Цианобактерии

| Цианобактерии Временной диапазон: (Возможные палеоархейские записи)

| |

|---|---|

| |

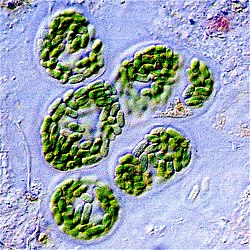

| Изображение под микроскопом Cylindrospermum , нитчатого рода цианобактерий. | |

| Научная классификация | |

| Домен: | Бактерии |

| Clade: | Terrabacteria |

| Clade: | Cyanobacteria-Melainabacteria group |

| Phylum: | Cyanobacteria Stanier, 1973 |

| Class: | Cyanophyceae |

| Orders[3] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List | |

Цианобактерии ( / s aɪ ˌ æ n oʊ b æ k ˈ t ɪər i . ə / ), также называемые Cyanobacteriota или Cyanophyta , представляют собой автотрофных тип грамотрицательных бактерий. [ 4 ] которые могут получать биологическую энергию посредством кислородного фотосинтеза . Название «цианобактерии» (от древнегреческого κύανος ( куанос ) «синий») относится к их голубовато-зеленому ( циановому ) цвету. [ 5 ] [ 6 ] что лежит в основе неофициального общего названия цианобактерий — сине-зеленые водоросли . [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] хотя, будучи прокариотами, они с научной точки зрения не классифицируются как водоросли . [ примечание 1 ]

Цианобактерии, вероятно, являются самым многочисленным таксоном , когда-либо существовавшим на Земле, и первыми известными организмами, производящими кислород . [ 10 ] появившись в среднем архее и зародившись, по-видимому, в пресноводной или земной среде . [ 11 ] Их фотопигменты могут поглощать частоты красного и синего спектра солнечного света (таким образом отражая зеленоватый цвет), расщепляя молекулы воды на ионы водорода и кислород. Ионы водорода используются для реакции с диоксидом углерода с образованием сложных органических соединений, таких как углеводы (процесс, известный как фиксация углерода ), а кислород выделяется в качестве побочного продукта . Считается, что непрерывно производя и выделяя кислород в течение миллиардов лет, цианобактерии превратили ранней Земли бескислородную, слабовосстанавливающую пребиотическую атмосферу в окислительную атмосферу со свободным газообразным кислородом (который ранее был немедленно удален различными поверхностными восстановителями ). что привело к Великому Событию окисления и « ржавлению Земли » в раннем протерозое . [12] dramatically changing the composition of life forms on Earth.[13] Последующая адаптация ранних одноклеточных организмов к выживанию в кислородной среде, вероятно, привела к эндосимбиозу между анаэробами и аэробами и, следовательно, к эволюции эукариот в палеопротерозое .

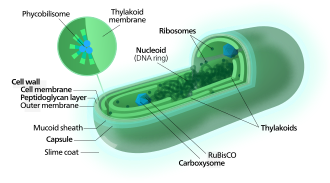

Cyanobacteria use photosynthetic pigments such as various forms of chlorophyll, carotenoids, phycobilins to convert the photonic energy in sunlight to chemical energy. Unlike heterotrophic prokaryotes, cyanobacteria have internal membranes. These are flattened sacs called thylakoids where photosynthesis is performed.[14][15] Photoautotrophic eukaryotes such as red algae, green algae and plants perform photosynthesis in chlorophyllic organelles that are thought to have their ancestry in cyanobacteria, acquired long ago via endosymbiosis. These endosymbiont cyanobacteria in eukaryotes then evolved and differentiated into specialized organelles such as chloroplasts, chromoplasts, etioplasts, and leucoplasts, collectively known as plastids.

Sericytochromatia, the proposed name of the paraphyletic and most basal group, is the ancestor of both the non-photosynthetic group Melainabacteria and the photosynthetic cyanobacteria, also called Oxyphotobacteria.[16]

The cyanobacteria Synechocystis and Cyanothece are important model organisms with potential applications in biotechnology for bioethanol production, food colorings, as a source of human and animal food, dietary supplements and raw materials.[17] Cyanobacteria produce a range of toxins known as cyanotoxins that can cause harmful health effects in humans and animals.

Overview

[edit]

Cyanobacteria are a very large and diverse phylum of photosynthetic prokaryotes.[19] They are defined by their unique combination of pigments and their ability to perform oxygenic photosynthesis. They often live in colonial aggregates that can take on a multitude of forms.[20] Of particular interest are the filamentous species, which often dominate the upper layers of microbial mats found in extreme environments such as hot springs, hypersaline water, deserts and the polar regions,[21] but are also widely distributed in more mundane environments as well.[22] They are evolutionarily optimized for environmental conditions of low oxygen.[23] Some species are nitrogen-fixing and live in a wide variety of moist soils and water, either freely or in a symbiotic relationship with plants or lichen-forming fungi (as in the lichen genus Peltigera).[24]

Cyanobacteria are globally widespread photosynthetic prokaryotes and are major contributors to global biogeochemical cycles.[25] They are the only oxygenic photosynthetic prokaryotes, and prosper in diverse and extreme habitats.[26] They are among the oldest organisms on Earth with fossil records dating back at least 2.1 billion years.[27] Since then, cyanobacteria have been essential players in the Earth's ecosystems. Planktonic cyanobacteria are a fundamental component of marine food webs and are major contributors to global carbon and nitrogen fluxes.[28][29] Some cyanobacteria form harmful algal blooms causing the disruption of aquatic ecosystem services and intoxication of wildlife and humans by the production of powerful toxins (cyanotoxins) such as microcystins, saxitoxin, and cylindrospermopsin.[30][31] Nowadays, cyanobacterial blooms pose a serious threat to aquatic environments and public health, and are increasing in frequency and magnitude globally.[32][25]

Cyanobacteria are ubiquitous in marine environments and play important roles as primary producers. They are part of the marine phytoplankton, which currently contributes almost half of the Earth's total primary production.[33] About 25% of the global marine primary production is contributed by cyanobacteria.[34]

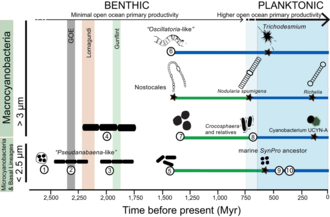

Within the cyanobacteria, only a few lineages colonized the open ocean: Crocosphaera and relatives, cyanobacterium UCYN-A, Trichodesmium, as well as Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus.[35][36][37][38] From these lineages, nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria are particularly important because they exert a control on primary productivity and the export of organic carbon to the deep ocean,[35] by converting nitrogen gas into ammonium, which is later used to make amino acids and proteins. Marine picocyanobacteria (Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus) numerically dominate most phytoplankton assemblages in modern oceans, contributing importantly to primary productivity.[37][38][39] While some planktonic cyanobacteria are unicellular and free living cells (e.g., Crocosphaera, Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus); others have established symbiotic relationships with haptophyte algae, such as coccolithophores.[36] Amongst the filamentous forms, Trichodesmium are free-living and form aggregates. However, filamentous heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria (e.g., Richelia, Calothrix) are found in association with diatoms such as Hemiaulus, Rhizosolenia and Chaetoceros.[40][41][42][43]

Marine cyanobacteria include the smallest known photosynthetic organisms. The smallest of all, Prochlorococcus, is just 0.5 to 0.8 micrometres across.[44] In terms of numbers of individuals, Prochlorococcus is possibly the most plentiful genus on Earth: a single millilitre of surface seawater can contain 100,000 cells of this genus or more. Worldwide there are estimated to be several octillion (1027, a billion billion billion) individuals.[45] Prochlorococcus is ubiquitous between latitudes 40°N and 40°S, and dominates in the oligotrophic (nutrient-poor) regions of the oceans.[46] The bacterium accounts for about 20% of the oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere.[47]

Morphology

[edit]Cyanobacteria are variable in morphology, ranging from unicellular and filamentous to colonial forms. Filamentous forms exhibit functional cell differentiation such as heterocysts (for nitrogen fixation), akinetes (resting stage cells), and hormogonia (reproductive, motile filaments). These, together with the intercellular connections they possess, are considered the first signs of multicellularity.[48][49][50][25]

Many cyanobacteria form motile filaments of cells, called hormogonia, that travel away from the main biomass to bud and form new colonies elsewhere.[51][52] The cells in a hormogonium are often thinner than in the vegetative state, and the cells on either end of the motile chain may be tapered. To break away from the parent colony, a hormogonium often must tear apart a weaker cell in a filament, called a necridium.

scale bars about 10 μm

• Non-heterocytous: (c) Arthrospira maxima,

Some filamentous species can differentiate into several different cell types:

- Vegetative cells – the normal, photosynthetic cells that are formed under favorable growing conditions

- Akinetes – climate-resistant spores that may form when environmental conditions become harsh

- Thick-walled heterocysts – which contain the enzyme nitrogenase vital for nitrogen fixation[54][55][56] in an anaerobic environment due to its sensitivity to oxygen.[56]

Each individual cell (each single cyanobacterium) typically has a thick, gelatinous cell wall.[57] They lack flagella, but hormogonia of some species can move about by gliding along surfaces.[58] Many of the multicellular filamentous forms of Oscillatoria are capable of a waving motion; the filament oscillates back and forth. In water columns, some cyanobacteria float by forming gas vesicles, as in archaea.[59] These vesicles are not organelles as such. They are not bounded by lipid membranes, but by a protein sheath.

Nitrogen fixation

[edit]

Some cyanobacteria can fix atmospheric nitrogen in anaerobic conditions by means of specialized cells called heterocysts.[55][56] Heterocysts may also form under the appropriate environmental conditions (anoxic) when fixed nitrogen is scarce. Heterocyst-forming species are specialized for nitrogen fixation and are able to fix nitrogen gas into ammonia (NH3), nitrites (NO−2) or nitrates (NO−3), which can be absorbed by plants and converted to protein and nucleic acids (atmospheric nitrogen is not bioavailable to plants, except for those having endosymbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria, especially the family Fabaceae, among others).

Free-living cyanobacteria are present in the water of rice paddies, and cyanobacteria can be found growing as epiphytes on the surfaces of the green alga, Chara, where they may fix nitrogen.[60] Cyanobacteria such as Anabaena (a symbiont of the aquatic fern Azolla) can provide rice plantations with biofertilizer.[61]

Photosynthesis

[edit]

Carbon fixation

[edit]Cyanobacteria use the energy of sunlight to drive photosynthesis, a process where the energy of light is used to synthesize organic compounds from carbon dioxide. Because they are aquatic organisms, they typically employ several strategies which are collectively known as a "CO2 concentrating mechanism" to aid in the acquisition of inorganic carbon (CO2 or bicarbonate). Among the more specific strategies is the widespread prevalence of the bacterial microcompartments known as carboxysomes,[63] which co-operate with active transporters of CO2 and bicarbonate, in order to accumulate bicarbonate into the cytoplasm of the cell.[64] Carboxysomes are icosahedral structures composed of hexameric shell proteins that assemble into cage-like structures that can be several hundreds of nanometres in diameter. It is believed that these structures tether the CO2-fixing enzyme, RuBisCO, to the interior of the shell, as well as the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, using metabolic channeling to enhance the local CO2 concentrations and thus increase the efficiency of the RuBisCO enzyme.[65]

Electron transport

[edit]In contrast to purple bacteria and other bacteria performing anoxygenic photosynthesis, thylakoid membranes of cyanobacteria are not continuous with the plasma membrane but are separate compartments.[66] The photosynthetic machinery is embedded in the thylakoid membranes, with phycobilisomes acting as light-harvesting antennae attached to the membrane, giving the green pigmentation observed (with wavelengths from 450 nm to 660 nm) in most cyanobacteria.[67]

While most of the high-energy electrons derived from water are used by the cyanobacterial cells for their own needs, a fraction of these electrons may be donated to the external environment via electrogenic activity.[68]

Respiration

[edit]Respiration in cyanobacteria can occur in the thylakoid membrane alongside photosynthesis,[69] with their photosynthetic electron transport sharing the same compartment as the components of respiratory electron transport. While the goal of photosynthesis is to store energy by building carbohydrates from CO2, respiration is the reverse of this, with carbohydrates turned back into CO2 accompanying energy release.

Cyanobacteria appear to separate these two processes with their plasma membrane containing only components of the respiratory chain, while the thylakoid membrane hosts an interlinked respiratory and photosynthetic electron transport chain.[69] Cyanobacteria use electrons from succinate dehydrogenase rather than from NADPH for respiration.[69]

Cyanobacteria only respire during the night (or in the dark) because the facilities used for electron transport are used in reverse for photosynthesis while in the light.[70]

Electron transport chain

[edit]Many cyanobacteria are able to reduce nitrogen and carbon dioxide under aerobic conditions, a fact that may be responsible for their evolutionary and ecological success. The water-oxidizing photosynthesis is accomplished by coupling the activity of photosystem (PS) II and I (Z-scheme). In contrast to green sulfur bacteria which only use one photosystem, the use of water as an electron donor is energetically demanding, requiring two photosystems.[71]

Attached to the thylakoid membrane, phycobilisomes act as light-harvesting antennae for the photosystems.[72] The phycobilisome components (phycobiliproteins) are responsible for the blue-green pigmentation of most cyanobacteria.[73] The variations on this theme are due mainly to carotenoids and phycoerythrins that give the cells their red-brownish coloration. In some cyanobacteria, the color of light influences the composition of the phycobilisomes.[74][75] In green light, the cells accumulate more phycoerythrin, which absorbs green light, whereas in red light they produce more phycocyanin which absorbs red. Thus, these bacteria can change from brick-red to bright blue-green depending on whether they are exposed to green light or to red light.[76] This process of "complementary chromatic adaptation" is a way for the cells to maximize the use of available light for photosynthesis.

A few genera lack phycobilisomes and have chlorophyll b instead (Prochloron, Prochlorococcus, Prochlorothrix). These were originally grouped together as the prochlorophytes or chloroxybacteria, but appear to have developed in several different lines of cyanobacteria. For this reason, they are now considered as part of the cyanobacterial group.[77][78]

Metabolism

[edit]In general, photosynthesis in cyanobacteria uses water as an electron donor and produces oxygen as a byproduct, though some may also use hydrogen sulfide[79] a process which occurs among other photosynthetic bacteria such as the purple sulfur bacteria.

Carbon dioxide is reduced to form carbohydrates via the Calvin cycle.[80] The large amounts of oxygen in the atmosphere are considered to have been first created by the activities of ancient cyanobacteria.[81] They are often found as symbionts with a number of other groups of organisms such as fungi (lichens), corals, pteridophytes (Azolla), angiosperms (Gunnera), etc.[82] The carbon metabolism of cyanobacteria include the incomplete Krebs cycle,[83] the pentose phosphate pathway, and glycolysis.[84]

There are some groups capable of heterotrophic growth,[85] while others are parasitic, causing diseases in invertebrates or algae (e.g., the black band disease).[86][87][88]

Ecology

[edit]

Cyanobacteria can be found in almost every terrestrial and aquatic habitat – oceans, fresh water, damp soil, temporarily moistened rocks in deserts, bare rock and soil, and even Antarctic rocks. They can occur as planktonic cells or form phototrophic biofilms. They are found inside stones and shells (in endolithic ecosystems).[90] A few are endosymbionts in lichens, plants, various protists, or sponges and provide energy for the host. Some live in the fur of sloths, providing a form of camouflage.[91]

Aquatic cyanobacteria are known for their extensive and highly visible blooms that can form in both freshwater and marine environments. The blooms can have the appearance of blue-green paint or scum. These blooms can be toxic, and frequently lead to the closure of recreational waters when spotted. Marine bacteriophages are significant parasites of unicellular marine cyanobacteria.[92]

Cyanobacterial growth is favoured in ponds and lakes where waters are calm and have little turbulent mixing.[93] Their lifecycles are disrupted when the water naturally or artificially mixes from churning currents caused by the flowing water of streams or the churning water of fountains. For this reason blooms of cyanobacteria seldom occur in rivers unless the water is flowing slowly. Growth is also favoured at higher temperatures which enable Microcystis species to outcompete diatoms and green algae, and potentially allow development of toxins.[93]

Based on environmental trends, models and observations suggest cyanobacteria will likely increase their dominance in aquatic environments. This can lead to serious consequences, particularly the contamination of sources of drinking water. Researchers including Linda Lawton at Robert Gordon University, have developed techniques to study these.[94] Cyanobacteria can interfere with water treatment in various ways, primarily by plugging filters (often large beds of sand and similar media) and by producing cyanotoxins, which have the potential to cause serious illness if consumed. Consequences may also lie within fisheries and waste management practices. Anthropogenic eutrophication, rising temperatures, vertical stratification and increased atmospheric carbon dioxide are contributors to cyanobacteria increasing dominance of aquatic ecosystems.[95]

Cyanobacteria have been found to play an important role in terrestrial habitats and organism communities. It has been widely reported that cyanobacteria soil crusts help to stabilize soil to prevent erosion and retain water.[96] An example of a cyanobacterial species that does so is Microcoleus vaginatus. M. vaginatus stabilizes soil using a polysaccharide sheath that binds to sand particles and absorbs water.[97] M. vaginatus also makes a significant contribution to the cohesion of biological soil crust.[98]

Some of these organisms contribute significantly to global ecology and the oxygen cycle. The tiny marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus was discovered in 1986 and accounts for more than half of the photosynthesis of the open ocean.[99] Circadian rhythms were once thought to only exist in eukaryotic cells but many cyanobacteria display a bacterial circadian rhythm.

"Cyanobacteria are arguably the most successful group of microorganisms on earth. They are the most genetically diverse; they occupy a broad range of habitats across all latitudes, widespread in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems, and they are found in the most extreme niches such as hot springs, salt works, and hypersaline bays. Photoautotrophic, oxygen-producing cyanobacteria created the conditions in the planet's early atmosphere that directed the evolution of aerobic metabolism and eukaryotic photosynthesis. Cyanobacteria fulfill vital ecological functions in the world's oceans, being important contributors to global carbon and nitrogen budgets." – Stewart and Falconer[100]

Cyanobionts

[edit]

Leaf and root colonization by cyanobacteria

(2) On the root surface, cyanobacteria exhibit two types of colonization pattern; in the root hair, filaments of Anabaena and Nostoc species form loose colonies, and in the restricted zone on the root surface, specific Nostoc species form cyanobacterial colonies.

(3) Co-inoculation with 2,4-D and Nostoc spp. increases para-nodule formation and nitrogen fixation. A large number of Nostoc spp. isolates colonize the root endosphere and form para-nodules.[101]

Some cyanobacteria, the so-called cyanobionts (cyanobacterial symbionts), have a symbiotic relationship with other organisms, both unicellular and multicellular.[102] As illustrated on the right, there are many examples of cyanobacteria interacting symbiotically with land plants.[103][104][105][106] Cyanobacteria can enter the plant through the stomata and colonize the intercellular space, forming loops and intracellular coils.[107] Anabaena spp. colonize the roots of wheat and cotton plants.[108][109][110] Calothrix sp. has also been found on the root system of wheat.[109][110] Monocots, such as wheat and rice, have been colonised by Nostoc spp.,[111][112][113][114] In 1991, Ganther and others isolated diverse heterocystous nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria, including Nostoc, Anabaena and Cylindrospermum, from plant root and soil. Assessment of wheat seedling roots revealed two types of association patterns: loose colonization of root hair by Anabaena and tight colonization of the root surface within a restricted zone by Nostoc.[111][101]

(a) O. magnificus with numerous cyanobionts present in the upper and lower girdle lists (black arrowheads) of the cingulum termed the symbiotic chamber.

(b) O. steinii with numerous cyanobionts inhabiting the symbiotic chamber.

(c) Enlargement of the area in (b) showing two cyanobionts that are being divided by binary transverse fission (white arrows).

The relationships between cyanobionts (cyanobacterial symbionts) and protistan hosts are particularly noteworthy, as some nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria (diazotrophs) play an important role in primary production, especially in nitrogen-limited oligotrophic oceans.[115][116][117] Cyanobacteria, mostly pico-sized Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus, are ubiquitously distributed and are the most abundant photosynthetic organisms on Earth, accounting for a quarter of all carbon fixed in marine ecosystems.[39][118][46] In contrast to free-living marine cyanobacteria, some cyanobionts are known to be responsible for nitrogen fixation rather than carbon fixation in the host.[119][120] However, the physiological functions of most cyanobionts remain unknown. Cyanobionts have been found in numerous protist groups, including dinoflagellates, tintinnids, radiolarians, amoebae, diatoms, and haptophytes.[121][122] Among these cyanobionts, little is known regarding the nature (e.g., genetic diversity, host or cyanobiont specificity, and cyanobiont seasonality) of the symbiosis involved, particularly in relation to dinoflagellate host.[102]

Collective behaviour

[edit]

Some cyanobacteria – even single-celled ones – show striking collective behaviours and form colonies (or blooms) that can float on water and have important ecological roles. For instance, billions of years ago, communities of marine Paleoproterozoic cyanobacteria could have helped create the biosphere as we know it by burying carbon compounds and allowing the initial build-up of oxygen in the atmosphere.[124] On the other hand, toxic cyanobacterial blooms are an increasing issue for society, as their toxins can be harmful to animals.[32] Extreme blooms can also deplete water of oxygen and reduce the penetration of sunlight and visibility, thereby compromising the feeding and mating behaviour of light-reliant species.[123]

As shown in the diagram on the right, bacteria can stay in suspension as individual cells, adhere collectively to surfaces to form biofilms, passively sediment, or flocculate to form suspended aggregates. Cyanobacteria are able to produce sulphated polysaccharides (yellow haze surrounding clumps of cells) that enable them to form floating aggregates. In 2021, Maeda et al. discovered that oxygen produced by cyanobacteria becomes trapped in the network of polysaccharides and cells, enabling the microorganisms to form buoyant blooms.[125] It is thought that specific protein fibres known as pili (represented as lines radiating from the cells) may act as an additional way to link cells to each other or onto surfaces. Some cyanobacteria also use sophisticated intracellular gas vesicles as floatation aids.[123]

The diagram on the left above shows a proposed model of microbial distribution, spatial organization, carbon and O2 cycling in clumps and adjacent areas. (a) Clumps contain denser cyanobacterial filaments and heterotrophic microbes. The initial differences in density depend on cyanobacterial motility and can be established over short timescales. Darker blue color outside of the clump indicates higher oxygen concentrations in areas adjacent to clumps. Oxic media increase the reversal frequencies of any filaments that begin to leave the clumps, thereby reducing the net migration away from the clump. This enables the persistence of the initial clumps over short timescales; (b) Spatial coupling between photosynthesis and respiration in clumps. Oxygen produced by cyanobacteria diffuses into the overlying medium or is used for aerobic respiration. Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) diffuses into the clump from the overlying medium and is also produced within the clump by respiration. In oxic solutions, high O2 concentrations reduce the efficiency of CO2 fixation and result in the excretion of glycolate. Under these conditions, clumping can be beneficial to cyanobacteria if it stimulates the retention of carbon and the assimilation of inorganic carbon by cyanobacteria within clumps. This effect appears to promote the accumulation of particulate organic carbon (cells, sheaths and heterotrophic organisms) in clumps.[126]

It has been unclear why and how cyanobacteria form communities. Aggregation must divert resources away from the core business of making more cyanobacteria, as it generally involves the production of copious quantities of extracellular material. In addition, cells in the centre of dense aggregates can also suffer from both shading and shortage of nutrients.[127][128] So, what advantage does this communal life bring for cyanobacteria?[123]

New insights into how cyanobacteria form blooms have come from a 2021 study on the cyanobacterium Synechocystis. These use a set of genes that regulate the production and export of sulphated polysaccharides, chains of sugar molecules modified with sulphate groups that can often be found in marine algae and animal tissue. Many bacteria generate extracellular polysaccharides, but sulphated ones have only been seen in cyanobacteria. In Synechocystis these sulphated polysaccharide help the cyanobacterium form buoyant aggregates by trapping oxygen bubbles in the slimy web of cells and polysaccharides.[125][123]

Previous studies on Synechocystis have shown type IV pili, which decorate the surface of cyanobacteria, also play a role in forming blooms.[130][127] These retractable and adhesive protein fibres are important for motility, adhesion to substrates and DNA uptake.[131] The formation of blooms may require both type IV pili and Synechan – for example, the pili may help to export the polysaccharide outside the cell. Indeed, the activity of these protein fibres may be connected to the production of extracellular polysaccharides in filamentous cyanobacteria.[132] A more obvious answer would be that pili help to build the aggregates by binding the cells with each other or with the extracellular polysaccharide. As with other kinds of bacteria,[133] certain components of the pili may allow cyanobacteria from the same species to recognise each other and make initial contacts, which are then stabilised by building a mass of extracellular polysaccharide.[123]

The bubble flotation mechanism identified by Maeda et al. joins a range of known strategies that enable cyanobacteria to control their buoyancy, such as using gas vesicles or accumulating carbohydrate ballasts.[134] Type IV pili on their own could also control the position of marine cyanobacteria in the water column by regulating viscous drag.[135] Extracellular polysaccharide appears to be a multipurpose asset for cyanobacteria, from floatation device to food storage, defence mechanism and mobility aid.[132][123]

Cellular death

[edit]

One of the most critical processes determining cyanobacterial eco-physiology is cellular death. Evidence supports the existence of controlled cellular demise in cyanobacteria, and various forms of cell death have been described as a response to biotic and abiotic stresses. However, cell death research in cyanobacteria is a relatively young field and understanding of the underlying mechanisms and molecular machinery underpinning this fundamental process remains largely elusive.[25] However, reports on cell death of marine and freshwater cyanobacteria indicate this process has major implications for the ecology of microbial communities/[137][138][139][140] Different forms of cell demise have been observed in cyanobacteria under several stressful conditions,[141][142] and cell death has been suggested to play a key role in developmental processes, such as akinete and heterocyst differentiation, as well as strategy for population survival.[136][143][144][48][25]

Cyanophages

[edit]Cyanophages are viruses that infect cyanobacteria. Cyanophages can be found in both freshwater and marine environments.[145] Marine and freshwater cyanophages have icosahedral heads, which contain double-stranded DNA, attached to a tail by connector proteins.[146] The size of the head and tail vary among species of cyanophages. Cyanophages, like other bacteriophages, rely on Brownian motion to collide with bacteria, and then use receptor binding proteins to recognize cell surface proteins, which leads to adherence. Viruses with contractile tails then rely on receptors found on their tails to recognize highly conserved proteins on the surface of the host cell.[147]

Cyanophages infect a wide range of cyanobacteria and are key regulators of the cyanobacterial populations in aquatic environments, and may aid in the prevention of cyanobacterial blooms in freshwater and marine ecosystems. These blooms can pose a danger to humans and other animals, particularly in eutrophic freshwater lakes. Infection by these viruses is highly prevalent in cells belonging to Synechococcus spp. in marine environments, where up to 5% of cells belonging to marine cyanobacterial cells have been reported to contain mature phage particles.[148]

The first cyanophage, LPP-1, was discovered in 1963.[149] Cyanophages are classified within the bacteriophage families Myoviridae (e.g. AS-1, N-1), Podoviridae (e.g. LPP-1) and Siphoviridae (e.g. S-1).[149]

Movement

[edit]

It has long been known that filamentous cyanobacteria perform surface motions, and that these movements result from type IV pili.[150][132][151] Additionally, Synechococcus, a marine cyanobacteria, is known to swim at a speed of 25 μm/s by a mechanism different to that of bacterial flagella.[152] Formation of waves on the cyanobacteria surface is thought to push surrounding water backwards.[153][154] Cells are known to be motile by a gliding method[155] and a novel uncharacterized, non-phototactic swimming method[156] that does not involve flagellar motion.

Many species of cyanobacteria are capable of gliding. Gliding is a form of cell movement that differs from crawling or swimming in that it does not rely on any obvious external organ or change in cell shape and it occurs only in the presence of a substrate.[157][158] Gliding in filamentous cyanobacteria appears to be powered by a "slime jet" mechanism, in which the cells extrude a gel that expands quickly as it hydrates providing a propulsion force,[159][160] although some unicellular cyanobacteria use type IV pili for gliding.[161][22]

Cyanobacteria have strict light requirements. Too little light can result in insufficient energy production, and in some species may cause the cells to resort to heterotrophic respiration.[21] Too much light can inhibit the cells, decrease photosynthesis efficiency and cause damage by bleaching. UV radiation is especially deadly for cyanobacteria, with normal solar levels being significantly detrimental for these microorganisms in some cases.[20][162][22]

Filamentous cyanobacteria that live in microbial mats often migrate vertically and horizontally within the mat in order to find an optimal niche that balances their light requirements for photosynthesis against their sensitivity to photodamage. For example, the filamentous cyanobacteria Oscillatoria sp. and Spirulina subsalsa found in the hypersaline benthic mats of Guerrero Negro, Mexico migrate downwards into the lower layers during the day in order to escape the intense sunlight and then rise to the surface at dusk.[163] In contrast, the population of Microcoleus chthonoplastes found in hypersaline mats in Camargue, France migrate to the upper layer of the mat during the day and are spread homogeneously through the mat at night.[164] An in vitro experiment using Phormidium uncinatum also demonstrated this species' tendency to migrate in order to avoid damaging radiation.[20][162] These migrations are usually the result of some sort of photomovement, although other forms of taxis can also play a role.[165][22]

Photomovement – the modulation of cell movement as a function of the incident light – is employed by the cyanobacteria as a means to find optimal light conditions in their environment. There are three types of photomovement: photokinesis, phototaxis and photophobic responses.[166][167][168][22]

Photokinetic microorganisms modulate their gliding speed according to the incident light intensity. For example, the speed with which Phormidium autumnale glides increases linearly with the incident light intensity.[169][22]

Phototactic microorganisms move according to the direction of the light within the environment, such that positively phototactic species will tend to move roughly parallel to the light and towards the light source. Species such as Phormidium uncinatum cannot steer directly towards the light, but rely on random collisions to orient themselves in the right direction, after which they tend to move more towards the light source. Others, such as Anabaena variabilis, can steer by bending the trichome.[170][22]

Finally, photophobic microorganisms respond to spatial and temporal light gradients. A step-up photophobic reaction occurs when an organism enters a brighter area field from a darker one and then reverses direction, thus avoiding the bright light. The opposite reaction, called a step-down reaction, occurs when an organism enters a dark area from a bright area and then reverses direction, thus remaining in the light.[22]

Evolution

[edit]Earth history

[edit]−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stromatolites are layered biochemical accretionary structures formed in shallow water by the trapping, binding, and cementation of sedimentary grains by biofilms (microbial mats) of microorganisms, especially cyanobacteria.[171]

During the Precambrian, stromatolite communities of microorganisms grew in most marine and non-marine environments in the photic zone. After the Cambrian explosion of marine animals, grazing on the stromatolite mats by herbivores greatly reduced the occurrence of the stromatolites in marine environments. Since then, they are found mostly in hypersaline conditions where grazing invertebrates cannot live (e.g. Shark Bay, Western Australia). Stromatolites provide ancient records of life on Earth by fossil remains which date from 3.5 Ga ago.[172] The oldest undisputed evidence of cyanobacteria is dated to be 2.1 Ga ago, but there is some evidence for them as far back as 2.7 Ga ago.[27] Cyanobacteria might have also emerged 3.5 Ga ago.[173] Oxygen concentrations in the atmosphere remained around or below 0.001% of today's level until 2.4 Ga ago (the Great Oxygenation Event).[174] The rise in oxygen may have caused a fall in the concentration of atmospheric methane, and triggered the Huronian glaciation from around 2.4 to 2.1 Ga ago. In this way, cyanobacteria may have killed off most of the other bacteria of the time.[175]

Oncolites are sedimentary structures composed of oncoids, which are layered structures formed by cyanobacterial growth. Oncolites are similar to stromatolites, but instead of forming columns, they form approximately spherical structures that were not attached to the underlying substrate as they formed.[176] The oncoids often form around a central nucleus, such as a shell fragment,[177] and a calcium carbonate structure is deposited by encrusting microbes. Oncolites are indicators of warm waters in the photic zone, but are also known in contemporary freshwater environments.[178] These structures rarely exceed 10 cm in diameter.

One former classification scheme of cyanobacterial fossils divided them into the porostromata and the spongiostromata. These are now recognized as form taxa and considered taxonomically obsolete; however, some authors have advocated for the terms remaining informally to describe form and structure of bacterial fossils.[179]

-

Stromatolites left behind by cyanobacteria are the oldest known fossils of life on Earth. This fossil is one billion years old.

-

Oncolitic limestone formed from successive layers of calcium carbonate precipitated by cyanobacteria

-

Cyanobacterial remains of an annulated tubular microfossil Oscillatoriopsis longa [180]

Scale bar: 100 μm

Origin of photosynthesis

[edit]Oxygenic photosynthesis only evolved once (in prokaryotic cyanobacteria), and all photosynthetic eukaryotes (including all plants and algae) have acquired this ability from endosymbiosis with cyanobacteria or their endosymbiont hosts. In other words, all the oxygen that makes the atmosphere breathable for aerobic organisms originally comes from cyanobacteria or their plastid descendants.[181]

Cyanobacteria remained the principal primary producers throughout the latter half of the Archean eon and most of the Proterozoic eon, in part because the redox structure of the oceans favored photoautotrophs capable of nitrogen fixation. However, their population is argued to have varied considerably across this eon.[10][182][183] Archaeplastids such as green and red algae eventually surpassed cyanobacteria as major primary producers on continental shelves near the end of the Neoproterozoic, but only with the Mesozoic (251–65 Ma) radiations of secondary photoautotrophs such as dinoflagellates, coccolithophorids and diatoms did primary production in marine shelf waters take modern form. Cyanobacteria remain critical to marine ecosystems as primary producers in oceanic gyres, as agents of biological nitrogen fixation, and, in modified form, as the plastids of marine algae.[184]

Origin of chloroplasts

[edit]Primary chloroplasts are cell organelles found in some eukaryotic lineages, where they are specialized in performing photosynthesis. They are considered to have evolved from endosymbiotic cyanobacteria.[185][186] After some years of debate,[187] it is now generally accepted that the three major groups of primary endosymbiotic eukaryotes (i.e. green plants, red algae and glaucophytes) form one large monophyletic group called Archaeplastida, which evolved after one unique endosymbiotic event.[188][189][190][191]

The morphological similarity between chloroplasts and cyanobacteria was first reported by German botanist Andreas Franz Wilhelm Schimper in the 19th century[192] Chloroplasts are only found in plants and algae,[193] thus paving the way for Russian biologist Konstantin Mereschkowski to suggest in 1905 the symbiogenic origin of the plastid.[194] Lynn Margulis brought this hypothesis back to attention more than 60 years later[195] but the idea did not become fully accepted until supplementary data started to accumulate. The cyanobacterial origin of plastids is now supported by various pieces of phylogenetic,[196][188][191] genomic,[197] biochemical[198][199] and structural evidence.[200] The description of another independent and more recent primary endosymbiosis event between a cyanobacterium and a separate eukaryote lineage (the rhizarian Paulinella chromatophora) also gives credibility to the endosymbiotic origin of the plastids.[201]

In addition to this primary endosymbiosis, many eukaryotic lineages have been subject to secondary or even tertiary endosymbiotic events, that is the "Matryoshka-like" engulfment by a eukaryote of another plastid-bearing eukaryote.[203][185]

Chloroplasts have many similarities with cyanobacteria, including a circular chromosome, prokaryotic-type ribosomes, and similar proteins in the photosynthetic reaction center.[204][205] The endosymbiotic theory suggests that photosynthetic bacteria were acquired (by endocytosis) by early eukaryotic cells to form the first plant cells. Therefore, chloroplasts may be photosynthetic bacteria that adapted to life inside plant cells. Like mitochondria, chloroplasts still possess their own DNA, separate from the nuclear DNA of their plant host cells and the genes in this chloroplast DNA resemble those in cyanobacteria.[206] DNA in chloroplasts codes for redox proteins such as photosynthetic reaction centers. The CoRR hypothesis proposes this co-location is required for redox regulation.

Marine origins

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

Cyanobacteria have fundamentally transformed the geochemistry of the planet.[210][207] Multiple lines of geochemical evidence support the occurrence of intervals of profound global environmental change at the beginning and end of the Proterozoic (2,500–542 Mya).[211] [212][213] While it is widely accepted that the presence of molecular oxygen in the early fossil record was the result of cyanobacteria activity, little is known about how cyanobacteria evolution (e.g., habitat preference) may have contributed to changes in biogeochemical cycles through Earth history. Geochemical evidence has indicated that there was a first step-increase in the oxygenation of the Earth's surface, which is known as the Great Oxidation Event (GOE), in the early Paleoproterozoic (2,500–1,600 Mya).[210][207] A second but much steeper increase in oxygen levels, known as the Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event (NOE),[212][81][214] occurred at around 800 to 500 Mya.[213][215] Recent chromium isotope data point to low levels of atmospheric oxygen in the Earth's surface during the mid-Proterozoic,[211] which is consistent with the late evolution of marine planktonic cyanobacteria during the Cryogenian;[216] both types of evidence help explain the late emergence and diversification of animals.[217][43]

Understanding the evolution of planktonic cyanobacteria is important because their origin fundamentally transformed the nitrogen and carbon cycles towards the end of the Pre-Cambrian.[215] It remains unclear, however, what evolutionary events led to the emergence of open-ocean planktonic forms within cyanobacteria and how these events relate to geochemical evidence during the Pre-Cambrian.[212] So far, it seems that ocean geochemistry (e.g., euxinic conditions during the early- to mid-Proterozoic)[212][214][218] and nutrient availability [219] likely contributed to the apparent delay in diversification and widespread colonization of open ocean environments by planktonic cyanobacteria during the Neoproterozoic.[215][43]

Genetics

[edit]Cyanobacteria are capable of natural genetic transformation.[220][221][222] Natural genetic transformation is the genetic alteration of a cell resulting from the direct uptake and incorporation of exogenous DNA from its surroundings. For bacterial transformation to take place, the recipient bacteria must be in a state of competence, which may occur in nature as a response to conditions such as starvation, high cell density or exposure to DNA damaging agents. In chromosomal transformation, homologous transforming DNA can be integrated into the recipient genome by homologous recombination, and this process appears to be an adaptation for repairing DNA damage.[223]

DNA repair

[edit]Cyanobacteria are challenged by environmental stresses and internally generated reactive oxygen species that cause DNA damage. Cyanobacteria possess numerous E. coli-like DNA repair genes.[224] Several DNA repair genes are highly conserved in cyanobacteria, even in small genomes, suggesting that core DNA repair processes such as recombinational repair, nucleotide excision repair and methyl-directed DNA mismatch repair are common among cyanobacteria.[224]

Classification

[edit]Phylogeny

[edit]| 16S rRNA based LTP_12_2021[225][226][227] | GTDB 08-RS214 by Genome Taxonomy Database[228][229][230] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Taxonomy

[edit]

Historically, bacteria were first classified as plants constituting the class Schizomycetes, which along with the Schizophyceae (blue-green algae/Cyanobacteria) formed the phylum Schizophyta,[231] then in the phylum Monera in the kingdom Protista by Haeckel in 1866, comprising Protogens, Protamaeba, Vampyrella, Protomonae, and Vibrio, but not Nostoc and other cyanobacteria, which were classified with algae,[232] later reclassified as the Prokaryotes by Chatton.[233]

The cyanobacteria were traditionally classified by morphology into five sections, referred to by the numerals I–V. The first three – Chroococcales, Pleurocapsales, and Oscillatoriales – are not supported by phylogenetic studies. The latter two – Nostocales and Stigonematales – are monophyletic as a unit, and make up the heterocystous cyanobacteria.[234][235]

The members of Chroococales are unicellular and usually aggregate in colonies. The classic taxonomic criterion has been the cell morphology and the plane of cell division. In Pleurocapsales, the cells have the ability to form internal spores (baeocytes). The rest of the sections include filamentous species. In Oscillatoriales, the cells are uniseriately arranged and do not form specialized cells (akinetes and heterocysts).[236] In Nostocales and Stigonematales, the cells have the ability to develop heterocysts in certain conditions. Stigonematales, unlike Nostocales, include species with truly branched trichomes.[234]

Most taxa included in the phylum or division Cyanobacteria have not yet been validly published under The International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (ICNP) except:

- The classes Chroobacteria, Hormogoneae, and Gloeobacteria

- The orders Chroococcales, Gloeobacterales, Nostocales, Oscillatoriales, Pleurocapsales, and Stigonematales

- The families Prochloraceae and Prochlorotrichaceae

- The genera Halospirulina, Planktothricoides, Prochlorococcus, Prochloron, and Prochlorothrix

The remainder are validly published under the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants.

Formerly, some bacteria, like Beggiatoa, were thought to be colorless Cyanobacteria.[237]

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN)[238] and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).[239] Class "Cyanobacteriia"

- Subclass "Gloeobacteria" Cavalier-Smith 2002

- Gloeobacterales Cavalier-Smith 2002

- Subclass "Phycobacteria" Cavalier-Smith 2002

- Acaryochloridales Miyashita et al. 2003 ex Strunecký & Mareš 2022 [incl. Thermosynechococcales]

- Aegeococcales Strunecký & Mareš 2022

- "Elainellales"

- "Eurycoccales"

- Geitlerinematales Strunecký & Mareš 2022

- Gloeoemargaritales Moreira et al. 2016

- "Leptolyngbyales" Strunecký & Mareš 2022

- Nodosilineales Strunecký & Mareš 2022

- Oculatellales Strunecký & Mareš 2022

- "Phormidesmiales"

- Prochlorococcaceae Komárek & Strunecky 2020 {"PCC-6307"}

- Pseudanabaenales Hoffmann, Komárek & Kastovsky 2005

- "Pseudophormidiales"

- Thermostichales Komárek & Strunecký 2020

- Synechococcophycidae Hoffmann, Komárek & Kastovsky 2005

- "Limnotrichales"

- Prochlorotrichales Strunecký & Mareš 2022 (PCC-9006)

- Synechococcales Hoffmann, Komárek & Kastovsky 2005

- Nostocophycidae Hoffmann, Komárek & Kastovsky 2005

- Cyanobacteriales Rippka & Cohen-Bazire 1983 (Chamaesiphonales, Chroococcales, Chroococcidiopsidales, Nostocales, Oscillatoriales, Pleurocapsales, Spirulinales, Stigonematales)

Relation to humans

[edit]Biotechnology

[edit]

The unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 was the third prokaryote and first photosynthetic organism whose genome was completely sequenced.[240] It continues to be an important model organism.[241] Cyanothece ATCC 51142 is an important diazotrophic model organism. The smallest genomes have been found in Prochlorococcus spp. (1.7 Mb)[242][243] and the largest in Nostoc punctiforme (9 Mb).[144] Those of Calothrix spp. are estimated at 12–15 Mb,[244] as large as yeast.

Recent research has suggested the potential application of cyanobacteria to the generation of renewable energy by directly converting sunlight into electricity. Internal photosynthetic pathways can be coupled to chemical mediators that transfer electrons to external electrodes.[245][246] In the shorter term, efforts are underway to commercialize algae-based fuels such as diesel, gasoline, and jet fuel.[68][247][248] Cyanobacteria have been also engineered to produce ethanol[249] and experiments have shown that when one or two CBB genes are being over expressed, the yield can be even higher.[250][251]

Cyanobacteria may possess the ability to produce substances that could one day serve as anti-inflammatory agents and combat bacterial infections in humans.[252] Cyanobacteria's photosynthetic output of sugar and oxygen has been demonstrated to have therapeutic value in rats with heart attacks.[253] While cyanobacteria can naturally produce various secondary metabolites, they can serve as advantageous hosts for plant-derived metabolites production owing to biotechnological advances in systems biology and synthetic biology.[254]

Spirulina's extracted blue color is used as a natural food coloring.[255]

Researchers from several space agencies argue that cyanobacteria could be used for producing goods for human consumption in future crewed outposts on Mars, by transforming materials available on this planet.[256]

Human nutrition

[edit]

Some cyanobacteria are sold as food, notably Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina) and others (Aphanizomenon flos-aquae).[257]

Some microalgae contain substances of high biological value, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids, amino acids, proteins, pigments, antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals.[258] Edible blue-green algae reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by inhibiting NF-κB pathway in macrophages and splenocytes.[259] Sulfate polysaccharides exhibit immunomodulatory, antitumor, antithrombotic, anticoagulant, anti-mutagenic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and even antiviral activity against HIV, herpes, and hepatitis.[260]

Health risks

[edit]Some cyanobacteria can produce neurotoxins, cytotoxins, endotoxins, and hepatotoxins (e.g., the microcystin-producing bacteria genus microcystis), which are collectively known as cyanotoxins.

Specific toxins include anatoxin-a, guanitoxin, aplysiatoxin, cyanopeptolin, cylindrospermopsin, domoic acid, nodularin R (from Nodularia), neosaxitoxin, and saxitoxin. Cyanobacteria reproduce explosively under certain conditions. This results in algal blooms which can become harmful to other species and pose a danger to humans and animals if the cyanobacteria involved produce toxins. Several cases of human poisoning have been documented, but a lack of knowledge prevents an accurate assessment of the risks,[261][262][263][264] and research by Linda Lawton, FRSE at Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen and collaborators has 30 years of examining the phenomenon and methods of improving water safety.[265]

Recent studies suggest that significant exposure to high levels of cyanobacteria producing toxins such as BMAA can cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). People living within half a mile of cyanobacterially contaminated lakes have had a 2.3 times greater risk of developing ALS than the rest of the population; people around New Hampshire's Lake Mascoma had an up to 25 times greater risk of ALS than the expected incidence.[266] BMAA from desert crusts found throughout Qatar might have contributed to higher rates of ALS in Gulf War veterans.[262][267]

Chemical control

[edit]Several chemicals can eliminate cyanobacterial blooms from smaller water-based systems such as swimming pools. They include calcium hypochlorite, copper sulphate, Cupricide (chelated copper), and simazine.[268] The calcium hypochlorite amount needed varies depending on the cyanobacteria bloom, and treatment is needed periodically. According to the Department of Agriculture Australia, a rate of 12 g of 70% material in 1000 L of water is often effective to treat a bloom.[268] Copper sulfate is also used commonly, but no longer recommended by the Australian Department of Agriculture, as it kills livestock, crustaceans, and fish.[268] Cupricide is a chelated copper product that eliminates blooms with lower toxicity risks than copper sulfate. Dosage recommendations vary from 190 mL to 4.8 L per 1000 m2.[268] Ferric alum treatments at the rate of 50 mg/L will reduce algae blooms.[268][269] Simazine, which is also a herbicide, will continue to kill blooms for several days after an application. Simazine is marketed at different strengths (25, 50, and 90%), the recommended amount needed for one cubic meter of water per product is 25% product 8 mL; 50% product 4 mL; or 90% product 2.2 mL.[268]

Climate change

[edit]Climate change is likely to increase the frequency, intensity and duration of cyanobacterial blooms in many eutrophic lakes, reservoirs and estuaries.[270][32] Bloom-forming cyanobacteria produce a variety of neurotoxins, hepatotoxins and dermatoxins, which can be fatal to birds and mammals (including waterfowl, cattle and dogs) and threaten the use of waters for recreation, drinking water production, agricultural irrigation and fisheries.[32] Toxic cyanobacteria have caused major water quality problems, for example in Lake Taihu (China), Lake Erie (USA), Lake Okeechobee (USA), Lake Victoria (Africa) and the Baltic Sea.[32][271][272][273]

Climate change favours cyanobacterial blooms both directly and indirectly.[32] Many bloom-forming cyanobacteria can grow at relatively high temperatures.[274] Increased thermal stratification of lakes and reservoirs enables buoyant cyanobacteria to float upwards and form dense surface blooms, which gives them better access to light and hence a selective advantage over nonbuoyant phytoplankton organisms.[275][93] Protracted droughts during summer increase water residence times in reservoirs, rivers and estuaries, and these stagnant warm waters can provide ideal conditions for cyanobacterial bloom development.[276][273]

The capacity of the harmful cyanobacterial genus Microcystis to adapt to elevated CO2 levels was demonstrated in both laboratory and field experiments.[277] Microcystis spp. take up CO2 and HCO−

3 and accumulate inorganic carbon in carboxysomes, and strain competitiveness was found to depend on the concentration of inorganic carbon. As a result, climate change and increased CO2 levels are expected to affect the strain composition of cyanobacterial blooms.[277][273]

Gallery

[edit]-

Cyanobacteria activity turns Coatepeque Caldera lake a turquoise color

-

Cyanobacterial bloom near Fiji

-

Cyanobacteria in Lake Köyliö.

-

Video – Oscillatoria and Gleocapsa – with oscillatory movement as filaments of Oscillatoria orient towards light

See also

[edit]- Archean Eon

- Bacterial phyla, other major lineages of Bacteria

- Biodiesel

- Cyanobiont

- Endosymbiotic theory

- Geological history of oxygen

- Hypolith

Notes

[edit]- ^ Botanists restrict the name algae to protist eukaryotes, which does not extend to cyanobacteria, which are prokaryotes. However, the common name blue-green algae continues to be used synonymously with cyanobacteria outside of the biological sciences.

References

[edit]- ^ Silva PC, Moe RL (December 2019). "Cyanophyceae". AccessScience. McGraw Hill Education. doi:10.1036/1097-8542.175300. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ Oren A (September 2004). "A proposal for further integration of the cyanobacteria under the Bacteriological Code". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 54 (Pt 5): 1895–1902. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.03008-0. PMID 15388760.

- ^ Komárek J, Kaštovský J, Mareš J, Johansen JR (2014). "Taxonomic classification of cyanoprokaryotes (cyanobacterial genera) 2014, using a polyphasic approach" (PDF). Preslia. 86: 295–335.

- ^ Sinha RP, Häder DP (2008). "UV-protectants in cyanobacteria". Plant Science. 174 (3): 278–289. Bibcode:2008PlnSc.174..278S. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.12.004.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "cyan". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ κύανος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ "Life History and Ecology of Cyanobacteria". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "Taxonomy Browser – Cyanobacteria". National Center for Biotechnology Information. NCBI:txid1117. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Allaby M, ed. (1992). "Algae". The Concise Dictionary of Botany. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crockford PW, Bar On YM, Ward LM, Milo R, Halevy I (November 2023). "The geologic history of primary productivity". Current Biology. 33 (21): 4741–4750.e5. Bibcode:2023CBio...33E4741C. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2023.09.040. PMID 37827153. S2CID 263839383.

- ^ Stal LJ, Cretoiu MS (2016). The Marine Microbiome: An Untapped Source of Biodiversity and Biotechnological Potential. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-3319330006.

- ^ Whitton BA, ed. (2012). "The fossil record of cyanobacteria". Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 17. ISBN 978-94-007-3855-3.

- ^ "Bacteria". Basic Biology. 18 March 2016.

- ^ Liberton M, Pakrasi HB (2008). "Chapter 10. Membrane Systems in Cyanobacteria". In Herrero A, Flore E (eds.). The Cyanobacteria: Molecular Biology, Genomics, and Evolution. Norwich, United Kingdom: Horizon Scientific Press. pp. 217–287. ISBN 978-1-904455-15-8.

- ^ Liberton M, Page LE, O'Dell WB, O'Neill H, Mamontov E, Urban VS, Pakrasi HB (February 2013). "Organization and flexibility of cyanobacterial thylakoid membranes examined by neutron scattering". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288 (5): 3632–3640. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.416933. PMC 3561581. PMID 23255600.

- ^ Monchamp ME, Spaak P, Pomati F (27 July 2019). "Long Term Diversity and Distribution of Non-photosynthetic Cyanobacteria in Peri-Alpine Lakes". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9: 3344. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.03344. PMC 6340189. PMID 30692982.

- ^ Pathak J, Rajneesh, Maurya PK, Singh SP, Haeder DP, Sinha RP (2018). "Cyanobacterial Farming for Environment Friendly Sustainable Agriculture Practices: Innovations and Perspectives". Frontiers in Environmental Science. 6. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2018.00007. ISSN 2296-665X.

- ^ Morrison J (11 January 2016). "Living Bacteria Are Riding Earth's Air Currents". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Whitton BA, Potts M (2012). "Introduction to the Cyanobacteria". In Whitton BA (ed.). Ecology of Cyanobacteria II. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-3855-3_1. ISBN 978-94-007-3854-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tamulonis C, Postma M, Kaandorp J (2011). "Modeling filamentous cyanobacteria reveals the advantages of long and fast trichomes for optimizing light exposure". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e22084. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622084T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022084. PMC 3138769. PMID 21789215.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stay LJ (5 July 2012). "Cyanobacterial Mats and Stromatolites". In Whitton BA (ed.). Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789400738553. Retrieved 15 February 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Tamulonis C, Postma M, Kaandorp J (2011). "Modeling filamentous cyanobacteria reveals the advantages of long and fast trichomes for optimizing light exposure". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e22084. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622084T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022084. PMC 3138769. PMID 21789215.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Weiss KR (30 July 2006). "A Primeval Tide of Toxins". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 14 August 2006.

- ^ Dodds WK, Gudder DA, Mollenhauer D (1995). "The ecology of 'Nostoc'". Journal of Phycology. 31 (1): 2–18. Bibcode:1995JPcgy..31....2D. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3646.1995.00002.x. S2CID 85011483.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Aguilera A, Klemenčič M, Sueldo DJ, Rzymski P, Giannuzzi L, Martin MV (2021). "Cell Death in Cyanobacteria: Current Understanding and Recommendations for a Consensus on Its Nomenclature". Frontiers in Microbiology. 12: 631654. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.631654. PMC 7965980. PMID 33746925.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Raven RA (5 July 2012). "Physiological Ecology: Carbon". In Whitton BA (ed.). Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time. Springer. p. 442. ISBN 9789400738553.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schirrmeister BE, de Vos JM, Antonelli A, Bagheri HC (January 2013). "Evolution of multicellularity coincided with increased diversification of cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (5): 1791–1796. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1791S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209927110. PMC 3562814. PMID 23319632.

- ^ Bullerjahn GS, Post AF (2014). "Physiology and molecular biology of aquatic cyanobacteria". Frontiers in Microbiology. 5: 359. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00359. PMC 4099938. PMID 25076944.

- ^ Tang W, Wang S, Fonseca-Batista D, Dehairs F, Gifford S, Gonzalez AG, et al. (February 2019). "Revisiting the distribution of oceanic N2 fixation and estimating diazotrophic contribution to marine production". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 831. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08640-0. PMC 6381160. PMID 30783106.

- ^ Bláha L, Babica P, Maršálek B (June 2009). "Toxins produced in cyanobacterial water blooms - toxicity and risks". Interdisciplinary Toxicology. 2 (2): 36–41. doi:10.2478/v10102-009-0006-2. PMC 2984099. PMID 21217843.

- ^ Paerl HW, Otten TG (May 2013). "Harmful cyanobacterial blooms: causes, consequences, and controls". Microbial Ecology. 65 (4): 995–1010. Bibcode:2013MicEc..65..995P. doi:10.1007/s00248-012-0159-y. PMID 23314096. S2CID 5718333.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Huisman J, Codd GA, Paerl HW, Ibelings BW, Verspagen JM, Visser PM (August 2018). "Cyanobacterial blooms". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 16 (8): 471–483. doi:10.1038/s41579-018-0040-1. PMID 29946124. S2CID 49427202.

- ^ Филд CB, Беренфельд М.Дж., Рандерсон Дж.Т., Фальковски П. (июль 1998 г.). «Первичная продукция биосферы: интеграция наземных и океанических компонентов» . Наука . 281 (5374): 237–240. Бибкод : 1998Sci...281..237F . дои : 10.1126/science.281.5374.237 . ПМИД 9657713 .

- ^ Кабельо-Йевес П.Дж., Сканлан Дж., Каллиери С., Пикасо А., Шалленберг Л., Хубер П. и др. (октябрь 2022 г.). «α-цианобактерии, обладающие формой IA RuBisCO, глобально доминируют в водных средах обитания» . Журнал ISME . 16 (10). ООО «Спрингер Сайенс энд Бизнес Медиа»: 2421–2432. Бибкод : 2022ISMEJ..16.2421C . дои : 10.1038/s41396-022-01282-z . ПМЦ 9477826 . ПМИД 35851323 .

Измененный текст был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен по международной лицензии Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 .

Измененный текст был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен по международной лицензии Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Зер Дж. П. (апрель 2011 г.). «Азотфиксация морскими цианобактериями». Тенденции в микробиологии . 19 (4): 162–173. дои : 10.1016/j.tim.2010.12.004 . ПМИД 21227699 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Томпсон А.В., Фостер Р.А., Крупке А., Картер Б.Дж., Мусат Н., Валот Д. и др. (сентябрь 2012 г.). «Одноклеточная цианобактерия, симбиотическая с одноклеточной эукариотической водорослью». Наука . 337 (6101): 1546–1550. Бибкод : 2012Sci...337.1546T . дои : 10.1126/science.1222700 . ПМИД 22997339 . S2CID 7071725 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джонсон З.И., Зинсер Э.Р., Коу А., МакНалти Н.П., Вудворд Э.М., Чисхолм С.В. (март 2006 г.). «Разделение ниш между экотипами Prochromococcus по градиентам окружающей среды в масштабе океана». Наука . 311 (5768): 1737–1740. Бибкод : 2006Sci...311.1737J . дои : 10.1126/science.1118052 . ПМИД 16556835 . S2CID 3549275 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сканлан Д.Д., Островски М., Мазар С., Дюфрен А., Гарчарек Л., Хесс В.Р. и др. (июнь 2009 г.). «Экологическая геномика морских пикоцианобактерий» . Обзоры микробиологии и молекулярной биологии . 73 (2): 249–299. дои : 10.1128/MMBR.00035-08 . ПМЦ 2698417 . ПМИД 19487728 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фломбаум П., Гальегос Дж.Л., Гордилло Р.А., Корнер Дж., Шафран Л.Л., Цзяо Н. и др. (июнь 2013 г.). «Настоящее и будущее глобальное распространение морских цианобактерий Prochromococcus и Synechococcus» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 110 (24): 9824–9 Бибкод : 2013PNAS..110.9824F . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1307701110 . ПМЦ 3683724 . ПМИД 23703908 .

- ^ Фостер Р.А., Кайперс М.М., Вагнер Т., Паерл Р.В., Мусат Н., Зер Дж.П. (сентябрь 2011 г.). «Фиксация и перенос азота в диатомо-цианобактериальных симбиозах открытого океана» . Журнал ISME . 5 (9): 1484–1493. Бибкод : 2011ISMEJ...5.1484F . дои : 10.1038/ismej.2011.26 . ПМК 3160684 . ПМИД 21451586 .

- ^ Вильярреал ТА (1990). «Лабораторная культура и предварительная характеристика азотфиксирующего симбиоза ризосолении и рихелии». Морская экология . 11 (2): 117–132. Бибкод : 1990Март..11..117В . дои : 10.1111/j.1439-0485.1990.tb00233.x .

- ^ Янсон С., Воутерс Дж., Бергман Б., Карпентер Э.Дж. (октябрь 1999 г.). «Специфичность хозяина в симбиозе Richelia-диатомовых водорослей, выявленная с помощью анализа последовательности гена hetR». Экологическая микробиология . 1 (5): 431–438. Бибкод : 1999EnvMi...1..431J . дои : 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00053.x . ПМИД 11207763 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Санчес-Баракальдо П. (декабрь 2015 г.). «Происхождение морских планктонных цианобактерий» . Научные отчеты . 5 : 17418. Бибкод : 2015NatSR...517418S . дои : 10.1038/srep17418 . ПМК 4665016 . ПМИД 26621203 .

Материал был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен по международной лицензии Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 .

Материал был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен по международной лицензии Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 .

- ^ Кеттлер Г.К., Мартини А.С., Хуанг К., Цукер Дж., Коулман М.Л., Родриг С. и др. (декабрь 2007 г.). «Закономерности и последствия приобретения и потери генов в эволюции прохлорококка» . ПЛОС Генетика . 3 (12): е231. дои : 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030231 . ПМК 2151091 . ПМИД 18159947 .

- ^ Немирофф Р., Боннелл Дж., ред. (27 сентября 2006 г.). «Земля от Сатурна» . Астрономическая картина дня . НАСА .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Партенский Ф., Гесс В.Р., Вало Д. (март 1999 г.). «Прохлорококк, морской фотосинтезирующий прокариот мирового значения» . Обзоры микробиологии и молекулярной биологии . 63 (1): 106–127. дои : 10.1128/ММБР.63.1.106-127.1999 . ПМК 98958 . ПМИД 10066832 .

- ^ «Самый важный микроб, о котором вы никогда не слышали» . npr.org .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Классен Д., Розен Д.Е., Койперс О.П., Согаард-Андерсен Л., ван Везель Г.П. (февраль 2014 г.). «Бактериальные решения проблемы многоклеточности: рассказ о биопленках, нитях и плодовых телах» (PDF) . Обзоры природы. Микробиология . 12 (2): 115–124. дои : 10.1038/nrmicro3178 . hdl : 11370/0db66a9c-72ef-4e11-a75d-9d1e5827573d . ПМИД 24384602 . S2CID 20154495 .

- ^ Нюрнбергский DJ, Марискаль В., Паркер Дж., Мастроянни Дж., Флорес Э., Муллино CW (март 2014 г.). «Ветвление и межклеточная коммуникация у цианобактерии Раздела V Mastigocladus laminosus, сложного многоклеточного прокариота». Молекулярная микробиология . 91 (5): 935–949. дои : 10.1111/mmi.12506 . hdl : 10261/99110 . ПМИД 24383541 . S2CID 25479970 .

- ^ Эрреро А., Ставанс Дж., Флорес Э. (ноябрь 2016 г.). «Многоклеточная природа нитчатых гетероцистообразующих цианобактерий». Обзоры микробиологии FEMS . 40 (6): 831–854. дои : 10.1093/femsre/fuw029 . hdl : 10261/140753 . ПМИД 28204529 .

- ^ Риссер Д.Д., Чу В.Г., Микс Дж.К. (апрель 2014 г.). «Генетическая характеристика локуса hmp, кластера генов, подобного хемотаксису, который регулирует развитие и подвижность гормогоний у Nostoc punctiforme» . Молекулярная микробиология . 92 (2): 222–233. дои : 10.1111/mmi.12552 . ПМИД 24533832 . S2CID 37479716 .

- ^ Хайатан Б., Бэйнс Д.К., Ченг М.Х., Чо Ю.В., Хьюнь Дж., Ким Р. и др. (май 2017 г.). «Предполагаемая O-связанная β- N -ацетилглюкозаминтрансфераза необходима для развития и подвижности гормонов в нитчатых цианобактериях Nostoc punctiforme» . Журнал бактериологии . 199 (9): e00075–17. дои : 10.1128/JB.00075-17 . ПМК 5388816 . ПМИД 28242721 .

- ^ Эстевес-Феррейра А.А., Кавальканти Дж.Х., Ваз М.Г., Альваренга Л.В., Нуньес-Неси А., Араужо В.Л. (2017). «Цианобактериальные нитрогеназы: филогенетическое разнообразие, регуляция и функциональные прогнозы» . Генетика и молекулярная биология . 40 (1 прил. 1): 261–275. дои : 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2016-0050 . ПМЦ 5452144 . ПМИД 28323299 .

- ^ Микс Дж.К., Элхай Дж., Тиль Т., Поттс М., Лаример Ф., Ламердин Дж. и др. (2001). «Обзор генома Nostoc punctiforme, многоклеточной симбиотической цианобактерии». Исследования фотосинтеза . 70 (1): 85–106. дои : 10.1023/А:1013840025518 . ПМИД 16228364 . S2CID 8752382 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Golden JW, Юн Х.С. (декабрь 1998 г.). «Формирование гетероцист в Анабаене». Современное мнение в микробиологии . 1 (6): 623–629. дои : 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80106-9 . ПМИД 10066546 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Фэй П. (июнь 1992 г.). «Кислородные отношения азотфиксации у цианобактерий» . Микробиологические обзоры . 56 (2): 340–373. дои : 10.1128/MMBR.56.2.340-373.1992 . ПМК 372871 . ПМИД 1620069 .

- ^ Сингх В., Панде ПК, Джайн Д.К. (ред.). «Цианобактерии, актиномицеты, микоплазмы и риккетсии» . Учебник по ботанике «Разнообразие микробов и криптогам» . Публикации Растоги. п. 72. ИСБН 978-8171338894 .

- ^ «Различия между бактериями и цианобактериями» . Заметки по микробиологии . 29 октября 2015 года . Проверено 21 января 2018 г.

- ^ Уолсби А.Е. (март 1994 г.). «Газовые пузырьки» . Микробиологические обзоры . 58 (1): 94–144. дои : 10.1128/ММБР.58.1.94-144.1994 . ПМК 372955 . ПМИД 8177173 .

- ^

Симс ГК, Дуниган EP (1984). «Суточные и сезонные изменения активности нитрогеназы C

22Ч

2 сокращение) корней риса». Биология и биохимия почвы . 16 : 15–18. doi : 10.1016/0038-0717(84)90118-4 . - ^ Бокки С., Мальджиольо А (2010). «Азолла-Анабаена как биоудобрение для рисовых полей в долине реки По, рисовой зоне с умеренным климатом в Северной Италии» . Международный журнал агрономии . 2010 : 1–5. дои : 10.1155/2010/152158 . hdl : 2434/149583 .

- ^ Хуокко Т., Ни Т., Дайкс Г.Ф., Симпсон Д.М., Браунридж П., Конради Ф.Д. и др. (июнь 2021 г.). «Изучение пути биогенеза и динамики тилакоидных мембран» . Природные коммуникации . 12 (1): 3475. Бибкод : 2021NatCo..12.3475H . дои : 10.1038/s41467-021-23680-1 . ПМЦ 8190092 . ПМИД 34108457 .

- ^ Керфельд Калифорния, Хайнхорст С, Кэннон GC (2010). «Бактериальные микрокомпарты» . Ежегодный обзор микробиологии . 64 (1): 391–408. дои : 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134211 . ПМК 6022854 . ПМИД 20825353 .

- ^ Рэй Б.Д., Лонг Б.М., Бэджер М.Р., Прайс Г.Д. (сентябрь 2013 г.). «Функции, состав и эволюция двух типов карбоксисом: многогранных микрокомпартментов, облегчающих фиксацию CO2 у цианобактерий и некоторых протеобактерий» . Обзоры микробиологии и молекулярной биологии . 77 (3): 357–379. дои : 10.1128/MMBR.00061-12 . ПМЦ 3811607 . ПМИД 24006469 .

- ^ Лонг Б.М., Бэджер М.Р., Уитни С.М., Прайс Г.Д. (октябрь 2007 г.). «Анализ карбоксисом Synechococcus PCC7942 выявил множественные комплексы Рубиско с карбоксисомными белками CcmM и CcaA» . Журнал биологической химии . 282 (40): 29323–29335. дои : 10.1074/jbc.M703896200 . ПМИД 17675289 .

- ^ Воткнехт Калифорнийский университет, Вестхофф П. (декабрь 2001 г.). «Биогенез и происхождение тилакоидных мембран» . Biochimica et Biophysical Acta (BBA) - Исследования молекулярных клеток . 1541 (1–2): 91–101. дои : 10.1016/S0167-4889(01)00153-7 . ПМИД 11750665 .

- ^ Собеховска-Сасим М, Стон-Эгерт Дж, Косаковска А (февраль 2014 г.). «Количественный анализ экстрагированных фикобилиновых пигментов в цианобактериях – оценка спектрофотометрическими и спектрофлуориметрическими методами» . Журнал прикладной психологии . 26 (5): 2065–2074. Бибкод : 2014JAPco..26.2065S . дои : 10.1007/s10811-014-0244-3 . ПМК 4200375 . ПМИД 25346572 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пишотта Дж.М., Зоу Ю., Баскаков И.В. (май 2010 г.). Ян Ч. (ред.). «Светозависимая электрогенная активность цианобактерий» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 5 (5): е10821. Бибкод : 2010PLoSO...510821P . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0010821 . ПМК 2876029 . ПМИД 20520829 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Вермаас В.Ф. (2001). «Фотосинтез и дыхание цианобактерий». Фотосинтез и дыхание цианобактерий. ЭЛС . John Wiley & Sons , Ltd. doi : 10.1038/npg.els.0001670 . ISBN 978-0-470-01590-2 . S2CID 19016706 .

- ^ Армстронф Дж. Э. (2015). Как Земля стала зеленой: краткая история растений за 3,8 миллиарда лет . университета Издательство Чикагского . ISBN 978-0-226-06977-7 .

- ^ Клатт Дж. М., де Бир Д., Хойслер С., Полерецкий Л. (2016). «Цианобактерии в микробных матах сульфидного источника могут осуществлять кислородный и аноксигенный фотосинтез одновременно в течение всего суточного периода» . Границы микробиологии . 7 : 1973. doi : 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01973 . ПМК 5156726 . ПМИД 28018309 .

- ^ Гроссман А.Р., Шефер М.Р., Чан Г.Г., Кольер Дж.Л. (сентябрь 1993 г.). «Фикобилисома, светособирающий комплекс, реагирующий на условия окружающей среды» . Микробиологические обзоры . 57 (3): 725–749. дои : 10.1128/MMBR.57.3.725-749.1993 . ПМК 372933 . PMID 8246846 .

- ^ «Цвета от бактерий | Причины цвета» . www.webexhibits.org . Проверено 22 января 2018 г.

- ^ Гарсия-Пишель Ф (2009). «Цианобактерии». В Шехтере М. (ред.). Энциклопедия микробиологии (третье изд.). стр. 107–24. дои : 10.1016/B978-012373944-5.00250-9 . ISBN 978-0-12-373944-5 .

- ^ Кехо Д.М. (май 2010 г.). «Хроматическая адаптация и эволюция светочувствительности у цианобактерий» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 107 (20): 9029–9030. Бибкод : 2010PNAS..107.9029K . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1004510107 . ПМЦ 2889117 . ПМИД 20457899 .

- ^ Кехо Д.М., Гуту А. (2006). «Реакция на цвет: регуляция дополнительной хроматической адаптации». Ежегодный обзор биологии растений . 57 : 127–150. doi : 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105215 . ПМИД 16669758 .

- ^ Паленик Б., Хазелькорн Р. (январь 1992 г.). «Множественное эволюционное происхождение прохлорофитов, прокариот, содержащих хлорофилл b». Природа . 355 (6357): 265–267. Бибкод : 1992Natur.355..265P . дои : 10.1038/355265a0 . ПМИД 1731224 . S2CID 4244829 .

- ^ Урбах Э., Робертсон Д.Л., Чисхолм С.В. (январь 1992 г.). «Множественное эволюционное происхождение прохлорофитов в цианобактериальной радиации». Природа . 355 (6357): 267–270. Бибкод : 1992Natur.355..267U . дои : 10.1038/355267a0 . ПМИД 1731225 . S2CID 2011379 .

- ^ Коэн Ю., Йоргенсен Б.Б., Ревсбех Н.П., Поплавски Р. (февраль 1986 г.). «Адаптация к сероводороду кислородного и аноксигенного фотосинтеза цианобактерий» . Прикладная и экологическая микробиология . 51 (2): 398–407. Бибкод : 1986ApEnM..51..398C . дои : 10.1128/АЕМ.51.2.398-407.1986 . ПМК 238881 . ПМИД 16346996 .

- ^ Бланкеншип RE (2014). Молекулярные механизмы фотосинтеза . Уайли-Блэквелл . стр. 147–73. ISBN 978-1-4051-8975-0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Оч Л.М., Шилдс-Чжоу Г.А. (январь 2012 г.). «Неопротерозойское событие оксигенации: экологические возмущения и биогеохимический цикл». Обзоры наук о Земле . 110 (1–4): 26–57. Бибкод : 2012ESRv..110...26O . doi : 10.1016/j.earscirev.2011.09.004 .

- ^ Адамс Д.Г., Бергман Б., Нирцвицки-Бауэр С.А., Дагган П.С., Рай А.Н., Шюсслер А (2013). «Цианобактериально-растительные симбиозы». Розенберг Э., Делонг Э.Ф., Лори С., Стакебрандт Э., Томпсон Ф. (ред.). Прокариоты . Шпрингер, Берлин, Гейдельберг. стр. 359–400. дои : 10.1007/978-3-642-30194-0_17 . ISBN 978-3-642-30193-3 .

- ^ Чжан С., Брайант Д.А. (декабрь 2011 г.). «Цикл трикарбоновых кислот у цианобактерий». Наука . 334 (6062): 1551–1553. Бибкод : 2011Sci...334.1551Z . дои : 10.1126/science.1210858 . ПМИД 22174252 . S2CID 206536295 .