Геологическая шкала времени

Геологическая шкала времени или геологическая шкала времени ( GTS ) представляет собой представление времени основанное на скале Земли , . Это система хронологического датирования , которая использует хроностратиграфию (процесс связывания слоев со временем) и геохронологии (научная ветвь геологии , которая направлена на определение возраста пород). Он используется в первую очередь учеными Земли (включая геологов , палеонтологов , геофизиков , геохимиков и палеоклиматологов ), чтобы описать время и отношения событий в геологической истории. Шкала времени была разработана благодаря изучению слоев горных пород и наблюдении их отношений и выявлением таких особенностей, как литологии , палеомагнитные свойства и окаменелости . Определение стандартизированных международных подразделений геологического времени является обязанностью Международной комиссии по стратиграфии (ICS), составляющему органу Международного союза геологических наук (IUGS), чья основная цель [ 1 ] это точное определение глобальных хроностратиграфических единиц международной хроностратиграфической диаграммы (ICC) [ 2 ] которые используются для определения подразделений геологического времени. Хроностратиграфические подразделения, в свою очередь, используются для определения геохронологических единиц. [ 2 ]

While some regional terms are still in use,[3] the table of geologic time conforms to the nomenclature, ages, and colour codes set forth by the ICS.[1][4]

Principles

[edit]The geologic time scale is a way of representing deep time based on events that have occurred throughout Earth's history, a time span of about 4.54 ± 0.05 Ga (4.54 billion years).[5] It chronologically organises strata, and subsequently time, by observing fundamental changes in stratigraphy that correspond to major geological or paleontological events. For example, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, marks the lower boundary of the Paleogene System/Period and thus the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene systems/periods. For divisions prior to the Cryogenian, arbitrary numeric boundary definitions (Global Standard Stratigraphic Ages, GSSAs) are used to divide geologic time. Proposals have been made to better reconcile these divisions with the rock record.[6][3]

Historically, regional geologic time scales were used[3] due to the litho- and biostratigraphic differences around the world in time equivalent rocks. The ICS has long worked to reconcile conflicting terminology by standardising globally significant and identifiable stratigraphic horizons that can be used to define the lower boundaries of chronostratigraphic units. Defining chronostratigraphic units in such a manner allows for the use of global, standardised nomenclature. The ICC represents this ongoing effort.

The relative relationships of rocks for determining their chronostratigraphic positions use the overriding principles of:[7][8][9][10]

- Superposition – Newer rock beds will lie on top of older rock beds unless the succession has been overturned.

- Horizontality – All rock layers were originally deposited horizontally.[note 1]

- Lateral continuity – Originally deposited layers of rock extend laterally in all directions until either thinning out or being cut off by a different rock layer.

- Biologic succession (where applicable) – This states that each stratum in a succession contains a distinctive set of fossils. This allows for a correlation of the stratum even when the horizon between them is not continuous.

- Cross-cutting relationships – A rock feature that cuts across another feature must be younger than the rock it cuts across.

- Inclusion – Small fragments of one type of rock but embedded in a second type of rock must have formed first, and were included when the second rock was forming.

- Relationships of unconformities – Geologic features representing periods of erosion or non-deposition, indicating non-continuous sediment deposition.

Terminology

[edit]The GTS is divided into chronostratigraphic units and their corresponding geochronologic units. These are represented on the ICC published by the ICS; however, regional terms are still in use in some areas.

Chronostratigraphy is the element of stratigraphy that deals with the relation between rock bodies and the relative measurement of geological time.[11] It is the process where distinct strata between defined stratigraphic horizons are assigned to represent a relative interval of geologic time.

A chronostratigraphic unit is a body of rock, layered or unlayered, that is defined between specified stratigraphic horizons which represent specified intervals of geologic time. They include all rocks representative of a specific interval of geologic time, and only this time span.[11] Eonothem, erathem, system, series, subseries, stage, and substage are the hierarchical chronostratigraphic units.[11] Geochronology is the scientific branch of geology that aims to determine the age of rocks, fossils, and sediments either through absolute (e.g., radiometric dating) or relative means (e.g., stratigraphic position, paleomagnetism, stable isotope ratios).[12]

A geochronologic unit is a subdivision of geologic time. It is a numeric representation of an intangible property (time).[12] Eon, era, period, epoch, subepoch, age, and subage are the hierarchical geochronologic units.[11] Geochronometry is the field of geochronology that numerically quantifies geologic time.[12]

A Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) is an internationally agreed upon reference point on a stratigraphic section which defines the lower boundaries of stages on the geologic time scale.[13] (Recently this has been used to define the base of a system)[14]

A Global Standard Stratigraphic Age (GSSA)[15] is a numeric only, chronologic reference point used to define the base of geochronologic units prior to the Cryogenian. These points are arbitrarily defined.[11] They are used where GSSPs have not yet been established. Research is ongoing to define GSSPs for the base of all units that are currently defined by GSSAs.

The numeric (geochronometric) representation of a geochronologic unit can, and is more often subject to change when geochronology refines the geochronometry, while the equivalent chronostratigraphic unit remains the same, and their revision is less common. For example, in early 2022 the boundary between the Ediacaran and Cambrian periods (geochronologic units) was revised from 541 Ma to 538.8 Ma but the rock definition of the boundary (GSSP) at the base of the Cambrian, and thus the boundary between the Ediacaran and Cambrian systems (chronostratigraphic units) has not changed, merely the geochronometry has been refined.

The numeric values on the ICC are represented by the unit Ma (megaannum, for 'million years'). For example, 201.4 ± 0.2 Ma, the lower boundary of the Jurassic Period, is defined as 201,400,000 years old with an uncertainty of 200,000 years. Other SI prefix units commonly used by geologists are Ga (gigaannum, billion years), and ka (kiloannum, thousand years), with the latter often represented in calibrated units (before present).

Divisions of geologic time

[edit]- An eon is the largest geochronologic time unit and is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic eonothem.[16] There are four formally defined eons: the Hadean, Archean, Proterozoic and Phanerozoic.[2]

- An era is the second largest geochronologic time unit and is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic erathem.[11][16] There are ten defined eras: the Eoarchean, Paleoarchean, Mesoarchean, Neoarchean, Paleoproterozoic, Mesoproterozoic, Neoproterozoic, Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic, with none from the Hadean eon.[2]

- A period is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic system.[11][16] There are 22 defined periods, with the current being the Quaternary period.[2] As an exception two subperiods are used for the Carboniferous Period.[11]

- An epoch is the second smallest geochronologic unit. It is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic series.[11][16] There are 37 defined epochs and one informal one. There are also 11 subepochs which are all within the Neogene and Quaternary.[2] The use of subepochs as formal units in international chronostratigraphy was ratified in 2022.[17]

- An age is the smallest hierarchical geochronologic unit and is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic stage.[11][16] There are 96 formal and five informal ages.[2]

- A chron is a non-hierarchical formal geochronology unit of unspecified rank and is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic chronozone.[11] These correlate with magnetostratigraphic, lithostratigraphic, or biostratigraphic units as they are based on previously defined stratigraphic units or geologic features.

The Early and Late subdivisions are used as the geochronologic equivalents of the chronostratigraphic Lower and Upper, e.g., Early Triassic Period (geochronologic unit) is used in place of Lower Triassic Series (chronostratigraphic unit).

Rocks representing a given chronostratigraphic unit are that chronostratigraphic unit, and the time they were laid down in is the geochronologic unit, i.e., the rocks that represent the Silurian Series are the Silurian Series and they were deposited during the Silurian Period.

| Chronostratigraphic unit (strata) | Geochronologic unit (time) | Time span[note 2] |

|---|---|---|

| Eonothem | Eon | Several hundred million years to two billion years |

| Erathem | Era | Tens to hundreds of millions of years |

| System | Period | Millions of years to tens of millions of years |

| Series | Epoch | Hundreds of thousands of years to tens of millions of years |

| Subseries | Subepoch | Thousands of years to millions of years |

| Stage | Age | Thousands of years to millions of years |

Naming of geologic time

[edit]The names of geologic time units are defined for chronostratigraphic units with the corresponding geochronologic unit sharing the same name with a change to the latter (e.g. Phanerozoic Eonothem becomes the Phanerozoic Eon). Names of erathems in the Phanerozoic were chosen to reflect major changes in the history of life on Earth: Paleozoic (old life), Mesozoic (middle life), and Cenozoic (new life). Names of systems are diverse in origin, with some indicating chronologic position (e.g., Paleogene), while others are named for lithology (e.g., Cretaceous), geography (e.g., Permian), or are tribal (e.g., Ordovician) in origin. Most currently recognised series and subseries are named for their position within a system/series (early/middle/late); however, the ICS advocates for all new series and subseries to be named for a geographic feature in the vicinity of its stratotype or type locality. The name of stages should also be derived from a geographic feature in the locality of its stratotype or type locality.[11]

Informally, the time before the Cambrian is often referred to as the Precambrian or pre-Cambrian (Supereon).[6][note 3]

| Name | Time span | Duration (million years) | Etymology of name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phanerozoic | 538.8 to 0 million years ago | 538.8 | From Greek φανερός (phanerós) 'visible' or 'abundant' and ζωή (zoē) 'life'. |

| Proterozoic | 2,500 to 538.8 million years ago | 1961.2 | From Greek πρότερος (próteros) 'former' or 'earlier' and ζωή (zoē) 'life'. |

| Archean | 4,031 to 2,500 million years ago | 1531 | From Greek ἀρχή (archē) 'beginning, origin'. |

| Hadean | 4,567.3 to 4,031 million years ago | 536.3 | From Hades, Greek: ᾍδης, translit. Háidēs, the god of the underworld (hell, the inferno) in Greek mythology. |

| Name | Time span | Duration (million years) | Etymology of name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cenozoic | 66 to 0 million years ago | 66 | From Greek καινός (kainós) 'new' and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Mesozoic | 251.9 to 66 million years ago | 185.902 | From Greek μέσο (méso) 'middle' and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Paleozoic | 538.8 to 251.9 million years ago | 286.898 | From Greek παλιός (palaiós) 'old' and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Neoproterozoic | 1,000 to 538.8 million years ago | 461.2 | From Greek νέος (néos) 'new' or 'young', πρότερος (próteros) 'former' or 'earlier', and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Mesoproterozoic | 1,600 to 1,000 million years ago | 600 | From Greek μέσο (méso) 'middle', πρότερος (próteros) 'former' or 'earlier', and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Paleoproterozoic | 2,500 to 1,600 million years ago | 900 | From Greek παλιός (palaiós) 'old', πρότερος (próteros) 'former' or 'earlier', and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Neoarchean | 2,800 to 2,500 million years ago | 300 | From Greek νέος (néos) 'new' or 'young' and ἀρχαῖος (arkhaîos) 'ancient'. |

| Mesoarchean | 3,200 to 2,800 million years ago | 400 | From Greek μέσο (méso) 'middle' and ἀρχαῖος (arkhaîos) 'ancient'. |

| Paleoarchean | 3,600 to 3,200 million years ago | 400 | From Greek παλιός (palaiós) 'old' and ἀρχαῖος (arkhaîos) 'ancient'. |

| Eoarchean | 4,031 to 3,600 million years ago | 431 | From Greek ἠώς (ēōs) 'dawn' and ἀρχαῖος (arkhaîos) 'ancient'. |

| Name | Time span | Duration (million years) | Etymology of name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternary | 2.6 to 0 million years ago | 2.58 | First introduced by Jules Desnoyers in 1829 for sediments in France's Seine Basin that appeared to be younger than Tertiary[note 4] rocks.[20] |

| Neogene | 23 to 2.6 million years ago | 20.45 | Derived from Greek νέος (néos) 'new' and γενεά (geneá) 'genesis' or 'birth'. |

| Paleogene | 66 to 23 million years ago | 42.97 | Derived from Greek παλιός (palaiós) 'old' and γενεά (geneá) 'genesis' or 'birth'. |

| Cretaceous | ~145 to 66 million years ago | ~79 | Derived from Terrain Crétacé used in 1822 by Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy in reference to extensive beds of chalk within the Paris Basin.[21] Ultimately derived from Latin crēta 'chalk'. |

| Jurassic | 201.4 to 145 million years ago | ~56.4 | Named after the Jura Mountains. Originally used by Alexander von Humboldt as 'Jura Kalkstein' (Jura limestone) in 1799.[22] Alexandre Brongniart was the first to publish the term Jurassic in 1829.[23][24] |

| Triassic | 251.9 to 201.4 million years ago | 50.502 | From the Trias of Friedrich August von Alberti in reference to a trio of formations widespread in southern Germany |

| Permian | 298.9 to 251.9 million years ago | 46.998 | Named after the historical region of Perm, Russian Empire.[25] |

| Carboniferous | 358.9 to 298.9 million years ago | 60 | Means 'coal-bearing', from the Latin carbō (coal) and ferō (to bear, carry).[26] |

| Devonian | 419.2 to 358.9 million years ago | 60.3 | Named after Devon, England.[27] |

| Silurian | 443.8 to 419.2 million years ago | 24.6 | Named after the Celtic tribe, the Silures.[28] |

| Ordovician | 485.4 to 443.8 million years ago | 41.6 | Named after the Celtic tribe, Ordovices.[29][30] |

| Cambrian | 538.8 to 485.4 million years ago | 53.4 | Named for Cambria, a latinised form of the Welsh name for Wales, Cymru.[31] |

| Ediacaran | 635 to 538.8 million years ago | ~96.2 | Named for the Ediacara Hills. Ediacara is possibly a corruption of Kuyani 'Yata Takarra' 'hard or stony ground'.[32][33] |

| Cryogenian | 720 to 635 million years ago | ~85 | From Greek κρύος (krýos) 'cold' and γένεσις (génesis) 'birth'.[3] |

| Tonian | 1,000 to 720 million years ago | ~280 | From Greek τόνος (tónos) 'stretch'.[3] |

| Stenian | 1,200 to 1,000 million years ago | 200 | From Greek στενός (stenós) 'narrow'.[3] |

| Ectasian | 1,400 to 1,200 million years ago | 200 | From Greek ἔκτᾰσῐς (éktasis) 'extension'.[3] |

| Calymmian | 1,600 to 1,400 million years ago | 200 | From Greek κάλυμμᾰ (kálumma) 'cover'.[3] |

| Statherian | 1,800 to 1,600 million years ago | 200 | From Greek σταθερός (statherós) 'stable'.[3] |

| Orosirian | 2,050 to 1,800 million years ago | 250 | From Greek ὀροσειρά (oroseirá) 'mountain range'.[3] |

| Rhyacian | 2,300 to 2,050 million years ago | 250 | From Greek ῥύαξ (rhýax) 'stream of lava'.[3] |

| Siderian | 2,500 to 2,300 million years ago | 200 | From Greek σίδηρος (sídēros) 'iron'.[3] |

| Name | Time span | Duration (million years) | Etymology of name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holocene | 0.012 to 0 million years ago | 0.0117 | From Greek ὅλος (hólos) 'whole' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Pleistocene | 2.58 to 0.012 million years ago | 2.5683 | Coined in the early 1830s from Greek πλεῖστος (pleîstos) 'most' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Pliocene | 5.33 to 2.58 million years ago | 2.753 | Coined in the early 1830s from Greek πλείων (pleíōn) 'more' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Miocene | 23.03 to 5.33 million years ago | 17.697 | Coined in the early 1830s from Greek μείων (meíōn) 'less' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Oligocene | 33.9 to 23.03 million years ago | 10.87 | Coined in the 1850s from Greek ὀλίγος (olígos) 'few' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Eocene | 56 to 33.9 million years ago | 22.1 | Coined in the early 1830s from Greek ἠώς (ēōs) 'dawn' and καινός (kainós) 'new', referring to the dawn of modern life during this epoch |

| Paleocene | 66 to 56 million years ago | 10 | Coined by Wilhelm Philippe Schimper in 1874 as a portmanteau of paleo- + Eocene, but on the surface from Greek παλαιός (palaios) 'old' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Upper Cretaceous | 100.5 to 66 million years ago | 34.5 | See Cretaceous |

| Lower Cretaceous | 145 to 100.5 million years ago | 44.5 | |

| Upper Jurassic |

161.5 to 145 million years ago | 16.5 | See Jurassic |

| Middle Jurassic | 174.7 to 161.5 million years ago | 13.2 | |

| Lower Jurassic |

201.4 to 174.7 million years ago | 26.7 | |

| Upper Triassic | 237 to 201.4 million years ago | 35.6 | See Triassic |

| Middle Triassic |

247.2 to 237 million years ago | 10.2 | |

| Lower Triassic | 251.9 to 247.2 million years ago | 4.702 | |

| Lopingian | 259.51 to 251.9 million years ago | 7.608 | Named for Loping, China, an anglicization of Mandarin 乐平 (lèpíng) 'peaceful music' |

| Guadalupian | 273.01 to 259.51 million years ago | 13.5 | Named for the Guadalupe Mountains of the American Southwest, ultimately from Arabic وَادِي ٱل (wādī al) 'valley of the' and Latin lupus 'wolf' via Spanish |

| Cisuralian | 298.9 to 273.01 million years ago | 25.89 | From Latin cis- (before) + Russian Урал (Ural), referring to the western slopes of the Ural Mountains |

| Upper Pennsylvanian | 307 to 298.9 million years ago | 8.1 | Named for the US state of Pennsylvania, from William Penn + Latin silvanus (forest) + -ia by analogy to Transylvania |

| Middle Pennsylvanian | 315.2 to 307 million years ago | 8.2 | |

| Lower Pennsylvanian | 323.2 to 315.2 million years ago | 8 | |

| Upper Mississippian | 330.9 to 323.2 million years ago | 7.7 | Named for the Mississippi River, from Ojibwe ᒥᐦᓯᓰᐱ (misi-ziibi) 'great river' |

| Middle Mississippian | 346.7 to 330.9 million years ago | 15.8 | |

| Lower Mississippian | 358.9 to 346.7 million years ago | 12.2 | |

| Upper Devonian | 382.7 to 358.9 million years ago | 23.8 | See Devonian |

| Middle Devonian | 393.3 to 382.7 million years ago | 10.6 | |

| Lower Devonian | 419.2 to 393.3 million years ago | 25.9 | |

| Pridoli | 423 to 419.2 million years ago | 3.8 | Named for the Homolka a Přídolí nature reserve near Prague, Czechia |

| Ludlow | 427.4 to 423 million years ago | 4.4 | Named after Ludlow, England |

| Wenlock | 433.4 to 427.4 million years ago | 6 | Named for the Wenlock Edge in Shropshire, England |

| Llandovery | 443.8 to 433.4 million years ago | 10.4 | Named after Llandovery, Wales |

| Upper Ordovician | 458.4 to 443.8 million years ago | 14.6 | See Ordovician |

| Middle Ordovician | 470 to 458.4 million years ago | 11.6 | |

| Lower Ordovician | 485.4 to 470 million years ago | 15.4 | |

| Furongian | 497 to 485.4 million years ago | 11.6 | From Mandarin 芙蓉 (fúróng) 'lotus', referring to the state symbol of Hunan |

| Miaolingian | 509 to 497 million years ago | 12 | Named for the Miao Ling mountains of Guizhou, Mandarin for 'sprouting peaks' |

| Cambrian Series 2 (informal) | 521 to 509 million years ago | 12 | See Cambrian |

| Terreneuvian | 538.8 to 521 million years ago | 17.8 | Named for Terre-Neuve, a French calque of Newfoundland |

History of the geologic time scale

[edit]Early history

[edit]While a modern geological time scale was not formulated until 1911[34] by Arthur Holmes, the broader concept that rocks and time are related can be traced back to (at least) the philosophers of Ancient Greece. Xenophanes of Colophon (c. 570–487 BCE) observed rock beds with fossils of shells located above the sea-level, viewed them as once living organisms, and used this to imply an unstable relationship in which the sea had at times transgressed over the land and at other times had regressed.[35] This view was shared by a few of Xenophanes' contemporaries and those that followed, including Aristotle (384–322 BCE) who (with additional observations) reasoned that the positions of land and sea had changed over long periods of time. The concept of deep time was also recognised by Chinese naturalist Shen Kuo[36] (1031–1095) and Islamic scientist-philosophers, notably the Brothers of Purity, who wrote on the processes of stratification over the passage of time in their treatises.[35] Their work likely inspired that of the 11th-century Persian polymath Avicenna (Ibn Sînâ, 980–1037) who wrote in The Book of Healing (1027) on the concept of stratification and superposition, pre-dating Nicolas Steno by more than six centuries.[35] Avicenna also recognised fossils as "petrifications of the bodies of plants and animals",[37] with the 13th-century Dominican bishop Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–1280) extending this into a theory of a petrifying fluid.[38][verification needed] These works appeared to have little influence on scholars in Medieval Europe who looked to the Bible to explain the origins of fossils and sea-level changes, often attributing these to the 'Deluge', including Ristoro d'Arezzo in 1282.[35] It was not until the Italian Renaissance when Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) would reinvigorate the relationships between stratification, relative sea-level change, and time, denouncing attribution of fossils to the 'Deluge':[39][35]

Of the stupidity and ignorance of those who imagine that these creatures were carried to such places distant from the sea by the Deluge...Why do we find so many fragments and whole shells between the different layers of stone unless they had been upon the shore and had been covered over by earth newly thrown up by the sea which then became petrified? And if the above-mentioned Deluge had carried them to these places from the sea, you would find the shells at the edge of one layer of rock only, not at the edge of many where may be counted the winters of the years during which the sea multiplied the layers of sand and mud brought down by the neighboring rivers and spread them over its shores. And if you wish to say that there must have been many deluges in order to produce these layers and the shells among them it would then become necessary for you to affirm that such a deluge took place every year.

These views of da Vinci remained unpublished, and thus lacked influence at the time; however, questions of fossils and their significance were pursued and, while views against Genesis were not readily accepted and dissent from religious doctrine was in some places unwise, scholars such as Girolamo Fracastoro shared da Vinci's views, and found the attribution of fossils to the 'Deluge' absurd.[35]

Establishment of primary principles

[edit]Niels Stensen, more commonly known as Nicolas Steno (1638–1686), is credited with establishing four of the guiding principles of stratigraphy.[35] In De solido intra solidum naturaliter contento dissertationis prodromus Steno states:[7][40]

- When any given stratum was being formed, all the matter resting on it was fluid and, therefore, when the lowest stratum was being formed, none of the upper strata existed.

- ...strata which are either perpendicular to the horizon or inclined to it were at one time parallel to the horizon.

- When any given stratum was being formed, it was either encompassed at its edges by another solid substance or it covered the whole globe of the earth. Hence, it follows that wherever bared edges of strata are seen, either a continuation of the same strata must be looked for or another solid substance must be found that kept the material of the strata from being dispersed.

- If a body or discontinuity cuts across a stratum, it must have formed after that stratum.

Respectively, these are the principles of superposition, original horizontality, lateral continuity, and cross-cutting relationships. From this Steno reasoned that strata were laid down in succession and inferred relative time (in Steno's belief, time from Creation). While Steno's principles were simple and attracted much attention, applying them proved challenging.[35] These basic principles, albeit with improved and more nuanced interpretations, still form the foundational principles of determining the correlation of strata relative to geologic time.

Over the course of the 18th-century geologists realised that:

- Sequences of strata often become eroded, distorted, tilted, or even inverted after deposition

- Strata laid down at the same time in different areas could have entirely different appearances

- The strata of any given area represented only part of Earth's long history

Formulation of a modern geologic time scale

[edit]The apparent, earliest formal division of the geologic record with respect to time was introduced by Thomas Burnet who applied a two-fold terminology to mountains by identifying "montes primarii" for rock formed at the time of the 'Deluge', and younger "monticulos secundarios" formed later from the debris of the "primarii".[41][35] This attribution to the 'Deluge', while questioned earlier by the likes of da Vinci, was the foundation of Abraham Gottlob Werner's (1749–1817) Neptunism theory in which all rocks precipitated out of a single flood.[42] A competing theory, Plutonism, was developed by Anton Moro (1687–1784) and also used primary and secondary divisions for rock units.[43][35] In this early version of the Plutonism theory, the interior of Earth was seen as hot, and this drove the creation of primary igneous and metamorphic rocks and secondary rocks formed contorted and fossiliferous sediments. These primary and secondary divisions were expanded on by Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti (1712–1783) and Giovanni Arduino (1713–1795) to include tertiary and quaternary divisions.[35] These divisions were used to describe both the time during which the rocks were laid down, and the collection of rocks themselves (i.e., it was correct to say Tertiary rocks, and Tertiary Period). Only the Quaternary division is retained in the modern geologic time scale, while the Tertiary division was in use until the early 21st century. The Neptunism and Plutonism theories would compete into the early 19th century with a key driver for resolution of this debate being the work of James Hutton (1726–1797), in particular his Theory of the Earth, first presented before the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1785.[44][8][45] Hutton's theory would later become known as uniformitarianism, popularised by John Playfair[46] (1748–1819) and later Charles Lyell (1797–1875) in his Principles of Geology.[9][47][48] Their theories strongly contested the 6,000 year age of the Earth as suggested determined by James Ussher via Biblical chronology that was accepted at the time by western religion. Instead, using geological evidence, they contested Earth to be much older, cementing the concept of deep time.

During the early 19th century William Smith, Georges Cuvier, Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy, and Alexandre Brongniart pioneered the systematic division of rocks by stratigraphy and fossil assemblages. These geologists began to use the local names given to rock units in a wider sense, correlating strata across national and continental boundaries based on their similarity to each other. Many of the names below erathem/era rank in use on the modern ICC/GTS were determined during the early to mid-19th century.

The advent of geochronometry

[edit]During the 19th century, the debate regarding Earth's age was renewed, with geologists estimating ages based on denudation rates and sedimentary thicknesses or ocean chemistry, and physicists determining ages for the cooling of the Earth or the Sun using basic thermodynamics or orbital physics.[5] These estimations varied from 15,000 million years to 0.075 million years depending on method and author, but the estimations of Lord Kelvin and Clarence King were held in high regard at the time due to their pre-eminence in physics and geology. All of these early geochronometric determinations would later prove to be incorrect.

The discovery of radioactive decay by Henri Becquerel, Marie Curie, and Pierre Curie laid the ground work for radiometric dating, but the knowledge and tools required for accurate determination of radiometric ages would not be in place until the mid-1950s.[5] Early attempts at determining ages of uranium minerals and rocks by Ernest Rutherford, Bertram Boltwood, Robert Strutt, and Arthur Holmes, would culminate in what are considered the first international geological time scales by Holmes in 1911 and 1913.[34][49][50] The discovery of isotopes in 1913[51] by Frederick Soddy, and the developments in mass spectrometry pioneered by Francis William Aston, Arthur Jeffrey Dempster, and Alfred O. C. Nier during the early to mid-20th century would finally allow for the accurate determination of radiometric ages, with Holmes publishing several revisions to his geological time-scale with his final version in 1960.[5][50][52][53]

Modern international geologic time scale

[edit]The establishment of the IUGS in 1961[54] and acceptance of the Commission on Stratigraphy (applied in 1965)[55] to become a member commission of IUGS led to the founding of the ICS. One of the primary objectives of the ICS is "the establishment, publication and revision of the ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart which is the standard, reference global Geological Time Scale to include the ratified Commission decisions".[1]

Following on from Holmes, several A Geological Time Scale books were published in 1982,[56] 1989,[57] 2004,[58] 2008,[59] 2012,[60] 2016,[61] and 2020.[62] However, since 2013, the ICS has taken responsibility for producing and distributing the ICC citing the commercial nature, independent creation, and lack of oversight by the ICS on the prior published GTS versions (GTS books prior to 2013) although these versions were published in close association with the ICS.[2] Subsequent Geologic Time Scale books (2016[61] and 2020[62]) are commercial publications with no oversight from the ICS, and do not entirely conform to the chart produced by the ICS. The ICS produced GTS charts are versioned (year/month) beginning at v2013/01. At least one new version is published each year incorporating any changes ratified by the ICS since the prior version.

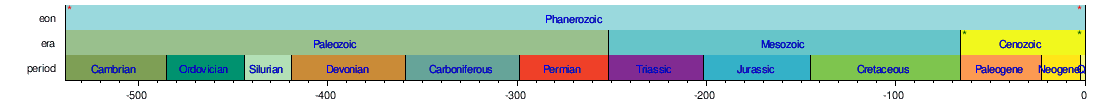

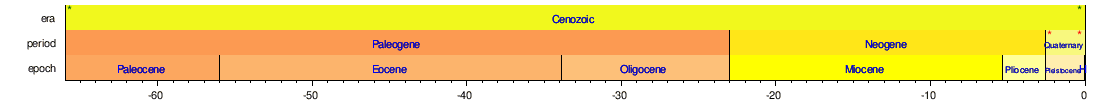

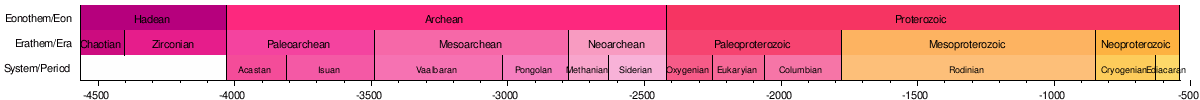

The following five timelines show the geologic time scale to scale. The first shows the entire time from the formation of the Earth to the present, but this gives little space for the most recent eon. The second timeline shows an expanded view of the most recent eon. In a similar way, the most recent era is expanded in the third timeline, the most recent period is expanded in the fourth timeline, and the most recent epoch is expanded in the fifth timeline.

Horizontal scale is Millions of years (above timelines) / Thousands of years (below timeline)

Major proposed revisions to the ICC

[edit]Proposed Anthropocene Series/Epoch

[edit]First suggested in 2000,[63] the Anthropocene is a proposed epoch/series for the most recent time in Earth's history. While still informal, it is a widely used term to denote the present geologic time interval, in which many conditions and processes on Earth are profoundly altered by human impact.[64] As of April 2022[update] the Anthropocene has not been ratified by the ICS; however, in May 2019 the Anthropocene Working Group voted in favour of submitting a formal proposal to the ICS for the establishment of the Anthropocene Series/Epoch.[65] Nevertheless, the definition of the Anthropocene as a geologic time period rather than a geologic event remains controversial and difficult.[66][67][68][69]

Proposals for revisions to pre-Cryogenian timeline

[edit]Shields et al. 2021

[edit]An international working group of the ICS on pre-Cryogenian chronostratigraphic subdivision have outlined a template to improve the pre-Cryogenian geologic time scale based on the rock record to bring it in line with the post-Tonian geologic time scale.[6] This work assessed the geologic history of the currently defined eons and eras of the pre-Cambrian,[note 3] and the proposals in the "Geological Time Scale" books 2004,[70] 2012,[3] and 2020.[71] Their recommend revisions[6] of the pre-Cryogenian geologic time scale were (changes from the current scale [v2023/09] are italicised):

- Three divisions of the Archean instead of four by dropping Eoarchean, and revisions to their geochronometric definition, along with the repositioning of the Siderian into the latest Neoarchean, and a potential Kratian division in the Neoarchean.

- Archean (4000–2450 Ma)

- Paleoarchean (4000–3500 Ma)

- Mesoarchean (3500–3000 Ma)

- Neoarchean (3000–2450 Ma)

- Kratian (no fixed time given, prior to the Siderian) – from Greek κράτος (krátos) 'strength'.

- Siderian (?–2450 Ma) – moved from Proterozoic to end of Archean, no start time given, base of Paleoproterozoic defines the end of the Siderian

- Archean (4000–2450 Ma)

- Refinement of geochronometric divisions of the Proterozoic, Paleoproterozoic, repositioning of the Statherian into the Mesoproterozoic, new Skourian period/system in the Paleoproterozoic, new Kleisian or Syndian period/system in the Neoproterozoic.

- Paleoproterozoic (2450–1800 Ma)

- Skourian (2450–2300 Ma) – from Greek σκουριά (skouriá) 'rust'.

- Rhyacian (2300–2050 Ma)

- Orosirian (2050–1800 Ma)

- Mesoproterozoic (1800–1000 Ma)

- Statherian (1800–1600 Ma)

- Calymmian (1600–1400 Ma)

- Ectasian (1400-1200 Ma)

- Stenian (1200–1000 Ma)

- Neoproterozoic (1000–538.8 Ma)[note 5]

- Kleisian or Syndian (1000–800 Ma) – respectively from Greek κλείσιμο (kleísimo) 'closure' and σύνδεση (sýndesi) 'connection'.

- Tonian (800–720 Ma)

- Cryogenian (720–635 Ma)

- Ediacaran (635–538.8 Ma)

- Paleoproterozoic (2450–1800 Ma)

Proposed pre-Cambrian timeline (Shield et al. 2021, ICS working group on pre-Cryogenian chronostratigraphy), shown to scale:[note 6]

Current ICC pre-Cambrian timeline (v2023/09), shown to scale:

Van Kranendonk et al. 2012 (GTS2012)

[edit]The book, Geologic Time Scale 2012, was the last commercial publication of an international chronostratigraphic chart that was closely associated with the ICS.[2] It included a proposal to substantially revise the pre-Cryogenian time scale to reflect important events such as the formation of the Solar System and the Great Oxidation Event, among others, while at the same time maintaining most of the previous chronostratigraphic nomenclature for the pertinent time span.[72] As of April 2022[update] these proposed changes have not been accepted by the ICS. The proposed changes (changes from the current scale [v2023/09]) are italicised:

- Hadean Eon (4567–4030 Ma)

- Chaotian Era/Erathem (4567–4404 Ma) – the name alluding both to the mythological Chaos and the chaotic phase of planet formation.[60][73][74]

- Jack Hillsian or Zirconian Era/Erathem (4404–4030 Ma) – both names allude to the Jack Hills Greenstone Belt which provided the oldest mineral grains on Earth, zircons.[60][73]

- Archean Eon/Eonothem (4030–2420 Ma)

- Paleoarchean Era/Erathem (4030–3490 Ma)

- Acastan Period/System (4030–3810 Ma) – named after the Acasta Gneiss, one of the oldest preserved pieces of continental crust.[60][73]

- Isuan Period (3810–3490 Ma) – named after the Isua Greenstone Belt.[60]

- Mesoarchean Era/Erathem (3490–2780 Ma)

- Vaalbaran Period/System (3490–3020 Ma) – based on the names of the Kaapvaal (Southern Africa) and Pilbara (Western Australia) cratons, to reflect the growth of stable continental nuclei or proto-cratonic kernels.[60]

- Pongolan Period/System (3020–2780 Ma) – named after the Pongola Supergroup, in reference to the well preserved evidence of terrestrial microbial communities in those rocks.[60]

- Neoarchean Era/Erathem (2780–2420 Ma)

- Methanian Period/System (2780–2630 Ma) – named for the inferred predominance of methanotrophic prokaryotes[60]

- Siderian Period/System (2630–2420 Ma) – named for the voluminous banded iron formations formed within its duration.[60]

- Paleoarchean Era/Erathem (4030–3490 Ma)

- Proterozoic Eon/Eonothem (2420–538.8 Ma)[note 5]

- Paleoproterozoic Era/Erathem (2420–1780 Ma)

- Oxygenian Period/System (2420–2250 Ma) – named for displaying the first evidence for a global oxidising atmosphere.[60]

- Jatulian or Eukaryian Period/System (2250–2060 Ma) – names are respectively for the Lomagundi–Jatuli δ13C isotopic excursion event spanning its duration, and for the (proposed)[75][76] first fossil appearance of eukaryotes.[60]

- Columbian Period/System (2060–1780 Ma) – named after the supercontinent Columbia.[60]

- Mesoproterozoic Era/Erathem (1780–850 Ma)

- Paleoproterozoic Era/Erathem (2420–1780 Ma)

Proposed pre-Cambrian timeline (GTS2012), shown to scale:

Current ICC pre-Cambrian timeline (v2023/09), shown to scale:

Table of geologic time

[edit]It has been suggested that the details about life in the "Major events" column of the table be split out into another article titled Timeline of the evolutionary history of life. (Discuss) (November 2023) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

The following table summarises the major events and characteristics of the divisions making up the geologic time scale of Earth. This table is arranged with the most recent geologic periods at the top, and the oldest at the bottom. The height of each table entry does not correspond to the duration of each subdivision of time. As such, this table is not to scale and does not accurately represent the relative time-spans of each geochronologic unit. While the Phanerozoic Eon looks longer than the rest, it merely spans ~539 million years (~12% of Earth's history), whilst the previous three eons[note 3] collectively span ~3,461 million years (~76% of Earth's history). This bias toward the most recent eon is in part due to the relative lack of information about events that occurred during the first three eons compared to the current eon (the Phanerozoic).[6][77] The use of subseries/subepochs has been ratified by the ICS.[17]

The content of the table is based on the official ICC produced and maintained by the ICS who also provide an online interactive version of this chart. The interactive version is based on a service delivering a machine-readable Resource Description Framework/Web Ontology Language representation of the time scale, which is available through the Commission for the Management and Application of Geoscience Information GeoSciML project as a service[78] and at a SPARQL end-point.[79][80]

| Eonothem/ Эон |

Эратем/ Эпоха |

Система/ Период |

Ряд/ Эпоха |

Этап/ Возраст |

Крупные события | СТАРЬ, миллион лет назад [ Примечание 7 ] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phanerozoic | Кайнозой [ Примечание 4 ] |

Quaternary | Holocene | Meghalayan | 4.2-kiloyear event, Austronesian expansion, increasing industrial CO2. | 0.0042 * |

| Northgrippian | 8.2-kiloyear event, Holocene climatic optimum. Sea level flooding of Doggerland and Sundaland. Sahara becomes a desert. End of Stone Age and start of recorded history. Humans finally expand into the Arctic Archipelago and Greenland. | 0.0082 * | ||||

| Greenlandian | Climate stabilises. Current interglacial and Holocene extinction begins. Agriculture begins. Humans spread across the wet Sahara and Arabia, the Extreme North, and the Americas (mainland and the Caribbean). | 0.0117 ± 0.000099 * | ||||

| Pleistocene | Upper/Late ('Tarantian') | Eemian interglacial, last glacial period, ending with Younger Dryas. Toba eruption. Pleistocene megafauna (including the last terror birds) extinction. Humans expand into Near Oceania and the Americas. | 0.129 | |||

| Chibanian | Mid-Pleistocene Transition occurs, high amplitude 100 ka glacial cycles. Rise of Homo sapiens. | 0.774 * | ||||

| Calabrian | Further cooling of the climate. Giant terror birds go extinct. Spread of Homo erectus across Afro-Eurasia. | 1.8 * | ||||

| Желазийский | Начало четвертичного оледенения и нестабильного климата. [ 81 ] Восстание плейстоценовой мегафауны и гомо Хабилиса . | 2.58 * | ||||

| Неоген | Плиоцен | Piacenzian | Гренландский ледяной щит развивается [ 82 ] как холод медленно усиливается к плейстоцене. Содержание атмосферы O 2 и CO 2 достигает современных уровней, в то время как земли также достигают их нынешних мест (например, перешейк Панамы присоединяется к Северной и Южной Америке , позволяя обмену фауной ). Последние немаземкирные метатеры вымерли. Australopithecus common в Восточной Африке; Каменный век начинается. [ 83 ] | 3.6 * | ||

| Zanclean | Затопление Zanclean Средиземного бассейна . Охлаждающий климат продолжается от миоцена. Первые лошади и слоны . Ardipithecus в Африке. [ 83 ] | 5.333 * | ||||

| Миоцен | Мессиниан | Мессинское событие с гиперсолинными озерами в пустом средиземноморском бассейне . Начинается формация пустыни Сахары. Умеренный климат в ледяном доме , акцентированный ледяными веками и восстановления Восточного Антарктического ледяного покрова . Choristoderes , последние неконтрокодильские крокодиломорфы и креодонты вымерли. После отделения от предков гориллы , шимпанзе и человеческие предки постепенно отделяются; Сахелантроп и Оррорин в Африке. | 7.246 * | |||

| Туртонинец | 11.63 * | |||||

| Серраваллиан | Средний миоценовый климат Оптимум временно обеспечивает теплый климат. [ 84 ] Вымирание в нарушениях среднего миоцена , уменьшение разнообразия акул. Первые бегемоты . Предок великих обезьян . | 13.82 * | ||||

| Вдыхать | 15.98 * | |||||

| Бурдигалянка | Орогения в северном полушарии . Начало кайкоры орогения, образуя южные Альпы в Новой Зеландии . Широко распространенные леса медленно привлекают огромное количество CO 2 , постепенно снижая уровень атмосферного CO 2 с 650 ppmv до примерно 100 ppmv во время миоцена. [ 85 ] [ Примечание 8 ] Современные семьи птиц и млекопитающих становятся узнаваемыми. Последний из примитивных китов вымер. Травы становятся вездесущими. Предок обезьян , включая людей. [ 86 ] [ 87 ] Афро-арабия сталкивается с Евразией, полностью образуя альпидский ремень и закрывая океан Тетис, позволяя обмену фаунией. В то же время афро-арабия распадается в Африку и Западную Азию . | 20.44 | ||||

| Аквитанский | 23.03 * | |||||

| Палеоген | Олигоцен | Чаттс | Гранд -купе. Начало широко распространенного антарктического оледенения . [ 88 ] Быстрая эволюция и диверсификация фауны, особенно млекопитающих (например, первые макроподы и печати ). Основная эволюция и рассеяние современных видов цветущих растений . Cimolestans , Miacoids и Conylarths вымерли. Первые неоцеты (современные, полностью водные киты) появляются. | 27.82 * | ||

| Рупелиан | 33.9 * | |||||

| эоцен | Приабонский | Умеренный, охлаждающий климат . Архаичные млекопитающие (например, креодонты , миакоиды , " мыщелки " и т. Д.) процветают и продолжают развиваться в эпоху. Появление нескольких «современных» семей млекопитающих. Примитивные киты и морские коровы диверсифицируются после возвращения в воду. Птицы продолжают диверсифицировать. Первая водоросли , дипротодонты , медведей и симианы . Многотуркуляция и лептиктидцы вымерли к концу эпохи. Реглацирование Антарктиды и образование его ледяной шапки ; Конец ларамида и севьерогеними Скалистых гор в Северной Америке. Геленическая орогения начинается в Греции и Эгейском море . | 37.71 * | |||

| Бартониан | 41.2 | |||||

| Лютец | 47.8 * | |||||

| Ипразиан | Два переходных события глобального потепления ( PETM и ETM-2 ) и нагревающего климата до оптимального эоценового климата . Событие Azolla снизило уровни CO 2 с 3500 ч / млн до 650 ч / млн, установив почву в течение длительного периода охлаждения. [ 85 ] [ Примечание 8 ] Большая Индия сталкивается с Евразией и начинает гималайскую орогению (позволяя биотическому обмену ), в то время как Евразия полностью отделяется от Северной Америки, создавая Северную Атлантическую океан . Морская Юго -Восточная Азия расходится от остальной части Евразии. Первые пробирки , жвачные животные , яполины , летучие мыши и настоящие приматы . | 56 * | ||||

| Палеоцен | Танетиан | Начинается с удара Chicxulub и события вымирания K-PG , уничтожая всех неавийских динозавров и птерозавров, большинство морских рептилий, многих других позвоночных (например, много лаурэзианских метатетриан), большинство других цефалопод (только Nautilidae и Coleodea выжили) и многие другие инвертебрат. Климат Тропический . Млекопитающие и птицы (птицы) быстро диверсифицируют в ряде линий после события вымирания (пока морская революция останавливается). Многотуркуляция и первые грызуны широко распространены. Первые крупные птицы (например, катисты и террористические птицы ) и млекопитающих (до медведя или маленького размера бегемота). Альпийская орогения в Европе и Азии начинается. Появляются первые хобоскейцы и Plesiadapiformes (приматы STEM). Некоторые сумчатые мигрируют в Австралию. | 59.2 * | |||

| Селандиан | 61.6 * | |||||

| Дани | 66 * | |||||

| Мезозой | Меловая | Верхний/поздний | Маастрихтский | Цветущие растения пролиферируют (после развития многих признаков со времен каменноугольного происхождения), наряду с новыми типами насекомых , в то время как другие семенные растения (спортивные годы и папоротники) снижаются. Более современная телеостровая рыба начинает появляться. Аммоноиды , белементы , рудистские двустворчатые молнии , морские ежи и губки - все это общее. Многие новые типы динозавров (например , тиранозавры , титанозавры , хадрозавры и цератопсиды ) развиваются на суше, в то время как крокодильцы появляются в воде и, вероятно, заставляют последних темносподит, которые выгибают; и мозасавры и современные виды акул появляются в море. Революция, начатая морские рептилии, и акулы достигают своего пика, хотя ихтиозавры исчезают через несколько миллионов лет после значительного сокращения на мероприятии Бонарелли . Зубные и беззубые птицы -птицы сосуществуют с птерозаврами. Современные монотримы , Metetherian (в том числе Marsupials , которые мигрируют в Южную Америку) и эврианские (включая плаценты , лептиктидцы и цимолесцы ), появляются млекопитающие, в то время как последние не млекопитающие цинодонты умирают. Первый наземные крабы . Многие улитки становятся наземными. Дальнейший распад Гондваны создает Южную Америку , Афро- Аравию , Антарктиду , Океанию , Мадагаскар , Большую Индию , а также Южную Атлантическую , Индийскую и Антарктическую океаны и острова индийского (и некоторых из Атлантических) океана. Начало ларамида и севьерогених Скалистых гор . Атмосферные уровни кислорода и углекислого газа аналогичны сегодняшнему дню. Акритархи исчезают. Климат изначально теплый, но позже он охлаждается. | 72.1 ± 0.2 * | |

| Кампанец | 83.6 ± 0.2 * | |||||

| Сантониан | 86.3 ± 0.5 * | |||||

| коньяк | 89.8 ± 0.3 * | |||||

| Туронский | 93.9 * | |||||

| Сеноманский | 100.5 * | |||||

| Ниже/рано | Альбиан | ~113 * | ||||

| Аптиан | ~121.4 | |||||

| Барреманец | ~125.77 * | |||||

| Гаутеривский | ~132.6 * | |||||

| Валангинский | ~139.8 | |||||

| Ягоды | ~145 | |||||

| Юрский период | Верхний/поздний | Титонийский | Климат снова становится влажным. Гимноспермы (особенно хвойные , цикады и цикадеиды ) и папоротники общие. Динозавры , в том числе сауроподы , карнозавры , стегозавры и колурозавры , становятся доминирующими земельными позвоночными. Млекопитающие диверсифицируются в Shuotheriids , Australosphenidans , Eutriconodonts , Multituberculates , SymmeTrodonts , DryoLestids и BoroeSphenidans , но в основном остаются небольшими. Первые птицы , ящерицы, змеи и черепахи . Первые коричневые водоросли , лучи , креветки , крабы и омары . Парвипельвианские Ихтиозавры и Плезиозавры разнообразны. Rhynchocephalians по всему миру. Двоящие молнии , аммоноиды и белеменцы изобилуют. Морские ежи очень распространены, наряду с криноидами , морскими зернами , губками , а также требратулидами и ринченеллидными брахиоподами . Распад Пангеи в Лорасию и Гондвану , причем последняя также разбивается на две основные части; Тихоокеанские формируют и арктические океаны . Tethys Океанские формы . Невадан орогенизии в Северной Америке. Rangitata и Cimmerian Orogenies сужаются. Атмосферные уровни CO 2 в 3–4 раза превышают современные уровни (1200–1500 м.д., по сравнению с сегодняшними 400 ppmv [ 85 ] [ Примечание 8 ] ) Крокодиломорфы (последние псевдосухин) ищут водный образ жизни. Мезозойская морская революция продолжается от позднего триаса. Пятницы исчезают. | 149.2 ± 0.9 | ||

| Kimmeridgian | 154.8 ± 1.0 * | |||||

| Оксфордский | 161.5 ± 1.0 | |||||

| Середина | Калловиан | 165.3 ± 1.2 | ||||

| Батониан | 168.2 ± 1.3 * | |||||

| Баджоциан | 170.9 ± 1.4 * | |||||

| Ааленский | 174.7 ± 1.0 * | |||||

| Ниже/рано | Toarcian | 184.2 ± 0.7 * | ||||

| Плайенсбахиан | 192.9 ± 1.0 * | |||||

| Синемурийский | 199.5 ± 0.3 * | |||||

| Хеттанган | 201.4 ± 0.2 * | |||||

| Триасы | Верхний/поздний | Выживать | Архозавры доминируют на суше как псевдосухин и в воздухе как птерозавры . Динозавры также возникают из двуногих архозавров. Ихтиозавры и нихозавры (группа сауроптерии) доминируют в крупной морской фауне. Cynodonts становятся меньше и ночными, в конечном итоге становятся первыми настоящими млекопитающими , в то время как другие оставшиеся синапсиды выгибают. Rhynchosaurs (родственники архозавра) также распространены. Семенные папоротники , называемые DiCroidium, оставались обычными в Gondwana, прежде чем его заменили продвинутые спортивные полки. Многие крупные водные темноспондильные амфибии. Ceratitidan аммоноиды чрезвычайно распространены. Современные кораллы и телеострные рыбы появляются, как и многие современные насекомых заказы и подчинения . Первая звезда . Андская орогения в Южной Америке. Cimmerian Orogeny в Азии. Rangitata Orogeny начинается в Новой Зеландии. Орогеней охотников в северной Австралии , Квинсленде и Новом Южном Уэльсе (ок. 260–225 млн лет). Карнианское плювиальное событие первых динозавров и лепидозавров (включая ринчоцефалов ). происходит около 234–232 млн. Лет, что позволяет излучать Триасовое событие вымирания произошло в 201 млн. Лет, вытирая все конодонты и последние парарептилы , многие морские рептилии (например, все сауроптеригии, кроме плесзиозавров и все ихтиозавры, кроме парвипелвианцев ), все крокопод, кроме крокодиломорфов, стр. ВСЕГО ЧЕРТИТИДА ), Двоящие молнии, брахиоподы, кораллы и губки. Первые диатомовые . [ 89 ] | ~208.5 | ||

| Нор | ~227 | |||||

| Карниан | ~237 * | |||||

| Середина | Ладинян | ~242 * | ||||

| Анисиан | 247.2 | |||||

| Ниже/рано | Oneolekinan | 251.2 | ||||

| Индуан | 251.902 ± 0.024 * | |||||

| Палеозой | Перми | Лопингян | Чангсинский | Landmasses объединяются в суперконтиненту Pangea , создавая Urals , Ouachitas и Appalachians , среди других горных хребтов (также формируется супер- панталасса или прото-тихоокеанский регион). Конец пермо-карбонового оледенения. Горячий и сухой климат. Возможное снижение уровня кислорода. Синапсиды ( пеликозавры и терапсиды ) становятся широко распространенными и доминирующими, в то время как парарептилы и термоспондильные амфибии остаются общими, а последние, вероятно, вызывают современные амфибии в этот период. В середине исполнителя ликофиты сильно заменены папоротниками и семенными растениями. Жуки и мухи развиваются. Очень большие членистоногие и не тетраподные тетрапудоморфы вымерли. Морская жизнь процветает в теплых мелких рифах; ProductId и Spiriferid брахиопод, двустворчатые моллюски, форамы , аммоноиды (включая гониаты) и ортокериданы все в изобилии. Короны возникают из более ранних диапсидов и разделяются на предков лепидозавров , куэхнеозавридов , хористодеров , архозавров , тестодинатанов , ихтиозавров , талаттозавров и Сауроптеригии . Cynodonts развиваются из более крупных терапидов. Вымирание Олсона (273 млн. Лет), вымирание в конечном счете (260 млн. Лет) и пермс-триассическое событие вымирания (252 млн. Лет) встречаются один за другим: более 80% жизни на Земле вымерли в последнем случае, включая большинство отретических планктона, Кораллы ( табулата и Rugosa полностью вымирают), брахиоподы, мжзильные сании, гастроподы, аммоноиды (гониаты Полностью умереть), насекомые, парарептилы, синапсиды, амфибии и криноиды (выжили только артикуляции ), и все европтериды , трилобиты , граптолиты , гиолиты , эдриоастероидные кринозои , бластоиды и акантодианы . Уахита и орогенианы в Северной Америке. Уралянка орогения в Европе/Азии сужается. Altaid Orogeny в Азии. Орогенство охотника на австралийском континенте начинается (ок. 260–225 млн. Лет), образуя пояс складки Новой Англии. | 254.14 ± 0.07 * | |

| Вучиапиан | 259.51 ± 0.21 * | |||||

| Гвадалупиан | Капитан | 264.28 ± 0.16 * | ||||

| Вордиан | 266.9 ± 0.4 * | |||||

| Дорога | 273.01 ± 0.14 * | |||||

| Цисуральный | Кунгуриан | 283.5 ± 0.6 | ||||

| Артинский | 290.1 ± 0.26 * | |||||

| Немедленно | 293.52 ± 0.17 * | |||||

| Ассол | 298.9 ± 0.15 * | |||||

| Карбоновое [ Примечание 9 ] |

Пенсильванский [ Примечание 10 ] |

Гжелиан | крылатые насекомые Внезапно излучают ; Некоторые (особенно протодоната и палеодиктиоптера ) из них, а также некоторые залив и скорпионы становятся очень большими. Первые угольные леса ( масштабные деревья , папоротники, клубные деревья , гигантские хвощи , кордоиты и т. Д.). Более высокие в атмосфере уровни кислорода . Ледниковый период продолжается до раннего перми. Гониатиты , брахиоподы, мжзиловые, двустворчатые моллюски и кораллы в морях и океанах. Первая Вудлис . ТЕСТАНАТ ФОРАМС пролиферируют. Еврамерика сталкивается с Гондваной и Сибири-Казахстанией, последняя из которых формирует Лауразию и уральской орогении . Variscan Orogeny продолжается (эти столкновения создали орогени и в конечном итоге Pangea ). Амфибии (например, темносподинс) распространились в Еврамерике, а некоторые становятся первыми амниотами . Происходит обрушение каменноугольного тропического леса , инициируя сухой климат, который предпочитает амниоты над амфибиями. Амниоты быстро диверсифицируют в синапсидах , парарептиле , котилозаврах , проторотиридидах и диапсидах . Rhizodonts оставались обычными до того, как они вымерли к концу периода. Первый Акулы . | 303.7 | ||

| Касимовиан | 307 ± 0.1 | |||||

| Московиец | 315.2 ± 0.2 | |||||

| Башкариан | 323.2 * | |||||

| Миссисиппинец [ Примечание 10 ] |

Серпуховский | Крупные ликоподийские примитивные деревья процветают, а амфибийные европтериды живут среди угольных прибрежных болот , излучая значительно в последний раз. Первые гимноскермы . Первые голометаболистые , паранеоптерановые , полиоптераны , одонатоптерановые и эфемероптерановые насекомые и первые саралы . Первые пяти цифровые тетраподы (амфибии) и земельные улитки . В океанах костные и хрящевые рыбы являются доминирующими и разнообразными; Эхинодермы (особенно криноиды и бластоиды ) изобилуют. Кораллы , мжзилости , ортоцериданы , гониатиты и брахиоподы ( Productida , Spiriferida и т. Д.) Восстают и снова становятся очень распространенными, но трилобиты и наоутилоиды снижаются. Оквалификация в Восточной Гондване продолжается от покойного Девонца. Tuhua Orogeny в Новой Зеландии сужается. Некоторая доля окрасила рыбу под названием Rhizodonts, становятся обильными и доминирующими в пресноводных водах. Сибири сталкивается с другим маленьким континентом, Казахстания . | 330.9 ± 0.2 | |||

| Висейн | 346.7 ± 0.4 * | |||||

| Турнеазийский | 358.9 ± 0.4 * | |||||

| Девонский | Верхний/поздний | Famennian | Первые ликоподы , папоротники , семенные растения ( папоротники семян , от более ранних прогимносперм ), первые деревья (Archaeopteris ) и первые крылатые насекомые (Palaeoptera и Neoptera). Строфоменид и атрипид брахиопод , морщинистые и табулятные кораллы и криноиды обильно в океанах. Первые полностью свернутые головоногих ( Ammonoidea и Nautilida , независимо) с бывшей группой очень обильной (особенно гониатиты ). Трилобиты и остракодермы снижаются, в то время как челюстные рыбы ( плакодермы , доли, костюмированные и конирующие рыбы , акандианцы и ранняя хрящевая рыба ) пролиферируют. Некоторая доля рыб превращается в цифровую рыбку , медленно становясь амфибийными. Последние не трилобитные артиоподы умирают. Первые декаподы (как креветки ) и изоподы . Давление со стороны челюстных рыб заставляет Eurypterids упасть, а несколько головоногих - терять свои раковины, в то время как аномалокариды исчезают. «Старый красный континент» Еврамерики сохраняется после формирования в каледонской орогении. Начало академической орогенизии для антиатласских гор в Северной Африке и Аппалачских горах Северной Америки, а также орогени в рогах , варискане и тухуа в Новой Зеландии. Серия событий вымирания, в том числе массивные келлвассеры и хангенберг , вытирают многие акритархи, кораллы, губки, моллюски, трилобиты, европтериды, граптолиты, брахиоподы, кринозои (например, все цистоиды ) и рыбу, включая все плаценты и остракодермы. | 372.2 ± 1.6 * | ||

| Фраснийский | 382.7 ± 1.6 * | |||||

| Середина | Givetian | 387.7 ± 0.8 * | ||||

| Эйфелев | 393.3 ± 1.2 * | |||||

| Ниже/рано | Эмсиан | 407.6 ± 2.6 * | ||||

| Пражиан | 410.8 ± 2.8 * | |||||

| Лочковиан | 419.2 ± 3.2 * | |||||

| Силурийский | Придоли | Озоновый слой сгущается. Первые сосудистые растения и полностью наземные членистоногие: мириаподы , гексаподы (включая насекомых ) и арахниды . Eurypterids быстро диверсифицируется, становясь широко распространенными и доминирующими. Цефалоподы продолжают процветать. Настоящие челюстные рыбы , наряду с остракодермами , также бродят по морям. Табулат и с трудом кораллы , брахиопод ( пентамерида , rhynchonellida и т. Д.), Цистоиды и криноиды - все это изобилует. Трилобиты и моллюски разнообразны; Граптолиты не так разнообразны. Три незначительных события вымирания. Некоторые эхинодермы вымерли. Начало каледонской орогеники (столкновение между Лаурентией, Балтией и одним из ранее маленьких гондвананских террейнов) для холмов в Англии, Ирландии, Уэльсе, Шотландии и скандинавских горах . Также продолжилось в Девонский период как акадская орогения , выше (таким образом, Еврамерики формируется). Taconic Orogeny сужается. Период ледяного дома заканчивается в конце этого периода после начала в позднем ордовике. Лахлан Орогеней на австралийском континенте сужается. | 423 ± 2.3 * | |||

| Ладлоу | Людфордский | 425.6 ± 0.9 * | ||||

| Горстиан | 427.4 ± 0.5 * | |||||

| Венлок | Гомериан | 430.5 ± 0.7 * | ||||

| Шейнвудский | 433.4 ± 0.8 * | |||||

| Llandovery | ТЕЛИЧИАН | 438.5 ± 1.1 * | ||||

| Аэрониан | 440.8 ± 1.2 * | |||||

| Рудданский | 443.8 ± 1.5 * | |||||

| Ордовик | Верхний/поздний | Дольше | Большое событие биорадификации ордовика происходит по мере увеличения количества планктона: беспозвоночные диверсифицируются во многих новых типах (особенно брахиопод и моллюсках; например, электрополоподы с длинными прямолинейными оболочками, такие как длительные и разнообразные ортокерида ). Ранние кораллы , четкие брахиоподы ( Orthida , Strophomenida и т. Д.), Двухбаллисты , головные (наоутилоиды), трилобиты , остракоды , мжзильные маозо , многие виды эхинодерм ( бластоиды , цистоиды , криноиды , морские ежи , морские и звезда огурцы и т. д.), разветвленные грапталиты и другие таксоны все общий. Акритархи все еще сохраняются и распространены. Цефалоподы становятся доминирующими и распространенными, с некоторыми тенденциями к спиральной раковине. Аномалокариды снижаются. Появляются таинственные etentaculitans . Первые появляются европтериды и остракодерма , последние, вероятно, вызовут челюстную рыбу в конце периода. Первые неудобные наземные грибы и полностью наземные растения . Ледяной период в конце этого периода, а также серия событий массового вымирания , убив некоторых головоногих и многих брахиопод, мжзителей, эхинодерм, граптолитов, трилобитов, двустворчатых моллюсков, кораллов и конодонтов . | 445.2 ± 1.4 * | ||

| Катин | 453 ± 0.7 * | |||||

| Песчаный | 458.4 ± 0.9 * | |||||

| Середина | Дарривилиан | 467.3 ± 1.1 * | ||||

| Дапингян | 470 ± 1.4 * | |||||

| Ниже/рано | Floian (Ранее Айриг ) |

477.7 ± 1.4 * | ||||

| Тремадоциан | 485.4 ± 1.9 * | |||||

| Камбрийский | Фуронгиан | Этап 10 | Основная диверсификация (ископаемых в основном показывает билатерационную) жизнь в кембрийском взрыве по мере увеличения уровня кислорода. Многочисленные окаменелости; большинство современных животных Phyla (включая членистоногие , моллюски , аннелиды , эхинодермы , гемихорды и хордоры Появляются ). Рассматривающие рифы археоокятанские губки первоначально в изобилии, затем исчезают. Строматолиты заменяют их, но быстро становятся жертвами агрономической революции , когда некоторые животные начали обрываться через микробные коврики (поражая и других животных). Первые артиоподы (включая трилобиты ), приапулидные черви, необразные брахиоподы (рассеянные бани), гиолиты , мжзильные , граптолиты , пентарадиальные эхинодермии (эг -бластозойцы , кринозоины и элеутозоицы ) и число других животных. Аномалокариды являются доминирующими и гигантскими хищниками, в то время как многие эдиакарские фауны выгибают . Раковые ракообразные и моллюски быстро диверсифицируются. Прокариоты , Протисты (например, Форамы ), водоросли и грибы продолжают сегодня. Первые позвоночные из более ранних хордовых. Питерманн Орогеней На австралийском континенте сужается (550–535 млн. Лет). Росс Орогеней в Антарктиде. Деламерианская орогения (ок. 514–490 млн. Лет) на австралийском континенте . Некоторые маленькие террассы откладываются от Гондваны. Содержание атмосферного CO 2 примерно в 15 раз современные ( голоценовые ) уровни (6000 ч / млн по сравнению с сегодняшними 400 ч / млн) [ 85 ] [ Примечание 8 ] Членистоногие и стрептофита начинают колонизировать землю. 3 события вымирания происходят 517, 502 и 488 млн. Лет, первая и последняя из которых уничтожает многие из аномалокаридов, артиопод, гиолитов, брахиопод, моллюсков и конодонтов (ранние челюстные позвоночные). | ~489.5 | ||

| Цзяншанян | ~494 * | |||||

| Пабиан | ~497 * | |||||

| Миалингианский | Гужангиан | ~500.5 * | ||||

| Барабан | ~504.5 * | |||||

| Вулиан | ~509 | |||||

| Серия 2 | Этап 4 | ~514 | ||||

| Этап 3 | ~521 | |||||

| Терреневский | Этап 2 | ~529 | ||||

| Фортуниан | 538.8 ± 0.2 * | |||||

| Протерозой | Неопротерозой | Эдиакаран | Хорошие окаменелости примитивных животных . Ediacaran Biota процветает по всему миру в морях, возможно, появившись после взрыва , возможно, вызванного крупномасштабным событием окисления. [ 90 ] Первые вендозоя (неизвестная близость среди животных), Cnidarians и Bilaterians . Загадочные вендозоицы включают в себя множество существа с мягкими железами в форме мешков, дисков или стеганых одеял (как Дикинсония ). Простые следовые окаменелости возможного червя, подобного трихофику и т. Д. Таконическая орогения в Северной Америке. Араавалли диапазон орогения на индийском субконтиненте . Начало панафриканской орогеники , что приводит к образованию недолгого эдиакарского суперконтинента Паннотии , которая к концу периода разбивается на Лаурентию , Балтию , Сибири и Гондвану . Петерманн Орогеней формирует на австралийском континенте . Beardmore Orogeny в Антарктиде, 633–620 млн. Лет. Озоновый слой формы. Повышение уровня минералов в океане . | ~635 * | ||

| Криоген | Возможный " Снежного кома" Земля период ". Окаменелости все еще редки. Покойный рукер / нимрод Орогеней в Антарктиде сужается. Первые неудобные окаменелости животных . Первые гипотетические наземные грибы [ 91 ] и Streptophyta . [ 92 ] | ~720 | ||||

| Тониан | Окончательная сборка суперконтинента Родинии происходит в раннем тонианском языке, с началом разрыва c. 800 млн. Sveconorwegian orogeny заканчивается. Гренвилль орогенизирует в Северной Америке. Озера Рукер / Нимрод Орогеней в Антарктиде, 1000 ± 150 млн. Лет. Эдмундианская орогения (ок. 920–850 млн. Лет), Гасскоинский комплекс , Западная Австралия. Осаждение Аделаиды Супербасин и Центрального Супербасина начинается на австралийском континенте . Первые гипотетические животные (от голоозон) и земные коврики для водорослей. Многие эндосимбиотические события, касающиеся красных и зеленых водорослей, переносят пластиды в охрофита (например , диатомовые лица , коричневые водоросли ), динофлагелляты , криптофита , гаптофита и эвглениды (события могли начаться в мезопротерозое) [ 93 ] В то время как первые срезок (например, Forams ) также появляются: эукариоты быстро диверсифицируются, включая водоросль, эукариоворические и биоминерализованные формы. Следы окаменелости простых многоклеточных эукариот. Событие неопротерозойской оксигенации (NOE), 850-540 млн. | 1000 [ Примечание 11 ] | ||||

| Мезопротерозой | Стениан | Узкие сильно метаморфические пояса из-за орогении в качестве формирования родинии , окруженных панафриканским океаном . SVECONORWEGIAN OROGENY начинается. Поздний Рукер / Нимрод Орогеней в Антарктиде, возможно, начинается. Musgrave Orogeny (c. 1,080–), Musgrave Block , Центральная Австралия . Строматолиты снижаются по мере пролиферирования водорослей . | 1200 [ Примечание 11 ] | |||

| Ectasian | Обложки платформы продолжают расширяться. водорослей Колонии в морях. Гренвилль Орогеней в Северной Америке. Колумбия расстается. | 1400 [ Примечание 11 ] | ||||

| Calymmian | Платформа покрывает расширение. Баррамунди орогении, бассейн Макартура , Северная Австралия и Исан Орогении, c. 1600 млн. М., гора Иса, Блок, Квинсленд. Первые архауэпластиды (первые эукариоты с пластидами из цианобактерий; например, красные и зеленые водоросли ) и опишхоконты (вызывая первые грибы и голоозо ). Акритархи (останки морских водорослей) начинают появляться в ископаемом записи. | 1600 [ Примечание 11 ] | ||||

| Палеопротерозой | Статериан | Первые неоспоримые эукариоты : профисты с ядрами и энтемембранной системой. Колумбия образуется как второй неоспоримый самый ранний суперконтинент. Кимбан орогения на австралийском континенте заканчивается. Япунку орогенизии на Йилгарн Кратон , в Западной Австралии. Mangaroon Orogeny, 1680–1620 млн. Лет, на комплексе Гаскайн в Западной Австралии. Караран Орогении (1650 млн лет), Gawler Craton, Южная Австралия . Уровни кислорода снова падают. | 1800 [ Примечание 11 ] | |||

| Орозирийский | Атмосфера в становится гораздо более кислородной, то время как более цианобактериальные строматолиты появляются. Вердефор и бассейн Садбери . Много орогения . Пенокан и транс-годзоновский орогени в Северной Америке. Ранний орогеней Рукера в Антарктиде, 2000–1700 млн. Лет. Гленбург Орогеней, Гленбург Террейн , Австралийский континент c. 2,005–1,920 мА. Kimban orogeny, Gawler Craton на австралийском континенте. | 2050 [ Примечание 11 ] | ||||

| Rhyacian | Бушвельд магматические сложные формы. Гунианский оледенение. Первые гипотетические эукариоты . Многоклеточная Франсвилльская биота . Kenorland разводит. | 2300 [ Примечание 11 ] | ||||

| Сидериан | Большое событие окисления (из -за цианобактерий ) увеличивает кислород. Sleeferd Orogeny на австралийском континенте , Gawler Craton 2440–2,420 мА. | 2500 [ Примечание 11 ] | ||||

| Архейский | Неоархин | Стабилизация большинства современных кратонов ; Возможное мантии событие переворачивания . Инселл орогения, 2650 ± 150 мА. Пояс Abitibi Greenstone в современном Онтарио и Квебеке начинает формироваться, стабилизируется на 2600 млн. Лет. Первый бесспорный суперконтинент , Кенорленд и первые наземные прокариоты . | 2800 [ Примечание 11 ] | |||

| Мезоархин | Первые строматолиты (вероятно, колониальные фототрофные бактерии, такие как цианобактерии). Старейшие макрофоссили . Орогеней Гумбольдта в Антарктиде. Комплекс Blake River MegaCaldera начинает образовываться в современных Онтарио и Квебеке , заканчивается примерно на 2696 млн. Лет. | 3200 [ Примечание 11 ] | ||||

| Палеоархин | Прокариотическая археи (например, метаногены ) и бактерии (например, цианобактерии ) быстро диверсифицируют, наряду с ранними вирусами . Первые известные фототрофные бактерии . Самые старые окончательные микрофоссили . Первые микробные коврики . Самые старые кратоны на Земле (такие как канадский щит и кратон Пилбара ), возможно, сформировались в течение этого периода. [ Примечание 12 ] Rayner Orogeny в Антарктиде. | 3600 [ Примечание 11 ] | ||||

| Eoarchean | Первые непревзойденные живые организмы : сначала протокели с генами на основе РНК около 4000 млн лет, после чего настоящие клетки ( прокариоты ) эволюционируют вместе с белками и ДНК генами на основе около 3800 млн. Лет. Конец поздней тяжелой бомбардировки . Орогеней Нейпир в Антарктиде, 4000 ± 200 млн. Лет. | 4031 [ Примечание 11 ] | ||||

| Хадин | Формирование протолита самой старой известной скалы ( асаста гнейс ) c. От 4031 до 3580 мА. [ 94 ] [ 95 ] Возможное первое появление тектоники пластины . Первые гипотетические формы жизни . Конец ранней фазы бомбардировки. Самый старый известный минерал ( циркон , 4,404 ± 8 млн. Лет). [ 96 ] Астероиды и кометы приносят воду на землю, образуя первые океаны. Формирование Луны (4510 млн лет), вероятно, от гигантского воздействия . Формирование Земли (от 4543 до 4540 мА) | 4567.3 ± 0.16 [ Примечание 11 ] | ||||

Геологические временные масштабы, основанные

[ редактировать ]Некоторые другие планеты и спутники в Солнечной системе имеют достаточно жесткие структуры, чтобы сохранить записи своей собственной истории, например, Венеру , Марс Земли и Луна . В основном планеты, такие как гигантские планеты , не сравнительно сохраняют свою историю. Помимо поздней тяжелой бомбардировки , события на других планетах, вероятно, мало что оказали непосредственное влияние на землю, и события на Земле оказали соответственно мало влияния на эти планеты. Следовательно, строительство временной шкалы, которая связывает планеты, является лишь ограниченной актуальностью для шкалы времени Земли, за исключением контекста солнечной системы. Существование, сроки и наземные последствия поздней тяжелой бомбардировки все еще являются вопросом дебатов. [ Примечание 13 ]

Лунная (селенологическая) шкала времени

[ редактировать ]Геологическая история луны Земли была разделена на шкалу времени, основанную на геоморфологических маркерах, а именно на кратере , вулканизм и эрозию . Этот процесс разделения истории Луны таким образом означает, что границы масштаба времени не подразумевают фундаментальные изменения в геологических процессах, в отличие от геологического масштаба времени Земли. Пять геологических систем/периодов ( до-нектарианский , нектарный , имбрийский , эратостенианский , коперник ), с имбрийским разделенным на две серии/эпохи (рано и поздно) были определены в последней масштабе времени лунного геологического времени. [ 97 ] Луна уникальна в солнечной системе, поскольку она является единственным другим телом, из которого люди имеют образцы породы с известным геологическим контекстом.

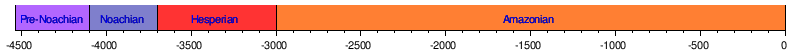

Марсианская геологическая шкала времени

[ редактировать ]Геологическая история Марса была разделена на две альтернативные временные шкалы. Впервые шкала для Марса были разработаны путем изучения плотности воздействия кратеров на марсианской поверхности. Благодаря этому методу было определена четыре периода, пре-ноаччик (~ 4500–4100 млн. Лет), Ноахиан (~ 4100–3700 млн. Лет), Геспериан (~ 3700–3000 млн лет) и амазон (~ 3000 млн. Лет до настоящего времени). [ 98 ] [ 99 ]

Эпохи:

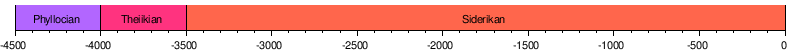

Вторая шкала времени, основанная на изменении минералов, наблюдаемое спектрометром омега на борту Mars Express . Используя этот метод, были определены три периода, филлоциан (~ 4500–4000 млн. Лет), тейкианский (~ 4000–3500 млн. Лет) и сидерианский (~ 3500 млн. Лет). [ 100 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Возраст земли

- Космический календарь

- Глубокое время

- Эволюционная история жизни

- Формирование и эволюция солнечной системы

- Геологическая история земли

- Геология Марса

- Геон (геология)

- Графическая временная шкала вселенной

- История Земли

- История геологии

- История палеонтологии

- Список окаменелостей

- Список геохронологических имен

- Логарифмическая временная шкала

- Лунный геологический временной шкале

- Марсианский геологический временной шкале

- Естественная история

- Геологическая масштаба времени Новой Зеландии

- Доисторическая жизнь

- Временная шкала большого взрыва

- Временная шкала эволюции

- Временная шкала геологической истории Соединенных Штатов

- Временная шкала человеческой эволюции

- Временная шкала естественной истории

- Временная шкала палеонтологии

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Теперь известно, что не все осадочные слои осаждаются чисто горизонтально, но этот принцип все еще является полезным концепцией.

- ^ Время пролета геологических временных подразделений варьируется в широком смысле, и не существует числовых ограничений на промежуток времени, который они могут представлять. Они ограничены временем временного интерната, к которым они принадлежат, и хроностратиграфическими границами, которые они определены.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Докембрийский или предварительный камбрий

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Третичный - теперь устаревшая геологическая система/период, охватывающая от 66 до 2,6 млн. Лет. Он не имеет точного эквивалента в современном МУС, но приблизительно эквивалентен объединенным палеогеновым и неогенным системам/периодам. [ 18 ] [ 19 ]

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Геохронометрическая дата для эдиакарана была скорректирована так, чтобы отразить ICC V2023/09, поскольку формальное определение основания кембрийского языка не изменилось.

- ^ Кратианский промежуток времени не приведен в статье. Он лежит в неоархинском и до сидера. Положение, показанное здесь, является произвольным разделением.

- ^ Указанные даты и неопределенности соответствуют Международной хроностратиграфической диаграмме международной комиссии по стратиграфии (V2023/06). Анонца * Указывает границы, где глобальный раздел граничного стратотипа и точка были согласованы на международном уровне.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Для получения дополнительной информации об этом см. Атмосферу Земли#Эволюция атмосферы Земли , углекислый газ в атмосфере Земли и изменение климата . Специфические графики реконструированных уровней CO в течение последних ~ 550, 65 и 5 миллионов лет можно увидеть в углекислый газ . файле 2 фанерозойский : Полем

- ^ Миссисипи -это официальные подсистемы / и Пенсильваниан подпериоды.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Это разделено на нижнюю/раннюю, среднюю и верхнюю/позднюю серию/эпохи

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м Определяется абсолютным возрастом ( глобальный стандартный стратиграфический возраст ).

- ^ Возраст самого старого измеримого кратона или континентальной коры датируется до 3600–3800 млн.

- ^ Недостаточно известно о дополнительных планетах для достойных спекуляций.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Статуи и руководящие принципы» . Международная комиссия по стратиграфии . Получено 5 апреля 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Коэн, Км; Финни, Южная Каролина; Гиббард, PL; Фан, J.-X. (1 сентября 2013 г.). «Международная хроностратиграфическая диаграмма ICS» . Эпизоды . 36 (3) (обновлено изд.): 199–204. doi : 10.18814/epiiugs/2013/v36i3/002 . ISSN 0705-3797 . S2CID 51819600 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м Ван Кранендон, Мартин Дж.; Altermann, Wladyslaw; Борода, Брайан Л.; Хоффман, Пол Ф.; Джонсон, Кларк М.; Каста, Джеймс Ф.; Мележик, Виктор А.; Nutman, Allen P. (2012), «Хроностратиграфическое разделение докембрийца» , Геологическая шкала времени , Elsevier, pp. 299–392, doi : 10.1016/b978-0-444-59425-9.00016-0 , ISBN 978-0-444-59425-9 , Получено 5 апреля 2022 года

- ^ «Международная комиссия по стратиграфии» . Международная геологическая шкала времени . Получено 5 июня 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). «Эпоха земли в двадцатом веке: проблема (в основном) решена». Специальные публикации, Геологическое общество Лондона . 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode : 2001gslsp.190..205d . doi : 10.1144/gsl.sp.2001.190.01.14 . S2CID 130092094 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Шилдс, Грэм А.; Страчан, Робин А.; Портер, Сюзанна М.; Halverson, Galen P.; Макдональд, Фрэнсис А.; Plumb, Kenneth A.; Де Альваренга, Карлос Дж.; Banerjee, Dhiraj M.; Беккер, Андрей; Бликер, Вутер; Брэйзер, Александр (2022). «Шаблон улучшенного подразделения на основе породы докриогенового временного масштаба» . Журнал геологического общества . 179 (1): JGS2020–222. Bibcode : 2022jgsoc.179..222S . doi : 10.1144/jgs2020-222 . ISSN 0016-7649 . S2CID 236285974 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Стено, Николас (1669). Николас Стенонис твердого внутреннего существа . W. Junk.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Хаттон, Джеймс (1795). Теория Земли . Тол. 1. Эдинбург.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Лайелл, сэр Чарльз (1832). Принципы геологии: быть попыткой объяснить первые изменения поверхности Земли, ссылаясь на причины, которые сейчас работают . Тол. 1. Лондон: Джон Мюррей.

- ^ «Международная комиссия по стратиграфии - стратиграфическое руководство - Глава 9. Хроностратиграфические единицы» . Stratygraphy.org . Получено 16 апреля 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л «Глава 9. Хроностратиграфические единицы» . Stratygraphy.org . Международная комиссия по стратиграфии . Получено 2 апреля 2022 года .