Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island | |

|---|---|

| Territory of Norfolk Island Teratri a' Norf'k Ailen (Pitcairn-Norfolk)[1] | |

| Motto: "Inasmuch"[2] | |

| Anthem: "Advance Australia Fair" Duration: 1 minute and 4 seconds. | |

| Territorial anthems: "Come Ye Blessed" "God Save the King" Duration: 1 minute and 4 seconds. | |

Location of Norfolk Island | |

| Sovereign state | Australia |

| Separation from Tasmania | 1 November 1856 |

| Transfer to Australia | 1 July 1914 |

| Named for | Mary Howard, Duchess of Norfolk |

| Capital | Kingston 29°03′22″S 167°57′40″E / 29.056°S 167.961°E |

| Largest town | Burnt Pine |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2016) | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Norfolk Islander[6] |

| Government | Directly administered dependency |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Sam Mostyn | |

| George Plant | |

| Parliament of Australia | |

• Senate | represented by ACT senators (since 2016) |

| included in the Division of Bean (since 2018) | |

| Area | |

• Total | 34.6 km2 (13.4 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Highest elevation | 319 m (1,047 ft) |

| Population | |

• 2021 census | 2,188[7] (not ranked) |

• Density | 61.9/km2 (160.3/sq mi) (not ranked) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | US$60,209,320[8] |

| Currency | Australian dollar (AU$) (AUD) |

| Time zone | UTC+11:00 (NFT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+12:00 (NFDT) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +672 |

| Postcode | NSW 2899 |

| ISO 3166 code | NF |

| Internet TLD | .nf |

Norfolk Island (/ˈnɔːrfək/ NOR-fək, locally /ˈnɔːrfoʊk/ NOR-fohk;[9] Norfuk: Norf'k Ailen[10]) is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, 1,412 kilometres (877 mi) directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about 900 kilometres (560 mi) from Lord Howe Island. Together with the neighbouring Phillip Island and Nepean Island, the three islands collectively form the Territory of Norfolk Island.[11] At the 2021 census, it had 2,188 inhabitants living on a total area of about 35 km2 (14 sq mi).[7] Its capital is Kingston.

East Polynesians were the first to settle Norfolk Island, but they had already departed when Great Britain settled it as part of its 1788 colonisation of Australia. The island served as a convict penal settlement from 6 March 1788 until 5 May 1855, except for an 11-year hiatus between 15 February 1814 and 6 June 1825,[12][13] when it lay abandoned. On 8 June 1856, permanent civilian residence on the island began when descendants of the Bounty mutineers were relocated from Pitcairn Island. In 1914, the UK handed Norfolk Island over to Australia to administer as an external territory.[14]

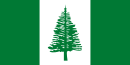

Native to the island, the evergreen Norfolk Island pine is a symbol of the island and is pictured on its flag. The pine is a key export for Norfolk Island, being a popular ornamental tree in Australia (where two related species grow), and also worldwide.

History

[edit]Early settlement

[edit]Norfolk Island was uninhabited when first settled by Europeans, but evidence of earlier habitation was obvious. Archaeological investigation suggests that in the 13th or 14th century the island was settled by East Polynesian seafarers, either from the Kermadec Islands north of mainland New Zealand, or from the North Island of New Zealand. However, both Polynesian and Melanesian artefacts have been found, so it is possible that people from New Caledonia, relatively close to the north, also reached Norfolk Island. Human occupation must have ceased at least a few hundred years before Europeans arrived in the late 18th century. Ultimately, the relative isolation of the island, and its poor horticultural environment, were not favourable to long-term settlement.[15]

First penal settlement (1788–1814)

[edit]The first European known to have sighted and landed on the island was Captain James Cook, on 10 October 1774,[12][13] on his second voyage to the South Pacific on HMS Resolution. He named it after Mary Howard, Duchess of Norfolk.[16] Sir John Call argued the advantages of Norfolk Island in that it was uninhabited and that New Zealand flax grew there.

After the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775 halted penal transportation to the Thirteen Colonies, British prisons started to overcrowd. Several stopgap measures proved ineffective, and the government announced in December 1785 that it would send convicts to parts of what is now known as Australia. In 1786, it included Norfolk Island as an auxiliary settlement, as proposed by John Call, in its plan for colonisation of the Colony of New South Wales. The decision to settle Norfolk Island was taken after Empress Catherine II of Russia restricted the sale of hemp.[17] At the time, practically all the hemp and flax required by the Royal Navy for cordage and sailcloth was imported from Russia.

When the First Fleet arrived at Port Jackson in January 1788, Governor Arthur Phillip ordered Lieutenant Philip Gidley King to lead a party of 15 convicts and seven free men to take control of Norfolk Island, and prepare for its commercial development. They arrived on 6 March. During the first year of the settlement, which was also called "Sydney" like its parent, more convicts and soldiers were sent to the island from New South Wales. Robert Watson, harbourmaster, arrived with the First Fleet as quartermaster of HMS Sirius, and was still serving in that capacity when the ship was wrecked at Norfolk Island in 1790. Next year, he obtained and cultivated a grant of 60 acres (24 ha) on the island.[18]

As early as 1794, Lieutenant-Governor of New South Wales Francis Grose suggested its closure as a penal settlement, as it was too remote and difficult for shipping and too costly to maintain.[19] The first group of people left in February 1805, and by 1808, only about 200 remained, forming a small settlement until the remnants were removed in 1813. A small party remained to slaughter stock and destroy all buildings, so that there would be no inducement for anyone, especially from other European powers, to visit and lay claim to the place. From February 1814 until June 1825, the island was uninhabited.

Second penal settlement (1824–1856)

[edit]

In 1824, the British government instructed the Governor of New South Wales, Thomas Brisbane, to reoccupy Norfolk Island as a place to send "the worst description of convicts". Its remoteness, previously seen as a disadvantage, was now viewed as an asset for the detention of recalcitrant male prisoners. The convicts detained have long been assumed to be hardcore recidivists, or 'doubly-convicted capital respites' – that is, men transported to Australia who committed fresh crimes in the colony for which they were sentenced to death, but were spared the gallows on condition of life on Norfolk Island. However, a 2011 study, using a database of 6,458 Norfolk Island convicts, has demonstrated that the reality was somewhat different: More than half were detained on Norfolk Island without ever receiving a colonial conviction, and only 15% had been reprieved from a death sentence. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of convicts sent to Norfolk Island had committed non-violent property offences, and the average length of detention there was three years.[20] Nonetheless, Norfolk Island went through periods of unrest with convicts staging a number of uprisings and mutinies between 1826 and 1846, all of which failed.[21] The British government began to wind down the second penal settlement after 1847, and the last convicts were removed to Tasmania in May 1855. The island was abandoned because transportation from the United Kingdom to Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) had ceased in 1853, to be replaced by penal servitude in the UK.

Settlement by Pitcairn Islanders (1856–present)

[edit]

The next settlement began on 8 June 1856, as the descendants of Tahitians and the HMS Bounty mutineers, including those of Fletcher Christian, were resettled from the Pitcairn Islands, which had become too small for their growing number. On 3 May 1856, 193 people left Pitcairn Islands aboard the Morayshire.[22] On 8 June 194 people arrived, a baby having been born in transit.[23] The Pitcairners occupied many of the buildings remaining from the penal settlements, and gradually established traditional farming and whaling industries on the island. Although some families decided to return to Pitcairn in 1858 and 1863, the island's population continued to grow. They accepted additional settlers, who often arrived on whaling vessels.

The island was a regular resort for whaling vessels in the age of sail. The first such ship was the Britannia in November 1793. The last on record was the Andrew Hicks in August–September 1907.[24] They came for water, wood and provisions, and sometimes they recruited islanders to serve as crewmen on their vessels.

In 1867, the headquarters of the Melanesian Mission of the Church of England was established on the island. In 1920, the Mission was relocated from Norfolk Island to the Solomon Islands to be closer to the focus of population.

Norfolk Island was the subject of several experiments in administration during the century. It began the 19th century as part of the Colony of New South Wales. On 29 September 1844, Norfolk Island was transferred from the Colony of New South Wales to the Colony of Van Diemen's Land.[25]: Recital 2 On 1 November 1856 Norfolk Island was separated from the Colony of Tasmania (formerly Van Diemen's Land) and constituted as a "distinct and separate Settlement, the affairs of which should until further Order in that behalf by Her Majesty be administered by a Governor to be for that purpose appointed".[26][27] The Governor of New South Wales was constituted as the Governor of Norfolk Island.[25]: Recital 3

On 19 March 1897, the office of the Governor of Norfolk Island was abolished and responsibility for the administration of Norfolk Island was vested in the Governor of the Colony of New South Wales. Yet, the island was not made a part of New South Wales and remained separate. The Colony of New South Wales ceased to exist upon the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901, and from that date responsibility for the administration of Norfolk Island was vested in the Governor of the State of New South Wales.[25]: Recitals 7 and 8

20th century

[edit]

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia accepted the territory by the Norfolk Island Act 1913 (Cth),[14]: p 886 [25] subject to British agreement; the Act received royal assent on 19 December 1913. In preparation for the handover, a proclamation by the Governor of New South Wales on 23 December 1913 (in force when gazetted on 24 December) repealed "all laws heretofore in force in Norfolk Island" and replaced them by re-enacting a list of such laws.[28] Among those laws was the Administration Law 1913 (NSW), which provided for appointment of an Administrator of Norfolk Island and of magistrates, and contained a code of criminal law.[29]

British agreement was expressed on 30 March 1914, in a UK Order in Council[30] made pursuant to the Australian Waste Lands Act 1855 (Imp).[26][14]: p 886 A proclamation by the Governor-General of Australia on 17 June 1914 gave effect to the Act and the Order as from 1 July 1914.[30]

During World War II, the island became a key airbase and refuelling depot between Australia and New Zealand and between New Zealand and the Solomon Islands. The airstrip was constructed by Australian, New Zealand and United States servicemen during 1942.[31] Since Norfolk Island fell within New Zealand's area of responsibility, it was garrisoned by a New Zealand Army unit known as N Force at a large army camp that had the capacity to house a 1,500-strong force. N Force relieved a company of the Second Australian Imperial Force. The island proved too remote to come under attack during the war, and N Force left the island in February 1944.

In 1979, Norfolk Island was granted limited self-government by Australia, under which the island elected a government that ran most of the island's affairs.[32]

21st century

[edit]In 2006, a formal review process took place in which the Australian government considered revising the island's model of government. The review was completed on 20 December 2006, when it was decided that there would be no changes in the governance of Norfolk Island.[33]

Financial problems and a reduction in tourism led to Norfolk Island's administration appealing to the Australian federal government for assistance in 2010. In return, the islanders were to pay income tax for the first time but would be eligible for greater welfare benefits.[34] However, by May 2013, agreement had not been reached and islanders were having to leave to find work and welfare.[35] An agreement was finally signed in Canberra on 12 March 2015 to replace self-government with a local council but against the wishes of the Norfolk Island government.[36][37] A majority of Norfolk Islanders objected to the Australian plan to make changes to Norfolk Island without first consulting them and allowing their say, with 68% of voters against forced changes.[38] An example of growing friction between Norfolk Island and increased Australian rule was featured in a 2019 episode of Discovery Channel's annual Shark Week. The episode featured Norfolk Island's policy of culling growing cattle populations by killing older cattle and feeding the carcasses to tiger sharks well off the coast. This is done to help prevent tiger sharks from coming further toward shore in search of food. Norfolk Island holds one of the largest populations of tiger sharks in the world. Australia has banned the culling policy as cruelty to animals. Norfolk Islanders fear this will lead to increased shark attacks and damage an already waning tourist industry.

On 4 October 2015, the time zone for Norfolk Island was changed from UTC+11:30 to UTC+11:00.[39]

Reduced autonomy 2016

[edit]In March 2015, the Australian Government announced comprehensive reforms for Norfolk Island.[40] The action was justified on the grounds it was necessary "to address issues of sustainability which have arisen from the model of self-government requiring Norfolk Island to deliver local, state and federal functions since 1979".[40] On 17 June 2015, the Norfolk Island Legislative Assembly was abolished, with the territory becoming run by an Administrator and an advisory council. Elections for a new Regional Council were held on 28 May 2016, with the new council taking office on 1 July 2016.[41]

From that date, most Australian Commonwealth laws were extended to Norfolk Island. This means that taxation, social security, immigration, customs and health arrangements apply on the same basis as in mainland Australia.[40] Travel between Norfolk Island and mainland Australia became domestic travel on 1 July 2016.[42] For the 2016 Australian federal election, 328 people on Norfolk Island voted in the ACT electorate of Canberra, out of 117,248 total votes.[43] Since 2018, Norfolk Island is covered by the electorate of Bean.[44]

There is opposition to the reforms, led by Norfolk Island People for Democracy Inc., an association appealing to the United Nations to include the island on its list of "non-self-governing territories".[45][46] There has also been movement to join New Zealand since the autonomy reforms.[47]

In October 2019, the Norfolk Island People For Democracy advocacy group conducted a survey of 457 island residents (about one quarter of the entire population) and found that 37% preferred free association with New Zealand, 35% preferred free association with Australia, 25% preferred full independence, and 3% preferred full integration with Australia.[48][49]

Geography

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2018) |

The Territory of Norfolk Island is located in the South Pacific Ocean, east of the Australian mainland. Norfolk Island itself is the main island of the island group that the territory encompasses and is located at 29°02′S 167°57′E / 29.033°S 167.950°E. It has an area of 34.6 square kilometres (13.4 sq mi), with no large-scale internal bodies of water and 32 km (20 mi) of coastline. Norfolk was formed from several volcanic eruptions between 3.1 and 2.3 million years ago.[50]

The island's highest point is Mount Bates reaching 319 metres (1,047 feet) above sea level, located in the northwest quadrant of the island. The majority of the terrain is suitable for farming and other agricultural uses. Phillip Island, the second largest island of the territory, is located at 29°07′S 167°57′E / 29.117°S 167.950°E, seven kilometres (4.3 miles) south of the main island.

The coastline of Norfolk Island consists, to varying degrees, of cliff faces. A downward slope exists towards Slaughter Bay and Emily Bay, the site of the original colonial settlement of Kingston. There are no safe harbour facilities on Norfolk Island, with loading jetties existing at Kingston and Cascade Bay. All goods not domestically produced are brought in by ship, usually to Cascade Bay. Emily Bay, protected from the Pacific Ocean by a small coral reef, is the only safe area for recreational swimming, although surfing waves can be found at Anson and Ball Bays.

The climate is subtropical and mild, with little seasonal differentiation. The island is the eroded remnant of a basaltic volcano active around 2.3 to 3 million years ago,[51] with inland areas now consisting mainly of rolling plains. It forms the highest point on the Norfolk Ridge, part of the submerged continent Zealandia.

The area surrounding Mount Bates is preserved as the Norfolk Island National Park. The park, covering around 10% of the land of the island, contains remnants of the forests which originally covered the island, including stands of subtropical rainforest.

The park also includes the two smaller islands to the south of Norfolk Island, Nepean Island and Phillip Island. The vegetation of Phillip Island was devastated due to the introduction during the penal era of pest animals such as pigs and rabbits, giving it a red-brown colour as viewed from Norfolk; however, pest control and remediation work by park staff has recently brought some improvement to the Phillip Island environment.

The major settlement on Norfolk Island is Burnt Pine, located predominantly along Taylors Road, where the shopping centre, post office, bottle shop, telephone exchange and community hall are located. Settlement also exists over much of the island, consisting largely of widely separated homesteads.

Government House, the official residence of the Administrator, is located on Quality Row in what was the penal settlement of Kingston. Other government buildings, including the court, Legislative Assembly and Administration, are also located there. Kingston's role is largely a ceremonial one, however, with most of the economic impetus coming from Burnt Pine.

Climate

[edit]Norfolk Island has a maritime-influenced humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cfa) with warm, humid summers and very mild, rainy winters. The highest recorded temperature is 28.5 °C (83.3 °F) on 23 January 2024, whilst the lowest is 6.2 °C (43.2 °F) on 29 July 1953.[52] The island has moderate rainfall 1,109.9 millimetres (43.70 in), with a maximum in winter; and 52.8 clear days annually.[53]

| Climate data for Norfolk Island Airport (29º03'S, 167º56'E, 112 m AMSL) (1991-2020 normals, extremes 1939-2024) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.5 (83.3) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

27.9 (82.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) |

25.3 (77.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.9 (58.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.1 (53.8) |

12.8 (55.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

6.2 (43.2) |

6.7 (44.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 80.3 (3.16) |

86.8 (3.42) |

106.8 (4.20) |

95.4 (3.76) |

101.5 (4.00) |

120.6 (4.75) |

122.5 (4.82) |

99.6 (3.92) |

78.4 (3.09) |

62.0 (2.44) |

72.0 (2.83) |

83.9 (3.30) |

1,109.9 (43.70) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.7 | 8.8 | 9.3 | 10.3 | 12.2 | 13.0 | 13.6 | 12.2 | 9.4 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 117.5 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 71 | 72 | 69 | 69 | 69 | 69 | 68 | 67 | 69 | 67 | 67 | 70 | 69 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 238.7 | 203.4 | 204.6 | 198.0 | 189.1 | 168.0 | 186.0 | 223.2 | 219.0 | 241.8 | 249.0 | 241.8 | 2,562.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 56 | 55 | 54 | 58 | 57 | 54 | 57 | 65 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 56 | 58 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology (1991-2020 normals, extremes 1939-2024)[54][55] | |||||||||||||

Environment

[edit]Norfolk Island is part of the Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia region "Pacific Subtropical Islands" (PSI), and forms subregion PSI02, with an area of 3,908 hectares (9,660 acres).[56] The country is home to the Norfolk Island subtropical forests terrestrial ecoregion.[57]

Flora

[edit]

Norfolk Island has 174 native plants; 51 of them are endemic. At least 18 of the endemic species are rare or threatened.[58] The Norfolk Island palm (Rhopalostylis baueri) and the smooth tree-fern (Cyathea brownii), the tallest tree-fern in the world,[58] are common in the Norfolk Island National Park but rare elsewhere on the island. Before European colonisation, most of Norfolk Island was covered with subtropical rain forest, the canopy of which was made of Araucaria heterophylla (Norfolk Island pine) in exposed areas, and the palm Rhopalostylis baueri and tree ferns Cyathea brownii and C. australis in moister protected areas. The understory was thick with lianas and ferns covering the forest floor. Only one small tract, 5 km2 (1.9 sq mi), of rainforest remains, which was declared as the Norfolk Island National Park in 1986.[58]

This forest has been infested with several introduced plants. The cliffs and steep slopes of Mount Pitt supported a community of shrubs, herbaceous plants, and climbers. A few tracts of cliff top and seashore vegetation have been preserved. The rest of the island has been cleared for pasture and housing. Grazing and introduced weeds currently threaten the native flora, displacing it in some areas. In fact, there are more weed species than native species on Norfolk Island.[58]

Fauna

[edit]As a relatively small and isolated oceanic island, Norfolk has few land birds but a high degree of endemicity among them. Norfolk Island is home to a radiation of about 40 endemic snail species.[59][60] Many of the endemic bird species and subspecies have become extinct as a result of massive clearance of the island's native vegetation of subtropical rainforest for agriculture, hunting and persecution as agricultural pests. The birds have also suffered from the introduction of mammals such as rats, cats, foxes, pigs and goats, as well as from introduced competitors such as common blackbirds and crimson rosellas.[61] Although the island is politically part of Australia, many of Norfolk Island's native birds show affinities to those of neighbouring New Zealand, such as the Norfolk kākā, Norfolk pigeon,[62] and Norfolk boobook.

Extinctions include that of the endemic Norfolk kākā, Norfolk ground dove and Norfolk pigeon, while of the endemic subspecies the starling, triller, thrush and boobook owl are extinct, although the latter's genes persist in a hybrid population descended from the last female. Other endemic birds are the white-chested white-eye, which may be extinct, the Norfolk parakeet, the Norfolk gerygone, the slender-billed white-eye and endemic subspecies of the Pacific robin and golden whistler. Subfossil bones indicate that a species of Coenocorypha snipe was also found on the island and is now extinct, but the taxonomic relationships of this are unclear and have not been scientifically described yet.[61]

The Norfolk Island Group Nepean Island is also home to breeding seabirds. The providence petrel was hunted to local extinction by the beginning of the 19th century but has shown signs of returning to breed on Phillip Island. Other seabirds breeding there include the white-necked petrel, Kermadec petrel, wedge-tailed shearwater, Australasian gannet, red-tailed tropicbird and grey ternlet. The sooty tern (known locally as the whale bird) has traditionally been subject to seasonal egg harvesting by Norfolk Islanders.[63]

Norfolk Island, with neighbouring Nepean Island, has been identified by BirdLife International as an Important Bird Area because it supports the entire populations of white-chested and slender-billed white-eyes, Norfolk parakeets and Norfolk gerygones, as well as over 1% of the world populations of wedge-tailed shearwaters and red-tailed tropicbirds. Nearby Phillip Island is treated as a separate IBA.[61]

Norfolk Island also has a botanical garden, which is home to a sizeable variety of plant species.[63] However, the island has only one native mammal, Gould's wattled bat (Chalinolobus gouldii). It is very rare, and may already be extinct on the island.

The Norfolk swallowtail (Papilio amynthor) is a species of butterfly that is found on Norfolk Island and the Loyalty Islands.[64]

Cetaceans were historically abundant around the island as commercial hunts on the island were operating until 1956. Today, numbers of larger whales have disappeared, but even today many species such humpback whale, minke whale, sei whale, and dolphins can be observed close to shore, and scientific surveys have been conducted regularly. Southern right whales were once regular migrants to Norfolk,[65] but were severely depleted by historical hunts, and further by recent illegal Soviet and Japanese whaling,[66] resulting in none or very few, if remnants still live, right whales in these regions along with Lord Howe Island.

Whale sharks can be encountered off the island, too.

-

Gannet

-

Masked boobies

-

White tern

-

Emily Bay

-

Norfolk Island pines

-

Captain Cook Lookout

-

Bird Rock (off the north coast)

-

Cathedral Rock (off the north coast)

List of endemic and extirpated native birds

[edit]- Norfolk parakeet, Cyanoramphus cookii (endangered)

- Norfolk kākā, Nestor productus (extinct)

- Brown goshawk, Accipiter fasciatus (extirpated)

- Norfolk pigeon, Hemiphaga novaseelandiae spadicea (extinct, subspecies of NZ pigeon)

- Norfolk ground dove, Aloepecoenas norfolkensis (extinct)

- Norfolk snipe, Coenocorypha spp. (extinct, undescribed)

- Norfolk rail, Gallirallus spp. (extinct, undescribed)

- Norfolk robin, Petroica multicolor (endangered)

- Norfolk golden whistler, Pachycephala pectoralis xanthoprocta (vulnerable, subspecies of golden whistler)

- Norfolk triller, Lalage leucopyga leucopyga (extinct, nominate subspecies of long-tailed triller)

- Norfolk Island thrush, Turdus poliocephalus poliocephalus (extinct, nominate subspecies of Island thrush)

- Norfolk Island starling, Aplonis fusca fusca (extinct, nominate subspecies of extinct Tasman starling)

- Norfolk boobook, Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata (extinct except for hybrids with nominate subspecies, subspecies of Morepork\Southern boobook)

- White-chested white-eye, Zosterops albogularis (critically endangered, possibly extinct)

- Slender-billed white-eye, Zosterops tenuirostris (near threatened)

- Norfolk gerygone, Gerygone modesta (near threatened)

- Norfolk grey fantail, Rhiphidura albiscapa pelzelni (least concern, subspecies of grey fantail)

- Norfolk petrel, Pterodroma spp. (extinct, undescribed)

Demographics

[edit]The population of Norfolk Island was 2,188 in the 2021 census,[7] which had declined from a high of 2,601 in 2001.

In 2011, residents were 78% of the census count, with the remaining 22% being visitors. 16% of the population were 14 years and under, 54% were 15 to 64 years, and 24% were 65 years and over. The figures showed an ageing population, with many people aged 20–34 having moved away from the island.[67]

Most islanders are of either European-only (mostly British) or combined European-Tahitian ancestry, being descendants of the Bounty mutineers as well as more recent arrivals from Australia and New Zealand. About half of the islanders can trace their roots back to Pitcairn Island.[68]

This common heritage has led to a limited number of surnames among the islanders – a limit constraining enough that the island's telephone directory also includes nicknames for many subscribers, such as Carrots, Dar Bizziebee, Diddles, Geek, Lettuce Leaf, Possum, Pumpkin, Smudgie, Truck and Wiggy.[68][69]

Structure of the population

[edit]Population

- 1748 (as of the 2016 census)

Population growth rate

- 0.01%

Ancestry[71]

- Australian (22.8%)

- English (22.4%)

- Pitcairn Islander (20%)

- Scottish (6%)

- Irish (5.2%)

Citizenship (as of the 2011 census)

- Australia 79.5%

- New Zealand 13.3%

- Fiji 2.5%

- Philippines 1.1%

- United Kingdom 1%

- Other 1.8%

- Unspecified 0.8%

Religion

[edit]62% of the islanders are Christians. After the death of the first chaplain Rev G. H. Nobbs in 1884, a Methodist church was formed, followed in 1891 by a Seventh-day Adventist congregation led by one of Nobbs' sons. Some unhappiness with G. H. Nobbs, the more organised and formal ritual of the Church of England service arising from the influence of the Melanesian Mission, decline in spirituality, the influence of visiting American whalers, literature sent by Christians overseas impressed by the Pitcairn story, and the adoption of Seventh-day Adventism by the descendants of the mutineers still on Pitcairn, all contributed to these developments.

The Roman Catholic Church began an ongoing presence on Norfolk Island in 1957.[72] In the late 1990s, a group left the former Methodist (then Uniting Church) and formed a charismatic fellowship. In the 2021 Census, 22% of the ordinary residents identified as Anglican (compared to 34% in 2011), 13% as Uniting Church, 11% as Roman Catholic and 3% as Seventh-day Adventist. 9% were from other religions. 35.7% had no religion (up from 24% in 2011), and 14.7% did not indicate a religion.[67][73] Typical ordinary congregations in any church do not exceed 30 local residents as of 2010[update]. The three older denominations have good facilities. Ministers are usually short-term visitors.

There are two Anglican churches on Norfolk Island, being All Saints Kingston (established 1870)[74] and St Barnabas Chapel (establish 1880 as the Melanesian Mission)[75] which are both part of the Diocese of Sydney, Anglican Church of Australia.[76]

There is one Roman Catholic church on Norfolk Island, the Church of St Philip Howard within the Archdiocese of Sydney.[72]

Statistics in 2016 Census:[77]

- Protestant 46.8%

- Anglican 29.2%

- Uniting Church in Australia 9.8%

- Seventh-Day Adventist 2.7%

- Roman Catholic 12.6%

- Other 1.4%

- None 26.7%

- Unspecified 9.5%

Country of birth

[edit]All information below is from the 2016 Census.[71]

- Australia (39.7%)

- Norfolk Island (22.1%)

- New Zealand (17.6%)

- Fiji (2.7%)

- England (2.6%)

- Philippines (2.3%)

Language

[edit]Islanders speak both English and a creole language known as Norfuk, a blend of 18th-century English and Tahitian, based on Pitkern. The Norfuk language is decreasing in popularity as more tourists visit the island, and more young people leave for work and education. However, efforts are being made to keep it alive via dictionaries and the renaming of some tourist attractions to their Norfuk equivalents.

In 2004, an act of the Norfolk Island Assembly made Norfuk a co-official language of the island.[3][78][79] The act is long-titled: "An Act to recognise the Norfolk Island Language (Norf'k) as an official language of Norfolk Island". The "language known as 'Norf'k'" is described as the language "that is spoken by descendants of the first free settlers of Norfolk Island who were descendants of the settlers of Pitcairn Island". The act recognises and protects use of the language but does not require it; in official use, it must be accompanied by an accurate translation into English.[80][81] 32% of the total population reported speaking a language other than English in the 2011 census, and just under three-quarters of the ordinarily resident population could speak Norfuk.[67]

| Language | 2016 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| English | 45.5% | 52.4% |

| Norfuk | 40.9% | 30.5% |

| Fijian | 2.0% | 1.2% |

| Tagalog | 1.0% | 0.8% |

| Filipino | 0.8% | 0.5% |

| Mandarin Chinese | 0.7% | 0.5% |

Education

[edit]

The sole school on the island, Norfolk Island Central School, provides education from kindergarten through to Year 12. The school had a contractual arrangement referred to as a Memorandum of Understanding with the New South Wales Department of Education regarding the provision of education services at the school, the latest of which took effect in January 2015.[83] In 2015 enrolment at the Norfolk Island Central School was 282 students.[84] As of January, 2022, The Department of Education (Queensland) took over the running of the Norfolk Island Central School in line with the transition of state services from the New South Wales Government to the Queensland Government. The NSW curriculum will continue to be utilised until the end of the 2023 school year.[85]

Children on the island learn English as well as Norfuk, in efforts to revive the language.[86]

No public tertiary education infrastructure exists on the island. The Norfolk Island Central School works in partnership with registered training organisations (RTOs) and local employers to support students accessing Vocational Education and Training (VET) courses.[87]

Literacy is not recorded officially, but can be assumed to be roughly at a par with Australia's literacy rate[original research?], as islanders attend a school which uses a New South Wales curriculum, before traditionally moving to the mainland for further study.

Culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

While there was no "indigenous" culture on the island at the time of settlement, the Tahitian influence of the Pitcairn settlers has resulted in some aspects of Polynesian culture being adapted to that of Norfolk, including the hula dance. Local cuisine also shows influences from the same region.

Islanders traditionally spend a lot of time outdoors, with fishing and other aquatic pursuits being common pastimes, an aspect which has become more noticeable as the island becomes more accessible to tourism. Most island families have at least one member involved in primary production in some form.

Religious observance remains an important part of life for some islanders, particularly the older generations, but actual attendance is about 8% of the resident population plus some tourists. In the 2006 census, 19.9% had no religion[88] compared with 13.2% in 1996.[89] Businesses are closed on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons and Sundays.[31]

One of the island's long-term residents was the novelist Colleen McCullough, whose works include The Thorn Birds and the Masters of Rome series as well as Morgan's Run, set, in large part, on Norfolk Island. Ruth Park, notable author of The Harp in the South and many other works of fiction, also lived on the island for several years after the death of her husband, writer D'Arcy Niland. Actress/singer Helen Reddy also moved to the island in 2002, and maintained a house there.[90]

American novelist James A. Michener, who served in the United States Navy during World War II, set one of the chapters of his episodic novel Tales of the South Pacific on Norfolk Island.

The island is one of the few locations outside North America to celebrate the holiday of Thanksgiving.[91]

Norfolk Island has a number of museums and heritage organisations, including Norfolk Island Museum and Bounty Museum. The former has five sites within the Kingston and Arthur's Vale Historic Area, a World Heritage Site also linked to the Australian Convict Sites.[92][93][94]

Cuisine

[edit]The cuisine of Norfolk Island is very similar to that of the Pitcairn Islands, as Norfolk Islanders trace their origins to Pitcairn. The local cuisine is a blend of British cuisine and Tahitian cuisine.[95][96]

Recipes from Norfolk Island of Pitcairn origin include mudda (green banana dumplings) and kumara pilhi.[97][98] The island's cuisine also includes foods not found on Pitcairn, such as chopped salads and fruit pies.[99]

Government and politics

[edit]Norfolk Island was the only non-mainland Australian territory to have had self-governance. The Norfolk Island Act 1979, passed by the Parliament of Australia in 1979, is the Act under which the island was governed until the passing of the Norfolk Island Legislation Amendment Act 2015 (Cth).[100] The Australian government maintains authority on the island through an Administrator, currently George Plant.[101]

From 1979 to 2015, a Legislative Assembly was elected by popular vote for terms of not more than three years, although legislation passed by the Australian Parliament could extend its laws to the territory at will, including the power to override any laws made by the assembly. The Assembly consisted of nine seats, with electors casting nine equal votes, of which no more than two could be given to any individual candidate. It is a method of voting called a "weighted first past the post system". Four of the members of the Assembly formed the Executive Council, which devised policy and acted as an advisory body to the Administrator. The last Chief Minister of Norfolk Island was Lisle Snell. Other ministers included: Minister for Tourism, Industry and Development; Minister for Finance; Minister for Cultural Heritage and Community Services; and Minister for Environment.

All seats were held by independent candidates. Norfolk Island did not embrace party politics. In 2007, a branch of the Australian Labor Party was formed on Norfolk Island, with the aim of reforming the system of government.

Since 2018, residents of Norfolk Island have been required to enroll in the Division of Bean. As is the case for all Australian citizens, enrolment and voting for Norfolk Islanders is compulsory.[102]

Disagreements over the island's relationship with Australia were put in sharper relief by a 2006 review undertaken by the Australian government.[33] Under the more radical of two models proposed in the review, the island's legislative assembly would have been reduced to the status of a local council.[68] However, in December 2006, citing the "significant disruption" that changes to the governance would impose on the island's economy, the Australian government ended the review leaving the existing governance arrangements unaltered.[103]

In a move that apparently surprised many islanders, the Chief Minister of Norfolk Island, David Buffett, announced on 6 November 2010 that the island would voluntarily surrender its self-government status in return for a financial bailout from the federal government to cover significant debts.[104]

It was announced on 19 March 2015 that self-governance for the island would be revoked by the Commonwealth and replaced by a local council with the state of New South Wales providing services to the island. A reason given was that the island had never gained self-sufficiency and was being heavily subsidised by the Commonwealth, being given $12.5 million in 2015 alone. It meant that residents would have to start paying Australian income tax, but they would also be covered by Australian welfare schemes such as Centrelink and Medicare.[105]

The Norfolk Island Legislative Assembly decided to hold a referendum on the proposal. On 8 May 2015, voters were asked if Norfolk Islanders should freely determine their political status and their economic, social and cultural development, and to "be consulted at referendum or plebiscite on the future model of governance for Norfolk Island before such changes are acted upon by the Australian parliament".[106] 68% out of 912 voters voted in favour. The Norfolk Island Chief Minister, Lisle Snell, said that "the referendum results blow a hole in Canberra's assertion that the reforms introduced before the Australian Parliament that propose abolishing the Legislative Assembly and Norfolk Island Parliament were overwhelmingly supported by the people of Norfolk Island".[38]

The Norfolk Island Legislation Amendment Act 2015 passed the Australian Parliament on 14 May 2015 (assented on 26 May 2015), abolishing self-government on Norfolk Island and transferring Norfolk Island into a council as part of New South Wales law.[100]

Between 1 July 2016 and 1 January 2022, New South Wales provided state-based services. Since 1 January 2022, Queensland has provided state-based services directly for Norfolk Island.[107]

The island's official capital is Kingston; it is, however, more a centre of government than a sizeable settlement. The largest settlement is at Burnt Pine.

The most important local holiday is Bounty Day, celebrated on 8 June, in memory of the arrival of the Pitcairn Islanders in 1856.

Local ordinances and acts apply on the island, where most laws are based on the Australian legal system. Australian common law applies when not covered by either Australian or Norfolk Island law. Suffrage is universal at age eighteen.

As a territory of Australia, Norfolk Island does not have diplomatic representation abroad, or within the territory, and is also not a participant in any international organisations, other than sporting organisations.

The flag is three vertical bands of green, white, and green with a large green Norfolk Island pine tree centred in the slightly wider white band.

The Norfolk Island Regional Council was established in July 2016 to govern the territory at the local level in line with local governments in mainland Australia.

Constitutional status

[edit]From 1788 until 1844, Norfolk Island was a part of the Colony of New South Wales. In 1844, it was severed from New South Wales and annexed to the Colony of Van Diemen's Land.[25]: Recital 2 With the demise of the third settlement and in contemplation that the inhabitants of Pitcairn Island would move to Norfolk Island,[108][109] the Australian Waste Lands Act 1855 (Imp), gave the Queen in Council the power to "separate Norfolk Island from the Colony of Van Diemen's Land and to make such provision for the government of Norfolk Island as might seem expedient".[26] In 1856, the Queen in Council ordered that Norfolk Island be a distinct and separate settlement, appointing the Governor of New South Wales to also be the Governor of Norfolk Island with "full power and authority to make laws for the order, peace, and good government" of the island.[27] Under these arrangements Norfolk Island was effectively self-governing,[110] Although Norfolk Island was a colony acquired by settlement, it was never within the British Settlements Act.[14]: p 885 [111]

The constitutional status of Norfolk Island was revisited in 1894 when the British government appointed an inquiry into the administration of justice on the island.[110] By this time, there had been steps in Australia towards federation including the 1891 constitutional convention. There was a correspondence between the Governor of Norfolk Island, the British colonial office and the Governor of New Zealand as to how the island should be governed and by whom. Even within NSW, it was felt that "the laws and system of government in the Colony of New South Wales would not prove suitable to the Island Community".[110] In 1896, the Governor of New Zealand wrote "I am advised that, as far as my Ministers can ascertain, if any change is to take place in the government of Norfolk Island, the Islanders, while protesting against any change, would prefer to come under the control of New Zealand rather than that of New South Wales".[110]

The British government decided not to annex Norfolk Island to the Colony of NSW and instead that the affairs of Norfolk Island would be administered by the Governor of NSW in that capacity rather than having a separate office as Governor of Norfolk Island. The order-in-council contemplated the future annexation of Norfolk Island to the Colony of NSW or to any federal body of which NSW form part.[110][112] Norfolk Island was not a part of NSW and residents of Norfolk Island were not entitled to have their names placed on the NSW electoral roll.[113] Norfolk Island was accepted as a territory of Australia, separate from any state, by the Norfolk Island Act 1913 (Cth),[25] passed under the territories power,[114] and made effective in 1914.[30] Norfolk Island was given a limited form of self-government by the Norfolk Island Act 1979 (Cth).[32]

There have been four challenges to the constitutional validity of the Australian Government's authority to administer Norfolk Island:

- In 1939, Samuel Hadley argued that the only valid laws in Norfolk Island were those made under the 1856 Order in Council and that all subsequent laws were invalid; his case was rejected by the High Court.[115]

- In 1965, the Supreme Court of Norfolk Island rejected Henry Newbery's appeal against conviction for failing to apply to be enrolled to vote in Norfolk Island Council elections. He had argued that in 1857 Norfolk Island had a constitution and a legislature such that the Crown could not abolish the legislature nor place Norfolk Island under the authority of Australia. In the Supreme Court, Eggleston J considered the constitutional history of Norfolk Island and concluded that the Australian Waste Lands Act 1855 (Imp) authorised any form of government, representative or non-representative, and that this included placing Norfolk Island under the authority of Australia.[109]

- As a result of the Australian Government's decision in 1972 to prevent Norfolk Island from being used as a tax haven, Berwick Ltd claimed to be resident in Norfolk Island but was convicted of failing to lodge a tax return. One of the arguments for Berwick Ltd was that Norfolk Island, as an external territory, was not part of Australia in the constitutional sense. In 1976, the High Court unanimously rejected this argument, approving the Newbery decision and holding that Norfolk Island was a part of Australia.[116]

- In 2004 the Australian Government amended the Norfolk Island Act 1979 (Cth) to remove the right for non-Australian citizens to enrol and stand for election to the Legislative Assembly of Norfolk Island.[117] The validity of the amendments was challenged in the High Court, arguing that as an external territory Norfolk Island was not part of Australia in the constitutional sense and that disenfranchising residents of Norfolk Island who were not Australian citizens was inconsistent with self-government. In 2007, the High Court of Australia rejected these arguments, again approving the Newbery decision and holding that Norfolk Island was part of Australia and that self-government did not require residency rather than citizenship to determine the entitlement to vote.[118]

The Government of Australia thus holds that:

- Norfolk Island has been an integral part of the Commonwealth of Australia since 1914, when it was accepted as an Australian territory under section 122 of the Constitution. The Island has no international status independent of Australia.[119]

Much of the self-government under the 1979 legislation was repealed with effect from 2016.[100] The reforms included, to the chagrin of some of the locals of Norfolk Island, a repeal of the preambular sections of the Act which originally were 3–4 pages recognising the particular circumstances in the history of Norfolk Island.[120]

Consistent with the Australian position, the United Nations Decolonization Committee[121] does not include Norfolk Island on its list of non-self-governing territories.

This legal position is disputed by some residents on the island. Some islanders claim that Norfolk Island was actually granted independence at the time Queen Victoria granted permission to Pitcairn Islanders to re-settle on the island.[122]

Following reforms to the status of Norfolk Island, there were mass protests by the local population.[123] In 2015, it was reported that Norfolk Island was taking its argument for self-governance to the United Nations.[124][125] A campaign to preserve the island's autonomy was formed, named Norfolk's Choice.[126] A formal petition was lodged with the United Nations by Geoffrey Robertson on behalf of the local population on 25 April 2016.[127]

Various suggestions for retaining the island's self-government have been proposed. In 2006, a UK MP, Andrew Rosindell, raised the possibility of the island becoming a self-governing British Overseas Territory.[128] In 2013, the island's last chief minister, Lisle Snell, suggested independence, to be supported by income from fishing, offshore banking and foreign aid.[129]

The laws of Norfolk Island were in a transitional state, under the Norfolk Island Applied Laws Ordinance 2016 (Cth), from 2016 until 2018.[130] Laws of New South Wales as applying in Norfolk Island were suspended (with five major exceptions, which the 2016 Ordinance itself amended) until the end of June 2018. From 1 July 2018, all laws of New South Wales apply in Norfolk Island and, as "applied laws", are subject to amendment, repeal or suspension by federal ordinance.[131][132] The Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) has been amended for application to Norfolk Island.[133]

Immigration and citizenship

[edit]The island was subject to separate immigration controls from the remainder of Australia. Before 1 July 2016, immigration to Norfolk Island, even by other Australian citizens was heavily restricted.[134] In 2012, immigration controls were relaxed with the introduction of an Unrestricted Entry Permit[135] for all Australian and New Zealand citizens upon arrival and the option to apply for residency; the only criteria were to pass a police check and be able to pay into the local health scheme.[136] From 1 July 2016, the Australian migration system replaced the immigration arrangements previously maintained by the Norfolk Island Government.[137] Holders of Australian visas who travelled to Norfolk Island would have departed the Australian Migration Zone before 1 July 2016. Unless they held a multiple-entry visa, the visa would have ceased; in which case they would require another visa to re-enter mainland Australia.[135][138]

Australian citizens and residents from other parts of the nation now have an automatic right of residence on the island after meeting these criteria (Immigration (Amendment No. 2) Act 2012). Australian citizens can carry either a passport or a form of photo identification to travel to Norfolk Island. The Document of Identity, which is no longer issued, is also acceptable within its validity period. Citizens of all other nations must carry a passport to travel to Norfolk Island even if arriving from other parts of Australia.

Неустралийские граждане, которые являются постоянными жителями острова Норфолк, могут подать заявку на гражданство в Австралии после удовлетворения нормальных требований к месту жительства и имеют право на проживание в материковой Австралии в любое время с помощью подтверждающей визы (резиденции) (подкласс 808). [ 139 ] Дети, родившиеся на острове Норфолк, являются гражданами Австралии, как указано в австралийском гражданском законодательстве .

Здравоохранение

[ редактировать ]Больница острова Норфолк является единственным медицинским центром на острове. С 1 июля 2016 года медицинское лечение на острове Норфолк охватывалось Medicare и схемой фармацевтических льгот , как это в Австралии. Серьезное лечение покрывается Medicare или частным страховщиком здравоохранения. [ 140 ] Хотя больница может выполнить незначительную операцию, серьезные заболевания не разрешаются лечить на острове, а пациенты возвращаются в материковую Австралию. Air Charter Transport может стоить до 30 000 долларов , что покрывается правительством Австралии. Для серьезных чрезвычайных ситуаций медицинские эвакуации были предоставлены Королевскими австралийскими ВВС ; В настоящее время эта услуга предоставляется Австралийскими услугами поиска. У острова есть одна скорая помощь, укомплектованная одним нанятым офицером Святого Иоанна и группой добровольцев скорой помощи Святого Иоанна Австралии .

Отсутствие медицинских учреждений, доступных в большинстве отдаленных сообществ, оказывает большое влияние на здравоохранение островитян Норфолка. [ 141 ] Как согласуется с другими чрезвычайно удаленными регионами, многие пожилые жители переезжают в Новую Зеландию или Австралию, чтобы получить доступ к требуемой медицинской помощи.

Защита и правоохранительные органы

[ редактировать ]Защита является обязанностью австралийских сил обороны . На острове Норфолк нет активных военных инсталляций или защитников. Администратор может запрашивать помощь австралийских сил обороны, если это необходимо. В рамках «Operation Resolute» военно флот Королевского австралийского военно -морского флота австралийских развернута патрульные лодки Кейп и Армидейл -морской для осуществления гражданских операций по безопасности на морских морских пограничных и сил , острова Кокоса (Килинг) , остров Маккуори и остров лорда Хоу . [ 142 ] Частично для выполнения этой миссии, по состоянию на 2023 год, лодки ВМФ -класса Армидейл находятся в процессе замены более крупными Арафуры патрульными судами . [ 143 ]

В 2023 году австралийские и американские войска проводили совместные военные учения в окрестностях острова Норфолк, означающий потенциал острова в качестве постановки для поддержания миротворцев, ухода за бедствиями и других операций в южной части Тихого океана. [ 144 ] [ 145 ]

Гражданские правоохранительные органы и общественная полицейская деятельность предоставляются федеральной полицией Австралии . Обычное развертывание на острове - один сержант и два констебля . Они дополняются пятью местными специальными членами, которые имеют полицейские полномочия, но не являются сотрудниками AFP.

Суды

[ редактировать ]Суд мелких сессий на острове Норфолка является эквивалентом магистратского суда и имеет дело с незначительными уголовными, гражданскими или нормативными вопросами. Главный магистрат острова Норфолк обычно является нынешним главным магистратом Австралийской столичной территории . Три местных судьи мира имеют полномочия магистрата, чтобы иметь дело с незначительными вопросами.

Верховный суд острова Норфолк имеет дело с более серьезными уголовными преступлениями, более сложными гражданскими вопросами, управлением умершими владениями и федеральными законами, поскольку они применяются к территории. Судьи Верховного суда острова Норфолк, как правило, назначаются из числа судей федерального суда Австралии и могут расположить на материке Австралии или созвать окружной суд . Апелляции в федеральном суде Австралии.

Как заявил Закон о юридической профессии 1993 года, [ 146 ] «Резидент -практикующий должен иметь сертификат практики на острове Норфолк». По состоянию на 2014 год [update], только один адвокат сохранил полную юридическую практику на острове Норфолк. [ 147 ]

Перепись

[ редактировать ]До 2016 года остров Норфолк принимал свои собственные переписи, отдельные от тех, которые были взяты Австралийским бюро статистики на оставшуюся часть Австралии. [ 148 ]

Почтовая служба

[ редактировать ]До 2016 года почтовая служба острова Норфолк отвечала за получение почты и доставку на острове и выпустила свои собственные почтовые марки. В связи с слиянием острова Норфолк в качестве регионального совета, почтовая служба острова Норфолк прекратилась, и все почтовые расходы в настоящее время обрабатываются Австралией Post . [ 149 ] Австралия Пост отправляет и получает почту с острова Норфолк с почтовым индексом 2899.

Экономика и инфраструктура

[ редактировать ]Туризм, основная экономическая деятельность, постоянно увеличивается с годами. Поскольку остров Норфолк запрещает импорт свежих фруктов и овощей, большинство продуктов выращиваются на месте. Говядина производится на месте и импортируется. У острова есть одна винодельня, две вина дымоходов . [ 150 ]

Правительство Австралии контролирует исключительную экономическую зону (ИЭЗ) и доходы от ИТ, продлевая 200 морских миль (370 км) вокруг острова Норфолк, примерно 428 000 км 2 (165 000 кв. Миль), а территориальное море претендует на 3 морских миль (5,6 км) от острова. На острове есть твердое убеждение в том, что некоторые из доходов, полученных из ИЭЗ Норфолка, должны быть доступны для предоставления таких услуг, как здоровье и инфраструктура на острове, за которые отвечает остров, аналогично тому, как Северная территория способна получить доступ к Доход от их минеральных ресурсов. [ 151 ] Эксклюзивная экономическая зона предоставляет островитянам рыбу, его единственный крупный природный ресурс. Остров Норфолк не имеет прямого контроля над какими -либо морскими районами, но имеет соглашение с Содружеством через Австралийское управление рыбным хозяйством (AFMA), чтобы ловить рыбу «развлекательно» в небольшом участке ИЭЗ, известного на местном уровне как «коробку». Хотя есть предположения о том, что зона может включать в себя нефтегазовые отложения, это не доказано. [ 68 ] Там нет крупных пахотных земель или постоянных сельхозугодий, хотя около 25 процентов острова являются постоянным пастбищами. Там нет орошаемых земель. Остров использует австралийский доллар в качестве своей валюты.

В 2015 году компания на острове Норфолк получила лицензию на экспорт лекарственного каннабиса. [ 152 ] Индустрия лекарственной каннабиса рассматривалась некоторыми как средство оживления экономики острова Норфолк. Содружество вмешалось, чтобы отменить решение, когда администратор острова, бывший депутат Либерала Гэри Хардгрейв, отменил местную лицензию, чтобы выращивать урожай. [ 153 ] (Законодательство, позволяющее выращивать каннабис в Австралии в медицинских или научных целях, принял федеральный парламент в феврале 2016 года. [ 154 ] Правительство Виктории будет проведено небольшим, строго контролируемым испытанием по выращиванию каннабиса в викторианском исследовательском центре. [ 155 ] )

Налоги

[ редактировать ]Ранее жители острова Норфолк не платили федеральные налоги в Австралии, [ 156 ] который создал налоговую гавань как для местных жителей, так и для посетителей. Не было подоходного налога , поэтому законодательное собрание острова собрала деньги с помощью импортной пошлина , сборов топлива, Medicare, налога на товары и услуги 12%и местные/международные телефонные звонки. [ 68 ] [ 156 ] Главный министр острова Норфолк Дэвид Баффетт объявил 6 ноября 2010 года, что остров добровольно сдаст свой безналоговый статус в обмен на финансовую спасение от федерального правительства, чтобы покрыть значительные долги. Внедрение налогообложения подоходного налогообложения вступило в силу 1 июля 2016 года. До этих реформ жители острова Норфолк не имели права на социальные услуги. [ 157 ] Реформы распространяются на частных лиц, компаний и попечителей. [ 158 ] [ 159 ]

Коммуникации

[ редактировать ]По состоянию на 2004 год [update], 2532 телефонных линий телефона были использованы, смесь аналоговых ( 2500 ) и цифровых ( 32 ) цепей. [ 6 ] Службы спутниковой связи запланированы. [ 160 ] У острова есть две местные радиостанции ( Radio Norfolk ), государственная станция, транслирующая на частотах AM и FM, и независимая станция 87.6 FM, принадлежащая фонду музея Гоунти. [ 161 ] Остров Норфолк не имеет собственной специальной радиостанции ABC , но остров покрыт ABC Western Plains , которая транслируется на 95,9 FM из своих студий в Даббо в материковой Австралии. Существует также одна телевизионная станция, Norfolk TV, в которой участвуют местные программы, а также передатчики для австралийских каналов ABC , SBS , девять (через Imparja Television ) и семь . [ 162 ] интернет Код -кода высшего уровня ( CCTLD ) является .NF . [ 163 ] Небольшая мобильная сеть GSM (2G) работает на острове на трех башнях, однако в этой сети нет никакой передачи данных. В ноябре 2018 года была установлена сеть из восьми башни 4G/LTE 1800 МГц, что значительно улучшило услуги данных на острове. [ 164 ] [ 165 ]

Транспорт

[ редактировать ]

На острове нет железных дорог, водных путей, портов или гаваней. [ 166 ] Загрузка причалов расположена в Кингстоне и Каскаде, но корабли не могут приблизиться ни к одному из них. Когда приходит судно снабжения, его опорожняют китовые лодки, буксируемые запусками, пять тонн за раз. Мобильный кран поднимает груз, используя сетки, ремни и поднимает груз на пирс. Какой пристани используется, зависит от преобладающей погоды дня; Причал на подветренной стороне острова часто используется. Если ветер значительно изменяется во время разгрузки/загрузки, корабль будет перемещаться на другую сторону. Посетители часто собираются, чтобы наблюдать за деятельностью, когда прибывает корабль снабжения. [ Цитация необходима ] Services Norfolk Forwarding является основной службой переправы в грузовой переход для обработки на острове Норфолк как SEA, так и Air -Freight. В 2017 году Норфолк Службы стимулирования отправили большую часть груза для проекта Cascade Pier в течение 18 месяцев. [ Цитация необходима ]

Остров проходит 80 километров (50 миль) дорог, из которых 53 км (33 миль) промотаны и 27 км (17 миль) грунтовые. Как и в остальной части Австралии, вождение находится на левой стороне дороги. Уникально, местное право дает домашний скот право проезда. [ 68 ] Пределы скорости ниже, чем у большинства австралийских дорог материка; Общее ограничение скорости составляет 50 км/ч (31 миль в час), снижая до 40 км/ч (25 миль в час) в городе и 30 км/ч (19 миль в час) возле школ. Водители на островной волне к другим проезжающим транспортным средствам, эта традиция прозвила «Норфолк -волна». [ 167 ]

Есть один аэропорт, аэропорт острова Норфолк . [ 6 ] Qantas управляет прямыми рейсами в Сидней и Брисбен , а Air Chathams летит в Окленд. Местная авиакомпания, Норфолк -Айленд Airlines , пробежала рейсы в Окленд и Брисбен до 2018 года. [ 168 ] В середине 2018 года Air Chathams объявила, что стремится восстановить рейсы между Оклендом и островом Норфолк. [ 169 ] Это началось еженедельное обслуживание между Оклендом и островом Норфолк 6 сентября 2019 года с использованием Convair 580 . [ Цитация необходима ] С момента вновь открытия пузырька транс-тасмана в 2021 году, [ 170 ] Служба Air Chathams Auckland работает по четвергам, используя 36-местный самолет Saab 340 .

Электричество

[ редактировать ]Электричество обеспечивается дизельными генераторами, управляемыми государственной организацией Норфолк -Айленда, государственной организацией. Некоторое электричество также обеспечивается частными солнечными панелями на крыше. [ 171 ]

Спорт

[ редактировать ]Остров Норфолка участвует на Играх Содружества и выиграл две бронзовые медали, обе в газонных чашах . [ 172 ] Территория также участвует в тихоокеанских играх и мини -играх Тихого океана .

Остров поддерживает Национальную лигу регби , крикет и нетбол . Это член мировой легкой атлетики . [ 173 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Библиография острова Норфолк

- Список островов Австралии

- Список вулканов в Австралии

- Схема острова Норфолк

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Баффет, Алиса, Энциклопдия на острове Норфолк , 1999 г.

- ^ «Законодательное собрание острова Норфолк» . Архивировано из оригинала 18 декабря 2014 года . Получено 18 октября 2014 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Закон о языке Норфолка (Норф'К) 2004» . Архивировано из оригинала 25 июля 2008 года . Получено 6 февраля 2018 года .

- ^ 2016 г. Перепись Quickstats Archived 2 октября 2017 года на The Wayback Machine - Остров Норфолк - происхождение, верхние ответы

- ^ «2021 Остров Норфолк, перепись всех людей Quickstats | Австралийское бюро статистики» . Архивировано с оригинала 1 ноября 2022 года . Получено 4 марта 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Остров Норфолк» . Мировой факт . Центральное разведывательное агентство. 16 октября 2012 года. Архивировано с оригинала 18 января 2021 года . Получено 27 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Австралийское бюро статистики (28 июня 2022 года). «Остров Норфолк (пригороды и населенные пункты)» . 2021 Перепись Quickstats . Получено 7 июля 2022 года .

- ^ KPMG (2019). Мониторинг экономики острова Норфолк (PDF) . Норфолкские острова: Департамент инфраструктуры, транспорта, городов и регионального развития. п. 4. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 9 августа 2021 года . Получено 9 августа 2021 года .

- ^ Уэллс, Джон С. (2008). Лонгман Словарь произношения (3 -е изд.). Лонгман. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0 .

- ^ "NI Прибытие карты" (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 13 ноября 2011 года . Получено 28 марта 2013 года .

- ^ «Закон о острове Норфолк 1979 года» . Федеральный реестр законодательства . 23 мая 2018 года. Архивировано с оригинала 16 июля 2019 года . Получено 17 июля 2019 года . График 1.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «История и культура на острове Норфолк» . Архивировано из оригинала 12 июля 2012 года . Получено 15 сентября 2016 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Остров Норфолка: короткая история» . Архивировано с оригинала 7 марта 2016 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Робертс-Врэй, Кеннет (1966). Содружество и колониальное право . Лондон: Стивенс.

- ^ Андерсон, Атолл ; Уайт, Питер (2001). «Доисторическое поселение на острове Норфолк и его океанического контекста» (PDF) . Записи австралийского музея . 27 (Дополнение 27): 135–141. doi : 10.3853/j.0812-7387.27.2001.1348 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 4 марта 2016 года . Получено 28 апреля 2015 года .

- ^ Channers на Информации о острове Норфолк Архивировал 3 ноября 2021 года на машине Wayback . Channersonsonorfolk.com (15 марта 2013 г.). Получено 16 июля 2013 года.

- ^ Меморандум Гренвилля по торговле Канадой, 4 ноября 1789 года, Национальный архив, Кью, Ко, 42/66, ff.403-7; Цитируется в Алан Фрост, осужденных и империи, военно -морской вопрос, Мельбурн, Оксфорд UP, 1980, с. 137, 218.

- ^ Lea-Scarlett, EJ (1967). «Уотсон, Роберт (1756–1819)» . Австралийский словарь биографии . Тол. 2. Канберра: Национальный центр биографии, Австралийский национальный университет . ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7 Полем ISSN 1833-7538 . OCLC 70677943 . Получено 7 июня 2018 года .

- ^ Grose to Hunter, 8 декабря 1794 года, Исторические записи о Новом Южном Уэльсе, Сидней, 1893, том 2, с. 275

- ^ Причин, Т. «Худшие типы субчерожных существ»: миф и реальность осужденных Уголовных поселений Норфолк-острова, архивируемых 20 апреля 2012 года на машине Wayback , 1825–1855, Острова Истории , Сидней, 2011, с. 8–31.

- ^ Cyriax, Oliver (1993). Преступление: энциклопедия . Андре Дойч. 9780233988214, с. 284–285

- ^ «Роковое путешествие» . Архивировано с оригинала 17 октября 2016 года . Получено 3 декабря 2018 года .

- ^ «Откройте для себя остров Норфолк» . Архивировано из оригинала 14 мая 2016 года.

- ^ Langdon, Robert (ed.) (1984) , куда пошли китобы: указатель для тихоокеанских портов и островов, посещаемых американскими китобами (и некоторыми другими кораблями) в 19 -м веке , Канберре, Бюро рукописей Тихого океана, с. 194–7. Полем ISBN 086784471X

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Закон о острове Норфолк 1913 (Cth).

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Австралийский закон о отходах 1855 года (PDF) , архивированный (PDF) из оригинала 12 июня 2018 года , извлечен 9 июня 2018 года (IMP).

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Прокламация - остров Норфолк» . Государственная газетта штата Новый Южный Уэльс . № 166. 1 ноября 1856 г. с. 2815. Архивировано из оригинала 15 февраля 2023 года . Получено 8 июня 2018 года - через Национальную библиотеку Австралии.

- ^ «Прокламация» . Государственная газетта штата Новый Южный Уэльс . № 205. 24 декабря 1913 г. с. 7659. Архивировано с оригинала 15 февраля 2023 года . Получено 9 июня 2018 года - через Национальную библиотеку Австралии.

- ^ «Закон об администрировании 1913» . Государственная газетта штата Новый Южный Уэльс . № 205. 24 декабря 1913 г. с. 7663. Архивировано с оригинала 12 июня 2018 года . Получено 9 июня 2018 года - через Национальную библиотеку Австралии.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Прокламация: Закон о острове Норфолк 1913 года» . Австралийская правительственная газета . № 35. 17 июня 1914 г. с. 1043. Архивировано с оригинала 12 июня 2018 года . Получено 8 июня 2018 года . Полем

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «У острова Норфолк есть еще кое -что» . Архивировано с оригинала 22 апреля 2016 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Закон о острове Норфолк 1979 года (CTH).

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Управление и администрация» . Генеральный прокурор. 28 февраля 2008 года. Архивировано с оригинала 20 сентября 2010 года.

- ^ «Остров Норфолк собирается претерпевать драматические изменения, чтобы обеспечить финансовую жизнь» . ABC News 7.30 Отчет. 26 января 2011 года. Архивировано с оригинала 21 февраля 2011 года.

- ^ «Боевой борьбы заставляет семьи с острова» . Сиднейский утренний геральд . 5 мая 2013 года. Архивировано из оригинала 7 мая 2013 года.

- ^ «Самоуправление на острове Норфолк будет отменено и заменено местным советом» . Хранитель . 19 марта 2015 года. Архивировано с оригинала 11 февраля 2017 года.

- ^ « Мы не австралиец»: Норфолк -островитяне приспосабливается к шоку от поглощения по материке » . Хранитель . 21 мая 2015 года. Архивировано с оригинала 7 августа 2017 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Голосование« да »на референдуме по управлению островами Норфолка» . Радио Новая Зеландия . 8 мая 2015 года. Архивировано из оригинала 18 мая 2015 года.

- ^ Хардгрейв, Гэри (3 сентября 2015 г.). «Норфолк -острова Стандартное время изменения времени 4 октября 2015 года» (пресс -релиз). Администратор острова Норфолк . Архивировано с оригинала 3 октября 2015 года . Получено 4 октября 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Реформа Норфолка острова» . Регионал.gov.au. Архивировано с оригинала 29 августа 2016 года . Получено 17 июля 2016 года .

- ^ «Остров Норфолка избирает свой первый совет» . Mister.infrastructure.gov.au. 3 июня 2016 года. Архивировано с оригинала 15 июля 2016 года . Получено 17 июля 2016 года .

- ^ Департамент инфраструктуры и регионального развития - Фактический лист: внутренние поездки между островом Норфолк и материковой Австралии, веб -сайт. Получено 12 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Комната Талли, Акт Канберры» . Австралийская избирательная комиссия. Архивировано из оригинала 20 мая 2019 года . Получено 15 мая 2019 года .

- ^ Уайт, Салли (6 апреля 2018 г.). «Новые федеральные избиратели ACT раскрыли» . Сиднейский утренний геральд . Архивировано из оригинала 15 мая 2019 года . Получено 15 мая 2019 года .

- ^ «Норфолк умоляет Канберру отложить поглощение Нового Южного Уэльса» . Radionz.co.nz. 18 июня 2016 года. Архивировано с оригинала 23 июля 2016 года . Получено 17 июля 2016 года .

- ^ «Норфолк -островитяне ищут незаправления» . Rnz . Radionz.co.nz. 28 апреля 2016 года. Архивировано с оригинала 23 июля 2016 года . Получено 17 июля 2016 года .

- ^ Рой, Элеонора Эйндж (23 августа 2017 г.). «Остров Норфолка должен стать частью Новой Зеландии, говорит бывший главный министр» . Guardian Australia . Архивировано с оригинала 24 сентября 2017 года . Получено 24 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ Джулия Холлингсворт (30 октября 2019 г.). «Остров Норфолка: почему жители хотят бросить Австралию на Новую Зеландию» . CNN . Архивировано из оригинала 3 апреля 2021 года . Получено 13 марта 2021 года .

- ^ «Опрос показывает, что более 96% людей на острове Норфолк выступают против нынешнего режима управления, наложенного Австралией. - Народ острова Норфолк для демократии» . 24 октября 2019 года. Архивировано с оригинала 24 октября 2019 года . Получено 13 марта 2021 года .

- ^ Джонс, JG; McDougall (1973). «Геологическая история Норфолк и Филипп -островов, юго -западного Тихого океана». Журнал Геологического общества Австралии . 20 (3): 239–257. Bibcode : 1973aujes..20..239j . doi : 10.1080/14400957308527916 .

- ^ Геологическое происхождение , Норфолкский остров туризм. Получено 13 апреля 2007 года. Архивировано 7 сентября 2008 года на машине Wayback

- ^ «Норфолк -остров аээро климатическая статистика» . Бюро метеорологии . Получено 22 июня 2024 года .

- ^ «Норфолк -остров аээро климатическая статистика» . Бюро метеорологии . Получено 22 июня 2024 года .

- ^ «Норфолк -остров аээро климатическая статистика» . Бюро метеорологии . Получено 22 июня 2024 года .

- ^ «Норфолк -остров аээро климатическая статистика» . Бюро метеорологии . Получено 22 июня 2024 года .

- ^ «Временная биогеографическая регионализация для регионов и кодов Австралии (IBRA7)» . Департамент устойчивости, окружающей среды, воды, населения и сообществ . Содружество Австралии. 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 31 января 2013 года . Получено 13 января 2013 года .

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; и др. (2017). «Основанный на экорегионе подход к защите половины наземного царства» . Биоссака . 67 (6): 534–545. doi : 10.1093/biosci/bix014 . ISSN 0006-3568 . PMC 5451287 . PMID 28608869 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Мировой фонд дикой природы. «Субтропические леса острова Норфолк» . eoearth.org . Архивировано из оригинала 17 января 2008 года.

- ^ Neuweger, D (2001). «Земля улитки с мест острова Норфолк» . Записи австралийского музея . Дополнение 27: 115–122. doi : 10.3853/j.0812-7387.27.2001.1346 .

- ^ Morgan-Richards, M (2020). «Записки с небольших островов - в Тихом океане» . Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2020 года . Получено 28 апреля 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Зона данных BirdLife: Норфолк -остров Архивировал 18 февраля 2015 года в The Wayback Machine , Birdlife International. (2015). Получено 17 февраля 2015 года.

- ^ Голдберг, Джулия; Тревик, Стивен А.; Powlesland, Ralph G. (2011). «Структура популяции и биогеография голубей Hemiphaga (Aves: Columbidae) на островах в Новой Зеландии». Журнал биогеографии . 38 (2): 285–298. Bibcode : 2011jbiog..38..285g . doi : 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02414.x . ISSN 1365-2699 . S2CID 55640412 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Норфолк -остров архивировал 24 октября 2012 года на машине Wayback в Австралийском национальном ботаническом саду. Environment Australia: Canberra, 2000.

- ^ Браби, Майкл Ф. (2008). Полное полевое руководство по бабочкам Австралии . CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09027-9 .

- ^ Николс, Дафни (2006). Лорд Хоу остров поднимается. Французский лес, Новый Южный Уэльс: Башня книги. ISBN 0-646-45419-6 . Получено 20 ноября 2015 года

- ^ Берзин А.; Ivashchenko vy; Clapham JP; Brownell LR Jr. (2008). «Правда о советском китобойном китонии: мемуары» . DigitalCommons@Университет штата Небраска - Линкольн . Архивировано с оригинала 5 марта 2016 года . Получено 20 ноября 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Норфолк -островной перепись населения и жилья: описание переписи, анализ и основные таблицы» (PDF) . 9 августа 2011 года. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 24 марта 2012 года . Получено 3 марта 2012 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон «Битва за остров Норфолк» . Би -би -си . 18 мая 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 24 ноября 2006 года.

- ^ «Телефонная книга Норфолка» . Архивировано из оригинала 19 декабря 2021 года . Получено 21 марта 2022 года .

- ^ «ЮНК - демографическая и социальная статистика» . enstats.un.org . Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2023 года . Получено 10 мая 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Перепись 2016 года Quickstats: Норфолк -остров» . Архивировано из оригинала 7 мая 2019 года . Получено 2 мая 2021 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Католическая церковь Святого Филиппа Говарда, остров Норфолк» . Собор Святой Марии Сидней . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2024 года . Получено 24 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «2021 Остров Норфолк, перепись всех людей быстро» . Австралийское бюро статистики . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2024 года . Получено 24 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «Церковь всех святых» . www.norfolkisland.com.au . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2024 года . Получено 24 марта 2024 года .

- ^ "Святой Барнабас" . Норфолк -остров Англии . 26 ноября 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 24 марта 2024 года . Получено 24 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «Приход острова Норфолк» . Англиканская церковь Австралийского каталога . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2024 года . Получено 24 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «Австралия-океания :: Норфолк остров» . ЦРУ мировой факт. 6 октября 2021 года. Архивировано с оригинала 18 января 2021 года . Получено 24 января 2021 года .

- ^ Пост Доминиона , 21 апреля 2005 г. (стр. B3)