Kurds

|

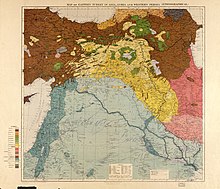

Kurds or Kurdish people (Kurdish: کورد, Kurd) are an Iranic[36][37][38] ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northern Syria.[39] There are exclaves of Kurds in Central Anatolia, Khorasan, and the Caucasus, as well as significant Kurdish diaspora communities in the cities of western Turkey (in particular Istanbul) and Western Europe (primarily in Germany). The Kurdish population is estimated to be between 30 and 45 million.[2][40]

Kurds speak the Kurdish languages and the Zaza–Gorani languages, which belong to the Western Iranian branch of the Iranian languages.[41][42]

Kurds do not comprise a majority in any country, making them a stateless people.[43] After World War I and the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, the victorious Western allies made provision for a Kurdish state in the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres. However, that promise was broken three years later, when the Treaty of Lausanne set the boundaries of modern Turkey and made no such provision, leaving Kurds with minority status in all of the new countries of Turkey, Iraq, and Syria.[44] Recent history of the Kurds includes numerous genocides and rebellions, along with ongoing armed conflicts in Turkish, Iranian, Syrian, and Iraqi Kurdistan. Kurds in Iraq and Syria have autonomous regions, while Kurdish movements continue to pursue greater cultural rights, autonomy, and independence throughout Kurdistan[when defined as?].

Etymology

The exact origins of the name Kurd are unclear.[45] The underlying toponym is recorded in Assyrian as Qardu and in Middle Bronze Age Sumerian as Kar-da.[46] Assyrian Qardu refers to an area in the upper Tigris basin, and it is presumably reflected in corrupted form in Classical Arabic Ǧūdī (جودي), re-adopted in Kurdish as Cûdî.[47] The name would be continued as the first element in the toponym Corduene, mentioned by Xenophon as the tribe who opposed the retreat of the Ten Thousand through the mountains north of Mesopotamia in the 4th century BC.

There are, however, dissenting views, which do not derive the name of the Kurds from Qardu and Corduene but opt for derivation from Cyrtii (Cyrtaei) instead.[48]

Regardless of its possible roots in ancient toponymy, the ethnonym Kurd might be derived from a term kwrt- used in Middle Persian as a common noun to refer to 'nomads' or 'tent-dwellers', which could be applied as an attribute to any Iranian group with such a lifestyle.[49]

The term gained the characteristic of an ethnonym following the Muslim conquest of Persia, as it was adopted into Arabic and gradually became associated with an amalgamation of Iranian and Iranianized tribes and groups in the region.[50][51]

Sharafkhan Bidlisi in the 16th century states that there are four division of Kurds: Kurmanj, Lur, Kalhor, and Guran, each of which speak a different dialect or language variation. Paul (2008) notes that the 16th-century usage of the term Kurd as recorded by Bidlisi, regardless of linguistic grouping, might still reflect an incipient Northwestern Iranian "Kurdish" ethnic identity uniting the Kurmanj, Kalhur, and Guran.[52]

Language

Kurdish (Kurdish: Kurdî or کوردی) is a collection of related dialects spoken by the Kurds.[52] It is mainly spoken in those parts of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey which comprise Kurdistan.[53] Kurdish holds official status in Iraq as a national language alongside Arabic, is recognized in Iran as a regional language, and in Armenia as a minority language. The Kurds are recognized as a people with a distinct language by Arab geographers such as Al-Masudi since the 10th century.[54]

Many Kurds are either bilingual or multilingual, speaking the language of their respective nation of origin, such as Arabic, Persian, and Turkish as a second language alongside their native Kurdish, while those in diaspora communities often speak three or more languages. Turkified and Arabised Kurds often speak little or no Kurdish.

According to Mackenzie, there are few linguistic features that all Kurdish dialects have in common and that are not at the same time found in other Iranian languages.[55]

The Kurdish dialects according to Mackenzie are classified as:[56]

- Northern group (the Kurmanji dialect group)

- Central group (part of the Sorani dialect group)

- Southern group (part of the Xwarin dialect group) including Laki

The Zaza and Gorani are ethnic Kurds,[57] but the Zaza–Gorani languages are not classified as Kurdish.[58]

Population

The number of Kurds living in Southwest Asia is estimated at between 30 and 45 million, with another one or two million living in the Kurdish diaspora. Kurds comprise anywhere from 18 to 25% of the population in Turkey,[1][59] 15 to 20% in Iraq;[1] 10% in Iran;[1] and 9% in Syria.[1][60] Kurds form regional majorities in all four of these countries, viz. in Turkish Kurdistan, Iraqi Kurdistan, Iranian Kurdistan and Syrian Kurdistan. The Kurds are the fourth-largest ethnic group in West Asia after Arabs, Persians, and Turks.

The total number of Kurds in 1991 was placed at 22.5 million, with 48% of this number living in Turkey, 24% in Iran, 18% in Iraq, and 4% in Syria.[61]

Recent emigration accounts for a population of close to 1.5 million in Western countries, about half of them in Germany.

A special case are the Kurdish populations in the Transcaucasus and Central Asia, displaced there mostly in the time of the Russian Empire, who underwent independent developments for more than a century and have developed an ethnic identity in their own right.[62] This groups' population was estimated at close to 0.4 million in 1990.[63]

Religion

Islam

Most Kurds are Sunni Muslims who adhere to the Shafiʽi school, while a significant minority adhere to the Hanafi school[64] and also Alevism. Moreover, many Shafi'i Kurds adhere to either one of the two Sufi orders Naqshbandi and Qadiriyya.[65]

Beside Sunni Islam, Alevism and Shia Islam also have millions of Kurdish followers.[66]

Yazidism

Yazidism is a monotheistic ethnic religion with roots in a western branch of an Iranic pre-Zoroastrian religion.[67][68][69][70] It is based on the belief of one God who created the world and entrusted it into the care of seven Holy Beings.[71][72] The leader of this heptad is Tawûsê Melek, who is symbolized with a peacock.[71][73] Its adherents number from 700,000 to 1 million worldwide[74] and are indigenous to the Kurdish regions of Iraq, Syria and Turkey, with some significant, more recent communities in Russia, Georgia and Armenia established by refugees fleeing persecution by Muslims in Ottoman Empire.[72] Yazidism shares with Kurdish Alevism and Yarsanism many similar qualities that date back to the pre-Islamic era.[75][76][77]

Yarsanism

Yarsanism (also known as Ahl-I-Haqq, Ahl-e-Hagh or Kakai) is also one of the religions that are associated with Kurdistan.

Although most of the sacred Yarsan texts are in the Gorani and all of the Yarsan holy places are located in Kurdistan, followers of this religion are also found in other regions. For example, while there are more than 300,000 Yarsani in Iraqi Kurdistan, there are more than 2 million Yarsani in Iran.[78] However, the Yarsani lack political rights in both countries.

Zoroastrianism

The Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism has had a major influence on the Iranian culture, which Kurds are a part of, and has maintained some effect since the demise of the religion in the Middle Ages. The Iranian philosopher Sohrevardi drew heavily from Zoroastrian teachings.[79] Ascribed to the teachings of the prophet Zoroaster, the faith's Supreme Being is Ahura Mazda. Leading characteristics, such as messianism, the Golden Rule, heaven and hell, and free will influenced other religious systems, including Second Temple Judaism, Gnosticism, Christianity, and Islam.[80]

In 2016, the first official Zoroastrian fire temple of Iraqi Kurdistan opened in Sulaymaniyah. Attendees celebrated the occasion by lighting a ritual fire and beating the frame drum or 'daf'.[81] Awat Tayib, the chief of followers of Zoroastrianism in the Kurdistan region, claimed that many were returning to Zoroastrianism but some kept it secret out of fear of reprisals from Islamists.[81]

Christianity

Although historically there have been various accounts of Kurdish Christians, most often these were in the form of individuals, and not as communities. However, in the 19th and 20th century various travel logs tell of Kurdish Christian tribes, as well as Kurdish Muslim tribes who had substantial Christian populations living amongst them. A significant number of these were allegedly originally Armenian or Assyrian,[82] and it has been recorded that a small number of Christian traditions have been preserved. Several Christian prayers in Kurdish have been found from earlier centuries.[83] In recent years some Kurds from Muslim backgrounds have converted to Christianity.[84][85][86]

Segments of the Bible were first made available in the Kurdish language in 1856 in the Kurmanji dialect. The Gospels were translated by Stepan, an Armenian employee of the American Bible Society and were published in 1857. Prominent historical Kurdish Christians include the brothers Zakare and Ivane Mkhargrdzeli.[87][88][89]

History

Antiquity

"The land of Karda" is mentioned on a Sumerian clay tablet dated to the 3rd millennium BC. This land was inhabited by "the people of Su" who dwelt in the southern regions of Lake Van; the philological connection between "Kurd" and "Karda" is uncertain, but the relationship is considered possible.[90] Other Sumerian clay tablets referred to the people, who lived in the land of Karda, as the Qarduchi (Karduchi, Karduchoi) and the Qurti.[91] Karda/Qardu is etymologically related to the Assyrian term Urartu and the Hebrew term Ararat.[92] However, some modern scholars do not believe that the Qarduchi are connected to Kurds.[93][94]

Qarti or Qartas, who were originally settled on the mountains north of Mesopotamia, are considered as a probable ancestor of the Kurds. The Akkadians were attacked by nomads coming through Qartas territory at the end of 3rd millennium BC and distinguished them as the Guti, speakers of a pre-Iranic language isolate. They conquered Mesopotamia in 2150 BC and ruled with 21 kings until defeated by the Sumerian king Utu-hengal.[95]

Many Kurds consider themselves descended from the Medes, an ancient Iranian people,[96] and even use a calendar dating from 612 BC, when the Assyrian capital of Nineveh was conquered by the Medes.[97] The claimed Median descent is reflected in the words of the Kurdish national anthem: "We are the children of the Medes and Kai Khosrow."[98] However, MacKenzie and Asatrian challenge the relation of the Median language to Kurdish.[99][100] The Kurdish languages, on the other hand, form a subgroup of the Northwestern Iranian languages like Median.[52][101] Some researchers consider the independent Kardouchoi as the ancestors of the Kurds,[102] while others prefer Cyrtians.[103] The term Kurd, however, is first encountered in Arabic sources of the seventh century.[104] Books from the early Islamic era, including those containing legends such as the Shahnameh and the Middle Persian Kar-Namag i Ardashir i Pabagan, and other early Islamic sources provide early attestation of the name Kurd.[105] The Kurds have ethnically diverse origins.[106][107]

During the Sassanid era, in Kar-Namag i Ardashir i Pabagan, a short prose work written in Middle Persian, Ardashir I is depicted as having battled the Kurds and their leader, Madig. After initially sustaining a heavy defeat, Ardashir I was successful in subjugating the Kurds.[108] In a letter Ardashir I received from his foe, Ardavan V, which is also featured in the same work, he is referred to as being a Kurd himself.

You've bitten off more than you can chew

and you have brought death to yourself.

O son of a Kurd, raised in the tents of the Kurds,

who gave you permission to put a crown on your head?[109]

The usage of the term Kurd during this time period most likely was a social term, designating Northwestern Iranian nomads, rather than a concrete ethnic group.[109][110]

Similarly, in AD 360, the Sassanid king Shapur II marched into the Roman province Zabdicene, to conquer its chief city, Bezabde, present-day Cizre. He found it heavily fortified, and guarded by three legions and a large body of Kurdish archers.[111] After a long and hard-fought siege, Shapur II breached the walls, conquered the city and massacred all its defenders. Thereafter he had the strategically located city repaired, provisioned and garrisoned with his best troops.[111]

Qadishaye, settled by Kavad in Singara, were probably Kurds[112] and worshiped the martyr Abd al-Masih.[113] They revolted against the Sassanids and were raiding the whole Persian territory. Later they, along with Arabs and Armenians, joined the Sassanids in their war against the Byzantines.[114]

There is also a 7th-century text by an unidentified author, written about the legendary Christian martyr Mar Qardagh. He lived in the 4th century, during the reign of Shapur II, and during his travels is said to have encountered Mar Abdisho, a deacon and martyr, who, after having been questioned of his origins by Mar Qardagh and his Marzobans, stated that his parents were originally from an Assyrian village called Hazza, but were driven out and subsequently settled in Tamanon, a village in the land of the Kurds, identified as being in the region of Mount Judi.[115]

Medieval period

Early Syriac sources use the terms Hurdanaye, Kurdanaye, Kurdaye to refer to the Kurds. According to Michael the Syrian, Hurdanaye separated from Tayaye Arabs and sought refuge with the Byzantine Emperor Theophilus. He also mentions the Persian troops who fought against Musa chief of Hurdanaye in the region of Qardu in 841. According to Barhebreaus, a king appeared to the Kurdanaye and they rebelled against the Arabs in 829. Michael the Syrian considered them as pagan, followers of mahdi and adepts of Magianism. Their mahdi called himself Christ and the Holy Ghost.[116]

In the early Middle Ages, the Kurds sporadically appear in Arabic sources, though the term was still not being used for a specific people; instead it referred to an amalgam of nomadic western Iranian tribes, who were distinct from Persians. However, in the High Middle Ages, the Kurdish ethnic identity gradually materialized, as one can find clear evidence of the Kurdish ethnic identity and solidarity in texts of the 12th and 13th centuries,[117] though, the term was also still being used in the social sense.[118] Since 10th century, Arabic texts including al-Masudi's works, have referred to Kurds as a distinct linguistic group.[119] From 11th century onward, the term Kurd is explicitly defined as an ethnonym and this does not suggest synonymity with the ethnographic category nomad.[120] Al-Tabari wrote that in 639, Hormuzan, a Sasanian general originating from a noble family, battled against the Islamic invaders in Khuzestan, and called upon the Kurds to aid him in battle.[121] However, they were defeated and brought under Islamic rule.

In 838, a Kurdish leader based in Mosul, named Mir Jafar, revolted against the Caliph Al-Mu'tasim who sent the commander Itakh to combat him. Itakh won this war and executed many of the Kurds.[122][123] Eventually, Arabs conquered the Kurdish regions and gradually converted the majority of Kurds to Islam, often incorporating them into the military, such as the Hamdanids whose dynastic family members also frequently intermarried with Kurds.[124][125]

In 934, the Daylamite Buyid dynasty was founded, and subsequently conquered most of present-day Iran and Iraq. During the time of rule of this dynasty, Kurdish chief and ruler, Badr ibn Hasanwaih, established himself as one of the most important emirs of the time.[126]

In the 10th–12th centuries, a number of Kurdish principalities and dynasties were founded, ruling Kurdistan and neighbouring areas:

- The Shaddadids (951–1174)[127][128][129][130] ruled parts of Armenia and Arran.

- The Rawadid (955–1221) They were Arab origin, later Kurdicized[130] and ruled Azerbaijan.

- The Hasanwayhids (959–1015)[129] ruled western Iran and upper Mesopotamia.

- The Marwanids (990–1096)[131][129][130] ruled eastern Anatolia.

- The Annazids (990–1117)[132][129] ruled western Iran and Upper Mesopotamia (succeeded the Hasanwayhids).

- The Hazaraspids (1148–1424)[133] ruled southwestern Iran.

- The Ayyubids (1171–1341)[134] ruled Egypt, Syria, Upper Mesopotamia, Hejaz, Yemen and parts of southeastern Anatolia.

Due to the Turkic invasion of Anatolia and Armenia, the 11th-century Kurdish dynasties crumbled and became incorporated into the Seljuk dynasty. Kurds would hereafter be used in great numbers in the armies of the Zengids.[135] The Ayyubid dynasty was founded by Kurdish ruler Saladin,[136][137][138][139] as succeeding the Zengids, the Ayyubids established themselves in 1171. Saladin led the Muslims to recapture the city of Jerusalem from the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin; also frequently clashing with the Assassins. The Ayyubid dynasty lasted until 1341 when the Ayyubid sultanate fell to Mongolian invasions.

Safavid period

The Safavid dynasty, established in 1501, also established its rule over Kurdish-inhabited territories. The paternal line of this family actually had Kurdish roots,[142] tracing back to Firuz-Shah Zarrin-Kolah, a dignitary who moved from Kurdistan to Ardabil in the 11th century.[143][144] The Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 that culminated in what is nowadays Iran's West Azerbaijan Province, marked the start of the Ottoman-Persian Wars between the Iranian Safavids (and successive Iranian dynasties) and the Ottomans. For the next 300 years, many of the Kurds found themselves living in territories that frequently changed hands between Ottoman Turkey and Iran during the protracted series of Ottoman-Persian Wars.

The Safavid king Ismail I (r. 1501–1524) put down a Yezidi rebellion which went on from 1506 to 1510. A century later, the year-long Battle of Dimdim took place, wherein the Safavid king Abbas I (r. 1588–1629) succeeded in putting down the rebellion led by the Kurdish ruler Amir Khan Lepzerin. Thereafter, many Kurds were deported to Khorasan, not only to weaken the Kurds, but also to protect the eastern border from invading Afghan and Turkmen tribes.[145] Other forced movements and deportations of other groups were also implemented by Abbas I and his successors, most notably of the Armenians, the Georgians, and the Circassians, who were moved en masse to and from other districts within the Persian empire.[146][147][148][149][150]

The Kurds of Khorasan, numbering around 700,000, still use the Kurmanji Kurdish dialect.[151][152] Several Kurdish noblemen served the Safavids and rose to prominence, such as Shaykh Ali Khan Zanganeh, who served as the grand vizier of the Safavid shah Suleiman I (r. 1666–1694) from 1669 to 1689. Due to his efforts in reforming the declining Iranian economy, he has been called the "Safavid Amir Kabir" in modern historiography.[153] His son, Shahqoli Khan Zanganeh, also served as a grand vizier from 1707 to 1716. Another Kurdish statesman, Ganj Ali Khan, was close friends with Abbas I, and served as governor in various provinces and was known for his loyal service.

Zand period

After the fall of the Safavids, Iran fell under the control of the Afsharid Empire ruled by Nader Shah at its peak. After Nader's death, Iran fell into civil war, with multiple leaders trying to gain control over the country. Ultimately, it was Karim Khan, a Laki general of the Zand tribe who would come to power.[154]

The country would flourish during Karim Khan's reign; a strong resurgence of the arts would take place, and international ties were strengthened.[155] Karim Khan was portrayed as being a ruler who truly cared about his subjects, thereby gaining the title Vakil e-Ra'aayaa (meaning Representative of the People in Persian).[155] Though not as powerful in its geo-political and military reach as the preceding Safavids and Afsharids or even the early Qajars, he managed to reassert Iranian hegemony over its integral territories in the Caucasus, and presided over an era of relative peace, prosperity, and tranquility. In Ottoman Iraq, following the Ottoman–Persian War (1775–76), Karim Khan managed to seize Basra for several years.[156][157]

After Karim Khan's death, the dynasty would decline in favour of the rival Qajars due to infighting between the Khan's incompetent offspring. It was not until Lotf Ali Khan, 10 years later, that the dynasty would once again be led by an adept ruler. By this time however, the Qajars had already progressed greatly, having taken a number of Zand territories. Lotf Ali Khan made multiple successes before ultimately succumbing to the rivaling faction. Iran and all its Kurdish territories would hereby be incorporated in the Qajar dynasty.

The Kurdish tribes present in Baluchistan and some of those in Fars are believed to be remnants of those that assisted and accompanied Lotf Ali Khan and Karim Khan, respectively.[158]

Ottoman period

When Sultan Selim I, after defeating Shah Ismail I in 1514, annexed Western Armenia and Kurdistan, he entrusted the organisation of the conquered territories to Idris, the historian, who was a Kurd of Bitlis. He divided the territory into sanjaks or districts, and, making no attempt to interfere with the principle of heredity, installed the local chiefs as governors. He also resettled the rich pastoral country between Erzerum and Erivan, which had lain in waste since the passage of Timur, with Kurds from the Hakkari and Bohtan districts. For the next centuries, from the Peace of Amasya until the first half of the 19th century, several regions of the wide Kurdish homelands would be contested as well between the Ottomans and the neighbouring rival successive Iranian dynasties (Safavids, Afsharids, Qajars) in the frequent Ottoman-Persian Wars.

The Ottoman centralist policies in the beginning of the 19th century aimed to remove power from the principalities and localities, which directly affected the Kurdish emirs. Bedirhan Bey was the last emir of the Cizre Bohtan Emirate after initiating an uprising in 1847 against the Ottomans to protect the current structures of the Kurdish principalities. Although his uprising is not classified as a nationalist one, his children played significant roles in the emergence and the development of Kurdish nationalism through the next century.[159]

The first modern Kurdish nationalist movement emerged in 1880 with an uprising led by a Kurdish landowner and head of the powerful Shemdinan family, Sheik Ubeydullah, who demanded political autonomy or outright independence for Kurds as well as the recognition of a Kurdistan state without interference from Turkish or Persian authorities.[160] The uprising against Qajar Persia and the Ottoman Empire was ultimately suppressed by the Ottomans and Ubeydullah, along with other notables, were exiled to Istanbul.

Kurdish nationalism of the 20th century

Kurdish nationalism emerged after World War I with the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, which had historically successfully integrated (but not assimilated) the Kurds, through use of forced repression of Kurdish independence movements. Revolts did occur sporadically but only in 1880 with the uprising led by Sheik Ubeydullah did the Kurds as an ethnic group or nation make demands. Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876–1909) responded with a campaign of integration by co-opting prominent Kurdish opponents to strengthen Ottoman power with offers of prestigious positions in his government. This strategy appears to have been successful, given the loyalty displayed by the Kurdish Hamidiye regiments during World War I.[161]

The Kurdish ethno-nationalist movement that emerged following World War I and the end of the Ottoman Empire in 1922 largely represented a reaction to the changes taking place in mainstream Turkey, primarily to the radical secularization, the centralization of authority, and to the rampant Turkish nationalism in the new Turkish Republic.[162]

Jakob Künzler, head of a missionary hospital in Urfa, documented the large-scale ethnic cleansing of both Armenians and Kurds by the Young Turks.[163] He has given a detailed account of the deportation of Kurds from Erzurum and Bitlis in the winter of 1916. The Kurds were perceived to be subversive elements who would take the Russian side in the war. In order to eliminate this threat, Young Turks embarked on a large-scale deportation of Kurds from the regions of Djabachdjur, Palu, Musch, Erzurum and Bitlis. Around 300,000 Kurds were forced to move southwards to Urfa and then westwards to Aintab and Marasch. In the summer of 1917 Kurds were moved to Konya in central Anatolia. Through these measures, the Young Turk leaders aimed at weakening the political influence of the Kurds by deporting them from their ancestral lands and by dispersing them in small pockets of exiled communities. By the end of World War I, up to 700,000 Kurds had been forcibly deported and almost half of the displaced perished.[164]

Some of the Kurdish groups sought self-determination and the confirmation of Kurdish autonomy in the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, but in the aftermath of World War I, Kemal Atatürk prevented such a result. Kurds backed by the United Kingdom declared independence in 1927 and established the Republic of Ararat. Turkey suppressed Kurdist revolts in 1925, 1930, and 1937–1938, while Iran in the 1920s suppressed Simko Shikak at Lake Urmia and Jaafar Sultan of the Hewraman region, who controlled the region between Marivan and north of Halabja. A short-lived Soviet-sponsored Kurdish Republic of Mahabad (January to December 1946) existed in an area of present-day Iran.

From 1922 to 1924 in Iraq a Kingdom of Kurdistan existed. When Ba'athist administrators thwarted Kurdish nationalist ambitions in Iraq, war broke out in the 1960s. In 1970 the Kurds rejected limited territorial self-rule within Iraq, demanding larger areas, including the oil-rich Kirkuk region.

During the 1920s and 1930s, several large-scale Kurdish revolts took place in Kurdistan. Following these rebellions, the area of Turkish Kurdistan was put under martial law and many of the Kurds were displaced. The Turkish government also encouraged resettlement of Albanians from Kosovo and Assyrians in the region to change the make-up of the population. These events and measures led to long-lasting mutual distrust between Ankara and the Kurds.[165]

Kurdish officers from the Iraqi army [...] were said to have approached Soviet army authorities soon after their arrival in Iran in 1941 and offered to form a Kurdish volunteer force to fight alongside the Red Army. This offer was declined.[166]

During the relatively open government of the 1950s in Turkey, Kurds gained political office and started working within the framework of the Turkish Republic to further their interests, but this move towards integration was halted with the 1960 Turkish coup d'état.[161] The 1970s saw an evolution in Kurdish nationalism as Marxist political thought influenced some in the new generation of Kurdish nationalists opposed to the local feudal authorities who had been a traditional source of opposition to authority; in 1978 Kurdish students would form the militant separatist organization PKK, also known as the Kurdistan Workers' Party in English. The Kurdistan Workers' Party later abandoned Marxism-Leninism.[167]

Kurds are often regarded as "the largest ethnic group without a state",[168][169][170][171][172][173] Some researchers, such as Martin van Bruinessen,[174] who seem to agree with the official Turkish position, argue that while some level of Kurdish cultural, social, political and ideological heterogeneity may exist, the Kurdish community has long thrived over the centuries as a generally peaceful and well-integrated part of Turkish society, with hostilities erupting only in recent years.[175][176][177] Michael Radu, who worked for the United States' Pennsylvania Foreign Policy Research Institute, notes that demands for a Kurdish state comes primarily from Kurdish nationalists, Western human-rights activists, and European leftists.[175]

Kurdish communities

Turkey

According to CIA Factbook, Kurds formed approximately 18% of the population in Turkey (approximately 14 million) in 2008. One Western source estimates that up to 25% of the Turkish population is Kurdish (approximately 18–19 million people).[59] Kurdish sources claim there are as many as 20 or 25 million Kurds in Turkey.[178] In 1980, Ethnologue estimated the number of Kurdish-speakers in Turkey at around five million,[179] when the country's population stood at 44 million.[180] Kurds form the largest minority group in Turkey, and they have posed the most serious and persistent challenge to the official image of a homogeneous society. To deny an existence of Kurds, the Turkish Government used several terms. "Mountain Turks" was a term was initially used by Abdullah Alpdoğan. In 1961, in a foreword to the book Doğu İlleri ve Varto Tarihi of Mehmet Şerif Fırat, the Turkish president Cemal Gürsel declared it of utmost importance to prove the Turkishness of the Kurds.[181] Eastern Turk was another euphemism for Kurds from 1980 onwards.[182] Nowadays the Kurds, in Turkey, are still known under the name Easterner (Doğulu).

Several large scale Kurdish revolts in 1925, 1930 and 1938 were suppressed by the Turkish government and more than one million Kurds were forcibly relocated between 1925 and 1938. The use of Kurdish language, dress, folklore, and names were banned and the Kurdish-inhabited areas remained under martial law until 1946.[183] The Ararat revolt, which reached its apex in 1930, was only suppressed after a massive military campaign including destruction of many villages and their populations.[184] By the 1970s, Kurdish leftist organizations such as Kurdistan Socialist Party-Turkey (KSP-T) emerged in Turkey which were against violence and supported civil activities and participation in elections. In 1977, Mehdi Zana a supporter of KSP-T won the mayoralty of Diyarbakir in the local elections. At about the same time, generational fissures gave birth to two new organizations: the National Liberation of Kurdistan and the Kurdistan Workers Party.[185]

The words "Kurds", "Kurdistan", or "Kurdish" were officially banned by the Turkish government.[186] Following the military coup of 1980, the Kurdish language was officially prohibited in public and private life.[187] Many people who spoke, published, or sang in Kurdish were arrested and imprisoned.[188] The Kurds are still not allowed to get a primary education in their mother tongue and they do not have a right to self-determination, even though Turkey has signed the ICCPR. There is ongoing discrimination against and "otherization" of Kurds in society.[189]

The Kurdistan Workers' Party or PKK (Kurdish: Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê) is Kurdish militant organization which has waged an armed struggle against the Turkish state for cultural and political rights and self-determination for the Kurds. Turkey's military allies the US, the EU, and NATO label the PKK as a terrorist organization while the UN,[190] Switzerland,[191] and Russia[192] have refused to add the PKK to their terrorist list.[193] Some of them have even supported the PKK.[194]

Between 1984 and 1999, the PKK and the Turkish military engaged in open war, and much of the countryside in the southeast was depopulated, as Kurdish civilians moved from villages to bigger cities such as Diyarbakır, Van, and Şırnak, as well as to the cities of western Turkey and even to western Europe. The causes of the depopulation included mainly the Turkish state's military operations, state's political actions, Turkish deep state actions, the poverty of the southeast and PKK atrocities against Kurdish clans which were against them.[195] Turkish state actions have included torture, rape,[196][197] forced inscription, forced evacuation, destruction of villages, illegal arrests and executions of Kurdish civilians.[198][199]

Since the 1970s, the European Court of Human Rights has condemned Turkey for the thousands of human rights abuses.[199][200] The judgments are related to executions of Kurdish civilians,[201] torturing,[202] forced displacements[203] systematic destruction of villages,[204] arbitrary arrests[205] murdered and disappeared Kurdish journalists.[206]

Leyla Zana, the first Kurdish female MP from Diyarbakir, caused an uproar in Turkish Parliament after adding the following sentence in Kurdish to her parliamentary oath during the swearing-in ceremony in 1994: "I take this oath for the brotherhood of the Turkish and Kurdish peoples."[207]

In March 1994, the Turkish Parliament voted to lift the immunity of Zana and five other Kurdish DEP members: Hatip Dicle, Ahmet Turk, Sirri Sakik, Orhan Dogan and Selim Sadak. Zana, Dicle, Sadak and Dogan were sentenced to 15 years in jail by the Supreme Court in October 1995. Zana was awarded the Sakharov Prize for human rights by the European Parliament in 1995. She was released in 2004 amid warnings from European institutions that the continued imprisonment of the four Kurdish MPs would affect Turkey's bid to join the EU.[208][209] The 2009 local elections resulted in 5.7% for Kurdish political party DTP.[210]

Officially protected death squads are accused of the disappearance of 3,200 Kurds and Assyrians in 1993 and 1994 in the so-called "mystery killings". Kurdish politicians, human-rights activists, journalists, teachers and other members of intelligentsia were among the victims. Virtually none of the perpetrators were investigated nor punished. Turkish government also encouraged Islamic extremist group Kurdish Hezbollah to assassinate suspected PKK members and often ordinary Kurds.[211] Azimet Köylüoğlu, the state minister of human rights, revealed the extent of security forces' excesses in autumn 1994: While acts of terrorism in other regions are done by the PKK; in Tunceli it is state terrorism. In Tunceli, it is the state that is evacuating and burning villages. In the southeast there are two million people left homeless.[212]

Iran

The Kurdish region of Iran has been a part of the country since ancient times. Nearly all Kurdistan was part of Persian Empire until its Western part was lost during wars against the Ottoman Empire.[213] Following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 Tehran had demanded all lost territories including Turkish Kurdistan, Mosul, and even Diyarbakır, but demands were quickly rejected by Western powers.[214] This area has been divided by modern Turkey, Syria and Iraq.[215] Today, the Kurds inhabit mostly northwestern territories known as Iranian Kurdistan but also the northeastern region of Khorasan, and constitute approximately 7–10%[216] of Iran's overall population (6.5–7.9 million), compared to 10.6% (2 million) in 1956 and 8% (800,000) in 1850.[217]

Unlike in other Kurdish-populated countries, there are strong ethnolinguistical and cultural ties between Kurds, Persians and others as Iranian peoples.[216] Some modern Iranian dynasties like the Safavids and Zands are considered to be partly of Kurdish origin. Kurdish literature in all of its forms (Kurmanji, Sorani, and Gorani) has been developed within historical Iranian boundaries under strong influence of the Persian language.[215] The Kurds sharing much of their history with the rest of Iran is seen as reason for why Kurdish leaders in Iran do not want a separate Kurdish state.[216][218][219]

The government of Iran has never employed the same level of brutality against its own Kurds like Turkey or Iraq, but it has always been implacably opposed to any suggestion of Kurdish separatism.[216] During and shortly after the First World War the government of Iran was ineffective and had very little control over events in the country and several Kurdish tribal chiefs gained local political power, even established large confederations.[218] At the same time waves of nationalism from the disintegrating Ottoman Empire partly influenced some Kurdish chiefs in border regions to pose as Kurdish nationalist leaders.[218] Prior to this, identity in both countries largely relied upon religion i.e. Shia Islam in the particular case of Iran.[219][220] In 19th-century Iran, Shia–Sunni animosity and the describing of Sunni Kurds as an Ottoman fifth column was quite frequent.[221]

During the late 1910s and early 1920s, tribal revolt led by Kurdish chieftain Simko Shikak struck north western Iran. Although elements of Kurdish nationalism were present in this movement, historians agree these were hardly articulate enough to justify a claim that recognition of Kurdish identity was a major issue in Simko's movement, and he had to rely heavily on conventional tribal motives.[218] Government forces and non-Kurds were not the only ones to suffer in the attacks, the Kurdish population was also robbed and assaulted.[218][222] Rebels do not appear to have felt any sense of unity or solidarity with fellow Kurds.[218] Kurdish insurgency and seasonal migrations in the late 1920s, along with long-running tensions between Tehran and Ankara, resulted in border clashes and even military penetrations in both Iranian and Turkish territory.[214] Two regional powers have used Kurdish tribes as tool for own political benefits: Turkey has provided military help and refuge for anti-Iranian Turcophone Shikak rebels in 1918–1922,[223] while Iran did the same during Ararat rebellion against Turkey in 1930. Reza Shah's military victory over Kurdish and Turkic tribal leaders initiated a repressive era toward non-Iranian minorities.[222] Government's forced detribalization and sedentarization in 1920s and 1930s resulted with many other tribal revolts in Iranian regions of Azerbaijan, Luristan and Kurdistan.[224] In particular case of the Kurds, this repressive policies partly contributed to developing nationalism among some tribes.[218]

As a response to growing Pan-Turkism and Pan-Arabism in region which were seen as potential threats to the territorial integrity of Iran, Pan-Iranist ideology has been developed in the early 1920s.[220] Some of such groups and journals openly advocated Iranian support to the Kurdish rebellion against Turkey.[225] Secular Pahlavi dynasty has endorsed Iranian ethnic nationalism[220] which saw the Kurds as integral part of the Iranian nation.[219] Mohammad Reza Pahlavi has personally praised the Kurds as "pure Iranians" or "one of the most noble Iranian peoples". Another significant ideology during this period was Marxism which arose among Kurds under influence of USSR. It culminated in the Iran crisis of 1946 which included a separatist attempt of KDP-I and communist groups[226] to establish the Soviet puppet government[227][228][229] called Republic of Mahabad. It arose along with Azerbaijan People's Government, another Soviet puppet state.[216][230] The state itself encompassed a very small territory, including Mahabad and the adjacent cities, unable to incorporate the southern Iranian Kurdistan which fell inside the Anglo-American zone, and unable to attract the tribes outside Mahabad itself to the nationalist cause.[216] As a result, when the Soviets withdrew from Iran in December 1946, government forces were able to enter Mahabad unopposed.[216]

Several nationalist and Marxist insurgencies continued for decades (1967, 1979, 1989–96) led by KDP-I and Komalah, but those two organization have never advocated a separate Kurdish state or greater Kurdistan as did the PKK in Turkey.[218][231][232][233] Still, many of dissident leaders, among others Qazi Muhammad and Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou, were executed or assassinated.[216] During Iran–Iraq War, Tehran has provided support for Iraqi-based Kurdish groups like KDP or PUK, along with asylum for 1.4 million Iraqi refugees, mostly Kurds. Kurdish Marxist groups have been marginalized in Iran since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In 2004 new insurrection started by PJAK, separatist organization affiliated with the Turkey-based PKK[234] and designated as terrorist by Iran, Turkey and the United States.[234] Some analysts claim PJAK do not pose any serious threat to the government of Iran.[235] Cease-fire has been established in September 2011 following the Iranian offensive on PJAK bases, but several clashes between PJAK and IRGC took place after it.[176] Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, accusations of "discrimination" by Western organizations and of "foreign involvement" by Iranian side have become very frequent.[176]

Kurds have been well integrated in Iranian political life during reign of various governments.[218] Kurdish liberal political Karim Sanjabi has served as minister of education under Mohammad Mossadegh in 1952. During the reign of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi some members of parliament and high army officers were Kurds, and there was even a Kurdish Cabinet Minister.[218] During the reign of the Pahlavis Kurds received many favours from the authorities, for instance to keep their land after the land reforms of 1962.[218] In the early 2000s, presence of thirty Kurdish deputies in the 290-strong parliament has also helped to undermine claims of discrimination.[236] Some of the more influential Kurdish politicians during recent years include former first vice president Mohammad Reza Rahimi and Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, Mayor of Tehran and second-placed presidential candidate in 2013. Kurdish language is today used more than at any other time since the Revolution, including in several newspapers and among schoolchildren.[236] Many Iranian Kurds show no interest in Kurdish nationalism,[216] particularly Kurds of the Shia faith who sometimes even vigorously reject idea of autonomy, preferring direct rule from Tehran.[216][231] The issue of Kurdish nationalism and Iranian national identity is generally only questioned in the peripheral Kurdish dominated regions where the Sunni faith is prevalent.[237]

Iraq

Kurds constitute approximately 17% of Iraq's population. They are the majority in at least three provinces in northern Iraq which are together known as Iraqi Kurdistan. Kurds also have a presence in Kirkuk, Mosul, Khanaqin, and Baghdad. Around 300,000 Kurds live in the Iraqi capital Baghdad, 50,000 in the city of Mosul and around 100,000 elsewhere in southern Iraq.[238]

Kurds led by Mustafa Barzani were engaged in heavy fighting against successive Iraqi regimes from 1960 to 1975. In March 1970, Iraq announced a peace plan providing for Kurdish autonomy. The plan was to be implemented in four years.[239] However, at the same time, the Iraqi regime started an Arabization program in the oil-rich regions of Kirkuk and Khanaqin.[240] The peace agreement did not last long, and in 1974, the Iraqi government began a new offensive against the Kurds. Moreover, in March 1975, Iraq and Iran signed the Algiers Accord, according to which Iran cut supplies to Iraqi Kurds. Iraq started another wave of Arabization by moving Arabs to the oil fields in Kurdistan, particularly those around Kirkuk.[241] Between 1975 and 1978, 200,000 Kurds were deported to other parts of Iraq.[242]

During the Iran–Iraq War in the 1980s, the regime implemented anti-Kurdish policies and a de facto civil war broke out. Iraq was widely condemned by the international community, but was never seriously punished for oppressive measures such as the mass murder of hundreds of thousands of civilians, the wholesale destruction of thousands of villages and the deportation of thousands of Kurds to southern and central Iraq.

The genocidal campaign, conducted between 1986 and 1989 and culminating in 1988, carried out by the Iraqi government against the Kurdish population was called Anfal ("Spoils of War"). The Anfal campaign led to destruction of over two thousand villages and killing of 182,000 Kurdish civilians.[243] The campaign included the use of ground offensives, aerial bombing, systematic destruction of settlements, mass deportation, firing squads, and chemical attacks, including the most infamous attack on the Kurdish town of Halabja in 1988 that killed 5000 civilians instantly.

After the collapse of the Kurdish uprising in March 1991, Iraqi troops recaptured most of the Kurdish areas and 1.5 million Kurds abandoned their homes and fled to the Turkish and Iranian borders. It is estimated that close to 20,000 Kurds succumbed to death due to exhaustion, lack of food, exposure to cold and disease. On 5 April 1991, UN Security Council passed resolution 688 which condemned the repression of Iraqi Kurdish civilians and demanded that Iraq end its repressive measures and allow immediate access to international humanitarian organizations.[244] This was the first international document (since the League of Nations arbitration of Mosul in 1926) to mention Kurds by name. In mid-April, the Coalition established safe havens inside Iraqi borders and prohibited Iraqi planes from flying north of 36th parallel.[107]: 373, 375 In October 1991, Kurdish guerrillas captured Erbil and Sulaimaniyah after a series of clashes with Iraqi troops. In late October, Iraqi government retaliated by imposing a food and fuel embargo on the Kurds and stopping to pay civil servants in the Kurdish region. The embargo, however, backfired and Kurds held parliamentary elections in May 1992 and established Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).[245]

The Kurdish population welcomed the American troops in 2003 by holding celebrations and dancing in the streets.[246][247][248][249] The area controlled by Peshmerga was expanded, and Kurds now have effective control in Kirkuk and parts of Mosul. The authority of the KRG and legality of its laws and regulations were recognized in the articles 113 and 137 of the new Iraqi Constitution ratified in 2005.[250] By the beginning of 2006, the two Kurdish administrations of Erbil and Sulaimaniya were unified. On 14 August 2007, Yazidis were targeted in a series of bombings that became the deadliest suicide attack since the Iraq War began, killing 796 civilians, wounding 1,562.[251]

Syria

Kurds account for 9% of Syria's population, a total of around 1.6 million people.[252] This makes them the largest ethnic minority in the country. They are mostly concentrated in the northeast and the north, but there are also significant Kurdish populations in Aleppo and Damascus. Kurds often speak Kurdish in public, unless all those present do not. According to Amnesty International, Kurdish human rights activists are mistreated and persecuted.[253] No political parties are allowed for any group, Kurdish or otherwise.

Techniques used to suppress the ethnic identity of Kurds in Syria include various bans on the use of the Kurdish language, refusal to register children with Kurdish names, the replacement of Kurdish place names with new names in Arabic, the prohibition of businesses that do not have Arabic names, the prohibition of Kurdish private schools, and the prohibition of books and other materials written in Kurdish.[254][255] Having been denied the right to Syrian nationality, around 300,000 Kurds have been deprived of any social rights, in violation of international law.[256][257] As a consequence, these Kurds are in effect trapped within Syria. In March 2011, in part to avoid further demonstrations and unrest from spreading across Syria, the Syrian government promised to tackle the issue and grant Syrian citizenship to approximately 300,000 Kurds who had been previously denied the right.[258]

On 12 March 2004, beginning at a stadium in Qamishli (a largely Kurdish city in northeastern Syria), clashes between Kurds and Syrians broke out and continued over a number of days. At least thirty people were killed and more than 160 injured. The unrest spread to other Kurdish towns along the northern border with Turkey, and then to Damascus and Aleppo.[259][260]

As a result of Syrian civil war, since July 2012, Kurds were able to take control of large parts of Syrian Kurdistan from Andiwar in extreme northeast to Jindires in extreme northwest Syria. The Syrian Kurds started the Rojava Revolution in 2013.

Kurdish-inhabited Afrin Canton has been occupied by Turkish Armed Forces and Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army since the Turkish military operation in Afrin in early 2018. Between 150,000 and 200,000 people were displaced due to the Turkish intervention.[261]

In October 2019, Turkey and the Syrian Interim Government began an offensive into Kurdish-populated areas in Syria, prompting about 100,000 civilians to flee from the area fearing that Turkey would commit an ethnic cleansing.[262][263]

Transcaucasus

Between the 1930s and 1980s, Armenia was a part of the Soviet Union, within which Kurds, like other ethnic groups, had the status of a protected minority. Armenian Kurds were permitted their own state-sponsored newspaper, radio broadcasts and cultural events. During the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, many non-Yazidi Kurds were forced to leave their homes since both the Azeri and non-Yazidi Kurds were Muslim.

In 1920, two Kurdish-inhabited areas of Jewanshir (capital Kalbajar) and eastern Zangazur (capital Lachin) were combined to form the Kurdistan Okrug (or "Red Kurdistan"). The period of existence of the Kurdish administrative unit was brief and did not last beyond 1929. Kurds subsequently faced many repressive measures, including deportations, imposed by the Soviet government. As a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, many Kurdish areas have been destroyed and more than 150,000 Kurds have been deported since 1988 by separatist Armenian forces.[264]

Diaspora

According to a report by the Council of Europe, approximately 1.3 million Kurds live in Western Europe. The earliest immigrants were Kurds from Turkey, who settled in Germany, Austria, the Benelux countries, the United Kingdom, Switzerland and France during the 1960s. Successive periods of political and social turmoil in the region during the 1980s and 1990s brought new waves of Kurdish refugees, mostly from Iran and Iraq under Saddam Hussein, came to Europe.[151] In recent years, many Kurdish asylum seekers from both Iran and Iraq have settled in the United Kingdom (especially in the town of Dewsbury and in some northern areas of London), which has sometimes caused media controversy over their right to remain.[265] There have been tensions between Kurds and the established Muslim community in Dewsbury,[266][267] which is home to very traditional mosques such as the Markazi. Since the beginning of the turmoil in Syria many of the refugees of the Syrian Civil War are Syrian Kurds and as a result many of the current Syrian asylum seekers in Germany are of Kurdish descent.[268][269]

There was substantial immigration of ethnic Kurds in Canada and the United States, who are mainly political refugees and immigrants seeking economic opportunity. According to a 2011 Statistics Canada household survey, there were 11,685 people of Kurdish ethnic background living in Canada,[270] and according to the 2011 Census, 10,325 Canadians spoke Kurdish languages.[271] In the United States, Kurdish immigrants started to settle in large numbers in Nashville in 1976,[272] which is now home to the largest Kurdish community in the United States and is nicknamed Little Kurdistan.[273] Kurdish population in Nashville is estimated to be around 11,000.[274] The total number of ethnic Kurds residing in the United States is estimated by the US Census Bureau to be 20,591.[25] Other sources claim that there are 20,000 ethnic Kurds in the United States.[275]

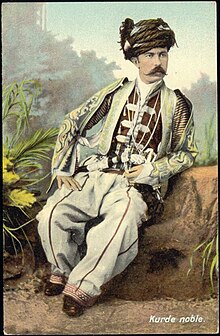

Culture

Kurdish culture is a legacy from the various ancient peoples who shaped modern Kurds and their society. As most other Middle Eastern populations, a high degree of mutual influences between the Kurds and their neighbouring peoples are apparent. Therefore, in Kurdish culture elements of various other cultures are to be seen. However, on the whole, Kurdish culture is closest to that of other Iranian peoples, in particular those who historically had the closest geographical proximity to the Kurds, such as the Persians and Lurs. Kurds, for instance, also celebrate Newroz (21 March) as New Year's Day.[276]

Education

A madrasa system was used before the modern era.[277][278] Mele are Islamic clerics and instructors.[279]

Women

In general, Kurdish women's rights and equality have improved in the 20th and 21st centuries due to progressive movements within Kurdish society. However, despite the progress, Kurdish and international women's rights organizations still report problems related to gender equality, forced marriages, honor killings and in Iraqi Kurdistan also female genital mutilation (FGM).[280]

Folklore

The Kurds possess a rich tradition of folklore, which, until recent times, was largely transmitted by speech or song, from one generation to the next. Although some of the Kurdish writers' stories were well known throughout Kurdistan; most of the stories told and sung were only written down in the 20th and 21st centuries. Many of these are, allegedly, centuries old.

Widely varying in purpose and style, among the Kurdish folklore one will find stories about nature, anthropomorphic animals, love, heroes and villains, mythological creatures and everyday life. A number of these mythological figures can be found in other cultures, like the Simurgh and Kaveh the Blacksmith in the broader Iranian Mythology, and stories of Shahmaran throughout Anatolia. Additionally, stories can be purely entertaining, or have an educational or religious aspect.[281]

Perhaps the most widely reoccurring element is the fox, which, through cunning and shrewdness triumphs over less intelligent species, yet often also meets his demise.[281] Another common theme in Kurdish folklore is the origin of a tribe.

Storytellers would perform in front of an audience, sometimes consisting of an entire village. People from outside the region would travel to attend their narratives, and the storytellers themselves would visit other villages to spread their tales. These would thrive especially during winter, where entertainment was hard to find as evenings had to be spent inside.[281]

Coinciding with the heterogeneous Kurdish groupings, although certain stories and elements were commonly found throughout Kurdistan, others were unique to a specific area; depending on the region, religion or dialect. The Kurdish Jews of Zakho are perhaps the best example of this; their gifted storytellers are known to have been greatly respected throughout the region, thanks to a unique oral tradition.[282] Other examples are the mythology of the Yezidis,[283] and the stories of the Dersim Kurds, which had a substantial Armenian influence.[284]

During the criminalization of the Kurdish language after the coup d'état of 1980, dengbêj (singers) and çîrokbêj (tellers) were silenced, and many of the stories had become endangered. In 1991, the language was decriminalized, yet the now highly available radios and TV's had as an effect a diminished interest in traditional storytelling.[285] However, a number of writers have made great strides in the preservation of these tales.

Weaving

Kurdish weaving is renowned throughout the world, with fine specimens of both rugs and bags. The most famous Kurdish rugs are those from the Bijar region, in the Kurdistan Province. Because of the unique way in which the Bijar rugs are woven, they are very stout and durable, hence their appellation as the 'Iron Rugs of Persia'. Exhibiting a wide variety, the Bijar rugs have patterns ranging from floral designs, medallions and animals to other ornaments. They generally have two wefts, and are very colorful in design.[286] With an increased interest in these rugs in the last century, and a lesser need for them to be as sturdy as they were, new Bijar rugs are more refined and delicate in design.

Another well-known Kurdish rug is the Senneh rug, which is regarded as the most sophisticated of the Kurdish rugs. They are especially known for their great knot density and high-quality mountain wool.[286] They lend their name from the region of Sanandaj. Throughout other Kurdish regions like Kermanshah, Siirt, Malatya and Bitlis rugs were also woven to great extent.[287]

Kurdish bags are mainly known from the works of one large tribe: the Jaffs, living in the border area between Iran and Iraq. These Jaff bags share the same characteristics of Kurdish rugs; very colorful, stout in design, often with medallion patterns. They were especially popular in the West during the 1920s and 1930s.[288]

Handicrafts

Outside of weaving and clothing, there are many other Kurdish handicrafts, which were traditionally often crafted by nomadic Kurdish tribes. These are especially well known in Iran, most notably the crafts from the Kermanshah and Sanandaj regions. Among these crafts are chess boards, talismans, jewelry, ornaments, weaponry, instruments etc.[citation needed]

Kurdish blades include a distinct jambiya, with its characteristic I-shaped hilt, and oblong blade. Generally, these possess double-edged blades, reinforced with a central ridge, a wooden, leather or silver decorated scabbard, and a horn hilt, furthermore they are often still worn decoratively by older men. Swords were made as well. Most of these blades in circulation stem from the 19th century.

Another distinct form of art from Sanandaj is 'Oroosi', a type of window where stylized wooden pieces are locked into each other, rather than being glued together. These are further decorated with coloured glass, this stems from an old belief that if light passes through a combination of seven colours it helps keep the atmosphere clean.

Among Kurdish Jews a common practice was the making of talismans, which were believed to combat illnesses and protect the wearer from malevolent spirits.

Tattoos

Adorning the body with tattoos (deq in Kurdish) is widespread among the Kurds; even though permanent tattoos are not permissible in Sunni Islam. Therefore, these traditional tattoos are thought to derive from pre-Islamic times.[289]

Tattoo ink is made by mixing soot with (breast) milk and the poisonous liquid from the gall bladder of an animal. The design is drawn on the skin using a thin twig and is injected under the skin using a needle. These have a wide variety of meanings and purposes, among which are protection against evil or illnesses; beauty enhancement; and the showing of tribal affiliations. Religious symbolism is also common among both traditional and modern Kurdish tattoos. Tattoos are more prevalent among women than among men, and were generally worn on feet, the chin, foreheads and other places of the body.[289][290]

The popularity of permanent, traditional tattoos has greatly diminished among newer generation of Kurds. However, modern tattoos are becoming more prevalent; and temporary tattoos are still being worn on special occasions (such as henna, the night before a wedding) and as tribute to the cultural heritage.[289]

Music and dance

Traditionally, there are three types of Kurdish classical performers: storytellers (çîrokbêj), minstrels (stranbêj), and bards (dengbêj). No specific music was associated with the Kurdish princely courts. Instead, music performed in night gatherings (şevbihêrk) is considered classical. Several musical forms are found in this genre. Many songs are epic in nature, such as the popular Lawiks, heroic ballads recounting the tales of Kurdish heroes such as Saladin. Heyrans are love ballads usually expressing the melancholy of separation and unfulfilled love. One of the first Kurdish female singers to sing heyrans is Chopy Fatah, while Lawje is a form of religious music and Payizoks are songs performed during the autumn. Love songs, dance music, wedding and other celebratory songs (dîlok/narînk), erotic poetry, and work songs are also popular.[citation needed]

Throughout the Middle East, there are many prominent Kurdish artists. Most famous are Ibrahim Tatlises, Nizamettin Arıç, Ahmet Kaya and the Kamkars. In Europe, well-known artists are Darin Zanyar, Sivan Perwer, and Azad.

Cinema

The main themes of Kurdish cinema are the poverty and hardship which ordinary Kurds have to endure. The first films featuring Kurdish culture were actually shot in Armenia. Zare, released in 1927, produced by Hamo Beknazarian, details the story of Zare and her love for the shepherd Seydo, and the difficulties the two experience by the hand of the village elder.[291] In 1948 and 1959, two documentaries were made concerning the Yezidi Kurds in Armenia. These were joint Armenian-Kurdish productions; with H. Koçaryan and Heciye Cindi teaming up for The Kurds of Soviet Armenia,[292] and Ereb Samilov and C. Jamharyan for Kurds of Armenia.[292]

The first critically acclaimed and famous Kurdish films were produced by Yılmaz Güney. Initially a popular, award-winning actor in Turkey with the nickname Çirkin Kral (the Ugly King, after his rough looks), he spent the later part of his career producing socio-critical and politically loaded films. Sürü (1979), Yol (1982) and Duvar (1983) are his best-known works, of which the second won Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival of 1982,[293] the most prestigious award in the world of cinema.

Another prominent Kurdish film director is Bahman Qubadi. His first feature film was A Time for Drunken Horses, released in 2000. It was critically acclaimed, and went on to win multiple awards. Other movies of his would follow this example,[294] making him one of the best known film producers of Iran of today. Recently, he released Rhinos Season, starring Behrouz Vossoughi, Monica Bellucci and Yilmaz Erdogan, detailing the tumultuous life of a Kurdish poet.

Other prominent Kurdish film directors that are critically acclaimed include Mahsun Kırmızıgül, Hiner Saleem and the aforementioned Yilmaz Erdogan. There's also been a number of films set or filmed in Kurdistan made by non-Kurdish film directors, such as The Wind Will Carry Us, Triage, The Exorcist, and The Market: A Tale of Trade.

Sports

The most popular sport among the Kurds is football. Because the Kurds have no independent state, they have no representative team in FIFA or the AFC; however a team representing Iraqi Kurdistan has been active in the Viva World Cup since 2008. They became runners-up in 2009 and 2010, before ultimately becoming champion in 2012.

On a national level, the Kurdish clubs of Iraq have achieved success in recent years as well, winning the Iraqi Premier League four times in the last five years. Prominent clubs are Erbil SC, Duhok SC, Sulaymaniyah FC and Zakho FC.

In Turkey, a Kurd named Celal Ibrahim was one of the founders of Galatasaray S.K. in 1905, as well as one of the original players. The most prominent Kurdish-Turkish club is Diyarbakirspor. In the diaspora, the most successful Kurdish club is Dalkurd FF and the most famous player is Eren Derdiyok.[295]

Another prominent sport is wrestling. In Iranian Wrestling, there are three styles originating from Kurdish regions:

- Zhir-o-Bal (a style similar to Greco-Roman wrestling), practised in Kurdistan, Kermanshah and Ilam;[296]

- Zouran-Patouleh, practised in Kurdistan;[296]

- Zouran-Machkeh, practised in Kurdistan as well.[296]

Furthermore, the most accredited of the traditional Iranian wrestling styles, the Bachoukheh, derives its name from a local Khorasani Kurdish costume in which it is practised.[296]

Kurdish medalists in the 2012 Summer Olympics were Nur Tatar,[297] Kianoush Rostami and Yezidi Misha Aloyan;[298] who won medals in taekwondo, weightlifting and boxing, respectively.

Architecture

The traditional Kurdish village has simple houses, made of mud. In most cases with flat, wooden roofs, and, if the village is built on the slope of a mountain, the roof on one house makes for the garden of the house one level higher. However, houses with a beehive-like roof, not unlike those in Harran, are also present.

Over the centuries many Kurdish architectural marvels have been erected, with varying styles. Kurdistan boasts many examples from ancient Iranian, Roman, Greek and Semitic origin, most famous of these include Bisotun and Taq-e Bostan in Kermanshah, Takht-e Soleyman near Takab, Mount Nemrud near Adiyaman and the citadels of Erbil and Diyarbakir.

The first genuinely Kurdish examples extant were built in the 11th century. Those earliest examples consist of the Marwanid Dicle Bridge in Diyarbakir, the Shadaddid Minuchir Mosque in Ani,[299] and the Hisn al Akrad near Homs.[300]

In the 12th and 13th centuries the Ayyubid dynasty constructed many buildings throughout the Middle East, being influenced by their predecessors, the Fatimids, and their rivals, the Crusaders, whilst also developing their own techniques.[301] Furthermore, women of the Ayyubid family took a prominent role in the patronage of new constructions.[302] The Ayyubids' most famous works are the Halil-ur-Rahman Mosque that surrounds the Pool of Sacred Fish in Urfa, the Citadel of Cairo[303] and most parts of the Citadel of Aleppo.[304] Another important piece of Kurdish architectural heritage from the late 12th/early 13th centuries is the Yezidi pilgrimage site Lalish, with its trademark conical roofs.

In later periods too, Kurdish rulers and their corresponding dynasties and emirates would leave their mark upon the land in the form mosques, castles and bridges, some of which have decayed, or have been (partly) destroyed in an attempt to erase the Kurdish cultural heritage, such as the White Castle of the Bohtan Emirate. Well-known examples are Hosap Castle of the 17th century,[305] Sherwana Castle of the early 18th century, and the Ellwen Bridge of Khanaqin of the 19th century.

Most famous is the Ishak Pasha Palace of Dogubeyazit, a structure with heavy influences from both Anatolian and Iranian architectural traditions. Construction of the Palace began in 1685, led by Colak Abdi Pasha, a Kurdish bey of the Ottoman Empire, but the building would not be completed until 1784, by his grandson, Ishak Pasha.[306][307] Containing almost 100 rooms, including a mosque, dining rooms, dungeons and being heavily decorated by hewn-out ornaments, this Palace has the reputation as being one of the finest pieces of architecture of the Ottoman Period, and of Anatolia.

In recent years, the KRG has been responsible for the renovation of several historical structures, such as Erbil Citadel and the Mudhafaria Minaret.[308]

Genetics

A 2005 study genetically examined three different groups of Zaza and Kurmanji speakers in Turkey and Kurmanji speakers in Georgia. In the study, mtDNA HV1 sequences, eleven Y chromosome bi-allelic markers and 9 Y-STR loci were analyzed to investigate lineage relationship among Kurdish groups. When both mtDNA and Y chromosome data are compared with those of the European, Caucasian, West Asian and Central Asian groups, it has been determined that the Kurdish groups are most closely related to West Asians and the furthest to Central Asians. Among the European and Caucasian groups, Kurds were found to be closer to Europeans than Caucasians when considering mtDNA, and the opposite was true for Y chromosome. This indicates a difference in maternal and paternal origins of Kurdish groups. According to the study, Kurdish groups in Georgia went through a genetic bottleneck while migrating to the Caucasus. It has also been revealed that these groups were not influenced by other Caucasian groups in terms of ancestry. Another phenomenon found in the research was that Zazas are closer to Kurdish groups rather than peoples of Northern Iran, where ancestral Zaza language hypothesized to be spoken before its spread to Anatolia.[309]

11 different Y-DNA haplogroups have been identified in Kurmanji-speaking Kurds in Turkey. Haplogroup I-M170 was the most prevalent with 16.1% of the samples belonging to it, followed by haplogroups J-M172 (13.8%), R1a1 (12.7%), K (12.7%), E (11.5%) and F (11.5%). P1 (8%), P (5.7%), R1 (4.6%), G (2.3%) and C (1.1%) haplogroups were also present in lower proportions. Y-DNA haplogroup diversity were determined to be much lower among Georgian Kurds, as 5 haplogroups were discovered in total, where the dominant haplogroups were P1 (44%) and J-M172 (32%). The lowest Y-DNA haplogroup diversity was observed in Turkmenistan Kurds with only 4 haplogroups in total; F (41%) and R1 (29%) were dominant in this population.[310][309]

Modern Kurdish-majority entities and governments

- Kurdistan Region (1992 to date) – Autonomous region in Iraq

- Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (2013 to date) – Autonomy of Syria

Gallery

-

Mercier. Kurde (Asie) by Auguste Wahlen, 1843

-

Kurdish warriors by Amadeo Preziosi

-

Armenian, Turkish and Kurdish females in their traditional clothes, 1873

-

Zakho Kurds by Albert Kahn, 1910s

-

Kurdish Cavalry in the passes of the Caucasus mountains (The New York Times, January 24, 1915)

-

A Kurdish chief

-

A Kurdish woman and a child from Bisaran, Eastern Kurdistan, 2017

-

A group of Kurdish men with traditional clothing, Hawraman

-

A Kurdish man wearing traditional clothes, Erbil

-

A Kurdish woman fighter from Rojava

See also

- A Modern History of the Kurds by David McDowall

- Chechen Kurds

- History of the Kurdish people

- Kurdology

- Kurds in Georgia

- Kurds in Lebanon

- Kurds in Turkey

- Khorasani Kurds

- List of Kurdish dynasties and countries

- List of Kurdish organisations

- List of Kurdish people

- National symbols of the Kurds

- Origins of the Kurds

- Zaza Kurds

References

Explanatory notes

Citations

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i The World Factbook (Online ed.). Langley, Virginia: US Central Intelligence Agency. 2015. ISSN 1553-8133. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2015. A rough estimate in this edition gives populations of 14.3 million in Turkey, 8.2 million in Iran, about 5.6 to 7.4 million in Iraq, and less than 2 million in Syria, which adds up to approximately 28–30 million Kurds in Kurdistan or in adjacent regions. The CIA estimates are as of August 2015[update] – Turkey: Kurdish 18%, of 81.6 million; Iran: Kurd 10%, of 81.82 million; Iraq: Kurdish 15–20%, of 37.01 million, Syria: Kurds, Armenians, and other 9.7%, of 17.01 million.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f The Kurdish Population by the Kurdish Institute of Paris, 2017 estimate. The Kurdish population is estimated at 15–20 million in Turkey, 10–12 million in Iran, 8–8.5 million in Iraq, 3–3.6 million in Syria, 1.2–1.5 million in the European diaspora, and 400k–500k in the former USSR—for a total of 36.4 million to 45.6 million globally.

- ^ ""Wir Kurden ärgern uns über die Bundesregierung" – Politik". Süddeutsche.de. 21 March 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ "Geschenk an Erdogan? Kurdisches Kulturfestival verboten". heise.de. 5 September 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ The cultural situation of the Kurds, A report by Lord Russell-Johnston, Council of Europe, July 2006.

- ^ Ismet Chériff Vanly, "The Kurds in the Soviet Union", in: Philip G. Kreyenbroek & S. Sperl (eds.), The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview (London: Routledge, 1992). pg 164: Table based on 1990 estimates: Azerbaijan (180,000), Armenia (50,000), Georgia (40,000), Kazakhstan (30,000), Kyrghizistan (20,000), Uzbekistan (10,000), Tajikistan (3,000), Turkmenistan (50,000), Siberia (35,000), Krasnodar (20,000), Other (12,000), Total 450,000

- ^ "3 Kurdish women political activists shot dead in Paris". CNN. 11 January 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ "NATO Membership for Sweden: Between Turkey and the Kurds". The Washington Institute. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "Will exiled Kurds pay price of Sweden's NATO entry?". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "NATO bid reignites Sweden's dispute with Turkey over Kurds". POLITICO. 24 May 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ TT (23 September 2017). "Svenskkurder: Självständighet kan inte vänta". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). ISSN 1101-2412. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "Diaspora Kurde". Institutkurde.org (in French). Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 г. Национальный состав населения Российской Федерации". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ "The Kurdish Diaspora". Institut Kurde de Paris. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ "QS211EW – Ethnic group (detailed)". nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ "Ethnic Group – Full Detail_QS201NI" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "Scotland's Census 2011 – National Records of Scotland – Ethnic group (detailed)" (PDF). Scotland Census. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ "Ethnic composition of Kazakhstan 2021". Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Information from the 2011 Armenian National Census" (PDF). Statistics of Armenia (in Armenian). Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Switzerland". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ "Fakta: Kurdere i Danmark". Jyllandsposten (in Danish). 8 May 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Al-Khatib, Mahmoud A.; Al-Ali, Mohammed N. "Language and Cultural Shift Among the Kurds of Jordan" (PDF). p. 12. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Austria". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ "Greece". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "2011–2015 American Community Survey Selected Population Tables". Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ "Ethnic Origin (279), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census". 25 October 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ "Language according to age and sex by region 1990 – 2021". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Population/Census" (PDF). geostat.ge.

- ^ "Number of resident population by selected nationality" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Australia – Ancestry". 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Atlas of the Languages of Iran A working classification". Languages of Iran. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Michiel Leezenberg (1993). "Gorani Influence on Central Kurdish: Substratum or Prestige Borrowing?" (PDF). ILLC – Department of Philosophy, University of Amsterdam: 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Kurds in Turkey".

- ^ "Learn About Kurdish Religion".

- ^ "Kurds of Iran: The missing piece in the Middle East Puzzle".

- ^ Bois, Th.; Minorsky, V.; MacKenzie, D.N. (24 April 2012). "Kurds, Kurdistān". Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. 5. Brill Online. p. 439.

The Kurds, an Iranian people of the Near East, live at the junction of (...)

- ^ Shoup, John A. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598843637.

- ^ Nezan, Kendal. A Brief Survey of the History of the Kurds. Kurdish Institute of Paris.

- ^ Bengio, Ofra (2014). Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-75813-1.

- ^ Based on arithmetic from World Factbook and other sources cited herein: A Near Eastern population of 28–30 million, plus approximately a 2 million diaspora gives 30–32 million. If the highest (25%) estimate for the Kurdish population of Turkey, in Mackey (2002), proves correct, this would raise the total to around 37 million.

- ^ "Kurds". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Encyclopedia.com. 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Windfuhr (2013). Iranian Languages. Routledge. p. 587. ISBN 978-1135797041.

- ^ "Timeline: The Kurds' Quest for Independence".

- ^ Who are the Kurds? by BBC News, 31 October 2017

- ^ Asatrian, G. (2009). Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds, Iran and the Caucasus. Vol. 13. pp. 1–58.

Generally, the etymons and primary meanings of tribal names or ethnonyms, as well as place names, are often irrecoverable; Kurd is also an obscurity

- ^ Рейнольдс, GS (октябрь -декабрь 2004 г.). «Размышления о двух корановых словах (Иблиса и Джуди), с вниманием к теориям А. Минганы». Журнал Американского восточного общества . 124 (4): 683, 684, 687. doi : 10.2307/4132112 . ISSN 0003-0279 . JSTOR 4132112 .

- ^ Илья Гершевич, Уильям Бэйн Фишер, «Кембриджская история Ирана: средний и ахаменский период», 964 с., Издательство Кембриджского университета, 1985, 1985 г. ISBN 0-521-20091-1 , ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2 (см. Сноску с.257)

- ^ G. asatrian, Prolegomena для изучения курдов, Ирана и Кавказа, том 13, с. 1–58, 2009 год: «Очевидно, что наиболее разумное объяснение этого этнонического Cyrtii (Cyrtaei) из классических авторов ».

- ^ Карнак Ардашир Папакан и Матадакан I Хазар Дастан . Г. Асатриан, Пролегомена для изучения курдов, Ирана и Кавказа, том 13, стр. 1–58, 2009. Выдержка 1: «Как правило, этимоны и первичные значения имен племен или этнонимов, а также место Имена часто невозможно; «Понятно, что Курт во всех контекстах имеет отчетливый социальный смысл,-кочевник, палаток». В равной степени это может быть атрибутом для любой иранской этнической группы, имеющей аналогичные характеристики. P. 24: «Материалы Pahlavi ясно показывают, что курд в доисламском Иране был социальным лейблом, все еще далеким от того, чтобы стать этнонимом или термином, обозначающим отдельную группу людей».

- ^ МакДауалл, Дэвид. 2000. Современная история курдов . Второе издание. Лондон: IB Tauris. п. 9

- ^ G. Asatrian, Prolegomena для изучения курдов, Ирана и Кавказа, том 13, с. 1–58, 2009