Президентские выборы 1960 года в США

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

537 членов Коллегии выборщиков Для победы необходимо 269 голосов выборщиков | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Опросы общественного мнения | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Оказаться | 63.8% [1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Kennedy/Johnson, red denotes those won by Nixon/Lodge, light blue denotes the electoral votes for Byrd/Thurmond by Alabama and Mississippi unpledged electors, and a vote for Byrd/Goldwater by an Oklahoma faithless elector. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

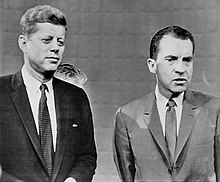

— Президентские выборы в США 1960 года 44-е президентские выборы , состоявшиеся раз в четыре года, состоявшиеся во вторник, 8 ноября 1960 года. Демократический билет сенатора Джона Ф. Кеннеди и его напарника, лидера сенатского большинства Линдона Б. Джонсона, с небольшим перевесом победил республиканский список действующий вице-президент Ричард Никсон и его кандидат на пост вице-президента, посол ООН Генри Кэбот Лодж-младший. Это были первые выборы, в которых приняли участие 50 штатов, что ознаменовало первое участие Аляски и Гавайев, и последние, в которых не участвовал округ Колумбия. Таким образом, это были единственные президентские выборы, на которых порог победы составлял 269 голосов выборщиков . Это были также первые выборы, на которых действующий президент — в данном случае Дуайт Д. Эйзенхауэр — не имел права баллотироваться на третий срок из-за ограничений срока полномочий, установленных 22-й поправкой .

This was the most recent election in which three of the four major party nominees for president and vice president were eventually elected president. Kennedy won the election, but was assassinated in 1963 and succeeded by Johnson, who won the election in 1964. Then, Nixon won the 1968 election. Only Republican vice-presidential nominee Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. failed to succeed to the presidency. As such, this was also the most recent election in which the defeated presidential nominee would later win the presidency.

The election saw the first time that a candidate won the presidency while carrying fewer states than the other candidate, which would not occur again until 1976. Kennedy became the youngest president elected to the presidency at 43 years, while Theodore Roosevelt remained the youngest president inaugurated to the presidency at 42 years and 10 months in September 1901, following the death of President William McKinley. Regardless of the winning candidate, America would elect its first president born in the 20th century as Kennedy was born in 1917, and Nixon in 1913. Nixon faced little opposition in the Republican race to succeed popular incumbent Dwight D. Eisenhower. Kennedy, a junior senator from Massachusetts, established himself as the Democratic front-runner with his strong performance in the 1960 Democratic primaries, including key victories in Wisconsin and West Virginia over Senator Hubert Humphrey. He defeated Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson on the first presidential ballot of the 1960 Democratic National Convention, and asked Johnson to serve as his running mate.

Kennedy won 303 to 219 in the Electoral College, and he won the reported national popular vote by 112,827, a margin of 0.17 percent. Fourteen unpledged electors from Mississippi and Alabama cast their vote for Senator Harry F. Byrd, as did a faithless elector from Oklahoma. The 1960 presidential election was the closest election since 1916, and this closeness can be explained by a number of factors.[5] Kennedy benefited from the economic recession of 1957–1958, which hurt the standing of the incumbent Republican Party, and he had the advantage of 17 million more registered Democrats than Republicans.[6] Furthermore, the new votes that Kennedy, a Roman Catholic, gained among Catholics almost neutralized the new votes Nixon gained among Protestants.[7] Nixon's advantages came from Eisenhower's popularity, and the economic prosperity of the past eight years. Kennedy strategically focused on campaigning in populous swing states, while Nixon exhausted time and resources campaigning in all fifty states. Kennedy emphasized his youth, while Nixon focused heavily on his experience. Kennedy relied on Johnson to hold the South, and used television effectively. Despite this, Kennedy's popular vote margin was the second narrowest in presidential history, only surpassed by the 0.11% margin of the election of 1880 and the smallest ever for a Democrat (notwithstanding the presidential elections where the winners lost the popular vote).

Nominations

[edit]Democratic Party

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

35th President of the United States Tenure Appointments Presidential campaign Assassination and legacy

| ||

| ||

|---|---|---|

Senator from Texas 37th Vice President of the United States 36th President of the United States First term Second term

Presidential and Vice presidential campaigns Post-presidency

| ||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| John F. Kennedy | Lyndon B. Johnson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. Senator from Massachusetts (1953–1960) | U.S. Senator from Texas (1949–1961) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Democratic candidates

[edit]- Senator John F. Kennedy from Massachusetts

- Senator Stuart Symington from Missouri

- Senator Hubert Humphrey from Minnesota

- Senator Wayne Morse from Oregon

- Senator George Smathers from Florida

The major candidates for the 1960 Democratic presidential nomination were United States Senator John F. Kennedy from Massachusetts, Governor Pat Brown of California, Senator Stuart Symington from Missouri, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson from Texas, former nominee Adlai Stevenson, Senator Wayne Morse from Oregon, and Senator Hubert Humphrey from Minnesota. Several other candidates sought support in their home state or region as "favorite son" candidates, without any realistic chance of winning the nomination. Symington, Stevenson, and Johnson all declined to campaign in the presidential primaries. While this reduced their potential delegate count going into the Democratic National Convention, each of these three candidates hoped that the other leading contenders would stumble in the primaries, thus causing the convention's delegates to choose him as a "compromise" candidate acceptable to all factions of the party.

Kennedy was initially dogged by suggestions from some Democratic Party elders (such as former United States President Harry S. Truman, who was supporting Symington) that he was too youthful and inexperienced to be president; these critics suggested that he should agree to be the running mate for another Democrat. Realizing that this was a strategy touted by his opponents to keep the public from taking him seriously, Kennedy stated frankly, "I'm not running for vice president; I'm running for president."[8]

The next step was the primaries. Kennedy's Roman Catholic religion was an issue. Kennedy first challenged Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey in the Wisconsin primary, and defeated him. Kennedy's sisters, brothers, and wife Jacqueline combed the state, looking for votes, leading Humphrey to complain that he "felt like an independent merchant competing against a chain store."[9] However, some political experts argued that Kennedy's margin of victory had come almost entirely from Catholic areas, and, thus, Humphrey decided to continue the contest in the heavily Protestant state of West Virginia. The first televised debate of 1960 was held in West Virginia. Kennedy outperformed Humphrey and, in the days following, Kennedy made substantial gains over Humphrey in the polls.[10][11] Humphrey's campaign was low on funds, and could not compete for advertising and other "get-out-the-vote" drives with Kennedy's well-financed and well-organized campaign, which was not above using dirty tricks to win; prior to the Wisconsin primary, Catholic neighborhoods in Milwaukee were flooded with anti-Catholic pamphlets postmarked from Minnesota. It was assumed Humphrey's campaign had sent them, and it may have helped tilt voters in Wisconsin away from him. In the end, Kennedy defeated Humphrey with over 60% of the vote, and Humphrey ended his presidential campaign. West Virginia showed that Kennedy, a Catholic, could win in a heavily Protestant state. Although Kennedy had only competed in nine presidential primaries,[12] Kennedy's rivals, Johnson and Symington, failed to campaign in any primaries. Even though Stevenson had twice been the Democratic Party's presidential candidate, and retained a loyal following of liberals, his two landslide defeats to Republican United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower led most party leaders and delegates to search for a "fresh face" who could win a national election. Following the primaries, Kennedy traveled around the nation, speaking to state delegations and their leaders. As the Democratic Convention opened, Kennedy was far in the lead, but was still seen as being just short of the delegate total he needed to win.

Democratic convention

[edit]The 1960 Democratic National Convention was held in Los Angeles, California. In the week before the convention opened, Kennedy received two new challengers, when Lyndon B. Johnson, the powerful Senate Majority Leader, and Adlai Stevenson, the party's nominee in 1952 and 1956, officially announced their candidacies. However, neither Johnson nor Stevenson was a match for the talented and highly efficient Kennedy campaign team led by Robert Kennedy. Johnson challenged Kennedy to a televised debate before a joint meeting of the Texas and Massachusetts delegations, which Kennedy accepted. Most observers believed that Kennedy won the debate, and Johnson was unable to expand his delegate support beyond the South. Stevenson's failure to launch his candidacy publicly until the week of the convention meant that many liberal delegates who might have supported him were already pledged to Kennedy, and Stevenson – despite the energetic support of former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt – could not break their allegiance. Kennedy won the nomination on the first ballot.

Then, in a move that surprised many, Kennedy asked Johnson to be his running mate. He realized that he could not be elected without the support of traditional Southern Democrats, most of whom had backed Johnson. He offered Johnson the vice presidential nomination at the Los Angeles Biltmore Hotel at 10:15 a.m. on July 14, 1960, the morning after being nominated for president.[13] Robert F. Kennedy, who hated Johnson for his attacks on the Kennedy family, and who favored labor leader Walter Reuther,[14] later said that his brother offered the position to Johnson as a courtesy and did not expect him to accept it. When he did accept, Robert Kennedy tried to change Johnson's mind, and failed.[15]

Biographers Robert Caro and W. Marvin Watson offer a different perspective: they write that the Kennedy campaign was desperate to win what was forecast to be a very close race against Nixon and Lodge. Johnson was needed on the ticket to help carry votes from Texas and the Southern United States. Caro's research showed that on July 14, Kennedy started the process, while Johnson was still asleep. At 6:30 a.m., Kennedy asked his brother to prepare an estimate of upcoming electoral votes, "including Texas".[13] Robert Kennedy called Pierre Salinger and Kenneth O'Donnell to assist him. Realizing the ramifications of counting Texas votes as their own, Salinger asked him whether he was considering a Kennedy–Johnson ticket, and Robert replied, "Yes".[13] Between 9 and 10 am, John Kennedy called Pennsylvania governor David L. Lawrence, a Johnson backer, to request that Lawrence nominate Johnson for vice president if Johnson were to accept the role, and then went to Johnson's suite to discuss a mutual ticket at 10:15 am. John Kennedy then returned to his suite to announce the Kennedy–Johnson ticket to his closest supporters and Northern political bosses. He accepted the congratulations of Ohio Governor Michael DiSalle, Connecticut Governor Abraham A. Ribicoff, New York City mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr., and Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley. Lawrence said that "Johnson has the strength where you need it most"; he then left to begin writing the nomination speech.[13] O'Donnell remembers being angry at what he considered a betrayal by John Kennedy, who had previously cast Johnson as anti-labor and anti-liberal. Afterward, Robert Kennedy visited with labor leaders who were extremely unhappy with the choice of Johnson, and, after seeing the depth of labor opposition to Johnson, he ran messages between the hotel suites of his brother and Johnson, apparently trying to undermine the proposed ticket without John Kennedy's authorization and to get Johnson to agree to be the Democratic Party chairman, rather than vice president. Johnson refused to accept a change in plans, unless it came directly from John Kennedy. Despite his brother's interference, John Kennedy was firm that Johnson was who he wanted as running mate, and met with staffers such as Larry O'Brien, his national campaign manager, to say Johnson was to be vice president. O'Brien recalled later that John Kennedy's words were wholly unexpected, but that, after a brief consideration of the electoral vote situation, he thought "it was a stroke of genius".[13]

Republican Party

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

Pre-vice presidency 36th Vice President of the United States Post-vice presidency 37th President of the United States

Judicial appointments Policies First term

Second term

Post-presidency Presidential campaigns Vice presidential campaigns  | ||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Richard Nixon | Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36th Vice President of the United States (1953–1961) | 3rd U.S. Ambassador to the UN (1953–1960) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Republican candidates

[edit]- Vice President Richard Nixon

- Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York

- State Senator James M. Lloyd from South Dakota

- Governor Cecil H. Underwood of West Virginia

With the ratification of the 22nd Amendment in 1951, President Dwight D. Eisenhower could not run for the office of president again; he had been elected in 1952 and 1956.

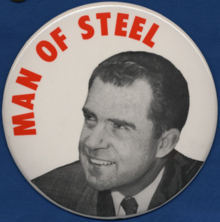

In 1959, it looked as if Vice President Richard Nixon might face a serious challenge for the Republican nomination from New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, the leader of the Republican moderate-to-liberal wing. However, Rockefeller announced that he would not be a candidate for president, after a national tour revealed that the great majority of Republicans favored Nixon.[16]

After Rockefeller's withdrawal, Nixon faced no significant opposition for the Republican nomination. At the 1960 Republican National Convention in Chicago, Illinois, Nixon was the overwhelming choice of the delegates, with conservative Senator Barry Goldwater from Arizona receiving 10 votes from conservative delegates. In earning the nomination, Nixon became the first sitting vice president to be nominated for president since John C. Breckinridge exactly a century prior. Nixon then chose former Massachusetts Senator and United Nations Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., as his vice presidential running mate. Nixon chose Lodge because his foreign-policy credentials fit into Nixon's strategy to campaign more on foreign policy than domestic policy, which he believed favored the Democrats. Nixon had previously sought Rockefeller as his running mate, but the governor had no ambitions to be vice president. However, he later served as Gerald Ford's vice president from 1974 to 1977.[17]

General election

[edit]Campaign promises

[edit]The issue of the Cold War dominated the election, as tensions were high between the United States and the Soviet Union. During the campaign, Kennedy charged that, under Eisenhower and the Republicans, the nation had militarily and economically fallen behind the Soviet Union in the Cold War. Kennedy pledged, if elected, he would "get America moving again". While the Eisenhower administration had established NASA in 1958, Kennedy also claimed the Republican Party had ignored the need to catch up to the Soviet Union in the Space Race. He promised that the new Democratic administration would fully appreciate the importance of space accomplishments for the national security and international prestige of the United States. Nixon responded that, if elected, he would continue the "peace and prosperity" that Eisenhower had brought the nation in the 1950s. Nixon also argued, with the nation engaged in the Cold War, he was more qualified to be president because of his greater political experience and that Kennedy was "too young and inexperienced" to be trusted with the presidency. Conversely, Nixon and Kennedy were only removed by four years in age. In spite of attacks, the Kennedy campaign made Kennedy's youthfulness, and his promise to bring about change, an asset. Kennedy had a slogan, reading, "who's seasoned through and through/but not so dog-gone seasoned that he won't try something new." He was also endorsed by celebrities such as Frank Sinatra, Henry Fonda, and Harry Belafonte. [18]

Campaign events

[edit]

Kennedy and Nixon both drew large and enthusiastic crowds throughout the campaign.[19] In August 1960, most polls gave Nixon a slim lead over Kennedy, and many political pundits regarded him as the favorite to win. However, Nixon was plagued with troubles throughout the fall campaign. In August, President Eisenhower, who had long been ambivalent about Nixon, held a televised press conference in which a reporter, Charles Mohr of Time, mentioned Nixon's claims that he had been a valuable administration insider and adviser. Mohr asked Eisenhower if he could give an example of a major idea of Nixon's that he had heeded. Eisenhower responded with the flip comment, "If you give me a week, I might think of one."[20] Although both Eisenhower and Nixon later claimed that he was merely joking with the reporter, the remark hurt Nixon, as it undercut his claims of having greater decision-making experience than Kennedy. The remark proved so damaging to Nixon that the Democrats turned Eisenhower's statement into a television commercial.[21]

At the Republican National Convention, Nixon pledged to campaign in all fifty states. This pledge backfired when, in August, Nixon injured his knee on a car door, while campaigning in North Carolina. The knee became infected, and Nixon had to cease campaigning for two weeks, while the infection was treated with antibiotics. When he left Walter Reed Hospital, Nixon refused to abandon his pledge to visit every state; he thus wasted valuable time visiting states that he had no chance of winning, that had few electoral votes and would be of little help at the election, or states that he would almost certainly win regardless. In his effort to visit all 50 states, Nixon spent the vital weekend before the election campaigning in Alaska, which had only three electoral votes, while Kennedy campaigned in more populous states such as New Jersey, Ohio, Michigan, and Pennsylvania.

Nixon visited Atlanta, Georgia, on August 26, and acquired a very large turnout to his event. He rode through a parade in Atlanta, and was greeted by 150,000 people.[22] Nixon mentioned in his speech in Atlanta, "In the last quarter of a century, there hasn't been a Democratic candidate for President that has bothered to campaign in the State of Georgia."[23] However, Kennedy would not let Nixon take the Democratic states that easily. Kennedy would change that statistic, and visit some surprising states, including Georgia. He visited the cities of Columbus, Warm Springs, and LaGrange on his campaign trail in Georgia. In his visit to Warm Springs, state troopers tried to keep Kennedy from an immense crowd; however, Kennedy reached out to shake hands of those who were sick with polio.[24] He also visited small towns across Georgia and saw a total of about 100,000 people in the state. Kennedy also spoke at a rehabilitation facility in Warm Springs. Warm Springs was near and dear to Kennedy's heart, due to the effects the facility had on Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt spent time at the rehabilitation facility, and died there in 1945.[23]

In Warm Springs, Kennedy spoke to supporters at the facility, and mentioned Roosevelt in his speech. He admired Roosevelt, and commended him for sticking up for the farmers, workers, small towns, big cities, those in poverty, and those who were sick.[23] He said Roosevelt had a "spirit of strength and progress, to get America moving".[23] Kennedy discussed his six-point plan for health care. Kennedy proposed: setting up a medical program for retirement, federal funding for the construction of medical schools and hospitals, government loans for students to attend medical school, providing grants to renovate old hospitals, more spending on medical research and, finally, expanding effort for rehabilitation and finding new ways to assist those in need.[23] Many Republicans disapproved of Kennedy's plan and described it as an "appeal to socialism".[25] Nevertheless, many residents of Warm Springs were supportive of Kennedy, with women wearing hats reading "Kennedy and Johnson" and[26] signs around the town saying "Douglas County For Kennedy, Except 17 Republicans 6 Old Grouches".[27] Joe O. Butts, the mayor of Warm Springs during Kennedy's visit, said: "He must've shaken hands with everybody within two miles of him, and he was smiling all the time."[28]

Despite the reservations Robert F. Kennedy had about Johnson's nomination, choosing Johnson as Kennedy's running mate proved to be a master stroke. Johnson vigorously campaigned for Kennedy, and was instrumental in helping the Democrats to carry several Southern states skeptical of him, especially Johnson's home state of Texas. Johnson made a "last-minute change of plans, and scheduled two 12-minute whistle-stop speeches in Georgia".[29] One of these visits included stopping in Atlanta to speak from the rear of a train at Terminal Station. In contrast, Ambassador Lodge, Nixon's running mate, ran a lethargic campaign and made several mistakes that hurt Nixon. Among them was a pledge, made without approval, that Nixon would name at least one African American to a Cabinet post. Nixon was furious at Lodge and accused him of spending too much time campaigning with minority groups instead of the white majority.[30]

Nixon was endorsed by 731 English-language newspapers while Kennedy was endorsed by 208. This was the largest amount of endorsements for a Democratic presidential candidate since 1932.[31]

Debates

[edit]There were four presidential debates and no vice presidential debates during the 1960 general election.[32]

| No. | Date | Host | Location | Panelists | Moderator | Participants | Viewership (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Monday, September 26, 1960 | WBBM-TV | Chicago, Illinois | Sander Vanocur Charles Warren Stuart Novins | Howard K. Smith | Senator John F. Kennedy Vice President Richard Nixon | 66.4[32] |

| P2 | Friday, October 7, 1960 | WRC-TV | Washington, D.C. | Paul Niven Edward P. Morgan Alan Spivak Harold R. Levy | Frank McGee | Senator John F. Kennedy Vice President Richard Nixon | 61.9[32] |

| P3 | Thursday, October 13, 1960 | ABC Studios Los Angeles (Nixon) | Los Angeles, California | Frank McGee Charles Van Fremd Douglass Cater Roscoe Drummond | Bill Shadel | Senator John F. Kennedy Vice President Richard Nixon | 63.7[32] |

| ABC Studios New York (Kennedy) | New York City | ||||||

| P4 | Friday, October 21, 1960 | ABC Studios New York | New York City | Frank Singiser John Edwards Walter Cronkite John Chancellor | Quincy Howe | Senator John F. Kennedy Vice President Richard Nixon | 60.4[32] |

The key turning point of the campaign came with the four Kennedy-Nixon debates; they were the first presidential debates ever (the Lincoln–Douglas debates of 1858 had been the first for senators from Illinois), also the first held on television and thus attracted enormous publicity. Nixon insisted on campaigning until just a few hours before the first debate started. He had not completely recovered from his stay in hospital, and thus looked pale, sickly, under-weight, and tired.[34] His eyes moved across the room during the debate, and at various moments, sweat was visible on his face. He also refused make-up for the first debate, and as a result, his facial stubble showed prominently on black-and-white TV screens. Furthermore, the debate set appeared darker once the paint dried up, causing Nixon's suit color to blend in with the background, reducing his stature.[34] Nixon's poor appearance on television in the first debate was reflected by the fact that his mother called him immediately following the debate to ask if he was sick.[35] Kennedy, by contrast, rested and prepared extensively beforehand and thus appeared tanned,[d] confident, and relaxed during the debate.[37] An estimated 70 million viewers watched the first debate.[38]

It is often claimed that people who watched the debate on television overwhelmingly believed Kennedy had won, while radio listeners (a smaller audience) thought Nixon had ended up defeating him.[38][39][40] However, that has been disputed.[41] Indeed, one study has speculated that the viewer/listener disagreement could be due to sample bias, in that those without TV could be a skewed subset of the population:[42]

Evidence in support of this belief [i. e., that Kennedy's physical appearance over-shadowed his performance during the first debate] is mainly limited to sketchy reports about a market survey, conducted by Sindlinger & Company, in which 49% of those who listened to the debates on radio said Nixon had won, compared to 21% naming Kennedy, while 30% of those who watched the debates on television said Kennedy had won, compared to 29% naming Nixon. Contrary to popular belief, the Sindlinger evidence suggests not that Kennedy won on television, but that the candidates tied on television, while Nixon won on radio. However, no details about the sample have ever been reported, and it is unclear whether the survey results can be generalized to a larger population. Moreover, since 87% of American households had a television in 1960 [and that the] fraction of Americans lacking access to television in 1960 was concentrated in rural areas, and particularly in southern and western states, places that were unlikely to hold significant proportions of Catholic voters.[37]

Nonetheless, Gallup polls in October 1960 showed Kennedy moving into a slight but consistent lead over Nixon after the candidates were in a statistical tie for most of August and September.[43] For the remaining three debates, Nixon regained his lost weight, wore television make-up, and appeared more forceful than in his initial appearance.

However, up to 20 million fewer viewers watched the three remaining debates than the first. Political observers at the time felt that Kennedy won the first debate,[44] Nixon won the second[45] and third debates,[46] while the fourth debate,[47] which was seen as the strongest performance by both men, was a draw.

The third debate has been noted, as it brought about a change in the debate process. This debate was a monumental step for television. For the first time ever, split-screen technology was used to bring two people from opposite sides of the country together so they were able to converse in real time. Nixon was in Los Angeles, while Kennedy was in New York. The men appeared to be in the same room, thanks to identical sets. Both candidates had monitors in their respective studios, containing the feed from the opposite studio, so that they could respond to questions. Bill Shadel moderated the debate from a different television studio in Los Angeles.[48] The main topic of this debate was whether military force should be used to prevent Quemoy and Matsu, two island archipelagos off the Chinese coast, from falling under Communist control.[49][50]

Campaign issues

[edit]A key concern in Kennedy's campaign was the widespread skepticism among Protestants about his Roman Catholic religion. Some Protestants, especially Southern Baptists and Lutherans, feared that having a Catholic in the White House would give undue influence to the Pope in the nation's affairs.[51] Radio evangelists such as G. E. Lowman wrote that, "Each person has the right to their own religious belief ... [but] ... the Roman Catholic ecclesiastical system demands the first allegiance of every true member, and says in a conflict between church and state, the church must prevail".[52] The religious issue was so significant that Kennedy made a speech before the nation's newspaper editors in which he criticized the prominence they gave to the religious issue over other topics – especially in foreign policy – that he felt were of greater importance.[53]

To address fears among Protestants that his Roman Catholicism would impact his decision-making, Kennedy told the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12, 1960: "I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for president who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters – and the Church does not speak for me."[54] He promised to respect the separation of church and state, and not to allow Catholic officials to dictate public policy to him.[55][56][57] Kennedy also raised the question of whether one-quarter of Americans were relegated to second-class citizenship just because they were Roman Catholic. Kennedy would become the first Roman Catholic to be elected president—it would be 60 years before another Roman Catholic, Joe Biden, was elected.[58]

Kennedy's campaign took advantage of an opening when Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the civil-rights leader, was arrested in Georgia while taking part in a sit-in.[59] Nixon asked President Dwight D. Eisenhower to intervene, but the President declined to do so (as the matter was under state jurisdiction, the President did not have the power to pardon King). Nixon refused to take further action, but Kennedy placed calls to local political authorities to get King released from jail, and he also called King's father and wife. As a result, King's father endorsed Kennedy, and he received much favorable publicity among the black electorate.[60] A letter to the Governor of Georgia regarding Martin Luther King Jr.'s, arrest also helped Kennedy garner many African American votes. John F. Kennedy asked Governor Ernest Vandiver to look into the harsh sentencing, and stated his claim that he did not want to have to get involved in Georgia's justice system.[61] A member of Kennedy's civil rights team and King's friend, Harris Wofford, and other Kennedy campaign members passed out a pamphlet to black churchgoers the Sunday before the presidential election that said, ""No Comment" Nixon versus a Candidate with a Heart, Senator Kennedy."[62] On election day, Kennedy won the black vote in most areas by wide margins, and this may have provided his margin of victory in states such as New Jersey, South Carolina, Illinois, and Missouri.[citation needed] Researchers found that Kennedy's appeal to African American voters appears to be largely responsible for his receiving more African-American votes than Adlai Stevenson in the 1956 election.[63] The same study conducted found that white voters were less influenced on the topic of civil rights than black voters in 1960. The Republican national chairman at the time, Thruston Ballard Morton, regarded the African-American vote as the single most crucial factor.[64]

The issue that dominated the election was the rising Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union.[65] In 1957, the Soviets had launched Sputnik, the first man-made satellite to orbit Earth.[65] Soon afterwards, some American leaders warned that the nation was falling behind communist countries in science and technology.[65] In Cuba, the revolutionary regime of Fidel Castro became a close ally of the Soviet Union in 1960, heightening fears of communist subversion in the Western Hemisphere.[65] Public opinion polls revealed that more than half the American people thought that war with the Soviet Union was inevitable.[65]

Kennedy took advantage of increased Cold War tension by emphasizing a perceived "missile gap" between the United States and Soviet Union. He argued that under the Republicans, the Soviets had developed a major advantage in the numbers of nuclear missiles.[66] He proposed a bi-partisan congressional investigation about the possibility that the Soviet Union was ahead of the United States in developing missiles.[28] He also noted in an October 18 speech that several senior US military officers had long criticized the Eisenhower Administration's defense spending policies.[67]

Both candidates also argued about the economy and ways in which they could increase the economic growth and prosperity of the 1950s, and make it accessible to more people (especially minorities). Some historians criticize Nixon for not taking greater advantage of Eisenhower's popularity (which was around 60–65% throughout 1960 and on election day), and for not discussing the prosperous economy of the Eisenhower presidency more often in his campaign.[68] As the campaign moved into the final two weeks, the polls and most political pundits predicted a Kennedy victory. However, President Eisenhower, who had largely sat out the campaign, made a vigorous campaign tour for Nixon over the last 10 days before the election. Eisenhower's support gave Nixon a badly needed boost. Nixon also criticized Kennedy for stating that Quemoy and Matsu, two small islands off the coast of Communist China that were held by Nationalist Chinese forces based in Taiwan, were outside the treaty of protection the United States had signed with the Nationalist Chinese. Nixon claimed the islands were included in the treaty, and accused Kennedy of showing weakness towards Communist aggression.[69] Aided by the Quemoy and Matsu issue, and by Eisenhower's support, Nixon began to gain momentum, and by election day, the polls indicated a virtual tie.[70]

Results

[edit]

The election was held on November 8, 1960. Nixon watched the election returns from his suite at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, while Kennedy watched them at the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. As the early returns poured in from large Northeastern and Midwestern cities, such as Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, and Chicago, Kennedy opened a large lead in the popular and electoral votes, and appeared headed for victory. However, as later returns came in from rural and suburban areas in the Midwest, the Rocky Mountain states, and the Pacific Coast states, Nixon began to steadily close the gap on Kennedy.[71]

Before midnight, The New York Times had gone to press with the headline, "Kennedy Elected President". As the election again became too close to call, Times managing editor Turner Catledge hoped that, as he recalled in his memoirs, "a certain Midwestern mayor would steal enough votes to pull Kennedy through", thus allowing the Times to avoid the embarrassment of announcing the wrong winner, as the Chicago Tribune had memorably done twelve years earlier in announcing that Thomas E. Dewey had defeated President Harry S. Truman.[72]

Nixon made a speech at about 3 am, and hinted that Kennedy might have won the election. News reporters were puzzled, as it was not a formal concession speech. He talked of how Kennedy would be elected if "the present trend continues".[73] It was not until the afternoon of the next day that Nixon finally conceded the election, and Kennedy claimed his victory.

Kennedy won in twenty-seven of the thirty-nine largest cities, but lost in Southern cities that had voted for Adlai Stevenson II although he maintained Atlanta, New Orleans, and San Antonio. New Orleans and San Antonio were the only cities in the Southern United States to have large Catholic populations and Atlanta was a traditional Democratic stronghold.[74] Of the 3,129 counties and county-equivalents making returns, Nixon won in 1,857 (59.35%), while Kennedy carried 1,200 (38.35%). "Unpledged" electors came first in 71 counties and parishes (2.27%) throughout Mississippi and Louisiana, and one borough (0.03%) in Alaska split evenly between Kennedy and Nixon. The Kennedy-Johnson ticket was the first successful all Senator ticket, which would only be replicated in 2008.

This election marked the beginning of a decisive realignment in the Democratic presidential coalition; whereas Democrats had until this point relied on dominating in Southern states to win the electoral college, Kennedy managed to win without carrying a number of these states. As such, this marked the first election in history in which a Republican candidate carried any of Oklahoma, Tennessee, Kentucky, Florida, Virginia, or Idaho without winning the presidency, and the first time since statehood that Arizona backed any losing candidate in a presidential election. This in many ways foreshadowed the results of subsequent elections, in which Democratic candidates from northern states would rely on their performance in the northeast and midwest to win, while Republican candidates would rely on success in the former Solid South and the Mountain West. This is the last time a Democrat won without Wisconsin.

A sample of how close the election was can be seen in California, Nixon's home state. Kennedy seemed to have carried the state by 37,000 votes when all of the voting precincts reported, but when the absentee ballots were counted a week later, Nixon came from behind to win the state by 36,000 votes.[75]

Similarly, in Hawaii, official results showed Nixon winning by a small margin of 141 votes, with the state being called for him early Wednesday morning. Acting Governor James Kealoha certified the Republican electors, and they cast Hawaii's three electoral votes for Nixon. However, clear discrepancies existed in the official electoral tabulations, and Democrats petitioned for a recount in Hawaii circuit court.[76] The court challenge was still ongoing at the time of the Electoral Count Act's safe harbor deadline, but Democratic electors still convened at the ʻIolani Palace on the constitutionally-mandated date of December 19 and cast their votes for Kennedy.[76] The recount, completed before Christmas, resulted in Kennedy being declared winner by 115 votes. On December 30, the circuit court ruled that Hawaii's three electoral votes should go to Kennedy. It was decided that a new certificate was necessary, with only two days remaining before Congress convened on January 6, 1961, to count and certify the Electoral College votes. A letter to Congress saying a certificate was on the way was rushed out by registered air mail. Both Democrat and Republican electoral votes from Hawaii were presented for counting on January 6, 1961, and Vice President Nixon who presided over the certification, graciously, and saying "without the intent of establishing a precedent",[77] requested unanimous consent that the Democratic votes for Kennedy to be counted.[78][79]

In the national popular vote, Kennedy beat Nixon by less than two-tenths of one percentage point (0.17%), the closest popular-vote margin of the 20th century. So close was the popular vote that a shift of 18,838 votes in Illinois and Missouri, both won by Kennedy by less than 1%, would have left both Kennedy and Nixon short of the 269 electoral votes required to win, thus forcing a contingent election in the House of Representatives. Furthermore, had all five of the states Kennedy won by a margin of less than 1% (Hawaii, Illinois, Missouri, New Jersey, and New Mexico) had been won by Nixon instead, it would have been enough for Nixon to win the election with 283 electoral votes (not accounting for a faithless elector in Oklahoma).

In the Electoral College, Kennedy's victory was larger, as he took 303 electoral votes, to Nixon's 219. A total of 15 electors – eight from Mississippi, six from Alabama, and one from Oklahoma – all refused to vote for either Kennedy or Nixon, and instead cast their votes for Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia, a conservative Democrat, even though he had not been a candidate for president.[80] Kennedy carried 12 states by three percentage points or less, while Nixon won six by similarly narrow margins. Kennedy carried all but three states in the populous Northeast, and he also carried the large states of Michigan, Illinois, and Missouri in the Midwest. With Lyndon Johnson's help, he also carried most of the South, including the large states of North Carolina, Georgia, and Texas. Nixon carried all but three of the Western states (including California), and he ran strong in the farm belt states, where his biggest victory was in Ohio.

The New York Times, summarizing the discussion in late November, spoke of a "narrow consensus" among the experts that Kennedy had won more than he lost "as a result of his Catholicism",[81] as Northern Catholics flocked to Kennedy because of attacks on his religion. Interviewing people who voted in both 1956 and 1960, a University of Michigan team analyzing the election returns discovered that people who voted Democratic in 1956 split 33–6 for Kennedy, while the Republican voters of 1956 split 44–17 for Nixon. That is, Nixon lost 28% (17/61) of the Eisenhower voters, while Kennedy lost only 15% of the Stevenson voters. The Democrats, in other words, did a better job of holding their 1956 supporters.[82]

Kennedy said that he saw the challenges ahead and needed the country's support to get through them. In his victory speech, he declared: "To all Americans, I say that the next four years are going to be difficult and challenging years for us all; that a supreme national effort will be needed to move this country safely through the 1960s. I ask your help, and I can assure you that every degree of my spirit that I possess will be devoted to the long-range interest of the United States and to the cause of freedom around the world."[83] This was the last time Ohio voted for the losing candidate until 2020.

Allegations of vote fraud

[edit]There were widespread allegations of vote fraud, especially in Texas, where Kennedy's running mate Lyndon B. Johnson was Senator, and Illinois, home of Mayor Richard Daley's powerful Chicago political machine.[75] These two states were important because if Nixon had carried both, he would have earned 270 electoral votes, one more than the 269 needed to win the presidency. Republican senators such as Everett Dirksen and Barry Goldwater claimed vote fraud "played a role in the election",[72] и что Никсон фактически выиграл всенародное голосование. Эрл Мазо , журналист, который был биографом Никсона, выдвинул обвинения в фальсификациях на выборах. [84]

Сотрудники предвыборного штаба Никсона убеждали его провести пересчет голосов и оспорить законность победы Кеннеди в нескольких штатах, особенно в Иллинойсе, Миссури и Нью-Джерси, где значительное большинство на католических избирательных участках отдало Кеннеди победу на выборах. [72] Однако через три дня после выборов Никсон выступил с речью, заявив, что не будет участвовать в выборах. [72] Председатель Национальной Республиканской партии, сенатор Трастон Баллард Мортон от Кентукки, посетил Ки-Бискейн, Флорида , куда Никсон взял свою семью на отдых, и потребовал пересчета голосов. [72] Мортон оспорил результаты в 11 штатах. [75] [85] сохраняли оспаривание в судах до середины 1961 года, но единственным результатом этих оспариваний стала потеря Кеннеди Гавайев при пересчете голосов.

Кеннеди выиграл Иллинойс с перевесом менее 9000 голосов из 4,75 миллиона поданных, с перевесом в 0,2%. [75] Никсон выиграл 92 из 101 округа штата. Победа Кеннеди в Иллинойсе пришла из Чикаго, который имел благоприятную для Кеннеди демографическую ситуацию и имел большое количество избирателей- католиков и афроамериканцев. [86] Его преимущество в победах в городе составило 318 736, а в округе Кук - 456 312. Утверждается, что Дейли позвонил предвыборному штабу Кеннеди и пообещал: «Если вам повезет и помогут несколько близких друзей, вы возьмете Иллинойс на вооружение». [87] Когда республиканская газета Chicago Tribune вышла в печать, об этом сообщили 79% избирательных участков округа Кук по сравнению со всего лишь 62% избирательных участков Иллинойса в целом. Более того, Никсон никогда не лидировал в Иллинойсе, а лидерство Кеннеди лишь уменьшалось по мере того, как шла ночь выборов. [86]

В Техасе Кеннеди победил Никсона с перевесом от 51 до 49%, или 46 000 голосов. [75] Некоторые республиканцы утверждали, что грозная политическая машина Джонсона украла достаточно голосов в округах вдоль границы с Мексикой, чтобы обеспечить Кеннеди победу. Защитники Кеннеди, такие как его спичрайтер и специальный помощник Артур М. Шлезингер-младший , утверждали, что преимущество Кеннеди в Техасе было просто слишком большим, чтобы фальсификация голосов могла стать решающим фактором.

Эрл Мазо в статье для New York Herald Tribune утверждал, что в Техасе «минимум 100 000 голосов за билет Кеннеди-Джонсона просто не существовало». [ нужна ссылка ] Обвинения в фальсификации результатов голосования были выдвинуты в Техасе. В округе Фэннин было всего 4895 зарегистрированных избирателей; тем не менее, в этом округе было подано 6 138 голосов, три четверти за Кеннеди. [72] На избирательном участке округа Анджелина Кеннеди получил 187 голосов против 24 за Никсона, хотя на участке было только 86 зарегистрированных избирателей. [72] Когда республиканцы потребовали пересчета голосов по всему штату, они узнали, что Избирательная комиссия штата, все члены которой были демократами, уже признала Кеннеди победителем. [72] Этот анализ был оспорен, поскольку в число зарегистрированных избирателей учитывались только люди, уплатившие подушный налог , а «ветераны, пожилые люди и некоторые другие изолированные группы» были освобождены от этого налога. [88] Анализ Эрла Мазо выявил доказательства того, что избиратели проголосовали до шести бюллетеней одновременно, руководители участков подкупали избирателей и использовали машины для голосования с предварительной загрузкой, одна из которых была поймана при регистрации 121 бюллетеня, когда проголосовали 43 человека. [ нужна ссылка ]

Иллинойс был местом самого обширного процесса оспаривания, который не увенчался успехом, несмотря на неоднократные усилия, предпринятые прокурором штата округа Кук Бенджамином Адамовски, республиканцем, который также проиграл свою заявку на переизбрание. Несмотря на демонстрацию чистых ошибок в пользу как Никсона, так и Адамовского (на некоторых избирательных участках, 40% в случае Никсона, были выявлены ошибки в их пользу, что указывает на ошибку, а не на мошенничество), найденные общие суммы не смогли полностью изменить результаты кандидатов. В то время как окружной судья, связанный с Дейли, Томас Ключинский (позже назначенный Кеннеди федеральным судьей по рекомендации Дейли), отклонил федеральный иск, «поданный для оспаривания» итогов голосования, [72] Избирательная комиссия штата, в которой доминируют республиканцы, единогласно отклонила оспаривание результатов. Более того, были признаки возможных нарушений в районах штата, контролируемых республиканцами, на которые демократы никогда серьезно не давили, поскольку вызовы республиканцев ни к чему не привели. [85] Более чем через месяц после выборов Национальный комитет Республиканской партии отказался от своих обвинений в мошенничестве на выборах в Иллинойсе. [75] Шлезингер и другие отметили, что даже если бы Никсон выиграл Иллинойс, штат не дал бы ему победы, поскольку Кеннеди все равно получил бы 276 голосов выборщиков против 246 голосов Никсона.

Специальный прокурор, назначенный по этому делу, выдвинул обвинения против 650 человек, но позже обвинения были сняты. [72] Трое избирательных работников Чикаго были осуждены за фальсификацию результатов голосования в 1962 году и отбыли непродолжительные сроки в тюрьме. [72] Позже Мазо сказал, что он «нашел имена погибших, голосовавших в Чикаго, а также 56 человек из одного дома». [72] Он также обнаружил случаи фальсификации результатов голосования республиканцев в южном Иллинойсе, но сказал, что общие цифры «не соответствуют чикагским фальсификациям, которые он обнаружил». [72] После того, как Мазо опубликовал четыре части запланированной серии из 12 частей о мошенничестве на выборах, документирующей его выводы, которые были переизданы на национальном уровне, он сказал: «Никсон попросил своего издателя остановить остальную часть серии, чтобы предотвратить конституционный кризис ». [72] Тем не менее газета «Чикаго Трибьюн» (которая регулярно поддерживала кандидатов в президенты от Республиканской партии, включая Никсона в 1960, 1968 и 1972 годах) писала, что «выборы 8 ноября характеризовались такими грубыми и ощутимыми фальсификациями, что оправдывают вывод о том, что [Никсон] был лишен победы». [72]

Академическое исследование 1985 года. [89] позже проанализировал бюллетени на двух спорных избирательных участках в Чикаго, которые подлежали пересчету. Было обнаружено, что, хотя существовала система неправильного подсчета голосов в пользу кандидатов от Демократической партии, Никсон пострадал от этого меньше, чем республиканцы в других гонках, и, более того, экстраполированная ошибка только уменьшила бы отрыв Кеннеди в Иллинойсе с 8858 голосов (по окончательным официальным данным). всего) до чуть менее 8000. Он пришел к выводу, что не было достаточных доказательств того, что его обманом лишили победы в Иллинойсе.

Личное решение Никсона не оспаривать результаты выборов было принято, несмотря на давление со стороны Эйзенхауэра, его жены Пэт и других. [72] В своих мемуарах он объяснил, что не сделал этого по ряду причин, одна из которых заключалась в том, что в каждом штате были разные избирательные законы, а в некоторых не было условий для пересчета голосов. Следовательно, пересчет голосов, если бы он был вообще возможен, занял бы месяцы, в течение которых страна осталась бы без президента. Более того, Никсон опасался, что это создаст плохой прецедент для других стран, особенно для государств Латинской Америки («каждый мелочный политик там начнет заявлять о мошенничестве, если проиграет выборы»). «Я не сомневался, что если бы результаты были обратными, Кеннеди без колебаний бросил бы вызов выборам». [ нужна ссылка ]

Популярные голоса

[ редактировать ]Алабама

[ редактировать ]Ситуация в Алабаме была противоречивой, поскольку количество голосов избирателей, полученных Кеннеди в Алабаме, определить сложно из-за необычной ситуации там. Вместо того, чтобы избиратели использовали один голос для выбора из списка выборщиков, в бюллетене для голосования в Алабаме избиратели выбирали выборщиков индивидуально, используя до 11 голосов. В такой ситуации за данным кандидатом традиционно закрепляется всенародное голосование выборщика, набравшего наибольшее количество голосов. Например, все 11 кандидатов-республиканцев в Алабаме были преданы Никсону, а 11 выборщиков-республиканцев получили от 230 951 голоса (за Джорджа Ведьмака) до 237 981 голоса (за Сесила Дарема); Таким образом, Никсон получил 237 981 голос избирателей от Алабамы.

Ситуация была более сложной на стороне демократов. На первичных выборах Демократической партии в штате Алабама были выбраны 11 кандидатов в Коллегию выборщиков, пятеро из которых обязались голосовать за Кеннеди, но остальные шесть из них не дали никаких обязательств и поэтому могли голосовать за любого, кого они выберут на пост президента. Все 11 кандидатов от Демократической партии победили на всеобщих выборах в Алабаме: от 316 394 голосов за Карла Харрисона до 324 050 голосов за Фрэнка М. Диксона . Все шесть избирателей-демократов, не подписавших обязательств, в конечном итоге проголосовали против Кеннеди и вместо этого проголосовали за сегрегационного сторонника диксикрата Гарри Ф. Берда . Поэтому количество голосов избирателей, полученных Кеннеди, подсчитать сложно. Обычно можно использовать три метода. Первый метод, который используется чаще всего, а также метод, используемый в таблице результатов на этой странице ниже, заключается в том, чтобы отдать Кеннеди 318 303 голоса в Алабаме (голоса, полученные самым популярным избирателем Кеннеди, К. Г. Алленом), и распределить 324 050 голосов в Алабама (голоса, полученные самым популярным избирателем-демократом, не подписавшим обязательств, Фрэнком М. Диксоном) среди избирателей, не подписавших обязательств. Однако использование этого метода дает общее количество голосов, которое намного превышает фактическое количество голосов, отданных за демократов в Алабаме. Второй метод, который можно использовать, — это дать Кеннеди 318 303 голоса в Алабаме и подсчитать оставшиеся 5747 голосов демократов в качестве незаявленных избирателей.

Третий метод дал бы совершенно иной взгляд на всенародное голосование как в Алабаме, так и в США в целом. Третий метод состоит в том, чтобы распределить голоса демократов в Алабаме между избирателями Кеннеди и избирателями, не имеющими обязательств, на процентной основе, отдав 5/11 из 324 050 голосов демократов Кеннеди (что составляет 147 295 голосов за Кеннеди) и 6/11 из 324 050 голосов демократов. голосов избирателям, не имеющим залога (что составляет 176 755 голосов для избирателей, не заключивших залог). Принимая во внимание, что самый высокий выборщик-республиканец/Никсон в Алабаме получил 237 981 голос, этот третий метод подсчета голосов в Алабаме означает, что Никсон выигрывает всенародное голосование в Алабаме и выигрывает всенародное голосование в США в целом, поскольку это дало бы Кеннеди 34 049 976 голосов. голосов на национальном уровне, а Никсон - 34 108 157 голосов на национальном уровне. [90]

Грузия

[ редактировать ]Число голосов избирателей, полученных Кеннеди и Никсоном в Джорджии, также сложно определить, поскольку избиратели проголосовали за 12 отдельных выборщиков. [91] Общее количество голосов 458 638 за Кеннеди и 274 472 за Никсона отражает количество голосов за выборщиков Кеннеди и Никсона, которые получили наибольшее количество голосов. Выборщики-республиканцы и демократы, получившие наибольшее количество голосов, отличались от остальных 11 выборщиков от своей партии. Среднее количество голосов для 12 выборщиков составило 455 629 для выборщиков-демократов и 273 110 для выборщиков-республиканцев. Это сокращает преимущество Кеннеди на выборах в Джорджии на 1647 голосов, до 182 519. [92]

Необязательные избиратели-демократы

[ редактировать ]

Многие южные демократы были против избирательного права афроамериканцев, живущих на Юге. Сторонники сегрегации призывали отказаться от голосов выборщиков или отдать голоса сенатору от Вирджинии Гарри Ф. Берду , демократу-сегрегационисту, в качестве независимого кандидата. [93] И до, и после съезда они пытались включить в избирательные бюллетени своих штатов незарегистрированных избирателей-демократов в надежде повлиять на гонку; существование таких избирателей может повлиять на то, какой кандидат будет выбран национальным съездом, и в тесной гонке такие избиратели могут иметь возможность добиться уступок от кандидатов в президенты от Демократической или Республиканской партии в обмен на их голоса выборщиков.

Большинство этих попыток провалились. Демократы в Алабаме выдвинули смешанный список из пяти избирателей, лояльных Кеннеди, и шести избирателей, не подписавших обязательств. Демократы в Миссисипи выдвинули два отдельных списка – один из сторонников Кеннеди и один из необъявленных избирателей. Луизиана также выдвинула два отдельных списка, хотя незаложенный список не получил ярлыка «Демократический». Грузия освободила своих избирателей-демократов от обязательств голосовать за Кеннеди, хотя все 12 выборщиков-демократов в Грузии в конечном итоге проголосовали за Кеннеди. Губернатор Эрнест Вандивер хотел, чтобы избиратели-демократы проголосовали против Кеннеди. Бывший губернатор Эллис Арналл поддержал Кеннеди, получив голоса выборщиков, а Арналл назвал позицию Вандивера «совершенно позорной». [94]

В общей сложности 14 выборщиков-демократов, не подписавших обязательств, выиграли выборы избирателей и предпочли не голосовать за Кеннеди: восемь из Миссисипи и шесть из Алабамы. Поскольку избиратели, присягнувшие Кеннеди, получили явное большинство голосов в Коллегии выборщиков, избиратели, не подписавшие обязательств, не могли повлиять на результаты. Тем не менее, они отказались голосовать за Кеннеди. Вместо этого они проголосовали за Берда, хотя он не был объявленным кандидатом и не добивался их голосов. Вдобавок Берд получил один голос выборщиков от неверного выборщика-республиканца в Оклахоме, что в общей сложности составило 15 голосов выборщиков. Неверный выборщик-республиканец в Оклахоме проголосовал за Барри Голдуотера на посту вице-президента; тогда как 14 выборщиков-демократов из Миссисипи и Алабамы, не подписавших обязательств, проголосовали за Строма Термонда на посту вице-президента.

| Кандидат в президенты | Вечеринка | Родной штат | Народное голосование | избирательный голосование | Напарник | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Считать | Процент | Кандидат в вице-президенты | Родной штат | Выборное голосование | ||||

| Джон Ф. Кеннеди | Демократический | Массачусетс | 34,220,984 (а) | 49.72% | 303 | Линдон Б. Джонсон | Техас | 303 |

| Ричард Никсон | республиканец | Калифорния | 34,108,157 | 49.55% | 219 | Генри Кэбот Лодж мл. | Массачусетс | 219 |

| Гарри Ф. Берд | Демократический | Вирджиния | — (б) | — (б) | 15 | Стром Термонд | Южная Каролина | 14 |

| Барри Голдуотер (с) | Аризона | 1 (с) | ||||||

| ( избиратели, не заключившие залога ) | Демократический | ( н / д ) | 286,359 | 0.42% | — (г) | ( н / д ) | ( н / д ) | — (г) |

| Эрик Хасс | Социалистический Труд | Нью-Йорк | 47,522 | 0.07% | 0 | Джорджия Коззини | Висконсин | 0 |

| Резерфорд Декер | Запрет | Миссури | 46,203 | 0.07% | 0 | Э. Гарольд Манн | Мичиган | 0 |

| Орвал Фаубус | Права штатов | Арканзас | 44,984 | 0.07% | 0 | Джон Дж. Кроммелин | Алабама | 0 |

| Фаррелл Доббс | Социалистические рабочие | Нью-Йорк | 40,175 | 0.06% | 0 | Майра Таннер Вайс | Нью-Йорк | 0 |

| Чарльз Л. Салливан | Конституция | Миссисипи | (Техас) 18 162 | 0.03% | 0 | Мерритт Б. Кертис | Калифорния | 0 |

| Дж. Брекен Ли | Консервативный | Юта | (Нью-Джерси) 8708 | 0.01% | 0 | Кент Кортни | Луизиана | 0 |

| Другой | 11,128 | 0.02% | — | Другой | — | |||

| Общий | 68,832,482 | 100% | 537 | 537 | ||||

| Нужно, чтобы выиграть | 269 | 269 | ||||||

- а. ^ Эта цифра проблематична; см. выше всенародное голосование в Алабаме .

- б. ↑ Берд не фигурировал непосредственно в бюллетенях для голосования. Вместо этого его голоса выборщиков исходили от необязательных избирателей-демократов и неверных избирателей.

- в. ^ из Оклахомы Неверный избиратель Генри Д. Ирвин , хотя и обещал голосовать за Ричарда Никсона и Генри Кэбота Лоджа-младшего, вместо этого проголосовал за некандидата Гарри Ф. Берда . Однако, в отличие от других избирателей, которые голосовали за Берда и Строма Термонда на посту вице-президента, Ирвин отдал свой голос вице-президента за сенатора-республиканца от Аризоны Барри Голдуотера.

- д. ↑ В Миссисипи победил список избирателей-демократов, не подписавших обязательств. Они отдали свои 8 голосов за Берда и Термонда.

Источник (народное голосование): Лейп, Дэвид. «Результаты президентских выборов 1960 года» . Атлас президентских выборов в США Дэйва Лейпа . Проверено 18 февраля 2012 г. Примечание: Салливан/Кёртис баллотировались только в Техасе. В Вашингтоне Конституционная партия выдвинула Кертиса на пост президента и Б.Н. Миллера на пост вице-президента, получив 1401 голос. Источник (избирательное голосование): «Результаты коллегии выборщиков за 1789–1996 годы» . Национальное управление архивов и документации . Проверено 2 августа 2005 г.

Было получено 537 голосов выборщиков по сравнению с 531 в 1956 году из-за добавления двух сенаторов США и одного представителя США от каждого из новых штатов Аляска и Гавайи. Чтобы учесть это, Палата представителей была временно расширена с 435 членов до 437, а после перераспределения, согласно переписи 1960 года, вернулась к 435. Перераспределение произошло после выборов 1960 года.

География результатов

[ редактировать ]

- Результаты по округам, заштрихованы в зависимости от процента голосов победившего кандидата.

Картографическая галерея

[ редактировать ]- Результаты президентских выборов по округам

- Результаты демократических президентских выборов по округам

- Результаты республиканских президентских выборов по округам

- Результаты президентских выборов необязательных избирателей по округам

- «Другие» результаты президентских выборов по округам

- Картограмма результатов президентских выборов по округам

- Картограмма результатов президентских выборов Демократической партии по округам

- Картограмма результатов республиканских президентских выборов по округам

- Картограмма результатов президентских выборов незарегистрированных избирателей по округам

- Картограмма результатов президентских выборов «Другие» по округам

Результаты по штатам

[ редактировать ]Источник: [95]

| Штаты, выигранные Кеннеди / Джонсоном |

| Штаты выиграли Берд / Термонд |

| Штаты, выигранные Никсоном / Лоджем |

| Джон Ф. Кеннеди Демократический | Ричард Никсон республиканец | Необязательные избиратели Необязательный демократ | Эрик Хасс Социалистический Труд | Допуск | Штат Всего | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Состояние | избирательный голоса | # | % | избирательный голоса | # | % | избирательный голоса | # | % | избирательный голоса | # | % | избирательный голоса | # | % | # | |

| Алабама | 11 | 318,303 | 56.39 | 5 | 237,981 | 42.16 | – | 324,050 | 0.00 | 6 | – | – | – | 80,322 | 14.23 | 564,478 | АЛ |

| Аляска | 3 | 29,809 | 49.06 | – | 30,953 | 50.94 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −1,144 | −1.88 | 60,762 | И |

| Аризона | 4 | 176,781 | 44.36 | – | 221,241 | 55.52 | 4 | – | – | – | 469 | 0.12 | – | −44,460 | −11.16 | 398,491 | ТО |

| Арканзас | 8 | 215,049 | 50.19 | 8 | 184,508 | 43.06 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 30,541 | 7.13 | 428,509 | АР |

| Калифорния | 32 | 3,224,099 | 49.55 | – | 3,259,722 | 50.10 | 32 | – | – | – | 1,051 | 0.02 | – | −35,623 | −0.55 | 6,506,578 | ЧТО |

| Колорадо | 6 | 330,629 | 44.91 | – | 402,242 | 54.63 | 6 | – | – | – | 2,803 | 0.38 | – | −71,613 | −9.73 | 736,246 | СО |

| Коннектикут | 8 | 657,055 | 53.73 | 8 | 565,813 | 46.27 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 91,242 | 7.46 | 1,222,883 | Коннектикут |

| Делавэр | 3 | 99,590 | 50.63 | 3 | 96,373 | 49.00 | – | – | – | – | 82 | 0.04 | – | 3,217 | 1.64 | 196,683 | ИЗ |

| Флорида | 10 | 748,700 | 48.49 | – | 795,476 | 51.51 | 10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −46,776 | −3.03 | 1,544,176 | Флорида |

| Грузия | 12 | 458,638 | 62.54 | 12 | 274,472 | 37.43 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 184,166 | 25.11 | 733,349 | Джорджия |

| Гавайи | 3 | 92,410 | 50.03 | 3 | 92,295 | 49.97 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 115 | 0.06 | 184,705 | ПРИВЕТ |

| Айдахо | 4 | 138,853 | 46.22 | – | 161,597 | 53.78 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −22,744 | −7.57 | 300,450 | ИДЕНТИФИКАТОР |

| Иллинойс | 27 | 2,377,846 | 49.98 | 27 | 2,368,988 | 49.80 | – | – | – | – | 10,560 | 0.22 | – | 8,858 | 0.19 | 4,757,409 | ТО |

| Индиана | 13 | 952,358 | 44.60 | – | 1,175,120 | 55.03 | 13 | – | – | – | 1,136 | 0.05 | – | −222,762 | −10.43 | 2,135,360 | В |

| Айова | 10 | 550,565 | 43.22 | – | 722,381 | 56.71 | 10 | – | – | – | 230 | 0.02 | – | −171,816 | −13.49 | 1,273,810 | Я |

| Канзас | 8 | 363,213 | 39.10 | – | 561,474 | 60.45 | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −198,261 | −21.35 | 928,825 | КС |

| Кентукки | 10 | 521,855 | 46.41 | – | 602,607 | 53.59 | 10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −80,752 | −7.18 | 1,124,462 | этот |

| Луизиана | 10 | 407,339 | 50.42 | 10 | 230,980 | 28.59 | – | 169,572 | 20.99 | – | – | – | – | 176,359 | 21.83 | 807,891 | ТО |

| Мэн | 5 | 181,159 | 42.95 | – | 240,608 | 57.05 | 5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −59,449 | −14.10 | 421,767 | МНЕ |

| Мэриленд | 9 | 565,808 | 53.61 | 9 | 489,538 | 46.39 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 76,270 | 7.23 | 1,055,349 | доктор медицинских наук |

| Массачусетс | 16 | 1,487,174 | 60.22 | 16 | 976,750 | 39.55 | – | – | – | – | 3,892 | 0.16 | – | 510,424 | 20.67 | 2,469,480 | И |

| Мичиган | 20 | 1,687,269 | 50.85 | 20 | 1,620,428 | 48.84 | – | 539 | 0.02 | – | 1,718 | 0.05 | – | 66,841 | 2.01 | 3,318,097 | МНЕ |

| Миннесота | 11 | 779,933 | 50.58 | 11 | 757,915 | 49.16 | – | – | – | – | 962 | 0.06 | – | 22,018 | 1.43 | 1,541,887 | Миннесота |

| Миссисипи | 8 | 108,362 | 36.34 | – | 73,561 | 24.67 | – | 116,248 | 38.99 | 8 | – | – | – | −7,886 | −2.64 | 298,171 | РС |

| Миссури | 13 | 972,201 | 50.26 | 13 | 962,221 | 49.74 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 9,980 | 0.52 | 1,934,422 | МО |

| Монтана | 4 | 134,891 | 48.60 | – | 141,841 | 51.10 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −6,950 | −2.50 | 277,579 | МТ |

| Небраска | 6 | 232,542 | 37.93 | – | 380,553 | 62.07 | 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −148,011 | −24.14 | 613,095 | NE |

| Невада | 3 | 54,880 | 51.16 | 3 | 52,387 | 48.84 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2,493 | 2.32 | 107,267 | НВ |

| Нью-Гэмпшир | 4 | 137,772 | 46.58 | – | 157,989 | 53.42 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −20,217 | −6.84 | 295,761 | Нью-Хэмпшир |

| Нью-Джерси | 16 | 1,385,415 | 49.96 | 16 | 1,363,324 | 49.16 | – | – | – | – | 4,262 | 0.15 | – | 22,091 | 0.80 | 2,773,111 | Нью-Джерси |

| Нью-Мексико | 4 | 156,027 | 50.15 | 4 | 153,733 | 49.41 | – | – | – | – | 570 | 0.18 | – | 2,294 | 0.74 | 311,107 | Нью-Мексико |

| Нью-Йорк | 45 | 3,830,085 | 52.53 | 45 | 3,446,419 | 47.27 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 383,666 | 5.26 | 7,291,079 | Нью-Йорк |

| Северная Каролина | 14 | 713,136 | 52.11 | 14 | 655,420 | 47.89 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 57,716 | 4.22 | 1,368,556 | Северная Каролина |

| Северная Дакота | 4 | 123,963 | 44.52 | – | 154,310 | 55.42 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −30,347 | −10.90 | 278,431 | без даты |

| Огайо | 25 | 1,944,248 | 46.72 | – | 2,217,611 | 53.28 | 25 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −273,363 | −6.57 | 4,161,859 | ОЙ |

| Оклахома | 8 | 370,111 | 40.98 | – | 533,039 | 59.02 | 7 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | – | – | – | −162,928 | −18.04 | 903,150 | ХОРОШО |

| Орегон | 6 | 367,402 | 47.32 | – | 408,060 | 52.56 | 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −40,658 | −5.24 | 776,421 | ИЛИ |

| Пенсильвания | 32 | 2,556,282 | 51.06 | 32 | 2,439,956 | 48.74 | – | – | – | – | 7,185 | 0.14 | – | 116,326 | 2.32 | 5,006,541 | Хорошо |

| Род-Айленд | 4 | 258,032 | 63.63 | 4 | 147,502 | 36.37 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 110,530 | 27.26 | 405,535 | РИ |

| Южная Каролина | 8 | 198,129 | 51.24 | 8 | 188,558 | 48.76 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 9,571 | 2.48 | 386,688 | СК |

| Южная Дакота | 4 | 128,070 | 41.79 | – | 178,417 | 58.21 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −50,347 | −16.43 | 306,487 | СД |

| Теннесси | 11 | 481,453 | 45.77 | – | 556,577 | 52.92 | 11 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −75,124 | −7.14 | 1,051,792 | ТН |

| Техас | 24 | 1,167,567 | 50.52 | 24 | 1,121,310 | 48.52 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 46,257 | 2.00 | 2,311,084 | Техас |

| Юта | 4 | 169,248 | 45.17 | – | 205,361 | 54.81 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −36,113 | −9.64 | 374,709 | ВНЕ |

| Вермонт | 3 | 69,186 | 41.35 | – | 98,131 | 58.65 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −28,945 | −17.30 | 167,324 | ВТ |

| Вирджиния | 12 | 362,327 | 46.97 | – | 404,521 | 52.44 | 12 | – | – | – | 397 | 0.05 | – | −42,194 | −5.47 | 771,449 | И |

| Вашингтон | 9 | 599,298 | 48.27 | – | 629,273 | 50.68 | 9 | – | – | – | 10,895 | 0.88 | – | −29,975 | −2.41 | 1,241,572 | Вашингтон |

| Западная Вирджиния | 8 | 441,786 | 52.73 | 8 | 395,995 | 47.27 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 45,791 | 5.47 | 837,781 | Западная Вирджиния |

| Висконсин | 12 | 830,805 | 48.05 | – | 895,175 | 51.77 | 12 | – | – | – | 1,310 | 0.08 | – | −64,370 | −3.72 | 1,729,082 | Висконсин |

| Вайоминг | 3 | 63,331 | 44.99 | – | 77,451 | 55.01 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −14,120 | −10.03 | 140,782 | МЫ |

| ИТОГО: | 537 | 34,220,984 | 49.72 | 303 | 34,108,157 | 49.55 | 219 | 286,359 | 0.42 | 15 | 47,522 | 0.07 | – | 112,827 | 0.16 | 68,832,482 | НАС |

Штаты, перешедшие от республиканцев к демократам

[ редактировать ]- Коннектикут

- Делавэр

- Иллинойс

- Луизиана

- Мэриленд

- Массачусетс

- Мичиган

- Миннесота

- Невада

- Нью-Джерси

- Нью-Мексико

- Нью-Йорк

- Пенсильвания

- Род-Айленд

- Техас

- Западная Вирджиния

Штаты, перешедшие от демократических к необязательным

[ редактировать ]Близкие состояния

[ редактировать ]Перевес менее 1% (95 голосов выборщиков):

- Гавайи, 0,06% (115 голосов)

- Иллинойс, 0,19% (8858 голосов) (штат переломного момента для победы Кеннеди без свободных от залога избирателей в Джорджии) [и] )

- Миссури, 0,52% (9980 голосов) (переломный момент для победы Кеннеди среди избирателей Джорджии, не дающих залога)

- Калифорния, 0,55% (35 623 голоса)

- Нью-Мексико, 0,74% (2294 голоса)

- Нью-Джерси, 0,80% (22 091 голос) (переломный момент в случае победы Никсона)

Перевес менее 5% (161 голос выборщиков):

- Миннесота, 1,43% (22 018 голосов)

- Делавэр, 1,64% (3217 голосов)

- Аляска, 1,88% (1144 голоса)

- Техас, 2,00% (46 257 голосов)

- Мичиган, 2,01% (66 841 голос)

- Невада, 2,32% (2493 голоса)

- Пенсильвания, 2,32% (116 326 голосов)

- Вашингтон, 2,41% (29 975 голосов)

- Южная Каролина, 2,48% (9571 голос)

- Монтана, 2,50% (6950 голосов)

- Миссисипи, 2,64% (7886 голосов)

- Флорида, 3,03% (46 776 голосов)

- Висконсин, 3,72% (64 370 голосов)

- Северная Каролина, 4,22% (57 716 голосов)

Перевес более 5%, но менее 10% (160 голосов выборщиков):

- Орегон, 5,24% (40 658 голосов)

- Нью-Йорк, 5,26% (383 666 голосов)

- Западная Вирджиния, 5,46% (45 791 голос)

- Вирджиния, 5,47% (42 194 голоса)

- Огайо, 6,57% (273 363 голоса)

- Нью-Гэмпшир, 6,84% (20 217 голосов)

- Арканзас, 7,13% (30 541 голос)

- Теннесси, 7,15% (75 124 голоса)

- Кентукки, 7,18% (80 752 голоса)

- Мэриленд, 7,22% (76 270 голосов)

- Коннектикут, 7,46% (91 242 голоса)

- Айдахо, 7,56% (22 744 голоса)

- Юта, 9,64% (36 113 голосов)

- Колорадо, 9,73% (71 613 голосов)

Статистика

[ редактировать ]Округа с наибольшим процентом голосов (демократические)

- Округ Семинол, Джорджия 95,35%

- Округ Миллер, Джорджия 94,74%

- Округ Харт, Джорджия 93,51%

- Округ Старр, Техас 93,49%

- Округ Мэдисон, Джорджия 92,18%

Округа с наибольшим процентом голосов (республиканцы)

- Округ Джексон, Кентукки 90,35%

- Округ Джонсон, Теннесси 86,74%

- Округ Оусли, Кентукки 86,24%

- Округ Хукер, Небраска 86,19%

- Округ Севьер, Теннесси 85,05%

Округа с наибольшим процентом голосов (другие)

- Округ Амит, штат Миссисипи 72,72%

- Округ Уилкинсон, штат Миссисипи 68,09%

- Округ Джефферсон, штат Миссисипи 66,54%

- Франклин Каунти, Миссисипи 66,37%

- Округ Рэнкин, Миссисипи 65,12%

Демография избирателей

[ редактировать ]| Президентские выборы 1960 года по демографическим подгруппам | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Демографическая подгруппа | Кеннеди | Никсон | ||||

| Всего голосов | 50.1 | 49.9 | ||||

| Пол | ||||||

| Мужчины | 52 | 48 | ||||

| Женщины | 49 | 51 | ||||

| Возраст | ||||||

| 18–29 лет | 54 | 46 | ||||

| 30–49 лет | 54 | 46 | ||||

| 50 и старше | 46 | 54 | ||||

| Раса | ||||||

| Белый | 49 | 51 | ||||

| Черный | 68 | 32 | ||||

| Религия | ||||||

| протестанты | 38 | 62 | ||||

| католики | 78 | 22 | ||||

| Вечеринка | ||||||

| Демократы | 84 | 16 | ||||

| республиканцы | 5 | 95 | ||||

| Независимые | 43 | 57 | ||||

| Образование | ||||||

| Меньше средней школы | 55 | 45 | ||||

| Средняя школа | 52 | 48 | ||||

| Выпускник колледжа или выше | 39 | 61 | ||||

| Занятие | ||||||

| Профессиональный и деловой | 42 | 58 | ||||

| Белый воротничок | 48 | 52 | ||||

| «Синие воротнички» | 60 | 40 | ||||

| Фермеры | 48 | 52 | ||||

| Область | ||||||

| Северо-восток | 53 | 47 | ||||

| Средний Запад | 48 | 52 | ||||

| Юг | 51 | 49 | ||||

| Запад | 49 | 51 | ||||

| Союзные домохозяйства | ||||||

| Союз | 65 | 35 | ||||

Источник: [96]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- История Соединенных Штатов (1945–1964)

- Инаугурация Джона Ф. Кеннеди

- Первичный (фильм)

- 1960 выборы в Палату представителей США.

- 1960 выборы в Сенат США.

- Президентские дебаты 1960 года в США

- Оспариваемые выборы в американской истории

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Официальные подсчеты всенародного голосования осложняются из-за того, что избиратели в Алабаме и Джорджии не взяли на себя обязательства. Избирателям Алабамы пришлось голосовать за каждого из 11 выборщиков президента в индивидуальных гонках; в то время как в каждой из 11 гонок участвовал избиратель-республиканец, присягнувший Никсону, только в пяти гонках участвовал выборщик-демократ, присягнувший Кеннеди, а в остальных шести гонках участвовал выборщик-демократ, не принявший обязательств. Кеннеди обычно получают голоса избирателей в Алабаме, набравших наибольшее количество голосов избирателя, давшего обещание Кеннеди, в то время как остальная часть голосов демократов отдается избирателям, не подписавшим обязательств. В Грузии победил первичный референдум, который не обязывал избирателей-демократов действовать без обязательств, а вместо этого дал им возможность голосовать свободно, исходя из своих обещаний, но после того, как стало ясно, что их 12 голосов выборщиков не повлияют на результаты, за которые в конечном итоге проголосовал каждый избиратель. Кеннеди. По этой причине всенародное голосование за беззалоговых избирателей приписывается Кеннеди. [2] [3] [4] см. в разделе «Алабама» . Подробности

- ^ Один неверный избиратель из Оклахомы проголосовал за Гарри Ф. Берда на пост президента и Барри Голдуотера на пост вице-президента.

- ↑ Любимые сыновья получили поддержку Миссури ( Стюарт Симингтон ), Флориды ( Джордж Смазерс ), Нью-Джерси ( Роберт Мейнер ), Миссисипи ( Кэрролл Гартин ) и Гавайев.

- ^ Его загорелый вид, вероятно, был вызван потемнением гиперпигментации кожи из-за болезни Аддисона . [36]

- ^ [3] [4] Дополнительную информацию см. на странице избирателей, не имеющих обязательств.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Явка VEP на всеобщих национальных выборах с 1789 года по настоящее время» . Проект выборов в США . CQ Пресс .

- ^ Результаты всеобщих президентских выборов 1960 года - Атлас президентских выборов в США Дэйва Лейпа в Алабаме

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «ИЗБИРАТЕЛИ В ГРУЗИИ «СВОБОЖДЕНЫ» ИЗБИРАТЕЛАМИ; демократы поддерживают незаложенный список - лидеры партии ссылаются на путаницу в формулировках (опубликовано в 1960 году)» . 16 сентября 1960 года . Проверено 15 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Новотный, Патрик (2004). «Джон Ф. Кеннеди, выборы 1960 года и необязавшие себя избиратели Джорджии в коллегии выборщиков» . Исторический ежеквартальный журнал Грузии . 88 (3): 375–397 . Проверено 15 февраля 2018 г.

- ^ Рорабо (2009)

- ^ Мэй, Энн Мари (1990). «Президент Эйзенхауэр, экономическая политика и президентские выборы 1960 года» . Журнал экономической истории . 50 (2): 417–427. дои : 10.1017/s0022050700036536 . JSTOR 2123282 . S2CID 45404782 .

- ^ Кейси (2009)

- ^ Зеленый, Джефф ; Босман, Джули (11 марта 2008 г.). «Обама отвергает идею места на заднем сиденье в билете» . Нью-Йорк Таймс .

- ^ Хамфри, Хьюберт Х. (1992). Кеннеди также победил Морса на праймериз в Мэриленде и Орегоне. Воспитание общественного деятеля , с. 152. Университет Миннесоты Пресс. ISBN 0-8166-1897-6 .

- ^ Рестон, Джеймс (5 мая 1960 г.). «Сенатор Кеннеди более эффективен в телевизионных дебатах» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Служба новостей Нью-Йорк Таймс. п. 2 . Проверено 13 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Лоуренс, штат Вашингтон (6 мая 1960 г.). «Опрос Западной Вирджинии показал выигрыш Кеннеди» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. 1 . Проверено 13 мая 2022 г.

- ^ «Еще одна гонка до финиша» . Новости и обозреватель . 2 ноября 2008 года. Архивировано из оригинала 15 января 2009 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2008 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Каро, Роберт А. (2012). Переход власти , стр. 121–135. Альфред А. Кнопф, Нью-Йорк. ISBN 978-0-679-40507-8

- ^ Косгрейв, Бен (24 мая 2014 г.). «Лицом к лицу: Джон Кеннеди и РФК, Лос-Анджелес, июль 1960 года» . Журнал «Тайм» . Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 19 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Артур М. Шлезингер-младший , Роберт Кеннеди и его времена (1978), стр. 206–211.

- ^ (Уайт, стр. 91–92)

- ^ (Уайт, стр. 242–243)

- ^ Ли, Бён Джун (сентябрь 2016 г.). «Атака на эфир: как телевидение изменило американскую президентскую кампанию». Журнал истории Новой Англии . 73 : 1–27.

- ^ Э. Томас Вуд , «Нэшвилл время от времени: Никсон красит город в красный цвет» . NashvillePost.com . 5 октября 2007 года. Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2008 года . Проверено 6 октября 2007 г.

- ^ Амброуз, Стивен Э. (1991). Эйзенхауэр: Солдат и президент , с. 525. Саймон и Шустер. ISBN 0-671-74758-4 .

- ^ «Опыт Никсона? (Кеннеди, 1960)» . Кандидат в гостиную . Музей движущегося изображения . Проверено 25 августа 2016 г.