Surname

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2023) |

A surname, family name, or last name is the mostly hereditary portion of one's personal name that indicates one's family.[1][2] It is typically combined with a given name to form the full name of a person, although several given names and surnames are possible in the full name. In modern times the "hereditary" requirement is a traditional, although common, interpretation, since in most countries a person has a right for a name change.[citation needed]

В зависимости от культуры фамилия может располагаться либо в начале имени человека, либо в конце. Количество фамилий, присвоенных человеку, также варьируется: в большинстве случаев это всего лишь одна, но во многих испаноязычных странах в юридических целях используются две фамилии. В зависимости от культуры не все члены семьи обязаны иметь одинаковые фамилии. В некоторых странах фамилии видоизменяются в зависимости от пола и семейного статуса человека. Сложные фамилии могут состоять из отдельных имен. [3]

Использование имен зафиксировано даже в самых старых исторических записях. Примеры фамилий задокументированы в 11 веке баронами Англии . Английские фамилии возникли как способ идентификации определенных аспектов личности, например, по профессии, имени отца, месту рождения или физическим особенностям, и не обязательно передавались по наследству. К 1400 году большинство английских семей, а также семей из Лоулендской Шотландии, переняли использование наследственных фамилий. [4]

Изучение имен собственных (в фамилиях, личных именах или местах) называется ономастикой .

История

[ редактировать ]Источник

[ редактировать ]Хотя использование имен для идентификации людей засвидетельствовано в самых старых исторических записях, фамилии появились относительно недавно. [5] Многие культуры использовали и продолжают использовать дополнительные описательные термины для идентификации людей. Эти термины могут указывать личные качества, место происхождения, род занятий, происхождение, покровительство, усыновление или принадлежность к клану. [6]

В Китае, согласно легенде, фамилии начались с императора Фу Си в 2000 году до нашей эры. [7] Его администрация стандартизировала систему именования, чтобы облегчить проведение переписи и использование переписной информации. Первоначально китайские фамилии возникли по материнской линии. [8] хотя ко времени династии Шан (1600–1046 гг. До н.э.) они стали отцовскими. [8] [9] Китайские женщины не меняют своих имен после замужества. [10] В Китае фамилии были нормой, по крайней мере, со II века до нашей эры. [11]

В ранний исламский период (640–900 гг. н.э.) и в арабском мире использование отчеств хорошо засвидетельствовано. Знаменитый ученый Разес ( ок. 865–925 гг. н. э .) упоминается как «ар-Рази» (буквально «из Рэя») из-за его происхождения из города Рэй , Иран. В Леванте фамилии использовались еще в эпоху высокого средневековья , и люди обычно получали свою фамилию от далекого предка, и исторически перед фамилией часто стояло «ибн» или «сын». Арабские фамилии часто обозначают племя , профессию , известного предка или место происхождения; но они не были универсальными. Например, Хунейн ибн Исхак (ок. 850 г. н. э.) был известен нисбахом «аль-Ибади», федерацией арабских христианских племен, живших в Месопотамии до появления ислама .

В Древней Греции, еще в архаический период, клановые имена и отчества («сын») также были распространены, как у Аристида как Λῡσῐμᾰ́χου - форма родительного падежа единственного числа, означающая сына Лисимаха. Например, Александр Великий был известен как Гераклид , как предполагаемый потомок Геракла , и под династическим именем Каранос / Каран , которое относилось к основателю династии, к которой он принадлежал . Эти отчества засвидетельствованы уже у многих персонажей произведений Гомера . В других случаях формальная идентификация обычно включала место происхождения. [12]

В период существования Римской республики и более поздней Империи соглашения об именах претерпели множество изменений. ( См. римские соглашения об именах . ) Номен , название рода ( племени), унаследованное по отцовской линии, как полагают, уже использовалось к 650 году до нашей эры. [13] Номен преномен должен был идентифицировать групповое родство, в то время как ( имя; множественное число преномина ) использовался для различения людей внутри группы. Женские преномины были менее распространены, поскольку женщины имели меньшее общественное влияние и были широко известны только по женской форме номена .

Средневековая эпоха и не только

[ редактировать ]Позже, с постепенным влиянием греческой и христианской культуры по всей Империи, христианские религиозные имена иногда ставились вместо традиционных прозвищ , но в конечном итоге люди вернулись к отдельным именам. [14] Ко времени падения Западной Римской империи в V веке фамилии были редкостью в Восточной Римской империи . В Западной Европе, где среди аристократии доминировала германская культура, фамилий почти не существовало. Они не появлялись снова в восточно-римском обществе до X века, очевидно, под влиянием семейной принадлежности армянской военной аристократии. [14] Практика использования фамилий распространилась по Восточной Римской империи, однако только в 11 веке фамилии стали использоваться в Западной Европе. [15]

Средневековая Испания использовала систему отчеств. Например, Альваро, сына Родриго, будут называть Альваро Родригес. Его сына Хуана будут звать не Хуан Родригес, а Хуан Альварес. Со временем многие из этих отчеств стали фамилиями и сегодня являются одними из самых распространенных имен в испаноязычном мире. Другими источниками фамилий являются внешний вид или привычки, например Дельгадо («худой») и Морено («темный»); географическое положение или этническая принадлежность, например, Алеман («немец»); и профессии, например, Молинеро («мельник»), Сапатеро («обувщик») и Герреро («воин»), хотя названия профессий гораздо чаще встречаются в сокращенной форме, относящейся к самой профессии, например Молина («мельница» «), Гуэрра («война») или Сапата (архаичная форма сапато , «обувь»). [16]

В Англии введение фамилий обычно связывают с подготовкой Книги судного дня в 1086 году, после норманнского завоевания . Факты указывают на то, что фамилии впервые были приняты среди феодальной знати и дворянства и постепенно распространились на другие части общества. Некоторые представители ранней нормандской знати, прибывшие в Англию во время нормандского завоевания, отличались тем, что добавляли букву «де» (оф) перед названием своей деревни во Франции. Это так называемая территориальная фамилия, следствие феодального землевладения. К 14 веку большинство англичан и большинство шотландцев использовали фамилии, а также в Уэльсе после объединения при Генрихе VIII в 1536 году. [17]

Четырехлетнее исследование, проведенное Университетом Западной Англии , завершившееся в 2016 году, проанализировало источники, датируемые 11-19 веками, чтобы объяснить происхождение фамилий на Британских островах . [18] Исследование показало, что более 90% из 45 602 фамилий в словаре являются родными для Великобритании и Ирландии, причем наиболее распространенными в Великобритании являются Смит , Джонс , Уильямс , Браун , Тейлор , Дэвис и Уилсон . [19] Результаты были опубликованы в Оксфордском английском словаре фамилий в Великобритании и Ирландии , а руководитель проекта Ричард Коутс назвал исследование «более подробным и точным», чем предыдущие. [18] Он подробно остановился на происхождении: «Некоторые фамилии имеют профессиональное происхождение – очевидными примерами являются Смит и Бейкер. Другие имена могут быть связаны с местом , например, Хилл или Грин, что связано с деревенской зеленью . - это те, в которых изначально запечатлено имя отца, например Джексон или Дженкинсон . Есть также имена, происхождение которых описывает первоначального носителя, например Браун, Шорт или Тонкий, хотя на самом деле Шорт может быть иронической фамилией «прозвище». высокий человек». [18]

В современную эпоху правительства приняли законы, требующие от людей брать фамилии. Это служило цели однозначной идентификации субъектов для целей налогообложения или наследования. [20] В эпоху позднего средневековья в Европе произошло несколько восстаний против мандата иметь фамилию. [21]

Современная эпоха

[ редактировать ]В современную эпоху многие культуры по всему миру приняли фамилии, особенно по административным причинам, особенно в эпоху европейской экспансии и особенно с 1600 года. Кодекс Наполеона, принятый в различных частях Европы, предусматривал, что люди должны быть известны как их имя (имена) и фамилия, которые не будут меняться из поколения в поколение. Другие известные примеры включают Нидерланды (1795–1811 гг.), Японию (1870-е гг.), Таиланд (1920 г.) и Турцию (1934 г.). Структура японского имени была официально оформлена правительством как фамилия + имя в 1868 году. [22]

В Бреслау Пруссия в 1790 году приняла Указ о Хойме, предписывающий принять еврейские фамилии. [ нужна ссылка ] [23] Наполеон также настоял на том, чтобы евреи приняли фиксированные имена в указе, изданном в 1808 году. [24]

Иногда имена могут быть изменены для защиты частной жизни (например, при защите свидетелей ) или в случаях, когда группы людей спасаются от преследования. [25] После прибытия в Соединенные Штаты европейские евреи, бежавшие от нацистских преследований, иногда переводили свои фамилии на английский язык, чтобы избежать дискриминации. [26] Правительства также могут принудительно менять имена людей, как это было, когда национал-социалистическое правительство Германии присвоило немецкие имена европейцам на завоеванных ими территориях. [27] В 1980-х годах Народная Республика Болгария принудительно изменила имена и фамилии своих турецких граждан на болгарские имена. [28]

Происхождение отдельных фамилий

[ редактировать ]Отчество и матронимические фамилии

[ редактировать ]Это самый старый и распространенный тип фамилии. [29] Это может быть имя, например «Вильгельм», отчество, например « Андерсен », матроним, например « Битон », или название клана, например « О'Брайен ». Несколько фамилий могут быть образованы от одного имени: например, считается, что существует более 90 итальянских фамилий, основанных на имени « Джованни ». [29]

Примеры

[ редактировать ]- Покровительственный покровительство ( Хикман означает «человек Хика», где Хик — любимая форма имени Ричард) или сильные религиозные связи Килпатрик (последователь Патрика ) или Килбрайд (последователь святой Бригиты Килдэр ). [ нужна ссылка ]

- Отчество , матронимика или родовое , часто от имени человека. например, от мужского имени: Ричардсон , Стивенсон , Джонс (по-валлийски Джонсон), Уильямс , Джексон , Уилсон , Томпсон , Бенсон , Джонсон , Харрис , Эванс , Симпсон , Уиллис , Дэвис , Рейнольдс , Адамс , Доусон , Льюис , Роджерс , Мерфи , Морроу , Николсон , Робинсон , Пауэлл , Фергюсон , Дэвис , Эдвардс , Хадсон , Робертс , Харрисон , Уотсон , или женские имена Молсон (от Молл для Мэри), Мэдисон (от Мод), Эммотт (от Эмма), Марриотт (от Мэри) ) или от имени клана (для лиц шотландского происхождения, например, Макдональд , Форбс , Хендерсон , Армстронг , Грант , Кэмерон , Стюарт , Дуглас , Кроуфорд , Кэмпбелл , Хантер ) с гэльским «Мак» для сына. [30]

Одноимённые фамилии

[ редактировать ]Это самый широкий класс фамилий, происходящих от прозвищ, [31] охватывающее множество типов происхождения. К ним относятся имена, основанные на внешности, такие как «Шварцкопф», «Коротышка» и, возможно, «Цезарь». [29] и имена, основанные на темпераменте и личности, такие как «Безумный», «Гутман» и «Мейден», которые, согласно ряду источников, были английским прозвищем, означающим «женоподобный». [29] [32]

Группа прозвищ выглядит как профессиональная: Король , Епископ , Аббат , Шериф , Рыцарь и т. д., но маловероятно, что человек с фамилией Кинг был королем или происходил от короля. Бернард Дикон предполагает, что первый носитель прозвища/фамилии мог действовать как король или епископ или был тучным как епископ. и т. д. [31]

Значительную группу фамильных прозвищ составляют этнонимы . [33] [34]

Декоративные фамилии

[ редактировать ]Декоративные фамилии состоят из имен, не связанных с каким-либо атрибутом (местом, происхождением, родом занятий, кастой) первого человека, получившим это имя, и проистекают из стремления среднего класса к своим собственным наследственным именам, как у дворян. Обычно они приобретались позже в истории и, как правило, тогда, когда в них нуждались те, у кого не было фамилий. В 1526 году король Дании и Норвегии Фредерик I приказал, чтобы благородные семьи взяли фиксированные фамилии, и многие из них взяли в качестве имени какой-либо элемент своего герба; например, семья Розенкранц («розовый венок») получила свою фамилию от венка из роз, составляющего торс их рук, [35] а семья Гильденшерн («золотая звезда») получила свое от семиконечной золотой звезды на своем щите. [36] Впоследствии многие скандинавские семьи среднего класса захотели иметь имена, похожие на дворянские, и также приняли «декоративные» фамилии. Большинство других традиций именования называют их «приобретенными». Их можно было вручать людям, недавно иммигрировавшим, завоеванным или обращенным, а также людям с неизвестным происхождением, ранее порабощенным или отцовам без фамильной традиции. [37] [38]

Декоративные фамилии более распространены в сообществах, которые приняли (или были вынуждены принять) фамилии в 18 и 19 веках. [39] Они обычно встречаются в Скандинавии, а также среди синти и цыган , а также евреев в Германии и Австрии. [29]

Приобретенные фамилии

[ редактировать ]В эпоху трансатлантической работорговли хозяева дали многим африканцам новые имена. Многие фамилии многих афроамериканцев возникли в рабстве ( т.е. рабские имена ). Некоторые освобожденные рабы позже сами создали себе фамилии. [40]

Еще одна категория приобретенных имен – имена подкидышей . Исторически сложилось так, что детей, рожденных от родителей, не состоящих в браке, или от крайне бедных родителей, бросали в общественном месте или анонимно помещали в подкидышное колесо . Религиозные деятели, лидеры общин или приемные родители могут заявить права на таких брошенных детей и дать им имена. Некоторым таким детям давали фамилии, отражавшие их состояние, например (итальянские) Эспозито , Инноченти , Делла Касагранде , Тровато , Аббандоната или (голландские) Вонделинг, Верлаетен, Бийстанд. Других детей назвали по улице/месту, где они были найдены (Юнион, Ликорпонд (улица), ди Палермо, Баан, Бийдам, ван ден Эйнгель (название магазина), ван дер Стоп , фон Трапп), дате их обнаружения ( понедельник). , сентябрь, весна, ди Женнайо) или праздник/праздник, который они основали или окрестили (Пасха, Сан-Хосе). Некоторым найденышам давали имена тех, кто их нашел. [41] [42] [43]

Профессиональные фамилии

[ редактировать ]Профессиональные имена включают Смит , Миллер , Фармер , Тэтчер , Шепард , Поттер и т. д., а также неанглийские имена, такие как немецкий Эйзенхауэр (железотесатель , позже англизированный в Америке как Эйзенхауэр ) или Шнайдер (портной) – или , как по-английски Шмидт (кузнец). Есть также более сложные имена, основанные на профессиональных титулах. В Англии слуги обычно использовали измененную версию профессии или имени своего работодателя в качестве своей фамилии. [ по мнению кого? ] буквы s добавление к слову , хотя это образование могло быть и отчеством . Например, считается, что фамилия Викерс возникла как профессиональное имя, принятое слугой викария. [44] в то время как Робертс мог быть усыновлен либо сыном, либо слугой человека по имени Роберт. Подмножество профессиональных названий на английском языке — это имена, которые, как полагают, заимствованы из средневековых мистерий . Участники часто играли одни и те же роли всю жизнь, передавая их старшим сыновьям. Имена, полученные от этого, могут включать Короля , Лорда и Деву . Первоначальное значение имен, основанное на средневековых профессиях, может больше не быть очевидным в современном английском языке. [ нужна ссылка ]

Топонимические фамилии

[ редактировать ]Названия мест (топонимических, жилищных) происходят от населенного пункта, связанного с человеком, носящим это имя. Такими локациями могут быть поселения любого типа, такие как усадьбы, фермы, вольеры, деревни, деревни, крепости или коттеджи. Один элемент названия жилья может описывать тип поселения. Примеры древнеанглийских элементов часто встречаются во втором элементе названий жилищ. Элементы среды обитания в таких названиях могут различаться по значению в зависимости от разных периодов, разных мест или от использования с некоторыми другими элементами. Например, древнеанглийский элемент tūn мог первоначально означать «огороженная территория» в одном названии, но мог означать «усадьба», «деревня», «поместье» или «поместье» в других названиях. [ нужна ссылка ]

Названия мест или жилищ могут быть такими общими, как «Монте» (по-португальски «гора»), «Górski» (по-польски «холм») или «Питт» (вариант слова «яма»), но могут также относиться к в определенные места. Например, считается, что «Вашингтон» означает «усадьбу семьи Васса». [32] а «Луччи» означает «житель Лукки ». [29] Хотя некоторые фамилии, такие как «Лондон», «Лиссабон» или «Белосток», происходят от крупных городов, больше людей отражают названия небольших сообществ, как в Ó Creachmhaoil , происходящем от деревни в графстве Голуэй . Считается, что это связано с тенденцией в Европе в средние века к миграции в основном из небольших общин в города и необходимостью вновь прибывших выбирать определяющую фамилию. [32] [39]

В португалоязычных странах редко, но не беспрецедентно, можно встретить фамилии, происходящие от названий стран, таких как Португалия, Франция, Бразилия, Голландия. Фамилии, производные от названий стран, также встречаются в английском языке, например «Англия», «Уэльс», «Испания».

Многие японские фамилии произошли от географических особенностей; например, Исикава (石川) означает «каменная река» (а также название одной из префектур Японии ), Ямамото (山本) означает «подножие горы», а Иноуэ (井上) означает «над колодцем».

Арабские имена иногда содержат фамилии, обозначающие город происхождения. Например, в случае с Саддамом Хусейном Тикрити. [45] Это означает, что Саддам Хусейн родом из Тикрита , города в Ираке . Этот компонент имени называется нисбах .

Примеры

[ редактировать ]- Названия поместий Для тех, кто происходит от землевладельцев, название их владений, замка, поместья или поместья, например, Эрнл , Виндзор , Стонтон.

- Названия мест обитания (мест), например, Бертон , Флинт , Гамильтон , Лондон , Лотон , Лейтон , Мюррей , Саттон , Трембле.

- Топографические названия (географические объекты), например, Мост или Мосты , Ручей или Ручьи , Буш , Кэмп , Холм , Озеро , Ли или Ли , Вуд , Роща , Холмс , Лес , Андервуд , Холл , Поле , Камень , Морли , Мур , Перри

Другой

[ редактировать ]Значения некоторых имен неизвестны или неясны. Самым распространенным европейским именем в этой категории может быть ирландское имя Райан , что на ирландском языке означает «маленький король». [32] [44] Также кельтское происхождение имени Артур, означающего « медведь ». имя Де Лука , вероятно, возникло либо в Лукании, либо вблизи нее, либо в семье кого-то по имени Лукас или Люциус; Другие фамилии могли возникнуть из более чем одного источника: например, [29] однако в некоторых случаях название могло возникнуть из Лукки, причем написание и произношение менялись со временем и в результате эмиграции. [29] Одно и то же имя может появиться в разных культурах по совпадению или латинизации; фамилия Ли используется в английской культуре, но также является латинизацией китайской фамилии Ли . [44] В Российской империи внебрачным детям иногда давали искусственные фамилии, а не фамилии их приемных родителей. [46] [47]

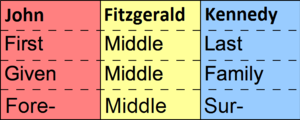

Порядок имен

[ редактировать ]Во многих культурах (особенно в европейских и находящихся под европейским влиянием культурах в Америке, Океании и т. д., а также в Западной Азии/Северной Африке, Южной Азии и большинстве культур Африки к югу от Сахары) фамилия или фамилия («последнее имя") ставится после личного имени, имени (в Европе) или имени ("имя"). В других культурах сначала ставится фамилия, а затем имя или имена. Последний часто называют восточным порядком именования , поскольку европейцам наиболее знакомы примеры из культурной сферы Восточной Азии , в частности, Большого Китая , Кореи (как Северной, так и Южной) , Японии и Вьетнама . То же самое происходит в Камбодже среди хмонгов Лаоса и и Таиланда . Телугу . на юге Индии также ставят фамилию перед личным именем В некоторых частях Европы, в частности в Венгрии , фамилия ставится перед личным именем. [48]

Поскольку в европейских обществах фамилии обычно пишутся последними, для обозначения фамилии обычно используются термины «фамилия» или «фамилия», в то время как в Японии (с вертикальным написанием) фамилия может называться «верхним именем» ( ue-no-). намэ ( 上の名前 ) .

Когда люди из регионов, использующих восточный порядок именования, пишут свое личное имя латинским алфавитом , обычно для удобства жителей Запада порядок имен и фамилий меняется на обратный, чтобы они знали, какое имя является фамилией для официальных/официальных имен. целей. Изменение порядка имен по той же причине принято также для балтийских финских народов и венгров , но другие уральские народы традиционно не имели фамилий, возможно, из-за клановой структуры их обществ. Саамы , в зависимости от обстоятельств их имен, либо не видели изменений, либо видели трансформацию своего имени. Например: Сир в некоторых случаях становился Сири, [49] и Хетта Яхкош Асслат превратился в Аслака Якобсена Хетту – как это было нормой . Недавно интеграция в ЕС и расширение связей с иностранцами побудили многих саамов изменить порядок своего полного имени: имя, за которым следует фамилия, чтобы их имя не было ошибочно принято за фамилию и не использовалось в качестве фамилии. [ нужна ссылка ]

Индийские фамилии часто могут обозначать деревню, профессию и/или касту и неизменно упоминаются вместе с личными именами. Однако наследственные фамилии не универсальны. В семьях на юге Индии, говорящих на телугу , фамилия ставится перед личным именем и в большинстве случаев отображается только как инициал (например, «С.» для Сурьяпета). [50]

In English and other languages like Spanish—although the usual order of names is "first middle last"—for the purpose of cataloging in libraries and in citing the names of authors in scholarly papers, the order is changed to "last, first middle," with the last and first names separated by a comma, and items are alphabetized by the last name.[51][52] In France, Italy, Spain, Belgium and Latin America, administrative usage is to put the surname before the first on official documents.[citation needed]

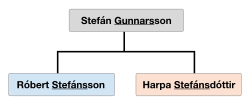

Gender-specific versions of surname

[edit]In most Balto-Slavic languages (such as Latvian, Lithuanian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Russian, Polish, Slovak, Czech, etc.) as well as in Greek, Irish, Icelandic, and Azerbaijani, some surnames change form depending on the gender of the bearer.[53]

| Language | Male form | Female form | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Icelandic surnames | Suffix -son | Suffix -dóttir | [54] |

| Greek surnames | Suffixes -os, -as, -is | Suffixes -ou, -a, -i | [55] |

| Irish surnames | Prefixes Mac, Ó, Ua, Mag | Prefixes Bean Uí, Nic, Bean Mhic, Ní, Mhic, Nig | [56] |

| Lithuanian surnames | Suffixes -as, -ys, -is, -us | Suffixes -ienė, -uvienė, -aitė, -utė, -iūtė, -ytė | [57] |

| Latvian surnames | Suffixes -us, -is, -s, -iņš | Suffixes -a, -e, -iņa | |

| Scottish Gaelic surnames | Prefix Mac- | Prefix Nic- | [58] |

| Bulgarian and Macedonian surnames | Suffixes -ov, -ev, -ski | Suffixes -ova, -eva, -ska | |

| East Slavic surnames | Suffixes -ov, -ev, -in, -iy, -oy, -yy, Patronymics -ovich, -ovych, -yovych | Suffixes -ova, -eva, -ina, -aya, Patronymics -ovna, -ivna, -yivna | [59] |

| Czech and Slovak surnames | Suffixes -ov, -ý, -ský, -cký | Suffixes -ová, -á, -ská, -cká | [60] |

| Polish surnames | Suffixes -ski, -cki, -dzki | Suffixes -ska, -cka, -dzka | [61] |

| Azerbaijani surnames | Suffixes -ov, -yev, Patronymic oğlu | Suffixes -ova, -yeva, Patronymic qızı |

In Slavic languages, substantivized adjective surnames have commonly symmetrical adjective variants for males and females (Podwiński/Podwińska in Polish, Nový/Nová in Czech or Slovak, etc.). In the case of nominative and quasi-nominative surnames, the female variant is derived from the male variant by a possessive suffix (Novák/Nováková, Hromada/Hromadová). In Czech and Slovak, the pure possessive would be Novákova, Hromadova, but the surname evolved to a more adjectivized form Nováková, Hromadová, to suppress the historical possessivity. Some rare types of surnames are universal and gender-neutral: examples in Czech are Janů, Martinů, Fojtů, Kovářů. These are the archaic form of the possessive, related to the plural name of the family. Such rare surnames are also often used for transgender persons during transition because most common surnames are gender-specific.[citation needed]

The informal dialectal female form in Polish and Czech dialects was also -ka (Pawlaczka, Kubeška). With the exception of the -ski/-ska suffix, most feminine forms of surnames are seldom observed in Polish.[citation needed]

Generally, inflected languages use names and surnames as living words, not as static identifiers. Thus, the pair or the family can be named by a plural form which can differ from the singular male and female form. For instance, when the male form is Novák and the female form Nováková, the family name is Novákovi in Czech and Novákovci in Slovak. When the male form is Hrubý and the female form is Hrubá, the plural family name is Hrubí (or "rodina Hrubých").[citation needed]

In Greece, if a man called Papadopoulos has a daughter, she will likely be named Papadopoulou (if the couple has decided their offspring will take his surname), the genitive form, as if the daughter is "of" a man named Papadopoulos. Likewise, the surnames of daughters of males with surnames ending in -as will end in -a, and those of daughters of males with the -is suffix will have the -i suffix.[citation needed]

Latvian, like Lithuanian, use strictly feminized surnames for women, even in the case of foreign names. The function of the suffix is purely grammar. Male surnames ending -e or -a need not be modified for women. An exception is 1) the female surnames which correspond to nouns in the sixth declension with the ending "-s" – "Iron", ("iron"), "rock", 2) as well as surnames of both genders, which are written in the same nominative case because corresponds to nouns in the third declension ending in "-us" "Grigus", "Markus"; 3) surnames based on an adjective have indefinite suffixes typical of adjectives "-s, -a" ("Stalts", "Stalta") or the specified endings "-ais, -ā" ("Čaklais", "Čaklā") ("diligent").[citation needed]

In Iceland, surnames have a gender-specific suffix (-dóttir = daughter, -son = son).[62]

Finnish used gender-specific suffixes up to 1929 when the Marriage Act forced women to use the husband's form of the surname. In 1985, this clause was removed from the act.[63]

Until at least 1850, women's surnames were suffixed with an -in in Tyrol.

Indication of family membership status

[edit]Some Slavic cultures originally distinguished the surnames of married and unmarried women by different suffixes, but this distinction is no longer widely observed. Some Czech dialects (Southwest-Bohemian) use the form "Novákojc" as informal for both genders. In the culture of the Sorbs (a.k.a. Wends or Lusatians), Sorbian used different female forms for unmarried daughters (Jordanojc, Nowcyc, Kubašec, Markulic), and for wives (Nowakowa, Budarka, Nowcyna, Markulina). In Polish, typical surnames for unmarried women ended -ówna, -anka, or -ianka, while the surnames of married women used the possessive suffixes -ina or -owa. In Lithuania, if the husband is named Vilkas, his wife will be named Vilkienė and his unmarried daughter will be named Vilkaitė. Male surnames have suffixes -as, -is, -ius, or -us, unmarried girl surnames aitė, -ytė, -iūtė or -utė, wife surnames -ienė. These suffixes are also used for foreign names, exclusively for grammar; Welby, the surname of the present Archbishop of Canterbury for example, becomes Velbis in Lithuanian, while his wife is Velbienė, and his unmarried daughter, Velbaitė.[citation needed]

Many surnames include prefixes that may or may not be separated by a space or punctuation from the main part of the surname. These are usually not considered true compound names, rather single surnames are made up of more than one word. These prefixes often give hints about the type or origin of the surname (patronymic, toponymic, notable lineage) and include words that mean from [a place or lineage], and son of/daughter of/child of.[citation needed]

The common Celtic prefixes "Ó" or "Ua" (descendant of) and "Mac" or "Mag" (son of) can be spelled with the prefix as a separate word, yielding "Ó Briain" or "Mac Millan" as well as the anglicized "O'Brien" and "MacMillan" or "Macmillan". Other Irish prefixes include Ní, Nic (daughter of the son of), Mhic, and Uí (wife of the son of).[citation needed]

A surname with the prefix "Fitz" can be spelled with the prefix as a separate word, as in "Fitz William", as well as "FitzWilliam" or "Fitzwilliam" (like, for example, Robert FitzRoy). Note that "Fitz" comes from French (fils) thus making these surnames a form of patronymic.[citation needed]

Surname law

[edit]A family name is typically a part of a person's personal name and, according to law or custom, is passed or given to children from at least one of their parents' family names. The use of family names is common in most cultures around the world, but each culture has its own rules as to how the names are formed, passed, and used. However, the style of having both a family name (surname) and a given name (forename) is far from universal (see §History below). In many cultures, it is common for people to have one name or mononym, with some cultures not using family names. Issues of family name arise especially on the passing of a name to a newborn child, the adoption of a common family name on marriage, the renunciation of a family name, and the changing of a family name.[citation needed]

Surname laws vary around the world. Traditionally in many European countries for the past few hundred years, it was the custom or the law for a woman, upon marriage, to use her husband's surname and for any children born to bear the father's surname. If a child's paternity was not known, or if the putative father denied paternity, the newborn child would have the surname of the mother. That is still the custom or law in many countries. The surname for children of married parents is usually inherited from the father.[64] In recent years, there has been a trend towards equality of treatment in relation to family names, with women being not automatically required, expected or, in some places, even forbidden, to take the husband's surname on marriage, with the children not automatically being given the father's surname. In this article, both family name and surname mean the patrilineal surname, which is handed down from or inherited from the father, unless it is explicitly stated otherwise. Thus, the term "maternal surname" means the patrilineal surname that one's mother inherited from either or both of her parents. For a discussion of matrilineal ('mother-line') surnames, passing from mothers to daughters, see matrilineal surname.[citation needed]

Surname of women

[edit]King Henry VIII of England (reigned 1509–1547) ordered that marital births be recorded under the surname of the father.[5] In England and cultures derived from there, there has long been a tradition for a woman to change her surname upon marriage from her birth name to her husband's family name. (See Maiden and married names.)[citation needed]

In the Middle Ages, when a man from a lower-status family married an only daughter from a higher-status family, he would often adopt the wife's family name.[citation needed] In the 18th and 19th centuries in Britain, bequests were sometimes made contingent upon a man's changing (or hyphenating) his family name, so that the name of the testator continued.[citation needed]

The United States followed the naming customs and practices of English common law and traditions until recent times. The first known instance in the United States of a woman insisting on the use of her birth name was that of Lucy Stone in 1855, and there has been a general increase in the rate of women using their birth name. Beginning in the latter half of the 20th century, traditional naming practices (writes one commentator) were recognized as "com[ing] into conflict with current sensitivities about children's and women's rights".[65] Those changes accelerated a shift away from the interests of the parents to a focus on the best interests of the child. The law in this area continues to evolve today mainly in the context of paternity and custody actions.[66]

Naming conventions in the US have gone through periods of flux, however, and the 1990s saw a decline in the percentage of name retention among women.[67] As of 2006, more than 80% of American women adopted the husband's family name after marriage.[68]

It is rare but not unknown for an English-speaking man to take his wife's family name, whether for personal reasons or as a matter of tradition (such as among matrilineal Canadian aboriginal groups, such as the Haida and Gitxsan). Upon marriage to a woman, men in the United States can change their surnames to that of their wives, or adopt a combination of both names with the federal government, through the Social Security Administration. Men may face difficulty doing so on the state level in some states.[citation needed]

It is exceedingly rare but does occur in the United States, where a married couple may choose an entirely new last name by going through a legal change of name. As an alternative, both spouses may adopt a double-barrelled name. For instance, when John Smith and Mary Jones marry each other, they may become known as "John Smith-Jones" and "Mary Smith-Jones". A spouse may also opt to use their birth name as a middle name, and e.g. become known as "Mary Jones Smith".[citation needed] An additional option, although rarely practiced[citation needed], is the adoption of the last name derived from a blend of the prior names, such as "Simones", which also requires a legal name change. Some couples keep their own last names but give their children hyphenated or combined surnames.[69]

In 1979, the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women ("CEDAW"), which declared in effect that women and men, and specifically wife and husband, shall have the same rights to choose a "family name", as well as a profession and an occupation.[70]

In some places, civil rights lawsuits or constitutional amendments changed the law so that men could also easily change their married names (e.g., in British Columbia and California).[71] Québec law permits neither spouse to change surnames.[72]

In France, until 1 January 2005, children were required by law to take the surname of their father. Article 311-21 of the French Civil code now permits parents to give their children the family name of either their father, mother, or hyphenation of both – although no more than two names can be hyphenated. In cases of disagreement, both names are used in alphabetical order.[73] This brought France into line with a 1978 declaration by the Council of Europe requiring member governments to take measures to adopt equality of rights in the transmission of family names, a measure that was echoed by the United Nations in 1979.[74]

Similar measures were adopted by West Germany (1976), Sweden (1982), Denmark (1983), Finland (1985) and Spain (1999). The European Community has been active in eliminating gender discrimination. Several cases concerning discrimination in family names have reached the courts. Burghartz v. Switzerland challenged the lack of an option for husbands to add the wife's surname to his surname, which they had chosen as the family name when this option was available for women.[75] Losonci Rose and Rose v. Switzerland challenged a prohibition on foreign men married to Swiss women keeping their surname if this option was provided in their national law, an option available to women.[76] Ünal Tekeli v. Turkey challenged prohibitions on women using their surname as the family name, an option only available to men.[77] The Court found all these laws to be in violation of the convention.[78]

From 1945 to 2021 in the Czech Republic women by law had to use family names with the ending -ová after the name of their father or husband (so-called přechýlení). This was seen as discriminatory by a part of the public. Since 1 January 2022, Czech women can decide for themselves whether they want to use the feminine or neutral form of their family name.[79]

Compound surnames

[edit]While in many countries surnames are usually one word, in others a surname may contain two words or more, as described below.[citation needed]

English

[edit]Compound surnames in English and several other European cultures feature two (or occasionally more) words, often joined by a hyphen or hyphens. However, it is not unusual for compound surnames to be composed of separate words not linked by a hyphen, for example Iain Duncan Smith, a former leader of the British Conservative Party, whose surname is "Duncan Smith".[citation needed]

Chinese

[edit]Some Chinese surnames use more than one character.

Multiple surnames

[edit]Spanish-speaking countries

[edit]In Spain and in most Spanish-speaking countries, the custom is for people to have two surnames, with the first surname coming from the father and the second from the mother; the opposite order is now legally allowed in Spain but still unusual. In informal situations typically only the first one is used, although both are needed for legal purposes. A child's first surname will usually be their father's first surname, while the child's second surname will usually be their mother's first surname. For example, if José García Torres and María Acosta Gómez had a child named Pablo, then his full name would be Pablo García Acosta. One family member's relationship to another can often be identified by the various combinations and permutations of surnames.[citation needed]

| José García Torres | María Acosta Gómez | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pablo García Acosta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

In some instances, when an individual's first surname is very common, such as for example in José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the second surname tends to gain preeminence over the first one in informal use. Rodríguez Zapatero, therefore is more often called just Zapatero and almost never Rodríguez only; in other cases, such as in writer Mario Vargas Llosa, a person becomes usually called by both surnames. This changes from person to person and stems merely from habit.[citation needed]

In Spain, feminist activism pushed for a law approved in 1999 that allows an adult to change the order of his/her family names,[80] and parents can also change the order of their children's family names if they (and the child, if over 12) agree, although this order must be the same for all their children.[81][82]

In Spain, especially Catalonia, the paternal and maternal surnames are often combined using the conjunction y ("and" in Spanish) or i ("and" in Catalan), see for example the economist Xavier Sala-i-Martin or painter Salvador Dalí i Domènech.[citation needed]

In Spain, a woman does not generally change her legal surname when she marries. In some Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America, a woman may, on her marriage, drop her mother's surname and add her husband's surname to her father's surname using the preposition de ("of"), del ("of the", when the following word is masculine) or de la ("of the", when the following word is feminine). For example, if "Clara Reyes Alba" were to marry "Alberto Gómez Rodríguez", the wife could use "Clara Reyes de Gómez" as her name (or "Clara Reyes Gómez", or, rarely, "Clara Gómez Reyes". She can be addressed as Sra. de Gómez corresponding to "Mrs Gómez"). Feminist activists have criticized this custom [when?] as they consider it sexist.[83][84] In some countries, this form may be mainly social and not an official name change, i.e. her name would still legally be her birth name. This custom, begun in medieval times, is decaying and only has legal validity [citation needed] in Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Honduras, Peru, Panama, and to a certain extent in Mexico (where it is optional but becoming obsolete), but is frowned upon by people in Spain, Cuba, and elsewhere. In Peru and the Dominican Republic, women normally conserve all family names after getting married. For example, if Rosa María Pérez Martínez marries Juan Martín De la Cruz Gómez, she will be called Rosa María Pérez Martínez de De la Cruz, and if the husband dies, she will be called Rosa María Pérez Martínez Vda. de De la Cruz (Vda. being the abbreviation for viuda, "widow" in Spanish). The law in Peru changed some years ago, and all married women can keep their maiden last name if they wish with no alteration.[citation needed]

Historically, sometimes a father transmitted his combined family names, thus creating a new one e.g., the paternal surname of the son of Javier (given name) Reyes (paternal family name) de la Barrera (maternal surname) may have become the new paternal surname Reyes de la Barrera. For example, Uruguayan politician Guido Manini Rios has inherited a compound surname constructed from the patrilineal and matrilineal surnames of a recent ancestor. De is also the nobiliary particle used with Spanish surnames. This can not be chosen by the person, as it is part of the surname, for example, "Puente" and "Del Puente" are not the same surname.[citation needed]

Sometimes, for single mothers or when the father would or could not recognize the child, the mother's surname has been used twice: for example, "Ana Reyes Reyes". In Spain, however, children with just one parent receive both surnames of that parent, although the order may also be changed. In 1973 in Chile, the law was changed to avoid stigmatizing illegitimate children with the maternal surname repeated.[citation needed]

Some Hispanic people, after leaving their country, drop their maternal surname, even if not formally, so as to better fit into the non-Hispanic society they live or work in. Similarly, foreigners with just one surname may be asked to provide a second surname on official documents in Spanish-speaking countries. When none (such as the mother's maiden name) is provided, the last name may simply be repeated.[citation needed]

A new trend in the United States for Hispanics is to hyphenate their father's and mother's last names. This is done because American-born English-speakers are not aware of the Hispanic custom of using two last names and thus mistake the first last name of the individual for a middle name. In doing so they would, for example, mistakenly refer to Esteban Álvarez Cobos as Esteban A. Cobos. Such confusion can be particularly troublesome in official matters. To avoid such mistakes, Esteban Álvarez Cobos, would become Esteban Álvarez-Cobos, to clarify that both are last names.[citation needed]

In some churches, such as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, where the family structure is emphasized, as well as a legal marriage, the wife is referred to as "hermana" [sister] plus the surname of her husband. And most records of the church follow that structure as well.[citation needed]

Informal traditional names

[edit]In many places, such as villages in Catalonia, Galicia, and Asturias and in Cuba, people are often informally known by the name of their dwelling or collective family nickname rather than by their surnames. For example, Remei Pujol i Serra who lives at Ca l'Elvira would be referred to as "Remei de Ca l'Elvira"; and Adela Barreira López who is part of the "Provisores" family would be known as "Adela dos Provisores".[citation needed]

Also in many places, such as Cantabria, the family's nickname is used instead of the surname: if one family is known as "Ñecos" because of an ancestor who was known as "Ñecu", they would be "José el de Ñecu" or "Ana la de Ñecu" (collective: the Ñeco's). Some common nicknames are "Rubiu" (blond or red hair), "Roju" (reddish, referring to their red hair), "Chiqui" (small), "Jinchu" (big), and a bunch of names about certain characteristics, family relationship or geographical origin (pasiegu, masoniegu, sobanu, llebaniegu, tresmeranu, pejinu, naveru, merachu, tresneru, troule, mallavia, marotias, llamoso, lipa, ñecu, tarugu, trapajeru, lichón, andarível).

Compound surnames

[edit]Beyond the seemingly "compound" surname system in the Spanish-speaking world, there are also true compound surnames. These true compound surnames are passed on and inherited as compounds. For instance, former Chairman of the Supreme Military Junta of Ecuador, General Luis Telmo Paz y Miño Estrella, has Luis as his first given name, Telmo as his middle name, the true compound surname Paz y Miño as his first (i.e. paternal) surname, and Estrella as his second (i.e. maternal) surname. Luis Telmo Paz y Miño Estrella is also known more casually as Luis Paz y Miño, Telmo Paz y Miño, or Luis Telmo Paz y Miño. He would never be regarded as Luis Estrella, Telmo Estrella, or Luis Telmo Estrella, nor as Luis Paz, Telmo Paz, or Luis Telmo Paz. This is because "Paz" alone is not his surname (although other people use the "Paz" surname on its own).[64] In this case, Paz y Miño is in fact the paternal surname, being a true compound surname. His children, therefore, would inherit the compound surname "Paz y Miño" as their paternal surname, while Estrella would be lost, since the mother's paternal surname becomes the children's second surname (as their own maternal surname). "Paz" alone would not be passed on, nor would "Miño" alone.[citation needed]

To avoid ambiguity, one might often informally see these true compound surnames hyphenated, for instance, as Paz-y-Miño. This is true especially in the English-speaking world, but also sometimes even in the Hispanic world, since many Hispanics are unfamiliar with this and other compound surnames, "Paz y Miño" might be inadvertently mistaken as "Paz" for the paternal surname and "Miño" for the maternal surname. Although Miño did start off as the maternal surname in this compound surname, it was many generations ago, around five centuries, that it became compounded, and henceforth inherited and passed on as a compound.[citation needed]

Other surnames which started off as compounds of two or more surnames, but which merged into one single word, also exist. An example would be the surname Pazmiño, whose members are related to the Paz y Miño, as both descend from the "Paz Miño" family[citation needed] of five centuries ago.

Álava, Spain is known for its incidence of true compound surnames, characterized for having the first portion of the surname as a patronymic, normally a Spanish patronymic or more unusually a Basque patronymic, followed by the preposition "de", with the second part of the surname being a placename from Álava.[citation needed]

Portuguese-speaking countries

[edit]In the case of Portuguese naming customs, the main surname (the one used in alpha sorting, indexing, abbreviations, and greetings), appears last.[citation needed]

Each person usually has two family names: though the law specifies no order, the first one is usually the maternal family name, whereas the last one is commonly the paternal family name. In Portugal, a person's full name has a minimum legal length of two names (one given name and one family name from either parent) and a maximum of six names (two first names and four surnames – he or she may have up to four surnames in any order desired picked up from the total of his/her parents and grandparents' surnames). The use of any surname outside this lot, or of more than six names, is legally possible, but it requires dealing with bureaucracy. Parents or the person him/herself must explain the claims they have to bear that surname (a family nickname, a rare surname lost in past generations, or any other reason one may find suitable). In Brazil, there is no limit of surnames used.[citation needed]

In general, the traditions followed in countries like Brazil, Portugal and Angola are somewhat different from the ones in Spain. In the Spanish tradition, usually, the father's surname comes first, followed by the mother's surname, whereas in Portuguese-speaking countries the father's name is the last, mother's coming first. A woman may adopt her husband's surname(s), but nevertheless, she usually keeps her birth name or at least the last one. Since 1977 in Portugal and 2012 in Brazil, a husband can also adopt his wife's surname. When this happens, usually both spouses change their name after marriage.[citation needed]

The custom of a woman changing her name upon marriage is recent. It spread in the late 19th century in the upper classes, under French influence, and in the 20th century, particularly during the 1930s and 1940, it became socially almost obligatory. Nowadays, fewer women adopt, even officially, their husbands' names, and among those who do so officially, it is quite common not to use it either in their professional or informal life.[citation needed]

The children usually bear only the last surnames of the parents (i.e., the paternal surname of each of their parents). For example, Carlos da Silva Gonçalves and Ana Luísa de Albuquerque Pereira (Gonçalves) (in case she adopted her husband's name after marriage) would have a child named Lucas Pereira Gonçalves. However, the child may have any other combination of the parents' surnames, according to euphony, social significance, or other reasons. For example, is not uncommon for the firstborn male to be given the father's full name followed by "Júnior" or "Filho" (son), and the next generation's firstborn male to be given the grandfather's name followed by "Neto" (grandson). Hence Carlos da Silva Gonçalves might choose to name his first born son Carlos da Silva Gonçalves Júnior, who in turn might name his first born son Carlos da Silva Gonçalves Neto, in which case none of the mother's family names are passed on.[citation needed]

| Carlos da Silva Gonçalves | Ana Luísa de Albuquerque Pereira | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lucas Pereira Gonçalves | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

In ancient times a patronymic was commonly used – surnames like Gonçalves ("son of Gonçalo"), Fernandes ("son of Fernando"), Nunes ("son of Nuno"), Soares ("son of Soeiro"), Sanches ("son of Sancho"), Henriques ("son of Henrique"), Rodrigues ("son of Rodrigo") which along with many others are still in regular use as very prevalent family names.[citation needed]

In Medieval times, Portuguese nobility started to use one of their estates' names or the name of the town or village they ruled as their surname, just after their patronymic. Soeiro Mendes da Maia bore a name "Soeiro", a patronymic "Mendes" ("son of Hermenegildo – shortened to Mendo") and the name of the town he ruled "Maia". He was often referred to in 12th-century documents as "Soeiro Mendes, senhor da Maia", Soeiro Mendes, lord of Maia. Noblewomen also bore patronymics and surnames in the same manner and never bore their husband's surnames. First-born males bore their father's surname, other children bore either both or only one of them at their will.[citation needed]

Only during the Early Modern Age, lower-class males started to use at least one surname; married lower-class women usually took up their spouse's surname, since they rarely ever used one beforehand. After the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, Portuguese authorities realized the benefits of enforcing the use and registry of surnames. Henceforth, they became mandatory, although the rules for their use were very liberal.[citation needed]

Until the end of the 19th century, it was common for women, especially those from a very poor background, not to have a surname and so to be known only by their first names. A woman would then adopt her husband's full surname after marriage. With the advent of republicanism in Brazil and Portugal, along with the institution of civil registries, all children now have surnames. During the mid-20th century, under French influence and among upper classes, women started to take up their husbands' surname(s). From the 1960s onwards, this usage spread to the common people, again under French influence, this time, however, due to the forceful legal adoption of their husbands' surname which was imposed onto Portuguese immigrant women in France.[citation needed]

From the 1974 Carnation Revolution onwards the adoption of their husbands' surname(s) receded again, and today both the adoption and non-adoption occur, with non-adoption being chosen in the majority of cases in recent years (60%).[85] Also, it is legally possible for the husband to adopt his wife's surname(s), but this practice is rare.[citation needed]

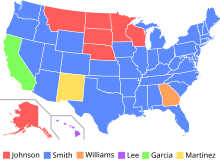

Prevalence

[edit]In the United States, 1,712 surnames cover 50% of the population, and about 1% of the population has the surname Smith, the most common American name.[86]

According to some estimates, 85% of China's population shares just 100 surnames. The names Wang (王), Zhang (张), and Li (李) are the most frequent.[87]

See also

[edit]- Dit name

- Genealogy

- Generation name

- Given name

- Legal name

- List of family name affixes

- Lists of most common surnames

- Maiden and married names

- Matriname

- Name blending

- Name change

- Names ending with -ington

- Naming law

- Nobiliary particle

- One-name study

- Patronymic surname

- Personal name

- Skin name

- Surname extinction

- Surname law

- Surname map

- Surnames by country

- Tussenvoegsel

- Irish surname additives

- Spanish nominal conjunctions

- Von

- Van

- Patronymic

- Toponymic surname

References

[edit]- ^ "Surname". Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "surname". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 20 January 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Haas, Ann; Elliott, Marc N; Dembosky, Jacob W; Adams, John L; Wilson-Frederick, Shondelle M; Mallett, Joshua S; Gaillot, Sarah; Haffer, Samuel C; Haviland, Amelia M (1 February 2019). "Imputation of race/ethnicity to enable measurement of HEDIS performance by race/ethnicity". Health Services Research. 54 (1): 13–23. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13099. ISSN 1475-6773. PMC 6338295. PMID 30506674.

- ^ "BBC – Family History – What's in a Name? Your Link to the Past". BBC History. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Doll, Cynthia Blevins (1992). "Harmonizing Filial and Parental Rights in Names: Progress, Pitfalls, and Constitutional Problems". Howard Law Journal. Vol. 35. Howard University School of Law. p. 227. ISSN 0018-6813. Note: content available by subscription only. The first page of content is available via Google Scholar.

- ^ Lederer, Richard (5 September 2015). "Our last names reveal a lot about our labor days". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Danesi, Marcel (2007). The Quest for Meaning. University of Toronto Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8020-9514-5. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Naming practices" (PDF). Berkeley Linguistics. 2004. Chinese naming practices (Mak et al., 2003). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2011.

- ^ Zhimin, An (1988). "Archaeological Research on Neolithic China". Current Anthropology. 29 (5): 753–759 [755, 758]. doi:10.1086/203698. JSTOR 2743616. S2CID 144920735.

- ^ Ch'ien, E.N.M. (2005). Weird English. Harvard University Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-674-02953-8. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Koon, Wee Kek (18 November 2016). "The complex origins of Chinese names demystified". Post Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Gill, N.S. (ed.). "Ancient Names – Greek and Roman Names". About Ancient / Classical History. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ Benet Salway, "What's in a Name? A Survey of Roman Onomastic Practice from c. 700 B.C. to A.D. 700", in Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 84, pp. 124–145 (1994).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chavez, Berret (9 November 2006). "Personal Names of the Aristocracy in the Roman Empire During the Later Byzantine Era". Official Web Page of the Laurel Sovereign of Arms for the Society for Creative Anachronism. Society for Creative Anachronism. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ^ Kennett, D. (2012). The Surnames Handbook: A Guide to Family Name Research in the 21st Century. History Press. p. 19-20. ISBN 978-0-7524-8349-8. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ "What is the origin of the last name Molina?". Last Name Meanings. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "BBC – Family History – What's in a Name? Your Link to the Past". Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Most common surnames in Britain and Ireland revealed". BBC. 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ Hanks, Patrick; Coates, Richard; McClure, Peter (17 November 2016). The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199677764.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967776-4. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Kennett 2012, p. 20.

- ^ Anderson, Raymond A. (2022). Credit Intelligence and Modelling: Many Paths Through the Forest of Credit Rating and Scoring. Oxford University Press. p. 193-194. ISBN 978-0-19-284419-4.

- ^ Nagata, Mary Louise. "Names and Name Changing in Early Modern Kyoto, Japan." International Review of Social History 07/2002; 47(02):243 – 259. P. 246.

- ^ Ury, S. (2012). Barricades and Banners: The Revolution of 1905 and the Transformation of Warsaw Jewry. Stanford Studies in Jewish History and Culture. Stanford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8047-8104-6. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Scott, James C.; Tehranian, John; Mathias, Jeremy (2002). "The Production of Legal Identities Proper to States: The Case of the Permanent Family Surname". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 44 (1). Cambridge University Press: 4–44. doi:10.1017/S0010417502000026. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 3879399. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Ahmed, S.R. (2020). Preventing Identity Crime: Identity Theft and Identity Fraud: An Identity Crime Model and Legislative Analysis with Recommendations for Preventing Identity Crime. Brill. p. 39. ISBN 978-90-04-39597-8. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Holton, G.; Sonnert, G. (25 December 2006). What Happened to the Children Who Fled Nazi Persecution. Springer. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-230-60179-6.

- ^ Lemkin, Raphael (2014). Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-58477-576-8.

- ^ Neuburger, M.C. (2011). The Orient Within: Muslim Minorities and the Negotiation of Nationhood in Modern Bulgaria. Cornell University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-5017-2023-9. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Hanks, Patrick and Hodges, Flavia. A Dictionary of Surnames. Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-19-211592-8.

- ^ Katherine M. Spadaro, Katie Graham (2001) Colloquial Scottish Gaelic: the complete course for beginners p.16. Routledge, 2001

- ^ Jump up to: a b [[Bernard Deacon (linguist)|]], Classifying surnames

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Cottle, Basil. Penguin Dictionary of Surnames. Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books, 1967. No ISBN.

- ^ Butkus, Alvydas, The Lithuanian Nicknames of Ethnonymic Origin, Indogermanische Forschungen; Strassburg Vol. 100, (Jan 1, 1995): 223.

- ^ Tamás Farkas, Surnames of Ethnonymic Origin in the Hungarian Language, In: Name and Naming. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Onomastics. Onomastics in Contemporary Public Space. Baia Mare, May 9–11, 2013, pp.504–517

- ^ Hiort-Lorensen, H.R., and Thiset, A. (1910) Danmarks Adels Aarbog, 27th ed. Copenhagen: Vilh. Trydes Boghandel, p. 371.

- ^ von Irgens-Bergh, G.O.A., and Bobe, L. (1926) Danmarks Adels Aarbog, 43rd ed. Copenhagen: Vilh. Trydes Boghandel, p. 3.

- ^ "Ornamental Name". Nordic Names. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "The History of Last Names". Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bowman, William Dodgson. The Story of Surnames. London, George Routledge & Sons, Ltd., 1932. No ISBN.

- ^ Craven, Julia (24 February 2022). "Many African American last names hold weight of Black history". NBC News. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ "Finding Foundlings: Searching for Abandoned Children in Italy". Legacy Tree Genealogists. 14 September 2017. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "England Regional, Ethnic, Foundling Surnames (National Institute)". FamilySearch Research Wiki. 4 September 2014. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "Deciphering Dutch Foundling Surnames". Dutch Ancestry Coach. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Reaney, P.H., and Wilson, R.M. A Dictionary of English Surnames. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. Rev. 3rd ed. ISBN 0-19-860092-5.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein's top aides hanged". BBC News. 15 January 2007. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Boris Unbegaun, Russian surnames, — Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972; Russian version: Русские фамилии, 1989, Chapter IX: "Artificial surnames"

- ^ НЕСТАНДАРТНЫЕ РУССКИЕ ФАМИЛИИ, citing Суслова А.В., Суперанская А.В., О русских именах, Л.: Лениздат, 1991

- ^ Kennett 2012, p. 10.

- ^ "Guttorm". Snl.no. 29 May 2017. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Brown, Charles Philip (1857). A Grammar of the Telugu Language. printed at the Christian Knowledge Society's Press. p. 209.

- ^ "Filing Rules" Archived 21 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine on the American Library Association website

- ^ "MLA Works Cited Page: Basic Format" Archived 7 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine on the Purdue Online Writing Lab website, Purdue University

- ^ Donner, Paul (2012). Differences in publication behaviour between female and male scientists. Bibliometric analysis of longitudinal data from 1980 to 2005 with regard to gender differences in productivity and involvement, collaboration and citation impact (Thesis). Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Heijnen, Adriënne (1 September 2010). "Relating through Dreams: Names, Genes and Shared Substance". History and Anthropology. 21 (3): 307–319. doi:10.1080/02757206.2010.499909. ISSN 0275-7206. S2CID 143703825.

- ^ Makri-Tsilipakou, Marianthi (November 2003). "Greek Diminutive Use Problematized: Gender, Culture and Common Sense". Discourse & Society. 14 (6): 699–726. doi:10.1177/09579265030146002. S2CID 145557628.

- ^ Mac Mathúna, Liam (2006). "What's in an irish name?". The Celtic Englishes IV: The interface between English and the Celtic languages; Proceedings of the Fourth International Colloquium on the "Celtic Englishes" held at the University of Potsdam in Golm (Germany) from 22–26 September 2004. Potsdam: University of Potsdam. pp. 64–87. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Smoriginaitė, Jovita (2022). Visuomenės reakcijos į kalbinę lyčių problematiką. Nepriesaginių moteriškų pavardžių atvejis Lietuvoje, "hen" įvardžio – Švedijoje (Thesis). Vilniaus universitetas. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Graham, Katie; Spadaro, Katherine M. (11 August 2005). Colloquial Scottish Gaelic: The Complete Course for Beginners. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-62415-7. Archived from the original on 7 October 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Canada, Library and Archives (1 September 2022). "Item – Theses Canada". Library-archives.canada.ca.

- ^ Kolek, Vít; Valdrová, Jana (6 August 2020). "Czech gender linguistics: Topics, attitudes, perspectives". Slovenščina 2.0: Empirične, aplikativne in interdisciplinarne raziskave. 8 (1): 35–65. doi:10.4312/slo2.0.2020.1.35-65. ISSN 2335-2736. S2CID 225419103.

- ^ Nalibow, Kenneth L. (1 June 1973). "The Opposition in Polish of Genus and Sexus in Women's Surnames". Names. 21 (2): 78–81. doi:10.1179/nam.1973.21.2.78. ISSN 0027-7738.

- ^ "Icelandic names – everything you need to know". Reykjavik Excursions. Archived from the original on 13 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ Paikkala, Sirkka (2014). "Which name upon marriage? Family names of women in Finland". eLS noms en la vida quotidiana. Actes del XXIV Congrés Internacional d'ICOS sobre Ciències Onomàstiques: 853–861. doi:10.2436/15.8040.01.88. Retrieved 6 June 2024 – via gencat.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kelly, 99 W Va L Rev at 10; see id. at 10 n 25 (The custom of taking the father's surname assumes that the child is born to parents in a "state-sanctioned marriage". The custom is different for children born to unmarried parents.). Cited in Doherty v. Wizner, Oregon Court of Appeals Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (2005)

- ^ Richard H. Thornton, The Controversy Over Children's Surnames: Familial Autonomy, Equal Protection, and the Child's Best Interests, 1979 Utah L Rev 303.

- ^ Joanna Grossman, Whose Surname Should a Child Have Archived 28 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, FindLaw's Writ column (12 August 2003), (last visited 7 December 2006).

- ^ Goldin, Claudia (2004). "Making a Name: Women's Surnames at Marriage and Beyond". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 18 (2): 143–160. doi:10.1257/0895330041371268. JSTOR 3216895.

- ^ "American Women, Changing Their Names" Archived 4 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, National Public Radio. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ Daniella Miletic (20 July 2012) Most women say 'I do' to husband's name. The Age.

- ^ UN Convention, 1979. "Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women". Archived at WebCite on 1 April 2011.

- ^ Risling, Greg (12 January 2007). "Man files lawsuit to take wife's name". The Boston Globe (Boston.com). Los Angeles. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

Because of Buday's case, a California state lawmaker has introduced a bill to put a space on the marriage license for either spouse to change names.

- ^ White, Marianne (8 August 2007). "Quebec newlywed furious she can't take her husband's name". canada.com. CanWest News Service. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ "Article 311-21 – Code civil". Légifrance. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women". Human Rights Web. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Burghartz v. Switzerland, no. 16213/90, 22 February 1994.

- ^ Losonci Rose and Rose v. Switzerland, no. 664/06, 9 November 2010.

- ^ Ünal Tekeli v Turkey, no. 29865/96, 16 November 2004.

- ^ "European Gender Equality Law Review – No. 1/2012" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. p. 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Novela zákona o matrikách, jménech a příijmeni". Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Govan, Fiona (1 June 2017). "Spain overhauls tradition of 'sexist' double-barrelled surnames". The Local Spain. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Art. 55 Ley de Registro Civil – Civil Register Law Archived 16 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine (article in Spanish)

- ^ Juan Carlos, R. (11 February 2000). "Real Decreto 193/2000, de 11 de febrero, de modificación de determinados artículos del Reglamento del Registro Civil en materia relativa al nombre y apellidos y orden de los mismos". Base de Datos de Legislación (in Spanish). Noticias Juridicas. Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008. Note: Google auto-translation of title into English: Royal Decree 193/2000, of 11 February, to amend certain articles of the Civil Registration Regulations in the field on the name and order.

- ^ "Proper married name?". Spanish Dict. 9 January 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Frank, Francine; Anshen, Frank (1985). Language and the Sexes. SUNY Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-87395-882-0.

- ^ "Identidade, submissão ou amor? O que significa adoptar o apelido do marido". Lifestyle.publico.pt. 18 November 2014. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Genealogy Archived 12 October 2010 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division (1995).

- ^ LaFraniere S. Name Not on Our List? Change It, China Says Archived 25 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. New York Times. 20 April 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Blark. Gregory, et al. The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility (Princeton University Press; 2014) 384 pages; uses statistical data on family names over generations to estimate social mobility in diverse societies and historical periods.

- Bowman, William Dodgson. The Story of Surnames (London, George Routledge & Sons, Ltd., 1932)

- Cottle, Basil. Penguin Dictionary of Surnames (1967)

- Hanks, Patrick and Hodges, Flavia. A Dictionary of Surnames (Oxford University Press, 1989)

- Hanks, Patrick, Richard Coates and Peter McClure, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland (Oxford University Press, 2016), which has a lengthy introduction with much comparative material.

- Reaney, P.H., and Wilson, R.M. A Dictionary of English Surnames (3rd ed. Oxford University Press, 1997)

External links

[edit]- Comprehensive surname information and resource site

- Dictionnaire des noms de famille de France et d'ailleurs Archived 13 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, French surname dictionary

- Family Facts Archive, Ancestry.com, including UK & US census distribution, immigration, and surname origins (Dictionary of American Family Names, Oxford University Press)

- Guild of One-Name Studies

- History of Jewish family Names

- Information on surname history and origins

- Italian Surnames, free searchable online database of Italian surnames.

- Short explanation of Polish surname endings and their origin Archived 15 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Summers, Neil (4 November 2006). "Welsh surnames and their meaning". Amlwch history databases. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- Wilkinson, Hugh E. (December 2010). "Some Common English Surnames: Especially Those Derived from Personal Names" (PDF). Aoyama Keiei Ronshu. 45 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2013.