Большое депрессивное расстройство

Эту статью необходимо обновить . Причина: множество устаревших источников и информации (старше пяти лет). ( июль 2024 г. ) |

Большое депрессивное расстройство ( БДР ), также известное как клиническая депрессия , представляет собой психическое расстройство. [ 9 ] характеризуется как минимум двумя неделями постоянного плохого настроения , низкой самооценки и потери интереса или удовольствия от обычно приятных занятий. Разработанный группой американских врачей в середине 1970-х годов, [ 10 ] этот термин был принят Американской психиатрической ассоциацией для этого кластера симптомов расстройств настроения в версии Диагностического и статистического руководства по психическим расстройствам (DSM-III) 1980 года и с тех пор стал широко использоваться. Это расстройство является причиной второго по количеству лет инвалидности после болей в пояснице . [ 11 ]

Диагноз большого депрессивного расстройства основывается на сообщениях о переживаниях человека, поведении, сообщенном родственниками или друзьями, а также на обследовании психического статуса . [ 12 ] There is no laboratory test for the disorder, but testing may be done to rule out physical conditions that can cause similar symptoms.[12] The most common time of onset is in a person's 20s,[3][4] with females affected about twice as often as males.[4] Течение расстройства широко варьирует: от одного эпизода, продолжающегося несколько месяцев, до пожизненного расстройства с повторяющимися эпизодами большой депрессии .

Those with major depressive disorder are typically treated with psychotherapy and antidepressant medication.[1] Medication appears to be effective, but the effect may be significant only in the most severely depressed.[13][14] Hospitalization (which may be involuntary) may be necessary in cases with associated self-neglect or a significant risk of harm to self or others. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be considered if other measures are not effective.[1]

Major depressive disorder is believed to be caused by a combination of genetic, environmental, and psychological factors,[1] with about 40% of the risk being genetic.[5] Risk factors include a family history of the condition, major life changes, childhood traumas, certain medications, chronic health problems, and substance use disorders.[1][5] It can negatively affect a person's personal life, work life, or education, and cause issues with a person's sleeping habits, eating habits, and general health.[1][5]

Symptoms and signs

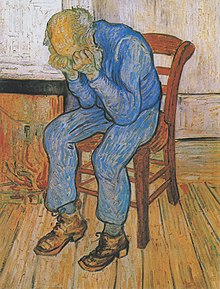

A person having a major depressive episode usually exhibits a low mood, which pervades all aspects of life, and an inability to experience pleasure in previously enjoyable activities.[15] Depressed people may be preoccupied with or ruminate over thoughts and feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt or regret, helplessness or hopelessness.[16]

Other symptoms of depression include poor concentration and memory,[17] withdrawal from social situations and activities, reduced sex drive, irritability, and thoughts of death or suicide. Insomnia is common; in the typical pattern, a person wakes very early and cannot get back to sleep. Hypersomnia, or oversleeping, can also happen,[18] as well as day-night rhythm disturbances, such as diurnal mood variation.[19] Some antidepressants may also cause insomnia due to their stimulating effect.[20] In severe cases, depressed people may have psychotic symptoms. These symptoms include delusions or, less commonly, hallucinations, usually unpleasant.[21] People who have had previous episodes with psychotic symptoms are more likely to have them with future episodes.[22]

A depressed person may report multiple physical symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, or digestive problems; physical complaints are the most common presenting problem in developing countries, according to the World Health Organization's criteria for depression.[23] Appetite often decreases, resulting in weight loss, although increased appetite and weight gain occasionally occur.[24]

Major depression significantly affects a person's family and personal relationships, work or school life, sleeping and eating habits, and general health.[25] Family and friends may notice agitation or lethargy.[18] Older depressed people may have cognitive symptoms of recent onset, such as forgetfulness,[26] and a more noticeable slowing of movements.[27]

Depressed children may often display an irritable rather than a depressed mood;[18] most lose interest in school and show a steep decline in academic performance.[28] Diagnosis may be delayed or missed when symptoms are interpreted as "normal moodiness".[24] Elderly people may not present with classical depressive symptoms.[29] Diagnosis and treatment is further complicated in that the elderly are often simultaneously treated with a number of other drugs, and often have other concurrent diseases.[29]

Cause

The etiology of depression is not yet fully understood.[31][32][33][34] The biopsychosocial model proposes that biological, psychological, and social factors all play a role in causing depression.[5][35] The diathesis–stress model specifies that depression results when a preexisting vulnerability, or diathesis, is activated by stressful life events. The preexisting vulnerability can be either genetic,[36][37] implying an interaction between nature and nurture, or schematic, resulting from views of the world learned in childhood.[38] American psychiatrist Aaron Beck suggested that a triad of automatic and spontaneous negative thoughts about the self, the world or environment, and the future may lead to other depressive signs and symptoms.[39][40]

Genetics

Genes play a major role in the development of depression.[41] Family and twin studies find that nearly 40% of individual differences in risk for major depressive disorder can be explained by genetic factors.[42] Like most psychiatric disorders, major depressive disorder is likely influenced by many individual genetic changes.[43] In 2018, a genome-wide association study discovered 44 genetic variants linked to risk for major depression;[44] a 2019 study found 102 variants in the genome linked to depression.[45] However, it appears that major depression is less heritable compared to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.[46][47] Research focusing on specific candidate genes has been criticized for its tendency to generate false positive findings.[48] There are also other efforts to examine interactions between life stress and polygenic risk for depression.[49]

Other health problems

Depression can also arise after a chronic or terminal medical condition, such as HIV/AIDS or asthma, and may be labeled "secondary depression".[50][51] It is unknown whether the underlying diseases induce depression through effect on quality of life, or through shared etiologies (such as degeneration of the basal ganglia in Parkinson's disease or immune dysregulation in asthma).[52] Depression may also be iatrogenic (the result of healthcare), such as drug-induced depression. Therapies associated with depression include interferons, beta-blockers, isotretinoin, contraceptives,[53] cardiac agents, anticonvulsants, antimigraine drugs, antipsychotics, and hormonal agents such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH agonist).[54] Celiac disease is another possible contributing factor.[55]

Substance use in early age is associated with increased risk of developing depression later in life.[56] Depression occurring after giving birth is called postpartum depression and is thought to be the result of hormonal changes associated with pregnancy.[57] Seasonal affective disorder, a type of depression associated with seasonal changes in sunlight, is thought to be triggered by decreased sunlight.[58] Vitamin B2, B6 and B12 deficiency may cause depression in females.[59]

Environmental

Adverse childhood experiences (incorporating childhood abuse, neglect and family dysfunction) markedly increase the risk of major depression, especially if more than one type.[5] Childhood trauma also correlates with severity of depression, poor responsiveness to treatment and length of illness. Some are more susceptible than others to developing mental illness such as depression after trauma, and various genes have been suggested to control susceptibility.[60] Couples in unhappy marriages have a higher risk of developing clinical depression.[61]

There appears to be a link between air pollution and depression and suicide. There may be an association between long-term PM2.5 exposure and depression, and a possible association between short-term PM10 exposure and suicide.[62]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of depression is not completely understood, but current theories center around monoaminergic systems, the circadian rhythm, immunological dysfunction, HPA-axis dysfunction and structural or functional abnormalities of emotional circuits.

Derived from the effectiveness of monoaminergic drugs in treating depression, the monoamine theory posits that insufficient activity of monoamine neurotransmitters is the primary cause of depression. Evidence for the monoamine theory comes from multiple areas. First, acute depletion of tryptophan—a necessary precursor of serotonin and a monoamine—can cause depression in those in remission or relatives of people who are depressed, suggesting that decreased serotonergic neurotransmission is important in depression.[63] Second, the correlation between depression risk and polymorphisms in the 5-HTTLPR gene, which codes for serotonin receptors, suggests a link. Third, decreased size of the locus coeruleus, decreased activity of tyrosine hydroxylase, increased density of alpha-2 adrenergic receptor, and evidence from rat models suggest decreased adrenergic neurotransmission in depression.[64] Furthermore, decreased levels of homovanillic acid, altered response to dextroamphetamine, responses of depressive symptoms to dopamine receptor agonists, decreased dopamine receptor D1 binding in the striatum,[65] and polymorphism of dopamine receptor genes implicate dopamine, another monoamine, in depression.[66][67] Lastly, increased activity of monoamine oxidase, which degrades monoamines, has been associated with depression.[68] However, the monoamine theory is inconsistent with observations that serotonin depletion does not cause depression in healthy persons, that antidepressants instantly increase levels of monoamines but take weeks to work, and the existence of atypical antidepressants which can be effective despite not targeting this pathway.[69]

One proposed explanation for the therapeutic lag, and further support for the deficiency of monoamines, is a desensitization of self-inhibition in raphe nuclei by the increased serotonin mediated by antidepressants.[70] However, disinhibition of the dorsal raphe has been proposed to occur as a result of decreased serotonergic activity in tryptophan depletion, resulting in a depressed state mediated by increased serotonin. Further countering the monoamine hypothesis is the fact that rats with lesions of the dorsal raphe are not more depressive than controls, the finding of increased jugular 5-HIAA in people who are depressed that normalized with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment, and the preference for carbohydrates in people who are depressed.[71] Already limited, the monoamine hypothesis has been further oversimplified when presented to the general public.[72] A 2022 review found no consistent evidence supporting the serotonin hypothesis, linking serotonin levels and depression.[73]

HPA-axis abnormalities have been suggested in depression given the association of CRHR1 with depression and the increased frequency of dexamethasone test non-suppression in people who are depressed. However, this abnormality is not adequate as a diagnosis tool, because its sensitivity is only 44%.[74] These stress-related abnormalities are thought to be the cause of hippocampal volume reductions seen in people who are depressed.[75] Furthermore, a meta-analysis yielded decreased dexamethasone suppression, and increased response to psychological stressors.[76] Further abnormal results have been obscured with the cortisol awakening response, with increased response being associated with depression.[77]

There is also a connection between the gut microbiome and the central nervous system, otherwise known as the Gut-Brain axis, which is a two-way communication system between the brain and the gut. Experiments have shown that microbiota in the gut can play an important role in depression as people with MDD often have gut-brain dysfunction. One analysis showed that those with MDD have different bacteria living in their guts. Bacteria Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were most affected in people with MDD, and they are also impacted in people with Irritable Bowel Syndrome.[78] Another study showed that people with IBS have a higher chance of developing depression, which shows the two are connected.[79] There is even evidence suggesting that altering the microbes in the gut can have regulatory effects on developing depression.[78]

Theories unifying neuroimaging findings have been proposed. The first model proposed is the limbic-cortical model, which involves hyperactivity of the ventral paralimbic regions and hypoactivity of frontal regulatory regions in emotional processing.[80] Another model, the cortico-striatal model, suggests that abnormalities of the prefrontal cortex in regulating striatal and subcortical structures result in depression.[81] Another model proposes hyperactivity of salience structures in identifying negative stimuli, and hypoactivity of cortical regulatory structures resulting in a negative emotional bias and depression, consistent with emotional bias studies.[82]

Immune Pathogenesis Theories on Depression

The newer field of psychoneuroimmunology, the study between the immune system and the nervous system and emotional state, suggests that cytokines may impact depression.

Immune system abnormalities have been observed, including increased levels of cytokines -cells produced by immune cells that affect inflammation- involved in generating sickness behavior, creating a pro-inflammatory profile in MDD.[83][84][85] Some people with depression have increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and some have decreased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines.[86] Research suggests that treatments can reduce pro-inflammatory cell production, like the experimental treatment of ketamine with treatment-resistant depression.[87] With this, in MDD, people will more likely have a Th-1 dominant immune profile, which is a pro-inflammatory profile. This suggests that there are components of the immune system affecting the pathology of MDD.[88]

Another way cytokines can affect depression is in the kynurenine pathway, and when this is overactivated, it can cause depression. This can be due to too much microglial activation and too little astrocytic activity. When microglia get activated, they release pro-inflammatory cytokines that cause an increase in the production of COX2. This, in turn, causes the production of PGE2, which is a prostaglandin, and this catalyzes the production of indolamine, IDO. IDO causes tryptophan to get converted into kynurenine and kynurenine becomes quinolinic acid.[89] Quinolinic acid is an agonist for NMDA receptors, so it activates the pathway. Studies have shown that the post-mortem brains of patients with MDD have higher levels of quinolinic acid than people who did not have MDD. With this, researchers have also seen that the concentration of quinolinic acid correlates to the severity of depressive symptoms.[90]

Diagnosis

Assessment

A diagnostic assessment may be conducted by a suitably trained general practitioner, or by a psychiatrist or psychologist,[25] who records the person's current circumstances, biographical history, current symptoms, family history, and alcohol and drug use. The assessment also includes a mental state examination, which is an assessment of the person's current mood and thought content, in particular the presence of themes of hopelessness or pessimism, self-harm or suicide, and an absence of positive thoughts or plans.[25] Specialist mental health services are rare in rural areas, and thus diagnosis and management is left largely to primary-care clinicians.[91] This issue is even more marked in developing countries.[92] Rating scales are not used to diagnose depression, but they provide an indication of the severity of symptoms for a time period, so a person who scores above a given cut-off point can be more thoroughly evaluated for a depressive disorder diagnosis. Several rating scales are used for this purpose;[93] these include the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression,[94] the Beck Depression Inventory[95] or the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised.[96]

Primary-care physicians have more difficulty with underrecognition and undertreatment of depression compared to psychiatrists. These cases may be missed because for some people with depression, physical symptoms often accompany depression. In addition, there may also be barriers related to the person, provider, and/or the medical system. Non-psychiatrist physicians have been shown to miss about two-thirds of cases, although there is some evidence of improvement in the number of missed cases.[97]

A doctor generally performs a medical examination and selected investigations to rule out other causes of depressive symptoms. These include blood tests measuring TSH and thyroxine to exclude hypothyroidism; basic electrolytes and serum calcium to rule out a metabolic disturbance; and a full blood count including ESR to rule out a systemic infection or chronic disease.[98] Adverse affective reactions to medications or alcohol misuse may be ruled out, as well. Testosterone levels may be evaluated to diagnose hypogonadism, a cause of depression in men.[99] Vitamin D levels might be evaluated, as low levels of vitamin D have been associated with greater risk for depression.[100] Subjective cognitive complaints appear in older depressed people, but they can also be indicative of the onset of a dementing disorder, such as Alzheimer's disease.[101][102] Cognitive testing and brain imaging can help distinguish depression from dementia.[103] A CT scan can exclude brain pathology in those with psychotic, rapid-onset or otherwise unusual symptoms.[104] No biological tests confirm major depression.[105] In general, investigations are not repeated for a subsequent episode unless there is a medical indication.

DSM and ICD criteria

The most widely used criteria for diagnosing depressive conditions are found in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). The latter system is typically used in European countries, while the former is used in the US and many other non-European nations,[106] and the authors of both have worked towards conforming one with the other.[107] Both DSM and ICD mark out typical (main) depressive symptoms.[108] The most recent edition of the DSM is the Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR),[109] and the most recent edition of the ICD is the Eleventh Edition (ICD-11).[110]

Under mood disorders, ICD-11 classifies major depressive disorder as either single episode depressive disorder (where there is no history of depressive episodes, or of mania) or recurrent depressive disorder (where there is a history of prior episodes, with no history of mania).[111] ICD-11 symptoms, present nearly every day for at least two weeks, are a depressed mood or anhedonia, accompanied by other symptoms such as "difficulty concentrating, feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt, hopelessness, recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, changes in appetite or sleep, psychomotor agitation or retardation, and reduced energy or fatigue."[111] These symptoms must affect work, social, or domestic activities. The ICD-11 system allows further specifiers for the current depressive episode: the severity (mild, moderate, severe, unspecified); the presence of psychotic symptoms (with or without psychotic symptoms); and the degree of remission if relevant (currently in partial remission, currently in full remission).[111] These two disorders are classified as "Depressive disorders", in the category of "Mood disorders".[111]

According to DSM-5, at least one of the symptoms is either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure. Depressed mood occurs nearly every day as subjective feelings like sadness, emptiness, and hopelessness or observations made by others (e.g. appears tearful). Loss of interest or pleasure occurs in all, or almost all activities of the day, nearly every day. These symptoms, as well as five out of the nine more specific symptoms listed, must frequently occur for more than two weeks (to the extent in which it impairs functioning) for the diagnosis.[112][113][failed verification] Major depressive disorder is classified as a mood disorder in the DSM-5.[114] The diagnosis hinges on the presence of single or recurrent major depressive episodes.[115] Further qualifiers are used to classify both the episode itself and the course of the disorder. The category Unspecified Depressive Disorder is diagnosed if the depressive episode's manifestation does not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode.[114]

Major depressive episode

A major depressive episode is characterized by the presence of a severely depressed mood that persists for at least two weeks.[24] Episodes may be isolated or recurrent and are categorized as mild (few symptoms in excess of minimum criteria), moderate, or severe (marked impact on social or occupational functioning). An episode with psychotic features—commonly referred to as psychotic depression—is automatically rated as severe.[114] If the person has had an episode of mania or markedly elevated mood, a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is made instead. Depression without mania is sometimes referred to as unipolar because the mood remains at one emotional state or "pole".[116]

Bereavement is not an exclusion criterion in the DSM-5, and it is up to the clinician to distinguish between normal reactions to a loss and MDD. Excluded are a range of related diagnoses, including dysthymia, which involves a chronic but milder mood disturbance;[117] recurrent brief depression, consisting of briefer depressive episodes;[118][119] minor depressive disorder, whereby only some symptoms of major depression are present;[120] and adjustment disorder with depressed mood, which denotes low mood resulting from a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor.[121]

Subtypes

The DSM-5 recognizes six further subtypes of MDD, called specifiers, in addition to noting the length, severity and presence of psychotic features:

- "Melancholic depression" is characterized by a loss of pleasure in most or all activities, a failure of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli, a quality of depressed mood more pronounced than that of grief or loss, a worsening of symptoms in the morning hours, early-morning waking, psychomotor retardation, excessive weight loss (not to be confused with anorexia nervosa), or excessive guilt.[122]

- "Atypical depression" is characterized by mood reactivity (paradoxical anhedonia) and positivity, significant weight gain or increased appetite (comfort eating), excessive sleep or sleepiness (hypersomnia), a sensation of heaviness in limbs known as leaden paralysis, and significant long-term social impairment as a consequence of hypersensitivity to perceived interpersonal rejection.[123]

- "Catatonic depression" is a rare and severe form of major depression involving disturbances of motor behavior and other symptoms. Here, the person is mute and almost stuporous, and either remains immobile or exhibits purposeless or even bizarre movements. Catatonic symptoms also occur in schizophrenia or in manic episodes, or may be caused by neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[124]

- "Depression with anxious distress" was added into the DSM-5 as a means to emphasize the common co-occurrence between depression or mania and anxiety, as well as the risk of suicide of depressed individuals with anxiety. Specifying in such a way can also help with the prognosis of those diagnosed with a depressive or bipolar disorder.[114]

- "Depression with peri-partum onset" refers to the intense, sustained and sometimes disabling depression experienced by women after giving birth or while a woman is pregnant. DSM-IV-TR used the classification "postpartum depression", but this was changed to not exclude cases of depressed woman during pregnancy. Depression with peripartum onset has an incidence rate of 3–6% among new mothers. The DSM-5 mandates that to qualify as depression with peripartum onset, onset occurs during pregnancy or within one month of delivery.[125]

- "Seasonal affective disorder" (SAD) is a form of depression in which depressive episodes come on in the autumn or winter, and resolve in spring. The diagnosis is made if at least two episodes have occurred in colder months with none at other times, over a two-year period or longer.[126]

Differential diagnoses

To confirm major depressive disorder as the most likely diagnosis, other potential diagnoses must be considered, including dysthymia, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, or bipolar disorder. Dysthymia is a chronic, milder mood disturbance in which a person reports a low mood almost daily over a span of at least two years. The symptoms are not as severe as those for major depression, although people with dysthymia are vulnerable to secondary episodes of major depression (sometimes referred to as double depression).[117] Adjustment disorder with depressed mood is a mood disturbance appearing as a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor, in which the resulting emotional or behavioral symptoms are significant but do not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode.[121]

Other disorders need to be ruled out before diagnosing major depressive disorder. They include depressions due to physical illness, medications, and substance use disorders. Depression due to physical illness is diagnosed as a mood disorder due to a general medical condition. This condition is determined based on history, laboratory findings, or physical examination. When the depression is caused by a medication, non-medical use of a psychoactive substance, or exposure to a toxin, it is then diagnosed as a specific mood disorder (previously called substance-induced mood disorder).[127]

Screening and prevention

Preventive efforts may result in decreases in rates of the condition of between 22 and 38%.[128] Since 2016, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for depression among those over the age 12;[129][130] though a 2005 Cochrane review found that the routine use of screening questionnaires has little effect on detection or treatment.[131] Screening the general population is not recommended by authorities in the UK or Canada.[132]

Behavioral interventions, such as interpersonal therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, are effective at preventing new onset depression.[128][133][134] Because such interventions appear to be most effective when delivered to individuals or small groups, it has been suggested that they may be able to reach their large target audience most efficiently through the Internet.[135]

The Netherlands mental health care system provides preventive interventions, such as the "Coping with Depression" course (CWD) for people with sub-threshold depression. The course is claimed to be the most successful of psychoeducational interventions for the treatment and prevention of depression (both for its adaptability to various populations and its results), with a risk reduction of 38% in major depression and an efficacy as a treatment comparing favorably to other psychotherapies.[133][136]

Management

The most common and effective treatments for depression are psychotherapy, medication, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT); a combination of treatments is the most effective approach when depression is resistant to treatment.[137] American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines recommend that initial treatment should be individually tailored based on factors including severity of symptoms, co-existing disorders, prior treatment experience, and personal preference. Options may include pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, exercise, ECT, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or light therapy. Antidepressant medication is recommended as an initial treatment choice in people with mild, moderate, or severe major depression, and should be given to all people with severe depression unless ECT is planned.[138] There is evidence that collaborative care by a team of health care practitioners produces better results than routine single-practitioner care.[139]

Psychotherapy is the treatment of choice (over medication) for people under 18,[140] and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), third wave CBT and interpersonal therapy may help prevent depression.[141] The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2004 guidelines indicate that antidepressants should not be used for the initial treatment of mild depression because the risk-benefit ratio is poor. The guidelines recommend that antidepressants treatment in combination with psychosocial interventions should be considered for:[140]

- People with a history of moderate or severe depression

- Those with mild depression that has been present for a long period

- As a second line treatment for mild depression that persists after other interventions

- As a first line treatment for moderate or severe depression.

The guidelines further note that antidepressant treatment should be continued for at least six months to reduce the risk of relapse, and that SSRIs are better tolerated than tricyclic antidepressants.[140]

Treatment options are more limited in developing countries, where access to mental health staff, medication, and psychotherapy is often difficult. Development of mental health services is minimal in many countries; depression is viewed as a phenomenon of the developed world despite evidence to the contrary, and not as an inherently life-threatening condition.[142] There is insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of psychological versus medical therapy in children.[143]

Lifestyle

Physical exercise has been found to be effective for major depression, and may be recommended to people who are willing, motivated, and healthy enough to participate in an exercise program as treatment.[144] It is equivalent to the use of medications or psychological therapies in most people.[7] In older people it does appear to decrease depression.[145] Sleep and diet may also play a role in depression, and interventions in these areas may be an effective add-on to conventional methods.[146] In observational studies, smoking cessation has benefits in depression as large as or larger than those of medications.[147]

Talking therapies

Talking therapy (psychotherapy) can be delivered to individuals, groups, or families by mental health professionals, including psychotherapists, psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical social workers, counselors, and psychiatric nurses. A 2012 review found psychotherapy to be better than no treatment but not other treatments.[148] With more complex and chronic forms of depression, a combination of medication and psychotherapy may be used.[149][150] There is moderate-quality evidence that psychological therapies are a useful addition to standard antidepressant treatment of treatment-resistant depression in the short term.[151] Psychotherapy has been shown to be effective in older people.[152][153] Successful psychotherapy appears to reduce the recurrence of depression even after it has been stopped or replaced by occasional booster sessions.

The most-studied form of psychotherapy for depression is CBT, which teaches clients to challenge self-defeating, but enduring ways of thinking (cognitions) and change counter-productive behaviors. CBT can perform as well as antidepressants in people with major depression.[154] CBT has the most research evidence for the treatment of depression in children and adolescents, and CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) are preferred therapies for adolescent depression.[155] In people under 18, according to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, medication should be offered only in conjunction with a psychological therapy, such as CBT, interpersonal therapy, or family therapy.[156] Several variables predict success for cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents: higher levels of rational thoughts, less hopelessness, fewer negative thoughts, and fewer cognitive distortions.[157] CBT is particularly beneficial in preventing relapse.[158][159] Cognitive behavioral therapy and occupational programs (including modification of work activities and assistance) have been shown to be effective in reducing sick days taken by workers with depression.[160] Several variants of cognitive behavior therapy have been used in those with depression, the most notable being rational emotive behavior therapy,[161] and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.[162] Mindfulness-based stress reduction programs may reduce depression symptoms.[163][164] Mindfulness programs also appear to be a promising intervention in youth.[165] Problem solving therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and interpersonal therapy are effective interventions in the elderly.[166]

Psychoanalysis is a school of thought, founded by Sigmund Freud, which emphasizes the resolution of unconscious mental conflicts.[167] Psychoanalytic techniques are used by some practitioners to treat clients presenting with major depression.[168] A more widely practiced therapy, called psychodynamic psychotherapy, is in the tradition of psychoanalysis but less intensive, meeting once or twice a week. It also tends to focus more on the person's immediate problems, and has an additional social and interpersonal focus.[169] In a meta-analysis of three controlled trials of Short Psychodynamic Supportive Psychotherapy, this modification was found to be as effective as medication for mild to moderate depression.[170]

Antidepressants

Conflicting results have arisen from studies that look at the effectiveness of antidepressants in people with acute, mild to moderate depression.[171] A review commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) concluded that there is strong evidence that SSRIs, such as escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline, have greater efficacy than placebo on achieving a 50% reduction in depression scores in moderate and severe major depression, and that there is some evidence for a similar effect in mild depression.[172] Similarly, a Cochrane systematic review of clinical trials of the generic tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline concluded that there is strong evidence that its efficacy is superior to placebo.[173] Antidepressants work less well for the elderly than for younger individuals with depression.[166]

To find the most effective antidepressant medication with minimal side-effects, the dosages can be adjusted, and if necessary, combinations of different classes of antidepressants can be tried. Response rates to the first antidepressant administered range from 50 to 75%, and it can take at least six to eight weeks from the start of medication to improvement.[138][174] Antidepressant medication treatment is usually continued for 16 to 20 weeks after remission, to minimize the chance of recurrence,[138] and even up to one year of continuation is recommended.[175] People with chronic depression may need to take medication indefinitely to avoid relapse.[25]

SSRIs are the primary medications prescribed, owing to their relatively mild side-effects, and because they are less toxic in overdose than other antidepressants.[176] People who do not respond to one SSRI can be switched to another antidepressant, and this results in improvement in almost 50% of cases.[177] Another option is to augment the atypical antidepressant bupropion to the SSRI as an adjunctive treatment.[178] Venlafaxine, an antidepressant with a different mechanism of action, may be modestly more effective than SSRIs.[179] However, venlafaxine is not recommended in the UK as a first-line treatment because of evidence suggesting its risks may outweigh benefits,[180] and it is specifically discouraged in children and adolescents as it increases the risk of suicidal thoughts or attempts.[181][182][183][184][185][186][187]

For children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe depressive disorder, fluoxetine seems to be the best treatment (either with or without cognitive behavioural therapy) but more research is needed to be certain.[188][182][189][183] Sertraline, escitalopram, duloxetine might also help in reducing symptoms. Some antidepressants have not been shown to be effective.[190][182] Medications are not recommended in children with mild disease.[191]

There is also insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness in those with depression complicated by dementia.[192] Any antidepressant can cause low blood sodium levels;[193] nevertheless, it has been reported more often with SSRIs.[176] It is not uncommon for SSRIs to cause or worsen insomnia; the sedating atypical antidepressant mirtazapine can be used in such cases.[194][195]

Irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors, an older class of antidepressants, have been plagued by potentially life-threatening dietary and drug interactions. They are still used only rarely, although newer and better-tolerated agents of this class have been developed.[196] The safety profile is different with reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors, such as moclobemide, where the risk of serious dietary interactions is negligible and dietary restrictions are less strict.[197]

It is unclear whether antidepressants affect a person's risk of suicide.[198] For children, adolescents, and probably young adults between 18 and 24 years old, there is a higher risk of both suicidal ideations and suicidal behavior in those treated with SSRIs.[199][200] For adults, it is unclear whether SSRIs affect the risk of suicidality. One review found no connection;[201] another an increased risk;[202] and a third no risk in those 25–65 years old and a decreased risk in those more than 65.[203] A black box warning was introduced in the United States in 2007 on SSRIs and other antidepressant medications due to the increased risk of suicide in people younger than 24 years old.[204] Similar precautionary notice revisions were implemented by the Japanese Ministry of Health.[205]

Other medications and supplements

The combined use of antidepressants plus benzodiazepines demonstrates improved effectiveness when compared to antidepressants alone, but these effects may not endure. The addition of a benzodiazepine is balanced against possible harms and other alternative treatment strategies when antidepressant mono-therapy is considered inadequate.[206]

For treatment-resistant depression, adding on the atypical antipsychotic brexpiprazole for short-term or acute management may be considered.[207] Brexpiprazole may be effective for some people, however, the evidence as of 2023 supporting its use is weak and this medication has potential adverse effects including weight gain and akathisia.[207] Brexpiprazole has not been sufficiently studied in older people or children and the use and effectiveness of this adjunctive therapy for longer term management is not clear.[207]

Ketamine may have a rapid antidepressant effect lasting less than two weeks; there is limited evidence of any effect after that, common acute side effects, and longer-term studies of safety and adverse effects are needed.[208][209] A nasal spray form of esketamine was approved by the FDA in March 2019 for use in treatment-resistant depression when combined with an oral antidepressant; risk of substance use disorder and concerns about its safety, serious adverse effects, tolerability, effect on suicidality, lack of information about dosage, whether the studies on it adequately represent broad populations, and escalating use of the product have been raised by an international panel of experts.[210][211]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and cytokine inhibitors are effective in treating depression. For instance, Celecoxib, an NSAID, is a selective COX-2 inhibitor– which is an enzyme that helps in the production of pain and inflammation.[212] In recent clinical trials, this NSAID has been shown helpful with treatment-resistant depression as it helps inhibit proinflammatory signaling.[213]

Statins, which are anti-inflammatory medications prescribed to lower cholesterol levels, have also been shown to have antidepressant effects. When prescribed for patients already taking SSRIs, this add-on treatment was shown to improve anti-depressant effects of SSRIs when compared to the placebo group. With this, statins have been shown to be effective in preventing depression in some cases too.[214]

There is insufficient high quality evidence to suggest omega-3 fatty acids are effective in depression.[215] There is limited evidence that vitamin D supplementation is of value in alleviating the symptoms of depression in individuals who are vitamin D-deficient.[100] Lithium appears effective at lowering the risk of suicide in those with bipolar disorder and unipolar depression to nearly the same levels as the general population.[216] There is a narrow range of effective and safe dosages of lithium thus close monitoring may be needed.[217] Low-dose thyroid hormone may be added to existing antidepressants to treat persistent depression symptoms in people who have tried multiple courses of medication.[218] Limited evidence suggests stimulants, such as amphetamine and modafinil, may be effective in the short term, or as adjuvant therapy.[219][220] Also, it is suggested that folate supplements may have a role in depression management.[221] There is tentative evidence for benefit from testosterone in males.[222]

Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a standard psychiatric treatment in which seizures are electrically induced in a person with depression to provide relief from psychiatric illnesses.[223]: 1880 ECT is used with informed consent[224] as a last line of intervention for major depressive disorder.[225] A round of ECT is effective for about 50% of people with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, whether it is unipolar or bipolar.[226] Follow-up treatment is still poorly studied, but about half of people who respond relapse within twelve months.[227] Aside from effects in the brain, the general physical risks of ECT are similar to those of brief general anesthesia.[228]: 259 Immediately following treatment, the most common adverse effects are confusion and memory loss.[225][229] ECT is considered one of the least harmful treatment options available for severely depressed pregnant women.[230]

A usual course of ECT involves multiple administrations, typically given two or three times per week, until the person no longer has symptoms. ECT is administered under anesthesia with a muscle relaxant.[231] Electroconvulsive therapy can differ in its application in three ways: electrode placement, frequency of treatments, and the electrical waveform of the stimulus. These three forms of application have significant differences in both adverse side effects and symptom remission. After treatment, drug therapy is usually continued, and some people receive maintenance ECT.[225]

ECT appears to work in the short term via an anticonvulsant effect mostly in the frontal lobes, and longer term via neurotrophic effects primarily in the medial temporal lobe.[232]

Other

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or deep transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive method used to stimulate small regions of the brain.[233] TMS was approved by the FDA for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (trMDD) in 2008[234] and as of 2014 evidence supports that it is probably effective.[235] The American Psychiatric Association,[236] the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Disorders,[237] and the Royal Australia and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists have endorsed TMS for trMDD.[238] Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is another noninvasive method used to stimulate small regions of the brain with a weak electric current. Several meta-analyses have concluded that active tDCS was useful for treating depression.[239][240]

There is a small amount of evidence that sleep deprivation may improve depressive symptoms in some individuals,[241] with the effects usually showing up within a day. This effect is usually temporary. Besides sleepiness, this method can cause a side effect of mania or hypomania.[242] There is insufficient evidence for Reiki[243] and dance movement therapy in depression.[244] Cannabis is specifically not recommended as a treatment.[245]

The microbiome of people with major depressive disorder differs from that of healthy people, and probiotic and synbiotic treatment may achieve a modest depressive symptom reduction.[246][247] With this, fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) are being researched as add-on therapy treatments for people who do not respond to typical therapies. It has been shown that the patient's depressive symptoms improved, with minor gastrointestinal issues, after a FMT, with improvements in symptoms lasting at least 4 weeks after the transplant.[248]

Prognosis

Studies have shown that 80% of those with a first major depressive episode will have at least one more during their life,[249] with a lifetime average of four episodes.[250] Other general population studies indicate that around half those who have an episode recover (whether treated or not) and remain well, while the other half will have at least one more, and around 15% of those experience chronic recurrence.[251] Studies recruiting from selective inpatient sources suggest lower recovery and higher chronicity, while studies of mostly outpatients show that nearly all recover, with a median episode duration of 11 months. Around 90% of those with severe or psychotic depression, most of whom also meet criteria for other mental disorders, experience recurrence.[252][253] Cases when outcome is poor are associated with inappropriate treatment, severe initial symptoms including psychosis, early age of onset, previous episodes, incomplete recovery after one year of treatment, pre-existing severe mental or medical disorder, and family dysfunction.[254]

A high proportion of people who experience full symptomatic remission still have at least one not fully resolved symptom after treatment.[255] Recurrence or chronicity is more likely if symptoms have not fully resolved with treatment.[255] Current guidelines recommend continuing antidepressants for four to six months after remission to prevent relapse. Evidence from many randomized controlled trials indicates continuing antidepressant medications after recovery can reduce the chance of relapse by 70% (41% on placebo vs. 18% on antidepressant). The preventive effect probably lasts for at least the first 36 months of use.[256]

Major depressive episodes often resolve over time, whether or not they are treated. Outpatients on a waiting list show a 10–15% reduction in symptoms within a few months, with approximately 20% no longer meeting the full criteria for a depressive disorder.[257] The median duration of an episode has been estimated to be 23 weeks, with the highest rate of recovery in the first three months.[258] According to a 2013 review, 23% of untreated adults with mild to moderate depression will remit within 3 months, 32% within 6 months and 53% within 12 months.[259]

Ability to work

Depression may affect people's ability to work. The combination of usual clinical care and support with return to work (like working less hours or changing tasks) probably reduces sick leave by 15%, and leads to fewer depressive symptoms and improved work capacity, reducing sick leave by an annual average of 25 days per year.[160] Helping depressed people return to work without a connection to clinical care has not been shown to have an effect on sick leave days. Additional psychological interventions (such as online cognitive behavioral therapy) lead to fewer sick days compared to standard management only. Streamlining care or adding specific providers for depression care may help to reduce sick leave.[160]

Life expectancy and the risk of suicide

Depressed individuals have a shorter life expectancy than those without depression, in part because people who are depressed are at risk of dying of suicide.[260] About 50% of people who die of suicide have a mood disorder such as major depression, and the risk is especially high if a person has a marked sense of hopelessness or has both depression and borderline personality disorder.[261][262] About 2–8% of adults with major depression die by suicide.[2][263] In the US, the lifetime risk of suicide associated with a diagnosis of major depression is estimated at 7% for men and 1% for women,[264] even though suicide attempts are more frequent in women.[265]

Depressed people also have a higher rate of dying from other causes.[266] There is a 1.5- to 2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease, independent of other known risk factors, and is itself linked directly or indirectly to risk factors such as smoking and obesity. People with major depression are less likely to follow medical recommendations for treating and preventing cardiovascular disorders, further increasing their risk of medical complications.[267] Cardiologists may not recognize underlying depression that complicates a cardiovascular problem under their care.[268]

Epidemiology

Major depressive disorder affected approximately 163 million people in 2017 (2% of the global population).[8] The percentage of people who are affected at one point in their life varies from 7% in Japan to 21% in France. In most countries the number of people who have depression during their lives falls within an 8–18% range. Lifetime rates are higher in the developed world (15%) compared to the developing world (11%).[4]

In the United States, 8.4% of adults (21 million individuals) have at least one episode within a year-long period; the probability of having a major depressive episode is higher for females than males (10.5% to 6.2%), and highest for those aged 18 to 25 (17%).[270] 15% of adolescents, ages 12 to 17, in America are also affected by depression, which is equal to 3.7 million teenagers.[271] Among individuals reporting two or more races, the US prevalence is highest.[270] Out of all the people suffering from MDD, only about 35% seek help from a professional for their disorder.[271]

Major depression is about twice as common in women as in men, although it is unclear why this is so, and whether factors unaccounted for are contributing to this.[272] The relative increase in occurrence is related to pubertal development rather than chronological age, reaches adult ratios between the ages of 15 and 18, and appears associated with psychosocial more than hormonal factors.[272] In 2019, major depressive disorder was identified (using either the DSM-IV-TR or ICD-10) in the Global Burden of Disease Study as the fifth most common cause of years lived with disability and the 18th most common for disability-adjusted life years.[273]

People are most likely to develop their first depressive episode between the ages of 30 and 40, and there is a second, smaller peak of incidence between ages 50 and 60.[274] The risk of major depression is increased with neurological conditions such as stroke, Parkinson's disease, or multiple sclerosis, and during the first year after childbirth (Postpartum depression).[275] It is also more common after cardiovascular illnesses, and is related more to those with a poor cardiac disease outcome than to a better one.[276][277] Depressive disorders are more common in urban populations than in rural ones and the prevalence is increased in groups with poorer socioeconomic factors, e.g., homelessness.[278] Depression is common among those over 65 years of age and increases in frequency beyond this age.[29] The risk of depression increases in relation to the frailty of the individual.[279] Depression is one of the most important factors which negatively impact quality of life in adults, as well as the elderly.[29] Both symptoms and treatment among the elderly differ from those of the rest of the population.[29]

Major depression was the leading cause of disease burden in North America and other high-income countries, and the fourth-leading cause worldwide as of 2006. In the year 2030, it is predicted to be the second-leading cause of disease burden worldwide after HIV, according to the WHO.[280] Delay or failure in seeking treatment after relapse and the failure of health professionals to provide treatment are two barriers to reducing disability.[281]

Comorbidity

Major depression frequently co-occurs with other psychiatric problems. The 1990–92 National Comorbidity Survey (US) reported that half of those with major depression also have lifetime anxiety and its associated disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder.[282] Anxiety symptoms can have a major impact on the course of a depressive illness, with delayed recovery, increased risk of relapse, greater disability and increased suicidal behavior.[283] Depressed people have increased rates of alcohol and substance use, particularly dependence,[284][285] and around a third of individuals diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) develop comorbid depression.[286] Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression often co-occur.[25] Depression may also coexist with ADHD, complicating the diagnosis and treatment of both.[287] Depression is also frequently comorbid with alcohol use disorder and personality disorders.[288] Depression can also be exacerbated during particular months (usually winter) in those with seasonal affective disorder. While overuse of digital media has been associated with depressive symptoms, using digital media may also improve mood in some situations.[289][290]

Depression and pain often co-occur. One or more pain symptoms are present in 65% of people who have depression, and anywhere from 5 to 85% of people who are experiencing pain will also have depression, depending on the setting—a lower prevalence in general practice, and higher in specialty clinics. Depression is often underrecognized, and therefore undertreated, in patients presenting with pain.[291] Depression often coexists with physical disorders common among the elderly, such as stroke, other cardiovascular diseases, Parkinson's disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[292]

History

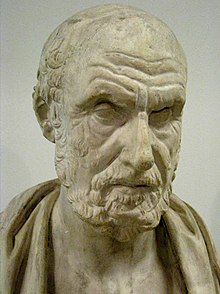

The Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates described a syndrome of melancholia (μελαγχολία, melankholía) as a distinct disease with particular mental and physical symptoms; he characterized all "fears and despondencies, if they last a long time" as being symptomatic of the ailment.[293] It was a similar but far broader concept than today's depression; prominence was given to a clustering of the symptoms of sadness, dejection, and despondency, and often fear, anger, delusions and obsessions were included.[294]

The term depression itself was derived from the Latin verb deprimere, meaning "to press down".[295] From the 14th century, "to depress" meant to subjugate or to bring down in spirits. It was used in 1665 in English author Richard Baker's Chronicle to refer to someone having "a great depression of spirit", and by English author Samuel Johnson in a similar sense in 1753.[296] The term also came into use in physiology and economics. An early usage referring to a psychiatric symptom was by French psychiatrist Louis Delasiauve in 1856, and by the 1860s it was appearing in medical dictionaries to refer to a physiological and metaphorical lowering of emotional function.[297] Since Aristotle, melancholia had been associated with men of learning and intellectual brilliance, a hazard of contemplation and creativity. However, by the 19th century, this association has largely shifted and melancholia became more commonly linked with women.[294]

Although melancholia remained the dominant diagnostic term, depression gained increasing currency in medical treatises and was a synonym by the end of the century; German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin may have been the first to use it as the overarching term, referring to different kinds of melancholia as depressive states.[298] Freud likened the state of melancholia to mourning in his 1917 paper Mourning and Melancholia. He theorized that objective loss, such as the loss of a valued relationship through death or a romantic break-up, results in subjective loss as well; the depressed individual has identified with the object of affection through an unconscious, narcissistic process called the libidinal cathexis of the ego. Such loss results in severe melancholic symptoms more profound than mourning; not only is the outside world viewed negatively but the ego itself is compromised.[299] The person's decline of self-perception is revealed in his belief of his own blame, inferiority, and unworthiness.[300] He also emphasized early life experiences as a predisposing factor.[294] Adolf Meyer put forward a mixed social and biological framework emphasizing reactions in the context of an individual's life, and argued that the term depression should be used instead of melancholia.[301] The first version of the DSM (DSM-I, 1952) contained depressive reaction and the DSM-II (1968) depressive neurosis, defined as an excessive reaction to internal conflict or an identifiable event, and also included a depressive type of manic-depressive psychosis within Major affective disorders.[302]

The term unipolar (along with the related term bipolar) was coined by the neurologist and psychiatrist Karl Kleist, and subsequently used by his disciples Edda Neele and Karl Leonhard.[303]

The term Major depressive disorder was introduced by a group of US clinicians in the mid-1970s as part of proposals for diagnostic criteria based on patterns of symptoms (called the "Research Diagnostic Criteria", building on earlier Feighner Criteria),[10] and was incorporated into the DSM-III in 1980.[304] The American Psychiatric Association added "major depressive disorder" to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III),[305] as a split of the previous depressive neurosis in the DSM-II, which also encompassed the conditions now known as dysthymia and adjustment disorder with depressed mood.[305] To maintain consistency the ICD-10 used the same criteria, with only minor alterations, but using the DSM diagnostic threshold to mark a mild depressive episode, adding higher threshold categories for moderate and severe episodes.[108][304] The ancient idea of melancholia still survives in the notion of a melancholic subtype.

The new definitions of depression were widely accepted, albeit with some conflicting findings and views. There have been some continued empirically based arguments for a return to the diagnosis of melancholia.[306][307] There has been some criticism of the expansion of coverage of the diagnosis, related to the development and promotion of antidepressants and the biological model since the late 1950s.[308]

Society and culture

Terminology

The term "depression" is used in a number of different ways. It is often used to mean this syndrome but may refer to other mood disorders or simply to a low mood. People's conceptualizations of depression vary widely, both within and among cultures. "Because of the lack of scientific certainty," one commentator has observed, "the debate over depression turns on questions of language. What we call it—'disease,' 'disorder,' 'state of mind'—affects how we view, diagnose, and treat it."[310] There are cultural differences in the extent to which serious depression is considered an illness requiring personal professional treatment, or an indicator of something else, such as the need to address social or moral problems, the result of biological imbalances, or a reflection of individual differences in the understanding of distress that may reinforce feelings of powerlessness, and emotional struggle.[311][312]

Cultural dimension

Cultural differences contribute to different prevalence of symptoms. "Do the Chinese somatize depression? A cross-cultural study" by Parker et al. discusses the cultural differences in prevalent symptoms of depression between individualistic and collectivistic cultures. The authors reveal that individuals with depression in collectivistic cultures tend to present more somatic symptoms and less affective symptoms compared to those in individualistic cultures. The finding suggests that individualistic cultures 'warranting' or validating one's expression of emotions explains this cultural difference since collectivistic cultures see this as a taboo against the social cooperation it deems one of the most significant values.[313]

Stigma

Historical figures were often reluctant to discuss or seek treatment for depression due to social stigma about the condition, or due to ignorance of diagnosis or treatments. Nevertheless, analysis or interpretation of letters, journals, artwork, writings, or statements of family and friends of some historical personalities has led to the presumption that they may have had some form of depression. People who may have had depression include English author Mary Shelley,[314] American-British writer Henry James,[315] and American president Abraham Lincoln.[316] Some well-known contemporary people with possible depression include Canadian songwriter Leonard Cohen[317] and American playwright and novelist Tennessee Williams.[318] Some pioneering psychologists, such as Americans William James[319][320] and John B. Watson,[321] dealt with their own depression.

There has been a continuing discussion of whether neurological disorders and mood disorders may be linked to creativity, a discussion that goes back to Aristotelian times.[322][323] British literature gives many examples of reflections on depression.[324] English philosopher John Stuart Mill experienced a several-months-long period of what he called "a dull state of nerves", when one is "unsusceptible to enjoyment or pleasurable excitement; one of those moods when what is pleasure at other times, becomes insipid or indifferent". He quoted English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Dejection" as a perfect description of his case: "A grief without a pang, void, dark and drear, / A drowsy, stifled, unimpassioned grief, / Which finds no natural outlet or relief / In word, or sigh, or tear."[325][326] English writer Samuel Johnson used the term "the black dog" in the 1780s to describe his own depression,[327] and it was subsequently popularized by British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill, who also had the disorder.[327] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in his Faust, Part I, published in 1808, has Mephistopheles assume the form of a black dog, specifically a poodle.

Social stigma of major depression is widespread, and contact with mental health services reduces this only slightly. Public opinions on treatment differ markedly to those of health professionals; alternative treatments are held to be more helpful than pharmacological ones, which are viewed poorly.[328] In the UK, the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal College of General Practitioners conducted a joint Five-year Defeat Depression campaign to educate and reduce stigma from 1992 to 1996;[329] a MORI study conducted afterwards showed a small positive change in public attitudes to depression and treatment.[330]

While serving his first term as Prime Minister of Norway, Kjell Magne Bondevik attracted international attention in August 1998 when he announced that he was suffering from a depressive episode, becoming the highest ranking world leader to admit to suffering from a mental illness while in office. Upon this revelation, Anne Enger became acting Prime Minister for three weeks, from 30 August to 23 September, while he recovered from the depressive episode. Bondevik then returned to office. Bondevik received thousands of supportive letters, and said that the experience had been positive overall, both for himself and because it made mental illness more publicly acceptable.[331][332]

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "Depression". U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). May 2016. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richards CS, O'Hara MW (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Depression and Comorbidity. Oxford University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-19-979704-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 165.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kessler RC, Bromet EJ (2013). "The epidemiology of depression across cultures". Annual Review of Public Health. 34: 119–38. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409. PMC 4100461. PMID 23514317.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 166.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association 2013, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, et al. (September 2013). Mead GE (ed.). "Exercise for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (9): CD004366. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6. ISSN 1464-780X. PMC 9721454. PMID 24026850.

- ^ Jump up to: a b GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (10 November 2018). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017". Lancet. 392 (10159): 1789–1858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. PMC 6227754. PMID 30496104.

- ^ Sartorius N, Henderson AS, Strotzka H, et al. "The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E (1975). "The development of diagnostic criteria in psychiatry" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2005. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Patton LL (2015). The ADA Practical Guide to Patients with Medical Conditions (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 339. ISBN 978-1-118-92928-5.

- ^ Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, et al. (January 2010). "Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis". JAMA. 303 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1943. PMC 3712503. PMID 20051569.

- ^ Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT (February 2008). "Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration". PLOS Medicine. 5 (2): e45. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. PMC 2253608. PMID 18303940.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 160.

- ^ American_Psychiatric_Association 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Everaert J, Vrijsen JN, Martin-Willett R, van de Kraats L, Joormann J (2022). "A meta-analytic review of the relationship between explicit memory bias and depression: Depression features an explicit memory bias that persists beyond a depressive episode". Psychological Bulletin. 148 (5–6): 435–463. doi:10.1037/bul0000367. ISSN 1939-1455. S2CID 253306482.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 163.

- ^ Murray G (September 2007). "Diurnal mood variation in depression: a signal of disturbed circadian function?". Journal of Affective Disorders. 102 (1–3): 47–53. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.12.001. PMID 17239958.

- ^ "Insomnia: Assessment and Management in Primary Care". American Family Physician. 59 (11): 3029–3038. 1999. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association 2000a, p. 412

- ^ Nelson JC, Bickford D, Delucchi K, Fiedorowicz JG, Coryell WH (September 2018). "Risk of Psychosis in Recurrent Episodes of Psychotic and Nonpsychotic Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 175 (9): 897–904. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17101138. PMID 29792050. S2CID 43951278.

- ^ Fisher JC, Powers WE, Tuerk DB, Edgerton MT (March 1975). "Development of a plastic surgical teaching service in a women's correctional institution". American Journal of Surgery. 129 (3): 269–72. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7284.482. PMC 1119689. PMID 11222428.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c American Psychiatric Association 2000a, p. 349

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Depression (PDF). National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ Delgado PL, Schillerstrom J (2009). "Cognitive Difficulties Associated With Depression: What Are the Implications for Treatment?". Psychiatric Times. 26 (3). Archived from the original on 22 July 2009.

- ^ Faculty of Psychiatry of Old Age, NSW Branch, RANZCP, Kitching D, Raphael B (2001). Consensus Guidelines for Assessment and Management of Depression in the Elderly (PDF). North Sydney, New South Wales: NSW Health Department. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7347-3341-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2015.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 164.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Depression treatment for the elderly". Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). 27 January 2015. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Hankin BL, Abela JR (2005). Development of Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective. SAGE Publications. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-1-4129-0490-2.

- ^ Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW, Pariante CM, Etkin A, Fava M, et al. (September 2016). "Major depressive disorder" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 2 (1). Springer Nature (published 15 September 2016): 16065. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.65. PMID 27629598. S2CID 4047310.

Despite advances in our understanding of the neuro-biology of MDD, no established mechanism can explain all aspects of the disease.

- ^ Boland RJ, Verduin ML (14 March 2022). Kaplan & Sadock's concise textbook of clinical psychiatry (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-9751-6748-6. OCLC 1264172789.

Although there is no single unifying theory, several theories have emerged over the last century that attempt to account for the various clinical, psychological, and biologic findings in depression.

- ^ Sontheimer H (20 May 2021). Diseases of the nervous system (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-12-821396-4. OCLC 1260160457.

A number of risk factors for depression are known or suspected, but only in rare cases is the link to disease strong.

- ^ Mann JJ, McGrath PJ, Roose SP, eds. (June 2013). Clinical handbook for the management of mood disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139175869. ISBN 978-1-107-05563-6. OCLC 843944119.

Although genes are an important cause of major depression and bipolar disorder, we have not confirmed the identity of the responsible genes.

- ^ Department of Health and Human Services (1999). "The fundamentals of mental health and mental illness" (PDF). Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. (July 2003). "Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene". Science. 301 (5631): 386–389. Bibcode:2003Sci...301..386C. doi:10.1126/science.1083968. PMID 12869766. S2CID 146500484.

- ^ Haeffel GJ, Getchell M, Koposov RA, Yrigollen CM, Deyoung CG, Klinteberg BA, et al. (January 2008). "Association between polymorphisms in the dopamine transporter gene and depression: evidence for a gene-environment interaction in a sample of juvenile detainees" (PDF). Psychological Science. 19 (1): 62–69. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02047.x. PMID 18181793. S2CID 15520723. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008.

- ^ Slavich GM (2004). "Deconstructing depression: A diathesis-stress perspective (Opinion)". APS Observer. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-89862-000-7. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Nieto I, Robles E, Vazquez C (December 2020). "Self-reported cognitive biases in depression: A meta-analysis". Clinical Psychology Review. 82: 101934. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101934. PMID 33137610. S2CID 226243519.

- ^ Do MC, Weersing VR (3 April 2017). Wenzel A (ed.). The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publishing. p. 1014. doi:10.4135/9781483365817. ISBN 978-1-4833-6582-4. OCLC 982958263.

Depression is highly heritable, as youths with a parent with a history of depression are approximately 4 times as likely to develop the disorder as youths who do not have a parent with depression.

- ^ Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS (October 2000). "Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 157 (10): 1552–1562. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. PMID 11007705.

- ^ Belmaker RH, Agam G (January 2008). "Major depressive disorder". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1056/NEJMra073096. PMID 18172175. S2CID 12566638.

It is clear from studies of families that major depression is not caused by any single gene but is a disease with complex genetic features.

- ^ Wray NR, Ripke S, Mattheisen M, Trzaskowski M, Byrne EM, Abdellaoui A, et al. (May 2018). "Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression". Nature Genetics. 50 (5): 668–681. doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3. hdl:11370/3a0e2468-99e7-40c3-80f4-9d25adfae485. PMC 5934326. PMID 29700475.

- ^ Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, Hafferty JD, Gibson J, Shirali M, et al. (March 2019). "Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions". Nature Neuroscience. 22 (3): 343–352. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7. PMC 6522363. PMID 30718901.

- ^ Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS (October 2000). "Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 157 (10): 1552–1562. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. PMID 11007705.

The heritability of major depression is likely to be in the range of 31%–42%. This is probably the lower bound, and the level of heritability is likely to be substantially higher for reliably diagnosed major depression or for subtypes such as recurrent major depression. In comparison, the heritabilities of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are estimated to be approximately 70%.

- ^ Jorde LB, Carey JC, Bamshad MJ (27 September 2019). Medical genetics (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-323-59653-4. OCLC 1138027525.

Thus it appears that bipolar disorder is more strongly influenced by genetic factors than is major depressive disorder.

- ^ Duncan LE, Keller MC (October 2011). "A critical review of the first 10 years of candidate gene-by-environment interaction research in psychiatry". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 168 (10): 1041–1049. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020191. PMC 3222234. PMID 21890791.

- ^ Peyrot WJ, Van der Auwera S, Milaneschi Y, Dolan CV, Madden PA, Sullivan PF, et al. (July 2018). "Does Childhood Trauma Moderate Polygenic Risk for Depression? A Meta-analysis of 5765 Subjects From the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium". Biological Psychiatry. 84 (2): 138–147. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.09.009. PMC 5862738. PMID 29129318.

- ^ Simon GE (November 2001). "Treating depression in patients with chronic disease: recognition and treatment are crucial; depression worsens the course of a chronic illness". The Western Journal of Medicine. 175 (5): 292–93. doi:10.1136/ewjm.175.5.292. PMC 1071593. PMID 11694462.

- ^ Clayton PJ, Lewis CE (March 1981). "The significance of secondary depression". Journal of Affective Disorders. 3 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(81)90016-1. PMID 6455456.

- ^ Kewalramani A, Bollinger ME, Postolache TT (1 January 2008). "Asthma and Mood Disorders". International Journal of Child Health and Human Development. 1 (2): 115–23. PMC 2631932. PMID 19180246.

- ^ Rogers D, Pies R (December 2008). "General medical with depression drugs associated". Psychiatry. 5 (12): 28–41. PMC 2729620. PMID 19724774.

- ^ Botts S, Ryan M. Drug-Induced Diseases Section IV: Drug-Induced Psychiatric Diseases Chapter 18: Depression. pp. 1–23. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010.

- ^ Zingone F, Swift GL, Card TR, Sanders DS, Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC (April 2015). "Psychological morbidity of celiac disease: A review of the literature". United European Gastroenterology Journal. 3 (2): 136–145. doi:10.1177/2050640614560786. PMC 4406898. PMID 25922673.

- ^ Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P, Whiteman M (November 2002). "Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders". Archives of General Psychiatry. 59 (11): 1039–44. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. PMID 12418937.

- ^ Meltzer-Brody S (9 January 2017). "New insights into perinatal depression: pathogenesis and treatment during pregnancy and postpartum". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 13 (1): 89–100. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/smbrody. PMC 3181972. PMID 21485749.