Аборт в Соединенном Королевстве

| Эта статья является частью серии, посвященной |

| Политика Соединенного Королевства |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| British law |

|---|

|

Аборт в Соединенном Королевстве де -факто доступен в соответствии с положениями Закона об абортах 1967 года в Великобритании и Положений об абортах (Северная Ирландия) (№ 2) 2020 года в Северной Ирландии . Производство аборта остается в Великобритании уголовным преступлением в соответствии с Законом о преступлениях против личности 1861 года , хотя Закон об абортах в некоторых случаях обеспечивает правовую защиту как беременной женщины, так и ее врача. Хотя до принятия Закона 1967 года действительно делалось некоторое количество абортов, в Соединенном Королевстве было сделано около 10 миллионов абортов. [1] делается около 200 000 абортов в Англии и Уэльсе Ежегодно и чуть менее 14 000 в Шотландии ; Наиболее распространенной причиной около 98% всех абортов, указанной в системе классификации МКБ-10, является «риск для психического здоровья женщины». [2]

В Соединенном Королевстве аборты разрешены на следующих основаниях:

- риск для жизни беременной женщины;

- предотвращение серьезного необратимого вреда ее физическому или психическому здоровью;

- риск причинения вреда физическому или психическому здоровью беременной женщины или существующих детей ее семьи (до срока беременности в 24 недели ); или

- substantial risk that, if the child were born, they would "suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped".[4]

The third ground is typically interpreted liberally with regards to mental health to create a de facto elective abortion service; 98% of the approximately quarter-million abortions performed in Great Britain are done so for that reason.[2][5]

In Northern Ireland, abortion is also permitted within the first 12 weeks of a pregnancy for any reason.[6]

Under the UK's devolution settlements, abortion policy is devolved to the Scottish Parliament and the Northern Ireland Assembly but not to the Welsh Parliament (Senedd). Abortion was previously highly restricted in Northern Ireland although it was permitted in limited cases. In 2019, during a time when the Assembly was not operating, the UK Parliament repealed most restrictions on abortion in Northern Ireland; the current Regulations were subsequently introduced by Parliament in 2020.[6][7][8][9]

Abortions which are carried out for grounds outside those permitted in law (e.g. in most cases after the 24-week term limit, or where appropriate consent has not been given) continue to be unlawful in each jurisdiction of the UK – under the Offences against the Person Act 1861 in England and Wales, Scottish common law, and the Northern Ireland Regulations. The Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 and the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1945 also outlaw child destruction in cases outside the grounds permitted in abortion law. Proposals to fully decriminalise abortion in Great Britain have occurred in 2024.[10]

History

[edit]Debates and practices relating to abortion, pregnancy and the beginning of human life are recorded in Roman medical literature which would have been become available in Britain from the 1st century AD onwards. The medical writer Soranus of Ephesus, for example, wrote in the early 2nd century:[11]

A contraceptive differs from an abortive, for the first does not let conception take place, while the latter destroys what has been conceived ... But a controversy has arisen. For one party banishes abortives, citing the testimony of Hippocrates who says: "I will give to no one an abortive"; moreover, because it is the specific task of medicine to guard and preserve what has been engendered by nature. The other party prescribes abortives, but with discrimination ... only to prevent subsequent danger in parturition [childbirth].

Similar issues would also have been discussed in Celtic culture, although written Celtic texts were only available from around the 4th century. An early Christian understanding of preventing abortion and infanticide, as outlined in the 1st century Didache[12] and similar writings, would have been known in the early British Church which experienced more freedom and influence following Constantine's Edict of Milan in 313 AD, and also in the early Irish Church after it was founded by Patrick around 432 AD.

Alongside this cultural change in Roman society, a more significant sense of value was associated with the life (and death) of infant and neo-natal children. Several studies of the burials of children who died before or close to the time of birth in Roman Britain have been made,[13][14] and the presence of neo-natal burials given the same burial rites as adults is "a pointer to identification of the cemetery as Christian" as such burials were rare before the 4th century.[15]Care for abandoned or unwanted children, such as kinship care within families and friendship circles, and the adoption and fostering of alumni, were also well-established in Roman society. In the early Middle Ages, in Britain and other regions of Northern Europe, parents who did not want to raise their children often gave them to monasteries along with a small fee – an practice known as oblation.[16]

Abortion was mainly dealt with by the ecclesiastical courts until their abolition during the Reformation. These cases were generally assigned to the ecclesiastical courts due to problems of evidence; the courts had wider evidential rules and more discretion regarding sentencing.[17] A number of cases such as the Twinslayers Case, in England in 1327, were heard in the secular courts as part of the common law. Later, under Scottish common law, abortion was defined as a criminal offence unless performed for "reputable medical reasons", a definition which could be interpreted as sufficiently broad as to essentially preclude prosecution.[18]

Early statute and modern case law

[edit]The legality of abortion, and the value of the lives of pregnant women and unborn children, in common law was discussed by several English jurists from the Middle Ages onwards, including Henry Bracton, William Stanford, Edward Coke and William Blackstone. For example, Blackstone wrote in his 1765 Commentaries on the Laws of England:

Life ... begins in contemplation of law as soon as an infant is able to stir in the mother's womb. For if a woman is quick with child, and by a potion, or otherwise, killeth it in her womb; or if any one beat her, whereby the child dieth in her body, and she is delivered of a dead child; this, though not murder, was by the ancient law homicide or manslaughter. But at present it is not looked upon in quite so atrocious a light, though it remains a very heinous misdemeanor.[19]

Shortly after his appointment as Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Edward Law, 1st Baron Ellenborough, codified abortion as an offence in statute law, in England and Wales and Ireland, through the Malicious Shooting or Stabbing Act 1803, which became known as Lord Ellenborough's Act. This legislation and the subsequent acts in the 19th century did not apply to Scotland due to its separate legal system based on common law.

The 1803 Act introduced capital punishment for wilfully, maliciously, and unlawfully administering "any deadly poison, or other noxious and destructive substance or thing, with intent … to cause and procure the miscarriage of any woman, then being quick with child" (section 1) and penalties, at the discretion of the court, up to and including penal transportation for using means to "cause the miscarriage of any woman not being, or not being proved to be, quick with child" (section 2).[20]

The offences created by the 1803 Act were consolidated in the first Offences Against the Person Act, introduced by Robert Peel and enacted for England in 1828, which outlined the same offences and punishments (section 13).[21] The same consolidation took place in Irish law through the Offences Against the Person (Ireland) 1829 (section 16). Both Acts were replaced by the Offences Against the Person Act 1837 which created a single abortion offence without a distinction around a pregnant woman being quick with child or not, and also repealed the death penalty for causing an abortion.

The law was again consolidated through the Offences against the Person Act 1861, which continues to be the main legislation for prosecuting personal injury in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The Act created two offences – administering drugs or using instruments to procure abortion (section 58), which replaced the previous legislation from 1839 and allowed for a sentence of life imprisonment; and procuring drugs, or any other means, to cause abortion (section 59) with a potential sentence of three years’ imprisonment. The content of the 1861 Act was applied in colonial legislation throughout the British Empire in subsequent years e.g. the Offences Against the Person Act 1866 in New Zealand.[22]

Alongside legislation against abortion, philanthropy encouraged more formal and organised arrangements to care for children born from unwanted pregnancies through the initiatives of social reformers; examples included the orphanage movement (which included the Foundling Hospital, London, in 1739); the pioneering of foster care in Cheshire in 1853 by John Armistead; and the Adoption of Children Act 1926, for England and Wales.[23]

In the late 19th century and early 20th centuries, abortifacents were discreetly advertised for women with unwanted pregnancies who were seeking abortions; there was also a considerable body of folklore about inducing miscarriages. So-called 'backstreet' abortionists using methods such as these were relatively common although their efforts could be fatal. Estimates of the number of illegal abortions varied widely; by one estimate, 100,000 women made efforts to procure an abortion in 1914, usually by drugs.[24]

The criminality of abortion in England and Wales was reaffirmed in 1929, when the Infant Life (Preservation) Act was passed; the Act criminalised the deliberate destruction of a child "capable of being born alive". This was to close a lacuna in the law, identified by the former High Court judge Charles Darling, 1st Baron Darling, which allowed for infants to be killed during birth, thus meaning that the perpetrator could neither be prosecuted for abortion or murder.[25] The Act included the presumption that all children in utero over 28 weeks of gestation were capable of being born alive. Where the life of child in utero was ended before this gestation, evidence was presented and considered to determine whether or not the child was capable of being born alive.

The Abortion Law Reform Association, a pro-choice lobbying group, was formed in 1936.

In 1938, the decision in R v. Bourne[26] allowed for further considerations to be taken into account. This case related to an abortion performed on a girl who had been raped, and extended the defence to abortion to include "mental and physical wreck" (Lord Justice McNaghtan). The gynaecologist concerned, Aleck Bourne, later became a founder member of the anti-abortion group, the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children (SPUC)[27] in 1966.

In 1939, the Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion, established by the Home Office and Ministry of Health, recommended a change to abortion laws but the intervention of World War II meant that all plans were shelved. Post-war, after decades of stasis, certain high-profile tragedies, including disability in unborn children caused by the thalidomide drug, and social changes brought the issue of abortion back into the political arena.

Westminster's responsibility for criminal justice and health policy, including around abortion, on the island of Ireland was transferred to the Northern Ireland Parliament (on its formation in 1921) and the Parliament of the Irish Free State (formed in December 1922). Both legislatures took an essentially conservative position, viewing abortion as an offence against the person, or an offence of child destruction, in line with existing legislation in England and Wales.

The 1967 Act

[edit]The Abortion Act 1967 sought to clarify the law in Britain. Introduced by David Steel and subject to heated debate, it allowed for legal abortion on a number of grounds, with the added protection of free provision through the National Health Service. The Act was passed on 27 October 1967 and came into effect on 27 April 1968.[28]

Before the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 amended the Act, the Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 acted as a buffer to the Abortion Act 1967. This meant that abortions could not be carried out if the child was "capable of being born alive". There was therefore no statutory limit put into the Abortion Act 1967, the limit being that which the courts decided as the time at which a child could be born alive. The C v S case in 1987 confirmed that, at that time, between 19 and 22 weeks a foetus was not capable of being born alive.[29] The 1967 Act required that the procedure must be certified by two doctors before being performed.

Proposals since 1967: Great Britain

[edit]During each Parliament, several private member's bills are generally introduced to seek to amend the law in relation to abortion.[30] In the years following a supportive report in favour of the 1967 Act by the Lane Committee in 1974, Members of Parliament introduced four bills which have resulted in substantive debate in the House of Commons (votes are indicated in brackets with ayes followed by noes):

- Abortion (Amendment) Bill 1975 - referred to a select committee (260-125);[31]

- Abortion (Amendment) Bill 1976 - referred to select committee (313-172);[32]

- Abortion (Amendment) Bill 1979 - approved at second stage (242-98) but not enacted;[33]

- Abortion (Amendment) Bill 1988 - approved at second stage (296-251) but not enacted;[34]

In addition, in 1990, members voted on several proposed amendments to clause 34 of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill relating to the termination of pregnancy.[35]The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990, as enacted, lowered the term limit from 28 to 24 weeks for abortion in cases of 'mental or physical injury' on the ground that medical technology had advanced sufficiently (since 1967) to justify the change but removed restrictions for late abortions in cases of risk to life, grave physical and mental injury to the woman, and the disability in the unborn child (by separating the legal effect of the Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 from the Abortion Act 1967).

When a further Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill (now enacted) was considered by Parliament in 2008, several votes were held on the term limit in Britain, as follows:

- reduction from 24 weeks to 12 weeks (71 ayes, 393 noes);[36]

- reduction from 24 weeks to 16 weeks (84 ayes, 386 noes);[37]

- reduction from 24 weeks to 20 weeks (190 ayes, 331 noes);[38] and

- reduction from 24 weeks to 22 weeks (233 ayes, 304 noes).[39]

Pro-choice groups strongly opposed any attempts to restrict abortion in the 2008 parliamentary debates and votes.[40][41][42] A number of pro-choice amendments were proposed by the Labour MPs Diane Abbott, Katy Clark and John McDonnell, including NC30 Amendment of the Abortion Act 1967: Application to Northern Ireland.[43][44][45] However, it was reported that the Labour government at the time asked MPs not to table these amendments (at least until third reading) and then used parliamentary mechanisms in order to prevent a vote; the government was, at the time, seeking to devolve policing and justice powers to the Northern Ireland Assembly (which had previously voted to oppose the extension of the 1967 Act).[46]

In 2017, the Reproductive Health (Access to Terminations) Bill was introduced by Labour Diana Johnson MP with the aim of repealing criminal law on abortion in England and Wales.[47] However, with the call for a general election, the bill fell and no further action was taken.[48]

Minor amendments to the Abortion Act 1967 have been introduced through government legislation, the most recent being the allowance of abortion consultations through telemedicine in the Health and Care Act 2022.[49]

Proposals since 1967: Northern Ireland

[edit]Health, social care and criminal justice policy was devolved to the Northern Ireland Parliament at the time of the Abortion Act 1967's passage at Westminster and the Parliament did not introduce abortion legislation before its suspension in 1972. Statute law was maintained unchanged under Conservative and Labour direct rule administrations and the first Northern Ireland Assembly in 1973-1974 although the law was interpreted through case law in local courts (during the 1990s) to also allow for the grounds of "a risk of real and serious adverse effect on ... [the] physical or mental health [of the woman] is either long term or permanent". From 1983 onwards, the Constitution of Ireland, covering the Republic with a territorial claim on Northern Ireland until 1998, acknowledged "the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother" and "guaranteed in its laws to respect, and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right."[50]

The new Northern Ireland Assembly, formed in 1998 following the Good Friday Agreement, voted in June 2000 to oppose the extension of the Abortion Act 1967 to Northern Ireland; the motion was proposed by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and supported by the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) which was, at the time, opposed to abortion but also emphasised an understanding of the social, economic and personal circumstances that gave rise to women choosing the option of an abortion.[51] While health policy had been devolved again to Northern Ireland in December 1999, on the formation of the first Northern Ireland Executive, criminal law (including in relation to abortion) continued to be reserved to Parliament at Westminster until the devolution of policing and justice powers in May 2010.[52]

Political debate around abortion issues was renewed following the opening of a private abortion clinic in Belfast in 2012, the Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act 2013 in the Republic, and the widespread discussion of a case of fatal foetal abnormality; several debates took place in the Northern Ireland Assembly and its members, in line with party policy and/or personal conscience, decided not to proceed with changes in the law.[53][54][55] An amendment by DUP MLA Jim Wells to "restrict lawful abortions to NHS premises, except in cases of urgency when access to NHS premises is not possible and where no fee is paid" was unsuccessful.[56][57] Later, as Health Minister, Jim Wells opposed abortion in cases of rape as the unborn child would be "punished for what has happened by having their life terminated" although he acknowledged that this would be "a tragic and difficult situation".[58]

Justice Minister David Ford (a member of the Alliance Party) issued a public consultation on amending the criminal law on abortion, which opened in October 2014 and closed in January 2015.[59] However, Ford also wrote that "it is not a debate on the wider issues of abortion law – issues often labelled as 'pro-choice' and 'pro-life'".[59] The Sinn Féin deputy First Minister, Martin McGuinness, had initially stated his party's opposition to abortion and noted that the party had "resisted any attempt to bring the British 1967 Abortion Act to the North."[53] At its 2015 annual conference, Sinn Féin adopted a policy of allowing abortion under certain circumstances such as fatal foetal abnormality; this was superseded by a newer and more liberal policy adopted at its 2018 conference.[60]

In February 2016, during debates on the Justice (No.2) Bill, the Assembly considered and debated an amendment to allow for abortion in cases of pregnancies caused by sexual crime (which was rejected by 64 notes to 32 ayes), and an amendment to allow for abortion in cases of fatal foetal abnormality (which was rejected by 59 noes to 40 ayes) . Sinn Féin and the Green Party voted in favour of both proposals whereas the DUP and the SDLP supported the existing law and members of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and Alliance Party voted on conscience.[61] The Abortion (Fatal Foetal Abnormality) Bill was introduced by David Ford, as a backbench MLA, in December 2016 but fell on the suspension of the Assembly in January 2017.[62]

In the 2017 UK general election, the Labour Party manifesto under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn MP stated: "Labour will continue to ensure a woman’s right to choose a safe, legal abortion – and we will work with the Assembly to extend that right to women in Northern Ireland."[63] The election resulted in a confidence and supply agreement between the Conservative Party and the (DUP). The Conservative Government, in June 2017, made a commitment to provide free abortion services in England for women from Northern Ireland due to pressure from Conservative MPs.[64] The Labour Party commitment was, in effect, delivered through private member's amendments enacted in the Northern Ireland Executive (Formation) Act 2019, which repealed the Offences against the Person Act 1861 (sections 58 and 59) in October 2019. The political context was also changed by legal challenges, the repeal of the Eighth Amendment in the Republic in 2018 (supported by Sinn Féin), and the SDLP's decision to consider abortion as a matter of conscience.

Shortly after the introduction of the Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020, the newly restored Northern Ireland Assembly voted – with 46 members in favour and 40 against – to reject "the imposition of abortion legislation that extends to all non-fatal disabilities, including Down's syndrome."[65] Following this vote, the Severe Fetal Impairment Abortion (Amendment) Bill – to remove the grounds for abortion for non-fatal disabilities – was introduced by DUP MLA Paul Givan in February 2021. It reached its consideration stage in December 2021 but MLAs decided – by 45 votes to 43 – against the main proposal in the Bill at that stage.[66]

Great Britain

[edit]The main legislation on abortion in England, Scotland and Wales is the Abortion Act 1967, as amended by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990. In Great Britain, abortion is generally allowed for socio-economic reasons during the first 24 weeks of the pregnancy (a later term limit than most other countries in Europe), and after this point for medical reasons.

England and Wales

[edit]The Offences against the Person Act 1861, in England and Wales, prohibits administering drugs or using instruments to procure an abortion and procuring drugs or other items to cause an abortion[67] although subsequent law has provided for a range of grounds which allow abortion to be widely available.

The Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 amended the law in England and Wales to create the offence of child destruction – in cases where any person "who, with intent to destroy the life of a child capable of being born alive, by any wilful act causes a child to die before it has an existence independent of its mother". For the purposes of this Act, a child whose mother has been pregnant for 28 weeks is deemed "capable of being born alive". The 1929 Act also provides a defence where it is proved that causing the death of the child was "done in good faith for the purpose only of preserving the life of the mother."[68]

The Abortion Act 1967 originally permitted abortion "by a registered medical practitioner if two registered medical practitioners are of the opinion, formed in good faith" on the following grounds:

- a risk to the life of the pregnant woman, or of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman or any existing children of her family; or

- a substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be "seriously handicapped".[69]

The Act came into operation in 1968, and originally applied a term limit of 28 weeks, in line with the Infant Life Preservation Act. It was subsequently amended by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990, to allow for the following grounds:

- Ground A – risk to the life of the pregnant woman;

- Ground B – to prevent grave permanent injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman;

- Ground C – risk of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman (up to 24 weeks in the pregnancy);

- Ground D – risk of injury to the physical or mental health of any existing children of the family of the pregnant woman (up to 24 weeks in the pregnancy);

- Ground E – substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped;

- Ground F – to save the life of the pregnant woman; or

- Ground G – to prevent grave permanent injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman in an emergency.[70]

The amendment therefore allowed for a reduction in the term limit to 24 weeks for Ground C and Ground D with the law changing to reflect advances in technology to enable premature children to be born alive earlier in a pregnancy. However, no term limit was applied to other grounds and abortion was permitted throughout the pregnancy in these cases. The changes took effect in April 1991.[71]

Abortion law was not devolved to the National Assembly for Wales under Government of Wales Act 1998[72] and was specifically reserved to the UK Parliament via the Government of Wales Act 2006.[73]

Scotland

[edit]Abortion became an offence in Scotland with the passing of the Abortion Act 1967 and refers to "any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion".[4] Prior to 1967, there was no offence of abortion in Scotland; however, if harm occurred consequent to an abortion, various offences could have applied with abortion forming part of the description of the elements forming the offence on the petition or indictment presented to a court.

The Scotland Act 1998, which established the Scottish Parliament, reserved abortion law to the UK Parliament[74] but it was subsequently devolved through the Scotland Act 2016.[75] The Abortion Act 1967 remains in place.

Interpretation

[edit]Section 58 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 reads as follows and prohibits administering drugs or using instruments to cause a miscarriage:

Every woman, being with child, who, with intent to procure her own miscarriage, shall unlawfully administer to herself any poison or other noxious thing, or shall unlawfully use any instrument or other means whatsoever with the like intent, and whosoever, with intent to procure the miscarriage of any woman whether she be or be not with child, shall unlawfully administer to her or cause to be taken by her any poison or other noxious thing, or unlawfully use any instrument or other means whatsoever with the like intent, shall be guilty of felony, and being convicted thereof shall be liable ... to be kept in penal servitude for life ...[67]

Section 59 of that Act reads as follows and prohibits the procurement of drugs or other items to cause a miscarriage:

Whosoever shall unlawfully supply or procure any poison or other noxious thing, or any instrument or thing whatsoever, knowing that the same is intended to be unlawfully used or employed with intent to procure the miscarriage of any woman, whether she be or be not with child, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and being convicted thereof shall be liable ... to be kept in penal servitude ...[67]

The following terms in the 1861 Act may be interpreted as follows:

- Unlawfully – for the purposes of sections 58 and 59 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861, and any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion, anything done with intent to procure a woman's miscarriage (or in the case of a woman carrying more than one foetus, her miscarriage of any foetus) is unlawfully done unless authorised by section 1 of the Abortion Act 1967 and, in the case of a woman carrying more than one foetus, anything done with intent to procure her miscarriage of any foetus is authorised by the said section 1 if the ground for termination of the pregnancy specified in subsection (1)(d) of the said section 1 applies in relation to any foetus and the thing is done for the purpose of procuring the miscarriage of that foetus, or any of the other ground for termination of the pregnancy specified in the said section 1 applies;[76]

- Felony and misdemeanour – see the Criminal Law Act 1967;

- Mode of trial – the offences under section 58 and 59 are indictable-only offences;

- Sentence – an offence under section 58 is punishable with imprisonment for life or for any shorter term[77] and an offence under section 59 is punishable with imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years.[78]

A death of a person in being which is caused by an unlawful attempt to procure an abortion, is at least manslaughter.[79][80]

The following terms in the 1967 Act may be interpreted as follows:

- The law relating to abortion – in England and Wales, this means sections 58 and 59 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 and any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion.[81] and in Scotland, this means any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion;[81]

- Terminated by a registered medical practitioner includes a procedure supervised by a medical practitioner – see Royal College of Nursing of the UK v DHSS [1981] AC 800, [1981] 2 WLR 279, [1981] 1 All ER 545, [1981] Crim LR 322, HL;

- Place where termination must be carried out – see sections 1(3) to (4);

- The opinion of two registered medical practitioners – see section 1(4);

- Good faith – see R v Smith (John Anthony James), 58 Cr App R 106, CA;

- Determining the risk of injury in ss. (a) & (b) – see section 1(2);

- Risk, greater than if the pregnancy were terminated, of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman – In R v British Broadcasting Corporation, ex parte ProLife Alliance, Lord Justice Laws said: "There is some evidence that many doctors maintain that the continuance of a pregnancy is always more dangerous to the physical welfare of a woman than having an abortion, a state of affairs which is said to allow a situation of de facto abortion on demand to prevail."[82]

Northern Ireland

[edit]Statute law before 2019

[edit]Before significant changes in 2019, there were two main laws on abortion in Northern Ireland:

- the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 (sections 58 and 59) prohibited attempts to cause a miscarriage;[67]

- the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1945 (sections 25 and 26)[83] provided an exception for acting "in good faith for the purpose only of preserving the life of the mother" and also created the offence of child destruction i.e. to cause a child to die "before it has an existence independent of its mother".

Case law before 2019

[edit]Between 1993 and 1999, a series of court cases had interpreted the law as also allowing for abortion in cases where, for the pregnant woman, "there is a risk of real and serious adverse effect on her physical or mental health, which is either long term or permanent".[84][85][86]

In Northern Ireland Health and Social Services Board v A and Others [1994] NIJB 1, Lord Justice MacDermott said that he was "satisfied that the statutory phrase, 'for the purpose only of preserving the life of the mother' does not relate only to some life-threatening situation. Life in this context means that physical or mental health or well-being of the mother and the doctor's act is lawful where the continuance of the pregnancy would adversely affect the mental or physical health of the mother. The adverse effect must however be a real and serious one and there will always be a question of fact and degree whether the perceived effect of non-termination is sufficiently grave to warrant terminating the unborn child."

In Western Health and Social Services Board v CMB and the Official Solicitor (1995, unreported), Mr Justice Pringle stated that "the adverse effect must be permanent or long-term and cannot be short term ... in most cases the adverse effect would need to be a probable risk of non-termination but a possible risk might be sufficient if the imminent death of the mother was a risk in question".[87]

In Family Planning Association of Northern Ireland v Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety (October 2004), Lord Justice Nicholson stated that "it is unlawful to procure a miscarriage where the foetus is abnormal but viable, unless there is a risk that the mother may die or is likely to suffer long-term harm, which is serious, to her physical or mental health".[88] In the same case, Lord Justice Sheil stated that "termination of a pregnancy based solely on abnormality of the foetus is unlawful and cannot lawfully be carried out in this jurisdiction".[89]

In November 2015, Lord Justice Horner made a declaration of incompatibility under the Human Rights Act 1998 to the effect that Northern Ireland's law on abortion (specifically its lack of provision in cases of fatal foetal abnormality or where the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest) could not be interpreted in a manner consistent with Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights i.e. a right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence; the convention also protects a right to life in Article 2.[90] In June 2017, the declaration of incompatibility was quashed by the Court of Appeal on the grounds that "a broad margin of appreciation must be accorded to the state" and "a fair balance has been struck by the law as it presently stands until the legislature decides otherwise".[91][92] In June 2018, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom held that the law of Northern Ireland was incompatible with the right to respect for private and family life, insofar as the law prohibited abortion in cases of rape, incest and fatal foetal abnormality. However, the court did not restore the declaration of incompatibility as it also held that the claimant did not have standing to bring the proceedings and accordingly the court had no jurisdiction to make a declaration of incompatibility reflect its view on the compatibility issues.[93][94] The judgments of the Supreme Court acknowledged that the court lacked jurisdiction to issue a declaration of incompatibility but included a non-binding opinion that an incompatibility existed, and that a future case in which the applicant had the necessary standing would be likely to succeed. It also urged the authorities "responsible for ensuring the compatibility of Northern Ireland law with the Convention rights" to "recognise and take account of these conclusions ... by considering whether and how to amend the law".[95][96]

Changes in law: 2019–2020

[edit]The law on abortion in Northern Ireland was changed by Parliament during a suspension of the Northern Ireland Executive, which took place between 2017 and 2020. Recommendations to liberalise abortion law in Northern Ireland were published in February 2018 by the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in the report of its Inquiry concerning the United Kingdom (under Article 8 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women).[97]

The Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019, enacted on 24 July 2019, extended the deadline for the restoration of the Executive to 21 October 2019. Under a private member's amendment introduced by Stella Creasy MP, if an Executive were not restored by that date, the Act would:

- require the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland to implement recommendations regarding abortion made in the CEDAW report;

- repeal sections 58 and 59 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 under the law of Northern Ireland; and

- require the Secretary of State, by regulation, to make further changes in the law for complying with the recommendations with those regulations coming into force on 31 March 2020.[98]

On 21 October 2019, as a result of the Executive not being restored, sections 58 and 59 of the 1861 Act were repealed.[99] Legal protection for the life of a child who was "capable of being born alive" continued under the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1945.

The Executive was restored in January 2020 but legislation on abortion continued to be implemented through Westminster. The Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020 were laid before Parliament on 25 March 2020 and took effect on 31 March 2020.[100][101] The Regulations allowed for abortion in Northern Ireland in the following circumstances:

- where the pregnancy has not exceeded its twelfth week;

- a risk of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman (up to a term limit of 24 weeks);

- a risk to life or risk of grave permanent injury to physical or mental health of the pregnant woman;

- a severe fetal impairment – "a substantial risk that if the child were born, it would suffer from such physical or mental impairment as to be seriously disabled" (with no term limit); or

- a fatal fetal abnormality – "a substantial risk that the death of the fetus is likely before, during or shortly after birth" (with no term limit).[102]

A person who intentionally terminates or procures the termination of a pregnancy other than in accordance with the Regulations commits an offence; this does not apply to a pregnant woman or where the act which caused the termination was done in good faith for the purpose only of saving the woman's life or preventing grave permanent injury. The 1945 Act remains in law, including the offence of child destruction, although this no longer applies to a pregnant woman, or a registered medical professional acting in accordance with the Regulations.[102]

The Regulations were replaced by the Abortion (Northern Ireland) (No. 2) Regulations 2020, which were materially the same with minor corrections and came into force on 14 May 2020.[6] In May 2022, just over two years after the change in the law, it was reported that abortion clinics and treatments available in Northern Ireland were limited and women seeking to have abortions continued to travel to Great Britain (mainly England).[103][104] By 2024, abortion services were now available in all five hospital trusts in Northern Ireland, enabling the majority of demand to be met locally. [105]

Political party approaches

[edit]Abortion, as with other sensitive issues, is regarded as a matter of conscience within the main political parties in Great Britain. Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat and Scottish National Party representatives, for example, considered and individually decided to vote for or against several proposed changes in the term limit in 2008.[106]

Minor British political parties which oppose abortion include the Heritage Party, Britain First and the Scottish Family Party.[107][108][109]

In Northern Ireland, for the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), and the Alliance Party, abortion is also a matter of conscience, in line with the approach at Westminster. The SDLP previously advocated an anti-abortion formal party position, including opposition to the extension of the Abortion Act 1967 to Northern Ireland;[110] this was changed by the party's membership to a conscience approach in May 2018.[111]

The Democratic Unionist Party and Traditional Unionist Voice supported the pre-2019 law on abortion and opposed the legislative changes introduced in 2020 through the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation) Act.[112][113] DUP MLA Paul Givan introduced the Severe Fetal Impairment Abortion (Amendment) Bill in February 2021, which sought to remove the ground for an abortion in cases of a severe disability in the unborn child (e.g. Down's Syndrome), which was supported by several representatives from other political parties on grounds of conscience.

Sinn Féin policy, as approved by its annual conference in June 2018, is for abortion to be available "where a woman's life, [physical] health or mental health is at risk and in cases of fatal foetal abnormality" and "without specific indication ... through a GP led service in a clinical context as determined by law and licensing practice for a limited gestational period".[114] The party previously held a more conservative position, for example in 2007 opposing the extension of the 1967 Act and preferring an approach to crisis pregnancy which involved comprehensive sex education, full access to affordable childcare, and comprehensive support services including include financial support for single parents.[115]

Following the policy decisions in 2018 by Sinn Féin and the SDLP, a new political party - Aontú - was formed with a policy of opposing abortion and upholding "the right to life of everyone irrespective of age, gender, race, creed, abilities or stage of development." Aontú has advocated for a "humane and compassionate response" to unwanted pregnancies, including economic support to take mothers out of poverty, pain relief being provided for the unborn child after 20 weeks of gestation, medical care for children who are born after an abortion procedure, and a legislative ban on abortion in cases of disability and gender selection.[116]

The Green Party in Northern Ireland and People Before Profit support the full decriminalisation of abortion (i.e. that it should be made available for any reason).[117][118]

Faith perspectives

[edit]Christian Churches and their members support women in crisis pregnancies and/or who have experienced a miscarriage or abortion through practical support and advice and counselling services, either through personal initiative, pastoral ministries, or through specific anti-abortion charities. As in other countries, there is a wide range of personal individual views on abortion within church denominations.

Roman Catholic

[edit]The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that human life "must be respected and protected absolutely from the moment of conception" and that from the first moment of existence, "a human being must be recognized as having the rights of a person – among which is the inviolable right of every innocent being to life." The Church has affirmed "the moral evil of every procured abortion" since the 1st Century AD and describes direct abortion "willed either as an end or a means" as gravely contrary to the moral law.[119] Pope John Paul II reaffirmed the Catechism in his papal encyclical Evangelium vitae (The Gospel of Life) in 1995, which taught on "bringing about a transformation of culture" in relation to abortion and the value of human life, including extensive care and support for pregnant women, their children and their families.[120]

During his pastoral visit to Great Britain in 1982, John Paul II remarked: "I support with all my heart those who recognize and defend the law of God which governs human life. We must never forget that every person, from the moment of conception to the last breath, is a unique child of God and has a right to life. This right should be defended by the attentive care of the medical and nursing professions and by the protection of the law."[121] Pope Benedict XVI, on his state visit to the United Kingdom in 2010, stated: "Life is a unique gift, at every stage from conception until natural death, and it is God’s alone to give and to take."[122]

Anglican

[edit]The Church of England combines strong opposition to abortion with a recognition that there can be "strictly limited" conditions under which it may be morally preferable to any available alternative. This is based on its view that the foetus is a human life with the potential to develop relationships, think, pray, choose and love. The Church has suggested that the case for further reductions of the time limit for abortions should be "sympathetically considered on the basis of advances in neo-natal care" and has stated that every possible support, especially by church members, needs to be given to those who are pregnant in difficult circumstances.[123]

Writing on the 40th anniversary of the 1967 Act, in 2007, the then Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams commented that most parliamentarians who voted for the Act "did so in the clear belief that they were making provision for extreme and tragic situations" but that its implementation since then demonstrated unintended consequences. The strengthening of the language of 'foetal rights' (i.e. that "the pregnant woman who smokes or drinks heavily is widely regarded as guilty of infringing the rights of her unborn child") could be contrasted with "the liberty of the pregnant woman herself to perform the actions that will terminate a pregnancy."[124]

The Church of Ireland – a province of the Anglican Communion alongside the Church of England – affirms that "every human being is created with intrinsic dignity in the image of God with the right to life." It has opposed the "extreme abortion legislation" imposed on Northern Ireland, asked that legislation is developed that safeguards the well-being of both the mother and unborn child, and encouraged its members to provide more support to mothers during pregnancy, particularly during times of crisis.[125] In relation to potential grounds for abortion, the Church recognises that there are "exceptional circumstances of strict and undeniable medical necessity where an abortion should be an option (or more rarely a necessity)."[126]

Presbyterian

[edit]The General Assembly of the (Presbyterian) Church of Scotland regards the foetus as "from the beginning, an independent human being" and therefore it can be threatened "only in the case of threat to maternal life, and that after the exhaustion of all alternatives".[127]

The Presbyterian Church in Ireland, the largest Protestant denomination in Northern Ireland, is strongly anti-abortion, and maintains that abortion should only be permitted in exceptional circumstances (e.g. where there is a real and substantial risk to the life of the mother) subject to the most stringent safeguards. The Church has affirmed the sanctity of human life, that human life begins at conception, and that complex medical and social issues such as abortion need to be handled with sensitivity and compassion.[128]

Methodist

[edit]The Conference of the Methodist Church of Great Britain stated in 1976 that the human foetus had "an inviolable right to life" and that abortion should never be seen as an alternative to contraception. The Church also recognised that foetus is "totally dependent" on his or her mother for at least the first twenty weeks of its life and said that the mother has "a total right to decide whether or not to continue the pregnancy." The Church has supported counselling opportunities for mothers so that they fully understand the decision, and the alternatives to abortion.[129]

Its sister church, the Methodist Church in Ireland, is opposed to what it describes as "abortion on demand" and urges support and resources for those who have a crisis pregnancy. The Church recognises that there are complex situations "in which early termination of pregnancy should be available" and considers that these include "when a mother's life is at risk, when a pregnancy is the result of a sexual crime, or in cases of fatal foetal abnormality."[130]

Others

[edit]The smaller Protestant churches are generally conservative on the issue of abortion.[131][132]

Congregations and members of major non-Christian religions in the UK likewise provide pastoral support for women, families and children whose circumstances are affected by crisis pregnancies and abortion, in a range of ways. Views on the morality and potential grounds for abortion vary within Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Judaism.

Campaign groups

[edit]Prominent campaign groups which are supportive of a conservative policy include Both Lives Matter, Christian Action Research and Education (CARE), Evangelical Alliance, Life, Society for the Protection of Unborn Children (SPUC) and the UK Life League. Campaigning organisations in support of a liberal policy include Amnesty International, the British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS), the Family Planning Association (FPA), Marie Stopes, MSI Reproductive Choices, and Humanists UK.

Abortion policy in Northern Ireland was the subject of intense discussion and campaigning in the decade leading up to changes in the law in 2019 and 2020. The issue is debated less frequently in Great Britain, where the law was last substantially changed in 1990.

Crown dependencies

[edit]Although Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man are not part of the United Kingdom, as they are part of the Common Travel Area, people resident on these islands who choose to have an abortion have travelled to the UK since the Abortion Act 1967.[133]

Jersey

[edit]It is lawful in Jersey to have an abortion in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy if the woman is in "distress" and requests it;[134][135] in the first 24 weeks in case of foetal abnormalities; and at any time to save the woman's life or prevent serious permanent injury to her health. The criteria were established in the Termination of Pregnancy (Jersey) Law 1997.[136]

Guernsey

[edit]The law of Guernsey allows abortion under the same grounds as in Great Britain: at any time to save the woman's life, prevent grave permanent injury to her health, or in case of significant foetal impairment; and in the first 24 weeks of gestation in case of "risk, greater than if the pregnancy were terminated, of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman or any existing children of her family".[137] As in Great Britain, the latter ground is considered to allow de facto elective abortion.

The conditions are specified in the Abortion (Guernsey) Law, 1997. As originally enacted, the law set a gestational limit of 24 weeks in case of foetal impairment and 12 weeks for risk to health greater than terminating the pregnancy, required the approval of two medical practitioners, and required that the abortion take place at Princess Elizabeth Hospital.[138] The law was amended, effective from 2022, to remove the gestational limit for foetal impairment and increase the other limit to 24 weeks, to reduce the required approval to only one medical practitioner, to remove the location requirement, to allow nurses and midwives to perform abortions, and to decriminalise the act of a woman attempting to or succeeding in ending her own pregnancy outside of a medical setting.[139]

The Guernsey law of 1997 and its amendment of 2022 do not apply to Alderney and Sark,[137] which are also part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey but continue to apply an earlier law, in French, identical to the Offences against the Person Act 1861 of England and Wales, which does not explicitly mention any legal ground for abortion.[140] However, the judicial decision Rex v Bourne in England and Wales clarified that the law always implicitly allowed abortion at least to save the woman's life, and the decision extended it also to preserve her health.[141] It is unclear whether Alderney and Sark apply only the original legal principle or also the extension by the judicial decision.

In practice, abortions are provided in Alderney under the same conditions as in Guernsey, as health services in Alderney operate under Guernsey law.[142] To clarify the legal situation, in 2022 the States of Alderney passed an abortion law identical to the one in Guernsey, but it awaits a regulation to establish the effective date.[143]

Isle of Man

[edit]Since 24 May 2019,[144] it is lawful in the Isle of Man to have an abortion during the first 14 weeks of pregnancy at will, then until the 24th week, so long as criteria specified by the act are met, and then onwards if there is a serious risk of grave injury or death. Abortion is governed by the Abortion Reform Act 2019.[145]

Statistics

[edit]Total number of abortions (including historical estimates)

[edit]

|

| ||||||||||||

- Abortion statistics in the UK + England and Wales

- Abortions in the UK over time

- Percentage of conceptions leading to abortion in the UK

- Live births + abortions in the UK

- Abortions in England and Wales over time

- Percentage of conceptions leading to abortion in age groups in England and Wales

- Abortions by age group in England and Wales

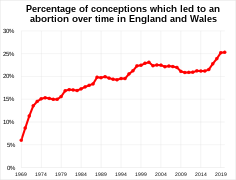

- Percentage of conceptions leading to an abortion over time in England and Wales

Legal abortions by ground

[edit]Statistics for legal abortions are published annually by the Department of Health and Social Care, for England and Wales, NHS Scotland, and the Department of Health in Northern Ireland. Where there is only a small number of abortions for a particular ground, the number is not published by statisticians to avoid the risk of disclosing the identity of the persons involved.

Legal abortions were carried out on the following grounds in England and Wales in 2020:

| Primary ground | Number | % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grounds A/F/G | 98 | 0.05 | Risk to life of pregnant woman (or in emergencies) |

| Ground B | 31 | 0.01 | Prevent grave permanent injury to pregnant woman |

| Ground C | 206,768 | 98.1 | Risk of injury to physical/mental health of pregnant woman |

| Ground D | 778 | 0.37 | Risk of injury to physical/mental health of other children |

| Ground E | 3,185 | 1.51 | Physical or mental abnormality in unborn child |

| Total | 210,860 | 100.0 |

Nearly all (99.9%) of abortions carried out under Ground C alone were reported as being performed because of a risk to the woman's mental health and were classified as F99 (mental disorder, not otherwise specified) under the ICD-10 classification system.[2]

Legal abortions were carried out on the following grounds in Scotland in the same year:

| Primary ground | Number | % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grounds A/B/D/F/G | 34 | 0.25 | Risk to life of pregnant woman (and other grounds not listed below) |

| Ground C | 13,572 | 98.2 | Risk of injury to physical/mental health of pregnant woman |

| Ground E | 209 | 1.51 | Physical or mental abnormality in unborn child |

| Total | 13,815 | 100.0 |

In Northern Ireland, the total number of terminations in 2017–2018 was 12, followed by 8 in 2018–2019, and 22 in 2019–2020.[151][152] As indicated above, for most of that time, abortions were permitted there if the act was to save the life of the mother, or if there was a risk of permanent and serious damage to the mental or physical health of the mother.

In 2020, a total of 371 women travelling from Northern Ireland received abortions in England and Wales:

- 367 – due to risk of injury to physical or mental health of the pregnant woman; and

- 4 – due to physical or mental abnormality in the unborn child.[153]

In the same year, 194 women travelling from the Republic of Ireland received abortions in England and Wales:

- 131 – due to risk of injury to physical or mental health of the pregnant woman; and

- 63 – due to physical or mental abnormality in the unborn child.[154]

The number of pregnant women from the island of Ireland travelling for an abortion was previously much more significant although this decreased following changes in legislation in both Northern Ireland and the Republic, and travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scottish statistics for abortion record the place of residence of the pregnant woman within Scotland (i.e. an NHS board or a local government area); these figures includes temporary addresses for students and a small number of women travelling to Scotland from elsewhere.[155]

Ethnicity

[edit]The broad multi-ethnic group of those getting an abortion is as follows:

| Ethnic group | Year[156][157] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | 2021 | |

| Percentage % (excludes Not Stated) | |||||||||||

| White | 75 | 76 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 77 | 78 |

| Mixed / British Mixed | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Asian / Asian British | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Black / Black British | 12 | 12 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Chinese or other groups | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

By individual ethnic group, including numbers and those which do not state an ethnicity:

| Ethnic group | Year[157][156] (includes Not stated as percentage) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2011 | 2016 | 2021 | |||||

| Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | |

| Total | 193,737 | 100% | 189,931 | 100% | 185,596 | 100% | 214,256 | 100% |

Legal abortions by gestation

[edit]A significant majority of abortions in Great Britain take place at less than 10 weeks of gestation. The numbers and percentages in England and Wales, Scotland, and Great Britain overall, were as follows in 2020. Information on gestation and abortion is not available in Northern Ireland for the same year.

| Gestation | England and Wales | % | Scotland | % | Great Britain | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–9 weeks | 185,559 | 88.0 | 12,108 | 87.6 | 197,667 | 88.0 |

| 10–12 weeks | 11,654 | 5.5 | 983 | 7.1 | 12,637 | 5.6 |

| 13–19 weeks | 10,736 | 5.4 | 651 | 4.7 | 11,387 | 5.1 |

| 20 weeks and over | 2,911 | 1.4 | 73 | 0.5 | 2,984 | 1.3 |

| Total | 210,860 | 100 | 13,815 | 100 | 224,675 | 100 |

Legal abortions by nation/region

[edit]В 2020 году регионом с наибольшим количеством абортов был Лондон, за которым следовали Юго-Восточная Англия, Уэст-Мидлендс и Северо-Западная Англия. Статистические данные об абортах, зарегистрированные на региональном или национальном уровне (отдельно для Англии, Уэльса и Шотландии), относятся к резидентам. Аборты среди нерезидентов также зарегистрированы в Англии и Уэльсе (в совокупности), хотя в этом году они были ниже, чем обычно (943 аборта) из-за ограничений на поездки во время пандемии COVID-19. Информация по Северной Ирландии регистрируется по финансовому году, а не по календарному году: в 2019–2020 годах было зарегистрировано 22 аборта.

| Нация/Регион | Количество абортов |

|---|---|

| Лондон | 42,630 |

| Юго-Восточная Англия | 28,723 |

| Юго-Западная Англия | 15,008 |

| Восток Англии | 19,819 |

| Уэст-Мидлендс | 23,159 |

| Ист-Мидлендс | 14,806 |

| Северо-Западная Англия | 29,927 |

| Йоркшир и Хамбер | 18,013 |

| Северо-Восточная Англия | 7,998 |

| Англия | 200,083 |

| Уэльс | 9,834 |

| Англия и Уэльс (резиденты) | 209,917 |

| Англия и Уэльс (нерезиденты) | 934 |

| Шотландия | 13,815 |

| Великобритания | 224,675 |

Правонарушения, связанные с абортами

[ редактировать ]Аборты, проводимые по причинам, выходящим за рамки разрешенных законом (например, в большинстве случаев после истечения 24-недельного срока или при отсутствии соответствующего согласия), продолжают оставаться незаконными в каждой юрисдикции Великобритании – в соответствии с Законом о преступлениях против личности. 1861 года в Англии и Уэльсе, шотландское общее право и Положения Северной Ирландии . Закон о сохранении младенческой жизни 1929 года и Закон об уголовном правосудии (Северная Ирландия) 1945 года также запрещают уничтожение детей в тех случаях, когда жизнь будущего ребенка была бы жизнеспособной вне утробы матери. [29] [160] [161] [162]

В связи с ростом доступности лекарств для абортов Агентство по регулированию лекарственных средств и товаров медицинского назначения заявило, что лекарства не являются обычными потребительскими товарами и могут как причинять вред, так и излечивать, а продажа мифепристона без медицинской квалификации является незаконной и может быть чрезвычайно опасной. опасен для пациентов. [163]

Статистика Министерства внутренних дел Англии и Уэльса зафиксировала в общей сложности 224 правонарушения, связанных с проведением незаконных абортов в 1900–1909 годах, которые увеличились до 527 в последующее десятилетие, 651 в 1920-х годах и 1028 в 1930-х годах (хотя данные за 1939 год недоступны). Число правонарушений значительно увеличилось с 1942 года, одновременно с прибытием американских военнослужащих во время Второй мировой войны , увеличившись до 649 в 1944 году и в общей сложности 3088 на протяжении 1940-х годов. Тенденция снизилась, но осталась значительной: с 1950 по 1959 год включительно было зарегистрировано 2040 правонарушений и 2592 в 1960-е годы. Однако одновременно с введением в действие Закона 1967 года количество правонарушений снизилось с 212 в 1970 году до трех в 1979 году, а количество правонарушений оставалось на уровне единичных цифр на протяжении оставшейся части 20-го века. С 1931 по 2002 год в юрисдикции также было зарегистрировано 109 случаев уничтожения детей, как это определено Законом о сохранении жизни младенцев 1929 года . [164]

С 2002–2003 по 2008–2009 годы в Англии и Уэльсе было зарегистрировано 30 случаев уничтожения детей и 46 случаев незаконных абортов, за которыми последовал 61 случай незаконных абортов и 80 случаев уничтожения детей в последующее десятилетие (между 2009–2010 и 2019 годами). –2020 включительно). [165] [166] В рекомендациях Королевской прокуратуры производство аборта (незаконное) квалифицируется как преступление, связанное с жестоким обращением с детьми. [167] и отмечает, что некоторые незаконные аборты могут совершаться как преступления против чести, совершаемые с целью наказания женщин за «предполагаемые или предполагаемые нарушения кодекса поведения семьи и/или сообщества». [168]

Преступления, связанные с абортами и уничтожением детей, исторически лишь изредка фиксировались в Северной Ирландии – возможный эффект сдерживающего фактора, предусмотренного законом, и полицейского надзора в меньшей юрисдикции. В период с 1998 по 2018 год Королевская полиция Ольстера и Полицейская служба Северной Ирландии зафиксировали 17 случаев организации незаконных абортов и три случая уничтожения детей. За несколько лет в течение этого периода правонарушений данного типа зафиксировано не было. [169] В отсутствие статутного закона об абортах в Шотландии до 1967 года медицинская и юридическая практика варьировалась на местном уровне. [170] Сравнение общего населения между юрисдикциями показало бы, что в Шотландии будет зафиксировано меньше правонарушений, чем в Англии и Уэльсе, и больше, чем в Северной Ирландии, хотя цифры обычно не публикуются. В 2022 году прозвучали призывы официально оформить преступление уничтожения детей в Шотландии, чтобы обеспечить более последовательный подход в соответствии с соседними юрисдикциями. [171]

Тенденции с 1967 года

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел необходимо обновить . ( ноябрь 2022 г. ) |

После 1967 года произошло быстрое увеличение ежегодного числа легальных абортов, а также снижение случаев сепсиса и смертности из-за незаконных абортов. [172] В 1978 году 121 754 абортов было сделано женщинам, проживающим в Великобритании, и 28 015 — женщинам-нерезидентам. [173] Темпы роста упали с начала 1970-х годов и фактически снизились с 1991 по 1995 год, прежде чем снова подняться. Возрастная группа с наибольшим количеством абортов на 1000 человек — это люди в возрасте 20–24 лет. Статистика за 2006 год по Англии и Уэльсу показала, что 48% абортов произошли у женщин старше 25 лет, 29% - в возрасте 20–24 лет; 21% в возрасте до 20 лет и 2% в возрасте до 16 лет. [174]

| Год | 1969 | 1971 | 1976 | 1981 | 1986 | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 | 2016 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Процент зачатий, приведших к аборту | 5.98% | 11.32% | 15.17% | 17.09% | 18.02% | 19.6% | 20.55% | 23% | 22.26% | 20.88% | 21.5% | 25.29% |

В 2004 году в Англии и Уэльсе было совершено 185 415 абортов. 87% абортов были произведены на сроке 12 недель или менее, а 1,6% (или 2914 абортов) произошли после 20 недель. Аборт для жителей бесплатен; [172] 82% абортов были проведены Национальной службой здравоохранения, финансируемой за счет налогов. [176]

Подавляющее большинство абортов (95% в 2004 г. в Англии и Уэльсе) были сертифицированы на законодательном основании риска причинения вреда психическому или физическому здоровью беременной женщины. [176]

К 2009 году количество абортов выросло до 189 100. Из этого числа 2085 возникли в результате того, что врачи решили, что существует существенный риск того, что в случае рождения ребенка у него будут такие физические или психические отклонения, что он станет серьезной инвалидностью. [177]

В письменном ответе Джиму Аллистеру министр здравоохранения Северной Ирландии Эдвин Путс сообщил, что в больницах Севера за период с 2005/06 по 2009/10 год было проведено 394 аборта, с примечанием, что причины абортов не собирались централизованно. [178]

В 2013 году в Англии и Уэльсе было зарегистрировано 190 800 абортов. Это на 0,2% меньше, чем в 2012 году; 185 331 человек пришлось на жителей Англии и Уэльса. Стандартизированный по возрасту показатель составил 15,9 абортов на 1000 местных женщин в возрасте 15–44 лет; этот показатель увеличился с 11,0 в 1973 году, достиг максимума в 17,9 в 2007 году и упал до 15,9 в 2013 году. [179] Для сравнения, средний показатель по ЕС составляет всего 4,4 аборта на 1000 женщин детородного возраста. [180]

С момента разрешения абортов в Великобритании с 1967 по 2014 год было выполнено 8 745 508 абортов.

В 2018 году общее количество абортов в Англии и Уэльсе составило 205 295. В этом году уровень абортов был самым высоким среди лиц в возрасте 21 года, а 81% приходилось на одиноких. [181]

Опросы и опросы общественного мнения

[ редактировать ]Опросы общественного мнения и исследования социальных настроений регулярно учитывают общественное мнение относительно абортов в Великобритании, по крайней мере, с 1980-х годов. Исследование British Social Attitudes (BSA) задало ряд вопросов об абортах за последние 40 лет и обнаружило почти единодушную поддержку права на аборт, если здоровье женщины будет поставлено под серьезную угрозу в случае продолжения беременности. Уровень поддержки абортов в ситуации, когда женщина самостоятельно решает, что она не желает иметь ребенка, был ниже, когда этот вопрос рассматривался в 2012 году: чуть более шести из десяти (62 процента) поддержали и треть ( 34 процента) — против. Однако это ознаменовало собой значительное изменение по сравнению с 1983 годом, когда 37 процентов считали, что закон должен разрешать это, а чуть более половины (55 процентов) считали, что этого не должно быть. [182]

Аналогичное исследование «Жизнь и время в Северной Ирландии» несколько раз опрашивало респондентов по поводу абортов, начиная с 1998 года. В том году 43% заявили, что «всегда неправильно» для женщины делать аборт по экономическим причинам (т. очень низкий доход и не может позволить себе больше детей»), при этом 14% сказали, что это «вообще не так», и множество других ответов между ними. [183] Те же самые ответы были широко распространены в 2008 году, когда большой процент людей (39 процентов) также подтвердили, что эмбрион является «человеческим существом в момент зачатия». [184]

Конкретный набор вопросов, заданный в ходе исследования Life and Times в 2016 и 2018 годах, охватывал широкий спектр проблем, связанных с абортами, и обнаружил следующие уровни поддержки ряда потенциальных оснований для аборта:

- 58% – фатальная патология у будущего ребенка;

- 54% – беременность, вызванная сексуальным преступлением;

- 46% – серьезная угроза здоровью беременной женщины;

- 45% – серьезные отклонения у будущего ребенка;

- 25% – беременная женщина от 15 лет (несовершеннолетние);

- 18% – беременная женщина 51 года;

- 17% – беременная женщина предпочитает не иметь детей;

- 13% – беременные женщины, живущие с низким доходом;

- 12% – беременная женщина, ставшая безработной;

- 11% – беременные женщины, собирающиеся приступить к новой работе. [185]

Опрос Amnesty International, проведенный в 2014 году, также показал, что большинство людей в Северной Ирландии согласились с изменениями в законе об абортах по трем конкретным причинам, а именно, когда беременность наступила в результате изнасилования или инцеста, или когда фатальная аномалия плода (или ограничивающая жизнь состояние) диагностировано у будущего ребенка. [186] [187]

Опрос YouGov / Daily Telegraph, проведенный в 2005 году, измерил мнение британского общественного мнения относительно гестационного возраста , при котором аборты должны быть разрешены, со следующими уровнями поддержки:

- 2% – аборт возможен на протяжении всей беременности;

- 25% – сохранение срока в 24 недели;

- 30% – сокращение срока до 20 недель;

- 19% – сокращение срока до 12 недель;

- 9% – сокращение срока до менее 12 недель; и

- 6% – аборты запрещены ни на каком этапе. [188]

Еще один опрос, проведенный MORI в 2011 году, исследовал отношение женщин к абортам и показал, что:

- 53% согласились, что если женщина хочет сделать аборт, ей не следует продолжать беременность (по сравнению с 22%, которые не согласились и не не согласились с этим утверждением, и 17%, которые не согласились);

- 37% согласились с утверждением, что «слишком многие женщины недостаточно хорошо думают, прежде чем сделать аборт» (при этом 28% не согласны, а 26% ни согласны, ни не согласны);

- 46% не согласились с введением дополнительных ограничений на аборт (23% согласны, а 23% ни согласны, ни не согласны). [189]

Консультации по вопросам кризисной беременности

[ редактировать ]Команда BBC Panorama исследовала консультационные центры по кризисной беременности и обнаружила, что более трети из них давали вводящую в заблуждение медицинскую информацию или неэтичные советы, или и то, и другое. Panorama изучила рекламу 57 консультационных центров по вопросам кризисной беременности, из них 34 направляли пользователей на веб-сайт Национальной службы здравоохранения или к регулируемым поставщикам абортов. Примерно 21 центр предоставил вводящую в заблуждение медицинскую информацию и/или неэтичные советы. В 7 центрах предположили, что ложный аборт может вызвать проблемы с психическим здоровьем, в 8 центрах предположили, что ложный аборт может вызвать бесплодие, а в 5 центрах предположили, что ложный аборт может вызвать повышенный риск рака молочной железы. Ведущий акушер доктор Джонатан Лорд заявил: «После аборта нет повышенного риска серьезных психических заболеваний, бесплодия или рака молочной железы. Эти центры созданы для того, чтобы ориентироваться на женщин, которые не могут принять свое решение, а затем давать им ложные советы, как попытаться отговорить их от аборта. Они рискуют нанести значительный вред и ущерб этим особенно уязвимым пациентам». Джо Холмс из Британская ассоциация консультирования и психотерапии заявила, что центр сделал предвзятые и осуждающие заявления. «Консультирование заключается в том, чтобы иметь возможность исследовать свои чувства в безопасном месте, без каких-либо суждений, но любая женщина, пришедшая на подобную сессию, останется глубоко травмированной». [190]

Утвержденные методы

[ редактировать ]Методы, используемые для прерывания беременности, делятся на две категории: [191] [192]

- Медикаментозный аборт: проводится путем приема двух таблеток: одна содержит мифепристон (перорально), а через 1–2 дня — еще одна, содержащая мизопростол (перорально или вагинально).

- Хирургический аборт: может быть выполнен любым

- Вакуумная аспирация: удаление беременности с помощью отсасывания с помощью трубки, вставленной в матку или

- Дилатация или эвакуация (ДиЭ): удаление беременности с помощью инструментов, называемых щипцами, вставленных в матку.

Использование различных методов зависит от стадии беременности и политики. Медикаментозные аборты обычно доступны на срок до 12 недель, но их также можно использовать для прерывания беременности на более поздних стадиях. [193] [192] Вакуумная аспирация проводится до 14 недель беременности, тогда как ДЭЭ проводится после 14 недель беременности. [192] Когда беременность прогрессирует до 20 недель, процедура усложняется. [193]

С тех пор как мифепристон был одобрен для использования в Великобритании в 1991 году, использование медикаментозного аборта постоянно растет, и в настоящее время это наиболее часто используемый метод аборта, особенно абортов на ранних сроках беременности. [194] В Англии и Уэльсе на медикаментозные аборты пришлось 86% всех абортов с января по июнь 2022 года, большинство из которых были проведены в первые 10 недель беременности. [195] В Шотландии в 2021 году 99,4% всех абортов были проведены по медицинским показаниям. [196]

Ранний медикаментозный аборт в домашних условиях

[ редактировать ]В 2011 году BPAS проиграла иск Высокого суда с требованием заставить министра здравоохранения разрешить женщинам, делающим ранние медикаментозные аборты в Англии, Шотландии и Уэльсе, принимать вторую дозу медикаментозного лечения дома. [197] Однако позже в 2019 году это решение было отменено, и женщинам разрешили принимать обе таблетки дома до 10 недель беременности. [198] Временные изменения также были связаны с увеличением количества абортов в пандемии COVID-19 . первый год [199] Оценка этой услуги показала, что она безопасна и эффективна, требует более короткого времени ожидания и пользуется предпочтением тех, кто через нее прошел. [200]

24 февраля 2022 года Министерство здравоохранения объявило, что в Англии собираются отказаться от схемы «таблетки дома». [201] В то же время Уэльс объявил, что намерен сделать эту схему постоянной. [202] Прежде чем принять решение о том, сделать ли схему постоянной, все три страны Соединенного Королевства провели общественные консультации. [203] [204] [205] Позже депутаты проголосовали за внесение поправок в Закон о здравоохранении и медицинском обслуживании 2022 года, чтобы сделать эту схему постоянной и разрешить телемедицинский аборт до десятой недели беременности. [49]

12 июня 2023 года женщина была приговорена к более чем двум годам тюремного заключения за то, что она вызвала аборт после установленного законом срока с помощью схемы «таблетки по почте», введя в заблуждение BPAS и ложно заявив, что срок ее беременности меньше 10 недель (считалось, что она на тот момент быть на 28 неделе беременности). [206] Позднее этот срок был сокращен до 14 месяцев условно после направления в Апелляционный суд . [207] Это привело к тому, что ряд защитников прав на аборт, групп по защите прав женщин, политиков и врачей призвали британское правительство реформировать законы об абортах. [208]

Аборты в тюрьмах

[ редактировать ]Политика HMPPS (охватывающая Англию и Уэльс) в отношении женщин, желающих сделать аборт во время пребывания в заключении, предусматривает, что тюрьмы обязаны обеспечивать своевременный доступ к услугам по поддержке прерывания беременности для женщин, нуждающихся в них. В этой политике также говорится, что после прерывания беременности женщинам должен быть предоставлен отдых, а в случае прерывания беременности по медицинским показаниям – беременность в уединении. [209]

На практике трудно определить, насколько легко женщины могут получить доступ к аборту или какую поддержку получают женщины в отношении решения о прерывании беременности. [210] В этой области мало исследований.

Запрос о свободе информации, поданный в Министерство здравоохранения и социального обеспечения (FOI-11107442) в 2017 году с вопросом, сколько женщин, находящихся в тюрьме, сделали аборты за период с 2006 по 2016 год, показал, что в среднем 30 женщин делают аборт, находясь в тюрьме каждая. год [211]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Аборт

- Закон об абортах

- Дебаты об абортах

- Права на аборт (организация)

- Сеть поддержки абортов

- Движение за права отцов в Соединенном Королевстве

- Законы Англии Холсбери

- Уставы Холсбери

- Лоббирование в Соединенном Королевстве

- Религия и аборты

Общая библиография

[ редактировать ]- Ормерод, Дэвид; Хупер, Энтони (2011), «Убийство и связанные с ним преступления: аборт» , в Ормерод, Дэвид; Хупер, Энтони , ред. (13 октября 2011 г.). Криминальная практика Блэкстоуна, 2012 год . Оксфорд: Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 226–230. ISBN 9780199694389 .

- Ричардсон, П.Дж., изд. (1999). Арчболд: уголовные дела, доказательства и практика . Лондон: Свит и Максвелл. ISBN 9780421637207 . Глава 19. Раздел III. Пункты с 19–149 по 19–165.

- Ормерод, Дэвид К. (2011), «Раздел 16.5 Дальнейшие убийства и связанные с ними преступления: уничтожение детей и аборты», в Ормероде, Дэвид К. (редактор), Уголовное право Смита и Хогана (13-е изд.), Оксфорд, Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета, стр. 602–615, ISBN. 9780199586493 .

- Кард, Ричард (1992), «Закон об абортах», в Кард, Ричард; Кросс, Руперт ; Джонс, Филип (ред.), Уголовное право (12-е изд.), Лондон: Баттервортс, стр. 230–235, ISBN. 9780406000866 .

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Проверка агитационных листовок об абортах» . Полный факт. 8 марта 2018 г. с. Английский . Проверено 8 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Статистика абортов в Англии и Уэльсе за 2020 год, 4.7 Законодательные основания для абортов» . www.gov.uk. Департамент здравоохранения и социальной защиты . Проверено 12 января 2022 г.

- ^ «Изменение моделей внебрачного деторождения в Соединенных Штатах» . CDC/Национальный центр статистики здравоохранения . 13 мая 2009 года . Проверено 11 января 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б

Эта статья включает текст, опубликованный в соответствии с Британской лицензией открытого правительства v3.0: «Закон об абортах 1967 года (с поправками)» . www.legislation.gov.uk . Национальный архив . Проверено 6 июля 2019 г.

Эта статья включает текст, опубликованный в соответствии с Британской лицензией открытого правительства v3.0: «Закон об абортах 1967 года (с поправками)» . www.legislation.gov.uk . Национальный архив . Проверено 6 июля 2019 г. - ^ Калкин, Сидней; Берни, Элла (19 августа 2021 г.). «Правовые и неправовые препятствия абортам в Ирландии и Великобритании» . Доступ к лекарствам @ Пункты оказания медицинской помощи . 5 : 239920262110400. doi : 10.1177/23992026211040023 . ISSN 2399-2026 . ПМЦ 9413599 . ПМИД 36204506 . S2CID 238942663 .