Национальная стрелковая ассоциация

| |

Headquarters in Fairfax, Virginia | |

| Founded | November 17, 1871 |

|---|---|

| Founder | |

| Founded at | New York City |

| Type | 501(c)(4)[1] |

| 53-0116130 | |

| Focus | |

| Location | |

Area served | United States |

| Services |

|

| Method |

|

Members | Approximately 5.5 million (self-reported)[a][citation needed] |

Key people |

|

| Subsidiaries |

|

Revenue (2018) | $412,233,508[citation needed] |

| Expenses (2018) | $423,034,158[citation needed] |

| Website | NRA.org |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Национальная стрелковая ассоциация Америки ( NRA ) — это группа по защите прав на оружие, базирующаяся в США. [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ б ] Основанная в 1871 году для развития стрельбы из винтовки , современная НРА стала известной организацией, лоббирующей права на оружие , продолжая при этом обучать технике безопасности и компетентности при обращении с огнестрельным оружием. Организация также издает несколько журналов и спонсирует соревнования по стрельбе. [ 5 ] По данным НРА, по состоянию на декабрь 2018 года в нем насчитывалось почти 5 миллионов членов. [update] хотя эта цифра не была независимо подтверждена. [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ]

НРА является одной из самых влиятельных правозащитных групп в политике США. [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ] NRA Институт законодательных действий (NRA-ILA) является его лоббистским подразделением, которое управляет комитетом политических действий (PAC), Фондом политической победы (PVF). За свою историю организация влияла на законодательство, участвовала в судебных процессах или инициировала их, а также поддерживала или выступала против различных кандидатов на местном, государственном и федеральном уровнях. Некоторые заметные лоббистские усилия со стороны NRA-ILA — это Закон о защите владельцев огнестрельного оружия , который ослабил ограничения Закона о контроле над огнестрельным оружием 1968 года , и Поправка Дикки , которая запрещает Центрам по контролю и профилактике заболеваний (CDC) использовать федеральные средства для пропаганды. для контроля над оружием.

Starting in the mid- to late 1970s, the NRA has been increasingly criticized by gun control and gun rights advocacy groups, political commentators, and politicians. This criticism began following changes in the NRA's organizational policies, following what is now referred to as the Revolt at Cincinnati at the 1977 NRA annual convention. The changes, which deposed former NRA executive vice president Maxwell Rich and included new organizational bylaws, have been described as moving the organization away from its previous focuses of "hunting, conservation, and marksmanship" and toward a focus on the defense of the right to bear arms.[12][13][14] The organization has been the focus of intense criticism in the aftermath of high-profile shootings, such as the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting and the Parkland High School shooting, after both of which they suggested adding armed security guards to schools.[15]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

A few months after the Civil War began in 1861, a national rifle association was proposed by Americans in England. In a letter that was sent to President Abraham Lincoln and published in The New York Times, R.G. Moulton and R.B. Perry recommended forming an organization similar to the National Rifle Association in Britain, which had formed a year and a half earlier. They suggested making a shooting range, perhaps on the base on Staten Island, and were offering Whitworth rifles for prizes for the first shooting competition with those rifles. They suggested a provisional committee to start the Association which would include: President Lincoln, Secretary of War, officers, and other prominent New Yorkers.[16][17][18]

The National Rifle Association of America was chartered in the State of New York on November 17, 1871[19][5] by Army and Navy Journal editor William Conant Church and Captain George Wood Wingate. On November 25, 1871, the group voted to elect its first corporate officers. Union Army Civil War General Ambrose Burnside, who had worked as a Rhode Island gunsmith, was elected president.[20] When Burnside resigned on August 1, 1872,[21] Church succeeded him as president.[22]

Union Army records for the Civil War indicate that its troops fired about 1,000 rifle shots for each Confederate hit, causing General Burnside to lament his recruits: "Out of ten soldiers who are perfect in drill and the manual of arms, only one knows the purpose of the sights on his gun or can hit the broad side of a barn."[23][24][25] The generals attributed this to the use of volley tactics, devised for earlier, less accurate smoothbore muskets.[26][27]

Recognizing a need for better training, Wingate sent emissaries to Canada, the United Kingdom, and Germany to observe militia and armies' marksmanship training programs.[28] With plans provided by Wingate, the New York Legislature funded the construction of a modern range at Creedmoor, Long Island, for long-range shooting competitions. The range officially opened on June 21, 1873.[29] The Central Railroad of Long Island established a railway station nearby, with trains running from Hunter's Point, with connecting boat service to 34th Street and the East River, allowing access from New York City.[30]

After beating England and Scotland to win the Elcho Shield in 1873 at Wimbledon, then a village outside London, the Irish Rifle Team issued a challenge through the New York Herald to riflemen of the United States to raise a team for a long-range match to determine an Irish-American championship.[31] A team was organized through the subsidiary Amateur Club of New York City.[31] Remington Arms and Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company produced breech-loading weapons for the team.[32] Although muzzle-loading rifles had long been considered more accurate, eight American riflemen won the 1874 Irish-American Match firing breech-loading rifles. Publicity of the event generated by the New York Herald helped to establish breech-loading firearms as suitable for military marksmanship training, and promoted the NRA to national prominence.[25]

In 1875, the NRA issued a challenge for an international rifle match as part of the 1876 Centennial celebrations of the founding of the nation.[33] Australia, Ireland, Scotland and Canada accepted the challenge, and the Centennial Trophy was commissioned from Tiffany & Co. (later known as the "Palma Trophy").[34] The United States won the 1876 match, and the Palma Match went on to be contested every four years as the World Long Range Rifle Championships.[35][36]

Rifle clubs

[edit]

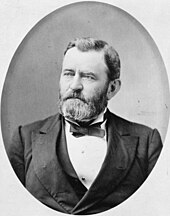

The NRA organized rifle clubs in other states, and many state National Guard organizations sought NRA advice to improve members' marksmanship. Wingate's marksmanship manual evolved into the United States Army marksmanship instruction program.[25] Former President Ulysses S. Grant served as the NRA's eighth president and General Philip H. Sheridan as its ninth.[37] The US Congress created the National Board for the Promotion of Rifle Practice in 1901 to include representatives from the NRA, National Guard, and United States military services. A program of annual rifle and pistol competitions was authorized, and included a national match open to military and civilian shooters. In 1907, NRA headquarters moved to Washington, D.C. to facilitate the organization's advocacy efforts.[25] Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal began the manufacture of M1903 Springfield rifles for civilian members of the NRA in 1910.[38] The Director of Civilian Marksmanship began manufacture of M1911 pistols for NRA members in August 1912.[39] Until 1927, the United States Department of War provided free ammunition and targets to civilian rifle clubs with a minimum membership of ten United States citizens at least 16 years of age.[40]

1934–1970s

[edit]After the passage of the National Firearms Act (NFA) of 1934, the first federal gun-control law in the US, the NRA formed its Legislative Affairs Division to update members with facts and analysis of upcoming bills.[41][42] Karl Frederick, NRA president in 1934, during congressional NFA hearings testified "I have never believed in the general practice of carrying weapons. I seldom carry one. I have when I felt it was desirable to do so for my own protection. I know that applies in most of the instances where guns are used effectively in self-defense or in places of business and in the home. I do not believe in the general promiscuous toting of guns. I think it should be sharply restricted and only under licenses."[43] Four years later, the NRA backed the Federal Firearms Act of 1938.[44]

The NRA supported the NFA along with the Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA), which together created a system to federally license gun dealers and established restrictions on particular categories and classes of firearms.[45] The organization opposed a national firearms registry, an initiative favored by then-President Lyndon Johnson.[44]

1970s–2000s

[edit]Until the 1970s, the NRA was nonpartisan.[46] Previously, the NRA mainly focused on sportsmen, hunters, and target shooters.[47][48] During the 1970s, it became increasingly aligned with the Republican Party.[46] After 1977, the organization expanded its membership by focusing heavily on political issues and forming coalitions with conservative politicians. Most of these are Republicans.[49]

However, the passage of the GCA galvanized a growing number of NRA gun rights activists, including Harlon Carter. In 1975, it began to focus more on politics and established its lobbying arm, the Institute for Legislative Action (NRA-ILA), with Carter as director. The next year, its political action committee (PAC), the Political Victory Fund, was created in time for the 1976 elections.[50]: 158 The 1977 annual convention was a defining moment for the organization and came to be known as "The Cincinnati Revolution"[51] (or as the Cincinnati Coup,[52] the Cincinnati Revolt,[53] or the Revolt at Cincinnati).[54] Leadership planned to relocate NRA headquarters to Colorado and to build a $30 million recreational facility in New Mexico, but activists within the organization, whose central concern was Second Amendment rights, defeated the incumbents (i.e. Maxwell Rich) and elected Carter as executive director and Neal Knox as head of the NRA-ILA.[55][56] Insurgents including Carter and Knox had demanded new leadership in part because they blamed incumbent leaders for existing gun control legislation like the GCA and believed that no compromise should be made.[57]

With a goal to weaken the GCA, Knox's ILA successfully lobbied Congress to pass the Firearm Owners Protection Act (FOPA) of 1986 and worked to reduce the powers of the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF). In 1982, Knox was ousted as director of the ILA, but began mobilizing outside the NRA framework and continued to promote opposition to gun control laws.[58]

At the 1991 national convention, Knox's supporters were elected to the board and named staff lobbyist Wayne LaPierre as the executive vice president. The NRA focused its attention on the gun control policies of the Clinton Administration.[56] Knox again lost power in 1997, as he lost reelection to a coalition of moderate leaders who supported movie star Charlton Heston, despite Heston's past support of gun control legislation.[59]

In 1994, the NRA unsuccessfully opposed the Federal Assault Weapons Ban (AWB), but successfully lobbied for the ban's 2004 expiration.[60] Heston was elected president in 1998 and became a highly visible spokesman for the organization. In an effort to improve the NRA's image, Heston presented himself as the voice of reason in contrast to Knox.[61]: 262–68

2018–present

[edit]Ackerman McQueen lawsuit

[edit]In April 2019, the group unexpectedly sued its longtime public relations firm Ackerman McQueen, which was responsible for two decades of aggressive gun-rights advertising on behalf of the NRA. The lawsuit alleges that the firm refused to turn over financial records to support its billings to the NRA, which amounted to $40 million in 2017. The lawsuit questioned recent programming on NRATV, an online channel operated by Ackerman, which has taken political positions unrelated to the NRA's traditional focus on gun-related issues. There were also concerns about possible conflicts of interest, such as the $1 million contract to host NRATV between Ackerman and NRA president Oliver North.[62][63] Leading up to the NRA's 2019 national convention in April, there were reports that North and LaPierre were at odds, with North demanding that LaPierre resign and LaPierre accusing North of extortion.[64] At the convention a letter was read from North, saying he had been told he would not be granted a second term as NRA president and adding that he intended to create a committee to investigate allegations of financial mismanagement.[65] A subsequent resolution to oust LaPierre over "highly suspect" financial practices was hotly debated for an hour before members voted not to discuss financial issues in public and to refer the resolution to the NRA board.[66] On June 25, 2019, the NRA severed all ties with Ackerman McQueen and shut down the NRATV operation.[67]

2024 New York State corruption verdict; 2021 bankruptcy filing

[edit]Following an 18-month investigation, on August 6, 2020, New York Attorney General Letitia James filed a civil lawsuit against the NRA, alleging fraud, financial misconduct, and misuse of charitable funds by some of its executives, including its long-time former CEO and EVP Wayne LaPierre, treasurer Wilson Phillips, former chief of staff and current executive director of general operations Joshua Powell,[68] and general counsel and secretary John Frazer.[69] The suit called for the dissolution of the NRA as being "fraught with fraud and abuse".[70][71][72] On the same date, Attorney General for the District of Columbia Karl Racine filed a lawsuit against the NRA for misusing charitable funds.[73]

On January 15, 2021, the NRA announced in a press release that it and one of its subsidiaries had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Texas in Dallas.[74] It also announced that it would reincorporate in Texas, subject to court approval, although its headquarters in Fairfax, Virginia, would not move.[74] During the bankruptcy trial LaPierre stated that he had kept the bankruptcy filing secret from the NRA's board of directors and most of its senior officials.[75] LaPierre's excessive compensation and exorbitant spending of NRA funds on himself and his wife, such as extremely expensive suits, chartered jet flights, and a traveling "glam squad" for his wife, became a subject of testimony in the eleven-day Texas proceedings.[76]

On May 11, 2021, Judge Harlin Hale of the federal bankruptcy court of the Northern District of Texas, dismissed the bankruptcy petition without prejudice, describing that it "was not filed in good faith", warning that if the NRA chose to file a new bankruptcy case, Hale's court would immediately revisit concerns about "disclosure, transparency, secrecy, conflicts of interest of litigation counsel", which could lead to the appointment of a trustee to oversee the organization's affairs.[77] Hale doubted that the NRA was "faced with financial difficulties", instead ruling that the true purposes of the lawsuit were "to gain an unfair litigation advantage" against the New York Attorney General, and to "avoid" regulation from New York.[77][78][79]

On March 2, 2022, New York state court in Manhattan ruled against Letitia James's effort to break up the NRA while allowing the portion of the legal actions against the NRA's leadership to continue. The judge found that dissolving the NRA would have a negative impact on the free speech and assembly rights of the organization's members. It was also found that the NRA as an organization did not benefit from the alleged misconduct of its leadership and "less intrusive" remedies against NRA officials could be sought instead.[80][81]

In February 2024, NRA leaders were found guilty of financial misconduct[82] and corruption by a Manhattan jury.[83]

Lobbying and political activity

[edit]

When the National Rifle Association of America was officially incorporated on November 16, 1871,[19] its primary goal was to "promote and encourage rifle shooting on a scientific basis". The NRA's website says the organization is "America's longest-standing civil rights organization".[84]

On February 7, 1872, the NRA created a committee to lobby for legislation in the interest of the organization.[85] Its first lobbying effort was to petition the New York State legislature for $25,000 to purchase land to set up a range.[86] Within three months, the legislation had passed and had been signed into law by Governor John T. Hoffman.[87]

In 1934, the National Rifle Association created a Legislative Affairs Division and testified in front of Congress in support of the first substantial federal gun control legislation in the US, the National Firearms Act.[88]

The Institute for Legislative Action (NRA-ILA), the lobbying branch of the NRA, was established in 1975. According to political scientists John M. Bruce and Clyde Wilcox, the NRA shifted its focus in the late 1970s to incorporate political advocacy, and started seeing its members as political resources rather than just as recipients of goods and services. Despite the impact on the volatility of membership, the politicization of the NRA has been consistent and its PAC, the Political Victory Fund established in 1976, ranked as "one of the biggest spenders in congressional elections" as of 1998.[89]

A 1999 Fortune magazine survey said that lawmakers and their staffers considered the NRA the most powerful lobbying organization three years in a row.[10] Chris W. Cox was the NRA's chief lobbyist and principal political strategist, a position he held from 2002 until 2019. In 2012, 88% of Republicans and 11% of Democrats in Congress had received an NRA PAC contribution at some point in their career. Of the members of the Congress that convened in 2013, 51% received funding from the NRA PAC within their political careers, and 47% received NRA money in their most recent race. According to Lee Drutman, political scientist and senior fellow at the Sunlight Foundation, "It is important to note that these contributions are probably a better measure of allegiance than of influence."[90]

Internationally, the NRA opposes the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT).[91] It has opposed Canadian gun registry,[92] supported Brazilian gun rights,[93][94] and criticized Australian gun laws.[95]

In 2016, the NRA raised a record $366 million and spent $412 million for political activities. The NRA also maintains a PAC which is excluded from these figures.[96] The organization donated to congressional races for both Republicans (223) and Democrats (9) to candidates for Congress.[97]

The NRA has been described as influential in shaping American gun control policy.[98][99] The organization influences legislators' voting behavior through its financial resources and ability to mobilize its large membership.[99] The organization has not lost a major battle over gun control legislation since the 1994 Federal Assault Weapons Ban.[98] At the federal level, the NRA successfully lobbied Congress in the mid-1990s to effectively halt governments-sponsored research into the public health effects of firearms, and to ensure the passage of legislation in 2005 largely immunizing gun manufacturers and dealers from lawsuits.[98] At the same time, the NRA stopped efforts at the federal level to increase regulation of firearms.[98] At the state and local level, the NRA successfully campaigned to deregulate guns, for example by pushing state governments to eliminate the ability of local governments to regulate guns and removing restrictions on guns in public places (such as bars and campuses).[98]

Elections

[edit]

The NRA Political Victory Fund (PVF) PAC was established in 1976 to challenge gun-control candidates and to support gun-rights candidates.[100] An NRA "A+" candidate is one who has "not only an excellent voting record on all critical NRA issues, but who has also made a vigorous effort to promote and defend the Second Amendment", whereas an NRA "F" candidate is a "true enemy of gun owners' rights".[101]

The NRA endorsed a presidential candidate for the first time in 1980, backing Ronald Reagan over Jimmy Carter.[102][103] The NRA has also made endorsements even when it viewed both candidates positively. For example, in the 2006 Pennsylvania Senate elections, the NRA endorsed Rick Santorum over Bob Casey Jr.,[104] even though they both had an "A" rating. Despite this endorsement, Santorum lost to Casey.

Republicans joined forces with the NRA and used the recently passed gun control measures to motivate voters in the 1994 midterm elections.[105] In 1993, with Democrats in the majority of both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, President Bill Clinton signed the Brady Bill, named after the press secretary who was shot and paralyzed during the 1981 assassination attempt of President Reagan.[105] The Brady Bill created a mechanism for background checks in order to enforce the GCA of 1968 and prevent criminals and minors from purchasing guns.[105] In addition, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 included a 10-year ban on the sale of assault weapons. In 1994, the ban was favored by 78% of Americans according to a CBS poll.[106]

According to Yale professor Reva Siegel, during the 1994 midterm elections, the NRA "spent more than $3.2 million on GOP campaigns and helped win nineteen of twenty-four 'priority' races the organization targeted, leading to a House with a majority of members who were 'A-rated' by the NRA."[107] Groups like the NRA seeking to expand interpretation of the Second Amendment to include an individual right to a gun, coincided with the 'New Right', a political movement concerned with gun control, and social issues such as school prayer and abortion.[108] Leader of the new House Majority Leader Newt Gingrich stated that support for or against gun control defined ones partisan identity.[107] NRA leader Knox echoed this sentiment, assuring members that Republicans would be defenders of Second Amendment rights and repeal recently passed gun control legislation.[107]

The NRA spent $40 million on United States elections in 2008,[109] including $10 million in opposition to the election of Senator Barack Obama in the 2008 presidential campaign.[110]

In 2010, Citizens United v. FEC was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, paving the way for dark money to flow into U.S. elections. As of mid-September 2018, the NRA has become one of just 15 groups which account for three-quarters of the anonymous cash.[111]

The NRA spent over $360,000 in the Colorado recall election of 2013, which resulted in the ouster of state senators John Morse and Angela Giron.[112] The Huffington Post called the recall "a stunning victory for the National Rifle Association and gun rights activists."[112] Morse and Giron helped to pass expanded background checks and ammunition magazine capacity limits after the 2012 Aurora, Colorado, and Sandy Hook, Connecticut, shootings.[113]

On May 20, 2016, the NRA endorsed Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential election.[114] The timing of the endorsement, before Trump became the official Republican nominee, was unusual, as the NRA typically endorses Republican nominees towards the end of the general election. The NRA said its early endorsement was due to the strong gun control stance of Hillary Clinton[115] In the 2016 United States presidential election the NRA reported spending more than $30 million in support of Donald Trump, more than any other independent group in that election, and three times what it spent in the 2012 presidential election.[116]

Russian influence

[edit]Investigations by the FBI and Special Counsel Robert Mueller resulted in indictments of Russian nationals on charges of developing and exploiting ties with the NRA to influence US politics by using the NRA to gain access to Republican politicians. Russian politician and gun-rights activist Aleksandr Torshin, a lifetime NRA member who is close to Russian President Vladimir Putin,[117][118] was suspected by some of illegally funneling money through the NRA to benefit Trump's 2016 campaign. In May 2018, Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee released a report stating it had obtained "a number of documents that suggest the Kremlin used the National Rifle Association as a means of accessing and assisting Mr. Trump and his campaign" through Torshin and his assistant Maria Butina, and that "The Kremlin may also have used the NRA to secretly fund Mr. Trump's campaign."[119][120]

Butina was arrested on July 15, 2018, and charged with conspiring to act as an unregistered agent of the Russian Federation and using Republican operative Paul Erickson for cover and connections as she developed an influence operation designed to "advance the interests of the Russian Federation." The FBI acquired an email Erickson had sent to an acquaintance in 2016 stating, "Unrelated to specific presidential campaigns, I've been involved in securing a VERY private line of communication between the Kremlin and key [GOP] leaders through, of all conduits, the [NRA]."[121][122] According to the affidavit, from 2015 through at least February 2017, Butina worked at the direction of Russian who was a high level government official and official at the Russian Central Bank.[123][124][125] In December, Butina agreed in a plea deal to cooperate with federal prosecutors.[126][127] Butina later denied accusations that she was a Russian agent.[128]

In 2018, in a letter sent to Sen. Ron Wyden and addressed to Congress, the NRA acknowledged it had accepted approximately $2,000 in membership dues and magazine subscriptions and $525 in contributions from 23 Russian nationals or people associated with Russian addresses since 2015. In an earlier news interview the NRA's lawyers stated that the NRA had received less than $1000 from only one Russian donor. According to a Wyden aide, the NRA letter would be referred to the Federal Elections Commission.[129][130] NRA's General Counsel John C. Frazer wrote to Senator Wyden: "While we do receive some contributions from foreign individuals and entities, those contributions are made directly to the NRA for lawful purposes. Our review of our records has found no foreign donations in connection with a United States election, either directly or through a conduit."[131]

According to the minority Democratic staff of the Senate Finance Committee the NRA acted as "a foreign asset" of Russia during the 2016 election, putting its tax exempt status at risk. The allegations were made in a 77-page report on an 18-month investigation released on September 27, 2019. An 18-page rebuttal by majority committee Republicans said the Democratic report demonstrated "little or nothing".[132][133][134][135]

Neither the FBI nor Special Counsel investigations found any Russian money funneling. The FBI investigation resulted in the conviction of Butina, not on any money-related charges, and the Mueller Report does not mention the NRA.[136] The Federal Election Commission has dismissed allegations of Russian money funneling as unsupported by the evidence.[137][138]

The ATF and Senate confirmations

[edit]The NRA has for decades sought to limit the ability of the ATF to regulate firearms by blocking nominees and lobbying against reforms that would increase the ability of the ATF to track gun crimes.[139] For instance, the NRA opposed ATF reforms to trace guns to owners electronically; the ATF currently does so through paper records.[139] In 2006, the NRA lobbied US Representative F. James Sensenbrenner to add a provision to the Patriot Act reauthorization that requires Senate confirmation of ATF director nominees.[140] For seven years after that, the NRA lobbied against and "effectively blocked" every presidential nominee.[140][141][142] First was President George W. Bush's choice, Michael Sullivan, whose confirmation was held up in 2008 by three Republican Senators who said the ATF was hostile to gun dealers. One of the Senators was Larry Craig, who was an NRA board member during his years in the Senate.[143] Confirmation of President Obama's first nominee, Andrew Traver, stalled in 2011 after the NRA expressed strong opposition.[139][140][144] Some Senators resisted confirming another Obama nominee, B. Todd Jones, because of the NRA's opposition,[142] until 2013, when the NRA said it was neutral on Jones' nomination and that it would not include the confirmation vote in its grading system.[140] Dan Freedman, national editor for Hearst Newspapers' Washington, D.C. bureau, stated that it, "clears the way for senators from pro-gun states—Democrats as well as at least some Republicans—to vote for Jones without fear of political repercussions".[145]

In 2014, Obama weighed the idea of delaying a vote on his nominee for Surgeon General, Vivek Murthy, when Republicans and some conservative Democrats criticized Murthy, after the NRA opposed him.[146] In February, the NRA wrote to Senate leaders Harry Reid and Mitch McConnell to say that it "strongly opposes" Murthy's confirmation, and told The Washington Times' Emily Miller that it would score the vote in its PAC grading system. "The NRA decision", wrote Miller, "will undoubtedly make vulnerable Democrats up for reelection in the midterms reconsider voting party line on this nominee."[147] The Wall Street Journal stated on March 15, "Crossing the NRA to support Dr. Murthy could be a liability for some of the Democrats running for re-election this year in conservative-leaning states".[148] Murthy's nomination received broad support from over 100 medical and public health organizations in the U.S., including the American College of Physicians, the American Public Health Association, the American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association, and the American Diabetes Association.[149] On December 15, 2014, Murthy's appointment as Surgeon General was approved by the Senate.[150]

The NRA also opposed the appointments of Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan as Supreme Court justices.[151]

Legislation

[edit]| Bill/Law | Year | Supported | Opposed |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Firearms Act | 1934 | ||

| Federal Firearms Act | 1938 | ||

| Gun Control Act | 1968 | ||

| Federal Assault Weapons Ban | 1994 | ||

| Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act | 2005 | ||

| Disaster Recovery Personal Protection Act | 2006 | ||

| Assault Weapons Ban | 2013 |

The NRA initially opposed the 1934 National Firearms Act, but gave their support after several changes including the removal of pistols and revolvers and redefinition of machine gun,[152][153] which regulated what were considered at the time "gangster weapons" such as machine guns, short-barreled rifles, short-barreled shotguns, and sound suppressors.[154] However, the organization's position on suppressors has since changed.[155]

The NRA supported the 1938 Federal Firearms Act (FFA) which established the Federal Firearms License (FFL) program. The FFA required all manufacturers and dealers of firearms who ship or receive firearms or ammunition in interstate or foreign commerce to have a license, and forbade them from transferring any firearm or most ammunition to any person interstate unless certain conditions were met.[156]

The NRA supported and opposed parts of the Gun Control Act of 1968, which broadly regulated the firearms industry and firearms owners, primarily focusing on regulating interstate commerce in firearms by prohibiting interstate firearms transfers except among licensed manufacturers, dealers and importers. The law was supported by America's oldest manufacturers (Colt, Smith & Wesson, etc.) in an effort to forestall even greater restrictions which were feared in response to recent domestic violence. The NRA supported elements of the law, such as those forbidding the sale of firearms to convicted criminals and the mentally ill.[157][158]

The NRA influenced the writing of the Firearm Owners Protection Act and worked for its passage.[159]

In 2004, the NRA opposed renewal of the Federal Assault Weapons Ban of 1994. The ban expired on September 13, 2004.[160]

In 2005, President George W. Bush signed into law the NRA-backed Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act which partially shields firearms manufacturers and dealers from being held liable for negligence when crimes have been committed with their products.[161][162]

Litigation

[edit]In November 2005, the NRA and other gun advocates filed a lawsuit challenging San Francisco Proposition H, which banned the ownership and sales of firearms. The NRA argued that the proposition overstepped local government authority and intruded into an area regulated by the state. The San Francisco County Superior Court agreed with the NRA position.[163] The city appealed the court's ruling, but lost a 2008 appeal.[164] In October 2008, San Francisco was forced to pay a $380,000 settlement to the National Rifle Association and other plaintiffs to cover the costs of litigating Proposition H.[165]

In April 2006, New Orleans, Louisiana, police began returning to citizens guns that had been confiscated after Hurricane Katrina. The NRA, Second Amendment Foundation (SAF), and other groups agreed to drop a lawsuit against the city in exchange for the return.[166]

The NRA filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court in the 2008 landmark gun rights case of District of Columbia v Heller.[167] In a 5 to 4 vote, the Supreme Court ruled that the District of Columbia's gun laws were unconstitutional, and for the first time held that an individual's right to a gun was unconnected to service in a militia.[107][168] Some legal scholars believe that the NRA was influential in altering the public's interpretation of the Second Amendment, providing the foundation for the majority's opinion in Heller.[168][169]

In 2009, the NRA again filed suit (Guy Montag Doe v. San Francisco Housing Authority) in the city of San Francisco challenging the city's ban of guns in public housing. On January 14, 2009, the San Francisco Housing Authority reached a settlement with the NRA, which allows residents to possess legal firearms within a SFHA apartment building.[170]

In 2010, the NRA sued the city of Chicago, Illinois (McDonald v. Chicago) and the Supreme Court ruled that like other substantive rights, the right to bear arms is incorporated via the Fourteenth Amendment to the Bill of Rights, and therefore applies to the states.[171][172]

In March 2013, the NRA joined a federal lawsuit with other gun rights groups challenging New York's gun control law (the NY SAFE Act), arguing that Governor Andrew Cuomo "usurped the legislative and democratic process" in passing the law, which included restrictions on magazine capacity and expanding the state's assault weapons ban.[173]

In November 2013, voters in Sunnyvale, California, passed an ordinance banning certain ammunition magazines along with three other firearm-related restrictions. The ordinance was passed by 66 percent in favor.[174] The ordinance requires city residents to "dispose, donate, or sell" any magazine capable of holding more than ten rounds within a proscribed period of time once the measure takes effect.[175] The following month, the NRA joined local residents in suing the city on second amendment grounds.[174] A federal judge dismissed the suit three months later, upholding the Sunnyvale's ordinance.[176][177]

The city of San Francisco then passed similar ordinances a short time later. The San Francisco Veteran Police Officers Association (SFVPOA), represented by NRA attorneys, filed a lawsuit challenging San Francisco's ban on the possession of high-capacity magazines, seeking an injunction.[178] A federal judge denied the injunction in February 2014.[176][179]

In 2014, the NRA lobbied for a bill in Pennsylvania which grants it and other advocacy groups legal standing to sue municipalities to overturn local firearm regulations passed in violation of a state law preempting such regulations, and which also allows the court to force cities to pay their legal fees. As soon as it became law, the NRA sued three cities: Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Lancaster. In Philadelphia, seven regulations the NRA sued to overturn included a ban on gun possession by those found to be a risk for harming themselves or others, and a requirement to report stolen guns to the police within twenty-four hours after discovery of the loss or theft.[180] In Lancaster, a city of fewer than 60,000, mayor Rick Gray, who has chaired the pro-gun control group Mayors Against Illegal Guns, was also named in the suit. In that city, the NRA challenged an ordinance requiring gun owners to tell police when a firearm is lost or stolen within 72 hours or face jail time.[181] The basis for the lawsuits is "a 1974 state law that bars municipalities against passing restrictions that are pre-empted by state gun laws". At least 20 Pennsylvania municipalities have rescinded regulations in response to threatened litigation.[182][183]

The NRA has worked with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in opposing NSA collection of the call records of calls in the United States.[184][185]

On September 4, 2019, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a non-binding resolution which declared the NRA a domestic terrorist organization and said the city should "take every reasonable step" to limit vendors which do business with the city from also doing business with the NRA. On September 9, the NRA filed a lawsuit in response, accusing city officials of violating the organization's free speech rights by discriminating against the organization "based on the viewpoint of their political speech."[186][187][188] On September 23, mayor London Breed and city attorney Dennis Herrera announced in a memo that "the city's contracting process and policies have not changed and will not change as a result of the resolution." On November 7, 2019, the NRA dropped their lawsuit against San Francisco.[189][190][191][192] Los Angeles had passed a similar ordinance but the NRA won a preliminary injunction on December 11, 2019[193] and subsequently dropped the lawsuit after Los Angeles repealed the law.[194]

Programs

[edit]

The National Rifle Association owns the National Firearms Museum in Fairfax County, Virginia, featuring exhibits on the evolution and history of firearms in America.[195] In August 2013, the NRA National Sporting Arms Museum opened at an expansive Bass Pro Shops retail store in Springfield, Missouri. It displays almost 1,000 firearms, including historically significant firearms from the NRA and other collections.[196] The NRA publishes a number of periodicals including American Rifleman and others.[197]

The NRA sponsors a range of programs about firearm safety for children and adults, including a program for school-age children, the NRA's "Eddie Eagle". The organization issues credentials and trains firearm instructors.[198][199]

In 1994, following disagreements between the NRA and athletes over control of the program of Olympic shooting sports, the US Olympic Committee recommended USA Shooting replace the NRA as the national governing body for Olympic shooting. The NRA dropped out just before the decision was announced, citing a lack of appreciation for their efforts.[200]

The NRA supports marksmanship training as well as hosting the National Rifle and Pistol Matches at Camp Perry, events which are described by the El Paso Times as "America's world series of competitive shooting".[201][202][203]

In 2014 the NRA temporarily moved the National Smallbore Matches to Bristol, Indiana in advance of Camp Perry hosting the 2015 Palma Match (Long Range World Championships).[204] In 2015 it was announced the change was permanent.[205][206] The move drew criticism from shooters as the Bristol ranges lacked affordable accommodation, trade stands per Camp Perry's "Commercial Row", or even interest from the NRA - whose own publications had only reported on the Camp Perry matches.[207] A fall in participant numbers led to the foundation of the American Smallbore Shooting Association in 2016 as an apolitical match organiser to address the NRA's perceived lack of interest in smallbore competition shooting.[208]

The National Rifle Association maintains ties with other organizations such as the Boy Scouts of America and 4-H and contributes to youth shooting programs.[209][210]

The NRA hosts annual meetings. The 2018 meeting was held on May 3 in Dallas, Texas. More than 800 exhibitors and 80,000 people attended the event, making it the largest in NRA history. President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence addressed attendees.[211]

Organizational structure and finances

[edit]Leadership

[edit]Executive staff and spokespersons

[edit]Since 1991, Wayne LaPierre has been the organization's executive vice president, and functions as the chief executive officer.[212] LaPierre's compensation averages $1 million per year and including a nearly $4 million retirement payout in 2015.[213] Previous notable holders of that office include: Milton Reckord, Floyd Lavinius Parks, Franklin Orth, Maxwell Rich, Harlon Carter, J. Warren Cassidy, and Gary Anderson.

Chris W. Cox was the executive director of the NRA's lobbying branch, the Institute for Legislative Action. He received more than $1.3 million in compensation in 2015.[214] Kyle Weaver is executive director of general operations.[215] Kayne B. Robinson is executive director of the General Operations Division and chairman of the Whittington Center.[216]

In 2017, political commentator Dana Loesch was appointed as the NRA's national spokesperson, with the formal title of "Special Assistant to the Executive Vice President for Public Communication."[217][218] Loesch hosts The DL on NRATV and has featured prominently in other NRA-produced videos.[219]

Actor Chuck Norris serves as the honorary chairman for the association's voter registration campaign.[220] Colion Noir hosts a video program on the NRA's online video channel.[221]

In May 2018, the NRA announced that Oliver North would become president of the organization.[222][223] North served one tumultuous term, marked by multiple legal battles and a power struggle with LaPierre; he was replaced by Carolyn D. Meadows on April 29, 2019.[224]

Board of directors

[edit]The NRA is governed by a board of 76 elected directors, 75 of whom serve three-year terms and one who is elected to serve as a cross-over director. The directors choose a president and other officers from among the membership, as well as the executive director of the NRA General Operations and the executive director of the NRA Institute for Legislative Action (NRA-ILA).[225] In 2015, 71 members were white and 65 were male. More came from Texas than any other state.[226] Only 7 percent of eligible members vote.[227] Most board nominations are vetted by an appointed nine-member Nominating Committee.[228][229] One member is George Kollitides of the Freedom Group.[228] The nomination committee has been called "kingmakers" by MSNBC and Jeff Knox says "the process is front-loaded to give incumbents and Nominating Committee candidates a significant advantage".[227]

Membership

[edit]According to the NRA, their membership reached 5.5 million total members in 2018, a record high, and membership dues went from $128,209,303 in 2017 to $170,391,374 in 2018; an increase of $42,182,071, or 33 percent.[230]

A 2017 Pew Research Center study found that 19% of US gun owners consider themselves NRA members.[231] Journalist Megan Wilson stated that the Pew study places membership at 14 million, far higher than the NRA's own report of 5 million. According to the NRA, some non-members typically claim to be members when surveyed, as a show of support.[232]

Notable members

[edit]Nine US presidents have been NRA members. In addition to Grant, they are: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush (who resigned in 1995), and Donald Trump.[233] Three US vice presidents, two chief justices of the US Supreme Court, and several US congressmen, as well as legislators and officials of state governments are or have been members.[234][235]

Current or past members also include journalist Hunter S. Thompson,[236] Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh,[237] documentarian Michael Moore (who joined with the intent of dismantling the organization),[238] actor Rick Schroder,[239] and singer James Hetfield.[240]

Interconnected organizations

[edit]The National Rifle Association is composed of several financially interconnected organizations under common leadership,[241] including the NRA Institute for Legislative Action (NRA-ILA) which manages the NRA's political action committee and the NRA Civil Defense Fund which does pro bono legal work for people with cases involving Second Amendment rights.[241] The NRA Civil Rights Defense Fund was established in 1978.[242] Harlon Carter and Neal Knox were responsible for its founding.[243]

In 1994, the Fund spent over $500,000 on legal fees to support legal cases involving guns and gun control measures. It donated $20,000 in 1996 for the defense of New York City resident Bernhard Goetz when he was sued by a man he shot and left paralyzed.[244] It paid the legal bills in the case of Brian Aitken, a New Jersey resident sentenced to seven years in state prison for transporting guns without a carry permit.[245] On December 20, 2010, Governor Chris Christie granted Aitken clemency and ordered Aitken's immediate release from prison.[citation needed]

NRA Foundation

[edit]The NRA Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization that raises and donates money to outdoors groups and others such as ROTC programs, 4-H and Boy Scouts. In 2010, the NRA Foundation distributed $21.2 million in grants for gun-related training and education programs: $12.6 million to the NRA itself, and the rest to community programs for hunters, competitive shooters, gun collectors, and law enforcement, and to women and youth groups.[246] The foundation has no staff and pays no salaries.[246]

Friends of NRA is a program that raises money for the NRA Foundation. Since its inception in 1992, Friends of NRA has held over 17,600 events, reached over 3.2 million attendees and raised over $600 million for The NRA Foundation.[247]

Political Victory Fund (NRA-PVF)

[edit]By 1976, as the NRA became more politically oriented, the Political Victory Fund (NRA-PVF), a PAC, was established as a subsidiary to the NRA, to support NRA-friendly politicians.[100] Chris W. Cox, who is the NRA's chief lobbyist and principal political strategist, is also the NRA-PVF chairman. Through the NRA-PVF, the NRA began to rate political candidates on their positions on gun rights. An NRA "A+" candidate is one who has "not only an excellent voting record on all critical NRA issues, but who has also made a vigorous effort to promote and defend the Second Amendment", whereas an NRA "F" candidate is deemed a "true enemy of gun owners' rights".[101]

In the 2008 elections, the PVF spent millions on "direct campaign donations" and "grassroots operation".[248] In 2012, NRA-PVF income was $14.4 million and expenses were $16.1 million.[249] By 2014, the NRA-PVF income rose to 21.9 million with expenses of 20.7 million.[250]

Finances

[edit]| Name | Year | Income in Millions | Expenses in Millions |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Rifle Association (NRA) | 2011[251] | 218.9 | 231.0 |

| NRA Institute for Legislative Action | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| NRA Civil Defense Fund | 2012[252] | 1.6 | 1.0 |

| NRA Civil Defense Fund | 2013[253] | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| NRA Foundation | 2012[254] | 43.0 | 29.1 |

| NRA Foundation | 2013[255] | 41.3 | 31.4 |

| NRA Freedom Action Foundation | 2012[256] | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| NRA Freedom Action Foundation | 2013[257] | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| NRA Political Victory Fund | 2012[249] | 14.4 | 16.1 |

| NRA Political Victory Fund | 2014[250] | 21.9 | 20.7 |

| NRA Special Contribution Fund | 2012[258] | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| NRA Special Contribution Fund | 2013[259] | 4.3 | 3.6 |

In 2010, the NRA reported revenue of $227.8 million and expenses of $243.5 million,[260] with revenue including roughly $115 million generated from fundraising, sales, advertising and royalties, and most of the rest from membership dues.[261] Less than half of the NRA's income comes from membership dues and program fees; the majority is from contributions, grants, royalties, and advertising.[246][261][262]

Corporate donors include a variety of companies such as outdoors-supply and sporting-goods companies, and firearm manufacturers.[246][261][262][263] From 2005 through 2011, the NRA received at least $14.8 million from more than 50 firearms-related firms.[261] An April 2011 Violence Policy Center presentation stated that the NRA had received between $14.7 million and $38.9 million from the firearms industry since 2005.[263] In 2008, Beretta exceeded $2 million in donations to the NRA, and in 2012 Smith & Wesson gave more than $1 million. Sturm, Ruger & Company raised $1.25 million through a program in which it donated $1 to the NRA-ILA for each gun it sold from May 2011 to May 2012. In a similar program, gun buyers and participating stores are invited to "round up" the purchase price to the nearest dollar as a voluntary contribution. According to the NRA's 2010 tax forms, the "round-up" funds have been allocated both to public-interest programs and to lobbying.[246]

2018 New York lawsuit

[edit]In 2018, the NRA alleged in an official Court document that it suffered tens of millions of dollars in damage from actions of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the State's financial regulator. The state's Department of Financial Services (DFS) was directed by the Cuomo administration to encourage institutions it oversees, insurance companies, banks and other financial services companies licensed in New York state, to review their business interactions with the NRA and "other similar organizations" and assess if they would pose "reputational risk". The NRA's suit states that Cuomo's actions violate the organization's first-amendment rights and the NRA had suffered tens of millions of dollars in financial losses.[264][265] The ACLU has filed a brief with the Northern District of New York court supporting the NRA's case. The brief noted that if proven true, the allegations disclose an abuse of government regulatory authority to retaliate against a disfavored advocacy organization by imposing a burden on the NRA's ability to conduct lawful business.[266][267]

On November 3, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case National Rifle Association of America v. Vullo about whether the director of the New York DFS violated the First Amendment by instructing financial institutions not to do business with the NRA.[268] The Court released its opinion on May 30, 2024, vacating the Second Circuit's decision and remanding the case to the lower court.[269]

2020 New York lawsuit

[edit]In August 2020, on behalf of the State of New York, Attorney General Letitia James sued the NRA and four individuals involved with the organization: CEO Wayne LaPierre; former chief of staff and the executive director of general operations Joshua Powell; former treasurer and CFO Wilson "Woody" Phillips; and corporate secretary and general counsel John Frazer. James charged the organization with illegal conduct, stating that the NRA mismanaged funds and assets and failed to follow state and federal laws. The suit claims that money was diverted away from its charitable mission, and instead used to fund personal expenses for senior leadership, resulting in a loss to the NPO of $64 million over three years.[270][271] While the NRA sought to dismiss the lawsuit, in June 2022, Manhattan Judge Joel M. Cohen ruled that the lawsuit could move forward.[272] NRA leadership was found guilty of corruption by a Manhattan jury in February 2024,[82][83] with former vice-president and CEO LaPierre found to have cost the NRA $5.4 million in damages and ordered to pay restitution of $4.35 million.[273]

Public opinion and image

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (February 2018) |

A Reuters/Ipsos poll in April 2012 found that 82% of Republicans and 55% of Democrats saw the NRA "in a positive light".[274] In seven of eight Gallup polls between 1993 and 2015, a majority of Americans reported holding a favorable opinion of the NRA. Its highest rating was at 60% favorability in 2005 (with 34% unfavorable), while its lowest rating was at 42% favorability in 1995 (with 51% unfavorable). In October 2015, 58% of Americans held a favorable opinion of the NRA, though there was a wide spread among political affiliations: 77% of conservatives, 56% of moderates and 30% of liberals held this view.[275]

A Washington Post/ABC News poll in January 2013 showed that only 36% of Americans had a favorable opinion of the NRA leadership.[276]

A 2017 poll conducted by the political action committee Americans for Responsible Solutions, which supports gun control, exclusively questioned 661 gun owners. 26% of the respondents stated they were a member of the NRA. The ARS reported that less than 50% of gun owners polled believed the NRA represented their interests, while 67% of them somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement that it had been "overtaken by lobbyists and the interests of gun manufacturers and lost its original purpose and mission." The NRA disputed the poll's veracity in an e-mail sent to Politico, which had published the story.[277]

Polling trends since 2018 show a significant decline in NRA favorability.[278][279][280][281] A 2018 NBC News/ Wall Street Journal poll found that "for the first time since at least 2000, Americans hold a net unfavorable view of the NRA"—the poll showed respondents view of the NRA was 40% negative and 37% positive.[282][283] The poll showed that compared to the same question in 2017, the favorability rating of the NRA overall dropped 5%, noting that the shift was largely due to favorability declines among certain demographics: married white women, urban residents, white women (overall), and moderate Republicans.[282][283]

A February 2018 Quinnipiac poll found that 51% of Americans believe that the policies supported by the NRA are bad for the U.S., a 4% increase since October 2017.[278]

The NRA calls itself "the oldest continuously operating civil liberties organization" and is "one of the largest and best-funded lobbying organizations" in the United States.[284][285] Its claim that it is one of the oldest civil rights organizations is disputed. While the NRA was founded in 1871, it did not pursue a gun rights agenda until 1934. The National Association for the Deaf (NAD, founded in 1880) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP, founded in 1909) both originated as civil rights organizations according to other sources.[286]

Criticism

[edit]This article's "criticism" or "controversy" section may compromise the article's neutrality. (June 2018) |

The National Rifle Association has been criticized by newspaper editorial boards, gun control and gun rights advocacy groups, political commentators, and politicians. Democrats and liberals frequently criticize the organization.[287][288] The NRA's oldest organized critics include the gun control advocacy groups the Brady Campaign, the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence (CSGV), and the Violence Policy Center (VPC). Twenty-first century groups include Everytown for Gun Safety (formerly Mayors Against Illegal Guns), Moms Demand Action, and Giffords.

Political involvement

[edit]

In 1995, former US President George H. W. Bush resigned his life membership to the organization after receiving a National Rifle Association Institute of Legislative Action (NRA-ILA) fund-raising letter, signed by executive vice president Wayne LaPierre, that referred to ATF agents as "jack-booted government thugs".[289][290] The NRA later apologized for the letter's language.[291]

In December 2008, The New York Times editorial board criticized the NRA's attacks, which it called false and misleading, on Barack Obama's presidential campaign.[292]

After US President Donald Trump's election, the NRA closely aligned with him.[293] At an event in February 2018, Trump said that he was a "big fan of the NRA" but said that "doesn't mean we have to agree on everything."[294]

Although the NRA has previously donated to and endorsed Democratic candidates, it has become more closely affiliated with the Republican Party since the 1990s. In 2016, only two Democratic House candidates received donations from the NRA, compared to 115 in the 1992 elections, in a reflection of decreasing Democratic support for the NRA and its mission.[295] Self-identified Republicans are far more likely to hold a positive view of the NRA than are Democrats.[296][297]

Gun control

[edit]In February 2013, USA Today editors criticized the NRA for flip-flopping on expansion of universal background checks to private and gun show sales, which the NRA now opposes.[298]

"As early as March 23 (2013), POLITICO had reported on rumors that the NRA and (WV Sen. Joe) Manchin were engaged in secret talks over background checks. Two days later, the National Association for Gun Rights (NAGR) sent out a bulletin to its members: "I've warned you from the beginning that our gravest danger was an inside-Washington driven deal," wrote NAGR executive Dudley Brown. He added that the deal was a "Manchin-NRA compromise bill". The Gun Owners of America followed suit a week later, urging its members to contact the NRA to voice their opinion. Neither of these groups had even a tenth of the NRA's membership, or its political power, but they threatened to chip away at the group's reputation. Whatever NRA HQ's position on the bill may have been, it was fast getting outflanked by ideologues on the right."[299]

In March 2014, The Washington Post criticized the NRA's interference in government research on gun violence,[300] and both Post and Los Angeles Times editors criticized its opposition of Vivek Murthy for US Surgeon General.[301] In November 2018, a social media dispute was seen, after a paper was published by the American College of Physicians that stated that medical professionals had a special responsibility to speak out on prevention of gun-related injuries and that they should support appropriate regulation of the purchase of legal weapons.[302] In response to the paper the NRA tweeted against the paper and "anti-gun doctors" and claimed that "half of the articles in Annals of Internal Medicine are pushing for gun control", and medical professional began posting their experiences of caring for gun violence victims.[303] Economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton have also noted that the NRA has been effective in pressuring Congress to not fund high-quality research on gun accessibility and suicide rates.[304]

A survey of NRA members found that the majority support certain gun control policies, such as a universal background check:

For instance, 84% of gun owners and 74% of NRA members (vs. 90% of non-gun owners) supported requiring a universal background-check system for all gun sales; 76% of gun owners and 62% of NRA members (vs. 83% of non-gun owners) supported prohibiting gun ownership for 10 years after a person has been convicted of violating a domestic-violence restraining order; and 71% of gun owners and 70% of NRA members (vs. 78% of non-gun owners) supported requiring a mandatory minimum sentence of 2 years in prison for a person convicted of selling a gun to someone who cannot legally have a gun.[305]

Gun manufacturing industry

[edit]Critics have charged that the NRA represents the interests of gun manufacturers rather than gun owners. The NRA receives donations from gun manufacturers.[306][307][308]

Mass shootings

[edit]

Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting

[edit]Following the high-profile 2012 shooting at the Sandy Hook Elementary School, the organization began to become the focus of intense criticism, due to its continued refusal to endorse any new restrictions on assault-style gun ownership, or to endorse any other types of new restrictions on gun ownership.[262][309] While supporters say the organization advances their rights to buy and own guns according to the constitution's Second Amendment, some critics have described it as a "terrorist organization" for advocating policies that enable and permit the widespread distribution and sale of assault-style weapons, and for its opposition to any other types of restrictions on gun sales or use.[310][311]

In December 2012, following the shooting, NRA broke its social media silence and media blackout to announce a press conference.[312] At the event, LaPierre announced an NRA-backed effort to assess the feasibility of placing armed security officers in the nation's 135,000 public and private schools under a "National School Shield Program". He called on Congress "to act immediately to appropriate whatever is necessary". The announcement came in the same week after President Obama had stated his support for a ban on military-style assault weapons and high-capacity magazines.[313][314][315]

The NRA has been criticized for their media strategy following mass shootings in the United States. Following the Sandy Hook shooting, the NRA released an online video which attacked Obama and mentioned Obama's daughters; New Jersey Governor Chris Christie called it "reprehensible" and said that it demeaned the organization.[316] A senior lobbyist for the organization later characterized the video as "ill-advised".[317]

2017 Las Vegas shooting

[edit]After the October 2017 shooting at a concert in Las Vegas, which left 58 people dead and 851 injured, the NRA was initially criticized for their silence.[318] After four days they issued a statement opposing additional gun control laws, which they said would not stop further attacks, and called for a federal law allowing people who have a concealed carry permit in one state to carry concealed weapons in all other states. The organization also suggested additional regulations on so-called bump fire stocks, which allow a semi-automatic weapon to function like a machine gun; the Las Vegas shooter had used such a device.[319]

Stoneman Douglas High School shooting

[edit]In February 2018 a school shooting at a high school in Florida left 17 dead and another 17 injured, and student survivors organized a movement called Never Again MSD to demand passage of certain gun control measures. Many of the students blamed the NRA, and the politicians who accept money from the organization, for preventing enactment of any gun control proposals after previous high-profile shootings.[320][321] An NRA spokesman responded by blaming the shooting on the FBI and the media.[322] The NRA also issued a statement that the incident was proof that more guns were immediately required in schools in the hands of a bolstered force of armed security personnel in order to "harden" them against any further similar assaults.[323] A Florida law passed in the wake of the shooting, which includes a provision to ban the sale of firearms to people under 21, was immediately challenged in federal court by the NRA on the grounds that it is "violating the constitutional rights of 18- to 21-year-olds."[324][325]

In May 2018, Cameron Kasky's father and other Parkland parents formed a super PAC, Families vs Assault Rifles PAC (FAMSVARPAC), with a stated goal of going "up against NRA candidates in every meaningful race in the country". The organization seeks federal legislation to ban "the most dangerous firearms", while not affecting the Second Amendment.[326][327][328]

Boycott

[edit]The NRA offers corporate discounts to its members at various businesses through its corporate affiliate programs. For several years, and increasingly in the aftermath of the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, "affiliate companies" have been targeted in social media as part of a boycott effort[329] to terminate their business relationships with the NRA.[330] As a result of this boycott movement, several major corporations such as Delta Air Lines, United Airlines, Hertz, Symantec, and MetLife have disaffiliated from the NRA, while others, such as FedEx have refused to disaffiliate.[331][332][333]

Media campaigns

[edit]In 2017, Zack Beauchamp of Vox and Mark Sumner of Daily Kos criticized a video advertisement from the NRA. In the video, Dana Loesch runs through a list of wrongs committed by an unspecified "they":

They use their media to assassinate real news. They use their schools to teach children that the president is another Hitler. They use their movie stars, and singers, and comedy shows, and award shows to repeat their narrative over and over again. And then they use their ex-president to endorse the resistance. All to make them march. Make them protest. Make them scream racism and sexism and xenophobia and homophobia. To smash windows, burn cars, shut down interstates and airports, bully and terrorize the law abiding. Until the only option left is for the police to do their jobs and stop the madness. And when that happens, they'll use it as an excuse for their outrage. The only way we stop this. The only way we save our country and our freedom, is to fight this violence of lies with the clenched fist of truth.

Sumner alleged the NRA was trying to boost gun sales by "convincing half of America to declare war on the other half." Beauchamp wrote, "It's a paranoid vision of American life that encourages the NRA's fans to see liberals not as political opponents, but as monsters."[334]

In May 2018, the NRA ran an advertisement which criticized the media for giving too much coverage to school shooters by showing their faces and revealing their names, in effect causing a "glorification of carnage in pursuit of ratings", and satirically suggested that Congress pass legislation to limit such coverage in order to make provocative point about gun control. In response, critics suggested that this would violate the First Amendment right of free speech.[335][336]

Pro-gun rights criticism

[edit]Pro-gun rights critics include Gun Owners of America (GOA), founded in the 1970s because some gun rights advocates believed the NRA was too flexible on gun issues.[337]: 110–11 Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership (JPFO) has also disagreed with NRA for what it perceives as a willingness to compromise on gun control.[338] The National Association for Gun Rights (NAGR) has been an outspoken critic of the NRA for a number of years. According to the Huffington Post, "NAGR is the much leaner, more pugnacious version of the NRA. Where the NRA has looked to find some common ground with gun reform advocates and at least appear to be reasonable, NAGR has been the unapologetic champion of opening up gun laws even more."[339] In June 2014, an open carry group in Texas threatened to withdraw its support of the NRA if it did not retract its statements critical of the practice. The NRA–ILA's Chris Cox said the statements were a staffer's personal opinion and a mistake.[340]

Lack of advocacy for black gun owners

[edit]The NRA has been accused of insufficiently defending African-American gun rights and of providing muted and delayed responses in gun rights cases involving black gun owners.[341] Others argue that the NRA's inaction in prominent gun rights cases involving black gun owners is a consequence of their reluctance to criticize law enforcement, noting NRA support for Otis McDonald and Shaneen Allen.[342][343]

In a well-publicized 2016 case, Philando Castile, an African-American and legal gun owner, was fatally shot by a police officer during a traffic stop while reaching for his wallet.[344][345] Castile had a valid firearm permit and informed the police officer of his gun prior to the shooting.[344][346] According to The Washington Post, the NRA had typically "been quick to defend other gun owners who made national news", but stayed silent on the Castile shooting.[344] Other gun rights advocates as well as some NRA members voiced similar criticisms.[344] In a delayed response to the shooting the NRA stated the death was "a terrible tragedy that could have been avoided."[347]

Adam Winkler, professor of constitutional law at the UCLA School of Law, has argued that there are historical precedents to the NRA's lack of advocacy for black gun owners, stating that the NRA promoted gun control legislation in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1960s with the intent to reduce gun ownership by immigrants and racial minorities.[clarification needed][348][349][350]

Lists of past and present leaders

[edit]Presidents

[edit]Presidents of the NRA are elected by the board of directors.

- Ambrose Burnside (1871–72)

- William Conant Church (1872–75)

- Alexander Shaler (1876)[351]

- Winfield S. Hancock (1881)[352]

- Ulysses S. Grant (1883–84)

- Philip H. Sheridan (1885)[353]

- George W. Wingate (1886–1900)[352]

- John C. Bates (1910–12)[352]

- William Libbey (1915–20)[352]

- Smith W. Brookhart (1921–25)

- Francis E. Warren (1925–26)[352]

- Benedict Crowell (1930–31)[352]

- Karl T. Frederick (1934–35)[352]

- Littleton W. T. Waller Jr. (1939–40)[352]

- Emmet O. Swanson (1948)[352]

- Merritt A. Edson (1949–50)[352]

- Morton C. Mumma (1955–56)[352]

- Harlon B. Carter (1965–67)

- Lloyd M. Mustin (1977–78)[352]

- Howard W. Pollock (1983–84)[352]

- Alonzo H. Garcelon (1985)

- Joe Foss (1988–90)

- Robert K. Corbin (1992–93)[352]

- Marion P. Hammer (1995–98)[354][355]

- Charlton Heston (1998–2003)

- Kayne Robinson (2003–05)

- Sandra Froman (2005–07)

- John C. Sigler (2007–09)

- Ron Schmeits (2009–11)

- David Keene (2011–13)

- James W. "Jim" Porter (2013–15)[356]

- Allan D. Cors (2015–17)

- Pete Brownell (2017–18)

- Oliver North (2018–19)

- Carolyn D. Meadows (2019–21)

- Charles L. Cotton (2021-24)

- Bob Barr (2024-present)

Directors

[edit]Notable directors, past and present, include:[226]

- Joe M. Allbaugh

- John M. Ashbrook[243]

- Bob Barr

- Ronnie Barrett

- Clel Baudler

- Ken Blackwell

- Matt Blunt

- John Bolton[357]

- Dan Boren

- Robert K. Brown

- Dave Butz

- Richard Childress

- Larry Craig

- Barbara Cubin[358]

- John Dingell[359]

- Merritt A. Edson

- R. Lee Ermey[360]

- Sandra Froman

- Jim Gilmore

- Marion P. Hammer

- Susan Howard

- Roy Innis

- David Keene

- Karl Malone

- John Milius[361]

- Zell Miller[362]

- Cleta Mitchell[363]

- Grover Norquist

- Oliver L. North

- Johnny Nugent

- Ted Nugent[364]

- Lee Purcell[365][366]

- Todd J. Rathner

- Wayne Anthony Ross

- Tom Selleck

- John C. Sigler

- Bruce Stern[367]

- Harold Volkmer[368]

- Don Young

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "National Rifle Association". ProPublica. May 9, 2013.

- ^ "NRA gets new bosses after ex-leader Wayne LaPierre's spending scandal - CBS News". www.cbsnews.com. May 21, 2024. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Korte, Gregory (May 4, 2013). "Post-Newtown, NRA membership surges to 5 million". USA Today.

- ^ Carter, Gregg Lee, ed. (2012). "National Rifle Association (NRA)". Guns in American Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, Culture, and the Law. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 616–20. ISBN 978-0313386701. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

The National Rifle Association (NRA) is the nation's largest, oldest, and most politically powerful interest group that opposes gun laws and favors gun rights.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A Brief History of NRA". National Rifle Association of America. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ^ "Analysis | Nobody knows how many members the NRA has, but its tax returns offer some clues". The Washington Post.

- ^ Sit, Ryan (March 30, 2018). "How big is the NRA? Gun group's membership might not be as powerful as it says". Newsweek. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ "About the NRA". home.nra.org. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ Lacombe, Matthew J. (2021). Firepower: How the NRA Turned Gun Owners into a Political Force. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-20746-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "FORTUNE Releases Annual Survey of Most Powerful Lobbying Organizations" (Press release). Time Warner. November 15, 1999. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- ^ Wilson, James Q.; et al. (2011). American Government: Institutions & Policies. Cengage Learning. p. 264. ISBN 978-0495802815.

- ^ LaPierre, Wayne. "Media Rage Against Trump And His Promise Of A Better Nation". America's 1st Freedom. NRA.

- ^ Davidson, Osha Gray (1998). Under Fire: the NRA and the Battle for Gun Control. University Of Iowa Press. pp. 28–36. ISBN 0877456461.

- ^ "Gun violence research: History of the federal funding freeze". apa.org. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ "Transcript of remarks from the NRA press conference on Sandy Hook school shooting". The Washington Post. December 21, 2012.

- ^ "A National Rifle Association.; Patriotic Action of Americans Residing Abroad". The New York Times. August 9, 1861. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833–1916: R.B. Perry and R.G. Moulton to Abraham Lincoln, Wednesday, June 12, 1861 (Loyal Americans in Europe volunteer services)". The Library of Congress. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "Prize Rifles A Note from Patriotic Americans in England". The New York Times. September 9, 1861. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The National Rifle Association". The New York Times. September 17, 1871.

A meeting of the National Rifle Association was held in the Seventh Regiment armory yesterday, Gen. J.P. Woodward, of the second Division, presided, and Col. H.G. Shaw officiated as Secretary. Articles of association were presented and adopted. The incorporators are composed of forty prominent officers and ex-officers of the National Guard. Membership in the Association is to be open to all persons interested in the promotion of the rifle practice. Regiments and companies in the National Guard are entitled by the by-laws to constitute all their regular members in good standing members of the Association on the payment of one-half of the entrance fees and annual dues.

- ^ "Meeting of the National Rifle Association Election of Officers". The New York Times. November 25, 1871. p. 3.

- ^ "Notes of the Day". The New York Times. August 1, 1872. p. 3.

- ^ "National Rifle Association". The New York Times. August 7, 1872. p. 2.

- ^ Bellini, Jason (December 20, 2012). "A Brief History of the NRA". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Achenbach, Joel; Higham, Scott; Horwitz Sari (January 12, 2013). "How NRA's true believers converted a marksmanship group into a mighty gun lobby". The Washington Post

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Craige, John Houston The Practical Book of American Guns (1950) Bramhall House pp. 84–93

- ^ "Timeline of the NRA", The Washington Post, January 12, 2013.

- ^ Kerr, Richard E. (1990). Wall of Fire – The Rifle and Civil War Infantry Tactics (PDF) (Thesis). US Army Command and General Staff College. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ Somerset, A.J. (December 20, 2015). "Excerpt: How Canadians helped create the NRA". Toronto Star.

- ^ "America's Wimbledon: The Inauguration". The New York Times. June 22, 1873. p. 5.

- ^ "The National Rifle Association". The New York Times. June 12, 1873. p. 5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b David Minshall. "Creedmoor and the International Rifle Matches". Research Press. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ "The Breechloading Sharps: History & Performance". American Rifleman. National Rifle Association of America. May 21, 2021. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Paul Nordquist (November 7, 2016). "Origin of the Palma Trophy and Matches". Shooting Sports USA. National Rifle Association of America. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ David Minshall. "Creedmoor and the International Rifle Matches - Events". Research Press. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ "History". International Confederation of Fullbore Rifle Associations. Archived from the original on February 24, 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

ICFRA is a confederation of independent autonomous national fullbore rifle associations and is the only World-wide body for the promotion of fullbore rifle shooting. It is the successor to the Palma Match Council. Its aims are set out in the Constitution and include the standardisation of fullbore rifle shooting rules and the promotion and control of international matches at World level, including World Championships for Target rifle and F-Class (Individual and Team).

- ^ "Historic Palma Match Results 1876-2015" (PDF). International Confederation of Fullbore Rifle Associations. August 30, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ "The 'Academy' Must Now Share Michael Moore's Cinematic Shame". National Rifle Association of America Institute for Legislative Action. March 27, 2003. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- ^ Canfield, Bruce N. (September 2008). "To promote marksmanship ... 'N.R.A.'-marked M1903 rifles". American Rifleman. 156 (9): 72–75.

- ^ Ness, Mark (June 1983). "American Rifleman". American Rifleman: 58.

- ^ Camp, Raymond R. (1948). The Hunter's Encyclopedia. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole and Heck. p. 599.