Великая хартия

| Великая хартия | |

|---|---|

Хлопок MS. Август II. 106 , одно из четырех выживающих примеров текста 1215 | |

| Созданный | 1215 |

| Расположение | Два в Британской библиотеке ; по одному в замке Линкольн и в соборе Солсбери |

| Автор (ы) |

|

| Purpose | Peace treaty |

| Full text | |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Monarchy |

|---|

|

|

|

Magna Carta Libertatum ( средневековая латынь для «Великой хартии свобод»), обычно называемая хартией или иногда магни магновской [ А ] Королевский хартия [ 4 ] [ 5 ] прав , согласованных королем Иоанном Англии в Раннимде , недалеко от Виндзора , 15 июня 1215 года. [ B ] Впервые составлен архиепископом Кентерберийским кардиналом Стивеном Лэнгтоном , чтобы заключить мир между непопулярным королем и группой повстанческих баронов , он обещал защиту прав церкви, защиту баронов от незаконного тюремного заключения, доступа к быстрому и беспристрастному правосудию и Ограничения на феодальные выплаты Короне должны быть реализованы через Совет по 25 баронам. Ни одна из сторон не противостояла их обязательствам, и Хартия была аннулирована Папой Innocent III , что привело к войне первых баронов .

After John's death, the regency government of his young son, Henry III, reissued the document in 1216, stripped of some of its more radical content, in an unsuccessful bid to build political support for their cause. At the end of the war in 1217, it formed part of the peace treaty agreed at Lambeth, where the document acquired the name "Magna Carta", to distinguish it from the smaller Charter of the Forest, which was issued at the same time. Short of funds, Henry reissued the charter again in 1225 in exchange for a grant of new taxes. His son, Edward I, repeated the exercise in 1297, this time confirming it as part of England's statute law. However, the Magna Carta was not unique; other legal documents of its time, both in England and beyond, made broadly similar statements of rights and limitations on the powers of the Crown. The charter became part of English political life and was typically renewed by each monarch in turn, although as time went by and the fledgling Parliament of England принял новые законы, он потерял часть своего практического значения.

At the end of the 16th century, there was an upsurge in interest in Magna Carta. Lawyers and historians at the time believed that there was an ancient English constitution, going back to the days of the Anglo-Saxons, that protected individual English freedoms. They argued that the Norman invasion of 1066 had overthrown these rights and that Magna Carta had been a popular attempt to restore them, making the charter an essential foundation for the contemporary powers of Parliament and legal principles such as habeas corpus. Although this historical account was badly flawed, jurists such as Sir Edward Coke used Magna Carta extensively in the early 17th century, arguing against the divine right of kings. Both James I and his son Charles I attempted to suppress the discussion of Magna Carta. The political myth of Magna Carta and its protection of ancient personal liberties persisted after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 until well into the 19th century. It influenced the early American colonists in the Thirteen Colonies and the formation of the United States Constitution, which became the supreme law of the land in the new republic of the United States.

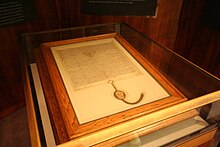

Research by Victorian historians showed that the original 1215 charter had concerned the medieval relationship between the monarch and the barons, rather than the rights of ordinary people. The majority of historians now see the interpretation of the charter as a unique and early charter of universal legal rights as a myth that was created centuries later. Despite the changes in views of historians, the charter has remained a powerful, iconic document, even after almost all of its content was repealed from the statute books in the 19th and 20th centuries. Magna Carta still forms an important symbol of liberty today, often cited by politicians and campaigners, and is held in great respect by the British and American legal communities, Lord Denning describing it in 1956 as "the greatest constitutional document of all times—the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot". In the 21st century, four exemplifications of the original 1215 charter remain in existence, two at the British Library, one at Lincoln Castle and one at Salisbury Cathedral. There are also a handful of the subsequent charters in public and private ownership, including copies of the 1297 charter in both the United States and Australia. The 800th anniversary of Magna Carta in 2015 included extensive celebrations and discussions, and the four original 1215 charters were displayed together at the British Library. None of the original 1215 Magna Carta is currently in force since it has been repealed; however, four clauses of the original charter are enshrined in the 1297 reissued Magna Carta and do still remain in force in England and Wales.[c]

History

13th century

Background

Magna Carta originated as an unsuccessful attempt to achieve peace between royalist and rebel factions in 1215, as part of the events leading to the outbreak of the First Barons' War. England was ruled by King John, the third of the Angevin kings. Although the kingdom had a robust administrative system, the nature of government under the Angevin monarchs was ill-defined and uncertain.[6][7] John and his predecessors had ruled using the principle of vis et voluntas, or "force and will", taking executive and sometimes arbitrary decisions, often justified on the basis that a king was above the law.[7] Many contemporary writers believed that monarchs should rule in accordance with the custom and the law, with the counsel of the leading members of the realm, but there was no model for what should happen if a king refused to do so.[7]

John had lost most of his ancestral lands in France to King Philip II in 1204 and had struggled to regain them for many years, raising extensive taxes on the barons to accumulate money to fight a war which ended in expensive failure in 1214.[8] Following the defeat of his allies at the Battle of Bouvines, John had to sue for peace and pay compensation.[9] John was already personally unpopular with many of the barons, many of whom owed money to the Crown, and little trust existed between the two sides.[10][11][12] A triumph would have strengthened his position, but in the face of his defeat, within a few months after his return from France, John found that rebel barons in the north and east of England were organising resistance to his rule.[13][14]

The rebels took an oath that they would "stand fast for the liberty of the church and the realm", and demanded that the King confirm the Charter of Liberties that had been declared by King Henry I in the previous century, and which was perceived by the barons to protect their rights.[14][15][16] The rebel leadership was unimpressive by the standards of the time, even disreputable, but were united by their hatred of John;[17] Robert Fitzwalter, later elected leader of the rebel barons, claimed publicly that John had attempted to rape his daughter,[18] and was implicated in a plot to assassinate John in 1212.[19]

John held a council in London in January 1215 to discuss potential reforms, and sponsored discussions in Oxford between his agents and the rebels during the spring.[20] Both sides appealed to Pope Innocent III for assistance in the dispute.[21] During the negotiations, the rebellious barons produced an initial document, which historians have termed "the Unknown Charter of Liberties", which drew on Henry I's Charter of Liberties for much of its language; seven articles from that document later appeared in the "Articles of the Barons" and the subsequent charter.[22][23][24]

It was John's hope that the Pope would give him valuable legal and moral support, and accordingly John played for time; the King had declared himself to be a papal vassal in 1213 and correctly believed he could count on the Pope for help.[21][25] John also began recruiting mercenary forces from France, although some were later sent back to avoid giving the impression that the King was escalating the conflict.[20] In a further move to shore up his support, John took an oath to become a crusader, a move which gave him additional political protection under church law, even though many felt the promise was insincere.[26][27]

Letters backing John arrived from the Pope in April, but by then the rebel barons had organised into a military faction. They congregated at Northampton in May and renounced their feudal ties to John, marching on London, Lincoln, and Exeter.[28] John's efforts to appear moderate and conciliatory had been largely successful, but once the rebels held London, they attracted a fresh wave of defectors from the royalists.[29] The King offered to submit the problem to a committee of arbitration with the Pope as the supreme arbiter, but this was not attractive to the rebels.[30] Stephen Langton, the archbishop of Canterbury, had been working with the rebel barons on their demands, and after the suggestion of papal arbitration failed, John instructed Langton to organise peace talks.[29][31]

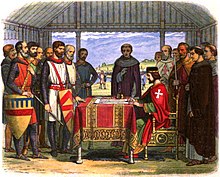

Great Charter of 1215

John met the rebel leaders at Runnymede, a water-meadow on the south bank of the River Thames, on 10 June 1215. Runnymede was a traditional place for assemblies, but it was also located on neutral ground between the royal fortress of Windsor Castle and the rebel base at Staines, and offered both sides the security of a rendezvous where they were unlikely to find themselves at a military disadvantage.[32][33] Here the rebels presented John with their draft demands for reform, the 'Articles of the Barons'.[29][31][34] Stephen Langton's pragmatic efforts at mediation over the next ten days turned these incomplete demands into a charter capturing the proposed peace agreement; a few years later, this agreement was renamed Magna Carta, meaning "Great Charter".[31][34][35] By 15 June, general agreement had been made on a text, and on 19 June, the rebels renewed their oaths of loyalty to John and copies of the charter were formally issued.[31][34]

Although, as the historian David Carpenter has noted, the charter "wasted no time on political theory", it went beyond simply addressing individual baronial complaints, and formed a wider proposal for political reform.[29][36] It promised the protection of church rights, protection from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and, most importantly, limitations on taxation and other feudal payments to the Crown, with certain forms of feudal taxation requiring baronial consent.[13][37] It focused on the rights of free men—in particular, the barons.[36] The rights of serfs were included in articles 16, 20 and 28.[38][d] Its style and content reflected Henry I's Charter of Liberties, as well as a wider body of legal traditions, including the royal charters issued to towns, the operations of the Church and baronial courts and European charters such as the Statute of Pamiers.[41][42] The Magna Carta reflected other legal documents of its time, in England and beyond, which made broadly similar statements of rights and limitations on the powers of the Crown.[43][44][45]

Under what historians later labelled "clause 61", or the "security clause", a council of 25 barons would be created to monitor and ensure John's future adherence to the charter.[46] If John did not conform to the charter within 40 days of being notified of a transgression by the council, the 25 barons were empowered by clause 61 to seize John's castles and lands until, in their judgement, amends had been made.[47] Men were to be compelled to swear an oath to assist the council in controlling the King, but once redress had been made for any breaches, the King would continue to rule as before.[48]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

|

In one sense this was not unprecedented. Other kings had previously conceded the right of individual resistance to their subjects if the King did not uphold his obligations. Magna Carta was novel in that it set up a formally recognised means of collectively coercing the King.[48] The historian Wilfred Warren argues that it was almost inevitable that the clause would result in civil war, as it "was crude in its methods and disturbing in its implications".[49] The barons were trying to force John to keep to the charter, but clause 61 was so heavily weighted against the King that this version of the charter could not survive.[47]

John and the rebel barons did not trust each other, and neither side seriously attempted to implement the peace accord.[46][50] The 25 barons selected for the new council were all rebels, chosen by the more extremist barons, and many among the rebels found excuses to keep their forces mobilised.[51][52][53] Disputes began to emerge between the royalist faction and those rebels who had expected the charter to return lands that had been confiscated.[54]

Clause 61 of Magna Carta contained a commitment from John that he would "seek to obtain nothing from anyone, in our own person or through someone else, whereby any of these grants or liberties may be revoked or diminished".[55][56] Despite this, the King appealed to Pope Innocent for help in July, arguing that the charter compromised the Pope's rights as John's feudal lord.[54][57] As part of the June peace deal, the barons were supposed to surrender London by 15 August, but this they refused to do.[58] Meanwhile, instructions from the Pope arrived in August, written before the peace accord, with the result that papal commissioners excommunicated the rebel barons and suspended Langton from office in early September.[59]

Once aware of the charter, the Pope responded in detail: in a letter dated 24 August and arriving in late September, he declared the charter to be "not only shameful and demeaning but also illegal and unjust" since John had been "forced to accept" it, and accordingly the charter was "null, and void of all validity for ever"; under threat of excommunication, the King was not to observe the charter, nor the barons try to enforce it.[54][58][60][61]

By then, violence had broken out between the two sides. Less than three months after it had been agreed, John and the loyalist barons firmly repudiated the failed charter: the First Barons' War erupted.[54][62][63] The rebel barons concluded that peace with John was impossible, and turned to Philip II's son, the future Louis VIII, for help, offering him the English throne.[54][64][e] The war soon settled into a stalemate. The King became ill and died on the night of 18 October 1216, leaving the nine-year-old Henry III as his heir.[65]

Charters of the Welsh Princes

Magna Carta was the first document in which reference is made to English and Welsh law alongside one another, including the principle of the common acceptance of the lawful judgement of peers.

Chapter 56: The return of lands and liberties to Welshmen if those lands and liberties had been taken by English (and vice versa) without a law abiding judgement of their peers.

Chapter 57: The return of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, illegitimate son of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (Llywelyn the Great) along with other Welsh hostages which were originally taken for "peace" and "good".[66][67]

Great Charter of 1216

Although the Charter of 1215 was a failure as a peace treaty, it was resurrected under the new government of the young Henry III as a way of drawing support away from the rebel faction. On his deathbed, King John appointed a council of thirteen executors to help Henry reclaim the kingdom, and requested that his son be placed into the guardianship of William Marshal, one of the most famous knights in England.[74] William knighted the boy, and Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, the papal legate to England, then oversaw his coronation at Gloucester Cathedral on 28 October.[75][76][77]

The young King inherited a difficult situation, with over half of England occupied by the rebels.[78][79] He had substantial support though from Guala, who intended to win the civil war for Henry and punish the rebels.[80] Guala set about strengthening the ties between England and the Papacy, starting with the coronation itself, during which Henry gave homage to the Papacy, recognising the Pope as his feudal lord.[75][81] Pope Honorius III declared that Henry was the Pope's vassal and ward, and that the legate had complete authority to protect Henry and his kingdom.[75] As an additional measure, Henry took the cross, declaring himself a crusader and thereby entitled to special protection from Rome.[75]

The war was not going well for the loyalists, but Prince Louis and the rebel barons were also finding it difficult to make further progress.[82][83] John's death had defused some of the rebel concerns, and the royal castles were still holding out in the occupied parts of the country.[83][84] Henry's government encouraged the rebel barons to come back to his cause in exchange for the return of their lands, and reissued a version of the 1215 Charter, albeit having first removed some of the clauses, including those unfavourable to the Papacy and clause 61, which had set up the council of barons.[85][86] The move was not successful, and opposition to Henry's new government hardened.[87]

Great Charter of 1217

In February 1217, Louis set sail for France to gather reinforcements.[88] In his absence, arguments broke out between Louis' French and English followers, and Cardinal Guala declared that Henry's war against the rebels was the equivalent of a religious crusade.[89] This declaration resulted in a series of defections from the rebel movement, and the tide of the conflict swung in Henry's favour.[90] Louis returned at the end of April, but his northern forces were defeated by William Marshal at the Battle of Lincoln in May.[91][92]

Meanwhile, support for Louis' campaign was diminishing in France, and he concluded that the war in England was lost.[93] He negotiated terms with Cardinal Guala, under which Louis would renounce his claim to the English throne. In return, his followers would be given back their lands, any sentences of excommunication would be lifted, and Henry's government would promise to enforce the charter of the previous year.[94] The proposed agreement soon began to unravel amid claims from some loyalists that it was too generous towards the rebels, particularly the clergy who had joined the rebellion.[95]

In the absence of a settlement, Louis stayed in London with his remaining forces, hoping for the arrival of reinforcements from France.[95] When the expected fleet arrived in August, it was intercepted and defeated by loyalists at the Battle of Sandwich.[96] Louis entered into fresh peace negotiations. The factions came to agreement on the final Treaty of Lambeth, also known as the Treaty of Kingston, on 12 and 13 September 1217.[96]

The treaty was similar to the first peace offer, but excluded the rebel clergy, whose lands and appointments remained forfeit. It included a promise that Louis' followers would be allowed to enjoy their traditional liberties and customs, referring back to the Charter of 1216.[97] Louis left England as agreed. He joined the Albigensian Crusade in the south of France, bringing the war to an end.[93]

A great council was called in October and November to take stock of the post-war situation. This council is thought to have formulated and issued the Charter of 1217.[98] The charter resembled that of 1216, although some additional clauses were added to protect the rights of the barons over their feudal subjects, and the restrictions on the Crown's ability to levy taxation were watered down.[99] There remained a range of disagreements about the management of the royal forests, which involved a special legal system that had resulted in a source of considerable royal revenue. Complaints existed over both the implementation of these courts, and the geographic boundaries of the royal forests.[100]

A complementary charter, the Charter of the Forest, was created, pardoning existing forest offences, imposing new controls over the forest courts, and establishing a review of the forest boundaries.[100] To distinguish the two charters, the term 'magna carta libertatum' ("the great charter of liberties") was used by the scribes to refer to the larger document, which in time became known simply as Magna Carta.[101][102]

Great Charter of 1225

Magna Carta became increasingly embedded into English political life during Henry III's minority.[103] As the King grew older, his government slowly began to recover from the civil war, regaining control of the counties and beginning to raise revenue once again, taking care not to overstep the terms of the charters.[104] Henry remained a minor and his government's legal ability to make permanently binding decisions on his behalf was limited. In 1223, the tensions over the status of the charters became clear in the royal court, when Henry's government attempted to reassert its rights over its properties and revenues in the counties, facing resistance from many communities that argued—if sometimes incorrectly—that the charters protected the new arrangements.[105][106]

This resistance resulted in an argument between Archbishop Langton and William Brewer over whether the King had any duty to fulfil the terms of the charters, given that he had been forced to agree to them.[107] On this occasion, Henry gave oral assurances that he considered himself bound by the charters, enabling a royal inquiry into the situation in the counties to progress.[108]

In 1225, the question of Henry's commitment to the charters re-emerged, when Louis VIII of France invaded Henry's remaining provinces in France, Poitou and Gascony.[109][110] Henry's army in Poitou was under-resourced, and the province quickly fell.[111] It became clear that Gascony would also fall unless reinforcements were sent from England.[112] In early 1225, a great council approved a tax of £40,000 to dispatch an army, which quickly retook Gascony.[113][114] In exchange for agreeing to support Henry, the barons demanded that the King reissue Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest.[115][116] The content was almost identical to the 1217 versions, but in the new versions, the King declared that the charters were issued of his own "spontaneous and free will" and confirmed them with the royal seal, giving the new Great Charter and the Charter of the Forest of 1225 much more authority than the previous versions.[116][117]

The barons anticipated that the King would act in accordance with these charters, subject to the law and moderated by the advice of the nobility.[118][119] Uncertainty continued, and in 1227, when he was declared of age and able to rule independently, Henry announced that future charters had to be issued under his own seal.[120][121] This brought into question the validity of the previous charters issued during his minority, and Henry actively threatened to overturn the Charter of the Forest unless the taxes promised in return for it were actually paid.[120][121] In 1253, Henry confirmed the charters once again in exchange for taxation.[122]

Henry placed a symbolic emphasis on rebuilding royal authority, but his rule was relatively circumscribed by Magna Carta.[77][123] He generally acted within the terms of the charters, which prevented the Crown from taking extrajudicial action against the barons, including the fines and expropriations that had been common under his father, John.[77][123] The charters did not address the sensitive issues of the appointment of royal advisers and the distribution of patronage, and they lacked any means of enforcement if the King chose to ignore them.[124] The inconsistency with which he applied the charters over the course of his rule alienated many barons, even those within his own faction.[77]

Despite the various charters, the provision of royal justice was inconsistent and driven by the needs of immediate politics: sometimes action would be taken to address a legitimate baronial complaint, while on other occasions the problem would simply be ignored.[125] The royal courts, which toured the country to provide justice at the local level, typically for lesser barons and the gentry claiming grievances against major lords, had little power, allowing the major barons to dominate the local justice system.[126] Henry's rule became lax and careless, resulting in a reduction in royal authority in the provinces and, ultimately, the collapse of his authority at court.[77][126]

In 1258, a group of barons seized power from Henry in a coup d'état, citing the need to strictly enforce Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest, creating a new baronial-led government to advance reform through the Provisions of Oxford.[127] The barons were not militarily powerful enough to win a decisive victory, and instead appealed to Louis IX of France in 1263–1264 to arbitrate on their proposed reforms. The reformist barons argued their case based on Magna Carta, suggesting that it was inviolable under English law and that the King had broken its terms.[128]

Louis came down firmly in favour of Henry, but the French arbitration failed to achieve peace as the rebellious barons refused to accept the verdict. England slipped back into the Second Barons' War, which was won by Henry's son, the Lord Edward. Edward also invoked Magna Carta in advancing his cause, arguing that the reformers had taken matters too far and were themselves acting against Magna Carta.[129] In a conciliatory gesture after the barons had been defeated, in 1267 Henry issued the Statute of Marlborough, which included a fresh commitment to observe the terms of Magna Carta.[130]

Witnesses in 1225

Great Charter of 1297: statute

King Edward I reissued the Charters of 1225 in 1297 in return for a new tax.[132] It is this version which remains in statute today, although with most articles now repealed.[133][134]

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Citation | 25 Edw. 1 |

|---|---|

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 1297 |

| Other legislation | |

| Amended by | Statute Law Revision Act 1887, Statute Law Revision Act 1948, Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969, Wild Creatures and Forest Laws Act 1971 |

| Relates to | Magna Carta (1297), Charter of the Forest, A Statute Concerning Tallage (1297) |

Status: Amended | |

| Text of the Confirmation of the Charters (1297) as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk. | |

The Confirmatio Cartarum (Confirmation of Charters) was issued in Norman French by Edward I in 1297.[135] Edward, needing money, had taxed the nobility, and they had armed themselves against him, forcing Edward to issue his confirmation of Magna Carta and the Forest Charter to avoid civil war.[136] The nobles had sought to add another document, the De Tallagio, to Magna Carta. Edward I's government was not prepared to concede this, they agreed to the issuing of the Confirmatio, confirming the previous charters and confirming the principle that taxation should be by consent,[132] although the precise manner of that consent was not laid down.[137]

A passage mandates that copies shall be distributed in "cathedral churches throughout our realm, there to remain, and shall be read before the people two times by the year",[138] hence the permanent installation of a copy in Salisbury Cathedral.[139] In the Confirmation's second article, it is confirmed that:

...if any judgement be given from henceforth contrary to the points of the charters aforesaid by the justices, or by any other our ministers that hold plea before them against the points of the charters, it shall be undone, and holden for nought.[140][141]

With the reconfirmation of the charters in 1300, an additional document was granted, the Articuli super Cartas (The Articles upon the Charters).[142] It was composed of 17 articles and sought in part to deal with the problem of enforcing the charters. Magna Carta and the Forest Charter were to be issued to the sheriff of each county, and should be read four times a year at the meetings of the county courts. Each county should have a committee of three men who could hear complaints about violations of the Charters.[143]

Pope Clement V continued the papal policy of supporting monarchs (who ruled by divine grace) against any claims in Magna Carta which challenged the King's rights, and annulled the Confirmatio Cartarum in 1305. Edward I interpreted Clement V's papal bull annulling the Confirmatio Cartarum as effectively applying to the Articuli super Cartas, although the latter was not specifically mentioned.[144] In 1306 Edward I took the opportunity given by the Pope's backing to reassert forest law over large areas which had been "disafforested". Both Edward and the Pope were accused by some contemporary chroniclers of "perjury", and it was suggested by Robert McNair Scott that Robert the Bruce refused to make peace with Edward I's son, Edward II, in 1312 with the justification: "How shall the king of England keep faith with me, since he does not observe the sworn promises made to his liege men ...".[145][146]

Magna Carta's influence on English medieval law

The Great Charter was referred to in legal cases throughout the medieval period. For example, in 1226, the knights of Lincolnshire argued that their local sheriff was changing customary practice regarding the local courts, "contrary to their liberty which they ought to have by the charter of the lord king".[147] In practice, cases were not brought against the King for breach of Magna Carta and the Forest Charter, but it was possible to bring a case against the King's officers, such as his sheriffs, using the argument that the King's officers were acting contrary to liberties granted by the King in the charters.[148]

In addition, medieval cases referred to the clauses in Magna Carta which dealt with specific issues such as wardship and dower, debt collection, and keeping rivers free for navigation.[149] Even in the 13th century, some clauses of Magna Carta rarely appeared in legal cases, either because the issues concerned were no longer relevant, or because Magna Carta had been superseded by more relevant legislation. By 1350 half the clauses of Magna Carta were no longer actively used.[150]

14th–15th centuries

During the reign of King Edward III six measures, later known as the Six Statutes, were passed between 1331 and 1369. They sought to clarify certain parts of the Charters. In particular the third statute, in 1354, redefined clause 29, with "free man" becoming "no man, of whatever estate or condition he may be", and introduced the phrase "due process of law" for "lawful judgement of his peers or the law of the land".[151]

Between the 13th and 15th centuries Magna Carta was reconfirmed 32 times according to Sir Edward Coke, and possibly as many as 45 times.[152][153] Often the first item of parliamentary business was a public reading and reaffirmation of the Charter, and, as in the previous century, parliaments often exacted confirmation of it from the monarch.[153] The Charter was confirmed in 1423 by King Henry VI.[154][155][156]

By the mid-15th century, Magna Carta ceased to occupy a central role in English political life, as monarchs reasserted authority and powers which had been challenged in the 100 years after Edward I's reign.[157] The Great Charter remained a text for lawyers, particularly as a protector of property rights, and became more widely read than ever as printed versions circulated and levels of literacy increased.[158]

16th century

During the 16th century, the interpretation of Magna Carta and the First Barons' War shifted.[159] Henry VII took power at the end of the turbulent Wars of the Roses, followed by Henry VIII, and extensive propaganda under both rulers promoted the legitimacy of the regime, the illegitimacy of any sort of rebellion against royal power, and the priority of supporting the Crown in its arguments with the Papacy.[160]

Tudor historians rediscovered the Barnwell chronicler, who was more favourable to King John than other 13th-century texts, and, as historian Ralph Turner describes, they "viewed King John in a positive light as a hero struggling against the papacy", showing "little sympathy for the Great Charter or the rebel barons".[161] Pro-Catholic demonstrations during the 1536 uprising cited Magna Carta, accusing the King of not giving it sufficient respect.[162]

The first mechanically printed edition of Magna Carta was probably the Magna Carta cum aliis Antiquis Statutis of 1508 by Richard Pynson, although the early printed versions of the 16th century incorrectly attributed the origins of Magna Carta to Henry III and 1225, rather than to John and 1215, and accordingly worked from the later text.[163][164][165] An abridged English-language edition was published by John Rastell in 1527. Thomas Berthelet, Pynson's successor as the royal printer during 1530–1547, printed an edition of the text along with other "ancient statutes" in 1531 and 1540.[166]

In 1534, George Ferrers published the first unabridged English-language edition of Magna Carta, dividing the Charter into 37 numbered clauses.[167]

The mid-sixteenth century funerary monument Sir Rowland Hill of Soulton, placed in St Stephens Wallbroke, included a full statue[168] of the Tudor statesman and judge holding a copy of Magna Carta.[169] Hill was a Mercer and a Lord Mayor of London; both of these statuses were shared with Serlo the Mercer who was a negotiator and enforcer of Magna Carta.[170] The original monument was lost in the Great Fire of London, but it was restated on a 110 foot tall column on his family's estates in Shropshire.[171]

At the end of the 16th century, there was an upsurge in antiquarian interest in Magna Carta in England.[162] Legal historians concluded that there was a set of ancient English customs and laws which had been temporarily overthrown by the Norman invasion of 1066, and been recovered in 1215 and recorded in Magna Carta, which in turn gave authority to important 16th-century legal principles.[162][172][173] Modern historians regard this narrative as fundamentally incorrect, and many refer to it as a "myth".[173][g]

The antiquarian William Lambarde published what he believed were the Anglo-Saxon and Norman law codes, tracing the origins of the 16th-century English Parliament back to this period, but he misinterpreted the dates of many documents concerned.[172] Francis Bacon argued that clause 39 of Magna Carta was the basis of the 16th-century jury system and judicial processes.[178] Antiquarians Robert Beale, James Morice and Richard Cosin argued that Magna Carta was a statement of liberty and a fundamental, supreme law empowering English government.[179] Those who questioned these conclusions, including the Member of Parliament Arthur Hall, faced sanctions.[180][181]

17th–18th centuries

Political tensions

In the early 17th century, Magna Carta became increasingly important as a political document in arguments over the authority of the English monarchy.[182] James I and Charles I both propounded greater authority for the Crown, justified by the doctrine of the divine right of kings, and Magna Carta was cited extensively by their opponents to challenge the monarchy.[175]

Magna Carta, it was argued, recognised and protected the liberty of individual Englishmen, made the King subject to the common law of the land, formed the origin of the trial by jury system, and acknowledged the ancient origins of Parliament: because of Magna Carta and this ancient constitution, an English monarch was unable to alter these long-standing English customs.[175][182][183][184] Although the arguments based on Magna Carta were historically inaccurate, they nonetheless carried symbolic power, as the charter had immense significance during this period; antiquarians such as Sir Henry Spelman described it as "the most majestic and a sacrosanct anchor to English Liberties".[173][175][182]

Sir Edward Coke was a leader in using Magna Carta as a political tool during this period. Still working from the 1225 version of the text – the first printed copy of the 1215 charter only emerged in 1610 – Coke spoke and wrote about Magna Carta repeatedly.[173] His work was challenged at the time by Lord Ellesmere, and modern historians such as Ralph Turner and Claire Breay have critiqued Coke as "misconstruing" the original charter "anachronistically and uncritically", and taking a "very selective" approach to his analysis.[175][185] More sympathetically, J. C. Holt noted that the history of the charters had already become "distorted" by the time Coke was carrying out his work.[186]

In 1621, a bill was presented to Parliament to renew Magna Carta; although this bill failed, lawyer John Selden argued during Darnell's Case in 1627 that the right of habeas corpus was backed by Magna Carta.[187][188] Coke supported the Petition of Right in 1628, which cited Magna Carta in its preamble, attempting to extend the provisions, and to make them binding on the judiciary.[189][190] The monarchy responded by arguing that the historical legal situation was much less clear-cut than was being claimed, restricted the activities of antiquarians, arrested Coke for treason, and suppressed his proposed book on Magna Carta.[188][191] Charles initially did not agree to the Petition of Right, and refused to confirm Magna Carta in any way that would reduce his independence as King.[192][193]

England descended into civil war in the 1640s, resulting in Charles I's execution in 1649. Under the republic that followed, some questioned whether Magna Carta, an agreement with a monarch, was still relevant.[194] An anti-Cromwellian pamphlet published in 1660, The English devil, said that the nation had been "compelled to submit to this Tyrant Nol or be cut off by him; nothing but a word and a blow, his Will was his Law; tell him of Magna Carta, he would lay his hand on his sword and cry Magna Farta".[195] In a 2005 speech the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Lord Woolf, repeated the claim that Cromwell had referred to Magna Carta as "Magna Farta".[196]

The radical groups that flourished during this period held differing opinions of Magna Carta. The Levellers rejected history and law as presented by their contemporaries, holding instead to an "anti-Normanism" viewpoint.[197] John Lilburne, for example, argued that Magna Carta contained only some of the freedoms that had supposedly existed under the Anglo-Saxons before being crushed by the Norman yoke.[198] The Leveller Richard Overton described the charter as "a beggarly thing containing many marks of intolerable bondage".[199]

Both saw Magna Carta as a useful declaration of liberties that could be used against governments they disagreed with.[200] Gerrard Winstanley, the leader of the more extreme Diggers, stated "the best lawes that England hath, [viz., Magna Carta] were got by our Forefathers importunate petitioning unto the kings that still were their Task-masters; and yet these best laws are yoaks and manicles, tying one sort of people to be slaves to another; Clergy and Gentry have got their freedom, but the common people still are, and have been left servants to work for them."[201][202]

Glorious Revolution

The first attempt at a proper historiography was undertaken by Robert Brady,[203] who refuted the supposed antiquity of Parliament and belief in the immutable continuity of the law. Brady realised that the liberties of the Charter were limited and argued that the liberties were the grant of the King. By putting Magna Carta in historical context, he cast doubt on its contemporary political relevance;[204] his historical understanding did not survive the Glorious Revolution, which, according to the historian J. G. A. Pocock, "marked a setback for the course of English historiography."[205]

According to the Whig interpretation of history, the Glorious Revolution was an example of the reclaiming of ancient liberties. Reinforced with Lockean concepts, the Whigs believed England's constitution to be a social contract, based on documents such as Magna Carta, the Petition of Right, and the Bill of Rights.[206] The English Liberties (1680, in later versions often British Liberties) by the Whig propagandist Henry Care (d. 1688) was a cheap polemical book that was influential and much-reprinted, in the American colonies as well as Britain, and made Magna Carta central to the history and the contemporary legitimacy of its subject.[207]

Ideas about the nature of law in general were beginning to change. In 1716, the Septennial Act was passed, which had a number of consequences. First, it showed that Parliament no longer considered its previous statutes unassailable, as it provided for a maximum parliamentary term of seven years, whereas the Triennial Act (1694) (enacted less than a quarter of a century previously) had provided for a maximum term of three years.[208]

It also greatly extended the powers of Parliament. Under this new constitution, monarchical absolutism was replaced by parliamentary supremacy. It was quickly realised that Magna Carta stood in the same relation to the King-in-Parliament as it had to the King without Parliament. This supremacy would be challenged by the likes of Granville Sharp. Sharp regarded Magna Carta as a fundamental part of the constitution, and maintained that it would be treason to repeal any part of it. He also held that the Charter prohibited slavery.[209]

Sir William Blackstone published a critical edition of the 1215 Charter in 1759, and gave it the numbering system still used today.[210] In 1763, Member of Parliament John Wilkes was arrested for writing an inflammatory pamphlet, No. 45, 23 April 1763; he cited Magna Carta continually.[211] Lord Camden denounced the treatment of Wilkes as a contravention of Magna Carta.[212] Thomas Paine, in his Rights of Man, would disregard Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights on the grounds that they were not a written constitution devised by elected representatives.[213]

Use in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States

When English colonists left for the New World, they brought royal charters that established the colonies. The Massachusetts Bay Company charter, for example, stated that the colonists would "have and enjoy all liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects."[214] The Virginia Charter of 1606, which was largely drafted by Sir Edward Coke, stated that the colonists would have the same "liberties, franchises and immunities" as people born in England.[215] The Massachusetts Body of Liberties contained similarities to clause 29 of Magna Carta; when drafting it, the Massachusetts General Court viewed Magna Carta as the chief embodiment of English common law.[216] The other colonies would follow their example. In 1638, Maryland sought to recognise Magna Carta as part of the law of the province, but the request was denied by Charles I.[217]

In 1687, William Penn published The Excellent Privilege of Liberty and Property: being the birth-right of the Free-Born Subjects of England, which contained the first copy of Magna Carta printed on American soil. Penn's comments reflected Coke's, indicating a belief that Magna Carta was a fundamental law.[218] The colonists drew on English law books, leading them to an anachronistic interpretation of Magna Carta, believing that it guaranteed trial by jury and habeas corpus.[219]

The development of parliamentary supremacy in the British Isles did not constitutionally affect the Thirteen Colonies, which retained an adherence to English common law, but it directly affected the relationship between Britain and the colonies.[220] When American colonists fought against Britain, they were fighting not so much for new freedom, but to preserve liberties and rights that they believed to be enshrined in Magna Carta.[221]

In the late 18th century, the United States Constitution became the supreme law of the land, recalling the manner in which Magna Carta had come to be regarded as fundamental law.[221] The Constitution's Fifth Amendment guarantees that "no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law", a phrase that was derived from Magna Carta.[222] In addition, the Constitution included a similar writ in the Suspension Clause, Article 1, Section 9: "The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it."[223]

Each of these proclaim that no person may be imprisoned or detained without evidence that he or she committed a crime. The Ninth Amendment states that "The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." The writers of the U.S. Constitution wished to ensure that the rights they already held, such as those that they believed were provided by Magna Carta, would be preserved unless explicitly curtailed.[224][225]

The U.S. Supreme Court has explicitly referenced Edward Coke's analysis of Magna Carta as an antecedent of the Sixth Amendment's right to a speedy trial.[226]

19th–21st centuries

Interpretation

Initially, the Whig interpretation of Magna Carta and its role in constitutional history remained dominant during the 19th century. The historian William Stubbs's Constitutional History of England, published in the 1870s, formed the high-water mark of this view.[228] Stubbs argued that Magna Carta had been a major step in the shaping of the English nation, and he believed that the barons at Runnymede in 1215 were not just representing the nobility, but the people of England as a whole, standing up to a tyrannical ruler in the form of King John.[228][229]

This view of Magna Carta began to recede. The late-Victorian jurist and historian Frederic William Maitland provided an alternative academic history in 1899, which began to return Magna Carta to its historical roots.[230] In 1904, Edward Jenks published an article entitled "The Myth of Magna Carta", which undermined the previously accepted view of Magna Carta.[231] Historians such as Albert Pollard agreed with Jenks in concluding that Edward Coke had largely "invented" the myth of Magna Carta in the 17th century; these historians argued that the 1215 charter had not referred to liberty for the people at large, but rather to the protection of baronial rights.[232]

This view also became popular in wider circles, and in 1930 Sellar and Yeatman published their parody on English history, 1066 and All That, in which they mocked the supposed importance of Magna Carta and its promises of universal liberty: "Magna Charter was therefore the chief cause of Democracy in England, and thus a Good Thing for everyone (except the Common People)".[233][234]

In many literary representations of the medieval past, however, Magna Carta remained a foundation of English national identity. Some authors used the medieval roots of the document as an argument to preserve the social status quo, while others pointed to Magna Carta to challenge perceived economic injustices.[230] The Baronial Order of Magna Charta was formed in 1898 to promote the ancient principles and values felt to be displayed in Magna Carta.[235] The legal profession in England and the United States continued to hold Magna Carta in high esteem; they were instrumental in forming the Magna Carta Society in 1922 to protect the meadows at Runnymede from development in the 1920s, and in 1957, the American Bar Association erected the Magna Carta Memorial at Runnymede.[ 222 ] [ 236 ] [ 237 ] Видный адвокат Лорд Деннинг назвал Великую хартию в 1956 году как «величайший конституционный документ всех времен - основание свободы человека против произвольной власти деспота». [ 238 ]

Отмена статей и конституционного влияния

Такие радикалы, как сэр Фрэнсис Бердетт, полагали, что ворья вольностей не может быть отменена, [ 239 ] но в 19 -м веке пункты, которые были устаревшими или были заменены, начали отменяться. Отмена пункта 26 в 1829 году в результате преступлений против лица 1828 года ( 9 Geo. 4. c. 31 с. 1) [ H ] [ 240 ] Был ли первый раз, когда пункт о Великой хартике был отменен. В течение следующих 140 лет почти всю магну [ 241 ] оставив только положения 1, 9 и 29 все еще в силе (в Англии и Уэльсе) после 1969 года. [ 242 ] [ 243 ] Большинство положений были отменены в Англии и Уэльсе в соответствии с Законом о пересмотре закона закона 1863 года , а также в современной Северной Ирландии , а также в Современной Республике Ирландия в соответствии с Законом о пересмотре закона о законе (Ирландия) 1872 года . [ 240 ]

Многие позже пытаются разработать конституционные формы правительства, отслеживают свою линию обратно в Великую хартию. Британские Доминионы, Австралия и Новая Зеландия, [ 244 ] Канада [ 245 ] (За исключением Квебека ), и ранее Союз Южной Африки и Южной Родезии отражал влияние магнитной хартики в их законах, и последствия Устава можно увидеть в законах других государств, которые превратились из Британской империи . [ 246 ]

Современное наследие

Magna Charta по -прежнему имеет мощный культовый статус в британском обществе, который цитируется политиками и адвокатами в поддержку конституционных позиций. [ 238 ] [ 247 ] Например, его воспринимаемая гарантия судебного разбирательства присяжных и других гражданских свобод привела к тому, что Тони Бенн в 2008 году была ссылкой на дебаты о том, можно ли увеличить максимальное время подозреваемых в терроризме без обвинений с 28 до 42 дней как «день Волшебная хартия была отменена ». [ 248 ] Несмотря на то, что в 2012 году в 2012 году протестующие в Лондоне редко вызывались в суде, в 2012 году пытались использовать максимальную хартию, чтобы противостоять их выселению с церковного двора Святого Павла у лондонского города . По его мнению, мастер рулонов дал этот короткий смягчение, отметив несколько суровым, что, хотя многие из пунктов 29 считали основой верховенства закона в Англии, он не считал его непосредственно относиться к делу, и что два других Выжившие положения по иронии судьбы касались прав церкви и лондонского города и не могли помочь ответчикам. [ 249 ] [ 250 ]

Magna Carta имеет небольшой юридический вес в современной Британии, поскольку большинство ее положений были отменены, а соответствующие права обеспечиваются другими законами, но историк Джеймс Холт отмечает, что выживание Хартии 1215 в национальной жизни - это «рефлексия непрерывного развития английского права и администрации "и символизирует многочисленную борьбу между властью и законом на протяжении веков. [ 251 ] Историк В.Л. Уоррен заметил, что «многие, кто мало знал и меньше заботился о содержании хартии, почти во всех возрастах вызывали свое название и по уважительной причине, потому что это означало больше, чем он сказал». [ 252 ]

Это также остается темой, представляющей большой интерес для историков; Натали Фрайд охарактеризовала Хартию как «один из самых святых коров в английской средневековой истории», с дебатами по поводу его интерпретации и значения вряд ли закончится. [ 229 ] Однако большинство современных историков рассматривают интерпретацию Хартии как уникальную и раннюю хартию законных прав как миф, созданный столетиями спустя. [ 253 ] [ 254 ] [ 255 ]

Во многих отношениях все еще «священный текст», Великая хартия, как правило, считается частью неофициальной конституции Соединенного Королевства ; В речи 2005 года Господь Главный судья Англии и Уэльса , Лорд Вулф , назвал это «первым серией инструментов, которые теперь признаны имеющими особый конституционный статус». [ 196 ] [ 256 ] Волшебная хартия была перепечатана в Новой Зеландии в 1881 году как один из имперских действий, действующих там. [ 257 ] Пункт 29 документа остается в силе в рамках Закона Новой Зеландии. [ 258 ]

Документ также по -прежнему удостоен чести в Соединенных Штатах как предшествующий конституции Соединенных Штатов и Билль о правах . [ 259 ] В 1976 году Великобритания предоставила один из четырех выживших оригиналов 1215 Magna Harta в Соединенные Штаты для их двухсотлетнего празднования, а также пожертвовал для него богато украшенное обоснование. Оригинал был возвращен через год, но реплика и дело все еще демонстрируются в в США Capitol Crypt в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия. [ 260 ]

Празднование 800 -летия

800 -летие первоначальной хартии произошло 15 июня 2015 года, а организации и учреждения запланировали праздничные мероприятия. [ 261 ] Британская библиотека собрала четыре существующие копии рукописи 1215 в феврале 2015 года для специальной выставки. [ 262 ] Британская художница Корнелия Паркер была поручена создать новое произведение искусства, Magna Carta (вышивка) , которое было показано в Британской библиотеке в период с мая по июль 2015 года. [ 263 ] Произведение искусства-это копия статьи в Википедии о Великой хартике (как она появилась в 799-летии документа, 15 июня 2014 года), вручную, вручную более 200 человек. [ 264 ]

15 июня 2015 года в Раннимде в Парке Национального фонда была проведена церемония поминовения, в которой приняли участие британские и американские сановники. [ 265 ] В тот же день Google отпраздновал юбилей с Google Doodle . [ 266 ]

Копия, принадлежащая Линкольнскому собору, была выставлена в Библиотеке Конгресса в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия, с ноября 2014 года по январь 2015 года. [ 267 ] Новый центр для посетителей в замке Линкольн был открыт для юбилей. [ 268 ] Королевский монетный двор выпустил две памятные двухфунтовые монеты . [ 269 ] [ 270 ]

В 2014 году Бери -Сент -Эдмундс в Саффолке отпраздновал 800 -летие Устава баронов о свободе, которые, как сообщалось, было тайно согласовано там в ноябре 1214 года. [ 271 ]

Содержание

Физический формат

Многочисленные копии, известные как примеры , были сделаны из различных хартиров, и многие из них все еще выживают. [ 272 ] Документы были написаны в сильно сокращенной средневековой латыни в четком почерке, используя перо на листах пергамента, сделанного из овец, примерно 15 на 20 дюймов (380 на 510 мм). [ 273 ] [ 274 ] Они были запечатаны с королевской великой печатью чиновником под названием Spigurnel, оснащенным специальным печатным прессом, используя пчелиный воск и смола. [ 274 ] [ 275 ] На хартии 1215 года не было никаких подписей, и присутствующие бароны не прикрепили к ней свои собственные печати . [ 276 ] Текст не был разделен на параграфы или пронумерованные предложения: система нумерации, используемая сегодня, была представлена юристом сэром Уильямом Блэкстоуном в 1759 году. [ 210 ]

Примеры

1215 Примеры

По крайней мере тринадцать оригинальных копий Хартии 1215 года были выпущены Королевской канцелярией в течение этого года, семь в первом транше, распределенном 24 июня и еще шесть позже; Их отправили в окружные шерифы и епископы, которые, вероятно, были обвинены в привилегии. [ 277 ] Между выжившими копиями существуют небольшие различия, и, вероятно, не было единой «мастер -копии». [ 278 ] Из этих документов только четыре выживают, все в Англии: два сейчас в Британской библиотеке , один в соборе Солсбери , и один, имущество Линкольнского собора , по постоянному займу в замок Линкольн . [ 279 ] Каждая из этих версий немного отличается по размеру и тексту, и каждая считается одинаково авторитетной. [ 280 ]

Два устав 1215, проведенные Британской библиотекой, известной как хлопок MS. Август II.106 и хлопковая хартия XIII.31A были приобретены антикварным сэром Робертом Коттоном в 17 веке. [ 281 ] Первый был найден Хамфри Уайемсом, лондонским адвокатом, который, возможно, обнаружил его в магазине портного и который дал его хлопку в январе 1629 года. [ 282 ] Второе было найдено в замке Дувра в 1630 году сэром Эдвардом Дейрином . Традиционно считалось, что в 1215 году в порты Чинкейка была приведена копия, отправленная в 1215 году в порты Чинк , [ 283 ] Но в 2015 году историк Дэвид Карпентер утверждал, что, скорее всего, это было отправлено в Кентерберийский собор , так как его текст был идентичен транскрипции, сделанной из копии собора Устав 1215 года в 1290 -х годах. [ 284 ] [ 285 ] [ 286 ] Эта копия была повреждена в огне хлопковой библиотеки 1731 года, когда ее печать сильно расплавлена. Пергамент был несколько сморщен, но в остальном относительно невредился. Выгравированный факсимил хартии был сделан Джоном Пайном в 1733 году. В 1830-х годах невооруженная и охваченная попытка очистки и сохранения сделала рукопись в значительной степени неразборчивой для невооруженного глаза. [ 287 ] [ 288 ] Это единственная выжившая копия 1215, которая все еще прикреплена к своей великой печати. [ 289 ] [ 290 ]

Копия Линкольна собора была проведена округом с 1215 года. Он был показан в общей палате в соборе, а затем переехал в другое здание в 1846 году. [ 279 ] [ 291 ] Между 1939 и 1940 годами он был показан в Британском павильоне на мировой ярмарке 1939 года в Нью -Йорке и в Библиотеке Конгресса . [ 292 ] Когда началась вторая мировая война, Уинстон Черчилль хотел дать хартию американскому народу, надеясь, что это побудит Соединенные Штаты, а затем нейтральные, вступить в войну против держав Оси , но собор не хотел, и планы были сброшены. [ 293 ] [ 294 ]

После декабря 1941 года копия была сохранена в Форт -Нокс , штат Кентукки , для безопасности, а затем была выставлена на выставку в 1944 году и вернулась в собор Линкольна в начале 1946 года. [ 292 ] [ 293 ] [ 295 ] [ 296 ] Он был выставлен в 1976 году в средневековой библиотеке собора . [ 291 ] Он был выставлен в Сан -Франциско и был вывезен на некоторое время, чтобы пройти сохранение в подготовке к другому визиту в Соединенные Штаты, где он был выставлен в 2007 году в Центре современного искусства Вирджинии и Национальном конституционном центре в Филадельфии. [ 291 ] [ 297 ] [ 298 ] В 2009 году он вернулся в Нью -Йорк, чтобы показать в Музее таверны Fraunces . [ 299 ] В настоящее время он находится на постоянном займе для хранилища Дэвида П.Дж. Росса в замке Линкольн , а также оригинальная копия Хартии леса 1217 года . [ 300 ] [ 301 ]

Четвертая копия, принадлежащая Солсбери, была впервые предоставлена в 1215 году своему предшественнику Старому Сарумскому собору . [ 302 ] Вновь открытый собором в 1812 году, он оставался в Солсбери на протяжении всей своей истории, за исключением случаев, когда его сняли за пределами площадки для восстановления. [ 303 ] [ 304 ] Возможно, это наиболее сохранившаяся из четырех, хотя на пергаменте можно увидеть небольшие отверстия для штифтов, откуда он когда -то был прикреплен. [ 304 ] [ 305 ] [ 306 ] Поправочный почерк на этой версии отличается от версии других трех, предполагая, что он был написан не королевским писцом, а скорее членом собора, который затем иллюстрировал его Королевским судом. [ 272 ] [ 303 ]

Позже примеры

Другие ранние версии чартеров выживают сегодня. Только одно из них выдерживается пример хартии 1216 года, проведенного в Дареме . [ 307 ] Существуют четыре копии хартии 1217 года; Три из них принадлежат библиотеке Бодлея в Оксфорде, а один - Херефордским собором . [ 307 ] [ 308 ] Копия Херефорда иногда отображается вместе с Маппа Мунди собора в цепной библиотеке и выживает вместе с небольшим документом под названием « Артикули» , которые были отправлены вместе с хартией, сообщив шерифу округа, как наблюдать за условиями, изложенными в документе Полем [ 309 ] Одна из копий Бодлеяна была выставлена в Калифорнийском дворце Сан -Франциско в Калифорнийском дворце Легиона Чести в 2011 году. [ 310 ]

Четыре примеры хартии 1225 года выживают: Британская библиотека держит одну, которая была сохранена в аббатстве Лакока до 1945 года; Даремский собор также владеет копией, а библиотека Бодлея держит третью. [ 308 ] [ 311 ] [ 312 ] Четвертая копия иллюстрации 1225 года была проведена в Музее государственного революционного управления и в настоящее время принадлежит Национальному архивам . [ 313 ] [ 314 ] Общество антикваров также содержит проект Устав 1215 года (обнаруженная в 2013 году в реестре конца 13-го века от Аббатства Питерборо ), копии третьего переиздания 1225 года (в течение начала 14-го века, коллекции статутов) и рулонная копия переиздания 1225. [ 315 ]

Только два примерирования магнитной хартии проводятся за пределами Англии, оба с 1297 года. Одним из них было приобретено в 1952 году правительством Австралии за 12 500 фунтов стерлингов в школе Кинг, Брутон , Англия. [ 316 ] Эта копия теперь демонстрируется в Зале парламента в Зале членов , Канберра. [ 317 ] Второй был первоначально принадлежит семье Бруденелл , графы Кардиган , прежде чем они продали его в 1984 году Фонду Перо в Соединенных Штатах, который в 2007 году продал его бизнесмену США Дэвиду Рубенштейну за 21,3 миллиона долларов США. [ 318 ] [ 319 ] [ 320 ] Рубенштейн прокомментировал: «Я всегда верил, что это был важный документ для нашей страны, хотя он не был составлен в нашей стране. Я думаю, что это было основой для Декларации независимости и основы для Конституции». Это пример в настоящее время находится на постоянном займе национальному архивам в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия, округ Колумбия. [ 321 ] [ 322 ] Выживают только два других примеров 1297, выживают, [ 323 ] один из которых проходит в национальном архиве Великобритании, [ 324 ] другой в Гилдхолле, Лондон . [ 323 ]

Семь экземпляров 1300 Иллюстрации Эдварда I Выживают, [ 323 ] [ 325 ] в Фавершаме , [ 326 ] Ориэльский колледж, Оксфорд , библиотека Бодлея , собор Дарема , Вестминстерское аббатство , Лондонский Сити (проводится в архивах в лондонском гилдхолле [ 327 ] ) и бутерброд (проводится в музее сэндвич -гилдхолл ). [ 328 ] Сэндвич -копия была заново открыта в начале 2015 года в викторианском альбоме в городском архиве Сэндвича, Кент , один из портов Чинква . [ 325 ] В случае примеров сэндвича и колледжа Ориэля копии хартии леса, первоначально выпущенной с ними, также выживают. [ 329 ]

Положения

Большая часть хартии 1215 и более поздних версий стремилась управлять феодальными правами Короны над баронами. [ 330 ] Под Angevin Kings и, в частности, во время правления Джона, права короля часто использовались непоследовательно, часто в попытке максимизировать королевский доход от баронов. Феодальное облегчение было одним из способов, которым король мог требовать денег, и пункты 2 и 3 установили сборы, подлежащие уплате, когда наследник унаследовал имущество или когда несовершеннолетний достиг совершеннолетия и завладел своими землями. [ 330 ]

Scutage была формой средневекового налогообложения. Все рыцари и дворяне были обязаны военной службой Короне в обмен на их земли, которые теоретически принадлежали королю. Многие предпочитают избегать этой услуги и вместо этого предлагают деньги. Корона часто использовала деньги для оплаты наемников. [ 331 ] Ставка загадки, которая должна подлежать уплате, и обстоятельства, при которых царь было уместно, было его требовать, была неопределенной и противоречивой. Положения 12 и 14 посвящены управлению процессом. [ 330 ]

Английская судебная система значительно изменилась в прошлом веке, когда королевские судьи сыграли более важную роль в предоставлении справедливости по всей стране. Джон использовал свое королевское усмотрение, чтобы вымогать большие суммы денег у баронов, эффективно принимая платеж, чтобы предложить справедливость в определенных случаях, и роль короны в предоставлении правосудия стала политически чувствительной среди баронов. Положения 39 и 40 потребовали применения надлежащей процедуры в системе королевской правосудия, в то время как пункт 45 требовал, чтобы король назначил знающих королевских чиновников к соответствующим ролям. [ 332 ]

Хотя эти положения не имели особого значения в первоначальной хартии, эта часть Великой хартии стала особенно важной в более поздние века. [ 332 ] Например, в Соединенных Штатах Верховный суд Калифорнии интерпретировал пункт 45 в 1974 году как установление требования общего права, согласно которому ответчик, столкнутый с потенциалом заключения, имеет право на судебное разбирательство, контролируемое юридически обученным судьей. [ 333 ]

Королевские леса были экономически важны в средневековой Англии и были защищены и эксплуатированы короной, поставляя короля охотничьими местами, сырью и деньгами. [ 334 ] [ 335 ] Они подвергались особой королевской юрисдикции, и результирующий лесной закон, по словам историка Ричарда Хукрофта, «суровым и произвольным, вопросом исключительно для воли короля». [ 334 ] Размер лесов расширился под Angevin Kings, непопулярным развитием. [ 336 ]

У чартера 1215 года было несколько пунктов, касающихся королевских лесов. Пункты 47 и 48 обещали вырубить земли, добавленные в леса под Джоном, и исследовать использование королевских прав в этой области, но в частности, не обращались к лесу предыдущих королей, в то время как пункт 53 обещал некоторую форму возмещения для тех, кто затронул Недавние изменения, и пункт 44 обещал некоторую облегчение от работы лесных судов. [ 337 ] Ни Магна Харта, ни последующая хартия леса не оказались совершенно удовлетворительными как способ управления политической напряженностью, возникающей в работе королевских лесов. [ 337 ]

Некоторые из пунктов решают более широкие экономические проблемы. Опасения баронов по поводу обращения с их долгами еврейским ростовщикам, которые занимали особую должность в средневековой Англии и были традициями под защитой короля, были рассмотрены по пунктам 10 и 11. [ 338 ] Хартия завершила этот раздел с фразой «долги из -за того, что евреи будут рассматриваться также», так что это спорно, в какой степени евреи выделяются этими предложениями. [ 339 ] Некоторые проблемы были относительно специфичными, такие как пункт 33, в котором упорядочено удаление всех рыболовных водослива - важного и растущего источника доходов в то время - от рек Англии. [ 337 ]

Роль английской церкви была вопросом для больших дебатов в годы до хартии 1215 года. Нормандские и Ангевинские короли традиционно проявляли большую власть над церковью на их территориях. С 1040 -х годов последовательные папы подчеркнули важность того, чтобы церковь более эффективно управляла из Рима, и создала независимую судебную систему и иерархическую цепь власти. [ 340 ] После 1140 -х годов эти принципы были в значительной степени приняты в английской церкви, даже если они сопровождались элементом беспокойства по поводу централизации власти в Риме. [ 341 ] [ 342 ]

Эти изменения ставят под сомнение обычные права мирян, таких как Джон, над церковными назначениями. [ 341 ] Как описано выше, Джон вышел на компромисс с Папойн Инницент III в обмен на его политическую поддержку царя, и пункт 1 Магна Карла заметно продемонстрировал это соглашение, обещая свободы и свободы церкви. [ 330 ] Важность этого пункта может также отражать роль архиепископа Лэнгтона в переговорах: Лэнгтон принял сильную линию по этому вопросу во время своей карьеры. [ 330 ]

Положения в деталях

Положения, оставшиеся в английском праве

Только три пункта магнитной хартии все еще остаются в уставе в Англии и Уэльсе. [ 247 ] Эти положения касаются 1) Свобода английской церкви, 2) «Древние свободы» Лондонского Сити (пункт 13 в Устав 1215, пункт 9 в Статуте 1297 года) и 3) право на должный юридический процесс ( пункты 39 и 40 в Устав 1215, пункт 29 в статуте 1297). [ 247 ] Подробно, эти положения (используя систему нумерации из статута 1297), утверждают, что:

- I. Во -первых, мы предоставили Богу, и благодаря этому наша нынешняя хартия подтвердили, для нас и наших наследников навсегда, что Англиканская церковь будет свободной и будет иметь все свои права и свободы неприкосновенности. Мы также предоставили и дали всем свободным людям нашего царства, для нас и наших наследников навсегда, эти свободы, незамеченные, иметь и держать их и их наследников, нас и наших наследников навсегда.

- IX. будет Лондонский город иметь все старые свободы и обычаи, которые он использовал. Более того, мы получим и предоставим, что все другие города, районы, города и бароны пяти портов и все другие порты должны иметь все свои свободы и бесплатные обычаи.

- Xxix. Ни один Фримен не должен быть взят или заключен в тюрьму, или не исселен от его свободы, или свободы, или свободных обычаев, или быть вне закона, или изгнанного, или любых других мудрых разрушенных; Мы не не передам ему и не осудим его, а за законным суждением о его сверстниках или по закону земли . Мы не будем продавать человеку, мы не будем отрицать и не откладывать ни одному человеку, либо справедливости. [ 240 ] [ 346 ]

Смотрите также

- Гражданские свободы в Великобритании

- Чартер леса

- Фундаментальные законы Англии

- Умение обращаться

- История демократии

- История прав человека

- Список самых дорогих книг и рукописей

- Magna Carta (вышивка) , 2015 год

- Magna Carta Hiberniae - выпуск английской ворки Magna Carta, или Великой Хартии свобод в Ирландии

- Постановления 1311 года

- Устава закладки

Пояснительные заметки

- ^ Латинское название документа написано либо магнитной хартией , либо магна -чартой (произношение одинаково), и может появиться на английском языке с или без определенной статьи «», хотя это более обычное, чтобы статья была опущена. [ 1 ] Латинский не имеет определенной статьи, эквивалентной «The». Правописание Charta происходит в 18 -м веке, как восстановление классической латинской чарты для средневековой латинской орфографической хартии . [ 2 ] В то время как «Charta» остается приемлемым вариантом правописания, оно никогда не стало распространенным в использовании английского языка. [ 3 ]

- ^ В рамках этой статьи до 14 сентября 1752 года находятся в календаре Юлиана. Более поздние даты находятся в григорианском календаре. Однако в григорианском календаре дата была бы 22 июня 1215 года.

- ^ Это было 1 (часть), 13, 39 и 40 Устава 1215, были пунктами 1, 9 и 29 закона 1297. Хотя ученые относятся к 63 пронумерованным «предложениям» магнитной хартии, это современная система нумерации, представленная сэром Уильямом Блэкстоуном в 1759 году; Оригинальная хартия сформировала один длинный непрерывный текст.

- ^ Устав свободы Runnymede не распространялся на Честер , который в то время был отдельным феодальным доменом . Эрл Ранульф предоставил свою собственную магнитную хартию Честера . [ 39 ] Некоторые из его статей были похожи на хартию Runnymede. [ 40 ]

- ^ Претензия Луи на английский трон, описанный как «спорный» историком Дэвидом Карпентером, полученной от его жены Бланш Кастилии , которая была внучкой короля Генриха II из Англии . Луи утверждал, что с тех пор, как Иоанн был законно свергнут, бароны могли законно назначить его королем из -за претензий сына Джона Генри. [ 54 ]

- ^ Роджер де Монтбегон назван только в одном из четырех ранних источников (BL, Harley MS 746, fol. 64); в то время как другие называют Роджер де Моубрей . Тем не менее, Холт считает, что в списке Harley является «лучшим», а записи De Mowbray - ошибка.

- ^ Среди историков, которые обсуждали «миф» о Магне хартике и древней английской конституции - Клэр Бри , Джеффри Хиндли, Джеймс Холт , Джон Покок , Дэнни Данцигер и Джон Джиллингем . [ 173 ] [ 174 ] [ 175 ] [ 176 ] [ 177 ]

- ^ То есть, раздел 1 31 -го закона, выпущенный на 9 -м году Джорджа IV; «Мы не будем» в пункте 29, правильно цитируется из этого источника.

Ссылки

- ^ "Великая хартия вольностей" . Оксфордский английский словарь (онлайн изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета . ( Требуется членство в учреждении подписки или участвующего учреждения .) «Обычно без статьи».

- ^ Du Cange s.v. 1 carta

- ^ Гарнер, Брайан А. (1995). Словарь современного юридического использования . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 541. ISBN 978-0195142365 Полем «Обычная - и лучшая - форма хартия . Великая - Magna Charta -это рекомендуемое правописание в немецкоязычной литературе. ( Дуден онлайн )

- ^ "Magna Charta 1215" . Британская библиотека . Получено 3 февраля 2019 года .

- ^ Питер Крукс (июль 2015 г.). «Экспорт Великой хартики: исключительные свободы в Ирландии и мире» . История Ирландия . 23 (4).

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 8

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Тернер 2009 , с. 149

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 7

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham 2004 , p. 168.

- ^ Тернер 2009 , с. 139

- ^ Уоррен 1990 , с. 181.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 6–7.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Карпентер 1990 , с. 9

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Тернер 2009 , с. 174.

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham 2004 , с. 256–258.

- ^ McGlynn 2013 , с. 131–132.

- ^ McGlynn 2013 , с. 130.

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham 2004 , p. 104

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham 2004 , p. 165.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Тернер 2009 , с. 178.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный McGlynn 2013 , с. 132.

- ^ Holt 1992a , p. 115.

- ^ Половина 1993 , с. 471-472.

- ^ Винсент 2012 , с. 59–60.

- ^ Тернер 2009 , с. 179

- ^ Уоррен 1990 , с. 233.

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham 2004 , с. 258–2.

- ^ Turner 2009 , с. 174, 179–180.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Тернер 2009 , с. 180.

- ^ Holt 1992a , p. 112.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый McGlynn 2013 , с. 137.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Таттон-Браун 2015 , с. 36

- ^ Холт 2015 , с. 219

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Уоррен 1990 , с. 236

- ^ Тернер 2009 , с. 180, 182.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Тернер 2009 , с. 182.

- ^ Turner 2009 , с. 184–185.

- ^ "Великая хартия вольностей" . Британская библиотека . Получено 16 марта 2016 года .

- ^ Hewit 1929 , p. 9

- ^ Holt 1992b , pp. 379–380.

- ^ Винсент 2012 , с. 61–63.

- ^ Carpenter 2004 , с. 293–294.

- ^ Гельмхольц 2016 , с. 869 «Во -первых, формулировка магнитной хартии в Англии не была изолированным событием. Она не была уникальной. Результаты встречи в Раннимде совпали со многими подобными заявлениями закона на континенте».

- ^ Holt 2015 , стр. 50–51: «Волшебная хартия была далекой от уникальной, по содержанию или в форме»

- ^ Blick 2015 , p. 39: «Это был один из таких наборов уступок, выпущенных королями, которые были установлены ограничениями на их способности, хотя у него был свой особый характер, и впоследствии он стал самым знаменитым и влиятельным из них . "

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Тернер 2009 , с. 189.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Danziger & Gillingham 2004 , с. 261–262.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Гудман 1995 , с. 260–261.

- ^ Уоррен 1990 , с. 239–240.

- ^ Половина 1993 , с. 479.

- ^ Turner 2009 , с. 189–191.

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham 2004 , p. 262

- ^ Уоррен 1990 , с. 239, 242.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Карпентер 1990 , с. 12

- ^ Карпентер 1996 , с. 13

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый "Все положения" . Проект Magna Carta . Университет Восточной Англии . Получено 9 ноября 2014 года .

- ^ Тернер 2009 , с. 190–191.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Тернер 2009 , с. 190.

- ^ Уоррен 1990 , с. 244–245.

- ^ Rothwell 1975 , с. 324–226.

- ^ Уоррен 1990 , с. 245–246.

- ^ Holt 1992a , p. 1

- ^ Crouch 1996 , p. 114

- ^ Carpenter 2004 , с. 264–267.

- ^ Уоррен 1990 , с. 254–255

- ^ "Великая хартия: Уэльс, Шотландия и Ирландия" . Получено 19 октября 2022 года .

- ^ Смит, Дж. Беверли (1984). «Великая харта и чартеры валлийских князей». Английский исторический обзор . XCIX (CCCXCI): 344–362. doi : 10.1093/ehr/xcix.cccxci.344 . ISSN 0013-8266 .

- ^ "Предисловие" . Magna Carta Project . Получено 17 мая 2015 года .

- ^ Holt 1992b , pp. 478–480: Список в коллекции юридических путей находится в Британской библиотеке , Harley MS 746, fol. 64; Список чтения аббатства в библиотеке Ламбет Палас, MS 371, fol. 56 В

- ^ «Профили поручителей Великой хартии и других сторонников» . Баронический ордень магны Charta . Получено 17 мая 2015 года .

- ^ «Magna Charta Barons в Runnymede» . Брукфилдский предок проект . Получено 4 ноября 2014 года .

- ^ Стрикленд, Мэтью (2005). «Обеспечение магнитной хартики (акт. 1215–1216)». Оксфордский словарь национальной биографии (онлайн -ред.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/ref: ODNB/93691 . ( Требуется членство в публичной библиотеке в Великобритании .)

- ^ Powicke 1929 .

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 14–15.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Карпентер 1990 , с. 13

- ^ McGlynn 2013 , с. 189.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Ridgeway 2010 .

- ^ Вейлер 2012 , с. 1

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 1

- ^ Mayr-Harting 2011 , с. 259–260.

- ^ Mayr-Harting 2011 , с. 260

- ^ Карпентер 2004 , с. 301.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Карпентер 1990 , с. 19–21.

- ^ Ear 2003 , p. 30

- ^ Carpenter 1990 , pp. 21–22, 24–25.

- ^ Powicke 1963 , p. 5

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 25

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 27

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 28–29.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 127–28.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 36–40.

- ^ McGlynn 2013 , с. 216

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Hallam & Everard 2001 , p. 173.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 41–42.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Карпентер 1990 , с. 42

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Карпентер 1990 , с. 44

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 41, 44–45.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 60

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 60–61.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Карпентер 1990 , с. 61–62.

- ^ Белый 1915 , с. 472–475.

- ^ Белый 1917 , с. 545–555.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 402

- ^ Carpenter 1990 , pp. 333–335, 382–383.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 295–296.

- ^ Jobson 2012 , p. 6

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 296–297.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 297

- ^ Hallam & Everard 2001 , p. 176

- ^ Вейлер 2012 , с. 20

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 371–373.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 374–375.

- ^ Carpenter 1990 , pp. 376, 378.

- ^ Hallam & Everard 2001 , с. 176–177.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 379.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Карпентер 2004 , с. 307

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 383.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 2–3, 383, 386

- ^ Карпентер 2004 , с. 307

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Clanchy 1997 , p. 147

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Дэвис 2013 , с. 71

- ^ Дэвис 2013 , с. 174.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Карпентер 1996 , с. 76, 99.

- ^ Карпентер 1990 , с. 3

- ^ Карпентер 1996 , с. 26, 29, 37, 43.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Карпентер 1996 , с. 105

- ^ Дэвис 2013 , стр. 195-197.

- ^ Jobson 2012 , p. 104

- ^ Дэвис 2013 , с. 224

- ^ Jobson 2012 , p. 163.

- ^ Holt 1992b , pp. 510–11.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Prestwich 1997 , p. 427.