Астма

| Астма | |

|---|---|

| |

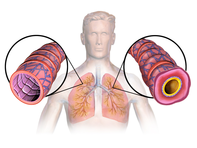

| Это изображение астматических дыхательных путей, оно опухло и полное слизистых. | |

| Произношение | |

| Специальность | Пульмонология |

| Симптомы | Повторяющиеся эпизоды хрипы , кашля , жесткость , одышка [ 3 ] |

| Осложнения | Гастроэзофагеальная рефлюксная болезнь (ГЭРБ), синусит , обструктивное апноэ во сне |

| Usual onset | Childhood |

| Duration | Long term[4] |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors[3] |

| Risk factors | Air pollution, allergens[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, response to therapy, spirometry[5] |

| Treatment | Avoiding triggers, inhaled corticosteroids, salbutamol[6][7] |

| Frequency | Approx. 262 million (2019)[8] |

| Deaths | Approx. 461,000 (2019)[8] |

Астма является долгосрочным воспалительным заболеванием путей легких дыхательных . [ 4 ] Он характеризуется переменными и повторяющимися симптомами, обратимой обструкцией воздушного потока и легко запускаемыми бронхоспазмами . [ 9 ] [ 10 ] Симптомы включают эпизоды хрипа , кашля , жесткость в груди и одышку . [ 3 ] Они могут происходить несколько раз в день или несколько раз в неделю. [ 4 ] В зависимости от человека, симптомы астмы могут стать хуже ночью или с физическими упражнениями. [ 4 ]

Считается, что астма вызвана сочетанием генетических и экологических факторов . [ 3 ] Факторы окружающей среды включают воздействие загрязнения воздуха и аллергенов . [ 4 ] Другие потенциальные триггеры включают такие лекарства, как аспирин и бета -блокаторы . [ 4 ] Диагноз обычно основан на схеме симптомов, ответе на терапию с течением времени и тестированию функции легких спирометрии . [ 5 ] Астма классифицируется в соответствии с частотой симптомов принудительного объема выдоха за одну секунду (FEV 1 ) и пиковую скорость выдоха . [ 11 ] Он также может быть классифицирован как атопический или неатопический, где атопия относится к предрасположенности к разработке реакции гиперчувствительности 1 типа . [12][13]

There is no known cure for asthma, but it can be controlled.[4] Symptoms can be prevented by avoiding triggers, such as allergens and respiratory irritants, and suppressed with the use of inhaled corticosteroids.[6][14] Long-acting beta agonists (LABA) or antileukotriene agents may be used in addition to inhaled corticosteroids if asthma symptoms remain uncontrolled.[15][16] Treatment of rapidly worsening symptoms is usually with an inhaled short-acting beta2 agonist such as salbutamol and corticosteroids taken by mouth.[7] In very severe cases, intravenous corticosteroids, magnesium sulfate, and hospitalization may be required.[17]

In 2019 asthma affected approximately 262 million people and caused approximately 461,000 deaths.[8] Most of the deaths occurred in the developing world.[4] Asthma often begins in childhood,[4] and the rates have increased significantly since the 1960s.[18] Asthma was recognized as early as Ancient Egypt.[19] The word asthma is from the Greek ἆσθμα, âsthma, which means 'panting'.[20]

Signs and symptoms

Asthma is characterized by recurrent episodes of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and coughing.[21] Sputum may be produced from the lung by coughing but is often hard to bring up.[22] During recovery from an asthma attack (exacerbation), the sputum may appear pus-like due to high levels of white blood cells called eosinophils.[23] Symptoms are usually worse at night and in the early morning or in response to exercise or cold air.[24] Some people with asthma rarely experience symptoms, usually in response to triggers, whereas others may react frequently and readily and experience persistent symptoms.[25]

Associated conditions

A number of other health conditions occur more frequently in people with asthma, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), rhinosinusitis, and obstructive sleep apnea.[26] Psychological disorders are also more common,[27] with anxiety disorders occurring in between 16 and 52% and mood disorders in 14–41%.[28] It is not known whether asthma causes psychological problems or psychological problems lead to asthma.[29] Current asthma, but not former asthma, is associated with increased all-cause mortality, heart disease mortality, and chronic lower respiratory tract disease mortality.[30] Asthma, particularly severe asthma, is strongly associated with development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[31][32][33] Those with asthma, especially if it is poorly controlled, are at increased risk for radiocontrast reactions.[34]

Cavities occur more often in people with asthma.[35] This may be related to the effect of beta2-adrenergic agonists decreasing saliva.[36] These medications may also increase the risk of dental erosions.[36]

Causes

Asthma is caused by a combination of complex and incompletely understood environmental and genetic interactions.[37][38] These influence both its severity and its responsiveness to treatment.[39] It is believed that the recent increased rates of asthma are due to changing epigenetics (heritable factors other than those related to the DNA sequence) and a changing living environment.[40] Asthma that starts before the age of 12 years old is more likely due to genetic influence, while onset after age 12 is more likely due to environmental influence.[41]

Environmental

Many environmental factors have been associated with asthma's development and exacerbation, including allergens, air pollution, and other environmental chemicals.[42] There are some substances that are known to cause asthma in exposed people and they are called asthmagens. Some common asthmagens include ammonia, latex, pesticides, solder and welding fumes, metal or wood dusts, spraying of isocyanate paint in vehicle repair, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, anhydrides, glues, dyes, metal working fluids, oil mists, molds.[43][44] Smoking during pregnancy and after delivery is associated with a greater risk of asthma-like symptoms.[45] Low air quality from environmental factors such as traffic pollution or high ozone levels[46] has been associated with both asthma development and increased asthma severity.[47] Over half of cases in children in the United States occur in areas when air quality is below the EPA standards.[48] Low air quality is more common in low-income and minority communities.[49]

Exposure to indoor volatile organic compounds may be a trigger for asthma; formaldehyde exposure, for example, has a positive association.[50] Phthalates in certain types of PVC are associated with asthma in both children and adults.[51][52] While exposure to pesticides is linked to the development of asthma, a cause and effect relationship has yet to be established.[53][54] A meta-analysis concluded gas stoves are a major risk factor for asthma, finding around one in eight cases in the U.S. could be attributed to these.[55]

The majority of the evidence does not support a causal role between paracetamol (acetaminophen) or antibiotic use and asthma.[56][57] A 2014 systematic review found that the association between paracetamol use and asthma disappeared when respiratory infections were taken into account.[58] Maternal psychological stress during pregnancy is a risk factor for the child to develop asthma.[59]

Asthma is associated with exposure to indoor allergens.[60] Common indoor allergens include dust mites, cockroaches, animal dander (fragments of fur or feathers), and mold.[61][62] Efforts to decrease dust mites have been found to be ineffective on symptoms in sensitized subjects.[63][64] Weak evidence suggests that efforts to decrease mold by repairing buildings may help improve asthma symptoms in adults.[65] Certain viral respiratory infections, such as respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus,[20] may increase the risk of developing asthma when acquired as young children.[66] Certain other infections, however, may decrease the risk.[20]

Hygiene hypothesis

The hygiene hypothesis attempts to explain the increased rates of asthma worldwide as a direct and unintended result of reduced exposure, during childhood, to non-pathogenic bacteria and viruses.[67][68] It has been proposed that the reduced exposure to bacteria and viruses is due, in part, to increased cleanliness and decreased family size in modern societies.[69] Exposure to bacterial endotoxin in early childhood may prevent the development of asthma, but exposure at an older age may provoke bronchoconstriction.[70] Evidence supporting the hygiene hypothesis includes lower rates of asthma on farms and in households with pets.[69]

Use of antibiotics in early life has been linked to the development of asthma.[71] Also, delivery via caesarean section is associated with an increased risk (estimated at 20–80%) of asthma – this increased risk is attributed to the lack of healthy bacterial colonization that the newborn would have acquired from passage through the birth canal.[72][73] There is a link between asthma and the degree of affluence which may be related to the hygiene hypothesis as less affluent individuals often have more exposure to bacteria and viruses.[74]

Genetic

| Endotoxin levels | CC genotype | TT genotype |

|---|---|---|

| High exposure | Low risk | High risk |

| Low exposure | High risk | Low risk |

Family history is a risk factor for asthma, with many different genes being implicated.[76] If one identical twin is affected, the probability of the other having the disease is approximately 25%.[76] By the end of 2005, 25 genes had been associated with asthma in six or more separate populations, including GSTM1, IL10, CTLA-4, SPINK5, LTC4S, IL4R and ADAM33, among others.[77] Many of these genes are related to the immune system or modulating inflammation. Even among this list of genes supported by highly replicated studies, results have not been consistent among all populations tested.[77] In 2006 over 100 genes were associated with asthma in one genetic association study alone;[77] more continue to be found.[78]

Some genetic variants may only cause asthma when they are combined with specific environmental exposures.[37] An example is a specific single nucleotide polymorphism in the CD14 region and exposure to endotoxin (a bacterial product). Endotoxin exposure can come from several environmental sources including tobacco smoke, dogs, and farms. Risk for asthma, then, is determined by both a person's genetics and the level of endotoxin exposure.[75]

Medical conditions

A triad of atopic eczema, allergic rhinitis and asthma is called atopy.[79] The strongest risk factor for developing asthma is a history of atopic disease;[66] with asthma occurring at a much greater rate in those who have either eczema or hay fever.[80] Asthma has been associated with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Churg–Strauss syndrome), an autoimmune disease and vasculitis.[81] Individuals with certain types of urticaria may also experience symptoms of asthma.[79]

There is a correlation between obesity and the risk of asthma with both having increased in recent years.[82][83] Several factors may be at play including decreased respiratory function due to a buildup of fat and the fact that adipose tissue leads to a pro-inflammatory state.[84]

Beta blocker medications such as propranolol can trigger asthma in those who are susceptible.[85] Cardioselective beta-blockers, however, appear safe in those with mild or moderate disease.[86][87] Other medications that can cause problems in asthmatics are angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, aspirin, and NSAIDs.[88] Use of acid-suppressing medication (proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers) during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of asthma in the child.[89]

Exacerbation

Some individuals will have stable asthma for weeks or months and then suddenly develop an episode of acute asthma. Different individuals react to various factors in different ways.[90] Most individuals can develop severe exacerbation from a number of triggering agents.[90]

Home factors that can lead to exacerbation of asthma include dust, animal dander (especially cat and dog hair), cockroach allergens and mold.[90][91] Perfumes are a common cause of acute attacks in women and children. Both viral and bacterial infections of the upper respiratory tract can worsen the disease.[90] Psychological stress may worsen symptoms – it is thought that stress alters the immune system and thus increases the airway inflammatory response to allergens and irritants.[47][92]

Asthma exacerbations in school-aged children peak in autumn, shortly after children return to school. This might reflect a combination of factors, including poor treatment adherence, increased allergen and viral exposure, and altered immune tolerance. There is limited evidence to guide possible approaches to reducing autumn exacerbations, but while costly, seasonal omalizumab treatment from four to six weeks before school return may reduce autumn asthma exacerbations.[93]

Pathophysiology

Asthma is the result of chronic inflammation of the conducting zone of the airways (most especially the bronchi and bronchioles), which subsequently results in increased contractability of the surrounding smooth muscles. This among other factors leads to bouts of narrowing of the airway and the classic symptoms of wheezing. The narrowing is typically reversible with or without treatment. Occasionally the airways themselves change.[21] Typical changes in the airways include an increase in eosinophils and thickening of the lamina reticularis. Chronically the airways' smooth muscle may increase in size along with an increase in the numbers of mucous glands. Other cell types involved include T lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. There may also be involvement of other components of the immune system, including cytokines, chemokines, histamine, and leukotrienes among others.[20]

Diagnosis

While asthma is a well-recognized condition, there is not one universal agreed-upon definition.[20] It is defined by the Global Initiative for Asthma as "a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways in which many cells and cellular elements play a role. The chronic inflammation is associated with airway hyper-responsiveness that leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing particularly at night or in the early morning. These episodes are usually associated with widespread but variable airflow obstruction within the lung that is often reversible either spontaneously or with treatment".[21]

There is currently no precise test for the diagnosis, which is typically based on the pattern of symptoms and response to therapy over time.[5][20] Asthma may be suspected if there is a history of recurrent wheezing, coughing or difficulty breathing and these symptoms occur or worsen due to exercise, viral infections, allergens or air pollution.[94] Spirometry is then used to confirm the diagnosis.[94] In children under the age of six the diagnosis is more difficult as they are too young for spirometry.[95]

Spirometry

Spirometry is recommended to aid in diagnosis and management.[96][97] It is the single best test for asthma. If the FEV1 measured by this technique improves more than 12% and increases by at least 200 milliliters following administration of a bronchodilator such as salbutamol, this is supportive of the diagnosis. It however may be normal in those with a history of mild asthma, not currently acting up.[20] As caffeine is a bronchodilator in people with asthma, the use of caffeine before a lung function test may interfere with the results.[98] Single-breath diffusing capacity can help differentiate asthma from COPD.[20] It is reasonable to perform spirometry every one or two years to follow how well a person's asthma is controlled.[99]

Others

The methacholine challenge involves the inhalation of increasing concentrations of a substance that causes airway narrowing in those predisposed. If negative it means that a person does not have asthma; if positive, however, it is not specific for the disease.[20]

Other supportive evidence includes: a ≥20% difference in peak expiratory flow rate on at least three days in a week for at least two weeks, a ≥20% improvement of peak flow following treatment with either salbutamol, inhaled corticosteroids or prednisone, or a ≥20% decrease in peak flow following exposure to a trigger.[100] Testing peak expiratory flow is more variable than spirometry, however, and thus not recommended for routine diagnosis. It may be useful for daily self-monitoring in those with moderate to severe disease and for checking the effectiveness of new medications. It may also be helpful in guiding treatment in those with acute exacerbations.[101]

Classification

| Severity | Symptom frequency | Night-time symptoms | %FEV1 of predicted | FEV1 variability | SABA use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent | ≤2/week | ≤2/month | ≥80% | <20% | ≤2 days/week |

| Mild persistent | >2/week | 3–4/month | ≥80% | 20–30% | >2 days/week |

| Moderate persistent | Daily | >1/week | 60–80% | >30% | daily |

| Severe persistent | Continuously | Frequent (7/week) | <60% | >30% | ≥twice/day |

Asthma is clinically classified according to the frequency of symptoms, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), and peak expiratory flow rate.[11] Asthma may also be classified as atopic (extrinsic) or non-atopic (intrinsic), based on whether symptoms are precipitated by allergens (atopic) or not (non-atopic).[12] While asthma is classified based on severity, at the moment there is no clear method for classifying different subgroups of asthma beyond this system.[102] Finding ways to identify subgroups that respond well to different types of treatments is a current critical goal of asthma research.[102] Recently, asthma has been classified based on whether it is associated with type 2 or non–type 2 inflammation. This approach to immunologic classification is driven by a developing understanding of the underlying immune processes and by the development of therapeutic approaches that target type 2 inflammation.[103]

Although asthma is a chronic obstructive condition, it is not considered as a part of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as this term refers specifically to combinations of disease that are irreversible such as bronchiectasis and emphysema.[104] Unlike these diseases, the airway obstruction in asthma is usually reversible; however, if left untreated, the chronic inflammation from asthma can lead the lungs to become irreversibly obstructed due to airway remodeling.[105] In contrast to emphysema, asthma affects the bronchi, not the alveoli.[106] The combination of asthma with a component of irreversible airway obstruction has been termed the asthma-chronic obstructive disease (COPD) overlap syndrome (ACOS). Compared to other people with "pure" asthma or COPD, people with ACOS exhibit increased morbidity, mortality and possibly more comorbidities.[107]

Asthma exacerbation

| Near-fatal | High PaCO2, or requiring mechanical ventilation, or both | |

|---|---|---|

| Life-threatening (any one of) | ||

| Clinical signs | Measurements | |

| Altered level of consciousness | Peak flow < 33% | |

| Exhaustion | Oxygen saturation < 92% | |

| Arrhythmia | PaO2 < 8 kPa | |

| Low blood pressure | "Normal" PaCO2 | |

| Cyanosis | ||

| Silent chest | ||

| Poor respiratory effort | ||

| Acute severe (any one of) | ||

| Peak flow 33–50% | ||

| Respiratory rate ≥ 25 breaths per minute | ||

| Heart rate ≥ 110 beats per minute | ||

| Unable to complete sentences in one breath | ||

| Moderate | Worsening symptoms | |

| Peak flow 50–80% best or predicted | ||

| No features of acute severe asthma | ||

An acute asthma exacerbation is commonly referred to as an asthma attack. The classic symptoms are shortness of breath, wheezing, and chest tightness.[20] The wheezing is most often when breathing out.[109] While these are the primary symptoms of asthma,[110] some people present primarily with coughing, and in severe cases, air motion may be significantly impaired such that no wheezing is heard.[108] In children, chest pain is often present.[111]

Signs occurring during an asthma attack include the use of accessory muscles of respiration (sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscles of the neck), there may be a paradoxical pulse (a pulse that is weaker during inhalation and stronger during exhalation), and over-inflation of the chest.[112] A blue color of the skin and nails may occur from lack of oxygen.[113]

In a mild exacerbation the peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) is ≥200 L/min, or ≥50% of the predicted best.[114] Moderate is defined as between 80 and 200 L/min, or 25% and 50% of the predicted best, while severe is defined as ≤ 80 L/min, or ≤25% of the predicted best.[114]

Acute severe asthma, previously known as status asthmaticus, is an acute exacerbation of asthma that does not respond to standard treatments of bronchodilators and corticosteroids.[115] Half of cases are due to infections with others caused by allergen, air pollution, or insufficient or inappropriate medication use.[115]

Brittle asthma is a kind of asthma distinguishable by recurrent, severe attacks.[108] Type 1 brittle asthma is a disease with wide peak flow variability, despite intense medication. Type 2 brittle asthma is background well-controlled asthma with sudden severe exacerbations.[108]

Exercise-induced

Exercise can trigger bronchoconstriction both in people with or without asthma.[116] It occurs in most people with asthma and up to 20% of people without asthma.[116] Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is common in professional athletes. The highest rates are among cyclists (up to 45%), swimmers, and cross-country skiers.[117] While it may occur with any weather conditions, it is more common when it is dry and cold.[118] Inhaled beta2 agonists do not appear to improve athletic performance among those without asthma;[119] however, oral doses may improve endurance and strength.[120][121]

Occupational

Asthma as a result of (or worsened by) workplace exposures is a commonly reported occupational disease.[122] Many cases, however, are not reported or recognized as such.[123][124] It is estimated that 5–25% of asthma cases in adults are work-related. A few hundred different agents have been implicated, with the most common being isocyanates, grain and wood dust, colophony, soldering flux, latex, animals, and aldehydes. The employment associated with the highest risk of problems include those who spray paint, bakers and those who process food, nurses, chemical workers, those who work with animals, welders, hairdressers and timber workers.[122]

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), also known as aspirin-induced asthma, affects up to 9% of asthmatics.[125] AERD consists of asthma, nasal polyps, sinus disease, and respiratory reactions to aspirin and other NSAID medications (such as ibuprofen and naproxen).[126] People often also develop loss of smell and most experience respiratory reactions to alcohol.[127]

Alcohol-induced asthma

Alcohol may worsen asthmatic symptoms in up to a third of people.[128] This may be even more common in some ethnic groups such as the Japanese and those with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease.[128] Other studies have found improvement in asthmatic symptoms from alcohol.[128]

Non-atopic asthma

Non-atopic asthma, also known as intrinsic or non-allergic, makes up between 10 and 33% of cases. There is negative skin test to common inhalant allergens. Often it starts later in life, and women are more commonly affected than men. Usual treatments may not work as well.[129] The concept that "non-atopic" is synonymous with "non-allergic" is called into question by epidemiological data that the prevalence of asthma is closely related to the serum IgE level standardized for age and sex (P<0.0001), indicating that asthma is almost always associated with some sort of IgE-related reaction and therefore has an allergic basis, although not all the allergic stimuli that cause asthma appear to have been included in the battery of aeroallergens studied (the "missing antigen(s)" hypothesis).[130] For example, an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of population-attributable risk (PAR) of Chlamydia pneumoniae biomarkers in chronic asthma found that the PAR for C. pneumoniae-specific IgE was 47%.[131]

Infectious asthma

Infectious asthma is an easily identified clinical presentation.[132] When queried, asthma patients may report that their first asthma symptoms began after an acute lower respiratory tract illness. This type of history has been labelled the "infectious asthma" (IA) syndrome,[133] or as "asthma associated with infection" (AAWI)[134] to distinguish infection-associated asthma initiation from the well known association of respiratory infections with asthma exacerbations. Reported clinical prevalences of IA for adults range from around 40% in a primary care practice[133] to 70% in a specialty practice treating mainly severe asthma patients.[135] Additional information on the clinical prevalence of IA in adult-onset asthma is unavailable because clinicians are not trained to elicit this type of history routinely, and recollection in child-onset asthma is challenging. A population-based incident case-control study in a geographically defined area of Finland reported that 35.8% of new-onset asthma cases had experienced acute bronchitis or pneumonia in the year preceding asthma onset, representing a significantly higher risk compared to randomly selected controls (odds ratio 7.2, 95% confidence interval 5.2–10).[136]

Phenotyping and endotyping

Asthma phenotyping and endotyping has emerged as a novel approach to asthma classification inspired by precision medicine which separates the clinical presentations of asthma, or asthma phenotypes, from their underlying causes, or asthma endotypes. The best-supported endotypic distinction is the type 2-high/type 2-low distinction. Classification based on type 2 inflammation is useful in predicting which patients will benefit from targeted biologic therapy.[137][138]

Differential diagnosis

Many other conditions can cause symptoms similar to those of asthma. In children, symptoms may be due to other upper airway diseases such as allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, as well as other causes of airway obstruction including foreign body aspiration, tracheal stenosis, laryngotracheomalacia, vascular rings, enlarged lymph nodes or neck masses.[139] Bronchiolitis and other viral infections may also produce wheezing.[140] According to European Respiratory Society, it may not be suitable to label wheezing preschool children with the term asthma because there is lack of clinical data on inflammation in airways.[141] In adults, COPD, congestive heart failure, airway masses, as well as drug-induced coughing due to ACE inhibitors may cause similar symptoms. In both populations vocal cord dysfunction may present similarly.[139]

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can coexist with asthma and can occur as a complication of chronic asthma. After the age of 65, most people with obstructive airway disease will have asthma and COPD. In this setting, COPD can be differentiated by increased airway neutrophils, abnormally increased wall thickness, and increased smooth muscle in the bronchi. However, this level of investigation is not performed due to COPD and asthma sharing similar principles of management: corticosteroids, long-acting beta-agonists, and smoking cessation.[142] It closely resembles asthma in symptoms, is correlated with more exposure to cigarette smoke, an older age, less symptom reversibility after bronchodilator administration, and decreased likelihood of family history of atopy.[143][144]

Prevention

The evidence for the effectiveness of measures to prevent the development of asthma is weak.[145] The World Health Organization recommends decreasing risk factors such as tobacco smoke, air pollution, chemical irritants including perfume, and the number of lower respiratory infections.[146][147] Other efforts that show promise include: limiting smoke exposure in utero, breastfeeding, and increased exposure to daycare or large families, but none are well supported enough to be recommended for this indication.[145]

Early pet exposure may be useful.[148] Results from exposure to pets at other times are inconclusive[149] and it is only recommended that pets be removed from the home if a person has allergic symptoms to said pet.[150]

Dietary restrictions during pregnancy or when breastfeeding have not been found to be effective at preventing asthma in children and are not recommended.[150] Omega-3 consumption, Mediterranean diet and antioxidants have been suggested by some studies to potentially help prevent crises but the evidence is still inconclusive.[151]

Reducing or eliminating compounds known to sensitive people from the workplace may be effective.[122] It is not clear if annual influenza vaccinations affect the risk of exacerbations.[152] Immunization, however, is recommended by the World Health Organization.[153] Smoking bans are effective in decreasing exacerbations of asthma.[154]

Management

While there is no cure for asthma, symptoms can typically be improved.[155] The most effective treatment for asthma is identifying triggers, such as cigarette smoke, pets or other allergens, and eliminating exposure to them. If trigger avoidance is insufficient, the use of medication is recommended. Pharmaceutical drugs are selected based on, among other things, the severity of illness and the frequency of symptoms. Specific medications for asthma are broadly classified into fast-acting and long-acting categories.[156][157] The medications listed below have demonstrated efficacy in improving asthma symptoms; however, real world use-effectiveness is limited as around half of people with asthma worldwide remain sub-optimally controlled, even when treated.[158][159][160] People with asthma may remain sub-optimally controlled either because optimum doses of asthma medications do not work (called "refractory" asthma) or because individuals are either unable (e.g. inability to afford treatment, poor inhaler technique) or unwilling (e.g., wish to avoid side effects of corticosteroids) to take optimum doses of prescribed asthma medications (called "difficult to treat" asthma). In practice, it is not possible to distinguish "refractory" from "difficult to treat" categories for patients who have never taken optimum doses of asthma medications. A related issue is that the asthma efficacy trials upon which the pharmacological treatment guidelines are based have systematically excluded the majority of people with asthma.[161][162] For example, asthma efficacy treatment trials always exclude otherwise eligible people who smoke, and smoking diminishes the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids, the mainstay of asthma control management.[163][164][165]

Bronchodilators are recommended for short-term relief of symptoms. In those with occasional attacks, no other medication is needed. If mild persistent disease is present (more than two attacks a week), low-dose inhaled corticosteroids or alternatively, a leukotriene antagonist or a mast cell stabilizer by mouth is recommended. For those who have daily attacks, a higher dose of inhaled corticosteroids is used. In a moderate or severe exacerbation, corticosteroids by mouth are added to these treatments.[7]

People with asthma have higher rates of anxiety, psychological stress, and depression.[166][167] This is associated with poorer asthma control.[166] Cognitive behavioral therapy may improve quality of life, asthma control, and anxiety levels in people with asthma.[166]

Improving people's knowledge about asthma and using a written action plan has been identified as an important component of managing asthma.[168] Providing educational sessions that include information specific to a person's culture is likely effective.[169] More research is necessary to determine if increasing preparedness and knowledge of asthma among school staff and families using home-based and school interventions results in long term improvements in safety for children with asthma.[170][171][172] School-based asthma self-management interventions, which attempt to improve knowledge of asthma, its triggers and the importance of regular practitioner review, may reduce hospital admissions and emergency department visits. These interventions may also reduce the number of days children experience asthma symptoms and may lead to small improvements in asthma-related quality of life.[173] More research is necessary to determine if shared decision-making is helpful for managing adults with asthma[174] or if a personalized asthma action plan is effective and necessary.[175] Some people with asthma use pulse oximeters to monitor their own blood oxygen levels during an asthma attack. However, there is no evidence regarding the use in these instances.[176]

Lifestyle modification

Avoidance of triggers is a key component of improving control and preventing attacks. The most common triggers include allergens, smoke (from tobacco or other sources), air pollution, nonselective beta-blockers, and sulfite-containing foods.[177][178] Cigarette smoking and second-hand smoke (passive smoke) may reduce the effectiveness of medications such as corticosteroids.[179] Laws that limit smoking decrease the number of people hospitalized for asthma.[154] Dust mite control measures, including air filtration, chemicals to kill mites, vacuuming, mattress covers and other methods had no effect on asthma symptoms.[63] There is insufficient evidence to suggest that dehumidifiers are helpful for controlling asthma.[180]

Overall, exercise is beneficial in people with stable asthma.[181] Yoga could provide small improvements in quality of life and symptoms in people with asthma.[182] More research is necessary to determine how effective weight loss is in improving quality of life, the usage of health care services, and adverse effects for people of all ages with asthma.[183][184]

Findings suggest that the Wim Hof Method may reduce inflammation in healthy and non-healthy participants as it increases epinephrine levels, causing an increase in interleukin-10 and a decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines.[185]

Medications

Medications used to treat asthma are divided into two general classes: quick-relief medications used to treat acute symptoms; and long-term control medications used to prevent further exacerbation.[156] Antibiotics are generally not needed for sudden worsening of symptoms or for treating asthma at any time.[186][187]

Medications for asthma exacerbations

- Short-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonists (SABAs), such as salbutamol (albuterol USAN) are the first-line treatment for asthma symptoms.[7] They are recommended before exercise in those with exercise-induced symptoms.[188]

- Anticholinergic medications, such as ipratropium, provide additional benefit when used in combination with SABA in those with moderate or severe symptoms and may prevent hospitalizations.[7][189][190] Anticholinergic bronchodilators can also be used if a person cannot tolerate a SABA.[104] If a child requires admission to hospital additional ipratropium does not appear to help over a SABA.[191] For children over 2 years old with acute asthma symptoms, inhaled anticholinergic medications taken alone is safe but is not as effective as inhaled SABA or SABA combined with inhaled anticholinergic medication.[192][189] Adults who receive combined inhaled medications, which include short-acting anticholinergics and SABA, may be at risk for increased adverse effects such as experiencing a tremor, agitation, and heart beat palpitations compared to people who are treated with SABAs alone.[190]

- Older, less selective adrenergic agonists, such as inhaled epinephrine, have similar efficacy to SABAs.[193] They are, however, not recommended due to concerns regarding excessive cardiac stimulation.[194]

- Corticosteroids can also help with the acute phase of an exacerbation because of their antiinflamatory properties. The benefit of systemic and oral corticosteroids is well established. Inhaled or nebulized corticosteroids can also be used.[151] For adults and children who are in the hospital due to acute asthma, systemic (IV) corticosteroids improve symptoms.[195][196] A short course of corticosteroids after an acute asthma exacerbation may help prevent relapses and reduce hospitalizations.[197]

- Other remedies, less established, are intravenous or nebulized magnesium sulfate and helium mixed with oxygen. Aminophylline could be used with caution as well.[151]

- Mechanical ventilation is the last resort in case of severe hypoxemia.[151]

- Intravenous administration of the drug aminophylline does not provide an improvement in bronchodilation when compared to standard inhaled beta2 agonist treatment.[198] Aminophylline treatment is associated with more adverse effects compared to inhaled beta2 agonist treatment.[198]

Long–term control

- Corticosteroids are generally considered the most effective treatment available for long-term control.[156] Inhaled forms are usually used except in the case of severe persistent disease, in which oral corticosteroids may be needed.[156] Dosage depends on the severity of symptoms.[199] High dosage and long-term use might lead to the appearance of common adverse effects which are growth delay, adrenal suppression, and osteoporosis.[151] Continuous (daily) use of an inhaled corticosteroid, rather than its intermitted use, seems to provide better results in controlling asthma exacerbations.[151] Commonly used corticosteroids are budesonide, fluticasone, mometasone and ciclesonide.[151]

- Long-acting beta-adrenoceptor agonists (LABA) such as salmeterol and formoterol can improve asthma control, at least in adults, when given in combination with inhaled corticosteroids.[200][201] In children this benefit is uncertain.[200][202][201] When used without steroids they increase the risk of severe side-effects,[203] and with corticosteroids they may slightly increase the risk.[204][205] Evidence suggests that for children who have persistent asthma, a treatment regime that includes LABA added to inhaled corticosteroids may improve lung function but does not reduce the amount of serious exacerbations.[206] Children who require LABA as part of their asthma treatment may need to go to the hospital more frequently.[206]

- Leukotriene receptor antagonists (anti-leukotriene agents such as montelukast and zafirlukast) may be used in addition to inhaled corticosteroids, typically also in conjunction with a LABA.[16][207][208][209] For adults or adolescents who have persistent asthma that is not controlled very well, the addition of anti-leukotriene agents along with daily inhaled corticosteriods improves lung function and reduces the risk of moderate and severe asthma exacerbations.[208] Anti-leukotriene agents may be effective alone for adolescents and adults; however, there is no clear research suggesting which people with asthma would benefit from anti-leukotriene receptor alone.[210] In those under five years of age, anti-leukotriene agents were the preferred add-on therapy after inhaled corticosteroids.[151][211] A 2013 Cochrane systematic review concluded that anti-leukotriene agents appear to be of little benefit when added to inhaled steroids for treating children.[212] A similar class of drugs, 5-LOX inhibitors, may be used as an alternative in the chronic treatment of mild to moderate asthma among older children and adults.[16][213] As of 2013[update] there is one medication in this family known as zileuton.[16]

- Mast cell stabilizers (such as cromolyn sodium) are safe alternatives to corticosteroids but not preferred because they have to be administered frequently.[156][16]

- Oral theophyllines are sometimes used for controlling chronic asthma, but their used is minimized due to side effects.[151]

- Omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody against IgE, is a novel way to lessen exacerbations by decreasing the levels of circulating IgE that play a significant role at allergic asthma.[151][214]

- Anticholinergic medications such as ipratropium bromide have not been shown to be beneficial for treating chronic asthma in children over 2 years old,[215] and are not suggested for routine treatment of chronic asthma in adults.[216]

- There is no strong evidence to recommend chloroquine medication as a replacement for taking corticosteroids by mouth (for those who are not able to tolerate inhaled steroids).[217] Methotrexate is not suggested as a replacement for taking corticosteriods by mouth ("steroid-sparing") due to the adverse effects associated with taking methotrexate and the minimal relief provided for asthma symptoms.[218]

- Macrolide antibiotics, particularly the azalide macrolide azithromycin, are a recently added Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)-recommended treatment option for both eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic severe, refractory asthma based on azithromycin's efficacy in reducing moderate and severe exacerbations combined.[219][220] Azithromycin's mechanism of action is not established, and could involve pathogen- and/or host-directed anti-inflammatory activities.[221] Limited clinical observations suggest that some patients with new-onset asthma and with "difficult-to-treat" asthma (including those with the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome – ACOS) may respond dramatically to azithromycin.[222][135] However, these groups of asthma patients have not been studied in randomized treatment trials and patient selection needs to be carefully individualized.

For children with asthma which is well-controlled on combination therapy of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting beta2-agonists (LABA), the benefits and harms of stopping LABA and stepping down to ICS-only therapy are uncertain.[223] In adults who have stable asthma while they are taking a combination of LABA and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), stopping LABA may increase the risk of asthma exacerbations that require treatment with corticosteroids by mouth.[224] Stopping LABA probably makes little or no important difference to asthma control or asthma-related quality of life.[224] Whether or not stopping LABA increases the risk of serious adverse events or exacerbations requiring an emergency department visit or hospitalisation is uncertain.[224]

Delivery methods

Medications are typically provided as metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) in combination with an inhaler spacer or as a dry powder inhaler. The spacer is a plastic cylinder that mixes the medication with air, making it easier to receive a full dose of the drug. A nebulizer may also be used. Nebulizers and spacers are equally effective in those with mild to moderate symptoms. However, insufficient evidence is available to determine whether a difference exists in those with severe disease.[225] For delivering short-acting beta-agonists in acute asthma in children, spacers may have advantages compared to nebulisers, but children with life-threatening asthma have not been studied.[226] There is no strong evidence for the use of intravenous LABA for adults or children who have acute asthma.[227] There is insufficient evidence to directly compare the effectiveness of a metered-dose inhaler attached to a homemade spacer compared to commercially available spacer for treating children with asthma.[228]

Adverse effects

Long-term use of inhaled corticosteroids at conventional doses carries a minor risk of adverse effects.[229] Risks include thrush, the development of cataracts, and a slightly slowed rate of growth.[229][230][231] Rinsing the mouth after the use of inhaled steroids can decrease the risk of thrush.[232] Higher doses of inhaled steroids may result in lower bone mineral density.[233]

Others

Inflammation in the lungs can be estimated by the level of exhaled nitric oxide.[234][235] The use of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FeNO) to guide asthma medication dosing may have small benefits for preventing asthma attacks but the potential benefits are not strong enough for this approach to be universally recommended as a method to guide asthma therapy in adults or children.[234][235]

When asthma is unresponsive to usual medications, other options are available for both emergency management and prevention of flareups. Additional options include:

- Humidified oxygen to alleviate hypoxia if saturations fall below 92%.[151]

- Corticosteroids by mouth, with five days of prednisone being the same two days of dexamethasone.[236] One review recommended a seven-day course of steroids.[237]

- Magnesium sulfate intravenous treatment increases bronchodilation when used in addition to other treatment in moderate severe acute asthma attacks.[17][238][239] In adults intravenous treatment results in a reduction of hospital admissions.[240] Low levels of evidence suggest that inhaled (nebulised) magnesium sulfate may have a small benefit for treating acute asthma in adults.[241] Overall, high-quality evidence do not indicate a large benefit for combining magnesium sulfate with standard inhaled treatments for adults with asthma.[241]

- Heliox, a mixture of helium and oxygen, may also be considered in severe unresponsive cases.[17]

- Intravenous salbutamol is not supported by available evidence and is thus used only in extreme cases.[242]

- Methylxanthines (such as theophylline) were once widely used, but do not add significantly to the effects of inhaled beta-agonists.[242] Their use in acute exacerbations is controversial.[243]

- The dissociative anesthetic ketamine is theoretically useful if intubation and mechanical ventilation is needed in people who are approaching respiratory arrest; however, there is no evidence from clinical trials to support this.[244] A 2012 Cochrane review found no significant benefit from the use of ketamine in severe acute asthma in children.[245]

- For those with severe persistent asthma not controlled by inhaled corticosteroids and LABAs, bronchial thermoplasty may be an option.[246] It involves the delivery of controlled thermal energy to the airway wall during a series of bronchoscopies.[246][247] While it may increase exacerbation frequency in the first few months it appears to decrease the subsequent rate. Effects beyond one year are unknown.[248]

- Monoclonal antibody injections such as mepolizumab,[249] dupilumab,[250] or omalizumab may be useful in those with poorly controlled atopic asthma.[251] However, as of 2019[update] these medications are expensive and their use is therefore reserved for those with severe symptoms to achieve cost-effectiveness.[252] Monoclonal antibodies targeting interleukin-5 (IL-5) or its receptor (IL-5R), including mepolizumab, reslizumab or benralizumab, in addition to standard care in severe asthma is effective in reducing the rate of asthma exacerbations. There is limited evidence for improved health-related quality of life and lung function.[253]

- Evidence suggests that sublingual immunotherapy in those with both allergic rhinitis and asthma improve outcomes.[254]

- It is unclear if non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in children is of use as it has not been sufficiently studied.[255]

Adherence to asthma treatments

Staying with a treatment approach for preventing asthma exacerbations can be challenging, especially if the person is required to take medicine or treatments daily.[256] Reasons for low adherence range from a conscious decision to not follow the suggested medical treatment regime for various reasons including avoiding potential side effects, misinformation, or other beliefs about the medication.[256] Problems accessing the treatment and problems administering the treatment effectively can also result in lower adherence. Various approaches have been undertaken to try and improve adherence to treatments to help people prevent serious asthma exacerbations including digital interventions.[256]

Alternative medicine

Many people with asthma, like those with other chronic disorders, use alternative treatments; surveys show that roughly 50% use some form of unconventional therapy.[257][258] There is little data to support the effectiveness of most of these therapies.

Evidence is insufficient to support the usage of vitamin C or vitamin E for controlling asthma.[259][260] There is tentative support for use of vitamin C in exercise induced bronchospasm.[261] Fish oil dietary supplements (marine n-3 fatty acids)[262] and reducing dietary sodium[263] do not appear to help improve asthma control. In people with mild to moderate asthma, treatment with vitamin D supplementation or its hydroxylated metabolites does not reduce acute exacerbations or improve control.[264] There is no strong evidence to suggest that vitamin D supplements improve day-to-day asthma symptoms or a person's lung function.[264] There is no strong evidence to suggest that adults with asthma should avoid foods that contain monosodium glutamate (MSG).[265] There have not been enough high-quality studies performed to determine if children with asthma should avoid eating food that contains MSG.[265]

Acupuncture is not recommended for the treatment as there is insufficient evidence to support its use.[266][267] Air ionisers show no evidence that they improve asthma symptoms or benefit lung function; this applied equally to positive and negative ion generators.[268] Manual therapies, including osteopathic, chiropractic, physiotherapeutic and respiratory therapeutic maneuvers, have insufficient evidence to support their use in treating asthma.[269] Pulmonary rehabilitation, however, may improve quality of life and functional exercise capacity when compared to usual care for adults with asthma.[270] The Buteyko breathing technique for controlling hyperventilation may result in a reduction in medication use; however, the technique does not have any effect on lung function.[157] Thus an expert panel felt that evidence was insufficient to support its use.[266] There is no clear evidence that breathing exercises are effective for treating children with asthma.[271]

Prognosis

The prognosis for asthma is generally good, especially for children with mild disease.[272] Mortality has decreased over the last few decades due to better recognition and improvement in care.[273] In 2010 the death rate was 170 per million for males and 90 per million for females.[274] Rates vary between countries by 100-fold.[274]

Globally it causes moderate or severe disability in 19.4 million people as of 2004[update] (16 million of which are in low and middle income countries).[275] Of asthma diagnosed during childhood, half of cases will no longer carry the diagnosis after a decade.[76] Airway remodeling is observed, but it is unknown whether these represent harmful or beneficial changes.[276] More recent data find that severe asthma can result in airway remodeling and the "asthma with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease syndrome (ACOS)" that has a poor prognosis.[277] Early treatment with corticosteroids seems to prevent or ameliorates a decline in lung function.[278] Asthma in children also has negative effects on quality of life of their parents.[279]

-

Asthma deaths per million persons in 20120–1011–1314–1718–2324–3233–4344–5051–6667–9596–251

-

Disability-adjusted life year for asthma per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004[280]no data0-100100–150150–200200–250250–300300–350350–400400–450450–500500–550550–600>600

Epidemiology

In 2019, approximately 262 million people worldwide were affected by asthma and approximately 461,000 people died from the disease.[8] Rates vary between countries with prevalences between 1 and 18%.[21] It is more common in developed than developing countries.[21] One thus sees lower rates in Asia, Eastern Europe and Africa.[20] Within developed countries it is more common in those who are economically disadvantaged while in contrast in developing countries it is more common in the affluent.[21] The reason for these differences is not well known.[21] Low- and middle-income countries make up more than 80% of the mortality.[282]

While asthma is twice as common in boys as girls,[21] severe asthma occurs at equal rates.[283] In contrast adult women have a higher rate of asthma than men[21] and it is more common in the young than the old.[20] In 2010, children with asthma experienced over 900,000 emergency department visits, making it the most common reason for admission to the hospital following an emergency department visit in the US in 2011.[284][285]

Global rates of asthma have increased significantly between the 1960s and 2008[18][286] with it being recognized as a major public health problem since the 1970s.[20] Rates of asthma have plateaued in the developed world since the mid-1990s with recent increases primarily in the developing world.[287] Asthma affects approximately 7% of the population of the United States[203] and 5% of people in the United Kingdom.[288] Canada, Australia and New Zealand have rates of about 14–15%.[289]

The average death rate from 2011 to 2015 from asthma in the UK was about 50% higher than the average for the European Union and had increased by about 5% in that time.[290] Children are more likely see a physician due to asthma symptoms after school starts in September.[291]

Population-based epidemiological studies describe temporal associations between acute respiratory illnesses, asthma, and development of severe asthma with irreversible airflow limitation (known as the asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease "overlap" syndrome, or ACOS).[292][293][31] Additional prospective population-based data indicate that ACOS seems to represent a form of severe asthma, characterised by more frequent hospitalisations, and to be the result of early-onset asthma that has progressed to fixed airflow obstruction.[32]

Economics

From 2000 to 2010, the average cost per asthma-related hospital stay in the United States for children remained relatively stable at about $3,600, whereas the average cost per asthma-related hospital stay for adults increased from $5,200 to $6,600.[294] In 2010, Medicaid was the most frequent primary payer among children and adults aged 18–44 years in the United States; private insurance was the second most frequent payer.[294] Among both children and adults in the lowest income communities in the United States there is a higher rate of hospital stays for asthma in 2010 than those in the highest income communities.[294]

History

Asthma was recognized in ancient Egypt and was treated by drinking an incense mixture known as kyphi.[19] It was officially named as a specific respiratory problem by Hippocrates circa 450 BC, with the Greek word for "panting" forming the basis of our modern name.[20] In 200 BC it was believed to be at least partly related to the emotions.[28] In the 12th century the Jewish physician-philosopher Maimonides wrote a treatise on asthma in Arabic, based partly on Arabic sources, in which he discussed the symptoms, proposed various dietary and other means of treatment, and emphasized the importance of climate and clean air.[295] Traditional Chinese medicine also offered medication for asthma, as indicated by a surviving 14th-century manuscript curated by the Wellcome Foundation.[296]

In 1873, one of the first papers in modern medicine on the subject tried to explain the pathophysiology of the disease while one in 1872, concluded that asthma can be cured by rubbing the chest with chloroform liniment.[297][298] Medical treatment in 1880 included the use of intravenous doses of a drug called pilocarpine.[299]

In 1886, F. H. Bosworth theorized a connection between asthma and hay fever.[300]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the focus was the avoidance of allergens as well as selective beta-2 adrenoceptor agonists were used as treatment strategies.[301][302]

Epinephrine was first referred to in the treatment of asthma in 1905.[303] Oral corticosteroids began to be used for the condition in 1950. The use of a pressurized metered-dose inhaler was developed in the mid-1950s for the administration of adrenaline and isoproterenol and was later used as a beta2-adrenergic agonist.

Inhaled corticosteroids and selective short-acting beta agonists came into wide use in the 1960s.[304][305]

A well-documented case in the 19th century was that of young Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919). At that time there was no effective treatment. Roosevelt's youth was in large part shaped by his poor health, partly related to his asthma. He experienced recurring nighttime asthma attacks that felt as if he was being smothered to death, terrifying the boy and his parents.[306]

During the 1930s to 1950s, asthma was known as one of the "holy seven" psychosomatic illnesses. Its cause was considered to be psychological, with treatment often based on psychoanalysis and other talking cures.[307] As these psychoanalysts interpreted the asthmatic wheeze as the suppressed cry of the child for its mother, they considered the treatment of depression to be especially important for individuals with asthma.[307]

In January 2021, an appeal court in France overturned a deportation order against a 40-year-old Bangladeshi man, who was a patient of asthma. His lawyers had argued that the dangerous levels of pollution in Bangladesh could possibly lead to worsening of his health condition, or even premature death.[308]

Notes

- ^ Jones D (2011). Roach P, Setter J, Esling J (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Wells JC (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Drazen GM, Bel EH (2020). "81. Asthma". In Goldman L, Schafer AI (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 1 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 527–535. ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "Asthma Fact sheet №307". WHO. November 2013. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lemanske RF, Busse WW (February 2010). "Asthma: clinical expression and molecular mechanisms". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 125 (2 Suppl 2): S95-102. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.047. PMC 2853245. PMID 20176271.

- ^ Jump up to: a b NHLBI Guideline 2007, pp. 169–72

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 214

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Asthma–Level 3 cause" (PDF). The Lancet. 396: S108–S109. October 2020.

- ^ NHLBI Guideline 2007, pp. 11–12

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 20,51

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Yawn BP (September 2008). "Factors accounting for asthma variability: achieving optimal symptom control for individual patients" (PDF). Primary Care Respiratory Journal. 17 (3): 138–147. doi:10.3132/pcrj.2008.00004. PMC 6619889. PMID 18264646. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster J (2010). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (8th ed.). Saunders. p. 688. ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5. OCLC 643462931.

- ^ Stedman's Medical Dictionary (28 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005. ISBN 978-0-7817-3390-8.

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 71

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 33

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Scott JP, Peters-Golden M (September 2013). "Antileukotriene agents for the treatment of lung disease". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 188 (5): 538–44. doi:10.1164/rccm.201301-0023PP. PMID 23822826.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c NHLBI Guideline 2007, pp. 373–75

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anandan C, Nurmatov U, van Schayck OC, Sheikh A (February 2010). "Is the prevalence of asthma declining? Systematic review of epidemiological studies". Allergy. 65 (2): 152–67. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02244.x. PMID 19912154. S2CID 19525219.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Manniche L (1999). Sacred luxuries: fragrance, aromatherapy, and cosmetics in ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press. pp. 49. ISBN 978-0-8014-3720-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Murray JF (2010). "Ch. 38 Asthma". In Mason RJ, Murray JF, Broaddus VC, Nadel JA, Martin TR, King Jr TE, Schraufnagel DE (eds.). Murray and Nadel's textbook of respiratory medicine (5th ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-4710-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i GINA 2011, pp. 2–5

- ^ Jindal SK, ed. (2011). Textbook of pulmonary and critical care medicine. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. p. 242. ISBN 978-93-5025-073-0. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016.

- ^ George RB (2005). Chest Medicine: Essentials of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7817-5273-2. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016.

- ^ British Guideline 2009, p. 14

- ^ GINA 2011, pp. 8–9

- ^ Boulet LP (April 2009). "Influence of Comorbid Conditions on Asthma". The European Respiratory Journal. 33 (4): 897–906. doi:10.1183/09031936.00121308. PMID 19336592.

- ^ Boulet LP, Boulay MÈ (June 2011). "Asthma-related comorbidities". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 5 (3): 377–393. doi:10.1586/ers.11.34. PMID 21702660.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harver A, Kotses H, eds. (2010). Asthma, Health and Society: A Public Health Perspective. New York: Springer. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-387-78285-0. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Thomas M, Bruton A, Moffat M, Cleland J (September 2011). "Asthma and psychological dysfunction". Primary Care Respiratory Journal. 20 (3): 250–256. doi:10.4104/pcrj.2011.00058. PMC 6549858. PMID 21674122.

- ^ He X, Cheng G, He L, Liao B, Du Y, Xie X, et al. (January 2021). "Adults with current asthma but not former asthma have higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a population-based prospective cohort study". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 1329. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.1329H. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79264-4. PMC 7809422. PMID 33446724.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Silva GE, Sherrill DL, Guerra S, Barbee RA (July 2004). "Asthma as a risk factor for COPD in a longitudinal study". Chest. 126 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1378/chest.126.1.59. PMID 15249443.

- ^ Jump up to: a b de Marco R, Marcon A, Rossi A, Antó JM, Cerveri I, Gislason T, et al. (September 2015). "Asthma, COPD and overlap syndrome: a longitudinal study in young European adults". The European Respiratory Journal. 46 (3): 671–679. doi:10.1183/09031936.00008615. PMID 26113674. S2CID 2169875.

- ^ Gibson PG, McDonald VM (July 2015). "Asthma-COPD overlap 2015: now we are six". Thorax. 70 (7): 683–691. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206740. PMID 25948695. S2CID 38550372.

- ^ Thomsen HS, Webb JA, eds. (2014). Contrast media : safety issues and ESUR guidelines (Third ed.). Dordrecht: Springer. p. 54. ISBN 978-3-642-36724-3.

- ^ Agostini BA, Collares KF, Costa FD, Correa MB, Demarco FF (August 2019). "The role of asthma in caries occurrence – meta-analysis and meta-regression". The Journal of Asthma. 56 (8): 841–852. doi:10.1080/02770903.2018.1493602. PMID 29972654. S2CID 49694304.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thomas MS, Parolia A, Kundabala M, Vikram M (June 2010). "Asthma and Oral Health: A Review". Australian Dental Journal. 55 (2): 128–133. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01226.x. PMID 20604752.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Martinez FD (January 2007). "Genes, environments, development and asthma: a reappraisal". The European Respiratory Journal. 29 (1): 179–84. doi:10.1183/09031936.00087906. PMID 17197483.

- ^ Miller RL, Ho SM (March 2008). "Environmental epigenetics and asthma: current concepts and call for studies". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 177 (6): 567–73. doi:10.1164/rccm.200710-1511PP. PMC 2267336. PMID 18187692.

- ^ Choudhry S, Seibold MA, Borrell LN, Tang H, Serebrisky D, Chapela R, et al. (July 2007). "Dissecting complex diseases in complex populations: asthma in latino americans". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 4 (3): 226–33. doi:10.1513/pats.200701-029AW. PMC 2647623. PMID 17607004.

- ^ Dietert RR (September 2011). "Maternal and childhood asthma: risk factors, interactions, and ramifications". Reproductive Toxicology. 32 (2): 198–204. Bibcode:2011RepTx..32..198D. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.04.007. PMID 21575714.

- ^ Tan DJ, Walters EH, Perret JL, Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, Matheson MC, Dharmage SC (February 2015). "Age-of-asthma onset as a determinant of different asthma phenotypes in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 9 (1): 109–23. doi:10.1586/17476348.2015.1000311. PMID 25584929. S2CID 23213216.

- ^ Kelly FJ, Fussell JC (August 2011). "Air pollution and airway disease". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 41 (8): 1059–71. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03776.x. PMID 21623970. S2CID 37717160.

- ^ «Профессиональные астмагены - Департамент здравоохранения штата Нью -Йорк» .

- ^ «Профессиональные астмагены - HSE» .

- ^ Джина 2011 , с

- ^ Джина 2011 , с

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Gold DR, Wright R (2005). «Разница населения в астме». Ежегодный обзор общественного здравоохранения . 26 : 89–113. doi : 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144528 . PMID 15760282 . S2CID 42988748 .

- ^ Американская ассоциация легких (2001). «Городское загрязнение воздуха и несправедливость в отношении здоровья: отчет о семинаре» . Перспективы здоровья окружающей среды . 109 (S3): 357–374. doi : 10.2307/3434783 . ISSN 0091-6765 . JSTOR 3434783 . PMC 1240553 . PMID 11427385 .

- ^ Brooks N, Sethi R (февраль 1997 г.). «Распределение загрязнения: характеристики сообщества и воздействие воздушных токсиков» . Журнал экономики окружающей среды и управления . 32 (2): 233–50. Bibcode : 1997Jeem ... 32..233b . doi : 10.1006/jeem.1996.0967 .

- ^ McGwin G, Lienert J, Kennedy Ji (март 2010 г.). «Формальдегидное воздействие и астма у детей: систематический обзор» . Перспективы здоровья окружающей среды . 118 (3): 313–7. doi : 10.1289/ehp.0901143 . PMC 2854756 . PMID 20064771 .

- ^ Jaakkola JJ, Knight TL (июль 2008 г.). «Роль воздействия фталатов из продуктов поливинилхлорида в разработке астмы и аллергии: систематический обзор и метаанализ» . Перспективы здоровья окружающей среды . 116 (7): 845–53. doi : 10.1289/ehp.10846 . PMC 2453150 . PMID 18629304 .

- ^ Bornehag CG, Nanberg E (апрель 2010 г.). «Фталатное воздействие и астма у детей» . Международный журнал андрологии . 33 (2): 333–45. doi : 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01023.x . PMID 20059582 .

- ^ Mamane A, Baldi I, Tessier JF, Raherison C, Bouvier G (июнь 2015 г.). «Профессиональное воздействие пестицидов и дыхательного здоровья» . Европейский респираторный обзор . 24 (136): 306–19. doi : 10.1183/16000617.00006014 . PMC 9487813 . PMID 26028642 .

- ^ Mamane A, Raherison C, Tessier JF, Baldi I, Bouvier G (сентябрь 2015 г.). «Воздействие на окружающую среду пестицидов и респираторное здоровье» . Европейский респираторный обзор . 24 (137): 462–73. doi : 10.1183/16000617.000061114 . PMC 9487696 . PMID 26324808 .

- ^ Gruenwald T, Seals BA, Knibbs LD, Hosgood HD (декабрь 2022 г.). «Население, относящаяся к долю газовых печей и детской астмы в Соединенных Штатах» . Международный журнал экологических исследований и общественного здравоохранения . 20 (1): 75. doi : 10.3390/ijerph20010075 . PMC 9819315 . PMID 36612391 .

- ^ Heintze K, Petersen Ku (июнь 2013 г.). «Случай причинности наркотиков детской астмы: антибиотики и парацетамол» . Европейский журнал клинической фармакологии . 69 (6): 1197–209. doi : 10.1007/s00228-012-1463-7 . PMC 3651816 . PMID 23292157 .

- ^ Хендерсон А.Дж., Шахин SO (март 2013 г.). «Ацетаминофен и астма». Педиатрические респираторные обзоры . 14 (1): 9–15, викторина 16. doi : 10.1016/j.prrv.2012.04.004 . PMID 23347656 .

- ^ Чело М., Лодж С.Дж., Дхармадж С.К., Симпсон Дж.А., Мэтисон М., Генрих Дж., Лоу А.Дж. (январь 2015 г.). «Воздействие парацетамола при беременности и раннем детстве и развитии детской астмы: систематический обзор и мета-анализ» . Архив болезни в детстве . 100 (1): 81–9. doi : 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303043 . PMID 25429049 . S2CID 13520462 .

- ^ из Loo KF, от Mother MM, Roukema J, Rolefield N, Merk PJ, Head CM (январь 2016 г.). «Пренатальный материнский психологический стресс и астма и колеса детской шляпы: мета -анализ» . Европейский респираторный журнал . 47 (1): 133–46. doi : 10 1183/1399303 00299-2015 . PMID 26541526 .

- ^ Ahluwalia SK, Matsui EC (апрель 2011 г.). «Внутренняя среда и ее влияние на детскую астму». Современное мнение об аллергии и клинической иммунологии . 11 (2): 137–43. doi : 10.1097/aci.0b013e3283445921 . PMID 21301330 . S2CID 35075329 .

- ^ Arshad SH (январь 2010 г.). «Способствует ли воздействие в помещении аллергенов в развитие астмы и аллергии?». Текущие отчеты об аллергии и астме . 10 (1): 49–55. doi : 10.1007/s11882-009-0082-6 . PMID 204255514 . S2CID 30418306 .

- ^ Custovic A, Simpson A (2012). «Роль ингаляционных аллергенов при аллергических болезнях дыхательных путей». Журнал исследуемой аллергологии и клинической иммунологии . 22 (6): 393–401, Qiuz Следуйте 401. PMID 23101182 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Gøtzsche PC , Johansen HK (апрель 2008 г.). «Домашние меры по борьбе с хлецом для астмы» . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 2008 (2): CD001187. doi : 10.1002/14651858.cd001187.pub3 . PMC 8786269 . PMID 18425868 .

- ^ Calderón MA, Linneberg A, Kleine-Tebbe J, De Blay F, Hernandez Fernandez de Rojas D, Virchow JC, Demoly P (июль 2015). "Респираторная аллергия, вызванная домашней пылевой клещами: что мы действительно знаем?" Полем Журнал аллергии и клинической иммунологии . 136 (1): 38–48. doi : 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.012 . PMID 25457152 .

- ^ Sauni R, Verbeek JH, Uitti J, Jauhiainen M, Kreiss K, Sigsgaard T (февраль 2015 г.). «Исправление зданий, поврежденных сыростью и плесенью для предотвращения или уменьшения симптомов, инфекций и астмы дыхательных путей» . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 2015 (2): CD007897. doi : 10.1002/14651858.cd007897.pub3 . PMC 6769180 . PMID 25715323 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный НХЛБИ Руководство 2007 , с. 11

- ^ CD Ramsey, Celleón JC (январь 2005 г.). «Гипотеза гигиены и астма». Современное мнение в легочной медицине . 11 (1): 14–20. doi : 10.1097/01.mcp.0000145791.13714.ae . PMID 15591883 . S2CID 44556390 .

- ^ Bufford JD, Gern Je (май 2005 г.). «Гипотеза гигиены повторно». Иммунология и аллергия клиники Северной Америки . 25 (2): 247–62, V - Vi. doi : 10.1016/j.ac.2005.03.005 . PMID 15878454 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Brooks C, Pearce N, Douwes J (февраль 2013 г.). «Гипотеза гигиены в аллергии и астме: обновление». Современное мнение об аллергии и клинической иммунологии . 13 (1): 70–7. doi : 10.1097/aci.0b013e32835ad0d2 . PMID 23103806 . S2CID 23664343 .

- ^ Rao D, Phipatanakul W (октябрь 2011 г.). «Влияние экологического контроля на детскую астму» . Текущие отчеты об аллергии и астме . 11 (5): 414–20. doi : 10.1007/s11882-011-0206-7 . PMC 3166452 . PMID 21710109 .

- ^ Murk W, Risnes KR, Bracken MB (июнь 2011 г.). «Пренатальное или раннее воздействие антибиотиков и риск детской астмы: систематический обзор». Педиатрия . 127 (6): 1125–38. doi : 10.1542/peds.2010-2092 . PMID 21606151 . S2CID 26098640 .

- ^ Британское руководство 2009 , с. 72

- ^ Neu J, Rushing J (июнь 2011 г.). «Кесарево сечение против вагинального родов: долгосрочные младенческие результаты и гипотеза гигиены» . Клиники в перинатологии . 38 (2): 321–31. doi : 10.1016/j.clp.2011.03.008 . PMC 3110651 . PMID 21645799 .

- ^ Von Hertzen Lc, Haahtela T (февраль 2004 г.). "Астма и атопия - цена на достаток?" Полем Аллергия . 59 (2): 124–37. doi : 10.1046/j.1398-9995.2003.00433.x . PMID 14763924 . S2CID 34049674 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Martinez FD (июль 2007 г.). «CD14, эндотоксин и риск астмы: действия и взаимодействия» . Труды Американского торакального общества . 4 (3): 221–5. doi : 10.1513/pats.200702-035aw . PMC 2647622 . PMID 17607003 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Elward G, Douglas KS (2010). Астма . Лондон: Manson Pub. Стр. 27-29. ISBN 978-1-84076-513-7 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2016 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Ober C, Hoffjan S (март 2006 г.). «Астма генетика 2006: Длинная и извилистая дорога к открытию генов». Гены и иммунитет . 7 (2): 95–100. doi : 10.1038/sj.gene.6364284 . PMID 16395390 . S2CID 1887559 .

- ^ Halapi E, Bjornsdottir US (январь 2009 г.). «Обзор текущего состояния генетики астмы». Клинический респираторный журнал . 3 (1): 2–7. doi : 10.1111/j.1752-699x.2008.00119.x . PMID 20298365 . S2CID 36471997 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Рапини Р.П., Болонья Дж.Л., Йориззо Дж.Л. (2007). Дерматология: 2-объемный набор Святой Иоанн Креститель. Луи: Мосби. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1 .

- ^ Джина 2011 , с

- ^ Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, et al. (Январь 2013). «Пересмотренная международная консенсусная конференция Capel Hill Consensus Nomenclaturation of Acculitides» . Артрит и ревматизм . 65 (1): 1–11. doi : 10.1002/art.37715 . PMID 23045170 .

- ^ Beuther Da (январь 2010 г.). «Недавнее понимание ожирения и астмы». Современное мнение в легочной медицине . 16 (1): 64–70. doi : 10.1097/mcp.0b013e3283338fa7 . PMID 19844182 . S2CID 34157182 .

- ^ Holguin F, Fitzpatrick A (март 2010 г.). «Ожирение, астма и окислительный стресс». Журнал прикладной физиологии . 108 (3): 754–9. doi : 10.1152/japplphysiol.00702.2009 . PMID 19926826 .

- ^ Вуд Л.Г., Гибсон П.Г. (июль 2009 г.). «Диетические факторы приводят к врожденной иммунной активации при астме». Фармакология и терапия . 123 (1): 37–53. doi : 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.03.015 . PMID 19375453 .

- ^ О'Рурк -стрит (октябрь 2007 г.). «Антиангинальные действия антагонистов бета-адренорецептора» . Американский журнал фармацевтического образования . 71 (5): 95. doi : 10.5688/aj710595 . PMC 2064893 . PMID 17998992 .

- ^ Salpeter S, Ormiston T, Salpeter E (2002). «Кардиоселективные бета-блокаторы для обратимой болезни дыхательных путей» . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 2011 (4): CD002992. doi : 10.1002/14651858.cd002992 . PMC 8689715 . PMID 12519582 .

- ^ Моралес Д.Р., Джексон С., Липворт Б.Дж., Доннан П.Т., Гатри Б (апрель 2014 г.). «Неблагоприятный респираторный эффект острого воздействия β-блокатора при астме: систематический обзор и мета-анализ рандомизированных контролируемых исследований». Грудь . 145 (4): 779–786. doi : 10.1378/грудь. 13-1235 . PMID 24202435 .

- ^ Ковар Р.А., Макомбер Б.А., Сефлер С.Дж. (февраль 2005 г.). «Лекарства как триггеры астмы». Иммунология и аллергия клиники Северной Америки . 25 (1): 169–90. doi : 10.1016/j.ac.2004.09.009 . PMID 15579370 .

- ^ Lai T, Wu M, Liu J, Luo M, He L, Wang X, et al. (Февраль 2018 г.). «Употребление кислот наркотиков во время беременности и риск детской астмы: метаанализ» . Педиатрия . 141 (2): E20170889. doi : 10.1542/peds.2017-0889 . PMID 29326337 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Baxi SN, Phipatanakul W (апрель 2010 г.). «Роль воздействия и избегания аллергена при астме» . Подростковая медицина . 21 (1): 57–71, viii -ix. PMC 2975603 . PMID 20568555 .

- ^ Sharpe RA, Bearman N, Thornton CR, Husk K, Osborne NJ (январь 2015 г.). «Разнообразие грибков в помещении и астма: метаанализ и систематический обзор факторов риска» . Журнал аллергии и клинической иммунологии . 135 (1): 110–22. doi : 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.002 . PMID 25159468 .

- ^ Чен Е., Миллер Г.Е. (ноябрь 2007 г.). «Стресс и воспаление у обострения астмы» . Мозг, поведение и иммунитет . 21 (8): 993–9. doi : 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.009 . PMC 2077080 . PMID 17493786 .

- ^ Пайк К.К., Ахбари М., Книл Д., Харрис К.М. (март 2018 г.). «Вмешательства по осенней обострению астмы у детей» . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 2018 (3): CD012393. doi : 10.1002/14651858.cd012393.pub2 . PMC 6494188 . PMID 29518252 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный НХЛБИ Руководство 2007 , с. 42

- ^ Джина 2011 , с

- ^ Американская академия аллергии, астмы и иммунологии . «Пять вещей врачей и пациентов должны подвергать сомнению» (PDF) . Выбирая мудро . Фонд Абима. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 3 ноября 2012 года . Получено 14 августа 2012 года .

- ^ Отчет экспертной группы 3: Руководство по диагностике и лечению астмы . Национальный институт сердца, легких и крови (США). 2007. 07-4051-через NCBI.

- ^ Уэльс Э.Дж., Бара А., Ячмень Е., Кейтс С.Дж. (январь 2010 г.). Валлийский EJ (ред.). «Кофеин для астмы» (PDF) . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 2010 (1): CD001112. doi : 10.1002/14651858.cd0011112.pub2 . PMC 7053252 . PMID 20091514 .

- ^ NHLBI Руководство 2007 , с. 58

- ^ Pinnock H, Shah R (апрель 2007 г.). "Астма" . BMJ . 334 (7598): 847–50. doi : 10.1136/bmj.39140.634896.be . PMC 1853223 . PMID 17446617 .

- ^ NHLBI Руководство 2007 , с. 59

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Мур WC, Pascual RM (июнь 2010 г.). «Обновление в астме 2009» . Американский журнал респираторной медицины и медицины интенсивной терапии . 181 (11): 1181–7. doi : 10.1164/rccm.201003-0321up . PMC 3269238 . PMID 20516492 .

- ^ Принципы внутренней медицины Харрисона (21 -е изд.). Нью -Йорк: МакГроу Хилл. 2022. с. 2150. ISBN 978-1-264-26850-4 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Self T, Chrisman C, Finch C (2009). "22. Астма". В Koda-Kimble MA, Alldredge Bk, et al. (ред.). Прикладная терапия: клиническое употребление лекарств (9 -е изд.). Филадельфия: Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс. OCLC 230848069 .

- ^ Delacourt C (июнь 2004 г.). «[Бронхиальные изменения в необработанной астме]» [бронхиальные изменения в необработанной астме]. Архив де Педиатри . 11 (Suppl 2): 71S - 73S. doi : 10.1016/s0929-693x (04) 90003-6 . PMID 15301800 .

- ^ Шиффман G (18 декабря 2009 г.). "Хроническая обструктивная болезнь легких" . Medicinenet. Архивировано из оригинала 28 августа 2010 года . Получено 2 сентября 2010 года .

- ^ Гибсон П.Г., Макдональд В.М. (июль 2015 г.). «Asthma-Copd Coverp 2015: теперь нам шесть» . Грудная клетка . 70 (7): 683–691. doi : 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206740 . PMID 25948695 . S2CID 38550372 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Британское руководство 2009 , с. 54

- ^ Текущий обзор астмы . Лондон: текущая медицина группа. 2003. с. 42. ISBN 978-1-4613-1095-2 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 8 сентября 2017 года.