Северная Каролина

Северная Каролина | |

|---|---|

| Псевдоним(а) : Штат Тархил , Старый Северный штат | |

| Девиз(ы) : | |

| Гимн: « Старый Северный штат ». [ 1 ] | |

Карта Соединенных Штатов с выделенной Северной Каролиной | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

| До государственности | Провинция Северная Каролина |

| Принят в Союз | 21 ноября 1789 г. (12-е) |

| Капитал | Роли |

| Крупнейший город | Шарлотта |

| Самый большой округ или его эквивалент | Будить |

| Крупнейшие метро и городские районы | Шарлотта |

| Правительство | |

| • Губернатор | Рой Купер ( з ) |

| • Вице-губернатор | Марк Робинсон ( R ) |

| Законодательная власть | Генеральная Ассамблея |

| • Верхняя палата | Сенат |

| • Нижняя палата | Палата представителей |

| судебная власть | Верховный суд Северной Каролины |

| Сенаторы США | Том Тиллис (R) Тед Бадд (R) |

| Делегация Палаты представителей США |

|

| Область | |

| • Общий | 53 819,16 квадратных миль (139 391,0 км ) 2 ) |

| • Земля | 48 617,91 квадратных миль (125 919,8 км ) 2 ) |

| • Вода | 5 201,25 квадратных миль (13 471,2 км ) 2 ) 9.66% |

| • Классифицировать | 28-е |

| Размеры | |

| • Длина | 500 [ 2 ] миль (804 км) |

| • Ширина | 184 миль (296 км) |

| Высота | 700 футов (210 м) |

| Самая высокая точка | 6684 футов (2037 м) |

| Самая низкая высота (Атлантический океан [ 3 ] ) | 0 футов (0 м) |

| Население ( 2020 ) | |

| • Общий | 10,439,388 |

| • Классифицировать | 9-е |

| • Плотность | 214,72/кв. миль (82,90/км) 2 ) |

| • Классифицировать | 14-е |

| • Средний доход домохозяйства | $52,752 [ 4 ] |

| • Рейтинг дохода | 39-е |

| Демон(ы) | Северная Каролина (официальный); Тархил (разговорный) |

| Язык | |

| • Официальный язык | Английский [ 5 ] |

| • Разговорный язык | По состоянию на 2010 год [ 6 ]

|

| Часовой пояс | UTC−05:00 ( восточное время ) |

| • Лето ( летнее время ) | UTC-04:00 ( ВОСТОЧНОЕ ВРЕМЯ ) |

| Аббревиатура USPS | Северная Каролина |

| Код ISO 3166 | США-Северная Каролина |

| Традиционная аббревиатура | Северная Каролина |

| Широта | От 33° 50′ с.ш. до 36° 35′ с.ш. |

| Долгота | От 75° 28′ з.д. до 84° 19′ з.д. |

| Веб-сайт | NC |

| Список государственных символов | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Девиз | Быть таким, каким кажется («Быть, а не казаться») [ а ] |

| Лозунг | Первый в полете, Первый в свободе (неофициально) |

| Песня | « Старый Северный штат » |

| Живые знаки отличия | |

| амфибия | Древесная лягушка Сосновых пустошей |

| Птица | Кардинал |

| Бабочка | Восточный тигровый ласточкин хвост |

| Порода собаки | Сюжетная гончая |

| Рыба | Красный барабан |

| Цветок | Цветущий кизил |

| Насекомое | Западная медоносная пчела |

| млекопитающее | Восточная серая белка |

| Сумчатый | Вирджинский опоссум |

| Рептилия | Восточная коробчатая черепаха |

| Дерево | Сосна |

| Неодушевленные знаки различия | |

| Напиток | Молоко |

| Цвет (а) | Красный и синий |

| Танец | Carolina shag |

| Еда | Виноград Скуппернонг и сладкий картофель |

| Ископаемое | мегалодона Зубы |

| драгоценный камень | Изумруд |

| Минерал | Золото |

| Камень | Гранит |

| Оболочка | Шотландский чепчик |

| Другой | Мраморная саламандра (саламандра) |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2001 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Северная Каролина ( / ˌ k ær ə ˈ l aɪ n ə / KARR -ə- LY -nə ) — штат в Юго-восточном регионе США . Он граничит с Вирджинией на севере, Атлантическим океаном на востоке, Южной Каролиной на юге, Джорджией на юго-западе и Теннесси на западе. Штат является 28-м по величине и 9-м по численности населения в США . Вместе с Южной Каролиной он составляет регион Каролины на восточном побережье . По переписи 2020 года население штата составляло 10 439 388 человек. [ 7 ] Роли штата — столица , а Шарлотта — самый густонаселенный город . с Столичный округ Шарлотта предполагаемым населением в 2 805 115 человек в 2023 году. [ 8 ] Это самый густонаселенный мегаполис в Северной Каролине, 22-й по численности населения в Соединенных Штатах и крупнейший банковский центр в стране после Нью-Йорка. [ 9 ] Исследовательский треугольник с предполагаемым населением в 2 368 947 человек в 2023 году является вторым по численности населения объединенным мегаполисом штата и 31-м по численности населения в Соединенных Штатах. [ 8 ] и является домом для крупнейшего исследовательского парка в Соединенных Штатах, Research Triangle Park .

Самые ранние свидетельства пребывания человека в Северной Каролине датируются 10 000 лет назад и были найдены на территории Хардуэя . Северная Каролина была населена каролинскими алгонкинскими , ирокезскими и сиуанскими До прибытия европейцев племенами коренных американцев. Король Карл II пожаловал восьми лордам-владельцам колонию, которую они назвали Каролиной в честь короля и которая была основана в 1670 году с первым постоянным поселением в Чарльз-Тауне (Чарльстон). Из-за сложности управления всей колонией из Чарльз-Тауна, колония в конечном итоге была разделена, и в 1729 году Северная Каролина стала королевской колонией и стала одной из Тринадцати колоний . Резолюция « Галифакс решает», принятая Северной Каролиной 12 апреля 1776 года, была первым официальным призывом к независимости от Великобритании среди американских колоний во время американской революции . [ 10 ]

21 ноября 1789 года Северная Каролина стала 12-м штатом, ратифицировавшим Конституцию США . В преддверии Гражданской войны в США Северная Каролина неохотно [ нужна ссылка ] объявил о своем выходе из Союза 20 мая 1861 года, став десятым из одиннадцати штатов, присоединившихся к Конфедеративным Штатам Америки . После гражданской войны штат был возвращен Союзу 4 июля 1868 года. [ 11 ] 17 декабря 1903 года Орвилл и Уилбур Райт успешно пилотировали первый в мире управляемый продолжительный полет самолета тяжелее воздуха с двигателем в Китти-Хок Северной Каролины во Внешних банках . Северная Каролина часто использует лозунг «Первый в полете» на государственных номерных знаках в ознаменование этого достижения, наряду с новым альтернативным дизайном со слоганом «Первый в свободе» со ссылкой на Мекленбургскую декларацию и «Решения Галифакса».

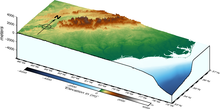

Северная Каролина отличается широким диапазоном возвышенностей и ландшафтов. С запада на восток возвышенность Северной Каролины спускается от Аппалачей до Пьемонта и Атлантической прибрежной равнины . в Северной Каролине Гора Митчелл высотой 6684 футов (2037 м) — самая высокая точка Северной Америки к востоку от реки Миссисипи . [ 12 ] Большая часть штата попадает в зону влажного субтропического климата ; однако в западной, гористой части штата климат субтропический высокогорный . [ 13 ]

История

Коренные американцы, потерянная колония и постоянное поселение

Северная Каролина была заселена на протяжении как минимум 10 000 лет преемниками доисторических культур коренных народов . На территории Хардуэя произошли основные периоды оккупации, датируемые 10 000 лет до нашей эры. До 200 года нашей эры люди строили земляные насыпи-платформы для церемониальных и религиозных целей. Последующие народы, в том числе представители культуры Южных Аппалачей и Миссисипи , основанной к 1000 году нашей эры в Пьемонте и горном регионе, продолжали строить курганы этого типа. В отличие от некоторых более крупных центров классической культуры Миссисипи в районе, который стал известен как Западная Каролина, северо-восточная Джорджия и юго-восточный Теннесси, в большинстве крупных городов была только одна центральная платформа-курган. В меньших поселениях их не было, но они находились рядом с более известными городами. Этот район стал известен как родина исторического народа чероки , который, как полагают, со временем мигрировал из района Великих озер .

За 500–700 лет, предшествовавших контакту с европейцами, культура Миссисипи построила сложные города и поддерживала обширные региональные торговые сети. Крупнейшим ее городом была Кахокия , имевшая многочисленные курганы различного назначения, высоко стратифицированное общество и располагавшаяся на территории современного юго-западного Иллинойса недалеко от реки Миссисипи. Начиная с 1540 года, коренные народы культуры Миссисипи распались и преобразовались в новые группы, такие как Катавба , из-за серии дестабилизирующих событий, известных как « зона разрушения Миссисипи ». Введение колониальных торговых соглашений и враждебных групп коренных жителей с севера, таких как индейцы Весто, ускорило изменения в и без того хрупкой региональной иерархии. [ 14 ] По описанию антрополога Робби Этриджа , зона раскола Миссисипи была временем большой нестабильности на территории нынешнего американского Юга, вызванной нестабильностью вождеств Миссисипи, высокой смертностью от новых евразийских болезней, переходом к аграрному обществу и сопутствующим ростом населения. и появление коренных «милитаристских рабовладельческих обществ». [ 15 ]

Исторически задокументированные племена в регионе Северной Каролины включают Каролино-алгонкинские племена прибрежных районов, такие как Чованок , Роанок , Памлико , Мачапунга и Кори , которые были первыми, с которыми столкнулись англичане; ирокезском языке говорящие на Мехеррин , Чероки и Тускарора внутренних районов; и юго-восточные племена, говорящие на сиуанском языке, такие как черо , ваксхо , сапони , ваккамау , индейцы мыса Страх и катавба из Пьемонта. [ 16 ] [ 17 ] [ 18 ] [ 19 ]

В конце 16-го века первые испанские исследователи, путешествовавшие вглубь страны, зафиксировали встречу с представителями культуры штата Миссисипи в Хоаре , региональном вождестве недалеко от того, что позже превратилось в Моргантон . [ 20 ] Записи Эрнандо де Сото свидетельствуют о его встрече с ними в 1540 году. В 1567 году капитан Хуан Пардо возглавил экспедицию, чтобы заявить права на эту территорию для испанской колонии и проложить другой путь, ведущий к серебряным рудникам в Мексике. [ 21 ] Пардо устроил зимнюю базу в Хоаре, которую переименовал в Куэнку . [ 22 ] [ 23 ] Его экспедиция построила форт Сан-Хуан и оставила там отряд из 30 испанцев, а Пардо отправился дальше. [ 22 ] Его войска построили и разместили гарнизоны еще в пяти фортах. Он вернулся другим маршрутом в Санта-Елену на острове Пэррис, Южная Каролина , тогдашнем центре испанской Флориды . Весной 1568 года туземцы убили всех испанцев, кроме одного, и сожгли шесть внутренних фортов, включая форт Сан-Хуан. [ 24 ] Хотя испанцы так и не вернулись во внутренние районы, эта попытка ознаменовала первую европейскую попытку колонизации внутренних территорий того, что впоследствии стало Соединенными Штатами. Журнал 16-го века, написанный писцом Пардо Бандерой, и археологические находки, проведенные с 1986 года в Джоаре, подтвердили наличие поселения. [ 25 ] [ 26 ]

Англо-европейское урегулирование

In 1584, Elizabeth I granted a charter to Sir Walter Raleigh, for whom the state capital is named, for land in present-day North Carolina (then part of the territory of Virginia).[27] It was the second American territory that the English attempted to colonize. Raleigh established two colonies on the coast in the late 1580s, but both failed. The colony established in 1587 saw 118 colonists 'disappear' when John White was unable to return from a supply run during battles with the Spanish Armada. The fate of the "Lost Colony" of Roanoke Island remains one of the most widely debated mysteries of American history. Two native Chieftains, Manteo and Wanchese, of which the former helped the colonists and the latter was distrustful, had involvement in the colony and even accompanied Raleigh to England on a previous voyage in 1585. Manteo was also the first Indigenous North American to be baptized by English settlers. Upon White's return in 1590, neither native nor Englishman were to be found. Popular theory holds that the colonists either traveled away with or assimilated into local native culture.[28] Virginia Dare, the first English person to be born in North America, was born on Roanoke Island on August 18, 1587; the surrounding Dare County is named for her.

As early as 1650, settlers from the Virginia colony had moved into the Albemarle Sound region. By 1663, King Charles II of England granted a charter to start a new colony on the North American continent; this would generally establish North Carolina's borders. He named it Carolina in honor of his father, Charles I.[29] By 1665, a second charter was issued to attempt to resolve territorial questions. This charter rewarded the Lords Proprietors, eight Englishmen to whom King Charles II granted joint ownership of a tract of land in the state. All of these men either had remained loyal to the Crown or aided Charles's restoration to the English throne after Cromwell. In 1712, owing to disputes over governance, the Carolina colony split into North Carolina and South Carolina. North Carolina became a crown colony in 1729.[30]

Most of the English colonists had arrived as indentured servants, hiring themselves out as laborers for a fixed period to pay for their passage. In the early years the line between indentured servants and African slaves or laborers was fluid. Some Africans were allowed to earn their freedom before slavery became a lifelong status. Most of the free colored families formed in North Carolina before the Revolution were descended from unions or marriages between free whites and enslaved or free Africans or African-Americans. If the mothers were free, their children were born free. Many had migrated or were descendants of migrants from colonial Virginia.[31] As the flow of indentured laborers to the colony decreased with improving economic conditions in Great Britain, planters imported more slaves, and the state's legal delineations between free and slave status tightened, effectively hardening the latter into a racial caste. Conditions for both slaves and workers worsened as the ranks of the former eclipsed the latter and expansion of farming operations into former Indigenous territories lowered prices. Unable to establish deep water ports such as at Charles Town and Norfolk, the economy's growth and prosperity was thus based on cheap labor and slave plantation systems, devoted primarily to the production of tobacco, then later cotton and textiles.[32]

In 1738–1739, smallpox caused high fatalities among the Native Americans, who had no immunity to the new disease (it had become endemic over centuries in Europe).[33] According to the historian Russell Thornton, "The 1738 epidemic was said to have killed one-half of the Cherokee, with other tribes of the area suffering equally."[34]

Colonial period

-

John White returns to find the colony abandoned

-

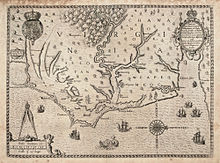

Map of the coast of Virginia and North Carolina, drawn 1585–1586 by Theodor de Bry, based on map by John White of the Roanoke Colony

-

Reconstructed royal governor's mansion Tryon Palace in New Bern

After the Spanish in the 16th century, the first permanent European settlers of North Carolina were English colonists who migrated south from Virginia. Virginia had grown rapidly and land was less available. Nathaniel Batts was documented as one of the first of these Virginian migrants. He settled south of the Chowan River and east of the Great Dismal Swamp in 1655.[35] By 1663, this northeastern area of the Province of Carolina, known as the Albemarle Settlements, was undergoing full-scale English settlement.[36] During the same period, the English monarch Charles II gave provincial land grants to the Lords Proprietors, the group of noblemen who had helped restore him to the throne in 1660. These grants were predicated on an agreement that the Lords would use their influence to bring in colonists and establish ports of trade. This new Province of Carolina was named in honor and memory of his father, Charles I (Latin: Carolus).

Lacking a viable coastal port city due to geography, towns grew at a slower pace and remained small. By the late 17th century, Carolina was essentially two colonies, one centered in the Albemarle region in the north and the other located in the south around Charleston.[32] In 1705 South Carolinian John Lawson purchased land on the Pamlico River and laid out Bath, North Carolina's first town. After returning to England, he published the book A New Voyage to Carolina, which became a travelogue and a marketing piece to encourage new colonists to Carolina. Lawson encouraged Baron Christoph Von Graffenried, the leader of a group of Swiss and German Protestants, to immigrate to Carolina. Von Graffenried purchased land between the Neuse and the Trent Rivers and established the town of New Bern. After an attack on New Bern in which hundreds were killed or injured, Lawson was caught then executed by Tuscarora Indians. A large revolt happened in the state in 1711, known as Cary's Rebellion. In 1712, North Carolina became a separate colony, and in 1729 it became a royal colony, with the exception of the Earl Granville holdings.[37]

In June 1718, Queen Anne's Revenge, the flagship of pirate Blackbeard, ran aground at Beaufort Inlet, North Carolina, in present-day Carteret County. After the grounding, her crew and supplies were transferred to smaller ships. In November 1718, after appealing to the governor of North Carolina, who promised safe-haven and a pardon, Blackbeard was killed in an ambush by troops from Virginia.[38] In 1996, Intersal, Inc., a private maritime research firm, discovered the remains of a vessel likely to be the Queen Anne's Revenge, which was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.[39][40]

North Carolina became one of the Thirteen Colonies and with the territory of South Carolina was originally known as the Province of North Carolina. The northern and southern parts of the original province separated in 1712, with North Carolina becoming a royal colony in 1729. Originally settled by small farmers, sometimes having a few slaves, who were oriented toward subsistence agriculture, the colony lacked large cities or towns. Pirates menaced the coastal settlements, but by 1718 piracy in the Carolinas was on the decline. Growth was strong in the middle of the 18th century, as the economy attracted Scots-Irish, Quaker, English and German immigrants. A majority of the North Carolina colonists generally supported the American Revolution, although there were some Loyalists. Loyalists in North Carolina were fewer in number than in some other colonies such as Georgia, South Carolina, Delaware, and New York.[41][42][43]

During colonial times, Edenton served as the state capital beginning in 1722, followed by New Bern becoming the capital in 1766. Construction of Tryon Palace, which served as the residence and offices of the provincial governor William Tryon, began in 1767 and was completed in 1771. In 1788, Raleigh was chosen as the site of the new capital, as its central location protected it from coastal attacks. Officially established in 1792 as both county seat and state capital, the city was named after Sir Walter Raleigh, sponsor of Roanoke, the "lost colony" on Roanoke Island.[44] The population of the colony more than quadrupled from 52,000 in 1740 to 270,000 in 1780 from high immigration from Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania, plus immigrants from abroad.[45]

North Carolina did not have any printer or print shops until 1749, when the North Carolina Assembly commissioned James Davis from Williamsburg Virginia to act as their official printer. Before this time the laws and legal journals of North Carolina were handwritten and were kept in a largely disorganized manner, prompting the hiring of Davis. Davis settled in New Bern, married, and in 1755 was appointed by Benjamin Franklin as North Carolina's first postmaster. In October of that year the North Carolina Assembly awarded Davis a contract to carry mail between Wilmington, North Carolina and Suffolk, Virginia. He was also active in North Carolina politics as a member of the Assembly and later as the Sheriff. Davis also founded and printed the North-Carolina Gazette, North Carolina's first newspaper, printed in his printing house in New Bern.[46][47]

Differences in the settlement patterns of eastern and western North Carolina, or the Atlantic coastal plain and uplands, affected the political, economic, and social life of the state from the 18th until the 20th century. Eastern North Carolina was settled chiefly by immigrants from rural England and Gaelic speakers from the Scottish Highlands. The Piedmont upcountry and western mountain region of North Carolina was settled chiefly by Scots-Irish, English, and German Protestants, the so-called "cohee". Arriving during the mid-to-late 18th century, the Scots-Irish, people of Scottish descent who migrated to and then emigrated from what is today Northern Ireland, were the largest non-English immigrant group before the Revolution; English indentured servants were overwhelmingly the largest immigrant group before the Revolution.[48][49][50][51]

Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War, the English and Gaelic speaking Highland Scots of eastern North Carolina tended to remain loyal to the British Crown, because of longstanding business and personal connections with Great Britain. The English, Welsh, Scots-Irish, and German settlers of western North Carolina tended to favor American independence from Britain. British loyalists dubbed the Mecklenburg County area to be 'a hornet's nest' of radicals, birthing the name of the future Charlotte NBA team. On April 12, 1776, the colony became the first to instruct its delegates to the Continental Congress to vote for independence from the British Crown, through the Halifax Resolves passed by the North Carolina Provincial Congress. The date of this event is memorialized on the state flag and state seal. Throughout the Revolutionary War, fierce guerrilla warfare erupted between bands of pro-independence and pro-British colonists. In some cases the war was also an excuse to settle private grudges and rivalries.[52][53]

North Carolina had around 7,800 Patriots join the Continental Army under General George Washington; and an additional 10,000 served in local militia units under such leaders as General Nathanael Greene.[54] There was some military action, especially in 1780–81. Many Carolinian frontiersmen had moved west over the mountains, into the Washington District (later known as Tennessee), but in 1789, following the Revolution, the state was persuaded to relinquish its claim to the western lands. It ceded them to the national government so the Northwest Territory could be organized and managed nationally.[55]

A major American victory in the war took place at King's Mountain along the North Carolina–South Carolina border; on October 7, 1780, a force of 1,000 Patriots from western North Carolina (including what is today the state of Tennessee) and southwest Virginia overwhelmed a force of some 1,000 British troops led by Major Patrick Ferguson. Most of the soldiers fighting for the British side in this battle were Carolinians who had remained loyal to the Crown (they were called "Tories" or Loyalists). The American victory at King's Mountain gave the advantage to colonists who favored American independence, and it prevented the British Army from recruiting new soldiers from the Tories.[56]

The road to Yorktown and America's independence from Great Britain led through North Carolina. As the British Army moved north from victories in Charleston and Camden, South Carolina, the Southern Division of the Continental Army and local militia prepared to meet them. Following General Daniel Morgan's victory over the British Cavalry Commander Banastre Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781, southern commander Nathanael Greene led British Lord Charles Cornwallis across the heartland of North Carolina, and away from the latter's base of supply in Charleston, South Carolina. This campaign is known as "The Race to the Dan" or "The Race for the River".[37]

In the Battle of Cowan's Ford, Cornwallis met resistance along the banks of the Catawba River at Cowan's Ford on February 1, 1781, in an attempt to engage General Morgan's forces during a tactical withdrawal.[57] Morgan had moved to the northern part of the state to combine with General Greene's newly recruited forces. Generals Greene and Cornwallis finally met at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in present-day Greensboro on March 15, 1781. Although the British troops held the field at the end of the battle, their casualties at the hands of the numerically superior Continental Army were crippling. Following this "Pyrrhic victory", Cornwallis chose to move to the Virginia coastline to get reinforcements, and to allow the Royal Navy to protect his battered army. This decision would result in Cornwallis' eventual defeat at Yorktown, Virginia, later in 1781. The Patriots' victory there guaranteed American independence. On November 21, 1789, North Carolina became the twelfth state to ratify the U.S. Constitution.

Antebellum period

After 1800, cotton and tobacco became important export crops. The eastern half of the state, especially the Coastal Plain region, developed a slave society based on a plantation system and slave labor. Planters owning large estates wielded significant political and socio-economic power in antebellum North Carolina. They placed their interests above those of the generally non-slave-holding "yeoman" farmers of North Carolina. While slaveholding was slightly less concentrated compared to some other Southern states, according to the 1860 census, more than 330,000 people, or 33% of the population out of 992,622 people in total, were enslaved African Americans.[58] They lived and worked chiefly on plantations in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions of the state. In addition, 30,463 free people of color lived in the state.[58] They were also mainly concentrated in the eastern coastal plain, especially at port cities such as Wilmington and New Bern, where a variety of jobs were available. Most were descendants from free African Americans who had migrated along with neighbors from Virginia during the 18th century. The majority were the descendants of unions in the working classes between white women, indentured servants or free, and African men, indentured, slave or free.[59]

After the American Revolution, Quakers and Mennonites worked to persuade slaveholders to free their slaves. Some were inspired by their efforts and the language of the Revolution to arrange for manumission of their slaves. The number of free people of color rose markedly in the first couple of decades after the Revolution.[60] Many free people of color migrated to the frontier, along with their European-American neighbors, where the social system was looser. By 1810, nearly three percent of the free population consisted of free people of color, who numbered slightly more than 10,000. The western areas of North Carolina were mainly white families of European descent, especially Scotch-Irish, who operated small subsistence farms. In the early national period, the state became a center of Jeffersonian and Jacksonian democracy, with a strong Whig presence, especially in the western part of the state. After Nat Turner's slave uprising in 1831, North Carolina and other southern states reduced the rights of free blacks. In 1835, the legislature withdrew their right to vote.

In mid-century, the state's rural and commercial areas were connected by the construction of a 129 mi (208 km) wooden plank road, known as a "farmer's railroad", from Fayetteville in the east to Bethania (northwest of Winston-Salem).[37] On October 25, 1836, construction began on the Wilmington and Raleigh Railroad[61] to connect the port city of Wilmington with the state capital of Raleigh. In 1840, the state capitol building in Raleigh was completed, and still stands today.

In 1849, the North Carolina Railroad was created by act of the legislature to extend that railroad west to Greensboro, High Point, and Charlotte. During the Civil War, the Wilmington-to-Raleigh stretch of the railroad would be vital to the Confederate war effort; supplies shipped into Wilmington would be moved by rail through Raleigh to the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.[62]

American Civil War

In 1860, North Carolina was a slave state, in which one-third of the state's total population were African-American slaves. The state did not vote to join the Confederacy until President Abraham Lincoln called on it to invade its sister state,[63] South Carolina, becoming the last or penultimate state to officially join the Confederacy. The title of "last to join the Confederacy" has been disputed; although Tennessee's informal secession on May 7, 1861, preceded North Carolina's official secession on May 20,[64][65] the Tennessee legislature did not formally vote to secede until June 8, 1861.[66]

Around 125,000 troops from North Carolina served in the Confederate Army, and about 15,000 North Carolina troops (both black and white) served in Union Army regiments, including those who left the state to join Union regiments elsewhere.[67] Over 30,000 North Carolina troops died from combat or disease during the war.[68] Elected in 1862, Governor Zebulon Baird Vance tried to maintain state autonomy against Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Richmond. The state government was reluctant to support the demands of the national government in Richmond, and the state was the scene of only small battles. In 1865, Durham County saw the largest single surrender of Confederate soldiers at Bennett Place, when Joseph E. Johnston surrendered the Army of Tennessee and all remaining Confederate forces still active in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, totalling 89,270 soldiers.[69]

Confederate troops from all parts of North Carolina served in virtually all the major battles of the Army of Northern Virginia, the Confederacy's most famous army. The largest battle fought in North Carolina was at Bentonville, which was a futile attempt by Confederate General Joseph Johnston to slow Union General William Tecumseh Sherman's advance through the Carolinas in the spring of 1865.[37] In April 1865, after losing the Battle of Morrisville, Johnston surrendered to Sherman at Bennett Place, in what is today Durham. North Carolina's port city of Wilmington, was the last Confederate port to fall to the Union, in February 1865, after the Union won the nearby Second Battle of Fort Fisher, its major defense downriver.

The first Confederate soldier to be killed in the Civil War was Private Henry Wyatt from North Carolina, in the Battle of Big Bethel in June 1861. At the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the 26th North Carolina Regiment participated in Pickett/Pettigrew's Charge and advanced the farthest into Union lines of any Confederate regiment. During the Battle of Chickamauga, the 58th North Carolina Regiment advanced farther than any other regiment on Snodgrass Hill to push back the remaining Union forces from the battlefield. At Appomattox Court House in Virginia in April 1865, the 75th North Carolina Regiment, a cavalry unit, fired the last shots of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the Civil War. The phrase "First at Bethel, Farthest at Gettysburg and Chickamauga, and Last at Appomattox", later became used through much of the early 20th century.[70]

After secession, some North Carolinians refused to support the Confederacy. Some of the yeoman farmers chiefly in the state's mountains and western Piedmont region remained neutral during the Civil War, with others covertly supporting the Union cause during the conflict.[71] Approximately 15,000 North Carolinians (both black and white) from across the state would enlist in the Union Army. Numerous slaves would also escape to Union lines, where they became essentially free.

Reconstruction era through late 19th century

Following the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865, North Carolina, along with other former Confederate States (except Tennessee), was put under direct control by the U.S. military and was relieved of its constitutional government and representation within the United States Congress in what is now referred to as the Reconstruction era. To earn back its rights, the state had to make concessions to Washington, one of which was ratifying the Thirteenth Amendment. Congressional Republicans during Reconstruction, commonly referred to as "radical Republicans", constantly pushed for new constitutions for each of the Southern states that emphasized equal rights for African-Americans. In 1868, a constitutional convention restored the state government of North Carolina. Though the Fifteenth Amendment was also adopted that same year, it remained in most cases ineffective for almost a century, not to mention paramilitary groups and their lynching with impunity.[72]

The elections in April 1868 following the constitutional convention led to a narrow victory for a Republican-dominated government, with 19 African-Americans holding positions in the North Carolina State Legislature. In attempt to put the reforms into effect, the new Republican Governor William W. Holden declared martial law on any county allegedly not complying with law and order using the passage of the Shoffner Act.

A Republican Party coalition of black freedmen, northern carpetbaggers and local scalawags controlled state government for three years. The white conservative Democrats regained control of the state legislature in 1870, in part by Ku Klux Klan violence and terrorism at the polls, to suppress black voting. Republicans were elected to the governorship until 1876, when the Red Shirts, a paramilitary organization that arose in 1874 and was allied with the Democratic Party, helped suppress black voting. More than 150 black Americans were murdered in electoral violence in 1876.[73][74]

Post–Civil War-debt cycles pushed people to switch from subsistence agriculture to commodity agriculture. Among this time the notorious Crop-Lien system developed and was financially difficult on landless whites and blacks, due to high amounts of usury. Also due to the push for commodity agriculture, the free range was ended. Prior to this time people fenced in their crops and had their livestock feeding on the free range areas. After the ending of the free range people now fenced their animals and had their crops in the open.[75][76]

Democrats were elected to the legislature and governor's office, but the Populists attracted voters displeased with them. In 1896 a biracial, Populist-Republican Fusionist coalition gained the governor's office and passed laws that would extend the voting franchise to blacks and poor whites. The Democrats regained control of the legislature in 1896 and passed laws to impose Jim Crow and racial segregation of public facilities. Voters of North Carolina's 2nd congressional district elected a total of four African-American congressmen through these years of the late 19th century.

Political tensions ran so high a small group of white Democrats in 1898 planned to take over the Wilmington government if their candidates were not elected. In the Wilmington Insurrection of 1898, white Democrats led around 2,000 of their supporters that attacked the black newspaper and neighborhood, killed an estimated 60 to 300 people, and ran off the white Republican mayor and aldermen. They installed their own people and elected Alfred M. Waddell as mayor, in the only successful coup d'état in United States history.[77]

In 1899, the state legislature passed a new constitution, with requirements for poll taxes and literacy tests for voter registration which disenfranchised most black Americans in the state.[78] Exclusion from voting had wide effects: it meant black Americans could not serve on juries or in any local office. After a decade of white supremacy, many people forgot North Carolina had ever had thriving middle-class black Americans.[79] Black citizens had no political voice in the state until after the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed to enforce their constitutional rights. It was not until 1992 that another African American was elected as a U.S. Representative from North Carolina.

Early through mid-20th century

After the reconstruction era, North Carolina had become a one-party state, dominated by the Democratic Party. The state mainly continued with an economy based on tobacco, cotton textiles and commodity agriculture. Large towns and cities remained in few numbers. However, a major industrial base emerged in the late 19th and early 20th century, in the counties of the Piedmont Triad, based on cotton mills established at the fall line. Railroads were built to connect the new industrializing cities.[80]

The state was the site of the first successful controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air flight, by the Wright brothers, near Kitty Hawk on December 17, 1903.

In the first half of the 20th century, many African Americans left the state to go North for better opportunities, in the Great Migration. Their departure changed the demographic characteristics of many areas.

North Carolina was hard hit by the Great Depression, but the New Deal programs of Franklin D. Roosevelt for cotton and tobacco significantly helped the farmers. After World War II, the state's economy grew rapidly, highlighted by the growth of such cities as Charlotte, Raleigh, and Durham in the Piedmont region.

Research Triangle Park, established in 1959, serves as the largest research park in the United States. Formed near Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill, the Research Triangle metro is a major area of universities and advanced scientific and technical research.

The Greensboro sit-ins in 1960 played a crucial role in the Civil Rights Movement to bring full equality to American blacks. By the late 1960s, spurred in part by the increasingly leftward tilt of national Democrats, conservative whites began to vote for Republican national candidates and gradually for more Republicans locally.[81][82]

Late 20th century to present

Since the 1970s, North Carolina has seen steady increases in population growth. This growth has largely occurred in metropolitan areas located within the Piedmont Crescent, in places such as Charlotte, Concord, Greensboro, Winston-Salem, Durham and Raleigh.[83] The Charlotte metropolitan area has experienced large growth mainly due to its finance, banking, and tech industries.[84]

By the 1990s, Charlotte had become a major regional and national banking center. Towards Raleigh, North Carolina State, Duke University, and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, have helped the Research Triangle area attract an educated workforce and develop more jobs.[85]

In 1988, North Carolina gained its first professional sports franchise, the Charlotte Hornets of the National Basketball Association (NBA). The hornets team name stems from the American Revolutionary War, when British General Cornwallis described Charlotte as a "hornet's nest of rebellion".[86] The Carolina Panthers of the National Football League (NFL) became based in Charlotte as well, with their first season being in 1995. The Carolina Hurricanes of the National Hockey League (NHL) moved to Raleigh in 1997, with their colors being the same as the NC State Wolfpack, who are also located in Raleigh.

By the late 20th century and into the early 21st century, economic industries such as technology, pharmaceuticals, banking, food processing, vehicle parts, and tourism started to emerge as North Carolina's main economic drivers. This marked a shift from the state's former main industries of tobacco, textiles, and furniture. Factors that played a role in this shift were globalization, the state's higher education system, national banking, the transformation of agriculture, and new companies moving to the state.[87]

Geography

North Carolina is bordered by South Carolina on the south, Georgia on the southwest, Tennessee on the west, Virginia on the north, and the Atlantic Ocean on the east. The United States Census Bureau places North Carolina in the South Atlantic division of the southern region.[88] It has a total area of 53,819.16 square miles (139,391.0 km2), of which 48,617.91 square miles (125,919.8 km2) is land and 5,201.25 square miles (13,471.2 km2) (9.66%) is water.[89]

North Carolina consists of three main geographic regions: the Atlantic coastal plain, occupying the eastern portion of the state; the central Piedmont region, and the mountain region in the west, which is part of the Appalachian Mountains. The coastal plain consists of more specifically defined areas known as the Outer Banks, a string of sandy, narrow barrier islands separated from the mainland by sounds or inlets, including Albemarle Sound and Pamlico Sound, the native home of the venus flytrap, and the inner coastal plain, where longleaf pine trees are native.

So many ships have been lost off Cape Hatteras that the area is known as the "Graveyard of the Atlantic"; more than a thousand ships have sunk in these waters since records began in 1526. The most famous of these is the Queen Anne's Revenge (flagship of the pirate Blackbeard), which went aground in Beaufort Inlet in 1718.[90]

The coastal plain transitions to the Piedmont region along the Atlantic Seaboard fall line, the elevation at which waterfalls first appear on streams and rivers. The Piedmont region of central North Carolina is the state's most populous region, containing the six largest cities in the state by population.[91] It consists of gently rolling countryside frequently broken by hills or low mountain ridges. Small, isolated, and deeply eroded mountain ranges and peaks are located in the Piedmont, including the Sauratown Mountains, Pilot Mountain, the Uwharrie Mountains, Crowder's Mountain, King's Pinnacle, the Brushy Mountains, and the South Mountains. The Piedmont ranges from about 300 feet (100 m) in elevation in the east to about 1,500 feet (500 m) in the west.

The western section of the state is part of the Blue Ridge Mountains of the larger Appalachian Mountain range. Among the subranges of the Blue Ridge Mountains located in the state are the Great Smoky Mountains and the Black Mountains.[92][93] The Black Mountains are the highest in the eastern United States, and culminate in Mount Mitchell at 6,684 feet (2,037 m), the highest point east of the Mississippi River.[93][94]

North Carolina has 17 major river basins. The five basins west of the Blue Ridge Mountains flow to the Gulf of Mexico, while the remainder flow to the Atlantic Ocean.[95] Of the 17 basins, 11 originate within the state of North Carolina, but only four are contained entirely within the state's border—the Cape Fear, the Neuse, the White Oak, and the Tar–Pamlico basin.[96]

Flora and fauna

Major rivers

Climate

Elevation above sea level is most responsible for temperature change across the state, with the mountainous regions being coolest year-round. The climate is also influenced by the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf Stream, especially in the coastal plain. These influences tend to cause warmer winter temperatures along the coast, where temperatures only occasionally drop below the freezing point at night. The coastal plain averages around 1 inch (2.5 cm) of snow or ice annually, and in many years, there may be no snow or ice at all.[97]

The Atlantic Ocean exerts less influence on the climate of the Piedmont region, which has hotter summers and colder winters than along the coast, though winters are still mild.[97]

North Carolina experiences severe weather both in summer and in winter, with summer bringing threat of hurricanes, tropical storms, heavy rain, and flooding.[98] Destructive hurricanes that have hit North Carolina include Hurricane Fran, Hurricane Florence, Hurricane Floyd, Hurricane Hugo, and Hurricane Hazel, the latter being the strongest storm ever to make landfall in the state, as a Category 4 in 1954. Hurricane Isabel ranks as the most destructive of the 21st century.[99][100]

North Carolina averages fewer than 20 tornadoes per year, many of them produced by hurricanes or tropical storms along the coastal plain. Tornadoes from thunderstorms are a risk, especially in the eastern part of the state. The western Piedmont is often protected by the mountains, which tend to break up storms as they try to cross over; the storms will often re-form farther east. A phenomenon known as "cold-air damming" often occurs in the northwestern part of the state, which can weaken storms but can also lead to major ice events in winter.[101]

In April 2011, the worst tornado outbreak in North Carolina's history occurred. Thirty confirmed tornadoes touched down, mainly in the Eastern Piedmont and Sandhills, killing at least 24 people.[102][103] In September 2019 Hurricane Dorian hit the area.

| Monthly normal high and low temperatures (Fahrenheit) for various North Carolina cities. | ||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asheville[104] | 47/27 | 51/30 | 59/35 | 68/43 | 75/51 | 81/60 | 84/64 | 83/63 | 77/56 | 68/45 | 59/36 | 49/29 |

| Boone[105] | 42/21 | 45/23 | 52/29 | 61/37 | 69/46 | 76/54 | 79/58 | 78/57 | 72/50 | 63/39 | 54/31 | 45/24 |

| Cape Hatteras[106] | 52/39 | 54/40 | 59/45 | 66/53 | 74/61 | 81/69 | 85/74 | 84/73 | 80/69 | 72/60 | 64/51 | 56/43 |

| Charlotte[104] | 51/30 | 55/33 | 63/39 | 72/47 | 79/56 | 86/64 | 89/68 | 88/67 | 81/60 | 72/49 | 62/39 | 53/32 |

| Fayetteville[107] | 54/33 | 59/35 | 66/42 | 75/50 | 82/59 | 89/68 | 91/72 | 90/70 | 84/64 | 75/52 | 67/43 | 56/35 |

| Greensboro[107] | 48/30 | 53/32 | 61/39 | 70/47 | 78/56 | 85/65 | 88/69 | 86/68 | 80/61 | 70/49 | 61/40 | 51/32 |

| Raleigh[107] | 51/31 | 55/34 | 63/40 | 72/48 | 80/57 | 87/66 | 90/70 | 88/69 | 82/62 | 73/50 | 64/41 | 54/33 |

| Wilmington[108] | 56/36 | 60/38 | 66/44 | 74/52 | 81/60 | 87/69 | 90/73 | 88/71 | 84/66 | 76/55 | 68/45 | 59/38 |

| Climate data for North Carolina | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 86 (30) |

90 (32) |

100 (38) |

102 (39) |

107 (42) |

108 (42) |

109 (43) |

110 (43) |

109 (43) |

102 (39) |

90 (32) |

87 (31) |

110 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 49.9 (9.9) |

53.7 (12.1) |

61.8 (16.6) |

71.0 (21.7) |

78.1 (25.6) |

85.2 (29.6) |

88.1 (31.2) |

86.8 (30.4) |

80.8 (27.1) |

71.6 (22.0) |

62.5 (16.9) |

52.5 (11.4) |

70.2 (21.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 39.2 (4.0) |

42.3 (5.7) |

49.5 (9.7) |

58.1 (14.5) |

66.1 (18.9) |

74.1 (23.4) |

77.5 (25.3) |

76.3 (24.6) |

69.9 (21.1) |

59.4 (15.2) |

50.4 (10.2) |

41.7 (5.4) |

58.7 (14.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 28.4 (−2.0) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

37.2 (2.9) |

45.2 (7.3) |

54.0 (12.2) |

63.0 (17.2) |

66.8 (19.3) |

65.8 (18.8) |

58.9 (14.9) |

47.2 (8.4) |

38.3 (3.5) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

47.2 (8.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −34 (−37) |

−31 (−35) |

−29 (−34) |

0 (−18) |

13 (−11) |

22 (−6) |

30 (−1) |

29 (−2) |

23 (−5) |

5 (−15) |

−22 (−30) |

−33 (−36) |

−34 (−37) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.7 (94) |

3.5 (89) |

4.2 (110) |

3.5 (89) |

3.8 (97) |

4.3 (110) |

4.8 (120) |

4.7 (120) |

4.3 (110) |

3.3 (84) |

3.3 (84) |

3.5 (89) |

46.9 (1,196) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 2.0 (5.1) |

1.4 (3.6) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.8 (2.0) |

5 (12.7) |

| Source 1: USA.com (averages)[109] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: North Carolina State Climate Office (extremes)[110] | |||||||||||||

Parks and recreation

North Carolina provides a large range of recreational activities, from swimming at the beach to skiing in the mountains. North Carolina offers fall colors, freshwater and saltwater fishing, hunting, birdwatching, agritourism, ATV trails, ballooning, rock climbing, biking, hiking, skiing, boating and sailing, camping, canoeing, caving (spelunking), gardens, and arboretums. North Carolina has theme parks, aquariums, museums, historic sites, lighthouses, elegant theaters, concert halls, and fine dining.[111][112]

North Carolinians enjoy outdoor recreation using numerous local bike paths, 34 state parks, and 14 national parks. National Park Service units include the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, the Blue Ridge Parkway, Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Cape Lookout National Seashore, Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site at Flat Rock, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site at Manteo, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Great Smoky Mountains Railroad, Guilford Courthouse National Military Park in Greensboro, Moores Creek National Battlefield near Currie in Pender County, the Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail, Old Salem National Historic Site in Winston-Salem, the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, and Wright Brothers National Memorial in Kill Devil Hills.

National Forests include Uwharrie National Forest in central North Carolina, Croatan National Forest in Eastern North Carolina, Pisgah National Forest in the western mountains, and Nantahala National Forest in the southwestern part of the state.

Major cities

In 2023, the U.S. Census Bureau released the 2022 population estimates for municipalities in North Carolina. Charlotte has the largest population, while Raleigh has the second-largest population in North Carolina.[113]

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Charlotte  Raleigh |

1 | Charlotte | Mecklenburg | 897,720 | 11 | Asheville | Buncombe | 93,776 |  Greensboro  Durham |

| 2 | Raleigh | Wake | 476,587 | 12 | Greenville | Pitt | 89,233 | ||

| 3 | Greensboro | Guilford | 301,115 | 13 | Gastonia | Gaston | 82,653 | ||

| 4 | Durham | Durham | 291,928 | 14 | Apex | Wake | 71,065 | ||

| 5 | Winston-Salem | Forsyth | 251,350 | 15 | Jacksonville | Onslow | 70,420 | ||

| 6 | Fayetteville | Cumberland | 208,873 | 16 | Huntersville | Mecklenburg | 63,035 | ||

| 7 | Cary | Wake | 180,388 | 17 | Chapel Hill | Orange | 62,098 | ||

| 8 | Wilmington | New Hanover | 120,324 | 18 | Burlington | Alamance | 59,287 | ||

| 9 | High Point | Guilford | 115,067 | 19 | Kannapolis | Cabarrus | 55,448 | ||

| 10 | Concord | Cabarrus | 109,896 | 20 | Rocky Mount | Nash | 54,013 | ||

Most populous counties

After the 2020 census, Wake County, with a population of 1,129,410, became the most populous county in the state, overtaking Mecklenburg County, with a population of 1,115,482, by a margin of about 14,000. Both counties are still the only to have populations over one million in North Carolina and the Carolinas region.[115][116]

Statistical areas

North Carolina has four major combined statistical areas (CSA) with a population over 1 million (as of 2023):[117][8]

- Charlotte Metro: Charlotte-Concord, NC-SC; population 3,387,115

- Research Triangle: Raleigh-Durham-Cary, NC; population: 2,368,947

- Hampton Roads: Virginia Beach-Chesapeake, VA-NC; population: 1,866,723

- Piedmont Triad: Greensboro–Winston-Salem–High Point, NC; population: 1,736,099

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 393,751 | — | |

| 1800 | 478,103 | 21.4% | |

| 1810 | 556,526 | 16.4% | |

| 1820 | 638,829 | 14.8% | |

| 1830 | 737,987 | 15.5% | |

| 1840 | 753,419 | 2.1% | |

| 1850 | 869,039 | 15.3% | |

| 1860 | 992,622 | 14.2% | |

| 1870 | 1,071,361 | 7.9% | |

| 1880 | 1,399,750 | 30.7% | |

| 1890 | 1,617,949 | 15.6% | |

| 1900 | 1,893,810 | 17.1% | |

| 1910 | 2,206,287 | 16.5% | |

| 1920 | 2,559,123 | 16.0% | |

| 1930 | 3,170,276 | 23.9% | |

| 1940 | 3,571,623 | 12.7% | |

| 1950 | 4,061,929 | 13.7% | |

| 1960 | 4,556,155 | 12.2% | |

| 1970 | 5,082,059 | 11.5% | |

| 1980 | 5,881,766 | 15.7% | |

| 1990 | 6,628,637 | 12.7% | |

| 2000 | 8,049,313 | 21.4% | |

| 2010 | 9,535,483 | 18.5% | |

| 2020 | 10,439,388 | 9.5% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 10,835,491 | [7] | 3.8% |

| Source: 1910–2020[118] | |||

The United States Census Bureau determined the population of North Carolina was 10,439,388 at the 2020 census.[119][120][121] Based on numbers in 2012 of the people residing in North Carolina 58.5% were born there; 33.1% were born in another state; 1.0% were born in Puerto Rico, U.S. island areas, or born abroad to American parent(s); and 7.4% were foreign-born.[122]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 9,382 homeless people in North Carolina.[123][124]

The top countries of origin for North Carolina's immigrants were Mexico, India, Honduras, China and El Salvador, as of 2018[update].[125]

Race and ethnicity

| Race and Ethnicity[126] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 60.5% | 63.9% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 20.2% | 21.8% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[c] | — | 10.7% | ||

| Asian | 3.3% | 4.0% | ||

| Native American | 1.0% | 2.5% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0.2% | ||

| Other | 0.4% | 1.1% | ||

| Racial composition | 1990[127] | 2000[128] | 2010[129] | 2020[130] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 75.6% | 72.1% | 68.5% | 62.2% |

| Black | 22.0% | 21.6% | 21.4% | 20.5% |

| Asian | 0.8% | 1.4% | 2.2% | 3.3% |

| Native | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.2% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Other race | 0.5% | 2.3% | 4.3% | 5.9% |

| Two or more races | – | 1.3% | 2.3% | 6.8% |

At the 2010 census,[131] the racial composition of North Carolina was: White: 68.5% (65.3% non-Hispanic white, 3.2% White Hispanic), Black or African American: 21.5%, Latin and Hispanic American of any race: 8.4%, some other race: 4.3%, Multiracial American: 2.2%, Asian American: 2.2%, and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander: 1%. In 2020, North Carolina like much of the U.S. experienced a decline in its non-Hispanic white population; at the 2020 census, non-Hispanic whites were 62.2%, Blacks or African Americans 20.5%, American Indian and Alaska Natives 1.2%, Asians 3.3%, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders 0.1%, people from other race 5.9%, and multiracial Americans 6.8%.[132]

Enslaved Africans were brought to North Carolina to be sold into slavery. A majority of the black population is now concentrated in the urban areas and northeastern part of the state.[133]

North Carolina's Hispanic population has grown rapidly. The Hispanic population more than doubled in size between 1990 and 2000. Many of North Carolina's Hispanic residents are of Mexican heritage. Many of North Carolina's newer Latino residents came from Mexico largely to work in agriculture, manufacturing, or on one of North Carolina's military installations.[134]

The most common ancestries in North Carolina are African-American, American, German, English, and Irish.[135]

North Carolina has the eighth-largest Native American population in the country.[136] The state is home to eight Native American tribes and four urban Native American organizations.[137]

Languages

| Language | Percentage of population (in 2010)[138] |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 6.93% |

| French | 0.32% |

| German | 0.27% |

| Chinese (including Mandarin) | 0.27% |

| Vietnamese | 0.24% |

| Arabic | 0.17% |

| Korean | 0.16% |

| Tagalog | 0.13% |

| Hindi | 0.12% |

| Gujarati, Russian, and Hmong (tied) | 0.11% |

| Italian and Japanese (tied) | 0.08% |

| Cherokee | 0.01%[139] |

North Carolina is home to a spectrum of different dialects of Southern American English and Appalachian English.

In 2010, 89.66% (7,750,904) of North Carolina residents age five and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 6.93% (598,756) spoke Spanish, 0.32% (27,310) French, 0.27% (23,204) German, and Chinese (which includes Mandarin) was spoken as a main language by 0.27% (23,072) of the population five and older. In total, 10.34% (893,735) of North Carolina's population age five and older spoke a mother language other than English.[138] In 2019, 87.7% of the population aged 5 and older spoke English and 12.3% spoke another language. The most common non-English language was Spanish at the 2019 American Community Survey.[140]

Religion

North Carolina residents since the colonial era have historically been overwhelmingly Protestant—first Anglican, then Baptist and Methodist. In 2010, the Southern Baptist Convention was the single largest Christian denomination, with 4,241 churches and 1,513,000 members. The second largest in 2024 was the Roman Catholic Church which is organised into two dioceses. In the west is the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charlotte which includes Charlotte and has 530,000 members in 196 parishes. In the east is the Diocese of Raleigh with a total of 80 parishes and nearly 500,000 Catholics.[142] The third largest was the United Methodist Church, with 660,000 members and 1,923 churches. The fourth largest was the Presbyterian Church (USA), with 186,000 members and 710 congregations; this denomination was brought by Scots-Irish immigrants who settled the backcountry in the colonial era.[143] In 2020, the Southern Baptists remained the largest with 1,324,747 adherents, though Methodists and others were collectively overtaken by non/interdenominational Protestants numbering 1,053,564.[144]

In 1845, the Baptists split into regional associations of the Northern United States and Southern U.S., over the issue of slavery. These new associations were the Northern Baptist Convention (today the American Baptist Churches USA) and Southern Baptist Convention. By the late 19th century, the largest Protestant denomination in North Carolina were Baptists. After emancipation, black Baptists quickly set up their own independent congregations in North Carolina and other states of the South, as they wanted to be free of white supervision.[145][146][147] Black Baptists developed their own state and national associations, such as the National Baptist Convention.[146] Other primarily African American Baptist conventions which grew in the state since the 20th century were the Progressive National Baptist Convention and Full Gospel Baptist Church Fellowship.

Methodists (the second largest group among North Carolinian Protestants) were divided along racial lines in the United Methodist Church and African Methodist Episcopal Church. The Methodist tradition tends to be strong in the northern Piedmont, especially in populous Guilford County. Other prominent Protestant groups in North Carolina as of the Pew Research Center's 2014 study were non/interdenominational Protestants and Pentecostalism. The Assemblies of God and Church of God in Christ are the largest Pentecostal denominations operating in the state, while notable minorities include Oneness Pentecostals primarily affiliated with the United Pentecostal Church International.

The state also has a special history with the Moravian Church, as settlers of this faith (largely of German origin) settled in the Winston-Salem area in the 18th and 19th centuries. Historically Scots-Irish have had a strong presence in Charlotte and in Scotland County.[148]

A wide variety of non-Christian faiths are practiced by other residents in the state, including: Judaism, Islam, Baháʼí, Buddhism, and Hinduism. The rapid influx of Northerners and immigrants from Latin America is steadily increasing ethnic and religious diversity within the state. The number of Roman Catholics and Jews in the state has increased, along with general religious diversity as a whole. There are also a substantial number of Quakers in Guilford County and northeastern North Carolina. Many universities and colleges in the state have been founded on religious traditions, and some currently maintain that affiliation, including:[149]

- Barton College (Disciples of Christ)

- Belmont Abbey College (Catholic)

- Bennett College for Women (United Methodist Church)

- Brevard College (United Methodist Church)

- Campbell University (Baptist)

- Catawba College (United Church of Christ)

- Chowan University (Baptist)

- Davidson College (Presbyterian)

- Duke University (Historically Methodist)

- Elon University (Historically United Church of Christ)

- Gardner–Webb University (Cooperative Baptist Fellowship)

- Greensboro College (Methodist)

- Guilford College (Religious Society of Friends/Quakers)

- High Point University (United Methodist Church)

- Lees-McRae College (Presbyterian)

- Lenoir-Rhyne University (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America)

- Livingstone College (African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church)

- Louisburg College (United Methodist Church)

- Mars Hill University (Christian)

- Methodist University (United Methodist Church)

- Montreat College (Christian)

- University of Mount Olive (Baptist)

- North Carolina Wesleyan University (United Methodist Church)

- William Peace University (Presbyterian)

- Pfeiffer University (Methodist)

- Queens University of Charlotte (Presbyterian)

- St. Andrews Presbyterian College (Presbyterian)

- Saint Augustine's College (Episcopal)

- Salem College (Moravian Church)

- Shaw University (Baptist)

- Wake Forest University (Historically Baptist)

- Warren Wilson College (Historically Presbyterian)

- Wingate University (Historically Baptist)

The state also has several major seminaries, including the Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, and the Hood Theological Seminary (AME Zion) in Salisbury.

Economy

North Carolina's 2018 total gross state product was $496 billion.[150] Based on American Community Survey 2010–2014 data, North Carolina's median household income was $46,693. It ranked forty-first out of fifty states plus the District of Columbia for median household income. North Carolina had the fourteenth highest poverty rate in the nation at 17.6%, with 13% of families that were below the poverty line.[151]

The state has a very diverse economy because of its great availability of hydroelectric power,[152] its pleasant climate, and its wide variety of soils. The state ranks third among the South Atlantic states in population, but leads the region in industry and agriculture.[153][154] North Carolina leads the nation in the production of tobacco.[155]

Charlotte, the state's largest city, is a major textile and trade center. According to a Forbes article written in 2013, employment in the "Old North State" has gained many different industry sectors. Science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) industries in the area surrounding North Carolina's capital have grown 17.9 percent since 2001. Raleigh ranked the third best city for technology in 2020 due to the state's growing technology sector.[156] In 2010, North Carolina's total gross state product was $424.9 billion,[157] while the state debt in November 2012, according to one source, totaled $2.4 billion,[158] while according to another, was in 2012 $57.8 billion.[159] In 2011, the civilian labor force was at around 4.5 million with employment near 4.1 million.

North Carolina is the leading U.S. state in production of flue-cured tobacco and sweet potatoes, and comes second in the farming of pigs and hogs, trout, and turkeys.[160][161] In the three most recent USDA surveys (2002, 2007, 2012), North Carolina also ranked second in the production of Christmas trees.[160][162][163]

North Carolina has 15 metropolitan areas,[117] and in 2010 was chosen as the third-best state for business by Forbes Magazine, and the second-best state by chief executive officer Magazine.[164] Since 2000, there has been a clear division in the economic growth of North Carolina's urban and rural areas. While North Carolina's urban areas have enjoyed a prosperous economy with steady job growth, low unemployment, and rising wages, many of the state's rural counties have suffered from job loss, rising levels of poverty, and population loss as their manufacturing base has declined. According to one estimate, one-half of North Carolina's 100 counties have lost population since 2010, primarily due to the poor economy in many of North Carolina's rural areas. However, the population of the state's urban areas is steadily increasing.[165]

Arts and culture

North Carolina has traditions in art, music, and cuisine. The nonprofit arts and culture industry generates $1.2 billion in direct economic activity in North Carolina, supporting more than 43,600 full-time equivalent jobs and generating $119 million in revenue for local governments and the state of North Carolina.[166] North Carolina established the North Carolina Museum of Art as the first major museum collection in the country to be formed by state legislation and funding[167] and continues to bring millions into the NC economy.[168]

One of the more famous arts communities in the state is Seagrove, the handmade-pottery capital of the U.S., where artisans create handcrafted pottery inspired by the same traditions that began in this community more than two hundred years ago.

TV and film

Music

North Carolina boasts a large number of noteworthy jazz musicians, some among the most important in the history of the genre. These include: John Coltrane, (Hamlet, High Point); Thelonious Monk (Rocky Mount); Billy Taylor (Greenville); Woody Shaw (Laurinburg); Lou Donaldson (Durham); Max Roach (Newland); Tal Farlow (Greensboro); Albert, Jimmy and Percy Heath (Wilmington); Nina Simone (Tryon); and Billy Strayhorn (Hillsborough).

North Carolina is also famous for its tradition of old-time music, and many recordings were made in the early 20th century by folk-song collector Bascom Lamar Lunsford. Musicians such as the North Carolina Ramblers helped solidify the sound of country music in the late 1920s, while the influential bluegrass musician Doc Watson also hailed from North Carolina. Both North and South Carolina are hotbeds for traditional rural blues, especially the style known as the Piedmont blues.

Ben Folds Five originated in Winston-Salem, and Ben Folds still records and resides in Chapel Hill.

The British band Pink Floyd is named, in part, after Chapel Hill bluesman Floyd Council.

The Research Triangle area has long been a well-known center for folk, rock, metal, jazz and punk.[169] James Taylor grew up around Chapel Hill, and his 1968 song "Carolina in My Mind" has been called an unofficial anthem for the state.[170][171][172] Other famous musicians from North Carolina include J. Cole, DaBaby, 9th Wonder, Shirley Caesar, Roberta Flack, Clyde McPhatter, Nnenna Freelon, Link Wray, Warren Haynes, Jimmy Herring, Michael Houser, Eric Church, Future Islands, Randy Travis, Ryan Adams, Ronnie Milsap, Anthony Hamilton, The Avett Brothers, Charlie Daniels, and Luke Combs.

Metal and punk acts such as Corrosion of Conformity, Between the Buried and Me, and Nightmare Sonata are native to North Carolina.

EDM producer Porter Robinson hails from Chapel Hill.

North Carolina is the home of more American Idol finalists than any other state: Clay Aiken (season two), Fantasia Barrino (season three), Chris Daughtry (season five), Kellie Pickler (season five), Bucky Covington (season five), Anoop Desai (season eight), Scotty McCreery (season ten), and Caleb Johnson (season thirteen). North Carolina also has the most American Idol winners with Barrino, McCreery, and Johnson.

In the mountains, the Brevard Music Center hosts choral, operatic, orchestral, and solo performances during its annual summer schedule.

North Carolina has five professional opera companies: Opera Carolina in Charlotte, NC Opera in Raleigh, Greensboro Opera in Greensboro, Piedmont Opera in Winston-Salem, and Asheville Lyric Opera in Asheville. Academic conservatories and universities also produce fully staged operas, such as the A. J. Fletcher Opera Institute of the University of North Carolina School of the Arts in Winston-Salem, the Department of Music of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and UNC Greensboro.

Among others, there are three high-level symphonic orchestras: NC Symphony in Raleigh, Charlotte Symphony, and Winston-Salem Symphony. The NC Symphony holds the North Carolina Master Chorale. The Carolina Ballet is headquartered in Raleigh, and there is also the Charlotte Ballet.

The state boasts three performing arts centers: DPAC in Durham, Duke Energy Center for the Performing Arts in Raleigh, and the Blumenthal Performing Art Centers in Charlotte. They feature concerts, operas, recitals, and traveling Broadway musicals.[173][174][175]

Shopping

North Carolina has a variety of shopping choices. SouthPark Mall in Charlotte is the largest and most upscale mall in the Carolinas, featuring multiple luxury tenants with their sole location in the state. Other major malls in Charlotte include Northlake Mall and Carolina Place Mall in nearby suburb Pineville. Other major malls throughout the state include Hanes Mall in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, The Thruway Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Crabtree Valley Mall, North Hills Mall, and Triangle Town Center in Raleigh; Friendly Center and Four Seasons Town Centre in Greensboro; Oak Hollow Mall in High Point; Concord Mills in Concord; Valley Hills Mall in Hickory; Cross Creek Mall in Fayetteville; and The Streets at Southpoint in Durham and Independence Mall in Wilmington, North Carolina, and Tanger Outlets in Charlotte, Nags Head, Blowing Rock, and Mebane, North Carolina.

Cuisine and agriculture

A culinary staple of North Carolina is pork barbecue. There are strong regional differences and rivalries over the sauces and methods used in making the barbecue. The common trend across Western North Carolina is the use of premium grade Boston butt. Western North Carolina pork barbecue uses a tomato-based sauce, and only the pork shoulder (dark meat) is used. Western North Carolina barbecue is commonly referred to as Lexington barbecue after the Piedmont Triad town of Lexington, home of the Lexington Barbecue Festival, which attracts more than 100,000 visitors each October.[176][177] Eastern North Carolina pork barbecue uses a vinegar-and-red-pepper-based sauce and the "whole hog" is cooked, thus integrating both white and dark meat.[178]

Krispy Kreme, an international chain of doughnut stores, was started in North Carolina; the company's headquarters are in Winston-Salem. Pepsi-Cola was first produced in 1898 in New Bern. A regional soft drink, Cheerwine, was created and is still based in the city of Salisbury. Despite its name, the hot sauce Texas Pete was created in North Carolina; its headquarters are also in Winston-Salem. The Hardee's fast-food chain was started in Rocky Mount. Another fast-food chain, Bojangles', was started in Charlotte, and has its corporate headquarters there. A popular North Carolina restaurant chain is Golden Corral. Started in 1973, the chain was founded in Fayetteville, with headquarters located in Raleigh. Popular pickle brand Mount Olive Pickle Company was founded in Mount Olive in 1926. Fast casual burger chain Hwy 55 Burgers, Shakes & Fries also makes its home in Mount Olive. Cook Out, a popular fast-food chain featuring burgers, hot dogs, and milkshakes in a wide variety of flavors, was founded in Greensboro in 1989 and has begun expanding outside North Carolina. In 2013 Southern Living named Durham–Chapel Hill the South's "Tastiest City".

Over the last decade, North Carolina has become a cultural epicenter and haven for internationally prize-winning wine (Noni Bacca Winery), internationally prized cheeses (Ashe County), "L'institut International aux Arts Gastronomiques: Conquerront Les Yanks les Truffes, January 15, 2010" international hub for truffles (Garland Truffles), and beer making, as tobacco land has been converted to grape orchards while state laws regulating alcohol by volume (ABV) in beer allowed a jump from six to fifteen percent. The Yadkin Valley in particular has become a strengthening market for grape production, while Asheville recently won the recognition of being named "Beer City USA". Asheville boasts the largest number of breweries per capita of any city in the United States. Recognized and marketed brands of beer in North Carolina include Highland Brewing, Duck Rabbit Brewery, Mother Earth Brewery, Weeping Radish Brewery, Big Boss Brewing, Foothills Brewing, Carolina Brewing Company, Lonerider Brewing, and White Rabbit Brewing Company.

North Carolina has large grazing areas for beef and dairy cattle. Truck farms can be found in North Carolina. A truck farm is a small farm where fruits and vegetables are grown to be sold at local markets. The state's shipping, commercial fishing, and lumber industries are important to its economy. Service industries, including education, health care, private research, and retail trade, are also important. Research Triangle Park, a large industrial complex located in the Raleigh-Durham area, is one of the major centers in the country for electronics and medical research.[179]

Tobacco was one of the first major industries to develop after the Civil War. Many farmers grew some tobacco, and the invention of the cigarette made the product especially popular. Winston-Salem is the birthplace of R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJR), founded by R. J. Reynolds in 1874 as one of sixteen tobacco companies in the town. By 1914 it was selling 425 million packs of Camels a year. Today it is the second-largest tobacco company in the U.S. (behind Altria Group). RJR is an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Reynolds American Inc., which in turn is 42% owned by British American Tobacco.[180]

Ships named for the state

Several ships have been named after the state, most famously USS North Carolina in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II. Now decommissioned, she is part of the USS North Carolina Battleship Memorial in Wilmington. Another USS North Carolina, a nuclear attack submarine, was commissioned in Wilmington on May 3, 2008.[181]

State parks

The state maintains a group of protected areas known as the North Carolina State Park System, which is managed by the North Carolina Division of Parks & Recreation (NCDPR), an agency of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources (NCDNCR).[182]

Armed forces installations

Fort Liberty, near Fayetteville and Southern Pines, is a large and comprehensive military base and is the headquarters of the XVIII Airborne Corps, 82nd Airborne Division, and the U.S. Army Special Operations Command. Serving as the air wing for Fort Liberty is Pope Field, also located near Fayetteville.

Located in Jacksonville, Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, combined with nearby bases Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Cherry Point, MCAS New River, Camp Geiger, Camp Johnson, Stone Bay and Courthouse Bay, makes up the largest concentration of Marines and sailors in the world. MCAS Cherry Point is home of the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing. Located in Goldsboro, Seymour Johnson Air Force Base is home of the 4th Fighter Wing and 916th Air Refueling Wing. One of the busiest air stations in the United States Coast Guard is located at the Coast Guard Air Station in Elizabeth City. Also stationed in North Carolina is the Military Ocean Terminal Sunny Point in Southport.

On January 24, 1961, a B-52G broke up in midair and crashed after suffering a severe fuel loss, near Goldsboro, dropping two nuclear bombs in the process without detonation.[183] In 2013, it was revealed that three safety mechanisms on one bomb had failed, leaving just one low-voltage switch preventing detonation.[184]

Tourism

Charlotte is the most-visited city in the state, attracting 28.3 million visitors in 2018.[185] Area attractions include Carolina Panthers NFL football team and Charlotte Hornets basketball team, Carowinds amusement park, Catawba Two Kings Casino (in nearby Kings Mountain), Charlotte Motor Speedway, U.S. National Whitewater Center, Discovery Place, Great Wolf Lodge, Sea Life Aquarium,[186] Bechtler Museum of Modern Art, Billy Graham Library, Carolinas Aviation Museum, Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture, Levine Museum of the New South, McColl Center for Art + Innovation, Mint Museum, and the NASCAR Hall of Fame.

Every year the Appalachian Mountains attract several million tourists to the western part of the state,[187] including the historic Biltmore Estate. The scenic Blue Ridge Parkway and Great Smoky Mountains National Park are the two most visited national park and unit in the United States with more than 25 million visitors in 2013.[188] The City of Asheville is consistently voted as one of the top places to visit and live in the United States, known for its rich art deco architecture, mountain scenery and outdoor activities.[189][190]

In Raleigh, many tourists visit the capital, African American Cultural Complex,[191] Contemporary Art Museum of Raleigh, Gregg Museum of Art & Design at NCSU, Haywood Hall House & Gardens, Marbles Kids Museum, North Carolina Museum of Art, North Carolina Museum of History, North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame, Raleigh City Museum, J. C. Raulston Arboretum, Joel Lane House, Mordecai House, Montfort Hall, and the Pope House Museum. The Carolina Hurricanes NHL hockey team is also located in the city.

In the Conover–Hickory area, attractions include Hickory Motor Speedway, RockBarn Golf and Spa,[192] home of the Greater Hickory Classic at Rock Barn; Catawba County Firefighters Museum,[193] the SALT Block,[194] and Valley Hills Mall.