Арабские граждане Израиля

просьба об изменении названия этой статьи на и арабских граждан Израиля Обсуждается палестинских . Пожалуйста, не перемещайте эту статью до закрытия обсуждения. |

араб 48 المواطنون الفلسطينيين في إسرائيلПалестинские граждане Израиля עֲרָבִים אֶזרָחֵי יִשְׂרָאֵלАрабские граждане Израиля | |

|---|---|

Карта арабских населенных пунктов Израиля , 2015 г. | |

| Общая численность населения | |

| Зеленая линия , 2023 год: 2,065,000 (21%) [1] [2] Восточный Иерусалим и Голанские высоты , 2012 год: 278,000 (~3%) | |

| Регионы со значительной численностью населения | |

| Языки | |

| арабский [а] и иврит | |

| Религия | |

| Ислам (84%) [б] Христианство (8%) [с] Друзы (8%) [3] | |

| Родственные этнические группы | |

| Ближневосточные народы |

Арабские граждане Израиля ( израильские арабы или израильские арабы ) являются крупнейшим этническим меньшинством страны. [4] [5] их в просторечии называют На арабском языке либо 48-арабами ( عرب ٤٨ 'Arab Thamaniya wa-Arba'in ), либо 48-палестинцами ( فلسطينيو ٤٨ Filasṭīniyyū Thamaniya wa-Arba'īn ), [6] обозначая тот факт, что они остались на израильской территории с тех пор, как Зеленая линия была согласована между Израилем и арабскими странами в рамках Соглашения о перемирии 1949 года . [7] По данным нескольких источников, большинство арабов в Израиле теперь предпочитают, чтобы их идентифицировали как палестинских граждан Израиля . [8] [9] [10] Международные средства массовой информации часто используют термин «арабо-израильский» или «израильско-арабский», чтобы отличить арабских граждан Израиля от палестинских арабов, проживающих на оккупированных Израилем территориях . [11] Они происходят от тех арабов, которые принадлежали к Палестине под британским мандатом на основании Указа о палестинском гражданстве 1925 года . Говорящие как на арабском, так и на иврите , они идентифицируют себя в широком диапазоне интерсекциональных гражданских (израильских или «в Израиле»), национальных (арабских, палестинских, израильских) и религиозных ( мусульманских , христианских , друзских ) идентичностей. [12]

После изгнания и бегства палестинцев в 1948 году арабы, оставшиеся в Израиле, подпадали под действие закона о израильском гражданстве , тогда как те, кто находился на аннексированном Иорданией Западном Берегу, подпадали под действие закона о гражданстве Иордании . Те, кто находился в оккупированном Египтом секторе Газа, не подпадали под действие закона о египетском гражданстве и вместо этого были связаны Всепалестинским протекторатом , который был создан Египтом во время арабо-израильской войны 1948 года . Этот трехсторонний раскол в отношении гражданства палестинских арабов сохранялся до арабо-израильской войны 1967 года , которая привела к продолжающейся оккупации Израилем палестинских территорий . В 1988 году Иордания отказалась от притязаний на суверенитет 1950 года, которые она предъявила Западному Берегу , фактически сделав более 750 000 палестинских жителей территории лицами без гражданства. Посредством Иерусалимского закона 1980 года и Закона о Голанских высотах 1981 года Израиль предоставил право на получение гражданства палестинцам в Восточном Иерусалиме , а также сирийцам и другим арабам на Голанских высотах ; этот статус не был распространен на неиерусалимских арабов на Западном Берегу, то есть на тех, кто живет на территории, которой управляет Израиль. Область Иудеи и Самарии . В результате Декларации независимости Палестины в 1988 году арабские лица без гражданства, проживающие на палестинских территориях, в конечном итоге стали признанными палестинскими гражданами и с 1995 года получили паспорта Палестинской автономии .

Традиционным языком большинства арабских граждан Израиля является левантийский арабский язык , включая ливанский арабский язык на севере Израиля, палестинский арабский язык в центральном Израиле и бедуинский арабский язык в Негеве . Поскольку современные арабские диалекты израильских арабов вобрали в себя множество заимствованных слов и фраз из иврита, их иногда называют израильско-арабским диалектом . [13] Совсем недавно появились сообщения о том, что израильские арабы также все больше ощущают чувство израильской идентичности и демонстрируют стремление к интеграции и общему будущему с основным израильским обществом. [14] [15] По религиозной принадлежности большинство израильтян арабского происхождения являются мусульманами, но, среди прочего, существуют значительные христианские и друзские меньшинства. [16]

По данным Центрального статистического бюро Израиля , в 2023 году арабское население Израиля составляло 2,1 миллиона человек, что составляло 21% от общей численности населения Израиля. [1] Большинство этих арабских граждан идентифицируют себя как арабы или палестинцы по национальности и как израильтяне по гражданству. [17] [18] [19] В основном они живут в городах и поселках с арабским большинством , некоторые из которых являются одними из самых бедных в стране, и обычно посещают школы, которые в некоторой степени отделены от тех, которые посещают израильские евреи . [20] Арабские политические партии традиционно не вступали в правящие коалиции до 2021 года, когда Объединенный арабский список стал первым, кто сделал это. [21] В 2017 году опрос, опубликованный газетой «Джерузалем Пост», показал, что 60% израильтян арабского происхождения относятся к стране положительно, при этом эта цифра представлена 49% арабов-мусульман, 61% арабов-христиан и 94% арабов-друзов. [22] Друзы и бедуины в Негеве и Галилее исторически выражают самую сильную нееврейскую близость к Израилю и с большей вероятностью идентифицируют себя как израильтяне, чем другие арабские граждане. [23] [24] [25] [26]

Согласно израильскому законодательству , арабские жители Восточного Иерусалима и Голанских высот имеют право стать гражданами Израиля, иметь право на муниципальные услуги и право голоса на муниципальном уровне. [27] В то же время, получение гражданства является недостаточным: только 5% палестинцев в Восточном Иерусалиме были гражданами Израиля в 2022 году. Первоначально отсутствие заявлений на получение гражданства было во многом связано с неодобрением палестинским обществом натурализации как соучастия в израильской оккупации . После Второй интифады это табу начало исчезать, но израильское правительство изменило структуру процесса, чтобы усложнить его, одобрив только 34% новых палестинских заявлений и предоставив множество причин для отклонения. Палестинцы-неграждане не могут голосовать на выборах в законодательные органы Израиля и должны получить пропуск для выезда за границу; многие рабочие места для них закрыты, и Израиль может лишить их статуса проживания, в результате чего они могут потерять медицинскую страховку и право на въезд в Иерусалим . [28]

Терминология и идентичность

Выбор терминов для обозначения арабских граждан Израиля является весьма политизированным вопросом, и существует широкий спектр ярлыков, которые члены этого сообщества используют для самоидентификации. [29] [30] Вообще говоря, сторонники Израиля, как правило, используют слова «израильский араб» или «араб-израильский» для обозначения этого населения, не упоминая Палестину, в то время как критики Израиля (или сторонники палестинцев) склонны использовать «палестинец» или «палестинский араб», не упоминая Израиль. [31] По данным The New York Times , по состоянию на 2012 год большинство предпочитали идентифицировать себя как палестинские граждане Израиля, а не как израильские арабы. [32] The New York Times использует как «палестинских израильтян», [33] и «израильские арабы» относятся к одному и тому же населению.

Отношения арабских граждан с Государством Израиль часто чреваты напряженностью и могут рассматриваться в контексте отношений между меньшинствами и государственными властями в других частях мира. [34] Арабские граждане считают себя коренным народом . [35] Напряженность между их национальной идентичностью палестинских арабов и их идентичностью как граждан Израиля была описана одним арабским общественным деятелем следующим образом: «Мое государство находится в состоянии войны с моей нацией». [36]

Список демонимов

Арабские/палестинские граждане Израиля могут называть себя самыми разными терминами. Каждое из этих названий, хотя и относится к одной и той же группе людей, означает разный баланс в том, что часто представляет собой многослойную идентичность, определяющую различные уровни приоритета или акцента на различных измерениях, которые могут быть историко-географическими (« Палестина (регион) »). , «национальные» или этнорелигиозные (палестинцы, арабы, израильтяне, друзы, черкесы), лингвистические (арабоязычные), гражданские (ощущение «израильтянина» или нет) и т.д.: [37]

- Палестинские граждане Израиля [37] [38] это термин, которым большинство арабских граждан Израиля предпочитают называть себя, [9] [8] и что некоторые СМИ ( BBC , New York Times , Washington Post , NBC News ) [39] и другие организации используют для обозначения израильских арабов либо последовательно, либо попеременно используя другие термины для обозначения израильских арабов.

- Палестинские арабы [38]

- Палестинские арабы в Израиле [17] [40] [41]

- Палестинские израильтяне [42]

- Палестинцы в Израиле [38]

- Израильские арабы [42] [38] [37]

- Израильские палестинские арабы [17] [40] [41]

- Израильские палестинцы [37]

- Арабские граждане Израиля [42]

- Арабские израильтяне [42]

- 48-е, [42] [37] '48 арабы [38]

Два наименования, среди других, перечисленных выше, не применяются к арабскому населению Восточного Иерусалима или к друзам на Голанских высотах , поскольку эти территории были оккупированы Израилем в 1967 году:

- Арабы внутри зеленой линии [17] [40] [41]

- арабы внутри (арабский: عرب الداخل , латинизированный: «Араб ад-Дахил »). [17] [40] [41]

Предпочтения демонимов

По данным The New York Times , по состоянию на 2012 год большинство израильских арабов предпочитали идентифицировать себя как палестинские граждане Израиля, а не как израильские арабы. [8] Совет по международным отношениям также заявляет, что большинство членов израильского арабского сообщества предпочитают этот термин. [9] В 2021 году газета Washington Post заявила, что «опросы показали», что израильские арабы предпочитают термин «палестинский гражданин Израиля» и что «однако для людей, которые часто чувствуют себя зажатыми между двумя мирами, контуры того, что значит быть палестинским гражданином Израиля», Израиль остается в стадии разработки». [10]

Однако эти результаты противоречат опросу Тель-Авивского университета 2017 года , который показал, что большинство израильтян идентифицируют себя либо как арабо-израильские, либо просто израильтяне. [43]

Похожие термины, которые могут использовать израильские арабы, средства массовой информации и другие организации, — это «Палестинские арабы в Израиле» и «израильские палестинские арабы» . Amnesty сообщает, что «арабские граждане Израиля» — это «объемный термин, используемый Израилем, который описывает ряд различных, в основном арабоязычных групп, включая арабов-мусульман», арабов-христиан, друзов и черкесов. По состоянию на конец 2019 года, если принять во внимание количество арабов-мусульман и арабов-христиан вместе взятых, население палестинских граждан Израиля составило около 1,8 миллиона человек. [44]

Есть как минимум два термина, которые конкретно исключают Восточного Иерусалима арабское население , а также друзов и других арабов на Голанских высотах : арабы внутри «зеленой линии» и арабы внутри (арабский: عرب الداخل , латинизированный: «Араб ад-Дахил »). . [17] [40] [41] Эти условия поясняют, что

- Хотя Израиль аннексировал Восточный Иерусалим в 1967 году, подавляющее большинство его арабского населения не имеет израильского гражданства.

- Хотя Израиль аннексировал Голанские высоты , изначально эта территория была частью Сирии , а не Подмандатной Палестины .

Идентификация как палестинец

Хотя они официально известны израильскому правительству только как « израильские арабы » или «израильтяне-арабы», развитие палестинского национализма и идентичности в 20-м и 21-м веках сопровождалось заметной эволюцией самоидентификации, отражающей растущую идентификацию с палестинцами. идентичность наряду с арабскими и израильскими означающими. [45] [17] [19] Многие палестинские граждане Израиля имеют семейные связи с палестинцами на Западном Берегу и в секторе Газа, а также с палестинскими беженцами в Иордании , Сирии и Ливане . [7]

В период с 1948 по 1967 год очень немногие арабские граждане Израиля открыто идентифицировали себя как «палестинцы», и преобладала «израильско-арабская» идентичность - любимая фраза израильского истеблишмента и общественности. [31] Публичное выражение палестинской идентичности, такое как демонстрация палестинского флага или пение и декламация националистических песен или стихов, было незаконным. [46] С окончанием военного административного правления в 1966 году и после войны 1967 года национальное сознание и его выражение среди арабских граждан Израиля распространились. [31] [46] Большинство тогда идентифицировало себя как палестинцы, предпочитая этот дескриптор израильскому арабу в многочисленных опросах, проводившихся на протяжении многих лет. [31] [47] [46] По данным телефонного опроса 2017 года, 40% арабских граждан Израиля идентифицировали себя как «араб в Израиле / арабский гражданин Израиля», 15% идентифицировали себя как «палестинцы», 8,9% как «палестинцы в Израиле / палестинские граждане Израиля» и 8,7 % как «араб»; [43] [48] фокус-группы, связанные с опросом, дали другой результат: «был достигнут консенсус в отношении того, что палестинская идентичность занимает центральное место в их сознании». [43] В ходе опроса, проведенного в ноябре 2023 года, респондентов из этой группы населения спросили, что для них является наиболее важным «компонентом их личной идентичности»; 33 процента ответили «израильское гражданство», 32 процента — «арабская идентичность», 23 процента — «религиозная принадлежность» и 8 процентов — «палестинская идентичность». [49] [50]

Профессор Хайфского университета Сэмми Смуха в 2019 году прокомментировал: «Самая крупная и наиболее растущая идентичность сейчас - это гибридная идентичность, то есть «палестинец в Израиле» или подобная комбинация. Я думаю, что именно это возьмет верх». [51]

Различие друзов и черкесских граждан

В отчете Amnesty International за 2022 год «Израильский апартеид против палестинцев: жестокая система доминирования и преступления против человечества» организация исключает израильских арабских друзов и неарабских черкесов из числа палестинских арабских граждан Израиля:

- Министерство иностранных дел Израиля официально классифицирует примерно 2,1 миллиона палестинских граждан Израиля как «арабских граждан Израиля», что отражает их приписывание всем им расового нееврейского, арабского статуса.

- Термин «арабские граждане Израиля» включает арабов-мусульман, включая бедуинов , арабов-христиан, 20–25 000 друзов и даже 4–5 000 черкесов , чье происхождение происходит с Кавказа , но в основном мусульмане.

- По данным Amnesty, израильское государство рассматривает и обращается с палестинскими гражданами Израиля иначе, чем с друзами и черкесами, которые, например, должны служить в армии, в то время как палестинские граждане не обязаны служить.

- Тем не менее, израильские власти и средства массовой информации называют тех, кто идентифицирует себя как палестинцев, «израильскими арабами».

Газета Washington Post включила друзов в число палестинцев. [52] Совет по международным отношениям заявил: «Большинство арабских граждан являются мусульманами-суннитами, хотя есть много христиан, а также друзов, которые чаще принимают израильскую идентичность». [53]

Идентификация как араб-израильтянин

Вопрос палестинской идентичности распространяется и на представительство в израильском Кнессете . Журналистка Рут Маргалит говорит о Мансуре Аббасе из « Объединённого арабского списка» , члене правящей коалиции : «Традиционный термин для этой группы – израильские арабы – становится всё более спорным, но Аббас предпочитает именно его». [54] Аббас дал интервью израильским СМИ в ноябре 2021 года и сказал: «Мои права проистекают не только из моего гражданства. Мои права также проистекают из того, что я являюсь членом палестинского народа, сыном этой палестинской родины. Нравится нам это или нет, Государство Израиль со своей идентичностью было создано внутри палестинской родины», [55] Сами Абу Шехаде из Балада является «откровенным защитником палестинской идентичности». [56] Он говорит, имея в виду израильско-палестинский кризис 2021 года : «... Если последние недели послужили уроками для международного сообщества, то главный из них заключается в том, что они не могут продолжать игнорировать палестинских граждан Израиля. Любое решение должно включать полное равенство. для всех граждан, а также уважение и признание наших прав как национального меньшинства». [57]

Некоторые средства массовой информации, использующие термины «палестинские граждане Израиля» или «палестинцы в Израиле», рассматривают эти термины как взаимозаменяемые с «арабскими гражданами Израиля» или «израильскими арабами» и не обсуждают, являются ли друзы и черкесы исключениями. [39] например, «Нью-Йорк Таймс» . [58] [59]

Израильские опросы

Исследования арабо-израильской самоидентификации разнообразны и часто дают разные, если не противоречивые результаты. В 2017 году Конрада Аденауэра Программа еврейско-арабского сотрудничества Фонда в Центре исследований Ближнего Востока и Африки Моше Даяна при Тель-Авивском университете провела телефонный опрос, результаты которого были такими: [43] [60]

- Национальная идентичность с израильским гражданским компонентом 49,7%, из которых

- Палестинец (гражданин) Израиля 8,9%

- Араб (гражданин) Израиля 40,8%

- Чистая национальная идентичность 24,1%, из них

- Палестинцы 15,4%

- Арабы 8,7%

- Гражданская идентичность: израильтяне 11,4%

- Религиозная идентичность 9,5%

- Другое/Не знаю 5,3%

Фокус-группы, связанные с опросом, дали другой результат: «был достигнут консенсус в отношении того, что палестинская идентичность занимает центральное место в их сознании». отражая «силу палестинско-арабской идентичности», и что они не видят противоречия между ней и израильской гражданской идентичностью. Фокус-группа выявила сильную оппозицию термину «израильско-арабский» и концепции «Дня независимости Израиля». Исследование пришло к выводу, что выводы фокус-группы о сильной палестинской национальной идентичности, не противоречащей израильской гражданской идентичности, совпадают с выводами, наблюдаемыми в общественной сфере. [43]

Согласно опросу, проведенному в 2019 году Хайфского университета профессором Сэмми Смухой , проведенному на арабском языке среди 718 взрослых арабов, 47% арабского населения выбрали палестинскую идентичность с израильским компонентом («израильский палестинец», «палестинец в Израиле», «палестинский араб в Израиле»). Израиль»), 36% предпочитают израильско-арабскую идентичность без палестинского компонента («Израильтянин», «Араб», «Араб в Израиле», «Израильский араб»), а 15% выбирают палестинскую идентичность без израильского компонента («Палестинец», «Палестинский араб»). Когда эти два компонента представлены как конкуренты, 69% выбрали исключительную или основную палестинскую идентичность, по сравнению с 30%, которые выбрали исключительную или основную израильско-арабскую идентичность. 66% арабского населения согласились с тем, что «идентичность «палестинского араба в Израиле» соответствует большинству арабов в Израиле». [61]

Согласно опросу, проведенному Камилем Фуксом из Тель-Авивского университета в 2020 году , 51% арабов идентифицируют себя как арабо-израильские, 7% идентифицируют себя как палестинцы, 23% идентифицируют себя как израильтяне, 15% идентифицируют себя как арабы и 4% идентифицируют себя как «другие». " Это существенно отличается от их опроса 2019 года, в котором 49% идентифицировали себя как арабы-израильтяне, 18% как палестинцы, 27% как арабы и 5% как израильтяне. [62]

Академическая практика

В современной академической литературе общепринятой практикой является определение этого сообщества как палестинского , поскольку именно так самоидентифицируется большинство (см. « Самоидентификация»). [ сломанный якорь ] для большего). [47] Термины, предпочитаемые большинством арабских граждан для идентификации себя, включают палестинцев , палестинцев в Израиле , израильских палестинцев , палестинцев 1948 года , палестинских арабов , палестинских арабских граждан Израиля или палестинских граждан Израиля . [17] [29] [30] [40] [46] [63] Однако есть люди среди арабских граждан, которые вообще отвергают термин « палестинец» . [29] Меньшая часть арабских граждан Израиля каким-то образом включает слово «израильтянин» в свой ярлык; большинство идентифицируют себя как палестинцы по национальности и израильтяне по гражданству . [18] [30]

Израильский истеблишмент

Израильский истеблишмент отдает предпочтение израильским арабам или арабам в Израиле , а также использует термины меньшинства , арабский сектор , арабы Израиля и арабские граждане Израиля . [17] [40] [46] [41] [64] Эти ярлыки подвергались критике за то, что они лишали это население политической или национальной идентификации, скрывая его палестинскую идентичность и связь с Палестиной . [46] [41] [64] Термин «израильские арабы», в частности, рассматривается как конструкция израильских властей. [46] [41] [64] [65] Тем не менее, его использует значительное меньшинство арабского населения, «отражая его доминирование в израильском социальном дискурсе». [30]

Исторический

Между 1920 и 1948 годами на территории тогдашней Подмандатной Палестины все граждане были известны как палестинцы, а две основные общины назывались британскими властями «арабами» и « евреями ». Между 1948 и 1967 годами очень немногие граждане Израиля открыто называли себя «палестинцами». Преобладала «израильско-арабская» идентичность, излюбленное выражение израильского истеблишмента и общественности. [31] Публичное выражение палестинской идентичности, такое как демонстрация палестинского флага или пение и декламация националистических песен или стихов, было незаконным. [46] Начиная с Накбы оставшихся в пределах перемирия 1949 года, просторечии называли «48 арабами» ( араб в 1948 года, палестинцев , границ . [56] С окончанием военного административного правления в 1966 году и после войны 1967 года национальное сознание и его выражение среди арабских граждан Израиля распространились. [31] [46] Большинство тогда идентифицировало себя как палестинцы, предпочитая этот дескриптор израильскому арабу в многочисленных опросах, проводившихся на протяжении многих лет. [31] [47] [46]

Восточный Иерусалим и Голанские высоты

Арабы в Восточном Иерусалиме и на Голанских высотах (сирийские Голаны) представляют собой особые случаи с точки зрения гражданства и идентичности.

Арабы, живущие в Восточном Иерусалиме , оккупированном и управляемом Израилем после Шестидневной войны 1967 года, имеют израильские удостоверения личности, но большинство из них являются постоянными жителями-негражданами, поскольку немногие приняли предложение Израиля о гражданстве после окончания войны, отказываясь признать его суверенитет. и большинство из них поддерживают тесные связи с Западным берегом. [66] Как постоянные жители, они имеют право голосовать на муниципальных выборах в Иерусалиме , хотя этим правом пользуется лишь небольшой процент.

Голанские высоты не были частью Подмандатной Палестины или предшествовавших ей османских политических образований, а скорее были частью Сирии, и ООН до сих пор признает их таковыми и называет их Сирийскими Голанами. [67] Оставшееся друзское население Голанских высот , оккупированных и управляемых Израилем в 1967 году, считается постоянными жителями в соответствии с Законом Израиля о Голанских высотах от 1981 года. По состоянию на середину 2022 года 4303 друза-гражданина Сирии получили израильское гражданство, или 20% общее количество друзов, проживающих на Голанских высотах. [68]

История

Арабо-израильская война 1948 года.

Большинство израильтян-евреев называют арабо-израильскую войну 1948 года Войной за независимость, тогда как большинство арабских граждан называют ее ан-Накба (катастрофа), что отражает различия в восприятии цели и результатов войны. [69] [70]

После войны 1947–1949 годов территория, ранее находившаяся под управлением Британской империи как Подмандатная Палестина, была де-факто разделена на три части: Государство Израиль, Западный Берег, контролируемый Иорданией , и сектор Газа, контролируемый Египтом . Из примерно 950 000 арабов, проживавших на территории, которая стала Израилем до войны, [71] более 80% бежали или были изгнаны. Остальные 20%, около 156 000, остались. [72] Некоторые из них поддерживают Израиль с самого начала. [73] Сегодня арабские граждане Израиля в основном состоят из оставшихся людей и их потомков. В число других входят выходцы из сектора Газа и Западного берега , которые получили израильское гражданство в соответствии с положениями о воссоединении семей, которые стали значительно более строгими после Второй интифады . [74]

Арабы, покинувшие свои дома в период вооруженного конфликта, но оставшиеся на территории, ставшей впоследствии Израилем, считались « присутствующими отсутствующими ». В некоторых случаях им было отказано в разрешении вернуться в свои дома, которые были экспроприированы и переданы в государственную собственность, как и собственность других палестинских беженцев . [75] [76] Около 274 000, или каждый четвертый арабский гражданин Израиля, являются «отсутствующими» или внутренне перемещенными палестинцами . [77] [78] Известные случаи «присутствующих отсутствующих» включают жителей Саффурии и галилейских деревень Кафр Бирим и Икрит . [79]

1949–1966

Между провозглашением независимости Израиля 14 мая 1948 года и принятием Закона о израильском гражданстве от 14 июля 1952 года формально не было граждан Израиля. [80]

Хотя большинству арабов, оставшихся в Израиле, было предоставлено гражданство, в первые годы существования государства для них было введено военное положение. [81] [82] Сионизм мало серьезно задумывался о том, как интегрировать арабов, и, по словам Яна Люстика, последующая политика «была реализована посредством строгого режима военного правления, который доминировал над тем, что осталось от арабского населения на территории, управляемой Израилем, что позволяло государству экспроприировать большую часть арабского населения». Земли, принадлежащие арабам, жестко ограничивают их доступ к инвестиционному капиталу и возможностям трудоустройства, а также устраняют практически все возможности использования гражданства в качестве средства достижения политического влияния». [83] Разрешения на поездки, комендантский час, административные задержания и высылки были частью жизни до 1966 года. Разнообразные законодательные меры Израиля способствовали передаче земель, оставленных арабами, в государственную собственность. К ним относятся Закон о заочной собственности 1950 года , который позволял государству экспроприировать собственность палестинцев, бежавших или изгнанных в другие страны, и Закон о приобретении земли 1953 года, который уполномочивал Министерство финансов передавать экспроприированную землю государству. Другие распространенные правовые меры включали использование чрезвычайных положений для объявления земель, принадлежащих арабским гражданам, закрытой военной зоной, с последующим использованием османского законодательства о заброшенных землях для взятия контроля над землей. [84] Разрешения на выезд, комендантский час, административные задержания и высылки были частью жизни до 1966 года.

Арабы, имевшие израильское гражданство, имели право голосовать в израильском Кнессете . Арабские члены Кнессета занимают свои посты со времен Первого Кнессета . Первыми арабскими членами Кнессета были Амин-Салим Джаджора и Сейф эль-Дин эль-Зуби , которые были членами партии «Демократический список Назарета» , и Тауфик Туби , член партии Маки .

В 1965 году радикальная независимая арабская группа под названием «Аль-Ард», сформировавшая «Арабский социалистический список», попыталась баллотироваться на выборах в Кнессет . Список был запрещен Центральной избирательной комиссией Израиля . [85]

В 1966 году военное положение было полностью отменено, и правительство приступило к отмене большинства дискриминационных законов, в то время как арабским гражданам были предоставлены те же права, что и еврейским гражданам по закону. [86]

1967–2000

После Шестидневной войны смогли связаться с палестинцами на Западном Берегу и в секторе Газа 1967 года арабские граждане впервые с момента создания государства . Это, наряду с отменой военного правления, привело к росту политической активности среди арабских граждан. [87] [88]

В 1974 году был создан комитет арабских мэров и членов муниципальных советов, который сыграл важную роль в представлении общины и оказании давления на израильское правительство. [89] За этим последовало в 1975 году формирование Комитета защиты земли, который стремился предотвратить продолжающуюся экспроприацию земель. [90] В том же году произошел политический прорыв: избрание арабского поэта Тауфика Зиада , члена Маки , мэром Назарета, что сопровождалось сильным коммунистическим присутствием в городском совете. [91] В 1976 году шесть арабских граждан Израиля были убиты израильскими силами безопасности во время протеста против экспроприации земель и сноса домов. Дата протеста, 30 марта, с тех пор ежегодно отмечается как День земли .

В 1980-е годы зародилось Исламское движение . В рамках более широкой тенденции в арабском мире Исламское движение сделало упор на проникновение ислама в политическую сферу. Исламское движение построило школы, предоставило другие важные социальные услуги, построило мечети и поощряло молитву и консервативную исламскую одежду. Исламское движение начало влиять на избирательную политику, особенно на местном уровне. [92] [93]

Многие арабские граждане поддержали Первую интифаду и помогали палестинцам на Западном Берегу и в секторе Газа, снабжая их деньгами, едой и одеждой. Ряд забастовок провели также арабские граждане в знак солидарности с палестинцами на оккупированных территориях. [92]

Годы, предшествовавшие подписанию соглашений в Осло, были временем оптимизма для арабских граждан. Во время правления Ицхака Рабина арабские партии сыграли важную роль в формировании правящей коалиции. Возросшее участие арабских граждан также наблюдалось на уровне гражданского общества. Однако напряженность продолжала существовать, поскольку многие арабы призывали Израиль стать « государством всех своих граждан », тем самым бросая вызов еврейской идентичности государства. На выборах премьер-министра 1999 года 94% арабского электората проголосовали за Эхуда Барака . Однако Барак сформировал широкое лево-правоцентристское правительство, не посоветовавшись с арабскими партиями, что разочаровало арабское сообщество. [87]

2000 – настоящее время

Напряженность между арабами и государством возросла в октябре 2000 года , когда 12 арабских граждан и один житель Газы были убиты во время протеста против реакции правительства на Вторую интифаду . В ответ на этот инцидент правительство создало Комиссию Ор . События октября 2000 года заставили многих арабов усомниться в природе своего израильского гражданства. В значительной степени они бойкотировали выборы в Израиле в 2001 году как средство протеста. [87] Этот бойкот помог Ариэлю Шарону победить Эхуда Барака; как уже упоминалось, на выборах 1999 года 94 процента арабского меньшинства Израиля проголосовали за Эхуда Барака. [94] ЦАХАЛ Призыв в бедуинов Израиля значительно сократился. [95]

Во время ливанской войны 2006 года арабские правозащитные организации жаловались, что израильское правительство потратило время и усилия на защиту еврейских граждан от нападений «Хезболлы», но пренебрегло арабскими гражданами. Они указали на нехватку бомбоубежищ в арабских городах и деревнях, а также на отсутствие базовой информации о чрезвычайных ситуациях на арабском языке. [96] Многие израильские евреи рассматривали оппозицию арабов политике правительства и симпатии к ливанцам как признак нелояльности. [97]

В октябре 2006 года напряженность возросла, когда премьер-министр Израиля Эхуд Ольмерт пригласил правую политическую партию «Исраэль Бейтейну» присоединиться к его коалиционному правительству. Лидер партии Авигдор Либерман выступал за обмен территориями на основе этнической принадлежности, « План Либермана» , путем передачи густонаселенных арабских территорий (в основном «Треугольника ») под контроль Палестинской автономии и аннексии крупных еврейских израильских поселенческих блоков на Западном Берегу вблизи зеленой линии. как часть мирного предложения. [98] Арабы, которые предпочли бы остаться в Израиле вместо того, чтобы стать гражданами палестинского государства, смогут переехать в Израиль. Все граждане Израиля, будь то евреи или арабы, должны будут принести присягу на верность, чтобы сохранить гражданство. Те, кто откажется, смогут остаться в Израиле в качестве постоянных жителей. [99]

В январе 2007 года первый арабский министр недрузов в истории Израиля Ралеб Маджаделе был назначен министром без портфеля ( Салах Тариф , друз , был назначен министром без портфеля в 2001 году). Это назначение подверглось критике со стороны левых, которые сочли это попыткой скрыть решение Лейбористской партии войти в правительство вместе с НДИ, и правых, которые увидели в этом угрозу статусу Израиля как еврейского государства . [100] [101] В 2021 году Мансур Аббас , лидер Объединенного арабского списка , вошел в историю, став первым израильским арабским политическим лидером, присоединившимся к израильской правящей коалиции . [102] [103]

Во время израильско-палестинского кризиса 2021 года массовые протесты и беспорядки усилились по всему Израилю, особенно в городах с большим арабским населением. В Лоде еврейские квартиры забрасывали камнями, а некоторые еврейские жители были эвакуированы полицией из своих домов. Синагоги и мусульманское кладбище подверглись вандализму. [104] Сообщалось о межобщинном насилии, включая «беспорядки, поножовщину, поджоги, попытки вторжения в дома и стрельбу», из Беэр-Шевы, Рахата, Рамлы, Лода, Насирии, Тверии, Иерусалима, Хайфы и Акры. [105]

В арабском сообществе Израиля в последние годы наблюдается значительный рост насилия и организованной преступности , включая рост числа убийств, связанных с бандами. [106] [107] В отчете « Инициативы Авраама» подчеркивается, что в 2023 году в Израиле были убиты 244 члена арабской общины, что более чем вдвое больше, чем в предыдущем году. [108] [109] В докладе приписывают этот всплеск убийств непосредственно министру национальной безопасности Итамару Бен Гвиру , который проводил кампанию на платформе, обещающей улучшить личную безопасность и курирующей правоохранительную деятельность. [110] Известные семьи организованной преступности среди израильских арабов включают Аль-Харири, Бакри, Джаруши и друзов Абу Латифса. [111] [112] [113]

С момента начала войны между Израилем и ХАМАС в 2023 году Израиль провел массовые аресты и задержания палестинских рабочих и арабских граждан Израиля. [114] [115] 5 ноября 2023 года канал CNN сообщил, что «десятки» палестинских жителей и израильтян арабского происхождения были арестованы в Израиле за выражение солидарности с гражданским населением Газы, обмен стихами из Корана или выражение «любой поддержки палестинскому народу». [116] «Гаарец» рассказала о широкомасштабных нападениях на израильтян-арабов со стороны израильских сил безопасности. [117] Ссылаясь на «сотни» допросов, газета El País сообщила 11 ноября, что Израиль все чаще обращается со своим арабским меньшинством как с «потенциальной пятой колонной ». [118] В то же время конфликт привел к усилению самоидентификации с Израилем среди арабских граждан. [119] Согласно различным опросам, большинство израильских арабов осудили резню 7 октября , но также выступили против массовых бомбардировок Газы. Многие израильские арабы выразили общее негодование по поводу войны, поскольку другие палестинцы считали их сторонниками Израиля, тогда как израильские евреи видели в них потенциальных сторонников Хамаса . [120] [121]

Сектантские и религиозные группировки

В 2006 году официальное число арабских жителей в Израиле, включая постоянных жителей Восточного Иерусалима и Голанских высот, многие из которых не являются гражданами, составляло 1 413 500 человек, что составляет около 20% населения Израиля. [122] Арабское население в 2023 году оценивалось в 2 065 000 человек, что составляет 21% населения страны. [1] [123] По данным Центрального статистического бюро Израиля (май 2003 г.), мусульмане, включая бедуинов, составляют 82% всего арабского населения Израиля, а также около 9% друзов и 9% христиан. [124] По прогнозам, основанным на данных 2010 года, к 2025 году израильтяне арабского происхождения будут составлять 25% населения Израиля. [125]

Национальным языком и родным языком арабских граждан, включая друзов, является арабский , а разговорной речью является палестинский арабский диалект. Знание и владение современным стандартным арабским языком варьируются. [126]

мусульмане

В 2019 году мусульмане составляют 17,9% населения Израиля. [127] Большинство мусульман в Израиле — арабы-сунниты . [128] с ахмадийским меньшинством. [129] В Израиле насчитывается около 4000 алавитов , и большинство из них живут в деревне Гаджар на оккупированных Голанских высотах недалеко от границы с Ливаном . Бедуины в Израиле также являются арабами-мусульманами, при этом некоторые бедуинские кланы участвуют в израильской армии . Небольшая черкесская община состоит из мусульман-суннитов, изгнанных с Северного Кавказа в конце 19 века. Кроме того, в Израиле также проживают меньшие группы курдов , цыган и турецких мусульман.

В 2020 году в Иерусалиме проживало самое большое мусульманское население Израиля, насчитывающее 346 000 жителей, что составляет 21,1% мусульманского населения Израиля и около 36,9% от общей численности жителей города. За ним следует Рахат со вторым по величине мусульманским населением с населением 71 300 человек, а в Умм аль-Фахме и Назарете проживает примерно 56 000 и 55 600 жителей соответственно. [127] В одиннадцати городах района Треугольника проживает около 250 000 израильских мусульман. [130]

Что касается регионального распределения, в 2020 году примерно 35,2% израильских мусульман проживали в Северном округе , 21,9% в Иерусалимском округе , 17,1% в Центральном округе , 13,7% в Хайфском округе , 10,9% в Южном округе и 1,2% в Тель -Авивский округ . [127] Мусульманское население Израиля особенно молодо: около 33,4% составляют люди в возрасте 14 лет и младше, тогда как на долю людей в возрасте 65 лет и старше приходится лишь 4,3%. Кроме того, мусульманская община в Израиле может похвастаться самым высоким уровнем рождаемости среди религиозных групп — 3,16 ребенка на одну женщину. [127]

Согласно исследованию, опубликованному исследовательским центром Pew в 2016 году, хотя мусульмане, живущие в Израиле, в целом более религиозны, чем израильские евреи, они менее религиозны, чем мусульмане, живущие во многих других странах Ближнего Востока. Мусульманские женщины чаще говорят, что религия имеет большое значение в их жизни, а молодые мусульмане, как правило, менее наблюдательны, чем старшие. [128] Согласно опросу Израильского института демократии, проведенному в 2015 году, 47% израильских мусульман идентифицируют себя как традиционные, 32% идентифицируют себя как религиозные, 17% идентифицируют себя как нерелигиозные вообще, 3% идентифицируют себя как очень религиозные. [131]

Поселенный

Традиционно оседлые общины арабов -мусульман составляют около 70% арабского населения Израиля. В 2010 году среднее количество детей на одну мать составляло 3,84, снизившись с 3,97 в 2008 году. Мусульманское население в основном молодое: 42% мусульман моложе 15 лет. Средний возраст израильтян-мусульман составляет 18 лет, а средний возраст евреев Израиля составляет 30. Процент людей старше 65 лет составляет менее 3% среди мусульман по сравнению с 12% среди еврейского населения. [124]

Бедуин

По данным министра иностранных дел Израиля , 110 000 бедуинов проживают в Негеве , 50 000 – в Галилее и 10 000 – в центральном регионе Израиля. [132]

До создания Израиля в 1948 году в Негеве проживало примерно 65 000–90 000 бедуинов. [132] Оставшиеся 11 000 человек были переселены израильским правительством в 1950-х и 1960-х годах в район на северо-востоке Негева, составляющий 10% пустыни Негев. [132] В период с 1979 по 1982 год правительство Израиля построило для бедуинов семь городов развития. Около половины бедуинского населения проживает в этих городах, крупнейшим из которых является город Рахат , а другими являются Ар'арат ан-Накаб (Ар'ара БаНегев), Бир Хададж , Хура , Кусейфе , Лакия , Шакиб аль-Салам (Сегев Шалом) и Тель ас-Саби (Тель-Шева). По оценкам, в 2005 году бедуины составляли 10% арабских граждан Израиля. [133] Примерно 40–50% бедуинов Израиля живут в 39–45 непризнанных деревнях , не подключенных к электросети и водопроводу. [134] [135] Исследование, опубликованное Центром исследований социальной политики Тауба в 2017 году, показало, что бедуины имеют самые низкие достижения в арабском секторе по всем индексам: баллам багрута , количеству выпускников колледжей и сферам трудоустройства. Потому что они, как правило, наименее образованы. [136] : 42

Друзы

Большинство израильских друзов проживают в северной части страны и официально признаны отдельной религиозной общиной со своими судами. [137] Они считают арабский язык и культуру неотъемлемой частью своей идентичности, а арабский язык является их основным языком. [138] Галилейские друзы и друзы региона Хайфы автоматически получили израильское гражданство в 1948 году. После того, как Израиль захватил Голанские высоты у Сирии в 1967 году и присоединил их к Израилю в 1981 году, друзам Голанских высот было предложено полное израильское гражданство в соответствии с Законом о Голанских высотах. . Большинство из них отказались от израильского гражданства и сохранили сирийское гражданство и идентичность и считаются постоянными жителями Израиля. [139] По состоянию на 2011 год менее 10% друзов на Голанских высотах приняли израильское гражданство. [140]

По состоянию на конец 2019 года примерно 81% населения израильских друзов проживало в Северном округе , а 19% — в Хайфском округе , а крупнейшим населением друзов были Далият аль-Кармель и Йирка . Израильские друзы живут в 19 городах и деревнях, по отдельности или смешанно с христианами и мусульманами, все они расположены на вершинах гор на севере Израиля ( Верхняя и Нижняя Галилея и гора Кармель ), включая Абу-Снан , Бейт-Джанн , Далият аль-Кармель. , Эйн аль-Асад , Хурфейш , Исфия , Джулис , Кафр Ясиф , Кисра-Сумей , Магхар , Пекинин , Рамех , Саджур , Шефа-Амр , Янух-Джат и Ярка . [141] осталось четыре друзских деревни На аннексированной Израилем части Голанских высот — Мадждал-Шамс , Масаде , Буката и Эйн-Кинийе , — в которых проживают 23 000 друзов. [142] [143] [144]

Во время британского мандата в Палестине друзы не поддерживали растущий арабский национализм того времени и не участвовали в ожесточенных столкновениях. В 1948 году многие друзы пошли добровольцами в израильскую армию, и ни одна друзская деревня не была разрушена или навсегда заброшена. [78] С момента создания государства друзы продемонстрировали солидарность с Израилем и дистанцировались от арабского и исламского радикализма. [145] Граждане-друзы мужского пола служат в Армии обороны Израиля . [146]

С 1957 года правительство Израиля официально признало друзов отдельной религиозной общиной. [147] [148] [149] и определяются как отдельная этническая группа в Министерства внутренних дел Израиля переписи населения . С другой стороны, Центральное статистическое бюро Израиля в своей переписи относит друзов к арабам. [150] Хотя израильская система образования в основном разделена на ивритские и арабоязычные школы, друзы имеют автономию в рамках арабоязычной ветви. [147] Израильские друзы — арабы по языку и культуре . [151] и их родным языком является арабский язык .

Некоторые ученые утверждают, что Израиль пытался отделить друзов от других арабских общин и что эти усилия повлияли на то, как израильские друзы воспринимают свою современную идентичность. [152] [153] Данные опроса показывают, что израильские друзы отдают приоритет своей идентичности, во-первых, как друзы (религиозно), во-вторых, как арабы (культурно и этнически) и, в-третьих, как израильтяне (с точки зрения гражданства). [154] Небольшое меньшинство из них идентифицирует себя как палестинцы , что отличает их от большинства других арабских граждан Израиля, которые преимущественно идентифицируют себя как палестинцы. [154]

По данным опроса, проведенного в 2008 году доктором Юсуфом Хасаном из Тель-Авивского университета, 94% респондентов-друзов идентифицировали себя как «друзы-израильтяне» в религиозном и национальном контексте. [155] [156] в то время как опрос Pew Research Center 2017 года показал, что, хотя 99% мусульман и 96% христиан идентифицируют себя как этнические арабы, меньшая доля друзов, 71%, идентифицирует себя так же. [157] По сравнению с другими христианами и мусульманами, друзы меньше внимания уделяют своей арабской идентичности и больше идентифицируют себя как израильтяне. Большинство из них не идентифицируют себя как палестинцы . [158] Однако они были менее готовы к личным отношениям с евреями по сравнению с израильскими мусульманами и христианами. [159] Ученые объясняют эту тенденцию культурными различиями между евреями и друзами. [160] В число политиков-друзов в Израиле входят Аюб Кара , который представлял Ликуд в Кнессете ; Маджалли Вахаби из партии «Кадима» , заместитель спикера Кнессета; и Саид Нафа из арабской партии «Балад» . [161]

Христиане

Арабы-христиане составляют около 9% арабского населения Израиля. По итогам 2019 года примерно 70,6% проживают в Северном округе , 13,3% в Хайфском округе , 9,5% в Иерусалимском округе , 3,4% в Центральном округе , 2,7% в Тель-Авивском округе и 0,5% в Южном округе. . [163] В Израиле проживает 135 000 или более арабов-христиан (и более 39 000 христиан-неарабов). [163] [164] По состоянию на 2014 год Мелькитская греко-католическая церковь была крупнейшей христианской общиной в Израиле, где около 60% израильских христиан принадлежали к Мелькитской греко-католической церкви. [165] в то время как около 30% израильских христиан принадлежали к Греческой православной церкви Иерусалима . [165] Христианские общины в Израиле управляют многочисленными школами , колледжами , больницами , клиниками , детскими домами , домами для престарелых, общежитиями , семейными и молодежными центрами, гостиницами и гостевыми домами. [166]

В Назарете проживает самое большое арабское христианское население, за ним следует Хайфа . [163] Большинство арабского меньшинства Хайфы также являются христианами. [167] Арабские христианские общины в Назарете и Хайфе, как правило, богаче и образованнее по сравнению с другими арабами в других частях Израиля. [168] [169] Арабские христиане живут также в ряде других местностей Галилеи ; такие как Абу Снан , Арраба , Биина , Дейр-Ханна , Ибиллин , Джадейди-Макр , Кафр-Канна , Мазраа , Мукейбл , Рас-эль-Эйн , Рейне , Сахнин , Шефа-Амр , Туран и Яфаан -Насерийе . [170] в таких населенных пунктах, как Эйлабун , Джиш , Кафр-Ясиф и Раме , преобладают христиане. [171] Почти все население Фассуты и Миильи — -мелькиты христиане . [172] Некоторые друзские деревни, такие как Далият аль-Кармель , [173] В Эйн-Кинийе , Хурфейше , Исфии , Кисра-Сумее , Магхаре , Мадждал-Шамсе и Пекине проживает небольшое арабское христианское население. [124] В смешанных городах, таких как Акко , Иерусалим , Лод , Маалот-Таршиха , Ноф-ха-Галиль , Рамла и Тель-Авив - Яффо проживает значительное количество арабов-христиан. [124]

Многие арабы-христиане занимали видное место в арабских политических партиях в Израиле, среди лидеров которых были архиепископ Джордж Хаким , Эмиль Тома , Тауфик Туби , Эмиль Хабиби и Азми Бишара . Известные христианские религиозные деятели включают мелькитских архиепископов Галилеи Элиаса Чакура и Бутроса Муаллема , латинского патриарха Иерусалима Мишеля Саббаха и епископа Муниба Юнана Лютеранской церкви Иордании и Святой Земли . Судьи Верховного суда Израиля Салим Джубран и Джордж Карра — арабы-христиане. [174] [175] Среди известных христианских деятелей в области науки и высоких технологий - Хоссам Хайк. [176] который внес большой вклад в междисциплинарные области, такие как нанотехнологии , наносенсоры и молекулярная электроника , [177] и Джонни Сроуджи, старший Apple президент вице- по аппаратным технологиям . [178] [179] [180]

Среди арабов-христиан в Израиле некоторые подчеркивают панарабизм , в то время как небольшое меньшинство записывается в Армию обороны Израиля . [181] [182] С сентября 2014 года христианские семьи или кланы, имеющие арамейское или маронитское культурное наследие, считаются этнической группой, отдельной от израильских арабов , и могут регистрироваться как арамейцы. Это признание пришло после семи лет деятельности Арамейского христианского фонда в Израиле, который вместо того, чтобы придерживаться арабской идентичности, желает ассимилироваться с израильским образом жизни. Арамом руководят майор ЦАХАЛа Шади Халлул Ришо и Израильский христианский рекрутинговый форум, возглавляемый отцом Габриэлем Наддафом из Греко-православной церкви и майором Ихабом Шлаяном. [183] [184] [185] Этот шаг был осужден Греческим православным патриархатом, который назвал его попыткой расколоть палестинское меньшинство в Израиле. [186] Другие просионистские сторонники, поддерживающие подобные идеи, получили широкое освещение в спонсируемых государством СМИ Израиля и еврейских новостных агентствах и подверглись резкой критике со стороны своих единоверцев (см. Йосефа Хаддада ).

Арабы-христиане — одна из самых образованных групп населения Израиля. [187] [188] По статистике, арабы-христиане в Израиле имеют самый высокий уровень образования среди всех религиозных общин. Согласно данным Центрального статистического бюро Израиля за 2010 год, 63% израильских арабов-христиан имели высшее или последипломное образование , что является самым высоким показателем среди всех религиозных и этнорелигиозная группа. [189] страны Несмотря на то, что арабы-христиане составляют лишь 2% от общей численности населения Израиля, в 2014 году они составляли 17% студентов университетов и 14% студентов колледжей . [190] больше, Христиан , получивших степень бакалавра или более высокую академическую степень, чем среди среднего населения Израиля. [162] Доля студентов, обучающихся в области медицины, была выше среди арабских студентов -христиан, чем среди студентов всех других секторов. [191] и процент арабских женщин-христианок, получающих высшее образование, также выше, чем у других групп. [192]

Центральное статистическое бюро Израиля отметило, что, принимая во внимание данные, зарегистрированные на протяжении многих лет, израильские арабы-христиане добились лучших результатов с точки зрения образования по сравнению с любой другой группой, получающей образование в Израиле. [162] [194] В 2012 году арабы-христиане имели самые высокие показатели успеваемости на вступительных экзаменах . [195] В 2016 году арабские христиане имели самые высокие показатели успеха на вступительных экзаменах , а именно 73,9%, как по сравнению с израильтянами-мусульманами и друзами (41% и 51,9% соответственно), так и со студентами различных ветвей иврита ( большинство составляют евреи) . ) система образования рассматривается как одна группа (55,1%). [196]

По своему социально-экономическому положению арабы-христиане больше похожи на еврейское население, чем на арабское мусульманское население. [197] У них самый низкий уровень бедности и самый низкий процент безработицы - 4,9% по сравнению с 6,5% среди еврейских мужчин и женщин. [198] У них также самый высокий средний доход семьи среди арабских граждан Израиля и второй по величине средний доход семьи среди израильских этнорелигиозных групп. [199] Также арабские христиане имеют высокие достижения в науке и в профессиях «белых воротничков» . [200] В Израиле арабы-христиане изображаются как трудолюбивое и меньшинство, принадлежащее к высшему среднему классу образованное этнорелигиозное . Согласно исследованию, большинство христиан в Израиле (68,2 процента) заняты в сфере услуг, то есть в банках, страховых компаниях, школах, туризме, больницах и т. д. [166]

Согласно исследованию Ханны Давид из Тель-Авивского университета «Являются ли арабы-христиане новыми израильскими евреями? Размышления об уровне образования арабских христиан в Израиле» , один из факторов, почему израильские арабы-христиане являются наиболее образованным сегментом населения Израиля. – высокий уровень христианских учебных заведений. Христианские школы в Израиле являются одними из лучших школ в стране, и хотя эти школы составляют лишь 4% арабского школьного сектора, около 34% студентов арабских университетов происходят из христианских школ . [201] и около 87% израильских арабов, работающих в секторе высоких технологий , получили образование в христианских школах. [202] [203] В статье Maariv 2011 года арабский христианский сектор описывается как «самый успешный в системе образования». [192] Это мнение поддерживается Центральным статистическим бюро Израиля и другими организациями, которые отмечают, что арабы-христиане преуспевают в лучшем плане образования по сравнению с любой другой группой, получающей образование в Израиле. [162]

Lebanese people

There are 3,500 Lebanese people in Israel,[204] most of them are former members of the South Lebanon Army (SLA) and their families. The SLA was a Christian-dominated militia allied with the Israel Defense Forces during the South Lebanon conflict until Israel's withdrawal from Lebanon in May 2000 that ended the Israeli occupation of Southern Lebanon.[204] The majority are Maronites but there are also Muslims, Druze and Christians of other denominations among them.[205] They are registered by the Ministry of Interior as "Lebanese" and hold Israeli citizenship.[204] They are located across the country, mainly in the Northern District, in cities such as Nahariya, Kiryat Shmona, Tiberias, and Haifa.[205]

The native language of former SLA members is Lebanese Arabic. However, the language is only partially transmitted from one generation to another. The majority of the second generation understand and speak Lebanese Arabic but are unable to read and write it. Young Lebanese Israeli mainly text in Hebrew or, more rarely, in Lebanese Arabic written in the Hebrew alphabet. Religious books for children and youths are similarly written in Classical Arabic (or in Lebanese Arabic for some songs) in Hebrew letters.[205]

Population

In 2006, the official number of Arab residents in Israel was 1,413,500 people, about 20% of Israel's population. This figure includes 209,000 Arabs (14% of the Israeli Arab population) in East Jerusalem, also counted in the Palestinian statistics, although 98% of East Jerusalem Palestinians have either Israeli residency or Israeli citizenship.[207] In 2012, the official number of Arab residents in Israel increased to 1,617,000 people, about 21% of Israel's population.[208] The Arab population in 2023 was estimated at 2,065,000 people, representing 21% of the country's population.[1]

According to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics census in 2010, "the Arab population lives in 134 towns and villages. About 44 percent of them live in towns (compared to 81 percent of the Jewish population); 48 percent live in villages with local councils (compared to 9 percent of the Jewish population). Four percent of the Arab citizens live in small villages with regional councils, while the rest live in unrecognized villages (the proportion is much higher, 31 percent in the Negev)".[209] The Arab population in Israel is located in five main areas: Galilee (54.6% of total Israeli Arabs), Triangle (23.5% of total Israeli Arabs), Golan Heights, East Jerusalem, and Northern Negev (13.5% of total Israeli Arabs).[209] Around 8.4% (approximately 102,000 inhabitants) of Israeli Arabs live in officially mixed Jewish-Arab cities (excluding Arab residents in East Jerusalem), including Haifa, Lod, Ramle, Jaffa-Tel Aviv, Acre, Nof HaGalil, and Ma'alot Tarshiha.[210]

In Israel's Northern District[212] Arab citizens of Israel form a majority of the population (52%) and about 50% of the Arab population lives in 114 different localities throughout Israel.[213] In total there are 122 primarily if not entirely Arab localities in Israel, 89 of them having populations over two thousand.[124] The seven townships as well as the Abu Basma Regional Council that have been constructed by the government for the Bedouin population of the Negev,[214][better source needed] are the only Arab localities to have been established since 1948, with the aim of relocating the Arab Bedouin citizens (see preceding section on Bedouin[broken anchor]).[citation needed]

46% of the country's Arabs (622,400 people) live in predominantly Arab communities in the north.[212] In 2022 Nazareth was the largest Arab city, with a population of 78,007,[215] roughly 40,000 of whom are Muslim. Shefa-'Amr has a population of approximately 43,543 and the city is mixed with sizable populations of Muslims, Christians, and Druze.

Jerusalem, a mixed city, has the largest overall Arab population. Jerusalem housed 332,400 Arabs in 2016 (37.7% of the city's residents)[216] and together with the local council of Abu Ghosh, some 19% of the country's entire Arab population.

14% of Arab citizens live in the Haifa District predominantly in the Wadi Ara region. Here is the largest Muslim city, Umm al-Fahm, with a population of 58,665. Baqa-Jatt is the second largest Arab population center in the district. The city of Haifa has an Arab population of 10%, much of it in the Wadi Nisnas, Abbas and Halissa neighborhoods.[217] Wadi Nisnas and Abbas neighborhoods, are largely Christian,[218][219] Halisa and Kababir are largely Muslim.[219]

10% of the country's Arab population resides in the Central District of Israel, primarily the cities of Tayibe, Tira, and Qalansawe as well as the mixed cities of Lod and Ramla which have mainly Jewish populations.[124]

Of the remaining 11%, 10% live in Bedouin communities in the northwestern Negev. The Bedouin city of Rahat is the only Arab city in the Southern District and it is the third largest Arab city in Israel.

The remaining 1% of the country's Arab population lives in cities that are almost entirely Jewish, such as Nazareth Illit with an Arab population of 22%[220] and Tel Aviv-Yafo, 4%.[124][213]

In February 2008, the government announced that the first new Arab city would be constructed in Israel. According to Haaretz, "[s]ince the establishment of the State of Israel, not a single new Arab settlement has been established, with the exception of permanent housing projects for Bedouins in the Negev".[221] The city, Givat Tantur, was never constructed even after 10 years.[222]

Major Arab localities

Arabs make up the majority of the population of the "heart of the Galilee" and of the areas along the Green Line including the Wadi Ara region. Bedouin Arabs make up the majority of the northeastern section of the Negev.

| Locality | Population | District |

|---|---|---|

| Nazareth | 74,600 | North |

| Rahat | 60,400 | South |

| Umm al-Fahm | 51,400 | Haifa |

| Tayibe | 40,200 | Center |

| Shefa-'Amr | 39,200 | North |

| Tamra | 31,700 | North |

| Sakhnin | 28,600 | North |

| Baqa al-Gharbiyye | 27,500 | Haifa |

| Tira | 24,400 | Center |

| Ar'ara | 23,600 | Haifa |

| Arraba | 23,500 | North |

| Kafr Qasim | 21,400 | Center |

| Maghar | 21,300 | North |

| Qalansawe | 21,000 | Center |

| Kafr Kanna | 20,800 | North |

| Source: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics | ||

Perceived demographic threat

The phrase demographic threat (or demographic bomb) is used within the Israeli political sphere to describe the growth of Israel's Arab citizenry as constituting a threat to its maintenance of its status as a Jewish state with a Jewish demographic majority. In the northern part of Israel the percentage of the population that is Jewish is declining.[224] The increasing population of Arabs within Israel, and the majority status they hold in two major geographic regions – the Galilee and the Triangle – has become a growing point of open political contention in recent years. Among Arabs, Muslims have the highest birth rate, followed by Druze, and then Christians.[citation needed]Israeli historian Benny Morris stated in 2004 that, while he strongly opposes expulsion of Israeli Arabs, in case of an "apocalyptic" scenario where Israel comes under total attack with non-conventional weapons and comes under existential threat, an expulsion might be the only option. He compared the Israeli Arabs to a "time bomb" and "a potential fifth column" in both demographic and security terms and said they are liable to undermine the state in time of war.[225]

Several politicians[226][227] have viewed the Arabs in Israel as a security and demographic threat.[228][229][230]

The phrase "demographic bomb" was famously used by Benjamin Netanyahu in 2003[231] when he noted that, if the percentage of Arab citizens rises above its current level of about 20 percent, Israel will not be able to maintain a Jewish demographic majority. Netanyahu's comments were criticized as racist by Arab Knesset members and a range of civil rights and human rights organizations, such as the Association for Civil Rights in Israel.[232] Even earlier allusions to the "demographic threat" can be found in an internal Israeli government document drafted in 1976 known as the Koenig Memorandum, which laid out a plan for reducing the number and influence of Arab citizens of Israel in the Galilee region.

In 2003, the Israeli daily Ma'ariv published an article entitled "Special Report: Polygamy is a Security Threat", detailing a report put forth by the Director of the Population Administration at the time, Herzl Gedj; the report described polygamy in the Bedouin sector a "security threat" and advocated means of reducing the birth rate in the Arab sector.[233] The Population Administration is a department of the Demographic Council, whose purpose, according to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, is: "...to increase the Jewish birthrate by encouraging women to have more children using government grants, housing benefits, and other incentives".[234] In 2008 the minister of the interior appointed Yaakov Ganot as new head of the Population Administration, which according to Haaretz is "probably the most important appointment an interior minister can make".[235]

A January 2006 study rejects the "demographic time bomb" threat based on statistical data that shows Jewish births have increased while Arab births have begun to drop.[236] The study noted shortcomings in earlier demographic predictions (for example, in the 1960s, predictions suggested that Arabs would be the majority in 1990). The study also demonstrated that Christian Arab and Druze birth rates were actually below those of Jewish birth rates in Israel. The study used data from a Gallup poll to demonstrate that the desired family size for Arabs in Israel and Jewish Israelis were the same. The study's population forecast for 2025 predicted that Arabs would comprise only 25% of the Israeli population. Nevertheless, the Bedouin population, with its high birth rates, continues to be perceived as a threat to a Jewish demographic majority in the south, and a number of development plans, such as the Blueprint Negev, address this concern.[237]

A study showed that in 2010, Jewish birthrates rose by 31% and 19,000 diaspora Jews immigrated to Israel, while the Arab birthrate fell by 2%.[238]

Land and population exchange

Some Israeli politicians advocate land-swap proposals in order to assure a continued Jewish majority within Israel. A specific proposal is that Israel transfer sovereignty of part of the Arab-populated Wadi Ara area (west of the Green Line) to a future Palestinian state, in return for formal sovereignty over the major Jewish settlement "blocks" that lie inside the West Bank east of the Green Line.[240]

Avigdor Lieberman of Yisrael Beiteinu, the fourth largest faction in the 17th Knesset, is one of the foremost advocates of the transfer of large Arab towns located just inside Israel near the border with the West Bank (e.g. Tayibe, Umm al-Fahm, Baqa al-Gharbiyye), to the jurisdiction of the Palestinian National Authority in exchange for Israeli settlements located inside the West Bank.[241][242][243][244][245][246][247]

In October 2006, Yisrael Beiteinu formally joined in the ruling government's parliamentary coalition, headed by Kadima. After the Israeli Cabinet confirmed Avigdor Lieberman's appointment to the position of "minister for strategic threats", Labour Party representative and science, sport and culture minister Ophir Pines-Paz resigned his post.[98][248] In his resignation letter to Ehud Olmert, Pines-Paz wrote: "I couldn't sit in a government with a minister who preaches racism."[249]

The Lieberman Plan caused a stir among Arab citizens of Israel. Various polls show that Arabs in Israel do not wish to move to the West Bank or Gaza if a Palestinian state is created there.[250] In a survey conducted by Kul Al-Arab among 1,000 residents of Um Al-Fahm, 83 percent of respondents opposed the idea of transferring their city to Palestinian jurisdiction, while 11 percent supported the proposal and 6 percent did not express their position.[239]

Of those opposed to the idea, 54% said that they were against becoming part of a Palestinian state because they wanted to continue living under a democratic regime and enjoying a good standard of living. Of these opponents, 18% said that they were satisfied with their present situation, that they were born in Israel and that they were not interested in moving to any other state. Another 14% of this same group said that they were not prepared to make sacrifices for the sake of the creation of a Palestinian state. Another 11 percent cited no reason for their opposition.[239]

Politics

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Arab political parties

There are three mainstream Arab parties in Israel: Hadash (a joint Arab-Jewish party with a large Arab presence), Balad, and the United Arab List, which is a coalition of several different political organizations including the Islamic Movement in Israel. In addition to these, there is Ta'al, which currently run with Hadash. All of these parties primarily represent Arab-Israeli and Palestinian interests, and the Islamic Movement is an Islamist organization with two factions: one that opposes Israel's existence, and another that opposes its existence as a Jewish state. Two Arab parties ran in Israel's first election in 1949, with one, the Democratic List of Nazareth, winning two seats. Until the 1960s all Arab parties in the Knesset were aligned with Mapai, the ruling party.

A minority of Arabs join and vote for Zionist parties; in the 2006 elections 30% of the Arab vote went to such parties, up from 25% in 2003,[252] though down on the 1999 (31%) and 1996 elections (33%).[253] Left-wing parties (i.e. Labor Party and Meretz-Yachad, and previously One Nation) are the most popular parties amongst Arabs, though some Druze have also voted for right-wing parties such as Likud and Yisrael Beiteinu, as well as the centrist Kadima.[254][255]

Arab-dominated parties typically do not join governing coalitions. However, historically these parties have formed alliances with dovish Jewish parties and promoted the formation of their governments by voting with them from the opposition. Arab parties are credited with keeping Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in power, and they have suggested they would do the same for a government led by Labor leader Isaac Herzog and peace negotiator Tzipi Livni.[256][257] A 2015 Haaretz poll found that a majority of Israeli Arabs would like their parties, then running on a joint list, to join the governing coalition.[258]

Representation in the Knesset

Palestinian Arabs sat in the state's first parliamentary assembly in 1949. In 2011, 13 of the 120 members of the Israeli Parliament are Arab citizens, most representing Arab political parties, and one of Israel's Supreme Court judges is a Palestinian Arab.[259]

The 2015 elections included 18 Arab members of Knesset. Along with 13 members of the Joint List, there were five Arab parliamentarians representing Zionist parties, which is more than double their number in the previous Knesset.[260][261]

Some Arab Members of the Knesset, past and present, are under police investigation for their visits to countries designated as enemy countries by Israeli law. This law was amended following MK Mohammad Barakeh's trip to Syria in 2001, such that MKs must explicitly request permission to visit these countries from the Minister of the Interior. In August 2006, Balad MKs Azmi Bishara, Jamal Zahalka, and Wasil Taha visited Syria without requesting nor receiving such permission, and a criminal investigation of their actions was launched. Former Arab Member of Knesset Mohammed Miari was questioned 18 September 2006 by police on suspicion of having entered a designated enemy country without official permission. He was questioned "under caution" for 2.5 hours in the Petah Tikva station about his recent visit to Syria. Another former Arab Member of Knesset, Muhammad Kanaan, was also summoned for police questioning regarding the same trip.[262] In 2010, six Arab MKs visited Libya, an openly anti-Zionist Arab state, and met with Muammar al-Gaddafi and various senior government officials. Gaddafi urged them to seek a one-state solution, and for Arabs to "multiply" in order to counter any "plots" to expel them.[263]

According to a study commissioned by the Arab Association of Human Rights entitled "Silencing Dissent", over the period 1999–2002, eight of nine of the then Arab Knesset members were beaten by Israeli forces during demonstrations.[264] Most recently according to the report, legislation has been passed, including three election laws [e.g., banning political parties], and two Knesset related laws aimed to "significantly curb the minority [Arab population] right to choose a public representative and for those representatives to develop independent political platforms and carry out their duties".[265]

The Knesset Ethics Committee has on several occasions banned Arab MKs that the committee felt were acting outside acceptable norms. In 2016, Hanin Zoabi and Jamal Zahalka were banned from plenary sessions for four months and Basel Ghattas for two months after they had visited families of Palestinian attackers killed by Israeli security forces.[266] Ghattas was again banned for six months in 2017 over charges of having smuggled cell phones to Palestinian prisoners[267] and Zoabi was banned for a week for having called IDF soldiers "murderers."[268]

In 2016, the Knesset passed a controversial law that would allow it to impeach any MK who incites racism or supports armed struggle against Israel. Critics said that the law was undemocratic and would mainly be used to silence Arab MKs.[269] As of 2020, no MK has been impeached by the law.[citation needed] In 2018, the Israeli supreme court of justice rejected arguments that the law would harm specific political parties and ruled that checks and balances within the law serve as sufficient protection against abuse of rights. For example, the law requires 70 Knesset members, 10 of whom must be from the opposition, to petition to the Knesset House Committee, and could only be finalized with a vote of 90 out of 120 MKs in favor of the impeachment.[270]

Representation in the civil service sphere

In the public employment sphere, by the end of 2002, 6% of 56,362 Israeli civil servants were Arab.[271] In January 2004, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon declared that every state-run company must have at least one Arab citizen of Israel on its board of directors.[272]

Representation in political, judicial and military positions

Knesset:Arab citizens of Israel have been elected to every Knesset, and as of 2015[update] held 17 of its 120 seats. The first female Arab MP was Hussniya Jabara, a Muslim Arab from central Israel, who was elected in 1999.[273]

Government: Until 2001, no Arab had been included Israel's cabinet. In 2001, this changed, when Salah Tarif, a Druze Arab citizen of Israel, was appointed a member of Ariel Sharon's cabinet without a portfolio. Tarif was later ejected after being convicted of corruption.[274] The first non-Druze Arab minister in Israel's history was Raleb Majadele, who in 2007 was appointed a minister without portfolio, and a month later appointed minister for Science, Culture and Sport.[100][275] Following this precedent, additional Muslim Arabs served as ministers or deputy ministers, including Issawi Frej, Abd el-Aziz el-Zoubi and Nawaf Massalha[276]

The appointment of Majadele was criticized by far-right Israelis, some of whom are also within the Cabinet, but this drew condemnation across the mainstream Israeli political spectrum.[101][277] Meanwhile, Arab lawmakers called the appointment an attempt to "whitewash Israel's discriminatory policies against its Arab minority".[278][279]

Supreme Court:Abdel Rahman Zuabi, a Muslim from northern Israel, was the first Arab on the Israeli Supreme Court, serving a 9-month term in 1999. In 2004, Salim Joubran, a Christian Arab from Haifa descended from Lebanese Maronites, became the first Arab to hold a permanent appointment on the Court. Joubran's expertise lies in the field of criminal law.[280][better source needed] George Karra, a Christian Arab from Jaffa has served as a Tel Aviv District Court judge since 2000. He was the presiding judge in the trial of Moshe Katsav. In 2011, he was nominated as a candidate for the Israeli Supreme Court.[281]

Foreign Service:Ali Yahya, an Arab Muslim, became the first Arab ambassador for Israel in 1995 when he was appointed ambassador to Finland. He served until 1999, and in 2006 was appointed ambassador to Greece. Other Arab ambassadors include Walid Mansour, a Druze, appointed ambassador to Vietnam in 1999, and Reda Mansour, also a Druze, a former ambassador to Ecuador. Mohammed Masarwa, an Arab Muslim, was Consul-General in Atlanta. In 2006, Ishmael Khaldi was appointed Israeli consul in San Francisco, becoming the first Bedouin consul of the State of Israel.[282]

Israel Defense Forces:Arab Generals in the IDF include Major General Hussain Fares, commander of Israel's border police, and Major General Yosef Mishlav, head of the Home Front Command and current Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories.[citation needed] Both are members of the Druze community. Other high-ranking officers in the IDF include Lieutenant Colonel Amos Yarkoni (born Abd el-Majid Haydar/ عبد الماجد حيدر) from the Bedouin community, a legendary officer in the Israel Defense Forces and one of six Israeli Arabs to have received the IDF's third highest decoration, the Medal of Distinguished Service.

Israeli Police:In 2011, Jamal Hakroush became the first Muslim Arab deputy Inspector-General in the Israeli Police. He has previously served as district commander of two districts.[283]

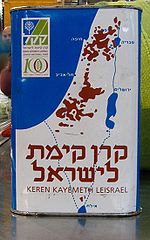

Jewish National Fund:In 2007, Ra'adi Sfori became the first Arab citizen of Israel to be elected as a JNF director, over a petition against his appointment. The court upheld the JNF's appointment, explaining, "As this is one director among a large number, there is no chance he will have the opportunity to cancel the organization's goals."[284]

Other political organizations and movements

- Abna el-Balad

Abnaa el-Balad[285] is a political movement that grew out of organizing by Arab university youth, beginning in 1969.[286][287] It is not affiliated with the Arab Knesset party Balad. While participating in municipal elections, Abnaa al-Balad firmly reject any participation in the Israeli Knesset. Political demands include "the return of all Palestinian refugees to their homes and lands, [an] end [to] the Israeli occupation and Zionist apartheid and the establishment [of] a democratic secular state in Palestine as the ultimate solution to the Arab-Zionist conflict."[288]

- High Follow-Up Committee for Arab Citizens of Israel

The High Follow-Up Committee for Arab Citizens of Israel is an extra-parliamentary umbrella organization that represents Arab citizens of Israel at the national level.[289] It is "the top representative body deliberating matters of general concern to the entire Arab community and making binding decisions."[290] While it enjoys de facto recognition from the State of Israel, it lacks official or de jure recognition from the state for its activities in this capacity.[289]

- Ta'ayush

Ta'ayush is "a grassroots movement of Arabs and Jews working to break down the walls of racism and segregation by constructing a true Arab-Jewish partnership."[291]

- Regional Council of Unrecognized Villages

The Regional Council of Unrecognized Villages is a body of unofficial representatives of the unrecognized villages throughout the Negev region in the south.

Attempts to ban Arab political parties

Amendment 9 to the 'Basic Law: The Knesset and the Law of Political Parties' states that a political party "may not participate in the elections if there is in its goals or actions a denial of the existence of the State of Israel as the state of the Jewish people, a denial of the democratic nature of the state, or incitement to racism."[292][293] There have been a number of attempts to disqualify Arab parties based on this rule, however as of 2010, all such attempts were either rejected by the Israeli Central Elections Committee or overturned by the Israeli Supreme Court.

Progressive List for Peace

An Israeli Central Elections Committee ruling which allowed the Progressive List for Peace to run for the Knesset in 1988 was challenged based on this amendment, but the committee's decision was upheld by the Israeli Supreme Court, which ruled that the PLP's platform calling for Israel to become "a state of all its citizens" does not violate the ideology of Israel as the State of the Jewish people, and thus section 7(a) does not apply.[294]

Balad