Военная история Австралии

| Эта статья является частью серии статей о |

| История Австралия |

|---|

|

|

Военная история Австралии охватывает 230-летнюю современную историю страны, от первых австралийских пограничных войн между аборигенами и европейцами до продолжающихся конфликтов в Ираке и Афганистане в начале 21 века. Хотя эта история коротка по сравнению с историей многих других стран, Австралия участвовала в многочисленных конфликтах и войнах, а война и военная служба оказали значительное влияние на австралийское общество и национальную идентичность, включая дух Анзака . Отношения между войной и австралийским обществом также сформировались под влиянием устойчивых тем австралийской стратегической культуры и уникальных проблем безопасности, с которыми она сталкивается.

The six British colonies in Australia participated in some of Britain's wars of the 19th century. In the early 20th century, as a federated dominion and later as an independent nation, Australia fought in the First World War and Second World War, as well as in the wars in Korea, Malaya, Borneo and Vietnam during the Cold War. In the Post-Vietnam era Australian forces have been involved in numerous international peacekeeping missions, through the United Nations and other agencies, including in the Sinai, Persian Gulf, Rwanda, Somalia, East Timor and the Solomon Islands, as well as many overseas humanitarian relief operations, while more recently they have also fought as part of multi-lateral forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. In total, nearly 103,000 Australians died during these conflicts.[note 1]

War and Australian society

[edit]

For most of the last century military service has been one of the single greatest shared experiences of white Australian males, and although this is now changing due to the professionalisation of the military and the absence of major wars during the second half of the 20th century, it continues to influence Australian society to this day.[2] War and military service have been defining influences in Australian history, while a major part of the national identity has been built on an idealised conception of the Australian experience of war and of soldiering, known as the Anzac spirit. These ideals include notions of endurance, courage, ingenuity, humour, larrikinism, egalitarianism and mateship; traits which, according to popular thought, defined the behaviour of Australian soldiers fighting at Gallipoli during the First World War.[2] The Gallipoli campaign was one of the first international events that saw Australians taking part as Australians and has been seen as a key event in forging a sense of national identity.[3]

The relationship between war and Australian society has been shaped by two of the more enduring themes of Australian strategic culture: bandwagoning with a powerful ally and expeditionary warfare.[4] Indeed, Australian defence policy was closely linked to Britain until the Japanese crisis of 1942, while since then an alliance with the United States has underwritten its security. Arguably, this pattern of bandwagoning—both for cultural reasons such as shared values and beliefs, as well as for more pragmatic security concerns—has ensured that Australian strategic policy has often been defined by relations with its allies. Regardless, a tendency towards strategic complacency has also been evident, with Australians often reluctant to think about defence issues or to allocate resources until a crisis arises; a trait which has historically resulted in unpreparedness for major military challenges.[4][5]

Reflecting both the realist and liberal paradigms of international relations and the conception of national interests, a number of other important themes in Australian strategic culture are also obvious. Such themes include: an acceptance of the state as the key actor in international politics, the centrality of notions of Westphalian sovereignty, a belief in the enduring relevance and legitimacy of armed force as a guarantor of security, and the proposition that the status quo in international affairs should only be changed peacefully.[6] Likewise, multilateralism, collective security and defence self-reliance have also been important themes.[7] Change has been more evolutionary than revolutionary and these strategic behaviours have persisted throughout its history, being the product of Australian society's democratic political tradition and Judaeo-Christian Anglo-European heritage, as well its associated values, beliefs and economic, political and religious ideology.[8] These behaviours are also reflective of its unique situation as a largely European island on the edge of the Asia-Pacific, and the geopolitical circumstances of a middle power physically removed from the centres of world power. To be sure, during threats to the core Australia has often found itself defending the periphery and perhaps as a result, it has frequently become involved in foreign wars.[7] Throughout these conflicts Australian soldiers—known colloquially as Diggers—have often been noted, somewhat paradoxically, for both their fighting abilities and their humanitarian qualities.[2]

History and services

[edit]Colonial era

[edit]British Forces in Australia, 1788–1870

[edit]

From 1788 until 1870 the defence of the Australian colonies was mostly provided by British Army regular forces. Originally Marines protected the early settlements at Sydney Cove and Norfolk Island, however they were relieved of these duties in 1790 by a British Army unit specifically recruited for colonial service, known as the New South Wales Corps. The New South Wales Corps subsequently was involved in putting down a rebellion of Irish convicts at Castle Hill in 1804. Soon however shortcomings in the corps convinced the War Office of the need for a more reliable garrison in New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land. Chief of these shortcomings was the Rum Rebellion, a coup mounted by its officers in 1808. As a result, in January 1810 the 73rd (Perthshire) Regiment of Foot arrived in Australia. By 1870, 25 British infantry regiments had served in Australia, as had a small number of artillery and engineer units.[9]

Although the primary role of the British Army was to protect the colonies against external attack, no actual threat ever materialised.[note 2] The British Army was instead used in policing, guarding convicts at penal institutions, combating bushranging, putting down convict rebellions—as occurred at Bathurst in 1830—and to suppress Aboriginal resistance to the extension of European settlement. Notably British soldiers were involved in the battle at the Eureka Stockade in 1854 on the Victorian goldfields. Members of British regiments stationed in Australia also saw action in India, Afghanistan, New Zealand and the Sudan.[10]

During the early years of settlement the naval defence of Australia was provided by units detached by the Royal Navy's Commander-in-Chief, East Indies, based in Sydney. However, in 1859 Australia was established as a separate squadron under the command of a commodore, marking the first occasion that Royal Navy ships had been permanently stationed in Australia. The Royal Navy remained the primary naval force in Australian waters until 1913, when the Australia Station ceased and responsibility handed over to the Royal Australian Navy; the Royal Navy's depots, dockyards and structures were given to the Australian people.[11]

Frontier warfare, 1788–1934

[edit]

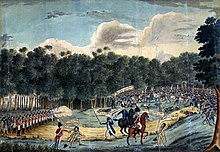

The reactions of the native Aboriginal inhabitants to the sudden arrival of British settlers in Australia were varied, but were inevitably hostile when the settlers' presence led to competition over resources, and to the occupation of the indigenous inhabitants' lands. European diseases decimated Aboriginal populations, and the occupation or destruction of lands and food resources sometimes led to starvation.[13] By and large neither the British nor the Aborigines approached the conflict in an organised sense and conflict occurred between groups of settlers and individual tribes rather than systematic warfare.[13] At times, however, the frontier wars did see the involvement of British soldiers and later mounted police units. Not all Aboriginal groups resisted white encroachment on their lands, while many Aborigines served in mounted police units and were involved in attacks on other tribes.[13]

Fighting between Aboriginal people and Europeans was localised as the Aboriginal people did not form confederations capable of sustained resistance. As a result, there was not a single war, but rather a series of violent engagements and massacres across the continent.[14] Organised or disorganised however, a pattern of frontier warfare emerged with Aboriginal resistance beginning in the 18th century and continuing into the early 20th century. This warfare contradicts the popular and at times academic "myth" of peaceful settlement in Australia. Faced with Aboriginal resistance settlers often reacted with violence, resulting in a number of indiscriminate massacres. Among the most famous is the Battle of Pinjarra in Western Australia in 1834. Such incidents were not officially sanctioned however, and after the Myall Creek massacre in New South Wales in 1838 seven Europeans were hanged for their part in the killings.[15] However, in Tasmania the so-called Black War was fought between 1828 and 1832, and aimed at driving most of the island's native inhabitants onto a number of isolated peninsulas. Although it began in failure for the British, it ultimately resulted in considerable casualties amongst the native population.[16][17]

It may be inaccurate though to depict the conflict as one sided and mainly perpetrated by Europeans on Aboriginal people. Although many more Aboriginal people died than British, this may have had more to do with the technological and logistic advantages enjoyed by the Europeans.[18] Aboriginal tactics varied, but were mainly based on pre-existing hunting and fighting practices—using spears, clubs and other primitive weapons. Unlike the indigenous peoples of New Zealand and North America, on the main Aboriginal people failed to adapt to meet the challenge of the Europeans. Although there were some instances of individuals and groups acquiring and using firearms, this was not widespread.[19] The Aboriginal people were never a serious military threat to European settlers, regardless of how much the settlers may have feared them.[20] On occasions large groups of Aboriginal people attacked the settlers in open terrain and a conventional battle ensued, during which the Aboriginal people would attempt to use superior numbers to their advantage. This could sometimes be effective, with reports of them advancing in crescent formation in an attempt to outflank and surround their opponents, waiting out the first volley of shots and then hurling their spears while the settlers reloaded. However, such open warfare usually proved more costly for the Aboriginal people than the Europeans.[21]

Central to the success of the Europeans was the use of firearms. However, the advantages afforded by firearms have often been overstated. Prior to the late 19th century, firearms were often cumbersome muzzle-loading, smooth-bore, single shot muskets with flint-lock mechanisms. Such weapons produced a low rate of fire, while suffering from a high rate of failure and were only accurate within 50 metres (160 ft). These deficiencies may have initially given the Aboriginal people an advantage, allowing them to move in close and engage with spears or clubs. Yet by 1850 significant advances in firearms gave the Europeans a distinct advantage, with the six-shot Colt revolver, the Snider single shot breech-loading rifle and later the Martini-Henry rifle, as well as rapid-fire rifles such as the Winchester rifle, becoming available. These weapons, when used on open ground and combined with the superior mobility provided by horses to surround and engage groups of Aboriginal people, often proved successful. The Europeans also had to adapt their tactics to fight their fast-moving, often hidden enemies. Tactics employed included night-time surprise attacks, and positioning forces to drive the natives off cliffs or force them to retreat into rivers while attacking from both banks.[22]

The conflict lasted for over 150 years and followed the pattern of British settlement in Australia.[23] Beginning in New South Wales with the arrival of the first Europeans in May 1788, it continued in Sydney and its surrounds until the 1820s. As the frontier moved west so did the conflict, pushing into outback New South Wales in the 1840s. In Tasmania, fighting can be traced from 1804 to the 1830s, while in Victoria and the southern parts of South Australia, the majority of the violence occurred during the 1830s and 1840s. The south-west of Western Australia experienced warfare from 1829 to 1850. The war in Queensland began in the area around Brisbane in the 1840s and continued until 1860, moving to central Queensland in the 1850s and 1860s, and then to northern Queensland from the 1860s to 1900. In Western Australia, the violence moved north with European settlement, reaching the Kimberley region by 1880, with violent clashes continuing until the 1920s. In the Northern Territory conflict lasted even later still, especially in central Australia, continuing from the 1880s to the 1930s. One estimate of casualties places European deaths at 2,500, while at least 20,000 Aboriginal people are believed to have perished. Far more devastating though was the effect of disease which significantly reduced the Aboriginal population by the beginning of the 20th century; a fact which may also have limited their ability to resist.[24]

New Zealand Wars, 1861–64

[edit]Taranaki War

[edit]

In 1861, the Victorian ship HMCSS Victoria was dispatched to help the New Zealand colonial government in its war against Māori in Taranaki. Victoria was subsequently used for patrol duties and logistic support, although a number of personnel were involved in actions against Māori fortifications. One sailor died from an accidental gunshot wound during the deployment.[25]

Invasion of the Waikato

[edit]In late 1863, the New Zealand government requested troops to assist in the invasion of the Waikato province against the Māori. Promised settlement on confiscated land, more than 2,500 Australians (over half of whom were from Victoria) were recruited to form four Waikato Regiments. Other Australians became scouts in the Company of Forest Rangers. Despite experiencing arduous conditions the Australians were not heavily involved in battle, and were primarily used for patrolling and garrison duties. Australians were involved in actions at Matarikoriko, Pukekohe East, Titi Hill, Ōrākau and Te Ranga. Fewer than 20 were believed to have been killed in action.[25][26] The conflict was over by 1864, and the Waikato Regiments disbanded in 1867. However, many of the soldiers who had chosen to claim farmland at the cessation of hostilities had drifted to the towns and cities by the end of the decade, while many others had returned to Australia.[27]

Colonial military forces, 1870–1901

[edit]

From 1870 until 1901, each of the six colonial governments was responsible for their own defence. The colonies had gained responsible government between 1855 and 1890, and while the Colonial Office in London retained control of some affairs, the Governor of the each colony was required to raise their own colonial militia. To do this, they were granted the authority from the British crown to raise military and naval forces. Initially these were militias in support of British regulars, but when military support for the colonies ended in 1870, the colonies assumed their own defence responsibilities. The colonial military forces included unpaid volunteer militia, paid citizen soldiers, and a small permanent component. They were mainly infantry, cavalry and mounted infantry, and were neither housed in barracks nor subject to full military discipline. Even after significant reforms in the 1870s—including the expansion of the permanent forces to include engineer and artillery units—they remained too small and unbalanced to be considered armies in the modern sense. By 1885, the forces numbered 21,000 men. Although they could not be compelled to serve overseas many volunteers subsequently did see action in a number conflicts of the British Empire during the 19th century, with the colonies raising contingents to serve in Sudan, South Africa and China.[28]

Despite a reputation of colonial inferiority, many of the locally raised units were highly organised, disciplined, professional, and well trained. During this period, defences in Australia mainly revolved around static defence by combined infantry and artillery, based on garrisoned coastal forts. However, by the 1890s, improved railway communications between the mainland eastern colonies led Major General James Edwards—who had recently completed a survey of colonial military forces—to the belief that the colonies could be defended by the rapid mobilisation of brigades of infantry. As a consequence he called for a restructure of defences, and defensive agreements to be made between the colonies. Edwards argued for the colonial forces to be federated and for professional units—obliged to serve anywhere in the South Pacific—to replace the volunteer forces. These views found support in the influential New South Wales Commandant, Major General Edward Hutton, however suspicions held by the smaller colonies towards New South Wales and Victoria stifled the proposal.[28] These reforms remaining unresolved however, and defence issues were generally given little attention in the debate on the political federation of the colonies.[29][30]

With the exception of Western Australia, the colonies also operated their own navies. In 1856, Victoria received its own naval vessel, HMCSS Victoria, and its deployment to New Zealand in 1860 during the First Taranaki War marked the first occasion that an Australian warship had been deployed overseas.[31] The colonial navies were expanded greatly in the mid-1880s and consisted of a number of gunboats and torpedo-boats for the defence of harbours and rivers, as well as naval brigades to man vessels and forts. Victoria became the most powerful of all the colonial navies, with the ironclad HMVS Cerberus in service from 1870, as well as the steam-sail warship HMS Nelson on loan from the Royal Navy, three small gunboats and five torpedo-boats. New South Wales formed a Naval Brigade in 1863 and by the start of the 20th century had two small torpedo-boats and a corvette. The Queensland Maritime Defence Force was established in 1885, while South Australia operated a single ship, HMCS Protector. Tasmania had also a small Torpedo Corps, while Western Australia's only naval defences included the Fremantle Naval Artillery. Naval personnel from New South Wales and Victoria took part in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900, while HMCS Protector was sent by South Australia but saw no action.[32] The separate colonies maintained control over their military and naval forces until Federation in 1901, when they were amalgamated and placed under the control of the new Commonwealth of Australia.[33]

Sudan, 1885

[edit]

During the early years of the 1880s, an Egyptian regime in the Sudan, backed by the British, came under threat from rebellion under the leadership of native Muhammad Ahmad (or Ahmed), known as Mahdi to his followers. In 1883, as part of the Mahdist War, the Egyptians sent an army to deal with the revolt, but they were defeated and faced a difficult campaign of extracting their forces. The British instructed the Egyptians to abandon the Sudan, and sent General Charles Gordon to co-ordinate the evacuation, but he was killed in January 1885. When news of his death arrived in New South Wales in February 1885, the government offered to send forces and meet the contingent's expenses.[34] The New South Wales Contingent consisted of an infantry battalion of 522 men and 24 officers, and an artillery battery of 212 men and sailed from Sydney on 3 March 1885.[35]

The contingent arrived in Suakin on 29 March and were attached to a brigade that consisted of Scots, Grenadier and Coldstream Guards. They subsequently marched for Tamai in a large "square" formation made up of 10,000 men. Reaching the village, they burned huts and returned to Suakin: three Australians were wounded in minor fighting. Most of the contingent was then sent to work on a railway line that was being laid across the desert towards Berber, on the Nile. The Australians were then assigned to guard duties, but soon a camel corps was raised and 50 men volunteered. They rode on a reconnaissance to Takdul on 6 May and were heavily involved in a skirmish during which more than 100 Arabs were killed or captured.[35][36] On 15 May, they made one last sortie to bury the dead from the fighting of the previous March. Meanwhile, the artillery were posted at Handoub and drilled for a month, but they soon rejoined the camp at Suakin.[34]

Eventually the British government decided that the campaign in Sudan was not worth the effort required and left a garrison in Suakin. The New South Wales Contingent sailed for home on 17 May, arriving in Sydney on 19 June 1885.[34] Approximately 770 Australians served in Sudan; nine subsequently died of disease during the return journey while three had been wounded during the campaign.[37]

Second Boer War, 1899–1902

[edit]

British encroachment into areas of South Africa already settled by the Afrikaner Boers and the competition for resources and land that developed between them as a result, led to the Second Boer War in 1899. Pre-empting the deployment of British forces, the Afrikaner Republics of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal Republic under President Paul Kruger declared war on 11 October 1899, striking deep into the British territories of Natal and the Cape Colony.[38] After the outbreak of war, plans for the dispatch of a combined Australian force were subsequently set aside by the British War Office and each of the six colonial governments sent separate contingents to serve with British formations, with two squadrons each of 125 men from New South Wales and Victoria, and one each from the other colonies.[39] The first troops arrived three weeks later, with the New South Wales Lancers—who had been training in England before the war, hurriedly diverted to South Africa. On 22 November, the Lancers came under fire for the first time near Belmont, and they subsequently forced their attackers to withdraw after inflicting significant casualties on them.[40]

Following a series of minor victories, the British suffered a major setback during Black Week between 10 and 17 December 1899, although no Australian units were involved. The first contingents of infantry from Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia, and Tasmania arrived in Cape Town on 26 November and were designated the Australian Regiment under the command of Colonel John Charles Hoad. With a need for increased mobility, they were soon converted into mounted infantry. Further units from Queensland and New South Wales arrived in December and were soon committed to the front.[41] The first casualties occurred soon after at Sunnyside on 1 January 1900, after 250 Queensland Mounted Infantry and a column of Canadians, British and artillery attacked a Boer laager at Belmont. Troopers David McLeod and Victor Jones were killed when their patrol clashed with the Boer forward sentries. Regardless, the Boers were surprised and during two hours of heavy fighting, more than 50 were killed and another 40 taken prisoner. Five hundred Queenslanders and the New South Wales Lancers subsequently took part in the Siege of Kimberley in February 1900.[42]

Despite serious set-backs at Colenso, Stormberg, Magersfontein, and Spion Kop in January—and with Ladysmith still under siege—the British mounted a five division counter-invasion of the Orange Free State in February. The attacking force included a division of cavalry commanded by Lieutenant General John French with the New South Wales Lancers, Queensland Mounted Infantry and New South Wales Army Medical Corps attached.[43] First, Kimberley was relieved following the battles of Modder River and Magersfontein, and the retreating Boers defeated at Paardeberg, with the New South Wales Mounted Rifles locating the Boer general, Piet Cronjé. The British entered Bloemfontein on 13 March 1900, while Ladysmith was relieved. Disease began to take its toll and scores of men died. Still the advance continued, with the drive to Pretoria in May including more than 3,000 Australians. Johannesburg fell on 30 May, and the Boers withdrew from Pretoria on 3 June. The New South Wales Mounted Rifles and Western Australians saw action again at Diamond Hill on 12 June. Mafeking was relieved on 17 May.[44]

Following the defeat of the Afrikaner republics still the Boers held out, forming small commando units and conducting a campaign of guerrilla warfare to disrupt British troop movements and lines of supply. This new phase of resistance led to further recruiting in the Australian colonies and the raising of the Bushmen's Contingents, with these soldiers usually being volunteers with horse-riding and shooting skills, but little military experience. After Federation in 1901, eight Australian Commonwealth Horse battalions of the newly created Australian Army were also sent to South Africa, although they saw little fighting before the war ended.[39] Some Australians later joined local South African irregular units, instead of returning home after discharge. These soldiers were part of the British Army, and were subject to British military discipline. Such units included the Bushveldt Carbineers which gained notoriety as the unit in which Harry "Breaker" Morant and Peter Handcock served in before their court martial and execution for war crimes.[45]

With the guerrillas requiring supplies, Koos de la Rey lead a force of 3,000 Boers against Brakfontein, on the Elands River in Western Transvaal. The post held a large quantity of stores and was defended by 300 Australians and 200 Rhodesians. The attack began on 4 August 1900 with heavy shelling causing 32 casualties. During the night the defenders dug in, enduring shelling and rifle fire. A relief force was stopped by the Boers, while a second column turned back believing that the post had already been relieved. The siege lasted 11 days, during which more than 1,800 shells were fired into the post. After calls to surrender were ignored by the defenders, and not prepared to risk a frontal attack, the Boers eventually retired. The Siege of Elands River was one of the major achievements of the Australians during the war, with the post finally relieved on 16 August.[46]

In response the British adopted counter-insurgency tactics, including a scorched earth policy involving the burning of houses and crops, the establishment of concentration camps for Boer women and children, and a system of blockhouses and field obstacles to limit Boer mobility and to protect railway communications. Such measures required considerable expenditure, and caused much bitterness towards the British, however they soon yielded results.[47] By mid-1901, the bulk of the fighting was over, and British mounted units would ride at night to attack Boer farmhouses or encampments, overwhelming them with superior numbers. Indicative of warfare in last months of 1901, the New South Wales Mounted Rifles travelled 1,814 miles (2,919 km) and were involved in 13 skirmishes, killing 27 Boers, wounding 15, and capturing 196 for the loss of five dead and 19 wounded.[48] Other notable Australian actions included Slingersfontein, Pink Hill, Rhenosterkop and Haartebeestefontein.[49]

Australians were not always successful however, suffering a number of heavy losses late in the war. On 12 June 1901, the 5th Victorian Mounted Rifles lost 19 killed and 42 wounded at Wilmansrust, near Middleburg after poor security allowed a force of 150 Boers to surprise them.[47][49] On 30 October 1901, Victorians of the Scottish Horse Regiment also suffered heavy casualties at Gun Hill, although 60 Boers were also killed in the engagement. Meanwhile, at Onverwacht on 4 January 1902, the 5th Queensland Imperial Bushmen lost 13 killed and 17 wounded.[45] Ultimately the Boers were defeated, and the war ended on 31 May 1902. In all 16,175 Australians served in South Africa, and perhaps another 10,000 enlisted as individuals in Imperial units; casualties included 251 killed in action, 267 died of disease and 43 missing in action, while a further 735 were wounded.[50][51] Six Australians were awarded the Victoria Cross.[52]

Boxer Rebellion, 1900–01

[edit]

The Boxer Rebellion in China began in 1900, and a number of western nations—including many European powers, the United States, and Japan—soon sent forces as part of the China Field Force to protect their interests. In June, the British government sought permission from the Australian colonies to dispatch ships from the Australian Squadron to China. The colonies also offered to assist further, but as most of their troops were still engaged in South Africa, they had to rely on naval forces for manpower. The force dispatched was a modest one, with Britain accepting 200 men from Victoria, 260 from New South Wales and the South Australian ship HMCS Protector, under the command of Captain William Creswell.[53] Most of these forces were made up of naval brigade reservists, who had been trained in both ship handling and soldiering to fulfil their coastal defence role. Amongst the naval contingent from New South Wales were 200 naval officers and sailors and 50 permanent soldiers headquartered at Victoria Barracks, Sydney who originally enlisted for the Second Boer War. The soldiers were keen to go to China but refused to be enlisted as sailors, while the New South Wales Naval Brigade objected to having soldiers in their ranks. The Army and Navy compromised and titled the contingent the NSW Marine Light Infantry.[54]

The contingents from New South Wales and Victoria sailed for China on 8 August 1900. Arriving in Tientsin, the Australians provided 300 men to an 8,000-strong multinational force tasked with capturing the Chinese forts at Pei Tang, which dominated a key railway. They arrived too late to take part in the battle, but were involved in the attack on the fortress at Pao-ting Fu, where the Chinese government was believed to have found asylum after Peking was captured by western forces. The Victorians joined a force of 7,500 men on a ten-day march to the fort, once again only to find that it had already surrendered. The Victorians then garrisoned Tientsin and the New South Wales contingent undertook garrison duties in Peking. HMCS Protector was mostly used for survey, transport, and courier duties in the Bohai Sea, before departing in November.[53] The naval brigades remained during the winter, unhappily performing policing and guard duties, as well as working as railwaymen and fire-fighters. They left China in March 1901, having played only a minor role in a few offensives and punitive expeditions and in the restoration of civil order. Six Australians died from sickness and injury, but none were killed as a result of enemy action.[53]

Australian military forces at Federation, 1901

[edit]The Commonwealth of Australia came into existence on 1 January 1901 as a result of the federation of the Australian colonies. Under the Constitution of Australia, defence responsibility was now vested in the new federal government. The co-ordination of Australia-wide defensive efforts in the face of Imperial German interest in the Pacific Ocean was one of driving forces behind federalism, and the Department of Defence immediately came into being as a result, while the Commonwealth Military Forces (early forerunner of the Australian Army) and Commonwealth Naval Force were also soon established.[55][note 3]

The Australian Commonwealth Military Forces came into being on 1 March 1901 and all the colonial forces—including those still in South Africa—became part of the new force.[56] 28,923 colonial soldiers, including 1,457 professional soldiers, 18,603 paid militia and 8,863 unpaid volunteers, were subsequently transferred. The individual units continued to be administered under the various colonial Acts until the Defence Act 1903 brought all the units under one piece of legislation. This Act also prevented the raising of standing infantry units and specified that militia forces could not be used in industrial disputes or serve outside Australia.[57] However, the majority of soldiers remained in militia units, known as the Citizen Military Forces (CMF). Major General Sir Edward Hutton—a former commander of the New South Wales Military Forces—subsequently became the first commander of the Commonwealth Military Forces on 26 December and set to work devising an integrated structure for the new army.[58] In 1911, following a report by Lord Kitchener the Royal Military College, Duntroon was established, as was a system of universal National Service.[58]

Prior to federation each self-governing colony had operated its own naval force. These navies were small and lacked blue water capabilities, forcing the separate colonies to subsidise the cost of a British naval squadron in their waters for decades. The colonies maintained control over their respective navies until 1 March 1901, when the Commonwealth Naval Force was created. This new force also lacked blue water capable ships, and ultimately did not lead to a change in Australian naval policy. In 1907 Prime Minister Alfred Deakin and Creswell, while attending the Imperial Conference in London, sought the British Government's agreement to end the subsidy system and develop an Australian navy. The Admiralty rejected and resented the challenge, but suggested diplomatically that a small fleet of destroyers and submarines would be sufficient. Deakin was unimpressed, and in 1908 invited the American Great White Fleet to visit Australia. This visit fired public enthusiasm for a modern navy and in part led to the order of two 700-ton River-class destroyers.[59] The surge in German naval construction prompted the Admiralty to change their position however and the Royal Australian Navy was subsequently formed in 1911, absorbing the Commonwealth Naval Force.[60] On 4 October 1913, the new fleet steamed through Sydney Heads, consisting of the battlecruiser HMAS Australia, three light cruisers, and three destroyers, while several other ships were still under construction. And as a consequence the navy entered the First World War as a formidable force.[59]

The Australian Flying Corps (AFC) was established as part of the Commonwealth Military Forces in 1912, prior to the formation of the Australian Military Forces in 1916 and was later separated in 1921 to form the Royal Australian Air Force, making it the second oldest air force in the world.[61] Regardless, the service branches were not linked by a single chain of command however, and each reported to their own minister and had separate administrative arrangements and government departments.[62]

First World War, 1914–18

[edit]Outbreak of hostilities

[edit]

When Britain declared war on Germany at the start of the First World War, the Australian government rapidly followed suit, with Prime Minister Joseph Cook declaring on 5 August 1914 that "...when the Empire is at war, so also is Australia"[63] and reflecting the sentiment of many Australians that any declaration of war by Britain automatically included Australia. This was itself in part due to the large number of British-born citizens and first generation Anglo-Australians that made up the Australian population at the time. Indeed, by the end of the war almost 20% of those who served in the Australian forces had been born in Britain.[64]

As the existing militia forces were unable to serve overseas under the provisions of the Defence Act 1903, an all-volunteer expeditionary force known as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) was formed and recruitment began on 10 August 1914. The government pledged 20,000 men, organised as one infantry division and one light horse brigade plus supporting units. Enlistment and organisation was primarily regionally based and was undertaken under mobilisation plans drawn up in 1912.[65] The first commander was Major General William Bridges, who also assumed command of the 1st Division.[66] Throughout the course of the conflict Australian efforts were predominantly focused upon the ground war, although small air and naval forces were also committed.[67]

Occupation of German New Guinea

[edit]Following the outbreak of war Australian forces moved quickly to reduce the threat to shipping posed by the proximity of Germany's Pacific colonies. The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF), a 2000-man volunteer force—separate from the AIF—and consisting of an infantry battalion plus 500 naval reservists and ex-sailors, was rapidly formed under the command of William Holmes. The objectives of the force were the wireless stations on Nauru, and those at Yap in the Caroline Islands, and at Rabaul in German New Guinea. The force reached Rabaul on 11 September 1914 and occupied it the next day, encountering only brief resistance from the German and native defenders during fighting at Bita Paka and Toma. German New Guinea surrendered on 17 September 1914. Australian losses were light, including six killed during the fighting, but were compounded by the mysterious loss offshore of the submarine AE1 with all 35 men aboard.[68]

Gallipoli

[edit]The AIF departed by ship in a single convoy from Albany on 1 November 1914. During the journey one of the convoy's naval escorts—HMAS Sydney—engaged and destroyed the German cruiser SMS Emden at the Battle of Cocos on 8 November, in the first ship-to-ship action involving the Royal Australian Navy.[69] Although originally bound for England to undergo further training and then for employment on the Western Front, the Australians were instead sent to British-controlled Egypt to pre-empt any Turkish attack against the strategically important Suez Canal, and with a view to opening another front against the Central Powers.[70][note 4]

Aiming to knock Turkey out of the war the British then decided to stage an amphibious lodgement at Gallipoli and following a period of training and reorganisation the Australians were included amongst the British, Indian and French forces committed to the campaign. The combined Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC)—commanded by British general William Birdwood—subsequently landed at Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli peninsula on 25 April 1915. Although promising to transform the war if successful, the Gallipoli Campaign was ill-conceived and ultimately lasted eight months of bloody stalemate, without achieving its objectives.[71] Australian casualties totalled 26,111, including 8,141 killed.[72]

For Australians and New Zealanders the Gallipoli campaign came to symbolise an important milestone in the emergence of both nations as independent actors on the world stage and the development of a sense of national identity.[73] Today, the date of the initial landings, 25 April, is known as Anzac Day in Australia and New Zealand and every year thousands of people gather at memorials in both nations, as well as Turkey, to honour the bravery and sacrifice of the original Anzacs, and of all those who have subsequently lost their lives in war.[74][75]

Egypt and Palestine

[edit]After the withdrawal from Gallipoli the Australians returned to Egypt and the AIF underwent a major expansion. In 1916 the infantry began to move to France while the cavalry units remained in the Middle East to fight the Turks. Australian troops of the Anzac Mounted Division and the Australian Mounted Division saw action in all the major battles of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, playing a pivotal role in fighting the Turkish troops that were threatening British control of Egypt.[76] The Australians first saw combat during the Senussi uprising in the Libyan Desert and the Nile Valley, during which the combined British forces successfully put down the primitive pro-Turkish Islamic sect with heavy casualties.[77] The Anzac Mounted Division subsequently saw considerable action in the Battle of Romani against the Turkish between 3–5 August 1916, with the Turks eventually pushed back.[78] Following this victory the British forces went on the offensive in the Sinai, although the pace of the advance was governed by the speed by which the railway and water pipeline could be constructed from the Suez Canal. Rafa was captured on 9 January 1917, while the last of the small Turkish garrisons in the Sinai were eliminated in February.[79]

The advance entered Palestine and an initial, unsuccessful attempt was made to capture Gaza on 26 March 1917, while a second and equally unsuccessful attempt was launched on 19 April. A third assault occurred between 31 October and 7 November and this time both the Anzac Mounted Division and the Australian Mounted Division took part. The battle was a complete success for the British, over-running the Gaza-Beersheba line and capturing 12,000 Turkish soldiers. The critical moment was the capture of Beersheba on the first day, after the Australian 4th Light Horse Brigade charged more than 4 miles (6.4 km). The Turkish trenches were overrun, with the Australians capturing the wells at Beersheeba and securing the valuable water they contained along with over 700 prisoners for the loss of 31 killed and 36 wounded.[80] Later, Australian troops assisted in pushing the Turkish forces out of Palestine and took part in actions at Mughar Ridge, Jerusalem and the Megiddo. The Turkish government surrendered on 30 October 1918.[81] Units of the Light Horse were subsequently used to help put down a nationalist revolt in Egypt in 1919 and did so with efficiency and brutality, although they suffered a number of fatalities in the process.[82]

Meanwhile, the AFC had undergone remarkable development, and its independence as a separate national force was unique among the Dominions. Deploying just a single aircraft to German New Guinea in 1914, the first operational flight did not occur until 27 May 1915 however, when the Mesopotamian Half Flight was called upon to assist in protecting British oil interests in Iraq. The AFC was soon expanded and four squadrons later saw action in Egypt, Palestine and on the Western Front, where they performed well.[83]

Western Front

[edit]Five infantry divisions of the AIF saw action in France and Belgium, leaving Egypt in March 1916.[84] I Anzac Corps subsequently took up positions in a quiet sector south of Armentières on 7 April 1916 and for the next two and a half years the AIF participated in most of the major battles on the Western Front, earning a formidable reputation. Although spared from the disastrous first day of the Battle of the Somme, within weeks four Australian divisions had been committed.[85] The 5th Division, positioned on the left flank, was the first in action during the Battle of Fromelles on 19 July 1916, suffering 5,533 casualties in a single day. The 1st Division entered the line on 23 July, assaulting Pozieres, and by the time that they were relieved by the 2nd Division on 27 July, they had suffered 5,286 casualties.[86] Mouquet Farm was attacked in August, with casualties totalling 6,300 men.[87] By the time the AIF was withdrawn from the Somme to re-organise, they had suffered 23,000 casualties in just 45 days.[86]

In March 1917, the 2nd and 5th Divisions pursued the Germans back to the Hindenburg Line, capturing the town of Bapaume. On 11 April, the 4th Division assaulted the Hindenburg Line in the disastrous First Battle of Bullecourt, losing over 3,000 casualties and 1,170 captured.[88] On 15 April, the 1st and 2nd Divisions were counter-attacked near Lagnicourt and were forced to abandon the town, before recapturing it again.[89] The 2nd Division then took part in the Second Battle of Bullecourt, beginning on 3 May, and succeeded in taking sections of the Hindenburg Line and holding them until relieved by the 1st Division.[88] Finally, on 7 May the 5th Division relieved the 1st, remaining in the line until the battle ended in mid-May. Combined these efforts cost 7,482 Australian casualties.[90]

On 7 June 1917, the II Anzac Corps—along with two British corps—launched an operation in Flanders to eliminate a salient south of Ypres.[91] The attack commenced with the detonation of a million pounds (454,545 kg) of explosives that had been placed underneath the Messines ridge, destroying the German trenches.[92] The advance was virtually unopposed, and despite strong German counterattacks the next day, it succeeded. Australian casualties during the Battle of Messines included nearly 6,800 men.[93] I Anzac Corps then took part in the Third Battle of Ypres in Belgium as part of the campaign to capture the Gheluvelt Plateau, between September and November 1917.[93] Individual actions took place at Menin Road, Polygon Wood, Broodseinde, Poelcappelle and Passchendaele and over the course of eight weeks fighting the Australians suffered 38,000 casualties.[94]

On 21 March 1918 the German Army launched its Spring Offensive in a last-ditched effort to win the war, unleashing sixty-three divisions over a 70 miles (110 km) front.[95] As the Allies fell back the 3rd and 4th Divisions were rushed south to Amiens on the Somme.[96] The offensive lasted for the next five months and all five AIF divisions in France were engaged in the attempt to stem the tide. By late May the Germans had pushed to within 50 miles (80 km) of Paris.[97] During this time the Australians fought at Dernancourt, Morlancourt, Villers-Bretonneux, Hangard Wood, Hazebrouck, and Hamel.[98] At Hamel the commander of the Australian Corps, Lieutenant General John Monash, successfully used combined arms—including aircraft, artillery and armour—in an attack for the first time.[99]

The German offensive ground to a halt in mid-July and a brief lull followed, during which the Australians undertook a series of raids, known as Peaceful Penetrations.[100] The Allies soon launched their own offensive—the Hundred Days Offensive—ultimately ending the war. Beginning on 8 August 1918 the offensive included four Australian divisions striking at Amiens.[101] Using the combined arms techniques developed earlier at Hamel, significant gains were made on what became known as the "Black Day" of the German Army.[102] The offensive continued for four months, and during Second Battle of the Somme the Australian Corps fought actions at Lihons, Etinehem, Proyart, Chuignes, and Mont St Quentin, before their final engagement of the war on 5 October 1918 at Montbrehain.[103] The AIF was subsequently out of the line when the armistice was declared on 11 November 1918.[104]

In all 416,806 Australians enlisted in the AIF during the war and 333,000 served overseas. 61,508 were killed and another 155,000 were wounded (a total casualty rate of 65%).[37] The financial cost to the Australian government was calculated at £376,993,052.[105] Two referendums on conscription for overseas service had been defeated during the war, preserving the volunteer status of the Australian force, but stretching the reserves of manpower available, particularly towards the end of the fighting. Consequently, Australia remained one of only two armies on either side not to resort to conscription during the war.[65][note 5]

The war had a profound effect on Australian society in other ways also. Indeed, for many Australians the nation's involvement is seen as a symbol of its emergence as an international actor, while many of the notions of Australian character and nationhood that exist today have their origins in the war. 64 Australians were awarded the Victoria Cross during the First World War.[52]

Inter-war years

[edit]Russian Civil War, 1918–19

[edit]

The Russian Civil War began after the Russian provisional government collapsed and the Bolshevik party assumed power in October 1917. Following the end of the First World War, the western powers—including Britain—intervened, giving half-hearted support to the pro-tsarist, anti-Bolshevik White Russian forces. Although the Australian government refused to commit forces, many Australians serving with the British Army became involved in the fighting. A small number served as advisors to White Russian units with the North Russian Expeditionary Force (NREF). Awaiting repatriation in England, about 150 Australians subsequently enlisted in the British North Russia Relief Force (NRRF), where they were involved in a number of sharp battles and several were killed.[82]

The Royal Australian Navy destroyer HMAS Swan was also briefly engaged, carrying out an intelligence gathering mission in the Black Sea in late 1918. Other Australians served as advisers with the British Military Mission to the White Russian General, Anton Denikin in South Russia, while several more advised Admiral Alexander Kolchak in Siberia.[106] Later, they also served in Mesopotamia as part of Dunsterforce and the Malleson Mission, although these missions were aimed at preventing Turkish access to the Middle East and India, and did little fighting.[107]

Although the motivations of those Australian's that volunteered to fight in Russia can only be guessed at, it seems unlikely to have been political.[107] Regardless, they confirmed a reputation for audacity and courage, winning the only two Victoria Crosses of the land campaign, despite their small numbers.[82] Yet Australian involvement was barely noticed at home at the time and made little difference to the outcome of the war.[108] Total casualties included 10 killed and 40 wounded, with most deaths being from disease during operations in Mesopotamia.[109]

Malaita, 1927

[edit]In October 1927, HMAS Adelaide was called to the British Solomon Islands Protectorate as part of a punitive expedition in response to the killing of a district officer and sixteen others by Kwaio natives at Sinalagu on the island of Malaita on 3 October, known as the Malaita massacre. Arriving at Tulagi on 14 October, the ship proceeded to Malaita to protect the landing of three platoons of troops, then remained in the area to provide personnel support for the soldiers as they searched for the killers. The ship's personnel took no part in operations ashore, providing only logistic and communications support. Adelaide returned to Australia on 23 November.[110][111]

Spanish Civil War, 1936–39

[edit]A small number of Australian volunteers fought on both sides of the Spanish Civil War, although they predominantly supported the Spanish Republic through the International Brigades. The Australians were subsequently allocated to the battalions of other nationalities, such as the British Battalion and the Lincoln Battalion, rather than forming their own units. Most were radicals motivated by ideological reasons, while a number were Spanish-born migrants who returned to fight in their country of origin. At least 66 Australians volunteered, with only one—Nugent Bull, a conservative Catholic who was later killed serving in the RAF during the Second World War—known to have fought for General Francisco Franco's Nationalist forces.[112]

While a celebrated cause for the Australian left—particularly the Communist Party of Australia and the trade union movement—the war failed to spark particular public interest and the government maintained its neutrality.[113] Australian opposition to the Republican cause was marshalled by B. A. Santamaria on an anti-communist basis, rather than a pro-Nationalist basis. Equally, although individual right wing Australians may have served with the Nationalist rebels, they received no public support. Service in a foreign armed force was illegal at the time, however as the government received no reports of Australians travelling to Spain to enlist, no action was taken.[112][note 6] Consequently, returned veterans were neither recognised by the government or the Returned and Services League of Australia (RSL). Although the number of Australian volunteers was relatively small compared to those from other countries, at least 14 were killed.[114]

Second World War, 1939–45

[edit]Europe and the Middle East

[edit]

Australia entered the Second World War on 3 September 1939. At the time of the declaration of war against Germany the Australian military was small and unready for war.[115] Recruiting for a Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) began in mid-September. While there was no rush of volunteers like the First World War, a high proportion of Australian men of military age had enlisted by mid-1940. Four infantry divisions were formed during 1939 and 1940, three of which were dispatched to the Middle East.[116] The RAAF's resources were initially mainly devoted to training airmen for service with the Commonwealth air forces through the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS), through which almost 28,000 Australians were trained during the war.[117]

The Australian military's first major engagements of the war were against Italian forces in the Mediterranean and North Africa. During 1940 the light cruiser HMAS Sydney and five elderly destroyers (dubbed the "Scrap Iron Flotilla" by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels—a title proudly accepted by the ships) took part in a series of operations as part of the British Mediterranean Fleet, and sank several Italian warships.[118] The Army first saw action in January 1941, when the 6th Division formed part of the Commonwealth forces during Operation Compass. The division assaulted and captured Bardia on 5 January and Tobruk on 22 January, with tens of thousands of Italian troops surrendering at both towns.[119] The 6th Division took part in the pursuit of the Italian Army and captured Benghazi on 4 February. In late February it was withdrawn for service in Greece, and was replaced by the 9th Division.[120]

The Australian forces in the Mediterranean endured a number of campaigns during 1941. During April, the 6th Division, other elements of I Corps and several Australian warships formed part of the Allied force which unsuccessfully attempted to defend Greece from German invasion during the Battle of Greece. At the end of this campaign, the 6th Division was evacuated to Egypt and Crete.[121] The force at Crete subsequently fought in the Battle of Crete during May, which also ended in defeat for the Allies. Over 5,000 Australians were captured in these campaigns, and the 6th Division required a long period of rebuilding before it was again ready for combat.[122] The Germans and Italians also went on the offensive in North Africa at the end of March and drove the Commonwealth force there back to near the border with Egypt. The 9th Division and a brigade of the 7th Division were besieged at Tobruk; successfully defending the key port town until they were replaced by British units in October.[123] During June, the main body of the 7th Division, a brigade of the 6th Division and the I Corps headquarters took part in the Syria-Lebanon Campaign against the Vichy French. Resistance was stronger than expected; Australians were involved in most of the fighting and sustained most of the casualties before the French capitulated in early July.[124]

The majority of Australian units in the Mediterranean returned to Australia in early 1942, after the outbreak of the Pacific War. The 9th Division was the largest unit to remain in the Middle East, and played a key role in the First Battle of El Alamein during June and the Second Battle of El Alamein in October.[125] The division returned to Australia in early 1943, but several RAAF squadrons and RAN warships took part in the subsequent Tunisia Campaign and the Italian Campaign from 1943 until the end of the war.[126]

The RAAF's role in the strategic air offensive in Europe formed Australia's main contribution to the defeat of Germany. Approximately 13,000 Australian airmen served in dozens of British and five Australian squadrons in RAF Bomber Command between 1940 and the end of the war.[127] Australians took part in all of Bomber Command's major offensives and suffered heavy losses during raids on German cities and targets in France.[128] Australian aircrew in Bomber Command had one of the highest casualty rates of any part of the Australian military during the Second World War and sustained almost 20 percent of all Australian deaths in combat; 3,486 were killed and hundreds more were taken prisoner.[129] Australian airmen in light bomber and fighter squadrons also participated in the liberation of Western Europe during 1944 and 1945[130] and two RAAF maritime patrol squadrons served in the Battle of the Atlantic.[131]

Asia and the Pacific

[edit]

From the 1920s Australia's defence thinking was dominated by British Imperial defence policy, which was embodied by the "Singapore strategy". This strategy involved the construction and defence of a major naval base at Singapore from which a large British fleet would respond to Japanese aggression in the region. To this end, a high proportion of Australian forces in Asia were concentrated in Malaya during 1940 and 1941 as the threat from Japan increased.[132] However, as a result of the emphasis on co-operation with Britain, relatively few Australian military units had been retained in Australia and the Asia-Pacific region. Measures were taken to improve Australia's defences as war with Japan loomed in 1941, but these proved inadequate. In December 1941, the Australian Army in the Pacific comprised the 8th Division, most of which was stationed in Malaya, and eight partially trained and equipped divisions in Australia. The RAAF was equipped with 373 aircraft, most of which were obsolete trainers, and the RAN had three cruisers and two destroyers in Australian waters.[133]

The Australian military suffered a series of defeats during the early months of the Pacific War. The 8th Division and RAAF squadrons in Malaya formed a part of the British Commonwealth forces which were unable to stop a smaller Japanese invasion force which landed on 7 December. The British Commonwealth force withdrew to Singapore at the end of January, but was forced to surrender on 15 February after the Japanese captured much of the island.[134] Smaller Australian forces were also overwhelmed and defeated during early 1942 at Rabaul, and in Ambon, Timor, and Java.[135] The Australian town of Darwin was heavily bombed by the Japanese on 19 February, to prevent it from being used as an Allied base.[136] Over 22,000 Australians were taken prisoner in early 1942 and endured harsh conditions in Japanese captivity. The prisoners were subjected to malnutrition, denied medical treatment and frequently beaten and killed by their guards. As a result, 8,296 Australian prisoners died in captivity.[137]

The rapid Allied defeat in the Pacific caused many Australians to fear that the Japanese would invade the Australian mainland. While elements of the Imperial Japanese Navy proposed this in early 1942, it was judged to be impossible by the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters, which instead adopted a strategy of isolating Australia from the United States by capturing New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Fiji, Samoa, and New Caledonia.[138] This fact was not known by the Allies at the time, and the Australian military was greatly expanded to meet the threat of invasion. Large numbers of United States Army and Army Air Forces units arrived in Australia in early 1942, and the Australian military was placed under the overall command of General Douglas MacArthur in March.[139]

Australians played a central role in the New Guinea campaign during 1942 and 1943. After an attempt to land troops at Port Moresby was defeated in the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Japanese attempted to capture the strategically important town by advancing overland across the Owen Stanley Ranges and Milne Bay. Australian Army units defeated these offensives in the Kokoda Track campaign and Battle of Milne Bay with the support of the RAAF and USAAF.[140] Australian and US Army units subsequently assaulted and captured the Japanese bases on the north coast of Papua in the hard-fought Battle of Buna-Gona.[141] The Australian Army also defeated a Japanese attempt to capture the town of Wau in January 1943 and went onto the offensive in the Salamaua-Lae campaign in April. In late 1943, the 7th and 9th Divisions played an important role in Operation Cartwheel, when they landed to the east and west of Lae and secured the Huon Peninsula during the Huon Peninsula campaign and Finisterre Range campaign.[142]

The Australian mainland came under attack during 1942 and 1943. Japanese submarines operated off Australia from May to August 1942 and January to June 1943. These attacks sought to cut the Allied supply lines between Australia and the US and Australia and New Guinea, but were unsuccessful.[143] On 14 May 1943 the hospital ship AHS Centaur was sunk by a Japanese submarine off Brisbane with the loss of 268 lives.[144] Japanese aircraft also conducted air raids against Allied bases in northern Australia which were being used to mount the North Western Area Campaign against Japanese positions in the Netherlands East Indies (NEI).[145]

Australia's role in the Pacific War declined from 1944. The increasing size of the US forces in the Pacific rendered the Australian military superfluous and labour shortages forced the Government to reduce the size of the armed forces to boost war production.[146] Nevertheless, the Government wanted the Australian military to remain active, and agreed to MacArthur's proposals that it be used in relatively unimportant campaigns. In late 1944, Australian troops and RAAF squadrons replaced US garrisons in eastern New Guinea, New Britain, and Bougainville, and launched offensives aimed at destroying or containing the remaining Japanese forces there. In May 1945, I Corps, the Australian First Tactical Air Force and USAAF and USN units began the Borneo Campaign, which continued until the end of the war. These campaigns contributed little to Japan's defeat and remain controversial.[147]

Following Japan's surrender on 15 August 1945 Australia assumed responsibility for occupying much of Borneo and the eastern Netherlands East Indies until British and Dutch colonial rule was restored. Australian authorities also conducted a number of war crimes trials of Japanese personnel. 993,000 Australians enlisted during the war, while 557,000 served overseas. Casualties included 39,767 killed and another 66,553 were wounded.[37][note 7] 20 Victoria Crosses were awarded to Australians.[52]

Post-war period

[edit]Demobilisation and peace-time defence arrangements

[edit]The demobilisation of the Australian military following the end of the Second World War was completed in 1947. Plans for post-war defence arrangements were predicated on maintaining a relatively strong peacetime force. It was envisioned the Royal Australian Navy would maintain a fleet that would include two light fleet carriers, two cruisers, six destroyers, 16 others ships in commission and another 52 in reserve. The Royal Australian Air Force would have a strength of 16 squadrons, including four manned by the Citizen Air Force. Meanwhile, in a significant departure from past Australian defence policy which had previously relied on citizen forces, the Australian Army would include a permanent field force of 19,000 regulars organised into a brigade of three infantry battalions with armoured support, serving alongside a part-time force of 50,000 men in the Citizen Military Forces.[148] The Australian Regular Army was subsequently formed on 30 September 1947, while the CMF was re-raised on 1 July 1948.[149]

Occupation of Japan, 1946–52

[edit]

In the immediate post-war period Australia contributed significant forces to the Allied occupation of Japan as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), which included forces from Australia, Britain, India and New Zealand.[150] At its height in 1946 the Australian component consisted of an infantry brigade, four warships and three fighter squadrons, totalling 13,500 personnel.[151] The Australian Army component initially consisted of the 34th Brigade which arrived in Japan in February 1946 and was based in Hiroshima Prefecture.[152][153] The three infantry battalions raised for occupation duties were designated the 1st, 2nd and 3rd battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment in 1949,[154] and the 34th Brigade became the 1st Brigade when it returned to Australia in December 1948, forming the basis of the post-war Regular Army. From that time the Australian Army contribution to the occupation of Japan was reduced to a single under-strength battalion. Australian forces remained until September 1951 when the BCOF ceased operations, although by that time the majority of units had been committed to the fighting on the Korean peninsula following the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950.[155] The RAAF component consisted of Nos. 76, 77 and 82 Squadrons as part of No. 81 Wing RAAF flying P-51 Mustangs, initially based at Bofu from March 1946, before transferring to Iwakuni in 1948. However, by 1950 only No. 77 Squadron remained in Japan.[156] A total of ten RAN warships served in Japan during this period, including HMA Ships Australia, Hobart, Shropshire, Arunta, Bataan, Culgoa, Murchison, Shoalhaven, Quadrant and Quiberon, while HMAS Ships Manoora, Westralia and Kanimbla also provided support.[157]

Cold War

[edit]Early planning and commitments

[edit]During the early years of the Cold War, Australian defence planning assumed that in the event of the outbreak of a global war between the Western world and Eastern bloc countries it would need to contribute forces under collective security arrangements as part of the United Nations, or a coalition led by either the United States or Britain. The Middle East was considered the most likely area of operations for Australian forces, where they were expected to operate with British forces.[158] Early commitments included the involvement of RAAF aircrew during the Berlin Airlift in 1948–49 and the deployment of No. 78 Wing RAAF to Malta in the Mediterranean from 1952 to 1954.[159] Meanwhile, defence preparedness initiatives included the introduction of a National Service Scheme in 1951 to provide manpower for the citizen forces of the Army, RAAF and RAN.[160][161]

Korean War, 1950–53

[edit]

On 25 June 1950, the North Korean Army (KPA) crossed the border into South Korea and advanced for the capital Seoul, which fell in less than a week. North Korean forces continued toward the port of Pusan and two days later the United States offered its assistance to South Korea. In response the United Nations Security Council requested members to assist in repelling the North Korean attack. Australia initially contributed P-51 Mustang fighter-bomber aircraft from No. 77 Squadron RAAF and infantry from the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR), both of which were stationed in Japan as part of the BCOF. In addition, it provided the majority of supply and support personnel to the British Commonwealth Forces Korea. The RAN frigate HMAS Shoalhaven, and the destroyer HMAS Bataan, were also committed. Later, an aircraft carrier strike group aboard HMAS Sydney was added to the force.[162]

By the time 3 RAR arrived in Pusan on 28 September, the North Koreans were in retreat following the Inchon landings. As a part of the invasion force under the UN Supreme Commander, General Douglas MacArthur, the battalion moved north and was involved in its first major action at Battle of Yongju near Pyongyang on 22 October, before advancing towards the Yalu River.[163] Further successful actions followed at Kujin on 25–26 October 1950 and at Chongju on 29 October 1950.[164] North Korean casualties were heavy, while Australian losses included their commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Green, who was wounded in the stomach by artillery fire after the battle and succumbed to his wounds and died two days later on 1 November.[165] Meanwhile, during the last weeks of October the Chinese had moved 18 divisions of the People's Volunteer Army across the Yalu River to reinforce the remnants of the KPA. Undetected by US and South Korean intelligence, the 13th Army Group crossed the border on 16 October and penetrated up to 100 kilometres (62 mi) into North Korea, and were reinforced in early November by 12 divisions from the 9th Army Group; in total 30 divisions composed of 380,000 men.[166] 3 RAR fought its first action against the Chinese at Pakchon on 5 November.[167] The fighting cost the battalion heavily and despite halting a Chinese division the new battalion commander was dismissed in the wake.[168] Following the Chinese intervention, the UN forces were defeated in successive battles and 3 RAR was forced to withdraw to the 38th parallel.[162]

A series of battles followed at Uijeongbu on 1–4 January 1951, as the British and Australians occupied defensive positions in an attempt to secure the northern approaches to the South Korean capital.[167] Further fighting occurred at Chuam-ni on 14–17 February 1951 following another Chinese advance, and later at Maehwa-San between 7–12 March 1951 as the UN resumed the offensive.[169] Australian troops subsequently participated in two more major battles in 1951, with the first taking place during fighting which later became known as the Battle of Kapyong. On 22 April, Chinese forces attacked the Kapyong valley and forced the South Korean defenders to withdraw. Australian and Canadian troops were ordered to halt this Chinese advance. After a night of fighting the Australians recaptured their positions, at the cost of 32 men killed and 59 wounded.[170] In July 1951, the Australian battalion became part of the combined Canadian, British, Australian, New Zealand, and Indian 1st Commonwealth Division. The second major battle took place during Operation Commando and occurred after the Chinese attacked a salient in a bend of the Imjin River. The 1st Commonwealth Division counter-attacked on 3 October, capturing a number of objectives including Hill 355 and Hill 317 during the Battle of Maryang San; after five days the Chinese retreated. Australian casualties included 20 dead and 104 wounded.[171]

The belligerents then became locked in static trench warfare akin to the First World War, in which men lived in tunnels, redoubts, and sandbagged forts behind barbed wire defences. From 1951 until the end of the war, 3 RAR held trenches on the eastern side of the division's positions in the hills northeast of the Imjin River. Across from them were heavily fortified Chinese positions. In March 1952, Australia increased its ground commitment to two battalions, sending 1 RAR. This battalion remained in Korea for 12 months, before being replaced by 2 RAR in April 1953.[172] The Australians fought their last battle during 24–26 July 1953, with 2 RAR holding off a concerted Chinese attack along the Samichon River and inflicting significant casualties for the loss of five killed and 24 wounded.[173] Hostilities were suspended on 27 July 1953. 17,808 Australians served during the war, with 341 killed, 1,216 wounded and 30 captured.[174]

Malayan Emergency, 1950–60

[edit]

The Malayan Emergency was declared on 18 June 1948, after three estate managers were murdered by members of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP).[175] Australian involvement began in June 1950, when in response to a British request, six Lincolns from No. 1 Squadron and a flight of Dakotas from No. 38 Squadron arrived in Singapore to form part of the British Commonwealth Far East Air Force (FEAF). The Dakotas were subsequently used on cargo runs, troop movement, as well as paratroop and leaflet drops, while the Lincoln bombers carried out bombing raids against the Communist Terrorist (CT) jungle bases.[176] The RAAF were particularly successful, and in one such mission known as Operation Termite, five Lincoln bombers destroyed 181 communist camps, killed 13 communists and forced one into surrender, in a joint operation with the RAF and ground troops.[176] The Lincolns were withdrawn in 1958, and were replaced by Canberra bombers from No. 2 Squadron and CAC Sabres from No. 78 Wing. Based at RAAF Base Butterworth they also carried out a number ground attack missions against the guerrillas.[177]

Australian ground forces were deployed to Malaya in October 1955 as part of the Far East Strategic Reserve. In January 1956, the first Australian ground forces were deployed on Malaysian peninsula, consisting of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (2 RAR). 2 RAR mainly participated in "mopping up" operations over the next 20 months, conducting extensive patrolling in and near the CT jungle bases, as part of 28th British Commonwealth Brigade. Contact with the enemy was infrequent and results small, achieving relatively few kills. 2 RAR left Malaysia October 1957 to be replaced by 3 RAR. 3 RAR underwent six weeks of jungle training and began driving MCP insurgents back into the jungle of Perak and Kedah. The new battalion extensively patrolled and was involved in food denial operations and ambushes. Again contact was limited, although 3 RAR had more success than its predecessor. By late 1959, operations against the MCP were in their final phase, and most communists had been pushed back and across the Thailand border. 3 RAR left Malaysia October 1959 and was replaced by 1 RAR. Though patrolling the border 1 RAR did not make contact with the insurgents, and in October 1960 it was replaced by 2 RAR, which stayed in Malaysia until August 1963. The Malayan Emergency officially ended on 31 July 1960.[176]

Australia also provided artillery and engineer support, along with an air-field construction squadron. The Royal Australian Navy also served in Malayan waters, firing on suspected communist positions between 1956 and 1957. The Emergency was the longest continued commitment in Australian military history; 7,000[37] Australians served and 51 died in Malaya—although only 15 were on operations—and another 27 were wounded.[176]

Military and Naval growth during the 1960s

[edit]

At the start of the 1960s, Prime Minister Robert Menzies greatly expanded the Australian military so that it could carry out the Government's policy of "Forward Defence" in South East Asia. In 1964, Menzies announced a large increase in defence spending. The strength of the Australian Army would be increased by 50% over three years from 22,000 to 33,000; providing a full three-brigade division with nine battalions. The RAAF and RAN would also both be increased by 25%. In 1964, conscription or National Service was re-introduced under the National Service Act, for selected 20-year-olds based on date of birth, for a period of two years' continuous full-time service (the previous scheme having been suspended in 1959).[178]

In 1961, three Charles F. Adams-class destroyers were purchased from the United States to replace the ageing Q-class destroyers. Traditionally, the RAN had purchased designs based on those of the Royal Navy and the purchase of American destroyers was significant. HMAS Perth and HMAS Hobart joined the fleet in 1965, followed by HMAS Brisbane in 1967. Other projects included the construction of six River-class frigates, the conversion of the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne to an anti-submarine role, the acquisition of ten Wessex helicopters, and the purchase of six Oberon-class submarines.[179]

The RAAF took delivery of their first Mirage fighters in 1967, equipping No. 3, No. 75 and No. 77 Squadrons with them. The service also received American F-111 strike aircraft, C-130 Hercules transports, P-3 Orion maritime reconnaissance aircraft and Italian Macchi trainers.[180]

Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation, 1962–66

[edit]

The Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation was fought from 1962 to 1966 between the British Commonwealth and Indonesia over the creation of the Federation of Malaysia, with the Commonwealth attempting to safeguard the security of the new state. The war remained limited, and was fought primarily on the island of Borneo, although a number of Indonesian seaborne and airborne incursions onto the Malay Peninsula did occur.[181] As part of Australia's continuing military commitment to the security of Malaysia, army, naval and airforce units were based there as part of the Far East Strategic Reserve. Regardless the Australian government was wary of involvement in a war with Indonesia and initially limited its involvement to the defence of the Malayan peninsula only. On two occasions Australian troops from 3 RAR were used to help mop up infiltrators from seaborne and airborne incursions at Labis and Pontian, in September and October 1964.[181]

Following these raids the government conceded to British and Malaysian requests to deploy an infantry battalion to Borneo. During the early phases, British and Malaysian troops had attempted only to control the Malaysian/Indonesian border, and to protect population centres. However, by the time the Australian battalion deployed the British had decided on more aggressive action, crossing the border into Kalimantan to obtain information and conduct ambushes to force the Indonesians to remain on the defensive, under the codename Operation Claret. The fighting took place in mountainous, jungle-clad terrain, and a debilitating climate, with operations characterised by the extensive use of company bases sited along the border, cross-border operations, the use of helicopters for troop movement and resupply, and the role of human and signals intelligence to determine enemy movements and intentions.[182]