электрификацией . Это имеет несколько преимуществ: электричество может эффективно перемещать тепло и транспортные средства и чисто в точке потребления. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] Переменные возобновляемые источники энергии - это те, которые имеют колеблющуюся природу, такие как энергия ветра и солнечная энергия. Напротив, контролируемые возобновляемые источники энергии включают в себя гидроэлектростанцию , биоэнергию или геотермальную мощность .

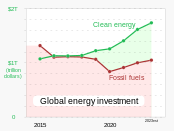

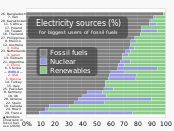

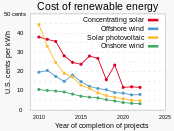

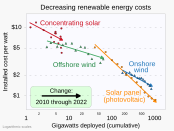

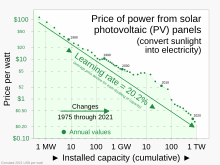

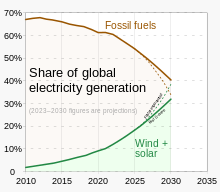

Renewable energy systems have rapidly become more efficient and cheaper over the past 30 years.[3] A large majority of worldwide newly installed electricity capacity is now renewable.[4] Renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, have seen significant cost reductions over the past decade, making them more competitive with traditional fossil fuels.[5] In most countries, photovoltaic solar or onshore wind are the cheapest new-build electricity.[6] From 2011 to 2021, renewable energy grew from 20% to 28% of global electricity supply. Power from the sun and wind accounted for most of this increase, growing from a combined 2% to 10%. Use of fossil energy shrank from 68% to 62%.[7] In 2022, renewables accounted for 30% of global electricity generation and are projected to reach over 42% by 2028.[8][9] Many countries already have renewables contributing more than 20% of their total energy supply, with some generating over half or even all their electricity from renewable sources.[10][11]

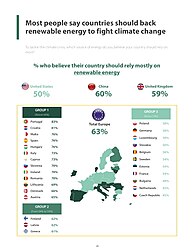

The main motivation to replace fossil fuels with renewable energy sources is to slow and eventually stop climate change, which is widely agreed to be caused mostly by greenhouse gas emissions. In general, renewable energy sources cause much lower emissions than fossil fuels.[12] The International Energy Agency estimates that to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, 90% of global electricity generation will need to be produced from renewable sources.[13] Renewables also cause much less air pollution than fossil fuels, improving public health, and are less noisy.[12]

The deployment of renewable energy still faces obstacles, especially fossil fuel subsidies,[14] lobbying by incumbent power providers,[15] and local opposition to the use of land for renewable installations.[16][17] Like all mining, the extraction of minerals required for many renewable energy technologies also results in environmental damage.[18] In addition, although most renewable energy sources are sustainable, some are not.

Overview

[edit]Definition

[edit]Renewable energy is usually understood as energy harnessed from continuously occurring natural phenomena. The International Energy Agency defines it as "energy derived from natural processes that are replenished at a faster rate than they are consumed". Solar power, wind power, hydroelectricity, geothermal energy, and biomass are widely agreed to be the main types of renewable energy.[21] Renewable energy often displaces conventional fuels in four areas: electricity generation, hot water/space heating, transportation, and rural (off-grid) energy services.[22]

Although almost all forms of renewable energy cause much fewer carbon emissions than fossil fuels, the term is not synonymous with low-carbon energy. Some non-renewable sources of energy, such as nuclear power,[contradictory]generate almost no emissions, while some renewable energy sources can be very carbon-intensive, such as the burning of biomass if it is not offset by planting new plants.[12] Renewable energy is also distinct from sustainable energy, a more abstract concept that seeks to group energy sources based on their overall permanent impact on future generations of humans. For example, biomass is often associated with unsustainable deforestation.[23]

Role in addressing climate change

[edit]As part of the global effort to limit climate change, most countries have committed to net zero greenhouse gas emissions.[24] In practice, this means phasing out fossil fuels and replacing them with low-emissions energy sources.[12] At the 2023 United Nations Climate Change Conference, around three-quarters of the world's countries set a goal of tripling renewable energy capacity by 2030.[25] The European Union aims to generate 40% of its electricity from renewables by the same year.[26]

Other benefits

[edit]Renewable energy is more evenly distributed around the world than fossil fuels, which are concentrated in a limited number of countries.[27] It also brings health benefits by reducing air pollution caused by the burning of fossil fuels. The potential worldwide savings in health care costs have been estimated at trillions of dollars annually.[28]

Intermittency

[edit]

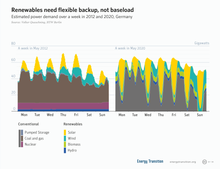

The two most important forms of renewable energy, solar and wind, are intermittent energy sources: they are not available constantly, resulting in lower capacity factors. In contrast, fossil fuel power plants are usually able to produce precisely the amount of energy an electricity grid requires at a given time. Solar energy can only be captured during the day, and ideally in cloudless conditions. Wind power generation can vary significantly not only day-to-day, but even month-to-month.[29] This poses a challenge when transitioning away from fossil fuels: energy demand will often be higher or lower than what renewables can provide.[30] Both scenarios can cause electricity grids to become overloaded, leading to power outages.

In the medium-term, this variability may require keeping some gas-fired power plants or other dispatchable generation on standby[31][32] until there is enough energy storage, demand response, grid improvement, and/or baseload power from non-intermittent sources. In the long-term, energy storage is an important way of dealing with intermittency.[33] Using diversified renewable energy sources and smart grids can also help flatten supply and demand.[34]

Sector coupling of the power generation sector with other sectors may increase flexibility: for example the transport sector can be coupled by charging electric vehicles and sending electricity from vehicle to grid.[35] Similarly the industry sector can be coupled by hydrogen produced by electrolysis,[36] and the buildings sector by thermal energy storage for space heating and cooling.[37]

Building overcapacity for wind and solar generation can help ensure sufficient electricity production even during poor weather. In optimal weather, it may be necessary to curtail energy generation if it is not possible to use or store excess electricity.[38]

Electrical energy storage

[edit]Electrical energy storage is a collection of methods used to store electrical energy. Electrical energy is stored during times when production (especially from intermittent sources such as wind power, tidal power, solar power) exceeds consumption, and returned to the grid when production falls below consumption. Pumped-storage hydroelectricity accounts for more than 85% of all grid power storage.[39] Batteries are increasingly being deployed for storage[40] and grid ancillary services[41] and for domestic storage.[42] Green hydrogen is a more economical means of long-term renewable energy storage, in terms of capital expenditures compared to pumped hydroelectric or batteries.[43][44]

Mainstream technologies

[edit]

Solar energy

[edit]| Installed capacity and other key design parameters | Value and year |

|---|---|

| Global electricity power generation capacity | 1419.0 GW (2023)[46] |

| Global electricity power generation capacity annual growth rate | 25% (2014-2023)[47] |

| Share of global electricity generation | 5.5% (2023)[48] |

| Levelized cost per megawatt hour | Utility-scale photovoltaics: USD 38.343 (2019)[49] |

| Primary technologies | Photovoltaics, concentrated solar power, solar thermal collector |

| Main applications | Electricity, water heating, heating, ventilation, air conditioning (HVAC) |

Solar power produced around 1.3 terrawatt-hours (TWh) worldwide in 2022,[10] representing 4.6% of the world's electricity. Almost all of this growth has happened since 2010.[50] Solar energy can be harnessed anywhere that receives sunlight; however, the amount of solar energy that can be harnessed for electricity generation is influenced by weather conditions, geographic location and time of day.[51]

There are two mainstream ways of harnessing solar energy: solar thermal, which converts solar energy into heat; and photovoltaics (PV), which converts it into electricity.[12] PV is far more widespread, accounting for around two thirds of the global solar energy capacity as of 2022.[52] It is also growing at a much faster rate, with 170 GW newly installed capacity in 2021,[53] compared to 25 GW of solar thermal.[52]

Passive solar refers to a range of construction strategies and technologies that aim to optimize the distribution of solar heat in a building. Examples include solar chimneys,[12] orienting a building to the sun, using construction materials that can store heat, and designing spaces that naturally circulate air.[54]

From 2020 to 2022, solar technology investments almost doubled from USD 162 billion to USD 308 billion, driven by the sector's increasing maturity and cost reductions, particularly in solar photovoltaic (PV), which accounted for 90% of total investments. China and the United States were the main recipients, collectively making up about half of all solar investments since 2013. Despite reductions in Japan and India due to policy changes and COVID-19, growth in China, the United States, and a significant increase from Vietnam's feed-in tariff program offset these declines. Globally, the solar sector added 714 gigawatts (GW) of solar PV and concentrated solar power (CSP) capacity between 2013 and 2021, with a notable rise in large-scale solar heating installations in 2021, especially in China, Europe, Turkey, and Mexico.[55]

Photovoltaics

[edit]

A photovoltaic system, consisting of solar cells assembled into panels, converts light into electrical direct current via the photoelectric effect.[58] PV has several advantages that make it by far the fastest-growing renewable energy technology. It is cheap, low-maintenance and scalable; adding to an existing PV installation as demanded arises is simple. Its main disadvantage is its poor performance in cloudy weather.[12]

PV systems range from small, residential and commercial rooftop or building integrated installations, to large utility-scale photovoltaic power station.[59] A household's solar panels can either be used for just that household or, if connected to an electrical grid, can be aggregated with millions of others.[60]

The first utility-scale solar power plant was built in 1982 in Hesperia, California by ARCO.[61] The plant was not profitable and was sold eight years later.[62] However, over the following decades, PV cells became significantly more efficient and cheaper.[63] As a result, PV adoption has grown exponentially since 2010.[64] Global capacity increased from 230 GW at the end of 2015 to 890 GW in 2021.[65] PV grew fastest in China between 2016 and 2021, adding 560 GW, more than all advanced economies combined.[66] Four of the ten biggest solar power stations are in China, including the biggest, Golmud Solar Park in China.[67]

Solar thermal

[edit]Unlike photovoltaic cells that convert sunlight directly into electricity, solar thermal systems convert it into heat. They use mirrors or lenses to concentrate sunlight onto a receiver, which in turn heats a water reservoir. The heated water can then be used in homes. The advantage of solar thermal is that the heated water can be stored until it is needed, eliminating the need for a separate energy storage system.[68] Solar thermal power can also be converted to electricity by using the steam generated from the heated water to drive a turbine connected to a generator. However, because generating electricity this way is much more expensive than photovoltaic power plants, there are very few in use today.[69]

Wind power

[edit]

| Installed capacity and other key design parameters | Value and year |

|---|---|

| Global electricity power generation capacity | 1017.2 GW (2023)[71] |

| Global electricity power generation capacity annual growth rate | 13% (2014-2023)[72] |

| Share of global electricity generation | 7.8% (2023)[48] |

| Levelized cost per megawatt hour | Land-based wind: USD 30.165 (2019)[73] |

| Primary technology | Wind turbine, windmill |

| Main applications | Electricity, pumping water (windpump) |

Humans have harnessed wind energy since at least 3500 BC. Until the 20th century, it was primarily used to power ships, windmills and water pumps. Today, the vast majority of wind power is used to generate electricity using wind turbines.[12] Modern utility-scale wind turbines range from around 600 kW to 9 MW of rated power. The power available from the wind is a function of the cube of the wind speed, so as wind speed increases, power output increases up to the maximum output for the particular turbine.[74] Areas where winds are stronger and more constant, such as offshore and high-altitude sites, are preferred locations for wind farms.

Wind-generated electricity met nearly 4% of global electricity demand in 2015, with nearly 63 GW of new wind power capacity installed. Wind energy was the leading source of new capacity in Europe, the US and Canada, and the second largest in China. In Denmark, wind energy met more than 40% of its electricity demand while Ireland, Portugal and Spain each met nearly 20%.[75]

Globally, the long-term technical potential of wind energy is believed to be five times total current global energy production, or 40 times current electricity demand, assuming all practical barriers needed were overcome. This would require wind turbines to be installed over large areas, particularly in areas of higher wind resources, such as offshore, and likely also industrial use of new types of VAWT turbines in addition to the horizontal axis units currently in use. As offshore wind speeds average ~90% greater than that of land, offshore resources can contribute substantially more energy than land-stationed turbines.[76]

Investments in wind technologies reached USD 161 billion in 2020, with onshore wind dominating at 80% of total investments from 2013 to 2022. Offshore wind investments nearly doubled to USD 41 billion between 2019 and 2020, primarily due to policy incentives in China and expansion in Europe. Global wind capacity increased by 557 GW between 2013 and 2021, with capacity additions increasing by an average of 19% each year.[55]

Hydropower

[edit]

| Installed capacity and other key design parameters | Value and year |

|---|---|

| Global electricity power generation capacity | 1,267.9 GW (2023)[77] |

| Global electricity power generation capacity annual growth rate | 1.9% (2014-2023)[78] |

| Share of global electricity generation | 14.3% (2023)[48] |

| Levelized cost per megawatt hour | USD 65.581 (2019)[79] |

| Primary technology | Dam |

| Main applications | Electricity, pumped storage, mechanical power |

Since water is about 800 times denser than air, even a slow flowing stream of water, or moderate sea swell, can yield considerable amounts of energy. Water can generate electricity with a conversion efficiency of about 90%, which is the highest rate in renewable energy.[80] There are many forms of water energy:

- Historically, hydroelectric power came from constructing large hydroelectric dams and reservoirs, which are still popular in developing countries.[81] The largest of them are the Three Gorges Dam (2003) in China and the Itaipu Dam (1984) built by Brazil and Paraguay.

- Small hydro systems are hydroelectric power installations that typically produce up to 50 MW of power. They are often used on small rivers or as a low-impact development on larger rivers. China is the largest producer of hydroelectricity in the world and has more than 45,000 small hydro installations.[82]

- Run-of-the-river hydroelectricity plants derive energy from rivers without the creation of a large reservoir. The water is typically conveyed along the side of the river valley (using channels, pipes and/or tunnels) until it is high above the valley floor, whereupon it can be allowed to fall through a penstock to drive a turbine. A run-of-river plant may still produce a large amount of electricity, such as the Chief Joseph Dam on the Columbia River in the United States.[83] However many run-of-the-river hydro power plants are micro hydro or pico hydro plants.

Much hydropower is flexible, thus complementing wind and solar.[84] In 2021, the world renewable hydropower capacity was 1,360 GW.[66] Only a third of the world's estimated hydroelectric potential of 14,000 TWh/year has been developed.[85][86] New hydropower projects face opposition from local communities due to their large impact, including relocation of communities and flooding of wildlife habitats and farming land.[87] High cost and lead times from permission process, including environmental and risk assessments, with lack of environmental and social acceptance are therefore the primary challenges for new developments.[88] It is popular to repower old dams thereby increasing their efficiency and capacity as well as quicker responsiveness on the grid.[89] Where circumstances permit existing dams such as the Russell Dam built in 1985 may be updated with "pump back" facilities for pumped-storage which is useful for peak loads or to support intermittent wind and solar power. Because dispatchable power is more valuable than VRE[90][91] countries with large hydroelectric developments such as Canada and Norway are spending billions to expand their grids to trade with neighboring countries having limited hydro.[92]

Bioenergy

[edit]| Installed capacity and other key design parameters | Value and year |

|---|---|

| Global electricity generation capacity | 150.3 GW (2023)[93] |

| Global electricity generation capacity annual growth rate | 5.8% (2014-2023)[94] |

| Share of global electricity generation | 2.4% (2022)[48] |

| Levelized cost per megawatt hour | USD 118.908 (2019)[95] |

| Primary technologies | Biomass, biofuel |

| Main applications | Electricity, heating, cooking, transportation fuels |

Biomass is biological material derived from living, or recently living organisms. Most commonly, it refers to plants or plant-derived materials. As an energy source, biomass can either be used directly via combustion to produce heat, or converted to a more energy-dense biofuel like ethanol. Wood is the most significant biomass energy source as of 2012[96] and is usually sourced from a trees cleared for silvicultural reasons or fire prevention. Municipal wood waste – for instance, construction materials or sawdust – is also often burned for energy.[97] The biggest per-capita producers of wood-based bioenergy are heavily forested countries like Finland, Sweden, Estonia, Austria, and Denmark.[98]

Bioenergy can be environmentally destructive if old-growth forests are cleared to make way for crop production. In particular, demand for palm oil to produce biodiesel has contributed to the deforestation of tropical rainforests in Brazil and Indonesia.[99] In addition, burning biomass still produces carbon emissions, although much less than fossil fuels (39 grams of CO2 per megajoule of energy, compared to 75 g/MJ for fossil fuels).[100]

Some biomass sources are unsustainable at current rates of exploitation (as of 2017).[101]

Biofuel

[edit]Biofuels are primarily used in transportation, providing 3.5% of the world's transport energy demand in 2022,[102] up from 2.7% in 2010.[103] Biojet is expected to be important for short-term reduction of carbon dioxide emissions from long-haul flights.[104]

Aside from wood, the major sources of bioenergy are bioethanol and biodiesel.[12] Bioethanol is usually produced by fermenting the sugar components of crops like sugarcane and maize, while biodiesel is mostly made from oils extracted from plants, such as soybean oil and corn oil.[105] Most of the crops used to produce bioethanol and biodiesel are grown specifically for this purpose,[106] although used cooking oil accounted for 14% of the oil used to produce biodiesel as of 2015.[105] The biomass used to produce biofuels varies by region. Maize is the major feedstock in the United States, while sugarcane dominates in Brazil.[107] In the European Union, where biodiesel is more common than bioethanol, rapeseed oil and palm oil are the main feedstocks.[108] China, although it produces comparatively much less biofuel, uses mostly corn and wheat.[109] In many countries, biofuels are either subsidized or mandated to be included in fuel mixtures.[99]

There are many other sources of bioenergy that are more niche, or not yet viable at large scales. For instance, bioethanol could be produced from the cellulosic parts of crops, rather than only the seed as is common today.[110] Sweet sorghum may be a promising alternative source of bioethanol, due to its tolerance of a wide range of climates.[111] Cow dung can be converted into methane.[112] There is also a great deal of research involving algal fuel, which is attractive because algae is a non-food resource, grows around 20 times faster than most food crops, and can be grown almost anywhere.[113]

Geothermal energy

[edit]

| Installed capacity and other key design parameters | Value and year |

|---|---|

| Global electricity power generation capacity | 14.9 GW (2023)[114] |

| Global electricity power generation capacity annual growth rate | 3.4% (2014-2023)[115] |

| Share of global electricity generation | <1% (2018)[116] |

| Levelized cost per megawatt hour | USD 58.257 (2019)[117] |

| Primary technologies | Dry steam, flash steam, and binary cycle power stations |

| Main applications | Electricity, heating |

Geothermal energy is thermal energy (heat) extracted from the Earth's crust. It originates from several different sources, of which the most significant is slow radioactive decay of minerals contained in the Earth's interior,[12] as well as some leftover heat from the formation of the Earth.[118] Some of the heat is generated near the Earth's surface in the crust, but some also flows from deep within the Earth from the mantle and core.[118] Geothermal energy extraction is viable mostly in countries located on tectonic plate edges, where the Earth's hot mantle is more exposed.[119] As of 2023, the United States has by far the most geothermal capacity (2.7 GW,[120] or less than 0.2% of the country's total energy capacity[121]), followed by Indonesia and the Philippines. Global capacity in 2022 was 15 GW.[120]

Geothermal energy can be either used directly to heat homes, as is common in Iceland, or to generate electricity. At smaller scales, geothermal power can be generated with geothermal heat pumps, which can extract heat from ground temperatures of under 30 °C (86 °F), allowing them to be used at relatively shallow depths of a few meters.[119] Electricity generation requires large plants and ground temperatures of at least 150 °C (302 °F). In some countries, electricity produced from geothermal energy accounts for a large portion of the total, such as Kenya (43%) and Indonesia (5%).[122]

Technical advances may eventually make geothermal power more widely available. For example, enhanced geothermal systems involve drilling around 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) into the Earth, breaking apart hot rocks and extracting the heat using water. In theory, this type of geothermal energy extraction could be done anywhere on Earth.[119]

Emerging technologies

[edit]There are also other renewable energy technologies that are still under development, including enhanced geothermal systems, concentrated solar power, cellulosic ethanol, and marine energy.[123][124] These technologies are not yet widely demonstrated or have limited commercialization. Some may have potential comparable to other renewable energy technologies, but still depend on further breakthroughs from research, development and engineering.[124]

Enhanced geothermal systems

[edit]Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) are a new type of geothermal power which does not require natural hot water reservoirs or steam to generate power. Most of the underground heat within drilling reach is trapped in solid rocks, not in water.[125] EGS technologies use hydraulic fracturing to break apart these rocks and release the heat they contain, which is then harvested by pumping water into the ground. The process is sometimes known as "hot dry rock" (HDR).[126] Unlike conventional geothermal energy extraction, EGS may be feasible anywhere in the world, depending on the cost of drilling.[127] EGS projects have so far primarily been limited to demonstration plants, as the technology is capital-intensive due to the high cost of drilling.[128]

Marine energy

[edit]

Marine energy (also sometimes referred to as ocean energy) is the energy carried by ocean waves, tides, salinity, and ocean temperature differences. Technologies to harness the energy of moving water include wave power, marine current power, and tidal power. Reverse electrodialysis (RED) is a technology for generating electricity by mixing fresh water and salty sea water in large power cells.[129] Most marine energy harvesting technologies are still at low technology readiness levels and not used at large scales. Tidal energy is generally considered the most mature, but has not seen wide deployment.[130] The world's largest tidal power station is on Sihwa Lake, South Korea,[131] which produces around 550 gigawatt-hours of electricity per year.[132]

Earth infrared thermal radiation

[edit]Earth emits roughly 1017 W of infrared thermal radiation that flows toward the cold outer space. Solar energy hits the surface and atmosphere of the earth and produces heat. Using various theorized devices like emissive energy harvester (EEH) or thermoradiative diode, this energy flow can be converted into electricity. In theory, this technology can be used during nighttime.[133][134]

Others

[edit]Algae fuels

[edit]Producing liquid fuels from oil-rich (fat-rich) varieties of algae is an ongoing research topic. Various microalgae grown in open or closed systems are being tried including some systems that can be set up in brownfield and desert lands.[135]

Space-based solar power

[edit]There have been numerous proposals for space-based solar power, in which very large satellites with photovoltaic panels would be equipped with microwave transmitters to beam power back to terrestrial receivers. A 2024 study by the NASA Office of Science and Technology Policy examined the concept and concluded that with current and near-future technologies it would be economically uncompetitive.[136]

Water vapor

[edit]Collection of static electricity charges from water droplets on metal surfaces is an experimental technology that would be especially useful in low-income countries with relative air humidity over 60%.[137]

Nuclear energy

[edit]Breeder reactors could, in principle, depending on the fuel cycle employed, extract almost all of the energy contained in uranium or thorium, decreasing fuel requirements by a factor of 100 compared to widely used once-through light water reactors, which extract less than 1% of the energy in the actinide metal (uranium or thorium) mined from the earth.[138] The high fuel-efficiency of breeder reactors could greatly reduce concerns about fuel supply, energy used in mining, and storage of radioactive waste. With seawater uranium extraction (currently too expensive to be economical), there is enough fuel for breeder reactors to satisfy the world's energy needs for 5 billion years at 1983's total energy consumption rate, thus making nuclear energy effectively a renewable energy.[139][140] In addition to seawater the average crustal granite rocks contain significant quantities of uranium and thorium with which breeder reactors can supply abundant energy for the remaining lifespan of the sun on the main sequence of stellar evolution.[141]

Artificial photosynthesis

[edit]Artificial photosynthesis uses techniques including nanotechnology to store solar electromagnetic energy in chemical bonds by splitting water to produce hydrogen and then using carbon dioxide to make methanol.[142] Researchers in this field strived to design molecular mimics of photosynthesis that use a wider region of the solar spectrum, employ catalytic systems made from abundant, inexpensive materials that are robust, readily repaired, non-toxic, stable in a variety of environmental conditions and perform more efficiently allowing a greater proportion of photon energy to end up in the storage compounds, i.e., carbohydrates (rather than building and sustaining living cells).[143] However, prominent research faces hurdles, Sun Catalytix a MIT spin-off stopped scaling up their prototype fuel-cell in 2012 because it offers few savings over other ways to make hydrogen from sunlight.[144]

Market and industry trends

[edit]Most new renewables are solar, followed by wind then hydro then bioenergy.[145] Investment in renewables, especially solar, tends to be more effective in creating jobs than coal, gas or oil.[146][147] Worldwide, renewables employ about 12 million people as of 2020, with solar PV being the technology employing the most at almost 4 million.[148] However, as of February 2024, the world's supply of workforce for solar energy is lagging greatly behind demand as universities worldwide still produce more workforce for fossil fuels than for renewable energy industries.[149]

In 2021, China accounted for almost half of the global increase in renewable electricity.[150]

There are 3,146 gigawatts installed in 135 countries, while 156 countries have laws regulating the renewable energy sector.[7][151]

Globally in 2020 there are over 10 million jobs associated with the renewable energy industries, with solar photovoltaics being the largest renewable employer.[152] The clean energy sectors added about 4.7 million jobs globally between 2019 and 2022, totaling 35 million jobs by 2022.[153]: 5

Usage by sector or application

[edit]Some studies say that a global transition to 100% renewable energy across all sectors – power, heat, transport and industry – is feasible and economically viable.[154][155][156]

One of the efforts to decarbonize transportation is the increased use of electric vehicles (EVs).[157] Despite that and the use of biofuels, such as biojet, less than 4% of transport energy is from renewables.[158] Occasionally hydrogen fuel cells are used for heavy transport.[159] Meanwhile, in the future electrofuels may also play a greater role in decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors like aviation and maritime shipping.[160]

Solar water heating makes an important contribution to renewable heat in many countries, most notably in China, which now has 70% of the global total (180 GWth). Most of these systems are installed on multi-family apartment buildings[161] and meet a portion of the hot water needs of an estimated 50–60 million households in China. Worldwide, total installed solar water heating systems meet a portion of the water heating needs of over 70 million households.

Heat pumps provide both heating and cooling, and also flatten the electric demand curve and are thus an increasing priority.[162] Renewable thermal energy is also growing rapidly.[163] About 10% of heating and cooling energy is from renewables.[164]

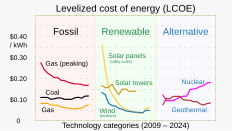

Cost comparison

[edit]The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) stated that ~86% (187 GW) of renewable capacity added in 2022 had lower costs than electricity generated from fossil fuels.[165] IRENA also stated that capacity added since 2000 reduced electricity bills in 2022 by at least $520 billion, and that in non-OECD countries, the lifetime savings of 2022 capacity additions will reduce costs by up to $580 billion.[165]

| Installed[166] TWp |

Growth TW/yr[166] |

Production per installed capacity*[167] |

Energy TWh/yr*[167] |

Growth TWh/yr*[167] |

Levelized cost US¢/kWh[168] |

Av. auction prices US¢/kWh[169] |

Cost development 2010–2019[168] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solar PV | 0.580 | 0.098 | 13% | 549 | 123 | 6.8 | 3.9 | −82% |

| Solar CSP | 0.006 | 0.0006 | 13% | 6.3 | 0.5 | 18.2 | 7.5 | −47% |

| Wind Offshore | 0.028 | 0.0045 | 33% | 68 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 8.2 | −30% |

| Wind Onshore | 0.594 | 0.05 | 25% | 1194 | 118 | 5.3 | 4.3 | −38% |

| Hydro | 1.310 | 0.013 | 38% | 4267 | 90 | 4.7 | +27% | |

| Bioenergy | 0.12 | 0.006 | 51% | 522 | 27 | 6.6 | −13% | |

| Geothermal | 0.014 | 0.00007 | 74% | 13.9 | 0.7 | 7.3 | +49% |

* = 2018. All other values for 2019.

Growth of renewables

[edit]Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a measure of the average net present cost of electricity generation for a generating plant over its lifetime.

The results of a recent review of the literature concluded that as greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters begin to be held liable for damages resulting from GHG emissions resulting in climate change, a high value for liability mitigation would provide powerful incentives for deployment of renewable energy technologies.[181]

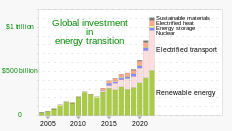

In the decade of 2010–2019, worldwide investment in renewable energy capacity excluding large hydropower amounted to US$2.7 trillion, of which the top countries China contributed US$818 billion, the United States contributed US$392.3 billion, Japan contributed US$210.9 billion, Germany contributed US$183.4 billion, and the United Kingdom contributed US$126.5 billion.[182] This was an increase of over three and possibly four times the equivalent amount invested in the decade of 2000–2009 (no data is available for 2000–2003).[182]

As of 2022, an estimated 28% of the world's electricity was generated by renewables. This is up from 19% in 1990.[183]

Future projections

[edit]

A December 2022 report by the IEA forecasts that over 2022-2027, renewables are seen growing by almost 2 400 GW in its main forecast, equal to the entire installed power capacity of China in 2021. This is an 85% acceleration from the previous five years, and almost 30% higher than what the IEA forecast in its 2021 report, making its largest ever upward revision. Renewables are set to account for over 90% of global electricity capacity expansion over the forecast period.[66] To achieve net zero emissions by 2050, IEA believes that 90% of global electricity generation will need to be produced from renewable sources.[17]

In June 2022 IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol said that countries should invest more in renewables to "ease the pressure on consumers from high fossil fuel prices, make our energy systems more secure, and get the world on track to reach our climate goals."[185]

China's five year plan to 2025 includes increasing direct heating by renewables such as geothermal and solar thermal.[186]

REPowerEU, the EU plan to escape dependence on fossil Russian gas, is expected to call for much more green hydrogen.[187]

After a transitional period,[188] renewable energy production is expected to make up most of the world's energy production. In 2018, the risk management firm, DNV GL, forecasts that the world's primary energy mix will be split equally between fossil and non-fossil sources by 2050.[189]

Middle eastern nations are also planning on reducing their reliance fossil fuel. Many planned green projects will contribute in 26% of energy supply for the region by 2050 achieving emission reductions equal to 1.1 Gt CO2/year.[190]

Massive Renewable Energy Projects in the Middle East:[190]

- Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park in Duba, UAE

- Shuaibah Two (2) Solar Facility in Mecca Province, Saudi Arabia

- NEOM Green Hydrogen Project in NEOM, Saudi Arabia

- Gulf of Suez Wind Power Project in Suez, Egypt

- Al-Ajban Solar Park in Abu Dhabi, UAE

Demand

[edit]In July 2014, WWF and the World Resources Institute convened a discussion among a number of major US companies who had declared their intention to increase their use of renewable energy. These discussions identified a number of "principles" which companies seeking greater access to renewable energy considered important market deliverables. These principles included choice (between suppliers and between products), cost competitiveness, longer term fixed price supplies, access to third-party financing vehicles, and collaboration.[191]

UK statistics released in September 2020 noted that "the proportion of demand met from renewables varies from a low of 3.4 per cent (for transport, mainly from biofuels) to highs of over 20 per cent for 'other final users', which is largely the service and commercial sectors that consume relatively large quantities of electricity, and industry".[192]

In some locations, individual households can opt to purchase renewable energy through a consumer green energy program.

Developing countries

[edit]Renewable energy in developing countries is an increasingly used alternative to fossil fuel energy, as these countries scale up their energy supplies and address energy poverty. Renewable energy technology was once seen as unaffordable for developing countries.[193] However, since 2015, investment in non-hydro renewable energy has been higher in developing countries than in developed countries, and comprised 54% of global renewable energy investment in 2019.[194] The International Energy Agency forecasts that renewable energy will provide the majority of energy supply growth through 2030 in Africa and Central and South America, and 42% of supply growth in China.[195]

Most developing countries have abundant renewable energy resources, including solar energy, wind power, geothermal energy, and biomass, as well as the ability to manufacture the relatively labor-intensive systems that harness these. By developing such energy sources developing countries can reduce their dependence on oil and natural gas, creating energy portfolios that are less vulnerable to price rises. In many circumstances, these investments can be less expensive than fossil fuel energy systems.[196]In Kenya, the Olkaria V Geothermal Power Station is one of the largest in the world.[197] The Grand Ethiopia Renaissance Dam project incorporates wind turbines.[198] Once completed, Morocco's Ouarzazate Solar Power Station is projected to provide power to over a million people.[199]

Policy

[edit]

Policies to support renewable energy have been vital in their expansion. Where Europe dominated in establishing energy policy in the early 2000s, most countries around the world now have some form of energy policy.[201]

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) is an intergovernmental organization for promoting the adoption of renewable energy worldwide. It aims to provide concrete policy advice and facilitate capacity building and technology transfer. IRENA was formed in 2009, with 75 countries signing the charter of IRENA.[202] As of April 2019, IRENA has 160 member states.[203] The then United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has said that renewable energy can lift the poorest nations to new levels of prosperity,[204] and in September 2011 he launched the UN Sustainable Energy for All initiative to improve energy access, efficiency and the deployment of renewable energy.[205]

The 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change motivated many countries to develop or improve renewable energy policies.[206] In 2017, a total of 121 countries adopted some form of renewable energy policy.[201] National targets that year existed in 176 countries.[206] In addition, there is also a wide range of policies at the state/provincial, and local levels.[103] Some public utilities help plan or install residential energy upgrades.

Many national, state and local governments have created green banks. A green bank is a quasi-public financial institution that uses public capital to leverage private investment in clean energy technologies.[207] Green banks use a variety of financial tools to bridge market gaps that hinder the deployment of clean energy.

Global and national policies related to renewable energy can be divided based on sectors, such as agriculture, transport, buildings, industry:

Climate neutrality (net zero emissions) by the year 2050 is the main goal of the European Green Deal.[208] For the European Union to reach their target of climate neutrality, one goal is to decarbonise its energy system by aiming to achieve "net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050."[209]

Finance

[edit]The International Renewable Energy Agency's (IRENA) 2023 report on renewable energy finance highlights steady investment growth since 2018: USD 348 billion in 2020 (a 5.6% increase from 2019), USD 430 billion in 2021 (24% up from 2020), and USD 499 billion in 2022 (16% higher). This trend is driven by increasing recognition of renewable energy's role in mitigating climate change and enhancing energy security, along with investor interest in alternatives to fossil fuels. Policies such as feed-in tariffs in China and Vietnam have significantly increased renewable adoption. Furthermore, from 2013 to 2022, installation costs for solar photovoltaic (PV), onshore wind, and offshore wind fell by 69%, 33%, and 45%, respectively, making renewables more cost-effective.[210][55]

Between 2013 and 2022, the renewable energy sector underwent a significant realignment of investment priorities. Investment in solar and wind energy technologies markedly increased. In contrast, other renewable technologies such as hydropower (including pumped storage hydropower), biomass, biofuels, geothermal, and marine energy experienced a substantial decrease in financial investment. Notably, from 2017 to 2022, investment in these alternative renewable technologies declined by 45%, falling from USD 35 billion to USD 17 billion.[55]

In 2023, the renewable energy sector experienced a significant surge in investments, particularly in solar and wind technologies, totaling approximately USD 200 billion—a 75% increase from the previous year. The increased investments in 2023 contributed between 1% and 4% to the GDP in key regions including the United States, China, the European Union, and India.[211]

The energy sector receives investments of approximately USD 3 trillion each year, with USD 1.9 trillion directed towards clean energy technologies and infrastructure. To meet the targets set in the Net Zero Emissions (NZE) Scenario by 2035, this investment must increase to USD 5.3 trillion per year.[212]: 15

Debates

[edit]Nuclear power proposed as renewable energy

[edit]

Whether nuclear power should be considered a form of renewable energy is an ongoing subject of debate. Statutory definitions of renewable energy usually exclude many present nuclear energy technologies, with the notable exception of the state of Utah.[213] Dictionary-sourced definitions of renewable energy technologies often omit or explicitly exclude mention of nuclear energy sources, with an exception made for the natural nuclear decay heat generated within the Earth.[214][215]

The most common fuel used in conventional nuclear fission power stations, uranium-235 is "non-renewable" according to the Energy Information Administration, the organization however is silent on the recycled MOX fuel.[215] The National Renewable Energy Laboratory does not mention nuclear power in its "energy basics" definition.[216]

In 1987, the Brundtland Commission (WCED) classified fission reactors that produce more fissile nuclear fuel than they consume (breeder reactors, and if developed, fusion power) among conventional renewable energy sources, such as solar power and hydropower.[217] The monitoring and storage of radioactive waste products is also required upon the use of other renewable energy sources, such as geothermal energy.[218]Geopolitics

[edit]

The geopolitical impact of the growing use of renewable energy is a subject of ongoing debate and research.[219] Many fossil-fuel producing countries, such as Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Norway, are currently able to exert diplomatic or geopolitical influence as a result of their oil wealth. Most of these countries are expected to be among the geopolitical "losers" of the energy transition, although some, like Norway, are also significant producers and exporters of renewable energy. Fossil fuels and the infrastructure to extract them may, in the long term, become stranded assets.[220] It has been speculated that countries dependent on fossil fuel revenue may one day find it in their interests to quickly sell off their remaining fossil fuels.[221]

Conversely, nations abundant in renewable resources, and the minerals required for renewables technology, are expected to gain influence.[222][223] In particular, China has become the world's dominant manufacturer of the technology needed to produce or store renewable energy, especially solar panels, wind turbines, and lithium-ion batteries.[224] Nations rich in solar and wind energy could become major energy exporters.[225] Some may produce and export green hydrogen,[226][225] although electricity is projected to be the dominant energy carrier in 2050, accounting for almost 50% of total energy consumption (up from 22% in 2015).[227] Countries with large uninhabited areas such as Australia, China, and many African and Middle Eastern countries have a potential for huge installations of renewable energy. The production of renewable energy technologies requires rare-earth elements with new supply chains.[228]

Countries with already weak governments that rely on fossil fuel revenue may face even higher political instability or popular unrest. Analysts consider Nigeria, Angola, Chad, Gabon, and Sudan, all countries with a history of military coups, to be at risk of instability due to dwindling oil income.[229]

A study found that transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy systems reduces risks from mining, trade and political dependence because renewable energy systems don't need fuel – they depend on trade only for the acquisition of materials and components during construction.[230]

In October 2021, European Commissioner for Climate Action Frans Timmermans suggested "the best answer" to the 2021 global energy crisis is "to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels."[231] He said those blaming the European Green Deal were doing so "for perhaps ideological reasons or sometimes economic reasons in protecting their vested interests."[231] Some critics blamed the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and closure of nuclear plants for contributing to the energy crisis.[232][233][234] European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said that Europe is "too reliant" on natural gas and too dependent on natural gas imports. According to Von der Leyen, "The answer has to do with diversifying our suppliers ... and, crucially, with speeding up the transition to clean energy."[235]

Metal and mineral extraction

[edit]The transition to renewable energy requires increased extraction of certain metals and minerals. Like all mining, this impacts the environment[236] and can lead to environmental conflict.[237] Wind power requires large amounts of copper and zinc, as well as smaller amounts of the rarer metal neodymium. Solar power is less resource-intensive, but still requires significant amounts of aluminum. The expansion of electrical grids requires both copper and aluminum. Batteries, which are critical to enable storage of renewable energy, use large quantities of copper, nickel, aluminum and graphite. Demand for lithium is expected to grow 42-fold from 2020 to 2040. Demand for nickel, cobalt and graphite is expected to grow by a factor of about 20–25.[238] For each of the most relevant minerals and metals, its mining is dominated by a single country: copper in Chile, nickel in Indonesia, rare earths in China, cobalt in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and lithium in Australia. China dominates processing of all of these.[238]

Recycling these metals after the devices they are embedded in are spent is essential to create a circular economy and ensure renewable energy is sustainable. By 2040, recycled copper, lithium, cobalt, and nickel from spent batteries could reduce combined primary supply requirements for these minerals by around 10%.[238]

A controversial approach is deep sea mining. Minerals can be collected from new sources like polymetallic nodules lying on the seabed.[239] This would damage local biodiversity,[240] but proponents point out that biomass on resource-rich seabeds is much scarcer than in the mining regions on land, which are often found in vulnerable habitats like rainforests.[241]

Due to co-occurrence of rare-earth and radioactive elements (thorium, uranium and radium), rare-earth mining results in production of low-level radioactive waste.[242] In several African countries, the green energy transition has created a mining boom, causing deforestation, and threatening already endangered species.[243]

Conservation areas

[edit]Installations used to produce wind, solar and hydropower are an increasing threat to key conservation areas, with facilities built in areas set aside for nature conservation and other environmentally sensitive areas. They are often much larger than fossil fuel power plants, needing areas of land up to 10 times greater than coal or gas to produce equivalent energy amounts.[244] More than 2000 renewable energy facilities are built, and more are under construction, in areas of environmental importance and threaten the habitats of plant and animal species across the globe. The authors' team emphasized that their work should not be interpreted as anti-renewables because renewable energy is crucial for reducing carbon emissions. The key is ensuring that renewable energy facilities are built in places where they do not damage biodiversity.[245]

In 2020 scientists published a world map of areas that contain renewable energy materials as well as estimations of their overlaps with "Key Biodiversity Areas", "Remaining Wilderness" and "Protected Areas". The authors assessed that careful strategic planning is needed.[246][247][248]

Recycling of solar panels

[edit]Solar panels are recycled to reduce electronic waste and create a source for materials that would otherwise need to be mined,[249] but such business is still small and work is ongoing to improve and scale-up the process.[250][251][252]

Society and culture

[edit]Public support

[edit]

Solar power plants may compete with arable land,[256][257] while on-shore wind farms often face opposition due to aesthetic concerns and noise.[258][259] Such opponents are often described as NIMBYs ("not in my back yard").[260] Some environmentalists are concerned about fatal collisions of birds and bats with wind turbines.[261] Although protests against new wind farms occasionally occur around the world, regional and national surveys generally find broad support for both solar and wind power.[262][263][264]

Community-owned wind energy is sometimes proposed as a way to increase local support for wind farms.[265] A 2011 UK Government document stated that "projects are generally more likely to succeed if they have broad public support and the consent of local communities. This means giving communities both a say and a stake."[266] In the 2000s and early 2010s, many renewable projects in Germany, Sweden and Denmark were owned by local communities, particularly through cooperative structures.[267][268] In the years since, more installations in Germany have been undertaken by large companies,[265] but community ownership remains strong in Denmark.[269]

History

[edit]Prior to the development of coal in the mid 19th century, nearly all energy used was renewable. The oldest known use of renewable energy, in the form of traditional biomass to fuel fires, dates from more than a million years ago. The use of biomass for fire did not become commonplace until many hundreds of thousands of years later.[270] Probably the second oldest usage of renewable energy is harnessing the wind in order to drive ships over water. This practice can be traced back some 7000 years, to ships in the Persian Gulf and on the Nile.[271] From hot springs, geothermal energy has been used for bathing since Paleolithic times and for space heating since ancient Roman times.[272] Moving into the time of recorded history, the primary sources of traditional renewable energy were human labor, animal power, water power, wind, in grain crushing windmills, and firewood, a traditional biomass.

In 1885, Werner Siemens, commenting on the discovery of the photovoltaic effect in the solid state, wrote:

In conclusion, I would say that however great the scientific importance of this discovery may be, its practical value will be no less obvious when we reflect that the supply of solar energy is both without limit and without cost, and that it will continue to pour down upon us for countless ages after all the coal deposits of the earth have been exhausted and forgotten.[273]

Max Weber mentioned the end of fossil fuel in the concluding paragraphs of his Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus (The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism), published in 1905.[274] Development of solar engines continued until the outbreak of World War I. The importance of solar energy was recognized in a 1911 Scientific American article: "in the far distant future, natural fuels having been exhausted [solar power] will remain as the only means of existence of the human race".[275]

The theory of peak oil was published in 1956.[276] In the 1970s environmentalists promoted the development of renewable energy both as a replacement for the eventual depletion of oil, as well as for an escape from dependence on oil, and the first electricity-generating wind turbines appeared. Solar had long been used for heating and cooling, but solar panels were too costly to build solar farms until 1980.[277]

New government spending, regulation and policies helped the renewables industry weather the 2009 global financial crisis better than many other sectors.[278] In 2022, renewables accounted for 30% of global electricity generation, up from 21% in 1985.[8]

See also

[edit]- Distributed generation – Decentralised electricity generation

- Efficient energy use – Methods for higher energy efficiency

- Fossil fuel phase-out – Gradual reduction of the use and production of fossil fuels

- Thermal energy storage – Technologies to store thermal energy

- List of countries by renewable electricity production

- List of renewable energy topics by country and territory

- Renewable heat – Application of renewable energy

References

[edit]- ^ Armaroli, Nicola; Balzani, Vincenzo (2011). "Towards an electricity-powered world". Energy and Environmental Science. 4 (9): 3193–3222. doi:10.1039/c1ee01249e. ISSN 1754-5692.

- ^ Armaroli, Nicola; Balzani, Vincenzo (2016). "Solar Electricity and Solar Fuels: Status and Perspectives in the Context of the Energy Transition". Chemistry – A European Journal. 22 (1): 32–57. doi:10.1002/chem.201503580. PMID 26584653.

- ^ "Global renewable energy trends". Deloitte Insights. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ "Renewable Energy Now Accounts for a Third of Global Power Capacity". irena.org. 2 April 2019. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "2023 Levelized Cost Of Energy+". www.lazard.com. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ IEA (2020). Renewables 2020 Analysis and forecast to 2025 (Report). p. 12. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Renewables 2022". Global Status Report (renewable energies): 44. 14 June 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Share of electricity production from renewables". Our World in Data. 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ "Renewables - Energy System". IEA. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max; Rosado, Pablo (January 2024). "Renewable Energy". Our World in Data.

- ^ Sensiba, Jennifer (28 October 2021). "Some Good News: 10 Countries Generate Almost 100% Renewable Electricity". CleanTechnica. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Ehrlich, Robert; Geller, Harold A.; Geller, Harold (2018). Renewable energy: a first course (2nd ed.). Boca Raton London New York: Taylor & Francis, CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-138-29738-8.

- ^ "Rapid rollout of clean technologies makes energy cheaper, not more costly". International Energy Agency. 30 May 2024. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ Timperley, Jocelyn (20 October 2021). "Why fossil fuel subsidies are so hard to kill". Nature. 598 (7881): 403–405. Bibcode:2021Natur.598..403T. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02847-2. PMID 34671143. S2CID 239052649.

- ^ Lockwood, Matthew; Mitchell, Catherine; Hoggett, Richard (May 2020). "Incumbent lobbying as a barrier to forward-looking regulation: The case of demand-side response in the GB capacity market for electricity". Energy Policy. 140: 111426. Bibcode:2020EnPol.14011426L. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111426.

- ^ Susskind, Lawrence; Chun, Jungwoo; Gant, Alexander; Hodgkins, Chelsea; Cohen, Jessica; Lohmar, Sarah (June 2022). "Sources of opposition to renewable energy projects in the United States". Energy Policy. 165: 112922. Bibcode:2022EnPol.16512922S. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2022.112922.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Net Zero by 2050 – Analysis". IEA. 18 May 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Isaacs-Thomas, Bella (1 December 2023). "Mining is necessary for the green transition. Here's why experts say we need to do it better". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ "Electricity production by source, World". Our World in Data, crediting Ember. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. OWID credits "Source: Ember's Yearly Electricity Data; Ember's European Electricity Review; Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy".

- ^ Friedlingstein, Pierre; Jones, Matthew W.; O'Sullivan, Michael; Andrew, Robbie M.; Hauck, Judith; Peters, Glen P.; Peters, Wouter; Pongratz, Julia; Sitch, Stephen; Le Quéré, Corinne; Bakker, Dorothee C. E. (2019). "Global Carbon Budget 2019". Earth System Science Data. 11 (4): 1783–1838. Bibcode:2019ESSD...11.1783F. doi:10.5194/essd-11-1783-2019. hdl:20.500.11850/385668. ISSN 1866-3508. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Harjanne, Atte; Korhonen, Janne M. (April 2019). "Abandoning the concept of renewable energy". Energy Policy. 127: 330–340. Bibcode:2019EnPol.127..330H. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.12.029.

- ^ REN21 Renewables Global Status Report 2010.

- ^ Kutscher, Charles F.; Milford, Jana B.; Kreith, Frank (2019). Principles of sustainable energy systems. Mechanical and aerospace engineering (3rd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-4987-8892-2.

- ^ Srouji, Jamal; Fransen, Taryn; Boehm, Sophie; Waskow, David; Carter, Rebecca; Larsen, Gaia (25 April 2024). "Next-generation Climate Targets: A 5-Point Plan for NDCs".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "COP28: New deals and evasive tactics". The economist. 19 December 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Abnett, Kate (20 April 2022). "European Commission analysing higher 45% renewable energy target for 2030". Reuters. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Overland, Indra; Juraev, Javlon; Vakulchuk, Roman (1 November 2022). "Are renewable energy sources more evenly distributed than fossil fuels?". Renewable Energy. 200: 379–386. Bibcode:2022REne..200..379O. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.09.046. hdl:11250/3033797. ISSN 0960-1481.

- ^ Scovronick, Noah; Budolfson, Mark; Dennig, Francis; Errickson, Frank; Fleurbaey, Marc; Peng, Wei; Socolow, Robert H.; Spears, Dean; Wagner, Fabian (7 May 2019). "The impact of human health co-benefits on evaluations of global climate policy". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 2095. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.2095S. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09499-x. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6504956. PMID 31064982.

- ^ Wan, Y. H. (January 2012). Long-term wind power variability (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

- ^ Olauson, Jon; Ayob, Mohd Nasir; Bergkvist, Mikael; Carpman, Nicole; Castellucci, Valeria; Goude, Anders; Lingfors, David; Waters, Rafael; Widén, Joakim (December 2016). "Net load variability in Nordic countries with a highly or fully renewable power system". Nature Energy. 1 (12): 16175. doi:10.1038/nenergy.2016.175. ISSN 2058-7546. S2CID 113848337. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Swartz, Kristi E. (8 December 2021). "Can U.S. phase out natural gas? Lessons from the Southeast". E&E News. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ "Climate change: phase out gas power by 2035, say businesses including Nestle, Thames Water, Co-op". Sky News. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ Roberts, David (30 November 2018). "Clean energy technologies threaten to overwhelm the grid. Here's how it can adapt". Vox. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ "AI and other tricks are bringing power lines into the 21st century". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Ramsebner, Jasmine; Haas, Reinhard; Ajanovic, Amela; Wietschel, Martin (July 2021). "The sector coupling concept: A critical review". WIREs Energy and Environment. 10 (4). Bibcode:2021WIREE..10E.396R. doi:10.1002/wene.396. ISSN 2041-8396. S2CID 234026069.

- ^ "4 questions on sector coupling". Wartsila.com. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ "Intelligent, flexible Sector Coupling in cities can double the potential for Wind and Solar". Energy Post. 16 December 2021. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ IEA (2020). World Energy Outlook 2020. International Energy Agency. p. 109. ISBN 978-92-64-44923-7. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Hydropower Special Market Report – Analysis". IEA. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "What role is large-scale battery storage playing on the grid today?". Energy Storage News. 5 May 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Zhou, Chen; Liu, Rao; Ba, Yu; Wang, Haixia; Ju, Rongbin; Song, Minggang; Zou, Nan; Li, Weidong (28 May 2021). "Study on the optimization of the day-ahead addition space for large-scale energy storage participation in auxiliary services". 2021 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Information Systems. ICAIIS 2021. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1145/3469213.3471362. ISBN 978-1-4503-9020-0. S2CID 237206056.

- ^ Heilweil, Rebecca (5 May 2022). "These batteries work from home". Vox. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Schrotenboer, Albert H.; Veenstra, Arjen A.T.; uit het Broek, Michiel A.J.; Ursavas, Evrim (October 2022). "A Green Hydrogen Energy System: Optimal control strategies for integrated hydrogen storage and power generation with wind energy" (PDF). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 168: 112744. arXiv:2108.00530. Bibcode:2022RSERv.16812744S. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112744. S2CID 250941369.

- ^ Lipták, Béla (24 January 2022). "Hydrogen is key to sustainable green energy". Control. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Source for data beginning in 2017: "Renewable Energy Market Update Outlook for 2023 and 2024" (PDF). IEA.org. International Energy Agency (IEA). June 2023. p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2023.

IEA. CC BY 4.0.

● Source for data through 2016: "Renewable Energy Market Update / Outlook for 2021 and 2022" (PDF). IEA.org. International Energy Agency. May 2021. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2023.IEA. Licence: CC BY 4.0

- ^ IRENA 2024, p. 21.

- ^ IRENA 2024, p. 21. Note: Compound annual growth rate 2014-2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Global Electricity Review 2024". Ember. 8 May 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ NREL ATB 2021, Utility-Scale PV.

- ^ "Data Page: Share of electricity generated by solar power". Our World in Data. 2023.

- ^ "Renewable Energy". Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. 27 October 2021. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weiss, Werner; Spörk-Dür, Monika (2023). Solar heat worldwide (PDF). International Energy Agency. p. 12.

- ^ «Солнечная - топливо и технологии» . IEA . Получено 27 июня 2022 года .

- ^ Зарбба, Анна; Креминьска, Алицжа; Козик, Рената; Adynkiewicz-Piragas, Mariusz; Кристианова, Катарина (17 марта 2022 г.). «Пассивные и активные солнечные системы в эко-архитектуре и эко-городском планировании» . Прикладные науки . 12 (6): 3095. doi : 10.3390/app12063095 . ISSN 2076-3417 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый «Глобальный ландшафт финансирования возобновляемых источников энергии 2023 года» (PDF) . Международное агентство по возобновляемой энергии (Ирена) . Февраль 2023 г. Архивировал из оригинала (PDF) 21 марта 2024 года . Получено 21 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «Солнечные (фотоэлектрические) цены панели против совокупной мощности» . OreWorldIndata.org . 2023. Архивировано из оригинала 29 сентября 2023 года . Farmer & Lafond (2016); Международное агентство по возобновляемой энергии (Ирена).

- ^ «Закон Свансона и делая нас солнечной масштабом, как Германия» . Greentech Media . 24 ноября 2014 года.

- ^ «Источники энергии: Солнечная» . Департамент энергетики . Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2011 года . Получено 19 апреля 2011 года .

- ^ «Солнечная интеграция в Нью -Джерси» . Jcwinnie.biz. Архивировано из оригинала 19 июля 2013 года . Получено 20 августа 2013 года .

- ^ «Получение максимальной отдачи от завтрашней сетки требует оцифровки и реакции спроса» . Экономист . ISSN 0013-0613 . Получено 24 июня 2022 года .

- ^ «История солнечной» (PDF) . Министерство энергетики США . Получено 7 апреля 2024 года .

- ^ Ли, Патрик (12 января 1990 г.). «Arco продает последние 3 солнечных завода за 2 миллиона долларов: энергия: продажа инвесторам в Нью -Мексико демонстрирует стратегию фирмы, сосредоточившись на его основном нефтяном бизнесе» . Los Angeles Times . Получено 7 апреля 2024 года .

- ^ «Пересечение пропасти» (PDF) . Deutsche Bank Markets Research. 27 февраля 2015 года. Архивировал (PDF) из оригинала 30 марта 2015 года.

- ^ Равишанкар, Рашми; Almahmoud, Elaf; Хабиб, Абдулела; Де Век, Оливье Л. (январь 2022 г.). «Оценка мощности солнечных ферм с использованием глубокого обучения на спутниковых образах высокого разрешения» . Дистанционное зондирование . 15 (1): 210. Bibcode : 2022Rems ... 15..210R . doi : 10.3390/rs15010210 . HDL : 1721.1/146994 . ISSN 2072-4292 .

- ^ «Возобновляемые электроэнергии и статистика генерации июнь 2018 года» . Архивировано с оригинала 28 ноября 2018 года . Получено 27 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в IEA (2022), возобновляемые источники энергии 2022, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2022 , лицензия: cc по 4.0

- ^ Ахмад, Мариам (30 мая 2023 г.). «Топ -10: крупнейшие солнечные энергетические парки» . EnergyDigital.com . Получено 7 апреля 2024 года .

- ^ Корен, Майкл (13 февраля 2024 г.). «Познакомьтесь с другой солнечной панелью» . The Washington Post .

- ^ Кингсли, Патрик; Elkayam, Amit (9 октября 2022 года). « Глаз Саурона»: ослепительная солнечная башня в израильской пустыне » . New York Times .

- ^ «Выработка энергии ветра по региону» . Наш мир в данных . Архивировано с оригинала 10 марта 2020 года . Получено 15 августа 2023 года .

- ^ Ирена 2024 , с. 14

- ^ Ирена 2024 , с. 14. ПРИМЕЧАНИЕ: Составной годовой темпы роста 2014-2023.

- ^ Nrel ATB 2021 , наземный ветер.

- ^ «Анализ энергии ветра в ЕС-25» (PDF) . Европейская ветроэнергетическая ассоциация. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 12 марта 2007 года . Получено 11 марта 2007 года .

- ^ «Электричество - из других возобновляемых источников - World Factbook» . www.cia.gov . Архивировано из оригинала 27 октября 2021 года . Получено 27 октября 2021 года .

- ^ «Оффшорные станции испытывают среднюю скорость ветра в 80 м, которые в среднем на 90% больше, чем на земле». Оценка глобальной архивной мощности ветра 25 мая 2008 г. В целом, исследователи рассчитали ветры на 80 метров [300 футов] над уровнем моря , пройденного по океану примерно на 8,6 метра в секунду и почти на 4,5 метра в секунду на земле [ 20 и 10 миль в час соответственно]. " Глобальная ветряная карта показывает лучшие местоположения ветряной фермы, архивные 24 мая 2005 года на машине Wayback . Получено 30 января 2006 года.

- ^ Ирена 2024 , с. 9. ПРИМЕЧАНИЕ: исключает чистое насосное хранилище.

- ^ Ирена 2024 , с. 9. ПРИМЕЧАНИЕ: исключает чистое насосное хранилище. Составной годовой темпы роста 2014-2023.

- ^ Nrel ATB 2021 , гидроэнергетика.

- ^ Анг, Цзханг; Салем, Мохамед; Камарол, Мохамад; Дас, Химадри Шехар; Назари, Мохаммад Альхуйи; Прабахаран, Натараджан (2022). «Комплексное исследование возобновляемых источников энергии: классификации, проблемы и предложения» . Обзоры энергетической стратегии . 43 : 100939. Bibcode : 2022enesr..4300939a . doi : 10.1016/j.esr.2022.100939 . ISSN 2211-467X . S2CID 251889236 .

- ^ Моран, Эмилио Ф.; Лопес, Мария Клаудия; Мур, Натан; Мюллер, Норберт; Hyndman, David W. (2018). «Устойчивая гидроэнергетика в 21 веке» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 115 (47): 11891–11898. Bibcode : 2018pnas..11511891M . doi : 10.1073/pnas.1809426115 . ISSN 0027-8424 . PMC 6255148 . PMID 30397145 .

- ^ "Dochdl2onpn-printrdy-01tmptarget" (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 9 ноября 2018 года . Получено 26 марта 2019 года .

- ^ Afework, Вефиль (3 сентября 2018 г.). «Гидроэлектростанция с рельефом» . Энергетическое образование . Архивировано с оригинала 27 апреля 2019 года . Получено 27 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ «Net Zero: Международная ассоциация гидроэнергетики» . www.hydropower.org . Получено 24 июня 2022 года .

- ^ «Отчет о состоянии гидроэнергетики» . Международная ассоциация гидроэнергетики . 11 июня 2021 года. Архивировано с оригинала 3 апреля 2023 года . Получено 30 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Перспективы энергетических технологий: сценарии и стратегии до 2050 года . Париж: Международное энергетическое агентство. 2006. с. 124. ISBN 926410982x Полем Получено 30 мая 2022 года .

- ^ «Воздействие на окружающую среду гидроэлектростанции | Союз заинтересованных ученых» . www.ucsusa.org . Архивировано из оригинала 15 июля 2021 года . Получено 9 июля 2021 года .

- ^ «Hydropower Special Market Report» (PDF) . IEA . С. 34–36. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 7 июля 2021 года . Получено 9 июля 2021 года .

- ^ Л. Лиа; Т. Дженсен; Ке Стенсби и; Г. Холм; Am Ruud. «Текущее состояние развития гидроэнергетики и строительства плотины в Норвегии» (PDF) . Ntnu.no. Архивировано из оригинала 25 мая 2017 года . Получено 26 марта 2019 года .

- ^ «Как Норвегия стала крупнейшим экспортером власти в Европе» . Силовая технология . 19 апреля 2021 года. Архивировано с оригинала 27 июня 2022 года . Получено 27 июня 2022 года .

- ^ «Торговый избыток взлетает на экспорт энергии | Новости Норвегии на английском языке - www.newsinenglish.no» . 17 января 2022 года . Получено 27 июня 2022 года .

- ^ «Новая линия передачи достигает вехи» . Vpr.net . Архивировано из оригинала 3 февраля 2017 года . Получено 3 февраля 2017 года .

- ^ Ирена 2024 , с. 30

- ^ Ирена 2024 , с. 30. ПРИМЕЧАНИЕ: Составной годовой темп роста 2014-2023.

- ^ Nrel ATB 2021 , другие технологии (EIA).

- ^ Шек, Джастин; Дуган, Ян Джинн (23 июля 2012 г.). «Деревянные растения генерируют нарушения» . Wall Street Journal . Архивировано из оригинала 25 июля 2021 года . Получено 18 июля 2021 года .

- ^ "Часто задаваемые вопросы • Что такое древесная биомасса и откуда она взялась?" Полем Правительство графства Пласер . Получено 5 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Пелкманс, Люк (ноябрь 2021 г.). Отчет стран биоэнергии IEA: реализация биоэнергетики в странах -членах BioEnergy IEA (PDF) . Международное энергетическое агентство. п. 10. ISBN 978-1-910154-93-9 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Лойола, Марио (23 ноября 2019 г.). «Остановить безумие этанола» . Атлантика . Получено 5 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Великобритания, Мария Меллор, Wired. «Биотопливо предназначен для очистки углеродного кризиса Flying. Они не будут» . Проводной . ISSN 1059-1028 . Получено 5 мая 2024 года .

{{cite magazine}}: Cs1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Timperly, Джоселин (23 февраля 2017 г.). «Субсидии биомассы« не подходят для цели », - говорит Чатем Хаус» . Carbon Brief Ltd © 2020 - Компания № 07222041. Архивировано из оригинала 6 ноября 2020 года . Получено 31 октября 2020 года .

- ^ «Биотопливо» . Международное энергетическое агентство . Получено 5 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный REN21 Renewables Global Status Report 2011 , стр. 13–14.

- ^ «Япония для создания цепочки поставок био -реактивного топлива в чистоте энергии» . Nikkei Asia . Получено 26 апреля 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Мартин, Джереми (22 июня 2016 г.). «Все, что вы когда -либо хотели знать о биодизеле (диаграммы и графики!)» . Уравнение . Получено 5 мая 2024 года .

- ^ «Энергетические культуры» . Сельскохозяйственные культуры выращиваются специально для использования в качестве топлива . Энергетический центр биомассы. Архивировано с оригинала 10 марта 2013 года . Получено 6 апреля 2013 года .

- ^ Лю, Синью; Квон, Хойонг; Ван, Майкл; О'Коннор, Дон (15 августа 2023 г.). «Выбросы парниковых газов жизненного цикла бразильского этанола сахарного тростника, оцениваемые с моделью приветствия с использованием данных, представленных в Реновабио» . Экологическая наука и технология . 57 (32): 11814–11822. Bibcode : 2023enst ... 5711814L . doi : 10.1021/acs.est.2c08488 . ISSN 0013-936X . PMC 10433513 . PMID 37527415 .

- ^ «Биотопливо» . Библиотека ОЭСР . 2022 . Получено 5 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Цинь, Чжангкай; Чжуан, Цяньлай; Cai, ximing; Он, Юджи; Хуан, Яо; Цзян, Донг; Лин, Эрда; Лю, Ялинг; Тан, я; Ван, Майкл Q. (февраль 2018 г.). «Биомасса и биотопливо в Китае: к потенциалам биоэнергии ресурсов и их воздействию на окружающую среду» . Возобновляемые и устойчивые обзоры энергии . 82 : 2387–2400. Bibcode : 2018rserv..82.2387q . doi : 10.1016/j.rser.2017.08.073 .

- ^ Крамер, Дэвид (1 июля 2022 года). "Что случилось с целлюлозном этанолом?" Полем Физика сегодня . 75 (7): 22–24. Bibcode : 2022pht .... 75G..22K . doi : 10.1063/pt.3.5036 . ISSN 0031-9228 .

- ^ Ахмад Дар, Руф; Ахмад Дар, Eajaz; Каур, Аджит; Гупта Футела, Урмила (1 февраля 2018 года). «Сладкий сорго-многообещающий альтернативный сырье для производства биотоплива» . Возобновляемые и устойчивые обзоры энергии . 82 : 4070–4090. Bibcode : 2018rserv..82.4070a . doi : 10.1016/j.rser.2017.10.066 . ISSN 1364-0321 .

- ^ Говард, Брайан (28 января 2020 г.). «Превращение коровьей отходы в чистую энергию в национальном масштабе» . Холм . Архивировано с оригинала 29 января 2020 года . Получено 30 января 2020 года .

- ^ Чжу, Лиандон; Ли, Чжауа; ХИЛТУНЕН, Эркки (28 июня 2018 г.). хлореллы вульгарская биомасса « Микроводоросли Биотехнология для биотоплива . 11 (1): 183. doi : 10.1186/s13068-018-1183-z . EISSN 1754-6834 . PMC 6022341 . PMID 29988300 .

- ^ Ирена 2024 , с. 43

- ^ Ирена 2024 , с. 43. Примечание: составные годовые темпы роста 2014-2023.

- ^ «Электричество» . Международное энергетическое агентство . 2020. Раздел браузера данных, выработка электроэнергии по индикатору источника. Архивировано из оригинала 7 июня 2021 года . Получено 17 июля 2021 года .

- ^ Nrel ATB 2021 , Geothermal.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Clauser, Christoph (2024), «Поле тепла и температуры Земли» , Введение в геофизику , учебники Springer в науках о Земле, география и окружающая среда, Cham: Springer International Publishing, стр. 247–325, doi : 10.1007/978-3-031 -17867-2_6 , ISBN 978-3-031-17866-5 , Получено 6 мая 2024 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Динсер, Ибрагим; Ezzat, Muhammad F. (2018), «3,6 Геотермальная энергетическая производство» , Комплексные энергетические системы , Elsevier, pp. 252–303, doi : 10.1016/b978-0-12-809597-3.00313-8 , ISBN 978-0-12-814925-6 , Получено 7 мая 2024 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ричи, Ханна; Росадо, Пабло; Розер, Макс (2023). «Страница данных: Геотермальная энергетическая емкость» . Наш мир в данных . Получено 7 мая 2024 года .

- ^ «Выработка электроэнергии, мощность и продажи в Соединенных Штатах» . Администрация энергетической информации США . Получено 7 мая 2024 года .

- ^ «Использование геотермальной энергии» . Администрация энергетической информации США . 22 ноября 2023 года . Получено 7 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Хуссейн, Ахтар; Ариф, Сайед Мухаммед; Аслам, Мухаммед (2017). «Новые возобновляемые и устойчивые энергетические технологии: состояние искусства». Возобновляемые и устойчивые обзоры энергии . 71 : 12–28. Bibcode : 2017rserv..71 ... 12H . doi : 10.1016/j.rser.2016.12.033 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Международное энергетическое агентство (2007). Возобновляемые источники энергии в глобальном энергоснабжении: лист фактов IEA (PDF), OECD, p. 3. Архивировано 12 октября 2009 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Дюхан, Дэйв; Браун, Дон (декабрь 2002 г.). «Геотермальная энергетическая исследования и разработка геотермальной энергетики в Фентон -Хилл, Нью -Мексико» (PDF) . Гео-хит-центр ежеквартальный бюллетень . Тол. 23, нет. 4. Кламат Фолс, Орегон: Орегонский технологический институт. С. 13–19. ISSN 0276-1084 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 17 июня 2010 года . Получено 5 мая 2009 года .