Махараштра

Махараштра | |

|---|---|

| Штат Махараштра | |

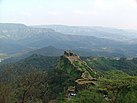

Сверху слева направо: пещеры Аджанта , храм Кайласа в пещерах Эллора , форт Пратапгад (недалеко от Махабалешвара ), расположенный в Западных Гатах , статуя Чатрапати возле форта Райгад , Шанивар Вада , Хазур Сахиб Нандед , конечная остановка Чхатрапати Шиваджи , Ворота Индии. | |

| Этимология: «маха» (Великий) и санскритская форма «династия Ратта». | |

| Прозвище: «Ворота Индии» | |

| Девиз(ы) : Пратипачандралекхева вардхишнурвишва вандита Махараштрасья раджьясйа мудра бхадрайа раджате (Слава Махараштры будет расти, как первая дневная луна. Ей будет поклоняться мир, и она будет сиять только на благо людей) | |

| Гимн: Джай Джай Махараштра Маджха. (Победа Моей Махараштре!) [1] | |

Расположение Махараштры в Индии | |

| Координаты: 18 ° 58' с.ш. 72 ° 49' в.д. / 18,97 ° с.ш. 72,82 ° в.д. | |

| Страна | |

| Область | Вест-Индия |

| Раньше было | Штат Бомбей (1950–1960) |

| Формирование ( по развилке ) | 1 мая 1960 г. |

| Капитал | Мумбаи Нагпур (зима) |

| Крупнейший город | Мумбаи |

| Крупнейшее метро | Столичный регион Мумбаи |

| Районы | 36 (6 дивизий) |

| Правительство | |

| • Тело | Правительство Махараштры |

| • Губернатор | КП Радхакришнан |

| • Главный министр | Экнат Шинде ( SHS ) |

| • Заместитель главного министра | Девендра Фаднавис ( БДП ) Аджит Павар ( NCP ) |

| Законодательное собрание штата | двухпалатный Законодательное собрание Махараштры |

| • Совет | Законодательный совет Махараштры ( 78 мест ) |

| • Сборка | Законодательное собрание Махараштры ( 288 мест ) |

| Национальный парламент | Парламент Индии |

| • Раджья Сабха | 19 мест |

| • Лок Сабха | 48 мест |

| Высокий суд | Высокий суд Бомбея |

| Область | |

| • Общий | 307 713 км 2 (118 809 квадратных миль) |

| • Классифицировать | 3-й |

| Размеры | |

| • Длина | 605 км (376 миль) |

| • Ширина | 870 км (540 миль) |

| Высота | 100 м (300 футов) |

| Самая высокая точка | 1646 м (5400 футов) |

| Самая низкая высота ( Аравийское море ) | −1 м (−3 фута) |

| Население (2011) [4] | |

| • Общий | |

| • Классифицировать | 2-й |

| • Плотность | 370/км 2 (1000/кв. миль) |

| • Городской | 45.22% |

| • Деревенский | 54.78% |

| Демоним | Махараштриан |

| Язык | |

| • Официальный | Маратхи [5] [6] |

| • Официальный сценарий | Сценарий деванагари |

| ВВП | |

| • Общий (2024–25) | |

| • Классифицировать | (1-й) |

| • На душу населения | |

| Часовой пояс | UTC+05:30 ( IST ) |

| Код ISO 3166 | ИН-МХ |

| Регистрация автомобиля | МХ |

| ИЧР (2022) | |

| Грамотность (2017) | |

| Соотношение полов (2021) | 966 ♀ /1000 ♂ [11] ( 23-е ) |

| Веб-сайт | Махараштра |

| Символы Махараштры | |

| |

| Песня | Джай Джай Махараштра Маджха (Победа Моей Махараштре!) [1] |

| День основания | День Махараштры |

| Птица | Желтоногий зеленый голубь [12] |

| Бабочка | Синий мормон [13] |

| Рыба | Серебряный Помфрет |

| Цветок | угли [12] [14] |

| млекопитающее | Индийская гигантская белка [12] |

| Дерево | Манговое дерево [12] [15] |

| Знак государственной автомагистрали | |

| |

| Государственное шоссе Махараштры МХ Ш1-МХ SH368 | |

| Список государственных символов Индии | |

| ^ Штат Бомбей был разделен на два штата, т.е. Махараштру и Гуджарат, в соответствии с Законом о реорганизации Бомбея 1960 года. [16] †† Общий высокий суд | |

Махараштра ( ISO : Махараштра ; Маратхи: [махаːɾaːʂʈɾə] — штат в западном полуостровном регионе Индии, занимающий значительную часть Деканского плато . Он граничит с Аравийским морем на западе, индийскими штатами Карнатака и Гоа на юге, Теланганой на юго-востоке и Чхаттисгархом на востоке, Гуджаратом и Мадхья-Прадешем на севере, а также индийской союзной территорией Дадра и Нагар-Хавели. и Даман и Диу на северо-западе. [17] Махараштра — второй по численности населения штат Индии.

Штат разделен на 6 округов и 36 округов , столицей которого является Мумбаи , самый густонаселенный городской район Индии, и Нагпур, служащий зимней столицей. [18] Годавари — две основные реки штата , и Кришна а леса покрывают 16,47 процента географической территории штата. В штате находятся шесть объектов всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО : пещеры Аджанта , пещеры Эллора , пещеры Элефанта , конечная остановка Чатрапати Шиваджи (бывшая конечная остановка Виктория), ансамбли викторианской готики и ар-деко Мумбаи и Западные Гаты , объект наследия, состоящий из 39 объектов. отдельные объекты недвижимости, из которых 4 находятся в Махараштре. [19] [20] Штат является крупнейшим вкладчиком в экономику Индии с долей 14 процентов в номинальном ВВП всей Индии . [21] [22] [23] Экономика Махараштры является крупнейшей в Индии: валовой внутренний продукт штата (ВВП) составляет фунтов стерлингов 42,5 триллиона (510 миллиардов долларов США) и ВВП на душу населения стерлингов 335 247 фунтов (4000 долларов США). [8] Сектор услуг доминирует в экономике штата, на его долю приходится 69,3 процента стоимости продукции страны. Хотя на сельское хозяйство приходится 12 процентов ВВП штата, в нем занято почти половина населения штата.

Махараштра – один из самых промышленно развитых штатов Индии. Столица штата Мумбаи является финансовой и коммерческой столицей Индии. [24] крупнейшая фондовая биржа Индии Бомбейская фондовая биржа В городе расположена , старейшая в Азии, а также Национальная фондовая биржа , которая является второй по величине фондовой биржей в Индии и одной из крупнейших в мире бирж деривативов . страны Государство сыграло значительную роль в социальной и политической жизни и широко считается лидером с точки зрения сельскохозяйственного и промышленного производства , торговли и транспорта, а также образования. [25] Махараштра занимает девятое место среди индийских штатов по индексу человеческого развития . [26]

Регион, в состав которого входит государство, имеет многотысячелетнюю историю. Известные династии, которые правили регионом, включают Асмаков , Маурьев , Сатаваханов , Западных Сатрапов , Абхиров , Вакатаков , Чалукьев , Раштракутов , Западных Чалукьев , Сеуна Ядавов , Халджи , Туглаков , Багамани и Моголы . В начале девятнадцатого века регион был разделен между доминионами пешвы в Конфедерации маратхов и Низаматом Хайдарабада . После двух войн и провозглашения Индийской империи регион стал частью провинции Бомбей , провинции Берар и центральных провинций Индии под прямым британским правлением и Агентства штатов Декан под сюзеренитетом Короны. Между 1950 и 1956 годами провинция Бомбей стала штатом Бомбей в Индийском союзе, а Берар, штаты Декан и штаты Гуджарат были объединены в штат Бомбей. 1 мая 1960 года штат Бомбей был разделен на штат Махараштра и штат Гуджарат после долгой борьбы за создание особого штата для людей, говорящих на языке маратхи, через Движение Самьюкта Махараштра ( перевод «Объединённое движение Махараштры» ).

Этимология

[ редактировать ]Современный язык маратхи произошел от Махараштри Пракрита , [27] а слово Мархатта (позже использованное для обозначения маратхов ) встречается в джайнской литературе Махараштры. Термин Махараштра, наряду с Махараштрианом, Маратхи и Маратхом, возможно, произошел от одного и того же корня. Однако их точная этимология неясна. [28]

Наиболее широко распространенная теория среди ученых-лингвистов заключается в том, что слова Маратха и Махараштра в конечном итоге произошли от комбинации слов Маха и Растрика , [28] [29] название племени или династии вождей, правивших в регионе Декан . [30] Альтернативная теория утверждает, что этот термин происходит от слов маха («великий») и ратха / ратхи (« колесница » / «возничий»), что относится к умелым северным боевым силам, которые мигрировали на юг в этот район. [30] [29]

В « Харивамсе » царство Ядавов , называемое Анаратта, описывается как населенное преимущественно абхирасами ( Абхира-прайя-манушьям). Страна Анартта и ее жители назывались Сурастра и Саурастра, вероятно, в честь Раттов (Растр), родственных Растрикам из каменных Указов Ашоки, ныне известных как Махарастра и Маратты . [31]

Альтернативная теория утверждает, что этот термин происходит от слов маха («великий») и раштра («нация / господство»). [32] Однако эта теория вызывает несколько споров среди современных ученых, которые считают ее санскритской интерпретацией более поздних авторов. [28]

История

[ редактировать ]

многочисленные памятники позднего Хараппа или энеолита, принадлежащие культуре Йорве ( ок. 1300–700 гг. До н.э.). По всему штату были обнаружены [33] [34] Самое крупное обнаруженное поселение этой культуры находится в Даймабаде , где в этот период были глиняные укрепления, а также эллиптический храм с ямами для костра. [35] [36] В позднехараппский период произошла крупная миграция людей из Гуджарата в северную Махараштру. [37]

Махараштра находилась под властью Империи Маурьев в четвертом и третьем веках до нашей эры. Около 230 г. до н.э. Махараштра попала под власть династии Сатавахана , которая правила ею в течение следующих 400 лет. [38] За правлением Сатаваханов последовало правление Западных Сатрапов , Империи Гуптов , Гурджара-Пратихара , Вакатака , Кадамбас , Империя Чалукья , династия Раштракута , а также Западная Чалукья и династия Ядава . Буддийские Аурангабаде пещеры Аджанта современном в демонстрируют влияние стилей Сатавахана и Вакатака. Пещеры, возможно, были раскопаны именно в этот период. [39]

Династия Чалукья правила регионом с шестого по восьмой века нашей эры, и двумя выдающимися правителями были Пулакешин II , победивший североиндийского императора Харшу , и Викрамадитья II , победивший арабских захватчиков в восьмом веке. Династия Раштракута правила Махараштрой с восьмого по десятый век. [40] Арабский путешественник Сулейман аль-Махри описывал правителя династии Раштракута Амогхаваршу как «одного из четырех великих царей мира». [41] Династия Шилахара началась как вассалы династии Раштракута, которая правила плато Декан между восьмым и десятым веками. С начала 11 века по 12 век на Деканском плато, включающем значительную часть Махараштры, доминировали Западная империя Чалукья и династия Чола . [42] Несколько сражений произошли между Западной Империей Чалукья и династией Чола на плато Декан во время правления Раджи Чолы I , Раджендры Чолы I , Джаясимхи II , Сомешвары I и Викрамадитьи VI . [43]

В начале 14 века династия Ядава , правившая большей частью территории современной Махараштры, была свергнута правителем султаната Делийского Алауддином Халджи . Позже Мухаммад бин Туглук завоевал часть Декана и временно перенес свою столицу из Дели в Даулатабад в Махараштре. После падения Туглуков в 1347 году к власти пришел местный Бахманийский султанат Гулбарга, управлявший регионом в течение следующих 150 лет. [44] После распада султаната Бахамани Махараштра разделилась на пять : Низамшах Ахмеднагара , 1518 году Адилшах Биджапура , в Кутубшах Голконды , деканских Бидаршах Бидара и Имадшах султанатов Эличпура . Эти королевства часто воевали друг с другом. Объединившись, они решительно разгромили империю Виджаянагара в 1565 году. южную [45] Нынешняя территория Мумбаи находилась под властью Султаната Гуджарат до ее захвата Португалией в 1535 году, а династия Фаруки управляла регионом Хандеш между 1382 и 1601 годами, прежде чем окончательно была присоединена к Империи Великих Моголов . Малик Амбар , регент династии Низамшахов Ахмеднагара , с 1607 по 1626 год [46] увеличил силу и могущество Муртазы Низам Шаха II и собрал большую армию. Говорят, что Амбар представил концепцию партизанской войны в регионе Декан. [47] Малик Амбар помогал императору Великих Моголов Шаху Джахану в Дели против его мачехи Нур Джахан , которая хотела возвести на престол своего зятя. [48] [49] Дедушка Шиваджи , Малоджи, и отец Шахаджи служили под началом Амбара. [50]

В начале 17 века Шахаджи Бхосале , амбициозный местный генерал, служивший Ахмаднагарскому султанату , Моголам и Адил-шаху Биджапура в разные периоды своей карьеры, попытался установить свое независимое правление. [51] Эта попытка не увенчалась успехом, но его сыну Шиваджи удалось основать Империю маратхов . [52] Вскоре после смерти Шиваджи в 1680 году император Великих Моголов Аурангзеб начал кампанию по завоеванию территорий маратхов, а также королевств Адилшахи и Говалконда. [53] Эта кампания, более известная как Войны Великих Моголов и Маратхов , стала стратегическим поражением Великих Моголов. Аурангзебу не удалось полностью завоевать территории маратхов, и эта кампания оказала разрушительное воздействие на казну и армию Великих Моголов. [54] Вскоре после смерти Аурангзеба в 1707 году маратхи под предводительством Пешвы Баджирао I и назначенных им генералов, таких как Раноджи Шинде и Малхаррао Холкар , начали завоевывать территории Великих Моголов на севере и западе Индии, и к 1750-м годам они или их преемники ограничили Великих Моголов городом. из Дели. [55] На востоке семья Бхонсале из Нагпура расширила контроль маратхов до Бенгалии. [56] [57] [58] [59] [а] На пике своего развития империя маратхов охватывала большую часть субконтинента, охватывая территорию площадью более 2,8 миллиона квадратных километров (1,1 × 10 6 квадратных миль). Маратхам во многом приписывают окончание правления Великих Моголов в Индии. [53] [61] [62] [63]

После поражения от Ахмад Шаха Абдали афганских войск в Третьей битве при Панипате в 1761 году маратхи потерпели поражение. Однако вскоре они вернули себе утраченные территории и правили центральной и северной Индией, включая Дели, до конца восемнадцатого века. Примерно в 1660-х годах маратхи также создали мощный военно-морской флот , который на пике своего развития под командованием Канходжи Ангре доминировал в территориальных водах западного побережья Индии от Мумбаи до Савантвади . [64] Он сопротивлялся британским , португальским , голландским и сиддийским военным кораблям и сдерживал их военно-морские амбиции. Чарльз Меткалф, британский государственный служащий, а затем исполняющий обязанности генерал-губернатора, сказал в 1806 году: [65]

В Индии есть не более двух великих держав — Великобритании и маратхов, и каждое другое государство признает влияние той или другой. Каждый дюйм, который мы отступим, будет занят ими.

Британская Ост-Индская компания в 18 веке медленно расширяла территории, находящиеся под ее управлением. Третья англо-маратхская война (1817–1818) привела к распаду Империи маратхов, и Ост-Индская компания захватила империю. [66] [67] Флот маратхов доминировал примерно до 1730-х годов, к 1770-м годам находился в состоянии упадка и прекратил свое существование к 1818 году. [68]

Британцы Карачи управляли западной Махараштрой в рамках президентства Бомбея , которое охватывало территорию от в Пакистане до северного Декана. Ряд штатов маратхов продолжали оставаться княжескими государствами , сохраняя автономию в обмен на признание британского сюзеренитета . Крупнейшими княжескими государствами на территории были Нагпур , Сатара и штат Колхапур ; Сатара была присоединена к президентству Бомбея в 1848 году, а Нагпур был присоединен в 1853 году и стал провинцией Нагпур , позже входившей в состав Центральных провинций . Берар , который был частью Низама королевства Хайдарабад , был оккупирован британцами в 1853 году и присоединен к центральным провинциям в 1903 году. [69] Однако большой регион под названием Маратвада оставался частью штата Хайдарабад Низама на протяжении всего британского периода. Британцы правили регионом Махараштра с 1818 по 1947 год и влияли на все аспекты жизни жителей региона. Они внесли ряд изменений в правовую систему, [70][71][72] built modern means of transport including roads[73] and Railways,[74][75] took various steps to provide mass education, including that for previously marginalised classes and women,[76] established universities based on western system and imparting education in science, technology,[77] and western medicine,[78][79][80] standardised the Marathi language,[81][82][83][84] and introduced mass media by utilising modern printing technologies.[85] The 1857 war of independence had many Marathi leaders, though the battles mainly took place in northern India. The modern struggle for independence started taking shape in the late 1800s with leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Justice Mahadev Govind Ranade, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Pherozeshah Mehta and Dadabhai Naoroji evaluating the company rule and its consequences. Jyotirao Phule was the pioneer of social reform in the Maharashtra region in the second half of the 19th century. His social work was continued by Shahu, Raja of Kolhapur and later by B. R. Ambedkar. After the partial autonomy given to the states by the Government of India Act 1935, B. G. Kher became the first chief minister of the Congress party-led government of tri-lingual Bombay Presidency.[86] The ultimatum to the British during the Quit India Movement was given in Mumbai and culminated in the transfer of power and independence in 1947.[citation needed]

After Indian independence, princely states and Jagirs of the Deccan States Agency were merged into Bombay State, which was created from the former Bombay Presidency in 1950.[87] In 1956, the States Reorganisation Act reorganised the Indian states along linguistic lines, and Bombay Presidency State was enlarged by the addition of the predominantly Marathi-speaking regions of Marathwada (Aurangabad Division) from erstwhile Hyderabad state and Vidarbha region from the Central Provinces and Berar. The southernmost part of Bombay State was ceded to Mysore. In the 1950s, Marathi people strongly protested against bilingual Bombay state under the banner of Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti.[88][89] The notable leaders of the samiti included Keshavrao Jedhe, S.M. Joshi, Shripad Amrit Dange, Pralhad Keshav Atre and Gopalrao Khedkar. The key demand of the samiti called for a Marathi speaking state with Mumbai as its capital.[90] In the Gujarati speaking areas of the state, a similar Mahagujarat Movement demanded a separate Gujarat state comprising majority Gujarati areas. After many years of protests, which saw 106 deaths amongst the protestors, and electoral success of the samiti in 1957 elections, the central government led by Prime minister Nehru split Bombay State into two new states of Maharashtra and Gujarat on 1 May 1960.[91]

The state continues to have a dispute with Karnataka regarding the region of Belgaum and Karwar.[92][93] The Government of Maharashtra was unhappy with the border demarcation of 1957 and filed a petition to the Ministry of Home affairs of India.[94] Maharashtra claimed 814 villages, and 3 urban settlements of Belagon, Karwar and Nippani, all part of then Bombay Presidency before freedom of the country.[95] A petition by Maharashtra in the Supreme Court of India, staking a claim over Belagon, is currently pending.[96]

Geography

[edit]Maharashtra with a total area of 307,713 km2 (118,809 sq mi), is the third-largest state by area in terms of land area and constitutes 9.36 per cent of India's total geographical area. The State lies between 15°35' N to 22°02' N latitude and 72°36' E to 80°54' E longitude. It occupies the western and central part of the country and has a coastline stretching 840 kilometres (520 mi)[97] along the Arabian Sea.[98] The dominant physical feature of the state is its plateau character, which is separated from the Konkan coastline by the mountain range of the Western Ghats, which runs parallel to the coast from north to south. The Western Ghats, also known as the Sahyadri Range, has an average elevation of 1,200 metres (3,900 ft); its slopes gently descending towards the east and southeast.[99] The Western Ghats (or the Sahyadri Mountain range) provide a physical barrier to the state on the west, while the Satpura Hills along the north and Bhamragad-Chiroli-Gaikhuri ranges on the east serve as its natural borders.[100] This state's expansion from North to South is 720 km (450 mi) and East to West is 800 km (500 mi). To the west of these hills lie the Konkan coastal plains, 50–80 km (31–50 mi) in width. To the east of the Ghats lies the flat Deccan Plateau. The main rivers of the state are the Krishna, and its tributary, Bhima, the Godavari, and its main tributaries, Manjara, and Wardha-Wainganga and the Tapi, and its tributary Purna.[98][101] Maharashtra is divided into five geographic regions. Konkan is the western coastal region, between the Western Ghats and the sea.[102] Khandesh is the north region lying in the valley of the Tapti, Purna river.[101] Nashik, Malegaon Jalgaon, Dhule and Bhusawal are the major cities of this region.[103] Desh is in the centre of the state.[104] Marathwada, which was a part of the princely state of Hyderabad until 1956, is located in the southeastern part of the state.[98][105] Aurangabad and Nanded are the main cities of the region.[106] Vidarbha is the easternmost region of the state, formerly part of the Central Provinces and Berar.[107]

The state has limited area under irrigation, low natural fertility of soils, and large areas prone to recurrent drought. Due to this the agricultural productivity of Maharashtra is generally low as compared to the national averages of various crops. Maharashtra has been divided in to nine agro-climatic zones on the basis of annual rainfall soil types, vegetation and cropping pattern.[108]

Climate

[edit]

Maharashtra experiences a tropical wet and dry climate with hot, rainy, and cold weather seasons. Some areas more inland experience a hot semi arid climate, due to a rain shadow effect caused by the Western Ghats.[109] The month of March marks the beginning of the summer and the temperature rises steadily until June. In the central plains, summer temperatures rise to between 40 °C or 104.0 °F and 45 °C or 113.0 °F. May is usually the warmest and January the coldest month of the year. The winter season lasts until February with lower temperatures occurring in December and January. On the Deccan plateau that lies on eastern side of the Sahyadri mountains, the climate is drier, however, dew and hail often occur, depending on seasonal weather.[110]

The rainfall patterns in the state vary by the topography of different regions. The state can be divided into four meteorological regions, namely coastal Konkan, Western Maharashtra, Marathwada, and Vidarbha.[111] The southwest monsoon usually arrives in the last week of June and lasts till mid-September. Pre-monsoon showers begin towards the middle of June and post-monsoon rains occasionally occur in October. The highest average monthly rainfall is during July and August. In the winter season, there may be a little rainfall associated with western winds over the region. The Konkan coastal area, west of the Sahyadri Mountains receives very heavy monsoon rains with an annual average of more than 3,000 millimetres (120 in). However, just 150 km (93 mi) to the east, in the rain shadow of the mountain range, only 500–700 mm/year will fall, and long dry spells leading to drought are a common occurrence. Maharashtra has many of the 99 Indian districts identified by the Indian Central water commission as prone to drought.[112] The average annual rainfall in the state is 1,181 mm (46.5 in) and 75 per cent of it is received during the southwest monsoon from June–to September. However, under the influence of the Bay of Bengal, eastern Vidarbha receives good rainfall in July, August, and September.[113] Thane, Raigad, Ratnagiri, and Sindhudurg districts receive heavy rains of an average of 2,000 to 2,500 mm or 80 to 100 in and the hill stations of Matheran and Mahabaleshwar over 5,000 mm (200 in). Contrariwise, the rain shadow districts of Nashik, Pune, Ahmednagar, Dhule, Jalgaon, Satara, Sangli, Solapur, and parts of Kolhapur receive less than 1,000 mm (39 in) annually. In winter, a cool dry spell occurs, with clear skies, gentle air breeze, and pleasant weather that prevails from October to February, although the eastern Vidarbha region receives rainfall from the north-east monsoon.[114]

Flora and fauna

[edit]

The state has three crucial biogeographic zones, namely Western Ghats, Deccan Plateau, and the West coast. The Ghats nurture endemic species, Deccan Plateau provides for vast mountain ranges and grasslands while the coast is home to littoral and swamp forests. Flora of Maharashtra is heterogeneous in composition. In 2012 the recorded thick forest area in the state was 61,939 km2 (23,915 sq mi) which was about 20.13 per cent of the state's geographical area.[115] There are three main Public Forestry Institutions (PFIs) in the Maharashtra state: the Maharashtra Forest Department (MFD), the Forest Development Corporation of Maharashtra (FDCM) and the Directorate of Social Forestry (SFD).[116] The Maharashtra State Biodiversity Board, constituted by the Government of Maharashtra in January 2012 under the Biological Diversity Act, 2002, is the nodal body for the conservation of biodiversity within and outside forest areas in the State.[117][118]

Maharashtra is ranked second among the Indian states in terms of the recorded forest area. Recorded Forest Area (RFA) in the state is 61,579 sq mi (159,489 km2) of which 49,546 sq mi (128,324 km2) is reserved forests, 6,733 sq mi (17,438 km2) is protected forest and 5,300 sq mi (13,727 km2) is unclassed forests. Based on the interpretation of IRS Resourcesat-2 LISS III satellite data of the period Oct 2017 to Jan 2018, the State has 8,720.53 sq mi (22,586 km2) under Very Dense Forest(VDF), 20,572.35 sq mi (53,282 km2) under Moderately Dense Forest (MDF) and 21,484.68 sq mi (55,645 km2) under Open Forest (OF). According to the Champion and Seth classification, Maharashtra has five types of forests:[119]

- Southern Tropical Semi-Evergreen forests - These are found in the western ghats at a height of 400–1,000 m (1,300–3,300 ft). Anjani, Hirda, Kinjal, and Mango are predominant tree species found here.

- Southern Tropical Moist Deciduous forests-These are a mix of Moist Teak bearing forests (Melghat) and Moist Mixed deciduous forests (Vidarbha and Thane district). Commercially important Teak, Shishum, and bamboo are found here. In addition to evergreen Teak, some of the other tree species found in this type of forest include Jambul, Ain, and Shisam.[120]

- Southern Tropical Dry Deciduous forests-these occupy a major part of the state. Southern Tropical Thorn forests are found in the low rainfall regions of Marathwada, Vidarbha, Khandesh, and Western Maharashtra. At present, these forests are heavily degraded. Babul, Bor, and Palas are some of the tree species found here.

- Littoral and Swamp forests are mainly found in the Creeks of Sindhudurg and Thane districts of the coastal Konkan region. The state harbours significant mangrove, coastal and marine biodiversity, with 304 km2 (117 sq mi) of the area under mangrove cover as per the India State of Forest Report (ISFR) of the Forest survey India in the coastal districts of the state.

The most common animal species present in the state are monkeys, wild pigs, tiger, leopard, gaur, sloth bear, sambar, four-horned antelope, chital, barking deer, mouse deer, small Indian civet, golden jackal, jungle cat, and hare.[121] Other animals found in this state include reptiles such as lizards, scorpions and snake species such as cobras and kraits.[122] The state provides legal protection to its tiger population through six dedicated tiger reserves under the precincts of the National Tiger Conservation Authority.

The state's 720 km (450 mi) of sea coastline of the Arabian Sea marks the presence of various types of fish and marine animals. The Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) found 1527 marine animal species, including molluscs with 581 species, many crustacean species including crabs, shrimps, and lobsters, 289 fish species, and 141 species types of annelids (sea worms).[123]

Regions, divisions and districts

[edit]

Maharashtra has following geographical regions:

- North Maharashtra

- Konkan

- Marathwada

- Vidarbha

- Desh or Western Maharashtra

It consists of six administrative divisions:[124]

The state's six divisions are further divided into 36 districts, 109 sub-divisions, and 358 talukas.[125] Maharashtra's top five districts by population, as ranked by the 2011 Census, are listed in the following table.

Each district is governed by a district collector or district magistrate, appointed either by the Indian Administrative Service or the Maharashtra Civil Service.[126] Districts are subdivided into sub-divisions (Taluka) governed by sub-divisional magistrates, and again into blocks.[127] A block consists of panchayats (village councils) and town municipalities.[128][129] Talukas are intermediate level panchayat between the Zilla Parishad (district councils) at the district level and gram panchayat (village councils) at the lower level.[127][130]

Out of the total population of Maharashtra, 45.22 per cent of people live in urban regions. The total figure of the population living in urban areas is 50.8 million. There are 27 Municipal Corporations in Maharashtra.[131]

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mumbai  Pune | 1 | Mumbai | Mumbai City district | 18,414,288 | 11 | Kolhapur | Kolhapur | 660,861 |  Nagpur  Nashik |

| 2 | Pune | Pune | 5,049,968 | 12 | Sangli | Sangli | 650,000 | ||

| 3 | Nagpur | Nagpur | 2,497,777 | ||||||

| 4 | Nashik | Nashik | 2,362,769 | ||||||

| 5 | Thane | Thane | 1,886,941 | ||||||

| 6 | Aurangabad | Aurangabad | 1,189,376 | ||||||

| 7 | Solapur | Solapur | 951,118 | ||||||

| 8 | Amravati | Amravati | 846,801 | ||||||

| 9 | Jalgaon | Jalgaon | 737,411 | ||||||

| 10 | Nanded | Nanded | 550,564 | ||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 19,391,643 | — |

| 1911 | 21,474,523 | +10.7% |

| 1921 | 20,849,666 | −2.9% |

| 1931 | 23,959,300 | +14.9% |

| 1941 | 26,832,758 | +12.0% |

| 1951 | 32,002,564 | +19.3% |

| 1961 | 39,553,718 | +23.6% |

| 1971 | 50,412,235 | +27.5% |

| 1981 | 62,782,818 | +24.5% |

| 1991 | 78,937,187 | +25.7% |

| 2001 | 96,878,627 | +22.7% |

| 2011 | 112,374,333 | +16.0% |

| Source: Census of India[132] | ||

According to the provisional results of the 2011 national census, Maharashtra was at that time the richest state in India and the second-most populous state in India with a population of 112,374,333. Contributing to 9.28 per cent of India's population, males and females are 58,243,056 and 54,131,277, respectively.[133] The total population growth in 2011 was 15.99 per cent while in the previous decade it was 22.57 per cent.[134][135] Since independence, the decadal growth rate of population has remained higher (except in the year 1971) than the national average. However, in the year 2011, it was found to be lower than the national average.[135] The 2011 census for the state found 55 per cent of the population to be rural with 45 per cent being urban-based.[136][137] Although, India hasn't conducted a caste-wise census since Independence, based on the British era census of 1931, it is estimated that the Maratha and the Maratha-kunbi numerically form the largest caste cluster with around 32 per cent of the population.[138] Maharashtra has a large Other Backward Class population constituting 41 per cent of the population. The scheduled tribes include Adivasis such as Thakar, Warli, Konkana and Halba.[139] The 2011 census found scheduled castes and scheduled tribes to account for 11.8 per cent and 8.9 per cent of the population, respectively.[140] The state also includes a substantial number of migrants from other states of India.[141] Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, and Karnataka account for the largest percentage of migrants to the Mumbai metropolitan area.[142]

The 2011 census reported the human sex ratio is 929 females per 1000 males, which were below the national average of 943. The density of Maharashtra was 365 inhabitants per km2 which was lower than the national average of 382 per km2. Since 1921, the populations of Ratnagiri and Sindhudurg shrank by −4.96 per cent and −2.30 per cent, respectively, while the population of Thane grew by 35.9 per cent, followed by Pune at 30.3 per cent. The literacy rate is 83.2 per cent, higher than the national rate at 74.04 per cent.[143] Of this, male literacy stood at 89.82 per cent and female literacy 75.48 per cent.[144]

Religion

[edit]According to the 2011 census, Hinduism was the principal religion in the state at 79.8 per cent of the total population. Muslims constituted 11.5 per cent of the total population. Maharashtra has the highest number of followers of Buddhism in India, accounting for 5.8 per cent of Maharashtra's total population with 6,531,200 followers. Marathi Buddhists account for 77.36 per cent of all Buddhists in India.[146] Sikhs, Christians, and Jains constituted 0.2 per cent, 1.0 per cent, and 1.2 per cent of the Maharashtra population respectively.[145]

Maharashtra, and particularly the city of Mumbai, is home to two tiny religious communities. This includes 5000 Jews, mainly belonging to the Bene Israel, and Baghdadi Jewish communities.[147] Parsi is the other community who follow Zoroastrianism. The 2011 census recorded around 44,000 parsis in Maharashtra.[148]

Language

[edit]Marathi is the official language although different regions have their own dialects.[5][150][151] Most people speak regional languages classified as dialects of Marathi in the census. Powari, Lodhi, and Varhadi are spoken in the Vidarbha region, Dangi is spoken near the Maharashtra-Gujarat border, Bhil languages are spoken throughout the northwest part of the state, Khandeshi (locally known as Ahirani) is spoken in Khandesh region. In the Desh and Marathwada regions, Dakhini Urdu is widely spoken, although Dakhini speakers are usually bilingual in Marathi.[152]

Konkani, and its dialect Malvani, is spoken along the southern Konkan coast. Telugu and Kannada are spoken along the border areas of Telangana and Karnataka, respectively. At the junction of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Chhattisgarh a variety of Hindi dialects are spoken such as Lodhi and Powari. Lambadi is spoken through a wide area of eastern Marathwada and western Vidarbha. Gondi is spoken by diminishing minorities throughout Vidarbha but is most concentrated in the forests of Gadchiroli and the Telangana border.[citation needed]

Marathi is the first language of a majority or plurality of the people in all districts of Maharashtra except Nandurbar, where Bhili is spoken by 45% of its population. The highest percentage of Khandeshi speakers are Dhule district (29%) and the highest percentage of Gondi speakers are in Gadchiroli district (24%).[149]

The highest percentages of mother-tongue Hindi speakers are in urban areas, especially Mumbai and its suburbs, where it is mother tongue to over a quarter of the population. Pune and Nagpur are also spots for Hindi-speakers. Gujarati and Urdu are also major languages in Mumbai, both are spoken by around 10% of the population.[149] Urdu and its dialect, the Dakhni are spoken by the Muslim population of the state.[153]

The Mumbai metropolitan area is home to migrants from all over India. In Mumbai, a wide range of languages are spoken, including Telugu, Tamil, Konkani, Kannada, Sindhi, Punjabi, Bengali, Tulu, and many more.[149]

Governance and administration

[edit]

The state is governed through a parliamentary system of representative democracy, a feature the state shares with other Indian states. Maharashtra is one of the six states in India where the state legislature is bicameral, comprising the Vidhan Sabha (Legislative Assembly) and the Vidhan Parishad (Legislative Council).[154] The legislature, the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly, consists of elected members and special office bearers such as the Speaker and Deputy Speaker, who are elected by the members. The Legislative Assembly consists of 288 members who are elected for five-year terms unless the Assembly is dissolved before to the completion of the term. The Legislative Council is a permanent body of 78 members with one-third (33 members) retiring every two years. Maharashtra is the second most important state in terms of political representation in the Lok Sabha, or the lower chamber of the Indian Parliament with 48 seats which is next only to Uttar Pradesh which has the highest number of seats than any other Indian state with 80 seats.[155] Maharashtra also has 19 seats in the Rajya Sabha, or the upper chamber of the Indian Parliament.[156][157]

The government of Maharashtra is a democratically elected body in India with the Governor as its constitutional head who is appointed by the President of India for a five-year term.[158] The leader of the party or coalition with a majority in the Legislative Assembly is appointed as the chief minister by the governor, and the Council of Ministers are appointed by the governor on the advice of the chief minister.[159] The governor remains a ceremonial head of the state, while the chief minister and his council are responsible for day-to-day government functions. The council of ministers consists of Cabinet Ministers and Ministers of State (MoS). The Secretariat headed by the Chief Secretary assists the council of ministers. The Chief Secretary is also the administrative head of the government. Each government department is headed by a Minister, who is assisted by an Additional Chief Secretary or a Principal Secretary, who is usually an officer of the Indian Administrative Service, the Additional Chief Secretary/Principal Secretary serves as the administrative head of the department they are assigned to. Each department also has officers of the rank of Secretary, Special Secretary, Joint Secretary, etc. assisting the Minister and the Additional Chief Secretary/Principal Secretary.[citation needed]

For purpose of administration, the state is divided into 6 divisions and 36 districts. Divisional Commissioner, an IAS officer is the head of administration at the divisional level. The administration in each district is headed by a District Magistrate, who is an IAS officer and is assisted by several officers belonging to state services. Urban areas in the state are governed by Municipal Corporations, Municipal Councils, Nagar Panchayats, and seven Cantonment Boards.[135][160] The Maharashtra Police is headed by an IPS officer of the rank of Director general of police. A Superintendent of Police, an IPS officer assisted by the officers of the Maharashtra Police Service, is entrusted with the responsibility of maintaining law and order and related issues in each district. The Divisional Forest Officer, an officer belonging to the Indian Forest Service, manages the forests, environment, and wildlife of the district, assisted by the officers of Maharashtra Forest Service and Maharashtra Forest Subordinate Service.[161]

The judiciary in the state consists of the Maharashtra High Court (The High Court of Bombay), district and session courts in each district and lower courts and judges at the taluka level.[162] The High Court has regional branches at Nagpur and Aurangabad in Maharashtra and Panaji which is the capital of Goa.[163] The state cabinet on 13 May 2015 passed a resolution favouring the setting up of one more bench of the Bombay high court in Kolhapur, covering the region.[164] The President of India appoints the chief justice of the High Court of the Maharashtra judiciary on the advice of the chief justice of the Supreme Court of India as well as the Governor of Maharashtra.[165] Other judges are appointed by the chief justice of the high court of the judiciary on the advice of the Chief Justice.[166] Subordinate Judicial Service is another vital part of the judiciary of Maharashtra.[167] The subordinate judiciary or the district courts are categorised into two divisions: the Maharashtra civil judicial services and higher judicial service.[168] While the Maharashtra civil judicial services comprises the Civil Judges (Junior Division)/Judicial Magistrates and civil judges (Senior Division)/Chief Judicial Magistrate, the higher judicial service comprises civil and sessions judges.[169] The Subordinate judicial service of the judiciary is controlled by the District Judge.[166][170]

Politics

[edit]The politics of the state in the first decades after its formation in 1960 was dominated by the Indian National Congress party or its offshoots such as the Nationalist Congress Party. At present, it has been dominated by four political parties, the Bharatiya Janata Party, the Nationalist Congress Party, the Indian National Congress and the Shivsena.The politics of the state in the last five years has seen long term alliances breaking up like that of undivided Shivsena and BJP, new ones being formed between Congress, NCP, and the Shivsena, regional parties like the Shivsena and NCP splitting up, and majority of their legislators joining a new alliance government with the BJP.[citation needed]

Just like in other states in India, dynastic politics is fairly common also among political parties in Maharashtra.[171] The dynastic phenomenon is seen from the national level down to the district level and even village level. The three-tier structure of Panchayati Raj created in the state in the 1960s also helped to create and consolidate this phenomenon in rural areas. Apart from controlling the government, political families also control cooperative institutions, mainly cooperative sugar factories and district cooperative banks in the state.[172] The Bharatiya Janata Party also features several senior leaders who are dynasts.[173][174] In Maharashtra, the NCP has a particularly high level of dynasticism.[174]

In the early years, the politics of Maharashtra was dominated by Congress party figures such as Yashwantrao Chavan, Vasantdada Patil, Vasantrao Naik, and Shankarrao Chavan. Sharad Pawar, who started his political career in the Congress party, has been a towering personality in state and national politics for over forty years. During his career, he has split the Congress twice with significant consequences for the state politics.[175][176] The Congress party enjoyed a near unchallenged dominance of the political landscape until 1995 when the Shiv Sena and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) secured an overwhelming majority in the state to form a coalition government.[177] After his second parting from the Congress party in 1999, Sharad Pawar founded the NCP but then formed a coalition with the Congress to keep out the BJP-Shiv Sena combine out of the Maharashtra state government for fifteen years until September 2014. Prithviraj Chavan of the Congress party was the last Chief Minister of Maharashtra under the Congress-NCP alliance.[178][179][180] For the 2014 assembly polls, the two alliances between NCP and Congress and that between BJP and Shiv Sena respectively broke down over seat allocations. In the election, the largest number of seats went to the Bharatiya Janata Party, with 122 seats. The BJP initially formed a minority government under Devendra Fadnavis. The Shiv Sena entered the Government after two months and provided a comfortable majority for the alliance in the Maharashtra Vidhansabha for the duration of the assembly.[181] In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP-Shiv Sena alliance secured 41 seats out of 48 from the state.[182] Later in 2019, the BJP and Shiv Sena alliance fought the assembly elections together but the alliance broke down after the election over the post of the chief minister. Uddhav Thackeray of Shiv Sena then formed an alternative governing coalition under his leadership with his erstwhile opponents from NCP, INC, and several independent members of the legislative assembly.[183][184] Thackeray served as the 19th Chief minister of Maharashtra of the Maha Vikas Aghadi coalition until June 2022.[185][186][187]

In late June 2022, Eknath Shinde, a senior Shiv Sena leader, and the majority of MLAs from Shiv Sena joined hands with the BJP.[188][189][190] Governor Bhagat Singh Koshyari called for a trust vote, an action that would later on be described as a "sad spectacle" by Supreme Court of India,[191] and draw criticism from Political Observers.[192] Uddhav Thackeray resigned from the post as chief minister well as a MLC member ahead of no-confidence motion on 29 June 2022.[193] Shinde subsequently formed a new coalition with the BJP, and was sworn in as the Chief Minister on 30 June 2022.[194] BJP leader, Devendra Fadnavis was given the post of Deputy Chief Minister in the new government.[194] Uddhav Thackeray filed a lawsuit in Supreme Court of India claiming that Eknath Shinde and his group's actions meant that they were disqualified under Anti-defection law, with Eknath Shinde claiming that he has not defected, but rather represents the true Shiv Sena party.[195][196] The Supreme court delivered its verdict in May 2023. In its verdict the five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme court ruled that the Maharashtra governor and assembly speaker did not act as per the law.[197] However, the court said that it cannot order the restoration of the Uddhav Thackeray government as Thackeray resigned without facing a floor test.[198][195][196] Supreme Court also asked the Assembly Speaker to decide on the matter of disqualification of 16 MLAs including Chief Minister Eknath Shinde.[199][200] The case for decision on which faction has rights to use Shiv Sena Name and Symbol is currently being heard by Supreme Court.[201][202]

In July 2023, NCP leader Ajit Pawar, and a number of NCP state assembly members joined the Shivsena- BJP government led by Eknath Shinde.[203] Sharad Pawar, the founder of NCP, has condemned the move and expelled the rebels. Ajit Pawar has claimed support from majority of party legislators and office holders of the party, and has claimed the right to the NCP election symbol with the Election Commission of India.[204]

Economy

[edit]| Net state domestic product at factor cost at current prices (2004–05 base)[205] Figures in crores of Indian rupees | |

| Year | Net state domestic product |

|---|---|

| 2004–2005 | ₹3.683 trillion (US$44 billion) |

| 2005–2006 | ₹4.335 trillion (US$52 billion) |

| 2006–2007 | ₹5.241 trillion (US$63 billion) |

| 2007–2008 | ₹6.140 trillion (US$74 billion) |

| 2008–2009 | ₹6.996 trillion (US$84 billion) |

| 2009–2010 | ₹8.178 trillion (US$98 billion) |

| 2013–2014 | ₹15.101 trillion (US$180 billion) |

| 2014–2015 | ₹16.866 trillion (US$200 billion) |

| 2021-2022 | ₹31.441 trillion (US$380 billion) |

| 2022-2023 | ₹36.458 trillion (US$440 billion) |

| 2023-2024 | ₹40.441 trillion (US$480 billion) |

The economy of Maharashtra is driven by manufacturing, international trade, Mass Media (television, motion pictures, video games, recorded music), aerospace, technology, petroleum, fashion, apparel, and tourism.[206] Maharashtra is the most industrialised state and has maintained the leading position in the industrial sector in India.[207] The State is a pioneer in small scale industries.[208] Mumbai, the capital of the state and the financial capital of India, houses the headquarters of most of the major corporate and financial institutions. India's main stock exchanges and capital market and commodity exchanges are located in Mumbai. The state continues to attract industrial investments from domestic as well as foreign institutions. Maharashtra has the largest proportion of taxpayers in India and its share markets transact almost 70 per cent of the country's stocks.[209]

The Service sector dominates the economy of Maharashtra, accounting for 61.4 per cent of the value addition and 69.3 per cent of the value of output in the state.[210] The state's per-capita income in 2014 was 40 per cent higher than the all-India average in the same year.[211] The gross state domestic product (GSDP) at current prices for 2021–22 is estimated at $420 billion and contributes about 14.2 per cent of the GDP. The agriculture and allied activities sector contributes 13.2 per cent to the state's income. In 2012, Maharashtra reported a revenue surplus of ₹1524.9 million (US$24 million), with total revenue of ₹1,367,117 million (US$22 billion) and spending of ₹1,365,592.1 million (US$22 billion).[210] Maharashtra is the largest FDI destination of India. The FDI inflows in the State since April 2000 to September 2021 was ₹9,59,746 crore, which was 28.2 per cent of total FDI inflows at All-India level. With a total of 11,308 startups, Maharashtra has the highest number of recognised startups.

Maharashtra contributes 25 per cent of the country's industrial output[212] and is the most indebted state in the country.[213][214] Industrial activity in state is concentrated in Seven districts: Mumbai City, Mumbai Suburban, Thane, Aurangabad, Pune, Nagpur, and Nashik.[215] Mumbai has the largest share in GSDP (19.5 per cent), both Thane and Pune districts contribute about same in the Industry sector, Pune district contributes more in the agriculture and allied activities sector, whereas Thane district contributes more in the Services sector.[215] Nashik district shares highest in the agricultural and allied activities sector, but is behind in the Industry and Services sectors as compared to Thane and Pune districts.[215] Industries in Maharashtra include chemical and chemical products (17.6 per cent), food and food products (16.1 per cent), refined petroleum products (12.9 per cent), machinery and equipment (8 per cent), textiles (6.9 per cent), basic metals (5.8 per cent), motor vehicles (4.7 per cent) and furniture (4.3 per cent).[216] Maharashtra is the manufacturing hub for some of the largest public sector industries in India, including Hindustan Petroleum Corporation, Tata Petrodyne and Oil India Ltd.[217]

Maharashtra is the leading Indian state for many Creative industries including advertising, architecture, art, crafts, design, fashion, film, music, performing arts, publishing, R&D, software, toys and games, TV and radio, and video games.[citation needed]

Maharashtra has an above-average knowledge industry in India, with Pune Metropolitan Region being the leading IT hub in the state. Approximately 25 per cent of the top 500 companies in the IT sector are based in Maharashtra.[218] The state accounts for 28 per cent of the software exports of India.[218]

Maharashtra and particularly Mumbai is a prominent location for the Indian entertainment industry, with many films, television series, books, and other media being set there.[219] Mumbai is the largest centre for film and television production and a third of all Indian films are produced in the state. Multimillion-dollar Bollywood productions, with the most expensive costing up to ₹1.5 billion (US$18 million), are filmed there.[220] Marathi films used to be previously made primarily in Kolhapur, but now are produced in Mumbai.[221]

The state houses important financial institutions such as the Reserve Bank of India, the Bombay Stock Exchange, the National Stock Exchange of India, the SEBI and the corporate headquarters of numerous Indian companies and multinational corporations. It is also home to some of India's premier scientific and nuclear institutes like BARC, NPCL, IREL, TIFR, AERB, AECI, and the Department of Atomic Energy.[215]

With more than half the population being rural, agriculture and allied industries play an important role in the states's economy and source of income for the rural population.[222] The agriculture and allied activities sector contributes 12.9 per cent to the state's income. Staples such as rice and millet are the main monsoon crops. Important cash crops include sugarcane, cotton, oilseeds, tobacco, fruit, vegetables, and spices such as turmeric.[100] Animal husbandry is an important agriculture-related activity. The State's share in the livestock and poultry population in India is about 7 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively. Maharashtra was a pioneer in the development of Agricultural Cooperative Societies after independence. It was an integral part of the then Governing Congress party's vision of 'rural development with local initiative'. A 'special' status was accorded to the sugar cooperatives and the government assumed the role of a mentor by acting as a stakeholder, guarantor, and regulator,[223][224][225] Apart from sugar, cooperatives play a crucial role in dairy,[226] cotton, and fertiliser industries.

The banking sector comprises scheduled and non-scheduled banks.[218] Scheduled banks are of two types, commercial and cooperative. Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs) in India are classified into five types: State Bank of India and its associates, nationalised banks, private sector banks, Regional Rural Banks, and others (foreign banks). In 2012, there were 9,053 banking offices in the state, of which about 26 per cent were in rural and 54 per cent were in urban areas. Maharashtra has a microfinance system, which refers to small-scale financial services extended to the poor in both rural and urban areas. It covers a variety of financial instruments, such as lending, savings, life insurance, and crop insurance.[227] The three largest urban cooperative banks in India are all based in Maharashtra.[228]

Transport

[edit]

The state has a large, multi-modal transportation system with the largest road network in India.[229] In 2011, the total length of surface road in Maharashtra was 267,452 km (166,187 mi);[230] national highways accounted for 4,176 km (2,595 mi),[231] and state highways 3,700 km (2,300 mi).[230] The Maharashtra State Road Transport Corporation (MSRTC) provides economical and reliable passenger road transport service in the public sector.[232] These buses, popularly called ST (State Transport), are the preferred mode of transport for much of the populace. Hired forms of transport include metered taxis and auto-rickshaws, which often ply specific routes in cities. Other district roads and village roads provide villages, accessibility to meet their social needs as well as the means to transport agricultural produce from villages to nearby markets. Major district roads provide a secondary function of linking between main roads and rural roads. Approximately 98 per cent of villages are connected either via the highways or modern roads in Maharashtra. Average speed on state highways varies between 50–60 km/h (31–37 mph) due to the heavy presence of vehicles; in villages and towns, speeds are as low as 25–30 km/h (16–19 mph).[233]

The first passenger train in India ran from Mumbai to Thane on 16 April 1853.[234] Rail transportation is run by the Central Railway, Western Railway, South Central Railway, and South East Central Railway zones of the Indian Railways with the first two zones being headquartered in Mumbai, at Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (CSMT) and Churchgate respectively. Konkan Railway is headquartered in Navi Mumbai.[235][236] The Mumbai Rajdhani Express, the fastest Rajdhani train, connects the Indian capital of New Delhi to Mumbai.[237] Thane and CSMT are the busiest railway stations in India,[238] the latter serving as a terminal for both long-distance trains and commuter trains of the Mumbai Suburban Railway.

The two principal seaports, Mumbai Port and Jawaharlal Nehru Port, which is also in the Mumbai region, are under the control and supervision of the government of India.[239] There are around 48 minor ports in Maharashtra.[240] Most of these handle passenger traffic and have a limited capacity. None of the major rivers in Maharashtra are navigable and so river transport does not exist in the state.[citation needed]

Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport (formerly Bombay International Airport), is the state's largest airport. The four other international airports are Pune International Airport, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport at Nagpur, Nashik Airport, Shirdi Airport. Aurangabad Airport, Kolhapur Airport, Jalgaon Airport, and Nanded Airport are domestic airports in the state. Most of the State's airfields are operated by the Airports Authority of India (AAI) while Reliance Airport Developers (RADPL), currently operates five non-metro airports at Latur, Nanded, Baramati, Osmanabad and Yavatmal on a 95-year lease.[241] The Maharashtra Airport Development Company (MADC) was set up in 2002 to take up development of airports in the state that are not under the AAI or the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC). MADC is playing the lead role in the planning and implementation of the Multi-modal International Cargo Hub and Airport at Nagpur (MIHAN) project.[242] Additional smaller airports include Akola, Amravati, Chandrapur, Ratnagiri, and Solapur.[243] Maharashtra Metro Rail Corporation Limited (Maha Metro), headquartered in Nagpur is a Joint Venture establishment of Government of India & Government of Maharashtra headquartered in Nagpur, India. Maha Metro is responsible for the implementation of all Maharashtra state metro projects, except the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. Mumbai Metro is operational since 8 June 2014.[citation needed]

Education

[edit]

Census of 2011 showed literacy rates in the state for males and females were around 88.38% and 75.87% respectively.[244]

Regions that comprise the present day state of Maharashtra have been known for their pioneering role in the development of the modern education system in India. Scottish missionary John Wilson, American Marathi mission, Indian nationalists such as Vasudev Balwant Phadke and Bal Gangadhar Tilak, social reformers such as Jyotirao Phule, Dhondo Keshav Karve and Bhaurao Patil played a leading role in the setting up of modern schools and colleges during the British colonial era.[245][246][247][248] The forerunner of Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute was established in 1821. The Shreemati Nathibai Damodar Thackersey Women's University, the oldest women's liberal arts college in South Asia, started its journey in 1916. College of Engineering Pune, established in 1854, is the third oldest college in Asia.[249] Government Polytechnic Nagpur, established in 1914, is one of the oldest polytechnics in India.[250] Most of the private colleges including religious and special-purpose institutions were set up in the last thirty years after the State Government of Vasantdada Patil liberalised the Education Sector in 1982.[251]

Primary and secondary level education

[edit]Schools in the state are either managed by the government or by private trusts, including religious institutions.The medium of instruction in most of the schools is mainly Marathi, English, or Hindi, though Urdu is also used. The secondary schools are affiliated with the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE), the Central Board for Secondary Education (CBSE), the National Institute of Open School (NIOS), and the Maharashtra State Board of Secondary and Higher Secondary Education. Under the 10+2+3 plan, after completing secondary school, students typically enroll for two years in a junior college, also known as pre-university, or in schools with a higher secondary facility affiliated with the Maharashtra State Board of Secondary and Higher Secondary Education or any central board. Students choose from one of three streams, namely liberal arts, commerce, or science. Upon completing the required coursework, students may enrol in general or professional degree programs.[citation needed]

Tertiary education

[edit]

Maharashtra has 24 universities with a turnout of 160,000 Graduates every year.[252][253] Established during the rule of East India company in 1857 as Bombay University, The University of Mumbai, is the largest university in the world in terms of the number of graduates.[254] It has 141 affiliated colleges.[255] According to a report published by The Times Education magazine, 5 to 7 Maharashtra colleges and universities are ranked among the top 20 in India.[256][257][258] Maharashtra is also home to notable autonomous institutes as Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Indian Institute of Information Technology Pune, College of Engineering Pune (CoEP), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Technological University, Institute of Chemical Technology, Homi Bhabha National Institute, Walchand College of Engineering, Sangli, and Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute (VJTI), Sardar Patel College of Engineering (SPCE).[259] Most of these autonomous institutes are ranked the highest in India and have very competitive entry requirements. The University of Pune (now Savitribai Phule Pune University), the National Defence Academy, Film and Television Institute of India, Armed Forces Medical College, and National Chemical Laboratory were established in Pune soon after the Indian independence in 1947. Mumbai has an IIT, has National Institute of Industrial Engineering and Nagpur has IIM and AIIMS. Other notable institutes in the state are: Maharashtra National Law University, Nagpur (MNLUN), Maharashtra National Law University, Mumbai (MNLUM), Maharashtra National Law University, Aurangabad (MNLUA), Government Law College, Mumbai (GLC), ILS Law College, and Symbiosis Law School (SLS)[citation needed]

Agricultural universities include Vasantrao Naik Marathwada Agricultural University, Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Dr. Panjabrao Deshmukh Krishi Vidyapeeth, and Dr. Balasaheb Sawant Konkan Krishi Vidyapeeth,[260] Regional universities viz. Sant Gadge Baba Amravati University, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, North Maharashtra University, Shivaji University, Solapur University, Swami Ramanand Teerth Marathwada University, and Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur University are established to cover the educational needs at the district levels of the state. deemed universities are established in Maharashtra, including Symbiosis International University, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, and Tilak Maharashtra University.[261]

Vocational training in different trades such as construction, plumbing, welding, automobile mechanics is offered by post-secondary school Industrial Training Institute (ITIs).[262] Local community colleges also exist with generally more open admission policies, shorter academic programs, and lower tuition.[263]

Infrastructure

[edit]Healthcare

[edit]

Health indicators of Maharashtra show that they have attained relatively high growth against a background of high per capita income (PCI).[264] In 2011, the health care system in Maharashtra consisted of 363 rural government hospitals,[265] 23 district hospitals (with 7,561 beds), 4 general hospitals (with 714 beds) mostly under the Maharashtra Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and 380 private medical establishments; these establishments provide the state with more than 30,000 hospital beds.[266] It is the first state in India to have nine women's hospitals serving 1,365 beds.[266] The state also has a significant number of medical practitioners who hold the Bachelor of Ayurveda, Medicine and Surgery qualifications. These practitioners primarily use the traditional Indian therapy of Ayurveda, nevertheless, modern western medicine is used as well.[267]

In Maharashtra as well as in the rest of India, Primary Health Centre (PHC) is part of the government-funded public health system and is the most basic unit of the healthcare system. They are essentially single-physician clinics usually with facilities for minor surgeries, too.[268] Maharashtra has a life expectancy at birth of 67.2 years in 2011, ranking it third among 29 Indian states.[269] The total fertility rate of the state is 1.9.[270] The Infant mortality rate is 28 and the maternal mortality ratio is 104 (2012–2013), which are lower than the national averages.[271][272] Public health services are governed by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), through various departments. The Ministry is divided into two departments: the Public Health Department, which includes family welfare and medical relief, and the Department of Medical Education and Drugs.[273][274]

Health insurance includes any program that helps pay for medical expenses, through privately purchased insurance, social insurance, or a social welfare program funded by the government.[275] In a more technical sense, the term is used to describe any form of insurance that protects against the costs of medical services.[276] This usage includes private insurance and social insurance programs such as National Health Mission, which pools resources and spreads the financial risk associated with major medical expenses across the entire population to protect everyone, as well as social welfare programs such as National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) and the Health Insurance Program, which assist people who cannot afford health coverage.[275][276][277]

Energy

[edit]

Although its population makes Maharashtra one of the country's largest energy users,[278][279] conservation mandates, mild weather in the largest population centres, and strong environmental movements have kept its per capita energy use to one of the smallest of any Indian state.[280] The high electricity demand of the state constitutes 13 per cent of the total installed electricity generation capacity in India, which is mainly from fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas.[281] Mahavitaran is responsible for the distribution of electricity throughout the state by buying power from Mahanirmiti, captive power plants, other state electricity boards, and private sector power generation companies.[280]

As of 2012[update], Maharashtra was the largest power generating state in India, with an installed electricity generation capacity of 26,838 MW.[279] The state forms a major constituent of the western grid of India, which now comes under the North, East, West and North Eastern (NEWNE) grids of India.[278] Maharashtra Power Generation Company (MAHAGENCO) operates thermal power plants.[282] In addition to the state government-owned power generation plants, there are privately owned power generation plants that transmit power through the Maharashtra State Electricity Transmission Company, which is responsible for the transmission of electricity in the state.[283]

Environmental protection and sustainability

[edit]Maharashtra Pollution Control Board (MPCB) is established and responsible for implementing various environmental legislations in the state principally including the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, Water (Cess) Act, 1977 and some of the provisions under Environmental (Protection) Act, 1986 and the rules framed there under it including, Biomedical Waste (M&H) Rules, 1998, Hazardous Waste (M&H) Rules, 2000, and Municipal Solid Waste Rules, 2000. MPCB is functioning under the administrative control of the Environment Department of the Government of Maharashtra.[284] The Maharashtra Plastic and Thermocol Products ban became effective as law on 23 June 2018, subjecting plastic users to fines and potential imprisonment for repeat offenders.[285][286]

Culture

[edit]

Cuisine

[edit]Maharashtrian cuisine includes a variety of dishes ranging from mild to very spicy ones. Wheat, rice, jowar, bajri, vegetables, lentils and fruit form staple food of the Maharashtrian diet. Some of the popular traditional dishes include puran poli, ukdiche modak, Thalipeeth.[287] Street food items like Batata wada, Misal Pav, Pav Bhaji and Vada pav are very popular among the locals and are usually sold on stalls and in small hotels.[288] Meals (mainly lunch and dinner) are served on a plate called thali. Each food item served on the thali is arranged in a specific way. All non-vegetarian and vegetarian dishes are eaten with boiled rice, chapatis or with bhakris, made of jowar, bajra or rice flours. A typical vegetarian thali is made of chapati or bhakri (Indian flat bread), dal, rice (varan bhaat), amti, bhaji or usal, chutney, koshimbir (salad) and buttermilk or Sol kadhi. A bhaji is a vegetable dish made of a particular vegetable or combination of vegetables. Aamti is variant of the curry, typically consisting of a lentil (tur) stock, flavoured with goda masala and sometimes with tamarind or amshul, and jaggery (gul).[288][289] Varan is nothing but plain dal, a common Indian lentil stew. More or less, most of the dishes use coconut, onion, garlic, ginger, red chili powder, green chilies, and mustard though some section of the population traditionally avoid onion and garlics.[290][288]

Maharashtrian cuisine varies with the regions. Malvani (Konkani), Kolhapuri, and Varhadhi cuisins are examples of well known regional cuisines.[290] Kolhapur is famous for Tambda Pandhra rassa, a dish made of either chicken or mutton.[291] Rice and seafood are the staple foods of the coastal Konkani people. Among seafood, the most popular is a fish variety called the Bombay duck (also known as bombil in Marathi).[citation needed]

Attire

[edit]

Traditionally, Marathi women commonly wore the sari, often distinctly designed according to local cultural customs.[292] Most middle-aged and young women in urban Maharashtra dress in western outfits such as skirts and trousers or shalwar kameez with the traditionally nauvari or nine-yard lugade,[293] disappearing from the markets due to a lack of demand.[294] Older women wear the five-yard sari. In urban areas, the five-yard sari, especially the Paithani, is worn by younger women for special occasions such as marriages and religious ceremonies.[295] Among men, western dressing has greater acceptance. Men also wear traditional costumes such as the dhoti, and pheta[296] on cultural occasions. The Gandhi cap is the popular headgear among older men in rural Maharashtra.[292][297][298] Women wear traditional jewellery derived from Maratha and Peshwa dynasties. Kolhapuri saaj, a special type of necklace, is also worn by Marathi women.[292] In urban areas, western attire is dominant amongst women and men.[298]

Music

[edit]Maharashtra and Maharashtrian artists have been influential in preserving and developing Hindustani classical music for more than a century. Notable practitioners of Kirana or Gwalior style called Maharashtra their home. The Sawai Gandharva Bhimsen Festival in Pune started by Bhimsen Joshi in the 1950s is considered the most prestigious Hindustani music festival in India, if not one of the largest.[299]

Cities like Kolhapur and Pune have been playing a major role in the preservation of music like Bhavageet and Natya Sangeet, which are inherited from Indian classical music. The biggest form of Indian popular music is songs from films produced in Mumbai. Film music, in 2009 made up 72 per cent of the music sales in India.[300] Many the influential music composers and singers have called Mumbai their home.[citation needed]

In recent decades, the music scene in Maharashtra, and particularly in Mumbai has seen a growth of newer music forms such as rap.[301] The city also holds festivals in western music genres such as blues.[302] In 2006, the Symphony Orchestra of India was founded, housed at the NCPA in Mumbai. It is today the only professional symphony orchestra in India and presents two concert seasons per year, with world-renowned conductors and soloists.[citation needed]

Maharashtra has a long and rich tradition of folk music. Some of the most common forms of folk music in practice are Bhajan, Bharud, Kirtan, Gondhal,[303] and Koli Geet.[304]

Dance

[edit]

Marathi dance forms draw from folk traditions. Lavani is popular form of dance in the state. The Bhajan, Kirtan and Abhangas of the Warkari sect (Vaishanav Devotees) have a long history and are part of their daily rituals.[305][306] Koli dance (called 'Koligeete') is among the most popular dances of Maharashtra. As the name suggests, it is related to the fisher folk of Maharashtra, who are called Koli. Popular for their unique identity and liveliness, their dances represent their occupation. This type of dance is represented by both men and women. While dancing, they are divided into groups of two. These fishermen display the movements of waves and casting of the nets during their koli dance performances.[307][308]

Theatre

[edit]

Modern Theatre in Maharashtra can trace its origins to the British colonial era in the middle of the 19th century. It is modelled mainly after the western tradition but also includes forms like Sangeet Natak (musical drama). In recent decades, Marathi Tamasha has also been incorporated in some experimental plays.[309] The repertoire of Marathi theatre ranges from humorous social plays, farces, historical plays, and musical, to experimental plays and serious drama. Marathi Playwrights such as Vijay Tendulkar, Purushottam Laxman Deshpande, Mahesh Elkunchwar, Ratnakar Matkari, and Satish Alekar have influenced theatre throughout India.[310] Besides Marathi theatre, Maharashtra and particularly, Mumbai, has had a long tradition of theatre in other languages such as Gujarati, Hindi, and English.[311]

The National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCP) is a multi-venue, multi-purpose cultural centre in Mumbai which hosts events in music, dance, theatre, film, literature, and photography from India as well other places. It also presents new and innovative work in the performing arts field.[citation needed]

Literature

[edit]

Maharashtra's regional literature is about the lives and circumstances of Marathi people in specific parts of the state. The Marathi language, which boasts a rich literary heritage, is written in the Devanagari script.[312] The earliest instance of Marathi literature is Dnyaneshwari, a commentary on the Bhagavad Gita by 13th-century Bhakti Saint Dnyaneshwar and devotional poems called abhangs by his contemporaries such as Namdev, and Gora Kumbhar. Devotional literature from the Early modern period includes compositions in praise of the God Pandurang by Bhakti saints such as Tukaram, Eknath, and Rama by Ramdas respectively.[313][314]

19th century Marathi literature includes mainly Polemic works of social and political activists such as Balshastri Jambhekar, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Gopal Hari Deshmukh, Mahadev Govind Ranade, Jyotirao Phule, and Vishnushastri Krushnashastri Chiplunkar. Keshavasuta was a pioneer in modern Marathi poetry. The Hindutva proponent, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was a prolific writer. His work in English and Marathi consists of many essays, two novels, poetry, and plays.

Four Marathi writers have been honoured with the Jnanpith Award, India's highest literary award. They include novelists, Vishnu Sakharam Khandekar, and Bhalchandra Nemade, Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar (Kusumagraj) and Vinda Karandikar. The last two were known for their poetry as well.[315] Other notable writers from the early and mid 20th century include playwright Ram Ganesh Gadkari, novelist Hari Narayan Apte, poet, and novelist B. S. Mardhekar, Pandurang Sadashiv Sane, Vyankatesh Madgulkar, Pralhad Keshav Atre, Chintamani Tryambak Khanolkar, and Lakshman Shastri Joshi. Vishwas Patil, Ranjit Desai, and Shivaji Sawant are known for novels based on Maratha history. P. L. Deshpande gained popularity in the period after independence for depicting the urban middle class society. His work includes humour, travelogues, plays, and biographies.[316] Narayan Gangaram Surve, Shanta Shelke, Durga Bhagwat, Suresh Bhat, and Narendra Jadhav are some of the more recent authors.

Dalit literature originally emerged in the Marathi language as a literary response to the everyday oppressions of caste in mid-twentieth-century independent India, critiquing caste practices by experimenting with various literary forms.[317] In 1958, the term "Dalit literature" was used for the first conference of Maharashtra Dalit Sahitya Sangha (Maharashtra Dalit Literature Society) in Mumbai.[318]

Maharashtra, and particularly the cities in the state such as Mumbai and Pune are diverse with different languages being spoken. Mumbai is called home by writers in English such as Rohinton Mistry, Shobha De, and Salman Rushdie. Their novels are set with Mumbai as the backdrop.[319] Many eminent Urdu poets such as Kaifi Azmi, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Gulzar, and Javed Akhtar have been residents of Mumbai.

Cinema

[edit]

The first Indian feature-length film, Raja Harishchandra, was made in Maharashtra by Dadasaheb Phalke in 1913.[323] Phalke is widely considered the father of Indian cinema.[324] The Dadasaheb Phalke Award is India's highest award in cinema, given annually by the Government of India for lifetime contribution to Indian cinema.[325]

The Marathi film industry, initially located in Kolhapur, has spread throughout Mumbai. Well known for its art films, the early Marathi film industry included acclaimed directors such as Dadasaheb Phalke, V. Shantaram, Raja Thakur, Bhalji Pendharkar, Pralhad Keshav Atre, Baburao Painter, and Dada Kondke. Some of the directors who made acclaimed films in Marathi are Jabbar Patel, Mahesh Manjrekar, Amol Palekar, and Sanjay Surkar.

Durga Khote was one of the first women from respectable families to enter the film industry, thus breaking a social taboo.[326] Lalita Pawar, Sulabha Deshpande, and Usha Kiran featured in Hindi and Marathi movies. In 70s and 80s, Smita Patil, Ranjana Deshmukh, Reema Lagoo featured in both art and mainstream movies in Hindi and Marathi. Rohini Hattangadi starred in a number of acclaimed movies, and is the only Indian actress to win the BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role for her performance as Kasturba Gandhi in Gandhi (1982).[327] Bhanu Athaiya was the first Indian to win an Oscar in Best Costume Design category for Gandhi (1982).[328][329] In 90s and 2000s, Urmila Matondkar and Madhuri Dixit starred in critically acclaimed and high grossing films in Hindi and Marathi.[citation needed]

In earliest days of Marathi cinema, Suryakant Mandhare was a leading star.[330] In later years, Shriram Lagoo, Nilu Phule, Vikram Gokhale, Dilip Prabhavalkar played character roles in theatre, and Hindi and Marathi films. Ramesh Deo and Mohan Joshi played leading men in Mainstream Marathi movies.[331][332] In 70s and 80s, Sachin Pilgaonkar, Ashok Saraf, Laxmikant Berde and Mahesh Kothare created a "comedy film wave" in Marathi Cinema.[citation needed]