Leprosy

| Leprosy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hansen's disease (HD)[1] |

| |

| Rash on the chest and abdomen caused by leprosy | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | Decreased ability to feel pain[3] |

| Causes | Mycobacterium leprae or Mycobacterium lepromatosis[4][5] |

| Risk factors | Close contact with a case of leprosy, living in poverty[3][6] |

| Treatment | Multidrug therapy[4] |

| Medication | Rifampicin, dapsone, clofazimine[3] |

| Frequency | 209,000 (2018)[4] |

| Named after | Gerhard Armauer Hansen |

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae or Mycobacterium lepromatosis.[4][7] Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes.[4] This nerve damage may result in a lack of ability to feel pain, which can lead to the loss of parts of a person's extremities from repeated injuries or infection through unnoticed wounds.[3] An infected person may also experience muscle weakness and poor eyesight.[3] Leprosy symptoms may begin within one year, but, for some people, symptoms may take 20 years or more to occur.[4]

Leprosy is spread between people, although extensive contact is necessary.[3][8] Leprosy has a low pathogenicity, and 95% of people who contract M. leprae do not develop the disease.[9] Spread is thought to occur through a cough or contact with fluid from the nose of a person infected by leprosy.[8][9] Genetic factors and immune function play a role in how easily a person catches the disease.[9][10] Leprosy does not spread during pregnancy to the unborn child or through sexual contact.[8] Leprosy occurs more commonly among people living in poverty.[3] There are two main types of the disease – paucibacillary and multibacillary, which differ in the number of bacteria present.[3] A person with paucibacillary disease has five or fewer poorly pigmented, numb skin patches, while a person with multibacillary disease has more than five skin patches.[3] The diagnosis is confirmed by finding acid-fast bacilli in a biopsy of the skin.[3]

Leprosy is curable with multidrug therapy.[4] Treatment of paucibacillary leprosy is with the medications dapsone, rifampicin, and clofazimine for six months.[9] Treatment for multibacillary leprosy uses the same medications for 12 months.[9] A number of other antibiotics may also be used.[3] These treatments are provided free of charge by the World Health Organization.[4]

Leprosy is not highly contagious.[11] People with leprosy can live with their families and go to school and work.[12] In the 1980s, there were 5.2 million cases globally, but by 2020 this decreased to fewer than 200,000.[4][13][14] Most new cases occur in 14 countries, with India accounting for more than half.[3][4] In the 20 years from 1994 to 2014, 16 million people worldwide were cured of leprosy.[4] About 200 cases per year are reported in the United States.[15] Central Florida accounted for 81% of cases in Florida and nearly 1 out of 5 leprosy cases nationwide.[16] Separating people affected by leprosy by placing them in leper colonies still occurs in some areas of India,[17] China,[18] Africa,[11] and Thailand.[19]

Leprosy has affected humanity for thousands of years.[3] The disease takes its name from the Greek word λέπρα (lépra), from λεπίς (lepís; 'scale'), while the term "Hansen's disease" is named after the Norwegian physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen.[3] Leprosy has historically been associated with social stigma, which continues to be a barrier to self-reporting and early treatment.[4] Leprosy is classified as a neglected tropical disease.[20] World Leprosy Day was started in 1954 to draw awareness to those affected by leprosy.[21][4]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Common symptoms present in the different types of leprosy include a runny nose; dry scalp; eye problems; skin lesions; muscle weakness; reddish skin; smooth, shiny, diffuse thickening of facial skin, ear, and hand; loss of sensation in fingers and toes; thickening of peripheral nerves; a flat nose from destruction of nasal cartilages; and changes in phonation and other aspects of speech production.[22] In addition, atrophy of the testes and impotence may occur.[23]

Leprosy can affect people in different ways.[9] The average incubation period is five years.[4] People may begin to notice symptoms within the first year or up to 20 years after infection.[4] The first noticeable sign of leprosy is often the development of pale or pink coloured patches of skin that may be insensitive to temperature or pain.[24] Patches of discolored skin are sometimes accompanied or preceded by nerve problems including numbness or tenderness in the hands or feet.[24][25] Secondary infections (additional bacterial or viral infections) can result in tissue loss, causing fingers and toes to become shortened and deformed, as cartilage is absorbed into the body.[26][27] A person's immune response differs depending on the form of leprosy.[28]

Approximately 30% of people affected with leprosy experience nerve damage.[29] The nerve damage sustained is reversible when treated early, but becomes permanent when appropriate treatment is delayed by several months. Damage to nerves may cause loss of muscle function, leading to paralysis. It may also lead to sensation abnormalities or numbness, which may lead to additional infections, ulcerations, and joint deformities.[29]

-

Paucibacillary leprosy (PB): Pale skin patch with loss of sensation

-

Skin lesions on the thigh of a person with leprosy

-

Hands deformed by leprosy

-

Face mildly deformed by leprosy

-

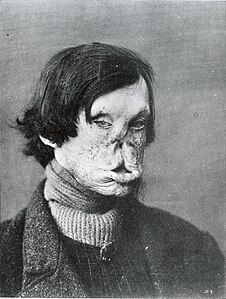

Face severely deformed by leprosy

Cause

[edit]M. leprae and M. lepromatosis

[edit]

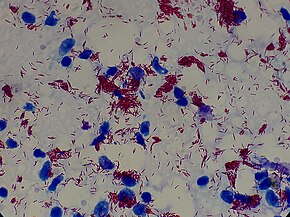

M. leprae and M. lepromatosis are the mycobacteria that cause leprosy.[29] M. lepromatosis is a relatively newly identified mycobacterium isolated from a fatal case of diffuse lepromatous leprosy in 2008.[5][30] M. lepromatosis is indistinguishable clinically from M. leprae.[31]

M. leprae is an intracellular, acid-fast bacterium that is aerobic and rod-shaped.[32] M. leprae is surrounded by the waxy cell envelope coating characteristic of the genus Mycobacterium.[32]

Genetically, M. leprae and M. lepromatosis lack the genes that are necessary for independent growth.[33] M. leprae and M. lepromatosis are obligate intracellular pathogens, and cannot be grown (cultured) in the laboratory.[33] The inability to culture M. leprae and M. lepromatosis creates difficulty definitively identifying the bacterial organism under a strict interpretation of Koch's postulates.[5][33]

While the causative organisms have to date been impossible to culture in vitro, it has been possible to grow them in animals such as mice and armadillos.[34][35]

Naturally occurring infection has been reported in nonhuman primates (including the African chimpanzee, the sooty mangabey, and the cynomolgus macaque), armadillos,[36] and red squirrels.[37] Multilocus sequence typing of the armadillo M. leprae strains suggests that they were of human origin for at most a few hundred years.[38] Thus, it is suspected that armadillos first acquired the organism incidentally from early European explorers of the Americas.[39] This incidental transmission was sustained in the armadillo population, and it may be transmitted back to humans, making leprosy a zoonotic disease (spread between humans and animals).[39]

Red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris), a threatened species in Great Britain, were found to carry leprosy in November 2016.[40] It has been suggested that the trade in red squirrel fur, highly prized in the medieval period and intensively traded, may have been responsible for the leprosy epidemic in medieval Europe.[41] A pre-Norman era skull excavated in Hoxne, Suffolk, in 2017 was found to carry DNA from a strain of Mycobacterium leprae, which closely matched the strain carried by modern red squirrels on Brownsea Island, UK.[41][42]

Risk factors

[edit]The greatest risk factor for developing leprosy is contact with another person infected by leprosy.[4] People who are exposed to a person who has leprosy are 5–8 times more likely to develop leprosy than members of the general population.[6] Leprosy also occurs more commonly among those living in poverty.[3] Not all people who are infected with M. leprae develop symptoms.[43][44]

Conditions that reduce immune function, such as malnutrition, other illnesses, or genetic mutations, may increase the risk of developing leprosy.[6] Infection with HIV does not appear to increase the risk of developing leprosy.[45] Certain genetic factors in the person exposed have been associated with developing lepromatous or tuberculoid leprosy.[46]

Transmission

[edit]Transmission of leprosy occurs during close contact with those who are infected.[4] Transmission of leprosy is through the upper respiratory tract.[9][47] Older research suggested the skin as the main route of transmission, but research has increasingly favored the respiratory route.[48] Transmission occurs through inhalation of bacilli present in upper airway secretion.[49]

Leprosy is not sexually transmitted and is not spread through pregnancy to the unborn child.[4][8] The majority (95%) of people who are exposed to M. leprae do not develop leprosy; casual contact such as shaking hands and sitting next to someone with leprosy does not lead to transmission.[4][50] People are considered non-infectious 72 hours after starting appropriate multi-drug therapy.[51]

Two exit routes of M. leprae from the human body often described are the skin and the nasal mucosa, although their relative importance is not clear. Lepromatous cases show large numbers of organisms deep in the dermis, but whether they reach the skin surface in sufficient numbers is doubtful.[52]

Leprosy may also be transmitted to humans by armadillos, although the mechanism is not fully understood.[8][53][54]

Genetics

[edit]| Name | Locus | OMIM | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPRS1 | 10p13 | 609888 | |

| LPRS2 | 6q25 | 607572 | PARK2, PACRG |

| LPRS3 | 4q32 | 246300 | TLR2 |

| LPRS4 | 6p21.3 | 610988 | LTA |

| LPRS5 | 4p14 | 613223 | TLR1 |

| LPRS6 | 13q14.11 | 613407 |

Not all people who are infected or exposed to M. leprae develop leprosy, and genetic factors are suspected to play a role in susceptibility to an infection.[55] Cases of leprosy often cluster in families and several genetic variants have been identified.[55] In many people who are exposed, the immune system is able to eliminate the leprosy bacteria during the early infection stage before severe symptoms develop.[56] A genetic defect in cell-mediated immunity may cause a person to be susceptible to develop leprosy symptoms after exposure to the bacteria.[57] The region of DNA responsible for this variability is also involved in Parkinson's disease, giving rise to current speculation that the two disorders may be linked at the biochemical level.[57]

Mechanism

[edit]Most leprosy complications are the result of nerve damage. The nerve damage occurs from direct invasion by the M. leprae bacteria and a person's immune response resulting in inflammation.[29] The molecular mechanism underlying how M. leprae produces the symptoms of leprosy is not clear,[14] but M. leprae has been shown to bind to Schwann cells, which may lead to nerve injury including demyelination and a loss of nerve function (specifically a loss of axonal conductance).[58] Numerous molecular mechanisms have been associated with this nerve damage including the presence of a laminin-binding protein and the glycoconjugate (PGL-1) on the surface of M. leprae that can bind to laminin on peripheral nerves.[58]

As part of the human immune response, white blood cell-derived macrophages may engulf M. leprae by phagocytosis.[58]

In the initial stages, small sensory and autonomic nerve fibers in the skin of a person with leprosy are damaged.[29] This damage usually results in hair loss to the area, a loss of the ability to sweat, and numbness (decreased ability to detect sensations such as temperature and touch). Further peripheral nerve damage may result in skin dryness, more numbness, and muscle weaknesses or paralysis in the area affected.[29] The skin can crack and if the skin injuries are not carefully cared for, there is a risk for a secondary infection that can lead to more severe damage.[29]

Diagnosis

[edit]

In countries where people are frequently infected, a person is considered to have leprosy if they have one of the following two signs:

Skin lesions can be single or many, and usually hypopigmented, although occasionally reddish or copper-colored.[4] The lesions may be flat (macules), raised (papules), or solid elevated areas (nodular).[4] Experiencing sensory loss at the skin lesion is a feature that can help determine if the lesion is caused by leprosy or by another disorder such as tinea versicolor.[4][59] Thickened nerves are associated with leprosy and can be accompanied by loss of sensation or muscle weakness, but muscle weakness without the characteristic skin lesion and sensory loss is not considered a reliable sign of leprosy.[4]

In some cases, acid-fast leprosy bacilli in skin smears are considered diagnostic; however, the diagnosis is typically made without laboratory tests, based on symptoms.[4] If a person has a new leprosy diagnosis and already has a visible disability caused by leprosy, the diagnosis is considered late.[29]

In countries or areas where leprosy is uncommon, such as the United States, diagnosis of leprosy is often delayed because healthcare providers are unaware of leprosy and its symptoms.[60] Early diagnosis and treatment prevent nerve involvement, the hallmark of leprosy, and the disability it causes.[4][60]

There is no recommended test to diagnose latent leprosy in people without symptoms.[9] Few people with latent leprosy test positive for anti PGL-1.[43] The presence of M. leprae bacterial DNA can be identified using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based technique.[61] This molecular test alone is not sufficient to diagnose a person, but this approach may be used to identify someone who is at high risk of developing or transmitting leprosy such as those with few lesions or an atypical clinical presentation.[61][62]

New approaches propose tools to diagnose leprosy through Artificial Intelligence.[63]

Classification

[edit]Several different approaches for classifying leprosy exist. There are similarities between the classification approaches.

- The World Health Organization system distinguishes "paucibacillary" and "multibacillary" based upon the proliferation of bacteria.[64] ("pauci-" refers to a small quantity.)

- The Ridley-Jopling scale provides five gradations.[65][66][67]

- The ICD-10, though developed by the WHO, uses Ridley-Jopling and not the WHO system. It also adds an indeterminate ("I") entry.[52]

- In MeSH, three groupings are used.

| WHO | Ridley-Jopling | ICD-10 | MeSH | Description | Lepromin test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paucibacillary | tuberculoid ("TT"), borderline tuberculoid ("BT") |

A30.1, A30.2 | Tuberculoid | It is characterized by one or more hypopigmented skin macules and patches where skin sensations are lost because of damaged peripheral nerves that have been attacked by the human host's immune cells. TT is characterized by the formation of epithelioid cell granulomas with a large number of epithelioid cells. In this form of leprosy Mycobacterium leprae are either absent from the lesion or occur in very small numbers. This type of leprosy is most benign.[58][68] | Positive |

| Multibacillary | midborderline or borderline ("BB") |

A30.3 | Borderline | Borderline leprosy is of intermediate severity and is the most common form. Skin lesions resemble tuberculoid leprosy, but are more numerous and irregular; large patches may affect a whole limb, and peripheral nerve involvement with weakness and loss of sensation is common. This type is unstable and may become more like lepromatous leprosy or may undergo a reversal reaction, becoming more like the tuberculoid form.[citation needed] | Negative |

| Multibacillary | borderline lepromatous ("BL"), and lepromatous ("LL") |

A30.4, A30.5 | Lepromatous | It is associated with symmetric skin lesions, nodules, plaques, thickened dermis, and frequent involvement of the nasal mucosa resulting in nasal congestion and nose bleeds, but, typically, detectable nerve damage is late. Loss of eyebrows and lashes can be seen in advanced disease.[69] LL is characterized by the absence of epithelioid cells in the lesions. In this form of leprosy, Mycobacteria leprae are found in lesions in large numbers. This is the most unfavorable clinical variant of leprosy, which occurs with a generalized lesion of the skin, mucous membranes, eyes, peripheral nerves, lymph nodes, and internal organs.[58][68] Histoid leprosy is a rare variation of multibacillary, lepromatous leprosy. | Negative |

Leprosy may also occur with only neural involvement, without skin lesions.[4][70][71][72][73][74]

Complications

[edit]Leprosy may cause the victim to lose limbs and digits but not directly. M. leprae attacks nerve endings and destroys the body's ability to feel pain and injury. Without feeling pain, people with leprosy have an increased risk of injuring themselves. Injuries become infected and result in tissue loss. Fingers, toes, and limbs become shortened and deformed as the tissue is absorbed into the body.[75]

Prevention

[edit]Early detection of the disease is important, since physical and neurological damage may be irreversible even if cured.[4] Medications can decrease the risk of those living with people who have leprosy from acquiring the disease and likely those with whom people with leprosy come into contact outside the home.[14] The WHO recommends that preventive medicine be given to people who are in close contact with someone who has leprosy.[9] The suggested preventive treatment is a single dose of rifampicin (SDR) in adults and children over 2 years old who do not already have leprosy or tuberculosis.[9] Preventive treatment is associated with a 57% reduction in infections within 2 years and a 30% reduction in infections within 6 years.[9]

The Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine offers a variable amount of protection against leprosy in addition to its closely related target of tuberculosis.[76] It appears to be 26% to 41% effective (based on controlled trials) and about 60% effective based on observational studies with two doses possibly working better than one.[77][78] The WHO concluded in 2018 that the BCG vaccine at birth reduces leprosy risk and is recommended in countries with high incidence of TB and people who have leprosy.[79] People living in the same home as a person with leprosy are suggested to take a BCG booster which may improve their immunity by 56%.[80][81] Development of a more effective vaccine is ongoing.[14][82][83][84]

A novel vaccine called LepVax entered clinical trials in 2017 with the first encouraging results reported on 24 participants published in 2020.[85][86] If successful, this would be the first leprosy-specific vaccine available.

Treatment

[edit]

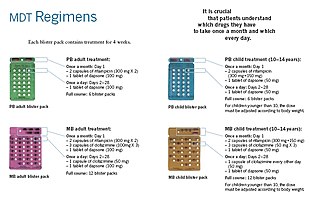

A number of leprostatic agents are available for treatment. A three-drug regimen of rifampicin, dapsone and clofazimine is recommended for all people with leprosy, for six months for paucibacillary leprosy and 12 months for multibacillary leprosy.[9]

Multidrug therapy (MDT) remains highly effective, and people are no longer infectious after the first monthly dose.[4] It is safe and easy to use under field conditions because of its presentation in calendar blister packs.[4] Post-treatment relapse rates remain low.[4] Resistance has been reported in several countries, although the number of cases is small.[87] People with rifampicin-resistant leprosy may be treated with second line drugs such as fluoroquinolones, minocycline, or clarithromycin, but the treatment duration is 24 months because of their lower bactericidal activity.[88] Evidence on the potential benefits and harms of alternative regimens for drug-resistant leprosy is not available.[9]

For people with nerve damage, protective footwear may help prevent ulcers and secondary infection.[29] Canvas shoes may be better than PVC boots.[29] There may be no difference between double rocker shoes and below-knee plaster.[29] Topical ketanserin seems to have a better effect on ulcer healing than clioquinol cream or zinc paste, but the evidence for this is weak.[29] Phenytoin applied to the skin improves skin changes to a greater degree when compared to saline dressings.[29]

Outcomes

[edit]Although leprosy has been curable since the mid-20th century, left untreated it can cause permanent physical impairments and damage to a person's nerves, skin, eyes, and limbs.[4] Despite leprosy not being very infectious and having a low pathogenicity, there is still significant stigma and prejudice associated with the disease.[89] Because of this stigma, leprosy can affect a person's participation in social activities and may also affect the lives of their family and friends.[89] People with leprosy are also at a higher risk for problems with their mental well-being.[89] The social stigma may contribute to problems obtaining employment, financial difficulties, and social isolation.[89] Efforts to reduce discrimination and reduce the stigma surrounding leprosy may help improve outcomes for people with leprosy.[90]

Epidemiology

[edit]

In 2018, there were 208,619 new cases of leprosy recorded, a slight decrease from 2017.[94] In 2015, 94% of the new leprosy cases were confined to 14 countries.[95] India reported the greatest number of new cases (60% of reported cases), followed by Brazil (13%) and Indonesia (8%).[95] Although the number of cases worldwide continues to fall, there are parts of the world where leprosy is more common, including Brazil, South Asia (India, Nepal, Bhutan), some parts of Africa (Tanzania, Madagascar, Mozambique), and the western Pacific.[95] About 150 to 250 cases are diagnosed in the United States each year.[96]

In the 1960s, there were tens of millions of leprosy cases recorded when the bacteria started to develop resistance to dapsone, the most common treatment option at the time.[4][14] International (e.g., the WHO's "Global Strategy for Reducing Disease Burden Due to Leprosy") and national (e.g., the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations) initiatives have reduced the total number and the number of new cases of the disease.[14][97]

The number of new leprosy cases is difficult to measure and monitor because of leprosy's long incubation period, delays in diagnosis after onset of the disease, and lack of medical care in affected areas.[98] The registered prevalence of the disease is used to determine disease burden.[99] Registered prevalence is a useful proxy indicator of the disease burden, as it reflects the number of active leprosy cases diagnosed with the disease and receiving treatment with MDT at a given point in time.[99] The prevalence rate is defined as the number of cases registered for MDT treatment among the population in which the cases have occurred, again at a given point in time.[99]

| Year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of new cases[100] | 296,479 | 258,980 | 252,541 | 249,018 | 244,797 | 228,488 | 224,344 | 232,847 | 215,636 | 213,861 | 211,945 | 217,927 | 210,973 | 208,613 | 202,166 | 127,506 | 140,546 | 174,059 |

History

[edit]

Historical distribution

[edit]Using comparative genomics, in 2005, geneticists traced the origins and worldwide distribution of leprosy from East Africa or the Near East along human migration routes. They found four strains of M. leprae with specific regional locations:[101] Monot et al. (2005) determined that leprosy originated in East Africa or the Near East and traveled with humans along their migration routes, including those of trade in goods and slaves. The four strains of M. leprae are based in specific geographic regions where each predominantly occurs:[101]

- strain 1 in Asia, the Pacific region, and East Africa;

- strain 2 in Ethiopia, Malawi, Nepal, north India, and New Caledonia;

- strain 3 in Europe, North Africa, and the Americas;

- strain 4 in West Africa and the Caribbean.

This confirms the spread of the disease along the migration, colonisation, and slave trade routes taken from East Africa to India, West Africa to the New World, and from Africa into Europe and vice versa.[102]

Skeletal remains discovered in 2009 represent the oldest documented evidence for leprosy, dating to the 2nd millennium BC.[103][104] Located at Balathal, Rajasthan, in northwest India, the discoverers suggest that, if the disease did migrate from Africa to India during the 3rd millennium BC "at a time when there was substantial interaction among the Indus Civilization, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, there needs to be additional skeletal and molecular evidence of leprosy in India and Africa to confirm the African origin of the disease".[105] A proven human case was verified by DNA taken from the shrouded remains of a man discovered by researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in a tomb in Akeldama, next to the Old City of Jerusalem, Israel, dated by radiocarbon methods to the first half of the 1st century.[106]

The oldest strains of leprosy known from Europe are from Great Chesterford in southeast England and dating back to AD 415–545. These findings suggest a different path for the spread of leprosy, meaning it may have originated in Western Eurasia. This study also indicates that there were more strains in Europe at the time than previously determined.[107]

Discovery and scientific progress

[edit]Literary attestation of leprosy is unclear because of the ambiguity of many early sources, including the Indian Atharvaveda and Kausika Sutra, the Egyptian Ebers Papyrus, and the Hebrew Bible's various sections regarding signs of impurity (tzaraath).[108] Clearly leprotic symptoms are attested in the Indian doctor Sushruta's Compendium, originally dating to c. 600 BC but only surviving in emended texts no earlier than the 5th century. They were separately described by Hippocrates in 460 BC. However, Hansen's disease probably did not exist in Greece or the Middle East before the Common Era.[109][110][111] In 1846, Francis Adams produced The Seven Books of Paulus Aegineta which included a commentary on all medical and surgical knowledge and descriptions and remedies to do with leprosy from the Romans, Greeks, and Arabs.[112][113]

Leprosy did not exist in the Americas before colonization by modern Europeans[114] nor did it exist in Polynesia until the middle of the 19th century.[115]

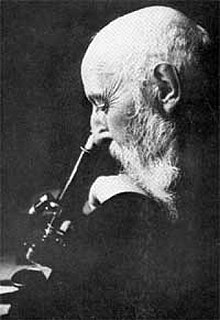

The causative agent of leprosy, M. leprae, was discovered by Gerhard Armauer Hansen in Norway in 1873, making it the first bacterium to be identified as causing disease in humans.[116]

Treatment

[edit]Chaulmoogra tree oil was used topically to manage Hansen's disease for centuries. Chaulmoogra oil could not be taken orally without causing nausea or injected without forming an abscess. [117] In 1915, Alice Ball, the first Black woman to graduate from the University of Hawai'i with a masters in chemistry, discovered how to make the oil water-soluble.[117] This technique led to marked improvements in patients with Hansen's disease who were treated in Hawai'i.[117]

The first effective drug (promin) became available in the 1940s.[118] In the 1950s, dapsone was introduced. The search for further effective antileprosy drugs led to the use of clofazimine and rifampicin in the 1960s and 1970s.[119] Later, Indian scientist Shantaram Yawalkar and his colleagues formulated a combined therapy using rifampicin and dapsone, intended to mitigate bacterial resistance.[120] Multi-drug therapy (MDT) combining all three drugs was first recommended by the WHO in 1981. These three antileprosy drugs are still used in the standard MDT regimens.[121]

Leprosy was once believed to be highly contagious and was treated with mercury, as was syphilis, which was first described in 1530. Many early cases thought to be leprosy could actually have been syphilis.[122]

Resistance has developed to initial treatment. Until the introduction of MDT in the early 1980s, leprosy could not be diagnosed and treated successfully within the community.[123]

Japan still has sanatoriums (although Japan's sanatoriums no longer have active leprosy cases, nor are survivors held in them by law).[124]

The importance of the nasal mucosa in the transmission of M. leprae was recognized as early as 1898 by Schäffer, in particular, that of the ulcerated mucosa.[125][verification needed] The mechanism of plantar ulceration in leprosy and its treatment was first described by Ernest W. Price.[126]

Etymology

[edit]The word "leprosy" comes from the Greek word "λέπος (lépos) – skin" and "λεπερός (leperós) – scaly man".[citation needed]

Society and culture

[edit]

Treatment cost

[edit]Between 1995 and 1999, the WHO, with the aid of the Nippon Foundation, supplied all endemic countries with free multidrug therapy in blister packs, channeled through ministries of health.[4] This free provision was extended in 2000 and again in 2005, 2010 and 2015 with donations by the multidrug therapy manufacturer Novartis through the WHO. In the latest agreement signed between the company and the WHO in October 2015, the provision of free multidrug therapy by the WHO to all endemic countries will run until the end of 2025.[127][4] At the national level, nongovernment organizations affiliated with the national program will continue to be provided with an appropriate free supply of multidrug therapy by the WHO.[128]

Historical texts

[edit]Written accounts of leprosy date back thousands of years. Various skin diseases translated as leprosy appear in the ancient Indian text, the Atharava Veda, by 600 BC.[129] Another Indian text, the Manusmriti (200 BC), prohibited contact with those infected with the disease and made marriage to a person infected with leprosy punishable.[130]

The Hebraic root tsara or tsaraath (צָרַע, – tsaw-rah' – to be struck with leprosy, to be leprous) and the Greek (λεπρός–lepros), are of broader classification than the more narrow use of the term related to Hansen's Disease.[131] Any progressive skin disease (a whitening or splotchy bleaching of the skin, raised manifestations of scales, scabs, infections, rashes, etc....), as well as generalized molds and surface discoloration of any clothing, leather, or discoloration on walls or surfaces throughout homes all, came under the "law of leprosy" (Leviticus 14:54–57).[132] Ancient sources such as the Talmud (Sifra 63) make clear that tzaraath refers to various types of lesions or stains associated with ritual impurity and occurring on cloth, leather, or houses, as well as skin. Traditional Judaism and Jewish rabbinical authorities, both historical and modern, emphasize that the tsaraath of Leviticus is a spiritual ailment with no direct relationship to Hansen's disease or physical contagions. The relation of tsaraath to "leprosy" comes from translations of Hebrew Biblical texts into Greek and ensuing misconceptions.[133]

All three Synoptic Gospels of the New Testament describe instances of Jesus healing people with leprosy (Matthew 8:1–4, Mark 1:40–45, and Luke 5:12–16). The Bible's description of leprosy is congruous (if lacking detail) with the symptoms of modern leprosy, but the relationship between this disease, tzaraath, and Hansen's disease has been disputed.[134] The biblical perception that people with leprosy were unclean can be found in a passage from Leviticus 13: 44–46. While this text defines the leper as impure, it did not explicitly make a moral judgement on those with leprosy.[135] Some Early Christians believed that those affected by leprosy were being punished by God for sinful behavior. Moral associations have persisted throughout history. Pope Gregory the Great (540–604) and Isidore of Seville (560–636) considered people with the disease to be heretics.[136]

Middle Ages

[edit]

The social perception of leprosy in the general population was in general mixed. On one hand, people feared getting infected with the disease and thought of people suspected of leprosy to be unclean, untrustworthy, and occasionally morally corrupt.[136] On the other hand, Jesus' interaction with lepers, the writing of church leaders and the Christian focus on charitable works led to viewing the lepers as "chosen by God"[137] or seeing the disease as a means of obtaining access to heaven.[138]

Early medieval understanding of leprosy was influenced by early Christian writers such as Gregory of Nazianzus and John Chrysostom, whose writings were later embraced by Byzantine and Latin writers.[139] Gregory, for example, did not only compose sermons urging Christians to assist victims of the disease, but also condemned pagans or Christians who justified rejecting lepers on the allegation that God had sent them the disease to punish them. As cases of leprosy increased during these years in the Eastern Roman Empire, becoming a major health issue, the ecclesiastic leaders of the time discussed how to assist those affected as well as change the attitude of society towards them. They also tried this by using the name "Holy disease" instead of the commonly used "Elephant's disease" (elephantiasis), implying that God did not create this disease to punish people but to purify them for heaven.[140] Although not always successful in persuading the public and a cure was never found by Greek medicians, they created an environment where victims could get palliative care and were never expressly banned from society, as sometimes happened in Western Europe. Theodore Balsamon, a 12th-century jurist in Constantinople, noted that lepers were allowed to enter the same churches, cities and assemblies that healthy people attended.[139]

As the disease became more prevalent in Western Europe in the fifth century, efforts began to set up permanent institutions to house and feed lepers. These efforts were, inclusively, the work of bishops in France at the end of the sixth century, such as in Chalon-sur-Saône.[139] The increase in hospitals or leprosaria (sing. leprosarium) that treated people with leprosy in the 12th and 13th century seems to indicate a rise in cases,[141][142][143] possibly in connection with the increase in urbanisation [144] as well as returning crusaders from the Middle East.[139] France alone had nearly 2,000 leprosaria during this period.[145] Additionally to the new leprosia, further steps were taken by secular and religious leaders to prevent further spread of the disease. The third Lateran Council of 1179 required lepers to have their own priests and churches[144][failed verification] and a 1346 edict by King Edward expelled lepers from city limits. Segregation from mainstream society became common, and people with leprosy were often required to wear clothing that identified them as such or carry a bell announcing their presence.[145] As in the East, it was the Church who took care of the lepers due to the still persisting moral stigma and who ran the leprosaria.[136][146] Although the leprosaria in Western Europe removed the sick from society, they were never a place to quarantine them or from which they could not leave: lepers would go beg for alms for the upkeep of the leprosaria or meet with their families.[144][139]

Multiple groups in western Europe from the middle ages faced social ostracization and discrimination that was justified, in part, due to claims that they were the descendants of lepers. These groups included the Cagots and the Caquins.[147][148][149]

19th century

[edit]

Norway

[edit]Norway was the location of a progressive stance on leprosy tracking and treatment and played an influential role in European understanding of the disease. In 1832, Dr. JJ Hjort conducted the first leprosy survey, thus establishing a basis for epidemiological surveys. Subsequent surveys resulted in the establishment of a national leprosy registry to study the causes of leprosy and for tracking the rate of infection.[citation needed]

Early leprosy research throughout Europe was conducted by Norwegian scientists Daniel Cornelius Danielssen and Carl Wilhelm Boeck. Their work resulted in the establishment of the National Leprosy Research and Treatment Center. Danielssen and Boeck believed the cause of leprosy transmission was hereditary. This stance was influential in advocating for the isolation of those infected by sex to prevent reproduction.[150][151][152]

Leprosy and imperialism

[edit]

Though leprosy rates were again on the decline in the Western world by the 1860s, authorities in the West frequently embraced isolation treatment due to a combination of reasons, including fears of the disease spreading from the Global South, efforts by Christian missionaries and a lack of understanding concerning bacteriology, medical diagnosis and how contagious the disease was.[153] The rapid expansion of Western imperialism during the Victorian era resulted in Westerners coming into increasing contact with regions where the disease was endemic, including British India. English surgeon Henry Vandyke Carter observed isolation treatment for leprosy patients first-hand while visiting Norway, applying these methods in British India with the financial and logistical assistance of Protestant missionaries. Colonialist and religious viewpoints of the disease continued to be a major factor in the treatment and public perception of the disease in the Global South until decolonization in the mid-twentieth century.[153]

20th century

[edit]India

[edit]In 1898, the colonial government in British India enacted the Leprosy Act of 1898, which mandated the compulsory segregation of people with leprosy by authorities in newly established leper asylums, where they were segregated by sex to prevent sexual activity. The act, which proved difficult to enforce, was repealed in 1983 by the Indian government after multidrug therapy had become widely available in India. In 1983, the National Leprosy Elimination Programme, previously the National Leprosy Control Programme, changed its methods from surveillance to the treatment of people with leprosy. India still accounts for over half of the global disease burden. According to WHO, new cases in India during 2019 diminished to 114,451 patients (57% of the world's total new cases).[154][153] Until 2019, Indians could justify a petition for divorce with their spouse's diagnosis of leprosy.[155]

Соединенные Штаты

[ редактировать ]Национальный лепрозарий в Карвилле, штат Луизиана , известный в 1955 году как дом Louisiana Leper, был единственной больницей проказа на материке США. Пациенты с проказой со всего Соединенных Штатов были отправлены в Карвилл, чтобы быть в изоляции вдали от общественности, так как в то время было известно мало о проказе, и стигма против пациентов с проказой была высокой (см. Стигма проказы ). Карвильский лепрозарий был известен своими инновациями в реконструктивной хирургии для людей с проказой. В 1941 году 22 пациентам в Карвилле прошли испытания нового препарата под названием PROMIN . Результаты были описаны как чудесные, и вскоре после успеха Pomin появился DAPSONE , лекарство, еще более эффективное в борьбе с проказой. [ 156 ]

21 век

[ редактировать ]Соединенные Штаты

[ редактировать ]Заболеваемость проказы достигла пика в Соединенных Штатах в 1983 году, за которым последовало резкое снижение. [ 157 ] Тем не менее, число случаев постепенно растет с 2000 года. В 2020 году в стране сообщалось о 159 случаях проказы. [ 157 ]

Стигма

[ редактировать ]Несмотря на эффективные усилия по лечению и образованию, стигма проказы по -прежнему является проблематичной в развивающихся странах, где эта болезнь распространена. Проказа является наиболее распространенной среди бедных населения, где социальная стигма, вероятно, усугубляется бедностью. Опасения перед остракизмом, потерей занятости или изгнания от семьи и общества могут способствовать отсроченному диагнозу и лечению. [ 158 ]

Народные убеждения, отсутствие образования и религиозная коннотация этой болезни продолжают влиять на социальное восприятие тех, кто пострадал во многих частях мира. Например, в Бразилии фольклор утверждает, что проказа - это болезнь, передаваемая собаками, или что он связан с сексуальной распущенностью или что это наказание за грехи или моральные нарушения (отличающиеся от других болезней и несчастья, которые в целом мыслите как существо в соответствии с волей Божьей). [ 159 ] Социально -экономические факторы также оказывают прямое влияние. Нижние классы домашних работников, которые часто работают у тех, кто находится в более высоком социально-экономическом классе, могут найти свою работу под угрозой, поскольку физические проявления заболевания становятся очевидными. Обесцвечивание кожи и более темная пигментация, возникающая в результате этой болезни, также имеют социальные последствия. [ 160 ]

В крайних случаях в северной Индии проказа приравнивается к «неприкасаемому» статусу, который часто сохраняется долго после того, как люди с проказой были излечены от этой болезни, создавая перспективы развода, выселения, выселения, потери занятости и остракизма от семьи и социальных Сети " [ 161 ]

-

Проказа в Таити, ок. 1895

-

26-летняя женщина с прокатными поражениями

-

13-летний мальчик с сильной проказой

Государственная политика

[ редактировать ]Цель Всемирной организации здравоохранения-«устранить проказу», а в 2016 году организация запустила «Глобальную стратегию проказы 2016–2020 гг. [ 162 ] [ 163 ] Устранение проказы определяется как «сокращение доли пациентов с проказой в сообществе до очень низких уровней, в частности до одного случая на 10 000 популяций». [ 164 ] Диагностика и лечение с помощью многолетней терапии эффективны, и снижение бремени заболевания на 45% произошло с тех пор, как многолетняя терапия стала более широкой. [ 165 ] Организация подчеркивает важность полной интеграции лечения проказы в услуги общественного здравоохранения, эффективную диагностику и лечение, а также доступ к информации. [ 165 ] Этот подход включает в себя поддержку увеличения медицинских работников, которые понимают болезнь, и скоординированную и обновленную политическую приверженность, которая включает координацию между странами и улучшения в методологии сбора и анализа данных. [ 162 ]

Вмешательства в «Глобальную стратегию проказы 2016–2020 гг. [ 162 ]

- Раннее обнаружение случаев, сосредоточенных на детях, чтобы уменьшить передачу и инвалидность.

- Усовершенствованные медицинские услуги и улучшенный доступ для людей, которые могут быть маргинализованы.

- Для стран, в которых проказа является эндемической, дальнейшие вмешательства включают улучшенный скрининг тесных контактов, улучшенные схемы лечения и вмешательства, чтобы уменьшить стигму и дискриминацию людей, которые имеют проказа.

В некоторых случаях в Индии реабилитация на уровне общин принимается как местные органы власти, так и НПО . Часто идентичность, культивируемая в общественной среде, предпочтительнее реинтеграции, и модели самоуправления и коллективного агентства, независимо от НПО и государственной поддержки, были желательными и успешными. [ 166 ]

Примечательные случаи

[ редактировать ]- Жозефина -кафрин Сейшельских островов имела проказу с 12 лет и вела личный журнал, который задокументировал ее борьбу и страдания. [ 167 ] [ 168 ] [ 169 ] Он был опубликован в качестве автобиографии в 1923 году. [ 167 ] [ 168 ] [ 169 ] [ 170 ]

- Святой Дэмиен де Вейстер , католический священник из Бельгии, сам в конечном итоге заключил проказу, служил прокаженным, которые были размещены под санкционированным правительством медицинского карантина на острове Молокаи в Королевстве Гавайи . [ 171 ]

- Болдуин IV из Иерусалима был католическим христианским королем латинского Иерусалима, у которого была проказа. [ 172 ]

- Ингеборг Гриттен , норвежский писатель, чья проказа, как полагают, повлияла на ее поэзию, которая характеризуется сильной религиозной верой в Божье спасение. [ 173 ]

- Йозефина Герреро была филиппинским шпионом во время Второй мировой войны , которая использовала японский страх перед своей проказой, чтобы выслушать свои планы битвы и доставить информацию американским войскам под руководством Дугласа Макартура . [ 174 ]

- Король Генрих IV из Англии (правящий с 1399 по 1413), возможно, имел проказу. [ 175 ]

- Вьетнамский поэт Хан Мак Ту [ 176 ]

- Ōtani yoshitsugu , японский Daimyō [ 177 ] (феодал).

- Британский писатель Питер Грив (1910–1977).

Проказа в СМИ

[ редактировать ]- Август 1891 г. в коллекции коротких рассказов - Гандикап Рудиарда Киплинга имеет историю «Знак зверя», в которой путешественник на лошади буквально наткнулся в колонию прокаженных в Индии. [ 178 ]

- 1909 - Джек Лондон опубликовал «Koolau The Leper» в своих рассказах о Гавайях о Молокае и людях, отправленных в него около 1893 года.

- 1959 - Джеймса Михенера Роман «Гавайи» драматизирует поселение прокаженного острова Молокая , включая отца Дэмиена.

- 1959 - Бен-Хур изображает мать главного героя, Мириам, и младшая сестра Тирза, заключены в тюрьму Римской империей. Когда они освобождаются через несколько лет, у них проказа и покидают город для долины прокаженных, а не оставаться и воссоединиться с Бен-Хуром. Они покидают колонию, и когда Иисус умирает на кресте, они чудесным образом вылечены.

- 1960 -Роман английского автора Грэма Грина «Сгоревшее дело» в колонии прокаженных в Бельгии Конго. История также в основном о разочарованном архитекторе, работающем с врачом, разработав новое лекарство и удобства для изуродованных жертв прокаженных; Название также относится к состоянию калечащих средств и обезжиренности при заболевании. [ 179 ]

- 1962 - Forugh Farrokhzad сделал 22-минутный документальный фильм о колонии проказы в Иране под названием «Дом»-черный . Фильм гуманизирует людей, пострадавших и открывается, говоря, что «в мире нет недостатка в уродстве, но, закрывая глаза на уродство, мы усилим его».

- Май 1965 г. - Роальда Даля рассказ , который посетитель в серии «Мой дядя Освальд» имеет персонаж с проказой.

- 1977 - Главный герой в «Хрониках Завета Томаса» Стивена Р. Дональдсона страдает проказой. Его состояние, кажется, вылечивается магией фантастической земли, в которой он оказывается, но он противостоит веру в ее реальность, например, продолжая выполнять регулярный визуальный надзор за конечностями в качестве проверки безопасности. Дональдсон получил опыт работы с этой болезнью в молодости в Индии, где его отец работал в миссионере для людей с проказой.

- Август 1988 - Death Metal Band Deather имеет альбом под названием Leprosy .

- В мае 2003 года - «Странно Ал» Янкович есть песня под названием «Вечеринка в колонии Leper» на его альбоме Poodle Hat .

- Май 2005 г. - В Царстве Небеса (Фильм) режиссер Ридли Скотт и написанный Уильямом Монаханом , Болдуин IV из Иерусалима , сыгранный Эдвардом Нортоном , изображается, носит маску, чтобы скрыть его прокачку. Нет исторического сообщения, что Болдуин носил маску, чтобы скрыть свою проказу.

- Декабрь 2005 г. - в 5 -м сезоне Monk (сериал) , Эпизод 10, «Мистер Монк и прокат», режиссер Рэнди Зиск , человек с прокрозией, который спрашивает частного следователя Адриана Монка (которого сыграл Тони Шалхуб ), чтобы действовать от своего имени в Слушание по задержке, но оказывается использованием внешних атрибутов хронического заболевания, чтобы скрыть смертельную тайную повестку дня.

- 2006 - Moloka'i - роман Алана Бреннета о колонии прокаженных на Гавайях. Этот роман следует истории о семилетней девочке, взятой у ее семьи, и наделой . прокажной урегулирования Молокая

- 2009 - Squint: Мое путешествие с проказой - мемуары Хосе П. Рамиреса. [ 180 ]

- Январь 2016 г. - В видеоигры Darkest Dungeon By Red Hook Studios герой, известный как прокажен, страдает от этой болезни. Когда -то он был доброжелательным королем, который обнял больных и пониженных, но отрекся от своего трона после попытки убийства после того, как он был заражен, чтобы бродить по миру и полюбоваться его красотой.

- 2021 - Вторая жизнь Мириэль Уэст , роман Аманды Скенандр, находится в Карвилле.

- 2022 - Ветер и расплата - это фильм о Пиилани, чей муж, Коулау и сын Кали, заключили болезнь Хансена. Семья боролась с теми, кто стремился запечатлеть и убить гавайцев, страдающих от болезни Хансена.

- Август 2022 г. - В Доме Дракона телевизионная адаптация Джорджа Р.Р. Мартина , пожара и крови король Висерис I Таргариен страдает от изнурительной болезни, где части его тела развивают поражения и с течением времени медленно гниют. Пэдди Консидайн , актер, играющий роль, объяснил на подкасте с развлечениями еженедельно , что Viserys страдает от «формы проказы». [ 181 ] Проказа не упоминается в романе, где Viserys вместо этого страдает от различных проблем со здоровьем, связанных с его ожирением, включая инфекции и подагра . [ 182 ]

- 2023 - Завет воды , семейный роман Саги Авраама Вергезе.

Инфекция животных

[ редактировать ]Дикие девятипозитивные броненосцы ( Dasypus Novemcinctus ) в южном центральном Соединенных Штатах часто несут микобактерии летра . [ 183 ] Считается, что это связано с тем, что у армадилло низкая температура тела. Повреждения проказы появляются в основном в более прохладных областях тела, таких как кожа и слизистые оболочки верхних дыхательных путей . Из -за брони Armadillos трудно увидеть поражения кожи. [ 184 ] Осадин вокруг глаз, носа и ног являются наиболее распространенными признаками. Зараженные Armadillos составляют большой резервуар M. leprae и могут быть источником инфекции для некоторых людей в Соединенных Штатах или других местах в домашнем диапазоне Armadillos. В проказе Armadillo поражения не сохраняются в месте въезда в животных, M. leprae умножается в макрофагах в месте инокуляции и лимфатических узлов. [ 185 ]

Вспышка в шимпанзе в Западной Африке показывает, что бактерии могут заразить другой вид, а также, возможно, иметь дополнительные хозяева грызунов. [ 186 ]

Исследования показали, что заболевание является эндемическим в британской популяции красной евразийской белки, с микобактерием летра и микобактерию лепроматоз, появляющиеся в разных популяциях. Штамм микобактерий лепраэ , обнаруженный на острове Браунси, приравнивается к одному, кто думал, что в человеческом населении умерла в человеческом населении. [ 187 ] Несмотря на это, и предположения о прошлой передаче посредством торговли белками, по -видимому, нет высокого риска белки для передачи человека от дикого населения. Хотя проказа продолжает диагностироваться у иммигрантов в Великобританию, последний известный случай проказы, возникающий в Великобритании, был зарегистрирован более 200 лет назад. [ 188 ]

Было показано, что проказа может перепрограммировать клетки на мыши [ 189 ] [ 190 ] и Армадильо [ 191 ] [ 192 ] Модели, аналогичные тем, как индуцированные плюрипотентные стволовые клетки генерируются факторами транскрипции , MYC , OCT3/4 , SOX2 и KLF4 .

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Софи М. Воробек (2008). «Лечение проказы/болезни Хансена в начале 21 -го века» . Дерматологическая терапия . 22 (6): 518–537. doi : 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01274.x . ISSN 1396-0296 . PMID 19889136 . S2CID 42203681 .

- ^ «Определение проказы» . Свободный словарь. Архивировано из оригинала 22 февраля 2015 года . Получено 25 января 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м не а Suzuki K, Akama T, Kawashima A, Yoshihara A, Yotsu RR, Ishii N (February 2012). "Current status of leprosy: epidemiology, basic science and clinical perspectives". The Journal of Dermatology. 39 (2): 121–129. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01370.x. PMID 21973237. S2CID 40027505.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м не а п Q. ведущий с Т в v В х и С аа Аб и объявление Но из в нравиться это к «Проказа» . Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ). Архивировано из оригинала 31 января 2021 года . Получено 10 февраля 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Новая бактерия проказы: ученые используют генетический отпечаток пальцев, чтобы прибить« убийство организма » . Scienceday . 28 ноября 2008 года. Архивировано с оригинала 13 марта 2010 года . Получено 31 января 2010 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Schreuder PA, Noto S, Richardus JH (январь 2016 г.). «Эпидемиологические тенденции проказы на 21 -й век». Клиники в дерматологии . 34 (1): 24–31. doi : 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2015.11.001 . PMID 26773620 .

- ^ Sotiriou MC, Stryjewska BM, Hill C (сентябрь 2016 г.). «Два случая проказы у братьев и сестер, вызванных микобактерием лепроматозом и обзором литературы» . Американский журнал тропической медицины и гигиены . 95 (3): 522–527. doi : 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0076 . PMC 5014252 . PMID 27402522 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и «Болезнь Хансена (проказа) передача» . CDC.gov . 29 апреля 2013 года. Архивировано с оригинала 13 марта 2015 года . Получено 28 февраля 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м Руководство по диагностике, лечению и профилактике проказы . Всемирная организация здравоохранения. Региональный офис Юго-Восточной Азии. 2018. с. xiii. HDL : 10665/274127 . ISBN 978-92-9022-638-3 .

- ^ Монтойя Д., Модлин Р.Л. (2010). Обучение на проказе: понимание человеческого врожденного иммунного ответа . Достижения в области иммунологии. Тол. 105. С. 1–24. doi : 10.1016/s0065-2776 (10) 05001-7 . ISBN 978-0-12-381302-2 Полем PMID 20510728 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Byrne JP (2008). Энциклопедия эпидемии, пандемиков и язв . Westport, Conn. [UA]: Greenwood Press. п. 351 . ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1 .

- ^ CDC (26 января 2018 г.). «Мировой день проказы» . Центры для контроля и профилактики заболеваний . Архивировано из оригинала 15 июня 2019 года . Получено 15 июля 2019 года .

- ^ «Глобальная ситуация проказы, 2012». Еженедельная эпидемиологическая запись . 87 (34): 317–328. Август 2012. PMID 22919737 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Rodrigues LC, Lockwood DN (июнь 2011 г.). «Сейчас проказа: эпидемиология, прогресс, проблемы и пробелы в исследованиях». Lancet. Заразительные заболевания . 11 (6): 464–470. doi : 10.1016/s1473-3099 (11) 70006-8 . PMID 21616456 .

- ^ «Данные и статистику болезни Хансена» . Администрация ресурсов и услуг здравоохранения . Архивировано с оригинала 4 января 2015 года . Получено 12 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Центральная Флорида - горячая точка для проказы, говорится в сообщении» . CNN . Август 2023 г. Архивировано с оригинала 6 августа 2023 года . Получено 6 августа 2023 года .

- ^ Уолш Ф. (31 марта 2007 г.). «Скрытые страдания индийских прокаженных» . BBC News . Архивировано из оригинала 29 мая 2007 года.

- ^ Лин Те (13 сентября 2006 г.). «Невежество порождает прокаженные колонии в Китае» . Independat News & Media. Архивировано из оригинала 8 апреля 2010 года . Получено 31 января 2010 года .

- ^ Писутипан А (6 июля 2020 года). «Забытые жертвы вируса» . Бангкок пост . Архивировано из оригинала 28 августа 2021 года . Получено 6 июля 2020 года .

- ^ «Заброшенные тропические заболевания» . CDC.gov . 6 июня 2011 года. Архивировано с оригинала 4 декабря 2014 года . Получено 28 ноября 2014 года .

- ^ McMenamin D (2011). Проказа и стигма в южной части Тихого океана: история региона по регионам с учетными записями от первого лица . Джефферсон, Северная Каролина: Макфарланд. п. 17. ISBN 978-0-7864-6323-7 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 19 мая 2016 года.

- ^ «Признаки и симптомы | Болезнь Хансена (проказа) | CDC» . www.cdc.gov . 22 октября 2018 года. Архивировано с оригинала 22 июля 2019 года . Получено 22 июля 2019 года .

- ^ «Патогенез и патология проказы» . Международный учебник проказы . 11 февраля 2016 года. Архивировано с оригинала 22 июля 2019 года . Получено 22 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Комитет эксперта ВОЗ по проказе - восемь отчетов (PDF) . Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ). 2012. С. 11–12. ISBN 978-9241209687 Полем Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 5 августа 2013 года . Получено 9 мая 2018 года .

- ^ Talhari C, Talhari S, Penna Go (2015). «Клинические аспекты проказы». Клиники в дерматологии . 33 (1): 26–37. doi : 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.07.002 . PMID 25432808 .

- ^ Kulkarni GS (2008). Учебник ортопедии и травмы (2 -е изд.). Jaypee Brothers Publishers. п. 779. ISBN 978-81-8448-242-3 .

- ^ «Q и о проказе» . Американские миссии проказы. Архивировано с оригинала 4 октября 2012 года . Получено 22 января 2011 года .

Пятницы и пальцы ног падают, когда кто -то получает проказу? Нет. Bacillus атакует нервные окончания и разрушает способность тела чувствовать боль и травмы. Не чувствуя боли, люди травмируют себя в огне, шипы, камни, даже горячие кофейные чашки. Травмы заражаются и приводят к потере тканей. Пятницы и пальцы ног укорачиваются и деформируются, когда хрящ впитывается в тело.

- ^ De Sousa Jr, Sotto MN, Simões Quaresma JA (28 ноября 2017 г.). «Проказам как сложная инфекция: разбивка иммунной парадигмы Th1 и Th2 в иммунопатогенезе заболевания» . Границы в иммунологии . 8 : 1635. DOI : 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01635 . PMC 5712391 . PMID 29234318 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м Рейнар Л.М., Форсетлунд Л., Леман Л.Ф., Бррберг К.Г. (июль 2019). «Вмешательства для изъязвления и других изменений кожи, вызванные повреждением нерва при проказе» . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 2019 (7): CD012235. doi : 10.1002/14651858.cd012235.pub2 . PMC 6699662 . PMID 31425632 .

- ^ Райан Ку, Рэй К.Дж., ред. (2004). Шеррис Медицинская микробиология (4 -е изд.). МакГроу Хилл. С. 451–53 . ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0 Полем OCLC 61405904 .

- ^ «Геномика понимает биологию и эволюцию проказы бацилл» . Международный учебник проказы . 11 февраля 2016 года. Архивировано с оригинала 12 февраля 2019 года . Получено 11 февраля 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный МакМюррей Д.Н. (1996). «Микобактерии и нокардия» . В Baron S, et al. (ред.). Медицинская микробиология барона (4 -е изд.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2 Полем OCLC 33838234 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 февраля 2009 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bhattacharya S, Vijayalakshmi N, Parija SC (октябрь 2002 г.). «Некультируемые бактерии: последствия и недавние тенденции к идентификации» . Индийский журнал медицинской микробиологии . 20 (4): 174–177. doi : 10.1016/s0255-0857 (21) 03184-4 . PMID 17657065 .

- ^ «Кто | Микробиология: культура in vitro» . Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ). Архивировано из оригинала 9 августа 2020 года . Получено 22 июля 2019 года .

- ^ «Модель Armadillo для проказы» . Международный учебник проказы . 11 февраля 2016 года. Архивировано с оригинала 22 июля 2019 года . Получено 22 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Loughry WJ, Truman RW, McDonough CM, Tilak MK, Garnier S, et al. (2009) «Распространена ли проказа среди девятиногенных броненосцев на юго-востоке Соединенных Штатов?» J Wildl DIS 45: 144–52.

- ^ Мередит А., Дель Позо Дж., Смит С., Милн Е., Стивенсон К., МакКаки Дж (сентябрь 2014 г.). «Проказа в красных белках в Шотландии». Ветеринарная запись . 175 (11): 285–286. doi : 10.1136/vr.g5680 . PMID 25234460 . S2CID 207046489 .

- ^ Monot M, Honoré N, Garnier T, Araoz R, Coppee JY, et al. (2005). «О происхождении проказы». Science 308: 1040–42.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Хан XY, Сильва Ф.Дж. (февраль 2014 г.). «В эпоху проказы» . ПЛО не пренебрегали тропическими заболеваниями . 8 (2): E2544. doi : 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002544 . PMC 3923669 . PMID 24551248 .

- ^ «Красные белки на Британских островах заражены проказой бацилли», архивировав 12 июня 2022 года на машине Wayback , доктор Андрей Бенджак, профессор Анна Мередит и другие. Science , 11 ноября 2016 года. [1] Архивировано 12 июня 2022 года на машине Wayback . Получено 11 ноября 2016 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Могла ли торговля мехом белки способствовать средневековой вспышке проказы в Англии?» Полем Scienceday . Архивировано с оригинала 22 ноября 2018 года . Получено 21 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Inskip S, Taylor GM, Anderson S, Stewart G (ноябрь 2017). «Проказам в дорманне Саффолк, Великобритания: биомолекулярный и геохимический анализ женщины из Хоксне» . Журнал медицинской микробиологии . 66 (11): 1640–1649. doi : 10.1099/jmm.0.000606 . PMID 28984227 . S2CID 33997231 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Penna ML, Penna Go, Iglesias PC, Natal S, Rodrigues LC (май 2016 г.). «Позитивность анти-PGL-1 как маркер риска для развития проказы между контактами случаев проказа: систематический обзор и метаанализ» . ПЛО не пренебрегали тропическими заболеваниями . 10 (5): E0004703. doi : 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004703 . PMC 4871561 . PMID 27192199 .

- ^ Alcaïs A, Mira M, Casanova JL, Schurr E, Abel L (февраль 2005 г.). «Генетическое рассечение иммунитета при проказе». Текущее мнение в иммунологии . 17 (1): 44–48. doi : 10.1016/j.coi.2004.11.006 . PMID 15653309 .

- ^ Локвуд Д.Н., Ламберт С.М. (январь 2011 г.). «Человеческий вирус иммунодефицита и проказа: обновление». Дерматологические клиники . 29 (1): 125–128. doi : 10.1016/j.det.2010.08.016 . PMID 21095536 .

- ^ «Эпидемиология проказы» . Международный учебник проказы . 11 февраля 2016 года. Архивировано с оригинала 23 июля 2019 года . Получено 30 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Chavarro-Portillo B, Soto Cy, Lim (сентябрь 2019). «Эволюция Mycobacterium leprae и экологическая адаптация». Acta Tropica . 197 : 105041. doi : 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105041 . PMID 31152726 . S2CID 173188912 .

- ^ Eichelmann K, González González SE, Salas-Alanis JC, Ocampo-Candiani J (September 2013). "Leprosy. An update: definition, pathogenesis, classification, diagnosis, and treatment". Actas Dermo-Sifiliograficas. 104 (7): 554–563. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2012.03.028. PMID 23870850. S2CID 3442319.

- ^ Джоэл Карлос Ланьон Дж.С., Миланез Моргадо де Абреу Ма (март -апрель 2014). «Проказа: обзор эпидемиологических, клинических и этиопатогенных аспектов - часть 1» . Бюстгальтер дерматол . 89 (2): 205–218. doi : 10.1590/ABD1806-4841.20142450 . PMC 4008049 . PMID 24770495 .

- ^ «Болезнь Хансена (проказа) передача» . CDC.gov . 29 апреля 2013 года. Архивировано с оригинала 13 марта 2015 года . Получено 28 февраля 2015 года .

- ^ Локвуд Д.Н., Кумар Б. (июнь 2004 г.). «Лечение проказы» . BMJ . 328 (7454): 1447–1448. doi : 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1447 . PMC 428501 . PMID 15205269 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Что такое проказа?" | От news-medical.net-последние медицинские новости и исследования со всего мира. Веб - 20 ноября 2010 г. "Что такое проказа?" Полем News-medical.net . 18 ноября 2009 года. Архивировано с оригинала 6 июня 2013 года . Получено 14 мая 2013 года . Полем

- ^ Трумэн Р.В., Сингх П., Шарма Р., Буссо П., Ругемонт Дж., Паниз-Мондольфи А. и др. (Апрель 2011). «Вероятная зооноза проказа на юге Соединенных Штатов» . Новая Англия Журнал медицины . 364 (17): 1626–1633. doi : 10.1056/nejmoa1010536 . PMC 3138484 . PMID 21524213 .

- ^ «Болезнь Хансена (проказа) передача» . CDC.gov . 29 апреля 2013 года. Архивировано с оригинала 13 марта 2015 года . Получено 28 февраля 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cambri G, Mira Mt (20 июля 2018 г.). «Генетическая восприимчивость к генам кандидатов, связанных с проказой из классических кандидатов, связанных с иммунитетом, к подходам целого генома без гипотез» . Границы в иммунологии . 9 : 1674. DOI : 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01674 . PMC 6062607 . PMID 30079069 .

- ^ Кук GC (2009). Тропические заболевания Мэнсона (22 -е изд.). [Эдинбург]: Сондерс. п. 1056. ISBN 978-1-4160-4470-3 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 4 сентября 2017 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Buschman E, Skamene E (июнь 2004 г.). «Связь восприимчивости к проказе к генам болезни Паркинсона» . Международный журнал проказы и других микобактериальных заболеваний . 72 (2): 169–170. doi : 10.1489/1544-581x (2004) 072 <0169: LOLSTP> 2,0.CO; 2 (неактивное 28 июня 2024 г.). PMID 15301585 . S2CID 43103579 .

{{cite journal}}: CS1 Maint: doi неактивен по состоянию на июнь 2024 года ( ссылка ) - ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Bhat RM, Prakash C (2012). «Проказа: обзор патофизиологии» . Междисциплинарные перспективы на инфекционные заболевания . 2012 : 181089. DOI : 10.1155/2012/181089 . PMC 3440852 . PMID 22988457 .

- ^ Moschella SL, Garcia-Albea V (сентябрь 2016 г.). «Международный учебник проказы» (PDF) . Дифференциальный диагноз проказы . п. 3, раздел 2.3. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 16 июля 2020 года . Получено 4 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Министерство здравоохранения и социальных служб США, Управление медицинских ресурсов и услуг. (ND). Программа национальной болезни Хансена (Leprosy) извлечена из «Национальная программа болезни Хансена (проказа)» . Архивировано из оригинала 10 февраля 2011 года . Получено 12 мая 2013 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Martinez AN, Talhari C, Moraes Mo, Talhari S (апрель 2014 г.). «Методы на основе ПЦР для диагностики проказы: от лаборатории к клинике» . ПЛО не пренебрегали тропическими заболеваниями . 8 (4): E2655. doi : 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002655 . PMC 3983108 . PMID 24722358 .

- ^ Tatipally S, Srikantam A, Kasetty S (октябрь 2018). «Полимеразная цепная реакция (ПЦР) в качестве потенциального лабораторного теста по уходу для диагностики проказы-систематический обзор» . Тропическая медицина и инфекционные заболевания . 3 (4): 107. doi : 10.3390/tropicalmed3040107 . PMC 6306935 . PMID 30275432 .

- ^ Quilter EE, Butlin CR, Carrion C, Ruiz-Postigo JA (1 июня 2024 г.). «Мобильное применение WHO Skin NTD - сдвиг парадигмы в диагностике проказы с помощью искусственного интеллекта?» Полем Проказа обзор . 95 (2): 1–3. doi : 10.47276/lr.95.2.2024030 . ISSN 2162-8807 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2024 года . Получено 27 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Смит Д.С. (19 августа 2008 г.). «Проказы: обзор» . инфекционные заболевания эмедицина . Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2010 года . Получено 1 февраля 2010 года .

- ^ Сингх Н., Мануча В., Бхаттачарья С.Н., Арора В.К., Бхатия А (июнь 2004 г.). «Подводные камни в цитологической классификации пограничной проказы в шкале Ридли-Джоплин» ». Диагностическая цитопатология . 30 (6): 386–388. doi : 10.1002/dc.20012 . PMID 15176024 . S2CID 29757876 .

- ^ Ridley DS, Jopling WH (1966). «Классификация проказы в соответствии с иммунитетом. Система из пяти групп». Международный журнал проказы и других микобактериальных заболеваний . 34 (3): 255–273. PMID 5950347 .

- ^ Джеймс В.Д., Бергер Т.Г., Элстон Д.М., Одом Р.Б. (2006). Болезни Эндрюса кожи: клиническая дерматология . Saunders Elsevier. С. 344 –46. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Lastória JC, Abreu MA (2014). "Leprosy: a review of laboratory and therapeutic aspects--part 2". Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 89 (3): 389–401. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142460. PMC 4056695. PMID 24937811.

- ^ Кумар, Бхушан, Упти, Шраддха, Догра, Сунил (11 февраля 2016 г.). «Клинический диагноз проказы» . Международный учебник проказы . Архивировано из оригинала 13 февраля 2019 года . Получено 12 февраля 2019 года .

- ^ Jardim MR, Antunes SL, Santos AR, Nascimento OJ, Nery JA, Sales AM, et al. (Июль 2003 г.). «Критерии диагностики чистой нейронной проказы». Журнал неврологии . 250 (7): 806–809. doi : 10.1007/s00415-003-1081-5 . PMID 12883921 . S2CID 20070335 .

- ^ Mendiratta V, Khan A, Jain A (2006). «Первичная невротическая проказа: переоценка в больнице третичной помощи». Индийский журнал проказы . 78 (3): 261–267. PMID 17120509 .

- ^ Ишида Y, Пекорини Л., Гулилмелли Е (июль 2000 г.). «Три случая проказы чистого невра (PN) при обнаружении, при которой поражения кожи стали видимыми во время их курса» . Нихон Хансенбио Гаккай Засши = японский журнал проказы . 69 (2): 101–106. doi : 10.5025/hansen.69.101 . PMID 10979277 .

- ^ Мишра Б., Мукерджи А., Гирдхар А., Хусейн С., Малавия Г.Н., Гирдхар Б.К. (1995). «Невротическая проказа: дальнейшая прогрессирование и значимость». Acta Leprogica . 9 (4): 187–194. PMID 8711979 .

- ^ Talwar S, Jha PK, Tiwari VD (сентябрь 1992 г.). «Невротическая проказа: эпидемиология и терапевтическая отзывчивость» . Проказа обзор . 63 (3): 263–268. doi : 10.5935/0305-7518.19920031 . PMID 1406021 .

- ^ «Обнимите деревню - FAQ» . 3 июня 2021 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2 февраля 2023 года . Получено 2 февраля 2023 года .

- ^ Дути М.С., Гиллис Т.П., Рид С.Г. (ноябрь 2011 г.). «Достижения и препятствия на пути к вакцине проказы» . Человеческие вакцины . 7 (11): 1172–1183. doi : 10.4161/hv.7.11.16848 . PMC 3323495 . PMID 22048122 .

- ^ Setia MS, Steinmaus C, Ho CS, Rutherford GW (март 2006 г.). «Роль BCG в профилактике проказы: метаанализ». Lancet. Заразительные заболевания . 6 (3): 162–170. doi : 10.1016/s1473-3099 (06) 70412-1 . PMID 16500597 .

- ^ Merle CS, Cunha SS, Rodrigues LC (февраль 2010 г.). «Вацинация вакцинации и проказы BCG: обзор текущих доказательств и статуса BCG в контроле проказы». Экспертный обзор вакцин . 9 (2): 209–222. doi : 10.1586/erv.09.161 . PMID 20109030 . S2CID 34309843 .

- ^ Всемирная организация здравоохранения (июнь 2018 г.). «Вакцина BCG: WHO Pusation Paper, февраль 2018 года - рекомендации». Вакцина . 36 (24): 3408–3410. doi : 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.009 . PMID 29609965 . S2CID 4570754 .

- ^ Moraes Mo, Düppre NC (январь 2021 г.). «Профилактика проказы после воздействия: инновации и точность общественного здравоохранения» . Lancet. Глобальное здоровье . 9 (1): E8 - E9. doi : 10.1016/s2214-109x (20) 30512-x . PMID 33338461 .

- ^ Yamazaki-Shima MA, Unzueta, Berenise Gámez-González L, González-Saldaña N, Sorensen Ru (август 2020 г.). «BCG: вакцина с несколькими лицами » Человеческие вакцины и иммунотерапевтика 16 (8): 1841–1 Doi : 10.1080/ 21645515.2019.170 PMC 7482865 PMID 3199544

- ^ «Прокажная вакцина» . Американские миссии проказы. Архивировано с оригинала 15 ноября 2015 года . Получено 20 октября 2015 года .

- ^ «Судебный процесс для первой в мире вакцины против проказы» . Хранитель . 6 июня 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 11 октября 2015 года . Получено 20 октября 2015 года .

- ^ «Марсовые планы Китая, проказа против вакцины и такси с самостоятельным вождением» . Природа . 537 (7618): 12–13. Сентябрь 2016 г. Bibcode : 2016nater.537 ... 12. Полем doi : 10.1038/537012a . PMID 27582199 .

- ^ Номер клинического испытания NCT03302897 для «Фаза 1 LEP-F1 + Испытание вакцины VACCINE у здоровых взрослых добровольцев» на ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Duthie MS, Frevol A, Day T, Coler RN, Vergara J, Rolf T, et al. (Февраль 2020 г.). «Исследование эскалации дозы антигена фазы 1 для оценки безопасности, переносимости и иммуногенности кандидата от проказы вакцины Lepvax (LEP-F1 + GLA-SE) у здоровых взрослых». Вакцина . 38 (7): 1700–1707. doi : 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.12.050 . PMID 31899025 . S2CID 209677501 .

- ^ «Кто | MDT и лекарственная устойчивость» . Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ). Архивировано с оригинала 4 октября 2014 года . Получено 22 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Рейбел Ф., Камбау Е, Обри А (сентябрь 2015 г.). «Обновление об эпидемиологии, диагностике и лечении проказы» . Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses . 45 (9): 383–393. doi : 10.1016/j.medmal.2015.09.002 . PMID 26428602 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Somar P, Waltz MM, Van Brakel WH (2020). «Влияние проказы на психическое благополучие людей, пострадавших от проказы и членов их семьи - систематический обзор» . Глобальное психическое здоровье . 7 : E15. doi : 10.1017/gmh.2020.3 . PMC 7379324 . PMID 32742673 .

- ^ Рао Д., Эльшафей А., Нгуен М., Хатценбюлер М.Л., Фрей С., Го В.Ф. (февраль 2019 г.). «Систематический обзор многоуровневых вмешательств стигмы: состояние науки и будущих направлений» . BMC Medicine . 17 (1): 41. doi : 10.1186/s12916-018-1244-y . PMC 6377735 . PMID 30770756 .

- ^ «Глобальное обновление проказы, 2016 год: ускорение снижения бремени заболевания». Еженедельная эпидемиологическая запись . 92 (35): 501–519. Сентябрь 2017 года. HDL : 10665/258841 . PMID 28861986 .

- ^ «Проказы новых показателей обнаружения дел, 2016» . Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ). Архивировано из оригинала 19 декабря 2019 года . Получено 19 декабря 2019 года .

- ^ «Смертность и бремя заболеваний для государств -членов ВОЗ в 2002 году» (XLS) . Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ). 2002. Архивировано из оригинала 16 января 2013 года.

- ^ «Кто | проказа: новые данные показывают устойчивое снижение в новых случаях» . ВОЗ . Архивировано с оригинала 22 октября 2019 года . Получено 26 февраля 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «WHO | Global Leprosy Update, 2015: время для действий, подотчетности и включения» . Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ). Архивировано с оригинала 18 октября 2016 года . Получено 14 января 2019 года .

- ^ Мэгги Витч (21 февраля 2019 г.). «Проказа все еще скрывается в Соединенных Штатах, говорится в исследовании» . CNN . Архивировано из оригинала 20 августа 2020 года . Получено 24 февраля 2019 года .

- ^ "О Ilep" . Ilep. Архивировано с оригинала 12 августа 2014 года . Получено 25 августа 2014 года .

- ^ «Эпидемиология проказы» . Международный учебник проказы . 11 февраля 2016 года. Архивировано с оригинала 23 июля 2019 года . Получено 23 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Организация WH (1985). Эпидемиология проказы в отношении контроля. Отчет учебной группы ВОЗ . Серия технических отчетов Всемирной организации здравоохранения. Тол. 716. Всемирная организация здравоохранения. С. 1–60. HDL : 10665/40171 . ISBN 978-92-4-120716-4 Полем OCLC 12095109 . PMID 3925646 .

- ^ «Количество новых случаев проказы» . Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ). 13 сентября 2021 года. Архивировано с оригинала 26 сентября 2021 года . Получено 3 июня 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Monot M, Honoré N, Garnier T, Araoz R, Coppée JY, Lacroix C, et al. (2005). «О происхождении проказы» (PDF) . Наука . 308 (5724): 1040–1042. doi : 10.1126/science/1109759 . PMID 15894530 . S2CID 86109194 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 25 января 2023 года . Получено 22 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Monot M, Honoré N, Garnier T, Araoz R, Coppée JY, Lacroix C, et al. (Май 2005 г.). «О происхождении проказы» (PDF) . Наука . 308 (5724): 1040–1042. doi : 10.1126/science/1109759 . PMID 15894530 . S2CID 86109194 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 25 января 2023 года . Получено 22 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Роббинс Г., Трипати В.М., Мисра В.Н., Моханти Р.К., Шинде В.С., Грей К.М. и др. (Май 2009 г.). «Древние скелетные доказательства проказы в Индии (2000 г. до н.э.)» . Plos один . 4 (5): E5669. Bibcode : 2009ploso ... 4.5669r . doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0005669 . PMC 2682583 . PMID 19479078 .

- ^ Роббинс Шуг Г., Блевинс К.Е., Кокс Б., Грей К, Мушриф-Трипати В (декабрь 2013 г.). «Инфекция, болезнь и биосоциальные процессы в конце цивилизации Инда» . Plos один . 8 (12): E84814. BIBCODE : 2013PLOSO ... 884814R . doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0084814 . PMC 3866234 . PMID 24358372 .

- ^ Роббинс Г., Трипати В.М., Мисра В.Н., Моханти Р.К., Шинде В.С., Грей К.М. и др. (Май 2009 г.). «Древние скелетные доказательства проказы в Индии (2000 г. до н.э.)» . Plos один . 4 (5): E5669. Bibcode : 2009ploso ... 4.5669r . doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0005669 . PMC 2682583 . PMID 19479078 .

- ^ «ДНК окутанного человеком Иисуса в Иерусалиме раскрывает самый ранний случай проказы» . Scienceday . 16 декабря 2009 г. Архивировано с оригинала 20 декабря 2009 года . Получено 31 января 2010 года .

- ^ Schuenemann VJ, Avanzi C, Krause-Koora B, Seitz A, Herbig A, Inskip S, et al. (Май 2018). «Древние геномы раскрывают высокое разнообразие микобактерии лепраэ в средневековой Европе» . PLO -патогены . 14 (5): E1006997. doi : 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006997 . PMC 5944922 . PMID 29746563 .

- ^ Lendrum FC (1954). «Имя« проказа » » . И т. Д.: Обзор общей семантики . Тол. 12. Институт общей семантики. С. 37–47. JSTOR 24234298 . Архивировано из оригинала 13 апреля 2022 года . Получено 13 апреля 2022 года .

- ^ Haubrich WS (2003). Медицинские значения: глоссарий слов происхождения . ACP Press. п. 133. ISBN 978-1-930513-49-5 .

- ^ Wilkins M, Evans CA, Bock D, Köstenberger AJ (1 октября 2013 г.). Евангелия и действия . B & H. п. 194. ISBN 978-1-4336-8101-1 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 12 января 2023 года . Получено 15 июля 2018 года .

- ^ Энциклопедия еврейской медицинской этики . Feldheim Publishers. 2003. с. 951. ISBN 978-1-58330-592-8 .

- ^ Адамс Ф. (1678). Семь книг «Паулюса Аэгинета»: переведены с греческого языка с комментариями, охватывающими полное представление о знаниях, обладающих греками, римлянами и арабскими, по всем предметам, связанным с медициной и хирургией . Лондон: Общество Сиденхэма.

- ^ Роман Цельс , Плиний , Серва Серена , Скрибоний , Келиус Аурелиан , Теймсон , Октавиус Горатиана , Марцеллус Импераник ; ГРИК: Аретаус , Плутарх , Гален , Орибасий ( Амида Амида или Сикатус Аэтиус ), Актуарий , Ноннус, Псаллус , Лео, Рок ; Арабский: Scrapion , Avenzoar , Albucasis , Haly Abbas, переведенный Стивеном Антиохией , Альшаравиусом , Рассом ( Абу Бакр аль-Рази ) и Гвидо де Каулиако .

- ^ Ротберг Р.И. (2001). История населения и семья: журнал междисциплинарной читателя истории . MIT Press. п. 132. ISBN 978-0-262-68130-8 .

- ^ Montgomerie JZ (1988). «Проказа в Новой Зеландии» . Журнал Полинезийского общества . 97 (2): 115–152. PMID 11617451 . Архивировано из оригинала 11 февраля 2018 года . Получено 3 сентября 2019 года .

- ^ Irgens LM (март 2002 г.). «Открытие проказы» [открытие проказы Bacillus]. Журнал Норвежской ассоциации обучения (на норвежском языке). 122 (7): 708–709. PMID 11998735 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Журнал S, Вонг К.М. «Грамовая химика чернокожих женщин, которая обнаружила лечение проказы» . Смитсоновский журнал . Архивировано из оригинала 11 декабря 2023 года . Получено 27 декабря 2023 года .