Монреаль

Монреаль Монреаль ( французский ) | |

|---|---|

| Город Монреаль | |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto: Concordia Salus ("well-being through harmony") | |

Interactive map of Montreal | |

| Coordinates: 45°30′32″N 73°33′15″W / 45.50889°N 73.55417°W[5] | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Quebec |

| Region | Montreal |

| Urban agglomeration | Montreal |

| Founded | May 17, 1642 |

| Incorporated | 1832 |

| Constituted | January 1, 2002 |

| Named for | Mount Royal |

| Boroughs | List |

| Government | |

| • Type | Montreal City Council |

| • Mayor | Valérie Plante |

| • Federal riding | List |

| • Provincial riding | List |

| • MPs | List of MPs |

| Area | |

| • City | 431.50 km2 (166.60 sq mi) |

| • Land | 365.13 km2 (140.98 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,293.99 km2 (499.61 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,604.26 km2 (1,777.71 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 233 m (764 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 6 m (20 ft) |

| Population (2021)[8] | |

| • City | 1,762,949 (2nd) |

| • Density | 4,828.3/km2 (12,505/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,291,732 (2nd) |

| • Metro density | 919/km2 (2,380/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | Montrealer Montréalais(e)[12] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| Postal codes | |

| Area codes | 514, 438 and 263 |

| Police | SPVM |

| GDP (Montreal CMA) | C$228.71 billion (2020)[13] |

| GDP per capita (Montreal CMA) | C$48,289 (2022)[14] |

| Website | montreal |

Монреаль [а] ( французский : Монреаль [б] ) — крупнейший город провинции в Квебек и , второй по величине Канаде Америке десятый по величине в Северной . Основан в 1642 году как Вилль-Мари , или «Город Марии». [18] теперь он назван в честь горы Роял , [19] холм с тремя вершинами, вокруг которого было построено раннее поселение. [20] Центр города находится на острове Монреаль. [21] [22] и несколько, гораздо меньших, периферийных островов, самый большой из которых — Иль-Бизар . Город находится в 196 км (122 миль) к востоку от столицы страны Оттавы и в 258 км (160 миль) к юго-западу от столицы провинции Квебека .

По состоянию на 2021 год [update] население города составляло 1 762 949 человек, [23] и столичное население составляет 4 291 732 человека, [24] что делает его вторым по величине мегаполисом в Канаде. Французский является официальным языком города. [25] [26] В 2021 году 85,7% населения города Монреаля считали, что свободно говорят по-французски, а 90,2% могли говорить на нем в столичном регионе. [27] [28] Монреаль — один из самых двуязычных городов Квебека и Канады, где 58,5% населения могут говорить как на французском, так и на английском языке. [29]

Исторически коммерческая столица Канады Монреаль в 1970-х годах превосходил Торонто по численности населения и экономической мощи . [30] Он остается важным центром искусства, культуры , литературы, кино и телевидения, музыки, торговли, аэрокосмической промышленности, транспорта , финансов, фармацевтики, технологий, дизайна, образования , туризма , еды, моды, разработки видеоигр и мировых дел. В Монреале находится штаб-квартира Международной организации гражданской авиации , и в 2006 году он был назван ЮНЕСКО городом дизайна . [31] [32] В 2017 году Монреаль занял 12-е место в рейтинге самых пригодных для жизни городов мира по версии журнала Economist Intelligence Unit в своем ежегодном глобальном рейтинге пригодности для жизни . [33] хотя его рейтинг опустился на 40-е место в индексе 2021 года, в первую очередь из-за нагрузки на систему здравоохранения из-за пандемии COVID-19 . [34] It is regularly ranked as one of the ten best cities in the world to be a university student in the QS World University Rankings.[35] In 2018, Montreal was ranked as a global city.[36]

Montreal has hosted numerous important international events, including the 1967 International and Universal Exposition, and is the only Canadian city to have hosted the Summer Olympics, having done so in 1976.[37][38] The city hosts the Canadian Grand Prix of Formula One;[39] the Montreal International Jazz Festival,[40] the largest jazz festival in the world;[41] the Just for Laughs festival, the largest comedy festival in the world;[42] and Les Francos de Montréal, the largest French-language music festival in the world.[43] In sports, it is home to multiple professional teams, most notably the Canadiens of the National Hockey League, who have won the Stanley Cup a record 24 times.

Etymology and original names

[edit]In the Ojibwe language, the land is called Mooniyaang[44] which was "the first stopping place" in the Ojibwe migration story as related in the seven fires prophecy.

In the Mohawk language, the land is called Tiohtià:ke.[45][46][47][48] This is an abbreviation of Teionihtiohtiá:kon, which loosely translates as "where the group divided/parted ways."[47][49]

French settlers from La Flèche in the Loire valley first named their new town, founded in 1642, Ville Marie ("City of Mary"),[18] named for the Virgin Mary.[50]

The current form of the name, Montréal, is generally thought to be derived from Mount Royal (Mont Royal in French),[19][51] the triple-peaked hill in the heart of the city. There are multiple explanations for how Mont Royal became Montréal. In 16th century French, the forms réal and royal were used interchangeably, so Montréal could simply be a variant of Mont Royal.[52][53][54] In the second explanation, the name came from an Italian translation. Venetian geographer Giovanni Battista Ramusio used the name Monte Real to designate Mount Royal in his 1556 map of the region.[51] However, the Commission de toponymie du Québec disputes this explanation.[53]

Historiographer François de Belleforest was the first to use the form Montréal with reference to the entire region in 1575.[51]

History

[edit]Pre-European contact

[edit]

Archaeological evidence in the region indicates that First Nations native people occupied the island of Montreal as early as 4,000 years ago.[55] By the year AD 1000, they had started to cultivate maize. Within a few hundred years, they had built fortified villages.[56] The Saint Lawrence Iroquoians, an ethnically and culturally distinct group from the Iroquois nations of the Haudenosaunee (then based in present-day New York), established the village of Hochelaga at the foot of Mount Royal two centuries before the French arrived. Archeologists have found evidence of their habitation there and at other locations in the valley since at least the 14th century.[57]The French explorer Jacques Cartier visited Hochelaga on October 2, 1535, and estimated the population of the native people at Hochelaga to be "over a thousand people".[57] Evidence of earlier occupation of the island, such as those uncovered in 1642 during the construction of Fort Ville-Marie, have effectively been removed.

Early European settlement (1600–1760)

[edit]In 1603, French explorer Samuel de Champlain reported that the St Lawrence Iroquoians and their settlements had disappeared altogether from the St Lawrence valley. This is believed to be due to outmigration, epidemics of European diseases, or intertribal wars.[57][58] In 1611, Champlain established a fur trading post on the Island of Montreal on a site initially named La Place Royale. At the confluence of Petite Riviere and St. Lawrence River, it is where present-day Pointe-à-Callière stands.[59] On his 1616 map, Champlain named the island Lille de Villemenon in honour of the sieur de Villemenon, a French dignitary who was seeking the viceroyship of New France.[60] In 1639, Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière obtained the Seigneurial title to the Island of Montreal in the name of the Notre Dame Society of Montreal to establish a Roman Catholic mission to evangelize natives.

Dauversiere hired Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, then age 30, to lead a group of colonists to build a mission on his new seigneury. The colonists left France in 1641 for Quebec and arrived on the island the following year. On May 17, 1642, Ville-Marie was founded on the southern shore of Montreal island, with Maisonneuve as its first governor. The settlement included a chapel and a hospital, under the command of Jeanne Mance.[61] By 1643, Ville-Marie had come under Iroquois raids. In 1652, Maisonneuve returned to France to raise 100 volunteers to bolster the colonial population. If the effort had failed, Montreal was to be abandoned and the survivors re-located downriver to Quebec City. Before these 100 arrived in the fall of 1653, the population of Montreal was barely 50 people.

By 1685, Ville-Marie was home to some 600 colonists, most of them living in modest wooden houses. Ville-Marie became a centre for the fur trade and a base for further exploration.[61] In 1689, the English-allied Iroquois attacked Lachine on the Island of Montreal, committing the worst massacre in the history of New France.[62] By the early 18th century, the Sulpician Order was established there. To encourage French settlement, it wanted the Mohawk to move away from the fur trading post at Ville-Marie. It had a mission village, known as Kahnewake, south of the St Lawrence River. The fathers persuaded some Mohawk to make a new settlement at their former hunting grounds north of the Ottawa River. This became Kanesatake.[63] In 1745, several Mohawk families moved upriver to create another settlement, known as Akwesasne. All three are now Mohawk reserves in Canada. The Canadian territory was ruled as a French colony until 1760, when Montreal fell to a British offensive during the Seven Years' War. The colony then surrendered to Great Britain.[64]

Ville-Marie was the name for the settlement that appeared in all official documents until 1705, when Montreal appeared for the first time, although people referred to the "Island of Montreal" long before then.[65]

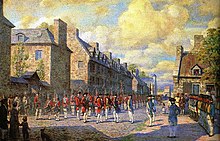

American occupation (1775–1776)

[edit]As part of the American Revolution, the invasion of Quebec resulted after Benedict Arnold captured Fort Ticonderoga in present-day upstate New York in May 1775 as a launching point to Arnold's invasion of Quebec in September. While Arnold approached the Plains of Abraham, Montreal fell to American forces led by Richard Montgomery on November 13, 1775, after it was abandoned by Guy Carleton. After Arnold withdrew from Quebec City to Pointe-aux-Trembles on November 19, Montgomery's forces left Montreal on December 1 and arrived there on December 3 to plot to attack Quebec City, with Montgomery leaving David Wooster in charge of the city. Montgomery was killed in the failed attack and Arnold, who had taken command, sent Brigadier General Moses Hazen to inform Wooster of the defeat.

Wooster left Hazen in command on March 20, 1776, as he left to replace Arnold in leading further attacks on Quebec City. On April 19, Arnold arrived in Montreal to take over command from Hazen, who remained as his second-in-command. Hazen sent Colonel Timothy Bedel to form a garrison of 390 men 40 miles upriver in a garrison at Les Cèdres, Quebec, to defend Montreal against the British army. In the Battle of the Cedars, Bedel's lieutenant Isaac Butterfield surrendered to George Forster.

Forster advanced to Fort Senneville on May 23. By May 24, Arnold was entrenched in Montreal's borough of Lachine. Forster initially approached Lachine, then withdrew to Quinze-Chênes. Arnold's forces then abandoned Lachine to chase Forster. The Americans burned Senneville on May 26. After Arnold crossed the Ottawa River in pursuit of Forster, Forster's cannons repelled Arnold's forces. Forster negotiated a prisoner exchange with Henry Sherburne and Isaac Butterfield, resulting in a May 27 boating of their deputy Lieutenant Park being returned to the Americans. Arnold and Forster negotiated further and more American prisoners were returned to Arnold at Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec, ("Fort Anne") on May 30 (delayed two days by wind).

Arnold eventually withdrew his forces back to the New York fort of Ticonderoga by the summer. On June 15, Arnold's messenger approaching Sorel spotted Carleton returning with a fleet of ships and notified him. Arnold's forces abandoned Montreal (attempting to burn it down in the process) prior to the June 17 arrival of Carleton's fleet.

The Americans did not return British prisoners in exchange, as previously agreed, due to accusations of abuse, with Congress repudiating the agreement at the protest of George Washington. Arnold blamed Colonel Timothy Bedel for the defeat, removing him and Lieutenant Butterfield from command and sending them to Sorel for court-martial. The retreat of the American army delayed their court martial until August 1, 1776, when they were convicted and cashiered at Ticonderoga. Bedel was given a new commission by Congress in October 1777 after Arnold was assigned to defend Rhode Island in July 1777.

Modern history as city (1832–present)

[edit]

Montreal was incorporated as a city in 1832.[66] The opening of the Lachine Canal permitted ships to bypass the unnavigable Lachine Rapids,[67] while the construction of the Victoria Bridge established Montreal as a major railway hub. The leaders of Montreal's business community had started to build their homes in the Golden Square Mile from about 1850. By 1860, it was the largest municipality in British North America and the undisputed economic and cultural centre of Canada.[68][69]

In the 19th century, maintaining Montreal's drinking water became increasingly difficult with the rapid increase in population. A majority of the drinking water was still coming from the city's harbour, which was busy and heavily trafficked, leading to the deterioration of the water within. In the mid-1840s, the City of Montreal installed a water system that would pump water from the St. Lawrence and into cisterns. The cisterns would then be transported to the desired location. This was not the first water system of its type in Montreal, as there had been one in private ownership since 1801. In the middle of the 19th century, water distribution was carried out by "fontainiers". The fountainiers[clarification needed] would open and close water valves outside of buildings, as directed, all over the city. As they lacked modern plumbing systems it was impossible to connect all buildings at once and it also acted as a conservation method. However, the population was not finished rising — it rose from 58,000 in 1852 to 267,000 by 1901.[70][71][72]

Montreal was the capital of the Province of Canada from 1844 to 1849, but lost its status when a Tory mob burnt down the Parliament building to protest the passage of the Rebellion Losses Bill.[73] Thereafter, the capital rotated between Quebec City and Toronto until in 1857, Queen Victoria herself established Ottawa as the capital due to strategic reasons. The reasons were twofold. First, because it was located more in the interior of the Province of Canada, it was less susceptible to attack from the United States. Second, and perhaps more importantly, because it lay on the border between French and English Canada, Ottawa was seen as a compromise between Montreal, Toronto, Kingston and Quebec City, which were all vying to become the young nation's official capital. Ottawa retained the status as capital of Canada when the Province of Canada joined with Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to form the Dominion of Canada in 1867.[citation needed]

An internment camp was set up at Immigration Hall in Montreal from August 1914 to November 1918.[74]

After World War I, the prohibition movement in the United States led to Montreal becoming a destination for Americans looking for alcohol.[75] Unemployment remained high in the city and was exacerbated by the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression.[76]

During World War II, Mayor Camillien Houde protested against conscription and urged Montrealers to disobey the federal government's registry of all men and women.[77] The federal government, part of the Allied forces, was furious over Houde's stand and held him in a prison camp until 1944.[78] That year, the government decided to institute conscription to expand the armed forces and fight the Axis powers. (See Conscription Crisis of 1944.)[77]

Montreal was the official residence of the Luxembourg royal family in exile during World War II.[79]

By 1951, Montreal's population had surpassed one million.[80] However, Toronto's growth had begun challenging Montreal's status as the economic capital of Canada. Indeed, the volume of stocks traded at the Toronto Stock Exchange had already surpassed that traded at the Montreal Stock Exchange in the 1940s.[81] The Saint Lawrence Seaway opened in 1959, allowing vessels to bypass Montreal. In time, this development led to the end of the city's economic dominance as businesses moved to other areas.[82] During the 1960s, there was continued growth as Canada's tallest skyscrapers, new expressways and the subway system known as the Montreal Metro were finished during this time. Montreal also held the World's Fair of 1967, better known as Expo67.

The 1970s ushered in a period of wide-ranging social and political changes, stemming largely from the concerns of the French-speaking majority about the conservation of their culture and language, given the traditional predominance of the English Canadian minority in the business arena.[83] The October Crisis and the 1976 election of the Parti Québécois, which supported sovereign status for Quebec, resulted in the departure of many businesses and people from the city.[84] In 1976, Montreal hosted the Summer Olympics. While the event brought the city international prestige and attention, the Olympic Stadium built for the event resulted in massive debt for the city.[85] During the 1980s and early 1990s, Montreal experienced a slower rate of economic growth than many other major Canadian cities. Montreal was the site of the 1989 École Polytechnique massacre, one of Canada's worst mass shootings, where 25-year-old Marc Lépine shot and killed 14 people, all of them women, and wounded 14 other people before shooting himself at École Polytechnique.

Montreal was merged with the 27 surrounding municipalities on the Island of Montreal on January 1, 2002, creating a unified city encompassing the entire island. There was substantial resistance from the suburbs to the merger, with the perception being that it was forced on the mostly English suburbs by the Parti Québécois. As expected, this move proved unpopular and several mergers were later rescinded. Several former municipalities, totalling 13% of the population of the island, voted to leave the unified city in separate referendums in June 2004. The demerger took place on January 1, 2006, leaving 15 municipalities on the island, including Montreal. Demerged municipalities remain affiliated with the city through an agglomeration council that collects taxes from them to pay for numerous shared services.[86] The 2002 mergers were not the first in the city's history. Montreal annexed 27 other cities, towns and villages beginning with Hochelaga in 1883, with the last prior to 2002 being Pointe-aux-Trembles in 1982.

The 21st century has brought with it a revival of the city's economic and cultural landscape. The construction of new residential skyscrapers, two super-hospitals (the Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal and McGill University Health Centre), the creation of the Quartier des Spectacles, reconstruction of the Turcot Interchange, reconfiguration of the Decarie and Dorval interchanges, construction of the new Réseau express métropolitain, gentrification of Griffintown, subway line extensions and the purchase of new subway cars, the complete revitalization and expansion of Trudeau International Airport, the completion of Quebec Autoroute 30, the reconstruction of the Champlain Bridge and the construction of a new toll bridge to Laval are helping Montreal continue to grow.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]

Montreal is in the southwest of the province of Quebec. The city covers most of the Island of Montreal at the confluence of the Saint Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers. The port of Montreal lies at one end of the Saint Lawrence Seaway, the river gateway that stretches from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic.[87] Montreal is defined by its location between the Saint Lawrence river to its south and the Rivière des Prairies to its north. The city is named after the most prominent geographical feature on the island, a three-head hill called Mount Royal, topped at 232 m (761 ft) above sea level.[88]

Montreal is at the centre of the Montreal Metropolitan Community, and is bordered by the city of Laval to the north; Longueuil, Saint-Lambert, Brossard, and other municipalities to the south; Repentigny to the east and the West Island municipalities to the west. The anglophone enclaves of Westmount, Montreal West, Hampstead, Côte Saint-Luc, the Town of Mount Royal and the francophone enclave Montreal East are all surrounded by Montreal.[89]

Climate

[edit]Montreal is classified as a warm-summer humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfb).[90][91]Summers are warm to hot and humid with a daily maximum average of 26 to 27 °C (79 to 81 °F) in July; temperatures in excess of 30 °C (86 °F) are common. Conversely, cold fronts can bring crisp, drier and windy weather in the early and later parts of summer.

Winter brings cold, snowy, windy, and, at times, icy weather, with a daily average ranging from −10.5 to −9 °C (13.1 to 15.8 °F) in January. However, some winter days rise above freezing, allowing for rain on an average of 4 days in January and February each. Usually, snow covering some or all bare ground lasts on average from the first or second week of December until the last week of March.[92] While the air temperature does not fall below −30 °C (−22 °F) every year,[93] the wind chill often makes the temperature feel this low to exposed skin.

Spring and fall are pleasantly mild but prone to drastic temperature changes; spring even more so than fall.[94] Late season heat waves as well as "Indian summers" are possible. Early and late season snow storms can occur in November and March, and more rarely in April. Montreal is generally snow free from late April to late October. However, snow can fall in early to mid-October as well as early to mid-May on rare occasions.

The lowest temperature in Environment Canada's books was −37.8 °C (−36 °F) on January 15, 1957, and the highest temperature was 37.6 °C (99.7 °F) on August 1, 1975, both at Dorval International Airport.[95]

Before modern weather record keeping (which dates back to 1871 for McGill),[96] a minimum temperature almost 5 degrees lower was recorded at 7 a.m. on January 10, 1859, where it registered at −42 °C (−44 °F).[97]

Annual precipitation is around 1,000 mm (39 in), including an average of about 210 cm (83 in) of snowfall, which occurs from November through March. Thunderstorms are common from late spring through summer to early fall; additionally, tropical storms or their remnants can cause heavy rains and gales. Montreal averages 2,050 hours of sunshine annually, with summer being the sunniest season, though slightly wetter than the others in terms of total precipitation—mostly from thunderstorms.[98]

| Climate data for Montreal (Montréal–Trudeau International Airport) WMO ID: 71627; coordinates 45°28′N 73°45′W / 45.467°N 73.750°W; elevation: 36 m (118 ft); 1991−2020 normals, extremes 1941−present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 13.5 | 14.7 | 28.0 | 33.8 | 40.9 | 45.0 | 45.8 | 46.8 | 42.8 | 34.1 | 26.2 | 18.1 | 46.8 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) | 15.1 (59.2) | 25.8 (78.4) | 30.0 (86.0) | 36.6 (97.9) | 35.0 (95.0) | 36.1 (97.0) | 37.6 (99.7) | 33.5 (92.3) | 28.3 (82.9) | 24.3 (75.7) | 18.0 (64.4) | 37.6 (99.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −5.0 (23.0) | −3.4 (25.9) | 2.4 (36.3) | 11.3 (52.3) | 19.4 (66.9) | 24.2 (75.6) | 26.7 (80.1) | 25.7 (78.3) | 21.1 (70.0) | 13.2 (55.8) | 6.1 (43.0) | −1.2 (29.8) | 11.7 (53.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −9.2 (15.4) | −8.0 (17.6) | −2.0 (28.4) | 6.2 (43.2) | 13.9 (57.0) | 19.0 (66.2) | 21.7 (71.1) | 20.6 (69.1) | 16.0 (60.8) | 8.9 (48.0) | 2.3 (36.1) | −5.0 (23.0) | 7.0 (44.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −13.5 (7.7) | −12.4 (9.7) | −6.5 (20.3) | 1.1 (34.0) | 8.3 (46.9) | 13.8 (56.8) | 16.7 (62.1) | 15.6 (60.1) | 10.9 (51.6) | 4.5 (40.1) | −1.7 (28.9) | −8.7 (16.3) | 2.3 (36.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −37.8 (−36.0) | −33.9 (−29.0) | −29.4 (−20.9) | −15.0 (5.0) | −4.4 (24.1) | 0.0 (32.0) | 6.1 (43.0) | 3.3 (37.9) | −2.2 (28.0) | −7.2 (19.0) | −19.4 (−2.9) | −32.4 (−26.3) | −37.8 (−36.0) |

| Record low wind chill | −49.1 | −46.0 | −42.9 | −26.3 | −9.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −4.8 | −11.6 | −30.7 | −46.0 | −49.1 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 85.8 (3.38) | 65.5 (2.58) | 77.2 (3.04) | 90.0 (3.54) | 85.6 (3.37) | 83.6 (3.29) | 91.1 (3.59) | 93.6 (3.69) | 89.2 (3.51) | 103.1 (4.06) | 84.2 (3.31) | 91.9 (3.62) | 1,040.8 (40.98) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 32.8 (1.29) | 16.9 (0.67) | 37.3 (1.47) | 74.9 (2.95) | 85.6 (3.37) | 83.6 (3.29) | 91.2 (3.59) | 93.6 (3.69) | 89.2 (3.51) | 101.6 (4.00) | 67.4 (2.65) | 44.2 (1.74) | 818.3 (32.22) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 52.0 (20.5) | 47.1 (18.5) | 37.1 (14.6) | 14.8 (5.8) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.1 (0.4) | 16.3 (6.4) | 48.2 (19.0) | 216.6 (85.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 17.1 | 13.7 | 13.7 | 12.4 | 13.8 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 13.5 | 14.3 | 16.8 | 163.5 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 4.5 | 3.8 | 7.0 | 11.4 | 13.7 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 13.2 | 11.1 | 6.7 | 119.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 15.4 | 12.4 | 9.0 | 3.0 | 0.04 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.63 | 4.8 | 12.8 | 58.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 15:00 LST) | 68.1 | 63.0 | 57.8 | 50.7 | 49.8 | 53.6 | 55.5 | 56.1 | 58.2 | 61.4 | 66.4 | 71.9 | 59.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 101.2 | 127.8 | 164.3 | 178.3 | 228.9 | 240.3 | 271.5 | 246.3 | 182.2 | 143.5 | 83.6 | 83.6 | 2,051.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 35.7 | 43.7 | 44.6 | 44.0 | 49.6 | 51.3 | 57.3 | 56.3 | 48.3 | 42.2 | 29.2 | 30.7 | 44.4 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada[99][100][101][102][103][104] and Weather Atlas[105] | |||||||||||||

Architecture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

For over a century and a half, Montreal was the industrial and financial centre of Canada.[106] This legacy has left a variety of buildings including factories, elevators, warehouses, mills, and refineries, that today provide an invaluable insight into the city's history, especially in the downtown area and the Old Port area. There are 50 National Historic Sites of Canada, more than any other city.[107]

Some of the city's earliest still-standing buildings date back to the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Although most are clustered around the Old Montreal area, such as the Sulpician Seminary adjacent to Notre-Dame Basilica that dates back to 1687, and Château Ramezay, which was built in 1705, examples of early colonial architecture are dotted throughout the city. Situated in Lachine, the Le Ber-Le Moyne House is the oldest complete building in the city, built between 1669 and 1671. In Point St. Charles, visitors can see the Maison Saint-Gabriel, which can trace its history back to 1698.[108] There are many historic buildings in Old Montreal in their original form: Notre-Dame Basilica, Bonsecours Market, and the 19th‑century headquarters of all major Canadian banks on St. James Street (French: Rue Saint Jacques). Montreal's earliest buildings are characterized by their uniquely French influence and grey stone construction.[109]

A few notable examples of the city's 20th-century architecture include Saint Joseph's Oratory, completed in 1967, Ernest Cormier's Art Deco Université de Montréal main building, the landmark Place Ville Marie office tower, and the controversial Olympic Stadium and surrounding structures. Pavilions designed for the 1967 International and Universal Exposition, popularly known as Expo 67, featured a wide range of architectural designs. Though most pavilions were temporary structures, several have become landmarks, including Buckminster Fuller's geodesic dome U.S. Pavilion, now the Montreal Biosphere, and Moshe Safdie's striking Habitat 67 apartment complex.[citation needed]

The Montreal Metro has public artwork by some of the biggest names in Quebec culture.[110]

In 2006, Montreal was named a UNESCO City of Design, one of only three design capitals in the world (the others being Berlin and Buenos Aires).[31] This distinguished title recognizes Montreal's design community. Since 2005, the city has been home to the International Council of Graphic Design Associations (Icograda)[111] and the International Design Alliance (IDA).[112]

The Underground City (officially RÉSO), an important tourist attraction, is an underground network connecting shopping centres, pedestrian thoroughfares, universities, hotels, restaurants, bistros, subway stations and more, in and around downtown with 32 km (20 mi) of tunnels over 12 km2 (4.6 sq mi) in the most densely populated part of Montreal.[citation needed]

Neighbourhoods

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

The city is composed of 19 large boroughs, subdivided into neighbourhoods.[113]The boroughs are:Côte-des-Neiges–Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, Le Plateau-Mont-Royal (The Plateau Mount Royal), Outremont and Ville-Marie in the centre; Mercier–Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, Rosemont–La Petite-Patrie and Villeray–Saint-Michel–Parc-Extension in the east; Anjou, Montréal-Nord, Rivière-des-Prairies–Pointe-aux-Trembles and Saint-Léonard in the northeast; Ahuntsic-Cartierville, L'Île-Bizard–Sainte-Geneviève, Pierrefonds-Roxboro and Saint-Laurent in the northwest; and Lachine, LaSalle, Le Sud-Ouest (The Southwest) and Verdun in the south.[114]

Many of these boroughs were independent cities that were forced to merge with Montreal in January 2002 following the 2002 municipal reorganization of Montreal.

The borough with the most neighbourhoods is Ville-Marie, which includes downtown, the historic district of Old Montreal, Chinatown, the Gay Village, the Latin Quarter, the gentrified Quartier international and Cité Multimédia as well as the Quartier des spectacles which is under development.[as of?] Other neighbourhoods of interest in the borough include the affluent Golden Square Mile neighbourhood at the foot of Mount Royal and the Shaughnessy Village/Concordia U area home to thousands of students at Concordia University. The borough also comprises most of Mount Royal Park, Saint Helen's Island, and Notre-Dame Island.[citation needed]

The Plateau Mount Royal borough was a working class francophone area. The largest neighbourhood is the Plateau (not to be confused with the whole borough), which was undergoing considerable gentrification as of 2009,[115] and a 2001 study deemed it as Canada's most creative neighbourhood because artists comprise 8% of its labour force.[116] The neighbourhood of Mile End in the northwestern part of the borough has been a very multicultural area of the city, and features two of Montreal's well-known bagel establishments, St-Viateur Bagel and Fairmount Bagel. The McGill Ghetto is in the extreme southwestern portion of the borough, its name being derived from the fact that it is home to thousands of McGill University students and faculty members.[citation needed]

The Southwest borough was home to much of the city's industry during the late 19th and early-to-mid 20th century. The borough included Goose Village and was historically home to the traditionally working-class Irish neighbourhoods of Griffintown and Point Saint Charles as well as the low-income neighbourhoods of Saint Henri and Little Burgundy.[citation needed]

Other notable neighbourhoods include the multicultural areas of Notre-Dame-de-Grâce and Côte-des-Neiges in the Côte-des-Neiges–Notre-Dame-de-Grace borough, and Little Italy in the borough of Rosemont–La Petite-Patrie and Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, home of the Olympic Stadium in the borough of Mercier–Hochelaga-Maisonneuve.[citation needed]

Old Montreal

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

Old Montreal is a historic area southeast of downtown containing many attractions such as the Old Port of Montreal, Place Jacques-Cartier, Montreal City Hall, the Bonsecours Market, Place d'Armes, Pointe-à-Callière Museum, the Notre-Dame de Montréal Basilica, and the Montreal Science Centre.[citation needed]

Architecture and cobbled streets in Old Montreal have been maintained or restored. Old Montreal is accessible from the downtown core via the underground city and is served by several STM bus routes and Metro stations, ferries to the South Shore and a network of bicycle paths.[citation needed]

The riverside area adjacent to Old Montreal is known as the Old Port. It was once the site of the Port of Montreal, but its shipping operations have been moved to a larger site downstream, leaving the former location as a recreational and historical area maintained by Parks Canada. The new Port of Montreal is Canada's largest container port and the largest inland port on Earth.[117]

Mount Royal

[edit]The mountain is the site of Mount Royal Park, one of Montreal's largest greenspaces. The park, most of which is wooded, was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, who also designed New York's Central Park, and was inaugurated in 1876.[118]

The park contains two belvederes, the more prominent of which is the Kondiaronk Belvedere, a semicircular plaza with a chalet overlooking Downtown Montreal. Other features of the park are Beaver Lake, a small man-made lake, a short ski slope, a sculpture garden, Smith House, an interpretive centre, and a well-known monument to Sir George-Étienne Cartier. The park hosts athletic, tourist and cultural activities.

The mountain is home to two major cemeteries, Notre-Dame-des-Neiges (founded in 1854) and Mount Royal (1852). Mount Royal Cemetery is a 165 acres (67 ha) terraced cemetery on the north slope of Mount Royal in the borough of Outremont. Notre Dame des Neiges Cemetery is much larger, predominantly French-Canadian and officially Catholic.[119] More than 900,000 people are buried there.[120]

Mount Royal Cemetery contains more than 162,000 graves and is the final resting place for a number of notable Canadians. It includes a veterans section with several soldiers who were awarded the British Empire's highest military honour, the Victoria Cross. In 1901, the Mount Royal Cemetery Company established the first crematorium in Canada.[121]

The first cross on the mountain was placed there in 1643 by Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, the founder of the city, in fulfilment of a vow he made to the Virgin Mary when praying to her to stop a disastrous flood.[118] Today, the mountain is crowned by a 31.4 m-high (103 ft) illuminated cross, installed in 1924 by the John the Baptist Society and now owned by the city.[118] It was converted to fibre optic light in 1992.[118] The new system can turn the lights red, blue, or purple, the last of which is used as a sign of mourning between the death of the Pope and the election of the next.[122]

Demographics

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (January 2023) |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1665 | 625 | — |

| 1667 | 760 | +21.6% |

| 1681 | 1,418 | +86.6% |

| 1685 | 724 | −48.9% |

| 1688 | 1,360 | +87.8% |

| 1692 | 801 | −41.1% |

| 1695 | 1,468 | +83.3% |

| 1698 | 1,185 | −19.3% |

| 1706 | 2,025 | +70.9% |

| 1739 | 4,210 | +107.9% |

| 1754 | 4,000 | −5.0% |

| 1765 | 5,733 | +43.3% |

| 1790 | 18,000 | +214.0% |

| 1825 | 31,516 | +75.1% |

| 1831 | 27,297 | −13.4% |

| 1841 | 40,356 | +47.8% |

| 1851 | 57,715 | +43.0% |

| 1861 | 90,323 | +56.5% |

| 1871 | 130,022 | +44.0% |

| 1881 | 176,263 | +35.6% |

| 1891 | 254,278 | +44.3% |

| 1901 | 325,653 | +28.1% |

| 1911 | 490,504 | +50.6% |

| 1921 | 618,506 | +26.1% |

| 1931 | 818,577 | +32.3% |

| 1941 | 903,007 | +10.3% |

| 1951 | 1,021,520 | +13.1% |

| 1961 | 1,201,559 | +17.6% |

| 1971 | 1,214,352 | +1.1% |

| 1976 | 1,080,545 | −11.0% |

| 1981 | 1,018,609 | −5.7% |

| 1986 | 1,015,420 | −0.3% |

| 1991 | 1,017,666 | +0.2% |

| 1996 | 1,016,376 | −0.1% |

| 2001 | 1,039,534 | +2.3% |

| 2006 | 1,620,693 | +55.9% |

| 2011 | 1,649,519 | +1.8% |

| 2016 | 1,704,694 | +3.3% |

| 2021 | 1,762,949 | +3.4% |

| Note: Many boroughs were independent cities that were forced to merge with Montreal in January 2002 following the 2002 municipal reorganization of Montreal. Source: [123] | ||

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Montréal had a population of 1,762,949 living in 816,338 of its 878,542 total private dwellings, a change of 3.4% from its 2016 population of 1,704,694. With a land area of 364.74 km2 (140.83 sq mi), it had a population density of 4,833.4/km2 (12,518.6/sq mi) in 2021.[124]

According to Statistics Canada, at the 2016 Canadian census the city had 1,704,694 inhabitants.[125] A total of 4,098,927 lived in the Montreal Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) at the same 2016 census, up from 3,934,078 at the 2011 census (within 2011 CMA boundaries), which is a population growth of 4.19% from 2011 to 2016.[126] In 2015, the Greater Montreal population was estimated at 4,060,700.[127][128] According to StatsCan, by 2030, the Greater Montreal Area is expected to number 5,275,000 with 1,722,000 being visible minorities.[129]In the 2016 census, children under 14 years of age (691,345) constituted 16.9%, while inhabitants over 65 years of age (671,690) numbered 16.4% of the total population of the CMA.[126]

Ethnicity

[edit]People of European ethnicities formed the largest cluster of ethnic groups. The largest reported European ethnicities in the 2006 census were French (23%), Italians (10%), Irish (5%), English (4%), Scottish (3%), and Spanish (2%).[130]

The panethnic breakdown of the city of Montreal as per the 2021 census was European[c] (1,038,940 residents or 60.3% of the population), African (198,610; 11.5%), Middle Eastern[d] (159,435; 9.3%), South Asian (79,670; 4.6%), Latin American (78,150; 4.5%), Southeast Asian[e] (65,260; 3.8%), East Asian[f] (64,825; 3.8%), Indigenous (15,315; 0.9%), and Other/Multiracial[g] (23,010; 1.3%).[131]

Visible minorities comprised 38.8% of the city of Montreal population in the 2021 census.[131] The five most numerous visible minorities are Black Canadians (11.5%), Arab Canadians (8.2%), South Asian Canadians (4.6%), Latin Americans (4.5%), and Chinese Canadians (3.3%).[131] Furthermore, some 27.2% of the population Greater Montreal are members of a visible minority group as of 2021,[132] up from 5.2% in 1981.[133] Visible minorities are defined by the Canadian Employment Equity Act as "persons, other than Aboriginals, who are non-white in colour".[134]

| Panethnic group | 2021[135] | 2016 | 2011 | 2006 | 2001 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| European | 1,038,940 | 60.29% | 1,082,620 | 65.09% | 1,092,465 | 67.74% | 1,171,295 | 73.49% | 784,420 | 76.92% |

| African | 198,610 | 11.53% | 171,385 | 10.3% | 147,100 | 9.12% | 122,880 | 7.71% | 68,245 | 6.69% |

| Middle Eastern | 159,435 | 9.25% | 137,525 | 8.27% | 114,780 | 7.12% | 76,910 | 4.83% | 34,035 | 3.34% |

| South Asian | 79,670 | 4.62% | 55,595 | 3.34% | 53,515 | 3.32% | 51,255 | 3.22% | 33,310 | 3.27% |

| Latin American | 78,150 | 4.54% | 67,525 | 4.06% | 67,160 | 4.16% | 53,970 | 3.39% | 31,190 | 3.06% |

| Southeast Asian | 65,260 | 3.79% | 58,315 | 3.51% | 61,320 | 3.8% | 47,950 | 3.01% | 33,505 | 3.29% |

| East Asian | 64,825 | 3.76% | 61,400 | 3.69% | 52,195 | 3.24% | 52,650 | 3.3% | 25,810 | 2.53% |

| Indigenous | 15,315 | 0.89% | 12,035 | 0.72% | 9,510 | 0.59% | 7,600 | 0.48% | 3,555 | 0.35% |

| Other | 23,010 | 1.34% | 16,835 | 1.01% | 14,585 | 0.9% | 9,205 | 0.58% | 5,675 | 0.56% |

| Total responses | 1,723,230 | 97.75% | 1,663,225 | 97.57% | 1,612,640 | 97.76% | 1,593,725 | 98.34% | 1,019,735 | 98.1% |

| Total population | 1,762,949 | 100% | 1,704,694 | 100% | 1,649,519 | 100% | 1,620,693 | 100% | 1,039,534 | 100% |

Language

[edit]As of the 2021 Census,[131] 47.0% of Montreal residents spoke French alone as a first language, while 13.0% spoke English alone. 2% spoke both English and French as first languages, 2.6% spoke both French and a non-official language and 1.5% spoke both English and a non-official language. 0.8% of residents spoke English, French and a non-official language as first languages. 32.8% of residents spoke one non-official language as a first language, and 0.3% spoke multiple non-official languages as first languages. The most common were Arabic (5.7%), Spanish (4.6%), Italian (3.3%), Chinese Languages (2.7%), Haitian Creole (1.6%), Vietnamese (1.1%), and Portuguese (1.0%).

Immigration

[edit]

The 2021 census reported that immigrants (individuals born outside Canada) comprise 576,125 persons or 33.4% of the total population of Montreal. Of the total immigrant population, the top countries of origin were Haiti (47,550 residents or 8.3% of the population), Algeria (43,840; 7.6%), France (39,275; 6.8%), Morocco (33,005; 5.7%), Italy (30,215; 5.2%), China (26,335; 4.6%), the Philippines (20,475; 3.6%), Lebanon (17,455; 3.0%), Vietnam (16,395; 2.8%), and India (13,575; 2.4%).[136]

Religion

[edit]The Greater Montreal Area is predominantly Catholic; however, weekly church attendance in Quebec was among the lowest in Canada in 1998.[138] Historically Montreal has been a centre of Catholicism in North America with its numerous seminaries and churches, including the Notre-Dame Basilica, the Cathédrale Marie-Reine-du-Monde, and Saint Joseph's Oratory.

Some 49.5% of the total population is Christian,[137] largely Roman Catholic (35.0%), primarily because of descendants of original French settlers, and others of Italian and Irish origins. Protestants which include Anglican Church in Canada, United Church of Canada, Lutheran, owing to British and German immigration, and other denominations number 11.3%, with a further 3.2% consisting mostly of Orthodox Christians, fuelled by a large Greek population. There is also a number of Russian and Ukrainian Orthodox parishes.

Islam is the largest non-Christian religious group, with 218,395 members,[139] the second-largest concentration of Muslims in Canada at 12.7%. The Jewish community in Montreal has a population of 90,780.[140] In cities such as Côte Saint-Luc and Hampstead, Jewish people constitute the majority, or a substantial part of the population. In 1971 the Jewish community in Greater Montreal numbered 109,480.[141] Political and economic uncertainties led many to leave Montreal and the province of Quebec.[142]

Economy

[edit]Montreal has the second-largest economy of Canadian cities based on GDP[143] and the largest in Quebec. In 2019, Metropolitan Montreal was responsible for CA$234.0 billion of Quebec's CA$425.3 billion GDP.[144] The city is today an important centre of commerce, finance, industry, technology, culture, world affairs and is the headquarters of the Montreal Exchange. In recent decades, the city was widely seen as weaker than that of Toronto and other major Canadian cities, but it has recently experienced a revival.[145]

Industries include aerospace, electronic goods, pharmaceuticals, printed goods, software engineering, telecommunications, textile and apparel manufacturing, tobacco, petrochemicals, and transportation. The service sector is also strong and includes civil, mechanical and process engineering, finance, higher education, and research and development. In 2002, Montreal was the fourth-largest centre in North America in terms of aerospace jobs.[146]The Port of Montreal is one of the largest inland ports in the world, handling 26 million tonnes of cargo annually as of 2008.[147] As one of the most important ports in Canada, it remains a transshipment point for grain, sugar, petroleum products, machinery, and consumer goods. For this reason, Montreal is the railway hub of Canada and has always been an extremely important rail city; it is home to the headquarters of the Canadian National Railway,[148] and was home to the headquarters of the Canadian Pacific Railway until 1995.[149]

The headquarters of the Canadian Space Agency is in Longueuil, southeast of Montreal.[150] Montreal also hosts the headquarters of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO, a United Nations body);[151] the World Anti-Doping Agency (an Olympic body);[152] the Airports Council International (the association of the world's airports – ACI World);[153] the International Air Transport Association (IATA),[154] IATA Operational Safety Audit and the International Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce (IGLCC),[155] as well as some other international organizations in various fields.

Montreal is a centre of film and television production. The headquarters of Alliance Films and five studios of the Academy Award-winning National Film Board of Canada are in the city, as well as the head offices of Telefilm Canada, the national feature-length film and television funding agency and Télévision de Radio-Canada. Given its eclectic architecture and broad availability of film services and crew members, Montreal is a popular filming location for feature-length films, and sometimes stands in for European locations.[156][157] The city is also home to many recognized cultural, film, and music festivals (Just For Laughs, Just For Laughs Gags, Montreal International Jazz Festival, and others), which contribute significantly to its economy. It is also home to one of the world's largest cultural enterprises, the Cirque du Soleil.[158]

Montreal is also a global hub for artificial intelligence research with many companies involved in this sector, such as Facebook AI Research (FAIR), Microsoft Research, Google Brain, DeepMind, Samsung Research and Thales Group (cortAIx).[159][160] The city is also home to Mila (research institute), an artificial intelligence research institute with over 500 researchers specializing in the field of deep learning, the largest of its kind in the world.[161]

The video game industry has been booming in Montreal since November 2, 1995, coinciding with the opening of Ubisoft Montreal.[162] Recently, the city has attracted world leading game developers and publishers studios such as EA, Eidos Interactive, BioWare, Artificial Mind and Movement, Strategy First, THQ, Gameloft mainly because of the quality of local specialized labour, and tax credits offered to the corporations. In 2010, Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment, a division of Warner Bros., announced that it would open a video game studio.[163] Relatively new to the video game industry, it will be Warner Bros. first studio opened, not purchased, and will develop games for such Warner Bros. franchises as Batman and other games from their DC Comics portfolio. The studio will create 300 jobs.

Montreal plays an important role in the finance industry. The sector employs approximately 100,000 people in the Greater Montreal Area.[164] As of March 2018, Montreal is ranked in the 12th position in the Global Financial Centres Index, a ranking of the competitiveness of financial centres around the world.[165] The city is home to the Montreal Exchange, the oldest stock exchange in Canada and the only financial derivatives exchange in the country.[166] The corporate headquarters of the Bank of Montreal and Royal Bank of Canada, two of the biggest banks in Canada, were in Montreal. While both banks moved their headquarters to Toronto, Ontario, their legal corporate offices remain in Montreal. The city is home to head offices of two smaller banks, National Bank of Canada and Laurentian Bank of Canada. The Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, an institutional investor managing assets totalling $408 billion CAD, has its main business office in Montreal.[167] Many foreign subsidiaries operating in the financial sector also have offices in Montreal, including HSBC, Aon, Société Générale, BNP Paribas and AXA.[166][168]

Several companies are headquartered in Greater Montreal Area including Rio Tinto Alcan,[169] Bombardier Inc.,[170] Canadian National Railway,[171] CGI Group,[172] Air Canada,[173] Air Transat,[174] CAE,[175] Saputo,[176] Cirque du Soleil, Stingray Group, Quebecor,[177] Ultramar, Kruger Inc., Jean Coutu Group,[178] Uniprix,[179] Proxim,[180] Domtar, Le Château,[181] Power Corporation, Cellcom Communications,[182] Bell Canada.[183] Standard Life,[184] Hydro-Québec, AbitibiBowater, Pratt and Whitney Canada, Molson,[185] Tembec, Canada Steamship Lines, Fednav, Alimentation Couche-Tard, SNC-Lavalin,[186] MEGA Brands,[187] Aeroplan,[188] Agropur,[189] Metro Inc.,[190] Laurentian Bank of Canada,[191] National Bank of Canada,[192] Transat A.T.,[193] Via Rail,[194] GardaWorld, Novacam Technologies, SOLABS,[195] Dollarama,[196] Rona[197] and the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec.

The Montreal Oil Refining Centre is the largest refining centre in Canada, with companies like Petro-Canada, Ultramar, Gulf Oil, Petromont, Ashland Canada, Parachem Petrochemical, Coastal Petrochemical, Interquisa (Cepsa) Petrochemical, Nova Chemicals, and more. Shell decided to close the refining centre in 2010, throwing hundreds out of work and causing an increased dependence on foreign refineries for eastern Canada.

Culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

Montreal was referred to as "Canada's Cultural Capital" by Monocle magazine.[32] The city is Canada's centre for French-language television productions, radio, theatre, film, multimedia, and print publishing. Montreal's many cultural communities have given it a distinct local culture. Montreal was designated as the World Book Capital for the year 2005 by UNESCO.[198]

Being at the confluence of the French and English traditions, Montreal has developed a unique and distinguished cultural face. The city has produced much talent in the fields of visual arts, theatre, dance, and music, with a tradition of producing both jazz and rock music. Another distinctive characteristic of cultural life is the vibrancy of its downtown, particularly during summer, prompted by cultural and social events, including its more than 100 annual festivals, the largest being the Montreal International Jazz Festival which is the largest jazz festival in the world. Other popular events have included Just for Laughs (the largest comedy festival in the world), the Montreal World Film Festival, the Festival du nouveau cinéma, the Fantasia Film Festival, Les FrancoFolies de Montréal, Nuits d'Afrique [fr], Pop Montreal, Divers/Cité, Fierté Montréal and the Montreal Fireworks Festival, Igloofest, Piknic Electronik, Montréal en Lumiere, Osheaga, Heavy Montreal, Mode + Design, Montréal complètement cirque, MUTEK, Black and Blue, and many smaller festivals. Montreal is also widely recognized for its diverse and vibrant night life, which is considered a vital part of the local cultural ecosystem.

A cultural heart of classical art and the venue for many summer festivals, the Place des Arts is a complex of different concert and theatre halls surrounding a large square in the eastern portion of downtown. Place des Arts has the headquarters of one of the world's foremost orchestras, the Montreal Symphony Orchestra. The Orchestre Métropolitain and the chamber orchestra I Musici de Montréal are two other well-regarded Montreal orchestras. Also performing at Place des Arts are the Opéra de Montréal and the city's chief ballet company Les Grands Ballets Canadiens. Internationally recognized avant-garde dance troupes such as Compagnie Marie Chouinard [fr], La La La Human Steps, O Vertigo [fr], and the Fondation Jean-Pierre Perreault [fr] have toured the world and worked with international popular artists on videos and concerts. The unique choreography of these troupes has paved the way for the success of the world-renowned Cirque du Soleil.

Nicknamed la ville aux cent clochers (the city of a hundred steeples), Montreal is renowned for its churches. There are an estimated 650 churches on the island, with 450 of them dating back to the 1800s or earlier.[199] Mark Twain noted, "This is the first time I was ever in a city where you couldn't throw a brick without breaking a church window."[200] The city has four Roman Catholic basilicas: Mary, Queen of the World Cathedral, Notre-Dame Basilica, St Patrick's Basilica, and Saint Joseph's Oratory. The Oratory is the largest church in Canada, with the second largest copper dome in the world, after Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome.[201]

Beginning in the 1940s, Quebec literature began to shift from pastoral tales romanticizing the French-Canadian countryside to writing set in the multicultural city of Montreal. Notable pioneering works describing the character of the city include Gabrielle Roy's 1945 novel Bonheur D'Occasion, translated as The Tin Flute, and Gwethalyn Graham's 1944 novel Earth and High Heaven. Subsequent writers of fiction who have set their work in Montreal have included Mordecai Richler, Claude Jasmin, Francine Noel, and Heather O'Neill, among many others.

Sports

[edit]The most popular sport is ice hockey. The professional hockey team, the Montreal Canadiens, is one of the Original Six teams of the National Hockey League (NHL), and has won an NHL-record 24 Stanley Cup championships. The Canadiens' most recent Stanley Cup victory came in 1993. They have major rivalries with the Toronto Maple Leafs and Boston Bruins, both of which are also Original Six teams, and with the Ottawa Senators, the closest team geographically. The Canadiens have played at the Bell Centre since 1996. Prior to that, they played at the Montreal Forum.

The Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League (CFL) play at Percival Molson Memorial Stadium on the campus of McGill University for their regular-season games. Late season and playoff games are sometimes played at the much larger, enclosed Olympic Stadium, which also hosted the 2008 Grey Cup. The Alouettes have won the Grey Cup eight times, most recently in 2023. The Alouettes have had two periods on hiatus. During the second one, the Montreal Machine played in the World League of American Football in 1991 and 1992. The McGill Redbirds, Concordia Stingers, and Université de Montréal Carabins play in the U Sports football league.

Montreal has a storied baseball history. The city was the home of the minor-league Montreal Royals of the International League until 1960. In 1946, Jackie Robinson broke the Baseball colour line with the Royals in an emotionally difficult year; Robinson was forever grateful for the local fans' fervent support.[202] Major League Baseball came to town in the form of the Montreal Expos in 1969. They played their games at Jarry Park Stadium until moving into Olympic Stadium in 1977. After 36 years in Montreal, the team relocated to Washington, D.C., in 2005 and re-branded themselves as the Washington Nationals.[203]

CF Montréal (formerly known as the Montreal Impact) are the city's professional soccer team. They play at a soccer-specific stadium called Saputo Stadium. They joined Major League Soccer in 2012. The Montreal games of the 2007 FIFA U-20 World Cup[204] and 2014 FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup[205] were held at Olympic Stadium, and the venue hosted Montreal games in the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup.[206]

Montreal is the site of a high-profile auto racing event each year: the Canadian Grand Prix of Formula One (F1) racing. This race takes place on the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve on Île Notre-Dame. In 2009, the race was dropped from the Formula One calendar, to the chagrin of some fans,[207] but the Canadian Grand Prix returned to the Formula One calendar in 2010. It was dropped from the calendar again in 2020 and 2021, due to COVID-19 pandemic, but racing resumed in 2022, with the 2022 Canadian Grand Prix. The Circuit Gilles Villeneuve also hosted a round of the Champ Car World Series from 2002 to 2007, and was home to the NAPA Auto Parts 200, a NASCAR Nationwide Series race, and the Montréal 200, a Grand Am Rolex Sports Car Series race.

Uniprix Stadium, built in 1993 on the site of Jarry Park, is used for the National Bank Open (formerly known as the Rogers Cup) men's and women's tennis tournaments. The men's tournament is a Masters 1000 event on the ATP Tour, and the women's tournament is a Premier tournament on the WTA Tour. The men's and women's tournaments alternate between Montreal and Toronto every year.[208]

Montreal was the host of the 1976 Summer Olympic Games. The stadium cost $1.5 billion;[209] with interest that figure ballooned to nearly $3 billion, and was paid off in December 2006.[210] Montreal also hosted the first ever World Outgames in the summer of 2006, attracting over 16,000 participants engaged in 35 sporting activities.

Montreal was the host city for the 17th unicycling world championship and convention (UNICON) in August 2014.

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal Canadiens | NHL | Ice hockey | Bell Centre | 1909 | 24 |

| PWHL Montreal | PWHL | Ice hockey | Verdun Auditorium | 2023 | 0 |

| Montréal Alouettes | CFL | Canadian football | Percival Molson Memorial Stadium Olympic Stadium | 1946 | 8 |

| CF Montréal | MLS | Soccer | Saputo Stadium | 2012 | 0 |

| Montreal Alliance | CEBL | Basketball | Verdun Auditorium | 2022 | 0 |

Media

[edit]Montreal is Canada's second-largest media market, and the centre of Canada's francophone media industry.

There are four over-the-air English-language television stations: CBMT-DT (CBC Television), CFCF-DT (CTV), CKMI-DT (Global) and CJNT-DT (Citytv). There are also five over-the-air French-language television stations: CBFT-DT (Ici Radio-Canada), CFTM-DT (TVA), CFJP-DT (Noovo), CIVM-DT (Télé-Québec), and CFTU-DT (Canal Savoir).

Montreal has three daily newspapers, the English-language Montreal Gazette and the French-language Le Journal de Montréal, and Le Devoir; another French-language daily, La Presse, became an online daily in 2018. There are two free French dailies, Métro and 24 Heures. Montreal has numerous weekly tabloids and community newspapers serving various neighbourhoods, ethnic groups and schools.

Government

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

The head of the city government in Montreal is the mayor, who is first among equals in the city council.

The city council is a democratically elected institution and is the final decision-making authority in the city, although much power is centralized in the executive committee. The council consists of 65 members from all boroughs.[211] The council has jurisdiction over many matters, including public security, agreements with other governments, subsidy programs, the environment, urban planning, and a three-year capital expenditure program. The council is required to supervise, standardize or approve certain decisions made by the borough councils.[citation needed]

Reporting directly to the council, the executive committee exercises decision-making powers similar to those of the cabinet in a parliamentary system and is responsible for preparing various documents including budgets and by-laws, submitted to the council for approval. The decision-making powers of the executive committee cover, in particular, the awarding of contracts or grants, the management of human and financial resources, supplies and buildings. It may also be assigned further powers by the city council.[citation needed]

Standing committees are the prime instruments for public consultation. They are responsible for the public study of pending matters and for making the appropriate recommendations to the council. They also review the annual budget forecasts for departments under their jurisdiction. A public notice of meeting is published in both French and English daily newspapers at least seven days before each meeting. All meetings include a public question period. The standing committees, of which there are seven, have terms lasting two years. In addition, the City Council may decide to create special committees at any time. Each standing committee is made up of seven to nine members, including a chairman and a vice-chairman. The members are all elected municipal officers, with the exception of a representative of the government of Quebec on the public security committee.[citation needed]

The city is only one component of the larger Montreal Metropolitan Community (Communauté Métropolitaine de Montréal, CMM), which is in charge of planning, coordinating, and financing economic development, public transportation, garbage collection and waste management, etc., across the metropolitan area. The president of the CMM is the mayor of Montreal. The CMM covers 4,360 km2 (1,680 sq mi), with 3.6 million inhabitants in 2006.[212]

Montreal is the seat of the judicial district of Montreal, which includes the city and the other communities on the island.[213]

| Year | Liberal | Conservative | Bloc Québécois | New Democratic | Green | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 48% | 348,308 | 9% | 64,857 | 19% | 133,718 | 18% | 132,395 | 2% | 14,565 | |

| 2019 | 48% | 377,036 | 8% | 63,376 | 20% | 156,398 | 16% | 129,517 | 6% | 45,845 | |

| Year | CAQ | Liberal | QC solidaire | Parti Québécois | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 18% | 119,806 | 38% | 254,069 | 25% | 164,153 | 13% | 89,353 | |

| 2014 | 11% | 81,844 | 54% | 414,477 | 14% | 106,335 | 19% | 149,792 | |

Policing

[edit]Law enforcement on the island itself is provided by the Service de Police de la Ville de Montréal, or the SPVM for short.

Crime

[edit]Since 1975, when Montreal's homicide rate peaked at around 10.3 per 100,000 people with a total of 112 murders, the overall crime rate in Montreal has declined, with a few notable exceptions, reaching a minimum in 2016 with 23 murders.[216][217] Sex crimes have increased 14.5 per cent between 2015 and 2016 and fraud cases have increased by 13 per cent over the same period.[217] The major criminal organizations active in Montreal are the Rizzuto crime family, Hells Angels and West End Gang. However, in the 2020s, the city has seen an increase in overall crime, with a notable increase in homicides. 25 homicides were reported in 2020 which matched the number reported in 2019. The next year saw a 48% increase in murders with a total of 37 in 2021, giving the city a homicide rate of around 2.1 per 100,000 people. The Montreal Police Annual Report for 2021 showed that there were 144 shootings across the city, or an average of one shooting every 2.5 days. In comparison, there were 71 shootings recorded the year before.[218] 2022 saw another 10.8% increase in homicides, with a total of 41 being reported (giving a slightly higher homicide rate of 2.3 per 100,000 people), the highest number since 2007, when there were 42.[219]

Education

[edit]The education system in Quebec is different from other systems in North America. Between high school (which ends at grade 11) and university, students must go through an additional school called CEGEP. CEGEPs offer pre-university (2-years) and technical (3-years) programs. In Montreal, seventeen CEGEPs offer courses in French and five in English.

French-language elementary and secondary public schools in Montreal are operated by the Centre de services scolaire de Montréal (CSSDM),[220] Centre de services scolaire Marguerite-Bourgeoys[221] and the Centre de services scolaire de la Pointe-de-l'Île.[222]

English-language elementary and secondary public schools on Montreal Island are operated by the English Montreal School Board and the Lester B. Pearson School Board.[223][224]

With four universities, ten other degree-awarding institutions, and 12 CEGEPs in an 8 km (5.0 mi) radius, Montreal has the highest concentration of post-secondary students of all major cities in North America (4.38 students per 100 residents, followed by Boston at 4.37 students per 100 residents).[225]

Higher education (English)

[edit]

- McGill University is one of Canada's leading post-secondary institutions and is widely regarded as a world-class institution. In 2021, McGill was ranked as the top medical-doctoral university in Canada for the seventeenth consecutive year by Maclean's[226] and second in Canada and the 27th best university in the world by the QS World University Rankings.[227]

- Concordia University was created from the merger of Sir George Williams University and Loyola College in 1974.[228] The university has been ranked as one of the top comprehensive universities in Canada by Macleans.[229]

Higher education (French)

[edit]

- Université de Montréal (UdeM) is the second largest research university in Canada and ranked as one of the top universities in Canada. Two separate institutions are affiliated to the university: the École Polytechnique de Montréal (School of Engineering) and HEC Montréal (School of Business). HEC Montreal was founded in 1907 and is considered one of the best business schools in Canada.[230]

- Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) is the Montreal campus of Université du Québec. UQAM generally specializes in liberal-arts, although many programs related to the sciences are available.

- The Université du Québec network also has three separately run schools in Montreal, notably the École de technologie supérieure (ETS), the École nationale d'administration publique (ÉNAP) and the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS).

- L'Institut de formation théologique de Montréal des Prêtres de Saint-Sulpice (IFTM) specializes in theology and philosophy.

- Institut d'hôtellerie et de tourisme du Québec (IHTQ) offers an Applied Bachelor in Hospitality and Hotel Management.

- Conservatoire de musique du Québec à Montréal offers both a Bachelor and a Master program in classical music.

Additionally, two French-language universities, Université de Sherbrooke and Université Laval have campuses in the nearby suburb of Longueuil on Montreal's south shore. Also, l'Institut de pastorale des Dominicains is Montreal's university centre of Ottawa's Collège Universitaire Dominicain/Dominican University College. The Faculté de théologie évangélique is Nova Scotia's Acadia University Montreal based serving French Protestant community in Canada by offering both a Bachelor and a Master program in theology

Transportation

[edit]

Like many major cities, Montreal has a problem with vehicular traffic congestion. Commuting traffic from the cities and towns in the West Island (such as Dollard-des-Ormeaux and Pointe-Claire) is compounded by commuters entering the city that use twenty-four road crossings from numerous off-island suburbs on the North and South Shores. The width of the Saint Lawrence River has made the construction of fixed links to the south shore expensive and difficult. There are presently four road bridges (including two of the country's busiest) along with one bridge-tunnel, two railway bridges, and a metro line. The far narrower Rivière des Prairies to the city's north, separating Montreal from Laval, is spanned by nine road bridges (seven to the city of Laval and two that span directly to the north shore) and a Metro line.

The island of Montreal is a hub for the Quebec Autoroute system, and is served by Quebec Autoroutes A-10 (known as the Bonaventure Expressway on the island of Montreal), A-15 (aka the Décarie Expressway south of the A-40 and the Laurentian Autoroute to the north of it), A-13 (aka Chomedey Autoroute), A-20, A-25, A-40 (part of the Trans-Canada Highway system, and known as "The Metropolitan" or simply "The Met" in its elevated mid-town section), A-520 and R-136 (aka the Ville-Marie Autoroute). Many of these Autoroutes are frequently congested at rush hour.[231] However, in recent years, the government has acknowledged this problem and is working on long-term solutions to alleviate the congestion. One such example is the extension of Quebec Autoroute 30 on Montreal's south shore, which will be a bypass for trucks and intercity traffic.[232]

Société de transport de Montréal

[edit]

Public local transport is served by a network of buses, subways, and commuter trains that extend across and off the island. The subway and bus system are operated by STM (Société de transport de Montréal, “Montreal Transit Company”). The STM bus network consists of 203 daytime and 23 night time routes. STM bus routes serve 1,347,900 passengers on an average weekday in 2010.[233] It also provides adapted transport and wheelchair-accessible buses.[234] The STM won the award of Outstanding Public Transit System in North America by the APTA in 2010. It was the first time a Canadian company won this prize.

The Metro was inaugurated in 1966 and has 68 stations on four lines.[235] Total daily passengers is 1,050,800 passengers on an average weekday (as of Q1 2010).[233] Each station was designed by different architects with individual themes and features original artwork, and the trains run on rubber tires, making the system quieter than most.[236] The project was initiated by Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau, who later brought the Summer Olympic Games to Montreal in 1976. The Metro system has long had a station on the South Shore in Longueuil, and in 2007 was extended to the city of Laval, north of Montreal, with three new stations.[237] The metro has recently been modernizing its trains, purchasing new Azur models with inter-connected wagons.[238]

Air

[edit]

Montreal has two international airports, one for passengers only, the other for cargo. Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport (also known as Dorval Airport) in the City of Dorval serves all commercial passenger traffic and is the headquarters of Air Canada[239] and Air Transat.[240] To the north of the city is Montreal Mirabel International Airport in Mirabel, which was envisioned as Montreal's primary airport but which now serves cargo flights along with MEDEVACs and general aviation and some passenger services.[241][242][243][244][245] In 2018, Trudeau was the third busiest airport in Canada by passenger traffic and aircraft movements, handling 19.42 million passengers,[246][247] and 240,159 aircraft movements.[248] With 63% of its passengers being on non-domestic flights it has the largest percentage of international flights of any Canadian airport.[249]

It is one of Air Canada's major hubs and operates on average approximately 2,400 flights per week between Montreal and 155 destinations, spread on five continents.

Airlines servicing Trudeau offer year-round non-stop flights to five continents, namely Africa, Asia, Europe, North America and South America.[250][251][252] It is one of only two airports in Canada with direct flights to five continents or more.

Железнодорожный

[ редактировать ]Компания Via Rail Canada со штаб-квартирой в Монреале обеспечивает железнодорожное сообщение с другими городами Канады, в частности с Квебеком и Торонто по коридору Квебек-Сити – Виндзор . Amtrak , национальная пассажирская железнодорожная система США, ежедневно курсирует из Адирондака в Нью-Йорк. Все междугородние поезда и большинство пригородных поездов отправляются с Центрального вокзала .

Канадско-Тихоокеанская железная дорога (CPR) была основана здесь в 1881 году. [253] Штаб-квартира компании занимала станцию Виндзор , 910 на Пил-стрит до 1995 года, когда она переехала в Калгари , Альберта. [149] Поскольку порт Монреаля открыт круглый год ледоколами, линии в Восточную Канаду стали избыточными, и теперь Монреаль является восточной и интермодальной грузовой конечной станцией компании-преемницы CPR, Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC). [254] CPKC соединяется в Монреале с портом Монреаля, железной дорогой Делавэра и Гудзона с Нью-Йорком, железной дорогой Квебека-Гатино с Квебеком и Букингемом , железной дорогой Центрального Мэна и Квебека с Галифаксом и Канадской национальной железной дорогой (CN). Флагманский поезд CPR, The Canadian , ежедневно курсировал от вокзала Виндзор до Ванкувера , но в 1978 году все пассажирские перевозки были переведены на Via. С 1990 года The Canadian завершает карьеру в Торонто, а не в Монреале.

Компания CN со штаб-квартирой в Монреале была основана в 1919 году канадским правительством после серии банкротств железнодорожных компаний по всей стране. Она была образована из компаний Grand Trunk , Midland и Canadian Northern Railways и стала главным конкурентом CPR в сфере грузовых перевозок в Канаде. [255] Как и CPR, CN отказалась от пассажирских перевозок в пользу Via. [256] Флагманский поезд CN, Super Continental , курсировал ежедневно от Центрального вокзала до Ванкувера и впоследствии стал поездом Via в 1978 году. В 1990 году он был отменен в пользу изменения маршрута The Canadian .

Система пригородных поездов управляется и обслуживается Exo , и она достигает окраин Большого Монреаля шестью линиями. В 2014 году он перевозил в среднем 79 000 пассажиров в день, что сделало его седьмым по загруженности в Северной Америке после Нью-Йорка, Чикаго, Торонто, Бостона, Филадельфии и Мехико. [257]

22 апреля 2016 года была представлена будущая автоматизированная скоростного транспорта система Réseau express métropolitain (REM). Закладка фундамента произошла 12 апреля 2018 года, а в следующем месяце началось строительство сети протяженностью 67 километров (42 мили), состоящей из трех веток, 26 станций, а также преобразование самой загруженной пригородной железной дороги в регионе. Открытие REM состоится в три этапа в 2022 году и будет завершено к середине 2024 года, став четвертой по величине автоматизированной сетью скоростного транспорта после Дубайского метрополитена , Сингапурского массового скоростного транспорта и Ванкуверского SkyTrain . Большую часть средств будет финансировать управляющий пенсионным фондом Caisse de dépôt et Placement du Québec (CDPQ Infra). [258]

Программа обмена велосипедами

[ редактировать ]Город Монреаль всемирно известен тем, что входит в двадцатку самых дружественных к велосипедистам городов мира. [259] Отсюда следует, что у них есть одна из самых успешных в мире систем велопроката BIXI. Впервые запущен в 2009 году [260] Благодаря находящимся в Монреале велосипедам PBSC Urban Solutions ICONIC схема совместного использования велосипедов с тех пор расширила свой парк, включив в него 750 док-станций и зарядных станций в разных районах, где пользователям доступно 9000 велосипедов. [261] Целью STM является объединение различных форм мобильности: владельцы транзитных карт теперь могут воспользоваться своим членством и арендовать велосипеды на некоторых станциях.

Известные люди

[ редактировать ]Международные отношения

[ редактировать ]Города-побратимы

[ редактировать ] Алжир , Алжир – 1999 г. [262]

Алжир , Алжир – 1999 г. [262]  Брюссель , Бельгия [263]

Брюссель , Бельгия [263]  Бухарест , Румыния [264]

Бухарест , Румыния [264]  Пусан , Южная Корея – 2000 г. [265] [266]

Пусан , Южная Корея – 2000 г. [265] [266]  Бостон , США – 1995 г.

Бостон , США – 1995 г.  Гвадалахара , Мексика – 2004 г.

Гвадалахара , Мексика – 2004 г.  Ханой , Вьетнам – 1997 г. [267]

Ханой , Вьетнам – 1997 г. [267]  Хиросима , Япония – 1998 г. [268]

Хиросима , Япония – 1998 г. [268]  Лион , Франция – 1979 г. [269]

Лион , Франция – 1979 г. [269]  Манила , Филиппины – 2005 г. [270]

Манила , Филиппины – 2005 г. [270]  Мельбурн , Австралия – 2007 г.

Мельбурн , Австралия – 2007 г.  Порт-о-Пренс , Гаити – 1995 г. [267]

Порт-о-Пренс , Гаити – 1995 г. [267]  Кито , Эквадор – 1997 г.

Кито , Эквадор – 1997 г.  Рио-де-Жанейро , Бразилия – 1998 г.

Рио-де-Жанейро , Бразилия – 1998 г.  Сан-Сальвадор , Сальвадор – 2001 г. [267]

Сан-Сальвадор , Сальвадор – 2001 г. [267]  Шанхай , Китай – 1985 г. [271]

Шанхай , Китай – 1985 г. [271]  Тунис , Тунис – 1999 г.

Тунис , Тунис – 1999 г.  Ереван , Армения – 1998 г. [272]

Ереван , Армения – 1998 г. [272]

Города дружбы

[ редактировать ]См. также

[ редактировать ]- Список англоязычных сообществ в Квебеке

- Список мэров Монреаля

- Список музыкальных площадок Монреаля

- Список торговых центров Монреаля

- Список самых высоких зданий Монреаля

- Монреальский саммит международных игр

- Орден Монреаля

- Королевские эпонимы в Канаде

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Канадский английский : / ˌ m ʌ n t r i ˈ ɔː l / , / m ɒ n- / МУН - ШИЛО , ПОН- дерево- [15] [16]

- ^ произносится [mɔ̃ʁeal] [17]

- ^ Статистика включает всех лиц, которые не составляли часть видимого меньшинства или коренной идентичности.

- ^ Статистика включает общее количество ответов «западноазиатских» и «арабских» в разделе видимых меньшинств переписи населения.

- ^ Статистика включает общее количество ответов «филиппинцев» и «юго-восточных азиатов» в разделе видимых меньшинств переписи населения.

- ^ Статистика включает общее количество ответов «китайцев», «корейцев» и «японцев» в разделе видимых меньшинств переписи населения.

- ^ Статистика включает общее количество ответов «Видимое меньшинство, nie » и «Несколько видимых меньшинств» в разделе «Видимые меньшинства» переписи населения.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Метрополис Квебека 1960–1992» . Монреальские архивы. Архивировано из оригинала 5 января 2013 года . Проверено 24 января 2013 г.

- ^ Гань, Жиль (31 мая 2012 г.). «Гаспези садится в мегаполисе» . Солнце (на французском языке). Квебек Сити. Архивировано из оригинала 5 июня 2013 года . Проверено 9 июня 2012 г.

- ^ Леклерк, Жан-Франсуа (2002). «Монреаль, город ста шпилей: виды монреалцев на их культовые сооружения». Éditions Fides (на французском языке). Квебек Сити.