Central Synagogue (Manhattan)

| Central Synagogue | |

|---|---|

The synagogue on Lexington Avenue, in 2023 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Reform Judaism |

| Ecclesiastical or organisational status | Synagogue |

| Leadership | Clergy:

|

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | 646–652 Lexington Avenue |

| Municipality | Midtown Manhattan, New York City |

| State | New York |

| Country | United States |

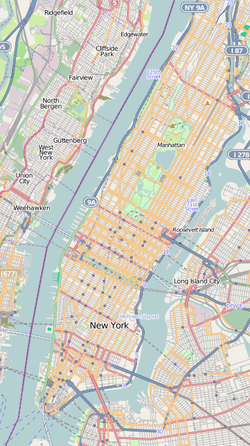

Location in Manhattan, New York City | |

| Geographic coordinates | 40°45′35″N 73°58′14″W / 40.7596°N 73.9705°W |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Henry Fernbach |

| Type | Synagogue |

| Style | Moorish Revival |

| Date established |

|

| Groundbreaking | December 14, 1870 |

| Completed | April 19, 1872 |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | East (main facade) |

| Capacity | 1,400 |

| Length | 140 ft (43 m) |

| Width | 93 ft (28 m) |

| Height (max) | 112 ft (34 m) |

| Materials | Brownstone, light stone |

| Website | |

| centralsynagogue | |

Central Synagogue | |

New York City Landmark No. 0276 | |

| |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000423 |

| NYSRHP No. | 06101.000429 |

| NYCL No. | 0276 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 9, 1970[3] |

| Designated NHL | May 15, 1975[4] |

| Designated NYSRHP | June 23, 1980[1] |

| Designated NYCL | July 7, 1966[2] |

| [5][6] | |

Central Synagogue (formerly Congregation Ahawath Chesed Shaar Hashomayim; colloquially Central) is a Reform Jewish congregation and synagogue at 652 Lexington Avenue, at the corner with 55th Street, in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. The current congregation was formed in 1898 through the merger of two 19th-century synagogues: Shaar Hashomayim and Ahawath Chesed. The synagogue building was constructed from 1870 to 1872 for Ahawath Chesed. As of 2014[update], Angela Buchdahl is Central's senior rabbi.

Shaar Hashomayim was founded in 1839 by German Jews, while Ahawath Chesed was founded in 1846 by Bohemian Jews. Both congregations originally occupied several sites on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Central was constructed as the fifth building of Ahawath Chesed, whose members had moved northward during the late 19th century. Though the congregations originally held services in German, they had become largely Anglophone by the time of their merger. Ahawath Chesed Shaar Hashomayim became known as Central by 1918 and briefly merged with the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue in the 1920s. The building has been renovated several times over the years, including in the 1880s and 1940s; it was extensively rebuilt from 1998 to 2001 following a fire.

Designed by Henry Fernbach in the Moorish Revival style, the building is a New York City designated landmark and a National Historic Landmark. The facade is made of brownstone with light-stone trim and includes stained glass windows and a geometric rose window; it is topped by octagonal towers. A vestibule leads to the synagogue's sanctuary—a two-level space, arranged similarly to a Gothic church—and there are various rooms in the basement. Central Synagogue has hosted various activities and programs over the years, and it contains a collection of Jewish artifacts. A community house, across 55th Street, hosts the synagogue's religious school and numerous groups.

Early history

[edit]Central Synagogue's congregation was formerly known as Congregation Ahawath Chesed Shaar Hashomayim.[7] It is descended from two 19th-century synagogues, Shaar Hashomayim and Ahawath Chesed, which merged in 1898.[8][9] When the congregations were founded in the Lower East Side neighborhood of Manhattan, that area was home to many German Jews, and the area was known as Little Germany.[10] Most of these German Jews came to the U.S. starting in the mid-19th century.[11] They had tried to join existing Ashkenazi congregations but were shunned by older members, leading them to form their own, breakaway congregations.[12] Central Synagogue's Lexington Avenue structure was originally built as Ahawath Chesed's fifth building.[13]

Shaar Hashomayim

[edit]Shaar Hashomayim was founded in 1839 by German Jews.[2][5][14] Its name, also spelled Shaarey Hashomayim or Shaar Hashamayim,[15] meant Gates of Heaven in Hebrew.[9][16] The first congregants were two groups of men who had left the Ansche Chesed congregation;[17] they met at 122 Attorney Street.[16] Originally, there was no rabbi; instead, services were led by some of the more knowledgeable congregants.[17] In 1845, Shaar Hashomayim agreed to develop a Jewish cemetery in conjunction with two other German Jewish congregations, Ansche Chesed and Rodeph Sholom.[18] It subsequently bought up land at Salem Fields Cemetery.[19]

Shaar Hashomayim's first rabbi, Max Lilienthal, joined the congregation in 1845.[16][20] The congregation resisted some of his reforms,[16] and Lilienthal left in 1847.[20] After Lilienthal left, the congregation was led by a hazzan, a cantor who was not ordained as a rabbi.[16] Shaar Hashomayim became involved in advocacy for Jewish causes in the 1850s. For example, it helped form the Association for the Free Distribution of Matsot for the Poor after the Panic of 1857, delivering matzot to thousands of Jews, and it was a founding member of Board of Delegates of American Israelites in 1859.[21]

Raphael Lasker became Shaar Hashomayim's senior rabbi in 1862,[22] a capacity in which he served for nine years.[23] Shaar Hashomayim subsequently moved to 15th Street on the East Side, where it stayed until 1898.[24][25] By the 1890s, the congregation had begun using a prayer book in English and Hebrew, and it was considering moving to the Upper East Side.[26] Solomon Sonneschein, who joined Shaar Hashomayim in 1895, was its last senior rabbi before the congregation merged with Ahawath Chesed in 1898.[27]

Ahawath Chesed

[edit]In 1846, German-speaking Bohemian Jews formed a minyan, or quorum of Jewish adults,[28][29] which was the predecessor to the Ahawath Chesed congregation.[14][30] Initially, they hosted social gatherings at the residence of one Leopold Schwarzkopf;[31] the gathering was called a Böhmischer Verein, German for "Bohemian club".[32] Eighteen of these men decided to form a more structured gathering,[29][31] and they began meeting at a hotel at 69 Ludlow Street on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.[8][31] Following the arrival of more Bohemian Jews to the U.S.,[28][32] several Bohemian Jews in New York City decided to formally establish a congregation in 1848. They had raised $58.32 and one-half cent by November,[i] which they used to buy a Torah scroll.[28][33]

Establishment and early years

[edit]

Ahawath Chesed (sometimes spelled Ahavath Chesed[34]) was officially formed on December 31, 1848;[28][35] its name meant Love of Mercy in Hebrew.[9][10][30] Ahawath Chesed rented space at 88 Ridge Street in August 1849,[28] paying $100[ii] annually for the upper stories of two structures.[29][36] At the time, the congregation charged a $1.50 annual membership fee.[iii][29][36] Initially, Ahawath Chesed was an Orthodox congregation with German-language services,[29] and it had a Jewish cemetery in Cypress Hills, Brooklyn.[28][19] The congregation also bought up land at Linden Hill Cemetery during its first 25 years.[19] The Ridge Street synagogue was expanded in February 1850.[28] Further growth of the congregation prompted Ahawath Chesed to acquire a house at 217 Columbia Street[33] in 1854 and relocate its synagogue there.[28][29] Ahawath Chesed held informal prayer sessions and used Ashkenazic prayer books, though it was less involved in communal advocacy than Shaar Hashomayim.[37]

By the 1860s, many congregants were talking with each other or leaving in the middle of prayer sessions, prompting the synagogue's board to enact more stringent rules.[37] In addition, the prayer books were entirely in Hebrew, which many congregants could not understand.[38] In 1864, Ahawath Chesed moved to the Eleventh Presbyterian Church,[32] located at the intersection of Avenue C and Fourth Street in the East Village.[39][40] The Avenue C synagogue cost $24,050[iv][36][35] and was designed by Henry Fernbach.[39][41] At the time, the congregation had 115 members,[39] whose names were inscribed on the pews.[42] In 1865, the congregation voted to hire a more progressive rabbi in the Reform tradition, running advertisements in Jewish magazines in Europe and the U.S.[29] The congregation also decided to buy its first organ[43] and hired the Bohemian cantor Samuel Weltsch to be their hazzan that year.[29][44] Adolph Huebsch, also of Bohemia, was hired as the congregation's rabbi in 1866,[45][46] and he began holding Reform rituals.[47][36]

The congregation adopted a new prayer book under Huebsch's leadership.[38][48] He also established a congregational school,[36][49] which had 127 students by late 1867.[49][19] Ahawath Chesed continued to grow along with the Jewish population in Little Germany,[50][51] with 142 members in the late 1860s.[52] The congregation attracted a wider range of Eastern European Jews who worked in a variety of professions, including beer, clothing, dry goods, and real estate—though not those in banking or mercantile trades, who instead joined Congregation Emanu-El of New York.[53] The Lower East Side was also becoming more crowded, prompting wealthier Jews to move uptown.[33][54]

Development of Lexington Avenue synagogue

[edit]Ahawath Chesed's trustees had first considered buying an existing religious building or erecting a new building in June 1867, but they were unable to find any suitable structure south of 42nd Street.[53] The trustees did identify several sites in Midtown Manhattan, including one near 45th Street and Madison Avenue, just before real-estate prices in the area decreased greatly.[55] In 1869, Ahawath Chesed's congregation voted to establish a committee for the acquisition of a new building.[50] The committee reported in April 1870 that it had acquired land further uptown, and it voted to sell its old site shortly thereafter.[50] The site, at the southwest corner of 55th Street and Lexington Avenue, covered 100 by 140 feet (30 by 43 m) and cost $63,250.[v][50][55] At the time, many of the congregation's members lived near Midtown.[41] The site was also relatively close to the then-recently-completed Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue, and the congregation wanted the synagogue's design to compete with that of Temple Emanu-El.[56]

Sixty-two people loaned a combined $68,100 for the synagogue's construction.[vi][50] Ahawath Chesed obtained additional money by selling pews, the cost of which ranged from $150 to more than $1,200.[vii][50][57][c] Ahawath Chesed's trustees and its allied organizations also loaned some money,[58] and the congregation earned $40,000 or $55,000 by selling its Avenue C property.[viii][50][59] The congregation hired Henry Fernbach, the architect of its Avenue C synagogue, to design a structure on the lot.[41] The design was controversial; some congregants felt the decorations were excessive.[41][60][61] The building was also being developed at a time when the congregation was starting to lose money, prompting concerns that congregants would leave Ahawath Chesed.[41]

Huebsch and Isaac Wise, the rabbi of B'nai Jeshurun in Cincinnati, jointly laid the synagogue's cornerstone on December 14, 1870.[35][62] The congregation continued to accept more members as the synagogue was built; its religious school expanded from 146 to 276 students between 1871 and 1872 alone.[50] Huebsch consecrated the new synagogue on April 19, 1872.[28][63] Following the building's dedication, Huebsch described the structure as "not only a house of worship, but an American-Jewish house of worship".[59][64] A Jewish Times article, describing the consecration, characterized it as evidence of a growing acceptance of Jews in the U.S.[64] The building had cost $250,000,[63] $264,000,[65] or $272,575 to construct.[ix][59] The synagogue's completion coincided with the development of rowhouses within East Midtown, which had been undeveloped as recently as five years previously.[66][67]

Late 19th century

[edit]

After moving to the new synagogue building, Ahawath Chesed began using a two-volume prayer book adapted to reflect more modern views.[68][69] The new prayer book, known as the Seder Tefillah,[d] remained in use for half a century, even after the congregation began using other prayer books.[70] The opening of the new building coincided with the Panic of 1873 and its subsequent financial crisis.[71] Nonetheless, the congregation was involved with charitable initiatives such as the Hebrew Charity Fair and Mount Sinai Hospital,[72] and Huebsch continued to expand Ahawath Chesed's school during his tenure.[73] He established a social group for the congregation's young men,[73][74] which counted sixty members by 1879.[75] The synagogue hosted music and lectures one weekday a month, eliminating the need for a Sunday service.[76] Ahawath Chesed additionally joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC), a group of Reform synagogues, in 1878.[51] Huebsch led the congregation until he died in 1884,[45][77] by which Ahawath Chesed had grown into a largely middle-class congregation.[77][78]

The Hungarian-American orator Alexander Kohut succeeded Huebsch as Ahawath Chesed's senior rabbi in May 1885.[79][80] Kohut's views were more conservative than Huebsch's, though the congregation generally respected him.[81][82] The building caught fire on February 28, 1886;[83][84] though no one was killed, firefighters had to destroy most of the stained-glass windows and some of the plasterwork.[85] Media sources estimated that the fire had caused between $5,000[84][85] and $7,000 in damage,[x][83] and the building was renovated afterward.[86] Like his predecessor, Kohut gave sermons in German,[25][87] although he also gave English sermons as early as 1887.[87] More descendants of Jewish immigrants spoke English.[25][88] After enrollment at the synagogue's German-only religious school declined,[89] it began teaching in English by 1890.[89][90] Kohut also agreed to host English services and publish an English translation of the Seder Tefillah,[87][90] and the synagogue began hosting regular sermons in English in 1893.[25] During his tenure, Kohut also expressed a wish to create a new siddur (prayer book).[91] Kohut's wife Rebekah established a congregational "sisterhood" that, by 1895, had 350 members.[92][93]

Kohut served as the senior rabbi until his death in 1894.[51][65] Ahawath Chesed took two years to hire its next senior rabbi, in part because the congregation only would talk to scholars who were fluent in English and German.[94] The American Israelite said the congregation fell "on the brink of despair" due to the lack of a rabbi.[95] David Davidson, a Talmud instructor and a leader of various Jewish institutions,[96][97] ultimately became the congregation's senior rabbi in 1895.[97][98] Davidson began holding English-only, Friday-night Shabbat services, but these were suspended in April 1896 after board members complained about reduced Saturday attendance.[99][100] Instead, he hosted bilingual Saturday-morning Shabbat services.[100][101] The congregation celebrated its 50th anniversary later that year with special services.[102]

Merger

[edit]Shaar Hashomayim had proposed merging with Ahawath Chesed as early as the 1860s, after the American Civil War, though Ahawath Chesed had declined the proposal at the time. A merger was again proposed in 1894, after Shaar Hashomayim's leaders at the time expressed interest in Kohut's translated prayer book, which they later adopted.[103] Negotiations continued over the next several years.[26][103] Ahawath Chesed and Shaar Hashomayim merged on June 20, 1898,[104] forming Ahawath Chesed Shaar Hashomayim,[e] which occupied the Ahawath Chesed synagogue at Lexington Avenue.[25][107] Shaar Hashomayim's congregation had 77 families, while Ahawath Chesed's had 166 families.[108] The merger boosted the congregations' membership, and the sale of Shaar Hashomayin's old building also raised money.[109] Davidson resigned in 1899,[110] partly due to his opposition to the congregations' merger.[109] With worshippers increasingly speaking English, the trustees decided in 1899 to keep congregational records in English.[25][101]

Combined congregation

[edit]

1900 to 1924

[edit]Moses leadership

[edit]After Davidson's resignation, the trustees of Ahawath Chesed Shaar Hashomayim took a year[111] to search for a bilingual rabbi.[25][112] The trustees interviewed William Rosenau,[113][114] Samuel Sale,[115][114] Joseph Stolz,[116] Israel Abrahams, and Gotthard Deutsch for the position.[117] They ultimately hired Isaac Moses, who joined the congregation in January 1901.[118] Moses was the last rabbi in the congregation to preach in both German and English,[104] as the congregation's board wanted to transition toward making English the synagogue's primary language.[119] In 1904, the board agreed to use the English-language Union Prayer Book, which Moses had helped create.[104][120]

During the early 1900s, Ahawath Chesed Shaar Hashomayim briefly considered moving uptown, as Midtown's other Jewish congregations did.[76][121] The members remained involved in charitable causes in the 1900s, and the synagogue's lights were electrified in 1903.[104] The trustees appointed a committee in 1909 to find another site; the committee identified two sites along Central Park West, but congregants voted against relocating in 1913.[122] Worshippers believed that the alternate sites were too expensive, that the old building had historic value, and that the New York City Subway's Lexington Avenue Line (which was under construction) would attract additional worshippers. In addition, nearly as many members lived on the Upper West Side as the Upper East Side.[123] Ahawath Chesed became a founding member of the Jewish Religious School Union of New York in 1913.[124] and it also assisted the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee during World War I.[104] The congregation's sisterhood, on East 101st Street in East Harlem, operated a kindergarten and children's nursery.[125] Ahawath Chesed Shaar Hashomayim also contemplated merging with the West End Synagogue or Temple Beth-El in 1915, but ultimately it decided to remain separate.[126]

Krass leadership and Free Synagogue merger

[edit]Moses announced his intention to retire in mid-1917, when the congregation had 900 members.[127] The congregation's trustees selected Nathan Krass as their next senior rabbi,[128][129] and Krass led his first service in January 1918.[130] Simultaneously, Ahawath Chesed Shaar Hashomayim began referring to itself as Central Synagogue or Central Temple,[26][126][129][f] though the congregation would not be officially renamed Central Synagogue until 1974.[26] The new English name was intended to reflect the congregation's Reform roots and to attract worshippers.[126] The congregation also formed a governing council and introduced revised bylaws in 1918.[74] The bylaws allowed congregants to send their children to Central's religious school for free, as well as special privileges regarding marriages and burial plots.[131] At the time, the congregation had eight committees and three affiliated organizations.[132]

During his tenure, Krass paid off the synagogue's $60,000 mortgage. The congregation's membership doubled between 1918 and 1923, bringing the synagogue to near capacity, and there was a waiting list for potential members.[133] Krass's speeches, which discussed a variety of Christian and Jewish topics, attracted both Jews and non-Jews.[134] By the early 1920s, the synagogue could not adequately accommodate many social functions and classes, putting it at a disadvantage compared to newer synagogues that had community centers to attract younger, less religious generations.[126] As such, one worshipper named Daniel Kops suggested the construction of a new community house at Ahawath Chesed's 75th anniversary in 1922.[135][136] Kops wanted to raise $100,000 for the community house, saying that it would attract younger congregants;[136] the congregation ultimately raised $70,000 for the facility.[133] Krass resigned in April 1923 to accept a position at Temple Emanu-El.[133][137]

Central proposed merging with the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue,[138] and the merger was finalized in May 1923, establishing the Central and Free Synagogues.[139][140] The Free Synagogue's rabbi Stephen S. Wise became the rabbi of the merged congregation, conducting services variously at Carnegie Hall, Central Synagogue's building, and the Free Synagogue's parish house on 68th Street.[138] Stephen Wise wanted to construct a new synagogue for the two congregations.[139][140] A Tudor-style Synagogue House at 40 West 68th Street was finished in March 1924;[141][142] it included an auditorium[143] and offices for the congregation's various departments.[142] The congregations were unable to find a site for a new synagogue,[144] and there were irreconcilable differences between the congregations.[145][146] For example, Central's classical Reform congregants did not appreciate Wise's neo-Reform services,[146] and the Free Synagogue's practice of open seating clashed with Central's practice of selling pews.[140][147] In February 1925, Stephen Wise announced that the congregations would split at the end of that May.[144]

1925 to 1959: Jonah Wise leadership

[edit]Before and during World War II

[edit]

Isaac Wise's son Jonah Wise (no relation to Stephen Wise) was selected as the newly independent Central Synagogue's rabbi in May 1925.[148] He took up the pulpit that September;[149] at the time, the congregation had 250 families.[150] Central's board of trustees bought the Studio Club at 35 East 62nd Street in February 1926[151] for use as a community house.[104][135] Central dedicated its community house in January 1927;[152] the structure housed the Women's Organization and later the Temple Brotherhood.[153] The Women's Organization replaced Central's existing women's associations in the mid-1920s,[154][155] while the Temple Brotherhood replaced the Young Men's Association in 1930.[156] The congregation became a founding member of the Association of Reform Congregations in 1927.[157] The Bohemian American Israelite Congregation merged with Central Synagogue in 1928 or 1929.[156][158]

The congregation struggled in the 1930s;[147][156] it accepted fewer than 12 new congregants annually during that decade.[147] Conversely, nearly a hundred congregants left the congregation in 1937 alone after they were unable to pay their dues.[159] Despite its struggles, Central expanded its charitable efforts beyond local advocacy during the 1930s.[160] For example, Wise chaired the National Joint Distribution Committee (later United Jewish Appeal), which aimed to help Jews in Nazi Germany,[161][162] and the congregation became involved with the Homesteads Project, a housing program financed by the federal government.[160] In addition, the Women's Organization operated a job center for unemployed women within its vestry rooms.[160][161][163] The Message of Israel, a weekly radio show broadcast from Central, was launched in 1934;[154][164] it consisted of a musical program followed by a speech.[165] For Ahawath Chesed's 90th anniversary in 1936, Central hosted various public forums and musical performances.[166]

By the mid-1930s, assistance for European Jews comprised a large part of Wise's activities at the synagogue.[162] The congregation's Brotherhood and Sisterhood helped re-house and retrain Jewish refugees before World War II.[167] The interior of the synagogue was repainted in 1937.[168] Central's cantor Frederich Lechner, who joined the congregation the same year, developed music both for the congregation and for The Message of Israel series.[154] The community house hosted various social events, such as concerts.[167] German Jewish refugees, led by Hugo Hahn, founded Congregation Habonim at Central Synagogue in 1939[169] and initially used Central's community house and main building.[154][170] Following rapid growth in Habonim's membership,[170] it split from Central in 1943.[169][g] Central's Sisterhood raised money for the Allies of World War II during the early 1940s.[172] In 1943, the synagogue also temporarily hosted the Rock Pentecostal congregation, which was developing a church for itself.[173]

After World War II

[edit]

David J. Seligson joined Central in 1945 and later became an associate rabbi under Wise.[174][175] Central's congregation celebrated Ahawath Chesed's centennial in 1946[176] and commissioned a portrait of Wise.[177] Simultaneously, Wise planned to renovate the synagogue to attract worshippers who would otherwise leave for newer synagogues in the suburbs.[178] The renovation, designed by Ely Jacques Kahn, removed many original design features.[86][168] The stained-glass windows were largely replaced with more abstract motifs,[168] and a metal roof replaced the original slate tiles.[168][179] The basement was also modified.[40] Though the rest of the facade and most of the interior remained unchanged, a memorial to Isaac Wise was added to the synagogue's vestry room,[180] and the synagogue was converted to electric power.[65][168] Four plane trees outside the building were also dedicated in 1947 to mark the synagogue's renovation,[181] and the building was formally rededicated in March 1949.[182][183] The project cost $270,000 in total.[183]

A plaque, dedicated to ten worshippers who died in World War II, was dedicated at Central in 1950.[184] The synagogue building was rededicated again in 1952 upon the structure's 80th anniversary.[185] Central again began attracting new members in the 1950s,[186] and it had 900 families by 1954.[186] Membership had leveled off at around 1,040 by the end of the decade, in part because of an outflow of older members, and the congregation also had a $200,000 shortfall.[186] When Wise died in February 1959, he had led the congregation for 34 years.[164][187]

1959 to 1991

[edit]Seligson leadership

[edit]Seligson was promoted as senior rabbi after Wise's death,[188][174] and Central's president announced that the community house would be expanded and renamed for Wise.[189] Initially, the congregation planned to replace the existing 62nd Street community house.[190][191] By the early 1960s, the congregation counted 1,100[192] or 1,200 families as members.[191] Central also announced plans in 1963 to redecorate the interior and restore some of the stained-glass windows.[193] The congregation acquired land at 125 East 55th Street for a community house in 1964[194] and began developing it two years later.[195] The congregation destroyed three houses on 55th Street to make way for the community house,[67] which was dedicated in September 1967.[196][197] Amid a declining local economy, the trustees allowed external organizations to rent space in the community house so the mortgage could be paid off.[198]

Meanwhile, Central's membership stopped expanding by the 1960s, and the trustees proposed implementing age-based membership fees to attract congregants.[174] The congregation became more involved in matters involving Israel following the Six-Day War in 1967,[199] and it also established a nursery school in 1968.[200] In advance of the Lexington Avenue synagogue's centennial, Central hired a company to find its cornerstone, which was discovered underneath the main steps.[201] To celebrate the centennial, Central's members re-laid the cornerstone on December 13, 1970,[202][203] and Central helped curate an exhibit about New York City's Jewish history at the New-York Historical Society.[204][205] Seligson stepped down as the synagogue's senior rabbi in 1972 and became its rabbi emeritus,[188] while Sheldon Zimmerman, who had been an assistant rabbi, was promoted as senior rabbi.[206][207]

Zimmerman and Davids leadership

[edit]

The Folksbiene theater company moved to Central in September 1973,[208] hosting performances in the community house.[209] During the 1970s, nearly as many members joined as left;[210] the congregation was composed of 1,025 families by the middle of that decade.[211] According to the historian Jeffrey Gurock, Zimmerman encouraged the congregation to become more involved with Israeli causes, including through celebrations, tours of the nation, and fundraisers.[212] Central became the first synagogue in Manhattan to allow Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in its building in the 1970s,[213][214] and it temporarily housed St. Peter's Lutheran Church while the church's sanctuary was being rebuilt as part of Citigroup Center.[213][215] The congregation also partnered with local churches to feed homeless people.[207] The staff began devising plans to make the synagogue accessible to disabled people in the early 1970s, but progress was delayed for over a decade because preservation laws made it difficult to modify the building.[216]

Despite the city's high crime rate and poor economic conditions, many members remained part of the congregation. In 1983, some congregants began holding weekday morning services, led by the laity.[217] The congregation sold the air rights over two adjacent buildings to the developer of a neighboring tower in the 1980s,[218] which raised money for the congregation.[219] Zimmerman resigned as senior rabbi in 1985,[206][220] and Stanley M. Davids was appointed as Central's senior rabbi the next year.[221] Concurrently, the congregation gained new members during the city's economic recovery,[217] and it had 1,300 or 1,400 families by the late 1980s.[222][223] Central Synagogue began holding bar and bat mitzvahs for adults in 1988 and hosted an estimated 150 adult bar and bat mitzvahs in the next seven years.[224] The main entrance doors were restored in 1988 in advance of Shaar Hashomayim's 150th anniversary,[225] and the synagogue itself was rededicated that year.[223]

1991 to 2013: Rubinstein leadership

[edit]Central selected Peter J. Rubinstein as its senior rabbi in 1991.[226][227] Rubinstein was initially reluctant to join the congregation, as he wanted to wear a kippah (skullcap) and tallit (prayer shawl) during services, even though Central's previous clergy had not worn these things.[226][228] By the 1990s, the congregation included six affiliate organizations and 16 committees. Its budget had increased tenfold in three decades, not only because of inflation but also because of the additional operating costs and the need for renovations.[132] Rubenstein further encouraged the congregation to support Israel through such activities as Hebrew language classes and missions to Israel.[229] During the late 20th century, congregants also established or sponsored various social-advocacy programs to help people who were hungry, homeless, or had HIV/AIDS.[223][230]

1990s restorations

[edit]A renovation of Central Synagogue's facade began in 1995, at which point the renovation was scheduled to cost $500,000.[40] SLCE Architects was hired to design the initial renovation.[168] The Phyllis and Lee Coffey Foundation donated part of a $10 million bequest to Central Synagogue that year.[231] At the time, Central Synagogue had an endowment fund of $10 million; the congregation hired a full-time development director in 1996 to raise money.[232] By mid-1998, congregants had raised $16 million.[232] The congregation temporarily relocated to its community house so the main building's roof, interior, and air conditioning systems could be renovated.[233] At the time, Central Synagogue had 1,400 families and was nearing capacity. During High Holy Days, which attracted up to 5,000 people, the synagogue had to host at least two services a day.[233]

On August 28, 1998, the synagogue caught fire while it was being renovated.[233][234] Although there were no casualties, the interior was damaged extensively when firefighters used water to fight the flames. The fire also caused the weakened roof to collapse into the synagogue.[233] The synagogue's Torah scrolls and architectural drawings had been moved off-site before the fire,[233][235] and other artifacts such as a menorah survived the fire.[236] Almost 50 institutions offered temporary space to Central Synagogue, while people from around the world offered to help finance the synagogue's reconstruction.[237] The Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, donated a mezuzah to the synagogue as well.[238] Ultimately, the state government agreed to lease the Park Avenue Armory to the congregation for High Holy days celebrations,[239] and prayer books, Torah scrolls, and pews were moved to the armory.[240][241] The congregation met at the community house for services.[242][243] The fire also displaced the Folksbiene,[244][245] which moved from the synagogue's community house to Theater Four in West Midtown.[246][245]

The congregation decided to restore the synagogue's original appearance, rather than redesign it in a more modern style.[247] The restoration was supervised by Hugh Hardy of Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer,[248][249] who was selected for the project in 1999.[242][250] Thornton Tomasetti and LZA Technology were the engineers,[251][252] and DPK&A was the restoration consultant.[252][243] Various consultants were hired for other aspects of the project.[243] The congregation hosted a groundbreaking ceremony for the renovation exactly one year after the fire.[253] The renovation included restoring the original architectural detail, upgrading mechanical systems, deepening the basement, and rebuilding the roof.[254][251] Workers consulted various archives during the renovation;[255] for example, they recreated the roof by looking at World War II-era surveillance photographs.[249][256] After the roof was completed at the end of 2000,[257] Hardy then restored the interior.[258] The bimah (or altar) and the audiovisual equipment were also upgraded.[257] In total, 700 workers spent a combined million man-hours on the renovation.[259]

2000s and early 2010s

[edit]By 2001, Central Synagogue had one of the United States' largest Jewish congregations with 4,000 people.[260] The synagogue building was rededicated on September 9, 2001,[261][262] in advance of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.[263] The project had cost almost $40 million,[252][261] of which $16 million came from insurance payouts and $24 million from fundraising.[259] That October, the synagogue settled a lawsuit against Turner Construction, the original renovation contractor whose worker had accidentally started the fire.[264] The project received a Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award from the New York Landmarks Conservancy,[265] and the American Institute of Architects gave the project an honor award for the interior restoration.[266] Following a $2.5 million donation from the businessman Michael A. Wiener and his family, the synagogue dedicated the Gabe M. Wiener Memorial Organ in 2002, replacing an organ destroyed in the fire.[267]

After the September 11 attacks in Lower Manhattan (two days after the synagogue's reopening), the congregation hired additional security guards[260] and added concrete bollards outside the building.[268] Rubinstein said that 400 families had joined the congregation in the three years following the fire, bringing the total membership to 1,700 families by 2001.[269] Central Synagogue started publishing a monthly calendar in 2004 to replace its newsletter,[270] and it began hosting a concert series, Prism Concerts, in 2005.[271] The synagogue had reached its capacity of 2,000 families by 2007,[226] and it was known as a "mega-shul".[270][272][h] Free livestreams of services began in 2008.[274] Central expanded its music program and school, launched programs to attract younger Jews, and formed partnerships with other synagogues. By 2011, the synagogue had 100 staff members, a $30 million endowment, and 80,000 square feet (7,400 m2) of space.[272] Potential worshippers had to wait as long as three years to join the congregation.[226][272]

2014 to present: Buchdahl leadership

[edit]Rubinstein announced in March 2013 that he would resign from Central,[226][275] and the congregation's board recommended that its senior cantor, Angela Warnick Buchdahl, be promoted as senior rabbi.[276] Buchdahl was installed as Central Synagogue's senior rabbi in 2014, becoming the first woman and the first Asian-American to hold that position.[277][278] In addition to the in-person membership, at least 20,000 worshippers attended services online.[270][278] The Jewish Broadcasting Service began broadcasting some of Central's holiday services in 2013 through its ShalomTV channel,[270][279] and it also began broadcasting Shabbat services the next year.[280] The synagogue's sound system was upgraded in 2015 to accommodate the congregation's livestreams.[281]

In the early 2010s, the administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed the Midtown East rezoning, which would allow St. Bartholomew's Church, St. Patrick's Cathedral, and Central Synagogue to sell the air rights above their buildings;[282] the three houses of worship were previously only allowed to sell their air rights to adjacent buildings, but there had been no potential buyers.[283] The rezoning was approved in 2017,[284] allowing the three institutions to sell their air rights across a wider area.[285] Subsequently, Central sold some of its air rights to JPMorgan Chase for the construction of 270 Park Avenue.[286] The synagogue needed $3.4 million in repairs, which had to be deferred until the air rights were sold.[287] In March 2019, the Islamic Society of Mid-Manhattan's nearby mosque was damaged by a fire;[288] at Buchdahl's invitation, the Islamic Society held services in the synagogue until the mosque was repaired.[289]

Central closed its building temporarily in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic,[290] hosting services remotely for several months.[291] During the pandemic shutdown, Central's Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur livestreams each recorded hundreds of thousands of viewers from around the world.[280] In-person services had resumed by 2021, initially with strict capacity limits.[292]

Building

[edit]

The synagogue building at 652 Lexington Avenue was designed by Henry Fernbach.[65][293] It is the only remaining synagogue building designed by Fernbach, who also designed commercial buildings in Manhattan, as well as institutional buildings such as the German Savings Bank, Harmonie Club, Hebrew Orphan Asylum of New York, and Staats-Zeitung Building.[294] The structure incorporates a mixture of Egyptian, Moorish, and Spanish architectural features, an allusion to the history of Jews in Muslim countries.[13][64] An Israelite article from 1870 described the building as a "Moorish Byzantic" structure;[294][295] Central was one of several synagogues in the U.S. designed in such a style during the 1860s and 1870s.[295] The New York Times cites the building as the state's oldest synagogue in continuous operation,[13] and Central has been continuously used by a congregation for longer than any other synagogue in New York City.[2][296][297] Central is also Midtown Manhattan's only remaining 19th-century synagogue[298] and one of the oldest existing synagogue buildings in the United States.[299]

The site measures 100 by 140 feet (30 by 43 m) across;[300] the synagogue occupies most of the site, measuring 93 feet (28 m) wide on Lexington Avenue and 140 feet (43 m) on 55th Street.[33][300][301] The building narrows to 83 feet (25 m) at its rear on the western end.[300] When the building was constructed, Ahawath Chesed paid for custom street lights on the adjacent streets.[40][61] The current lanterns are replicas,[302] which were installed in 1989.[40] The site was originally surrounded by residential buildings, which gave way to commercial buildings and office skyscrapers.[303] The synagogue still shares the block with several of these structures, including 116 and 122 East 55th Street.[67][304]

Exterior

[edit]The facade shares some design features with those of the Dohány Street Synagogue in Budapest[14][293] and the Isaac M. Wise Temple in Cincinnati, Ohio.[305] It is made of New Jersey brownstone, though some of the trim was sourced from Ohio.[63][40] The Ohio stone has a lighter yellow hue, contrasting with the dark brownstone.[40][56] While other synagogues in New York City are generally oriented toward Jerusalem in the east, Central Synagogue faces west. This is because the congregation wanted that land lot with the building's main entrance on Lexington Avenue.[306]

Facade

[edit]

Central Synagogue's Lexington Avenue elevation is divided vertically into three bays, similar to the Dohány Street Synagogue.[307] The central bay contains an entrance with three arches.[307] The outermost bays also include "stair wings", which lead to side entrances that connect with the aisles and the gallery level.[33] These outer bays are based on the design of two structures that flank the Dohány Street Synagogue.[307] The main stairway was shortened during a 2001 renovation;[86][243] prior to the modifications, each step was 2 inches (51 mm) higher than normal.[308] There is a geometric rose window above the main entrance, as well as a small row of arches just below the cornice.[2][5]

The northern elevation, on 55th Street, has a wheelchair ramp from the sidewalk to the basement.[302] There are six double-height stained glass windows each on the north (55th Street) and south elevation; these are topped by circular clerestory windows.[256] A stone band stretches across the facade at the second story, passing through the stained-glass windows.[2] One of the stained-glass windows is dedicated to New York City Fire Department firefighters who responded to the 1998 fire and saved that window.[261] Almost all of the windows are replicas, as the original windows were mostly destroyed in the fire.[309][310] Two of the windows are replicas of the 1872 originals, while the other windows are replicas of windows that existed in 1998.[310]

The exterior is dominated by two 112-foot-tall (34 m) octagonal towers.[40][241] They had been built against the advice of Ahawath Chesed's financial committee, which had wanted simpler structures.[311] The tops of the onion-shaped domes are decorated with gilded bands.[251][261] The modern-day domes are ornamented with 23-karat gold leaf from Germany, and they also contain depictions of gold stars.[256][261][302] The domes are topped by crenellations made of fiberglass, which are replicas of the original galvanized steel crenellations.[256] Two smaller copper finials were removed in the 1920s, and replicas were added to the roof in 2001.[251][256] There are also bands of cast stone beneath the parapets of the towers.[256]

Roof

[edit]The slate roof, measuring 99 by 140 feet (30 by 43 m), is covered in 30,000 gray and red shingles.[256] The modern roof, built in 1999,[308] is a nearly exact replica of the original that existed between 1872 and the 1940s. Unlike the original roof, there is a layer of plywood and a protective membrane below the modern slate roof.[312] The modern roof also has five ventilators,[302] which supplement several restored Victorian-style copper ventilators on the roof.[256][302] The synagogue's bimah is illuminated by a skylight at the roof's western end. Under the skylight are three windows measuring 6 by 6 feet (1.8 by 1.8 m).[309][256]

Interior

[edit]The building was restored in its original style after the 1998 fire.[313] Sixty-nine hues were used, including shades of red, blue, brown, and gold. The decorations included geometric shapes such as circles and lines, in addition to motifs like small flowers and stars. Over five thousand stencils were used to decorate the interior,[86][293] and there are more than 200 distinct patterns on the walls.[259] The AIA Guide to New York City described the interior as being "stenciled with rich blues, earthy reds, ocher, and gilt – Moorish, but distinctly 19th century American."[6] A source from the synagogue's opening described the interior as having arabesque ornamentation.[33] The original bright interiors were toned down during the 2001 renovation, since modern illumination was more powerful than in the 1870s.[314][315]

There is also woodwork, wainscoting, plasterwork, and floor tiles.[251] The synagogue contains 70,000 tiles, including 30,000 replicas[309] manufactured in 2001 by the English firm that built the original tiles.[309][259] An air-conditioning system was installed in the synagogue in 2001.[243]

Vestibule

[edit]Originally, the steps on Lexington Avenue led up to a vestibule measuring 17 by 34 feet (5.2 by 10.4 m) across. The vestibule had three doors leading into the main sanctuary and two leading to the gallery.[33] The original lobby was located at the same level as the sanctuary,[86] but the lobby was lowered by 14 inches (360 mm)[168][308][314] or 24 inches (610 mm) during the synagogue's 2001 renovation.[86] As part of the renovation, two steps in the lobby were removed and replaced with four new stairs in the sanctuary itself.[308] According to the then-rabbi, Peter Rubenstein, the lowered lobby created the effect that one is "rising up into the sanctuary".[86] Inside the vestibule were originally two sets of stairs, one of which was removed in the 2001 renovation.[302]

Sanctuary

[edit]

The synagogue's sanctuary was arranged in a similar manner to a Gothic church.[61][301] The interior is divided into two aisles, which flank a central nave.[254][294] Original plans had called for a sanctuary measuring 80 by 100 feet (24 by 30 m) across and 60 feet (18 m) tall.[300] The nave and the aisles are separated by wooden piers measuring 12 by 12 inches (30 by 30 cm) across; these support a clerestory above each of the aisles.[252][254] The woodwork is made of black walnut, with oak trim.[61] The rear end of the nave is 102 feet (31 m) from the organ gallery and contains the bimah, which was originally a raised platform with a pulpit. There was a tabernacle behind an ornate arch leading from the rear of the nave.[33] The original elevated, stationary bimah was replaced in 2001 by a movable bimah that can slide down toward the pews.[302][314]

The interior is divided into several sections, including the organ gallery, nave, and choir.[301] There was originally an organ gallery above the entrance leading from the lobby.[33] The original three-manual organ in the gallery was built in 1872 by George Jardine & Son; it was replaced in 1937 by another three-manual organ, which burned down in 1998.[316] The current organ, the Gabe M. Wiener Memorial Organ, was dedicated in 2002[267][316] and has four manuals with a total of 4,345 pipes.[309][267] There is a smaller, two-manual organ at the bimah, which was installed in 2001.[316] The Torah ark is placed at the west end of the sanctuary.[61] The ark is 38 feet (12 m) high[168][314] and is coated with worn-down gold sheeting.[243]

Central originally had a seating capacity of 1,500,[33][61] but this was reduced to 1,400 seats in 2001.[317] Unusually for a Reform Jewish synagogue, Central Synagogue contains a balcony. In contrast to Orthodox Jewish synagogues, where balconies are used to segregate the genders, Central Synagogue's balcony is used by both genders.[248] There are microphones, speakers, and cameras concealed within the balcony, allowing live broadcasts of services.[314][318] Each pew originally had eight seats[57] and bore the names of congregational members who paid for them.[42] Some of the original stationary pews were replaced with movable pews in the late 1990s.[254][258] By 2001, the synagogue had 148 pews in total;[258] the front rows have movable pews.[272][317] The current pews are made of milled wood. The pews directly beneath the balcony are positioned at a 45-degree angle toward the center of the nave. An elevator connects the balcony, main level, and basement.[302]

The ceiling is decorated in a bright-blue color and is interspersed with eight-pointed gold stars.[314][259] Twelve large chandeliers illuminate the main part of the sanctuary,[309][259] while twelve smaller chandeliers in the gallery and various accent lighting fixtures provide additional illumination.[259][314] There are also six bronze grilles on the ceiling, which contain star patterns.[309] The roof above the sanctuary measures 50 feet (15 m)[254] or 62 feet (19 m) tall.[61][301] It is made of wooden beams measuring as much as 20 feet (6.1 m) long and 12 inches (300 mm) wide.[308] When the roof was reconstructed, workers used wood because it is more fire-resistant than steel, even though steel can carry heavier loads.[308][319] The roof is supported by seven timber trusses between the clerestory walls, measuring 35 feet (11 m)[302][319] or 40 feet (12 m) long.[254]

Other spaces

[edit]The basement is placed on a foundation of solid rock.[300] The basement was originally supported by cast iron columns atop 4-by-4-foot (1.2 by 1.2 m) piers.[254] At the time of the synagogue's construction, religious buildings had only just started using cast-iron columns.[311] When the Lexington Avenue synagogue was built, it did not have any offices, classrooms, or other ancillary spaces. As such, the basement was expanded during the synagogue's 1998–2001 renovation.[320] The basement floor was lowered by 3 feet (0.91 m), while the cast iron columns were supported by sturdier steel columns.[254] In addition, a multipurpose room and classrooms were built in the basement.[251][320] In contrast to the main sanctuary, the basement space contains little ornamentation.[310]

Commentary and landmark designations

[edit]When the current synagogue building was completed, one writer said that the building was "not so impressive" as Temple Emanu-El but also "less faulty".[33] Hugh Hardy wrote that the building's "exterior form and detail were—and still are—in sharp contrast to other religious structures of the city".[303] The Forward said the building "practically oozed excess" and that its pulpit "placed the rabbi on a stage fit for a Broadway play."[259] Conversely, The Forward said that, in the years after the synagogue's completion, there were concerns that the synagogue's ornate design dissuaded congregants from talking among each other.[259] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) described the brownstone exterior in 1966 as "the finest extant example of the Moorish Revival style in New York City".[2][5]

When the synagogue partially burned down in 1998, UAHC president Alexander M. Schindler said the building had been "a place that made the spirit soar".[13] A writer for The Forward said the synagogue had "a similar architectural effect to Notre Dame in Paris, or the Dmitrevsky Sobor of Vladimir, Russia", and that the architecture had compelled congregants to worship.[321] Following the 2001 restoration, architectural critic Paul Goldberger wrote that "This isn't one of those old buildings that coddle you. It wakes you up."[86]

The New York Community Trust and Municipal Art Society installed a plaque outside Central Synagogue in 1958, commemorating the building's history.[322] The LPC designated the building as an official city landmark in 1966,[40][296] three years after the LPC proposed designating it as one of the city's first official landmarks.[323] It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970[3] and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1975.[296][324] A plaque marking the National Historic Landmark designation was placed outside the synagogue in 1976.[211]

Clergy

[edit]

Central Synagogue's senior rabbi is Angela Buchdahl.[277] Central's other rabbis include Maurice A. Salth, Ari S. Lorge, and Daniel S. Ross. Several rabbis also direct specific parts of the synagogue, including Sarah Berman, the adult education director; Hilly Haber, the social justice and education director; Andrew Kaplan Mandel, the online community engagement director; Rebecca Rosenthal, the youth and family education director; Lisa Rubin, the Center for Exploring Judaism director; and Peter J. Rubinstein, the rabbi emeritus. In addition, the staff includes senior cantor Daniel Mutlu and cantor Jenna Pearsall.[325]

Previous senior rabbis of Central Synagogue and its predecessors have included:[27]

| Rabbi | Congregation | Start year | End year | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Lilienthal | Shaar Hashomayim | 1845 | 1847 | [20] |

| Raphael Lasker | 1862 | 1871 | [22] | |

| Adolph Huebsch | Ahawath Chesed | 1866 | 1884 | [45] |

| Alexander Kohut | 1885 | 1894 | [51] | |

| Raphael Benjamin | Shaar Hashomayim | 1889 | 1894 | [326] |

| Solomon Sonneschein | 1895 | 1898[i] | [27] | |

| David Davidson | Ahawath Chesed | 1895 | 1898[i] | [98] |

| Central Synagogue | 1898[i] | 1899 | [110] | |

| Isaac S. Moses | 1901 | 1918 | [104] | |

| Nathan Krass | 1918 | 1923 | [104] | |

| Stephen Wise | Central and Free Synagogues | 1923[j] | 1925 | [144] |

| Jonah Wise | Central Synagogue | 1925 | 1959 | [164] |

| David J. Seligson | 1959 | 1972 | [188] | |

| Sheldon Zimmerman | 1972 | 1985 | [206] | |

| Stanley M. Davids | 1986 | 1991 | [27] | |

| Peter J. Rubinstein | 1991 | 2014 | [226] | |

| Angela Buchdahl | 2014 | Present | [277] |

Central Synagogue has had numerous lay presidents, who were not part of the clergy[327] but controlled its governance.[328] All the lay presidents were men until the 1980s. Although the lay presidents' wives were named to the synagogue's board of trustees, in practice they deferred to their husbands.[327] As of 2024[update], Shonni Silverberg is Central's president.[329]

Services and programs

[edit]As of 2024[update], Central hosts numerous weekly services, including a morning minyan, two Shabbat services (one each on Friday and Saturday), and a Shabbat mishkan service.[330] Since the 2010s, some of the synagogue's services have been broadcast online.[270][280] Central charges membership dues,[331] which have sometimes been waived for worshippers who could not afford them.[332]

Over the years, Central has also had various affiliate organizations and committees.[132] During much of the mid-20th century, the Central Synagogue Brotherhood sponsored Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts programs, adult education, synagogue usher services, and programs for the blind.[156] The congregation has continued to offer these programs through the 21st century.[332] As of 2024[update], Central operates a nursery for children under 5 years old, and a religious school.[333] Docents also lead tours of the synagogue once a week.[334]

Community houses

[edit]Central Synagogue's first community house opened in 1927 at 35 East 62nd Street.[152] The structure had been built in 1905 as Miss Keller's School for Girls.[135][335] The facility, serving as Central's social center,[153] had space for the congregation's offices, library, and 300 religious-school students.[104] It hosted the Temple Brotherhood's events and meetings, as well as the Women's Organization's dances, meetings, exhibits, and classes.[153] The community house included a meeting room, built in 1947 and named after Julius and Hilda Loeb.[336] After Central moved out of the building, it became a school and a residence.[335]

Central Synagogue operates the Phyllis and Lee Coffey Community House,[296][337] which is housed in a nine-story granite structure at 125 East 55th Street designed by Kahn and Jacobs.[196] The current community house was completed in September 1967.[196][197] The center includes a 450-seat sanctuary with fused-glass panels, in addition to an auditorium and theater, meeting rooms, and 16 classrooms.[196] It houses the synagogue's collection of artifacts, as well as its religious school, a gift shop, and various spaces for other activities.[338] When the community house opened, it was used by the Boy and Girl Scouts, blind and deaf persons' organizations, and the American Red Cross.[196]

Artifacts

[edit]Central Synagogue contains a collection of Jewish artifacts.[233] A Torah from the Czech town of Lipnik, which was printed in the early 19th century and owned by the Memorial Scrolls Trust,[339] was loaned to Central in 1967.[340] Prior to 1998, Central also contained two brass menorahs measuring 3 feet (0.91 m) high.[236] One of the menorahs was fabricated in the 18th century and was a bequest from one of the congregation's founding members.[13] In the mid-20th century, the congregation also owned three shofar musical horns.[341]

Notable people

[edit]The synagogue has had numerous notable members, some of whom have had their funerals there.[14]

- Bill Ackman, hedge fund manager[342]

- David Belasco, theatrical producer[343]

- Barbara Fedida, news executive[344]

- Jay Furman, real estate developer[345]

- Samuel B. Hamburger, lawyer[346]

- Henry M. Goldfogle, U.S. representative[347]

- Jacob K. Javits, U.S. senator[348]

- Evelyn Lauder, businesswoman, socialite, and philanthropist[349]

- Ronald Lauder, businessman[272]

- Howard Michaels, real estate developer[350]

- Neri Oxman, designer and professor[342]

- Fred Pressman, fashion executive[351]

- Richard Ravitch, transportation executive[352]

- Julia Richman, educator[353]

- A. M. Rosenthal, journalist[354]

- Samuel Roxy Rothafel, theatrical operator[355]

- Lewis Rudin, real estate investor and developer[356]

- Jerry Speyer, real estate developer[272]

- Stephen Susman, attorney[357]

- Jonathan Tisch, businessman[358]

- Laurence A. Tisch, businessman and investor[359]

- Morris C. Troper, accountant[360]

It has also hosted memorial services, including those for Martin Luther King Jr.[361] and first responders who died in the September 11 attacks.[362] The synagogue has also hosted weddings, such as those of the businessman Jonathan Tisch,[358] the TV anchor Maria Bartiromo,[363] and Bill Ackman and Neri Oxman.[342]

See also

[edit]- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- List of synagogues in the United States

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Explanatory notes

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Sources disagree on whether the most expensive pews cost $1,230[57] or $1,250.[50] This is equivalent to between $28,155 and $28,613 in 2023.[a]

- ^ Different sources have called it the Seder Tefilah (with one "l")[68] or Seder Tefillah (with two "l"s).[69]

- ^ Slightly different spellings have been used, e.g. Ahawath Chesed Shaaray Hashomayim[105] or Ahavat Chesed Shaarey Hashomayim.[106]

- ^ Contemporary sources reported the name change in conjunction with Moses's retirement and Krass's selection, which took place at the end of 1917.[129] One source gives a differing date of 1920 for when Central Synagogue began using its new name.[104]

- ^ A New York Herald Tribune article describes Habonim as having continued to use Central's community house until Habonim's new synagogue opened in 1958.[171]

- ^ "Shul" is the Yiddish term for "synagogue".[273]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ahawath Chesed and Shaar Hashomayim merged into one congregation in 1898. David Davidson took over the combined congregation.

- ^ Wise was the senior rabbi at the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue prior to 1923, when the Free Synagogue merged with Central Synagogue.[140]

Inflation figures

- ^ About $2,054 in 2023[a]

- ^ About $3,662 in 2023[a]

- ^ About $53 in 2023[a]

- ^ About $381,400 in 2023[b]

- ^ About $1,286,785 in 2023[b]

- ^ About $1,182,011 in 2023[b]

- ^ Between $3,434 and $27,468 in 2023[a]

- ^ About $813,777 or $1,118,943 in 2023[b]

- ^ Equivalent to between $6,358,000 and $6,932,000 in 2023[a]

- ^ Equivalent to between $149,841 and $209,777 in 2023[b]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. November 7, 2014. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Central Synagogue Designation Report (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 7, 1966. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 14, 2023. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Federal Register: 44 Fed. Reg. 7107 (Feb. 6, 1979)" (PDF). Library of Congress. February 6, 1979. p. 7538 (PDF p. 338). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ "Central Synagogue". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 10, 2007. Archived from the original on July 14, 2009. Retrieved September 10, 2007; Pitts, Carolyn (February 2, 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Central Synagogue" (pdf). National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2024; Accompanying 5 photos, exterior and interior, from 1973 and undated (1.53 MB)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ Гузик, Э.М. (2003). Генеалогические ресурсы в Нью-Йорке . Еврейское генеалогическое общество. п. 21. ISBN 978-0-9621863-1-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Браварски, Сэнди (5 ноября 2019 г.). «История, занимающая центральное место в еврейской жизни Нью-Йорка» . Еврейское телеграфное агентство . Архивировано из оригинала 30 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 18 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Служба национальных парков 1975 , с. 3.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Долкарт 2001 , с. 8.

- ^ Буш 2004 , с. 187.

- ^ Буш 2004 , стр. 187–188.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Сакс, Сьюзен (29 августа 1998 г.). «Живая история американского иудаизма» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 19 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Данлэп, Дэвид В. (2004). От Абиссинского до Сиона: Путеводитель по молитвенным домам Манхэттена . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Колумбийского университета . п. 40. ИСБН 0-231-12543-7 .

- ^ Зола 2008 , с. 72.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Фулд, Стоун и Росс 1979 , с. 3.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гурок 2014 , с. 11.

- ^ Гурок 2014 , стр. 12–13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , с. 12.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Гурок 2014 , с. 13.

- ^ Гурок 2014 , стр. 14–15.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Адлер, Сайрус; Ханеман, Фредерик Т. (1903). «Ласкер, Рафаэль» . Еврейская энциклопедия . Архивировано из оригинала 3 декабря 2023 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «Биографические очерки раввинов и канторов, служащих в Соединенных Штатах» . Американский еврейский ежегодник . 5 . Американский еврейский комитет: 72. 1903. ISSN 0065-8987 . JSTOR 23600123 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 августа 2023 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , с. 5.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Долкарт 2001 , с. 30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Гурок 2014 , с. 23.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Наши старшие раввины» . Центральная синагога . 9 сентября 2001 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я «Местные предметы». Еврейский посланник . 19 апреля 1872 г. с. 5. ПроКвест 884013319 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Буш 2004 , с. 188.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вульф, Греция; Хорошо, младший; Борден, Н. (2013). Синагоги Нижнего Ист-Сайда Нью-Йорка:: Ретроспектива и современный взгляд, 2-е издание . Издательство Фордхэмского университета. п. 2. ISBN 978-0-8232-5000-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Гурок 2014 , с. 12.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Золя 2008 , с. 20.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к Лантер, Магия (3 мая 1872 г.). «Освящение храма Ахават Хесед на Лексингтон-авеню и Пятьдесят пятой улице». Израильтянин . п. 6. ПроКвест 892477726 .

- ^ Американское еврейское историческое общество (1909). Публикации Американского еврейского исторического общества . Американское еврейское историческое общество. п. 216. Архивировано из оригинала 30 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Новый еврейский храм; закладка краеугольного камня – интересные церемонии – английские и немецкие речи» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 15 декабря 1870 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 19 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Фулд, Стоун и Росс 1979 , с. 4.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гурок 2014 , с. 16.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гурок 2014 , с. 17.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Внутренние записи: освящение храма Ахават Хесед в Нью-Йорке». Израильтянин . 10 июня 1864 г. с. 395. ПроКвест 892501337 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я Грей, Кристофер (2 апреля 1995 г.). «Уличные пейзажи/Центральная синагога; реставрация шедевра 1872 года стоимостью 500 000 долларов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 18 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Долкарт 2001 , с. 15.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , с. 8.

- ^ Зола 2008 , стр. 24–25.

- ^ Коэн, Дж. М. (2019). Еврейская религиозная музыка в Америке девятнадцатого века: восстановление саундтрека к синагоге . Издательство Университета Индианы. п. 190. ИСБН 978-0-253-04024-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Хюбш, Адольф (1885). Преподобный доктор Адольф Хюбш: покойный раввин общины Ахават Хесед, Нью-Йорк. Мемориал (на немецком языке). АЛ Гетцль. п. 7. Архивировано из оригинала 19 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Адам, Томас (2005). Германия и Америка: культура, политика и история [3 тома] . Трансатлантические отношения. Издательство Блумсбери. п. 519. ИСБН 978-1-85109-633-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Долкарт 2001 , с. 10.

- ^ Зола 2008 , стр. 30–32.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Золя 2008 , с. 26.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я Буш 2004 , с. 189.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Долкарт 2001 , с. 11.

- ^ Зола 2008 , с. 25.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Долкарт 2001 , стр. 11–12.

- ^ Долкарт 2001 , стр. 12–13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Долкарт 2001 , с. 13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Долкарт 2001 , с. 20.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , с. 9.

- ^ Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , стр. 9–10.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Долкарт 2001 , с. 23.

- ^ Грей, Кристофер (1 мая 2003 г.). Уличные пейзажи Нью-Йорка (1-е изд.). Гарри Н. Абрахамс. п. 188. ИСБН 978-0810944411 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 28 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Стерн, Роберт AM; Меллинз, Томас; Фишман, Дэвид (1999). Нью-Йорк 1880: Архитектура и урбанизм в позолоченный век . Моначелли Пресс. п. 330. ИСБН 978-1-58093-027-7 . OCLC 40698653 .

- ^ « Агават Хесед»: закладка краеугольного камня нового еврейского храма на Лексингтон-авеню». Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 15 декабря 1870 г. с. 8. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 572490627 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Освящение еврейского храма Ахават Хесед» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 20 апреля 1872 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 18 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Буш 2004 , с. 191.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Фулд, Стоун и Росс 1979 , с. 6.

- ^ Долкарт 2001 , с. 24.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Грей, Кристофер (27 декабря 1998 г.). «Уличные пейзажи: / Восточная 55-я улица между Парком и Лексингтон-авеню; среди каньонов Мидтауна, 8 живописных таунхаусов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 20 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 20 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гурок 2014 , с. 18.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Золя 2008 , с. 32.

- ^ Зола 2008 , стр. 32–33.

- ^ Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , с. 14.

- ^ Фулд, Стоун и Росс 1979 , с. 8.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Золя 2008 , стр. 26–27.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , с. 17.

- ^ «Местные новости: кратко о городе». Еврейский посланник . 24 января 1879 г. с. 2. ПроКвест 882848949 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Айзекс, Абрам С. (21 июня 1907 г.). «Среди наших синагог Нью-Йорка: Введение». Американский иврит и еврейский посланник . п. 175. ПроКвест 884031349 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Золя 2008 , с. 34.

- ^ Гурок 2014 , с. 111.

- ^ «Приветствие нового раввина; Первая беседа доктора Кохута в храме Ахават Хесед» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 10 мая 1885 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 20 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 20 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Зола 2008 , с. 35.

- ^ Зола 2008 , стр. 40–41.

- ^ Гурок 2014 , стр. 21–22.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Пожар в синагоге; храм Ахават Хесед поврежден на сумму 7000 долларов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 1 марта 1886 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 20 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 20 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Оживленные дни Ахават Хесед» . Солнце . 1 марта 1886 г. с. 5. Архивировано из оригинала 24 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 24 апреля 2024 г. - через газеты.com.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Пожар в священных зданиях: часовня и синагога пострадали, храм Ахават Хесед слегка поврежден - часовня полностью утрачена». Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 1 марта 1886 г. с. 1. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 573203963 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Гольдбергер, Пол (3 сентября 2001 г.). «Синагога снова возрождается» . Житель Нью-Йорка . Архивировано из оригинала 7 июля 2016 года . Проверено 20 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Золя 2008 , с. 44.

- ^ Зола 2008 , с. 42.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Золя 2008 , стр. 43–44.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гурок 2014 , стр. 22–23.

- ^ Зола 2008 , с. 45.

- ^ Гурок 2014 , с. 24.

- ^ Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , с. 16.

- ^ Зола 2008 , стр. 48–49.

- ^ «Нью-Йорк: новый министр Ахават Хесед, заботливый благотворительный клуб Национального женского совета «Курильщики» . Американский израильтянин . 7 марта 1895 г. с. 2. ПроКвест 908912610 .

- ^ Фулд, Стоун и Росс 1979 , с. 7.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Золя 2008 , стр. 49–50.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Американское еврейское историческое общество (1905 г.). Публикации Американского еврейского исторического общества . Американское еврейское историческое общество. п. 86. Архивировано из оригинала 21 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2024 г .; «Ахават Хесед: выбор раввина». Еврейский представитель . 14 июня 1895 г. с. 4. ПроКвест 901528909 .

- ^ Зола 2008 , стр. 50–51.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гурок 2014 , стр. 33–35.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Золя 2008 , с. 51.

- ^ «Юбилей Ахават-Хесед: Храм будет отмечать свое пятидесятилетие в течение трех дней». Нью-Йорк Таймс . 14 ноября 1896 г. с. 6. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 1013630961 ; «Годовщина Ахават-Хесед». Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 14 ноября 1896 г. с. 5. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 574324782 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Золя 2008 , с. 47.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж Фулд, Стоун и Росс 1979 , с. 13.

- ^ «Город». Американский иврит . 3 ноября 1899 г. с. 819. ПроКвест 869211796 .

- ^ Белл, Чарльз В. (27 марта 1999 г.). «Концерт возрождения / Концерт в помощь поврежденному храму». Нью-Йорк Дейли Ньюс . п. 21. ISSN 2692-1251 . ПроКвест 313669170 .

- ^ Бендавид (26 августа 1898 г.). «Союз некоторых общин: Ахават Хесед - Шаар Хашомаим». Американский иврит . п. 480. ПроКвест 871494372 .

- ^ Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , стр. 7–8.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , с. 15.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Конер, Маркус; Ричман, Дэниел В. (23 июня 1899 г.). «Храм Ахамат Хесед Шаар Хашомаим: Лексингтон-авеню, угол 55-й улицы, Нью-Йорк». Американский иврит . п. 221. ПроКвест 869211246 .

- ^ Зола 2008 , стр. 52–53.

- ^ Зола 2008 , с. 52.

- ^ «Звонен раввин из Балтимора. Храм Ахават Хесед хочет, чтобы здесь был доктор Розан» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 12 мая 1900 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 18 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Золя 2008 , с. 53.

- ^ «Город: санаторий для еврейских детей доктора Сейла и сельскохозяйственной школы Ахават Хесед демонстрирует сионистский митинг Еврейской ассоциации молодых мужчин, длинные записи синагоги». Американский иврит . 10 августа 1900 г. с. 351. ПроКвест 888471391 .

- ^ «Отказывается от звонка в Нью-Йорк» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 27 января 1900 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г .; «Без названия» . Курьерский экспресс Буффало . 27 января 1900 г. с. 5. Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г. - через газеты.com.

- ^ Зола 2008 , стр. 52–53.

- ^ «Город: Ахават Хесед Шаар Хасомаим». Американский иврит . 4 января 1901 г. с. 239. ПроКвест 888473326 ; «Инсталляция раввина Моисея» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 9 января 1901 г. с. 7. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г. - через газеты.com.

- ^ Зола 2008 , с. 64.

- ^ Гурок 2014 , с. 35.

- ^ Долкарт 2001 , стр. 30–32.

- ^ Долкарт 2001 , стр. 43–44.

- ^ Долкарт 2001 , с. 44.

- ^ «Объединим еврейские школы; новое общество стремится сделать религиозное образование единым» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 15 апреля 1913 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г .; «Союз еврейских религиозных школ». Еврейский представитель . 18 апреля 1913 г. с. 8. ПроКвест 2801096186 .

- ^ «Еврейские сестричества Нью-Йорка». Американский иврит и еврейский посланник . 26 марта 1915 г. с. 540. ПроКвест 901336557 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Долкарт 2001 , с. 45.

- ^ «Доктор Красс вызван в город: известному бруклинскому раввину предложена кафедра на Пятьдесят пятой улице». Американский иврит и еврейский посланник . 6 июля 1917 г. с. 234. ПроКвест 899832660 .

- ^ «Доктор Красс принимает вызов из Манхэттена». Американский иврит и еврейский посланник . 10 августа 1917 г. с. 349. ПроКвест 899833686 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Добро пожаловать к доктору Крассу. Конгрегация Центрального храма отдает дань уважения своему почетному раввину» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 17 декабря 1917 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г .; «Добро пожаловать к доктору Крассу: Конгрегация Нью-Йорка отдает дань уважения своему почетному раввину». Американский израильтянин . 3 января 1918 г. с. 4. ПроКвест 918130985 .

- ^ «Установлен доктор Красс: нового раввина Центральной синагоги приветствует большое прихожане - планы воскресных служб». Американский иврит и еврейский посланник . 11 января 1918 г. с. 290. ПроКвест 899833729 .

- ^ Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , стр. 11–12.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Блэкмар и Горен 2003 , с. 27.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Наше письмо из Нью-Йорка: доктор Красс принимает звонок Эману-элю». Еврейский представитель . 13 апреля 1923 г. с. 6. ПроКвест 2786977995 .

- ^ Гурок 2014 , с. 37.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Долкарт 2001 , с. 47.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гурок 2014 , с. 33.

- ^ «Храм Эману-эль звонит доктору Крассу; раввин Центральной синагоги принимает приглашение на новую кафедру» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 5 апреля 1923 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Свободные и центральные синагоги объединяются; попечители должны представить план федерации обеим конгрегациям - доктор Уайз станет раввином» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 16 апреля 1923 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г .; «Переписка: События в Нью-Йорке». Американский израильтянин . 19 апреля 1923 г. с. 2. ПроКвест 1009411986 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Тяжелые волны раздвинули швы Seaconnet; корабль, построенный в рекордные сроки во время войны, наполнился водой и затонул» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 1 мая 1923 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2024 г .; «Две синагоги голосуют за объединение общин: доктор Уайз станет раввином; планируется построить здание стоимостью 2 000 000 долларов». Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 1 мая 1923 г. с. 5. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1221760276 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Долкарт 2001 , с. 48.

- ^ «Дом синагоги, посвященный институту религии». «Нью-Йорк Геральд», «Нью-Йорк Трибьюн» . 24 марта 1924 г. с. 5. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1112947317 ; «Посвящен новый дом синагоги: доктор Уайз проводит упражнения в здании стоимостью 500 000 долларов». Американский израильтянин . 27 марта 1924 г. с. 7. ПроКвест 1009420198 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Новый Дом Синагоги». Нью-Йорк Таймс . 9 марта 1924 г. с. РЕ14. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 103293057 .