Жестокое обращение с детьми

Насилие над детьми (также называемая угрозой для детей или жестокое обращение с детьми ) является физическим , сексуальным , эмоциональным и/или психологическим жестоким обращением или пренебрежением ребенка, особенно родителем или опекуном. Насилие над детьми может включать в себя любые действия или неспособность действовать родителем или попечителя, который приводит к фактическому или потенциальному неправомерному вреду для ребенка и может произойти в доме ребенка, или в организациях, школах или сообществах, с которыми ребенок взаимодействует.

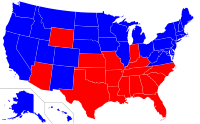

Различные юрисдикции имеют разные требования для обязательной отчетности и разработали различные определения того, что представляет собой злоупотребление детьми, и, следовательно, имеют разные критерии для устранения детей из их семей или преследовать уголовное обвинение .

История

[ редактировать ]Еще в 19 -м веке жестокость по поводу детей, совершенная работодателями и учителями, была обычной и широко распространенной, а телесные наказания были обычными во многих странах, но во время первой половины 19 -го века патологи изучали фийцид (убийство родителей детей. ) сообщили о случаях смерти от отцовской ярости, [ 1 ] повторяющееся физическое жестокое обращение, [ 2 ] голод, [ 3 ] и сексуальное насилие. [ 4 ] В статье 1860 года французский судебный медицинский эксперт по медицинским показаниям Оглу Амброиз Тардие собрал серию из 32 таких случаев, из которых 18 были смертельными, дети, умирающие от голода и/или повторяющегося физического насилия; Это включало в себя случай Аделины Дейферт, которая была возвращена ее бабушкой и дедушкой в возрасте 8 лет, и в течение 9 лет пытали ее родители - ежедневно взбивали, подвешивались ее большими пальцами и избитыми пригволенной планой, сожженной горячими углями и Ее раны опались в азотной кислоте и дефлотированы дубинкой. [ 5 ] Тардие совершил домашние визиты и наблюдал за влиянием на детей; Он заметил, что печаль и страх на их лицах исчезли, когда они были помещены под защиту. Он прокомментировал: «Когда мы рассмотрим нежный возраст этих бедных беззащитных существ, ежедневно и почти ежечасно диким злодеяниям, невообразимыми пытками и суровыми лишениями, их жизни - одна длинная мученичество - и когда мы сталкиваемся с тем, что их мучители являются самими матерями. Кто дал им жизнь, мы сталкиваемся с одной из самых ужасных проблем, которые могут нарушить душу моралиста или совесть справедливости ». [ 6 ] Его наблюдения были повторены Boileau de Castélnau (который представил термин Misopédie - ненависть к детям), [ 7 ] и подтверждено Обри [ 8 ] и несколько тезисов . [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ]

Эти ранние французские наблюдения не смогли преодолеть языковой барьер , и другие страны оставались не знающими причиной многих травмирующих поражений у младенцев и малышей; Почти сто лет пройдет, прежде чем человечество начало систематически противостоять «ужасной проблеме» Тардие. В 20 -м веке начались данные из патологии и детской радиологии, особенно в связи с хронической субдуральной гематомой и переломами конечностей: субдуральная гематома имела любопытное бимодальное распределение, идиопатическое у младенцев и травматическое у взрослых, [ 12 ] в то время как необъяснимый окостенительный периостит длинных костей был похож на то, что произошло после экстракции казенного. [ 13 ] В 1946 году Джон Каффи, американский основатель детской радиологии, обратил внимание на связь переломов длинных костей и хронической субдуральной гематомы, [ 14 ] И в 1955 году было замечено, что у младенцев отстранены от ухода за агрессивными, незрелыми и эмоционально больными родителями, не имели новых поражений. [ 15 ]

В результате профессиональное исследование этой темы снова началось в 1960 -х годах. [ 16 ] Публикация статьи в июле 1962 года «Избитый ребенок-синдром», написанный главным образом педиатром С. Генри Кемпе и опубликованным в Журнале Американской медицинской ассоциации, представляет собой момент, когда жестокое обращение с детьми вступило в мейнстримскую осведомленность. Перед публикацией статьи травмы детей - даже повторные переломы костей - не были обычно признаны результатами преднамеренной травмы. Вместо этого врачи часто искали недиагностированные заболевания костей или принятые родители, рассказы о случайных неудачах, таких как падения или нападения соседских хулиганов. [ 17 ] : 100–103

Изучение жестокого обращения с детьми стало академической дисциплиной в начале 1970 -х годов в Соединенных Штатах. Элизабет Янг-Бюль утверждала, что, несмотря на растущее число защитников детей и интерес к защите детей, группировку детей в «насильственных» и «без навязчих» создали искусственное различие, которое сузило концепцию прав детей на Просто защита от жестокого обращения и заблокировало расследование того, как дети в целом подвергаются дискриминации в обществе. По словам Янг-Бюль, еще один эффект от жестокого обращения с детьми и пренебрежения заключался в том, чтобы закрыть рассмотрение того, как сами дети воспринимают жестокое обращение и важность, которое они придают им для взрослых. Янг-Бюль писал, что, когда в обществе присутствует вера в необоснованность детей для взрослых, все дети страдают от того, называется ли их лечение как «злоупотребление». [ 17 ] : 15–16

Двое из многих ученых, которые изучали и опубликовали о жестоком обращении с детьми и пренебрежением, Жанна М. Джованнони и Розина М. Беррара, опубликованные определение жестокого обращения с детьми в 1979 году. В нем (по словам издателей) они используют методологию социальных исследований для определения ребенка Злоупотребление, освещать стратегии для исправления и предотвращения жестокого обращения с детьми, и изучить, как профессионалы и сообщество рассматривают плохое обращение с детьми . [ 18 ] [ 19 ]

Определения

[ редактировать ]Определения того, что составляет жестокое обращение с детьми, различаются среди профессионалов, между социальными и культурными группами и во времени. [ 20 ] [ 21 ] Термины злоупотребления и жестокого обращения часто используются взаимозаменяемо в литературе. [ 22 ] : 11 Желание ребенка также может быть зонтичным термином, охватывающим все формы жестокого обращения с детьми и пренебрежения детей . [ 16 ] Определение жестокого обращения с детьми зависит от преобладающих культурных ценностей, связанных с детьми, развития детей и воспитания детей . [ 23 ] Определения жестокого обращения с детьми может варьироваться в зависимости от секторов общества, которые касаются этой проблемы, [ 23 ] такие как агентства по защите детей , юридические и медицинские сообщества, чиновники общественного здравоохранения , исследователи, практикующие врачи и адвокаты детей . Поскольку члены этих различных областей, как правило, используют свои собственные определения, общение между дисциплинами может быть ограничено, затрудняя усилия по выявлению, оценке, отслеживанию, лечению и предотвращению жестокого обращения с детьми. [ 22 ] : 3 [ 24 ]

В целом, злоупотребление относится к (обычно преднамеренным) актам комиссии, в то время как пренебрежение относится к актам упущения. [ 16 ] [ 25 ] Желание ребенка включает в себя как акты комиссии, так и упущение со стороны родителей или лиц, осуществляющих уход, которые причиняют фактический или угрожающий вред ребенку. [ 16 ] Некоторые специалисты здравоохранения и авторы считают пренебрежение как часть определения злоупотребления , а другие - нет; Это связано с тем, что вред мог быть непреднамеренным, или потому, что уход не понимал серьезности проблемы, которая могла быть результатом культурных убеждений о том, как воспитывать ребенка. [ 26 ] [ 27 ] Задержка последствий жестокого обращения с детьми и пренебрежения, особенно эмоционального пренебрежения, и разнообразие действий, которые квалифицируются как жестокое обращение с детьми, также являются факторами. [ 27 ]

Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ) определяет жестокое обращение с детьми и жестокое обращение с детьми как «все формы физического и/или эмоционального жестокого лечения, сексуального насилия, пренебрежения или небрежного лечения или коммерческого или другого эксплуатации, что приводит к фактическому или потенциальному вреду для здоровья ребенка , выживание, развитие или достоинство в контексте отношений ответственности, доверия или власти ». [ 28 ] ВОЗ также говорит: «Насилие в отношении детей включает в себя все формы насилия в отношении людей в возрасте до 18 лет, будь то, совершаемые родителями или другими лицами, осуществляющими уход, сверстники, романтические партнеры или незнакомцы». [ 29 ] В Соединенных Штатах Центры по контролю и профилактике заболеваний (CDC) используют термин « жестокое обращение с детьми для обозначения обоих актов комиссии» (злоупотребление), которые включают «слова или явные действия, которые причиняют вред, потенциальный вред или угрозу вреда Ребенок »и« Акты бездействия »(пренебрежение), что означает« неспособность обеспечить основные физические, эмоциональные или образовательные потребности ребенка или защитить ребенка от вреда или потенциального вреда ». [ 22 ] : 11 федерального жестокого обращения с детьми Соединенных Штатов Закон о предотвращении и лечении определяет жестокое обращение с детьми и пренебрежение , как минимум, «любой недавний акт или неспособность действовать со стороны родителя или смотрителя, что приводит к смерти, серьезным физическим или эмоциональным вредам, сексуальному насилию или эксплуатация «или« акт или неспособность действовать, что представляет неизбежный риск серьезного вреда ». [ 30 ] [ 31 ]

Формы злоупотребления

[ редактировать ]По состоянию на 2006 г. [update]Всемирная организация здравоохранения различает четыре типа жестокого обращения с детьми: физическое насилие ; сексуальное насилие ; эмоциональное (или психологическое) злоупотребление ; и пренебрежение . [ 32 ]

Физическое насилие

[ редактировать ]Среди профессионалов и широкой публики существуют разногласия относительно того, какое поведение представляет собой физическое насилие над ребенком. [ 33 ] Физическое насилие часто возникает не в изоляции, но в рамках созвездия поведения, включая авторитарный контроль, поведение, вызывающее беспокойство, и отсутствие родительского тепла. [ 34 ] Кто определяет физическое насилие как:

Преднамеренное использование физической силы против ребенка, которое приводит к или имеет высокую вероятность, что приводит к повреждению здоровья, выживания, развития или достоинства ребенка. Это включает в себя удары, избиение, удар, трясение, кусание, удушение, обжигание, сжигание, отравление и удушение. Большое физическое насилие в отношении детей в доме причиняется объектом наказания. [ 32 ]

Перекрывающиеся определения физического насилия и физического наказания детей подчеркивают тонкое или несуществующее различие между злоупотреблением и наказанием, [ 35 ] Но большая часть физического насилия является физическим наказанием «в намерениях, форме и эффекте». [ 36 ] Например, по состоянию на 2006 год Пауло Серхио Пинхайро написал в исследовании Генерального секретаря ООН по насилию в отношении детей:

Телесное наказание включает в себя удары («удары», «пощечивание», «шлепки») детей, с рукой или с помощью орудия - кнут, палка, ремень, обувь, деревянная ложка и т. Д., Но это также может включать, например, удары по ногу , встряхивая или бросая детей, царапают, зажимают, кусали, натягивают волосы или боксерские уши, заставляя детей оставаться в неудобных положениях, сжигания, сжигания или принудительного приема (например, мыть детские рты или заставлять их проглотить горячие специи. ) [ 37 ]

Большинство стран с законами о жестоком обращении с детьми считают, что преднамеренное нанесение серьезных травм или действия, которые ставят ребенка на явный риск серьезных травм или смерти, быть незаконными. [ 38 ] Ушибы, царапины, ожоги, сломанные кости, рваные раны - или повторные «неудачи» и грубое лечение, которое может вызвать физические повреждения - могут быть физическим насилием. [ 39 ] Многочисленные травмы или переломы на разных стадиях заживления могут вызвать подозрение в злоупотреблении.

Психолог Алиса Миллер , отмеченная своими книгами о жестоком обращении с детьми, приняла мнение о том, что унижения, порки и избиения, пощечины по лицу и т. Д. - все это формы злоупотребления, потому что они травмируют целостность и достоинство ребенка, даже если если Их последствия не видны сразу. [ 40 ]

Physical abuse as a child can lead to physical and mental difficulties in the future, including re-victimization, personality disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dissociative disorders, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, eating disorders, substance use disorders, и агрессия. Физическое насилие в детстве также было связано с бездомностью во взрослом возрасте. [ 41 ]

Синдром избитого ребенка

[ редактировать ]C. Генри Кемпе и его коллеги были первыми, кто описал синдром избитого ребенка в 1962 году. [ 42 ] Синдром избитого ребенка-это термин, используемый для описания коллекции травм, которые маленькие дети получают в результате повторного физического насилия или пренебрежения. [ 43 ] [ 44 ] Эти симптомы могут включать в себя: переломы костей , множественные травмы мягких тканей, субдуральная гематома (кровотечение в мозге), недоедание и плохую гигиену кожи. [44][45]

Children suffering from battered-child syndrome may come to the doctor's attention for a problem unrelated to abuse or after experiencing an acute injury, but when examined, they show signs of long-term abuse.[46] In most cases, the caretakers try to justify the visible injuries by blaming them on minor accidents.[46] When asked, parents may attribute the injuries to a child's behaviour or habits, such as being fussy or clumsy. Despite the abuse, the child may show attachment to the parent.[46]

Sexual abuse

[edit]Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a form of child abuse in which an adult or older adolescent abuses a child for sexual stimulation.[47] Sexual abuse refers to the participation of a child in a sexual act aimed toward the physical gratification or the financial profit of the person committing the act.[39][48] Forms of CSA include asking or pressuring a child to engage in sexual activities (regardless of the outcome), indecent exposure of the genitals to a child, displaying pornography to a child, actual sexual contact with a child, physical contact with the child's genitals, viewing of the child's genitalia without physical contact, or using a child to produce child pornography.[47][49][50] Selling the sexual services of children may be viewed and treated as child abuse rather than simple incarceration.[51]

Effects of child sexual abuse on the victim(s) include guilt and self-blame, flashbacks, nightmares, insomnia, fear of things associated with the abuse (including objects, smells, places, doctor's visits, etc.), self-esteem difficulties, sexual dysfunction, chronic pain, addiction, self-injury, suicidal ideation, somatic complaints, depression,[52] PTSD,[53] anxiety,[54] other mental illnesses including borderline personality disorder[55] and dissociative identity disorder,[55] propensity to re-victimization in adulthood,[56] bulimia nervosa,[57] and physical injury to the child, among other problems.[58] Children who are the victims are also at an increased risk of sexually transmitted infections due to their immature immune systems and a high potential for mucosal tears during forced sexual contact.[59] Sexual victimization at a young age has been correlated with several risk factors for contracting HIV including decreased knowledge of sexual topics, increased prevalence of HIV, engagement in risky sexual practices, condom avoidance, lower knowledge of safe sex practices, frequent changing of sexual partners, and more years of sexual activity.[59]

As of 2016[update], in the United States, about 15% to 25% of women and 5% to 15% of men were sexually abused when they were children.[60][61][62] Most sexual abuse offenders are acquainted with their victims; approximately 30% are relatives of the child, most often brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, uncles or cousins; around 60% are other acquaintances such as friends of the family, babysitters, or neighbours; strangers are the offenders in approximately 10% of child sexual abuse cases.[60] In over one-third of cases, the perpetrator is also a minor.[63]

In 1999 the BBC reported on the RAHI Foundation's survey of sexual abuse in India, in which 76% of respondents said they had been abused as children, 40% of those stating the perpetrator was a family member.[64]

Psychological abuse

[edit]There are multiple definitions of child psychological abuse:

- In 1995, The American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children (APSAC) defined it as: spurning, terrorizing, isolating, exploiting, corrupting, denying emotional responsiveness, or neglect" or "A repeated pattern of caregiver behavior or extreme incident(s) that convey to children that they are worthless, flawed, unloved, unwanted, endangered, or only of value in meeting another's needs"[65]

- In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) added Child Psychological Abuse to the DSM-5, describing it as "nonaccidental verbal or symbolic acts by a child's parent or caregiver that result, or have reasonable potential to result, in significant psychological harm to the child."[66]

- In the United States, states' laws vary, but most have laws against "mental injury"[67] against minors.

- Some have defined it as the production of psychological and social defects in the growth of a minor as a result of behavior such as loud yelling, coarse and rude attitude, inattention, harsh criticism, and denigration of the child's personality.[39] Other examples include name-calling, ridicule, degradation, destruction of personal belongings, torture or killing of a pet, excessive or extreme unconstructive criticism, inappropriate or excessive demands, withholding communication, and routine labeling or humiliation.[68]

- Many psychological abuse that happens to adults are harder to change to improve[69] and turn back due to fixed habits and living style after abuse. Child abuse can create a big toll on psychological behavior that put many risk to unhealthy thoughts. In order to minimize these negative outcomes, many need to seek help to spread awareness to those around them for preventative measures.[70]

In 2014, the APA found that child psychological abuse is the most prevalent form of childhood abuse in the United States, affecting nearly 3 million children annually.[71] Research has suggested that the consequences of child psychological abuse may be equally as harmful as those of sexual or physical abuse.[71][72][73]

Victims of emotional abuse may react by distancing themselves from the abuser, internalizing the abusive words, or fighting back by insulting the abuser. Emotional abuse can result in abnormal or disrupted attachment development, a tendency for victims to blame themselves (self-blame) for the abuse, learned helplessness, and overly passive behavior in order to avoid such a situation again.[68]

Neglect

[edit]Child neglect is the failure of a parent or other person with responsibility for the child, to provide needed food, clothing, shelter, medical care, or supervision to the degree that the child's health, safety or well-being may be threatened with harm. Neglect is also a lack of attention from the people surrounding a child, and the non-provision of the relevant and adequate necessities for the child's survival, which would be a lack of attention, love, and nurturing.[39]

Some observable signs of child neglect include: the child is frequently absent from school, begs or steals food or money, lacks needed medical and dental care, is consistently dirty, or lacks appropriate clothing for the weather.[74] The 2010 Child Maltreatment Report (NCANDS), a yearly United States federal government report based on data supplied by state Child Protective Services (CPS) Agencies in the U.S., found that neglect/neglectful behavior was the "most common form of child maltreatment".[75]

Neglectful acts can be divided into six sub-categories:[25]

- Supervisory neglect: characterized by the absence of a parent or guardian which can lead to physical harm, sexual abuse, or criminal behavior;

- Physical neglect: characterized by the failure to provide the basic physical necessities, such as a safe and clean home;

- Medical neglect: characterized by the lack of providing medical care;

- Emotional neglect: characterized by a lack of nurturance, encouragement, and support;

- Educational neglect: characterized by the caregivers lack to provide an education and additional resources to actively participate in the school system; and

- Abandonment: when the parent or guardian leaves a child alone for a long period of time without a babysitter or caretaker.

Neglected children may experience delays in physical and psychosocial development, possibly resulting in psychopathology and impaired neuropsychological functions including executive function, attention, processing speed, language, memory and social skills.[76] Researchers investigating maltreated children have repeatedly found that neglected children in the foster and adoptive populations manifest different emotional and behavioral reactions to regain lost or secure relationships and are frequently reported to have disorganized attachments and a need to control their environment. Such children are not likely to view caregivers as being a source of safety, and instead typically show an increase in aggressive and hyperactive behaviors which may disrupt healthy or secure attachment with their adopted parents. These children seem to have learned to adapt to an abusive and inconsistent caregiver by becoming cautiously self-reliant, and are often described as glib, manipulative and disingenuous in their interactions with others as they move through childhood.[77] Children who are victims of neglect can have a more difficult time forming and maintaining relationships, such as romantic or friendship, later in life due to the lack of attachment they had in their earlier stages of life.

Effects

[edit]Child abuse can result in immediate adverse physical effects but it is also strongly associated with developmental problems[78] and with many chronic physical and psychological effects, including subsequent ill-health, including higher rates of chronic conditions, high-risk health behaviors and shortened lifespan.[79][80] Child abuse has also been linked to suicide, according to a May 2019 study, published in the Cambridge University Press.[81]

Maltreated children may be at risk to become maltreating adults.[82][83][84]

Emotional

[edit]Physical and emotional abuse have comparable effects on a child's emotional state and have been linked to childhood depression, low self-compassion, and negative automatic thoughts.[85] Some research suggests that high stress levels from child abuse may cause structural and functional changes within the brain, and therefore cause emotional and social disruptions.[86] Abused children can grow up experiencing insecurities, low self-esteem, and lack of development. Many abused children experience ongoing difficulties with trust, social withdrawal, trouble in school, and forming relationships.[87]

Babies and other young children can be affected differently by abuse than their older counterparts. Babies and pre-school children who are being emotionally abused or neglected may be overly affectionate towards strangers or people they have not known for very long.[88] They can lack confidence or become anxious, appear to not have a close relationship with their parent, exhibit aggressive behavior or act nasty towards other children and animals.[88] Older children may use foul language or act in a markedly different way to other children at the same age, struggle to control strong emotions, seem isolated from their parents, lack social skills or have few, if any, friends.[88]

Children can also experience reactive attachment disorder (RAD). RAD is defined as markedly disturbed and developmentally inappropriate social relatedness, that usually begins before the age of 5 years.[89] RAD can present as a persistent failure to start or respond in a developmentally appropriate fashion to most social situations. The long-term impact of emotional abuse has not been studied widely, but recent studies have begun to document its long-term consequences. Emotional abuse has been linked to increased depression, anxiety, and difficulties in interpersonal relationships (Spertus, Wong, Halligan, & Seremetis, 2003).[89] Victims of child abuse and neglect are more likely to commit crimes as juveniles and adults.[90]

Domestic violence also takes its toll on children; although the child is not the one being abused, the child witnessing the domestic violence is greatly influenced as well. Research studies conducted such as the "Longitudinal Study on the Effects of Child Abuse and Children's Exposure to Domestic Violence", show that 36.8% of children engage in felony assault compared to the 47.5% of abused/assaulted children. Research has shown that children exposed to domestic violence increases the chances of experienced behavioral and emotional problems (depression, irritability, anxiety, academic problems, and problems in language development).[91]

Physical

[edit]

The immediate physical effects of abuse or neglect can be relatively minor (bruises or cuts) or severe (broken bones, hemorrhage, death). Certain injuries, such as rib fractures or femoral fractures in infants that are not yet walking, may increase suspicion of child physical abuse, although such injuries are only seen in a fraction of children suffering physical abuse.[92][93] Cigarette burns or scald injuries may also prompt evaluation for child physical abuse.[94]

The long-term impact of child abuse and neglect on physical health and development can be:

- Shaken baby syndrome. Shaking a baby is a common form of child abuse that often results in permanent neurological damage (80% of cases) or death (30% of cases).[95] Damage results from intracranial hypertension (increased pressure in the skull) after bleeding in the brain, damage to the spinal cord and neck, and rib or bone fractures.[96]

- Impaired brain development. Child abuse and neglect have been shown, in some cases, to cause important regions of the brain to fail to form or grow properly, resulting in impaired development.[97][98] Structural brain changes as a result of child abuse or neglect include overall smaller brain volume, hippocampal atrophy, prefrontal cortex dysfunction, decreased corpus callosum density, and delays in the myelination of synapses.[99][100] These alterations in brain maturation have long-term consequences for cognitive, language, and academic abilities.[101] In addition, these neurological changes impact the amygdala and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis which are involved in stress response and may cause PTSD symptoms.[100]

- Poor physical health. In addition to possible immediate adverse physical effects, household dysfunction and childhood maltreatment are strongly associated with many chronic physical and psychological effects, including subsequent ill-health in childhood,[102] adolescence[103] and adulthood, with higher rates of chronic conditions, high-risk health behaviors and shortened lifespan.[79][80] Adults who experienced abuse or neglect during childhood are more likely to have physical ailments such as allergies, arthritis, asthma, bronchitis, high blood pressure, and ulcers.[80][104][105][106] There may be a higher risk of developing cancer later in life,[107] as well as possible immune dysfunction.[108]

- Exposure to violence during childhood is associated with shortened telomeres and with reduced telomerase activity.[109] The increased rate of telomere length reduction correlates to a reduction in lifespan of 7 to 15 years.[108]

- Data from a recent study supports previous findings that specific neurobiochemical changes are linked to exposure to violence and abuse, several biological pathways can possibly lead to the development of illness, and certain physiological mechanisms can moderate how severe illnesses become in patients with past experience with violence or abuse.[110]

- Recent studies give evidence of a link between stress occurring early in life and epigenetic modifications that last into adulthood.[98][111]

Adverse Childhood Experiences Study

[edit]

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study is a long-running investigation into the relationship between childhood adversity, including various forms of abuse and neglect, and health problems in later life. The initial phase of the study was conducted in San Diego, California from 1995 to 1997.[112] The World Health Organization summarizes the study as:[32]

childhood maltreatment and household dysfunction contribute to the development – decades later – of the chronic diseases that are the most common causes of death and disability in the United States... A strong relationship was seen between the number of adverse experiences (including physical and sexual abuse in childhood) and self-reports of cigarette smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, attempted suicide, sexual promiscuity and sexually transmitted diseases in later life.

A long-term study of adults retrospectively reporting adverse childhood experiences including verbal, physical and sexual abuse, as well as other forms of childhood trauma found 25.9% of adults reported verbal abuse as children, 14.8% reported physical abuse, and 12.2% reported sexual abuse. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System corroborate these high rates.[113] There is a high correlation between the number of different adverse childhood experiences (A.C.E.s) and risk for poor health outcomes in adults including cancer, heart attack, mental illness, reduced longevity, and drug and alcohol abuse.[114] An anonymous self-reporting survey of Washington State students finds 6–7% of 8th, 10th and 12th grade students actually attempt suicide. Rates of depression are twice as high. Other risk behaviors are even higher.[115] There is a relationship between child physical and sexual abuse and suicide.[116] For legal and cultural reasons as well as fears by children of being taken away from their parents most childhood abuse goes unreported and unsubstantiated.

It has been discovered that childhood abuse can lead to the addiction of drugs and alcohol in adolescence and adult life. Studies show that any type of abuse experienced in childhood can cause neurological changes making an individual more prone to addictive tendencies. A significant study examined 900 court cases of children who had experienced sexual and physical abuse along with neglect. The study found that a large sum of the children who were abused are now currently addicted to alcohol. This case study outlines how addiction is a significant effect of childhood abuse.[117]

Psychological

[edit]Children who have a history of neglect or physical abuse are at risk of developing psychiatric problems,[118][119] or a disorganized attachment style.[120][121][122] In addition, children who experience child abuse or neglect are 59% more likely to be arrested as juveniles, 28% more likely to be arrested as adults, and 30% more likely to commit violent crime.[123] Disorganized attachment is associated with a number of developmental problems, including dissociative symptoms,[124] as well as anxiety, depressive, and acting out symptoms.[125][126] A study by Dante Cicchetti found that 80% of abused and maltreated infants exhibited symptoms of disorganized attachment.[127][128] When some of these children become parents, especially if they have PTSD, dissociative symptoms, and other sequelae of child abuse, they may encounter difficulty when faced with their infant and young children's needs and normative distress, which may in turn lead to adverse consequences for their child's social-emotional development.[129][130] Additionally, children may find it difficult to feel empathy towards themselves or others, which may cause them to feel alone and unable to make friends.[91] Despite these potential difficulties, psychosocial intervention can be effective, at least in some cases, in changing the ways maltreated parents think about their young children.[131]

Physically abused children may exhibit various types of psychopathology and behavioral deviancy. These include a general impairment of ego functioning, which can be associated with cognitive and intellectual problems.[132] They may also struggle with forming healthy relationships and may fail to develop basic trust in others.[132] Additionally, these children may experience traumatic reactions that can result in acute anxiety states.[132] As a way of coping, physically abused children may rely on primitive defense mechanisms such as projection, introjection, splitting, and denial.[132] They may also have impaired impulse control and a negative self-concept, which can lead to self-destructive behavior.[132]

Victims of childhood abuse also have different types of physical health problems later in life. Some reportedly have some type of chronic head, abdominal, pelvic, or muscular pain with no identifiable reason.[133] Even though the majority of childhood abuse victims know or believe that their abuse is, or can be, the cause of different health problems in their adult life, for the great majority their abuse was not directly associated with those problems, indicating that they were most likely diagnosed with other possible causes for their health problems, instead of their childhood abuse.[133] One long-term study found that up to 80% of abused people had at least one psychiatric disorder at age 21, with problems including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and suicide attempts.[134] One Canadian hospital found that between 36% and 76% of women mental health outpatients had been sexually abused, as had 58% of female patients with schizophrenia and 23% of male patients with schizophrenia.[135] A recent study has discovered that a crucial structure in the brain's reward circuits is compromised by childhood abuse and neglect, and predicts Depressive Symptoms later in life.[136]

In the case of 23 of the 27 illnesses listed in the questionnaire of a French INSEE survey, some statistically significant correlations were found between repeated illness and family traumas encountered by the child before the age of 18 years. According to Georges Menahem, the French sociologist who found out these correlations by studying health inequalities, these relationships show that inequalities in illness and suffering are not only social. Health inequality also has its origins in the family, where it is associated with the degrees of lasting affective problems (lack of affection, parental discord, the prolonged absence of a parent, or a serious illness affecting either the mother or father) that individuals report having experienced in childhood.[137]

Many children who have been abused in any form develop some sort of psychological disorder. These disorders may include: anxiety, depression, eating disorders, OCD, co-dependency, or even a lack of human connections. There is also a slight tendency for children who have been abused to become child abusers themselves. In the U.S. in 2013, of the 294,000 reported child abuse cases only 81,124 received any sort of counseling or therapy. Treatment is greatly important for abused children.[138]

On the other hand, there are some children who are raised in child abuse, but who manage to do unexpectedly well later in life regarding the preconditions. Such children have been termed dandelion children, as inspired from the way that dandelions seem to prosper irrespective of soil, sun, drought, or rain.[139] Such children (or currently grown-ups) are of high interest in finding factors that mitigate the effects of child abuse.

Causes

[edit]Child abuse is a complex phenomenon with multiple causes.[140] No single factor can be identified as to why some adults behave abusively or neglectfully toward children. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (ISPCAN) identify multiple factors at the level of the individual, their relationships, their local community, and their society at large, that combine to influence the occurrence of child maltreatment. At the individual level, studies have shown that age, mental health, and substance use, and a personal history of abuse may serve as risk factors of child abuse.[141] At the level of society, factors contributing to child maltreatment include cultural norms that encourage harsh physical punishment of children, economic inequality, and the lack of social safety nets.[32] WHO and ISPCAN state that understanding the complex interplay of various risk factors is vital for dealing with the problem of child maltreatment.[32]

Factors related to relationships include marital strife and tension. Parents who physically abuse their spouses are more likely than others to physically abuse their children.[142] However, it is impossible to know whether marital strife is a cause of child abuse, or if both the marital strife and the abuse are caused by tendencies in the abuser.[142] Parents may also set expectations for their child that are clearly beyond the child's capability (e.g., preschool children who are expected to be totally responsible for self-care or provision of nurturance to parents), and the resulting frustration caused by the child's non-compliance may function as a contributory factor of the occurrence of child abuse.[143]

Most acts of physical violence against children are undertaken with the intent to punish.[144] In the United States, interviews with parents reveal that as many as two thirds of documented instances of physical abuse begin as acts of corporal punishment meant to correct a child's behavior, while a large-scale Canadian study found that three quarters of substantiated cases of physical abuse of children have occurred within the context of physical punishment.[145] Other studies have shown that children and infants who are spanked by parents are several times more likely to be severely assaulted by their parents or suffer an injury requiring medical attention. Studies indicate that such abusive treatment often involves parents attributing conflict to their child's willfulness or rejection, as well as "coercive family dynamics and conditioned emotional responses".[36] Factors involved in the escalation of ordinary physical punishment by parents into confirmed child abuse may be the punishing parent's inability to control their anger or judge their own strength, and the parent being unaware of the child's physical vulnerabilities.[34]

Children resulting from unintended pregnancies are more likely to be abused or neglected.[146][147] In addition, unintended pregnancies are more likely than intended pregnancies to be associated with abusive relationships,[148] and there is an increased risk of physical violence during pregnancy.[149] They also result in poorer maternal mental health,[149] and lower mother-child relationship quality.[149]

There is some limited evidence that children with moderate or severe disabilities are more likely to be victims of abuse than non-disabled children.[150] A study on child abuse sought to determine: the forms of child abuse perpetrated on children with disabilities; the extent of child abuse; and the causes of child abuse of children with disabilities. A questionnaire on child abuse was adapted and used to collect data in this study. Participants comprised a sample of 31 pupils with disabilities (15 children with vision impairment and 16 children with hearing impairment) selected from special schools in Botswana. The study found that the majority of participants were involved in doing domestic chores. They were also sexually, physically and emotionally abused by their teachers. This study showed that children with disabilities were vulnerable to child abuse in their schools.[151]

Substance use disorder can be a major contributing factor to child abuse. One U.S. study found that parents with documented substance use, most commonly alcohol, cocaine, and heroin, were much more likely to mistreat their children, and were also much more likely to reject court-ordered services and treatments.[152] Another study found that over two-thirds of cases of child maltreatment involved parents with substance use disorders. This study specifically found relationships between alcohol and physical abuse, and between cocaine and sexual abuse.[153] Also, parental stress caused by substance increases the likelihood of the minor exhibiting internalizing and externalizing behaviors.[154] Although the abuse victim does not always realize the abuse is wrong, the internal confusion can lead to chaos. Inner anger turns to outer frustration. Once aged 17/18, drink and drugs are used to numb the hurt feelings, nightmares, and daytime flashbacks. Acquisitive crimes to pay for the chemicals are inevitable if the victim is unable to find employment.[155]

Unemployment and financial difficulties are associated with increased rates of child abuse.[156] In 2009 CBS News reported that child abuse in the United States had increased during the economic recession. It gave the example of a father who had never been the primary care-taker of the children. Now that the father was in that role, the children began to come in with injuries.[157] Parental mental health has also been seen as a factor towards child maltreatment.[158] According to a recent Children's HealthWatch study, mothers with positive symptoms of depression display a greater rate of food insecurity, poor health care for their children, and greater number of hospitalizations.[159]

The American psychoanalyst Elisabeth Young-Bruehl maintains that harm to children is justified and made acceptable by widely held beliefs in children's inherent subservience to adults, resulting in a largely unacknowledged prejudice against children she terms childism. She contends that such prejudice, while not the immediate cause of child maltreatment, must be investigated in order to understand the motivations behind a given act of abuse, as well as to shed light on societal failures to support children's needs and development in general.[17]: 4–6 Founding editor of the International Journal of Children's Rights, Michael Freeman, also argues that the ultimate causes of child abuse lie in prejudice against children, especially the view that human rights do not apply equally to adults and children. He writes, "the roots of child abuse lie not in parental psycho-pathology or in socio-environmental stress (though their influences cannot be discounted) but in a sick culture which denigrates and depersonalizes, which reduces children to property, to sexual objects so that they become the legitimate victims of both adult violence and lust".[160]

Worldwide

[edit]The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (April 2024) |

Child abuse is an international public health crisis. Poverty and substance use disorders are common social problems worldwide, and no matter the location, show a similar trend in the correlation to child abuse.[163] Differences in cultural perspectives play a significant role in how children are treated.[164] Laws reflect the population's views on what is acceptable – for example whether child corporal punishment is legal or not.[164]

A study conducted by members from several Baltic and Eastern European countries, together with specialists from the United States, examined the causes of child abuse in the countries of Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia and Moldova. In these countries, respectively, 33%, 42%, 18% and 43% of children reported at least one type of child abuse.[165] According to their findings, there was a series of correlations between the potential risk factors of parental employment status, alcohol abuse, and family size within the abuse ratings.[166] In three of the four countries, parental substance use was considerably correlated with the presence of child abuse, and although it was a lower percentage, still showed a relationship in the fourth country (Moldova).[166] Each country also showed a connection between the father not working outside of the home and either emotional or physical child abuse.[166] After the fall of the communism regime, some positive changes have followed with regard to tackling child abuse. While there is a new openness and acceptance regarding parenting styles and close relationships with children, child abuse has certainly not ceased to exist. While controlling parenting may be less of a concern, financial difficulty, unemployment, and substance use remain dominating factors in child abuse throughout Eastern Europe.[166]

There is some evidence that countries in conflict or transitioning out of conflict have increased rates of child abuse.[141] This increasing prevalence may be secondary to displacement and family disruption, as well as trauma.[141]

Asian parenting perspectives hold different ideals from American culture. Many have described their traditions as including physical and emotional closeness that ensures a lifelong bond between parent and child, as well as establishing parental authority and child obedience through harsh discipline.[167] Balancing disciplinary responsibilities within parenting is common in many Asian cultures, including China, Japan, Singapore, Vietnam and Korea.[167] To some cultures, forceful parenting may be seen as abuse, but in other societies such as these, the use of force is looked at as a reflection of parental devotion.[167]

These cultural differences can be studied from many perspectives. Most importantly, overall parental behavior is genuinely different in various countries. Each culture has their own "range of acceptability", and what one may view as offensive, others may seem as tolerable. Behaviors that are normal to some may be viewed as abusive to others, all depending on the societal norms of that particular country.[166] The differences in these cultural beliefs demonstrate the importance of examining all cross-cultural perspectives when studying the concept of child abuse. Some professionals argue that cultural norms that sanction physical punishment are one of the causes of child abuse, and have undertaken campaigns to redefine such norms.[168][169][170]

In April 2015, public broadcasting reported that the rate of child abuse in South Korea had increased to 13% compared with the previous year, and 75% of attackers were the children's own parents.[171]

Possible link to animal abuse

[edit]There are studies providing evidence of a link between child abuse and cruelty to animals. A large national survey by the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies found a "substantial overlap between companion animal abuse and child abuse" and that cruelty to animals "most frequently co-occurred with psychological abuse and less severe forms of physical child abuse," which "resonates with conceptualizations of domestic abuse as an ongoing pattern of psychological abuse and coercive control."[172]

Investigation

[edit]Suspicion for physical abuse is recommended when injuries occur in a child who is not yet able to walk independently.[173] Additionally, having multiple injuries that are in different stages of healing and having injuries in unusual location, such as the torso, ears, face, or neck, may prompt evaluation for child abuse.[173] Medical professionals may also become suspicious of child abuse when a caregiver is not able to provide an explanation for an injury that is consistent with the type or severity of the injury.[174]

In many jurisdictions, suspected abuse, even if not necessarily proven, requires reporting to child protection agencies, such as the Child Protection Services in the United States. Recommendations for healthcare workers, such as primary care providers and nurses, who are often suited to encounter suspected abuse are advised to firstly determine the child's immediate need for safety. A private environment away from suspected abusers is desired for interviewing and examining. Leading statements that can distort the story are avoided. As disclosing abuse can be distressing and sometimes even shameful, reassuring the child that he or she has done the right thing by telling and that they are not bad or that the abuse was not their fault helps in disclosing more information. Dolls are sometimes used to help explain what happened. In Mexico, psychologists trial using cartoons to speak to children who may be more likely to disclose information than to an adult stranger.[175] For the suspected abusers, it is also recommended to use a nonjudgmental, nonthreatening attitude towards them and to withhold expressing shock, in order to help disclose information.[176]

A key part of child abuse work is assessment. A few methods of assessment include Projective tests, clinical interviews, and behavioral observations.[177]

- Projective tests allow for the child to express themselves through drawings, stories, or even descriptions in order to get help establish an initial understanding of the abuse that took place

- Clinical interviews are comprehensive interviews performed by professionals to analyze the mental state of the one being interviewed[178]

- Behavioral observation gives an insight into things that trigger a child's memory of the abuse through observation of the child's behavior when interacting with other adults or children

A particular challenge arises where child protection professionals are assessing families where neglect is occurring. Neglect is a complex phenomenon without a universally-accepted definition[179] and professionals cite difficulty in knowing which questions to ask to identify neglect.[180] Younger children, children living in poverty, and children with more siblings are at increased risk of neglect.[181]

Prevention

[edit]A support-group structure is needed to reinforce parenting skills and closely monitor the child's well-being. Visiting home nurse or social-worker visits are also required to observe and evaluate the progress of the child and the caretaking situation. The support-group structure and visiting home nurse or social-worker visits are not mutually exclusive. Many studies have demonstrated that the two measures must be coupled together for the best possible outcome.[182] Studies show that if health and medical care personnel in a structured way ask parents about important psychosocial risk factors in connection with visiting pediatric primary care and, if necessary, offering the parent help may help prevent child maltreatment.[183][184]

Children's school programs regarding "good touch ... bad touch" can provide children with a forum in which to role-play and learn to avoid potentially harmful scenarios. Pediatricians can help identify children at risk of maltreatment and intervene with the aid of a social worker or provide access to treatment that addresses potential risk factors such as maternal depression.[185] Videoconferencing has also been used to diagnose child abuse in remote emergency departments and clinics.[186] Unintended conception increases the risk of subsequent child abuse, and large family size increases the risk of child neglect.[147] Thus, a comprehensive study for the National Academy of Sciences concluded that affordable contraceptive services should form the basis for child abuse prevention.[147][187] "The starting point for effective child abuse programming is pregnancy planning," according to an analysis for US Surgeon General C. Everett Koop.[147][188]

Findings from research published in 2016 support the importance of family relationships in the trajectory of a child's life: family-targeted interventions are important for improving long-term health, particularly in communities that are socioeconomically disadvantaged.[189]

Resources for child-protection services are sometimes limited. According to Hosin (2007), "a considerable number of traumatized abused children do not gain access to protective child-protection strategies."[where?][190] Briere (1992) argues that only when "lower-level violence" of children[clarification needed] ceases to be culturally tolerated will there be changes in the victimization and police protection of children.[191]

United States

[edit]Child sexual abuse prevention programs were developed in the United States of America during the 1970s and originally delivered to children. Programmes delivered to parents were developed in the 1980s and took the form of one-off meetings, two to three hours long.[192][193][194][195][196][197] In the last 15 years, web-based programmes have been developed.

Since 1983, April has been designated Child Abuse Prevention Month in the United States.[198] U.S. President Barack Obama continued that tradition by declaring April 2009 Child Abuse Prevention Month.[199] One way the Federal government of the United States provides funding for child-abuse prevention is through Community-Based Grants for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (CBCAP).[200]

An investigation by The Boston Globe and ProPublica published in 2019[201] found that the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico were all out of compliance with the requirements of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, and that underfunding of child welfare agencies and substandard procedures in some states caused failures to prevent avoidable child injuries and deaths.

A number of policies and programs have been put in place in the U.S. to try to better understand and to prevent child abuse fatalities, including: safe-haven laws, child fatality review teams, training for investigators, shaken baby syndrome prevention programs, and child abuse death laws which mandate harsher sentencing for taking the life of a child.[202]

Treatments

[edit]A number of treatments are available to victims of child abuse.[203] However, children who experience childhood trauma do not heal from abuse easily.[204] Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, first developed to treat sexually abused children, is now used for victims of any kind of trauma.[203] It targets trauma-related symptoms in children including PTSD, clinical depression and anxiety. It also includes a component for non-offending parents. Several studies have found that sexually abused children undergoing TF-CBT improved more than children undergoing certain other therapies. Data on the effects of TF-CBT for children who experienced non-sexual abuse was not available as of 2006[update].[203] The purpose of dealing with the thoughts and feelings associated with the trauma is to deal with nightmares, flashbacks and other intrusive experiences that might be spontaneously brought on by any number of discriminative stimuli in the environment or in the individual's brain. This would aid the individual in becoming less fearful of specific stimuli that would arouse debilitating fear, anger, sadness or other negative emotion. In other words, the individual would have some control or mastery over those emotions.[77]

Rational Cognitive Emotive Behavior Therapy is another available treatment and is intended to provide abused children and their adoptive parents with positive behavior change, corrective interpersonal skills, and greater control over themselves and their relationships.[77]

Parent–child interaction therapy was designed to improve the child-parent relationship following the experience of domestic violence. It targets trauma-related symptoms in infants, toddlers, and preschoolers, including PTSD, aggression, defiance, and anxiety. It is supported by two studies of one sample.[203]

School-based programs have also been developed to treat children who are survivors of abuse.[205] This approach teaches children, parents, teachers, and other school staff how to identify the signs of child maltreatment as well as skills that can be helpful in preventing child maltreatment.[206]

Other forms of treatment include group therapy, play therapy, and art therapy. Each of these types of treatment can be used to better assist the client, depending on the form of abuse they have experienced. Play therapy and art therapy are ways to get children more comfortable with therapy by working on something that they enjoy (coloring, drawing, painting, etc.). The design of a child's artwork can be a symbolic representation of what they are feeling, relationships with friends or family, and more. Being able to discuss and analyze a child's artwork can allow a professional to get a better insight of the child.[207]

Interventions targeting the offending parents are rare. Parenting training can prevent child abuse in the short term, and help children with a range of emotional, conduct and behavioral challenges, but there is insufficient evidence about whether it has impact on parents who already abuse their children.[208] Abuse-focused cognitive behavioral therapy may target offending parents, but most interventions exclusively target victims and non-offending parents.[203]

Prevalence

[edit]Child abuse is complex and difficult to study. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), estimates of the rates of child maltreatment vary widely by country, depending on how child maltreatment is defined, the type of maltreatment studied, the scope and quality of data gathered, and the scope and quality of surveys that ask for self-reports from victims, parents, and caregivers. Despite these limitations, international studies show that a quarter of all adults report experiencing physical abuse as children, and that 1 in 5 women and 1 in 13 men report experiencing childhood sexual abuse. Emotional abuse and neglect are also common childhood experiences.[209]

As of 2014[update], an estimated 41,000 children under 15 are victims of homicide each year. The WHO states that this number underestimates the true extent of child homicide; a significant proportion of child deaths caused by maltreatment are incorrectly attributed to unrelated factors such as falls, burns, and drowning. Also, girls are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence, exploitation and abuse in situations of armed conflict and refugee settings, whether by combatants, security forces, community members, aid workers, or others.[209]

United States

[edit]The National Research Council wrote in 1993 that "...the available evidence suggests that child abuse and neglect is an important, prevalent problem in the United States [...] Child abuse and neglect are particularly important compared with other critical childhood problems because they are often directly associated with adverse physical and mental health consequences in children and families".[210]: 6

In 1995, a one-off judicial decision found that parents failing to sufficiently speak the national standard language at home to their children was a form of child abuse by a judge in a child custody matter.[211]

In 1998, Douglas Besharov, the first Director of the U.S. Center on Child Abuse and Neglect, stated "the existing laws are often vague and overly broad"[212] and there was a "lack of consensus among professionals and Child Protective Services (CPS), personnel about what the terms abuse and neglect mean".[213]

In 2012, Child Protective Services (CPS) agencies estimated that about 9 out of 1000 children in the United States were victims of child maltreatment. Most (78%) were victims of neglect. Physical abuse, sexual abuse, and other types of maltreatment, were less common, making up 18%, 9%, and 11% of cases, respectively ("other types" included emotional abuse, parental substance use, and inadequate supervision). According to data reported by the Children's Bureau of the US Department of Health and Human Services, more than 3.5 million allegations of child abuse were looked into by child protective services who in turn confirmed 674,000 of those cases in 2017.[214] However, CPS reports may underestimate the true scope of child maltreatment. A non-CPS study estimated that one in four children experience some form of maltreatment in their lifetimes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[215]

In February 2017, the American Public Health Association published a Washington University study estimating 37% of American children experienced a child protective services investigation by age 18 (or 53% if African American).[216]

According to David Finkelhor who tracked Child Maltreatment Report (NCANDS) data from 1990 to 2010, sexual abuse had declined 62% from 1992 to 2009 and the long-term trend for physical abuse was also down by 56% since 1992. He stated: "It is unfortunate that information about the trends in child maltreatment are not better publicized and more widely known. The long-term decline in sexual and physical abuse may have important implications for public policy."[217]

A child abuse fatality occurs when a child's death is the result of abuse or neglect, or when abuse or neglect are contributing factors to a child's death. In 2008, 1,730 children died in the United States due to factors related to abuse; this is a rate of 2 per 100,000 U.S. children.[218] Family situations which place children at risk include moving, unemployment, and having non-family members living in the household. A number of policies and programs have been put in place in the U.S. to try to better understand and to prevent child abuse fatalities, including: safe-haven laws, child fatality review teams, training for investigators, shaken baby syndrome prevention programs, and child abuse death laws which mandate harsher sentencing for taking the life of a child.[202]

In a year-long period between 2019 and 2020, approximately 8.4 out of every 1,000 children were abused or neglected, a number equating to 618,000 children. 77.2% of the perpetrators were parents, the majority of which were one parent acting alone. 37.6% of child abuse was perpetrated by mothers acting alone, and 23.6% was perpetrated by fathers acting alone. 20.7% of child abuse was committed by both parents.[219]

Examples

[edit]Child labor

[edit]

Child trafficking is the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of children for the purpose of exploitation.[220] Children are trafficked for purposes such as of commercial sexual exploitation, bonded labour, camel jockeying, child domestic labour, drug couriering, child soldiering, illegal adoptions, and begging.[221][222][223] It is difficult to obtain reliable estimates concerning the number of children trafficked each year, primarily due to the covert and criminal nature of the practice.[224][225] The International Labour Organization estimates that 1.2 million children are trafficked each year.[226]

Child labor refers to the employment of children in any work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful.[227] The International Labour Organization considers such labor to be a form of exploitation and abuse of children.[228][229] Child labor refers to those occupations which infringe the development of children (due to the nature of the job or lack of appropriate regulation) and does not include age appropriate and properly supervised jobs in which minors may participate. According to ILO, globally, around 215 million children work, many full-time. Many of these children do not go to school, do not receive proper nutrition or care, and have little or no time to play. More than half of them are exposed to the worst forms of child labor, such as child prostitution, drug trafficking, armed conflicts and other hazardous environments.[230] There exist several international instruments protecting children from child labor, including the Minimum Age Convention, 1973 and the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention.

More girls under 16 work as domestic workers than any other category of child labor, often sent to cities by parents living in rural poverty[231] such as in restaveks in Haiti.

Forced adoption

[edit]Children in poverty have been removed from their families with their welfare being used an argument to do so. The European Court of Human Rights ruled that Norway, which disproportionately removes children of immigrant background and argues it gives them a better future, was mistaking poverty for neglect and that there are other ways to help destitute children.[232][233] In Switzerland, between the 1850s and the mid-20th century, hundreds of thousands of children mostly from poor or single parents were forcefully removed from their parents by the authorities, and sent to work on farms, living with new families. They were known as contract children or Verdingkinder.[234][235][236][237]

Removing children of ethnic minorities from their families to be adopted by those of the dominant ethnic group has been used as a method of forced assimilation. The Stolen Generations in Australia involved Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.[238][239] In Canada, the Canadian Indian residential school system involved First Nations, Métis and Inuit children, who often suffered severe abuse.[240][241][242][243][244] As part of the persecution of Uyghurs in China, in 2017 alone at least half a million children were also forcefully separated from their families, and placed in pre-school camps with prison-style surveillance systems and 10,000 volt electric fences.[245]

Child harvesting

[edit]It is speculated that, for-profit orphanages are increasing and push for children to join even though demographic data show that even the poorest extended families usually take in children whose parents have died and it would be cheaper to aid close relatives who want to take in the orphans. Experts maintain that separating children from their families often harm children's development.[246] Adoption fees result in such orphanages and similar networks such as "baby factories" in Nigeria coercing or abducting and raping women to sell their babies for adoption.[247][248] During the One Child Policy in China, when women were only allowed to have one child, local governments would often allow the woman to give birth and then they would take the baby away. Child traffickers, often paid by the government, would sell the children to orphanages that would arrange international adoptions worth tens of thousands of dollars, turning a profit for the government.[249]

Infanticide

[edit]Under natural conditions, mortality rates for girls under five are slightly lower than boys for biological reasons. However, after birth, neglect and diverting resources to male children can lead to some countries having a skewed ratio with more boys than girls, with such practices killing an approximate 230,000 girls under five in India each year.[250] While sex-selective abortion is more common among the higher income population, who can access medical technology, abuse after birth, such as infanticide and abandonment, is more common among the lower income population.[251] Baby farming is practice of accepting custody of a child in exchange for payment. As it became profitable, baby 'farmers' would neglect or murder the babies to keep costs down. Illegitimacy and its attendant social stigma were usually the impetus for a mother's decision to give her child to a baby farmer. Methods proposed to deal with the issue are baby hatches to drop off unwanted babies and safe-haven laws, which decriminalize abandoning babies unharmed.[252]

Body modification

[edit]

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."[254] It is practiced mainly in 28 countries in Africa, and in parts of Asia and the Middle East.[255][256] FGM is mostly found in a geographical area ranging across Africa, from east to west – from Somalia to Senegal, and from north to south – from Egypt to Tanzania.[257] FGM is most often carried out on young girls aged between infancy and 15 years.[254] FGM is classified into four types, of which type 3 – infibulation – is the most extreme form.[254] The consequences of FGM include physical, emotional and sexual problems, and include serious risks during childbirth.[258][259] The countries which choose to ratify the Istanbul Convention, the first legally binding instrument in Europe in the field of violence against women and domestic violence,[260] are bound by its provisions to ensure that FGM is criminalized.[261] Labia stretching is the act of lengthening the labia minora and may be initiated in girls from ages 8 to 14 years.[262]

The practice of using hot stones or other implements to flatten the breast tissue of pubescent girls is widespread in Cameroon[263] and exists elsewhere in West Africa as well. It is believed to have come with that diaspora to Britain,[264] where the government declared it a form of child abuse and said that it could be prosecuted under existing assault laws.[265]

Sexual rites of passage

[edit]A tradition often performed in some regions in Africa involves a man initiating a girl into womanhood by having sex with her, usually after her first period, in a practice known as "sexual cleansing". The rite can last for three days and there is an increased risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections as the ritual requires condoms not be worn.[266]

Violence against girl students

[edit]

In some parts of the world, girls are strongly discouraged from attending school.[267] They are sometimes attacked by members of the community if they do so.[268][269][270][271] In parts of South Asia, girls schools are set on fire by vigilante groups.[272][273] Such attacks are common in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Notable examples include the kidnapping of hundreds of female students in Chibok in 2014 and Dapchi in 2018.

Child marriage

[edit]A child marriage is a marriage in which one or both participants are minors, often before the age of puberty. Child marriages are common in many parts of the world, especially in parts of Asia and Africa. The United Nations considers those below the age of 18 years to be incapable of giving valid consent to marriage and therefore regards such marriages as a form of forced marriage; and that marriages under the age of majority have significant potential to constitute a form of child abuse.[274] In many countries, such practices are lawful or – even where laws prohibit child marriage – often unenforced.[275] India has more child brides than any other nation, with 40% of the world total.[276] The countries with the highest rates of child marriage are: Niger (75%), Central African Republic and Chad (68%), and Bangladesh (66%).[277]

Bride kidnapping, also known as marriage by abduction or marriage by capture, has been practiced around the world and throughout history, and sometimes involves minors. It is still practiced in parts of Central Asia, the Caucasus region, and some African countries. In Ethiopia, marriage by abduction is widespread, and many young girls are kidnapped this way.[278] In most countries, bride kidnapping is considered a criminal offense rather than a valid form of marriage.[279] In many cases, the groom also rapes his kidnapped bride, in order to prevent her from returning to her family due to shame.[280]

Money marriage refers to a marriage where a girl, usually, is married off to a man to settle debts owed by her parents.[281][282] The female is referred to as a "money wife"[283]

Sacred prostitution often involves girls being pledged to priests or those of higher castes, such as fetish slaves in West Africa.

Violence against children with superstitious accusations

[edit]Customary beliefs in witchcraft are common in many parts of the world, even among the educated. Anthropologists have argued that those with disabilities are often viewed as bad omens as raising a child with a disability in such communities are an insurmountable hurdle.[284] For example, in southern Ethiopia, children with physical abnormalities are considered to be ritually impure or mingi, the latter are believed to exert an evil influence upon others, so disabled infants have traditionally been disposed of without a proper burial.[285] A 2010 UNICEF report notes that accusations against children are a recent phenomenon with women and the elderly usually being accused 10–20 years ago. Greater urbanization and the growing economic burden of raising children is attributed as a factor.[286][287] As of 2006[update], between 25,000 and 50,000 children in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, had been accused of witchcraft and abandoned.[288] In Malawi it is common practice to accuse children of witchcraft and many children have been abandoned, abused and even killed as a result.[289] In the Nigerian, Akwa Ibom State and Cross River State about 15,000 children were branded as witches.[290] This practice is also found in communities in the Amazon. Children who are specifically at risk include orphans, street-children, albinos, disabled children, children who are unusually gifted, children who were born prematurely or in unusual positions, twins,[291] children of single mothers and children who express gender identity issues[284] and can involve children as young as eight.[286] Consequently, those accused of being a witch are ostracized and subjected to punishment, torture and even murdered,[292][293] often by being buried alive or left to starve.[284] Reports by UNICEF, UNHCR, Save The Children and Human Rights Watch have highlighted the violence and abuse towards children accused of witchcraft in Africa.[294][295][296][297]

Ethics

[edit]One of the most challenging ethical dilemmas arising from child abuse relates to the parental rights of abusive parents or caretakers with regard to their children, particularly in medical settings.[298] In the United States, the 2008 New Hampshire case of Andrew Bedner drew attention to this legal and moral conundrum. Bedner, accused of severely injuring his infant daughter, sued for the right to determine whether or not she remain on life support; keeping her alive, which would have prevented a murder charge, created a motive for Bedner to act that conflicted with the apparent interests of his child.[298][299][300] Bioethicists Jacob M. Appel and Thaddeus Mason Pope recently argued, in separate articles, that such cases justify the replacement of the accused parent with an alternative decision-maker.[298][301]

Child abuse also poses ethical concerns related to confidentiality, as victims may be physically or psychologically unable to report abuse to authorities. Accordingly, many jurisdictions and professional bodies have made exceptions to standard requirements for confidentiality and legal privileges in instances of child abuse. Medical professionals, including doctors, therapists, and other mental health workers typically owe a duty of confidentiality to their patients and clients, either by law or the standards of professional ethics, and cannot disclose personal information without the consent of the individual concerned. This duty conflicts with an ethical obligation to protect children from preventable harm. Accordingly, confidentiality is often waived when these professionals have a good faith suspicion that child abuse or neglect has occurred or is likely to occur and make a report to local child protection authorities. This exception allows professionals to breach confidentiality and make a report even when children or their parents or guardians have specifically instructed to the contrary. Child abuse is also a common exception to physician–patient privilege: a medical professional may be called upon to testify in court as to otherwise privileged evidence about suspected child abuse despite the wishes of children or their families.[302] Some child abuse policies in Western countries have been criticized both by some conservatives, who claim such policies unduly interfere in the privacy of the family, and by some feminists of the left wing, who claim such policies disproportionally target and punish disadvantaged women who are often themselves in vulnerable positions.[303] There has also been concern that ethnic minority families are disproportionally targeted.[304][305]

Legislation

[edit]Canada

[edit]Laws and legislation against child abuse are enacted on the provincial and Federal Territories level. Investigations into child abuse are handled by Provincial and Territorial Authorities through government social service departments and enforcement is through local police and courts.[306]

Germany

[edit]In Germany, the abuse of vulnerable persons (including children) is punishable according to the German Criminal code § 225 with a from 6 months to 10 years, in aggravated cases at least 1 year (to 15 years pursuant to § 38). If the case is only an attempt, the penalty can be lower (§ 23). However, crimes against children must be prosecuted within 10 years (in aggravated cases 20 years) of the victims reaching 30 years of age (§ 78b and § 78).[307]

As of 2020, Germany and the Netherlands are 2 out of all 27 EU countries that do not have any reporting obligations for civilians or professionals. There is no mandatory reporting law, which would grant reporters of child abuse anonymity and immunity.[308]

United States

[edit]In the 1960s, mandatory reporting in the United States was introduced and had been adopted in some form by all 50 states by 1970.[309][310]: 3 In 1974, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) was introduced and began an upswing in reported child sexual abuse cases which lasted until the 1990s.[311] The Child Abuse Victims Rights Act of 1986 gave victims of child abuse the ability to file lawsuits against abuse perpetrators and their employers after the statute of limitations had expired.[311] The Victims of Child Abuse Act of 1990 further gave victims of abuse capacity to press charges by permitting the court to assign lawyers to advise, act in the best interest of, and elevate the voices of child victims of abuse.[312] The Adoption and Safe Families Act (1997) followed, shifting emphasis away from court-sanctioned reunification of families to giving parents or guardians time-bound opportunities for rehabilitation prior to making long term plans for children.[313] Child Abuse Reform and Enforcement Act was enacted in 2000 to further reduce the incidence of child abuse and neglect.