Каталония

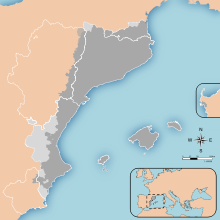

Каталония ( / ˌ k æ ˈ t ə l oʊ n i ə / ; каталонский : Catalunya [ kətəˈluɲə] ; Испанский : Каталония [cataluɲa] ; Окситанский : Каталония [каталония] ) [ 9 ] является автономным сообществом Испании , обозначенным как гражданство согласно Статуту автономии . [ д ] [ 11 ] Большая часть ее территории (кроме Валь д'Аран ) лежит на северо-востоке Пиренейского полуострова , южнее Пиренейского горного хребта. Каталония административно разделена на четыре провинции или восемь вегерий (регионов), которые, в свою очередь, делятся на 42 комарка . Столица и крупнейший город Барселона является вторым по численности населения муниципалитетом Испании и пятым по численности населения городским районом Европейского Союза . [ 12 ]

Modern-day Catalonia comprises most of the medieval and early modern Principality of Catalonia (with the remainder northern area now part of France's Pyrénées-Orientales). It is bordered by France (Occitanie) and Andorra to the north, the Mediterranean Sea to the east, and the Spanish autonomous communities of Aragon to the west and Valencia to the south. In addition to about 580 km of coastline, Catalonia also has major high landforms such as the Pyrenees and the Pre-Pyrenees, the Transversal Range (Serralada Transversal) or the Central Depression.[13] The official languages are Catalan, Spanish and the Aranese dialect of Occitan.[6]

In the late 8th century, various counties across the eastern Pyrenees were established by the Frankish kingdom as a defensive barrier against Muslim invasions. In the 10th century, the County of Barcelona became progressively independent.[14] In 1137, Barcelona and the Kingdom of Aragon were united by marriage, resulting in a composite monarchy known as the Crown of Aragon. Within the Crown, the Catalan counties merged in to a polity, the Principality of Catalonia, developing its own institutional system, such as Catalan Courts, Generalitat and constitutions, becoming the base for the Crown's Mediterranean trade and expansionism. In the later Middle Ages, Catalan literature flourished. In 1469, the monarchs of the crowns of Aragon and Castile were married and ruled their realms together, retaining all of their distinct institutions and legislation.

During the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659), the Principality of Catalonia revolted (1640–1652) against a burdensome presence of the royal army, being briefly proclaimed a republic under French protection. By the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), the northern parts of Catalonia, mostly the Roussillon, were ceded to France. During the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), the Crown of Aragon sided against the Bourbon Philip V of Spain, but after the Peace of Utrecht (1713) the Catalans were defeated with the fall of Barcelona on 11 September 1714. Philip V subsequently imposed a unifying administration across Spain, enacting the Nueva Planta decrees which, like in the other realms of the Crown of Aragon, suppressed Catalan institutions and legislation. As a consequence, Catalan as a language of government and literature was eclipsed by Spanish.

In the 19th century, Catalonia was severely affected by the Napoleonic and Carlist Wars. In the second third of the century, it experienced industrialisation. As wealth from the industrial expansion grew, it saw a cultural renaissance coupled with incipient nationalism while several workers' movements appeared. The establishment of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939) granted self-governance to Catalonia, being restored the Generalitat as the autonomous government. After the Spanish Civil War, the Francoist dictatorship enacted repressive measures, abolishing Catalan self-government and banning the official use of the Catalan language. After a period of autarky, from the late 1950s through to the 1970s Catalonia saw rapid economic growth, drawing many workers from across Spain, making Barcelona one of Europe's largest industrial metropolitan areas and turning Catalonia into a major tourist destination. During the Spanish transition to democracy (1975–1982), the Generalitat was reestablished and Catalonia regained self-government, remaining one of the most economically dynamic communities in Spain.

In the 2010s, there was growing support for Catalan independence. On 27 October 2017, the Catalan Parliament unilaterally declared independence following a referendum that was deemed unconstitutional by the Spanish state. The Spanish Senate voted in favour of enforcing direct rule by removing the Catalan government and calling a snap regional election. The Spanish Supreme Court imprisoned seven former ministers of the Catalan government on charges of rebellion and misuse of public funds, while several others—including then-President Carles Puigdemont—fled to other European countries. Those in prison[e] were pardoned by the Spanish government in 2021.

In the early-to-mid 2020s, support for independence in Catalonia declined again.

Etymology and pronunciation

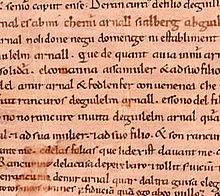

[edit]The name "Catalonia" (Medieval Latin: Cathalaunia), spelled Cathalonia, began to be used for the homeland of the Catalans (Cathalanenses) in the late 11th century and was probably used before as a territorial reference to the group of counties that comprised part of the March of Gothia and the March of Hispania under the control of the Count of Barcelona and his relatives.[16] The origin of the name Catalunya is subject to diverse interpretations because of a lack of evidence.

One theory suggests that Catalunya derives from the name Gothia (or Gauthia) Launia ("Land of the Goths"), since the origins of the Catalan counts, lords and people were found in the March of Gothia, known as Gothia, whence Gothland > Gothlandia > Gothalania > Cathalaunia > Catalonia theoretically derived.[17][18] During the Middle Ages, Byzantine chroniclers claimed that Catalania derives from the local medley of Goths with Alans, initially constituting a Goth-Alania.[19]

Other theories suggest:

- Catalunya derives from the term "land of castles", having evolved from the term castlà or castlan, the medieval term for a castellan (a ruler of a castle).[17][20] This theory therefore suggests that the names Catalunya and Castile have a common root.

- The source is the Celtic catalauni, meaning "chiefs of battle", similar to the Celtic given name *Katuwalos;[21] although the area is not known to have been occupied by the Celtiberians, a Celtic culture was present within the interior of the Iberian Peninsula in pre-Roman times.[22]

- The Lacetani, an Iberian tribe that lived in the area and whose name, due to the Roman influence, could have evolved by metathesis to Katelans and then Catalans.[23]

- Miguel Vidal, finding serious shortcomings with earlier proposals (such as that an original -t- would have, by normal sound laws in the local Romance languages, developed into -d-), suggested an Arabic etymology: qattāl (قتال, pl. qattālūn قتالون) – meaning "killer" – could have been applied by Muslims to groups of raiders and bandits on the southern border of the Marca Hispanica.[24] The name, originally derogatory, could have been reappropriated by Christians as an autonym. This is comparable to attested development of the term Almogavar in nearby areas. In this model, the name Catalunya derives from the plural qattālūn while the adjective and language name català derives from the singular qattāl, both with the addition of common Romance suffixes.[25]

In English, Catalonia is pronounced /kætəˈloʊniə/. The native name, Catalunya, is pronounced [kətəˈluɲə] in Central Catalan, the most widely spoken variety, and [kataˈluɲa] in North-Western Catalan. The Spanish name is Cataluña ([kataˈluɲa]), and the Aranese name is Catalonha ([kataˈluɲa]).

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]

The first known human settlements in what is now Catalonia were at the beginning of the Middle Paleolithic. The oldest known trace of human occupation is a mandible found in Banyoles, described by some sources[which?] as pre-Neanderthal, that is, some 200,000 years old; other sources suggest it to be only about one third that old.[26] From the next prehistoric era, the Epipalaeolithic or Mesolithic, important remains survive, the greater part dated between 8000 and 5000 BC, such as those of Sant Gregori (Falset) and el Filador (Margalef de Montsant). The most important sites from these eras, all excavated in the region of Moianès, are the Balma del Gai (Epipaleolithic) and the Balma de l'Espluga (late Epipaleolithic and Early Neolithic).[27]

The Neolithic era began in Catalonia around 5000 BC, although the population was slower to develop fixed settlements than in other places, thanks to the abundance of woods, which allowed the continuation of a fundamentally hunter-gatherer culture. An example of such settlements would be La Draga at Banyoles, an "early Neolithic village which dates from the end of the 6th millennium BC."[28]

The Chalcolithic period developed in Catalonia between 2500 and 1800 BC, with the beginning of the construction of copper objects. The Bronze Age occurred between 1800 and 700 BC. There are few remnants of this era, but there were some known settlements in the low Segre zone. The Bronze Age coincided with the arrival of the Indo-Europeans through the Urnfield Culture, whose successive waves of migration began around 1200 BC, and they were responsible for the creation of the first proto-urban settlements.[29] Around the middle of the 7th century BC, the Iron Age arrived in Catalonia.

Pre-Roman and Roman period

[edit]

In pre-Roman times, the area that is now called Catalonia in the north-east of Iberian Peninsula – like the rest of the Mediterranean side of the peninsula – was populated by the Iberians. The Iberians of this area – the Ilergetes, Indigetes and Lacetani (Cerretains) – also maintained relations with the peoples of the Mediterranean. Some urban agglomerations became relevant, including Ilerda (Lleida) inland, Hibera (perhaps Amposta or Tortosa) or Indika (Ullastret). Coastal trading colonies were established by the ancient Greeks, who settled around the Gulf of Roses, in Emporion (Empúries) and Roses in the 8th century BC. The Carthaginians briefly ruled the territory in the course of the Second Punic War and traded with the surrounding Iberian population.

After the Carthaginian defeat by the Roman Republic, the north-east of Iberia became the first to come under Roman rule and became part of Hispania, the westernmost part of the Roman Empire. Tarraco (modern Tarragona) was one of the most important Roman cities in Hispania and the capital of the province of Tarraconensis. Other important cities of the Roman period are Ilerda (Lleida), Dertosa (Tortosa), Gerunda (Girona) as well as the ports of Empuriæ (former Emporion) and Barcino (Barcelona). As for the rest of Hispania, Latin law was granted to all cities under the reign of Vespasian (69–79 AD), while Roman citizenship was granted to all free men of the empire by the Edict of Caracalla in 212 AD (Tarraco, the capital, was already a colony of Roman law since 45 BC). It was a rich agricultural province (olive oil, wine, wheat), and the first centuries of the Empire saw the construction of roads (the most important being the Via Augusta, parallel to Mediterranean coastline) and infrastructure like aqueducts.

Conversion to Christianity, attested in the 3rd century, was completed in urban areas in the 4th century. Although Hispania remained under Roman rule and did not fall under the rule of Vandals, Suebi and Alans in the 5th century, the main cities suffered frequent sacking and some deurbanization.

Middle Ages

[edit]

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the area was conquered by the Visigoths and was ruled as part of the Visigothic Kingdom for almost two and a half centuries. In 718, it came under Muslim control and became part of Al-Andalus, a province of the Umayyad Caliphate. From the conquest of Roussillon in 760, to the conquest of Barcelona in 801, the Frankish empire took control of the area between Septimania and the Llobregat river from the Muslims and created heavily militarised, self-governing counties. These counties formed part of the historiographically known as the Gothic and Hispanic Marches, a buffer zone in the south of the Frankish Empire in the former province of Septimania and in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, to act as a defensive barrier for the Frankish Empire against further Muslim invasions from Al-Andalus.[30]

These counties came under the rule of the counts of Barcelona, who were Frankish vassals nominated by the emperor of the Franks, to whom they were feudatories (801–988). The earliest known use of the name "Catalonia" for these counties dates to 1117. At the end of the 9th century, the Count of Barcelona Wilfred the Hairy (878–897) made his titles hereditaries and thus founded the dynasty of the House of Barcelona, which reigned in Catalonia until 1410.

In 988 Borrell II, Count of Barcelona, did not recognise the new French king Hugh Capet as his king, evidencing the loss of dependency from Frankish rule and confirming his successors (from Ramon Borrell I onwards) as independent of the Capetian crown whom they regarded as usurpers of the Carolingian Frankish realm.[31] At the beginning of eleventh century the Catalan counties experienced an important process of feudalisation, however, the efforts of church's sponsored Peace and Truce Assemblies and the intervention of Ramon Berenguer I, count of Barcelona (1035–1076) in the negotiations with the rebel nobility resulted in the partial restoration of the comital authority under the new feudal order. To fulfill that purpose, Ramon Berenguer began the modification of the legislation in the written Usages of Barcelona, being one of the first European compilations of feudal law.

In 1137, Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona decided to accept King Ramiro II of Aragon's proposal to receive the Kingdom of Aragon and to marry his daughter Petronila, establishing the dynastic union of the County of Barcelona with Aragon, creating a composite monarchy later known as the Crown of Aragon and making the Catalan counties that were vassalized or merged with the County of Barcelona into a principality of the Aragonese Crown. During the reign of his son Alphons, in 1173, Catalonia was regarded as a legal entity for the first time, while the Usages of Barcelona were compiled in the process to turn them into the law and custom of Catalonia (Consuetudinem Cathalonie), being considered one of the "milestones of Catalan political identity".[32]

In 1258, by means of the Treaty of Corbeil, James I of Aragon King of Aragon and Count of Barcelona, king of Mallorca and of Valencia, renounced his family rights and dominions in Occitania, while the king of France, Louis IX, formally relinquished to any historical claim of feudal lordship he might have over the Catalan counties, except the County of Foix, despite the opposition of king James.[33] This treaty confirmed, from French point of view, the independence of the Catalan counties established and exercised during the previous three centuries, but also meant the irremediable separation between the geographical areas of Catalonia and Languedoc.

As a coastal territory, Catalonia became the base of the Aragonese Crown's maritime forces, which spread the power of the Crown in the Mediterranean, turning Barcelona into a powerful and wealthy city. In the period of 1164–1410, new territories, the Kingdom of Valencia, the Kingdom of Majorca, the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Kingdom of Sicily, and, briefly, the Duchies of Athens and Neopatras, were incorporated into the dynastic domains of the House of Aragon. The expansion was accompanied by a great development of the Catalan trade, creating an extensive trade network across the Mediterranean which competed with those of the maritime republics of Genoa and Venice.

At the same time, the Principality of Catalonia developed a complex institutional and political system based in the concept of a pact between the estates of the realm and the king. The legislation of Catalonia had to be passed the Catalan Courts (Corts Catalanes), one of the first parliamentary bodies of Europe that, since 1283, obtained the power to legislate with the monarch.[34] The Courts were composed of the three Estates organized into "arms" (braços), were presided over by the monarch, and approved the Catalan constitutions, which established a compilation of rights for the inhabitants of the Principality. In order to collect general taxes, the Catalan Courts of 1359 established a permanent representative body, known as the "Deputation of the General" or Generalitat, which gained considerable political power over the next centuries.[35]

The domains of the Aragonese Crown were severely affected by the Black Death pandemic and by later outbreaks of the plague. Between 1347 and 1497 Catalonia lost 37 percent of its population.[36] In 1410, the last reigning monarch of the House of Barcelona, King Martin I died without surviving descendants. Under the Compromise of Caspe (1412), the representatives of the kingdoms of Aragon, Valencia and the Principality of Catalonia appointed Ferdinand from the Castilian House of Trastámara as King of the Crown of Aragon.[37] During the reign of his son, John II, the persistent economic crisis and social and political tensions in the Principality led to the Catalan Civil War (1462–1472) and the War of the Remences (1462–1486) that left Catalonia exhausted. The Sentencia Arbitral de Guadalupe (1486) liberated the remença peasants from the feudal evil customs.

In the later Middle Ages, Catalan literature flourished in Catalonia proper and in the kingdoms of Majorca and Valencia, with such remarkable authors as the philosopher Ramon Llull, the Valencian poet Ausiàs March, and Joanot Martorell, author of the novel Tirant lo Blanch, published in 1490.

Modern era

[edit]

Ferdinand II of Aragon, the grandson of Ferdinand I, and Queen Isabella I of Castile were married in 1469, later taking the title the Catholic Monarchs; subsequently, this event was seen by historiographers as the dawn of a unified Spain. At this time, though united by marriage, the Crowns of Castile and Aragon maintained distinct territories, each keeping its own traditional institutions, parliaments, laws and currency.[38] Castile commissioned expeditions to the Americas and benefited from the riches acquired in the Spanish colonisation of the Americas, but, in time, also carried the main burden of military expenses of the united Spanish kingdoms. After Isabella's death, Ferdinand II personally ruled both crowns.

By virtue of descent from his maternal grandparents, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, in 1516 Charles I of Spain became the first king to rule the Crowns of Castile and Aragon simultaneously by his own right. Following the death of his paternal (House of Habsburg) grandfather, Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, he was also elected Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1519.[39]

Over the next few centuries, the Principality of Catalonia was generally on the losing side of a series of wars that led steadily to an increased centralization of power in Spain. Despite this fact, between the 16th and 18th centuries, the participation of the political community in the local and the general Catalan government grew (thus consolidating its constitutional system), while the kings remained absent, represented by a viceroy. Tensions between Catalan institutions and the monarchy began to arise. The large and burdensome presence of the Spanish royal army in the Principality due to the Franco-Spanish War led to an uprising of peasants, provoking the Reapers' War (1640–1652), which saw Catalonia rebel (briefly as a republic led by the chairman of the Generalitat, Pau Claris) with French help against the Spanish Crown for overstepping Catalonia's rights during the Thirty Years' War.[40] Within a brief period France took full control of Catalonia. Most of Catalonia was reconquered by the Spanish monarchy but Catalan rights were recognised. Roussillon and half of Cerdanya was lost to France by the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659).[41]

The most significant conflict concerning the governing monarchy was the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1715), which began when the childless Charles II of Spain, the last Spanish Habsburg, died without an heir in 1700. Charles II had chosen Philip V of Spain from the French House of Bourbon. Catalonia, like other territories that formed the Crown of Aragon, rose up in support of the Austrian Habsburg pretender Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, in his claim for the Spanish throne as Charles III of Spain. The fight between the houses of Bourbon and Habsburg for the Spanish Crown split Spain and Europe.

The fall of Barcelona on 11 September 1714 to the Bourbon king Philip V militarily ended the Habsburg claim to the Spanish Crown, which became legal fact in the Treaty of Utrecht. Philip felt that he had been betrayed by the Catalan Courts, as it had initially sworn its loyalty to him when he had presided over it in 1701. In retaliation for the betrayal, and inspired by the French model, the first Bourbon king enacted the Nueva Planta decrees of 1707, 1715 and 1716, incorporating the realms of the Crown of Aragon, including the Principality of Catalonia in 1716, as provinces of the Crown of Castile, terminating their status as separate states along with their parliaments, institutions and public and administrative laws, as well as their pactist politics, within a French-style centralized and absolutist kingdom of Spain.[42] In the second half of the 17th century and the 18th century (excluding the parentesis of the Succession War and the post-war inestability) Catalonia carried out a successful process of economic growth and proto-industrialization, reinforced in the late quarter of the century when Castile's trade monopoly with American colonies ended.

The beginning of the Spanish nation state

[edit]After the War of the Spanish Succession, the assimilation of the Crown of Aragon by the Castilian Crown through the Nueva Planta Decrees was the first step in the creation of the Spanish nation state. Like other European nation-states in formation,[43] it was not on a uniform ethnic basis, but by imposing the political and cultural characteristics of the capital, in this case Madrid and Central Spain, on those of the other areas, whose inhabitants would become national minorities to be assimilated through nationalist policies.[44][45] These nationalist policies, sometimes very aggressive,[46][47][48][49] and still in force,[50][51][52] have been and are the seed of repeated territorial conflicts within the state.

Late modern history

[edit]

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Catalonia was severely affected by the Napoleonic Wars. In 1808, it was occupied by French troops under general Guillaume Philibert Duhesme after he conquered Barcelona; the resistance against the occupation eventually developed into the Peninsular War. The rejection of French dominion was institutionalized with the creation of "juntas" (councils) who, remaining loyal to the Bourbons, exercised the sovereignty and representation of the territory due to the disappearance of the old institutions. Napoleon took direct control of Catalonia to reestablish order, creating the Government of Catalonia under the rule of Marshall Augereau, and making Catalan briefly an official language again. Between 1812 and 1814, Catalonia was annexed to France and organized as four departments.[53] The French troops evacuated Catalan territory at the end of 1814. After the Bourbon restoration in Spain and the death of the absolutist king Ferdinand VII (1833), Carlist Wars erupted against the newly established liberal state of Isabella II. Catalonia was divided, with the coastal and most industrialized areas supporting liberalism, while most of the countryside were in the hands of the Carlist faction; the latter proposed to reestablish the institutional systems suppressed by the Nueva Planta decrees in the ancient realms of the Crown of Aragon. The consolidation of the liberal state saw a new provincial division of Spain, including Catalonia, which was divided into four provinces (Barcelona, Girona, Lleida and Tarragona).

In the second third of the 19th century, Catalonia became an important industrial center, particularly focused on textiles. This process was a consequence of the conditions of proto-industrialisation of textile production in the prior two centuries, growing capital from wine and brandy export, [54]: 27 and was later boosted by the government support for domestic manufacturing. In 1832, the Bonaplata Factory in Barcelona became the first factory in the country to make use of the steam engine. [55]: 308 The first railway on the Iberian Peninsula was built between Barcelona and Mataró in 1848.[citation needed] A policy to encourage company towns also saw the textile industry flourish in the countryside in the 1860s and 1870s. Although the policy of Spanish governments oscillated between free trade and protectionism, protectionist laws [es] become more common. To this day Catalonia remains one of the most industrialised areas of Spain.

In the same period, Barcelona was the focus of industrial conflict and revolutionary uprisings known as "bullangues". In Catalonia, a republican current began to develop among the progressives, attrackting many Catalans who favored the federalisation of Spain. Meanwhile, the Catalan language saw a Romantic cultural renaissance from the second third of the century onwards, the Renaixença, among both the working class and the bourgeoisie. Right after the fall of the First Spanish Republic (1873–1874) and the subsequent restoration of the Bourbon dynasty (1874), Catalan nationalism began to be organized politically under the leadership of the republican federalist Valentí Almirall.

The anarchist movement had been active throughout the last quarter of the 19th century and the early 20th century, founding the CNT trade union in 1910 and achieving one of the first eight-hour workdays in Europe in 1919.[56] Growing resentment of conscription and of the military culminated in the Tragic Week (Catalan: Setmana Tràgica) in Barcelona in 1909. Under the hegemony of the Regionalist League, Catalonia gained a degree of administrative unity for the first time in the Modern era. In 1914, the four Catalan provinces were authorized to create a commonwealth (Catalan: Mancomunitat de Catalunya), lacking any legislative power or specific political autonomy, which carried out an ambitious program of modernization, but it was disbanded in 1925 by the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (1923–1930). During the final stage of the Dictatorship, with Spain beginning to suffer an economic crisis, Barcelona hosted the 1929 International Exposition.[57]

After the fall of the dictatorship and a brief proclamation of the Catalan Republic, during the events of the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic (14–17 April 1931),[58] Catalonia received in 1932, its first Statute of Autonomy from the Spanish Republic's Parliament, granting it a considerable degree of self-government, establishing an autonomous body, the Generalitat of Catalonia, which included a parliament, an executive and a court of cassation. The left-wing pro-independence leader Francesc Macià was appointed its first president. Under the Statute, Catalan became an official language. The governments of the Republican Generalitat, led by the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) leaders Francesc Macià (1931–1933) and Lluís Companys (1933–1940), sought to implement a modernizing and progressive social agenda, despite the internal difficulties. This period was marked by political unrest, the effects of the economic crisis and their social repercussions. The Statute of Autonomy was suspended in 1934, due to the Events of 6 October in Barcelona, as a response[clarification needed] to the accession of right-wing Spanish nationalist party CEDA to the government of the Republic, considered close to fascism.[59] After the electoral victory of the left wing Popular Front in February 1936, the Government of Catalonia was pardoned and the self-government was restored.

Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and Franco's rule (1939–1975)

[edit]The defeat of the military rebellion against the Republican government in Barcelona placed Catalonia firmly in the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War. During the war, there were two rival powers in Catalonia: the de jure power of the Generalitat and the de facto power of the armed popular militias.[60] Violent confrontations between the workers' parties (CNT-FAI and POUM against the PSUC) culminated in the defeat of the first ones in 1937. The situation resolved itself progressively in favor of the Generalitat, but at the same time the Generalitat lost most of its autonomous powers within Republican Spain. In 1938 Franco's troops broke the Republican territory in two, isolating Catalonia from the rest of the Republican territory. The defeat of the Republican army in the Battle of the Ebro led in 1938 and 1939 to the occupation of Catalonia by Franco's forces.

The defeat of the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War brought to power the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, whose first ten-year rule was particularly violent, autocratic, and repressive both in a political, cultural, social, and economical sense.[61] In Catalonia, any kind of public activities associated with Catalan nationalism, republicanism, anarchism, socialism, liberalism, democracy or communism, including the publication of books on those subjects or simply discussion of them in open meetings, was banned.

Franco's regime banned the use of Catalan in government-run institutions and during public events, and the Catalan institutions of self-government were abolished. The pro-Republic of Spain president of Catalonia, Lluís Companys, was taken to Spain from his exile in the German-occupied France and was tortured and executed in the Montjuïc Castle of Barcelona for the crime of 'military rebellion'.[62]

During later stages of Francoist Spain, certain folkloric and religious celebrations in Catalan resumed and were tolerated. Use of Catalan in the mass media had been forbidden but was permitted from the early 1950s[63] in the theatre. Despite the ban during the first years and the difficulties of the next period, publishing in Catalan continued throughout his rule.[64]

The years after the war were extremely hard. Catalonia, like many other parts of Spain, had been devastated by the war. Recovery from the war damage was slow and made more difficult by the international trade embargo and the autarkic politics of Franco's regime. By the late 1950s, the region had recovered its pre-war economic levels and in the 1960s was the second-fastest growing economy in the world in what became known as the Spanish miracle. During this period there was a spectacular[65] growth of industry and tourism in Catalonia that drew large numbers of workers to the region from across Spain and made the area around Barcelona one of Europe's largest industrial metropolitan areas.[citation needed]

Transition and democratic period (1975–present)

[edit]

After Franco's death in 1975, Catalonia voted for the adoption of a democratic Spanish Constitution in 1978, in which Catalonia recovered political and cultural autonomy, restoring the Generalitat (exiled since the end of the Civil War in 1939) in 1977 and adopting a new Statute of Autonomy in 1979, which defined Catalonia as a "nationality". The first elections to the Parliament of Catalonia under this Statute gave the Catalan presidency to Jordi Pujol, leader of Convergència i Unió (CiU), a center-right Catalan nationalist electoral coalition, with Pujol re-elected until 2003. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the institutions of Catalan autonomy were deployed, among them an autonomous police force, the Mossos d'Esquadra, in 1983,[66] and the broadcasting network Televisió de Catalunya and its first channel TV3, created in 1983.[67] An extensive program of normalization of Catalan language was carried out. Today, Catalonia remains one of the most economically dynamic communities of Spain. The Catalan capital and largest city, Barcelona, is a major international cultural centre and a major tourist destination. In 1992, Barcelona hosted the Summer Olympic Games.[68]

Independence movement

[edit]In November 2003, elections to the Parliament of Catalonia gave the government to a left-wing Catalanist coalition formed by the Socialists' Party of Catalonia (PSC-PSOE), Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) and Initiative for Catalonia Greens (ICV), and the socialist Pasqual Maragall was appointed president. The new government redacted a new version of the Statute of Autonomy, with the aim of consolidate and expand certain aspects of self-government.

The new Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, approved after a referendum in 2006, was contested by important sectors of the Spanish society, especially by the conservative People's Party, which sent the law to the Constitutional Court of Spain. In 2010, the Court declared non-valid some of the articles that established an autonomous Catalan system of Justice, improved aspects of the financing, a new territorial division, the status of Catalan language or the symbolical declaration of Catalonia as a nation.[69] This decision was severely contested by large sectors of Catalan society, which increased the demands of independence.[70]

A controversial independence referendum was held in Catalonia on 1 October 2017, using a disputed voting process.[71][72] It was declared illegal and suspended by the Constitutional Court of Spain, because it breached the 1978 Constitution.[73][74] Subsequent developments saw, on 27 October 2017, a symbolic declaration of independence by the Parliament of Catalonia, the enforcement of direct rule by the Spanish government through the use of Article 155 of the Constitution,[75][76][77][78][79] the dismissal of the Executive Council and the dissolution of the Parliament, with a snap regional election called for 21 December 2017, which ended with a victory of pro-independence parties.[80] Former President Carles Puigdemont and five former cabinet ministers fled Spain and took refuge in other European countries (such as Belgium, in Puigdemont's case), whereas nine other cabinet members, including vice-president Oriol Junqueras, were sentenced to prison under various charges of rebellion, sedition, and misuse of public funds.[81][82] Quim Torra became the 131st President of the Government of Catalonia on 17 May 2018,[83] after the Spanish courts blocked three other candidates.[84]

In 2018, the Assemblea Nacional Catalana joined the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) on behalf of Catalonia.[85]

On 14 October 2019, the Spanish Supreme court sentenced several Catalan political leaders, involved in organizing a referendum on Catalonia's independence from Spain, and convicted them on charges ranging from sedition to misuse of public funds, with sentences ranging from 9 to 13 years in prison. This decision sparked demonstrations around Catalonia.[86] They were later pardoned by the Spanish government and left prison in June 2021.[87][88]

In the early-to-mid 2020s support for independence declined.[89][90][91][92]

Geography

[edit]Climate

[edit]

- Mediterranean climate of alpine influence

- Inland Mediterranean climate

- Mediterranean climate of continental influence

The climate of Catalonia is diverse. The populated areas lying by the coast in Tarragona, Barcelona and Girona provinces feature a Hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa). The inland part (including the Lleida province and the inner part of Barcelona province) show a mostly Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa). The Pyrenean peaks have a continental (Köppen D) or even Alpine climate (Köppen ET) at the highest summits, while the valleys have a maritime or oceanic climate sub-type (Köppen Cfb).

In the Mediterranean area, summers are dry and hot with sea breezes, and the maximum temperature is around 26–31 °C (79–88 °F). Winter is cool or slightly cold depending on the location. It snows frequently in the Pyrenees, and it occasionally snows at lower altitudes, even by the coastline. Spring and autumn are typically the rainiest seasons, except for the Pyrenean valleys, where summer is typically stormy.

The inland part of Catalonia is hotter and drier in summer. Temperature may reach 35 °C (95 °F), some days even 40 °C (104 °F). Nights are cooler there than at the coast, with the temperature of around 14–17 °C (57–63 °F). Fog is not uncommon in valleys and plains; it can be especially persistent, with freezing drizzle episodes and subzero temperatures during winter, mainly along the Ebro and Segre valleys and in Plain of Vic.

Topography

[edit]

- Pyrenees

- Pre-Pyrenees

- Catalan Central Depression

- Smaller mountain ranges of

the Central Depression - Catalan Transversal Range

- Catalan Pre-Coastal Range

- Catalan Coastal Range

- Catalan Coastal Depression

and other coastal and pre-coastal plains

Catalonia has a marked geographical diversity, considering the relatively small size of its territory. The geography is conditioned by the Mediterranean coast, with 580 kilometres (360 miles) of coastline, and the towering Pyrenees along the long northern border. Catalonia is divided into three main geomorphological units:[93]

- The Pyrenees: mountainous formation that connects the Iberian Peninsula with the European continental territory (see passage above);

- The Catalan Coastal mountain ranges or the Catalan Mediterranean System: an alternating delevacions and planes parallel to the Mediterranean coast;

- The Catalan Central Depression: structural unit which forms the eastern sector of the Valley of the Ebro.

The Catalan Pyrenees represent almost half in length of the Pyrenees, as it extends more than 200 kilometres (120 miles). Traditionally differentiated the Axial Pyrenees (the main part) and the Pre-Pyrenees (southern from the Axial) which are mountainous formations parallel to the main mountain ranges but with lower altitudes, less steep and a different geological formation. The highest mountain of Catalonia, located north of the comarca of Pallars Sobirà is the Pica d'Estats (3,143 m), followed by the Puigpedrós (2,914 m). The Serra del Cadí comprises the highest peaks in the Pre-Pyrenees and forms the southern boundary of the Cerdanya valley.

The Central Catalan Depression is a plain located between the Pyrenees and Pre-Coastal Mountains. Elevation ranges from 200 to 600 metres (660 to 1,970 feet). The plains and the water that descend from the Pyrenees have made it fertile territory for agriculture and numerous irrigation canals have been built. Another major plain is the Empordà, located in the northeast.

The Catalan Mediterranean system is based on two ranges running roughly parallel to the coast (southwest–northeast), called the Coastal and the Pre-Coastal Ranges. The Coastal Range is both the shorter and the lower of the two, while the Pre-Coastal is greater in both length and elevation. Areas within the Pre-Coastal Range include Montserrat, Montseny and the Ports de Tortosa-Beseit. Lowlands alternate with the Coastal and Pre-Coastal Ranges. The Coastal Lowland is located to the East of the Coastal Range between it and the coast, while the Pre-Coastal Lowlands are located inland, between the Coastal and Pre-Coastal Ranges, and includes the Vallès and Penedès plains.

Flora and fauna

[edit]

Catalonia is a showcase of European landscapes on a small scale. Just over 30,000 square kilometres (12,000 square miles) hosting a variety of substrates, soils, climates, directions, altitudes and distances to the sea. The area is of great ecological diversity and a remarkable wealth of landscapes, habitats and species.

The fauna of Catalonia comprises a minority of animals endemic to the region and a majority of non-endemic animals. Much of Catalonia enjoys a Mediterranean climate (except mountain areas), which makes many of the animals that live there adapted to Mediterranean ecosystems. Of mammals, there are plentiful wild boar, red foxes, as well as roe deer and in the Pyrenees, the Pyrenean chamois. Other large species such as the bear have been recently reintroduced.

The waters of the Balearic Sea are rich in biodiversity, and even the megafaunas of the oceans; various types of whales (such as fin, sperm, and pilot) and dolphins can be found in the area.[94][95]

Hydrography

[edit]

Most of Catalonia belongs to the Mediterranean Basin. The Catalan hydrographic network consists of two important basins, the one of the Ebro and the one that comprises the internal basins of Catalonia (respectively covering 46.84% and 51.43% of the territory), all of them flow to the Mediterranean. Furthermore, there is the Garona river basin that flows to the Atlantic Ocean, but it only covers 1.73% of the Catalan territory.

The hydrographic network can be divided in two sectors, an occidental slope or Ebro river slope and one oriental slope constituted by minor rivers that flow to the Mediterranean along the Catalan coast. The first slope provides an average of 18,700 cubic hectometres (4.5 cubic miles) per year, while the second only provides an average of 2,020 hm3 (0.48 cu mi)/year. The difference is due to the big contribution of the Ebro river, from which the Segre is an important tributary. Moreover, in Catalonia there is a relative wealth of groundwaters, although there is inequality between comarques, given the complex geological structure of the territory.[96] In the Pyrenees there are many small lakes, remnants of the ice age. The biggest are the lake of Banyoles and the recently recovered lake of Ivars.

The Catalan coast is almost rectilinear, with a length of 580 kilometres (360 mi) and few landforms—the most relevant are the Cap de Creus and the Gulf of Roses to the north and the Ebro Delta to the south. The Catalan Coastal Range hugs the coastline, and it is split into two segments, one between L'Estartit and the town of Blanes (the Costa Brava), and the other at the south, at the Costes del Garraf.

The principal rivers in Catalonia are the Ter, Llobregat, and the Ebro (Catalan: Ebre), all of which run into the Mediterranean.

Anthropic pressure and protection of nature

[edit]The majority of Catalan population is concentrated in 30% of the territory, mainly in the coastal plains. Intensive agriculture, livestock farming and industrial activities have been accompanied by a massive tourist influx (more than 20 million annual visitors), a rate of urbanization and even of major metropolisation which has led to a strong urban sprawl: two thirds of Catalans live in the urban area of Barcelona, while the proportion of urban land increased from 4.2% in 1993 to 6.2% in 2009, a growth of 48.6% in sixteen years, complemented with a dense network of transport infrastructure. This is accompanied by a certain agricultural abandonment (decrease of 15% of all areas cultivated in Catalonia between 1993 and 2009) and a global threat to natural environment. Human activities have also put some animal species at risk, or even led to their disappearance from the territory, like the gray wolf and probably the brown bear of the Pyrenees. The pressure created by this model of life means that the country's ecological footprint exceeds its administrative area.[97]

Faced with these problems, Catalan authorities initiated several measures whose purpose is to protect natural ecosystems. Thus, in 1990, the Catalan government created the Nature Conservation Council (Catalan: Consell de Protecció de la Natura), an advisory body with the aim to study, protect and manage the natural environments and landscapes of Catalonia. In addition, the Generalitat has carried out the Plan of Spaces of Natural Interest (Pla d'Espais d'Interès Natural or PEIN) in 1992 while eighteen Natural Spaces of Special Protection (Espais Naturals de Protecció Especial or ENPE) have been instituted.

There's a National Park, Aigüestortes i Estany de Sant Maurici; fourteen Natural Parks, Alt Pirineu, Aiguamolls de l'Empordà, Cadí-Moixeró, Cap de Creus, Sources of Ter and Freser, Collserola, Ebro Delta, Ports, Montgrí, Medes Islands and Baix Ter, Montseny, Montserrat, Sant Llorenç del Munt and l'Obac, Serra de Montsant, and the Garrotxa Volcanic Zone; as well as three Natural Places of National Interest (Paratge Natural d'Interes Nacional or PNIN), the Pedraforca, the Poblet Forest and the Albères.

Politics

[edit] |

|---|

After Franco's death in 1975 and the adoption of a democratic constitution in Spain in 1978, Catalonia recovered and extended the powers that it had gained in the Statute of Autonomy of 1932[98] but lost with the fall of the Second Spanish Republic[99] at the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939.

This autonomous community has gradually achieved more autonomy since the approval of the Spanish Constitution of 1978. The Generalitat holds exclusive jurisdiction in education, health, culture, environment, communications, transportation, commerce, public safety and local government, and only shares jurisdiction with the Spanish government in justice.[100] In all, some analysts argue that formally the current system grants Catalonia with "more self-government than almost any other corner in Europe".[101]

The support for Catalan nationalism ranges from a demand for further autonomy and the federalisation of Spain to the desire for independence from the rest of Spain, expressed by Catalan independentists.[102] The first survey following the Constitutional Court ruling that cut back elements of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy, published by La Vanguardia on 18 July 2010, found that 46% of the voters would support independence in a referendum.[103] In February of the same year, a poll by the Open University of Catalonia gave more or less the same results.[104] Other polls have shown lower support for independence, ranging from 40 to 49%.[105][106][107] Although it is established in the whole of the territory, support for independence is significantly higher in the hinterland and the northeast, away from the more populous coastal areas such as Barcelona.[108]

Since 2011 when the question started to be regularly surveyed by the governmental Center for Public Opinion Studies (CEO), support for Catalan independence has been on the rise.[109] According to the CEO opinion poll from July 2016, 47.7% of Catalans would vote for independence and 42.4% against it while, about the question of preferences, according to the CEO opinion poll from March 2016, a 57.2 claim to be "absolutely" or "fairly" in favour of independence.[110][111] Other polls have shown lower support for independence, ranging from 40 to 49%.[105][106][107] Other polls show more variable results, according with the Spanish CIS, as of December 2016, 47% of Catalans rejected independence and 45% supported it.[112]

In hundreds of non-binding local referendums on independence, organised across Catalonia from 13 September 2009, a large majority voted for independence, although critics argued that the polls were mostly held in pro-independence areas. In December 2009, 94% of those voting backed independence from Spain, on a turn-out of 25%.[113] The final local referendum was held in Barcelona, in April 2011. On 11 September 2012, a pro-independence march pulled in a crowd of between 600,000 (according to the Spanish Government), 1.5 million (according to the Guàrdia Urbana de Barcelona), and 2 million (according to its promoters);[114][115] whereas poll results revealed that half the population of Catalonia supported secession from Spain.

Two major factors were Spain's Constitutional Court's 2010 decision to declare part of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia unconstitutional, as well as the fact that Catalonia contributes 19.49% of the central government's tax revenue, but only receives 14.03% of central government's spending.[116]

Parties that consider themselves either Catalan nationalist or independentist have been present in all Catalan governments since 1980. The largest Catalan nationalist party, Convergence and Union, ruled Catalonia from 1980 to 2003, and returned to power in the 2010 election. Between 2003 and 2010, a leftist coalition, composed by the Catalan Socialists' Party, the pro-independence Republican Left of Catalonia and the leftist-environmentalist Initiative for Catalonia-Greens, implemented policies that widened Catalan autonomy.[citation needed]

In the 25 November 2012 Catalan parliamentary election, sovereigntist parties supporting a secession referendum gathered 59.01% of the votes and held 87 of the 135 seats in the Catalan Parliament. Parties supporting independence from the rest of Spain obtained 49.12% of the votes and a majority of 74 seats.

Artur Mas, then the president of Catalonia, organised early elections that took place on 27 September 2015. In these elections, Convergència and Esquerra Republicana decided to join, and they presented themselves under the coalition named Junts pel Sí (in Catalan, Together for Yes). Junts pel Sí won 62 seats and was the most voted party, and CUP (Candidatura d'Unitat Popular, a far-left and independentist party) won another 10, so the sum of all the independentist forces/parties was 72 seats, reaching an absolute majority, but not in number of individual votes, comprising 47,74% of the total.[117]

Statute of Autonomy

[edit]

The Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia is the fundamental organic law, second only to the Spanish Constitution from which the Statute originates.

In the Spanish Constitution of 1978 Catalonia, along with the Basque Country and Galicia, was defined as a "nationality".[dubious – discuss] The same constitution gave Catalonia the automatic right to autonomy, which resulted in the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 1979.[further explanation needed]

Both the 1979 Statute of Autonomy and the current one, approved in 2006, state that "Catalonia, as a nationality, exercises its self-government constituted as an Autonomous Community in accordance with the Constitution and with the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, which is its basic institutional law, always under the law in Spain".[118]

The Preamble of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia states that the Parliament of Catalonia has defined Catalonia as a nation, but that "the Spanish Constitution recognizes Catalonia's national reality as a nationality".[119] While the Statute was approved by and sanctioned by both the Catalan and Spanish parliaments, and later by referendum in Catalonia, it has been subject to a legal challenge by the surrounding autonomous communities of Aragon, Balearic Islands and Valencia,[120] as well as by the conservative People's Party. The objections are based on various issues such as disputed cultural heritage but, especially, on the Statute's alleged breaches of the principle of "solidarity between regions" in fiscal and educational matters enshrined by the Constitution.[121]

Spain's Constitutional Court assessed the disputed articles and on 28 June 2010, issued its judgment on the principal allegation of unconstitutionality presented by the People's Party in 2006. The judgment granted clear passage to 182 articles of the 223 that make up the fundamental text. The court approved 73 of the 114 articles that the People's Party had contested, while declaring 14 articles unconstitutional in whole or in part and imposing a restrictive interpretation on 27 others.[122] The court accepted the specific provision that described Catalonia as a "nation", however ruled that it was a historical and cultural term with no legal weight, and that Spain remained the only nation recognised by the constitution.[123][124][125][126]

Government and law

[edit]The Catalan Statute of Autonomy establishes that Catalonia, as an autonomous community, is organised politically through the Generalitat of Catalonia (Catalan: Generalitat de Catalunya), confirmed by the Parliament, the Presidency of the Generalitat, the Government or Executive Council and the other institutions established by the Parliament, among them the Ombudsman (Síndic de Greuges), the Office of Auditors (Sindicatura de Comptes) the Council for Statutory Guarantees (Consell de Garanties Estatutàries) or the Audiovisual Council of Catalonia (Consell de l'Audiovisual de Catalunya).

The Parliament of Catalonia (Catalan: Parlament de Catalunya) is the unicameral legislative body of the Generalitat and represents the people of Catalonia. Its 135 members (diputats) are elected by universal suffrage to serve for a four-year period. According to the Statute of Autonomy, it has powers to legislate over devolved matters such as education, health, culture, internal institutional and territorial organization, nomination of the President of the Generalitat and control the Government, budget and other affairs. The last Catalan election was held on 14 February 2021, and its current speaker (president) is Laura Borràs, incumbent since 12 March 2018.

The President of the Generalitat of Catalonia (Catalan: president de la Generalitat de Catalunya) is the highest representative of Catalonia, and is also responsible of leading the government's action, presiding the Executive Council. Since the restoration of the Generalitat on the return of democracy in Spain, the Presidents of Catalonia have been Josep Tarradellas (1977–1980, president in exile since 1954), Jordi Pujol (1980–2003), Pasqual Maragall (2003–2006), José Montilla (2006–2010), Artur Mas (2010–2016), Carles Puigdemont (2016–2017) and, after the imposition of direct rule from Madrid, Quim Torra (2018–2020) and Pere Aragonès (2021–).

The Executive Council (Catalan: Consell Executiu) or Government (Govern), is the body responsible of the government of the Generalitat, it holds executive and regulatory power, being accountable to the Catalan Parliament. It comprises the President of the Generalitat, the First Minister (conseller primer) or the Vice President, and the ministers (consellers) appointed by the president. Its seat is the Palau de la Generalitat, Barcelona. In 2021 the government was a coalition of two parties, the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) and Together for Catalonia (Junts) and is made up of 14 ministers, including the vice President, alongside to the president and a secretary of government, but in October 2022 Together for Catalonia (Junts) left the coalition and the government.[127]

Security forces and Justice

[edit]Catalonia has its own police force, the Mossos d'Esquadra (officially called Mossos d'Esquadra-Policia de la Generalitat de Catalunya), whose origins date back to the 18th century. Since 1980 they have been under the command of the Generalitat, and since 1994 they have expanded in number in order to replace the national Civil Guard and National Police Corps, which report directly to the Homeland Department of Spain. The national bodies retain personnel within Catalonia to exercise functions of national scope such as overseeing ports, airports, coasts, international borders, custom offices, the identification of documents and arms control, immigration control, terrorism prevention, arms trafficking prevention, amongst others.

Most of the justice system is administered by national judicial institutions, the highest body and last judicial instance in the Catalan jurisdiction, integrating the Spanish judiciary, is the High Court of Justice of Catalonia. The criminal justice system is uniform throughout Spain, while civil law is administered separately within Catalonia. The civil laws that are subject to autonomous legislation have been codified in the Civil Code of Catalonia (Codi civil de Catalunya) since 2002.[128]

Catalonia, together with Navarre and the Basque Country, are the Spanish communities with the highest degree of autonomy in terms of law enforcement.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Catalonia is organised territorially into provinces or regions, further subdivided into comarques and municipalities. The 2006 Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia establishes the administrative organisation of the later three.

Provinces

[edit]Much like the rest of Spain, Catalonia is divided administratively into four provinces, the governing body of which is the Provincial Deputation (Catalan: Diputació Provincial, Occitan: Deputacion Provinciau, Spanish: Diputación Provincial). As of 2010, the four provinces and their populations were:[129]

- Province of Barcelona: 5,701,708 population

- Province of Girona: 777,258 population

- Province of Lleida: 437,939 population

- Province of Tarragona: 830,804 population

Unlike vegueries, provinces do not follow the limitations of the subdivisional counties, notably Baixa Cerdanya, which is split in half between the demarcations of Lleida and Girona. This situation has led some isolated municipalities to request province changes from the Spanish government.[130]

Vegueries

[edit]Besides provinces, Catalonia is internally divided into eight regions or vegueries, based on the feudal administrative territorial jurisdiction of the Principality of Catalonia.[131] Established in 2006, vegueries are used by the Generalitat de Catalunya with the aim to more effectively divide Catalonia administratively. In addition, vegueries are intended to become Catalonia's first-level administrative division and a full replacement for the four deputations of the Catalan provinces, creating a council for each vegueria,[132][133][134] but this has not been realised as changes to the statewide provinces system are unconstitutional.[135]

The territorial plan of Catalonia (Pla territorial general de Catalunya) provided six general functional areas,[136] but was amended by Law 24/2001, of 31 December, recognizing Alt Pirineu and Aran as a new functional area differentiated of Ponent.[137] After some opposition from some territories, it was made possible for the Aran Valley to retain its government (the vegueria is renamed to Alt Pirineu, although the name Alt Pirineu and Aran is still used by the regional plan)[138] and in 2016, the Catalan Parliament approved the eighth vegueria, Penedès, split from the Barcelona region.[139][131]

As of 2022, the eight regions and their populations were:

- Alt Pirineu (capital La Seu d'Urgell): 63,892 population

- Barcelona (capital Barcelona): 4,916,847 population

- Camp de Tarragona (capital Tarragona): 536,453 population

- Central Catalonia (capital Manresa): 413,349 population

- Girona (capital Girona): 761,690 population

- Ponent (capital Lleida): 365,289 population

- Penedès (capital Vilanova i la Geltrú): 497,764 population

- Terres de l'Ebre (capital Tortosa): 182,231 population

- Aran Valley (capital Vielha e Mijaran): 10,194 population

Comarques

[edit]Comarques (often known as counties in English, but different from the historical Catalan counties[140][141][142]) are entities composed of municipalities to internally manage their responsibilities and services. The current regional division has its roots in a decree of the Generalitat de Catalunya of 1936, in effect until 1939, when it was suppressed by Franco. In 1987 the Catalan Government reestablished the comarcal division and in 1988 three new comarques were added (Alta Ribagorça, Pla d'Urgell and Pla de l'Estany). Some further revisions have been realised since then, such as the additions of Moianès and Lluçanès counties, in 2015 and 2023 respectively. Except for Barcelonès, every comarca is administered by a comarcal council (consell comarcal).

As of 2024, Catalonia is divided in 42 counties plus the Aran Valley. The latter, although previously (and still informally) considered a comarca, obtained in 1990 a particular status within Catalonia due to its differences in culture and language, being administered by a body known as the Conselh Generau d'Aran (General Council of Aran), and in 2015 it was defined as a "unique territorial entity" instead of a county.[143]

Municipalities

[edit]There are at present 947 municipalities (municipis) in Catalonia. Each municipality is run by a council (ajuntament) elected every four years by the residents in local elections. The council consists of a number of members (regidors) depending on population, who elect the mayor (alcalde or batlle). Its seat is the town hall (ajuntament, casa de la ciutat or casa de la vila).

- Catalan regional capitals

-

An aerial view of Barcelona

-

La Seu d'Urgell from the Solsona tower

-

The city of Tarragona

-

The city of Manresa from the Balconada viewpoint

-

The city of Girona

-

The city of Lleida by the Segre river

-

Vilanova i la Geltrú from the city's port

-

The city of Tortosa

-

Vielha e Mijaran from the Vielha viewpoint

Economy

[edit]

A highly industrialized region, the nominal GDP of Catalonia in 2018 was €228 billion (second after the community of Madrid, €230 billion) and the per capita GDP was €30,426 ($32,888), behind Madrid (€35,041), the Basque Country (€33,223), and Navarre (€31,389).[144] That year, the GDP growth was 2.3%.[145]

Catalonia's long-term credit rating is BB (Non-Investment Grade) according to Standard & Poor's, Ba2 (Non-Investment Grade) according to Moody's, and BBB- (Low Investment Grade) according to Fitch Ratings.[146][147][148] Catalonia's rating is tied for worst with between 1 and 5 other autonomous communities of Spain, depending on the rating agency.[148]

The city of Barcelona occupies the eighth position as one of the world's best cities to live, work, research and visit in 2021, according to the report "The World's Best Cities 2021", prepared by Resonance Consultancy.[149]

The Catalan capital, despite the current moment of crisis,[when?] is also one of the European bases of "reference for start-ups" and the fifth city in the world to establish one of these companies, behind London, Berlin, Paris and Amsterdam, according to the Eu-Starts-Up 2020 study. Barcelona is behind London, New York, Paris, Moscow, Tokyo, Dubai and Singapore and ahead of Los Angeles and Madrid.[150]

In the context of the financial crisis of 2007–2008, Catalonia was expected to suffer a recession amounting to almost a 2% contraction of its regional GDP in 2009.[151] Catalonia's debt in 2012 was the highest of all Spain's autonomous communities,[152] reaching €13,476 million, i.e. 38% of the total debt of the 17 autonomous communities,[153] but in recent years its economy recovered a positive evolution and the GDP grew a 3.3% in 2015.[154]

Catalonia is amongst the List of country subdivisions by GDP over 100 billion US dollars and is a member of the Four Motors for Europe organisation.

The distribution of sectors is as follows:[155]

- Primary sector: 3%. The amount of land devoted to agricultural use is 33%.

- Secondary sector: 37% (compared to Spain's 29%)

- Tertiary sector: 60% (compared to Spain's 67%)

The main tourist destinations in Catalonia are the city of Barcelona, the beaches of the Costa Brava in Girona, the beaches of the Costa del Maresme and Costa del Garraf from Malgrat de Mar to Vilanova i la Geltrú and the Costa Daurada in Tarragona. In the High Pyrenees there are several ski resorts, near Lleida. On 1 November 2012, Catalonia started charging a tourist tax.[156] The revenue is used to promote tourism, and to maintain and upgrade tourism-related infrastructure.

Many of Spain's leading savings banks were based in Catalonia before the independence referendum of 2017. However, in the aftermath of the referendum, many of them moved their registered office to other parts of Spain. That includes the two biggest Catalan banks at that moment, La Caixa, which moved its office to Palma de Mallorca, and Banc Sabadell, ranked fourth among all Spanish private banks and which moved its office to Alicante.[157][158] That happened after the Spanish government passed a law allowing companies to move their registered office without requiring the approval of the company's general meeting of shareholders.[159] Overall, there was a negative net relocation rate of companies based in Catalonia moving to other autonomous communities of Spain. From the 2017 independence referendum until the end of 2018, for example, Catalonia lost 5454 companies to other parts of Spain (mainly Madrid), 2359 only in 2018, gaining 467 new ones from the rest of the country during 2018.[160][161] It has been reported that the Spanish government and the Spanish King Felipe VI pressured some of the big Catalan companies to move their headquarters outside of the region.[162][163]

The stock market of Barcelona, which in 2016 had a volume of around €152 billion, is the second largest of Spain after Madrid, and Fira de Barcelona organizes international exhibitions and congresses to do with different sectors of the economy.[164]

The main economic cost for Catalan families is the purchase of a home. According to data from the Society of Appraisal on 31 December 2005 Catalonia is, after Madrid, the second most expensive region in Spain for housing: 3,397 €/m2 on average[citation needed] (see Spanish property bubble).

Unemployment

[edit]The unemployment rate stood at 10.5% in 2019 and was lower than the national average.[165]

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.6% | 6.5% | 11.8% | 16.9% | 17.9% | 20.4% | 23.8% | 21.9% | 19.9% | 17.7% | 14.9% | 12.6% | 11.8% | 10.5% |

Transport

[edit]Airports

[edit]

Airports in Catalonia are owned and operated by Aena (a Spanish Government entity) except two airports in Lleida which are operated by Aeroports de Catalunya (an entity belonging to the Government of Catalonia).

- Barcelona El Prat Airport (Aena)

- Girona-Costa Brava Airport (Aena)

- Reus Airport (Aena)

- Lleida-Alguaire Airport (Aeroports de Catalunya)

- Sabadell Airport (Aena)

- La Seu d'Urgell Airport (Aeroports de Catalunya)

Ports

[edit]

Since the Middle Ages, Catalonia has been well integrated into international maritime networks. The port of Barcelona (owned and operated by Puertos del Estado, a Spanish Government entity) is an industrial, commercial and tourist port of worldwide importance. With 1,950,000 TEUs in 2015, it is the first container port in Catalonia, the third in Spain after Valencia and Algeciras in Andalusia, the 9th in the Mediterranean Sea, the 14th in Europe and the 68th in the world. It is sixth largest cruise port in the world, the first in Europe and the Mediterranean with 2,364,292 passengers in 2014. The ports of Tarragona (owned and operated by Puertos del Estado) in the southwest and Palamós near Girona at northeast are much more modest. The port of Palamós and the other ports in Catalonia (26) are operated and administered by Ports de la Generalitat [ca], a Catalan Government entity.

The development of these infrastructures, resulting from the topography and history of the Catalan territory, responds strongly to the administrative and political organization of this autonomous community.

Roads

[edit]

There are 12,000 kilometres (7,500 mi) of roads throughout Catalonia.

The principal highways are AP-7 (Autopista de la Mediterrània) and A-7 (Autovia de la Mediterrània). They follow the coast from the French border to Valencia, Murcia and Andalusia. The main roads generally radiate from Barcelona. The AP-2 ![]() (Autopista del Nord-est) and A-2 (Autovia del Nord-est) connect inland and onward to Madrid.

(Autopista del Nord-est) and A-2 (Autovia del Nord-est) connect inland and onward to Madrid.

Other major roads are:

| ID | Itinerary |

|---|---|

| N-II | Lleida-La Jonquera |

| C-12 | Amposta-Àger |

| C-16 | Barcelona-Puigcerdà |

| C-17 |

Barcelona-Ripoll |

| C-25 | Cervera-Girona |

| A-26 | Llançà-Olot |

| C-32 |

El Vendrell-Tordera |

| C-60 |

Argentona-La Roca del Vallès |

Public-own roads in Catalonia are either managed by the autonomous government of Catalonia (e.g., C- roads) or the Spanish government (e.g., AP- , A- , N- roads).

Railways

[edit]

Catalonia saw the first railway construction in the Iberian Peninsula in 1848, linking Barcelona with Mataró. Given the topography, most lines radiate from Barcelona. The city has both suburban and inter-city services. The main east coast line runs through the province connecting with the SNCF (French Railways) at Portbou on the coast.

There are two publicly owned railway companies operating in Catalonia: the Catalan FGC that operates commuter and regional services, and the Spanish national Renfe that operates long-distance and high-speed rail services (AVE and Avant) and the main commuter and regional service Rodalies de Catalunya, administered by the Catalan government since 2010.

High-speed rail (AVE) services from Madrid currently reach Barcelona, via Lleida and Tarragona. The official opening between Barcelona and Madrid took place 20 February 2008. The journey between Barcelona and Madrid now takes about two-and-a-half hours. A connection to the French high-speed TGV network has been completed (called the Perpignan–Barcelona high-speed rail line) and the Spanish AVE service began commercial services on the line 9 January 2013, later offering services to Marseille on their high speed network.[166][167] This was shortly followed by the commencement of commercial service by the French TGV on 17 January 2013, leading to an average travel time on the Paris-Barcelona TGV route of 7h 42m.[167][168] This new line passes through Girona and Figueres with a tunnel through the Pyrenees.

Demographics

[edit]| Rank | Comarca | Pop. | Rank | Comarca | Pop. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Barcelona  L'Hospitalet de Llobregat |

1 | Barcelona | Barcelonès | 1,664,182 | 11 | Girona | Gironès | 103,369 |  Terrassa  Badalona |

| 2 | L'Hospitalet de Llobregat | Barcelonès | 269,382 | 12 | Sant Cugat del Vallès | Vallès Occidental | 92,977 | ||

| 3 | Terrassa | Vallès Occidental | 223,627 | 13 | Cornellà de Llobregat | Baix Llobregat | 89,936 | ||

| 4 | Badalona | Barcelonès | 223,166 | 14 | Sant Boi de Llobregat | Baix Llobregat | 84,500 | ||

| 5 | Sabadell | Vallès Occidental | 216,590 | 15 | Rubí, Barcelona | Vallès Occidental | 78,591 | ||

| 6 | Lleida | Segrià | 140,403 | 16 | Manresa | Bages | 78,246 | ||

| 7 | Tarragona | Tarragonès | 136,496 | 17 | Vilanova i la Geltrú | Garraf | 67,733 | ||

| 8 | Mataró | Maresme | 129,661 | 18 | Castelldefels | Baix Llobregat | 67,460 | ||

| 9 | Santa Coloma de Gramenet | Barcelonès | 120,443 | 19 | Viladecans | Baix Llobregat | 67,197 | ||

| 10 | Reus | Baix Camp | 106,168 | 20 | El Prat de Llobregat | Baix Llobregat | 65,385 | ||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 1,966,382 | — |

| 1910 | 2,084,868 | +6.0% |

| 1920 | 2,344,719 | +12.5% |

| 1930 | 2,791,292 | +19.0% |

| 1940 | 2,890,974 | +3.6% |

| 1950 | 3,240,313 | +12.1% |

| 1960 | 3,925,779 | +21.2% |

| 1970 | 5,122,567 | +30.5% |

| 1981 | 5,949,829 | +16.1% |

| 1990 | 6,062,273 | +1.9% |

| 2000 | 6,174,547 | +1.9% |

| 2010 | 7,462,044 | +20.9% |

| 2021 | 7,749,896 | +3.9% |

| Source: INE | ||

As of 2017, the official population of Catalonia was 7,522,596.[169] 1,194,947 residents did not have Spanish citizenship, accounting for about 16% of the population.[170]

The Urban Region of Barcelona includes 5,217,864 people and covers an area of 2,268 km2 (876 sq mi). The metropolitan area of the Urban Region includes cities such as L'Hospitalet de Llobregat, Sabadell, Terrassa, Badalona, Santa Coloma de Gramenet and Cornellà de Llobregat.

In 1900, the population of Catalonia was 1,966,382 people and in 1970 it was 5,122,567.[169] The sizeable increase of the population was due to the demographic boom in Spain during the 1960s and early 1970s[171] as well as in consequence of large-scale internal migration from the rural economically weak regions to its more prospering industrial cities. In Catalonia, that wave of internal migration arrived from several regions of Spain, especially from Andalusia, Murcia[172] and Extremadura.[173] As of 1999, it was estimated that over 60% of Catalans descended from 20th century migrations from other parts of Spain.[174]

Immigrants from other countries settled in Catalonia since the 1990s;[175] a large percentage comes from Africa, Latin America and Eastern Europe, and smaller numbers from Asia and Southern Europe, often settling in urban centers such as Barcelona and industrial areas.[176] In 2017, Catalonia had 940,497 foreign residents (11.9% of the total population) with non-Spanish ID cards, without including those who acquired Spanish citizenship.[177]

| Foreign Population by Nationality[179] | Number | % |

| 2022 | ||

| TOTAL FOREIGNERS | 1,271,810 | |

| EUROPE | 401,605 | |

| EUROPEAN UNION | 295,896 | |

| OTHER EUROPE | 105,709 | |

| AFRICA | 324,260 | |

| SOUTH AMERICA | 247,821 | |

| CENTRAL AMERICA | 368,461 | |

| NORTH AMERICA | 18,332 | |

| ASIA | 184,846 | |

| OCEANIA | 1,015 | |

| Instituto Nacional de Estadística | ||

Religion

[edit]Religion in Catalonia (2020):[180]

Historically, all the Catalan population was Christian, specifically Catholic, but since the 1980s there has been a trend of decline of Christianity. Nevertheless, according to the most recent study sponsored by the Government of Catalonia, as of 2020, 62.3% of the Catalans identify as Christians (up from 61.9% in 2016[181] and 56.5% in 2014[182]) of whom 53.0% Catholics, 7.0% Protestants and Evangelicals, 1.3% Orthodox Christians and 1.0% Jehovah's Witnesses. At the same time, 18.6% of the population identify as atheists, 8.8% as agnostics, 4.3% as Muslims, and a further 3.4% as being of other religions.[180]

Languages

[edit]| First habitual language, 2018 Demographic Survey[183] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Identification language | Habitual language | |

| Spanish | 2 978 000 (46.6%) | 3 104 000 (48.6%) | |

| Catalan | 2 320 000 (36.3%) | 2 305 000 (36.1%) | |

| Both languages | 440 000 (6.9%) | 474 000 (7.4%) | |

| Other languages | 651 000 (10.2%) | 504 000 (7.9%) | |

| Arabic | 114 000 (1.8%) | 61 000 (0.9%) | |

| Romanian | 58 000 (0.9%) | 24 000 (0.4%) | |

| English | 29 000 (0.5%) | 26 000 (0.4%) | |

| French | 26 000 (0.4%) | 16 000 (0.2%) | |

| Berber | 25 000 (0.4%) | 20 000 (0.3%) | |

| Chinese | 20 000 (0.3%) | 18 000 (0.3%) | |

| Other languages | 281 000 (4.4%) | 153 000 (2.4%) | |

| Other combinations | 96 000 (1.5%) | 193 000 (3.0%) | |

| Total population 15 year old and over | 6 386 000 (100.0%) | 6 386 000 (100.0%) | |

According to the linguistic census held by the Government of Catalonia in 2013, Spanish is the most spoken language in Catalonia (46.53% claim Spanish as "their own language"), followed by Catalan (37.26% claim Catalan as "their own language"). In everyday use, 11.95% of the population claim to use both languages equally, whereas 45.92% mainly use Spanish and 35.54% mainly use Catalan. There is a significant difference between the Barcelona metropolitan area (and, to a lesser extent, the Tarragona area), where Spanish is more spoken than Catalan, and the more rural and small town areas, where Catalan clearly prevails over Spanish.[184]

Originating in the historic territory of Catalonia, Catalan has enjoyed special status since the approval of the Statute of Autonomy of 1979 which declares it to be "Catalonia's own language",[185] a term which signifies a language given special legal status within a Spanish territory, or which is historically spoken within a given region. The other languages with official status in Catalonia are Spanish, which has official status throughout Spain, and Aranese Occitan, which is spoken in Val d'Aran.

Since the Statute of Autonomy of 1979, Aranese (a Gascon dialect of Occitan) has also been official and subject to special protection in Val d'Aran. This small area of 7,000 inhabitants was the only place where a dialect of Occitan had received full official status. Then, on 9 August 2006, when the new Statute came into force, Occitan became official throughout Catalonia. Occitan is the mother tongue of 22.4% of the population of Val d'Aran, which has attracted heavy immigration from other Spanish regions to work in the service industry.[186] Catalan Sign Language is also officially recognised.[6]

Although not considered an "official language" in the same way as Catalan, Spanish, and Occitan, the Catalan Sign Language, with about 18,000 users in Catalonia,[187] is granted official recognition and support: "The public authorities shall guarantee the use of Catalan sign language and conditions of equality for deaf people who choose to use this language, which shall be the subject of education, protection and respect."[6]

As was the case since the ascent of the Bourbon dynasty to the throne of Spain after the War of the Spanish Succession, and with the exception of the short period of the Second Spanish Republic, under Francoist Spain Catalan was banned from schools and all other official use, so that for example families were not allowed to officially register children with Catalan names.[188] Although never completely banned, Catalan language publishing was severely restricted during the early 1940s, with only religious texts and small-run self-published texts being released. Some books were published clandestinely or circumvented the restrictions by showing publishing dates prior to 1936.[189] This policy was changed in 1946, when restricted publishing in Catalan resumed.[190]

Rural–urban migration originating in other parts of Spain also reduced the social use of Catalan in urban areas and increased the use of Spanish. Lately, a similar sociolinguistic phenomenon has occurred with foreign immigration. Catalan cultural activity increased in the 1960s and the teaching of Catalan began thanks to the initiative of associations such as Òmnium Cultural.