Мехико

Мехико

| |

|---|---|

| Псевдоним(ы): CDMX, Город дворцов (Город дворцов) | |

| Девиз(ы): Инновационный город и права (Город с инновациями и правами) | |

| Гимн: Гимн Мехико. [ 1 ] | |

Мехико в Мексике | |

Расположение в Мексике | |

| Координаты: 19 ° 26' с.ш. 99 ° 8' з.д. / 19,433 ° с.ш. 99,133 ° з.д. | |

| Страна | |

| Основан |

|

| Основан |

|

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Martí Batres (MORENA) |

| Area | |

| • Capital and megacity | 1,485 km2 (573 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 7,866 km2 (3,037 sq mi) |

| Ranked 32nd | |

| Elevation | 2,240 m (7,350 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 3,930 m (12,890 ft) |

| Population (2020)[8] | |

| • Capital and megacity | 9,209,944 |

| • Rank | 1st in North America 1st in Mexico |

| • Density | 6,200/km2 (16,000/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Urban | 23,146,802 |

| • Metro | 21,804,515 |

| Demonyms |

|

| GDP | |

| • Capital and megacity | MXN 4.3 trillion US$ 212 billion (2021) |

| • Metro area | MXN 6.8 trillion US$ 340 billion (2021) |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (CST) |

| Postal code | 00–16 |

| Area code | 55/56 |

| ISO 3166 code | MX-CMX |

| Patron Saint | Philip of Jesus (Spanish: San Felipe de Jesús) |

| HDI | |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Historic center of Mexico City, Xochimilco and Central University City Campus of the UNAM |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1987, 2007 (11th, 31st sessions) |

| Reference no. | 412, 1250 |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| ^ b. Area of Mexico City that includes non-urban areas at the south | |

Мехико (исп. Ciudad de México , [ б ] [ 11 ] локально [sjuˈða(ð) ðe ˈmexico] ; сокр.: CDMX ; Центральный науатль : Мехико , [ 12 ] Произношение на науатле: [meːˈʃiʔko wejaːlˈtepeːt͡ɬ] ; [ 13 ] Отоми : 'Монда ) — столица и крупнейший город Мексики Америке , а также самый густонаселенный город в Северной . [ 14 ] [ 15 ] Мехико – один из важнейших культурных и финансовых центров мира. [ 16 ] Он расположен в Мексиканской долине на высоком центральном плато Мексики , на высоте 2240 метров (7350 футов). В городе 16 районов , или территориальных демаркаций , которые, в свою очередь, разделены на районы или колонии .

Население города в 2020 году составляло 9 209 944 человека. [ 8 ] с площадью земли 1495 квадратных километров (577 квадратных миль). [ 17 ] Согласно последнему определению, согласованному федеральным правительством и правительствами штатов, население Большого Мехико составляет 21 804 515 человек, что делает его шестым по величине мегаполисом в мире, второй по величине городской агломерацией в Западном полушарии (после Сан-Франциско) . Пауло , Бразилия ) и крупнейший испаноязычный город (собственно город) в мире. [ 18 ] Большого Мехико в 2011 году составил ВВП 411 миллиардов долларов, что делает его одним из самых продуктивных городских районов в мире . [ 19 ] На город приходилось 15,8% ВВП Мексики, а на долю мегаполиса приходилось около 22% ВВП страны. [ 20 ] Если бы в 2013 году Мехико была независимой страной, она стала бы пятой по величине экономикой в Латинской Америке . [ 21 ]

Мехико – старейшая столица Америки и одна из двух, основанных коренными народами . [ с ] Первоначально город был построен на группе островов озера Тескоко мексиканцами около 1325 года под названием Теночтитлан . Он был практически полностью разрушен во время осады Теночтитлана в 1521 году и впоследствии перепроектирован и перестроен в соответствии с испанскими городскими стандартами . В 1524 году был основан муниципалитет Мехико, известный как Мексика Теночтитлан . [ 22 ] а с 1585 года он был официально известен как Сьюдад-де-Мехико (Мехико). [ 22 ] Мехико играл важную роль в испанской колониальной империи как политический, административный и финансовый центр. [ 23 ] После обретения независимости от Испании федеральный округ в 1824 году был основан .

После многих лет требований большей политической автономии жители наконец получили право избирать как главу правительства , так и представителей однопалатного Законодательного собрания путем выборов в 1997 году. С тех пор левые партии (сначала Партия демократической революции и позже Движение национального возрождения ) контролировали их обоих. [ 24 ] В городе проводится несколько прогрессивных политик, [ 25 ] [ 26 ] такие как плановые аборты , [ 27 ] ограниченная форма эвтаназии , [ 28 ] развод без вины , [ 29 ] однополые браки , [ 30 ] и юридическое изменение пола . [ 31 ] 29 января 2016 года он перестал быть Федеральным округом (исп. Distrito Federal или DF ) и теперь официально известен как Сьюдад-де-Мехико (или CDMX ) с большей степенью автономии. [ 32 ] [ 33 ] Однако пункт Конституции Мексики не позволяет ей стать штатом в составе Мексиканской федерации, пока она остается столицей страны. [ 34 ]

Прозвища и девизы

[ редактировать ]Мехико традиционно был известен как Ла-Сьюдад-де-лос-Паласиос («Город дворцов»), прозвище , присвоенное барону Александру фон Гумбольдту во время посещения города в 19 веке, который, отправляя письмо обратно в Германию, сказал, что Мехико мог бы соперничать с любым крупным городом Европы. Но именно английский политик Чарльз Латроб на самом деле написал следующее: «...посмотрите на их произведения: молы, акведуки, церкви, дороги — и роскошный Город дворцов , выросший из глиняных руин Теночтитлана.. .», на странице 84 письма V газеты «Рамблер» в Мексике . [ 35 ]

During the colonial period, the city's motto was "Muy Noble e Insigne, Muy Leal e Imperial" (Very Noble and Distinguished, Very Loyal and Imperial).[36][37] During Andrés Manuel López Obrador's administration a political slogan was introduced: la Ciudad de la Esperanza (lit. 'The City of Hope'). This motto was quickly adopted as a city nickname but has faded since the new motto, Capital en Movimiento ("Capital in Movement"), was adopted by the administration headed by Marcelo Ebrard, though the latter is not treated as often as a nickname in media. Up until 2013, it was common to refer to the city by the initialism "DF" from "Distrito Federal de México". Since 2013, the abbreviation "CDMX" (Ciudad de México) has been more common, particularly in relation to government campaigns.

The city is colloquially known as Chilangolandia after the locals' nickname chilangos.[38] Chilango is used pejoratively by people living outside Mexico City to "connote a loud, arrogant, ill-mannered, loutish person".[39] For their part those living in Mexico City designate insultingly those who live elsewhere as living in la provincia ('the provinces', 'the periphery') and many proudly embrace the term chilango.[40] Residents of Mexico City are more recently called defeños (deriving from the postal abbreviation of the Federal District in Spanish: D.F., which is read "De-Efe"). They are formally called capitalinos (in reference to the city being the capital of the country), but "[p]erhaps because capitalino is the more polite, specific, and correct word, it is almost never utilized".[41]

History

[edit]The oldest signs of human occupation in the area of Mexico City are those of the "Peñón woman" and others found in San Bartolo Atepehuacan (Gustavo A. Madero). They were believed to correspond to the lower Cenolithic period (9500–7000 BC).[42] However, a 2003 study placed the age of the Peñon woman at 12,700 years old (calendar age),[43] one of the oldest human remains discovered in the Americas. Studies of her mitochondrial DNA suggest she was either of Asian[44] or European[45] or Aboriginal Australian origin.[46]

The area was the destination of the migrations of the Teochichimecas during the 8th and 13th centuries, people that would give rise to the Toltec, and Mexica (Aztecs) cultures. The latter arrived around the 14th century to settle first on the shores of the lake.

Aztec period

[edit]

The city of Mexico-Tenochtitlan was founded by the Mexica people in 1325 or 1327.[47] The old Mexica city that is now referred to as Tenochtitlan was built on an island in the center of the inland lake system of the Valley of Mexico, which is shared with a smaller city-state called Tlatelolco.[48] According to legend, the Mexicas' principal god, Huitzilopochtli, indicated the site where they were to build their home by presenting a golden eagle perched on a prickly pear devouring a rattlesnake.[49]

Between 1325 and 1521, Tenochtitlan grew in size and strength, eventually dominating the other city-states around Lake Texcoco and in the Valley of Mexico. When the Spaniards arrived, the Aztec Empire had reached much of Mesoamerica, touching both the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.[49]

Spanish conquest

[edit]

After landing in Veracruz, Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés advanced upon Tenochtitlan with the aid of many of the other native peoples,[50] arriving there on 8 November 1519.[51] Cortés and his men marched along the causeway leading into the city from Iztapalapa (Ixtapalapa), and the city's ruler, Moctezuma II, greeted the Spaniards; they exchanged gifts, but the camaraderie did not last long.[52] Cortés put Moctezuma under house arrest, hoping to rule through him.[53]

Tensions increased until, on the night of 30 June 1520 – during a struggle known as "La Noche Triste" – the Aztecs rose up against the Spanish intrusion and managed to capture or drive out the Europeans and their Tlaxcalan allies.[54] Cortés regrouped at Tlaxcala. The Aztecs thought the Spaniards were permanently gone, and they elected a new king, Cuitláhuac, but he soon died; the next king was Cuauhtémoc.[55] Cortés began a siege of Tenochtitlan in May 1521. For three months, the city suffered from the lack of food and water as well as the spread of smallpox brought by the Europeans.[50] Cortés and his allies landed their forces in the south of the island and slowly fought their way through the city.[56] Cuauhtémoc surrendered in August 1521.[50] The Spaniards practically razed Tenochtitlan during the final siege of the conquest.[51]

Cortés first settled in Coyoacán, but decided to rebuild the Aztec site to erase all traces of the old order.[51] He did not establish a territory under his own personal rule, but remained loyal to the Spanish crown. The first Spanish viceroy arrived in Mexico City fourteen years later. By that time, the city had again become a city-state, having power that extended far beyond its borders.[57] Although the Spanish preserved Tenochtitlan's basic layout, they built Catholic churches over the old Aztec temples and claimed the imperial palaces for themselves.[57] Tenochtitlan was renamed "Mexico" because the Spanish found the word easier to pronounce.[51]

Growth of colonial Mexico City

[edit]

The city had been the capital of the Aztec Empire and in the colonial era, Mexico City became the capital of New Spain. The viceroy of Mexico or vice-king lived in the viceregal palace on the main square or Zócalo. The Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral, the seat of the Archbishopric of New Spain, was constructed on another side of the Zócalo, as was the archbishop's palace, and across from it the building housing the city council or ayuntamiento of the city. A late seventeenth-century painting of the Zócalo by Cristóbal de Villalpando depicts the main square, which had been the old Aztec ceremonial center. The existing central plaza of the Aztecs was effectively and permanently transformed to the ceremonial center and seat of power during the colonial period, and remains to this day in modern Mexico, the central plaza of the nation. The rebuilding of the city after the siege of Tenochtitlan was accomplished by the abundant indigenous labor in the surrounding area. Franciscan friar Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, one of the Twelve Apostles of Mexico who arrived in New Spain in 1524, described the rebuilding of the city as one of the afflictions or plagues of the early period:

The seventh plague was the construction of the great City of Mexico, which, during the early years used more people than in the construction of Jerusalem. The crowds of laborers were so numerous that one could hardly move in the streets and causeways, although they are very wide. Many died from being crushed by beams, or falling from high places, or in tearing down old buildings for new ones.[58]

Preconquest Tenochtitlan was built in the center of the inland lake system, with the city reachable by canoe and by wide causeways to the mainland. The causeways were rebuilt under Spanish rule with indigenous labor. Colonial Spanish cities were constructed on a grid pattern, if no geographical obstacle prevented it. In Mexico City, the Zócalo (main square) was the central place from which the grid was then built outward. The Spanish lived in the area closest to the main square in what was known as the traza, in orderly, well laid-out streets. Indigenous residences were outside that exclusive zone and houses were haphazardly located.[59] Spaniards sought to keep indigenous people separate but since the Zócalo was a center of commerce for Amerindians, they were a constant presence in the central area, so strict segregation was never enforced.[60] At intervals Zócalo was where major celebrations took place as well as executions. It was also the site of two major riots in the seventeenth century, one in 1624, the other in 1692.[61]

The city grew as the population did, coming up against the lake's waters. As the depth of the lake water fluctuated, Mexico City was subject to periodic flooding. A major labor draft, the desagüe, compelled thousands of indigenous over the colonial period to work on infrastructure to prevent flooding. Floods were not only an inconvenience but also a health hazard, since during flood periods human waste polluted the city's streets. By draining the area, the mosquito population dropped as did the frequency of the diseases they spread. However, draining the wetlands also changed the habitat for fish and birds and the areas accessible for indigenous cultivation close to the capital.[62] The 16th century saw a proliferation of churches, many of which can still be seen today in the historic center.[57] Economically, Mexico City prospered as a result of trade. Unlike Brazil or Peru, Mexico had easy contact with both the Atlantic and Pacific worlds. Although the Spanish crown tried to completely regulate all commerce in the city, it had only partial success.[63]

The concept of nobility flourished in New Spain in a way not seen in other parts of the Americas. Spaniards encountered a society in which the concept of nobility mirrored that of their own. Spaniards respected the indigenous order of nobility and added to it. In the ensuing centuries, possession of a noble title in Mexico did not mean one exercised great political power, for one's power was limited even if the accumulation of wealth was not.[64] The concept of nobility in Mexico was not political but rather a very conservative Spanish social one, based on proving the worthiness of the family. Most of these families proved their worth by making fortunes in New Spain outside of the city itself, then spending the revenues in the capital, building churches, supporting charities and building extravagant palatial homes. The craze to build the most opulent residence possible reached its height in the last half of the 18th century. Many of these palaces can still be seen today, leading to Mexico City's nickname of "The city of palaces" given by Alexander Von Humboldt.[51][57][64]

The Grito de Dolores ("Cry of Dolores"), also known as El Grito de la Independencia ("Cry of Independence"), marked the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence. The Battle of Guanajuato, the first major engagement of the insurgency, occurred four days later. After a decade of war, Mexico's independence from Spain was effectively declared in the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire on 27 September 1821.[65] Agustín de Iturbide is proclaimed Emperor of the First Mexican Empire by Congress, crowned in the Cathedral of Mexico.

The Mexican Federal District was established by the new government and by the signing of their new constitution, where the concept of a federal district was adapted from the United States Constitution.[66] Before this designation, Mexico City had served as the seat of government for both the State of Mexico and the nation as a whole. Texcoco de Mora and then Toluca became the capital of the State of Mexico.[67]

Battle of Mexico City in the U.S.–Mexican War of 1847

[edit]

During the 19th century, Mexico City was the center stage of all the political disputes of the country. It was the imperial capital on two occasions (1821–1823 and 1864–1867), and of two federalist states and two centralist states that followed innumerable coups d'états in the space of half a century before the triumph of the Liberals after the Reform War. It was also the objective of one of the two French invasions to Mexico (1861–1867), and occupied for a year by American troops in the framework of the Mexican–American War (1847–1848).

The Battle for Mexico City was the series of engagements from 8 to 15 September 1847, in the general vicinity of Mexico City during the U.S. Mexican War. Included are major actions at the battles of Molino del Rey and Chapultepec, culminating with the fall of Mexico City. The U.S. Army under Winfield Scott scored a major success that ended the war. The American invasion into the Federal District was first resisted during the Battle of Churubusco on 8 August, where the Saint Patrick's Battalion, which was composed primarily of Catholic Irish and German immigrants but also Canadians, English, French, Italians, Poles, Scots, Spaniards, Swiss, and Mexicans, fought for the Mexican cause, repelling the American attacks. After defeating the Saint Patrick's Battalion, the Mexican–American War came to a close after the United States deployed combat units deep into Mexico resulting in the capture of Mexico City and Veracruz by the U.S. Army's 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Divisions.[68] The invasion culminated with the storming of Chapultepec Castle in the city itself.[69]

During this battle, on 13 September, the 4th Division, under John A. Quitman, spearheaded the attack against Chapultepec and carried the castle. Future Confederate generals George E. Pickett and James Longstreet participated in the attack. Serving in the Mexican defense were the cadets later immortalized as Los Niños Héroes (the "Boy Heroes"). The Mexican forces fell back from Chapultepec and retreated within the city. Attacks on the Belén and San Cosme Gates came afterwards. The treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in what is now the far north of the city.[70]

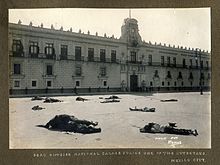

Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)

[edit]

The capital escaped the worst of the violence of the ten-year conflict of the Mexican Revolution. The most significant episode of this period for the city was the Decena Trágica ("Ten Tragic Days") of February 1913, when forces counter to the elected government of Francisco I. Madero staged a successful coup. The center of the city was subjected to artillery attacks from the army stronghold of the ciudadela or citadel, with significant civilian casualties and the undermining of confidence in the Madero government. Victoriano Huerta, chief general of the Federal Army, saw a chance to take power, forcing Madero and Pino Suarez to sign resignations. The two were murdered later while on their way to Lecumberri prison.[72] Huerta's ouster in July 1914 saw the entry of the armies of Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, but the city did not experience violence. Huerta had abandoned the capital and the conquering armies marched in. Venustiano Carranza's Constitutionalist faction ultimately prevailed in the revolutionary civil war and Carranza took up residence in the presidential palace.

20th century to present

[edit]

In the 20th century the phenomenal growth of the city and its environmental and political consequences dominate. In 1900, the population of Mexico City was about 500,000.[73] The city began to grow rapidly westward in the early part of the 20th century[57] and then began to grow upwards in the 1950s, with the Torre Latinoamericana becoming the city's first skyscraper.[50]

The rapid development of Mexico City as a center for modernist architecture was most fully manifested in the mid-1950s construction of the Ciudad Universitaria, Mexico City, the main campus of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Designed by the most prestigious architects of the era, including Mario Pani, Eugenio Peschard, and Enrique del Moral, the buildings feature murals by artists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Chávez Morado. It has since been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[74]

The 1968 Olympic Games brought about the construction of large sporting facilities.[57] In 1969, the Mexico City Metro was inaugurated.[50] Explosive growth in the population of the city started in the 1960s, with the population overflowing the boundaries of the Federal District into the neighboring State of Mexico, especially to the north, northwest, and northeast. Between 1960 and 1980 the city's population more than doubled to nearly 9 million.[57]

In 1980, half of all the industrial jobs in Mexico were located in Mexico City. Under relentless growth, the Mexico City government could barely keep up with services. Villagers from the countryside who continued to pour into the city to escape poverty only compounded the city's problems. With no housing available, they took over lands surrounding the city, creating huge shanty towns.

The inhabitants of Mexico City faced serious air pollution and water pollution problems, as well as groundwater-related subsidence.[75] Air and water pollution has been contained and improved in several areas due to government programs, the renovation of vehicles and the modernization of public transportation.

The autocratic government that ruled Mexico City since the Revolution was tolerated, mostly because of the continued economic expansion since World War II. This was the case even though this government could not handle the population and pollution problems adequately. Nevertheless, discontent and protests began in the 1960s leading to the massacre of an unknown number of protesting students in Tlatelolco.[76]

Three years later, a demonstration in the Maestros avenue, organized by former members of the 1968 student movement, was violently repressed by a paramilitary group called "Los Halcones", composed of gang members and teenagers from many sports clubs who received training in the US.

On 19 September 1985, at 7:19am CST, the area was struck by the 1985 Mexico City earthquake.[77] The earthquake proved to be a disaster politically for the one-party state government. The Mexican government was paralyzed by its own bureaucracy and corruption, forcing ordinary citizens to create and direct their own rescue efforts and to reconstruct much of the housing that was lost as well.[78]

However, the last straw may have been the controversial elections of 1988. That year, the presidency was set between the P.R.I.'s candidate, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, and a coalition of left-wing parties led by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, son of the former president Lázaro Cárdenas. The counting system "fell" because coincidentally the power went out and suddenly, when it returned, the winning candidate was Salinas, even though Cárdenas had the upper hand.

As a result of the fraudulent election, Cárdenas became a member of the Party of the Democratic Revolution. Discontent over the election eventually led Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas to become the first elected mayor of Mexico City in 1997. Cárdenas promised a more democratic government, and his party claimed some victories against crime, pollution, and other major problems. He resigned in 1999 to run for the presidency.

Geography

[edit]

Mexico City is located in the Valley of Mexico, sometimes called the Basin of Mexico. This valley is located in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt in the high plateaus of south-central Mexico.[79][80]

It has a minimum altitude of 2,200 meters (7,200 feet) above sea level and is surrounded by mountains and volcanoes that reach elevations of over 5,000 meters (16,000 feet).[81] This valley has no natural drainage outlet for the waters that flow from the mountainsides, making the city vulnerable to flooding. Drainage was engineered through the use of canals and tunnels starting in the 17th century.[79][81]

Mexico City primarily rests on what was Lake Texcoco.[79] Seismic activity is frequent there.[82] Lake Texcoco was drained starting from the 17th century. Although none of the lake waters remain, the city rests on the lake bed's heavily saturated clay. This soft base is collapsing due to the over-extraction of groundwater, called groundwater-related subsidence.

Since the beginning of the 20th century the city has sunk as much as nine meters (30 feet) in some areas. On average Mexico City sinks 20 inches (1 foot and 8 inches) or 50 centimetres (1/2 meters) every year.[83] This sinking is causing problems with runoff and wastewater management, leading to flooding problems, especially during the summer.[81][82][84] The entire lake bed is now paved over and most of the city's remaining forested areas lie in the southern boroughs of Milpa Alta, Tlalpan and Xochimilco.[82]

| Mexico City geophysical maps | |||

|

|

| |

| Topography | Hydrology | Climate patterns | |

Environment

[edit]

Originally much of the valley lay beneath the waters of Lake Texcoco, a system of interconnected salt and freshwater lakes. The Aztecs built dikes to separate the fresh water used to raise crops in chinampas and to prevent recurrent floods. These dikes were destroyed during the siege of Tenochtitlan, and during colonial times the Spanish regularly drained the lake to prevent floods. Only a small section of the original lake remains, located outside Mexico City, in the municipality of Atenco, State of Mexico.

Architects Teodoro González de León and Alberto Kalach along with a group of Mexican urbanists, engineers and biologists have developed the project plan for Recovering the City of Lakes. If approved by the government the project will contribute to the supply of water from natural sources to the Valley of Mexico, the creation of new natural spaces, a great improvement in air quality, and greater population establishment planning.

Pollution

[edit]

By the 1990s Mexico City had become infamous as one of the world's most polluted cities; however, the city has since become a model for drastically lowering pollution levels. By 2014 carbon monoxide pollution had dropped drastically, while sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide were at levels about a third of those in 1992. The levels of signature pollutants in Mexico City are similar to those of Los Angeles.[85] Despite the cleanup, the metropolitan area is still the most ozone-polluted part of the country, with ozone levels 2.5 times beyond WHO-defined safe limits.[86]

To clean up pollution, the federal and local governments implemented numerous plans including the constant monitoring and reporting of environmental conditions, such as ozone and nitrogen oxides.[87] When the levels of these two pollutants reached critical levels, contingency actions were implemented which included closing factories, changing school hours, and extending the A day without a car program to two days of the week.[87] The government also instituted industrial technology improvements, a strict biannual vehicle emission inspection and the reformulation of gasoline and diesel fuels.[87] The introduction of Metrobús bus rapid transit and the Ecobici bike-sharing were among efforts to encourage alternate, greener forms of transportation.[86]

Parks and recreation

[edit]

Chapultepec, the city's most iconic public park, has history back to the Aztec emperors who used the area as a retreat. It is south of Polanco district, and houses the Chapultepec Zoo the main city's zoo, several ponds and seven museums, including the National Museum of Anthropology. Other iconic city parks include the Alameda Central, it is recognized as the oldest public park in the Americas.[90][91] Parque México and Parque España in the hip Condesa district; Parque Hundido and Parque de los Venados in Colonia del Valle, and Parque Lincoln in Polanco.[92] There are many smaller parks throughout the city. Most are small "squares" occupying two or three square blocks amid residential or commercial districts. Several other larger parks such as the Bosque de Tlalpan and Viveros de Coyoacán, and in the east Alameda Oriente, offer many recreational activities. Northwest of the city is a large ecological reserve, the Bosque de Aragón. In the southeast is the Xochimilco Ecological Park and Plant Market, a World Heritage Site. West of Santa Fe district are the pine forests of the Desierto de los Leones National Park. Amusement parks include Six Flags México, in Ajusco neighborhood which is the largest in Latin America. There are numerous seasonal fairs present in the city.

Mexico City has three zoos. Chapultepec Zoo, the San Juan de Aragon Zoo and Los Coyotes Zoo. Chapultepec Zoo is located in the first section of Chapultepec Park in the Miguel Hidalgo. It was opened in 1924.[93] Visitors can see about 243 specimens of different species including kangaroos, giant panda, gorillas, caracal, hyena, hippos, jaguar, giraffe, lemur, lion, among others.[94] Zoo San Juan de Aragon is near the San Juan de Aragon Park in the Gustavo A. Madero. In this zoo, opened in 1964,[95] there are species that are in danger of extinction such as the jaguar and the Mexican wolf. Other guests are the golden eagle, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, caracara, zebras, African elephant, macaw, hippo, among others.[96] Zoo Los Coyotes is a 27.68-acre (11.2 ha) zoo located south of Mexico City in the Coyoacan. It was inaugurated on 2 February 1999.[97] It has more than 301 specimens of 51 species of wild native or endemic fauna from the area, featuring eagles, ajolotes, coyotes, macaws, bobcats, Mexican wolves, raccoons, mountain lions, teporingos, foxes, white-tailed deer.[98]

Climate

[edit]

Mexico City has a subtropical highland climate (Köppen climate classification Cwb), due to its tropical location but high elevation. The lower region of the valley receives less rainfall than the upper regions of the south; the lower boroughs of Iztapalapa, Iztacalco, Venustiano Carranza and the east portion of Gustavo A. Madero are usually drier and warmer than the upper southern boroughs of Tlalpan and Milpa Alta, a mountainous region of pine and oak trees known as the range of Ajusco. The average annual temperature varies from 12 to 16 °C (54 to 61 °F), depending on the altitude of the borough. The temperature is rarely below 3 °C (37 °F) or above 30 °C (86 °F).[99] At the Tacubaya observatory, the lowest temperature ever registered was −4.4 °C (24 °F) on 13 February 1960, and the highest temperature on record was 34.7 °C (94.5 °F) on 25 May 2024.[100] Overall precipitation is heavily concentrated in the summer months, and includes dense hail.

Snow falls in the city scarcely, although somewhat more often on nearby mountaintops. Throughout its history, the Central Valley of Mexico was accustomed to having several snowfalls per decade (including a period between 1878 and 1895 in which every single year—except 1880—recorded snowfalls[101]), mostly lake-effect snow. The effects of the draining of Lake Texcoco and global warming have greatly reduced snowfalls after the snow flurries of 12 February 1907.[102] Since 1908, snow has only fallen three times, snow on 14 February 1920;[103] snow flurries on 14 March 1940;[104] and on 12 January 1967, when 8 centimeters (3 in) of snow fell on the city, the most on record.[105] The 1967 snowstorm coincided with the operation of Deep Drainage System that resulted in the total draining of what was left of Lake Texcoco.[101][106] After the disappearance of Lake Texcoco, snow has never fallen again over Mexico City.[101] The region of the Valley of Mexico receives anti-cyclonic systems. The weak winds of these systems do not allow for the dispersion, outside the basin, of the air pollutants which are produced by the 50,000 industries and 4 million vehicles operating in and around the metropolitan area.[107]

The area receives about 820 millimeters (32 in) of annual rainfall, which is concentrated from May through October with little or no precipitation for the remainder of the year.[81] The area has two main seasons. The wet humid summer runs from May to October when winds bring in tropical moisture from the sea, the wettest month being July. The cool sunny winter runs from November to April, when the air is relatively drier, the driest month being December. This season is subdivided into a cold winter period and a warm spring period. The cold period spans from November to February, when polar air masses push down from the north and keep the air fairly dry. The warm period extends from March to May when subtropical winds again dominate but do not yet carry enough moisture for rain to form.[108]

| Climate data for Mexico City (Tacubaya), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1877–2024[109] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.2 (82.8) |

30.8 (87.4) |

32.9 (91.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

34.7 (94.5) |

33.8 (92.8) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.4 (84.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.2 (84.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

34.7 (94.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22.3 (72.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 15.7 (60.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

18.9 (66.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.9 (69.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

18.8 (65.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

13.7 (56.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

13.1 (55.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.2 (24.4) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 12.5 (0.49) |

5.9 (0.23) |

11.7 (0.46) |

24.9 (0.98) |

62.5 (2.46) |

137.1 (5.40) |

177.1 (6.97) |

175.1 (6.89) |

160.2 (6.31) |

71.2 (2.80) |

17.6 (0.69) |

5.0 (0.20) |

860.8 (33.89) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.9 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 8.2 | 13.1 | 17.2 | 16.9 | 14.4 | 7.2 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 89.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 54.0 | 48.0 | 43.5 | 45.2 | 52.8 | 63.7 | 69.6 | 69.2 | 69.9 | 64.0 | 57.1 | 55.3 | 57.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 233.4 | 232.5 | 262.3 | 238.6 | 232.2 | 180.9 | 178.6 | 176.9 | 148.3 | 190.9 | 224.4 | 226.9 | 2,525.8 |

| Source 1: Servicio Meteorologico Nacional[110][111] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (humidity and sun 1981–2010)[112] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 3,365,081 | — |

| 1960 | 5,479,184 | +62.8% |

| 1970 | 8,830,947 | +61.2% |

| 1980 | 13,027,620 | +47.5% |

| 1990 | 15,642,318 | +20.1% |

| 2000 | 18,457,027 | +18.0% |

| 2010 | 20,136,681 | +9.1% |

| 2019 | 21,671,908 | +7.6% |

| for Mexico City Agglomeration:[113] | ||

Historically, and since Pre-Columbian times, the Valley of Anahuac has been one of the most densely populated areas in Mexico. When the Federal District was created in 1824, the urban area of Mexico City extended approximately to the area of today's Cuauhtémoc borough. At the beginning of the 20th century, the elites began migrating to the south and west and soon the small towns of Mixcoac and San Ángel were incorporated by the growing conurbation. According to the 1921 census, 54.78% of the city's population was considered Mestizo (Indigenous mixed with European), 22.79% considered European, and 18.74% considered Indigenous.[114]

Up to the 1990s, the Federal District was the most populous federal entity in Mexico, but since then, its population has remained stable at around 8.7 million. The growth of the city has extended beyond the limits of the city proper to 59 municipalities of the State of Mexico and 1 in the state of Hidalgo.[115] With a population of approximately 19.8 million inhabitants (2008),[116] it is one of the most populous conurbations in the world. Nonetheless, the annual rate of growth of the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City is much lower than that of other large urban agglomerations in Mexico,[117] a phenomenon most likely attributable to the environmental policy of decentralization. The net migration rate of Mexico City from 1995 to 2000 was negative.[118]

Metropolitan area

[edit]

The metropolitan area, Greater Mexico City ('Zona Metropolitana del Valle de México' or 'ZMVM' in Spanish) consists of Mexico City itself plus 60 municipalities in the State of Mexico and one in Hidalgo state. With a population of 21,804,515 (2020 census), Greater Mexico City is both the biggest and the densest metropolitan area in the country. Of the ca. 21.8 million, 9.2 million live in Mexico City proper[8] and 12.4 million in the State of Mexico (ca. 75% of the state's population), including the municipalities of:[8]

- Ecatepec de Morelos (pop. 1,645,352)

- Nezahualcóyotl (pop. 1,077,208)

- Naucalpan (pop. 834,434)

- Chimalhuacán (pop. 705,193)

- Tlalnepantla de Baz (pop. 672,202)

Megalopolis

[edit]

Greater Mexico City, in turn, forms part of an even larger megalopolis officially known as the Corona regional del centro de México (Mexico City megalopolis), with a population of 33.4 million, more than one quarter of the country's population according to the 2020 census. The megalopolis as defined by the Environmental Commission of the Megalopolis (CAMe) covers Mexico City and the states of Mexico, Hidalgo, Puebla, Tlaxcala, Morelos, and since 2019, Querétaro,[119] thus encompassing the metropolitan areas of Mexico City, Puebla, Querétaro, Toluca, Cuernavaca, Pachuca, and others.[120]

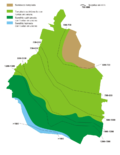

Growth

[edit]Greater Mexico City was the fastest growing metropolitan area in the country until the late 1980s. Since then, government policies have supported decentralization with the aim of reducing pollution in Greater Mexico City. While still growing, the annual rate of growth has decreased and is lower than that of Greater Guadalajara and Greater Monterrey.[117]

The net migration rate of Mexico City proper from 1995 to 2000 was negative,[121] which implies that residents are moving to the suburbs of the metropolitan area, or to other states of Mexico. In addition, some inner suburbs are losing population to outer suburbs, indicating the continuing expansion of Greater Mexico City.

Religion

[edit]

The majority (82%) of the residents in Mexico City are Catholic, slightly lower than the 2010 census national percentage of 87%, making it the largest Christian denomination, though it has been decreasing over the last decades.[122] Many other religions and philosophies are also practiced in the city: many different types of Protestant groups, different types of Jewish communities, Buddhist, Islamic and other spiritual and philosophical groups. There are also growing[123] numbers of irreligious people, whether agnostic or atheist. The patron saint of Mexico City is Saint Philip of Jesus, a Mexican Catholic missionary who became one of the Twenty-six Martyrs of Japan.[124]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mexico is the largest archdiocese in the world.[125] There are two Catholic cathedrals in the city, the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral and the Iztapalapa Cathedral, and three former Catholic churches who are now the cathedrals of other rites, the San José de Gracia Cathedral (Anglican church), the Porta Coeli Cathedral (Melkite Greek Catholic church) and the Valvanera Cathedral (Maronite church).

Ethnic groups

[edit]Representing around 18.74% of the city's population, indigenous peoples from different areas of Mexico have migrated to the capital in search of better economic opportunities. Nahuatl, Otomi, Mixtec, Zapotec and Mazahua are the indigenous languages with the greatest number of speakers in Mexico City.[126] According to the 2020 Census, 2.03% of Mexico City's population identified as Black, Afro-Mexican, or of African descent.[127]

Additionally, Mexico City is home to large communities of expatriates and immigrants from the rest of North America (U.S. and Canada), from South America (mainly from Argentina and Colombia, but also from Brazil, Chile, Uruguay and Venezuela), from Central America and the Caribbean (mainly from Cuba, Guatemala, El Salvador, Haiti and Honduras); from Europe (mainly from Spain, Germany and Switzerland, but also from Czech Republic, Hungary, France, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland and Romania),[128][129] and from the Arab world (mostly from Lebanon, and other countries like Syria and Egypt).[130]

Mexico City is home to the largest population of Americans living outside the United States. Estimates are as high as 700,000 Americans living in Mexico City, while in 1999 the U.S. Bureau of Consular Affairs estimated over 440,000 Americans lived in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area.[131][132]

Health

[edit]

Mexico City is home to some of the best private hospitals in the country, including Hospital Ángeles, Hospital ABC and Médica Sur. The national public healthcare institution for private-sector employees, IMSS, has its largest facilities in Mexico City—including the National Medical Center and the La Raza Medical Center—and has an annual budget of over 6 billion pesos. The IMSS and other public health institutions, including the ISSSTE (Public Sector Employees' Social Security Institute) and the National Health Ministry (SSA) maintain large specialty facilities in the city. These include the National Institutes of Cardiology, Nutrition, Psychiatry, Oncology, Pediatrics, Rehabilitation, among others.

Education

[edit]

Among its many public and private schools (K–13), the city offers multi-cultural, multi-lingual and international schools attended by Mexican and foreign students. Best known are the Colegio Alemán (German school with three main campuses), the Liceo Mexicano Japonés (Japanese), the Centro Cultural Coreano en México (Korean), the Lycée Franco-Mexicain (French), the American School, The Westhill Institute (American School), the Edron Academy and the Greengates School (British). Mexico City joined the UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities in 2015.[133]

In the Plaza de las Tres Culturas is the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco that is recognized for being the first and oldest European school of higher learning in the Americas[134] and the first major school of interpreters and translators in the New World.[135] Other, the now-defunct Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico is considered the father of the UNAM, and it was located in the city and was the third oldest university in the Americas.

The National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), located in Mexico City, is the largest university on the continent, with more than 300,000 students from all backgrounds. Three Nobel laureates, several Mexican entrepreneurs and most of Mexico's modern-day presidents are among its former students. UNAM conducts 50% of Mexico's scientific research and has presence all across the country with satellite campuses, observatories and research centers. UNAM ranked 74th in the Top 200 World University Ranking published by Times Higher Education (then called Times Higher Education Supplement) in 2006,[137] making it the highest ranked Spanish-speaking university in the world. The sprawling main campus of the university, known as Ciudad Universitaria, was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2007.[136]

The second largest higher-education institution is the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), which includes among many other relevant centers the Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados (Cinvestav), where varied high-level scientific and technological research is done. Other major higher-education institutions in the city include the Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM), the National School of Anthropology and History (ENAH), the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM), the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (3 campuses), the Universidad Panamericana (UP), the Universidad La Salle, the Universidad Intercontinental (UIC), the Universidad del Valle de México (UVM), the Universidad Anáhuac, Simón Bolívar University (USB), the Universidad Intercontinental (UIC), the Alliant International University, the Universidad Iberoamericana, El Colegio de México (Colmex), Escuela Libre de Derecho and the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económica, (CIDE). In addition, the prestigious University of California maintains a campus known as "Casa de California" in the city.[138] The Universidad Tecnológica de México is also in Mexico City.

Politics

[edit]Political structure

[edit]

The Acta Constitutiva de la Federación of 31 January 1824, and the Federal Constitution of 4 October 1824,[139] fixed the political and administrative organization of the United Mexican States after the Mexican War of Independence. In addition, Section XXVIII of Article 50 gave the new Congress the right to choose where the federal government would be located. This location would then be appropriated as federal land, with the federal government acting as the local authority. The two main candidates to become the capital were Mexico City and Querétaro.[140]

Due in large part to the persuasion of representative Servando Teresa de Mier, Mexico City was chosen because it was the center of the country's population and history, even though Queretaro was closer to the center geographically. The choice was official on 18 November 1824, and Congress delineated a surface area of two leagues square (8,800 acres) centered on the Zocalo. This area was then separated from the State of Mexico, forcing that state's government to move from the Palace of the Inquisition (now Museum of Mexican Medicine) in the city to Texcoco. This area did not include the population centers of the towns of Coyoacán, Xochimilco, Mexicaltzingo and Tlalpan, all of which remained as part of the State of Mexico.[141]

In 1854 president Antonio López de Santa Anna enlarged the area of Mexico City almost eightfold from the original 220 to 1,700 km2 (80 to 660 sq mi), annexing the rural and mountainous areas to secure the strategic mountain passes to the south and southwest to protect the city in event of a foreign invasion. (The Mexican–American War had just been fought.) The last changes to the limits of Mexico City were made between 1898 and 1902, reducing the area to the current 1,479 km2 (571 sq mi) by adjusting the southern border with the state of Morelos. By that time, the total number of municipalities within Mexico City was twenty-two. In 1941, the General Anaya borough was merged with the Central Department, which was then renamed "Mexico City" (thus reviving the name but not the autonomous municipality). From 1941 to 1970, the Federal District comprised twelve delegaciones and Mexico City. In 1970, Mexico City was split into four different delegaciones: Cuauhtémoc, Miguel Hidalgo, Venustiano Carranza and Benito Juárez, increasing the number of delegaciones to 16. Since then, the whole Federal District, whose delegaciones had by then almost formed a single urban area, began to be considered de facto a synonym of Mexico City.[142]

The lack of a de jure stipulation left a legal vacuum that led to a number of sterile discussions about whether one concept had engulfed the other or if the latter had ceased to exist altogether. In 1993, the situation was solved by an amendment to the 44th article of the Constitution of Mexico; Mexico City and the Federal District were stated to be the same entity. The amendment was later introduced into the second article of the Statute of Government of the Federal District.[142]

On 29 January 2016, Mexico City ceased to be the Federal District (Spanish: Distrito Federal or D.F.), and was officially renamed "Ciudad de México" (or "CDMX").[32] On that date, Mexico City began a transition to becoming the country's 32nd federal entity, giving it a level of autonomy comparable to that of a state. It will have its own constitution and its legislature, and its delegaciones will now be headed by mayors.[32] Because of a clause in the Mexican Constitution, however, as it is the seat of the powers of the federation, it can never become a state, or the capital of the country has to be relocated elsewhere.[34]

In response to the demands, Mexico City received a greater degree of autonomy, with the 1987 elaboration the first Statute of Government (Estatuto de Gobierno) and the creation of an assembly of representatives.[143]: 149–150 The city has a Statute of Government, and as of its ratification on 31 January 2017, a constitution,[144][145] similar to the states of the Union. As part of the recent changes in autonomy, the budget is administered locally; it is proposed by the head of government and approved by the Legislative Assembly. Nonetheless, it is the Congress of the Union that sets the ceiling to internal and external public debt issued by the city government.[146]

The politics pursued by the administrations of heads of government in Mexico City at the end of the 20th century have usually been more liberal than those of the rest of the country,[147][148] whether with the support of the federal government, as was the case with the approval of several comprehensive environmental laws in the 1980s, or by laws that were since approved by the Legislative Assembly. The Legislative Assembly expanded provisions on abortions, becoming the first federal entity to expand abortion in Mexico beyond cases of rape and economic reasons, to permit it at the choice of the mother before the 12th week of pregnancy.[149] In December 2009, the then Federal District became the first city in Latin America and one of very few in the world to legalize same-sex marriage.[150]

Boroughs and neighborhoods

[edit]

After the political reforms in 2016, the city is divided for administrative purposes into 16 boroughs (demarcaciones territoriales, colloquially alcaldías), formerly called delegaciones. While they are not fully equivalent to municipalities, the boroughs have gained significant autonomy.[151] Formerly appointed by the Federal District's head of government, local authorities were first elected directly by plurality in 2000. From 2016, each borough is headed by a mayor, expanding their local government powers.[151]

The boroughs of Mexico City with their 2020 populations are:[152]

|

1. Álvaro Obregón (pop. 759,137) |

9. Iztapalapa (pop. 1,835,486) |

The Human Development Index report of 2005[153] shows that there were three boroughs with a very high Human Development Index, 12 with a high HDI value (9 above .85), and one with a medium HDI value (almost high). Benito Juárez borough had the highest HDI of the country (0.9510) followed by Miguel Hidalgo, which came up fourth nationally with an HDI of (0.9189), and Coyoacán was fifth nationally, with an HDI of (0.9169). Cuajimalpa (15th), Cuauhtémoc (23rd), and Azcapotzalco (25th) also had very high values of 0.8994, 0.8922, and 0.8915, respectively.[153]

In contrast, the boroughs of Xochimilco (172nd), Tláhuac (177th), and Iztapalapa (183rd) presented the lowest HDI values of Mexico City, with values of 0.8481, 0.8473, and 0.8464, respectively, which are still in the global high-HDI range. The only borough that did not have a high HDI was that of rural Milpa Alta, which had a "medium" HDI of 0.7984, far below those of all the other boroughs (627th nationally, the rest being in the top 200). Mexico City's HDI for the 2005 report was 0.9012 (very high), and its 2010 value of 0.9225 (very high), or (by newer methodology) 0.8307, was Mexico's highest.[153]

Law enforcement

[edit]

The Secretariat of Public Security of Mexico City (Secretaría de Seguridad Pública de la Ciudad de México – SSP) manages a combined force of over 90,000 officers in Mexico City. The SSP is charged with maintaining public order and safety in the heart of Mexico City. The historic district is also roamed by tourist police, aiming to orient and serve tourists. These horse-mounted agents dress in traditional uniforms. The investigative Judicial Police of Mexico City (Policía Judicial de la Ciudad de México – PJCDMX) is organized under the Office of the Attorney General of Mexico City (the Procuraduría General de Justicia de la Ciudad de México). The PGJCDMX maintains 16 precincts (delegaciones) with an estimated 3,500 judicial police, 1,100 investigating agents for prosecuting attorneys (agentes del ministerio público), and nearly 1,000 criminology experts or specialists (peritos).

Between 2000 and 2004 an average of 478 crimes were reported each day in Mexico City; however, the actual crime rate is thought to be much higher "since most people are reluctant to report crime".[154] Under policies enacted by Mayor Marcelo Ebrard between 2009 and 2011, Mexico City underwent a major security upgrade with violent and petty crime rates both falling significantly despite the rise in violent crime in other parts of the country. Some of the policies enacted included the installation of 11,000 security cameras around the city and a very large expansion of the police force. Mexico City has one of the world's highest police officer-to-resident ratios, with one uniformed officer per 100 citizens.[155] Since 1997 the prison population has increased by more than 500%.[156] Political scientist Markus-Michael Müller argues that mostly informal street vendors are hit by these measures. He sees punishment "related to the growing politicization of security and crime issues and the resulting criminalization of the people living at the margins of urban society, in particular those who work in the city's informal economy".[156]

In 2016, the incidence of femicides was 3.2 per 100 000 inhabitants, the national average being 4.2.[157] A 2015 city government report found that two of three women over the age of 15 in the capital suffered some form of violence.[158] In addition to street harassment, one of the places where women in Mexico City are subjected to violence is on and around public transport. Annually the Metro of Mexico City receives 300 complaints of sexual harassment.[159]

International relations

[edit]Mexico City is twinned with:[160][161]

Cusco, Peru, 1987

Cusco, Peru, 1987 Berlin, Germany, 1993[162]

Berlin, Germany, 1993[162] Havana, Cuba, 1997

Havana, Cuba, 1997 Quito, Ecuador, 1999

Quito, Ecuador, 1999 Tegucigalpa, Honduras, 1999

Tegucigalpa, Honduras, 1999 San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba, 1999

San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba, 1999 Cerro (Havana), Cuba, 1999

Cerro (Havana), Cuba, 1999 San José, Costa Rica, 2000

San José, Costa Rica, 2000 Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2006

Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2006 Nagoya, Japan, 2007

Nagoya, Japan, 2007 Los Angeles, United States, 2007

Los Angeles, United States, 2007 Cádiz, Spain, 2009

Cádiz, Spain, 2009 Beijing, China, 2009

Beijing, China, 2009 Istanbul, Turkey, 2010

Istanbul, Turkey, 2010 Kuwait City, Kuwait, 2011

Kuwait City, Kuwait, 2011 Chicago, United States[163]

Chicago, United States[163]

Economy

[edit]

Mexico City is one of the most important economic hubs in Latin America. The city proper produces 15.8% of the country's gross domestic product.[165] In 2002, Mexico City had a Human Development Index score of 0.915,[166] identical to that of South Korea. In 2007, residents in the top twelve percent of GDP per capita holders in the city had a mean disposable income of US$98,517. The high spending power of Mexico City inhabitants makes the city attractive for companies offering prestige and luxury goods. According to a 2009 study conducted by PwC, Mexico City had a GDP of $390 billion, ranking it as the eighth richest city in the world and the richest in Latin America.[167] In 2009, Mexico City alone would rank as the 30th largest economy in the world.[168]

Mexico City is the greatest contributor to the country's industrial GDP (15.8%) and also the greatest contributor to the country's GDP in the service sector (25.3%). Due to the limited non-urbanized space at the south—most of which is protected through environmental laws—the contribution of Mexico City in agriculture is the smallest of all federal entities in the country.[165] The economic reforms of President Carlos Salinas de Gortari had a tremendous effect on the city, as a number of businesses, including banks and airlines, were privatized. He also signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This led to decentralization[169] and a shift in Mexico City's economic base, from manufacturing to services, as most factories moved away to either the State of Mexico, or more commonly to the northern border. By contrast, corporate office buildings set their base in the city.

Mexico City offers an immense and varied consumer retail market, ranging from basic foods to ultra high-end luxury goods. Consumers may buy in fixed indoor markets, in mobile markets (tianguis), from street vendors, from downtown shops in a street dedicated to a certain type of good, in convenience stores and traditional neighborhood stores, in modern supermarkets, in warehouse and membership stores and the shopping centers that they anchor, in department stores, in big-box stores, and in modern shopping malls. In addition, "tianguis" or mobile markets set up shop on streets in many neighborhoods, depending on day of week. Sundays see the largest number of these markets.

The city's main source of fresh produce is the Central de Abasto. This in itself is a self-contained mini-city in Iztapalapa borough covering an area equivalent to several dozen city blocks. The wholesale market supplies most of the city's "mercados", supermarkets and restaurants, as well as people who come to buy the produce for themselves. Tons of fresh produce are trucked in from all over Mexico every day. The principal fish market is known as La Nueva Viga, in the same complex as the Central de Abastos.[170] The world-renowned market of Tepito occupies 25 blocks, and sells a variety of products. A staple for consumers in the city is the omnipresent "mercado". Every major neighborhood in the city has its own borough-regulated market, often more than one. These are large well-established facilities offering most basic products, such as fresh produce and meat/poultry, dry goods, tortillerías, and many other services such as locksmiths, herbal medicine, hardware goods, sewing implements; and a multitude of stands offering freshly made, home-style cooking and drinks in the tradition of aguas frescas and atole.

Street vendors ply their trade from stalls in the tianguis as well as at non-officially controlled concentrations around metro stations and hospitals; at plazas comerciales, where vendors of a certain "theme" (e.g. stationery) are housed; originally these were organized to accommodate vendors formerly selling on the street; or simply from improvised stalls on a city sidewalk.[171] In addition, food and goods are sold from people walking with baskets, pushing carts, from bicycles or the backs of trucks, or simply from a tarp or cloth laid on the ground.[172] In the center of the city informal street vendors are increasingly targeted by laws and prosecution.[156] The weekly San Felipe de Jesús Tianguis is reported to be the largest in Latin America.[173]

The Historic Center of Mexico City is widely known for specialized, often low-cost retailers. Certain blocks or streets are dedicated to shops selling a certain type of merchandise, with areas dedicated to over 40 categories such as home appliances, lamps and electricals, closets and bathrooms, housewares, wedding dresses, jukeboxes, printing, office furniture and safes, books, photography, jewelry, and opticians.[174]

Tourism

[edit]

Mexico City is a destination for many foreign tourists. The Historic center of Mexico City (Centro Histórico) and the "floating gardens" of Xochimilco in the southern borough have been declared World Heritage Sites by UNESCO. Landmarks in the Historic Center include the Plaza de la Constitución (Zócalo), the main central square with its epoch-contrasting Spanish-era Metropolitan Cathedral and National Palace, ancient Aztec temple ruins Templo Mayor ("Major Temple") and modern structures, all within a few steps of one another. (The Templo Mayor was discovered in 1978 while workers were digging to place underground electric cables).

The most recognizable icon of Mexico City is the golden Angel of Independence on the wide, elegant avenue Paseo de la Reforma, modeled by the order of the Emperor Maximilian of Mexico after the Champs-Élysées in Paris. This avenue was designed over the Americas' oldest known major roadway in the 19th century to connect the National Palace (seat of government) with the Castle of Chapultepec, the imperial residence. Today, this avenue is an important financial district in which the Mexican Stock Exchange and several corporate headquarters are located. Another important avenue is the Avenida de los Insurgentes, which extends 28.8 km (17.9 mi) and is one of the longest single avenues in the world.

Chapultepec Park houses the Chapultepec Castle, now a museum on a hill that overlooks the park and its numerous museums, monuments and the national zoo and the National Museum of Anthropology (which houses the Aztec Calendar Stone).

Another piece of architecture is the Palacio de Bellas Artes, a white marble theater/museum whose weight is such that it has gradually been sinking into the soft ground below. Its construction began during the presidency of Porfirio Díaz and ended in 1934, after being interrupted by the Mexican Revolution in the 1920s.

The Plaza de las Tres Culturas, in this square are located the College of Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, that is the first and oldest European school of higher learning in the Americas,[134] and the archeological site of the city-state of Tlatelolco, and the shrine and Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe are also important sites. There is a double-decker bus, known as the "Turibus", that circles most of these sites, and has timed audio describing the sites in multiple languages as they are passed.

In addition, according to the Secretariat of Tourism, the city has about 170 museums—is among the top ten of cities in the world with highest number of museums[176]—over 100 art galleries, and some 30 concert halls, all of which maintain a constant cultural activity during the whole year. Many areas (e.g. Palacio Nacional and the National Institute of Cardiology) have murals painted by Diego Rivera. He and his wife Frida Kahlo lived in Coyoacán, where several of their homes, studios, and art collections are open to the public. The house where Leon Trotsky was initially granted asylum and finally murdered in 1940 is also in Coyoacán. In addition, there are several haciendas that are now restaurants, such as the San Ángel Inn, the Hacienda de Tlalpan, Hacienda de Cortés and the Hacienda de los Morales.

Transportation

[edit]Airports

[edit]

Mexico City International Airport is Mexico City's primary airport (IATA Airport Code: MEX), and serves as the hub of Aeroméxico (Skyteam). Felipe Ángeles International Airport (IATA Airport Code: NLU) is Mexico City's secondary airport, and was opened in 2022, rebuilt from the former Santa Lucía Air Force Base. It is located in Zumpango, State of Mexico, 48.8 kilometres (30 mi) north-northeast of the historic center of Mexico City by car.[177]

Sistema de Movilidad Integrada

[edit]In 2019, the graphic designer Lance Wyman was engaged to create an integrated map of the multimodal public transportation system; he presented a new logo for the Sistema de Movilidad Integrada, describing eight distinct modes of transportation. The head of the government, Claudia Sheinbaum, said the branding would be used for a new single payment card to streamline public transportation fare collection.[178]

Metro

[edit]

Mexico City is served by the Mexico City Metro, a 225.9 km (140 mi) metro system, which is the largest in Latin America. The first portions were opened in 1969 and it has expanded to 12 lines with 195 stations, transporting 4.4 million people every day.[179]

Tren Suburbano

[edit]A suburban rail system, the Tren Suburbano serves the metropolitan area, beyond the reach of the metro, with one line serving to municipalities such as Tlalnepantla and Cuautitlán Izcalli, but with future lines planned to serve e.g. Chalco and La Paz.

Electric transport other than the metro also exists, in the form of several Mexico City trolleybus routes and the Xochimilco Light Rail line, both of which are operated by Servicio de Transportes Eléctricos. The central area's last streetcar line (tramway, or tranvía) closed in 1979.

Bus

[edit]

Mexico City has an extensive bus network, consisting of public buses, bus rapid transit, and trolleybuses.

Roads

[edit]Mexico City has a large road network, and relatively high private car usage, estimated at more than 4.5 million in 2016.[180] There is an environmental program, called Hoy No Circula ("Today Does Not Run", or "One Day without a Car"), whereby vehicles that have not passed emissions testing are restricted from circulating on certain days according to the ending digit of their license plates, in an attempt to cut down on pollution and traffic congestion.[181][182][183]

Cycling

[edit]

The Mexico City local government oversees the administration of Ecobici, North America's second-largest bicycle sharing system. Established to promote sustainable urban transportation, Ecobici facilitates convenient access to bicycles for residents and visitors alike. As of September 2013, the system comprised 276 stations strategically positioned across an expansive area extending from the Historic center to Polanco, a prominent district in the city. Within this network, approximately 4,000 bicycles are available for public use, enabling individuals to navigate the metropolitan landscape efficiently and reduce reliance on traditional motorized modes of transportation. Ecobici serves as a model for environmentally conscious urban mobility initiatives, reflecting Mexico City's commitment to fostering sustainable development and enhancing the quality of life for its populace.[184][185][186]

Culture

[edit]Art

[edit]

Secular works of art of this period include the equestrian sculpture of Charles IV of Spain, locally known as El Caballito ("The little horse"). This piece, in bronze, was the work of Manuel Tolsá and it has been placed at the Plaza Tolsá, in front of the Palacio de Mineria (Mining Palace). Directly in front of this building is the Museo Nacional de Arte (Munal) (the National Museum of Art).

During the 19th century, an important producer of art was the Academia de San Carlos (San Carlos Art Academy), founded during colonial times, and which later became the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (the National School of Arts) including painting, sculpture and graphic design, one of UNAM's art schools. Many of the works produced by the students and faculty of that time are now displayed in the Museo Nacional de San Carlos (National Museum of San Carlos). One of the students, José María Velasco, is considered one of the greatest Mexican landscape painters of the 19th century. Porfirio Díaz's regime sponsored arts, especially those that followed the French school. Popular arts in the form of cartoons and illustrations flourished, e.g. those of José Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Manilla. The permanent collection of the San Carlos Museum also includes paintings by European masters such as Rembrandt, Velázquez, Murillo, and Rubens.

After the Mexican Revolution, an avant-garde artistic movement originated in Mexico City: muralism. Many of the works of muralists José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera are displayed in numerous buildings in the city, most notably at the National Palace and the Palacio de Bellas Artes. Frida Kahlo, wife of Rivera, with a strong nationalist expression, was also one of the most renowned of Mexican painters. Her house has become a museum that displays many of her works.[187]

The former home of Rivera muse Dolores Olmedo houses the namesake museum. The facility is in Xochimilco borough in southern Mexico City and includes several buildings surrounded by sprawling manicured lawns. It houses a large collection of Rivera and Kahlo paintings and drawings, as well as living Xoloizcuintles (Mexican Hairless Dog). It also regularly hosts small but important temporary exhibits of classical and modern art (e.g. Venetian Masters and Contemporary New York artists).

During the 20th century, many artists immigrated to Mexico City from different regions of Mexico, such as Leopoldo Méndez, an engraver from Veracruz, who supported the creation of the socialist Taller de la Gráfica Popular (Popular Graphics Workshop), designed to help blue-collar workers find a venue to express their art. Other painters came from abroad, such as Catalan painter Remedios Varo and other Spanish and Jewish exiles. It was in the second half of the 20th century that the artistic movement began to drift apart from the Revolutionary theme. José Luis Cuevas opted for a modernist style in contrast to the muralist movement associated with social politics.

Museums

[edit]

В Мехико есть множество музеев, посвященных искусству, в том числе мексиканскому колониальному, современному и современному искусству , а также международному искусству. Музей Тамайо был открыт в середине 1980-х годов для размещения коллекции международного современного искусства, подаренной мексиканским художником Руфино Тамайо . В коллекцию входят произведения Пикассо, Клее, Кандинского, Уорхола и многих других, однако большая часть коллекции хранится во время посещения экспонатов. Museo de Arte Moderno является хранилищем мексиканских художников 20-го века, в том числе Риверы, Ороско, Сикейроса, Кало, Герцо , Кэррингтона, Тамайо, а также регулярно проводит временные выставки международного современного искусства. На юге Мехико музей Каррильо Хила демонстрирует художников-авангардистов, а также Музей Universitario Arte Contemporáneo , спроектированный мексиканским архитектором Теодоро Гонсалесом де Леоном и открытый в конце 2008 года.

Музей Сумайя , названный в честь жены мексиканского магната Карлоса Слима , имеет самую большую частную коллекцию оригинальных скульптур Родена за пределами Франции. [ 188 ] Он также имеет большую коллекцию скульптур Дали , и недавно начал демонстрировать произведения из коллекции своих мастеров, включая Эль Греко , Веласкеса , Пикассо и Каналетто . В 2011 году музей открыл новый объект футуристического дизайна к северу от Поланко, сохранив при этом меньший объект на площади Лорето на юге Мехико. Colección Júmex — музей современного искусства, расположенный на обширной территории компании по производству соков Jumex в северном промышленном пригороде Экатепек . Он обладает крупнейшей частной коллекцией современного искусства в Латинской Америке и включает в себя произведения из своей постоянной коллекции, а также передвижные выставки. Музей Сан-Ильдефонсо, расположенный в Антигуо Коледжио-де-Сан-Ильдефонсо в историческом центре города Мехико, представляет собой дворец с колоннадой 17-го века, в котором находится художественный музей, в котором регулярно проводятся выставки мексиканского и международного искусства мирового уровня. Национальный музей искусств также расположен в бывшем дворце в историческом центре. Здесь хранится большая коллекция произведений всех крупнейших мексиканских художников за последние 400 лет, а также проводятся посещаемые выставки.

Джек Керуак , известный американский писатель, проводил в городе продолжительное время и написал в 1959 году свой шедевральный сборник стихов «Блюз Мехико» здесь . Другой американский писатель, Уильям С. Берроуз , также жил в Колонии Рома , где случайно застрелил свою жену. Большинство музеев Мехико можно посетить со вторника по воскресенье с 10:00 до 17:00, хотя некоторые из них имеют расширенное расписание, например Музей антропологии и истории, который открыт до 19:00. Кроме того, вход в большинство музеев в воскресенье бесплатный. В некоторых случаях может взиматься небольшая плата. [ 189 ]

Музей памяти и толерантности , открытый в 2011 году, демонстрирует исторические события дискриминации и геноцида. Постоянные экспозиции включают экспонаты, посвященные Холокосту и другим крупномасштабным злодеяниям. Здесь также размещаются временные выставки; один в Тибете был открыт Далай -ламой в сентябре 2011 года. [ 190 ]

Музыка, театр и развлечения

[ редактировать ]

Мехико является домом для ряда оркестров, предлагающих сезонные программы. К ним относятся Филармония Мехико , [ 191 ] который выступает в Зале Оллин Йолицтли; Национальный симфонический оркестр , базой которого является Дворец изящных искусств (Дворец изящных искусств ), шедевр стилей модерн и ар-деко; Филармонический оркестр Национального автономного университета Мексики ( ОФУНАМ ), [ 192 ] и Горный симфонический оркестр , [ 193 ] оба из них выступают в Sala Nezahualcóyotl , который был первым концертным залом в западном полушарии, когда он был открыт в 1976 году. Есть также множество небольших ансамблей, которые обогащают музыкальную сцену города, в том числе Молодежный симфонический оркестр Карлоса Чавеса , Cuarteto Latinoamericano. , Оркестр Нового Света (Orquesta del Nuevo Mundo), Национальный политехнический симфонический оркестр и Камерный оркестр Bellas Artes (Orquesta de Cámara de Bellas Artes).

Город также является ведущим центром популярной культуры и музыки. Есть множество площадок, где выступают испанские и иностранные исполнители. на 10 000 мест К ним относятся Национальный зал выступают испанские и англоязычные исполнители поп- и рок-музыки, а также многие ведущие мира искусства исполнительского ансамбли , в котором регулярно . экраны определений. В 2007 году Национальная аудитория была признана лучшим местом в мире по версии различных жанровых СМИ. на 3000 мест Другие площадки для выступлений поп-артистов включают Театр Метрополитен , Дворец Депортес на 15 000 мест и более крупный стадион Форо Соль на 50 000 мест , где регулярно выступают популярные международные артисты. Цирк дю Солей провел несколько сезонов в Карпа Санта-Фе , в районе Санта-Фе в западной части города. Есть множество площадок для выступления небольших музыкальных ансамблей и сольных исполнителей. К ним относятся Hard Rock Live , Bataclan, Foro Scotiabank, Lunario, Circo Volador и Voilá Acoustique. на 20 000 мест Недавние дополнения включают Arena Ciudad de México , Всемирный торговый центр Pepsi Center на 3 000 мест и Blackberry Auditorium на 2 500 мест.

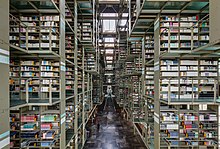

Centro Nacional de las Artes ( Национальный центр искусств ) имеет несколько площадок для музыки, театра и танцев. В главном кампусе UNAM, также расположенном в южной части города, находится Centrocultural Universitario ( Университетский культурный центр ) (CCU). В CCU также находятся Национальная библиотека , интерактивный Universum, Museo de las Ciencias , [ 194 ] концертный зал Сала Несауалькойотль, несколько театров и кинотеатров, а также новый университетский музей современного искусства (MUAC). [ 195 ] Филиал культурного центра CCU Национального университета был открыт в 2007 году на территории бывшего Министерства иностранных дел , известного как Тлателолко, в северо-центральной части Мехико.

Библиотека Хосе Васконселоса , национальная библиотека, расположена на территории бывшего железнодорожного вокзала Буэнависта в северной части города. Папалоте Museo del Niño (Детский музей воздушных змеев), в котором находится самый большой в мире купольный экран, расположен в лесопарке Чапультепек , недалеко от Museo Tecnológico и La Feria , бывшего парка развлечений . Тематический парк Six Flags México (крупнейший парк развлечений в Латинской Америке) расположен в районе Ахуско , в районе Тлалпан, на юге Мехико. Зимой главная площадь Сокало превращается в гигантский каток , который считается самым большим в мире после московской Красной площади .

Cineteca Nacional (Мексиканская кинобиблиотека), расположенная недалеко от пригорода Койоакана, демонстрирует множество фильмов и проводит множество кинофестивалей, в том числе ежегодный International Showcase , а также множество более мелких, начиная от скандинавского и уругвайского кино до еврейского и ЛГБТ. -тематические фильмы. Cinépolis и Cinemex , две крупнейшие сети кинобизнеса , также проводят в течение года несколько кинофестивалей, как национальных, так и международных фильмов. В Мехико есть несколько кинотеатров IMAX , предоставляющих жителям и гостям доступ к фильмам, от документальных до блокбастеров, на этих больших экранах.

Кухня

[ редактировать ]