Археоастрономия

Археоастрономия (также пишется как археоастрономия ) — это междисциплинарная наука. [1] или междисциплинарный [2] изучение того, как люди в прошлом «понимали явления в небе , как они использовали эти явления и какую роль небо играло в их культурах ». [3] Клайв Рагглс утверждает, что ошибочно считать археоастрономию изучением древней астрономии , поскольку современная астрономия является научной дисциплиной, в то время как археоастрономия рассматривает символически богатые культурные интерпретации явлений в небе, исходящие от других культур. [4] [5] Его часто связывают с этноастрономией , антропологическим исследованием наблюдения за небом в современных обществах. Археоастрономия также тесно связана с исторической астрономией , использованием исторических записей небесных событий для решения астрономических проблем и историей астрономии , которая использует письменные записи для оценки прошлой астрономической практики. [6]

Археоастрономия использует различные методы для обнаружения свидетельств прошлых практик, включая археологию, антропологию, астрономию, статистику и вероятность, а также историю. [7] Поскольку эти методы разнообразны и используют данные из таких разных источников, объединение их в последовательную аргументацию было долгосрочной трудностью для археоастрономов. [8] Археоастрономия заполняет взаимодополняющие ниши в ландшафтной археологии и когнитивной археологии . Материальные доказательства и их связь с небом могут показать, как более широкий ландшафт может быть интегрирован в представления о природных циклах , такие как астрономия майя и ее связь с сельским хозяйством. [9] Другие примеры, объединившие идеи познания и ландшафта, включают исследования космического порядка, встроенного в дороги поселений. [10] [11]

Археоастрономию можно применять ко всем культурам и всем периодам времени. Значения неба варьируются от культуры к культуре; тем не менее, существуют научные методы, которые можно применять в разных культурах при изучении древних верований. [12] Возможно, именно необходимость сбалансировать социальные и научные аспекты археоастрономии побудила Клайва Рагглза описать ее как «область с академической работой высокого качества на одном конце и неконтролируемыми спекуляциями, граничащими с безумием, на другом». [13]

История

[ редактировать ]В своей краткой истории «Астроархеологии» Джон Мичелл утверждал, что статус исследований древней астрономии улучшился за последние два столетия, пройдя «от безумия к ереси, к интересным идеям и, наконец, к вратам ортодоксальности». Спустя почти два десятилетия мы все еще можем задаться вопросом: археоастрономия все еще ждет у ворот ортодоксальности или уже проникла в ворота?

- Тодд Боствик цитирует Джона Мичелла [14]

За двести лет до того, как Джон Мичелл написал вышеизложенное, не было археоастрономов и не было профессиональных археологов , но были астрономы и антиквары . Некоторые из их работ считаются предшественниками археоастрономии; антиквары интерпретировали астрономическую ориентацию руин, разбросанных по английской сельской местности, как Уильям Стьюкли интерпретировал Стоунхендж в 1740 году. [15] в то время как Джон Обри в 1678 году [16] и Генри Чонси в 1700 году искали аналогичные астрономические принципы, лежащие в основе ориентации церквей. [17] В конце девятнадцатого века такие астрономы, как Ричард Проктор и Чарльз Пьяцци Смит, исследовали астрономическую ориентацию пирамид . [18]

Термин археоастрономия был предложен Элизабет Чесли Бейти (по предложению Юана Макки) в 1973 году. [19] [20] но как тема исследования она может быть намного старше, в зависимости от того, как определяется археоастрономия. Клайв Рагглз [21] говорит, что Генрих Ниссен , работавший в середине девятнадцатого века, был, возможно, первым археоастрономом. Рольф Синклер [22] говорит, что Нормана Локьера , работавшего в конце 19 — начале 20 веков, можно было бы назвать «отцом археоастрономии». Юэн Макки [23] поместил бы происхождение еще позже, заявив: «...происхождение и современный расцвет археоастрономии, несомненно, должны лежать в работах Александра Тома в Великобритании между 1930-ми и 1970-ми годами».

In the 1960s the work of the engineer Alexander Thom and that of the astronomer Gerald Hawkins, who proposed that Stonehenge was a Neolithic computer,[24] inspired new interest in the astronomical features of ancient sites. The claims of Hawkins were largely dismissed,[25] but this was not the case for Alexander Thom's work, whose survey results of megalithic sites hypothesized widespread practice of accurate astronomy in the British Isles.[26] Euan MacKie, recognizing that Thom's theories needed to be tested, excavated at the Kintraw standing stone site in Argyllshire in 1970 and 1971 to check whether the latter's prediction of an observation platform on the hill slope above the stone was correct. There was an artificial platform there and this apparent verification of Thom's long alignment hypothesis (Kintraw was diagnosed as an accurate winter solstice site) led him to check Thom's geometrical theories at the Cultoon stone circle in Islay, also with a positive result. MacKie therefore broadly accepted Thom's conclusions and published new prehistories of Britain.[27] In contrast a re-evaluation of Thom's fieldwork by Clive Ruggles argued that Thom's claims of high accuracy astronomy were not fully supported by the evidence.[28] Nevertheless, Thom's legacy remains strong, Edwin C. Krupp[29] wrote in 1979, "Almost singlehandedly he has established the standards for archaeo-astronomical fieldwork and interpretation, and his amazing results have stirred controversy during the last three decades." His influence endures and practice of statistical testing of data remains one of the methods of archaeoastronomy.[30][31]

The approach in the New World, where anthropologists began to consider more fully the role of astronomy in Amerindian civilizations, was markedly different. They had access to sources that the prehistory of Europe lacks such as ethnographies[32][33] and the historical records of the early colonizers. Following the pioneering example of Anthony Aveni,[34][35] this allowed New World archaeoastronomers to make claims for motives which in the Old World would have been mere speculation. The concentration on historical data led to some claims of high accuracy that were comparatively weak when compared to the statistically led investigations in Europe.[36]

This came to a head at a meeting sponsored by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in Oxford in 1981.[37] The methodologies and research questions of the participants were considered so different that the conference proceedings were published as two volumes.[38][39] Nevertheless, the conference was considered a success in bringing researchers together and Oxford conferences have continued every four or five years at locations around the world. The subsequent conferences have resulted in a move to more interdisciplinary approaches with researchers aiming to combine the contextuality of archaeological research,[40] which broadly describes the state of archaeoastronomy today, rather than merely establishing the existence of ancient astronomies, archaeoastronomers seek to explain why people would have an interest in the night sky.

Relations to other disciplines

[edit]...[O]ne of the most endearing characteristics of archaeoastronomy is its capacity to set academics in different disciplines at loggerheads with each other.

— Clive Ruggles[41]

Archaeoastronomy has long been seen as an interdisciplinary field that uses written and unwritten evidence to study the astronomies of other cultures. As such, it can be seen as connecting other disciplinary approaches for investigating ancient astronomy: astroarchaeology (an obsolete term for studies that draw astronomical information from the alignments of ancient architecture and landscapes), history of astronomy (which deals primarily with the written textual evidence), and ethnoastronomy (which draws on the ethnohistorical record and contemporary ethnographic studies).[42][43]

Reflecting Archaeoastronomy's development as an interdisciplinary subject, research in the field is conducted by investigators trained in a wide range of disciplines. Authors of recent doctoral dissertations have described their work as concerned with the fields of archaeology and cultural anthropology; with various fields of history including the history of specific regions and periods, the history of science and the history of religion; and with the relation of astronomy to art, literature and religion. Only rarely did they describe their work as astronomical, and then only as a secondary category.[44]

Both practicing archaeoastronomers and observers of the discipline approach it from different perspectives. Other researchers relate archaeoastronomy to the history of science, either as it relates to a culture's observations of nature and the conceptual framework they devised to impose an order on those observations[45] or as it relates to the political motives which drove particular historical actors to deploy certain astronomical concepts or techniques.[46][47] Art historian Richard Poss took a more flexible approach, maintaining that the astronomical rock art of the North American Southwest should be read employing "the hermeneutic traditions of western art history and art criticism"[48] Astronomers, however, raise different questions, seeking to provide their students with identifiable precursors of their discipline, and are especially concerned with the important question of how to confirm that specific sites are, indeed, intentionally astronomical.[49]

The reactions of professional archaeologists to archaeoastronomy have been decidedly mixed. Some expressed incomprehension or even hostility, varying from a rejection by the archaeological mainstream of what they saw as an archaeoastronomical fringe to an incomprehension between the cultural focus of archaeologists and the quantitative focus of early archaeoastronomers.[50] Yet archaeologists have increasingly come to incorporate many of the insights from archaeoastronomy into archaeology textbooks[51] and, as mentioned above, some students wrote archaeology dissertations on archaeoastronomical topics.

Since archaeoastronomers disagree so widely on the characterization of the discipline, they even dispute its name. All three major international scholarly associations relate archaeoastronomy to the study of culture, using the term Astronomy in Culture or a translation. Michael Hoskin sees an important part of the discipline as fact-collecting, rather than theorizing, and proposed to label this aspect of the discipline Archaeotopography.[52] Ruggles and Saunders proposed Cultural Astronomy as a unifying term for the various methods of studying folk astronomies.[53] Others have argued that astronomy is an inaccurate term, what are being studied are cosmologies and people who object to the use of logos have suggested adopting the Spanish cosmovisión.[54]

When debates polarise between techniques, the methods are often referred to by a colour code, based on the colours of the bindings of the two volumes from the first Oxford Conference, where the approaches were first distinguished.[55] Green (Old World) archaeoastronomers rely heavily on statistics and are sometimes accused of missing the cultural context of what is a social practice. Brown (New World) archaeoastronomers in contrast have abundant ethnographic and historical evidence and have been described as 'cavalier' on matters of measurement and statistical analysis.[56] Finding a way to integrate various approaches has been a subject of much discussion since the early 1990s.[57][58]

Methodology

[edit]For a long time I have believed that such diversity requires the invention of some all-embracing theory. I think I was very naïve in thinking that such a thing was ever possible.

— Stanislaw Iwaniszewski[59]

There is no one way to do archaeoastronomy. The divisions between archaeoastronomers tend not to be between the physical scientists and the social scientists. Instead, it tends to depend on the location and/or kind of data available to the researcher. In the Old World, there is little data but the sites themselves; in the New World, the sites were supplemented by ethnographic and historic data. The effects of the isolated development of archaeoastronomy in different places can still often be seen in research today. Research methods can be classified as falling into one of two approaches, though more recent projects often use techniques from both categories.

Green archaeoastronomy

[edit]Green archaeoastronomy is named after the cover of the book Archaeoastronomy in the Old World.[60] It is based primarily on statistics and is particularly apt for prehistoric sites where the social evidence is relatively scant compared to the historic period. The basic methods were developed by Alexander Thom during his extensive surveys of British megalithic sites.

Thom wished to examine whether or not prehistoric peoples used high-accuracy astronomy. He believed that by using horizon astronomy, observers could make estimates of dates in the year to a specific day. The observation required finding a place where on a specific date the Sun set into a notch on the horizon. A common theme is a mountain that blocked the Sun, but on the right day would allow the tiniest fraction to re-emerge on the other side for a 'double sunset'. The animation below shows two sunsets at a hypothetical site, one the day before the summer solstice and one at the summer solstice, which has a double sunset.

To test this idea he surveyed hundreds of stone rows and circles. Any individual alignment could indicate a direction by chance, but he planned to show that together the distribution of alignments was non-random, showing that there was an astronomical intent to the orientation of at least some of the alignments. His results indicated the existence of eight, sixteen, or perhaps even thirty-two approximately equal divisions of the year. The two solstices, the two equinoxes and four cross-quarter days, days halfway between a solstice and the equinox were associated with the medieval Celtic calendar.[61] While not all these conclusions have been accepted, it has had an enduring influence on archaeoastronomy, especially in Europe.

Euan MacKie has supported Thom's analysis, to which he added an archaeological context by comparing Neolithic Britain to the Mayan civilization to argue for a stratified society in this period.[27] To test his ideas he conducted a couple of excavations at proposed prehistoric observatories in Scotland. Kintraw is a site notable for its four-meter high standing stone. Thom proposed that this was a foresight to a point on the distant horizon between Beinn Shianaidh and Beinn o'Chaolias on Jura.[62] This, Thom argued, was a notch on the horizon where a double sunset would occur at midwinter. However, from ground level, this sunset would be obscured by a ridge in the landscape, and the viewer would need to be raised by two meters: another observation platform was needed. This was identified across a gorge where a platform was formed from small stones. The lack of artifacts caused concern for some archaeologists and the petrofabric analysis was inconclusive, but further research at Maes Howe[63] and on the Bush Barrow Lozenge[64] led MacKie to conclude that while the term 'science' may be anachronistic, Thom was broadly correct upon the subject of high-accuracy alignments.[65]

In contrast Clive Ruggles has argued that there are problems with the selection of data in Thom's surveys.[66][67] Others have noted that the accuracy of horizon astronomy is limited by variations in refraction near the horizon.[68] A deeper criticism of Green archaeoastronomy is that while it can answer whether there was likely to be an interest in astronomy in past times, its lack of a social element means that it struggles to answer why people would be interested, which makes it of limited use to people asking questions about the society of the past. Keith Kintigh wrote: "To put it bluntly, in many cases it doesn't matter much to the progress of anthropology whether a particular archaeoastronomical claim is right or wrong because the information doesn't inform the current interpretive questions."[69] Nonetheless, the study of alignments remains a staple of archaeoastronomical research, especially in Europe.[70]

Brown archaeoastronomy

[edit]In contrast to the largely alignment-oriented statistically led methods of green archaeoastronomy, brown archaeoastronomy has been identified as being closer to the history of astronomy or to cultural history, insofar as it draws on historical and ethnographic records to enrich its understanding of early astronomies and their relations to calendars and ritual.[55] The many records of native customs and beliefs made by Spanish chroniclers and ethnographic researchers means that brown archaeoastronomy is often associated with studies of astronomy in the Americas.[71][72][32][33]

One famous site where historical records have been used to interpret sites is Chichen Itza. Rather than analyzing the site and seeing which targets appear popular, archaeoastronomers have instead examined the ethnographic records to see what features of the sky were important to the Mayans and then sought archaeological correlates. One example which could have been overlooked without historical records is the Mayan interest in the planet Venus. This interest is attested to by the Dresden codex which contains tables with information about Venus's appearances in the sky.[73] These cycles would have been of astrological and ritual significance as Venus was associated with Quetzalcoatl or Xolotl.[74] Associations of architectural features with settings of Venus can be found in Chichen Itza, Uxmal, and probably some other Mesoamerican sites.[75]

The Temple of the Warriors bears iconography depicting feathered serpents associated with Quetzalcoatl or Kukulcan. This means that the building's alignment towards the place on the horizon where Venus first appears in the evening sky (when it coincides with the rainy season) may be meaningful.[76] However, since both the date and the azimuth of this event change continuously, a solar interpretation of this orientation is much more likely.[77]

Aveni claims that another building associated with the planet Venus in the form of Kukulcan, and the rainy season at Chichen Itza is the Caracol.[78] This is a building with a circular tower and doors facing the cardinal directions. The base faces the most northerly setting of Venus. Additionally the pillars of a stylobate on the building's upper platform were painted black and red. These are colours associated with Venus as an evening and morning star.[79] However the windows in the tower seem to have been little more than slots, making them poor at letting light in, but providing a suitable place to view out.[80] In their discussion of the credibility of archaeoastronomical sites, Cotte and Ruggles considered the interpretation that the Caracol is an observatory site was debated among specialists, meeting the second of their four levels of site credibility.[81]

Aveni states that one of the strengths of the brown methodology is that it can explore astronomies invisible to statistical analysis and offers the astronomy of the Incas as another example. The empire of the Incas was conceptually divided using ceques, radial routes emanating from the capital at Cusco. Thus there are alignments in all directions which would suggest there is little of astronomical significance, However, ethnohistorical records show that the various directions do have cosmological and astronomical significance with various points in the landscape being significant at different times of the year.[82][83] In eastern Asia archaeoastronomy has developed from the history of astronomy and much archaeoastronomy is searching for material correlates of the historical record. This is due to the rich historical record of astronomical phenomena which, in China, stretches back into the Han dynasty, in the second century BC.[84]

A criticism of this method is that it can be statistically weak. Schaefer in particular has questioned how robust the claimed alignments in the Caracol are.[85][86] Because of the wide variety of evidence, which can include artefacts as well as sites, there is no one way to practice archaeoastronomy.[87] Despite this it is accepted that archaeoastronomy is not a discipline that sits in isolation. Because archaeoastronomy is an interdisciplinary field, whatever is being investigated should make sense both archaeologically and astronomically. Studies are more likely to be considered sound if they use theoretical tools found in archaeology like analogy and homology and if they can demonstrate an understanding of accuracy and precision found in astronomy. Both quantitative analyses and interpretations based on ethnographic analogies and other contextual evidence have recently been applied in systematic studies of architectural orientations in the Maya area[88] and in other parts of Mesoamerica.[89]

Source materials

[edit]Because archaeoastronomy is about the many and various ways people interacted with the sky, there are a diverse range of sources giving information about astronomical practices.

Alignments

[edit]A common source of data for archaeoastronomy is the study of alignments. This is based on the assumption that the axis of alignment of an archaeological site is meaningfully oriented towards an astronomical target. Brown archaeoastronomers may justify this assumption through reading historical or ethnographic sources, while green archaeoastronomers tend to prove that alignments are unlikely to be selected by chance, usually by demonstrating common patterns of alignment at multiple sites.

An alignment is calculated by measuring the azimuth, the angle from north, of the structure and the altitude of the horizon it faces[90] The azimuth is usually measured using a theodolite or a compass. A compass is easier to use, though the deviation of the Earth's magnetic field from true north, known as its magnetic declination must be taken into account. Compasses are also unreliable in areas prone to magnetic interference, such as sites being supported by scaffolding. Additionally a compass can only measure the azimuth to a precision of a half a degree.[91]

A theodolite can be considerably more accurate if used correctly, but it is also considerably more difficult to use correctly. There is no inherent way to align a theodolite with North and so the scale has to be calibrated using astronomical observation, usually the position of the Sun.[92] Because the position of celestial bodies changes with the time of day due to the Earth's rotation, the time of these calibration observations must be accurately known, or else there will be a systematic error in the measurements. Horizon altitudes can be measured with a theodolite or a clinometer.

Artifacts

[edit]

For artifacts such as the Sky Disc of Nebra, alleged to be a Bronze Age artefact depicting the cosmos,[93][94] the analysis would be similar to typical post-excavation analysis as used in other sub-disciplines in archaeology. An artefact is examined and attempts are made to draw analogies with historical or ethnographical records of other peoples. The more parallels that can be found, the more likely an explanation is to be accepted by other archaeologists.

A more mundane example is the presence of astrological symbols found on some shoes and sandals from the Roman Empire. The use of shoes and sandals is well known, but Carol van Driel-Murray has proposed that astrological symbols etched onto sandals gave the footwear spiritual or medicinal meanings.[95] This is supported through citation of other known uses of astrological symbols and their connection to medical practice and with the historical records of the time.[96]

Another well-known artefact with an astronomical use is the Antikythera mechanism. In this case analysis of the artefact, and reference to the description of similar devices described by Cicero, would indicate a plausible use for the device. The argument is bolstered by the presence of symbols on the mechanism, allowing the disc to be read.[97]

Art and inscriptions

[edit]

Art and inscriptions may not be confined to artefacts, but also appear painted or inscribed on an archaeological site. Sometimes inscriptions are helpful enough to give instructions to a site's use. For example, a Greek inscription on a stele (from Itanos) has been translated as:"Patron set this up for Zeus Epopsios. Winter solstice. Should anyone wish to know: off 'the little pig' and the stele the sun turns."[98] From Mesoamerica come Mayan and Aztec codices. These are folding books made from Amatl, processed tree bark on which are glyphs in Mayan or Aztec script. The Dresden codex contains information regarding the Venus cycle, confirming its importance to the Mayans.[73]

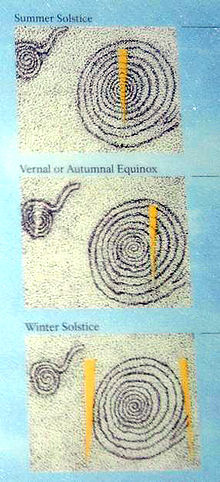

More problematic are those cases where the movement of the Sun at different times and seasons causes light and shadow interactions with petroglyphs.[99] A widely known example is the Sun Dagger of Fajada Butte at which a glint of sunlight passes over a spiral petroglyph.[100] The location of a dagger of light on the petroglyph varies throughout the year. At the summer solstice a dagger can be seen through the heart of the spiral; at the winter solstice two daggers appear to either side of it. It is proposed that this petroglyph was created to mark these events. Recent studies have identified many similar sites in the US Southwest and Northwestern Mexico.[101][102] It has been argued that the number of solstitial markers at these sites provides statistical evidence that they were intended to mark the solstices.[103] The Sun Dagger site on Fajada Butte in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, stands out for its explicit light markings that record all the key events of both the solar and lunar cycles: summer solstice, winter solstice, equinox, and the major and minor lunar standstills of the Moon's 18.6 year cycle.[104][105] In addition at two other sites on Fajada Butte, there are five light markings on petroglyphs recording the summer and winter solstices, equinox and solar noon.[106] Numerous buildings and interbuilding alignments of the great houses of Chaco Canyon and outlying areas are oriented to the same solar and lunar directions that are marked at the Sun Dagger site.[107]

If no ethnographic nor historical data are found which can support this assertion then acceptance of the idea relies upon whether or not there are enough petroglyph sites in North America that such a correlation could occur by chance. It is helpful when petroglyphs are associated with existing peoples. This allows ethnoastronomers to question informants as to the meaning of such symbols.

Ethnographies

[edit]As well as the materials left by peoples themselves, there are also the reports of other who have encountered them. The historical records of the Conquistadores are a rich source of information about the pre-Columbian Americans. Ethnographers also provide material about many other peoples.

Aveni uses the importance of zenith passages as an example of the importance of ethnography. For peoples living between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn there are two days of the year when the noon Sun passes directly overhead and casts no shadow. In parts of Mesoamerica this was considered a significant day as it would herald the arrival of rains, and so play a part in the cycle of agriculture. This knowledge is still considered important amongst Mayan Indians living in Central America today. The ethnographic records suggested to archaeoastronomers that this day may have been important to the ancient Mayans. There are also shafts known as 'zenith tubes' which illuminate subterranean rooms when the Sun passes overhead found at places like Monte Albán and Xochicalco. It is only through the ethnography that we can speculate that the timing of the illumination was considered important in Mayan society.[108] Alignments to the sunrise and sunset on the day of the zenith passage have been claimed to exist at several sites. However, it has been shown that, since there are very few orientations that can be related to these phenomena, they likely have different explanations.[109]

Ethnographies also caution against over-interpretation of sites. At a site in Chaco Canyon can be found a pictograph with a star, crescent and hand. It has been argued by some astronomers that this is a record of the 1054 Supernova.[110] However recent reexaminations of related 'supernova petroglyphs' raises questions about such sites in general.[111] Cotte and Ruggles used the Supernova petroglyph as an example of a completely refuted site[81] and anthropological evidence suggests other interpretations. The Zuni people, who claim a strong ancestral affiliation with Chaco, marked their sun-watching station with a crescent, star, hand and sundisc, similar to those found at the Chaco site.[112]

Ethnoastronomy is also an important field outside of the Americas. For example, anthropological work with Aboriginal Australians is producing much information about their Indigenous astronomies[113][114] and about their interaction with the modern world.[115]

Recreating the ancient sky

[edit]...[A]lthough different ways to do science and different scientific results do arise in different cultures, this provides little support for those who would use such differences to question the sciences' ability to provide reliable statements about the world in which we live.

— Stephen McCluskey[116]

Once the researcher has data to test, it is often necessary to attempt to recreate ancient sky conditions to place the data in its historical environment.

Declination

[edit]To calculate what astronomical features a structure faced a coordinate system is needed. The stars provide such a system. On a clear night observe the stars spinning around the celestial pole can be observed. This point is +90° of the North Celestial Pole or −90° observing the Southern Celestial Pole.[117] The concentric circles the stars trace out are lines of celestial latitude, known as declination. The arc connecting the points on the horizon due East and due West (if the horizon is flat) and all points midway between the Celestial Poles is the Celestial Equator which has a declination of 0°. The visible declinations vary depending where you are on the globe. Only an observer on the North Pole of Earth would be unable to see any stars from the Southern Celestial Hemisphere at night (see diagram below). Once a declination has been found for the point on the horizon that a building faces it is then possible to say whether a specific body can be seen in that direction.

Solar positioning

[edit]While the stars are fixed to their declinations the Sun is not. The rising point of the Sun varies throughout the year. It swings between two limits marked by the solstices a bit like a pendulum, slowing as it reaches the extremes, but passing rapidly through the midpoint. If an archaeoastronomer can calculate from the azimuth and horizon height that a site was built to view a declination of +23.5° then he or she need not wait until 21 June to confirm the site does indeed face the summer solstice.[118] For more information see History of solar observation.

Lunar positioning

[edit]The Moon's appearance is considerably more complex. Its motion, like the Sun, is between two limits—known as lunistices rather than solstices. However, its travel between lunistices is considerably faster. It takes a sidereal month to complete its cycle rather than the year-long trek of the Sun. This is further complicated as the lunistices marking the limits of the Moon's movement move on an 18.6 year cycle. For slightly over nine years the extreme limits of the Moon are outside the range of sunrise. For the remaining half of the cycle the Moon never exceeds the limits of the range of sunrise. However, much lunar observation was concerned with the phase of the Moon. The cycle from one New Moon to the next runs on an entirely different cycle, the Synodic month.[119] Thus when examining sites for lunar significance the data can appear sparse due to the extremely variable nature of the Moon. See Moon for more details.

Stellar positioning

[edit]

Finally there is often a need to correct for the apparent movement of the stars. On the timescale of human civilisation the stars have largely maintained the same position relative to each other. Each night they appear to rotate around the celestial poles due to the Earth's rotation about its axis. However, the Earth spins rather like a spinning top. Not only does the Earth rotate, it wobbles. The Earth's axis takes around 25,800 years to complete one full wobble.[120] The effect to the archaeoastronomer is that stars did not rise over the horizon in the past in the same places as they do today. Nor did the stars rotate around Polaris as they do now.

The movement of the Earth's axis was already noticed by the Sumerians over six thousand years ago, when they were able to observe the star Canopus culminating directly above the horizon on the southern meridian for the first time in their oldest and southernmost city Eridu. For several decades, Canopus was not yet visible in the neighbouring town of Ur to the north-east of Eridu, and therefore, it was called the "Star of the City of Eridu" in Sumerian.[121][122]

In the case of the Egyptian pyramids, it has been shown they were aligned towards Thuban, a faint star in the constellation of Draco.[123] The effect can be substantial over relatively short lengths of time, historically speaking. For instance a person born on 25 December in Roman times would have been born with the Sun in the constellation Capricorn. In the modern period a person born on the same date would have the Sun in Sagittarius due to the precession of the equinoxes.

Transient phenomena

[edit]

Additionally there are often transient phenomena, events which do not happen on an annual cycle. Most predictable are events like eclipses. In the case of solar eclipses these can be used to date events in the past. A solar eclipse mentioned by Herodotus enables us to date a battle between the Medes and the Lydians, which following the eclipse failed to happen, to 28 May, 585 BC.[124]

Some comets are predictable, most famously Halley's Comet. Yet as a class of object they remain unpredictable and can appear at any time. Some have extremely lengthy orbital periods which means their past appearances and returns cannot be predicted. Others may have only ever passed through the Solar System once and so are inherently unpredictable.[125]

Meteor showers should be predictable, but some meteors are cometary debris and so require calculations of orbits which are currently impossible to complete.[126] Other events noted by ancients include aurorae, sun dogs and rainbows all of which are as impossible to predict as the ancient weather, but nevertheless may have been considered important phenomena.

Major topics of archaeoastronomical research

[edit]What has astronomy brought into the lives of cultural groups throughout history? The answers are many and varied...

— Von Del Chamberlain and M. Jane Young[127]

The use of calendars

[edit]A common justification for the need for astronomy is the need to develop an accurate calendar for agricultural reasons. Ancient texts like Hesiod's Works and Days, an ancient farming manual, would appear to partially confirm this: astronomical observations are used in combination with ecological signs, such as bird migrations to determine the seasons. Ethnoastronomical studies of the Hopi of the southwestern United States indicate that they carefully observed the rising and setting positions of the Sun to determine the proper times to plant crops.[128] However, ethnoastronomical work with the Mursi of Ethiopia shows that their luni-solar calendar was somewhat haphazard, indicating the limits of astronomical calendars in some societies.[129] All the same, calendars appear to be an almost universal phenomenon in societies as they provide tools for the regulation of communal activities.

One such example is the Tzolk'in calendar of 260 days. Together with the 365-day year, it was used in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, forming part of a comprehensive calendrical system, which combined a series of astronomical observations and ritual cycles.[130] Archaeoastronomical studies throughout Mesoamerica have shown that the orientations of most structures refer to the Sun and were used in combination with the 260-day cycle for scheduling agricultural activities and the accompanying rituals. The distribution of dates and intervals marked by orientations of monumental ceremonial complexes in the area along the southern Gulf Coast in Mexico, dated to about 1100 to 700 BCE, represents the earliest evidence of the use of this cycle.[131]

Other peculiar calendars include ancient Greek calendars. These were nominally lunar, starting with the New Moon. In reality the calendar could pause or skip days with confused citizens inscribing dates by both the civic calendar and ton theoi, by the moon.[132] The lack of any universal calendar for ancient Greece suggests that coordination of panhellenic events such as games or rituals could be difficult and that astronomical symbolism may have been used as a politically neutral form of timekeeping.[133] Orientation measurements in Greek temples and Byzantine churches have been associated to deity's name day, festivities, and special events.[134][135][136]

Myth and cosmology

[edit]

Another motive for studying the sky is to understand and explain the universe. In these cultures myth was a tool for achieving this, and the explanations, while not reflecting the standards of modern science, are cosmologies.

The Incas arranged their empire to demonstrate their cosmology. The capital, Cusco, was at the centre of the empire and connected to it by means of ceques, conceptually straight lines radiating out from the centre.[137] These ceques connected the centre of the empire to the four suyus, which were regions defined by their direction from Cusco. The notion of a quartered cosmos is common across the Andes. Gary Urton, who has conducted fieldwork in the Andean villagers of Misminay, has connected this quartering with the appearance of the Milky Way in the night sky.[138] In one season it will bisect the sky and in another bisect it in a perpendicular fashion.

The importance of observing cosmological factors is also seen on the other side of the world. The Forbidden City in Beijing is laid out to follow cosmic order though rather than observing four directions. The Chinese system was composed of five directions: North, South, East, West and Centre. The Forbidden City occupied the centre of ancient Beijing.[139] One approaches the Emperor from the south, thus placing him in front of the circumpolar stars. This creates the situation of the heavens revolving around the person of the Emperor. The Chinese cosmology is now better known through its export as feng shui.

There is also much information about how the universe was thought to work stored in the mythology of the constellations. The Barasana of the Amazon plan part of their annual cycle based on observation of the stars. When their constellation of the Caterpillar-Jaguar (roughly equivalent to the modern Scorpius) falls they prepare to catch the pupating caterpillars of the forest as they fall from the trees.[140] The caterpillars provide food at a season when other foods are scarce.[141]

A more well-known source of constellation myth are the texts of the Greeks and Romans. The origin of their constellations remains a matter of vigorous and occasionally fractious debate.[142][143]

The loss of one of the sisters, Merope, in some Greek myths may reflect an astronomical event wherein one of the stars in the Pleiades disappeared from view by the naked eye.[144]

Giorgio de Santillana, professor of the History of Science in the School of Humanities at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, along with Hertha von Dechend believed that the old mythological stories handed down from antiquity were not random fictitious tales but were accurate depictions of celestial cosmology clothed in tales to aid their oral transmission. The chaos, monsters and violence in ancient myths are representative of the forces that shape each age. They believed that ancient myths are the remains of preliterate astronomy that became lost with the rise of the Greco-Roman civilization. Santillana and von Dechend in their book Hamlet's Mill, An Essay on Myth and the Frame of Time (1969) clearly state that ancient myths have no historical or factual basis other than a cosmological one encoding astronomical phenomena, especially the precession of the equinoxes.[145] Santillana and von Dechend's approach is not widely accepted.

Displays of power

[edit]

By including celestial motifs in clothing it becomes possible for the wearer to make claims the power on Earth is drawn from above. It has been said that the Shield of Achilles described by Homer is also a catalogue of constellations.[146] In North America shields depicted in Comanche petroglyphs appear to include Venus symbolism.[147]

Solsticial alignments also can be seen as displays of power. When viewed from a ceremonial plaza on the Island of the Sun (the mythical origin place of the Sun) in Lake Titicaca, the Sun was seen to rise at the June solstice between two towers on a nearby ridge. The sacred part of the island was separated from the remainder of it by a stone wall and ethnographic records indicate that access to the sacred space was restricted to members of the Inca ruling elite. Ordinary pilgrims stood on a platform outside the ceremonial area to see the solstice Sun rise between the towers.[148]

In Egypt the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak has been the subject of much study. Evaluation of the site, taking into account the change over time of the obliquity of the ecliptic show that the Great Temple was aligned on the rising of the midwinter Sun.[149] The length of the corridor down which sunlight would travel would have limited illumination at other times of the year.

In a later period the Serapeum of Alexandria was also said to have contained a solar alignment so that, on a specific sunrise, a shaft of light would pass across the lips of the statue of Serapis thus symbolising the Sun saluting the god.[150]

Major sites of archaeoastronomical interest

[edit]Clive Ruggles and Michel Cotte recently edited a book on heritage sites of astronomy and archaeoastronomy which discussed a worldwide sample of astronomical and archaeoastronomical sites and provided criteria for the classification of archaeoastronomical sites.[151]

At Stonehenge in England and at Carnac in France, in Egypt and Yucatán, across the whole face of the earth, are found mysterious ruins of ancient monuments, monuments with astronomical significance... They mark the same kind of commitment that transported us to the moon and our spacecraft to the surface of Mars.

— Edwin Krupp[152]

Newgrange

[edit]

Newgrange is a passage tomb in the Republic of Ireland dating from around 3,300 to 2,900 BC[153] For a few days around the Winter Solstice light shines along the central passageway into the heart of the tomb. What makes this notable is not that light shines in the passageway, but that it does not do so through the main entrance. Instead it enters via a hollow box above the main doorway discovered by Michael O'Kelly.[154] It is this roofbox which strongly indicates that the tomb was built with an astronomical aspect in mind. In their discussion of the credibility of archaeoastronomical sites, Cotte and Ruggles gave Newgrange as an example of a Generally accepted site, the highest of their four levels of credibility.[81] Clive Ruggles notes:

...[F]ew people—archaeologists or astronomers—have doubted that a powerful astronomical symbolism was deliberately incorporated into the monument, demonstrating that a connection between astronomy and funerary ritual, at the very least, merits further investigation.[117]

Egypt

[edit]

Since the first modern measurements of the precise cardinal orientations of the Giza pyramids by Flinders Petrie, various astronomical methods have been proposed for the original establishment of these orientations.[155][156][157] It was recently proposed that this was done by observing the positions of two stars in the Plough / Big Dipper which was known to Egyptians as the thigh. It is thought that a vertical alignment between these two stars checked with a plumb bob was used to ascertain where north lay. The deviations from true north using this model reflect the accepted dates of construction.[158]

Some[who?] have argued that the pyramids were laid out as a map of the three stars in the belt of Orion, although this theory has been criticized by reputable astronomers.[159][160] The site was instead probably governed by a spectacular hierophany which occurs at the summer solstice, when the Sun, viewed from the Sphinx terrace, forms—together with the two giant pyramids—the symbol Akhet, which was also the name of the Great Pyramid. Further, the south east corners of all the three pyramids align towards the temple of Heliopolis, as first discovered by the Egyptologist Mark Lehner.

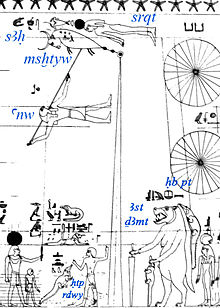

The astronomical ceiling of the tomb of Senenmut (c. 1470 BC) contains the Celestial Diagram depicting circumpolar constellations in the form of discs. Each disc is divided into 24 sections suggesting a 24-hour time period. Constellations are portrayed as sacred deities of Egypt. The observation of lunar cycles is also evident.

El Castillo

[edit]El Castillo, also known as Kukulcán's Pyramid, is a Mesoamerican step-pyramid built in the centre of Mayan center of Chichen Itza in Mexico. Several architectural features have suggested astronomical elements. Each of the stairways built into the sides of the pyramid has 91 steps. Along with the extra one for the platform at the top, this totals 365 steps, which is possibly one for each day of the year (365.25) or the number of lunar orbits in 10,000 rotations (365.01).

A visually striking effect is seen every March and September as an unusual shadow occurs around the equinoxes. Light and shadow phenomena have been proposed to explain a possible architectural hierophany involving the sun at Chichén Itzá in a Maya Toltec structure dating to about 1000 CE.[161] A shadow appears to descend the west balustrade of the northern stairway. The visual effect is of a serpent descending the stairway, with its head at the base in light. Additionally the western face points to sunset around 25 May, traditionally the date of transition from the dry to the rainy season.[162] The intended alignment was, however, likely incorporated in the northern (main) facade of the temple, as it corresponds to sunsets on May 20 and July 24, recorded also by the central axis of Castillo at Tulum.[163] The two dates are separated by 65 and 300 days, and it has been shown that the solar orientations in Mesoamerica regularly correspond to dates separated by calendrically significant intervals (multiples of 13 and 20 days).[164] In their discussion of the credibility of archaeoastronomical sites, Cotte and Ruggles used the "equinox hierophany" at Chichén Itzá as an example of an Unproven site, the third of their four levels of credibility.[81]

Stonehenge

[edit]

Many astronomical alignments have been claimed for Stonehenge, a complex of megaliths and earthworks in the Salisbury Plain of England. The most famous of these is the midsummer alignment, where the Sun rises over the Heel Stone. However, this interpretation has been challenged by some archaeologists who argue that the midwinter alignment, where the viewer is outside Stonehenge and sees the Sun setting in the henge, is the more significant alignment, and the midsummer alignment may be a coincidence due to local topography.[165] In their discussion of the credibility of archaeoastronomical sites, Cotte and Ruggles gave Stonehenge as an example of a Generally accepted site, the highest of their four levels of credibility.[81]

As well as solar alignments, there are proposed lunar alignments. The four station stones mark out a rectangle. The short sides point towards the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset. The long sides if viewed towards the south-east, face the most southerly rising of the Moon. Aveni notes that these lunar alignments have never gained the acceptance that the solar alignments have received.[166]

Maeshowe

[edit]

This is an architecturally outstanding Neolithic chambered tomb on the mainland of Orkney, Scotland—probably dating to the early 3rd millennium BC, and where the setting Sun at midwinter shines down the entrance passage into the central chamber (see Newgrange). In the 1990s further investigations were carried out to discover whether this was an accurate or an approximate solar alignment. Several new aspects of the site were discovered. In the first place the entrance passage faces the hills of the island Hoy, about 10 miles away. Secondly, it consists of two straight lengths, angled at a few degrees to each other. Thirdly, the outer part is aligned towards the midwinter sunset position on a level horizon just to the left of Ward Hill on Hoy. Fourthly the inner part points directly at the Barnhouse standing stone about 400m away and then to the right end of the summit of Ward Hill, just before it dips down to the notch between it at Cuilags to the right. This indicated line points to sunset on the first Sixteenths of the solar year (according to A. Thom) before and after the winter solstice and the notch at the base of the right slope of the Hill is at the same declination. Fourthly a similar 'double sunset' phenomenon is seen at the right end of Cuilags, also on Hoy; here the date is the first Eighth of the year before and after the winter solstice, at the beginning of November and February respectively—the Old Celtic festivals of Samhain and Imbolc. This alignment is not indicated by an artificial structure but gains plausibility from the other two indicated lines. Maeshowe is thus an extremely sophisticated calendar site which must have been positioned carefully in order to use the horizon foresights in the ways described.[63]

Uxmal

[edit]

Uxmal is a Mayan city in the Puuc Hills of Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico. The Governor's Palace at Uxmal is often used as an exemplar of why it is important to combine ethnographic and alignment data. The palace is aligned with an azimuth of 118° on the pyramid of Cehtzuc. This alignment corresponds approximately to the southernmost rising and, with a much greater precision, to the northernmost setting of Venus; both phenomena occur once every eight years. By itself this would not be sufficient to argue for a meaningful connection between the two events. The palace has to be aligned in one direction or another and why should the rising of Venus be any more important than the rising of the Sun, Moon, other planets, Sirius et cetera? The answer given is that not only does the palace point towards significant points of Venus, it is also covered in glyphs which stand for Venus and Mayan zodiacal constellations.[167] Moreover, the great northerly extremes of Venus always occur in late April or early May, coinciding with the onset of the rainy season. The Venus glyphs placed in the cheeks of the Maya rain god Chac, most likely referring to the concomitance of these phenomena, support the west-working orientation scheme.[168]

Chaco Canyon

[edit]

In Chaco Canyon, the center of the ancient Pueblo culture in the American Southwest, numerous solar and lunar light markings and architectural and road alignments have been documented. These findings date to the 1977 discovery of the Sun Dagger site by Anna Sofaer.[169] Three large stone slabs leaning against a cliff channel light and shadow markings onto two spiral petroglyphs on the cliff wall, marking the solstices, equinoxes and the lunar standstills of the 18.6 year cycle of the moon.[105] Subsequent research by the Solstice Project and others demonstrated that numerous building and interbuilding alignments of the great houses of Chaco Canyon are oriented to solar, lunar and cardinal directions.[170][171] In addition, research shows that the Great North Road, a thirty-five mile engineered "road", was constructed not for utilitarian purposes but rather to connect the ceremonial center of Chaco Canyon with the direction north.[172]

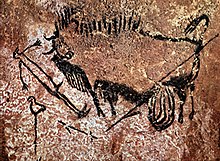

Lascaux Cave

[edit]

В последние годы новые исследования показали, что наскальные рисунки Ласко во Франции могут включать в себя доисторические звездные карты. Михаэль Раппенглюк из Мюнхенского университета утверждает, что некоторые нефигуративные скопления точек и точки на некоторых фигуративных изображениях коррелируют с созвездиями Тельца , Плеяд и группировкой, известной как « Летний треугольник ». [173] На основе собственного исследования астрономического значения петроглифов бронзового века в Валле-де-Мервей. [174] и ее обширное исследование других мест доисторической наскальной живописи в регионе (большинство из которых, по-видимому, были выбраны потому, что интерьеры освещены заходящим Солнцем в день зимнего солнцестояния ), французская исследовательница Шанталь Жег-Волькевиз далее предположила, что Галерея фигуративных изображений в Большом зале представляет собой обширную звездную карту, и ключевые точки на основных фигурах группы соответствуют звездам основных созвездий , какими они были в палеолите. [175] [176] Применяя филогенетику к мифам о Космической Охоте, Жюльен д'Юи предположил, что палеолитическая версия этой истории может быть следующей: существует животное, являющееся рогатым травоядным, особенно лось. Один человек преследует это копытное. Охота находит или добирается до неба. Животное живо, когда оно превращается в созвездие. Он образует Большую Медведицу. Эту историю можно представить в знаменитой «сцене» шахты Ласко. [177]

Пограничная археоастрономия

[ редактировать ]По крайней мере, теперь у нас есть все археологические факты, подтверждающие мнение астрономов, друидов, сторонников плоской Земли и всех остальных.

— Сэр Джоселин Стивенс [178]

Археоастрономия имеет плохую репутацию среди ученых из-за того, что ею время от времени злоупотребляют для продвижения ряда псевдоисторических отчетов. В 1930-х годах Отто С. Рейтер составил исследование под названием Germanische Himmelskunde , или «Тевтонский Скайлор». Астрономическая ориентация древних памятников, на которую претендует Рейтер и его последователи, поставила бы древние германские народы впереди Древнего Ближнего Востока в области астрономии, продемонстрировав интеллектуальное превосходство « ариев » (индоевропейцев) над семитами . [179]

Совсем недавно Галлахер, [180] Пайл, [181] и упал [182] интерпретировал надписи в Западной Вирджинии как описание огам предполагаемого указателя зимнего солнцестояния на этом месте кельтским алфавитом . Спорный перевод предположительно был подтвержден проблематичным археоастрономическим указанием, согласно которому Солнце зимнего солнцестояния сияло на надписи Солнца на этом месте. Последующие анализы подвергли критике его культурную неуместность, а также его лингвистические и археоастрономические особенности. [183] утверждает, что описывает это как пример « культовой археологии ». [184]

Археоастрономию иногда связывают с периферийной дисциплиной археокриптографии , когда ее последователи пытаются найти основные математические порядки, лежащие в основе пропорций, размера и расположения археоастрономических объектов, таких как Стоунхендж и пирамида Кукулькана в Чичен-Ице. [185]

Индия

[ редактировать ]Начиная с XIX века, многие ученые пытались использовать археоастрономические расчеты , чтобы продемонстрировать древность древнеиндийской ведической культуры, вычисляя даты астрономических наблюдений, неоднозначно описанных в древней поэзии, до 4000 г. до н.э. [186] Дэвид Пингри , историк индийской астрономии, осудил «учёных, которые выдвигают дикие теории доисторической науки и называют себя археоастрономами». [187]

Организации

[ редактировать ]В настоящее время существует несколько академических организаций для ученых-археоастрономов (включая этноастрономию и астрономию коренных народов).

ISAAC – Международное общество археоастрономии и астрономии в культуре – было основано в 1996 году как глобальное общество в этой области. Он спонсирует Оксфордские конференции и журнал «Астрономия в культуре» .

SEAC – Европейское общество астрономии в культуре – было основано в 1992 году с акцентом на Европу в целом. SEAC проводит ежегодные конференции в Европе и ежегодно публикует материалы рецензируемых конференций.

SIAC – Межамериканское общество астрономии в культуре было основано в 2003 году с упором на Латинскую Америку .

SCAAS — Общество культурной астрономии на юго-западе Америки было основано в 2009 году как региональная организация, занимающаяся астрономией коренных народов юго -запада США ; с тех пор он провел семь встреч и семинаров. [188]

AAAC - Австралийская ассоциация астрономии в культуре была основана в 2020 году в Австралии и занимается астрономией аборигенов и жителей островов Торресова пролива.

Румынское общество культурной астрономии было основано в 2019 году, проведя ежегодную международную конференцию и опубликовав первую монографию по архео- и этноастрономии в Румынии (2019). [189]

SMART – Общество астрономических исследований и традиций маори было основано в Аотеароа (Новая Зеландия) в 2013 году и занимается астрономией маори.

Native Skywatchers была основана в 2007 году в Миннесоте, США, с целью популяризации звездных знаний коренных американцев, особенно народов лакота и оджибве на севере США и Канады.

Публикации

[ редактировать ]Кроме того, Журнал истории астрономии публикует множество археоастрономических статей. В двадцати семи томах (с 1979 по 2002 год) публиковалось ежегодное приложение «Археоастрономия» .

Журнал астрономической истории и наследия , культуры и космоса и журнал Skyscape Archeology также публикуют статьи по археоастрономии.

Академические программы

[ редактировать ]Национальные проекты и университетские программы, включая культурную астрономию или посвященные ей, встречаются во всем мире. Они включают в себя:

Софийский центр космологии в культуре при Уэльском университете — Тринити-Сент-Дэвид в Лампетере, Великобритания.

Программа культурной астрономии в Мельбурнском университете в Австралии.

Интересные выводы в этой области сделал Институт фундаментальных исследований Тата . [190]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Список археоастрономических памятников, отсортированный по странам

- Список артефактов, важных для археоастрономии

- Астрономическая хронология

- Астрономический проект австралийских аборигенов

- Культурная астрономия

- Лунный застой

- Медицинское колесо

- Мегалит

- Строители курганов

- Петроформс

- Плеяды в фольклоре и литературе

- Поклонение небесным светилам

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Будущее 1982: 1

- ^ Авени, Энтони Ф. (1995), «Фромборк 1992: Где сталкиваются миры и дисциплины», Археоастрономия: Приложение к журналу истории астрономии , 26 (20): S74–S79, Бибкод : 1995JHAS...26.. .74A , doi : 10.1177/002182869502602007 , S2CID 220911940

- ^ Синклер 2006:13

- ^ Рагглс 2005:19

- ^ Рагглс 1999: 155

- ^ Бержерон, Жаклин (1993). «История астрономии: Совместная комиссия IAU-IUHPS». Доклады по астрономии . стр. 461–462. дои : 10.1007/978-94-011-1100-3_31 . ISBN 978-94-010-4481-3 .

- ^ Брош, Ной (29 марта 2011 г.). «Размышления об археоастрономии». История и философия физики . arXiv : 1103.5600 .

- ^ Иванишевский 2003, 7–10.

- ^ Будущее 1980 г.

- ^ Чиу и Моррисон 1980

- ^ Магли 2008 г.

- ^ Маккласки 2005 г.

- ^ Карлсон 1999 г.

- ^ Боствик 2006:13

- ^ Мичелл, 2001: 9–10.

- ^ Джонсон, 1912:225.

- ^ Хоскин, 2001:7

- ^ Мичелл, 2001: 17–18.

- ^ Бэйти, Элизабет Чесли (1973), «Археоастрономия и этноастрономия до сих пор», Current Anthropology , 14 (4): 389–390, doi : 10.1086/201351 , JSTOR 2740842 , S2CID 146933891

- ^ Синклер 2006:17

- ^ Рагглс 2005: 312–13

- ^ Синклер 2006: 8

- ^ Маки 2006: 243

- ^ Хокинс 1976

- ^ Аткинсон 1966

- ^ Том 1988: 9–10

- ^ Jump up to: а б Макки 1977 г.

- ^ Джинджерич 2000

- ^ Крупп 1979:18

- ^ Хикс 1993

- ^ Иванишевский 1995 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б С 1985 года

- ^ Jump up to: а б С 1986 года

- ^ Милбрейт 1999: 8

- ^ Брода 2000:233

- ^ Хоскин 1996 г.

- ^ Рагглс 1993:ix

- ^ Будущее 1982 г.

- ^ Хегги 1982

- ^ Авени, 1989a: xi – xiii.

- ^ Рагглс 2000

- ^ Будущее 1981: 1–2

- ^ Будущее 2003: 150

- ^ Маккласки 2004 г.

- ^ Маккласки 2001

- ^ Брода 2006

- ^ Алдана 2007: 14–15.

- ^ Возможно 2005:97

- ^ Шефер 2006a: 30

- ^ Рагглс 1999: 3–9

- ^ Фишер 2006

- ^ Хоскин 2001: 13–14.

- ^ Рагглс и Сондерс 1993: 1–31.

- ^ Рагглс 2005: 115–17

- ^ Jump up to: а б Будущее 1986 года

- ^ Хоскин 2001:2

- ^ Рагглс и Сондерс, 1993 г.

- ^ Иванишевский 2001

- ^ Иванишевский 2003:7

- ^ Будущее 1989: 1

- ^ Том 1967: 107–17.

- ^ Рагглс 1999: 25–29

- ^ Jump up to: а б Макки 1997 г.

- ^ Макки 2006: 362

- ^ Макки 2009

- ^ Рагглс 1999: 19–29

- ^ Рагглс и Барклай 2000: 69–70.

- ^ Шефер и Лиллер 1990.

- ^ Кинтиг 1992

- ^ Хоскин 2001

- ^ Будущее 1989 г.

- ^ Хадсон, Ли и Хеджес, 1979 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Келли и Милон 2005: 369–70.

- ^ Келли и Милон 2005: 367–68.

- ^ Шпрайц, Иван (1996). Звезда Кетцалькоатля: Планета Венера в Мезоамерике . Мехико: Редакционная Диана. ISBN 978-968-13-2947-1 .

- ^ Милбрейт 1988: 70–71

- ^ Санчес Нава, Педро Франциско; Шпрайц, Иван (2015). Астрономические ориентации в архитектуре равнинных майя . Мехико: Национальный институт антропологии и истории. ISBN 978-607-484-727-7 .

- ^ Будущее 2006: 60–64.

- ^ Будущее 1979: 175–83

- ^ Будущее 1997: 137–38.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Рагглс, Клинтон ; Котт, М. (2010). «Заключение: Астрономическое наследие в контексте Конвенции ЮНЕСКО о всемирном наследии: развитие профессионального и рационального подхода». В Рагглсе, CLN; Котт, М. (ред.). Объекты наследия астрономии и археоастрономии в контексте Конвенции о всемирном наследии ЮНЕСКО: тематическое исследование (PDF) . Париж: ИКОМОС/МАС. стр. 271–2. ISBN 978-2-918086-01-7 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 18 марта 2016 г. Проверено 21 января 2018 г .: Их четыре уровня достоверности: (1) общепринятые, (2) обсуждаемые среди специалистов, (3) недоказанные и (4) полностью опровергнутые.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: постскриптум ( ссылка ) - ^ Будущее 1989: 5

- ^ Бауэр и Дирборн, 1995 г.

- ^ Сюй и др. 2000: 1–7

- ^ Шефер 2006a: 42–48.

- ^ Шефер 2006b

- ^ Иванишевский 2003

- ^ Гонсалес-Гарсия, А. Цезарь; Спрайц, Иван (2016). «Астрономическое значение архитектурных ориентаций в низменностях майя: статистический подход». Журнал археологической науки: отчеты . 9 : 191–202. Бибкод : 2016JArSR...9..191G . дои : 10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.07.020 .

- ^ Шпрайц, Иван (2018). «Астрономия, архитектура и ландшафт в доиспанской Мезоамерике». Журнал археологических исследований . 26 (2): 197–251. дои : 10.1007/s10814-017-9109-z . S2CID 149439162 .

- ^ Рагглс, 2005: 112–13.

- ^ «Руководство по эксплуатации Brunton Pocket Transit» (PDF) . п. 22. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 4 марта 2006 г. Проверено 2 марта 2008 г.

- ^ Рагглс 2005: 423–25

- ^ Шольссер 2002

- ^ Меллер 2004 г.

- ^ ван Дрил-Мюррей, 2002 г.

- ^ Доктор Ричард Пирсон (2020). История астрономии . Соединенное Королевство: Астропубликация. п. 7. ISBN 9780244866501 .

- ^ Т. Фрит и др. 2006 г.

- ^ Критские надписи III iv 11; Исагер и Скайдсгаард 1992:163.

- ^ Уильямсон 1987: 109–14

- ^ Диваны 2008 г.

- ^ Фонтан 2005 г.

- ^ Робинс и Юинг, 1989 г.

- ^ Престон и Престон 2005: 115–18.

- ^ Science Mag, Sofaer et al. 1979: 126

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кембриджский университет, 1982 г., диваны и др.: 126.

- ^ Диван и Синклер: 1987. UNM, ABQ

- ^ Sofaer 1998: Лексон Эд, штат Юта: 165

- ^ Будущее 1980: 40–43.

- ^ Шпрайц и Санчес 2013

- ^ Брандт и Уильямсон, 1979 г.

- ^ Круп. и др. 2010: 42

- ^ Рагглс 2005:89

- ^ Кэрнс, 2005 г.

- ^ Хамахер 2012

- ^ Сэтре 2007

- ^ Маккласки 2005:78

- ^ Jump up to: а б Рагглс 1999:18

- ^ А. Ф. Авени 1997: 23–27.

- ^ Рагглс 1999: 36–37

- ^ Рагглс 2005: 345–47

- ^ Бауч, Маркус; Педде, Фридхельм (1 мая 2023 г.). Обсерватория Вильгельма Ферстера eV / Планетарий Цейсса на острове Инсуланер (ред.). «Канопус, «Звезда города Эриду» » (PDF) . Близко к небу. (на немецком языке) (17). Берлин: 8-9. ISSN 2940-9330 . Проверено 16 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Бауч, Маркус. «Канопус / Месопотамия – Wikibooks, коллекция бесплатных учебников, научно-популярной и специальной литературы» . Близко к небесам (на немецком языке) (17): 8–9 . Проверено 16 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Рагглс 2005: 354–55

- ^ Геродот . Истории I.74 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 февраля 2009 г. Проверено 22 марта 2008 г.

- ↑ Предсказание следующей яркой кометы. Архивировано 13 мая 2008 г. на Wayback Machine , Space.com.

- ^ Сталь 1999 г.

- ^ Чемберлен и Янг 2005:xi

- ^ Маккласки 1990

- ^ Тертон и Рагглс, 1978 г.

- ^ Будущее 1989б

- ^ Шпрайц и др. в 2023 году

- ^ Маккласки 2000

- ^ Соль и Буцикас 2005 г.

- ^ Лирицис, И; Василиу, Х (2002). «Астрономические ориентации древних храмов на Родосе и Аттике с предварительной интерпретацией». Средиземноморская археология и археометрия . 2 (1): 69–79. Бибкод : 2002MAA.....2...69L .

- ^ Лирицис.И и Василиу.Х (2006) Были ли греческие храмы ориентированы на полярное сияние? Астрономия и геофизика , вып. 47, 2, 1.14–1.18

- ^ Liritzis.I и Vassiliou.H (2006) Коррелирует ли день восхода солнца с восточной ориентацией византийских церквей во время значительных солнечных дат и названия дня святого? Предварительное исследование. Byzantinische Zeitscrift (KG Saur Munchen, Лейпциг) 99, 2, 523–34.

- ^ Бауэр и Дирборн, 1995 г.

- ^ Уртон 1981

- ^ Крупп 1997a: 196–99.

- ^ Хоскин 1999: 15–16.

- ^ Хью-Джонс 1982: 191–93

- ^ Шефер 2002

- ^ Бломберг 2003, особенно стр. 76

- ↑ Плеяды в мифологии. Архивировано 10 апреля 2019 г. в Wayback Machine , Pleiade Associates, Бристоль, Великобритания, по состоянию на 7 июня 2012 г.

- ↑ Джорджио де Сантильяна и Герта фон Дехенд, «Мельница Гамлета» , Дэвид Р. Годин: Бостон, 1977.

- ^ Ханна 1994

- ^ Крупп 1997a: 252–53.

- ^ Дирборн, Седдон и Бауэр, 1998.

- ^ Крупп 1988

- ^ Руфинус

- ^ Клайв Рагглз и Мишель Котт (ред.), Объекты наследия астрономии и археоастрономии. ИКОМОС и МАС, Париж, 2010 г.

- ^ Крупп. 1979:1

- ^ Эоган 1991

- ^ О'Келли 1982: 123–24

- ^ Бельмонте 2001

- ^ Нойгебауэр 1980

- ^ Туманы 2013

- ^ Спенс 2000

- ^ Фэйролл, 1999 г.

- ^ Крупп 1997б

- ^ Оксфордская энциклопедия мезоамериканских культур . Издательство Оксфордского университета. 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-510815-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 9 августа 2020 г. Проверено 13 июля 2020 г.

- ^ Крупп 1997a: 267–69.

- ^ Шпрайц, Иван; Санчес Нава, Педро Франциско (2013). «Астрономия в архитектуре Чичен-Ицы: переоценка» . Исследования культуры майя . XLI (41): 31–60. дои : 10.1016/S0185-2574(13)71376-5 .

- ^ Шпрайц, И. (2018). «Астрономия, архитектура и ландшафт в доиспанской Мезоамерике». Журнал археологических исследований . 26 (2): 197–251. дои : 10.1007/s10814-017-9109-z . S2CID 149439162 .

- ^ Паркер Пирсон и др. 2007 год

- ^ Будущее 1997: 65–66.

- ^ Рагглс 2005: 163–65

- ^ Спрайц 2015

- ^ Журнал Science , Sofaer et al., 1979: 126.

- ^ Малвилл и Патнэм, 1989. Johnson Books: 111.

- ^ Sofaer 1998. Lexson Ed, Университет штата Юта: 165.

- ^ Софаер, Маршалл и Синклер, 1989. Кембридж: 112.

- ^ Уайтхаус, Дэвид (9 августа 2000 г.). «Обнаружена звездная карта ледникового периода» . Новости Би-би-си . Архивировано из оригинала 7 июля 2017 года . Проверено 30 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ «Валле де Мервей» (на французском языке). Археоциэль. Архивировано из оригинала 18 декабря 2010 г. Проверено 1 января 2011 г.

- ^ «Archeociel: Chantal Jègues Wolkiewiez» (на французском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 17 декабря 2010 года . Проверено 1 января 2011 г.

- ^ «Пещера Ласко: доисторическая карта неба...» световая медитация. Архивировано из оригинала 15 августа 2010 года . Проверено 1 января 2011 г.

- ^ Жюльен д'Юи. 2012. Медведь в звездах: филогенетическое исследование доисторического мифа. Архивировано 3 мая 2018 г. в Wayback Machine . Юго-западная предыстория , 20 (1), 91–106; Жюльен д'Юи. 2013. Космическая охота в берберском небе. Архивировано 11 июля 2015 г. в Wayback Machine . Les Cahiers de l’AARS , 16, 93–106.

- ^ Сэр Джоселин Стивенс, цитата из The Times , 8 июля 1994 г., стр. 8.

- ^ Педерсен 1982: 269

- ^ Галлахер 1983

- ^ Пайл 1983

- ^ Осень 1983 г.

- ^ Мудрый 2003 г.

- ^ Лессер, 1983

- ^ Шме, Клаус (2012), «Патология криптологии – текущий обзор», Cryptologia , 36 : 19–20, doi : 10.1080/01611194.2011.632803 , S2CID 36073676

- ^ Витцель 2001

- ^ Пингри 1982: 554–63, особенно. п. 556

- ^ Бейтс, Брайан; Мансон, Грег. «Краткая история Общества культурной астрономии на юго-западе Америки» . Общество культурной астрономии на юго-западе Америки. Архивировано из оригинала 01 марта 2021 г. Проверено 14 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Астрономия Страбунилор» . carturesti.ro (на румынском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 30 сентября 2020 г. Проверено 05 января 2020 г.

- ^ «Первая индийская запись сверхновой обнаружена в Кашмире» . Индус . 12 июля 2011 года. Архивировано из оригинала 16 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 8 июля 2013 г.

Библиография

[ редактировать ]- Алдана, Г. (2007). Апофеоз Джанаба Пакаля: наука, история и религия в классическом майя Паленке Боулдер: Университетское издательство Колорадо. ISBN 978-0-87081-866-0 .

- Аткинсон, RJC (1966). «Самогон в Стоунхендже». Античность . 49 (159): 212–16. дои : 10.1017/S0003598X0003252X . S2CID 163140537 .

- Авени, А.Ф. (1979). «Астрономия в Древней Мезоамерике» . В EC Krupp (ред.). В поисках древней астрономии . Чатто и Виндус. стр. 154–85 . ISBN 978-0-7011-2314-7 .

- Авени, А.Ф. (1980). Наблюдатели за небом Древней Мексики . Техасский университет. ISBN 978-0-292-77578-7 .

- Авени, А.Ф. (1981). «Археоастрономия». В Майкле Б. Шиффере (ред.). Достижения археологического метода и теории . Том. 4. Академическая пресса. п. 177. ИСБН 978-0-12-003104-7 .

- Авени. АФ, изд. (1982). Археоастрономия в Новом Свете: американская примитивная астрономия . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-24731-3 .

- Авени. А.Ф. (1986). «Археоастрономия: прошлое, настоящее и будущее». Небо и телескоп . 72 : 456–60. Бибкод : 1986S&T....72..456A .

- Авени, А.Ф. (1989a). Мировая археоастрономия . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-34180-6 .

- Авени, А.Ф. (1989b). Империи времени . Основные книги. ISBN 978-0-465-01950-2 .

- Авени, А.Ф. (1997). Лестницы к звездам: наблюдение за небом в трех великих древних культурах . Джон Уайли и сыновья. ISBN 978-0-471-32976-3 .

- Авени. АФ (2001). «Археоастрономия». В Дэвиде Карраско (ред.). Оксфордская энциклопедия мезоамериканских культур: Цивилизации Мексики и Центральной Америки . Том. 1. Издательство Оксфордского университета . стр. 35–37. ISBN 0-19-510815-9 . OCLC 44019111 .

- Авени. АФ (2003). «Археоастрономия в Древней Америке» (PDF) . Журнал археологических исследований . 11 (2): 149–91. дои : 10.1023/А:1022971730558 . S2CID 161787154 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 марта 2016 г. Проверено 25 февраля 2016 г.

- Авени, А.Ф. (2006). «Доказательства и намеренность: данные в археоастрономии». В Тодде В. Боствике; Брайан Бейтс (ред.). Взгляд на небо сквозь культуру прошлого и настоящего: избранные доклады VII Оксфордской международной конференции по археоастрономии . Антропологические документы Музея Пуэбло-Гранде. Том. 15. Департамент парков и отдыха города Феникс. стр. 57–70. ISBN 978-1-882572-38-0 .

- Бан, П. (1995). Археология: очень краткое введение . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-285379-0 .

- Бауэр Б. и Дирборн Д. (1995). Астрономия и империя в древних Андах: культурные истоки наблюдения за небом инков . Техасский университет. ISBN 978-0-292-70837-2 .

- Бельмонте, Дж. А. (2001). «О ориентации египетских пирамид Древнего царства». Археоастрономия: Приложение к журналу истории астрономии . 32 (26): С1–С20. Бибкод : 2001JHAS...32....1B . дои : 10.1177/002182860103202601 . S2CID 120619970 .

- Бломберг, П. (2003). «Ранняя эллинская карта неба, реконструированная на основе археоастрономических и текстовых исследований». В Аманде-Алисе Маравелии (ред.). Ad Astra per Aspera et per Ludum: Европейская археоастрономия и ориентация памятников в Средиземноморском бассейне: материалы сессии I.13, состоявшейся на восьмом ежегодном собрании Европейской ассоциации археологов в Салониках, 2002 г. BAR International Series 1154. Археопресс. стр. 71–76. ISBN 978-1-84171-524-7 .

- Боствик, ТВ (2006). «Археоастрономия у ворот православия: Введение в Оксфордскую VII конференцию по археоастрономическим документам». В Тодде В. Боствике; Брайан Бейтс (ред.). Взгляд на небо сквозь культуру прошлого и настоящего: избранные доклады VII Оксфордской международной конференции по археоастрономии . Антропологические документы Музея Пуэбло-Гранде. Том. 15. Департамент парков и отдыха города Феникс. стр. 1–10. ISBN 978-1-882572-38-0 .

- Брандт, Дж. К. и Уильямсон, Р. А. (1979). «Сверхновая звезда 1054 года и американское наскальное искусство». Археоастрономия: Приложение к журналу истории астрономии . 1 (10): С1–С38. Бибкод : 1979JHAS...10....1B .

- Брода, Дж. (2000). «Мезоамериканская археоастрономия и ритуальный календарь». В Хелейн Селин (ред.). Астрономия в разных культурах . Клювер, Дордрект. стр. 225–67. ISBN 978-0-7923-6363-7 .

- Брода, Дж. (2006). «Наблюдения за зенитом и концептуализация географической широты в древней Мезоамерике: исторический междисциплинарный подход». В Тодде В. Боствике; Брайан Бейтс (ред.). Взгляд на небо через прошлые и настоящие культуры; Избранные доклады VII Оксфордской международной конференции по археоастрономии . Антропологические документы Музея Пуэбло-Гранде. Том. 15. Департамент парков и отдыха города Феникс. стр. 183–212. ISBN 978-1-882572-38-0 .

- Кэрнс, ХК (2005). «Открытия в картографии неба аборигенов (Австралия)». В Фонтане Джона В.; Рольф М. Синклер (ред.). Современные исследования в области археоастрономии: беседы во времени и пространстве . Дарем, Северная Каролина: Каролина Академик Пресс. стр. 523–38. ISBN 978-0-89089-771-3 .

- Карлсон, Дж. (осень 1999 г.). «Редакционная статья: Наш собственный профессор» . Новости археоастрономии и этноастрономии (Осеннее равноденствие). 33 . Архивировано из оригинала 13 мая 2008 г. Проверено 22 марта 2008 г.

- Чемберлен, В.Д. и Янг, М.Дж. (2005). "Введение". В Фон Дель Чемберлен; Джон Карлсон и М. Джейн Янг (ред.). Песни с неба: местные астрономические и космологические традиции мира . Книги Окарины. стр. xi – xiv. ISBN 978-0-9540867-2-5 .

- Чиу, Британская Колумбия, и Моррисон, П. (1980). «Астрономическое происхождение смещенной уличной сетки в Теотиуакане». Археоастрономия: Приложение к журналу истории астрономии . 11 (18): С55–С64. Бибкод : 1980JHAS...11...55C .

- Дирборн, DSP; Седдон, М.Ф. и Бауэр, Б.С. (1998). «Святилище Титикака: место, где Солнце возвращается на Землю». Латиноамериканская древность . 9 (3): 240–58. дои : 10.2307/971730 . JSTOR 971730 . S2CID 163867549 .

- Эоган, Г. (1991). «Доисторические и раннеисторические культурные изменения в Бруг-на-Бойне». Труды Королевской ирландской академии . 91С : 105–132.

- Фэйролл, А. (1999). «Прецессия и планировка древнеегипетских пирамид» . Астрономия и геофизика . 40 (4): 3.4. дои : 10.1093/астрог/40.3.3.4 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2008 г. Проверено 22 марта 2008 г.

- Фелл, Б. (1983). «Христианские послания староирландским письмом, расшифрованные по наскальным рисункам в Западной Вирджинии» . Замечательная Западная Вирджиния (47): 12–19. Архивировано из оригинала 9 мая 2008 года . Проверено 27 апреля 2008 г.

- Фишер, В.Б. (2006). «Игнорирование археоастрономии: умирающая традиция в американской археологии». В Тодде В. Боствике; Брайан Бейтс (ред.). Взгляд на небо через прошлые и настоящие культуры; Избранные доклады VII Оксфордской международной конференции по археоастрономии . Антропологические документы Музея Пуэбло-Гранде. Том. 15. Департамент парков и отдыха города Феникс. стр. 1–10. ISBN 978-1-882572-38-0 .

- Фонтан, Дж. (2005). «База данных солнечных маркеров наскального искусства». В Фонтане Джона В.; Рольф М. Синклер (ред.). Современные исследования в области археоастрономии: беседы во времени и пространстве . Дарем, Северная Каролина: Каролина Академик Пресс. ISBN 978-0-89089-771-3 .

- Фрит, Т; Битсакис, Ю; Муссас, X; Сейрадакис, Дж. Х.; Целикас, А; Мангу, Х; Зафейропулу, М; Хэдланд, Р.; и др. (30 ноября 2006 г.). «Расшифровка древнегреческого астрономического калькулятора, известного как Антикиферский механизм». Природа . 444 (7119): 587–91. Бибкод : 2006Natur.444..587F . дои : 10.1038/nature05357 . ПМИД 17136087 . S2CID 4424998 .

- Галлахер, Эй Джей (1983). «Светлые рассветы в истории Западной Вирджинии» . Замечательная Западная Вирджиния (47): 7–11. Архивировано из оригинала 11 мая 2008 года . Проверено 27 апреля 2008 г.

- Джинджерич, О. (24 марта 2000 г.). «Камень и звезды» . Приложение Times Higher Education : 24. Архивировано из оригинала 4 февраля 2009 г. Проверено 22 марта 2008 г.