Коренные народы

Общепринятого определения коренных народов не существует . [ а ] [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] хотя в 21 веке основное внимание уделялось самоидентификации, культурным отличиям от других групп в государстве, особым отношениям со своей традиционной территорией, а также опыту порабощения и дискриминации в рамках доминирующей культурной модели. [ 4 ]

По оценкам, численность населения коренных народов колеблется от 250 до 600 миллионов человек. [ 5 ] Существует около 5000 различных коренных народов, проживающих во всех обитаемых климатических зонах и континентах мира, за исключением Антарктиды. [ 6 ] [ 7 ] Большинство коренных народов составляют меньшинство в государстве или традиционной территории, которую они проживают, и испытывают на себе доминирование других групп, особенно некоренных народов. [ 8 ] [ 9 ] Хотя многие коренные народы пережили колонизацию поселенцев из европейских стран, [ 10 ] Коренная идентичность не определяется западной колонизацией. [ 4 ]

Права коренных народов изложены в национальном законодательстве, договорах и международном праве. Конвенция Международной организации труда (МОТ) 1989 года о коренных народах и народах, ведущих племенной образ жизни, защищает коренные народы от дискриминации и определяет их права на развитие, обычное право, земли, территории и ресурсы, занятость, образование и здоровье. [ 11 ] В 2007 году Организация Объединенных Наций (ООН) приняла Декларацию о правах коренных народов, включая их права на самоопределение и защиту своей культуры, самобытности, языков, церемоний и доступа к занятости, здравоохранению, образованию и природным ресурсам. [ 12 ]

Коренные народы продолжают сталкиваться с угрозами своему суверенитету, экономическому благополучию, языкам, культурному наследию и доступу к ресурсам, от которых зависит их культура. [ 13 ] В 21 веке группы коренных народов и защитники коренных народов выявили многочисленные очевидные нарушения прав коренных народов.

Этимология

Коренной народ происходит от латинского слова indigena , что означает «выросший из земли, уроженец». [ 14 ] Латинское слово indigena основано на древнелатинском indu «внутри» + gignere «рождать, производить». Инду — это расширенная форма протоиндоевропейского слова « эн» или «ин». [ 15 ] [ 16 ]

Определения

В ООН и международном праве не существует общепринятого определения коренных народов. [ 17 ] Различные национальные и международные организации, неправительственные организации, правительства, группы коренных народов и ученые разработали определения или отказались их дать. [ 18 ]

Исторический

В качестве обозначения группы людей термин «коренной» впервые был использован европейцами, чтобы отличить коренные народы Америки от порабощенных африканцев. Первое известное использование было сделано сэром Томасом Брауном в 1646 году, который написал: «И хотя во многих его частях в настоящее время существуют стаи негров, служащих под началом испанца , все же они все были перевезены из Африки после открытия Колумба ; коренные или настоящие коренные жители Америки ». [ 19 ] [ 20 ]

В 1970-х годах этот термин использовался как способ связать опыт, проблемы и борьбу групп колонизированных народов через международные границы. В это время термин «коренные народы» также стал использоваться для описания правовой категории в законе коренных народов, созданной в международном и национальном законодательстве. Использование слова «народы» во множественном числе признает культурные различия между различными коренными народами. [ 21 ] [ 22 ]

Первое заседание Рабочей группы ООН по коренным народам (WGIP) состоялось 9 августа 1982 года, и теперь эта дата отмечается как Международный день коренных народов мира . [ 23 ]

Недавний

В XXI веке понятие коренных народов понимается в более широком контексте, чем только колониальный опыт. Основное внимание уделялось самоидентификации в качестве коренных народов, культурным отличиям от других групп в государстве, особым отношениям со своей традиционной территорией, а также опыту порабощения и дискриминации в рамках доминирующей культурной модели. [ 4 ]

Объединенные Нации

Никакое определение коренных народов не было принято ни одним учреждением Организации Объединенных Наций. Секретариат Постоянного форума по вопросам коренных народов заявляет: «В случае с концепцией «коренные народы» сегодня преобладает точка зрения, что никакого формального универсального определения этого термина не требуется, учитывая, что единое определение неизбежно будет - или недостаточно инклюзивным, имеющим смысл в одних обществах, но не в других». [ 24 ]

Однако ряд агентств ООН предоставили заявления об освещении конкретных международных соглашений, касающихся коренных народов, или «рабочие определения» для конкретных отчетов. [ 24 ]

В Конвенции Международной организации труда (МОТ) о коренных народах и народах, ведущих племенной образ жизни, 1989 года (Конвенция МОТ № 169) говорится, что конвенция охватывает:

народы в независимых странах, которые считаются коренными в силу их происхождения от населения, населявшего страну или географический регион, к которому принадлежит страна, во время завоевания или колонизации или установления нынешних государственных границ и которые, независимо от своего правового статуса, сохраняют некоторые или все свои социальные, экономические, культурные и политические институты. [ 25 ]

Конвенция также распространяется на «племенные народы», которые отличаются от коренных народов и описываются как «племенные народы в независимых странах, чьи социальные, культурные и экономические условия отличают их от других частей национального сообщества и чей статус полностью или частично регулируется их собственными обычаями или традициями или специальными законами или постановлениями». [ 26 ]

В конвенции говорится, что самоидентификация как коренного или племенного человека является фундаментальным критерием для определения групп, к которым применяется конвенция. [ 17 ] Декларация ООН о правах коренных народов не дает определения коренным народам, но подтверждает их право на самоопределение, включая определение своей собственной идентичности. [ 27 ]

Межамериканская комиссия по правам человека

Межамериканская комиссия по правам человека не дает определения коренных народов, заявляя, что «такое определение не является необходимым для целей защиты их прав человека». При определении охвата коренных народов комиссия использует критерии, разработанные в таких документах, как Конвенция МОТ № 169 и Декларация Организации Объединенных Наций о правах коренных народов. Комиссия заявляет, что самоидентификация как коренного населения является фундаментальным критерием. [28]

World Bank

The World Bank states, "Indigenous Peoples are distinct social and cultural groups that share collective ancestral ties to the lands and natural resources where they live, occupy or from which they have been displaced."[29]

Amnesty International

Amnesty International does not provide a definition of Indigenous peoples but states that they can be identified according to certain characteristics:[30]

- Self identification as Indigenous peoples

- A historical link with those who inhabited a country or region at the time when people of different cultures or ethnic origins arrived

- A strong link to territories and surrounding natural resources

- Distinct social, economic or political systems

- A distinct language, culture and beliefs

- Marginalized and discriminated against by the state

- They maintain and develop their ancestral environments and systems as distinct peoples

Scholars

Academics and other scholars have developed various definitions of Indigenous peoples. In 1986–87, José Martínez Cobo, developed the following "working definition" :

Indigenous communities, peoples, and nations are those that, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing in those territories, or parts of them. They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop, and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal systems.[31]

Martínez Cobo states that the following factors are relevant to historical continuity: occupation of ancestral lands, or at least of part of them; common ancestry with the original occupants of these lands; cultural factors such as religion, tribalism, dress, etc.; language; residence in certain parts of the country, or in certain regions of the world; and other relevant factors.[32]

In 2004, James Anaya, defined Indigenous peoples as "living descendants of pre-invasion inhabitants of lands now dominated by others. They are culturally distinct groups that find themselves engulfed by other settler societies born of forces of empire and conquest".[33]

In 2012, Tuck and Yang propose a criterion based on accounts of origin: "Indigenous peoples are those who have creation stories, not colonization stories, about how we/they came to be in a particular place – indeed how we/they came to be a place. Our/their relationships to land comprise our/their epistemologies, ontologies, and cosmologies".[34]

Other views

It is sometimes argued that all Africans are Indigenous to Africa, all Asians are Indigenous to parts of Asia, or that there can be no Indigenous peoples in countries which did not experience large-scale Western settler colonialism.[4] Many countries have avoided the term Indigenous peoples or have denied that Indigenous peoples exist in their territory, and have classified minorities who identify as Indigenous in other ways, such as 'hill tribes' in Thailand, 'scheduled tribes' in India, 'national minorities' in China, 'cultural minorities' in the Philippines, 'isolated and alien peoples' in Indonesia, and various other terms.[18]

History

Classical antiquity

Greek sources of the Classical period acknowledge Indigenous people whom they referred to as "Pelasgians". Ancient writers saw these people either as the ancestors of the Greeks,[35] or as an earlier group of people who inhabited Greece before the Greeks.[36] The disposition and precise identity of this former group is elusive, and sources such as Homer, Hesiod and Herodotus give varying, partially mythological accounts. Dionysius of Halicarnassus in his book, Roman Antiquities, gives a synoptic interpretation of the Pelasgians based on the sources available to him then, concluding that Pelasgians were Greek.[37] Greco-Roman society flourished between 330 BCE and 640 CE and undertook successive campaigns of conquest that subsumed more than half of the known world of the time. But because preexisting populations within other parts of Europe at the time of classical antiquity had more in common – culturally speaking – with the Greco-Roman world, the intricacies involved in expansion across the European frontier were not so contentious relative to Indigenous issues.[38][irrelevant citation]

Africa

In European late antiquity, many Berbers, Copts and Nubians of north Africa converted to various forms of Christianity under Roman rule, although elements of traditional religious beliefs were retained.[39] Following the Arab invasions of North Africa in the 7th century, many Berbers were enslaved or recruited into the army. The majority of Berbers, however, remained nomadic pastoralists who also engaged in trade as far as sub-Saharan Africa.[40] Coptic Egyptians remained in possession of their lands and many preserved their language and Christian religion. By the 10th century, however, the majority of the population of north Africa spoke Arabic and practiced Islam.[41]

From 1402, the Guanche of the Canary Islands resisted Spanish attempts at colonization. The islands finally came under Spanish control in 1496. Mohamed Adhikari has called the conquest of the islands a genocide.[42][43]

Early 15th-century Portuguese exploration of the west coast of Africa was motivated by a quest for gold and crusading against Islam.[44] Portugal's first attempt at colonization in what is now Senegal ended in failure.[45] In the 1470s, the Portuguese established a fortified trading post on the West coast of Africa, south of the Akan goldfields. The Portuguese engaged in extensive trade of goods for gold and, in later years, slaves for their sugar plantations in the islands off West Africa and in the New World.[46] In 1488, Portuguese ships rounded the Cape of Good Hope[47] and by the 17th century, Portugal had established seaborn trading routes and fortified coastal trading posts from West Africa to India and Southern China, and a settler colony in Brazil.[48]

In 1532, the first African slaves were transported directly to the Americas. The trade in slaves expanded sharply in the 17th century, with the involvement of the French, Dutch and English, before declining in the 19th century. At least 12 million slaves were transported from Africa.[49] The slave trade increased inter-tribal warfare and stunted population growth and economic development in the west African interior.[50][51]

Americas

Indigenous encounters with Europeans increased during the age of discovery. The Europeans were motivated by a range of factors including trade,[42][52] the exploitation of natural resources,[42][53] spreading Christianity,[54] and establishing strategic military bases, colonies and settlements.[55]

From 1492, the Arawak peoples of the Caribbean islands encountered Spanish colonizers initially led by Christopher Columbus. The Spanish enslaved some of the native population and forced others to work on farms and gold mines in a system of labor called encomienda. Spanish settlements spread from Hispaniola to Puerto Rico, the Bahamas and Cuba, leading to a severe decline in the Indigenous populations from disease, malnutrition, settler violence and cultural disruption.[56][57]

In the 1520s, the peoples of Mesoamerica encountered the Spanish who entered their lands in search of gold and other resources. Some indigenous peoples chose to ally with the Spanish to end Aztec rule. The Spanish incursions led to the conquest of the Aztec Empire and its fall. The Cempoalans, Tlaxcalans and other allies of the Spanish were given some autonomy, but the Spanish were de facto rulers of Mexico. Smallpox devastated the indigenous population and aided the Spanish conquest.[58]

In 1530, the Spanish sailed south from Panama to the lands of the Inca Empire in the west of South America. The Inca, weakened by a smallpox epidemic and civil war, were defeated by the Spanish at Cajamarca in 1532, and the emperor Atahualpa was captured and executed. The Spanish appointed a puppet emperor and captured the Inca capital of Cuzco with the support of a number of native peoples. The Spanish established a new capital in 1535 and defeated an Inca rebellion in 1537, thus consolidating the conquest of Peru.[59]

In the 1560s, the Spanish established colonies in Florida and in 1598 founded a colony in New Mexico.[60] However, the heartland of the Spanish colonies remained New Spain (including Mexico and most of Central America) and Peru (including most of South America).[61]

In the 17th century, French, English and Dutch trading posts multiplied in northern America to exploit whaling, fishing and fur trading. French settlements progressed up the St Lawrence river to the Great Lakes and down the Mississippi to Louisiana.[62] English and Dutch settlements multiplied down the Atlantic coast from modern Massachusetts to Georgia.[63] Native peoples formed alliances with the Europeans in order to promote trade, preserve their autonomy, and gain allies in conflicts with other native peoples.[62][64] However, horses and new weapons made inter-tribal conflicts more deadly and the native population was devastated by introduced diseases. Native peoples also experienced losses from violent conflict with the colonists and the progressive dispossession of their traditional lands.[65]

In 1492, the population of the Americas as a whole was about 50 to 100 million. By 1700, introduced diseases had reduced the native population by 90%.[66] European migration and transfer of slaves from Africa reduced the native population to a minority. By 1800 the population of North America comprised about 5 million Europeans and their descendants, one million Africans and 600,000 indigenous Americans.[67]

Native populations also encountered new animals and plants introduced by Europeans. These included pigs, horses, mules, sheep and cattle; wheat, barley, rye, oats, grasses and grapevines. These exotic animals and plants radically transformed the local environment and disrupted traditional agriculture and hunting practices.[67]

Oceania

The indigenous populations of the Pacific had increasing contact with Europeans in the 18th century as British, French and Spanish expeditions explored the region. The natives of Tahiti had encounters with the expeditions of Wallis (1766), Bougainville (1768), Cook (1769) and many others before being colonized by the French.[68] The indigenous inhabitants of the Hawaiian Islands first encountered Europeans in 1778 when Cook explored the region.[69] Following increasing contact with European missionaries, traders and scientific expeditions, the indigenous population fell before their lands were annexed by the United States in 1893.[70]

The Māori of New Zealand also had sporadic encounters with Europeans in the 17th and 18th centuries. Following encounters with Cook's exploration parties in 1769–70, New Zealand was visited by numerous European and North American whaling, sealing, and trading ships.[71] From the early 19th century, Christian missionaries began to settle New Zealand, eventually converting most of the Māori population.[72] The Māori population declined to around 40% of its pre-contact level during the 19th century; introduced diseases were the major factor.[73] New Zealand became a British Crown colony in 1841.[74][75]

The Aboriginal inhabitants of Australia, after brief encounters with European explorers in the 17th and 18th centuries, had extensive contact with Europeans when the continent was progressively colonized by the British from 1788. During colonization, the Aboriginal people experienced depopulation from disease and settler violence, dispossession of their land, and severe disruption of their traditional cultures. By 1850, indigenous peoples were a minority in Australia.[76]

European justifications for colonization

From the 15th to the 19th centuries, European powers used a number of rationales for the colonization of newly-encountered lands populated by indigenous peoples. These included a duty to spread the Gospel to non-Christians, to bring civilization to barbarian peoples, a natural law right to explore and trade freely with other peoples, and a right to settle and cultivate uninhabited or uncultivated land which they considered terra nullius ("no one's land").[77]

Robert J. Miller, Jacinta Ruru, Larissa Behrendt and Tracey Lindberg argue that European powers rationalized their colonization of the New World by the discovery doctrine, which they trace back to papal decrees authorizing Spain and Portugal to conquer newly discovered non-Christian lands and convert their populations to Christianity.[78] Kent McNeil, however, states, "While Spain and Portugal favoured discovery and papal grants because it was generally in their interests to do so, France and Britain relied more on symbolic acts, colonial charters, and occupation."[79] Benton and Strauman argue that European powers often adopted multiple, sometimes contradictory, legal rationales for their acquisition of territory as a deliberate strategy in defending their claims against European rivals.[80]

Settler independence and continuing colonialism

Although the establishment of colonies throughout the world by various European powers aimed to expand those powers' wealth and influence, settler populations in some localities became anxious to assert their own autonomy. For example, settler independence movements in thirteen of the British American colonies were successful by 1783, following the American Revolutionary War. This resulted in the establishment of the United States of America as an entity separate from the British Empire. The United States continued and expanded European colonial doctrine through adopting a version of the discovery doctrine as law in 1823 with the US Supreme Court case Johnson v. McIntosh. Statements at the Johnson court case illuminated the United States' support for the principles of the discovery doctrine:[81]

The United States ... [and] its civilized inhabitants now hold this country. They hold, and assert in themselves, the title by which it was acquired. They maintain, as all others have maintained, that discovery gave an exclusive right to extinguish the Indian title of occupancy, either by purchase or by conquest; and gave also a right to such a degree of sovereignty, as the circumstances of the people would allow them to exercise. ... [This loss of native property and sovereignty rights was justified, the Court said, by] the character and religion of its inhabitants ... the superior genius of Europe ... [and] ample compensation to the [Indians] by bestowing on them civilization and Christianity, in exchange for unlimited independence.

Population and distribution

Estimates of the population of Indigenous peoples range from 250 million to 600 million.[82] The United Nations estimates that there are over 370 million Indigenous people living in over 90 countries worldwide. This would equate to just fewer than 6% of the total world population. This includes at least 5,000 distinct peoples.[83][84]

As there is no universally accepted definition of Indigenous Peoples, their classification as such varies between countries and organizations.[85] In the Americas, Australia and New Zealand, Indigenous status is often applied unproblematically to groups descended from the peoples who lived there prior to European settlement. However, In Asia and Africa, Indigenous status has sometimes been rejected by certain peoples, denied by governments or applied to peoples who may not be considered "Indigenous" in other contexts.[86] The concept of indigenous peoples is rarely used in Europe, where very few indigenous groups are recognized, with the exception of groups such as the Sámi.[87]

Indigenous societies range from those who have been significantly exposed to the colonizing or expansionary activities of other societies (such as the Maya peoples of Mexico and Central America) through to those who as yet remain in comparative isolation from any external influence (such as the Sentinelese and Jarawa of the Andaman Islands).[citation needed]

Contemporary distinct Indigenous groups survive in populations ranging from only a few dozen to hundreds of thousands and more. Many Indigenous populations have undergone a dramatic decline and even extinction, and remain threatened in many parts of the world. Some have also been assimilated by other populations or have undergone many other changes. In other cases, Indigenous populations are undergoing a recovery or expansion in numbers.[citation needed]

Certain Indigenous societies survive even though they may no longer inhabit their "traditional" lands, owing to migration, relocation, forced resettlement or having been supplanted by other cultural groups. In many other respects, the transformation of culture of Indigenous groups is ongoing, and includes permanent loss of language, loss of lands, encroachment on traditional territories, and disruption in traditional ways of life due to contamination and pollution of waters and lands.[citation needed]

Environmental and economic benefits of the Indigenous stewardship of land

This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. (January 2022) |

A WRI report mentions that "tenure-secure" Indigenous lands generates billions and sometimes trillions of dollars' worth of benefits in the form of carbon sequestration, reduced pollution, clean water and more. It says that tenure-secure Indigenous lands have low deforestation rates,[88][89] they help to reduce GHG emissions, control erosion and flooding by anchoring soil, and provide a suite of other local, regional and global ecosystem services. However, many of these communities find themselves on the front lines of the deforestation crisis, and their lives and livelihoods threatened.[90][91][92]

Indigenous peoples and the environment

Misconceptions about the historical relationship between Indigenous populations and their landbase has informed some Westerners view of California's "wild Eden", which may influence policy decisions about the "wilderness". Some academics assumed that the only pre-Colonial human interactions with nature were as "hunter-gatherers". Others say that the relationship was one of "calculated tempered use of nature as active agents of environmental change and stewardship". They argue that a view of "wilderness" as uninhabited nature has resulted in removal of Indigenous inhabitants to preserve "the wild", and that depriving the land of traditional Indigenous practices such as controlled burns, harvesting, and seed scattering has yielded dense understory shrubbery or tickets of young trees which are inhospitable to life. Recent studies indicate that Indigenous peoples used land sustainably, without causing substantial losses of biodiversity, for thousands of years.[93]

A goal is to ascertain an unbiased view of Indigenous practices of resource management.[94][95][96][97] Historical literature, archaeological findings, ecological field studies, and Native Peoples' cultures show indications that Indigenous land management practices were largely successful in promoting habitat heterogeneity, increasing biodiversity, and maintaining certain vegetation types, sustaining human lives while conserving natural resources.[98]

Recently, it has come to light that the deforestation rate of Indonesian rainforests has been far greater than estimated. Such a rate could not have been the product of globalization as understood before; rather, it seemed that ordinary local people dependent on these forests for their livelihoods are in fact "joining distant corporations in creating uninhabitable landscapes."[99]

In eastern Penan, three categories of misrepresentation are noticeable: The Molong concept is purely a stewardship notion of resource management. Communities or individuals take ownership of specific trees, maintaining and harvesting from them sustainably over a long period of time. Some feel this practice has been romanticized in environmentalist writings. Landscape features and particularly their names in local languages provided geographical and historical information for Penan people; whereas in environmentalist accounts, it has turned into a spiritual practice where trees and rivers represent forest spirits that are sacred to the Penan people. A typical stereotype of some environmentalists' approach to ecological ethnography is to present Indigenous "knowledge" of nature as "valuable" to the outside world because of its hidden medicinal benefits. In reality, eastern Penan populations do not identify a medicinal stream of "knowledge". These misrepresentations in the "narrative" of Indigeneity and "value" of Indigenous knowledge might have been helpful for Penan's people in their struggle to protect their environment, but it might also have disastrous consequences. What happens if another case did not fit in this romantic narrative, or another Indigenous knowledge did not seem beneficial to the outside world. These people were being uprooted in the first place because their communities did not fit well with the state's system of values.[100]

Indigenous peoples by region

Indigenous populations are distributed in regions throughout the globe. The numbers, condition and experience of Indigenous groups may vary widely within a given region. A comprehensive survey is further complicated by sometimes contentious membership and identification.

Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa

In the postcolonial period, the concept of specific Indigenous peoples within the African continent has gained wider acceptance, although not without controversy. The highly diverse and numerous ethnic groups that comprise most modern, independent African states contain within them various peoples whose situation, cultures and pastoralist or hunter-gatherer lifestyles are generally marginalized and set apart from the dominant political and economic structures of the nation. Since the late 20th century these peoples have increasingly sought recognition of their rights as distinct Indigenous peoples, in both national and international contexts.

Though the vast majority of African peoples are "indigenous" in the sense that they originate from that continent, in practice, identity as an Indigenous people per the modern definition is more restrictive, and certainly not every African ethnic group claims identification under these terms. Groups and communities who do claim this recognition are those who, by a variety of historical and environmental circumstances, have been placed outside of the dominant state systems, and whose traditional practices and land claims often come into conflict with the objectives and policies implemented by governments, companies and surrounding dominant societies.

North Africa

The indigenous peoples of North Africa predominantly comprise the Berbers in the Maghreb and the Copts and Nubians in the Nile Valley. The vast majority of them have been Arabized after the Islamic conquests under the Rashidun and Umayyad caliphates.

Americas

Indigenous peoples of the Americas are broadly recognized as being those groups and their descendants who inhabited the region before the arrival of European colonizers and settlers (i.e., pre-Columbian). Indigenous peoples who maintain, or seek to maintain, traditional ways of life are found from the high Arctic north to the southern extremities of Tierra del Fuego.

The impacts of historical and ongoing European colonization of the Americas on Indigenous communities have been in general quite severe, with many authorities estimating ranges of significant population decline primarily due to disease, land theft and violence. Several peoples have become extinct, or very nearly so. But there are and have been many thriving and resilient Indigenous nations and communities.

North America

North America is sometimes referred to by Indigenous peoples as Abya Yala or Turtle Island.

In Mexico, about 11 million people, or 9% of Mexico's total population, self-reported as Indigenous in 2015, making it the country with the highest Indigenous population in North America.[101][102] In the southern states of Oaxaca (65.73%) and Yucatán (65.40%), the majority of the population is Indigenous, as reported in 2015. Other states with high populations of Indigenous peoples include Campeche (44.54%), Quintana Roo, (44.44%), Hidalgo, (36.21%), Chiapas (36.15%), Puebla (35.28%), and Guerrero (33.92%).[103][104]

Indigenous peoples in Canada comprise the First Nations,[105] Inuit[106] and Métis.[107] The descriptors "Indian" and "Eskimo" have fallen into disuse in Canada.[108][109] More currently, the term "Aboriginal" is being replaced with "Indigenous". Several national organizations in Canada changed their names from "Aboriginal" to "Indigenous". Most notable was the change of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) to Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) in 2015, which then split into Indigenous Services Canada and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Development Canada in 2017.[110] According to the 2016 Census, there are around 1,670,000 Indigenous people in Canada.[111] There are currently over 600 recognized First Nations governments or bands spread across Canada, such as the Cree, Mohawk, Mikmaq, Blackfoot, Coast Salish, Innu, Dene and more, with distinctive Indigenous cultures, languages, art, and music.[112][113] First Nations peoples signed 11 numbered treaties[114] across much of what is now known as Canada between 1871 and 1921, except in parts of British Columbia.

The Inuit have achieved a degree of administrative autonomy with the creation in 1999 of the territories of Nunavik (in Northern Quebec), Nunatsiavut (in Northern Labrador) and Nunavut, which was until 1999 a part of the Northwest Territories. The autonomous territory of Greenland within the Kingdom of Denmark is also home to a recognized Indigenous and majority population of Inuit (about 85%) who settled the area in the 13th century, displacing the Indigenous European Greenlandic Norse.[115][116][117][118]

In the United States, the combined populations of Native Americans, Inuit and other Indigenous designations totaled 2,786,652 (constituting about 1.5% of 2003 U.S. census figures). Some 563 scheduled tribes are recognized at the federal level, and a number of others recognized at the state level.

Central and South America

In some countries (particularly in Latin America), Indigenous peoples form a sizable component of the overall national population – in Bolivia, they account for an estimated 56–70% of the total nation, and at least half of the population in Guatemala and the Andean and Amazonian nations of Peru. In English, Indigenous peoples are collectively referred to by different names that vary by region, age and ethnicity of speakers, with no one term being universally accepted. While still in use in-group, and in many names of organizations, "Indian" is less popular among younger people, who tend to prefer "Indigenous" or simply "Native, with most preferring to use the specific name of their tribe or Nation instead of generalities. In Spanish or Portuguese speaking countries, one finds the use of terms such as índios, pueblos indígenas, amerindios, povos nativos, povos indígenas, and, in Peru, Comunidades Nativas (Native Communities), particularly among Amazonian societies like the Urarina[119] and Matsés. In Chile, there the most populous indigenous peoples are the Mapuche in the Center-South and the Aymaras in the North.[120] Rapa Nui of Easter Island, who are a Polynesian people, are the only non-Amerindian indigenous people in Chile.

Indigenous peoples make up 0.4% of all Brazilian population, or about 700,000 people.[121] Indigenous peoples are found in the entire territory of Brazil, although the majority of them live in Indian reservations in the North and Center-Western part of the country. On 18 January 2007, FUNAI reported that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted peoples in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. With this addition Brazil has now overtaken the island of New Guinea as the country having the largest number of uncontacted peoples.[122]

Asia

West Asia

- Armenians are the Indigenous people of the Armenian Highlands.[123][124][125][126] There are currently more Armenians living outside their ancestral homeland because of the Armenian genocide of 1915.

- Arabs are indigenous to the Arabian Peninsula, having spread to the greater middle East and North Africa following the Muslim conquests in 7th and 8th centuries.[127][128][129]

- Anatolian Greeks, including the Pontic Greeks and Cappadocian Greeks, are the Greek-speaking minorities that existed in Anatolia millennia before Turkic conquest. They are indigenous to Asiatic Turkey.[123][130][131][132] Most were either killed in the Greek genocide or displaced during the following population exchange; however, some remain in Turkey.[133][134] There has been a Greek presence in Anatolia since at least the 1000s BCE,[135][136] and Greek traders visited western Anatolia beginning in 1900 BCE.[137]

- Assyrians are indigenous to Mesopotamia.[138][139][123][140] They claim descent from the ancient Neo-Assyrian Empire, and lived in what was Assyria, their original homeland, and still speak dialects of Aramaic, the official language of the Assyrian Empire.

- Copts are an ethnoreligious group, indigenous to Egypt and parts of the Sudan and Libya, one of the oldest Christian communities in the world.[141][142]

- Kurds are one of the Indigenous peoples of Mesopotamia.[143][144][145][146][147]

- Yazidis are indigenous to Upper Mesopotamia.[148][123][149][150][151]

There are competing claims that Palestinian Arabs and Jews are indigenous to historic Palestine/the Land of Israel.[152][153][154] The argument entered the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in the 1990s, with Palestinians claiming Indigenous status as a pre-existing population displaced by Jewish settlement, and currently constituting a minority in the State of Israel.[155][156] Israeli Jews have also claimed indigeneity, citing religious and historical connections to the land as their ancient homeland; some have disputed the authenticity of Palestinian claims.[157][158][159] In 2007, the Negev Bedouin were officially recognized as Indigenous peoples of Israel by the United Nations.[160] This has been criticized both by scholars associated with the Israeli state, who dispute the Bedouin's claim to indigeneity,[161] and those who argue that recognizing just one group of Palestinians as indigenous risks undermining others' claims and "fetishizing" nomadic cultures.[162]

South Asia

India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Indian Ocean are also home to several Indigenous groups such as the Andamanese of Strait Island[citation needed], the Jarawas of Middle Andaman and South Andaman Islands[citation needed], the Onge of Little Andaman Island[citation needed] and the uncontacted Sentinelese of North Sentinel Island[citation needed]. They are registered and protected by the Indian government.[citation needed]

In Sri Lanka, the Indigenous Vedda people constitute a small minority of the population today.[163]

Northeast Asia

Ainu people are an ethnic group indigenous to Hokkaidō, the Kuril Islands, and much of Sakhalin. As Japanese settlement expanded, the Ainu were pushed northward and fought against the Japanese in Shakushain's Revolt and Menashi–Kunashir Rebellion, until by the Meiji period they were confined by the government to a reservation near Lake Akan in Hokkaidō.[164] In a ground-breaking 1997 decision involving the Ainu people of Japan, the Japanese courts recognized their claim in law, stating that "If one minority group lived in an area prior to being ruled over by a majority group and preserved its distinct ethnic culture even after being ruled over by the majority group, while another came to live in an area ruled over by a majority after consenting to the majority rule, it must be recognized that it is only natural that the distinct ethnic culture of the former group requires greater consideration."[165]

The Dzungar Oirats are indigenous to the Dzungaria in Northern Xinjiang.

The Sarikoli Pamiris are indigenous to Tashkurgan in Xinjiang.

The Tibetans are indigenous to Tibet.

The Ryukyuan people are indigenous to the Ryukyu Islands.

The languages of Taiwanese aborigines have significance in historical linguistics, since in all likelihood Taiwan was the place of origin of the entire Austronesian language family, which spread across Oceania.[166][167][168]

In Hong Kong, the indigenous inhabitants of the New Territories are defined in the Sino-British Joint Declaration as people descended through the male line from a person who was in 1898, before Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory.[169] There are several different groups that make up the indigenous inhabitants, the Punti, Hakka, Hoklo, and Tanka. All are nonetheless considered part of the Cantonese majority, although some like the Tanka have been shown to have genetic and anthropological roots in the Baiyue people, the pre-Han Chinese inhabitants of Southern China.

The Russians invaded Siberia and conquered the indigenous people in the 17th–18th centuries.

Nivkh people are an ethnic group indigenous to Sakhalin, having a few speakers of the Nivkh language, but their fisher culture has been endangered due to the development of oil field of Sakhalin from 1990s.[170]

In Russia, definition of "Indigenous peoples" is contested largely referring to a number of population (less than 50,000 people), and neglecting self-identification, origin from indigenous populations who inhabited the country or region upon invasion, colonization or establishment of state frontiers, distinctive social, economic and cultural institutions.[171][172] Thus, indigenous peoples of Russia such as Sakha, Komi, Karelian and others are not considered as such due to the size of the population (more than 50,000 people), and consequently they "are not the subjects of the specific legal protections."[173] The Russian government recognizes only 40 ethnic groups as indigenous peoples, even though there are 30 other groups to be counted as such. The reason of nonrecognition is the size of the population and relatively late advent to their current regions, thus indigenous peoples in Russia should be numbered less than 50,000 people.[172][174][175]

Southeast Asia

The Malay Singaporeans are the Indigenous people of Singapore, inhabiting it since the Austronesian migration. They had established the Kingdom of Singapura back in the 13th century. The name "Singapore" is an anglicisation of the Malay name Singapura which is derived from the Sanskrit word for 'lion city'. The native Malay name for the main island of Singapore is Pulau Ujong.

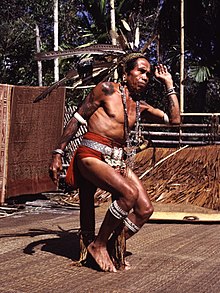

Dayak People are one of the Indigenous groups of Borneo. It is a loose term for over 200 riverine and hill-dwelling ethnic groups, located in Borneo, each with its own dialect, customs, laws, territory, and culture, although common distinguishing traits are readily identifiable.

The Cham are the Indigenous people of the former state of Champa which was conquered by Vietnam in the Cham–Vietnamese wars during Nam tiến. The Cham in Vietnam are only recognized as a minority, and not as an Indigenous people by the Vietnamese government despite being indigenous to the region.

The Degar (Montagnards) are indigenous to Central Highlands (Vietnam) and were conquered by the Vietnamese in the Nam tiến.

The Khmer Krom are the Indigenous people of the Mekong Delta and Saigon which were acquired by Vietnam from Cambodian King Chey Chettha II in exchange for a Vietnamese princess.

In Indonesia, there are 50 to 70 million people who are classified as Indigenous peoples by the local Indigenous rights advocacy group Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara.[176] However, the Indonesian government does not recognize the existence of indigenous peoples, classifying every Native Indonesian ethnic group as "indigenous" despite the clear cultural distinctions of certain groups.[177] This problem is shared by many other countries in the ASEAN region.

In the Philippines, there are 135 ethno-linguistic groups, 110 of which are considered as Indigenous peoples by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples.[178] The Indigenous people of Cordillera Administrative Region and Cagayan Valley in the Philippines are the Igorot people. The Indigenous peoples of Mindanao are the Lumad peoples and the Moro (Tausug, Maguindanao Maranao and others) who also live in the Sulu archipelago. There are also others sets of Indigenous peoples in Palawan, Mindoro, Visayas, and the rest central and south Luzon. The country has one of the largest Indigenous peoples population in the world. The recognition of the rights of Indigenous peoples was legally enshrined in 1997 with the Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act.[178]

In Myanmar, indigenous peoples include the Shan, the Karen, the Rakhine, the Karenni, the Chin, the Kachin and the Mon. However, there are more ethnic groups that are considered indigenous, for example, the Akha, the Lisu, the Lahu or the Mru, among others.[179]

Europe

Various ethnic groups have lived in Europe for millennia. However, the concept of Indigenous peoples is rarely used in the European context[180] and the UN recognizes very few Indigenous populations within Europe; those which are recognized as such are confined to the far north and far east of the continent.

Indigenous minority populations in Europe include the Sámi peoples of northern Norway, Sweden, and Finland and northwestern Russia (in an area also referred to as Sápmi);[181][182] the Nenets of northern Russia,[182] and the Inuit of Greenland.[182][183] Some sources describe the Sámi as the only recognized Indigenous peoples in Europe,[184][185][186] with others describing them as the only Indigenous people in the European Union.[187][188][189][190]

Other groups, particularly in Central, Western and Southern Europe, that might be considered to fit the description of Indigenous peoples in the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989, such as the Sorbs, are generally categorized as national minorities instead.[180]

Oceania

Australia

In Australia, the Indigenous populations are the Aboriginal Australian peoples (comprising many different nations and language groups) and the Torres Strait Islander peoples (also with sub-groups). These two groups are often referred to as Indigenous Australians,[191] although terms such as First Nations[192] and First Peoples are also used.[193]

Pacific Islands

Polynesian, Melanesian and Micronesian peoples originally populated many of the present-day Pacific Island countries in the Oceania region over the course of thousands of years. European, American, Chilean and Japanese colonial expansion in the Pacific brought many of these areas under non-Indigenous administration, mainly during the 19th century. During the 20th century, several of these former colonies gained independence and nation-states formed under local control. However, various peoples have put forward claims for Indigenous recognition where their islands are still under external administration; examples include the Chamorros of Guam and the Northern Marianas, and the Marshallese of the Marshall Islands. Some islands remain under administration from Paris, Washington, London or Wellington.

The remains of at least 25 miniature humans, who lived between 1,000 and 3,000 years ago, were recently found on the islands of Palau in Micronesia.[194]

In most parts of Oceania, Indigenous peoples outnumber the descendants of colonists. Exceptions include Australia, New Zealand and Hawaii. In New Zealand, based on various factors including census data and self-identification, the proportion of full or part Māori of the population on 30 June 2021 was estimated to be 17%.[195] Māori developed from Polynesian people who settled in New Zealand after migrations from other Pacific islands, probably in the 13th century.[196] Many leaders of Māori nations (iwi) signed a written agreement with the British Crown in 1840, known as the Treaty of Waitangi.[197][198][199]

A majority of the Papua New Guinea population is Indigenous, with more than 700 different nationalities recognized in a total population of 8 million.[200] The country's constitution and key statutes identify traditional or custom-based practices and land tenure, and explicitly set out to promote the viability of these traditional societies within the modern state. However, conflicts and disputes concerning land use and resource rights continue between indigenous groups, the government, and corporate entities.

Indigenous rights and other issues

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

| Governmental organizations |

| United Nations initiatives |

| International Treaties |

| NGOs and political groups |

| Issues |

| Countries |

| Category |

The 1989 ILO Convention on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples mainly concerns non-discrimination but also covers indigenous peoples’ rights to development, customary laws, lands, territories and resources, employment, education and health. By 2013, the convention had been ratified by 22 countries, mainly in Latin America.[11]

In 2007, the United Nations (UN) adopted a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) specifying the collective rights of Indigenous peoples, including their rights to self-determination and to protect their cultures, identities, languages, ceremonies, and access to employment, health, education and natural resources.[201] The declaration is not a formally binding treaty but some provisions might be considered customary international law. The declaration has been endorsed by at least 148 states but its provisions have not been consistently implemented.[202]

Indigenous peoples confront a diverse range of concerns associated with their status and interaction with other cultural groups, as well as changes in their inhabited environment. Some challenges are specific to particular groups; however, other challenges are commonly experienced.[203] These issues include cultural and linguistic preservation, land rights, ownership and exploitation of natural resources, political determination and autonomy, environmental degradation and incursion, poverty, health, and discrimination.[citation needed]

The interactions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous societies throughout history and contemporarily have been complex, ranging from outright conflict and subjugation to some degree of mutual benefit and cultural transfer. A particular aspect of anthropological study involves investigation into the ramifications of what is termed first contact, the study of what occurs when two cultures first encounter one another. The situation can be further confused when there is a complicated or contested history of migration and population of a given region, which can give rise to disputes about primacy and ownership of the land and resources.[citation needed]

Wherever Indigenous cultural identity is asserted, common societal issues and concerns arise. These concerns are often not unique to Indigenous groups. Despite the diversity of Indigenous peoples, they share common problems and issues in dealing with the prevailing, or invading, society. They are generally concerned that the cultures and lands of Indigenous peoples are being lost and that Indigenous peoples suffer both discrimination and pressure to assimilate into the surrounding or colonizing societies. This is borne out by the fact that the lands and cultures of nearly all of the peoples listed at the end of this article are under threat. Notable exceptions are the Sakha and Komi peoples (two northern Indigenous peoples of Russia), who now control their own autonomous republics within the Russian state, and the Canadian Inuit, who form a majority of the territory of Nunavut (created in 1999). Despite the control of their territories, many Sakha people have lost their lands as a result of the Russian Homestead Act, which allows any Russian citizen to own any land in the Far Eastern region of Russia.

In Australia, a landmark case, Mabo v Queensland (No 2),[204] saw the High Court of Australia reject the idea of terra nullius. This rejection ended up recognizing that there was a pre-existing system of law practiced by the Meriam people.[citation needed]

A 2009 United Nations publication says:[205]

Although indigenous peoples are often portrayed as a hindrance to development, their cultures and traditional knowledge are also increasingly seen as assets. It is argued that it is important for the human species as a whole to preserve as wide a range of cultural diversity as possible, and that the protection of indigenous cultures is vital to this enterprise.

Human rights violations

According to Samuel Totten, some governments do not respect the rights of Indigenous peoples.[206] In the latter part of the twentieth century the genocide of Indigenous peoples in Australia and Namibia attracted more attention from the international community including scholars and human rights organizations.[207]

The Bangladeshi government has stated that there are "no indigenous peoples in Bangladesh".[208] This statement has angered the Indigenous peoples of Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh, collectively known as the Jumma.[209] Experts have protested against this move of the Bangladesh government and have questioned the government's definition of the term "indigenous peoples".[210][211] This move by the Bangladesh government is seen by the Indigenous peoples of Bangladesh as another step by the Government to further erode their already limited rights.[212]

Hindu Chams and Muslim Chams have both experienced religious and ethnic persecution and restrictions on their faith under the current Vietnamese government, with the Vietnamese state confiscating Cham property and forbidding Cham from observing their religious beliefs. Hindu temples were turned into tourist sites against the wishes of the Cham Hindus. In 2010 and 2013 several incidents occurred in Thành Tín and Phươc Nhơn villages where Cham were murdered by Vietnamese. In 2012, Vietnamese police in Chau Giang village stormed into a Cham Mosque, stole the electric generator, and also raped Cham girls.[213] Cham in the Mekong Delta have also been economically marginalized, with ethnic Vietnamese settling on land previously owned by Cham people with state support.[214]

The Indonesian government has outright denied the existence of Indigenous peoples within the countries' borders. In 2012, Indonesia stated that 'The Government of Indonesia supports the promotion and protection of indigenous people worldwide ... Indonesia, however, does not recognize the application of the indigenous peoples concept ... in the country'.[215] Along with the brutal treatment of the country's Papuan people (a conservative estimate places the violent deaths at 100,000 people in West New Guinea since Indonesian occupation in 1963, see Papua conflict) has led to Survival International condemning Indonesia for treating its Indigenous peoples as the worst in the world.[215]

The Vietnamese viewed and dealt with the Indigenous Montagnards from the Central Highlands of Vietnam as "savages", which caused a Montagnard uprising against the Vietnamese.[216] The Vietnamese were originally centered around the Red River Delta but engaged in conquest and seized new lands such as Champa, the Mekong Delta (from Cambodia) and the Central Highlands during Nam Tien. While the Vietnamese received strong Chinese influence in their culture and civilization and were Sinicized, and the Cambodians and Laotians were Indianized, the Montagnards in the Central Highlands maintained their own Indigenous culture without adopting external culture and were the true Indigenous of the region. To hinder encroachment on the Central Highlands by Vietnamese nationalists, the term Pays Montagnard du Sud-Indochinois (PMSI) emerged for the Central Highlands along with the indigenous being addressed by the name Montagnard.[217] The tremendous scale of Vietnamese Kinh colonists flooding into the Central Highlands has significantly altered the demographics of the region.[218] The anti-ethnic minority discriminatory policies by the Vietnamese, environmental degradation, deprivation of lands from the Indigenous people, and settlement of Indigenous lands by an overwhelming number of Vietnamese settlers led to massive protests and demonstrations by the Central Highland's indigenous ethnic minorities against the Vietnamese in January–February 2001. This event gave a tremendous blow to the claim often published by the Vietnamese government that in Vietnam "There has been no ethnic confrontation, no religious war, no ethnic conflict. And no elimination of one culture by another."[219]

In May 2016, the Fifteenth Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) affirmed that Indigenous peoples are distinctive groups protected in international or national legislation as having a set of specific rights based on their linguistic and historical ties to a particular territory, prior to later settlement, development or occupation of a region.[220] The session affirms that, since Indigenous peoples are vulnerable to exploitation, marginalization, oppression, forced assimilation, and genocide by nation states formed from colonizing populations or by different, politically dominant ethnic groups, individuals and communities maintaining ways of life indigenous to their regions are entitled to special protection.

The Indigenous people from Tanzania's Maasai community were reportedly subjected to eviction from their ancestral land to make way for a luxury game reserve by Otterlo Business Corporation in June 2022. The game reserve was reportedly being set up for the royals of the United Arab Emirates also linked to OBC or the Otterlo Business Corporation. According to lawyers and human rights groups and activists, approximately 30 Maasai people were injured by security forces in the process of eviction and delimiting a land area of 1,500 km2 (580 sq mi). A 2019 UN report has described OBC as a 'UAE-based' luxury-game hunting company, granted a license to hunt by the Tanzanian government in 1992 for "the UAE royal family to organize private hunting trips", denying the Maasai people access to their own land.[221]

Health issues

In December 1993, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the International Decade of the World's Indigenous People, and requested UN specialized agencies to consider with governments and indigenous people how they can contribute to the success of the Decade of Indigenous People, commencing in December 1994. As a consequence, the World Health Organization (WHO), at its Forty-seventh World Health Assembly, established a core advisory group of Indigenous representatives with special knowledge of the health needs and resources of their communities, thus beginning a long-term commitment to the issue of the health of Indigenous peoples.[222]

The WHO noted in 2003 that "Statistical data on the health status of indigenous peoples is scarce. This is especially notable for indigenous peoples in Africa, Asia and eastern Europe", but snapshots from various countries (where such statistics are available) show that indigenous people are in worse health than the general population, in advanced and developing countries alike: higher incidence of diabetes in some regions of Australia;[223] higher prevalence of poor sanitation and lack of safe water among Twa households in Rwanda;[224] a greater prevalence of childbirths without prenatal care among ethnic minorities in Vietnam;[225] suicide rates among Inuit youth in Canada are eleven times higher than the national average;[226] infant mortality rates are higher for Indigenous peoples everywhere.[227]

The first UN publication on the State of the World's Indigenous Peoples revealed alarming statistics about indigenous peoples' health. Health disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous populations are evident in both developed and developing countries. Native Americans in the United States are 600 times more likely to acquire tuberculosis and 62% more likely to commit suicide than the non-Indian population. Tuberculosis, obesity, and type 2 diabetes are major health concerns for the indigenous in developed countries.[228] Globally, health disparities touch upon nearly every health issue, including HIV/AIDS, cancer, malaria, cardiovascular disease, malnutrition, parasitic infections, and respiratory diseases, affecting indigenous peoples at much higher rates. Many causes of Indigenous children's mortality could be prevented. Poorer health conditions amongst indigenous peoples result from longstanding societal issues, such as extreme poverty and racism, but also the intentional marginalization and dispossession of Indigenous peoples by dominant, non-Indigenous populations and societal structures.[228]

Racism and discrimination

Indigenous peoples have frequently been subjected to various forms of racism and discrimination. Indigenous peoples have been denoted as being barbaric, primitive, savage[229] or uncivilized. These terms were commonly used during the heyday of European colonial expansion, and they are still being used by certain societies in modern times.[230]

During the 17th century, Europeans commonly labeled Indigenous peoples "uncivilized". Some philosophers, such as Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), considered Indigenous people mere "savages". Others (especially literary figures in the 18th century) popularized the concept of "noble savages". Those who were close to the Hobbesian view tended to believe that they had a duty to "civilize" and "modernize" the Indigenous.

Survival International runs a campaign to stamp out media portrayals of Indigenous peoples as "primitives" or "savages".[231]

After World War I (1914–1918), many Europeans came to doubt the morality of the means which were used to "civilize" peoples. At the same time, the anti-colonial movement, and advocates for the rights of Indigenous peoples, argued that words such as "civilized" and "savage" were products and tools of colonialism, and they also argued that colonialism itself was savagely destructive. In the mid-20th century, European attitudes began to shift to the view that Indigenous and tribal peoples are the only peoples who should have the right to decide what should happen to their ancient cultures and their ancestral lands.[232]

Cultural appropriation

New Age and Neopagan adherents often look to the cultures of Indigenous peoples seeking to find ancient traditional truths and spiritual practices to appropriate into their lifestyles and worldviews.[233]

Environmental injustice

At an international level, Indigenous peoples have received increased recognition of their environmental rights since 2002, but few countries respect these rights in reality. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted by the General Assembly in 2007, established Indigenous peoples' right to self-determination, stating rights to manage natural resources, and cultural and intellectual property. In countries where these rights are recognized, land titling and demarcation procedures are often put on delay, or leased out by the state as concessions for extractive industries without consulting Indigenous communities.[228]

Many in the United States federal government are in favor of exploiting oil reserves in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, where the Gwich'in Indigenous people rely on herds of caribou. Oil drilling could destroy thousands of years of culture for the Gwich'in. On the other hand, some of the Inupiat people, from another Indigenous community in the region, favor oil drilling because they could benefit economically.[235]

Внедрение промышленных сельскохозяйственных технологий, таких как удобрения, пестициды и крупные плантации, разрушило экосистемы, от которых раньше зависели коренные общины, что привело к переселению. Проекты развития, такие как строительство плотин, трубопроводов и добыча ресурсов, привели к перемещению большого количества коренных народов, часто без предоставления компенсации. Правительства вынудили коренные народы покинуть земли своих предков во имя экотуризма и развития национальных парков. Женщины из числа коренного населения особенно страдают от лишения земли, поскольку им приходится преодолевать большие расстояния за водой и топливной древесиной. Эти женщины также становятся экономически зависимыми от мужчин, когда теряют средства к существованию. Заявление групп коренного населения о своих правах чаще всего приводило к пыткам, тюремному заключению или смерти. [ 228 ]

Строительство плотин может нанести вред коренным народам, нанося ущерб экосистемам, которые обеспечивают их водой и пищей. Например, жители Мундуруку, живущие в тропических лесах Амазонки, выступают против строительства плотины Тапажос. [ 236 ] с помощью Гринпис. [ нужна ссылка ]

Большинство коренного населения уже подвержено пагубным последствиям изменения климата. Изменение климата имеет не только экологические последствия, но также последствия для прав человека и социально-экономические последствия для коренных народов. Всемирный банк признает, что изменение климата является препятствием на пути достижения Целей развития тысячелетия , в частности, борьбы с бедностью, болезнями и детской смертностью, а также экологической устойчивости . [ 228 ]

Использование знаний коренных народов

Знания коренных народов считаются очень важными для решения вопросов, связанных с устойчивым развитием . [ 237 ] [ 238 ] Профессор Мартин Наката является пионером в области распространения знаний коренных народов среди ведущих ученых и средств массовой информации посредством цифровой документации уникального вклада аборигенов. [ 239 ]

Реконструкция знаний

Западные и восточные пенаны — две основные группы коренного населения Малайзии . Восточные пенаны известны своим сопротивлением лесозаготовителям, угрожающим их природным ресурсам, особенно пальмам саго и различным фруктовым деревьям. Из-за международной известности Пенана, экологи часто посещали этот район, чтобы задокументировать такие события и узнать больше о местных людях и от них, в том числе об их взглядах на вторжение на эту землю. Хотя коренные народы составляют менее 5% населения, на их долю приходится более 80% мирового биоразнообразия. [ 240 ]

Защитники окружающей среды, такие как Дэвис и Хенли, которые, как пишет Брозиус, объединили все коренные группы Малайзии в одну однородную группу с одинаковыми идеями и традициями и не имели диалектических связей, необходимых для глубокого понимания пенана, не имели полного знания удельного веса ситуации для коренных народов. . [ 241 ] Эти двое отправились на миссию, заявив, что хотели помочь в сохранении земельных ресурсов Пенана, но Брозиус утверждает, что они были среди многих, кто переупаковал традиционные знания во что-то, что соответствовало западному повествованию и повестке дня, и что Дэвис и Хенли романтизировали и неверно истолковывали традиционная пенанская концепция молонг (что означает «сохранять» - пенан помечает деревья для личного использования и сохраняет их для будущего сбора фруктов или материалов). [ 241 ]

Еще одним распространенным явлением является расширение знаний коренных народов за их пределы и в несвязанные значения, которые западные потребители считают духовно глубокими. Эта тенденция журналистов выходит за рамки Дэвиса и Хенли. Он служит некоренным народам, чтобы добавить повествование и ценность помимо того, что уже существует в базе знаний коренных народов. Эти вымышленные рассказы о некоторых знаниях и традициях коренных народов не только искажают убеждения зрителей, но также способствуют культурному геноциду, поскольку реальные духовные и религиозные верования коренных народов исчезают и заменяются вестернизированным вымыслом. [ 241 ]

См. также

- Коллективные права

- Колониализм

- Культурное присвоение

- Этническое меньшинство

- Экотуризм § Влияние на коренное население и земли коренных народов

- Геноцид коренных народов

- Права человека

- Образцовая экспедиция

- коренное население

- Коренные футуризмы

- Интеллектуальная собственность коренных народов

- Инициатива коренных народов по оценке изменения климата

- Права коренных народов

- Нематериальное культурное наследие

- Международный день коренных народов мира

- Национальный день коренных народов , Канада

- День коренных народов (США)

- Он такой же

- Список действующих неправительственных организаций национальных меньшинств, коренных народов и диаспор

- Список этнических групп

- Список коренных народов

- Пропавшие без вести и убитые женщины коренных народов

- Неконтактные народы

- Постоянный форум Организации Объединенных Наций по вопросам коренных народов

- Организация непредставленных наций и народов

- Эпидемия целины

Примечания

- ^ Также известный как Первые народы , Первые нации , Аборигены , Коренные народы , Коренные жители или Автохтонные народы . С 2020 года большинство руководств по стилю рекомендуют писать слово «коренные» с заглавной буквы при упоминании конкретных коренных народов как этнических групп , наций, а также граждан или членов этих групп. [ 242 ] [ 243 ] [ 244 ] [ 245 ] [ 246 ]

Ссылки

- ^ Права человека Организации Объединенных Наций, Управление Верховного комиссара (2013). «Коренные народы и система прав человека Организации Объединенных Наций, информационный бюллетень № 9/Rev.2» . Объединенные Нации . п. 2 . Проверено 29 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ «Права коренных народов и народов, ведущих племенной образ жизни, на земли своих предков и природные ресурсы» . cidh.org . Архивировано из оригинала 1 июня 2020 года . Проверено 30 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Макинтош, Ян (сентябрь 2000 г.). «Есть ли в Азии коренные народы?» . Ежеквартальный журнал «Культурное выживание» . Архивировано из оригинала 22 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 1 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Секретариат Постоянного форума по вопросам коренных народов, 2009 г. , с. 6.

- ^ Макл, Роберт Дж. (2012). Коренные народы Северной Америки: краткий антропологический обзор . Университет Торонто Пресс. п. 18. ISBN 978-1-4426-0416-2 .

- ^ «Коренные народы и система прав человека Организации Объединенных Наций» (PDF) . Объединенные Нации. п. 2 . Проверено 21 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Ачарья, Дипак и Шривастава Аншу (2008): Травяные лекарства коренных народов: племенные составы и традиционные методы лечения травами, дистрибьютор Aavishkar Publishers, Джайпур, Индия. ISBN 978-81-7910-252-7 . п. 440

- ^ Информационный бюллетень УООНПЧ № 9, 2013 г. , стр. 3.

- ^ Тейлор Сайто, Нацу (2020). «Тревожные рассказы». Поселенческий колониализм, раса и закон: почему структурный расизм сохраняется (электронная книга) . Нью-Йорк Пресс. ISBN 978-0-8147-0802-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 15 марта 2023 года . Проверено 21 декабря 2020 г. .

...несколько тысяч стран были произвольно (и, как правило, непреднамеренно) включены примерно в двести политических конструкций, которые мы называем независимыми государствами...

- ^ Миллер, Роберт Дж.; Руру, Хасинта; Берендт, Лариса; Линдберг, Трейси (2010). Открытие земель коренных народов: доктрина открытий в английских колониях . ОУП Оксфорд. стр. 9–13. ISBN 978-0-19-957981-5 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Информационный бюллетень УООНПЧ № 9, 2013 г. , с. 9.

- ^ Бодли 2008 , с. 2.

- ^ Информационный бюллетень УООНПЧ № 9, 2013 г. , стр. 4.

- ^ "Абориген, прил. и н." ОЭД онлайн . Издательство Оксфордского университета, сентябрь 2016 г. Интернет. 22 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «коренной (прил.)» . Интернет-словарь этимологии . Архивировано из оригинала 9 марта 2021 года . Проверено 4 марта 2021 г.

- ^ Питерс, Майкл А.; Мика, Карл Т. (10 ноября 2017 г.). «Аборигены, индейцы, коренные народы или первые нации?» . Образовательная философия и теория . 49 (13): 1229–1234. дои : 10.1080/00131857.2017.1279879 . ISSN 0013-1857 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Информационный бюллетень УООНПЧ № 9, 2013 г. , с. 2

- ^ Jump up to: а б Макинтош, Ян (сентябрь 2000 г.). «Есть ли в Азии коренные народы?» . Ежеквартальный журнал «Культурное выживание» . Архивировано из оригинала 22 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 1 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Мэтьюсон, Кент (2004). «Наркотики, моральная география и коренные народы: некоторые первоначальные карты и основные проблемы». Опасный урожай: лекарственные растения и трансформация местных ландшафтов . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-514319-5 .

Как заметил сэр Томас Браун в 1646 году (похоже, это первое употребление слова в его современном смысле).

- ^ Браун, сэр Томас (1646). «Pseudodoxia Epidemica. Глава X. О черноте негров» . Чикагский университет . Архивировано из оригинала 15 марта 2023 года . Проверено 3 марта 2021 г.

- ^ Смит, Линда Тухивай (2012). Методологии деколонизации: исследования и коренные народы (2-е изд.). Данидин, Новая Зеландия: Издательство Университета Отаго. ISBN 978-1-877578-28-1 . OCLC 805707083 .

- ^ Роберт К. Хичкок, Диана Виндинг, Права коренных народов в Южной Африке , IWGIA, 2004, стр. 8 на основе рабочего документа Председателя-докладчика г-жи Эрики-Ирен А. Даес о концепции коренных народов. Документ ООН E/CN.4/Sub.2/AC.4/1996/2 ( [1] Архивировано 14 сентября 2016 г. в Wayback Machine , unhchr.ch)

- ^ «Международный день коренных народов мира – 9 августа» . www.un.org . Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2019 года . Проверено 11 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Секретариат Постоянного форума по вопросам коренных народов (2009 г.). Состояние коренных народов мира . Нью-Йорк: Организация Объединенных Наций. стр. 4–7.

- ^ Сандерс, Дуглас Э. (1999). «Коренные народы: вопросы определения». Международный журнал культурных ценностей . 8 (1): 4–13. дои : 10.1017/s0940739199770591 . ISSN 0940-7391 . S2CID 154898887 .

- ^ Секретариат Постоянного форума по вопросам коренных народов, 2009 г. , с. 5.

- ^ Информационный бюллетень УООНПЧ № 9, 2013 г. , стр. 4–5.

- ^ «Права коренных народов и народов, ведущих племенной образ жизни, на земли своих предков и природные ресурсы» . cidh.org . Архивировано из оригинала 1 июня 2020 года . Проверено 30 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Коренные народы» . Всемирный банк . 6 апреля 2023 г. Проверено 28 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Международная амнистия (2023 г.). «Коренные народы» . Международная амнистия . Проверено 30 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ «Рабочее определение Хосе Мартинеса Кобо» . IWGIA — Международная рабочая группа по делам коренных народов . 9 апреля 2011 года. Архивировано из оригинала 26 октября 2019 года . Проверено 11 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Секретариат Постоянного форума по вопросам коренных народов, 2009 г. , стр. 4–5.

- ^ С. Джеймс Анайя, Коренные народы в международном праве , 2-е изд., Oxford University Press, 2004, стр. 3; Профессор Анайя преподает право коренных американцев и является третьим специальным докладчиком Комиссии по правам человека по правам человека и основным свободам коренных народов.

- ^ Так, Ева и К. Уэйн Янг. «Деколонизация – это не метафора». Табула Раса 38 (2012): 61–111.

- ^ Абель, В. Линн Снайдер (1966). Пятый век до нашей эры. Представления пеласгов . Стэнфордский университет. стр. 12 и 49.

- ^ Колвин, Стивен (5 декабря 2013 г.). Краткая история древнегреческого языка . Джон Уайли и сыновья. ISBN 978-1-118-61072-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 15 марта 2023 года . Проверено 15 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Дионисий Галикарнасский. Римские древности , 1.17. Архивировано 15 декабря 2022 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Холл, Джилетт и Гарри Энтони Патринос. Коренные народы, бедность и человеческое развитие в Латинской Америке. Нью-Йорк: Пэлгрейв Макмиллан и Google Scholar. Веб. 11 марта 2013 г.

- ^ Шиллингтон, Кевин (2019). История Африки (4-е изд.). Лондон: Red Globe Press. стр. 188–91. ISBN 978-1-137-50403-6 .

- ^ Шиллингтон (2019). п. 202

- ^ Шиллингтон (2019). стр. 194-95

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Тейлор, Алан (2013). Колониальная Америка: очень краткое введение . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 15–16.

- ^ Адхикари, Мохамед (7 сентября 2017 г.). «Первое колониальное вторжение поселенцев Европы в Африку: геноцид аборигенов Канарских островов». Африканский исторический обзор . 49 (1): 1–26. дои : 10.1080/17532523.2017.1336863 . S2CID 165086773 .

- ^ Пагден (2001). стр. 100-1 58-59

- ^ Пагден (2001). п. 93

- ^ Шиллингтон (2019). стр. 343-46

- ^ Буркхолдер, Марк А.; Джонсон, Лайман Л. (2001). Колониальная Латинская Америка (4-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 33. ISBN 0-19-513702-7 .

- ^ Пагден (2001). стр. 100-1 59-60,

- ^ Шиллингтон (2019). п. 350.

- ^ Шиллингтон (2019). стр. 350-52

- ^ Пагден (2001). стр. 100-1 108-11

- ^ Пагден (2001). стр. 100-1 91-95

- ^ Падген (2001). стр. 84-85

- ^ Пагден (2002). стр. 100-1 72-73

- ^ Бентон, Лорен; Штрауманн, Бенджамин (февраль 2010 г.). «Приобретение империи по закону: от римской доктрины к европейской практике раннего Нового времени». Обзор права и истории. Американское общество истории права . 28 (1): 1–38 [34–36]. дои : 10.1017/S0738248009990022 . JSTOR 40646121 . S2CID 143079931 .

- ^ Буркхолдер и Джонсон (2001). стр. 34-39

- ^ Тейлор (2013). п. 17

- ^ Буркхолдер и Джонсон (2001). стр. 42-50.

- ^ Буркхолдер и Лайман (2001). стр. 50-56

- ^ Тейлор (2013). стр. 28-30

- ^ Тейлор (2013). п. 33

- ^ Jump up to: а б Тейлор (2013). стр. 35-38, 83

- ^ Тейлор (2013). стр. 51-76, 80

- ^ Пагден (2002). стр. 100-1 95-9

- ^ Тейлор (2013). стр. 43, 76

- ^ Тейлор (2013). п. 17-18

- ^ Jump up to: а б Тейлор (2013). п. 20

- ^ Пагден (2001). стр. 100-1 120-2

- ^ Пагден (2001). стр. 100-1 30-3

- ^ Пагден (2001). стр. 100-1 129-3

- ^ Король (2003). п. 122

- ^ Вагстрем, Тор (2005). «Сломанные языки и чужие сердца». В Броке, Пегги (ред.). Коренные народы и религиозные изменения . Бостон: Издательство Brill Academic Publishers . стр. 71 и 73. ISBN. 978-90-04-13899-5 .

- ^ Ланге, Реберн (1999). Да живут люди: история развития здравоохранения маори в 1900–1920 гг . Издательство Оклендского университета . п. 18. ISBN 978-1-86940-214-3 .

- ^ «Эпоха коронной колонии – генерал-губернатор» . НЖИстория . Министерство культуры и наследия Новой Зеландии . Март 2009 года . Проверено 7 января 2011 г.

- ^ Мун, Пол (2010). Свидетельства о рождении Новой Зеландии – 50 учредительных документов Новой Зеландии . АУТ Медиа. п. 66. ИСБН 978-0-95829971-8 .

- ^ Макинтайр, Стюарт (2020). Краткая история Австралии (5-е изд.). Мельбурн: Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 38–39, 71–77, 83. ISBN. 978-1-108-72848-5 .

- ^ Слэттери, Брайан (2005). «Бумажные империи: правовые аспекты французских и английских предприятий в Северной Америке». В McLaren, Джон; Бак, Арканзас; Райт, Нэнси Э. (ред.). Деспотический доминион, права собственности в обществах британских поселенцев . Ванкувер: Издательство Университета Британской Колумбии. С. 51, 55, 58, 62–65, 67, 69.

- ^ Миллер, Роберт Дж.; Руру, Хасинта; Берендт, Лариса; Линдберг, Трейси (2010). Открытие коренных земель, учение об открытиях в английских колониях . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 9–12. ISBN 9780199651856 .

- ^ Макнил (2016). п. 707

- ^ Бентон и Штрауман (2010). стр. 3, 12

- ^ Миллер, Роберт Дж. (2006). Коренная Америка, открытая и завоеванная: Томас Джефферсон, Льюис и Кларк и Manifest Destiny . Публикации Прагера. стр. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-275-99011-4 .