Собор Святого Джайлса

| Собор Святого Джайлса | |

|---|---|

| Верховный Кирк Эдинбургский | |

Собор Святого Джайлса | |

Западный фасад церковного здания | |

| |

| 55 ° 56'58 "N 03 ° 11'27" W / 55,94944 ° N 3,19083 ° W | |

| Расположение | Королевская миля , Эдинбург |

| Страна | Шотландия |

| Номинал | Церковь Шотландии |

| Предыдущий номинал | Римско-католический |

| Веб-сайт | www |

| История | |

| Статус | Приходская церковь |

| Основан | 12 век |

| Преданность | Сент-Джайлс |

| Посвященный | 6 октября 1243 г. |

| Бывший епископ (ы) | Епископ Эдинбургский |

| Архитектура | |

| Функциональное состояние | Активный |

| Обозначение наследия | Памятник категории А |

| Назначен | 14 декабря 1970 г. |

| Стиль | Готика |

| Технические характеристики | |

| Длина | 196 футов (60 метров) |

| Ширина | 125 футов (38 метров) [ 1 ] |

| Высота | 52 фута (16 метров) [ 2 ] |

| Высота шпиля | 145 футов (44 метра) [ 3 ] |

| Колокола | 3 |

| Администрация | |

| Пресвитерия | Эдинбург |

| Духовенство | |

| Министр(ы) | Вакантный |

| Ассистент | Сэм Нвокоро |

| Миряне | |

| Органист/Музыкальный руководитель | Майкл Харрис |

Внесенное в список зданий – Категория А | |

| Официальное название | Хай-стрит и Парламентская площадь, Сент-Джайлс (Хай) Кирк |

| Назначен | 14 декабря 1970 г. |

| Справочный номер. | LB27381 |

Собор Святого Джайлса ( шотландский гэльский : Cathair-eaglais Naomh Giles ), или Кирк Эдинбурга , — приходская церковь в Шотландской церкви Старом городе Эдинбурга Высокий . Нынешнее здание было начато в 14 веке и продлено до начала 16 века; значительные изменения были предприняты в 19 и 20 веках, включая добавление Часовни Чертополоха . [ 4 ] Собор Святого Джайлса тесно связан со многими событиями и фигурами в истории Шотландии, включая Джона Нокса , который служил служителем церкви после Шотландской Реформации . [ 5 ]

Вероятно, основан в 12 веке. [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ а ] [ б ] Посвященная Святому Джайлсу , церковь была повышена до коллегиального статуса Папой Павлом II в 1467 году. В 1559 году церковь стала протестантской, а ее министром стал Джон Нокс, выдающийся деятель шотландской Реформации. После Реформации собор Святого Джайлса был разделен внутри для обслуживания нескольких общин, а также для светских целей, например, в качестве тюрьмы и места заседаний парламента Шотландии . В 1633 году Карл I Святого Джайлса собором сделал собор вновь созданной Эдинбургской епархии . Попытка Чарльза навязать доктринальные изменения пресвитерианскому шотландскому Кирку, включая Молитвенник, вызвавший бунт в Сент-Джайлсе 23 июля 1637 года, что ускорило формирование Ковенантеров и начало Войн Трех Королевств . [ 8 ] Роль Сент-Джайлса в шотландской Реформации и восстании ковенантеров привела к тому, что его стали называть « Материнской церковью мирового пресвитерианства ». [ 12 ]

зданий Шотландии Церковь Святого Джайлса — одно из самых важных средневековых приходских церковных . [ 13 ] Первая церковь Святого Джайлса представляла собой небольшое романское здание, от которого сохранились лишь фрагменты. В 14 веке его заменили нынешнее здание, которое было расширено в период с конца 14 по начало 16 веков. Церковь была перестроена между 1829 и 1833 годами Уильямом Берном и восстановлена между 1872 и 1883 годами Уильямом Хэем при поддержке Уильяма Чемберса . Чемберс надеялся сделать Сент-Джайлс «Вестминстерским аббатством Шотландии», обогатив церковь и добавив памятники известным шотландцам. часовня Чертополоха, спроектированная Робертом Лоримером . Между 1909 и 1911 годами к церкви была пристроена [ 4 ] [ 14 ]

Со времен средневековья Сент-Джайлс был местом проведения мероприятий и услуг национального значения; службы Ордена Чертополоха там проходят . Помимо активной прихожан, церковь является одним из самых популярных мест для посетителей в Шотландии: в 2018 году ее посетило более миллиона человек. [ 15 ]

Имя и посвящение

[ редактировать ]

Святой Джайлс – покровитель прокаженных . Хотя он в основном связан с аббатством Сен-Жиль в современной Франции , он был популярным святым в средневековой Шотландии . [ 16 ] [ 17 ] [ с ] Церковью сначала владели монахи ордена Святого Лазаря , служившие среди прокаженных; если Давид I или Александр I являются основателями церкви, посвящение может быть связано с их сестрой Матильдой , которая основала церковь Святого Джайлса в полях . [ 18 ]

До Реформации церковь Святого Джайлса была единственной приходской церковью в Эдинбурге. [ 19 ] а некоторые современные писатели, такие как Жан Фруассар , ссылаются просто на «Эдинбургскую церковь». [ 20 ] С момента ее повышения до коллегиального статуса в 1467 году и до Реформации полное название церкви было «Соборная церковь Святого Джайлса Эдинбургского». [ 21 ] Даже после Реформации церковь засвидетельствована как «колледж-кирк Санкт-Гейля». [ 22 ] В хартии 1633 года, возведенной в собор Святого Джайлса, его общее название записано как «Кирк Святого Джайлса». [ 23 ]

Собор Святого Джайлса имел статус собора между 1633 и 1638 годами, а также между 1661 и 1689 годами, в периоды епископства в Шотландской церкви. [ 19 ] С 1689 года Шотландская церковь, как пресвитерианская церковь, не имела епископов и, следовательно, соборов . Собор Святого Джайлса — один из многих бывших соборов Шотландской церкви, таких как собор Глазго или собор Данблейн , которые сохранили свой титул, несмотря на утрату этого статуса. [ 24 ] С момента первоначального повышения статуса церкви до статуса собора, здание в целом обычно называлось Собором Святого Джайлса, Кирком или церковью Святого Джайлза или просто Церковью Святого Джайлза. [ 25 ]

Титул «Высокий Кирк» кратко засвидетельствован во время правления Якова VI как относящийся ко всему зданию. В приказе Тайного совета Шотландии от 1625 года община Великого Кирка, которая тогда собиралась в Сент-Джайлсе, называется «Высоким Кирком». Название вышло из употребления, пока в конце 18 века оно не было повторно применено к Восточному (или Новому) Кирку, самой известной из четырех общин, собиравшихся тогда в церкви. [ 26 ] [ 27 ] С 1883 года община Высокого Кирка заняла все здание. [ 28 ]

Расположение

[ редактировать ]

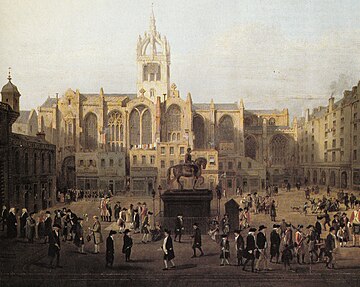

Королевская комиссия по древним и историческим памятникам Шотландии определила Сент-Джайлс как «центральный центр Старого города ». [ 29 ] Церковь занимает видную и плоскую часть хребта, ведущего вниз от Эдинбургского замка ; он расположен на южной стороне Хай-стрит: главной улицы Старого города и одной из улиц, составляющих Королевскую милю . [ 9 ] [ 30 ]

С момента своего первоначального строительства в 12 веке до 14 века собор Святого Джайлса располагался недалеко от восточной окраины Эдинбурга. [ 31 ] [ 32 ] Ко времени строительства Королевской стены в середине 15 века город расширился, и собор Святого Джайлса находился недалеко от его центральной точки. [ 33 ] В период позднего средневековья и раннего Нового времени собор Святого Джайлса также был расположен в центре общественной жизни Эдинбурга: Толбут – административный центр Эдинбурга – находился непосредственно к северо-западу от церкви, а Крест Меркат – коммерческий и символический центр Эдинбурга – стоял непосредственно к северо-востоку от него. [ 34 ]

С момента постройки Толбутса в конце 14 века до начала 19 века церковь Святого Джайлса находилась в самой стесненной точке Хай-стрит, а Лакенбутс и Толбут вдавались в Хай-стрит непосредственно к северу и северо-западу от церкви. [ 35 ] Переулок, известный как Стиль Стинканд (или Стиль Кирка), образовался в узком пространстве между Лакенбутсами и северной стороной церкви. [ 36 ] [ 37 ] В этом переулке открытые киоски, известные как Крамес. были установлены между контрфорсами церкви [ 38 ]

Сент-Джайлс образует северную сторону Парламентской площади, а суды - на южной стороне площади. [ 30 ] Район непосредственно к югу от церкви первоначально был кладбищем , которое простиралось вниз по склону до Каугейта . [ 39 ] Более 450 лет собор Святого Джайлса служил приходским захоронением для всего города. В наибольшей степени могильники занимали площадь почти 0,5 га. [ 40 ] Он был закрыт для захоронений в 1561 году и передан городскому совету в 1566 году. После постройки здания парламента в 1639 году бывший кладбищенский двор был развит и образовалась площадь. Западный фасад Сент-Джайлса обращен к бывшим зданиям округа Мидлотиан напротив площади Западного Парламента. [ 41 ]

История

[ редактировать ]Ранние годы

[ редактировать ]

Основание церкви Святого Джайлса обычно датируется 1124 годом и приписывается I. Давиду Приход , вероятно, был отделен от старого прихода Святого Катберта . [ 42 ] [ 43 ] Давид возвысил Эдинбург до статуса города , и во время его правления впервые засвидетельствовано, что церковь и ее земли ( поместье Святого Джайлса ) находились во владении монахов Ордена Святого Лазаря . [ 11 ] [ 44 ] Остатки разрушенной романской церкви имеют сходство с церковью в Дальмени , построенной между 1140 и 1166 годами. [ 19 ] Собор Святого Джайлса был освящен Дэвидом де Бернхэмом , епископом Сент-Эндрюса, 6 октября 1243 года. Как засвидетельствовано почти веком ранее, это, вероятно, было повторное освящение, чтобы исправить потерю каких-либо записей о первоначальном посвящении. [ 45 ]

В 1322 году во время Первой шотландской войны за независимость войска английского короля Эдуарда II разграбили Холирудское аббатство и, возможно, также напали на Сент-Джайлс. [ 46 ] Жан Фруассар сообщает, что в 1384 году шотландские рыцари и бароны тайно встретились с французскими посланниками в Сент-Джайлсе и, вопреки желанию Роберта II , планировали набег на северные графства Англии. [ 47 ] Хотя набег увенчался успехом, Ричард II Английский принял возмездие на шотландских границах и в Эдинбурге в августе 1385 года, а собор Святого Джайлса был сожжен. Сообщается, что в 19 веке на столбах перехода все еще были видны следы ожогов. [ 48 ]

В какой-то момент в 14 веке романская церковь Святого Джайлса 12 века была заменена нынешней готической церковью. По крайней мере, переправа и неф были построены к 1387 году, поскольку в том же году проректор Эндрю Йихтсон и Адам Форрестер из Незер-Либертона поручили Джону Скайеру, Джону Примроузу и Джону Скону добавить пять часовен к южной стороне нефа. [ 49 ] [ 50 ]

В 1370-х годах монахи-лазариты поддержали короля Англии, и собор Святого Джайлса вернулся под шотландскую корону. [ 48 ] В 1393 году Роберт III передал собор Святого Джайлса аббатству Скоун в качестве компенсации за расходы, понесенные аббатством в 1390 году во время коронации короля и похорон его отца. [ 51 ] [ 52 ] Последующие записи показывают, что назначения клерков в церкви Святого Джайлса были сделаны монархом, что позволяет предположить, что вскоре после этого церковь вернулась к короне. [ 53 ]

Соборная церковь

[ редактировать ]В 1419 году Арчибальд Дуглас, 4-й граф Дуглас, подал безуспешную петицию Папе Мартину V о повышении статуса собора Святого Джайлса до коллегиального статуса. Безуспешные петиции в Рим последовали в 1423 и 1429 годах. [ 54 ] В 1466 году бург подал еще одно прошение о коллегиальном статусе, которое было удовлетворено Папой Павлом II в феврале 1467 года. [ 55 ] Фонд заменил роль викария проректором в сопровождении викария , шестнадцати каноников , бидла , служителя хора и четырех певчих. [ 56 ]

В период этих петиций Уильям Престон из Гортона с разрешения французского короля Карла VII привез из Франции кость руки Святого Джайлса, важную реликвию . С середины 1450-х годов Престона к южной стороне хора был пристроен проход в память об этом благотворителе; Старшим потомкам Престона мужского пола было предоставлено право нести реликвию во главе процессии в честь Дня Святого Джайлза каждое 1 сентября. [ 57 ] [ 58 ] Около 1460 года расширение алтаря и добавление к нему фонаря были поддержаны Марией Гельдерской , возможно, в память о ее муже Якове II . [ 59 ]

В годы, последовавшие за повышением статуса Сент-Джайлса до коллегиального статуса, число капелланов и пожертвований значительно увеличилось, и к моменту Реформации в соборе Сент-Джайлса могло быть до пятидесяти алтарей. [ 60 ] [ 61 ] [ д ] В 1470 году Папа Павел II еще больше повысил статус Сент-Джайлса, удовлетворив прошение Якова III об освобождении церкви от юрисдикции епископа Сент-Эндрюса . [ 63 ]

Во время правления Гэвина Дугласа собор Святого Джайлса играл центральную роль в реакции Шотландии на национальную катастрофу битвы при Флоддене в 1513 году. Поскольку городской совет приказал мужчинам Эдинбурга защищать город, его женщинам было приказано собраться в Сент-Джайлсе, чтобы молитесь за Якова IV и его армию. [ 64 ] Реквиемная месса по королю и поминальная месса по погибшим в битве были проведены в Сент-Джайлсе, и Уолтер Чепман построил часовню Распятия в нижней части кладбища в память о короле. [ 65 ] [ 66 ]

Летом 1544 года, во время войны, известной как « Грубое ухаживание» , после того, как английская армия сожгла Эдинбург , регент Арран содержал гарнизон артиллеристов в башне церкви. [ 67 ] Новые партеры для хора построили Роберт Фендур и Эндрю Мансиун между 1552 и 1554 годами. [ 68 ]

Самое раннее упоминание о реформатских настроениях в Сент-Джайлсе относится к 1535 году, когда Эндрю Джонстон, один из капелланов, был вынужден покинуть Шотландию по причине ереси. [ 69 ] В октябре 1555 года городской совет торжественно сжег книги на английском языке, вероятно, тексты реформаторов, возле Сент-Джайлса. [ 70 ] Кража из церкви изображений Богородицы , Святого Франциска и Троицы в 1556 году могла быть агитацией реформаторов. [ 71 ] В июле 1557 года статуя покровителя церкви, Святого Джайлза, была украдена и, по словам Джона Нокса , утоплена в Нор-Лохе , а затем сожжена. [ 72 ] Для использования в процессии в честь Дня Святого Джайлса в том году статуя была заменена статуей, позаимствованной у францисканцев Эдинбурга ; хотя оно также было повреждено, когда протестанты сорвали мероприятие. [ 73 ]

Реформация

[ редактировать ]

В начале 1559 года, когда шотландская Реформация набирала силу, городской совет нанял солдат для защиты Сент-Джайлса от реформаторов; Совет также распределил церковные сокровища между доверенными горожанами на хранение. [ 74 ] В 15:00 29 июня 1559 года армия лордов Конгрегации без сопротивления вошла в Эдинбург, и в тот же день Джон Нокс , выдающийся деятель Реформации в Шотландии, впервые проповедовал в Сент-Джайлсе. [ 75 ] [ 76 ] На следующей неделе Нокс был избран священником церкви Сент-Джайлс, а еще через неделю началась чистка римско-католической обстановки церкви. [ 77 ]

Мария де Гиз (которая тогда правила регентом своей дочери Марии ) предложила Холирудское аббатство в качестве места поклонения для тех, кто хотел остаться в римско-католической вере, в то время как собор Святого Джайлса служил протестантам Эдинбурга. Мария де Гиз также предложила лордам Конгрегации, чтобы приходская церковь Эдинбурга после 10 января 1560 года оставалась в той конфессии, которая окажется наиболее популярной среди жителей города. [ 78 ] [ 79 ] Эти предложения, однако, ни к чему не привели, и лорды Конгрегации подписали перемирие с римско-католическими силами и покинули Эдинбург. [ 79 ] Нокс, опасаясь за свою жизнь, покинул город 24 июля 1559 года. [ 80 ] Однако собор Святого Джайлса остался в руках протестантов. Заместитель Нокса, Джон Уиллок , продолжал проповедовать, даже когда французские солдаты прерывали его проповеди, а лестницы, которые будут использоваться во время осады Лейта . в церкви были построены [ 79 ] [ 81 ]

После этого события шотландской Реформации на короткое время повернулись в пользу римско-католической партии: они вернули Эдинбург, а французский агент Николя де Пеллеве , епископ Амьена , 9 ноября 1559 года повторно освятил церковь Святого Джайлса в римско-католическую церковь. [ 79 ] [ 82 ] После того, как Бервикский договор обеспечил вмешательство Елизаветы I Английской на стороне реформаторов, они вернули Эдинбург. 1 апреля 1560 года церковь Святого Джайлса снова стала протестантской церковью, а 23 апреля 1560 года Нокс вернулся в Эдинбург. [ 79 ] [ 83 ] Парламент Шотландии постановил, что с 24 августа 1560 года Папа не имеет власти в Шотландии. [ 84 ]

Рабочим при помощи моряков из порта Лейт потребовалось девять дней, чтобы расчистить каменные алтари и памятники церкви. Были проданы драгоценные предметы, использовавшиеся в богослужении до Реформации. [ 85 ] Церковь была побелена, ее столбы выкрашены в зеленый цвет, а Десять заповедей и Молитва Господня . на стенах нарисованы [ 86 ] Были установлены сиденья для детей, а также городских советов и корпораций . Также была установлена кафедра , вероятно , на восточной стороне перехода . [ 87 ] В 1561 году кладбище к югу от церкви было закрыто, и большинство последующих захоронений проводилось на кладбище Грейфрайарс . [ 88 ]

Церковь и корона: 1567–1633 гг.

[ редактировать ]

В 1567 году Мария, королева Шотландии, была свергнута, и ей наследовал ее маленький сын Яков VI . Церковь Святого Джайлса стала центром последовавшей Марианской гражданской войны . После его убийства в январе 1570 года регент Морей , главный противник Марии, королевы Шотландии в церкви был похоронен ; Джон Нокс проповедовал на этом мероприятии. [ 22 ] Эдинбург ненадолго пал перед войсками Марии, и в июне и июле 1572 года Уильям Кирколди из Грейнджа разместил в башне солдат и пушки. [ 89 ] Хотя его девятилетний коллега Джон Крейг оставался в Эдинбурге во время этих событий, Нокс, из-за ухудшения здоровья, удалился в Сент-Эндрюс . Депутация из Эдинбурга отозвала его в церковь Святого Джайлса, и там он произнес свою последнюю проповедь 9 ноября 1572 года. [ 90 ] Нокс умер позже в том же месяце и был похоронен на кладбище в присутствии регента Мортона . [ 91 ] [ 92 ]

После Реформации часть Сент-Джайлса была отдана под светские нужды. В 1562 и 1563 годах три западных пролета церкви были перегорожены стеной, чтобы служить пристройкой к Толбуту : в этом качестве он использовался как место заседаний городских уголовных судов, Сессионного суда , и Парламент Шотландии . [ 93 ] Непокорные римско-католические священнослужители (а позже и закоренелые грешники) были заключены в комнату над северной дверью. [ 94 ] К концу 16 века башня также использовалась как тюрьма. [ 95 ] Дева – – ранняя форма гильотины хранилась в церкви. [ 96 ] Ризницу переоборудовали в кабинет и библиотеку для городского клерка, а ткачам разрешили разместить на чердаке свои ткацкие станки. [ 97 ]

Примерно в 1581 году интерьер был разделен на два молитвенных дома: алтарь стал Восточным (или Малым, или Новым) Кирком, а переход и остальная часть нефа стали Большим (или Старым) Кирком. Эти общины, наряду с Тринити-колледжем Кирка и часовней Магдалины , обслуживались на совместной сессии Кирка . В 1598 году верхний этаж перегородки Толбута был преобразован в Западный (или Толбут) Кирк. [ 98 ] [ 99 ]

В период раннего большинства Джеймса VI министры Сент-Джайлса – во главе с преемником Нокса Джеймсом Лоусоном – сформировали, по словам Кэмерона Лиза , «своего рода духовный конклав, с которым государству приходилось считаться перед любым из своих предложений». относительно церковных вопросов может стать законом». [ 100 ] Во время своего пребывания в Большом Кирке Джеймса часто критиковали в проповедях министров, и отношения между королем и реформатским духовенством ухудшились. [ 101 ] Несмотря на противодействие со стороны министров Сент-Джайлса, Джеймс с 1584 года ввел последовательные законы об установлении епископства в Шотландской церкви . [ 102 ] Отношения достигли своего апогея после беспорядков в Сент-Джайлсе 17 декабря 1596 года. Король ненадолго переехал в Линлитгоу , и министров обвинили в подстрекательстве толпы; они бежали из города, вместо того чтобы подчиниться призыву предстать перед королем. [ 103 ] Чтобы ослабить министров, Джеймс в апреле 1598 года издал приказ городского совета от 1584 года о разделении Эдинбурга на отдельные приходы . [ 104 ] В 1620 году община Верхнего Толбута освободила Сент-Джайлс для недавно основанного Грейфрайерс Кирка . [ 105 ] [ 106 ]

Кафедральный собор

[ редактировать ]

Сын и преемник Джеймса, Карл I , впервые посетил Сент-Джайлс 23 июня 1633 года во время своего визита в Шотландию для коронации. Он прибыл в церковь без предупреждения и вытеснил чтеца духовенством, которое провело службу по обрядам англиканской церкви . [ 107 ] 29 сентября того же года Чарльз, отвечая на прошение Джона Споттисвуда , архиепископа Сент-Эндрюса , повысил собор Святого Джайлса до статуса собора , который будет служить резиденцией нового епископа Эдинбургского . [ 23 ] [ 108 ] Начались работы по удалению внутренних перегородок и обустройству интерьера в стиле Даремского собора . [ 109 ]

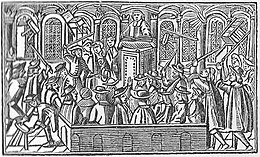

Работа над церковью была неполной, когда 23 июля 1637 года замена Книги общего порядка англиканской церкви Святого Джайлса Нокса шотландской версией Книги общих молитв спровоцировала беспорядки из-за предполагаемого сходства последней с римско-католическим ритуалом. . Традиция свидетельствует, что этот бунт начался, когда рыночная торговка по имени Дженни Геддес бросила свой табурет в декана Джеймса Хэннея. [ 110 ] [ 111 ] В ответ на беспорядки услуги в Сент-Джайлсе были временно приостановлены. [ 112 ]

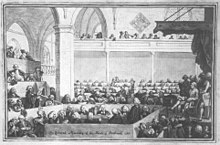

События 23 июля 1637 года привели к подписанию Национального договора в феврале 1638 года, что, в свою очередь, привело к Епископским войнам , первому конфликту Войн Трех Королевств . [ 113 ] Церковь Святого Джайлса снова стала пресвитерианской церковью, и перегородки были восстановлены. [ 114 ] До 1643 года Престонский проход также был оборудован как постоянное место встреч Генеральной Ассамблеи Шотландской церкви . [ 115 ]

Осенью 1641 года Карл I присутствовал на пресвитерианской службе в Восточном Кирке под руководством его министра Александра Хендерсона , ведущего ковенантера . Король проиграл епископские войны и прибыл в Эдинбург, потому что Рипонский договор вынудил его ратифицировать акты парламента Шотландии, принятые во время господства Ковенантеров. [ 116 ]

После поражения ковенантеров в битве при Данбаре войска Содружества Англии под командованием Оливера Кромвеля вошли в Эдинбург и заняли Восточный Кирк в качестве гарнизонной церкви. [ 117 ] Генерал Джон Ламберт и сам Кромвель были среди английских солдат, проповедовавших в церкви, и во времена Протектората Восточный Кирк и Толбут Кирк были разделены на две части. [ 118 ] [ 119 ]

Во время Реставрации 1660 года кромвельская перегородка была удалена из Восточного Кирка и там был построен новый королевский чердак. [ 120 ] В 1661 году парламент Шотландии под руководством Карла II восстановил епископство, и собор Святого Джайлса снова стал собором. [ 121 ] По приказу Чарльза тело Джеймса Грэма, 1-го маркиза Монтроуза - старшего сторонника Карла I , казненного Ковенантерами, - было перезахоронено в Сент-Джайлсе. [ 122 ] Повторное введение епископов вызвало новый период восстания, и после битвы при Руллион-Грин в 1666 году ковенантеры были заключены в бывшую тюрьму священников над северной дверью , которая к тому времени стала известна как «Дыра Хаддо». «из-за заключения там в 1644 году роялистов лидера сэра Джона Гордона, 1-го баронета Хаддо . [ 123 ]

После Славной революции шотландские епископы остались верны Якову VII . [ 124 ] По совету Уильяма Карстерса , который позже стал министром Высокого Кирка, Вильгельм II поддержал отмену епископов в Шотландской церкви, и в 1689 году парламент Шотландии восстановил пресвитерианское государство . [ 125 ] [ 126 ] [ 127 ] В ответ многие служители и прихожане покинули Шотландскую церковь , фактически основав независимую Шотландскую епископальную церковь . [ 128 ] Только в Эдинбурге возникло одиннадцать молитвенных домов этого отделения, включая общину, которая стала церковью Старого Святого Павла , которая была основана, когда Александр Роуз , последний епископ Эдинбурга в официальной церкви, вывел большую часть своей общины из церкви Святого Джайлса. [ 129 ] [ 130 ] [ 131 ]

Четыре церкви в одной: 1689–1843 гг.

[ редактировать ]

В 1699 году зал суда в северной половине перегородки Толбута был преобразован в Новый Северный (или Дыру Хаддо) Кирк . [ 132 ] В Союзе парламентов Шотландии и Англии в 1707 году звучала мелодия «Почему мне грустить в день свадьбы?» раздался звук недавно установленного в Сент-Джайлсе карильона . [ 133 ] Во время восстания якобитов в 1745 году жители Эдинбурга встретились в Сент-Джайлсе и согласились сдать город наступающей армии Чарльза Эдварда Стюарта . [ 134 ]

С 1758 по 1800 год Хью Блэр , ведущая фигура шотландского Просвещения и умеренный религиозный деятель, служил министром Высокого Кирка; его проповеди были известны по всей Британии и привлекли Роберта Бернса и Сэмюэля Джонсона в церковь . Современник Блэра, Александр Вебстер , был ведущим евангелистом , который со своей кафедры в Толбут-Кирк излагал строгую кальвинистскую доктрину. [ 135 ] [ 136 ]

В начале 19 века Лакенбутс и Толбутс , окружавшие северную сторону церкви, были снесены вместе с магазинами, построенными вокруг стен церкви. [ 137 ] Внешний вид церкви показал, что ее стены наклонены наружу. [ 26 ] В 1817 году городской совет поручил Арчибальду Эллиоту разработать план восстановления церкви. Радикальные планы Эллиота оказались противоречивыми, и из-за нехватки средств с ними ничего не было сделано. [ 138 ] [ 139 ]

Георг IV присутствовал на службе в Высоком Кирке во время своего визита в Шотландию в 1822 году . [ 140 ] Огласка визита короля дала толчок к восстановлению ныне полуразрушенного здания. [ 141 ] Благодаря 20 000 фунтов стерлингов, предоставленным городским советом и правительством, Уильяму Берну было поручено возглавить реставрацию. [ 142 ] [ 143 ] Первоначальные планы Бёрна были скромными, но под давлением властей Бёрн создал нечто, более близкое к планам Эллиота. [ 138 ] [ 144 ]

Между 1829 и 1833 годами Берн значительно изменил церковь: он облицовал внешнюю часть тесаным камнем , поднял линию крыши церкви и уменьшил ее площадь. Он также добавил северную и западную двери и переместил внутренние перегородки, чтобы создать церковь в нефе, церковь в хоре и место собраний Генеральной Ассамблеи Шотландской церкви в южной части. Между ними переход и северный трансепт образовывали большой вестибюль. Берн также уничтожил внутренние памятники; место встречи Генеральной Ассамблеи в Престон-Айл; а также полицейский участок и дом пожарной машины , последние светские помещения в здании. [ 145 ] [ 146 ] [ 138 ]

Современники Бёрна разделились на тех, кто поздравлял его с созданием более чистого и стабильного здания, и тех, кто сожалел о том, что было потеряно или изменено. [ 147 ] [ 148 ] В викторианскую эпоху и в первой половине 20-го века работы Берна не пользовались популярностью у комментаторов. [ 149 ] [ 150 ] Среди его критиков был Роберт Льюис Стивенсон , который заявил: «…ревностные судьи и заблуждающийся архитектор урезали образ мужественности и оставили его бедным, обнаженным и жалко претенциозным». [ 151 ] Со второй половины 20 века работа Бёрна была признана спасшей церковь от возможного разрушения. [ 152 ] [ 153 ] [ 154 ]

Высокий Кирк вернулся в хор в 1831 году. Толбут Кирк вернулся в неф в 1832 году; когда они уехали в новую церковь на Каслхилле в 1843 году, неф был занят прихожанами Хаддос-Хоул. Генеральная Ассамблея сочла свой новый зал заседаний неподходящим и собралась там только один раз, в 1834 году; община Старого Кирка переехала в это место. [ 155 ] [ 156 ]

викторианская эпоха

[ редактировать ]

Во время 1843 года беспорядков Роберт Гордон и Джеймс Бьюкенен , служители Верховного Кирка, оставили своих подопечных и существующую церковь, чтобы присоединиться к недавно основанной Свободной церкви . [ и ] Значительная часть их прихожан ушла вместе с ними; как и Уильям Кинг Твиди, первый министр Толбут Кирка, [ ж ] и Чарльз Джон Браун, министр Хаддос-Хоул-Кирк . [ 147 ] [ 159 ] [ 160 ] Конгрегация Олд-Кирк была подавлена в 1860 году. [ 161 ] [ г ]

На публичном собрании в Эдинбургских городских палатах 1 ноября 1867 года Уильям Чемберс , издатель и лорд-мэр Эдинбурга , впервые выдвинул свое стремление убрать внутренние перегородки и восстановить Сент-Джайлс как « Вестминстерское аббатство для Шотландии». [ 164 ] Чемберс поручил Роберту Морэму разработать первоначальный план. [ 138 ] Линдси Маккерси, адвокат и секретарь Верховного Кирка, поддерживала работу Чемберса, а Уильям Хэй был нанят в качестве архитектора; Также было создано управление по надзору за проектированием новых окон и памятников. [ 165 ] [ 166 ]

Реставрация была частью движения за литургическое конца XIX века украшение в шотландском пресвитерианстве , и многие евангелисты опасались, что восстановленный собор Святого Джайлса будет больше напоминать римско-католическую церковь, чем пресвитерианскую. [ 167 ] [ 168 ] Тем не менее, пресвитерия Эдинбурга утвердила планы в марте 1870 года, и в период с июня 1872 по март 1873 года Высокий Кирк был восстановлен: скамьи и галереи были заменены киосками и стульями, и впервые со времен Реформации витражи и орган были восстановлены . представил. [ 138 ] [ 169 ]

Восстановление бывшего Старого Кирка и Западного Кирка началось в январе 1879 года. В 1881 году Западный Кирк покинул Сент-Джайлс. [ 170 ] Во время реставрации было обнаружено множество человеческих останков; их перевезли в пяти больших ящиках для повторного захоронения в Грейфрайарс Киркьярд . [ 171 ] Хотя ему удалось осмотреть воссоединенную внутреннюю часть, Уильям Чемберс умер 20 мая 1883 года, всего за три дня до того, как Джон Гамильтон-Гордон, 7-й граф Абердин , лорд-верховный комиссар Генеральной Ассамблеи Шотландской церкви , торжественно открыл отреставрированную церковь. ; Похороны Чемберса прошли в церкви через два дня после ее открытия. [ 138 ] [ 172 ]

20 и 21 века

[ редактировать ]

В 1911 году Георг V открыл недавно построенную часовню рыцарей Ордена Чертополоха в юго-восточном углу церкви. [ 173 ]

Хотя в церкви проводилась специальная служба для Церковной лиги за избирательное право женщин, отказ Уоллеса Уильямсона молиться за заключенных суфражисток привел к тому, что их сторонники срывали службы в конце 1913 и начале 1914 года. [ 174 ]

Девяносто девять членов общины, включая помощника священника Мэтью Маршалла, погибли во время Первой мировой войны . [ 174 ] В 1917 году в Сент-Джайлсе состоялись похороны Элси Инглис , пионера медицины и члена общины. [ 175 ] [ 176 ]

В преддверии воссоединения Объединенной свободной церкви Шотландии и Шотландской церкви в 1929 году Закон 1925 года о Шотландской церкви (собственность и пожертвования) передал право собственности на собор Святого Джайлса от городского совета Эдинбурга к Церкви Шотландии. [ 177 ] [ 178 ]

Церковь избежала Второй мировой войны неповрежденной. Через неделю после Дня Победы королевская семья посетила благодарственную службу в Сент-Джайлсе. Проход Олбани на северо-западе церкви впоследствии был преобразован в мемориальную часовню 39 членам общины, погибшим в ходе конфликта. [ 179 ]

В ознаменование своего первого визита в Шотландию после коронации Елизавета II была удостоена Почестей Шотландии на национальной службе благодарения в Сент-Джайлсе 24 июня 1953 года. [ 180 ]

С 1973 по 2013 год Гиллесбьюг Макмиллан занимал пост министра Сент-Джайлса. [ 181 ] Во время правления Макмиллана церковь была восстановлена, а интерьер переориентирован вокруг центрального стола причастия, внутренний пол был выровнен, а подземное пространство было создано Бернардом Фейлденом . [ 138 ] [ 182 ]

Церковь Святого Джайлса остается действующей приходской церковью, а также здесь проводятся концерты, специальные службы и мероприятия. [ 183 ] В 2018 году Сент-Джайлс был четвертым по популярности местом для посетителей в Шотландии: в этом году его посетило более 1,3 миллиона человек. [ 15 ]

12 сентября 2022 года гроб покойной королевы Елизаветы II был доставлен в собор для благодарственной службы, он прибыл из замка Балморал во дворец Холирудхаус . накануне [ 184 ] [ 185 ] Затем гроб королевы покоился в соборе в течение 24 часов под постоянной охраной Королевской роты лучников, что позволило народу Шотландии выразить свое почтение. Вечером дети королевы; Король Карл III , королевская принцесса , граф Инвернесс и граф Форфар провели в соборе бдение - обычай, известный как Бдение принцев . [ 186 ]

5 июля 2023 года Почести Шотландии были вручены Королю Карлу III на церемонии, состоявшейся в соборе Святого Джайлса, . Церемония была официально описана как Национальная служба благодарения и посвящения в честь коронации короля Карла III и королевы Камиллы . [ 187 ]

Архитектура

[ редактировать ]«Ни одна другая шотландская церковь не имела такой запутанной истории архитектуры». [ 13 ]

Ян Ханна , История Шотландии в камне (1934)

Первый собор Святого Джайлса, вероятно, представлял собой небольшое романское здание XII века с прямоугольным нефом и полукруглым апсидальным алтарем . До середины 13 века придел . к югу от церкви был пристроен [ 18 ] Археологические раскопки 1980-х годов показали, что церковь XII века, скорее всего, была построена из розового песчаника и серого винного камня. [ 40 ] Раскопки показали, что первая церковь была построена на прочной глиняной платформе, созданной для выравнивания крутого склона местности. Эта платформа была окружена пограничным рвом. [ 40 ]

К 1385 году это здание, вероятно, было заменено ядром нынешней церкви: нефом и приделами из пяти пролетов , переходом и трансептами , а также хором из четырех пролетов. [ 188 ] Церковь расширялась поэтапно между 1387 и 1518 годами. [ 19 ] [ 189 ] По словам Ричарда Фосетта , это «почти случайное добавление большого количества часовен» привело к «чрезвычайно сложному плану». [ 190 ] Возникающее в результате обилие внешних нефов типично для французской средневековой церковной архитектуры , но необычно для Великобритании. [ 191 ] [ 192 ]

Помимо внутреннего разделения церкви после Реформации , до реставрации Уильямом Берном в 1829–1833 годах было внесено несколько значительных изменений, которые включали удаление нескольких пролетов церкви, добавление фонарей к нефу и трансепты и внешняя отделка церкви полированным тесаным камнем . [ 138 ] Церковь была значительно восстановлена при Уильяме Хэе между 1872 и 1883 годами, включая удаление последних внутренних перегородок. В конце 19 века по периметру церкви было пристроено несколько помещений на первом этаже. Часовня Чертополоха была пристроена к юго-восточному углу церкви Робертом Лоримером в 1909–1911 годах. [ 138 ] [ 154 ] Самая значительная последующая реставрация началась в 1979 году под руководством Бернарда Фейлдена и Симпсона и Брауна: она включала выравнивание пола и перестановку интерьера вокруг центрального стола причастия. [ 138 ] [ 193 ]

Экстерьер

[ редактировать ]Внешний вид церкви, за исключением башни, почти полностью датируется реставрацией Уильяма Берна в 1829–1833 годах и позже. [ 138 ] [ 194 ] До этой реставрации церковь Святого Джайлса имела то, что Ричард Фосетт назвал «уникально сложным внешним видом» в результате многочисленных расширений церкви; внешне ряд часовен подчеркивался фронтонами . [ 195 ]

После сноса в начале 19 века Лакенбутса , Толбута и магазинов, построенных напротив церкви Сент-Джайлс, стены церкви местами оказались наклонены наружу на целых полтора фута. Ожог покрыл внешнюю часть здания полированным тесаным камнем из серого песчаника из Куллало в Файфе . Этот слой привязан к существующим стенам железными скобами и имеет ширину от восьми дюймов (20 см) у основания стен до пяти дюймов (12,5 см) вверху. [ 194 ] Берн сотрудничал с Робертом Ридом , архитектором новых зданий на Парламентской площади, чтобы гарантировать, что экстерьеры их зданий дополняют друг друга. [ 196 ] Берн значительно изменил профиль церкви: он расширил трансепты , создал фонарь в нефе , добавил новые дверные проемы в западном фасаде, а также в северном и южном трансептах, а также воспроизвел остроконечный гребень восточного конца церкви по всему парапету . [ 138 ] Помимо часовни Чертополоха , пристройки после реставрации Берна включают пристройки Уильяма Хэя 1883 года: комнаты к югу от прохода Морей, к востоку от южного трансепта и к западу от северного трансепта; в 1891 году МакГиббон и Росс добавили женскую ризницу (ныне магазин) к востоку от северного трансепта. [ 197 ] [ 198 ]

Берн создал симметричный западный фасад , заменив западное окно прохода Олбани в северо-западном углу церкви двойной нишей и переместив западное окно внутреннего прохода южного нефа, чтобы повторить это расположение в южной половине. [ 199 ] Западный дверной проем датируется викторианской реставрацией и принадлежит Уильяму Хэю : дверной проем окружен нишами, содержащими небольшие статуи шотландских монархов и их супруг (слева направо: Александр I , Давид I , Александр III , Святая Маргарита , Маргарита Тюдор , Роберт Брюс , Джеймс I и Джеймс IV ) и церковники (слева направо Гэвин Дуглас , Джон Нокс , Уильям Форбс и Александр Хендерсон ) , Джоном Райндом который также вырезал рельеф Святого Джайлса в тимпане . [ 200 ] Металлоконструкции западной двери выполнены компанией Skidmore . [ 201 ] Associates добавила к западной двери новые ступени и пандус В 2006 году компания Morris and Steedman . [ 202 ]

Чтобы улучшить доступ к Парламентской площади, Берн снес два самых западных пролета внешнего южного нефа, включая южное крыльцо и дверь. Берн также удалил западный пролет из Нефа Святой Крови на юге церкви, а с северной стороны нефа удалил северное крыльцо вместе с прилегающим пролетом. [ 203 ] [ 204 ] Потерянные крыльца, вероятно, датируются концом 15-го века и могут сравниться только с крыльцами в Кирке Святого Иоанна в Перте и Кирке Святого Михаила в Линлитгоу как самые величественные двухэтажные крыльца в шотландских средневековых церквях. Как и крыльцо в Линлитгоу, на котором они, вероятно, были основаны, веранды в Сент-Джайлсе имели входную арку под эркерным окном . [ 205 ] Берн повторил эту договоренность в новом дверном проеме к западу от прохода Морей. [ 199 ]

Посещая церковь перед реставрацией Берна , Томас Рикман написал: «... на некоторых окнах сохранился узор , но в большинстве из них он был срезан». [ 206 ] На видах церкви до реставрации Ожога видны пересекающиеся узоры в некоторых окнах хоров и петлевые узоры в окнах Нефа Святой Крови. [ 207 ] Берн сохранил узор большого восточного окна, восстановленного Джоном Милном Младшим в середине 17 века. В других окнах Берн вставил новый узор, основанный на шотландских образцах позднего средневековья. [ 199 ] [ 208 ]

Башня и коронный шпиль

[ редактировать ]

собора Святого Джайлса есть центральная башня Над перекрестком : такое расположение распространено в более крупных шотландских средневековых светских церквях. [ 209 ] [ 210 ] Башня строилась в два этапа. Нижняя часть башни имеет стрельчатые отверстия с Y-образным узором со всех сторон. [ 211 ] Вероятно, это было завершено к 1416 году, и в этом году Scoticronicon сообщает, что здесь гнездились аисты . [ 212 ] Верхняя ступень башни имеет группы из трех остроконечных стрельчатых отверстий с каждой стороны. Дата этой работы неизвестна, но она может относиться как к штрафам, взимаемым со строительных работ в Сент-Джайлсе в 1486 году, так и к правилам 1491 года для мастера-каменщика и его людей. [ 211 ] [ 213 ] По крайней мере, с 1590 года на башне был циферблат , а к 1655 году их стало три. Циферблаты часов были удалены в 1911 году. [ 214 ]

Святого Джайлса Коронный шпиль — одна из самых известных и самобытных достопримечательностей Эдинбурга. [ 211 ] [ 215 ] [ 216 ] Кэмерон Лис писал о шпиле: «Без него Эдинбург не был бы Эдинбургом». [ 217 ] Дендрохронологический анализ датирует шпиль короны периодом между 1460 и 1467 годами. [ 218 ] [ ч ] Шпиль является одним из двух сохранившихся средневековых шпилей короны в Шотландии: другой находится в Королевском колледже в Абердине и датируется 1505 годом. [ 221 ] Джон Хьюм назвал коронный шпиль Святого Джайлса «безмятежным напоминанием об имперских устремлениях покойных монархов Стюартов ». [ 222 ] Однако дизайн имеет английское происхождение: он был найден в церкви Святого Николая в Ньюкасле до того, как был представлен Шотландии в церкви Святого Джайлса; средневековый собор Сент-Мэри-ле-Боу в Лондоне, возможно, также имел шпиль с короной. [ 211 ] [ 223 ] [ 224 ] Еще один шпиль короны существовал в приходской церкви Святого Михаила в Линлитгоу до 1821 года, а другие, возможно, были запланированы и, возможно, начаты в приходских церквях Хаддингтона и Данди . [ 225 ] Эти другие примеры состоят только из диагональных аркбутанов, исходящих из четырех углов башни; тогда как шпиль Святого Джайлса уникален среди средневековых коронных шпилей, поскольку состоит из восьми контрфорсов: четырех, выходящих из углов, и четырех, выходящих из центра каждой стороны башни. [ 226 ] [ 227 ] [ 228 ]

К приезду в Эдинбург Анны Датской в 1590 году 21 флюгер к гребням шпиля был добавлен ; они были удалены до 1800 года, а в 2005 году были установлены новые. [ 227 ] [ 229 ] Шпиль был отремонтирован Джоном Милном Младшим в 1648 году. Милн добавил вершины на полпути к гребням контрфорсов; башни он также в значительной степени ответственен за нынешний внешний вид центральной вершины и, возможно, перестроил ажурный парапет . [ 227 ] [ 230 ] Флюгер ; на вершине центральной вершины был создан Александром Андерсоном в 1667 году он заменил более ранний флюгер 1567 года работы Александра Ханимана. [ 231 ]

Неф

[ редактировать ]В серии « Здания Шотландии» неф назван «археологически самой сложной частью церкви». [ 232 ] Хотя неф датируется 14 веком и является одной из старейших частей церкви, с тех пор он был значительно изменен и расширен. [ 233 ]

Потолок над центральной частью нефа представляет собой свод гипсовый ярусный ; это было добавлено во время Уильяма Берна реставрации в 1829–1833 годах. Берн также увеличил стены центральной части нефа на 16 футов (4,8 метра), добавив окна для создания фонаря . [ 219 ] Берну обычно приписывают удаление средневекового сводчатого потолка из нефа; однако современных записей об этом нет, и, возможно, они были удалены до времен Бёрна. [ 234 ] Консоли , и валы ведущие к пружинам сводов, были добавлены Уильямом Хэем в 1882 году. [ 232 ] Берн также удалил чердак над центральной частью нефа: там было несколько комнат и размещался церковный звонарь. [ 96 ] [ 235 ] Очертания крыши нефа до реставрации Ожога можно увидеть на стене над западной аркой перехода. [ 236 ]

Хэй также отвечает за нынешнюю аркаду . [ 232 ] Ранее Берн усилил средневековую аркаду и заменил восьмиугольные колонны 14 века колоннами по образцу 15 века в проходе Олбани. Хэй заменил эти колонны копиями восьмиугольных колонн хора XIV века. [ 232 ] [ 219 ] Первоначально южная аркада нефа была нижней, с окном фонаря над каждой аркой. Нижняя высота первоначальной аркады обозначена фрагментом арки, исходящей от юго-западной опоры перехода. [ 219 ] Арки окон фонаря, теперь заполненные, все еще видны над каждой аркой аркады на южной стороне нефа. [ 232 ] Две арки, ближайшие к пересечению аркады южного нефа, представляют собой более высокие арки, которые, вероятно, относятся к средневековой схеме увеличения аркады; однако наличие этих глухих арок только в двух отсеках позволяет предположить, что эта схема оказалась неудачной. [ 232 ] [ 219 ]

Северный неф и часовни

[ редактировать ]Потолок северного нефа представляет собой ребристый свод в стиле, похожем на проход Олбани: это предполагает, что проход северного нефа относится к той же строительной кампании на рубеже 15 века. [ 237 ] [ 238 ] [ 239 ]

В первом десятилетии 15-го века проход Олбани был построен как продолжение на север двух самых западных заливов прохода северного нефа. [ 19 ] [ 194 ] Неф состоит из двух пролетов под каменным ребристым сводом . [ 240 ] [ 241 ] Западное окно часовни было заложено во время Бернской реставрации 1829–1833 гг. [ 239 ] В северной стене прохода находится полукруглая ниша для гробницы. [ 237 ] [ 239 ] Потолочные своды поддерживаются объединенной колонной, которая поддерживает лиственную капитель и восьмиугольные счеты , на которых находятся гербы дарителей прохода: Роберта Стюарта, герцога Олбани , и Арчибальда Дугласа, 4-го графа Дугласа . [ 237 ] [ 238 ] Это самый старый пример столба, повторяющегося в более поздних пристройках к собору Святого Джайлса. [ 242 ] [ 243 ] Ричард Фосетт описывает повторение этого стиля колонн и аркад как обеспечивающее «некоторую меру контроля […] для достижения определенной степени архитектурного единства». [ 190 ] Ни Олбани, ни Дуглас не были тесно связаны с собором Святого Джайлса, и традиция гласит, что этот проход был пожертвован в качестве покаяния за их причастность к смерти Дэвида Стюарта, герцога Ротсейского . [ 238 ] [ 244 ] [ 245 ] [ 246 ] В 1882 году пол прохода Олбани был выложен плиткой Минтон , полосами ирландского мрамора и выложенными плиткой медальонами с изображением герба Шотландии ; Роберт Стюарт, герцог Олбани ; и Арчибальд Дуглас, 4-й граф Дуглас . [ 247 ] Для открытия прохода в качестве мемориальной часовни после Второй мировой войны плитка Минтона была заменена брусчаткой Леоха из Данди, а геральдические медальоны и мраморные полосы были сохранены. [ 248 ]

К востоку от прохода Олбани два светлых камня под « Черного дозора мемориалом Египетской кампании » отмечают место нормандской северной двери. До его удаления в конце 18 века дверной проем был единственной особенностью романской церкви 12 века на месте . [ 19 ] [ 194 ] [ я ] На иллюстрации 1799 года дверной проем изображен как богато украшенная конструкция, имеющая сходство с дверными проемами в церквях Далмени и Леухара . [ 19 ] [ 250 ] Крыльцо стояло над местом северной двери до ожоговой реставрации 1829–1833 годов. Он представлял собой комнату над дверным проемом, куда можно было попасть из церкви по шлагбауму . [ 239 ] [ 251 ] Стрельчатая арка лестничной двери теперь обрамляет мемориал Второму батальону Королевских шотландских стрелков Второй англо-бурской войны . К востоку от бывшего дверного проема находится утопленная ступица . [ 237 ] [ 239 ] [ 252 ]

Две часовни раньше стояли к северу от двух восточных ниш северного нефа. Только самый восточный из них, проход Святого Элои , пережил реставрацию Ожога. [ 253 ] Его потолок представляет собой цилиндрический свод с неглубокими ребрами: он был установлен во время реставрации Уильяма Хэя в 1881–1883 годах и включает выступ из оригинального хранилища. Арка между проходом Святого Элои и проходом северного нефа является оригинальной постройкой 15 века. [ 237 ] На западной стене прохода Святого Элоя находится романская капитель оригинальной церкви. Он был обнаружен во время расчистки завалов вокруг средневекового восточного окна северного трансепта в 1880 году и был возвращен на свое нынешнее место. [ 194 ] [ 237 ] [ 254 ] Пол прохода Св. Элои выложен мрамором с мозаичными панелями Минтона , изображающими эмблему Объединения Молотменов между символами четырех евангелистов . [ 255 ]

проходы южного нефа

[ редактировать ]

Внутренний и внешний южные нефы, вероятно, были начаты в конце 15 века, примерно во времена Престонского прохода, на который они очень похожи. [ 237 ] алтари Святой Троицы , Святой Аполлонии и Святого Фомы . Вероятно, они были завершены к 1510 году, когда к западному концу внутреннего нефа были добавлены [ 237 ] Нынешние нефы заменили первоначальный неф южного нефа и пять часовен Джона Примроуза, Джона Скайера и Джона Перта, названных в контракте 1387 года. [237] The inner aisle retains its original quadripartite vault; however, the plaster tierceron vault of the outer aisle (known as the Moray Aisle) dates to William Burn's restoration.[237][239] During the Burn restoration, the two westernmost bays of the outer aisle were removed. There remains a prominent gap between the pillars of the missing bays and the 19th century wall. At the west end of the outer aisle, Burn added a new wall with a door and oriel window.[239] Burn also replaced the window of the inner aisle with a smaller window, centred north of the original in order to accommodate a double niche on the exterior wall. The outline of the original window is still visible in the interior wall.[237]

In 1513, Alexander Lauder of Blyth commissioned an aisle of two bays at the eastern end of the outer south nave aisle: the Holy Blood Aisle is the easternmost and only surviving bay of this aisle.[1] It is named for the Confraternity of the Holy Blood, to whom it was granted upon completion in 1518.[256] The western bay of the Aisle and the pillar separating the two bays were removed during the Burn restoration and the remainder was converted to a heating chamber.[257] The Aisle was restored to ecclesiastical use under William Hay.[237] An elaborate late Gothic tomb recess occupies the south wall of the aisle.[237][239]

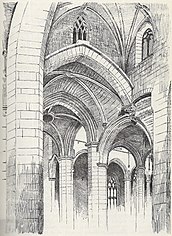

Crossing and transepts

[edit]The piers of the crossing date to the original building campaign of the 14th century and may be the oldest part of the present church.[19] The piers were likely raised around 1400, at which time the present vault and bell hole were created.[239][258] The first stages of both transepts were likely completed by 1395, in which year the St John's Aisle was added to the north of the north transept.[19]

Initially, the north transept extended no further than the north wall of the aisles and possessed a tunnel-vaulted ceiling at the same height as those in the crossing and aisles. The arches between the transept and north aisles of the choir and nave appear to be 14th century.[239][259] The St John's Chapel, extending north of the line of the aisles, was added in 1395; in its western end was a turnpike stair, which, at the Burn restoration, was re-set in the thick wall between the St Eloi Aisle and the north transept.[19][239][254][259] The remains of St John's Chapel are visible in the east wall of the north transept: these include fragments of vaulting and a medieval window, which faces into the Chambers Aisle. The bottom half of this window's tracery, as far as its embattled transom, is original; curvilinear tracery was added to the upper half by MacGibbon and Ross in 1889–91.[239][254][259] At the Burn restoration, the north transept was heightened and a clerestory and plaster vaulted ceiling inserted.[239][259] A screen of 1881-83 by William Hay crosses the transept in line with the original north wall, creating a vestibule for the north door. The screen contains sculptures of the patron saints of the Incorporated Trades of Edinburgh by John Rhind as well as the arms of William Chambers.[259][260] The ceiling and open screens within the vestibule were designed by Esmé Gordon and added in 1940.[259] A fragment of medieval blind tracery is visible at the western end of this screen.[259]

Initially, the south transept only extended to the line of the south aisles; it was extended in stages as the Preston, Chepman, and Holy Blood Aisles were added.[232] The original barrel vault remains as far as an awkwardly inserted transverse arch supported on heavy corbels between the inner transept arches: this arch was likely inserted after the creation of the Preston Aisle, when the inner transept arches were expanded accordingly.[232][239] The transverse arch carries an extension to the lower part of the tower, including a 15th-century traceried window.[261] The south transept was heightened and a clerestory and plaster vaulted ceiling were inserted during the Burn restoration.[232]

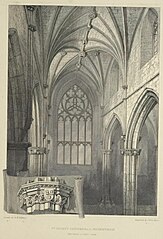

Choir

[edit]The Buildings of Scotland series calls the choir the "finest piece of late medieval parish church architecture in Scotland".[227] The choir dates to two periods of building: one in the 14th century and one in the 15th.[262] The archaeological excavations indicate the choir was extended to almost its current size in a single phase before the mid-15th-century work.[40]

The choir was initially built as a hall church: as such, it was unique in Scotland.[227] The western three bays of the choir date to this initial period of construction. The arcades of these bays are supported by simple, octagonal pillars.[227] In the middle of the 15th century, two bays were added to the east end of the choir and the central section was raised to create a clerestory under a tierceron-vaulted ceiling in stone.[263] The springers of the original vault are still visible above some of the capitals of the choir pillars and the outline of the original roof is visible above the eastern arch of the crossing.[236] A grotesque at the intersection of the central rib of the ceiling and the east wall of the tower may be a fragment of the 12th century church.[44] The two pillars and two demi-pillars constructed during this expansion in the easternmost bays of the choir are similar in type to those in the Albany Aisle.[263]

Of the two pillars added during this extension, the northern one is known as the "King's Pillar" as its capital bears the arms of James III on its east face; James II on its west face; Mary of Guelders on its north face; and France on its south face.[264][265] These arms date the work between the birth of James II in 1453 and the death of Mary of Guelders in 1463; the incomplete tressure in the arms of James II may indicate he was dead when the work commenced, dating it to after 1460.[266] The southern pillar is known as the "Town's Pillar".[265] Its capital bears the arms of William Preston of Gorton on its east face; James Kennedy, Bishop of St Andrews on its west face; Nicholas Otterbourne, Vicar of Edinburgh on its north face; and Edinburgh on its south face. The south respond bears the arms of Thomas Cranstoun, Chief Magistrate of Edinburgh; the north respond bears the arms of Alexander Napier of Merchiston, Provost of Edinburgh.[267] Archaeological excavations in the 1980s found evidence these works and the creation of the Preston Aisle may have been partially spurred by a structural failure of parts of the church due to poor foundations and the need for renovations.[40]

Choir aisles

[edit]Of the two choir aisles, the north is only two thirds the width of the south aisle, which contained the Lady Chapel prior to the Reformation.[227][220] Richard Fawcett suggests this indicates that both choir aisles were rebuilt after 1385.[220] In both aisles, the curvature of the spandrels between the ribs gives the effect of a dome in each bay.[235][244][268] The ribs appear to serve a structural purpose; however, the lack of any intersection between the lateral and longitudinal cells of each bay means that these vaults are effectively pointed barrel vaults.[13][269] Having been added as part of the mid-15th century extension, the eastern bays of both aisles contain proper lateral cells.[263] The north wall of the north choir aisle contains a 15th-century tomb recess; in this wall, a grotesque, which may date to the 12th century church, has been re-set.[44][263] At the east end of the south aisle is a stone staircase added by Bernard Feilden and Simpson & Brown in 1981–82.[263]

The Chambers Aisle stands north of the westernmost bay of the north choir aisle. This chapel was created in 1889–91 by MacGibbon and Ross as a memorial to William Chambers.[263] This Aisle stands on the site of the medieval vestry, which, at the Reformation, was converted to the Town Clerk's office before being restored to its original use by William Burn.[270] MacGibbon and Ross removed the wall between the vestry and the church and inserted a new arch and vaulted ceiling, both of which incorporate medieval masonry.[263][271]

The Preston Aisle stands south of the western three bays of the south choir aisle. It is named for William Preston of Gorton, who donated Saint Giles' arm-bone to the church; Preston's arms recur in the bosses and capitals of the chapel.[254][272] The town council began the Aisle's construction in 1455, undertaking to complete it within seven years; however, the presence in the Aisle of a boss bearing the arms of Lord Hailes, Provost of Edinburgh in the 1480s, suggests construction took significantly longer.[263] The Aisle's tierceron vault and pillars are similar to those in the 15th century extension of the choir.[254][259] The pillars and capitals also bear a strong resemblance to those between the inner and outer south nave aisles.[273]

The Chepman Aisle extends south of the westernmost bay of the Preston Aisle. The Aisle was founded by Walter Chepman; permission for construction was granted in 1507 and consecration took place in 1513.[259] The ceiling of the Aisle is a pointed barrel vault whose central boss depicts an angel bearing Chepman's arms impaled with those of his first wife, Mariota Kerkettill.[259][273] The Aisle was divided into three storeys during the Burn restoration then restored in 1888 under the direction of Robert Rowand Anderson.[274]

Stained glass

[edit]St Giles' is glazed with 19th and 20th century stained glass by a diverse array of artists and manufacturers. Between 2001 and 2005, the church's stained glass was restored by the Stained Glass Design Partnership of Kilmaurs.[275]

Fragments of the medieval stained glass were discovered in the 1980s: none was obviously pictorial and some may have been grisaille.[61] A pre-Reformation window depicting an elephant and the emblem of the Incorporation of Hammermen survived in the St Eloi Aisle until the 19th century.[276] References to the removal of the stained glass windows after the Reformation are unclear.[86][277] A scheme of coloured glass was considered as early as 1830: three decades before the first new coloured glass in a Church of Scotland building was installed at Greyfriars Kirk in 1857; however, the plan was rejected by the town council.[204][278]

Victorian windows

[edit]

By the 1860s, attitudes to stained glass had liberalised within Scottish Presbyterianism and the insertion of new windows was a key component of William Chambers' plan to restore St Giles'.[164] The firm of James Ballantine was commissioned to produce a sequence depicting the life of Christ, as suggested by the artists Robert Herdman and Joseph Noel Paton. This sequence commences with a window of 1874 in the north choir aisle and climaxes in the great east window of 1877, depicting the Crucifixion and Ascension.[279][280]

Other windows by Ballantine & Son are the Prodigal Son window in the south wall of the south nave aisle; the west window of the Albany Aisle, depicting the parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins and the parable of the talents (1876); and the west window of the Preston Aisle, depicting Saint Paul (1881).[281] Ballantine & Son are also responsible for the window of the Holy Blood Aisle, depicting the assassination and funeral of the Regent Moray (1881): this is the only window of the church that depicts events from Scottish history.[282][283][284] Andrew Ballantine produced the west window in the south wall of the inner south nave aisle (1886): this depicts scenes from the life of Moses.[282] The subsequent generation of the Ballantine firm, Ballantine & Gardiner, produced windows depicting the first Pentecost (1895) and Saint Peter (1895–1900) in the Preston Aisle; David and Jonathan in the east window of the south side of the outer south nave aisle (1900–01); Joseph in the east window of the south wall of the inner south nave aisle (1898); and, in the windows of the Chambers Aisle, Solomon's construction of the Temple (1892) and scenes from the life of John the Baptist (1894).[281][271]

Multiple generations of the Ballantine firm executed heraldic windows in the oriel window of the outer south nave aisle (1883) and in the clerestory of the choir (1877–92): the latter series depicts the arms of the Incorporated Trades of Edinburgh. David Small is responsible for the easternmost window of the north side of the clerestory (1879).[281] Ballantine & Son also produced the window of the Chepman Aisle, showing the arms of notable 17th century Royalists (1888); in the St Eloi Aisle, the Glass Stainers' Company produced a companion window, showing the arms of notable Covenanters (1895).[282][285]

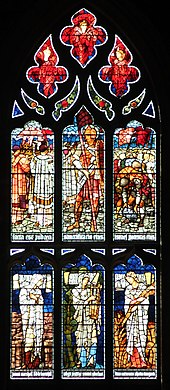

Daniel Cottier designed the east window of the north side of the north nave aisle, depicting the Christian virtues (1890). Cottier also designed the great west window, now-replaced, depicting the Prophets (1886).[282][286][287] Edward Burne-Jones designed the window in the west wall of the north nave aisle (1886). This was produced by Morris & Co. and shows Joshua and the Israelites in the upper section with Jephthah's daughter, Miriam, and Ruth in the lower section.[282][286][287] Other stained glass artists of the Victorian era represented in St Giles' are Burlison & Grylls, who executed the Patriarchs window in the west wall of the inner south nave aisle and Charles Eamer Kempe, who created the west window of the south side of the outer south nave aisle: this depicts biblical writers.[282]

20th century windows

[edit]

Oscar Paterson is responsible for the west window of the north side of the north nave aisle (1906): this shows saints associated with St Giles'.[282] Karl Parsons designed the west window of the south side of the south choir aisle (1913): this depicts saints associated with Scotland.[280] Douglas Strachan is responsible for the windows of the choir clerestory that depict saints (1932–35) and for the north transept window (1922): this shows Christ walking on water and stilling the Sea of Galilee, alongside golden angels subduing demons that represent the four winds of the earth.[175][282][288]

Windows of the later 20th century include a window in the north transept clerestory by William Wilson, depicting Saint Andrew (1954), and the east window of the Albany Aisle, on the theme of John the Divine, designed by Francis Spear and painted by Arthur Pearce (1957).[282][289][290] The most significant recent window is the great west window, a memorial to Robert Burns (1985). This was designed by Leifur Breiðfjörð to replace the Cottier window of 1886, the glass of which had failed.[282][291][292] A scheme of coloured glass, designed by Christian Shaw, was installed in the south transept behind the organ in 1991.[290]

Memorials

[edit]

There are over a hundred memorials in St. Giles'; most date from the 19th century onwards.[293]

In the medieval period, the floor of St Giles' was paved with memorial stones and brasses; these were gradually cleared after the Reformation.[294] At the Burn restoration of 1829–1833, most post-Reformation memorials were destroyed; fragments were removed to Culter Mains and Swanston.[295]

The installation of memorials to notable Scots was an important component of William Chambers' plans to make St Giles' the "Westminster Abbey of Scotland".[294][164] To this end, a management board was set up in 1880 to supervise the installation of new monuments; it continued in this function until 2000.[296] All the memorials were conserved between 2008 and 2009.[297]

Ancient memorials

[edit]

Medieval tomb recesses survive in the Preston Aisle, Holy Blood Aisle, Albany Aisle, and north choir aisle; alongside these, fragments of memorial stones have been re-incorporated into the east wall of the Preston Aisle: these include a memorial to "Johannes Touris de Innerleith" and a carving of the coat of arms of Edinburgh.[295]

A memorial brass to the Regent Moray is situated on his monument in the Holy Blood Aisle. The plaque depicts female personifications of Justice and Religion flanking the Regent's arms and an inscription by George Buchanan. The plaque was inscribed by James Gray on the rear of a fragment of a late 15th century memorial brass: a fibreglass replica of this side of the brass is installed on the opposite wall.[295][298] The plaque was originally set in a monument of 1570 by Murdoch Walker and John Ryotell: this was destroyed at the Burn restoration but the plaque was saved and reinstated in 1864, when John Stuart, 12th Earl of Moray commissioned David Cousin to design a replica of his ancestor's memorial.[280][298]

A memorial tablet in the basement vestry commemorates John Stewart, 4th Earl of Atholl, who was buried in the Chepman Aisle in 1579.[295] A plaque commemorating the Napiers of Merchiston is located on the north exterior wall of the choir.[211] This was likely installed on the south side of the church by Archibald Napier, 1st Lord Napier in 1637; it was moved to its present location during the Burn restoration.[226][295]

Victorian and Edwardian memorials

[edit]Most memorials installed between the Burn restoration of 1829–1833 and the Chambers restoration of 1872–83 are now located in the north transept: these include white marble tablets commemorating Major General Robert Henry Dick (died 1846); Patrick Robertson, Lord Robertson (died 1855); and Aglionby Ross Carson (1856).[299][300] The largest of these memorials is a massive plaque surmounted by an urn designed by David Bryce to commemorate George Lorimer, Dean of Guild and hero of the 1865 Theatre Royal fire (1867).[299][301]

William Chambers, who funded the restoration of 1872–83, commissioned the memorial plaque to Walter Chepman in the Chepman Aisle (1879): this was designed by William Hay and produced by Francis Skidmore.[280][302] Chambers himself is commemorated by a large plaque in a red marble frame (1894): located in the Chambers Aisle, this was designed by David MacGibbon with the bronze plaque produced by Hamilton and Inches.[303] William Hay, the architect who oversaw the restoration (died 1888), is commemorated by a plaque in the north transept vestibule with a relief portrait by John Rhind.[299][304]

The first memorial installed after the Chambers restoration was a brass plaque dedicated to Dean James Hannay, the cleric whose reading of Charles I's Scottish Prayer Book in 1637 sparked rioting (1882).[285][305] In response, and John Stuart Blackie and Robert Halliday Gunning supported a monument to Jenny Geddes, who, according to tradition, threw a stool at Hannay. An 1885 plaque on the floor between south nave aisles now marks the putative spot of Geddes' action.[285][306] Other historical figures commemorated by plaques of this period include Agnes Keith, Countess of Moray (1893); Robert Leighton (1883); Gavin Douglas (1883); Alexander Henderson (1883); William Carstares (1884); and John Craig (1883), and James Dalrymple, 1st Viscount Stair (1906).[307]

The largest memorials of this period are the Jacobean-style monuments to James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose in the Chepman Aisle (1888) and to his rival, Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll, in the St Eloi Aisle (1895); both are executed in alabaster and marble and take the form of aedicules in which lie life-size effigies of their dedicatees. The Montrose monument was designed by Robert Rowand Anderson and carved by John and William Birnie Rhind. The Argyll monument, funded by Robert Halliday Gunning, was designed by Sydney Mitchell and carved by Charles McBride.[308][309]

Other prominent memorials of this period include the Jacobean-style plaque on the south wall of the south choir aisle, commemorating John Inglis, Lord Glencorse and designed by Robert Rowand Anderson (1892); the memorial to Arthur Penrhyn Stanley (died 1881) in the Preston Aisle, including a relief portrait by Mary Grant; and the large bronze relief of Robert Louis Stevenson by Augustus Saint-Gaudens on the west wall of the Moray Aisle (1904).[308] A life-size bronze statue of John Knox by James Pittendrigh MacGillivray (1906) stands in the north nave aisle. This initially stood in a Gothic niche in the east wall of the Albany Aisle; the niche was removed in 1951 and between 1965 and 1983, the statue stood outside the church, in Parliament Square.[310]

20th and 21st century memorials

[edit]

In the north choir aisle, the bronze plaque commemorating Sophia Jex-Blake (died 1912) and the stone plaque to James Nicoll Ogilvie (1928) were designed by Robert Lorimer.[311] Lorimer himself is commemorated by a large stone plaque in the Preston Aisle (1932): this was designed by Alexander Paterson.[312] A number of plaques in the "Writers' Corner" in the Moray Aisle incorporate relief portraits of their dedicatees: these include memorials to Robert Fergusson (1927) and Margaret Oliphant (1908), sculpted by James Pittendrigh Macgillivray; John Brown (1924), sculpted by Pilkington Jackson; and John Stuart Blackie (died 1895) and Thomas Chalmers (died 1847), designed by Robert Lorimer.[280][313] Further relief portrait plaques commemorate Robert Inches (1922) in the former session house and William Smith (1929) in the Chambers Aisle; the former was sculpted by Henry Snell Gamley.[314] Pilkington Jackson executed a pair of bronze relief portraits in pedimented Hopton Wood stone frames to commemorate Cameron Lees (1931) and Wallace Williamson (1936): these flank the entrance to the Thistle Chapel in the south choir aisle.[299]

Modern sculptures include the memorial to Wellesley Bailey in the south choir aisle, designed by James Simpson (1987) and Merilyn Smith's bronze sculpture of a stool in the south nave aisle, commemorating Jenny Geddes (1992).[315] The most recent memorials are plaques by Kindersley Cardozo Workshop of Cambridge commemorating James Young Simpson (1997) and Ronald Colville, 2nd Baron Clydesmuir (2003) in the Moray Aisle and marking the 500th anniversary of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in the north choir aisle (2005).[316]

Military memorials

[edit]Victorian

[edit]Victorian military memorials are concentrated at the west end of the church. The oldest military memorial is John Steell's memorial to members of the 78th (Highlanders) Regiment of Foot killed by disease in Sindh between 1844 and 1845 (1850): this white marble tablet contains a relief of a mourning woman and is located on the west wall of the nave.[317] Nearby is the second-oldest military memorial, William Brodie's Indian Rebellion of 1857 memorial for the 93rd (Sutherland Highlanders) Regiment of Foot (1864): this depicts, in white marble, two Highland soldiers flanking a tomb.[318][319]

John Rhind sculpted the Royal Scots Greys' Sudan memorial (1886): a large brass Celtic cross on grey marble. John Rhind and William Birnie Rhind sculpted the Highland Light Infantry's Second Boer War memorial: a marble-framed brass plaque. William Birnie Rhind and Thomas Duncan Rhind sculpted the Royal Scots 1st Battalion's Second Boer War memorial: a bronze relief within a pedimented marble frame (1903); WS Black designed the Royal Scots 3rd Battalion's Second Boer War memorial: a portrait marble plaque surmounted by an angel flanked by obelisks.[320]

World Wars

[edit]

The Elsie Inglis memorial in the north choir aisle was designed by Frank Mears and sculpted in rose-tinted French stone and slate by Pilkington Jackson (1922): it depicts the angels of Faith, Hope, and Love.[321] Jackson also executed the Royal Scots 5th Battalion's Gallipoli Campaign memorial – bronze with a marble tablet (1921) – and the 16th (McCrae's) Battalion's First World War memorial, showing Saint Michael and sculpted in Portland stone: this was designed by Robert Lorimer, who also designed the bronze memorial plaque to the Royal Army Medical Corps in the north choir aisle.[299][322] Individual victims of the war commemorated in St Giles' include Neil Primrose (1918) and Sir Robert Arbuthnot, 4th Baronet (1917). Ministers and students of the Church of Scotland and United Free Church of Scotland are commemorated by a large oak panel at the east end of the north nave aisle by Messrs Begg and Lorne Campbell (1920).[323]

Henry Snell Gamley is responsible for the congregation's First World War memorial (1926): located in the Albany Aisle, this consists of a large bronze relief of an angel crowning the "spirit of a soldier", its green marble tablet names the 99 members of the congregation killed in the conflict.[324] Gamley is also responsible for the nearby white marble and bronze tablet to Scottish soldiers killed in France (1920); the Royal Scots 9th Battalion's white marble memorial in the south nave aisle (1921); and the bronze relief portrait memorial to Edward Maxwell Salvesen in the north choir aisle (1918).[325]

The names of 38 members of the congregation killed in the Second World War are inscribed on tablets designed by Esmé Gordon within a medieval tomb recess in the Albany Aisle: these were unveiled at the dedication of the Albany Aisle as a war memorial chapel in 1951. As part of this memorial, a cross with panels by Elizabeth Dempster was mounted on the east wall of the Aisle.[62][248] Other notable memorials of the Second World War include Basil Spence's large wooden plaque to the 94th (City of Edinburgh) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery (1954) in the north choir aisle and the nearby Church of Scotland chaplains memorial (1950): this depicts Saint Andrew in bronze relief and was manufactured by Charles Henshaw.[299]

Features

[edit]Prior to the Reformation, St Giles' was furnished with as many as fifty stone subsidiary altars, each with their own furnishings and plate.[62][d] The Dean of Guild's accounts from the 16th century also indicate the church possessed an Easter sepulchre, sacrament house, rood loft, lectern, pulpit, wooden chandeliers, and choir stalls.[2] On 16 December 1558, the goldsmith James Mosman weighed and valued the treasures of St Giles' including the reliquary of the saint's arm bone with a diamond ring on his finger, a silver cross, and a ship for incense.[326] At the Reformation, the interior was stripped and a new pulpit at the east side of the crossing became the church's focal point. Seating was installed for children and the burgh's council and trade guilds and a stool of penitence was added. After the Reformation, St Giles' was gradually partitioned into smaller churches.[87]

At the church's restoration by William Hay in 1872–83, the last post-Reformation internal partitions were removed and the church was oriented to face the communion table at the east end; the nave was furnished with chairs and the choir with stalls; a low railing separated the nave from the choir. The Buildings of Scotland series described this arrangement as "High Presbyterian (Low Anglican)". Most of the church's furnishings date from this restoration onwards. From 1982, the church was reoriented with seats in the choir and nave facing a central communion table under the crossing.[62]

Furniture

[edit]Pulpits, tables, and font

[edit]The pulpit dates to 1883 and was carved in Caen stone and green marble by John Rhind to a design by William Hay. The pulpit is octagonal with relief panels depicting the acts of mercy.[327] An octagonal oak pulpit of 1888 with a tall steepled canopy stands in the Moray Aisle: this was designed by Robert Rowand Anderson.[62] St Giles' possessed a wooden pulpit prior to the Reformation. In April 1560, this was replaced with a wooden pulpit with two locking doors, likely located at the east side of the crossing; a lectern was also installed.[328] A brass eagle lectern stands on the south side of the crossing: this was given by an anonymous couple for use in the Moray Aisle.[329] The bronze lectern steps were sculpted by Jacqueline Stieger and donated in 1991 by the Normandy Veterans' Association.[330][331] Until 1982, a Caen stone lectern, designed by William Hay stood opposite the pulpit at the west end of the choir.[332]

Situated in the crossing, the communion table is a Carrara marble block unveiled in 2011: it was donated by Roger Lindsay and designed by Luke Hughes. This replaced a wooden table in use since 1982.[333] The plain communion table used after the Chambers restoration was donated to the West Parish Church of Stirling in 1910 and replaced by an oak communion table designed by Robert Lorimer and executed by Nathaniel Grieve. The table displays painted carvings of the Lamb of God, Saint Giles, and angels; it was lengthened in 1953 by Scott Morton & Co. and now stands in the Preston Aisle.[334][335] The Albany Aisle contains a neo-Jacobean communion table by Whytock and Reid, which was installed at the time of the Aisle's dedication as a war memorial chapel in 1951.[62][248] A small communion table with Celtic knot and floral designs was added to the Preston Aisle in 2019; this was designed by Sheanna Ashton and made by Grassmarket Furniture.[336]

The communion table and reredos of the Chambers Aisle were designed by Robert Lorimer and John Fraser Matthew in 1927–29. The reredos contains a relief of the adoration of the infant Christ by angels: this is the work of Morris and Alice Meredith Williams.[62] In 1931, Matthew designed a reredos and communion table for the Moray Aisle; these were removed in 1981 and later sold to the National Museum of Scotland.[337][338] A reredos in the form of a Gothic arcade stood at the east end of the church from the Chambers restoration; this was designed by William Hay and executed in Caen stone with green marble pillars. In 1953, this was replaced with a fabric reredos, designed by Esmé Gordon. The Gordon reredos was removed in 1971; the east wall is now bare.[339]

The Caen stone font by John Rhind is in the form of a kneeling angel holding a scallop; the font is an exact replica of Bertel Thorvaldsen's font for the Church of Our Lady, Copenhagen. Initially, it stood near the pulpit before being moved to the west end of the south nave aisle; between 1916 and 1951, it stood in the Albany Aisle; it was then moved to near the west door and has stood in the north choir aisle since 2015.[62][340]

Seating

[edit]Since 2003, new chairs, many of which bear small brass plaques naming donors, have replaced chairs of the 1880s by West and Collier throughout the church.[341] Two banks of choir stalls in a semi-circular arrangement occupy the south transept; these were installed by Whytock & Reid in 1984. Whytock & Reid also provided box pews for the nave in 1985; these have since been removed.[329] In 1552, prior to the Reformation, Andrew Mansioun executed the south bank of choir stalls; the north bank were likely imported. In 1559, at the outset of the Scottish Reformation, these were removed to the Tolbooth for safe-keeping; they may have been re-used to furnish the church after the Reformation.[87][2]

There has been a royal loft or pew in St Giles' since the regency of Mary of Guise.[j] Standing between the south choir aisle and Preston Aisle, the current monarch's seat possess a tall back and canopy, on which stand the royal arms of Scotland; this oak seat and desk were created in 1953 to designs of Esmé Gordon and incorporate elements of the former royal pew of 1885 by William Hay.[62][248] Hay's royal pew stood in the Preston Aisle; it replaced an oak royal pew of 1873, also designed by Hay and executed by John Taylor & Son: this was re-purposed as an internal west porch and was removed in 2008.[62][202]

Metalwork, lighting, and plate