Антиславские настроения

| Часть серии на |

| Дискриминация |

|---|

|

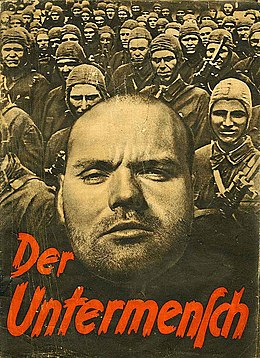

Антиславические чувства , также называемые славяно-славянскими народами , относятся к различным славянским народам . Сопровождающий расизм и ксенофобия , наиболее распространенным проявлением антиславских настроений на протяжении всей истории было утверждение, что славянки уступают другим народам . Это мнение достигло пика во время Второй мировой войны , когда нацистская Германия классифицировала славян, особенно поляки , русские , белорусские и украинцы - как «субчеловеки» ( Untermenschen ) и планировали уничтожить большое количество из них через общий план и голода . [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Славофобия также появлялась дважды в Соединенных Штатах : первый раз в прогрессивную эпоху , когда иммигранты из Восточной Европы были встречены с оппозицией со стороны доминирующего класса западно -европейских граждан; и снова во время холодной войны , когда Соединенные Штаты стали заперты в интенсивном глобальном соперничестве с Советским Союзом . [ 4 ]

По стране

[ редактировать ]Albania

[edit]At the beginning of the 20th century, anti-Slavism in Albania was developed by the work of the Franciscan friars [citation needed] who had studied in monasteries in Austria-Hungary,[5] after the recent massacres and expulsions of Albanians by their Slavic neighbours.[unreliable source?][6] The Albanian intelligentsia proudly asserted, "We Albanians are the original and autochthonous race of the Balkans. The Slavs are conquerors and immigrants who came but yesterday from Asia." [unreliable source?][7] In Soviet historiography, anti-Slavism in Albania was inspired by the Catholic clergy,[citation needed] which opposed the Slavic people because of the role the Catholic clergy[citation needed] and Slavs opposed "rapacious plans of Austro-Hungarian imperialism in Albania".[8]

Italy

[edit]

In the 1920s, Italian fascists hated the Yugoslavs, especially the Serbs. They accused the Serbs of having "atavistic impulses" and they also claimed that the Yugoslavs were conspiring on behalf of "Grand Orient Masonry and its funds". One anti-Semitic claim stated that the Serbs were involved in a "social-democratic, masonic Jewish internationalist plot".[9]

Benito Mussolini considered the Slavic race inferior and barbaric.[10][11] He believed that the Croats were a threat to Italy because they wanted to seize Dalmatia, a region which was claimed by Italy, and he also claimed that the threat rallied Italians at the end of World War I: "The danger of seeing the Jugo-Slavians settle along the whole Adriatic shore had caused a bringing together in Rome of the cream of our unhappy regions. Students, professors, workmen, citizens—representative men—were entreating the ministers and the professional politicians."[12] These claims often tended to emphasize the "foreignness" of the Yugoslavs by stating that they were newcomers to the area, unlike the ancient Italians, whose territories were occupied by the Slavs.

Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's son in law, and the Foreign Minister of Fascist Italy who was later executed by Mussolini, wrote the following entry in his diary:[13]

Vidussoni comes to see me. After having spoken about a few casual things, he makes some political allusions and announces savage plans against the Slovenes. He wants to kill them all. I take the liberty of observing that there are a million of them. "That does not matter." he answers firmly.

Canada

[edit]In Canada, many xenophobic white supremacists were deeply tied to their nation's "Anglo-Saxon" culture, specifically from the early 1900s to the end of World War II. The Ku Klux Klan in Canada was prominent in the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, both of which have a relatively high Eastern European ethnic population. Immigrants from Ukraine, Russia, and Poland were frequently denounced and targeted.[14]

During World War I, thousands of Ukrainian Canadians were seen as "enemy aliens" as Canadian nativists saw them as a "threat" to Canada's Western European heritage. Due to this, many of them were interned in concentration camps. There was constant discrimination towards Ukrainians who recently immigrated from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[15]

Germany

[edit]Though anti-Slavic sentiments reached their peak during Nazi Germany, Germany has had a long history of Slavophobia. In particular, the Germanic people of Prussia often depicted Polish people in a negative light, which paralleled future Slavophobia in the Nazi regime.[16]

Nikolay Ulyanov in his 1968 article " Замолчанный Маркс" (Hushed-up Marx) provides ample evidence of anti-Slavism the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.[17] For example, in his 1849 article "The Magyar Struggle," Engels wrote that the Slavs living in the Austrian Empire were "barbarians" who "needed to be saved" by the Germanic Austrians.[18]

Gustav Freytag's 1855 novel Soll und Haben ("Debt and Credit") was one of the most-read German novels of the 19th century, and contained antisemitic sentiments as well as depictions of Poles as incompetent.[19]

Nazi Germany

[edit]

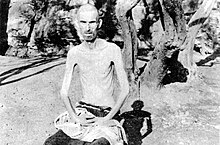

Anti-Slavic racism played a significant role within the ideology of Nazism.[21] Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party held the belief that Slavic countries - particularly Poland, Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia, as well as their respective peoples - were "Untermenschen" (subhumans). According to their viewpoint, these Slavic nations were deemed to be foreign entities and were not considered part of the Aryan master race. Nazi Germany depicted the Soviet Union as an "Asiatic enemy" of Europeans, in addition to portraying its population as inferior subhumans controlled by Jews and communists.[22]

Hitler’s autobiography Mein Kampf was openly anti-Slavic. He wrote: “One ought to cast the utmost doubt on the state-building power of the Slavs,” and from the beginning, he rejected the idea of incorporating the Slavs into Greater Germany.[23] There were exceptions for some minorities in these states which were deemed by the Nazis to be the descendants of ethnic Germanic settlers, and not merely Slavs who were willing to be Germanized.[21]

Hitler considered the Slavs to be racially inferior, because, in his view, the Bolshevik Revolution had put the Jews in power over the mass of Slavs, who were, by his own definition, incapable of ruling themselves but were instead being ruled by Jewish masters.[24] He considered the development of modern Russia to have been the work of Germanic, not Slavic, elements in the nation, but believed those achievements had been undone and destroyed by the October Revolution,[25] in Mein Kampf, he wrote, “The organization of a Russian state formation was not the result of the political abilities of the Slavs in Russia, but only a wonderful example of the state-forming efficacity of the German element in an inferior race.”[26]

Because, according to the Nazis, the German people needed more territory to sustain its surplus population, an ideology of conquest and depopulation was formulated for Central and Eastern Europe according to the principle of Lebensraum, itself based on an older theme in German nationalism which maintained that Germany had a "natural yearning" to expand its borders eastward (Drang Nach Osten).[21] The Nazis' policy towards Slavs was to exterminate or enslave the vast majority of the Slavic population and repopulate their lands with millions of ethnic Germans and other Germanic peoples.[27][28] According to the resulting genocidal Generalplan Ost, millions of German and other "Germanic" settlers would be moved into the conquered territories, and the original Slavic inhabitants were to be annihilated, removed or enslaved.[21] The policy was focused especially on the Soviet Union, as it alone was deemed capable of providing enough territory to accomplish this goal.[29]

"Hitler gave the already existing ideas of anti-Semitism, anti-Bolshevism and anti-Slavism the form of a genocidal alternative: either we survive or the Jews, Bolsheviks, Slavs – the people of the East – do. Based on theories of a racial hierarchy, he built the directives for an extermination programme aimed at part of the population of Europe and Asia and the creation of a Teutonic “New Order”. ... The concept of Nazi Lebensraum cannot be fully explained without bluntly stating an important motivational element of his conquests in the East: anti-Slavism."[30]

- Polish historian Jerzy Wojciech Borejsza

As part of the Generalplan Ost, Nazi Germany developed the Hunger Plan, a forced starvation programme which involved the seizure of all of the food which was produced on Eastern European lands and the delivery of it to Germany, primarily to the German army. The full implementation of this plan would have ultimately resulted in the starvation and death of 20 to 30 million people (mainly Russians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians). It is estimated that in accordance with this plan, over four million Soviet citizens were starved to death from 1941 to 1944.[31] The resettlement policy reached a much more advanced stage in occupied Poland because of its immediate proximity to Germany.[21]

For strategic reasons, the Nazis deviated from some of their ideological theories by forging alliances with Ukrainian collaborators, the Independent State of Croatia (established after the invasion of Yugoslavia), the Slovak State (established after the occupation of Czechoslovakia) and Bulgaria. Yugoslav general Milan Nedić would also lead Nazi Germany's Serbian puppet government.[32] The Nazis officially justified these alliances by stating that the Croats were "more Germanic than Slav", a notion which was propagated by Croatia's fascist dictator Ante Pavelić, who espoused the view that the "Croats were the descendants of the ancient Goths" who "had the pan-Slavic idea forced upon them as something artificial".[33][34] However, the Nazi regime continued to classify the Croats as "subhumans" despite its alliance with them.[35] Hitler also believed that the Bulgarians were "Turkoman", while the Czechs and Slovaks were Mongolians in their origins.[34] After conquering Yugoslavia, attention was instead focused on targeting mainly the nation's Jewish and Roma (Gypsy) population.[32]

After Nazi Germany

[edit]Though Slavophobia became less prevalent after WWII, it still persisted to some degree and still persists today. Slavic immigrants in Germany experience discrimination due to their accents, their surnames, and their cuisine.[36] Since the invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022, Russian speakers in Germany have faced increased discrimination, including collective blame for Russia's actions in the war, despite most having lived in Germany for decades and many not being Russian at all. Since the Russian language was the lingua franca of the Soviet Union, an immigrant living in Germany who speaks Russian could be from anywhere that was influenced by the Soviet Union.[19]

Greece

[edit]Traditionally,[when?] in Greece, Slavic people were considered "invaders who separated the glory of Greek Antiquity, by bringing an era of decline and ruin to Greece – the Dark Ages".[37] In 1913, when Greece took control of Slavic-inhabited areas in Northern Greece, the Slavic toponyms were changed to Greek, and according to the Greek government, this was "the elimination of all the names which pollute and disfigure the beautiful appearance of our fatherland."[38]

Anti-Slavic sentiment escalated during the Greek Civil War, when Macedonian partisans, who aligned themselves with the Democratic Army of Greece, were not treated as equals and suffered discrimination everywhere, they were accused of committing a "sin" because they chose to identify themselves as Slavs rather than Greeks.[39] The Macedonian partisans were subjected to threats of extermination, physical attacks, murder, attacks on their settlements, forcible expulsions, restrictions on freedom of movement, and bureaucratic problems, among other discriminatory acts.[39] Although they were allied with the Greek Left, due to their Slavic identity, the Macedonians were viewed with suspicion and animosity by the Greek Left.[40]

In 1948, the Democratic Army of Greece evacuated tens of thousands of child refugees, both Greek and Slavic in origin.[41] In 1985, the refugees were allowed to re-enter Greece, claim Greek citizenship, and reclaim property, but only if they were "Greek by genus", thus prohibiting those with a Slavic identity from obtaining Greek citizenship, entering Greece, and claiming property.[42][43]

Today, the Greek state does not recognize its ethnic Macedonian and other Slavic minorities, claiming that they do not exist, with Greece therefore having the right not to grant them any of the rights that are guaranteed to them by human-rights treaties.[44]

United States

[edit]The United States of America has a long history of Slavophobia. Slavophobia began in earnest during the "second wave" of European immigration in the early 1900s, when many people from Southern and Eastern Europe were immigrating to the US.[4] They faced opposition from the "old" immigrants, who were mostly from Northern and Western Europe. These attitudes culminated in the Immigration Act of 1924, which established quotas for and limited the numbers of people from Southern and Eastern European countries who were allowed to enter the US.[45] Slavic peoples were considered to be people of an "inferior race" who were unable to assimilate into American society.[4] They were originally not considered to be "fully white" (and thus fully American), and Slavic peoples' "whiteness" continues to be a debate to this day.[46]

Slavophobia in the US ramped up again during the Cold War, when Slavic peoples of all nationalities were considered enemies due to the United States' distrust of the Soviet Union.[47] War in the Balkans (which America often had a part in) was considered inevitable due to the Balkan peoples' "propensity for extreme war violence."[47] The United States government, while claiming to advocate for national determination for small countries, has denied national determination to many of the countries in Eastern Europe and the Balkans.[48] As a result, many Slavic people in the US and Western countries felt pressure (and continue to feel pressure) to Anglicize their surnames and downplay their Slavic culture.[49]

In American pop culture, Slavic people (specifically Russians) are usually portrayed as either nefarious, violent criminals[50] or as unintelligent, oblivious comic relief.[51][52] "Dumb Pole" jokes or "Polish jokes" (derogatory jokes towards Polish people) are just one manifestation of anti-Polish sentiment in America, and can be found in all sorts of media from many time periods.[53]

Slavophobia has had a resurgence in America following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, where Russian-Americans and people of Russian descent have been collectively blamed for the Russian government's actions.[49][54]

See also

[edit]- Anti-Catholicism

- Anti-Croat sentiment

- Anti-Polish sentiment

- Anti-Russian sentiment

- Anti-Serbian sentiment

- Anti-Ukrainian sentiment

- Expulsion of Yugoslavs from Albania (1948–1954)

- Final Solution of the Czech Question

- Pan-Slavism

- Persecution of Eastern Orthodox Christians

- Refugees of the Greek Civil War

- Slavic speakers of Greek Macedonia

- Zamość Uprising

- Slavophilia

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- ^ Ingrao, Christian (2015). Intellectuals in the SS War Machine. Translated by Brown, Andrew (English ed.). 65 Bridge Street, Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK: Polity Press. pp. 127–130, 157. ISBN 978-0-7456-6027-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Fritz, Stephen G. (2011). Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 93–95, 253–260, 317. ISBN 978-0-8131-3416-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Roucek, Joseph S. “The Image of the Slav in U.S. History and in Immigration Policy.” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 28, no. 1, 1969, pp. 29–48. JSTOR, JSTOR 3485555. Accessed 6 Feb. 2024.

- ^ Detrez, Raymond; Plas, Pieter (2005), Developing cultural identity in the Balkans: convergence vs divergence, Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang S.A., p. 220, ISBN 90-5201-297-0,

it led to adoption of anti-Slavic component

- ^ Koliqi, Ernesto & Rahmani, Nazmi (2003). Vepra. Shtëpía Botuese Faik Konica. p. 183.

- ^ Kolarz, Walter (1972), Myths and realities in eastern Europe, Kennikat Press, p. 227, ISBN 978-0-8046-1600-3,

Albanian intelligentsia, despite the backwardness of their country and culture: 'We Albanians are the original and autochthonous race of the Balkans. The Slavs are conquerors and immigrants who came but yesterday from Asia.'

- ^ Elsie, Robert. "Gjergj Fishta, The Voice of The Albanian Nation". Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

Great Soviet Encyclopaedia of Moscow... (March 1950): "The literary activities of the Catholic priest Gjergj Fishta reflect the role played by the Catholic clergy in preparing for Italian aggression against Albania. As a former agent of Austro-Hungarian imperialism, Fishta... took a position against the Slavic peoples who opposed the rapacious plans of Austro-Hungarian imperialism in Albania. In his chauvinistic, anti-Slavic poem 'The highland lute,' this spy extolled the hostility of the Albanians towards the Slavic peoples, calling for an open fight against the Slavs".

- ^ Burgwyn, H. James (1997) Italian Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period, 1918–1940. Greenwood Publishing Group. p.43.

- ^ Sestani, Armando, ed. (10 February 2012). "Il confine orientale: una terra, molti esodi" [The Eastern Border: One Land, Multiple Exoduses]. I profugi istriani, dalmati e fiumani a Lucca [The Istrian, Dalmatian and Rijeka Refugees in Lucca] (PDF) (in Italian). Instituto storico della Resistenca e dell'Età Contemporanea in Provincia di Lucca. pp. 12–13.

When dealing with such a race as Slavic – inferior and barbarian – we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy. We should not be afraid of new victims. The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps. I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians.

[permanent dead link] - ^ Resistance, Suffering, Hope. The Slovene Partisan Movement 1941-1945, Ljubljana 2008, ISBN 978-961-6681-02-5, p. 27

- ^ Mussolini, Benito; Child, Richard Washburn; Ascoli, Max; & Lamb, Richard (1988) My rise and fall. New York: Da Capo Press. pp.105–106.

- ^ Ciano, Galeazzo, conte (2015). The war diaries of Count Galeazzo Ciano 1939–1943. Alan Sutton. [Stroud]. ISBN 978-1-78155-448-7. OCLC 910968625.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Eastern European Canadians - Minority Rights Group". 19 June 2015.

- ^ "Ukrainian Internment in Canada | the Canadian Encyclopedia".

- ^ Jaworska, Sylvia. "Anti-Slavic imagery in German radical nationalist discourse at the turn of the twentieth century: a prelude to Nazi ideology?". Patterns of Prejudice (45): 435–452.

- ^ Nikolay Ylyanov https://vtoraya-literatura.com/pdf/uljanov_zamolchanny_marx_1969_text.pdf " Замолчанный Маркс" (Hushed-up Marx)], «Возрождение» № 201, 1968, reprinted in 1969 by Possev-Verlag

- ^ Engels, Friedrich (January 1849). "The Magyar Struggle". Neue Rheinische Zeitung.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Petersen, Hans-Christian. "Between Marginalization and Instrumentalization: Anti-Eastern European and Anti-Slavic Racism | illiberalism.org". www.illiberalism.org/. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Sources:

- Müller, R. Ueberschar, Rolf-Dieter, Gerd (2009). Hitler's war in the East, 1941-1945. 150 Broadway, New York, NY 10038, United States: Berghahn Books. p. 245. ISBN 978-1-84545-501-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Der Untermensch". Bulmash Family Holocaust Collection. January 1942. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020.

- E. Aschheim, Steven (1992). "8: Nietzsche in the Third Reich". The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany, 1890-1990. Los Angeles, California, United States: University of California Press. pp. 236, 237. ISBN 0-520-08555-8.

- Müller, R. Ueberschar, Rolf-Dieter, Gerd (2009). Hitler's war in the East, 1941-1945. 150 Broadway, New York, NY 10038, United States: Berghahn Books. p. 245. ISBN 978-1-84545-501-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Bendersky, Joseph W. (2007).A concise history of Nazi Germany Plymouth, U.K.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 161-2

- ^ Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- ^ A Ridiculous Hundred Million Slavs: Concerning Adolf Hitler's World-view Jerzy Wojciech Borejsza, page 41, Wydawnictwo Neriton and Instytut Historii Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2006

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2007). War of Annihilation: Combat And Genocide on the Eastern Front, 1941. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-7425-4482-6.

- ^ Bendersky, Joseph W. (2000) A History of Nazi Germany: 1919–1945. Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield. p.177.

- ^ Martyn Housden, Hitler: Study of a Revolutionary?, page 36.

- ^ Housden, Martyn (2000). Hitler: Study of a Revolutionary?. Taylor & Francis. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-415-16359-0.

- ^ Perrson, Hans-Åke & Stråth, Bo (2007). Reflections on Europe: Defining a Political Order in Time and Space. Peter Lang. pp. 336–. ISBN 978-90-5201-065-6.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf (1926). Mein Kampf, Chapter XIV: Eastern Orientation or Eastern Policy. Quote: "If we speak of soil [to be conquered for German settlement] in Europe today, we can primarily have in mind only Russia and her vassal border states."

- ^ Borejsza, Jerzy W. (2017). A ridiculous hundred million Slavs: Concerning Adolf Hitler's world-view. Translated by French, David. Warsaw, Poland: Polskiej Akademii Nauk. p. 176. ISBN 978-83-63352-88-2.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2010) Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books. p.411.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Axis Invasion Of Yugoslavia". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Rich, Norman (1974) Hitler's War Aims: the Establishment of the New Order. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p.276-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hitler, Adolf and Gerhard, Weinberg (2007). Hitler's Table Talk, 1941–1944: His Private Conversations. Enigma Books. p.356. Quoting Hitler: "For example to label the Bulgarians as Slavs is pure nonsense; originally they were Turkomans."

- ^ Davies, Norman (2008) Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. Pan Macmillan. pp.167,209.

- ^ Zingher, Erica (22 November 2020). "Jüdische Kontingentflüchtlinge: Was wächst auf Beton?". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ КУРТА, Флорин (30 января 2011 г.). Эдинбургская история греков , ок. От 500 до 1050 . Эдинбургский университет издательство. п. 3. doi : 10.3366/Эдинбург/9780748638093.001.0001 . ISBN 978-0-7486-3809-3Полем

Но во время и после гражданской войны 1943-1949 годов сами «славяны» стали национальным врагом. На протяжении всей гражданской войны славянские македонцы Северной Греции вносили важный вклад в коммунистическое дело. Таким образом, была установлена сильная связь между национальной идентичностью и политической ориентацией, так как гражданская война и последующее поражение левого движения превратили славянских македонцев в судетенс Греции (Августинос 1989: 23). К 1950 году те, кто охватил идеологию справа, считали своих политических соперников как воплощение всего, что было антинациональным, коммунистическим и славянским. Таким образом, чтобы сдерживать взгляды Фоллмерайера, стали криминовым Laesae Maiestatis. Dionysios A. Zakythinos, автор «Первой монографии по средневековым славям в Греции», написал о темных веках, отделяющих античность от средневековья как эпоху упадка и руина, которые были принесены славянскими захватчиками (Zakythinos 1945: 72 и 1966: 300 , 302 и 316). В Соединенных Штатах Питер Чаранис считал императора NikePhoros I как герой, который спас Грецию от славянизма (Charanis 1946). Таким образом, ранние средневековые славяны стали историографической проблемой для Slavikon Zetema.

- ^ Danforth, Loring M (1995). Македонский конфликт: этнический национализм в транснациональном мире . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА. п. 69. ISBN 0-691-04357-4 Полем OCLC 32237371 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Россос, Эндрю (1997). «Несовместимые союзники: греческий коммунизм и македонский национализм в гражданской войне в Греции, 1943–1949». Журнал современной истории . 69 (1): 56. doi : 10.1086/245440 . ISSN 0022-2801 . S2CID 143512864 .

Террорная кампания, которая была выпущена после Варкизы против всего слева греческим правом, была направлена с особой тяжкой против македонцев. В дополнение к идеологическому «предательству» поддержки EAM-Elas, они подверглись нападению за совершение окончательного «греха» не быть, или, скорее, не рассматривать себя, греков. Они были осуждены как булгар, комитаджи, сотрудники, автономисты, судей балканов и т. Д., И угрожали истребранным.

- ^ Россос, Эндрю (1997). «Несовместимые союзники: греческий коммунизм и македонский национализм в гражданской войне в Греции, 1943–1949». Журнал современной истории . 69 (1): 42–43. doi : 10.1086/245440 . ISSN 0022-2801 . S2CID 143512864 .

- ^ Данфорт, Лоринг М. (1995). Македонский конфликт: этнический национализм в транснациональном мире . Принстон, Нью -Джерси: Принстон Унив. Нажимать. п. 54. ISBN 0-691-04357-4 Полем OCLC 243828619 .

- ^ Отрицание этнической идентичности: македонцы Греции . Хьюман Райтс Вотч/Хельсинки (организация: США). Нью -Йорк: Хьюман Райтс Вотч. 1994. с. 27. ISBN 1-56432-132-0 Полем OCLC 30643687 .

{{cite book}}: Cs1 maint: другие ( ссылка ) - ^ "Пресс-релиз" .

- ^ Европейская комиссия против расизма и нетерпимости (2009). «Отчет ECRI о Греции (четвертый цикл мониторинга)». Совет Европы : 62.

- ^ Журнал, Смитсоновский институт; Алмаз, Анна. «Закон 1924 года, который ударил дверь иммигрантов и политиков, которые отталкивали ее назад» . Смитсоновский журнал . Получено 6 февраля 2024 года .

- ^ «Не совсем белый: арабы, славяны и контуры оспариваемой белизны | Культурный центр шелкового дороги» . silkroadculturatcenter.org . Получено 6 февраля 2024 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Михайл, Юджин. «Западное отношение к войне на Балканах и изменяющиеся значения насилия, 1912-91». Журнал современной истории , вып. 47, нет. 2, 2012, с. 219–39. JStor , JSTOR 23249185 . Доступ 6 февраля 2024 года.

- ^ Кухнер, Джеффри Т. «Островая сланофобия» . Вашингтон Таймс .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Брукс, Ханна (2 мая 2022 г.). «Мнение | бабушка и дедушка моего ребенка не хотели, чтобы у нее была русская фамилия. Теперь я понимаю, почему» . NBC News . Получено 6 февраля 2024 года .

- ^ « Я хочу, чтобы ты отказался от Азимоффа!» - Восточно-европейские стереотипы на американском телевидении » . Радио Свободная Европа/Радио Свобода . 5 сентября 2012 года . Получено 6 февраля 2024 года .

- ^ Раскин, Ханна Рэйчел (11 апреля 2007 г.). «Для создания пользы писателя замечательного сатирического романа» . Горная Xpress . Получено 6 февраля 2024 года .

- ^ Орлова, Олеся Геннадьевна (2021). «Американские фильмы как дискурс и кисние русских стереотипов» . Европейское разбирательство . Европейские труды социальных и поведенческих наук. Язык и технологии в междисциплинарной парадигме: 123–136. doi : 10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.17 .

- ^ «Анатомия польской шутки» . Культура.pl . Получено 6 февраля 2024 года .

- ^ Умбраско, Рикардс. «За пределами Украины: Запад имеет проблему в Восточной Европе | Мнение | Гарвардский малиновый» . www.thecrimson.com . Получено 6 февраля 2024 года .

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Borejsza, Jerzy W. (1988). Абольф Гитлера Анти -болотизм . Варшава: Читатель. ISBN 9788307017259 .

- Borejsza, Jerzy W. (1989). «Расизм и антиславизм в Гитлере». Нацистская политика Париж: Альбин Мишель. стр. 57–74. ISBN 9782226038753 .

- БИССТРОВ, VU и AE KOTOV. «Демо в своей абсолютной красоте»: консервативная критика славян и либерального панславизма в 1860-1880-х годах ». Studia culturae 35 (2019): 9+ онлайн .

- Коннелли, Джон (1999). «Нацисты и славяны: от расовой теории до расистской практики». Центральная европейская история . 32 (1): 1–33. doi : 10.1017/s0008938900020628 . PMID 20077627 . S2CID 41052845 .

- Коннелли, Джон (2010). «Гипси, гомосексуалы и славяне». Оксфордский справочник по исследованиям Холокоста . Нью -Йорк: издательство Оксфордского университета. С. 274–289. ISBN 9780199211869 .

- Đorghević, Vladimir, et al. «Помимо современной стипендии и к изучению нынешних проявлений панславизма». Канадско-американские славянские исследования 55,2 (2021): 147–159.

- Внешний вид, Иоганн Самуэль , изд. «Земля описание» . Общая литературная газета . 2 (177). Halle-Leipzig: 465–472.

- Фагард, Мишель (1977). Немецкий антиславизм через специализированные публикации 1914–1921 . Докторская диссертация. Париж: Университет Парижа VIII.

- Ferrari-Zumbini, Massimo (1994). «Великая миграция и антиславизм: негативные картинки в восточной части Джуден в империи» . Ежегодник для исследований антисемитизма . 3 : 194–226. ISBN 9783593350301 .

- Собака, Вульф Д.; Коллер, Кристиан; Циммерманн, Моше, ред. (2011). Расизмы, сделанные в Германии . Мюнстер: Lit Verlag. ISBN 9783643901255 .

- Jaworska, Sylvia (2011). «Антиславические образы в немецком радикальном националистическом дискурсе на рубеже двадцатого века: прелюдия к нацистской идеологии?» (PDF) . Модели предрассудков . 45 (5): 435–452. doi : 10.1080/0031322x.2011.624762 . S2CID 3743556 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 22 октября 2018 года . Получено 19 февраля 2018 года .

- Константинова, Юра. «Славянская и антиславическая идея в контексте дилеммы восток-запад. Словенцы, болгары и греки в конце 19 и начале 20 веков». Etudes Balkaniques 3 (2015): 126–149.

- Leiberich, Michel (1977). Немецкий антиславизм в политической и повседневной жизни Kulturkapampf накануне Первой мировой войны . Докторская диссертация. Париж: Университет Парижа VIII.

- Либретти, Джованни (1998). «Предполагаемый антиславизм Энгельса» . Вклад в исследование Маркса-Энгелса : 191–202.

- Филлипс, Меган. «Не верьте всему, что вы видите в фильмах: влияние антикоммунистической и антиславской правительственной пропаганды в голливудском кино в течение десятилетия после Второй мировой войны». Александрийский 4.1 (2015). онлайн

- Pomitzer, Christian (2003). «Южные славяны в австрийском воображении: сербы и словензии в изменении германского национализма к национальному социализму». Создание другого: этнический конфликт и национализм в Габсбурге Центральной Европе . Нью -Йорк: Berghahn Books. С. 183–215. ISBN 9781782388524 .

- Rash, Felicity (2012). Немецкие изображения себя и другого: националистический, колониалистический и антисемитский дискурс 1871-1918 . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230282650 . [ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- Россино, Александр Б. наносит удар по Польше: Блицкриг, Идеология и зверство (Университетскаяда Канзас, 2003) . Гитлер

- Serrier, Thomas (2004). «Антиславизм и антисемитизм в восточных границах Германии в 19 веке». Культурные стандарты и строительство отклонения . Париж: Практическая школа с высоким уровнем обучения. стр. 91–102. ISBN 9782952156301 .

- Sulyak, SG «Славянский фактор в истории Молдовы: научные исследования и мифы». Русин 49,3 (2017): 144–162. онлайн

- Wingfield, Nancy M., ed. (2003). Создание другого: этнический конфликт и национализм в Габсбурге Центральной Европе . Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781782388524 .

- Wollman, Frank (1968). Славизм и антиславизмы весной народов . Праха: Академия.

Примеры антиславской литературы

[ редактировать ]- Зекер, Роберт М. « Славян может жить в грязи, которая убила бы белого человека»: раса и европейский «другой». Раса и Америка иммигрантская пресса: как словаки учили думать как белые люди . Лондон: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011. 68–102.

Bloomsbury Collections. Веб - 5 октября 2021 года .