Саудовская Аравия

Королевство Саудовская Аравия | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: لَا إِلٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰه، مُحَمَّدٌ رَسُوْلُ ٱللَّٰهНет бога, кроме Аллаха, Мухаммад – посланник Бога. Ля иляха илля-Ллах, Мухаммад – Посланник Аллаха. «Нет бога, кроме Аллаха , Мухаммад — посланник Бога» [1] [а] ( степень ) | |

| Гимн: ٱلنَّشِيْد ٱلْوَطَنِي ٱلسُّعُوْدِيГосударственный гимн Саудовской Аравии « ан-Нашид аль-Ватаний ас-Сауди » «Песнь саудовской нации» | |

| Капитал и крупнейший город | Эр-Рияд 24 ° 39' с.ш., 46 ° 46' в.д. / 24,650 ° с.ш., 46,767 ° в.д. |

| Официальные языки | арабский [5] |

| Этнические группы | 90% арабы 10% афро-арабов (только для граждан Саудовской Аравии) |

| Религия (2010) [8] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Правительство | Унитарная исламская абсолютная монархия |

• Король | Салман |

| Мохаммед бин Салман | |

| Законодательная власть | никто [с] |

| Учреждение | |

| 1727 | |

| 1824 | |

| 13 января 1902 г. | |

| 23 сентября 1932 г. | |

| 24 октября 1945 г. | |

| 31 января 1992 г. | |

| Область | |

• Общий | 2,149,690 [11] км 2 (830 000 квадратных миль) ( 12-е место ) |

• Вода (%) | 0.0 |

| Население | |

• Перепись 2022 года | |

• Плотность | 15/км 2 (38,8/кв. миль) ( 174-е место ) |

| ВВП ( ГЧП ) | оценка на 2024 год |

• Общий | |

• На душу населения | |

| ВВП (номинальный) | оценка на 2024 год |

• Общий | |

• На душу населения | |

| Джини (2013) | середина |

| ИЧР (2022) | очень высокий ( 40-й ) |

| Валюта | Саудовский риал (SR) [д] ( САР ) |

| Часовой пояс | UTC +3 ( АСТ ) |

| Формат даты | дд/мм/гггг ( АЧ ) |

| Ведущая сторона | верно |

| Код вызова | +966 |

| Код ISO 3166 | на |

| Интернет-ДВУ | |

Саудовская Аравия , [и] официально Королевство Саудовская Аравия ( КСА ), [ф] — страна в Западной Азии и на Ближнем Востоке . Он охватывает большую часть Аравийского полуострова и имеет площадь около 2 150 000 км². 2 (830 000 квадратных миль), что делает его пятой по величине страной в Азии и крупнейшей на Ближнем Востоке. он граничит с Красным морем На западе ; Иордания , Ирак и Кувейт на севере; Персидский залив , Бахрейн , [17] Катар и Объединенные Арабские Эмираты на востоке; Оман на юго-востоке; и Йемен на юге. Залив Акаба на северо-западе отделяет Саудовскую Аравию от Египта и Израиля . Саудовская Аравия — единственная страна, имеющая береговую линию вдоль Красного моря и Персидского залива, и большая часть ее территории состоит из засушливых пустынь , низменностей, степей и гор . Столица и крупнейший город — Эр-Рияд ; другие крупные города включают Джидду и два самых священных города ислама , Мекку и Медину . Саудовская Аравия с населением почти 32,2 миллиона человек является четвертой по численности населения страной в арабском мире .

Доисламская Аравия , территория, составляющая современную Саудовскую Аравию, имеет одни из самых ранних следов человеческой деятельности за пределами Африки. [18] Ислам , вторая по величине религия в мире, [19] возникла на территории нынешней Саудовской Аравии в начале седьмого века. Исламский пророк Мухаммед объединил население Аравийского полуострова и создал единое исламское религиозное государство. После его смерти в 632 году его последователи расширили мусульманское правление за пределы Аравии, завоевав территории в Северной Африке , Центральной , Южной Азии и Иберии в течение десятилетий. [20] [21] [22] Арабские династии, происходящие из современной Саудовской Аравии, основали халифаты Рашидун (632–661), Омейядов (661–750), Аббасидов (750–1517) и Фатимидов (909–1171), а также множество других династий в Азии. Африка и Европа .

Королевство Саудовская Аравия было основано в 1932 году королем Абдель Азизом (также известным как Ибн Сауд ), который объединил регионы Хиджаз , Неджд , части Восточной Аравии (Аль-Ахса) и Южной Аравии ( «Асир ) в единое государство посредством серия завоеваний , начавшаяся в 1902 году с захвата Эр-Рияда , прародины его семьи, Дома Саудов . С тех пор Саудовская Аравия является абсолютной монархией , управляемой авторитарным режимом без участия общественности. [23] В своем Основном законе Саудовская Аравия определяет себя как суверенное арабское исламское государство , , официальной религией которого является ислам а арабский язык официальным языком - . Ультраконсервативное ваххабитов религиозное движение в рамках суннитского ислама было преобладающей политической и культурной силой в стране до 2000-х годов. [24] [25] Правительство Саудовской Аравии подвергалось критике за различную политику, такую как вмешательство в гражданскую войну в Йемене , предполагаемое спонсорство терроризма и широко распространенные нарушения прав человека. [26] [27]

Саудовская Аравия считается одновременно региональной и средней державой. [28] [29] С тех пор как обнаружена нефть была в 1938 году в стране , [30] [31] Королевство стало третьим по величине производителем нефти в мире в мире и ведущим экспортером нефти, контролируя вторые по величине запасы нефти и шестые по величине запасы газа . [32] Саудовская Аравия отнесена Всемирным банком к странам с высокими доходами и является единственной арабской страной среди крупнейших экономик G20 . [33] [34] Экономика Саудовской Аравии является крупнейшей на Ближнем Востоке в мире , девятнадцатой по номинальному ВВП и семнадцатой по ППС . Занимая очень высокие позиции в Индексе человеческого развития , [35] Саудовская Аравия предлагает бесплатное университетское образование , отсутствие подоходного налога с населения, [36] и бесплатное всеобщее здравоохранение . Из-за своей зависимости от иностранной рабочей силы в мире Саудовская Аравия занимает третье место по численности иммигрантов . Жители Саудовской Аравии являются одними из самых молодых людей в мире : примерно половина из них моложе 25 лет. [37] [38] Саудовская Аравия является активным членом Совета сотрудничества стран Персидского залива , Организации Объединенных Наций , Организации исламского сотрудничества , Лиги арабских государств и ОПЕК , а также партнером по диалогу Шанхайской организации сотрудничества .

Этимология

После объединения Королевства Хиджаз и Неджд Абдулазиз бин Сауд издал королевский указ 23 сентября 1932 года, назвав новое государство аль-Мамлака аль-Арабия ас-Судийя ( арабское المملكة العربية السعودية Саудовской Аравии). [39] но буквально означает «Королевство Саудовской Аравии», [40] или «Арабское Саудовское Королевство». [41]

Слово «Саудовская» происходит от элемента ас-Судийя в арабском названии страны, которое представляет собой разновидность прилагательного, известного как нисба , образованного от династического имени саудовской королевской семьи Аль Сауд ( араб . آل) . Сытый ). Его включение выражает мнение, что страна является личным владением королевской семьи. [42] [43] Аль Сауд — арабское имя , образованное добавлением слова Аль , что означает «семья» или «Дом». [44] личному имени предка. В случае Аль Сауда это Сауд ибн Мухаммад ибн Мукрин , отец основателя династии в 18 веке Мухаммада бин Сауда . [45]

История

Предыстория

Есть свидетельства того, что человеческое жилье на Аравийском полуострове возникло примерно 125 000 лет назад. [46] Исследование 2011 года показало, что первые современные люди, распространившиеся на восток через Азию, покинули Африку около 75 000 лет назад через Баб-эль-Мандеб, соединяющий Африканский Рог и Аравию. [47] Аравийский полуостров считается центральным местом в понимании эволюции и расселения человека. Аравия претерпела сильные колебания окружающей среды В четвертичном периоде , которые привели к глубоким эволюционным и демографическим изменениям. Аравия имеет богатую летопись нижнего палеолита , и количество стоянок, подобных Олдуану, в этом регионе указывает на значительную роль, которую Аравия сыграла в ранней колонизации Евразии гомининами. [48]

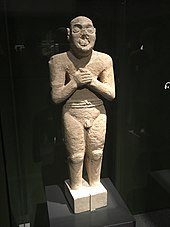

In the Neolithic period, prominent cultures such as Al-Magar, whose centre lay in modern-day southwestern Najd, flourished. Al-Magar could be considered a "Neolithic Revolution" in human knowledge and handicraft skills.[49] The culture is characterized as being one of the world's first to involve the widespread domestication of animals, particularly the horse, during the Neolithic period.[50][51] Al-Magar statues were made from local stone, and it seems that the statues were fixed in a central building that might have had a significant role in the social and religious life of the inhabitants.[52]

In November 2017, hunting scenes showing images of most likely domesticated dogs (resembling the Canaan Dog) and wearing leashes were discovered in Shuwaymis, a hilly region of northwestern Saudi Arabia. These rock engravings date back more than 8000 years, making them the earliest depictions of dogs in the world.[53]

At the end of the 4th millennium BC, Arabia entered the Bronze Age; metals were widely used, and the period was characterized by its 2 m high burials which were simultaneously followed by the existence of numerous temples that included many free-standing sculptures originally painted with red colours.[54]

In May 2021, archaeologists announced that a 350000-year-old Acheulean site named An Nasim in the Hail region could be the oldest human habitation site in northern Saudi Arabia. 354 artefacts, including hand axes and stone tools, provided information about tool-making traditions of the earliest living man inhabited south-west Asia. Paleolithic artefacts are similar to material remains uncovered at the Acheulean sites in the Nefud Desert.[55][56][57][58]

Pre-Islamic

The earliest sedentary culture in Saudi Arabia dates back to the Ubaid period at Dosariyah. Climatic change and the onset of aridity may have brought about the end of this phase of settlement, as little archaeological evidence exists from the succeeding millennium.[60] The settlement of the region picks up again in the period of Dilmun in the early 3rd millennium. Known records from Uruk refer to a place called Dilmun, associated on several occasions with copper, and in later periods it was a source of imported woods in southern Mesopotamia. Scholars have suggested that Dilmun originally designated the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, notably linked with the major Dilmunite settlements of Umm an-Nussi and Umm ar-Ramadh in the interior and Tarout on the coast. It is likely that Tarout Island was the main port and the capital of Dilmun.[59] Mesopotamian inscribed clay tablets suggest that, in the early period of Dilmun, a form of hierarchical organized political structure existed. In 1966, an earthwork in Tarout exposed an ancient burial field that yielded a large statue dating to the Dilmunite period (mid 3rd millennium BC). The statue was locally made under the strong Mesopotamian influence on the artistic principle of Dilmun.[59]

By 2200 BC, the centre of Dilmun shifted for unknown reasons from Tarout and the Saudi Arabian mainland to the island of Bahrain, and a highly developed settlement emerged there, where a laborious temple complex and thousands of burial mounds dating to this period were discovered.[59]

By the late Bronze Age, a historically recorded people and land (Midian and the Midianites) in the north-western portion of Saudi Arabia are well-documented in the Bible. Centred in Tabouk, it stretched from Wadi Arabah in the north to the area of al-Wejh in the south.[61] The capital of Midian was Qurayyah,[62] it consists of a large, fortified citadel encompassing 35 hectares and below it lies a walled settlement of 15 hectares. The city hosted as many as 12,000 inhabitants.[63] The Bible recounts Israel's two wars with Midian, somewhere in the early 11th century BC. Politically, the Midianites were described as having a decentralized structure headed by five kings (Evi, Rekem, Tsur, Hur, and Reba); the names appears to be toponyms of important Midianite settlements.[64] It is common to view that Midian designated a confederation of tribes, the sedentary element settled in the Hijaz while its nomadic affiliates pastured and sometimes pillaged as far away as Palestine.[65] The nomadic Midianites were one of the earliest exploiters of the domestication of camels that enabled them to navigate through the harsh terrains of the region.[65]

At the end of the 7th century BC, an emerging kingdom appeared in north-western Arabia. It started as a sheikdom of Dedan, which developed into the kingdom of Lihyan.[67][68] During this period, Dedan transformed into a kingdom that encompassed a much wider domain.[67] In the early 3rd century BC, with bustling economic activity between the south and north, Lihyan acquired large influence suitable to its strategic position on the caravan road.[69] The Lihyanites ruled over a large domain from Yathrib in the south and parts of the Levant in the north.[70] In antiquity, Gulf of Aqaba used to be called Gulf of Lihyan, a testimony to the extensive influence that Lihyan acquired.[71]

The Lihyanites fell into the hands of the Nabataeans around 65 BC upon their seizure of Hegra then marching to Tayma, and to their capital Dedan in 9 BC. The Nabataeans ruled large portions of north Arabia until their domain was annexed by the Roman Empire, which renamed it Arabia Petraea, and remained under the rule of the Romans until 630.[72]

Middle Ages and rise of Islam

Shortly before the advent of Islam, apart from urban trading settlements (such as Mecca and Medina), much of what was to become Saudi Arabia was populated by nomadic pastoral tribal societies.[75] The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born in Mecca in about 570 CE. In the early 7th century, Muhammad united the various tribes of the peninsula and created a single Islamic religious polity.[76] Following his death in 632, his followers expanded the territory under Muslim rule beyond Arabia, conquering territory in the Iberian Peninsula in the west to parts of Central and South Asia in the east[citation needed] in a matter of decades.[20][21][22] Arabia became a more politically peripheral region of the Muslim world as the focus shifted to the newly conquered lands.[76]

Arabs originating from modern-day Saudi Arabia, the Hejaz in particular, founded the Rashidun (632–661), Umayyad (661–750), Abbasid (750–1517), and the Fatimid (909–1171) caliphates. From the 10th century to the early 20th century, Mecca and Medina were under the control of a local Arab ruler known as the Sharif of Mecca, but at most times the sharif owed allegiance to the ruler of one of the major Islamic empires based in Baghdad, Cairo or Istanbul. Most of the remainder of what became Saudi Arabia reverted to traditional tribal rule.[77][78]

For much of the 10th century, the Isma'ili-Shi'ite Qarmatians were the most powerful force in the Persian Gulf. In 930, the Qarmatians pillaged Mecca, outraging the Muslim world, particularly with their theft of the Black Stone.[79] In 1077–1078, an Arab sheikh named Abdullah bin Ali Al Uyuni defeated the Qarmatians in Bahrain and al-Hasa with the help of the Seljuq Empire and founded the Uyunid dynasty.[80][81] The Uyunid Emirate later underwent expansion with its territory stretching from Najd to the Syrian Desert.[82] They were overthrown by the Usfurids in 1253.[83] Usfurid rule was weakened after Persian rulers of Hormuz captured Bahrain and Qatif in 1320.[84] The vassals of Ormuz, the Shia Jarwanid dynasty came to rule eastern Arabia in the 14th century.[85][86] The Jabrids took control of the region after overthrowing the Jarwanids in the 15th century and clashed with Hormuz for more than two decades over the region for its economic revenues, until finally agreeing to pay tribute in 1507.[85] Al-Muntafiq tribe later took over the region and came under Ottoman suzerainty. The Bani Khalid tribe later revolted against them in the 17th century and took control.[87] Their rule extended from Iraq to Oman at its height, and they too came under Ottoman suzerainty.[88][89]

Ottoman Hejaz

In the 16th century, the Ottomans added the Red Sea and Persian Gulf coast (the Hejaz, Asir and Al-Ahsa) to the empire and claimed suzerainty over the interior. One reason was to thwart Portuguese attempts to attack the Red Sea (hence the Hejaz) and the Indian Ocean.[90] The Ottoman degree of control over these lands varied over the next four centuries with the fluctuating strength or weakness of the empire's central authority.[91][92] These changes contributed to later uncertainties, such as the dispute with Transjordan over the inclusion of the sanjak of Ma'an, including the cities of Ma'an and Aqaba.[citation needed]

Saud dynasty and unification

The emergence of what was to become the Saudi royal family, known as the Al Saud, began at the town of Diriyah in Nejd in central Arabia with the accession as emir of Muhammad bin Saud on 22 February 1727.[93][94] In 1744 he joined forces with the religious leader Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab,[95] founder of the Wahhabi movement, a strict puritanical form of Sunni Islam.[96] This alliance provided the ideological impetus to Saudi expansion and remains the basis of Saudi Arabian dynastic rule today.[97]

The Emirate of Diriyah established in the area around Riyadh rapidly expanded and briefly controlled most of the present-day territory of Saudi Arabia, sacking Karbala in 1802, and capturing Mecca in 1803. In 1818, it was destroyed by the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt, Mohammed Ali Pasha.[98] The much smaller Emirate of Nejd was established in 1824. Throughout the rest of the 19th century, the Al Saud contested control of the interior of what was to become Saudi Arabia with another Arabian ruling family, the Al Rashid, who ruled the Emirate of Jabal Shammar. By 1891, the Al Rashid were victorious and the Al Saud were driven into exile in Kuwait.[77]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire continued to control or have a suzerainty over most of the peninsula. Subject to this suzerainty, Arabia was ruled by a patchwork of tribal rulers,[99][100] with the Sharif of Mecca having pre-eminence and ruling the Hejaz.[101] In 1902, Abdul Rahman's son, Abdul Aziz—later known as Ibn Saud—recaptured control of Riyadh bringing the Al Saud back to Nejd, creating the third "Saudi state".[77] Ibn Saud gained the support of the Ikhwan, a tribal army inspired by Wahhabism and led by Faisal Al-Dawish, and which had grown quickly after its foundation in 1912.[102] With the aid of the Ikhwan, Ibn Saud captured Al-Ahsa from the Ottomans in 1913.

In 1916, with the encouragement and support of Britain (which was fighting the Ottomans in World War I), the Sharif of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali, led a pan-Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire to create a united Arab state.[103] Although the revolt failed in its objective, the Allied victory in World War I resulted in the end of Ottoman suzerainty and control in Arabia, and Hussein bin Ali became King of Hejaz.[104]

Ibn Saud avoided involvement in the Arab Revolt and instead continued his struggle with the Al Rashid. Following the latter's final defeat, he took the title Sultan of Nejd in 1921. With the help of the Ikhwan, the Kingdom of Hejaz was conquered in 1924–25, and on 10 January 1926, Ibn Saud declared himself king of Hejaz.[105] For the next five years, he administered the two parts of his dual kingdom as separate units.[77]

After the conquest of the Hejaz, the Ikhwan leadership's objective switched to expansion of the Wahhabist realm into the British protectorates of Transjordan, Iraq and Kuwait, and began raiding those territories. This met with Ibn Saud's opposition, as he recognized the danger of a direct conflict with the British. At the same time, the Ikhwan became disenchanted with Ibn Saud's domestic policies which appeared to favour modernization and the increase in the number of non-Muslim foreigners in the country. As a result, they turned against Ibn Saud and, after a two-year struggle, were defeated in 1929 at the Battle of Sabilla, where their leaders were massacred.[106] On Ibn Saud's behalf, Prince Faisal declared the unification on 23 September 1932, and the two kingdoms of Hejaz and Nejd were unified as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.[77] That date is now a national holiday called Saudi National Day.[107]

20th century

The new kingdom was reliant on limited agriculture and pilgrimage revenues.[108] In 1938, vast reserves of oil were discovered in the Al-Ahsa region along the coast of the Persian Gulf, and full-scale development of the oil fields began in 1941 under the US-controlled Aramco (Arabian American Oil Company). Oil provided Saudi Arabia with economic prosperity and substantial political leverage internationally.[77]

Cultural life rapidly developed, primarily in the Hejaz, which was the centre for newspapers and radio. However, the large influx of foreign workers in Saudi Arabia in the oil industry increased the pre-existing propensity for xenophobia. At the same time, the government became increasingly wasteful and extravagant. By the 1950s this had led to large governmental deficits and excessive foreign borrowing.[77]

In 1953, Saud of Saudi Arabia succeeded as the king of Saudi Arabia. In 1964 he was deposed in favour of his half brother Faisal of Saudi Arabia, after an intense rivalry, fuelled by doubts in the royal family over Saud's competence. In 1972, Saudi Arabia gained a 20% control in Aramco, thereby decreasing US control over Saudi oil.[109] In 1973, Saudi Arabia led an oil boycott against the Western countries that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War against Egypt and Syria, leading to the quadrupling of oil prices.[77] In 1975, Faisal was assassinated by his nephew, Prince Faisal bin Musaid and was succeeded by his half-brother King Khalid.[110]

By 1976, Saudi Arabia had become the largest oil producer in the world.[111] Khalid's reign saw economic and social development progress at an extremely rapid rate, transforming the infrastructure and educational system of the country;[77] in foreign policy, close ties with the US were developed.[110] In 1979, two events occurred which greatly concerned the government[112] and had a long-term influence on Saudi foreign and domestic policy. The first was the Iranian Islamic Revolution. It was feared that the country's Shi'ite minority in the Eastern Province (which is also the location of the oil fields) might rebel under the influence of their Iranian co-religionists. There were several anti-government uprisings in the region such as the 1979 Qatif Uprising.[113] The second event was the Grand Mosque Seizure in Mecca by Islamist extremists. The militants involved were in part angered by what they considered to be the corruption and un-Islamic nature of the Saudi government.[113] The government regained control of the mosque after 10 days, and those captured were executed. Part of the response of the royal family was to enforce the much stricter observance of traditional religious and social norms in the country (for example, the closure of cinemas) and to give the ulema a greater role in government.[114] Neither entirely succeeded as Islamism continued to grow in strength.[115]

In 1980, Saudi Arabia bought out the American interests in Aramco.[116] King Khalid died of a heart attack in June 1982. He was succeeded by his brother, King Fahd, who added the title "Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques" to his name in 1986 in response to considerable fundamentalist pressure to avoid the use of "majesty" in association with anything except God. Fahd continued to develop close relations with the United States and increased the purchase of American and British military equipment.[77]

The vast wealth generated by oil revenues was beginning to have an even greater impact on Saudi society. It led to rapid technological (but not cultural) modernization, urbanization, mass public education, and the creation of new media. This and the presence of increasingly large numbers of foreign workers greatly affected traditional Saudi norms and values. Although there was a dramatic change in the social and economic life of the country, political power continued to be monopolized by the royal family[77] leading to discontent among many Saudis who began to look for wider participation in government.[117]

In the 1980s, Saudi Arabia spent $25 billion in support of Saddam Hussein in the Iran–Iraq War;[118] however, Saudi Arabia condemned the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and asked the US to intervene.[77] King Fahd allowed American and coalition troops to be stationed in Saudi Arabia. He invited the Kuwaiti government and many of its citizens to stay in Saudi Arabia, but expelled citizens of Yemen and Jordan because of their governments' support of Iraq. In 1991, Saudi Arabian forces were involved both in bombing raids on Iraq and in the land invasion that helped to liberate Kuwait.[109]

Saudi Arabia's relations with the West was one of the issues that led to an increase in Islamist terrorism in Saudi Arabia, as well as Islamist terrorist attacks in Western countries by Saudi nationals. Osama bin Laden was a Saudi citizen (until stripped of his citizenship in 1994) and was responsible for the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in East Africa and the 2000 USS Cole bombing near the port of Aden, Yemen. 15 of the hijackers involved in the September 11 attacks were Saudi nationals.[119] Many Saudis who did not support the Islamist terrorists were nevertheless deeply unhappy with the government's policies.[120]

Islamism was not the only source of hostility to the government. Although extremely wealthy by the 21st century, Saudi Arabia's economy was near stagnant. High taxes and a growth in unemployment have contributed to discontent and have been reflected in a rise in civil unrest, and discontent with the royal family. In response, a number of limited reforms were initiated by King Fahd. In March 1992, he introduced the "Basic Law", which emphasized the duties and responsibilities of a ruler. In December 1993, the Consultative Council was inaugurated. It is composed of a chairman and 60 members—all chosen by the King. Fahd made it clear that he did not have democracy in mind, saying: "A system based on elections is not consistent with our Islamic creed, which [approves of] government by consultation [shūrā]."[77]

In 1995, Fahd suffered a debilitating stroke, and the Crown Prince, Abdullah, assumed the role of de facto regent; however, his authority was hindered by conflict with Fahd's full brothers (known, with Fahd, as the "Sudairi Seven").[121]

21st century

Signs of discontent included, in 2003 and 2004, a series of bombings and armed violence in Riyadh, Jeddah, Yanbu and Khobar.[122] In February–April 2005, the first-ever nationwide municipal elections were held in Saudi Arabia. Women were not allowed to take part.[77]

In 2005, King Fahd died and was succeeded by Abdullah, who continued the policy of minimum reform and clamping down on protests. The king introduced economic reforms aimed at reducing the country's reliance on oil revenue: limited deregulation, encouragement of foreign investment, and privatization. In February 2009, Abdullah announced a series of governmental changes to the judiciary, armed forces, and various ministries to modernize these institutions including the replacement of senior appointees in the judiciary and the Mutaween (religious police) with more moderate individuals and the appointment of the country's first female deputy minister.[77]

On 29 January 2011, hundreds of protesters gathered in Jeddah in a rare display of criticism against the city's poor infrastructure after flooding killed 11 people.[123] Police stopped the demonstration after about 15 minutes and arrested 30 to 50 people.[124]

Since 2011, Saudi Arabia has been affected by its own Arab Spring protests.[125] In response, King Abdullah announced on 22 February 2011 a series of benefits for citizens amounting to $36 billion, of which $10.7 billion was earmarked for housing.[126][127][128] No political reforms were included, though some prisoners indicted for financial crimes were pardoned.[129] Abdullah also announced a package of $93 billion, which included 500000 new homes to a cost of $67 billion, in addition to creating 60000 new security jobs.[130][131] Although male-only municipal elections were held on 29 September 2011,[132][133] Abdullah allowed women to vote and be elected in the 2015 municipal elections, and also to be nominated to the Shura Council.[134]

Geography

Saudi Arabia occupies about 80% of the Arabian Peninsula (the world's largest peninsula),[137] lying between latitudes 16° and 33° N, and longitudes 34° and 56° E. Because the country's southeastern and southern borders with the United Arab Emirates and Oman are not precisely marked, the exact size of the country is undefined.[137] The United Nations Statistics Division estimates 2149690 km2 (830000 sq mi) and lists Saudi Arabia as the world's 12th largest state. It is geographically the largest country in the Middle East and on the Arabian Plate.[138]

Saudi Arabia's geography is dominated by the Arabian Desert, associated semi-desert, shrubland, steppes, several mountain ranges, volcanic lava fields and highlands. The 647500 km2 (250001 sq mi) Rub' al Khali ("Empty Quarter") in the southeastern part of the country is the world's largest contiguous sand desert.[139][140] Though there are lakes in the country, Saudi Arabia is the largest country in the world by area with no permanent rivers. Wadis, non-permanent rivers, however, are very numerous throughout the kingdom. The fertile areas are to be found in the alluvial deposits in wadis, basins, and oases.[139] There are approximately 1,300 islands in the Red Sea and Arabian Gulf.[141]

The main topographical feature is the central plateau which rises abruptly from the Red Sea and gradually descends into the Nejd and toward the Arabian Gulf. On the Red Sea coast, there is a narrow coastal plain, known as the Tihamah, parallel to which runs along an imposing escarpment. The southwest province of Asir is mountainous and contains the 3002 m (9849 ft) Jabal Ferwa, which is the highest point in the country.[139] Saudi Arabia is home to more than 2,000 dormant volcanoes.[135] Lava fields in Hejaz, known locally by their Arabic name of harrat (the singular is harrah), form one of Earth's largest alkali basalt regions, covering some 180,000 square kilometres (69,000 sq mi).[136]

Except for the southwestern regions such as Asir, Saudi Arabia has a desert climate with very high day-time temperatures during the summer and a sharp temperature drop at night. Average summer temperatures are around 45 °C (113 °F) but can be as high as 54 °C (129 °F). In the winter the temperature rarely drops below 0 °C (32 °F) with the exception of mostly the northern regions of the country where annual snowfall, in particular in the mountainous regions of Tabuk Province, is not uncommon.[142] The lowest recorded temperature, −12.0 °C (10.4 °F), was measured in Turaif.[143]

In the spring and autumn the heat is temperate, temperatures average around 29 °C (84 °F). Annual rainfall is very low. The southern regions differ in that they are influenced by the Indian Ocean monsoons, usually occurring between October and March. An average of 300 mm (12 in) of rainfall occurs during this period, which is about 60% of the annual precipitation.[144]

Biodiversity

Saudi Arabia is home to five terrestrial ecoregions: Arabian Peninsula coastal fog desert, Southwestern Arabian foothills savanna, Southwestern Arabian montane woodlands, Arabian Desert, and Red Sea Nubo-Sindian tropical desert and semi-desert.[145] Wildlife includes the Arabian leopard,[146][147] Arabian wolf, striped hyena, mongoose, baboon, Cape hare, sand cat, and jerboa. Animals such as gazelles, oryx, leopards and cheetahs[148] were relatively numerous until the 19th century, when extensive hunting reduced these animals almost to extinction. The culturally important Asiatic lion occurred in Saudi Arabia until the late 19th century before it was hunted to extinction in the wild.[149] Birds include falcons (which are caught and trained for hunting), eagles, hawks, vultures, sandgrouse, and bulbuls. There are several species of snakes, many of which are venomous. Domesticated animals include the legendary Arabian horse, Arabian camel, sheep, goats, cows, donkeys, chickens, etc.

The Red Sea is a rich and diverse ecosystem with more than 1,200 species of fish[150] around 10% of which are endemic.[151] This also includes 42 species of deep water fish.[150] The rich diversity is partly owed to the 2000 km (1240 mi) of coral reef extending along the coastline; these fringing reefs are largely formed of stony acropora and porites corals. The reefs form platforms and sometimes lagoons along the coast and occasional other features such as cylinders (such as the Blue Hole at Dahab). These coastal reefs are also visited by pelagic species, including some of the 44 species of shark. There are many offshore reefs including several atolls. Many of the unusual offshore reef formations defy classic (i.e., Darwinian) coral reef classification schemes and are generally attributed to the high levels of tectonic activity that characterize the area.

Reflecting the country's dominant desert conditions, plant life mostly consists of herbs, plants, and shrubs that require little water. The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) is widespread.[139]

Government and politics

Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy;[152] however, according to the Basic Law of Saudi Arabia adopted by royal decree in 1992, the king must comply with Sharia (Islamic law) and the Quran, while the Quran and the Sunnah (the traditions of Muhammad) are declared to be the country's constitution.[153] No political parties or national elections are permitted.[152] While some critics consider it to be a totalitarian state,[154][155] others regard it as lacking aspects of totalitarianism but nevertheless classify it as an authoritarian regime.[156][157][158] The Economist ranked the Saudi government 150th out of 167 in its 2022 Democracy Index,[159] and Freedom House gave it its lowest "Not Free" rating, giving it a score of 8 out of 100 for 2023.[160] According to the 2023 V-Dem Democracy Indices, Saudi Arabia is the least democratic country in the Middle East.[161]

In the absence of national elections and political parties,[152] politics in Saudi Arabia takes place in two distinct arenas: within the royal family, the Al Saud, and between the royal family and the rest of Saudi society.[162] Outside of the Al Saud, participation in the political process is limited to a relatively small segment of the population and takes the form of the royal family consulting with the ulema, tribal sheikhs, and members of important commercial families on major decisions.[139] This process is not reported by the Saudi media.[163]

By custom, all males of full age have a right to petition the king directly through the traditional tribal meeting known as the majlis.[164] In many ways the approach to government differs little from the traditional system of tribal rule. Tribal identity remains strong, and outside of the royal family, political influence is frequently determined by tribal affiliation, with tribal sheikhs maintaining a considerable degree of influence over local and national events.[139] In recent years there have been limited steps to widen political participation such as the establishment of the Consultative Council in the early 1990s and the National Dialogue Forum in 2003.[165] In 2005, the first municipal elections were held. In 2007, the Allegiance Council was created to regulate the succession.[165] In 2009, the king made significant personnel changes to the government by appointing reformers to key positions and the first woman to a ministerial post;[166][167] however, these changes have been criticized as being too slow or merely cosmetic.[168]

The rule of the Al Saud faces political opposition from four sources: Sunni Islamist activism; liberal critics; the Shi'ite minority—particularly in the Eastern Province; and long-standing tribal and regionalist particularistic opponents (for example in the Hejaz).[169] Of these, the minority activists have been the most prominent threat to the government and have in recent years been involved in violent incidents in the country.[122] However, open protest against the government, even if peaceful, is not tolerated.[170]

Monarchy and royal family

The king combines legislative, executive, and judicial functions[139] and royal decrees form the basis of the country's legislation.[171] Until 2022, the king was also the prime minister, and presided over the Council of Ministers of Saudi Arabia and Consultative Assembly of Saudi Arabia. The royal family dominates the political system. The family's vast numbers allows it to control most of the kingdom's important posts and to have an involvement and presence at all levels of government.[172] The number of princes is estimated to be at least 7000, with most power and influence being wielded by the 200 or so male descendants of Ibn Saud.[173] The key ministries are generally reserved for the royal family,[152] as are the 13 regional governorships.[174]

The Saudi government[175][176][177] and the royal family[178][179][180] have often been accused of corruption over many years,[181] and this continues into the 21st century.[182] In a country that is said to "belong" to the royal family and is named for them,[43] the lines between state assets and the personal wealth of senior princes are blurred.[173] The extent of corruption has been described as systemic[183] and endemic,[184] and its existence was acknowledged[185] and defended[186] by Prince Bandar bin Sultan (a senior member of the royal family)[187] in an interview in 2001.[188]

In its Corruption Perceptions Index for 2010, Transparency International gave Saudi Arabia a score of 4.7 (on a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 is "highly corrupt" and 10 is "highly clean").[189] Saudi Arabia has undergone a process of political and social reform, such as to increase public transparency and good governance, but nepotism and patronage are widespread when doing business in the country; the enforcement of the anti-corruption laws is selective and public officials engage in corruption with impunity. As many as 500 people, including prominent Saudi Arabian princes, government ministers, and businesspeople, were arrested in an anti-corruption campaign in November 2017.[190]

Al ash-Sheikh and role of the ulema

Saudi Arabia is unique in giving the ulema (the body of Islamic religious leaders and jurists) a direct role in government.[191] The preferred ulema are of the Salafi movement. The ulema have been a key influence in major government decisions, for example the imposition of the oil embargo in 1973 and the invitation to foreign troops to Saudi Arabia in 1990.[192] In addition, they have had a major role in the judicial and education systems[193] and a monopoly of authority in religious and social morals.[194]

By the 1970s, as a result of oil wealth and the modernization initiated by King Faisal, important changes to Saudi society were underway, and the power of the ulema was in decline.[195] However, this changed following the seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979 by Islamist radicals.[196] The government's response to the crisis included strengthening the ulema's powers and increasing their financial support:[114] in particular, they were given greater control over the education system[196] and allowed to enforce the stricter observance of Wahhabi rules of moral and social behaviour.[114] After his accession to the throne in 2005, King Abdullah took steps to reduce the powers of the ulema, for instance transferring control over girls' education to the Ministry of Education.[197]

The ulema have historically been led by the Al ash-Sheikh,[198] the country's leading religious family.[194] The Al ash-Sheikh are the descendants of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, the 18th-century founder of the Wahhabi form of Sunni Islam which is today dominant in Saudi Arabia.[199] The family is second in prestige only to the Al Saud (the royal family)[200] with whom they formed a "mutual support pact"[201] and power-sharing arrangement nearly 300 years ago.[192] The pact, which persists to this day,[201] is based on the Al Saud maintaining the Al ash-Sheikh's authority in religious matters and upholding and propagating Wahhabi doctrine. In return, the Al ash-Sheikh support the Al Saud's political authority[202] thereby using its religious-moral authority to legitimize the royal family's rule.[203] Although the Al ash-Sheikh's domination of the ulema has diminished in recent decades,[204] they still hold the most important religious posts and are closely linked to the Al Saud by a high degree of intermarriage.[194]

Legal system

The primary source of law is the Islamic Sharia derived from the teachings of the Qur'an and the Sunnah (the traditions of the Prophet).[171] Saudi Arabia is unique among modern Muslim states in that Sharia is not codified and there is no system of judicial precedent, allowing judges to use independent legal reasoning to make a decision. Thus, divergent judgments arise even in apparently identical cases,[206] making predictability of legal interpretation difficult.[207] Saudi judges tend to follow the principles of the Hanbali school of jurisprudence (fiqh) found in pre-modern texts[208] and noted for its literalist interpretation of the Qur'an and hadith.[209] However, in 2021, Saudi Arabia announced judicial reforms which will lead to an entirely codified law that eliminates discrepancies.[210]

Royal decrees are the other main source of law but are referred to as regulations rather than laws because they are subordinate to the Sharia.[171] Royal decrees supplement Sharia in areas such as labour, commercial and corporate law. Additionally, traditional tribal law and custom remain significant.[211] Extra-Sharia government tribunals usually handle disputes relating to specific royal decrees.[212] Final appeal from both Sharia courts and government tribunals is to the king, and all courts and tribunals follow Sharia rules of evidence and procedure.[213]

Retaliatory punishments, or Qisas, are practised: for instance, an eye can be surgically removed at the insistence of a victim who lost his own eye.[214] Families of someone unlawfully killed can choose between demanding the death penalty or granting clemency in return for a payment of diyya (blood money), by the perpetrator.[215]

Administrative divisions

Saudi Arabia is divided into 13 regions[216] (Arabic: مناطق إدارية; manatiq idāriyya, sing. منطقة إدارية; mintaqah idariyya). The regions are further divided into 118 governorates (Arabic: محافظات; muhafazat, sing. محافظة; muhafazah). This number includes the 13 regional capitals, which have a different status as municipalities (Arabic: أمانة; amanah) headed by mayors (Arabic: أمين; amin). The governorates are further subdivided into sub-governorates (Arabic: مراكز; marakiz, sing. مركز; markaz).

Foreign relations

Saudi Arabia joined the UN in 1945[39][217] and is a founding member of the Arab League, Gulf Cooperation Council, Muslim World League, and the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation).[218] It plays a prominent role in the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and in 2005 joined the World Trade Organization.[39]

Since 1960, as a founding member of OPEC, its oil pricing policy has been generally to stabilize the world oil market and try to moderate sharp price movements so as not to jeopardize the Western economies.[39][219] In 1973, Saudi Arabia and other Arab nations imposed an oil embargo against the United States, United Kingdom, Japan and other Western nations which supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War of October 1973.[220] The embargo caused an oil crisis with many short- and long-term effects on global politics and the global economy.[221]

Saudi Arabia and the United States are strategic allies, and Saudi Arabia is considered to be pro-Western.[222][223][224][225] On 20 May 2017, President Donald Trump and King Salman signed a series of letters of intent for Saudi Arabia to purchase arms from the United States totaling $350 billion over 10 years.[226][227] Saudi Arabia's role in the 1991 Gulf War, particularly the stationing of US troops on Saudi soil from 1991, prompted the development of a hostile Islamist response internally.[228] As a result, Saudi Arabia has, to some extent, distanced itself from the US and, for example, refused to support or to participate in the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.[139]

China and Saudi Arabia are major allies, with the relationship between the two countries growing significantly in recent decades. A significant number of Saudi Arabians have also expressed a positive view of China.[229][230][231] In February 2019, Crown Prince Mohammad defended China's Xinjiang re-education camps for Uyghur Muslims.[232][233] According to The Diplomat, Saudi Arabia's human rights record has "come under frequent attack abroad and so defending China becomes a roundabout way of defending themselves."[234]

The consequences of the 2003 invasion and the Arab Spring led to increasing alarm within the Saudi monarchy over the rise of Iran's influence in the region.[235] These fears were reflected in comments of King Abdullah,[197] who privately urged the United States to attack Iran and "cut off the head of the snake".[236]

Saudi Arabia has been seen as a moderating influence in the Arab–Israeli conflict, periodically putting forward a peace plan between Israel and the Palestinians and condemning Hezbollah.[237] Saudi Arabia halted new trade and investment dealings with Canada and suspended diplomatic ties in a dramatic escalation of a dispute over the kingdom's arrest of women's rights activist Samar Badawi on 6 August 2018.[238][239]

In 2017, as part of its nuclear power programme, Saudi Arabia planned to extract uranium domestically, taking a step towards self-sufficiency in producing nuclear fuel.[240]

Allegations of sponsoring global terrorism

Saudi Arabia has been accused of sponsoring Islamic terrorism.[241][242] According to Iraq Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki in March 2014, Saudi Arabia along with Qatar provided political, financial, and media support to terrorists against the Iraqi government.[243] Similarly, President of Syria Bashar al-Assad noted that the sources of the extreme ideology of the terrorist organization ISIS and other such salafist extremist groups are the Wahabbism that has been supported by the royal family of Saudi Arabia.[244]

Relations with the U.S. became strained following 9/11 terror attacks.[245] American politicians and media accused the Saudi government of supporting terrorism and tolerating a jihadist culture.[246] Indeed, Osama bin Laden and 15 out of the 19 9/11 hijackers were from Saudi Arabia;[247] in ISIL-occupied Raqqa, in mid-2014, all 12 judges were Saudi.[248] The leaked 2014 U.S. Department of State memo says that "governments of Qatar and Saudi Arabia...are providing clandestine financial and logistic support to ISIS and other radical groups in the region."[249] According to former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, "Saudi Arabia remains a critical financial support base for al-Qaida, the Taliban, LeT and other terrorist groups... Donors in Saudi Arabia constitute the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide."[250] Former CIA director James Woolsey described it as "the soil in which Al-Qaeda and its sister terrorist organizations are flourishing."[251] The Saudi government denies these claims or that it exports religious or cultural extremism.[252] In September 2016, the U.S. Congress passed the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act that would allow relatives of victims of the 11 September attacks to sue Saudi Arabia for its government's alleged role in the attacks.[253]

According to Sir William Patey, former British ambassador to Saudi Arabia, the kingdom funds mosques throughout Europe that have become hotbeds of extremism. "They are not funding terrorism. They are funding something else, which may down the road lead to individuals being radicalized and becoming fodder for terrorism," Patey said. He said that Saudi has been funding an ideology that leads to extremism and the leaders of the kingdom are not aware of the consequences.[254]

However, since 2016 the kingdom began backing away from Islamist ideologies.[255] Several reforms took place including curbing the powers of religious police,[256] restricting the volume of loudspeakers in mosques,[257][258] reducing the number of hours spent on Islamic education in schools,[259] stopping funding mosques in foreign countries,[260] and allowing the first mixed-gender concert performed by women.[261] In 2017, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman declared a return to "moderate Islam".[262]

Military

Saudi Arabia's military forces include the Armed Forces of Saudi Arabia under the Ministry of Defence, which consist of the Royal Saudi Land Forces (which include the Royal Guard), the Air Force, the Navy, the Air Defence, and the Strategic Missile Force; the Saudi Arabian National Guard under the Ministry of National Guard; paramilitary forces under the Minister of Interior, including the Saudi Arabian Border Guard and the Facilities Security Force; and the Presidency of State Security, including the Special Security Force and the Emergency Force. As of 2023 there are 127,000 active personnel in the Armed Forces, 130,000 in the National Guard, and 24,500 in the paramilitary security forces. The National Guard is made up of tribal forces that are loyal to the Saudi royal family and have a role in both domestic security and foreign defence.[263][264] Saudi Arabia has security relationships with the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, which provide it with training and weapons.[265]

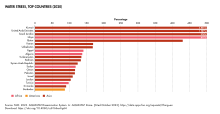

Saudi Arabia has one of the highest percentages of military expenditure in the world, spending around 8% of its GDP in its military, according to the 2020 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimate,[266] which places it as the world's third largest military spender behind the United States and China,[267] and the world's largest arms importer from 2015 to 2019, receiving half of all the U.S. arms exports to the Middle East.[268][269] Spending on defence and security has increased significantly since the mid-1990s and was about US$78.4 billion as of 2019.[267] According to the BICC, Saudi Arabia is the 28th most militarized country in the world and possesses the second-best military equipment qualitatively in the region, after Israel.[270] Its modern high-technology arsenal makes Saudi Arabia among the world's most densely armed nations.[271]

The kingdom has a long-standing military relationship with Pakistan; it has long been speculated that Saudi Arabia secretly funded Pakistan's atomic bomb programme and seeks to purchase atomic weapons from Pakistan in the near future.[272][273]

In March 2015, Saudi Arabia mobilized 150,000 troops and 100 fighter jets to support its intervention in the civil war in neighbouring Yemen.[274][275] By early 2016, Saudi ground forces and their coalition allies captured Aden and parts of southwest Yemen, though the Houthis continued to control northern Yemen and the capital city Sanaa. From there the Houthis launched successful attacks across the border into Saudi Arabia.[276] The Saudi military has also carried out an aerial bombing campaign and a naval blockade aimed at stopping weapons shipments to the Houthis.[277][278]

Human rights

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (June 2023) |

The Saudi government, which mandates Muslim and non-Muslim observance of Sharia law under the absolute rule of the House of Saud, has been denounced by various international organizations and governments for violating human rights within the country.[279] The authoritarian regime is consistently ranked among the "worst of the worst" in Freedom House's annual survey of political and civil rights.[280] According to Amnesty International, security forces continue to torture and ill-treat detainees to extract confessions to be used as evidence against them at trial.[281] Saudi Arabia abstained from the United Nations vote adopting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, saying it contradicted Sharia.[282] Mass executions, such as those carried out in 2016, in 2019, and in 2022, have been condemned by international rights groups.[283]

Since 2001, Saudi Arabia has engaged in widespread internet censorship. Most online censorship generally falls into two categories: one based on censoring "immoral" (mostly pornographic and LGBT-supportive websites along with websites promoting any religious ideology other than Sunni Islam) and one based on a blacklist run by Saudi Arabia's Ministry of Media, which primarily censors websites critical of the Saudi regime or associated with parties that are opposed to or opposed by Saudi Arabia.[284][285][286]

Saudi Arabian law does not recognize sexual orientations or religious freedom, and the public practice of non-Muslim religions is actively prohibited.[288] The justice system regularly engages in capital punishment, which has included public executions by beheading.[289][290] In line with Sharia in the Saudi justice system, the death penalty can theoretically be imposed for a wide range of offenses,[291] including murder, rape, armed robbery, repeated drug use, apostasy,[292] adultery,[293] witchcraft and sorcery,[294] and can be carried out by beheading with a sword,[292] stoning or firing squad,[293] followed by crucifixion (exposure of the body after execution).[294] In 2022, the Saudi Crown Prince stated that capital punishments will be removed "except for one category mentioned in the Quran", namely homicide, under which certain conditions must be applied.[295] In April 2020, Saudi Supreme Court issued a directive to eliminate the punishment of flogging from the Saudi court system, replaced by imprisonment or fines.[296][297]

Historically, Saudi women faced discrimination in many aspects of their lives and under the male guardianship system were effectively treated as legal minors.[298] The treatment of women had been referred to as "sex segregation"[299][300] and "gender apartheid".[301][302] As of June 2023, the kingdom has reportedly reversed its ban on women "becoming lawyers, engineers, or geologists" and established "aggressive affirmative action programs", doubling the female labour force participation rate. It has added "its first female newspaper editors, diplomats, TV anchors and public prosecutors", with a female head of the Saudi stock exchange and member on the board of Saudi Aramco.[303]

Saudi Arabia is a notable destination country for men and women trafficked for the purposes of slave labour and commercial sexual exploitation.[304] Migrants from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East are employed in the country's construction, hospitality, and domestic work sectors under the kafala system which human rights groups say is linked to abuses including modern slavery.[305][306]

Economy

As of October 2018[update], Saudi Arabia is the largest economy in the Middle East and the 18th largest in the world.[307] It has the world's second-largest proven petroleum reserves and is the largest exporter of petroleum.[308][309] The country has the world's second-largest oil reserves[310] and the sixth-largest proven natural gas reserves.[32] Saudi Arabia is considered an "energy superpower,"[311][312] having the second highest total estimated value of natural resources, valued at US$34.4 trillion in 2016.[313]

The command economy is petroleum-based; roughly 63%[314] of budget revenues and 67%[315] of export earnings come from the oil industry. The oil industry constitutes about 45% of Saudi Arabia's nominal gross domestic product, compared with 40% from the private sector. It is strongly dependent on foreign workers with about 80% of those employed in the private sector being non-Saudi.[316][317] Challenges to the economy include halting or reversing the decline in per-capita income, improving education to prepare youth for the workforce and providing them with employment, diversifying the economy, stimulating the private sector and housing construction, and diminishing corruption and inequality.[318]

OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) limits its members' oil production based on their "proven reserves." Saudi Arabia's published reserves have shown little change since 1980, with the main exception being an increase of about 100 billion barrels (1.6×1010 m3) between 1987 and 1988.[319] Matthew Simmons has suggested that Saudi Arabia is greatly exaggerating its reserves and may soon show production declines (see peak oil).[320]

From 2003 to 2013, "several key services" were privatized—municipal water supply, electricity, telecommunications—and parts of education and health care, traffic control and car accident reporting were also privatized. According to Arab News columnist Abdel Aziz Aluwaisheg, "in almost every one of these areas, consumers have raised serious concerns about the performance of these privatized entities."[321] In November 2005, Saudi Arabia was approved as a member of the World Trade Organization. Negotiations to join had focused on the degree to which Saudi Arabia is willing to increase market access to foreign goods and in 2000, the government established the Saudi Arabian General Investment Authority to encourage foreign direct investment in the kingdom. Saudi Arabia maintains a list of sectors in which foreign investment is prohibited, but the government plans to open some closed sectors such as telecommunications, insurance, and power transmission/distribution over time. The government has also made an attempt at "Saudizing" the economy, replacing foreign workers with Saudi nationals with limited success.[322]

In addition to petroleum and gas, Saudi has a significant gold mining sector in the Mahd adh Dhahab region and significant other mineral industries, an agricultural sector (especially in the southwest) based on vegetables, fruits, dates etc. and livestock, and large number of temporary jobs created by the roughly two million annual hajj pilgrims.[318] Saudi Arabia has had five-year "Development Plans" since 1970. Among its plans were to launch "economic cities" (e.g. King Abdullah Economic City) in an effort to diversify the economy and provide jobs. The cities will be spread around Saudi Arabia to promote diversification for each region and their economy, and the cities are projected to contribute $150 billion to the GDP.

Saudi Arabia is increasingly activating its ports in order to participate in trade between Europe and China in addition to oil transport. To this end, ports such as Jeddah Islamic Port or King Abdullah Economic City are being rapidly expanded, and investments are being made in logistics. The country is historically and currently part of the Maritime Silk Road.[324][325][326][327]

Statistics on poverty in the kingdom are not available through the UN resources because the Saudi government does not issue any.[328] The Saudi state discourages calling attention to or complaining about poverty. In December 2011, the Saudi interior ministry arrested three reporters and held them for almost two weeks for questioning after they uploaded a video on the topic to YouTube.[329][330][331] Authors of the video claim that 22% of Saudis may be considered poor.[332] Observers researching the issue prefer to stay anonymous[333] because of the risk of being arrested.

The unexpected impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy, along with Saudi Arabia's poor human rights records, laid unforeseen challenges before the development plans of the kingdom, where some of the programmes under 'Vision 2030' were also expected to be affected.[334] In May 2020, the Finance Minister of Saudi Arabia admitted that the country's economy was facing a severe economical crisis for the first time in decades, because of the pandemic as well as declining global oil markets. Mohammed Al-Jadaan said that the country will take "painful" measures and keep all options open to deal with the impact.[335]

On July 2024 Saudi Arabia's Renewable Energy Localisation Company (RELC) has formed three joint ventures with Chinese companies to advance the kingdom's clean energy infrastructure. As part of Saudi Arabia's 2030 targets, the Public Investment Fund is actively promoting the localization of renewable energy components. RELC, a division of the sovereign fund, facilitates partnerships between global manufacturers and Saudi private sector firms to strengthen local supply chains. The joint ventures include partnerships with Envision Energy for wind turbine components, Jinko Solar for photovoltaic cells, and Lumetech for solar photovoltaic ingots and wafers. These initiatives aim to localize up to 75% of the components used in Saudi Arabia's renewable projects by 2030, positioning the country as a major global exporter of renewable technologies.[336]

Saudi Minister of Economy and Planning, Faisal Al Ibrahim, emphasized Saudi Arabia's progress in global climate goals at the 2024 High-Level Political Forum for Sustainable Development in New York, citing over 80 initiatives and investments exceeding $180 billion for the country's green economy, as reported by Saudi Gazette. He highlighted the alignment of these efforts with Vision 2030 objectives, focusing on local sustainability, sector integration, and societal advancement.[337]

Agriculture

Initial attempts to develop dairy farming on a commercial scale occurred in the Al Kharj District (just south of Riyadh) during the 1950s.[338] Serious large-scale agricultural development began in the 1970s,[339] particularly with wheat.[340] The government launched an extensive programme to promote modern farming technology; to establish rural roads, irrigation networks and storage and export facilities; and to encourage agricultural research and training institutions. As a result, there has been a phenomenal growth in the production of all basic foods. Saudi Arabia is self-sufficient in numerous foodstuffs, including meat, milk, and eggs. The country exports dates, dairy products, eggs, fish, poultry, fruits, vegetables, and flowers. Dates, once a staple of the Saudi diet, are now mainly grown for global humanitarian aid.In addition, Saudi farmers grow substantial amounts of other grains such as barley, sorghum, and millet. As of 2016, in the interest of preserving precious water resources, domestic production of wheat, which it used to export, ended.[341] Consuming non-renewable groundwater resulted in the loss of an estimated four-fifths of the total groundwater reserves by 2012.[342]

The kingdom has some of the most modern and largest dairy farms in the Middle East. Milk production boasts a remarkably productive annual rate of 6,800 litres (1,800 US gallons) per cow, one of the highest in the world. The local dairy manufacturing company Almarai is the largest vertically integrated dairy company in the Middle East.[343]

The olive tree is indigenous to Saudi Arabia. The Al Jouf region has millions of olive trees, and the number is expected to increase to 20 million trees.[344]

As part of the country's ongoing plan to plant 100 Mangrove seedlings along its coastlines, the National Centre for Vegetation Cover Development and Combating Desertification has announced that it has planted 13M seedlings.[345]

Water supply and sanitation

One of the main challenges for Saudi Arabia is water scarcity. Substantial investments have been undertaken in seawater desalination, water distribution, sewerage and wastewater treatment. Today about 50% of drinking water comes from desalination, 40% from the mining of non-renewable groundwater, and 10% from surface water in the mountainous southwest of the country.[346] Saudi Arabia is suffering from a major depletion of the water in its underground aquifers and a resultant break down and disintegration of its agriculture as a consequence.[347][348] As a result of the catastrophe, Saudi Arabia has bought agricultural land in the United States,[349][350] Argentina,[351] and Africa.[352][353][354][355] Saudi Arabia ranked as a major buyer of agricultural land in foreign countries.[356][357]

According to the Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) for Water Supply and Sanitation of the WHO and UNICEF, the latest reliable source on access to water and sanitation in Saudi Arabia is the 2004 census. It indicates that 97% of the population had access to an improved source of drinking water and 99% had access to improved sanitation. For 2015, the JMP estimates that access to sanitation increased to 100%. Sanitation was primarily through on-site solutions, and about 40% of the population was connected to sewers.[359] In 2015, 886,000 people lacked access to "improved" water.[360][361]

Tourism

In 2019, Saudi Arabia adopted a general tourism travel visa to allow non-Muslims to visit.[362] Although most tourism largely involves religious pilgrimages, there is growth in the leisure tourism sector. According to the World Bank, approximately 14.3 million people visited Saudi Arabia in 2012, making it the world's 19th-most-visited country.[363] Tourism is an important component of the Saudi Vision 2030, and according to a report conducted by BMI Research in 2018 both religious and non-religious tourism have significant potential for expansion.[364]

The kingdom offers an electronic visa for foreign visitors to attend sports events and concerts.[365] In 2019, the kingdom announced its plans to open visa applications for visitors, where people from about 50 countries would be able to get tourist visas to Saudi.[366] In 2020 it was announced that holders of a US, UK or Schengen visa are eligible for a Saudi electronic visa upon arrival.[367]

- Thee Ain village located in Al Bahah Province

- The desert of Al-Rub' Al-Khali (The Empty Quarter)

- Elephant Rock in Al-'Ula

- Ummahat islands, The Red Sea Project

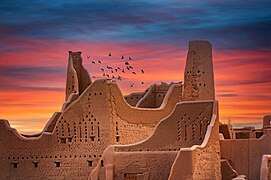

- Salwa Palace in At-Turaif District, Diriyah

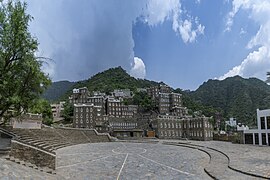

- Rijal Almaa historic village

- Qasr al-Farid Tomb in Mada'in Salih

- Al-Rifai House gate in Farasan Islands

Demographics

Saudi Arabia's reported population is 32,175,224 as of 2022,[368] making it the fourth most populous country in the Arab world.[369] Close to 42% of its inhabitants are immigrants,[370] mostly from the Middle East, Asia, and Africa.[371]

The Saudi population has grown rapidly since 1950, when it was estimated at 3 million.[372] For much of the 20th century, the country had one of the highest population growth rates in the world, at around 3% annually;[373] it continues to grow at a rate of 1.62% per year,[374] slightly higher than the rest of the Middle East and North Africa. Consequently, the Saudi people are quite young by global standards, with over half the population under 25 years old,[375]

The ethnic composition of Saudi citizens is 90% Arab and 10% Afro-Arab.[376] Most Saudis are concentrated in the southwest; Hejaz, which is the most populated region,[377] is home to one-third of the population, followed by neighbouring Najd (28%) and the Eastern Province (15%).[378] As late as 1970, most Saudis lived a subsistence life in the rural provinces, but in the last half of the 20th century, the kingdom has urbanized rapidly: as of 2023, about 85% of Saudis live in urban metropolitan areas—specifically Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam.[379][380]As recently as the early 1960s, Saudi Arabia's slave population was estimated at 300000.[381] Slavery was officially abolished in 1962.[382][383]

Largest cities or towns in Saudi Arabia Data.gov.sa (2013/2014/2016) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Regions | Pop. | Rank | Name | Regions | Pop. | ||

Riyadh  Jeddah | 1 | Riyadh | Riyadh | [384] 6,506,700 | 11 | Qatif | Eastern | [385] 559,300 |  Mecca  Medina |

| 2 | Jeddah | Mecca | [386] 3,976,400 | 12 | Khamis Mushait | Asir | [387] 549,000 | ||

| 3 | Mecca | Mecca | [386] 1,919,900 | 13 | Ha'il | Ha'il | [388] 441,900 | ||

| 4 | Medina | Medina | [389] 1,271,800 | 14 | Hafar al-Batin | Eastern | [385] 416,800 | ||

| 5 | Hofuf | Eastern | [385] 1,136,900 | 15 | Jubail | Eastern | [385] 411,700 | ||

| 6 | Ta'if | Mecca | [386] 1,109,800 | 16 | Kharj | Riyadh | [390] 404,100 | ||

| 7 | Dammam | Eastern | [385] 975,800 | 17 | Abha | Asir | [387] 392,500 | ||

| 8 | Buraidah | Al-Qassim | [391] 658,600 | 18 | Najran | Najran | [392] 352,900 | ||

| 9 | Khobar | Eastern | [385] 626,200 | 19 | Yanbu | Al Madinah | [389] 320,800 | ||

| 10 | Tabuk | Tabuk | [393] 609,000 | 20 | Al Qunfudhah | Mecca | [386] 304,400 | ||

Language

The official language is Arabic.[11][5] There are four main regional dialect groups spoken by Saudis: Najdi (about 14.6 million speakers[394]), Hejazi (about 10.3 million speakers[395]), Gulf (about 0.96 million speakers[396]) including Baharna dialects, and Southern Hejaz and Tihama[397] dialects. Faifi is spoken by about 50000. The Mehri language is also spoken by around 20000 Mehri citizens.[398] Saudi Sign Language is the principal language of the deaf community, amounting to around 100000 speakers. The large expatriate communities also speak their own languages, the most numerous of which, according to 2018 data, are Bengali (~1 500000), Tagalog (~900000), Punjabi (~800000), Urdu (~740000), Egyptian Arabic (~600000), Rohingya, North Levantine Arabic (both ~500000)[399] and Malayalam.[400]

Religion

Virtually all Saudi citizens[401] and residents are Muslim;[402][403] by law, all citizens of the country are Muslim. Estimates of the Sunni population range between 85% and 90%, with the remaining 10 to 15% being Shia Muslim,[404][405][406][407] practicing either Twelver Shi'ism or Sulaymani Ismailism. The official and dominant form of Sunni Islam is Salafism, commonly known as Wahhabism,[408][409][g] which was founded in the Arabian Peninsula by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab in the 18th century. Other denominations, such as the minority Shia Islam, are systematically suppressed.[410] Shia Muslims in Saudi Arabia are largely found in the Eastern Provice, particularly in Qatif and Al–Ahsa.[411]

There are an estimated 1.5 million Christians in Saudi Arabia, almost all foreign workers.[412] Saudi Arabia allows Christians to enter the country as temporary foreign workers but does not allow them to practice their faith openly. There are officially no Saudi citizens who are Christians,[413] as Saudi Arabia forbids religious conversion from Islam (apostasy) and punishes it by death.[414] According to the Pew Research Center, there are 390000 Hindus in Saudi Arabia, almost all foreign workers.[415] There may be a significant fraction of atheists and agnostics,[416][417] although they are officially called "terrorists".[418] In its 2017 religious freedom report, the U.S. State Department named Saudi Arabia a Country of Particular Concern, denoting systematic, ongoing, and egregious violations of religious freedom.[419]

Najran was home to local Christian and Jewish communities.[420] Prior to establishment of Israel, Najran was home to 260 Jews and had friendly relations with Ibn Saud.[420] They had a Yemenite Jewish background.[420] After the establishment of Israel and the 1948 Arab–Israeli war, all the Jews fled for Yemen and from there headed to Israel.[420]

Education

Education is free at all levels, although higher education is restricted to citizens only.[421] The school system is composed of elementary, intermediate, and secondary schools. Classes are segregated by sex. At the secondary level, students are able to choose from three types of schools: general education, vocational and technical, or religious.[422] The rate of literacy is 99% among males and 96% among females in 2020.[423][424] Youth literacy rose to approximately 99.5% for both sexes.[425][426]

Higher education has expanded rapidly, with large numbers of universities and colleges being founded particularly since 2000. Institutions of higher education include King Saud University, the Islamic University at Medina, and the King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah. Princess Norah University is the largest women's university in the world. King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, known as KAUST, is the first mixed-gender university campus in Saudi Arabia and was founded in 2009. Other colleges and universities emphasize curricula in sciences and technology, military studies, religion, and medicine. Institutes devoted to Islamic studies, in particular, abound. Women typically receive college instruction in segregated institutions.[139]

The Academic Ranking of World Universities, known as Shanghai Ranking, ranked five Saudi institutions among its 2022 list of the 500 top universities in the world.[427] The QS World University Rankings lists 14 Saudi universities among the 2022 world's top universities and 23 universities among the top 100 in the Arab world.[428] The 2022 list of U.S. News & World Report Best Global University Ranking ranked King Abdulaziz University among the top 50 universities in the world and King Abdullah University of Science and Technology among the top 100 universities in the world.[429]

In 2018, Saudi Arabia ranked 28th worldwide in terms of high-quality research output according to the scientific journal Nature.[430]This makes Saudi Arabia the best performing Middle Eastern, Arab, and Muslim country.[citation needed] Saudi Arabia spends 8.8% of its gross domestic product on education, compared with the global average of 4.6%.[431] Saudi Arabia was ranked 48th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, up from 68th in 2019.[432][433][434]

The Saudi education system has been accused of encouraging Islamic terrorism, leading to reform efforts.[435][436] Following the 9/11 attacks, the government aimed to tackle the twin problems of encouraging extremism and the inadequacy of the country's university education for a modern economy, by slowly modernizing the education system through the "Tatweer" reform programme.[435] The Tatweer programme is reported to have a budget of approximately US$2 billion and focuses on moving teaching away from the traditional Saudi methods of memorization and rote learning towards encouraging students to analyse and problem-solve. It also aims to create an education system which will provide a more secular and vocationally based training.[437][438]

In 2021, the Washington Post reported on the measures taken by Saudi Arabia to clean textbooks from paragraphs considered antisemitic and sexist. The paragraphs dealing with the punishment of homosexuality or same-sex relations have been deleted, and expressions of admiration for the extremist martyrdom. Antisemitic expressions and calls to fight the Jews became fewer. David Weinberg, director of international affairs for the Anti-Defamation League, said that references to demonizing Jews, Christians, and Shiites have been removed from some places or have toned down. The U.S. State Department expressed in an email that it welcomed the changes. The Saudi Ministry of Foreign Affairs supports a training programme for Saudi teachers.[439]

Health care

Saudi Arabia has a national health care system in which the government provides free health care services through government agencies. Saudi Arabia has been ranked among the 26 best countries in providing high quality healthcare.[440] The Ministry of Health is the major government agency entrusted with the provision of preventive, curative, and rehabilitative health care. The ministry's origins can be traced to 1925, when several regional health departments were established, with the first in Makkah. The various healthcare institutions were merged to become a ministerial body in 1950.[441] The Health Ministry created a friendly competition between each of the districts and between different medical services and hospitals. This idea resulted in the creation of the "Ada'a" project launched in 2016. The new system is a nationwide performance indicator, for services and hospitals. Waiting times and other major measurements improved dramatically across the kingdom.[442]

A new strategy has been developed by the ministry, known as Diet and Physical Activity Strategy or DPAS for short,[443] to address bad lifestyle choices. The ministry advised that there should be a tax increase on unhealthy food, drink and cigarettes. This additional tax could be used to improve healthcare offerings. The tax was implemented in 2017.[444] As part of the same strategy, calorie labels were added in 2019 to some food and drink products. Ingredients were also listed as an aim to reduce obesity and inform citizens with health issues, to manage their diet.[445] As part of the ongoing focus on tackling obesity, women-only gyms were allowed to open in 2017. Sports offered in each of these gyms include bodybuilding, running and swimming to maintain higher standards of health.[446][447]

Smoking in all age groups is widespread. In 2009 the lowest median percentage of smokers was university students (~13.5%) while the highest was elderly people (~25%). The study also found the median percentage of male smokers to be much higher than that of females (~26.5% for males, ~9% for females). Before 2010, Saudi Arabia had no policies banning or restricting smoking.

The MOH has been awarded "Healthy City" certificates by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the cities of Unayzah and Riyadh Al Khabra as 4th and 5th Healthy Cities in Saudi Arabia.[448]The WHO had earlier classified three Saudi Arabian cities, Ad Diriyah, Jalajil, and Al-Jamoom as "Healthy city", as part of the WHO Healthy Cities Programme. Recently Al-Baha has also been classified as a healthy city to join the list of global healthy cities approved by the World Health Organization.[449]

In May 2019, the then Saudi Minister of Health Tawfiq bin Fawzan AlRabiah received a global award on behalf of the Kingdom for combatting smoking through social awareness, treatment, and application of regulations.[450] The award was presented as part of the 72nd session of the World Health Assembly, held in Geneva in May 2019. After becoming one of the first nations to ratify the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2005, it plans to reduce tobacco use from 12.7% in 2017, to 5% in 2030.[450]