Сидней

| Сидней Новый Южный Уэльс | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Карта агломерации Сиднея | |||||||||

| Координаты | 33 ° 52'04 "ю.ш., 151 ° 12'36" в.д. / 33,86778 ° ю.ш., 151,21000 ° в.д. | ||||||||

| Население | 5,450,496 (2023) [1] ( 1-й ) | ||||||||

| • Плотность | 441/км 2 (1140/кв. миль) (2023 г.) [1] | ||||||||

| Учредил | 26 января 1788 г | ||||||||

| Область | 12 367,7 км 2 (4775,2 квадратных миль) (GCCSA) [2] | ||||||||

| Часовой пояс | Восточное восточное время ( UTC+10 ) | ||||||||

| • Лето ( летнее время ) | АЕДТ ( UTC+11 ) | ||||||||

| Расположение | |||||||||

| LGA(s) | Разное (33) | ||||||||

| Графство | Камберленд [3] | ||||||||

| Государственный электорат (ы) | Разное (49) | ||||||||

| Федеральное подразделение (а) | Разное (24) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Сидней — столица штата Новый и Южный Уэльс самый густонаселенный город Австралии . Расположенный на восточном побережье Австралии, мегаполис окружает гавань Сиднея и простирается примерно на 80 км (50 миль) от Тихого океана на востоке до Голубых гор на западе и примерно на 80 км (50 миль) от Ку-ринг-гай. Национальный парк Чейз и река Хоксбери на севере и северо-западе, Королевский национальный парк и Макартур на юге и юго-западе. [5] Большой Сидней состоит из 658 пригородов, расположенных на 33 территориях местного самоуправления. Жителей города в просторечии называют «сиднейсайдцами». [6] Расчетная численность населения в июне 2023 года составляла 5 450 496 человек. [1] что составляет около 66% населения штата. [7] Прозвища города включают «Изумрудный город» и «Портовый город». [8]

Австралийские аборигены населяли регион Большого Сиднея не менее 30 000 лет, и их гравюры и культурные объекты широко распространены. Традиционными хранителями земли, на которой стоит современный Сидней, являются кланы народов даруг , дхаравал и эора . [9] Во время своего первого путешествия по Тихому океану в 1770 году Джеймс Кук нанес на карту восточное побережье Австралии и вышел на берег в заливе Ботани . В 1788 году Первый флот каторжников во главе с Артуром Филлипом основал Сидней как британскую исправительную колонию , первое европейское поселение в Австралии. [10] После Второй мировой войны в Сиднее произошла массовая миграция, и к 2021 году более 40 процентов населения родилось за границей. Зарубежными странами рождения с наибольшим представительством являются материковый Китай, Индия, Великобритания, Вьетнам и Филиппины. [11]

Несмотря на то, что это один из самых дорогих городов мира, [12] [13] Сидней часто входит в десятку самых пригодных для жизни городов . [14] [15] [16] классифицирует его как Альфа-город Сеть исследования глобализации и мировых городов , что указывает на его влияние в регионе и во всем мире. [17] [18] Занимает одиннадцатое место в мире по экономическим возможностям. [19] Сидней имеет развитую рыночную экономику с сильными сторонами в сфере образования, финансов, производства и туризма . [20] [21] и Сиднейский университет Университет Нового Южного Уэльса занимают 19-е место в мире. [22]

Сидней принимал крупные международные спортивные мероприятия, такие как летние Олимпийские игры 2000 года . Город входит в пятнадцать самых посещаемых городов. [23] миллионы туристов приезжают каждый год, чтобы увидеть достопримечательности города. [24] В городе более 1 000 000 га (2 500 000 акров) природных заповедников и парков . [25] и его примечательные природные особенности включают гавань Сиднея и Королевский национальный парк . Мост Харбор-Бридж в Сиднее , внесенный в список Всемирного наследия, и Сиднейский оперный театр являются основными туристическими достопримечательностями. Центральный вокзал является центром пригородных и легкорельсовых сетей Сиднея, а также служб дальнего следования, платформы метро находятся в стадии строительства. Основным пассажирским аэропортом, обслуживающим город, является аэропорт Кингсфорд Смит , один из старейших постоянно действующих аэропортов мира. [26]

Топонимия

[ редактировать ]В 1788 году капитан Артур Филлип , первый губернатор Нового Южного Уэльса, назвал бухту, где было основано первое британское поселение, Сиднейской бухтой в честь министра внутренних дел Томаса Таунсенда, 1-го виконта Сиднея . [27] Бухту называли Варрейн . аборигены [28] Филипп подумывал назвать поселение Альбион , но официально это название никогда не использовалось. [27] К 1790 году Филипп и другие официальные лица регулярно звонили в поселок Сидней. [29] Сидней был объявлен городом в 1842 году. [30]

Клан Гадигал Гади (Кадигал), территория которого простирается вдоль южного берега Порт-Джексона от Саут-Хед до Дарлинг-Харбор , являются традиционными владельцами земель, на которых изначально было основано британское поселение, и называют свою территорию ( Кади ) . Названия кланов аборигенов в регионе Сиднея часто образовывались путем добавления суффикса «-гал» к слову, обозначающему название их территории, конкретного места на их территории, источника пищи или тотема. Большой Сидней охватывает традиционные земли 28 известных кланов аборигенов. [31]

История

[ редактировать ]Первые жители региона

[ редактировать ]

Первыми людьми, населявшими территорию, ныне известную как Сидней, были австралийские аборигены , мигрировавшие из Юго-Восточной Азии через северную Австралию. [32] Чешуйчатая галька, найденная в гравийных отложениях Западного Сиднея, может указывать на человеческое существование от 45 000 до 50 000 лет назад. [33] в то время как радиоуглеродное датирование показало свидетельства человеческой деятельности в этом регионе примерно 30 000 лет назад. [34] До прибытия британцев в регионе Большого Сиднея проживало от 4000 до 8000 аборигенов. [35] [9]

Жители питались рыбной ловлей, охотой, собирательством растений и моллюсков. Диета прибрежных кланов в большей степени основывалась на морепродуктах, тогда как кланы внутренних районов ели больше лесных животных и растений. У кланов было своеобразное снаряжение и оружие, в основном сделанное из камня, дерева, растительных материалов, костей и панцирей. Они также различались украшениями на теле, прическами, песнями и танцами. Кланы аборигенов вели богатую церемониальную жизнь, являвшуюся частью системы верований, основанной на предках, тотемических и сверхъестественных существах. Люди из разных кланов и языковых групп собирались вместе для участия в инициации и других церемониях. Эти события способствовали торговле, бракам и клановым союзам. [36]

Первые британские поселенцы записали слово « Эора » как термин аборигенов, означающий либо «люди», либо «из этого места». [37] [9] Кланы Сиднея занимали земли с традиционными границами. Однако ведутся споры о том, к какой группе или нации принадлежали эти кланы, а также о степени различий в языке и обрядах. Основными группами были прибрежные народы Эора, Дхаруга (Даруга), занимавшие внутреннюю территорию от Парраматты до Голубых гор, и народ Дхаравал к югу от залива Ботани. [9] На языках даргинунг и гундунгурра говорили на окраинах Сиднея. [38]

Первая встреча аборигенов и британских исследователей произошла 29 апреля 1770 года, когда лейтенант Джеймс Кук высадился в заливе Ботани (Камай). [41] ) и столкнулся с кланом Гвеагал . [42] Двое мужчин из Гвеагала выступили против десанта, один был ранен. [43] [44] Кук и его команда пробыли в заливе Ботани неделю, собирая воду, древесину, корм и ботанические образцы, а также исследуя окрестности. Кук безуспешно пытался наладить отношения с аборигенным населением. [45]

Каторжный городок (1788–1840)

[ редактировать ]

Великобритания отправляла заключенных в свои американские колонии на протяжении большей части восемнадцатого века, и потеря этих колоний в 1783 году стала толчком к созданию исправительной колонии в Ботани-Бэй. Сторонники колонизации также указывали на стратегическую важность новой базы в Азиатско-Тихоокеанском регионе и ее потенциал для обеспечения военно-морского флота столь необходимой древесиной и льном. [46]

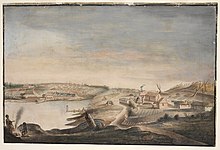

Первый флот из 11 кораблей под командованием капитана Артура Филлипа прибыл в залив Ботани в январе 1788 года. В его составе было более тысячи поселенцев, в том числе 736 каторжников. [47] Вскоре флот двинулся в более подходящий Порт-Джексон, было основано поселение в Сиднейской бухте . где 26 января 1788 года [48] Колония Новый Южный Уэльс была официально провозглашена губернатором Филиппом 7 февраля 1788 года. Сиднейская бухта предлагала запасы пресной воды и безопасную гавань, которую Филип описал как «лучшую гавань в мире… Здесь тысяча парусов линии». может ездить в самой совершенной безопасности». [49]

Поселение планировалось превратить в самодостаточную исправительную колонию, основанную на натуральном сельском хозяйстве. Торговля и судостроение были запрещены, чтобы изолировать осужденных. Однако почва вокруг поселения оказалась плохой, и первый урожай не удался, что привело к нескольким годам голода и строгому нормированию. Продовольственный кризис разрешился с прибытием Второго флота в середине 1790 года и Третьего флота в 1791 году. [50] Бывшие заключенные получили небольшие земельные наделы, а государственные и частные фермы распространились на более плодородные земли вокруг Парраматты , Виндзора и Камдена на Камберлендской равнине . К 1804 году колония была самообеспечена продовольствием. [51]

Эпидемия оспы в апреле 1789 года унесла жизни около половины коренного населения региона. [9] [52] В ноябре 1790 года Беннелонг привел группу выживших представителей сиднейских кланов в поселение, установив постоянное присутствие австралийских аборигенов в населенном Сиднее. [53]

Филиппу не было дано никаких инструкций по городскому развитию, но в июле 1788 года он представил план нового города в Сиднейской бухте . Он включал широкий центральный проспект, постоянный Дом правительства, суды, больницу и другие общественные здания, но не предусматривал складов, магазинов или других коммерческих зданий. Филипп сразу же проигнорировал свой план, и незапланированная застройка стала особенностью топографии Сиднея. [54] [55]

После отъезда Филиппа в декабре 1792 года офицеры колонии начали приобретать землю и ввозить потребительские товары с заходивших кораблей. Бывшие осужденные занимались торговлей и открывали малый бизнес. Солдаты и бывшие заключенные строили дома на земле Короны, с официальным разрешением или без него, в месте, которое теперь обычно называлось Сиднеем. Губернатор Уильям Блай (1806–08) ввел ограничения на торговлю и приказал снести здания, построенные на землях Короны, в том числе некоторые, принадлежавшие бывшим и действующим военным офицерам. Возникший конфликт завершился Ромовым восстанием 1808 года, в ходе которого Блай был свергнут Корпусом Нового Южного Уэльса . [56] [57]

Губернатор Лахлан Маккуори (1810–1821) сыграл ведущую роль в развитии Сиднея и Нового Южного Уэльса, основав банк, валюту и больницу. Он нанял планировщика для проектирования улиц Сиднея и заказал строительство дорог, пристаней, церквей и общественных зданий. Парраматта-роуд , связывающая Сидней и Парраматту, была открыта в 1811 году. [58] а дорога через Голубые горы была завершена в 1815 году, открыв путь для крупномасштабного земледелия и выпаса скота к западу от Большого Водораздельного хребта . [59] [60]

После отъезда Маккуори официальная политика поощряла эмиграцию свободных британских поселенцев в Новый Южный Уэльс. Иммиграция в колонию увеличилась с 900 свободных поселенцев в 1826–1830 годах до 29 000 в 1836–40 годах, многие из которых поселились в Сиднее. [61] [62] К 1840-м годам в Сиднее возник географический разрыв между бедными жителями и жителями рабочего класса, живущими к западу от Танк-Стрим в таких районах, как Рокс , и более богатыми жителями, живущими к востоку от него. [62] Свободные поселенцы, свободнорожденные жители и бывшие заключенные теперь представляли подавляющее большинство населения Сиднея, что привело к усилению общественной агитации за ответственное правительство и прекращение транспорта. Транспортировка в Новый Южный Уэльс прекратилась в 1840 году. [63]

Конфликт на Камберлендской равнине

[ редактировать ]В 1804 году ирландские заключенные возглавили около 300 повстанцев в восстании Касл-Хилл , попытке пройти маршем на Сидней, захватить корабль и уплыть на свободу. [64] Плохо вооруженные и с захваченным в плен лидером Филипом Каннингемом, основные силы повстанцев были разбиты примерно 100 солдатами и добровольцами в Роуз-Хилл . В ходе восстания и последующих казней было убито не менее 39 осужденных. [65] [66]

По мере того как колония распространялась на более плодородные земли вокруг реки Хоксбери Сиднея, конфликт между поселенцами и народом даруг усиливался, достигнув пика с 1794 по 1810 год. -западу от , к северо сын Тедбери сжигал посевы, убивал скот и совершал набеги на магазины поселенцев, создавая образец сопротивления, который должен был повториться по мере расширения колониальных границ . В 1795 году на Хоксбери был создан военный гарнизон. Число погибших с 1794 по 1800 год составило 26 поселенцев и до 200 даругов. [67] [68]

Конфликт снова вспыхнул с 1814 по 1816 год, когда колония расширилась до страны Дхаравал в регионе Непин к юго-западу от Сиднея. После гибели нескольких поселенцев губернатор Маккуори направил три военных отряда на земли Дхаравала, кульминацией чего стала резня в Аппине (апрель 1816 г.), в которой было убито по меньшей мере 14 аборигенов. [69] [70]

Колониальный город (1841–1900)

[ редактировать ]Законодательный совет Нового Южного Уэльса стал полуизбираемым органом в 1842 году. В том же году Сидней был объявлен городом, и был создан управляющий совет, избранный на основе ограничительного права собственности. [63]

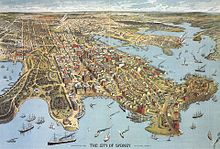

Открытие золота в Новом Южном Уэльсе и Виктории в 1851 году первоначально вызвало экономический кризис, поскольку люди перебрались на золотые прииски. Вскоре Мельбурн обогнал Сидней как крупнейший город Австралии, что привело к непрекращающемуся соперничеству между ними. Однако рост иммиграции из-за границы и богатство от экспорта золота увеличили спрос на жилье, потребительские товары, услуги и городские удобства. [71] Правительство Нового Южного Уэльса также стимулировало экономический рост, инвестируя значительные средства в железные дороги, трамваи, дороги, порты, телеграф, школы и городские службы. [72] Население Сиднея и его пригородов выросло с 95 600 в 1861 году до 386 900 в 1891 году. [73] В городе развились многие характерные черты. Растущее население теснилось в ряды домов с террасами на узких улицах. Появилось множество новых общественных зданий из песчаника, в том числе в Сиднейском университете (1854–1861 гг.), [74] Австралийский музей (1858–66), [75] Ратуша (1868–88), [76] и Главный почтамт (1866–92). [77] изысканные кофейные дворцы и отели. Были построены [78] Купание в дневное время на пляжах Сиднея было запрещено, но раздельное купание в специально отведенных океанских ваннах было популярно. [79]

Засуха, свертывание общественных работ и финансовый кризис привели к экономической депрессии в Сиднее на протяжении большей части 1890-х годов. Тем временем базирующийся в Сиднее премьер-министр Нового Южного Уэльса Джордж Рид стал ключевой фигурой в процессе создания федерации. [80]

Столица штата (1901 – настоящее время)

[ редактировать ]

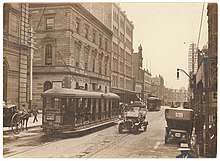

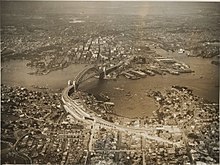

Когда 1 января 1901 года шесть колоний объединились, Сидней стал столицей штата Новый Южный Уэльс. Распространение бубонной чумы в 1900 году побудило правительство штата модернизировать причалы и снести трущобы в центре города. С началом Первой мировой войны в 1914 году в вооруженные силы добровольно вступило больше мужчин из Сиднея, чем власти Содружества смогли обработать, и это помогло снизить безработицу. Тем, кто вернулся с войны в 1918 году, были обещаны «дома, достойные героев» в новых пригородах, таких как Дейсивилл и Матравиль. «Садовые пригороды» и смешанная промышленная и жилая застройка также выросли вдоль железнодорожных и трамвайных коридоров. [62] Население достигло одного миллиона в 1926 году, после того как Сидней вернул себе позицию самого густонаселенного города Австралии. [81] Правительство создало рабочие места с помощью масштабных государственных проектов, таких как электрификация железнодорожной сети Сиднея и строительство моста Харбор-Бридж в Сиднее. [82]

Сидней сильнее пострадал от Великой депрессии 1930-х годов, чем региональный Новый Южный Уэльс или Мельбурн. [83] Новое строительство почти остановилось, и к 1933 году уровень безработицы среди рабочих-мужчин составлял 28 процентов, но более 40 процентов в рабочих районах, таких как Александрия и Редферн. Многие семьи были выселены из своих домов, а вдоль побережья Сиднея и Ботани-Бей выросли трущобы, крупнейшим из которых была «Счастливая долина» в Лаперузе . [84] Депрессия также обострила политические разногласия. В марте 1932 года, когда премьер-министр-популист от Лейбористской партии Джек Лэнг попытался открыть мост Харбор-Бридж в Сиднее, его отодвинул на второй план Фрэнсис де Гроот из крайне правой Новой гвардии , который перерезал ленточку саблей. [85]

В январе 1938 года Сидней отпраздновал Имперские игры и полуторасотлетие европейского поселения в Австралии. Один журналист написал: «Золотые пляжи. Загорелые мужчины и девушки... Виллы с красными крышами, расположенные террасами над голубыми водами гавани... Даже Мельбурн кажется каким-то серым и величественным городом Северной Европы по сравнению с субтропическим великолепием Сиднея. ." Конгресс «Аборигенов Австралии» объявил 26 января « Днем траура » по «захвату нашей страны белыми людьми». [86]

С началом Второй мировой войны в 1939 году Сидней пережил всплеск промышленного развития. Безработица практически исчезла, и женщины заняли рабочие места, ранее обычно предназначенные для мужчин. Сидней подвергся нападению японских подводных лодок в мае и июне 1942 года, в результате чего погиб 21 человек. Домохозяйства построили бомбоубежища и провели учения. [87] Военные учреждения в ответ на Вторую мировую войну в Австралии включали систему туннелей Гарден-Айленд , единственный туннельный военный комплекс в Сиднее, а также внесенные в список наследия военные фортификационные системы Bradleys Head Fortification Complex и Middle Head Fortifications , которые были частью общей системы обороны. для Сиднейской гавани . [88]

Послевоенный иммиграционный и бэби-бум привел к быстрому увеличению населения Сиднея и распространению жилья с низкой плотностью застройки в пригородах по всей равнине Камберленд. Иммигранты — в основном из Великобритании и континентальной Европы — и их дети составляли более трех четвертей прироста населения Сиднея в период с 1947 по 1971 год. [89] Недавно созданный Совет графства Камберленд курировал жилые комплексы с низкой плотностью застройки, самые крупные в Грин-Вэлли и Маунт-Друитт . Старые жилые центры, такие как Парраматта, Бэнкстаун и Ливерпуль, стали пригородами мегаполиса. [90] В промышленности, защищенной высокими тарифами, с 1945 по 1960-е годы было занято более трети рабочей силы. Однако по мере развития длительного послевоенного экономического бума розничная торговля и другие сферы услуг стали основным источником новых рабочих мест. [91]

Приблизительно один миллион зрителей, большая часть населения города, наблюдали, как королева Елизавета II приземлилась в 1954 году в бухте Фарм, где капитан Филипп поднял Юнион Джек 165 лет назад, начав свое королевское турне по Австралии . Это был первый раз, когда правящий монарх ступил на австралийскую землю. [92]

Рост высотной застройки в Сиднее и расширение пригородов за пределы «зеленого пояса», предусмотренного планировщиками 1950-х годов, привели к протестам населения. В начале 1970-х годов профсоюзы и местные инициативные группы ввели зеленый запрет на проекты развития в исторических районах, таких как Рокс. Федеральные органы власти, правительства штатов и местные органы власти приняли законодательство о наследии и охране окружающей среды. [62] Сиднейский оперный театр также вызвал споры из-за своей стоимости и споров между архитектором Йорном Утцоном и правительственными чиновниками. Однако вскоре после открытия в 1973 году он стал главной туристической достопримечательностью и символом города. [93] Постепенное снижение тарифной защиты с 1974 года положило начало превращению Сиднея из производственного центра в «мировой город». [94] С 1980-х годов зарубежная иммиграция быстро росла, причем основными источниками стали Азия , Ближний Восток и Африка . К 2021 году население Сиднея превысило 5,2 миллиона человек, из которых 40% населения родились за рубежом. Китай и Индия обогнали Англию как крупнейшие страны-источники иностранцев. [95]

География

[ редактировать ]Топография

[ редактировать ]

Сидней представляет собой прибрежный бассейн с Тасмановым морем на востоке, Голубыми горами на западе, рекой Хоксбери на севере и плато Воронора на юге.

Сидней охватывает два географических региона. Равнина Камберленд расположена к югу и западу от гавани и относительно плоская. Плато Хорнсби расположено на севере и расчленено крутыми долинами. Равнинные районы юга были застроены первыми; только после строительства моста Харбор-Бридж в Сиднее северные районы стали более густонаселенными. Вдоль береговой линии можно найти семьдесят пляжей для серфинга , самым известным из которых является пляж Бонди.

The Nepean River wraps around the western edge of the city and becomes the Hawkesbury River before reaching Broken Bay. Most of Sydney's water storages can be found on tributaries of the Nepean River. The Parramatta River is mostly industrial and drains a large area of Sydney's western suburbs into Port Jackson. The southern parts of the city are drained by the Georges River and the Cooks River into Botany Bay.

There is no single definition of the boundaries of Sydney. The Australian Statistical Geography Standard definition of Greater Sydney covers 12,369 km2 (4,776 sq mi) and includes the local government areas of Central Coast in the north, Hawkesbury in the north-west, Blue Mountains in the west, Sutherland Shire in the south, and Wollondilly in the south-west.[96] The local government area of the City of Sydney covers about 26 square kilometres from Garden island in the east to Bicentennial Park in the west, and south to the suburbs of Alexandria and Rosebery.[97]

Geology

[edit]

Sydney is made up of mostly Triassic rock with some recent igneous dykes and volcanic necks (typically found in the Prospect dolerite intrusion, west of Sydney).[98] The Sydney Basin was formed in the early Triassic period.[99] The sand that was to become the sandstone of today was laid down between 360 and 200 million years ago. The sandstone has shale lenses and fossil riverbeds.[99]

The Sydney Basin bioregion includes coastal features of cliffs, beaches, and estuaries. Deep river valleys known as rias were carved during the Triassic period in the Hawkesbury sandstone of the coastal region. The rising sea level between 18,000 and 6,000 years ago flooded the rias to form estuaries and deep harbours.[99] Port Jackson, better known as Sydney Harbour, is one such ria.[100] Sydney features two major soil types: sandy soils (which originate from the Hawkesbury sandstone) and clay (which are from shales and volcanic rocks), though some soils may be a mixture of the two.[101]

Directly overlying the older Hawkesbury sandstone is the Wianamatta shale, a geological feature found in western Sydney that was deposited in connection with a large river delta during the Middle Triassic. The Wianamatta shale generally comprises fine grained sedimentary rocks such as shales, mudstones, ironstones, siltstones and laminites, with less common sandstone units.[102] The Wianamatta Group is made up of Bringelly Shale, Minchinbury Sandstone and Ashfield Shale.[103]

Ecology

[edit]

The most prevalent plant communities in the Sydney region are grassy woodlands (i.e. savannas)[104] and some pockets of dry sclerophyll forests,[105] which consist of eucalyptus trees, casuarinas, melaleucas, corymbias and angophoras, with shrubs (typically wattles, callistemons, grevilleas and banksias), and a semi-continuous grass in the understory.[106] The plants in this community tend to have rough, spiky leaves due to low soil fertility. Sydney also features a few areas of wet sclerophyll forests in the wetter, elevated areas in the north and northeast. These forests are defined by straight, tall tree canopies with a moist understory of soft-leaved shrubs, tree ferns and herbs.[107]

The predominant vegetation community in Sydney is the Cumberland Plain Woodland in Western Sydney (Cumberland Plain),[108] followed by the Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest in the Inner West and Northern Sydney,[109] the Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub in the coastline and the Blue Gum High Forest scantily present in the North Shore – all of which are critically endangered.[110][111] The city also includes the Sydney Sandstone Ridgetop Woodland found in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park on the Hornsby Plateau to the north.[112]

Sydney is home to dozens of bird species,[113] which commonly include the Australian raven, Australian magpie, crested pigeon, noisy miner and the pied currawong. Introduced bird species ubiquitously found in Sydney are the common myna, common starling, house sparrow and the spotted dove.[114] Reptile species are also numerous and predominantly include skinks.[115][116] Sydney has a few mammal and spider species, such as the grey-headed flying fox and the Sydney funnel-web, respectively,[117][118] and has a huge diversity of marine species inhabiting its harbour and beaches.[119]

Climate

[edit]

Under the Köppen–Geiger classification, Sydney has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa)[120] with "warm, sometimes hot" summers and "generally mild",[121][122][123] to "cool" winters.[124] The El Niño–Southern Oscillation, the Indian Ocean Dipole and the Southern Annular Mode[125][126] play an important role in determining Sydney's weather patterns: drought and bushfire on the one hand, and storms and flooding on the other, associated with the opposite phases of the oscillation in Australia. The weather is moderated by proximity to the ocean, and more extreme temperatures are recorded in the inland western suburbs.[127]

At Sydney's primary weather station at Observatory Hill, extreme temperatures have ranged from 45.8 °C (114.4 °F) on 18 January 2013 to 2.1 °C (35.8 °F) on 22 June 1932.[128][129][130] An average of 14.9 days a year have temperatures at or above 30 °C (86 °F) in the central business district (CBD).[127] In contrast, the metropolitan area averages between 35 and 65 days, depending on the suburb.[131] The hottest day in the metropolitan area occurred in Penrith on 4 January 2020, where a high of 48.9 °C (120.0 °F) was recorded.[132] The average annual temperature of the sea ranges from 18.5 °C (65.3 °F) in September to 23.7 °C (74.7 °F) in February.[133] Sydney has an average of 7.2 hours of sunshine per day[134] and 109.5 clear days annually.[4] Due to the inland location, frost is recorded early in the morning in Western Sydney a few times in winter. Autumn and spring are the transitional seasons, with spring showing a larger temperature variation than autumn.[135]

Sydney experiences an urban heat island effect.[136] This makes certain parts of the city more vulnerable to extreme heat, including coastal suburbs.[136][137] In late spring and summer, temperatures over 35 °C (95 °F) are not uncommon,[138] though hot, dry conditions are usually ended by a southerly buster,[139] a powerful southerly that brings gale winds and a rapid fall in temperature.[140] Since Sydney is downwind of the Great Dividing Range, it occasionally experiences dry, westerly foehn winds typically in winter and early spring (which are the reason for its warm maximum temperatures).[141][142][143] Westerly winds are intense when the Roaring Forties (or the Southern Annular Mode) shift towards southeastern Australia,[144] where they may damage homes and affect flights, in addition to making the temperature seem colder than it actually is.[145][146]

Rainfall has a moderate to low variability and has historically been fairly uniform throughout the year, although in recent years it has been more summer-dominant and erratic.[147][148][149][150] Precipitation is usually higher in summer through to autumn,[122] and lower in late winter to early spring.[125][151][127][152] In late autumn and winter, east coast lows may bring large amounts of rainfall, especially in the CBD.[153] In the warm season black nor'easters are usually the cause of heavy rain events, though other forms of low-pressure areas, including remnants of ex-cyclones, may also bring heavy deluge and afternoon thunderstorms.[154][155] Snowfall was last reported in 1836, though a fall of graupel, or soft hail, in the Upper North Shore was mistaken by many for snow, in July 2008.[156] In 2009, dry conditions brought a severe dust storm towards the city.[157][158]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 45.8 (114.4) | 42.1 (107.8) | 39.8 (103.6) | 35.4 (95.7) | 30.0 (86.0) | 26.9 (80.4) | 26.5 (79.7) | 31.3 (88.3) | 34.6 (94.3) | 38.2 (100.8) | 41.8 (107.2) | 42.2 (108.0) | 45.8 (114.4) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 36.8 (98.2) | 34.1 (93.4) | 32.2 (90.0) | 29.7 (85.5) | 26.2 (79.2) | 22.3 (72.1) | 22.9 (73.2) | 25.4 (77.7) | 29.9 (85.8) | 33.6 (92.5) | 34.1 (93.4) | 34.4 (93.9) | 38.8 (101.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) | 26.8 (80.2) | 25.7 (78.3) | 23.6 (74.5) | 20.9 (69.6) | 18.3 (64.9) | 17.9 (64.2) | 19.3 (66.7) | 21.6 (70.9) | 23.2 (73.8) | 24.2 (75.6) | 25.7 (78.3) | 22.8 (73.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.5 (74.3) | 23.4 (74.1) | 22.1 (71.8) | 19.5 (67.1) | 16.6 (61.9) | 14.2 (57.6) | 13.4 (56.1) | 14.5 (58.1) | 17.0 (62.6) | 18.9 (66.0) | 20.4 (68.7) | 22.1 (71.8) | 18.8 (65.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) | 19.9 (67.8) | 18.4 (65.1) | 15.3 (59.5) | 12.3 (54.1) | 10.0 (50.0) | 8.9 (48.0) | 9.7 (49.5) | 12.3 (54.1) | 14.6 (58.3) | 16.6 (61.9) | 18.4 (65.1) | 14.7 (58.5) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 16.1 (61.0) | 16.1 (61.0) | 14.2 (57.6) | 11.0 (51.8) | 8.3 (46.9) | 6.5 (43.7) | 5.7 (42.3) | 6.1 (43.0) | 8.0 (46.4) | 9.8 (49.6) | 12.0 (53.6) | 13.9 (57.0) | 5.3 (41.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) | 9.6 (49.3) | 9.3 (48.7) | 7.0 (44.6) | 4.4 (39.9) | 2.1 (35.8) | 2.2 (36.0) | 2.7 (36.9) | 4.9 (40.8) | 5.7 (42.3) | 7.7 (45.9) | 9.1 (48.4) | 2.1 (35.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 91.1 (3.59) | 131.5 (5.18) | 117.5 (4.63) | 114.1 (4.49) | 100.8 (3.97) | 142.0 (5.59) | 80.3 (3.16) | 75.1 (2.96) | 63.4 (2.50) | 67.7 (2.67) | 90.6 (3.57) | 73.0 (2.87) | 1,149.7 (45.26) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 8.2 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 9.3 | 7.2 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 95.2 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 60 | 62 | 59 | 58 | 58 | 56 | 52 | 47 | 49 | 53 | 57 | 58 | 56 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) | 17.2 (63.0) | 15.4 (59.7) | 12.7 (54.9) | 10.3 (50.5) | 7.8 (46.0) | 6.1 (43.0) | 5.4 (41.7) | 7.8 (46.0) | 10.2 (50.4) | 12.6 (54.7) | 14.6 (58.3) | 11.4 (52.5) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 232.5 | 205.9 | 210.8 | 213.0 | 204.6 | 171.0 | 207.7 | 248.0 | 243.0 | 244.9 | 222.0 | 235.6 | 2,639 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 53 | 54 | 55 | 63 | 63 | 57 | 66 | 72 | 67 | 61 | 55 | 55 | 60 |

| Source 1: Bureau of Meteorology[159][160][161][162] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Bureau of Meteorology, Sydney Airport (sunshine hours)[163] | |||||||||||||

Regions

[edit]

The Greater Sydney Commission divides Sydney into three "cities" and five "districts" based on the 33 LGAs in the metropolitan area. The "metropolis of three cities" comprises Eastern Harbour City, Central River City and Western Parkland City.[164] The Australian Bureau of Statistics also includes City of Central Coast (the former Gosford City and Wyong Shire) as part of Greater Sydney for population counts,[165] adding 330,000 people.[166]

Inner suburbs

[edit]

The CBD extends about 3 km (1.9 mi) south from Sydney Cove. It is bordered by Farm Cove within the Royal Botanic Garden to the east and Darling Harbour to the west. Suburbs surrounding the CBD include Woolloomooloo and Potts Point to the east, Surry Hills and Darlinghurst to the south, Pyrmont and Ultimo to the west, and Millers Point and The Rocks to the north. Most of these suburbs measure less than 1 km2 (0.4 sq mi) in area. The Sydney CBD is characterised by narrow streets and thoroughfares, created in its convict beginnings.[167]

Several localities, distinct from suburbs, exist throughout Sydney's inner reaches. Central and Circular Quay are transport hubs with ferry, rail, and bus interchanges. Chinatown, Darling Harbour, and Kings Cross are important locations for culture, tourism, and recreation. The Strand Arcade, located between Pitt Street Mall and George Street, is a historical Victorian-style shopping arcade. Opened on 1 April 1892, its shop fronts are an exact replica of the original internal shopping facades.[168] Westfield Sydney, located beneath the Sydney Tower, is the largest shopping centre by area in Sydney.[169]

Since the late 20th century, there has been a trend of gentrification amongst Sydney's inner suburbs. Pyrmont, located on the harbour, was redeveloped from a centre of shipping and international trade to an area of high density housing, tourist accommodation, and gambling.[170] Originally located well outside of the city, Darlinghurst is the location of the historic Darlinghurst Gaol, manufacturing, and mixed housing. For a period it was known as an area of prostitution. The terrace-style housing has largely been retained and Darlinghurst has undergone significant gentrification since the 1980s.[171][172][173]

Green Square is a former industrial area of Waterloo which is undergoing urban renewal worth $8 billion. On the city harbour edge, the historic suburb and wharves of Millers Point are being built up as the new area of Barangaroo.[174][175] The suburb of Paddington is known for its restored terrace houses, Victoria Barracks, and shopping including the weekly Oxford Street markets.[176]

Inner West

[edit]

The Inner West generally includes the Inner West Council, Municipality of Burwood, Municipality of Strathfield, and City of Canada Bay. These span up to about 11 km west of the CBD. Historically, especially prior to the building of the Harbour Bridge,[177] the outer suburbs of the Inner West such as Strathfield were the location of "country" estates for the colony's elites. By contrast, the inner suburbs in the Inner West, being close to transport and industry, have historically housed working-class industrial workers. These areas have undergone gentrification in the late 20th century, and many parts are now highly valued residential suburbs.[178] As of 2021, an Inner West suburb (Strathfield) remained one of the 20 most expensive postcodes in Australia by median house price (the others were all in metropolitan Sydney, all in Northern Sydney or the Eastern Suburbs).[179] The University of Sydney is located in this area, as well as the University of Technology, Sydney and a campus of the Australian Catholic University. The Anzac Bridge spans Johnstons Bay and connects Rozelle to Pyrmont and the city, forming part of the Western Distributor.

The Inner West is today well known as the location of village commercial centres with cosmopolitan flavours, such as the "Little Italy" commercial centres of Leichardt, Five Dock and Haberfield,[180] "Little Portugal" in Petersham,[181] "Little Korea" in Strathfield[182] or "Little Shanghai" in Ashfield.[183] Large-scale shopping centres in the area include Westfield Burwood, DFO Homebush and Birkenhead Point Outlet Centre. There is a large cosmopolitan community and nightlife hub on King Street in Newtown.

The area is serviced by the T1, T2, and T3 railway lines, including the Main Suburban Line, which was the first to be constructed in New South Wales. Strathfield railway station is a secondary railway hub within Sydney, and major station on the Suburban and Northern lines. It was constructed in 1876.[184] The future Sydney Metro West will also connect this area with the City and Parramatta. The area is also serviced by the Parramatta River services of Sydney Ferries,[185] numerous bus routes and cycleways.[186]

Eastern suburbs

[edit]

The Eastern Suburbs encompass the Municipality of Woollahra, the City of Randwick, the Waverley Municipal Council, and parts of the Bayside Council. They include some of the most affluent and advantaged areas in the country, with some streets being amongst the most expensive in the world. As at 2014, Wolseley Road, Point Piper, had a top price of $20,900 per square metre, making it the ninth-most expensive street in the world.[188] More than 75% of neighbourhoods in the Electoral District of Wentworth fall under the top decile of SEIFA advantage, making it the least disadvantaged area in the country.[189] As of 2021, of the 20 most expensive postcodes in Australia by median house price, nine were in the Eastern Suburbs.[179]

Major landmarks include Bondi Beach, which was added to the Australian National Heritage List in 2008;[190] and Bondi Junction, featuring a Westfield shopping centre and an estimated office workforce of 6,400 by 2035,[191] as well as a railway station on the T4 Eastern Suburbs Line. The suburb of Randwick contains Randwick Racecourse, the Royal Hospital for Women, the Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney Children's Hospital, and University of New South Wales Kensington Campus.[192]

Construction of the CBD and South East Light Rail was completed in April 2020.[193] The project aims to provide reliable and high-capacity tram services to residents in the City and South-East.

Major shopping centres in the area include Westfield Bondi Junction and Westfield Eastgardens.

Southern Sydney

[edit]

The Southern district of Sydney includes the suburbs in the local government areas of the Georges River Council (collectively known as St George) and the Sutherland Shire (colloquially known as 'The Shire'), on the southern banks of the Georges River.

The Kurnell peninsula, near Botany Bay, is the site of the first landfall on the eastern coastline made by James Cook in 1770. La Perouse, a historic suburb named after the French navigator Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse, is notable for its old military outpost at Bare Island and the Botany Bay National Park.

The suburb of Cronulla in southern Sydney is close to Royal National Park, Australia's oldest national park. Hurstville, a large suburb with commercial and high-rise residential buildings dominating the skyline, has become a CBD for the southern suburbs.[194]

Northern Sydney

[edit]

'Northern Sydney' may also include the suburbs in the Upper North Shore, Lower North Shore and the Northern Beaches.

The Northern Suburbs include several landmarks – Macquarie University, Gladesville Bridge, Ryde Bridge, Macquarie Centre and Curzon Hall in Marsfield. This area includes suburbs in the local government areas of Hornsby Shire, Ku-ring-gai Council, City of Ryde, the Municipality of Hunter's Hill and parts of the City of Parramatta.

The North Shore includes the commercial centres of North Sydney and Chatswood. North Sydney itself consists of a large commercial centre, which contains the second largest concentration of high-rise buildings in Sydney after the CBD. North Sydney is dominated by advertising, marketing and associated trades, with many large corporations holding offices.

The Northern Beaches area includes Manly, one of Sydney's most popular holiday destinations for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The region also features Sydney Heads, a series of headlands which form the entrance to Sydney Harbour. The Northern Beaches area extends south to the entrance of Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour), west to Middle Harbour and north to the entrance of Broken Bay. The 2011 Australian census found the Northern Beaches to be the most white and mono-ethnic district in Australia, contrasting with its more-diverse neighbours, the North Shore and the Central Coast.[195]

As of the end of 2021, half of the 20 most expensive postcodes in Australia (by median house price) were in Northern Sydney, including four on the Northern Beaches, two on the Lower North Shore, three on the Upper North Shore, and one straddling Hunters Hill and Woolwich.[179]

Hills district

[edit]The Hills district generally refers to the suburbs in north-western Sydney including the local government areas of The Hills Shire, parts of the City of Parramatta Council and Hornsby Shire. Actual suburbs and localities that are considered to be in the Hills District can be somewhat amorphous. For example, the Hills District Historical Society restricts its definition to the Hills Shire local government area, yet its study area extends from Parramatta to the Hawkesbury. The region is so named for its characteristically comparatively hilly topography as the Cumberland Plain lifts up, joining the Hornsby Plateau. Windsor and Old Windsor Roads are the second and third roads, respectively, laid in Australia.[196]

Western suburbs

[edit]

The greater western suburbs encompasses the areas of Parramatta, the sixth largest business district in Australia, settled the same year as the harbour-side colony,[197] Bankstown, Liverpool, Penrith, and Fairfield. Covering 5,800 km2 (2,200 sq mi) and having an estimated population as at 2017 of 2,288,554, western Sydney has the most multicultural suburbs in the country – Cabramatta has earned the nickname "Little Saigon" due to its Vietnamese population, Fairfield has been named "Little Assyria" for its predominant Assyrian population and Harris Park is known as "Little India" with its plurality of Indian and Hindu population.[198][199][200][201] The population is predominantly of a working class background, with major employment in the heavy industries and vocational trade.[202] Toongabbie is noted for being the third mainland settlement (after Sydney and Parramatta) set up after British colonisation began in 1788, although the site of the settlement is actually in the separate suburb of Old Toongabbie.[203]

The western suburb of Prospect, in the City of Blacktown, is home to Raging Waters, a water park operated by Parques Reunidos.[204] Auburn Botanic Gardens, a botanical garden in Auburn, attracts thousands of visitors each year, including many from outside Australia.[205] The greater west also includes Sydney Olympic Park, a suburb created to host the 2000 Summer Olympics, and Sydney Motorsport Park, a circuit in Eastern Creek.[206] Prospect Hill, a historically significant ridge in the west and the only area in Sydney with ancient volcanic activity,[207] is also listed on the State Heritage Register.[208]

To the northwest, Featherdale Wildlife Park, a zoo in Doonside, near Blacktown, is a major tourist attraction.[209] Sydney Zoo, opened in 2019, is another prominent zoo situated in Bungaribee.[210] Established in 1799, the Old Government House, a historic house museum and tourist spot in Parramatta, was included in the Australian National Heritage List on 1 August 2007 and World Heritage List in 2010 (as part of the 11 penal sites constituting the Australian Convict Sites), making it the only site in greater western Sydney to be featured in such lists.[211] The house is Australia's oldest surviving public building.[212]

Further to the southwest is the region of Macarthur and the city of Campbelltown, a significant population centre until the 1990s considered a region separate to Sydney proper. Macarthur Square, a shopping complex in Campbelltown, has become one of the largest shopping complexes in Sydney.[213] The southwest also features Bankstown Reservoir, the oldest elevated reservoir constructed in reinforced concrete that is still in use and is listed on the State Heritage Register.[214] The southwest is home to one of Sydney's oldest trees, the Bland Oak, which was planted in the 1840s by William Bland in Carramar.[215]

Urban structure

[edit]Architecture

[edit]The earliest structures in the colony were built to the bare minimum of standards. Governor Macquarie set ambitious targets for the design of new construction projects. The city now has a world heritage listed building, several national heritage listed buildings, and dozens of Commonwealth heritage listed buildings as evidence of the survival of Macquarie's ideals.[217][218][219]

In 1814, the Governor called on a convict named Francis Greenway to design Macquarie Lighthouse.[220] The lighthouse's Classical design earned Greenway a pardon from Macquarie in 1818 and introduced a culture of refined architecture that remains to this day.[221] Greenway went on to design the Hyde Park Barracks in 1819 and the Georgian style St James's Church in 1824.[222][223] Gothic-inspired architecture became more popular from the 1830s. John Verge's Elizabeth Bay House and St Philip's Church of 1856 were built in Gothic Revival style along with Edward Blore's Government House of 1845.[224][225] Kirribilli House, completed in 1858, and St Andrew's Cathedral, Australia's oldest cathedral,[226] are rare examples of Victorian Gothic construction.[224][227]

From the late 1850s there was a shift towards Classical architecture. Mortimer Lewis designed the Australian Museum in 1857.[228] The General Post Office, completed in 1891 in Victorian Free Classical style, was designed by James Barnet.[229] Barnet also oversaw the 1883 reconstruction of Greenway's Macquarie Lighthouse.[220][221] Customs House was built in 1844.[230] The neo-Classical and French Second Empire style Town Hall was completed in 1889.[231][232] Romanesque designs gained favour from the early 1890s. Sydney Technical College was completed in 1893 using both Romanesque Revival and Queen Anne approaches.[233] The Queen Victoria Building was designed in Romanesque Revival fashion by George McRae; completed in 1898,[234] it accommodates 200 shops across its three storeys.[235]

As the wealth of the settlement increased and Sydney developed into a metropolis after Federation in 1901, its buildings became taller. Sydney's first tower was Culwulla Chambers which topped out at 50 m (160 ft) making 12 floors. The Commercial Traveller's Club, built in 1908, was of similar height at 10 floors. It was built in a brick stone veneer and demolished in 1972.[236] This heralded a change in Sydney's cityscape and with the lifting of height restrictions in the 1960s there came a surge of high-rise construction.[237]

The Great Depression had a tangible influence on Sydney's architecture. New structures became more restrained with far less ornamentation. The most notable architectural feat of this period is the Harbour Bridge. Its steel arch was designed by John Bradfield and completed in 1932. A total of 39,000 tonnes of structural steel span the 503 m (1,650 ft) between Milsons Point and Dawes Point.[238][239]

Modern and International architecture came to Sydney from the 1940s. Since its completion in 1973 the city's Opera House has become a World Heritage Site and one of the world's most renowned pieces of Modern design. Jørn Utzon was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2003 for his work on the Opera House.[240] Sydney is home to Australia's first building by renowned Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry, the Dr Chau Chak Wing Building (2015). An entrance from The Goods Line–a pedestrian pathway and former railway line–is located on the eastern border of the site.

Contemporary buildings in the CBD include Citigroup Centre,[241] Aurora Place,[242] Chifley Tower,[243][244] the Reserve Bank building,[245] Deutsche Bank Place,[246] MLC Centre,[247] and Capita Centre.[248] The tallest structure is Sydney Tower, designed by Donald Crone and completed in 1981.[249] Due to the proximity of Sydney Airport, a maximum height restriction was imposed, now sitting at 330 metres (1083 feet).[250] Green bans and heritage overlays have been in place since at least 1977 to protect Sydney's heritage after controversial demolitions in the 1970s.[251]

Housing

[edit]

Sydney surpasses both New York City and Paris real estate prices, having some of the most expensive in the world.[252][253] The city remains Australia's most expensive housing market, with the mean house price at $1,142,212 as of December 2019 (over 25% higher the national mean house price).[254] It is only second to Hong Kong with the average property costing 14 times the annual Sydney salary as of December 2016.[255]

There were 1.76 million dwellings in Sydney in 2016 including 925,000 (57%) detached houses, 227,000 (14%) semi-detached terrace houses and 456,000 (28%) units and apartments.[256] Whilst terrace houses are common in the inner city areas, detached houses dominate the landscape in the outer suburbs. Due to environmental and economic pressures, there has been a noted trend towards denser housing, with a 30% increase in the number of apartments between 1996 and 2006.[257] Public housing in Sydney is managed by the Government of New South Wales.[258] Suburbs with large concentrations of public housing include Claymore, Macquarie Fields, Waterloo, and Mount Druitt.

A range of heritage housing styles can be found throughout Sydney. Terrace houses are found in the inner suburbs such as Paddington, The Rocks, Potts Point and Balmain, many of which have been the subject of gentrification.[259][260] These terraces, particularly those in suburbs such as The Rocks, were historically home to Sydney's miners and labourers. In the present day, terrace houses now make up some of the most valuable real estate in the city.[261] Surviving large mansions from the Victorian era are mostly found in the oldest suburbs, such as Double Bay, Darling Point, Rose Bay and Strathfield.[262]

Federation homes, constructed around the time of Federation in 1901, are located in a large number of suburbs that developed thanks to the arrival of railways in the late 19th century, such as Penshurst and Turramurra, and in large-scale planned "garden suburbs" such as Haberfield. Workers cottages are found in Surry Hills, Redfern, and Balmain. California bungalows are common in Ashfield, Concord, and Beecroft. Larger modern homes are predominantly found in the outer suburbs, such as Stanhope Gardens, Kellyville Ridge, Bella Vista to the northwest, Bossley Park, Abbotsbury, and Cecil Hills to the west, and Hoxton Park, Harrington Park, and Oran Park to the southwest.[263]

Parks and open spaces

[edit]The Anzac War Memorial in Hyde Park is a public memorial dedicated to the Australian Imperial Force of World War I.

The Royal Botanic Garden is the most iconic green space in the region, hosting both scientific and leisure activities.[264] There are 15 separate parks under the City administration.[265] Parks within the city centre include Hyde Park, The Domain and Prince Alfred Park.

The Centennial Parklands is the largest park in the City of Sydney, comprising 189 ha (470 acres).

The inner suburbs include Centennial Park and Moore Park in the east (both within the City of Sydney local government area), while the outer suburbs contain Sydney Park and Royal National Park in the south, Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park in the north, and Western Sydney Parklands in the west, which is one of the largest urban parks in the world. The Royal National Park was proclaimed in 1879 and with 13,200 ha (51 sq mi) is the second oldest national park in the world.[267]

Hyde Park is the oldest parkland in the country.[269] The largest park in the Sydney metropolitan area is Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, established in 1894 with an area of 15,400 ha (59 sq mi).[270] It is regarded for its well-preserved records of indigenous habitation – more than 800 rock engravings, cave drawings and middens.[271]

The area now known as The Domain was set aside by Governor Arthur Phillip in 1788 as his private reserve.[272] Under the orders of Macquarie the land to the immediate north of The Domain became the Royal Botanic Garden in 1816. This makes them the oldest botanic garden in Australia.[272] The Gardens host scientific research with herbarium collections, a library and laboratories.[273] The two parks have a total area of 64 ha (0.2 sq mi) with 8,900 individual plant species and receive over 3.5 million annual visits.[274]

To the south of The Domain is Hyde Park, the oldest public parkland in Australia which measures 16.2 ha (0.1 sq mi).[275] Its location was used for both relaxation and grazing of animals from the earliest days of the colony.[276] Macquarie dedicated it in 1810 for the "recreation and amusement of the inhabitants of the town" and named it in honour of Hyde Park in London.

Economy

[edit]

Researchers from Loughborough University have ranked Sydney amongst the top ten world cities that are highly integrated into the global economy.[278] The Global Economic Power Index ranks Sydney eleventh in the world.[279] The Global Cities Index recognises it as fourteenth in the world based on global engagement.[280] There is a significant concentration of foreign banks and multinational corporations in Sydney and the city is promoted as Australia's financial capital and one of Asia Pacific's leading financial hubs.[281][282]

The prevailing economic theory during early colonial days was mercantilism, as it was throughout most of Western Europe.[283] The economy struggled at first due to difficulties in cultivating the land and the lack of a stable monetary system. Governor Macquarie created two coins from every Spanish silver dollar in circulation.[283] The economy was capitalist in nature by the 1840s as the proportion of free settlers increased, the maritime and wool industries flourished, and the powers of the East India Company were curtailed.[283]

Wheat, gold, and other minerals became export industries towards the end of the 1800s.[283] Significant capital began to flow into the city from the 1870s to finance roads, railways, bridges, docks, courthouses, schools and hospitals. Protectionist policies after federation allowed for the creation of a manufacturing industry which became the city's largest employer by the 1920s.[283] These same policies helped to relieve the effects of the Great Depression during which the unemployment rate in New South Wales reached as high as 32%.[283] From the 1960s onwards Parramatta gained recognition as the city's second CBD and finance and tourism became major industries and sources of employment.[283]

Sydney's nominal gross domestic product was AU$400.9 billion and AU$80,000 per capita[284] in 2015.[285][282] Its gross domestic product was AU$337 billion in 2013, the largest in Australia.[285] The financial and insurance services industry accounts for 18.1% of gross product, ahead of professional services with 9% and manufacturing with 7.2%. The creative and technology sectors are also focus industries for the City of Sydney and represented 9% and 11% of its economic output in 2012.[286][287]

Businesses

[edit]There were 451,000 businesses based in Sydney in 2011, including 48% of the top 500 companies in Australia and two-thirds of the regional headquarters of multinational corporations.[288] Global companies are attracted to the city in part because its time zone spans the closing of business in North America and the opening of business in Europe. Most foreign companies in Sydney maintain significant sales and service functions but comparably less production, research, and development capabilities.[289] There are 283 multinational companies with regional offices in Sydney.[290]

Domestic economics

[edit]

Sydney has been ranked between the fifteenth and the fifth most expensive city in the world and is the most expensive city in Australia.[292] Of the 15 categories only measured by UBS in 2012, workers receive the seventh highest wage levels of 77 cities in the world.[292] Working residents of Sydney work an average of 1,846 hours per annum with 15 days of leave.[292]

The labour force of Greater Sydney Region in 2016 was 2,272,722 with a participation rate of 61.6%.[293] It comprised 61.2% full-time workers, 30.9% part-time workers, and 6.0% unemployed individuals.[256][294] The largest reported occupations are professionals, clerical and administrative workers, managers, technicians and trades workers, and community and personal service workers.[256] The largest industries by employment across Greater Sydney are Health Care and Social Assistance (11.6%), Professional Services (9.8%), Retail Trade (9.3%), Construction (8.2%), Education and Training (8.0%), Accommodation and Food Services (6.7%), and Financial and Insurance Services (6.6%).[2] The Professional Services and Financial and Insurance Services industries account for 25.4% of employment within the City of Sydney.[295]

In 2016, 57.6% of working-age residents had a weekly income of less than $1,000 and 14.4% had a weekly income of $1,750 or more.[296] The median weekly income for the same period was $719 for individuals, $1,988 for families, and $1,750 for households.[297]

Unemployment in the City of Sydney averaged 4.6% for the decade to 2013, much lower than the current rate of unemployment in Western Sydney of 7.3%.[282][298] Western Sydney continues to struggle to create jobs to meet its population growth despite the development of commercial centres like Parramatta. Each day about 200,000 commuters travel from Western Sydney to the CBD and suburbs in the east and north of the city.[298]

Home ownership in Sydney was less common than renting prior to the Second World War but this trend has since reversed.[257] Median house prices have increased by an average of 8.6% per annum since 1970.[299][300] The median house price in March 2014 was $630,000.[301] The primary cause of rising prices is the increasing cost of land and scarcity.[302] 31.6% of dwellings in Sydney are rented, 30.4% are owned outright and 34.8% are owned with a mortgage.[256] 11.8% of mortgagees in 2011 had monthly loan repayments of less than $1,000 and 82.9% had monthly repayments of $1,000 or more.[2] 44.9% of renters for the same period had weekly rent of less than $350 whilst 51.7% had weekly rent of $350 or more. The median weekly rent in Sydney in 2011 was $450.[2]

Financial services

[edit]

Macquarie gave a charter in 1817 to form the first bank in Australia, the Bank of New South Wales.[303] New private banks opened throughout the 1800s but the financial system was unstable. Bank collapses were frequent and a crisis point was reached in 1893 when 12 banks failed.[303]

The Bank of New South Wales exists to this day as Westpac.[304] The Commonwealth Bank of Australia was formed in Sydney in 1911 and began to issue notes backed by the resources of the nation. It was replaced in this role in 1959 by the Reserve Bank of Australia, also based in Sydney.[303] The Australian Securities Exchange began operating in 1987 and with a market capitalisation of $1.6 trillion is now one of the ten largest exchanges in the world.[305]

The Financial and Insurance Services industry now constitutes 43% of the economic product of the City of Sydney.[281] Sydney makes up half of Australia's finance sector and has been promoted by consecutive Commonwealth Governments as Asia Pacific's leading financial centre.[20][21][306] In the 2017 Global Financial Centres Index, Sydney was ranked as having the eighth most competitive financial centre in the world.[307]

In 1985 the Federal Government granted 16 banking licences to foreign banks and now 40 of the 43 foreign banks operating in Australia are based in Sydney, including the People's Bank of China, Bank of America, Citigroup, UBS, Mizuho Bank, Bank of China, Banco Santander, Credit Suisse, Standard Chartered, State Street, HSBC, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, Royal Bank of Canada, Société Générale, Royal Bank of Scotland, Sumitomo Mitsui, ING Group, BNP Paribas, and Investec.[281][303][308][309]

Manufacturing

[edit]Sydney has been a manufacturing city since the 1920s. By 1961 the industry accounted for 39% of all employment and by 1970 over 30% of all Australian manufacturing jobs were in Sydney.[310] Its status has declined in recent decades, making up 12.6% of employment in 2001 and 8.5% in 2011.[2][310] Between 1970 and 1985 there was a loss of 180,000 manufacturing jobs.[310] Despite this, Sydney still overtook Melbourne as the largest manufacturing centre in Australia in the 2010s,[311] with a manufacturing output of $21.7 billion in 2013.[312] Observers have credited Sydney's focus on the domestic market and high-tech manufacturing for its resilience against the high Australian dollar of the early 2010s.[312] The Smithfield-Wetherill Park Industrial Estate in Western Sydney is the largest industrial estate in the Southern Hemisphere and is the centre of manufacturing and distribution in the region.[313]

Tourism and international education

[edit]

Sydney is a gateway to Australia for many international visitors and ranks among the top sixty most visited cities in the world.[314] It has hosted over 2.8 million international visitors in 2013, or nearly half of all international visits to Australia. These visitors spent 59 million nights in the city and a total of $5.9 billion.[24] The countries of origin in descending order were China, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States, South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Germany, Hong Kong, and India.[315]

The city also received 8.3 million domestic overnight visitors in 2013 who spent a total of $6 billion.[315] 26,700 workers in the City of Sydney were directly employed by tourism in 2011.[316] There were 480,000 visitors and 27,500 people staying overnight each day in 2012.[316] On average, the tourism industry contributes $36 million to the city's economy per day.[316]

Popular destinations include the Sydney Opera House, the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Watsons Bay, The Rocks, Sydney Tower, Darling Harbour, the Royal Botanic Garden, the Australian Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Queen Victoria Building, Sea Life Sydney Aquarium, Taronga Zoo, Bondi Beach, Luna Park and Sydney Olympic Park.[317]

Major developmental projects designed to increase Sydney's tourism sector include a casino and hotel at Barangaroo and the redevelopment of East Darling Harbour, which involves a new exhibition and convention centre, now Australia's largest.[318][319][320]

Sydney is the highest-ranking city in the world for international students. More than 50,000 international students study at the city's universities and a further 50,000 study at its vocational and English language schools.[280][321] International education contributes $1.6 billion to the local economy and creates demand for 4,000 local jobs each year.[322]

Housing affordability

[edit]In 2023, Sydney was ranked the least affordable city to buy a house in Australia and the second least affordable city in the world, after Hong Kong,[323] with the average Sydney house price in late 2023 costing A$1.59 million, and the average unit price costing A$795,000.[324] As of early 2024, Sydney is often described in the media as having a housing shortage, or suffering a housing crisis.[325][326]

Demographics

[edit]

The population of Sydney in 1788 was less than 1,000.[328] With convict transportation it almost tripled in ten years to 2,953.[329] For each decade since 1961 the population has increased by more than 250,000.[330] The 2021 census recorded the population of Greater Sydney as 5,231,150.[1] The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) projects the population will grow to between 8 and 8.9 million by 2061, but that Melbourne will replace Sydney as Australia's most populous city by 2030.[331][332] The four most densely populated suburbs in Australia are located in Sydney with each having more than 13,000 residents per square kilometre (33,700 residents per square mile).[333] Between 1971 and 2018, Sydney experienced a net loss of 716,832 people to the rest of Australia, but its population grew due to overseas arrivals and a healthy birth rate.[334]

The median age of Sydney residents is 37 and 14.8% of people are 65 or older.[256] 48.6% of Sydney's population is married whilst 36.7% have never been married.[256] 49.0% of families are couples with children, 34.4% are couples without children, and 14.8% are single-parent families.[256]

Ancestry and immigration

[edit]| Birthplace[N 1] | Population |

|---|---|

| Australia | 2,970,737 |

| Mainland China | 238,316 |

| India | 187,810 |

| England | 153,052 |

| Vietnam | 93,778 |

| Philippines | 91,339 |

| New Zealand | 85,493 |

| Lebanon | 61,620 |

| Nepal | 59,055 |

| Iraq | 52,604 |

| South Korea | 50,702 |

| Hong Kong SAR | 46,182 |

| South Africa | 39,564 |

| Italy | 38,762 |

| Indonesia | 35,413 |

| Malaysia | 35,002 |

| Fiji | 34,197 |

| Pakistan | 31,025 |

Most immigrants to Sydney between 1840 and 1930 were British, Irish or Chinese. At the 2021 census, the most common ancestries were:[11]

At the 2021 census, 40.5% of Sydney's population was born overseas. Foreign countries of birth with the greatest representation are Mainland China, India, England, Vietnam, Philippines and New Zealand.[11]

At the 2021 census, 1.7% of Sydney's population identified as being Indigenous — Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders.[N 3][337]

Language

[edit]42% of households in Sydney use a language other than English, with the most common being Mandarin (5%), Arabic (4.2%), Cantonese (2.8%), Vietnamese (2.2%) and Hindi (1.5%).[337]

Religion

[edit]

In 2021, Christianity was the largest religious affiliation at 46%, the largest denominations of which were Catholicism at 23.1% and Anglicanism at 9.2%. 30.3% of Sydney residents identified as having no religion. The most common non-Christian religious affiliations were Islam (6.3%), Hinduism (4.8%), Buddhism (3.8%), Sikhism (0.7%), and Judaism (0.7%). About 500 people identified with traditional Aboriginal religions.[11]

The Church of England was the only recognised church before Governor Macquarie appointed official Catholic chaplains in 1820.[338] Macquarie also ordered the construction of churches such as St Matthew's, St Luke's, St James's, and St Andrew's. Religious groups, alongside secular institutions, have played a significant role in education, health and charitable services throughout Sydney's history.[339]

Crime

[edit]Crime in Sydney is low, with The Independent ranking Sydney as the fifth safest city in the world in 2019.[340] However, drug use is a significant problem. Methamphetamine is heavily consumed compared to other countries, while heroin is less common.[341] One of the biggest crime-related issues in recent times was the introduction of lockout laws in February 2014,[342] in an attempt to curb alcohol-fuelled violence. Patrons could not enter clubs or bars in the inner-city after 1:30am, and last drinks were called at 3am. The lockout laws were removed in January 2020.[343]

Culture

[edit]Science, art, and history

[edit]

Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park is rich in Indigenous Australian heritage, containing around 1,500 pieces of Aboriginal rock art – the largest cluster of Indigenous sites in Australia. The park's indigenous sites include petroglyphs, art sites, burial sites, caves, marriage areas, birthing areas, midden sites, and tool manufacturing locations, which are dated to be around 5,000 years old. The inhabitants of the area were the Garigal people.[344][345] Other rock art sites exist in the Sydney region, such as in Terrey Hills and Bondi, although the locations of most are not publicised to prevent damage by vandalism, and to retain their quality, as they are still regarded as sacred sites by Indigenous Australians.[346]

The Australian Museum opened in Sydney in 1827 with the purpose of collecting and displaying the natural wealth of the colony.[347] It remains Australia's oldest natural history museum. In 1995 the Museum of Sydney opened on the site of the first Government House. It recounts the story of the city's development.[348] Other museums include the Powerhouse Museum and the Australian National Maritime Museum.[349][350]

The State Library of New South Wales holds the oldest library collections in Australia, being established as the Australian Subscription Library in 1826.[351] The Royal Society of New South Wales, formed in 1866, encourages "studies and investigations in science, art, literature, and philosophy". It is based in a terrace house in Darlington owned by the University of Sydney.[352] The Sydney Observatory building was constructed in 1859 and used for astronomy and meteorology research until 1982 before being converted into a museum.[353]

The Museum of Contemporary Art was opened in 1991 and occupies an Art Deco building in Circular Quay. Its collection was founded in the 1940s by artist and art collector John Power and has been maintained by the University of Sydney.[354] Sydney's other significant art institution is the Art Gallery of New South Wales which coordinates the Archibald Prize for portraiture.[355] Sydney is also home to contemporary art gallery Artspace, housed in the historic Gunnery Building in Woolloomooloo, fronting Sydney Harbour.[356]

Entertainment

[edit]

Sydney's first commercial theatre opened in 1832 and nine more had commenced performances by the late 1920s. The live medium lost much of its popularity to the cinema during the Great Depression before experiencing a revival after World War II.[357] Prominent theatres in the city today include State Theatre, Theatre Royal, Sydney Theatre, The Wharf Theatre, and Capitol Theatre. Sydney Theatre Company maintains a roster of local, classical, and international plays. It occasionally features Australian theatre icons such as David Williamson, Hugo Weaving, and Geoffrey Rush. The city's other prominent theatre companies are New Theatre, Belvoir, and Griffin Theatre Company. Sydney is also home to Event Cinemas' first theatre, which opened on George St in 1913, under its former Greater Union brand; the theatre currently operates, and is regarded as one of Australia's busiest cinema locations.

The Sydney Opera House is the home of Opera Australia and Sydney Symphony. It has staged over 100,000 performances and received 100 million visitors since opening in 1973.[240] Two other important performance venues in Sydney are Town Hall and the City Recital Hall. The Sydney Conservatorium of Music is located adjacent to the Royal Botanic Garden and serves the Australian music community through education and its biannual Australian Music Examinations Board exams.[358]

Many writers have originated in and set their work in Sydney. Others have visited the city and commented on it. Some of them are commemorated in the Sydney Writers Walk at Circular Quay. The city was the headquarters for Australia's first published newspaper, the Sydney Gazette.[359] Watkin Tench's A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay (1789) and A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson in New South Wales (1793) have remained the best-known accounts of life in early Sydney.[360] Since the infancy of the establishment, much of the literature set in Sydney were concerned with life in the city's slums and working-class communities, notably William Lane's The Working Man's Paradise (1892), Christina Stead's Seven Poor Men of Sydney (1934) and Ruth Park's The Harp in the South (1948).[361] The first Australian-born female novelist, Louisa Atkinson, set several novels in Sydney.[362] Contemporary writers, such as Elizabeth Harrower, were born in the city and set most of their work there–Harrower's debut novel Down in the City (1957) was mostly set in a King's Cross apartment.[363][364][365] Well known contemporary novels set in the city include Melina Marchetta's Looking for Alibrandi (1992), Peter Carey's 30 Days in Sydney: A Wildly Distorted Account (1999), J. M. Coetzee's Diary of a Bad Year (2007) and Kate Grenville's The Secret River (2010). The Sydney Writers' Festival is held annually between April and May.[366]

Filmmaking in Sydney was prolific until the 1920s when spoken films were introduced and American productions gained dominance.[367] The Australian New Wave saw a resurgence in film production, with many notable features shot in the city between the 1970s and 80s, helmed by directors such as Bruce Beresford, Peter Weir and Gillian Armstrong.[368] Fox Studios Australia commenced production in Sydney in 1998. Successful films shot in Sydney since then include The Matrix, Lantana, Mission: Impossible 2, Moulin Rouge!, Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, Australia, Superman Returns, and The Great Gatsby. The National Institute of Dramatic Art is based in Sydney and has several famous alumni such as Mel Gibson, Judy Davis, Baz Luhrmann, Cate Blanchett, Hugo Weaving and Jacqueline Mckenzie.[369]

Sydney hosts several festivals throughout the year. The city's New Year's Eve celebrations are the largest in Australia.[370] The Royal Easter Show is held every year at Sydney Olympic Park. Sydney Festival is Australia's largest arts festival.[371] The travelling rock music festival Big Day Out originated in Sydney. The city's two largest film festivals are Sydney Film Festival and Tropfest. Vivid Sydney is an annual outdoor exhibition of art installations, light projections, and music. In 2015, Sydney was ranked the 13th top fashion capital in the world.[372] It hosts the Australian Fashion Week in autumn. Sydney Mardi Gras has commenced each February since 1979.

Sydney's Chinatown has had numerous locations since the 1850s. It moved from George Street to Campbell Street to its current setting in Dixon Street in 1980.[373] Little Italy is located in Stanley Street.[283]

Restaurants, bars and nightclubs can be found in the entertainment hubs in the Sydney CBD (Darling Harbour, Barangaroo, The Rocks and George Street), Oxford Street, Surry Hills, Newtown and Parramatta.[374][375] Kings Cross was previously considered the red-light district. The Star is the city's casino and is situated next to Darling Harbour while the new Crown Sydney resort is in nearby Barangaroo.[376]

Media

[edit]

The Sydney Morning Herald is Australia's oldest newspaper still in print; it has been published continuously since 1831.[377] Its competitor is The Daily Telegraph, in print since 1879.[378] Both papers have Sunday tabloid editions called The Sun-Herald and The Sunday Telegraph respectively. The Bulletin was founded in Sydney in 1880 and became Australia's longest running magazine. It closed after 128 years of continuous publication.[379] Sydney heralded Australia's first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette, published until 1842.

Each of Australia's three commercial television networks and two public broadcasters is headquartered in Sydney. Nine's offices and news studios are in North Sydney, Ten is based in Pyrmont, and Seven is based in South Eveleigh in Redfern.[380][381][382][383] The Australian Broadcasting Corporation is located in Ultimo,[384] and the Special Broadcasting Service is based in Artarmon.[385] Multiple digital channels have been provided by all five networks since 2000. Foxtel is based in North Ryde and sells subscription cable television to most of the urban area.[386] Sydney's first radio stations commenced broadcasting in the 1920s. Radio has managed to survive despite the introduction of television and the Internet.[387] 2UE was founded in 1925 and under the ownership of Nine Entertainment is the oldest station still broadcasting.[387] Competing stations include the more popular 2GB, ABC Radio Sydney, KIIS 106.5, Triple M, Nova 96.9 and 2Day FM.[388]

Sport and outdoor activities

[edit]Sydney's earliest migrants brought with them a passion for sport but were restricted by the lack of facilities and equipment. The first organised sports were boxing, wrestling, and horse racing from 1810 in Hyde Park.[389] Horse racing remains popular and events such as the Golden Slipper Stakes attract widespread attention. The first cricket club was formed in 1826 and matches were played within Hyde Park throughout the 1830s and 1840s.[389] Cricket is a favoured sport in summer and big matches have been held at the Sydney Cricket Ground since 1878. The New South Wales Blues compete in the Sheffield Shield league and the Sydney Sixers and Sydney Thunder contest the national Big Bash Twenty20 competition.

First played in Sydney in 1865, rugby grew to be the city's most popular football code by the 1880s. One-tenth of the state's population attended a New South Wales versus New Zealand rugby match in 1907.[389] Rugby league separated from rugby union in 1908. The New South Wales Waratahs contest the Super Rugby competition, while the Sydney Rays represent the city in the National Rugby Championship. The national Wallabies rugby union team competes in Sydney in international matches such as the Bledisloe Cup, Rugby Championship, and World Cup. Sydney is home to nine of the seventeen teams in the National Rugby League competition: Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs, Cronulla-Sutherland Sharks, Manly-Warringah Sea Eagles, Penrith Panthers, Parramatta Eels, South Sydney Rabbitohs, St George Illawarra Dragons, Sydney Roosters, and Wests Tigers. New South Wales contests the annual State of Origin series against Queensland.

Sydney FC and the Western Sydney Wanderers compete in the A-League Men and A-League Women competitions. The Sydney Swans and Greater Western Sydney Giants are local Australian rules football clubs that play in the Australian Football League and the AFL Women's. The Sydney Kings compete in the National Basketball League. The Sydney Uni Flames play in the Women's National Basketball League. The Sydney Blue Sox contest the Australian Baseball League. The NSW Pride are a member of the Hockey One League. The Sydney Bears and Sydney Ice Dogs play in the Australian Ice Hockey League. The Swifts are competitors in the national women's netball league.

Major sporting venues

[edit]