Эстония

Эстонская Республика Эстонская Республика ( эстонский ) | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: Моя страна, мое счастье и радость (на английском языке: «Моя Родина, мое счастье и радость» [1] ) | |

![Расположение Эстонии (темно-зеленый) – в Европе (зеленый и темно-серый) – в Европейском Союзе (зеленый) – [Легенда]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/EU-Estonia.svg/250px-EU-Estonia.svg.png) Location of Estonia (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Tallinn 59°25′N 24°45′E / 59.417°N 24.750°E |

| Official language | Estonian[a] |

| Ethnic groups (2024[10]) | |

| Religion (2021[11]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Estonian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Alar Karis | |

| Kristen Michal | |

| Legislature | Riigikogu |

| Independence | |

| 23–24 February 1918 | |

• Joined the League of Nations | 22 September 1921 |

| 1940–1991 | |

| 20 August 1991 | |

• Joined the European Union | 1 May 2004 |

| Area | |

• Total | 45,335[12] km2 (17,504 sq mi) (129thd) |

• Water (%) | 4.6 |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• 2021 census | 1,331,824[14] |

• Density | 30.3/km2 (78.5/sq mi) (148th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | medium |

| HDI (2022) | very high (31st) |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+03:00 (EEST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +372 |

| ISO 3166 code | EE |

| Internet TLD | .ee |

| |

Эстония , [б] официально Эстонская Республика , [с] Страна на берегу Балтийского моря в Северной Европе . [д] На севере она граничит с Финским заливом , напротив Финляндии , на западе с морем , напротив Швеции , на юге с Латвией , а на востоке с Чудским озером и Россией . Территория Эстонии состоит из материка , крупных островов Сааремаа и Хийумаа , а также более 2300 других островов и островков на восточном побережье Балтийского моря. [12] общей площадью 45 335 квадратных километров (17 504 квадратных миль). Таллинн Столица и Тарту районами являются двумя крупнейшими городскими . Эстонский язык является коренным и официальным языком . Это первый язык большинства . населения в 1,4 миллиона человек [14]

The land of present-day Estonia has been inhabited by humans since at least 9,000 BCE. The medieval indigenous population of Estonia was one of the last pagan civilisations in Europe to adopt Christianity following the Papal-sanctioned Northern Crusades in the 13th century.[22] After centuries of successive rule by the Teutonic Order, Denmark, Sweden, and the Russian Empire, a distinct Estonian national identity began to emerge in the mid-19th century. This culminated in the 1918 Estonian Declaration of Independence from the then-warring Russian and German empires. Democratic throughout most of the interwar period, Estonia declared neutrality at the outbreak of World War II, however the country was repeatedly contested, invaded, and occupied; first by the Soviet Union in 1940, then Nazi Germany in 1941, and ultimately reoccupied in 1944 by, and annexed into, the USSR as an administrative subunit (Estonian SSR). Throughout the 1944–91 Soviet occupation,[23] благодаря де-юре Преемственность государства дипломатическим Эстонии сохранялась представителям и правительству в изгнании . После бескровной эстонской « поющей революции была восстановлена полная независимость страны » 1988–1990 годов, направленной против советской власти, 20 августа 1991 года .

Estonia is a developed country with a high-income advanced economy, ranking 31st (out of 191) in the Human Development Index.[24] The sovereign state of Estonia is a democratic unitary parliamentary republic, administratively subdivided into 15 maakond (counties). It is one of the least populous members of the European Union and NATO. Estonia has consistently ranked highly in international rankings for quality of life,[25] education,[26] press freedom, digitalisation of public services[27][28] and the prevalence of technology companies.[29]

Name

The name Estonia (Estonian: Eesti [ˈeˑstʲi] ) has been connected to Aesti, a people first mentioned by Ancient Roman historian Tacitus around 98 CE. Some modern historians believe he was referring to Balts, while others have proposed that the name then applied to the whole eastern Baltic Sea region.[30] Scandinavian sagas and Viking runestones[31] referring to Eistland are the earliest known sources that definitely use the name in its modern geographic meaning.[32] From Old Norse the toponym spread to other Germanic vernaculars and reached literary Latin by the end of 12th century.[33][34]

History

Prehistory and Viking Age

Human settlement in Estonia became possible 13,000–11,000 years ago, when the ice from the last glacial era melted. The oldest known settlement in Estonia is the Pulli settlement, on the banks of Pärnu river in southwest Estonia. According to radiocarbon dating, it was settled around 11,000 years ago.[35]

The earliest human habitation during the Mesolithic period is connected to the Kunda culture. At that time the country was covered with forests, and people lived in semi-nomadic communities near bodies of water. Subsistence activities consisted of hunting, gathering and fishing.[36] Around 4900 BCE, ceramics appear of the neolithic period, known as Narva culture.[37] Starting from around 3200 BC the Corded Ware culture appeared; this included new activities like primitive agriculture and animal husbandry.[38]The Bronze Age started around 1800 BCE, and saw the establishment of the first hill fort settlements.[39] A transition from hunter-fisher subsistence to single-farm-based settlement started around 1000 BC, and was complete by the beginning of the Iron Age around 500 BC.[35][40] The large amount of bronze objects indicate the existence of active communication with Scandinavian and Germanic tribes.[41]

The middle Iron Age produced threats appearing from different directions. Several Scandinavian sagas referred to major confrontations with Estonians, notably when in the early 7th century "Estonian Vikings" defeated and killed Ingvar Harra, the King of Swedes.[42][additional citation(s) needed] Similar threats appeared to the east, where East Slavic principalities were expanding westward. Around 1030 the troops of Kievan Rus led by Yaroslav the Wise defeated Estonians and established a fort in modern-day Tartu. This foothold may have lasted until ca 1061 when an Estonian tribe, the Sosols, destroyed it.[43][44][45][46] Around the 11th century, the Scandinavian Viking era around the Baltic Sea was succeeded by the Baltic Viking era, with seaborne raids by Curonians and by Estonians from the island of Saaremaa, known as Oeselians. In 1187 Estonians (Oeselians), Curonians or/and Karelians sacked Sigtuna, which was a major city of Sweden at the time.[47][48]

Estonia could be divided into two main cultural areas. The coastal areas of north and west Estonia had close overseas contacts with Scandinavia and Finland, while inland south Estonia had more contacts with Balts and Pskov.[49] The landscape of Ancient Estonia featured numerous hillforts.[50] Prehistoric or medieval harbour sites have been found on the coast of Saaremaa.[50] Estonia also has a number of graves from the Viking Age, both individual and collective, with weapons and jewellery including types found commonly throughout Northern Europe and Scandinavia.[50][51]In the early centuries AD, political and administrative subdivisions began to emerge in Estonia. Two larger subdivisions appeared: the parish (Estonian: kihelkond) and the county (Estonian: maakond), which consisted of multiple parishes. A parish was led by elders and centered on a hill fort; in some rare cases a parish had multiple forts. By the 13th century, Estonia comprised eight major counties: Harjumaa, Järvamaa, Läänemaa, Revala, Saaremaa, Sakala, Ugandi, and Virumaa; and six minor, single-parish counties: Alempois, Jogentagana, Mõhu, Nurmekund, Soopoolitse, and Vaiga. Counties were independent entities and engaged only in a loose cooperation against foreign threats.[52][53]

Little is known of medieval Estonians' spiritual and religious practices before Christianization. The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia mentions Tharapita as the superior deity of the then inhabitants of Saaremaa (Oeselians). There is some historical evidence about sacred groves, especially groves of oak trees, having served as places of "pagan" worship.[54][55]

Crusades and the Catholic Era

In 1199, Pope Innocent III declared a crusade to "defend the Christians of Livonia".[56] Fighting reached Estonia in 1206, when Danish King Valdemar II unsuccessfully invaded Saaremaa. The German Livonian Brothers of the Sword, who had previously subjugated Livonians, Latgalians, and Selonians, started campaigning against the Estonians in 1208, and over next few years both sides made numerous raids and counter-raids. A major leader of the Estonian resistance was Lembitu, an elder of Sakala County, but in 1217 the Estonians suffered a significant defeat in the Battle of St. Matthew's Day, where Lembitu was killed. In 1219, Valdemar II landed at Lindanise, defeated the Estonians in the Battle of Lyndanisse, and started conquering Northern Estonia.[57][58] The next year, Sweden invaded Western Estonia, but were repelled by the Oeselians. In 1223, a major revolt ejected the Germans and Danes from the whole of Estonia, except Reval, but the crusaders soon resumed their offensive, and in 1227, Saaremaa was the last maakond (county) to surrender.[59][60]

After the crusade, the territory of present-day south Estonia and Latvia was named Terra Mariana; later on it became known simply as Livonia.[61] Northern Estonia became the Danish Duchy of Estonia, while the rest was divided between the Sword Brothers and prince-bishoprics of Dorpat and Ösel–Wiek. In 1236, after suffering a major defeat, the Sword Brothers merged into the Teutonic Order becoming the Livonian Order.[62] In the next decades there were several uprisings against the Teutonic rulers in Saaremaa. In 1343, a major uprising encompassed over north Estonia and Saaremaa. The Teutonic Order suppressed the rebellion by 1345, and in 1346 the Danish king sold his possessions in Estonia to the Order.[63][64] The unsuccessful rebellion led to a consolidation of power for the upper-class German minority.[65] For the subsequent centuries Low German remained the language of the ruling elite in both Estonian cities and the countryside.[66]

Reval (Tallinn), the capital of Danish Estonia founded on the site of Lindanise, adopted the Lübeck law and received full town rights in 1248.[67] The Hanseatic League controlled trade on the Baltic Sea, and overall the four largest towns in Estonia became members: Reval, Dorpat (Tartu), Pernau (Pärnu), and Fellin (Viljandi). Reval acted as a trade intermediary between Novgorod and western Hanseatic cities, while Dorpat filled the same role with Pskov. Many artisans' and merchants guilds were formed during the period.[68] Protected by their stone walls and membership in the Hansa, prosperous cities like Reval and Dorpat often defied other rulers of the medieval Livonian Confederation.[69][e]

Post-Reformation Era

The Reformation began in central Europe in 1517, and soon spread northward to Livonia despite some opposition by the Livonian Order.[71] Towns were the first to embrace Protestantism in the 1520s, and by the 1530s the majority of the landowners and rural population had adopted Lutheranism.[72][73] Church services were now conducted in vernacular language, which initially meant Low German, but already from the 1530s onward the regular religious services were held in Estonian.[72][74]

During the 16th century, the expansionist monarchies of Muscovy, Sweden, and Poland–Lithuania consolidated power, posing a growing threat to decentralised Livonia weakened by disputes between cities, nobility, bishops, and the Order.[72][75]

In 1558, Tsar Ivan the Terrible of Russia (Muscovy) invaded Livonia, starting the Livonian War. The Livonian Order was decisively defeated in 1560. The majority of Livonia accepted Polish rule, while Reval and the nobles of northern Estonia swore loyalty to the Swedish king, and the Bishop of Ösel-Wiek sold his lands to the Danish king. Tsar Ivan's forces were at first able to conquer the larger part of Livonia, however in the 1570s the Polish-Lithuanian and Swedish armies went on the offensive and the war ended in 1583 with Russian defeat.[75][76] As a result of the war, northern Estonia became Swedish Duchy of Estonia, southern Estonia became Polish Duchy of Livonia, and Saaremaa remained under Danish control.[77]

In 1600, the Polish–Swedish War broke out, causing further devastation. The protracted war ended in 1629 with Sweden gaining Livonia, including the regions of Southern Estonia and Northern Latvia.[78] Danish Saaremaa was transferred to Sweden in 1645.[79] The wars had halved the population of Estonia from about 250–270,000 people in the mid 16th century to 115–120,000 in the 1630s.[80]

While large parts of the rural population remained in serfdom during the Swedish rule, legal reforms strengthened both serfs' and free tenant farmers' land usage and inheritance rights – hence this period got the reputation of "The Good Old Swedish Time" in historical memory.[81] Swedish King Gustaf II Adolf established gymnasiums in Reval and Dorpat; the latter was upgraded to Tartu University in 1632. Printing presses were also established in both towns. The beginnings of the Estonian public education system appeared in the 1680s, largely due to efforts of Bengt Forselius, who also introduced orthographical reforms to written Estonian.[82] The population of Estonia grew rapidly until the Great Famine of 1695–97 in which 70,000–75,000 people died – about 20% of the population.[83]

During the 1700–1721 Great Northern War, the Tsardom of Russia (Muscovy) conquered the whole of Estonia by 1710.[84] The war again devastated the population of Estonia, with the 1712 population estimated at only 150,000–170,000.[85] In 1721, Estonia was divided into two governorates: the Governorate of Estonia, which included Tallinn and the northern part of Estonia, and the southern Governorate of Livonia, which extended to the northern part of Latvia.[86] The tsarist administration restored all the political and landholding rights of the local aristocracy.[87] The rights of local farmers reached their lowest point, as serfdom completely dominated agricultural relations during the 18th century.[88] Serfdom was formally abolished in 1816–1819, but this initially had very little practical effect; major improvements in farmers' rights started with reforms in the mid-19th century.[89]

National Awakening

The Estonian national awakening began in the 1850s as several leading figures started promoting an Estonian national identity among the general populace. Widespread farm buyouts by Estonians and the resulting rapidly growing class of land-owning farmers provided the economic basis for the formation of this new "Estonian identity". In 1857, Johann Voldemar Jannsen started publishing one of the first successful circulating Estonian-language weekly newspapers, Perno Postimees, and began popularising the denomination of oneself as eestlane (Estonian).[90] Schoolmaster Carl Robert Jakobson and clergyman Jakob Hurt became leading figures in a nationalist movement, encouraging Estonian farmers to take pride in their language and ethnic Estonian identity.[91] The first nationwide movements formed, such as a campaign to establish the Estonian language Alexander School, the founding of the Society of Estonian Literati and the Estonian Students' Society, and the first national song festival, held in 1869 in Tartu.[92][93][94] Linguistic reforms helped to develop the Estonian language.[95] The national epic Kalevipoeg was published in 1862, and 1870 saw the first performances of Estonian theatre.[96][97] In 1878 a major split happened in the national movement. The moderate wing led by Hurt focused on development of culture and Estonian education, while the radical wing led by Jakobson started demanding increased political and economical rights.[93]

At the end of the 19th century, Russification began, as the central government initiated various administrative and cultural measures to tie Baltic governorates more closely to the empire.[92] The Russian language replaced German and Estonian in most secondary schools and universities, and many social and cultural activities in local languages were suppressed.[97] In the late 1890s, there was a new surge of nationalism with the rise of prominent figures like Jaan Tõnisson and Konstantin Päts. In the early 20th century, Estonians started taking over control of local governments in towns from Germans.[98]

During the 1905 Revolution, the first legal Estonian political parties were founded. An Estonian national congress was convened and demanded the unification of Estonian areas into a single autonomous territory and an end to Russification. The unrest was accompanied by both peaceful political demonstrations and violent riots with looting in the commercial district of Tallinn and in a number of wealthy landowners' manors in the Estonian countryside. The Tsarist government responded with a brutal crackdown; some 500 people were executed and hundreds more jailed or deported to Siberia.[99][100]

Independence

In 1917, after the February Revolution, the governorate of Estonia was expanded by the Russian Provisional Government to include Estonian-speaking areas of Livonia and was granted autonomy, enabling the election of the Estonian Provincial Assembly.[101] The Bolsheviks seized power in Estonia in November 1917, and the Provincial Assembly was disbanded. However, the Provincial Assembly established the Salvation Committee, and during the short interlude between Bolshevik retreat and German arrival, the committee declared independence and formed the Estonian Provisional Government on 24 February 1918 in the capital Tallinn. German occupation immediately followed, but after their defeat in World War I, the Germans were forced to hand over power back to the Provisional Government of independent Estonia on 19 November 1918.[102][103]

On 28 November 1918, Soviet Russia invaded, starting the Estonian War of Independence.[104] The Red Army came within 30 km of Tallinn, but in January 1919, the Estonian Army, led by Johan Laidoner, went on a counter-offensive, ejecting Bolshevik forces from Estonia within a few weeks. Renewed Soviet attacks failed, and in the spring of 1919, the Estonian army, in co-operation with White Russian forces, advanced into Russia and Latvia.[105][106] In June 1919, Estonia defeated the German Landeswehr which had attempted to dominate Latvia, restoring power to the government of Kārlis Ulmanis there. After the collapse of the White Russian forces, the Red Army launched a major offensive against Narva in late 1919, but failed to achieve a breakthrough. On 2 February 1920, the Tartu Peace Treaty was signed by Estonia and Soviet Russia, with the latter pledging to permanently give up all sovereign claims to Estonia.[105][107]

In April 1919, the Estonian Constituent Assembly was elected. The Constituent Assembly passed a sweeping land reform expropriating large estates, and adopted a new highly liberal constitution establishing Estonia as a parliamentary democracy.[108][109] In 1924, the Soviet Union organised a communist coup attempt, which quickly failed.[110] Estonia's cultural-autonomy law for ethnic minorities, adopted in 1925, is widely recognised as one of the most liberal in the world at that time.[111] The Great Depression put heavy pressure on Estonia's political system, and in 1933, the right-wing Vaps movement spearheaded a constitutional reform establishing a strong presidency.[112][113] On 12 March 1934 the acting head of state, Konstantin Päts, extended a state of emergency over the entire country, under the pretext that the Vaps movement had been planning a coup. Päts went on to rule by decree for several years, while the parliament did not reconvene ("era of silence").[114] A new constitution was adopted in a 1937 referendum, and in 1938 a new bicameral parliament was elected in a popular vote, where both pro-government and opposition candidates participated.[115] The Päts régime was relatively benign compared to other authoritarian régimes in interwar Europe, and the régime never used violence against political opponents.[116]

Estonia joined the League of Nations in 1921.[117] Attempts to establish a larger alliance together with Finland, Poland, and Latvia failed, with only a mutual-defence pact being signed with Latvia in 1923, and later was followed up with the Baltic Entente of 1934.[118][119] In the 1930s, Estonia also engaged in secret military co-operation with Finland.[120] Non-aggression pacts were signed with the Soviet Union in 1932, and with Germany in 1939.[117][121] In 1939, Estonia declared neutrality, but this proved futile in World War II.[122]

World War II

A week before the outbreak of World War II, on 23 August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. In the pact's secret protocol Poland, Romania, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland were divided between USSR and Germany into "spheres of influence", with Estonia assigned to the Soviet "sphere".[123] On 24 September 1939, the Soviet dictator Stalin presented the Estonian government an ultimatum demanding that Estonia immediately sign a treaty that would allow the USSR to establish military bases in Estonia, or else face war. The Estonian government decided to avoid military conflict, and a "mutual assistance treaty" was signed in Moscow on 28 September 1939.[124] On 14 June 1940 the Soviet Union instituted a full naval and air blockade on Estonia. On the same day, the airliner Kaleva was shot down by the Soviet Air Force. On 16 June, the USSR presented an ultimatum demanding completely free passage of the Red Army into Estonia and the establishment of a pro-Soviet government. Feeling that resistance was hopeless, the Estonian government complied and, on the next day, the whole country was occupied.[125][126] On 6 August 1940, Estonia was annexed by the Soviet Union as the Estonian SSR.[127]

The USSR established a repressive wartime regime in occupied Estonia. Many of the country's high-ranking civil and military officials, intelligentsia and industrialists were arrested. Soviet repressions culminated on 14 June 1941 with mass deportation of around 11,000 people to Russia.[128][129] When Operation Barbarossa (accompanied by Estonian guerrilla soldiers called "Forest Brothers"[130]) began against the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 in the form of the "Summer War" (Estonian: Suvesõda), around 34,000 young Estonian men were forcibly drafted into the Red Army, fewer than 30% of whom survived the war. Soviet destruction battalions initiated a scorched earth policy. Political prisoners who could not be evacuated were executed by the NKVD.[131][132] Many Estonians went into the forest, starting an anti-Soviet guerrilla campaign. In July, German Wehrmacht reached south Estonia. The USSR evacuated Tallinn in late August with massive losses, and capture of the Estonian islands was completed by German forces in October.[133]

Initially, many Estonians were hopeful that Germany would help to restore Estonia's independence, but this soon proved to be in vain. Only a puppet collaborationist administration was established, and occupied Estonia was merged into Reichskommissariat Ostland, with its economy being fully subjugated to German military needs.[134] About a thousand Estonian Jews who had not managed to leave were almost all quickly killed in 1941. Numerous forced labour camps were established where thousands of Estonians, foreign Jews, Romani, and Soviet prisoners of war perished.[135] German occupation authorities started recruiting men into small volunteer units but, as these efforts provided meagre results and the military situation worsened, forced conscription was instituted in 1943, eventually leading to formation of the Estonian Waffen-SS division.[136] Thousands of Estonians who did not want to fight in the German military secretly escaped to Finland, where many volunteered to fight together with Finns against Soviets.[137]

The Red Army reached the Estonian borders again in early 1944, but its advance into Estonia was stopped in heavy fighting near Narva for six months by German forces, including numerous Estonian units.[138] In March, the Soviet Air Force carried out heavy bombing raids against Tallinn and other Estonian towns.[139] In July, the Soviets started a major offensive from the south, forcing the Germans to abandon mainland Estonia in September and the Estonian islands in November.[138] As German forces were retreating from Tallinn, the last pre-war prime minister Jüri Uluots appointed a government headed by Otto Tief in an unsuccessful attempt to restore Estonia's independence.[140] Tens of thousands of people, including most of the Estonian Swedes, fled westwards to avoid the new Soviet occupation.[141]

Overall, Estonia lost about 25% of its population through deaths, deportations and evacuations in World War II.[142] Estonia also suffered some irrevocable territorial losses, as the Soviet Union transferred border areas comprising about 5% of Estonian pre-war territory from the Estonian SSR to the Russian SFSR.[143]

Second Soviet occupation

Thousands of Estonians opposing the second Soviet occupation joined a guerrilla movement known as the "Forest Brothers". The armed resistance was heaviest in the first few years after the war, but Soviet authorities gradually wore it down through attrition, and resistance effectively ceased to exist in the mid-1950s.[144] The Soviets initiated a policy of collectivisation, but as farmers remained opposed to it a campaign of terror was unleashed. In March 1949 about 20,000 Estonians were deported to Siberia. Collectivization was fully completed soon afterwards.[128][145]

The Russian-dominated occupation authorities under the Soviet Union began Russification, with hundreds of thousands of ethnic Russians and other "Soviet people" being induced to settle in occupied Estonia, in a process which eventually threatened to turn indigenous Estonians into a minority in their own native land.[146] In 1945 Estonians formed 97% of the population, but by 1989 their share of the population had fallen to 62%.[147] Occupying authorities carried out campaigns of ethnic cleansing, mass deportation of indigenous populations, and mass colonization by Russian settlers which led to Estonia losing 3% of its native population.[148] By March 1949, 60,000 people were deported from Estonia and 50,000 from Latvia to the gulag system in Siberia, where death rates were 30%. The occupying regime established an Estonian Communist Party, where Russians were the majority in party membership.[149] Economically, heavy industry was strongly prioritised, but this did not improve the well-being of the local population, and caused massive environmental damage through pollution.[150] Living standards under the Soviet occupation kept falling further behind nearby independent Finland.[146] The country was heavily militarised, with closed military areas covering 2% of territory.[151] Islands and most of the coastal areas were turned into a restricted border zone which required a special permit for entry.[152] Estonia was quite closed until the second half of the 1960s, when gradually Estonians began to covertly watch Finnish television in the northern parts of the country, thus getting a better picture of the way of life behind the Iron Curtain.[153]

The majority of Western countries considered the annexation of Estonia by the Soviet Union illegal.[154] Legal continuity of the Estonian state was preserved through the government-in-exile and the Estonian diplomatic representatives which Western governments continued to recognise.[155][156]

Independence restored

The introduction of perestroika by the Soviet central government in 1987 made open political activity possible again in Estonia, which triggered an independence restoration process later known as laulev revolutsioon ("the Singing revolution").[157] The environmental Fosforiidisõda ("Phosphorite war") campaign became the first major protest movement against the central government.[158] In 1988, new political movements appeared, such as the Popular Front of Estonia, which came to represent the moderate wing in the independence movement, and the more radical Estonian National Independence Party, which was the first non-communist party in the Soviet Union and demanded full restoration of independence.[159] On 16 November 1988, after the first non-rigged multi-candidate elections in half a century, the parliament of Soviet-controlled Estonia issued the Sovereignty Declaration, asserting the primacy of Estonian laws. Over the next two years, many other administrative parts (or "republics") of the USSR followed the Estonian example, issuing similar declarations.[160][161] On 23 August 1989, about 2 million Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians participated in a mass demonstration, forming the Baltic Way human chain across the three countries.[162] In February 1990, elections were held to form the Congress of Estonia.[163] In March 1991, a referendum was held where 78.4% of voters supported full independence. During the coup attempt in Moscow, Estonia declared restoration of independence on 20 August 1991.[164]

Soviet authorities recognised Estonian independence on 6 September 1991, and on 17 September Estonia was admitted into the United Nations.[165] The last units of the Russian army left Estonia in 1994.[166]

On 28 September 1994, the MS Estonia sank as the ship was crossing the Baltic Sea, en route from Tallinn, Estonia, to Stockholm, Sweden. The disaster claimed the lives of 852 people (501 of them were Swedes[167]), being one of the worst maritime disasters of the 20th century.[168]

In 1992 radical economic reforms were launched for switching over to a market economy, including privatisation and currency reform.[169] Estonia has been a member of the WTO since 13 November 1999.[170]

Since regaining independence in 1991, Estonian foreign policy has been aligned with other Western democracies, and in 2004 Estonia joined both the European Union and NATO.[171] On 9 December 2010, Estonia became a member of OECD.[172] On 1 January 2011, Estonia joined the eurozone and adopted the euro, the single currency of EU.[173] Estonia was a member of the UN Security Council from 2020 to 2021.[174]

The 100th Anniversary of the Estonian Republic was celebrated on 24 February 2018.[175]

English is the most widely spoken foreign language in Estonia today. According to the most recent (2021) census data 76% of the population can speak a foreign language. After English, Russian is the second most widely spoken foreign language in Estonia, and in the census 17% of the native speakers of standard Estonian reported that they can also speak a dialect of Estonian.[176][177]

Geography

Estonia is situated in Europe,[d] on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, on the East European Plain between 57°30′ and 59°49′ N and 21°46′ and 28°13′ E.[178][179][180] It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Lake Peipsi and Russia.[181] Estonian territory covers 45,335 km2 (17,504 sq mi), of which internal waters comprise 4.6%.[178] When including the territorial sea, the Estonian border encompasses 70,177 km2 (27,095 sq mi).[182]

Estonia has a 3,794 kilometres (2,357 mi) long coastline, notable for its limestone cliffs at the northern coast and largest islands.[179][183] The total number of Estonian islands, including those in internal waters, is 2,355, of which 2,222 are in the Baltic Sea. The largest islands are Saaremaa and Hiiumaa. There are over 1560 natural lakes, the largest being Lake Peipus at the border of Russia, and Võrtsjärv in central Estonia. Additionally there are many artificial water reservoirs. There are over 7000 rivers, streams, and canals in the country; of these, only ten are longer than 100 kilometres (62 mi). The longest rivers of Estonia are Võhandu — 162 kilometres (101 mi) and Pärnu —144 kilometres (89 mi), followed by the Põltsamaa, Pedja, Kasari, Keila, and Jägala rivers. Bogs and mires cover 23.2% of the land. Generally the terrain is flat, average elevation above the sea level being about 50 metres (164 ft). Only 10% of the country's terrain is greater than 100 metres (328 ft) in height, with Haanja Upland containing the highest peak, Suur Munamägi, at 318 metres (1,043 ft).[178]

Location in Europe

Located in Northern Europe, Estonia has also been classified as Eastern or Central Europe in some contexts. Various sources classify Estonia differently for statistical and other purposes. For example, the United Nations,[18] and Eurovoc[19] classify Estonia as part of Northern Europe, the OECD[20] classifies it as a Central and Eastern European country, the CIA World Factbook[21] classifies it as Eastern Europe. A recent version of the online Encyclopædia Britannica locates it in "northeastern Europe".[184]

Climate

Estonia is situated in the temperate climate zone, and in the transition zone between maritime and continental climate, characterized by warm summers and fairly mild winters. Primary local differences are caused by the Baltic Sea, which warms the coastal areas in winter, and cools them in the spring.[178][179] Average temperatures range from 17.8 °C (64.0 °F) in July, the warmest month, to −3.8 °C (25.2 °F) in February, the coldest month, with the annual average being 6.4 °C (43.5 °F).[185] The highest recorded temperature is 35.6 °C (96.1 °F) from 1992, and the lowest is −43.5 °C (−46.3 °F) from 1940.[186] The annual average precipitation is 662 millimetres (26.1 in),[187] with the daily record being 148 millimetres (5.8 in).[188] Snow cover varies significantly on different years.[179] Prevailing winds are westerly, southwesterly, and southerly, with average wind speed being 3–5 m/s inland and 5–7 m/s on coast.[179] The average monthly sunshine duration ranges from 290 hours in August, to 21 hours in December.[189]

Biodiversity

Due to varied climatic and soil conditions, and plethora of sea and internal waters, Estonia is one of the most biodiverse regions among the similar sized territories at the same latitude.[179] Many species extinct in most other European countries can be still found in Estonia.[190]

Recorded species include 64 mammals, 11 amphibians, and 5 reptiles.[178] Large mammals present in Estonia include the grey wolf, lynx, brown bear, red fox, badger, wild boar, moose, roe deer, beaver, otter, grey seal, and ringed seal. The critically endangered European mink has been successfully reintroduced to the island of Hiiumaa, and the rare Siberian flying squirrel is present in east Estonia.[190] The red deer, once extirpated, has also been successfully reintroduced.[191] In the beginning of the 21st century, an isolated population of European jackals was confirmed in Western Estonia, much further north than their earlier known range. The number of jackals has grown quickly in coastal areas of Estonia and can be found in Matsalu National Park.[192][193] Introduced mammals include sika deer, fallow deer, raccoon dog, muskrat, and American mink.[178]

Over 300 bird species have been found in Estonia, including the white-tailed eagle, lesser spotted eagle, golden eagle, western capercaillie, black and white stork, numerous species of owls, waders, geese and many others.[194] The barn swallow is the national bird of Estonia.[195]

Phytogeographically, Estonia is shared between the Central European and Eastern European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Estonia belongs to the ecoregion of Sarmatic mixed forests.[196] Estonia has a rich composition of floristic groups, with estimated 6000 (3461 identified) fungi, 3000 (2500 identified) algae and cyanobacteria, 850 (786 identified) lichens, and 600 (507 identified) bryophytes. Forests cover approximately half of the country. 87 native and over 500 introduced tree and bush species have been identified, with most prevalent tree species being pine (41%), birch (28%), and spruce (23%).[178] Since 1969, the cornflower (Centaurea cyanus) has been the national flower of Estonia.[197]

Protected areas cover 19.4% of Estonian land and 23% of its total area together with territorial sea. Overall there are 3,883 protected natural objects, including 6 national parks, 231 nature conservation areas, and 154 landscape reserves.[198]

Politics

Estonia is a unitary parliamentary republic. The unicameral parliament Riigikogu serves as the legislature and the government as the executive.[199]

Estonian parliament Riigikogu is elected by citizens over 18 years of age for a four-year term by proportional representation, and has 101 members. Riigikogu's responsibilities include approval and preservation of the national government, passing legal acts, passing the state budget, and conducting parliamentary supervision. On proposal of the president Riigikogu appoints the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the chairman of the board of the Bank of Estonia, the Auditor General, the Legal Chancellor, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Forces.[200][201]

The Government of Estonia is formed by the Prime Minister of Estonia at recommendation of the President, and approved by the Riigikogu. The government, headed by the Prime Minister, carries out domestic and foreign policy. Ministers head ministries and represent its interests in the government. Sometimes ministers with no associated ministry are appointed, known as ministers without portfolio.[202] Estonia has been ruled by coalition governments because no party has been able to obtain an absolute majority in the parliament.[199]

The head of the state is the President who has a primarily representative and ceremonial role. There is no popular vote on the election of the president, but the president is elected by the Riigikogu, or by a special electoral college.[203] The President proclaims the laws passed in the Riigikogu, and has the right to refuse proclamation and return law in question for a new debate and decision. If Riigikogu passes the law unamended, then the President has right to propose to the Supreme Court to declare the law unconstitutional. The President also represents the country in international relations.[199][204]

The Constitution of Estonia also provides possibility for direct democracy through referendum, although since adoption of the constitution in 1992 the only referendum has been the referendum on European Union membership in 2003.[205]

Estonia has pursued the development of the e-government, with 99 percent of the public services being available on the web 24 hours a day.[206] In 2005, Estonia became the first country in the world to introduce nationwide binding Internet voting in local elections of 2005.[207] In the 2023 parliamentary elections 51% of the total votes were cast over the internet, becoming the first time when more than half of votes were cast online.[208]

In the most recent parliamentary elections of 2023, six parties gained seats at Riigikogu. The head of the Reform Party, Kaja Kallas, formed the government together with Estonia 200 and Social Democratic Party, while Conservative People's Party, Centre Party and Isamaa became the opposition.[209][210]

Law

The Constitution of Estonia is the fundamental law, establishing the constitutional order based on five principles: human dignity, democracy, rule of law, social state, and the Estonian identity.[211] Estonia has a civil law legal system based on the Germanic legal model.[212] The court system has a three-level structure. The first instance are county courts which handle all criminal and civil cases, and administrative courts which hear complaints about government and local officials, and other public disputes. The second instance are district courts which handle appeals about the first instance decisions.[213] The Supreme Court is the court of cassation, conducts constitutional review, and has 19 members.[214] The judiciary is independent, judges are appointed for life, and can be removed from office only when convicted of a crime.[215] The justice system has been rated among the most efficient in the European Union by the EU Justice Scoreboard.[216]As of June 2023, gay registered partners and married couples have the right to adopt. Gay couples gained the right to marriage in Estonia in 2024.[217][218]

Foreign relations

Estonia was a member of the League of Nations from 22 September 1921, and became a member of the United Nations on 17 September 1991.[219][220] Since restoration of independence Estonia has pursued close relations with the Western countries, and has been member of NATO and the European Union since 2004.[220] In 2007, Estonia joined the Schengen Area, and in 2011 the Eurozone.[220] The European Union Agency for large-scale IT systems is based in Tallinn, and started operations at the end of 2012.[221] Estonia held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the second half of 2017.[222]

Since the early 1990s, Estonia has been involved in active trilateral Baltic states co-operation with Latvia and Lithuania, and Nordic-Baltic co-operation with the Nordic countries. Estonia is a member of the interparliamentary Baltic Assembly, the intergovernmental Baltic Council of Ministers and the Council of the Baltic Sea States.[223] Estonia has built close relationship with the Nordic countries, especially Finland and Sweden, and is a member of Nordic-Baltic Eight.[220][224] Joint Nordic-Baltic projects include the education programme Nordplus[225] and mobility programmes for business and industry[226] and for public administration.[227] The Nordic Council of Ministers has an office in Tallinn with a subsidiaries in Tartu and Narva.[228][229] The Baltic states are members of Nordic Investment Bank, European Union's Nordic Battle Group, and in 2011 were invited to co-operate with Nordic Defence Cooperation in selected activities.[230][231][232][233]

The beginning of the attempt to redefine Estonia as "Nordic" was seen in December 1999, when then Estonian foreign minister (and President of Estonia from 2006 until 2016) Toomas Hendrik Ilves delivered a speech entitled "Estonia as a Nordic Country" to the Swedish Institute for International Affairs,[234] with the potential political calculation behind it being the wish to distinguish Estonia from its more slowly progressing southern neighbours, which could have postponed early participation in European Union enlargement.[235] Andres Kasekamp argued in 2005, that relevance of identity discussions in Baltic states decreased with their entrance into EU and NATO together, but predicted, that in the future, attractiveness of Nordic identity in Baltic states will grow and eventually, five Nordic states plus three Baltic states will become a single unit.[235]

Other Estonian international organisation memberships include OECD, OSCE, WTO, IMF, the Council of the Baltic Sea States,[220][236][237] and on 7 June 2019, was elected a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council for a two-year term that began on 1 January 2020.[238]

Since the Soviet era, the relations with Russia remain generally cold, even though practical co-operation has taken place in between.[239] Since 24 February 2022, the relations with Russia have further deteriorated due to Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Estonia has very actively supported Ukraine during the war, providing highest support relative to its gross domestic product.[240][241]

Military

The Estonian Defence Forces consist of land forces, navy, and air force. The current national military service is compulsory for healthy men between ages of 18 and 28, with conscripts serving 8- or 11-month tours of duty, depending on their education and position provided by the Defence Forces.[242] The peacetime size of the Estonian Defence Forces is about 6,000 persons, with half of those being conscripts. The planned wartime size of the Defence Forces is 60,000 personnel, including 21,000 personnel in high readiness reserve.[243] Since 2015, the Estonian defence budget has been over 2% of GDP, fulfilling its NATO defence spending obligation.[244]

The Estonian Defence League is a voluntary national defence organisation under management of Ministry of Defence. It is organised based on military principles, has its own military equipment, and provides various different military training for its members, including in guerilla tactics. The Defence League has 17,000 members, with additional 11,000 volunteers in its affiliated organisations.[245][246]

Estonia co-operates with Latvia and Lithuania in several trilateral Baltic defence co-operation initiatives. As part of Baltic Air Surveillance Network (BALTNET) the three countries manage the Baltic airspace control center, Baltic Battalion (BALTBAT) has participated in the NATO Response Force, and a joint military educational institution Baltic Defence College is located in Tartu.[247]

Estonia joined NATO on 29 March 2004.[248] NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence was established in Tallinn in 2008.[249] In response to Russian war in Ukraine, since 2017 a NATO Enhanced Forward Presence battalion battle group has been based in Tapa Army Base.[250] Also part of NATO, the Baltic Air Policing deployment has been based in Ämari Air Base since 2014.[251] In the European Union, Estonia participates in Nordic Battlegroup and Permanent Structured Cooperation.[252][253]

Since 1995, Estonia has participated in numerous international security and peacekeeping missions, including: Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Kosovo, and Mali.[254] The peak strength of Estonian deployment in Afghanistan was 289 soldiers in 2009.[255] Eleven Estonian soldiers have been killed in missions of Afghanistan and Iraq.[256]

Administrative divisions

Estonia is a unitary country with a single-tier local government system. Local affairs are managed autonomously by local governments. Since administrative reform in 2017, there are in total 79 local governments, including 15 towns and 64 rural municipalities. All municipalities have equal legal status and form part of a maakond (county), which is an administrative subunit of the state.[257] Representative body of local authorities is municipal council, elected at general direct elections for a four-year term. The council appoints local government. For towns, the head of the local government is linnapea (mayor) and vallavanem for parishes. For additional decentralization the local authorities may form municipal districts with limited authority, currently those have been formed in Tallinn and Hiiumaa.[258]

Separately from administrative units, there are also settlement units: village, small borough, borough, and town. Generally, villages have less than 300, small boroughs have between 300 and 1000, boroughs and towns have over 1000 inhabitants.[258]

Economy

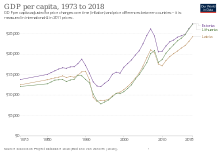

As a member of the European Union and OECD, Estonia is considered a high-income economy by the World Bank. The GDP (PPP) per capita of the country was $46,385 in 2023 according to the International Monetary Fund, ranked 40th.[15]

Estonia ranks highly in international rankings for quality of life,[259] education,[260] press freedom, digitalisation of public services[261][262] and the prevalence of technology companies.[263]

Beginning 1 January 2011, Estonia adopted the euro and became the 17th eurozone member state.[264]

Estonia produces about 75% of its consumed electricity.[265] In 2011, about 85% of it was generated with locally mined oil shale.[266] Alternative energy sources such as wood, peat, and biomass make up approximately 9% of primary energy production. Renewable wind energy was about 6% of total consumption in 2009.[267] Estonia imports petroleum products from western Europe and Russia. Estonia imports 100% of its natural gas from Russia.[268] Oil shale energy, telecommunications, textiles, chemical products, banking, services, food and fishing, timber, shipbuilding, electronics, and transportation are key sectors of the economy.[269] The ice-free port of Muuga, near Tallinn, is a modern facility featuring good transhipment capability, a high-capacity grain elevator, chill/frozen storage, and new oil tanker off-loading capabilities.[270]

Because of the global economic recession that began in 2007, the GDP of Estonia decreased by 1.4% in the 2nd quarter of 2008, over 3% in the 3rd quarter of 2008, and over 9% in the 4th quarter of 2008. The Estonian government made a supplementary negative budget, which was passed by Riigikogu. The revenue of the budget was decreased for 2008 by EEK 6.1 billion and the expenditure by EEK 3.2 billion.[271] In 2010, the economic situation stabilised and started a growth based on strong exports. In the fourth quarter of 2010, Estonian industrial output increased by 23% compared to the year before. The country has been experiencing economic growth ever since.[272]

According to Eurostat data, Estonian PPS GDP per capita stood at 67% of the EU average in 2008.[273] In 2017, the average monthly gross salary in Estonia was €1221.[274]

However, there are vast disparities in GDP between different areas of Estonia; currently, over half of the country's GDP is created in Tallinn.[275] In 2008, the GDP per capita of Tallinn stood at 172% of the Estonian average,[276] which makes the per capita GDP of Tallinn as high as 115% of the European Union average, exceeding the average levels of other counties.

The unemployment rate in March 2016 was 6.4%, which is below the EU average,[274] while real GDP growth in 2011 was 8.0%,[277] five times the euro-zone average. In 2012, Estonia remained the only euro member with a budget surplus, and with a national debt of only 6%, it is one of the least indebted countries in Europe.[278]

Economic indicators

Estonia's economy continues to benefit from a transparent government and policies that sustain a high level of economic freedom, ranking 6th globally and 2nd in Europe.[279][280] The rule of law remains strongly buttressed and enforced by an independent and efficient judicial system. A simplified tax system with flat rates and low indirect taxation, openness to foreign investment, and a liberal trade regime have supported the resilient and well-functioning economy.[281] As of May 2018[update], the Ease of Doing Business Index by the World Bank Group places the country 16th in the world.[282] The strong focus on the IT sector through its e-Estonia program has led to much faster, simpler and efficient public services where for example filing a tax return takes less than five minutes and 98% of banking transactions are conducted through the internet.[283][284] Estonia has the 13th lowest business bribery risk in the world, according to TRACE Matrix.[285]

Estonia is a developed country with an advanced, high-income economy that was among the fastest-growing in the EU since its entry in 2004.[286] The country ranks very high in the Human Development Index,[287] and compares well in measures of economic freedom, civil liberties, education,[288] and press freedom.[289] Estonian citizens receive universal health care,[290] free education,[291] and the longest paid maternity leave in the OECD.[292] One of the world's most digitally-advanced societies,[293]in 2005 Estonia became the first state to hold elections over the Internet, and in 2014, the first state to provide e-residency.[294]

Historic development

In 1928, a stable currency, the kroon, was established. It is issued by the Bank of Estonia, the country's central bank. The word kroon (Estonian pronunciation: [ˈkroːn], "crown") is related to that of the other Nordic currencies (such as the Swedish krona and the Danish and Norwegian krone). The kroon succeeded the mark in 1928 and was used until 1940. After Estonia regained its independence, the kroon was reintroduced in 1992.

After restoring full independence, in the 1990s, Estonia styled itself as the "gateway between East and West" and aggressively pursued economic reform and reintegration with the West.[295][296][297][298] In 1994, applying the economic theories of Milton Friedman, Estonia became one of the first countries to adopt a flat tax, with a uniform rate of 26% regardless of personal income. This rate has since been reduced several times, e.g., to 24% in 2005, 23% in 2006, and to 21% in 2008.[299] The Government of Estonia finalised the design of Estonian euro coins in late 2004, and adopted the euro as the country's currency on 1 January 2011, later than planned due to continued high inflation.[264][300] A Land Value Tax is levied which is used to fund local municipalities. It is a state-level tax, but 100% of the revenue is used to fund Local Councils. The rate is set by the Local Council within the limits of 0.1–2.5%. It is one of the most important sources of funding for municipalities.[301] The Land Value Tax is levied on the value of the land only with improvements and buildings not considered. Very few exemptions are considered on the land value tax and even public institutions are subject to the tax.[301] The tax has contributed to a high rate (~90%)[301] of owner-occupied residences within Estonia, compared to a rate of 67.4% in the United States.[302]

In 1999, Estonia experienced its worst year economically since it regained independence in 1991, largely because of the impact of the 1998 Russian financial crisis.[303] Estonia joined the WTO in November 1999. With assistance from the European Union, the World Bank and the Nordic Investment Bank, Estonia completed most of its preparations for European Union membership by the end of 2002. Estonia joined the OECD in 2010.[304]

Transport

The Port of Tallinn, taking into account both cargo and passenger traffic, is one of the largest port enterprises of the Baltic Sea. In 2018, the enterprise was listed in Tallinn Stock Exchange. It was the first time in nearly 20 years in Estonia when a state-owned company went public in Estonia. It was also the 2nd largest IPO in Nasdaq Tallinn in the number of retail investors participating. The Republic of Estonia remains the largest shareholder and holds 67% of the company.[305]

Owned by AS Eesti Raudtee, there are many significant railroad connections in Estonia, such as Tallinn–Narva railway, which is 209.6 km (130.2 mi) long main connection to St. Petersburg. The most important highways in Estonia, in other hand, includes Narva Highway (E20), Tartu Highway (E263) and Pärnu Highway (E67).

The Lennart Meri Tallinn Airport in Tallinn is the largest airport in Estonia and serves as a hub for the national airline Nordica, as well as the secondary hub for AirBaltic[306] and LOT Polish Airlines.[307] Total passengers using the airport has increased on average by 14.2% annually since 1998. On 16 November 2012 Tallinn Airport has reached two million passenger landmark for the first time in its history.[308]

Resources

Although Estonia is in general resource-poor, the land still offers a large variety of smaller resources. The country has large oil shale and limestone deposits. In addition to oil shale and limestone, Estonia also has large reserves of phosphorite, pitchblende, and granite that currently are not mined, or not mined extensively.[312]

Significant quantities of rare-earth oxides are found in tailings accumulated from 50 years of uranium ore, shale and loparite mining at Sillamäe.[313] Because of the rising prices of rare earths, extraction of these oxides has become economically viable. The country currently exports around 3000 tonnes per annum, representing around 2% of world production.[314]

As of 2012, Estonia had forests that covered 48% of the land.[315] Since at least 2009, there has been a substantial increase in logging, and logging occurs not only nationwide in private land, but even in supposedly protected land like the national park.[316] Estonia needs to cut significantly less forest to retain biodiversity and meet the country's carbon sequestration goal,[317] but it is increasing, and in 2022 the government ministry responsible for forestry, the RMK, reported a record profit of 1.4 billion euros.[318]

Industry and environment

Food, construction, and electronic industries are currently among the most important branches of Estonia's industry.[319] In 2007, the construction industry employed more than 80,000 people, around 12% of the entire country's workforce.[320] Another important industrial sector is the machinery and chemical industry, which is mainly located in Ida-Viru county and around Tallinn.

The oil shale-based mining industry, also concentrated in East Estonia, produces around 73% of the entire country's electricity.[321] Although the number of pollutants emitted has been falling since the 1980s,[322] the air is still contaminated with sulphur dioxide from the mining industry the Soviet Union rapidly developed in the early 1950s. In some areas, coastal seawater is polluted, mainly around the Sillamäe industrial complex.[323]

Estonia is dependent on other countries for energy. In recent years, many local and foreign companies have been investing in renewable energy sources.[324][325][326] Wind power has been increasing steadily in Estonia and the total current amount of energy produced from wind is nearly 60 MW; another roughly 399 MW worth of projects are currently being developed and more than 2800 MW being proposed in the Lake Peipus area and coastal areas of Hiiumaa.[327][328][329]

Currently[when?], there are plans to renovate some older units of the Narva Power Plants, establish new power stations, and provide higher efficiency in oil shale-based energy production.[330] Estonia liberalised 35% of its electricity market in April 2010; the electricity market as whole was to be liberalised by 2013.[331]

Together with Lithuania, Poland, and Latvia, the country considered participating in constructing the Visaginas nuclear power plant in Lithuania to replace the Ignalina nuclear plant.[332][333] However, due to the slow pace of the project and problems with the nuclear sector (like the Fukushima disaster and bad example of Olkiluoto plant), Eesti Energia shifted its main focus to shale oil production, seen as far more profitable.[334]

The Estonian electricity network forms a part of the Nord Pool Spot network.[335]

Estonia has a strong information technology sector, partly owing to the Tiigrihüpe project undertaken in the mid-1990s, and has been mentioned as the most "wired" and advanced country in Europe in the terms of e-Government of Estonia.[336] The 2014 e-residency program began offering those services to non-residents in Estonia.

Skype was written by Estonia-based developers Ahti Heinla, Priit Kasesalu and Jaan Tallinn, who had also originally developed Kazaa.[337] Other notable startups that originated from Estonia include Bolt, GrabCAD, Fortumo and Wise (formerly known as TransferWise). It has been reported that Estonia has the highest startups per person ratio in the world.[338] As of January 2022, there are 1,291 startups from Estonia, seven of which are unicorns, equalling nearly 1 startup per 1,000 Estonians.[339][340]

Trade

Estonia has had a market economy since the end of the 1990s and one of the highest per capita income levels in Eastern Europe.[341] Proximity to the Scandinavian and Finnish markets, its location between the East and West, competitive cost structure and a highly skilled labour force have been the major Estonian comparative advantages in the beginning of the 2000s (decade). As the largest city, Tallinn has emerged as a financial centre and the Tallinn Stock Exchange joined recently with the OMX system. Several cryptocurrency trading platforms are officially recognised by the government, such as CoinMetro.[342] The current government has pursued tight fiscal policies, resulting in balanced budgets and low public debt.

In 2007, however, a large current account deficit and rising inflation put pressure on Estonia's currency, which was pegged to the Euro, highlighting the need for growth in export-generating industries.Estonia exports mainly machinery and equipment, wood and paper, textiles, food products, furniture, and metals and chemical products.[343] Estonia also exports 1.562 billion kilowatt hours of electricity annually.[343] At the same time Estonia imports machinery and equipment, chemical products, textiles, food products and transportation equipment.[343] Estonia imports 200 million kilowatt hours of electricity annually.[343]

Between 2007 and 2013, Estonia received 53.3 billion kroons (3.4 billion euros) from various European Union Structural Funds as direct supports, creating the largest foreign investments into Estonia.[344] Majority of the European Union financial aid will be invested into the following fields: energy economies, entrepreneurship, administrative capability, education, information society, environment protection, regional and local development, research and development activities, healthcare and welfare, transportation and labour market.[345] Main sources of foreign direct investments to Estonia are Sweden and Finland (As of 31 December 2016[update] 48.3%).[346]

Demographics

Before World War II, ethnic Estonians made up 88% of the population, with national minorities constituting the remaining 12%.[348] The largest minority groups in 1934 were Russians, Germans, Swedes, Latvians, Jews, Poles, and Finns. Other smaller minorities in Estonia are Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Moldovans, Chuvash, Karelians and Romani people.[349]

The share of Baltic Germans in Estonia had fallen from 5.3% (~46,700) in 1881 to 1.3% (16,346) by 1934,[348][350] mainly due to emigration to Germany in the light of general Russification at the end of the 19th century[citation needed] and the independence of Estonia in the 20th century.

Between 1945 and 1989, the share of ethnic Estonians in the population resident within the currently defined boundaries of Estonia dropped to 61%, caused primarily by the Soviet occupation and programme promoting mass immigration of urban industrial workers from Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, as well as by wartime emigration and Joseph Stalin's mass deportations and executions.[351] By 1989, ethnic minorities constituted more than one-third of the population, as the number of non-Estonians had grown almost fivefold.

At the end of the 1980s, Estonians perceived their demographic change as a national catastrophe. This was a result of the migration policies essential to the Sovietization program, which aimed to russify Estonia.[citation needed] In the decade after the restoration of Estonian independence, large-scale emigration by ethnic Russians and the removal of Russian military bases in 1994 caused[citation needed] the proportion of ethnic Estonians in Estonia to increase from 61% to 69% in 2006.

Modern Estonia is a fairly ethnically homogeneous country, but this historical homogeneity is a feature of 13 of the country's 15 maakond (counties). The mostly Russian-speaking immigrant population is concentrated in urban areas which administratively belong to two counties. Thus 13 of Estonia's 15 counties are over 80% ethnic Estonian, the most homogeneous being Hiiumaa, where Estonians account for 98.4% of the population. In the counties of Harju (including the capital city Tallinn) and Ida-Viru, however, ethnic Estonians make up 60% and 20% of the population, respectively. The ethnic Russian immigrant minority makes up about 24% of the country's total population today, but accounts for 35% of the population in Harju county and for a near-70% majority in Ida-Viru county.

The Estonian Cultural Autonomy law that was passed in 1925 was unique in Europe at that time.[352] Cultural autonomies could be granted to minorities numbering more than 3,000 people with longstanding ties to the Republic of Estonia. Before the Soviet occupation, the German and Jewish minorities managed to elect a cultural council. The Law on Cultural Autonomy for National Minorities was reinstated in 1993. Historically, large parts of Estonia's northwestern coast and islands have been populated by the indigenous ethnic group of rannarootslased ("Coastal Swedes").

In recent years, the number of Swedish residents in Estonia has risen again, numbering almost 500 people by 2008, owing to property reforms enacted in the early 1990s. In 2004, the Ingrian Finnish minority in Estonia elected a cultural council and was granted cultural autonomy. The Estonian Swedes minority similarly received cultural autonomy in 2007.[353]During the Russo-Ukrainian war of 2022, tens of thousands of Ukrainian refugees have arrived in Estonia.

There is also a Roma community in Estonia. Approximately 1,000-1,500 Roma live in Estonia.[354]

Society

The Estonian society has undergone considerable changes since the country had restored full independence in 1991.[355] Some of the more notable changes have taken effect in the level of stratification and distribution of family income. The Gini coefficient has held steadily higher than the European Union average (31 in 2009),[356] although it has clearly dropped. The registered unemployment rate in January 2021 was 6.9%.[357]

Estonia's population on 31 December 2021 (1,331,824 people) was about 3% higher than in the previous census of 2011. 84% of people residing in Estonia in 2021 lived in Estonia at the time of the previous census as well. 11% had been added by births and 5% by immigration over the ten years 2011–2021. Nowadays, 211 different self-reported ethnic groups are represented in the country's population and 243 different mother tongues are spoken. Census data indicate that Estonia has continued to stand out among European countries for its highly educated population – 43% of the population aged 25–64 have a university education, which puts Estonia in 7th place in Europe (Estonian women rank 3rd in terms of educational attainment).

More people of different ethnic origin live in Estonia than ever before, however the share of Estonians in the population has remained stable over the three censuses (2000: 68.3%; 2011: 69.8%; 2021: 69.4%). Estonian is spoken by 84% of the population: 67% of people speak it as their mother tongue and 17% as a foreign language. Compared with previous censuses, the proportion of people who speak Estonian has increased (2000: 80%; 2011: 82%), particularly due to people who have learned to speak Estonian as a foreign language (2000: 12%; 2011: 14%). It has been estimated that 76% of Estonia's population can speak a foreign language. As of 2021 census data, English is the most widely spoken foreign language in Estonia (overtaking the top position from Russian, which had still been the most widely spoken foreign language in Estonia in 2011 and earlier censuses). An estimated 17% of the native Estonian-speaking population speak a dialect of Estonia. [358]

As of 2 July 2010[update], 84.1% of Estonian residents were Estonian citizens, 8.6% were citizens of other countries and 7.3% were "citizens with undetermined citizenship".[359] Since 1992, roughly 140,000 people have acquired Estonian citizenship by passing naturalisation exams.[360] Estonia has also accepted quota refugees under the migrant plan agreed upon by EU member states in 2015.[361]

Ethnic distribution in Estonia is very homogeneous at a county level; in most counties, over 90% of residents are ethnic Estonians. In contrast, in the capital city Tallinn and the urban areas of Ida-Viru county (which neighbours Russia) ethnic Estonians account for around 60% of the population and the remainder is mostly composed of Russian and Ukrainian immigrants, who mostly arrived in Estonia during the period of Soviet occupation (1944–1991), however now also includes over 62,000 (ca 6% of total population) war refugees from Ukraine who have settled in Estonia in 2022.[362]

The 2008 United Nations Human Rights Council report called "extremely credible" the description of the citizenship policy of Estonia as "discriminatory".[363] According to surveys, only 5% of the Russian community have considered returning to Russia in the near future. Estonian Russians have developed their own identity – more than half of the respondents recognized that Estonian Russians differ noticeably from the Russians in Russia. When compared with results from a 2000 survey, Russians had a more positive attitude toward the future.[364]

Estonia was the first former Soviet republic to legalize civil unions for same-sex couples, with a law approved in October 2014.[365] Political disagreements delayed adoption of the necessary implementing legislation, and same-sex couples were not able to sign cohabitation agreements until January 1, 2016.

Urbanization

Tallinn is the capital and the largest city of Estonia, and lies on the northern coast of Estonia, along the Gulf of Finland. There are 33 cities and several town-parish towns in the country. In total, there are 47 linna, with "linn" in English meaning both "cities" and "towns". More than 70% of the population lives in towns.

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tallinn  Tartu | 1 | Tallinn | Harju | 457,572 | 11 | Valga | Valga | 12,173 | |

| 2 | Tartu | Tartu | 97,759 | 12 | Võru | Võru | 12,112 | ||

| 3 | Narva | Ida-Viru | 53,360 | 13 | Keila | Harju | 10,964 | ||

| 4 | Pärnu | Pärnu | 41,520 | 14 | Jõhvi | Ida-Viru | 10,880 | ||

| 5 | Kohtla-Järve | Ida-Viru | 33,434 | 15 | Haapsalu | Lääne | 9,693 | ||

| 6 | Viljandi | Viljandi | 17,255 | 16 | Paide | Järva | 8,073 | ||

| 7 | Maardu | Harju | 17,017 | 17 | Saue | Harju | 6,227 | ||

| 8 | Rakvere | Lääne-Viru | 15,695 | 18 | Elva | Tartu | 5,692 | ||

| 9 | Kuressaare | Saare | 13,185 | 19 | Põlva | Põlva | 5,498 | ||

| 10 | Sillamäe | Ida-Viru | 12,352 | 20 | Tapa | Lääne-Viru | 5,492 | ||

Religion

Religion in Estonia (2011)[367][368]

Estonia has a diverse religious history, owing to influences from various neighboring societies. In recent years it has become increasingly secular, with either a plurality or a majority of the population declaring themselves nonreligious in recent censuses, followed by those who identify as religiously "undeclared". The largest minority groups are the various Christian denominations, principally Lutheran and Orthodox Christians, with very small numbers of adherents of non-Christian faiths, namely Judaism, Islam and Buddhism. Other polls suggest the country is broadly split between Christians and the non-religious / religiously undeclared.

Before the Second World War, Estonia was approximately 80% Protestant, overwhelmingly Lutheran,[369][370][371] followed by Calvinism and other Protestant branches. Many Estonians today profess not to be particularly religious because religion through the 19th century was associated with German feudal rule.[372] There has historically been a small but noticeable minority of Russian Old-believers near the Lake Peipus area in Tartu county.

Today, Estonia's constitution guarantees freedom of religion, separation of church and state, and individual rights to privacy of belief and religion.[373] According to the Dentsu Communication Institute Inc, Estonia is one of the least religious countries in the world, with 75.7% of the population claiming to be irreligious. The Eurobarometer Poll 2005 found that only 16% of Estonians profess a belief in a god, the lowest belief of all countries studied.[374] A 2009 Gallup poll found similar results, with only 16% of Estonians describing religion as "important" in their daily lives, making Estonia the most irreligious of the nations surveyed.[375]

Polls about religiosity in the European Union in 2012 by Eurobarometer found that Christianity was the largest religion in Estonia accounting for 45% of Estonians.[376] Eastern Orthodox were the largest Christian group in Estonia, accounting for 17% of citizens,[376] while Protestants made up 6%, and those identifying otherwise as Christian made up 22%. Agnostic individuals were 22%, atheists 15%, and an additional 15% did not declare a response.[376]

A 2015 study by Pew Research Center, found that 51% of the population of Estonia declared itself to be Christian, 45% religiously unaffiliated—a category which includes atheists, agnostics and those who describe their religion as "nothing in particular", while 2% belonged to other faiths.[377] The Christians were divided between 25% Eastern Orthodox, 20% Lutherans, 1% Catholic and 5% other Christians.[378] Meanwhile, the religiously unaffiliated were divided between 9% as atheists, 1% as agnostics and 35% as believing in “nothing in particular”.[379]

Traditionally, the largest religious denomination in the country was Lutheranism, which was adhered to by 160,000 Estonians (or 13% of the population) according to the 2000 census, principally ethnic Estonians. According to the Lutheran World Federation, the historic Lutheran denomination has 180,000 registered members.[380] Other organisations, such as the World Council of Churches, report that there are as many as 265,700 Estonian Lutherans.[381] Additionally, there are between 8,000 and 9,000 members abroad. However, the 2011 census indicated that Eastern Orthodoxy had surpassed Lutheranism, accounting for 16.5% of the population (176,773 people). While not being a state church, the Lutheran church had historically been the national church of Estonia with an agreement giving preferential status to the Lutheran church ending in 2023.[382]

Eastern Orthodoxy is practised chiefly by the ethnic Russian minority, as well as by the small ethnic Estonian Seto minority. The Estonian Orthodox Church, affiliated with the Russian Orthodox Church, is the primary Orthodox denomination. The Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church, under the Greek-Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarchate, claims another 28,000 members.[citation needed]

Catholics are a small minority in Estonia. They are organised under the Latin Apostolic Administration of Estonia and two Greek Catholic parishes.

According to the census of 2000 (data in table to the right), there were about 1,000 adherents of the Taara faith[383][384][385] or Maausk in Estonia (see Maavalla Koda). The Jewish community has an estimated population of about 1,900 (see History of the Jews in Estonia), and the Muslim community numbers just over 1,400. Around 68,000 people consider themselves atheists.[386]

Languages

The official language, Estonian, is a Finnic language, and is conventionally classified as a member of the Uralic language family. Estonian is closely related to Finnish, and one of the few languages of Europe that is not of Indo-European origin. Unlike Estonian and Finnish, the languages of their nearest geographical neighbouring countries, Swedish, Latvian, and Russian, are all Indo-European languages.

The Estonian language is the world's second-most spoken Finnic language as well as the world's third-most spoken Uralic language (after Hungarian and Finnish).

Although the Estonian and Germanic languages are of different origins, one can identify many similar words in Estonian and German. This is primarily because the Estonian language has borrowed nearly one-third of its vocabulary from Germanic languages, mainly from Low Saxon (Middle Low German) during the period of German rule, and High German (including standard German). The percentage of Low Saxon and High German loanwords can be estimated at 22–25 percent, with Low Saxon making up about 15 percent.

South Estonian languages are spoken by 100,000 people and include the dialects of Võro and Seto. The languages are spoken in South-Eastern Estonia and are genealogically distinct from northern Estonian, but are traditionally and officially considered as dialects and "regional forms of the Estonian language", not separate language(s).[387]

Russian is the most spoken minority language in the country. There are towns in Estonia with large concentrations of Russian speakers, and there are towns where Estonian speakers are in the minority (especially in the northeast, e.g. Narva). Russian is spoken as a secondary language by many 40- to 70-year-old ethnic Estonians because Russian was the unofficial language of the Estonian SSR from 1944 to 1990 and was taught as a compulsory second language during the Soviet era. In the period between 1990 and 1995, the Russian language was granted an official special status according to Estonian language laws.[388] In 1995 it lost its official status. In 1998, most first- and second-generation industrial immigrants from the former Soviet Union (mainly the Russian SFSR) did not speak Estonian.[389] However, by 2010, 64.1% of non-ethnic Estonians spoke Estonian.[390] The latter, mostly Russian-speaking ethnic minorities, reside predominantly in the capital city of Tallinn and the industrial urban areas in Ida-Viru county.

From the 13th to the 20th century, there were Swedish-speaking communities in Estonia, particularly in the coastal areas and on the islands, which today have almost disappeared. From 1918 to 1940, when Estonia was independent, the small Swedish community was well treated. Municipalities with a Swedish majority, mainly found along the coast, used Swedish as the administrative language and Swedish-Estonian culture saw an upswing. However, most Swedish-speaking people fled to Sweden before the end of World War II, before the invasion of Estonia by the Soviet army in 1944. Only a handful of older speakers remain.

Apart from many other areas, the influence of Swedish is distinct in the Noarootsi Parish of Lääne county, where there are many villages with bilingual Estonian or Swedish names and street signs.[391][392]

The most common foreign languages learned by Estonian students are English, Russian, German, and French. Other popular languages include Finnish, Spanish, and Swedish.[393]

Lotfitka Romani is spoken by the Roma minority in Estonia.[394]

Education and science