Англиканская церковь

( Англиканская церковь C of E ) является признанной христианской церковью в Англии и зависимых территориях Короны . Это источник англиканской традиции, сочетающей в себе черты как реформатской , так и католической христианской практики. Ее приверженцев называют англиканцами.

The English church traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain by the 3rd century and to the 6th-century Gregorian mission to Kent led by Augustine of Canterbury. It renounced papal authority in 1534, when King Henry VIII failed to secure a papal annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. The English Reformation accelerated under the regents of his successor, King Edward VI, before a brief restoration of papal authority under Queen Mary I and King Philip. The Act of Supremacy 1558 renewed the breach, and the Elizabethan Settlement charted a course enabling the English church to describe itself as both Reformed and Catholic. In the earlier phase of the English Reformation there were both Roman Catholic martyrs and Protestant martyrs. The later phases saw the Penal Laws punish Roman Catholics and nonconforming Protestants. In the 17th century, the Puritan and Presbyterian factions continued to challenge the leadership of the church, which under the Stuarts veered towards a more Catholic interpretation of the Elizabethan Settlement, especially under Archbishop Laud and the rise of the concept of Англиканство как связующее звено между римским католицизмом и радикальным протестантизмом. После победы парламентариев Книга общих молитв была упразднена и доминировали пресвитерианская и независимая фракции. Епископство Реставрация было упразднено в 1646 году, но восстановила Англиканскую церковь, епископство и Книгу общих молитв . Папское признание Георга III в 1766 году привело к большей религиозной терпимости .

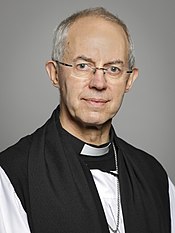

Since the English Reformation, the Church of England has used the English language in the liturgy. As a broad church, the Church of England contains several doctrinal strands. The main traditions are known as Anglo-Catholic, high church, central church and low church, the latter producing a growing evangelical wing. Tensions between theological conservatives and liberals find expression in debates over the ordination of women and homosexuality. The British monarch (currently Charles III) is the supreme governor and the Archbishop of Canterbury (currently Justin Welby) is the most senior cleric. The governing structure of the church is based on dioceses, each presided over by a bishop. Within each diocese are local parishes. The General Synod of the Church of England is the legislative body for the church and comprises bishops, other clergy and laity. Its measures must be approved by the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

History

[edit]Middle Ages

[edit]

There is evidence for Christianity in Roman Britain as early as the 3rd century. After the fall of the Roman Empire, England was conquered by the Anglo-Saxons, who were pagans, and the Celtic church was confined to Cornwall and Wales.[2] In 597, Pope Gregory I sent missionaries to England to Christianise the Anglo-Saxons. This mission was led by Augustine, who became the first archbishop of Canterbury. The Church of England considers 597 the start of its formal history.[3][4][5]

In Northumbria, Celtic missionaries competed with their Roman counterparts. The Celtic and Roman churches disagreed over the date of Easter, baptismal customs, and the style of tonsure worn by monks.[6] King Oswiu of Northumbria summoned the Synod of Whitby in 664. The king decided Northumbria would follow the Roman tradition because Saint Peter and his successors, the bishops of Rome, hold the keys of the kingdom of heaven.[7]

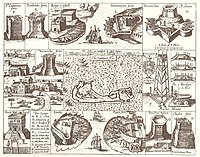

By the late Middle Ages, Catholicism was an essential part of English life and culture. The 9,000 parishes covering all of England were overseen by a hierarchy of deaneries, archdeaconries, dioceses led by bishops, and ultimately the pope who presided over the Catholic Church from Rome.[8] Catholicism taught that the contrite person could cooperate with God towards their salvation by performing good works (see synergism).[9] God's grace was given through the seven sacraments.[10] In the Mass, a priest consecrated bread and wine to become the body and blood of Christ through transubstantiation. The church taught that, in the name of the congregation, the priest offered to God the same sacrifice of Christ on the cross that provided atonement for the sins of humanity.[11][12] The Mass was also an offering of prayer by which the living could help souls in purgatory.[13] While penance removed the guilt attached to sin, Catholicism taught that a penalty still remained. It was believed that most people would end their lives with these penalties unsatisfied and would have to spend time in purgatory. Time in purgatory could be lessened through indulgences and prayers for the dead, which were made possible by the communion of saints.[14]

Reformation

[edit]In 1527, Henry VIII was desperate for a male heir and asked Pope Clement VII to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. When the pope refused, Henry used Parliament to assert royal authority over the English church. In 1533, Parliament passed the Act in Restraint of Appeals, barring legal cases from being appealed outside England. This allowed the Archbishop of Canterbury to annul the marriage without reference to Rome. In November 1534, the Act of Supremacy formally abolished papal authority and declared Henry Supreme Head of the Church of England.[15]

Henry's religious beliefs remained aligned to traditional Catholicism throughout his reign. In order to secure royal supremacy over the church, however, Henry allied himself with Protestants, who until that time had been treated as heretics.[16] The main doctrine of the Protestant Reformation was justification by faith alone rather than by good works.[17] The logical outcome of this belief is that the Mass, sacraments, charitable acts, prayers to saints, prayers for the dead, pilgrimage, and the veneration of relics do not mediate divine favour. To believe they can would be superstition at best and idolatry at worst.[18][19]

Between 1536 and 1540, Henry engaged in the dissolution of the monasteries, which controlled much of the richest land. He disbanded religious houses, appropriated their income, disposed of their assets, and provided pensions for the former residents. The properties were sold to pay for the wars. Historian George W. Bernard argues:

The dissolution of the monasteries in the late 1530s was one of the most revolutionary events in English history. There were nearly 900 religious houses in England, around 260 for monks, 300 for regular canons, 142 nunneries and 183 friaries; some 12,000 people in total, 4,000 monks, 3,000 canons, 3,000 friars and 2,000 nuns....one adult man in fifty was in religious orders.[20]

In the reign of Edward VI (1547–1553), the Church of England underwent an extensive theological reformation. Justification by faith was made a central teaching.[21] Government-sanctioned iconoclasm led to the destruction of images and relics. Stained glass, shrines, statues, and roods were defaced or destroyed. Church walls were whitewashed and covered with biblical texts condemning idolatry.[22] The most significant reform in Edward's reign was the adoption of an English liturgy to replace the old Latin rites.[23] Written by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, the 1549 Book of Common Prayer implicitly taught justification by faith,[24] and rejected the Catholic doctrines of transubstantiation and the sacrifice of the Mass.[25] This was followed by a greatly revised 1552 Book of Common Prayer that was even more Protestant in tone, going so far as to deny the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist.[26][27]

During the reign of Mary I (1553–1558), England was briefly reunited with the Catholic Church. Mary died childless, so it was left to the new regime of her half-sister Queen Elizabeth I to resolve the direction of the church. The Elizabethan Religious Settlement returned the Church to where it stood in 1553 before Edward's death. The Act of Supremacy made the monarch the Church's supreme governor. The Act of Uniformity restored a slightly altered 1552 Book of Common Prayer. In 1571, the Thirty-nine Articles received parliamentary approval as a doctrinal statement for the Church. The settlement ensured the Church of England was Protestant, but it was unclear what kind of Protestantism was being adopted.[28] The prayer book's eucharistic theology was vague. The words of administration neither affirmed nor denied the real presence. Perhaps, a spiritual presence was implied, since Article 28 of the Thirty-nine Articles taught that the body of Christ was eaten "only after an heavenly and spiritual manner".[29] Nevertheless, there was enough ambiguity to allow later theologians to articulate various versions of Anglican eucharistic theology.[27]

The Church of England was the established church (constitutionally established by the state with the head of state as its supreme governor). The exact nature of the relationship between church and state would be a source of continued friction into the next century.[30][31][32]

Stuart period

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2020) |

Struggle for control of the church persisted throughout the reigns of James I and his son Charles I, culminating in the outbreak of the First English Civil War in 1642. The two opposing factions consisted of Puritans, who sought to "purify" the church and enact more far-reaching Protestant reforms, and those who wanted to retain traditional beliefs and practices. In a period when many believed "true religion" and "good government" were the same thing, religious disputes often included a political element, one example being the struggle over bishops. In addition to their religious function, bishops acted as state censors, able to ban sermons and writings considered objectionable, while lay people could be tried by church courts for crimes including blasphemy, heresy, fornication and other 'sins of the flesh', as well as matrimonial or inheritance disputes.[33] They also sat in the House of Lords and often blocked legislation opposed by the Crown; their ousting from Parliament by the 1640 Clergy Act was a major step on the road to war.[34]

Following Royalist defeat in 1646, the episcopacy was formally abolished.[35] In 1649, the Commonwealth of England outlawed a number of former practices and Presbyterian structures replaced the episcopate. The Thirty-nine Articles were replaced by the Westminster Confession. Worship according to the Book of Common Prayer was outlawed and replace by the Directory of Public Worship. Despite this, about one quarter of English clergy refused to conform to this form of state presbyterianism.[citation needed] It was also opposed by religious Independents who rejected the very idea of state-mandated religion, and included Congregationalists like Oliver Cromwell, as well as Baptists, who were especially well represented in the New Model Army.[36]

After the Stuart Restoration in 1660, Parliament restored the Church of England to a form not far removed from the Elizabethan version. Until James II of England was ousted by the Glorious Revolution in November 1688, many Nonconformists still sought to negotiate terms that would allow them to re-enter the church.[37] In order to secure his political position, William III of England ended these discussions and the Tudor ideal of encompassing all the people of England in one religious organisation was abandoned. The religious landscape of England assumed its present form, with the Anglican established church occupying the middle ground and Nonconformists continuing their existence outside. One result of the Restoration was the ousting of 2,000 parish ministers who had not been ordained by bishops in the apostolic succession or who had been ordained by ministers in presbyter's orders. Official suspicion and legal restrictions continued well into the 19th century. Roman Catholics, perhaps 5% of the English population (down from 20% in 1600) were grudgingly tolerated, having had little or no official representation after the Pope's excommunication of Queen Elizabeth in 1570, though the Stuarts were sympathetic to them. By the end of 18th century they had dwindled to 1% of the population, mostly amongst upper middle-class gentry, their tenants, and extended families.[citation needed]

Union with the Church of Ireland

[edit]By the Fifth Article of the Union with Ireland 1800, the Church of England and Church of Ireland were united into "one Protestant Episcopal church, to be called, the United Church of England and Ireland".[38] Although "the continuance and preservation of the said united church ... [was] deemed and taken to be an essential and fundamental part of the union",[39] the Irish Church Act 1869 separated the Irish part of the church again and disestablished it, the Act coming into effect on 1 January 1871.

Overseas developments

[edit]

As the English Empire (after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, the British Empire) expanded, English (after 1707, British) colonists and colonial administrators took the established church doctrines and practices together with ordained ministry and formed overseas branches of the Church of England.

The Diocese of Nova Scotia was created on 11 August 1787 by Letters Patent of George III which "erected the Province of Nova Scotia into a bishop's see" and these also named Charles Inglis as first bishop of the see.[40] The diocese was the first Church of England see created outside England and Wales (i.e. the first colonial diocese). At this point, the see covered present-day New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Quebec.[41] From 1825 to 1839, it included the nine parishes of Bermuda, subsequently transferred to the Diocese of Newfoundland.[42]

As they developed, beginning with the United States of America, or became sovereign or independent states, many of their churches became separate organisationally, but remained linked to the Church of England through the Anglican Communion. In the provinces that made up Canada, the church operated as the "Church of England in Canada" until 1955 when it became the Anglican Church of Canada.[43]

In Bermuda, the oldest remaining British overseas possession, the first Church of England services were performed by the Reverend Richard Buck, one of the survivors of the 1609 wreck of the Sea Venture which initiated Bermuda's permanent settlement. The nine parishes of the Church of England in Bermuda, each with its own church and glebe land, rarely had more than a pair of ordained ministers to share between them until the 19th century. From 1825 to 1839, Bermuda's parishes were attached to the See of Nova Scotia. Bermuda was then grouped into the new Diocese of Newfoundland and Bermuda from 1839. In 1879, the Synod of the Church of England in Bermuda was formed. At the same time, a Diocese of Bermuda became separate from the Diocese of Newfoundland, but both continued to be grouped under the Bishop of Newfoundland and Bermuda until 1919, when Newfoundland and Bermuda each received its own bishop.[citation needed]

The Church of England in Bermuda was renamed in 1978 as the Anglican Church of Bermuda, which is an extra-provincial diocese,[44] with both metropolitan and primatial authority coming directly from the Archbishop of Canterbury. Among its parish churches is St Peter's Church in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of St George's Town, which is the oldest Anglican church outside of the British Isles, and the oldest Protestant church in the New World.[45]

The first Anglican missionaries arrived in Nigeria in 1842 and the first Anglican Nigerian was consecrated a bishop in 1864. However, the arrival of a rival group of Anglican missionaries in 1887 led to infighting that slowed the Church's growth. In this large African colony, by 1900 there were only 35,000 Anglicans, about 0.2% of the population. However, by the late 20th century the Church of Nigeria was the fastest growing of all Anglican churches, reaching about 18 percent of the local population by 2000.[43]

The church established its presence in Hong Kong and Macau in 1843. In 1951, the Diocese of Hong Kong and Macao became an extra-provincial diocese, and in 1998 it became a province of the Anglican Communion, under the name Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui.

From 1796 to 1818 the Church began operating in Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon), following the 1796 start of British colonisation, when the first services were held for the British civil and military personnel. In 1799, the first Colonial Chaplain was appointed, following which CMS and SPG missionaries began their work, in 1818 and 1844 respectively. Subsequently the Church of Ceylon was established: in 1845 the diocese of Colombo was inaugurated, with the appointment of James Chapman as Bishop of Colombo. It served as an extra-provincial jurisdiction of the archbishop of Canterbury, who served as its metropolitan.

Early 21st century

[edit]Deposition from holy orders overturned

[edit]Under the guidance of Rowan Williams and with significant pressure from clergy union representatives, the ecclesiastical penalty for convicted felons to be defrocked was set aside from the Clergy Discipline Measure 2003. The clergy union argued that the penalty was unfair to victims of hypothetical miscarriages of criminal justice, because the ecclesiastical penalty is considered irreversible. Although clerics can still be banned for life from ministry, they remain ordained as priests.[46]

Continued decline in attendance and church response

[edit]

Bishop Sarah Mullally has insisted that declining numbers at services should not necessarily be a cause of despair for churches, because people may still encounter God without attending a service in a church; for example hearing the Christian message through social media sites or in a café run as a community project.[47] Additionally, 9.7 million people visit at least one of its churches every year and 1 million students are educated at Church of England schools (which number 4,700).[48] In 2019, an estimated 10 million people visited a cathedral and an additional "1.3 million people visited Westminster Abbey, where 99% of visitors paid / donated for entry".[49] In 2022, the church reported than an estimated 5.7 million people visited a cathedral and 6.8 million visited Westminster Abbey.[50] Nevertheless, the archbishops of Canterbury and York warned in January 2015 that the Church of England would no longer be able to carry on in its current form unless the downward spiral in membership were somehow to be reversed, as typical Sunday attendance had halved to 800,000 in the previous 40 years:[51]

The urgency of the challenge facing us is not in doubt. Attendance at Church of England services has declined at an average of one per cent per annum over recent decades and, in addition, the age profile of our membership has become significantly older than that of the population... Renewing and reforming aspects of our institutional life is a necessary but far from sufficient response to the challenges facing the Church of England. ... The age profile of our clergy has also been increasing. Around 40 per cent of parish clergy are due to retire over the next decade or so.

Between 1969 and 2010, almost 1,800 church buildings, roughly 11% of the stock, were closed (so-called "redundant churches"); the majority (70%) in the first half of the period; only 514 being closed between 1990 and 2010.[52] Some active use was being made of about half of the closed churches.[53] By 2019 the rate of closure had steadied at around 20 to 25 per year (0.2%); some being replaced by new places of worship.[54] Additionally, in 2018 the church announced a £27 million growth programme to create 100 new churches.[55]

Low salaries

[edit]In 2015 the Church of England admitted that it was embarrassed to be paying staff under the living wage. The Church of England had previously campaigned for all employers to pay this minimum amount. The archbishop of Canterbury acknowledged it was not the only area where the church "fell short of its standards".[56]

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]The COVID-19 pandemic had a sizeable effect on church attendance, with attendance in 2020 and 2021 dropping well below that of 2019. By 2022, the first full year without substantial restrictions related to the pandemic, numbers were still notably down on pre-pandemic participation. According to the 2022 release of "Statistics for Mission" by the church, the median size of each church's "Worshipping Community" (those who attend in person or online at least as regularly as once a month) now stands at 37 people, with average weekly attendance having declined from 34 to 25; while Easter and Christmas services have seen falls from 51 to 38 and 80 to 56 individuals respectively. Examples of wider declines across the whole church include:[57]

| Estimated change, 2019 to 2020 | Estimated change, 2019 to 2021 | Estimated change, 2019 to 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worshipping Community | -7% | -13% | -12% |

| All age average weekly attendance (October) | -60% | -29% | -23% |

| All age average Sunday attendance (October) | -53% | -28% | -23% |

| Easter attendance | N/A | -56% | -27% |

| Christmas attendance | -79% | -58% | -30% |

Doctrine and practice

[edit]

The canon law of the Church of England identifies the Christian scriptures as the source of its doctrine. In addition, doctrine is also derived from the teachings of the Church Fathers and ecumenical councils (as well as the ecumenical creeds) in so far as these agree with scripture. This doctrine is expressed in the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, the Book of Common Prayer, and the Ordinal containing the rites for the ordination of deacons, priests, and the consecration of bishops.[58] Unlike other traditions, the Church of England has no single theologian that it can look to as a founder. However, Richard Hooker's appeal to scripture, church tradition, and reason as sources of authority,[59] as well as the work of Thomas Cranmer, which inspired the doctrinal status of the church, continue to inform Anglican identity.

The Church of England's doctrinal character today is largely the result of the Elizabethan Settlement, which sought to establish a comprehensive middle way between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. The Church of England affirms the protestant reformation principle that scripture contains all things necessary to salvation and is the final arbiter in doctrinal matters. The Thirty-nine Articles are the church's only official confessional statement. Though not a complete system of doctrine, the articles highlight areas of agreement with Lutheran and Reformed positions, while differentiating Anglicanism from Roman Catholicism and Anabaptism.[59]

While embracing some themes of the Protestant Reformation, the Church of England also maintains Catholic traditions of the ancient church and teachings of the Church Fathers, unless these are considered contrary to scripture. It accepts the decisions of the first four ecumenical councils concerning the Trinity and the Incarnation. The Church of England also preserves catholic order by adhering to episcopal polity, with ordained orders of bishops, priests and deacons. There are differences of opinion within the Church of England over the necessity of episcopacy. Some consider it essential, while others feel it is needed for the proper ordering of the church.[59] In sum these express the 'Via Media' viewpoint that the first five centuries of doctrinal development and church order as approved are acceptable as a yardstick by which to gauge authentic catholicity, as minimum and sufficient; Anglicanism did not emerge as the result of charismatic leaders with particular doctrines. It is light on details compared to Roman Catholic, Reformed and Lutheran teachings. The Bible, the Creeds, Apostolic Order, and the administration of the Sacraments are sufficient to establish catholicity. The Reformation in England was initially much concerned about doctrine but the Elizabethan Settlement tried to put a stop to doctrinal contentions. The proponents of further changes, nonetheless, tried to get their way by making changes in Church Order (abolition of bishops), governance (Canon Law) and liturgy ('too Catholic'). They did not succeed because the monarchy and the Church resisted and the majority of the population were indifferent. Moreover, "despite all the assumptions of the Reformation founders of that Church, it had retained a catholic character." The Elizabethan Settlement had created a cuckoo in a nest..." a Protestant theology and program within a largely pre-Reformation Catholic structure whose continuing life would arouse a theological interest in the Catholicism that had created it; and would result in the rejection of predestinarian theology in favor of sacraments, especially the eucharist, ceremonial, and anti-Calvinist doctrine".[60] The existence of cathedrals "without substantial alteration" and "where the "old devotional world cast its longest shadow for the future of the ethos that would become Anglicanism,"[61] This is "One of the great mysteries of the English Reformation,"[61] that there was no complete break with the past but a muddle that was per force turned into a virtue. The story of the English Reformation is the tale of retreat from the Protestant advance of 1550 which could not proceed further in the face of the opposition of the institution which was rooted in the medieval past,[62] and the adamant opposition of Queen Elizabeth I.[citation needed]

The Church of England has, as one of its distinguishing marks, a breadth of opinion from liberal to conservative clergy and members.[63] This tolerance has allowed Anglicans who emphasise the catholic tradition and others who emphasise the reformed tradition to coexist. The three schools of thought (or parties) in the Church of England are sometimes called high church (or Anglo-Catholic), low church (or evangelical Anglican) and broad church (or liberal). The high church party places importance on the Church of England's continuity with the pre-Reformation Catholic Church, adherence to ancient liturgical usages and the sacerdotal nature of the priesthood. As their name suggests, Anglo-Catholics maintain many traditional catholic practices and liturgical forms.[64] The Catholic tradition, strengthened and reshaped from the 1830s by the Oxford movement, has stressed the importance of the visible Church and its sacraments and the belief that the ministry of bishops, priests and deacons is a sign and instrument of the Church of England's Catholic and apostolic identity.[65] The low church party is more Protestant in both ceremony and theology.[66] It has emphasized the significance of the Protestant aspects of the Church of England's identity, stressing the importance of the authority of Scripture, preaching, justification by faith and personal conversion.[65] Historically, the term 'broad church' has been used to describe those of middle-of-the-road ceremonial preferences who lean theologically towards liberal protestantism.[67] The liberal broad church tradition has emphasized the importance of the use of reason in theological exploration. It has stressed the need to develop Christian belief and practice in order to respond creatively to wider advances in human knowledge and understanding and the importance of social and political action in forwarding God's kingdom.[65] The balance between these strands of churchmanship is not static: in 2013, 40% of Church of England worshippers attended evangelical churches (compared with 26% in 1989), and 83% of very large congregations were evangelical. Such churches were also reported to attract higher numbers of men and young adults than others.[68]

Worship and liturgy

[edit]

In 1604, James I ordered an English language translation of the Bible known as the King James Version, which was published in 1611 and authorised for use in parishes, although it was not an "official" version per se.[69] The Church of England's official book of liturgy as established in English Law is the 1662 version of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP). In the year 2000, the General Synod approved a modern liturgical book, Common Worship, which can be used as an alternative to the BCP. Like its predecessor, the 1980 Alternative Service Book, it differs from the Book of Common Prayer in providing a range of alternative services, mostly in modern language, although it does include some BCP-based forms as well, for example Order Two for Holy Communion. (This is a revision of the BCP service, altering some words and allowing the insertion of some other liturgical texts such as the Agnus Dei before communion.) The Order One rite follows the pattern of more modern liturgical scholarship.[citation needed]

The liturgies are organised according to the traditional liturgical year and the calendar of saints. The sacraments of baptism and the eucharist are generally thought necessary to salvation. Infant baptism is practised. At a later age, individuals baptised as infants receive confirmation by a bishop, at which time they reaffirm the baptismal promises made by their parents or sponsors. The eucharist, consecrated by a thanksgiving prayer including Christ's Words of Institution, is believed to be "a memorial of Christ's once-for-all redemptive acts in which Christ is objectively present and effectually received in faith".[70]

The use of hymns and music in the Church of England has changed dramatically over the centuries. Traditional Choral evensong is a staple of most cathedrals. The style of psalm chanting harks back to the Church of England's pre-reformation roots. During the 18th century, clergy such as Charles Wesley introduced their own styles of worship with poetic hymns.[71]

In the latter half of the 20th century, the influence of the Charismatic Movement significantly altered the worship traditions of numerous Church of England parishes, primarily affecting those of evangelical persuasion. These churches now adopt a contemporary worship form of service, with minimal liturgical or ritual elements, and incorporating contemporary worship music.[72]

Just as the Church of England has a large conservative or "traditionalist" wing, it also has many liberal members and clergy. Approximately one third of clergy "doubt or disbelieve in the physical resurrection".[73] Others, such as Giles Fraser, a contributor to The Guardian, have argued for an allegorical interpretation of the virgin birth of Jesus.[74] The Independent reported in 2014 that, according to a YouGov survey of Church of England clergy, "as many as 16 per cent are unclear about God and two per cent think it is no more than a human construct."[75][76] Moreover, many congregations are seeker-friendly environments. For example, one report from the Church Mission Society suggested that the church open up "a pagan church where Christianity [is] very much in the centre" to reach out to spiritual people.[77]

The Church of England is launching a project on "gendered language" in Spring 2023 in efforts to "study the ways in which God is referred to and addressed in liturgy and worship".[78]

Women's ministry

[edit]Women were appointed as deaconesses from 1861, but they could not function fully as deacons and were not considered ordained clergy. Women have historically been able to serve as lay readers. During the First World War, some women were appointed as lay readers, known as "bishop's messengers", who also led missions and ran churches in the absence of men. After the war, no women were appointed as lay readers until 1969.[79]

Legislation authorising the ordination of women as deacons was passed in 1986 and they were first ordained in 1987. The ordination of women as priests was approved by the General Synod in 1992 and began in 1994. In 2010, for the first time in the history of the Church of England, more women than men were ordained as priests (290 women and 273 men),[80] but in the next two years, ordinations of men again exceeded those of women.[81]

In July 2005, the synod voted to "set in train" the process of allowing the consecration of women as bishops. In February 2006, the synod voted overwhelmingly for the "further exploration" of possible arrangements for parishes that did not want to be directly under the authority of a bishop who is a woman.[82] On 7 July 2008, the synod voted to approve the ordination of women as bishops and rejected moves for alternative episcopal oversight for those who do not accept the ministry of bishops who are women.[83] Actual ordinations of women to the episcopate required further legislation, which was narrowly rejected in a General Synod vote in November 2012.[84][85] On 20 November 2013, the General Synod voted overwhelmingly in support of a plan to allow the ordination of women as bishops, with 378 in favour, 8 against and 25 abstentions.[86]

On 14 July 2014, the General Synod approved the ordination of women as bishops. The House of Bishops recorded 37 votes in favour, two against with one abstention. The House of Clergy had 162 in favour, 25 against and four abstentions. The House of Laity voted 152 for, 45 against with five abstentions.[87] This legislation had to be approved by the Ecclesiastical Committee of the Parliament before it could be finally implemented at the November 2014 synod. In December 2014, Libby Lane was announced as the first woman to become a bishop in the Church of England. She was consecrated as a bishop in January 2015.[88] In July 2015, Rachel Treweek was the first woman to become a diocesan bishop in the Church of England when she became the Bishop of Gloucester.[89] She and Sarah Mullally, Bishop of Crediton, were the first women to be ordained as bishops at Canterbury Cathedral.[89] Treweek later made headlines by calling for gender-inclusive language, saying that "God is not to be seen as male. God is God."[90]

In May 2018, the Diocese of London consecrated Dame Sarah Mullally as the first woman to serve as the Bishop of London.[91] Bishop Sarah Mullally occupies the third most senior position in the Church of England.[92] Mullally has described herself as a feminist and will ordain both men and women to the priesthood.[93] She is also considered by some to be a theological liberal.[94] On women's reproductive rights, Mullally describes herself as pro-choice while also being personally pro-life.[95] On marriage, she supports the current stance of the Church of England that marriage is between a man and a woman, but also said that: "It is a time for us to reflect on our tradition and scripture, and together say how we can offer a response that is about it being inclusive love."[96]

Same-sex unions and LGBT clergy

[edit]The Church of England has been discussing same-sex marriages and LGBT clergy.[97][98] The church holds that marriage is a union of one man with one woman.[99][100] The church does not allow clergy to perform same-sex marriages, but in February 2023 approved of blessings for same-sex couples following a civil marriage or civil partnership.[101][102] The church teaches "Same-sex relationships often embody genuine mutuality and fidelity."[103][104] In January 2023, the Bishops approved "prayers of thanksgiving, dedication and for God's blessing for same-sex couples."[105][106][107] The commended prayers of blessing for same-sex couples, known as "Prayers of Love and Faith," may be used during ordinary church services, and in November 2023 General Synod voted to authorise "standalone" blessings for same-sex couples on a trial basis, while permanent authorisation will require additional steps.[108][109] The church also officially supports celibate civil partnerships; "We believe that Civil Partnerships still have a place, including for some Christian LGBTI couples who see them as a way of gaining legal recognition of their relationship."[110]

Civil partnerships for clergy have been allowed since 2005, so long as they remain sexually abstinent,[111][112][113] and the church extends pensions to clergy in same-sex civil partnerships.[114] In a missive to clergy, the church communicated that "there was a need for committed same-sex couples to be given recognition and 'compassionate attention' from the Church, including special prayers."[115] "There is no prohibition on prayers being said in church or there being a 'service'" after a civil union.[116] After same-sex marriage was legalised, the church sought continued availability of civil unions, saying "The Church of England recognises that same-sex relationships often embody fidelity and mutuality. Civil partnerships enable these Christian virtues to be recognised socially and legally in a proper framework."[117] In 2024, the General Synod voted in support of eventually permitting clergy to enter into civil same-sex marriages.[118][119]

In 2014, the bishops released guidelines that permit "more informal kind of prayer" for couples.[120] In the guidelines, "gay couples who get married will be able to ask for special prayers in the Church of England after their wedding, the bishops have agreed."[103] In 2016, the bishop of Grantham, Nicholas Chamberlain, announced that he is gay, in a same-sex relationship and celibate, becoming the first bishop to do so in the church.[121] The church had decided in 2013 that gay clergy in civil partnerships so long as they remain sexually abstinent could become bishops.[113][122] "The House [of Bishops] has confirmed that clergy in civil partnerships, and living in accordance with the teaching of the church on human sexuality, can be considered as candidates for the episcopate."[123]

In 2017, the House of Clergy voted against the motion to "take note" of the bishops' report defining marriage as between a man and a woman.[124] Due to passage in all three houses being required, the motion was rejected.[125] After General Synod rejected the motion, the archbishops of Canterbury and York called for "radical new Christian inclusion" that is "based on good, healthy, flourishing relationships, and in a proper 21st century understanding of being human and of being sexual."[126] The church officially opposes "conversion therapy", a practice which attempts to change a gay or lesbian person's sexual orientation, calling it unethical and supports the banning of "conversion therapy" in the UK.[127][128] The Diocese of Hereford approved a motion calling for the church "to create a set of formal services and prayers to bless those who have had a same-sex marriage or civil partnership."[129] In 2022, "The House [of Bishops] also agreed to the formation of a Pastoral Consultative Group to support and advise dioceses on pastoral responses to circumstances that arise concerning LGBTI+ clergy, ordinands, lay leaders and the lay people in their care."[130]

Regarding transgender issues, the 2017 General Synod voted in favour of a motion saying that transgender people should be "welcomed and affirmed in their parish church".[131][132] The motion also asked the bishops "to look into special services for transgender people."[133][134] The bishops initially said "the House notes that the Affirmation of Baptismal Faith, found in Common Worship, is an ideal liturgical rite which trans people can use to mark this moment of personal renewal."[135] The Bishops also authorised services of celebration to mark a gender transition that will be included in formal liturgy.[136][137] Transgender people may marry in the Church of England after legally making a transition.[138] "Since the Gender Recognition Act 2004, trans people legally confirmed in their gender identity under its provisions are able to marry someone of the opposite sex in their parish church."[139] The church further decided that same-gender couples may remain married when one spouse experiences gender transition provided that the spouses identified as opposite genders at the time of the marriage.[140][141] Since 2000, the church has allowed priests to undergo gender transition and remain in office.[142] The church has ordained openly transgender clergy since 2005.[143] The Church of England ordained the church's first openly non-binary priest.[144][145]

In January 2023, a meeting of the Bishops of the Church of England rejected demands for clergy to conduct same-sex marriages. However, proposals would be put to the General Synod that clergy should be able to hold church blessings for same-sex civil marriages, albeit on a voluntary basis for individual clergy. This comes as the Church continued to be split on same-sex marriages.[146]

In February 2023, ten archbishops of the Global South Fellowship of Anglican Churches released a statement stating that they had broken communion and no longer recognised Justin Welby as "the first among equals" or "primus inter pares" in the Anglican Communion in response to the General Synod's decision to approve the blessing of same-sex couples following a civil marriage or partnership, leading to questions as to the status of the Church of England as the mother church of the international Anglican Communion.[147][148][149]

In November 2023, the General Synod narrowly voted to allow church blessings for same-sex couples on a trial basis.[150] In December 2023, the first blessings of same-sex couples began in the Church of England.[151][152] In 2024, the General Synod voted to support moving forward with "stand-alone" services of blessing for same-sex couples after a civil marriage or civil partnership.[153][154][155]

Bioethics issues

[edit]The Church of England is generally opposed to abortion but believes "there can be strictly limited conditions under which abortion may be morally preferable to any available alternative".[156] The church also opposes euthanasia. Its official stance is that "While acknowledging the complexity of the issues involved in assisted dying/suicide and voluntary euthanasia, the Church of England is opposed to any change in the law or in medical practice that would make assisted dying/suicide or voluntary euthanasia permissible in law or acceptable in practice." It also states that "Equally, the Church shares the desire to alleviate physical and psychological suffering, but believes that assisted dying/suicide and voluntary euthanasia are not acceptable means of achieving these laudable goals."[157] In 2014, George Carey, a former archbishop of Canterbury, announced that he had changed his stance on euthanasia and now advocated legalising "assisted dying".[158] On embryonic stem-cell research, the church has announced "cautious acceptance to the proposal to produce cytoplasmic hybrid embryos for research".[159]

In the 19th century, English law required the burial of people who had died by suicide to occur only between the hours of 9 p.m. and midnight and without religious rites.[160] The Church of England permitted the use of alternative burial services for people who had died by suicide. In 2017, the Church of England changed its rules to permit the full, standard Christian burial service regardless of whether a person had died by suicide.[161]

Social work

[edit]Church Urban Fund

[edit]The Church of England set up the Church Urban Fund in the 1980s to tackle poverty and deprivation. It sees poverty as trapping individuals and communities with some people in urgent need, leading to dependency, homelessness, hunger, isolation, low income, mental health problems, social exclusion and violence. They feel that poverty reduces confidence and life expectancy and that people born in poor conditions have difficulty escaping their disadvantaged circumstances.[162]

Child poverty

[edit]In parts of Liverpool, Manchester and Newcastle two-thirds of babies are born to poverty and have poorer life chances, also a life expectancy 15 years lower than babies born in the best-off fortunate communities.[163]

The deep-rooted unfairness in our society is highlighted by these stark statistics. Children being born in this country, just a few miles apart, couldn't witness a more wildly differing start to life. In child poverty terms, we live in one of the most unequal countries in the western world. We want people to understand where their own community sits alongside neighbouring communities. The disparity is often shocking but it's crucial that, through greater awareness, people from all backgrounds come together to think about what could be done to support those born into poverty. [Paul Hackwood, the Chair of Trustees at Church Urban Fund][164]

Action on hunger

[edit]Many prominent people in the Church of England have spoken out against poverty and welfare cuts in the United Kingdom. Twenty-seven bishops are among 43 Christian leaders who signed a letter which urged David Cameron to make sure people have enough to eat.

We often hear talk of hard choices. Surely few can be harder than that faced by the tens of thousands of older people who must 'heat or eat' each winter, harder than those faced by families whose wages have stayed flat while food prices have gone up 30% in just five years. Yet beyond even this we must, as a society, face up to the fact that over half of people using food banks have been put in that situation by cutbacks to and failures in the benefit system, whether it be payment delays or punitive sanctions.[165]

Thousands of UK citizens use food banks. The church's campaign to end hunger considers this "truly shocking" and called for a national day of fasting on 4 April 2014.[165]

Membership

[edit]As of 2009[update], the Church of England estimated that it had approximately 26 million baptised members – about 47% of the English population.[166][167] This number has remained consistent since 2001 and was cited again in 2013 and 2014.[168][169][170] According to a 2016 study published by the Journal of Anglican Studies, the Church of England continued to claim 26 million baptised members, while it also had approximately 1.7 million active baptised members.[171][172][173] Due to its status as the established church, in general, anyone may be married, have their children baptised or their funeral in their local parish church, regardless of whether they are baptised or regular churchgoers.[174]

Between 1890 and 2001, churchgoing in the United Kingdom declined steadily.[175] In the years 1968 to 1999, Anglican Sunday church attendances almost halved, from 3.5 percent of the population to 1.9 per cent.[176] By 2014, Sunday church attendances had declined further to 1.4 per cent of the population.[177] One study published in 2008 suggested that if current trends continued, Sunday attendances could fall to 350,000 in 2030 and 87,800 in 2050.[178] The Church of England releases an annual publication, Statistics for Mission, detailing numerous criteria relating to participation with the church. Below is a snapshot of several key metrics from every five years since 2001 (2022 has been used in place of 2021 to avoid the impact of Covid restrictions).

| Category | 2001[179] | 2006[179] | 2011[180] | 2016[180] | 2022[181][c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worshipping Community[d] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,138,800 | 984,000 |

| All Age Weekly Attendance | 1,205,000 | 1,163,000 | 1,050,300 | 927,300 | 654,000 |

| All Age Sunday Attendance | 1,041,000 | 983,000 | 858,400 | 779,800 | 547,000 |

| Easter Attendance | 1,593,000 | 1,485,000 | 1,378,200 | 1,222,700 | 861,000 |

| Christmas Attendance | 2,608,000 | 2,994,000 | 2,641,500 | 2,580,000 | 1,622,000 |

Personnel

[edit]In 2020, there were almost 20,000 active clergy serving in the Church of England, including 7,200 retired clergy who continued to serve. In that year, 580 were ordained (330 in stipendiary posts and 250 in self-supporting parochial posts) and a further 580 ordinands began their training.[182] In that year, 33% of those in ordained ministry were female, an increase from the 26% reported in 2016.[182]

Structure

[edit]

Article XIX ('Of the Church') of the Thirty-nine Articles defines the church as follows:

The visible Church of Christ is a congregation of faithful men, in which the pure Word of God is preached, and the sacraments be duly ministered according to Christ's ordinance in all those things that of necessity are requisite to the same.[183]

Британский монарх имеет конституционный титул Верховного губернатора англиканской церкви . Канонический закон англиканской церкви гласит: «Мы признаем, что высочайшее Величество Короля, действуя в соответствии с законами королевства, является высшей властью под властью Бога в этом королевстве и имеет высшую власть над всеми людьми во всех отношениях. как церковное, так и гражданское». [184] На практике эта власть часто осуществляется через парламент и по рекомендации премьер-министра .

и Ирландская церковь Церковь Уэльса отделились от англиканской церкви в 1869 году. [185] и 1920 г. [186] соответственно и являются автономными церквями Англиканской общины; Национальная церковь Шотландии, Церковь Шотландии , является пресвитерианской , но Шотландская епископальная церковь является частью Англиканской общины. [187]

Помимо Англии, юрисдикция англиканской церкви распространяется на остров Мэн , Нормандские острова и несколько приходов во Флинтшире , Монмутшире и Поуисе в Уэльсе, которые проголосовали за то, чтобы остаться с англиканской церковью, а не присоединяться к церкви в Уэльсе. . [188] Конгрегации экспатриантов на европейском континенте стали Гибралтарской епархией в Европе .

Церковь устроена следующим образом (от самого нижнего уровня вверх): [ нужна ссылка ]

- Приход — это самый местный уровень, часто состоящий из одного церковного здания ( приходской церкви ) и общины, хотя многие приходы объединяют свои усилия различными способами по финансовым причинам. За приходом присматривает приходской священник , который по историческим или юридическим причинам может быть назначен на одну из следующих должностей: викарий , настоятель , ответственный священник , настоятель команды, викарий команды. Первый, второй, четвертый и пятый из них также могут быть известны как «действующие лица». Управление приходом является совместной ответственностью действующего президента и приходского церковного совета (PCC), который состоит из приходского духовенства и избранных представителей прихожан. Гибралтарская епархия в Европе формально не разделена на приходы.

- Есть ряд поместных церквей, у которых нет прихода. В городских районах есть несколько частных часовен (в основном построенных в 19 веке, чтобы справиться с урбанизацией и ростом населения). Кроме того, в последние годы появляется все больше новых церквей и новых форм церкви, в результате чего в таких местах, как школы или пабы, создаются новые общины для распространения Евангелия Христа нетрадиционными способами.

- Деканат , например , Льюишам или Раннимид. Это область, за которую сельский декан отвечает (или районный декан). Он состоит из ряда приходов в определенном районе. Сельский благочинный обычно является главой одного из входящих в его состав приходов. Приходы избирают мирских (нерукоположенных) представителей в синод благочиния . Каждый член благочинного синода имеет право голоса при избрании представителей в епархиальный синод.

- Архидиаконство, например , семь в Гибралтарской епархии в Европе . Это территория, находящаяся под юрисдикцией архидьякона . В его состав входит ряд деканатов.

- Епархия , например , епархия Дарема , епархия Гилфорда , епархия Сент-Олбанса . Это территория, находящаяся под юрисдикцией епархиального епископа, например , епископов Дарема, Гилфорда и Сент-Олбанса, и на ней будет собор. может быть один или несколько епископов-суфраганов В епархии , которые помогают епархиальному епископу в его служении, например , в епархии Гилфорда - епископ Доркингский. В некоторых очень крупных епархиях была принята юридическая мера по созданию «епископских областей», где епархиальный епископ сам управляет одной такой областью и назначает «областных епископов» для управления другими областями как мини-епархиями, юридически делегируя многие из своих полномочий областные епископы. Епархии с епископскими областями включают Лондон , Челмсфорд , Оксфорд , Чичестер , Саутварк и Личфилд . Епископы работают с выборным органом мирян и рукоположенных представителей, известным как Епархиальный Синод , для управления епархией. Епархия подразделяется на ряд архидиаконриев.

- Провинция , то есть Кентербери или Йорк. Это территория, находящаяся под юрисдикцией архиепископа , то есть архиепископов Кентерберийского и Йоркского. За принятие решений в провинции отвечает Генеральный синод (см. также выше). Провинция делится на епархии.

- Первенство , т.е. англиканская церковь. Титул архиепископа Йоркского «Примас Англии» по существу почетен и не несет в себе никаких полномочий, кроме тех, которые присущи архиепископу и митрополиту провинции Йорк . [189] С другой стороны, архиепископ Кентерберийский , «Примас всей Англии», обладает полномочиями, распространяющимися на всю Англию, а также на Уэльс — например, через свой факультет он может выдать «специальное разрешение на брак», разрешающее стороны заключают брак иначе, чем в церкви: например, в часовне школы, колледжа или университета; [190] или где угодно, если одной из сторон предполагаемого брака грозит неминуемая смерть. [191] [и]

- Royal Peculiar , небольшое количество церквей, которые более тесно связаны с Короной , например, Вестминстерское аббатство , и очень немногие, более тесно связанные с законом, которые, хотя и соответствуют обрядам Церкви, находятся за пределами епископальной юрисдикции.

Все ректора и викарии назначаются патронами , которыми могут быть частные лица, юридические лица, такие как соборы, колледжи или тресты, либо епископом, либо непосредственно Короной. Никакое духовенство не может быть учреждено и введено в приход, не принеся присяги на верность Его Величеству и не приняв присягу канонического послушания «во всем законном и честном» епископу. Обычно они учреждаются епископом в бенефиции, а затем вводятся архидьяконом во владение бенефициарным имуществом — церковью и приходским домом. Кураты (помощники духовенства) назначаются настоятелями и викариями или, если ответственные священники, епископом после консультации с патроном. Духовенство собора (обычно декан и различное количество постоянных каноников, составляющих капитул собора) назначается либо Короной, епископом, либо самими деканом и капитулом. Духовенство исполняет обязанности в епархии либо потому, что оно занимает должность бенефициарного духовенства, либо имеет лицензию епископа при назначении, либо просто с разрешения. [ нужна ссылка ]

Приматы

[ редактировать ]

Самым старшим епископом англиканской церкви является архиепископ Кентерберийский , который является митрополитом южной провинции Англии, провинции Кентербери. Имеет статус примаса всей Англии. Он является центром единства всемирной англиканской общины независимых национальных или региональных церквей. Джастин Уэлби был архиепископом Кентерберийским с момента подтверждения его избрания 4 февраля 2013 года. [192]

Вторым по старшинству епископом является архиепископ Йоркский , который является митрополитом северной провинции Англии, провинции Йорк. По историческим причинам (относящимся ко времени контроля Йорка датчанами ) [193] его называют примасом Англии. Стивен Коттрелл стал архиепископом Йоркским в 2020 году. [194] Епископ Лондона , Епископ Дарема и Епископ Винчестера занимают следующие три позиции, поскольку обладатели этих кафедр автоматически становятся членами Палаты лордов . [195] [ф]

Епархиальные архиереи

[ редактировать ]Процесс назначения епархиальных епископов сложен по историческим причинам, балансирующим между иерархией и демократией, и осуществляется Королевским комитетом по выдвижению кандидатур , который представляет имена премьер-министру (действующему от имени Короны) на рассмотрение. [196]

Представительные органы

[ редактировать ]У англиканской церкви есть законодательный орган – Генеральный синод. Это может создать два типа законодательства, мер и канонов . Меры должны быть одобрены, но не могут быть изменены британским парламентом до того, как они получат королевское одобрение и станут частью законодательства Англии. [197] Хотя это установленная церковь только в Англии, ее меры должны быть одобрены обеими палатами парламента, включая членов неанглийского происхождения. Каноны требуют королевской лицензии и королевского согласия, но формируют закон церкви, а не закон страны. [198]

Еще одно собрание — это Созыв английского духовенства , который старше Генерального синода и его предшественника — Церковной ассамблеи. Постановлением Синодального правительства 1969 года почти все функции созывов были переданы Генеральному Синоду. Кроме того, существуют епархиальные синоды и благочинные синоды , которые являются органами управления подразделениями Церкви. [ нужна ссылка ]

палата лордов

[ редактировать ]Из 42 епархиальных архиепископов и епископов англиканской церкви 26 разрешено заседать в Палате лордов . Архиепископы Кентерберийский и Йоркский автоматически получают места, а также епископы Лондона , Дарема и Винчестера . Остальные 21 место заполняются в порядке старшинства по дате посвящения . Епархиальному епископу может потребоваться несколько лет, чтобы попасть в Палату лордов, после чего он или она станет Лордом Духовным . Епископ Содора и Мана и епископ Гибралтара в Европе не имеют права заседать в Палате лордов, поскольку их епархии находятся за пределами Соединенного Королевства. [199]

Зависимости Короны

[ редактировать ]Хотя они не являются частью Англии или Соединенного Королевства, англиканская церковь также является официальной церковью в владениях Короны острова Мэн , бейливике Джерси и бейливике Гернси . На острове Мэн есть собственная епархия Содора и Мэна , а епископ Содора и Мэна является по должности членом законодательного совета Тинвальда на острове. [200] Исторически Нормандские острова находились под властью епископа Винчестера эти полномочия были временно переданы епископу Дувра , но с 2015 года . В Джерси декан Джерси является членом Штатов Джерси без права голоса . На Гернси церковью является англиканская церковь официальной , хотя декан Гернси не является членом штата Гернси . [201]

Сексуальное насилие

[ редактировать ]В отчете Независимого расследования сексуального насилия над детьми за 2020 год обнаружено несколько случаев сексуального насилия в англиканской церкви и сделан вывод, что Церковь не защищает детей от сексуального насилия и позволяет насильникам скрываться. [202] [203] [204] Церковь потратила больше усилий на защиту предполагаемых насильников, чем на поддержку жертв или защиту детей и молодежи. [202] Обвинения не были восприняты всерьез, и в некоторых случаях священнослужители были рукоположены даже после сексуального насилия над детьми. [205] Епископ Питер Болл был осужден в октябре 2015 года по нескольким обвинениям в непристойном нападении на молодых мужчин. [203] [204] [206]

В июне 2023 года Совет архиепископов уволил трех членов правления Независимого совета по охране, который был создан в 2021 году, «чтобы привлечь Церковь к ответственности, при необходимости публично, за любые недостатки, которые мешают осуществлению надлежащей защиты». В заявлении архиепископов Кентерберийского и Йоркского говорится, что «нет перспектив разрешения разногласий и что они мешают жизненно важной работе по оказанию помощи жертвам и выжившим». Ясвиндер Сангера и Стив Ривз, два независимых члена правления, пожаловались на вмешательство Церкви в их работу. [207] Епископ Биркенхеда Джули Кональти , выступая на BBC Radio 4 в связи с увольнениями, сказала: «Я думаю, что в культурном отношении мы как церковь устойчивы к ответственности и критике. И поэтому я не полностью доверяю церкви, хотя Я ключевая часть этого процесса и лидер, потому что я вижу, что ветер всегда дует в определенном направлении». [208]

20 июля 2023 года было объявлено, что архиепископы Кентерберийский и Йоркский назначили Алексиса Джея представить предложения по независимой системе защиты англиканской церкви. [209]

Финансирование и финансы

[ редактировать ]Несмотря на то, что Англиканская церковь является официальной церковью, она не получает никакой прямой государственной поддержки, за исключением некоторого финансирования строительных работ. Пожертвования составляют его крупнейший источник дохода, и он также в значительной степени зависит от доходов от различных исторических пожертвований. В 2005 году англиканская церковь оценила общие расходы примерно в 900 миллионов фунтов стерлингов. [210]

Англиканская церковь управляет инвестиционным портфелем стоимостью более 8 миллиардов фунтов стерлингов. [211]

Интернет-церковные каталоги

[ редактировать ]Англиканская церковь управляет A Church Near You , онлайн-справочником церквей. Ресурс, редактируемый пользователями, в настоящее время насчитывает более 16 000 церквей и имеет 20 000 редакторов в 42 епархиях. [212] Каталог позволяет приходам сохранять точную информацию о местонахождении, контактах и событиях, которая передается другим веб-сайтам и мобильным приложениям . Сайт позволяет общественности найти местную верующую общину и предлагает церквям бесплатные ресурсы. [213] такие как гимны, видеоролики и графика для социальных сетей.

Отчет о церковном наследии включает информацию о более чем 16 000 церковных зданиях, включая историю архитектуры, археологию, историю искусства и окружающую природную среду. [214] Поиск можно осуществлять по таким элементам, как название церкви, епархия, дата постройки, размер площади, класс листинга и тип церкви. Выявленные типы церквей включают в себя:

- Основная приходская церковь: «одни из самых особенных, значимых и любимых культовых сооружений в Англии», обладающая «наиболее» характеристиками: большая (более 1000 кв. м), внесенная в список (обычно I или II степени *). , имеющий «исключительное значение и / или проблемы, требующие плана управления сохранением» и имеющий местную роль, выходящую за рамки обычной приходской церкви. По состоянию на декабрь 2021 г. [update] в базе данных 312 таких церквей. [215] [216] Эти церкви имеют право присоединиться к Сети крупных церквей .

- Фестивальная церковь: церковь, которая не используется для еженедельных служб, а используется для периодических служб и других мероприятий. [217] Эти церкви имеют право вступить в Ассоциацию фестивальных церквей. [218] По состоянию на декабрь 2021 г. [update] в базе данных 19 таких церквей. [219]

- Церковь CCT: церковь, находящаяся под опекой Фонда сохранения церквей . По состоянию на декабрь 2021 г. [update] в базе данных 345 таких церквей. [220]

- Церковь без друзей: по состоянию на декабрь 2021 г. [update] в базе данных 24 таких храма; [221] Организация « Друзья церквей без друзей» заботится о 60 церквях по всей Англии и Уэльсу. [222]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Акты превосходства

- Апостольская забота

- Архитектура средневековых соборов Англии

- Дела о сексуальном насилии в Англиканской общине

- Церковные комиссары

- Газета англиканской церкви

- Дезистэблиментарианство

- Роспуск монастырей

- Английский пакт

- Английская Реформация

- Историческое развитие епархий англиканской церкви

- Список архидьяконов англиканской церкви

- Список епископов англиканской церкви

- Список первых 32 женщин, рукоположенных в священники англиканской церкви

- Список крупнейших протестантских организаций

- Союз матерей

- Имущество и финансы англиканской церкви

- Ритуализм в англиканской церкви

- Женщины и церковь

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ С различными богословскими и доктринальными взглядами, включая англо-католическую, либеральную, евангелическую.

- ^ Широкая церковь (включая варианты высокой и низкой церкви )

- ^ Использование 2022 года из-за ограничений Covid в 2021 году.

- ^ Посещаемость не реже одного раза в месяц, впервые использовалась после 2012 года.

- ↑ Полномочия выдавать специальные разрешения на брак, назначать государственных нотариусов и присуждать степени Ламбета вытекают из так называемых «легатинских полномочий», которые принадлежали легату Папы в Англии до Реформации и были переданы архиепископу. Кентерберийского Законом о церковных лицензиях 1533 года. Таким образом, они, строго говоря, не вытекают из статуса архиепископа Кентерберийского как «примаса всей Англии». По этой причине они распространяются также на Уэльс. [189]

- ↑ В разделе епископы названы в таком порядке.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Англиканская церковь во Всемирном совете церквей

- ^ Мурман 1973 , стр. 3–4, 9.

- ^ «История англиканской церкви» . Англиканская церковь. Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ Бути, Джон Э.; Сайкс, Стивен; Найт, Джонатан, ред. (1998). Изучение англиканства . Лондон: Книги Крепости. п. 477. ИСБН 0-281-05175-5 .

- ^ Делани, Джон П. (1980). Словарь святых (Второе изд.). Гарден-Сити, Нью-Йорк: Даблдей. стр. 67–68 . ISBN 978-0-385-13594-8 .

- ^ Мурман 1973 , с. 19.

- ^ «Синод Уитби | История английской церкви» . Британская энциклопедия .

- ^ Маршалл 2017a , с. 11.

- ^ МакКаллох 1996 , с. 210.

- ^ Маршалл 2017a , с. 7.

- ^ Маршалл 2017a , стр. 8–9.

- ^ Хефлинг 2021 , стр. 97–98.

- ^ МакКаллох, Диармайд (2001). Поздняя Реформация в Англии, 1547–1603 гг . Британская история в перспективе (2-е изд.). Пэлгрейв. стр. 1–2. ISBN 9780333921395 .

- ^ Маршалл 2017a , стр. 16–17.

- ^ Шаган 2017 , стр. 29–31.

- ^ Шаган 2017 , с. 32.

- ^ Хефлинг 2021 , с. 96.

- ^ Хефлинг 2021 , с. 97.

- ^ Маршалл 2017a , с. 126.

- ^ Г.В. Бернар, «Роспуск монастырей», History (2011) 96#324 стр. 390.

- ^ Маршалл 2017a , с. 308.

- ^ Даффи, Имон (2005). Разбор алтарей: традиционная религия в Англии, ок. 1400 – ок. 1580 г. (2-е изд.). Издательство Йельского университета. стр. 450–454 и 458. ISBN. 978-0-300-10828-6 .

- ^ Шаган 2017 , стр. 41.

- ^ Джинс, Гордон (2006). «Кранмер и общая молитва» . В Хефлинге, Чарльз; Шаттак, Синтия (ред.). Оксфордский путеводитель по Книге общей молитвы: всемирный обзор . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-529756-0 .

- ^ МакКаллох 1996 , стр. 412, 414.

- ^ Хей, Кристофер (1993). Английские реформации: религия, политика и общество при Тюдорах . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 179. ИСБН 978-0-19-822162-3 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Маршалл 2017b , с. 51.

- ^ Маршалл 2017b , стр. 49–51.

- ^ Маршалл 2017b , стр. 50–51.

- ^ Эберле, Эдвард Дж. (2011). Церковь и государство в западном обществе . Ашгейт Паблишинг, ООО с. 2. ISBN 978-1-4094-0792-8 . Проверено 9 ноября 2012 г.

Позже Англиканская церковь стала официальной государственной протестантской церковью, функции которой контролировал монарх.

- ^ Фокс, Джонатан (2008). Мировой обзор религии и государства . Издательство Кембриджского университета . п. 120. ИСБН 978-0-521-88131-9 . Проверено 9 ноября 2012 г.

Англиканская церковь (англиканская) и Шотландская церковь (пресвитерианская) являются официальными религиями Великобритании.

- ^ Ферранте, Джоан (2010). Социология: глобальная перспектива . Cengage Обучение . п. 408. ИСБН 978-0-8400-3204-1 . Проверено 9 ноября 2012 г.

Англиканская церковь [англиканская], которая остается официальной государственной церковью

- ^ Гельмгольц 2003 , с. 102.

- ^ Веджвуд 1958 , с. 31.

- ^ Кинг 1968 , стр. 523–537.

- ^ Сперр 1998 , стр. 11–12.

- ^ Миллер, Джон (1978). Джеймс II; Исследование королевской власти . Ментуэн. стр. 172–173. ISBN 978-0413652904 .

- ^ Пикеринг, Дэнби (1799). Общие статуты от Великой хартии вольностей до закрытия одиннадцатого парламента Великобритании, год 1761 г. [продолжался до 1806 г.]. Дэнби Пикеринг . Дж. Бентам. п. 653.

- ^ «Акт о Союзе Великобритании и Ирландии 1800 года - статья пятая (так в оригинале)» . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2018 года.

- ^ «№12910» . Лондонская газета . 7 августа 1787 г. с. 373.

- ^ Епархиальный сайт - История. Архивировано 16 июня 2014 г. на Wayback Machine (по состоянию на 31 декабря 2012 г.).

- ^ Пайпер, Лиза (2000). «Англиканская церковь» . Наследие Ньюфаундленда и Лабрадора . Веб-сайт наследия Ньюфаундленда и Лабрадора . Проверено 17 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Миранда Трелфолл-Холмс (2012). Основная история христианства . СПКК. стр. 133–134. ISBN 9780281066438 .

- ^ «Церкви-члены» . www.anglicancommunion.org .

- ^ «Добро пожаловать в церковь Святого Петра в Сент-Джордж, Бермудские острова» . Святого Петра . Проверено 23 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ Бингхэм, Джон (13 июля 2015 г.). «Англиканская церковь может вернуться к лишению сана священников-изгоев после скандалов, связанных с жестоким обращением с детьми» . «Дейли телеграф» . Архивировано из оригинала 10 января 2022 года . Проверено 4 февраля 2019 г. .

- ^ Бингхэм, Джон (9 июня 2015 г.). «Пустые скамьи — это не конец света, — говорит новый епископ англиканской церкви» . Телеграф . Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2023 года.

- ^ «Факты и статистика англиканской церкви» . Англиканская церковь. Архивировано из оригинала 8 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 8 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ «Основные направления исследований» . Англиканская церковь . Проверено 26 октября 2021 г.

- ^ писатель, Сотрудники (13 апреля 2023 г.). «Количество посетителей собора резко возросло после пандемии» . www.christiantoday.com . Проверено 20 мая 2024 г.

- ^ «Англиканская церковь не может продолжать жить так, как есть, если «срочно» не обратить вспять упадок - Уэлби и Сентаму» , The Daily Telegraph , 12 января 2015 г.

- ^ «Отдел закрытых церквей» . Архивировано из оригинала 29 декабря 2010 года . Проверено 30 июня 2018 г.

- ^ «Архивная копия» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 21 июня 2017 года . Проверено 30 июня 2018 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: архивная копия в заголовке ( ссылка ) - ^ «Закрытые церкви» . Англиканская церковь .

- ^ «Англиканская церковь объявляет о запуске 100 новых церквей в рамках программы роста стоимостью 27 миллионов фунтов стерлингов» . www.anglicannews.org .

- ^ «Англиканская церковь: Джастин Уэлби говорит, что низкая зарплата «смущает» » . Новости Би-би-си .

- ^ «Статистика миссий 2022» (PDF) . Англиканская церковь . Проверено 27 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Канон А5. Каноны англиканской церкви. Архивировано 25 марта 2009 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Шеперд-младший и Мартин 2005 , стр. 349–350.

- ^ МакКаллох 1990 , стр. 78–86.

- ^ Jump up to: а б МакКаллох 1990 , с. 79.

- ^ МакКаллох 1990 , с. 142.

- ^ Браун, Эндрю (13 июля 2014 г.). «Либерализм усиливается по мере того, как власть в англиканской церкви переходит к мирянам» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Проверено 1 мая 2016 г.

- ^ «Высокая церковь», Новая католическая энциклопедия , 2-е изд., том. 6 (Детройт: Гейл, 2003), стр. 823–824.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «История англиканской церкви» . Англиканская церковь . Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 17 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ «Низкая церковь», Новая католическая энциклопедия , 2-е изд., том. 8 (Детройт: Гейл, 2003), с. 836.

- ^ Э. Макдермотт, «Широкая церковь», Новая католическая энциклопедия , 2-е изд., том. 2 (Детройт: Гейл, 2003), стр. 624–625.

- ^ «Новые направления», май 2013 г.

- ^ Cowart & Knappen 2007 , с. ?.

- ^ Шеперд-младший и Мартин 2005 , с. 350.

- ^ «BBC – Религии – Христианство: Чарльз Уэсли» . Би-би-си . Проверено 27 января 2021 г.

- ^ «Харизматическое вторжение в англиканство? | Дейл М. Коултер» . Первые вещи . 7 января 2014 года . Проверено 20 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Петре, Джонатан. «Треть священнослужителей не верят в Воскресение» . «Дейли телеграф» . Архивировано из оригинала 10 января 2022 года . Проверено 1 мая 2016 г.

- ^ «История непорочного зачатия противоречит сути христианства» . Хранитель . 24 декабря 2015 г. ISSN 0261-3077 . Проверено 1 мая 2016 г.

- ^ «Опрос показал, что 2 процента англиканских священников неверующие» . Независимый . 27 октября 2014 года . Проверено 1 мая 2016 г.

- ^ «YouGov / Дебаты о вере в Ланкастерском и Вестминстерском университетах» (PDF) . YouGov . 23 октября 2014 г. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 23 февраля 2015 г. . Проверено 2 мая 2016 г.

- ^ «Англиканская церковь создает «языческую церковь» для набора членов» . «Дейли телеграф» . Архивировано из оригинала 10 января 2022 года . Проверено 1 мая 2016 г.

- ^ «Является ли Бог Они/Они? Англиканская церковь считает гендерно-нейтральными местоимениями» . Вашингтон Пост . ISSN 0190-8286 . Проверено 13 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ тойсиаб. «Значение и содержание просмотра истории англиканской церкви - hmoob.in» . www.hmoob.in . Проверено 5 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «Впервые новых женщин-священников больше, чем мужчин» . «Дейли телеграф» . 4 февраля 2012 г. Архивировано из оригинала 10 января 2022 г. . Проверено 11 июля 2012 года .

- ^ Арнетт, Джордж (11 февраля 2014 г.). «Какая часть духовенства англиканской церкви — женщины?» . Хранитель .

- ^ Церковь подавляющим большинством голосов голосует за компромисс в отношении женщин-епископов . Экклесия .

- ^ «Церковь будет рукополагать женщин-епископов» . Новости Би-би-си . 7 июля 2008 года . Проверено 7 июля 2008 г.

- ^ Пиготт, Роберт. (14 февраля 2009 г.) Синод борется за женщин-епископов . Новости Би-би-си.

- ^ «Генеральный синод англиканской церкви голосует против женщин-епископов» , BBC News, 20 ноября 2012 г.

- ^ «Синод англиканской церкви подавляющим большинством голосов голосует в поддержку женщин-епископов» . Описатель . 20 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 20 ноября 2013 г.

- ^ «ПРЯМОЙ ЭФИР: Голосование в поддержку женщин-епископов» . Би-би-си . 14 июля 2014 года . Проверено 14 июля 2014 г.

- ^ «После беспорядков англиканская церковь посвящает первую женщину-епископа» . Рейтер . Архивировано из оригинала 24 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 30 июня 2017 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Посвящена первая женщина-епархиальный епископ в регионе C of E. Anglicannews.org. Проверено 23 июля 2015 г.

- ^ Шервуд, Харриет (24 октября 2015 г.). « Бог — это не он и не она», — говорит первая женщина-епископ, заседавшая в Палате лордов» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Проверено 30 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ «Установлена первая женщина-епископ Лондона» . www.churchtimes.co.uk . Проверено 20 мая 2018 г.

- ^ «Установлена первая женщина-епископ Лондона» . Новости Би-би-си . 12 мая 2018 года . Проверено 20 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Хеллен, Николас (13 мая 2018 г.). «Новая женщина-епископ идет на войну за женщин-викариев» . Санди Таймс . ISSN 0956-1382 . Проверено 20 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Райт, Роберт (18 декабря 2017 г.). «Сара Маллалли станет первой женщиной-епископом Лондона» . Файнэншл Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 10 декабря 2022 года.

- ^ "Выбор" . Созерцание в тени автостоянки . 9 марта 2012 года . Проверено 20 мая 2018 г.

- ^ «Бывшая главная медсестра станет первой женщиной-епископом Лондона» . www.churchtimes.co.uk . Проверено 20 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Редакция Рейтер. «Англиканская церковь предлагает праздновать однополые браки» . Великобритания . Проверено 1 октября 2017 г.

{{cite news}}:|author=имеет общее имя ( справка ) - ^ Биллсон, Шантель (21 октября 2023 г.). «Благословение англиканской церкви для однополых пар вряд ли произойдет раньше 2025 года: «Мы не все согласны» » . ПинкНьюс . Проверено 21 октября 2023 г.

- ^ «Архивная копия» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 23 октября 2017 года . Проверено 22 октября 2017 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: архивная копия в заголовке ( ссылка ) - ^ «Англиканская церковь отвергает однополые браки и заявляет, что союз заключается между «одним мужчиной и одной женщиной на всю жизнь» » . www.cbsnews.com . 18 января 2023 г. Проверено 21 января 2023 г.

- ^ Шервуд, Харриет (9 февраля 2023 г.). «Англиканская церковь голосует за благословение однополых союзов» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Проверено 10 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Кирка, Даника. «Англиканская церковь разрешает благословение однополым парам» . Новости АВС . Проверено 10 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Бингхэм, Джон (15 февраля 2014 г.). «Церковь молится после однополых свадеб, но запрещает священникам-геям вступать в брак» . «Дейли телеграф» . Проверено 25 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ «Пастырское руководство Дома епископов по однополым бракам» . Англиканская церковь . 15 февраля 2014 года . Проверено 24 января 2020 г.

- ^ «Епископы возносят молитвы благодарения, посвящения и Божьего благословения за однополые пары» . Англиканская церковь . 18 января 2023 г. Проверено 21 января 2023 г.

- ^ Уорд, Юан (20 января 2023 г.). «Англиканская церковь благословит однополые пары, но не женит их» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Проверено 21 января 2023 г.

- ^ «Англиканская церковь отказывается поддерживать однополые браки» . АП НОВОСТИ . 18 января 2023 г. Проверено 21 января 2023 г.

- ^ Шервуд, Харриет (15 ноября 2023 г.). «Англиканская церковь поддерживает планы пробного благословения однополых браков» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Проверено 20 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ «Англиканская церковь поддерживает услуги для однополых пар» . Новости Би-би-си . 15 ноября 2023 г. Проверено 20 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ «Сохраняйте гражданское партнерство, — призывает правительство англиканской церкви» . Премьер . 18 мая 2018 года . Проверено 20 мая 2018 г.

- ^ «Свадьба священнослужителя-гея с партнером» . Новости Би-би-си . Проверено 27 марта 2017 г.

- ^ Алекс, Стюарт; э. (2 июня 2018 г.). «Гей-священнослужитель баллотируется на должность Бречина» . Курьер . Проверено 29 октября 2019 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уокер, Питер (4 января 2013 г.). «Англиканская церковь постановила, что геи, состоящие в гражданском партнерстве, могут стать епископами» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Проверено 24 октября 2016 г.

- ^ Бейтс, Стивен (11 февраля 2010 г.). «Генеральный синод англиканской церкви расширяет пенсионные права для партнеров-геев» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Проверено 25 февраля 2016 г. .

- ^ «Англиканская церковь благословляет признание гражданских партнерств» . Телеграф.co.uk . Архивировано из оригинала 10 января 2022 года . Проверено 23 октября 2016 г.

- ^ «Гражданское партнерство и определение брака» . www.churchtimes.co.uk . Проверено 3 апреля 2018 г.