Иордания

Асхиемитное королевство Иордан | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: Бог, родина, король Аллах, Аль-Ванан, Аль-Малик "Бог, страна, король" [ 1 ] | |

| Гимн: иорданский королевский мир Аль-Салас аль-Малаки аль-Урдуни " Королевский гимн Джордана " | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Amman 31°57′N 35°56′E / 31.950°N 35.933°E |

| Official languages | Arabic[2] |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Jordanian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Abdullah II |

| Jafar Hassan | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

• Emirate | 11 April 1921 |

| 25 May 1946 | |

| 11 January 1952 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 89,342 km2 (34,495 sq mi) (110th) |

• Water (%) | 0.6 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 11,484,805[3] (84th) |

• 2015 census | 9,531,712[4] |

• Density | 114/km2 (295.3/sq mi) (70th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2011) | 35.4[6] medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | high (99th) |

| Currency | Jordanian dinar (JOD) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +962 |

| ISO 3166 code | JO |

| Internet TLD | .jo .الاردن |

Website jordan.gov.jo | |

Иордан , [ А ] официально Хасемитское королевство Иордании , [ B ] является страной в Левант южном регионе в Западной Азии . Джордан граничит с Сирией на севере, Ираком на востоке, Саудовской Аравией на юг, и Израиль и оккупированных палестинских территорий на западе. Река Иордан , поступающая в Мертвое море , расположена вдоль западной границы страны. Джордан также имеет небольшую береговую линию вдоль Красного моря на его юго -западе, отделенной Акабской заливом от Египта . Амман страны является столицей и крупнейшим городом , а также самым густонаселенным городом в Леванте .

Modern-day Jordan has been inhabited by humans since the Paleolithic period. Three kingdoms emerged in Transjordan at the end of the Bronze Age: Ammon, Moab and Edom. In the third century BC, the Arab Nabataeans established their kingdom centered in Petra. Later rulers of the Transjordan region include the Assyrian, Babylonian, Roman, Byzantine, Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid, and the Ottoman empires. After the 1916 Great Arab Revolt against the Ottomans during World War I, the Greater Syria region was partitioned, leading to the establishment of the Emirate of Transjordan in 1921, which became a British protectorate. In 1946, the country gained independence and became officially known as the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.[c] Страна захватила и аннексировала Западный берег во время арабской войны 1948 года, пока не была занята Израилем в 1967 году . Джордан отказался от своей претензии на территорию палестинцам в 1988 году и подписал мирный договор с Израилем в 1994 году.

Jordan is a semi-arid country, covering an area of 89,342 km2 (34,495 sq mi), with a population of 11.5 million, making it the eleventh-most populous Arab country. The dominant majority, or around 95% of the country's population, is Sunni Muslim, with the rest being mostly Arab Christian. Jordan was mostly unscathed by the violence that swept the region following the Arab Spring in 2010. From as early as 1948, Jordan has accepted refugees from multiple neighbouring countries in conflict. An estimated 2.1 million Palestinian refugees, most of whom hold Jordanian citizenship, as well as 1.4 million Syrian refugees, were residing in Jordan as of 2015.[4] The kingdom is also a refuge for thousands of Christian Iraqis fleeing persecution.[8][9] While Jordan continues to accept refugees, the large Syrian influx during the 2010s has placed substantial strain on national resources and infrastructure.[10]

The sovereign state is a constitutional monarchy, but the king holds wide executive and legislative powers. Jordan is a founding member of the Arab League and the Organisation of Islamic Co-operation. The country has a high Human Development Index, ranking 99th, and is considered a lower middle income economy. The Jordanian economy, one of the smallest economies in the region, is attractive to foreign investors based upon a skilled workforce.[11] The country is a major tourist destination, also attracting medical tourism due to its well developed health sector.[12] Nonetheless, a lack of natural resources, large flow of refugees, and regional turmoil have hampered economic growth.[13]

Etymology

Jordan takes its name from the Jordan River, which forms much of the country's northwestern border.[14] While several theories for the origin of the river's name have been proposed, it is most plausible that it derives from the Hebrew word Yarad (Hebrew: ירד), meaning "the descender", reflecting the river's declivity.[15] Much of the area that makes up modern Jordan was historically called Transjordan, meaning "across the Jordan"; the term is used to denote the lands east of the river.[15] The Hebrew Bible uses the term Hebrew: עבר הירדן, romanized: Ever ha'Yarden, lit. 'The other side of the Jordan' for the area.[15] Early Arab chronicles call the river Al-Urdunn (a term cognate to the Hebrew Yarden).[16] Jund Al-Urdunn was a military district around the river in the early Islamic era.[16] Later, during the Crusades in the beginning of the second millennium, a lordship was established in the area under the name of Oultrejordain.[17]

History

Ancient period

The oldest known evidence of hominid habitation in Jordan dates back at least 200,000 years.[18] Jordan is a rich source of Paleolithic human remains (up to 20,000 years old) due to its location within the Levant, where various migrations of hominids out of Africa converged,[19] and its more humid climate during the Late Pleistocene, which resulted in the formation of numerous remains-preserving wetlands in the region.[20] Past lakeshore environments attracted different groups of hominids, and several remains of tools dating from the Late Pleistocene have been found there.[19] Scientists have found the world's oldest known evidence of bread-making at a 14,500-year-old Natufian site in Jordan's northeastern desert.[21]

During the Neolithic period (10,000–4,500 BC), there was a transition there from a hunter-gatherer culture to a culture with established populous agricultural villages.[22] 'Ain Ghazal, one such village located at a site in the eastern part of present-day Amman, is one of the largest known prehistoric settlements in the Near East.[23] Dozens of plaster statues of the human form, dating to 7250 BC or earlier, have been uncovered there; they are one of the oldest large-scale representations of humans ever found.[24] During the Chalcolithic period (4500–3600 BC), several villages emerged in Transjordan including Tulaylet Ghassul in the Jordan Valley;[25] a series of circular stone enclosures in the eastern basalt desert from the same period have long baffled archaeologists.[26]

Fortified towns and urban centres first emerged in the southern Levant early in the Bronze Age (3600–1200 BC).[27] Wadi Feynan became a regional centre for copper extraction - the metal was exploited on a large scale to produce bronze.[28] Trade and movement of people in the Middle East peaked, spreading cultural innovations and whole civilizations to spread.[29] Villages in Transjordan expanded rapidly in areas with reliable water-resources and arable land.[29] Ancient Egyptian populations expanded towards the Levant and came to control both banks of the Jordan River.[30]

During the Iron Age (1200–332 BC), after the withdrawal of the Egyptians, Transjordan was home to the Kingdoms of Ammon, Edom and Moab.[31] The peoples of these kingdoms spoke Semitic languages of the Canaanite group; archaeologists have concluded that their polities were tribal kingdoms rather than states.[31] Ammon was located in the Amman plateau; Moab in the highlands east of the Dead Sea; and Edom in the area around Wadi Araba in the south.[31] The northwestern region of the Transjordan, known then as Gilead, was settled by the Israelites.[32] The Transjordanian kingdoms of Ammon, Edom and Moab continually clashed with the neighbouring Hebrew kingdoms of Israel and Judah, centered west of the Jordan River.[33] One record of this is the Mesha Stele, erected by the Moabite king Mesha in 840 BC; in an inscription on it, he lauds himself for the building projects that he initiated in Moab and commemorates his glory and his victory against the Israelites.[34] The stele constitutes one of the most important archeological parallels to accounts recorded in the Bible.[35] At the same time, Israel and the Kingdom of Aram-Damascus competed for control of the Gilead.[36][37]

Around the period between 740 and 720 BC, Israel and Aram Damascus were conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The kingdoms of Ammon, Edom & Moab were subjugated, but were allowed to maintain some degree of independence.[38] Then, in 627 BC, following after the disintegration of the Assyrians' empire, Babylonians took control of the area.[38] Although the kingdoms supported the Babylonians against Judah in the 597 BC sack of Jerusalem, they rebelled against Babylon a decade later.[38] The kingdoms were reduced to vassals, a status they retained under the Persian and Hellenic Empires.[38] By the beginning of Roman rule around 63 BC, the kingdoms of Ammon, Edom and Moab had lost their distinct identities and were assimilated into the Roman culture.[31] Some Edomites survived longer – driven by the Nabataeans, they had migrated to southern Judea, which became known as Idumaea; they were later converted to Judaism by the Hasmoneans.[39]

Classical period

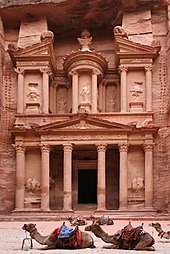

Alexander the Great's conquest of the Persian Empire in 332 BC introduced Hellenistic culture to the Middle East.[40] After Alexander's death in 323 BC, the empire split among his generals, and in the end much of Transjordan was disputed between the Ptolemies based in Egypt and the Seleucids based in Syria.[40] The Nabataeans, nomadic Arabs based south of Edom, managed to establish an independent kingdom in 169 BC by exploiting the struggle between the two Greek powers.[40] The Nabataean Kingdom controlled much of the trade routes of the region, and it stretched south along the Red Sea coast into the Hejaz desert, up to as far north as Damascus, which it controlled for a short period (85–71) BC.[41] The Nabataeans massed a fortune from their control of the trade routes, often drawing the envy of their neighbours.[42] Petra, Nabataea's barren capital, flourished in the 1st century AD, driven by its extensive water irrigation systems and agriculture.[43] The Nabataeans were also talented stone carvers, building their most elaborate structure, Al-Khazneh, in the first century AD.[44] It is believed to be the mausoleum of the Arab Nabataean King Aretas IV.[44]

Roman legions under Pompey conquered much of the Levant in 63 BC, inaugurating a period of Roman rule that lasted four centuries.[45] In 106 AD, Emperor Trajan annexed Nabataea unopposed, and rebuilt the King's Highway which became known as the Via Traiana Nova road.[45] The Romans gave the Greek cities of Transjordan—Philadelphia (Amman), Gerasa (Jerash), Gedara (Umm Quays), Pella (Tabaqat Fahl) and Arbila (Irbid)—and other Hellenistic cities in Palestine and southern Syria, a level of autonomy by forming the Decapolis, a ten-city league.[46] Jerash is one of the best preserved Roman cities in the East; it was even visited by Emperor Hadrian during his journey to Palestine.[47]

In 324 AD, the Roman Empire split and the Eastern Roman Empire, later known as the Byzantine Empire, continued to control or influence the region until 636.[48] Christianity had become legal within the empire in 313 after co-emperors Constantine and Licinius signed an edict of toleration.[48] In 380, the Edict of Thessalonica made Christianity the official state religion. Transjordan prospered during the Byzantine era, and Christian churches were built everywhere.[49] The Aqaba Church in Ayla was built during this era, it is considered to be the world's first purpose built Christian church.[50] Umm ar-Rasas in southern Amman contains at least 16 Byzantine churches.[51] Meanwhile, Petra's importance declined as sea trade routes emerged, and after a 363 earthquake destroyed many structures, it declined further, eventually being abandoned.[44] The Sassanian Empire in the east became the Byzantines' rivals, and frequent confrontations sometimes led to the Sassanids controlling some parts of the region, including Transjordan.[52]

Islamic era

In 629 AD, during the Battle of Mu'tah in what is today Karak Governorate, the Byzantines and their Arab Christian clients, the Ghassanids, staved off an attack by a Muslim Rashidun force that marched northwards towards the Levant from the Hejaz (in modern-day Saudi Arabia).[53] The Byzantines however were defeated by the Muslims in 636 at the decisive Battle of the Yarmuk just north of Transjordan.[53] Transjordan was an essential territory for the conquest of Damascus.[54] The first, or Rashidun, caliphate was followed by that of the Umayyads (661–750).[54]

Under the Umayyad Caliphate, several desert castles were constructed in Transjordan, including: Qasr Al-Mshatta and Qasr Al-Hallabat.[54] The Abbasid Caliphate's campaign to take over the Umayyad's began in a village in Transjordan known as Humayma.[55] The powerful 749 earthquake is thought to have contributed to the Umayyads' defeat by the Abbasids, who moved the caliphate's capital from Damascus to Baghdad.[55] During Abbasid rule (750–969), several Arab tribes moved northwards and settled in the Levant.[54] As had happened during the Roman era, growth of maritime trade diminished Transjordan's central position, and the area became increasingly impoverished.[56] After the decline of the Abbasids, Transjordan was ruled by the Fatimid Caliphate (969–1070), then by the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem (1115–1187).[57]

The Crusaders constructed several Crusader castles as part of the Lordship of Oultrejordain, including those of Montreal and Al-Karak.[58] The Ayyubids built the Ajloun Castle and rebuilt older castles, to be used as military outposts against the Crusaders.[59] During the Battle of Hattin (1187) near Lake Tiberias just north of Transjordan, the Crusaders lost to Saladin, the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty (1187–1260).[59] Villages in Transjordan under the Ayyubids became important stops for Muslim pilgrims going to Mecca who travelled along the route that connected Syria to the Hejaz.[60] Several of the Ayyubid castles were used and expanded by the Mamluks (1260–1516), who divided Transjordan between the provinces of Karak and Damascus.[61] During the next century Transjordan experienced Mongol attacks, but the Mongols were ultimately repelled by the Mamluks after the Battle of Ain Jalut (1260).[62]

In 1516, the Ottoman Caliphate's forces conquered Mamluk territory.[63] Agricultural villages in Transjordan witnessed a period of relative prosperity in the 16th century, but were later abandoned.[64] Transjordan was of marginal importance to the Ottoman authorities.[65] As a result, Ottoman presence was virtually absent and reduced to annual tax collection visits.[64] More Arab Bedouin tribes moved into Transjordan from Syria and the Hejaz during the first three centuries of Ottoman rule, including the Adwan, the Bani Sakhr and the Howeitat.[66] These tribes laid claims to different parts of the region, and with the absence of a meaningful Ottoman authority, Transjordan slid into a state of anarchy that continued until the 19th century.[67] This led to a short-lived occupation by the Wahhabi forces (1803–1812), an ultra-orthodox Islamic movement that emerged in Najd (in modern-day Saudi Arabia).[68] Ibrahim Pasha, son of the governor of the Egypt Eyalet, rooted out the Wahhabis under the request of the Ottoman sultan by 1818.[69] In 1833 Ibrahim Pasha turned on the Ottomans and established his rule over the Levant.[70] His policies led to the unsuccessful peasants' revolt in Palestine in 1834.[70] Transjordanian cities of As-Salt and Al-Karak were destroyed by Ibrahim Pasha's forces for harboring a peasants' revolt leader.[70] Egyptian rule was forcibly ended in 1841, with Ottoman rule restored.[70]

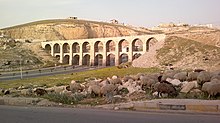

Only after Ibrahim Pasha's campaign did the Ottoman Empire try to solidify its presence in the Syria Vilayet, which Transjordan was part of.[71] A series of tax and land reforms (Tanzimat) in 1864 brought some prosperity back to agriculture and to abandoned villages; the end of virtual autonomy led a backlash in other areas of Transjordan.[71] Muslim Circassians and Chechens, fleeing Russian persecution, sought refuge in the Levant.[72] In Transjordan and with Ottoman support, Circassians first settled in the long-abandoned vicinity of Amman in 1867, and later in the surrounding villages.[72] The Ottoman authorities' establishment of its administration, conscription and heavy taxation policies led to revolts in the areas it controlled.[73] Transjordan's tribes in particular revolted during the Shoubak (1905) and the Karak Revolts (1910), which were brutally suppressed.[72] The construction of the Hejaz Railway in 1908–stretching across the length of Transjordan and linking Damascus with Medina helped the population economically, as Transjordan became a stopover for pilgrims.[72]

Modern era

Increasing policies of Turkification and centralization adopted by the Ottoman Empire in the wake of the 1908 Young Turk Revolution disenchanted the Arabs of the Levant, which contributed to the development of an Arab nationalist movement. These changes led to the outbreak of the 1916 Arab Revolt during World War I, which would end four centuries of stagnation under Ottoman rule.[72] The revolt was led by Sharif Hussein of Mecca, scion of the Hashemite family of the Hejaz, and his sons Abdullah, Faisal and Ali. Locally, the revolt garnered the support of the Transjordanian tribes, including Bedouins, Circassians and Christians.[74] The Allies of World War I, including Britain and France, whose imperial interests converged with the Arabist cause, offered support.[75] The revolt started on 5 June 1916 from Medina and pushed northwards until the fighting reached Transjordan in the Battle of Aqaba on 6 July 1917.[76] The revolt reached its climax when Faisal entered Damascus in October 1918, and established an Arab-led military administration in OETA East, later declared as the Arab Kingdom of Syria, both of which Transjordan was part of.[74] During this period, the southernmost region of the country, including Ma'an and Aqaba, was also claimed by the neighbouring Kingdom of Hejaz.

The nascent Hashemite Kingdom over the region of Syria was forced to surrender to French troops on 24 July 1920 during the Battle of Maysalun;[77] the French occupied only the northern part of the Syrian Kingdom, leaving Transjordan in a period of interregnum. Arab aspirations failed to gain international recognition, due mainly to the secret 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement, which divided the region into French and British spheres of influence, and the 1917 Balfour Declaration, in which Britain announced its support for the establishment of a "national home" for Jews in Palestine.[78] This was seen by the Hashemites and the Arabs as a betrayal of their previous agreements with the British,[79] including the 1915 McMahon–Hussein Correspondence, in which the British stated their willingness to recognize the independence of a unified Arab state stretching from Aleppo to Aden under the rule of the Hashemites.[80]

The British High Commissioner, Herbert Samuel, travelled to Transjordan on 21 August 1920 to meet with As-Salt's residents. He there declared to a crowd of six hundred Transjordanian notables that the British government would aid the establishment of local governments in Transjordan, which is to be kept separate from that of Palestine. The second meeting took place in Umm Qais on 2 September, where the British government representative Major Fitzroy Somerset received a petition that demanded: an independent Arab government in Transjordan to be led by an Arab prince (emir); land sale in Transjordan to Jews be stopped as well as the prevention of Jewish immigration there; that Britain establish and fund a national army; and that free trade be maintained between Transjordan and the rest of the region.[81]

Abdullah, the second son of Sharif Hussein, arrived from Hejaz by train in Ma'an in southern Transjordan on 21 November 1920 to redeem the Greater Syrian Kingdom his brother had lost.[82] Transjordan then was in disarray, widely considered to be ungovernable with its dysfunctional local governments.[83] Abdullah gained the trust of Transjordan's tribal leaders before scrambling to convince them of the benefits of an organized government.[84] Abdullah's successes drew the envy of the British, even when it was in their interest.[85] The British reluctantly accepted Abdullah as ruler of Transjordan after having given him a six-month trial.[86] In March 1921, the British decided to add Transjordan to their Mandate for Palestine, in which they would implement their "Sharifian Solution" policy without applying the provisions of the mandate dealing with Jewish settlement. On 11 April 1921, the Emirate of Transjordan was established with Abdullah as Emir.[87]

In September 1922, the Council of the League of Nations recognized Transjordan as a state under the terms of the Transjordan memorandum.[88][89] Transjordan remained a British mandate until 1946, but it had been granted a greater level of autonomy than the region west of the Jordan River.[90] Multiple difficulties emerged upon the assumption of power in the region by the Hashemite leadership.[91] In Transjordan, small local rebellions at Kura in 1921 and 1923 were suppressed by the Emir's forces with the help of the British.[91] Wahhabis from Najd regained strength and repeatedly raided the southern parts of his territory in (1922–1924), seriously threatening the Emir's position.[91] The Emir was unable to repel those raids without the aid of the local Bedouin tribes and the British, who maintained a military base with a small RAF detachment close to Amman.[91]

Post-independence

The Treaty of London, signed by the British Government and the Emir of Transjordan on 22 March 1946, recognised the independence of the state upon ratification by both countries' parliaments.[92] On 25 May 1946, the day that the treaty was ratified by the Transjordan parliament, Transjordan was raised to the status of a kingdom under the name of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in Arabic, with Abdullah as its first king; although it continued to be referred to as the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan in English until 1949.[93][94] 25 May is now celebrated as the nation's Independence Day, a public holiday.[95] Jordan became a member of the United Nations on 14 December 1955.[96]

On 15 May 1948, as part of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Jordan intervened in Palestine together with many other Arab states.[97] Following the war, Jordan controlled the West Bank and on 24 April 1950 Jordan formally annexed these territories after the Jericho conference.[98][99] In response, some Arab countries demanded Jordan's expulsion from the Arab League.[98] On 12 June 1950, the Arab League declared that the annexation was a temporary, practical measure and that Jordan was holding the territory as a "trustee" pending a future settlement.[100] King Abdullah was assassinated at the Al-Aqsa Mosque in 1951 by a Palestinian militant, amid rumors he intended to sign a peace treaty with Israel.[101]

Abdullah was succeeded by his son Talal, who would soon abdicate due to illness in favour of his eldest son Hussein.[102] Talal established the country's modern constitution in 1952.[102] Hussein ascended to the throne in 1953 at the age of 17.[101] Jordan witnessed great political uncertainty in the following period.[103] The 1950s were a period of political upheaval, as Nasserism and Pan-Arabism swept the Arab World.[103] On 1 March 1956, King Hussein Arabized the command of the Army by dismissing a number of senior British officers, an act made to remove remaining foreign influence in the country.[104] In 1958, Jordan and neighbouring Hashemite Iraq formed the Arab Federation as a response to the formation of the rival United Arab Republic between Nasser's Egypt and Syria.[105] The union lasted only six months, being dissolved after Iraqi King Faisal II (Hussein's cousin) was deposed by a bloody military coup on 14 July 1958.[105]

Jordan signed a military pact with Egypt just before Israel launched a preemptive strike on Egypt to begin the Six-Day War in June 1967, where Jordan and Syria joined the war.[106] The Arab states were defeated and Jordan lost control of the West Bank to Israel.[106] The War of Attrition with Israel followed, which included the 1968 Battle of Karameh where the combined forces of the Jordanian Armed Forces and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) repelled an Israeli attack on the Karameh camp on the Jordanian border with the West Bank.[106] Despite the fact that the Palestinians had limited involvement against the Israeli forces, the events at Karameh gained wide recognition and acclaim in the Arab world.[107] As a result, the time period following the battle witnessed an upsurge of support for Palestinian paramilitary elements (the fedayeen) within Jordan from other Arab countries.[107] The fedayeen activities soon became a threat to Jordan's rule of law.[107] In September 1970, the Jordanian army targeted the fedayeen and the resultant fighting led to the expulsion of Palestinian fighters from various PLO groups into Lebanon, in a conflict that became known as Black September.[107]

In 1973, Egypt and Syria waged the Yom Kippur War on Israel, and fighting occurred along the 1967 Jordan River cease-fire line.[107] Jordan sent a brigade to Syria to attack Israeli units on Syrian territory but did not engage Israeli forces from Jordanian territory.[107] At the Rabat summit conference in 1974, in the aftermath of the Yom-Kippur War, Jordan agreed, along with the rest of the Arab League, that the PLO was the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people".[107] Subsequently, Jordan renounced its claims to the West Bank in 1988.[107]

At the 1991 Madrid Conference, Jordan agreed to negotiate a peace treaty sponsored by the US and the Soviet Union.[107] The Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace was signed on 26 October 1994.[107] In 1997, in retribution for a bombing, Israeli agents entered Jordan using Canadian passports and poisoned Khaled Meshal, a senior Hamas leader living in Jordan.[107] Bowing to intense international pressure, Israel provided an antidote to the poison and released dozens of political prisoners, including Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, after King Hussein threatened to annul the peace treaty.[107]

On 7 February 1999, Abdullah II ascended the throne upon the death of his father Hussein, who had ruled for nearly 50 years.[108] Abdullah embarked on economic liberalization when he assumed the throne, and his reforms led to an economic boom which continued until 2008.[109] Abdullah II has been credited with increasing foreign investment, improving public-private partnerships and providing the foundation for Aqaba's free-trade zone and Jordan's flourishing information and communication technology (ICT) sector.[109] He also set up five other special economic zones.[109] However, during the following years Jordan's economy experienced hardship as it dealt with the effects of the Great Recession and spillover from the Arab Spring.[110]

Al-Qaeda under Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's leadership launched coordinated explosions in three hotel lobbies in Amman on 9 November 2005, resulting in 60 deaths and 115 injured.[111] The bombings, which targeted civilians, caused widespread outrage among Jordanians.[111] The attack is considered to be a rare event in the country, and Jordan's internal security was dramatically improved afterwards.[111] No major terrorist attacks have occurred since then.[112] Abdullah and Jordan are viewed with contempt by Islamic extremists for the country's peace treaty with Israel, its relationship with the West, and its mostly non-religious laws.[113]

The Arab Spring were large-scale protests that erupted in the Arab World in 2011, demanding economic and political reforms.[114] Many of these protests tore down regimes in some Arab nations, leading to instability that ended with violent civil wars.[114] In Jordan, in response to domestic unrest, Abdullah replaced his prime minister and introduced a number of reforms including: reforming the Constitution, and laws governing public freedoms and elections.[114] Proportional representation was re-introduced to the Jordanian parliament in the 2016 general election, a move which he said would eventually lead to establishing parliamentary governments.[115] Jordan was left largely unscathed from the violence that swept the region despite an influx of 1.4 million Syrian refugees into the natural resources-lacking country and the emergence of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).[115]

On 4 April 2021, 19 people were arrested, including Prince Hamzeh, the former crown prince of Jordan, who was placed under house arrest, after having been accused of working to "destabilize" the kingdom.

Geography

Jordan sits strategically at the crossroads of the continents of Asia, Africa and Europe,[116] in the Levant area of the Fertile Crescent, a cradle of civilization.[117] It is 89,341 square kilometres (34,495 sq mi) large, and 400 kilometres (250 mi) long between its northernmost and southernmost points; Umm Qais and Aqaba respectively.[14] The kingdom lies between 29° and 34° N, and 34° and 40° E. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the south and the east, Iraq to the north-east, Syria to the north, and Israel and Palestine (West Bank) to the west.

The east is an arid plateau irrigated by oases and seasonal water streams.[14] Major cities are overwhelmingly located on the north-western part of the kingdom due to its fertile soils and relatively abundant rainfall.[118] These include Irbid, Jerash and Zarqa in the northwest, the capital Amman and As-Salt in the central west, and Madaba, Al-Karak and Aqaba in the southwest.[118] Major towns in the eastern part of the country are the oasis towns of Azraq and Ruwaished.[117]

In the west, a highland area of arable land and Mediterranean evergreen forestry drops suddenly into the Jordan Rift Valley.[117] The rift valley contains the Jordan River and the Dead Sea, which separates Jordan from Israel.[117] Jordan has a 26 kilometres (16 mi) shoreline on the Gulf of Aqaba in the Red Sea, but is otherwise landlocked.[119] The Yarmuk River, an eastern tributary of the Jordan, forms part of the boundary between Jordan and Syria (including the occupied Golan Heights) to the north.[119] The other boundaries are formed by several international and local agreements and do not follow well-defined natural features.[117] The highest point is Jabal Umm al Dami, at 1,854 m (6,083 ft) above sea level, while the lowest is the Dead Sea −420 m (−1,378 ft), the lowest land point on Earth.[117]

Jordan has a diverse range of habitats, ecosystems and biota due to its varied landscapes and environments.[120] The Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature was set up in 1966 to protect and manage Jordan's natural resources.[121] Nature reserves in Jordan include the Dana Biosphere Reserve, the Azraq Wetland Reserve, the Shaumari Wildlife Reserve and the Mujib Nature Reserve.[121]

Climate

The climate in Jordan varies greatly. Generally, the further inland from the Mediterranean, there are greater contrasts in temperature and less rainfall.[14] The country's average elevation is 812 m (2,664 ft) (SL).[14] The highlands above the Jordan Valley, mountains of the Dead Sea and Wadi Araba and as far south as Ras Al-Naqab are dominated by a Mediterranean climate, while the eastern and northeastern areas of the country are arid desert.[122] Although the desert parts of the kingdom reach high temperatures, the heat is usually moderated by low humidity and a daytime breeze, while the nights are cool.[123]

Summers, lasting from May to September, are hot and dry, with temperatures averaging around 32 °C (90 °F) and sometimes exceeding 40 °C (104 °F) between July and August.[123] The winter, lasting from November to March, is relatively cool, with temperatures averaging around 11.08 °C (52 °F).[122] Winter also sees frequent showers and occasional snowfall in some western elevated areas.[122]

Biodiversity

Over 2,000 plant species have been recorded in Jordan.[124] Many of the flowering plants bloom in the spring after the winter rains and the type of vegetation depends largely on the levels of precipitation. The mountainous regions in the northwest are clothed in forests, while further south and east the vegetation becomes more scrubby and transitions to steppe-type vegetation.[125] Forests cover 1.5 million dunums (1,500 km2), less than 2% of Jordan, making Jordan among the world's least forested countries, the international average being 15%.[126]

Plant species and genera include the Aleppo pine, Sarcopoterium, Salvia dominica, black iris, Tamarix, Anabasis, Artemisia, Acacia, Mediterranean cypress and Phoenecian juniper.[127] The mountainous regions in the northwest are clothed in natural forests of pine, deciduous oak, evergreen oak, pistachio and wild olive.[128] Mammal and reptile species include, the long-eared hedgehog, Nubian ibex, wild boar, fallow deer, Arabian wolf, desert monitor, honey badger, glass snake, caracal, golden jackal and the roe deer, among others.[129][130][131] Bird include the hooded crow, Eurasian jay, lappet-faced vulture, barbary falcon, hoopoe, pharaoh eagle-owl, common cuckoo, Tristram's starling, Palestine sunbird, Sinai rosefinch, lesser kestrel, house crow and the white-spectacled bulbul.[132]

Four terrestrial ecoregions lie with Jordan's borders: Syrian xeric grasslands and shrublands, Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests, Mesopotamian shrub desert, and Red Sea Nubo-Sindian tropical desert and semi-desert.[133]

Government and politics

Jordan is a unitary state under a constitutional monarchy. Jordan's constitution, adopted in 1952 and amended a number of times since, is the legal framework that governs the monarch, government, bicameral legislature and judiciary.[134] The king retains wide executive and legislative powers from the government and parliament.[135] The king exercises his powers through the government that he appoints for a four-year term, which is responsible before the parliament that is made up of two chambers: the Senate and the House of Representatives. The judiciary is independent according to the constitution, but in practice often lacks independence.[134]

The king is the head of state and commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces. He can declare war and peace, ratify laws and treaties, convene and close legislative sessions, call and postpone elections, dismiss the government and dissolve the parliament.[134] The appointed government can also be dismissed through a majority vote of no confidence by the elected House of Representatives. After a bill is proposed by the government, it must be approved by the House of Representatives then the Senate, and becomes law after being ratified by the king. A royal veto on legislation can be overridden by a two-thirds vote in a joint session of both houses. The parliament also has the right of interpellation.[134]

The 65 members of the upper Senate are directly appointed by the king, the constitution mandates that they be veteran politicians, judges and generals who previously served in the government or in the House of Representatives.[136] The 130 members of the lower House of Representatives are elected through party-list proportional representation in 23 constituencies for a 4-year term.[137] Minimum quotas exist in the House of Representatives for women (15 seats, though they won 20 seats in the 2016 election), Christians (9 seats) and Circassians and Chechens (3 seats).[138]

Courts are divided into three categories: civil, religious, and special.[139] The civil courts deal with civil and criminal matters, including cases brought against the government.[139] The civil courts include Magistrate Courts, Courts of First Instance, Courts of Appeal,[139] High Administrative Courts which hear cases relating to administrative matters,[140] and the Constitutional Court which was set up in 2012 in order to hear cases regarding the constitutionality of laws.[141] Although Islam is the state religion, the constitution preserves religious and personal freedoms. Religious law only extends to matters of personal status such as divorce and inheritance in religious courts, and is partially based on Islamic Sharia law.[142] The special court deals with cases forwarded by the civil one.[143]

The capital city of Jordan is Amman, located in north-central Jordan.[144] Jordan is divided into 12 governorates (muhafazah) (informally grouped into three regions: northern, central, southern). These are subdivided into a total of 52 districts (Liwaa'), which are further divided into neighbourhoods in urban areas or into towns in rural ones.[145]

The monarch, Abdullah II, ascended to the throne in February 1999 after the death of his father King Hussein. Abdullah re-affirmed Jordan's commitment to the peace treaty with Israel and its relations with the United States. He refocused the government's agenda on economic reform, during his first year. King Abdullah's eldest son, Prince Hussein, is the Crown Prince of Jordan.[146] The prime minister is Jafar Hassan who was appointed on 15 September 2024.[147] Abdullah had announced his intention to move Jordan to a parliamentary system, where the largest bloc in parliament forms a government. However, the underdevelopment of political parties in a country where tribal identity remains strong has hampered the effort.[148] Jordan has approximately fifty political parties representing nationalist, leftist, Islamist, and liberal ideologies.[149] Political parties contested one-fifth of the seats in the 2016 elections, the remainder belonging to independent politicians.[150]

Freedom House ranked Jordan as "Not Free" in the Freedom in the World 2022 report.[151] Jordan ranked 94th globally in the Cato Institute's Human Freedom Index in 2021,[152] and ranked 58th in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) issued by Transparency International in 2021.[153] In the 2023 Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders, Jordan ranked 146 out of 180 countries. The overall score for Jordan 42.79, based on a scale from 0 (least free) to 105 (most free). The 2015 report noted "the Arab Spring and the Syrian conflict have led the authorities to tighten their grip on the media and, in particular, the Internet, despite an outcry from civil society".[154] Jordanian media consists of public and private institutions. Popular Jordanian newspapers include Al Ghad and the Jordan Times. Al-Mamlaka, Roya TV and Jordan TV are some Jordanian television channels.[155] Internet penetration in Jordan reached 76% in 2015.[156] There were concerns that the government would use the COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan to silence dissidents.[157][158]

Largest cities

| Rank | Name | Governorate | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Amman  Zarqa |

1 | Amman | Amman Governorate | 1,812,059 |  Irbid  Russeifa | ||||

| 2 | Zarqa | Zarqa Governorate | 635,160 | ||||||

| 3 | Irbid | Irbid Governorate | 502,714 | ||||||

| 4 | Russeifa | Zarqa Governorate | 472,604 | ||||||

| 5 | Ar-Ramtha | Amman Governorate | 155,693 | ||||||

| 6 | Aqaba | Aqaba Governorate | 148,398 | ||||||

| 7 | Al-Mafraq | Mafraq Governorate | 106,008 | ||||||

| 8 | Madaba | Madaba Governorate | 105,353 | ||||||

| 9 | As-Salt | Balqa Governorate | 99,890 | ||||||

| 10 | Jerash | Jerash Governorate | 50,745 | ||||||

Administrative divisions

The first level subdivision in Jordan is the muhafazah or governorate. The governorates are divided into liwa or districts, which are often further subdivided into qda or sub-districts.[160] Control for each administrative unit is in a "chief town" (administrative centre) known as a nahia.[160]

| Map | Governorate | Capital | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern region | |||||

| 1 | Irbid | Irbid | 1,770,158 | ||

| 2 | Mafraq | Mafraq | 549,948 | ||

| 3 | Jerash | Jerash | 237,059 | ||

| 4 | Ajloun | Ajloun | 176,080 | ||

| Central region | |||||

| 5 | Amman | Amman | 4,007,256 | ||

| 6 | Zarqa | Zarqa | 1,364,878 | ||

| 7 | Balqa | As-Salt | 491,709 | ||

| 8 | Madaba | Madaba | 189,192 | ||

| Southern region | |||||

| 9 | Karak | Al-Karak | 316,629 | ||

| 10 | Aqaba | Aqaba | 188,160 | ||

| 11 | Ma'an | Ma'an | 144,083 | ||

| 12 | Tafilah | Tafila | 96,291 | ||

Foreign relations

The kingdom has followed a pro-Western foreign policy and maintained close relations with the United States and the United Kingdom. During the first Gulf War (1990), these relations were damaged by Jordan's neutrality and its maintenance of relations with Iraq. Later, Jordan restored its relations with Western countries through its participation in the enforcement of UN sanctions against Iraq and in the Southwest Asia peace process. After King Hussein's death in 1999, relations between Jordan and the Persian Gulf countries greatly improved.[161]

Jordan is a key ally of the US and UK and, together with Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, is one of only three Arab nations to have signed peace treaties with Israel, Jordan's direct neighbour.[162] Jordan views an independent Palestinian state with the 1967 borders, as part of the two-state solution and of supreme national interest.[163] The ruling Hashemite dynasty has had custodianship over holy sites in Jerusalem since 1924, a position re-inforced in the Israel–Jordan peace treaty. Turmoil in Jerusalem's Al-Aqsa mosque between Israelis and Palestinians created tensions between Jordan and Israel concerning the former's role in protecting the Muslim and Christian sites in Jerusalem.[164]

Jordan is a founding member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and of the Arab League.[165][166] It enjoys "advanced status" with the European Union and is part of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which aims to increase links between the EU and its neighbours.[167] Jordan and Morocco tried to join the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in 2011, but the Gulf countries offered a five-year development aid programme instead.[168]

Military

The first organised army in Jordan was established on 22 October 1920, and was named the "Arab Legion".[91] The Legion grew from 150 men in 1920 to 8,000 in 1946.[169] Jordan's capture of the West Bank during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War proved that the Arab Legion, known today as the Jordan Armed Forces, was the most effective among the Arab troops involved in the war.[169] The Royal Jordanian Army, which boasts around 110,000 personnel, is considered to be among the most professional in the region, due to being particularly well-trained and organised.[169] The Jordanian military enjoys strong support and aid from the United States, the United Kingdom and France. This is due to Jordan's critical position in the Middle East.[169] The development of Special Operations Forces has been particularly significant, enhancing the capability of the military to react rapidly to threats to homeland security, as well as training special forces from the region and beyond.[170] Jordan provides extensive training to the security forces of several Arab countries.[171]

There are about 50,000 Jordanian troops working with the United Nations in peacekeeping missions across the world. Jordan ranks third internationally in participation in U.N. peacekeeping missions,[172] with one of the highest levels of peacekeeping troop contributions of all U.N. member states.[173] Jordan has dispatched several field hospitals to conflict zones and areas affected by natural disasters across the region.[174]

In 2014, Jordan joined an aerial bombardment campaign by an international coalition led by the United States against the Islamic State as part of its intervention in the Syrian Civil War.[175] In 2015, Jordan participated in the Saudi Arabian-led military intervention in Yemen against the Houthis and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was deposed in the 2011 uprising.[176]

Law enforcement

Jordan's law enforcement is under the purview of the Public Security Directorate (which includes approximately 50,000 persons) and the General Directorate of Gendarmerie, both of which are subordinate to the country's Ministry of Interior. The first police force in the Jordanian state was organised after the fall of the Ottoman Empire on 11 April 1921.[177] Until 1956 police duties were carried out by the Arab Legion and the Transjordan Frontier Force. After that year the Public Safety Directorate was established.[177] The number of female police officers is increasing. In the 1970s, it was the first Arab country to include women in its police force.[178] Jordan's law enforcement was ranked 37th in the world and 3rd in the Middle East, in terms of police services' performance, by the 2016 World Internal Security and Police Index.[179][180]

Economy

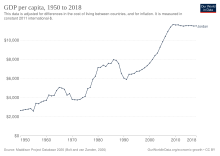

Jordan is classified by the World Bank as a lower middle income country.[181] Approximately 15.7% of the population lives below the national poverty line as of 2018,[182] while almost a third fell below the national poverty line during some time of the year—known as transient poverty.[183] The economy, which has a GDP of $39.453 billion (as of 2016[update]),[5] grew at an average rate of 8% per annum between 2004 and 2008, and around 2.6% 2010 onwards.[14] GDP per capita rose by 351% in the 1970s, declined 30% in the 1980s, and rose 36% in the 1990s—currently $9,406 per capita by purchasing power parity.[184] The Jordanian economy is one of the smallest economies in the region, and the country's populace suffers from relatively high rates of unemployment and poverty.[14]

Jordan's economy is relatively well-diversified. Trade and finance combined account for nearly one-third of GDP; transportation and communication, public utilities, and construction account for one-fifth, and mining and manufacturing constitute nearly another fifth.[13] Net official development assistance to Jordan in 2009 totalled US$761 million; according to the government, approximately two-thirds of this was allocated as grants, of which half was direct budget support.[185]

The official currency is the Jordanian dinar, which is pegged to the IMF's special drawing rights (SDRs), equivalent to an exchange rate of 1 US$ ≡ 0.709 dinar, or approximately 1 dinar ≡ 1.41044 dollars.[186] In 2000, Jordan joined the World Trade Organization and signed the Jordan–United States Free Trade Agreement, thus becoming the first Arab country to establish a free trade agreement with the United States. Jordan enjoys advanced status with the EU, which has facilitated greater access to export to European markets.[187] Due to slow domestic growth, high energy and food subsidies and a bloated public-sector workforce, Jordan usually runs annual budget deficits.[188]

The Great Recession and the turmoil caused by the Arab Spring have depressed Jordan's GDP growth, damaging trade, industry, construction and tourism.[14] Tourist arrivals have dropped sharply since 2011.[189] Since 2011, the natural gas pipeline in Sinai supplying Jordan from Egypt was attacked 32 times by Islamic State affiliates. Jordan incurred billions of dollars in losses because it had to substitute more expensive heavy-fuel oils to generate electricity.[190] In November 2012, the government cut subsidies on fuel, increasing its price.[191] The decision, which was later revoked, caused large scale protests to break out across the country.[188][189]

Jordan's total foreign debt in 2011 was $19 billion, representing 60% of its GDP. In 2016, the debt reached $35.1 billion representing 93% of its GDP.[110] This substantial increase is attributed to effects of regional instability causing a decrease in tourist activity, decreased foreign investments, increased military expenditures, attacks on Egyptian pipelines, the collapse of trade with Iraq and Syria, expenses from hosting Syrian refugees, and accumulated interest from loans.[110] According to the World Bank, Syrian refugees have cost Jordan more than $2.5 billion a year, amounting to 6% of the GDP and 25% of the government's annual revenue.[192] Foreign aid covers only a small part of these costs, 63% of the total costs are covered by Jordan.[193] An austerity programme was adopted by the government which aims to reduce Jordan's debt-to-GDP ratio to 77 percent by 2021.[194] The programme succeeded in preventing the debt from rising above 95% in 2018.[195]

The proportion of well-educated and skilled workers in Jordan is among the highest in the region in sectors such as ICT and industry, due to a relatively modern educational system. This has attracted large foreign investments to Jordan and has enabled the country to export its workforce to Persian Gulf countries.[11] Flows of remittances to Jordan grew rapidly, particularly during the end of the 1970s and 1980s, and remains an important source of external funding.[196] Remittances from Jordanian expatriates were $3.8 billion in 2015, a notable rise in the amount of transfers compared to 2014 where remittances reached over $3.66 billion, making Jordan the fourth-largest recipient in the region.[197]

Transportation

Jordan is ranked as having the 35th best infrastructure in the world, one of the highest rankings in the developing world, according to the 2010 World Economic Forum's Index of Economic Competitiveness. This high infrastructural development is necessitated by its role as a transit country for goods and services mainly to Palestine and Iraq.[198]

According to data from the Jordanian Ministry of Public Works and Housing, as of 2011[update], the Jordanian road network consisted of 2,878 km (1,788 mi) of main roads; 2,592 km (1,611 mi) of rural roads and 1,733 km (1,077 mi) of side roads. The Hejaz Railway built during the Ottoman Empire which extended from Damascus to Mecca will act as a base for future railway expansion plans. Currently, the railway has little civilian activity; it is primarily used for transporting goods. A national railway project is currently undergoing studies and seeking funding sources.[199] The capital Amman has a network of public transportation buses including the Amman Bus and the Amman Bus Rapid Transit and is connected to nearby Zarqa through the Amman-Zarqa Bus Rapid Transit.

Jordan has three commercial airports, all receiving and dispatching international flights. Two are in Amman and the third is in Aqaba, King Hussein International Airport. Amman Civil Airport serves several regional routes and charter flights while Queen Alia International Airport is the major international airport in Jordan and is the hub for Royal Jordanian Airlines, the flag carrier. Queen Alia International Airport expansion was completed in 2013 with new terminals costing $700 million, to handle over 16 million passengers annually.[200] It is now considered a state-of-the-art airport and was awarded 'the best airport by region: Middle East' for 2014 and 2015 by Airport Service Quality (ASQ) survey, the world's leading airport passenger satisfaction benchmark programme.[201]

The Port of Aqaba is the only port in Jordan. In 2006, the port was ranked as being the "Best Container Terminal" in the Middle East by Lloyd's List. The port was chosen due to it being a transit cargo port for other neighbouring countries, its location between four countries and three continents, being an exclusive gateway for the local market and for the improvements it has recently witnessed.[202]

Tourism

The tourism sector is considered a cornerstone of the economy and is a large source of employment, hard currency, and economic growth. In 2010, there were 8 million visitors to Jordan. The majority of tourists coming to Jordan are from European and Arab countries.[12] The tourism sector in Jordan has been severely affected by regional turbulence.[203] The most recent blow to the tourism sector was caused by the Arab Spring. Jordan experienced a 70% decrease in the number of tourists from 2010 to 2016.[204] Tourist numbers started to recover as of 2017.[204]

According to the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, Jordan is home to around 100,000 archaeological and tourist sites.[205] Some very well preserved historical cities include Petra and Jerash, the former being Jordan's most popular tourist attraction and an icon of the kingdom.[204] Jordan, as part of the Holy Land, has numerous biblical sites, including: Al-Maghtas—a traditional location for the Baptism of Jesus, Mount Nebo, Umm ar-Rasas, Madaba and Machaerus.[206] Islamic sites include shrines of the prophet Muhammad's companions such as Abd Allah ibn Rawahah, Zayd ibn Harithah and Muadh ibn Jabal.[207] Ajloun Castle, built by Muslim Ayyubid leader Saladin in the 12th century during his wars with the Crusaders, is also a popular tourist attraction.[116]

Modern entertainment, recreation and souqs in urban areas, mostly in Amman, also attract tourists. Recently, the nightlife in Amman, Aqaba and Irbid has started to emerge and the number of bars, discos and nightclubs is on the rise.[208] Alcohol is widely available in tourist restaurants, liquor stores and even some supermarkets.[209] Valleys including Wadi Mujib and hiking trails in different parts of the country attract adventurers. Hiking is getting more and more popular among tourists and locals. Places such as Dana Biosphere Reserve and Petra offer numerous signposted hiking trails. Moreover, seaside recreation is present on the shores of Aqaba and the Dead Sea through several international resorts.[210]

Jordan has been a medical tourism destination in the Middle East since the 1970s. A study conducted by Jordan's Private Hospitals Association found that 250,000 patients from 102 countries received treatment in Jordan in 2010, compared to 190,000 in 2007, bringing over $1 billion in revenue. Jordan is the region's top medical tourism destination, as rated by the World Bank, and fifth in the world overall.[211] The majority of patients come from Yemen, Libya and Syria due to the ongoing civil wars in those countries. Jordanian doctors and medical staff have gained experience in dealing with war patients through years of receiving such cases from various conflict zones in the region.[212] Jordan also is a hub for natural treatment methods in both Ma'in Hot Springs and the Dead Sea. The Dead Sea is often described as a 'natural spa'. It contains 10 times more salt than the average ocean, which makes it impossible to sink in. The high salt concentration of the Dead Sea has been proven therapeutic for many skin diseases.[213] The uniqueness of this lake attracts several Jordanian and foreign vacationers, which boosted investments in the hotel sector in the area.[214]

The Jordan Trail, a 650 km (400 mi) hiking trail stretching the entire country from north to south, crossing several of Jordan's attractions was established in 2015.[215] The trail aims to revive the Jordanian tourism sector.[215]

Natural resources

Jordan is among the most water-scarce nations on earth. At 97 cubic metres of water per person per year, it is considered to face "absolute water scarcity" according to the Falkenmark Classification.[216] Scarce resources to begin with have been aggravated by the massive influx of Syrian refugees into Jordan, many of whom face issues of access to clean water due to living in informal settlements (see "Immigrants and Refugees" below).[217] Jordan shares both of its two main surface water resources, the Jordan and Yarmuk rivers, with neighbouring countries, adding complexity to water allocation decisions.[216] Water from Disi aquifer and ten major dams historically played a large role in providing Jordan's need for freshwater.[218] The Jawa Dam in northeastern Jordan, which dates back to the fourth millennium BC, is the world's oldest dam.[219] The Dead Sea is receding at an alarming rate. Multiple canals and pipelines were proposed to reduce its recession, which had begun causing sinkholes. The Red Sea–Dead Sea Water Conveyance project, carried out by Jordan, will provide water to the country and to Israel and Palestine, while the brine will be carried to the Dead Sea to help stabilise its levels. The first phase of the project is scheduled to begin in 2019 and to be completed in 2021.[220]

Natural gas was discovered in Jordan in 1987, however, the estimated size of the reserve discovered was about 230 billion cubic feet, a minuscule quantity compared with its oil-rich neighbours. The Risha field, in the eastern desert beside the Iraqi border, produces nearly 35 million cubic feet of gas a day, which is sent to a nearby power plant to generate a small amount of Jordan's electricity needs.[221] This led to a reliance on importing oil to generate almost all of its electricity. Regional instability over the decades halted oil and gas supply to the kingdom from various sources, making it incur billions of dollars in losses. Jordan built a liquified natural gas port in Aqaba in 2012 to temporarily substitute the supply, while formulating a strategy to rationalize energy consumption and to diversify its energy sources. Jordan receives 330 days of sunshine per year, and wind speeds reach over 7 m/s in the mountainous areas, so renewables proved a promising sector.[222] King Abdullah inaugurated large-scale renewable energy projects in the 2010s including the 117 MW Tafila Wind Farm, the 53 MW Shams Ma'an, and the 103 MW Quweira solar power plants, with several more projects planned. By early 2019, it was reported that more than 1090 MW of renewable energy projects had been completed, contributing to 8% of Jordan's electricity up from 3% in 2011, while 92% was generated from gas.[223] After having initially set the percentage of renewable energy Jordan aimed to generate by 2020 at 10%, the government announced in 2018 that it sought to beat that figure and aim for 20%.[224]

Jordan has the 5th largest oil-shale reserves in the world, which could be commercially exploited in the central and northwestern regions of the country.[225] Official figures estimate the kingdom's oil shale reserves at more than 70 billion tonnes. The extraction of oil-shale had been delayed a couple of years due to technological difficulties and the relatively higher costs.[226] The government overcame the difficulties and in 2017 laid the groundbreaking for the Attarat Power Plant, a $2.2 billion oil shale-dependent power plant that is expected to generate 470 MW after it is completed in 2020.[227] Jordan also aims to benefit from its large uranium reserves by tapping nuclear energy. The original plan involved constructing two 1000 MW reactors but has been scrapped due to financial constraints.[228] Currently, the country's Atomic Energy Commission is considering building small modular reactors instead, whose capacities hover below 500 MW and can provide new water sources through desalination. In 2018, the commission announced that Jordan was in talks with multiple companies to build the country's first commercial nuclear plant, a helium-cooled reactor that is scheduled for completion by 2025.[229] Phosphate mines in the south have made Jordan one of the largest producers and exporters of the mineral in the world.[230]

Industry

Jordan's well developed industrial sector, which includes mining, manufacturing, construction, and power, accounted for approximately 26% of the GDP in 2004 (including manufacturing, 16.2%; construction, 4.6%; and mining, 3.1%). More than 21% of Jordan's labor force was employed in industry in 2002. In 2014, industry accounted for 6% of the GDP.[231] The main industrial products are potash, phosphates, cement, clothes, and fertilisers. The most promising segment of this sector is construction. Petra Engineering Industries Company, which is considered to be one of the main pillars of Jordanian industry, has gained international recognition with its air-conditioning units reaching NASA.[232] Jordan is now considered to be a leading pharmaceuticals manufacturer in the MENA region led by Jordanian pharmaceutical company Hikma.[233]

Jordan's military industry thrived after the Jordan Design and Development Bureau defence company was established by King Abdullah II in 1999, to provide an indigenous capability for the supply of scientific and technical services to the Jordanian Armed Forces, and to become a global hub in security research and development. It manufactures all types of military products, many of which are presented at the bi-annually held international military exhibition SOFEX. In 2015, KADDB exported $72 million worth of industries to over 42 countries.[234]

Science and technology

Science and technology is the country's fastest developing economic sector. This growth is occurring across multiple industries, including information and communications technology (ICT) and nuclear technology. Jordan contributes 75% of the Arabic content on the Internet.[236] In 2014, the ICT sector accounted for more than 84,000 jobs and contributed to 12% of the GDP. More than 400 companies are active in telecom, information technology, and video game development. 600 companies are operating in active technologies and 300 start-up companies.[236] Jordan was ranked 71st in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, up from 86th in 2019.[237][238]

Nuclear science and technology are also expanding. The Jordan Research and Training Reactor, which began working in 2016, is a 5 MW training reactor located at the Jordan University of Science and Technology in Ar Ramtha.[239] The facility is the first nuclear reactor in the country and will provide Jordan with radioactive isotopes for medical usage and provide training to students to produce a skilled workforce for the country's planned commercial nuclear reactors.[239]

Jordan also hosts the Synchrotron-Light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East (SESAME) facility, which is the only particle accelerator in the Middle East, and one of only 60 synchrotron radiation facilities in the world.[240] SESAME, supported by UNESCO and CERN, was opened in 2017 and allows for collaboration between scientists from various rival Middle Eastern countries.[240]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 200,000 | — |

| 1922 | 225,000 | +6.07% |

| 1948 | 400,000 | +2.24% |

| 1952 | 586,200 | +10.03% |

| 1961 | 900,800 | +4.89% |

| 1979 | 2,133,000 | +4.91% |

| 1994 | 4,139,500 | +4.52% |

| 2004 | 5,100,000 | +2.11% |

| 2015 | 9,531,712 | +5.85% |

| 2018 | 10,171,480 | +2.19% |

| Source: Department of Statistics[241] | ||

The 2015 census showed Jordan's population to be 9,531,712 (female: 47%; males: 53%). Around 2.9 million (30%) were non-citizens, a figure including refugees, and illegal immigrants.[4] There were 1,977,534 households in Jordan in 2015, with an average of 4.8 persons per household (compared to 6.7 persons per household for the census of 1979).[4] The capital and largest city of Jordan is Amman, which is one of the world's oldest continuously inhabited cities and one of the most modern in the Arab world.[242] The population of Amman was 65,754 in 1946, but exceeded 4 million by 2015.

Arabs make up about 98% of the population. The remaining 2% consist largely of peoples from the Caucasus including Circassians, Armenians, and Chechens, along with smaller minority groups.[14] About 84.1% of the population live in urban areas.[14]

Refugees, immigrants and expatriates

Jordan was home to 2,175,491 Palestinian refugees as of December 2016; most of them, but not all, had been granted Jordanian citizenship.[243] The first wave of Palestinian refugees arrived during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and peaked in the 1967 Six-Day War and the 1990 Gulf War. In the past, Jordan had given many Palestinian refugees citizenship, however recently Jordanian citizenship is given only in rare cases. 370,000 of these Palestinians live in UNRWA refugee camps.[243] Following the capture of the West Bank by Israel in 1967, Jordan revoked the citizenship of thousands of Palestinians to thwart any attempt to permanently resettle from the West Bank to Jordan. West Bank Palestinians with family in Jordan or Jordanian citizenship were issued yellow cards guaranteeing them all the rights of Jordanian citizenship if requested.[244]

Up to 1,000,000 Iraqis moved to Jordan following the Iraq War in 2003,[245] and most of them have returned. In 2015, their number in Jordan was 130,911. Many Iraqi Christians (Assyrians/Chaldeans) however settled temporarily or permanently in Jordan.[246] Immigrants also include 15,000 Lebanese who arrived following the 2006 Lebanon War.[247] Since 2010, over 1.4 million Syrian refugees have fled to Jordan to escape the violence in Syria,[4] the largest population being in the Zaatari refugee camp. The kingdom has continued to demonstrate hospitality, despite the substantial strain the flux of Syrian refugees places on the country. The effects are largely affecting Jordanian communities, as the vast majority of Syrian refugees do not live in camps. The refugee crisis effects include competition for job opportunities, water resources and other state provided services, along with the strain on the national infrastructure.[10]

In 2007, there were up to 150,000 Assyrian Christians; most are Eastern Aramaic speaking refugees from Iraq.[248] Kurds number some 30,000, and like the Assyrians, many are refugees from Iraq, Iran and Turkey.[249] Descendants of Armenians that sought refuge in the Levant during the 1915 Armenian genocide number approximately 5,000 persons, mainly residing in Amman.[250] A small number of ethnic Mandeans also reside in Jordan, again mainly refugees from Iraq.[251] Around 12,000 Iraqi Christians have sought refuge in Jordan after the Islamic State took the city of Mosul in 2014.[252] Several thousand Libyans, Yemenis and Sudanese have also sought asylum in Jordan to escape instability and violence in their respective countries.[10] The 2015 Jordanian census recorded that there were 1,265,000 Syrians, 636,270 Egyptians, 634,182 Palestinians, 130,911 Iraqis, 31,163 Yemenis, 22,700 Libyans and 197,385 from other nationalities residing in the country.[4]

There are around 1.2 million illegal, and 500,000 legal migrant workers and expatriates in the kingdom.[253] Thousands of foreign women, mostly from the Middle East and Eastern Europe, work in nightclubs, hotels and bars across the kingdom.[254][255][256] American and European expatriate communities are concentrated in the capital, as the city is home to many international organisations and diplomatic missions.[209]

Religion

Sunni Islam is the dominant religion in Jordan. Muslims make up about 95% of the country's population; in turn, 93% of those self-identify as Sunnis.[257] There are also a small number of Ahmadi Muslims,[258] and some Shiites. Many Shia are Iraqi and Lebanese refugees.[259] Muslims who convert to another religion as well as missionaries from other religions face societal and legal discrimination.[260]

Jordan contains some of the oldest Christian communities in the world, dating as early as the 1st century AD after the crucifixion of Jesus.[261] Christians today make up about 4% of the population,[262] down from 20% in 1930, though their absolute number has grown.[263] This is due to high immigration rates of Muslims into Jordan, higher emigration rates of Christians to the West and higher birth rates for Muslims.[264] Jordanian Christians number around 250,000, all of whom are Arabic-speaking, according to a 2014 estimate by the Orthodox Church, though the study excluded minority Christian groups and the thousands of Western, Iraqi and Syrian Christians residing in Jordan.[262] Christians are well integrated in Jordanian society and enjoy a high level of freedom.[265] Christians traditionally occupy two cabinet posts, and are reserved nine seats out of the 130 in the parliament.[266] The highest political position reached by a Christian is the Deputy Prime Minister, held by Rajai Muasher.[267] Christians are also influential in the media.[268]

Smaller religious minorities include Druze, Baháʼís and Mandaeans. Most Jordanian Druze live in the eastern oasis town of Azraq, some villages on the Syrian border, and the city of Zarqa, while most Jordanian Baháʼís live in the village of Adassiyeh bordering the Jordan Valley.[269] It is estimated that 1,400 Mandaeans live in Amman; they came from Iraq after the 2003 invasion fleeing persecution.[270]

Languages

The official language is Modern Standard Arabic, a literary language taught in the schools.[271] Most Jordanians natively speak one of the non-standard Arabic dialects known as Jordanian Arabic. Jordanian Sign Language is the language of the deaf community. English, though without official status, is widely spoken throughout the country and is the de facto language of commerce and banking, as well as a co-official status in the education sector; almost all university-level classes are held in English and almost all public schools teach English along with Standard Arabic.[271] Chechen, Circassian, Armenian, Tagalog, and Russian are popular among their communities.[272] French is offered as an elective in many schools, mainly in the private sector.[271] German is an increasingly popular language; it has been introduced at a larger scale since the establishment of the German Jordanian University in 2005.[273]

Health and education

Life expectancy in Jordan was around 74.8 years in 2017.[14] The leading cause of death is cardiovascular diseases, followed by cancer.[275] Childhood immunization rates have increased steadily over the past 15 years; by 2002 immunisations and vaccines reached more than 95% of children under five.[276] In 1950, water and sanitation was available to only 10% of the population; in 2015, it reached 98% of Jordanians.[277]

Jordan prides itself on its health services, some of the best in the region.[278] Qualified medics, a favourable investment climate and Jordan's stability has contributed to the success of this sector.[279] The country's health care system is divided between public and private institutions. On 1 June 2007, Jordan Hospital (as the biggest private hospital) was the first general specialty hospital to gain the international accreditation JCAHO.[276] The King Hussein Cancer Center is a leading cancer treatment centre.[280] 66% of Jordanians have medical insurance.[4]

The Jordanian educational system comprises 2 years of pre-school education, 10 years of compulsory basic education, and two years of secondary academic or vocational education, after which the students sit for the General Certificate of Secondary Education Exam (Tawjihi) exams.[281] Scholars may attend either private or public schools. According to the UNESCO, the literacy rate in 2015 was 98.01% and is considered to be the highest in the Middle East and the Arab world, and one of the highest in the world.[274] UNESCO ranked Jordan's educational system 18th out of 94 nations for providing gender equality in education.[282] Jordan has the highest number of researchers in research and development per million people among all the 57 countries that are members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). In Jordan, there are 8060 researchers per million people, while the world average is 2532 per million.[283] Primary education is free in Jordan.[284]

Jordan has 10 public universities, 19 private universities and 54 community colleges, of which 14 are public, 24 private and others affiliated with the Jordanian Armed Forces, the Civil Defense Department, the Ministry of Health and UNRWA.[285] There are over 200,000 Jordanian students enrolled in universities each year. An additional 20,000 Jordanians pursue higher education abroad primarily in the United States and Europe.[286] According to the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities, the top-ranking universities in the country are the University of Jordan (UJ) (1,220th worldwide), Jordan University of Science & Technology (JUST) (1,729th) and Hashemite University (2,176th).[287] UJ and JUST occupy 8th and 10th between Arab universities.[288] Jordan has 2,000 researchers per million people.[289]

Culture

Art and museums

Many institutions in Jordan aim to increase cultural awareness of Jordanian Art and to represent Jordan's artistic movements in fields such as paintings, sculpture, graffiti and photography.[290] The art scene has been developing in the past few years[291] and Jordan has been a haven for artists from surrounding countries.[292] In January 2016, for the first time ever, a Jordanian film called Theeb was nominated for the Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film.[293]

The largest museum in Jordan is The Jordan Museum. It contains much of the valuable archaeological findings in the country, including some of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Neolithic limestone statues of 'Ain Ghazal and a copy of the Mesha Stele.[294] Most museums in Jordan are located in Amman including The Children's Museum Jordan, The Martyr's Memorial and Museum and the Royal Automobile Museum. Museums outside Amman include the Aqaba Archaeological Museum.[295] The Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts is a major contemporary art museum located in Amman.[295]

Music in Jordan is now developing with a lot of new bands and artists, who are now popular in the Middle East. Artists such as Omar Al-Abdallat, Toni Qattan, Diana Karazon and Hani Mitwasi have increased the popularity of Jordanian music.[296] The Jerash Festival is an annual music event that features popular Arab singers.[296] Pianist and composer Zade Dirani has gained wide international popularity.[297] There is also an increasing growth of alternative Arabic rock bands, who are dominating the scene in the Arab world, including: El Morabba3, Autostrad, JadaL, Akher Zapheer and Aziz Maraka.[298]

Jordan unveiled its first underwater military museum off the coast of Aqaba. Several military vehicles, including tanks, troop carriers and a helicopter are in the museum.[299]

Cuisine

As the eighth-largest producer of olives in the world, olive oil is the main cooking oil in Jordan.[300] A common appetizer is hummus, which is a puree of chickpeas blended with tahini, lemon, and garlic. Ful medames is another well-known appetiser. A typical worker's meal, it has since made its way to the tables of the upper class. A typical Jordanian meze often contains koubba maqliya, labaneh, baba ghanoush, tabbouleh, olives and pickles.[301] Meze is generally accompanied by the Levantine alcoholic drink arak, which is made from grapes and aniseed and is similar to ouzo, rakı and pastis. Jordanian wine and beer are also sometimes used. The same dishes, served without alcoholic drinks, can also be termed "muqabbilat" (starters) in Arabic.[209]

The most distinctive Jordanian dish is mansaf, the national dish of Jordan. The dish is a symbol for Jordanian hospitality and is influenced by the Bedouin culture. Mansaf is eaten on different occasions such as funerals, weddings and on religious holidays. It consists of a plate of rice with meat that was boiled in thick yogurt, sprayed with pine nuts and sometimes herbs. As an old tradition, the dish is eaten using one's hands, but the tradition is not always used.[301] Simple fresh fruit is often served towards the end of a Jordanian meal, but there is also dessert, such as baklava, hareeseh, knafeh, halva and qatayef, a dish made specially for Ramadan. In Jordanian cuisine, drinking coffee and tea flavoured with na'na or meramiyyeh is almost a ritual.[302]

Sports

While both team and individual sports are widely played in Jordan, the Kingdom has enjoyed its biggest international achievements in taekwondo. The highlight came at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games when Ahmad Abughaush won Jordan's first ever medal[303] of any colour at the Games by taking gold in the −67 kg weight.[304] Medals have continued to be won at World and Asian level in the sport since to establish Taekwondo as the Kingdom's favourite sport alongside football[209] and basketball.[305]

Football is the most popular sport in Jordan.[306] The national football team came within a play-off of reaching the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil,[307] but lost the two-legged tie against Uruguay.[308] They previously reached the quarter-finals of the AFC Asian Cup in 2004 and 2011, and lost in the final against Qatar in 2023.[309]

Jordan has a strong policy for inclusive sport, and invests heavily in encouraging girls and women to participate in all sports. The women's football team gaining reputation,[310] and in March 2016 ranked 58th in the world.[311] In 2016, Jordan hosted the FIFA U-17 Women's World Cup, with 16 teams representing six continents. The tournament was held in four stadiums in the three Jordanian cities of Amman, Zarqa and Irbid. It was the first women's sports tournament in the Middle East.[312]

Basketball is another sport that Jordan continues to punch above its weight in, having qualified to the FIBA 2010 World Basketball Cup and more recently reaching the 2019 World Cup in China.[313] Jordan came within a point of reaching the 2012 Olympics after losing the final of the 2010 Asian Cup to China by the narrowest of margins, 70–69, and settling for silver instead. Jordan's national basketball team is participating in various international and Middle Eastern tournaments. Local basketball teams include: Al-Orthodoxi Club, Al-Riyadi, Zain, Al-Hussein and Al-Jazeera.[314]