Политика США в области изменения климата

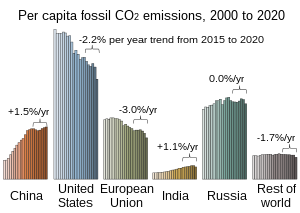

Политика Соединенных Штатов в области изменения климата оказывает серьезное воздействие на глобальное изменение климата и смягчение последствий глобального изменения климата . Это связано с тем, что Соединенные Штаты являются вторым по величине источником выбросов парниковых газов в мире после Китая и входят в число стран с самыми высокими выбросами парниковых газов на душу населения в мире. В совокупности Соединенные Штаты выбросили более триллиона тонн парниковых газов, больше, чем любая другая страна в мире. [ 1 ]

Политика в области изменения климата разрабатывается на местном уровне . [ нужна цитата для проверки ] уровне штата и федеральном уровне власти. [ 2 ] Агентство по охране окружающей среды (EPA) определяет изменение климата как «любое существенное изменение показателей климата, продолжающееся в течение длительного периода времени». По сути, изменение климата включает в себя серьезные изменения температуры, осадков или режима ветра, а также другие последствия, которые происходят в течение нескольких десятилетий или дольше. [ 3 ] Политика с крупнейшими инвестициями США в смягчение последствий изменения климата — это Закон о сокращении инфляции 2022 года .

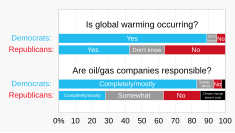

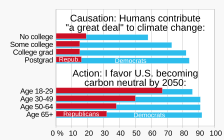

Политика изменения климата поляризовала некоторые политические партии и другие организации. [ 4 ] Демократическая партия выступает за расширение политики смягчения последствий изменения климата, тогда как Республиканская партия склонна скептически относиться к последствиям для бизнеса, а также выступает за более медленные изменения, бездействие или отмену существующей политики смягчения последствий изменения климата. Большая часть лоббирования климатической политики в Соединенных Штатах осуществляется корпорациями, которые публично выступают против сокращения выбросов углекислого газа. [5]

Federal policy

[edit]International law

[edit]The United States, although a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol, has neither ratified nor withdrawn from the protocol. In 1997, the US Senate voted unanimously under the Byrd–Hagel Resolution that it was not the sense of the Senate that the United States should be a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol. In 2001, former National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, stated that the Protocol "is not acceptable to the Administration or Congress".[8][9]

In October 2003, the Pentagon published a report titled An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and Its Implications for United States National Security by Peter Schwartz and Doug Randall. The authors conclude by stating, "this report suggests that, because of the potentially dire consequences, the risk of abrupt climate change, although uncertain and quite possibly small, should be elevated beyond a scientific debate to a U.S. national security concern."[10]

Congress

[edit]In October 2003 and again in June 2005, the McCain-Lieberman Climate Stewardship Act failed a vote in the US Senate.[11] In the 2005 vote, Republicans opposed the Bill 49–6, while Democrats supported it 37–10.[12]

In January 2007, Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced she would form a United States Congress subcommittee to examine global warming.[13] Sen. Joe Lieberman said, "I'm hot to get something done. It's hard not to conclude that the politics of global warming has changed and a new consensus for action is emerging and it is a bipartisan consensus."[14] Senators Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Barbara Boxer (D-CA) introduced the Global Warming Pollution Reduction Act on January 15, 2007. The measure would provide funding for R&D on geologic sequestration of carbon dioxide (CO2), set emissions standards for new vehicles and a renewable fuels requirement for gasoline beginning in 2016, establish energy efficiency and renewable portfolio standards beginning in 2008 and low-carbon electric generation standards beginning in 2016 for electric utilities, and require periodic evaluations by the National Academy of Sciences to determine whether emissions targets are adequate.[15] However, the bill died in committee. Two more bills, the Climate Protection Act and the Sustainable Energy Act, proposed February 14, 2013, also failed to pass committee.[16]

The House of Representatives approved the American Clean Energy and Security Act (ACES) on June 26, 2009, by a vote of 219–212, but the bill failed to pass the Senate.[17][18]

In March 2011, the Republicans submitted a bill to the U.S. Congress that would prohibit the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from regulating greenhouse gasses as pollutants.[19] As of 2012, the EPA was still overseeing regulation under the Clean Air Act.[20][21]

In 2019, there were 130 elected congresspeople who had expressed doubt about the science of climate change.[22]

Clinton administration

[edit]Upon the start of his presidency in 1993, Bill Clinton committed the United States to lowering their greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2000 through his biodiversity treaty,[23] reflecting his attempt to return the United States to the global platform of climate policy. Clinton's British Thermal Unit (BTU) Tax and Climate Change Action Plan were also announced within the first year of his presidency, calling for a tax on energy heat content and plans for energy efficiency and joint implementations, respectively.

The Climate Change Action Plan was announced on October 19, 1993. This plan aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2000.[24] Clinton described this goal as "ambitious but achievable," and called for 44 action steps to achieve this goal. Among these steps were voluntary participation by industry, especially those in the commercial and energy supply fields. Clinton allotted $1.9 billion to fund this plan from the federal budget and called for an additional $60 billion funding to come voluntarily businesses and industries.[24]

The British Thermal Tax proposed by Clinton in early 1993 called for a tax on producers of gasoline, oil, and other fuels based on fuel content in accordance to the British Thermal Unit (BTU). The British Thermal Unit is a measure of heat corresponding to the quantity of heat needed to raise the temperature of water by one degree Fahrenheit.[25] The tax also applied to electricity produced by hydro and nuclear power, but exempted renewable energy sources such as geothermal, solar, and wind. The Clinton Administration planned to collect up to $22.3 billion in revenue from the tax by 1997.[26] The tax was opposed by the energy-intensive industry, who feared that the price increase caused by the tax would make U.S. products undesirable on an international level, and thus was never fully implemented.[27]

In 1994, the U.S. called for a new limit on greenhouse gas emissions post-2000 in at the August 1994 INC-10. They also called for a focus on joint implementation, and for new developing countries to limit their emissions. Environmental groups, including the Climate Action Network (CAN), critiqued these efforts, questioning U.S. focus on limiting the emissions of other countries when it had not established its own.[28]

The U.S. government under Clinton succeeded in pushing its agenda for joint implementation in the 1995 Conference of the Parties (COP-1). This victory is noted in the Berlin Mandate of April 1995, which called for developed countries to lead the implementation of national mitigation policies.[29]

Clinton signed the Kyoto Protocol on behalf of the United States in 1997, pledging the country to a non-binding 7% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.[30] He claimed that the agreement was "environmentally strong and economically sound," and expressed a desire for greater involvement in the treaty by developing nations.[31]

In his second term, Clinton announced his FY00 proposal, which allotted funding for a new set of environmental policies. Under this proposal, the President announced a new Clean Air Partnership Fund, new tax incentives and investments, and funding for environmental research of both natural and man-made changes to the climate.[32]

The Clean Air Partnership Fund was proposed to finance state and local government efforts for greenhouse gas emission reductions in cooperation with EPA. Under this fund, $200 million was allotted to promote and finance innovation projects meant to reduce air pollution. It also supported the creation of partnerships between the local and federal governments, and private sector.[33]

The Climate Change Technology Initiative provided $4 billion in tax incentives over a five-year period. The tax credits applied to energy efficient homes and building equipment, implementation of solar energy systems, electric and hybrid vehicles, clean energy, and the power industry.[34] The Climate Change Technology Initiative also provided funding for additional research and development on clean technology, especially in the building, electricity, industry, and transportation sectors.[32]

G.W. Bush administration

[edit]In March 2001, the George W. Bush Administration announced that it would not implement the Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty signed in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan that would require nations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, claiming that ratifying the treaty would create economic setbacks in the U.S. and does not put enough pressure to limit emissions from developing nations.[35] In February 2002, President Bush announced his alternative to the Kyoto Protocol, by bringing forth a plan to reduce the intensity of greenhouse gasses by 18 percent over 10 years. The intensity of greenhouse gasses specifically is the ratio of greenhouse gas emissions and economic output, meaning that under this plan, emissions would still continue to grow, but at a slower pace. Bush stated that this plan would prevent the release of 500 million metric tons of greenhouse gases, which is about the equivalent of 70 million cars from the road. This target would achieve this goal by providing tax credits to businesses that use renewable energy sources.[36]

The Bush administration has been accused of implementing an industry-formulated disinformation campaign designed to mislead the American public on global warming and to forestall limits on "climate polluters", according to a report in Rolling Stone magazine that reviewed hundreds of internal government documents and former government officials.[37] The book Hell and High Water asserts that there has been a disingenuous, concerted and effective campaign to convince Americans that the science is not proven, or that global warming is the result of natural cycles, and that there needs to be more research. The book claims that, to delay action, industry and government spokesmen suggest falsely that "technology breakthroughs" will eventually save us with hydrogen cars and other fixes. It calls on voters to demand immediate government action to curb emissions.[38] Papers presented at an International Scientific Congress on Climate Change, held in 2009 under the sponsorship of the University of Copenhagen in cooperation with nine other universities in the International Alliance of Research Universities (IARU), maintained that the climate change skepticism that is so prevalent in the USA[39] "was largely generated and kept alive by a small number of conservative think tanks, often with direct funding from industries having special interests in delaying or avoiding the regulation of greenhouse gas emissions".[40]

According to testimony taken by the U.S. House of Representatives, the Bush White House pressured American scientists to suppress discussion of global warming[41][42] "High-quality science" was "struggling to get out", as the Bush administration pressured scientists to tailor their writings on global warming to fit the Bush administration's skepticism, in some cases at the behest of an ex-oil industry lobbyist. "Nearly half of all respondents perceived or personally experienced pressure to eliminate the words 'climate change,' 'global warming' or other similar terms from a variety of communications." Similarly, according to the testimony of senior officers of the Government Accountability Project, the White House attempted to bury the report "National Assessment of the Potential Consequences of Climate Variability and Change", produced by U.S. scientists pursuant to U.S. law,[43] Some U.S. scientists resigned their jobs rather than give in to White House pressure to underreport global warming.[41] and removed key portions of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report given to the U.S. Senate Environment and Public Works Committee about the dangers to human health of global warming.[44]

The Bush Administration worked to undermine state efforts to mitigate global warming. Mary Peters, the Transportation Secretary at that time, personally directed US efforts to urge governors and dozens of members of the House of Representatives to block California's first-in-the-nation limits on greenhouse gases from cars and trucks, according to e-mails obtained by Congress.[45]

Obama administration

[edit]This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (April 2021) |

New Energy for America is a plan to invest in renewable energy, reduce reliance on foreign oil, address the global climate crisis, and make coal a less competitive energy source. It was announced during Barack Obama's presidential campaign. A form of it was signed into law in February 2009 as the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act, which invests $26.6 billion in renewable energy, $19.9 billion in energy efficiency and conservation, $18.1 billion in transit and high-speed rail, $10.5 billion in electric power transmission upgrades, $6.1 billion in alternative fuel vehicles, $3.4 billion in carbon capture and storage, and at least $600 million in Superfund, underground fuel tank and brownfield land cleanups.[46][47] An estimate in 2016 by Obama's Council of Economic Advisers found the ARRA boosted GDP by 2-3%, supported 900,000 clean energy job-years and leveraged $150 billion in private sector clean energy investments.[48]

On November 17, 2008, President-elect Barack Obama proposed, in a talk recorded for YouTube, that the US should enter a cap and trade system to limit global warming.[49] The American Clean Energy and Security Act, a cap and trade bill, was passed on June 26, 2009, in the House of Representatives, but was not passed by the Senate.

President Obama established a new office in the White House, the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy, and selected Carol Browner as Assistant to the President for Energy and Climate Change. Browner is a former administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and was a principal of The Albright Group LLC, a firm that provides strategic advice to companies.[50]

On January 27, 2009, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton appointed Todd Stern as the department's Special Envoy for Climate Change.[51] Clinton said, "we are sending an unequivocal message that the United States will be energetic, focused, strategic and serious about addressing global climate change and the corollary issue of clean energy."[52] Stern, who had coordinated global warming policy in the late 1990s under the Bill Clinton administration, said that "The time for denial, delay and dispute is over.... We can only meet the climate challenge with a response that is genuinely global. We will need to engage in vigorous, dramatic diplomacy."[52]

In February 2009, Stern said that the US would take a lead role in the formulation of a new climate change treaty in Copenhagen in December 2009. He made no indication that the U.S. would ratify the Kyoto Protocol in the meantime.[53] US Embassy dispatches subsequently released by whistleblowing site WikiLeaks showed how the US 'used spying, threats and promises of aid' to gain support for the Copenhagen Accord, under which its emissions pledge is the lowest by any leading nation.[54][55]

President Obama said in September 2009 that if the international community would not act swiftly to deal with climate change that "we risk consigning future generations to an irreversible catastrophe... our prosperity, our health, and our safety are in jeopardy, and the time we have to reverse this tide is running out." [56] In 2010, the president said, similarly, that it was time for the United States "to aggressively accelerate" its transition from oil to alternative sources of energy and vowed to push for quick action on climate change legislation, arguably seeking to harness the deepening anger over the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.[57]

The 2010 United States federal budget proposed to support clean energy development with a 10-year investment of US$15 billion per year, generated from the sale of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions credits. Under the proposed cap-and-trade program, all GHG emissions credits would be auctioned off, generating an estimated $83 billion in new revenue by FY 2019.[58]

New rules for power plants were proposed March 2012.[59][60]

In the US and China's Sunnylands Summit on June 8, 2013, President Obama and Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping worked in accordance for the first time, formulating a landmark agreement to reduce both production and consumption of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). This agreement had the unofficial goal of decreasing roughly 90 gigatons of CO2 by 2050 and implementation was to be led by the institutions created under the Montreal Protocol, while progress was tracked using the reported emissions that were mandated under the Kyoto Protocol. The Obama administration viewed HFCs as a "serious climate mitigation concern."[61]

On March 31, 2015, the Obama administration formally submitted the US Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) for greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The United States committed to reducing emissions 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025, a reflection of the Obama administration's goal to convert the U.S. economy into one of low-carbon reliance.[62][63]

In 2015, Obama also announced the Clean Power Plan, which was the final version of regulations originally proposed by the EPA the previous year, and which pertained to carbon dioxide emissions from power plants.[64] Even though it had never been fully implemented, it was replaced by the Trump administration's Affordable Clean Energy rule in 2019,[65] itself voided by the DC Circuit Court of Appeals in 2021.[66][67]

In the same year, President Obama announced his aim for a 40-45% reduction below 2012 levels in methane emissions by 2025. In March 2016, the President would later solidify this goal in an agreement with Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, stating that the two federal governments will jointly work together to reduce methane emissions in North America, coordinating particularly on research and development and standards creation.[68]

On May 12, 2016, the administration released an Information Collection Request (ICR), requiring all methane-emitting operations to provide emission levels reports to EPA analysts to deal with high-emitting sources. New standards set emission limits for methane; reductions were to be made through transition to newer and cleaner production equipment, fixed monitoring of leaks at operation sites using innovative techniques, and the capturing of emissions from hydraulic fracturing.[69]

A September 2016 study from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory analyzed a set of definite and proposed climate change policies for the United States and found that these were insufficient to meet the US intended nationally determined contribution (INDC) under the 2015/2016 Paris Agreement. Additional greenhouse gas reduction measures were required to meet this international commitment.[70][71]

An October 2016 report compared US government spending on climate security and military security and found the latter to be 28 times greater. The report estimated that public sector spending of $55 billion was needed to tackle climate change. The 2017 national budget contained $21 billion for such expenditures, leaving a shortfall of $34 billion that could be recouped by scrapping underperforming weapons programs. The report recommended the F-35 fighter and close-to-shore combat ship projects as possible targets.[72][73][74]

Transportation

[edit]President's 21st century clean transportation plan

[edit]In June 2015, the Obama administration released the President's 21st Century Clean Transportation Plan with the goal of reducing carbon pollution by converting the nation's century old infrastructure into one based on clean energy. The President's multibillion-dollar proposal provided incentives to reduce reliance on international oil and fossil fuels. It involved adding $20 billion per year transit and high-speed rail investments, $10 billion per year to improved regional transportation planning reform, and $2 billion per year to alternative fuel and autonomous vehicle research.[75]

Previously, similar investments in transportation were supported by the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (FAST), an act passed in December 2015 by the Obama administration. FAST was formulated to reduce traffic and increase the quality of air by reducing emissions, yet it proved to be slow in gathering infrastructure investments.[76] Thus, the President proposed a tax on oil of $10 per barrel to pay for it. The plan failed in the House due to the Republican majority.[77]

Climate Action Plan progress report

[edit]In June 2015, under Obama's Climate Action Plan Progress Report, the EPA announced that they were going to propose new standards for both medium and heavy-duty engines and vehicles, building off standards that were already enacted. These proposals were projected to decrease emissions by 270 million metric tons and save vehicle owners around $50 billion in fuel costs.[78]

The Climate Action Plan progress report also addressed aircraft, transit, and maritime emissions. The EPA proposed a rule tightening carbon pollution standards in civil aviation. Additionally, under the Next Generation Air Transportation System, the Federal Aviation Administration worked with the aviation industry on lower-emissions technologies, the Maritime Administration oversaw an increase of investments into more fuel-efficient ships, and incentives made it possible for buses and other forms of transit to switch to other forms of energy such as natural gas and electric.[78]

EPA tailpipe emissions standards

[edit]In April 2010, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of Transportation's National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) formulated a national program that would finalize new standards for model year 2012 through 2016 most consumer road vehicles. With these new standards, vehicles were required to meet an average emissions level of 250 grams of carbon dioxide per mile by model year 2016. This was the first time the EPA had taken measures to regulate vehicular GHG emissions under the Clean Air Act.

Additionally, the administration established Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act.[79]

In August 2012, the administration expanded on these standards for model years 2017 through 2025 vehicles, issuing final rules and standards that were to result in a 163 gram emission per mile by model year 2025.[80]

Trump administration

[edit]It'll start getting cooler. You just watch. ...

I don't think science knows, actually.

—Donald Trump, on climate change

September 13, 2020[81]

During his campaign, Donald Trump promised to roll back some of the Obama-era regulations enacted with the purpose of combating climate change. He questioned the existence of climate change and stated that efforts to curb fossil fuel emissions could harm the United States' global competitiveness.[82] He pledged to roll back regulations placed on the oil and gas industry by the EPA under the Obama administration in order to boost the productivity of both industries.[83]

As president, Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Climate Agreement, a major international convention to address climate change.[84]

Appointment of energy industry-affiliated officials

[edit]As president, Trump appointed Scott Pruitt, a climate change denialist with a history of close ties to energy industry interests,[85][86] to head the EPA. While serving as Attorney General of Oklahoma, Pruitt removed Oklahoma's environmental protection unit and sued the EPA a total of fourteen times, thirteen of which involved "industry players" as co-parties.[87] He was confirmed to head the EPA on February 17, 2017, with a 52–46 vote[88] and resigned on July 5, 2018, amid ethics violation controversies. Trump then nominated Andrew Wheeler, an attorney who worked as a coal lobbyist.[89][90][91] who was confirmed as head of the EPA on February 28, 2019, by a 52–47 vote.[92]

Trump nominated Rex W. Tillerson, the former CEO and chairman of Exxon Mobil, the multinational oil and gas giant, as Secretary of State. His nomination was confirmed on February 1, 2017, by a 56–43 vote.[93] He was fired on March 31, 2018, and replaced by Mike Pompeo.

Pipeline expansion and attempts at major cuts to EPA

[edit]After less than a week as president, on January 24, 2017, Trump issued an executive order that removed barriers from the Keystone XL and Dakota Access Pipelines, making it easier for the companies sponsoring them to continue with production.[94] On March 28, 2017, President Trump signed an executive order aimed towards boosting the coal industry. The executive order rolls back on Obama-era climate regulations on the coal industry in order to grow the coal sector and create new American jobs. The White House indicated that any climate change policies that they deem hinder the growth of American jobs will not be pursued. In addition, the executive order rolled back on six Obama-made orders aimed at reducing climate change and carbon dioxide emissions and called for a review of the Clean Power Plan.[95]

Suppression and politicization of climate science

[edit]In his first year in office, President Trump ordered the Environmental Protection Agency to remove references to climate change from its website, suppressed government publication of scientific reports showing the threat of climate change and the effectiveness of renewable energy, and politicized decisions made at the EPA.[96][97][98][99][100] In a similar vein, the Trump Administration prevented scientists from reporting to Congress regarding the threat of climate change and the urgent need to address it.[101] However, buried inside a 500-page Environmental Impact Statement (EIP) published by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the Trump administration acknowledged that, without a course correction, the planet is on track for global average temperature warming by approximately four degrees Celsius by the end of the century, compared with preindustrial levels. Such warming would be catastrophic for organized human life, according to scientists. The EIP supports the U.S. government's decision to maintain without increase fuel-efficiency standards for cars and other vehicles.[102]

In his budget proposal for 2018, President Trump proposed cutting the EPA's budget by 31% (reducing its current $8.2 billion to $5.7 billion). Had it passed, it would have been the lowest EPA budget in 40 years adjusted for inflation,[103] but Congress did not approve it. Trump tried again unsuccessfully in his budget proposal for 2019 to cut EPA funding by 26%.[104][105] The EPA provides technical assistance to cities as they update their infrastructure to adapt to climate change, according to Joel Scheraga, the EPA senior advisor for climate change adaptation who has worked for the EPA for three decades. Scheraga said he was working with a reduced staff under the Trump administration.[106]

Environmental justice

[edit]The shift in direction of environmental policy in the United States under the Trump administration has led to a change in the environmental justice sector. On March 9, 2017, Mustafa Ali, a leader of the environmental justice office at EPA, resigned over proposed cuts to the agency's environmental justice program. The preliminary budget proposals would cut the environmental justice office's budget by 1/4, causing a 20% reduction in its workforce. The program is one of a dozen vulnerable to losing all governmental funding.[107]

Biden administration

[edit]

The Biden administration paused construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline,[108] created a National Climate Task Force, paused oil and gas leases on public lands,[109] and re-joined the Paris Agreement. His administration proposed spending on climate change in his $2.1 trillion infrastructure bill, including $174 billion for electric cars and $35 billion for research and development in climate-focused technology.[110]

In June 2021 the Keystone XL pipeline, considered by some as dangerous for climate, was cancelled, following strong objection from environmentalists, indigenous peoples, the Democratic Party, and the Joe Biden administration.[111]

However, in 2023, the Biden administration approved the Willow project, a new oil refinery in northern Alaska,[112] and faced many objections from climate activists, who said it would contribute 287 million tons of carbon emissions.[113] It came amid a slew of hundreds of other new oil and gas project approvals under Biden.[114] In response, Biden stopped oil and gas leases in and around the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (though not the Willow lease itself) in September 2023,[115] and temporarily suspended regulatory approvals for new natural gas export terminals in January 2024,[116] though this suspension was halted by Louisiana federal judge James D. Cain Jr. in July.[117]

Even still, the Biden administration presided over record oil and gas production highs, reaching 12.9 million barrels per day in 2023[118] and 530,000 barrels per day from public lands since 2020 (despite a campaign pledge to halt drilling on said lands), though growth has been driven more by Permian Basin drilling than by the administration's policies.[119]

Biden's goals in developing a federal climate change policy were hampered by the Supreme Court ruling in West Virginia v. EPA, where the court ruled against the EPA's ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions.[120][121]

Around spring 2024, the Biden administration announced several changes to its climate policy approach. First, the EPA issued new tailpipe emissions limits that it projected would cut emissions by 7 billion metric tons, or 56% of 2026 levels, by 2032.[122] Second, the Interior Department raised royalty rates from 12.5% to 16.7%, doubled rents and increased lease bond minimums by a factor of 15 on federal lands for oil and gas companies.[123] Third, it allowed wildlife conservation groups to pay rents to restore federal lands for the first time.[124] Fourth, the EPA finalized new standards for power plant carbon emissions, projecting cuts of 65,000 tons by 2028 and 1.38 billion tons by 2047.[125] Fifth, the DOE announced that it would assume the role of default lead agency on regulatory approvals for most new power transmission projects, streamline permitting approvals, enact a two-year deadline, require only one environmental impact statement per project, and increase transparency around the permitting process.[126] Lastly, it issued a new rule to make large water heaters much more energy-efficient by 2029, cutting carbon emissions by a projected 332 million tons over 30 years, as part of the DOE's overall effort since 2020 to drive 2.5 billion tons in 30-year appliance emissions cuts.[127] [128]

In May 2024, the Biden administration doubled tariffs on solar cells imported from China and more than tripled tariffs on lithium-ion electric vehicle batteries imported from China.[129] The increased tariffs will be phased in over a period of three years.[129]

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

[edit]In 2021, due to pressure from Senate Republicans, Biden's infrastructure plan was shrunk to $1.2 trillion, and signed into law as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The Act makes several investments germane to climate policy. These include the largest investment in public transit in American history at $89.9 billion,[130][131] $66 billion in rail transport,[132] $11 billion in electric power transmission reform, $8.6 billion in carbon capture and storage projects, $7 billion in hydrogen economy projects, $430 million in factory decarbonization projects,[133][134] $8 billion in Western state drought mitigation programs,[135] $7.5 billion in charging stations,[131] and boosts to transit-oriented development,[136] freeway removal,[137] cycling and complete streets,[138] and numerous ecosystem restoration and wildlife conservation programs.[139][140]

However, before its passage into law, the impact of the Act on climate was forecast to be small (with emissions reductions on the order of 200 million metric tons in the best-case scenario), and highly dependent on implementation of the highway provisions.[141][142]

Under the IIJA, in April 2023, President Biden's administration made $450 million available for solar farms and other sustainable energy projects at the sites of active or former coal mines.[143][144]

Inflation Reduction Act

[edit]The Inflation Reduction Act was a reconciliation bill that was the largest investment in climate change mitigation in US history to date, setting out provisions to invest in increasing renewable energy and electrifying areas of the US economy. The legislation, signed into law by Biden on August 16, 2022, invests approximately $400 billion to climate-related projects, primarily in the form of tax credits for consumers and private businesses. The majority of these investments is intended to increase the amount of wind and solar energy in the United States grid by providing tax incentives to renewable energy producers, as well as companies that manufacture batteries and wind and solar power components.[145][146][147][148] The Act may also invest $28–48 billion in building retrofits and energy efficiency, $23–436 billion in clean transportation, $22–26 billion in environmental justice, land use, air pollution reduction and resilience, and $3–21 billion in sustainable agriculture.[149][150][151]

However, the law also requires that for federal lands, oil and gas projects be considered before wind and solar rights of way, even as it brought about the aforementioned royalty rate increases.[152]

The law explicitly defines carbon dioxide as an air pollutant under the Clean Air Act to make the Act's EPA enforcement provisions harder to challenge in court,[153] and created a first-of-its-kind green bank, among a wide variety of other provisions to cut pollution.[154] According to several independent analyses, the law is projected to reduce 2030 U.S. greenhouse gas emissions to 40% below 2005 levels.[155]

By the Act's first anniversary, emissions projections had begun to shift. According to Rhodium Group and the World Economic Forum, in the first year of implementation, the Act had a significant impact on the environment: their expectations for GHG emissions reductions by 2030, relative to 2005 levels, moved from 17%-30% to 29%-42%, and to 32%-51% by 2035. The EPA used dozens of millions of dollars to improve air quality and hundreds of millions for environmental justice and local climate plans, NOAA spent hundreds of millions to adapt coastlines to climate change, and more than $1 billion was allocated to equitable access to urban heat island reductions.[156][157][158]

State and local policy

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (May 2024) |

Across the country, regional organizations, states, and cities are achieving real emissions reductions and gaining valuable policy experience as they take action on climate change. These actions include increasing renewable energy generation, selling agricultural carbon sequestration credits, and encouraging efficient energy use.[159] The U.S. Climate Change Science Program is a joint program of over twenty U.S. cabinet departments and federal agencies, all working together to investigate climate change. In June 2008, a report issued by the program stated that weather would become more extreme, due to climate change.[160][161]

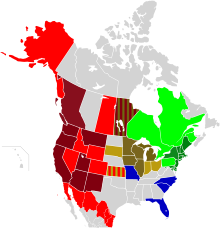

As described in a 2007 brief by the PEW Center on Global Climate Change, "States and municipalities often function as "policy laboratories", developing initiatives that serve as models for federal action. This has been especially true with environmental regulation—most federal environmental laws have been based on state models. In addition, state actions can have a significant impact on emissions, because many individual states emit high levels of greenhouse gases. Texas, for example, emits more than France, while California's emissions exceed those of Brazil."[162]

City and state governments often act as liaisons to the business sector, working with stakeholders to meet standards and increase alignment with city and state goals.[163] This section will provide an overview of major statewide climate change policies as well as regional initiatives.

Arizona

[edit]On September 8, 2006, Arizona Governor Janet Napolitano signed an executive order calling on the state to create initiatives to cut greenhouse gas emissions to the 2000 level by the year 2020 and to 50 percent below the 2000 level by 2040.[164][165]

California

[edit]As the most populous state in the United States,[166] California's climate policies influence both global climate change and federal climate policy. In line with the views of climate scientists, the state of California has progressively passed emission-reduction legislation.

California has taken legislative steps in the hope of mitigating the risks of potential effects of climate change in California by incentives and plans for clean cars, renewable energy, and pollution controls on industry.[167] In California, climate change policy has been developed through both the executive and legislative branches of the state government.[168] Many of the policies have specifically targeted greenhouse gas emissions, which have been shown to raise global temperatures and skew natural rhythms.[169]

One of the most notable pieces of climate legislation in California was Assembly Bill 32. This landmark piece of legislation required many actors in California’s economy to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020.[170] The bill also appointed the California Air Resources Board (CARB) to devise policies and mechanisms for reaching the goal.[170] CARB ultimately implemented the state’s cap-and-trade program, a type of emissions trading, the first such program in the United States.[171] California was able to reach the emissions target four years ahead of schedule, in 2016.[172]

California (the world's fifth largest economy) has long been seen as the state-level pioneer in environmental issues related to global warming and has shown some leadership in the last four years[when?]. On July 22, 2002, Governor Gray Davis approved AB 1493, a bill directing the California Air Resources Board to develop standards to achieve the maximum feasible and cost-effective reduction of greenhouse gases from motor vehicles. Now the California Vehicle Global Warming law, it requires automakers to reduce emissions by 30% by 2016. Although it has been challenged in the courts by the automakers, support for the law is growing as other states have adopted similar legislation. On September 7, 2002, Governor Davis approved a bill requiring the California Climate Action Registry to adopt procedures and protocols for project reporting and carbon sequestration in forests. (SB 812. Approved by Governor Davis on September 7, 2002) California has convened an interagency task force, housed at the California Energy Commission, to develop these procedures and protocols. Staff are currently seeking input on a host of technical questions.

In June 2005, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed an executive order calling for the following reductions in state greenhouse gas emissions: to reduce GHG emissions to 2000 levels by 2010, to reduce GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2020, to reduce GHG emissions to 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050.[174] Measures to meet these targets include tighter automotive emissions standards, and requirements for renewable energy as a proportion of electricity production. The Union of Concerned Scientists has calculated that by 2020, drivers would save $26 billion per year if California's automotive standards were implemented nationally.[175]

On August 30, 2006, Schwarzenegger and the California Legislature reached an agreement on AB32, the Global Warming Solutions Act. He signed the bill into law on September 27, 2006, saying, "We simply must do everything we can in our power to slow down global warming before it is too late... The science is clear. The global warming debate is over." The Act caps California's greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels by 2020, and institutes a mandatory emissions reporting system to monitor compliance, representing the first enforceable statewide program in the U.S. to cap all GHG emissions from major industries that includes penalties for non-compliance. It required the State Air Resources Board to establish a program for statewide greenhouse gas emissions reporting and to monitor and enforce compliance with this program, authorizes the state board to adopt market-based compliance mechanisms[176] including cap-and-trade, and allows a one-year extension of the targets under extraordinary circumstances.[177] Thus far, flexible mechanisms in the form of project based offsets have been suggested for five main project types. A carbon project would create offsets by showing that it has reduced carbon dioxide and equivalent gases. The project types include: manure management, forestry, building energy, SF6, and landfill gas capture.

Additionally, on September 26 Governor Schwarzenegger signed SB 107, which requires California's three major biggest utilities – Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric – to produce at least 20% of their electricity using renewable sources by 2010. This shortens the time span originally enacted by Gov. Davis in September 2002 to increase utility renewable energy sales 1% annually to 20% by 2017.

Gov. Schwarzenegger also announced he would seek to work with Prime Minister Tony Blair of Great Britain, and various other international efforts to address global warming, independently of the federal government.[178]Connecticut

[edit]The state of Connecticut passed a number of bills on global warming in the early to mid 1990s, including—in 1990—the first state global warming law to require specific actions for reducing CO2. Connecticut is one of the states that agreed, under the auspices of the New England Governors and Eastern Canadian Premiers (NEG/ECP), to a voluntary short-term goal of reducing regional greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2010 and by 10 percent below 1990 levels by 2020. The NEG/ECP long-term goal is to reduce emissions to a level that eliminates any dangerous threats to the climate—a goal scientists suggest will require reductions 75 to 85 percent below current levels.[179] These goals were announced in August 2001. The state has also acted to require additions in renewable electric generation by 2009.[180]

Maryland

[edit]Maryland began a partnership with the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES) in 2015 to research impacts and solutions to climate change called the Maryland Climate Change Commission.[181]

Minnesota

[edit]In 2007, the state of Minnesota implemented a goal of 80% greenhouse gas emissions reductions from 2005 levels, by 2030. However, under the state's 2022 Climate Action Framework, the goal was revised to 50% by 2030, and 100% by 2050.[182]

Under a Democratic trifecta headed by Tim Walz, from 2023 to 2024, the state enacted 40 Framework initiatives to deal with climate change. These include a clean energy standard of 100% by 2040, a green-collar worker apprenticeship program, a new green bank, improvements to electric vehicle charging networks, weatherization and building-related embedded emissions programs, and increased financial aid to peatland, stream and forest conservation and pollinator breeders.[183] The state government also passed a $9 billion transportation package focused on raising the gas tax and improving transit, biking and walking,[184] and implemented a bipartisan energy permitting reform bill.[185][186] It implemented California's stricter tailpipe emissions standards for cars,[187] and set a goal of 20% electric vehicles as a share of all cars by 2030.[188]

However, the state government came under criticism for its lax approach to regulatory capture regarding climate action in the agricultural[189] and iron processing[190] sectors, and for its fast-tracking of the Line 3 pipeline expansion and police brutality-filled response to the indigenous-led Stop Line 3 protests.[191][192]

New York

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (April 2021) |

In August 2009, Governor David Paterson created the New York State Climate Action Council (NYSCAC) and tasked them with creating a direct action plan. In 2010, the NYSCAC released a 428-page Interim Report which outlined a plan to reduce emissions and highlighted the impact climate change will have in the future.[193] In 2010, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority also commissioned a report about statewide climate change impacts, later published in November 2011. After Hurricanes Sandy and Irene along with Tropical Storm Lee, the state updated vulnerability in regards to the condition of its critical infrastructure.

According to the 2015 New York State Energy Plan, renewable sources, which include wind, hydropower, solar, geothermal, and sustainable biomass, have the potential to meet 40 percent of the state's energy needs by 2030. As of 2018[update], sustainable energy use comprises 11 percent of all energy usage.[194] The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority offers incentives in the form of grants and loans to its residents to adopt renewable energy technologies and create renewable energy businesses.

Other state climate change mitigation laws have gone into effect. The net metering laws make it easier for both residents and businesses to use solar power by feeding unused energy back into electrical fields and receive credit from their power suppliers. Although one version was released in 1997, it was exclusively limited to residential systems using up to 10 kilowatts of power. However, on June 1, 2011, the laws were expanded to include farm and non-residential buildings.[195] The Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard set a statewide target for renewable energy and offered incentives to residents to use the new technologies.[194]

In June 2018, the state announced its first major update in over two decades to its Environmental Quality Review (EQR) regulations. The update involves streamlining the environmental review process and encouraging renewable energy. It also expanded the Type II actions, or "list of actions not subject to further review", including green infrastructure upgrades and retrofits. Furthermore, solar arrays are set to be installed in sites like brownfields, wastewater treatment facilities, and land zoned for industry. The regulations will take effect on January 1, 2019.[193]

New York State Energy Plan

[edit]In 2014, Governor Andrew Cuomo enforced the state's hallmark energy policy, Reforming the Energy Vision. This involves building a new network that will connect the central grid with clean, locally generated power. The method for this undertaking falls to the Energy Plan, a comprehensive plan to build a clean, resilient, affordable energy system for all New Yorkers. It will foster "economic prosperity and environmental stewardship" and cooperation between government and industry. Concrete goals thus far include a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas from 1990 levels, electricity sourced from 50% of renewable energy sources, and a 600 billion BTU increase in statewide energy efficiency.[196]

Washington

[edit]Under the administration of Governor Jay Inslee, the Washington state government has enacted laws creating the following:

- "A landmark 100% clean electricity policy that puts Washington on the nation’s most ambitious pathway to 100% clean electricity by 2045

- "A nation-leading clean buildings policy

- "A cap-and-invest program [i.e., cap-and-trade] that will help fund new climate-friendly transportation options and community reinvestments that help businesses and families to transition away from fossil fuels

- "Rapid electric vehicle adoption

- "Launch of a state Clean Energy Fund, the Clean Energy Institute at University of Washington, and the Institute for Northwest Energy Futures at Washington State University"[197]

Regional initiatives

[edit]Clean Energy Standards

[edit]Clean Energy Standard (CES) policies are policies which favor lowering non-renewable energy emissions and increasing renewable energy use. They are helping to drive the transition to cleaner energy, by building upon existing energy portfolio standards, and could be applied broadly at the federal level and developed more acutely at the regional and state levels. CES policies have had success at the federal level, gaining bipartisan support during the Obama administration. Iowa was the first state to adopt CES policies, and now a majority of states have adopted CES policies.[198] Similar to CES policies, Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) are standards set in place to ensure a greater integration of renewable energies in state and regional energy portfolios. Both CES and RPS are helping increase the use of clean and renewable energies in the United States.

Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

[edit]In 2003, New York State proposed and attained commitments from nine Northeast states to form a cap and trade carbon dioxide emissions program for power generators, called the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). This program launched on January 1, 2009, with the aim to reduce the carbon "budget" of each state's electricity generation sector to 10 percent below their 2009 allowances by 2018.[199] 11 Northeastern US states are involved in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative,[200] It is believed that the state-level program will apply pressure on the federal government to support Kyoto Protocol.[201] The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is a cap and trade system for CO2 emissions from power plants in the member states. Emission permit auctioning began in September 2008, and the first three-year compliance period began on January 1, 2009.[202] Proceeds will be used to promote energy conservation and renewable energy.[203] The system affects fossil fuel power plants with 25 MW or greater generating capacity ("compliance entities").[202] Since 2005, the participating states have collectively seen an over 45% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by RGGI-affected power plants. This has resulted in cleaner air, better health, and economic growth.[204]

- Participating states: Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Massachusetts, Maryland, Rhode Island

- Observer states and regions: Pennsylvania, District of Columbia, Quebec, New Brunswick, Ontario.[205]

Western Climate Initiative

Since February 2007, seven U.S. states and four Canadian provinces have joined to create the Western Climate Initiative, a regional greenhouse gas emissions trading system.[206] The Initiative was created when the West Coast Global Warming Initiative (California, Oregon, and Washington) and the Southwest Climate Change Initiative (Arizona and New Mexico) joined efforts with Utah and Montana, along with British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec.[207]

The nonprofit organization WCI, Inc., was established in 2011 and supports implementation of state and regional greenhouse gas trading programs.[208]

Powering the Plains Initiative

[edit]The Powering the Plains Initiative (PPI) began in 2001 and aims to expand alternative energy technologies and improve climate-friendly agricultural practices.[209][210] Its most significant accomplishment was a 50-year energy transition roadmap for the upper Midwest, released in June 2007.[211]

- Participating states: Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Dakota, South Dakota, Canadian Province of Manitoba

Litigation by states

[edit]Several lawsuits have been filed over global warming. In 2007 the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency that the Clean Air Act gives the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority to regulate greenhouse gases, such as tailpipe emissions. A similar approach was taken by California Attorney General Bill Lockyer who filed a lawsuit California v. General Motors Corp. to force car manufacturers to reduce vehicles' emissions of carbon dioxide. A third case, Comer v. Murphy Oil, was filed by Gerald Maples, a trial attorney in Mississippi, in an effort to force fossil fuel and chemical companies to pay for damages caused by global warming.[212]

In June 2011, the United States Supreme Court overturned 8–0 a U.S. appeals court ruling against five big power utility companies, brought by U.S. states, New York City, and land trusts, attempting to force cuts in United States greenhouse gas emissions regarding global warming. The decision gives deference to reasonable interpretations of the United States Clean Air Act by the Environmental Protection Agency.[213][214][215]

Held v. Montana was the first constitutional law climate lawsuit to go to trial in the United States, on June 12, 2023.[216] The case was filed in March 2020 by sixteen youth residents of Montana, then aged 2 through 18,[217] who argued that the state's support of the fossil fuel industry had worsened the effects of climate change on their lives, thus denying their right to a "clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and future generations"[218]:Art. IX, § 1 as required by the Constitution of Montana.[219] On August 14, 2023, the trial court judge ruled in the youth plaintiffs' favor, though the state indicated it would appeal the decision.[220] Montana's Supreme Court heard oral arguments on July 10, 2024, its seven justices taking the case under advisement.[221]

In June 2023, Multnomah County, Oregon filed a lawsuit against seven defendants, including Exxon Mobil, Shell, Chevron and the Western States Petroleum Association, for materially contributing to the 2021 heat wave in the Pacific Northwest, which is thought to have killed hundreds of people.[222] According to the Center for Climate Integrity, the Multnomah County lawsuit is the 36th action filed against fossil fuel interests for worsening the effects of climate change.[222]

Position of political parties and other political organizations

[edit]In the 2016 presidential campaigns, the two major parties established different positions on the issue of global warming and climate change policy. The Democratic Party seeks to develop policies which curb negative effects from climate change.[228] The Republican Party, whose leading members have frequently denied the existence of global warming,[229] continues to meet its party goals of expanding the energy industries [230] and curbing the efforts of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[231] Other parties, including the Green Party, the Libertarian Party, and the Constitution Party possess various views of climate change and mostly maintain their parties' own long-standing positions to influence their party members.

Democratic Party

[edit]In its 2016 platform, the Democratic Party views climate change as "an urgent threat and a defining challenge of our time." Democrats are dedicated to "curbing the effects of climate change, protecting America's natural resources, and ensuring the quality of our air, water, and land for current and future generations."[228]

With respect to climate change, the Democratic Party believes that "carbon dioxide, methane, and other greenhouse gasses should be priced to reflect their negative externalities, and to accelerate the transition to a clean energy economy and help meet our climate goals."[232] Democrats are also committed to "implementing, and extending smart pollution and efficiency standards, including the Clean Power Plan, fuel economy standards for automobiles and heavy-duty vehicles, building codes and appliance standards."[232]

Democrats emphasize the importance of environmental justice. The party calls attention to the environmental racism as the climate change has disproportionately impacted low-income and minority communities, tribal nations and Alaska Native villages. The party believes "clean air and clean water are basic rights of all Americans."[232]

Republican Party

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (April 2021) |

The Republican Party has varied views on climate change.[233] The most recent 2016 Republican Platform denies the existence of climate change and dismisses scientists’ efforts of easing global warming.

The GOP does champion some energy initiatives following: opening up public lands and the ocean for further oil exploration; fast tracking permits for oil and gas wells; and hydraulic fracturing. It also supports dropping "restrictions to allow responsible development of nuclear energy."[228]

In 2014, President Barack Obama proposed a series of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations, known as the Clean Power Plan that would reduce carbon pollution from coal-fired power plants. The Republican Party has viewed these efforts as a "war on coal" and has significantly opposed them. Instead, it advocates building the Keystone XL pipeline, outlawing a carbon tax, and stopping all fracking regulations.

Donald Trump, the former President of the United States, has said that "climate change is a hoax invented by and for Chinese."[234] During his political campaign, he blamed China for doing little helping the environment on the earth, but he seemed to ignore many projects organized by China to slow global warming. While Trump's words might be counted as his campaign strategy to attract voters, it brought concerns from the left about environmental justice.

From 2008 to 2017, the Republican Party went from "debating how to combat human-caused climate change to arguing that it does not exist," according to The New York Times.[235] In 2011 "more than half of the Republicans in the House and three-quarters of Republican senators" said "that the threat of global warming, as a man-made and highly threatening phenomenon, is at best an exaggeration and at worst an utter 'hoax'", according to Judith Warner writing The New York Times Magazine.[236] In 2014, more than 55% of congressional Republicans were climate change deniers, according to NBC News.[237][238] According to PolitiFact in May 2014, "...relatively few Republican members of Congress...accept the prevailing scientific conclusion that global warming is both real and man-made...eight out of 278, or about 3 percent."[229][239] A 2017 study by the Center for American Progress Action Fund of climate change denial in the United States Congress found 180 members who deny the science behind climate change; all were Republicans.[240][241]

However, many Republicans see ways to address the issue of climate change using conservative principles. In 2019, Luntz Global released polling indicating that a majority of Republican voters would support government action on emissions reduction, and worry the GOP's position on climate hurts its standing within young voting blocs.[242] Also in 2019, several Republican legislators broke with the party to advocate taking action on climate change, with market-based solutions rather than traditional regulations.[243] Additionally, groups of younger Republicans began advocacy efforts in favor of a climate policy response, such as Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions and Young Conservatives For Carbon Dividends (YCCD).[244][245][246] republicEn.org is a conservative non-profit in support of a national, revenue-neutral carbon tax.

By 2022, a group of Republican state treasurers had formed which actively opposed private sector climate initiatives. The group also raised objections to government appointments and regulations due to climate-related issues.[247]

Green Party

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (April 2021) |

The Green Party of the United States advocates for reductions of greenhouse gas emissions and increased government regulation.

In 2010 Platform on Climate Change, the Green Party leaders released their proposal to solve and integrate the problem and policy of climate change with six parts. First, Greens (the members of the Green Party) want a stronger international climate treaty to decrease greenhouse gases at least 40% by 2020 and 95% by 2050. Second, Greens advocate economic policies to create a safer atmosphere. The economic policies include setting carbon taxes on fossil fuels, removing subsidies for fossil fuels, nuclear power, biomass and waste incineration, and biofuels, and preventing corrupt actions from the rise of carbon prices. Third, countries with few contributions should pay for adaption to climate change. Fourth, Greens champion more efficient but low-cost public transportation system and less energy demand economy. Fifth, the government should train more workers to operate and develop the new, green energy economy. Last, Greens think necessary to transform commercial plants where have uncontrolled animal feeding operations and overuse of fossil fuel to health farms with organic practices.[248]

Libertarian Party

[edit]In its 2016 platform, the Libertarian Party states that "competitive free markets and property rights stimulate the technological innovations and behavioral changes required to protect our environment and ecosystems."[249] The Libertarians believe the government has no rights or responsibilities to regulate and control the environmental issues. The environment and natural resources belong to the individuals and private corporations.

Constitution Party

[edit]The Constitution Party, in the 2014 Platform, states that "it is our responsibility to be prudent, productive, and efficient stewards of God's natural resources."[250] On the issue of global warming, it says that "globalists are using the global warming threat to gain more control via worldwide sustainable development."[251] According to the party, eminent domain is unlawful because "under no circumstances may the federal government take private property, by means of rules and regulations which preclude or substantially reduce the productive use of the property, even with just compensation."[250]

In regards to energy, the party calls attention to "the continuing need of the United States for a sufficient supply of energy for national security and for the immediate adoption of a policy of free market solutions to achieve energy independence for the United States," and calls for the "repeal of federal environmental protections."[252] The party also advocates the abolition of the Department of Energy.

Nebraska Farmers Union

[edit]In September 2019, the Nebraska Farmers Union called for "more government action on climate change." The organization wants better agricultural research that develops tools for increasing carbon sequestration in soils, and increased participation by government at state and national levels.[253]

Climate justice

[edit]

Climate justice is part of environmental justice, which EPA defines as: "The fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies."[255]

Poor and disempowered groups often do not have the resources to prepare for, cope with or recover from climate disasters such as droughts, floods, heat waves, hurricanes, etc.[256] This occurs not only within the United States but also between rich nations, who predominantly create the problem of climate change by dumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, and poor nations who have to deal more heavily with the consequences.[256]

State and regional policies

[edit]States and local governments are often tasked with defense against climate change affecting areas and peoples under state and local jurisdiction.

Mayors National Climate Action Agenda

[edit]The Mayors National Climate Action Agenda was founded by Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti, former Houston mayor Annise Parker, and former Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter in 2014.[257] The MNCAA aims to bring climate change policy into the hands of local government and to make federal climate change policies more accountable.[258][259]

As a part of MNCAA, 75 mayors from across the United States, known as the "Climate Mayors", wrote to President Trump on March 28, 2017, in opposition to proposed rollbacks of several major climate change departments and initiatives. They maintain that the federal government should continue to build up climate change policies, stating "we are also standing up for our constituents and all Americans harmed by climate change, including those most vulnerable among us: coastal residents confronting erosion and sea level rise; young and old alike suffering from worsening air pollution and at risk during heatwaves; mountain residents engulfed by wildfires; farmers struggling at harvest time due to drought; and communities across our nation challenged by extreme weather."[260][unreliable source?][261] Climate Mayors currently has over 400 cities involved in the network.[262] Their current key initiative is the Electric Vehicle Request for Information (EV RFI).[263] They have also produced responses to the announcement of the plan for the United States to withdraw from the Paris Agreement[264] and opposition to the proposed repeal of the Clean Power Plan.[265]

United States Climate Alliance

[edit]The United States Climate Alliance is a group of states committed to meeting the Paris Agreement emissions targets despite President Trump's announced withdrawal from the agreement. Currently, there are 22 states that are members of this network.[266] This network is a bipartisan network of governors across the United States and is governed by three core principles: "States are continuing to lead on climate change", "State-level climate action is benefiting our economies and strengthening our communities", "States are showing the nation and the world that ambitious climate action is achievable."[267] Their current initiatives include green banks, grid modernizations, solar soft costs, short-lived climate pollutants, natural and working lands, climate resilience, international cooperation, clean transportation, and improving data and tools.[268]

California

[edit]The California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (commonly known as AB 32) mandates a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by the year 2020.[269] The Environmental Defense Fund and the Air Resources Board recruited staffers with environmental justice expertise as well as community leaders in order to appease environmental justice groups and ensure the safe passage of the bill.[270]

The environmental justice groups who worked on AB 32 strongly opposed cap and trade programs being made mandatory.[270] A cap and trade plan was put in place, and a 2016 study by a group of California academics found that carbon offsets under the plan were not used to benefit people in California who lived near power plants, who are mostly less well off than people who live far from them.[271]

Regional

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (May 2024) |

Twenty-eight states have climate action plans and nine have statewide emission targets. The states of California and New Mexico have committed most recently to emission reductions targets, joining New Jersey, Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Washington and Oregon.

Региональные инициативы могут быть более эффективными, чем программы на уровне штата, поскольку они охватывают более широкую географическую территорию, исключают дублирование работы и создают более единообразную нормативно-правовую среду. За последние несколько лет ряд региональных инициатив начали разработку систем по сокращению выбросов углекислого газа электростанциями, увеличению производства возобновляемой энергии , отслеживанию кредитов на возобновляемую энергию, а также исследованиям и установлению базовых показателей для связывания углерода .

Государственные инициативы

[ редактировать ]Эту статью необходимо обновить . ( февраль 2019 г. ) |

Региональная инициатива по выбросам парниковых газов

[ редактировать ]В декабре 2005 года губернаторы семи северо-восточных и среднеатлантических штатов согласовали Региональную инициативу по парниковым газам (RGGI), систему ограничения и торговли выбросами углекислого газа (CO 2 ) на региональных электростанциях. В настоящее время (на момент редактирования) Коннектикут, Делавэр, Мэн, Нью-Гэмпшир, Нью-Джерси, Нью-Йорк и Вермонт подписали, а губернатор Мэриленда Роберт Эрлих подписал в марте 2006 года закон, который обязывает Мэриленд присоединиться к RGGI к 2007 году. Чтобы облегчить соблюдение целевых показателей по сокращению выбросов, RGGI предоставит гибкие механизмы, которые включают кредиты за сокращение выбросов, достигнутое за пределами электроэнергетического сектора. Успешная реализация модели RGGI создаст основу для того, чтобы другие государства присоединились или сформировали свои собственные региональные системы ограничения выбросов и торговли, а также может стимулировать расширение программы на другие парниковые газы и другие сектора. [ 272 ] Штаты RGGI, наряду с Пенсильванией, Массачусетсом и Род-Айлендом, также разрабатывают реестр парниковых газов, называемый Восточным климатическим регистром .

29 ноября 2011 г. Нью-Джерси вышел из инициативы с 1 января 2012 г. [ 273 ] Такие группы, как Acadia Center, с тех пор сообщили о потере доходов в результате ухода Нью-Джерси и выступили за возобновление участия. [ 274 ]

После избрания Ральфа Нортэма на выборах губернатора Вирджинии в 2017 году и Фила Мерфи на выборах губернатора Нью-Джерси в 2017 году Нью-Джерси и Вирджиния начали предпринимать предварительные шаги по присоединению к RGGI. [ 275 ] [ 276 ]

Ассоциация западных губернаторов

[ редактировать ]Инициатива по чистой и диверсифицированной энергетике Ассоциации западных губернаторов (WGA), включающая 18 западных штатов, начала исследование стратегий по повышению эффективности и использованию возобновляемых источников энергии в своих электроэнергетических системах. Губернаторы Ричардсон (Нью-Мексико), Шварценеггер (Калифорния), Фройденталь (Вайоминг) и Хувен (Северная Дакота) выступают в качестве ведущих управляющих в рамках этой инициативы. Для достижения своих целей консультативный комитет Инициативы (CDEAC) назначил восемь технических целевых групп для разработки рекомендаций, основанных на обзорах конкретных вариантов чистой энергии и эффективности. CDEAC представил окончательные рекомендации Ассоциации губернаторов западных стран 11 июня 2006 г. [ 277 ] Кроме того, WGA и Калифорнийская энергетическая комиссия создают Западный информационный штат по производству возобновляемой энергии (WREGIS). WREGIS — это добровольная система кредитов на возобновляемую энергию, которая отслеживает кредиты на возобновляемую энергию (REC) в 11 западных штатах, чтобы облегчить торговлю в целях соответствия стандартам портфеля возобновляемых источников энергии.

Другие инициативы

[ редактировать ]По состоянию на 2020 год несколько штатов на северо-востоке США обсуждали региональную систему ограничения и торговли выбросами углерода из источников автомобильного топлива, называемую Транспортной климатической инициативой . [ 278 ] В 2021 году Массачусетс отказался от участия, сославшись в качестве одной из причин на то, что в этом больше нет необходимости. [ 279 ]

Губернаторы Аризоны и Нью-Мексико подписали соглашение о создании Инициативы по изменению климата на юго-западе в феврале 2006 года. Оба штата сотрудничали в оценке выбросов парниковых газов и устранении последствий изменения климата на юго-западе. [ 280 ] а 8 сентября 2006 г. губернатор Аризоны Джанет Наполитано издала указ о выполнении рекомендаций, включенных в План действий по изменению климата Консультативной группы по изменению климата. [ 281 ] Штаты Западного побережья — Вашингтон, Орегон и Калифорния — сотрудничают в рамках стратегии по сокращению выбросов парниковых газов, известной как Инициатива губернаторов Западного побережья по глобальному потеплению. [ 282 ] Наконец, 26 февраля 2007 года эти пять западных штатов (Вашингтон, Орегон, Калифорния, Аризона и Нью-Мексико) договорились объединить свои усилия для разработки региональных целей по сокращению выбросов парниковых газов, создав Западную региональную инициативу по борьбе с изменением климата . [ 283 ]

В 2001 году шесть штатов Новой Англии взяли на себя обязательства по выполнению Плана действий губернаторов Новой Англии и премьер-министров Восточной Канады (NEG-ECP) по изменению климата на 2001 год , включая краткосрочные и долгосрочные цели по сокращению выбросов парниковых газов. Powering the Plains, запущенный в 2002 году, представляет собой региональную инициативу, в которой участвуют участники из Дакоты, Миннесоты, Айовы, Висконсина и канадской провинции Манитоба. Эта инициатива направлена на разработку стратегий, политики и демонстрационных проектов в области альтернативных источников энергии и технологий, а также экологически безопасного сельскохозяйственного развития. [ 284 ]

Муниципальные инициативы

[ редактировать ]ИКЛЕИ

[ редактировать ]В 1993 году по приглашению ICLEI муниципальные лидеры встретились в ООН в Нью-Йорке и приняли декларацию, призывающую к созданию всемирного движения местных органов власти по сокращению выбросов парниковых газов, улучшению качества воздуха и повышению устойчивости городов. Результатом стала кампания «Города за защиту климата» (CCP). С момента своего создания кампания CCP выросла и охватила более 650 местных органов власти по всему миру, которые интегрируют смягчение последствий изменения климата в свои процессы принятия решений. [ 285 ]

Соглашение мэров США о защите климата

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел необходимо обновить . ( апрель 2021 г. ) |

16 февраля 2005 года Сиэтла мэр Грег Никелс выступил с инициативой по продвижению целей Киотского протокола посредством лидерства и действий как минимум 141 американского города, и по состоянию на октябрь 2006 года 319 мэров, представляющих более 51,4 миллиона американцев, приняли этот вызов. . [ 286 ] По условиям Центра по защите климата мэров , города должны взять на себя обязательства по трем действиям, стремясь соблюдать Киотский протокол в своих сообществах. [ 287 ] Эти действия включают в себя:

- Стремиться достичь или превзойти цели Киотского протокола в своих сообществах, посредством действий, начиная от политики по борьбе с разрастанием землепользования и заканчивая проектами по восстановлению городских лесов и кампаниями по информированию общественности;

- Призвать правительства своих штатов и федеральное правительство принять политику и программы, направленные на достижение или превышение целевого показателя сокращения выбросов парниковых газов, предложенного для Соединенных Штатов в Киотском протоколе, — сокращение на 7% по сравнению с уровнем 1990 года к 2012 году; и

- Призвать Конгресс США принять двухпартийный закон о сокращении выбросов парниковых газов, который установит национальную систему торговли выбросами.

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Список инициатив по изменению климата § Северная Америка

- План действий по изменению климата 2001 года — План действий губернаторов Новой Англии и премьер-министров Восточной Канады (NEG-ECP) по изменению климата 2001 года.

- Цены на выбросы углерода

- Гражданское климатическое лобби

- Изменение климата в США

- Изменение климата и сельское хозяйство в США

- Выбросы парниковых газов в США

- Соглашение по парниковым газам Среднего Запада

- Подключаемые электромобили в США

- Политика Соединенных Штатов

- Политика изменения климата в Оклахоме

- Общественное мнение об изменении климата

- Регулирование выбросов парниковых газов в соответствии с Законом о чистом воздухе

- Научный консенсус по вопросу изменения климата

- Климатический регистр

- Республиканская война с наукой - книга Криса Муни , 2005 г.

- Научная программа США по изменению климата

- Политика США в области ветроэнергетики

- Западная климатическая инициатива

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Рис. 4 | Научные данные» . Природа .

- ^ «Федеральные действия по климату» . Центр климатических и энергетических решений . 21 октября 2017 года . Проверено 26 февраля 2020 г.

- ^ «Изменение климата: основная информация» . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Агентство по охране окружающей среды США (EPA). 17 января 2017 г.

- ^ «Политика климата» . Исследовательский центр Пью «Наука и общество» . 4 октября 2016 г. Проверено 20 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Кори, Джаред; Лернер, Майкл; Осгуд, Иэн (2020). «Связи цепочки поставок и расширенная углеродная коалиция» (PDF) . Американский журнал политической науки . 65 : 69–87. дои : 10.1111/ajps.12525 . hdl : 2027.42/166293 . ISSN 1540-5907 . S2CID 219437282 .

- ^ ● «Территориальный (MtCO2)» . GlobalCarbonAtlas.org . Проверено 30 декабря 2021 г. (выберите «Просмотр диаграммы»; используйте ссылку для скачивания)

● Данные за 2020 год также представлены в Попович, Надя; Пламер, Брэд (12 ноября 2021 г.). «Кто несет наибольшую историческую ответственность за изменение климата?» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 29 декабря 2021 года.