Государство Палестина

Государство Палестина | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: « Коммандос ». " Фидаи " [ 1 ] «Воин-федаин» | |

![Оккупированные палестинские территории (зеленые).[2] Территория, аннексированная Израилем (светло-зеленый).](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ad/State_of_Palestine_%28orthographic_projection%29.svg/220px-State_of_Palestine_%28orthographic_projection%29.svg.png) | |

| Status | UN observer state under Israeli occupation[a] Recognized by 145 UN member states |

| |

| Largest city | Gaza City (before 2023), currently in flux[3][4] |

| Official languages | Arabic |

| Demonym(s) | Palestinian |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic[5] |

| Mahmoud Abbas[c] | |

| Mohammad Mustafa | |

| Aziz Dweik | |

| Legislature | National Council |

| Formation | |

| 15 November 1988 | |

| 29 November 2012 | |

• Sovereignty dispute with Israel | Ongoing[d][6][7] |

| Area | |

• Total | 6,020[8] km2 (2,320 sq mi) (163rd) |

• Water (%) | 3.5[9] |

| 5,655 km2 | |

| 365 km2[10] | |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 5,483,450[11] (121st) |

• Density | 731/km2 (1,893.3/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2021 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2016) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2021) | high (106th) |

| Currency |

|

| Time zone | UTC+2 (Palestine Standard Time) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (Palestine Summer Time) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +970 |

| ISO 3166 code | PS |

| Internet TLD | .ps |

Палестина , [ я ] официально Государство Палестина , [ ii ] [ и ] — страна в южном регионе Леванта в Западной Азии, признанная 145 из 193 государств-членов ООН . Он охватывает оккупированный Израилем Западный берег реки Иордан и сектор Газа , известные под общим названием « Палестинские территории» , в рамках более широкого географического и исторического региона Палестины . Страна разделяет большую часть своих границ с Израилем , а также граничит с Иорданией на востоке и Египтом на юго-западе. Его общая площадь составляет 6020 квадратных километров (2320 квадратных миль), а его население превышает пять миллионов человек. Его провозглашенной столицей является Иерусалим , а Рамалла является его административным центром. Город Газа был его крупнейшим городом до 2023 года . [ 3 ] [ 4 ]

Расположенный на перекрестке континентов , регион Палестины находился под властью различных империй и переживал различные демографические изменения от древности до современности. [ 19 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ] Продолжающийся израильско-палестинский конфликт восходит к подъему сионистского движения и еврейской иммиграции в регион , которую поддерживало Великобритания Первой мировой во время войны . Война привела к тому, что Великобритания оккупировала Палестину у Османской империи , где она создала Подмандатную Палестину под эгидой Лиги Наций . [22][23] During this period, large-scale Jewish immigration allowed by the British authorities led to increased tensions and violence with the local Palestinian Arab population.[22] By 1947, Britain handed the issue to the United Nations, which proposed a partition plan, for two independent Arab and Jewish states and an independent entity for Jerusalem,[24] but a civil war broke out, and the plan was not implemented.[25]

The 1948 Palestine war saw the forcible displacement of most of its predominantly Palestinian Arab population, and consequently the establishment of Israel, in what Palestinians call the Nakba.[26] During the Six-Day War in 1967, Israel occupied the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, which had been held by Jordan and Egypt respectively. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) declared the independence of the State of Palestine in 1988. In 1993, the PLO signed the Oslo peace accords with Israel, creating limited PLO governance in the West Bank and Gaza Strip through the Palestinian Authority (PA). In 2005, Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip in its unilateral disengagement, but the territory is still considered to be under military occupation and was put under blockade by Israel. In 2007, internal divisions between Palestinian political factions led to a takeover of the Gaza Strip by Hamas. Since then, the West Bank has been governed in part by the PA, led by Fatah, while the Gaza Strip has remained under the control of Hamas. Israel has constructed large settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories since 1967, where currently more than 670,000 Israeli settlers live in Israeli settlements in the West Bank, which are illegal under international law.

Currently, the biggest challenges to the country include the Israeli occupation, a blockade, restrictions on movement, Israeli settlements and settler violence, as well as an overall poor security situation. The questions of Palestine's borders, the legal and diplomatic status of Jerusalem, and the right of return of Palestinian refugees remain unsolved. Despite these challenges, the country maintains an emerging economy and sees frequent tourism. Arabic is the official language of the country. The majority of Palestinians practice Islam while Christianity also has a presence. Palestine is also a member of several international organizations, including the Arab League and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation. It has been a non-member observer state of the United Nations since 2012.[27][28][29][30]

Etymology

The term "Palestine" (in Latin, Palæstina) is thought to have been a term coined by the Ancient Greeks for the area of land occupied by the Philistines, although there are other explanations.[31] The term "Palestine" has been used to refer to the area at the southeast corner of the Mediterranean Sea beside Syria since ancient Greece, when Herodotus wrote The Histories in the 5th century BC. He described a "district of Syria, called Palaistine" in which Phoenicians interacted with other maritime peoples.[32][33]

Terminology

This article uses the terms "Palestine", "State of Palestine", "occupied Palestinian territory (oPt or OPT)" interchangeably depending on context. Specifically, the term "occupied Palestinian territory" refers as a whole to the geographical area of the Palestinian territory occupied by Israel since 1967. Palestine can, depending on contexts, be referred to as a country or a state, and its authorities can generally be identified as the Government of Palestine.[34][35]

History

From prehistory to the Ottoman era

Situated between three continents, Palestine has a tumultuous history as a crossroads for religion, culture, commerce, and politics. The region was among the earliest to see human habitation, agricultural communities and civilization. In the Bronze Age, the Canaanites established city-states influenced by surrounding civilizations, among them Egypt, which ruled the area in the Late Bronze Age. During the Iron Age, two related Israelite kingdoms, Israel and Judah, controlled much of Palestine, while the Philistines occupied its southern coast. The Assyrians conquered the region in the 8th century BCE, then the Babylonians in c. 601 BCE, followed by the Persians who conquered the Babylonian Empire in 539 BCE. Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire in the late 330s BCE, beginning Hellenization.

In the late 2nd century BCE, the Hasmonean Kingdom conquered most of Palestine, but the kingdom became a vassal of Rome, which annexed it in 63 BCE. Roman Judea was troubled by Jewish revolts in 66 CE, so Rome destroyed Jerusalem and the Second Jewish Temple in 70 CE. In the 4th century, as the Roman Empire transitioned to Christianity, Palestine became a center for the religion, attracting pilgrims, monks and scholars. Following Muslim conquest of the Levant in 636–641, ruling dynasties succeeded each other: the Rashiduns; Umayyads, Abbasids; the semi-independent Tulunids and Ikhshidids; Fatimids; and the Seljuks. In 1099, the Crusaders established the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which the Ayyubid Sultanate reconquered in 1187. Following the invasion of the Mongol Empire in the late 1250s, the Egyptian Mamluks reunified Palestine under its control, before the Ottoman Empire conquered the region in 1516 and ruled it as Ottoman Syria to the 20th century, largely undisrupted.Rise of Palestinian nationalism

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as nationalist sentiments grew across the region, Palestinian Arab nationalism also began to emerge.[36] Intellectuals and elites in Palestine expressed a sense of identity and called for greater autonomy and self-governance.[37] This period coincided with the rise of the Young Turks movement within the Ottoman Empire, which introduced some political reforms but also faced opposition from various groups.[38] In the early 20th century, the Zionist movement gained momentum, aiming to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine.[39][40] Jewish immigration increased, and Zionist organizations purchased land from local landowners, leading to tensions between Jews and Arabs.[41] Abdul Hamid, the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire, opposed the Zionist movement's efforts in Palestine. The end of the Ottoman Empire's rule in Palestine came with the conclusion of World War I. Following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, the region came under British control with the implementation of the British Mandate for Palestine in 1920.[42][43]

British Mandate

The defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I resulted in the dismantling of their rule.[44] In 1920, the League of Nations granted Britain the mandate to govern Palestine, leading to the subsequent period of British administration.[44] In 1917, Jerusalem was captured by British forces led by General Allenby, marking the end of Ottoman rule in the city.[44] By 1920, tensions escalated between Jewish and Arab communities, resulting in violent clashes and riots across Palestine.[44] The League of Nations approved the British Mandate for Palestine in 1922, entrusting Britain with the administration of the region.[44] Throughout the 1920s, Palestine experienced growing resistance from both Jewish and Arab nationalist movements, which manifested in sporadic violence and protests against British policies.[44] In 1929, violent riots erupted in Palestine due to disputes over Jewish immigration and access to the Western Wall in Jerusalem.[44] The 1930s witnessed the outbreak of the Arab Revolt, as Arab nationalists demanded an end to Jewish immigration and the establishment of an independent Arab state.[44] In response to the Arab Revolt, the British deployed military forces and implemented stringent security measures in an effort to quell the uprising.[44]

Arab nationalist groups, led by the Arab Higher Committee, called for an end to Jewish immigration and land sales to Jews.[45] The issuance of the 1939 White Paper by the British government aimed to address escalating tensions between Arabs and Jews in Palestine.[45] This policy document imposed restrictions on Jewish immigration and land purchases, with the intention to limit the establishment of a Jewish state.[45] Met with strong opposition from the Zionist movement, the White Paper was perceived as a betrayal of the Balfour Declaration and Zionist aspirations for a Jewish homeland.[45] In response to the White Paper, the Zionist community in Palestine organized a strike in 1939, rallying against the restrictions on Jewish immigration and land acquisition.[45] This anti-White Paper strike involved demonstrations, civil disobedience, and a shutdown of businesses.[45] Supported by various Zionist organizations, including the Jewish Agency and the Histadrut (General Federation of Jewish Labor), the anti-White Paper strike aimed to protest and challenge the limitations imposed by the British government.[45]

In the late 1930s and 1940s, several Zionist militant groups, including the Irgun, Hagana, and Lehi, carried out acts of violence against British military and civilian targets in their pursuit of an independent Jewish state.[45] While the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, collaborated with Nazi Germany during World War II, into all Muslims supported his actions, and there were instances where Muslims helped rescue Jews during the Holocaust.[45] In 1946, a bombing orchestrated by the Irgun at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem resulted in the deaths of 91 people, including British officials, civilians, and hotel staff.[45] Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir, who later became political leaders in the state of Israel, were behind these terrorist attacks.[46] The Exodus 1947 incident unfolded when a ship carrying Jewish Holocaust survivors, who sought refuge in Palestine, was intercepted by the British navy, leading to clashes and the eventual deportation of the refugees back to Europe.[45] During World War II, Palestine served as a strategically significant location for British military operations against Axis forces in North Africa.[45] In 1947, the United Nations proposed a partition plan for Palestine, suggesting separate Jewish and Arab states, but it was rejected by Arab nations while accepted by Jewish leaders.[45]

Arab–Israeli wars

In 1947, the UN adopted a partition plan for a two-state solution in the remaining territory of the mandate. The plan was accepted by the Jewish leadership but rejected by the Arab leaders, and Britain refused to implement the plan. On the eve of final British withdrawal, the Jewish Agency for Israel, headed by David Ben-Gurion, declared the establishment of the State of Israel according to the proposed UN plan. The Arab Higher Committee did not declare a state of its own and instead, together with Transjordan, Egypt, and the other members of the Arab League of the time, commenced military action resulting in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. During the war, Israel gained additional territories that were designated to be part of the Arab state under the UN plan. Egypt occupied the Gaza Strip, and Transjordan occupied and then annexed the West Bank. Egypt initially supported the creation of an All-Palestine Government but disbanded it in 1959. Transjordan never recognized it and instead decided to incorporate the West Bank with its own territory to form Jordan. The annexation was ratified in 1950 but was rejected by the international community.

In 1964, when the West Bank was controlled by Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organization was established there with the goal to confront Israel. The Palestinian National Charter of the PLO defines the boundaries of Palestine as the whole remaining territory of the mandate, including Israel. The Six-Day War in 1967, when Israel fought against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, ended with Israel occupying the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, besides other territories.[47][better source needed] Following the Six-Day War, the PLO moved to Jordan, but later relocated to Lebanon in 1971.[48][better source needed]

The October 1974 Arab League summit designated the PLO as the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people" and reaffirmed "their right to establish an independent state of urgency."[49] In November 1974, the PLO was recognized as competent on all matters concerning the question of Palestine by the UN General Assembly granting them observer status as a "non-state entity" at the UN.[50][51] Through the Camp David Accords of 1979, Egypt signaled an end to any claim of its own over the Gaza Strip. In July 1988, Jordan ceded its claims to the West Bank—with the exception of guardianship over Haram al-Sharif—to the PLO.

After Israel captured and occupied the West Bank from Jordan and Gaza Strip from Egypt, it began to establish Israeli settlements there. Administration of the Arab population of these territories was performed by the Israeli Civil Administration of the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories and by local municipal councils present since before the Israeli takeover. In 1980, Israel decided to freeze elections for these councils and to establish instead Village Leagues, whose officials were under Israeli influence. Later this model became ineffective for both Israel and the Palestinians, and the Village Leagues began to break up, with the last being the Hebron League, dissolved in February 1988.[52]

Uprising, declaration and peace treaty

The first Intifada broke out in 1987, characterized by widespread protests, strikes, and acts of civil disobedience by Palestinians in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank against Israeli occupation.[18] In November 1988, the PLO legislature, while in exile, declared the establishment of the "State of Palestine".[18] In the month following, it was quickly recognized by many states, including Egypt and Jordan.[18] In the Palestinian Declaration of Independence, the State of Palestine is described as being established on the "Palestinian territory", without explicitly specifying further.[18][53] After the 1988 Declaration of Independence, the UN General Assembly officially acknowledged the proclamation and decided to use the designation "Palestine" instead of "Palestine Liberation Organization" in the UN.[18][53] In spite of this decision, the PLO did not participate at the UN in its capacity of the State of Palestine's government.[54] Violent clashes between Palestinian protesters and Israeli forces intensified throughout 1989, resulting in a significant loss of life and escalating tensions in the occupied territories.[53] 1990 witnessed the imposition of strict measures by the Israeli government, including curfews and closures, in an attempt to suppress the Intifada and maintain control over the occupied territories.[53]

The 1990–1991 Gulf War brought increased attention to conflict, leading to heightened diplomatic efforts to find a peaceful resolution.[55][56] Saddam Hussein was a supporter of Palestinian cause and won support from Arafat during the war.[55] Following the invasion of Kuwait, Saddam surprised the international community by presenting a peace offer to Israel and withdrawing Iraqi forces from Kuwait, in exchange of withdrawal from the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem and Golan Heights.[55][56] Though the peace offer was rejected, Saddam then ordered firing of scud missiles into Israeli territory.[55] This movement was supported by Palestinians.[55] The war also led expulsion of Palestinians from Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, as their government supported Iraq.[55][56]

In 1993, the Oslo Accords were signed between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), leading to the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA) and a potential path to peace.[57] Yasser Arafat was elected as president of the newly formed Palestinian Authority in 1994, marking a significant step towards self-governance.[d]

Israel acknowledged the PLO negotiating team as "representing the Palestinian people", in return for the PLO recognizing Israel's right to exist in peace, acceptance of UN Security Council resolutions 242 and 338, and its rejection of "violence and terrorism".[57] As a result, in 1994 the PLO established the Palestinian National Authority (PNA or PA) territorial administration, that exercises some governmental functions[d] in parts of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.[66][67] As envisioned in the Oslo Accords, Israel allowed the PLO to establish interim administrative institutions in the Palestinian territories, which came in the form of the PNA.[66][67] It was given civilian control in Area B and civilian and security control in Area A, and remained without involvement in Area C.[67]

The peace process gained opposition from both Palestinians and Israelis. Islamist militant organizations such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad opposed the attack and responded by conducting attacks on civilians across Israel. In 1994, Baruch Goldstein, an Israeli extremist shot 29 people to death in Hebron, known as the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre. These events led an increase in Palestinian opposition to the peace process. Tragically, in 1995, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by Yigal Amir – an extremist, causing political instability in the region.

The first-ever Palestinian general elections took place in 1996, resulting in Arafat's re-election as president and the formation of a Palestinian Legislative Council. Initiating the implementation of the Oslo Accords, Israel began redeploying its forces from select Palestinian cities in the West Bank in 1997.[68] Negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority continued, albeit with slow progress and contentious debates on Jerusalem, settlements, and refugees in 1998.[68] In 1997, Israeli government led by Benjamin Netanyahu and the Palestinian government signed the Hebron Protocol, which outlined the redeployment of Israeli forces from parts of Hebron in the West Bank, granting the government greater control over the city.[68] Israel and the Palestinian government signed the Wye River Memorandum in 1998, aiming to advance the implementation of the Oslo Accords.[68] The agreement included provisions for Israeli withdrawals and security cooperation.[68][69]

The period of the Oslo Years brought a great prosperity to the government-controlled areas, despite some economic issues. The Palestinian Authority built the country's second airport in Gaza, after the Jerusalem International Airport. Inaugural ceremony of the airport was attended by Bill Clinton and Nelson Mandela. In 1999, Ehud Barak assumed the position of Israeli Prime Minister, renewing efforts to reach a final status agreement with the Palestinians. The Camp David Summit in 2000 aimed to resolve the remaining issues but concluded without a comprehensive agreement, serving as a milestone in the peace process.

Second intifada and civil war

A peace summit between Yasser Arafat and Ehud Barak was mediated by Bill Clinton in 2000.[70][71] It was supposed to be the final agreement ending conflict officially forever. However the agreement failed to address the Palestinian refugee issues, status of Jerusalem and Israeli security concerns.[70][71] Both sides blamed each other for the summit failures.[70][71] This became of the main triggers for the uprising that would happen next.[70][71] In September 2000, then opposition leader from the Likud Party – Ariel Sharon made a proactive visit to the Temple Mount and delivered a controversial speech, which angered Palestinian Jerusalemites.[70][71] The tensions escalated into riots.[70][71] Bloody clashes took place around Jerusalem. Escalating violence resulted closure of Jerusalem Airport, which haven't operated till date.[70] More and more riots between Jews and Arabs took place in October 2000 in Israel.[70][71]

In the same month, two Israeli soldiers were lynched and killed in Ramallah.[70] Between November and December clashes between Palestinians and Israelis increased further.[70] In 2001 Taba summit was held between Israel and Palestine.[70] But the summit failed to implement and Ariel Sharon became prime minister in the 2001 elections.[70] By 2001, attacks from Palestinian militant groups towards Israel increased.[70][71] Gaza Airport was destroyed in an airstrike by the Israeli army in 2001, claiming itself in retaliation to previous attacks by Hamas.[70][71] In January 2002, the IDF Shayetet 13 naval commandos captured the Karine A, a freighter carrying weapons from Iran towards Israel.[70] UNSC Resolution 1397 was passed, which reaffirmed a two-state solution and laid the groundwork for a road map for peace.[70] Another attack by Hamas left 30 people killed in Netanya.[70] A peace summit was organized by the Arab League in Beirut, which was endorsed by Arafat and nearly ignored by Israel.[70]

In 2002, Israel launched Operation Defensive Shield after the Passover massacre.[71] Heavy fighting between IDF and Palestinian fighters took place in Jenin.[71][69][72] The Church of the Nativity was besieged by the IDF for one week until successful negotiations took place, which resulted withdrawal of the Israeli troops from the church.[71] Between 2003 and 2004, people from Qawasameh tribe in Hebron were either killed or blew themselves in suicide bombing.[71][68] Ariel Sharon ordered construction of barriers across Palestinian-controlled areas and Israeli settlements in the West Bank to prevent future attacks.[71] Saddam Hussein provided financial support to Palestinian militants from Iraq during the intifada period, from 2000 until his overthrow in 2003.[71] A peace proposal was made in 2003, which was supported by Arafat and rejected by Sharon.[71] In 2004 Hamas's leader and co-founder Ahmed Yassin was assassinated by the Israeli army in Gaza.[71][68] Yasser Arafat was confined to his headquarters in Ramallah.[71] On 11 November, Yasser Arafat died in Paris.[71]

In the first week of 2005, Mahmoud Abbas was elected as the president of the State of Palestine.[71] In 2005, Israel completely withdrew from the Gaza Strip by destroying its settlements over there.[71] By 2005, the situation began de-escalating.[71] In 2006, Hamas won in Palestinian legislative elections.[73] This led a political standoff with Fatah.[73] Armed clashes took place across both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.[73] The clashes turned into a civil war, which ended in a bloody clashes on the Gaza Strip.[73] As a result, Hamas gained control over all the territory of Gaza.[73] Hundreds of people were killed in the civil war, including militants and civilians.[73] Since then Hamas has gained more independence in its military practices.[73] Since 2007, Israel has been leading a partial blockade on Gaza.[73] Another peace summit was organized by the Arab League in 2007, with the same offer which was presented in 2002 summit.[73] However the peace process could not progress.[73][74][75] The PNA gained full control of the Gaza Strip with the exception of its borders, airspace, and territorial waters.[d]

Continued conflict

The division between the West Bank and Gaza complicated efforts to achieve Palestinian unity and negotiate a comprehensive peace agreement with Israel. Multiple rounds of reconciliation talks were held, but no lasting agreement was reached. The division also hindered the establishment of a unified Palestinian state and led to different governance structures and policies in the two territories.[76]

Throughout this period, there were sporadic outbreaks of violence and tensions between Palestinians and Israelis. Since 2001, Incidents of rocket attacks from Gaza into Israeli territory and Israeli military operations in response often resulted in casualties and further strained the situation.[77] Following the inter-Palestinian conflict in 2006, Hamas took over control of the Gaza Strip (it already had majority in the PLC), and Fatah took control of the West Bank. From 2007, the Gaza Strip was governed by Hamas, and the West Bank by the Fatah party led Palestinian Authority.[78]

International efforts to revive the peace process continued. The United States, under the leadership of different administrations, made various attempts to broker negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians.[79]

However, significant obstacles such as settlement expansion, the status of Jerusalem, borders, and the right of return for Palestinian refugees, remained unresolved.[80][81][82][83] In recent years, diplomatic initiatives have emerged, including the normalization agreements between Israel and several Arab states, known as the Abraham Accords.[84] These agreements, while not directly addressing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, have reshaped regional dynamics and raised questions about the future of Palestinian aspirations for statehood.[85][86] The status quo remains challenging for Palestinians, with ongoing issues of occupation, settlement expansion, restricted movement, and economic hardships.[87]

The most recent outbreak of violence in the region is the Israel-Hamas war (2023-present), involving fighting between Israel and Hamas-led Palestinian forces in the Gaza Strip, with a simultaneous spillover of the war occurring in the West Bank.

Geography

Areas claimed by the country, known as the Palestinian territories, lie in the Southern Levant of the Middle East region.[88] Palestine is part of the Fertile Crescent, along with Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Syria. The Gaza Strip borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Egypt to the south, and Israel to the north and east.[88] The West Bank is bordered by Jordan to the east, and Israel to the north, south, and west.[88] Palestine shares its maritime borders with Israel, Egypt and Cyprus. Thus, the two enclaves constituting the area claimed by the State of Palestine have no geographical border with one another, being separated by Israel.[88] These areas would constitute the world's 163rd largest country by land area.[8][88][89][better source needed]

The West Bank is a mountainous region. It is divided in three regions, namely the Mount Nablus (Jabal Nablus), the Hebron Hills and Jerusalem Mountains (Jibal al–Quds).[90] The Samarian Hills and Judean Hills are mountain ranges in the West Bank, with Mount Nabi Yunis at a height of 1,030 metres (3,380 ft) in Hebron Governorate as their highest peak.[91][92][93] Until 19th century, Hebron was highest city in the Middle East.[93] While Jerusalem is located on a plateau in the central highlands and is surrounded by valleys.[93] The territory consists of fertile valleys, such as the Jezreel Valley and the Jordan River Valley. Palestine is home to world's largest olive tree, located in Jerusalem.[94][93] Around 45% of Palestine's land is dedicated to growing olive trees.[95]

Palestine features significant lakes and rivers that play a vital role in its geography and ecosystems.[96] The Jordan River flows southward, forming part of Palestine's eastern border and passing through the Sea of Galilee before reaching the Dead Sea.[97] According to Christian traditions, it is site of the baptism of Jesus.[97] The Dead Sea, bordering the country's east is the lowest point on the earth.[98] Jericho, located nearby is lowest city in the world.[99] Villages and suburban area around Jerusalem is home to anciet water bodies.[100] There are several river valleys (wadi) across the country.[96] These waterways provide essential resources for agriculture, recreation, and support various ecosystems.[96]

Three terrestrial ecoregions are found in the area: Eastern Mediterranean conifer–sclerophyllous–broadleaf forests, Arabian Desert, and Mesopotamian shrub desert.[101] Palestine has a number of environmental issues; issues facing the Gaza Strip include desertification; salination of fresh water; sewage treatment; water-borne diseases; soil degradation; and depletion and contamination of underground water resources. In the West Bank, many of the same issues apply; although fresh water is much more plentiful, access is restricted by the ongoing dispute.[102]

Climate

Temperatures in Palestine vary widely. The climate in the West Bank is mostly Mediterranean, slightly cooler at elevated areas compared with the shoreline, west to the area. In the east, the West Bank includes much of the Judean Desert including the western shoreline of the Dead Sea, characterised by dry and hot climate. Gaza has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSh) with mild winters and dry hot summers.[citation needed] Spring arrives around March–April and the hottest months are July and August, with the average high being 33 °C (91 °F). The coldest month is January with temperatures usually at 7 °C (45 °F). Rain is scarce and generally falls between November and March, with annual precipitation rates approximately at 4.57 inches (116 mm).[103]

Biodiversity

Palestine does not have officially recognized national parks or protected areas. However, there are areas within the West Bank that are considered to have ecological and cultural significance and are being managed with conservation efforts. These areas are often referred to as nature reserves or protected zones. Located near Jericho in the West Bank, Wadi Qelt is a desert valley with unique flora and fauna.

The reserve is known for its rugged landscapes, natural springs, and historical sites such as the St. George Monastery.[104] Efforts have been made to protect the biodiversity and natural beauty of the area.[105] The Judaean Desert is popular for "Judaean Camels". Qalqilya Zoo in Qalqilya Governorate, is the only zoo currently active in the country. Gaza Zoo was closed due to poor conditions. Israeli government have built various national parks in the Area C, which is also considered illegal under international law.

Government and politics

Palestine operates a semi-presidential system of government.[106] The country consists of the institutions that are associated with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which includes President of the State of Palestine[107][c] – appointed by the Palestinian Central Council,[110] Palestinian National Council – the legislature that established the State of Palestine[5] and Executive Committee of the Palestine Liberation Organization – performs the functions of a government in exile,[108][109][111][112] maintaining an extensive foreign-relations network. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) is combination of several political parties.

These should be distinguished from the President of the Palestinian National Authority, Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) and PNA Cabinet, all of which are instead associated with the Palestinian National Authority. The State of Palestine's founding document is the Palestinian Declaration of Independence,[5] and it should be distinguished from the unrelated PLO Palestinian National Covenant and PNA Palestine Basic Law.

The Palestinian government is divided into two geographic entities – the Palestinian Authority governed by Fatah, which has partial control over the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, which is under control of the militant group Hamas.[113][114] Fatah is a secular party, which was founded by Yasser Arafat and relatively enjoys good relations with the western powers. On other hand, Hamas is a militant group, based on Palestinian nationalist and Islamic ideology, inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood.[115][116] Hamas has tense relations with the United States, but receives support from Iran. Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine is another popular secular party, which was founded by George Habash. Mahmoud Abbas is the president of the country since 2005.[117] Mohammad Shtayyeh was the prime minister of Palestine, who resigned in 2024.[118] In 2024, Mohammad Mustafa was appointed as the new prime minister of the country, after resigning of Shtayyeh.[119] While Yahya Sinwar is leader of Hamas government in the Gaza Strip.[120] According to Freedom House, the PNA governs Palestine in an authoritarian manner, including by repressing activists and journalists critical of the government.[121]

Jerusalem including Haram ash-Sharif, is claimed as capital by Palestine, which has been under occupation by Israel.[122] Currently the temporary administration center is in Ramallah, which is 10 km from Jerusalem.[123] Muqata hosts state ministries and representative office.[124] The former building Gaza was destroyed in 2009 war.[125] In 2000, a government building was built in Jerusalem suburb of Abu Dis, to house office of Yasser Arafat and Palestinian parliament.[126] Since second intifada, condition of the town made this site unsuitable to operate as a capital, either temporarily or permanently.[127] Nevertheless, the Palestinian entity have maintained their presence in the city. As few parts of the city is also under Palestinian control and many some countries have their consulates in Jerusalem.

Administrative divisions

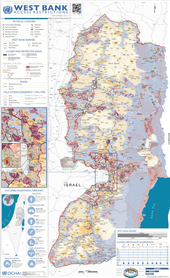

The State of Palestine is divided into sixteen administrative divisions. The governorates in the West Bank are grouped into three areas per the Oslo II Accord. Area A forms 18% of the West Bank by area, and is administered by the Palestinian government.[128][129] Area B forms 22% of the West Bank, and is under Palestinian civil control, and joint Israeli-Palestinian security control.[128][129] Area C, except East Jerusalem, forms 60% of the West Bank, and is administered by the Israeli Civil Administration, however, the Palestinian government provides the education and medical services to the 150,000 Palestinians in the area,[128] an arrangement agreed upon in the Oslo II accord by Israeli and Palestinian leadership. More than 99% of Area C is off limits to Palestinians, due to security concerns and is a point of ongoing negotiation.[130][131] There are about 330,000 Israelis living in settlements in Area C.[132] Although Area C is under martial law, Israelis living there are entitled to full civic rights.[133] Palestinian enclaves currently under Palestinian administration in red (Areas A and B; not including Gaza Strip, which is under Hamas rule).

East Jerusalem (comprising the small pre-1967 Jordanian eastern-sector Jerusalem municipality together with a significant area of the pre-1967 West Bank demarcated by Israel in 1967) is administered as part of the Jerusalem District of Israel but is claimed by Palestine as part of the Jerusalem Governorate. It was effectively annexed by Israel in 1967, by application of Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration under a 1948 law amended for the purpose, this purported annexation being constitutionally reaffirmed (by implication) in Basic Law: Jerusalem 1980,[128] but this annexation is not recognised by any other country.[134] In 2010 of the 456,000 people in East Jerusalem, roughly 60% were Palestinians and 40% were Israelis.[128][135] However, since the late 2000s, Israel's West Bank Security Barrier has effectively re-annexed tens of thousands of Palestinians bearing Israeli ID cards to the West Bank, leaving East Jerusalem within the barrier with a small Israeli majority (60%).[citation needed] Under Oslo Accords, Jerusalem was proposed to be included in future negotiations and according to Israel, Oslo Accords prohibits the Palestinian Authority to operates in Jerusalem. However, certain parts of Jerusalem, those neighborhoods which are located outside the historic Old City but are part of East Jerusalem, were allotted to the Palestinian Authority.[136]a[iii]

| Name | Area (km2)[137] | Population | Density (per km2) | Muhafazah (district capital) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jenin | 583 | 311,231 | 533.8 | Jenin |

| Tubas | 402 | 64,719 | 161.0 | Tubas |

| Tulkarm | 246 | 182,053 | 740.0 | Tulkarm |

| Nablus | 605 | 380,961 | 629.7 | Nablus |

| Qalqiliya | 166 | 110,800 | 667.5 | Qalqilya |

| Salfit | 204 | 70,727 | 346.7 | Salfit |

| Ramallah & Al-Bireh | 855 | 348,110 | 407.1 | Ramallah |

| Jericho & Al Aghwar | 593 | 52,154 | 87.9 | Jericho |

| Jerusalem | 345 | 419,108a | 1214.8[iv] | Jerusalem (see Status of Jerusalem) |

| Bethlehem | 659 | 216,114 | 927.9 | Bethlehem |

| Hebron | 997 | 706,508 | 708.6 | Hebron |

| North Gaza | 61 | 362,772 | 5947.1 | Jabalya[citation needed] |

| Gaza | 74 | 625,824 | 8457.1 | Gaza City |

| Deir Al-Balah | 58 | 264,455 | 4559.6 | Deir al-Balah |

| Khan Yunis | 108 | 341,393 | 3161.0 | Khan Yunis |

| Rafah | 64 | 225,538 | 3524.0 | Rafah |

- ^ Arabic: فلسطين, romanized: Filasṭīn, pronounced [fɪlastˤiːn]

- ^ Arabic: دولة فلسطين, romanized: Dawlat Filasṭīn, pronounced [dawlat fɪlastˤiːn]

- ^ Data from Jerusalem includes occupied East Jerusalem with its Israeli population

- ^ Data from Jerusalem includes occupied East Jerusalem with its Israeli population

Foreign relations

Foreign relations are maintained in the framework of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) represents the State of Palestine and maintains embassies in countries that recognize it. It also participates in international organizations as a member, associate, or observer. In some cases, due to conflicting sources, it is difficult to determine if the participation is on behalf of the State of Palestine, the PLO as a non-state entity, or the Palestinian National Authority (PNA). The Vatican shifted recognition to the State of Palestine in May 2015, following the 2012 UN vote.[138] This change aligned with the Holy See's evolving position.[139]

Currently, 139 UN member states (72%) recognize the State of Palestine. Though some do not recognize it, they acknowledge the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people. The PLO's executive committee acts as the government, empowered by the PNC.[140] It is full-time member of the Arab League, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and the Union for the Mediterranean. Sweden took a significant step in 2013 by upgrading the status of the Palestinian representative office to a full embassy. They became the first EU member state outside the former communist bloc to officially recognize the state of Palestine.[141][142][143][144]

Members of the Arab League and member of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation have strongly supported the country's position in its conflict with Israel.[145][146] Iran have been strongest ally of Palestine since the Islamic revolution and provide military support to Palestinian fedayeen and militant groups including Hamas through its Axis of Resistance, which includes military coalition of governments and rebels from Iraq,[147] Syria,[148] Lebanon[149] and Yemen.[150][151][152][153][154] Hamas is also part of the axis of resistance. Even before emergence of Iranian-backed group, Iraq was a strong supporter of Palestine when it was under the Ba'athist government of Saddam Hussein.[155][156][157] Turkey is a supporter of Hamas and Qatar has been a key-financial supporter and host Hamas leaders.[158] India was the first non-Arab country to reject the UN partition plan and officially recognized the statehood declaration.[159] Once a strong ally of Palestine, India have strengthen its ties with Israel since 1991.[160] However India still supports the legitimacy of Palestine's issue.[161]

Muammar Gaddafi of Libya was a supporter of Palestinian independence and was sought as a mediator in the Arab–Israeli conflict, when he presented a one-state peace offer titled Isratin in 2000.[162] Relations with the United Arab Emirates deteriorated, when it signed normalization agreement with Israel. During the Sri Lankan Civil War, the PLO provided training for Tamil rebels to fight against the Sri Lankan government.[163][164][165] The Republic of Ireland, Venezuela and South Africa are political allies of Palestine and have strongly advocated for establishment of independent Palestine.[166][167][168] As a result of the ongoing war, support for the country have increased. Since Israel's invasion of Gaza, many countries in support of Palestinians have officially recognized the country. This includes Armenia, Spain, Norway, The Bahamas, Jamaica, Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago.[169]

Status and recognition

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) declared the establishment of the State of Palestine on 15 November 1988. There is a wide range of views on the legal status of the State of Palestine, both among international states and legal scholars.[170] The existence of a state of Palestine is recognized by the states that have established bilateral diplomatic relations with it.[171][172] In January 2015, the International Criminal Court affirmed Palestine's "State" status after its UN observer recognition,[173] a move condemned by Israeli leaders as a form of "diplomatic terrorism."[174] In December 2015, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution demanding Palestinian sovereignty over natural resources in the occupied territories. It called on Israel to cease exploitation and damage while granting Palestinians the right to seek restitution. In 1988, the State of Palestine's declaration of independence was acknowledged by the General Assembly with Resolution 43/177.[175] In 2012, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 67/19, granting Palestine "non-member observer state" status, effectively recognizing it as a sovereign state.[176][177]

In August 2015, Palestine's representatives at the United Nations presented a draft resolution that would allow the non-member observer states Palestine and the Holy See to raise their flags at the United Nations headquarters. Initially, the Palestinians presented their initiative as a joint effort with the Holy See, which the Holy See denied.[178] In a letter to the Secretary General and the President of the General Assembly, Israel's Ambassador at the UN Ron Prosor called the step "another cynical misuse of the UN ... in order to score political points".[179] After the vote, which was passed by 119 votes to 8 with 45 countries abstaining,[180][181][182] the US Ambassador Samantha Power said that "raising the Palestinian flag will not bring Israelis and Palestinians any closer together".[183] US Department of State spokesman Mark Toner called it a "counterproductive" attempt to pursue statehood claims outside of a negotiated settlement.[184]

At the ceremony itself, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said the occasion was a "day of pride for the Palestinian people around the world, a day of hope",[185] and declared "Now is the time to restore confidence by both Israelis and Palestinians for a peaceful settlement and, at last, the realization of two states for two peoples."[180]

International recognition

The State of Palestine has been recognized by 145 of the 193 UN members and since 2012 has had a status of a non-member observer state in the United Nations.[186][187][188] This limited status is largely due to the fact that the United States, a permanent member of the UN Security Council with veto power, has consistently used its veto or threatened to do so to block Palestine's full UN membership.[28][29]

On 29 November 2012, in a 138–9 vote (with 41 abstentions and 5 absences),[189] the United Nations General Assembly passed resolution 67/19, upgrading Palestine from an "observer entity" to a "non-member observer state" within the United Nations System, which was described as recognition of the PLO's sovereignty.[187][188][190][108][191] Palestine's new status is equivalent to that of the Holy See.[192] The UN has permitted Palestine to title its representative office to the UN as "The Permanent Observer Mission of the State of Palestine to the United Nations",[193] and Palestine has instructed its diplomats to officially represent "The State of Palestine"—no longer the Palestinian National Authority.[191] On 17 December 2012, UN Chief of Protocol Yeocheol Yoon declared that "the designation of 'State of Palestine' shall be used by the Secretariat in all official United Nations documents",[194] thus recognising the title 'State of Palestine' as the state's official name for all UN purposes; on 21 December 2012, a UN memorandum discussed appropriate terminology to be used following GA 67/19. It was noted therein that there was no legal impediment to using the designation Palestine to refer to the geographical area of the Palestinian territory. At the same time, it was explained that there was also no bar to the continued use of the term "Occupied Palestinian Territory including East Jerusalem" or such other terminology as might customarily be used by the Assembly.[195] As of 21 June 2024, 145 (75.1%) of the 193 member states of the United Nations have recognised the State of Palestine.[108][196] Many of the countries that do not recognise the State of Palestine nevertheless recognise the PLO as the "representative of the Palestinian people". The PLO's Executive Committee is empowered by the Palestinian National Council to perform the functions of government of the State of Palestine.[109]

On 2 April 2024, Riyad Mansour, the Palestinian ambassador to the UN, requested that the Security Council consider a renewed application for membership. As of April, seven UNSC members recognize Palestine but the US has indicated that it opposes the request and in addition, US law stipulates that US funding for the UN would be cut off in the event of full recognition without an Israeli-Palestinian agreement.[197] On 18 April, the US vetoed a widely supported UN resolution that would have admitted Palestine as a full UN member.[198][199][200]

Military

The Palestinian Security Services consists of the armed forces and intelligence agencies, which were established during the Oslo Accords. Their function is to maintain internal security and enforce law in the PA-controlled areas. It does not operate as an independent armed force of a country. Before the Oslo Accords, the PLO led armed rebellion against Israel, which included coalition of militant groups and included its own military branch – the Palestine Liberation Army.[201] However, since the 1993–1995 agreements, it has been inactive and operates only in Syria. Palestinian fedayeen are the Palestinian militants and guerilla army. They are considered as "freedom fighter" by Palestinians and "terrorists" by Israelis.[202] Hamas considers itself as an independent force, which is more powerful and influential than PSF, along with other militant organizations such as Islamic Jihad (Al-Quds Bridage).[203] It is a guerilla army, which is supported by Iran, Qatar and Turkey.[204] According to the CIA World Factbook, the Qassam Brigades have 20,000 to 25,000 members, although this number is disputed.[205] Israel's 2005 withdrawal from Gaza provided Hamas with the opportunity to develop its military wing.[204]

Iran and Hezbollah have smuggled weapons to Hamas overland through Sinai via Sudan and Libya, as well as by sea.[206] Intensive military training and accumulated weapons have allowed Hamas to gradually organize regional units as large as brigades containing 2,500–3,500 fighters each.[206] Joint exercises since 2020 (such as this one) conducted with other Gazan armed factions like the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) have habituated units to operating in a coordinated fashion, supported Hamas command and control, and facilitated cooperation between Hamas and smaller factions.[206] Such efforts began in earnest once Hamas seized power in the Gaza Strip in 2007.[206] Iran has since supplied materiel and know-how for Hamas to build a sizable rocket arsenal, with more than 10,000 rockets and mortar shells fired in the current conflict.[206] With Iran's help, Hamas has developed a robust domestic rocket-making industry that uses pipes, electrical wiring, and other everyday materials for improvised production.[206]

Law and security

The State of Palestine has a number of security forces, including a Civil Police Force, National Security Forces and Intelligence Services, with the function of maintaining security and protecting Palestinian citizens and the Palestinian State. All of these forces are part of Palestinian Security Services. The PSF is primarily responsible for maintaining internal security, law enforcement, and counterterrorism operations in areas under Palestinian Authority control.[207]

The Palestinian Liberation Army (PLA) is the standing army of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).[208] It was established during the early years of the Palestinian national movement but has largely been inactive since the Oslo Accords.[209] The PLA's role was intended to be a conventional military force but has shifted to a more symbolic and political role.[210]

Economy

Palestine is classified as a middle income and developing country by the IMF. In 2023, GDP of the country was $40 billion and per-capita around $4,500. Due to its disputed status, the economic condition have been affected.[211][212][213] The CO2 emission (metric tons per capita) was 0.6 in 2010. According to a survey of 2011, Palestine's poverty rate was 25.8%. According to a new World Bank report, Palestinian economic growth is expected to soften in 2023. Economy of Palestine relies heavily on international aids, remittances by overseas Palestinians and local industries.[214]

According to a report by the World Bank, the economic impact of Israel's closure policy has been profound, directly contributing to a significant decline in economic activity, widespread unemployment, and a rise in poverty since the onset of the Second Intifada in September 2000.[215] The Israeli restrictions imposed on Area C alone result in an estimated annual loss of approximately $3.4 billion, which accounts for nearly half of the current Palestinian GDP.[215] These restrictions have severely hindered economic growth and development in the region.[215] In the aftermath of Israel's military offensive on the Gaza Strip in winter 2014, where a staggering number of structures were damaged or destroyed, the flow of construction and raw materials into Gaza has been severely limited.[215] Additionally, regular exports from the region have been completely halted, exacerbating the economic challenges faced by the population.[215]

One of the burdensome measures imposed by Israel is the "back-to-back" system enforced at crossing points within Palestinian territories.[215] This policy forces shippers to unload and reload their goods from one truck to another, resulting in significant transportation costs and longer transit times for both finished products and raw materials.[215] These additional expenses further impede economic growth and viability.[215] Under the Oslo II accords signed in 1995, it was agreed that governance of Area C would be transferred to the Palestinian Authority within 18 months, except for matters to be determined in the final status agreement.[215] However, Israel has failed to fulfill its obligations under the Oslo agreement, highlighting the urgent need for accountability and an end to impunity.[215] The European Commission has highlighted the detrimental impact of the separation barrier constructed by Israel, estimating that it has led to an annual economic impoverishment of Palestinians by 2–3% of GDP.[215] Furthermore, the escalating number of internal and external closures continues to have a devastating effect on any prospects for economic recovery in the region.[215]

A recent study, conservatively estimating the economic impact of Israel's occupation and practices, revealed alarming findings.[215] In 2010 alone, Israel's illegal use of Palestinian natural resources accounted for US$1.83 billion, equivalent to 22% of Palestine's GDP that year.[215] According to a World Bank report, the manufacturing sector's share of GDP decreased from 19% to 10% since the signing of the Oslo Accords until 2011.[215] The same report, which adopted conservative estimates, suggests that access to Area 'C' in specific sectors like Dead Sea minerals, telecommunications, mining, tourism, and construction could contribute at least 22% to Palestinian GDP.[215] In fact, the report notes that Israel and Jordan together generate around $4.2 billion annually from the sale of these products, representing 6% of the global potash supply and 73% of global bromine output.[215] Overall, if Palestinians had unrestricted access to their own land in Area 'C,' the potential economic benefits for Palestine could increase by 35% of GDP, amounting to at least $3.4 billion annually.[215] Similarly, water restrictions incurred a cost of US$1.903 billion, equivalent to 23.4% of GDP, while Israel's ongoing blockade on the Gaza Strip resulted in a cost of $1.908 billion US$, representing 23.5% of GDP in 2010.[215] These burdens are unsustainable for any economy, artificially limiting Palestine's economic potential and its right to develop a prosperous society with a stable economy and sustainable growth.[215]

The State of Palestine's overall gross-domestic-product (GDP) has declined by 35% in the first quarter of 2024, due to the ongoing war in Gaza, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) reports.[216][217] There was a stark difference between the West Bank, which witnessed a decline of 25% and in the Gaza Strip, the number is 86% amid the ongoing war.[216] The manufacturing sector decreased by 29% in the West Bank and 95% in Gaza, while the construction sector decreased by 42% in the West Bank and essentially collapsed in Gaza, with a 99% decrease.[216][218]

Agriculture

After Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1967, Palestinian agriculture suffered significant setbacks.[219] The sector's contribution to the GDP declined, and the agricultural labor force decreased.[219] The cultivated areas in the West Bank continuously declined since 1967.[219] Palestinian farmers face obstacles in marketing and distributing their products, and Israeli restrictions on water usage have severely affected Palestinian agriculture.[219] Over 85% of Palestinian water from the West Bank aquifers is used by Israel, and Palestinians are denied access to water resources from the Jordan and Yarmouk Rivers.[219]

In Gaza, the coastal aquifer is suffering from saltwater intrusion.[219] Israeli restrictions have limited irrigation of Palestinian land, with only 6% of West Bank land cultivated by Palestinians being irrigated, while Israeli settlers irrigate around 70% of their land.[219] The Gulf War in 1991 had severe repercussions on Palestinian agriculture, as the majority of exports were previously sent to Arab Gulf countries.[219] Palestinian exports to the Gulf States declined by 14% as a result of the war, causing a significant economic impact.[219]

Water supply and sanitation

Water supply and sanitation in the Palestinian territories are characterized by severe water shortage and are highly influenced by the Israeli occupation. The water resources of Palestine are partially controlled by Israel due in part from historical and geographical complexities with Israel granting partial autonomy in 2017.[220] The division of groundwater is subject to provisions in the Oslo II Accord, agreed upon by both Israeli and Palestinian leadership.[citation needed] Israel provides the Palestinian territories water from its own water supply and desalinated water supplies, in 2012 supplying 52 MCM.[221][222]

Generally, the water quality is considerably worse in the Gaza Strip when compared to the West Bank. About a third to half of the delivered water in the Palestinian territories is lost in the distribution network. The lasting blockade of the Gaza Strip and the Gaza War have caused severe damage to the infrastructure in the Gaza Strip.[223][224] Concerning wastewater, the existing treatment plants do not have the capacity to treat all of the produced wastewater, causing severe water pollution.[225] The development of the sector highly depends on external financing.[226]

Manufacturing

Manufacturing and exports in Palestine includes sectors such as textiles, food processing, pharmaceuticals, construction materials, furniture, plastic products, stone, and electronics.[227] Some notable products are garments, olive oil, dairy products, furniture, ceramics, and construction materials.[228] Before the second intifada, Palestine had a strong industrial base in Jerusalem and Gaza. Barriers erected in the West Bank have made movement of goods difficult; the blockade of the Gaza Strip has severely affected the territory's economic conditions. As of 2023, according to the Ministry of Economy, the manufacturing sector expected to grow by 2.5% and create 79,000 jobs over the following six years.[229] Palestine mainly exports articles of stone (limestone, marble – 13.3%), furniture (11.7%), plastics (10.2%) and iron and steel (9.1%). Most of these products are exported to Jordan, the United States, Israel and Egypt.

Hebron is industrially most advanced city in the region and serves as an export hub for Palestinian products. More than 40% of the national economy produced there.[230] The most advanced printing press in the Middle East is in Hebron.[230] Many quarries are in the surrounding region.[231] Silicon reserves are found in the Gaza territory. Jerusalem stone, extracted in the West Bank, has been used for constructing many structures in Jerusalem. Hebron is widely known for its glass production. Nablus is noted for its Nablus soap. Some of the companies operating in the Palestinian territories include Siniora Foods, Sinokrot Industries, Schneider Electric, PepsiCo and Coca-Cola.[232]

Israeli–Palestinian economic peace efforts have resulted in several initiatives, such as the Valley of Peace initiative and Breaking the Impasse, which promote industrial projects between Israel, Palestine and other Arab countries, with the goal of promoting peace and ending conflict.[233] These include joint industrial parks opened in Palestine. The Palestinian Authority has built industrial cities in Gaza, Bethlehem, Jericho, Jenin and Hebron. Some are in joint cooperation with European countries.[234]

Energy

Palestine does not produce its own oil or gas. But as per UN reports, "sizeable reserves of oil and gas" lie in the Palestinian territories. Due to its state of conflict, most of the energy and fuel in Palestine are imported from Israel and other all neighboring countries such as Egypt, Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

In 2012, electricity available in West Bank and Gaza was 5,370 GW-hour (3,700 in the West Bank and 1,670 in Gaza), while the annual per capita consumption of electricity (after deducting transmission loss) was 950 kWh. The Gaza Power Plant is the only power plant in the Gaza Strip. It is owned by Gaza Power Generating Company (GPGC), a subsidiary of the Palestine Electric Company (PEC). Jerusalem District Electricity Company, a subsidiary of PEC, provides electricity to Palestinan residents of Jerusalem.

Government officials have increasingly focused on solar energy to reduce dependency on Israel for energy. Palestine Investment Fund have launched "Noor Palestine", a project which aims to provide power in Palestine.[235] Qudra Energy, a joint venture between Bank of Palestine and NAPCO have established solar power plants across Jammala, Nablus, Birzeit and Ramallah.[236] In 2019, under Noor Palestine campaign, first solar power plant and solar park was inaugurated in Jenin. Two more solar parks have been planned for Jericho and Tubas.[237] A new solar power plant is under construction at Abu Dis campus of Al-Quds University, for serving Palestinian Jerusalemites.[238]

Oil and gas

Palestine holds massive potential reserves of oil and gas.[239] Over 3 billion barrels (480,000,000 m3) of oil are estimated to exist off the coast and beneath occupied Palestinian lands.[239][240] The Levant Basin holds around 1.7 billion barrels (270,000,000 m3) of oil, with another 1.5 billion barrels (240,000,000 m3) barrels beneath the occupied West Bank area.[240] Around 2 billion barrels (320,000,000 m3) of oil reserves are believed to exist in shore of the Gaza Strip.[240][241] According to a report by the UNCTAD, around 1,250 billion barrels (1.99×1011 m3) of oil reserves are in the occupied Palestinian territory of the West Bank, probably the Meged oil field. As per the Palestinian Authority, 80% of this oil field falls under the lands owned by Palestinians.

Masadder, a subsidiary of the Palestine Investment Fund is developing the oilfield in the West Bank.[241] Block-1 field, which spans an area of 432 square kilometres (167 sq mi) from northwest Ramallah to Qalqilya in Palestine, has significant potential for recoverable hydrocarbon resources.[241][242] It is estimated to have a P90 (a level of certainty) of 0.03 billion barrels (4,800,000 m3) of recoverable oil and 6,000,000,000 cubic feet (170,000,000 m3).[241] The estimated cost for the development of the field is $390 million, and it will be carried out under a production sharing agreement with the Government of Palestine.[241][243][244] Currently, an initial pre-exploration work program is underway to prepare for designing an exploration plan for approval, which will precede the full-fledged development of the field.[241]

Natural gas in Palestine is mostly found in Gaza Strip.[243] Gaza Marine is a natural gas field, located around 32 kilometres (20 mi) from the coast of the territory in the Mediterranean shore.[245] It holds gas reserves ranging between 28 billion cubic metres (990 billion cubic feet) to 32 billion cubic metres (1.1 trillion cubic feet).[246] These estimates far exceed the needs of the Palestinian territories in energy.[247] The gas field was discovered by the British Gas Group in 1999.[248] Upon the discovery of the gas field, it was lauded by Yasser Arafat as a "Gift from God". A regional cooperation between the Palestinian Authority, Israel and Egypt were signed for developing the field and Hamas also gave approval to the Palestinian Authority.[249][250] However, since the ongoing war in Gaza, this project have been delayed.[250]

Transportation

Two airports of Palestine – Jerusalem International Airport and Gaza International Airport were destroyed by Israel in the early years of the second intifada.[251] Since then no any airport has been operational in the country. Palestinians used to travel through airports in Israel – Ben Gurion Airport and Ramon Airport and Queen Alia International Airport of Amman, capital of Jordan. Many proposals have been made by both the government and private entities to build airports in the country. In 2021, the most recent proposal was made by both the Palestinian government and Israeli government to redevelop Qalandia Airport as a binational airport for both Israelis and Palestinians.[252]

Gaza Strip is the only coastal region of Palestine, where Port of Gaza is located. It is under naval siege by Israel, since the territory's blockade. During Oslo years, the Palestinian government collaborated with the Netherlands and France to build an international seaport but the project was abandoned. In 2021, then prime minister of Israel Naftali Bennett launched a development project for Gaza, which would include a seaport.[253]

Tourism

Tourism in the country refers to tourism in East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. In 2010, 4.6 million people visited the Palestinian territories, compared to 2.6 million in 2009. Of that number, 2.2 million were foreign tourists while 2.7 million were domestic.[254] Most tourists come for only a few hours or as part of a day trip itinerary. In the last quarter of 2012 over 150,000 guests stayed in West Bank hotels; 40% were European and 9% were from the United States and Canada.[255] Lonely Planet travel guide writes that "the West Bank is not the easiest place in which to travel but the effort is richly rewarded."[256] Sacred sites such as the Western Wall, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and the Al-Aqsa Mosque draw countless pilgrims and visitors each year.

In 2013 Palestinian Authority Tourism minister Rula Ma'ay'a stated that her government aims to encourage international visits to Palestine, but the occupation is the main factor preventing the tourism sector from becoming a major income source to Palestinians.[257] There are no visa conditions imposed on foreign nationals other than those imposed by the visa policy of Israel. Access to Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza is completely controlled by the government of Israel. Entry to the occupied Palestinian territories requires only a valid international passport.[258] Tourism is mostly centered around Jerusalem and Bethlehem. Jericho is a popular tourist spot for local Palestinians.

Communications

Palestine is known as the "Silicon Valley of NGOs".[259] The high tech industry in Palestine, have experienced good growth since 2008.[260] The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) and the Ministry of Telecom and Information Technology said there were 4.2 million cellular mobile subscribers in Palestine compared to 2.6 million at the end of 2010 while the number of ADSL subscribers in Palestine increased to about 363 thousand by the end of 2019 from 119 thousand over the same period.[260] 97% of Palestinian households have at least one cellular mobile line while at least one smartphone is owned by 86% of households (91% in the West Bank and 78% in Gaza Strip).[260] About 80% of the Palestinian households have access to the internet in their homes and about a third have a computer.[260]

On 12 June 2020, the World Bank approved a US$15 million grant for the Technology for Youth and Jobs (TechStart) Project aiming to help the Palestinian IT sector upgrade the capabilities of firms and create more high-quality jobs. Kanthan Shankar, World Bank Country Director for West Bank and Gaza said "The IT sector has the potential to make a strong contribution to economic growth. It can offer opportunities to Palestinian youth, who constitute 30% of the population and suffer from acute unemployment."[261]

Financial services

The Palestine Monetary Authority has issued guidelines for the operation and provision of electronic payment services including e-wallet and prepaid cards.[262] Protocol on Economic Relations, also known as Paris Protocol was signed between the PLO and Israel, which prohibited Palestinian Authority from having its own currency. This agreement paved a way for the government to collect taxes.

Prior to 1994, the occupied Palestinian territories had limited banking options, with Palestinians avoiding Israeli banks.[263] This resulted in an under-banked region and a cash-based economy.[263] Currently, there are 14 banks operating in Palestine, including Palestinian, Jordanian, and Egyptian banks, compared to 21 in 2000.[263] The number of banks has decreased over time due to mergers and acquisitions.[263] Deposits in Palestinian banks have seen significant growth, increasing from US$1.2 billion in 2007 to US$6.9 billion in 2018, representing a 475% increase.[263] The banking sector has shown impressive annual growth rates in deposits and loan portfolios, surpassing global averages.[263]

The combined loan facilities provided by all banks on 31 December 2018, amounted to US$8.4 billion, marking a significant growth of 492 percent compared to US$1.42 billion in 2007.[263] Palestinian registered banks accounted for US$0.60 billion or 42 percent of total deposits in 2007, while in 2018, the loans extended by Palestinian registered banks reached US$5.02 billion, representing 61 percent of total loans.[263] This showcases a remarkable 737 percent increase between 2007 and 2018.[263] Currently, Palestinian registered banks hold 57 percent of customer deposits and provide 61 percent of the loans, compared to 26 percent of deposits and 42 percent of loans in 2007.[263]

Demographics

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), as of 26 May 2021, the State of Palestine 2021 mid-year population is 5,227,193.[11] Ala Owad, the president of the PCBS, estimated a population of 5.3 million as of end year 2021.[264] Within an area of 6,020 square kilometres (2,320 sq mi), there is a population density of about 827 people per square kilometer.[89] To put this in a wider context, the average population density of the world was 25 people per square kilometre as of 2017.[265]

Half of the Palestinian population live in the diaspora or are refugees.[266] Due to being in a state of conflict with Israel, the subsequent wars have resulted in the widespread displacement of Palestinians, known as Nakba or Naksa.[267][268] In the 1948 war, around 700,000 Palestinians were expelled.[269] Most of them are seeking refuge in neighboring Arab countries like Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon and Egypt,[270] while others live as expats in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman and Kuwait.[271][268] A large number of Palestinians can be found in the United States, the United Kingdom and the rest of Europe.[272]

Population

| Rank | Name | Governorate | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gaza ![Jerusalem[274]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/GOL_Jerusalem.jpg/120px-GOL_Jerusalem.jpg) Jerusalem[274] |

1 | Gaza | Gaza Governorate | 766,331 |  Hebron  Nablus | ||||

| 2 | Jerusalem[274] | Jerusalem Governorate | 542,400 | ||||||

| 3 | Hebron | Hebron Governorate | 308,750 | ||||||

| 4 | Nablus | Nablus Governorate | 239,772 | ||||||

| 5 | Khan Yunis | Khan Yunis Governorate | 179,701 | ||||||

| 6 | Jabalia | North Gaza Governorate | 165,110 | ||||||

| 7 | Rafah | Rafah Governorate | 158,414 | ||||||

| 8 | Jenin | Jenin Governorate | 115,305 | ||||||

| 9 | Ramallah | Ramallah and al-Bireh | 104,173 | ||||||

| 10 | Beit Lahia | North Gaza Governorate | 86,526 | ||||||

Religion

The country has been known for its religious significance and site of many holy places, with religion playing an important role in shaping the country's society and culture. It is traditionally part of the Holy Land, which is considered sacred land to Abrahamic religions and other faiths as well. The Basic Law states that Islam is the official religion but also grants freedom of religion, calling for respect for other faiths.[275] Religious minorities are represented in the legislature for the Palestinian National Authority.[275]

93% of Palestinians are Muslim, the vast majority of whom are followers of the Sunni branch of Islam and a small minority of Ahmadiyya.[276][277][278] 15% are nondenominational Muslims.[279] Palestinian Christians represent a significant minority of 6%, followed by much smaller religious communities, including Druze and Samaritans.[280][281] The largest concentration of Christians can be found in Bethlehem, Beit Sahour, and Beit Jala in the West Bank, as well as in the Gaza Strip.[281] Majority of the Palestinian Christians belong to the Eastern Orthodox Churches, including Greek Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, and Syriac Orthodox.[281] Additionally, there are significant group of Roman Catholics, Greek Catholics (Melkites), and Protestant denominations.[281]

With a population of 350 people, Samaritans are highly concentrated around the Mount Gerizim.[275] Due to similarities between their religion and Judaism, Samaritans are often referred to as "the Jews of Palestine".[275] The PLO considers those Jews as Palestinians, who lived in the region peacefully before the rise of Zionism.[282] Certain individuals, especially anti-Zionists, consider themselves Palestinian Jews, such as Ilan Halevi and Uri Davis.[283] Around 600,000 Israeli settlers, mostly Jews, live in the Israeli settlements, illegal under international law, across the West Bank. Jericho synagogue, situated in Jericho is the only synagogue maintained by the Palestinian Authority.

- Holy sites in the State of Palestine

-

Jerusalem is home to the Al-Aqsa Mosque, which is 3rd holiest site in Islam

-

The Church of the Nativity is one of the most important sites for Christians

-

Mount Gerizim is sacred to Samaritan people

-

Nabi Musa is considered as "Tomb of Moses" in Islamic traditions

-

Jericho synagogue is managed by the Palestinian Authority

-

Nabi Yahya Mosque contains traditional tomb of John the Baptist

Ethnicity

Palestinians are natively Arab, and speak the Arabic language.[11][89] Bedouin communities of Palestinian nationality comprise a minority in the West Bank, particularly around the Hebron Hills and rural Jerusalem.[284][285][286] As of 2013, approximately 40,000 Bedouins reside in the West Bank and 5,000 Bedouins live in the Gaza Strip.[287][288] Jahalin and Ta'amireh are two major Bedouin tribes in the country.[286] A large number of non-Arab ethnic groups also live in the country, and are considered part of Palestine.[289] These includes groups of Kurds, Nawar, Assyrians, Romani, Druze, Africans, Dom, Russians, Turks and Armenians.

Most of the non-Arab Palestinian communities reside around Jerusalem. About 5,000 Assyrians live in Palestine, mostly in the holy cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem.[286] An estimated population of between 200 and 450 black Africans, known as Afro-Palestinians, live in Jerusalem.[290] A small community of Kurds live in Hebron.[291][292] The Nawar are a small Dom and Romani community, living in Jerusalem, who trace their origins to India.[293] The Russian diaspora is also found in Palestine, particularly in the Russian Compound of Jerusalem and in Hebron.[294] Most of them are Christians of the Russian Orthodox Church.[295]

In 2022, an estimate of approximately 5,000–6,000 Armenians lived across Israel and Palestine,[296] of which around 1,000 Armenians lived in Jerusalem (Armenian Quarter) and the rest lived in Bethlehem.[297] Since 1987, 400,000 to 500,000 Turks live in Palestine.[298] Due to the 1947–1949 civil war, many Turkish families fled the region and settled in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon.[299] According to a 2022 news article by Al Monitor, many families of Turkish origin in Gaza have been migrating to Turkey due to the "deteriorating economic conditions in the besieged enclave."[300] Minorities of the country are also subjected to occupation and restrictions by Israel.[301]

Education

The literacy rate of Palestine was 96.3% according to a 2014 report by the United Nations Development Programme, which is high by international standards.[302] There is a gender difference in the population aged above 15 with 5.9% of women considered illiterate compared to 1.6% of men.[303] Illiteracy among women has fallen from 20.3% in 1997 to less than 6% in 2014.[303] In the State of Palestine, the Gaza Strip has the highest literacy rate. According to a press blog of Columbia University, Palestinians are the most educated refugees.[304]

The education system in Palestine encompasses both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and it is administered by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education.[305][306][307] Basic education in Palestine includes primary school (grades 1–4) and preparatory school (grades 5–10).[308] Secondary education consists of general secondary education (grades 11–12) and vocational education.[309] The curriculum includes subjects such as Arabic, English, mathematics, science, social studies, and physical education. Islamic and Christian religious studies are also part of the curriculum as per the educational ministry.[310]