Оксфордский университет

| |

| Английский : Оксфордский университет | |

Другое имя | Канцлер, магистры и ученые Оксфордского университета [1] |

|---|---|

| Девиз | На латыни : Господь — мое просвещение. |

Девиз на английском языке | Господь - мой свет |

| Type | Public research university Ancient university |

| Established | c. 1096[2] |

| Endowment | £8.066 billion (2023; including colleges)[5] |

| Budget | £2.924 billion (2022/23)[4] |

| Chancellor | The Lord Patten of Barnes |

| Vice-Chancellor | Irene Tracey[6] |

Academic staff | 6,945 (2022)[7] |

| Students | 26,945 (2023)[8][9] |

| Undergraduates | 12,580 |

| Postgraduates | 13,445 |

Other students | 430 |

| Location | , England 51°45′18″N 01°15′18″W / 51.75500°N 1.25500°W |

| Campus | University town |

| Colours | Oxford Blue[10] |

| Affiliations | |

| Website | ox |

| |

— Оксфордский университет университетский исследовательский университет в Оксфорде , Англия. Есть свидетельства обучения еще в 1096 году. [2] что делает его старейшим университетом в англоязычном мире и вторым старейшим постоянно действующим университетом в мире . [2] [11] [12] Оно быстро росло с 1167 года, когда Генрих II запретил английским студентам посещать Парижский университет . [2] После споров между студентами и горожанами Оксфорда некоторые оксфордские ученые бежали на северо-восток в Кембридж , где в 1209 году они основали Кембриджский университет . [13] Два древних английских университета имеют много общих черт и вместе называются Оксбриджем . [14]

Оксфордский университет состоит из 43 составляющих колледжей, состоящих из 36 полуавтономных колледжей , четырех постоянных частных залов и трех обществ (колледжей, которые являются отделениями университета, без собственной королевской хартии ), [15] [16] и ряд академических отделов, которые разделены на четыре подразделения . [17] Каждый колледж является самоуправляющимся учреждением внутри университета, контролирующим свой состав и имеющим свою внутреннюю структуру и деятельность. Все студенты являются членами колледжа. [15] У университета нет главного кампуса, но его здания и помещения разбросаны по всему центру города. Обучение на бакалавриате в небольших группах в Оксфорде состоит из лекций, занятий в колледжах и залах, семинаров, лабораторных работ и иногда дополнительных занятий, проводимых центральными факультетами и кафедрами университета. Последипломное обучение осуществляется преимущественно централизованно.

Oxford operates the Ashmolean Museum, the world's oldest university museum; Oxford University Press, the largest university press in the world; and the largest academic library system nationwide.[18] In the fiscal year ending 31 July 2023, the university had a total consolidated income of £2.92 billion, of which £789 million was from research grants and contracts.[4]

Oxford has educated a wide range of notable alumni, including 31 prime ministers of the United Kingdom and many heads of state and government around the world.[19] As of October 2022,[update] 73 Nobel Prize laureates, 4 Fields Medalists, and 6 Turing Award winners have matriculated, worked, or held visiting fellowships at the University of Oxford, while its alumni have won 160 Olympic medals.[20] Oxford is the home of numerous scholarships, including the Rhodes Scholarship, one of the oldest international graduate scholarship programmes.

History

[edit]

Founding

[edit]

The University of Oxford's foundation date is unknown.[21] In the 14th century, the historian Ranulf Higden wrote that the university was founded in the 10th century by Alfred the Great, but this story is apocryphal.[22] It is known that teaching at Oxford existed in some form as early as 1096, but it is unclear when the university came into being.[2] Scholar Theobald of Étampes lectured at Oxford in the early 1100s.

It grew quickly from 1167 when English students returned from the University of Paris.[2] The historian Gerald of Wales lectured to such scholars in 1188, and the first known foreign scholar, Emo of Friesland, arrived in 1190. The head of the university had the title of chancellor from at least 1201, and the masters were recognised as a universitas or corporation in 1231.[2][23] The university was granted a royal charter in 1248 during the reign of King Henry III.[24]

After disputes between students and Oxford townsfolk in 1209, some academics fled from the violence to Cambridge, later forming the University of Cambridge.[13][25]

The students associated together on the basis of geographical origins, into two 'nations', representing the North (northerners or Boreales, who included the English people from north of the River Trent and the Scots) and the South (southerners or Australes, who included English people from south of the Trent, the Irish and the Welsh).[26][27] In later centuries, geographical origins continued to influence many students' affiliations when membership of a college or hall became customary in Oxford. In addition, members of many religious orders, including Dominicans, Franciscans, Carmelites, and Augustinians, settled in Oxford in the mid-13th century, gained influence and maintained houses or halls for students.[28] At about the same time, private benefactors established colleges as self-contained scholarly communities. Among the earliest such founders were William of Durham, who in 1249 endowed University College,[28] and John Balliol, father of a future King of Scots; Balliol College bears his name.[26] Another founder, Walter de Merton, a Lord Chancellor of England and afterwards Bishop of Rochester, devised a series of regulations for college life;[29][30] Merton College thereby became the model for such establishments at Oxford,[31] as well as at the University of Cambridge. Thereafter, an increasing number of students lived in colleges rather than in halls and religious houses.[28]

In 1333–1334, an attempt by some dissatisfied Oxford scholars to found a new university at Stamford, Lincolnshire, was blocked by the universities of Oxford and Cambridge petitioning King Edward III.[32] Thereafter, until the 1820s, no new universities were allowed to be founded in England, even in London; thus, Oxford and Cambridge had a duopoly, which was unusual in large western European countries.[33][34]

Renaissance period

[edit]

The new learning of the Renaissance greatly influenced Oxford from the late 15th century onwards. Among university scholars of the period were William Grocyn, who contributed to the revival of Greek language studies,[35] and John Colet, the noted biblical scholar.[36]

With the English Reformation and the breaking of communion with the Roman Catholic Church, recusant scholars from Oxford fled to continental Europe, settling especially at the University of Douai.[37] The method of teaching at Oxford was transformed from the medieval scholastic method to Renaissance education, although institutions associated with the university suffered losses of land and revenues. As a centre of learning and scholarship, Oxford's reputation declined in the Age of Enlightenment; enrolments fell and teaching was neglected.[38]

In 1636,[39] William Laud, the chancellor and Archbishop of Canterbury, codified the university's statutes. These, to a large extent, remained its governing regulations until the mid-19th century. Laud was also responsible for the granting of a charter securing privileges for the University Press, and he made significant contributions to the Bodleian Library, the main library of the university. From the beginnings of the Church of England as the established church until 1866, membership of the church was a requirement to graduate as a Bachelor of Arts, and "dissenters" were only permitted to be promoted to Master of Arts in 1871.[40]

The university was a centre of the Royalist party during the English Civil War (1642–1649), while the town favoured the opposing Parliamentarian cause.[41]

Wadham College, founded in 1610, was the undergraduate college of Sir Christopher Wren. Wren was part of a brilliant group of experimental scientists at Oxford in the 1650s, the Oxford Philosophical Club, which included Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke. This group, which has at times been linked with Boyle's "Invisible College", held regular meetings at Wadham under the guidance of the college's Warden, John Wilkins, and the group formed the nucleus that went on to found the Royal Society.[42]

Modern period

[edit]Students

[edit]Before reforms in the early 19th century, the curriculum at Oxford was notoriously narrow and impractical. Sir Spencer Walpole, a historian of contemporary Britain and a senior government official, had not attended any university. He said, "Few medical men, few solicitors, few persons intended for commerce or trade, ever dreamed of passing through a university career." He quoted the Oxford University Commissioners in 1852 stating: "The education imparted at Oxford was not such as to conduce to the advancement in life of many persons, except those intended for the ministry."[43] Nevertheless, Walpole argued:

Among the many deficiencies attending a university education there was, however, one good thing about it, and that was the education which the undergraduates gave themselves. It was impossible to collect some thousand or twelve hundred of the best young men in England, to give them the opportunity of making acquaintance with one another, and full liberty to live their lives in their own way, without evolving in the best among them, some admirable qualities of loyalty, independence, and self-control. If the average undergraduate carried from University little or no learning, which was of any service to him, he carried from it a knowledge of men and respect for his fellows and himself, a reverence for the past, a code of honour for the present, which could not but be serviceable. He had enjoyed opportunities... of intercourse with men, some of whom were certain to rise to the highest places in the Senate, in the Church, or at the Bar. He might have mixed with them in his sports, in his studies, and perhaps in his debating society; and any associations which he had this formed had been useful to him at the time, and might be a source of satisfaction to him in after life.[44]

Out of the students who matriculated in 1840, 65% were sons of professionals (34% were Anglican ministers). After graduation, 87% became professionals (59% as Anglican clergy). Out of the students who matriculated in 1870, 59% were sons of professionals (25% were Anglican ministers). After graduation, 87% became professionals (42% as Anglican clergy).[45][46]

M. C. Curthoys and H. S. Jones argue that the rise of organised sport was one of the most remarkable and distinctive features of the history of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was carried over from the athleticism prevalent at the public schools such as Eton, Winchester, Shrewsbury, and Harrow.[47]

All students, regardless of their chosen area of study, were required to spend (at least) their first year preparing for a first-year examination that was heavily focused on classical languages. Science students found this particularly burdensome and supported a separate science degree with Greek language study removed from their required courses. This concept of a Bachelor of Science had been adopted at other European universities (London University had implemented it in 1860) but an 1880 proposal at Oxford to replace the classical requirement with a modern language (like German or French) was unsuccessful. After considerable internal wrangling over the structure of the arts curriculum, in 1886 the "natural science preliminary" was recognised as a qualifying part of the first year examination.[48]

At the start of 1914, the university housed about 3,000 undergraduates and about 100 postgraduate students. During the First World War, many undergraduates and fellows joined the armed forces. By 1918 virtually all fellows were in uniform, and the student population in residence was reduced to 12 per cent of the pre-war total.[49] The University Roll of Service records that, in total, 14,792 members of the university served in the war, with 2,716 (18.36%) killed.[50] Not all the members of the university who served in the Great War were on the Allied side; there is a remarkable memorial to members of New College who served in the German armed forces, bearing the inscription, 'In memory of the men of this college who coming from a foreign land entered into the inheritance of this place and returning fought and died for their country in the war 1914–1918'. During the war years the university buildings became hospitals, cadet schools and military training camps.[49]

Reforms

[edit]Two parliamentary commissions in 1852 issued recommendations for Oxford and Cambridge. Archibald Campbell Tait, a former headmaster of Rugby School, was a key member of the Oxford Commission; he wanted Oxford to follow the German and Scottish model in which the professorship was paramount. The commission's report envisioned a centralised university run predominantly by professors and faculties, with a much stronger emphasis on research. The professional staff should be strengthened and better paid. For students, restrictions on entry should be dropped, and more opportunities given to poorer families. It called for an enlargement of the curriculum, with honours to be awarded in many new fields. Undergraduate scholarships should be open to all Britons. Graduate fellowships should be opened up to all members of the university. It recommended that fellows be released from an obligation for ordination. Students were to be allowed to save money by boarding in the city, instead of in a college.[51][52]

The system of separate honour schools for different subjects began in 1802, with Mathematics and Literae Humaniores.[53] Schools of "Natural Sciences" and "Law, and Modern History" were added in 1853.[53] By 1872, the last of these had split into "Jurisprudence" and "Modern History". Theology became the sixth honour school.[54] In addition to these B.A. Honours degrees, the postgraduate Bachelor of Civil Law (B.C.L.) was, and still is, offered.[55]

The mid-19th century saw the impact of the Oxford Movement (1833–1845), led among others by the future Cardinal John Henry Newman.

Administrative reforms during the 19th century included the replacement of oral examinations with written entrance tests, greater tolerance for religious dissent, and the establishment of four women's colleges. Privy Council decisions in the 20th century (e.g. the abolition of compulsory daily worship, dissociation of the Regius Professorship of Hebrew from clerical status, diversion of colleges' theological bequests to other purposes) loosened the link with traditional belief and practice. Furthermore, although the university's emphasis had historically been on classical knowledge, its curriculum expanded during the 19th century to include scientific and medical studies.

The University of Oxford began to award doctorates for research in the first third of the 20th century. The first Oxford DPhil in mathematics was awarded in 1921.[56]

The list of distinguished scholars at the University of Oxford is long and includes many who have made major contributions to politics, the sciences, medicine, and literature. As of October 2022, 73 Nobel laureates and more than 50 world leaders have been affiliated with the University of Oxford.[19]

Women's education

[edit]The university passed a statute in 1875 allowing examinations for women at roughly undergraduate level;[57] for a brief period in the early 1900s, this allowed the "steamboat ladies" to receive ad eundem degrees from the University of Dublin.[58] In June 1878, the Association for the Education of Women (AEW) was formed, aiming for the eventual creation of a college for women in Oxford. Some of the more prominent members of the association were George Granville Bradley, T. H. Green and Edward Stuart Talbot. Talbot insisted on a specifically Anglican institution, which was unacceptable to most of the other members. The two parties eventually split, and Talbot's group founded Lady Margaret Hall in 1878, while T. H. Green founded the non-denominational Somerville College in 1879.[59] Lady Margaret Hall and Somerville opened their doors to their first 21 students (12 at Somerville, 9 at Lady Margaret Hall) in 1879, who attended lectures in rooms above an Oxford baker's shop.[57] There were also 25 women students living at home or with friends in 1879, a group which evolved into the Society of Oxford Home-Students and in 1952 into St Anne's College.[60][61]

These first three societies for women were followed by St Hugh's (1886)[62] and St Hilda's (1893).[63] All of these colleges later became coeducational, starting with Lady Margaret Hall and St Anne's in 1979,[64][60] and finishing with St Hilda's, which began to accept male students in 2008.[65] In the early 20th century, Oxford and Cambridge were widely perceived to be bastions of male privilege;[66] however, the integration of women into Oxford moved forward during the First World War. In 1916 women were admitted as medical students on a par with men, and in 1917 the university accepted financial responsibility for women's examinations.[49]

On 7 October 1920 women became eligible for admission as full members of the university and were given the right to take degrees.[67] In 1927 the university's dons created a quota that limited the number of female students to a quarter that of men, a ruling which was not abolished until 1957.[57] However, during this period Oxford colleges were single sex, so the number of women was also limited by the capacity of the women's colleges to admit students. It was not until 1959 that the women's colleges were given full collegiate status.[68]

In 1974, Brasenose, Jesus, Wadham, Hertford and St Catherine's became the first previously all-male colleges to admit women.[69][70] The majority of men's colleges accepted their first female students in 1979,[70] with Christ Church following in 1980,[71] and Oriel becoming the last men's college to admit women in 1985.[72] Most of Oxford's graduate colleges were founded as coeducational establishments in the 20th century, with the exception of St Antony's, which was founded as a men's college in 1950 and began to accept women only in 1962.[73] By 1988, 40% of undergraduates at Oxford were female;[74] in 2016, 45% of the student population, and 47% of undergraduate students, were female.[75][76]

In June 2017, Oxford announced that starting the following academic year, history students may choose to sit a take-home exam in some courses, with the intention that this will equalise rates of firsts awarded to women and men at Oxford.[77] That same summer, maths and computer science tests were extended by 15 minutes, in a bid to see if female student scores would improve.[78][79]

The detective novel Gaudy Night by Dorothy L. Sayers, herself one of the first women to gain an academic degree from Oxford, is largely set in the all-female Shrewsbury College, Oxford (based on Sayers' own Somerville College[80]), and the issue of women's education is central to its plot. Social historian and Somerville College alumna Jane Robinson's book Bluestockings: A Remarkable History of the First Women to Fight for an Education gives a very detailed and immersive account of this history.[81]

Buildings and sites

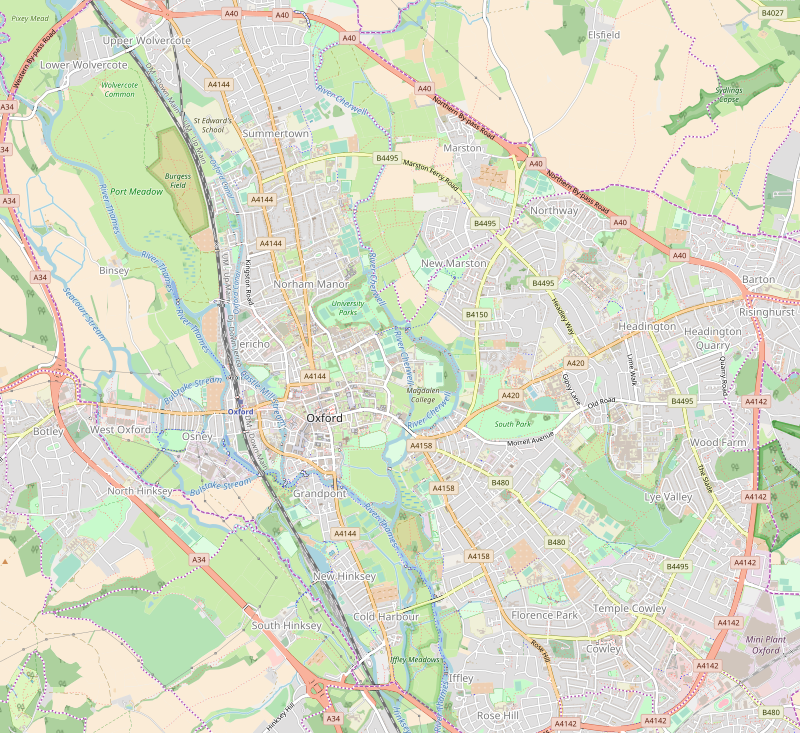

[edit]Map

[edit]| Map of the University of Oxford | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

Main sites

[edit]

The university is a "city university" in that it does not have a main campus; instead, colleges, departments, accommodation, and other facilities are scattered throughout the city centre. The Science Area, in which most science departments are located, is the area that bears closest resemblance to a campus. The ten-acre (4-hectare) Radcliffe Observatory Quarter in the northwest of the city is currently under development.

Iconic university buildings include the Radcliffe Camera, the Sheldonian Theatre used for music concerts, lectures, and university ceremonies, and the Examination Schools, where examinations and some lectures take place. The University Church of St Mary the Virgin was used for university ceremonies before the construction of the Sheldonian.

In 2012–2013, the university built the controversial one-hectare (400 m × 25 m) Castle Mill development of 4–5-storey blocks of student flats overlooking Cripley Meadow and the historic Port Meadow, blocking views of the spires in the city centre.[82] The development has been likened to building a "skyscraper beside Stonehenge".[83]

Parks

[edit]

The University Parks are a 70-acre (28 ha) parkland area in the northeast of the city, near Keble College, Somerville College and Lady Margaret Hall. It is open to the public during daylight hours.

The Botanic Garden on the High Street is the oldest botanic garden in the UK. It contains over 8,000 different plant species on 1.8 ha (4+1⁄2 acres). It is one of the most diverse yet compact major collections of plants in the world and includes representatives of over 90% of the higher plant families. The Harcourt Arboretum is a 130-acre (53 ha) site six miles (9.7 km) south of the city that includes native woodland and 67 acres (27 hectares) of meadow. The 1,000-acre (4.0 km2) Wytham Woods are owned by the university and used for research in zoology and climate change.[84]

There are also various college-owned open spaces open to the public, including Bagley Wood and most notably Christ Church Meadow.[85]

Organisation

[edit]Colleges arrange the tutorial teaching for their undergraduates, and the members of an academic department are spread around many colleges. Though certain colleges do have subject alignments (e.g., Nuffield College as a centre for the social sciences), these are exceptions, and most colleges will have a broad mix of academics and students from a diverse range of subjects. Facilities such as libraries are provided on all these levels: by the central university (the Bodleian), by the departments (individual departmental libraries, such as the English Faculty Library), and by colleges (each of which maintains a multi-discipline library for the use of its members).[86]

Central governance

[edit]

The university's formal head is the Chancellor, currently Lord Patten of Barnes (due to retire in 2024), though as at most British universities, the Chancellor is a titular figurehead and is not involved with the day-to-day running of the university. The Chancellor is elected by the members of Convocation, a body comprising all graduates of the university, and may hold office until death.[87]

The Vice-Chancellor, currently Irene Tracey,[6] is the de facto head of the university. Five pro-vice-chancellors have specific responsibilities for education; research; planning and resources; development and external affairs; and personnel and equal opportunities.

Two university proctors, elected annually on a rotating basis from any two of the colleges, are the internal ombudsmen who make sure that the university and its members adhere to its statutes. This role incorporates student discipline and complaints, as well as oversight of the university's proceedings.[88] The university's professors are collectively referred to as the Statutory Professors of the University of Oxford. They are particularly influential in the running of the university's graduate programmes. Examples of statutory professors are the Chichele Professorships and the Drummond Professor of Political Economy.

The University of Oxford is only a "public university" in the sense that it receives some public money from the government, but it is a "private university" in the sense that it is entirely self-governing and, in theory, could choose to become entirely private by rejecting public funds.[89]

Colleges

[edit]

To be a member of the university, all students, and most academic staff, must also be a member of a college or hall. There are thirty-nine colleges of the University of Oxford and four permanent private halls (PPHs), each controlling its membership and with its own internal structure and activities.[15] Not all colleges offer all courses, but they generally cover a broad range of subjects.

The colleges are:

- All Souls College

- Balliol College

- Brasenose College

- Christ Church

- Corpus Christi College

- Exeter College

- Green Templeton College

- Harris Manchester College

- Hertford College

- Jesus College

- Keble College

- Kellogg College

- Lady Margaret Hall

- Linacre College

- Lincoln College

- Magdalen College

- Mansfield College

- Merton College

- New College

- Nuffield College

- Oriel College

- Pembroke College

- The Queen's College

- Reuben College

- St Anne's College

- St Antony's College

- St Catherine's College

- St Cross College

- St Edmund Hall

- St Hilda's College

- St Hugh's College

- St John's College

- St Peter's College

- Somerville College

- Trinity College

- University College

- Wadham College

- Wolfson College

- Worcester College

The permanent private halls were founded by different Christian denominations. One difference between a college and a PPH is that whereas colleges are governed by the fellows of the college, the governance of a PPH resides, at least in part, with the corresponding Christian denomination. The four current PPHs are:

The PPHs and colleges join as the Conference of Colleges, which represents the common concerns of the several colleges of the university, to discuss matters of shared interest and to act collectively when necessary, such as in dealings with the central university.[90][91] The Conference of Colleges was established as a recommendation of the Franks Commission in 1965.[92]

Teaching members of the colleges (i.e. fellows and tutors) are collectively and familiarly known as dons, although the term is rarely used by the university itself. In addition to residential and dining facilities, the colleges provide social, cultural, and recreational activities for their members. Colleges have responsibility for admitting undergraduates and organising their tuition; for graduates, this responsibility falls upon the departments.

Finances

[edit]

In 2017–18, the university had an income of £2,237m; key sources were research grants (£579.1m) and academic fees (£332.5m).[93] The colleges had a total income of £492.9m.[94]

While the university has a larger annual income and operating budget, the colleges have a larger aggregate endowment: over £6.4bn compared to the university's £1.2bn.[95] The central University's endowment, along with some of the colleges', is managed by the university's wholly-owned endowment management office, Oxford University Endowment Management, formed in 2007.[96] The university used to maintain substantial investments in fossil fuel companies.[97] However, in April 2020, the university committed to divest from direct investments in fossil fuel companies and to require indirect investments in fossil fuel companies be subjected to the Oxford Martin Principles.[98][99]

The total assets of the colleges of £6.3 billion also exceed total university assets of £4.1 billion.[94][93] The college figure does not reflect all the assets held by the colleges as their accounts do not include the cost or value of many of their main sites or heritage assets such as works of art or libraries.[100]

The university was one of the first in the UK to raise money through a major public fundraising campaign, the Campaign for Oxford. The current campaign, its second, was launched in May 2008 and is entitled "Oxford Thinking – The Campaign for the University of Oxford".[101] This is looking to support three areas: academic posts and programmes, student support, and buildings and infrastructure;[102] having passed its original target of £1.25 billion in March 2012, the target was raised to £3 billion.[103] The campaign had raised a total of £2.8 billion by July 2018.[93]

Funding criticisms

[edit]The university has faced criticism for some of its sources of donations and funding. In 2017, attention was drawn to historical donations including All Souls College receiving £10,000 from slave trader Christopher Codrington in 1710,[104] and Oriel College having receiving taken £100,000 from the will of the imperialist Cecil Rhodes in 1902.[105][106] In 1996 a donation of £20 million was received from Wafic Saïd who was involved in the Al-Yammah arms deal,[107][108] and taking £150 million from the US billionaire businessman Stephen A. Schwarzman in 2019.[109] The university has defended its decisions saying it "takes legal, ethical and reputational issues into consideration".

The university has also faced criticism, as noted above, over its decision to accept donations from fossil fuel companies having received £21.8 million from the fossil fuel industry between 2010 and 2015[110] and £18.8 million between 2015 and 2020.[111][112]

The university accepted £6 million from The Alexander Mosley Charitable Trust in 2021. Former racing driver Max Mosley said he set up the trust "to house the fortune he inherited" from his father,[113] Oswald Mosley, who was founder of two far right groups: Union Movement and the British Union of Fascists.[114]

Affiliations

[edit]Oxford is a member of the Russell Group of research-led British universities, the G5, the League of European Research Universities, and the International Alliance of Research Universities. It is also a core member of the Europaeum and forms part of the "golden triangle" of highly research intensive and elite English universities.[115]

Academic profile

[edit]Admission

[edit]| 2023[116] | 2022[117] | 2021[118] | 2020[119] | 2019[120] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applications | 23,211 | 23,819 | 24,338 | 23,414 | 23,020 |

| Offer Rate (%) | 16.0 | 15.3 | 14.6 | 16.8 | 16.9 |

| Enrolments | 3,219 | 3,271 | 3,298 | 3,695 | 3,280 |

| Yield (%) | 86.5 | 89.7 | 92.8 | 94.0 | 84.3 |

| Applicant/Enrolled Ratio | 7.21 | 7.28 | 7.38 | 6.34 | 7.02 |

| Average Entry Tariff[121] | — | — | 205 | 201 | 200 |

In common with most British universities, prospective undergraduate students apply through the UCAS application system, but prospective applicants for the University of Oxford, along with those for medicine, dentistry, and University of Cambridge applicants, must observe an earlier deadline of 15 October.[128] The Sutton Trust maintains that Oxford University and Cambridge University recruit undergraduates disproportionately from 8 schools which accounted for 1,310 Oxbridge places during three years, contrasted with 1,220 from 2,900 other schools.[129]

To allow a more personalised judgement of students, who might otherwise apply for both, undergraduate applicants are not permitted to apply to both Oxford and Cambridge in the same year. The only exceptions are applicants for organ scholarships[130] and those applying to read for a second undergraduate degree.[131]Oxford has the lowest offer rate of all Russell Group universities.[132]

Most applicants choose to apply to one of the individual colleges. For undergraduates, these colleges work with each other to ensure that the best students gain a place somewhere at the university regardless of their college preferences. For postgraduates, all applicants who receive an offer from the university are guaranteed a college place, even if they do not receive a place at their chosen college.[133]

Undergraduate shortlisting is based on achieved and predicted exam results, school references, and, in some subjects, written admission tests or candidate-submitted written work. Approximately 60% of applicants are shortlisted, although this varies by subject. If a large number of shortlisted applicants for a subject choose one college, then students who named that college may be reallocated randomly to under-subscribed colleges for the subject. The colleges then invite shortlisted candidates for interview, where they are provided with food and accommodation for around three days in December. Most undergraduate applicants will be individually interviewed by academics at more than one college. In 2020 interviews were moved online,[134] and they will remain online until at least 2027.[135]

Undergraduate offers are sent out in early January, with each offer usually being from a specific college. One in four successful candidates receives an offer from a college that they did not apply to. Some courses may make "open offers" to some candidates, who are not assigned to a particular college until A Level results day in August.[136][137]

The university has come under criticism for the number of students it accepts from private schools;[138] for instance, Laura Spence's rejection from the university in 2000 led to widespread debate.[139] In 2016, the University of Oxford gave 59% of offers to UK students to students from state schools, while about 93% of all UK pupils and 86% of post-16 UK pupils are educated in state schools.[140][141][142] However, 64% of UK applicants were from state schools and the university notes that state school students apply disproportionately to oversubscribed subjects.[143] The proportion of students coming from state schools has been increasing. From 2015 to 2019, the state proportion of total UK students admitted each year was: 55.6%, 58.0%, 58.2%, 60.5% and 62.3%.[144] Oxford University spends over £6 million per year on outreach programs to encourage applicants from underrepresented demographics.[140]

In 2018 the university's annual admissions report revealed that eight of Oxford's colleges had accepted fewer than three black applicants in the past three years.[145] Labour MP David Lammy said, "This is social apartheid and it is utterly unrepresentative of life in modern Britain."[146] In 2020, Oxford had increased its proportion of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) students to record levels.[147][148] The number of BAME undergraduates accepted to the university in 2020 rose to 684 students, or 23.6% of the UK intake, up from 558 or 22% in 2019; the number of Black students was 106 (3.7% of the intake), up from 80 students (3.2%).[148][149] UCAS data also showed that Oxford is more likely than comparable institutions to make offers to ethnic minority and socially disadvantaged pupils.[147]

Teaching and degrees

[edit]Undergraduate teaching is centred on the tutorial, where 1–4 students spend an hour with an academic discussing their week's work, usually an essay (humanities, most social sciences, some mathematical, physical, and life sciences) or problem sheet (most mathematical, physical, and life sciences, and some social sciences). The university itself is responsible for conducting examinations and conferring degrees. Undergraduate teaching takes place during three eight-week academic terms: Michaelmas, Hilary and Trinity.[150] (These are officially known as 'Full Term': 'Term' is a lengthier period with little practical significance.) Internally, the weeks in a term begin on Sundays, and are referred to numerically, with the initial week known as "first week", the last as "eighth week" and with the numbering extended to refer to weeks before and after term (for example "noughth week" precedes term).[151] Undergraduates must be in residence from Thursday of 0th week. These teaching terms are shorter than those of most other British universities,[152] and their total duration amounts to less than half the year. However, undergraduates are also expected to do some academic work during the three holidays (known as the Christmas, Easter, and Long Vacations).

Research degrees at the master's and doctoral level are conferred in all subjects studied at graduate level at the university.[citation needed]

Scholarships and financial support

[edit]

There are many opportunities for students at Oxford to receive financial help during their studies. The Oxford Opportunity Bursaries, introduced in 2006, are university-wide means-based bursaries available to any British undergraduate, with a total possible grant of £10,235 over a 3-year degree. In addition, individual colleges also offer bursaries and funds to help their students. For graduate study, there are many scholarships attached to the university, available to students from all sorts of backgrounds, from Rhodes Scholarships to the relatively new Weidenfeld Scholarships.[153] Oxford also offers the Clarendon Scholarship which is open to graduate applicants of all nationalities.[154] The Clarendon Scholarship is principally funded by Oxford University Press in association with colleges and other partnership awards.[155][156] In 2016, Oxford University announced that it is to run its first free online economics course as part of a "massive open online course" (Mooc) scheme, in partnership with a US online university network.[157] The course available is called 'From Poverty to Prosperity: Understanding Economic Development'.

Students successful in early examinations are rewarded by their colleges with scholarships and exhibitions, normally the result of a long-standing endowment, although since the introduction of tuition fees the amounts of money available are purely nominal. Scholars, and exhibitioners in some colleges, are entitled to wear a more voluminous undergraduate gown; "commoners" (originally those who had to pay for their "commons", or food and lodging) are restricted to a short, sleeveless garment. The term "scholar" in relation to Oxford therefore has a specific meaning as well as the more general meaning of someone of outstanding academic ability. In previous times, there were "noblemen commoners" and "gentlemen commoners", but these ranks were abolished in the 19th century. "Closed" scholarships, available only to candidates who fitted specific conditions such as coming from specific schools, were abolished in the 1970s and 1980s.[158]

Libraries

[edit]

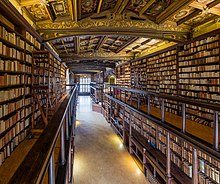

The university maintains the largest university library system in the UK,[18] and, with over 11 million volumes housed on 120 miles (190 km) of shelving, the Bodleian group is the second-largest library in the UK, after the British Library. The Bodleian is a legal deposit library, which means that it is entitled to request a free copy of every book published in the UK. As such, its collection is growing at a rate of over three miles (five kilometres) of shelving every year.[159]

The buildings referred to as the university's main research library, The Bodleian, consist of the original Bodleian Library in the Old Schools Quadrangle, founded by Sir Thomas Bodley in 1598 and opened in 1602,[160] the Radcliffe Camera, the Clarendon Building, and the Weston Library. A tunnel underneath Broad Street connects these buildings, with the Gladstone Link, which opened to readers in 2011, connecting the Old Bodleian and Radcliffe Camera.

The Bodleian Libraries group was formed in 2000, bringing the Bodleian Library and some of the subject libraries together.[161] It now comprises 28[162] libraries, a number of which have been created by bringing previously separate collections together, including the Sackler Library, Law Library, Social Science Library and Radcliffe Science Library.[161] Another major product of this collaboration has been a joint integrated library system, OLIS (Oxford Libraries Information System),[163] and its public interface, SOLO (Search Oxford Libraries Online), which provides an electronic catalogue covering all member libraries, as well as the libraries of individual colleges and other faculty libraries, which are not members of the group but do share cataloguing information.[164]

A new book depository opened in South Marston, Swindon, in October 2010,[165] and recent building projects include the remodelling of the New Bodleian building, which was renamed the Weston Library when it reopened in 2015.[166][167] The renovation is designed to better showcase the library's various treasures (which include a Shakespeare First Folio and a Gutenberg Bible) as well as temporary exhibitions.

The Bodleian engaged in a mass-digitisation project with Google in 2004.[168][169] Notable electronic resources hosted by the Bodleian Group include the Electronic Enlightenment Project, which was awarded the 2010 Digital Prize by the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies.[170]

Museums

[edit]

Oxford maintains a number of museums and galleries, open for free to the public. The Ashmolean Museum, founded in 1683, is the oldest museum in the UK, and the oldest university museum in the world.[171] It holds significant collections of art and archaeology, including works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Turner, and Picasso, as well as treasures such as the Scorpion Macehead, the Parian Marble and the Alfred Jewel. It also contains "The Messiah", a pristine Stradivarius violin, regarded by some as one of the finest examples in existence.[172]

The University Museum of Natural History holds the university's zoological, entomological and geological specimens. It is housed in a large neo-Gothic building on Parks Road, in the university's Science Area.[173][174] Among its collection are the skeletons of a Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops, and the most complete remains of a dodo found anywhere in the world. It also hosts the Simonyi Professorship of the Public Understanding of Science, currently held by Marcus du Sautoy.[175]

Adjoining the Museum of Natural History is the Pitt Rivers Museum, founded in 1884, which displays the university's archaeological and anthropological collections, currently holding over 500,000 items. It recently built a new research annexe; its staff have been involved with the teaching of anthropology at Oxford since its foundation, when as part of his donation General Augustus Pitt Rivers stipulated that the university establish a lectureship in anthropology.[176]

The Museum of the History of Science is housed on Broad Street in the world's oldest-surviving purpose-built museum building.[177] It contains 15,000 artefacts, from antiquity to the 20th century, representing almost all aspects of the history of science. In the Faculty of Music on St Aldate's is the Bate Collection of Musical Instruments, a collection mostly of instruments from Western classical music, from the medieval period onwards. Christ Church Picture Gallery holds a large collection of old master paintings and drawings.[178]

Publishing

[edit]The Oxford University Press is the world's second oldest and currently the largest university press by the number of publications.[179] More than 6,000 new books are published annually,[180] including many reference, professional, and academic works (such as the Oxford English Dictionary, the Concise Oxford English Dictionary, the Oxford World's Classics, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and the Concise Dictionary of National Biography).

Reputation and ranking

[edit]| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[181] | 2 |

| Guardian (2024)[182] | 2 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2024)[183] | 2 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2023)[184] | 7 |

| QS (2025)[185] | 3 |

| THE (2024)[186] | 1 |

Due to its age[187][188] and its social and academic status,[189][190] the University of Oxford is considered to be one of Britain's most prestigious or elite universities[191][192] and to form, along with the University of Cambridge, a top two that stand above other UK universities in this regard.[187][189][190][193]

Oxford is regularly ranked within the top five universities in the world in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings,[194][195] as well as the Forbes's World University Rankings.[196] It held the number one position in the Times Good University Guide for eleven consecutive years,[197] and the medical school has also maintained first place in the "Clinical, Pre-Clinical & Health" table of the Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings for the past seven consecutive years.[198] In 2021, it ranked sixth among the universities around the world by SCImago Institutions Rankings.[199] The THE has also recognised Oxford as one of the world's "six super brands" on its World Reputation Rankings, along with Berkeley, Cambridge, Harvard, MIT, and Stanford.[200] The university is fifth worldwide on the US News ranking.[201] Its Saïd Business School came 13th in the world in Financial Times Global MBA Ranking.[202]

Oxford was ranked 13th in the world in 2022 by the Nature Index, which measures the largest contributors to papers published in 82 leading journals.[203][204] It is ranked fifth best university worldwide and first in Britain for forming CEOs according to the Professional Ranking World Universities,[205] and first in the UK for the quality of its graduates as chosen by the recruiters of the UK's major companies.[206]

In the 2018 Complete University Guide, all 38 subjects offered by Oxford rank within the top 10 nationally meaning Oxford was one of only two multi-faculty universities (along with Cambridge) in the UK to have 100% of their subjects in the top 10.[207] Computer Science, Medicine, Philosophy, Politics and Psychology were ranked first in the UK by the guide.[208]

According to the QS World University Rankings by Subject, the University of Oxford also ranks as number one in the world for four Humanities disciplines: English Language and Literature, Modern Languages, Geography, and History. It also ranks second globally for Anthropology, Archaeology, Law, Medicine, Politics & International Studies, and Psychology.[209]

Student life

[edit]Traditions

[edit]

Academic dress is required for examinations, matriculation, disciplinary hearings, and when visiting university officers. A referendum held among the Oxford student body in 2015 showed 76% against making it voluntary in examinations – 8,671 students voted, with the 40.2% turnout the highest ever for a UK student union referendum.[210] This was widely interpreted by students as being a vote not so much on making subfusc voluntary, but rather, in effect, on abolishing it by default, in that if a minority of people came to exams without subfusc, the rest would soon follow.[211] In July 2012 the regulations regarding academic dress were modified to be more inclusive to transgender people.[212]

'Trashing' is a tradition of spraying those who just finished their last examination of the year with alcohol, flour and confetti. The sprayed student stays in the academic dress worn to the exam. The custom began in the 1970s when friends of students taking their finals waited outside Oxford's Examination Schools where exams for most degrees are taken.[213]

Other traditions and customs vary by college. For example, some colleges have formal hall six times a week, but in others this only happens occasionally, or even not at all.

Balls are major events held by colleges; the largest, held triennially in ninth week of Trinity Term, are called commemoration balls; the dress code is usually white tie. Many other colleges hold smaller events during the year that they call summer balls or parties.

Clubs and societies

[edit]

The Oxford Union (not to be confused with the Oxford University Student Union) is an independent debating society which hosts weekly debates and high-profile speakers.

There are two weekly student newspapers: the independent Cherwell and OUSU's The Oxford Student. Other publications include the Isis magazine, the satirical Oxymoron, the graduate Oxonian Review, the Oxford Political Review,[214] and the online only newspaper The Oxford Blue. The student radio station is Oxide Radio.

Sport is played between college teams, in tournaments known as cuppers (the term is also used for some non-sporting competitions). In particular, much attention is given to the termly intercollegiate rowing regattas: Christ Church Regatta, Torpids, and Summer Eights. In addition, there are higher standard university wide teams. Significant focus is given to annual varsity matches played against Cambridge, the most famous of which is The Boat Race, watched by a TV audience of between five and ten million viewers. A blue is an award given to those who compete at the university team level in certain sports.

Party political groups include Oxford University Conservative Association and Oxford University Labour Club.

Music, drama, and other arts societies exist both at the collegiate level and as university-wide groups, such as the Oxford University Dramatic Society and the Oxford Revue. Most colleges have chapel choirs. The Oxford Imps, a comedy improvisation troupe, perform weekly at The Jericho Tavern during term time.[215]

Most academic areas have student societies of some form, for example the Scientific Society.

Private members' clubs for students include Vincent's Club (primarily for sportspeople)[216] and The Gridiron Club.[217] A number of invitation-only student dining clubs also exist, including the Bullingdon Club.

Student union and common rooms

[edit]The Oxford University Student Union, formerly better known by its acronym OUSU and now rebranded as Oxford SU,[218] exists to represent students in the university's decision-making, to act as the voice for students in the national higher education policy debate, and to provide direct services to the student body. Reflecting the collegiate nature of the University of Oxford itself, OUSU is both an association of Oxford's more than 21,000 individual students and a federation of the affiliated college common rooms, and other affiliated organisations that represent subsets of the undergraduate and graduate students.

The importance of collegiate life is such that for many students their college JCR (Junior Common Room, for undergraduates) or MCR (Middle Common Room, for graduates) is seen as more important than OUSU. JCRs and MCRs each have a committee, with a president and other elected students representing their peers to college authorities. Additionally, they organise events and often have significant budgets to spend as they wish (money coming from their colleges and sometimes other sources such as student-run bars). (JCR and MCR are terms that are used to refer to rooms for use by members, as well as the student bodies.)

Notable alumni

[edit]Throughout its history, a sizeable number of Oxford alumni, known as Oxonians, have become notable in many varied fields, both academic and otherwise. A total of 70 Nobel prize-winners have studied or taught at Oxford, with prizes won in all six categories.[19]More information on notable members of the university can be found in the individual college articles. An individual may be associated with two or more colleges, as an undergraduate, postgraduate and/or member of staff.

Politics

[edit]Thirty-one British prime ministers have attended Oxford, including William Gladstone, H. H. Asquith, Clement Attlee, Harold Macmillan, Edward Heath, Harold Wilson, Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair, David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer. Of all the post-war prime ministers, only Gordon Brown was educated at a university other than Oxford (the University of Edinburgh), while Winston Churchill, James Callaghan and John Major never attended a university.[219]

Over 100 Oxford alumni were elected to the House of Commons in 2010.[219] This includes former Leader of the Opposition, Ed Miliband, and numerous members of the cabinet and shadow cabinet. Additionally, over 140 Oxonians sit in the House of Lords.[19]

At least 30 other international leaders have been educated at Oxford.[19] This number includes Harald V of Norway,[220] Abdullah II of Jordan,[19] William II of the Netherlands, five Prime Ministers of Australia (John Gorton, Malcolm Fraser, Bob Hawke, Tony Abbott, and Malcolm Turnbull),[221][222][223] six Prime Ministers of Pakistan (Liaquat Ali Khan, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Sir Feroz Khan Noon, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Benazir Bhutto and Imran Khan),[19] two Prime Ministers of Canada (Lester B. Pearson and John Turner),[19][224] two Prime Ministers of India (Manmohan Singh and Indira Gandhi, though the latter did not finish her degree),[19][225] S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike (Prime Minister of Ceylon), Eric Williams (Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago), Abhisit Vejjajiva (Prime Minister of Thailand), Norman Manley (Premier of Jamaica),[226] Haitham bin Tariq Al Said (Sultan of Oman),[227] and Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (President of Peru). Bill Clinton is the first President of the United States to have attended Oxford; he attended as a Rhodes Scholar.[19][228] Arthur Mutambara (Deputy Prime Minister of Zimbabwe), was a Rhodes Scholar in 1991. Seretse Khama, first president of Botswana, spent a year at Balliol College. Festus Mogae (former president of Botswana) was a student at University College. The Burmese democracy activist and Nobel laureate, Aung San Suu Kyi, was a student of St Hugh's College.[229] Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, the current reigning Druk Gyalpo (Dragon King) of Bhutan, was a member of Magdalen College.[230] The world's youngest Nobel Prize laureate, Malala Yousafzai, completed a BA degree in philosophy, politics and economics.[231]

Sports and adventures

[edit]Sir Roger Gilbert Bannister, who had been at Exeter College and Merton College, ran the first sub-four-minute mile in Oxford.

Some 150 Olympic medal-winners have academic connections with the university, including Sir Matthew Pinsent, quadruple gold-medallist rower.[19][232]

Oxford students have also excelled in other sports, such as Imran Khan, Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi, Bill Bradley and Iftikhar Ali Khan Pataudi.

Three of the most well-known adventurers and explorers who attended Oxford are Walter Raleigh, one of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era; T. E. Lawrence, whose life was the basis of the 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia; and Thomas Coryat. The latter, the author of "Coryat's Crudities hastily gobbled up in Five Months Travels in France, Italy, &c'" (1611) and court jester of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, is credited with introducing the table fork and umbrella to England and being the first Briton to do a Grand Tour of Europe.[233]

Other notable figures include Gertrude Bell, an explorer, archaeologist,[234] cartographer[235] and spy[236] who, along with T. E. Lawrence,[237] helped establish the Hashemite dynasties in what is today Jordan and Iraq and played a major role in establishing and administering the modern state of Iraq;[234][238]

Law

[edit]Oxford has produced a large number of distinguished jurists, judges and lawyers around the world. Lords Bingham and Denning, commonly recognised as two of the most influential English judges in the history of the common law,[239][240][241][242] both studied at Oxford. Within the United Kingdom, five of the current justices of the Supreme Court are Oxford-educated: Robert Reed (President of the Supreme Court),Michael Briggs, Lord Sales, Lord Hamblen, Lord Burrows, and Lady Rose;[243][244] retired Justices include David Neuberger (President of the Supreme Court 2012–2017), Jonathan Mance (Deputy President of the Supreme Court 2017–2018), Alan Rodger, Jonathan Sumption, Mark Saville, John Dyson, Simon Brown, and Nicholas Wilson. The twelve Lord Chancellors and nine Lord Chief Justices that have been educated at Oxford include Stanley Buckmaster, Thomas More,[245] Thomas Wolsey,[246] Gavin Simonds.[247] The twenty-two Law Lords count amongst them Lennie Hoffmann, Kenneth Diplock, Richard Wilberforce, James Atkin, Nick Browne-Wilkinson, Robert Goff, Brian Hutton, Jonathan Mance, Alan Rodger, Mark Saville, Leslie Scarman, Johan Steyn;[248] Master of the Rolls Wilfrid Greene;[242] Lord Justices of Appeal include John Laws, Brian Leveson and John Mummery. The British Government's Attorneys General have included Dominic Grieve, Nicholas Lyell, Patrick Mayhew, John Hobson, Reginald Manningham-Buller, Lionel Heald, Frank Soskice, David Maxwell Fyfe, Donald Somervell, William Jowitt; Directors of Public Prosecutions include Sir Thomas Hetherington QC, Dame Barbara Mills QC and Sir Keir Starmer KC.

In the United States, two of the nine incumbent Justices of the Supreme Court are Oxonians, namely Elena Kagan,[249] and Neil Gorsuch;[250] retired Justices include John Marshall Harlan II,[251] David Souter,[252] Stephen Breyer,[253] and Byron White.[254] Internationally, Oxonians Sir Humphrey Waldock[255] served in the International Court of Justice; Akua Kuenyehia, sat in the International Criminal Court; Sir Nicolas Bratza[256] and Paul Mahoney sat in the European Court of Human Rights; Kenneth Hayne,[257] Dyson Heydon, as well as Patrick Keane sat in the High Court of Australia; both Kailas Nath Wanchoo, A. N. Ray served as Chief Justices of the Supreme Court of India; Cornelia Sorabji, Oxford's first female law student, was India's first female advocate; in Hong Kong, Aarif Barma, Thomas Au and Doreen Le Pichon[258] currently serve in the Court of Appeal (Hong Kong), while Charles Ching and Henry Litton both served as Permanent Judges of the Court of Final Appeal of Hong Kong;[259] Laurie Ackermann[260] and Edwin Cameron[261] served on South Africa's Constitutional Court; six Puisne Justices of the Supreme Court of Canada and a chief justice of the now defunct Federal Court of Canada were also educated at Oxford.

The list of noted legal scholars includes H. L. A. Hart,[262] Ronald Dworkin,[262] Andrew Burrows, Sir Guenter Treitel, Jeremy Waldron, A. V. Dicey, William Blackstone, John Gardner, Robert A. Gorman, Timothy Endicott, Peter Birks, John Finnis, Andrew Ashworth, Joseph Raz, Paul Craig, Leslie Green, Tony Honoré, Neil MacCormick and Hugh Collins. Other distinguished practitioners who have attended Oxford include Lord Pannick KC,[263] Geoffrey Robertson KC, Amal Clooney,[264] Lord Faulks KC, and Dinah Rose KC.

Mathematics and sciences

[edit]Four Oxford mathematicians, Michael Atiyah, Daniel Quillen, Simon Donaldson and James Maynard, have won Fields Medals, often called the "Nobel Prize for mathematics". Andrew Wiles, who proved Fermat's Last Theorem, was educated at Oxford and is currently the Regius Professor and Royal Society Research Professor in Mathematics at Oxford.[265] Marcus du Sautoy and Roger Penrose are both currently mathematics professors, and Jackie Stedall was a professor of the university. Stephen Wolfram, chief designer of Mathematica and Wolfram Alpha studied at the university, along with Tim Berners-Lee,[19] inventor of the World Wide Web,[266] Edgar F. Codd, inventor of the relational model of data,[267] and Tony Hoare, programming languages pioneer and inventor of Quicksort.

The university is associated with 11 winners of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, six in physics, and 16 in medicine.[268]

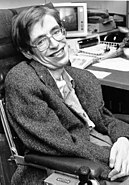

Scientists who performed research in Oxford include chemist Dorothy Hodgkin who received her Nobel Prize for "determinations by X-ray techniques of the structures of important biochemical substances",[269] Howard Florey who shared the 1945 Nobel prize "for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases", and John B. Goodenough, who shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2019 "for the development of lithium-ion batteries".[270] Both Richard Dawkins[271] and Frederick Soddy[272] studied at the university and returned for research purposes. Robert Hooke,[19] Edwin Hubble,[19] and Stephen Hawking[19] all studied at Oxford.

Robert Boyle, a founder of modern chemistry, never formally studied or held a post within the university, but resided within the city to be part of the scientific community and was awarded an honorary degree.[273] Notable scientists who spent brief periods at Oxford include Albert Einstein[274] developer of general theory of relativity and the concept of photons; and Erwin Schrödinger who formulated the Schrödinger equation and the Schrödinger's cat thought experiment. Structural engineer Roma Agrawal, responsible for London's Shard, attributes her love of engineering to a summer placement during her undergraduate physics degree at Oxford.

Economists Adam Smith, Alfred Marshall, E. F. Schumacher, and Amartya Sen all spent time at Oxford.

Literature, music, and drama

[edit]Writers associated with Oxford include Kingsley and Martin Amis, Vera Brittain, A. S. Byatt, Lewis Carroll,[275] Penelope Fitzgerald, John Fowles, Theodor Geisel, Robert Graves, Graham Greene,[276] Joseph Heller,[277] Christopher Hitchens, Aldous Huxley,[278] Samuel Johnson, Nicole Krauss, C. S. Lewis,[279] Thomas Middleton, Iris Murdoch, V. S. Naipaul, Philip Pullman,[19] Dorothy L. Sayers, Vikram Seth,[19] J. R. R. Tolkien,[280] Evelyn Waugh,[281] Oscar Wilde,[282] the poets Percy Bysshe Shelley,[283] John Donne,[284] A. E. Housman,[285] Gerard Manley Hopkins, W. H. Auden,[286] T. S. Eliot, and Philip Larkin,[287] and seven poets laureate: Thomas Warton,[288] Henry James Pye,[289] Robert Southey,[290] Robert Bridges,[291] Cecil Day-Lewis,[292] Sir John Betjeman,[293] and Andrew Motion.[294]

Composers Hubert Parry, George Butterworth, John Taverner, William Walton, James Whitbourn, and Andrew Lloyd Webber have all been involved with the university.

Actors Hugh Grant,[295] Kate Beckinsale,[295] Rosamund Pike, Felicity Jones, Gemma Chan, Dudley Moore,[296] Michael Palin,[19] Terry Jones,[297] Anna Popplewell, and Rowan Atkinson were students at the university, as were filmmakers Ken Loach[298] and Richard Curtis.[19]

Religion

[edit]Oxford has also produced at least 12 saints, 19 English cardinals, and 20 Archbishops of Canterbury, the most recent Archbishop being Rowan Williams, who studied at Wadham College and was later a Canon Professor at Christ Church.[19][299] Duns Scotus' teaching is commemorated with a monument in the University Church of St. Mary. Religious reformer John Wycliffe was an Oxford scholar, for a time Master of Balliol College. John Colet, Christian humanist, Dean of St Paul's, and friend of Erasmus, studied at Magdalen College. Several of the Caroline Divines e.g. in particular William Laud as President of St. John's and Chancellor of the university, and the Non-Jurors, e.g. Thomas Ken had close Oxford connections. The founder of Methodism, John Wesley, studied at Christ Church and was elected a fellow of Lincoln College.[300] Britain's first woman to be an ordained minister, Constance Coltman, studied at Somerville College. The Oxford Movement (1833–1846) was closely associated with the Oriel fellows John Henry Newman, Edward Bouverie Pusey and John Keble. Other religious figures were Mirza Nasir Ahmad, the third Caliph of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, Shoghi Effendi, one of the appointed leaders of the Baháʼí Faith, and Joseph Cordeiro, the first Pakistani Catholic cardinal.[301]

Philosophy

[edit]Oxford's philosophical tradition started in the medieval era, with Robert Grosseteste[302] and William of Ockham,[302] commonly known for Occam's razor, among those teaching at the university. Thomas Hobbes,[303][304] Jeremy Bentham and the empiricist John Locke received degrees from Oxford. Though the latter's main works were written after leaving Oxford, Locke was heavily influenced by his twelve years at the university.[302]

Oxford philosophers of the 20th century include Richard Swinburne, a leading philosopher in the tradition of substance dualism; Peter Hacker, philosopher of mind, language, anthropology, and he is also known for his critique of cognitive neuroscience; J. L. Austin, a leading proponent of ordinary-language philosophy; Gilbert Ryle,[302] author of The Concept of Mind; and Derek Parfit, who specialised in personal identity. Other commonly read modern philosophers to have studied at the university include A. J. Ayer,[302] Elizabeth Anscombe, Paul Grice, Mary Midgley, Iris Murdoch, Thomas Nagel, Bernard Williams, Robert Nozick, Onora O'Neill, John Rawls, Michael Sandel, and Peter Singer. John Searle, presenter of the Chinese room thought experiment, studied and began his academic career at the university.[305] Likewise, Philippa Foot, who mentioned the trolley problem, studied and taught at Somerville College.[306]

Oxford in literature and popular media

[edit]The University of Oxford is the setting for numerous works of fiction. Oxford was mentioned in fiction as early as 1400 when Chaucer, in Canterbury Tales, referred to a "Clerk [student] of Oxenford".[307] Mortimer Proctor argues the first campus novel was The Adventures of Oxymel Classic, Esq; Once an Oxford Scholar (1768).[308] It is filled with violence and debauchery, with obnoxious, foolish dons becoming easy prey for cunning students.[309] Proctor argues that by 1900, "novels about Oxford and Cambridge were so numerous that they clearly represent a striking literary phenomenon."[310] By 1989, 533 novels based in Oxford had been identified and the number continues to rise.[311]

Famous literary works range from Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh, which in 1981 was adapted as a television serial, to the trilogy His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman, which features an alternate-reality version of the university and was adapted for film in 2007 and as a BBC television series in 2019.

Other notable examples include:

- Zuleika Dobson (1911) by Max Beerbohm, a satire about undergraduate life.

- Gaudy Night (1935) by Dorothy L. Sayers, herself a graduate of Somerville College, a Lord Peter Wimsey mystery novel.

- The Inspector Morse detective novels (1975–1999) by Colin Dexter, adapted for television as Inspector Morse (1987–2000), the spin-off Lewis (2006–2015), and the prequel Endeavour (2012–2023).

- True Blue (1996), a film about the mutiny at the time of the Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race of 1987.

- The History Boys (2004) by Alan Bennett, alumnus of Exeter College, a play about a group of grammar school boys in Sheffield in 1983 applying to read history at Oxford and Cambridge. It premiered at the National Theatre and was adapted for film in 2006.

- Posh (2010), a play by Laura Wade, and its film adaptation The Riot Club (2014), about a fictionalised equivalent of the Bullingdon Club.

- Testament of Youth (2014), a drama film based on the memoir of the same name written by Somerville alumna Vera Brittain.

- Middle England (2019), the prize-winning novel by Jonathan Coe, portrays a deeply divided Britain in the 2010s that is so frustrating that dissatisfied Oxford dons reject elite academia and take their talents elsewhere.[312]

- Saltburn (2023), a film about an Oxford student, by Emerald Fennell, alumna of Greyfriars, Oxford.

Notable non-fiction works on Oxford include Oxford by Jan Morris.[313]

The university is parodied in Terry Pratchett's Discworld series with "Unseen University" and "Brazeneck College" (in reference to Brasenose College).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Includes those who indicate that they identify as Asian, Black, Mixed Heritage, Arab or any other ethnicity except White.

- ^ Calculated from the Polar4 measure, using Quintile1, in England and Wales. Calculated from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) measure, using SIMD20, in Scotland.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "The University as a charity". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Introduction and History". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ "Aggregated College Accounts: Consolidated and College Balance Sheets For the year ended 31 July 2023" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Financial Statements 2022/23" (PDF). University of Oxford. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Colleges (group) £6,387.7M,[3] University (consolidated) £1,678.0M[4]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Professor Irene Tracey, CBE, FMedSci". Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ «Кто работает в HE?» . ХЕСА. Архивировано из оригинала 29 июля 2019 года . Проверено 24 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Оксфордский университет – статистика студентов» . Программное обеспечение Табло . Архивировано из оригинала 15 января 2022 года . Проверено 7 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ «Студенческие номера» . Оксфордский университет . Архивировано из оригинала 15 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 24 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Фирменный цвет – синий Оксфорд» . Ox.ac.uk. Архивировано из оригинала 24 мая 2013 года . Проверено 16 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Сагер, Питер (2005). Оксфорд и Кембридж: необычная история . п. 36.

- ^ «50 лучших университетов по репутации» . Высшее образование Таймс . 3 ноября 2020 года. Архивировано из оригинала 24 октября 2021 года . Проверено 26 ноября 2020 г. .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Ранние записи» . Кембриджский университет. 28 января 2013 г. Архивировано из оригинала 11 октября 2013 г. Проверено 10 октября 2013 г.

- ^ «Оксбридж» . oed.com (3-е изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета . 2005. Архивировано из оригинала 28 июля 2020 года . Проверено 20 января 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Что такое Оксфордский колледж?» . Оксфордский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 16 марта 2023 года . Проверено 31 октября 2022 г.

- ^ «Организация | Оксфордский университет» . www.ox.ac.uk. Архивировано из оригинала 28 января 2016 года . Проверено 14 июня 2024 г.

Три общества – Колледж Келлогг, Колледж Рубена и Колледж Сент-Кросс – действуют во многом так же, как и другие колледжи, но считаются факультетами университета, а не независимыми колледжами, поскольку, в отличие от других, у них нет королевской хартии.

- ^ «Оксфордские дивизии» . Оксфордский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 20 октября 2013 года . Проверено 26 ноября 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Библиотеки» . Оксфордский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 ноября 2012 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р с т «Знаменитые оксонианцы» . Оксфордский университет. 30 октября 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала 7 июня 2014 г. Проверено 13 июня 2014 г.

- ^ «Оксфорд на Олимпийских играх» . Оксфордский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 26 мая 2019 года . Проверено 26 августа 2018 г.

- ^ «Предисловие: Конституция и законодательные полномочия университета» . Оксфордский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 4 января 2014 года . Проверено 4 января 2014 г.

- ^ Ферт, Мэтью (2024). «Что в имени? Прослеживание истоков Альфреда «Великого» » . Английский исторический обзор . дои : 10.1093/ehr/ceae078 . ISSN 1477-4534 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2024 года . Проверено 3 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Катто, JI, изд. (1984). «2 Университет как юридическое лицо». История Оксфордского университета . Том. Я: Ранние оксфордские школы. Издательство Оксфордского университета . п. 49. ИСБН 978-0-19-951011-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2023 года . Проверено 14 января 2021 г.

- ^ Баллард, Адольф; Тейт, Джеймс (31 октября 2010 г.). Уставы британских районов 1216–1307 гг. (на латыни). Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 222. ИСБН 978-1-108-01034-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 марта 2023 года . Проверено 13 декабря 2015 г.

- ^ Дэвис, Марк (4 ноября 2010 г.). « «Лизать лорда и избивать хама»: Оксфордский «Town & Gown» » . Новости Би-би-си . Би-би-си. Архивировано из оригинала 4 января 2014 года . Проверено 3 января 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Солтер, HE; Лобель, Мэри Д., ред. (1954). «Оксфордский университет» . История графства Оксфорд: Том 3: Оксфордский университет . Лондон: История округа Виктория. стр. 1–38. Архивировано из оригинала 16 января 2014 года . Проверено 15 января 2014 г.

- ^ Рашдалл, Х. Европейские университеты . стр. 100-1 III, 55–60.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Брук и Хайфилд (1988)

- ^ Персиваль, Эдвард Франс. Устав Фонда Мертон-Колледжа, Оксфорд .

- ^ Уайт, Генри Джулиан (1906). Мертон-Колледж, Оксфорд .

- ^ Мартин, Г.Х.; Хайфилд, JRL (1997). История Мертон-колледжа в Оксфорде .

- ^ Маккисак, май (1963). Четырнадцатый век 1307–1399 гг . Оксфордская история Англии. п. 501.

- ^ Бурстин, Дэниел Дж. (1958). Американцы; Колониальный опыт . Винтаж. стр. 171–184 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2010 года.

- ^ Брук и Хайфилд (1988) , с. 56

- ^ «Уильям Гроцин | Преподаватель английского языка» . Британская энциклопедия . Архивировано из оригинала 11 января 2023 года . Проверено 11 января 2023 г.

- ^ «Джон Колет | Английский теолог и педагог» . Британская энциклопедия . Архивировано из оригинала 11 января 2023 года . Проверено 11 января 2023 г.

- ^ Муди, Теодор Уильям; Мартин, Фрэнсис Ксавьер; Бирн, Фрэнсис Джон, ред. (1991). Ирландия раннего Нового времени, 1534–1691 гг . Кларендон Пресс. п. 618. ИСБН 978-0-19-820242-4 .

- ^ «Оксфордский университет | Энциклопедия.com» . www.энциклопедия.com . Архивировано из оригинала 7 августа 2023 года . Проверено 7 августа 2023 г.

- ^ «Устав Оксфордского университета, 2012–2013 гг.» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 22 февраля 2018 г. Проверено 31 января 2018 г.

- ^ «Закон об университетских тестах 1871 года» . Парламент Великобритании. Архивировано из оригинала 1 января 2016 года . Проверено 30 декабря 2015 г.

- ^ «Гражданская война: капитуляция Оксфорда» . Схема Оксфордширских синих табличек . Доска с синими табличками Оксфордшира. 2013. Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2020 года . Проверено 30 декабря 2015 г.

- ^ «Невидимая коллегия (акт. 1646–1647)» . Оксфордский национальный биографический словарь (онлайн-изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. 2004. doi : 10.1093/ref:odnb/95474 . Проверено 21 февраля 2023 г. (Требуется подписка или членство в публичной библиотеке Великобритании .)

- ^ Сэр Спенсер Уолпол (1903). История двадцати пяти лет: том 4: 1870–1875 . стр. 136–37. Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2017 года . Проверено 3 марта 2017 г.

- ^ Уолпол, Спенсер (1904). Лайалл, Альфред Комин (ред.). История двадцати пяти лет . Том. 3: 1870–1875. Лонгманс, Грин и Ко. р. 140.

- ^ Уильям Д. Рубинштейн , «Социальное происхождение и модели карьеры абитуриентов Оксфорда и Кембриджа, 1840–1900». Исторические исследования 82.218 (2009): 715–730, данные на страницах 719 и 724.

- ^ Для получения более подробной информации см. Марка К. Куртхойса, «Происхождение и пункты назначения: социальная мобильность мужчин и женщин Оксфорда» в книге Майкла Г. Брока и Марка К. Куртойса, ред. История Оксфордского университета, том 7: Девятнадцатый век (2000), часть 2, стр. 571–95.

- ^ Куртойс, MC; Джонс, HS (1995). «Оксфордский атлетизм, 1850–1914: переоценка». История образования . 24 (4): 305–317. дои : 10.1080/0046760950240403 . ISSN 0046-760X .

- ^ Брок, Майкл Г.; Куртойс, Марк К., ред. (1997). История Оксфордского университета: Оксфорд девятнадцатого века, тома 6–7 . Кларендон Пресс. п. 355. ИСБН 978-0-19-951016-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2023 года . Проверено 7 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Харрисон, Брайан; Астон, Тревор Генри (1994). История Оксфордского университета: Том VIII: Двадцатый век - Оксфордская стипендия . doi : 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198229742.001.0001 . ISBN 978-0-19-822974-2 .

- ^ «Список услуг Оксфордского университета: Оксфордский университет: бесплатная загрузка и потоковая передача» . Интернет-архив . Архивировано из оригинала 11 марта 2016 года . Проверено 10 ноября 2015 г.

- ^ Сэр Спенсер Уолпол (1903). История двадцати пяти лет: том 4: 1870–1875 . стр. 145–51. Архивировано из оригинала 5 марта 2017 года . Проверено 4 марта 2017 г.

- ^ Гольдман, Лоуренс (2004). «Оксфорд и идея университета в Британии девятнадцатого века». Оксфордский обзор образования . 30 (4): 575–592. JSTOR 4127167 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Боас, Чарльз Уильям (1887). Оксфорд (2-е изд.). стр. 208–209. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 27 сентября 2023 года . Проверено 3 февраля 2013 г.

- ^ Новые экзаменационные статуи , Оксфорд: Clarendon Press, 1872 г. , получено 4 февраля 2013 г.

- ^ Новые экзаменационные статуи , Оксфорд: Clarendon Press, 1873 г. , получено 4 февраля 2013 г.

- ^ Олдрич, Джон. «Доктор философии по математике в Великобритании: заметки по истории - экономике» . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2016 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Ланнон, Фрэнсис (30 октября 2008 г.). «Ее Оксфорд» . Высшее образование Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 2 января 2014 года . Проверено 27 марта 2013 г.

- ^ «Пароходницы Тринити-холла» . Новости Троицы. 14 марта 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 12 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 9 сентября 2012 года .

- ^ Оксфордский путеводитель Олдена . Оксфорд: Олден и компания, 1958; стр. 120–21

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Наша история» . Колледж Святой Анны, Оксфорд . Архивировано из оригинала 28 апреля 2014 года . Проверено 4 мая 2018 г.

- ^ «Колледж Святой Анны» . британская история.ac.uk. Архивировано из оригинала 2 октября 2018 года . Проверено 2 октября 2018 г.

- ^ «История колледжа» . Колледж Святого Хью Оксфордского университета. Архивировано из оригинала 18 июня 2014 года . Проверено 14 октября 2010 г.

- ^ «Конституционная история» . Колледж Святой Хильды. Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2012 года . Проверено 25 марта 2013 г.

- ^ «Хронология колледжа | Леди Маргарет Холл» . Леди Маргарет Холл . Архивировано из оригинала 27 августа 2017 года . Проверено 4 мая 2018 г.

- ^ «Женщины в Оксфорде» . Оксфордский университет . Архивировано из оригинала 7 мая 2018 года . Проверено 4 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Педерсен, Джойс С. (май 1996 г.). «Рецензия на книгу (Нет различия пола? Женщины в британских университетах, 1870–1939)» . Обзоры H-Net . Х-Альбион. Архивировано из оригинала 17 сентября 2011 года . Проверено 14 октября 2010 г.

- ^ Справочник Оксфордского университета . Оксфордский университет. 1965. с. 43.

- ^ «Брошюра по истории Святой Анны» (PDF) . st-annes.ox.ac.uk. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 13 ноября 2018 года . Проверено 2 октября 2018 г.