Тайвань под японским правлением

Тайвань | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895–1945 | |||||||||||

Гимн:

| |||||||||||

| Национальная печать: Печать губернатора Тайваня Печать генерал-губернатора Тайваня  National badge: 臺字章 Daijishō  | |||||||||||

Taiwan within the Empire of Japan | |||||||||||

| Status | Part of the Empire of Japan (colony)[1] | ||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | |||||||||||

| Official languages | Japanese | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Taiwanese Hakka Formosan languages | ||||||||||

| Religion | State Shinto Buddhism Taoism Confucianism Chinese folk religion | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) |

| ||||||||||

| Government | Government-General | ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

• 1895–1912 | Meiji | ||||||||||

• 1912–1926 | Taishō | ||||||||||

• 1926–1945 | Shōwa | ||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||

• 1895–1896 (first) | Kabayama Sukenori | ||||||||||

• 1944–1945 (last) | Rikichi Andō | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Empire of Japan | ||||||||||

| 17 April 1895 | |||||||||||

| 21 October 1895 | |||||||||||

| 27 October 1930 | |||||||||||

| 2 September 1945 | |||||||||||

| 25 October 1945 | |||||||||||

| 28 April 1952 | |||||||||||

| 5 August 1952 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Taiwanese yen | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | TW | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of China (Taiwan) | ||||||||||

| Taiwan | |||

|---|---|---|---|

"Taiwan" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||

| Chinese name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣 or 台灣 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾 | ||

| Postal | Taiwan | ||

| |||

| Japanese ruled Taiwan | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 日治臺灣 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 日治台湾 | ||

| |||

| Japanese occupied Taiwan | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 日據臺灣 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 日據台湾 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

| Hiragana | だいにっぽんていこくたいわん | ||

| Katakana | ダイニッポンテイコクタイワン | ||

| Kyūjitai | 大日本帝國臺灣 | ||

| Shinjitai | 大日本帝国台湾 | ||

| |||

| History of Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronological | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Topical | ||||||||||||||||

| Local | ||||||||||||||||

| Lists | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

Остров Тайвань вместе с островами Пенху стал аннексированной территорией Империи Японии в 1895 году, когда династия Цин уступила провинцию Фуцзян-Тайвань в договоре Симоносеки после победы Японии в первой кин-японской войне . Последующее движение Республики Формоза на Тайвань было побеждено Японией с капитуляцией Тайнана . Япония управляла Тайванем в течение 50 лет. Его столица была расположена на Тайхоку (Тайбэй) во главе с генерал-губернатором Тайваня .

в Японии Тайвань был первой колонией и может рассматриваться как первый шаг в реализации их « южной доктрины расширения » конца 19 -го века. Японские намерения заключались в том, чтобы превратить Тайвань в демонстрацию «модельную колонию» с большими усилиями по улучшению экономики острова, общественных работ , промышленности , культурной Японии и поддержке потребностей японской военной агрессии в Азиатско-Тихоокеанском регионе . [ 2 ] Япония создала монополии и к 1945 году взяла на себя все продажи опиума, соли, камфоры, табака, алкоголя, матчей, весов и мер и нефти на острове. [ 3 ]

Japanese administrative rule of Taiwan ended following the surrender of Japan in September 1945 during the World War II period, and the territory was placed under the control of the Republic of China (ROC) with the issuing of General Order No. 1 by US General Douglas MacArthur.[4] Japan formally renounced its sovereignty over Taiwan in the Treaty of San Francisco effective April 28, 1952. The experience of Japanese rule continues to cause divergent views among several issues in Post-WWII Taiwan, such as the February 28 massacre of 1947, Taiwan Retrocession Day, and Taiwanese comfort women. It also made significant impact in construction of distinct Taiwanese national identity, ethnic identity, and prelude to the emergence of Taiwan independence movement.

Terminology

[edit]Whether the period should called "Taiwan under Japanese rule" (Chinese: 日治時期) or "Taiwan under Japanese occupation" (Chinese: 日據時期) in Chinese is a controversial issue in Taiwan and highly depends on the speaker's political stance.[5][6][7][8][9][10]

In 2013, the Executive Yuan under the Kuomintang rule ordered the government to use "Taiwan under Japanese occupation".[8][11][12] In 2016, after the government switching to the Democratic Progressive Party, the Executive Yuan said the very order was not in force.[13]

Taiwanese historical scholar Chou Wan-yao (周婉窈), believed the term "Taiwan under Japanese rule" is more accurate and natural when describing the period, and compared it with "India under British rule".[7] In contrast, Taiwanese political scientist Chang Ya-chung insisted that the term "Taiwan under Japanese occupation" respecting the long resistance history in Taiwan under Japanese rule.[14] Taiwanese historical scholar Wang Zhongfu (王仲孚), indicated that the terminology controversy is more about historical perspective than historical fact.[8]

The term "Japanese period" (Chinese: 日本時代; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ji̍t-pún sî-tāi) has been used in Taiwanese Hokkien and Taiwanese Hakka.[13]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]Early contact

[edit]The Japanese had been trading for Chinese products in Taiwan (formerly known as "Highland nation" (Japanese: 高砂国, Hepburn: Takasago-koku)) since before the Dutch arrived in 1624. In 1593, Toyotomi Hideyoshi planned to incorporate Taiwan into his empire and sent an envoy with a letter demanding tribute.[15] The letter was never delivered since there was no authority to receive it. In 1609, the Tokugawa shogunate sent Harunobu Arima on an exploratory mission of the island.[16] In 1616, Nagasaki official Murayama Tōan sent 13 vessels to conquer Taiwan. The fleet was dispersed by a typhoon and the one junk that reached Taiwan was ambushed by headhunters, after which the expedition left and raided the Chinese coast instead.[15][17][18]

In 1625, the senior leadership of the Dutch United East India Company (Dutch: Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) in Batavia (modern Jakarta) ordered the governor of the Dutch colony on Taiwan (known to the Dutch as Formosa) to prevent the Japanese from trading on the island. The Chinese silk merchants refused to sell to the company because the Japanese paid more. The Dutch also restricted Japanese trade with the Ming dynasty. In response, the Japanese took on board 16 inhabitants from the aboriginal village of Sinkan and returned to Japan. Suetsugu Heizō Masanao housed the Sinkanders in Nagasaki. The Company sent a man named Peter Nuyts to Japan where he learned about the Sinkanders. The shogun declined to meet the Dutch and gave the Sinkanders gifts. Nuyts arrived in Taiwan before the Sinkanders and refused to allow them to land before the Sinkanders were jailed and their gifts confiscated. The Japanese took Nuyts hostage and only released him in return for their safe passage back to Japan with 200 picols of silk as well as the Sinkanders' freedom and the return of their gifts.[19] The Dutch blamed the Chinese for instigating the Sinkanders.[20]

The Dutch dispatched a ship to repair relations with Japan, but it was seized and its crew imprisoned upon arrival. The loss of the Japanese trade made the Taiwanese colony far less profitable and the authorities in Batavia considered abandoning it before the Dutch Council of Formosa urged them to keep it unless they wanted the Portuguese and Spanish to take over. In June 1630, Suetsugu died and his son, Masafusa, allowed the company officials to reestablish communication with the shogun. Nuyts was sent to Japan as a prisoner and remained there until 1636 when he returned to the Netherlands. After 1635, the shogun forbade Japanese from going abroad and eliminated the Japanese threat to the company. The VOC expanded into previous Japanese markets in Southeast Asia. In 1639, the shogun ended all contact with the Portuguese, the company's major silver trade competitor.[19]

The Kingdom of Tungning's merchant fleets continued to operate between Japan and Southeast Asian countries, reaping profits as a center of trade. They extracted a tax from traders for safe passage through the Taiwan Strait. Zheng Taiwan held a monopoly on certain commodities such as deer skin and sugarcane, which sold at a high price in Japan.[21]

Mudan incident

[edit]

In December 1871, a Ryukyuan vessel shipwrecked on the southeastern tip of Taiwan and 54 sailors were killed by aborigines.[22] The survivors encountered aboriginal men, presumably Paiwanese, who they followed to a small settlement, Kuskus, where they were given food and water. They claim they were robbed by their Kuskus hosts during the night and in the morning they were ordered to stay put while hunters left to search for game to provide a feast. The Ryukyuans departed while the hunting party was away and found shelter in the home of a trading-post serviceman, Deng Tianbao. The Paiwanese men found the Ryukyuans and slaughtered them. Nine Ryukyuans hid in Deng's home. They moved to another settlement where they found refuge with Deng's son-in-law, Yang Youwang. Yang arranged for the ransom of three men and sheltered the survivors before sending them to Taiwan Prefecture (modern Tainan). The Ryukuans headed home in July 1872.[23] The shipwreck and murder of the sailors came to be known as the Mudan incident, although it did not take place in Mudan (J. Botan), but at Kuskus (Gaoshifo).[24]

The Mudan incident did not immediately cause any concern in Japan. A few officials knew of it by mid-1872 but it was not until April 1874 that it became an international concern. The repatriation procedure in 1872 was by the books and had been a regular affair for several centuries. From the 17th to 19th centuries, the Qing had settled 401 Ryukyuan shipwreck incidents both on the coast of mainland China and Taiwan. The Ryukyu Kingdom did not ask Japanese officials for help regarding the shipwreck. Instead its king, Shō Tai, sent a reward to Chinese officials in Fuzhou for the return of the 12 survivors.[25]

Japanese invasion (1874)

[edit]The Imperial Japanese Army started urging the government to invade Taiwan in 1872.[26] The king of Ryukyu was dethroned by Japan and preparations for an invasion of Taiwan were undertaken in the same year. Japan blamed the Qing for not ruling Taiwan properly and claimed that the perpetrators of the Mudan incident were "all Taiwan savages beyond Chinese education and law."[26] Therefore, Japan reasoned that the Taiwanese aboriginal people were outside the borders of China and Qing China consented to Japan's invasion.[27] Japan sent Kurooka Yunojo as a spy to survey eastern Taiwan.[28]

In October 1872, Japan sought compensation from the Qing dynasty of China, claiming the Kingdom of Ryūkyū was part of Japan. In May 1873, Japanese diplomats arrived in Beijing and put forward their claims; however, the Qing government immediately rejected Japanese demands on the ground that the Kingdom of Ryūkyū at that time was an independent state and had nothing to do with Japan. The Japanese refused to leave and asked if the Chinese government would punish those "barbarians in Taiwan". The Qing authorities explained that there were two kinds of aborigines in Taiwan: those directly governed by the Qing, and those unnaturalized "raw barbarians... beyond the reach of Chinese culture. Thus could not be directly regulated." They indirectly hinted that foreigners traveling in those areas settled by indigenous people must exercise caution. The Qing dynasty made it clear to the Japanese that Taiwan was definitely within Qing jurisdiction, even though part of that island's aboriginal population was not yet under the influence of Chinese culture. The Qing also pointed to similar cases all over the world where an aboriginal population within a national boundary was not under the influence of the dominant culture of that country.[29]

Japan announced that they were attacking aboriginals in Taiwan on 3 May 1874. In early May, Japanese advance forces established camp at Langqiao Bay. On 17 May, Saigō Jūdō led the main force, 3,600 strong, aboard four warships in Nagasaki head to Tainan.[30] A small scouting party was ambushed and the Japanese camp sent 250 reinforcements to search the villages. The next day, Samata Sakuma encountered Mudan fighters, around 70 strong, occupying a commanding height. A twenty-men party climbed the cliffs and shot at the Mudan people, forcing them to flee.[31] On 6 June, the Japanese emperor issued a certificate condemning the Taiwan "savages" for killing our "nationals", the Ryukyuans killed in southeastern Taiwan.[32] The Japanese army split into three forces and headed in different directions to burn the aboriginal villages. On 3 June, they burnt all the villages that had been occupied. On 1 July, the new leader of the Mudan tribe and the chief of Kuskus surrendered.[33] The Japanese settled in and established large camps with no intention of withdrawing, but in August and September 600 soldiers fell ill. The death toll rose to 561. Negotiations with Qing China began on 10 September. The Western Powers pressured China not to cause bloodshed with Japan as it would negatively impact the coastal trade. The resulting Peking Agreement was signed on 30 October. Japan gained the recognition of Ryukyu as its vassal and an indemnity payment of 500,000 taels. Japanese troops withdrew from Taiwan on 3 December.[34]

Sino-Japanese War

[edit]The First Sino-Japanese War broke out between Qing dynasty China and Japan in 1894 following a dispute over the sovereignty of Korea. The acquisition of Taiwan by Japan was the result of Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi's "southern strategy" adopted during the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894–95 and the following diplomacy in the spring of 1895. Prime Minister Hirobumi's southern strategy, supportive of Japanese navy designs, paved the way for the occupation of Penghu Islands in late March as a prelude to the takeover of Taiwan. Soon after, while peace negotiations continued, Hirobumi and Mutsu Munemitsu, his minister of foreign affairs, stipulated that both Taiwan and Penghu were to be ceded by imperial China.[35] Li Hongzhang, China's chief diplomat, was forced to accede to these conditions as well as to other Japanese demands, and the Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed on April 17, then duly ratified by the Qing court on 8 May. The formal transfer of Taiwan and Penghu took place on a ship off the Keelung coast on June 2. This formality was conducted by Li's adopted son, Li Ching-fang, and Admiral Kabayama Sukenori, a staunch advocate of annexation, whom Itō had appointed as governor-general of Taiwan.[36][37]

The annexation of Taiwan was also based on considerations of productivity and ability to provide raw materials for Japan's expanding economy and to become a ready market for Japanese goods. Taiwan's strategic location was deemed advantageous as well. As envisioned by the navy, the island would form a southern bastion of defense from which to safeguard southernmost China and southeastern Asia.[38]

The period of Japanese rule in Taiwan has been divided into three periods under which different policies were prevalent: military suppression (1895–1915), dōka (同化): assimilation (1915–37), and kōminka (皇民化): Japanization (1937–45). A separate policy for aborigines was implemented.[39][40]

Armed resistance

[edit]

As Taiwan was ceded by a treaty, the period that followed is referred to by some as its colonial era. Others who focus on the decades as a culmination of preceding war refer to it as the occupation period. The loss of Taiwan would become an irredentist rallying point for the Chinese nationalist movement in the years that followed.[41]

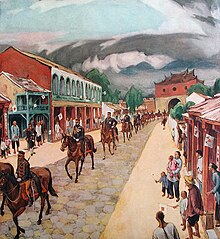

The cession ceremony took place on board a Japanese vessel as the Chinese delegate feared reprisal from local residents.[42] Japanese authorities encountered violent opposition in much of Taiwan. Five months of sustained warfare occurred after the invasion of Taiwan in 1895 and partisan attacks continued until 1902. For the first two years, colonial authority relied mainly on military action and local pacification efforts. Disorder and panic were prevalent in Taiwan after Penghu was seized by Japan in March 1895. On 20 May, Qing officials were ordered to leave their posts. General mayhem and destruction ensued in the following months.[43]

Japanese forces landed on the coast of Keelung on 29 May and Tamsui's harbor was bombarded. Remnant Qing units and Guangdong irregulars briefly fought against Japanese forces in the north. After the fall of Taipei on 7 June, local militia and partisan bands continued the resistance. In the south, a small Black Flag force led by Liu Yongfu delayed Japanese landings. Governor Tang Jingsong attempted to carry out anti-Japanese resistance efforts as the Republic of Formosa, however he still professed to be a Qing loyalist. The declaration of a republic was, according to Tang, to delay the Japanese so that Western powers might be compelled to defend Taiwan.[43] The plan quickly turned to chaos as the Green Standard Army and Yue soldiers from Guangxi took to looting and pillaging Taiwan. Given the choice between chaos at the hands of bandits or submission to the Japanese, Taipei's gentry elite sent Koo Hsien-jung to Keelung to invite the advancing Japanese forces to proceed to Taipei and restore order.[44] The Republic, established on 25 May, disappeared 12 days later when its leaders left for the mainland.[43] Liu Yongfu formed a temporary government in Tainan but escaped to the mainland as well as Japanese forces closed in.[45] Between 200,000 and 300,000 people fled Taiwan in 1895.[46][47] Chinese residents in Taiwan were given the option of selling their property and leaving by May 1897, or become Japanese citizens. From 1895 to 1897, an estimated 6,400 people, mostly gentry elites, sold their property and left Taiwan. The vast majority did not have the means or will to leave.[48][49][50]

Upon Tainan's surrender, Kabayama declared Taiwan pacified, however his proclamation was premature. In December, a series of anti-Japanese uprisings occurred in northern Taiwan, and would continue to occur at a rate of roughly one per month. Armed resistance by Hakka villagers broke out in the south. A series of prolonged partisan attacks, led by "local bandits" or "rebels", lasted throughout the next seven years. After 1897, uprisings by Chinese nationalists were commonplace. Luo Fuxing, a member of the Tongmenghui organization preceding the Kuomintang, was arrested and executed along with two hundred of his comrades in 1913.[51] Japanese reprisals were often more brutal than the guerrilla attacks staged by the rebels. In June 1896, 6,000 Taiwanese were slaughtered in the Yunlin Massacre. From 1898 to 1902, some 12,000 "bandit-rebels" were killed in addition to the 6,000–14,000 killed in the initial resistance war of 1895.[45][52][53] During the conflict, 5,300 Japanese were killed or wounded, and 27,000 were hospitalized.[54]

Rebellions were often caused by a combination of unequal colonial policies on local elites and extant millenarian beliefs of the local Taiwanese and plains indigenous.[55] Ideologies of resistance drew on different ideals such as Taishō democracy, Chinese nationalism, and nascent Taiwanese self-determination.[56] Support for resistance was partly class-based and many of the wealthy Han people in Taiwan preferred the order of colonial rule to the lawlessness of insurrection.[57]

"The cession of the island to Japan was received with such disfavour by the Chinese inhabitants that a large military force was required to effect its occupation. For nearly two years afterwards, a bitter guerrilla resistance was offered to the Japanese troops, and large forces – over 100,000 men, it was stated at the time – were required for its suppression. This was not accomplished without much cruelty on the part of the conquerors, who, in their march through the island, perpetrated all the worst excesses of war. They had, undoubtedly, considerable provocation. They were constantly attacked by ambushed enemies, and their losses from battle and disease far exceeded the entire loss of the whole Japanese army throughout the Manchurian campaign. But their revenge was often taken on innocent villagers. Men, women, and children were ruthlessly slaughtered or became the victims of unrestrained lust and rapine. The result was to drive from their homes thousands of industrious and peaceful peasants, who, long after the main resistance had been completely crushed, continued to wage a vendetta war, and to generate feelings of hatred which the succeeding years of conciliation and good government have not wholly eradicated." – The Cambridge Modern History, Volume 12[58]

Major armed resistance was largely crushed by 1902 but minor rebellions started occurring again in 1907, such as the Beipu uprising by Hakka and Saisiyat people in 1907, Luo Fuxing in 1913 and the Tapani Incident of 1915.[55][59] The Beipu uprising occurred on 14 November 1907 when a group of Hakka insurgents killed 57 Japanese officers and members of their family. In the following reprisal, 100 Hakka men and boys were killed in the village of Neidaping.[60] Luo Fuxing was an overseas Taiwanese Hakka involved with the Tongmenghui. He planned to organize a rebellion against the Japanese with 500 fighters, resulting in the execution of more than 1,000 Taiwanese by Japanese police. Luo was killed on 3 March 1914.[52][61] In 1915, Yu Qingfang organized a religious group that openly challenged Japanese authority. Indigenous and Han forces led by Chiang Ting and Yu stormed multiple Japanese police stations. In what is known as the Tapani incident, 1,413 members of Yu's religious group were captured. Yu and 200 of his followers were executed.[62] After the Tapani rebels were defeated, Andō Teibi ordered Tainan's Second Garrison to retaliate through massacre. Military police in Tapani and Jiasian announced that they would pardon any anti-Japanese militants and that those who had fled into the mountains should return to their village. Once they returned, the villagers were told to line up in a field, dig holes, and were then executed by firearm. According to oral tradition, at least 5,000–6,000 people died in this incident.[63][64][65]

Non-violent resistance

[edit]Nonviolent means of resistance such as the Taiwanese Cultural Association (TCA), founded by Chiang Wei-shui in 1921, continued to exist after most violent means were exhausted. Chiang was born in Yilan in 1891 and was raised on a Confucian education paid by a father who identified as a Han Chinese. In 1905, Chiang started attending Japanese elementary school. At the age of 20, he was admitted to Taiwan Sotokufu Medical School and in his first year of college, Chiang joined the Taiwan Branch of the "Chinese United Alliance" founded by Sun Yat-sen. The TCA's anthem, composed by Chiang, promoted friendship between China and Japan, Han and Japanese, and peace between Asians and white people. He saw Taiwanese people as Japanese nationals of Han Chinese ethnicity and wished to position the TCA as an intermediary between China and Japan. The TCA also aimed to "adopt a stance of national self-determination, enacting the enlightenment of the Islanders, and seeking legal extension of civil rights."[66] He told the Japanese authorities that the TCA was not a political movement and would not engage in politics.[67]

Statements aspiring to self determination and Taiwan belonging to the Taiwanese were possible at the time due to the relatively progressive era of Taishō Democracy. At the time most Taiwanese intellectuals did not wish for Taiwan to be an extension of Japan. "Taiwan is Taiwan people's Taiwan" became a common position for all anti-Japanese groups for the next decade. In December 1920, Lin Hsien-tang and 178 Taiwanese residents filed a petition to Tokyo seeking self-determination. It was rejected.[68] Taiwanese intellectuals, led by New People Society, started a movement to petition to the Japanese Diet to establish a self-governing parliament in Taiwan, and to reform the government-general. The Japanese government attempted to dissuade the population from supporting the movement, first by offering the participants membership in an advisory Consulative Council, then ordered the local governments and public schools to dismiss locals suspected of supporting the movement. The movement lasted 13 years.[69] Although unsuccessful, the movement prompted the Japanese government to introduce local assemblies in 1935.[70] Taiwan also had seats in House of Peers.[71]

The TCA had over 1,000 members composed of intellectuals, landlords, public school graduates, medical practitioners, and the gentry class. TCA branches were established across Taiwan except in indigenous areas. They gave cultural lecture tours and taught Classical Chinese as well as other more modern subjects. The TCA sought to promote vernacular Chinese language. Cultural Lecture Tours were treated as a festivity, using firecrackers traditionally used to ward off evil as a challenge against Japanese authority. If any criticism of Japan was heard, the police immediately ordered the speaker to step down. In 1923 the TCA co-founded Taiwan People's News which was published in Tokyo and then shipped to Taiwan. It was subjected to severe censorship by Japanese authorities. As many as seven or eight issues were banned. Chiang and others applied to set up an "Alliance to Urge for a Taiwan Parliament." It was deemed legal in Tokyo but illegal in Taiwan. In 1923, 99 Alliance members were arrested and 18 were tried in court. Chiang was forced to defend against the charge of "asserting 'Taiwan has 3.6 million Zhonghua Minzu/Han People' in petition leaflets."[72] Thirteen were convicted: 6 fined, 7 imprisoned (including Chiang). Chiang was imprisoned more than ten times.[73]

The TCA split in 1927 to form the New TCA and the Taiwanese People's Party. The TCA had been influenced by communist ideals resulting in Chiang and Lin's departure to form the Taiwan People's Party (TPP). The New TCA later became a subsidiary of the Taiwanese Communist Party, founded in Shanghai in 1928, and the only organization advocating for Taiwan's independence. The TPP's flag was designed by Chiang and drew on the Republic of China's flag for inspiration. In February 1931, the TPP was banned by the Japanese colonial government. The TCA was also banned in the same year. Chiang died from typhoid on 23 August.[75][76] However, right-leaning members such as Lin Hsien-tang, who were more cooperative with the Japanese, formed the Taiwanese Alliance for Home Rule, and the organization survived until WW2.[77]

Assimilation movement

[edit]The "early years" of Japanese administration on Taiwan typically refers to the period between the Japanese forces' first landing in May 1895 and the Tapani Incident of 1915, which marked the high point of armed resistance. During this period, popular resistance to Japanese rule was high, and the world questioned whether a non-Western nation such as Japan could effectively govern a colony of its own. An 1897 session of the Japanese Diet debated whether to sell Taiwan to France.[78] In 1898, the Meiji government of Japan appointed Count Kodama Gentarō as the fourth Governor-General, with the talented civilian politician Gotō Shinpei as his Chief of Home Affairs, establishing the carrot and stick approach towards governance that would continue for several years.[41]

Gotō Shinpei reformed the policing system, and he sought to co-opt existing traditions to expand Japanese power. Out of the Qing baojia system, he crafted the Hoko system of community control. The Hoko system eventually became the primary method by which the Japanese authorities went about all sorts of tasks from tax collecting, to opium smoking abatement, to keeping tabs on the population. Under the Hoko system, every community was broken down into Ko, groups of ten neighboring households. When a person was convicted of a serious crime, the person's entire Ko would be fined. The system only became more effective as it was integrated with the local police.[79] Under Gotō, police stations were established in every part of the island. Rural police stations took on extra duties with those in the aboriginal regions operating schools known as "savage children's educational institutes" to assimilate aboriginal children into Japanese culture. The local police station also controlled the rifles which aboriginal men relied upon for hunting as well as operated small barter stations which created small captive economies.[79]

In 1914, Itagaki Taisuke briefly led a Taiwan assimilation movement as a response to appeals from influential Taiwanese spokesmen such as the Wufeng Lin family and Lin Hsien-t'ang and his cousin. Wealthy Taiwanese made donations to the movement. In December 1914, Itagaki formally inaugurated the Taiwan Dōkakai, an assimilation society. Within a week, over 3,000 Taiwanese and 45 Japanese residents joined the society. After Itagaki left later that month, leaders of the society were arrested and its Taiwanese members detained or harassed. In January 1915, the Taiwan Dōkakai was disbanded.[80]

Japanese colonial policy sought to strictly segregate the Japanese and Taiwanese population until 1922.[81] Taiwanese students who moved to Japan for their studies were able to associate more freely with Japanese and took to Japanese ways more readily than their island counterparts. However full assimilation was rare. Even acculturated Taiwanese seem to have become more aware of their distinctiveness and island background while living in Japan.[82]

An attempt to fully Japanize the Taiwanese people was made during the kōminka period (1937–45). The reasoning was that only as fully assimilated subjects could Taiwan's inhabitants fully commit to Japan's war and national aspirations.[83] The kōminka movement was generally unsuccessful and few Taiwanese became "true Japanese" due to the short time period and large population. In terms of acculturation under controlled circumstances, it can be considered relatively effective.[84]

Policies for indigenous peoples

[edit]Status

[edit]The Japanese administration followed the Qing classification of indigenous into acculturated (shufan), semi-acculturated (huafan), and non-acculturated aborigines (shengfan). Acculturated indigenous were treated the same as Chinese people and lost their aboriginal status. Han Chinese and shufan were both treated as natives of Taiwan by the Japanese. Below them were the semi-acculturated and non-acculturated "barbarians" who lived outside normal administrative units and upon whom government laws did not apply.[85] According to the Sōtokufu (Office of the Governor-General), although the mountain aborigines were technically humans in biological and social terms, they were animals under international law.[86]

Land rights

[edit]The Sōtokufu claimed all unreclaimed and forest land in Taiwan as government property.[87] New use of forest land was forbidden. In October 1895, the government declared that these areas belonged to the government unless claimants could provide hard documentation or evidence of ownership. No investigation into the validity of titles or survey of land were conducted until 1911. The Japanese authority denied the rights of indigenous to their property, land, and anything on the land. Although the Japanese government did not control indigenous land directly prior to military occupation, the Han and acculturated indigenous were forbidden from any contractual relationships with indigenous.[88] The indigenous were living on government land but did not submit to government authority, and as they did not have political organization, they could not enjoy property ownership.[86] The acculturated indigenous also lost their rent holder rights under the new property laws, although they were able to sell them. Some reportedly welcomed the sale of rent rights because they had difficulty collecting rent.[89]

In practice, the early years of Japanese rule were spent fighting mostly Chinese insurgents and the government took on a more conciliatory approach to the indigenous. Starting in 1903, the government implemented stricter and more coercive policies. It expanded the guard lines, previously the settler-aboriginal boundary, to restrict the indigenous' living space. By 1904 the guard lines had increased by 80 km from the end of Qing rule. Sakuma Samata launched a five-year plan for aboriginal management, which saw attacks against the indigenous and landmines and electrified fences used to force them into submission. Electrified fences were no longer necessary by 1924 due to the overwhelming government advantage.[90]

After Japan subjugated the mountain indigenous, a small portion of land was set aside for indigenous use. From 1919 to 1934, indigenous were relocated to areas that would not impede forest development. At first, they were given a small compensation for land use, but this was discontinued later on, and the indigenous were forced to relinquish all claims to their land. In 1928, it was decided that each indigenous would be allotted three hectares of reserve land. Some of the allotted land was taken for forest enterprise when it was discovered that the indigenous population was bigger than the estimated 80,000. The size of the allotted land was reduced but allotments were not adhered to anyway. In 1930, the government relocated indigenous to the foothills and invested in agricultural infrastructure to turn them into subsistence farmers. They were given less than half the originally promised land,[91] amounting to one-eighth of their ancestral lands.[92]

Indigenous peoples resistance

[edit]Indigenous resistance to the heavy-handed Japanese policies of acculturation and pacification lasted up until the early 1930s.[55] By 1903, indigenous rebellions had resulted in the deaths of 1,900 Japanese in 1,132 incidents.[57] In 1911 a large military force invaded Taiwan's mountainous areas to gain access to timber resources. By 1915, many indigenous villages had been destroyed. The Atayal and Bunun resisted the hardest against colonization.[93] The Bunun and Atayal were described as the "most ferocious" indigenous peoples, and police stations were targeted by indigenous in intermittent assaults.[94]

The Bunun under Chief Raho Ari engaged in guerrilla warfare against the Japanese for twenty years. Raho Ari's revolt, called the Taifun Incident was sparked when the Japanese implemented a gun control policy in 1914 against the indigenous peoples in which their rifles were impounded in police stations when hunting expeditions were over. The revolt began at Taifun when a police platoon was slaughtered by Raho Ari's clan in 1915. A settlement holding 266 people called Tamaho was created by Raho Ari and his followers near the source of the Rōnō River and attracted more Bunun rebels to their cause. Raho Ari and his followers captured bullets and guns and slew Japanese in repeated hit and run raids against Japanese police stations by infiltrating over the Japanese "guardline" of electrified fences and police stations as they pleased.[95] As a result, head hunting and assaults on police stations by indigenous still continued after that year.[96][97] In one of Taiwan's southern towns nearly 5,000 to 6,000 were slaughtered by Japanese in 1915.[98]

As resistance to the long-term oppression by the Japanese government, many Taivoan people from Kōsen led the first local rebellion against Japan in July 1915, called the Jiasian Incident (Japanese: 甲仙埔事件, Hepburn: Kōsenpo jiken). This was followed by a wider rebellion from Tamai in Tainan to Kōsen in Takao in August 1915, known as the Seirai-an Incident (Japanese: 西来庵事件, Hepburn: Seirai-an jiken) in which more than 1,400 local people died or were killed by the Japanese government. Twenty-two years later, the Taivoan people struggled to carry on another rebellion; since most of the indigenous people were from Kobayashi, the resistance taking place in 1937 was named the Kobayashi Incident (Japanese: 小林事件, Hepburn: Kobayashi jiken).[99] Between 1921 and 1929 indigenous raids died down, but a major revival and surge in indigenous armed resistance erupted from 1930 to 1933 for four years during which the Musha incident occurred and Bunun carried out raids, after which armed conflict again died down.[100] The 1930 "New Flora and Silva, Volume 2" said of the mountain indigenous that "the majority of them live in a state of war against Japanese authority".[101]

The last major indigenous rebellion, the Musha Incident, occurred on 27 October 1930 when the Seediq people, angry over their treatment while laboring in camphor extraction, launched the last headhunting party. Groups of Seediq warriors led by Mona Rudao attacked policed stations and the Musha Public School. Approximately 350 students, 134 Japanese, and 2 Han Chinese dressed in Japanese garbs were killed in the attack. The uprising was crushed by 2,000–3,000 Japanese troops and indigenous auxiliaries with the help of poison gas. The armed conflict ended in December when the Seediq leaders committed suicide. According to Japanese colonial records, 564 Seediq warriors surrendered and 644 were killed or committed suicide.[102] [103] The incident caused the government to take a more conciliatory stance towards the indigenous, and during World War 2, the government tried to assimilate them as loyal subjects.[90] According to a 1933-year book, wounded people in the war against the indigenous numbered around 4,160, with 4,422 civilians dead and 2,660 military personnel killed.[104] According to a 1935 report, 7,081 Japanese were killed in the armed struggle from 1896 to 1933 while the Japanese confiscated 29,772 Aboriginal guns by 1933.[105]

Japanization

[edit]

As Japan embarked on full-scale war with China in 1937, it implemented the "kōminka" imperial Japanization project to instill the "Japanese Spirit" in Taiwanese residents, and ensure the Taiwanese would remain imperial subjects (kōmin) of the Japanese Emperor rather than support a Chinese victory. The goal was to make sure the Taiwanese people did not develop a sense of "their national identity, pride, culture, language, religion, and customs".[106] To this end, the cooperation of the Taiwanese would be essential, and the Taiwanese would have to be fully assimilated as members of Japanese society. As a result, earlier social movements were banned and the Colonial Government devoted its full efforts to the "Kōminka movement" (皇民化運動, kōminka undō), aimed at fully Japanizing Taiwanese society.[41] Although the stated goal was to assimilate the Taiwanese, in practice the Kōminka hōkōkai organization that formed segregated the Japanese into their own separate block units, despite co-opting Taiwanese leaders.[107] The organization was responsible for increasing war propaganda, donation drives, and regimenting Taiwanese life during the war.[108]

As part of the kōminka policies, Chinese language sections in newspapers and Classical Chinese in the school curriculum were removed in April 1937.[83] China and Taiwan's history were also erased from the educational curriculum.[106] Chinese language use was discouraged, which reportedly increased the percentage of Japanese speakers among the Taiwanese, but the effectiveness of this policy is uncertain. Even some members of model "national language" families from well-educated Taiwanese households failed to learn Japanese to a conversational level. A name-changing campaign was launched in 1940 to replace Chinese names with Japanese ones. Seven percent of the Taiwanese had done so by the end of the war.[83] Characteristics of Taiwanese culture considered "un-Japanese" or undesirable were to be replaced with Japanese ones. Taiwanese opera, puppet plays, fireworks, and burning gold and silver paper foil at temples were banned. Chinese clothing, betel-nut chewing, and noisiness were discouraged in public. The Taiwanese were encouraged to pray at Shinto shrines and expected to have domestic altars to worship paper amulets sent from Japan. Some officials were ordered to remove religious idols and artifacts from native places of worship.[109] Funerals were supposed to be conducted in the modern "Japanese-style" way but the meaning of this was ambiguous.[110]

World War II

[edit]

War

[edit]As Japan embarked on full-scale war with China in 1937, it expanded Taiwan's industrial capacity to manufacture war material. By 1939, industrial production had exceeded agricultural production in Taiwan. The Imperial Japanese Navy operated heavily out of Taiwan. The "South Strike Group" was based out of the Taihoku Imperial University (now National Taiwan University) in Taiwan. Taiwan was used as a launchpad for the invasion of Guangdong in late 1938 and for the occupation of Hainan in February 1939. A joint planning and logistical center was established in Taiwan to assist Japan's southward advance after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.[112] Taiwan served as a base for Japanese naval and air attacks on the island Luzon until the surrender of the Philippines in May 1942. It also served as a rear staging ground for further attacks on Myanmar. As the war turned against Japan in 1943, Taiwan suffered due to Allied submarine attacks on Japanese shipping, and the Japanese administration prepared to be cut off from Japan. In the latter part of 1944, Taiwan's industries, ports, and military facilities were bombed in U.S. air raids.[113] By the end of the war in 1945, industrial and agricultural output had dropped far below prewar levels, with agricultural output 49% of 1937 levels and industrial output down by 33%. Coal production dropped from 200,000 metric tons to 15,000 metric tons.[114] An estimated 16,000–30,000 civilians died from the bombing.[115] By 1945, Taiwan was isolated from Japan and its government prepared to defend against an expected invasion.[113]

During WWII, the Japanese authorities maintained prisoner of war camps in Taiwan. Allied prisoners of war (POW) were used as forced labor in camps throughout Taiwan with the camp serving the copper mines at Kinkaseki being especially heinous.[116] Of the 430 Allied POW deaths across all fourteen Japanese POW camps on Taiwan, the majority occurred at Kinkaseki.[117]

Military service

[edit]Starting in July 1937, Taiwanese began to play a role on the battlefield, initially in noncombatant positions. Taiwanese people were not recruited for combat until late in the war. In 1942, the Special Volunteer System was implemented, allowing even aborigines to be recruited as part of the Takasago Volunteers. From 1937 to 1945, over 207,000 Taiwanese were employed by the Japanese military. Roughly 50,000 went missing in action or died, another 2,000 were disabled, 21 were executed for war crimes, and 147 were sentenced to imprisonment for two or three years.[118]

Some Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers claim they were coerced and did not choose to join the army. Accounts range from having no way to refuse recruitment, to being incentivized by the salary, to being told that the "nation and emperor needed us."[119] In one account, a man named Chen Chunqing said he was motivated by his desire to fight the British and Americans but became disillusioned after being sent to China and tried to defect, although the effort was fruitless.[120]

Racial discrimination was commonplace despite rare occasions of camaraderie. Some experienced greater equality during their time in the military. One Taiwanese serviceman recalled being called "chankoro" (Qing slave[39]) by a Japanese soldier.[120] Some of the Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers were ambivalent about Japan's defeat and could not imagine what liberation from Japan would look like. One person recalled surrender leaflets dropped by U.S. planes stating that Taiwan would return to China and recalling that his grandfather had once told him that he was Chinese.[121]

After Japan's surrender, the Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers were abandoned by Japan and no transportation back to Taiwan or Japan was provided. Many of them faced difficulties in mainland China, Taiwan, and Japan due to anti-rightist and anti-communist campaigns in addition to accusations of taking part in the February 28 incident. In Japan they were faced with ambivalence. An organization of Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers tried to get the Japanese government to pay their unpaid wages several decades later. They failed.[122]

Comfort women

[edit]Between 1,000 and 2,000 Taiwanese women were part of the comfort women system. Indigenous women served Japanese military personnel in the mountainous region of Taiwan. They were first recruited as housecleaning and laundry workers for soldiers, then they were coerced into providing sex. They were gang-raped and served as comfort women in the evening hours. Han Taiwanese women from low income families were also part of the comfort women system. Some were pressured into it by financial reasons while others were sold by their families.[123][124] However some women from well to do families also ended up as comfort women.[125] More than half of the young women were minors with some as young as 14. Very few women who were sent overseas understood what the true purpose of their journey was.[123] Some of the women believed they would be serving as nurses in the Japanese military prior to becoming comfort women. Taiwanese women were told to provide sexual services to the Japanese military "in the name of patriotism to the country."[125] By 1940, brothels were set up in Taiwan to service Japanese males.[123]

End of Japanese rule

[edit]In 1942, after the United States entered the war against Japan and on the side of China, the Chinese government under the KMT renounced all treaties signed with Japan before that date and made Taiwan's return to China (as with Manchuria, ruled as the Japanese wartime puppet state of "Manchukuo") one of the wartime objectives. In the Cairo Declaration of 1943, the Allied Powers declared the return of Taiwan (including the Pescadores) to the Republic of China as one of several Allied demands. The Cairo Declaration was never signed or ratified and is not legally binding. In 1945, Japan unconditionally surrendered with the signing of the instrument of surrender and ended its rule in Taiwan as the territory was put under the administrative control of the Republic of China government in 1945 by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration.[126][127] The Office of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers ordered Japanese forces in China and Taiwan to surrender to Chiang Kai-shek, who would act as the representative of the Allied Powers for accepting surrender in Taiwan. On 25 October 1945, Governor-General Rikichi Andō handed over the administration of Taiwan and the Penghu islands to the head of the Taiwan Investigation Commission, Chen Yi.[128][129] On 26 October, the government of the Republic of China declared that Taiwan had become a province of China.[130] The Allied Powers, on the other hand, did not recognize the unilateral declaration of annexation of Taiwan made by the government of the Republic of China because a peace treaty between the Allied Powers and Japan had not been concluded.[131]

After Japan's surrender, most of Taiwan's approximately 300,000 Japanese residents were expelled.[132]

Administration

[edit]

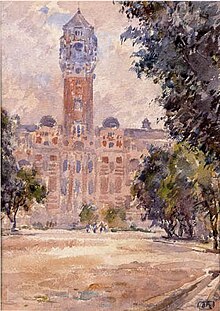

As the highest colonial authority in Taiwan during the period of Japanese rule, the Government-General of Taiwan was headed by a Governor-General of Taiwan appointed by Tōkyō. Power was highly centralized with the Governor-General wielding supreme executive, legislative, and judicial power, effectively making the government a dictatorship.[41]

In its earliest incarnation, the Colonial Government was composed of three bureaus: Home Affairs, Army, and Navy. The Home Affairs Bureau was further divided into four offices: Internal Affairs, Agriculture, Finance, and Education. The Army and Navy bureaus were merged to form a single Military Affairs Bureau in 1896. Following reforms in 1898, 1901, and 1919 the Home Affairs Bureau gained three more offices: General Affairs, Judicial, and Communications. This configuration would continue until the end of colonial rule. The Japanese colonial government was responsible for building harbors and hospitals as well as constructing infrastructure like railroads and roads. By 1935 the Japanese expanded the roads by 4,456 kilometers, in comparison with the 164 kilometers that existed before the Japanese occupation. The Japanese government invested a lot of money in the sanitation system of the island. These campaigns against rats and unclean water supplies contributed to a decrease of diseases such as cholera and malaria.[133]

Economy

[edit]

The Japanese colonial government introduced to Taiwan a unified system of weights and measures, a centralized bank, education facilities to increase skilled labor, farmers' associations, and other institutions. An island wide system of transportation and communications as well as facilities for travel between Japan and Taiwan were developed. Construction of large scale irrigation facilities and power plants followed. Agricultural development was the primary emphasis of Japanese colonization in Taiwan. The objective was for Taiwan to provide Japan with food and raw materials. Fertilizer and production facilities were imported from Japan. Industrial farming, electric power, chemical industries, aluminum, steel, machinery, and shipbuilding facilities were set up. Textile and paper industries were developed near the end of Japanese rule for self-sufficiency. By the 1920s modern infrastructure and amenities had become widespread, although they remained under strict government control, and Japan was managing Taiwan as a model colony. All modern and large enterprises were owned by the Japanese.[134][135]

Shortly after the cession of Taiwan to Japanese rule in September 1895, an Ōsaka bank opened a small office in Kīrun. By June of the following year the Governor-General had granted permission for the bank to establish the first Western-style banking system in Taiwan. In March 1897, the Japanese Diet passed the "Taiwan Bank Act", establishing the Bank of Taiwan (台湾銀行, Taiwan ginkō), which began operations in 1899. In addition to normal banking duties, the Bank would also be responsible for minting the currency used in Taiwan throughout Japanese rule. The function of central bank was fulfilled by the Bank of Taiwan.[136] The Taiwan Agricultural Research institute (TARI) was founded in 1895 by the Japanese colonial powers.[137]

Губернатора Шипи Гото В соответствии с правилом многие крупные проекты общественных работ были завершены. Тайваньская железнодорожная система, соединяющая юг и север, и модернизации портов Кирун и Такао, была завершена для облегчения транспортировки и доставки сырья и сельскохозяйственных продуктов. [ 138 ] Экспорт увеличился в четыре раза. Пятьдесят пять процентов сельскохозяйственных земель были покрыты ирригационными системами, поддерживаемыми плотиной. Производство продуктов питания увеличилось в четыре раза, а производство сахарного тростника увеличилось в 15 раз в период с 1895 по 1925 год, и Тайвань стал крупной пищевой корзиной, обслуживающей промышленную экономику Японии. Система здравоохранения была широко установлена, и инфекционные заболевания были почти полностью уничтожены. Средняя продолжительность жизни для жителя тайваньского языка станет 60 лет к 1945 году. [ 139 ] Они построили бетонные плотины , водохранилища и акведуки , которые образуют обширную систему орошения, такую как ирригация Чианна . Уходородные земли для производства риса и сахарного тростника увеличились более чем на 74% и 30% соответственно. Они также создали ассоциации фермеров. Сельскохозяйственный сектор доминировал в экономике Тайваня в то время. В 1904 году в качестве сельскохозяйственных земель использовались 23% площади Тайваня. [ 140 ] К 1939 году Тайвань был третьим по величине экспортером бананов и консервированных ананасов в мире. [ 141 ]

До японского колониального периода большая часть риса, выращенного на Тайване, была давнозернистым рисом индика; Японцы представили короткозернированную Japonica, которая быстро изменила как сельское хозяйство, так и схемы питания тайваньского языка. [ 142 ] Коммерческое производство кофе на Тайване началось в японский колониальный период. [ 143 ] Японцы разработали отрасль для кормления экспортного рынка. [ 144 ] Производство достигло пика в 1941 году после введения кофейных растений Arabica. Производство снизилось вскоре после этого в результате Второй мировой войны. [ 143 ] Выращивание какао на Тайване началось в японский период, но поддержка закончилась после Второй мировой войны. [ 145 ]

Экономика Тайваня во время японского правления была по большей части, колониальной экономикой. А именно, человеческие и природные ресурсы Тайваня использовались для помощи в развитии Японии, политики, которая началась при генерал-губернаторе Кодаме и достигла своего пика в 1943 году, в середине Второй мировой войны . С 1900 по 1920 год в экономике Тайваня доминировала сахарная промышленность, в то время как с 1920 по 1930 год Райс был основным экспортом. В течение этих двух периодов основной экономической политикой колониального правительства была «промышленность для Японии, сельское хозяйство для Тайваня». После 1930 года, из -за нужд войны, колониальное правительство начало проводить политику индустриализации. [ 41 ]

После 1939 года война в Китае и в конечном итоге другие места начали оказывать вредное воздействие на сельскохозяйственное производство Тайваня, поскольку военный конфликт взял на себя все ресурсы Японии. Тайваньский реальный ВВП на душу населения достиг пика в 1942 году на 1522 долл. США и снизился до 693 долл. США к 1944 году. [ 146 ] Бомбардировка на войне Тайваня нанесла значительный ущерб многим городам и гавану на Тайване. Железные дороги, заводы и другие производственные мощности были либо сильно повреждены, либо разрушены. [ 147 ] Только 40 процентов железных дорог были пригодны для использования, а более 200 фабрик были бомбили, большинство из которых содержали жизненно важную отрасль Тайваня. Из четырех электрических электростанций Тайваня три были уничтожены. [ 148 ] Потеря крупных промышленных объектов оценивается в 506 миллионов долларов, или 42 процента постоянных производственных активов. [ 146 ] Повреждение сельского хозяйства было относительно сдержано в сравнении, но большинство событий остановились, и ирригационные помещения были отброшены. Поскольку все ключевые должности были заняты японцами, их отъезд привел к потере 20 000 техников и 10 000 профессиональных работников, оставив Тайвань с серьезным отсутствием обученного персонала. Инфляция была распространена в результате войны и позже ухудшилась из -за экономической интеграции с Китаем, потому что Китай также испытывал высокую инфляцию. [ 147 ] Тайваньская промышленная добыча, восстановившаяся до 38 процентов своего уровня 1937 года к 1947 году, и восстановление в довоенных стандартах жизни не происходило до 1960-х годов. [ 149 ]

Образование

[ редактировать ]система элементарных общих школ ( kōgakkō Была введена ). Эти начальные школы преподавали японский язык и культуру, классическую китайский, конфуцианскую этику и практические предметы, такие как наука. [ 150 ] Классический китайский был включен в рамках усилий по победе над тайваньскими родителями высшего класса, но акцент делался на японском языке и этике. [ 151 ] Эти государственные школы обслуживали небольшой процент населения тайваньского школьного возраста, в то время как японские дети посещали свои отдельные начальные школы ( Shōgakkō ). Немногие тайваньцы посещали среднюю школу или смогли поступить в медицинский колледж. Из -за ограниченного доступа к государственным учебным заведениям, сегмент населения продолжал регистрироваться в частных школах, аналогичных эре Цин. Большинство мальчиков посещали китайские школы ( Shobo ), в то время как меньшая часть мужчин и женщин прошла обучение в религиозных школах (доминиканских и пресвитерианских). Универсальное образование считалось нежелательным в первые годы с тех пор, как ассимиляция Хань Тайваняна казалась маловероятной. Начальное образование предлагало как моральное, так и научное образование тем, кто мог себе это позволить. Надежда заключалась в том, что благодаря селективному образованию самых ярких тайваньцев появится новое поколение тайваньских лидеров, реагирующих на реформу и модернизацию. [ 150 ]

Многие из класса Джентри испытывали смешанные чувства по поводу модернизации и культурных изменений, особенно в то же время, продвигаемое государственным образованием. Джентри был настоятельно рекомендован продвигать «новое обучение», слияние неоконфуцианства и образования в стиле Мэйдзи, однако те, которые инвестировали в стиль образования Китая, казалось, обижены на предлагаемое слияние. [ 152 ] Молодое поколение тайваньцев, более подверженное модернизации и изменениям в общественных делах в 1910 -х годах. Многие были обеспокоены получением современных образовательных учреждений и дискриминации, с которой они столкнулись при получении мест в немногих государственных школах. Местные лидеры в Тайчунг начали проводить кампанию за инаугурацию средней школы Тайчу, но столкнулись с оппозицией со стороны японских чиновников, не желающих разрешить среднюю школу для тайваньских мужчин. [ 153 ]

В 1922 году была введена интегрированная школьная система, в которой общие и начальные школы были открыты как на тайваньском и японском языке, основанными на их опыте на разговорном японском языке. [ 154 ] Начальное образование было разделено между начальными школами для японских носителей и государственных школ для тайваньских носителей. Поскольку немногие тайваньские дети могли свободно говорить по -японски, на практике только детям очень богатых тайваньских семей с тесными связями с японскими поселенцами было разрешено изучать вместе с японскими детьми. [ 155 ] Количество тайваньцев в ранее японских начальных школах было ограничено 10 процентами. [ 151 ] Японские дети также посещали детский сад, во время которого они были отделены от тайваньских детей. В одном случае в тайваньской группе был поставлен японский ребенок, ожидая, что они узнают у нее японцев, но эксперимент потерпел неудачу, а японский ребенок изучил тайваньцев. [ 155 ]

Конкурсная ситуация в Тайване заставила некоторых тайваньцев искать среднее образование и возможности в Японии и Манчукуо , а не на Тайване. [ 151 ] В 1943 году начальное образование стало обязательным, и к следующему году почти три из четырех детей были зачислены в начальную школу. [ 156 ] Тайваньский также учился в Японии. К 1922 году по меньшей мере 2000 Тайваньцев были зачислены в учебные заведения в столичной Японии. Количество увеличилось до 7000 к 1942 году. [ 82 ] К 1944 году в Тайване было 944 начальных школ, общий уровень зачисления в 71,3% для тайваньских детей, 86,4% для детей из числа коренных народов и 99,6% для японских детей на Тайване. В результате показатели зачисления в начальную школу в Тайване были одними из самых высоких в Азии, уступая только самой Японии. [ 41 ]

Демография

[ редактировать ]В рамках акцента на государственный контроль, колониальное правительство выполняло подробные переписи Тайваня каждые пять лет, начиная с 1905 года. Статистика показала темпы роста населения от 0,988 до 2,835% в год в японском правлении. В 1905 году население Тайваня составляло примерно 3 миллиона человек. [ 157 ] К 1940 году население выросло до 5,87 миллиона, а к концу Второй мировой войны в 1946 году это насчитывало 6,09 миллиона. По состоянию на 1938 год в Тайване жили около 309 000 человек японского происхождения. [ 158 ]

Коренные народы

[ редактировать ]Согласно переписи 1905 года, в коренные народы были более 45 000 рав. [ Цитация необходима ] которые были почти полностью ассимилированы в Ханьское китайское общество и 113 000 человек. [ 159 ]

За рубежом китайцы

[ редактировать ]Генеральный консульство Китайской Республики в Тайхоку была дипломатической миссией правительства Китайской Республики (ROC), которая открылась 6 апреля 1931 года, и закрылась в 1945 году после передачи Тайваня в ROC. Даже после того, как Тайвань был уступил Японии династией Цин , к 1920 -м годам он все еще привлек более 20 000 китайских иммигрантов. 17 мая 1930 года Министерство иностранных дел Китая назначило Лин Шао-Нан Генеральным консулом [ 160 ] и Юань Чиа-Та в качестве заместителя генерального консула.

Японские колонисты

[ редактировать ]Японские простые люди начали прибывать на Тайвань в апреле 1896 года. [ 161 ] Японским мигрантам было рекомендовано переехать в Тайвань, потому что это считалось наиболее эффективным способом интеграции Тайваня в японскую империю. Немногие японцы переехали в Тайвань в первые годы колонии из -за плохой инфраструктуры, нестабильности и страха перед болезнями. Позже, когда больше японцев поселились на Тайване, некоторые поселенцы пришли, чтобы рассматривать остров как свою родину, а не как Японию. Была опасения, что японские дети, родившиеся на Тайване, под его тропическим климатом, не смогут понять Японию. В 1910 -х годах начальные школы проводили поездки в Японию, чтобы воспитывать свою японскую идентичность и предотвратить тайвантизацию. Из необходимости японским полицейским было рекомендовано изучить местные варианты Миннана и диалекта Гуандунга Хакки . Были языковые экзамены для сотрудников полиции, чтобы получить пособия и рекламные акции. [ 155 ] К концу 1930 -х годов японцы составили около 5,4 процента от общей численности населения Тайваня, но имели 20–25 процентов от культивируемой земли, которая также имела более высокое качество. Они также владели большинством крупных земельных владений. Правительство Японии помогло им в приобретении земли и принудировало китайские владельцы земли продавать японским предприятиям. Японские сахарные компании имели 8,2 процента пахотных земель. [ 162 ]

В конце Второй мировой войны в Тайване жили почти 350 000 японских гражданских лиц. Они были назначены зарубежными японцами ( никкью ) или зарубежными ryukyuans ( ryūukou ). [ 163 ] Потомство смешанного брака считалось японским, если их тайваньская мать выбрала японское гражданство или если их тайваньский отец не подал заявку на гражданство ROC. [ 164 ] Половина японцев, покинувших Тайвань после 1945 года, родились на Тайване. [ 163 ] Тайваньцы не участвовали в широко распространенных актах мести или стремления к их немедленному удалению, хотя они быстро захватили или пытались занять имущество, которое, по их мнению, была несправедливо получена в предыдущие десятилетия. [ 165 ] Японские активы были собраны, и националистическое правительство сохранило большую часть имущества для правительственного использования в ужасе тайваньцев. [ 166 ] Кража и акты насилия действительно произошли, однако это было связано с давлением политики военного времени. [ 165 ] Чен Йи , который отвечал за Тайвань, удалил японских бюрократов и полицейских из своих постов, что привело к непривычным экономическим трудностям для японских граждан. Их трудности в Тайване также были встречены новостями о трудностях в Японии. Опрос показал, что 180 000 японских гражданских лиц хотели уйти в Японию, в то время как 140 000 хотели остаться. Приказ о депортации японских гражданских лиц был издан в январе 1946 года. [ 167 ] С февраля по май подавляющее большинство японцев покинули Тайвань и прибыли в Японию без особых проблем. Зарубежным рюкюанам было приказано помочь в процессе депортации, строя лагеря и работают в качестве носильщиков для зарубежных японцев. Каждому человеку было разрешено уйти с двумя кусочками багажа и 1000 иен. [ 168 ] Японцы и рюкюанцы, оставшиеся на Тайване, к концу апреля сделали это по указанию правительства. Их дети посещали японские школы, чтобы подготовиться к жизни в Японии. [ 169 ]

Социальная политика

[ редактировать ]

"Три порока"

[ редактировать ]«Три порока» ( 三大陋習 , Santai Rōshū ), рассматриваемые Управлением генерал-губернатора как архаичным и нездоровым, были использованием опия , переплета ног и ношения очередей . [ 170 ] [ 171 ]

В 1921 году тайваньская народная партия обвинила колониальные власти перед Лигой наций в соучастии в зависимости от более чем 40 000 человек, при этом получая прибыль от продаж опия. Чтобы избежать противоречий, колониальное правительство выпустило новый тайваньский опиум 28 декабря и связанные сведения о новой политике 8 января следующего года. Согласно новым законам, количество выданных разрешений на опия было уменьшено, реабилитационная клиника была открыта на Тайхоку , а также была запущена согласованная антинаторная кампания. [ 172 ] Несмотря на директиву, правительство оставалось связанным с торговлей опиумом до июня 1945 года. [ 173 ]

Литература

[ редактировать ]

Тайваньские студенты, обучающиеся в Tōkyō, сначала реструктурировали Общество Просвещения в 1918 году, позже переименовали новое народное общество (新民会, Shinminkai ) после 1920 года. Это было проявлением для различных предстоящих политических и социальных движений на Тайване. Многие новые публикации, такие как тайваньская литература и искусство (1934) и новая тайваньская литература (1935), начались вскоре после этого. Они привели к появлению народного движения в обществе в целом, когда современное литературное движение оторвалось от классических форм древней поэзии. В 1915 году эта группа людей, возглавляемая Рин Кендо , внесла первоначальный и большой финансовый вклад, чтобы создать первую среднюю школу в Тайчу для аборигенов и тайваньцев. [ 174 ]

Литературные движения не исчезали, даже когда они находились под цензурой со стороны колониального правительства. В начале 1930 -х годов известные дебаты о тайваньском сельском языке развернулись формально. Это событие оказало многочисленные последствия для тайваньской литературы, языка и расового сознания. In 1930, Taiwanese-Japanese resident Kō Sekiki (黄 石輝, Huáng Shíhuī ) started the debate on rural literature in Tōkyō. Он выступал за то, чтобы тайваньская литература была о Тайване, оказывает влияние на широкую аудиторию и использовать тайваньский Хоккиен . В 1931 году Каку Шусеи (郭秋生, Гуу -цюшунг ), житель Тайхоку, известно, поддержал точку зрения Кес. Каку начал дискуссию на тайваньском сельском языке, которая выступала за литературу, опубликованную на тайваньском языке. Это было сразу поддержано Рай Ва (頼 和, Lài Hé ), который считается отцом тайваньской литературы. После этого спор о том, должна ли литература Тайваня использовать тайваньцев или китайцев , и стал ли предмет касаться Тайвань, стал центром нового тайваньского литературного движения. Однако из -за предстоящей войны и распространенного японского культурного образования эти дебаты не могут развиваться дальше. Они, наконец, потеряли тягу в рамках политики Японии, установленной правительством. [ 175 ]

Тайваньская литература в основном сосредоточена на тайваньском духе и сущности тайваньской культуры. Люди в литературе и искусстве начали думать о проблемах тайваньской культуры и пытались создать культуру, которая действительно принадлежала Тайвану. Значительное культурное движение на протяжении всего колониального периода возглавлялось молодым поколением, которые были высоко образованы в формальных японских школах. Образование сыграло такую ключевую роль в поддержке правительства и в большей степени, развивая экономический рост Тайваня. [ Цитация необходима ] Однако, несмотря на основные усилия правительства в области начального образования и нормального образования, было ограниченное количество средних школ, примерно 3 по всей стране, поэтому предпочтительные варианты для выпускников уезжали в Tōkyō или другие города, чтобы получить образование. Иностранное образование молодых студентов проводилось исключительно самостоятельной мотивацией и поддержкой отдельных лиц со стороны семьи. Образование за рубежом получило свою популярность, особенно от префектуры Тайчу , с стремлением приобретать навыки и знания цивилизации даже при положении ни колониального правительства, ни общества, не способного гарантировать их светлое будущее; без плана работы для этих образованных людей после их возвращения. [ 176 ]

Искусство

[ редактировать ]Искусство было впервые институционализировано на Тайване в японский колониальный период с созданием государственных школ, посвященных изобразительным искусствам. Японцы ввели нефтяные и акварельные картины на Тайване, и их японские коллеги находились под сильным влиянием тайваньских художников. Как это было типично для колониальных правителей, японцы не создавали высших учебных заведений для художественного образования на Тайване, все студенты, желающие получить высшее образование в области искусства, должны были поехать в Японию, чтобы сделать это. [ 177 ]

В 1920 -х годах новое культурное движение повлияло на поколение художников, которые использовали искусство как способ продемонстрировать свое равенство или даже их превосходство над своими колонизаторами. [ 178 ]

Изменение руководящего полномочия

[ редактировать ]

Япония сдалась союзникам 14 августа 1945 года. 29 августа Чианг Кай-Шек назначил Чэнь Йи исполнительным директором провинции Тайвань и объявил о создании Управления исполнительного директора провинции Тайвань и Тайваньского гарнизона 1 сентября, 1 сентября, 1 сентября, 1 сентября, 1 сентября. с Чен Йи также в качестве командира последнего тела. После нескольких дней подготовки к Тайхоку переехала на Тайхоку, когда в Тайване жили больше сотрудников из Шанхая и Чунцина . [ 158 ] Между японской капитуляцией Тайваня в 1945 и 25 апреля 1946 года, Китайская Республика, войска, репатриировали 90% японцев, живущих на Тайване в Японию. [ 179 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- История Тайваня

- Япония -Тайваньские отношения

- Японские иммигрантские деревни на Тайване

- Японская опиумная политика на Тайване (1895–1945)

- Политические подразделения Тайваня (1895–1945)

- Зная Тайвань

- Остатки тюремных стен Тайбэя

- Тайвань под правилом Цин

- Тайваньское сопротивление японскому вторжению (1895)

Примечания

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Pastreich, Emanuel (июль 2003 г.). «Суверенитет, богатство, культура и технологии: материковый Китай и Тайвань, сражаются с параметрами« национального государства »в 21 -м веке» . Историческая реальная онлайн . Программа по борьбе с вооружением, разоружением и международной безопасностью, Университет Иллинойса в Урбана-Шампейн. OCLC 859917872 . Архивировано с оригинала 14 апреля 2018 года . Получено 22 декабря 2014 года .

- ^ Pastreich, Emanuel (июль 2003 г.). «Суверенитет, богатство, культура и технологии: материковый Китай и Тайвань, сражаются с параметрами« национального государства »в 21 -м веке» . Историческая реальная онлайн . Программа по борьбе с вооружением, разоружением и международной безопасностью, Университет Иллинойса в Урбана-Шампейн. OCLC 859917872 . Архивировано с оригинала 14 апреля 2018 года . Получено 22 декабря 2014 года .

- ^ Экхардт, Джаппе; Клык, Дженнифер; Ли, Келли (4 марта 2017 г.). «Тайваньская корпорация табака и спиртных напитков:« присоединиться к рядам глобальных компаний » . Глобальное общественное здравоохранение . 12 (3): 335–350. doi : 10.1080/17441692.2016.1273366 . ISSN 1744-1692 . PMC 5553428 . PMID 28139964 .

- ^ Чен, С. Питер. «Сдача Японии» . База данных Второй мировой войны . Lava Development, LLC. Архивировано с оригинала 2 января 2016 года . Получено 22 декабря 2014 года .

- ^ « На китайском языке (Тайвань)). Тайбэй: Центральное информационное агентство: 27 января 2014 года. Архивировано из оригинала на разделе 25, 2019.

- ^ Хециан ( г. 2013 5 ) . сентября Сюй

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный 4 мая 2012 Чжоу Ванхан ( . г. ) , 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в чиновники . Тайваньские » «

- ^ , японский экономический Shimbun . оригинала 23 июля 2013 года. Архивировано из « Тайвань 23 апреля 2015 года.

- ^ «Японский колониальный век в колониальном возрасте? Замечания? » Тайване . на Учебники

- ^ использовать термин« японская . «Будущие официальные оккупация документы будут »

- ^ официальные документы используют« . оккупацию Японскую « Vermarkets » институты ? Правительственные :

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Книга ограничена« японской оккупацией »? Политический суд: Unefrened Politics Free Electronic News » . News.ltn.com.tw. 30 октября 2016 г. Архивировано с оригинала 6 марта 2019 года.

- ^ Чжан Ячхон (12 сентября 2013 г.) . « (В торговых китайцах). Благословение Земли. Архивировано из оригинала 17 декабря 2013 года. Получено 10 декабря 2013 года . Уважение соответствует национальному стилю нашей страны. ... В 1952 году Китай и Япония подписали «Мирный договор о Китае». 9 -го. Хотя японское колониальное правление Тайваня является фактом, согласно договору, и Китай, и Япония согласились с «Магуанским договором» как недействительным. Основываясь на уважении договора и национальной позиции, правильное использование так называемого «японского правила» должно быть «колониальным правлением в японский период». ... Японское правительство приняло «Магуанский договор» в «Китайском договоре о мире», подписанном нашей страной. Давайте посмотрим на историю. Если мы все еще находимся в законности колониального правления в Японии, использование «японского правления» эквивалентно клевете на жертву анти -японских мудрецов в то время. Эластичный

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Хуан, Фу-Сан (2005). «Глава 3» . Краткая история Тайваня . ROC Правительственное информационное управление. Архивировано из оригинала 1 августа 2007 года . Получено 18 июля 2006 года .

- ^ Уиллс (2006) .

- ^ Smits, Грегори (2007). «Недавние тенденции в области стипендии по истории отношений Рюкю с Китаем и Японией» (PDF) . В ölschleger, Ганс Дитер (ред.). Теории и методы в японских исследованиях: текущее состояние и будущие события (документы в честь Йозефа Крейнера) . Göttingen: Bonn University Press через V & R Unipress. С. 215–228. ISBN 978-3-89971-355-8 Полем Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 2 марта 2012 года . Получено 4 июля 2023 года .

- ^ Фрей, Генри П., Япония на юг и Австралия, Univ of Hawaii Press, Гонолулу, ç1991. С.34 - «... приказал губернатору Нагасаки, Мурайама Тоан, вторгнуться в Формозу с флотом из тринадцати судов и около 4000 человек. Только ураган сорвал эти усилия и нанесла их раннее возвращение»

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Andrade 2008b .

- ^ Andrade 2008c .

- ^ Вонг 2017 , с. 116

- ^ Barclay 2018 , с. 50

- ^ Barclay 2018 , с. 51-52.

- ^ Barclay 2018 , с. 52

- ^ Barclay 2018 , с. 53–54.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Вонг 2022 , с. 124–126.

- ^ Леунг (1983) , с.

- ^ Вонг 2022 , с. 127–128.

- ^ Zhao, Jiaoing (1994). Современная китайская дипломатическая история [ Дипломатическая история Китая ] (на китайском языке) (1 -е изд.) . 9787810325776 .

- ^ Вонг 2022 , с. 132.

- ^ Вонг 2022 , с. 134–137.

- ^ Вонг 2022 , с. 130.

- ^ Вонг 2022 , с. 137–138.

- ^ Вонг 2022 , с. 141–143.

- ^ Чен, Эдвард I-Te (ноябрь 1977 г.). «Решение Японии приложить Тайвань: исследование дипломатии Ито-Муцу, 1894–95» . Журнал азиатских исследований . 37 (1): 66–67. doi : 10.2307/2053328 . JSTOR 2053328 . S2CID 162461372 .

- ^ Подробный отчет о передаче Тайваня, переведенный с Японской почты , появляется в Дэвидсоне (1903) , с. 293–295

- ^ Рубинштейн 1999 , с. 203.

- ^ Chen (1977) , с. 71–72 утверждает, что ITō и Mutsu хотели, чтобы Япония получила равенство с западными державами. Решение Японии об аннексировании Тайвань не было основано на каком-либо дальнем дизайне для будущей агрессии.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ши 2022 , с. 327.

- ^ Ching, Leo TS (2001). Стать «Японским»: колониальный Тайвань и политика формирования идентичности. Беркли: Университет Калифорнийской прессы. С. 93–95. ISBN 0-520-22553-8 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Хуан, Фу-Сан (2005). «Глава 6: Колонизация и модернизация под японским правлением (1895–1945)» . Краткая история Тайваня . ROC Правительственное информационное управление. Архивировано из оригинала 17 марта 2007 года . Получено 18 июля 2006 года .

- ^ Дэвидсон (1903) , с. 293.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Рубинштейн 1999 , с. 205–206.

- ^ Моррис (2002) , с. 4–18.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Рубинштейн 1999 , с. 207

- ^ Деньги 2006 , с. 95

- ^ Дэвидсон 1903 , с. 561.

- ^ Рубинштейн 1999 , с. 208

- ^ Брукс 2000 , с. 110.

- ^ Доули, Эван. "Тайвань когда -нибудь действительно частью Китая?" Полем thediplomat.com . Дипломат. Архивировано из оригинала 10 июня 2021 года . Получено 10 июня 2021 года .

- ^ Чжан (1998) , с. 515.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Чанг 2003 , с. 56

- ^ «Тайвань - история» . Окна на Азии . Азиатский учебный центр, Мичиганский государственный университет . Архивировано с оригинала 22 декабря 2014 года . Получено 22 декабря 2014 года .

- ^ Рубинштейн 1999 , с. 207–208.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Кац (2005) .

- ^ Чжан (1998) , с. 514.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Цена 2019 , с. 115.

- ^ Сэр Адольф Уильям Уорд ; Джордж Уолтер Протеро ; Сэр Стэнли Мордаунт Конел ; Эрнест Альфред Бенианс (1910). Кембриджская современная история . Макмиллан. С. 573 -.

- ^ Хуан-Вэнь Лай (2015). «Голоса женщины черепахи: многоязычные стратегии сопротивления и ассимиляции на Тайване под японским колониальным правлением» (опубликован PDF = 2007) . п. 113 . Получено 11 ноября 2015 года .

- ^ Меньшие драконы: народы меньшинства Китая . Книги Reaktion. 15 мая 2018 года. ISBN 9781780239521 .

- ^ Место и дух в Тайване: Туди Гонг в рассказах, стратегиях и воспоминаниях о повседневной жизни . Routledge. 29 августа 2003 г. ISBN 9781135790394 .

- ^ Цай 2009 , с. 134.

- ^ Деньги 2000 , с. 113.

- ^ С 1980 , с. 447-448.

- ^ «Правительственность и ее последствия в колониальном Тайване: тематическое исследование инцидента Тапа-Ни» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 24 сентября 2007 года.

- ^ Ши 2022 , с. 329.

- ^ Ши 2022 , с. 330.

- ^ Ши 2022 , с. 330–331.