Португальская колониальная война

| Португальская колониальная война Португальская колониальная война | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Часть холодной войны и деколонизации Африки | |||||||||

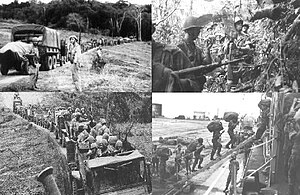

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Angola:Guinea:Mozambique: | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Angola:Guinea:Mozambique: | Angola:Guinea:Mozambique: | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

1,400,000 total men mobilized for military and civilian support service.[7]

| 40–60,000 guerrillas[9]

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

~29,000 casualties

| 41,000+ casualties | ||||||||

| Civilian killed: 70,000–110,000 civilians killedOver 300,000 Portuguese nationals evacuated. | |||||||||

Португальская колониальная война ( португальский : Guerra Colonial Portuguesa ), также известная в Португалии как Заморская война ( Guerra do Ultramar ) или в бывших колониях как Война за освобождение ( Guerra de Libertação ), а также известная как Ангольская , Гвинея- Бисау и Война за независимость Мозамбика — 13-летний конфликт между португальскими военными и возникающими националистическими движениями в африканских колониях Португалии в период с 1961 по 1974 год. Португальский режим того времени, Estado Novo , был свергнут в результате военного переворота. в 1974 году , и смена правительства положила конец конфликту. Война стала решающей идеологической борьбой в португалоязычной Африке, соседних странах и материковой Португалии.

Преобладающий португальский и международный исторический подход рассматривает Португальскую колониальную войну так, как она воспринималась в то время - единый конфликт, который велся на трех отдельных театрах военных действий в Анголе , Гвинее-Бисау и Мозамбике , а не ряд отдельных конфликтов, возникших в возникших африканских странах. помогали друг другу и были поддержаны одними и теми же мировыми державами и даже Организацией Объединенных Наций во время войны. Аннексия Индией Дадры и Нагар-Хавели в 1954 году и аннексия Гоа в 1961 году иногда включаются в состав конфликта.

Unlike other European nations during the 1950s and 1960s, the Portuguese Estado Novo regime did not withdraw from its African colonies, or the overseas provinces (províncias ultramarinas) as those territories had been officially called since 1951. During the 1960s, various armed independence movements became active—the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola, National Liberation Front of Angola, National Union for the Total Independence of Angola in Angola, African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde in Portuguese Guinea, and the Mozambique Liberation Front in Mozambique. During the ensuing conflict, atrocities were committed by all forces involved.[22]

Throughout the period, Portugal faced increasing dissent, arms embargoes, and other punitive sanctions imposed by the international community, including by some Western Bloc governments, either intermittently or continuously.[23] The anti-colonial guerrillas and movements of Portuguese Africa were heavily supported and instigated with money, weapons, training and diplomatic lobbying by the Communist Bloc which had the Soviet Union as its lead nation. By 1973, the war had become increasingly unpopular due to its length and financial costs, the worsening of diplomatic relations with other United Nations members, and the role it had always played as a factor of perpetuation of the entrenched Estado Novo regime and the nondemocratic status quo in Portugal.

The end of the war came with the Carnation Revolution military coup of April 1974 in mainland Portugal. The withdrawal resulted in the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Portuguese citizens[24] plus military personnel of European, African, and mixed ethnicity from the former Portuguese territories and newly independent African nations.[25][26][27] This migration is regarded as one of the largest peaceful, if forced, migrations in the world's history although most of the migrants fled the former Portuguese territories as destitute refugees.[28]

The former colonies faced severe problems after independence. Devastating civil wars followed in Angola and Mozambique, which lasted several decades, claimed millions of lives, and resulted in large numbers of displaced refugees.[29] Angola and Mozambique established state-planned economies after independence,[30] and struggled with inefficient judicial systems and bureaucracies,[30] corruption,[30][31][32] poverty and unemployment.[31] A level of social order and economic development comparable to what had existed under Portuguese rule, including during the period of the Colonial War, became the goal of the independent territories.[33]

The former Portuguese territories in Africa became sovereign states, with Agostinho Neto in Angola, Samora Machel in Mozambique, Luís Cabral in Guinea-Bissau, Manuel Pinto da Costa in São Tomé and Príncipe, and Aristides Pereira in Cape Verde as the heads of state.

Political context

[edit]15th century

[edit]When the Portuguese began trading on the west coast of Africa in the 15th century, they concentrated their energies on Guinea and Angola. Hoping at first for gold, they soon found that slaves were the most valuable commodity available in the region for export. The Islamic Empire was already well-established in the African slave trade, for centuries linking it to the Arab slave trade. However, the Portuguese who had conquered the Islamic port of Ceuta in 1415 and several other towns in current-day Morocco in a Crusade against Islamic neighbors, managed to successfully establish themselves in the area.

In Guinea, rival European powers had established control over the trade routes in the region, while local African rulers confined the Portuguese to the coast. These rulers then sent enslaved Africans to the Portuguese ports, or to forts in Africa from where they were exported. Thousands of kilometers down the coast, in Angola, the Portuguese found consolidating their early advantage in establishing hegemony over the region even harder, due to the encroachment of Dutch traders. Nevertheless, the fortified Portuguese towns of Luanda (established in 1587 with 400 Portuguese settlers) and Benguela (a fort from 1587, a town from 1617) remained almost continuously in Portuguese hands.[citation needed]

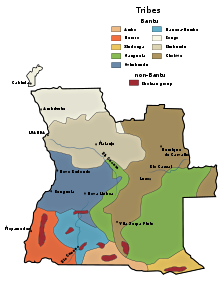

As in Guinea, the slave trade became the basis of the local economy in Angola. Excursions traveled ever farther inland to procure captives who were sold by African rulers; the primary source of these slaves were those captured as a result of losing a war or interethnic skirmish with other African tribes. More than a million men, women, and children were shipped from Angola across the Atlantic. In this region, unlike Guinea, the trade remained largely in Portuguese hands. Nearly all the slaves were destined for the Portuguese colony of Brazil.[citation needed]

In Mozambique, reached in the 15th century by Portuguese sailors searching for a maritime spice trade route, the Portuguese settled along the coast and made their way into the hinterland as sertanejos (backwoodsmen). These sertanejos lived alongside Swahili traders and even obtained employment among Shona kings as interpreters and political advisers. One such sertanejo managed to travel through almost all the Shona kingdoms, including the Mutapa Empire's (Mwenemutapa) metropolitan district, between 1512 and 1516.[34]

By the 1530s, small bands of Portuguese traders and prospectors penetrated the interior regions seeking gold, where they set up garrisons and trading posts at Sena and Tete on the Zambezi River and tried to establish a monopoly over the gold trade. The Portuguese finally entered into direct relations with the Mwenemutapa in the 1560s.[35] However, the Portuguese traders and explorers settled in the coastal strip with greater success, and established strongholds safe from their main rivals in East Africa – the Omani Arabs, including those of Zanzibar.[citation needed]

Scramble for Africa and the World Wars

[edit]

Portugal's colonial claim to the region was recognized by the other European powers during the 1880s, during the Scramble for Africa, and the final boundaries of Portuguese Africa were agreed by negotiation in Europe in 1891. At the time, Portugal was in effective control of little more than the coastal strip of both Angola and Mozambique, but important inroads into the interior had been made since the first half of the 19th century. In Angola, construction of a railway from Luanda to Malanje, in the fertile highlands, was started in 1885.[36]

Work began in 1903 on a commercially significant line from Benguela all the way inland to the Katanga region, aiming to provide access to the sea for the richest mining district of the Belgian Congo.[37] The line reached the Congo border in 1928.[37] In 1914, both Angola and Mozambique had Portuguese army garrisons of around 2,000 men, African troops led by European officers. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Portugal sent reinforcements to both colonies, because the fighting in the neighboring German African colonies was expected to spill over the borders into its territories.

After Germany declared war on Portugal in March 1916, the Portuguese government sent more reinforcements to Mozambique (the South Africans had captured German South West Africa in 1915). These troops supported British, South African and Belgian military operations against German colonial forces in German East Africa. In December 1917, German colonial forces led by Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck invaded Mozambique from German East Africa. Portuguese, British and Belgian forces spent all of 1918 chasing Lettow-Vorbeck and his men across Mozambique, German East Africa and Northern Rhodesia. Portugal sent a total of 40,000 reinforcements to Angola and Mozambique during World War I.[38]

By this time, the regime in Portugal had been through two major political upheavals—from monarchy to republic in 1910 and then to a military dictatorship after a coup in 1926. These changes resulted in a tightening of Portuguese control in Angola. In the early years of the expanded colony, near-constant warfare was occurring between the Portuguese and the various African rulers of the region. A systematic campaign of conquest and pacification was undertaken by the Portuguese. One by one, the local kingdoms were overwhelmed and abolished.

By the middle of the 1920s, the whole of Angola was under control. Slavery had officially ended in Portuguese Africa, but the plantations were worked on a system of paid serfdom by African labour composed of the large majority of ethnic Africans who did not have resources to pay Portuguese taxes and were considered unemployed by the authorities. After World War II and the first decolonization events, this system gradually declined, but paid forced labor, including labor contracts with forced relocation of people, continued in many regions of Portuguese Africa until it was finally abolished in 1961.[39]

Post-World War II

[edit]In the late 1950s, the Portuguese Armed Forces saw themselves confronted with the paradox generated by the dictatorial regime of the Estado Novo that had been in power since 1933; on one hand, the policy of Portuguese neutrality in World War II placed the Portuguese Armed Forces out of the way of a possible East-West conflict; on the other, the regime felt the increased responsibility of keeping Portugal's vast overseas territories under control and protecting the citizenry there. Portugal joined NATO as a founding member in 1949, and was integrated within the various fledgling military commands of NATO.[40]

NATO's focus on preventing a conventional Soviet attack against Western Europe was to the detriment of military preparations against guerrilla uprisings in Portugal's overseas provinces that were considered essential for the survival of the nation. The integration of Portugal in NATO resulted in the formation of a military élite who were critical in the planning and implementation of operations during the Overseas War. This "NATO generation" ascended quickly to the highest political positions and military command without having to provide evidence of loyalty to the regime.

The Colonial War established a split between the military structure – heavily influenced by the western powers with democratic governments – and the political power of the regime. Some analysts see the "Botelho Moniz coup" of 1961 (also known as A Abrilada) against the Portuguese government and backed by the U.S. administration,[41] as the beginning of this rupture, the origin of a lapse on the part of the regime to keep up a unique command center, an armed force prepared for threats of conflict in the colonies. This situation caused, as was verified later, a lack of coordination between the three general staffs (Army, Air Force, and Navy).

The FNLA, which was headed by Holden Roberto, attacked Portuguese settlers and Africans living in northern Angola from its bases in Congo-Léopoldville.[42][43] Many of the victims were African farm workers living under labor contracts that required seasonal relocation from the desertified Southwest and Bailundo areas of Angola. Photos of Africans killed by the FLNA, which included photos of decapitated civilians, men, women and children of both white and black ethnicity, was later displayed in the UN by Portuguese diplomats.[44] The emergence of labor strikes, attacks by newly organized guerrilla movements, and the Santa Maria hijacking by Henrique Galvão began a path to open warfare in Angola.

According to historical researchers such as José Freire Antunes, U.S. President John F. Kennedy[45] sent a message to President António de Oliveira Salazar advising Portugal to abandon its African colonies shortly after the outbreak of violence in 1961. Instead, after a coup led by pro-U.S. forces failed to depose him,[citation needed][specify] Salazar consolidated power and immediately sent reinforcements to the overseas territories, setting the stage for continued conflict in Angola. Similar situations played out in other overseas Portuguese territories.

Multiethnic societies, competing ideologies, and armed conflict in Portuguese Africa

[edit]

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (October 2023) |

By the 1950s, the European mainland Portuguese territory was inhabited by a society that was poorer and had a much higher illiteracy rate than the average Western European societies or those of North America. It was ruled by an authoritarian and conservative right-leaning dictatorship, known as the Estado Novo regime. By this time, the Estado Novo regime ruled both the Portuguese mainland and several centuries-old overseas territories as theoretically co-equal departments. The possessions were Angola, Cape Verde, Macau, Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea, Portuguese India, Portuguese Timor, São João Baptista de Ajudá, and São Tomé and Príncipe.

In reality, the relation of mainland Portuguese to their overseas possessions was that of colonial administrator to a subservient colony. Political, legislative, administrative, commercial, and other institutional relations between the colonies and Portugal-based individuals and organizations were numerous, though migration to, from, and between Portugal and its overseas departments was limited in size, due principally to the long distance and low annual income of the average Portuguese and that of the indigenous overseas populations.

An increasing number of African anticolonial movements called for total independence of the overseas African territories from Portugal. Some, like the UPA[46] wanted national self-determination, while others wanted a new form of government based on Marxist principles. Portuguese leaders, including Salazar, attempted to stave off calls for independence by defending a policy of assimilation, multiracialism, and civilising mission, or lusotropicalism, as a way of integrating Portuguese colonies, and their peoples, more closely with Portugal itself.[47]

For the Portuguese ruling regime, the overseas empire was a matter of national interest, to be preserved at all costs. As far back as 1919, a Portuguese delegate to the International Labour Conference in Geneva declared: "The assimilation of the so-called inferior races, by cross-breeding, by means of the Christian religion, by the mixing of the most widely divergent elements; freedom of access to the highest offices of state, even in Europe – these are the principles which have always guided Portuguese colonisation in Asia, in Africa, in the Pacific, and previously in America."[48]

As late as the 1950s, the policy of "colorblind" access and mixing of races did not extend to all of Portugal's African territories, particularly Mozambique, where in tune with other minority white regimes of the day in Southern Africa, the territory was segregated along racial lines. Strict qualification criteria ensured that fewer than one in 100 black Mozambicans became full Portuguese citizens.[49]

Settlement subsidies

[edit]Numerous subsidies were offered by the Estado Novo regime to those Portuguese who agreed to settle in Angola or Mozambique, including a special premium for each Portuguese man who agreed to marry an African woman.[50] Salazar himself was fond of restating the old Portuguese policy maxim that any indigenous resident of Portugal's African territories was, in theory, eligible to become a member of Portuguese government, even its president. In practice, this never took place, though trained black Africans living in Portugal's overseas African possessions were allowed to occupy positions in a variety of areas including the military, civil service, clergy, education, and private business—providing they had the requisite education and technical skills.

While access to basic, secondary, and technical education remained poor until the 1960s, a few Africans were able to attend schools locally or in some cases in Portugal itself. This resulted in the advancement of certain black Portuguese Africans who became prominent individuals during the war and its aftermath, including Samora Machel, Mário Pinto de Andrade, Marcelino dos Santos, Eduardo Mondlane, Agostinho Neto, Amílcar Cabral, Jonas Savimbi, Joaquim Chissano, and Graça Machel. Two state-run universities were founded in Portuguese Africa in the 1962 by the Minister of the Overseas Adriano Moreira (the Universidade de Luanda in Angola and the Universidade de Lourenço Marques in Mozambique, awarding a range of degrees from engineering to medicine[51]); however, most of their students came from Portuguese families living in the two territories. Several personalities in Portuguese society, including one of the most idolized sports stars in Portuguese football history, a black football player from Portuguese East Africa named Eusébio, were other examples of efforts towards assimilation and multiracialism in the post-World War II period.

Composition of the Portuguese Army

[edit]According to Mozambican historian João Paulo Borges Coelho,[52] the Portuguese colonial army was largely segregated along terms of race and ethnicity until 1960. There were originally three classes of soldier in Portuguese overseas service: commissioned soldiers (whites), overseas soldiers (African assimilados), and native or indigenous Africans (indigenato'). These categories were renamed to first, second, and third class in 1960, which effectively corresponded to the same categories. Later, after official discrimination based on skin colour was outlawed, some Portuguese commanders such as General António de Spínola began a process of "Africanization" of Portuguese forces fighting in Africa. In Portuguese Guinea, this included a large increase in African recruitment along with the establishment of all-black military formations such as the Black Militias (Milícias negras) commanded by Major Carlos Fabião and the African Commando Battalion (Batalhão de Comandos Africanos) commanded by General Almeida Bruno.[53]

While sub-Saharan African soldiers constituted a mere 18% of the total number of troops fighting in Portugal's African territories in 1961, this percentage rose dramatically over the next 13 years, with black soldiers constituting over 50% of all government forces fighting in Africa by April 1974. Coelho noted that perceptions of African soldiers varied a good deal among senior Portuguese commanders during the conflict in Angola, Guinea, and Mozambique. General Francisco da Costa Gomes, perhaps the most successful counterinsurgency commander, sought good relations with local civilians, and employed African units within the framework of an organized counterinsurgency plan.[54] General António de Spínola, by contrast, appealed for a more political and psycho-social use of African soldiers.[54] On the other hand, General Kaúlza de Arriaga, the most conservative of the three, appears to have doubted the reliability of African forces outside his strict control, while continuing to view African soldiers as inferior to Portuguese troops.[54][55]

As the war progressed, Portugal rapidly increased its mobilized forces. Under the Salazar regime, a military draft required all males to serve three years of obligatory military service; many of those called up to active military duty were deployed to combat zones in Portugal's African overseas provinces. The national service period was increased to four years in 1967, and virtually all conscripts faced a mandatory two-year tour of service in Africa.[56] The existence of the draft and likelihood of combat in African counterinsurgency operations over time resulted in a sharp increase in emigration by Portuguese men seeking to avoid such service. By the end of the Portuguese colonial war in 1974, black African participation had become crucial due to declining numbers of recruits available from Portugal itself.[57]

Native African troops, although widely deployed, were initially used in subordinate roles as enlisted troops or noncommissioned officers. Portuguese colonial administrators were handicapped by their policies in education, which largely barred indigenous Africans from adequate education until well after the outbreak of the insurgency.[58] With illiteracy rates approaching 99% and almost no African enrollment in secondary schools,[58] few African candidates could qualify for Portugal's officer candidate programs; most African officers obtained their commission as the result of individual competence and valour on the battlefield. As the war went on, an increasing number of native Africans served as noncommissioned or commissioned officers by the 1970s, including such officers as Captain (later Lt. Colonel) Marcelino da Mata, a Portuguese citizen born of native Guinean parents who rose to command from a first sergeant in a road engineering unit to a commander in the elite all-African Comandos Africanos, where he eventually became one of the most decorated soldiers in the Portuguese Army. Many native Angolans rose to positions of command, though of junior rank.

By the early 1970s, the Portuguese authorities had fully perceived racial discriminatory policies and lack of investment in education as wrong and contrary to their overseas ambitions in Portuguese Africa, and willingly accepted a true color blindness policy with more spending in education and training opportunities, which started to produce a larger number of black high ranked professionals, including military personnel.

Intervention by Cold War powers

[edit]After the World War II, as communist and anticolonial ideologies spread across Africa, many clandestine political movements were established in support of independence using various interpretations of Marxist revolutionary ideology. These new movements seized on anti-Portuguese and anti-colonial sentiment[59] to advocate the complete overthrow of existing governmental structures in Portuguese Africa. These movements alleged that Portuguese policies and development plans were primarily designed by the ruling authorities for the benefit of the territories' ethnic Portuguese population at the expense of local tribal control, the development of native communities, and the majority of the indigenous population, who suffered both state-sponsored discrimination and enormous social pressure to comply with government policies largely imposed from Lisbon. Many felt they had received too little opportunity or resources to upgrade their skills and improve their economic and social situation to a degree comparable to that of the Europeans. Statistically, Portuguese Africa's white Portuguese population were indeed wealthier and more educated than the indigenous majority.

After conflict erupted between the UPA and MPLA and Portuguese military forces, U.S. President John F. Kennedy[45] advised António de Oliveira Salazar (via the US consulate in Portugal) that Portugal should abandon its African colonies, and that course of action by Kennedy would lead to a political crisis between Portugal and the United States. A failed Portuguese military coup known as the Abrilada, attempted in an effort to overthrow the authoritarian Estado Novo regime of António de Oliveira Salazar, received covert U.S. support.[41] In response, Salazar moved to consolidate his power, ordering an immediate military response to the violence occurring in Angola.[56] The U.S.'s official stance on Portugal would shift following Richard Nixon's election as president. Under the advice of Henry Kissinger, Nixon sought to reduce America's involvement in the Third World, delegating this role to "regional policemen" such as Joseph Mobutu of Congo-Léopoldville. This led to Nixon cutting off aid to Holden Roberto's FNLA and resuming normal trade relations with Portugal.[60]

While Portuguese forces had all but won the guerrilla war in Angola, and had stalemated FRELIMO in Mozambique, colonial forces were forced on the defensive in Guinea, where PAIGC forces had carved out a large area of the rural countryside under effective insurgent control, using Soviet-supplied AA cannon and ground-to-air missiles to protect their encampments from attack by Portuguese air assets.[62][63] Overall, the increasing success of Portuguese counterinsurgency operations and the inability or unwillingness of guerrilla forces to destroy the economy of Portugal's African territories was seen as a victory for the Portuguese government policies.

The Soviet Union,[64] realising that military success by insurgents in Angola and Mozambique was becoming increasingly remote, shifted much of its military support to the PAIGC in Guinea, while increasing diplomatic efforts to isolate Portugal from the world community.[65] The success of the socialist bloc in isolating Portugal diplomatically extended inside Portugal itself into the armed forces, where younger officers disenchanted with the Estado Novo regime and promotional opportunities began to identify ideologically with those calling for overthrow of the government and the establishment of a state based on Marxist principles.[66]

Nicolae Ceaușescu's Romania offered consistent support to the African liberation movements. Romania was the first state that recognized the independence of Guinea-Bissau, as well as the first to sign agreements with the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde and Angola's MPLA.[67] In May 1974, Ceaușescu reaffirmed Romania's support for Angolan independence.[68] As late as September 1975, Bucharest publicly supported all three Angolan liberation movements (FNLA, MPLA and UNITA).[69] In the spring of 1972, Romania allowed FRELIMO to open a diplomatic mission in Bucharest, the first of its kind in Eastern Europe. In 1973, Ceaușescu recognized FRELIMO as "the only legitimate representative of the Mozambican people", an important precedent. Samora Machel stressed that—during his trip to the Soviet Union—he and his delegation were granted "the status that we are entitled to" due to Romania's official recognition of FRELIMO. In terms of material support, Romanian trucks were used to transport weapons and ammunition to the front, as well as medicine, school material and agricultural equipment. Romanian tractors contributed to the increase in agricultural production. Romanian weapons and uniforms—reportedly of "excellent quality"—played a "decisive role" in FRELIMO's military progress. It was in early 1973 that FRELIMO made these statements about Romania's material support, in a memorandum sent to the Romanian Communist Party's Central Committee.[70] In 1974, Romania became the first country to formally recognize Mozambique.[71]

By early 1974, guerrilla operations in Angola and Mozambique had been reduced to sporadic ambush operations against the Portuguese in the rural countryside areas, far from the main centers of population.[57] The only exception was Portuguese Guinea, where PAIGC guerrilla operations, strongly supported by neighbouring allies like Guinea and Senegal, were largely successful in liberating and securing large areas of Portuguese Guinea. According some historians, Portugal recognized its inability to win the conflict in Guinea at the outset, but was forced to fight on to prevent an independent Guinea from serving as an inspirational model for insurgents in Angola and Mozambique.[72]

Despite continuing attacks by insurgent forces against targets throughout the Portuguese African territories, the economies of both Portuguese Angola and Mozambique had actually improved each year of the conflict, as had the economy of Portugal proper.[73] Angola enjoyed an unprecedented economic boom during the 1960s, and the Portuguese government built new transportation networks to link the well-developed and highly urbanized coastal strip with the remote inland regions of the territory.[56]

The number of ethnic European Portuguese migrants from mainland Portugal (the metrópole) continued to increase as well, though always constituting a small minority of each territory's total population.[74] Nevertheless, the costs of continuing the wars in Africa imposed a heavy burden on Portugal's resources; by the 1970s, the country was spending 40 percent of its annual budget on the war effort.[56]

General Spínola was dismissed by Dr. Marcelo Caetano, the last prime minister of Portugal under the Estado Novo regime, over the general's publicly announced desire to open negotiations with the PAIGC in Portuguese Guinea. The dismissal caused considerable public indignation in Portugal, and created favorable conditions for a military overthrow of the existing regime, which had lost all public support. On 25 April 1974 a military coup organized by left-wing Portuguese military officers, the Armed Forces Movement (MFA), overthrew the Estado Novo regime in what came to be known as the Carnation Revolution in Lisbon, Portugal.[66]

The coup resulted in a period of economic collapse and political instability, but received general support from the public in its aim of ending the Portuguese war effort in Africa. In the ex-colonies, officers suspected of sympathizing with the prior regime, even black officers, such as Captain Marcelino da Mata, were imprisoned and tortured, while African soldiers who had served in native Portuguese Army units were forced to petition for Portuguese citizenship or else face reprisals from their former enemies in Angola, Guinea, or Mozambique.

The Carnation Revolution of 25 April 1974 came as a shock to the United States and other Western powers, as most analysts and the Nixon administration had concluded that Portuguese military success on the battlefield would resolve any political divisions within Portugal concerning the conduct of the war in Portuguese Africa, providing the conditions for US investment there.[75] Most concerned was the apartheid government of South Africa, which launched a deep border incursion operation into Angola to attack guerrilla-controlled areas of the country following the coup.

Theatres of war

[edit]Angola

[edit]

On 3 January 1961 Angolan peasants in the region of Baixa de Cassanje, Malanje boycotted the Cotonang Company's cotton fields where they worked, demanding better working conditions and higher wages. Cotonang, a company owned by European investors, used native African labor to produce an annual cotton crop for export abroad. The uprising, later to become known as the Baixa de Cassanje revolt, was led by two previously unknown Angolans, António Mariano and Kulu-Xingu.[76] During the protests, African workers burned their identification cards and attacked Portuguese traders. The Portuguese Air Force responded to the rebellion by bombing twenty villages in the area, allegedly using napalm in an attack that resulted in some 400 indigenous Angolan deaths.[77][78]

In the Portuguese Overseas Province of Angola, the call for revolution was taken up by two insurgent groups, the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), and the União das Populações de Angola (UPA), which became the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) in 1962. The MPLA commenced activities in an area of Angola known as the Zona Sublevada do Norte (ZSN or the Rebel Zone of the North), consisting of the provinces of Zaire, Uíge and Cuanza Norte.[79]

Insurgent attacks

[edit]

On 4 February 1961, using arms largely captured from Portuguese soldiers and police[80] 250 MPLA guerrillas attacked the São Paulo fortress prison and police headquarters in Luanda in an attempt to free what it termed 'political prisoners'. The attack was unsuccessful, and no prisoners were released, but seven Portuguese policemen and forty Angolans were killed, mostly MPLA insurgents.[80] Portuguese authorities responded with a sweeping counterinsurgency response in which over 5,000 Angolans were arrested, and a Portuguese mob raided the musseques (shanty towns) of Luanda, killing several dozen Angolans in the process.[81]

On 15 March 1961, the UPA led by Holden Roberto launched an incursion into the Bakongo region of northern Angola with 4,000–5,000 insurgents. The insurgents called for local Bantu farmworkers and villagers to join them, unleashing an orgy of violence and destruction. The insurgents attacked farms, government outposts, and trading centers, killing everyone they encountered, including women, children and newborns.[82]

In surprise attacks, drunken and buoyed by belief in tribal spells that they believed made them immune to bullets, the attackers spread terror and destruction in the whole area.[82] At least 1,000 Portuguese settlers and an unknown but larger number of indigenous Angolans were killed by the insurgents during the attacks.[83] The violence of the uprising received worldwide press attention and engendered sympathy for the Portuguese, while adversely affecting the international reputation of Roberto and the UPA.[84]

Portuguese response

[edit]

In response, Portuguese Armed Forces instituted a harsh policy of reciprocity by torturing and massacring rebels and protesters. Some Portuguese soldiers decapitated rebels and impaled their heads on stakes, pursuing a policy of "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth". Much of the initial offensive operations against Angolan UPA and MPLA insurgents was undertaken by four companies of Caçadores Especiais (Special Hunter) troops skilled in light infantry and antiguerrilla tactics, and who were already stationed in Angola at the outbreak of fighting.[85] Individual Portuguese counterinsurgency commanders such as Second Lieutenant Fernando Robles of the 6ª Companhia de Caçadores Especiais became well known throughout the country for their ruthlessness in hunting down insurgents.[86]

The Portuguese Army steadily pushed the UPA back across the border into Congo-Kinshasa in a brutal counteroffensive that also displaced some 150,000 Bakongo refugees, taking control of Pedra Verde, the UPA's last base in northern Angola, on 20 September 1961.[84] Within the next few weeks Portuguese military forces pushed the MPLA out of Luanda northeast into the Dembos region, where the MPLA established the "1st Military Region". For the moment, the Angolan insurgency had been defeated, but new guerrilla attacks later broke out in other regions of Angola such as Cabinda province, the central plateaus, and eastern and southeastern Angola.

By most accounts, Portugal's counterinsurgency campaign in Angola was the most successful of all its campaigns in the Colonial War.[57] Angola is a large territory, and the long distances from safe havens in neighboring countries supporting the rebel forces made it difficult for the latter to escape detection. Distances from the major Angolan urban centres to neighbouring Zaïre and Zambia were so large that the eastern part of Angola's territory was known by the Portuguese as Terras do Fim do Mundo (the lands of the far side of the world).

Another factor was internecine struggles between three competing revolutionary movements – FNLA, MPLA, and UNITA – and their guerrilla armies. For most of the conflict, the three rebel groups spent as much time fighting each other as they did fighting the Portuguese. For example, during the 1961 Ferreira Incident, a UPA patrol captured 21 MPLA insurgents as prisoners, then summarily executed them on 9 October, sparking open confrontation between the two insurgent groups. These divisions grew so deep, that by 1972, UNITA ceased military operations entirely against the Portuguese and began coordinating with them against the MPLA by providing intelligence on MPLA positions, numbers, and troop movements.[87]

Strategy also played a role, as a successful hearts and minds campaign led by General Francisco da Costa Gomes helped blunt the influence of the various revolutionary movements. Finally, as in Mozambique, Portuguese Angola was able to receive support of South Africa. South African military operations proved to be of significant assistance to Portuguese military forces in Angola, who sometimes referred to their South African counterparts as primos (cousins).

Several unique counter-insurgency forces were developed and deployed in the campaign in Angola:

- Batalhões de Caçadores Pára-quedistas (Paratrooper Hunter Battalions): employed throughout the conflicts in Africa, were the first forces to arrive in Angola when the war began.

- Comandos (Commandos): born out of the war in Angola, they were created as an elite counter-guerrilla special forces, and later used in Guinea and Mozambique.

- Caçadores Especiais (Special Hunters): were in Angola from the start of the conflict in 1961.

- Fiéis (Faithfuls): a force composed by Katanga exiles, black soldiers that opposed the rule of Mobutu Sese Seko in Congo-Kinshasa

- Leais (Loyals): a force composed by exiles from Zambia, black soldiers that were against Kenneth Kaunda

- Grupos Especiais (Special Groups): units of volunteer black soldiers that had commando training; also used in Mozambique

- Tropas Especiais (Special Troops): the name of Special Groups in Cabinda

- Flechas (Arrows): a successful indigenous formation of scouts, controlled by the Portuguese secret police PIDE/DGS, and composed by Bushmen that specialized in tracking, reconnaissance and pseudo-terrorist operations. Also employed in Mozambique, the Flechas inspired the formation of the Rhodesian Selous Scouts.

- Grupo de Cavalaria Nº1 (1st Cavalry Group): a mounted cavalry unit, armed with the 7.62 mm Espingarda m/961 rifle and the m/961 Walther P38 pistol, tasked with reconnaissance and patrolling. The 1st was also known as the "Angolan Dragoons" (Dragões de Angola). The Rhodesians also later developed a similar concept of horse-mounted counter-insurgency forces, forming the Grey's Scouts.

- Batalhão de Cavalaria 1927 (1927 Cavalry Battalion): a tank unit equipped with the M5A1 tank. The battalion was used for supporting infantry forces and as a rapid reaction force. Again the Rhodesians developed a similar unit, forming the Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment.

Portuguese Guinea

[edit]

In Portuguese Guinea (also referred to as Guinea at that time), the Marxist African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) started fighting in January 1963. Its guerrilla fighters attacked the Portuguese headquarters in Tite, located to the south of Bissau, the capital, near the Corubal river. Similar actions quickly spread across the entire colony, requiring a strong response from the Portuguese forces.

The war in Guinea has been termed "Portugal's Vietnam". The PAIGC was well-trained, well-led and equipped and received substantial support from safe havens in neighbouring countries like Senegal and the Republic of Guinea (Guinea-Conakry). The jungles of Guinea and the proximity of the PAIGC's allies near the border proved to be of significant advantage in providing tactical superiority during cross-border attacks and resupply missions for the guerrillas.The conflict in Portuguese Guinea involving the PAIGC guerrillas and the Portuguese Army proved the most intense and damaging of all conflicts in the Portuguese Colonial War, blocking Portuguese attempts to pacify the disputed territory via new economic and socioeconomic policies that had been applied with some success in Portuguese Angola and Portuguese Mozambique. In 1965 the war spread to the eastern part of Guinea; that year, the PAIGC carried out attacks in the north of the territory where at the time only the Front for the Liberation and Independence of Guinea (FLING), a minor insurgent group, was active. By this time, the PAIGC had begun to openly receive military support from Cuba, China, and the Soviet Union.

In Guinea, the success of PAIGC guerrilla operations put Portuguese armed forces on the defensive, forcing them to limit their response to defending territories and cities already held. Unlike Portugal's other African territories, successful small-unit Portuguese counterinsurgency tactics were slow to evolve in Guinea. Defensive operations, where soldiers were dispersed in small numbers to guard critical buildings, farms, or infrastructure were particularly devastating to the regular Portuguese infantry, who became vulnerable to guerrilla attacks outside of populated areas by the forces of the PAIGC. They were also demoralized by the steady growth of PAIGC liberation sympathizers and recruits among the rural population. In a relatively short time, the PAIGC had succeeded in reducing Portuguese military and administrative control of the territory to a relatively small area of Guinea. The scale of this success can be seen in the fact that native Guineans in the 'liberated territories' ceased payment of debts to Portuguese landowners and the payment of taxes to the colonial administration.[88] The branch stores of the Companhia União Fabril (CUF), Mario Lima Whanon, and Manuel Pinto Brandão companies were seized and inventoried by the PAIGC in the areas they controlled, while the use of Portuguese currency in the areas under guerrilla control was banned.[88] In order to maintain the economy in the liberated territories, the PAIGC established its own administrative and governmental bureaucracy at an early stage, which organized agricultural production, educated PAIGC farmworkers on how to protect crops from destruction from aerial attack by the Portuguese Air Force, and opened armazens do povo (people's stores) to supply urgently needed tools and supplies in exchange for agricultural produce.[88]

In 1968, General António de Spínola, the Portuguese general responsible for the Portuguese military operations in Guinea, was appointed as governor. General Spínola began a series of civil and military reforms designed to weaken PAIGC control of the Guinea and rollback insurgent gains. This included a 'hearts and minds' propaganda campaign designed to win the trust of the indigenous population, an effort to eliminate some of the discriminatory practices against native Guineans, a massive construction campaign for public works including new schools, hospital, an improved telecommunications and road network, and a large increase in recruitment of native Guineans into the Portuguese armed forces serving in Guinea as part of an Africanization strategy.

Until 1960, Portuguese military forces serving in Guinea were composed of units led by white officers, with commissioned soldiers (whites), overseas soldiers (African assimilados), and native or indigenous Africans (indigenato) serving in the enlisted ranks. General Spínola's Africanization policy eliminated these discriminatory colour bars, and called for the integration of indigenous Guinea Africans into Portuguese military forces in Africa. Two special indigenous African counterinsurgency detachments were formed by the Portuguese Armed Forces. The first of these was the African Commandos (Comandos Africanos), consisting of a battalion of commandos composed entirely of black soldiers (including the officers). The second was the African Special Marines (Fuzileiros Especiais Africanos), Marine units entirely composed of black soldiers. The African Special Marines supplemented other Portuguese elite units conducting amphibious operations in the riverine areas of Guinea in an attempt to interdict and destroy guerrilla forces and supplies. General Spínola's Africanization policy also fostered a large increase in indigenous recruitment into the armed forces, culminating the establishment of all-black military formations such as the Black Militias (Milícias negras) commanded by Major Carlos Fabião.[53] By the early 1970s, an increasing percentage of Guineans were serving as noncommissioned or commissioned officers in Portuguese military forces in Africa, including such higher-ranking officers as Captain (later Lt. Colonel) Marcelino da Mata, a black Portuguese citizen born of Guinean parents who rose from a first sergeant in a road engineering unit to a commander in the Comandos Africanos.

During the latter part of the 1960s, military tactical reforms instituted by Gen. Spínola began to improve Portuguese counterinsurgency operations in Guinea. Naval amphibious operations were instituted to overcome some of the mobility problems inherent in the underdeveloped and marshy areas of the territory, using Destacamentos de Fuzileiros Especiais (DFE) (special marine assault detachments) as strike forces. The Fuzileiros Especiais were lightly equipped with folding-stock m/961 (G3) rifles, 37mm rocket launchers, and light machine guns such as the Heckler & Koch HK21 to enhance their mobility in the difficult, swampy terrain.

Portugal commenced Operação Mar Verde or Operation Green Sea on 22 November 1970 in an attempt to overthrow Ahmed Sékou Touré, the leader of the Guinea-Conakry and staunch PAIGC ally, to capture the leader of the PAIGC, Amílcar Cabral, and to cut off supply lines to PAIGC insurgents. The operation involved a daring raid on Conakry, a PAIGC safe haven, in which 400 Portuguese Fuzileiros (amphibious assault troops) attacked the city. The attempted coup d'état failed, though the Portuguese managed to destroy several PAIGC ships and free hundreds of Portuguese prisoners of war (POWs) at several large POW camps. One immediate result of Operation Green Sea was an escalation in the conflict, with countries such as Algeria and Nigeria now offering support to the PAIGC as well as the Soviet Union, which sent warships to the region (known by NATO as the West Africa Patrol) in a show of force calculated to deter future Portuguese amphibious attacks on the territory of the Guinea-Conakry. The United Nations passed several resolutions condemning cross-border attacks of the Portuguese military against the PAIGC guerrilla bases in both neighbouring Guinea-Conakry and Senegal, like the United Nations Security Council Resolution 290, United Nations Security Council Resolution 294 and the United Nations Security Council Resolution 295.

Between 1968 and 1972, the Portuguese forces increased their offensive posture, in the form of raids into PAIGC-controlled territory. At this time Portuguese forces also adopted unorthodox means of countering the insurgents, including attacks on the political structure of the nationalist movement. This strategy culminated in the assassination of Amílcar Cabral in January 1973. Nonetheless, the PAIGC continued to increase its strength, and began to heavily press Portuguese defense forces. This became even more apparent after the PAIGC received heavy radar-guided anti-aircraft cannon and other AA munitions provided by the Soviets, including SA-7 shoulder-launched anti-aircraft missiles, all of which seriously impeded Portuguese air operations.[63][89]

After the Carnation Revolution military coup in Lisbon on 25 April 1974, the new revolutionary leaders of Portugal and the PAIGC signed an accord in Algiers, Algeria, in which Portugal agreed to remove all troops by the end of October and to officially recognize the Republic of Guinea-Bissau government controlled by the PAIGC, on 26 August 1974 and after a series of diplomatic meetings.[11] Demobilized by the departing Portuguese military authorities after the independence of Portuguese Guinea had been agreed, a total of 7,447 black Guinea-Bissauan African soldiers who had served in Portuguese native commando forces and militia were summarily executed by the PAIGC after the independence of the new African country.[11][13]

Mozambique

[edit]

The Portuguese Overseas Province of Mozambique was the last territory to start the war of liberation. Its nationalist movement was led by the Marxist-Leninist Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO), which carried out the first attack against Portuguese targets on 25 September 1964, in Chai, Cabo Delgado Province. The fighting later spread to Niassa, Tete in central Mozambique. A report from Battalion No. 558 of the Portuguese army makes references to violent actions, also in Cabo Delgado, on 21 August 1964.

On 16 November of the same year, the Portuguese troops suffered their first losses fighting in the north of the territory, in the region of Xilama. By this time, the size of the guerrilla movement had substantially increased; this, along with the low numbers of Portuguese troops and colonists, allowed a steady increase in FRELIMO's strength. It quickly started moving south in the direction of Meponda and Mandimba, linking to Tete with the aid of Malawi.

Until 1967, the FRELIMO showed less interest in Tete region, putting its efforts on the two northernmost districts of Mozambique where the use of landmines became very common. In the region of Niassa, FRELIMO's intention was to create a free corridor to Zambezia Province. Until April 1970, the military activity of FRELIMO increased steadily, mainly due to the strategic work of Samora Machel in the region of Cabo Delgado.

Rhodesia was involved in the war in Mozambique, supporting the Portuguese troops in operations and conducting operations independently. By 1973, the territory was mostly under Portuguese control.[90] The Operation "Nó Górdio" (Gordian Knot Operation)—conducted in 1970 and commanded by Portuguese Brigadier General Kaúlza de Arriaga—a conventional-style operation to destroy the guerrilla bases in the north of Mozambique, was the major military operation of the Portuguese Colonial War. A hotly disputed issue, the Gordian Knot Operation was considered by several historians and military strategists as a failure that worsened the situation for the Portuguese. Others did not share this view, including its main architect,[91] troops, and officials who had participated on both sides of the operation, including high ranked elements from the FRELIMO guerrillas. It was also described as a tremendous success of the Portuguese Armed Forces.[92] Arriaga, however, was removed from his powerful military post in Mozambique by Marcelo Caetano shortly before the events in Lisbon that triggered the end of the war and the independence of the Portuguese territories in Africa. The reason for Arriaga's abrupt fate was an alleged incident with indigenous civilian populations, and the Portuguese government's suspicion that Arriaga was planning a military coup against Marcelo's administration in order to avoid the rise of leftist influences in Portugal and the loss of the African overseas provinces.

The construction of the Cahora Bassa Dam tied up nearly 50 percent of the Portuguese troops in Mozambique, and brought the FRELIMO to the Tete Province, closer to some cities and more populated areas in the south. The FRELIMO failed, however, to halt the construction of the dam. In 1974, the FRELIMO launched mortar attacks against Vila Pery (now Chimoio), an important city and the first (and only) heavy populated area to be hit by the FRELIMO.

In Mozambique special units were also used by the Portuguese Armed Forces:

- Grupos Especiais (Special Groups): locally raised counter-insurgency troops similar to those used in Angola

- Grupos Especiais Pára-Quedistas (Paratrooper Special Groups): units of volunteer black soldiers that were given airborne training

- Grupos Especiais de Pisteiros de Combate (Combat Tracking Special Groups): special units trained in tracking and locating guerrillas forces

- Flechas (Arrows), a special forces unit of the Portuguese secret police, formation of indigenous scouts and trackers, similar to the one employed in Angola

Major counter-insurgency operations

[edit]- 1970 Mozambique – Gordian Knot Operation (Operação Nó Górdio)

- 1970 Guinea-Bissau – Operation Green Sea (Operação Mar Verde)

- 1971 Angola – Frente Leste (Portuguese for "Eastern Front")

Role of the Organisation of African Unity

[edit]The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was founded May 1963. Its basic principles were co-operation between African nations and solidarity between African peoples. Another important objective of the OAU was an end to all forms of colonialism in Africa. This became the major objective of the organization in its first years and soon OAU pressure led to the situation in the Portuguese colonies being brought up at the UN Security Council.

The OAU established a committee based in Dar es Salaam, with representatives from Ethiopia, Algeria, Uganda, Egypt, Tanzania, Zaire, Guinea, Senegal, Nigeria, to support African liberation movements. The support provided by the committee included military training and weapon supplies.

The OAU also took action in order to promote the international acknowledgment of the legitimacy of the Revolutionary Government of Angola in Exile (GRAE), composed by the FNLA. This support was transferred to the MPLA and to its leader, Agostinho Neto in 1967. In November 1972, both movements were recognized by the OAU in order to promote their merger. After 1964, the OAU recognized PAIGC as the legitimate representatives of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde and in 1965 recognised FRELIMO for Mozambique.

Armament and tactics

[edit]Portugal

[edit]

In 1961, the Portuguese had 79,000 in arms: 58,000 in the Army, 8,500 in the Navy and 12,500 in the Air Force (Cann, 1997). These grew quickly, and by the end of the conflict in 1974, due to the Carnation Revolution (a military coup in Lisbon), the total in the Portuguese Armed Forces had risen to 217,000.

Prior to their own Colonial War the Portuguese military had studied conflicts such as the First Indochina War, the Algerian War and the Malayan Emergency. Based on their analysis of operations in those theatres and considering their own situation in Africa, the Portuguese military took the unusual decision to restructure their entire armed forces, from top to bottom, for counterinsurgency. This transformation did, however, take seven years to complete and only took its final form in 1968. By 1974, the counterinsurgency efforts were successful in the Portuguese territories of Angola and Mozambique, but in Portuguese Guinea the local guerrillas were making progress. As the conflict escalated, the Portuguese authorities developed progressively tougher responses, these included the Gordian Knot Operation and the Operation Green Sea.[citation needed]

When conflict erupted in 1961, Portuguese forces were badly equipped to cope with the demands of a counter-insurgency conflict. It was standard procedure, up to that point, to send the oldest and most obsolete material to the colonies. Thus, initial military operations were conducted using World War II radios, the old m/937 7.92mm Mauser rifle, the Portuguese m/948 9mm FBP submachine gun, and the equally elderly German m/938 7.92mm (MG 13) Dreyse and Italian 8×59mm RB m/938 (Breda M37) machine guns.[93] Much of Portugal's older small arms came from Germany in various deliveries made mostly before World War II, including the Austrian Steyr/Erma MP 34 submachine gun (m/942). Later, Portugal purchased arms and military equipment from France, West Germany, South Africa, and to a lesser extent, from Belgium, Israel and the US.

Some 9×19mm submachine guns, including the m/942, the Portuguese m/948, and the West-German manufactured version of the Israeli Uzi (known in Portuguese service as the Pistola-Metralhadora m/61) were also used, mainly by officers, NCOs, horse-mounted cavalry, reserve and paramilitary units, and security forces.[93]Within a short time, the Portuguese Army saw the need for a modern selective-fire combat rifle, and in 1961 adopted the 7.62×51mm NATO caliber Espingarda m/961 (Heckler & Koch G3) as the standard infantry weapon for most of its forces, that was produced in large quantities in the Fábrica do Braço de Prata, a Portuguese small arms producer.[94] However, quantities of the 7.62×51mm FN and Belgian G1 FAL battle rifle, known as the m/962, were also issued; the FAL was a favored weapon of members serving in elite commando units such as the Caçadores Especiais.[94] At the beginning of the war, the elite airborne units (Caçadores Pára-quedistas) rarely used the m/961, having adopted the modern 7.62 mm NATO ArmaLite AR-10 (produced by the Netherlands-based arms manufacturer Artillerie Inrichtingen) in 1960.[95][96] In the days before attached grenade launchers became standard, Portuguese paratroopers frequently resorted to the use of ENERGA anti-tank rifle grenades fired from their AR-10 rifles. Some Portuguese-model AR-10s were fitted with A.I.-modified upper receivers in order to mount 3× or 3.6× telescopic sights.[97] These rifles were used by marksmen accompanying small patrols to eliminate individual enemy at extended ranges in open country.[98] After the Netherlands embargoed further sales of the AR-10, the paratroop battalions were issued a collapsible-stock version of the regular m/961 (G3) rifle, also in 7.62×51mm NATO caliber.[99]

The powerful recoil and heavy weight of the 7.62mm NATO cartridge used in Portuguese rifle-caliber arms such as the m/961 limited the amount of ammunition that could be carried as well as accuracy in automatic fire, generally precluding the use of the latter except in emergencies. Instead, most infantryman used their rifles to fire individual shots. While the heavy m/961 and its relatively lengthy barrel were well-suited to patrol operations in open savannah, it tended to put Portuguese infantry at a disadvantage when clearing the low-ceilinged interiors of native buildings or huts, or when moving through thick bush, where ambush by a concealed insurgent with an automatic weapon was always a possibility. In these situations the submachine gun, hand grenade or rifle-launched grenade often became a more useful weapon than the rifle. Spanish rifle grenades were sourced from Instalaza, but in due course, the Dilagrama m/65 was more commonly used, using a derivative of the M26 grenade made under licence by INDEP, the M312.[100]

For the general purpose machine gun role, the German MG42 in 8mm and later 7.62mm NATO caliber was used until 1968, when the 7.62mm m/968 Metralhadora Ligeira became available.

To destroy enemy emplacements, other weapons were employed, including the 37 mm (1.46 in), 60 mm (2.5 in), and 89 mm (3.5 in.) Lança-granadas-foguete (Bazooka), along with several types of recoilless rifles.[99][101] Because of the mobile nature of counterinsurgency operations, heavy support weapons were less frequently used. However, the m/951 12.7mm (.50 caliber) U.S. M2 Browning heavy machine gun was used in ground and vehicle mounts, as were 60mm, 81mm, and later, 120mm mortars.[101] Artillery and mobile howitzers were used in a few operations.

Mobile ground operations consisted of patrol sweeps by armored car and reconnaissance vehicles. Supply convoys used both armored and unarmored vehicles. Typically, armored vehicles were placed at the front, centre, and tail of a motorized convoy. Several armoured cars were used, including the Panhard AML, Panhard EBR, Fox and (in the 1970s) the Chaimite.

Unlike the Vietnam War, Portugal's limited national resources did not allow for widespread use of the helicopter. Only those troops involved in coups de main attacks (called golpe de mão in Portuguese)—mainly Commandos and Paratroopers—deployed by helicopter. Most deployments were either on foot or in vehicles (Berliet and Unimog trucks). The helicopters were reserved for support (in a gunship role) or medical evacuation (MEDEVAC). The Alouette III was the most widely used helicopter, although the Puma was also used with great success. Other aircraft were employed: for air support the T-6 Texan, the F-86 Sabre and the Fiat G.91 were used, along with a quantity of B-26 Invaders covertly acquired in 1965; for reconnaissance the Dornier Do 27 was employed. In the transport role, the Portuguese Air Force originally used the Junkers Ju 52, followed by the Nord Noratlas, the C-54 Skymaster, and the C-47 Skytrain (all of these aircraft were also used for Paratroop drop operations). From 1965, Portugal began to purchase the Fiat G.91 to deploy to its African overseas territories of Mozambique, Guinea and Angola in the close-support role.[102] The first 40 G.91 were purchased second-hand from the Luftwaffe, aircraft that had been produced for Greece and which differed from the rest of the Luftwaffe G.91s enough to create maintenance problems. The aircraft replaced the Portuguese F-86 Sabre.

The Portuguese Navy (particularly the Marines, known as Fuzileiros) made extensive use of patrol boats, landing craft, and Zodiac inflatable boats. They were employed especially in Guinea, but also in the Congo River (and other smaller rivers) in Angola and in the Zambezi (and other rivers) in Mozambique. Equipped with standard or collapsible-stock m/961 rifles, grenades, and other gear, they used small boats or patrol craft to infiltrate guerrilla positions. In an effort to intercept infiltrators, the Fuzileiros even manned small patrol craft on Lake Malawi. The Navy also used Portuguese civilian cruisers as troop transports, and drafted Portuguese Merchant Navy personnel to man ships carrying troops and material and into the Marines.

There were also many Portuguese irregular forces in the Overseas War such as the Flechas and others, as mentioned above.

Native black warriors were employed in Africa by the Portuguese colonial rulers since the 16th century. Portugal had employed regular native troops (companhias indigenas) in its colonial army since the early 19th century. After 1961, with the beginning of the colonial wars in its overseas territories, Portugal began to incorporate black Portuguese Africans into integrated units as part of the war effort in Angola, Portuguese Guinea, and Mozambique, based on concepts of multi-racialism and preservation of the empire. African participation on the Portuguese side of the conflict varied from marginal roles as laborers and informers to participation in highly trained operational combat units like the Flechas. As the war progressed, use of African counterinsurgency troops increased; on the eve of the military coup of 25 April 1974, black ethnic Africans accounted for more than 50 percent of Portuguese forces fighting the war.

From 1961 to the end of the Colonial War, the paratrooper nurses nicknamed Marias, were women who served the Portuguese armed forces being deployed in Portuguese Africa's dangerous guerrilla-infiltrated combat zones to perform rescue operations.[103][104]

Throughout the war period Portugal had to deal with increasing dissent, arms embargoes and other punitive sanctions imposed by most of the international community. Although, at least in the early stages of the conflict, Portugal was sold arms by France and West Germany with the knowledge that they were being used to suppress Portugal's colonial uprisings. Apart from these limited exceptions, Portugal was faced with UN-sponsored sanctions, Non-Aligned Movement-led defamation, and myriad boycotts and protests performed by both foreign and domestic political organizations, like the clandestine Portuguese Communist Party (PCP). Near the end of the conflict, a report by the British priest Adrian Hastings, alleging atrocities and war crimes on the part of the Portuguese military, was printed a week before the Portuguese prime minister Marcelo Caetano was due to visit Britain to celebrate the 600th anniversary of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance in 1973. Portugal's growing isolation following Hastings's claims has often been cited as a factor that helped to bring about the "carnation revolution" coup in Lisbon which deposed the Caetano regime in 1974, ending the Portuguese African counter-insurgency campaigns and triggering the rapid collapse of the Portuguese Empire.[105]

Guerrilla movements

[edit]

The armament of the nationalist groups came mainly from the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, Eastern Europe. However, they also used small arms of U.S. manufacture (such as the .45 M1 Thompson submachine gun), along with British, French, and German weapons came from neighboring countries sympathetic to the rebellion. Later in the war, most guerrillas would use roughly the same infantry rifles of Soviet origin: the Mosin–Nagant bolt-action rifle, the SKS carbine, and most importantly the AKM series of 7.62×39mm assault rifle, or Kalashnikov. Rebel forces also made extensive use of machine guns for ambush and positional defense.

Среди скорострельного оружия, имевшегося у повстанцев, были 7,62×54 ммР ДП-28 , пулемет РПД 7,62×39 мм (наиболее широко используемый из всех), калибра 8×57 мм Mauser MG 34 универсальный пулемет , а также 12,7×108-мм ДШК и 7,62×54-мм СГ-43 Горюнова крупнокалиберные пулеметы , 7,62×25-мм ППШ-41 и ППС-43 , 9×19-мм Са вз. 23 , Стерлинг , MP 40 , МАТ-49 работа пистолета-пулемета . Вспомогательное вооружение включало минометы, безоткатные орудия и, в частности, реактивные установки советского производства РПГ-2 и РПГ-7 . зенитное вооружение Также применялось , особенно ПАИГК и ФРЕЛИМО . Зенитная пушка калибра 14,5×114 мм ЗПУ была наиболее широко используемой, но, безусловно, самой эффективной была ракета «Стрела-2» , впервые представленная партизанским силам в Гвинее в 1973 году и в Мозамбике в следующем году советскими техническими специалистами.

Многие португальские солдаты высоко оценили партизанские винтовки АКМ и их варианты, поскольку они были более мобильными, чем m/961 (G3), и в то же время позволяли пользователю вести большой объем автоматического огня на близких дистанциях, обычно встречающихся в боях. Бушная война. [106] Боекомплект АКМ также был легче. [106] Среднестатистический ангольский или мозамбикский повстанец мог легко носить с собой 150 патронов 7,62×39 мм (пять магазинов по 30 патронов) во время операций в кустах, по сравнению со 100 патронами 7,62×51 мм (пять магазинов по 20 патронов), которые обычно несет португальский пехотинец во время патрулирования. . [106] Хотя распространено заблуждение, что португальские солдаты использовали трофейное оружие типа АКМ, это справедливо лишь в отношении нескольких элитных подразделений для выполнения специальных задач. Как и в случае с американскими войсками во Вьетнаме, трудности с пополнением запасов боеприпасов и очевидная опасность быть принятыми за партизан при стрельбе из вражеского оружия в целом исключали их использование.

Мины и другие мины-ловушки были одним из основных видов оружия, которое повстанцы с большим успехом использовали против португальских механизированных сил, которые обычно патрулировали в основном грунтовые дороги своих территорий, используя автомобили и бронированные разведывательные машины. [107] Чтобы противостоять минной угрозе, португальские инженеры приступили к титанической задаче по асфальтированию сети сельских дорог. [108] Обнаружение мин осуществлялось не только с помощью электронных миноискателей, но и за счет использования обученных солдат ( пикадоров ), идущих в ряд с длинными щупами для обнаружения неметаллических дорожных мин.

Партизаны во всех различных революционных движениях использовали различные мины, часто сочетая противотанковые и противопехотные мины, чтобы устраивать засады на португальские формирования с разрушительными результатами. Обычная тактика заключалась в установке больших противотранспортных мин на проезжей части, граничащей с очевидным укрытием, например, арыком, а затем засеиванием канавы противопехотными минами. Детонация автомобильной мины заставила бы португальские войска развернуться и искать укрытия в канаве, где противопехотные мины могли бы привести к новым жертвам.

Если повстанцы планировали открыто противостоять португальцам, они должны были разместить один или два крупнокалиберных пулемета для прочесывания рва и других вероятных укрытий. Среди других использованных мин были ПМН («Черная вдова») , ТМ-46 и ПОМЗ . Использовались даже десантные мины, такие как ДПМ , а также многочисленные самодельные противопехотные деревянные коробчатые мины и другие неметаллические взрывные устройства. Воздействие минных операций не только привело к человеческим жертвам, но и подорвало мобильность португальских сил, отвлекая войска и технику от операций по обеспечению безопасности и наступательных операций на задачи по защите конвоев и разминированию.

В целом ПАИГК в Гвинее была лучше всего вооружена, обучена и руководима из всех партизанских движений. К 1970 году у него даже были кандидаты, прошедшие обучение в Советском Союзе, которые учились управлять самолетами Микояна-Гуревича МиГ-15 и управлять поставленными Советским Союзом десантными кораблями и БТР .

Оппозиция в Португалии

[ редактировать ]

Правительство представило как общее мнение, что колонии являются частью национального единства, ближе к заморским провинциям, чем к настоящим колониям. Коммунисты были первой партией , выступившей против официальной точки зрения, поскольку они считали присутствие Португалии в колониях актом, противоречащим праву колоний на самоопределение . Во время своего V Конгресса в 1957 году нелегальная Коммунистическая партия Португалии ( Partido Comunista Português – PCP) была первой политической организацией, которая потребовала немедленной и полной независимости колоний.

Однако, будучи единственным по-настоящему организованным оппозиционным движением, ПКП должна была играть две роли. Одна роль заключалась в роли коммунистической партии с антиколониалистской позицией; другая роль заключалась в том, чтобы быть сплоченной силой, объединяющей широкий спектр противоборствующих партий. Поэтому ей пришлось присоединиться к взглядам, которые не отражали ее истинную антиколониальную позицию.

Некоторые деятели оппозиции за пределами ПКП также придерживались антиколониальных взглядов, например, кандидаты на фальсифицированных президентских выборах, такие как Нортон де Матуш (в 1949 году), Кинтао Мейрелеш (в 1951 году) и Умберто Дельгадо (в 1958 году). Кандидаты от коммунистов имели такие же позиции. Среди них были Руй Луис Гомес и Арлиндо Висенте; первому не разрешили участвовать в выборах, а второй поддержал Дельгадо в 1958 году.

После фальсификаций на выборах 1958 года Умберто Дельгадо сформировал Независимое национальное движение ( Movimento Nacional Independente – MNI), которое в октябре 1960 года согласилось с необходимостью подготовить людей в колониях, прежде чем дать им право на самоопределение. . Несмотря на это, не было разработано никакой подробной политики для достижения этой цели. [ нужна ссылка ]

В 1961 году номер 8 журнала Military Tribune носил название « Давайте покончим с войной в Анголе ». Авторы были связаны с Советами патриотических действий ( Juntas de Accão Patriótica – JAP), сторонниками Умберто Дельгадо и несут ответственность за нападение на казармы Бежа. Фронт национального освобождения Португалии ( Frente Portuguesa de Libertação Nacional – FPLN), основанный в декабре 1962 года, атаковал примирительные позиции. Официальное мнение португальского государства, несмотря на все это, было одним и тем же: Португалия имела неотъемлемые и законные права на колонии, и именно это транслировалось через средства массовой информации и через государственную пропаганду.

В апреле 1964 года Директория демократических социальных действий ( Acção Democrato-Social – ADS) представила политическое решение, а не военное. Согласившись с этой инициативой в 1966 году, Мариу Соарес предложил провести референдум по внешней политике, которой должна следовать Португалия, и что референдуму должна предшествовать общенациональная дискуссия, которая состоится за шесть месяцев до референдума. [ нужна ссылка ]

Конец правления Салазара в 1968 году из-за болезни не привел к каким-либо изменениям в политической панораме. [ нужна ссылка ] Радикализация оппозиционных движений началась с молодых людей, которые также чувствовали себя жертвами продолжения войны. [ нужна ссылка ]

Радикализация (начало 1970-х гг.)

[ редактировать ]

Ключевую роль в распространении этой позиции сыграли университеты. Было создано несколько журналов и газет, таких как Cadernos Circunstância , Cadernos Necessários , Tempo e Modo и Polémica , которые поддержали эту точку зрения. Студенты, участвовавшие в этой подпольной оппозиции, сталкивались с серьезными последствиями, если их поймала ПИДЕ — от немедленного ареста до автоматического призыва в боевой род войск (пехота, морская пехота и т. д.), расположенный в «горячей» зоне боевых действий (Гвинея, провинция Тете в Мозамбике или Восточная Ангола). Именно в этой среде возникли Вооруженное революционное действие ( Acção Revolucionária Armada – ARA), вооруженное отделение Коммунистической партии Португалии, созданное в конце 1960-х годов, и Революционные бригады ( Brigadas Revolucionárias – BR), левая организация. сила сопротивления войне, осуществляющая многочисленные диверсии и бомбардировки военных объектов.

АРА начала свои военные действия в октябре 1970 года и продолжала их до августа 1972 года. Основными действиями были нападение на авиабазу Танкос, в результате которого было уничтожено несколько вертолетов 8 марта 1971 года, и нападение на штаб-квартиру НАТО в Оэйрасе в октябре 1971 года. тот же год. БР, со своей стороны, начала вооруженные действия 7 ноября 1971 года с диверсии на базе НАТО в Пиньял-де-Армейру, последняя акция была проведена 9 апреля 1974 года против корабля «Ниасса» , который готовился покинуть Лиссабон с войсками для будет развернут в Португальской Гвинее . БР действовала даже в колониях, заложив бомбу в военном командовании Бисау 22 февраля 1974 года.

К началу 1970-х годов бушевала португальская колониальная война, которая съела целых 40 процентов годового бюджета Португалии. [56] Португальские вооруженные силы были перегружены, несмотря на мобилизацию 7% всего населения страны, и не было никакого политического решения или конца. Хотя человеческие потери были относительно небольшими, война в целом уже вступила во второе десятилетие. Правящий в Португалии режим Estado Novo столкнулся с критикой со стороны международного сообщества и становился все более изолированным. Это оказало глубокое влияние на Португалию: тысячи молодых людей избежали призыва в армию , эмигрировав нелегально, в основном во Францию и США.

Война на португальских заморских территориях Африки становилась все более непопулярной в самой Португалии, поскольку люди уставали от войны и отказывались от ее постоянно растущих расходов. Многие этнические португальцы из заморских территорий Африки также все больше были готовы принять независимость, если можно было сохранить их экономический статус. Кроме того, молодые выпускники португальских военных академий возмутились программой, введенной Марчелло Каэтано , согласно которой офицеры милиции, прошедшие краткую программу обучения и участвовавшие в оборонительных кампаниях на заморских территориях, могли быть присвоены тому же званию, что и выпускники военной академии.

Правительство Каэтано начало программу (которая включала несколько других реформ) с целью увеличить количество чиновников, задействованных в борьбе с африканскими повстанцами, и в то же время сократить военные расходы, чтобы облегчить и без того перегруженный государственный бюджет. Таким образом, группа революционных военных повстанцев начиналась как военный профессиональный класс. [109] протест португальских вооруженных сил капитанов против закона-декрета: декабрьский закон № 353/73 1973 года, который организовался в слабо связанную группу, известную как Движение дас Армадас (МФА). [110] [111]

Революция гвоздик (1974)

[ редактировать ]

Столкнувшись с негибкостью правительства в отношении предлагаемых реформ, некоторые португальские младшие военные офицеры, многие из которых принадлежали к малообеспеченным слоям населения и которых все больше привлекала марксистская философия своих африканских противников-повстанцев, [66] начал сдвигать МИД в политическое левое положение. [112] 25 апреля 1974 года португальские военные офицеры МИД устроили бескровный военный переворот, в результате которого был свергнут преемник Антониу де Оливейра Салазара Марсело Каэтано и успешно свергнут режим Estado Novo .

Позже восстание стало известно как Революция гвоздик. Генералу Спиноле было предложено занять пост президента, но он подал в отставку через несколько месяцев после того, как стало ясно, что его желание создать систему федерализованного самоуправления на африканских территориях не разделялось остальными членами МИД, которые хотели немедленное прекращение войны (достижимое только путем предоставления независимости провинциям португальской Африки). [112] Переворот 25 апреля привел к созданию ряда временных правительств, что ознаменовалось национализацией многих важных областей экономики.

Последствия

[ редактировать ]