Шизофрения

Шизофрения – психическое расстройство [17] характеризуются галлюцинациями (обычно слышанием голосов ), бредом (т. е. паранойей ), дезорганизованным мышлением и поведением , [10] и плоский или неуместный аффект . [7] Симптомы развиваются постепенно и обычно начинаются в молодом возрасте и никогда не проходят. [3] [10] Объективного диагностического теста не существует; диагноз основывается на наблюдаемом поведении, психиатрическом анамнезе , который включает в себя рассказанный опыт человека и сообщения других людей, знакомых с этим человеком. [10] Для постановки диагноза шизофрении необходимо наличие описанных симптомов в течение не менее шести месяцев (по DSM-5 ) или одного месяца (по МКБ-11 ). [10] [18] Многие люди, страдающие шизофренией, имеют другие психические расстройства, особенно депрессию , тревожные расстройства и обсессивно-компульсивное расстройство . [10]

Приблизительно от 0,3% до 0,7% людей диагностируют шизофрению в течение жизни. [19] По оценкам, в 2017 году во всем мире было зарегистрировано 1,1 миллиона новых случаев, а в 2022 году — 24 миллиона. [2] [20] Males are more often affected and on average have an earlier onset than females.[2] The causes of schizophrenia may include genetic and environmental factors.[7] Genetic factors include a variety of common and rare genetic variants.[21] Possible environmental factors include being raised in a city, childhood adversity, cannabis use during adolescence, infections, the age of a person's mother or father, and poor nutrition during pregnancy.[7][22]

About half of those diagnosed with schizophrenia will have a significant improvement over the long term with no further relapses, and a small proportion of these will recover completely.[10][23] The other half will have a lifelong impairment.[24] In severe cases, people may be admitted to hospitals.[23] Social problems such as long-term unemployment, poverty, homelessness, exploitation and victimization are commonly correlated with schizophrenia.[25][26] Compared to the general population, people with schizophrenia have a higher suicide rate (about 5% overall) and more physical health problems,[27][28] leading to an average decrease in life expectancy by 20[13] to 28 years.[14] In 2015, an estimated 17,000 deaths were linked to schizophrenia.[16]

The mainstay of treatment is antipsychotic medication, including olanzapine and risperidone, along with counseling, job training and social rehabilitation.[7] Up to a third of people do not respond to initial antipsychotics, in which case clozapine gained approval by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment-resistant cases.[29] In a network comparative meta-analysis of 15 antipsychotic drugs, clozapine was significantly more effective than all other drugs, although clozapine's heavily multimodal action may cause more significant side effects.[30] In situations where doctors judge that there is a risk of harm to self or others, they may impose short involuntary hospitalization.[31] Long-term hospitalization is used on a small number of people with severe schizophrenia.[32] In some countries where supportive services are limited or unavailable, long-term hospital stays are more common.[33]

Signs and symptoms

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by significant alterations in perception, thoughts, mood, and behavior.[34] Symptoms are described in terms of positive, negative and cognitive symptoms.[3][35] The positive symptoms of schizophrenia are the same for any psychosis and are sometimes referred to as psychotic symptoms. These may be present in any of the different psychoses and are often transient, making early diagnosis of schizophrenia problematic. Psychosis noted for the first time in a person who is later diagnosed with schizophrenia is referred to as a first-episode psychosis (FEP).[36][37]

Positive symptoms

Positive symptoms are those symptoms that are not normally experienced, but are present in people during a psychotic episode in schizophrenia, including delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized thoughts, speech and behavior or inappropriate affect, typically regarded as manifestations of psychosis.[36] Hallucinations occur at some point in the lifetimes of 80% of those with schizophrenia[38] and most commonly involve the sense of hearing (most often hearing voices), but can sometimes involve any of the other senses of taste, sight, smell and touch.[39] The frequency of hallucinations involving multiple senses is double the rate of those involving only one sense.[38] They are also typically related to the content of the delusional theme.[40] Delusions are bizarre or persecutory in nature. Distortions of self-experience such as feeling that others can hear one's thoughts or that thoughts are being inserted into one's mind, sometimes termed passivity phenomena, are also common.[41] [3] Positive symptoms generally respond well to medication[7] and become reduced over the course of the illness, perhaps linked to the age-related decline in dopamine activity.[10]

Negative symptoms

Negative symptoms are deficits of normal emotional responses, or of other thought processes. The five recognized domains of negative symptoms are: blunted affect – showing flat expressions (monotone) or little emotion; alogia – a poverty of speech; anhedonia – an inability to feel pleasure; asociality – the lack of desire to form relationships, and avolition – a lack of motivation and apathy.[42][43] Avolition and anhedonia are seen as motivational deficits resulting from impaired reward processing.[44][45] Reward is the main driver of motivation and this is mostly mediated by dopamine.[45] It has been suggested that negative symptoms are multidimensional and they have been categorised into two subdomains of apathy or lack of motivation, and diminished expression.[42][46] Apathy includes avolition, anhedonia, and social withdrawal; diminished expression includes blunt affect and alogia.[47] Sometimes diminished expression is treated as both verbal and non-verbal.[48]

Apathy accounts for around 50 percent of the most often found negative symptoms and affects functional outcome and subsequent quality of life. Apathy is related to disrupted cognitive processing affecting memory and planning including goal-directed behaviour.[49] The two subdomains have suggested a need for separate treatment approaches.[50] A lack of distress is another noted negative symptom.[51] A distinction is often made between those negative symptoms that are inherent to schizophrenia, termed primary; and those that result from positive symptoms, from the side effects of antipsychotics, substance use disorder, and social deprivation – termed secondary negative symptoms.[52] Negative symptoms are less responsive to medication and the most difficult to treat.[50] However, if properly assessed, secondary negative symptoms are amenable to treatment.[46]

Scales for specifically assessing the presence of negative symptoms, and for measuring their severity, and their changes have been introduced since the earlier scales such as the PANNS that deals with all types of symptoms.[50] These scales are the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS), and the Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS) also known as second-generation scales.[50][51][53] In 2020, ten years after its introduction, a cross-cultural study of the use of BNSS found valid and reliable psychometric evidence for its five-domain structure cross-culturally. The BNSS can assess both the presence and severity of negative symptoms of the five recognized domains and an additional item of reduced normal distress. It has been used to measure changes in negative symptoms in trials of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions.[51]

Cognitive symptoms

An estimated 70% of those with schizophrenia have cognitive deficits, and these are most pronounced in early-onset and late-onset illness.[54][55] These are often evident long before the onset of illness in the prodromal stage, and may be present in childhood or early adolescence.[56][57] They are a core feature but not considered to be core symptoms, as are positive and negative symptoms.[58][59] However, their presence and degree of dysfunction is taken as a better indicator of functionality than the presentation of core symptoms.[56] Cognitive deficits become worse at first episode psychosis but then return to baseline, and remain fairly stable over the course of the illness.[60][61]

The deficits in cognition are seen to drive the negative psychosocial outcome in schizophrenia, and are claimed[by whom?] to equate to a possible reduction in IQ from the norm of 100 to 70–85.[62][63] Cognitive deficits may be of neurocognition (nonsocial) or of social cognition.[54] Neurocognition is the ability to receive and remember information, and includes verbal fluency, memory, reasoning, problem solving, speed of processing, and auditory and visual perception.[61] Verbal memory and attention are seen to be the most affected.[63][64] Verbal memory impairment is associated with a decreased level of semantic processing (relating meaning to words).[65] Another memory impairment is that of episodic memory.[66] An impairment in visual perception that is consistently found in schizophrenia is that of visual backward masking.[61] Visual processing impairments include an inability to perceive complex visual illusions.[67] Social cognition is concerned with the mental operations needed to interpret, and understand the self and others in the social world.[61][54] This is also an associated impairment, and facial emotion perception is often found to be difficult.[68][69] Facial perception is critical for ordinary social interaction.[70] Cognitive impairments do not usually respond to antipsychotics, and there are a number of interventions that are used to try to improve them; cognitive remediation therapy is of particular help.[59]

Neurological soft signs of clumsiness and loss of fine motor movement are often found in schizophrenia, which may resolve with effective treatment of FEP.[18][71]

Onset

Onset typically occurs between the late teens and early 30s, with the peak incidence occurring in males in the early to mid-twenties, and in females in the late twenties.[3][10][18] Onset before the age of 17 is known as early-onset,[72] and before the age of 13, as can sometimes occur, is known as childhood schizophrenia or very early-onset.[10][73] Onset can occur between the ages of 40 and 60, known as late-onset schizophrenia.[54] Onset over the age of 60, which may be difficult to differentiate as schizophrenia, is known as very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis.[54] Late onset has shown that a higher rate of females are affected; they have less severe symptoms and need lower doses of antipsychotics.[54] The tendency for earlier onset in males is later seen to be balanced by a post-menopausal increase in the development in females. Estrogen produced pre-menopause has a dampening effect on dopamine receptors but its protection can be overridden by a genetic overload.[74] There has been a dramatic increase in the numbers of older adults with schizophrenia.[75]

Onset may happen suddenly or may occur after the slow and gradual development of a number of signs and symptoms, a period known as the prodromal stage.[10] Up to 75% of those with schizophrenia go through a prodromal stage.[76] The negative and cognitive symptoms in the prodrome stage can precede FEP (first episode psychosis) by many months and up to five years.[60][77] The period from FEP and treatment is known as the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) which is seen to be a factor in functional outcome. The prodromal stage is the high-risk stage for the development of psychosis.[61] Since the progression to first episode psychosis is not inevitable, an alternative term is often preferred of at risk mental state.[61] Cognitive dysfunction at an early age impacts a young person's usual cognitive development.[78] Recognition and early intervention at the prodromal stage would minimize the associated disruption to educational and social development and has been the focus of many studies.[60][77]

Risk factors

Schizophrenia is described as a neurodevelopmental disorder with no precise boundary, or single cause, and is thought to develop from gene–environment interactions with involved vulnerability factors.[7][79][80] The interactions of these risk factors are complex, as numerous and diverse insults from conception to adulthood can be involved.[80] A genetic predisposition on its own, without interacting environmental factors, will not give rise to the development of schizophrenia.[80][81] The genetic component means that prenatal brain development is disturbed, and environmental influence affects the postnatal development of the brain.[82] Evidence suggests that genetically susceptible children are more likely to be vulnerable to the effects of environmental risk factors.[82]

Genetic

Estimates of the heritability of schizophrenia are between 70% and 80%, which implies that 70% to 80% of the individual differences in risk of schizophrenia are associated with genetics.[21][83] These estimates vary because of the difficulty in separating genetic and environmental influences, and their accuracy has been queried.[84][85] The greatest risk factor for developing schizophrenia is having a first-degree relative with the disease (risk is 6.5%); more than 40% of identical twins of those with schizophrenia are also affected.[86] If one parent is affected the risk is about 13% and if both are affected the risk is nearly 50%.[83] However, the DSM-5 indicates that most people with schizophrenia have no family history of psychosis.[10] Results of candidate gene studies of schizophrenia have generally failed to find consistent associations,[87] and the genetic loci identified by genome-wide association studies explain only a small fraction of the variation in the disease.[88]

Many genes are known to be involved in schizophrenia, each with small effects and unknown transmission and expression.[21][89][90] The summation of these effect sizes into a polygenic risk score can explain at least 7% of the variability in liability for schizophrenia.[91] Around 5% of cases of schizophrenia are understood to be at least partially attributable to rare copy number variations (CNVs); these structural variations are associated with known genomic disorders involving deletions at 22q11.2 (DiGeorge syndrome) and 17q12 (17q12 microdeletion syndrome), duplications at 16p11.2 (most frequently found) and deletions at 15q11.2 (Burnside–Butler syndrome).[92] Some of these CNVs increase the risk of developing schizophrenia by as much as 20-fold, and are frequently comorbid with autism and intellectual disabilities.[92]

The genes CRHR1 and CRHBP are associated with the severity of suicidal behavior. These genes code for stress response proteins needed in the control of the HPA axis, and their interaction can affect this axis. Response to stress can cause lasting changes in the function of the HPA axis possibly disrupting the negative feedback mechanism, homeostasis, and the regulation of emotion leading to altered behaviors.[81]

The question of how schizophrenia could be primarily genetically influenced, given that people with schizophrenia have lower fertility rates, is a paradox. It is expected that genetic variants that increase the risk of schizophrenia would be selected against, due to their negative effects on reproductive fitness. A number of potential explanations have been proposed, including that alleles associated with schizophrenia risk confers a fitness advantage in unaffected individuals.[93][94] While some evidence has not supported this idea,[85] others propose that a large number of alleles each contributing a small amount can persist.[95]

A meta-analysis found that oxidative DNA damage was significantly increased in schizophrenia.[96]

Environmental

Environmental factors, each associated with a slight risk of developing schizophrenia in later life include oxygen deprivation, infection, prenatal maternal stress, and malnutrition in the mother during prenatal development.[97] A risk is associated with maternal obesity, in increasing oxidative stress, and dysregulating the dopamine and serotonin pathways.[98] Both maternal stress and infection have been demonstrated to alter fetal neurodevelopment through an increase of pro-inflammatory cytokines.[99] There is a slighter risk associated with being born in the winter or spring possibly due to vitamin D deficiency[100] or a prenatal viral infection.[86] Other infections during pregnancy or around the time of birth that have been linked to an increased risk include infections by Toxoplasma gondii and Chlamydia.[101] The increased risk is about five to eight percent.[102] Viral infections of the brain during childhood are also linked to a risk of schizophrenia during adulthood.[103] Cat exposure is also associated with an increased risk of broadly defined schizophrenia-related disorders, with an odds ratio of 2.4.[104]

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), severe forms of which are classed as childhood trauma, range from being bullied or abused, to the death of a parent.[105] Many adverse childhood experiences can cause toxic stress and increase the risk of psychosis.[105][106][107] Chronic trauma, including ACEs, can promote lasting inflammatory dysregulation throughout the nervous system.[108] It is suggested that early stress may contribute to the development of schizophrenia through these alterations in the immune system.[108] Schizophrenia was the last diagnosis to benefit from the link made between ACEs and adult mental health outcomes.[109]

Living in an urban environment during childhood or as an adult has consistently been found to increase the risk of schizophrenia by a factor of two,[27][110] even after taking into account drug use, ethnic group, and size of social group.[111] A possible link between the urban environment and pollution has been suggested to be the cause of the elevated risk of schizophrenia.[112] Other risk factors include social isolation, immigration related to social adversity and racial discrimination, family dysfunction, unemployment, and poor housing conditions.[86][113] Having a father older than 40 years, or parents younger than 20 years are also associated with schizophrenia.[7][114]

Substance use

About half of those with schizophrenia use recreational drugs including alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis excessively.[115][116] Use of stimulants such as amphetamine and cocaine can lead to a temporary stimulant psychosis, which presents very similarly to schizophrenia. Rarely, alcohol use can also result in a similar alcohol-related psychosis.[86][117] Drugs may also be used as coping mechanisms by people who have schizophrenia, to deal with depression, anxiety, boredom, and loneliness.[115][118] The use of cannabis and tobacco are not associated with the development of cognitive deficits, and sometimes a reverse relationship is found where their use improves these symptoms.[59] However, substance use disorders are associated with an increased risk of suicide, and a poor response to treatment.[119][120]

Cannabis use may be a contributory factor in the development of schizophrenia, potentially increasing the risk of the disease in those who are already at risk.[121][122][123] The increased risk may require the presence of certain genes within an individual.[22] Its use is associated with doubling the rate.[124]

Causes

The causes of schizophrenia are unknown, and a number of models have been put forward to explain the link between altered brain function and schizophrenia.[27] The prevailing model of schizophrenia is that of a neurodevelopmental disorder, and the underlying changes that occur before symptoms become evident are seen as arising from the interaction between genes and the environment.[125] Extensive studies support this model.[76] Maternal infections, malnutrition and complications during pregnancy and childbirth are known risk factors for the development of schizophrenia, which usually emerges between the ages of 18 and 25, a period that overlaps with certain stages of neurodevelopment.[126] Gene-environment interactions lead to deficits in the neural circuitry that affect sensory and cognitive functions.[76]

The common dopamine and glutamate models proposed are not mutually exclusive; each is seen to have a role in the neurobiology of schizophrenia.[127] The most common model put forward was the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, which attributes psychosis to the mind's faulty interpretation of the misfiring of dopaminergic neurons.[128] This has been directly related to the symptoms of delusions and hallucinations.[129][130][131] Abnormal dopamine signaling has been implicated in schizophrenia based on the usefulness of medications that affect the dopamine receptor and the observation that dopamine levels are increased during acute psychosis.[132][133] A decrease in D1 receptors in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex may also be responsible for deficits in working memory.[134][135]

The glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia links alterations between glutamatergic neurotransmission and the neural oscillations that affect connections between the thalamus and the cortex.[136] Studies have shown that a reduced expression of a glutamate receptor – NMDA receptor, and glutamate blocking drugs such as phencyclidine and ketamine can mimic the symptoms and cognitive problems associated with schizophrenia.[136][137][138] Post-mortem studies consistently find that a subset of these neurons fail to express GAD67 (GAD1),[139] in addition to abnormalities in brain morphometry. The subsets of interneurons that are abnormal in schizophrenia are responsible for the synchronizing of neural ensembles needed during working memory tasks. These give the neural oscillations produced as gamma waves that have a frequency of between 30 and 80 hertz. Both working memory tasks and gamma waves are impaired in schizophrenia, which may reflect abnormal interneuron functionality.[139][140][141][142] An important process that may be disrupted in neurodevelopment is astrogenesis – the formation of astrocytes. Astrocytes are crucial in contributing to the formation and maintenance of neural circuits and it is believed that disruption in this role can result in a number of neurodevelopmental disorders including schizophrenia.[143] Evidence suggests that reduced numbers of astrocytes in deeper cortical layers are assocociated with a diminished expression of EAAT2, a glutamate transporter in astrocytes; supporting the glutamate hypothesis.[143]

Deficits in executive functions, such as planning, inhibition, and working memory, are pervasive in schizophrenia. Although these functions are separable, their dysfunction in schizophrenia may reflect an underlying deficit in the ability to represent goal related information in working memory, and to use this to direct cognition and behavior.[144][145] These impairments have been linked to a number of neuroimaging and neuropathological abnormalities. For example, functional neuroimaging studies report evidence of reduced neural processing efficiency, whereby the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is activated to a greater degree to achieve a certain level of performance relative to controls on working memory tasks. These abnormalities may be linked to the consistent post-mortem finding of reduced neuropil, evidenced by increased pyramidal cell density and reduced dendritic spine density. These cellular and functional abnormalities may also be reflected in structural neuroimaging studies that find reduced grey matter volume in association with deficits in working memory tasks.[146]

Positive symptoms have been linked to cortical thinning in the superior temporal gyrus.[147] The severity of negative symptoms has been linked to reduced thickness in the left medial orbitofrontal cortex.[148] Anhedonia, traditionally defined as a reduced capacity to experience pleasure, is frequently reported in schizophrenia. However, a large body of evidence suggests that hedonic responses are intact in schizophrenia,[149] and that what is reported to be anhedonia is a reflection of dysfunction in other processes related to reward.[150] Overall, a failure of reward prediction is thought to lead to impairment in the generation of cognition and behavior required to obtain rewards, despite normal hedonic responses.[151]

Another theory links abnormal brain lateralization to the development of being left-handed which is significantly more common in those with schizophrenia.[152] This abnormal development of hemispheric asymmetry is noted in schizophrenia.[153] Studies have concluded that the link is a true and verifiable effect that may reflect a genetic link between lateralization and schizophrenia.[152][154]

Bayesian models of brain functioning have been used to link abnormalities in cellular functioning to symptoms.[155][156] Both hallucinations and delusions have been suggested to reflect improper encoding of prior expectations, thereby causing expectation to excessively influence sensory perception and the formation of beliefs. In approved models of circuits that mediate predictive coding, reduced NMDA receptor activation, could in theory result in the positive symptoms of delusions and hallucinations.[157][158][159]

Diagnosis

Criteria

Schizophrenia is diagnosed based on criteria in either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) published by the American Psychiatric Association or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) published by the World Health Organization (WHO). These criteria use the self-reported experiences of the person and reported abnormalities in behavior, followed by a psychiatric assessment. The mental status examination is an important part of the assessment.[160] An established tool for assessing the severity of positive and negative symptoms is the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).[161] This has been seen to have shortcomings relating to negative symptoms, and other scales – the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS), and the Brief Negative Symptoms Scale (BNSS) have been introduced.[50] The DSM-5, published in 2013, gives a Scale to Assess the Severity of Symptom Dimensions outlining eight dimensions of symptoms.[58]

DSM-5 states that to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, two diagnostic criteria have to be met over the period of one month, with a significant impact on social or occupational functioning for at least six months. One of the symptoms needs to be either delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech. A second symptom could be one of the negative symptoms, or severely disorganized or catatonic behaviour.[10] A different diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder can be made before the six months needed for the diagnosis of schizophrenia.[10]

In Australia, the guideline for diagnosis is for six months or more with symptoms severe enough to affect ordinary functioning.[162] In the UK diagnosis is based on having the symptoms for most of the time for one month, with symptoms that significantly affect the ability to work, study, or carry on ordinary daily living, and with other similar conditions ruled out.[163]

The ICD criteria are typically used in European countries; the DSM criteria are used predominantly in the United States and Canada, and are prevailing in research studies. In practice, agreement between the two systems is high.[164] The current proposal for the ICD-11 criteria for schizophrenia recommends adding self-disorder as a symptom.[41]

A major unresolved difference between the two diagnostic systems is that of the requirement in DSM of an impaired functional outcome. WHO for ICD argues that not all people with schizophrenia have functional deficits and so these are not specific for the diagnosis.[58]

Comorbidities

Many people with schizophrenia may have one or more other mental disorders, such as anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, or substance use disorder. These are separate disorders that require treatment.[10] When comorbid with schizophrenia, substance use disorder and antisocial personality disorder both increase the risk for violence.[165] Comorbid substance use disorder also increases the risk of suicide.[119]

Sleep disorders often co-occur with schizophrenia, and may be an early sign of relapse.[166] Sleep disorders are linked with positive symptoms such as disorganized thinking and can adversely affect cortical plasticity and cognition.[166] The consolidation of memories is disrupted in sleep disorders.[167] They are associated with severity of illness, a poor prognosis, and poor quality of life.[168][169] Sleep onset and maintenance insomnia is a common symptom, regardless of whether treatment has been received or not.[168] Genetic variations have been found associated with these conditions involving the circadian rhythm, dopamine and histamine metabolism, and signal transduction.[170]

Schizophrenia is also associated with a number of somatic comorbidities including diabetes mellitus type 2, autoimmune diseases, and cardiovascular diseases. The association of these with schizophrenia may be partially due to medications (e.g. dyslipidemia from antipsychotics), environmental factors (e.g. complications from an increased rate of cigarette smoking), or associated with the disorder itself (e.g. diabetes mellitus type 2 and some cardiovascular diseases are thought to be genetically linked). These somatic comorbidities contribute to reduced life expectancy among persons with the disorder.[171]

Differential diagnosis

To make a diagnosis of schizophrenia other possible causes of psychosis need to be excluded.[172]: 858 Psychotic symptoms lasting less than a month may be diagnosed as brief psychotic disorder, or as schizophreniform disorder. Psychosis is noted in Other specified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders as a DSM-5 category. Schizoaffective disorder is diagnosed if symptoms of mood disorder are substantially present alongside psychotic symptoms. Psychosis that results from a general medical condition or substance is termed secondary psychosis.[10]

Psychotic symptoms may be present in several other conditions, including bipolar disorder,[11] borderline personality disorder,[12] substance intoxication, substance-induced psychosis, and a number of drug withdrawal syndromes. Non-bizarre delusions are also present in delusional disorder, and social withdrawal in social anxiety disorder, avoidant personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder. Schizotypal personality disorder has symptoms that are similar but less severe than those of schizophrenia.[10] Schizophrenia occurs along with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) considerably more often than could be explained by chance, although it can be difficult to distinguish obsessions that occur in OCD from the delusions of schizophrenia.[173] There can be considerable overlap with the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.[174]

A more general medical and neurological examination may be needed to rule out medical illnesses which may rarely produce psychotic schizophrenia-like symptoms, such as metabolic disturbance, systemic infection, syphilis, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, epilepsy, limbic encephalitis, and brain lesions. Stroke, multiple sclerosis, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and dementias such as Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, frontotemporal dementia, and the Lewy body dementias may also be associated with schizophrenia-like psychotic symptoms.[175] It may be necessary to rule out a delirium, which can be distinguished by visual hallucinations, acute onset and fluctuating level of consciousness, and indicates an underlying medical illness. Investigations are not generally repeated for relapse unless there is a specific medical indication or possible adverse effects from antipsychotic medication.[176] In children hallucinations must be separated from typical childhood fantasies.[10] It is difficult to distinguish childhood schizophrenia from autism.[73]

Prevention

Prevention of schizophrenia is difficult as there are no reliable markers for the later development of the disorder.[177]

Early intervention programs diagnose and treat patients in the prodromal phase of the illness. There is some evidence that these programs reduce symptoms. Patients tend to prefer early treatment programs to ordinary treatment and are less likely to disengage from them. As of 2020, it is unclear whether the benefits of early treatment persist once the treatment is terminated.[178]

Cognitive behavioral therapy may reduce the risk of psychosis in those at high risk after a year[179] and is recommended in this group, by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).[34] Another preventive measure is to avoid drugs that have been associated with development of the disorder, including cannabis, cocaine, and amphetamines.[86]

Antipsychotics are prescribed following a first-episode psychosis, and following remission, a preventive maintenance use is continued to avoid relapse. However, it is recognized that some people do recover following a single episode and that long-term use of antipsychotics will not be needed but there is no way of identifying this group.[180]

Management

The primary treatment of schizophrenia is the use of antipsychotic medications, often in combination with psychosocial interventions and social supports.[27][181] Community support services including drop-in centers, visits by members of a community mental health team, supported employment,[182] and support groups are common. The time between the onset of psychotic symptoms to being given treatment – the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) – is associated with a poorer outcome in both the short term and the long term.[183]

Voluntary or involuntary admission to hospital may be imposed by doctors and courts who deem a person to be having a severe episode. In the UK, large mental hospitals termed asylums began to be closed down in the 1950s with the advent of antipsychotics, and with an awareness of the negative impact of long-term hospital stays on recovery.[25] This process was known as deinstitutionalization, and community and supportive services were developed to support this change. Many other countries followed suit with the US starting in the 60s.[184] There still remain a smaller group of people who do not improve enough to be discharged.[25][32] In some countries that lack the necessary supportive and social services, long-term hospital stays are more usual.[33]

Medication

The first-line treatment for schizophrenia is an antipsychotic. The first-generation antipsychotics, now called typical antipsychotics like Flupentixol, are dopamine antagonists that block D2 receptors, and affect the neurotransmission of dopamine. Those brought out later, the second-generation antipsychotics known as atypical antipsychotics, including olanzapine and risperidone, can also have an effect on another neurotransmitter, serotonin. Antipsychotics can reduce the symptoms of anxiety within hours of their use but for other symptoms they may take several days or weeks to reach their full effect.[36][185] They have little effect on negative and cognitive symptoms, which may be helped by additional psychotherapies and medications.[186] There is no single antipsychotic suitable for first-line treatment for everyone, as responses and tolerances vary between people.[187] Stopping medication may be considered after a single psychotic episode where there has been a full recovery with no symptoms for twelve months. Repeated relapses worsen the long-term outlook and the risk of relapse following a second episode is high, and long-term treatment is usually recommended.[188][189]

About half of those with schizophrenia will respond favourably to antipsychotics, and have a good return of functioning.[190] However, positive symptoms persist in up to a third of people. Following two trials of different antipsychotics over six weeks, that also prove ineffective, they will be classed as having treatment resistant schizophrenia (TRS), and clozapine will be offered.[191][29] Clozapine is of benefit to around half of this group although it has the potentially serious side effect of agranulocytosis (lowered white blood cell count) in less than 4% of people.[27][86][192]

About 30 to 50 percent of people with schizophrenia do not accept that they have an illness or comply with their recommended treatment.[193] For those who are unwilling or unable to take medication regularly, long-acting injections of antipsychotics may be used,[194] which reduce the risk of relapse to a greater degree than oral medications.[195] When used in combination with psychosocial interventions, they may improve long-term adherence to treatment.[196]

Adverse effects

Extrapyramidal symptoms, including akathisia, are associated with all commercially available antipsychotic to varying degrees.[197]: 566 There is little evidence that second generation antipsychotics have reduced levels of extrapyramidical symptoms compared to typical antipsychotics.[197]: 566 Tardive dyskinesia can occur due to long-term use of antipsychotics, developing after months or years of use.[198] The antipsychotic clozapine is also associated with thromboembolism (including pulmonary embolism), myocarditis, and cardiomyopathy.

Psychosocial interventions

A number of psychosocial interventions that include several types of psychotherapy may be useful in the treatment of schizophrenia such as: family therapy,[199] group therapy, cognitive remediation therapy (CRT),[200] cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and metacognitive training.[201][202] Skills training, help with substance use, and weight management – often needed as a side effect of an antipsychotic – are also offered.[203] In the US, interventions for first episode psychosis have been brought together in an overall approach known as coordinated speciality care (CSC) and also includes support for education.[36] In the UK care across all phases is a similar approach that covers many of the treatment guidelines recommended.[34] The aim is to reduce the number of relapses and stays in the hospital.[199]

Other support services for education, employment, and housing are usually offered. For people with severe schizophrenia, who are discharged from a stay in the hospital, these services are often brought together in an integrated approach to offer support in the community away from the hospital setting. In addition to medicine management, housing, and finances, assistance is given for more routine matters such as help with shopping and using public transport. This approach is known as assertive community treatment (ACT) and has been shown to achieve positive results in symptoms, social functioning and quality of life.[204][205] Another more intense approach is known as intensive care management (ICM). ICM is a stage further than ACT and emphasises support of high intensity in smaller caseloads, (less than twenty). This approach is to provide long-term care in the community. Studies show that ICM improves many of the relevant outcomes including social functioning.[206]

Some studies have shown little evidence for the effectiveness of CBT in either reducing symptoms or preventing relapse.[207][208] However, other studies have found that CBT does improve overall psychotic symptoms (when in use with medication) and it has been recommended in Canada, but has been seen to have no effect on social function, relapse, or quality of life.[209] In the UK it is recommended as an add-on therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia.[185][208] Arts therapies are seen to improve negative symptoms in some people, and are recommended by NICE in the UK.[185] This approach is criticised as having not been well-researched,[210][211] and arts therapies are not recommended in Australian guidelines for example.[212] Peer support, in which people with personal experience of schizophrenia, provide help to each other, is of unclear benefit.[213]

Other

Exercise including aerobic exercise has been shown to improve positive and negative symptoms, cognition, working memory, and improve quality of life.[214][215] Exercise has also been shown to increase the volume of the hippocampus in those with schizophrenia. A decrease in hippocampal volume is one of the factors linked to the development of the disease.[214] However, there still remains the problem of increasing motivation for, and maintaining participation in physical activity.[216] Supervised sessions are recommended.[215] In the UK healthy eating advice is offered alongside exercise programs.[217]

An inadequate diet is often found in schizophrenia, and associated vitamin deficiencies including those of folate, and vitamin D are linked to the risk factors for the development of schizophrenia and for early death including heart disease.[218][219] Those with schizophrenia possibly have the worst diet of all the mental disorders. Lower levels of folate and vitamin D have been noted as significantly lower in first episode psychosis.[218] The use of supplemental folate is recommended.[220] A zinc deficiency has also been noted.[221] Vitamin B12 is also often deficient and this is linked to worse symptoms. Supplementation with B vitamins has been shown to significantly improve symptoms, and to put in reverse some of the cognitive deficits.[218] It is also suggested that the noted dysfunction in gut microbiota might benefit from the use of probiotics.[221]

Prognosis

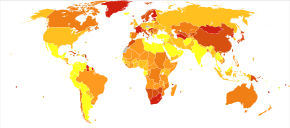

| no data ≤ 185 185–197 197–207 207–218 218–229 229–240 | 240–251 251–262 262–273 273–284 284–295 ≥ 295 |

Schizophrenia has great human and economic costs.[7] It decreases life expectancy by between 20[13] and 28 years.[14] This is primarily because of its association with heart disease,[222] diabetes,[14] obesity, poor diet, a sedentary lifestyle, and smoking, with an increased rate of suicide playing a lesser role.[13][223] Side effects of antipsychotics may also increase the risk.[13]

Almost 40% of those with schizophrenia die from complications of cardiovascular disease which is seen to be increasingly associated.[219] An underlying factor of sudden cardiac death may be Brugada syndrome (BrS) – BrS mutations that overlap with those linked with schizophrenia are the calcium channel mutations.[219] BrS may also be drug-induced from certain antipsychotics and antidepressants.[219] Primary polydipsia, or excessive fluid intake, is relatively common in people with chronic schizophrenia.[224][225] This may lead to hyponatremia which can be life-threatening. Antipsychotics can lead to a dry mouth, but there are several other factors that may contribute to the disorder; it may reduce life expectancy by 13 percent.[225] Barriers to improving the mortality rate in schizophrenia are poverty, overlooking the symptoms of other illnesses, stress, stigma, and medication side effects.[226]

Schizophrenia is a major cause of disability. In 2016, it was classed as the 12th most disabling condition.[227] Approximately 75% of people with schizophrenia have ongoing disability with relapses.[228] Some people do recover completely and others function well in society.[229] Most people with schizophrenia live independently with community support.[27] About 85% are unemployed.[7] In people with a first episode of psychosis in schizophrenia a good long-term outcome occurs in 31%, an intermediate outcome in 42% and a poor outcome in 31%.[230] Males are affected more often than females, and have a worse outcome.[231] Studies showing that outcomes for schizophrenia appear better in the developing than the developed world[232] have been questioned.[233] Social problems, such as long-term unemployment, poverty, homelessness, exploitation, stigmatization and victimization are common consequences, and lead to social exclusion.[25][26]

There is a higher than average suicide rate associated with schizophrenia estimated at 5% to 6%, most often occurring in the period following onset or first hospital admission.[18][28] Several times more (20 to 40%) attempt suicide at least once.[10][100] There are a variety of risk factors, including male sex, depression, a high IQ,[234] heavy smoking,[235] and substance use.[119] Repeated relapse is linked to an increased risk of suicidal behavior.[180] The use of clozapine can reduce the risk of suicide, and of aggression.[236]

A strong association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking has been shown in worldwide studies.[237][238] Smoking is especially high in those diagnosed with schizophrenia, with estimates ranging from 80 to 90% being regular smokers, as compared to 20% of the general population.[238] Those who smoke tend to smoke heavily, and additionally smoke cigarettes with high nicotine content.[40] Some propose that this is in an effort to improve symptoms.[239] Among people with schizophrenia use of cannabis is also common.[119]

Schizophrenia leads to an increased risk of dementia.[240]

Violence

Most people with schizophrenia are not aggressive, and are more likely to be victims of violence rather than perpetrators.[10] People with schizophrenia are commonly exploited and victimized by violent crime as part of a broader dynamic of social exclusion.[25][26] People diagnosed with schizophrenia are also subject to forced drug injections, seclusion, and restraint at high rates.[31][32]

The risk of violence by people with schizophrenia is small. There are minor subgroups where the risk is high.[165] This risk is usually associated with a comorbid disorder such as a substance use disorder – in particular alcohol, or with antisocial personality disorder.[165] Substance use disorder is strongly linked, and other risk factors are linked to deficits in cognition and social cognition including facial perception and insight that are in part included in theory of mind impairments.[241][242] Poor cognitive functioning, decision-making, and facial perception may contribute to making a wrong judgement of a situation that could result in an inappropriate response such as violence.[243] These associated risk factors are also present in antisocial personality disorder which when present as a comorbid disorder greatly increases the risk of violence.[244][245]

Epidemiology

In 2017,[needs update] the Global Burden of Disease Study estimated there were 1.1 million new cases;[20] in 2022 the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a total of 24 million cases globally.[2] Schizophrenia affects around 0.3–0.7% of people at some point in their life.[19][14] In areas of conflict this figure can rise to between 4.0 and 6.5%.[246] It occurs 1.4 times more frequently in males than females and typically appears earlier in men.[86]

Worldwide, schizophrenia is the most common psychotic disorder.[55] The frequency of schizophrenia varies across the world,[10] within countries,[247] and at the local and neighborhood level;[248] this variation in prevalence between studies over time, across geographical locations, and by gender is as high as fivefold.[7]

Schizophrenia causes approximately one percent of worldwide disability adjusted life years[needs update][86] and resulted in 17,000 deaths in 2015.[16]

In 2000,[needs update] WHO found the percentage of people affected and the number of new cases that develop each year is roughly similar around the world, with age-standardized prevalence per 100,000 ranging from 343 in Africa to 544 in Japan and Oceania for men, and from 378 in Africa to 527 in Southeastern Europe for women.[249]

History

Conceptual development

Accounts of a schizophrenia-like syndrome are rare in records before the 19th century; the earliest case reports were in 1797 and 1809.[250] Dementia praecox, meaning premature dementia, was used by German psychiatrist Heinrich Schüle in 1886, and then in 1891 by Arnold Pick in a case report of hebephrenia. In 1893 Emil Kraepelin used the term in making a distinction, known as the Kraepelinian dichotomy, between the two psychoses – dementia praecox, and manic depression (now called bipolar disorder).[13] When it became evident that the disorder was not a degenerative dementia, it was renamed schizophrenia by Eugen Bleuler in 1908.[251]

The word schizophrenia translates as 'splitting of the mind' and is Modern Latin from the Greek words schizein (Ancient Greek: σχίζειν, lit. 'to split') and phrēn, (Ancient Greek: φρήν, lit. 'mind')[252] Its use was intended to describe the separation of function between personality, thinking, memory, and perception.[251]

In the early 20th century, the psychiatrist Kurt Schneider categorized the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia into two groups – hallucinations and delusions. The hallucinations were listed as specific to auditory and the delusions included thought disorders. These were seen as important symptoms, termed first-rank. The most common first-rank symptom was found to belong to thought disorders.[page needed][253][page needed][254] In 2013 the first-rank symptoms were excluded from the DSM-5 criteria;[255] while they may not be useful in diagnosing schizophrenia, they can assist in differential diagnosis.[256]

Subtypes of schizophrenia – classified as paranoid, disorganized, catatonic, undifferentiated, and residual – were difficult to distinguish and are no longer recognized as separate conditions by DSM-5 (2013) or ICD-11.[257][258][259]

Breadth of diagnosis

Before the 1960s, nonviolent petty criminals and women were sometimes diagnosed with schizophrenia, categorizing the latter as ill for not performing their duties within patriarchy as wives and mothers.[260] In the mid-to-late 1960s, black men were categorized as "hostile and aggressive" and diagnosed as schizophrenic at much higher rates, their civil rights and Black Power activism labeled as delusions.[260][261]

In the early 1970s in the US, the diagnostic model for schizophrenia was broad and clinically based using DSM II. Schizophrenia was diagnosed far more in the US than in Europe which used the ICD-9 criteria. The US model was criticised for failing to demarcate clearly those people with a mental illness. In 1980 DSM III was published and showed a shift in focus from the clinically based biopsychosocial model to a reason-based medical model.[262] DSM IV brought an increased focus on an evidence-based medical model.[263]

Historical treatment

In the 1930s a number of shock procedures which induced seizures (convulsions) or comas were used to treat schizophrenia.[264] Insulin shock involved injecting large doses of insulin to induce comas, which in turn produced hypoglycemia and convulsions.[264][265] The use of electricity to induce seizures was in use as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) by 1938.[266]

Psychosurgery, including the lobotomy and frontal lobotomy – carried out from the 1930s until the 1970s in the United States, and until the 1980s in France – are recognized as a human rights abuse.[267][268] In the mid-1950s the first typical antipsychotic, chlorpromazine, was introduced,[269] followed in the 1970s by the first atypical antipsychotic, clozapine.[270]

Political abuse

From the 1960s until 1989, psychiatrists in the USSR and Eastern Bloc diagnosed thousands of people with sluggish schizophrenia,[271][272] without signs of psychosis, based on "the assumption that symptoms would later appear".[273] Now discredited, the diagnosis provided a convenient way to confine political dissidents.[274]

Society and culture

In the United States, the annual cost of schizophrenia – including direct costs (outpatient, inpatient, drugs, and long-term care) and non-healthcare costs (law enforcement, reduced workplace productivity, and unemployment) – was estimated at $62.7 billion for the year 2002.[275][a] In the UK the cost in 2016 was put at £11.8 billion per year with a third of that figure directly attributable to the cost of hospital, social care and treatment.[7]

Stigma

In 2002, the term for schizophrenia in Japan was changed from seishin-bunretsu-byō (精神分裂病, lit. 'mind-split disease') to tōgō-shitchō-shō (統合失調症, lit. 'integration–dysregulation syndrome') to reduce stigma.[278] The new name, also interpreted as "integration disorder", was inspired by the biopsychosocial model.[279] A similar change was made in South Korea in 2012 to attunement disorder.[280]

Cultural depictions

Media coverage, especially movies, reinforce the public perception of an association between schizophrenia and violence.[281] A majority of movies have historically depicted characters with schizophrenia as criminal, dangerous, violent, unpredictable and homicidal, and depicted delusions and hallucinations as the main symptoms of schizophrenic characters, ignoring other common symptoms,[282] furthering stereotypes of schizophrenia including the idea of a split personality.[283]

The book A Beautiful Mind chronicled the life of John Forbes Nash who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. The book was made into a film with the same name; an earlier documentary film was A Brilliant Madness.

In the UK, guidelines for reporting conditions and award campaigns have shown a reduction in negative reporting since 2013.[284]

In 1964 a case study of three males diagnosed with schizophrenia who each had the delusional belief that they were Jesus Christ was published as The Three Christs of Ypsilanti; a film with the title Three Christs was released in 2020.[285][286]

Research directions

A 2015 Cochrane review found unclear evidence of benefit from brain stimulation techniques to treat the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, in particular auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs).[287] Most studies focus on transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCM), and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).[288] Techniques based on focused ultrasound for deep brain stimulation could provide insight for the treatment of AVHs.[288]

The study of potential biomarkers that would help in diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia is an active area of research as of 2020. Possible biomarkers include markers of inflammation,[99] neuroimaging,[289] brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF),[290] and speech analysis. Some markers such as C-reactive protein are useful in detecting levels of inflammation implicated in some psychiatric disorders but they are not disorder-specific. Other inflammatory cytokines are found to be elevated in first episode psychosis and acute relapse that are normalized after treatment with antipsychotics, and these may be considered as state markers.[291] Deficits in sleep spindles in schizophrenia may serve as a marker of an impaired thalamocortical circuit, and a mechanism for memory impairment.[167] MicroRNAs are highly influential in early neuronal development, and their disruption is implicated in several CNS disorders; circulating microRNAs (cimiRNAs) are found in body fluids such as blood and cerebrospinal fluid, and changes in their levels are seen to relate to changes in microRNA levels in specific regions of brain tissue. These studies suggest that cimiRNAs have the potential to be early and accurate biomarkers in a number of disorders including schizophrenia.[292][293]

Explanatory notes

References

- ^ Jones D (2003) [1917]. Roach P, Hartmann J, Setter J (eds.). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Schizophrenia Fact sheet". World Health Organization. 10 January 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Schizophrenia". Health topics. US National Institute of Mental Health. April 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ "Medicinal treatment of psychosis/schizophrenia". Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ Proietto Sr J (November 2004). "Diabetes and Antipsychotic Drugs". Medsafe.

- ^ Holt RI (September 2019). "Association Between Antipsychotic Medication Use and Diabetes". Current Diabetes Reports. 19 (10). National Center for Biotechnology Information: 96. doi:10.1007/s11892-019-1220-8. ISSN 1534-4827. PMC 6718373. PMID 31478094.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB (July 2016). "Schizophrenia". The Lancet. 388 (10039): 86–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6. PMC 4940219. PMID 26777917.

- ^ Miller B (2 February 2020). "Drug Psychosis May Pull the Schizophrenia Trigger". Psychiatric Times.

- ^ Gruebner O, Rapp MA, Adli M, Kluge U, Galea S, Heinz A (February 2017). "Cities and Mental Health". Deutsches Arzteblatt International. 114 (8): 121–127. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2017.0121. PMC 5374256. PMID 28302261.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 99–105. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ferri FF (2010). "Chapter S". Ferri's differential diagnosis: a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-07699-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Paris J (December 2018). "Differential Diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 41 (4): 575–582. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2018.07.001. PMID 30447725. S2CID 53951650.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB (2014). "Excess early mortality in schizophrenia". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 10: 425–448. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153657. PMID 24313570.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Schizophrenia". Statistics. US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). 22 April 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Schizophrenia Fact Sheet and Information". World Health Organization.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ "ICD-11: 6A20 Schizophrenia". World Health Organization. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ferri FF (2019). Ferri's clinical advisor 2019: 5 books in 1. Elsevier. pp. 1225–1226. ISBN 9780323530422.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Javitt DC (June 2014). "Balancing therapeutic safety and efficacy to improve clinical and economic outcomes in schizophrenia: a clinical overview". The American Journal of Managed Care. 20 (8 Suppl): S160-165. PMID 25180705.

- ^ Jump up to: a b James SL, Abate D (November 2018). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017". The Lancet. 392 (10159): 1789–1858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. PMC 6227754. PMID 30496104.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c van de Leemput J, Hess JL, Glatt SJ, Tsuang MT (2016). Genetics of Schizophrenia: Historical Insights and Prevailing Evidence. Advances in Genetics. Vol. 96. pp. 99–141. doi:10.1016/bs.adgen.2016.08.001. ISBN 978-0-12-809672-7. PMID 27968732.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Parakh P, Basu D (August 2013). "Cannabis and psychosis: have we found the missing links?". Asian Journal of Psychiatry (Review). 6 (4): 281–287. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2013.03.012. PMID 23810133.

Cannabis acts as a component cause of psychosis, that is, it increases the risk of psychosis in people with certain genetic or environmental vulnerabilities, though by itself, it is neither a sufficient nor a necessary cause of psychosis.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vita A, Barlati S (May 2018). "Recovery from schizophrenia: is it possible?". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 31 (3): 246–255. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000407. PMID 29474266. S2CID 35299996.

- ^ Lawrence RE, First MB, Lieberman JA (2015). "Chapter 48: Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses". In Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA, First MB, Riba MB (eds.). Psychiatry (fourth ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 798, 816, 819. doi:10.1002/9781118753378.ch48. ISBN 978-1-118-84547-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Killaspy H (September 2014). "Contemporary mental health rehabilitation". East Asian Archives of Psychiatry. 24 (3): 89–94. PMID 25316799.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Diminic S, Stockings E, Scott JG, et al. (October 2018). "Global Epidemiology and Burden of Schizophrenia: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 44 (6): 1195–1203. doi:10.1093/schbul/sby058. PMC 6192504. PMID 29762765.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f van Os J, Kapur S (August 2009). "Schizophrenia" (PDF). Lancet. 374 (9690): 635–645. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. PMID 19700006. S2CID 208792724. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hor K, Taylor M (November 2010). "Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 24 (4 Suppl): 81–90. doi:10.1177/1359786810385490. PMC 2951591. PMID 20923923.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Siskind D, Siskind V, Kisely S (November 2017). "Clozapine Response Rates among People with Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Data from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 62 (11): 772–777. doi:10.1177/0706743717718167. PMC 5697625. PMID 28655284.

- ^ Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019. S2CID 32085212.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Becker T, Kilian R (2006). "Psychiatric services for people with severe mental illness across western Europe: what can be generalized from current knowledge about differences in provision, costs and outcomes of mental health care?". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 113 (429): 9–16. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00711.x. PMID 16445476. S2CID 34615961.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Capdevielle D, Boulenger JP, Villebrun D, Ritchie K (September 2009). "Durées d'hospitalisation des patients souffrant de schizophrénie: implication des systèmes de soin et conséquences médicoéconomiques" [Schizophrenic patients' length of stay: mental health care implication and medicoeconomic consequences]. L'Encéphale (in French). 35 (4): 394–399. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2008.11.005. PMID 19748377.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Narayan KK, Kumar DS (January 2012). "Disability in a Group of Long-stay Patients with Schizophrenia: Experience from a Mental Hospital". Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 34 (1): 70–75. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.96164. PMC 3361848. PMID 22661812.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). March 2014. pp. 4–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Stępnicki P, Kondej M, Kaczor AA (20 August 2018). "Current Concepts and Treatments of Schizophrenia". Molecules. 23 (8): 2087. doi:10.3390/molecules23082087. PMC 6222385. PMID 30127324.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "RAISE Questions and Answers". US National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Marshall M (September 2005). "Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review". Archives of General Psychiatry. 62 (9): 975–983. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975. PMID 16143729. S2CID 13504781.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Montagnese M, Leptourgos P, Fernyhough C, et al. (January 2021). "A Review of Multimodal Hallucinations: Categorization, Assessment, Theoretical Perspectives, and Clinical Recommendations". Schizophr Bull. 47 (1): 237–248. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbaa101. PMC 7825001. PMID 32772114.

- ^ Császár N, Kapócs G, Bókkon I (27 May 2019). "A possible key role of vision in the development of schizophrenia". Reviews in the Neurosciences. 30 (4): 359–379. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2018-0022. PMID 30244235. S2CID 52813070.

- ^ Jump up to: a b American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 299–304. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Heinz A, Voss M, Lawrie SM, Mishara A, Bauer M, Gallinat J, et al. (September 2016). "Shall we really say goodbye to first rank symptoms?". European Psychiatry. 37: 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.04.010. PMID 27429167. S2CID 13761854.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Adida M, Azorin JM, Belzeaux R, Fakra E (December 2015). "[Negative Symptoms: Clinical and Psychometric Aspects]". L'Encephale. 41 (6 Suppl 1): 6S15–17. doi:10.1016/S0013-7006(16)30004-5. PMID 26776385.

- ^ Mach C, Dollfus S (April 2016). "[Scale for Assessing Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review]". L'Encephale. 42 (2): 165–171. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2015.12.020. PMID 26923997.

- ^ Waltz JA, Gold JM (2016). "Motivational Deficits in Schizophrenia and the Representation of Expected Value". Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 27: 375–410. doi:10.1007/7854_2015_385. ISBN 978-3-319-26933-7. PMC 4792780. PMID 26370946.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Husain M, Roiser JP (August 2018). "Neuroscience of apathy and anhedonia: a transdiagnostic approach". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 19 (8): 470–484. doi:10.1038/s41583-018-0029-9. PMID 29946157. S2CID 49428707.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Galderisi S, Mucci A, Buchanan RW, Arango C (August 2018). "Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: new developments and unanswered research questions". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 5 (8): 664–677. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30050-6. PMID 29602739. S2CID 4483198.

- ^ Klaus F, Dorsaz O, Kaiser S (19 September 2018). "[Negative symptoms in schizophrenia – overview and practical implications]". Revue médicale suisse. 14 (619): 1660–1664. doi:10.53738/REVMED.2018.14.619.1660. PMID 30230774. S2CID 246764656.

- ^ Batinic B (June 2019). "Cognitive Models of Positive and Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia and Implications for Treatment". Psychiatria Danubina. 31 (Suppl 2): 181–184. PMID 31158119.

- ^ Бортолон С., Макгрегор А., Капдевиль Д., Раффард С. (сентябрь 2018 г.). «Апатия при шизофрении: обзор нейропсихологических и нейроанатомических исследований». Нейропсихология . 118 (Часть Б): 22–33. doi : 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.09.033 . ПМИД 28966139 . S2CID 13411386 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Мардер С.Р., Киркпатрик Б. (май 2014 г.). «Определение и измерение негативных симптомов шизофрении в клинических исследованиях». Европейская нейропсихофармакология . 24 (5): 737–743. дои : 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.10.016 . ПМИД 24275698 . S2CID 5172022 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Тацуми К., Киркпатрик Б., Штраус Г.П., Оплер М. (апрель 2020 г.). «Краткая шкала негативных симптомов в переводе: обзор психометрических свойств и не только». Европейская нейропсихофармакология . 33 : 36–44. doi : 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.01.018 . ПМИД 32081498 . S2CID 211141678 .

- ^ Клаус Ф., Кайзер С., Киршнер М. (июнь 2018 г.). «[Негативные симптомы шизофрении – обзор]». Терапевтический Умшау . 75 (1): 51–56. дои : 10.1024/0040-5930/a000966 . ПМИД 29909762 . S2CID 196502392 .

- ^ Войчак П., Рыбаковски Ю. (30 апреля 2018 г.). «Клиническая картина, патогенез и психометрическая оценка негативных симптомов шизофрении» . Психиатрия Польска . 52 (2): 185–197. дои : 10.12740/PP/70610 . ПМИД 29975360 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Муранте Т., Коэн К.И. (январь 2017 г.). «Когнитивная функция у пожилых людей с шизофренией» . Фокус (Американское психиатрическое издательство) . 15 (1): 26–34. дои : 10.1176/appi.focus.20160032 . ПМК 6519630 . ПМИД 31975837 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кар С.К., Джайн М. (июль 2016 г.). «Современные представления о познании и нейробиологических коррелятах шизофрении» . Журнал нейронаук в сельской практике . 7 (3): 412–418. дои : 10.4103/0976-3147.176185 . ПМЦ 4898111 . ПМИД 27365960 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бозикас, вице-президент, Андреу С (февраль 2011 г.). «Продольные исследования когнитивных функций при первом эпизоде психоза: систематический обзор литературы». Австралийский и новозеландский журнал психиатрии . 45 (2): 93–108. дои : 10.3109/00048674.2010.541418 . ПМИД 21320033 . S2CID 26135485 .

- ^ Шах Дж.Н., Куреши С.У., Джавайд А., Шульц П.Е. (июнь 2012 г.). «Есть ли доказательства позднего снижения когнитивных функций при хронической шизофрении?». Психиатрический ежеквартальный журнал . 83 (2): 127–144. дои : 10.1007/s11126-011-9189-8 . ПМИД 21863346 . S2CID 10970088 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бидерманн Ф., Флейшхакер В.В. (август 2016 г.). «Психотические расстройства в DSM-5 и МКБ-11». Спектры ЦНС . 21 (4): 349–354. дои : 10.1017/S1092852916000316 . ПМИД 27418328 . S2CID 24728447 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Видайлхет П (сентябрь 2013 г.). «[Первый эпизод психоза, когнитивные трудности и их исправление]». L'Encéphale (на французском языке). 39 (Приложение 2): S83-92. дои : 10.1016/S0013-7006(13)70101-5 . ПМИД 24084427 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Хасимото К. (5 июля 2019 г.). «Последние достижения в области раннего вмешательства при шизофрении: будущее направление на основе доклинических результатов». Текущие отчеты психиатрии . 21 (8): 75. дои : 10.1007/s11920-019-1063-7 . ПМИД 31278495 . S2CID 195814019 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Грин М.Ф., Хоран В.П., Ли Дж. (июнь 2019 г.). «Несоциальное и социальное познание при шизофрении: текущие данные и будущие направления» . Мировая психиатрия . 18 (2): 146–161. дои : 10.1002/wps.20624 . ПМК 6502429 . ПМИД 31059632 .

- ^ Джавитт, округ Колумбия, Свит РА (сентябрь 2015 г.). «Слуховая дисфункция при шизофрении: интеграция клинических и основных особенностей» . Обзоры природы. Нейронаука . 16 (9): 535–550. дои : 10.1038/nrn4002 . ПМЦ 4692466 . ПМИД 26289573 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мегрея А.М. (2016). «Восприятие лица при шизофрении: специфический дефицит». Когнитивная нейропсихиатрия . 21 (1): 60–72. дои : 10.1080/13546805.2015.1133407 . ПМИД 26816133 . S2CID 26125559 .

- ^ Иэк С.М. (июль 2012 г.). «Когнитивная коррекция: новое поколение психосоциальных вмешательств для людей с шизофренией» . Социальная работа . 57 (3): 235–246. дои : 10.1093/sw/sws008 . ПМЦ 3683242 . ПМИД 23252315 .

- ^ Помарол-Клоте Э., О М., Лоус КР, Маккенна П.Дж. (февраль 2008 г.). «Семантический прайминг при шизофрении: систематический обзор и метаанализ» . Британский журнал психиатрии . 192 (2): 92–97. дои : 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032102 . hdl : 2299/2735 . ПМИД 18245021 .

- ^ Голдберг Т.Е., Киф Р.С., Голдман Р.С., Робинсон Д.Г., Харви П.Д. (апрель 2010 г.). «Обстоятельства, при которых практика не достигает совершенства: обзор литературы о практическом влиянии шизофрении и ее актуальность для исследований клинического лечения» . Нейропсихофармакология . 35 (5): 1053–1062. дои : 10.1038/нпп.2009.211 . ПМК 3055399 . ПМИД 20090669 .

- ^ Кинг DJ, Ходжкинс Дж., Шуинар П.А., Шуинар В.А., Сперандио I (июнь 2017 г.). «Обзор отклонений в восприятии зрительных иллюзий при шизофрении» . Психономический бюллетень и обзор . 24 (3): 734–751. дои : 10.3758/s13423-016-1168-5 . ПМЦ 5486866 . ПМИД 27730532 .

- ^ Колер К.Г., Уокер Дж.Б., Мартин Э.А., Хили К.М., Моберг П.Дж. (сентябрь 2010 г.). «Восприятие лицевых эмоций при шизофрении: метааналитический обзор» . Бюллетень шизофрении . 36 (5): 1009–1019. дои : 10.1093/schbul/sbn192 . ПМЦ 2930336 . ПМИД 19329561 .

- ^ Ле Галль Э., Якимова Г. (декабрь 2018 г.). «[Социальное познание при шизофрении и расстройствах аутистического спектра: точки соприкосновения и функциональные различия]». Л'Энсефаль . 44 (6): 523–537. дои : 10.1016/j.encep.2018.03.004 . ПМИД 30122298 . S2CID 150099236 .

- ^ Гриль-Спектор К., Вайнер К.С., Кей К., Гомес Дж. (сентябрь 2017 г.). «Функциональная нейроанатомия восприятия человеческого лица» . Ежегодный обзор Vision Science . 3 : 167–196. doi : 10.1146/annurev-vision-102016-061214 . ПМК 6345578 . ПМИД 28715955 .

- ^ Фунтулакис К.Н., Панагиотидис П., Кимискидис В., Ниматудис И., Гонда Х (февраль 2019 г.). «Неврологические мягкие признаки при семейной и спорадической шизофрении». Психиатрические исследования . 272 : 222–229. дои : 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.105 . ПМИД 30590276 . S2CID 56476015 .

- ^ Бургу Гаха С., Халайем Дуиб С., Амадо И., Боуден А. (июнь 2015 г.). «[Неврологические мягкие признаки шизофрении с ранним началом]». Л'Энцефале . 41 (3): 209–214. дои : 10.1016/j.encep.2014.01.005 . ПМИД 24854724 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Да Фонсека Д., Фурнере П. (декабрь 2018 г.). «[Шизофрения с очень ранним началом]». Л'Энцефале . 44 (6С): С8–С11. дои : 10.1016/S0013-7006(19)30071-5 . ПМИД 30935493 . S2CID 150798223 .

- ^ Хэфнер Х (2019). «От начала и продромальной стадии до пожизненного течения шизофрении и ее симптомов: как пол, возраст и другие факторы риска влияют на заболеваемость и течение болезни» . Психиатрический журнал . 2019 : 9804836. doi : 10.1155/2019/9804836 . ПМК 6500669 . ПМИД 31139639 .

- ^ Коэн С.И., Фриман К., Гонейм Д., Венгассери А., Гезелайа Б., Рейнхардт М.М. (март 2018 г.). «Достижения в концептуализации и изучении шизофрении в дальнейшей жизни». Психиатрические клиники Северной Америки . 41 (1): 39–53. дои : 10.1016/j.psc.2017.10.004 . ПМИД 29412847 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Джордж М., Махешвари С., Чандран С., Манохар Дж.С., Сатьянараяна Рао Т.С. (октябрь 2017 г.). «Понимание продромального периода шизофрении» . Индийский журнал психиатрии . 59 (4): 505–509. doi : 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_464_17 (неактивен 31 января 2024 г.). ПМК 5806335 . ПМИД 29497198 .

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI неактивен по состоянию на январь 2024 г. ( ссылка ) - ^ Перейти обратно: а б Конрой С., Фрэнсис М., Халвершорн Л.А. (март 2018 г.). «Выявление и лечение продромальных фаз биполярного расстройства и шизофрении» . Современные варианты лечения в психиатрии . 5 (1): 113–128. дои : 10.1007/s40501-018-0138-0 . ПМК 6196741 . ПМИД 30364516 .

- ^ Лекардер Л., Менье-Кюссак С., Дольфюс С. (май 2013 г.). «[Когнитивный дефицит у пациентов с первым эпизодом психоза и людей с риском развития психоза: от диагностики к лечению]». Л'Энцефале . 39 (Приложение 1): С64-71. дои : 10.1016/j.encep.2012.10.011 . ПМИД 23528322 .

- ^ Маллин А.П., Гохале А., Морено-Де-Лука А., Саньял С., Уоддингтон Дж.Л., Фаундес В. (декабрь 2013 г.). «Нарушения развития нервной системы: механизмы и определения границ геномов, интерактомов и протеомов» . Трансляционная психиатрия . 3 (12): е329. дои : 10.1038/tp.2013.108 . ПМК 4030327 . ПМИД 24301647 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Дэвис Дж., Эйр Х., Джека Ф.Н., Додд С., Дин О., МакИвен С. и др. (июнь 2016 г.). «Обзор уязвимости и рисков шизофрении: за пределами гипотезы двух поражений» . Неврологические и биоповеденческие обзоры . 65 : 185–194. doi : 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.017 . ПМЦ 4876729 . ПМИД 27073049 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Перкович М.Н., Эрьявец Г.Н., Страч Д.С., Узун С., Кожумплик О., Пивач Н. (март 2017 г.). «Тераностические биомаркеры шизофрении» . Международный журнал молекулярных наук . 18 (4): 733. doi : 10.3390/ijms18040733 . ПМЦ 5412319 . ПМИД 28358316 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сувисаари Дж (2010). «[Факторы риска шизофрении]». Дуодецим; Laaketieteellien Aikauskirja (на финском языке). 126 (8): 869–876. ПМИД 20597333 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Комбс Д.Р., Мюзер К.Т., Гутьеррес М.М. (2011). «Глава 8: Шизофрения: Этиологические соображения» . В Hersen M, Beidel DC (ред.). Психопатология и диагностика взрослых (6-е изд.). Джон Уайли и сыновья. ISBN 978-1-118-13884-7 .

- ^ О'Донован MC, Уильямс, Н.М., Оуэн М.Дж. (октябрь 2003 г.). «Последние достижения в генетике шизофрении» . Молекулярная генетика человека . 12 Спецификация № 2: R125–133. дои : 10.1093/hmg/ddg302 . ПМИД 12952866 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Торри Э.Ф., Йолкен Р.Х. (август 2019 г.). «Шизофрения как псевдогенетическое заболевание: необходимость дополнительных исследований генов и окружающей среды». Психиатрические исследования . 278 : 146–150. doi : 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.006 . ПМИД 31200193 . S2CID 173991937 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Пиккиони М.М., Мюррей Р.М. (июль 2007 г.). "Шизофрения" . БМЖ . 335 (7610): 91–95. дои : 10.1136/bmj.39227.616447.BE . ЧВК 1914490 . ПМИД 17626963 .

- ^ Фаррелл М.С., Вердж Т., Склар П., Оуэн М.Дж., Офофф Р.А., О'Донован М.К. и др. (май 2015 г.). «Оценка исторических генов-кандидатов шизофрении» . Молекулярная психиатрия . 20 (5): 555–562. дои : 10.1038/mp.2015.16 . ПМЦ 4414705 . ПМИД 25754081 .

- ^ Шульц СК, Грин МФ, Нельсон К.Дж. (2016). Шизофрения и расстройства психотического спектра . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 124–125. ISBN 9780199378067 .

- ^ Шорк А.Дж., Ван Й., Томпсон В.К., Дейл А.М., Андреассен О.А. (февраль 2016 г.). «Новые статистические подходы используют полигенную архитектуру шизофрении — последствия для лежащей в ее основе нейробиологии» . Современное мнение в нейробиологии . 36 : 89–98. дои : 10.1016/j.conb.2015.10.008 . ПМК 5380793 . ПМИД 26555806 .

- ^ Коэлей Л., Кертис Д. (2018). «Мини-обзор: Последние новости о генетике шизофрении» . Анналы генетики человека . 82 (5): 239–243. дои : 10.1111/ahg.12259 . ISSN 0003-4800 . ПМИД 29923609 . S2CID 49311660 .

- ^ Кендлер КС (март 2016 г.). «Показатель полигенного риска шизофрении: к чему он предрасполагает в подростковом возрасте?». JAMA Психиатрия . 73 (3): 193–194. дои : 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2964 . ПМИД 26817666 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Лоутер С., Костейн Дж., Барибо Д.А., Бассетт А.С. (сентябрь 2017 г.). «Геномные расстройства в психиатрии - что нужно знать клиницисту?». Текущие отчеты психиатрии . 19 (11): 82. дои : 10.1007/s11920-017-0831-5 . ПМИД 28929285 . S2CID 4776174 .

- ^ Банди Х., Шталь Д., Маккейб Дж.Х. (февраль 2011 г.). «Систематический обзор и метаанализ фертильности пациентов с шизофренией и их незатронутых родственников: фертильность при шизофрении». Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica . 123 (2): 98–106. дои : 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01623.x . ПМИД 20958271 . S2CID 45179016 .