Māori language

| Māori | |

|---|---|

| Māori, te reo Māori | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈmaːɔɾi] |

| Native to | New Zealand |

| Region | Polynesia |

| Ethnicity | Māori |

Native speakers | 50,000 (well or very well) (2015)[1] 186,000 (some knowledge) (2018)[2] |

| Latin (Māori alphabet) Māori Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | New Zealand |

| Regulated by | Māori Language Commission |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | mi |

| ISO 639-2 | mao (B) mri (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | mri |

| Glottolog | maor1246 |

| ELP | Māori |

| Glottopedia | Maori[3] |

| Linguasphere | 39-CAQ-a |

| IETF | mi-NZ |

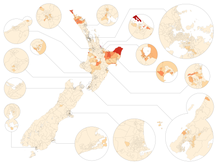

Māori language distribution within New Zealand | |

Māori is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. [4] | |

| Māori topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Māori (Māori: [ˈmaːɔɾi] ; endonym: te reo Māori 'the Māori language', commonly shortened to te reo) is an Eastern Polynesian language and the language of the Māori people, the indigenous population of mainland New Zealand. A member of the Austronesian language family, it is related to Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan, and Tahitian. The Maori Language Act 1987 gave the language recognition as one of New Zealand's official languages. There are regional dialects.[5] Prior to contact with Europeans, Māori lacked a written language or script.[a] Written Māori now uses the Latin script, which was adopted and the spelling standardised by Northern Māori in collaboration with English Protestant clergy in the 19th century.

In the second half of the 19th century European children in rural areas spoke Māori with Māori children. It was common for prominent parents of these children, such as government officials, to use Māori in the community.[7][8] Māori declined due to the increase of the European population and linguistic discrimination, including the Native Schools Act 1867, which barred the speaking of Māori in schools.[9][10] The number of speakers fell sharply after 1945,[11] but a Māori language revival movement began in the late 20th century and slowed the decline. The Māori protest movement and the Māori renaissance of the 1970s caused greater social awareness of and support for the language.[12]

The 2018 New Zealand census reported that about 190,000 people, or 4% of the population, could hold an everyday conversation in Māori. As of 2015[update], 55% of Māori adults reported some knowledge of the language; of these, 64% use Māori at home and around 50,000 people can speak the language "well".[13] As of 2023, around 7% of New Zealand primary and secondary school students are taught fully or partially in Māori, and another 24% learn Māori as an additional language.[14]

In Māori culture, the language is considered to be among the greatest of all taonga, or cultural treasures.[15][16] Māori is known for its metaphorical poetry and prose,[17][18] often in the form of karakia, whaikōrero, whakapapa and karanga, and in performing arts such as mōteatea, waiata, and haka.[19]

Name

[edit]The English word Maori is a borrowing from the Māori language, where it is spelled Māori. In New Zealand, the Māori language is often referred to as te reo [tɛ ˈɾɛ.ɔ] ("the language"), short for te reo Māori ("the Māori language").[20]

The Māori-language spelling ⟨Māori⟩ (with a macron) has become common in New Zealand English in recent years, particularly in Māori-specific cultural contexts,[20][21] although the traditional macron-less English spelling is still sometimes seen in general media and government use.[22]

Preferred and alternative pronunciations in English vary by dictionary, with /ˈmaʊri/ being most frequent today, and /mɑːˈɒri/, /ˈmɔːri/, and /ˈmɑːri/ also given, while the 'r' is always a voiced alveolar flap.[23]

Official status

[edit]

New Zealand has two de jure official languages: Māori and New Zealand Sign Language,[24] whereas New Zealand English acts as a de facto official language.[25][26] Te reo Māori gained its official status with the passing of the Māori Language Act 1987.[27]

Most government departments and agencies have bilingual names—for example, the Department of Internal Affairs is alternatively Te Tari Taiwhenua—and places such as local government offices and public libraries display bilingual signs and use bilingual stationery; some government services now even use the Māori version solely as the official name.[28] Personal dealings with government agencies may be conducted in Māori, but in practice, this almost always requires interpreters, restricting its everyday use to the limited geographical areas of high Māori fluency, and to more formal occasions, such as during public consultation. An interpreter is on hand at sessions of the New Zealand Parliament for instances when a member wishes to speak in Māori.[21][29] Māori may be spoken in judicial proceedings, but any party wishing to do so must notify the court in advance to ensure an interpreter is available. Failure to notify in advance does not preclude the party speaking in Māori, but the court must be adjourned until an interpreter is available and the party may be held liable for the costs of the delay.[30]

A 1994 ruling by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (then New Zealand's highest court) held the Government responsible under the Treaty of Waitangi (1840) for the preservation of the language.[31] Accordingly, since March 2004, the state has funded Māori Television, broadcast partly in Māori. On 28 March 2008, Māori Television launched its second channel, Te Reo, broadcast entirely in the Māori language, with no advertising or subtitles. The first Māori TV channel, Aotearoa Television Network (ATN) was available to viewers in the Auckland region from 1996 but lasted for only one year.[32]

In 2008, Land Information New Zealand published the first list of official place names with macrons. Previous place name lists were derived from computer systems (usually mapping and geographic information systems) that could not handle macrons.[33][failed verification]

Political dimensions

[edit]The official status of Māori, and especially its use in official names and titles, is a political issue in New Zealand. In 2022 a 70,000 strong petition from Te Pāti Māori went to Parliament calling for New Zealand to be officially renamed Aotearoa, and was accepted for debate by the Māori Affairs select committee.[34] During New Zealand First's successful campaign to return to Parliament in 2023, party leader Winston Peters ridiculed the proposal as "ideological mumbo jumbo"[35] and criticised the use of the name in government reports.[36] Peters promised his party would remove Māori names from government departments,[37] saying "Te Whatu Ora, excuse me, I don't want to speak the Māori language when I go to hospital."[38] As part of its coalition agreement with New Zealand First, the National-led government agreed to ensure all public service departments had their primary name in English except for those specifically related to Māori.[39][40]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

by W. L. Williams, third Bishop of Waiapu

According to legend, Māori came to New Zealand from Hawaiki. Current anthropological thinking places their origin in eastern Polynesia, mostly likely from the Southern Cook or Society Islands region (see Māori history § Origins from Polynesia), and says that they arrived by deliberate voyages in seagoing canoes,[41] possibly double-hulled, and probably sail-rigged. These settlers probably arrived by AD 1350 at the latest.[42]

Māori evolved in isolation from other Polynesian languages. Six dialectal variations emerged among iwi due to geographical separation.[43] The language had no written form, but historian Sarah J. K. Gallagher has argued that tā moko, the indigenous art of tattooing, is arguably "a pre-European textual culture in New Zealand... as the Moko can be read, it can be accepted as a form of communication".[44] The idea that tā moko is a written language of sorts has been discussed before.[45][46]

Since its origin, the Māori language has been rich in metaphorical poetry and prose.[17][18] Forms of this include karakia, whaikōrero, whakapapa and karanga, and in performing arts such as mōteatea, waiata and haka.[19] Karakia are Māori incantations used to invoke spiritual guidance and protection, and are used before eating or gathering, to increase spiritual goodwill and to declare things officially open.[47] Whaikōrero is the term given to traditional oratory given on marae, and whakapapa is the story of one's ancestry. According to historian Atholl Anderson, whakapapa used "mnemonic devices, repetitive patterns [and] rhyme" to leave a lasting impression. "Casting knowledge in formulaic or other standarised story forms.. helped to fix the information in the minds of speakers and listeners".[48]

European contact

[edit]Through the nineteenth century, the Māori language had a tumultuous history. It started this period as the predominant language of New Zealand, and it was adopted by European traders and missionaries for their purposes.[49] In the 1860s, it became a minority language in the shadow of the English spoken by many settlers, missionaries, gold-seekers, and traders. In the late 19th century, the colonial governments of New Zealand and its provinces introduced an English-style school system for all New Zealanders. From the mid-19th century, due to the Native Schools Act and later the Native Schools Code, the use of Māori in schools was slowly filtered out of the curriculum.[10] Increasing numbers of Māori people learned English.[43]

Decline

[edit]Until the Second World War (1939–1945), most Māori people spoke Māori as their first language. Worship took place in Māori; it functioned as the language of Māori homes; Māori politicians conducted political meetings in Māori; and some literature appeared in Māori, along with many newspapers.[50]

Before 1880, some Māori parliamentarians suffered disadvantages because parliamentary proceedings took place in English.[51] However, by 1900, all Māori members of parliament, such as Āpirana Ngata, were university graduates who spoke fluent English. From this period greater emphasis was placed on Māori learning English, but it was not until the migration of Māori to urban areas after the Second World War (the urban Māori) that the number of speakers of Māori began to decline rapidly.[50][43] During this period, Māori was forbidden at many schools, and any use of the language was met with corporal punishment. In recent years, prominent Māori have spoken with sadness about their experiences or experiences of their family members being caned, strapped or beaten in school.[52][53][54]

By the 1980s, fewer than 20 per cent of Māori spoke the language well enough to be classed as native speakers. Even many of those people no longer spoke Māori in their homes. As a result, many Māori children failed to learn their ancestral language, and generations of non-Māori-speaking Māori emerged.[55]

In 1984, Naida Glavish, a tolls operator, was demoted for using the Māori greeting "kia ora" with customers. The "Kia Ora Incident" was the subject of public and political scrutiny before having her job reinstated by Prime Minister Robert Muldoon, and became a major symbol of long-standing linguicism in New Zealand.[56]

Revitalisation efforts

[edit]

By the 1950s some Māori leaders had begun to recognise the dangers of the loss of te reo Māori.[57] By the 1970s there were many strategies used to save the language.[57] This included Māori-language revitalization programs such as the Kōhanga Reo movement, which from 1982 immersed infants in Māori from infancy to school age.[58] There followed in 1985 the founding of the first Kura Kaupapa Māori (Years 1 to 8 Māori-medium education programme) and later the first Wharekura (Years 9 to 13 Māori-medium education programme). In 2011 it was reported that although "there was a true revival of te reo in the 1980s and early to mid-1990s ... spurred on by the realisation of how few speakers were left, and by the relative abundance of older fluent speakers in both urban neighbourhoods and rural communities", the language has continued to decline."[58] The decline is believed "to have several underlying causes".[59] These include:

- the ongoing loss of older native speakers who have spearheaded the Māori-language revival movement

- complacency brought about by the very existence of the institutions which drove the revival

- concerns about quality, with the supply of good teachers never matching demand (even while that demand has been shrinking)

- excessive regulation and centralised control, which has alienated some of those involved in the movement

- an ongoing lack of educational resources needed to teach the full curriculum in te reo Māori[59]

- natural language attrition caused by the overwhelming increase of spoken English.

Based on the principles of partnership, Māori-speaking government, general revitalisation and dialectal protective policy, and adequate resourcing, the Waitangi Tribunal has recommended "four fundamental changes":[60]

- Te Taura Whiri (the Māori Language Commission) should become the lead Māori language sector agency. This will address the problems caused by the lack of ownership and leadership identified by the Office of the Auditor-General.[61]

- Te Taura Whiri should function as a Crown–Māori partnership through the equal appointment of Crown and Māori appointees to its board. This reflects [the Tribunal's] concern that te reo revival will not work if responsibility for setting the direction is not shared with Māori.

- Te Taura Whiri will also need increased powers. This will ensure that public bodies are compelled to contribute to te reo's revival and that key agencies are held properly accountable for the strategies they adopt. For instance, targets for the training of te reo teachers must be met, education curricula involving te reo must be approved, and public bodies in districts with a sufficient number and/or proportion of te reo speakers and schools with a certain proportion of Māori students must submit Māori language plans for approval.

- These regional public bodies and schools must also consult iwi (Māori tribes or tribal confederations) in the preparation of their plans. In this way, iwi will come to have a central role in the revitalisation of te reo in their own areas. This should encourage efforts to promote the language at the grassroots.[62]

The changes set forth by the Tribunal are merely recommendations; they are not binding upon government.[63]

There is, however, evidence that the revitalisation efforts are taking hold, as can be seen in the teaching of te reo in the school curriculum, the use of Māori as an instructional language, and the supportive ideologies surrounding these efforts.[64] In 2014, a survey of students ranging in age from 18 to 24 was conducted; the students were of mixed ethnic backgrounds, ranging from Pākehā to Māori who lived in New Zealand. This survey showed a 62% response saying that te reo Māori was at risk.[64] Albury argues that these results come from the language either not being used enough in common discourse, or from the fact that the number of speakers was inadequate for future language development.[64]

The policies for language revitalisation have been changing in attempts to improve Māori language use and have been working with suggestions from the Waitangi Tribunal on the best ways to implement the revitalisation. The Waitangi Tribunal in 2011 identified a suggestion for language revitalisation that would shift indigenous policies from the central government to the preferences and ideologies of the Māori people.[63] This change recognises the issue of Māori revitalisation as one of indigenous self-determination, instead of the job of the government to identify what would be best for the language and Māori people of New Zealand.[65]

Revival since 2015

[edit]Beginning in about 2015, the Māori language underwent a revival as it became increasingly popular, as a common national heritage and shared cultural identity, even among New Zealanders without Māori roots. Surveys from 2018 indicated that "the Māori language currently enjoys a high status in Māori society and also positive acceptance by the majority of non-Māori New Zealanders".[66][67]

As the status and prestige of the language rose, so did the demand for language classes. Businesses, including Google, Microsoft, Vodafone NZ and Fletcher Building, were quick to adopt the trend as it became apparent that using te reo made customers think of a company as "committed to New Zealand". The language became increasingly heard in the media and in politics. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern—who gave her daughter a Māori middle name, and said she would learn both Māori and English—made headlines when she toasted Commonwealth leaders in 2018 with a Māori proverb, and the success of Māori musical groups such as Alien Weaponry and Maimoa further increased the language's presence in social media.[66][67][68] Disney has dubbed its animated films in Māori since Moana (2017).[69]

In August 2017, Rotorua became the first city in New Zealand to declare itself as bilingual in the Māori and English languages, meaning that both languages would be promoted. In 2019, the New Zealand government launched the Maihi Karauna Māori language revitalisation strategy with a goal of 1 million people speaking te reo Māori by 2040.[70][71] Also in 2019, Kotahi Rau Pukapuka Trust and Auckland University Press began work on publishing a sizeable library of local and international literature in the language, including the Harry Potter books.[72]

Some New Zealanders have pushed against the revival, debating the replacement of English-language place names with original Māori names, criticising a police car having Māori language and graphics, and complaining about te reo Māori being used by broadcasters.[67] In March 2021, the Broadcasting Standards Authority (BSA) said it would no longer entertain complaints regarding the use of the Māori language in broadcasts. This followed a fivefold increase in complaints to the BSA. The use of Māori in itself does not breach any broadcasting standards.[73]

Linguistic classification

[edit]Comparative linguists classify Māori as a Polynesian language, specifically as an Eastern Polynesian language belonging to the Tahitic subgroup, which includes Cook Islands Māori, spoken in the southern Cook Islands, and Tahitian, spoken in Tahiti and the Society Islands. Other major Eastern Polynesian languages include Hawaiian, Marquesan (languages in the Marquesic subgroup), and the Rapa Nui language of Easter Island.[74][75][76]

While the preceding are all distinct languages, they remain similar enough that Tupaia, a Tahitian travelling with Captain James Cook in 1769–1770, communicated effectively with Māori.[77] Hawaiian newspaper Ka Nupepa Kuokoa in 1911 covering Ernest Kaʻai and his Royal Hawaiians' band tour of New Zealand reported that Kaʻai himself wrote to them about the band able to communicate with Māori while visiting their rural maraes.[78] Māori actors, travelling to Easter Island for production of the film Rapa-Nui noticed a marked similarity between the native tongues, as did arts curator Reuben Friend, who noted that it took only a short time to pick up any different vocabulary and the different nuances to recognisable words.[79] Speakers of modern Māori generally report that they find the languages of the Cook Islands, including Rarotongan, the easiest among the other Polynesian languages to understand and converse in.

Geographic distribution

[edit]

Nearly all speakers are ethnic Māori residents of New Zealand. Estimates of the number of speakers vary: the 1996 census reported 160,000,[80] while a 1995 national survey reported about 10,000 "very fluent" adult speakers.[81] As reported in the 2013 national census, only 21.3% of self-identified Māori had a conversational knowledge of the language, and only around 6.5% of those speakers, 1.4% of the total Māori population, spoke the Māori language only. This percentage has been in decline in recent years, from around a quarter of the population[when?] to 21%. In the same census, Māori speakers were 3.7% of the total population.[82]

The level of competence of self-professed Māori speakers varies from minimal to total. Statistics have not been gathered for the prevalence of different levels of competence. Only a minority of self-professed speakers use Māori as their main language at home.[83] The rest use only a few words or phrases (passive bilingualism).[citation needed]

Māori still[update] is a community language in some predominantly Māori settlements in the Northland, Urewera and East Cape areas. Kohanga reo Māori-immersion kindergartens throughout New Zealand use Māori exclusively.[83]

Urbanisation after the Second World War led to widespread language shift from Māori predominance (with Māori the primary language of the rural whānau) to English predominance (English serving as the primary language in the Pākehā cities). Therefore, Māori speakers almost always communicate bilingually, with New Zealand English as either their first or second language. Only around 9,000 people speak only in Māori.[65]

In the 2023 school year, around 7.2% of primary and secondary school students in New Zealand were taught fully or partially in Māori. An additional 24.4% were formally taught Māori as an additional language, and 37.1% were taught Māori informally. However, very few students pass through the New Zealand education system without any Māori language education. For example, only 2.1% of students in Year 1 (aged 5) didn't receive any Māori language education in 2023.[14]

The use of the Māori language in the Māori diaspora is far lower than in New Zealand itself. Census data from Australia show it as the home language of 11,747, just 8.2% of the total Australian Māori population in 2016.[84]

Orthography

[edit]The modern Māori alphabet has 15 letters, two of which are digraphs (character pairs). The five vowels have both short and long forms, with the long forms denoted by macrons marked above them.

| Consonants | Vowels | |

|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | |

The order of the alphabet is as follows: A, E, H, I, K, M, N, O, P, R, T, U, W, Ng, Wh.

This standard orthography may be tweaked to represent certain dialects of Māori:

- An underlined "ḵ" sometimes appears when writing the Southern dialect, to indicate that the /k/ in question corresponds to the ng of the standard language.

- Both L and G are also encountered in the Southern dialect, though not in standard Māori.

- Various methods are used to indicate glottal stops when writing the Whanganui dialect.

History

[edit]There was originally no native writing system for Māori. It has been suggested that the petroglyphs once used by the Māori developed into a script similar to the Rongorongo of Easter Island.[85] However, there is no evidence that these petroglyphs ever evolved into a true system of writing. Some distinctive markings among the kōwhaiwhai (rafter paintings) of meeting houses were used as mnemonics in reciting whakapapa (genealogy) but again, there was no systematic relation between marks and meanings.

Attempts to write Māori words using the Latin script began with Captain James Cook and other early explorers, with varying degrees of success. Consonants seem to have caused the most difficulty, but medial and final vowels are often missing in early sources. Anne Salmond[86] records aghee for aki (in the year 1773, from the North Island East Coast, p. 98), Toogee and E tanga roak for Tuki and Tangaroa (1793, Northland, p. 216), Kokramea, Kakramea for Kakaramea (1801, Hauraki, p. 261), toges for tokis, Wannugu for Uenuku and gumera for kumara (1801, Hauraki, pp. 261, 266 and 269), Weygate for Waikato (1801, Hauraki, p. 277), Bunga Bunga for pungapunga, tubua for tupua and gure for kurī (1801, Hauraki, p. 279), as well as Tabooha for Te Puhi (1823, Northern Northland, p. 385).

From 1814, missionaries tried to define the sounds of the language. Thomas Kendall published a book in 1815 entitled A korao no New Zealand, which in modern orthography and usage would be He Kōrero nō Aotearoa. Beginning in 1817, professor Samuel Lee of Cambridge University worked with the Ngāpuhi chief Tītore and his junior relative Tui (also known as Tuhi or Tupaea),[87] and then with chief Hongi Hika[88] and his junior relative Waikato; they established a definitive orthography based on Northern usage, published as the First Grammar and Vocabulary of the New Zealand Language (1820).[87] The missionaries of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) did not have a high regard for this book. By 1830 the CMS missionaries had revised the orthography for writing the Māori language; for example, 'Kiddeekiddee' was changed to the modern spelling, 'Kerikeri'.[89][non-primary source needed]

The Māori embraced literacy enthusiastically, and missionaries reported in the 1820s that Māori all over the country taught each other to read and write, using sometimes quite innovative materials in the absence of paper, such as leaves and charcoal, and flax.[90] Missionary James West Stack recorded the scarcity of slates and writing materials at the native schools and the use sometimes of "pieces of board on which sand was sprinkled, and the letters traced upon the sand with a pointed stick".[91]

Long vowels

[edit]The alphabet devised at Cambridge University does not mark vowel length. The examples in the following table show that vowel length is phonemic in Māori.

| ata | morning | āta | carefully |

| keke | cake | kēkē | armpit |

| mana | prestige | māna | for him/her |

| manu | bird | mānu | to float |

| tatari | to wait for | tātari | to filter or analyse |

| tui | to sew | tūī | parson bird |

| wahine | woman | wāhine | women |

Māori devised ways to mark vowel length, sporadically at first. Occasional and inconsistent vowel-length markings occur in 19th-century manuscripts and newspapers written by Māori, including macron-like diacritics and doubling of letters. Māori writer Hare Hongi (Henry Stowell) used macrons in his Maori-English Tutor and Vade Mecum of 1911,[92] as does Sir Āpirana Ngata (albeit inconsistently) in his Maori Grammar and Conversation (7th printing 1953). Once the Māori language was taught in universities in the 1960s, vowel-length marking was made systematic. Bruce Biggs, of Ngāti Maniapoto descent and professor at the University of Auckland, promoted the use of double vowels (e.g. waahine); this style was standard at the university until Biggs died in 2000.

Macrons (tohutō) are now the standard means of indicating long vowels,[93] after becoming the favoured option of the Māori Language Commission—set up by the Māori Language Act 1987 to act as the authority for Māori spelling and orthography.[94][95] Most news media now use macrons; Stuff websites and newspapers since 2017,[96] TVNZ[97] and NZME websites and newspapers since 2018.[98]

Technical limitations in producing macronised vowels are sometimes resolved by using a diaeresis[99] or circumflex[100] instead of a macron (e.g., wähine or wâhine). In other cases, it is resolved by omitting the macron all together (e.g. wahine).[101]

Double vowels continue to be used in a few exceptional cases, including:

- The Waikato-Tainui iwi preference is for using doubled vowels;[102] hence in the Waikato region, double vowels are used by the Hamilton City Council,[103] Waikato District Council[104] and Waikato Museum.

- Inland Revenue continues to spell its Māori name Te Tari Taake instead of Te Tari Tāke, mainly to reduce the resemblance of tāke to the English word 'take'.[105]

- A considerable number of governmental and non-governmental organisations continue to use the older spelling of ⟨roopu⟩ ('association') in their names rather than the more modern form ⟨rōpū⟩. Examples include Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa ('the national Māori weavers' collective') and Te Roopu Pounamu (a Māori-specific organisation within the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand).

- Double vowels are also used instead of macrons in long vowels resultant from compounding (e.g. Mātaatua) or reduplication.[106]

Phonology

[edit]Māori has five phonemically distinct vowel articulations, and ten consonant phonemes.

Vowels

[edit]| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i, iː | u, uː | |

| Mid | e, eː | o, oː | |

| Open | a, aː | ||

Although it is commonly claimed that vowel realisations (pronunciations) in Māori show little variation, linguistic research has shown this not to be the case.[107][b]

Vowel length is phonemic, but four of the five long vowels occur in only a handful of word roots, the exception being /aː/.[108][c] As noted above, it has recently become standard in Māori spelling to indicate a long vowel with a macron. For older speakers, long vowels tend to be more peripheral and short vowels more centralised, especially with the low vowel, which is long [aː] but short [ɐ]. For younger speakers, they are both [a]. For older speakers, /u/ is only fronted after /t/; elsewhere it is [u]. For younger speakers, it is fronted [ʉ] everywhere, as with the corresponding phoneme in New Zealand English. Due to the influence of New Zealand English, the vowel [e] is raised to be near [i], so that pī and kē (or piki and kete) now largely share the very same vowel space.[109]: 198–199

Beside monophthongs Māori has many diphthong vowel phonemes. Although any short vowel combinations are possible, researchers disagree on which combinations constitute diphthongs.[110] Formant frequency analysis distinguish /aĭ/, /aĕ/, /aŏ/, /aŭ/, /oŭ/ as diphthongs.[111] As in many other Polynesian languages, diphthongs in Māori vary only slightly from sequences of adjacent vowels, except that they belong to the same syllable, and all or nearly all sequences of nonidentical vowels are possible. All sequences of nonidentical short vowels occur and are phonemically distinct.[112][113]

Consonants

[edit]The consonant phonemes of Māori are listed in the following table. Seven of the ten Māori consonant letters have the same pronunciation as they do in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For those that do not, the IPA phonetic transcription is included, enclosed in square brackets per IPA convention.

| Labial | Coronal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ng [ŋ] | |

| Plosive | p | t | k | |

| Continuant | wh [f, ɸ] | r [ɾ] | w | h |

The pronunciation of ⟨wh⟩ is extremely variable,[114] but its most common pronunciation (its canonical allophone) is the labiodental fricative, IPA [f] (as in the English word fill). Another allophone is the voiceless bilabial fricative, IPA [ɸ], which is usually supposed to be the sole pre-European pronunciation, although linguists are not sure of the truth of this supposition.[citation needed] At least until the 1930s, the bilabial fricative was considered to be the correct pronunciation.[115] The fact that English ⟨f⟩ gets substituted by ⟨p⟩ and not ⟨wh⟩ in borrowings (for example, English February becomes Pēpuere instead of Whēpuere) would strongly hint that the Māori did not perceive English /f/ to be the same sound as their ⟨wh⟩.

Because English stops /p, t, k/ primarily have aspiration, speakers of English often hear the Māori nonaspirated stops as English /b, d, ɡ/. However, younger Māori speakers tend to aspirate /p, t, k/ as in English. English speakers also tend to hear Māori /r/ as English /l/ in certain positions (cf. Japanese r).

/ŋ/ can come at the beginning of a word (like 'sing-along' without the "si"), which may be difficult for English speakers outside of New Zealand to manage.

In some western areas of the North Island, ⟨h⟩ is pronounced as a glottal stop [ʔ] instead of [h], and the digraph ⟨wh⟩ is pronounced as [ʔw] instead of [f] or [ɸ].

/ɾ/ is typically a flap, especially before /a/. However, elsewhere it is sometimes trilled.

In borrowings from English, many consonants are substituted by the nearest available Māori consonant. For example, the English affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/, and the fricative /s/ are replaced by /h/, /f/ becomes /p/, and /l/ becomes /ɾ/ (the /l/ is sometimes retained in the southern dialect, as noted below).

Syllables and phonotactics

[edit]Syllables in Māori have one of the following forms: V, VV, CV, CVV. This set of four can be summarised by the notation, (C)V(V), in which the segments in parentheses may or may not be present. A syllable cannot begin with two consonant sounds (the digraphs ng and wh represent single consonant sounds), and cannot end in a consonant, although some speakers may occasionally devoice a final vowel. All possible CV combinations are grammatical, though wo, who, wu, and whu occur only in a few loanwords from English such as wuru, "wool" and whutuporo, "football".[116]

As in many other Polynesian languages, e.g., Hawaiian, the rendering of loanwords from English includes representing every English consonant of the loanword (using the native consonant inventory; English has 24 consonants to 10 for Māori) and breaking up consonant clusters. For example, "Presbyterian" has been borrowed as Perehipeteriana; no consonant position in the loanword has been deleted, but /s/ and /b/ have been replaced with /h/ and /p/, respectively.

Stress is typically within the last four vowels of a word, with long vowels and diphthongs counting double. That is, on the last four moras. However, stressed moras are longer than unstressed moras, so the word does not have the precision in Māori that it does in some other languages. It falls preferentially on the first long vowel, on the first diphthong if there is no long vowel (though for some speakers never a final diphthong), and on the first syllable otherwise. Compound words (such as names) may have a stressed syllable in each component word. In long sentences, the final syllable before a pause may have a stress in preference to the normal stressed syllable.

Dialects

[edit]

Biggs proposed that historically there were two major dialect groups, North Island and South Island, and that South Island Māori is extinct.[118] Biggs has analysed North Island Māori as comprising a western group and an eastern group with the boundary between them running pretty much along the island's north–south axis.[119]

Within these broad divisions regional variations occur, and individual regions show tribal variations. The major differences occur in the pronunciation of words, variation of vocabulary, and idiom. A fluent speaker of Māori has no problem understanding other dialects.

There is no significant variation in grammar between dialects. "Most of the tribal variation in grammar is a matter of preferences: speakers of one area might prefer one grammatical form to another, but are likely on occasion to use the non-preferred form, and at least to recognise and understand it."[120] Vocabulary and pronunciation vary to a greater extent, but this does not pose barriers to communication.

North Island dialects

[edit]In the southwest of the island, in the Whanganui and Taranaki regions, the phoneme ⟨h⟩ is a glottal stop and the phoneme ⟨wh⟩ is [ʔw]. This difference was the subject of considerable debate during the 1990s and 2000s over the then-proposed change of the name of the city Wanganui to Whanganui.

In Tūhoe and the Eastern Bay of Plenty (northeastern North Island) ⟨ng⟩ has merged with ⟨n⟩. In parts of the Far North, ⟨wh⟩ has merged with ⟨w⟩.[citation needed]

South Island dialects

[edit]

In South Island dialects, ng merged with k in many regions. Thus Kāi Tahu and Ngāi Tahu are variations in the name of the same iwi (the latter form is the one used in acts of Parliament). Since 2000, the government has altered the official names of several southern place names to the southern dialect forms by replacing ng with k. New Zealand's highest mountain, known for centuries as Aoraki in southern Māori dialects that merge ng with k, and as Aorangi by other Māori, was later named "Mount Cook". Now its sole official name is Aoraki / Mount Cook, which favours the local dialect form. Similarly, the Māori name for Stewart Island, Rakiura, is cognate with the name of the Canterbury town of Rangiora. Likewise, Dunedin's main research library, the Hocken Collections, has the name Uare Taoka o Hākena rather than the northern (standard) Te Whare Taonga o Hākena.[d] Maarire Goodall and George Griffiths say there is also a voicing of k to g, which explains why the region of Otago (southern dialect) and the settlement it is named after – Otakou (standard Māori) – vary in spelling (the pronunciation of the latter having changed over time to accommodate the northern spelling).[121]

The standard Māori r is also found occasionally changed to an l in these southern dialects and the wh to w. These changes are most commonly found in place names, such as Lake Waihola,[122] and the nearby coastal settlement of Wangaloa (which would, in standard Māori, be rendered Whangaroa), and Little Akaloa, on Banks Peninsula. Goodall and Griffiths suggest that final vowels are given a centralised pronunciation as schwa or that they are elided (pronounced indistinctly or not at all), resulting in such seemingly bastardised place names as The Kilmog, which in standard Māori would have been rendered Kirimoko, but which in southern dialect would have been pronounced very much as the current name suggests.[123] This same elision is found in numerous other southern placenames, such as the two small settlements called The Kaik (from the term for a fishing village, kainga in standard Māori), near Palmerston and Akaroa, and the early spelling of Lake Wakatipu as Wagadib. In standard Māori, Wakatipu would have been rendered Whakatipua, showing further the elision of a final vowel.[citation needed]

Despite the dialect being officially regarded as extinct,[e] its use in signage and official documentation is encouraged by many government and educational agencies in Otago and Southland.[125][126]

Grammar and syntax

[edit]Māori has mostly a verb-subject-object (VSO) word order.[127] It is also analytical, featuring almost no inflection, and makes extensive use of grammatical particles to indicate grammatical categories of tense, mood, aspect, case, topicalization, among others. The personal pronouns have a distinction in clusivity, singular, dual and plural numbers,[128] and the genitive pronouns have different classes (a class, o class and neutral) according to whether the possession is alienable or the possessor has control of the relationship (a category), or the possession is inalienable or the possessor has no control over the relationship (o category), and a third neutral class that only occurs for singular pronouns and must be followed by a noun.[129] There is also subject-object-verb (SOV) word order used in passive sentences. Examples of this include Nāku te ngohi i tunu ("I cooked the fish"; literally I the fish cooked) and Mā wai te haka e kaea? ("Who will lead the haka?").

Bases

[edit]Biggs (1998) developed an analysis that the basic unit of Māori speech is the phrase rather than the word.[130] The lexical word forms the "base" of the phrase. Biggs identifies five types of bases.

Noun bases include those bases that can take a definite article, but cannot occur as the nucleus of a verbal phrase; for example: ika (fish) or rākau (tree).[131] Plurality is marked by various means, including the definite article (singular te, plural ngā),[132] deictic particles tērā rākau (that tree), ērā rākau (those trees),[133] possessives taku whare (my house), aku whare (my houses).[134] A few nouns lengthen a vowel in the plural, such as wahine (woman); wāhine (women).[135] In general, bases used as qualifiers follow the base they qualify, e.g. "matua wahine" (mother, female elder) from "matua" (parent, elder) "wahine" (woman).[136]

Universal bases are verbs which can be used passively. When used passively, these verbs take a passive form. Biggs gives three examples of universals in their passive form: inumia (drunk), tangihia (wept for), and kīa (said).[137]

Stative bases serve as bases usable as verbs but not available for passive use, such as ora, alive or tika, correct.[137] Grammars generally refer to them as "stative verbs". When used in sentences, statives require different syntax than other verb-like bases.[138]

Locative bases can follow the locative particle ki (to, towards) directly, such as runga, above, waho, outside, and placenames (ki Tamaki, to Auckland).[139]

Personal bases take the personal article a after ki, such as names of people (ki a Hohepa, to Joseph), personified houses, personal pronouns, wai? who? and mea, so-and-so.[139]

Particles

[edit]Like all other Polynesian languages, Māori has a rich array of particles, which include verbal particles, pronouns, locative particles, articles and possessives.

Verbal particles indicate aspectual, tense-related or modal properties of the verb which they relate to. They include:

- i (past)

- e (non-past)

- i te (past continuous)

- kei te (present continuous)[140]

- kua (perfect)

- e ... ana (imperfect, continuous)

- ka (inceptive, future)

- kia (desiderative)

- me (prescriptive)

- kei (warning, "lest")

- ina or ana (punctative-conditional, "if and when")[141]

- kāti (cessative)[142]

- ai (habitual)[143]

Locative particles (prepositions) refer to position in time and/or space, and include:

- ki (to, towards)

- kei (at)

- i (past position)

- hei (future position)[144]

Possessives fall into one of two classes of prepositions marked by a and o, depending on the dominant versus subordinate relationship between possessor and possessed: ngā tamariki a te matua, the children of the parent but te matua o ngā tamariki, the parent of the children.[145]

Determiners

[edit]Articles

[edit]| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Definite | te | ngā |

| Indefinite1 | he | |

| Indefinite2 | tētahi | ētahi |

| Proper | a | |

The definite articles are te (singular) and ngā (plural).[146][147] Several other determiners termed definitives are related to the singular definite article te, such as the definitive possessive constructions with tā and tō and the demonstrative determiners.[129]

The Māori definite articles are frequently used where the equivalent, the, is not used in English, such as when referring generically to an entire class. In these cases, the singular te can even be used with a morphologically plural noun, as in

te

DEF.SG

tamariki

child.PL

"children (in general)"

as opposed to

ngā

DEF . PL

tamariki

child. PL

"(конкретная группа) детей"

В других синтаксических средах определенная статья может использоваться для введения существительной фразы, которая прагматично неопределенна из-за ограничений на использование HE , как обсуждается ниже. [ 147 ]

Неопределенная статья, которую он чаще всего использует в предикате, а иногда и в предмете предложения, хотя она не допускается в предметной позиции во всех типах предложений. [ 148 ] В предикате неопределенная статья он может представить либо существительные, либо прилагательные. [ 149 ] Статья либо может быть переведена на английский «а» или «какой -то», но число не будет указано он . С существительными, которые показывают морфологическое число, он может использоваться либо с единственными или множественными формами. Неопределенная статья, которую он при использовании с массовыми существительными, такими как вода и песок, всегда будет означать «некоторые». [ 150 ]

| человек | человек | некоторые мужчины |

| Девушка | Девушка | Некоторые девушки |

| Дом | деревня | Некоторые деревни |

| Яблоко | яблоко | некоторые яблоки |

| человек | человек | – |

| Есть люди | – | некоторые люди |

Неопределенная статья он сильно ограничен в своем использовании и несовместима с предыдущим предлогом. По этой причине его нельзя использовать в грамматическом объекте предложения, так как они отмечены сознанием, либо с I, либо с I или KI . Во многих случаях ораторы просто используют определенные статьи TE и NGā в позициях, где он неопределенные статьи , чтобы запрещен, однако в этих ситуациях можно использовать подчеркнуть неопределенность. [ 151 ]

я

Тихоокеанское стандартное время

видеть

видеть

мне

1с

я

Акк

а

DEF . SG

Собак

собака

«Я видел собаку ».

(«Я видел собаку ».)

я

Тихоокеанское стандартное время

видеть

видеть

мне

1с

я

Акк

любой

INDEF . SG

Собак

собака

«Я видел собаку ».

В позициях, где могут возникнуть и он , и Tētahi / ētahi , иногда существуют различия в значении между ними, как указывают следующие примеры. [ 152 ]

Нет

Отрицательный

любой

Подготовительный Невозможный

человек

person. SG

я

Тихоокеанское стандартное время

идти

идти

Может.

На пути к

(1) « Кто -то не пришел». / « Конкретный человек не пришел».

(2) « Никто не пришел».

Нет

Отрицательный

он

Невозможный

человек

person. SG

я

Тихоокеанское стандартное время

идти

идти

Может.

На пути к

« Никто не пришел».

Правильная статья А используется перед личными и локативными существительными, действующими в качестве предмета предложения или перед личными существительными и местоимениями в рамках предлога, возглавляемых предложениями, заканчивающимися в I (а именно I , Ki , Kei и Hei ). [ 151 ]

В

Предварительный МЕСТО

хороший

где

а

ИСКУССТВО

Пита ?

Петр

"Где Петр ?"

В

Предварительный МЕСТО

хороший

где

ia?

3с

"Где он ?"

В

Предварительный МЕСТО

Окленд

Окленд

а

ИСКУССТВО

Лаваш

Петр

« Питер в Окленде».

В

Предварительный МЕСТО

Окленд

Окленд

это

3с

« Он в Окленде».

я

Тихоокеанское стандартное время

видеть

видеть

мне

1с

я

Акк

а

ИСКУССТВО

Лаваш

Петр

"Я видел Питера ".

я

Тихоокеанское стандартное время

видеть

видеть

мне

1с

я

Акк

а

ИСКУССТВО

это

3с

«Я видел его ».

Личные существительные не сопровождаются определенными или неопределенными статьями, если они не являются внутренней частью имени, как в Te rauparaha . [ 153 ]

В

Предварительный МЕСТО

хороший

где

а

ИСКУССТВО

А

А

Rauparate ?

Посадить

"Где Те Раупарха ?"

В

Предварительный МЕСТО

T-Your

Дефект SG - inal -1s

дом

дом

а

ИСКУССТВО

А

А

Rauparaha .

Посадить

«Те Раупарха у меня дома».

Надлежащим существительным не предшествует надлежащая статья, когда они не действуют как субъект предложения, ни в предловой фразе, возглавляемой I , KI , KEI или HEI . Например, после фокусирующей частицы KO , правильная статья не используется.

Что

ОГОНЬ

Молитва

Молитва

T-Your

Дефект SG - inal - 1s

Имя.

имя

«Меня зовут Равири ».

Что

ОГОНЬ

А

А

Посадить

Посадить

это

Демография Подготовительный Расстояние

Люди.

person. SG

«Этот человек (там) - это Те Раупарха ».

Демонстративные определения и наречия

[ редактировать ]Демонстрации происходят после существительного и имеют дектическую функцию, и включают в себя Tēnei , это (рядом со мной), Tēnā , что (рядом с вами), Tērā , что (далеко от нас обоих) и тауа , вышеупомянутые (анафорические). Эти демонстрации, имеющие связь с определенной статьей TE, называются определенными. Другие определенные включают Tēhea? (Что?) и Tētahi , (определенный). Множественное число образуется просто отбросив T : Tēnei (this), ēnei (это). Связанные наречия являются Nei (здесь), на (там, рядом с вами), Rā (рядом с ним). [ 154 ]

Фразы, представленные демонстративными, также могут быть выражены с использованием определенной статьи TE или NGā, предшествующей существительному, за которым следует одна из декических частиц Nei , Nā или rā . T в единственной определенной статье появляется в единственных демонстраторах, но заменяется ∅ во множественном числе, не имея связи с NGā в большинстве диалектов.

а

DEF . SG

дом

дом

в

Прокс

=

=

этот

Демография Подготовительный Прокс

дом

дом

"Этот дом"

условия

DEF . PL

дом

дом

в

Прокс

=

=

эти

Демография Пл . Прокс

дом

дом

"Эти дома"

Однако на диалектах области Вайкато множественные формы демонстративных, начиная с NG- обнаруживаются , такие как ngēnei «эти» вместо более распространенных ēnei (а также и обладающих такими, как ng (e) ōku 'my (множественное число, неотъемлемо) 'вместо ōku ). [ 156 ]

В следующей таблице показаны наиболее распространенные формы демонстративных по разным диалектам.

| Единственный | Множественное число | Наречие | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Проксимальный | этот | эти | в |

| Медиал | пожалуйста | в тени | а |

| Дистальный | это | те | солнце |

| Вышеупомянутый | такой же | не |

Местоимение

[ редактировать ]Личные местоимения

[ редактировать ]Местоимения имеют единственное, двойное и множественное число. Различные формы от первого лица как в двойном, так и во множественном числе используются для групп, включающих, или исключительно обращенных к лицу (-ам).

- 1

- 2

- 3

| Единственный | Двойной | Множественное число | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 -й человек | эксклюзивный | Я / я | Мы знаем? | мы |

| включительно | важный | нас | ||

| 2 -й человек | ты | ты | ты | |

| 3 -е лицо | это | их | они | |

Как и другие полинезийские языки, у маори есть три числа для местоимений и одержимости: единственного, двойного и множественного числа. Например: ia (он/она), рауа (эти два), рату (они, три или более). Местоимения маори и обладающие еще более различными исключительными «мы» от инклюзивных «мы», второе и третье место. У него есть местоимения во множественном числе: мату (мы, экс), тату (мы, вкл.), Куту (ты), Рату (они). На языке изображены двойные местоимения: Мауа (я и другой), тауа (я и вы), kōrua (вы двое), рауа (эти двое). Разница между исключительной и инклюзивной ложью в обращении с адресованным человеком. Мату ссылается на спикера и других, но не к человеку или людям, с которыми говорили («я и некоторые другие, но не к вам»), и Тату ссылается на спикера, человека или людей, с которыми разговаривали, и всем остальным («вы, я и другие "): [ 157 ]

- Спасибо : Привет (одному человеку)

- Пожалуйста, сделайте : привет (ваши люди)

- Спасибо : Привет (более двух человек) [ 158 ]

Притяжательные местоимения

[ редактировать ]Притяжательные местоимения варьируются в зависимости от человека, числа, больших классов и притяжательного класса (класс или класс O). Пример: Таку Пен (моя ручка), аку Пен (мои ручки). Для размышлений о двойных и множественных предметах, притяжательная форма является аналитической, просто поместив притяжательную частицу ( Tā/Tō для единственных объектов или ā/ō для объектов множественного числа) перед личными местоимениями, например , Tātou karaihe (наш класс), tō rāua Whare (их [двойной] дом); ā tātou karaihe (наши классы). Сейтрист должен сопровождаться существительным и происходит только для единственного числа первого, второго и третьего человека. Таку - это мой, Аку - это мое (множественное число, для многих одержимых предметов). Множественное число производится путем удаления начального [t]. [ 129 ]

| Предмет | Объект | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Число | Человек | Единственный | Множественное число | ||||

| класс | o класс | нейтральный | класс | o класс | нейтральный | ||

| Единственный | 1 | согласно | мой | мой | мой | такой я | я |

| 2 | делает | твой | тащить | ты | все твое | вашего | |

| 3 | его | его | она | тот, кто есть | его | пещера | |

Интеррогативные местоимения

[ редактировать ]- вода («что»)

- ага («что»)

- hea ('где')

- Где (откуда ')

- Когда ('Когда')

- E Hia («Сколько [вещей]»)

- Увеличиться («сколько [людей]»)

- Что («как»)

- который ('который'), который (', который [pl.]'

- он ага ... ай («Почему [разум]»)

- Почему все ... ei ('ly [cane]') [ 159 ]

Фраза грамматика

[ редактировать ]Фраза, произнесенная в маори, может быть разбита на две части: «ядро» или «голова» и «периферия» (модификаторы, определители). Ядро можно рассматривать как значение и является центром фразы, тогда как периферия - это то, где грамматическое значение передается и происходит до и/или после ядра. [ 160 ]

| Периферия | Ядро | Периферия |

|---|---|---|

| а | дом | в |

| Если | дом |

Ядро может быть переведено как « дом », периферия TE аналогична статье «The», а периферия Nei указывает на близость к говорящему. Вся фраза, Te Whare Nei , может быть переведена как «этот дом». [ 161 ]

Фразовые частицы

[ редактировать ]Определенное и декларативное предложение (может быть совокупным предложением) начинается с декларативной частицы KO . [ 162 ] Если предложение акцентировано (тема агента, только в непрерывных предложениях) предложение начинается с частицы Nā (прошлое время) или частицы Mā (будущее, несовершенное), за которым следует агент/субъект. В этих случаях порядок слов изменяется на субъект-верб-объект. Эти агенты, активирующие частицы, могут сокращаться с единственными личными местоимениями и варьироваться в зависимости от притяжательных классов: наку можно рассматривать как значение «как для меня» и ведут себя как решительное или дательное местоимение. [ 163 ]

| Прошлое | Будущее | |

|---|---|---|

| 1с | незаконно | Я / для меня |

| 2S | Представлять на рассмотрение | для вас / для |

| 3с | Он / он / она | Он / он / она |

Частицы корпуса

[ редактировать ]- Номинативное: KO [ 164 ]

- Винительный вечер: я [ 165 ]

- Дативный/направленный локативный: ки [ 166 ]

- Родительный падеж: A/O. [ 167 ]

Отрицание

[ редактировать ]Формирование негативных фраз в маори довольно грамматически сложное. Есть несколько разных отрицателей, которые используются при различных конкретных обстоятельствах. [ 168 ] Основные отрицатели следующие: [ 168 ]

| Негатор | Описание |

|---|---|

| нет | Отрицательный ответ на полярный вопрос. |

| Ничего / нет / нет | Наиболее распространенный словесный отрицатель. |

| нет | Сильный отрицательный, эквивалентный «никогда». |

| НЕ | Негативные императивы; запретительный |

| нет | Отрицание для коулативных фраз, актуальных и акцентирующих фраз |

Kīhai и Tē - два отрицателя, которые можно увидеть на определенных диалектах или в более старых текстах, но не широко используются. [ 168 ] Наиболее распространенным отрицателем является Кахор , который может возникнуть в одной из четырех форм, причем форма Kāo используется только в ответ на вопрос. [ 168 ] Негативные фразы, помимо использования Kāore , также влияют на форму словесных частиц, как показано ниже.

| Положительный | Отрицательный | |

|---|---|---|

| Прошлое | я | я |

| Будущее | а | я/е |

| Подарок | является | чем |

| Несовершенный | Я ... | |

| Прошлое идеально | уже | в любое время |

Общее использование Кахора можно увидеть в следующих примерах. Субъект обычно поднимается в негативных фразах, хотя это не обязательно. [ 169 ] Каждый пример негативной фразы представлен с его аналоговой положительной фразой для сравнения.

|

Нет Отрицательный нас 1pl . Внедорожник и Т/а идти двигаться пещера Т/а завтра завтра 'Мы не собираемся завтра' [ 170 ] Нет Отрицательный снова еще он а люди люди в любое время Подметание приезжать приезжать Может сюда 'Никто еще не прибыл' [ 170 ]

|

Пассивные предложения

[ редактировать ]Пассивный голос глаголов изготавливается суффиксом в глагол. Например, -ia (или просто -a, если глагол заканчивается в [i]). Другие пассивные суффиксы, некоторые из которых очень редки,: -hanga/-hia/-hina/-ina/-kia/-kina/-mia/-na/-nga/-ngia/-ria/-rina/ -tia/-whia/-whina/. [ 171 ] Использование пассивного суффикса -ia дается в этом предложении: Kua Hanga Ia te Marae e ngā tohunga (Marae была построена экспертами). Активная форма этого предложения представлена как: Kua Hanga ngā tohunga I Te Marae (эксперты построили Marae). Можно видеть, что активное предложение содержит маркер объекта «I», которого нет в пассивном предложении, в то время как пассивное предложение имеет маркер агента «E», которого нет в активном предложении. [ 172 ]

Полярные вопросы

[ редактировать ]Полярные вопросы (да/нет вопросов) могут быть сделаны путем изменения интонации предложения. Ответы могут быть (Да) или Као (нет). [ 173 ]

Деривационная морфология

[ редактировать ]Хотя маори в основном аналитическая, есть несколько деривационных аффиксов:

- -Read, -res, -Rechnology (суффикс депонды) (суффикс зависит) (суффикс зависит) (суффикс зависит Suppix ' выборы ' выборы '

- -Nga (номинализатор) [ 174 ]

- Кай- (агент существительное) [ 175 ] (например, работа », « работа работник / сотрудник ')

- MA- (прилагательные) [ 176 ]

- tua- (порядковые цифры) [ 177 ] (например, « один», первое «первое / первичное»)

- (Стромные души) [ 178 ]

Влияние на новозеландский английский

[ редактировать ]Новозеландский английский получил много заемных слов от маори, в основном имена птиц, растений, рыб и мест. Например, киви , национальная птица , берет свое название от Te reo . « Kia ora » (буквально «быть здоровым») - это широко принятое приветствие происхождения маори, с предполагаемым значением «Привет». [ 179 ] Это также может означать «спасибо» или означать соглашение с докладчиком на собрании. Приветствующие маори Tēnā koe (одному человеку), Tēnā kōrua (двум людям) или Tēnā Koutou (для трех или более людей) также широко используются, как и прощание, такие как haere rā . Фраза маори kia kaha , «будь сильным», часто встречается как показатель моральной поддержки для кого -то, начинающего стрессовое обязательство или иное в трудной ситуации. Многие другие слова, такие как Whānau (то есть «семья») и кай (что означает «еда»), также широко понятны и используются новозеландцами. Фраза маори кайт кайт anō означает «пока я не увижу тебя снова».

47 слов или выражений из новозеландского английского, в основном из Te reo Māori . В 2023 году в Оксфордский английский словарь были добавлены [ 180 ]

Демография

[ редактировать ]| Место | Маори, распыляющее население |

|---|---|

| Новая Зеландия | 185,955 |

| Квинсленд | 4,264 [ 181 ] |

| Западная Австралия | 2,859 [ 182 ] |

| Новый Южный Уэльс | 2,429 [ 183 ] |

| Виктория | 1,680 [ 184 ] |

| Южная Австралия | 222 [ 182 ] |

| Северная территория | 178 [ 185 ] |

| Австралийская столичная территория | 58 [ 186 ] |

| Тасмания | 52 [ 187 ] |

Онлайн -переводчики

[ редактировать ]Маори доступен в Google Translate , Microsoft Translator и Yandex Translate . Еще один популярный онлайн -словарь - это словарь маори . [ 188 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- День языка маори

- Неделя языка маори (Неделя языка маори)

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- , Татуировки лица используемые в 19 веке, были представлены как форма текстового языка, но не коррелируют с разговорными маори. [ 6 ]

- ^ Бауэр упоминает, что Биггс 1961 объявил о аналогичном выводе.

- ^ Бауэр даже поднял возможность анализа маори как на самом деле с шестью гласными фонемами, a, ā, e, i, o, u ( [a, aː, ɛ, i, ɔ, ʉ] ).

- ^ Библиотека Хокена содержит несколько ранних журналов и ноутбуков ранних миссионеров, документирующих капризы южного диалекта. Некоторые из них показаны в Blackman, A. Некоторые источники для южного диалекта маори .

- ^ Как и во многих «мертвых» языках, существует вероятность того, что южный диалект может быть восстановлен, особенно с упомянутым ободрением. « Язык Мурихику - Mulihig ', вероятно, лучше выражает его состояние в 1844 году - живет в списке словарных запасов Уотькина и во многих терминах , все еще используемых и может снова процветать в новом климате маоритаки ». [ 124 ]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Источники речи: где маори говорят на языке - инфографике» . Статистика Новая Зеландия. Архивировано из оригинала 17 февраля 2021 года . РЕТРЕЙВЕР 2 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ «Перепись 2018 года по темам - национальные основные моменты (обновляются)» . Статистика Новая Зеландия. 30 апреля 2020 года. Архивировано с оригинала 24 января 2022 года . Получено 7 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Глотопия статья о языке маори .

- ^ «Маори в Новой Зеландии | ЮНЕСКО ВАЛ» .

- ^ «История языка маори» . Nzhistory.govt.nz . Получено 14 марта 2024 года .

- ^ « Любопытный документ»: Ta Moko в качестве доказательства доевропейской текстовой культуры в Новой Зеландии | nzetc » . nzetc.victoria.ac.nz . Получено 14 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «История языка маори» . Nzhistory.govt.nz . Получено 14 марта 2024 года .

- ^ "Пост" . www.thepost.co.nz . Получено 15 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «Закон о местных школах 1867 (31 Виктория 1867 № 41)» . www.nzlii.org . Получено 14 марта 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Калман, Росс. «Образование маори - Матауранга - Система местной школы, с 1867 по 1969 год» . Teara.govt.nz . Министерство культуры и наследия Новой Зеландии Те Манату. п. 3. Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2019 года . Получено 16 марта 2021 года .

- ^ Это Окленд: сообщайте о претензиях, посвященном новозеландскому закону и культуре и идентичности маори Новой Зеландии - второго уровня (PDF) . Веллингтон, Новая Зеландия: Вайтанги Тубнал. 2011. ISBN 978-1-869563-01-1 Полем WAI 262. Архивировал (PDF) из оригинала 5 октября 2021 года . Получено 5 октября 2021 года .

- ^ «Языковые вопросы маори - Комиссия по языку маори - Комиссия по языку маори» . 2 января 2002 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2 января 2002 года . Получено 14 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «Источники речи: где маори говорят на языке - инфографике» . Статистика Новая Зеландия. Архивировано из оригинала 17 февраля 2021 года . РЕТРЕЙВЕР 2 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Язык маори в обучении» . Образование подсчет . Министерство образования Новой Зеландии. Октябрь 2023 года.

- ^ "Те Рео Маори (язык маори)" . Новая Зеландия Правительство . 7 июля 2021 года . Получено 14 марта 2024 года .

- ^ Таонга, Права и интересы: некоторые наблюдения на WAI 262 и рамки защиты для языка маори - Стивенс, Мамари, (2010) NZACL Ежегодник 16

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Коуэн, Джеймс: Маори: вчера и сегодня автор: Детали публикации: Whitcombe and Tombs Limited, 1930, Крайстчерч. Часть: Новозеландская коллекция текстов. Этот текст является предметом: Каталог библиотеки Университета Виктории Университета Веллингтона

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Krupa, Victor: метафоры в словаре маори и традиционной поэзии* (2006) Институт восточных исследований, Словацкая академия наук

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Тейлор, Ричард (1855). Те ика мауи; Или, Новая Зеландия и ее жители: иллюстрируя происхождение, манеры, обычаи, мифология, религия, обряды, песни, пословицы, басни и язык туземцев: вместе с геологией, естественной историей, постановками и климатом страны; его состояние в отношении христианства; Эскизы главных чилсов и их нынешняя позиция . Лондон: Вертхайм и Макинтош. п. 72 Получено 2 сентября 2013 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Хиггинс, Rawinia; Кин, Василий (1 сентября 2015 г.). "Te reo māori - язык маори" . Дорога: энциклопедия Новой Зеландии . Получено 29 июня 2017 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Закон о языке маори 1987 № 176 (по состоянию на 30 апреля 2016 года), Содержание общественного акта - Законодательство о Новой Зеландии» . Законодательство.govt.nz . Архивировано с оригинала 9 октября 2014 года . Получено 29 июня 2017 года .

- ^ Например: «Маори и Закон о местном органе власти» . Департамент внутренних дел Новой Зеландии . Архивировано из оригинала 11 октября 2017 года . Получено 29 июня 2017 года .

- ^ Новый Оксфордский американский словарь (третье издание); Коллинз английский словарь - полное и неограниченное 10 -е издание; Dictionary.com

- ^ «Наши языки - ō tātou reo» . Министерство этнических сообществ. Архивировано из оригинала 18 мая 2022 года . Получено 5 мая 2022 года .

- ^ «Языки в Аотеароа Новая Зеландия» (PDF) . rolyalsociety.org.nz . Королевское общество Новой Зеландии Те Апаранги. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 5 марта 2022 года . Получено 5 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Уолтерс, Лора (16 февраля 2018 г.). «Анализ: почему английский не должен быть официальным языком» . Stuff.co.nz. Архивировано из оригинала 12 мая 2022 года . Получено 5 мая 2022 года .

- ^ «Признание языка маори» . Новая Зеландия Правительство. Архивировано из оригинала 7 февраля 2012 года . Получено 29 декабря 2011 года .

- ^ Сток, Роб (14 сентября 2021 года). «Правительственные и бизнес -лидеры объясняют названия маори своих организаций» . Вещи . Архивировано из оригинала 20 февраля 2022 года . Получено 21 февраля 2022 года .

- ^ Iorns Magallanes, Catherine J. (декабрь 2003 г.). «Выделенные парламентские места для коренных народов: политическое представительство как элемент самоопределения коренных народов» . Университет Мердока Электронный журнал права . 10 SSRN 2725610 . Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2017 года . Получено 29 июня 2017 года .

- ^ «Teure Mō Te reo Māori 2016 № 17 (по состоянию на 01 марта 2017 года), публичный акт 7 Право говорить о маори в судебном процессе - законодательство о Новой Зеландии» . Законодательство.govt.nz . Архивировано с оригинала 8 июля 2019 года . Получено 8 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Новозеландский совет маори v Генерального прокурора [1994] 1 NZLR 513

- ^ Данливи, Триша (29 октября 2014 г.). "Телевидение - телевидение маори " Чай: энциклопедия Новой Зеландии Получено 24 августа

- ^ «Новая Зеландия Gazetteer официальных географических имен» . Земля Информация Новая Зеландия. Архивировано с оригинала 11 октября 2014 года . Получено 22 февраля 2009 года .

- ^ Траффорд, Уилл (25 октября 2022 года). «Петиция о восстановлении Аотеароа в качестве официального названия Новой Зеландии, принятой отбранным комитетом» . Te AO News . Получено 7 мая 2024 года .

- ^ McGuire, Casper (20 августа 2023 г.). «Уинстон Петерс предлагает сделать английский на официальном языке» . 1 новости . TVNZ . Получено 7 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Ченг, Дерек (20 июня 2021 года). «Уинстон Питерс объявляет, что Новая Зеландия первой вернется в 2023 году» . Новая Зеландия Herald . Получено 7 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Десмарайс, Феликс (24 марта 2023 г.). «Уинстон Петерс: Новая Зеландия снимает имена маори из правительства» . 1 новости . TVNZ . Получено 7 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Тан, Линкольнл (10 сентября 2023 г.). «Выборы 2023 года: Уинстон Петерс утверждает, что« маори не коренные »во время встречи Нельсона с первыми сторонниками Новой Зеландии» . Новая Зеландия Herald . Получено 7 мая 2024 года .

- ^ «Министр инструктирует сотрудников Waka Kotahi сначала использовать английское имя» . 1 новости . TVNZ . 4 декабря 2023 года . Получено 7 мая 2024 года .

- ^ «Вака Котахи, чтобы использовать свое английское имя сначала после давления со стороны правительства» . Rnz . 8 декабря 2023 года . Получено 7 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Хоу, КР (4 марта 2009 г.). «Идеи о происхождении маори - 1920–2000: новое понимание» . Те Ара: Энциклопедия Новой Зеландии . п. 5

- ^ Уолтерс, Ричард; Бакли, Халли; Джейкомб, Крис; Матису-Смит, Элизабет (7 октября 2017 г.). «Массовая миграция и полинезийское поселение Новой Зеландии» . Журнал мировой предыстории . 30 (4): 351–376. doi : 10.1007/s10963-017-9110-y .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Риз, Элейн; Киган, Питер; Макнотон, Стюарт; Кинг, Те Кани; Карр, Полли Ататоа; Шмидт, Джоанна; Мохал, Джатендер; Грант, Кэмерон; Мортон, Сьюзен (март 2018 г.). «Te Reo Māori: овладение языком коренных народов в контексте новозеландского английского» . Журнал детского языка . 45 (2): 340–367. doi : 10.1017/s0305000917000241 . PMID 28679455 .

- ^ « Любопытный документ»: Ta Moko в качестве доказательства доевропейской текстовой культуры в Новой Зеландии | nzetc » . nzetc.victoria.ac.nz . Получено 15 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «Та Моко важное выражение культуры» . NZ Herald . 15 марта 2024 года . Получено 15 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «Моко сейчас, татуировки татуировки» . Критик - осмотреть . Ретривер 15 марта 2024 года .

- ^ " Каракия ", веб -сайт Университета Отаго. 23 июля

- ^ Андерсон, Атолл; и др. (Ноябрь 2015). Tangata whenua (1 -е изд.). Окленд: Бриджит Уильямс книги. с. 47, 48. ISBN 9780908321537 .

{{cite book}}: Cs1 Maint: дата и год ( ссылка ) - ^ Коффи, Клэр. «Спрос на языковые навыки маори на работе растут в Новой Зеландии» . Lightcast . Получено 15 марта 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «История языка маори» . Министерство культуры и наследия. 10 октября 2017 года. Архивировано с оригинала 6 апреля 2020 года . Получено 22 сентября 2019 года .

- ^ «Депутаты -маори» . Министерство культуры и наследия. 15 июля 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 22 сентября 2019 года . Получено 22 сентября 2019 года .

- ^ « Меня избили, пока я не кровоточил » . Rnz . 1 сентября 2015 года. Архивировано с оригинала 22 февраля 2021 года . Получено 3 января 2021 года .

- ^ «Обязательные занятия помогут исправить неправильно после того, как Te reo Māori« избил »из школьников поколение назад - сэр Пита Шарплс» . 1 новости . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Получено 24 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Грэм-Маклай, Шарлотта (12 сентября 2022 г.). «По мере того, как использование языка маори растет в Новой Зеландии, задача состоит в том, чтобы соответствовать словам с словами» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Получено 24 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «Розина Випарата: наследие языкового образования маори» . Вечные годы . 23 февраля 2015 года. Архивировано с оригинала 15 ноября 2017 года . Получено 15 ноября 2017 года .

- ^ Хейден, Леони (7 августа 2019 г.). «Леди Киа Ора: Дама Рангимари Наида Главиш, по ее собственным словам» . Дополнение . Получено 7 июля 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Harris, Love (2015), «World Rung: The Change World» история : история Bridout, , , Bridnight, 978081537 , ISBN 9780908321537 , Получено 23 ноября 2022 года

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Это Окленд: сообщайте о претензиях, посвященном новозеландскому закону и культуре и идентичности маори Новой Зеландии - второго уровня (PDF) . Веллингтон, Новая Зеландия: Вайтанги Тубнал. 2011. ISBN 978-1-869563-01-1 Полем WAI 262. Архивировал (PDF) из оригинала 5 октября 2021 года . Получено 5 октября 2021 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Трибунал Вайтанги (2011, стр. 440).

- ^ Трибунал Вайтанги (2011, стр. 470).

- ^ «Контроллер и генерал-аудитор» . Офис Генерального аудитора . Веллингтон , Новая Зеландия. 2017. Архивировано с оригинала 4 декабря 2017 года . Получено 3 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Трибунал Вайтанги (2011, стр. 471).

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Трибунал Вайтанги» . wabtangi-tribunal.govt.nz . Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2013 года . Получено 9 ноября 2016 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Олбери, Натан Джон (2 октября 2015 г.). «Коллективные (белые) воспоминания о потере языка маори (или нет)». Языковая осведомленность . 24 (4): 303–315. doi : 10.1080/09658416.2015.1111899 . ISSN 0965-8416 . S2CID 146532249 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Олбери, Натан Джон (2 апреля 2016 года). «Старая проблема с новыми направлениями: оживление языка маори и политические идеи молодежи». Текущие проблемы в планировании языка . 17 (2): 161–178. doi : 10.1080/14664208.2016.1147117 . ISSN 1466-4208 . S2CID 147076237 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Рой, Элеонора Эйндж (28 июля 2018 г.). «Google и Disney присоединяются к Rush, чтобы заработать, так как маори становится мейнстримом» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 28 июля 2018 года . Получено 28 июля 2018 года .

Джон МакКаффери, эксперт по языку в школе образования Университета Окленда, говорит, что этот язык процветает, а другие коренные народы путешествуют в Новую Зеландию, чтобы узнать, как маори сделал такое поразительное возвращение. «Это было действительно драматично, в частности, в частности, маори стал мейнстримом», - сказал он.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Грэм-Маклай, Шарлотта (16 сентября 2018 года). «Язык маори, когда -то избегающий, имеет эпохи Возрождения в Новой Зеландии» . New York Times . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 ноября 2022 года . Получено 7 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «В Новой Зеландии« Привет »стал« Kia Ora ». Это спасет язык маори? " Полем Время . Получено 7 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «Моана в маори попадает на большой экран» . Rnz . 11 сентября 2017 года. Архивировано с оригинала 9 августа 2020 года . Получено 29 мая 2022 года .

- ^ «Планируйте, чтобы 1 миллион человек выступали в маори в Te reo к 2040 году» . Rnz . 21 февраля 2019 года. Архивировано с оригинала 7 ноября 2022 года . Получено 7 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «Майхи Карауна» . www.tpk.govt.nz. Архивировано из оригинала 10 ноября 2022 года . Получено 7 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «Гарри Поттер должен быть переведен в Te reo Māori» . Stuff.co.nz . Архивировано из оригинала 8 декабря 2019 года . Получено 10 декабря 2019 года .

- ^ «Сигналы BSA заканчиваются жалобами на маори» . Rnz . 9 марта 2021 года. Архивировано с оригинала 15 марта 2021 года . Получено 25 марта 2021 года .

- ^ Биггс 1994 , с. 96–105.

- ^ Clark 1994 , pp. 123–135.

- ^ Harlow 1994 , с. 106–122.

- ^ БАНКА 1771 , 9 октября 1769 года: «Мы снова вышли на сторону реки с Тупией, которая теперь обнаружила, что язык людей настолько похож на его собственный, что он мог хорошо их понять, и они его».

- ^ См.:

- "Смажьте еду (жилое слово другого орд -станции]] Приложение noe (на гавайском языке) 30 июня 1911 года. P. 8

- Низкий, Андреа (8 мая 2024 г.). «Яркое небо выше: гавайская диаспора в Аотеароа» . Пост . [ страница необходима ]

- ^ «Экспедиция Rapanui раскрывает сходство с Te reo Maori» . Радио Новая Зеландия . 16 октября 2012 года. Архивировано с оригинала 29 марта 2019 года . Получено 29 марта 2019 года .

- ^ «Quickstats о маори» . Статистика Новая Зеландия. 2006. Архивировано из оригинала 21 сентября 2013 года . Получено 14 ноября 2007 года . (Пересмотренный 2007)

- ^ «Языковые проблемы маори - Комиссия маори» . Комиссия по языку маори. Архивировано из оригинала 2 января 2002 года . Получено 12 февраля 2011 года .

- ^ «Спикеры по языку маори» . Статистика Новая Зеландия . 2013. Архивировано с оригинала 2 сентября 2017 года . Получено 2 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Олбери, Натан (2016). Проект - это народная лингвиза. Иегова 20 (3): 287–311. doi : 10.111/Josl . HDL : 10852/58904 , p. 301.

- ^ «Перепись 2016 года, язык, на котором говорят дома по сексу (SA2+)» . Австралийское бюро статистики . Архивировано с оригинала 26 декабря 2018 года . Получено 28 октября 2017 года .

- ^ Aldworth, Джон (12 мая 2012 г.). «Скалы могли бы раскачивать историю» . Новая Зеландия Вестник . Архивировано из оригинала 21 августа 2017 года . Получено 5 мая 2017 года .

- ^ Салмонд, Энн (1997). Между мирами: ранние обмены между маори и европейцами, 1773–1815 . Окленд: викинг.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Браунсон, Рон (23 декабря 2010 г.). "Застава" . Персонал и друзья Оклендской художественной галереи Toi O Tāmaki. Архивировано с оригинала 26 января 2018 года . Получено 13 января 2018 года .

- ^ Хика, Хонги. «Образец письма Шунги [Хонги Хика] на борту активного» . Марсден онлайн архив . Университет Отаго. Архивировано из оригинала 25 мая 2015 года . Получено 25 мая 2015 года .

- ^ "Миссионерский регистр" . Ранние новозеландские книги (ENZB), библиотека Университета Окленда . 1831. С. 54–55. Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2018 года . Получено 9 марта 2019 года .

- ^ Мэй, Хелен; Каур, Балджит; Prochner, Larry (2016). Империя, образование и детство коренных народов: миссионерские детские школы девятнадцатого века в трех британских колониях . Routledge. п. 206. ISBN 978-1-317-14434-2 Полем Получено 16 февраля 2020 года .

- ^ Stack, Джеймс Уэст (1938). Рид, Альфред Хэмиш (ред.). Раннее маориленд приключения JW Stack . п. 217

- ^ Стоуэлл, Генри М. (ноябрь 2008 г.). Маори-английский репетитор и вад . Читать книги. ISBN 9781443778398 Полем Это была первая попытка автора маори в грамматике маори.

- ^ Апануи, Нгахиви (11 сентября 2017 г.). «Что это за маленькая линия? Какой у тебя маленький список?» Полем Вещи . Вещи. Архивировано из оригинала 16 июня 2018 года . Получено 16 июня 2018 года .

- ^ «Орфографические соглашения маори» . Комиссия по языку маори. Архивировано из оригинала 6 сентября 2009 года . Получено 11 июня 2010 года .

- ^ Кин, Василий (11 марта 2010 г.). «Технология образования - информационные технологии - язык маори в Интернете» . Дорога: энциклопедия Новой Зеландии . Получено 29 июня 2017 года .

- ^ «Почему вещи представляют макроны для слов маори теори» . Вещи . 10 сентября 2017 года . Получено 10 октября 2018 года .

- ^ «Семь острых - почему макроны так важны в маори» . tvnz.co.nz. Архивировано с оригинала 11 октября 2018 года . Получено 10 октября 2018 года .

- ^ Штатные репортеры. «Официальный язык, чтобы получить все наши усилия» . Новая Зеландия Вестник . ISSN 1170-0777 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 апреля 2020 года . Получено 10 октября 2018 года .

- ^ Кин, Василий (11 марта 2010 г.). «Технология образования - информационные технологии - язык маори в Интернете» . Дорога: энциклопедия Новой Зеландии . Получено 16 февраля 2020 года .