Алжир

Народная Демократическая Республика Алжира Народная Демократическая Республика ( арабский язык ) Аль-Джумхурияту L-Jazāʾiriyaatu D-димукраиняту Ш-Шахбия | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: люди и люди "Bicsh-Sha? "Люди и для людей" [ 1 ] [ 2 ] | |

| Гимн: раздел Касаман "Мы обещаем" | |

Расположение Алжира (темно -зеленый) | |

| Капитал и самый большой город | Алжир 36 ° 42′N 3 ° 13′E / 36,700 ° N 3,217 ° E |

| Официальные языки | |

| Национальный народ | Алжирский арабский [ B ] |

| Иностранные языки | Французский [ C ] Английский [ D ] |

| Этнические группы (2024) [ E ] | |

| Религия (2012) [ 16 ] |

|

| Демоним (ы) | Алжир |

| Правительство | Унитарная полупрецентная республика |

| Абдельмаджид Теббун | |

| Редкий Ларбауи | |

| Неправильный Гуджил | |

| Ибрагим Бафхали | |

| Законодательный орган | Парламент |

| Совет страны | |

| Народное национальное собрание | |

| Формация | |

• Numidia | 202 г. до н.э. |

| 1516 | |

| 5 июля 1830 года | |

| 5 июля 1962 года | |

| Область | |

• Общий | 2 381 741 км 2 (919 595 кв. МИ) ( 10th ) |

| Население | |

• Оценка 2024 года | 46,700,000 [ 17 ] [ 18 ] [ 19 ] ( 33 -й ) |

• Плотность | 19/км 2 (49,2/кв. МИ) ( 171 -е ) |

| ВВП ( ГПП ) | 2024 Оценка |

• Общий | |

• случиться | |

| ВВП (номинальный) | 2024 Оценка |

• Общий | |

• случиться | |

| Джини (2011) | 27.6 [ 21 ] [ 22 ] Низкое неравенство |

| HDI (2022) | Высокий ( 93 -й ) |

| Валюта | Алжир Динар ( DZD ) |

| Часовой пояс | UTC +1 ( CET ) |

| Формат даты | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Ездит на | верно |

| Вызовный код | +213 |

| ISO 3166 Код | DZ |

| Интернет Tld | |

Алжир , [ f ] официально Народная Демократическая Республика Алжира , [ G ] является страной в регионе Магриб в Северной Африке . Он граничит с северо Тунисом ; -востоком на восток Ливией ; к юго -востоку от Нигера ; на юго -запад Мали ; , Мавританией и Западной Сахары на запад Марокко ; и на север у Средиземного моря . Столица и крупнейший город - Алжир , расположенный на дальнем севере на побережье Средиземного моря.

Засеченный ранним человеком со времен плейстоценовой эпохи , Алжир находился на перекрестке многочисленных культур и цивилизаций, в том числе феникийцев , римлян , вандалов , византийских греков и турков . Его современная идентичность коренится в столетиях арабских мусульманских миграционных волн седьмого века и последующей арабилизации берберского с населения. [ 24 ] После преемственности исламских арабских и берберских династий между восьмым и 15 -м веками регенство Алжир было создано в 1516 году как в значительной степени независимое притоки Османской империи . Спустя почти три столетия в качестве основной силы в Средиземноморье, страна была захвачена Францией в 1830 году и официально аннексирована в 1848 году, хотя она не была полностью завоевана и умиротворена до 1903 года. Французское правило принесло массовое европейское поселение , которое выдвинуло местное население, которое, как население, которое, как население, которое, как был уменьшен до одной трети из-за войны, болезней и голода. [ 25 ] Резня в Сетифе и Гулме в 1945 году катализировала местное сопротивление, которое завершилось вспышкой алжирской войны в 1954 году. Алжир получил свою независимость в 1962 году. Страна спустилась в кровавую гражданскую войну с 1992 по 2002 год.

в мире Проживание 2 381 741 квадратных километров (919 595 кв. Миль), Алжир-это десятая по величине страна по районам и крупнейшей нации в Африке . [ 26 ] Он имеет полузасушливый климат, причем Сахара в большей части территории доминирует пустыня , за исключением ее плодородного и горного севера, где сконцентрирована большая часть населения. С населением 44 миллиона человек Алжир является десятой наиболее густонаселенной страной в Африке и 32-й самой густонаселенной страной в мире. Официальные языки Алжира являются арабскими и тамазайтами ; Французский язык используется в средствах массовой информации, образования и некоторых административных вопросах. Подавляющее большинство населения говорят на алжирском диалекте арабского языка . Большинство алжирцев - арабы , с берберами, образующими значительное меньшинство. Суннитский ислам является официальной религией и практикуется на 99 процентов населения. [ 14 ]

Алжир-это полупреждающая республика, состоящая из 58 провинций ( Виллая ) и 1541 коммуна . Это региональная власть в Северной Африке и средняя власть в глобальных делах. Страна имеет второй по величине индекс развития человеческого роста в континентальной Африке и одна из крупнейших экономик в Африке , в основном из-за его крупных запасов нефти и природного газа, которые являются шестнадцатыми и девятными по величине в мире, соответственно. Sonatrach , национальная нефтяная компания, является крупнейшей компанией в Африке и крупным поставщиком природного газа в Европу. Алжирские военные являются одним из крупнейших в Африке, с самым высоким оборонительным бюджетом на континенте и одним из самых высоких в мире (22 -е место в мире). [ 27 ] Алжир является членом Африканского союза , Лиги арабских , ОИК , ОПЕК , Организации Объединенных Наций и Арабского союза Магриба , членом которого он является.

Имя

Различные формы имени Алжир включают: арабский : الجزائر , романизированный : аль-джазашир , алжирский арабский : دزاير , романизированный: dzāyer , французский : L'Algérie . Полное имя страны официально - Народная Демократическая Республика Алжира [ 28 ] : ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜ ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜ Эрбер Ик Тифингх ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜ ⵜⴰⴳⴷⵓⴷⴰ RADP; Berber Tifinagh: ⵜⴰⴳⴷⵓⴷⴰ ⵜⴰⵣⵣⴰⵢⵔⵉⵜ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⴳⴷⴰⵢⵜ ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜ, [ 29 ] [ 30 ] [ H ] Бербер -латинский алфавит : Алжирская республиканская республика [ 32 ] ).

Этимология

Имя Алжира происходит от города Алжир , который, в свою очередь, происходит от арабского аль-джазашира ( الجزائر , «Острова»), ссылаясь на четырех небольших островов у его побережья, [ 33 ] Усечен для старого Джазашира Бани Мазгна ( جزائر بني مزغنة , «Острова открытых мазгны»). [ 34 ] [ 35 ] [ страница необходима ] [ 36 ] [ страница необходима ] Название было дано Булуггином Ибн Зири после того, как он основал город на руинах финикийского города Икосиум в 950 году. [ 37 ] Это было использовано средневековыми географами, такими как Мухаммед аль-Идризи и Якут аль-Хамави .

Алжир взял свое название у Регентства Алжира [ 38 ] [ 39 ] [ 40 ] или Regency of Algiers, [ 41 ] Когда в Центральном Магрибе было установлено Османское правление в Центральном Магрибе . В этом периоде была установлена политическая и административная организация, которая участвовала в создании Ватан -эль -Джазаира ( وطن الجزائر , Страны Алжир) и определения его границ с соседними странами на Востоке и Западе. [ 42 ] Османские турки , поселившиеся в Алжире [ 43 ] [ 44 ] [ 45 ] и народы как « алжирцы ». [ 46 ] [ 38 ] Выступая в качестве центральной военной и политической власти в регентства, османские турки сформировали современную политическую идентичность Алжира как государства, обладающего всеми атрибутами суверенной независимости, несмотря на то, что все еще номинально подчиняется османскому султану . [ 47 ] [ 48 ] Алжирский националист, историк и государственный деятель Ахмед Тьюфик Эль Мадани считал регентство как «первое алжирское государство» и «Алжирскую Османскую Республику». [ 44 ] [ 49 ] [ 50 ]

История

Предыстория и древняя история

Считалось, что около 1,8 миллионов каменных артефактов из Айн Ханеча (Алжир) представляют собой самые старые археологические материалы в Северной Африке. [ 51 ] Каменные артефакты и маркированные кости, которые были раскопаны из двух близлежащих депозитов в Ain Boucherit, оцениваются в ~ 1,9 миллиона лет, и даже более старые каменные артефакты составляют ~ 2,4 миллиона лет. [ 51 ] Следовательно, доказательства Ain Boucherit показывают, что наследственные гоминины населяли средиземноморскую полосу в северной Африке намного раньше, чем считали ранее. Данные решительно утверждают раннее рассеяние производства и использования каменных инструментов из Восточной Африки, или возможный сценарий многооооопригарных технологий как в Восточной, так и в Северной Африке.

Неандертальские производители инструментов производили ручные оси в леваллоизийских и мустерских стилях (43 000 г. до н.э.), похожие на те, которые в леванте . [ 52 ] [ 53 ] Алжир был местом наивысшего состояния разработки методов среднего палелитического хлопья . [ 54 ] Инструменты этой эпохи, начиная с 30 000 до н.э., называются атерианами (после археологического места Бир -эль -Атер , к югу от Тебессы ).

Самые ранние промышленности Blade в Северной Африке называются иберомавриан (в основном в регионе Орана ). Эта отрасль, по -видимому, распространилась по всему прибрежным регионам Магриба от 15 000 до 10 000 до н.э. Неолитическая цивилизация (одомашнивание и сельское хозяйство животных) развилась в сахарском и средиземноморском магрибе, возможно, уже в 11 000 до н.э. [ 55 ] или уже от 6000 до 2000 г. до н.э. Эта жизнь, богато изображенная на рисунках Тассили Н'Аджер , преобладала в Алжире до классического периода. Смесь народов Северной Африки в конечном итоге превратилась в отдельное коренное население, которое стало называться берберами , которые являются коренными народами Северной Африки. [ 56 ]

Из своего основного центра власти в Карфагене карфагенцы расширили и установили небольшие поселения вдоль побережья Северной Африки; К 600 г. до н.э. финикийское ) присутствовало в Типасе , к востоку от Черчелла , Риджиуса (современная Аннаба ) и Русикад (современная Skikda присутствие (современная Skikda ). Эти поселения служили рыночными городами, а также якорями.

По мере роста карфагенской власти ее влияние на население коренных народов резко возросло. Бербер -цивилизация уже находилась на стадии, на котором сельское хозяйство, производство, торговля и политическая организация поддержала несколько штатов. Торговые связи между Карфагеном и берберами во внутренних пунктах росли, но территориальная экспансия также привела к порабощению или военному набору некоторых берберов и извлечению дани у других.

К началу 4 -го века до нашей эры берберы сформировали самый большой элемент карфагенской армии. В восстании наемников берберские солдаты восстали с 241 до 238 г. до н.э. после неоплачиваемого после поражения Карфагена в Первой Пунической войне . [ 57 ] Им удалось получить контроль над большей частью территории Северной Африки Карфагена, и они измельчали монеты с названием Ливиян, используемого на греческом языке для описания местных жителей Северной Африки. Карфагенское государство отказалось из -за последовательных поражений римлян в Пунических войнах . [58]

In 146 BC the city of Carthage was destroyed. As Carthaginian power waned, the influence of Berber leaders in the hinterland grew. By the 2nd century BC, several large but loosely administered Berber kingdoms had emerged. Two of them were established in Numidia, behind the coastal areas controlled by Carthage. West of Numidia lay Mauretania, which extended across the Moulouya River in modern-day Morocco to the Atlantic Ocean. The high point of Berber civilisation, unequalled until the coming of the Almohads and Almoravids more than a millennium later, was reached during the reign of Masinissa in the 2nd century BC.

After Masinissa's death in 148 BC, the Berber kingdoms were divided and reunited several times. Masinissa's line survived until 24 AD, when the remaining Berber territory was annexed to the Roman Empire.

For several centuries Algeria was ruled by the Romans, who founded many colonies in the region. Algeria is home to the second-largest number of Roman sites and remains after Italy. Rome, after getting rid of its powerful rival Carthage in the year 146 BC, decided a century later to include Numidia to become the new master of North Africa. They built more than 500 cities.[59] Like the rest of North Africa, Algeria was one of the breadbaskets of the empire, exporting cereals and other agricultural products. Saint Augustine was the bishop of Hippo Regius (modern-day Annaba, Algeria), located in the Roman province of Africa. The Germanic Vandals of Geiseric moved into North Africa in 429, and by 435 controlled coastal Numidia.[60] They did not make any significant settlement on the land, as they were harassed by local tribes.[citation needed] In fact, by the time the Byzantines arrived Leptis Magna was abandoned and the Msellata region was occupied by the indigenous Laguatan who had been busy facilitating an Amazigh political, military and cultural revival.[60][61] Furthermore, during the rule of the Romans, Byzantines, Vandals, Carthaginians, and Ottomans the Berber people were the only or one of the few in North Africa who remained independent.[62][63][64][65] The Berber people were so resistant that even during the Muslim conquest of North Africa they still had control and possession over their mountains.[66][67]

The collapse of the Western Roman Empire led to the establishment of a native Kingdom based in Altava (modern-day Algeria) known as the Mauro-Roman Kingdom. It was succeeded by another Kingdom based in Altava, the Kingdom of Altava. During the reign of Kusaila its territory extended from the region of modern-day Fez in the west to the western Aurès and later Kairaouan and the interior of Ifriqiya in the east.[68][69][70][71][72][73]

Middle Ages

After negligible resistance from the locals, Muslim Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate conquered Algeria in the early 8th century.

Large numbers of the indigenous Berber people converted to Islam. Christians, Berber and Latin speakers remained in the great majority in Tunisia until the end of the 9th century and Muslims only became a vast majority some time in the 10th.[74] After the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate, numerous local dynasties emerged, including the Rustamids, Aghlabids, Fatimids, Zirids, Hammadids, Almoravids, Almohads and the Zayyanids. The Christians left in three waves: after the initial conquest, in the 10th century and the 11th. The last were evacuated to Sicily by the Normans and the few remaining died out in the 14th century.[74]

During the Middle Ages, North Africa was home to many great scholars, saints and sovereigns including Judah Ibn Quraysh, the first grammarian to mention Semitic and Berber languages, the great Sufi masters Sidi Boumediene (Abu Madyan) and Sidi El Houari, and the Emirs Abd Al Mu'min and Yāghmūrasen. It was during this time that the Fatimids or children of Fatima, daughter of Muhammad, came to the Maghreb. These "Fatimids" went on to found a long lasting dynasty stretching across the Maghreb, Hejaz and the Levant, boasting a secular inner government, as well as a powerful army and navy, made up primarily of Arabs and Levantines extending from Algeria to their capital state of Cairo. The Fatimid caliphate began to collapse when its governors the Zirids seceded. To punish them the Fatimids sent the Arab Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym against them. The resultant war is recounted in the epic Tāghribāt. In Al-Tāghrībāt the Amazigh Zirid Hero Khālīfā Al-Zānatī asks daily, for duels, to defeat the Hilalan hero Ābu Zayd al-Hilalī and many other Arab knights in a string of victories. The Zirids, however, were ultimately defeated ushering in an adoption of Arab customs and culture. The indigenous Amazigh tribes, however, remained largely independent, and depending on tribe, location and time controlled varying parts of the Maghreb, at times unifying it (as under the Fatimids). The Fatimid Islamic state, also known as Fatimid Caliphate made an Islamic empire that included North Africa, Sicily, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, the Red Sea coast of Africa, Tihamah, Hejaz and Yemen.[75][76][77] Caliphates from Northern Africa traded with the other empires of their time, as well as forming part of a confederated support and trade network with other Islamic states during the Islamic Era.

The Berber people historically consisted of several tribes. The two main branches were the Botr and Barnès tribes, who were divided into tribes, and again into sub-tribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several tribes (for example, Sanhadja, Houara, Zenata, Masmouda, Kutama, Awarba, and Berghwata). All these tribes made independent territorial decisions.[78]

Several Amazigh dynasties emerged during the Middle Ages in the Maghreb and other nearby lands. Ibn Khaldun provides a table summarising the Amazigh dynasties of the Maghreb region, the Zirid, Ifranid, Maghrawa, Almoravid, Hammadid, Almohad, Merinid, Abdalwadid, Wattasid, Meknassa and Hafsid dynasties.[79] Both of the Hammadid and Zirid empires as well as the Fatimids established their rule in all of the Maghreb countries. The Zirids ruled land in what is now Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, Libya, Spain, Malta and Italy. The Hammadids captured and held important regions such as Ouargla, Constantine, Sfax, Susa, Algiers, Tripoli and Fez establishing their rule in every country in the Maghreb region.[80][81][82] The Fatimids which was created and established by the Kutama Berbers[83][84] conquered all of North Africa as well as Sicily and parts of the Middle East.

Following the Berber revolt numerous independent states emerged across the Maghreb. In Algeria the Rustamid Kingdom was established. The Rustamid realm stretched from Tafilalt in Morocco to the Nafusa mountains in Libya including south, central and western Tunisia therefore including territory in all of the modern day Maghreb countries, in the south the Rustamid realm expanded to the modern borders of Mali and included territory in Mauritania.[85][86][87]

Once extending their control over all of the Maghreb, part of Spain[88] and briefly over Sicily,[89] originating from modern Algeria, the Zirids only controlled modern Ifriqiya by the 11th century. The Zirids recognized nominal suzerainty of the Fatimid caliphs of Cairo. El Mu'izz the Zirid ruler decided to end this recognition and declared his independence.[90][91] The Zirids also fought against other Zenata Kingdoms, for example the Maghrawa, a Berber dynasty originating from Algeria and which at one point was a dominant power in the Maghreb ruling over much of Morocco and western Algeria including Fez, Sijilmasa, Aghmat, Oujda, most of the Sous and Draa and reaching as far as M'sila and the Zab in Algeria.[92][93][94][95]

As the Fatimid state was at the time too weak to attempt a direct invasion, they found another means of revenge. Between the Nile and the Red Sea were living Bedouin nomad tribes expelled from Arabia for their disruption and turbulency. The Banu Hilal and the Banu Sulaym for example, who regularly disrupted farmers in the Nile Valley since the nomads would often loot their farms. The then Fatimid vizier decided to destroy what he could not control, and broke a deal with the chiefs of these Bedouin tribes.[96] The Fatimids even gave them money to leave.

Whole tribes set off with women, children, elders, animals and camping equipment. Some stopped on the way, especially in Cyrenaica, where they are still one of the essential elements of the settlement but most arrived in Ifriqiya by the Gabes region, arriving 1051.[97] The Zirid ruler tried to stop this rising tide, but with each encounter, the last under the walls of Kairouan, his troops were defeated and the Arabs remained masters of the battlefield. The Arabs usually did not take control over the cities, instead looting them and destroying them.[91]

The invasion kept going, and in 1057 the Arabs spread on the high plains of Constantine where they encircled the Qalaa of Banu Hammad (capital of the Hammadid Emirate), as they had done in Kairouan a few decades ago. From there they gradually gained the upper Algiers and Oran plains. Some of these territories were forcibly taken back by the Almohads in the second half of the 12th century. The influx of Bedouin tribes was a major factor in the linguistic, cultural Arabization of the Maghreb and in the spread of nomadism in areas where agriculture had previously been dominant.[98] Ibn Khaldun noted that the lands ravaged by the Banu Hilal tribes had become completely arid desert.[99]

The Almohads originating from modern day Morocco, although founded by a man originating from modern day Algeria[100] known as Abd al-Mu'min would soon take control over the Maghreb. During the time of the Almohad Dynasty Abd al-Mu'min's tribe, the Koumïa, were the main supporters of the throne and the most important body of the empire.[101] Defeating the weakening Almoravid Empire and taking control over Morocco in 1147,[102] they pushed into Algeria in 1152, taking control over Tlemcen, Oran, and Algiers,[103] wrestling control from the Hilian Arabs, and by the same year they defeated Hammadids who controlled Eastern Algeria.[103]

Following their decisive defeat in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212 the Almohads began collapsing, and in 1235 the governor of modern-day Western Algeria, Yaghmurasen Ibn Zyan declared his independence and established the Kingdom of Tlemcen and the Zayyanid dynasty. Warring with the Almohad forces attempting to restore control over Algeria for 13 years, they defeated the Almohads in 1248 after killing their Caliph in a successful ambush near Oujda.[104]

The Zayyanids retained their control over Algeria for 3 centuries. Much of the eastern territories of Algeria were under the authority of the Hafsid dynasty,[105] although the Emirate of Bejaia encompassing the Algerian territories of the Hafsids would occasionally be independent from central Tunisian control. At their peak the Zayyanid kingdom included all of Morocco as its vassal to the west and in the east reached as far as Tunis which they captured during the reign of Abu Tashfin.[106][107][108][109][110][111]

After several conflicts with local Barbary pirates sponsored by the Zayyanid sultans,[112] Spain decided to invade Algeria and defeat the native Kingdom of Tlemcen. In 1505, they invaded and captured Mers el Kébir,[113] and in 1509 after a bloody siege, they conquered Oran.[114] Following their decisive victories over the Algerians in the western-coastal areas of Algeria, the Spanish decided to get bolder, and invaded more Algerian cities. In 1510, they led a series of sieges and attacks, taking over Bejaia in a large siege,[115] and leading a semi-successful siege against Algiers. They also besieged Tlemcen. In 1511, they took control over Cherchell[116] and Jijel, and attacked Mostaganem where although they were not able to conquer the city, they were able to force a tribute on them.

Early modern era

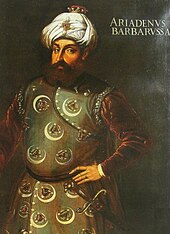

In 1516, the Turkish privateer brothers Aruj and Hayreddin Barbarossa, who operated successfully under the Hafsids, moved their base of operations to Algiers. They succeeded in conquering Jijel and Algiers from the Spaniards with help from the locals who saw them as liberators from the Christians, but the brothers eventually assassinated the local noble Salim al-Tumi and took control over the city and the surrounding regions. Their state is known as the Regency of Algiers. When Aruj was killed in 1518 during his invasion of Tlemcen, Hayreddin succeeded him as military commander of Algiers. The Ottoman sultan gave him the title of beylerbey and a contingent of some 2,000 janissaries. With the aid of this force and native Algerians, Hayreddin conquered the whole area between Constantine and Oran (although the city of Oran remained in Spanish hands until 1792).[117][118]

The next beylerbey was Hayreddin's son Hasan, who assumed the position in 1544. He was a Kouloughli or of mixed origins, as his mother was an Algerian Mooresse.[119] Until 1587 Beylerbeylik of Algiers was governed by Beylerbeys who served terms with no fixed limits. Subsequently, with the institution of a regular administration, governors with the title of pasha ruled for three-year terms. The pasha was assisted by an autonomous janissary unit, known in Algeria as the Ojaq who were led by an agha. Discontent among the ojaq rose in the mid-1600s because they were not paid regularly, and they repeatedly revolted against the pasha. As a result, the agha charged the pasha with corruption and incompetence and seized power in 1659.[117]

Plague had repeatedly struck the cities of North Africa. Algiers lost between 30,000 and 50,000 inhabitants to the plague in 1620–21, and had high fatalities in 1654–57, 1665, 1691 and 1740–42.[120]

The Barbary pirates preyed on Christian and other non-Islamic shipping in the western Mediterranean Sea.[120] The pirates often took the passengers and crew on the ships and sold them or used them as slaves.[121] They also did a brisk business in ransoming some of the captives. According to Robert Davis, from the 16th to 19th century, pirates captured 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans as slaves.[122] They often made raids on European coastal towns to capture Christian slaves to sell at slave markets in North Africa and other parts of the Ottoman Empire.[123] In 1544, for example, Hayreddin Barbarossa captured the island of Ischia, taking 4,000 prisoners, and enslaved some 9,000 inhabitants of Lipari, almost the entire population.[124] In 1551, the Ottoman governor of Algiers, Turgut Reis, enslaved the entire population of the Maltese island of Gozo. Barbary pirates often attacked the Balearic Islands. The threat was so severe that residents abandoned the island of Formentera.[125] The introduction of broad-sail ships from the beginning of the 17th century allowed them to branch out into the Atlantic.[126]

In July 1627 two pirate ships from Algiers under the command of Dutch pirate Jan Janszoon sailed as far as Iceland,[127] raiding and capturing slaves.[128][129][130] Two weeks earlier another pirate ship from Salé in Morocco had also raided in Iceland. Some of the slaves brought to Algiers were later ransomed back to Iceland, but some chose to stay in Algeria. In 1629, pirate ships from Algeria raided the Faroe Islands.[131]

In 1659, the Janissaries stationed in Algiers, also known commonly as the Odjak of Algiers; and the Reis or the company of corsair captains rebelled, they removed the Ottoman viceroy from power, and placed one of its own in power. The new leader received the title of "Agha" then "Dey" in 1671, and the right to select passed to the divan, a council of some sixty military senior officers. Thus Algiers became a sovereign military republic. It was at first dominated by the odjak; but by the 18th century, it had become the dey's instrument. Although Algiers remained nominally part of the Ottoman Empire,[117] in reality they acted independently from the rest of the Empire,[132][133] and often had wars with other Ottoman subjects and territories such as the Beylik of Tunis.[134]

The dey was in effect a constitutional autocrat. The dey was elected for a life term, but in the 159 years (1671–1830) that the system was in place, fourteen of the twenty-nine deys were assassinated. Despite usurpation, military coups and occasional mob rule, the day-to-day operation of the Deylikal government was remarkably orderly. Although the regency patronised the tribal chieftains, it never had the unanimous allegiance of the countryside, where heavy taxation frequently provoked unrest. Autonomous tribal states were tolerated, and the regency's authority was seldom applied in the Kabylia,[117] although in 1730 the Regency was able to take control over the Kingdom of Kuku in western Kabylia.[135] Many cities in the northern parts of the Algerian desert paid taxes to Algiers or one of its Beys.[136]

Barbary raids in the Mediterranean continued to attack Spanish merchant shipping, and as a result, the Spanish Empire launched an invasion in 1775, then the Spanish Navy bombarded Algiers in 1783 and 1784.[118] For the attack in 1784, the Spanish fleet was to be joined by ships from such traditional enemies of Algiers as Naples, Portugal and the Knights of Malta. Over 20,000 cannonballs were fired, but all these military campaigns were doomed and Spain had to ask for peace in 1786 and paid 1 million pesos to the Dey.

In 1792, Algiers took back Oran and Mers el Kébir, the two last Spanish strongholds in Algeria.[137] In the same year, they conquered the Moroccan Rif and Oujda, which they then abandoned in 1795.[138]

In the 19th century, Algerian pirates forged affiliations with Caribbean powers, paying a "license tax" in exchange for safe harbor of their vessels.[139]

Attacks by Algerian pirates on American merchantmen resulted in the First and Second Barbary Wars, which ended the attacks on U.S. ships in 1815. A year later, a combined Anglo-Dutch fleet, under the command of Lord Exmouth bombarded Algiers to stop similar attacks on European fishermen. These efforts proved successful, although Algerian piracy would continue until the French conquest in 1830.[140]

French colonization (1830–1962)

Under the pretext of a slight to their consul, the French invaded and captured Algiers in 1830.[141][142] According to several historians, the methods used by the French to establish control over Algeria reached genocidal proportions.[143][144][145] Historian Ben Kiernan wrote on the French conquest of Algeria: "By 1875, the French conquest was complete. The war had killed approximately 825,000 indigenous Algerians since 1830."[146] French losses from 1831 to 1851 were 92,329 dead in the hospital and only 3,336 killed in action.[147][148] In 1872, The Algerian population stood at about 2.9 million.[149][unreliable source?] French policy was predicated on "civilising" the country.[150] The slave trade and piracy in Algeria ceased following the French conquest.[121] The conquest of Algeria by the French took some time and resulted in considerable bloodshed. A combination of violence and disease epidemics caused the indigenous Algerian population to decline by nearly one-third from 1830 to 1872.[151][152][unreliable source?] On 17 September 1860, Napoleon III declared "Our first duty is to take care of the happiness of the three million Arabs, whom the fate of arms has brought under our domination."[153] During this time, only Kabylia resisted, the Kabylians were not colonized until after the Mokrani Revolt in 1871.[citation needed]

Alexis de Tocqueville wrote and never completed an unpublished essay outlining his ideas for how to transform Algeria from an occupied tributary state to a colonial regime, wherein he advocated for a mixed system of "total domination and total colonization" whereby French military would wage total war against civilian populations while a colonial administration would provide rule of law and property rights to settlers within French occupied cities.[154]

From 1848 until independence, France administered the whole Mediterranean region of Algeria as an integral part and département of the nation. One of France's longest-held overseas territories, Algeria became a destination for hundreds of thousands of European immigrants, who became known as colons and later, as Pied-Noirs. Between 1825 and 1847, 50,000 French people emigrated to Algeria.[155][156] These settlers benefited from the French government's confiscation of communal land from tribal peoples, and the application of modern agricultural techniques that increased the amount of arable land.[157] Many Europeans settled in Oran and Algiers, and by the early 20th century they formed a majority of the population in both cities.[158]

During the late 19th and early 20th century, the European share was almost a fifth of the population. The French government aimed at making Algeria an assimilated part of France, and this included substantial educational investments especially after 1900. The indigenous cultural and religious resistance heavily opposed this tendency, but in contrast to the other colonized countries' path in central Asia and Caucasus, Algeria kept its individual skills and a relatively human-capital intensive agriculture.[159]

During the Second World War, Algeria came under Vichy control before being liberated by the Allies in Operation Torch, which saw the first large-scale deployment of American troops in the North African campaign.[160]

Gradually, dissatisfaction among the Muslim population, which lacked political and economic status under the colonial system, gave rise to demands for greater political autonomy and eventually independence from France. In May 1945, the uprising against the occupying French forces was suppressed through what is now known as the Sétif and Guelma massacre. Tensions between the two population groups came to a head in 1954, when the first violent events of what was later called the Algerian War began after the publication of the Declaration of 1 November 1954. Historians have estimated that between 30,000 and 150,000 Harkis and their dependents were killed by the National Liberation Front (FLN) or by lynch mobs in Algeria.[161] The FLN used hit and run attacks in Algeria and France as part of its war, and the French conducted severe reprisals. In addition, the French destroyed over 8,000 villages[162] and relocated over 2 million Algerians to concentration camps.[163]

The war led to the death of hundreds of thousands of Algerians and hundreds of thousands of injuries. Historians, like Alistair Horne and Raymond Aron, state that the actual number of Algerian Muslim war dead was far greater than the original FLN and official French estimates but was less than the 1 million deaths claimed by the Algerian government after independence. Horne estimated Algerian casualties during the span of eight years to be around 700,000.[164] The war uprooted more than 2 million Algerians.[165]

The war against French rule concluded in 1962, when Algeria gained complete independence following the March 1962 Evian agreements and the July 1962 self-determination referendum.

The first three decades of independence (1962–1991)

The number of European Pied-Noirs who fled Algeria totaled more than 900,000 between 1962 and 1964.[166] The exodus to mainland France accelerated after the Oran massacre of 1962, in which hundreds of militants entered European sections of the city and began attacking civilians.

Algeria's first president was the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) leader Ahmed Ben Bella. Morocco's claim to portions of western Algeria led to the Sand War in 1963. Ben Bella was overthrown in 1965 by Houari Boumédiène, his former ally and defence minister. Under Ben Bella, the government had become increasingly socialist and authoritarian; Boumédienne continued this trend. However, he relied much more on the army for his support, and reduced the sole legal party to a symbolic role. He collectivised agriculture and launched a massive industrialisation drive. Oil extraction facilities were nationalised. This was especially beneficial to the leadership after the international 1973 oil crisis.

Boumédienne's successor, Chadli Bendjedid, introduced some liberal economic reforms. He promoted a policy of Arabisation in Algerian society and public life. Teachers of Arabic, brought in from other Muslim countries, spread conventional Islamic thought in schools and sowed the seeds of a return to Orthodox Islam.[167]

The Algerian economy became increasingly dependent on oil, leading to hardship when the price collapsed during the 1980s oil glut.[168] Economic recession caused by the crash in world oil prices resulted in Algerian social unrest during the 1980s; by the end of the decade, Bendjedid introduced a multi-party system. Political parties developed, such as the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS), a broad coalition of Muslim groups.[167]

Civil War (1991–2002) and aftermath

In December 1991 the Islamic Salvation Front dominated the first of two rounds of legislative elections. Fearing the election of an Islamist government, the authorities intervened on 11 January 1992, cancelling the elections. Bendjedid resigned and a High Council of State was installed to act as the Presidency. It banned the FIS, triggering a civil insurgency between the Front's armed wing, the Armed Islamic Group, and the national armed forces, in which more than 100,000 people are thought to have died. The Islamist militants conducted a violent campaign of civilian massacres.[169][failed verification] At several points in the conflict, the situation in Algeria became a point of international concern, most notably during the crisis surrounding Air France Flight 8969, a hijacking perpetrated by the Armed Islamic Group. The Armed Islamic Group declared a ceasefire in October 1997.[167]

Algeria held elections in 1999, considered biased by international observers and most opposition groups[170] which were won by President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. He worked to restore political stability to the country and announced a "Civil Concord" initiative, approved in a referendum, under which many political prisoners were pardoned, and several thousand members of armed groups were granted exemption from prosecution under a limited amnesty, in force until 13 January 2000. The AIS disbanded and levels of insurgent violence fell rapidly. The Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (GSPC), a splinter group of the Armed Islamic Group, continued a terrorist campaign against the Government.[167]

Bouteflika was re-elected in the April 2004 presidential election after campaigning on a programme of national reconciliation. The programme comprised economic, institutional, political and social reform to modernise the country, raise living standards, and tackle the causes of alienation. It also included a second amnesty initiative, the Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation, which was approved in a referendum in September 2005. It offered amnesty to most guerrillas and Government security forces.[167]

In November 2008, the Algerian Constitution was amended following a vote in Parliament, removing the two-term limit on Presidential incumbents. This change enabled Bouteflika to stand for re-election in the 2009 presidential elections, and he was re-elected in April 2009. During his election campaign and following his re-election, Bouteflika promised to extend the programme of national reconciliation and a $150-billion spending programme to create three million new jobs, the construction of one million new housing units, and to continue public sector and infrastructure modernisation programmes.[167]

A continuing series of protests throughout the country started on 28 December 2010, inspired by similar protests across the Middle East and North Africa. On 24 February 2011, the government lifted Algeria's 19-year-old state of emergency.[171] The government enacted legislation dealing with political parties, the electoral code, and the representation of women in elected bodies.[172] In April 2011, Bouteflika promised further constitutional and political reform.[167] However, elections are routinely criticised by opposition groups as unfair and international human rights groups say that media censorship and harassment of political opponents continue.

On 2 April 2019, Bouteflika resigned from the presidency after mass protests against his candidacy for a fifth term in office.[173]

In December 2019, Abdelmadjid Tebboune became Algeria's president, after winning the first round of the presidential election with a record abstention rate – the highest of all presidential elections since Algeria's democracy in 1989. Tebboune is accused of being close to the military and being loyal to the deposed president. Tebboune rejects these accusations, claiming to be the victim of a witch hunt. He also reminds his detractors that he was expelled from the Government in August 2017 at the instigation of oligarchs languishing in prison.[174]

Geography

Since the 2011 breakup of Sudan, and the creation of South Sudan, Algeria has been the largest country in Africa, and the Mediterranean Basin. Its southern part includes a significant portion of the Sahara. To the north, the Tell Atlas forms with the Saharan Atlas, further south, two parallel sets of reliefs in approaching eastbound, and between which are inserted vast plains and highlands. Both Atlas tend to merge in eastern Algeria. The vast mountain ranges of Aures and Nememcha occupy the entire northeastern Algeria and are delineated by the Tunisian border. The highest point is Mount Tahat (3,003 metres or 9,852 feet).

Algeria lies mostly between latitudes 19° and 37°N (a small area is north of 37°N and south of 19°N), and longitudes 9°W and 12°E. Most of the coastal area is hilly, sometimes even mountainous, and there are a few natural harbours. The area from the coast to the Tell Atlas is fertile. South of the Tell Atlas is a steppe landscape ending with the Saharan Atlas; farther south, there is the Sahara desert.[176]

The Hoggar Mountains (Arabic: جبال هقار), also known as the Hoggar, are a highland region in central Sahara, southern Algeria. They are located about 1,500 km (932 mi) south of the capital, Algiers, and just east of Tamanghasset. Algiers, Oran, Constantine, and Annaba are Algeria's main cities.[176]

Climate and hydrology

In this region, midday desert temperatures can be hot year round. After sunset, however, the clear, dry air permits rapid loss of heat, and the nights are cool to chilly. Enormous daily ranges in temperature are recorded.

Rainfall is fairly plentiful along the coastal part of the Tell Atlas, ranging from 400 to 670 mm (15.7 to 26.4 in) annually, the amount of precipitation increasing from west to east. Precipitation is heaviest in the northern part of eastern Algeria, where it reaches as much as 1,000 mm (39.4 in) in some years.

Farther inland, the rainfall is less plentiful. Algeria also has ergs, or sand dunes, between mountains. Among these, in the summer time when winds are heavy and gusty, temperatures can go up to 43.3 °C (110 °F).

Fauna and flora

The varied vegetation of Algeria includes coastal, mountainous and grassy desert-like regions which all support a wide range of wildlife.

In Algeria forest cover is around 1% of the total land area, equivalent to 1,949,000 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, up from 1,667,000 hectares (ha) in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 1,439,000 hectares (ha) and planted forest covered 510,000 hectares (ha). Of the naturally regenerating forest 0% was reported to be primary forest (consisting of native tree species with no clearly visible indications of human activity) and around 6% of the forest area was found within protected areas. For the year 2015, 80% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership, 18% private ownership and 2% with ownership listed as other or unknown.[180][181]

Many of the creatures constituting the Algerian wildlife live in close proximity to civilisation. The most commonly seen animals include the wild boars, jackals, and gazelles, although it is not uncommon to spot fennecs (foxes), and jerboas. Algeria also has a small African leopard and Saharan cheetah population, but these are seldom seen. A species of deer, the Barbary stag, inhabits the dense humid forests in the north-eastern areas. The fennec fox is the national animal of Algeria.[182]

A variety of bird species makes the country an attraction for bird watchers. The forests are inhabited by boars and jackals. Barbary macaques are the sole native monkey. Snakes, monitor lizards, and numerous other reptiles can be found living among an array of rodents throughout the semi arid regions of Algeria. Many animals are now extinct, including the Barbary lions, Atlas bears and crocodiles.[183]

In the north, some of the native flora includes Macchia scrub, olive trees, oaks, cedars and other conifers. The mountain regions contain large forests of evergreens (Aleppo pine, juniper, and evergreen oak) and some deciduous trees. Fig, eucalyptus, agave, and various palm trees grow in the warmer areas. The grape vine is indigenous to the coast. In the Sahara region, some oases have palm trees. Acacias with wild olives are the predominant flora in the remainder of the Sahara. Algeria had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.22/10, ranking it 106th globally out of 172 countries.[184]

Camels are used extensively; the desert also abounds with venomous and nonvenomous snakes, scorpions, and numerous insects.

Government and politics

Elected politicians have relatively little sway over Algeria. Instead, a group of unelected civilian and military "décideurs" ("deciders"), known as "le pouvoir" ("the power"), de facto rule the country, even deciding who should be president.[185][186][187] The most powerful man might have been Mohamed Mediène, the head of military intelligence, before he was brought down during the 2019 protests.[188] In recent years, many of these generals have died, retired, or been imprisoned. After the death of General Larbi Belkheir, previous president Bouteflika put loyalists in key posts, notably at Sonatrach, and secured constitutional amendments that made him re-electable indefinitely, until he was brought down in 2019 during protests.[189]

The head of state is the President of Algeria, who is elected for a five-year term. The president is limited to two five-year terms. The most recent presidential election was planned to be in April 2019, but widespread protests erupted on 22 February against the president's decision to participate in the election, which resulted in President Bouteflika announcing his resignation on 3 April.[190] Abdelmadjid Tebboune, an independent candidate, was elected as president after the election eventually took place on 12 December 2019. Protestors refused to recognise Tebboune as president, citing demands for comprehensive reform of the political system.[191] Algeria has universal suffrage at 18 years of age.[16] The President is the head of the army, the Council of Ministers and the High Security Council. He appoints the Prime Minister who is also the head of government.[192]

The Algerian parliament is bicameral; the lower house, the People's National Assembly, has 462 members who are directly elected for five-year terms, while the upper house, the Council of the Nation, has 144 members serving six-year terms, of which 96 members are chosen by local assemblies and 48 are appointed by the president.[193] According to the constitution, no political association may be formed if it is "based on differences in religion, language, race, gender, profession, or region". In addition, political campaigns must be exempt from the aforementioned subjects.[194]

Parliamentary elections were last held in May 2017. In the elections, the FLN lost 44 of its seats, but remained the largest party with 164 seats, the military-backed National Rally for Democracy won 100, and the Muslim Brotherhood-linked Movement of the Society for Peace won 33.[195]

Foreign relations

Algeria is included in the European Union's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) which aims at bringing the EU and its neighbours closer. Giving incentives and rewarding best performers, as well as offering funds in a faster and more flexible manner, are the two main principles underlying the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI) that came into force in 2014. It has a budget of €15.4 billion and provides the bulk of funding through a number of programmes.

In 2009, the French government agreed to compensate victims of nuclear tests in Algeria. Defence Minister Hervé Morin stated that "It's time for our country to be at peace with itself, at peace thanks to a system of compensation and reparations," when presenting the draft law on the payouts. Algerian officials and activists believe that this is a good first step and hope that this move would encourage broader reparation.[196]

Tensions between Algeria and Morocco in relation to the Western Sahara have been an obstacle to tightening the Arab Maghreb Union, nominally established in 1989, but which has carried little practical weight.[197] On 24 August 2021, Algeria announced the break of diplomatic relations with Morocco.[198]

Military

The military of Algeria consists of the People's National Army (ANP), the Algerian National Navy (MRA), and the Algerian Air Force (QJJ), plus the Territorial Air Defence Forces.[14] It is the direct successor of the National Liberation Army (Armée de Libération Nationale or ALN), the armed wing of the nationalist National Liberation Front which fought French colonial occupation during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62).

Total military personnel include 147,000 active, 150,000 reserve, and 187,000 paramilitary staff (2008 estimate).[199] Service in the military is compulsory for men aged 19–30, for a total of 12 months.[200] The military expenditure was 4.3% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2012.[14] Algeria has the second-largest military in North Africa with the largest defence budget in Africa ($10 billion).[201] Most of Algeria's weapons are imported from Russia, with whom they are a close ally.[201][202]

In 2007, the Algerian Air Force signed a deal with Russia to purchase 49 MiG-29SMT and 6 MiG-29UBT at an estimated cost of $1.9 billion. Russia is also building two 636-type diesel submarines for Algeria.[203]

Algeria is the 90th most peaceful country in the world, according to the 2024 Global Peace Index.[204]

Human rights

Algeria has been categorised by the US government funded Freedom House as "not free" since it began publishing such ratings in 1972, with the exception of 1989, 1990, and 1991, when the country was labelled "partly free."[205] In December 2016, the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor issued a report regarding violation of media freedom in Algeria. It clarified that the Algerian government imposed restrictions on freedom of the press; expression; and right to peaceful demonstration, protest and assembly as well as intensified censorship of the media and websites. Due to the fact that the journalists and activists criticise the ruling government, some media organisations' licenses are cancelled.[206]

Independent and autonomous trade unions face routine harassment from the government, with many leaders imprisoned and protests suppressed. In 2016, a number of unions, many of which were involved in the 2010–2012 Algerian Protests, have been deregistered by the government.[207][208][209]

Homosexuality is illegal in Algeria.[210] Public homosexual behavior is punishable by up to two years in prison.[211] Despite this, about 26% of Algerians think that homosexuality should be accepted, according to the survey conducted by the BBC News Arabic-Arab Barometer in 2019. Algeria showed the highest LGBT acceptance compared to other Arab countries where the survey was conducted.[212]

Human Rights Watch has accused the Algerian authorities of using the COVID-19 pandemic as an excuse to prevent pro-democracy movements and protests in the country, leading to the arrest of youths as part of social distancing.[213]

Administrative divisions

Algeria is divided into 58 provinces (wilayas), 553 districts (daïras)[214] and 1,541 municipalities (baladiyahs). Each province, district, and municipality is named after its seat, which is usually the largest city.

The administrative divisions have changed several times since independence. When introducing new provinces, the numbers of old provinces are kept, hence the non-alphabetical order. With their official numbers, currently (since 1983) they are:[14]

| # | Wilaya | Area (km2) | Population | map | # | Wilaya | Area (km2) | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adrar | 402,197 | 439,700 |  |

30 | Ouargla | 211,980 | 552,539 |

| 2 | Chlef | 4,975 | 1,013,718 | 31 | Oran | 2,114 | 1,584,607 | |

| 3 | Laghouat | 25,057 | 477,328 | 32 | El Bayadh | 78,870 | 262,187 | |

| 4 | Oum El Bouaghi | 6,768 | 644,364 | 33 | Illizi | 285,000 | 54,490 | |

| 5 | Batna | 12,192 | 1,128,030 | 34 | Bordj Bou Arréridj | 4,115 | 634,396 | |

| 6 | Béjaïa | 3,268 | 915,835 | 35 | Boumerdes | 1,591 | 795,019 | |

| 7 | Biskra | 20,986 | 730,262 | 36 | El Taref | 3,339 | 411,783 | |

| 8 | Béchar | 161,400 | 274,866 | 37 | Tindouf | 58,193 | 159,000 | |

| 9 | Blida | 1,696 | 1,009,892 | 38 | Tissemsilt | 3,152 | 296,366 | |

| 10 | Bouïra | 4,439 | 694,750 | 39 | El Oued | 54,573 | 673,934 | |

| 11 | Tamanrasset | 556,200 | 198,691 | 40 | Khenchela | 9,811 | 384,268 | |

| 12 | Tébessa | 14,227 | 657,227 | 41 | Souk Ahras | 4,541 | 440,299 | |

| 13 | Tlemcen | 9,061 | 945,525 | 42 | Tipaza | 2,166 | 617,661 | |

| 14 | Tiaret | 20,673 | 842,060 | 43 | Mila | 9,375 | 768,419 | |

| 15 | Tizi Ouzou | 3,568 | 1,119,646 | 44 | Ain Defla | 4,897 | 771,890 | |

| 16 | Algiers | 273 | 2,947,461 | 45 | Naâma | 29,950 | 209,470 | |

| 17 | Djelfa | 66,415 | 1,223,223 | 46 | Ain Timouchent | 2,376 | 384,565 | |

| 18 | Jijel | 2,577 | 634,412 | 47 | Ghardaia | 86,105 | 375,988 | |

| 19 | Sétif | 6,504 | 1,496,150 | 48 | Relizane | 4,870 | 733,060 | |

| 20 | Saïda | 6,764 | 328,685 | 49 | El M'Ghair | 8,835 | 162,267 | |

| 21 | Skikda | 4,026 | 904,195 | 50 | El Menia | 62,215 | 57,276 | |

| 22 | Sidi Bel Abbès | 9,150 | 603,369 | 51 | Ouled Djellal | 11,410 | 174,219 | |

| 23 | Annaba | 1,439 | 640,050 | 52 | Bordj Baji Mokhtar | 120,026 | 16,437 | |

| 24 | Guelma | 4,101 | 482,261 | 53 | Béni Abbès | 101,350 | 50,163 | |

| 25 | Constantine | 2,187 | 943,112 | 54 | Timimoun | 65,203 | 122,019 | |

| 26 | Médéa | 8,866 | 830,943 | 55 | Touggourt | 17,428 | 247,221 | |

| 27 | Mostaganem | 2,269 | 746,947 | 56 | Djanet | 86,185 | 17,618 | |

| 28 | M'Sila | 18,718 | 991,846 | 57 | In Salah | 131,220 | 50,392 | |

| 29 | Mascara | 5,941 | 780,959 | 58 | In Guezzam | 88,126 | 11,202 |

Economy

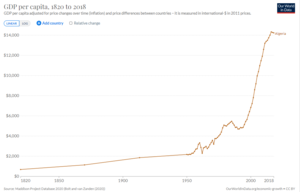

Algeria's currency is the dinar (DZD). The economy remains dominated by the state, a legacy of the country's socialist post-independence development model. On June, 2024 The World Bank's 2024 report marks a turning point for Algeria, which joins the select club of upper-middle-income countries. This economic rise, the result of an ambitious development strategy, places the country in the same category as emerging powers such as China, Brazil and Turkey [215][216][217] In recent years, the Algerian government has halted the privatization of state-owned industries and imposed restrictions on imports and foreign involvement in its economy.[14] These restrictions are just starting to be lifted off recently although questions about Algeria's slowly-diversifying economy remain.[citation needed]

Algeria has struggled to develop industries outside hydrocarbons in part because of high costs and an inert state bureaucracy. The government's efforts to diversify the economy by attracting foreign and domestic investment outside the energy sector have done little to reduce high youth unemployment rates or to address housing shortages.[14] The country is facing a number of short-term and medium-term problems, including the need to diversify the economy, strengthen political, economic and financial reforms, improve the business climate and reduce inequalities among regions.[172]

A wave of economic protests in February and March 2011 prompted the Algerian government to offer more than $23 billion in public grants and retroactive salary and benefit increases. Public spending has increased by 27% annually during the past five years. The 2010–14 public-investment programme will cost US$286 billion, 40% of which will go to human development.[172]

Thanks to strong hydrocarbon revenues, Algeria has a cushion of $173 billion in foreign currency reserves and a large hydrocarbon stabilisation fund. In addition, Algeria's external debt is extremely low at about 2% of GDP.[14] The economy remains very dependent on hydrocarbon wealth, and, despite high foreign exchange reserves (US$178 billion, equivalent to three years of imports), current expenditure growth makes Algeria's budget more vulnerable to the risk of prolonged lower hydrocarbon revenues.[218]

Algeria has not joined the WTO, despite several years of negotiations but is a member of the Greater Arab Free Trade Area,[219][unreliable source] the African Continental Free Trade Area,[220] and has an association agreement with the European Union.[221][222]

Turkish direct investments have accelerated in Algeria, with total value reaching $5 billion. As of 2022, the number of Turkish companies present in Algeria has reached 1,400. In 2020, despite the pandemic, more than 130 Turkish companies were created in Algeria.[223]

Oil and natural resources

Algeria, whose economy is reliant on petroleum, has been an OPEC member since 1969. Its crude oil production stands at around 1.1 million barrels/day, but it is also a major gas producer and exporter, with important links to Europe.[224] Hydrocarbons have long been the backbone of the economy, accounting for roughly 60% of budget revenues, 30% of GDP, and 87.7%[225] of export earnings. Algeria has the 10th-largest reserves of natural gas in the world and is the sixth-largest gas exporter. The U.S. Energy Information Administration reported that in 2005, Algeria had 4.5 trillion cubic metres (160×1012 cu ft) of proven natural gas reserves.[226] It also ranks 16th in oil reserves.[14]

Non-hydrocarbon growth for 2011 was projected at 5%. To cope with social demands, the authorities raised expenditure, especially on basic food support, employment creation, support for SMEs, and higher salaries. High hydrocarbon prices have improved the current account and the already large international reserves position.[218]

Income from oil and gas rose in 2011 as a result of continuing high oil prices, though the trend in production volume is downward.[172] Production from the oil and gas sector in terms of volume continues to decline, dropping from 43.2 million tonnes to 32 million tonnes between 2007 and 2011. Nevertheless, the sector accounted for 98% of the total volume of exports in 2011, against 48% in 1962,[227] and 70% of budgetary receipts, or US$71.4 billion.[172]

The Algerian national oil company is Sonatrach, which plays a key role in all aspects of the oil and natural gas sectors in Algeria. All foreign operators must work in partnership with Sonatrach, which usually has majority ownership in production-sharing agreements.[228]

Access to biocapacity in Algeria is lower than world average. In 2016, Algeria had 0.53 global hectares[229] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much less than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[230] In 2016, Algeria used 2.4 global hectares of biocapacity per person – their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use just under 4.5 times as much biocapacity as Algeria contains. As a result, Algeria is running a biocapacity deficit.[229] In April 2022, diplomats from Italy and Spain held talks after Rome's move to secure large volume of Algerian gas stoked concerns in Madrid.[231] Under the deal between Algeria's Sonatrach and Italy's Eni, Algeria will send an additional 9 billion cubic metres of gas to Italy by next year and in 2024.[232]

Research and alternative energy sources

Algeria has invested an estimated 100 billion dinars towards developing research facilities and paying researchers. This development program is meant to advance alternative energy production, especially solar and wind power.[233] Algeria is estimated to have the largest solar energy potential in the Mediterranean, so the government has funded the creation of a solar science park in Hassi R'Mel. Currently, Algeria has 20,000 research professors at various universities and over 780 research labs, with state-set goals to expand to 1,000. Besides solar energy, areas of research in Algeria include space and satellite telecommunications, nuclear power and medical research.

Labour market

The overall rate of unemployment was 10% in 2011, but remained higher among young people, with a rate of 21.5% for those aged between 15 and 24. The government strengthened in 2011 the job programs introduced in 1988, in particular in the framework of the program to aid those seeking work (Dispositif d'Aide à l'Insertion Professionnelle).[172]

Despite a decline in total unemployment, youth and women unemployment is high.[218]

Tourism

The development of the tourism sector in Algeria had previously been hampered by a lack of facilities, but since 2004 a broad tourism development strategy has been implemented resulting in many hotels of a high modern standard being built.

There are several UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Algeria[234] including Al Qal'a of Beni Hammad, the first capital of the Hammadid empire; Tipasa, a Phoenician and later Roman town; and Djémila and Timgad, both Roman ruins; M'Zab Valley, a limestone valley containing a large urbanized oasis; and the Casbah of Algiers, an important citadel. The only natural World Heritage Site is the Tassili n'Ajjer, a mountain range.

Transport

Two trans-African automobile routes pass through Algeria:

The Algerian road network is the densest in Africa; its length is estimated at 180,000 km (110,000 mi) of highways, with more than 3,756 structures and a paving rate of 85%. This network will be complemented by the East-West Highway, a major infrastructure project currently under construction. It is a three-way, 1,216-kilometre-long (756 mi) highway, linking Annaba in the extreme east to the Tlemcen in the far west. Algeria is also crossed by the Trans-Sahara Highway, which is now completely paved. This road is supported by the Algerian government to increase trade between the six countries crossed: Algeria, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, and Tunisia.

Demographics

Algeria has a population of an estimated 44 million, of which the majority, 75%[5] to 85% are ethnically Arab.[14][235][236] At the outset of the 20th century, its population was approximately four million.[237] About 90% of Algerians live in the northern, coastal area; the inhabitants of the Sahara desert are mainly concentrated in oases, although some 1.5 million remain nomadic or partly nomadic. 28.1% of Algerians are under the age of 15.[14]

Between 90,000 and 165,000 Sahrawis from Western Sahara live in the Sahrawi refugee camps,[238][239] in the western Algerian Sahara desert.[240] There are also more than 4,000 Palestinian refugees, who are well integrated and have not asked for assistance from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).[238][239] In 2009, 35,000 Chinese migrant workers lived in Algeria.[241]

The largest concentration of Algerian migrants outside Algeria is in France, which has reportedly over 1.7 million Algerians of up to the second generation.[242]

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Algiers  Oran |

1 | Algiers | Algiers Province | 2,364,230 | 11 | Tébessa | Tébessa Province | 194,461 |  Constantine  Annaba |

| 2 | Oran | Oran Province | 803,329 | 12 | El Oued | El Oued Province | 186,525 | ||

| 3 | Constantine | Constantine Province | 448,028 | 13 | Skikda | Skikda Province | 182,903 | ||

| 4 | Annaba | Annaba Province | 342,703 | 14 | Tiaret | Tiaret Province | 178,915 | ||

| 5 | Blida | Blida Province | 331,779 | 15 | Béjaïa | Béjaïa Province | 176,139 | ||

| 6 | Batna | Batna Province | 289,504 | 16 | Tlemcen | Tlemcen Province | 173,531 | ||

| 7 | Djelfa | Djelfa Province | 265,833 | 17 | Ouargla | Ouargla Province | 169,928 | ||

| 8 | Sétif | Sétif Province | 252,127 | 18 | Béchar | Béchar Province | 165,241 | ||

| 9 | Sidi Bel Abbès | Sidi Bel Abbès Province | 210,146 | 19 | Mostaganem | Mostaganem Province | 162,885 | ||

| 10 | Biskra | Biskra Province | 204,661 | 20 | Bordj Bou Arréridj | Bordj Bou Arréridj Province | 158,812 | ||

Ethnic groups

Arabs and indigenous Berbers as well as Phoenicians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantine Greeks, Turks, various Sub-Saharan Africans, and French have contributed to the history and culture of Algeria.[244] Descendants of Andalusi refugees are also present in the population of Algiers and other cities.[245] Moreover, Spanish was spoken by these Aragonese and Castillian Morisco descendants deep into the 18th century, and even Catalan was spoken at the same time by Catalan Morisco descendants in the small town of Grish El-Oued.[246]

Centuries of Arab migrations to the Maghreb since the seventh century shifted the demographic scope in Algeria. Estimates vary based on different sources. The majority of the population of Algeria is ethnically Arab, constituting between 75%[5][15][7][8] and 80%[9][10][247] to 85%[248][249] of the population. Berbers who make up between 15%[14] and 20%[10][9][250] to 24%[15][7][8] of the population are divided into many groups with varying languages. The largest of these are the Kabyles, who live in the Kabylie region east of Algiers, the Chaoui of Northeast Algeria, the Tuaregs in the southern desert and the Shenwa people of North Algeria.[251][page needed] During the colonial period, there was a large (10% in 1960)[252] European population who became known as Pied-Noirs. They were primarily of French, Spanish and Italian origin. Almost all of this population left during the war of independence or immediately after its end.[253]

Languages

Modern Standard Arabic and Berber are the official languages.[254] Algerian Arabic (Darja) is the language used by the majority of the population. Colloquial Algerian Arabic has some Berber loanwords which represent 8% to 9% of its vocabulary.[255]

Berber has been recognised as a "national language" by the constitutional amendment of 8 May 2002.[256] Kabyle, the predominant Berber language, is taught and is partially co-official (with a few restrictions) in parts of Kabylie. Kabyle has a significant Arabic, French, Latin, Greek, Phoenician and Punic substratum, and Arabic loanwords represent 35% of the total Kabyle vocabulary.[257] In February 2016, the Algerian constitution passed a resolution that made Berber an official language alongside Arabic. Algeria emerged as a bilingual state after 1962.[258] Colloquial Algerian Arabic is spoken by about 83% of the population and Berber by 27%.[259]

Although French has no official status in Algeria, it has one of the largest Francophone populations in the world,[260] and French is widely used in government, media (newspapers, radio, local television), and both the education system (from primary school onwards) and academia due to Algeria's colonial history. It can be regarded as a lingua franca of Algeria. In 2008, 11.2 million Algerians could read and write in French.[261] In 2013, it was estimated that 60% of the population could speak or understand French.[262] In 2022, it was estimated that 33% of the population was Francophone.[263]

The use of English in Algeria, though limited in comparison to the previously mentioned languages, has increased due to globalization.[264][265] In 2022 it was announced that English would be taught in elementary schools.[266]

Religion

Islam is the predominant religion in Algeria, with its adherents, mostly Sunnis, accounting for 99% of the population according to a 2021 CIA World Factbook estimate,[14] and 97.9% according to Pew Research in 2020.[267] There are about 290,000 Ibadis in the M'zab Valley in the region of Ghardaia.

Prior to independence, Algeria was home to more than 1.3 million Christians (mostly of European ancestry).[268] Most of the Christian settlers left to France after the country's independence.[269][270] Today, estimates of the Christian population range from 20,000 to 200,000.[271] Algerian citizens who are Christians predominantly belong to Protestant denominations, which have seen increased pressure from the government in recent years including many forced closures.[271]

According to the Arab Barometer in 2018–2019, the vast majority of Algerians (99.1%) continue to identify as Muslim.[272] The June 2019 Arab Barometer-BBC News report found that the percentage of Algerians identifying as non-religious has grown from around 8% in 2013 to around 15% in 2018.[273] The Arab Barometer December 2019, found that the growth in the percentage of Algerians identifying as non-religious is largely driven by young Algerians, with roughly 25% describing themselves as non-religious.[274] However, the 2021 Arab Barometer report found that those who said they were not religious among Algerians has decreased, with just 2.6% identifying as non-religious. In that same report, 69.5% of Algerians identified as religious and another 27.8% identifying as somewhat religious.[272][275]

Algeria has given the Muslim world a number of prominent thinkers, including Emir Abdelkader, Abdelhamid Ben Badis, Mouloud Kacem Naît Belkacem, Malek Bennabi and Mohamed Arkoun.

Health

In 2018, Algeria had the highest numbers of physicians in the Maghreb region (1.72 per 1,000 people), nurses (2.23 per 1,000 people), and dentists (0.31 per 1,000 people). Access to "improved water sources" was around 97.4% of the population in urban areas and 98.7% of the population in the rural areas. Some 99% of Algerians living in urban areas, and around 93.4% of those living in rural areas, had access to "improved sanitation". According to the World Bank, Algeria is making progress toward its goal of "reducing by half the number of people without sustainable access to improved drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015". Given Algeria's young population, policy favours preventive health care and clinics over hospitals. In keeping with this policy, the government maintains an immunisation program. However, poor sanitation and unclean water still cause tuberculosis, hepatitis, measles, typhoid fever, cholera and dysentery. The poor generally receive healthcare free of charge.[276]

Health records have been maintained in Algeria since 1882 and began adding Muslims living in the south to their vital record database in 1905 during French rule.[277]

Education

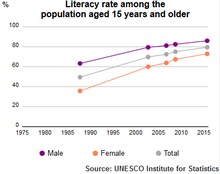

Since the 1970s, in a centralised system that was designed to significantly reduce the rate of illiteracy, the Algerian government introduced a decree by which school attendance became compulsory for all children aged between 6 and 15 years who have the ability to track their learning through the 20 facilities built since independence, now the literacy rate is around 92.6%.[278] Since 1972, Arabic is used as the language of instruction during the first nine years of schooling. From the third year, French is taught and it is also the language of instruction for science classes. The students can also learn English, Italian, Spanish and German. In 2008, new programs at the elementary appeared, therefore the compulsory schooling does not start at the age of six anymore, but at the age of five.[279] Apart from the 122 private schools, the Universities of the State are free of charge. After nine years of primary school, students can go to a high school or to an educational institution. The school offers two programs: general or technical. At the end of the third year of secondary school, students pass the exam of the baccalaureate, which allows once it is successful to pursue graduate studies in universities and institutes.[280]

Education is officially compulsory for children between the ages of six and 15. In 2008, the illiteracy rate for people over 10 was 22.3%, 15.6% for men and 29.0% for women. The province with the lowest rate of illiteracy was Algiers Province at 11.6%, while the province with the highest rate was Djelfa Province at 35.5%.[281]

Algeria has 26 universities and 67 institutions of higher education, which must accommodate a million Algerians and 80,000 foreign students in 2008. The University of Algiers, founded in 1879, is the oldest, it offers education in various disciplines (law, medicine, science and letters). Twenty-five of these universities and almost all of the institutions of higher education were founded after the independence of the country.

Even if some of them offer instruction in Arabic like areas of law and the economy, most of the other sectors such as science and medicine continue to be provided in French and English. Among the most important universities, there are the University of Sciences and Technology Houari Boumediene, the University of Mentouri Constantine, and University of Oran Es-Senia. The University of Abou Bekr Belkaïd in Tlemcen and University of Batna Hadj Lakhdar occupy the 26th and 45th row in Africa.[282] Algeria was ranked 119th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[283][284]

Culture

Modern Algerian literature, split between Arabic, Tamazight and French, has been strongly influenced by the country's recent history. Famous novelists of the 20th century include Mohammed Dib, Albert Camus, Kateb Yacine and Ahlam Mosteghanemi while Assia Djebar is widely translated. Among the important novelists of the 1980s were Rachid Mimouni, later vice-president of Amnesty International, and Tahar Djaout, murdered by an Islamist group in 1993 for his secularist views.[285]

Malek Bennabi and Frantz Fanon are noted for their thoughts on decolonization; Augustine of Hippo was born in Tagaste (modern-day Souk Ahras); and Ibn Khaldun, though born in Tunis, wrote the Muqaddima while staying in Algeria. The works of the Sanusi family in pre-colonial times, and of Emir Abdelkader and Sheikh Ben Badis in colonial times, are widely noted. The Latin author Apuleius was born in Madaurus (Mdaourouch), in what later became Algeria.

Contemporary Algerian cinema is varied in terms of genre, exploring a wider range of themes and issues. There has been a transition from cinema which focused on the war of independence to films more concerned with the everyday lives of Algerians.[286]

Media

Art

Algerian painters, like Mohammed Racim and Baya, attempted to revive the prestigious Algerian past prior to French colonisation, at the same time that they have contributed to the preservation of the authentic values of Algeria. In this line, Mohamed Temam, Abdelkhader Houamel have also returned through this art, scenes from the history of the country, the habits and customs of the past and the country life. Other new artistic currents including the one of M'hamed Issiakhem, Mohammed Khadda and Bachir Yelles, appeared on the scene of Algerian painting, abandoning figurative classical painting to find new pictorial ways, to adapt Algerian paintings to the new realities of the country through its struggle and its aspirations. Mohammed Khadda[287] and M'hamed Issiakhem have been notable in recent years.[287]

Literature

The historic roots of Algerian literature go back to the Numidian and Roman African era, when Apuleius wrote The Golden Ass, the only Latin novel to survive in its entirety. This period had also known Augustine of Hippo, Nonius Marcellus and Martianus Capella, among many others. The Middle Ages have known many Arabic writers who revolutionised the Arab world literature, with authors like Ahmad al-Buni, Ibn Manzur and Ibn Khaldoun, who wrote the Muqaddimah while staying in Algeria, and many others.

Albert Camus was an Algerian-born French Pied-Noir author. In 1957, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature.

Today Algeria contains, in its literary landscape, big names having not only marked the Algerian literature, but also the universal literary heritage in Arabic and French.

As a first step, Algerian literature was marked by works whose main concern was the assertion of the Algerian national entity, there is the publication of novels as the Algerian trilogy of Mohammed Dib, or even Nedjma of Kateb Yacine novel which is often regarded as a monumental and major work. Other known writers will contribute to the emergence of Algerian literature whom include Mouloud Feraoun, Malek Bennabi, Malek Haddad, Moufdi Zakaria, Abdelhamid Ben Badis, Mohamed Laïd Al-Khalifa, Mouloud Mammeri, Frantz Fanon, and Assia Djebar.

In the aftermath of the independence, several new authors emerged on the Algerian literary scene, they will attempt through their works to expose a number of social problems, among them there are Rachid Boudjedra, Rachid Mimouni, Leila Sebbar, Tahar Djaout and Tahir Wattar.

Currently, a part of Algerian writers tends to be defined in a literature of shocking expression, due to the terrorism that occurred during the 1990s, the other party is defined in a different style of literature who staged an individualistic conception of the human adventure. Among the most noted recent works, there is the writer, the swallows of Kabul and the attack of Yasmina Khadra, the oath of barbarians of Boualem Sansal, memory of the flesh of Ahlam Mosteghanemi and the last novel by Assia Djebar nowhere in my father's House.

Cinema

The Algerian state's interest in film-industry activities can be seen in the annual budget of DZD 200 million (EUR 1.3 million) allocated to production, specific measures and an ambitious programme plan implemented by the Ministry of Culture to promote national production, renovate the cinema stock and remedy the weak links in distribution and exploitation.

The financial support provided by the state, through the Fund for the Development of the Arts, Techniques and the Film Industry (FDATIC) and the Algerian Agency for Cultural Influence (AARC), plays a key role in the promotion of national production. Between 2007 and 2013, FDATIC subsidised 98 films (feature films, documentaries and short films). In mid-2013, AARC had already supported a total of 78 films, including 42 feature films, 6 short films and 30 documentaries.

According to the European Audiovisual Observatory's LUMIERE database, 41 Algerian films were distributed in Europe between 1996 and 2013; 21 films in this repertoire were Algerian-French co-productions. Days of Glory (2006) and Outside the Law (2010) recorded the highest number of admissions in the European Union, 3,172,612 and 474,722, respectively.[289]

Algeria won the Palme d'Or for Chronicle of the Years of Fire (1975), two Oscars for Z (1969), and other awards for the Italian-Algerian movie The Battle of Algiers.

Cuisine

Algerian cuisine is rich and diverse as a result of interactions and exchanges with other cultures and nations over the centuries.[290] It is based on both land and sea products. Conquests or demographic movement towards the Algerian territory were two of the main factors of exchanges between the different peoples and cultures. The Algerian cuisine is a mix of Arab, Berber, Turkish and French roots.[291][290]