Иоаннин запятая

Иоаннинская запятая ( латынь : запятая Йоханнеум ) - это интерполированная фраза ( запятая ) в стихах 5: 7–8 первого послания Джона . [ 2 ]

Текст (с запятой в курсиве и прилагаемый квадратными скобками) в короля Джеймса версии Библии читается:

7 Ибо есть три, которые записывают медведя [ на небесах, Отце, Слово и Святом Духе: и эти три один. ] 8 [ И есть три, которые несут свидетель на земле ], дух и вода, и кровь, и эти трое согласны в одном.

- версия короля Джеймса (1611)

В греческом текстовом рецепту (TR) стих читается таким образом: [ 3 ]

Что вы свидетели на небесах, Отца, Слово и Святого Духа;

It became a touchpoint for the Christian theological debate over the doctrine of the Trinity from the early church councils to the Catholic and Protestant disputes in the early modern period.[4]

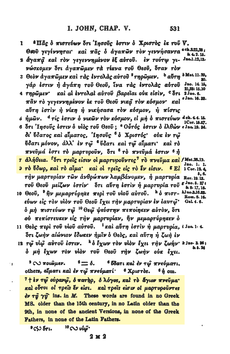

It may first be noted that the words "in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one" (KJV) found in older translations at 1 John 5:7 are thought by some to be spurious additions to the original text. A footnote in the Jerusalem Bible, a Catholic translation, says that these words are "not in any of the early Greek MSS [manuscripts], or any of the early translations, or in the best MSS of the Vulg[ate] itself." In A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Bruce Metzger (1975, pp. 716–718) traces in detail the history of the passage, asserting its first mention in the 4th-century treatise Liber Apologeticus, and that it appears in Old Latin and Vulgate manuscripts beginning in the 6th century. Modern translations as a whole (both Catholic and Protestant, such as the Revised Standard Version, New English Bible, and New American Bible) do not include them in the main body of the text due to their ostensibly spurious nature. [5][6]

The comma is mainly only attested in the Latin manuscripts of the New Testament, being absent from the vast majority of Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, the earliest Greek manuscript being 14th century.[7] It is also totally absent in the Ethiopic, Aramaic, Syriac, Georgian, Arabic and from the early pre-12th century Armenian[8] witnesses to the New Testament. Despite its absence from these manuscripts, it was contained in many printed editions of the New Testament in the past, including the Complutensian Polyglot (1517ad), the different editions of the Textus Receptus (1516-1894ad), the London Polyglot (1655)[7] and the Patriarchal text (1904ad).[9] And it is contained in many Reformation-era vernacular translations of the Bible due to the inclusion of the verse within the Textus Receptus. In spite of its late date, members of the King James Only movement and those who advocate for the superiority for the Textus Receptus have argued for its authenticity.

The Comma Johanneum is among the most noteworthy variants found within the Textus Receptus in addition to the confession of the Ethiopian eunuch, the long ending of Mark, the Pericope Adulterae, the reading "God" in 1 Timothy 3:16 and the "Book of Life" in Revelation 22:19.[10]

Text

[edit]The "Johannine Comma" is a short clause found in 1 John 5:7–8.

Erasmus omitted the text of the Johannine Comma from his first and second editions of the Greek-Latin New Testament (the Novum Instrumentum omne) because it was not in his Greek manuscripts. He added the text to his Novum Testamentum omne in 1522 after being accused of reviving Arianism and after he was informed of a Greek manuscript that contained the verse,[12] although he expressed doubt as to its authenticity in his Annotations.[13][14]

Many subsequent early printed editions of the Bible include it, such as the Coverdale Bible (1535), the Geneva Bible (1560), the Douay-Rheims Bible (1610), and the King James Bible (1611). Later editions based on the Textus Receptus, such as Robert Young's Literal Translation (1862) and the New King James Version (1979), include the verse. In the 1500s it was not always included in Latin New Testament editions, though it was in the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate (1592). However, Martin Luther did not include it in his Luther Bible.[15]

The text (with the Comma in square brackets and italicised) in the King James Bible reads:

7For there are three that beare record [in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.] 8[And there are three that beare witnesse in earth], the Spirit, and the Water, and the Blood, and these three agree in one.

— King James Version (1611)

The text (with the Comma in square brackets and italicised) in the Latin of the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate reads:

7Quoniam tres sunt, qui testimonium dant [in caelo: Pater, Verbum, et Spiritus Sanctus: et hi tres unum sunt.] 8[Et tres sunt, qui testimonium dant in terra]: spiritus, et aqua, et sanguis: et hi tres unum sunt.

— Sixto-Clementine Vulgate (1592)

The text (with the Comma in square brackets and italicised) in the Greek of the Novum Testamentum omne reads:

7ὅτι τρεῖς εἰσιν οἱ μαρτυροῦντες [ἐν τῷ οὐρανῷ ὁ πατήρ ὁ λόγος καὶ τὸ ἅγιον πνεῦμα καὶ οὗτοι οἱ τρεῖς ἕν εἰσιν] 8[καὶ τρεῖς εἰσιν οἱ μαρτυροῦντες ἐν τῇ γῇ] τὸ πνεῦμα καὶ τὸ ὕδωρ καὶ τὸ αἷμα καὶ οἱ τρεῖς εἰς τὸ ἕν εἰσιν.

— Novum Testamentum omne (1522; absent in earlier editions)

There are several variant versions of the Latin and Greek texts.[2]

English translations based on a modern critical text have omitted the comma from the main text since the English Revised Version (1881), including the New American Standard Bible (NASB), English Standard Version (ESV), and New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

Origin

[edit]

Several early sources that might be expected to include the Comma Johanneum in fact omit it. For example, Clement of Alexandria's (c. 200) quotation of 1 John 5:8 does not include the Comma.[16]

Among the earliest possible references to the Comma appears by the 3rd-century Church Father Cyprian (died 258), who in Unity of the Church 1.6[17] quoted John 10:30: "Again it is written of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, 'And these three are one.'"[18] However, some believe that he was giving an interpretation of the three elements mentioned in the uncontested part of the verse.[19]

The first undisputed work to quote the Comma Johanneum as an actual part of the Epistle's text appears to be the 4th-century Latin homily Liber Apologeticus, probably written by Priscillian of Ávila (died 385), or his close follower Bishop Instantius.[19]

Manuscripts

[edit]

The Comma is not in two of the oldest extant Vulgate manuscripts, Codex Fuldensis and the Codex Amiatinus, although it is referenced in the Prologue to the Canonical Epistles of Fuldensis, and appears in Old Latin manuscripts of similar antiquity.

The earliest extant Latin manuscripts supporting the Comma are dated from the 5th to 7th century. The Freisinger fragment,[21] León palimpsest,[22] besides the younger Codex Speculum, New Testament quotations extant in an 8th- or 9th-century manuscript.[23]

The comma does not appear in the older Greek manuscripts. Nestle-Aland is aware of eight Greek manuscripts that contain the Comma.[24] The date of the addition is late, probably dating to the time of Erasmus.[25] In one manuscript, back-translated into Greek from the Vulgate, the phrase "and these three are one" is absent.

Both Novum Testamentum Graece (NA27) and the United Bible Societies (UBS4) provide three variants. The numbers here follow UBS4, which rates its preference for the first variant as { A }, meaning "virtually certain" to reflect the original text. The second variant is a longer Greek version found in the original text of five manuscripts and the margins of five others. All of the other 500 plus Greek manuscripts that contain 1 John support the first variant. The third variant is found only in Latin manuscripts and patristic works. The Latin variant is considered a trinitarian gloss,[26] explaining or paralleled by the second Greek variant.

- The Comma in Greek. All non-lectionary evidence cited: Minuscules 61 (Codex Montfortianus, c. 1520), 629 (Codex Ottobonianus, 14th/15th century), 918 (Codex Escurialensis, Σ. I. 5, 16th century), 2318 (18th century) and 2473 (17th century). It is also found in the Complutensian Polyglot (1520) in both Greek and Latin.[27][28] Its first full appearance in Greek is from the Greek version of the Acts of the Lateran Council in 1215.[19] Although it later appears in the writings of Emmanuel Calecas (died 1410), Joseph Bryennius (1350 – 1431/38) and in the Orthodox Confession of Moglas (1643).[29][30][7] There are no full Patristic Greek references to the comma, however, F.H.A. Scrivener mentions two possible allusions in Greek to the comma in the 4th or 5th century from the Synopsis of Holy Scripture and the Disputation with Arius from Pseudo-Athanasius.[31]

- The Comma at the margins of Greek. At the margins of minuscules 88 (Codex Regis, 11th century with margins added at the 16th century), 177 (BSB Cod. graec. 211), 221 (10th century with margins added at the 15th/16th century), 429 (Codex Guelferbytanus, 14th century with margins added at the 16th century), 636 (16th century).

- The Comma in Latin. testimonium dicunt [or dant] in terra, spiritus [or: spiritus et] aqua et sanguis, et hi tres unum sunt in Christo Iesu. 8 et tres sunt, qui testimonium dicunt in caelo, pater verbum et spiritus. [... "giving evidence on earth, spirit, water and blood, and these three are one in Christ Jesus. 8 And the three, which give evidence in heaven, are father word and spirit."] All evidence from Fathers cited: Clementine edition of Vulgate translation; Pseudo-Augustine's Speculum Peccatoris (V), also (these three with some variation) Cyprian (3rd century), Priscillian (died 385) Liber Apologeticus, Expositio Fidei (4th century), Contra-Varimadum (439-484), Eugenius of Carthage (5th century),[31] Council of Carthage (483), Pseudo-Jerome (5th century) Prologue to the Catholic Epistles, Fulgentius of Ruspe (died 527) Responsio contra Arianos, Cassiodorus (6th century) Complexiones in Ioannis Epist. ad Parthos, Donation of Constantine (8th century). It is also found in the quotations of multiple later medieval writers, including: Peter Abelard (12th century), Peter Lombard (12th century), Bernard of Clairvaux (12th century), Thomas Aquinas (13th century) and William of Ockham (14th century).[7]

- The Comma in other languages: According to Scrivener, the Johannine Comma is found in a few late Slavonic manuscripts, and also in the margin of the Moscow edition of 1663, published under Alexis of Russia.[32] Due to Latin influence, the Johannine Comma also found its way into the Armenian language after the 12th century under King Haithom.[8] It was quoted in the 13th century in the Armenian synod of Sis and found in Uscan’s Armenian translation of the Bible of the 17th century.[33] The Syriac writer Jacob of Edessa (640–708) has been proposed to have referenced the Comma by making a trinitarian reference alongside the water, blood, and Spirit. However, his statements are also seen as possibly referring to the Latin work Against Varimadus, especially with Jacob's mention that the Trinity exists “within us.” This suggests Jacob's reference might be to this Latin text rather than a quotation of 1 John 5:7.[7]

The appearance of the Comma in the manuscript evidence is represented in the following tables:

| Latin manuscripts | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Name | Place | Other information |

| 5th century | Codex Speculum (m) | Holy Cross Monastery (Sessorianus), Rome, Italy | Vetus Latina, scripture quotations |

| 546 AD | Codex Fuldensis (F) | Fulda, Hesse, Germany | The oldest Vulgate manuscript does not have the verse, it does have the Vulgate Prologue which discusses the verse |

| 5th-7th century | Frisingensia Fragmenta (r) or (q) | Bavarian State Library, Munich, Bavaria, Germany | Vetus Latina, Spanish - earthly before heavenly, formerly Fragmenta Monacensia |

| 7th century | León palimpsest (l) Beuron 67 | León Cathedral, Spain | Spanish - "and there are three which bear testimony in heaven, the Father, and the Word, and the Holy Spirit, and these three are one in Christ Jesus" - earthly before heavenly

The text is a mixture of readings from the Vetus Latina and from the Vulgate. |

| 8th century | Codex Wizanburgensis | Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel[34] | the dating is controversial.[35] |

| 9th century | Codex Cavensis C | La Cava de' Tirreni, Biblioteca della Badia, ms memb. 1 | Spanish - earthly before heavenly |

| 9th century | Codex Ulmensis U or σU | British Museum, London 11852 | Spanish |

| 927 AD | Codex Complutensis I (C) | Biblical University Centre 31; Madrid | Spanish - purchased by Cardinal Ximenes, used for Complutensian Polyglot, earthly before heavenly, one in Christ Jesus. |

| 8th–9th century | Codex Theodulphianus | Bibliothéque nationale de France, Paris (BnF) - Latin 9380 | Franco-Spanish |

| 8th–9th century | Codex Sangallensis 907 | Abbey of Saint Gall, Saint Gallen | Franco-Spanish |

| 9th century | Codex Lemovicensis-32 (L) | National Library of France Lain 328, Paris | |

| 9th century | Codex Vercellensis | Rome, Biblioteca Vallicelliana ms B vi | representing the recension of Alcuin, completed in 801 |

| 9th century | Codex Sangallensis 63 | Abbey of Saint Gall, Saint Gallen | Latin, added later into the margin.[20] |

| 960 AD | Codex Gothicus Legionensis | Biblioteca Capitular y Archivo de la Real Colegiata de San Isidoro, ms 2 | |

| 10th century | Codex Toletanus | Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional ms Vitr. 13-1 | Spanish - earthly before heavenly |

| 12th century | Codex Demidovianus[36] | An Old Latin manuscript[37] | |

| Greek manuscripts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Manuscript no. | Name | Place | Other information |

| 14th [38] –15th century | 629 | Codex Ottobonianus 298 | Vatican | Original.Diglot, Latin and Greek texts. |

| c. 1520[38] | 61 | Codex Montfortianus | Dublin | Original. Articles are missing before nouns. |

| 14th century | 209 | Venice, Biblioteca Marciana | The manuscript is written in Greek, however the comma was added into the margin in Latin during the 15th century by Cardinal Basil Bessarion.[7] | |

| 16th century[38] | 918 | Codex Escurialensis Σ.I.5 | Escorial(Spain) | Original. |

| 16th century | Ravianus (Berolinensis) | Berlin | Original, facsimile of printed Complutensian Polyglot Bible, removed from NT ms. list in 1908 | |

| c. 12th century[38] | 88 | Codex Regis | Victor Emmanuel III National Library, Napoli | Margin: 16th century[38] |

| c. 14th century[38] | 429 | Codex Guelferbytanus | Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbuttel, Germany | Margin: 16th century[citation needed] |

| 15th century[38] - 16th century[39][38] | 636 | Victor Emmanuel III National Library, Naples | Margin: 16th century[citation needed] | |

| 11th century | 177 | BSB Cod. graec. 211 | Bavarian State Library, Munich | Margin: late 16th century or later[40][38] |

| 17th century | 2473 | National Library, Athens | Original. | |

| 18th century[38] | 2318 | Romanian Academy, Bucharest | Original.Commentary mss. perhaps Oecumenius | |

| c. 10th century[38] | 221 | Bodleian Library, Oxford University | Margin: 19th century[citation needed] | |

| 11th century | 635 | Biblioteca Nazionale Vittorio Emanuele III | This manuscript has sometimes been cited as having the comma added later in the margin.[41][42][7] According to Metzger, it was added in the 17th century.[43] | |

Doubtful proposed manuscript attestation

[edit]The Codex Vaticanus in some places contains umlauts to indicate knowledge of variants. Although there has been some debate on the age of these umlauts and if they were added at a later date, according to a paper made by Philip B. Payne, the ink seems to match that of the original scribe.[44] The Codex Vaticanus contains these dots around 1 John 5:7, which is why some have assumed it to be a reference to the Johannine Comma. However, according to McDonald, G. R, it is far more likely that the scribe had encountered other variants in the verse than the Johannine comma, which is not attested in any Greek manuscript until the 14th century.[7]

No extant Syriac manuscripts contain the Johannine Comma,[45] nevertheless some past advocates of the inclusion of the Johannine comma such as Thomas Burgess (1756-1837) have proposed that the inclusion of the conjuctive participle "and" within the text of 1 John 5:7 in Syriac manuscripts is an indication of its past inclusion within the Syriac textual tradition.[46]

It is known that Erasmus was aware of a codex from Antwerp which was presented to him at the Franciscan monastery. This manuscript was likely lost during the times of Napoleon, however it was said to have contained the Johannine Comma in the margin, as Erasmus mentions it in his Annotations. Nevertheless, Erasmus doubted the originality of that marginal note within the manuscript and believed that it was a recent addition within it. The exact nature of this manuscript from Antwerp is unknown, scholars such as Mills, Küster and Allen have argued that it was a Greek New Testament manuscript. However, others such as Wettstein have proposed that this was instead a manuscript of the commentary of Bede (672/3 – 26 May 735).[7]

Patristic writers

[edit]Clement of Alexandria

[edit]

The comma is absent from an extant fragment of Clement of Alexandria (c. 200), through Cassiodorus (6th century), with homily style verse references from 1 John, including verse 1 John 5:6 and 1 John 5:8 without verse 7, the heavenly witnesses.

He says, "This is He who came by water and blood"; and again, – For there are three that bear witness, the spirit, which is life, and the water, which is regeneration and faith, and the blood, which is knowledge; "and these three are one. For in the Saviour are those saving virtues, and life itself exists in His own Son."[16][47]

Another reference that is studied is from Clement's Prophetic Extracts:

Every promise is valid before two or three witnesses, before the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit; before whom, as witnesses and helpers, what are called the commandments ought to be kept.[48]

This is seen by some[49] as allusion evidence that Clement was familiar with the verse.

Tertullian

[edit]Tertullian, in Against Praxeas (c. 210), supports a Trinitarian view by quoting John 10:30:

So the close series of the Father in the Son and the Son in the Paraclete makes three who cohere, the one attached to the other: And these three are one substance, not one person, (qui tres unum sunt, non unus) in the sense in which it was said, "I and the Father are one" in respect of unity of substance, not of singularity of number.[50]

While many other commentators have argued against any Comma evidence here, most emphatically John Kaye's, "far from containing an allusion to 1 Jo. v. 7, it furnishes most decisive proof that he knew nothing of the verse".[51] Georg Strecker comments cautiously "An initial echo of the Comma Johanneum occurs as early as Tertullian Adv. Pax. 25.1 (CChr 2.1195; written c. 215). In his commentary on John 16:14 he writes that the Father, Son, and Paraclete are one (unum), but not one person (unus). However, this passage cannot be regarded as a certain attestation of the Comma Johanneum."[52]

References from Tertullian in De Pudicitia 21:16 (On Modesty):

The Church, in the peculiar and the most excellent sense, is the Holy Ghost, in which the Three are One, and therefore the whole union of those who agree in this belief (viz. that God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost are one), is named the Church, after its founder and sanctifier (the Holy Ghost).[53]

and De Baptismo:

Now if every word of God is to be established by three witnesses ... For where there are the three, namely the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, there is the Church which is a body of the three.[54]

have also been presented as verse allusions.[55]

Treatise on Rebaptism

[edit]The Treatise on Rebaptism, placed as a 3rd-century writing and transmitted with Cyprian's works, has two sections that directly refer to the earthly witnesses, and thus has been used against authenticity by Nathaniel Lardner, Alfred Plummer and others. However, because of the context being water baptism and the precise wording being "et isti tres unum sunt", the Matthew Henry Commentary uses this as evidence for Cyprian speaking of the heavenly witnesses in Unity of the Church. Arthur Cleveland Coxe and Nathaniel Cornwall also consider the evidence as suggestively positive, as do Westcott and Hort. After approaching the Tertullian and Cyprian references negatively, "morally certain that they would have quoted these words had they known them" Westcott writes about the Rebaptism Treatise:

the evidence of Cent. III is not exclusively negative, for the treatise on Rebaptism contemporary with Cyp. quotes the whole passage simply thus (15: cf. 19), "quia tres testimonium perhibent, spiritus et aqua et sanguis, et isti tres unum sunt".[56]

Jerome

[edit]The Catholic Encyclopedia of 1910 asserts that Jerome "does not seem to know the text",[23] but Charles Forster suggests that the "silent publication of [the text] in the Vulgate ... gives the clearest proof that down to his time the genuineness of this text had never been disputed or questioned."[57]

Many Vulgate manuscripts, including the Codex Fuldensis, the earliest extant Vulgate manuscript, include a Prologue to the Canonical Epistles referring to the Comma:

If the letters were also rendered faithfully by translators into Latin just as their authors composed them, they would not cause the reader confusion, nor would the differences between their wording give rise to contradictions, nor would the various phrases contradict each other, especially in that place where we read the clause about the unity of the Trinity in the first letter of John. Indeed, it has come to our notice that in this letter some unfaithful translators have gone far astray from the truth of the faith, for in their edition they provide just the words for three [witnesses]—namely water, blood and spirit—and omit the testimony of the Father, the Word and the Spirit, by which the Catholic faith is especially strengthened, and proof is tendered of the single substance of divinity possessed by Father, Son and Holy Spirit.77[58]

The Prologue presents itself as a letter of Jerome to Eustochium, to whom Jerome dedicated his commentary on the prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel. Despite the first-person salutation, some claim it is the work of an unknown imitator from the late 5th century.[59] (The Codex Fuldensis Prologue references the Comma, but the Codex's version of 1 John omits it, which has led many to believe that the Prologue's reference is spurious.)[60] Its inauthenticity is arguably stressed by the omission of the passage from the manuscript's own text of 1 John; however, this can also be seen as confirming the claim in the Prologue that scribes tended to drop the text.

Marcus Celedensis

[edit]Coming down with the writings of Jerome is the extant statement of faith attributed to Marcus Celedensis, friend and correspondent to Jerome, presented to Cyril:

To us there is one Father, and his only Son [who is] very [or true] God, and one Holy Spirit, [who is] very God, and these three are one; – one divinity, and power, and kingdom. And they are three persons, not two nor one.[61][62]

Phoebadius of Agen

[edit]Similarly, Jerome wrote of Phoebadius of Agen in his Lives of Illustrious Men. "Phoebadius, bishop of Agen, in Gaul, published a book Against the Arians. There are said to be other works by him, which I have not yet read. He is still living, infirm with age."[63] William Hales looks at Phoebadius:

Phoebadius, A. D. 359, in his controversy with the Arians, Cap, xiv. writes, "The Lord says, I will ask of my Father, and He will give you another advocate." (John xiv. 16) Thus, the Spirit is another from the Son as the Son is another from the Father; so, the third person is in the Spirit, as the second, is in the Son. All, however, are one God, because the three are one, (tres unum sunt.) ... Here, 1 John v. 7, is evidently connected, as a scriptural argument, with John xiv. 16.[64]

Griesbach argued that Phoebadius was only making an allusion to Tertullian,[65] and his unusual explanation was commented on by Reithmayer.[66][67]

Augustine

[edit]Augustine of Hippo has been said to be completely silent on the matter, which has been taken as evidence that the Comma did not exist as part of the epistle's text in his time.[68] This argumentum ex silentio has been contested by other scholars, including Fickermann and Metzger.[69] In addition, some Augustine references have been seen as verse allusions.[70]

The City of God section, from Book V, Chapter 11:

Therefore God supreme and true, with His Word and Holy Spirit (which three are one), one God omnipotent ...[71]

has often been referenced as based upon the scripture verse of the heavenly witnesses.[72] George Strecker acknowledges the City of God reference: "Except for a brief remark in De civitate Dei (5.11; CChr 47.141), where he says of Father, Word, and Spirit that the three are one. Augustine († 430) does not cite the Comma Johanneum. But it is certain on the basis of the work Contra Maximum 2.22.3 (PL 42.794–95) that he interpreted 1 John 5:7–8 in trinitarian terms."[52] Similarly, Homily 10 on the first Epistle of John has been asserted as an allusion to the verse:

And what meaneth "Christ is the end"? Because Christ is God, and "the end of the commandment is charity" and "Charity is God": because Father and Son and Holy Ghost are One.[73][74]

Contra Maximinum has received attention especially for these two sections, especially the allegorical interpretation.

I would not have thee mistake that place in the epistle of John the apostle where he saith, "There are three witnesses: the spirit, and the water, and the blood: and the three are one." Lest haply thou say that the spirit and the water and the blood are diverse substances, and yet it is said, "the three are one": for this cause I have admonished thee, that thou mistake not the matter. For these are mystical expressions, in which the point always to be considered is, not what the actual things are, but what they denote as signs: since they are signs of things, and what they are in their essence is one thing, what they are in their signification another. If then we understand the things signified, we do find these things to be of one substance ... But if we will inquire into the things signified by these, there not unreasonably comes into our thoughts the Trinity itself, which is the One, Only, True, Supreme God, Father and Son and Holy Ghost, of whom it could most truly be said, "There are Three Witnesses, and the Three are One": there has been an ongoing dialog about context and sense.

John Scott Porter writes:

Augustine, in his book against Maximin the Arian, turns every stone to find arguments from the Scriptures to prove that the Spirit is God, and that the Three Persons are the same in substance, but does not adduce this text; nay, clearly shows that he knew nothing of it, for he repeatedly employs the 8th verse, and says, that by the Spirit, the Blood, and the Water—the persons of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, are signified (see Contr. Maxim, cap. xxii.).[75]

Thomas Joseph Lamy offers a different view based on the context and Augustine's purpose.[76] Similarly Thomas Burgess.[77] And Norbert Fickermann's reference and scholarship supports the idea that Augustine may have deliberately bypassed a direct quote of the heavenly witnesses.

Leo the Great

[edit]In the Tome of Leo, written to Archbishop Flavian of Constantinople, read at the Council of Chalcedon on 10 October 451 AD,[78] and published in Greek, Leo the Great's usage of 1 John 5 has him moving in discourse from verse 6 to verse 8:

This is the victory which overcometh the world, even our faith"; and: "Who is he that overcometh the world, but he that believeth that Jesus is the Son of God? This is he that came by water and blood, even Jesus Christ; not by water only, but by water and blood; and it is the Spirit that beareth witness, because the Spirit is truth. For there are three that bear witness, the spirit, the water, and the blood; and the three are one." That is, the Spirit of sanctification, and the blood of redemption, and the water of baptism; which three things are one, and remain undivided ...[79]

This epistle from Leo was considered by Richard Porson to be the "strongest proof" of verse inauthenticity.[80] In response, Thomas Burgess points out that the context of Leo's argument would not call for the 7th verse. And that the verse was referenced in a fully formed manner centuries earlier than Porson's claim, at the time of Fulgentius and the Council of Carthage.[81] Burgess pointed out that there were multiple confirmations that the verse was in the Latin Bibles of Leo's day. Burgess argued, ironically, that the fact that Leo could move from verse 6 to 8 for argument context is, in the bigger picture, favourable to authenticity. "Leo's omission of the Verse is not only counterbalanced by its actual existence in contemporary copies, but the passage of his Letter is, in some material respects, favourable to the authenticity of the Verse, by its contradiction to some assertions confidently urged against the Verse by its opponents, and essential to their theory against it."[82] Today, with the discovery of additional Old Latin evidences in the 19th century, the discourse of Leo is rarely referenced as a significant evidence against verse authenticity.

Cyprian of Carthage - Unity of the Church

[edit]

The 3rd-century Church father Cyprian (c. 200–58), in writing on the Unity of the Church 1.6, quoted John 10:30 and another scriptural spot:

The Lord says, "I and the Father are one"

and again it is written of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,

"And these three are one."[83]

The Catholic Encyclopedia concludes "Cyprian ... seems undoubtedly to have had it in mind".[18] Against this view, Daniel B. Wallace writes that since Cyprian does not quote 'the Father, the Word, and the Holy Spirit', "this in the least does not afford proof that he knew of such wording".[84] The fact that Cyprian did not quote the "exact wording… indicates that a Trinitarian interpretation was superimposed on the text by Cyprian".[85] The Critical Text apparatuses have taken varying positions on the Cyprian reference.[86]

The Cyprian citation, dating to more than a century before any extant Epistle of John manuscripts and before the Arian controversies that are often considered pivotal in verse addition/omission debate, remains a central focus of comma research and textual apologetics. The Scrivener view is often discussed.[87] Westcott and Hort assert: "Tert and Cyp use language which renders it morally certain that they would have quoted these words had they known them; Cyp going so far as to assume a reference to the Trinity in the conclusion of v. 8"[88][89]

In the 20th century, Lutheran scholar Francis Pieper wrote in Christian Dogmatics emphasizing the antiquity and significance of the reference.[90] Frequently commentators have seen Cyprian as having the verse in his Latin Bible, even if not directly supporting and commenting on verse authenticity.[91] Some writers have also seen the denial of the verse in the Bible of Cyprian as worthy of special note and humor.[92]

Daniel B. Wallace notes that although Cyprian uses 1 John to argue for the Trinity, he appeals to this as an allusion via the three witnesses—"written of"—rather than by quoting a proof-text—"written that".[85] Therefore, despite the view of some that Cyprian referred to the passage, the fact that other theologians such as Athanasius of Alexandria and Sabellius and Origen never quoted or referred to that passage is one reason why even many Trinitarians later on also considered the text spurious, and not to have been part of the original text.

Ad Jubaianum (Epistle 73)

[edit]The second, lesser reference from Cyprian that has been involved in the verse debate is from Ad Jubaianum 23.12. Cyprian, while discussing baptism, writes:

If he obtained the remission of sins, he was sanctified, and if he was sanctified, he was made the temple of God. But of what God? I ask. The Creator?, Impossible; he did not believe in him. Christ? But he could not be made Christ's temple, for he denied the deity of Christ. The Holy Spirit? Since the Three are One, what pleasure could the Holy Spirit take in the enemy of the Father and the Son?[93]

Knittel emphasizes that Cyprian would be familiar with the Bible in Greek as well as Latin. "Cyprian understood Greek. He read Homer, Plato, Hermes Trismegistus and Hippocrates ... he translated into Latin the Greek epistle written to him by Firmilianus".[94] UBS-4 has its entry for text inclusion as (Cyprian).

Ps-Cyprian - Hundredfold Reward for Martyrs and Ascetics

[edit]The Hundredfold Reward for Martyrs and Ascetics: De centesima, sexagesimal tricesima[95] speaks of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit as "three witnesses" and was passed down with the Cyprian corpus. This was only first published in 1914 and thus does not show up in the historical debate. UBS-4 includes this in the apparatus as (Ps-Cyprian).[96]

Origen and Athanasius

[edit]Those who see Cyprian as negative evidence assert that other church writers, such as Athanasius of Alexandria and Origen,[97] never quoted or referred to the passage, which they would have done if the verse was in the Bibles of that era. The contrasting position is that there are in fact such references, and that "evidences from silence" arguments, looking at the extant early church writer material, should not be given much weight as reflecting absence in the manuscripts—with the exception of verse-by-verse homilies, which were uncommon in the Ante-Nicene era.

Origen's scholium on Psalm 123:2

[edit]In the scholium on Psalm 123 attributed to Origen is the commentary:

spirit and body are servants to masters,

Father and Son, and the soul is handmaid to a mistress, the Holy Ghost;

and the Lord our God is the three (persons),

for the three are one.

This has been considered by many commentators, including the translation source Nathaniel Ellsworth Cornwall, as an allusion to verse 7.[98] Ellsworth especially noted the Richard Porson comment in response to the evidence of the Psalm commentary: "The critical chemistry which could extract the doctrine of the Trinity from this place must have been exquisitely refining".[99] Fabricius wrote about the Origen wording "ad locum 1 Joh v. 7 alludi ab origene non est dubitandum".[100]

Athanasius and Arius at the Council of Nicea

[edit]Traditionally, Athanasius was considered to lend support to the authenticity of the verse, one reason being the Disputation with Arius at the Council of Nicea which circulated with the works of Athanasius, where is found:

Likewise is not the remission of sins procured by that quickening and sanctifying ablution, without which no man shall see the kingdom of heaven, an ablution given to the faithful in the thrice-blessed name. And besides all these, John says, And the three are one.[101]

Today, many scholars consider this a later work Pseudo-Athanasius, perhaps by Maximus the Confessor. Charles Forster in New Plea argues for the writing as stylistically Athanasius.[102] While the author and date are debated, this is a Greek reference directly related to the doctrinal Trinitarian-Arian controversies, and one that purports to be an account of Nicaea when those doctrinal battles were raging. The reference was given in UBS-3 as supporting verse inclusion, yet was removed from UBS-4 for reasons unknown.

The Synopsis of Scripture, often ascribed to Athanasius, has also been referenced as indicating awareness of the Comma.

Priscillian of Avila

[edit]The earliest quotation which some scholars consider a direct reference to the heavenly witnesses from the First Epistle of John is from the Spaniard Priscillian c. 380. The Latin reads:

Sicut Ioannes ait: tria sunt quae testimonium dicunt in terra aqua caro et sanguis et haec tria in unum sunt, et tria sunt quae testimonium dicent in caelo pater uerbum et spiritus et haiec tria unum sunt in Christo Iesu.[103]

The English translation:

As John says and there are three which give testimony on earth the water the flesh the blood and these three are in one and there are three which give testimony in heaven the Father the Word and the Spirit and these three are one in Christ Jesus.[104]

Theodor Zahn calls this "the earliest quotation of the passage which is certain and which can be definitely dated (circa 380)",[105] a view expressed by Westcott, Brooke, Metzger and others.[106]

Priscillian was probably a Sabellianist or Modalist Monarchian.[107] Some interpreters have theorized that Priscillian created the Comma Johanneum. However, there are signs of the Comma Johanneum, although no certain attestations, even before Priscillian".[52] And Priscillian in the same section references The Unity of the Church section from Cyprian.[108] In the early 1900s the Karl Künstle theory of Priscillian origination and interpolation was popular: "The verse is an interpolation, first quoted and perhaps introduced by Priscillian (a.d. 380) as a pious fraud to convince doubters of the doctrine of the Trinity."[109]

Expositio Fidei

[edit]Another complementary early reference is an exposition of faith published in 1883 by Carl Paul Caspari from the Ambrosian manuscript, which also contains the Muratorian (canon) fragment.

pater est Ingenitus, filius uero sine Initio genitus a patre est, spiritus autem sanctus processit a patre et accipit de filio, Sicut euangelista testatur quia scriptum est, "Tres sunt qui dicunt testimonium in caelo pater uerbum et spiritus:" et haec tria unum sunt in Christo lesu. Non tamen dixit "Unus est in Christo lesu."

Edgar Simmons Buchanan,[110] points out that the reading "in Christo Iesu" is textually valuable, referencing 1 John 5:7.

The authorship is uncertain, however it is often placed around the same period as Priscillian. Karl Künstle saw the writing as anti-Priscillianist, which would have competing doctrinal positions utilizing the verse. Alan England Brooke[111] notes the similarities of the Expositio with the Priscillian form, and the Priscillian form with the Leon Palimpsest. Theodor Zahn[112] refers to the Expositio as "possibly contemporaneous" to Priscillian, "apparently taken from the proselyte Isaac (alias Ambrosiaster)".

John Chapman looked closely at these materials and the section in Liber Apologeticus around the Priscillian faith statement "Pater Deus, Filius, Deus, et Spiritus sanctus Deus; haec unum sunt in Christo Iesu". Chapman saw an indication that Priscillian found himself bound to defend the comma by citing from the "Unity of the Church" Cyprian section.[113]

Council of Carthage, 484

[edit]"The Comma ... was invoked at Carthage in 484 when the Catholic bishops of North Africa confessed their faith before Huneric the Vandal (Victor de Vita, Historia persecutionis Africanae Prov 2.82 [3.11]; CSEL, 7, 60)."[114] The Confession of Faith representing the hundreds of Orthodox bishops[115] included the following section, emphasizing the heavenly witnesses to teach luce clarius ("clearer than the light"):

And so, no occasion for uncertainty is left. It is clear that the Holy Spirit is also God and the author of his own will, he who is most clearly shown to be at work in all things and to bestow the gifts of the divine dispensation according to the judgment of his own will, because where it is proclaimed that he distributes graces where he wills, servile condition cannot exist, for servitude is to be understood in what is created, but power and freedom in the Trinity. And so that we may teach the Holy Spirit to be of one divinity with the Father and the Son still more clearly than the light, here is proof from the testimony of John the evangelist. For he says: "There are three who bear witness in heaven, the Father, the Word and the Holy Spirit, and these three are one." Surely he does not say "three separated by a difference in quality" or "divided by grades which differentiate, so that there is a great distance between them"? No, he says that the "three are one". But so that the single divinity which the Holy Spirit has with the Father and the Son might be demonstrated still more in the creation of all things, you have in the book of Job the Holy Spirit as a creator: "It is the divine Spirit" .. [116][117]

De Trinitate and Contra Varimadum

[edit]There are additional heavenly witnesses references that are considered to be from the same period as the Council of Carthage, including references that have been attributed to Vigilius Tapsensis who attended the Council. Raymond Brown gives one summary:

... in the century following Priscillian, the chief appearance of the Comma is in tractates defending the Trinity. In PL 62 227–334 there is a work De Trinitate consisting of twelve books ... In Books 1 and 10 (PL 62, 243D, 246B, 297B) the Comma is cited three times. Another work on the Trinity consisting of three books Contra Varimadum ... North African origin ca. 450 seems probable. The Comma is cited in 1.5 (CC 90, 20–21).[118]

One of the references in De Trinitate, from Book V:

But the Holy Ghost abides in the Father, and in the Son [Filio] and in himself; as the Evangelist St. John so absolutely testifies in his Epistle: And the three are one. But how, ye heretics, are the three ONE, if their substance he divided or cut asunder? Or how are they one, if they be placed one before another? Or how are the three one. if the Divinity be different in each? How are they one, if there reside not in them the united eternal plenitude of the Godhead?[119] These references are in the UBS apparatus as Ps-Vigilius.

The Contra Varimadum reference:

John the Evangelist, in his Epistle to the Parthians (i.e. his 1st Epistle), says there are three who afford testimony on earth, the Water, the Blood, and the Flesh, and these three are in us; and there are three who afford testimony in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Spirit, and these three are one.[120]

This is in the UBS apparatus as Varimadum.

Ebrard, in referencing this quote, comments, "We see that he had before him the passage in his New Testament in its corrupt form (aqua, sanguis et caro, et tres in nobis sunt); but also, that the gloss was already in the text, and not merely in a single copy, but that it was so widely diffused and acknowledged in the West as to be appealed to by him bona fide in his contest with his Arian opponents."[121]

Fulgentius of Ruspe

[edit]In the 6th century, Fulgentius of Ruspe, like Cyprian a father of the North African Church, skilled in Greek as well as his native Latin, used the verse in the doctrinal battles of the day, giving an Orthodox explanation of the verse against Arianism and Sabellianism.

Contra Arianos

[edit]From Responsio contra Arianos ("Reply against the Arians"; Migne (Ad 10; CC 91A, 797)):

In the Father, therefore, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, we acknowledge unity of substance, but dare not confound the persons. For St. John the apostle, testifieth saying, "There are three that bear witness in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Spirit, and these three are one."

Then Fulgentius discusses the earlier reference by Cyprian, and the interweaving of the two Johannine verses, John 10:30 and 1 John 5:7.

Which also the blessed martyr Cyprian, in his epistle de unitate Ecclesiae (Unity of the Church), confesseth, saying, Who so breaketh the peace of Christ, and concord, acteth against Christ: whoso gathereth elsewhere beside the Church, scattereth. And that he might shew, that the Church of the one God is one, he inserted these testimonies, immediately from the scriptures; The Lord said, "I and the Father are one." And again, of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, it is written, "and these three are one".[122]

Contra Fabianum

[edit]Another heavenly witnesses reference from Fulgentius is in Contra Fabianum Fragmenta (Migne (Frag. 21.4: CC 01A,797)):[123]

The blessed Apostle, St. John evidently says, And the three are one; which was said of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, as I have before shewn, when you demanded of me for a reason[124]

De Trinitate ad Felicem

[edit]Also from Fulgentius in De Trinitate ad Felicem:

See, in short you have it that the Father is one, the Son another, and the Holy Spirit another, in Person, each is other, but in nature they are not other. In this regard He says: "The Father and I, we are one." He teaches us that one refers to Their nature, and we are to Their persons. In like manner it is said: "There are three who bear witness in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Spirit; and these three are one."[125]

Today these references are generally accepted as probative to the verse being in the Bible of Fulgentius.[126]

Adversus Pintam episcopum Arianum

[edit]A reference in De Fide Catholica adversus Pintam episcopum Arianum that is a Testimonia de Trinitate:

in epistola Johannis, tres sunt in coelo, qui testimonium reddunt,

Pater, Verbum, et Spiritus: et hi tres unum sunt[127]

has been assigned away from Fulgentius to a "Catholic controvertist of the same age".[128]

Cassiodorus

[edit]Cassiodorus wrote Bible commentaries, and was familiar with Old Latin and Vulgate manuscripts,[129] seeking out sacred manuscripts. Cassiodorus was also skilled in Greek. In Complexiones in Epistolis Apostolorum, first published in 1721 by Scipio Maffei, in the commentary section on 1 John, from the Cassiodorus corpus, is written:

On earth three mysteries bear witness,

the water, the blood, and the spirit,

which were fulfilled, we read, in the passion of the Lord.

In heaven, are the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit,

and these three are one God.[130]

Thomas Joseph Lamy describes the Cassiodorus section[131] and references that Tischendorf saw this as Cassiodorus having the text in his Bible. However, earlier "Porson endeavoured to show that Cassiodorus had, in his copy, no more than the 8th verse, to which he added the gloss of Eucherius, with whose writings he was acquainted."[132]

Isidore of Seville

[edit]In the early 7th century, the Testimonia Divinae Scripturae et Patrum is often attributed to Isidore of Seville:

De Distinctions personarum, Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti.

In Epistola Joannis. Quoniam tres sunt qui testimonium dant in terra Spiritus, aqua, et sanguis; et tres unum sunt in Christo Jesu; et tres sunt qui testimonium dicunt in coelo, Pater, Verbum, et Spiritus, et tres unum sunt.

Arthur-Marie Le Hir asserts that evidences like Isidore and the Ambrose Ansbert Commentary on Revelation show early circulation of the Vulgate with the verse and thus also should be considered in the issues of Jerome's original Vulgate text and the authenticity of the Vulgate Prologue.[134] Cassiodorus has also been indicated as reflecting the Vulgate text, rather than simply the Vetus Latina.[135]

Commentary on Revelation

[edit]Ambrose Ansbert refers to the scripture verse in his Revelation commentary:

Although the expression of faithful witness found therein, refers directly to Jesus Christ alone, – yet it equally characterises the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost; according to these words of St. John. There are three which bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost, and these three are one.[136]

"Ambrose Ansbert, in the middle of the eighth century, wrote a comment upon the Apocalypse, in which this verse is applied, in explaining the 5th verse of the first chapter of the Revelation".[137]

Medieval use

[edit]Fourth Lateran Council

[edit]In the Middle Ages a Trinitarian doctrinal debate arose around the position of Joachim of Fiore (1135–1202) which was different from the more traditional view of Peter Lombard (c. 1100–1160). When the Fourth Council of the Lateran was held in 1215 at Rome, with hundreds of Bishops attending, the understanding of the heavenly witnesses was a primary point in siding with Lombard, against the writing of Joachim.

For, he says, Christ's faithful are not one in the sense of a single reality which is common to all. They are one only in this sense, that they form one church through the unity of the catholic faith, and finally one kingdom through a union of indissoluble charity. Thus we read in the canonical letter of John: For there are three that bear witness in heaven, the Father and the Word and the holy Spirit, and these three are one; and he immediately adds, And the three that bear witness on earth are the spirit, water and blood, and the three are one, according to some manuscripts.[138]

The Council thus printed the verse in both Latin and Greek, and this may have contributed to later scholarship references in Greek to the verse. The reference to "some manuscripts" showed an acknowledgment of textual issues, yet this likely related to "and the three are one" in verse eight, not the heavenly witnesses in verse seven.[139] The manuscript issue for the final phrase in verse eight and the commentary by Thomas Aquinas were an influence upon the text and note of the Complutensian Polyglot.

Latin commentaries

[edit]In this period, the greater portion of Bible commentary was written in Latin. The references in this era are extensive and wide-ranging. Some of the better-known writers who utilized the comma as scripture, in addition to Peter Lombard and Joachim of Fiore, include Gerbert of Aurillac (Pope Sylvester), Peter Abelard, Bernard of Clairvaux, Duns Scotus, Roger of Wendover (historian, including the Lateran Council), Thomas Aquinas (many verse uses, including one which has Origen relating to "the three that give witness in heaven"), William of Ockham (of razor fame), Nicholas of Lyra and the commentary of the Glossa Ordinaria.[58]

Greek commentaries

[edit]Emanual Calecas in the 14th and Joseph Bryennius (c. 1350–1430) in the 15th century reference the comma in their Greek writings.

The Orthodox accepted the comma as Johannine scripture notwithstanding its absence in the Greek manuscripts line. The Orthodox Confession of Faith, published in Greek in 1643 by the multilingual scholar Peter Mogila specifically references the comma. "Accordingly the Evangelist teacheth (1 John v. 7.) There are three that bear Record in Heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost and these three are one …"[29]

Armenia – Synod of Sis

[edit]The Epistle of Gregory, the Bishop of Sis, to Haitho c. 1270 utilized 1 John 5:7 in the context of the use of water in the mass. The Synod of Sis of 1307 expressly cited the verse, and deepened the relationship with Rome.[33]

Commentators generally see the Armenian text from the 13th century on as having been modified by the interaction with the Latin church and Bible, including the addition of the comma in some manuscripts.

Manuscripts and special notations

[edit]There are a number of special manuscript notations and entries relating to 1 John 5:7. Vulgate scholar Samuel Berger reports on Corbie MS 13174 in the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris that shows the scribe listing four distinct textual variations of the heavenly witnesses. Three are understood by the scribe to have textual lineages of Athanasius, Augustine (two) and Fulgentius. And there is in addition a margin text of the heavenly witnesses that matches the Theodulphian recension.[140] The Franciscan Correctorium gives a note about there being manuscripts with the verses transposed.[141] The Regensburg ms. referenced by Fickermann discusses the positions of Jerome and Augustine. Contarini,[142] The Glossa Ordinaria discusses the Vulgate Prologue in the Preface, in addition to its commentary section on the verse. John J. Contrini in Haimo of Auxerre, Abbot of Sasceium (Cessy-les-Bois), and a New Sermon on I John v. 4–10 discusses a 9th-century manuscript and the Leiden sermon.

Inclusion by Erasmus

[edit]

The central figure in the 16th-century history of the Johannine Comma is the humanist Erasmus,[143] and his efforts leading to the publication of the Greek New Testament. The comma was omitted in the first edition in 1516, the Nouum instrumentum omne: diligenter ab Erasmo Roterodamo recognitum et emendatum and the second edition of 1519. The verse is placed in the third edition, published in 1522, and those of 1527 and 1535.

Erasmus included the comma, with commentary, in his paraphrase edition, first published in 1520.[144] And in Ratio seu methodus compendio perueniendi ad ueram theologiam, first published in 1518, Erasmus included the comma in the interpretation of John 12 and 13. Erasmian scholar John Jack Bateman, discussing the Paraphrase and the Ratio uerae theologiae, says of these uses of the comma that "Erasmus attributes some authority to it despite any doubts he had about its transmission in the Greek text."[145]

The New Testament of Erasmus provoked critical responses that focused on a number of verses, including his text and translation decisions on Romans 9:5, John 1:1, 1 Timothy 1:17, Titus 2:13 and Philippians 2:6.[clarification needed] The absence of the comma from the first two editions received a sharp response from churchmen and scholars, and was discussed and defended by Erasmus in the correspondence with Edward Lee and Diego López de Zúñiga (Stunica), and Erasmus is also known to have referenced the verse in correspondence with Antoine Brugnard in 1518.[146] The first two Erasmus editions only had a small note about the verse. The major Erasmus writing regarding comma issues was in the Annotationes to the third edition of 1522, expanded in the fourth edition of 1527 and then given a small addition in the fifth edition of 1535.

Erasmus is said to have replied to his critics that the comma did not occur in any of the Greek manuscripts he could find, but that he would add it to future editions if it appeared in a single Greek manuscript. When a single such manuscript (the Codex Montfortianus), was subsequently found to contain it, he added the comma to his 1522 edition, though he expressed doubt as to the authenticity of the passage in his Annotations[13] and added a lengthy footnote setting out his suspicion that the manuscript had been prepared expressly to confute him. This manuscript had probably been produced in 1520 by a Franciscan who translated it from the Vulgate.[13] This change was accepted into editions based on the Textus Receptus, the chief source for the King James Version, thereby fixing the comma firmly in the English-language scriptures for centuries.[13] There is no explicit evidence, however, that such a promise was ever made.[147]

The authenticity of the story of Erasmus is questioned by many scholars. Bruce Metzger removed this story from his book's (The Text of the New Testament) third edition although it was included in the first and second editions in the same book.[148]

Despite being a commonly accepted fact in modern scholarship, some people in the past such as Thomas Burgess (1756 – 19 February 1837) have disputed the identification of Erasmus' "Codex Britannicus" as the same manuscript as the Codex Montfortianus, instead proposing that it is a now lost Greek manuscript.[149][13]

Modern reception

[edit]

In 1807 Charles Butler[150] described the dispute to that point as consisting of three distinct phases.

Erasmus and the Reformation

[edit]The 1st phase began with the disputes and correspondence involving Erasmus with Edward Lee followed by Jacobus Stunica. And about the 16th-century controversies, Thomas Burgess summarized "In the sixteenth century its chief opponents were Socinus, Blandrata, and the Fratres Poloni; its defenders, Ley, Beza, Bellarmine, and Sixtus Senensis."[151] In the 17th century John Selden in Latin and Francis Cheynell and Henry Hammond were English writers with studies on the verse, Johann Gerhard and Abraham Calovius from the German Lutherans, writing in Latin.

Simon, Newton, Mill and Bengel

[edit]The 2nd dispute stage begins with Sandius, the Arian around 1670. Francis Turretin published De Tribus Testibus Coelestibus in 1674 and the verse was a central focus of the writings of Symon Patrick. In 1689 the attack on authenticity by Richard Simon was published in English, in his Critical History of the Text of the New Testament. Many responded directly to the views of Simon, including Thomas Smith,[152] Friedrich Kettner,[153] James Benigne Bossuet,[154] Johann Majus, Thomas Ittigius, Abraham Taylor[155] and the published sermons of Edmund Calamy. There was the verse defences by John Mill and later by Johann Bengel. Also in this era was the David Martin and Thomas Emlyn debate. There were attacks on authenticity by Richard Bentley and Samuel Clarke and William Whiston and defence of authenticity by John Guyse in the Practical Expositor. There were writings by numerous additional scholars, including posthumous publication in London of Isaac Newton's Two Letters in 1754 (An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture), which he had written to John Locke in 1690. The mariner's compass poem of Bengel was given in a slightly modified form by John Wesley.[156]

Travis and Porson debate

[edit]The third stage of the controversy begins with the quote from Edward Gibbon in 1776:

Even the Scriptures themselves were profaned by their rash and sacrilegious hands. The memorable text, which asserts the unity of the three who bear witness in heaven, is condemned by the universal silence of the orthodox fathers, ancient versions, and authentic manuscripts. It was first alleged by the Catholic bishops whom Hunneric summoned to the conference of Carthage. An allegorical interpretation, in the form, perhaps, of a marginal note, invaded the text of the Latin Bibles, which were renewed and corrected in a dark period of ten centuries.[157]

It is followed by the response of George Travis that led to the Porson–Travis debate. In the 1794 3rd edition of Letters to Edward Gibbon, Travis included a 42-part appendix with source references. Another event coincided with the inauguration of this stage of the debate: "a great stirring in sacred science was certainly going on. Griesbach's first edition of the New Testament (1775–7) marks the commencement of a new era."[158] The Griesbach GNT provided an alternative to the Received Text editions to assist as scholarship textual legitimacy for opponents of the verse.

19th century

[edit]Some highlights from this era are the Nicholas Wiseman Old Latin and Speculum scholarship, the defence of the verse by the Germans Immanuel Sander, Besser, Georg Karl Mayer and Wilhelm Kölling, the Charles Forster New Plea book which revisited Richard Porson's arguments, and the earlier work by his friend Arthur-Marie Le Hir,[159] Discoveries included the Priscillian reference and Exposito Fidei. Also Old Latin manuscripts including La Cava, and the moving up of the date of the Vulgate Prologue due to its being found in Codex Fuldensis. Ezra Abbot wrote on 1 John V.7 and Luther's German Bible and Scrivener's analysis came forth in Six Lectures and Plain Introduction. In the 1881 Revision came the full removal of the verse.[160] Daniel McCarthy noted the change in position among the textual scholars,[161] and in French there was the sharp Roman Catholic debate in the 1880s involving Pierre Rambouillet, Auguste-François Maunoury, Jean Michel Alfred Vacant, Elie Philippe and Paulin Martin.[162] In Ireland Charles Vincent Dolman wrote about the Revision and the comma in the Dublin Review, noting that "the heavenly witnesses have departed".[163]

20th century

[edit]The 20th century saw the scholarship of Alan England Brooke and Joseph Pohle, the RCC controversy following the 1897 Papal declaration as to whether the verse could be challenged by Catholic scholars, the Karl Künstle Priscillian-origin theory, the detailed scholarship of Augustus Bludau in many papers, the Eduard Riggenbach book, and the Franz Pieper and Edward F. Hills defences. There were specialty papers by Anton Baumstark (Syriac reference), Norbert Fickermann (Augustine), Claude Jenkins (Bede), Mateo del Alamo, Teófilo Ayuso Marazuela, Franz Posset (Luther) and Rykle Borger (Peshitta). Verse dismissals, such as that given by Bruce Metzger, became popular.[164] There was the fine technical scholarship of Raymond Brown. And the continuing publication and studies of the Erasmus correspondence, writings and Annotations, some with English translation. From Germany came Walter Thiele's Old Latin studies and sympathy for the comma being in the Bible of Cyprian, and the research by Henk de Jonge on Erasmus and the Received Text and the comma.

Recent scholarship

[edit]В первые 20 лет 21 -го века наблюдалось популярное возрождение интереса к историческим противоречиям и текстовым дебатам. Факторы включают рост интереса к полученному тексту и авторизованную версию (включая движение только в версии короля Джеймса) и допрос теорий критического текста, книга 1995 года Майкла Мейнарда, документируя исторические дебаты по 1 Иоанна 5: 7, а также Способность Интернета стимулировать исследования и обсуждение с участием взаимодействия. В этот период защитники и оппоненты короля Джеймса написали ряд документов о запятой Иоганнине, обычно публикуемых в евангелической литературе и в Интернете. В кругах стипендии текстовой критики книга Клауса Вахтел -дер -византиниша текста Дер Католисхен: Eine Untersuchung Zur Entstehung der Koine des Neuen Testaments , 1995 г. содержит раздел с подробными исследованиями в сменах. Точно так же Der Einzig Wahre Bibeltext? , опубликовано в 2006 году К. Мартином Хайде. Особые интерес были предоставлены исследованиям Codex Vaticanus Umlauts Филиппа Бартона Пейна и Пола Канарта, старшего палерографа в библиотеке Ватикана. [ 165 ] Продолжались исследования Erasmus, включая исследования валладолидного расследования Питера Г. Биетенхольца и Лу Энн Хомзы. Ян Кранс написал на предположительную поправку и другие текстовые темы, внимательно следя за полученной текстовой работой Erasmus и Beza. И некоторые элементы недавнего стипендиального комментария были особенно пренебрежительными и негативными. [ 166 ]

Католическая церковь

[ редактировать ]Католическая церковь в Совете Трента в 1546 году определила библейский канон как «все книги со всеми их частями, так как они, как правило, читаются в католической церкви и содержатся в старом латинском вульгате». Запятая появилась как в шестидесятилетних (1590), так и в изданиях Клементина (1592) Вульгата. [ 167 ] Хотя пересмотренный Vulgate содержал запятую, самые ранние известные копии этого не сделали, оставив статус запятой Йоханнеума неясным. [ 23 ] 13 января 1897 года, в течение периода реакции в церкви, Священное канцелярия постановила, что католические богословы не могут «с безопасностью» отрицания или привлечь к сомнению подлинность запятой. Папа Лео XIII одобрил это решение через два дня, хотя его одобрение не было в Forma Speica [ 23 ] - То есть, Лео XIII не вкладывал свою полную папскую власть в этот вопрос, оставив указ с обычной властью, одержимой Священной должностью. Три десятилетия спустя, 2 июня 1927 года, папа Пий XI постановил, что запятая Йоханнеума была открыта для расследования. [ 168 ] [ 169 ]

Движение только короля Джеймса

[ редактировать ]В последние годы запятая стала актуальной для движения только короля Джеймса , протестантского развития, наиболее распространенного в фундаменталистской и независимой баптистской филиалах баптистских церквей. Многие сторонники рассматривают запятую как важный тринитарный текст. [ 170 ] Защита стиха Эдварда Фриер Хиллз в 1956 году в его книге «Королевская версия» защищалась в разделе «Иоганновая запятнанная (1 Иоанна 5: 7)» была необычной из -за стипендий по текстовой критике Хиллз.

Грамматический анализ

[ редактировать ]В 1 Иоанна 5: 7–8 в критическом тексте и тексте большинства, хотя и не полученный текст, у нас есть более короткий текст только с земными свидетелями. И появляются следующие слова.

1 Иоанна 5: 7-8… что трое свидетелей духа и воды, кровь и кровь

1 Иоанна 5: 7-8… Ибо трое, которые имеют свидетельство, дух и вода, и кровь, а трое согласны в одном.

Грант Роберт Макдональд дает историю письма 1780 года [ 171 ] от Евгения Болгариса (1716–1806) вместе с объяснением грамматического гендерного вопроса о разнообразии, когда в тексте есть только земные свидетели.

«В качестве дополнительных доказательств подлинности запятой, Болгарис отметил отсутствие грамматической координации между мужскими тремя свидетелями и тремя существительными нейтетрами духа и водой и кровью. Греческий, чтобы согласовать мужские или женские существительные отходы через Грамматика ... " Библейская критика в ранней современной Англии с. 114 [3]

Ранее Desiderius Erasmus заметил необычную грамматику, когда у его текста есть только земные свидетели, [ 172 ] [ 173 ] и Томас Нагеоргус (1511–1578) также задавался вопросом о грамматике. [ 174 ]

Кроме того, Matthaei сообщил о Scholium примерно от 1000 нашей эры. [ 175 ] Письма Порсона Трэвису дают текст схлиума как «три в мужском поле, в токене Троицы: Дух Бога; вода, просвещающего знания человечеству, духом; кровь, воплощения. "

В 300 -х годах Грегори Назианзен в речи 37 оспаривал некоторых македонских христиан. Контекст указывает на то, что они указали на грамматическую проблему. [ 176 ]

Евгений Болгарис видел «небесных свидетелей» как грамматически необходимые, чтобы объяснить мужскую грамматику, иначе только земные свидетели были бы солетизмом. Фредерик Нолан , [ 177 ] В своей книге 1815 года, расследование целостности греческого вульгата, привело аргумент Евгении в английских дебатах. Джон Оксли , [ 178 ] В дебатах с Ноланом заняли позицию, что грамматика «земных свидетелей» была здравой. Роберт Дабни [ 179 ] занял позицию, похожую на Евгениуса Болгариса и Фредерика Нолана, как и Эдвард Хиллз . [ 180 ] Даниэль Уоллес [ 181 ] предлагает возможное объяснение для короткой текстовой грамматики.

В 1 Иоанна 5: 7-8 в полученном тексте появляются следующие слова (слова, жирным шрифтом, являются словами Иоганнинской запятой).

(Получен текст) 1 Иоанна 5: 7 ... Свидетели в Небесном Отце и Святой Дух ... 8 ... Свидетели Духа , воду и кровь ...

В 1 Иоанна 5: 7-8 в критическом тексте и тексте большинства появляются следующие слова.

(Критический текст и большинство текста) 1 Иоанна 5: 7 ... Свидетели 8 Духа, вода и кровь ...

По словам Иоганна Бенгеля , [ 182 ] Юджин Болгария [ 183 ] Джон Оксли [ 184 ] и Даниэль Уоллес , [ 185 ] Каждая фраза с участием статьи (свидетели) в 1 Иоанна 5: 7-8 функционирует как существенная и соглашается с естественным полом (мужским), выражаемой (лиц), чтобы (предшествовало статье) существительные.

По словам Фредерика Нолана , [ 186 ] Роберт Дабни [ 187 ] и Эдвард Хиллз , [ 188 ] Каждая фраза статьи в статье в 1 Иоанна 5: 7-8 функционирует как прилегание, которая модифицирует три последующих суставных существительных, согласны с грамматическим полом (мужской / нейтральный) первого последующего суставного существительного (отец / дух).

Titus 2:13 является примером того, как изображается фраза, прилагаемая статья (или статья, независимо от статьи), когда она функционирует как прилагательное, которое изменяет несколько последующих существительных.

(Получен текст) Титу 2: 13… Благословенная надежда и поверхность ...

От Матфея 23:23 является примером того, как изображается фраза, прилагающая статью (или статью-партии), когда она функционирует как существенное, к которому добавляются множественные последующие суставные существительные.

(Получен текст) Матфея 23: 23 ... самый тяжелый из закона суда, ада и веры ...

По словам Бенгеля, Болгариса, Оксли и Уоллеса, 1 Иоанна 5: 7-8 похожа на Матфея 23:23, не как Титу 2:13.

По словам Нолана, Дабни и Хиллз, 1 Иоанна 5: 7-8 похожа на Титу 2:13, не как Матфея 23:23.

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Список стихов Нового Завета, не включенные в современные переводы на английский язык

- Текстовая критика

- Эразм

- Ричард Саймон (священник)

- Исаак Ньютон

- Дэвид Мартин (Французский Божественный) - переводчик французского библейского переводчика, который также защищал подлинность запятой Йоханнеума

- Евгениос Вулгарис - греческий ученый, который подчеркнул солецизм в коротком тексте

- Ричард Порсон - против подлинности, написал Contra George Travis

- Фредерик Нолан (богослов)

- Томас Берджесс (епископ) - написал книги, которые подчеркивают защиту Небесных Свидетелей

- Эдвард Ф. Хиллз

- Кодекс Равиан

Другие спорные отрывки Нового Завета

[ редактировать ]- Более длительное окончание знака

- Перикопский прелюбодей - женщина, попавшая в прелюбодеяние

- Матфея 16: 2b - 3 -, вы можете различить лицо неба; Но не можете ли вы не заметить признаки времени?

- Иоанна 5: 3b - 4 - бассейн Бетесды, Ангел обеспокоен водой

- Доксология для молитвы Господа

- Луки 22: 19b - 20

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Хайде, Мартин (7 февраля 2023 г.). «Эразм и поиск оригинального текста Нового Завета» . Текст и канонский институт . Получено 19 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Метцгер, Брюс М. (1994). Текстовый комментарий к греческому Новому Завету: том компаньона для греческого Нового Завета Объединенных Библейских обществ (четвертое пересмотренное издание) (2 изд.). Штутгарт: Deutsche Biblegesellschaft. С. 647–649. ISBN 978-3-438-06010-5 .

- ^ «Библейские шлюзы Проход: 1 Иоанна 5: 7 - Новый английский перевод» . Библейские шлюз . Получено 19 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Герри, Питер (2018). "Запятая Йоханнеум" В Хантере, Дэвид Г.; Ван Геест, Пол Джей Джей; Lietert Peerbolte, Bert Jan (Eds.). Брилл энциклопедия раннего христианства онлайн Лиден и Бостон : Brill издатели Doi : 10.1163/ 2589-7993_eco_sim_0 ISSN 2589-7

- ^ "Дух". Понимание по Священным Писаниям- Том 2. Сторожевая башня Библии и Общества трактатов Пенсильвании. п. 1019

- ^ Метцгер, Брюс. Текстовый комментарий к греческому Новому Завету. С. 716-718. 1975.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я McDonald, G. R (2011). Повышение призрака Ария: Эразм, Иоаннинская запятая и религиозная разница в ранней современной Европе (докторская диссертация). Лейденский университет. HDL : 1887/16486 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Католическая энциклопедия: Послания святого Иоанна» . www.newadvent.org . Получено 24 мая 2024 года .

Армянские рукописи, которые предпочитают чтение Вульгата, признаются, что представляют собой латинское влияние, которое датируется двенадцатым веком

- ^ Новый Завет . Эллинское Библейское общество. 2020. ISBN 978-618-5078-45-4 .

- ^ Эндрюс, Эдвард Д. (15 июня 2023 г.). Textus Receptus: «полученный текст» Нового Завета . Христианский издательство. ISBN 979-8-3984-5852-7 .

- ^ «Иоаннинская запятая» . www.bible-researcher.com . Получено 13 июня 2024 года .

- ^ Грантли Макдональд, Иоаннинская запятая от Эразма до Вестминстера (2017). Священная писательная власть и библейская критика в голландском золотом веке: слово Божье задано вопрос . УП Оксфорд. С. 64–. ISBN 978-0-19-252982-4 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Метцгер, Брюс М.; Эрман, Барт Д. (2005) [1964]. «Глава 3. Периочный период. Происхождение и доминирование текстового рецептуса». Текст Нового Завета: его передача, коррупция и восстановление (4 -е изд.). Нью -Йорк: издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 146. ISBN 9780195161229 .

- ^ Erasmus, Desiderius (1 августа 1993 г.). Рив, Энн (ред.). Аннотации Эразма на Новом Завете: Галатам для Апокалипсиса. Факсимил последнего латинского текста со всеми более ранними вариантами . Исследования в истории христианских традиций, том: 52. Брилл. п. 770. ISBN 978-90-04-09906-7 .

- ^ Переписка Erasmus: буквы с 1802 по 1925 год . Университет Торонто Пресс. 1 апреля 2010. ISBN 978-1-4875-2337-4 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Фрагменты Клеменса Александрия» , переведенный преподобным Уильямом Уилсоном, раздел 3.

- ^ Ccel: трактаты киприана

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный И снова Отец, Сын и Священный Сценарий-и эти трое-один . Киприан, единство церкви ( о единстве церкви ) 4. Послания Святого Иоанна » католическая энциклопедия .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Запятая Йоханнеум и Киприан | Bible.org» . Bible.org . Получено 19 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Скривенер, Фредерик Генри Амброуз; Эдвард Миллер (1894). Простое введение в критику Нового Завета. 2 (4 изд.). Лондон: Джордж Белл и сыновья. п. 86

- ^ 'r' в UBS-4 также «IT-Q» и Beuron 64 являются именами аппаратов сегодня. Эти фрагменты ранее были известны как Fragmenta Monacensia , как в Руководстве по текстовой критике Нового Завета Фредерика Джорджа Кениона, 1901, с. 178.

- ^ Аланд, Б.; Аланд, К.; Дж. Чопулос, К.М. Мартини , Б. Метцгер, А. Викрен (1993). Греческий Новый Завет Штутгарт: Объединенные библейские общества. П. 819. ISBN 978-3-438-05110-3 .

{{cite book}}: Cs1 maint: несколько имен: списки авторов ( ссылка ) [UBS4] - ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Католическая энциклопедия, «Послания святого Иоанна»

- ^ Na26: MSS 61, 629, 918, 2318, кроме MSS. 88, 221, 429, 636 как более поздние дополнения.

- ^ Католическая энциклопедия: «Только в четырех довольно недавних проклятиях - один из пятнадцатого и трех из шестнадцатого века». Это обновляется в списке ниже.

- ^ Джон Пейнтер, Даниэль Дж. Харрингтон . 1, 2 и 3 Джон

- ^ Erasmus, Desiderius (26 марта 2019 г.). Стипендия Нового Завета об Erasmus: введение с префаксами Erasmus и вспомогательными работами . Университет Торонто Пресс. ISBN 978-0-8020-9222-9 .

- ^ Переписка Erasmus: буквы с 1802 по 1925 год . Университет Торонто Пресс. 1 апреля 2010. ISBN 978-1-4875-2337-4 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Православное признание католической и апостолической восточной церкви , с.16, 1762. Греческий и латинский в Шаффе Символ Символа христианства с. 275, 1877

- ^ Шафф: Кридс христианства, с историей и критическими примечаниями. Том I. « Филипп www.ccel.org . Получено 19 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Скривенер, Фредерик Генри Амброуз (1894). Простое введение в критику Нового Завета для использования библейских студентов . Г. Белл.

- ^ Скривенер, Фредерик Х. (12 ноября 1997 г.). Простое введение в критику Нового Завета, 2 тома . WIPF и издатели. ISBN 978-1-57910-071-1 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Хорн, Томас Хартвелл (1856). Введение в критическое изучение и знание Священного Писания ... Третье издание, исправлено и т . Д.

- ^ FirstJohnch5v7

- ^ Некоторые ученые по ошибке считали это греческой рукописью, но это рукопись латинского вульгата. Wizanburgensis Revisited

- ^ Бенгель, Джон Албор (1858). Гномон Нового Завета .

- ^ Брюс М. Метцгер , Ранние версии Нового Завета , издательство Оксфордского университета, 1977, с. 302

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k Уоллес, Даниэль Б. (7 февраля 2010 г.). «Запятая Йоханнеум в пропущенной рукописи» . Центр изучения рукописей Нового Завета . Архивировано из оригинала 25 июля 2010 года . Получено 5 июня 2022 года .

- ^ По словам Брюса М. Метцгера , текстовый комментарий, 2 -е издание, стр. 647

- ^ «Примечание написана гораздо более поздней рукой - по крайней мере, вторая половина шестнадцатого века, как видно из введения, которое указывает« против 7. » Номера стихов не были изобретены до 1551 года, в четвертом издании Стефана его греческого Нового Завета. столетие "

- ^ Никол, Фрэнсис Дэвид (1956). Седьмый ДЕНЬ ДЕЙСТВИТЕЛЬНЫЙ КОММЕНТАРИЙ: Святая Библия с экзегетическим и разъяснительным комментарием . Обзор и Herald Pub. Ассоциация

- ^ Хиберт, Дэвид Э. (1991). Послания Иоанна: экспозиционный комментарий . Боб Джонс Университет Пресс. ISBN 978-0-89084-588-2 .

- ^ Метцгер, Брюс М. (Брюс Мэннинг) (1994). Текстовый комментарий к греческому Новому Завету: том компаньона для греческого Нового Завета Объединенных Библейских обществ . Интернет -архив (четвертый пересмотренный изд.). Штутгарт: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft; США: Объединенные библейские общества. ISBN 978-3-438-06010-5 .

- ^ Пейн, Филип Б.; Канарт, Пол (2000). «Оригинальность текстовых символов в Codex Vaticanus» . Novum testamentum . 42 (2): 105–113. doi : 10.1163/156853600506799 . ISSN 0048-1009 . JSTOR 1561327 .

- ^ «Католическая энциклопедия: Послания святого Иоанна» . www.newadvent.org . Получено 6 августа 2024 года .

- ^ Берджесс, Томас (1821). Оценка 1 Джона, ст. 7 от возражений М. Грисбаха: в котором дается новое представление о внешних доказательствах; с греческими властями для подлинности стиха, не до сих пор приведенного в его защите . Калифорнийский колледж Святой Марии. Лондон: Rivingtons.

- ^ Чарльз Форстер в новой просьбе к подлинности текста трех небесных свидетелей P 54–55 (1867) отмечает, что цитата стиха 6 является частичной, обходные фразы в стихе 6, а также в стихе 7. И что Клемент " Слова и ирум четко обозначают интерполяцию других тем и промежуточного текста, между двумя цитатами ». ET Iterum - это «и снова» в английском переводе.

- ^ Eclogse Prophetic 13.1 Ben David Monthly Review, 1826 с. 277)

- ^ Бенгель, Джон Гилл, Бен Дэвид и Томас Берджесс

- ^ Систематическое богословие: римско -католические перспективы, Фрэнсис Шусслер Фиоренца, Джон П. Гальвин, 2011, с. 159, стандарт «так связан с сыном, а дети в Параклете, три у коера

- ^ Джон Кей, Церковная история второго и третьего века, проиллюстрированная из писаний Тертуллиана 1826 года. С. 550.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Георг Стрекер , «Иоганнинские письма» (Герменяя); Миннеаполис: Fortress Press, 1996. «Экскурс: текстовая традиция« запятой Йоханнеум ».

- ^ Август неандер, история христианской религии и церкви в течение трех первых веков, том 2 , 1841, с. 184. Стандартный, предмет Pudic. 21. Церковь - это правильно и в основном дух, в котором Троица одного Божественного Отца и Сына и Святого Духа. Тишендорф Машина