Ньюарк, Нью-Джерси

Ньюарк, Нью-Джерси | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): Brick City, The Gateway City, City By The River[1] | |

Interactive map of Newark | |

Location in Essex County | |

| Coordinates: 40°44′8″N 74°10′20″W / 40.73556°N 74.17222°W[2][3] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Essex |

| Founded | Religious colony (1663) |

| Township | October 31, 1693 |

| City | April 11, 1836 |

| Named for | Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire, England |

| Government | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act (mayor–council) |

| • Body | Municipal Council of Newark |

| • Mayor | Ras Baraka (D, term ends June 30, 2026)[4][5] |

| • Administrator | Eric E. Pennington[6] |

| • Municipal clerk | Kecia Daniels (acting)[7] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 25.88 sq mi (67.04 km2) |

| • Land | 24.14 sq mi (62.53 km2) |

| • Water | 1.74 sq mi (4.51 km2) 6.72% |

| • Rank | 102nd of 565 in state 1st of 22 in county[2] |

| Elevation | 13 ft (4 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 311,549 |

| • Estimate | 304,960 |

| • Rank | 66th in country (as of 2022)[13] 1st of 565 in state 1st of 22 in county[15] |

| • Density | 12,903.8/sq mi (4,982.2/km2) |

| • Rank | 22nd of 565 in state 4th of 22 in county[15] |

| Demonym | Newarker[16] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Codes | |

| Area code(s) | 862/973, 201, 551, 732, 848, 908[19][20] |

| FIPS code | 3401351000[2][21][22] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885317[2][23] |

| Website | newarknj |

Ньюарк ( / ˈ nj uː ər k / NEW -ərk , [ 24 ] локально: [nʊɹk] ) [ 25 ] — самый густонаселенный город в американском штате , Нью-Джерси административный центр округа Эссекс и главный город агломерации Нью-Йорка . [ 26 ] [ 27 ] [ 28 ] По данным переписи 2020 года , население города составляло 311 549 человек. [ 11 ] [ 12 ] Программа оценки населения подсчитала, что на 2023 год численность населения составит 304 960 человек, что сделает его 66-м по численности населения муниципалитетом в стране. [ 13 ]

Ньюарк , основанный в 1666 году пуританами из колонии Нью-Хейвен , является одним из старейших городов США. Его расположение в устье реки Пассаик , где она впадает в залив Ньюарк города , сделало набережную неотъемлемой частью порта Нью-Йорка и Нью-Джерси . Порт Ньюарк-Элизабет — основной контейнерный терминал самого загруженного морского порта восточного побережья США . Международный аэропорт Ньюарк Либерти был первым муниципальным коммерческим аэропортом в США и стал одним из самых загруженных. [ 29 ] [ 30 ] [ 31 ]

Several companies are headquartered in Newark, including Prudential, PSEG, Panasonic Corporation of North America, Audible.com, IDT Corporation, Manischewitz, and AeroFarms. Higher education institutions in the city include the Newark campus of Rutgers University, which includes law and medical schools and the Rutgers Institute of Jazz Studies; University Hospital; the New Jersey Institute of Technology; and Seton Hall University's law school. Newark is a home to numerous governmental offices, largely concentrated at Government Center and the Essex County Government Complex. Cultural venues include the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, Newark Symphony Hall, the Prudential Center, The Newark Museum of Art, and the New Jersey Historical Society. Branch Brook Park is the oldest county park in the United States and is home to the nation's largest collection of cherry blossom trees, numbering over 5,000.

Newark is divided into five political wards (East, West, South, North and Central).[32] The majority of Black residents reside in the South, Central, and West Wards of the city, while the North and East Wards are mostly populated by Latinos.[33] Ras Baraka has served as mayor of Newark since 2014.

History

[edit]

Newark was settled in 1666 by Connecticut Puritans led by Robert Treat from the New Haven Colony.[34][35] It was conceived as a theocratic assembly of the faithful, though this did not last for long as new settlers came with different ideas.[36] On October 31, 1693, it was organized as a New Jersey township based on the Newark Tract, which was first purchased on July 11, 1667. Newark was granted a royal charter on April 27, 1713. It was incorporated on February 21, 1798, by the New Jersey Legislature's Township Act of 1798, as one of New Jersey's initial group of 104 townships. During its time as a township, portions were taken to form Springfield Township (April 14, 1794), Caldwell Township (February 16, 1798; now known as Fairfield Township), Orange Township (November 27, 1806), Bloomfield Township (March 23, 1812) and Clinton Township (April 14, 1834, remainder reabsorbed by Newark on March 5, 1902). Newark was reincorporated as a city on April 11, 1836, replacing Newark Township, based on the results of a referendum passed on March 18, 1836. The previously independent Vailsburg borough was annexed by Newark on January 1, 1905. In 1926, South Orange Township changed its name to Maplewood. As a result of this, a portion of Maplewood known as Ivy Hill was re-annexed to Newark's Vailsburg.[37]

The name of the city is thought to derive from Newark-on-Trent, England, because of the influence of the original pastor, Abraham Pierson, who came from Yorkshire but may have ministered in Newark, Nottinghamshire.[38][39][40] But Pierson is also supposed to have said that the community reflecting the new task at hand should be named "New Ark" for "New Ark of the Covenant"[41] and some of the colonists saw it as "New-Work", the settlers' new work with God. Whatever the origins, the name was shortened to Newark, although references to the name "New Ark" are found in preserved letters written by historical figures such as David A. Ogden in his claim for compensation, and James McHenry, as late as 1787.[42]

During the American Revolutionary War, British troops made several raids into the town.[43] The city saw tremendous industrial and population growth during the 19th century and early 20th century, and experienced racial tension and urban decline in the second half of the 20th century, culminating in the 1967 Newark riots, which led to an increase in white flight, with 100,000 white residents leaving the city in the 1960s, though the exodus of white residents from the city had started after World War II as housing availability was limited in the city, while white residents were able to buy homes in the western suburbs of Essex County, where the population grew rapidly.[44]

The city has experienced revitalization since the 1990s, with major office, arts and sports projects representing $2 billion in investment.[45] The city's population, which had dropped by more than a third from 1950 to its post-war low in 2000, has since rebounded, with 38,000 new residents added from 2000 to 2020.[46]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 25.89 square miles (67.1 km2), including 24.14 square miles (62.5 km2) of land and 1.74 square miles (4.5 km2) of water (6.72%).[2][3] It has the third-smallest land area among the 100 most populous cities in the U.S., behind neighboring Jersey City and Hialeah, Florida.[47] The city's altitude ranges from 0 (sea level) in the east to approximately 230 feet (70 m) above sea level in the western section of the city for an average elevation of 115 feet (35 m).[48][49] Newark is essentially a large basin sloping towards the Passaic River, with a few valleys formed by meandering streams. Historically, Newark's high places have been its wealthier neighborhoods. In the 19th century and early 20th century, the wealthy congregated on the ridges of Forest Hill, High Street, and Weequahic.[50]

Until the 20th century, the marshes on Newark Bay were difficult to develop, as the marshes were essentially wilderness, with a few dumps, warehouses, and cemeteries on their edges. During the 20th century, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey was able to reclaim 68 acres (28 ha) of the marshland for the further expansion of Newark Liberty International Airport, as well as the growth of the port lands.[31]

Newark is surrounded by residential suburbs to the west (on the slope of the Watchung Mountains), the Passaic River and Newark Bay to the east, dense urban areas to the south and southwest, and middle-class residential suburbs and industrial areas to the north. The city is the largest in New Jersey's Gateway Region, which is said to have received its name from Newark's nickname as the "Gateway City".[51]

The city borders the municipalities of Belleville, Bloomfield, East Orange, Irvington, Maplewood and South Orange in Essex County; Bayonne, East Newark, Harrison, Jersey City and Kearny in Hudson County; and Elizabeth and Hillside in Union County.[52][53][54]

Neighborhoods

[edit]

Newark is the second-most racially diverse municipality in the state, behind neighboring Jersey City.[55] It is divided into five political wards,[56] which are often used by residents to identify their place of habitation. In recent years, residents have begun to identify with specific neighborhood names instead of the larger ward appellations. Nevertheless, the wards remain relatively distinct. Industrial uses, coupled with the airport and seaport lands, are concentrated in the East and South wards, while residential neighborhoods exist primarily in the North, Central, and West Wards.[57]

State law requires that wards be compact and contiguous and that the largest ward may not exceed the population of the smallest by more than 10% of the average ward size. Ward boundaries are redrawn, as needed, by a board of ward commissioners consisting of two Democrats and two Republicans appointed at the county level and the municipal clerk.[58] Redrawing of ward lines in previous decades have shifted traditional boundaries, so that downtown currently occupies portions of the East and Central wards. The boundaries of the wards are altered for various political and demographic reasons and sometimes gerrymandered.[59][60][61]

Newark's Central Ward, formerly known as the old Third Ward, contains much of the city's history including the original squares Lincoln Park, Military Park and Harriet Tubman Square. The ward contains the University Heights, The Coast, historic Grace Episcopal Church, Government Center, Springfield/Belmont and Seventh Avenue neighborhoods. Of these neighborhood designations only University Heights, a more recent designation for the area that was the subject of the 1968 novel Howard Street by Nathan Heard, is still in common usage. The Central Ward extends at one point as far north as 2nd Avenue.

In the 19th century, the Central Ward was inhabited by Germans and other white Catholic and Protestant groups. The German inhabitants were later replaced by Jews, who were then replaced by African Americans. The increased academic footprint in the University Heights neighborhood has produced gentrification, with landmark buildings undergoing renovation. Located in the Central Ward is the nation's largest health sciences university, UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School. It is also home to three other universities – New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), Rutgers University – Newark, and Essex County College. The Central Ward forms the present-day heart of Newark, and includes 26 public schools, two police precincts, including headquarters, four firehouses, and one branch library.[62]

The North Ward is surrounded by Branch Brook Park. Its neighborhoods include Broadway, Mount Pleasant, Upper Roseville and the affluent Forest Hill section.[63] Forest Hill contains the Forest Hill Historic District, which is registered on state and national historic registers, and contains many older mansions and colonial homes. A row of residential towers with security guards and secure parking line Mt. Prospect Avenue in the Forest Hill neighborhood. The North Ward has lost geographic area in recent times; its southern boundary is now significantly further north than the traditional boundary near Interstate 280. The North Ward had its own Little Italy, centered on heavily Italian Seventh Avenue and the area of St. Lucy's Church; demographics have transitioned to Latino in recent decades, though the ward as a whole remains ethnically diverse.[63]

The West Ward comprises the neighborhoods of Vailsburg, Ivy Hill, West Side, Fairmount and Lower Roseville. It is home to the historic Fairmount Cemetery. The West Ward, once a predominantly Irish-American, Polish, and Ukrainian neighborhood, is now home to neighborhoods composed primarily of Latinos, African Americans, and Caribbean Americans.[64] Relative to other parts of the city, the West Ward has for many decades struggled with elevated rates of crime, particularly violent crime.[65]

The South Ward comprises the Weequahic, Clinton Hill, Dayton, and South Broad Valley neighborhoods. The South Ward, once home to residents of predominantly Jewish descent, now has ethnic neighborhoods made up primarily of African Americans and Hispanics. The city's second-largest hospital, Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, is in the South Ward, as are seventeen public schools, five daycare centers, three branch libraries, one police precinct, a mini-precinct, and three fire houses.[66]

The East Ward consists of much of Newark's Downtown commercial district, as well as the Ironbound neighborhood, where much of Newark's industry was in the 19th century. Today, the Ironbound (also known as "Down Neck" and "The Neck")[67] is a destination for shopping, dining, and nightlife.[68] A historically immigrant-dominated section of the city, the Ironbound in recent decades has been termed "Little Portugal" and "Little Brazil" due to its heavily Portuguese and Brazilian population, Newark being home to one of the largest Portuguese speaking communities in the United States. In addition, the East Ward has become home to various Latin Americans, especially Ecuadorians, Peruvians, and Colombians, alongside Puerto Ricans, African Americans, and commuters to Manhattan. Public education in the East Ward consists of East Side High School and six elementary schools. The ward is densely packed, with well-maintained housing and streets, primarily large apartment buildings and rowhouses.[57][69][70]

Climate

[edit]Newark lies in the transition between a humid subtropical and humid continental climate (Köppen Cfa/Dfa), with cold winters and hot humid summers. The January daily mean is 32.8 °F (0.4 °C),[71] and although temperatures below 10 °F (−12 °C) are to be expected in most years,[72] sub-0 °F (−18 °C) readings are rare; conversely, some days may warm up to 50 °F (10 °C). The average seasonal snowfall is 31.5 inches (80 cm), though variations in weather patterns may bring sparse snowfall in some years and several major nor'easters in others, with the heaviest 24-hour fall of 25.9 inches (66 cm) occurring on December 26, 1947.[71] Spring and autumn in the area are generally unstable yet mild. The July daily mean is 78.2 °F (25.7 °C), and highs exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on an average 28.3 days per year,[71] not factoring in the often higher heat index. Precipitation is evenly distributed throughout the year with the summer months being the wettest and fall months being the driest.

The city receives precipitation ranging from 2.9 to 4.6 inches (74 to 117 mm) per month, usually falling on 8 to 12 days per month. Extreme temperatures have ranged from −14 °F (−26 °C) on February 9, 1934, to 108 °F (42 °C) on July 22, 2011.[71] The January freezing isotherm that separates Newark into Dfa and Cfa zones approximates the NJ Turnpike.

| Climate data for Newark, New Jersey (Newark Liberty Int'l), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) |

80 (27) |

89 (32) |

97 (36) |

99 (37) |

103 (39) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

96 (36) |

85 (29) |

76 (24) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 61.8 (16.6) |

62.5 (16.9) |

72.3 (22.4) |

84.4 (29.1) |

91.4 (33.0) |

95.9 (35.5) |

98.7 (37.1) |

95.9 (35.5) |

91.5 (33.1) |

82.4 (28.0) |

72.2 (22.3) |

63.8 (17.7) |

100.0 (37.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 40.0 (4.4) |

43.0 (6.1) |

50.9 (10.5) |

62.6 (17.0) |

72.6 (22.6) |

81.8 (27.7) |

86.9 (30.5) |

84.7 (29.3) |

77.7 (25.4) |

66.0 (18.9) |

54.9 (12.7) |

44.8 (7.1) |

63.8 (17.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 32.8 (0.4) |

35.1 (1.7) |

42.5 (5.8) |

53.3 (11.8) |

63.3 (17.4) |

72.7 (22.6) |

78.2 (25.7) |

76.4 (24.7) |

69.2 (20.7) |

57.5 (14.2) |

47.0 (8.3) |

38.0 (3.3) |

55.5 (13.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 25.5 (−3.6) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

34.2 (1.2) |

44.1 (6.7) |

53.9 (12.2) |

63.6 (17.6) |

69.4 (20.8) |

68.0 (20.0) |

60.7 (15.9) |

49.0 (9.4) |

39.0 (3.9) |

31.2 (−0.4) |

47.1 (8.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 9.1 (−12.7) |

12.1 (−11.1) |

19.4 (−7.0) |

32.3 (0.2) |

42.5 (5.8) |

52.5 (11.4) |

61.9 (16.6) |

59.2 (15.1) |

48.3 (9.1) |

36.1 (2.3) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

17.2 (−8.2) |

7.0 (−13.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −10 (−23) |

−14 (−26) |

3 (−16) |

13 (−11) |

33 (1) |

41 (5) |

49 (9) |

45 (7) |

34 (1) |

25 (−4) |

12 (−11) |

−13 (−25) |

−14 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.42 (87) |

2.98 (76) |

4.13 (105) |

3.87 (98) |

3.97 (101) |

4.34 (110) |

4.66 (118) |

4.15 (105) |

3.82 (97) |

3.79 (96) |

3.33 (85) |

4.14 (105) |

46.60 (1,184) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 9.1 (23) |

10.1 (26) |

5.6 (14) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.6 (1.5) |

5.4 (14) |

31.5 (80) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 5.6 (14) |

6.3 (16) |

3.2 (8.1) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.4 (1.0) |

3.7 (9.4) |

10.8 (27) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.6 | 10.0 | 10.9 | 11.5 | 11.4 | 10.9 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 8.7 | 9.4 | 8.8 | 11.1 | 123.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.6 | 3.8 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 14.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 65.4 | 63.3 | 59.9 | 57.5 | 62.0 | 63.0 | 63.4 | 66.2 | 67.9 | 66.3 | 66.5 | 66.7 | 64.0 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 19.2 (−7.1) |

20.5 (−6.4) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

35.2 (1.8) |

47.7 (8.7) |

57.0 (13.9) |

62.2 (16.8) |

62.4 (16.9) |

56.1 (13.4) |

44.6 (7.0) |

35.2 (1.8) |

24.8 (−4.0) |

41.0 (5.0) |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity and dew point 1961-1989)[71][73][74] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[75] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Newark | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 41.7 (5.4) |

39.7 (4.3) |

40.2 (4.5) |

45.1 (7.3) |

52.5 (11.4) |

64.5 (18.1) |

72.1 (22.3) |

74.1 (23.4) |

70.1 (21.2) |

63.0 (17.3) |

54.3 (12.4) |

47.2 (8.4) |

55.4 (13.0) |

| Source: Weather Atlas[75] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 8,008 | * | — |

| 1820 | 6,507 | * | −18.7% |

| 1830 | 10,953 | 68.3% | |

| 1840 | 17,290 | * | 57.9% |

| 1850 | 38,894 | 125.0% | |

| 1860 | 71,941 | 85.0% | |

| 1870 | 105,059 | 46.0% | |

| 1880 | 136,508 | 29.9% | |

| 1890 | 181,830 | 33.2% | |

| 1900 | 246,070 | 35.3% | |

| 1910 | 347,469 | * | 41.2% |

| 1920 | 414,524 | 19.3% | |

| 1930 | 442,337 | * | 6.7% |

| 1940 | 429,760 | −2.8% | |

| 1950 | 438,776 | 2.1% | |

| 1960 | 405,220 | −7.6% | |

| 1970 | 381,930 | −5.7% | |

| 1980 | 329,248 | −13.8% | |

| 1990 | 275,221 | −16.4% | |

| 2000 | 273,546 | −0.6% | |

| 2010 | 277,140 | 1.3% | |

| 2020 | 311,549 | 12.4% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 304,960 | [11][13][14] | −2.1% |

| Population sources: 1810–1920[76] 1810–1910[77] 1840[78] 1850–1870[79] 1850[80] 1870[81] 1880–1890[82] 1890–1910[83] 1840–1930[84] 1940–2000[85] 2000[86][87] 2010[88][89][90][91] 2020[11][12] * = Territory change in previous decade.[37] | |||

Newark had a population of 311,549 in 2020.[11] The Population Estimates Program calculated a population of 305,344 for 2022, making Newark the 66th-most populous municipality in the nation.[13] The city was ranked 67th in population in 2010 and 63rd in 2000.[92][93][90]

From 2000 to 2010, the increase of 3,594 inhabitants (+1.3%) from the 273,546 counted in the 2000 U.S. census marked the second census in 70 years in which the city's population had grown from the previous enumeration.[88][89][94][95] This trend continued in 2020, where Newark had an increase of 34,409 (12.4%) from the 277,140 counted in the 2010 census, the largest percentage increase in 100 years.

After reaching a peak of 442,337 residents counted in the 1930 census, and a post-war population of 438,776 in 1950, the city's population saw a decline of nearly 40% as residents moved to surrounding suburbs. White flight from Newark to the suburbs started in the 1940s and accelerated in the 1960s, due in part to the construction of the Interstate Highway System.[96] The 1967 riots resulted in a significant population loss of the city's middle class, many of them Jewish, which continued from the 1970s through to the 1990s.[97] On net, the city lost about 130,000 residents between 1960 and 1990.

At the 2010 census, there were 91,414 households, and 62,239 families in Newark. There were 108,907 housing units at an average density of 4,552.5 per square mile (1,757.7/km2).[32] In 2000, there were 273,546 people, 91,382 households, and 61,956 families residing in the city. The population density was 11,495.0 inhabitants per square mile (4,438.2/km2). There were 100,141 housing units at an average density of 4,208.1 per square mile (1,624.6//km2).[21]

The U.S. Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $35,659 (with a margin of error of +/- $1,009) and the median family income was $41,684 (+/- $1,116). Males had a median income of $34,350 (+/- $1,015) versus $32,865 (+/- $973) for females. The per capita income for the township was $17,367 (+/- $364). About 22% of families and 25% of the population were below the poverty line, including 34.9% of those under age 18 and 22.4% of those age 65 or over.[98]

The median income for a household in 2000 was $26,913, and the median income for a family was $30,781. Males had a median income of $29,748 versus $25,734 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,009. 28.4% of the population and 25.5% of families were below the poverty line. 36.6% of those under the age of 18 and 24.1% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line. The city's unemployment rate was 8.5%.[86][87]

Race and ethnicity

[edit]| Historical racial composition | 2020[11] | 2010[99] | 2000[100] | 1990[100] | 1950[100] | 1900[100] |

|---|

2020

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 1990[101] | Pop 2000[102] | Pop 2010[103] | Pop 2020[104] | % 1990 | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 45,344 | 38,950 | 32,122 | 24,916 | 16.48% | 14.24% | 11.59% | 8.00% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 153,703 | 142,083 | 138,074 | 147,905 | 55.85% | 51.94% | 49.82% | 47.47% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 502 | 529 | 713 | 572 | 0.18% | 0.19% | 0.26% | 0.18% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 2,826 | 3,138 | 4,318 | 4,871 | 1.03% | 1.15% | 1.56% | 1.56% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | N/A | 69 | 68 | 63 | N/A | 0.03% | 0.02% | 0.02% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 1,085 | 2,034 | 3,899 | 7,379 | 0.39% | 0.74% | 1.41% | 2.37% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | N/A | 6,121 | 4,200 | 12,469 | N/A | 2.24% | 1.52% | 4.00% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 71,761 | 80,622 | 93,746 | 113,374 | 26.07% | 29.47% | 33.83% | 36.39% |

| Total | 275,221 | 273,546 | 277,140 | 311,549 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

From the 1950s to 1967, Newark's non-Hispanic white population shrank from 363,000 to 158,000; its black population grew from 70,000 to 220,000.[105] The percentage of non-Hispanic whites declined from 82.8% in 1950 to 11.6% by 2010.[100][106][46] The percentage of Latinos and Hispanics in Newark grew between 1980 and 2010, from 18.6% to 33.8% while that of Blacks and African Americans decreased from 58.2% to 52.4%.[107][108][109][110]

At the American Community Survey's 2018 estimates, non-Hispanic whites made up 8.9% of the population. Black or African Americans were 47.0% of the population, Asian Americans were 2.1%, some other race 1.6%, and multiracial Americans 1.1%. Hispanics or Latinos of any race made up 39.2% of the city's population in 2018.[111]

In 2010, 35.74% of the population was white, 58.86% African American, 3.99% Native American or Alaska Native, 2.19% Asian, .01% Pacific Islander, 10.4% from other races, and 10.95% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race made up 33.39% of the population at the 2010 U.S. census.[32]

The racial makeup of the city in 2000 was 53.46% (146,250) black or African American, 26.52% (72,537) white, 1.19% (3,263) Asian, 0.37% (1,005) Native American, 0.05% (135) Pacific Islander, 14.05% (38,430) from other races, and 4.36% (11,926) from two or more races. 29.47% (80,622) of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[86][87] 49.2% of the city's 80,622 residents who identified themselves as Hispanic or Latino were from Puerto Rico, while 9.4% were from Ecuador and 7.8% from the Dominican Republic.[112] There is a significant Portuguese-speaking community concentrated in the Ironbound district. 2000 census data showed that Newark had 15,801 residents of Portuguese ancestry (5.8% of the population), while an additional 5,805 (2.1% of the total) were of Brazilian ancestry.[113]

In advance of the 2000 census, city officials made a push to encourage residents to respond and participate in the enumeration, citing calculations by city officials that as many as 30,000 people were not reflected in estimates by the Census Bureau, which resulted in the loss of government aid and political representation.[114] It is believed that heavily immigrant areas of Newark were significantly undercounted in the 2010 census, especially in the East Ward. Many households refused to participate in the census, with immigrants often reluctant to submit census forms because they believed that the information could be used to justify their deportation.[115]

At one time, there was an Italian American community in the Seventh Avenue neighborhood.[116]

Religion

[edit]

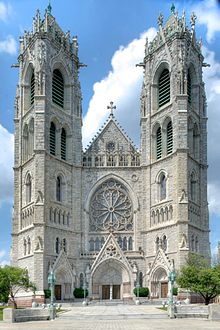

Roughly 60% of Newarkers identified with a religion as of 2020.[117] The largest Christian group in Newark is the Catholic Church (34.3%), followed by Baptists (5.2%). The city's Catholic population are divided into Latin and Eastern Catholics. The Latin Church-based Archdiocese of Newark, serving Bergen, Essex, Hudson and Union counties, is headquartered in the city. Its episcopal seat is the Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart. Eastern Catholics in the area are served by the Syriac Catholic Eparchy of Our Lady of Deliverance of Newark, an eparchy of the Syriac Catholic Church, and by the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Baptist churches in Newark are affiliated with the American Baptist Churches USA,[118] Progressive National Baptist Convention, the National Baptist Convention of America, and National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc.

Following, 2.4% identified with Methodism and the United Methodist Church and African Methodist Episcopal and AME Zion churches.[119][120] 1.6% of Christian Newarkers are Presbyterian and 1.3% identified as Pentecostal. The Presbyterian community is dominated by the Presbyterian Church (USA) and Presbyterian Church in America.[121][122] The Pentecostal community is dominated by the Church of God in Christ and Assemblies of God USA.[123]

0.9% of Christians in the city and nearby suburbs identify as Anglican or Episcopalian. Most are served by the Newark Diocese of the Episcopal Church in the United States. The remainder identified with Continuing Anglican or Evangelical Episcopal bodies including the Reformed Episcopal Church and Anglican Church in North America. ACNA and REC-affiliated churches form the Diocese of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic.

0.6% of Christians are members of the Latter Day Saint movement, followed by Lutherans (0.2%). 3.0% of the city's Christian populace were of other Christian denominations including the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches,[124][125] Independent sacramental churches, the Jehovah's Witnesses,[126] non-denominational Protestants, and the United Church of Christ.[127] The largest Eastern Orthodox jurisdictions in Newark include the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America (Ecumenical Patriarchate) and the Diocese of New York and New Jersey (Orthodox Church in America). The largest Oriental Orthodox bodies include the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria and Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

Judaism and Islam were tied as the second-largest religious community (3.0%). Up to 1967, Jewish Americans formed a substantial portion of the middle class. Sunni, Shia and Ahmadiyya Muslims are the largest Islamic denominational demographic, though some Muslims in the area may be Quranists. Most Sunni mosques are members of the Islamic Society of North America. The Nation of Islam had a former mosque in Newark presided by Louis Farrakhan.

A little over 1.2% practiced an eastern religion including Sikhism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. The remainder of Newark was spiritual but not religious, agnostic, deistic, or atheist, though some Newarkers identified with neo-pagan religions including Wicca and other smaller new religious movements.

Economy

[edit]

More than 100,000 people commute to Newark each workday,[128] making it the state's largest employment center with many white-collar jobs in insurance, finance, import-export, healthcare, and government.[129] As a major courthouse venue including federal, state, and county facilities, it is home to more than 1,000 law firms. The city also has a significant number of college students, with nearly 50,000 attending the city's universities and medical and law schools.[130][131] Its airport, maritime port, rail facilities, and highway network make Newark the busiest transshipment hub on the U.S. East Coast in terms of volume.[132][133]

Though Newark is not the industrial colossus of the past, the city does have a considerable amount of industry and light manufacturing.[134] The southern portion of the Ironbound, also known as the Industrial Meadowlands, has seen many factories built since World War II, including a large Anheuser-Busch brewery that opened in 1951 and distributed 7.5 million barrels of beer in 2007. Grain comes into the facility by rail.[135] The service industry is also growing rapidly, replacing those in the manufacturing industry, which was once Newark's primary economy. In addition, transportation has become a large business in Newark, accounting for more than 17,000 jobs in 2011.[136]

Newark is the third-largest insurance center in the United States, behind New York City and Hartford, Connecticut.[137] Prudential Financial, Mutual Benefit Life, Fireman's Insurance, and American Insurance Company all originated in the city, while Prudential still has its home office in Newark.[138] Many other companies are headquartered in the city, including IDT Corporation, NJ Transit, Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG), Manischewitz, Horizon Blue Cross and Blue Shield of New Jersey,[139][140] and Edison Properties.

After the election of Cory Booker as mayor, millions of dollars of public-private partnership investment were made in Downtown development, but persistent underemployment continue to characterize many of the city's neighborhoods.[141][142][143][144][145][146] Poverty remains a consistent problem in Newark. As of 2010, roughly one-third of the city's population was impoverished.[147]

Portions of Newark are part of an Urban Enterprise Zone. The city was selected in 1983 as one of the initial group of 10 zones chosen to participate in the program.[148] In addition to other benefits to encourage employment within the Zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3.3125% sales tax rate (half of the 6+5⁄8% rate charged statewide) at eligible merchants.[149] Established in January 1986, the city's Urban Enterprise Zone status expires in December 2023.[150]

The UEZ program in Newark and four other original UEZ cities had been allowed to lapse as of January 1, 2017, after Governor Chris Christie, who called the program an "abject failure", vetoed a compromise bill that would have extended the status for two years.[151] In May 2018, Governor Phil Murphy signed a law that reinstated the program in these five cities and extended the expiration date in other zones.[152]

Newark is one of nine cities in New Jersey designated as eligible for Urban Transit Hub Tax Credits by the state's Economic Development Authority. Developers who invest a minimum of $50 million within 0.5 miles (0.8 km) of a train station are eligible for pro-rated tax credit.[153][154]

Technology industry

[edit]The technology industry in Newark has grown significantly after Audible, an online audiobook and podcast company, moved its headquarters to Newark in 2007. The company was later acquired by Amazon.[155] Panasonic moved its North America headquarters to the city in 2013.[156] Other technology-focus companies followed suit. In 2015, AeroFarms, a developer of an aeroponic technology for farming moved its headquarters from Finger Lakes to Newark.[157] By 2016, it had built the world's largest vertical farm in a Newark warehouse.[158] The company was recognized in 2019 by Fast Company as one of the world's most innovative companies in data science.[159] Broadridge Financial Solutions, a public FinTech company, announced a relocation of 1,000 jobs to Newark in 2017.[160] In 2021, WebMD, an online publisher, announced that it will relocate and create up to 700 new jobs in the city.[161]

In 2018, Newark was selected as one of 20 finalists for the location of Amazon HQ2, a new headquarters of Amazon. The advantages of Newark included proximity to New York City, lower land costs, tech labor force and higher education institutions, a major airport, and fiber optic networks.[162] The extensive fiber optic networks in Newark started in the 1990s when telecommunication companies installed fiber optic network to put Newark as a strategic location for data transfer between Manhattan and the rest of the country during the dot-com boom. At the same time, the city encouraged those companies to install more than they needed.[163] A vacant department store was converted into a telecommunication center called 165 Halsey Street.[164] It became one of the world's largest carrier hotels.[165] As a result, after the dot-com bust, there were a surplus of dark fiber (unused fiber optic cables). Twenty years later, the city and other private companies began utilizing the dark fiber to create high performance networks within the city.[163]

As a concentration of technology workforce increased and investments grew in the city, it created an ecosystem for technology startups. Newark Venture Partners, an early-stage venture capital and startup accelerator launched in 2017, invested $42 million in its first funding round in 97 portfolio companies. In 2021, its second funding round raised up to $85 million.[155][166] VentureLink@NJIT, the state's largest startup incubator, is located in New Jersey Institute of Technology campus. It has partnerships with international organizations such as National Association of Software and Services Companies of India.[155] In 2021, HAX Accelerator, an early stage accelerator focused on hard tech startups, announced that it will create its US headquarters in Newark and build out a facility for industrial engineering, chemical engineering and systems integrators to fund industrial, healthcare, and green tech startups.[167]

Newark Retail Reactivation Initiative

[edit]In the fall of 2023, in an effort to stimulate rental of empty storefronts along a parallel strip of Broad, Halsey and Washington streets, the city launched the Newark Retail Reactivation Initiative.[168] The program makes monetary grants to certain qualifying businesses opening on Halsey and on other streets within the zone bordered by Broad Street to the east, Washington Street to the west, Washington Place to the north and William Street to the south.[169] The district has a mix of residential, commercial and office spaces.[170]

Port Newark

[edit]

Port Newark is the part of Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal and the largest cargo facility in the Port of New York and New Jersey. On Newark Bay, it is run by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and serves as the principal container ship facility for goods entering and leaving the New York metropolitan area and the northeastern quadrant of North America. The Port moved over $100 billion in goods in 2003, making it the 15th busiest in the world at the time, but was the number one container port as recently as 1985.[171] Plans are underway for billions of dollars of improvements–larger cranes, bigger railyard facilities, deeper channels, and expanded wharves.[172]

Property taxes

[edit]In 2018, the city had an average property tax bill of $6,481, the lowest in the county, compared to an average bill of $12,248 in Essex County and $8,767 statewide.[173][174]

Arts and culture

[edit]Architecture

[edit]

There are several notable Beaux-Arts buildings, such as the Veterans' Administration building, The Newark Museum of Art, the Newark Public Library, and the Cass Gilbert-designed Essex County Courthouse. Notable Art Deco buildings include several 1930s era skyscrapers, such as the National Newark Building and Eleven 80, the restored Newark Penn Station, and Arts High School. Gothic architecture can be found at the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart by Branch Brook Park, which is one of the largest Gothic cathedrals in the United States. It is rumored to have as much stained glass as the Cathedral of Chartres. Moorish Revival buildings include Newark Symphony Hall and the Prince Street Synagogue, one of the oldest synagogue buildings in New Jersey.[175]

Performing arts

[edit]

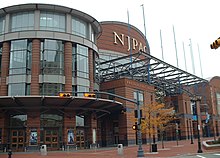

The New Jersey Performing Arts Center, near Military Park, opened in 1997, is the home of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra and the New Jersey State Opera, The center's programs of national and international music, dance, and theater make it the nation's sixth-largest performing arts center, attracting over 400,000 visitors each year.[176]

Prior to the opening of the performing arts center, Newark Symphony Hall was home to the New Jersey Symphony, the New Jersey State Opera, and the Garden State Ballet, which still maintains an academy there.[177] The 1925 neo-classical building, originally built by the Shriners, has three performance spaces, including the main concert hall named in honor of famous Newarker Sarah Vaughan, offering rhythm and blues, rap, hip-hop, and gospel music concerts, and is part of the modern-day Chitlin' Circuit.[178]

The Newark Boys Chorus, founded in 1966, performs regularly in the city. The African Globe Theater Works presents new works seasonally. The biennial Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival took place in Newark for the first time in 2010.[179]

Venues at the universities in the city are also used to present professional and semi-professional theater, dance, and music. Since its opening in 2007, the Prudential Center has presented Diana Ross, Katy Perry, Lady Gaga, Britney Spears, The Eagles, Hannah Montana/Miley Cyrus, Bruce Springsteen, Spice Girls, Jonas Brothers, Metro Station, Metallica, Alicia Keys, Fleetwood Mac, Demi Lovato, David Archuleta, Aerosmith, Taylor Swift, Paul McCartney, and American Idol Live!, among others. The Rolling Stones broadcast their last show on their 50th anniversary tour live on pay-per-view from the arena on December 15, 2012. Bon Jovi performed a series of ten concerts to mark the venue's opening.[180]

In the house music and garage house genres and scene, Newark is known as an innovator.[181] Newark's Club Zanzibar, along with other gay and straight clubs in the 1970s and 1980s, was famous as both a gay and straight nightlife destination. Famed DJ Tony Humphries helped "spawn the sometimes raw but always soulful, gospel-infused subgenre" of house music known as the New Jersey sound.[182][183] The club scene also gave rise to the ball culture scene in Newark hotels and nightclubs.[184] Brick City club, a dance-oriented electronic music genre, is native to the city.[185]

Museums, libraries, and galleries

[edit]

The Newark Museum of Art, formerly known as the Newark Museum, is the largest museum in New Jersey. Its art collection is ranked 12 among art museums in North America with highlights on American and Tibetan art.[186] The museum also contains science galleries, a planetarium, a gallery for children's exhibits, a fire museum, a sculpture garden and an 18th-century schoolhouse. Also part of the museum is the historic John Ballantine House, a restored Victorian mansion which is a National Historic Landmark.

The city is also home to the New Jersey Historical Society, which has rotating exhibits on New Jersey and Newark. The Newark Public Library has eight locations.[187] The library houses more than a million volumes and has frequent exhibits on a variety of topics, many featuring items from its Fine Print and Special Collections.[188] The library also hosts daily programs including ESL classes, yoga classes, arts and crafts, history talks, and more.[189]

Since 1962, Newark has been home to the Institute of Jazz Studies, the world's foremost jazz archives and research libraries.[190] Located in the John Cotton Dana Library at Rutgers-Newark, the Institute houses more than 200,000 jazz recordings in all commercially available formats, more than 6,000 monograph titles, including discographies, biographies, history and criticism, published music, film and video; over 600 periodicals and serials, dating back to the early 20th century; and one of the country's most comprehensive jazz oral history collections, featuring more than 150 jazz oral histories, most with typed transcripts.[191]

The Jewish Museum of New Jersey, located at 145 Broadway in the Broadway neighborhood, opened in December 2007.[192] The museum is dedicated to the cultural heritage of New Jersey's Jewish people. The museum is housed at Ahavas Sholom, the last continually operating synagogue in Newark.[193][194] By the 1950s there were 50 synagogues in Newark serving a Jewish population of 70,000 to 80,000, once the sixth-largest Jewish community in the United States.[195][196]

The Grammy Museum Experience was an interactive, experiential museum devoted to the history and winners of the Grammy Awards at the Prudential Center from 2017 to 2023.

Newark is also home to numerous art galleries including the Paul Robeson Galleries at Rutgers University–Newark,[197] as well as Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art, City Without Walls, Gallery Aferro and Sumei Arts Center.[198]

Public art

[edit]Newark has four public works by Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum in Newark, which include Seated Lincoln (1911), Indian and the Puritan (1916), First Landing Party of the Founders of Newark (1916), and Wars of America (1926).

Newark Murals

[edit]Since 2009, the Newark Planning Office, in collaboration with local arts organizations, has sponsored Newark Murals, and seen the creation of dozens of outdoor murals about significant people, places, and events in the city.[199]

The Portraits mural, a massive multi-artist painting the length of 25 football fields created in 2016, is the longest continuous mural on the East Coast, and the second longest in the country.[200] Seventeen artists contributed sections to the mural, including Adrienne Wheeler, Akintola Hanif, David Oquendo, Don Rimx, El Decertor, GAIA, GERA, Kevin Darmanie, Khari Johnson-Ricks, Lunar New Year, Manuel Acevedo, Mata Ruda, Nanook, Nina Chanel Abney, Sonni, Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, WERC and Zeh Palito.[201] "Portraits" begins roughly at the intersection of Poiner Street and McCarter Highway in the South Ironbound district and stretches northwards 1.39 miles (2.24 km) along the century-old stone walls supporting the Northeast Corridor and PATH tracks facing Newark's McCarter Highway (New Jersey Route 21).[202]

Festivals and parades

[edit]Festivals and parades held annually or bi-annually include the Cherry Blossom Festival (April) in Branch Brook Park and the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival (October, biennial) at various venues and the citywide Open Doors (October),[203]

Music festivals include the McDonald's Gospelfest (spring) at Prudential Center, the Lincoln Park Music Festival (July)[204] at Lincoln Park, the Afro Beat Fest (July) at Military Park,[205] and the James Moody Jazz Festival, named for James Moody, the jazz artist raised in Newark (week-long event in November).[206] The Weequahic Park House Music Festival takes place every September in Weequahic Park.[207]

The Portugal Day Festival in the Ironbound section, takes place in June. St. Lucy's Church, a historically Italian parish in what was Newark's Little Italy, features an annual October procession and festival for St. Gerard Majella. Our Lady of Mt. Carmel in the Ironbound hosts its annual Italian Street Festival every July.

Newark is home to a number of annual film festivals, including the Newark Black Film Festival.[208] The North to Shore Festival, inaugurated in June 2023, featured music and other entertainment events in Newark as well as Asbury Park and Atlantic City.[209]

Parks and recreation

[edit]Colonial commons

[edit]

- Military Park in Downtown Newark, the town commons since 1869 and home to the Wars of America sculpture by Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum and the casual restaurant, Burg.[210] As of 2018, the park is privately operated. Managed by a nonprofit corporation, the Military Park Partnership, which is staffed by Dan Biederman and Biederman Redevelopment Ventures, credited with transforming Manhattan's Bryant Park. The Military Park Partnership manages the programs, events, operations, security, and horticulture of the park.

- Lincoln Park in the Arts District, one of three original colonial-era commons in Newark. From the 1920s to the 1950s, Lincoln Park was at the southern end of Newark's jazz and nightlife strip known as "The Coast."

- Harriet Tubman Square, the northernmost of the three original colonial-era commons in Newark. Formerly known as Washington Park, the equestrian statue of George Washington by J. Massey Rhind was dedicated here in 1912.[211] Philip Roth's narrator in Goodbye, Columbus visits the park, saying "Sitting there in the park, I felt a deep knowledge of Newark, an attachment so rooted that it could not help but branch out into affection."[212]

Passaic River waterfront

[edit]

- Riverfront Park, which stretches along the Passaic River, includes the "Orange Boardwalk" & paths with views of the water.[213][214][215][216][217]

County parks

[edit]

Several parks in the city are part of the Essex County Park System.

- Branch Brook Park is home to Newark's annual Cherry Blossom Festival.[218] The park is the oldest county park in the United States and is home to the nation's largest collection of cherry blossom trees, numbering over 5,000.[219][220][221][222] The park also features a lake and a pond. It was designed by the Olmsted Brothers firm, who carried on the firm of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted.[223]

- Independence Park is in the Ironbound district.[224][225][226]

- Ivy Hill Park in Ivy Hill[227][228]

- Vailsburg Park, covering 30.32 acres (12.27 ha), is in the Vailsburg neighborhood.[229]

- Riverbank Park[230] in the Ironbound along the Passaic River.[231]

- Veterans Memorial Park is adjacent to the county courthouse complex.[232]

- Weequahic Park, also designed by Olmsted Brothers, located in the South Ward in the Dayton section, east of the formerly heavily Jewish[233] Weequahic neighborhood. It features 80-acre (320,000 m2) Weequahic Lake, an anthropogenic lake formed out of a marsh.[234] Author Philip Roth describes the park in his historical fantasy novel The Plot Against America (2004). The non-profit Weequahic Park Sports Authority helps maintain the park.[235][236]

- West Side Park is a 30.36-acre (12.29 ha) park in the West Side neighborhood.[237][238]

Municipal parks and squares

[edit]- Peter Francisco Park, the gateway to the Ironbound at Five Corners.

- Jesse Allen Park, in the Central Ward. The 8-acre (3.2 ha) Jesse Allen Park is Newark's second-largest city-owned park and is named for a former member of the Municipal Council of Newark.[239][240]

- The Greater Newark Conservancy maintains the Judith L. Shipley Urban Environmental Center,[241][242] and the Prudential Outdoor Learning Center.[243][244] It offers urban farming and gardening displays and instruction and also includes a small pond.

- Mulberry Commons is a park between Prudential Center and Penn Station near what was once the heart of Newark's Chinatown.[245]

- Nat Turner Park. Dedicated in July 2009, Newark's largest city-owned park is located in the Central Ward. It is named for the famous 19th-century American slave rebellion leader, Nat Turner.[246]

Golf and other recreational facilities

[edit]- Sharpe James/Kenneth A. Gibson (Ironbound) Recreation Center.[247]

- John F. Kennedy Recreation & Aquatic Center[247]

- Rotunda Recreation & Wellness Center[247]

- Marquis "Bo" Porter Recreation & Aquatic Center[247]

- Hayes Park West Recreation Center[247]

- Bradley Court Housing Complex[247]

- Weequahic Golf Course is an 18-hole public course.[248] The facility was described in 2016 by the Golf Channel as a "hidden gem".[249] Home to The First Tee Program of Essex County and golf pro Wiley Williams, who was one of the first African-American golfers to win a major New Jersey golf event and works to introduce city youth to the sport.[250][251]

- Jesse Allen Skateboard Park.[252]

Media

[edit]Newark is within the metro New York media market.[253]

Newspapers

[edit]

The state's leading newspaper, The Star-Ledger, owned by Advance Publications, is based in Newark. The newspaper sold its headquarters in July 2014, with the offices of the publisher, the editorial board, columnists, and magazine relocating to the Gateway Center.[254] The Newark Targum is a weekly student newspaper published by the Targum Publishing Company for the student population of the Newark campus of Rutgers University.

Other news outlets

[edit]- TAP Into Newark is an online news site devoted to Newark.[255]

- Newark Patch is a daily online news source dedicated to local Newark news.[256]

- Local Talk is a local paper on Newark and the surrounding area.[257]

- The Newarker is a quarterly journal about culture, history, and society in Newark and surrounding areas.[258]

- The Newark Times is an online news media platform dedicated to Newark lifestyle, events, and culture.[259]

- The Newark Metro covers metropolitan life from Newark to North Jersey to New York City and is a journalism project at Rutgers Newark.[260]

- RLS Media covers breaking news from Newark and surrounding municipalities.[261]

- The City of Newark shares news and events via its official Twitter account.[262]

- The Pod, developed by Black Owned New Jersey, is a weekly podcast that helps small businesses build, grow, and maintain their business.

Radio

[edit]

Pioneer radio station WOR was started by Bamberger Broadcasting Service in 1922 and broadcast from studios at its retailer's downtown department store. Today the building serves telecom, colocation, and computer support industries known as 165 Halsey Street.[263]

Radio station WJZ (now WABC) made its first broadcast in 1921 from the Westinghouse plant near Broad Street Station. It moved to New York City in the 1920s. Radio station WNEW-AM (now WBBR) was founded in Newark in 1934 and later moved to New York City. WBGO, a National Public Radio affiliate with a format of standard and contemporary jazz, is at 54 Park Place in downtown Newark. WNSW AM-1430 (formerly WNJR) and WQXR (which was formerly WHBI and later WCAA) 105.9 FM are also licensed to Newark.[264]

Telephone

[edit]In 1915, the Bell System under ownership of American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) tested newly developed panel switching technology in Newark when they cutover the telephone exchanges Mulberry and Waverly to semi-mechanical operation on January 16 and June 12, respectively. The Panel system was the Bell System solution to the big city problem, where an exchange had to serve large numbers of subscribers on both manual as well as automatically switched central offices, without negatively impacting established user convenience and reliability. As originally introduced in these exchanges, subscribers' telephones had no dials and customers continued to make calls by asking an operator to ring their called party, at which point the operator keyed the telephone number into the panel equipment, instead of making cord connections manually.[265]

Most Panel installations across the country were replaced by modern systems during the 1970s and the last Panel switch was decommissioned in the BIgelow central office in Newark in 1983.[266]

While Newark, like all of New Jersey, had area code 201 assigned for long-distance calling since 1947, the rate center was reassigned to area code 973 in 1997, which was overlaid with area code 551 in 2001. With cellular service proliferating in Northern New Jersey in the 21st century, central office prefixes from the adjacent New Jersey NPAs (201, 551, 732/848, 908) were made available in the Newark rate center for cellular and voice over IP (VoIP) services.[20]

Television

[edit]

New Jersey's first television station, WATV Channel 13, signed-on May 15, 1948, from studios at the Mosque Theater known as the "Television Center Newark." The studios were home to WNTA-13 beginning in 1958 and WNJU-47 until 1989.[267]

WNET, the successor to WATV, is flagship station of the Public Broadcasting Service serving the New York market. Spanish-language WFUT-TV Channel 68, a UniMás owned-and-operated station, is also licensed to Newark. Tempo Networks, producing for the pan-Caribbean television market, is based in the city.[268] NwkTV has been the city's government access channel since 2009 and broadcast as Channel 78 on Optimum.[269][270] The company has a high-tech call center in Newark, employing over 500 people. PBS network NJTV's main broadcasting studios (NJTV is also a sister station of the Newark-licensed WNET) are also in the Gateway Center Office Complex.[271]

Film

[edit]The Newark Black Film Festival has been held annually since in 1974. The Newark International Film Festival is an annual event that has hosted screenings, workshops and stunt exhibitions in Newark since 2015. They are held under the auspices of the North to Shore Festival.[272]

The New Jersey Motion Picture and Television Commission is headquartered in the Newark.[273] In 2011, the city created the Newark Office of Film and Television in order to promote the making of media productions.[274][275]

There have been several film and TV productions depicting life in Newark. Life of Crime was originally produced in 1988 and was followed by a 1998 sequel.[276] New Jersey Drive is a 1995 film about the city when it was considered the "car theft capital of the world".[277] Street Fight is an Academy Award-nominated documentary film which covered the 2002 mayoral election between incumbent Sharpe James and challenger Cory Booker. In 2009, the Sundance Channel aired Brick City, a five-part television documentary about Newark, focusing on the community's attempt to become a better and safer place to live, against a history of nearly a half century of violence, poverty and official corruption. The second season premiered January 30, 2011.[278] Revolution '67 is a documentary which examines the causes and events of the 1967 Newark riots. The Once and Future Newark (2006) is a documentary travelogue about places of cultural, social and historical significance by Rutgers History Professor Clement Price.[279] The HBO television series The Sopranos filmed many of its scenes in Newark.[280] The Many Saints of Newark is a Sopranos prequel by David Chase set in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[281] Heart of Stone (2009) reflects on white flight in the heavily Jewish Weequahic section and Weequahic High School.[282] Rob Peace, is a film adaptation of The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace, the life story of a Newark native murdered in 2011.[283]

Numerous movies, television programs, and music videos have been shot in Newark, its period architecture and its streetscape seen as an ideal "urban setting". In 2012 the city hosted the seventh season of the reality show competition America's Got Talent.[284] Among the films shot in Newark are Bloodhounds of Broadway (1989),[285] Joker (depicting the abandoned movie palace known as the Newark Paramount Theatre),[286] Cat Person, and the 2022 horror movie, Smile, with several locations, including Murphy Varnish Lofts and Rutgers Medical School.[287] The movie The Perfect Find also had scenes filmed in Newark as did the movie, The Greatest Beer Run Ever.[288] Scenes for the movie Bros were filmed throughout the city in 2021, including at the Newark Museum, exterior of the which are shown as the LGBT museum.[287]

Studios

[edit]In 2009, the Ironbound Film & Television Studios, the only "stay and shoot" facility in the metro area opened, its first production being Bar Karma.[289]

In 2022, the city announced that a major new film and television production studio overlooking Weequahic Park and Weequahic Golf Course, to be called Lionsgate Newark Studios, would open in 2024 on the 15-acre former Seth Boyden housing projects site in the Dayton section of the city.[290][291][292]

Theatres

[edit]

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Newark had many theaters and movie houses that were vaudeville or burlesque style. As innovation occurred in film, Newark contributed to the development to the American film industry with local inventors' innovation of celluloid and its use as movie film.[293] The Newark movie theatres during this early part of the 20th century had established a large audience, with 62 movie houses in the city by 1922.[294]

Later, many of these locations were used for live performances of notable actors prior to becoming renowned. The introduction of television for entertainment during the 1940s and 1950s was the start of a decades-long decline in attendance in movie theaters. The last two downtown movie theatres were the Adams and the Newark Paramount Theatre, which both closed in 1986.[295] Attempts for movie theatre revivals were established in the 1990s. As of 2024, the CityPlex 12 Newark movie theatre, located off Springfield Avenue and Bergen Street, is the only theater in operation in the city. The New Jersey Performing Arts Center, located at 1 Center Street, is currently operating as theatre production and concerts.[296] The 2,800-seat Newark Symphony Hall located at 1020 Broad Street has been in operations since 1925.[297]

Sports

[edit]Newark has hosted many teams, though much of the time without an MLB, NBA, NHL, or NFL team in the city proper. Currently, the city is home to just one, the NHL's New Jersey Devils. As the second-largest city in the New York metropolitan area, Newark is part of the regional professional sports and media markets.[253][298][299]

The Prudential Center, a multi-purpose indoor arena designed by HOK Sport, is located in downtown adjacent to Newark Penn Station.[300] Known as "The Rock", the arena opened in 2007 and is the home of the Devils and the NCAA's Seton Hall Pirates men's basketball team, seating 18,711 for basketball and 16,514 for hockey.[301]

Downtown was also home to Bears & Eagles Riverfront Stadium, which was a 6,200-seat baseball park built near the Passaic River to house the Newark Bears, an independent minor league baseball team, and opened in 1999. Also serving as the home stadium for Rutgers-Newark and NJIT's college baseball teams, Riverfront Stadium closed in 2014 after the Bears ceased operations.[302] In 2016, the stadium was sold to a developer, and three years later it was demolished.[303]

| Club | Sport | Established | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Jersey Devils | Ice hockey | 1974 (Moved to East Rutherford in 1982, then Newark in 2007) | NHL | Prudential Center |

| Metropolitan Riveters | Ice hockey | 2016 | NWHL | Barnabas Health Hockey Center |

| Seton Hall Pirates | Basketball | 1908–1909 | NCAA Big East | Prudential Center |

The New Jersey Nets played two seasons (2010–2012) at the Prudential Center until moving to the Barclays Center.[304] The New York Liberty of the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) also played there for three seasons (2011–2013) during renovations of Madison Square Garden.[305] The center has hosted the 2012 Stanley Cup Finals, the 2011 NBA draft, and the 2013 NHL Entry Draft. EliteXC: Primetime, a mixed martial arts (MMA) event which took place on May 31, 2008, was the first MMA event aired in primetime on major American network television.[306]

Newark was a host city and its airport a gateway for Super Bowl XLVIII which was played on February 2, 2014.[307][308][309] The game took place at MetLife Stadium, home of the hosting teams New York Giants and New York Jets. Media Day, the first event leading up to the game, took place on January 28 at the Prudential Center. The original Vince Lombardi Trophy, produced by Tiffany & Co. in Newark in 1967 and borrowed from the Green Bay Packers, was displayed at the Newark Museum from January 8 until March 30, 2014.[310] Ultimate Fighting Championship's annual Super Bowl weekend mixed martial arts event, UFC 169: Cruz vs. Barao, took place on February 1 at the Prudential Center.[311]

Government

[edit]Local

[edit]The city is governed within the Faulkner Act, formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law, under the Mayor-Council Plan C form of local government, which became effective as of July 1, 1954, after the voters of the city of Newark passed a referendum held on November 3, 1953.[8][312] The city is one of 79 municipalities (of the 564) statewide that use this form of government.[313] The governing body is comprised of the Mayor and the City Council, who are elected concurrently on a non-partisan basis to four-year terms of office at the May municipal election. The mayor is directly elected by the residents of Newark. The city council comprises nine members, with one council member from each of the city's five wards and four council members who are elected on an at-large basis.[314] The structure of the council was established after a 1953 referendum, in which more than 65% of voters approved a change from a five-member commission.[315]

As of 2023[update], the Mayor of Newark is Ras Baraka, who is serving a third term of office ending on June 30, 2026;[4] Baraka first took office as the city's 40th mayor on July 1, 2014.[316] Members of Newark's Municipal Council are Council President LaMonica McIver (Central Ward), Luis A. Quintana (at-large), Patrick O. Council (South Ward), C. Lawrence Crump (at-large), Carlos M. Gonzalez (at-large), Dupré L. Kelly (West Ward), Anibal Ramos Jr. (North Ward), Louise Scott-Rountree (at-large) and Michael J. Silva (East Ward), all serving concurrent terms of office ending June 30, 2026.[317][318][319][320][321]

Federal, state, and county

[edit]Newark is split between the 8th and 10th Congressional Districts[322] and is part of New Jersey's 28th and 29th state legislative districts.[323][324][325][326] Prior to the 2010 census, Newark had been split between the 10th Congressional District and the 13th Congressional District, a change made by the New Jersey Redistricting Commission that took effect in January 2013, based on the results of the November 2012 general elections.[326] As part of the split that took effect in 2013, 123,763 residents in two non-contiguous sections in the city's north and northeast were placed in the 8th District and 153,377 in the southern and western portions of the city were placed in the 10th District.[322][327]

For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 8th congressional district is represented by Rob Menendez (D, Jersey City).[328][329] For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 10th congressional district is represented by Donald Payne Jr. (D, Newark).[330][331] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027)[332] and Bob Menendez (Englewood Cliffs, term ends 2025).[333][334]

For the 2024-2025 session, the 28th legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Renee Burgess (D, Irvington) and in the General Assembly by Garnet Hall (D, Maplewood) and Cleopatra Tucker (D, Newark).[335] For the 2024-2025 session, the 29th legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Teresa Ruiz (D, Newark) and in the General Assembly by Eliana Pintor Marin (D, Newark) and Shanique Speight (D, Newark).[336]

Essex County is governed by a directly elected county executive, with legislative functions performed by the Board of County Commissioners. As of 2024[update], the County Executive is Joseph N. DiVincenzo Jr. (D, Roseland), whose four-year term of office ends December 31, 2026.[337] The county's Board of County Commissioners is composed of nine members, five of whom are elected from districts and four of whom are elected on an at-large basis. They are elected for three-year concurrent terms and may be re-elected to successive terms at the annual election in November.[338] Essex County's Commissioners are:

Robert Mercado (D, District 1 – Newark's North and East Wards, parts of Central and West Wards; Newark, 2026),[339] A'Dorian Murray-Thomas (D, District 2 – Irvington, Maplewood and parts of Newark's South and West Wards; Newark, 2026),[340] Vice President Tyshammie L. Cooper (D, District 3 - Newark: West and Central Wards; East Orange, Orange and South Orange; East Orange, 2026),[341] Leonard M. Luciano (D, District 4 – Caldwell, Cedar Grove, Essex Fells, Fairfield, Livingston, Millburn, North Caldwell, Roseland, Verona, West Caldwell and West Orange; West Caldwell, 2026),[342] President Carlos M. Pomares (D, District 5 – Belleville, Bloomfield, Glen Ridge, Montclair and Nutley; Bloomfield, 2026),[343] Brendan W. Gill (D, at large; Montclair, 2026),[344] Romaine Graham (D, at large; Irvington, 2026),[345] Wayne Richardson (D, at large; Newark, 2026),[346] Patricia Sebold (D, at-large; Livingston, 2026).[347][348][349][350][351]

Constitutional officers elected countywide are: Clerk Christopher J. Durkin (D, West Caldwell, 2025),[352][353] Register of Deeds Juan M. Rivera Jr. (D, Newark, 2025),[354][355] Sheriff Armando B. Fontoura (D, Fairfield, 2024),[356][357] and Surrogate Alturrick Kenney (D, Newark, 2028).[358][359]

Politics

[edit]On the national level, Newark leans strongly toward the Democratic Party. As of March 23, 2011, out of a 2010 census population of 277,140 in Newark, there were 136,785 registered voters (66.3% of the 2010 population ages 18 and over of 206,253, vs. 77.7% in all of Essex County of the 589,051 ages 18 and up) of which 68,393 (50.0% vs. 45.9% countywide) were registered as Democrats, 3,548 (2.6% vs. 9.9% countywide) were registered as Republicans, 64,812 (47.4% vs. 44.1% countywide) were registered as Unaffiliated and there were 30 voters registered to other parties.[360]

In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 90.8% of the vote (77,112 ballots cast), ahead of Republican John McCain who received 7.0% of the vote (5,957 votes), with 84,901 of the city's 140,946 registered voters participating, for a turnout of 60.2% of registered voters.[361] In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 95.0% of the vote (78,352 cast), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 4.7% (3,852 votes), and other candidates with 0.4% (298 votes), among the 82,030 ballots cast by the city's 145,059 registered voters for a turnout of 56.5%.[362][363] In the 2016 presidential election, Democrat Hillary Clinton received 90.7% of the vote (69,042 cast); Republican Donald Trump received 6.7% of the vote (5,094 cast); and other candidates received 1.5% of the vote (1,139 cast).[364]

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Democrat Barbara Buono received 80.8% of the vote (29,039 cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 17.9% (6,443 votes), and other candidates with 1.2% (437 votes), among the 37,114 ballots cast by the city's 149,778 registered voters (1,195 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 24.8%.[365][366] In the 2009 Gubernatorial Election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 90.2% of the vote (36,637 ballots cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie who received 8.3% of the vote (3,355 votes), with 40,613 of the city's 134,195 registered voters (30.3%) participating.[367]

Political corruption

[edit]Newark has been marred with political corruption throughout the years. Five of the previous[when?] seven mayors of Newark have been indicted on criminal charges, including the three mayors before Cory Booker: Hugh Addonizio, Kenneth Gibson and Sharpe James. As reported by Newsweek: "... every mayor since 1962 (except one, Cory Booker) has been indicted for crimes committed while in office".[368]

Addonizio was mayor of Newark from 1962 to 1970. A son of Italian immigrants, a tailor and World War II veteran, he ran on a reform platform, defeating the incumbent, Leo Carlin, whom, ironically, Addonizio characterized as corrupt and a part of the political machine of the era. In December 1969, Addonizio and nine present or former officials of the municipal administration in Newark were indicted by a Federal grand jury; five other persons were also indicted.[369] In July 1970, the former mayor, and four other defendants, were found guilty by a Federal jury on 64 counts each, one of conspiracy and 63 of extortion.[370] In September 1970, Addonizio was sentenced to ten years in federal prison and fined $25,000 by Federal Judge George H. Barlow for his role in a plot that involved the extortion of $1.5 million in kickbacks, a crime that the judge said "tore at the very heart of our civilized society and our form of representative government".[371][372]

His successor was Kenneth Gibson, the city's first African American mayor, elected in 1970. He pleaded guilty to federal tax evasion in 2002 as part of a plea agreement on fraud and bribery charges. During his tenure as mayor in 1980, Gibson was tried and acquitted of giving out no-show jobs by an Essex County jury.[373]

Sharpe James, who defeated Gibson in 1986 and declined to run for a sixth term in 2006, was indicted on 33 counts of conspiracy, mail fraud, and wire fraud by a federal grand jury sitting in Newark. The grand jury charged James with spending $58,000 on city-owned credit cards for personal gain and orchestrating a scheme to sell city-owned land at below-market prices to his companion, who immediately re-sold the land to developers and gained a profit of over $500,000. James pleaded not guilty on 25 counts at his initial court appearance on July 12, 2007. On April 17, 2008, James was found guilty for his role in the conspiring to rig land sales at nine city-owned properties for personal gain. The former mayor was sentenced to serve up to 27 months in prison, and was released on April 6, 2010, for good behavior.[374]

Education

[edit]Colleges and universities

[edit]Newark is the home of multiple institutions of higher education, including: a Berkeley College campus,[375] the main campus of Essex County College,[376] New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT),[377] the Newark Campus of Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences (formerly University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey),[378] Rutgers University–Newark,[379] Seton Hall University School of Law,[380] and Pillar College. Kean University is located in adjacent Union, New Jersey. Most of Newark's academic institutions are in the city's University Heights district. The colleges and universities have worked together to help revitalize the area, which serves more than 60,000 students and faculty.[381]

Public schools

[edit]

In the 2013–2017 American Community Survey, 13.6% of Newark residents ages 25 and over had never attended high school and 12.5% did not graduate from high school, while 74.1% had graduated from high school, including the 14.4% who had earned a bachelor's degree or higher.[382] The total school enrollment in Newark was 77,097 in the 2013–2017 ACS, with nursery and preschool enrollment of 7,432, elementary / high school (K–12) enrollment of 49,532 and total college / graduate school enrollment of 20,133.[383]

The Newark Public Schools, a state-operated school district for two decades and until 2018,[384] is the largest school system in New Jersey. The district was one of 31 former Abbott districts statewide that were established pursuant to the decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court in Abbott v. Burke[385] which are now referred to as "SDA Districts" based on the requirement for the state to cover all costs for school building and renovation projects in these districts under the supervision of the New Jersey Schools Development Authority.[386][387] As of the 2020–21 school year, the district, comprised of 65 schools, had an enrollment of 40,423 students and 2,886.5 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 14.0:1.[388]

Science Park High School, which was the 69th-ranked public high school in New Jersey out of 322 schools statewide, in New Jersey Monthly magazine's September 2010 cover story on the state's "Top Public High Schools", after being ranked 50th in 2008 out of 316 schools. Technology High School has a GreatSchools rating of 9/10 and was ranked 165th in New Jersey Monthly's 2010 rankings. Newark high schools ranked in the bottom 10% of the New Jersey Monthly 2010 list include Central (274th), East Side (293rd), Newark Vocational (304th), Weequahic (310th), Barringer (311th), Malcolm X Shabazz (314th) and West Side (319th).[389] Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg donated a challenge grant of $100 million to the district in 2010, choosing Newark because he stated he believed in Mayor Cory Booker and Governor Chris Christie's abilities.[390]

Charter schools in Newark include the Robert Treat Academy Charter School, a National Blue Ribbon School drawing students from all over Newark. It remains one of the top performing K–8 schools in New Jersey based on standardized test scores.[391] University Heights Charter School is another charter school, serving children in grades K–5, recognized as a 2011 Epic Silver Gain School.[392] Gray Charter School, like Robert Treat, also won a Blue Ribbon Award.[393] Also, Newark Collegiate Academy (NCA) opened in August 2007 and serves 420 students in grades 9–12. It will ultimately serve over 570 students, mostly matriculating from other charter schools in the area.[394]

Private schools

[edit]The city hosts three high schools as part of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark: the coeducational Christ The King Prep, founded in 2007, is part of the Cristo Rey Community; Saint Benedict's Preparatory School is an all-boys Roman Catholic high school founded in 1868 and conducted by the Benedictine monks of Newark Abbey, whose campus has grown to encompass both sides of MLK Jr. Blvd. near Market Street and includes a dormitory for boarding students; and Saint Vincent Academy which is an all-girls Roman Catholic high school founded and sponsored by the Sisters of Charity of Saint Elizabeth and operated continuously since 1869.[395]

Link Community School is a non-denominational coeducational day school that serves approximately 128 students in seventh and eighth grades. The Newark Boys Chorus School was founded in the 1960s.[396] University Heights Charter School, which opened in 2006, taught 614 students in grades Pre-K–8 in 2014–2015.[397]

Public safety

[edit]Newark Department of Public Safety

[edit]In 2016, under Mayor Ras Baraka's direction, the city consolidated the then-separate departments of Fire, Police, and Office of Emergency Management as divisions under the newly created Department Of Public Safety.[398]

Fire department

[edit]