George H. W. Bush

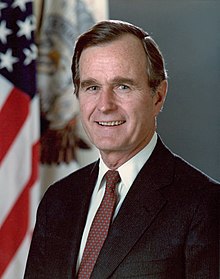

George H. W. Bush | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1989 | |

| 41st President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1989 – January 20, 1993 | |

| Vice President | Dan Quayle |

| Preceded by | Ronald Reagan |

| Succeeded by | Bill Clinton |

| 43rd Vice President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1981 – January 20, 1989 | |

| President | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | Walter Mondale |

| Succeeded by | Dan Quayle |

| 11th Director of Central Intelligence | |

| In office January 30, 1976 – January 20, 1977 | |

| President | Gerald Ford |

| Deputy | |

| Preceded by | William Colby |

| Succeeded by | Stansfield Turner |

| 2nd Chief of the U.S. Liaison Office to the People's Republic of China | |

| In office September 26, 1974 – December 7, 1975 | |

| President | Gerald Ford |

| Preceded by | David K. E. Bruce |

| Succeeded by | Thomas S. Gates Jr. |

| Chair of the Republican National Committee | |

| In office January 19, 1973 – September 16, 1974 | |

| Preceded by | Bob Dole |

| Succeeded by | Mary Smith |

| 10th United States Ambassador to the United Nations | |

| In office March 1, 1971 – January 18, 1973 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Charles Yost |

| Succeeded by | John A. Scali |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Texas's 7th district | |

| In office January 3, 1967 – January 3, 1971 | |

| Preceded by | John Dowdy |

| Succeeded by | Bill Archer |

| Personal details | |

| Born | George Herbert Walker Bush June 12, 1924 Milton, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | November 30, 2018 (aged 94) Houston, Texas, U.S. |

| Resting place | George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | Bush family |

| Education | Yale University (BA) |

| Occupation |

|

| Civilian awards | Full list |

| Signature | |

| Website | Presidential Library |

| Nickname | "Skin" |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1942–1955 (reserve, active service 1942–1945) |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Unit | Fast Carrier Task Force |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Military awards | |

George Herbert Walker Bush[a] (June 12, 1924 – November 30, 2018) was an American politician, diplomat, and businessman who served as the 41st president of the United States from 1989 to 1993. A member of the Republican Party, he also served as the 43rd vice president from 1981 to 1989 under Ronald Reagan and previously in various other federal positions.[2]

Born into a wealthy, established family in Milton, Massachusetts, Bush was raised in Greenwich, Connecticut. He attended Phillips Academy and served as a pilot in the United States Navy Reserve during World War II before graduating from Yale and moving to West Texas, where he established a successful oil company. Following an unsuccessful run for the United States Senate in 1964, he was elected to represent Texas's 7th congressional district in 1966. President Richard Nixon appointed Bush as the ambassador to the United Nations in 1971 and as chairman of the Republican National Committee in 1973. President Gerald Ford appointed him as the chief of the Liaison Office to the People's Republic of China in 1974 and as the director of Central Intelligence in 1976. Bush ran for president in 1980 but was defeated in the Republican presidential primaries by Reagan, who then selected Bush as his vice presidential running mate. In the 1988 presidential election, Bush defeated Democrat Michael Dukakis.

Foreign policy drove Bush's presidency as he navigated the final years of the Cold War and played a key role in the reunification of Germany. He presided over the invasion of Panama and the Gulf War, ending the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait in the latter conflict. Though the agreement was not ratified until after he left office, Bush negotiated and signed the North American Free Trade Agreement, which created a trade bloc consisting of the United States, Canada and Mexico. Domestically, Bush reneged on a 1988 campaign promise by enacting legislation to raise taxes to justify reducing the budget deficit. He championed and signed three pieces of bipartisan legislation in 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Immigration Act and the Clean Air Act Amendments. He also appointed David Souter and Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. Bush lost the 1992 presidential election to Democrat Bill Clinton following an economic recession, his turnaround on his tax promise, and the decreased emphasis of foreign policy in a post–Cold War political climate.[3]

After leaving office in 1993, Bush was active in humanitarian activities, often working alongside Clinton. With the victory of his son, George W. Bush, in the 2000 presidential election, the two became the second father–son pair to serve as the nation's president, following John Adams and John Quincy Adams. Another son, Jeb Bush, unsuccessfully sought the Republican presidential nomination in the 2016 primaries. Historians generally rank Bush as an above-average president.

Early life and education (1924–1948)

George Herbert Walker Bush was born on June 12, 1924, in Milton, Massachusetts.[4] He was the second son of Prescott Bush and Dorothy (Walker) Bush,[5] and a younger brother of Prescott Bush Jr. His paternal grandfather, Samuel P. Bush, worked as an executive for a railroad parts company in Columbus, Ohio,[6] while his maternal grandfather and namesake, George Herbert Walker, led Wall Street investment bank W. A. Harriman & Co.[7] Walker was known as "Pop", and young Bush was called "Poppy" as a tribute to him.[8]

The Bush family moved to Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1925, and Prescott took a position with W. A. Harriman & Co., which later merged into Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. the following year.[9] Bush spent most of his childhood in Greenwich, at the family vacation home in Kennebunkport, Maine,[b] or at his maternal grandparents' plantation in South Carolina.[11]

Because of the family's wealth, Bush was largely unaffected by the Great Depression.[12] He attended Greenwich Country Day School from 1929 to 1937 and Phillips Academy, an elite private academy in Massachusetts, from 1937 to 1942.[13] While at Phillips Academy, he served as president of the senior class, secretary of the student council, president of the community fund-raising group, a member of the editorial board of the school newspaper, and captain of the varsity baseball and soccer teams.[14]

World War II

On his 18th birthday, immediately after graduating from Phillips Academy, he enlisted in the United States Navy as a naval aviator.[15] After a period of training, he was commissioned as an ensign in the Naval Reserve at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi on June 9, 1943, becoming one of the youngest pilots in the Navy.[16][c] Beginning in 1944, Bush served in the Pacific theater, where he flew a Grumman TBF Avenger, a torpedo bomber capable of taking off from aircraft carriers.[21] His squadron was assigned to the USS San Jacinto as a member of Air Group 51, where his lanky physique earned him the nickname "Skin".[22]

Bush flew his first combat mission in May 1944, bombing Japanese-held Wake Island,[23] and was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) on August 1, 1944. During an attack on a Japanese installation in Chichijima, Bush's aircraft successfully attacked several targets but was downed by enemy fire.[20] Though both of Bush's fellow crew members died, Bush successfully bailed out from the aircraft and was rescued by the submarine USS Finback.[24][d] Several of the aviators shot down during the attack were captured and executed, and their livers were cannibalized by their captors.[25] Bush's survival after such a close brush with death shaped him profoundly, leading him to ask, "Why had I been spared and what did God have for me?"[26] He was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his role in the mission.[27]

Bush returned to San Jacinto in November 1944, participating in operations in the Philippines. In early 1945, he was assigned to a new combat squadron, VT-153, where he trained to participate in an invasion of mainland Japan. Between March and May 1945, he trained in Auburn, Maine, where he and Barbara lived in a small apartment.[28] On September 2, 1945, before any invasion took place, Japan formally surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[29] Bush was released from active duty that same month but was not formally discharged from the Navy until October 1955, when he had reached the rank of lieutenant.[20] By the end of his period of active service, Bush had flown 58 missions, completed 128 carrier landings, and recorded 1228 hours of flight time.[30]

Marriage

Bush met Barbara Pierce at a Christmas dance in Greenwich in December 1941,[31] and, after a period of courtship, they became engaged in December 1943.[32] While Bush was on leave from the Navy, they married in Rye, New York, on January 6, 1945.[33] The Bushes enjoyed a strong marriage, and Barbara would later be a popular First Lady, seen by many as "a kind of national grandmother".[34][e] They had six children: George W. (b. 1946), Robin (1949–1953), Jeb (b. 1953), Neil (b. 1955), Marvin (b. 1956), and Doro (b. 1959).[15] Their oldest daughter, Robin, died of leukemia in 1953.[37][38]

College years

Bush enrolled at Yale College, where he took part in an accelerated program that enabled him to graduate in two and a half years rather than the usual four.[15] He was a member of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity and was elected its president.[39] He also captained the Yale baseball team and played in the first two College World Series as a left-handed first baseman.[40] Like his father, he was a member of the Yale cheerleading squad[41] and was initiated into the Skull and Bones secret society. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1948 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics.[42]

Business career (1948–1963)

After graduating from Yale, Bush moved his young family to West Texas. Biographer Jon Meacham writes that Bush's relocation to Texas allowed him to move out of the "daily shadow of his Wall Street father and Grandfather Walker, two dominant figures in the financial world," but would still allow Bush to "call on their connections if he needed to raise capital."[43] His first position in Texas was an oil field equipment salesman[44] for Dresser Industries, which was led by family friend Neil Mallon.[45] While working for Dresser, Bush lived in various places with his family: Odessa, Texas; Ventura, Bakersfield and Compton, California; and Midland, Texas.[46] In 1952, he volunteered for the successful presidential campaign of Republican candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower. That same year, his father won election to represent Connecticut in the United States Senate as a member of the Republican Party.[47]

With support from Mallon and Bush's uncle, George Herbert Walker Jr., Bush and John Overbey launched the Bush-Overbey Oil Development Company in 1951.[48] In 1953, he co-founded the Zapata Petroleum Corporation, an oil company that drilled in the Permian Basin in Texas.[49] In 1954, he was named president of the Zapata Offshore Company, a subsidiary which specialized in offshore drilling.[50] Shortly after the subsidiary became independent in 1959, Bush moved the company and his family from Midland to Houston.[51] There, he befriended James Baker, a prominent attorney who later became an important political ally.[52] Bush remained involved with Zapata until the mid-1960s, when he sold his stock in the company for approximately $1 million.[53]

In 1988, The Nation published an article alleging that Bush worked as an operative of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the 1960s; Bush denied this claim.[54]

Early political career (1963–1971)

Entry into politics

By the early 1960s, Bush was widely regarded as an appealing political candidate, and some leading Democrats attempted to convince Bush to become a Democrat. He declined to leave the Republican Party, later citing his belief that the national Democratic Party favored "big, centralized government". The Democratic Party had historically dominated Texas, but Republicans scored their first major victory in the state with John G. Tower's victory in a 1961 special election to the United States Senate. Motivated by Tower's victory and hoping to prevent the far-right John Birch Society from coming to power, Bush ran for the chairmanship of the Harris County Republican Party, winning election in February 1963.[55] Like most other Texas Republicans, Bush supported conservative Senator Barry Goldwater over the more centrist Nelson Rockefeller in the 1964 Republican Party presidential primaries.[56]

In 1964, Bush sought to unseat liberal Democrat Ralph W. Yarborough in Texas's U.S. Senate election.[57] Bolstered by superior fundraising, Bush won the Republican primary by defeating former gubernatorial nominee Jack Cox in a run-off election. In the general election, Bush attacked Yarborough's vote for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned racial and gender discrimination in public institutions and many privately owned businesses. Bush argued that the act unconstitutionally expanded the federal government's powers, but he was privately uncomfortable with the racial politics of opposing the act.[58] He lost the election 56 percent to 44 percent, though he did run well ahead of Barry Goldwater, the Republican presidential nominee.[57] Despite the loss, The New York Times reported that Bush was "rated by political friend and foe alike as the Republicans' best prospect in Texas because of his attractive personal qualities and the strong campaign he put up for the Senate".[59]

U.S. House of Representatives

In 1966, Bush ran for the United States House of Representatives in Texas's 7th congressional district, a newly redistricted seat in the Greater Houston area. Initial polling showed him trailing his Democratic opponent, Harris County District Attorney Frank Briscoe, but he ultimately won the race with 57 percent of the vote.[60] To woo potential candidates in the South and Southwest, House Republicans secured Bush an appointment to the powerful United States House Committee on Ways and Means, making Bush the first freshman to serve on the committee since 1904.[61] His voting record in the House was generally conservative. He supported the Nixon administration's Vietnam policies but broke with Republicans on the issue of birth control, which he supported. He also voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1968, although it was generally unpopular in his district.[62][63][64][65] In 1968, Bush joined several other Republicans in issuing the party's Response to the State of the Union address; Bush's part of the address focused on a call for fiscal responsibility.[66]

Though most other Texas Republicans supported Ronald Reagan in the 1968 Republican Party presidential primaries, Bush endorsed Richard Nixon, who went on to win the party's nomination. Nixon considered selecting Bush as his running mate in the 1968 presidential election, but he ultimately chose Spiro Agnew instead. Bush won re-election to the House unopposed, while Nixon defeated Hubert Humphrey in the presidential election.[67] In 1970, with President Nixon's support, Bush gave up his seat in the House to run for the Senate against Yarborough. Bush easily won the Republican primary, but Yarborough was defeated by the more conservative Lloyd Bentsen in the Democratic primary.[68] Ultimately, Bentsen defeated Bush, taking 53.5 percent of the vote.[69]

Nixon and Ford administrations (1971–1977)

Ambassador to the United Nations

After the 1970 Senate election, Bush accepted a position as a senior adviser to the president, but he convinced Nixon to instead appoint him as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations.[70] The position represented Bush's first foray into foreign policy, as well as his first major experiences with the Soviet Union and China, the two major U.S. rivals in the Cold War.[71] During Bush's tenure, the Nixon administration pursued a policy of détente, seeking to ease tensions with both the Soviet Union and China.[72] Bush's ambassadorship was marked by a defeat on the China question, as the United Nations General Assembly voted, in Resolution 2758, to expel the Republic of China and replace it with the People's Republic of China in October 1971.[73] In the 1971 crisis in Pakistan, Bush supported an Indian motion at the UN General Assembly to condemn the Pakistani government of Yahya Khan for waging genocide in East Pakistan (modern Bangladesh), referring to the "tradition which we have supported that the human rights question transcended domestic jurisdiction and should be freely debated".[74] Bush's support for India at the UN put him into conflict with Nixon who was supporting Pakistan, partly because Yahya Khan was a useful intermediary in his attempts to reach out to China and partly because the president was fond of Yahya Khan.[75]

Chairman of the Republican National Committee

After Nixon won a landslide victory in the 1972 presidential election, he appointed Bush as chair of the Republican National Committee (RNC).[76][77] In that position, he was charged with fundraising, candidate recruitment, and making appearances on behalf of the party in the media.

When Agnew was being investigated for corruption, Bush assisted, at the request of Nixon and Agnew, in pressuring John Glenn Beall Jr., the U.S. Senator from Maryland, to force his brother, George Beall the U.S. Attorney in Maryland, to shut down the investigation into Agnew. Attorney Beall ignored the pressure.[78]

During Bush's tenure at the RNC, the Watergate scandal emerged into public view; the scandal originated from the June 1972 break-in of the Democratic National Committee but also involved later efforts to cover up the break-in by Nixon and other members of the White House.[79] Bush initially defended Nixon steadfastly, but as Nixon's complicity became clear he focused more on defending the Republican Party.[62]

Following the resignation of Vice President Agnew in 1973 for a scandal unrelated to Watergate, Bush was considered for the position of vice president, but the appointment instead went to Gerald Ford.[80] After the public release of an audio recording that confirmed that Nixon had plotted to use the CIA to cover up the Watergate break-in, Bush joined other party leaders in urging Nixon to resign.[81] When Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, Bush noted in his diary that "There was an aura of sadness, like somebody died... The [resignation] speech was vintage Nixon—a kick or two at the press—enormous strains. One couldn't help but look at the family and the whole thing and think of his accomplishments and then think of the shame... [President Gerald Ford's swearing-in offered] indeed a new spirit, a new lift."[82]

Head of U.S. Liaison Office in China

Upon his ascension to the presidency, Ford strongly considered Bush, Donald Rumsfeld, and Nelson Rockefeller for the vacant position of vice president. Ford ultimately chose Nelson Rockefeller, partly because of the publication of a news report claiming that Bush's 1970 campaign had benefited from a secret fund set up by Nixon; Bush was later cleared of any suspicion by a special prosecutor.[83] Bush accepted appointment as Chief of the U.S. Liaison Office in the People's Republic of China, making him the de facto ambassador to China.[84] According to biographer Jon Meacham, Bush's time in China convinced him that American engagement abroad was needed to ensure global stability and that the United States "needed to be visible but not pushy, muscular but not domineering."[85]

Director of Central Intelligence

In January 1976, Ford brought Bush back to Washington to become the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), placing him in charge of the CIA.[86] In the aftermath of the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War, the CIA's reputation had been damaged for its role in various covert operations. Bush was tasked with restoring the agency's morale and public reputation.[87][f] During Bush's year in charge of the CIA, the U.S. national security apparatus actively supported Operation Condor operations and right-wing military dictatorships in Latin America.[88][89]

Meanwhile, Ford decided to drop Rockefeller from the ticket for the 1976 presidential election; he considered Bush as his running mate, but ultimately chose Bob Dole.[90] In his capacity as DCI, Bush gave national security briefings to Jimmy Carter both as a presidential candidate and as president-elect.[91]

1980 presidential election

Presidential campaign

Bush's tenure at the CIA ended after Carter narrowly defeated Ford in the 1976 presidential election. Out of public office for the first time since the 1960s, Bush became chairman on the executive committee of the First International Bank in Houston.[92] He also spent a year as a part-time professor of Administrative Science at Rice University's Jones School of Business,[93] continued his membership in the Council on Foreign Relations, and joined the Trilateral Commission. Meanwhile, he began to lay the groundwork for his candidacy in the 1980 Republican Party presidential primaries.[94] In the 1980 Republican primary campaign, Bush faced Ronald Reagan, who was widely regarded as the front-runner, as well as other contenders like Senator Bob Dole, Senator Howard Baker, Texas Governor John Connally, Congressman Phil Crane, and Congressman John B. Anderson.[95]

Bush's campaign cast him as a youthful, "thinking man's candidate" who would emulate the pragmatic conservatism of President Eisenhower.[96] Amid the Soviet–Afghan War, which brought an end to a period of détente, and the Iran hostage crisis, in which 52 Americans were taken hostage, the campaign highlighted Bush's foreign policy experience.[97] At the outset of the race, Bush focused heavily on winning the January 21 Iowa caucuses, making 31 visits to the state.[98] He won a close victory in Iowa with 31.5% to Reagan's 29.4%. After the win, Bush stated that his campaign was full of momentum, or "the Big Mo",[99] and Reagan reorganized his campaign.[100] Partly in response to the Bush campaign's frequent questioning of Reagan's age (Reagan turned 69 in 1980), the Reagan campaign stepped up attacks on Bush, painting him as an elitist who was not truly committed to conservatism.[101] Prior to the New Hampshire primary, Bush and Reagan agreed to a two-person debate, organized by The Nashua Telegraph but paid for by the Reagan campaign.[100]

Days before the debate, Reagan announced that he would invite four other candidates to the debate; Bush, who had hoped that the one-on-one debate would allow him to emerge as the main alternative to Reagan in the primaries, refused to debate the other candidates. All six candidates took the stage, but Bush refused to speak in the presence of the other candidates. Ultimately, the other four candidates left the stage, and the debate continued, but Bush's refusal to debate anyone other than Reagan badly damaged his campaign in New Hampshire.[102] He decisively lost New Hampshire's primary to Reagan, winning just 23 percent of the vote.[100] Bush revitalized his campaign with a victory in Massachusetts but lost the next several primaries. As Reagan built up a commanding delegate lead, Bush refused to end his campaign, but the other candidates dropped out of the race.[103] Criticizing his more conservative rival's policy proposals, Bush famously labeled Reagan's supply side–influenced plans for massive tax cuts as "voodoo economics".[104] Though he favored lower taxes, Bush feared that dramatic reductions in taxation would lead to deficits and, in turn, cause inflation.[105]

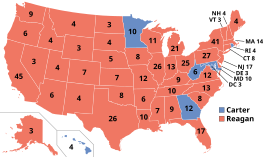

Vice presidential campaign

After Reagan clinched a majority of delegates in late May, Bush reluctantly dropped out of the race.[106] At the 1980 Republican National Convention, Reagan made the last-minute decision to select Bush as his vice presidential nominee after negotiations with Ford regarding a Reagan–Ford ticket collapsed.[107] Though Reagan had resented many of the Bush campaign's attacks during the primary campaign, and several conservative leaders had actively opposed Bush's nomination, Reagan ultimately decided that Bush's popularity with moderate Republicans made him the best and safest pick. Bush, who had believed his political career might be over following the primaries, eagerly accepted the position and threw himself into campaigning for the Reagan–Bush ticket.[108] The 1980 general election campaign between Reagan and Carter was conducted amid a multitude of domestic concerns and the ongoing Iran hostage crisis, and Reagan sought to focus the race on Carter's handling of the economy.[109] Though the race was widely regarded as a close contest for most of the campaign, Reagan ultimately won over the large majority of undecided voters.[110] Reagan took 50.7 percent of the popular vote and 489 of the 538 electoral votes, while Carter won 41% of the popular vote and John Anderson, running as an independent candidate, won 6.6% of the popular vote.[111]

Vice presidency (1981–1989)

As vice president, Bush generally maintained a low profile, recognizing the constitutional limits of the office; he avoided decision-making or criticizing Reagan in any way. This approach helped him earn Reagan's trust, easing tensions left over from their earlier rivalry.[100] Bush also generally enjoyed a good relationship with Reagan staffers, including Bush's close friend James Baker, who served as Reagan's initial chief of staff.[112] His understanding of the vice presidency was heavily influenced by Vice President Walter Mondale, who enjoyed a strong relationship with President Carter in part because of his ability to avoid confrontations with senior staff and Cabinet members, and by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller's difficult relationship with some members of the White House staff during the Ford administration.[113] The Bushes attended a large number of public and ceremonial events in their positions, including many state funerals, which became a common joke for comedians. As the president of the Senate, Bush also stayed in contact with members of Congress and kept the president informed on occurrences on Capitol Hill.[100]

First term

On March 30, 1981, while Bush was in Texas, Reagan was shot and seriously wounded by John Hinckley Jr. Bush immediately flew back to Washington D.C.; when his plane landed, his aides advised him to proceed directly to the White House by helicopter to show that the government was still functioning.[100] Bush rejected the idea, fearing that such a dramatic scene risked giving the impression that he sought to usurp Reagan's powers and prerogatives.[114] During Reagan's short period of incapacity, Bush presided over Cabinet meetings, met with congressional and foreign leaders, and briefed reporters. Still, he consistently rejected invoking the Twenty-fifth Amendment.[115] Bush's handling of the attempted assassination and its aftermath made a positive impression on Reagan, who recovered and returned to work within two weeks of the shooting. From then on, the two men would have regular Thursday lunches in the Oval Office.[116]

Reagan assigned Bush to chair two special task forces, one on deregulation and one on international drug smuggling. Both were popular issues with conservatives, and Bush, largely a moderate, began courting them through his work. The deregulation task force reviewed hundreds of rules, making specific recommendations on which ones to amend or revise to curb the size of the federal government.[100] The Reagan administration's deregulation push strongly impacted broadcasting, finance, resource extraction, and other economic activities, and the administration eliminated numerous government positions.[117] Bush also oversaw the administration's national security crisis management organization, which had traditionally been the responsibility of the National Security Advisor.[118] In 1983, Bush toured Western Europe as part of the Reagan administration's ultimately successful efforts to convince skeptical NATO allies to support the deployment of Pershing II missiles.[119]

Reagan's approval ratings fell after his first year in office, but they bounced back when the United States began to emerge from recession in 1983.[120] Former vice president Walter Mondale was nominated by the Democratic Party in the 1984 presidential election. Down in the polls, Mondale selected Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate in hopes of galvanizing support for his campaign, thus making Ferraro the first female major party vice presidential nominee in U.S. history.[121] She and Bush squared off in a single televised vice presidential debate.[100] Public opinion polling consistently showed a Reagan lead in the 1984 campaign, and Mondale was unable to shake up the race.[122] In the end, Reagan won re-election, winning 49 of 50 states and receiving 59% of the popular vote to Mondale's 41%.[123]

Second term

Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union in 1985. Rejecting the ideological rigidity of his three elderly sick predecessors, Gorbachev insisted on urgently needed economic and political reforms called "glasnost" (openness) and "perestroika" (restructuring).[124] At the 1987 Washington Summit, Gorbachev and Reagan signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which committed both signatories to the total abolition of their respective short-range and medium-range missile stockpiles.[125] The treaty began a new era of trade, openness, and cooperation between the two powers.[126] President Reagan and Secretary of State George Shultz took the lead in these negotiations, but Bush sat in on many meetings. Bush did not agree with many of the Reagan policies, but he did tell Gorbachev that he would seek to continue improving relations if he succeeded Reagan.[127] On July 13, 1985, Bush became the first vice president to serve as acting president when Reagan underwent surgery to remove polyps from his colon; Bush served as the acting president for approximately eight hours.[128]

In 1986, the Reagan administration was shaken by a scandal when it was revealed that administration officials had secretly arranged weapon sales to Iran during the Iran–Iraq War. The officials had used the proceeds to fund the Contra rebels in their fight against the leftist Sandinista government in Nicaragua. Democrats had passed a law that appropriated funds could not be used to help the Contras. Instead, the administration used non-appropriated funds from the sales.[100] When news of the affair broke to the media, Bush stated that he had been "out of the loop" and unaware of the diversion of funds.[129] Biographer Jon Meacham writes that "no evidence was ever produced proving Bush was aware of the diversion to the contras," but he criticizes Bush's "out of the loop" characterization, writing that the "record is clear that Bush was aware that the United States, in contravention of its own stated policy, was trading arms for hostages".[130] The Iran–Contra scandal, as it became known, did serious damage to the Reagan presidency, raising questions about Reagan's competency.[131] Congress established the Tower Commission to investigate the scandal, and, at Reagan's request, a panel of federal judges appointed Lawrence Walsh as a special prosecutor charged with investigating the Iran–Contra scandal.[132] The investigations continued after Reagan left office, and, though Bush was never charged with a crime, the Iran–Contra scandal would remain a political liability for him.[133]

On July 3, 1988, the guided missile cruiser USS Vincennes accidentally shot down Iran Air Flight 655, killing 290 passengers.[134] Bush, then-vice president, defended his country at the United Nations by arguing that the U.S. attack had been a wartime incident and the crew of Vincennes had acted appropriately to the situation.[135]

1988 presidential election

Bush began planning for a presidential run after the 1984 election, and he officially entered the 1988 Republican Party presidential primaries in October 1987.[100] He put together a campaign led by Reagan staffer Lee Atwater, which also included his son, George W. Bush, and media consultant Roger Ailes.[136] Though he had moved to the right during his time as vice president, endorsing a Human Life Amendment and repudiating his earlier comments on "voodoo economics", Bush still faced opposition from many conservatives in the Republican Party.[137] His major rivals for the Republican nomination were Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole of Kansas, Representative Jack Kemp of New York, and Christian televangelist Pat Robertson.[138] Reagan did not publicly endorse any candidate but privately expressed support for Bush.[139]

Though considered the early front-runner for the nomination, Bush came in third in the Iowa caucus, behind Dole and Robertson.[140] Much as Reagan had done in 1980, Bush reorganized his staff and concentrated on the New Hampshire primary.[100] With help from Governor John H. Sununu and an effective campaign attacking Dole for raising taxes, Bush overcame an initial polling deficit and won New Hampshire with 39 percent of the vote.[141] After Bush won South Carolina and 16 of the 17 states holding a primary on Super Tuesday, his competitors dropped out of the race.[142]

Bush, occasionally criticized for his lack of eloquence compared to Reagan, delivered a well-received speech at the Republican convention. Known as the "thousand points of light" speech, it described Bush's vision of America: he endorsed the Pledge of Allegiance, prayer in schools, capital punishment, and gun rights.[143] Bush also pledged that he would not raise taxes, stating: "Congress will push me to raise taxes, and I'll say no, and they'll push, and I'll say no, and they'll push again. And all I can say to them is: read my lips. No new taxes."[144] Bush selected little-known Senator Dan Quayle of Indiana as his running mate. Though Quayle had compiled an unremarkable record in Congress, he was popular among many conservatives, and the campaign hoped that Quayle's youth would appeal to younger voters.[145]

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party nominated Governor Michael Dukakis, known for presiding over an economic turnaround in Massachusetts.[146] Leading in the general election polls against Bush, Dukakis ran an ineffective, low-risk campaign.[147] The Bush campaign attacked Dukakis as an unpatriotic liberal extremist and seized on the Willie Horton case, in which a convicted felon from Massachusetts raped a woman while on a prison furlough, a program Dukakis supported as governor. The Bush campaign charged that Dukakis presided over a "revolving door" that allowed dangerous convicted felons to leave prison.[148] Dukakis damaged his own campaign with a widely mocked ride in an M1 Abrams tank and poor performance at the second presidential debate.[149] Bush also attacked Dukakis for opposing a law that would require all students to recite the Pledge of Allegiance.[143] The election is widely considered to have had a high level of negative campaigning, though political scientist John Geer has argued that the share of negative ads was in line with previous presidential elections.[150]

Bush defeated Dukakis by a margin of 426 to 111 in the Electoral College, and he took 53.4 percent of the national popular vote.[151] Bush ran well in all the major regions of the country, but especially in the South.[152] He became the fourth sitting vice president to be elected president and the first to do so since Martin Van Buren in 1836 and the first person to succeed a president from his own party via election since Herbert Hoover in 1929.[100][g] In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats retained control of both houses of Congress.[154]

Presidency (1989–1993)

Bush was inaugurated on January 20, 1989, succeeding Reagan. In his inaugural address, Bush said:

I come before you and assume the Presidency at a moment rich with promise. We live in a peaceful, prosperous time, but we can make it better. For a new breeze is blowing, and a world refreshed by freedom seems reborn; for in man's heart, if not in fact, the day of the dictator is over. The totalitarian era is passing, its old ideas blown away like leaves from an ancient, lifeless tree. A new breeze is blowing, and a nation refreshed by freedom stands ready to push on. There is new ground to be broken, and new action to be taken.[155]

Bush's first major appointment was that of James Baker as Secretary of State.[156] Leadership of the Department of Defense went to Dick Cheney, who had previously served as Gerald Ford's chief of staff and would later serve as vice president under his son George W. Bush.[157] Jack Kemp joined the administration as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, while Elizabeth Dole, the wife of Bob Dole and a former Secretary of Transportation, became the Secretary of Labor under Bush.[158] Bush retained several Reagan officials, including Secretary of the Treasury Nicholas F. Brady, Attorney General Dick Thornburgh, and Secretary of Education Lauro Cavazos.[159] New Hampshire Governor John Sununu, a strong supporter of Bush during the 1988 campaign, became chief of staff.[156] Brent Scowcroft was appointed as the National Security Advisor, a role he had also held under Ford.[160]

Foreign affairs

End of the Cold War

During the first year of his tenure, Bush paused Reagan's détente policy toward the Soviet Union.[161] Bush and his advisers were initially divided on Gorbachev; some administration officials saw him as a democratic reformer, but others suspected him of trying to make the minimum changes necessary to restore the Soviet Union to a competitive position with the United States.[162] In 1989, all the Communist governments collapsed in Eastern Europe. Gorbachev declined to send in the Soviet military, effectively abandoning the Brezhnev Doctrine. The U.S. was not directly involved in these upheavals, but the Bush administration avoided gloating over the demise of the Eastern Bloc to avoid undermining further democratic reforms.[163]

Bush and Gorbachev met at the Malta Summit in December 1989. Though many on the right remained wary of Gorbachev, Bush came away believing that Gorbachev would negotiate in good faith.[164] For the remainder of his term, Bush sought cooperative relations with Gorbachev, believing he was the key to peace.[165] The primary issue at the Malta Summit was the potential reunification of Germany. While Britain and France were wary of a reunified Germany, Bush joined German chancellor Helmut Kohl in pushing for German reunification.[166] Bush believed that a reunified Germany would serve American interests.[167] After extensive negotiations, Gorbachev agreed to allow a reunified Germany to be a part of NATO, and Germany officially reunified in October 1990 after paying billions of marks to Moscow.[168]

Gorbachev used force to suppress nationalist movements within the Soviet Union itself.[169] A crisis in Lithuania left Bush in a difficult position, as he needed Gorbachev's cooperation in the reunification of Germany and feared that the collapse of the Soviet Union could leave nuclear arms in dangerous hands. The Bush administration mildly protested Gorbachev's suppression of Lithuania's independence movement but took no action to intervene directly.[170] Bush warned independence movements of the disorder that could come with secession from the Soviet Union; in a 1991 address that critics labeled the "Chicken Kiev speech", he cautioned against "suicidal nationalism".[171] In July 1991, Bush and Gorbachev signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) treaty, in which both countries agreed to cut their strategic nuclear weapons by 30 percent.[172]

In August 1991, hard-line Communists launched a coup against Gorbachev; while the coup quickly fell apart, it broke the remaining power of Gorbachev and the central Soviet government.[173] Later that month, Gorbachev resigned as general secretary of the Communist party, and Russian president Boris Yeltsin ordered the seizure of Soviet property. Gorbachev clung to power as the President of the Soviet Union until December 1991, when the Soviet Union dissolved.[174] Fifteen states emerged from the Soviet Union, and of those states, Russia was the largest and most populous. Bush and Yeltsin met in February 1992, declaring a new era of "friendship and partnership".[175] In January 1993, Bush and Yeltsin agreed to START II, which provided for further nuclear arms reductions on top of the original START treaty.[176]

Invasion of Panama

Through the late 1980s, the U.S. provided aid to Manuel Noriega, the anti-Communist leader of Panama. Noriega had long-standing ties to United States intelligence agencies, including during Bush's tenure as Director of Central Intelligence, and was also deeply involved in drug trafficking.[177] In May 1989, Noriega annulled the results of a democratic presidential election in which Guillermo Endara had been elected. Bush objected to the annulment of the election and worried about the status of the Panama Canal with Noriega still in office.[178] Bush dispatched 2,000 soldiers to the country, where they began conducting regular military exercises violating prior treaties.[179] After Panamanian forces shot a U.S. serviceman in December 1989, Bush ordered the United States invasion of Panama, known as "Operation Just Cause". The invasion was the first large-scale American military operation unrelated to the Cold War in more than 40 years. American forces quickly took control of the Panama Canal Zone and Panama City. Noriega surrendered on January 3, 1990, and was quickly transported to a prison in the United States. Twenty-three Americans died in the operation, while another 394 were wounded. Noriega was convicted and imprisoned on racketeering and drug trafficking charges in April 1992.[178] Historian Stewart Brewer argues that the invasion "represented a new era in American foreign policy" because Bush did not justify the invasion under the Monroe Doctrine or the threat of Communism, but rather because it was in the best interests of the United States.[180]

Gulf War

Faced with massive debts and low oil prices in the aftermath of the Iran–Iraq War, Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein decided to conquer the country of Kuwait, a small, oil-rich country situated on Iraq's southern border.[181] After Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, Bush imposed economic sanctions on Iraq and assembled a multi-national coalition opposed to the invasion.[182] Some in the administration feared that a failure to respond to the invasion would embolden Hussein to attack Saudi Arabia or Israel.[183] Robert Gates attempted to convince Brent Scowcroft that Bush should tone down the rhetoric but Bush insisted it was his primary concern to discourage other countries from "unanswered aggression".[184] Bush also wanted to ensure continued access to oil, as Iraq and Kuwait collectively accounted for 20 percent of the world's oil production, and Saudi Arabia produced another 26 percent of the world's oil supply.[185]

At Bush's insistence, in November 1990, the United Nations Security Council approved a resolution authorizing the use of force if Iraq did not withdraw from Kuwait by January 15, 1991.[186] Gorbachev's support and China's abstention helped ensure passage of the United Nations resolution.[187] Bush convinced Britain, France, and other nations to commit soldiers to an operation against Iraq. He won important financial backing from Germany, Japan, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.[188] In January 1991, Bush asked Congress to approve a joint resolution authorizing a war against Iraq.[189] Bush believed that the United Nations resolution had already provided him with the necessary authorization to launch a military operation against Iraq. Still, he wanted to show that the nation was united behind military action.[190] Despite the opposition of a majority of Democrats in both the House and the Senate, Congress approved the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 1991.[189]

After the January 15 deadline passed without an Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait, U.S. and coalition forces conducted a bombing campaign that devastated Iraq's power grid and communications network and resulted in the desertion of about 100,000 Iraqi soldiers. In retaliation, Iraq launched Scud missiles at Israel and Saudi Arabia, but most missiles did little damage. On February 23, coalition forces began a ground invasion into Kuwait, evicting Iraqi forces by the end of February 27. About 300 Americans and approximately 65 soldiers from other coalition nations died during the military action.[191] A ceasefire was arranged on March 3, and the United Nations passed a resolution establishing a peacekeeping force in a demilitarized zone between Kuwait and Iraq.[192] A March 1991 Gallup poll showed that Bush had an approval rating of 89 percent, the highest presidential approval rating in the history of Gallup polling.[193] After 1991, the United Nations maintained economic sanctions against Iraq, and the United Nations Special Commission was assigned to ensure that Iraq did not revive its weapons of mass destruction program.[194]

NAFTA

In 1987, the U.S. and Canada reached a free trade agreement that eliminated many tariffs between the two countries. President Reagan had intended it as the first step towards a larger trade agreement to eliminate most tariffs among the United States, Canada, and Mexico.[195] The Bush administration, along with the Progressive Conservative Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney, spearheaded the negotiations of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Mexico. In addition to lowering tariffs, the proposed treaty would affect patents, copyrights, and trademarks.[196] In 1991, Bush sought fast track authority, which grants the president the power to submit an international trade agreement to Congress without the possibility of amendment. Despite congressional opposition led by House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt, both houses of Congress voted to grant Bush fast track authority. NAFTA was signed in December 1992, after Bush lost reelection,[197] but President Clinton won ratification of NAFTA in 1993.[198] NAFTA was controversial for its impact on wages, jobs, and overall economic growth.[199] In 2020, it was replaced entirely by the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA).

Domestic affairs

Economy and fiscal issues

The U.S. economy had generally performed well since emerging from recession in late 1982, but it slipped into a mild recession in 1990. The unemployment rate rose from 5.9 percent in 1989 to a high of 7.8 percent in mid-1991.[200][201] Large federal deficits, spawned during the Reagan years, rose from $152.1 billion in 1989[202] to $220 billion for 1990;[203] the $220 billion deficit represented a threefold increase since 1980.[204] As the public became increasingly concerned about the economy and other domestic affairs, Bush's well-received handling of foreign affairs became less of an issue for most voters.[205] Bush's top domestic priority was to end federal budget deficits, which he saw as a liability for the country's long-term economic health and standing in the world.[206] As he was opposed to major defense spending cuts[207] and had pledged not to raise taxes, the president had major difficulties in balancing the budget.[208]

Bush and congressional leaders agreed to avoid major changes to the budget for fiscal year 1990, which began in October 1989. However, both sides knew spending cuts or new taxes would be necessary for the following year's budget to avoid the draconian automatic domestic spending cuts required by the Gramm–Rudman–Hollings Balanced Budget Act of 1987.[209] Bush and other leaders also wanted to cut deficits because Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan refused to lower interest rates and thus stimulate economic growth unless the federal budget deficit was reduced.[210] In a statement released in late June 1990, Bush said that he would be open to a deficit reduction program which included spending cuts, incentives for economic growth, budget process reform, as well as tax increases.[211] To fiscal conservatives in the Republican Party, Bush's statement represented a betrayal, and they heavily criticized him for compromising so early in the negotiations.[212]

In September 1990, Bush and congressional Democrats announced a compromise to cut mandatory and discretionary programs funding while raising revenue, partly through a higher gas tax. The compromise additionally included a "pay as you go" provision that required that new programs be paid for at the time of implementation.[213] House Minority Whip Newt Gingrich led the conservative opposition to the bill, strongly opposing any form of tax increase.[214] Some liberals also criticized the budget cuts in the compromise, and in October, the House rejected the deal, resulting in a brief government shutdown. Without the strong backing of the Republican Party, Bush agreed to another compromise bill, this one more favorable to Democrats. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA-90), enacted on October 27, 1990, dropped much of the gasoline tax increase in favor of higher income taxes on top earners. It included cuts to domestic spending, but the cuts were not as deep as those proposed in the original compromise. Bush's decision to sign the bill damaged his standing with conservatives and the general public, but it also laid the groundwork for the budget surpluses of the late 1990s.[215]

Discrimination

"Even the strongest person couldn't scale the Berlin Wall to gain the elusive promise of independence that lay just beyond. And so, together we rejoiced when that barrier fell. And now I sign legislation which takes a sledgehammer to another wall, one which has for too many generations separated Americans with disabilities from the freedom they could glimpse, but not grasp."

—Bush's remarks at the signing ceremony for the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990[216]

The disabled had not received legal protections under the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, and many faced discrimination and segregation by the time Bush took office. In 1988, Lowell P. Weicker Jr. and Tony Coelho introduced the Americans with Disabilities Act, which barred employment discrimination against qualified individuals with disabilities. The bill had passed the Senate but not the House and was reintroduced in 1989. Though some conservatives opposed the bill due to its costs and potential burdens on businesses, Bush strongly supported it, partly because his son, Neil, had struggled with dyslexia. After the bill passed both houses of Congress, Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 into law in July 1990.[217] The act required employers and public accommodations to make "reasonable accommodations" for disabled people while providing an exception when such accommodations imposed an "undue hardship".[218]

Senator Ted Kennedy later led the congressional passage of a separate civil rights bill designed to facilitate launching employment discrimination lawsuits.[219] In vetoing the bill, Bush argued that it would lead to racial quotas in hiring.[220][221] In November 1991, Bush signed the Civil Rights Act of 1991, which was largely similar to the bill he had vetoed in the previous year.[219]

In August 1990, Bush signed the Ryan White CARE Act, the largest federally funded program dedicated to assisting persons living with HIV/AIDS.[222] Throughout his presidency, the AIDS epidemic grew dramatically in the U.S. and around the world, and Bush often found himself at odds with AIDS activist groups who criticized him for not placing a high priority on HIV/AIDS research and funding. Frustrated by the administration's lack of urgency on the issue, ACT UP dumped the ashes of deceased HIV/AIDS patients on the White House lawn during a viewing of the AIDS Quilt in 1992.[223] By that time, HIV had become the leading cause of death in the U.S. for men aged 25–44.[224]

Environment

In June 1989, the Bush administration proposed a bill to amend the Clean Air Act. Working with Senate Majority Leader George J. Mitchell, the administration won passage of the amendments over the opposition of business-aligned members of Congress who feared the impact of tougher regulations.[225] The legislation sought to curb acid rain and smog by requiring decreased emissions of chemicals such as sulfur dioxide,[226] and was the first major update to the Clean Air Act since 1977.[227] Bush also signed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 in response to the Exxon Valdez oil spill. However, the League of Conservation Voters criticized some of Bush's other environmental actions, including his opposition to stricter auto-mileage standards.[228]

Points of Light

Bush devoted attention to voluntary service to solve some of America's most serious social problems. He often used the "thousand points of light" theme to describe the power of citizens to solve community problems. In his 1989 inaugural address, Bush said, "I have spoken of a thousand points of light, of all the community organizations that are spread like stars throughout the Nation, doing good."[229] During his presidency, Bush honored numerous volunteers with the Daily Point of Light Award, a tradition that his presidential successors continued.[230] In 1990, the Points of Light Foundation was created as a nonprofit organization in Washington to promote this spirit of volunteerism.[231] In 2007, the Points of Light Foundation merged with the Hands On Network to create a new organization, Points of Light.[232]

Judicial appointments

Bush appointed two justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. In 1990, Bush appointed a largely unknown state appellate judge, David Souter, to replace liberal icon William J. Brennan Jr.[233] Souter was easily confirmed and served until 2009, but joined the liberal bloc of the court, disappointing Bush.[233] In 1991, Bush nominated conservative federal judge Clarence Thomas to succeed Thurgood Marshall, a long-time liberal stalwart. Thomas, the former head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), faced heavy opposition in the Senate, as well as from pro-choice groups and the NAACP. His nomination faced another difficulty when Anita Hill accused Thomas of having sexually harassed her during his time as the chair of EEOC. Thomas won confirmation in a narrow 52–48 vote; 43 Republicans and 9 Democrats voted to confirm Thomas's nomination, while 46 Democrats and 2 Republicans voted against confirmation.[234] Thomas became one of the most conservative justices of his era.[235]

Other issues

Bush's education platform consisted mainly of offering federal support for a variety of innovations, such as open enrollment, incentive pay for outstanding teachers, and rewards for schools that improve performance with underprivileged children.[236] Though Bush did not pass a major educational reform package during his presidency, his ideas influenced later reform efforts, including Goals 2000 and the No Child Left Behind Act.[237] Bush signed the Immigration Act of 1990,[238] which led to a 40 percent increase in legal immigration to the United States.[239] The act more than doubled the number of visas given to immigrants on the basis of job skills.[240] In the wake of the savings and loan crisis, Bush proposed a $50 billion package to rescue the savings and loans industry, and also proposed the creation of the Office of Thrift Supervision to regulate the industry. Congress passed the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989, which incorporated most of Bush's proposals.[241]

Public image

Bush was widely seen as a "pragmatic caretaker" president who lacked a unified and compelling long-term theme in his efforts.[242][243][244] A Bush sound bite, referring to the issue of overarching purpose as "the vision thing", has become a metonym applied to other political figures accused of similar difficulties.[245][246][247][248][249][250] His ability to gain broad international support for the Gulf War and the war's result were seen as both a diplomatic and military triumph,[251] rousing bipartisan approval,[252] though his decision to withdraw without removing Saddam Hussein left mixed feelings, and attention returned to the domestic front and a souring economy.[253] A New York Times article mistakenly depicted Bush as being surprised to see a supermarket barcode reader;[254][255] the report of his reaction exacerbated the notion that he was "out of touch".[254]

Bush was popular throughout most of his presidency. After the Gulf war concluded in February 1991, his approval rating saw a high of 89 percent, before gradually declining for the rest of the year, and eventually falling below 50 percent according to a January 1992 Gallup poll.[256][257][258] His sudden drop in his favorability was likely due to the early 1990s recession, which shifted his image from "conquering hero" to "politician befuddled by economic matters".[259] At the elite level, several commentators and political experts lamented the state of American politics in 1991–1992 and reported the voters were angry. Many analysts blamed the poor quality of national election campaigns.[260]

1992 presidential campaign

Bush announced his reelection bid in early 1992; with a coalition victory in the Persian Gulf War and high approval ratings, Bush's reelection initially looked likely.[261] As a result, many leading Democrats, including Mario Cuomo, Dick Gephardt, and Al Gore, declined to seek their party's presidential nomination.[262] However, Bush's tax increase angered many conservatives, who believed that Bush had strayed from the conservative principles of Ronald Reagan.[263] He faced a challenge from conservative political columnist Pat Buchanan in the 1992 Republican primaries.[264] Bush fended off Buchanan's challenge and won his party's nomination at the 1992 Republican National Convention. Still, the convention adopted a socially conservative platform strongly influenced by the Christian right.[265]

Meanwhile, the Democrats nominated Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas. A moderate who was affiliated with the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), Clinton favored welfare reform, deficit reduction, and a tax cut for the middle class.[266] In early 1992, the race took an unexpected twist when Texas billionaire H. Ross Perot launched a third-party bid, claiming that neither Republicans nor Democrats could eliminate the deficit and make government more efficient. His message appealed to voters across the political spectrum disappointed with both parties' perceived fiscal irresponsibility.[267] Perot also attacked NAFTA, which he claimed would lead to major job losses.[268] National polling taken in mid-1992 showed Perot in the lead, but Clinton experienced a surge through effective campaigning and the selection of Senator Al Gore, a popular and relatively young Southerner, as his running mate.[269]

Clinton won the election, taking 43 percent of the popular vote and 370 electoral votes, while Bush won 37.5 percent of the popular vote and 168 electoral votes.[270] Perot won 19% of the popular vote, one of the highest totals for a third-party candidate in U.S. history, drawing equally from both major candidates, according to exit polls.[271] Clinton performed well in the Northeast, the Midwest, and the West Coast, while also waging the strongest Democratic campaign in the South since the 1976 election.[272] Several factors were important in Bush's defeat. The ailing economy which arose from recession may have been the main factor in Bush's loss, as 7 in 10 voters said on election day that the economy was either "not so good" or "poor".[273][274] On the eve of the 1992 election, the unemployment rate stood at 7.8%, which was the highest it had been since 1984.[275] The president was also damaged by his alienation of many conservatives in his party.[276] Bush partially blamed Perot for his defeat, though exit polls showed that Perot drew his voters about equally from Clinton and Bush.[277]

Despite his defeat, Bush left office with a 56 percent job approval rating in January 1993.[278] Like many of his predecessors, Bush issued a series of pardons during his last days in office. In December 1992, he granted executive clemency to six former senior government officials implicated in the Iran-Contra scandal, most prominently former Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger.[279] The charges against the six were that they lied to or withheld information from Congress. The pardons effectively brought an end to the Iran-Contra scandal.[280]

According to Seymour Martin Lipset, the 1992 election had several unique characteristics. Voters felt that economic conditions were worse than they were, which harmed Bush. A rare event was the presence of a strong third-party candidate. Liberals launched a backlash against 12 years of a conservative White House. The chief factor was Clinton uniting his party and winning over several heterogeneous groups.[281]

Post-presidency (1993–2018)

Appearances

After leaving office, Bush and his wife built a retirement house in the community of West Oaks, Houston.[282] He established a presidential office within the Park Laureate Building on Memorial Drive in Houston.[283] He also frequently spent time at his vacation home in Kennebunkport, took annual cruises in Greece, went on fishing trips in Florida, and visited the Bohemian Club in Northern California. He declined to serve on corporate boards but delivered numerous paid speeches and was an adviser to The Carlyle Group, a private equity firm.[284] He never published his memoirs, but he and Brent Scowcroft co-wrote A World Transformed, a 1998 work on foreign policy. Portions of his letters and his diary were later published as The China Diary of George H. W. Bush and All the Best, George Bush.[285]

During a 1993 visit to Kuwait, Bush was targeted in an assassination plot directed by the Iraqi Intelligence Service. President Clinton retaliated when he ordered the firing of 23 cruise missiles at Iraqi Intelligence Service headquarters in Baghdad.[286] Bush did not publicly comment on the assassination attempt or the missile strike, but privately spoke with Clinton shortly before the strike took place.[287]

In the 1994 gubernatorial elections, his sons George W. and Jeb concurrently ran for Governor of Texas and Governor of Florida. Concerning their political careers, he advised them both that "[a]t some point both of you may want to say 'Well, I don't agree with my Dad on that point' or 'Frankly I think Dad was wrong on that.' Do it. Chart your own course, not just on the issues but on defining yourselves".[288] George W. won his race against Ann Richards while Jeb lost to Lawton Chiles. After the results came in, the elder Bush told ABC, "I have very mixed emotions. Proud father, is the way I would sum it all up."[289] Jeb would again run for governor of Florida in 1998 and win at the same time that his brother George W. won re-election in Texas. It marked the second time in United States history that a pair of brothers served simultaneously as governors.[290]

Bush supported his son's candidacy in the 2000 presidential election but did not actively campaign in the election and did not deliver a speech at the 2000 Republican National Convention.[291] George W. Bush defeated Al Gore in the 2000 election and was re-elected in 2004. Bush and his son thus became the second father–son pair to each serve as President of the United States, following John Adams and John Quincy Adams.[292] Through previous administrations, the elder Bush had ubiquitously been known as "George Bush" or "President Bush", but following his son's election, the need to distinguish between them has made retronymic forms such as "George H. W. Bush" and "George Bush Sr." and colloquialisms such as "Bush 41" and "Bush the Elder" more common.[293] Bush advised his son on some personnel choices, approving of the selection of Dick Cheney as running mate and the retention of George Tenet as CIA Director. However, he was not consulted on all appointments, including that of his old rival, Donald Rumsfeld, as Secretary of Defense.[294] Though he avoided giving unsolicited advice to his son, Bush and his son also discussed some policy matters, especially regarding national security issues.[295]

In his retirement, Bush used the public spotlight to support various charities.[296] Despite earlier political differences with Bill Clinton, the two former presidents eventually became friends.[297] They appeared together in television ads, encouraging aid for victims of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami and Hurricane Katrina.[298] However, when interviewed by Jon Meacham, Bush criticized Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, and even his son George W. Bush for their handling of foreign policy after the September 11 attacks.[299]

Final years

Bush supported Republican John McCain in the 2008 presidential election,[300] and Republican Mitt Romney in the 2012 presidential election,[301] but both were defeated by Democrat Barack Obama. In 2011, Obama awarded Bush with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the United States.[302]

Bush supported his son Jeb's bid in the 2016 Republican primaries.[303] Jeb Bush's campaign struggled, however, and he withdrew from the race during the primaries. Neither George H. W. nor George W. Bush endorsed the eventual Republican nominee, Donald Trump;[304] all three Bushes emerged as frequent critics of Trump's policies and speaking style, while Trump frequently criticized George W. Bush's presidency. George H. W. later said he voted for the Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, in the general election.[305] After the election, Bush wrote a letter to President-elect Donald Trump in January 2017 to inform him that because of his poor health, he would not be able to attend Trump's inauguration on January 20; he gave him his best wishes.[306]

In August 2017, after the violence at Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, both presidents Bush released a joint statement saying, "America must always reject racial bigotry, anti-Semitism, and hatred in all forms[. ...] As we pray for Charlottesville, we are all reminded of the fundamental truths recorded by that city's most prominent citizen in the Declaration of Independence: we are all created equal and endowed by our Creator with unalienable rights."[307][308]

On April 17, 2018, Barbara Bush died at the age of 92[309] at her home in Houston, Texas. Her funeral was held at St. Martin's Episcopal Church in Houston four days later.[310][311] Bush, along with former presidents Barack Obama, George W. Bush (son), Bill Clinton and First Ladies Melania Trump, Michelle Obama, Laura Bush (daughter-in-law) and Hillary Clinton attended the funeral and posed together for a photo as a sign of unity.[312][313]

On November 1, 2018, Bush went to the polls to vote early in the midterm elections. This would be his final public appearance.[314]

Death and funeral

After a long battle with vascular Parkinson's disease, Bush died at his home in Houston on November 30, 2018, at the age of 94.[315][316] At the time of his death he was the longest-lived U.S. president,[317] a distinction now held by Jimmy Carter.[318] He was also the third-oldest vice president.[h] Bush lay in state in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol from December 3 through December 5; he was the 12th U.S. president to be accorded this honor.[320][321] Then, on December 5, Bush's casket was transferred from the Capitol rotunda to Washington National Cathedral where a state funeral was held.[322] After the funeral, Bush's body was transported to George H.W. Bush Presidential Library in College Station, Texas, where he was buried next to his wife Barbara and daughter Robin.[323] At the funeral, former president George W. Bush eulogized his father saying, "He looked for the good in each person, and he usually found it."[322]

Личная жизнь

В мае 1991 года The New York Times сообщила, что у Буша развилась болезнь Грейвса , незаразное заболевание щитовидной железы , которым также страдала его жена Барбара. [ 324 ] Буш перенес две отдельные операции по замене тазобедренного сустава в 2000 и 2007 годах. [ 325 ] После этого Буш начал испытывать слабость в ногах, что было связано с сосудистым паркинсонизмом , формой болезни Паркинсона. У него постепенно развивались проблемы с ходьбой: сначала ему требовалась трость для передвижения, прежде чем с 2011 года он, в конечном итоге, стал полагаться на инвалидную коляску. [ 326 ]

Буш всю жизнь был членом епископальной церкви и членом епископальной церкви Св. Мартина в Хьюстоне. В качестве президента Буш регулярно посещал службы в епископальной церкви Св. Иоанна в Вашингтоне. [ 327 ] Он упомянул различные моменты своей жизни, посвященные углублению его веры, в том числе побег от японских войск в 1944 году и смерть его трехлетней дочери Робин в 1953 году. [ 328 ] Его вера нашла отражение в его речи о «тысяче точек света», его поддержке молитвы в школах и его поддержке движения в защиту жизни (после его избрания на пост вице-президента). [ 329 ] [ 328 ]

Наследие

Историческая репутация

Опросы историков и политологов поставили Буша в первую половину президентов. По результатам опроса, проведенного в 2018 году секцией президентов и исполнительной политики Американской ассоциации политических наук, Буш занял 17-е место среди лучших президентов из 44. [ 330 ] 2017 года Опрос историков C-SPAN также поставил Буша на 20-е место среди 43 лучших президентов. [ 331 ] Ричард Роуз описал Буша как президента-хранителя, и многие другие историки и политологи аналогичным образом описали Буша как пассивного, невмешательного президента, который «в основном доволен тем, что есть». [ 332 ] Профессор Стивен Нотт пишет, что «в целом президентство Буша считается успешным во внешних делах, но разочарованием во внутренних делах». [ 333 ]

Биограф Джон Мичем пишет, что после того, как он покинул свой пост, многие американцы считали Буша «милостивым и недооцененным человеком, у которого было много добродетелей, но который не смог продемонстрировать достаточную самобытность и видение, чтобы преодолеть экономические проблемы 1991–92 годов и выиграть второй срок». [ 334 ] Сам Буш отмечал, что его наследие «терялось между славой Рейгана… и испытаниями и невзгодами моих сыновей». [ 335 ] В 2010-х годах Буша с любовью вспоминали за его готовность идти на компромисс, что контрастировало с эпохой крайне партийной ориентации, последовавшей за его президентством. [ 336 ]

В 2018 году Vox выделил Буша за его «прагматизм» как умеренного президента-республиканца, работающего наперекор. [ 337 ] Они особо отметили достижения Буша во внутренней политике, заключив двухпартийные соглашения, включая увеличение налогового бюджета среди богатых с помощью Закона о сводном бюджетном согласовании 1990 года. Буш также помог принять Закон об американцах-инвалидах 1990 года, который The New York Times описала как « самый радикальный антидискриминационный закон со времен Закона о гражданских правах 1964 года. [ 338 ] В ответ на разлив нефти Exxon Valdez Буш создал еще одну двухпартийную коалицию для усиления поправок к Закону о чистом воздухе 1990 года. [ 339 ] [ 340 ] Буш также поддержал и подписал Закон об иммиграции 1990 года, масштабную двухпартийную иммиграционную реформу, которая облегчила иммигрантам легальный въезд в страну, а также предоставила иммигрантам, спасающимся от насилия, визу с временным защищенным статусом, а также отменила предварительный -процесс натурализации в английском языке и, наконец, «устранил исключение гомосексуалистов в соответствии с тем, что Конгресс теперь считал необоснованной с медицинской точки зрения классификацией «сексуальных девиантов», которая была включена в закон 1965 года. ." [ 341 ] [ 342 ] Буш заявил: «Иммиграция - это не только связь с нашим прошлым, но и мост в будущее Америки». [ 343 ]

По данным USA Today , наследие президентства Буша определялось его победой над Ираком после вторжения в Кувейт и его руководством при распаде Советского Союза и воссоединении Германии . [ 344 ] Майкл Бешлосс и Строуб Тэлботт высоко оценивают действия Буша по отношению к Советскому Союзу, особенно то, как он подталкивал Горбачева к освобождению контроля над государствами-сателлитами и разрешению объединения Германии – и особенно объединенной Германии в НАТО. [ 345 ] Эндрю Басевич считает администрацию Буша «морально тупой» в свете ее «обычного» отношения к Китаю после резни на площади Тяньаньмэнь и ее некритической поддержки Горбачева во время распада Советского Союза. [ 346 ] Дэвид Роткопф утверждает:

В новейшей истории внешней политики США не было ни одного президента или какой-либо президентской команды, которые, столкнувшись с глубокими международными изменениями и вызовами, ответили бы такой продуманной и хорошо управляемой внешней политикой... [администрация Буша была ] мост через одну из величайших линий разлома в истории, [который] положил начало «новому мировому порядку», который он описал с большим мастерством и профессионализмом. [ 347 ]

Однако TIME раскритиковал внутреннюю политику Буша , связанную с «наркотиками, бездомностью, расовой враждебностью, пробелами в образовании и проблемами с окружающей средой», и утверждает, что эти проблемы в Соединенных Штатах усугубились в 21 веке, главным образом из-за настроек Буша. плохой пример и его обращение с этими концепциями во время своего президентства. [ 348 ]

Мемориалы, награды и почести

В 1990 году журнал Time назвал его Человеком года . [ 349 ] В 1997 году Межконтинентальный аэропорт Хьюстона был переименован в Межконтинентальный аэропорт имени Джорджа Буша . [ 350 ] В 1999 году штаб-квартира ЦРУ в Лэнгли, штат Вирджиния , была названа Центром разведки Джорджа Буша . в его честь [ 351 ] В 2011 году Буш, заядлый игрок в гольф, был занесен во Всемирный зал славы гольфа . [ 352 ] Военный корабль США «Джордж Буш-старший» (CVN-77), десятый и последний «Нимиц» , был назван в честь Буша. класса суперавианосец ВМС США [ 353 ] [ 354 ] Память о Буше увековечена на почтовой марке, выпущенной Почтовой службой США в 2019 году. [ 355 ] В декабре 2020 года Монетный двор США наградил Буша монетой президентского доллара .

Президентская библиотека и музей Джорджа Буша-старшего , десятая президентская библиотека США , была построена в 1997 году. [ 356 ] Он содержит президентские и вице-президентские документы Буша, а также вице-президентские документы Дэна Куэйла. [ 357 ] Библиотека расположена на участке площадью 90 акров (36 га) в западном кампусе Техасского университета A&M в Колледж-Стейшн, штат Техас. [ 358 ] В Техасском университете A&M также находится Школа государственного управления и государственной службы Буша , высшая школа государственной политики . [ 358 ] В 2012 году Академия Филлипса также наградила Буша Почетной премией выпускников. [ 359 ]

См. также

- Избирательная история Джорджа Буша-старшего

- Список членов Американского легиона

- Список президентов США

Примечания

- ↑ После 1990-х годов он стал более известен как Джордж Буш-старший , « Буш-старший », « Буш-41 » и даже « Буш-старший », чтобы отличать его от старшего сына Джорджа Буша-младшего , который служил 43-м президент США с 2001 по 2009 год; раньше его обычно называли просто Джорджем Бушем .

- ^ Позже Буш приобрел поместье, которое теперь известно как поместье Буша . [ 10 ]

- ↑ На протяжении десятилетий Буш считался самым молодым авиатором ВМС США за период его службы. [ 17 ] но такие утверждения сейчас рассматриваются как спекуляции. [ 18 ] В его официальной биографии ВМФ в 2001 году он был назван «самым молодым». [ 19 ] но к 2018 году в биографии ВМФ он был описан как «один из самых молодых». [ 20 ]

- ↑ Членами экипажа Буша по миссии были Уильям Дж. Уайт и Джон Делани. По свидетельствам американского пилота и японца, еще один парашют самолета Буша раскрылся, но тела Уайта и Делейни так и не были обнаружены. [ 24 ]

- ↑ На момент смерти жены 17 апреля 2018 года Джордж-старший был женат на Барбаре 73 года, что на тот момент было самым продолжительным президентским браком в американской истории. [ 35 ] В 2019 году продолжительность их брака превзошла свадьба Джимми и Розалин Картер . [ 36 ]

- ↑ Биограф Джон Мичем пишет, что в то время широко предполагалось, что Дональд Рамсфельд спланировал назначение Буша директором ЦРУ, поскольку этот пост считался «политическим кладбищем». Мичем пишет, что, скорее всего, ключевым фактором в назначении Буша было то, что Форд считал, что Буш будет лучше работать с госсекретарем Генри Киссинджером, чем Эллиот Ричардсон , первоначально выбранный им на пост ЦРУ. [ 87 ]

- ↑ Президентские выборы 1988 года остаются единственными президентскими выборами с 1948 года, на которых какая-либо партия выиграла третий срок подряд. [ 153 ]

- ↑ Самый долгоживущий вице-президент США — Джон Нэнс Гарнер , который умер 7 ноября 1967 года, за 15 дней до своего 99-летия. [ 319 ]

Ссылки

- ^ «Джордж Герберт Уокер Буш» . Командование военно-морской истории и наследия. 29 августа 2019 года . Проверено 12 января 2020 г.

- ^

- «Джордж Буш-старший, американский дипломат» . Ассоциация дипломатических исследований и обучения .

- «В память о Джордже Герберте Уокере Буше (1924–2018): ветеране, государственном деятеле, дипломате» . Государственный департамент, Национальный музей американской дипломатии . 20 декабря 2018 г.

- «Джордж Буш-старший: дипломаты помнят» . Американская ассоциация дипломатической службы .

- «Президент Джордж Буш-старший: внешняя политика» . Study.com .

- Памела Фальк (3 декабря 2018 г.). «Джордж Буш-старший выделялся как жесткий переговорщик на мировой арене» . Новости CBS.

- «Профессор международных отношений Джорджа Буша-старшего» . Университет Джонса Хопкинса, Школа перспективных международных исследований Пола Х. Нитце . 14 июля 2016 г.

- ^ Келли, Джон (2 декабря 2018 г.). «Джордж Буш-старший: Что делает президента на один срок?» . Новости Би-би-си . Архивировано из оригинала 17 августа 2021 года . Проверено 22 марта 2022 г.

- ^ «Президентский проспект: Джордж Буш» . Президентский проспект. Архивировано из оригинала 8 октября 2007 года . Проверено 29 марта 2008 г.

- ^ Мичем 2015 , стр. 19–20.

- ^ Мичем 2015 , стр. 8–9.