Киевская Русь

Киевская Русь , [а] [б] также известная как Киевская Русь , [с] [7] [8] было первым восточнославянским государством, а затем объединением княжеств. [9] в Восточной Европе с конца 9 до середины 13 вв. [10] [11] Охватывает различные государства и народы, в том числе восточнославянские , норвежские , [12] [13] и Финский , им управляла династия Рюриковичей , основанная варяжским князем Рюриком . [14] Название было придумано русскими историками в 19 веке для описания периода, когда Киев центром города был середине XI века Киевская Русь простиралась от Белого моря на севере до Черного моря на юге и от истоков Вислы . В наибольшем своем размахе в на западе до Таманского полуострова на востоке. [15] [16] объединение восточнославянских племен. [11]

According to the Primary Chronicle, the first ruler to unite East Slavic lands into what would become Kievan Rus' was Oleg the Wise (r. 879–912). He extended his control from Novgorod south along the Dnieper river valley to protect trade from Khazar incursions from the east,[11] and took control of the city. Sviatoslav I (r. 943–972) achieved the first major territorial expansion of the state, fighting a war of conquest against the Khazars. Vladimir the Great (r. 980–1015) spread Christianity with his own baptism and, by decree, extended it to all inhabitants of Kiev and beyond. Kievan Rus' reached its greatest extent under Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054); his sons assembled and issued its first written legal code, the Russkaya Pravda, shortly after his death.[2]

The state began to decline in the late 11th century, gradually disintegrating into various rival regional powers throughout the 12th century.[17] It was further weakened by external factors, such as the decline of the Byzantine Empire, its major economic partner, and the accompanying diminution of trade routes through its territory.[18] It finally fell to the Mongol invasion in the mid-13th century, though the Rurik dynasty would continue to rule until the death of Feodor I of Russia in 1598.[19] The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all claim Kievan Rus' as their cultural ancestor,[d] with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it, and the name Kievan Rus' derived from what is now the capital of Ukraine.[13][7]

Names

During its existence, Kievan Rus' was known as the "Rus' land" (Old East Slavic: ро́усьскаѧ землѧ́, romanized: rusĭskaę zemlę, from the ethnonym Роусь, Rusĭ; Medieval Greek: Ῥῶς, romanized: Rhos; Arabic: الروس, romanized: ar-Rūs), in Greek as Ῥωσία, Rhosia, in Old French as Russie, Rossie, in Latin as Rusia or Russia (with local German spelling variants Ruscia and Ruzzia), and from the 12th century also as Ruthenia or Rutenia.[21][22] Various etymologies have been proposed, including Ruotsi, the Finnish designation for Sweden or Ros, a tribe from the middle Dnieper valley region.[23]

According to the prevalent theory, the name Rus', like the Proto-Finnic name for Sweden (*rootsi), is derived from an Old Norse term for 'men who row' (rods-) because rowing was the main method of navigating the rivers of Eastern Europe, and could be linked to the Swedish coastal area of Roslagen (Rus-law) or Roden.[24][25] The name Rus' would then have the same origin as the Finnish and Estonian names for Sweden: Ruotsi and Rootsi.[25][26]

When the Varangian princes arrived, the name Rus' was associated with them and came to be associated with the territories they controlled. Initially the cities of Kiev, Chernigov, and Pereyaslavl and their surroundings came under Varangian control.[28][29]: 697 From the late tenth century, Vladimir the Great and Yaroslav the Wise tried to associate the name with all of the extended princely domains. Both meanings persisted in sources until the Mongol conquest: the narrower one, referring to the triangular territory east of the middle Dnieper, and the broader one, encompassing all the lands under the hegemony of Kiev's grand princes.[28][30]

The Russian term Kiyevskaya Rus (Russian: Ки́евская Русь) was coined in the 19th century in Russian historiography to refer to the period when the centre was in Kiev.[31] In the 19th century it also appeared in Ukrainian as Kyivska Rus (Ukrainian: Ки́ївська Русь).[32] Later, the Russian term was rendered into Belarusian as Kiyewskaya Rus' or Kijeŭskaja Ruś (Belarusian: Кіеўская Русь) and into Rusyn as Kyïvska Rus' (Rusyn: Київска Русь).[citation needed]

In English, the term was introduced in the early 20th century, when it was found in the 1913 English translation of Vasily Klyuchevsky's A History of Russia,[33] to distinguish the early polity from successor states, which were also named Rus'. The variant Kyivan Rus' appeared in English-language scholarship by the 1950s.[34][original research?]

The Varangian Rus' from Scandinavia used the Old Norse name Garðaríki, which, according to a common interpretation, means "land of towns".

History

Origin

Prior to the emergence of Kievan Rus' in the 9th century, most of the area north of the Black Sea was primarily populated by eastern Slavic tribes.[35] In the northern region around Novgorod were the Ilmen Slavs[36] and neighboring Krivichi, who occupied territories surrounding the headwaters of the West Dvina, Dnieper and Volga rivers. To their north, in the Ladoga and Karelia regions, were the Finnic Chud tribe. In the south, in the area around Kiev, were the Poliane,[37] the Drevliane to the west of the Dnieper, and the Severiane to the east. To their north and east were the Vyatichi, and to their south was forested land settled by Slav farmers, giving way to steppelands populated by nomadic herdsmen.[38]

There was once controversy over whether the Rus' were Varangians or Slavs (see anti-Normanism), however, more recently scholarly attention has focused more on debating how quickly an ancestrally Norse people assimilated into Slavic culture.[e] This uncertainty is due largely to a paucity of contemporary sources. Attempts to address this question instead rely on archaeological evidence, the accounts of foreign observers, and legends and literature from centuries later.[40] To some extent the controversy is related to the foundation myths of modern states in the region.[4] This often unfruitful debate over origins has periodically devolved into competing nationalist narratives of dubious scholarly value being promoted directly by various government bodies in a number of states. This was seen in the Stalinist period, when Soviet historiography sought to distance the Rus' from any connection to Germanic tribes, in an effort to dispel Nazi propaganda claiming the Russian state owed its existence and origins to the supposedly racially superior Norse tribes.[41] More recently, in the context of resurgent nationalism in post-Soviet states, Anglophone scholarship has analyzed renewed efforts to use this debate to create ethno-nationalist foundation stories, with governments sometimes directly involved in the project.[42] Conferences and publications questioning the Norse origins of the Rus' have been supported directly by state policy in some cases, and the resultant foundation myths have been included in some school textbooks in Russia.[43]

While Varangians were Norse traders and Vikings,[44] many Russian and Ukrainian nationalist historians argue that the Rus' were themselves Slavs.[45][46][47][48] Normanist theories focus on the earliest written source for the East Slavs, the Primary Chronicle, which was produced in the 12th century.[49] Nationalist accounts on the other hand have suggested that the Rus' were present before the arrival of the Varangians,[50] noting that only a handful of Scandinavian words can be found in Russian and that Scandinavian names in the early chronicles were soon replaced by Slavic names.[51]

Nevertheless, the close connection between the Rus' and the Norse is confirmed both by extensive Scandinavian settlement in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine and by Slavic influences in the Swedish language.[52][53] Though the debate over the origin of the Rus' remains politically charged, there is broad agreement that if the proto-Rus' were indeed originally Norse, they were quickly nativized, adopting Slavic languages and other cultural practices. This position, roughly representing a scholarly consensus (at least outside of nationalist historiography), was summarized by the historian, F. Donald Logan, "in 839, the Rus were Swedes; in 1043 the Rus were Slavs".[39]

Ahmad ibn Fadlan, an Arab traveler during the 10th century, provided one of the earliest written descriptions of the Rus': "They are as tall as a date palm, blond and ruddy, so that they do not need to wear a tunic nor a cloak; rather the men among them wear garments that only cover half of his body and leaves one of his hands free."[54] Liutprand of Cremona, who was twice an envoy to the Byzantine court (949 and 968), identifies the "Russi" with the Norse ("the Russi, whom we call Norsemen by another name")[55] but explains the name as a Greek term referring to their physical traits ("A certain people made up of a part of the Norse, whom the Greeks call [...] the Russi on account of their physical features, we designate as Norsemen because of the location of their origin.").[56] Leo the Deacon, a 10th-century Byzantine historian and chronicler, refers to the Rus' as "Scythians" and notes that they tended to adopt Greek rituals and customs.[57]

Calling of the Varangians

According to the Primary Chronicle, the territories of the East Slavs in the 9th century were divided between the Varangians and the Khazars.[58] The Varangians are first mentioned imposing tribute from Slavic and Finnic tribes in 859.[59][non-primary source needed] In 862, various tribes rebelled against the Varangians, driving them "back beyond the sea and, refusing them further tribute, set out to govern themselves".[59]

They said to themselves, "Let us seek a prince who may rule over us, and judge us according to the Law." They accordingly went overseas to the Varangian Rus'. ... The Chuds, the Slavs, the Krivichs and the Ves then said to the Rus', "Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us". They thus selected three brothers with their kinfolk, who took with them all the Rus' and migrated.[60]

Modern scholars find this an unlikely series of events, probably made up by the 12th-century Orthodox priests who authored the Chronicle as an explanation how the Vikings managed to conquer the lands along the Varangian route so easily, as well as to support the legitimacy of the Rurikid dynasty.[61] The three brothers—Rurik, Sineus and Truvor—supposedly established themselves in Novgorod, Beloozero and Izborsk, respectively.[62] Two of the brothers died, and Rurik became the sole ruler of the territory and progenitor of the Rurik dynasty.[63] A short time later, two of Rurik's men, Askold and Dir, asked him for permission to go to Tsargrad (Constantinople). On their way south, they came upon "a small city on a hill", Kiev, which was a tributary of the Khazars at the time, stayed there and "established their dominion over the country of the Polyanians."[64][60][61]

The Primary Chronicle reports that Askold and Dir continued to Constantinople with a navy to attack the city in 863–66, catching the Byzantines by surprise and ravaging the surrounding area,[65][non-primary source needed] though other accounts date the attack in 860.[66][67] Patriarch Photius vividly describes the "universal" devastation of the suburbs and nearby islands,[68] and another account further details the destruction and slaughter of the invasion.[69] The Rus' turned back before attacking the city itself, due either to a storm dispersing their boats, the return of the Emperor, or in a later account, due to a miracle after a ceremonial appeal by the Patriarch and the Emperor to the Virgin.[66][67] The attack was the first encounter between the Rus' and Byzantines and led the Patriarch to send missionaries north to engage and attempt to convert the Rus' and the Slavs.[70][71]

Foundation of the Kievan state

Rurik led the Rus' until his death in about 879 or 882, bequeathing his kingdom to his kinsman, Prince Oleg, as regent for his young son, Igor.[72] According to the Primary Chronicle, in 880–82, Oleg led a military force south along the Dnieper river, capturing Smolensk and Lyubech before reaching Kiev, where he deposed and killed Askold and Dir: "Oleg set himself up as prince in Kiev, and declared that it should be the "mother of Rus' cities".[73][f] Oleg set about consolidating his power over the surrounding region and the riverways north to Novgorod, imposing tribute on the East Slav tribes.[64]

In 883, he conquered the Drevlians, imposing a fur tribute on them. By 885 he had subjugated the Poliane, Severiane, Vyatichi, and Radimichs, forbidding them to pay further tribute to the Khazars. Oleg continued to develop and expand a network of Rus' forts in Slavic lands, begun by Rurik in the north.[75]

The new Kievan state prospered due to its abundant supply of furs, beeswax, honey and slaves for export,[76] and because it controlled three main trade routes of Eastern Europe. In the north, Novgorod served as a commercial link between the Baltic Sea and the Volga trade route to the lands of the Volga Bulgars, the Khazars, and across the Caspian Sea as far as Baghdad, providing access to markets and products from Central Asia and the Middle East.[77][78] Trade from the Baltic also moved south on a network of rivers and short portages along the Dnieper known as the "route from the Varangians to the Greeks," continuing to the Black Sea and on to Constantinople.[79]

Kiev was a central outpost along the Dnieper route and a hub with the east–west overland trade route between the Khazars and the Germanic lands of Central Europe.[79] and may have been a staging post for Radhanite Jewish traders between Western Europe, Itil and China.[80] These commercial connections enriched Rus' merchants and princes, funding military forces and the construction of churches, palaces, fortifications, and further towns.[78] Demand for luxury goods fostered production of expensive jewelry and religious wares, allowing their export, and an advanced credit and money-lending system may have also been in place.[76]

Early foreign relations

Volatile steppe politics

The rapid expansion of the Rus' to the south led to conflict and volatile relationships with the Khazars and other neighbors on the Pontic steppe.[81][82] The Khazars dominated trade from the Volga-Don steppes to eastern Crimea and the northern Caucasus during the 8th century, an era historians call the 'Pax Khazarica',[83] trading and frequently allying with the Byzantine Empire against Persians and Arabs. In the late 8th century, the collapse of the Göktürk Khaganate led the Magyars and the Pechenegs, Ugrians and Turkic peoples from Central Asia, to migrate west into the steppe region,[84] leading to military conflict, disruption of trade, and instability within the Khazar Khaganate.[85] The Rus' and Slavs had earlier allied with the Khazars against Arab raids on the Caucasus, but they increasingly worked against them to secure control of the trade routes.[86]

The Byzantine Empire was able to take advantage of the turmoil to expand its political influence and commercial relationships, first with the Khazars and later with the Rus' and other steppe groups.[87] The Byzantines established the Theme of Cherson, formally known as Klimata, in the Crimea in the 830s to defend against raids by the Rus' and to protect vital grain shipments supplying Constantinople.[67] Cherson also served as a key diplomatic link with the Khazars and others on the steppe, and it became the centre of Black Sea commerce.[88] The Byzantines also helped the Khazars build a fortress at Sarkel on the Don river to protect their northwest frontier against incursions by the Turkic migrants and the Rus', and to control caravan trade routes and the portage between the Don and Volga rivers.[89]

The expansion of the Rus' put further military and economic pressure on the Khazars, depriving them of territory, tributaries and trade.[90] In around 890, Oleg waged an indecisive war in the lands of the lower Dniester and Dnieper rivers with the Tivertsi and the Ulichs, who were likely acting as vassals of the Magyars, blocking Rus' access to the Black Sea.[91] In 894, the Magyars and Pechenegs were drawn into the wars between the Byzantines and the Bulgarian Empire. The Byzantines arranged for the Magyars to attack Bulgarian territory from the north, and Bulgaria in turn persuaded the Pechenegs to attack the Magyars from their rear.[92][93]

Boxed in, the Magyars were forced to migrate further west across the Carpathian Mountains into the Hungarian plain, depriving the Khazars of an important ally and a buffer from the Rus'.[92][93] The migration of the Magyars allowed access for the Rus' to the Black Sea,[94] and they soon launched excursions into Khazar territory along the sea coast, up the Don river, and into the lower Volga region. The Rus' were raiding and plundering into the Caspian Sea region from 864,[g] with the first large-scale expedition in 913, when they extensively raided Baku, Gilan, Mazandaran and penetrated into the Caucasus.[h][96][97][98]

As the 10th century progressed, the Khazars were no longer able to command tribute from the Volga Bulgars, and their relationship with the Byzantines deteriorated, as Byzantium increasingly allied with the Pechenegs against them.[99] The Pechenegs were thus secure to raid the lands of the Khazars from their base between the Volga and Don rivers, allowing them to expand to the west.[100] Relations between the Rus' and Pechenegs were complex, as the groups alternately formed alliances with and against one another. The Pechenegs were nomads roaming the steppe raising livestock which they traded with the Rus' for agricultural goods and other products.[101]

The lucrative Rus' trade with the Byzantine Empire had to pass through Pecheneg-controlled territory, so the need for generally peaceful relations was essential. Nevertheless, while the Primary Chronicle reports the Pechenegs entering Rus' territory in 915 and then making peace, they were waging war with one another again in 920.[102][103][non-primary source needed] Pechenegs are reported assisting the Rus' in later campaigns against the Byzantines, yet allied with the Byzantines against the Rus' at other times.[104]

Rus'–Byzantine relations

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2023) |

After the Rus' attack on Constantinople in 860, the Byzantine Patriarch Photius sent missionaries north to convert the Rus' and the Slavs to Christianity. Prince Rastislav of Moravia had requested the Emperor to provide teachers to interpret the holy scriptures, so in 863 the brothers Cyril and Methodius were sent as missionaries, due to their knowledge of the Slavonic language.[71][105][failed verification][106][non-primary source needed] The Slavs had no written language, so the brothers devised the Glagolitic alphabet, later replaced by Cyrillic (developed in the First Bulgarian Empire) and standardized the language of the Slavs, later known as Old Church Slavonic. They translated portions of the Bible and drafted the first Slavic civil code and other documents, and the language and texts spread throughout Slavic territories, including Kievan Rus'.[citation needed] The mission of Cyril and Methodius served both evangelical and diplomatic purposes, spreading Byzantine cultural influence in support of imperial foreign policy.[107][dead link] In 867 the Patriarch announced that the Rus' had accepted a bishop, and in 874 he speaks of an "Archbishop of the Rus'."[70]

Relations between the Rus' and Byzantines became more complex after Oleg took control over Kiev, reflecting commercial, cultural, and military concerns.[108] The wealth and income of the Rus' depended heavily upon trade with Byzantium. Constantine Porphyrogenitus described the annual course of the princes of Kiev, collecting tribute from client tribes, assembling the product into a flotilla of hundreds of boats, conducting them down the Dnieper to the Black Sea, and sailing to the estuary of the Dniester, the Danube delta, and on to Constantinople.[101][109] On their return trip they would carry silk fabrics, spices, wine, and fruit.[70][110]

The importance of this trade relationship led to military action when disputes arose. The Primary Chronicle reports that the Rus' attacked Constantinople again in 907, probably to secure trade access. The Chronicle glorifies the military prowess and shrewdness of Oleg, an account imbued with legendary detail.[70][110] Byzantine sources do not mention the attack, but a pair of treaties in 907 and 911 set forth a trade agreement with the Rus',[102][111] the terms suggesting pressure on the Byzantines, who granted the Rus' quarters and supplies for their merchants and tax-free trading privileges in Constantinople.[70][112]

The Chronicle provides a mythic tale of Oleg's death. A sorcerer prophesies that the death of the prince would be associated with a certain horse. Oleg has the horse sequestered, and it later dies. Oleg goes to visit the horse and stands over the carcass, gloating that he had outlived the threat, when a snake strikes him from among the bones, and he soon becomes ill and dies.[113][114][non-primary source needed] The Chronicle reports that Prince Igor succeeded Oleg in 913, and after some brief conflicts with the Drevlians and the Pechenegs, a period of peace ensued for over twenty years.[citation needed]

In 941, Igor led another major Rus' attack on Constantinople, probably over trading rights again.[70] A navy of 10,000 vessels, including Pecheneg allies, landed on the Bithynian coast and devastated the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus.[115] The attack was well timed, perhaps due to intelligence, as the Byzantine fleet was occupied with the Arabs in the Mediterranean, and the bulk of its army was stationed in the east. The Rus' burned towns, churches and monasteries, butchering the people and amassing booty. The emperor arranged for a small group of retired ships to be outfitted with Greek fire throwers and sent them out to meet the Rus', luring them into surrounding the contingent before unleashing the Greek fire.[116]

Liutprand of Cremona wrote that "the Rus', seeing the flames, jumped overboard, preferring water to fire. Some sank, weighed down by the weight of their breastplates and helmets; others caught fire." Those captured were beheaded. The ploy dispelled the Rus' fleet, but their attacks continued into the hinterland as far as Nicomedia, with many atrocities reported as victims were crucified and set up for use as targets. At last a Byzantine army arrived from the Balkans to drive the Rus' back, and a naval contingent reportedly destroyed much of the Rus' fleet on its return voyage (possibly an exaggeration since the Rus' soon mounted another attack). The outcome indicates increased military might by Byzantium since 911, suggesting a shift in the balance of power.[115]

Igor returned to Kiev keen for revenge. He assembled a large force of warriors from among neighboring Slavs and Pecheneg allies, and sent for reinforcements of Varangians from "beyond the sea".[116][117] In 944, the Rus' force advanced again on the Greeks, by land and sea, and a Byzantine force from Cherson responded. The Emperor sent gifts and offered tribute in lieu of war, and the Rus' accepted. Envoys were sent between the Rus', the Byzantines, and the Bulgarians in 945, and a peace treaty was completed. The agreement again focused on trade, but this time with terms less favorable to the Rus', including stringent regulations on the conduct of Rus' merchants in Cherson and Constantinople and specific punishments for violations of the law.[118][non-primary source needed] The Byzantines may have been motivated to enter the treaty out of concern of a prolonged alliance of the Rus', Pechenegs, and Bulgarians against them,[119] though the more favorable terms further suggest a shift in power.[115]

Sviatoslav

Following the death of Igor in 945, his wife Olga ruled as regent in Kiev until their son Sviatoslav reached maturity (c. 963).[i] His decade-long reign over Kievan Rus' was marked by rapid expansion through the conquest of the Khazars of the Pontic steppe and the invasion of the Balkans. By the end of his short life, Sviatoslav carved out for himself the largest state in Europe, eventually moving his capital from Kiev to Pereyaslavets on the Danube in 969.[citation needed]

In contrast with his mother's conversion to Christianity[broken anchor], Sviatoslav, like his druzhina, remained a staunch pagan. Due to his abrupt death in an ambush in 972, Sviatoslav's conquests, for the most part, were not consolidated into a functioning empire, while his failure to establish a stable succession led to a fratricidal feud among his sons, which resulted in two of his three sons being killed.[citation needed]

Reign of Vladimir and Christianisation

It is not clearly documented when the title of the Grand Duke was first introduced, but the importance of the Kiev principality was recognized after the death of Sviatoslav I in 972 and the ensuing struggle between Vladimir and Yaropolk. The region of Kiev dominated the region for the next two centuries. The grand prince (or grand duke) of Kiev controlled the lands around the city, and his formally subordinate relatives ruled the other cities and paid him tribute. The zenith of the state's power came during the reigns of Vladimir the Great (r. 980–1015) and Prince Yaroslav I the Wise (r. 1019–1054). Both rulers continued the steady expansion of Kievan Rus' that had begun under Oleg.[citation needed]

Vladimir had been prince of Novgorod when his father Sviatoslav I died in 972. He was forced to flee to Scandinavia in shortly after. In Scandinavia, with the help of his uncle Earl Håkon Sigurdsson, ruler of Norway,[citation needed][failed verification] Vladimir assembled a Viking army and reconquered Novgorod and Kiev from Yaropolk, his half-brother who had attempted to seize Novgorod and Kiev.[121]

Although sometimes solely attributed to Vladimir, the Christianization of Kievan Rus' was a long and complicated process that began before the state's formation.[122] As early as the 1st century AD, Greeks in the Black Sea Colonies converted to Christianity, and the Primary Chronicle even records the legend of Andrew the Apostle's mission to these coastal settlements, as well as blessing the site of present-day Kyiv.[122] The Goths migrated to through the region in the 3rd century, adopting Arian Christianity in the 4th century, leaving behind 4th- and 5th-century churches excavated in Crimea, although the Hunnic invasion of the 370s halted Christianisation for several centuries.[122] Some of the earliest Kievan princes and princesses such as Askold and Dir and Olga of Kiev reportedly converted to Christianity, but Oleg, Igor and Sviatoslav remained pagans.[123]

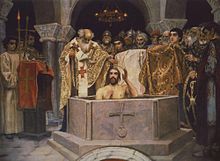

The Primary Chronicle records the legend that when Vladimir had decided to accept a new faith instead of traditional Slavic paganism, he sent out some of his most valued advisors and warriors as emissaries to different parts of Europe. They visited the Christians of the Latin Church, the Jews, and the Muslims before finally arriving in Constantinople. They rejected Islam because, among other things, it prohibited the consumption of alcohol, and Judaism because the god of the Jews had permitted his chosen people to be deprived of their country.[124] They found the ceremonies in the Roman church to be dull. But at Constantinople, they were so astounded by the beauty of the cathedral of Hagia Sophia and the liturgical service held there that they made up their minds there and then about the faith they would like to follow. Upon their arrival home, they convinced Vladimir that the faith of the Byzantine Rite was the best choice of all, upon which Vladimir made a journey to Constantinople and arranged to marry Princess Anna, the sister of Byzantine emperor Basil II.[124] Historically, it is more likely that he adopted Byzantine Christianity in order to strengthen his diplomatic relations with Constantinople.[125] Vladimir's choice of Eastern Christianity may have reflected his close personal ties with Constantinople, which dominated the Black Sea and hence trade on Kiev's most vital commercial route, the Dnieper River.[126] According to the Primary Chronicle, Vladimir was baptised in c. 987, and ordered the population of Kiev to be baptised in August 988.[125] The greatest resistance against Christianisation appears to have occurred in northern towns including Novgorod, Suzdal, and Belozersk.[125]

Adherence to the Eastern Church had long-range political, cultural, and religious consequences.[126] The church had a liturgy written in Cyrillic and a corpus of translations from Greek that had been produced for the Slavic peoples. This literature facilitated the conversion to Christianity of the Eastern Slavs and introduced them to rudimentary Greek philosophy, science, and historiography without the necessity of learning Greek (there were some merchants who did business with Greeks and likely had an understanding of contemporary business Greek).[126] Following the Great Schism of 1054, the Kievan church maintained communion with both Rome and Constantinople for some time, but along with most of the Eastern churches it eventually split to follow the Eastern Orthodox. That being said, unlike other parts of the Greek world, Kievan Rus' did not have a strong hostility to the Western world.[127]

Reign of Yaroslav

Yaroslav, known as "the Wise", struggled for power with his brothers. A son of Vladimir the Great, he was prince of Novgorod at the time of his father's death in 1015.[128]

Although he first established his rule over Kiev in 1019, he did not have uncontested rule of all of Kievan Rus' until 1036. Like Vladimir, Yaroslav was eager to improve relations with the rest of Europe, especially the Byzantine Empire. Yaroslav's granddaughter, Eupraxia, the daughter of his son Vsevolod I, was married to Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor. Yaroslav also arranged marriages for his sister and three daughters to the kings of Poland, France, Hungary and Norway.[citation needed]

Yaroslav promulgated the first law code of Kievan Rus', the Russkaya Pravda; built Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev and Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod; patronized local clergy and monasticism; and is said to have founded a school system. Yaroslav's sons developed the great Kiev Pechersk Lavra (monastery).[citation needed]

Succession issues

In the centuries that followed the state's foundation, Rurik's descendants shared power over Kievan Rus'. The means by which royal power was transferred from one Rurikid ruler to the next is unclear, however, historian Paul Magocsi mentioned that 'Scholars have debated what the actual system of succession was or whether there was any system at all.'[129] According to historian Nancy Kollmann, the rota system was used with the princely succession moving from elder to younger brother and from uncle to nephew, as well as from father to son. Junior members of the dynasty usually began their official careers as rulers of a minor district, progressed to more lucrative principalities, and then competed for the coveted throne of Kiev.[130] Whatever the case, according to professor Ivan Katchanovski 'no adequate system of succession to the Kievan throne was developed' after the death of Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054), commencing a process of gradual disintegration.[131]

The unconventional power succession system fomented constant hatred and rivalry within the royal family. Familicide was frequently deployed to obtain power and can be traced particularly during the time of the Yaroslavichi (sons of Yaroslav), when the established succession system was skipped in the establishment of Vladimir II Monomakh as the Grand Prince of Kiev (r. 1113–1125), in turn creating major squabbles between the Olegovichi (sons of Oleg I) from Chernigov, the Monomakhovichi from Pereyaslavl, the Izyaslavichi (sons of Iziaslav) from Turov–Volhynia, and the Polotsk Princes. The position of the grand prince of Kiev was weakened by the growing influence of regional clans.[citation needed]

Fragmentation and decline

The rival Principality of Polotsk was contesting the power of the Grand Prince by occupying Novgorod, while Rostislav Vladimirovich was fighting for the Black Sea port of Tmutarakan belonging to Chernigov. Three of Yaroslav's sons that first allied together found themselves fighting each other especially after their defeat to the Cuman forces in 1068 at the Battle of the Alta River.[citation needed]

The ruling Grand Prince Iziaslav fled to Poland asking for support and in a couple of years returned to establish the order. The affairs became even more complicated by the end of the 11th century driving the state into chaos and constant warfare. On the initiative of Vladimir II Monomakh in 1097 the Council of Liubech of Kievan Rus' took place near Chernigov with the main intention to find an understanding among the fighting sides.[citation needed]

By 1130, all descendants of Vseslav the Seer had been exiled to the Byzantine Empire by Mstislav the Great. The most fierce resistance to the Monomakhs was posed by the Olegovichi when the izgoi Vsevolod II managed to become the Grand Prince of Kiev. The Rostislavichi, who had initially established in the lands of Galicia by 1189, were defeated by the Monomakh-Piast descendant Roman the Great.[citation needed]

The decline of Constantinople—a main trading partner of Kievan Rus'—played a significant role in the decline of the Kievan Rus'. The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks, along which the goods were moving from the Black Sea (mainly Byzantine) through eastern Europe to the Baltic, was a cornerstone of Kievan wealth and prosperity. These trading routes became less important as the Byzantine Empire declined in power and Western Europe created new trade routes to Asia and the Near East. As people relied less on passing through the territories of Kievan Rus' for trade, the economy of Kievan Rus' suffered.[132]

The last ruler to maintain a united state was Mstislav the Great. After his death in 1132, Kievan Rus' fell into recession and a rapid decline, and Mstislav's successor Yaropolk II of Kiev, instead of focusing on the external threat of the Cumans, was embroiled in conflicts with the growing power of the Novgorod Republic. In March 1169, a coalition of native princes led by Andrei Bogolyubsky of Vladimir sacked Kiev.[133] This changed the perception of Kiev and was evidence of the fragmentation of the Kievan Rus'.[134] By the end of the 12th century, the Kievan state fragmented even further, into roughly twelve different principalities.[135]

The Crusades brought a shift in European trade routes that accelerated the decline of Kievan Rus'. In 1204, the forces of the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople, making the Dnieper trade route marginal.[18] At the same time, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword (of the Northern Crusades) were conquering the Baltic region and threatening the Lands of Novgorod.[citation needed]

In the north, the Novgorod Republic prospered because it controlled trade routes from the River Volga to the Baltic Sea. As Kievan Rus' declined, Novgorod became more independent. A local oligarchy ruled Novgorod; major government decisions were made by a town assembly, which also elected a prince as the city's military leader. In 1136, Novgorod revolted against Kiev, and became independent.[136] Now an independent city republic, and referred to as "Lord Novgorod the Great" it would spread its "mercantile interest" to the west and the north; to the Baltic Sea and the low-populated forest regions, respectively.[136]

In 1199, Prince Roman Mstislavych united the two previously separate principalities of Galicia and Volhynia.[137] His son Daniel (r. 1238–1264) looked for support from the West.[138] He accepted a crown from the Roman papacy.[138]

Final disintegration

Following the Mongol invasion of Cumania (or the Kipchaks), in which case many Cuman rulers fled to Rus', such as Köten, the state finally disintegrated under the pressure of the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus', fragmenting it into successor principalities who paid tribute to the Golden Horde (the so-called Tatar Yoke). Just prior to the Mongol invasion, Kievan Rus' had been a relatively prosperous region. International trade as well as skilled artisans flourished, while its farms produced enough to feed the urban population. After the invasion of the late 1230s, the economy shattered, and its population were either slaughtered or sold into slavery; while skilled laborers and artisans were sent to the Mongol's steppe regions.[139]

On the southwestern periphery, Kievan Rus' was succeeded by the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. Later, as these territories, now part of modern central Ukraine and Belarus, fell to the Gediminids, the powerful, largely Ruthenized Grand Duchy of Lithuania drew heavily on the cultural and legal traditions of the Rus'. From 1398 until the Union of Lublin in 1569, its full name was the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Ruthenia and Samogitia.[140]

On the north-eastern periphery of Kievan Rus', traditions were adapted in the Vladimir-Suzdal principality that gradually gravitated towards Moscow. To the very north, the Novgorod and Pskov feudal republics were less autocratic than Vladimir-Suzdal-Moscow until they were absorbed by the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Modern historians from Belarus, Russia and Ukraine alike consider Kievan Rus' the first period of their modern countries' histories.[131][20]

Society

Culture

Земли Киевской Руси в основном состояли из лесов и степей (см. Восточноевропейская лесостепь и Центральноевропейские смешанные леса ), а все ее основные реки берут начало на Валдайской возвышенности : Днепр , и в основном населены славянскими и финскими племенами . [141] Все племена в той или иной степени были охотниками-собирателями , но славяне были прежде всего земледельцами, выращивавшими зерновые и зерновые культуры, а также разводившими скот. [40] До возникновения Киевского государства эти племена имели своих вождей и богов, а взаимодействие между племенами иногда сопровождалось торговлей товарами или боевыми сражениями. [40] Наиболее ценными товарами, которыми торговали, были пленные рабы и меховые шкуры (обычно в обмен на серебряные монеты или восточные наряды), а общими торговыми партнерами были Волжский Булгар , Хазарский Итиль и византийский Херсонес . [40] К началу 9 века банды скандинавских авантюристов, известные как варяги , а позже и русы, начали грабить различные (славянские) деревни в регионе, позже собирая дань в обмен на защиту от грабежей со стороны других варягов. [40] Со временем эти отношения дани ради защиты превратились в более постоянные политические структуры: русские владыки стали князьями, а славянское население — их подданными. [142]

Экономика

В начале X века Киевская Русь в основном торговала с другими племенами Восточной Европы и Скандинавии . «Не было особой необходимости в сложных социальных структурах для осуществления этих обменов в лесах к северу от степей. Пока предприниматели действовали в небольшом количестве и держались на севере, они не привлекали внимания наблюдателей или писателей». Русь также имела прочные торговые связи с Византией , особенно в начале 900-х годов, как указывают договоры 911 и 944 годов. Эти договоры касаются обращения с беглыми византийскими рабами и ограничениями на количество определенных товаров, таких как шелк , которые можно было купить в Византии. Используемые русскими бревенчатые плоты сплавлялись по реке Днепр славянскими рабов , племенами для перевозки товаров, особенно в Византию . [143]

В киевскую эпоху торговля и транспорт во многом зависели от сети рек и портов. [144] К этому периоду торговые сети расширились, чтобы удовлетворить не только местный спрос. Об этом свидетельствует исследование стеклянной посуды, обнаруженной более чем на 30 объектах от Суздаля, Друцка и Белозерья, в результате которого выяснилось, что значительная часть стеклянной посуды была изготовлена в Киеве. Киев был главным складом и транзитным пунктом в торговле между собой, Византией и Причерноморьем . Хотя эта торговая сеть уже существовала, объемы которой быстро расширились в 11 веке. Киев также доминировал во внутренней торговле между городами Руси; он удерживал монополию на изделия из стекла (стеклянные сосуды, глазурованную керамику и оконное стекло) вплоть до начала-середины XII века, пока не уступил свою монополию другим городам Руси. Техника изготовления инкрустированной эмали была заимствована из Византии. Вдоль среднего Днепра были найдены византийские амфоры, вино и оливковое масло, что позволяет предположить торговлю между Киевом и торговыми городами с Византией. [145]

Зимой киевский правитель выезжал на обходы, посещая дреговичей , кривичей , древлян , северян и другие подчинённые племена. Некоторые платили дань деньгами, некоторые мехами или другими товарами, а некоторые рабами. Эта система называлась полиудией . [146] [147]

Религия

По словам Мартина (2009), «христианство, иудаизм и ислам издавна были известны на этих землях, и Ольга лично приняла христианство. Однако, когда Владимир вступил на престол, он установил на вершине холма в Киеве идолов скандинавских, славянских, финских и иранских богов, которым поклонялись разрозненные элементы его общества, в попытке создать единый пантеон для своего народа. Но по причинам, которые остаются неясными, он вскоре отказался от этой попытки в пользу христианства». [148]

Архитектура

Архитектура Киевской Руси — древнейший период русской, украинской и белорусской архитектуры, использующий основы византийской культуры, но с большим использованием новаций и архитектурных особенностей. Большинство останков представляют собой русские православные церкви или части ворот и укреплений городов. [ нужна ссылка ]

Административное деление

Восточнославянские земли первоначально были разделены на княжеские владения, называемые землями , «землями» или волостями (от термина, означающего «власть» или «правительство»). [149] Меньшая по размеру клановая единица называлась вервом или погостом , возглавляемым копой или виче . [150]

С 11 по 13 века княжества делились на волости , центр которых обычно назывался пригородом (или Гордом — укреплённым поселением). [151] [149] Волость состояла из нескольких верв или громад (общины или общины). [149] Местный чиновник назывался волостелем или старостой . [149]

Ярослав Мудрый отдавал приоритет крупным княжествам, чтобы уменьшить семейные конфликты по поводу престолонаследия . [129]

- Киево-Новгородское княжество для старшего сына Киевляни Изяслава I , ставшего великим князем.

- Княжество Черниговское и Тмутараканское для Святослава II Киевского.

- Principality of Pereyaslavl and Rostov-Suzdal , for Vsevolod I of Kiev

- Смоленское княжество , для Вячеслава Ярославича

- Княжество Волынское , для Игоря Ярославича

Не упоминались Ярославом Полоцкое княжество , которым правил старший брат Ярослава Изяслав Полоцкий , которое должно было остаться под контролем его потомков, и Галицкое княжество , в конечном итоге захваченное династией его внука Ростислава. [129]

Международные отношения

Военная история

Степные народы

С IX века у печенегов- кочевников были непростые отношения с Киевской Русью. На протяжении более двух столетий они совершали спорадические набеги на Русь, которые иногда перерастали в полномасштабные войны, как, например, война 920 года с печенегами Игоря Киевского, о которой сообщается в « Первой летописи» , но существовали и временные военные союзы, например, 943 Византийский поход Игоря. [Дж] В 968 году печенеги напали и осадили город Киев . [152]

Боняк был половецким ханом , который возглавил серию вторжений на Киевскую Русь. В 1096 году Боняк напал на Киев, разграбил Киево-Печерский монастырь и сжёг княжеский дворец в Берестове . Он был разбит в 1107 году Владимиром Мономахом , Олегом, Святополком и другими князьями Руси. [153]

Византийская империя

Византия быстро стала главным торговым и культурным партнером Киева, но отношения не всегда были дружескими. совершали путь из Киева в Константинополь Одним из крупнейших военных свершений династии Рюриковичей было нападение на Византию в 960 году. Паломники-русы уже много лет , и Константин Багрянородный , император Византийской империи , считал, что это дал им важную информацию о трудных участках пути и о том, где путешественники подвергались наибольшему риску, что было бы уместно в случае вторжения. Этот маршрут пролегал через владения печенегов , путешествуя преимущественно по реке. В июне 941 года русы устроили морскую засаду на византийские войска, компенсируя их меньшую численность небольшими маневренными лодками. Эти лодки были плохо оборудованы для перевозки большого количества сокровищ, что позволяет предположить, что грабеж не был целью. Возглавил набег, согласно « Первой летописи» , царь по имени Игорь. Три года спустя в договоре 944 г. говорилось, что всем кораблям, приближающимся к Византии, должно предшествовать письмо князя Рюриковичей с указанием количества кораблей и заверением в их мирных намерениях. Это указывает не только на страх перед новым внезапным нападением, но и на усиление присутствия Киева в регионе. Черное море . [154]

Монголы

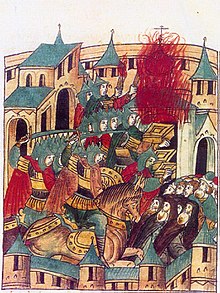

Монгольская империя вторглась в Киевскую Русь в 13 веке, опустошив многочисленные города, в том числе Рязань , Коломну , Москву , Владимир и Киев. Осада Киева монголами в 1240 году обычно понимается как конец Киевской Руси. Батый-хан покорил Галицию и Волынь, совершил набег на Польшу и Венгрию и основал Золотую Орду в Сарае в 1242 году. [155] Завоевания в основном прекратились из-за кризиса престолонаследия после смерти хана Угедея , что побудило Бату вернуться в Монголию, чтобы выбрать следующего повелителя клана. [155]

Историческая оценка

Киевская Русь, хотя и малонаселенная по сравнению с Западной Европой, [156] было не только крупнейшим современным европейским государством по площади, но и развитым в культурном отношении. [157] Грамотность в Киеве, Новгороде и других крупных городах была высокой. [158] [к] В Новгороде была канализация и деревянные тротуары, которые в то время редко встречались в других городах. [160] « Русская правда» ограничивала наказания штрафами и вообще не применяла смертную казнь . [л] определенные права Женщинам были предоставлены , такие как права собственности и наследования . [162] [163] [164]

Экономическое развитие Киевской Руси может отразиться на ее демографии. По оценкам ученых, численность населения Киева около 1200 человек колеблется от 36 000 до 50 000 (в то время в Париже проживало около 50 000, а в Лондоне - 30 000). [165] В Новгороде проживало от 10 000 до 15 000 жителей на 1000 человек, а к 1200 году это число было примерно вдвое больше, в то время как Чернигов имел большую площадь земли, чем Киев и Новгород в то время, и, следовательно, по оценкам, в нем было еще больше жителей. [165] Константинополь, тогда один из крупнейших городов мира, около 1180 года имел население около 400 000 человек. [166] Советский ученый Михаил Тихомиров подсчитал, что накануне монгольского нашествия в Киевской Руси было около 300 городских центров. [167]

Киевская Русь также играла важную генеалогическую роль в европейской политике. Ярослав Мудрый , мачеха которого принадлежала к македонской династии , правившей Византийской империей с 867 по 1056 год, женился на единственной законной дочери короля, христианизировавшего Швецию. Его дочери стали королевами Венгрии, Франции и Норвегии; его сыновья женились на дочерях польского короля и византийского императора и племяннице папы; и его внучки были немецкой императрицей и (согласно одной теории) королевой Шотландии . Внук женился на единственной дочери последнего англосаксонского короля Англии. Таким образом, Рюриковичи были царской семьей того времени с хорошими связями. [м] [н]

Сергей Плохий (2006) предложил «денационализировать» Киевскую Русь: вопреки современным националистическим интерпретациям, он выступал за «отделение Киевской Руси» как многоэтнического государства от национальных историй России, Украины и Белоруссии. Это относится и к слову Русь, и к понятию Русской Земли». [170] По мнению Гальперина (2010), «подход Плохого не отменяет анализ конкурирующих претензий Московии, Литвы или Украины на киевское наследство; оно просто полностью относит такие претензии к сфере идеологии». [171]

В популярной культуре

- Финская фолк-метал- группа Turisas выпустила различные песни для своих альбомов The Varangian Way (2007) и Stand Up and Fight (2011), в которых используются скандинавские имена ( Jarisleif в «In the Court of Jarisleif» для великого князя Ярослава ) и древнескандинавские экзонимы для топонимы (такие как Хольмгард в « В Холмгард и дальше » для Великого Новгорода и Миклагард в «Миклагардской увертюре» для Константинополя ), связанные с Киевской Русью. По словам Боссельмана (2018) и ДиДжиои (2020), Турисас использует скандинавские имена «как способ передать исторический контекст сюжета песен», а именно «истории скандинавского дохристианского населения и их путешествий на восток». по пути, известному как « Путь варяг к грекам в Константинополь». [172] [173]

Галерея

Коллекция карт

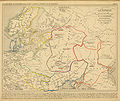

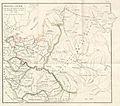

- Карта Руси VIII-IX веков Леонарда Ходзко (1861 г.)

- Карта Руси 9-го века Антуана Филиппа Уза (1844 г.)

- Карта Руси IX века Ф. С. Веллера (1893 г.)

- Карта Руси в Европе 1000 года (1911 г.)

- Карта Руси 1097 года (1911 года)

- Карта 1139 года работы Иоахима Лелевеля ; северо-восток идентифицируется как «транслесные колонии» (Залесье).

- Фрагмент Табулы Рожериана 1154 года работы Мухаммада аль-Идриси.

- Обзор княжеств Киевской Руси

Искусство и архитектура

- Корабельное захоронение русского вождя по описанию арабского путешественника Ахмада ибн Фадлана , посетившего Северо - Восточную Европу в X веке.

Генрих Семирадский (1883) - Модель оригинального Софийского собора, Киев ; использован на современных 2 гривнах Украины

- Рождество , киевская (возможно, галицкая) иллюминация из Псалтири Гертруды.

- Доспехи всадника и конское снаряжение. Железо, XII–XIII вв., с. Липовец, Киевская губерния, курган 264, воинское захоронение. Государственный Эрмитаж.

См. также

- De Administando Imperio - византийский источник X века, написанный императором Константином VII.

- История Беларуси

- История России

- История Украины

- Русская летопись – жанр древнеславянской литературы.

- славистика

- Европейская часть России

Ссылки

Пояснительные примечания

- ^ "Возвышение Киевской Руси" [4]

- ^ «В эти первые века восточнославянские племена и их соседи объединились в христианское государство Киевская Русь». [5]

- ^ "История Киевской (Киевской) Руси, средневекового восточнославянского государства..." [6]

- ^ «Несмотря на все существенные различия между этими тремя постсоветскими народами, они имеют много общего, когда дело касается их культуры и истории, которая восходит к Киевской Руси», средневековому восточнославянскому государству, базирующемуся в столице нынешнего Украина,' [20]

- ^ «Споры о природе Руси и происхождении российского государства сбивали с толку исследования викингов, да и историю России, на протяжении более века. Исторически достоверно, что русы были шведами. Доказательства неопровержимы, и что Дебаты по этому вопросу – бесполезные, ожесточенные, тенденциозные, доктринерские – служили затемнению самой серьезной и подлинной исторической проблемы, которая остается: ассимиляции. этих викингов-русов в славянский народ, среди которого они жили. Главный исторический вопрос не в том, были ли русы скандинавами или славянами, а в том, как быстро эти скандинавские русы впитались в славянскую жизнь и культуру». [39]

- ↑ Ученые-норманисты принимают этот момент как основу государства Киевская Русь, в то время как антинорманисты указывают на другие записи летописи , утверждая, что восточнославянские поляны уже находились в процессе формирования независимого государства. [74]

- ^ Абаскун, впервые записанный Птолемеем как Соканаа , был задокументирован в арабских источниках как «самый известный порт Хазарского моря». Он находился в трех днях пути от Горгана . Южная часть Каспийского моря была известна как «море Абаскуна». [95]

- ↑ Хазарский каган первоначально предоставил русам безопасный проход в обмен на долю добычи, но напал на них на обратном пути, убив большую часть налетчиков и забрав их добычу.

- ↑ Если бы Ольга действительно родилась в 879 году, как следует из « Первой летописи» , на момент рождения Святослава ей было бы около 65 лет. С хронологией явно есть проблемы. [120]

- ^ Ибн Хаукаль описывает печенегов как давних союзников народа русов X века , которых они неизменно сопровождали во время каспийских экспедиций . [ нужна ссылка ]

- ^ "К чести Владимира и его советников они построили не только церкви, но и школы. За этим обязательным крещением последовало обязательное образование... Таким образом, школы были основаны не только в Киеве, но и в губернских городах. Из " Житие святого Феодосия» мы знаем, что школа существовала в Курске около 1023 года. Ко времени правления Ярослава (1019–1054) образование пустило корни и польза его стала очевидна. Около 1030 года Ярослав основал богословскую школу. в Новгороде обучить «книжному учению» 300 детей из числа мирян и духовенства. В качестве общей меры он заставил приходских священников «учить народ». [159]

- ^ "Наиболее примечательным аспектом уголовных положений было то, что наказания принимали форму конфискации имущества, ссылки или, чаще, уплаты штрафа. Даже убийства и другие тяжкие преступления ( поджоги , организованные конокрады и грабежи ) преследовались разрешалось денежными штрафами, хотя смертная казнь была введена Владимиром Великим, но вскоре она также была заменена штрафами». [161]

- ^ «В средневековой Европе признаком престижа и могущества династии была готовность, с которой другие ведущие династии вступали с ней в супружеские отношения. Если судить по этому стандарту, престиж Ярослава, должно быть, действительно был велик... Неудивительно, что Ярослав Историки часто называют его «тестем Европы». [168]

- ^ «Благодаря этим брачным связям Киевская Русь стала широко известна во всей Европе». [169]

Цитаты

- ^ Славянская культура в средние века . Калифорнийские славянские исследования. Издательство Калифорнийского университета. 2021. с. 141. ИСБН 9780520309180 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Бушкович 2011 , с. 11.

- ^ Б.Ц.Урланис. Рост населения в Европе (PDF) (на русском языке). п. 89. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 23 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 17 ноября 2016 г. .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Магоци 2010 , с. 55.

- ^ Мартин 2009b , с. 1.

- ^ Плохий 2006 , с. 10.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Рубин, Барнетт Р.; Снайдер, Джек Л. (1998). Постсоветский политический порядок: конфликт и государственное строительство . Лондон: Рутледж. п. 93.

Как столица Киевской Руси...

. «Золотой век Киевской Руси » . gis.huri.harvard.edu . Архивировано из оригинала 30 октября 2022 года . Проверено 30 октября 2022 г. «Украина – История, раздел «Киевская (Киевская) Русь» » . Британская энциклопедия . 5 марта 2020 года. Архивировано из оригинала 6 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 2 июля 2020 г.- Ждан, Михаил (1988). «Киевская Русь » . Энциклопедия Украины . Архивировано из оригинала 26 марта 2023 года . Проверено 2 июля 2020 г.

- ^ Каччановский и др. 2013 , с. 196.

- ^ Мартин 2009b , с. 1–5.

- ^ Кертис, Гленн Элдон (1998). Россия: страновое исследование . Отдел федеральных исследований Библиотеки Конгресса. ISBN 978-0-8444-0866-8 .

Киевская Русь, первое восточнославянское государство, возникла в девятом веке нашей эры и развила сложную и зачастую нестабильную политическую систему, которая процветала до тринадцатого века, а затем резко пришла в упадок.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Джон Ченнон и Роберт Хадсон, Исторический атлас России Penguin (Penguin, 1995), стр. 14–16.

- ^ «Русь | народ | Британика» . www.britanica.com . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2022 года . Проверено 1 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Литтл, Бекки (4 декабря 2019 г.). «Когда короли и королевы викингов правили средневековой Россией» . ИСТОРИЯ . Архивировано из оригинала 6 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 1 апреля 2022 г.

- ↑ Киевская Русь. Архивировано 18 мая 2015 года в Wayback Machine , Британская энциклопедия Online.

- ↑ Киевская Русь. Архивировано 26 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine , Энциклопедия Украины, том. 2 (1988), Канадский институт украинских исследований.

- ^ См . Историческую карту Киевской Руси с 980 по 1054 год. Архивировано 11 мая 2021 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Пол Роберт Магочи , Исторический атлас Центрально-Восточной Европы (1993), стр.15.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Цивилизация в Восточной Европе, Византии и православной Европе» . occawlonline.pearsoned.com. 2000. Архивировано из оригинала 22 января 2010 года.

- ^ Пикова, Дана, К истокам Российского государства, в: Исторический обзор 18, 2007, № 11/12, стр. 253–261.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Плохий 2006 , с. 10–15.

- ^ (in Russian) Назаренко А. В. Глава I Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine // Древняя Русь на международных путях: Междисциплинарные очерки культурных, торговых, политических связей IX—XII вв. Archived 31 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine — М.: Языки русской культуры, 2001. — c. 40, 42—45, 49—50. — ISBN 5-7859-0085-8 .

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 72–73.

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 56–57.

- ^ Блёндал, Сигфус (1978). Варяги Византии . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-03552-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2023 года . Проверено 2 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Стефан Бринк, «Кем были викинги?», в The Viking World. Архивировано 14 апреля 2023 года в Wayback Machine , изд. Стефан Бринк и Нил Прайс (Абингдон: Routledge, 2008), стр. 4–10 (стр. 6–7).

- ^ "Русь, прил. и н." OED Online, Oxford University Press, июнь 2018 г., www.oed.com/view/Entry/169069. По состоянию на 12 января 2021 г.

- ^ Motsia, Oleksandr (2009). «Русская» терминология в Киевском и Галицко-Волынском летописных сводах ["Русинский" вопрос в Киевских и Галицко-Волынских летописных сводах] (PDF) . Археология (1). дои : 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.1492467.V1 . ISSN 0235-3490 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 2 февраля 2014 года . Проверено 25 января 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Магоци 2010 , с. 72.

- ^ Мельникова Е.А.; Петрухин, В.Я. ; Институт всеобщей истории РАН, под ред. (2014). Древняя Русь в средневековом мире: энциклопедия [ Ранняя Русь в средневековом мире: энциклопедия ]. Москва: Ладомир. OCLC 1077080265 .

- ^ Флоря, Борис Николаевич (1993). "Исторические судьбы Руси и этническое самосознание восточных славян в XII—XV веках" (PDF) . Славяноведение (in Russian). 2 : 12-15 . Retrieved 21 December 2023 .

- ^ Tolochko, A. P. (1999). "Khimera "Kievskoy Rusi" ". Rodina (in Russian) (8): 29–33.

- ^ Колесса, Александр Михайлович (1898). Столетие обновленной украинско-русской литературы: (1798–1898) . Львов: Из типографии Научного общества имени Шевченко под зарядом К. Беднарского. p. 26.

В XII и XIII в., во времена, когда южная, Киевская Русь породила такой жемчуг литературный ... )

- ^ Василий Ключевский , История России , т. 1, с. 3, стр. 98, 104.

- ^ Орелецкий, Василий (1957). «Ведущая черта украинского права» (PDF) . Украинское обозрение . 4 (3): 49. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 10 марта 2022 года . Проверено 5 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ Мартин 2004 , с. 2–4.

- ^ Карл Уолдман и Кэтрин Мейсон, Энциклопедия европейских народов (2006). Архивировано 22 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine , стр. 415.

- ^ Фриз, Грегори Л. (2009). Россия: История . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-956041-7 .

- Чедвик, Нора К. (2013). Начало русской истории: исследование источников . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 17. ISBN 978-1-107-65256-9 .

- ^ Мартин 2004 , с. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Логан 2005 , с. 184.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Мартин 2009b , с. 2.

- ^ Елена Мельникова, «Варяжская проблема»: наука в тисках идеологии и политики», в книге « Идентичность России в международных отношениях: образы, восприятия, заблуждения» , под ред. Рэй Тарас (Абингдон: Routledge, 2013), стр. 42–52.

- ^ Джонатан Шепард, «Обзорная статья: Назад в Древнюю Русь и СССР: археология, история и политика», English Historical Review , vol. 131 (№ 549) (2016), 384–405 doi : 10.1093/ehr/cew104 (стр. 387), цитируется Лео С. Клейн, Советская археология: тенденции, школы и история , пер. Рош Айрленд и Кевин Виндл (Оксфорд: Oxford University Press, 2012), стр. 119.

- ^ Артем Истранин и Александр Дроно, «Конкурирующие исторические повествования в русских учебниках», в книге « Взаимные образы: школьные представления об исторических соседях на Востоке Европы» , под ред. Янош М. Бак и Роберт Майер, Эккерт. Досье, 10 ([Брауншвейг]: Институт международных исследований учебников имени Георга Эккерта, 2017), 31–43 (стр. 35–36).

- ^ «Киевская Русь» . Энциклопедия всемирной истории . Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 24 мая 2020 г.

- Николай Карамзин (1818). История Российского государства . Штутгарт: Штайнер. Архивировано из оригинала 27 октября 2020 года . Проверено 2 августа 2020 г.

- Сергей Соловьев (1851). История России с древнейших времен . Штутгарт: Штайнер. Архивировано из оригинала 11 мая 2021 года . Проверено 2 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Смит, Грэм (10 сентября 1998 г.). Национальное строительство на постсоветском приграничье: политика национальных идентичностей . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-59968-9 .

Украинофилы заявляют, что, как сказано в декларации независимости Украины 1991 года, украинцы имеют «тысячелетнюю традицию государственного строительства»... Как и в русофильской историографии, «норманистская теория» о том, что Русь на самом деле была установленный посланниками викингов, отвергается как немецкое изобретение.

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 56.

- ^ Николай В. Рясановский, История России, стр. 23–28 (Oxford Press, 1984).

- ^ Интернет-энциклопедия Украины. Архивировано 7 сентября 2018 г. в Wayback Machine Норманистская теория.

- ^ Рясановский, с. 25.

- ^ Рясановский, с. 25–27.

- ^ Дэвид Р. Стоун , Военная история России: от Ивана Грозного до войны в Чечне (2006), стр. 2–3.

- ^ Уильямс, Том (28 февраля 2014 г.). «Викинги в России» . blog.britishmuseum.org . Британский музей. Архивировано из оригинала 21 января 2021 года . Проверено 15 января 2021 г.

Предметы, которые сейчас переданы в аренду Британскому музею для выставки BP «Викинги: жизнь и легенды», указывают на масштабы расселения скандинавов от Балтийского до Черного моря. . .

- ^ Франклин, Саймон; Шепард, Джонатан (1996). Возникновение Руси: 750–1200 гг . Лонгман История России. Эссекс: Харлоу. ISBN 0-582-49090-1 .

- ^ Фадлан, Ибн (2005). (Ричард Фрей) Путешествие Ибн Фадлана в Россию . Принстон, Нью-Джерси: Издательство Маркуса Винера.

- ^ Rusios, quos alio nos nomine Nordmannos апелляция . (на польском языке) Генрик Пашкевич (2000). Рост могущества Москвы , стр.13, Краков. ISBN 83-86956-93-3

- ^ Под северной частью утвердился некий род, который греки называют по качеству своего тела [...] русиосами, а мы называем их нордманами по положению места . Джеймс Ли Кейт. Средневековые и историографические очерки в честь Джеймса Вестфолла Томпсона . стр. 482 Издательство Чикагского университета, 1938 г.

- ^ Лео Дьякон, История Льва Дьякона: Византийская военная экспансия в десятом веке (Алиса-Мэри Талбот и Денис Салливан, ред., 2005), стр. 193–94. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 59.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1930 , с. 6.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор, 1953 , с. 7.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Констам, Ангус (2005). Исторический атлас мира викингов . Лондон: Mercury Books Лондон. п. 165. ИСБН 1904668127 .

Это маловероятное приглашение явно служило средством объяснения аннексии этих территорий викингами и придания власти более позднему поколению русских правителей.

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 55, 59–60.

- ^ Томас МакКрей, Россия и бывшие советские республики (2006), с. 26

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мартин 2009а , с. 37.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1953 , с. 8.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Острогорский 1969 , с. 228.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Маеска 2009 , с. 51.

- ^ Логан 2005 , с. 172–73.

- ^ Житие святого Георгия Амастриского описывает русов как варварский народ, «жестокий и грубый, не несущий в себе никаких остатков любви к человечеству». Дэвид Дженкинс, Жизнь святого Георгия Амастриса. Архивировано 5 августа 2019 года в Wayback Machine (University of Notre Dame Press, 2001), стр.18.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Маеска 2009 , с. 52.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Дмитрий Оболенский, Византия и славяне (1994), стр.245. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Мартин 2009b , с. 3.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1953 , с. 7–8.

- ^ Мартин 2009a , с. 37–40.

- ^ Вернадский 1973 , с. 23.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уолтер Мосс, История России: до 1917 года (2005), с. 37. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 96.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мартин 2009а , с. 47.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мартин 2009а , с. 40, 47.

- ^ Перри, Морин; Ливен, DCB; Суни, Рональд Григор (2006). Кембриджская история России: Том 1, От Древней Руси до 1689 года . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-81227-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 марта 2023 года . Проверено 28 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 62, 66.

- ^ Мартин 2004 , с. 16–19.

- ^ Виктор Спинеи, Румыны и тюркские кочевники к северу от дельты Дуная с десятого до середины тринадцатого века (2009), стр. 47–49. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Питер Б. Голден, Центральная Азия в мировой истории (2011), с. 63. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 62–63.

- ^ Вернадский 1973 , с. 20.

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 62.

- ^ Анжелики Папагеоргиу, «Тема Херсона (Климаты)». Архивировано 29 ноября 2014 года в Wayback Machine , Энциклопедия эллинского мира (Foundation of the Hellenic World, 2008).

- ^ Кевин Алан Брук, Евреи Хазарии (2006), стр. 31–32. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Мартин 2004 , с. 15–16.

- ^ Вернадский 1973 , с. 62.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Джон В.А. Файн, Раннесредневековые Балканы: критический обзор с шестого по конец двенадцатого века (1991), стр. 138–139. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Спаней (2009), стр. 66, 70 .

- ^ Вернадский 1973 , с. 28.

- ^ Б. Н. Заходер (1898–1960). Каспийский сборник записей о Восточной Европе ( онлайн-версия. Архивировано 1 мая 2021 года на Wayback Machine ) (на русском языке).

- ^ Вернадский 1973 , с. 32–33.

- ^ Гунилла Ларссон. Корабль и общество: морская идеология в Швеции позднего железного века. Архивировано 23 апреля 2023 года в Wayback Machine Упсальского университета, факультет археологии и древней истории, 2007. ISBN 91-506-1915-2 . п. 208.

- ↑ Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique, том 35, номер 4. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine . Мутон, 1994 г. (первоначально из Калифорнийского университета , оцифровано 9 марта 2010 г.)

- ^ Мосс (2005), с. 29. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 66.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мартин 2004 , с. 17.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Магоци 2010 , с. 67.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1930 , с. 71.

- ↑ Мосс (2005), стр. 29–30. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 г. в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Святые Кирилл и Мефодий, [1] Архивировано 5 мая 2015 года в Wayback Machine Британской энциклопедии .

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1930 , с. 62–63.

- ^ Оболенский (1994), стр. 244–246. Архивировано 22 марта 2023 г. в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 66–67.

- ^ Вернадский 1973 , с. 28–31.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Вернадский 1973 , с. 22.

- ^ Джон Линд, Варяги на восточной и северной периферии Европы, Ennen & nyt (2004:4).

- ^ Логан 2005 , с. 192.

- ^ Вернадский 1973 , с. 22–23.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1930 , с. 69.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Острогорский 1969 , с. 277.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Логан 2005 , с. 193.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1930 , с. 72.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1930 , с. 73–78.

- ^ Шипы, стр.93.

- ^ Островский 2018 , стр. 41–42.

- ^ «Владимир I (великий князь Киевский) – Британская энциклопедия» . Британика.com. 28 марта 2014 г. Архивировано из оригинала 17 октября 2014 г. Проверено 7 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Качановский и др. 2013 , с. 74.

- ^ Каччановский и др. 2013 , с. 74–75.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мартин 2004 , с. 6–7.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Качановский и др. 2013 , с. 75.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Франклин, Саймон (1992). «Греки в Киевской Руси ». Документы Думбартон-Окса . 46 : 69–81. дои : 10.2307/1291640 . JSTOR 1291640 .

- ^ Колуччи, Мишель (1989). «Образ западного христианства в культуре Киевской Руси ». Гарвардские украинские исследования . 13.12: 576–586.

- ^ «Ярослав I (Киевский князь) – Британская энциклопедия» . Британика.com. 22 мая 2014 г. Архивировано из оригинала 17 октября 2014 г. . Проверено 7 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Магоци 2010 , с. 82.

- ^ Нэнси Шилдс Коллманн, «Сопутствующее правопреемство в Киевской Руси». Гарвардские украинские исследования 14 (1990): 377–87.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Качановский и др. 2013 , с. 1.

- ^ Томпсон, Джон М. (Джон Минс) (25 июля 2017 г.). Россия: историческое введение от Киевской Руси до современности . Уорд, Кристофер Дж., 1972– (Восьмое изд.). Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк. п. 20. ISBN 978-0-8133-4985-5 . OCLC 987591571 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ^ Франклин, Саймон; Шепард, Джонатан (1996), Появление России 750–1200 , Routledge, стр. 323–4, ISBN 978-1-317-87224-5 , заархивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2023 года , получено 14 ноября 2020 года.

- ^ Пеленский, Ярослав (1987). «Разграбление Киева 1169 года: его значение для правопреемства Киевской Руси» . Гарвардские украинские исследования . 11 : 303–316.

- ^ Коллманн, Нэнси (1990). «Сопутствующее правопреемство в Киевской Руси». Гарвардские украинские исследования . 14 : 377–387.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Магоци 2010 , с. 85.

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 124.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Магоци 2010 , с. 126.

- ^ Гальперин, Чарльз Дж. (1985). Россия и Золотая Орда: влияние монголов на средневековую русскую историю . Блумингтон: Издательство Университета Индианы. стр. 75–77. ISBN 978-0-253-35033-6 .

- ^ "Русина О.В. Великое княжество ЛИТОВСКОЕ // Энциклопедия истории Украины: Т. 1: А-В / Редкол.: В. А. Смолий (председатель) и др. НАН Украины. Институт истории Украины. – К.: В- во "Научная мысль", 2003. – 688 с.: ил" . Archived из original на 21 апреля 2016 . Retrieved 21 December 2019 .

- ^ Мартин 2009b , с. 1–2.

- ^ Мартин 2009b , с. 2, 5.

- ^ Франклин, Саймон и Джонатан Шепард (1996). Возникновение Руси 750–1200 гг . Харлоу, Эссекс: Longman Group, Ltd., стр. 27–28, 127.

- ^ Уильям Х. Макнил (1 января 1979 г.). Жан Кюизенье (ред.). Европа как культурное пространство . Мировая антропология. Вальтер де Грюйтер. стр. 32–33. ISBN 978-3-11-080070-8 . Проверено 8 февраля 2016 г.

Некоторое время казалось, что скандинавское стремление к монархии и централизации может привести к созданию двух впечатляющих имперских структур: Датской империи северных морей и Варяжской империи русских рек со штаб-квартирой в Киеве... с востока новые орды степных кочевников, только что пришедшие из Центральной Азии, вторглись в речную империю варягов, захватив ее южную часть.

- ^ Саймон, Фрэнк (1996). Возникновение Руси, 750–1200 гг . Лонгман. п. 281. ИСБН 978-0-582-49091-8 .

- ^ Мартин 2004 , с. 12–13.

- ^ История Европы с древнейших времен до наших дней. Т. 2. М.: Наука, 1988. ISBN 978-5-02-009036-1 . С. 201.

- ^ Мартин 2009b , с. 6.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Жуковский, Аркадий (1993). «Волость» . Интернет-энциклопедия Украины . Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 24 января 2023 г.

- ^ «Верв» . Интернет-энциклопедия Украины . Архивировано из оригинала 1 января 2023 года . Проверено 24 января 2023 г.

- ^ Каччановский и др. 2013 , с. 11.

- ^ Lowe, Steven; Ryaboy, Dmitriy V. The Pechenegs, History and Warfare .

- ^ Боняк [Бониак]. Большая советская энциклопедия (на русском языке). 1969–1978. Архивировано из оригинала 6 июля 2013 года . Проверено 10 января 2014 г.

- ^ Франклин, Саймон и Джонатан Шепард (1996). Возникновение Руси 750–1200 гг . Харлоу, Эссекс: Longman Group, Ltd., стр. 112–119.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мартин 2007 , с. 155.

- ^ «Средневековый справочник: Таблицы численности населения в средневековой Европе» . Фордэмский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 10 января 2010 года . Проверено 30 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Шерман, Чарльз Финеас (1917). "Россия" . Римское право в современном мире . Бостон: Бостонская книжная компания. п. 191. Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2023 года . Проверено 14 ноября 2020 г.

За принятием Владимиром христианства... последовала торговля с Византийской империей . Следом за ним пришло византийское искусство и культура. И в течение следующего столетия то, что сейчас является Юго-Восточной Россией, стало более развитым в цивилизованном отношении, чем любое западноевропейское государство того периода , поскольку Россия получила долю византийской культуры, которая тогда значительно превосходила по грубости западные нации.

- ^ Тихомиров, Михаил Николаевич (1956). «Грамотность среди горожан» . Древнерусские города (Города Древней Руси ). Москва. п. 261. Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2010 года . Проверено 18 марта 2006 г.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ^ Вернадский 1973 , с. 277.

- ^ Miklashevsky, N.; et al. (2000). "Istoriya vodoprovoda v Rossii" . ИСТОРИЯ ВОДОПРОВОДА В РОССИИ [ История водоснабжения в России ] (на русском языке). Санкт-Петербург, Россия: ?. п. 240. ИСБН 978-5-8206-0114-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 марта 2006 года . Проверено 18 марта 2006 г.

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 95.

- ^ Tikhomirov, Mikhail Nikolaevich (1953). Пособие для изучения Русской Правды (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Moscow: Издание Московского университета. p. 190. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006 . Retrieved 18 March 2006 .

- ^ Мартин 2004 , с. 72.

- ^ Вернадский 1973 , с. 154.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мартин 2004 , с. 61.

- ^ Дж. Филлипс, Четвертый крестовый поход и разграбление Константинополя, стр. 144

- ^ Тихомиров, Михаил Николаевич (1956). «Происхождение русских городов» . Древнерусские города (Города Древней Руси ). Москва. стр. 36, 39, 43. Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2010 года . Проверено 18 марта 2006 г.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ^ Субтельный, Орест (1988). Украина: История . Торонто: Университет Торонто Press. п. 35. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6 . )

- ^ Магочи 2010 , с. 81.

- ^ Гальперин 2010 , с. 2.

- ^ Гальперин 2010 , с. 3.

- ^ ДиДжиоя, Аманда (2020). Многоязычная металлическая музыка: социокультурные, лингвистические и литературные взгляды на тексты хэви-метала . Бингли: Издательство Emerald Group. п. 85. ИСБН 9781839099489 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 января 2023 года . Проверено 27 января 2023 г.

- ^ Веласко Лагуна, Мануэль (2012). Краткая история викингов (расширенная версия) (на испанском языке). Мадрид: Ноутилус. п. 168. ИСБН 9788499673479 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 января 2023 года . Проверено 27 января 2023 г.

Первоисточники

- Кросс, Сэмюэл Хаззард; Шербовиц-Ветзор, Ольгерд П. (1930). Русская начальная летопись, Лаврентьевский текст. Переведено и отредактировано Сэмюэлем Хаззардом Кроссом и Ольгердом П. Шербовицем-Вецором (1930) (PDF) . Кембридж, Массачусетс: Средневековая академия Америки. п. 325 . Проверено 26 января 2023 г.

- Кросс, Сэмюэл Хаззард; Шербовиц-Ветзор, Ольгерд П. (2013) [1953]. СЛА 218. Украинская литература и культура. Отрывки из «Повести временных лет, ПВЛ» (PDF) . Торонто: Электронная библиотека украинской литературы, Университет Торонто. п. 16. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 30 мая 2014 года . Проверено 26 января 2023 г.

Вторичные источники

- Бушкович, Пол (2011). Краткая история России . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 491. ИСБН 9781139504447 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2023 года . Проверено 26 января 2023 г.

- Глисон, Эбботт (2009). Спутник русской истории . Чичестер: Джон Уайли и сыновья. п. 566. ИСБН 9781444308426 . Проверено 26 января 2023 г.

- Мартин, Джанет (2009a). «Глава третья: Первое восточнославянское государство». Спутник русской истории . Чичестер: Джон Уайли и сыновья. стр. 34–50. ISBN 9781444308426 . Проверено 26 января 2023 г.

- Мажеска, Джордж (2009). «Глава четвертая: Русь и Византийская империя». Спутник русской истории . Чичестер: Джон Уайли и сыновья. стр. 51–65. ISBN 9781444308426 . Проверено 26 января 2023 г.

- Качановский, Иван ; Кохут, Зенон Э .; Несебио, Богдан Ю.; Юркевич, Мирослав (2013). Исторический словарь Украины . Ланхем, Мэриленд ; Торонто ; Плимут : Scarecrow Press. п. 992. ИСБН 9780810878471 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2023 года . Проверено 22 января 2023 г.

- Логан, Ф. Дональд (2005). Викинги в истории . Нью-Йорк: Рутледж (Тейлор и Фрэнсис). п. 205. ИСБН 9780415327565 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2023 года . Проверено 26 января 2023 г. (третье издание)

- Магоци, Пол Р. (2010). История Украины: Земля и ее народы . Торонто: Университет Торонто Press. п. 896. ИСБН 978-1-4426-1021-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2023 года . Проверено 26 января 2023 г.

- Мартин, Джанет (1993). Средневековая Россия: 980–1584 гг . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 0521368324 . (оригинал). Более поздние издания, цитируемые в этой статье:

- Мартин, Джанет (1995). Средневековая Россия: 980–1584 гг . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 0521362768 . (впервые опубликовано)