Южный Океан

| Земный океан |

|---|

|

Основная пять океанов дивизион: Дальнейшее подразделение: Маргинальные моря |

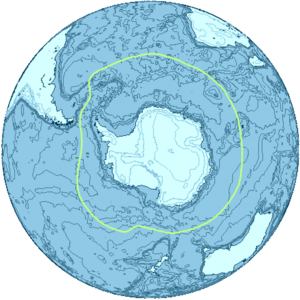

Южный океан , также известный как Антарктический океан , [ 1 ] [ Примечание 4 ] Содержит самые южные воды в мире океана , которые обычно находятся на юге от 60 ° S, и окружают Антарктиду . [ 5 ] С размером 20 327 000 км 2 (7 848 000 кв. МИ), это второе место из пяти основных океанических дивизий, меньше, чем Тихоокеанский , Атлантический и Индийский океаны, и больше, чем в Северном океане . [ 6 ]

Максимальная глубина южного океана, используя определение, которое он находится к югу от 60 -й параллели, была обследована пяти глубокой экспедицией в начале февраля 2019 года. Многоцепочечная команда экспедиции определила самую глубокую точку при 60 ° 28 '46 "с, 025 ° 32 '32 дюйма, с глубиной 7,434 метра (24 390 футов). Руководитель экспедиции и главный пилотный пилот Виктор Весково предложил назвать этот самый глубокий момент «фактором глубокой», основанный на названии экипажного погружного DSV -фактора , в котором он успешно посетил дно впервые 3 февраля 2019 Полем [ 7 ]

Своими путешествиями в 1770 -х годах Джеймс Кук доказал, что воды охватывали южные широты земного шара. Тем не менее, географы часто не согласны с тем, следует ли определить южный океан как тело воды, связанного сезонно флуктуирующей антарктической конвергенцией - океанической зоной , где холодные, текущие воды на севере из антарктической смеси с более теплыми субантарктическими водами, водами, водами, с более теплыми субантарктическими водами , водами теплыми субантарктическими водами. [ 8 ] или вообще не определен, с его водами, вместо этого рассматривались как южные пределы Тихого океана, Атлантики и Индийского океана. Международная гидрографическая организация (IHO), наконец, установила дебаты после того, как была установлена полная важность переворачивающей циркуляции в Южном океане , и термин «Южный океан» теперь определяет водоем, который находится к югу от северного предела этого циркуляции. [ 9 ]

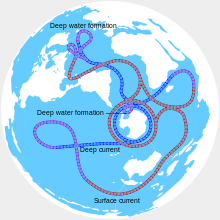

Обвижение южного океана важна, потому что она составляет вторую половину глобальной термогалиновой циркуляции после более известной атлантической меридиональной переворачивающей циркуляции (AMOC). [ 10 ] Подобно тому, как AMOC, это также повлияло на изменение климата , таким образом, что увеличило стратификацию океана , [ 11 ] и что также может привести к тому, что циркуляция существенно замедлит или даже пропустить переломный момент и сжатие. Последний окажет неблагоприятное воздействие на глобальную погоду и функцию морских экосистем здесь, разворачиваясь на протяжении веков. [ 12 ] [ 13 ] Непрерывное потепление уже меняет морские экосистемы здесь. [ 14 ]

Определение и термин использование

[ редактировать ]

Границы и имена для океанов и морей были согласованы на международном уровне, когда Международное гидрографическое бюро , предшественник IHO, созвал первую международную конференцию 24 июля 1919 года. Затем IHO опубликовал их в своих пределах океанов и морей , первое издание 1928 года. . С 1953 года он был опущен из официальной публикации и оставлен в местных гидрографических учреждениях, чтобы определить свои собственные пределы.

IHO включил океан и его определение как воды к югу от 60 -го параллельного юга в его изменениях 2000 года, но это не было официально принято из -за продолжающихся упущенных по поводу некоторых из содержания, таких как споры именования над Японским морем Полем Определение IHO 2000 года распространялось как проект издания в 2002 году и используется некоторыми в IHO и других организациях, таких как World Factbook CIA и Merriam-Webster . [ 6 ] [ 15 ]

Правительство Австралии считает Южный Океан как лежащий непосредственно к югу от Австралии (см. ). [ 16 ] [ 17 ]

Национальное географическое общество признало океан официально в июне 2021 года. [ 18 ] [ 19 ] До этого он изобразил его в шрифте, отличном от других мировых океанов; Вместо этого он показывает тихоокеанский, атлантический и индийский океаны, простирающиеся до Антарктиды как на его печатных, так и на онлайн -картах. [ 20 ] [ 21 ] Картовые издатели, использующие термин «Южный океан» на их картах, включают карты HEMA [ 22 ] и Geonova. [ 23 ]

До 20-го века

[ редактировать ]

«Южный океан» является устаревшим названием Тихоокеанского океана или южной части Тихого океана, придуманного испанским исследователем Васко Нуньез де Бальбоа , первым европейцем, обнаружившим Тихий океан, который подошел к нему с севера в Панаме . [ 24 ] «Южные моря» - менее архаичный синоним. Британский акт парламента 1745 года установил приз за открытие северо -западного прохода в «Западный и южный океан Америки ». [ 25 ]

Авторы, использующие «Южный океан», чтобы назвать воды, окружающие неизвестные южные полярные области, использовали различные пределы. Джеймса Кука Рассказ о его втором путешествии подразумевает, что новая Каледония граничит с ним. [ 26 ] Павлина 1795 года Географический словарь сказал, что он лежит на юге Америки и Африки »; [ 27 ] Джон Пейн в 1796 году использовал 40 градусов в качестве северного лимита; [ 28 ] 1827 года Edinburgh Gazetteer использовал 50 градусов. [ 29 ] Семейный журнал в 1835 году разделил «Великий южный океан» на «Южный океан» и «Антарктик [ sic ] океан» вдоль Антарктического круга, а северный предел южного океана - линии, соединяющиеся с Кейп -Хорном, наимень Надежда, Земля Ван Димен и юг Новой Зеландии. [ 30 ]

в Соединенном Королевстве Закон Южной Австралии 1834 года описал воды, образующие южный предел новой провинции Южной Австралии как «Южный океан». часть Отдела разграниченная Закон о законодательном совете Колонии Виктории 1881 года Бэрнсдейла как «вдоль границы Нового Южного Уэльса до южного океана». [ 31 ]

1928 Разграничение

[ редактировать ]

В первом издании в 1928 году пределы океанов и морей Южный океан был очерчен наземными пределами: Антарктидой на юге, и Южная Америка, Африка, Австралия и остров Бротон, Новая Зеландия на севере.

Подробные используемые земли были от Кейп Хорн в Чили на восток до мыса Агулхас в Африке, а затем дальше на восток до южного побережья материковой Австралии до Кейп Леувин , Западная Австралия . От мыса Леувина, затем лимит следовал на восток вдоль побережья материковой Австралии до мыса Отуэй , Виктория , затем на юг через бас -пролив до мыса Уикхем , остров Кинг , вдоль западного побережья острова Кинг, а затем оставшаяся часть пути на юг через бас. Пролив Кейп Грим , Тасмания .

Затем этот предел последовал за западным побережью Тасмании на юг к юго -восточному мысу , а затем пошел на восток на остров Бротон, Новая Зеландия, прежде чем вернуться в Кейп Хорн. [ 32 ]

1937 Разграничение

[ редактировать ]

Северные границы Южного океана были перемещены на юг во втором выпуске IHO 1937 года о пределах океанов и морей . Из этого издания большая часть северного лимита океана прекратилась, чтобы примириться.

Во втором издании южный океан затем простирался от Антарктиды на север до широты 40 ° С между Агулхас . 20 °. Кейп в Африке (длинный S между Оклендским островом Новой Зеландии (165 или 166 ° E East) и Кейп Хорн в Южной Америке (67 ° W). [ 33 ]

Как обсуждается более подробно ниже, до издания 2002 года пределы океанов явно исключали моря, лежащие в каждом из них. Великий австралийский Bight был неназван в издании 1928 года и очерчен, как показано на рисунке выше в издании 1937 года. Поэтому он охватывал бывшие воды в Южном океане, как указано в 1928 году, но технически не было ни одного из трех соседних океанов к 1937 году.

В драфте 2002 года IHO обозначили «моря» как подразделения в «океанах», так что Bight все еще находился в южном океане в 1937 году, если бы тогда было принято конвенция 2002 года. Чтобы провести прямое сравнение текущих и прежних пределов океанов, необходимо рассмотреть или, по крайней мере, быть в курсе того, как изменение в терминологии IHO в 2002 году для «морей» может повлиять на сравнение.

1953 Разграничение

[ редактировать ]Южный океан не появился в третьем издании « Пределов океанов и морей» 1953 года , записка в издании гласит:

Антарктический или южный океан был опущен в этой публикации, поскольку большинство мнений, полученных с момента выпуска 2 -го издания в 1937 году, в том, что не существует реального оправдания для применения термина океана к этому водому, северные пределы из которых трудно сложить из -за их сезонных изменений. Поэтому границы атлантических, тихоокеанских и индийских океанов были продлены на юг до антарктического континента.

Поэтому гидрографические офисы, которые выпускают отдельные публикации, касающиеся этой области, остаются для определения своих собственных северных пределов (Великобритания использует широту 55 юга.) [ 34 ] : 4

Тихоокеанские океаны (которые ранее не касались до 1953 года, согласно первым и вторым изданиям). Вместо этого, в публикации IHO 1953 года, атлантические, индийские и тихоокеанские океаны были продлены на юг, индийские и и южные пределы великого австралийского бура и Тасманского моря были перемещены на север. [ 34 ]

2002 Проект разграничения

[ редактировать ]

IHO прочитал вопрос о Южном океане в опросе в 2000 году. Из 68 стран -членов 28 ответили, и все отвечающие члены, кроме Аргентины, согласились пересмотреть океан, отразив важность океанографов на океанических токах . Предложение по названию Southern Ocean нанесло 18 голосов, обыграв альтернативный Антарктический океан . Половина голосов поддержала определение северного предела океана на 60 -м параллельном юге - без перерывов на землю в этой широте - с другими 14 голосами, поданным за другие определения, в основном 50 -й параллельный юг , но некоторые настолько на север, как 35 -й параллельный юг . Примечательно, что система наблюдений за южным океаном сопоставляет данные из широты выше 40 градусов на юг.

В августе 2002 года в августе 2002 года был распространен проект четвертого издания ограничений океанов и морей (иногда называется «издание 2000 года», поскольку оно суммировало прогресс в 2000 году). [ 36 ] Он еще не опубликован из -за «проблемных областей» нескольких стран, связанных с различными проблемами именования по всему миру - в первую очередь из -за спора на названии моря Японии - и были внесены различные изменения, 60 морей были даны новые имена, и даже Название публикации было изменено. [ 37 ] Австралия также была подана резервации в отношении пределов южного океана. [ 38 ] По сути, третье издание, которое не определило южный океан, оставляя разграничение в местные гидрографические офисы, еще не заменяется.

Несмотря на это, определение четвертого издания имеет частичное де -факто использование многих народов, ученых и таких организаций, как США ( World Factbook CIA использует «Южный океан», но ни одно из других новых имен моря в «Южном океане», такие как " Cosmonauts Sea ") и Merriam-Webster , [ 6 ] [ 15 ] [ 21 ] ученые и народы - и даже некоторые внутри IHO. [ 39 ] Гидрографические офисы некоторых наций определили свои собственные границы; Соединенное Королевство использовало 55 -й параллельный юг , например. [ 34 ] Другие организации предпочитают более северные ограничения для южного океана. Например, Encyclopædia Britannica описывает Южный океан как простирающийся на север, как Южная Америка, и дает большое значение для Антарктической конвергенции , однако его описание Индийского океана противоречит этому, описывая Индийский океан как простирание на юг до Антарктиды. [ 40 ] [ 41 ]

Другие источники, такие как Национальное географическое общество , показывают, что Атлантический , Тихоокеанский и Индийский океаны распространяются на Антарктиду на своих картах, хотя статьи на веб -сайте National Geographic начали ссылаться на Южный океан. [ 21 ]

Радикальный сдвиг от прошлых практик IHO (1928–1953) также был замечен в драфте 2002 года, когда IHO определил «моря» в качестве подраздел в пределах «океанов». В то время как IHO часто считаются полномочиями для таких конвенций, сдвиг привел их в соответствие с практикой других публикаций (например, в мировой книге ЦРУ ), которая уже приняла принцип, согласно которому моря содержатся в океанах. Эта разница в практике заметно наблюдается для Тихого океана на соседней фигуре. Так, например, ранее Тасманское море между Австралией и Новой Зеландией не рассматривалось IHO в рамках Тихого океана, но начиная с драфта 2002 года.

Новое разграничение морей как подразделения океанов избежало необходимости прервать северную границу Южного океана, где пересекается проход Дрейка , который включает в себя все воды от Южной Америки до побережья Антарктики, а также не прервать его Шотландии в Также простирается ниже 60 -го параллельного юга. Новое разграничение морей также означало, что давние названные моря вокруг Антарктиды, исключенная из издания 1953 года (карта 1953 года даже не распространялась на это далеко на юг), автоматически является частью южного океана.

Австралийская точка зрения

[ редактировать ]В Австралии картографические власти определяют южный океан как включающий весь водоснабжение между Антарктидой и южными побережьями Австралии и Новой Зеландии, а также до 60 ° S в других местах. [ 42 ] Прибрежные карты Тасмании и Южной Австралии называют морские районы как южный океан [ 43 ] и мыс Леувин в Западной Австралии описывается как точка, где встречаются индийские и южные океаны. [ 44 ]

История исследования

[ редактировать ]Неизвестная южная земля

[ редактировать ]

Исследование Южного океана было вдохновлено верой в существование терра -австралийских - обширный континент на дальнем юге земного шара, чтобы «уравновесить» северные земли Евразии и Северной Африки - который существовал со времен Птолемея . Округление мыса Доброй надежды в 1487 году Бартоломеу Диасом впервые вызвало исследователей в связи с антарктическим холодом и доказало, что океан, отделяющий Африку от любой антарктической земли, которая может существовать. [ 45 ] Фердинанд Магеллан , который прошел через Магеллан в 1520 году, предположил, что острова Тьерра -дель -Фуэго на юге были продолжением этой неизвестной южной земли. В 1564 году Авраам Ортелиус опубликовал свою первую карту Typus orbis terrarum , настенную карту мира с восемью лициями, на которой он идентифицировал Регио Паталис с локахом как расширение на север Terra Australis , достигнув до Новой Гвинеи . [ 46 ] [ 47 ]

Европейские географы продолжали соединять побережье Тьерра -дель -Фуэго с побережью Новой Гвинеи на их глобусах и позволяя их воображениям управлять бунтами в обширных неизвестных пространствах Южной Атлантики, Южной Индии и Тихого океана. Они нарисовали очертания терра Australis Incognita («Неизвестная южная земля»), обширный континент, простирающийся по частям в тропиках. Поиск этой великой южной земли был ведущим мотивом исследователей в 16 -м и начале 17 -го веков. [ 45 ]

Испанец . Габриэль де Кастилья , который утверждал, что в 1603 году был признан «заснеженные горы» за 64 ° S в 1603 году, признан первым исследователем, который обнаружил континент Антарктиды, хотя его игнорировали в свое время

В 1606 году Педро Фернандес де Куйрос завладел королем Испании на все земли, которые он обнаружил в Австралии дель Эспириту Санто ( новые гебриджи ), и те, которые он обнаружил, «даже на шесте». [ 45 ]

Фрэнсис Дрейк , как и испанские исследователи перед ним, предположил, что может быть открытый канал к югу от Тьерра -дель -Фуэго. Когда Виллем Шутен и Джейкоб Ле Мейр обнаружили южную конечность Тьерра -дель -Фуэго и назвали его в 1615 году на мысе Хорн , они доказали, что архипелаг Тьерра -дель -Фуэго имел небольшую степень и не связан с южной землей, как считалось ранее. Впоследствии, в 1642 году, Абель Тасман показал, что даже Новая Голландия (Австралия) была отделена морем от любого непрерывного южного континента. [ 45 ]

К югу от антарктической конвергенции

[ редактировать ]

Посещение Южной Грузии Энтони де ла Рош в 1675 году стало первым в истории открытием земли к югу от Антарктической конвергенции , т.е. в южном океане/Антарктике. [ 48 ] [ 49 ] Вскоре после того, как картографы путешествия начали изображать « остров Рош », в честь предварительного директора. Джеймс Кук знал о открытии Ла Роше, когда обследование и картирование острова в 1775 году. [ 50 ]

Эдмонда Галлея Путешествие в HMS Paramour для магнитных исследований в Южной Атлантике встретилось с ICE Pack в 52 ° S в январе 1700 года, но широта (он достиг 140 миль [230 км] от северного побережья Южной Георгии ) была его дальнейшей юг. Определенные усилия со стороны французского военно-морского офицера Жана-Батиста Чарльза Буве де Лозье обнаружили «Южную землю», описанную половиной легендарной « Сьер де Гоннивилль », привел к открытию острова Бувет в 54 ° 10 , и в навигации 48 ° долготы моря, проведенного в 55 ° С в 1730 году. [ 45 ]

В 1771 году Ив Джозеф Кергелен отплыл из Франции с инструкциями, чтобы идти на юг от Маврикия в поисках «очень большого континента». Он зажег на землю в 50 ° ю.ш. , которую он назвал Южным Францией и, как полагал, является центральной массой южного континента. Его снова послали, чтобы завершить исследование новой земли, и обнаружил, что это всего лишь раздражительный остров, который он переименовал в остров пустынь, но в конечном итоге был назван в его честь . [ 45 ]

К югу от Антарктического круга

[ редактировать ]

Одержимость неоткрытого континента завершился мозгом Александра Далримпла , блестящего и неустойчивого гидрографа , который был назначен Королевским обществом, чтобы командовать транзитом Экспедиции Венеры в Таити в 1769 году. Команда экспедиции была дана помиралтом к капитану. Джеймс Кук . Парусный спорт в 1772 году с резолюцией , судно из 462 тонн под его собственным командованием и приключениями 336 тонн под руководством капитана Тобиаса Ферно , Кук сначала обыскал остров Бувет , а затем отправился на 20 градусов по долготе по западу по широте 58 ° С , а затем на 30 ° к востоку по большей части к югу от 60 ° с , нижняя южная широта, чем когда -либо добровольно вводилось любым судном. 17 января 1773 года Антарктический круг впервые был пересечен в истории, и два корабля достигли 67 ° 15 на 39 ° 35 'e , где их курс был остановлен льдом. [ 45 ]

Затем Кук повернулся на север, чтобы найти французские южные и антарктические земли , от открытия которых он получил новости в Кейптауне , но от грубой определения своей долготы Кергеленом Кук достиг назначенной широты на 10 ° слишком далеко и не сделал увидеть это. Он снова повернулся на юг и был остановлен льдом в 61 ° 52 'с на 95 ° в.д. и продолжался на восток почти на параллели от 60 до 147 ° в.д. 16 марта приближающаяся зима побудила его на север, чтобы отдохнуть в Новую Зеландию и тропические острова Тихого океана. В ноябре 1773 года Кук покинул Новую Зеландию, расстав компанию с приключениями , и достиг 60 ° С к 177 ° W , откуда он плыл на восток, оставившись на юге, как разрешено плавучий лед. Антарктический круг был пересечен 20 декабря, а Кук оставался на юге в течение трех дней, вынужденный после достижения 67 ° 31 'с, чтобы снова стоять на север в 135 ° С. [ 45 ]

Длинный обход до 47 ° 50 -х годов не было наземной связи служил, чтобы показать, что между Новой Зеландией и Тьерра -дель -Фуэго . Повернувшись на юг, Кук пересек Антарктический круг в третий раз при 109 ° 30 ′ Вт до того, как его прогресс снова был заблокирован на льду через четыре дня при 71 ° 10 ′ с 106 ° 54 ′ w . Этот момент, достигнутый 30 января 1774 года, был самым дальним югом, достигнутым в 18 веке. С большим обходом на востоке, почти до побережья Южной Америки, экспедиция восстановила Таити для обновления. В ноябре 1774 года Кук начал с Новой Зеландии и пересек южную часть Тихого океана, не наблюдая за землей между 53 ° до 57 ° С до Тиерра -дель -Фуэго; Затем, пройдя через Кейп Хорн 29 декабря, он заново открыл остров Роше , переименовав его в остров Грузии и обнаружил южные сэндвич-острова (названная сэндвич им Кейп Доброй надежды между 55 ° и 60 ° . Таким образом, он открыл путь для будущих исследований Антарктики, взрывая миф о обитаемом южном континенте. Самое южное открытие земли Кука лежало на умеренной стороне 60 -й параллель , и он убедил себя, что, если земля лежит дальше на юг, она была практически недоступна и без экономической ценности. [ 45 ]

Voyagers, окружающие Кейп Хорн, часто встречались с противоположными ветрами и были переезжали на юг в снежное небо и моря, обремененные льдом; Но, насколько это возможно, никто из них до 1770 года не достиг Антарктического круга или знал, если бы они это сделали.

В путешествии с 1822 по 1824 год Джеймс Уэдделл командовал 160-тонным бриганом Джейн в сопровождении его второго корабля Beaufoy, капитаном Мэтью Брисбена. Вместе они отплыли на южные оркни, где запечатывание оказалось разочаровывающим. Они повернулись на юг в надежде найти лучшую герметичную землю. Сезон был необычайно мягким и спокойным, и 20 февраля 1823 года два корабля достигли широты 74 ° 15 и долготы 34 ° 16'45 ″ с самым южным положением, которое когда -либо достигало любого корабля. Несколько айсбергов были замечены, но до сих пор не было видов земли, что привело к теоретизированию Ведделла о том, что море продолжалось до Южного полюса. Еще два дня парусного спорта принесли бы его на землю пальто (к востоку от моря Уэдделла ), но Уэдделл решил повернуть назад. [ 52 ]

Первое наблюдение за землей

[ редактировать ]

Первая земля к югу от параллельной 60 ° Южной широты была обнаружена англичанином Уильямом Смитом , который увидел остров Ливингстон 19 февраля 1819 года. Несколько месяцев спустя Смит вернулся, чтобы исследовать другие острова Архипелаго Южного Шетланда , приземленные на острове Король Георг Георг и претендовал на новые территории для Британии.

Тем временем, испанский флот Сан -Тельмо затонул в сентябре 1819 года, пытаясь пересечь Кейп Хорн. Части ее обломков были найдены через несколько месяцев герметиками на северном побережье острова Ливингстон ( Южные Шетландии ). Неизвестно, удалось ли каким -то выжившим первым, кто ступил на эти острова Антарктики.

Первое подтвержденное наблюдение за материковой Антарктидой не может быть точно связано с одним человеком. Это может быть сужено до трех человек. Согласно различным источникам, [ 53 ] [ 54 ] [ 55 ] Все три человека увидели ледяное шельф или континент в течение нескольких дней или месяцев друг от друга: Фабиан Готлиб фон Беллингшаузен , капитан русского имперского флота ; Эдвард Брансфилд , капитан Королевского флота ; и Натаниэль Палмер , американский моряк из Стонингтона, Коннектикут . Несомненно, что экспедиция, возглавляемая фон Беллингшаузеном и Лазарев на кораблях Восток и Мирни , достигла точки в пределах 32 км (20 миль) от побережья принцессы Марты и записала вид ледяного шельфа 69 ° 21′28 ″ S 2 ° 14′50 ″ W / 69,35778 ° S 2,24722 ° W [ 56 ] Это стало известно как ледяной шельф Fimbul . 30 января 1820 года Брансфилд увидел Троицкий полуостров , самая северная точка на материковой части Антарктики, в то время как Палмер увидел материк в районе к югу от Троицкого полуострова в ноябре 1820 года. Экспедиция фон Беллингшаузена также обнаружила остров Петра I и остров Александр I , первые острова. быть обнаруженным к югу от круга.

-

1683 Карта французского картографа Алена Манессон Маллет из его публикации описание de l'Unit . Показывает море под Атлантическим и Тихоокеанским океаном в то время, когда Тирра дель -Фуэго считалось, что присоединилась к Антарктиде. Море называется Мер Магелланика после Фердинанда Магеллана .

-

Самуила Данна в 1794 году Генеральная карта мира или терракового глобуса показывает южный океан (но означает то, что сегодня называется Южной Атлантикой) и южным ледяным океаном .

-

Новая карта Азии, от последних властей, Джона Кэри , гравера, 1806 года , показывает южный океан, лежащий на юге как Индийского океана, так и Австралии.

-

Карта Freycinet 1811 года - была получена в 1800–1803 годах Французской экспедиции Боудина в Австралию и была первой полной картой Австралии, которая когда -либо была опубликована. На французском языке карта назвала океан непосредственно под Австралией в качестве Grand Océan Austral («Великий южный океан»).

-

1863 Карта Австралии показывает южный океан , лежащий сразу к югу от Австралии.

-

1906 г. Карта немецкого издателя Юстуса Перта, показывающая Антарктиду, охваченную Антарктиссером (Sudl. Eismeer) океаном - Антарктическим (Южной Арктикой) океаном ».

-

Карта мира в 1922 году Национальным географическим обществом, показывающая Антарктический (южный) океан .

Антарктические экспедиции

[ редактировать ]

, в рамках « Экспедиции 1838–42 гг . » декабре В 1839 года USS Peacock , бригарная свинья , полное облегчение корабля и две шхуны морской чайки и USS летающая рыба . Они отправились в Антарктический океан, как это было тогда известно, и сообщили об открытии «Антарктического континента к западу от острова Баллин » 25 января 1840 года. Эта часть Антарктиды была позже названа « земля Уилкс », и имя, которое она поддерживает этот день.

Исследователь Джеймс Кларк Росс прошел через то, что теперь известно как Море Росс , и обнаружил остров Росс (оба из которых были названы в его честь) в 1841 году. Он отплыл вдоль огромной ледяной стены, которая позже была названа ледяным шельфом Росса . Гора Эребус и гора террор названы в честь двух кораблей из его экспедиции: HMS Erebus и HMS Terror . [ 57 ]

Императорская транс-антарктическая экспедиция 1914 года, возглавляемая Эрнестом Шеклтоном , намеревалась пересечь континент через полюс, но их корабль, выносливость , был пойман в ловушку и раздавлена Pack Ice еще до того, как они приземлились. Члены экспедиции выжили после эпического путешествия на санях над пакетом льда на остров Слон . Затем Шеклтон и пять других пересекли Южный океан, в открытой лодке под названием Джеймс Кэрд , а затем отправились в южную Джорджию, чтобы поднять тревогу на китобойной станции Гритвикен .

В 1946 году контр -адмирал ВМС США Ричард Э. Берд и более 4700 военнослужащих посетили Антарктику в экспедиции под названием «Операция HighJump» . Сообщается общественности как научная миссия, детали были в секрете, и, возможно, на самом деле это была миссия по обучению или тестированию для военных. Экспедиция, как в военном, так и с точки зрения научного планирования, собрана очень быстро. Группа содержала необычайно большое количество военной техники, в том числе авианосец, подводные лодки, военные корабли, штурмовые войска и военные транспортные средства. Экспедиция планировалась продлиться на восемь месяцев, но была неожиданно прекращена через два месяца. За исключением некоторых эксцентричных записей в дневниках адмирала Берда, никакого реального объяснения раннего прекращения никогда не было официально дано.

Капитан Финн Ронн , исполнительный директор Берда, вернулся в Антарктиду со своей собственной экспедицией в 1947–1948 годах с поддержкой ВМФ, тремя самолетами и собаками. Он опроверг представление о том, что континент был разделен на две части, и установил, что Восточная и Западная Антарктида были одним континентом, то есть, что море Уэдделла и Море Росса не связаны. [ 58 ] Экспедиция исследовала и нанесла на карту большую часть Палмер Лэнд и береговую линию моря Уэдделла и опознала ледяной шельф Ронн , названный им его женой Джеки Ронн . [ 59 ] Он покрыл 3600 миль (5790 км) на лыжах и собачьих санях - больше, чем любой другой исследователь в истории. [ 60 ] обнаружила Исследовательская экспедиция Ронна и нанесла на карту последнюю неизвестную береговую линию в мире и была первой антарктической экспедицией, когда -либо включающей женщин. [ 61 ]

Постатлантический договор

[ редактировать ]

Антарктический договор был подписан 1 декабря 1959 года и вступил в силу 23 июня 1961 года. Помимо других положений, этот договор ограничивает военную деятельность в Антарктике поддержкой научных исследований.

Первым человеком, который плавал в одиночку в Антарктиду, был новозеландский Дэвид Генри Льюис , в 1972 году в 10-метровой (30-футовой) стальной шлюпной птице .

Ребенок по имени Эмилио Маркос де Пальма родился возле залива Хоуп -Бэй 7 января 1978 года, став первым ребенком, родившимся на континенте. Он также родился дальше на юг, чем кто -либо в истории. [ 62 ]

MV , Explorer был круизным лайнером управляемым шведским исследователем Ларсом-Эриком Линдбладом . Наблюдатели указывают на Explorer экспедиционный круиз 1969 года в Антарктиду в качестве лидера на сегодняшний день [ когда? ] Морский туризм в этом регионе. [ 63 ] [ 64 ] Explorer был первым круизным лайнером, используемым специально для плавания в ледяные воды Антарктического океана, и первым погрузился там [ 65 ] Когда 23 ноября 2007 года она ударила по неопознанному погруженному объекту. [ 66 ] Исследователь был брошен рано утром 23 ноября 2007 года после того, как взял воду возле острова Южного Шетланда в Южном океане, область, которая обычно является штормовой, но в то время была спокойной. [ 67 ] Исследователь был подтвержден чилийским военно -морским флотом , чтобы потопить при приблизительном положении: 62 ° 24 ′ на юг, 57 ° 16 ′ к западу, [ 68 ] Примерно в 600 м воды. [ 69 ]

Британский инженер Ричард Дженкинс разработал беспилотный парусник [ 70 ] Это завершило первое автономное кругосветное плавание в Южном океане 3 августа 2019 года после 196 дней в море. [ 71 ]

Первая полностью экспедиция на человеке на Южном океане была проведена 25 декабря 2019 года командой гребцов, в состав которого входила капитан Фианн Пол (Исландия), первое партнер Колин О'Бради (США), Эндрю Таун (США), Кэмерон Беллами (Юг Африка), Джейми Дуглас-Гамилтон (Великобритания) и Джон Петерсен (США). [ 72 ]

География

[ редактировать ]Южный океан, геологически самый молодой из океанов, был образован, когда Антарктида и Южная Америка перешли на части, открыв проход Дрейка , примерно 30 миллионов лет назад. Разделение континентов позволило образовать антарктический циркумполярный ток .

С северным пределом при 60 ° С южный океан отличается от других океанов тем, что ее самая большая граница, северная граница, не приземится на сухопутную массу (как это было с первым изданием пределов океанов и морей ). Вместо этого северный лимит с Атлантическим, Индийским и Тихоокеанским океаном.

Одна из причин рассматривать его как отдельный океан проистекает из того факта, что большая часть воды южного океана отличается от воды в других океанах. Вода довольно быстро транспортируется вокруг южного океана из -за антарктического циркумполярного тока , которое циркулирует вокруг Антарктиды. Вода в южном океане к югу от, например, в Новой Зеландии, напоминает воду в южном океане к югу от Южной Америки, чем напоминает воду в Тихом океане.

Южный океан имеет типичную глубину от 4000 до 5000 м (13 000 и 16 000 футов) в большей части его протяженности с ограниченными областями мелкой воды. Самая большая глубина Южного океана в 7 236 м (23 740 футов) происходит в южном конце южной сэндвич -траншеи , при 60 ° 00, 024 ° W. Антарктический континентальный шельф, как правило, кажется узким и необычайно глубоким, его край лежит на глубине до 800 м (2600 футов) по сравнению со средним глобальным средним значением 133 м (436 футов).

Равноденствие в равноденствие в соответствии с сезонным влиянием Солнца, антарктический ледовой пакет колеблется от среднего минимума 2,6 миллиона квадратных километров (1,0 × 10 6 SQ MI) В марте примерно до 18,8 млн. Квадратных километров (7,3 × 10 6 SQ MI) В сентябре более чем в семикратном увеличении площади.

Подразделения

[ редактировать ]

Подразделения океанов - это географические особенности, такие как «моря», «пролив», «бухты», «каналы» и «заливы». Существует множество подразделений южного океана, определенного в никогда не одобренном драфте 2002 года четвертого издания IHO Publication Limits of Oceans и Seas . В порядке по часовой стрелке они включают (с сектором):

- Weddell Sea (57 ° 18'w - 12 ° 16'e)

- Король Хаакон VII море [ Примечание 5 ] (20 ° W - 45 ° E)

- Lazarev Sea (0 ° - 14 ° E)

- Riiser-Larsen Sea (14 ° -30 ° E)

- Море космонавтов (30 ° - 50 ° E)

- Сотрудничество море (59 ° 34 ' - 85 ° E)

- Дэвис -море (82 ° - 96 ° E)

- Море Моусон (95 ° 45 ' - 113 ° E)

- Дюмон из Урвилльского моря (140 ° E)

- Somov Sea (150° – 170°E)

- Росс -море (166 ° E - 155 ° W)

- Amundsen Sea (102 ° 20 ′ - 126 ° W)

- Беллингшаузен море (57 ° 18 ' - 102 ° 20'W)

- Часть прохода Дрейка [ Примечание 6 ] (54 ° - 68 ° W)

- Брансфилд пролив (54 ° - 62 ° W)

- Часть Шотланского моря [ Примечание 7 ] (26 ° 30 ' - 65 ° W)

Несколько из них, такие как российское «море космонавтов» в 2002 году, «Сотрудничество моря» и «Совм (середина 1950-х годов Российского Полярного Исследователя) море» не включены в документ IHO 1953 года, который остается в настоящее время в силе. [ 34 ] Потому что они получили свои имена, в основном возникшие с 1962 года. Ведущие географические власти и атласы не используют эти последние три имена, в том числе 10-е издание Atlas 10th Edition от Национального географического общества е издание British Times Atlas мирового Соединенных Штатов и 12 - Полем [ 73 ] [ 74 ]

Самое большое море

[ редактировать ]Лучшие большие моря: [ 75 ] [ 76 ] [ 77 ]

- Weddell Sea - 2800 000 км 2 (1 100 000 кв. МИ)

- Somov Sea – 1,150,000 km 2 (440 000 кв. МИ)

- Riiser -Larsen Sea -1,138 000 км 2 (439 000 кв. МИ)

- Lazarev Sea - 929 000 км 2 (359 000 кв. МИ)

- Scotia Sea - 900 000 км 2 (350 000 кв. МИ)

- Cosmonauts Sea - 699 000 км 2 (270 000 кв. МИ)

- Ross Sea - 637 000 км 2 (246 000 кв. МИ)

- Bellingshausen Sea - 487 000 км 2 (188 000 кв. МИ)

- Mawson Sea - 333 000 км 2 (129 000 кв. МИ)

- Сотрудничество море - 258 000 км 2 (100 000 кв. МИ)

- Амундсен море - 98 000 км 2 (38 000 кв. МИ)

- Дэвис Море - 21 000 км 2 (8100 кв. МИ)

- Урвилльское море

- Король Хаакон VII море

Природные ресурсы

[ редактировать ]

есть крупные и, возможно, гигантские нефтегазовые В Южном океане , вероятно , месторождения на континентальном краю . отложения для россыпения , накопление ценных полезных ископаемых, таких как золото, образованные гравитационным разделением во время осадочных процессов. Ожидается, что на южном океане также существуют [ 5 ]

узелки марганца Ожидается, что будут существовать в южном океане. Узелки марганца - это каменные конкреции на морском дне, образованных из концентрических слоев железа и марганца гидроксидов вокруг ядра. Ядро может быть микроскопически небольшим и иногда полностью трансформируется в минералы марганца путем кристаллизации . Интерес к потенциальной эксплуатации полиметаллических узелков вызвал большую активность среди проспективных консорциумов в горнодобывающей промышленности в 1960 -х и 1970 -х годах. [ 5 ]

Айсберги , , которые каждый год образуются в южном океане, содержат достаточно пресной воды чтобы удовлетворить потребности каждого человека на земле в течение нескольких месяцев. В течение нескольких десятилетий были предложения, которые еще не были выполнены или успешны, чтобы буксировать айсберги из Южного океана в более засушливые северные регионы (такие как Австралия), где их можно собирать. [ 78 ]

Природные опасности

[ редактировать ]

Айсберги могут возникнуть в любое время года по всему океану. Некоторые могут иметь проекты до нескольких сотен метров; Меньшие айсберги, фрагменты айсберга и морской конь (как правило, толщиной от 0,5 до 1 м) также создают проблемы для кораблей. Глубокий континентальный шельф имеет пол ледниковых отложений, сильно различающихся на короткие расстояния.

Моряки знают широты от 40 до 70 градусов на юг , как « ревущие сороковые годы », «яростные пятидесятые» и «визг шестьдесятых» из-за сильных ветров и больших волн, которые образуются, когда ветры дуют вокруг всего глобуса, не снятого любой приземленной массой. Айсберги, особенно в мае по октябрь, делают этот район еще более опасной. Отдаленность региона делает источники поиска и спасения дефицитом.

Физическая океанография

[ редактировать ]

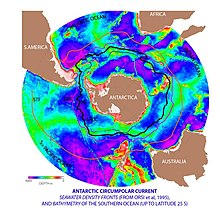

Антарктический циркумполярный ток и конвергенция антарктической

[ редактировать ]В то время как Южный является вторым наименьшим океаном, он содержит уникальный и весьма энергичный антарктический циркумполярный ток , который движется постоянно на восток - гонясь и присоединяется к себе, и на 21 000 км (13 000 миль) - он включает в себя самый длинный в мире океан, транспортируя 130 миллионов миллионов человек. кубические метры в секунду (4,6 × 10 9 Cu ft/s) воды - в 100 раз больше потока всех мировых рек. [ 79 ]

Несколько процессов работают вдоль побережья Антарктиды для производства в южном океане типы водных масс , не производимых в других местах в океанах Южного полушария . Одним из них является антарктическая дновая вода , очень холодная, очень физиологическая, густая вода, которая образуется под морским льдом . Другой - циркумполярная глубокая вода , смесь антарктической нижней воды и северной Атлантической глубокой воды .

С циркумполярным током связана антарктическая конвергенция , окружающая Антарктику, где холодные, текущие к северу, антарктические воды, соответствующие относительно теплым водам субантарктики , смешивания и подпрыги антарктические воды преимущественно погружаются под субантарктическими водами, в то время как связанные зоны Полем Эти высокие уровни фитопланктона с соответствующими чепухами и антарктическим крильом , а также результирующие продукты, поддерживающие рыбу, киты, печати, пингвины, альбатросы и множество других видов. [ 80 ]

Антарктическая конвергенция считается лучшим естественным определением северной степени южного океана.

Upwelling

[ редактировать ]Крупномасштабное восхождение встречается в южном океане. Сильные западные (восток) ветры дуют вокруг Антарктиды , приводя к значительному потоку воды на север. Это на самом деле тип прибрежного подъема. Поскольку в полосе открытых широт между Южной Америкой нет континентов между Южной Америкой и кончиком Антарктического полуострова , часть этой воды состоит из больших глубин. Во многих численных моделях и синтезах наблюдения южный океан Upwelling представляет собой основное средство, с помощью которого глубоко плотная вода выводит на поверхность. Менее, ветроэнергетическое подъем также встречается у западных побережье Северной и Южной Америки, северо-запада и юго-западной Африки, а также на юго-западе и юго-востоке Австралии , все это связано с океаническими субтропическими циркуляциями высокого давления.

Росс и Уэдделл Гирес

[ редактировать ]Ross Gyre и Weddell Gyre - это два круга , которые существуют в южном океане. Гиры расположены в море Росс и Море Уэдделла соответственно, и оба вращаются по часовой стрелке. Гире образуются путем взаимодействия между антарктическим циркумполярным током и континентальным шельфом Антарктики .

Было отмечено, что морской лед настойчив в центральном районе Росса Гира. [ 81 ] Есть некоторые доказательства того, что глобальное потепление привело к некоторому снижению солености вод Росс -Гира с 1950 -х годов. [ 82 ]

Из -за эффекта Кориолиса, действующего влево в южном полушарии , и полученного в результате транспортировки Экмана в центре гимр Ведделла, эти регионы очень продуктивны из -за холодной, богатой питательными веществами воды.

Observation

[edit]Observation of the Southern Ocean is coordinated through the Southern Ocean Observing System (SOOS).[83][84] This provides access to meta data for a significant proportion of the data collected in the regions over the past decades including hydrographic measurements and ocean currents. The data provision is set up to emphasize records that are related to Essential Ocean Variables (EOVs)[85] for the ocean region south of 40°S.

Climate

[edit]Sea temperatures vary from about −2 to 10 °C (28 to 50 °F). Cyclonic storms travel eastward around the continent and frequently become intense because of the temperature contrast between ice and open ocean. The ocean from about latitude 40 south to the Antarctic Circle has the strongest average winds found anywhere on Earth.[86] In winter the ocean freezes outward to 65 degrees south latitude in the Pacific sector and 55 degrees south latitude in the Atlantic sector, lowering surface temperatures well below 0 degrees Celsius. At some coastal points, persistent intense drainage winds from the interior keep the shoreline ice-free throughout the winter.

Change

[edit]

As human-caused greenhouse gas emissions cause increased warming, one of the most notable effects of climate change on oceans is the increase in ocean heat content, which accounted for over 90% of the total global heating since 1971.[95] Since 2005, from 67% to 98% of this increase has occurred in the Southern Ocean.[96] In West Antarctica, the temperature in the upper layer of the ocean has warmed 1 °C (1.8 °F) since 1955, and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is also warming faster than the global average.[97] This warming directly affects the flow of warm and cold water masses which make up the overturning circulation, and it also has negative impacts on sea ice cover in Southern Hemisphere, (which is highly reflective and so elevates the albedo of Earth's surface), as well as mass balance of Antarctica's ice shelves and peripheral glaciers.[98] For these reasons, climate models consistently show that the year when global warming will reach 2 °C (3.6 °F) (inevitable in all climate change scenarios where greenhouse gas emissions have not been strongly lowered) depends on the status of the circulation more than any other factor besides the emissions themselves.[99]

Greater warming of this ocean water increases ice loss from Antarctica, and also generates more fresh meltwater, at a rate of 1100-1500 billion tons (GT) per year.[98]: 1240 This meltwater from the Antarctic ice sheet then mixes back into the Southern Ocean, making its water fresher.[100] This freshening of the Southern Ocean results in increased stratification and stabilization of its layers,[101][98]: 1240 and this has the single largest impact on the long-term properties of Southern Ocean circulation.[102] These changes in the Southern Ocean cause the upper cell circulation to speed up, accelerating the flow of major currents,[103] while the lower cell circulation slows down, as it is dependent on the highly saline Antarctic bottom water, which already appears to have been observably weakened by the freshening, in spite of the limited recovery during 2010s.[104][105][106][98]: 1240 Since the 1970s, the upper cell has strengthened by 3-4 sverdrup (Sv; represents a flow of 1 million cubic meters per second), or 50-60% of its flow, while the lower cell has weakened by a similar amount, but because of its larger volume, these changes represent a 10-20% weakening.[107][89] However, they were not fully caused by climate change, as the natural cycle of Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation had also played an important role.[108][109]

Similar processes are taking place with Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), which is also affected by the ocean warming and by meltwater flows from the declining Greenland ice sheet.[111] It is possible that both circulations may not simply continue to weaken in response to increased warming and freshening, but eventually collapse to a much weaker state outright, in a way which would be difficult to reverse and constitute an example of tipping points in the climate system.[99] There is paleoclimate evidence for the overturning circulation being substantially weaker than now during past periods that were both warmer and colder than now.[110] However, Southern Hemisphere is only inhabited by 10% of the world's population, and the Southern Ocean overturning circulation has historically received much less attention than the AMOC. Consequently, while multiple studies have set out to estimate the exact level of global warming which could result in AMOC collapsing, the timeframe over which such collapse may occur, and the regional impacts it would cause, much less equivalent research exists for the Southern Ocean overturning circulation as of the early 2020s. There has been a suggestion that its collapse may occur between 1.7 °C (3.1 °F) and 3 °C (5.4 °F), but this estimate is much less certain than for many other tipping points.[99]

The impacts of Southern Ocean overturning circulation collapse have also been less closely studied, though scientists expect them to unfold over multiple centuries. A notable example is the loss of nutrients from Antarctic bottom water diminishing ocean productivity and ultimately the state of Southern Ocean fisheries, potentially leading to the extinction of some species of fish, and the collapse of some marine ecosystems.[112] Reduced marine productivity would also mean that the ocean absorbs less carbon (though not within the 21st century[93]), which could increase the ultimate long-term warming in response to anthropogenic emissions (thus raising the overall climate sensitivity) and/or prolong the time warming persists before it starts declining on the geological timescales.[87] There is also expected to be a decline in precipitation in the Southern Hemisphere countries like Australia, with a corresponding increase in the Northern Hemisphere. However, the decline or an outright collapse of the AMOC would have similar but opposite impacts, and the two would counteract each other up to a point. Both impacts would also occur alongside the other effects of climate change on the water cycle and effects of climate change on fisheries.[112]Biodiversity

[edit]

Animals

[edit]A variety of marine animals exist and rely, directly or indirectly, on the phytoplankton in the Southern Ocean. Antarctic sea life includes penguins, blue whales, orcas, colossal squids and fur seals. The emperor penguin is the only penguin that breeds during the winter in Antarctica, while the Adélie penguin breeds farther south than any other penguin. The rockhopper penguin has distinctive feathers around the eyes, giving the appearance of elaborate eyelashes. King penguins, chinstrap penguins, and gentoo penguins also breed in the Antarctic.

The Antarctic fur seal was very heavily hunted in the 18th and 19th centuries for its pelt by sealers from the United States and the United Kingdom. The Weddell seal, a "true seal", is named after Sir James Weddell, commander of British sealing expeditions in the Weddell Sea. Antarctic krill, which congregates in large schools, is the keystone species of the ecosystem of the Southern Ocean, and is an important food organism for whales, seals, leopard seals, fur seals, squid, icefish, penguins, albatrosses and many other birds.[113]

The benthic communities of the seafloor are diverse and dense, with up to 155,000 animals found in 1 square metre (10.8 sq ft). As the seafloor environment is very similar all around the Antarctic, hundreds of species can be found all the way around the mainland, which is a uniquely wide distribution for such a large community. Deep-sea gigantism is common among these animals.[114]

A census of sea life carried out during the International Polar Year and which involved some 500 researchers was released in 2010. The research is part of the global Census of Marine Life (CoML) and has disclosed some remarkable findings. More than 235 marine organisms live in both polar regions, having bridged the gap of 12,000 km (7,500 mi). Large animals such as some cetaceans and birds make the round trip annually. More surprising are small forms of life such as mudworms, sea cucumbers and free-swimming snails found in both polar oceans. Various factors may aid in their distribution – fairly uniform temperatures of the deep ocean at the poles and the equator which differ by no more than 5 °C (9.0 °F), and the major current systems or marine conveyor belt which transport egg and larva stages.[115] Among smaller marine animals generally assumed to be the same in the Antarctica and the Arctic, more detailed studies of each population have often—but not always—revealed differences, showing that they are closely related cryptic species rather than a single bipolar species.[116][117][118]

Birds

[edit]The rocky shores of mainland Antarctica and its offshore islands provide nesting space for over 100 million birds every spring. These nesters include species of albatrosses, petrels, skuas, gulls and terns.[119] The insectivorous South Georgia pipit is endemic to South Georgia and some smaller surrounding islands. Freshwater ducks inhabit South Georgia and the Kerguelen Islands.[120]

The flightless penguins are all located in the Southern Hemisphere, with the greatest concentration located on and around Antarctica. Four of the 18 penguin species live and breed on the mainland and its close offshore islands. Another four species live on the subantarctic islands.[121] Emperor penguins have four overlapping layers of feathers, keeping them warm. They are the only Antarctic animal to breed during the winter.[122]

Fish

[edit]There are relatively few fish species in few families in the Southern Ocean. The most species-rich family are the snailfish (Liparidae), followed by the cod icefish (Nototheniidae)[123] and eelpout (Zoarcidae). Together the snailfish, eelpouts and notothenioids (which includes cod icefish and several other families) account for almost 9⁄10 of the more than 320 described fish species of the Southern Ocean (tens of undescribed species also occur in the region, especially among the snailfish).[124] Southern Ocean snailfish are generally found in deep waters, while the icefish also occur in shallower waters.[123]

Icefish

[edit]

Cod icefish (Nototheniidae), as well as several other families, are part of the Notothenioidei suborder, collectively sometimes referred to as icefish. The suborder contains many species with antifreeze proteins in their blood and tissue, allowing them to live in water that is around or slightly below 0 °C (32 °F).[125][126] Antifreeze proteins are also known from Southern Ocean snailfish.[127]

The crocodile icefish (family Channichthyidae), also known as white-blooded fish, are only found in the Southern Ocean. They lack hemoglobin in their blood, resulting in their blood being colourless. One Channichthyidae species, the mackerel icefish (Champsocephalus gunnari), was once the most common fish in coastal waters less than 400 metres (1,312 ft) deep, but was overfished in the 1970s and 1980s. Schools of icefish spend the day at the seafloor and the night higher in the water column eating plankton and smaller fish.[125]

There are two species from the genus Dissostichus, the Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) and the Patagonian toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides). These two species live on the seafloor 100–3,000 metres (328–9,843 ft) deep, and can grow to around 2 metres (7 ft) long weighing up to 100 kilograms (220 lb), living up to 45 years. The Antarctic toothfish lives close to the Antarctic mainland, whereas the Patagonian toothfish lives in the relatively warmer subantarctic waters. Toothfish are commercially fished, and overfishing has reduced toothfish populations.[125][128]

Another abundant fish group is the genus Notothenia, which like the Antarctic toothfish have antifreeze in their bodies.[125]

An unusual species of icefish is the Antarctic silverfish (Pleuragramma antarcticum), which is the only truly pelagic fish in the waters near Antarctica.[129]

Mammals

[edit]Seven pinniped species inhabit Antarctica. The largest, the elephant seal (Mirounga leonina), can reach up to 4,000 kilograms (8,818 lb), while females of the smallest, the Antarctic fur seal (Arctophoca gazella), reach only 150 kilograms (331 lb). These two species live north of the sea ice, and breed in harems on beaches. The other four species can live on the sea ice. Crabeater seals (Lobodon carcinophagus) and Weddell seals (Leptonychotes weddellii) form breeding colonies, whereas leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) and Ross seals (Ommatophoca rossii) live solitary lives. Although these species hunt underwater, they breed on land or ice and spend a great deal of time there, as they have no terrestrial predators.[130]

The four species that inhabit sea ice are thought to make up 50% of the total biomass of the world's seals.[131] Crabeater seals have a population of around 15 million, making them one of the most numerous large animals on the planet.[132] The New Zealand sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri), one of the rarest and most localised pinnipeds, breeds almost exclusively on the subantarctic Auckland Islands, although historically it had a wider range.[133] Out of all permanent mammalian residents, the Weddell seals live the furthest south.[134]

There are 10 cetacean species found in the Southern Ocean: six baleen whales, and four toothed whales. The largest of these, the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), grows to 24 metres (79 ft) long weighing 84 tonnes. Many of these species are migratory, and travel to tropical waters during the Antarctic winter.[135]

Invertebrates

[edit]Arthropods

[edit]Five species of krill, small free-swimming crustaceans, have been found in the Southern Ocean.[136] The Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) is one of the most abundant animal species on earth, with a biomass of around 500 million tonnes. Each individual is 6 centimetres (2.4 in) long and weighs over 1 gram (0.035 oz).[137] The swarms that form can stretch for kilometres, with up to 30,000 individuals per 1 cubic metre (35 cu ft), turning the water red.[136] Swarms usually remain in deep water during the day, ascending during the night to feed on plankton. Many larger animals depend on krill for their own survival.[137] During the winter when food is scarce, adult Antarctic krill can revert to a smaller juvenile stage, using their own body as nutrition.[136]

Many benthic crustaceans have a non-seasonal breeding cycle, and some raise their young in a brood pouch. Glyptonotus antarcticus is an unusually large benthic isopod, reaching 20 centimetres (8 in) in length weighing 70 grams (2.47 oz). Amphipods are abundant in soft sediments, eating a range of items, from algae to other animals.[114] The amphipods are highly diverse with more than 600 recognized species found south of the Antarctic Convergence and there are indications that many undescribed species remain. Among these are several "giants", such as the iconic epimeriids that are up to 8 cm (3.1 in) long.[138]

Slow moving sea spiders are common, sometimes growing as large as a human hand. They feed on the corals, sponges, and bryozoans that litter the seabed.[114]

Molluscs, urchins, squid and sponges

[edit]Many aquatic molluscs are present in Antarctica. Bivalves such as Adamussium colbecki move around on the seafloor, while others such as Laternula elliptica live in burrows filtering the water above.[114]

There are around 70 cephalopod species in the Southern Ocean,[139] the largest of which is the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni), which at up to 14 metres (46 ft) is among the largest invertebrate in the world.[140] Squid makes up most of the diet of some animals, such as grey-headed albatrosses and sperm whales, and the warty squid (Moroteuthis ingens) is one of the subantarctic's most preyed upon species by vertebrates.[139]

The sea urchin genus Abatus burrow through the sediment eating the nutrients they find in it.[114] Two species of salps are common in Antarctic waters: Salpa thompsoni and Ihlea racovitzai. Salpa thompsoni is found in ice-free areas, whereas Ihlea racovitzai is found in the high-latitude areas near ice. Due to their low nutritional value, they are normally only eaten by fish, with larger animals such as birds and marine mammals only eating them when other food is scarce.[141]

Antarctic sponges are long-lived and sensitive to environmental changes due to the specificity of the symbiotic microbial communities within them. As a result, they function as indicators of environmental health.[142]

Environment

[edit]Increased solar ultraviolet radiation resulting from the Antarctic ozone hole has reduced marine primary productivity (phytoplankton) by as much as 15% and has started damaging the DNA of some fish.[143] Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, especially the landing of an estimated five to six times more Patagonian toothfish than the regulated fishery, likely affects the sustainability of the stock. Long-line fishing for toothfish causes a high incidence of seabird mortality.

International agreements

[edit]

All international agreements regarding the world's oceans apply to the Southern Ocean. It is also subject to several regional agreements:

The Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) prohibits commercial whaling south of 40 degrees south (south of 60 degrees south between 50 degrees and 130 degrees west). Japan regularly does not recognize this provision, because the sanctuary violates IWC charter. Since the scope of the sanctuary is limited to commercial whaling, in regard to its whaling permit and whaling for scientific research, a Japanese fleet carried out an annual whale-hunt in the region. On 31 March 2014, the International Court of Justice ruled that Japan's whaling program, which Japan has long claimed is for scientific purposes, was a cloak for commercial whaling, and no further permits would be granted.

The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals is part of the Antarctic Treaty System. It was signed at the conclusion of a multilateral conference in London on 11 February 1972.[144]

The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources is part of the Antarctic Treaty System. It entered into force on 7 April 1982 with a goal to preserve marine life and environmental integrity in and near Antarctica. It was established largely due to concerns that an increase in krill catches in the Southern Ocean could seriously impact populations of other marine life which are dependent upon krill for food.[145]

Many nations prohibit the exploration for and the exploitation of mineral resources south of the fluctuating Antarctic Convergence,[146] which lies in the middle of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and serves as the dividing line between the very cold polar surface waters to the south and the warmer waters to the north. The Antarctic Treaty covers the portion of the globe south of 60 degrees south;[147] it prohibits new claims to Antarctica.[148]

The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources applies to the area south of 60° South latitude as well as the areas further north up to the limit of the Antarctic Convergence.[149]

Economy

[edit]Between 1 July 1998 and 30 June 1999, fisheries landed 119,898 tonnes (118,004 long tons; 132,165 short tons), of which 85% consisted of krill and 14% of Patagonian toothfish. International agreements came into force in late 1999 to reduce illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, which in the 1998–99 season landed five to six times more Patagonian toothfish than the regulated fishery.

Ports and harbors

[edit]

Major operational ports include: Rothera Station, Palmer Station, Villa Las Estrellas, Esperanza Base, Mawson Station, McMurdo Station, and offshore anchorages in Antarctica.

Few ports or harbors exist on the southern (Antarctic) coast of the Southern Ocean, since ice conditions limit use of most shores to short periods in midsummer; even then some require icebreaker escort for access. Most Antarctic ports are operated by government research stations and, except in an emergency, remain closed to commercial or private vessels; vessels in any port south of 60 degrees south are subject to inspection by Antarctic Treaty observers.

The Southern Ocean's southernmost port operates at McMurdo Station at 77°50′S 166°40′E / 77.833°S 166.667°E. Winter Quarters Bay forms a small harbor, on the southern tip of Ross Island where a floating ice pier makes port operations possible in summer. Operation Deep Freeze personnel constructed the first ice pier at McMurdo in 1973.[150]

Based on the original 1928 IHO delineation of the Southern Ocean (and the 1937 delineation if the Great Australian Bight is considered integral), Australian ports and harbors between Cape Leeuwin and Cape Otway on the Australian mainland and along the west coast of Tasmania would also be identified as ports and harbors existing in the Southern Ocean. These would include the larger ports and harbors of Albany, Thevenard, Port Lincoln, Whyalla, Port Augusta, Port Adelaide, Portland, Warrnambool, and Macquarie Harbour.

Even though organizers of several yacht races define their routes as involving the Southern Ocean, the actual routes don't enter the actual geographical boundaries of the Southern Ocean. The routes involve instead South Atlantic, South Pacific and Indian Ocean.[151][152][153]

See also

[edit]- Borders of the oceans

- List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

- List of countries by southernmost point

- List of seamounts in the Southern Ocean

- Seven Seas

- International Bathymetric Chart of the Southern Ocean

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also a translation of its former French name (Grand Océan Austral) in reference to its position below the Pacific, the "Grand Océan".

- ^ Used by Dr. Hooker in his accounts of his Antarctic voyages.[4] Also a translation of the ocean's Japanese name Nankyoku Kai (南極海).

- ^ Also a translation of the ocean's Chinese name Nánbīng Yáng (南冰洋).

- ^ Historic names include the "South Sea",[2] the "Great Southern Ocean",[3][note 1] the "South Polar Ocean" or "South-Polar Ocean",[note 2] and the "Southern Icy Ocean".[2][note 3]

- ^ Reservation by Norway: Norway recognizes the name Kong Håkon VII Hav, which covers the sea area adjacent to Dronning Maud Land and stretching from 20°W to 45°E.[36]

- ^ The Drake Passage is situated between the southern and eastern extremities of South America and the South Shetland Islands, lying north of the Antarctic Peninsula.[36]

- ^ The Scotia Sea is an area defined by the southeastern extremity of South America and the South Shetland Islands on the west and by South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands to the north and east. As they extend north of 60°S, Drake Passage and the Scotia Sea are also described as forming part of the South Atlantic Ocean.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ EB (1878).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sherwood, Mary Martha (1823), An Introduction to Geography, Intended for Little Children, 3rd ed., Wellington: F. Houlston & Son, p. 10

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 422.

- ^ Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1843), Flora Antarctica: The Botany of the Antarctic Voyage, London: Reeve

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Geography – Southern Ocean". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

... the Southern Ocean has the unique distinction of being a large circumpolar body of water totally encircling the continent of Antarctica; this ring of water lies between 60 degrees south latitude and the coast of Antarctica and encompasses 360 degrees of longitude.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Introduction – Southern Ocean". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

...As such, the Southern Ocean is now the fourth largest of the world's five oceans (after the Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, and Indian Ocean, but larger than the Arctic Ocean).

- ^ "Explorer completes another historic submersible dive". For The Win. 6 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Pyne, Stephen J. (1986). The Ice: A Journey to Antarctica. University of Washington Press.

- ^ "Do You Know the World's Newest Ocean?". ThoughtCo.

- ^ "NOAA Scientists Detect a Reshaping of the Meridional Overturning Circulation in the Southern Ocean". NOAA. 29 March 2023.

- ^ Haumann, F. Alexander; Gruber, Nicolas; Münnich, Matthias; Frenger, Ivy; Kern, Stefan (September 2016). "Sea-ice transport driving Southern Ocean salinity and its recent trends". Nature. 537 (7618): 89–92. Bibcode:2016Natur.537...89H. doi:10.1038/nature19101. hdl:20.500.11850/120143. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 27582222. S2CID 205250191.

- ^ Lenton, T. M.; Armstrong McKay, D.I.; Loriani, S.; Abrams, J.F.; Lade, S.J.; Donges, J.F.; Milkoreit, M.; Powell, T.; Smith, S.R.; Zimm, C.; Buxton, J.E.; Daube, Bruce C.; Krummel, Paul B.; Loh, Zoë; Luijkx, Ingrid T. (2023). The Global Tipping Points Report 2023 (Report). University of Exeter.

- ^ Logan, Tyne (29 March 2023). "Landmark study projects 'dramatic' changes to Southern Ocean by 2050". ABC News.

- ^ Constable, Andrew J.; Melbourne-Thomas, Jessica; Corney, Stuart P.; Arrigo, Kevin R.; Barbraud, Christophe; Barnes, David K. A.; Bindoff, Nathaniel L.; Boyd, Philip W.; Brandt, Angelika; Costa, Daniel P.; Davidson, Andrew T. (2014). "Climate change and Southern Ocean ecosystems I: how changes in physical habitats directly affect marine biota". Global Change Biology. 20 (10): 3004–3025. Bibcode:2014GCBio..20.3004C. doi:10.1111/gcb.12623. ISSN 1365-2486. PMID 24802817. S2CID 7584865.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Southern Ocean". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Darby, Andrew (22 December 2003). "Canberra all at sea over position of Southern Ocean". The Age. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Names and Limits of Oceans and Seas around Australia" (PDF). Australian Hydrographic Office. Department of Defence. 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ "There's a New Ocean Now". National Geographic Society. 8 June 2021. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Wong, Wilson (10 June 2021). "National Geographic adds 5th ocean to world map". ABC News. NBC Universal. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

National Geographic announced Tuesday that it is officially recognizing the body of water surrounding the Antarctic as the Earth's fifth ocean: the Southern Ocean.

- ^ NGS (2014).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Maps Home". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ "Upside Down World Map". Hema Maps. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "Classic World Wall Map". GeoNova. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "Balboa, or Pan-Pacific Day". The Mid-Pacific Magazine. 20 (10). Pan-Pacific Union: 16.

He named it the Southern Ocean, but in 1520 Magellan sailed into the Southern Ocean and named it Pacific

- ^ Tomlins, Sir Thomas Edlyne; Raithby, John (1811). "18 George II c. 17". The statutes at large, of England and of Great-Britain: from Magna Carta to the union of the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland. Printed by G. Eyre and A. Strahan. p. 153. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Cook, James (1821). "March 1775". Three Voyages of Captain James Cook Round the World. Longman. p. 244. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

These voyages of the French, though undertaken by private adventurers, have contributed something toward exploring the Southern Ocean. That of Captain Surville, clears up a mistake, which I was led into, in imagining the shoals off the west end of New Caledonia was to extend to the west, but as far as New Holland.

- ^ A Compendious Geographical Dictionary, Containing, a Concise Description of the Most Remarkable Places, Ancient and Modern, in Europe, Asia, Africa, & America, ... (2nd ed.). London: W. Peacock. 1795. p. 29.

- ^ Payne, John (1796). Geographical extracts, forming a general view of earth and nature... illustrated with maps. London: G.G. and J. Robinson. p. 80. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ The Edinburgh Gazetteer: Or, Geographical Dictionary: Containing a Description of the Various Countries, Kingdoms, States, Cities, Towns, Mountains, &c. of the World; an Account of the Government, Customs, and Religion of the Inhabitants; the Boundaries and Natural Productions of Each Country, &c. &c. Forming a Complete Body of Geography, Physical, Political, Statistical, and Commercial with Addenda, Containing the Present State of the New Governments in South America... Vol. 1. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. 1827. p. lix.

- ^ "Physical Geography". Family Magazine: Or Monthly Abstract of General Knowledge. 3 (1). New York: Redfield & Lindsay: 16. June 1835.

- ^ "45 Vict. No. 702" (PDF). Australasian Legal Information Institute. 28 November 1881. p. 87. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ "Map accompanying first edition of IHO Publication Limits of Oceans and Seas, Special Publication 23". NOAA Photo Library. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "Map accompanying second edition of IHO Publication Limits of Oceans and Seas, Special Publication 23". NOAA Photo Library. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

Alternate location: AWI (DOI 10013/epic.37175.d001 scan archived). - ^ "Pacific Ocean". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "IHO Publication S-23, Limits of Oceans and Seas, Draft 4th Edition". International Hydrographic Organization. 2002. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2002.

- ^ "IHO Special Publication 23". Korean Hydrographic and Oceanographic Administration. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Darby, Andrew (22 December 2003). "Canberra all at sea over position of Southern Ocean". The Age. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ Schenke, Hans Werner (September 2003). "Proposal for the preparation of a new International Bathymetric Chart of the Southern Ocean" (PDF). IHO International Hydrographic Committee on Antarctica (HCA). Third HCA Meeting, 8–10 September 2003. Monaco: International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ "Indian Ocean". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Southern Ocean". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ "AHS – AA609582" (PDF) (PDF). The Australian Hydrographic Service. 5 July 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ For example: Chart Aus343: Australia South Coast – South Australia – Whidbey Isles to Cape Du Couedic, Australian Hydrographic Service, 29 June 1990, archived from the original on 26 May 2009, retrieved 11 October 2010, Chart Aus792: Australia – Tasmania – Trial Harbour to Low Rocky Point, Australian Hydrographic Service, 18 July 2008, retrieved 11 October 2010

- ^ "Assessment Documentation for Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse" (PDF). Register of Heritage Places. 13 May 2005. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Mill, Hugh Robert (1911). "Polar Regions". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 961–972.

- ^ Joost Depuydt, 'Ortelius, Abraham (1527–1598)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ Peter Barber, "Ortelius' great world map", National Library of Australia, Mapping our World: Terra Incognita to Australia, Canberra, National Library of Australia, 2013, p. 95.

- ^ Dalrymple, Alexander. (1775). A Collection of Voyages Chiefly in The Southern Atlantick Ocean. London. pp.85-88.

- ^ Headland, Robert K. (6 December 1984). The Island of South Georgia. London New York Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25274-1.

- ^ Cook, James. (1777). A Voyage Towards the South Pole, and Round the World. Performed in His Majesty's Ships the Resolution and Adventure, In the Years 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775. In which is included, Captain Furneaux's Narrative of his Proceedings in the Adventure during the Separation of the Ships. Volume II. London: Printed for W. Strahan and T. Cadell. (Relevant fragment)

- ^ Dance, Nathaniel (c. 1776). "Captain James Cook, 1728–79". Royal Museums Greenwich. Commissioned by Sir Joseph Banks. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Weddel, James (1970) [1825]. A voyage towards the South Pole: performed in the years 1822–24, containing an examination of the Antarctic Sea. United States Naval Institute. p. 44.

- ^ U.S. Antarctic Program External Panel. "Antarctica – past and present" (PDF). NSF. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ Guy G. Guthridge. "Nathaniel Brown Palmer". NASA. Archived from the original on 2 February 2006. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ Palmer Station. ucsd.edu

- ^ Erki Tammiksaar (14 December 2013). "Punane Bellingshausen" [Red Bellingshausen]. Postimees. Arvamus. Kultuur (in Estonian).

- ^ "South-Pole – Exploring Antarctica". South-Pole.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2006. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ "Milestones, 28 January 1980". Time. 28 January 1980. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Historic Names – Norwegian-American Scientific Traverse of East Antarctica Archived 21 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Traverse.npolar.no. Retrieved on 29 January 2012.

- ^ Navy Military History Archived 2 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. History.navy.mil. Retrieved on 29 January 2012.

- ^ Finn Ronne. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition 2008

- ^ antarctica.org Archived 6 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine – Science: in force...

- ^ "Mar 28 – Hump Day" Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, British Antarctic Survey.

- ^ Scope of Antarctic Tourism – A Background Presentation Archived 16 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, IAATO official website.

- ^ Reel, Monte (24 November 2007). "Cruise Ship Sinks Off Antarctica". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "154 Rescued From Sinking Ship In Antarctic: Passengers, Crew Boarding Another Ship After Wait In Lifeboats; No Injuries Reported". CBS News. 23 November 2007. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "Doomed Ship Defies Antarctica Odds". Reuters. 25 November 2007. Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- ^ "MS Explorer – situation report". The Falkland Islands News. 23 November 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012.

- ^ "MV Explorer Cruise Ship Sinking in South Atlantic". The Shipping Times. 23 November 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ "What Is a Saildrone and How Does It Work?". www.saildrone.com. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "Saildrone Completes First Autonomous Circumnavigation of Antarctica". www.saildrone.com. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "First row across the Drake Passage". Guinness World Records. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ imgbyid.asp (1609x1300) (in Russian). Archived from the original on 20 March 2007.

- ^ "Map of Antarctica and surrounding waters in Russian". Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ "The World's Biggest Oceans and Seas". Livescience.com. 4 June 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "World Map". worldatlas.com. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "List of seas". listofseas.com. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Water from Icebergs". Ocean Explorer. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Fraser, Ceridwen; Christina, Hulbe; Stevens, Craig; Griffiths, Huw (6 December 2020). "An Ocean Like No Other: the Southern Ocean's ecological richness and significance for global climate". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Antarctica Detail". U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. 18 October 2000. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Michael L., Van Woert; et al. (2003). "The Ross Sea Circulation During the 1990s". In DiTullio, Giacomo R.; Dunbar, Robert B. (eds.). Biogeochemistry of the Ross Sea. American Geophysical Union. pp. 4–34. ISBN 0-87590-972-8.[permanent dead link] p. 10.

- ^ Florindo, Fabio; Siegert, Martin J. (2008). Antarctic Climate Evolution. Elsevier. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-444-52847-6.

- ^ "Home". soos.aq. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Rintoul, S. R.; Meredith, M. P.; Schofield, O.; Newman, L. (2012). "The southern ocean observing system". Oceanography. 25 (3): 68–69. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2012.76. S2CID 129434229.

- ^ Constable, A. J.; Costa, D. P.; Schofield, O.; Newman, L.; Urban Jr, E. R.; Fulton, E. A.; Melbourne-Thomas, J.; Ballerini, T.; Boyd, P. W.; Brandt, A; Willaim, K. (2016). "Developing priority variables ("ecosystem Essential Ocean Variables"—eEOVs) for observing dynamics and change in Southern Ocean ecosystems". Journal of Marine Systems. 161: 26–41. Bibcode:2016JMS...161...26C. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2016.05.003. S2CID 3530105.

- ^ "The World Fact Book: Climate". U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Liu, Y.; Moore, J. K.; Primeau, F.; Wang, W. L. (22 December 2022). "Reduced CO2 uptake and growing nutrient sequestration from slowing overturning circulation". Nature Climate Change. 13: 83–90. doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01555-7. OSTI 2242376. S2CID 255028552.

- ^ Schine, Casey M. S.; Alderkamp, Anne-Carlijn; van Dijken, Gert; Gerringa, Loes J. A.; Sergi, Sara; Laan, Patrick; van Haren, Hans; van de Poll, Willem H.; Arrigo, Kevin R. (22 February 2021). "Massive Southern Ocean phytoplankton bloom fed by iron of possible hydrothermal origin". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 1211. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.1211S. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21339-5. PMC 7900241. PMID 33619262.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "NOAA Scientists Detect a Reshaping of the Meridional Overturning Circulation in the Southern Ocean". NOAA. 29 March 2023.

- ^ Marshall, John; Speer, Kevin (26 February 2012). "Closure of the meridional overturning circulation through Southern Ocean upwelling". Nature Geoscience. 5 (3): 171–180. Bibcode:2012NatGe...5..171M. doi:10.1038/ngeo1391.

- ^ Hausfather, Zeke; Peters, Glen (29 January 2020). "Emissions – the 'business as usual' story is misleading". Nature. 577 (7792): 618–20. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..618H. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00177-3. PMID 31996825.

- ^ Phiddian, Ellen (5 April 2022). "Explainer: IPCC Scenarios". Cosmos. Retrieved 30 September 2023.