Экономический рост

| Part of a series on |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

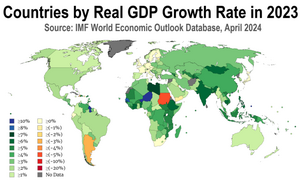

Экономический рост можно определить как увеличение или улучшение рыночной стоимости товаров и услуг, произведенных экономикой в финансовом году с поправкой на инфляцию. [1] Статистики традиционно измеряют такой рост как процентный темп прироста реального и номинального валового внутреннего продукта (ВВП). [2]

Рост обычно рассчитывается в реальном выражении – т.е. с поправкой на инфляцию – чтобы устранить искажающее влияние инфляции на цены производимых товаров . Для измерения экономического роста используется учет национального дохода . [3] Поскольку экономический рост измеряется как годовое процентное изменение валового внутреннего продукта (ВВП), он имеет все преимущества и недостатки этого показателя. Темпы экономического роста стран обычно сравниваются с использованием отношения ВВП к численности населения ( доход на душу населения ). [4]

«Темпы экономического роста» относятся к геометрическим годовым темпам роста ВВП между первым и последним годом за определенный период времени. Этот темп роста представляет собой тенденцию среднего уровня ВВП за период и игнорирует любые колебания ВВП вокруг этой тенденции.

Economists refer to economic growth caused by more efficient use of inputs (increased productivity of labor, of physical capital, of energy or of materials) as intensive growth. In contrast, GDP growth caused only by increases in the amount of inputs available for use (increased population, for example, or new territory) counts as extensive growth.[5]

Development of new goods and services also generates economic growth. As it so happens, in the U.S. about 60% of consumer spending in 2013 went on goods and services that did not exist in 1869.[6]

Measurement

[edit]

The economic growth rate is typically calculated as real GDP growth rate or real GDP per capita growth rate.

Long-term growth

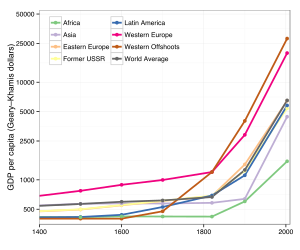

[edit]Living standards vary widely from country to country, and furthermore, the change in living standards over time varies widely from country to country. Below is a table which shows GDP per person and annualized per person GDP growth for a selection of countries over a period of about 100 years. The GDP per person data are adjusted for inflation, hence they are "real". GDP per person (more commonly called "per capita" GDP) is the GDP of the entire country divided by the number of people in the country; GDP per person is conceptually analogous to "average income".

| Country | Period | Real GDP per person at beginning of period | Real GDP per person at end of period | Annualized growth rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | 1890–2008 | $1,504 | $35,220 | 2.71% |

| Brazil | 1900–2008 | $779 | $10,070 | 2.40% |

| Mexico | 1900–2008 | $1,159 | $14,270 | 2.35% |

| Germany | 1870–2008 | $2,184 | $35,940 | 2.05% |

| Canada | 1870–2008 | $2,375 | $36,220 | 1.99% |

| China | 1900–2008 | $716 | $6,020 | 1.99% |

| United States | 1870–2008 | $4,007 | $46,970 | 1.80% |

| Argentina | 1900–2008 | $2,293 | $14,020 | 1.69% |

| United Kingdom | 1870–2008 | $4,808 | $36,130 | 1.47% |

| India | 1900–2008 | $675 | $2,960 | 1.38% |

| Indonesia | 1900–2008 | $891 | $3,830 | 1.36% |

| Bangladesh | 1900–2008 | $623 | $1,440 | 0.78% |

Seemingly small differences in yearly GDP growth lead to large changes in GDP when compounded over time. For instance, in the above table, GDP per person in the United Kingdom in the year 1870 was $4,808. At the same time in the United States, GDP per person was $4,007, lower than the UK by about 20%. However, in 2008 the positions were reversed: GDP per person was $36,130 in the United Kingdom and $46,970 in the United States, i.e. GDP per person in the US was 30% more than it was in the UK. As the above table shows, this means that GDP per person grew, on average, by 1.80% per year in the US and by 1.47% in the UK. Thus, a difference in GDP growth by only a few tenths of a percent per year results in large differences in outcomes when the growth is persistent over a generation. This and other observations have led some economists to view GDP growth as the most important part of the field of macroeconomics:

...if we can learn about government policy options that have even small effects on long-term growth rates, we can contribute much more to improvements in standards of living than has been provided by the entire history of macroeconomic analysis of countercyclical policy and fine-tuning. Economic growth [is] the part of macroeconomics that really matters.[8]

Growth and innovation

[edit]

It has been observed that GDP growth is influenced by the size of the economy. The relation between GDP growth and GDP across the countries at a particular point of time is convex. Growth increases as GDP reaches its maximum and then begins to decline. There exists some extremum value. This is not exactly middle-income trap. It is observed for both developed and developing economies. Actually, countries having this property belong to conventional growth domain. However, the extremum could be extended by technological and policy innovations and some countries move into innovative growth domain with higher limiting values.[9]

Determinants of per capita GDP growth

[edit]

In national income accounting, per capita output can be calculated using the following factors: output per unit of labor input (labor productivity), hours worked (intensity), the percentage of the working-age population actually working (participation rate) and the proportion of the working-age population to the total population (demographics). "The rate of change of GDP/population is the sum of the rates of change of these four variables plus their cross products."[10]

Economists distinguish between long-run economic growth and short-run economic changes in production. Short-run variation in economic growth is termed the business cycle. Generally, according to economists, the ups and downs in the business cycle can be attributed to fluctuations in aggregate demand. In contrast, economic growth is concerned with the long-run trend in production due to structural causes such as technological growth and factor accumulation.

Productivity

[edit]Increases in labor productivity (the ratio of the value of output to labor input) have historically been the most important source of real per capita economic growth.[11][12][13][14][15] In a famous estimate, MIT Professor Robert Solow concluded that technological progress has accounted for 80 percent of the long-term rise in U.S. per capita income, with increased investment in capital explaining only the remaining 20 percent.[16]

Increases in productivity lower the real cost of goods. Over the 20th century, the real price of many goods fell by over 90%.[17]

Economic growth has traditionally been attributed to the accumulation of human and physical capital and the increase in productivity and creation of new goods arising from technological innovation.[18] Further division of labour (specialization) is also fundamental to rising productivity.[19]

Before industrialization technological progress resulted in an increase in the population, which was kept in check by food supply and other resources, which acted to limit per capita income, a condition known as the Malthusian trap.[20][21] The rapid economic growth that occurred during the Industrial Revolution was remarkable because it was in excess of population growth, providing an escape from the Malthusian trap.[22] Countries that industrialized eventually saw their population growth slow down, a phenomenon known as the demographic transition.

Increases in productivity are the major factor responsible for per capita economic growth—this has been especially evident since the mid-19th century. Most of the economic growth in the 20th century was due to increased output per unit of labor, materials, energy, and land (less input per widget). The balance of the growth in output has come from using more inputs. Both of these changes increase output. The increased output included more of the same goods produced previously and new goods and services.[23]

During the Industrial Revolution, mechanization began to replace hand methods in manufacturing, and new processes streamlined production of chemicals, iron, steel, and other products.[24] Machine tools made the economical production of metal parts possible, so that parts could be interchangeable.[25] (See: Interchangeable parts.)

During the Second Industrial Revolution, a major factor of productivity growth was the substitution of inanimate power for human and animal labor. Also there was a great increase in power as steam-powered electricity generation and internal combustion supplanted limited wind and water power.[24] Since that replacement, the great expansion of total power was driven by continuous improvements in energy conversion efficiency.[26] Other major historical sources of productivity were automation, transportation infrastructures (canals, railroads, and highways),[27][28] new materials (steel) and power, which includes steam and internal combustion engines and electricity. Other productivity improvements included mechanized agriculture and scientific agriculture including chemical fertilizers and livestock and poultry management, and the Green Revolution. Interchangeable parts made with machine tools powered by electric motors evolved into mass production, which is universally used today.[25]

Great sources of productivity improvement in the late 19th century were railroads, steam ships, horse-pulled reapers and combine harvesters, and steam-powered factories.[29][30] The invention of processes for making cheap steel were important for many forms of mechanization and transportation. By the late 19th century both prices and weekly work hours fell because less labor, materials, and energy were required to produce and transport goods. However, real wages rose, allowing workers to improve their diet, buy consumer goods and afford better housing.[29]

Mass production of the 1920s created overproduction, which was arguably one of several causes of the Great Depression of the 1930s.[31] Following the Great Depression, economic growth resumed, aided in part by increased demand for existing goods and services, such as automobiles, telephones, radios, electricity and household appliances. New goods and services included television, air conditioning and commercial aviation (after 1950), creating enough new demand to stabilize the work week.[32] The building of highway infrastructures also contributed to post-World War II growth, as did capital investments in manufacturing and chemical industries.[33] The post-World War II economy also benefited from the discovery of vast amounts of oil around the world, particularly in the Middle East. By John W. Kendrick's estimate, three-quarters of increase in U.S. per capita GDP from 1889 to 1957 was due to increased productivity.[15]

Economic growth in the United States slowed down after 1973.[34] In contrast, growth in Asia has been strong since then, starting with Japan and spreading to Four Asian Tigers, China, Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent and Asia Pacific.[35] In 1957 South Korea had a lower per capita GDP than Ghana,[36] and by 2008 it was 17 times as high as Ghana's.[37] The Japanese economic growth has slackened considerably since the late 1980s.

Productivity in the United States grew at an increasing rate throughout the 19th century and was most rapid in the early to middle decades of the 20th century.[38][39][40][41][42] U.S. productivity growth spiked towards the end of the century in 1996–2004, due to an acceleration in the rate of technological innovation known as Moore's law.[43][44][45][46] After 2004 U.S. productivity growth returned to the low levels of 1972–96.[43]

Factor accumulation

[edit]Capital in economics ordinarily refers to physical capital, which consists of structures (largest component of physical capital) and equipment used in business (machinery, factory equipment, computers and office equipment, construction equipment, business vehicles, medical equipment, etc.).[3] Up to a point increases in the amount of capital per worker are an important cause of economic output growth. Capital is subject to diminishing returns because of the amount that can be effectively invested and because of the growing burden of depreciation. In the development of economic theory, the distribution of income was considered to be between labor and the owners of land and capital.[47] In recent decades there have been several Asian countries with high rates of economic growth driven by capital investment.[48]

The work week declined considerably over the 19th century.[49][50] By the 1920s the average work week in the U.S. was 49 hours, but the work week was reduced to 40 hours (after which overtime premium was applied) as part of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933.

Demographic factors may influence growth by changing the employment to population ratio and the labor force participation rate.[11] Industrialization creates a demographic transition in which birth rates decline and the average age of the population increases.

Women with fewer children and better access to market employment tend to join the labor force in higher percentages. There is a reduced demand for child labor and children spend more years in school. The increase in the percentage of women in the labor force in the U.S. contributed to economic growth, as did the entrance of the baby boomers into the workforce.[11]

See: Spending wave

Other factors affecting growth

[edit]Human capital

[edit]Many theoretical and empirical analyses of economic growth attribute a major role to a country's level of human capital, defined as the skills of the population or the work force. Human capital has been included in both neoclassical and endogenous growth models.[51][52][53]

A country's level of human capital is difficult to measure since it is created at home, at school, and on the job. Economists have attempted to measure human capital using numerous proxies, including the population's level of literacy, its level of numeracy, its level of book production/capita, its average level of formal schooling, its average test score on international tests, and its cumulative depreciated investment in formal schooling. The most commonly-used measure of human capital is the level (average years) of school attainment in a country, building upon the data development of Robert Barro and Jong-Wha Lee.[54] This measure is widely used because Barro and Lee provide data for numerous countries in five-year intervals for a long period of time.

One problem with the schooling attainment measure is that the amount of human capital acquired in a year of schooling is not the same at all levels of schooling and is not the same in all countries. This measure also presumes that human capital is only developed in formal schooling, contrary to the extensive evidence that families, neighborhoods, peers, and health also contribute to the development of human capital. Despite these potential limitations, Theodore Breton has shown that this measure can represent human capital in log-linear growth models because across countries GDP/adult has a log-linear relationship to average years of schooling, which is consistent with the log-linear relationship between workers' personal incomes and years of schooling in the Mincer model.[55]

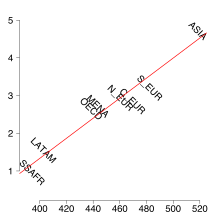

Eric Hanushek and Dennis Kimko introduced measures of students' mathematics and science skills from international assessments into growth analysis.[56] They found that this measure of human capital was very significantly related to economic growth. Eric Hanushek and Ludger Wößmann have extended this analysis.[57][58] Theodore Breton shows that the correlation between economic growth and students' average test scores in Hanushek and Wößmann's analyses is actually due to the relationship in countries with less than eight years of schooling. He shows that economic growth is not correlated with average scores in more educated countries.[55] Hanushek and Wößmann further investigate whether the relationship of knowledge capital to economic growth is causal. They show that the level of students' cognitive skills can explain the slow growth in Latin America and the rapid growth in East Asia.[59]

Joerg Baten and Jan Luiten van Zanden employ book production per capita as a proxy for sophisticated literacy capabilities and find that "Countries with high levels of human capital formation in the 18th century initiated or participated in the industrialization process of the 19th century, whereas countries with low levels of human capital formation were unable to do so, among them many of today's Less Developed Countries such as India, Indonesia, and China."[60]

Health

[edit]Here, health is approached as a functioning from Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum's capability approach that an individual has to realise the achievements like economic success. Thus health in a broader sense is not the absence of illness, but the opportunity for people to biologically develop to their full potential their entire lives [61] It is established that human capital is an important asset for economic growth, however, it can only be so if that population is healthy and well-nourished. One of the most important aspects of health is the mortality rate and how the rise or decline can affect the labour supply predominant in a developing economy.[62] Mortality decline triggers greater investments in individual human capital and an increase in economic growth. Matteo Cervellati and Uwe Sunde[63] and Rodrigo.R Soares[64] consider frameworks in which mortality decline has an influence on parents to have fewer children and to provide quality education for those children, as a result instituting an economic-demographic transition.

The relationship between health and economic growth is further nuanced by distinguishing the influence of specific diseases on GDP per capita from that of aggregate measures of health, such as life expectancy[65] Thus, investing in health is warranted both from the growth and equity perspectives, given the important role played by health in the economy. Protecting health assets from the impact of systemic transitional costs on economic reforms, pandemics, economic crises and natural disasters is also crucial. Protection from the shocks produced by illness and death, are usually taken care of within a country’s social insurance system. In areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa, where the prevalence of HIV and AIDS, has a comparative negative impact on economical development. It will be interesting to see how research in the areas of health in near future uncover how the world will be performing living with the SARS-CoV-2, especially looking at the economic impacts it already has in a space of two years. Ultimately, when people live longer on average, human capital expenditures are more likely to pay off, and all of these mechanisms center around the complementarity of longevity, health, and education, for which there is ample empirical evidence.[65][61][63][64][62]

Political institutions

[edit]"As institutions influence behavior and incentives in real life, they forge the success or failure of nations."[66]

In economics and economic history, the transition from earlier economic systems to capitalism was facilitated by the adoption of government policies which fostered commerce and gave individuals more personal and economic freedom. These included new laws favorable to the establishment of business, including contract law, laws providing for the protection of private property, and the abolishment of anti-usury laws.[67][68]

Much of the literature on economic growth refers to the success story of the British state after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, in which high fiscal capacity combined with constraints on the power of the king generated some respect for the rule of law.[69][70][71][66] However, others have questioned that this institutional formula is not so easily replicable elsewhere as a change in the Constitution—and the type of institutions created by that change—does not necessarily create a change in political power if the economic powers of that society are not aligned with the new set of rule of law institutions.[72] In England, a dramatic increase in the state's fiscal capacity followed the creation of constraints on the crown, but elsewhere in Europe increases in state capacity happened before major rule of law reforms.[73]

There are many different ways through which states achieved state (fiscal) capacity and this different capacity accelerated or hindered their economic development. Thanks to the underlying homogeneity of its land and people, England was able to achieve a unified legal and fiscal system since the Middle Ages that enabled it to substantially increase the taxes it raised after 1689.[73] On the other hand, the French experience of state building faced much stronger resistance from local feudal powers keeping it legally and fiscally fragmented until the French Revolution despite significant increases in state capacity during the seventeenth century.[74][75] Furthermore, Prussia and the Habsburg empire—much more heterogeneous states than England—were able to increase state capacity during the eighteenth century without constraining the powers of the executive.[73] Nevertheless, it is unlikely that a country will generate institutions that respect property rights and the rule of law without having had first intermediate fiscal and political institutions that create incentives for elites to support them. Many of these intermediate level institutions relied on informal private-order arrangements that combined with public-order institutions associated with states, to lay the foundations of modern rule of law states.[73]

In many poor and developing countries much land and housing are held outside the formal or legal property ownership registration system. In many urban areas the poor "invade" private or government land to build their houses, so they do not hold title to these properties. Much unregistered property is held in informal form through various property associations and other arrangements. Reasons for extra-legal ownership include excessive bureaucratic red tape in buying property and building. In some countries, it can take over 200 steps and up to 14 years to build on government land. Other causes of extra-legal property are failures to notarize transaction documents or having documents notarized but failing to have them recorded with the official agency.[76]

Not having clear legal title to property limits its potential to be used as collateral to secure loans, depriving many poor countries of one of their most important potential sources of capital. Unregistered businesses and lack of accepted accounting methods are other factors that limit potential capital.[76]

Businesses and individuals participating in unreported business activity and owners of unregistered property face costs such as bribes and pay-offs that offset much of any taxes avoided.[76]

"Democracy Does Cause Growth", according to Acemoglu et al. Specifically, they state that "democracy increases future GDP by encouraging investment, increasing schooling, inducing economic reforms, improving public goods provision, and reducing social unrest".[77] UNESCO and the United Nations also consider that cultural property protection, high-quality education, cultural diversity and social cohesion in armed conflicts are particularly necessary for qualitative growth.[78]

According to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson, the positive correlation between high income and cold climate is a by-product of history. Europeans adopted very different colonization policies in different colonies, with different associated institutions. In places where these colonizers faced high mortality rates (e.g., due to the presence of tropical diseases), they could not settle permanently, and they were thus more likely to establish extractive institutions, which persisted after independence; in places where they could settle permanently (e.g. those with temperate climates), they established institutions with this objective in mind and modeled them after those in their European homelands. In these 'neo-Europes' better institutions in turn produced better development outcomes. Thus, although other economists focus on the identity or type of legal system of the colonizers to explain institutions, these authors look at the environmental conditions in the colonies to explain institutions. For instance, former colonies have inherited corrupt governments and geopolitical boundaries (set by the colonizers) that are not properly placed regarding the geographical locations of different ethnic groups, creating internal disputes and conflicts that hinder development. In another example, societies that emerged in colonies without solid native populations established better property rights and incentives for long-term investment than those where native populations were large.[79]

In Why Nations Fail, Acemoglu and Robinson said that the English in North America started by trying to repeat the success of the Spanish Conquistadors in extracting wealth (especially gold and silver) from the countries they had conquered. This system repeatedly failed for the English. Their successes rested on giving land and a voice in the government to every male settler to incentivize productive labor. In Virginia it took twelve years and many deaths from starvation before the governor decided to try democracy.[80]

Economic growth, its sustainability and its distribution remain central aspects of government policy. For example, the UK Government recognises that "Government can play an important role in supporting economic growth by helping to level the playing field through the way it buys public goods, works and services",[81] and "Post-Pandemic Economic Growth" has been featured in a series of inquiries undertaken by the parliamentary Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee, which argues that the UK Government "has a big job to do in helping businesses survive, stimulating economic growth and encouraging the creation of well-paid meaningful jobs".[82]

Democracy and economic growth

[edit]| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

Entrepreneurs and new products

[edit]Policymakers and scholars frequently emphasize the importance of entrepreneurship for economic growth. However, surprisingly few research empirically examine and quantify entrepreneurship's impact on growth. This is due to endogeneity—forces that drive economic growth also drive entrepreneurship. In other words, the empirical analysis of the impact of entrepreneurship on growth is difficult because of the joint determination of entrepreneurship and economic growth. A few papers use quasi-experimental designs, and have found that entrepreneurship and the density of small businesses indeed have a causal impact on regional growth.[84][85]

Another major cause of economic growth is the introduction of new products and services and the improvement of existing products. New products create demand, which is necessary to offset the decline in employment that occurs through labor-saving technology (and to a lesser extent employment declines due to savings in energy and materials).[44][86] In the U.S. by 2013 about 60% of consumer spending was for goods and services that did not exist in 1869. Also, the creation of new services has been more important than invention of new goods.[87]

Structural change

[edit]Economic growth in the U.S. and other developed countries went through phases that affected growth through changes in the labor force participation rate and the relative sizes of economic sectors. The transition from an agricultural economy to manufacturing increased the size of the sector with high output per hour (the high-productivity manufacturing sector), while reducing the size of the sector with lower output per hour (the lower productivity agricultural sector). Eventually high productivity growth in manufacturing reduced the sector size, as prices fell and employment shrank relative to other sectors.[88][89] The service and government sectors, where output per hour and productivity growth is low, saw increases in their shares of the economy and employment during the 1990s.[11] The public sector has since contracted, while the service economy expanded in the 2000s.

The structural change could also be viewed from another angle. It is possible to divide real economic growth into two components: an indicator of extensive economic growth—the ‘quantitative’ GDP—and an indicator of the improvement of the quality of goods and services—the ‘qualitative’ GDP.[90]

Growth theories

[edit]Adam Smith

[edit]Adam Smith pioneered modern economic growth and performance theory in his book The Wealth of Nations, first published in 1776. For Smith, the main factors of economic growth are division of labour and capital accumulation. However, these are conditioned by what he calls "the extent of the market". This is conditioned notably by geographic factors but also institutional ones such as the political-legal environment.[91]

Malthusian theory

[edit]Malthusianism is the idea that population growth is potentially exponential while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population die off. The Malthusian theory also proposes that over most of human history technological progress caused larger population growth but had no impact on income per capita in the long run. According to the theory, while technologically advanced economies over this epoch were characterized by higher population density, their level of income per capita was not different from those among technologically regressed society.

The conceptual foundations of the Malthusian theory were formed by Thomas Malthus,[92] and a modern representation of these approach is provided by Ashraf and Galor.[93] In line with the predictions of the Malthusian theory, a cross-country analysis finds a significant positive effect of the technological level on population density and an insignificant effect on income per capita significantly over the years 1–1500.[93]

Classical growth theory

[edit]In classical (Ricardian) economics, the theory of production and the theory of growth are based on the theory of sustainability and law of variable proportions, whereby increasing either of the factors of production (labor or capital), while holding the other constant and assuming no technological change, will increase output, but at a diminishing rate that eventually will approach zero. These concepts have their origins in Thomas Malthus’s theorizing about agriculture. Malthus's examples included the number of seeds harvested relative to the number of seeds planted (capital) on a plot of land and the size of the harvest from a plot of land versus the number of workers employed.[94] (See also Diminishing returns)

Criticisms of classical growth theory are that technology, an important factor in economic growth, is held constant and that economies of scale are ignored.[95]

One popular theory in the 1940s was the big push model, which suggested that countries needed to jump from one stage of development to another through a virtuous cycle, in which large investments in infrastructure and education coupled with private investments would move the economy to a more productive stage, breaking free from economic paradigms appropriate to a lower productivity stage.[96] The idea was revived and formulated rigorously, in the late 1980s by Kevin Murphy, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny.[97]

Solow–Swan model

[edit]Robert Solow and Trevor Swan developed what eventually became the main model used in growth economics in the 1950s.[98][99] This model assumes that there are diminishing returns to capital and labor. Capital accumulates through investment, but its level or stock continually decreases due to depreciation. Due to the diminishing returns to capital, with increases in capital/worker and absent technological progress, economic output/worker eventually reaches a point where capital per worker and economic output/worker remain constant because annual investment in capital equals annual depreciation. This condition is called the 'steady state'.

In the Solow–Swan model if productivity increases through technological progress, then output/worker increases even when the economy is in the steady state. If productivity increases at a constant rate, output/worker also increases at a related steady-state rate. As a consequence, growth in the model can occur either by increasing the share of GDP invested or through technological progress. But at whatever share of GDP invested, capital/worker eventually converges on the steady state, leaving the growth rate of output/worker determined only by the rate of technological progress. As a consequence, with world technology available to all and progressing at a constant rate, all countries have the same steady state rate of growth. Each country has a different level of GDP/worker determined by the share of GDP it invests, but all countries have the same rate of economic growth. Implicitly in this model rich countries are those that have invested a high share of GDP for a long time. Poor countries can become rich by increasing the share of GDP they invest. One important prediction of the model, mostly borne out by the data, is that of conditional convergence; the idea that poor countries will grow faster and catch up with rich countries as long as they have similar investment (and saving) rates and access to the same technology.

The Solow–Swan model is considered an "exogenous" growth model because it does not explain why countries invest different shares of GDP in capital nor why technology improves over time. Instead, the rate of investment and the rate of technological progress are exogenous. The value of the model is that it predicts the pattern of economic growth once these two rates are specified. Its failure to explain the determinants of these rates is one of its limitations.

Although the rate of investment in the model is exogenous, under certain conditions the model implicitly predicts convergence in the rates of investment across countries. In a global economy with a global financial capital market, financial capital flows to the countries with the highest return on investment. In the Solow-Swan model countries with less capital/worker (poor countries) have a higher return on investment due to the diminishing returns to capital. As a consequence, capital/worker and output/worker in a global financial capital market should converge to the same level in all countries.[100] Since historically financial capital has not flowed to the countries with less capital/worker, the basic Solow–Swan model has a conceptual flaw. Beginning in the 1990s, this flaw has been addressed by adding additional variables to the model that can explain why some countries are less productive than others and, therefore, do not attract flows of global financial capital even though they have less (physical) capital/worker.

In practice, convergence was rarely achieved. In 1957, Solow applied his model to data from the U.S. gross national product to estimate contributions. This showed that the increase in capital and labor stock only accounted for about half of the output, while the population increase adjustments to capital explained eighth. This remaining unaccounted growth output is known as the Solow Residual. Here the A of (t) "technical progress" was the reason for increased output. Nevertheless, the model still had flaws. It gave no room for policy to influence the growth rate. Few attempts were also made by the RAND Corporation the non-profit think tank and frequently visiting economist Kenneth Arrow to work out the kinks in the model. They suggested that new knowledge was indivisible and that it is endogenous with a certain fixed cost. Arrow's further explained that new knowledge obtained by firms comes from practice and built a model that "knowledge" accumulated through experience.[101]

According to Harrod, the natural growth rate is the maximum rate of growth allowed by the increase of variables like population growth, technological improvement and growth in natural resources.

In fact, the natural growth rate is the highest attainable growth rate which would bring about the fullest possible employment of the resources existing in the economy.

Endogenous growth theory

[edit]Unsatisfied with the assumption of exogenous technological progress in the Solow–Swan model, economists worked to "endogenize" (i.e., explain it "from within" the models) productivity growth in the 1980s. The resulting endogenous growth theory, most notably advanced by Robert Lucas, Jr. and his student Paul Romer, includes a mathematical explanation of technological advancement.[18][102] This model was notable for its incorporation of human capital, which is interpreted from changes to investment patterns in education, training, and healthcare by private sector firms or governments. Notwithstanding the implications this component has for policy, the endogenous perspective on human capital investment emphasizes the possibility for broad-based effects which can be realized by other firms in the economy. Accordingly, human capital is theorized to deliver increasing rates of return unlike physical capital. Research done in this area has focused on what increases human capital (e.g. education) or technological change (e.g. innovation).[103] The quantity theory of endogenous productivity growth was proposed by Russian economist Vladimir Pokrovskii. It explains growth as a consequence of the dynamics of three factors, including the technological characteristics of production equipment. Without any arbitrary parameters, historical rates of economic growth can be predicted with considerable precision.[104][105][106]

On Memorial Day weekend in 1988, a conference in Buffalo brought together influential thinkers to evaluate the conflicting theories of growth. Romer, Krugman, Barro, and Becker were in attendance along with many other high profiled economists of the time. Amongst many papers that day the one that stood out was Romer's "Micro Foundations for Aggregate Technological Change." The Micro Foundation claimed that endogenous technological change had the concept of Intellectual Property imbedded and that knowledge is an input and output of production. Romer argued that outcomes to the national growth rates were significantly affected by public policy, trade activity, and intellectual property. He stressed that cumulative capital and specialization were key, and that not only population growth can increase capital of knowledge, it was human capital that is specifically trained in harvesting new ideas.[107]

While intellectual property may be important, Baker (2016) cites multiple sources claiming that "stronger patent protection seems to be associated with slower growth". That's particularly true for patents in the ethical health care industry. In effect taxpayers pay twice for new drugs and diagnostic procedures: First in tax subsidies and second for the high prices of diagnostic procedures treatments. If the results of research paid by taxpayers were placed in the public domain, Baker claims that people everywhere would be healthier, because better diagnoses and treatment would be more affordable the world over.[108]

One branch of endogenous growth theory was developed on the foundations of the Schumpeterian theory, named after the 20th-century Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter.[109] The approach explains growth as a consequence of innovation and a process of creative destruction that captures the dual nature of technological progress: in terms of creation, entrepreneurs introduce new products or processes in the hope that they will enjoy temporary monopoly-like profits as they capture markets. In doing so, they make old technologies or products obsolete. This can be seen as an annulment of previous technologies, which makes them obsolete, and "destroys the rents generated by previous innovations".[110]: 855 [111] A major model that illustrates Schumpeterian growth is the Aghion–Howitt model.[112][110]

Unified growth theory

[edit]Unified growth theory was developed by Oded Galor and his co-authors to address the inability of endogenous growth theory to explain key empirical regularities in the growth processes of individual economies and the world economy as a whole.[113][114] Unlike endogenous growth theory that focuses entirely on the modern growth regime and is therefore unable to explain the roots of inequality across nations, unified growth theory captures in a single framework the fundamental phases of the process of development in the course of human history: (i) the Malthusian epoch that was prevalent over most of human history, (ii) the escape from the Malthusian trap, (iii) the emergence of human capital as a central element in the growth process, (iv) the onset of the fertility decline, (v) the origins of the modern era of sustained economic growth, and (vi) the roots of divergence in income per capita across nations in the past two centuries. The theory suggests that during most of human existence, technological progress was offset by population growth, and living standards were near subsistence across time and space. However, the reinforcing interaction between the rate of technological progress and the size and composition of the population has gradually increased the pace of technological progress, enhancing the importance of education in the ability of individuals to adapt to the changing technological environment. The rise in the allocation of resources towards education triggered a fertility decline enabling economies to allocate a larger share of the fruits of technological progress to a steady increase in income per capita, rather than towards the growth of population, paving the way for the emergence of sustained economic growth. The theory further suggests that variations in biogeographical characteristics, as well as cultural and institutional characteristics, have generated a differential pace of transition from stagnation to growth across countries and consequently divergence in their income per capita over the past two centuries.[113][114]

Inequality and growth

[edit]Theories

[edit]The prevailing views about the role of inequality in the growth process has radically shifted in the past century.[115]

The classical perspective, as expressed by Adam Smith, and others, suggests that inequality fosters the growth process.[116][117] Specifically, since the aggregate saving increases with inequality due to higher property to save among the wealthy, the classical viewpoint suggests that inequality stimulates capital accumulation and therefore economic growth.[118]

The Neoclassical perspective that is based on representative agent approach denies the role of inequality in the growth process. It suggests that while the growth process may affect inequality, income distribution has no impact on the growth process.

The modern perspective which has emerged in the late 1980s suggests, in contrast, that income distribution has a significant impact on the growth process. The modern perspective, originated by Galor and Zeira,[119][120] highlights the important role of heterogeneity in the determination of aggregate economic activity, and economic growth. In particular, Galor and Zeira argue that since credit markets are imperfect, inequality has an enduring impact on human capital formation, the level of income per capita, and the growth process.[121] In contrast to the classical paradigm, which underlined the positive implications of inequality for capital formation and economic growth, Galor and Zeira argue that inequality has an adverse effect on human capital formation and the development process, in all but the very poor economies.

Later theoretical developments have reinforced the view that inequality has an adverse effect on the growth process. Specifically, Alesina and Rodrik and Persson and Tabellini advance a political economy mechanism and argue that inequality has a negative impact on economic development since it creates a pressure for distortionary redistributive policies that have an adverse effect on investment and economic growth.[122][123]

In accordance with the credit market imperfection approach, a study by Roberto Perotti showed that inequality is associated with lower level of human capital formation (education, experience, apprenticeship) and higher level of fertility, while lower level of human capital is associated with lower growth and lower levels of economic growth. In contrast, his examination of the political economy channel found no support for the political economy mechanism.[124] Consequently, the political economy perspective on the relationship between inequality and growth have been revised and later studies have established that inequality may provide an incentive for the elite to block redistributive policies and institutional changes. In particular, inequality in the distribution of land ownership provides the landed elite with an incentive to limit the mobility of rural workers by depriving them from education and by blocking the development of the industrial sector.[125]

A unified theory of inequality and growth that captures that changing role of inequality in the growth process offers a reconciliation between the conflicting predictions of classical viewpoint that maintained that inequality is beneficial for growth and the modern viewpoint that suggests that in the presence of credit market imperfections, inequality predominantly results in underinvestment in human capital and lower economic growth. This unified theory of inequality and growth, developed by Oded Galor and Omer Moav,[126] suggests that the effect of inequality on the growth process has been reversed as human capital has replaced physical capital as the main engine of economic growth. In the initial phases of industrialization, when physical capital accumulation was the dominating source of economic growth, inequality boosted the development process by directing resources toward individuals with higher propensity to save. However, in later phases, as human capital become the main engine of economic growth, more equal distribution of income, in the presence of credit constraints, stimulated investment in human capital and economic growth.

In 2013, French economist Thomas Piketty postulated that in periods when the average annual rate on return on investment in capital (r) exceeds the average annual growth in economic output (g), the rate of inequality will increase.[127] According to Piketty, this is the case because wealth that is already held or inherited, which is expected to grow at the rate r, will grow at a rate faster than wealth accumulated through labor, which is more closely tied to g. An advocate of reducing inequality levels, Piketty suggests levying a global wealth tax in order to reduce the divergence in wealth caused by inequality.

Evidence: reduced form

[edit]The reduced form empirical relationship between inequality and growth was studied by Alberto Alesina and Dani Rodrik, and Torsten Persson and Guido Tabellini.[122][123] They find that inequality is negatively associated with economic growth in a cross-country analysis.

Robert Barro reexamined the reduced form relationship between inequality on economic growth in a panel of countries.[128] He argues that there is "little overall relation between income inequality and rates of growth and investment". However, his empirical strategy limits its applicability to the understanding of the relationship between inequality and growth for several reasons. First, his regression analysis control for education, fertility, investment, and it therefore excludes, by construction, the important effect of inequality on growth via education, fertility, and investment. His findings simply imply that inequality has no direct effect on growth beyond the important indirect effects through the main channels proposed in the literature. Second, his study analyzes the effect of inequality on the average growth rate in the following 10 years. However, existing theories suggest that the effect of inequality will be observed much later, as is the case in human capital formation, for instance. Third, the empirical analysis does not account for biases that are generated by reverse causality and omitted variables.

Recent papers based on superior data, find negative relationship between inequality and growth. Andrew Berg and Jonathan Ostry of the International Monetary Fund, find that "lower net inequality is robustly correlated with faster and more durable growth, controlling for the level of redistribution".[129] Likewise, Dierk Herzer and Sebastian Vollmer find that increased income inequality reduces economic growth.[130]

Evidence: mechanisms

[edit]The Galor and Zeira's model predicts that the effect of rising inequality on GDP per capita is negative in relatively rich countries but positive in poor countries.[119][120] These testable predictions have been examined and confirmed empirically in recent studies.[131][132] In particular, Brückner and Lederman test the prediction of the model by in the panel of countries during the period 1970–2010, by considering the impact of the interaction between the level of income inequality and the initial level of GDP per capita. In line with the predictions of the model, they find that at the 25th percentile of initial income in the world sample, a 1 percentage point increase in the Gini coefficient increases income per capita by 2.3%, whereas at the 75th percentile of initial income a 1 percentage point increase in the Gini coefficient decreases income per capita by -5.3%. Moreover, the proposed human capital mechanism that mediates the effect of inequality on growth in the Galor-Zeira model is also confirmed. Increases in income inequality increase human capital in poor countries but reduce it in high and middle-income countries.

This recent support for the predictions of the Galor-Zeira model is in line with earlier findings. Roberto Perotti showed that in accordance with the credit market imperfection approach, developed by Galor and Zeira, inequality is associated with lower level of human capital formation (education, experience, apprenticeship) and higher level of fertility, while lower level of human capital is associated with lower levels of economic growth.[124] Princeton economist Roland Benabou's finds that the growth process of Korea and the Philippines "are broadly consistent with the credit-constrained human-capital accumulation hypothesis".[133] In addition, Andrew Berg and Jonathan Ostry[129] suggest that inequality seems to affect growth through human capital accumulation and fertility channels.

In contrast, Perotti argues that the political economy mechanism is not supported empirically. Inequality is associated with lower redistribution, and lower redistribution (under-investment in education and infrastructure) is associated with lower economic growth.[124]

Importance of long-run growth

[edit]Over long periods of time, even small rates of growth, such as a 2% annual increase, have large effects. For example, the United Kingdom experienced a 1.97% average annual increase in its inflation-adjusted GDP between 1830 and 2008.[134] In 1830, the GDP was 41,373 million pounds. It grew to 1,330,088 million pounds by 2008. A growth rate that averaged 1.97% over 178 years resulted in a 32-fold increase in GDP by 2008.

The large impact of a relatively small growth rate over a long period of time is due to the power of exponential growth. The rule of 72, a mathematical result, states that if something grows at the rate of x% per year, then its level will double every 72/x years. For example, a growth rate of 2.5% per annum leads to a doubling of the GDP within 28.8 years, whilst a growth rate of 8% per year leads to a doubling of GDP within nine years. Thus, a small difference in economic growth rates between countries can result in very different standards of living for their populations if this small difference continues for many years.

Quality of life

[edit]One theory that relates economic growth with quality of life is the "Threshold Hypothesis", which states that economic growth up to a point brings with it an increase in quality of life. But at that point – called the threshold point – further economic growth can bring with it a deterioration in quality of life.[135] This results in an upside-down-U-shaped curve, where the vertex of the curve represents the level of growth that should be targeted. Happiness has been shown to increase with GDP per capita, at least up to a level of $15,000 per person.[136]

Economic growth has the indirect potential to alleviate poverty, as a result of a simultaneous increase in employment opportunities and increased labor productivity.[137] A study by researchers at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) of 24 countries that experienced growth found that in 18 cases, poverty was alleviated.[137]

В некоторых случаях факторы качества жизни, такие как результаты здравоохранения и уровень образования, а также социальные и политические свободы, не улучшаются по мере экономического роста. [138] [ сомнительно – обсудить ]

Рост производительности не всегда приводит к увеличению заработной платы, как это можно видеть на примере США , где разрыв между производительностью и заработной платой увеличивается с 1980-х годов. [137]

Справедливый рост

[ редактировать ]Признавая центральную роль, которую экономический рост потенциально может сыграть в человеческом развитии , сокращении бедности и достижении Целей развития тысячелетия , в сообществе, занимающемся вопросами развития, становится широко понятно, что необходимо прилагать особые усилия для обеспечения возможности участия более бедных слоев общества в этом процессе. в экономическом росте. [139] [140] [141] Влияние экономического роста на сокращение бедности – эластичность бедности по росту – может зависеть от существующего уровня неравенства. [142] [143] Например, при низком уровне неравенства страна с темпами роста 2% на душу населения и 40% населения, живущего в бедности, может сократить бедность вдвое за десять лет, но стране с высоким уровнем неравенства потребуется почти 60 лет, чтобы добиться такого же сокращения. . [144] [145] По словам Генерального секретаря ООН Пан Ги Муна : «Хотя экономический рост необходим, его недостаточно для прогресса в сокращении бедности». [139]

Воздействие на окружающую среду

[ редактировать ]Критики, такие как Римский клуб, утверждают, что узкий взгляд на экономический рост в сочетании с глобализацией создает сценарий, в котором мы можем стать свидетелями системного краха природных ресурсов нашей планеты. [146] [147]

Обеспокоенность по поводу негативных последствий экономического роста для окружающей среды побудила некоторых людей выступать за более низкие уровни роста или вообще отказаться от него. такие концепции, как неэкономический рост , устойчивая экономика , эконалоги , зеленые инвестиции, гарантии базового дохода , а также более радикальные подходы, связанные с деростом , объединением , экосоциализмом и экоанархизмом. В научных кругах для достижения этой цели были разработаны и преодолеть возможные императивы роста . [148] [149] [150] [151] В политике партии зеленых придерживаются Глобальной хартии зеленых , признавая, что «... догма экономического роста любой ценой, а также чрезмерное и расточительное использование природных ресурсов без учета несущей способности Земли вызывают крайнее ухудшение состояния окружающей среды и массовый вымирание видов». [152] : 2

за 2019 год В докладе о глобальной оценке биоразнообразия и экосистемных услуг , опубликованном научно-политической платформой ООН Межправительственной по биоразнообразию и экосистемным услугам, содержится предупреждение о том, что, учитывая значительную потерю биоразнообразия , обществу не следует сосредотачиваться исключительно на экономическом росте. [153] [154] Антрополог Эдуардо С. Брондицио, один из сопредседателей доклада, сказал: «Нам необходимо изменить наши нарративы. Как наши индивидуальные нарративы, которые связывают расточительное потребление с качеством жизни и статусом, так и нарративы экономических систем, которые все еще считают, что деградация окружающей среды и социальное неравенство являются неизбежными последствиями экономического роста. Экономический рост – это средство, а не цель. Нам нужно стремиться к повышению качества жизни на планете». [155]

Те, кто более оптимистичен в отношении воздействия экономического роста на окружающую среду, полагают, что, хотя локальные экологические последствия могут иметь место, крупномасштабные экологические последствия незначительны. Аргумент, выдвинутый комментатором Джулианом Линкольном Саймоном , в 1981 году заявил, что если эти экологические последствия глобального масштаба существуют, человеческая изобретательность найдет способы адаптироваться к ним. [156] И наоборот, Партха Дасгупта в докладе об экономике биоразнообразия за 2021 год, подготовленном по заказу Министерства финансов Великобритании, утверждал, что биоразнообразие разрушается быстрее, чем когда-либо в истории человечества, в результате требований современной человеческой цивилизации, которые «намного превосходят возможности природы снабжать нас товарами и услугами, на которые мы все полагаемся. Нам потребуется 1,6 Земли, чтобы поддерживать нынешний уровень жизни в мире». Он говорит, что потребуются серьезные преобразующие изменения, «подобные или даже более масштабные, чем те, что предусмотрены в Плане Маршалла», включая отказ от ВВП как меры экономического успеха и социального прогресса. [157] Филип Кафаро, профессор философии Школы глобальной экологической устойчивости Университета штата Колорадо , написал в 2022 году, что возник научный консенсус, который демонстрирует, что человечество находится на грани крупного вымирания и что «причина глобального биоразнообразия потеря очевидна: другие виды вытесняются быстро растущей человеческой экономикой». [158]

В 2019 году в предупреждении об изменении климата, подписанном 11 000 ученых из более чем 150 стран, говорилось, что экономический рост является движущей силой «чрезмерной добычи материалов и чрезмерной эксплуатации экосистем» и что это «необходимо быстро ограничить для поддержания долгосрочной устойчивости биосфера». Они добавляют, что «наши цели должны перейти от роста ВВП и стремления к изобилию к поддержанию экосистем и улучшению благосостояния людей путем определения приоритетности основных потребностей и сокращения неравенства». [159] [160] В статье, опубликованной в 2021 году ведущими учеными журнала Frontiers in Conservation Science, утверждается, что, учитывая экологические кризисы, включая потерю биоразнообразия и изменение климата , а также возможное «ужасное будущее», стоящее перед человечеством, должны произойти «фундаментальные изменения в глобальном капитализме», включая «отмену постоянный экономический рост». [161] [162] [163]

Глобальное потепление

[ редактировать ]До настоящего времени существует тесная корреляция между экономическим ростом и уровнем выбросов углекислого газа в разных странах, хотя существует также значительная разница в углеродоемкости (выбросы углерода на ВВП). [164] До настоящего времени также существует прямая связь между мировым экономическим благосостоянием и уровнем глобальных выбросов. [165] В Stern Review отмечается, что прогноз о том, что «при обычном сценарии глобальных выбросов будет достаточно, чтобы поднять концентрацию парниковых газов до уровня более 550 частей на миллион CO 2 к 2050 году и более 650–700 частей на миллион к концу этого столетия, является устойчивым к широкому спектру диапазон изменений в предположениях модели». Научный консенсус заключается в том, что функционирование планетарной экосистемы без возникновения опасных рисков требует стабилизации на уровне 450–550 частей на миллион. [166]

Как следствие, экономисты-экологи, ориентированные на рост, предлагают вмешательство правительства в переключение источников производства энергии, отдавая предпочтение ветровой , солнечной , гидроэлектрической и атомной энергии . Это в значительной степени ограничит использование ископаемого топлива либо для бытовых нужд приготовления пищи (например, для керосиновых горелок), либо там, где технология улавливания и хранения углерода может быть экономически эффективной и надежной. [167] В «Stern Review» , опубликованном правительством Соединенного Королевства в 2006 году, сделан вывод, что инвестиций в размере 1% ВВП (позже измененных на 2%) будет достаточно, чтобы избежать наихудших последствий изменения климата, и что невыполнение этого требования может поставить под угрозу изменение климата. -связанные расходы равны 20% ВВП. Поскольку улавливание и хранение углерода еще не доказано, а его долгосрочная эффективность (например, в сдерживании «утечек» углекислого газа) неизвестна, а также из-за текущей стоимости альтернативных видов топлива, эти политические меры в значительной степени основаны на вере в технологические изменения.

Британский консервативный политик и журналист Найджел Лоусон назвал торговлю выбросами углекислого газа «неэффективной системой нормирования ». Вместо этого он выступает за налоги на выбросы углерода , чтобы в полной мере использовать эффективность рынка. Однако, чтобы избежать миграции энергоемких производств, такой налог должен ввести весь мир, а не только Великобритания, отметил Лоусон. Нет смысла брать на себя инициативу, если никто не последует этому примеру. [168]

Ограничение ресурсов

[ редактировать ]Многие более ранние предсказания истощения ресурсов, такие как предсказания Томаса Мальтуса 1798 года о приближающемся голоде в Европе, «Демографическая бомба» , [169] [170] и пари Саймона-Эрлиха (1980) [171] не материализовались. Снижения производства большинства ресурсов до сих пор не произошло, одна из причин заключается в том, что достижения в области технологий и науки позволили производить некоторые ранее недоступные ресурсы. [171] В некоторых случаях замена литых металлов более распространенными материалами, такими как пластмассы, снизила рост использования некоторых металлов. В случае ограниченности земельных ресурсов голод был облегчен сначала революцией в транспорте, вызванной железными дорогами и пароходами, а затем Зеленой революцией и химическими удобрениями, особенно процессом Габера для синтеза аммиака. [172] [173]

Качество ресурсов зависит от множества факторов, включая качество руды, местоположение, высоту над или ниже уровня моря, близость к железным дорогам, автомагистралям, водоснабжение и климат. Эти факторы влияют на капитальные и эксплуатационные затраты на добычу ресурсов. Что касается полезных ископаемых, добываются минеральные ресурсы более низкого качества, что требует более высоких затрат капитала и энергии как для добычи, так и для переработки. Содержание медной руды значительно снизилось за последнее столетие. [174] [175] Другим примером является природный газ из сланцев и других пород с низкой проницаемостью, добыча которого требует гораздо более высоких затрат энергии, капитала и материалов, чем обычный газ в предыдущие десятилетия. Морская нефть и газ имеют экспоненциальный рост стоимости по мере увеличения глубины воды.

Некоторые ученые-физики, такие как Саньям Миттал, считают непрерывный экономический рост неустойчивым. [176] [177] Несколько факторов могут сдерживать экономический рост, например: ограниченность, пик или истощение ресурсов .

В 1972 году исследование «Пределы роста» смоделировало ограничения бесконечного роста; изначально высмеивали, [169] [170] [178] некоторые из прогнозируемых тенденций материализовались, что вызывает опасения по поводу надвигающегося коллапса или упадка экономики из-за нехватки ресурсов. [179] [180] [181]

Мальтузианцы, такие как Уильям Р. Каттон-младший, скептически относятся к технологическим достижениям, которые улучшают доступность ресурсов. Они предполагают, что такие достижения и повышение эффективности просто ускоряют истощение ограниченных ресурсов. Кэттон утверждает, что растущие темпы добычи ресурсов «... жадно крадут будущее». [182]

Энергия

[ редактировать ]Энергетические экономические теории утверждают, что темпы потребления энергии и энергоэффективность причинно связаны с экономическим ростом. Соотношение Гаррета утверждает, что существует фиксированная связь между текущими темпами глобального потребления энергии и историческим накоплением мирового ВВП, независимо от рассматриваемого года. Отсюда следует, что экономический рост, представленный ростом ВВП, требует более высоких темпов роста энергопотребления. Как это ни парадоксально , но они поддерживаются за счет повышения энергоэффективности. [183] Повышение энергоэффективности было частью увеличения совокупной факторной производительности . [15] Некоторые из наиболее технологически важных инноваций в истории были связаны с повышением энергоэффективности. К ним относятся значительные улучшения в эффективности преобразования тепла в работу, повторное использование тепла, уменьшение трения и передача энергии, особенно посредством электрификации . [184] [185] Существует сильная корреляция между потреблением электроэнергии на душу населения и экономическим развитием. [186] [187]

Возможность бесконечного экономического роста

[ редактировать ]

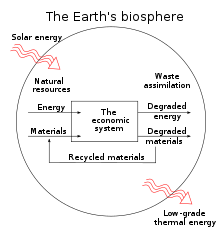

Экологическая экономика критикует возможность бесконечного экономического роста на ограниченной планете. Современные экономические модели игнорируют физические ограничения и, таким образом, предполагают, что экономика может непрерывно расти как вечный двигатель . Однако по законам термодинамики вечных двигателей не существует. [188] Таким образом, ни одна система не может существовать без поступления новой энергии, которая уходит в виде отходов с высокой энтропией . Точно так же, как ни одно животное не может жить на собственных отходах, ни одна экономика не может перерабатывать отходы, которые она производит, без затрат новой энергии для воспроизводства. [188]

Материя и энергия входят в экономику в форме природного капитала с низкой энтропией , такого как солнечная энергия , нефтяные скважины , рыболовство и шахты . Эти материалы и энергия используются как домашними хозяйствами, так и фирмами для создания продуктов и богатства. После того, как материалы израсходованы, энергия и вещество покидают экономику в виде отходов с высокой энтропией, которые больше не представляют ценности для экономики. Природные материалы, которые обеспечивают движение экономической системы из окружающей среды, и отходы должны быть поглощены более широкой экосистемой, в которой существует экономика. [189]

Нельзя игнорировать тот факт, что экономике по своей сути необходимы природные ресурсы и образование отходов, которые необходимо каким-то образом поглощать. Экономика может продолжать развиваться только в том случае, если у нее есть материя и энергия для ее питания, а также способность поглощать создаваемые ею отходы. Эта материя, энергия с низкой энтропией и способность поглощать отходы существуют в конечном количестве, и, таким образом, существует конечное количество входов в поток и выходов потока, с которыми может справиться окружающая среда, подразумевая, что существует устойчивый предел движения . и, следовательно, рост экономики. [188] В «Пределах роста» говорится, что из-за ограничений, вызванных термодинамическими законами , доступность ресурсов будет уменьшаться в контексте постоянного роста, что приведет к увеличению цен на эти ресурсы и, следовательно, к уменьшению инвестиций в промышленность. Этот спад промышленности в конечном итоге приведет к нехватке товаров и услуг, что в конечном итоге может привести к ухудшению условий жизни и увеличению уровня смертности во всем мире. [190]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- рост

- Американская исключительность

- Цивилизаторская миссия

- Изменение климата

- Критика политической экономии

- Уменьшение роста

- Теория развития

- Экономическое развитие

- Экспортно-ориентированная индустриализация

- Жадность

- Зеленый рост

- Зеленая новая сделка

- Учет роста

- Индуистские темпы роста

- Пределы роста

- Список стран по темпам роста реального ВВП

- Явная судьба

- Православное развитие

- Пост-рост

- Продуктивизм

- Прогресс

- Пропаганда

- Процветание без роста

- Статус-кво

- Экономика достаточности

- Устойчивое развитие

- Устойчивое развитие

- Термоэкономика

- Неэкономический рост

- Единая теория роста

- Универсальный базовый доход

- Перераспределение богатства

- Бремя белого человека

- Мировоззрение

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Розер, Макс (2021). «Что такое экономический рост? И почему он так важен?» . Наш мир в данных .

- ^ Статистика роста мирового валового внутреннего продукта (ВВП) с 2003 по 2013 год. Архивировано 3 мая 2013 года в Wayback Machine , МВФ, октябрь 2012 года. - «Валовой внутренний продукт, также называемый ВВП, представляет собой рыночную стоимость товаров. и услуг, произведенных страной в определенный период времени».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бьорк 1999 , с. 251.

- ^ Бьорк 1999 , с. 67.

- ^ Бьорк 1999 , стр. 2 , 67 .

- ^ Гордон, Роберт Дж. (29 августа 2017 г.). Взлет и падение экономического роста Америки: уровень жизни в США после гражданской войны . Издательство Принстонского университета. стр. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-691-17580-5 .

- ^ Мэнкью, Грегори (2011). Принципы макроэкономики (6-е изд.). Cengage Обучение. п. 236 . ISBN 978-0538453066 .

- ^ Барро, Роберт; Сала-и-Мартин, Ксавье (2004). Экономический рост (2-е изд.). п. 6. АСИН B003Q7WARA .

- ^ Дас, Тухин К. (2019). «Поперечные взгляды на рост ВВП в свете инноваций». Электронный журнал экономического роста . дои : 10.2139/ssrn.3503386 . S2CID 219383124 . ССНР 3503386 .

- ^ Бьорк 1999 , с. 68.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Бьорк 1999 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Рубини, Нуриэль; Бэкус, Дэвид (1998). «Производительность и рост» . Лекции по макроэкономике .

- ^ Ван, Пин (2014). «Учет роста» (PDF) . п. 2. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 15 июля 2014 г.

- ^ Корри, Дэн; Валеро, Анна; Ван Ринен, Джон (ноябрь 2011 г.). «Экономические показатели Великобритании с 1997 года» (PDF) .

Высокий рост ВВП на душу населения в Великобритании был обусловлен сильным ростом производительности (ВВП в час), которая уступала только США.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кендрик, Джон В. (1961). Тенденции производительности в США (PDF) . Издательство Принстонского университета для NBER. п. 3.

- ^ Кругман, Пол (1994). «Миф об азиатском чуде» . Иностранные дела . 73 (6): 62–78. дои : 10.2307/20046929 . JSTOR 20046929 .

- ^ Розенберг, Натан (1982). Внутри черного ящика: технологии и экономика . Кембридж, Нью-Йорк: Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 258 . ISBN 978-0-521-27367-1 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Лукас, RE (1988). «О механике экономического развития». Журнал денежно-кредитной экономики . 22 (1): 3–42. дои : 10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7 . S2CID 154875771 .

- ^ Райсман, Джордж (1998). Капитализм: Полное понимание природы и ценности экономической жизни человека . Книги Джеймсона. ISBN 0-915463-73-3 .

- ^ Галор, Одед (2005). «От стагнации к росту: единая теория роста» . Справочник экономического роста . Том. 1. Эльзевир. стр. 171–293.

- ^ Кларк 2007 , с. [ нужна страница ] , Часть I: Мальтузианская ловушка.

- ^ Кларк 2007 , с. [ нужна страница ] , Часть 2: Промышленная революция.

- ^ Кендрик, JW 1961 « Тенденции производительности в Соединенных Штатах. Архивировано 4 марта 2019 г. в Wayback Machine », Princeton University Press.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ландес, Дэвид. С. (1969). Освобожденный Прометей: технологические изменения и промышленное развитие в Западной Европе с 1750 года по настоящее время . Кембридж, Нью-Йорк: Пресс-синдикат Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-09418-4 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хауншелл, Дэвид А. (1984), От американской системы к массовому производству, 1800–1932: Развитие производственных технологий в Соединенных Штатах , Балтимор, Мэриленд: Издательство Университета Джонса Хопкинса , ISBN 978-0-8018-2975-8 , LCCN 83016269 , OCLC 1104810110

- ^ Эйрс, Роберт У.; Уорр, Бенджамин (июнь 2005 г.). «Учет роста: роль физической работы» . Структурные изменения и экономическая динамика . 16 (2): 181–209. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1085.9040 . doi : 10.1016/j.strueco.2003.10.003 . Проверено 9 августа 2022 г.

- ^ Грублер, Арнульф (1990). Взлет и падение инфраструктур (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 1 марта 2012 г. Проверено 1 февраля 2011 г.

- ^ Тейлор, Джордж Роджерс (1951). Транспортная революция, 1815–1860 гг . Райнхарт. ISBN 978-0873321013 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уэллс, Дэвид А. (1890). Недавние экономические изменения и их влияние на производство и распределение богатства и благосостояние общества . Д. Эпплтона и компании. Нью-Йорк: ISBN 978-0543724748 .

- ^ Атак, Джереми; Пасселл, Питер (1994). Новый экономический взгляд на американскую историю . Нью-Йорк: WW Norton and Co. ISBN 978-0-393-96315-1 .

- ^ Бодро, Бернар К. (1996). Массовое производство, крах фондового рынка и Великая депрессия . Нью-Йорк, Линкольн, Шанги: Выбор авторов.

- ^ Мур, Стивен; Саймон, Джулиан (15 декабря 1999 г.). «Величайший век, который когда-либо был: 25 чудесных тенденций за последние 100 лет» (PDF) . Политический анализ (364). Институт Катона. Кривые диффузии различных инноваций начинаются с рис. 14.

- ^ Филд, Александр Дж. (2011). Большой скачок вперед: депрессия 1930-х годов и экономический рост США . Нью-Хейвен, Лондон: Издательство Йельского университета. ISBN 978-0-300-15109-1 .

- ^ Федеральная резервная система Сент-Луиса. Архивировано 13 апреля 2015 г. в Wayback Machine. Реальный ВВП на душу населения в США вырос с 17 747 долларов в 1960 году до 26 281 доллара в 1973 году, при темпах роста 3,07% в год. Расчет: (26 281/17 747)^(1/13). С 1973 по 2007 год темп роста составил 1,089%. Расчет: (49 571/26 281)^(1/34) С 2000 по 2011 год среднегодовой рост составил 0,64%.

- ^ «Рынок литейного производства полупроводников: глобальные отраслевые тенденции в 2019 году, рост, доля, размер и прогнозный исследовательский отчет на 2021 год» . МаркетВотч . 28 ноября 2019 г. Архивировано из оригинала 20 декабря 2019 г. Проверено 20 декабря 2019 г.

- ↑ Передовая статья: Африка должна тратить осторожно. Архивировано 24 января 2012 г. в Wayback Machine . Независимый. 13 июля 2006 г.

- ^ Данные относятся к 2008 году. ВВП Кореи — 26 341 доллар, Ганы — 1513 долларов. База данных «Перспективы мировой экономики» – октябрь 2008 г. Международный валютный фонд .

- ^ Кендрик, Джон (1991). «Показатели производительности труда в США в перспективе, экономика бизнеса, 1 октября 1991 г.». Экономика бизнеса . 26 (4): 7–11. JSTOR 23485828 .

- ^ Филд, Алезандер Дж. (2007). «Экономический рост США в позолоченный век» (PDF) . Журнал макроэкономики . 31 : 173–190. дои : 10.1016/j.jmacro.2007.08.008 . S2CID 154848228 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 8 января 2016 г. Проверено 12 июля 2014 г.

- ^ Филд, Александр (2004). «Технологические изменения и экономический рост в межвоенные годы и 1990-е годы» . Журнал экономической истории . 66 (1): 203–236. doi : 10.1017/S0022050706000088 (неактивен 28 июля 2024 г.). S2CID 154757050 . ССНН 1105634 .

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI неактивен по состоянию на июль 2024 г. ( ссылка ) - ^ Гордон, Роберт Дж. (июнь 2000 г.). «Интерпретация «одной большой волны» долгосрочного роста производительности в США» . Рабочий документ NBER № 7752 . дои : 10.3386/w7752 .

- ^ Абрамовиц, Моисей; Дэвид, Пол А. (2000). Два столетия американского макроэкономического роста от эксплуатации изобилия ресурсов к развитию, основанному на знаниях (PDF) . Стэнфордский университет. стр. 24–5 (pdf, стр. 28–9). Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 31 июля 2020 г. Проверено 13 июля 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гордон, Роберт Дж. (весна 2013 г.). «Рост производительности в США: замедление возобновилось после временного оживления» (PDF) . Международный монитор производительности, Центр изучения уровня жизни . 25 : 13–9. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 9 августа 2014 г. Проверено 19 июля 2014 г.

Экономика США достигла темпа роста производительности труда 2,48 процента в год в течение 81 года, затем в течение 24 лет - 1,32 процента, затем временное восстановление до 2,48 процента и окончательное замедление до 1,35 процента. Весьма примечательно сходство темпов роста 1891–1972 гг. с 1996–2004 гг., а 1972–1996 гг. – с 1996–2011 гг.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дейл В. Йоргенсон ; Мун С. Хо; Джон Д. Сэмюэлс (12 мая 2014 г.). «Долгосрочные оценки производительности и роста США» (PDF) . Всемирная конференция КЛЕМС . Викиданные Q111455533 .

- ^ Дейл В. Йоргенсон; Мун С. Хо; Кевин Дж. Стиро (2008). «Ретроспективный взгляд на восстановление роста производительности труда в США» . Журнал экономических перспектив . 22 (1): 3–24. дои : 10.1257/jep.22.1.3 .

- ^ Брюс Т. Гримм; Брент Р. Моултон; Дэвид Б. Вассхаузен (2002). «Оборудование и программное обеспечение для обработки информации в национальных счетах» (PDF) . Бюро экономического анализа Министерства торговли США . Проверено 15 мая 2014 г.

- ^ Хант, ЕК; Лаутценхайзер, Марк (2014). История экономической мысли: критическая перспектива . Обучение PHI. ISBN 978-0765625991 .

- ^ Кругман, Пол (1994). «Миф об азиатском чуде» . Иностранные дела . 73 (6): 62–78. дои : 10.2307/20046929 . JSTOR 20046929 .

- ^ «Часы работы в истории США» . 2010. Архивировано из оригинала 26 октября 2011 г.

- ^ Уэплс, Роберт (июнь 1991 г.). «Сокращение американской рабочей недели: экономический и исторический анализ его контекста, причин и последствий». Журнал экономической истории . 51 (2): 454–7. дои : 10.1017/s0022050700039073 . S2CID 153813437 .

- ^ Мэнкью, Н. Грегори ; Ромер, Дэвид ; Вейль, Дэвид (1992). «Вклад в эмпирику экономического роста». Ежеквартальный экономический журнал . 107 (2): 407–37. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.335.6159 . дои : 10.2307/2118477 . JSTOR 2118477 . S2CID 1369978 .

- ^ Сала-и-Мартин, Ксавье; Доппельхофер, Гернот; Миллер, Рональд И. (2004). «Детерминанты долгосрочного роста: подход байесовского усреднения классических оценок (BACE)» (PDF) . Американский экономический обзор . 94 (4): 813–35. дои : 10.1257/0002828042002570 . S2CID 55710066 .