История ассирийцев

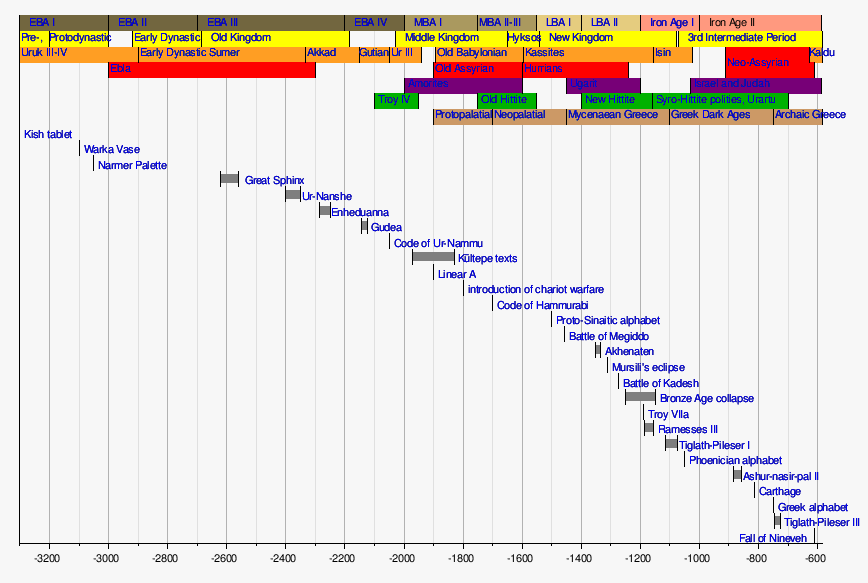

История ассирийцев охватывает почти пять тысячелетий, охватывая историю древней месопотамской цивилизации Ассирии , включая ее территорию, культуру и население, а также более позднюю историю ассирийского народа после падения Неоассирийской империи в 609 году. до нашей эры. [а] Для целей историографии древняя ассирийская история часто делится современными исследователями, исходя из политических событий и постепенных изменений языка, на раннеассирийскую ( ок . 2600–2025 до н. э.), древнеассирийскую ( ок. 2025–1364 до н. э.), среднеазиатскую. Ассирийский ( ок. 1363–912 до н. э.), неоассирийский (911–609 до н. э.) и постимперский (609 до н. э. – ок . 240 н. э.) периоды. [10] [11] эпохи Сасанидов Асористан с 240 г. по 637 г. н.э. и период после исламского завоевания до наших дней.

Ассирия получила свое название от древнего города Ашшур , основанного ок. 2600 г. до н.э. На протяжении большей части своей ранней истории Ассур находился под властью иностранных государств и политий из южной Месопотамии, например, попадая под гегемонию шумерского города Киш , будучи включенным в этнически ту же Аккадскую империю и попадая под власть Третьей династии Ур . Город и его окрестности стали независимым городом-государством под собственной линией правителей во время распада Третьей династии Ура, достигнув независимости при Пузур-Ашуре I в. 2025 год до нашей эры. Династия Пузур-Ашура продолжала управлять Ассуром, который стал региональной державой с колониями в Анатолии и влиянием на Южную Месопотамию, пока трон не был узурпирован аморейским завоевателем Шамши-Ададом I ок. 1808 г. до н.э. Этот период иногда называют Старой Ассирийской империей , а позднее — «Империей Шамши Адада». После нескольких десятилетий вавилонского господства в середине 18 века до нашей эры Ассирийское государство было восстановлено как независимое государство, возможно, царем Пузур-Син или его преемник Адаси , оба разгромили вавилонян и амореев. В 15 веке до нашей эры Ассирия ненадолго попала под сюзеренитет Митаннийского царства . После войн между Митанни и хеттами Ассур вырвался на свободу, а при Ашшур-убаллите I ( ок. 1363–1328 до н. э.) уничтожил империю Хурри-Митанни, аннексировал большую часть территории хеттской империи и перешел в мощную территориальную державу. государство, управлявшее все более обширной территорией в Месопотамии, Анатолии и Леванте, образуя Среднеассирийскую империю .

в XIV и XIII веках до нашей эры При царях-воинах Адад-Нирари I , Салманасаре I и Тукульти-Нинурте I Среднеассирийская империя стала одной из великих держав древнего Ближнего Востока , на какое-то время даже оккупировавшей Вавилонию на юге. После смерти Ашур-бел-кала в 1056 г. до н. э. Ассирия пережила длительный период упадка, иногда прерываемый энергичными царями-воинами, которые ограничивали Ассирию немногим большим, чем центральная часть Ассирии и прилегающие территории, хотя ассирийское военное мастерство оставалось лучшим. в мире. Новые усилия ассирийских царей 10 и 9 веков до нашей эры обратили этот упадок вспять и привели к возобновлению периода расширения. При Ашурнасирпале II в начале 9 века до нашей эры Ассирия (ныне Неоассирийская империя ) снова стала доминирующей политической и военной державой на Ближнем Востоке. Ассирийский экспансионизм и могущество достигли своего пика при Тиглатпаласаре III в 8 веке до нашей эры и последующей династии царей Саргонидов , при которой Неоассирийская империя простиралась от Египет , Ливия и Аравийский полуостров на юге до Кавказа на севере, от Персии на востоке до Кипра на западе. Вавилония была отвоевана, и ассирийские кампании были проведены как в Анатолию , так и в современную Армению. Империя и Ассирия как государство прекратили свое существование в конце VII века до нашей эры в результате медо-вавилонского завоевания Ассирийской империи после того, как истощающая гражданская война между конкурирующими претендентами на ассирийский трон серьезно ослабила ее.

После падения Неоассирийской империи ассирийский народ продолжал выживать в северной Месопотамии и юго-восточной Анатолии, и ассирийские культурные традиции сохранились. Хотя вавилоняне и мидяне сильно опустошили ассирийские города, регион вскоре был значительно перестроен и возрожден под властью Империи Ахеменидов , Селевкидов и Парфянской империи с 4 века до нашей эры до 3 века нашей эры. Сам Ассур процветал в поздний постимперский период, возможно, снова под своей собственной линией правителей как полуавтономный город-государство. Во время Парфянской империи со 2-го века до нашей эры до середины 3-го века нашей эры возник ряд неоассирийских государств, в том числе Ассур , Адиабена , Осроена , Бет Нухадра , Бет Гармаи и частично ассирийская Хатра . Однако эти государства были завоеваны Сасанидской империей ок. 240 год нашей эры. Начиная с I века нашей эры, ассирийцы были обращены в христианство , хотя приверженцы старой древней месопотамской религии продолжали выживать в течение многих столетий, вплоть до Позднее средневековье в некоторых регионах. Ассирийцы продолжали составлять значительную, если не большинство, часть населения северной Месопотамии, Северо-Восточной Сирии и Юго-Восточной Анатолии до подавления и массовых убийств при Ильханате и Империи Тимуридов в 14 веке. Эти зверства низвели ассирийцев до уровня местного коренного этнического, языкового и религиозного меньшинства. Конец 19-го и начало 20-го века были отмечены дальнейшими преследованиями и массовыми убийствами, в первую очередь Сайфо (ассирийский геноцид) в Османской империи в 1910-х годах, в результате которого погибло около 250 000 ассирийцев. [б] Это время зверств также было отмечено ростом ассирийского культурного сознания; первая ассирийская газета « Захрире д-Бахра » («Лучи света») начала выходить в 1848 году, а самая ранняя ассирийская политическая партия, Ассирийская социалистическая партия много неудачных предложений , была основана в 1917 году. На протяжении всего 20-го века и до сих пор было . были сделаны ассирийцами для автономии или независимости. Дальнейшие массовые убийства и преследования, проводимые как правительствами, так и террористическими группировками, такими как « Исламское государство», привели к тому, что большая часть ассирийского народа живет в диаспоре .

Древняя Ассирия (2600 г. до н.э. – 240 г. н.э.)

[ редактировать ]Ранний ассирийский период (2600–2025 до н.э.)

[ редактировать ]

Известно, что сельскохозяйственные деревни в регионе, который позже стал Ассирией, существовали ко времени культуры Хассуна . [13] в. 6300–5800 гг. до н.э. [14] Хотя известно, что места некоторых близлежащих городов, которые позже будут включены в центральную часть Ассирии, такие как Ниневия , были заселены со времен неолита . [15] самые ранние археологические свидетельства из Ассура относятся к раннему династическому периоду , ок. 2600 г. до н.э., [16] время, когда окружающий регион уже был относительно урбанизирован. [13] Возможно, город был основан раньше; [17] [15] большая часть ранних исторических руин Ассура, возможно, была разрушена во время обширных строительных проектов более поздних ассирийских царей , которые работали над созданием ровного фундамента для зданий, которые они возводили в городе. [18] Нет никаких свидетельств того, что ранний Ассур был независимым поселением. [17] и, возможно, изначально он вообще не назывался Ассур, а скорее Балтил или Балтила , что в более поздние времена использовалось для обозначения самой старой части города. [19] Название этого места впервые упоминается в документах аккадского периода 24 века до нашей эры. [20]

Ранний Ассур, вероятно, был местным религиозным и племенным центром и, должно быть, был городом некоторого размера, поскольку в нем были монументальные храмы. [21] [22] [23] Он был расположен в очень стратегическом месте, на холме с видом на реку Тигр , защищенном рекой с одной стороны и каналом с другой. [17] Сохранившиеся археологические и литературные свидетельства некоторые историки предполагают, что Ассур в его ранней истории мог быть населен хурритами , а также семитскими предками ассирийцев, хотя другие отвергают эту гипотезу. [13] [24] Ассур был местом культа плодородия , посвященного ассирийско-аккадской богине Иштар . [25] Самые ранние известные археологические находки на этом месте — это храмы раннединастического периода, посвященные Иштар. Эти храмы и артефакты внутри них также демонстрируют значительное сходство с храмами и артефактами из Шумера в южной Месопотамии, что может указывать на то, что в городе также жила группа шумеров. [26] что в какой-то момент он был завоеван неизвестным шумерским правителем или просто является примером слияния шумерской и аккадской языковой культуры в Месопотамии. [27] The East Semitic-speaking ancestors of the later Assyrians settled in Mesopotamia at some point during the 35th and 31st century BC, either assimilating[13] or displacing the previous population. The earliest Assyrian king named Tudia appears to have lived in the mid 25th century BC.[24]

During much of the early Assyrian period, Assur was dominated by states and polities from southern Mesopotamia.[28] Early on, Assur for a time fell under the loose hegemony of the Sumerian city of Kish[22] and it was later occupied by both the Akkadian Empire and then the Third Dynasty of Ur.[17] The Akkadian Empire probably conquered Assur in the time of its first ruler, Sargon (c. 2334–2279 BC),[22] and is known to have controlled the city at least from the reign of Manishtushu (c. 2270–2255 BC) onwards since contemporary inscriptions dedicated to Manishtushu have been recovered from the city.[29] The earliest historically attested rulers[c] of Assur were local governors under the Akkadian kings, including figures such as Ititi[33] and Azazu,[34] who bore the title Išši'ak Aššur (governor of Assur).[29][34] Assur was strongly influenced both culturally and linguistically by the period under Akkadian rule (the Akkadians and Assyrians being ethno-linguistically the same people) and the period would be regarded as a golden age by later Assyrian kings, who often sought to emulate the Akkadian rulers who they viewed as their ancestors.[35]

Assur was largely destroyed in the late Akkadian period, possibly by the Lullubi,[36] but was rebuilt and later conquered by the Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur in the late 22nd or early 21st century BC. Under the rulers of Ur, Assur became a peripheral city state under its own governors, such as Zariqum, who paid tribute to the southern kings.[37] This period of Sumerian dominance over the city came to an end as the last king of the Third Dynasty of Ur, Ibbi-Sin (c. 2028–2004 BC) lost his administrative grip on the peripheral regions of his empire and Assur became an independent city-state controlling areas of northern Mesopotamia under its own rulers, beginning with Puzur-Ashur I c. 2025 BC, although it appears kings such as Ushpia c. 2080 BC were also independent.[36]

Old Assyrian period (2025–1364 BC)

[edit]

Puzur-Ashur I and the succeeding kings of his dynasty, the Puzur-Ashur dynasty, did not technically claim the dignity of "king" (šar) for themselves, but continued to use the style rulers of Assur had used while the city was under foreign rule, Išši'ak ("governor"). The use of this style asserted that the actual king of the city was the Assyrian national deity Ashur and that the Assyrian ruler was merely his representative on Earth.[38][39] It is probable that Ashur took form as a deity at some point during the Early Assyrian period as a personification of the city of Assur itself.[40] During the rule of the Puzur-Ashur dynasty, Assur was home to less than 10,000 people and the military power of the city is likely to have been limited to local regions; no sources describe any military conquests whatsoever and no surrounding cities appear to have been subjected to the rule of the Assyrian kings.[41] The earliest known surviving inscription by an Assyrian king was written by Puzur-Ashur I's son and successor Shalim-ahum, and records the king having built a temple dedicated to Ashur "for his own life and the life of his city".[38] The fourth king of the dynasty, Erishum I (r. c. 1974–1934 BC), is the earliest king whose length of reign is recorded in the Assyrian King List, a later document recording the kings of Assyria and their reigns.[31] Erishum is noteworthy for being the earliest known ruler in world history to experiment with free trade, leaving the initiative for trade and large-scale foreign transactions entirely to his populace. Though large institutions, such as the temples and the king himself, did take part in trade, the financing itself was provided by private bankers, who in turn bore nearly all the risk (but also earned nearly all the profits) of the trading ventures. The king earned a portion of the profit through imposing tolls and the money gained was used to expand Assur and its institutions.[42] Through Erishum's efforts, Assur quickly established itself as a prominent trading state in northern Mesopotamia and Anatolia.[43]

It is clear that an extensive long-distance Assyrian trade network was established relatively quickly,[44] the first notable impression Assyria left in the historical record.[28] Notable collections of Old Assyrian cuneiform tablets have been found in trading colonies established by the Assyrians in their trade network. The most notable locality excavated is Kültepe, near the modern city of Kayseri in Turkey. At this time, Kültepe was also a city-state ruled by its own line of kings.[45] Over 22,000 Assyrian cuneiform clay tablets have been found at the site.[44] In some way, Assur was able to maintain its central position in its trade network despite being small and having no known history of military activity, though it may be that military activity did in fact play a part. Assur's importance as a trading center declined in the 19th century BC, perhaps chiefly because of increasing conflict between states and rulers of the ancient Near East leading to a general decrease in trade.[46] From this time to the end of the Old Assyrian period, Assur frequently fell into conflict with larger foreign states and empires.[47] In particular, the nearby centers of Eshnunna and Ekallatum threatened the continued existence of the Assur city-state. However Assyrian records during the reigns of Ilu-shuma, Erishum I and Sargon I show signs of intervention in southern Mesopotamia, which was under pressure from Elamites to the east and Amorites to the west. It is unclear whether this was military intervention in support of their fellow Akkadian speakers, favourable trading terms or both. The original city-state came to an end c. 1808 BC when it was conquered by the Amorite ruler of Ekallatum, Shamshi-Adad I,[48] who deposed Erishum II, the last king of the Puzur-Ashur dynasty after having been repelked by his predecessor,[49][50] and took the city for himself.[46]

Shamshi-Adad's extensive conquests in northern Mesopotamia eventually made him the ruler of the entire region,[46] founding what some scholars have termed the "Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia".[51] To rule his realm, Shamshi-Adad established his capital at the city of Shubat-Enlil.[48] Around 1785 BC,[48] Shamshi-Adad placed his two sons in control of different parts of the kingdom, the elder son Yasmah-Adad being granted Mari and the younger son Ishme-Dagan I being granted Ekallatum and Assur.[46] Though the locals in Assur considered Shamshi-Adad and his family to be foreign conquerors,[52] Shamshi-Adad did have certain respect for Assur and sometimes stayed in the city and partook in its religious ceremonies. Shamshi-Adad also oversaw the renovation of the city, the rebuilding of the temple of Ashur and the addition of a sanctuary dedicated to the head of the Mesopotamian pantheon, Enlil.[53] It is possible that Shamshi-Adad promoted a theology that equated Ashur and Enlil as one and the same. In that case, his theology was hugely influential as Assyrians in later times attributed the role of "king of the gods" to Ashur, a role otherwise typically attributed to Enlil.[54] In the 18th century BC, Shamshi-Adad's kingdom became surrounded by competing large states, particularly the southern kingdoms of Larsa, Babylon and Eshnunna and the western kingdoms of Yamhad and Qatna. The success and survival of his own realm chiefly relied on his personal strength and charisma. Shamshi-Adad's death in c. 1776 BC led to the collapse of the kingdom.[55] His principal successor, Ishme-Dagan I, ruled from Ekallatum[56] and retained control only of that city and of Assur.[57]

The time between the collapse of Shamshi-Adad's kingdom in the 18th century BC and the rise of the Middle Assyrian Empire in the 14th century BC is often regarded by modern scholars as an Assyrian "Dark Age" due to the lack of sufficient historical evidence to clearly establish events during this time.[57] It is clear from surviving records that the geopolitical situation in northern Mesopotamia was highly volatile, with frequent shifts in power. In c. 1772 BC Ibal-pi-el II of Eshnunna invaded and conquered Ishme-Dagan's kingdom,[53] though he returned to power not long thereafter. A few years later, an army from Elam invaded northern Mesopotamia and seized a few cities.[58][59] In c. 1761 BC, Assur, perhaps only briefly, fell under the control of the Old Babylonian Empire under Hammurabi.[58][59] At some point, Assur returned to being an independent city-state.[57] There was during this time also significant infighting within the government of Assur itself, as members of Shamshi-Adad's dynasty fought with native Assyrians and Hurrians for control of the city.[60] Eventually, the Shamshi-Adad dynasty's rule over Assur came to an end through the Assyrian usurper Puzur-Sin re-establishing native rule.[61][62] The defeat of the Babylonians and Amorites did not mean an end to the troubles, as there was a time of non-dynastic kings and further infighting before the rise of Bel-bani c. 1700 BC.[50][63] Bel-bani founded the Adaside dynasty, which after his reign ruled Assyria for about a thousand years.[64]

In large parts, the invasion or raid of southern Mesopotamia by the Hittite king Mursili I in c. 1595 BC was critical to Assyria's later development. This invasion destroyed the then dominant power in southern Mesopotamia, the Old Babylonian Empire, which created a vacuum of power that led to the formation of the Kassite kingdom of Babylonia in the south[65] and the Hurrian[60] Mitanni state to the north of Assyria.[65] Assyrian rulers from c. 1520 to c. 1430 were more politically assertive than their predecessors, both regionally and internationally. Puzur-Ashur III (r. c. 1521–1498 BC) is the earliest Assyrian king to appear in the Synchronistic History, a later text concerning border disputes between Assyria and Babylonia, suggesting that Assyria first entered into diplomacy and conflict with Babylonia at this time[66] and that Assur at this time ruled a small stretch of territory beyond the city itself.[67] Around c. 1430 BC, Assur was subjugated by Mitanni and forced to become a vassal, an arrangement that lasted for about 70 years, until c. 1360 BC.[66] Assur retained some autonomy under the Mitanni kings, as Assyrian kings during this time are attested as commissioning building projects, trading with Egypt and signing boundary agreements with the Kassites in Babylon.[68] Another Hittite invasion, by Šuppiluliuma I in the early 14th century BC, effectively crippled the Mitanni kingdom. After his invasion, Assyria succeeded in freeing itself from its suzerain, achieving independence once more in the early 14th century BC, and under Ashur-uballit I (r. c. 1363–1328 BC), whose rise to power and conquests at the expense of the Mitanni and Babylonians traditionally marks the transition between the Old and Middle Assyrian periods.[69]

Middle Assyrian period (1363–912 BC)

[edit]Rise of Assyria

[edit]

Ashur-uballit I was the first native Assyrian ruler to claim the royal title šar ("king").[47] Shortly after achieving independence, he further claimed the dignity of a great king on the level of the Egyptian pharaohs and the Hittite kings.[69] Ashur-uballit's claim to be a great king meant that he also embedded himself in the ideological implications of that role; a great king was expected to expand the borders of his realm to incorporate "uncivilized" territories, ideally eventually ruling the entire world.[70] Ashur-uballit's reign was often regarded by later generations of Assyrians as the true birth of Assyria.[70] The term "land of Ashur" (māt Aššur), i.e. designating Assyria as comprising a larger kingdom, is first attested as being used in his time.[71] Assyria's rise was intertwined with the decline and fall of the Mitanni kingdom, its former suzerain, which allowed the early Middle Assyrian kings to expand and consolidate territories in northern Mesopotamia.[72] Ashur-uballit mainly warred against small states in the southern vicinity of the Assyrian heartland. He engaged in diplomacy with both Babylonia, ruled by Burnaburiash II,[73] and Egypt, ruled by Akhenaten.[74] Ashur-uballit's successors Enlil-nirari (r. c. 1327–1318 BC) and Arik-den-ili (r. c. 1317–1306 BC) were less successful than Ashur-uballit in expanding and consolidating Assyrian power, and as such the new empire developed somewhat haltingly and remained fragile.[75] Enlil-nirari's reign was the beginning of the historical enmity between Assyria and Babylonia after Kurigalzu II, a king the Assyrians had helped gain the Babylonian throne, attacked Assyria. Kurigalzu's betrayal resulted in deep trauma and was still referenced in Assyrian writings concerning Babylonia more than a century later.[76]

Under the warrior-kings Adad-nirari I (r. c. 1305–1274 BC), Shalmaneser I (r. c. 1273–1244 BC) and Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. c. 1243–1207 BC), Assyria began to realize its aspirations of becoming a significant regional power.[77] Adad-nirari was the first Assyrian king to march against the remnants of the Mitanni kingdom[77] and the first Assyrian king to include lengthy narratives of his campaigns in his royal inscriptions.[78] Adad-nirari early in his reign defeated Shattuara I of Mitanni and forced him to pay tribute to Assyria as a vassal ruler.[78] After a revolt by Shattuara's son Wasashatta Adad-niari annexed some Mitanni lands and constructed a royal palace for himself at Taite, a former Mitanni capital.[78] Adad-nirari also fought with Babylonia, defeating the Babylonian king Nazi-Maruttash at the Battle of Kār Ištar c. 1280 BC and redrawing the border between the two kingdoms in Assyria's favor.[79]

Assyrian campaigns and conquests intensified under Shalmaneser I.[81] Shalmaneser's most significant wars were those directed towards the west and north. After the Mitanni king Shattuara II rebelled against Assyrian authority,[81] Shalmaneser campaigned against him to suppress the resistance.[77] As a result of Shalmaneser's victory in the campaign, the Mitanni capital of Washukanni was sacked[81] and the Mitanni lands were formally annexed into the Assyrian Empire.[77] Shalmaneser's reign also saw worsening relations with the Hittites,[79] who had supported Shattuara II's revolt.[81] Shalmaneser warred several times against Hittite vassals in the Levant.[82] Conflict with the Hittites continued in the reign of Shalmaneser's son Tukulti-Ninurta I until the Assyrian victory at the Battle of Nihriya c. 1237 BC, which marked the beginning of the end of Hittite influence in northern Mesopotamia and the annexation of formerly Hittite territories in the Levant and Anatolia.[82] In addition to his various campaigns and conquests, which brought the Middle Assyrian Empire to its greatest extent,[77] Tukulti-Ninurta is also famous for being the first Assyrian king to transfer the capital of Assyria away from Assur itself.[83] In his eleventh year as king (c. 1233 BC),[84] Tukulti-Ninurta inaugurated the new capital city Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta,[83] named after himself (the name meaning "fortress of Tukulti-Ninurta").[84] The city only served as the capital during Tukulti-Ninurta's reign, with later kings returning to ruling from Assur.[83]

Tukulti-Ninurta's main goal was Babylonia in the south; he intentionally escalated conflict with the Babylonian king Kashtiliash IV through claiming "traditionally Assyrian" lands along the eastern Tigris river.[82] Shortly thereafter, he invaded Babylonia in an unprovoked attack.[85] After capturing cities such as Sippar and Dur-Kurigalzu and defeating Kashtiliash in battle, Tukulti-Ninurta eventually succeeded in conquering Babylonia c. 1225 BC.[86][87] He was the first Assyrian king to assume the traditionally southern Mesopotamian title "king of Sumer and Akkad" and the first native Mesopotamian to be crowned king of Babylon, its previous rulers having all been Amorites and Kassites.[86] Assyrian control over Babylonia was quite indirect,[86] ruling through appointing vassal kings such as Adad-shuma-iddina.[88] After putting down a Babylonian uprising, Tukulti-Ninurta added to his title the style šamšu kiššat niše ("sun[god] of all people"),[89] a highly unusual style since the Assyrian king was typically regarded to be the representative of a god and not divine himself.[90] Eventually Babylonia fell out of Tukulti-Ninurta's grasp. An uprising led by Adad-shuma-usur, perhaps a son of Kashtiliash IV,[e] drove the Assyrians out of Babylonia[92] c. 1216 BC.[93] The loss of Babylonia increased growing dissatisfaction with Tukulti-Ninurta's rule.[94] His long and prosperous reign ended with his assassination, which in turn was followed by inter-dynastic conflict and a significant drop in Assyrian power.[95]

Troubles and decline

[edit]

The successors of Tukulti-Ninurta were unable to maintain Assyrian power and the empire became increasingly restricted to just the Assyrian heartland.[95] The decline of the Middle Assyrian Empire broadly coincided with the latter period of the Late Bronze Age collapse, a time when the ancient Near East, North Africa, Caucasus and Southeast Europe experienced monumental geopolitical changes; within a single generation, the Hittite Empire and the Kassite dynasty of Babylon had fallen, and Egypt had been severely weakened through losing its lands in the Levant.[95] Modern researchers tend to varyingly ascribe the Bronze Age collapse to large-scale migrations, invasions by the mysterious Sea Peoples, new warfare technology and its effects, starvation, epidemics, climate change and an unsustainable exploitation of the working population.[96] Tukulti-Ninurta's direct dynastic line came to an end c. 1192 BC,[93] when the grand vizier Ninurta-apal-Ekur, a descendant of Adad-nirari I,[97] took the throne for himself. Ninurta-apal-Ekur and his immediate successors were no more able than Tukulti-Ninurta's descendants to halt the decline of the empire.[98]

Ninurta-apal-Ekur's son Ashur-dan I (r. c. 1178–1133 BC),[93] improved the situation somewhat, campaigning against the Babylonian king Zababa-shuma-iddin,[98] but his two sons Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur and Mutakkil-Nusku struggled for power with each other after his death. Though Mutakkil-Nusku emerged victorious,[98] he ruled for less than a year.[93] Mutakkil-Nusku warred against the Babylonian king[98] Itti-Marduk-balatu,[99] a conflict which continued in the reign of his son Ashur-resh-ishi I (r. 1132–1115 BC). In the Synchronistic History (a later Assyrian document), Ashur-resh-ishi is cast as a savior of the Assyrian Empire, defeating the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar I in several battles. In some of his inscriptions, Ashur-resh-ishi claimed the epithet "avenger of Assyria" (mutēr gimilli māt Aššur).[100]

Due to Ashur-resh-ishi's victories over Babylonia, his son Tiglath-Pileser I (r. 1114–1076 BC) could focus his attention on other territories without worrying about southern attacks. Texts written already during his first few regnal years demonstrate that Tiglath-Pileser ruled with more confidence than his immediate predecessors, using titles such as "unrivalled king of the universe, king of the four quarters, king of all princes, lord of lords" and epithets such as "splendid flame which covers the hostile land like a rain storm". Tiglath-Pileser went on significant campaigns to the west and north, incorporating both territories lost after Tukulti-Ninurta's reign and territories that had never before been under Assyrian rule.[101] Tiglath-Pileser's inscriptions are the first Assyrian inscriptions to describe punitive measures against rebelling cities and regions in any detail. He also increased the size of the Assyrian cavalry and introducing war chariots on a grander scale than previous kings.[102] Though one of the most successful Middle Assyrian kings, Some of Tiglath-Pileser's conquests were not long-lasting and several territories, especially in the west, were likely lost again before or just after his death. Assyria became overstretched and Tiglath-Pileser's successors were forced to adapt to be on the defensive. An increasing problem from the late reign of Ashur-bel-kala onwards were the Aramean tribes in the west. Due to the Aramean tactics of avoiding open battle and instead attacking the Assyrians in numerous minor skirmishes, the Assyrian army could in conflict with them not take advantage of their combat, technical and numerical superiority.[103]

From the time of Eriba-Adad II (r. 1056–1054 BC) onwards, the kings were unable to maintain the achievements of their predecessors. This period of renewed decline was not reversed until the middle of the 10th century BC.[104] Though this period is poorly documented,[f] it is clear that Assyria underwent a major crisis.[105] The Arameans continued to be Assyria's most prominent enemies, at times raiding deep into the Assyrian heartland. Their attacks were uncoordinated raids carried out by individual groups, which meant that even though the Assyrians defeated several Aramean groups in battle, their guerrilla tactics and ability to withdraw into difficult terrain quickly prevented the Assyrians from ever achieving a lasting victory.[106] Though control was lost over most of the Middle Assyrian Empire, the Assyrian heartland remained safe and intact, protected by its geographical remoteness and the military capabilities of its army.[107] Assyria was not the only realm fragmented during this period, which meant that the fragmented territories now surrounding the Assyrian heartland in time proved to be easy conquests for the Assyrian army. Ashur-dan II (r. 934–912 BC) reversed Assyrian decline, campaigning in the peripheries of the Assyrian heartland, primarily in the northeast and northwest. His campaigns paved the way for grander efforts to restore and expand Assyrian power under his successors, and the end of his reign marks the transition to the Neo-Assyrian period.[108]

Neo-Assyrian period (911–609 BC)

[edit]Revitalization, expansion and dominance

[edit]Through decades of military conquests, the early Neo-Assyrian kings worked to retake the former lands of their empire[109] and re-establish the position of Assyria as it was at the height of the Middle Assyrian Empire.[110] The reigns of Adad-nirari II (r. 911–891 BC) and Tukulti-Ninurta II (r. 890–884 BC) saw the slow beginning of this project.[111] Since the reconquista had to begun nearly from scratch, its eventual success was an extraordinary achievement.[112] Adad-nirari's most important conquest was the reincorporation of the city of Arrapha (modern-day Kirkuk) into Assyria, which in later times served as the launching point of innumerable Assyrian campaigns to the east. Adad-nirari also managed to secure a border agreement with the Babylonian king Nabu-shuma-ukin I, a clear indicator that Assyrian power was on the rise.[113] The second and more substantial phase of early Neo-Assyrian expansion began under Tukulti-Ninurta's son Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BC), whose conquests made the Neo-Assyrian Empire the dominant political power in the Near East.[114]

One of Ashurnasirpal's most persistent enemies was the Aramean king Ahuni of Bit Adini. Ahuni's forces broke through across the Khabur and Euphrates several times and it was only after years of war that he at last accepted Ashurnasirpal as his suzerain. Ahuni's defeat was highly important since it marked the first time since Ashur-bel-kala (r. 1073–1056 BC), two centuries prior, that Assyrian forces had the opportunity to campaign further west than the Euphrates.[115] Making use of this opportunity, Ashurnasirpal in his ninth campaign marched to the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, collecting tribute from various Phoenician, Aramean, Cilician, and Neo-Hittite kingdoms on the way.[115] A significant development during Ashurnasirpal's reign was the second transfer of the Assyrian capital away from Assur. Ashurnasirpal restored the ancient and ruined town of Kalhu (the biblical Calah and Medieval Nimrud) also located in the Assyrian heartland, and in 879 BC designated that city as the new capital of the empire, employing thousands of workers to construct new fortifications, palaces and temples in the city.[115] Though no longer the political capital, Assur remained the ceremonial and religious center of Assyria.[116]

The reign of Ashurnasirpal's son Shalmaneser III (r. 859–824 BC) also saw a considerable expansion of Assyrian territory. Lands conquered under Ashurnasirpal were consolidated and divided into further provinces and Shalmaneser's campaigns were also more wide-ranging than those of his predecessors. The most powerful and threatening enemy of Assyria at this point was the Hurro-Urartian speaking kingdom of Urartu in the north; following in the footsteps of the Assyrians, the Urartian administration, culture, writing system and religion closely followed those of Assyria. The Urartian kings were also autocrats very similar to the Assyrian kings.[116] The imperialist expansionism of both states often led to military clashes, despite being separated by the Taurus Mountains. Shalmaneser for a time neutralized the Urartian threat after he in an ambitious campaign in 856 BC sacked the Urartian capital of Arzashkun and devastated the heartland of the kingdom.[117] In 853 BC, Shalmaneser was forced to fight against a large coalition of western states assembled at Tell Qarqur in Syria, led by the Aramean Hadadezer, the king of Aram-Damascus. Though Shalmaneser fought them at the Battle of Qarqar in the same year, the battle appears to have been indecisive. After Qarqar, Shalmaneser focused on the south. He allied with the Babylonian king Marduk-zakir-shumi I, aiding his southern neighbor in both defeating the usurper Marduk-bel-ushati and in fighting against the migrating Chaldeans in the far south of Mesopotamia. After the death of Hadadezer in 841 BC, Shalmaneser managed to incorporate some further western territories.[117] In the 830s, his armies reached into Cilicia and Cappadocia in Anatolia and in 836, Shalmaneser reached Ḫubušna (near modern-day Ereğli), one of the westernmost places ever reached by Assyrian forces.[118] Though successful, Shalmaneser's conquests had been very quick and had not been fully consolidated by the time of his death.[118]

From the late reign of Shalmaneser III onwards, the Neo-Assyrian Empire entered into what scholars call the "age of the magnates", when powerful officials and generals were the principal wielders of political power, rather than the king.[119] The last few campaigns of Shalmaneser's reign were not led by the king, probably on account of old age, but rather by the capable turtanu (commander-in-chief) Dayyan-Assur. Shalmaneser's final years became preoccupied by an internal crisis when one of his sons, Ashur-danin-pal, rebelled in an attempt to seize the throne, possibly because the younger son Shamshi-Adad had been designated as heir instead of himself.[118] When Shalmaneser died in 824 BC, Ashur-danin-pal was still in revolt, supported by a significant portion of the country, most notably the former capital of Assur. Shamshi-Adad acceded to the throne as Shamshi-Adad V, perhaps initially still a minor and a puppet of Dayyan-Assur. Though Dayyan-Assur died during the early stages of the civil war, Shamshi-Adad was eventually victorious, apparently due to help from the Babylonian king Marduk-zakir-shumi or his successor Marduk-balassu-iqbi.[119] The age of the magnates is typically characterized as a period of decline,[120] with little to no further territorial expansion and weak central power.[119] This does not mean that there were no successes in this time. In 812 BC, Shamshi-Adad managed to termporarily conquer large portions of Babylonia[121] and numerous campaigns were conducted under his son Adad-nirari III (r. 811–783 BC) which resulted in new territory both in the west and east.[122] Early in Adad-nirari's reign, Adad-nirari and his mother Shammuramat (the inspiration for the mythical Assyrian queen Semiramis) expanded Assyrian control in Syria and Ancient Iran.[121] The low point of the age of the magnates were the reigns of Adad-nirari's sons Shalmaneser IV (r. 783–773 BC), Ashur-dan III (r. 773–755 BC) and Ashur-nirari V (r. 755–745 BC), from which very few royal documents are known and officials grew even more bold, in some cases no longer even crediting the kings for their achievements.[122]

Ashur-nirari V was succeeded by Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 BC), probably his brother and generally assumed to have usurped the throne.[123][124] Tiglath-Pileser's accession ushered in a new age of the Neo-Assyrian Empire;[125] while the conquests of earlier kings were impressive, they contributed little to Assyria's full rise as a consolidated empire.[126] Through campaigns aimed at outright conquest and not just extraction of seasonal tribute, as well as reforms meant to efficiently organize the army and centralize the realm, Tiglath-Pileser is by some regarded as the first true initiator of Assyria's "imperial" phase.[109][127] Tiglath-Pileser is the earliest Assyrian king mentioned in the Babylonian Chronicles and in the Hebrew Bible and thus the earliest king for which there exists important outside perspectives on his reign.[128] Early on, Tiglath-Pileser reduced the influence of the powerful magnates.[128] Tiglath-Pileser campaigned in all directions with resounding success. His most impressive achievements were the conquest and vassalization of the entirety of the Levant all the way to the Sinai and Egyptian border, his domination of the Persians and Medes to the east, the Arabs to the south of Babylonia, and the 729 conquest of Babylonia, after which he and later Assyrian kings often ruled as both "king of Assyria" and "king of Babylon". By the time of his death in 727 BC, Tiglath-Pileser had more than doubled the territory of the empire. His policy of direct rule rather than rule through vassal states brought important changes to the Assyrian state and its economy; rather than tribute, the empire grew more reliant on taxes collected by provincial governors, a development which increased administrative costs but also reduced the need for military intervention. Also noteworthy was the large scale in which Tiglath-Pileser undertook resettlement policies, settling tens, if not hundreds, of thousand foreigners in both the Assyrian heartland and in far-away underdeveloped provinces.[129]

Sargonid dynasty

[edit]Tiglath-Pileser's son Shalmaneser V (r. 727–722 BC) was after only a brief reign usurped by Sargon II (r. 722–705 BC), either his brother or a non-dynastic usurper.[130][131] Sargon founded the Sargonid dynasty, which would rule until the fall of the Assyrian Empire. Sargon's accession, possible marking the end of the nearly thousand-year long Adaside dynasty, was met with considerable internal unrest. In his own inscriptions Sargon claims to have deported 6,300 "guilty Assyrians", probably Assyrians from the heartland who opposed his accession. Several peripheral regions of the empire also revolted and regained their independence.[132] The most significant of the revolts was the successful uprising of the Chaldean warlord Marduk-apla-iddina II, who took control of Babylon, restoring Babylonian independence, and allied with the Elamite king Ḫuban‐nikaš I.[133] While Sargon was campaigning in the east in 720 BC, his generals also put down a major revolt in the western provinces, led by Yau-bi'di of Hamath.[133]

After securing the silver treasury of the city of Carchemish in 717 BC, Sargon began construction of another new imperial capital. The new city was named Dur-Sharrukin ("Fort Sargon") after himself. Unlike Ashurnasirpal's project at Nimrud, Sargon was not simply expanding an existing, albeit ruined, site but building a new settlement from scratch.[133] Sargon was militarily successful and frequently went to war. Between just 716 and 713, Sargon fought against Urartu, the Medes, Arab tribes, and Ionian pirates in the eastern Mediterranean. In 710 BC, Sargon retook Babylon, driving Marduk-apla-iddina into exile in Elam.[132] Between 710 and 707 BC, Sargon resided in Babylon, receiving foreign delegations there and participating in local traditions, such as the Akitu festival. In 707 BC, Sargon returned to Nimrud and in 706 BC, Dur-Sharrukin was inaugurated as the empire's new capital. Sargon did not get to enjoy his new city for long; in 705 BC he embarked on his final campaign, directed against Tabal, and died in battle in Anatolia.[134]

Sargon's son Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC) moved the capital to Nineveh,[135] which was extensively renovated in his reign.[136] Sargon's battlefield death had theological implications and some of the conquered regions of the empire once again began to assert their right to independence. Most prominently, the vassal states in the Levant stopped paying tribute to Sennacherib and Marduk-apla-iddina retook Babylon with the aid of the Elamites. It took several years for Sennacherib to defeat all of his enemies. Towards the end of 704 BC, Sennacherib retook Babylonia, though Marduk-apla-iddina escaped to Elam again. The Babylonian noble Bel-ibni, raised at the Assyrian court was appointed as vassal ruler of Babylon. In 701 BC, Sennacherib invaded the Levant, the most famous campaign of his reign. Bel-ibni's tenure as Babylonian vassal ruler did not last long and he was continually opposed by Marduk-apla-iddina and another Chaldean warlord, Mushezib-Marduk, who hoped to seize power for themselves. In 700 BC, Sennacherib invaded Babylonia again and drove Marduk-apla-iddina and Mushezib-Marduk away. Needing a vassal ruler with stronger authority, he placed his eldest son Ashur-nadin-shumi on the Babylonian throne.[137]

In 694 BC, Sennacherib invaded Elam[136] with the explicit goal to root out Marduk-apla-iddina and his supporters.[138] Sennacherib sailed across the Persian Gulf with a fleet built by Phoenician and Greek shipwrights[136] and captured and sacked countless Elamite cities. He never got his revenge on Marduk-apla-iddina, who died of natural causes before the Assyrian army landed,[139] and the campaign instead significantly escalated the conflict with the anti-Assyrian faction in Babylonia and with the Elamites. The Elamite king Hallushu-Inshushinak took revenge on Sennacherib by marching on Babylonia while the Assyrians were busy in his lands and captured Ashur-nadin-shumi, who was taken to Elam and probably executed. In his place, the Elamites and Babylonians crowned the Babylonian noble Nergal-ushezib as king of Babylon.[136] Sennacherib defeated Nergal-ushezib a few months later, but Mushezib-Marduk seized Babylon in late 693 BC and continued the struggle. In 689 BC, Sennacherib defeated Mushezib-Marduk and nearly completely destroyed Babylon. Sennacherib's reign came to an end in 684 BC, murdered by his eldest surviving son Arda-Mulissu due to having made the younger son Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC) heir.[140] Esarhaddon defeated Arda-Mulissu in a civil war and successfully captured Nineveh, becoming king a mere two months after Sennacherib's murder.[140][141]

Esarhaddon was deeply troubled, distrustful of his officials and family members owing to his tumultuous rise to the throne. His paranoia had the side-effect of leading to an increased standing of the royal women; his mother Naqi'a, queen Esharra-hammat and daughter Serua-eterat were all more powerful and prominent than most women in earlier Assyrian history.[142] Despite his paranoia, and despite suffering from both disease and depression,[143] Esarhaddon was one of Assyria's most successful kings. He rebuilt Babylon[144] and led several successful military campaigns. Many of his campaigns were farther from the Assyrian heartland than those of any previous king. In the east, he in one campaign reached as far into modern-day Iran as Dasht-e Kavir.[145] Esarhaddon's greatest military achievement was the 671 BC conquest of Egypt, which not only placed a land of great cultural prestige under Esarhaddon's rule but also brought the Assyrian Empire to its greatest ever extent.[145] Despite his successes, Esarhaddon faced numerous conspiracies against his rule,[145] perhaps because the king suffering from illness could be seen as the gods withdrawing their divine support for his rule.[143] Through a well-developed network of spies and informants, Esarhaddon uncovered all of these coup attempts and in 670 BC had a large number of high-ranking officials put to death.[146] In 672 BC, Esarhaddon decreed that his younger son Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BC) would succeed him in Assyria and that the older son Shamash-shum-ukin would rule Babylon.[147] To ensure that the succession to the throne after his own death would go more smoothly than his own accession, Esarhaddon forced everyone in the empire, not only the prominent officials but also far-away vassal rulers and members of the royal family, to swear oaths of allegiance to the successors and respect the arrangement.[148]

Ashurbanipal is often regarded to have been the last great king of Assyria. His reign saw the last time Assyrian troops marched in all directions of the Near East.[149] One of the issues of Ashurbanipal's early reign were disagreements between Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin.[150] While Esarhaddon's documents suggest that Shamash-shum-ukin was intended to inherit all of Babylonia, it appears that he only controlled the immediate vicinity of Babylon itself since numerous other Babylonian cities apparently ignored him and considered Ashurbanipal to be their king.[151] Over time, it seems that Shamash-shum-ukin grew to resent his brother's overbearing control[152] and he revolted in 652 BC, aided by several Elamite kings. Ashurbanipal defeated his brother in 648 BC and Shamash-shum-ukin might have died by setting himself on fire in his palace. As vassal king of Babylon he was replaced by the puppet ruler Kandalanu. After his victory in Babylonia, Ashurbanipal marched on Elam. The Elamite capital of Susa was captured and devastated and large numbers of Elamite prisoners were brought to Nineveh, tortured and humiliated.[153]

Though Ashurbanipal's inscriptions present Assyria as an uncontested and divinely supported hegemon of the entire world, cracks were starting to form in the empire during his reign. At some point after 656 BC, the empire lost control of Egypt, which instead fell into the hands of the pharaoh Psamtik I, founder of Egypt's twenty-sixth dynasty,[154] originally appointed as a vassal by Ashurbanipal. Assyrian control faded from Egypt only gradually, without the need for revolt.[155] Ashurbanipal went on numerous campaigns against various Arab tribes which failed to consolidate rule over their lands and instead wasted Assyrian resources. Perhaps most importantly, his devastation of Babylon after defeating Shamash-shum-ukin fanned anti-Assyrian sentiments in southern Mesopotamia, which soon after his death would have disastrous consequences. Ashurbanipal's reign also appears to have seen a growing disconnect between the king and the traditional elite of the empire; eunuchs grew unprecedently powerful in his time, being granted large tracts of lands and numerous tax exemptions.[154] After Ashurbanipal's death in 631 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire quickly collapsed. His son and successor Ashur-etil-ilani ruled only briefly before another son of Ashurbanipal, Sinsharishkun, became king in 627 BC.[156] In 626 BC Babylonia revolted again, this time led by Nabopolassar,[64] probably a member of a prominent political family in Uruk.[157] Though Nabopolassar was more successful than previous Babylonian rebels, it is unlikely that he would have been victorious in the end had the Medes under Cyaxares not entered the conflict in 615/614 BC.[158] In 614 BC, the Medes and Babylonians sacked and destroyed Assur and in 612 BC, they captured and plundered Nineveh, Sinsharishkun dying in the capital's defense.[159] Though the prince Ashur-uballit II, possibly Sinsharishkun's son, attempted to lead the resistance against the Medes and Babylonians from Harran in the west,[160] he was defeated in 609 BC, marking the end of the ancient line of Assyrian kings and of Assyria as a state.[161][158]

Post-imperial period (609 BC–AD 240)

[edit]

The fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire after its final war with the Babylonians and Medes had dramatic consequences for the geopolitics of the ancient Near East: Babylonia, now the heart of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, experienced an unprecedented time of prosperity and growth, trade routes were redrawn and the economical organization and political power of the entire region was restructured.[11] Archaeological surveys of the Assyrian heartland have consistently shown that there was a dramatic decrease in the size and number of inhabited sites in Assyria during the Neo-Babylonian period, suggesting a significant societal breakdown in the region. Archaeological evidence suggests that the former Assyrian capital cities, such as Assur, Nimrud and Nineveh, were initially nearly completely abandoned.[162] The breakdown in society does not necessarily reflect an enormous drop in population; it is clear that the region became less rich and less densely populated, but it is also clear that Assyria was not entirely uninhabited, nor poor in any real sense. It is possible that large portions of the remaining Assyrian populace might have turned to nomadism due to the collapse of the local settlements and economy.[163] Throughout the time of the Neo-Babylonian and later Achaemenid Empire, Assyria was a marginal and sparsely populated region,[164] perhaps chiefly due to the limited interest of the Neo-Babylonian kings to invest resources into its economic and societal development.[165] Individuals with Assyrian names are attested at multiple sites in Babylonia during the Neo-Babylonian Empire, including Babylon itself, Nippur, Uruk, Sippar, Dilbat and Borsippa. The Assyrians in Uruk apparently continued to exist as a community until the reign of the Achaemenid king Cambyses II (r. 530–522 BC) and were closely linked to a local cult dedicated to Ashur.[166] Towards the end of the 6th century BC, the Assyrian dialect of the Akkadian language went extinct, having towards the end of the Neo-Assyrian Empire already largely been replaced by Aramaic as a vernacular language.[167]

After the Achaemenid conquest of Babylon in 539 BC, Assyria was incorporated into the Achaemenid Empire, organized into the province[g] Athura (Aθūrā).[168] Some former Assyrian territory was also incorporated into the satrapy of Media (Mada).[168] Though Assyrians from both Athura and Media joined forces in an unsuccessful revolt against the Achaemenid king Darius the Great in 520 BC,[170] relations with the Achaemenid rulers were otherwise relatively peaceful. The Achaemenid kings interfered little with the internal affairs of their individual provinces as long as tribute and taxes were continuously provided, which allowed Assyrian culture and customs to survive under Persian rule.[168] After the Achaemenid conquest of Babylon, the remaining inhabitants of Assur received the permission of Cyrus the Great to rebuild the city's ancient temple dedicated to Ashur[171] and Cyrus even returned Ashur's cult statue from Babylon.[172] The organization of Assyria into the single administrative unit Athura effectively kept the region on the map as a distinct political entity throughout the time of Achaemenid rule.[173] In the aftermath of the Achaemenid Empire's conquest by Alexander the Great in 330 BC, Assyria and much of the rest of the former Achaemenid lands came under the control of the Seleucid Empire, founded by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander's generals.[164] Though Assyria was centrally located within this empire, and must thus have been a significant base of power,[164][174] the region is rarely mentioned in textual sources from the period,[164] perhaps because the significant centers of the Seleucid Empire was in the south in Babylon and Seleucia and in the west in Antioch.[164] There were however significant developments in Assyria during this time.[175] Archaeological finds such as coins and pottery from prominent Assyrian sites indicate that cities such as Assur, Nimrud and perhaps Nineveh were resettled under the Seleucids, as were a large number of villages.[175]

The most significant phase of ancient Assyrian history following the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire transpired after the region was conquered by the Parthian Empire in the 2nd century BC. Under Parthian rule, the slow recovery of Assyria initiated under the Seleucids continued. This process eventually resulted in an unprecedented return to prosperity and revival in the 1st to 3rd centuries AD. The Parthians oversaw an intense resettlement and rebuilding of the region. In this time, the archaeological evidence shows that the population and settlement density of the region reached heights not seen since the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[175] Under Parthian suzerainty, several small and semi-independent kingdoms of Assyrian character and large Assyrian populations cropped up in the former Assyrian heartland, including Osroene, Adiabene and Hatra. These kingdoms lasted until the 3rd or 4th centuries AD, though they were mostly ruled by dynasties of Iranian or Arab, not Assyrian, descent and culture.[177][178] Aspects of old Assyrian culture endured in these new kingdoms, despite their foreign rulers. For instance, the main god worshipped at Hatra was the old Mesopotamian sun-god Shamash.[179] Assur itself flourished under Parthian rule, with a large amount of buildings being either repaired or constructed from scratch.[177][180] From around or shortly after the end of the 2nd century BC,[181] the city may have become the capital of its own small semi-autonomous realm,[177] either under the suzerainty of Hatra,[182] or under direct Parthian suzerainty.[180] Stelae erected by the local rulers of Assur in this time resemble the stelae erected by the Neo-Assyrian kings,[177] the rulers appearing to have viewed themselves as continuing the old Assyrian royal tradition.[183] The ancient temple dedicated to Ashur was restored for a second time in the 2nd century AD.[177][180] Ancient Assyria's last golden age came to an end with the sack of Assur by the Sasanian Empire c. 240.[184] During the sack, the Ashur temple was destroyed again and the city's population was dispersed.[182]

Late antiquity and Middle Ages (240–1552)

[edit]Assyria under the Sasanian Empire (240–637)

[edit]Christianization

[edit]

Though tradition holds that Christianity was first spread to Mesopotamia by Thomas the Apostle,[185] the exact timespan when the Assyrians were first Christianized is unknown. The city of Arbela was an important early Christian center. According to the later Chronicle of Arbela, Arbela became the seat of a bishop already in AD 100, but the reliability of this document is questioned among scholars. It is known that both Arbela and Kirkuk later served as important Assyrian Christian centers in the Sasanian and later Islamic periods.[179] According to some traditions, Christianity took hold in Assyria when Saint Thaddeus of Edessa converted King Abgar V of Osroene in the mid-1st century AD.[186] From the 3rd century AD onwards, it is clear that Christianity was becoming the major religion of the region,[187] with the Christian god replacing the old Mesopotamian deities.[9] Assyrians had by this time already intellectually contributed to Christian thought; in the 1st century AD, the Christian Assyrian writer Tatian composed the influential Diatessaron, a synoptic rendition of the gospels.[186]

Assyrian Christians were periodically persecuted in the Sasanian Empire until 422, when the Roman Empire instituted tolerance for Zoroastrianism (the official Persian religion in ancient times) and the Sasanians in turn officially allowed Christianity.[188] The Assyrian churches became separate from those of the wider Christian world in the aftermath of the 451 Council of Chalcedon, which was rejected by the groups that would later be known as the Assyrian Church of the East and the Syriac Orthodox Church. The followers of the Church of the East where often pejoratively referred to as "Nestorians" by foreigners in later times, after Nestorius (c. 386–450), an Archbishop of Constantinople whose teachings, including denying the hypostatic union (that Jesus was both fully God and fully man), were condemned at Chalcedon. The followers of the Syriac Orthodox Church were often called "Jacobites", after Jacob Baradaeus, an anti-Chalcedon bishop of Edessa.[189] The Sasanians, who geopolitically opposed the Romans and often found themselves at war with them, deliberately cultivated and supported the now schismatic Church of the East.[190] In 421, the Synod of Markabta decided that the head of the church, now styled as the Patriarch of the Church of the East, was declared answerable only to Christ himself, in effect declaring the Church of the East independent.[191] The church's independence was upheld under the authority of the Sasanian King of Kings Jamasp, who in 497 authorized a synod which also declared it independent and abolished the rule of celibacy for the clergy.[192]

Histories and folklore

[edit]

Though once more without any real political power, the population of northern Mesopotamia (called Asoristan by the Sassanids) continued to keep the memory of their ancient civilization alive and positively connected with the Assyrian Empire in local histories written during the Sasanian period.[9] There continued to be important continuities between ancient and contemporary Mesopotamia in terms of religion, literary culture and settlement[193] and Christians in northern Mesopotamia during the Sasanian period and later times connected themselves to the ancient Assyrian civilization.[194][h] Figures like Sargon II,[196] Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin long figured in local folklore and literary tradition.[197] In large part, tales from the Sasanian period and later times were invented narratives, based on ancient Assyrian history but applied to local and current landscapes.[198] Medieval tales written in Aramaic (or Syriac) for instance by and large characterize Sennacherib as an archetypical pagan king assassinated as part of a family feud, whose children convert to Christianity.[197] The legend of the Saints Behnam and Sarah, set in the 4th century but written long thereafter, casts Sennacherib, under the name Sinharib, as their royal father. After Behnam converts to Christianity, Sinharib orders his execution, but is later struck by a dangerous disease that is cured through being baptized by Saint Matthew in Assur. Thankful, Sinharib then converts to Christianity and founds an important monastery near Mosul, called Deir Mar Mattai.[184]

The 7th-century Assyrian History of Mar Qardagh made the titular saint, Mar Qardagh, out to be a descendant of the legendary Biblical Mesopotamian king Nimrod and the historical Sennacherib, with his illustrious descent manifesting in Mar Qardagh's mastery of archery, hunting and polo.[199] A sanctuary constructed for Mar Qardagh during this time was built directly on top of the ruins of a Neo-Assyrian temple.[193] Though some historians have argued that these tales were based only on the Bible, and not actual remembrance of ancient Assyria,[193] some figures who appear in them, such as Esarhaddon and Sargon II, are only briefly mentioned in the Bible. The texts are also very much a local Assyrian phenomenon, as their historical accounts are at odds with those of other historical writings of the Sasanian Empire.[200] The legendary figure Nimrod, otherwise viewed as simply Mesopotamian, is explicitly referred to as Assyrian in many of the Sasanian-period texts and is inserted into the line of Assyrian kings.[196] Nimrod, as well as other legendary Mesopotamian (though explicitly Assyrian in the texts) rulers, such as Belus and Ninus, sometimes play significant roles in the writings.[201] Certain Christian texts considered the Biblical figure Balaam to have prophesied the Star of Bethlehem; a local Assyrian version of this narrative appears in some Syriac-language writings from the Sasanian period, which allege that Balaam's prophecy was remembered only through being transmitted through the ancient Assyrian kings.[202] In some stories, explicit claims of descent are made. According to the 6th-century History of Karka, twelve of the noble families of Karka (ancient Arrapha) were descendants of ancient Assyrian nobility who lived in the city during the time of Sargon II.[203]

Āsōristān, Atūria and Nōdšīragān

[edit]

The Sasanian Empire confusingly[i] applied the name Āsōristān ("land of the Assyrians") to a province corresponding roughly to the borders of ancient Babylonia, thus excluding the historical Assyria in northern Mesopotamia. The population of Southern Mesopotamia was however during this time also largely made up of Aramaic-speaking Christians.[204] The reason for naming Babylonia Āsōristān is not clear; perhaps the name originated during a time when northern Mesopotamia was occupied by the Roman Empire (and thus designated the remaining part of Mesopotamia under Sasanian control) or perhaps the name derived from the Sasanians also making the connection between the present Aramaic-speaking Christians of the regions and the ancient Assyrians.[8]

Syriac-language sources continued to connect the term "land of the Assyrians" not to the Sasanian province in the south, but to the ancient Assyrian heartland in the north.[8] Armenian historians, such as Anania Shirakatsi, also continued to identify Assyria as northern Mesopotamia; Shirakatsi referred to Aruastan as a region bordering Armenia and including Nineveh.[205] The Sasanians divided northern Mesopotamia into Arbāyistān in the west and Nōdšīragān in the east. Nōdšīragān was the Sasanian name for Adiabene, which included much of the old Assyrian lands and continued to function as a vassal kingdom under Sasanian rule as well, perhaps (at least at times) ruled by Sasanian princes.[206] A handful of Sasanian sources made the connection between northern Mesopotamia and Assyria as well, despite Āsōristān being used for the south. The province of Nōdšīragān is in some records alternatively referred to as Atūria or Āthōr (i.e. Assyria). Records from a 585 synod also testify to the existence of a metropolitan bishop of the Āṯōrayē (Assyrians), who was from northern Mesopotamia.[207]

The Adiabene vassal kingdom was abolished c. 379, with Adiabene thereafter being governed by royally appointed governors.[208] Because of the size and wealth of the region, these governors, though not kings, could still be influential. In the 6th-century, one such governor, Denḥa bar Šemraita, is referred to as "grand prince of all the region of Adiabene".[209]

Muslim conquest (637–1096)

[edit]

With the fall of Ctesiphon in 637, the Sasanian Empire lost control of its political heartland in Mesopotamia, which instead fell under the rule of the Rashidun Caliphate. Due to missionary work by the Church of the East, a significant share of the population in Mesopotamia and Persia were Christian by the time of the Muslim conquests. Episcopal sees had been established as far from Mesopotamia as Uzbekistan, India and China.[210] Though the new caliphate did not officially persecute its Christian subjects, and even offered freedom of worship and a certain extent of self-administration, there were many local Muslim administrators who acted against the Christians, and as non-Muslims conquered through jihad, Christians such as the Assyrians had a choice between conversion to Islam, death, slavery or relegation to dhimmi, paying a special tax (jizya) to live under protected status.[211] Some local Christians fled from the conquered territories into the lands under Roman rule[212] and some, probably few in number, chose to convert to Islam for economic or political reasons.[211][212] Certain Syriac Christian authors viewed the Muslim Conquest as a positive development and as a part of the struggle between the eastern churches and the Chalcedonians. The Muslim Conquest also strengthened local identities, such as that of the Assyrians, through to a large extent shattering the communications between local Christians and those in the Roman Empire.[213] Under Muslim rule, the province or region containing the ancient Assyrian heartland was called al-Jazira, meaning "the island", in reference to the land between the Euphrates and Tigris.[214]

Christian communities were thus not thrown into total upheaval[211] and most Christians remained where they were and did not convert.[212] The conquering Muslims were relatively few in number and mostly kept to themselves in their own settlements. At first, the Muslim conquerors discouraged conversions to Islam as they depended on the taxes collected from Christians and Jews. Discrimination against Christians was considerably milder than discrimination against Zoroastrians given that the Muslims saw Christianity as a forerunner of their own religion; in most respects the situation of the Christians under the early Muslim rulers differed little from their status under the Sasanians. Over time however, the growth of the Church of the East declined and eventually gradually reversed due to emigrations and conversions. Because Christians were barred from converting Muslims, the decline could not be stopped.[215] In addition to repression, additional measures were also implemented from the time of the earliest Muslim rulers to harass and humiliate Christians. For instance, Christians were not allowed to build new churches (but were allowed to conduct repairs on current ones), they had to wear a distinct turban and belt, they were forbidden to disturb Muslims by ringing church bells and praying, and they were forbidden from riding horses and carrying weapons.[216] These measures were however only rarely enforced and could in most cases be avoided through bribery. Additionally, contacts between Christians and Muslims were probably very infrequent under the Rashidun (637–661) and succeeding Umayyad Caliphate (661–750); many Christians lived in rural communities run administratively by village headmen (dihqans) and country squires (shaharija), positions occupied by other Christians. A large number of Christians under Rashidun and Umayyad rule likely lived their entire lives without once seeing a Muslim.[217]

There were a number of positions available largely only to Christians under the Umayyad caliphs. The Academy of Gondishapur in southern Mesopotamia, founded by Assyrians from Nisibis in the north, continued to operate and produce skilled Christian physicians under Muslim rule, many of whom were employed by the caliphs. There were also many Christians who rose to other high offices as scribes, accountants and teachers.[217] The cultural and scientific flourishing in the Islamic Golden Age (8th to 14th century) was in large part possible through ancient Greek works previously having been copied and translated by Syriac Christian authors, which profoundly influenced science and philosophy in the Islamic world.[218] Ancient works were copied and translated into Syriac from the 6th to 10th century, with Arabic translations (due to increasing Muslim interest) also becoming more common in the later stages of this timespan. Through the translation and copying of ancient works, the early medieval Syriac-language authors not only contributed to mainstream intellectual history, but also left a significant mark on the local Christian denominations.[218] Among the most famous Syriac-language translators and scholars of this period were Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873) and Theophilus of Edessa (695–785), both of whom translated the works of ancient authors such as Aristotle and also wrote their own scholarly works.[219]

The fall of the Umayyad Caliphate and the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate in its place in 750 was viewed positively by many Christians under Muslim rule, as the Abbasids were considered to be even more positively inclined towards Christians. In terms of church affairs, the Assyrians benefitted especially much from the regime change since the Abbasids ruled from Baghdad in Mesopotamia, and the Patriarchs of the Church of the East were thus closer to the seat of power than they had been under the Umayyads (who ruled from Damascus). Their influence increased under Abbasid rule, since the patriarchs were placed on the council of state of the caliphs. Under the Abbasids, Baghdad was transformed into a great center of learning, and debates were often held among intellectuals, regardless of their religion. At the same time as this more lenient approach, pressures on Christians gradually increased due to the Abbasids wishing to spread Islam. While converting influential Christians was often approached through polite conversation, Christians of lower classes were pressured through measures such as increasing the jizya tax. Through these policies, it was chiefly under the Abbasids that the Christian churches of Mesopotamia began their long period of decline. Though there were some influential patriarchs of the Church of the East under the Abbasids, such as Timothy I (780–823), they were considerably weaker than patriarchs such as Ishoyahb III (649–659) had been under the Umayyads.[220] In the tenth century, there was a decisive religious shift in the religion among the populations under Muslim rule; before 850, Muslims had often been an elite minority, making up on average less than 20% of the population, but after 950 they were the majority and accounted for more than 60%. Emigrations and conversions continued to happen and many of the remaining Christians banded together for safety; adherents of the Church of the East migrated from southern Mesopotamia and Persia to northern Mesopotamia, where they still remained in substantial numbers.[221]

Under the Seljuk Empire, which conquered much of the Middle East in the 11th century, the number of Christians in Mesopotamia and elsewhere continued to fall. Under the Seljuks, conversions were motivated not only by political and economic reasons but also by fear. In the face of the Crusades, Muslim attitudes towards Christians grew more hostile. The church officials of the Church of the East meanwhile grew rich and corrupt, something admitted even by several contemporary Christian writers, and spent most of their time in squabbles against officials from rival churches, such as the Syriac Orthodox Church and the Melkite Greek Catholic Church. They continued to enjoy institutional relationships with the Abbasid caliphs, who held a mainly ceremonial role under the Seljuks.[221]

Crusaders, Mongols and Timurids (1096–1552)

[edit]Literary renaissance and changes in fortune

[edit]

In the 10th–13th centuries, Syriac-language literature experienced something of a renaissance,[218][222][223] indicated by the production of several significant pieces of literature, including the Chronicle of Michael the Great, written by Michael the Syrian, patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church, as well as the theological works of Dionysius bar Salibi and Abdisho bar Berika, and the scientific writings of Bar Hebraeus. This short heyday came to an end with persecutions in the 13th and 14th centuries.[222][223] Records of personal names from this time demonstrate that the names of some Assyrians continued to be connected to ancient Mesopotamia even at this late time; an Arabic-language manuscript created 1272–1275 at Rumkale, a fortress on the Euphrates, records that a son of a physician and priest named Simeon was named Nebuchadnezzar (rendered Bukthanaṣar in the Arabic text). Simeon and Nebuchadnezzar were members of a prominent ecclesiastical family which also included Philoxenus Nemrud (a name deriving from Nimrud or Nimrod), a Patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church.[224]

In the 11th century, substantial populations of Armenians and Syriac Christians lived in Cilicia in southern Anatolia and in northern Syria, referenced in, among other sources, accounts written by the Crusaders of the First Crusade.[225] For propaganda purposes, the Crusaders typically described the Christians under Turkish rule as oppressed and in need of liberation, though it is clear from surviving accounts that the views of the Armenians and Assyrians themselves were more complex.[226] Though it was the local Greeks, Armenians and Assyrians who opened the gates to the Crusaders at the Siege of Antioch in 1098, allowing them to capture the city, many indigenous Christians also collaborated with the Turks against the Crusaders. Sources written by the Crusaders describe difficulties in distinguishing Turks from local Christians, suggesting that the two groups had somewhat assimilated with each other despite the then short period of Turkish rule. This issue several times led to persecutions and massacres directed at the Turkish inhabitants of the captured cities also strongly affecting the local Christians. It is probable that large segments of the Christian population, Assyrians and the other groups, preferred the Turks rule over the Crusaders due to the Crusaders tending to be significantly more violent than the Seljuk Turks. Also affecting perceptions of Crusaders negatively was the large crusading armies exhausting the finances and food of any region they passed through, leading to famine. Some local Christians, more knowledgeable of the area than the Crusaders, are attested as selling food to crusading forces for enormously inflated prices in times of famine, profiting at the expense of the invading armies.[227]

The Assyrians experienced their first major post-Muslim conquest change in fortune when the Mongol Empire conquered central Asia and the Middle East in the early 13th century. Though the Mongols followed tengrism and shamanism, their public policy in the vast regions they conquered was consistently to support religious freedom. Because several of the Mongol tribes that had followed Genghis Khan, the founder of the empire, were predominantly Christian and many tribal leaders had Christian wives or mothers, Christianity received special respect by the Mongol Khagans. Many among the Church of the East hoped that one of the Khagans might in time themselves convert to Christianity and declare the Mongol Empire a Christian Empire, like how Constantine the Great made the Roman Empire Christian.[228] Hopes for a Mongol conversion to Christianity reached their zenith in the 1250s, when Hulagu Khan, ruler of the Ilkhanate (at this time the semi-autonomous Middle Eastern part of the Mongol Empire, later an independent state), drove the Seljuk Turks from Persia and Assyria, conquering cities like Baghdad and Mosul and reaching as far west as Damascus. Because many of the Mongol generals were Christians, Christians in conquered cities were often spared violence whereas Muslims were slaughtered. After his conquests, Hulagu further lifted restrictions imposed on the Christians, a move which was celebrated by the Christian population. When the Muslims retook Damascus shortly thereafter, the Christians were heavily persecuted as vengeance for their arrogance against the Muslims while the city was under Mongol rule.[229]

Persecution under the Ilkhanate and Timurids

[edit]

The period of freedom experienced by the Assyrians and other Christians came to an end when the Ilkhan Ghazan (r. 1295–1304) converted to Islam in 1295 and as one of his first acts as ruler ordered that all Buddhist temples, Jewish synagogues and Christian churches in his domain were to be destroyed. After the Muslims under his rule were inspired by the decree to direct violence towards the Christians, Ghazan intervened and somewhat reduced the severity of his decree, but some violence continued throughout his reign. The situation for the Assyrians and other Christians deteriorated even further under Ghazan's brother and successor, Öljaitü (r. 1304–1316).[230] In 1310, the Assyrians and other Christians of Erbil (ancient Arbela) tried to escape persecution and captured the city's citadel. Despite the efforts of the Patriarch of the East, Yahballaha III, to calm the situation down, the insurrection was violently suppressed by the Kurds and the local Mongol governor, who captured the citadel on 1 July 1310 and massacred all the defenders, as well as all of the Christian inhabitants of the lower town in the city.[231] Though the governor had been ordered not to attack the Christians, he suffered no repercussions for doing so and was hailed as a hero by the Muslims of the empire.[232] After twenty years of persecution under Ghazan and Öljaitü, the internal structure and hierarchy of the Church of the East had been more or less destroyed and most of its church buildings were gone. The final general gathering of leaders of the church in Iran took place at a synod in 1318.[233]

Some small communities of Assyrians thrived outside of Mongol control. In the early 14th century there was a thriving small Assyrian community in the Kingdom of Cyprus. The Assyrians of Cyprus, concentrated in Famagusta, had been relocated there from Tyre at some point after the Crusaders captured the city in 1187. Though they were few in number they were able to maintain trade connections with cities in Egypt, such as Damietta and Alexandria. Among the prominent members of this community were the metropolitan Eliya and the two traders Francis and Nicholas Lakhas. The Lakhas brothers were noted as extremely wealthy, often providing gifts to King Peter I of Cyprus and his court, though they fell into poverty after the Republic of Genoa invaded the island in 1373.[234]