Yukio Mishima

Yukio Mishima | |||

|---|---|---|---|

三島由紀夫 | |||

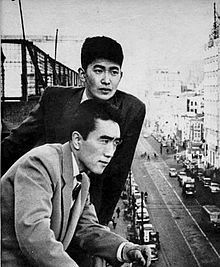

Mishima in 1955 | |||

| Born | Kimitake Hiraoka 14 January 1925 | ||

| Died | 25 November 1970 (aged 45)

| ||

| Cause of death | Suicide by seppuku | ||

| Resting place | Tama Cemetery, Tokyo | ||

| Education | University of Tokyo | ||

| Occupations |

| ||

| Employers |

| ||

| Organization | Tatenokai ("Shield Society") | ||

| Writing career | |||

| Language | Japanese | ||

| Period | Contemporary (20th century) | ||

| Genres |

| ||

| Literary movement |

| ||

| Years active | 1938–1970 | ||

| Notable works | |||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 三島 由紀夫 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 平岡 公威 | ||

| |||

| Signature | |||

| |||

Yukio Mishima[a] (三島 由紀夫, Mishima Yukio), born Kimitake Hiraoka (平岡 公威, Hiraoka Kimitake, 14 January 1925 – 25 November 1970), was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, nationalist, and founder of the Tatenokai. Mishima is considered one of the most important post-war stylists of the Japanese language. He was considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature five times in the 1960s—including in 1968, but that year the award went to his countryman and benefactor Yasunari Kawabata.[6] His works include the novels Confessions of a Mask and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, and the autobiographical essay Sun and Steel. Mishima's work is characterized by "its luxurious vocabulary and decadent metaphors, its fusion of traditional Japanese and modern Western literary styles, and its obsessive assertions of the unity of beauty, eroticism and death",[7] according to author Andrew Rankin.

Mishima's political activities made him a controversial figure, which he remains in modern Japan.[8][9][10][11] From his mid-30s, Mishima's right-wing ideology and reactionary beliefs were increasingly evident.[11][12][13] He was proud of the traditional culture and spirit of Japan, and opposed what he saw as western-style materialism, along with Japan's postwar democracy (戦後民主主義, Sengo minshushugi), globalism, and communism, worrying that by embracing these ideas the Japanese people would lose their "national essence" (kokutai) and their distinctive cultural heritage (Shinto and Yamato-damashii) to become a "rootless" people.[14][15][16][17] Mishima formed the Tatenokai for the avowed purpose of restoring sacredness and dignity to the Emperor of Japan.[15][16][17] On 25 November 1970, Mishima and four members of his militia entered a military base in central Tokyo, took its commandant hostage, and unsuccessfully tried to inspire the Japan Self-Defense Forces to rise up and overthrow Japan's 1947 Constitution (which he called "a constitution of defeat").[17][14] After his speech and screaming of "Long live the Emperor!", he committed seppuku.

Life and work

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Yukio Mishima (三島由紀夫, Mishima Yukio) was born Kimitake Hiraoka (平岡公威, Hiraoka Kimitake) in Nagazumi-cho, Yotsuya-ku of Tokyo City (now part of Yotsuya, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo). He chose his pen name when he was 16.[18] His father was Azusa Hiraoka (平岡梓), a government official in the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce,[19] and his mother, Shizue (平岡倭文重), was the daughter of the 5th principal of the Kaisei Academy. Shizue's father, Kenzō Hashi (橋健三), was a scholar of the Chinese classics, and the Hashi family had served the Maeda clan for generations in Kaga Domain. Mishima's paternal grandparents were Sadatarō Hiraoka, the third Governor-General of Karafuto Prefecture, and Natsuko (family register name: Natsu) (平岡なつ). Mishima received his birth name Kimitake (公威, also read Kōi in on-yomi) in honor of Furuichi Kōi who was a benefactor of Sadatarō.[20] He had a younger sister, Mitsuko (平岡美津子), who died of typhus in 1945 at the age of 17, and a younger brother, Chiyuki (平岡千之).[21][1]

Mishima's childhood home was a rented house, though a fairly large two-floor house that was the largest in the neighborhood. He lived with his parents, siblings and paternal grandparents, as well as six maids, a houseboy, and a manservant. His grandfather was in debt, so there were no remarkable household items left on the first floor.[22]

Mishima's early childhood was dominated by the presence of his grandmother, Natsuko, who took the boy and separated him from his immediate family for several years.[23] She was the granddaughter of Matsudaira Yoritaka, the daimyō of Shishido, which was a branch domain of Mito Domain in Hitachi Province;[b] therefore, Mishima was a descendant of the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Tokugawa Ieyasu, through his grandmother.[24][25][26] Natsuko's father, Nagai Iwanojō (永井岩之丞), had been a Supreme Court justice, and Iwanojō's adoptive father, Nagai Naoyuki, had been a bannerman of the Tokugawa House during the Bakumatsu.[24] Natsuko had been raised in the household of Prince Arisugawa Taruhito, and she maintained considerable aristocratic pretensions even after marrying Sadatarō, a bureaucrat who had made his fortune in the newly opened colonial frontier in the north, and who eventually became Governor-General of Karafuto Prefecture on Sakhalin Island.[27] Sadatarō's father, Takichi Hiraoka (平岡太吉), and grandfather, Tazaemon Hiraoka (平岡太左衛門), had been farmers.[24][c] Natsuko was prone to violent outbursts, which are occasionally alluded to in Mishima's works,[29] and to whom some biographers have traced Mishima's fascination with death.[30] She did not allow Mishima to venture into the sunlight, engage in any kind of sport, or play with other boys. He spent much of his time either alone or with female cousins and their dolls.[31][29]

Mishima returned to his immediate family when he was 12. His father Azusa had a taste for military discipline, and worried Natsuko's style of childrearing was too soft. When Mishima was an infant, Azusa employed parenting tactics such as holding Mishima up to the side of a speeding train. He also raided his son's room for evidence of an "effeminate" interest in literature, and often ripped his son's manuscripts apart.[32] Although Azusa forbade him to write any further stories, Mishima continued to write in secret, supported and protected by his mother, who was always the first to read a new story.[32]

Azusa was determined to raise his son to be a strong man, and the sight of his son holding a lovely cat and petting it on his lap seemed like unmanly and irritating behavior, so Azusa threw the cat away.[32] But, Mishima quickly found another cat from somewhere and took care of it just like the previous cat again.[32] After repeating this, Azusa mixed iron powder into the cat's food and tried to make it die. However, instead of becoming weaker, the cat became more energetic.[32]

When Mishima was 13, Natsuko took him to see his first Kabuki play: Kanadehon Chūshingura, an allegory of the story of the 47 Rōnin. He was later taken to his first Noh play (Miwa, a story featuring Amano-Iwato) by his maternal grandmother Tomi Hashi (橋トミ). From these early experiences, Mishima became addicted to Kabuki and Noh. He began attending performances every month and grew deeply interested in these traditional Japanese dramatic art forms.[33]

Schooling and early works

[edit]

Mishima was enrolled at the age of six in the elite Gakushūin, the Peers' School in Tokyo, which had been established in the Meiji period to educate the Imperial family and the descendants of the old feudal nobility.[34] At 12, Mishima began to write his first stories. He read myths (Kojiki, Greek mythology, etc.) and the works of numerous classic Japanese authors as well as Raymond Radiguet, Jean Cocteau, Oscar Wilde, Rainer Maria Rilke, Thomas Mann, Friedrich Nietzsche, Charles Baudelaire, l'Isle-Adam, and other European authors in translation. He also studied German. After six years at school, he became the youngest member of the editorial board of its literary society. Mishima was attracted to the works of the Japanese poet Shizuo Itō (伊東静雄), poet and novelist Haruo Satō, and poet Michizō Tachihara, who inspired Mishima's appreciation of classical Japanese waka poetry. Mishima's early contributions to the Gakushūin literary magazine Hojinkai-zasshi (輔仁会雑誌)[d] included haiku and waka poetry before he turned his attention to prose.[35]

In 1941, at the age of 16, Mishima was invited to write a short story for the Hojinkai-zasshi, and he submitted Forest in Full Bloom (花ざかりの森, Hanazakari no Mori), a story in which the narrator describes the feeling that his ancestors somehow still live within him. The story uses the type of metaphors and aphorisms that became Mishima's hallmarks.[e] He mailed a copy of the manuscript to his Japanese teacher Fumio Shimizu (清水文雄) for constructive criticism. Shimizu was so impressed that he took the manuscript to a meeting of the editorial board of the prestigious literary magazine Bungei Bunka (文藝文化), of which he was a member. At the editorial board meeting, the other board members read the story and were very impressed; they congratulated themselves for discovering a genius and published it in the magazine. The story was later published as a limited book edition (4,000 copies) in 1944 due to a wartime paper shortage. Mishima had it published as a keepsake to remember him by, as he assumed that he would die in the war.[38][32]

In order to protect him from potential backlash from Azusa, Shimizu and the other editorial board members coined the pen-name Yukio Mishima.[39] They took "Mishima" from Mishima Station, which Shimizu and fellow Bungei Bunka board member Hasuda Zenmei passed through on their way to the editorial meeting, which was held in Izu, Shizuoka. The name "Yukio" came from yuki (雪), the Japanese word for "snow", because of the snow they saw on Mount Fuji as the train passed.[39] In the magazine, Hasuda praised Mishima's genius as follows:

This youthful author is a heaven-sent child of eternal Japanese history. He is much younger than we are, but has arrived on the scene already quite mature.[40]

Hasuda, who became something of a mentor to Mishima, was an ardent nationalist and a fan of Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801), a scholar of kokugaku from the Edo period who preached Japanese traditional values and devotion to the Emperor.[41] Hasuda had previously fought for the Imperial Japanese Army in China in 1938, and in 1943 he was recalled to active service for deployment as a first lieutenant in the Southeast Asian theater.[42] At a farewell party thrown for Hasuda by the Bungei Bunka group, Hasuda offered the following parting words to Mishima:

I have entrusted the future of Japan to you.

According to Mishima, these words were deeply meaningful to him, and had a profound effect on the future course of his life.[43][44][45]

Later in 1941, Mishima wrote in his notebook an essay about his deep devotion to Shintō, titled The Way of the Gods (惟神之道, Kannagara no michi).[46] Mishima's story The Cigarette (煙草, Tabako), published in 1946, describes a homosexual love he felt at school and being teased from members of the school's rugby union club because he belonged to the literary society. Another story from 1954, The Boy Who Wrote Poetry (詩を書く少年, Shi o kaku shōnen), was also based on Mishima's memories of his time at Gakushūin Junior High School.[47]

On 9 September 1944, Mishima graduated Gakushūin High School at the top of the class, and became a graduate representative.[48][49] Emperor Hirohito was present at the graduation ceremony, and Mishima later received a silver watch from the Emperor at the Imperial Household Ministry.[48][49][50][51]

On 27 April 1944, during the final years of World War II, Mishima received a draft notice for the Imperial Japanese Army and barely passed his conscription examination on 16 May 1944, with a less desirable rating of "second class" conscript. He had a cold during his medical check on convocation day (10 February 1945), and the young army doctor misdiagnosed Mishima with tuberculosis, declared him unfit for service, and sent him home.[52][32] Scholars have argued that Mishima's failure to receive a "first class" rating on his conscription examination (reserved only for the most physically fit recruits), in combination with the illness which led him to be erroneously declared unfit for duty, contributed to an inferiority complex over his frail constitution that later led to his obsession with physical fitness and bodybuilding.[53]

The day before his failed medical examination, Mishima wrote a farewell message to his family, ending with the words "Long live the Emperor!" (天皇陛下万歳, Tennō heika banzai), and prepared clippings of his hair and nails to be kept as mementos by his parents.[32][54] The troops of the unit that Mishima was supposed to have joined were sent to the Philippines, where most of them were killed.[52] Mishima's parents were ecstatic that he did not have to go to war, but Mishima's mood was harder to read; Mishima's mother overheard him say he wished he could have joined a "Special Attack" unit.[32] Around that time, Mishima admired kamikaze pilots and other "special attack" units in letters to friends and private notes.[48][55][56]

Mishima was deeply affected by Emperor Hirohito's radio broadcast announcing Japan's surrender on 15 August 1945, and vowed to protect Japanese cultural traditions and help rebuild Japanese culture after the destruction of the war.[57] He wrote in his diary:

Only by preserving Japanese irrationality will we be able contribute to world culture 100 years from now.[58]

On 19 August, four days after Japan's surrender, Mishima's mentor Zenmei Hasuda, who had been drafted and deployed to the Malay peninsula, shot and killed his superior officer who attributed the defeat to the Emperor and slandered the imperial army's future and preached the destruction of the Japanese spirit.[59] Hasuda had long suspected the officer to be a Korean spy.[59] After shooting him, Hasuda turned his pistol on himself.[59] Mishima learned of the incident a year later and contributed poetry in Hasuda's honor at a memorial service in November 1946.[59] On 23 October 1945 (Showa 20), Mishima's beloved younger sister Mitsuko died suddenly at the age of 17 from typhoid fever by drinking untreated water.[32][60] Around that same time he also learned that Kuniko Mitani (三谷邦子), a classmate's sister whom he had hoped to marry, was engaged to another man.[61][62][f] These tragic incidents in 1945 became a powerful motive force in inspiring Mishima's future literary work.[64]

At the end of the war, his father Azusa "half-allowed" Mishima to become a novelist. He was worried that his son could actually become a professional novelist, and hoped instead that his son would be a bureaucrat like himself and Mishima's grandfather Sadatarō. He advised his son to enroll in the Faculty of Law instead of the literature department.[32] Attending lectures during the day and writing at night, Mishima graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1947. He obtained a position in the Ministry of the Treasury and seemed set up for a promising career as a government bureaucrat. However, after just one year of employment Mishima had exhausted himself so much that his father agreed to allow him to resign from his post and devote himself to writing full time.[32]

In 1945, Mishima began the short story A Story at the Cape (岬にての物語, Misaki nite no Monogatari) and continued to work on it through the end of World War II. After the war, it was praised by Shizuo Itō (伊東静雄) whom Mishima respected.[65]

Post-war literature

[edit]

After Japan's defeat in World War II, the country was occupied by the U.S.-led Allied Powers. At the urging of the occupation authorities, many people who held important posts in various fields were purged from public office. The media and publishing industry were also censored, and were not allowed to engage in forms of expression reminiscent of wartime Japanese nationalism.[g] In addition, literary figures, including many of those who had been close to Mishima before the end of the war, were branded "war criminal literary figures". Some people denounced them and converted to left-wing politics, whom Mishima criticized as "opportunists" in his letters to friends.[70][71][72] Some prominent literary figures became leftists, and joined the Communist Party as a reaction against wartime militarism and writing socialist realist literature that might support the cause of socialist revolution.[73] Their influence had increased in the Japanese literary world following the end of the war, which Mishima found difficult to accept. Although Mishima was just 20 years old at this time, he worried that his type of literature, based on the 1930s Japanese Romantic School (日本浪曼派, Nihon Rōman Ha), had already become obsolete.[33]

Mishima had heard that famed writer Yasunari Kawabata had praised his work before the end of the war. Uncertain of who else to turn to, Mishima took the manuscripts for The Middle Ages (中世, Chūsei) and The Cigarette (煙草, Tabako) with him, visited Kawabata in Kamakura, and asked for his advice and assistance in January 1946.[33] Kawabata was impressed, and in June 1946, following Kawabata's recommendation, The Cigarette was published in the new literary magazine Humanity (人間, Ningen), followed by The Middle Ages in December 1946.[74] The Middle Ages is set in Japan's historical Muromachi Period and explores the motif of shudō (man-boy love) against a backdrop of the death of the ninth Ashikaga shogun Ashikaga Yoshihisa in battle at the age of 25, and his father Ashikaga Yoshimasa's resultant sadness. The story features the fictional character Kikuwaka, a beautiful teenage boy who was beloved by both Yoshihisa and Yoshimasa, who fails in an attempt to follow Yoshihisa in death by committing suicide. Thereafter, Kikuwaka devotes himself to spiritualism in an attempt to heal Yoshimasa's sadness by allowing Yoshihisa's ghost to possess his body, and eventually dies in a double-suicide with a miko (shrine maiden) who falls in love with him. Mishima wrote the story in an elegant style drawing upon medieval Japanese literature and the Ryōjin Hishō, a collection of medieval imayō songs. This elevated writing style and the homosexual motif suggest the germ of Mishima's later aesthetics.[74] Later in 1948 Kawabata, who praised this work, published an autobiographical work Boy (少年, Shōnen) describing his experience of falling in love for the first time with a boy two years his junior.[75]

Kawabata 's relationship with Mishima was described as being a literary alliance and far less intense than the impression Dazai's remark left on him. Kawabata committed suicide eighteen months following Mishima's suicide.[76] [77]

In 1946, Mishima began his first novel, Thieves (盗賊, Tōzoku), a story about two young members of the aristocracy drawn towards suicide. It was published in 1948, and placed Mishima in the ranks of the Second Generation of Postwar Writers. The following year, he published Confessions of a Mask, a semi-autobiographical account of a young homosexual man who hides behind a mask to fit into society. The novel was extremely successful and made Mishima a celebrity at the age of 24. In 1947, a brief encounter with Osamu Dazai, a popular novelist known for his suicidal themes, left a lasting impression on him.[78] Around 1949, Mishima also published a literary essay about Kawabata, for whom he had always held a deep appreciation, in Modern Literature (近代文学, Kindai Bungaku).[79]

Mishima enjoyed international travel. In 1952, he took a world tour and published his travelogue as The Cup of Apollo (アポロの杯, Aporo no Sakazuki). He visited Greece during his travels, a place which had fascinated him since childhood. His visit to Greece became the basis for his 1954 novel The Sound of Waves, which drew inspiration from the Greek legend of Daphnis and Chloe. The Sound of Waves, set on the small island of "Kami-shima" where a traditional Japanese lifestyle continued to be practiced, depicts a pure, simple love between a fisherman and a female pearl and abalone diver. Although the novel became a best-seller, leftists criticized it for "glorifying old-fashioned Japanese values", and some people began calling Mishima a "fascist".[80][81][82] Looking back on these attacks in later years, Mishima wrote, "The ancient community ethics portrayed in this novel were attacked by progressives at the time, but no matter how much the Japanese people changed, these ancient ethics lurk in the bottom of their hearts. We have gradually seen this proven to be the case."[83]

Mishima made use of contemporary events in many of his works. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, published in 1956, is a fictionalization of the burning down of the Kinkaku-ji Buddhist temple in Kyoto in 1950 by a mentally disturbed monk.[84]

In 1959, Mishima published the artistically ambitious novel Kyōko no Ie. The novel tells the interconnected stories of four young men who represented four different facets of Mishima's personality. His athletic side appears as a boxer, his artistic side as a painter, his narcissistic, performative side as an actor, and his secretive, nihilistic side as a businessman who goes through the motions of living a normal life while practicing "absolute contempt for reality". According to Mishima, he was attempting to describe the time around 1955 in the novel, when Japan was entering into its era of high economic growth and the phrase "The postwar is over" was prevalent.[h] Mishima explained, "Kyōko no Ie is, so to speak, my research into the nihilism within me."[86][87] Although the novel was well received by a small number of critics from the same generation as Mishima and sold 150,000 copies in a month, it was widely panned in broader literary circles,[88][89] and was rapidly branded as Mishima's first "failed work".[90][89] It was Mishima's first major setback as an author, and the book's disastrous reception came as a harsh psychological blow.[91][92]

Until 1960, Mishima had not written works that were seen as especially political.[88] In the summer of 1960, Mishima became interested in the massive Anpo protests against an attempt by U.S.-backed Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi to revise the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States and Japan (known as "Anpo" in Japanese) in order to cement the U.S.–Japan military alliance into place.[93] Although he did not directly participate in the protests, he often went out in the streets to observe the protestors in action and kept extensive newspaper clippings covering the protests.[94] In June 1960, at the climax of the protest movement, Mishima wrote a commentary in the Mainichi Shinbun newspaper, entitled "A Political Opinion".[95] In the critical essay, he argued that leftist groups such as the Zengakuren student federation, the Socialist Party, and the Communist Party were falsely wrapping themselves in the banner of "defending democracy" and using the protest movement to further their own ends. Mishima warned against the dangers of the Japanese people following ideologues who told lies with honeyed words. Although Mishima criticized Kishi as a "nihilist" who had subordinated himself to the United States, Mishima concluded that he would rather vote for a strong-willed realist "with neither dreams nor despair" than a mendacious but eloquent ideologue.[96]

Shortly after the Anpo Protests ended, Mishima began writing one of his most famous short stories, Patriotism, glorifying the actions of a young right-wing ultranationalist Japanese army officer who commits suicide after a failed revolt against the government during the February 26 Incident.[95] The following year, he published the first two parts of his three-part play Tenth-Day Chrysanthemum (十日の菊, Tōka no kiku), which celebrates the actions of the 26 February revolutionaries.[95]

Mishima's newfound interest in contemporary politics shaped his novel After the Banquet, also published in 1960, which so closely followed the events surrounding politician Hachirō Arita's campaign to become governor of Tokyo that Mishima was sued for invasion of privacy.[97] The next year, Mishima published The Frolic of the Beasts, a parody of the classical Noh play Motomezuka, written in the 14th-century playwright Kiyotsugu Kan'ami. In 1962, Mishima produced his most artistically avant-garde work Beautiful Star, which at times comes close to science fiction. Although the novel received mixed reviews from the literary world, prominent critic Takeo Okuno (奥野健男) singled it out for praise as part of a new breed of novels that was overthrowing longstanding literary conventions in the tumultuous aftermath of the Anpo Protests. Alongside Kōbō Abe's Woman of the Dunes, published that same year, Okuno considered A Beautiful Star an "epoch-making work" which broke free of literary taboos and preexisting notions of what literature should be in order to explore the author's personal creativity.[98]

In 1965, Mishima wrote the play Madame de Sade that explores the complex figure of the Marquis de Sade, traditionally upheld as an exemplar of vice, through a series of debates between six female characters, including the Marquis' wife, the Madame de Sade. At the end of the play, Mishima offers his own interpretation of what he considered to be one of the central mysteries of the de Sade story—the Madame de Sade's unstinting support for her husband while he was in prison and her sudden decision to renounce him upon his release.[99][100] Mishima's play was inspired in part by his friend Tatsuhiko Shibusawa's 1960 Japanese translation of the Marquis de Sade's novel Juliette and a 1964 biography Shibusawa wrote of de Sade.[101] Shibusawa's sexually explicit translation became the focus of a sensational obscenity trial remembered in Japan as the "Juliette Case" (サド裁判, Sado saiban), which was ongoing as Mishima wrote the play.[99] In 1994, Madame de Sade was evaluated as the "greatest drama in the history of postwar theater" by Japanese theater criticism magazine Theater Arts (シアター・アーツ).[102][103]

Mishima was considered for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1963, 1964, 1965, 1967 and 1968 (he and Rudyard Kipling are both the youngest nominees in history),[104] and was a favorite of many foreign publications.[105] However, in 1968 his early mentor Kawabata won the Nobel Prize and Mishima realized that the chances of it being given to another Japanese author in the near future were slim.[106] In a work published in 1970, Mishima wrote that the writers he paid most attention to in modern western literature were Georges Bataille, Pierre Klossowski, and Witold Gombrowicz.[107]

Acting and modelling

[edit]

Mishima was also an actor, and starred in Yasuzo Masumura's 1960 film, Afraid to Die, for which he also sang the theme song (lyrics by himself; music by Shichirō Fukazawa).[108][109] He performed in films like Patriotism or the Rite of Love and Death directed by himself, 1966, Black Lizard directed by Kinji Fukasaku, 1968 and Hitokiri directed by Hideo Gosha, 1969. Maki Isaka has discussed how his knowledge of performance and theatrical forms influenced short stories including Onnagata (女方, Onnagata).[110]

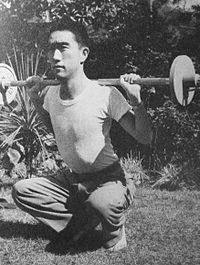

Mishima was featured as the photo model in photographer Eikoh Hosoe's book Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses (薔薇刑, Bara-kei), as well as in Tamotsu Yatō's photobooks Young Samurai: Bodybuilders of Japan (体道~日本のボディビルダーたち, Taidō: Nihon no bodybuilder tachi) and Otoko: Photo Studies of the Young Japanese Male (男, Otoko). American author Donald Richie gave an eyewitness account of seeing Mishima, dressed in a loincloth and armed with a sword, posing in the snow for one of Tamotsu Yatō's photoshoots.[111]

In the men's magazine Heibon Punch, to which Mishima had contributed various essays and criticisms, he won first place in the "Mr. Dandy" reader popularity poll in 1967 with 19,590 votes, beating second place Toshiro Mifune by 720 votes.[112] In the next reader popularity poll, "Mr. International", Mishima ranked second behind French President Charles de Gaulle.[112] At that time in the late 1960s, Mishima was the first celebrity to be described as a "superstar" (sūpāsutā) by the Japanese media.[113]

Private life

[edit]

In 1955, Mishima took up weight training to overcome his weak composition, and his strictly observed workout regimen of three sessions per week was not disrupted for the final 15 years of his life. In his 1968 essay Sun and Steel,[114] Mishima deplored the emphasis given by intellectuals to the mind over the body. He later became very skilled (5th Dan) at kendo (traditional Japanese swordsmanship), and became 2nd Dan in battōjutsu, and 1st Dan in karate. In 1956, he tried boxing for a short period of time. In the same year, he developed an interest in UFOs and became a member of the "Japan Flying Saucer Research Association" (日本空飛ぶ円盤研究会, Nihon soratobu enban kenkyukai).[115] In 1954, he fell in love with Sadako Toyoda (豊田貞子), who became the model for main characters in The Sunken Waterfall (沈める滝, Shizumeru taki) and The Seven Bridges (橋づくし, Hashi zukushi).[116][117] Mishima hoped to marry her, but they broke up in 1957.[60][118]

After briefly considering marriage with Michiko Shōda, who later married Crown Prince Akihito and became Empress Michiko,[119] Mishima married Yōko (瑤子, née Sugiyama), the daughter of Japanese-style painter Yasushi Sugiyama on 1 June 1958. The couple had two children: a daughter named Noriko (紀子) (born 2 June 1959) and a son named Iichirō (威一郎) (born 2 May 1962).[120] Noriko eventually married the diplomat Koji Tomita.[121]

While working on his novel Forbidden Colors, Mishima visited gay bars in Japan.[122] Mishima's sexual orientation was an issue that bothered his wife, and she always denied his homosexuality after his death.[123] In 1998, the writer Jirō Fukushima (福島次郎) published an account of his relationship with Mishima in 1951, including fifteen letters (not love letters) from the famed novelist.[124] Mishima's children successfully sued Fukushima and the publisher for copyright violation over the use of Mishima's letters.[125][124][126] Publisher Bungeishunjū had argued that the contents of the letters were "practical correspondence" rather than copyrighted works. However, the ruling for the plaintiffs declared, "In addition to clerical content, these letters describe the Mishima's own feelings, his aspirations, and his views on life, in different words from those in his literary works."[127][i]

In February 1961, Mishima became embroiled in the aftermath of the Shimanaka incident. In 1960, the author Shichirō Fukazawa had published the satirical short story The Tale of an Elegant Dream (風流夢譚, Fūryū Mutan) in the mainstream magazine Chūō Kōron. It contained a dream sequence (in which the Emperor and Empress are beheaded by a guillotine) that led to outrage from right-wing ultra-nationalist groups, and numerous death threats against Fukazawa, any writers believed to have been associated with him, and Chūō Kōron magazine itself.[130] On 1 February 1961, Kazutaka Komori, a seventeen-year-old rightist, broke into the home of Hōji Shimanaka, the president of Chūō Kōron, killed his maid with a knife and severely wounded his wife.[131] In the aftermath, Fukazawa went into hiding, and dozens of writers and literary critics, including Mishima, were provided with round-the-clock police protection for several months;[132] Mishima was included because a rumor that Mishima had personally recommended The Tale of an Elegant Dream for publication became widespread, and even though he repeatedly denied the claim, he received hundreds of death threats.[132] In later years, Mishima harshly criticized Komori, arguing that those who harm women and children are neither patriots nor traditional right-wingers, and that an assassination attempt should be a one-on-one confrontation with the victim at the risk of the assassin's life. Mishima also argued that it was the custom of traditional Japanese patriots to immediately commit suicide after committing an assassination.[133]

In 1963, "The Harp of Joy Incident" (喜びの琴事件, Yorokobi no Koto Jiken) occurred within the theatrical troupe Bungakuza, to which Mishima belonged. He wrote a play titled The Harp of Joy (喜びの琴, Yorokobi no koto), but star actress Haruko Sugimura and other Communist Party-affiliated actors refused to perform because the protagonist held anti-communist views and mentioned criticism about a conspiracy of world communism in his lines. As a result of this ideological conflict, Mishima quit Bungakuza and later formed the troupe Neo Littérature Théâtre (劇団NLT, Gekidan NLT) with playwrights and actors who had quit Bungakuza along with him, including Seiichi Yashio (矢代静一), Takeo Matsuura (松浦竹夫), and Nobuo Nakamura. When Neo Littérature Théâtre experienced a schism in 1968, Mishima formed another troupe, the Roman Theatre (浪曼劇場, Rōman Gekijō), and worked with Matsuura and Nakamura again.[134][135][136]

During the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, Mishima interviewed various athletes every day and wrote articles as a newspaper correspondent.[137][138] He had eagerly anticipated the long-awaited return of the Olympics to Japan after the 1940 Tokyo Olympics were cancelled due to Japan's war in China. Mishima expressed his excitement in his report on the opening ceremonies: "It can be said that ever since Lafcadio Hearn called the Japanese "the Greeks of the Orient," the Olympics were destined to be hosted by Japan someday."[139]

Mishima hated Ryokichi Minobe, who was a communist and the governor of Tokyo beginning in 1967.[140] Influential persons in the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), including Takeo Fukuda and Kiichi Aichi, had been Mishima's superiors during his time at the Ministry of the Treasury, and Prime Minister Eisaku Satō came to know Mishima because his wife, Hiroko, was a fan of Mishima's work. Based on these connections LDP officials solicited Mishima to run for the LDP as governor of Tokyo against Minobe, but Mishima had no intention of becoming a politician.[140]

Mishima was fond of manga and gekiga, especially the drawing style of Hiroshi Hirata, a mangaka best known for his samurai gekiga; the slapstick, absurdist comedy in Fujio Akatsuka's Mōretsu Atarō, and the imaginativeness of Shigeru Mizuki's GeGeGe no Kitarō.[141][142] Mishima especially loved reading the boxing manga Ashita no Joe in Weekly Shōnen Magazine every week.[143][j] Ultraman and Godzilla were his favorite kaiju fantasies, and he once compared himself to "Godzilla's egg" in 1955.[144][145] On the other hand, he disliked story manga with humanist or cosmopolitan themes, such as Osamu Tezuka's Phoenix.[141][142]

Mishima was a fan of science fiction, contending that "science fiction will be the first literature to completely overcome modern humanism".[146] He praised Arthur C. Clarke's Childhood's End in particular. While acknowledging "inexpressible unpleasant and uncomfortable feelings after reading it," he declared, "I'm not afraid to call it a masterpiece."[147]

Mishima traveled to Shimoda on the Izu Peninsula with his wife and children every summer from 1964 onwards.[148][149] In Shimoda, Mishima often enjoyed eating local seafood with his friend Henry Scott-Stokes.[149] Mishima never showed any hostility towards the US in front of foreign friends like Scott-Stokes, until Mishima heard that the name of the inn where Scott-Stokes was staying was Kurofune (lit. 'black ship'), at which point his voice suddenly became low and he said in a sullen manner, "Why? Why do you stay at a place with such a name?". Mishima liked ordinary American people after the war, and he and his wife had even visited Disneyland as newlyweds.[k] However, he clearly retained a strong sense of hostility toward the "black ships" of Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who forcibly opened Japan up to unequal international relations at the end of the Edo period, and had destroyed the peace of Edo, where vivid chōnin culture was flourishing.[149]

Later life

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Japan |

|---|

|

Mishima's nationalism grew towards the end of his life. In 1966, he published his short story The Voices of the Heroic Dead (英霊の聲, Eirei no koe), in which he denounced Emperor Hirohito for renouncing his own divinity after World War II. He argued that the soldiers who had died in the February 26 Incident and the Japanese Special Attack Units had died for their "living god" Emperor, and that Hirohito's renunciation of his own divinity meant that all those deaths had been in vain. Mishima said that His Imperial Majesty had become a human when he should be a God.[151][152]

In February 1967, Mishima joined fellow authors Yasunari Kawabata, Kōbō Abe, and Jun Ishikawa in issuing a statement condemning China's Cultural Revolution for suppressing academic and artistic freedom.[153][154] However, only one Japanese newspaper carried the full text of their statement.[155]

In September 1967 Mishima and his wife visited India at the invitation of the Indian government. He traveled widely and met with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and President Zakir Hussain.[156] He left extremely impressed by Indian culture, and what he felt was the Indian people's determination to resist Westernization and protect traditional ways.[157] Mishima feared that his fellow Japanese were too enamored of modernization and western-style materialism to protect traditional Japanese culture.[156] While in New Delhi, he spoke at length with an unnamed colonel in the Indian Army who had experienced skirmishes with Chinese troops on the Sino-Indian border. The colonel warned Mishima of the strength and fighting spirit of the Chinese troops. Mishima later spoke of his sense of danger regarding what he perceived to be a lack of concern in Japan about the need to bolster Japan's national defense against the threat from Communist China.[158][159][l] On his way home from India, Mishima also stopped in Thailand and Laos; his experiences in the three nations became the basis for portions of his novel The Temple of Dawn, the third in his tetralogy The Sea of Fertility.[161]

In 1968, Mishima wrote a play titled My Friend Hitler, in which he depicted the historical figures of Adolf Hitler, Gustav Krupp, Gregor Strasser, and Ernst Röhm as mouthpieces to express his own views on fascism and beauty.[88] Mishima explained that after writing the all-female play Madame de Sade, he wanted to write a counterpart play with an all-male cast.[162] Mishima wrote of My Friend Hitler, "You may read this tragedy as an allegory of the relationship between Ōkubo Toshimichi and Saigō Takamori" (two heroes of Japan's Meiji Restoration who initially worked together but later had a falling out).[163]

That same year, he wrote Life for Sale, a humorous story about a man who, after failing to commit suicide, advertises his life for sale.[164] In a review of the English translation, novelist Ian Thomson called it a "pulp noir" and a "sexy, camp delight", but also noted that, "beneath the hard-boiled dialogue and the gangster high jinks is a familiar indictment of consumerist Japan and a romantic yearning for the past."[165]

Mishima was hated by leftists who said Hirohito should have abdicated to take responsibility for the loss of life in the war. They also hated him for his outspoken commitment to bushido, the code of the samurai in The way of the samurai (葉隠入門, Hagakure Nyūmon), his support for the abolition of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, and for his contention in his critique The Defense of Culture (文化防衛論, Bunka Bōeiron) that preached the importance of the Emperor in Japanese cultures. Mishima regarded the postwar era of Japan, where no poetic culture and supreme artist was born, as an era of fake prosperity, and stated in The Defense of Culture:

In the postwar prosperity called Shōwa Genroku, where there are no Chikamatsu Monzaemon, Ihara Saikaku, Matsuo Bashō, only infestation of flashy manners and customs in there. Passion is dried up, strong realism dispels the ground, and the deepening of poetry is neglected. That is, there are no Chikamatsu, Saikaku, or Basho now.[166]

In other critical essays,[m] Mishima argued that the national spirit which cultivated in Japan's long history is the key to national defense, and he had apprehensions about the insidious "indirect aggression" of the Chinese Communist Party, North Korea, and the Soviet Union.[15][16] In critical essays in 1969, Mishima explained Japan's difficult and delicate position and peculiarities between China, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

To put it simply, support for the Security Treaty means agreeing with the United States, and to oppose it means agreeing with the Soviet Union or the Chinese Communist Party, so after all, it's only just a matter of which foreign country to rely on, and therein the question of "what is Japan" is completely lacking. If you ask the Japanese, "Hey you, do you choose America, Soviet Union, or Chinese Communist Party?", if he is a true Japanese, he will withhold his attitude.[167][168]

In regards to those who strongly opposed the US military base in Okinawa and the Security Treaty:

They may appear to be nationalists and right-wingers in the foreign common sense, but in Japan, most of them are in fact left-wingers and communists.[169][168]

Throughout this period, Mishima continued to work on his magnum opus, The Sea of Fertility tetralogy of novels, which began appearing in a monthly serialized format in September 1965.[170] The four completed novels were Spring Snow (1969), Runaway Horses (1969), The Temple of Dawn (1970), and The Decay of the Angel (published posthumously in 1971). Mishima aimed for a very long novel with a completely different raison d'être from Western chronicle novels of the 19th and 20th centuries; rather than telling the story of a single individual or family, Mishima boldly set his goal as interpreting the entire human world.[171] In The Decay of the Angel, four stories convey the transmigration of the human soul as the main character goes through a series of reincarnations.[171] Mishima hoped to express in literary terms something akin to pantheism.[172] Novelist Paul Theroux blurbed the first edition of the English translation of The Sea of Fertility as "the most complete vision we have of Japan in the twentieth century" and critic Charles Solomon wrote in 1990 that "the four novels remain one of the outstanding works of 20th-Century literature and a summary of the author's life and work".[173]

Coup attempt and ritual suicide

[edit]In August 1966, Mishima visited Ōmiwa Shrine in Nara Prefecture, thought to be one of the oldest Shintō shrines in Japan, as well as the hometown of his mentor Zenmei Hasuda and the areas associated with the Shinpūren rebellion, an uprising against the Meiji government by samurai in 1876. This trip would become the inspiration for portions of Runaway Horses, the second novel in the Sea of Fertility tetralogy. While in Kumamoto, Mishima purchased a Japanese sword for 100,000 yen. Mishima envisioned the reincarnation of Kiyoaki, the protagonist of the first novel Spring Snow, as a man named Isao who put his life on the line to bring about a restoration of direct rule by the Emperor against the backdrop of the "League of Blood Incident" in 1932.

From 12 April to 27 May 1967, Mishima underwent basic training with the Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF).[174] Mishima had originally lobbied to train with the GSDF for six months, but was met with resistance from the Defense Agency.[174] Mishima's training period was finalized to 46 days, which required using some of his connections.[174] His participation in GSDF training was kept secret, both because the Defense Agency did not want to give the impression that anyone was receiving special treatment, and because Mishima wanted to experience "real" military life.[174][175] Accordingly, Mishima trained under his birth name, Kimitake Hiraoka, and most of his fellow soldiers did not recognize him.[174]

From June 1967, Mishima became a leading figure in a plan to create a 10,000-man "Japan National Guard" (祖国防衛隊, Sokoku Bōeitai) as a civilian complement to Japan's Self Defense Forces. He began leading groups of right-wing college students to undergo basic training with the GSDF in the hope of training 100 officers to lead the National Guard.[176][177][175]

Like many other right-wingers, Mishima was especially alarmed by the riots and revolutionary actions undertaken by radical "New Left" university students, who took over dozens of college campuses in Japan in 1968 and 1969. On 26 February 1968, the 32nd anniversary of the February 26 Incident, he and several other right-wingers met at the editorial offices of the recently founded right-wing magazine Controversy Journal (論争ジャーナル, Ronsō jaanaru), where they pricked their little fingers and signed a blood oath promising to die if necessary to prevent a left-wing revolution from occurring in Japan.[178][179] Mishima showed his sincerity by signing his birth name, Kimitake Hiraoka, in his own blood.[178][179]

When Mishima found that his plan for a large-scale Japan National Guard with broad public and private support failed to catch on,[180] he formed the Tatenokai on 5 October 1968, a private militia composed primarily of right-wing college students who swore to protect the Emperor of Japan. The activities of the Tatenokai primarily focused on martial training and physical fitness, including traditional kendo sword-fighting and long-distance running.[181][182] Mishima personally oversaw this training. Initial membership was around 50, and was drawn primarily from students from Waseda University and individuals affiliated with Controversy Journal. The number of Tatenokai members later increased to 100.[183][176] Some of the members had graduated from university and were employed, while some were already working adults when they enlisted.[184]

On 25 November 1970, Mishima and four members of the Tatenokai—Masakatsu Morita, Masahiro Ogawa (小川正洋), Masayoshi Koga (小賀正義), and Hiroyasu Koga—used a pretext to visit the commandant Kanetoshi Mashita (益田兼利) of Camp Ichigaya (防衛省市ヶ谷地区), a military base in central Tokyo and the headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Japan Self-Defense Forces.[123] Inside, they barricaded the office and tied the commandant to his chair. Mishima wore a white hachimaki headband with a red hinomaru circle in the center bearing the kanji for "To be reborn seven times to serve the country" (七生報國, Shichishō hōkoku), which was a reference to the last words of Kusunoki Masasue, the younger brother of the 14th-century imperial loyalist samurai Kusunoki Masashige, as the two brothers died fighting to defend the Emperor.[185] With a prepared manifesto and a banner listing their demands, Mishima stepped out onto the balcony to address the soldiers gathered below. His speech was intended to inspire a coup d'état to restore the power of the emperor. He succeeded only in irritating the soldiers, and was heckled, with jeers and the noise of helicopters drowning out some parts of his speech. In his speech Mishima rebuked the JSDF for their passive acceptance of a constitution that "denies (their) own existence" and shouted to rouse them, "Where has the spirit of the samurai gone?" In his final written appeal (檄, Geki) that Morita and Ogawa scattered copies of from the balcony, Mishima expressed his dissatisfaction with the half-baked nature of the JSDF:

It is self-evident that the United States would not be pleased with a true Japanese volunteer army protecting the land of Japan.[186][187]

After he finished reading his prepared speech in a few minutes' time, Mishima cried out "Long live the Emperor!" (天皇陛下万歳, Tenno-heika banzai) three times. He then retreated into the commandant's office and apologized to the commandant, saying,

"We did it to return the JSDF to the Emperor. I had no choice but to do this."[188][189][190]

Mishima then committed seppuku, a form of ritual suicide by disembowelment associated with the samurai. Morita had been assigned to serve as Mishima's second (kaishakunin), cutting off his head with a sword at the end of the rite to spare him unnecessary pain. However, Morita proved unable to complete his task, and after three failed attempts to sever Mishima's head, Koga had to step in and complete the task.[188][189][190]

According to the testimony of the surviving coup members, originally all four Tatenokai members had planned to commit seppuku along with Mishima. However, Mishima attempted to dissuade them and three of the members acquiesced to his wishes. Only Morita persisted, saying, "I can't let Mr. Mishima die alone." But Mishima knew that Morita had a girlfriend and still hoped he might live. Just before his seppuku, Mishima tried one more time to dissuade him, saying "Morita, you must live, not die."[191][192][n] Nevertheless, after Mishima's seppuku, Morita knelt and stabbed himself in the abdomen and Koga acted as kaishakunin again.[193]

This coup attempt is called "The Mishima Incident" (三島事件, Mishima jiken) in Japan.[o]

Another traditional element of the suicide ritual was the composition of so-called death poems by the Tatenokai members before their entry into the headquarters.[195] Having been enlisted in the Ground Self-Defense Force for about four years, Mishima and other Tatenokai members, alongside several officials, were secretly researching coup plans for a constitutional amendment. They thought there was a chance when security dispatch (治安出動, Chian Shutsudo) was dispatched to subjugate the Zenkyoto revolt. However, Zenkyoto was suppressed easily by the Riot Police Unit in October 1969. These officials gave up the coup of constitutional amendment, and Mishima was disappointed in them and the actual circumstances in Japan after World War II.[196] Officer Kiyokatsu Yamamoto (山本舜勝), Mishima's training teacher, explained further:

The officers had a trusty connection with the U.S.A.F. (includes U.S.F.J), and with the approval of the U.S. army side, they were supposed to carry out a security dispatch toward the Armed Forces of the Japan Self-Defense Forces. However, due to the policy change (reversal) of U.S. by Henry Kissinger who prepared for visiting China in secret (changing relations between U.S. and China), it became a situation where the Japanese military was not allowed legally.[196]

Mishima planned his suicide meticulously for at least a year and no one outside the group of hand-picked Tatenokai members knew what he was planning.[197][198] His biographer, translator John Nathan, suggests that the coup attempt was only a pretext for the ritual suicide of which Mishima had long dreamed.[199] His friend Scott-Stokes, another biographer, says that "Mishima is the most important person in postwar Japan", and described the shackles of the constitution of Japan:

Mishima cautioned against the lack of reality in the basic political controversy in Japan and the particularity of Japan's democratic principles.[200]

Scott-Stokes noted a meeting with Mishima in his diary entry for 3 September 1970, at which Mishima, with a dark expression on his face, said:

Japan lost its spiritual tradition, and materialism infested instead. Japan is under the curse of a Green Snake now. The Green Snake bites on Japanese chest. There is no way to escape this curse.[201]

Scott-Stokes told Takao Tokuoka in 1990 that he took the Green Snake to mean the U.S. dollar.[202] Between 1968 and 1970, Mishima also said words about Japan's future. Mishima's senior friend and father heard from Mishima:

Japan will be hit hard. One day, the United States suddenly contacts China over Japan's head, Japan will only be able to look up from the bottom of the valley and eavesdrop on the conversation slightly. Our friend Taiwan will say that "it will no longer be able to count on Japan", and Taiwan will go somewhere. Japan may become an orphan in the Orient, and may eventually fall into the product of slave dealers.[203]

Mishima's corpse was returned home the day after his death. His father Azusa had been afraid to see his son whose appearance had completely changed. However, when he looked into the casket fearfully, Mishima's head and body had been sutured neatly, and his dead face, to which makeup had been beautifully applied, looked as if he were alive. Police officers handling Mishima's body had applied the makeup, saying: "We applied funeral makeup carefully with special feelings, because it is the body of Dr. Mishima, whom we have always respected secretly."[204] Mishima's body was dressed in the Tatenokai uniform, and the guntō was firmly clasped at the chest according to the will that Mishima entrusted to his friend Kinemaro Izawa (伊沢甲子麿).[204][205] Azusa put the manuscript papers and fountain pen that his son cherished in the casket together.[204][p] Mishima had made sure his affairs were in order and left money for the legal defence of the three surviving Tatenokai members—Masahiro Ogawa (小川正洋), Masayoshi Koga (小賀正義), and Hiroyasu Koga.[198][q] After the incident, there were exaggerated media commentaries that "it was a fear of the revival of militarism".[202][209] The commandant who was made a hostage said in the trial,

I didn't feel hate towards the defendants even at that time. Thinking about the country of Japan, thinking about the JSDF, the pure hearts of thinking about our country that did that kind of thing, I want to buy it as an individual.[188]

The day of the Mishima Incident (25 November) was the date when Hirohito (Emperor Shōwa) became regent and the Emperor Shōwa made the Humanity Declaration at the age of 45. Researchers believe that Mishima chose that day to revive the "God" by dying as a scapegoat, at the same age as when the Emperor became a human.[210][211] There are also views that the day corresponds to the date of execution (after the adoption of the Gregorian calendar) of Yoshida Shōin, whom Mishima respected,[204] or that Mishima had set his period of bardo for reincarnation because the 49th day after his death was his birthday, 14 January.[212] On his birthday, Mishima's remains were buried in the grave of the Hiraoka Family at Tama Cemetery.[204] In addition, 25 November is the day he began writing Confessions of a Mask, and this work was announced as "Techniques of Life Recovery", "Suicide inside out". Mishima also wrote down in notes for this work,

This book is a will for leave in the Realm of Death where I used to live. If you take a movie of a suicide jumped, and rotate the film in reverse, the suicide person jumps up from the valley bottom to the top of the cliff at a furious speed and he revives.[213][214]

Writer Takashi Inoue believes he wrote Confessions of a Mask to live in postwar Japan, and to get away from his "Realm of Death"; by dying on the same date that he began to write Confessions of a Mask, Mishima intended to dismantle all of his postwar creative activities and return to the "Realm of Death" where he used to live.[214]

Legacy

[edit]

Much speculation has surrounded Mishima's suicide. At the time of his death he had just completed the final book in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy.[123] He was recognized as one of the most important post-war stylists of the Japanese language. Mishima wrote 34 novels, about 50 plays, about 25 books of short stories, at least 35 books of essays, one libretto, and one film.[215]

Mishima's grave is located at the Tama Cemetery in Fuchū, Tokyo. The Mishima Prize was established in 1988 to honor his life and works. On 3 July 1999, "Yukio Mishima Literary Museum" (三島由紀夫文学館, Mishima Yukio Bungaku-kan) was opened in Yamanakako, Yamanashi Prefecture.[216]

The Mishima Incident helped inspire the formation of "New Right groups in Japan" (新右翼, Shin uyoku), such as the "Issuikai", founded by Tsutomu Abe (阿部勉), who was one of Tatenokai members and Mishima's follower. Compared to older groups such as Bin Akao's Greater Japan Patriotic Party that took a pro-American, anti-communist stance, New Right groups such as the Issuikai tended to emphasize ethnic nationalism and anti-Americanism.[217]

A memorial service deathday for Mishima, called "Patriotism Memorial" (憂国忌, Yūkoku-ki), is held every year in Japan on 25 November by the "Yukio Mishima Study Group" (三島由紀夫研究会, Mishima Yukio Kenkyūkai) and former members of the "Japan Student Alliance" (日本学生同盟, Nihon Gakusei Dōmei).[218] Apart from this, a memorial service is held every year by former Tatenokai members, which began in 1975, the year after Masahiro Ogawa, Masayoshi Koga, and Hiroyasu Koga were released on parole.[219]

A variety of cenotaphs and memorial stones have been erected in honor of Mishima's memory in various places around Japan. For example, stones have been erected at Hachiman Shrine in Kakogawa City, Hyogo Prefecture, where his grandfather's permanent domicile was;[220] in front of the 2nd company corps at JGSDF Camp Takigahara;[221] and in one of Mishima's acquaintance's home garden.[222] There is also a "Monument of Honor Yukio Mishima & Masakatsu Morita" in front of the Rissho University Shonan High school in Shimane Prefecture.[223]

The Mishima Yukio Shrine was built in the suburb of Fujinomiya, Shizuoka Prefecture, on 9 January 1983.[224][225]

A 1985 biographical film by Paul Schrader titled Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters depicts his life and work; however, it has never been given a theatrical presentation in Japan. A 2012 Japanese film titled 11:25 The Day He Chose His Own Fate also looks at Mishima's last day. The 1983 gay pornographic film Beautiful Mystery satirised the homosexual undertones of Mishima's career.[226][12]

In 2020, documentary film titled Mishima Yukio vs. Zenkyōtō of Tokyo University: the Truth revealed in the 50th year (三島由紀夫vs東大全共闘〜50年目の真実〜, Mishima Yukio vs Todai Zenkyōtō〜50 nen me no Sinjitsu) based on the debate between Mishima and the Zenkyōtō of Tokyo University in May 13, 1969. The record of this debate was published in June 1969 under the title Debate: Yukio Mishima vs. Zenkyōtō of Tokyo University: Beauty, Community, and the Tokyo University Struggle (討論 三島由紀夫vs.東大全共闘―美と共同体と東大闘争, Tōron: Mishima Yukio vs. Zenkyōtō of Tokyo University: Bi to Kyōdōtai to Todai Ronsō).

Awards

[edit]- Shincho Prize from Shinchosha Publishing, 1954, for The Sound of Waves

- Kishida Prize for Drama from Shinchosha Publishing, 1955 for Termites' Nest (白蟻の巣, Shiroari no Su)

- Yomiuri Prize from Yomiuri Newspaper Co., for best novel, 1956, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion[227]

- Shuukan Yomiuri Prize for Shingeki from Yomiuri Newspaper Co., 1958, for Rose and Pirate (薔薇と海賊, Bara to Kaizoku)

- Yomiuri Prize from Yomiuri Newspaper Co., for best drama, 1961, The Chrysanthemum on the Tenth (The Day After the Fair) (十日の菊, Tōka no kiku)

- One of six finalists for the Nobel Prize in Literature, 1963.[228]

- Mainichi Art Prize from Mainichi Shimbun, 1964, for Silk and Insight

- Art Festival Prize from the Ministry of Education, 1965, for Madame de Sade

Major works

[edit]Literature

[edit]| Japanese title | English title | Year (first appeared) | English translator | Year (English translation) | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

"Forest in Full Bloom" | 1941 | Andrew Rankin | 2000 | |

|

"The Circus" | 1948 | Andrew Rankin | 1999[229] | |

|

Thieves | 1947–1948 | |||

|

Confessions of a Mask | 1949 | Meredith Weatherby | 1958 | 0-8112-0118-X |

|

Thirst for Love | 1950 | Alfred H. Marks | 1969 | 4-10-105003-1 |

|

Pure White Nights | 1950 | |||

|

The Age of Blue | 1950 | |||

|

Forbidden Colors | 1951–1953 | Alfred H. Marks | 1968–1974 | 0-375-70516-3 |

|

Death in Midsummer | 1952 | Edward G. Seidensticker | 1956 | |

|

The Sound of Waves | 1954 | Meredith Weatherby | 1956 | 0-679-75268-4 |

|

"The Boy Who Wrote Poetry" | 1954 | Ian H. Levy (Hideo Levy) | 1977[229] | |

|

The Sunken Waterfall | 1955 | |||

|

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion | 1956 | Ivan Morris | 1959 | 0-679-75270-6 |

|

Rokumeikan | 1956 | Hiroaki Sato | 2002 | 0-231-12633-6 |

|

Kyoko's House | 1959 | |||

|

After the Banquet | 1960 | Donald Keene | 1963 | 0-399-50486-9 |

|

Star (novella) | 1960[230] | Sam Bett | 2019 | 978-0-8112-2842-8 |

|

"Patriotism" | 1961 | Geoffrey W. Sargent | 1966 | 0-8112-1312-9 |

|

The Black Lizard | 1961 | Mark Oshima | 2007 | 1-929280-43-2 |

|

The Frolic of the Beasts | 1961 | Andrew Clare | 2018 | 978-0-525-43415-3 |

|

Beautiful Star | 1962 | Stephen Dodd | 2022[231][232] |

|

|

The School of Flesh | 1963 | |||

|

The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea | 1963 | John Nathan | 1965 | 0-679-75015-0 |

|

Silk and Insight | 1964 | Hiroaki Sato | 1998 | 0-7656-0299-7 |

|

"Acts of Worship" | 1965 | John Bester | 1995 | 0-87011-824-2 |

|

"The Peacocks" | 1965 | Andrew Rankin | 1999 | 1-86092-029-2 |

|

Madame de Sade | 1965 | Donald Keene | 1967 | 1-86092-029-2 |

|

"The Voices of the Heroic Dead" | 1966 | |||

|

The Decline and Fall of The Suzaku | 1967 | Hiroaki Sato | 2002 | 0-231-12633-6 |

|

Life for Sale | 1968 | Stephen Dodd | 2019 | 978-0-241-33314-3 |

|

My Friend Hitler and Other Plays | 1968 | Hiroaki Sato | 2002 | 0-231-12633-6 |

|

The Terrace of The Leper King | 1969 | Hiroaki Sato | 2002 | 0-231-12633-6 |

|

The Sea of Fertility tetralogy: | 1965–1971 | 0-677-14960-3 | ||

| I. 春の雪Haru no Yuki | 1. Spring Snow | 1965–1967 | Michael Gallagher | 1972 | 0-394-44239-3 |

| II. 奔馬Honba | 2. Runaway Horses | 1967–1968 | Michael Gallagher | 1973 | 0-394-46618-7 |

| III. 曉の寺Akatsuki no Tera | 3. The Temple of Dawn | 1968–1970 | E. Dale Saunders and Cecilia S. Seigle | 1973 | 0-394-46614-4 |

| IV. 天人五衰Tennin Gosui | 4. The Decay of the Angel | 1970–1971 | Edward Seidensticker | 1974 | 0-394-46613-6 |

Critical essay

[edit]| Japanese title | English title | Year (first appeared) | English translation, year | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The Cup of Apollo | 1952 | ||

|

Lectures on Immoral Education | 1958–1959 | ||

|

My Wandering Period | 1963 | ||

|

Sun and Steel | 1965–1968 | John Bester | 4-7700-2903-9 |

|

Way of the Samurai | 1967 | Kathryn Sparling, 1977 | 0-465-09089-3 |

|

The Defense of the Culture | 1968 | ||

|

|

1970 | Harris I. Martin, 1971[229] |

Plays for classical Japanese theatre

[edit]In addition to contemporary-style plays such as Madame de Sade, Mishima wrote for two of the three genres of classical Japanese theatre: Noh and Kabuki (as a proud Tokyoite, he would not even attend the Bunraku puppet theatre, always associated with Osaka and the provinces).[233]

Though Mishima took themes, titles and characters from the Noh canon, his twists and modern settings, such as hospitals and ballrooms, startled audiences accustomed to the long-settled originals.

Donald Keene translated Five Modern Noh Plays (Tuttle, 1981; ISBN 0-8048-1380-9). Most others remain untranslated and so lack an "official" English title; in such cases it is therefore preferable to use the rōmaji title.

| Year (first appeared) | Japanese title | English title | Genre |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 |

|

The Magic Pillow | Noh |

| 1951 | The Damask Drum | Noh | |

| 1952 | Komachi at the Gravepost | Noh | |

| 1954 | The Lady Aoi | Noh | |

| 1954 |

|

The Sardine Seller's Net of Love | Kabuki |

| 1955 | The Waiting Lady with the Fan | Noh | |

| 1955 |

|

|

Kabuki |

| 1957 | Dōjōji Temple | Noh | |

| 1959 | Yuya | Noh | |

| 1960 | The Blind Young Man | Noh | |

| 1969 |

|

|

Kabuki |

Films

[edit]Mishima starred in multiple films. Patriotism was written and funded by himself, and he directed it in close cooperation with Masaki Domoto. Mishima also wrote a detailed account of the whole process, in which the particulars regarding costume, shooting expenses and the film's reception are delved into. Patriotism won the second prize at the Tours International Short Film Festival in January 1966.[234][235]

| Year | Title | United States release title(s) | Character | Director |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 |

|

Unreleased in the U.S. | an extra (dance party scene) | Hideo Ōba |

| 1959 |

|

Unreleased in the U.S. | himself as navigator | Katsumi Nishikawa |

| 1960 |

|

Afraid to Die |

|

Yasuzo Masumura |

| 1966 |

|

|

|

|

| 1968 |

|

Black Lizard | Human Statue | Kinji Fukasaku |

| 1969 |

|

Tenchu! | Tanaka Shinbei | Hideo Gosha |

Works about Mishima

[edit]- Collection of Photographs

- Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses (薔薇刑) by Eikō Hosoe and Mishima (photoerotic collection of images of Mishima, with his own commentary, 1963) (Aperture 2002 ISBN 0-89381-169-6)[236][237]

- Grafica: Yukio Mishima (Grafica Mishima Yukio (グラフィカ三島由紀夫)) by Kōichi Saitō, Kishin Shinoyama, Takeyoshi Tanuma, Ken Domon, Masahisa Fukase, Eikō Hosoe, Ryūji Miyamoto etc. (photoerotic collection of Yukio Mishima) (Shinchosha 1990 ISBN 978-4-10-310202-1)[238]

- Yukio Mishima's house (Mishima Yukio no Ie (三島由紀夫の家)) by Kishin Shinoyama (Bijutsu Shuppansha 1995 ISBN 978-4-568-12055-4)[239]

- The Death of a Man (Otoko no shi (男の死)) by Kishin Shinoyama and Mishima (photo collection of death images of Japanese men including a sailor, a construction worker, a fisherman, and a soldier, those were Mishima did modeling in 1970) (Rizzoli 2020 ISBN 978-0-8478-6869-8)[240]

- Books

- Reflections on the Death Of Mishima by Henry Miller (1972, ISBN 0-912264-38-1) [241]

- The Day He Himself Shall Wipe My Tears Away (Mizukara waga namida wo nuguitamau hi (みずから我が涙をぬぐいたまう日)) by Kenzaburō Ōe (Kodansha, 1972, NCID BN04777478) – In addition to this, Kenzaburō Ōe wrote several works that mention the Mishima incident and Mishima a little.[242]

- The Head of Yukio Mishima (Mishima Yukio no Kubi (三島由紀夫の首)) by Tetsuji Takechi (Toshi shuppann, 1972, NCID BN05185496) - A mysterious tale of Mishima's head flying over the Kantō region and arguing with the head of Taira no Masakado.[243]

- Mishima: A Biography by John Nathan (Boston, Little, Brown and Company 1974, ISBN 0-316-59844-5)[244][245]

- The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima, by Henry Scott-Stokes (London : Owen, 1975 ISBN 0-7206-0123-1)[245][246]

- La mort volontaire au Japon, by Maurice Pinguet (Gallimard, 1984 ISBN 2070701891)[247][248]

- Der Magnolienkaiser: Nachdenken über Yukio Mishima by Hans Eppendorfer (1984, ISBN 3924040087)[249]

- Teito Monogatari (vol. 5–10) by Hiroshi Aramata (a historical fantasy novel. Mishima appears in series No.5, and he reincarnates a woman Michiyo Ohsawa in series No.6), (Kadokawa Shoten 1985 ISBN 4-04-169005-6)[250][251]

- Yukio Mishima by Peter Wolfe ("reviews Mishima's life and times, discusses, his major works, and looks at important themes in his novels", 1989, ISBN 0-8264-0443-X)[252]

- Escape from the Wasteland: Romanticism and Realism in the Fiction of Mishima Yukio and Oe Kenzaburo (Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series, No 33) by Susan J. Napier (Harvard University Press, 1991 ISBN 0-674-26180-1)[253]

- Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence, and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima by Roy Starrs (University of Hawaii Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8248-1630-7 and ISBN 0-8248-1630-7)[254]

- Rogue Messiahs: Tales of Self-Proclaimed Saviors by Colin Wilson (Mishima profiled in context of phenomenon of various "outsider" Messiah types), (Hampton Roads Publishing Company 2000 ISBN 1-57174-175-5)

- Mishima ou la vision du vide (Mishima : A Vision of the Void), essay by Marguerite Yourcenar trans. by Alberto Manguel 2001 ISBN 0-226-96532-5)[255][256]

- Yukio Mishima, Terror and Postmodern Japan by Richard Appignanesi (2002, ISBN 1-84046-371-6)

- Yukio Mishima's Report to the Emperor by Richard Appignanesi (2003, ISBN 978-0-9540476-6-5)

- The Madness and Perversion of Yukio Mishima by Jerry S. Piven. (Westport, Connecticut, Praeger Publishers, 2004 ISBN 0-275-97985-7)[257]

- Mishima's Sword – Travels in Search of a Samurai Legend by Christopher Ross (2006, ISBN 0-00-713508-4)[258]

- Mishima Reincarnation (Mishima tensei (三島転生)) by Akitomo Ozawa (小沢章友) (Popurasha, 2007, ISBN 978-4-591-09590-4) – A story in which the spirit of Mishima, who died at the Ichigaya chutonchi, floating and looks back on his life.[259]

- Biografia Ilustrada de Mishima by Mario Bellatin (Argentina, Editorian Entropia, 2009, ISBN 978-987-24797-6-3)

- Impossible (Fukano (不可能)) by Hisaki Matsuura (Kodansha, 2011, ISBN 978-4-06-217028-4) – A novel that assumed that Mishima has been survived the Mishima Incident.[260]

- Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima by Naoki Inose with Hiroaki Sato (Berkeley, California, Stone Bridge Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1-61172-008-2)[261]

- Yukio Mishima (Critical Lives) by Damian Flanagan (Reaktion Books, 2014, ISBN 978-1-78023-345-1)[262]

- Portrait of the Author as a Historian by Alexander Lee – an analysis of the central political and social threads in Mishima's novels (pages 54–55 "History Today" April 2017)

- Mishima, Aesthetic Terrorist: An Intellectual Portrait by Andrew Rankin (University of Hawaii Press, 2018, ISBN 0-8248-7374-2)[263]

- Film, TV

- Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), a film directed by Paul Schrader[264]

- The Strange Case of Yukio Mishima (1985) BBC documentary directed by Michael Macintyre

- Yukio Mishima: Samurai Writer, a BBC documentary on Yukio Mishima, directed by Michael Macintyre, (1985, VHS ISBN 978-1-4213-6981-5, DVD ISBN 978-1-4213-6982-2)

- Miyabi: Yukio Mishima (みやび 三島由紀夫) (2005), a documentary film directed by Chiyoko Tanaka[265]

- 11:25 The Day He Chose His Own Fate (2012), a film directed by Kōji Wakamatsu[266]

- Mishima Yukio vs. Zenkyōtō of Tokyo University: the Truth revealed in the 50th year (三島由紀夫vs東大全共闘〜50年目の真実〜) (2020), a documentary film directed by Keisuke Toyoshima (豊島圭介)[267]

- Music

- Harakiri, by Péter Eötvös (1973). An opera music composed based on the Japanese translation of István Bálint's poetry Harakiri that inspired by Mishima's hara-kiri. This work is included in Ryoko Aoki (青木涼子)'s album Noh x Contemporary Music (能×現代音楽) in June 2014.[268]

- String Quartet No.3, "Mishima", by Philip Glass. A reworking of parts of his soundtrack for the film Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, it has a duration of 18 minutes.

- "Death and Night and Blood (Yukio)", a song by the Stranglers from the Black and White album (1978). (Death and Night and Blood is the phrase from Mishima's novel Confessions of a Mask)[269]

- "Forbidden Colours", a song on Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence soundtrack by Ryuichi Sakamoto with lyrics by David Sylvian (1983). Inspired by Mishima's novel Forbidden Colors.[270]

- Sonatas for Yukio – C.P.E. Bach: Harpsichord Sonatas, by Jocelyne Cuiller (2011).[268] A program composed of Bach sonatas for each scene of the novel "Spring Snow".

- Theatre

- Yukio Mishima, a play by Adam Darius and Kazimir Kolesnik, first performed at Holloway Prison, London, in 1991, and later in Finland, Slovenia and Portugal.

- M, a ballet spectacle work homage to Mishima by Maurice Béjart in 1993[271]

- Manga, Games

- Shin Megami Tensei by Atlus (1992) – A character Gotou who started a coup in Ichigaya, modeled on Mishima.

- Tekken by Namco (1994) – Mishima surname comes from Yukio Mishima, and a main character, Kazuya Mishima, had his way of thinking based on Mishima.

- Jakomo Fosukari (Jakomo Fosukari (ジャコモ・フォスカリ)) by Mari Yamazaki (2012) – The characters modeled on Mishima and Kōbō Abe appears in.[272][268]

- Poetry

- Harakiri, by István Bálint.[268]

- Grave of Mishima (Yukio Mishima no haka (ユキオ・ミシマの墓)) by Pierre Pascal (1970) – 12 Haiku poems and three Tanka poems. Appendix of Shinsho Hanayama (花山信勝)'s book translated into French.[273]

- Art

- Kou (Kou (恒)) by Junji Wakebe (分部順治) (1976) – Life-sized male sculpture modeled on Mishima. The work was requested by Mishima in the fall of 1970, he went to Wakebe's atelier every Sunday. It was exhibited at the 6th Niccho Exhibition on 7 April 1976.[274]

- Season of fiery fire / Requiem for someone: Number 1, Mishima (Rekka no kisetsu/Nanimonoka eno rekuiemu: Sono ichi Mishima (烈火の季節/なにものかへのレクイエム・その壱 ミシマ)) and Classroom of beauty, listen quietly: bi-class, be quiet (Bi no kyositsu, seicho seyo (美の教室、清聴せよ)) by Yasumasa Morimura (2006, 2007) – Disguise performance as Mishima[275][268]

- Objectglass 12 and The Death of a Man (Otoko no shi (男の死)) by Kimiski Ishizuka (石塚公昭) (2007, 2011) – Mishima dolls[ 276 ] [ 268 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Хахиноки Кай - круг чата, к которому принадлежала Мисима.

- Атака Японской федерации бизнеса - инцидент в 1977 году с участием четырех человек (включая одного бывшего члена Татенокая ), связанных с инцидентом Мисимы.

- Kosaburo Eto -Мисима заявляет, что он был впечатлен серьезностью самосожжения ETO , «самой интенсивной критикой политики как мечты или искусства». [ 277 ]

- Кумо, если Кай - группа литературных движений под председательством Кун Кун Куно Кишида в 1950–1954 годах, к которой принадлежала Мисима.

- Манджиро Хираока -Grand-езжа Мисима. Садааро Хираока Старший брат . Он был адвокатом и политиком.

- Приз Мисима Юкио - литературная награда, созданная в сентябре 1987 года.

- ФЕДО - Книга Мишима читала в свои последующие годы.

- Suegen - традиционный аутентичный ресторан в японском стиле в Синбаши , который известен как последнее обеденное место для Мисимы и четыре члена Татенокая (Масакацу Морита, Хироясу Кога, Масахиро Огава, Масайоши Кога).

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Произношение: Великобритания : / M ɪ ʃ / m /,, Us : - m ː , ˈ m iː ʃ i m ː , m ɪ ˈ ː m ə / ,,,, / [ 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Японский: [Miɕima] .

- Старшим сыном Йоритаки был Мацудайра Йоринори , которая умерла в возрасте 33 лет, когда ему было приказано совершить Сеппуку с сёгунатом во время восстания Тенгуто , потому что он сочувствовал Тенгу -Ту ( 天狗党 ) Джуи Сонн . [ 24 ]

- ^ Мишима рассказал о своей родословной; «Я потомка крестьян и самураи, и мой способ работы похож на самый трудолюбивый крестьянин». [ 28 ]

- ^ 輔仁 ( Hojin ) - это восточноазиатское имя, состоящее из двух персонажей, которые индивидуально означают «помощь» и «доброжелательность».

- ^ В конце этой дебютной работы нарисовано смягченное «спокойствие», и некоторые литературные исследователи часто указывают, что у него есть что -то общее с окончанием посмертной работы Мисимы « Море плодородия ». [ 36 ] [ 37 ]

- ^ Куника Митани, сестра Макото Митани ( 三谷信 ) , станет моделью «Соноко» в «Признаниях маски » . Мишима написала в письме знакомому, что «я бы не жил, если бы не написал о ней». [ 63 ]

- ^ В оккупации Японии , Scap Canced « Охота на меч », и 3 миллиона мечей, которые принадлежали японцам, были конфискованы. Далее Кендо был запрещен, и даже когда он едва разрешил в форме «конкуренции с бамбуковым мечами», Scap сильно запретил Кендо кричит, [ 68 ] и они запретили Кабуки , у которого была тема мести или вдохновил самурайский дух. [ 69 ]

- ^ В 1956 году японское правительство выпустило экономическую белую статью, которая, как известно, заявила: « послевоенный Послевоенный [ 85 ]

- ^ Что касается оценки книги Фукусимы, она привлекает внимание как материал для изучения дружбы Мисимы при написании запретных цветов ; Тем не менее, были критические замечания, что эта книга была смущена читателями, потому что была написана настоящие имена всех персонажей, таких как научная литература, в то же время Фукусима указал «роман о мистере Юкио Мишиме», «Эта работа», «Это роман "во введении и эпилоге [ 128 ] Или это рекламировалось как «автобиографический роман», поэтому у издателя не было уверенности, чтобы сказать, что все было правдой; Единственными ценными отчетами в этой книге были письма Мисимы. [ 124 ] Кроме того, были яростные критические замечания в том, что это содержание книги было незначительным по сравнению с его преувеличенной рекламой, или было отмечено, что были противоречия и неестественные адаптации, такие как выдуманная история в окрестностях гей. [ 124 ] Gō Itasaka ( 板坂剛 ) , который, как думает Мишима, была гомосексуалиста, сказал об этой книге, как показано ниже: «Платье Фукусимы только описывало только мелкую мисиму, Мишима иногда была вульгарной, но никогда не был скромным человеком. Яд сам по себе (как доступен для использования в любое время), не всегда был для него отвращением ». [ 124 ] Джакучо Сетуши и Акихиро Мива сказали об этой книге, и Фукусиму, как ниже: «Это худший способ для мужчины или женщины писать плохие слова о ком -то, кого вы когда -то нравились, и Фукусима - роскошный, потому что его позаботились различными способами Когда он был беден, Мисимой и его родителями. [ 129 ]

- ^ Однажды, когда Мисима пропустил новый выпуск еженедельного журнала Shōnen в день его выпуска, потому что он снимал фильм «Черная ящерица», в полночь он внезапно появился в редакционном отделе журнала и потребовал: «Я хочу, чтобы вы продали мне Еженедельный журнал Shōnen только что вышел сегодня ». [ 143 ]

- ^ После этого Диснейленд стал любимым Мишимой. И, в новом 1970 году, в год, когда он был полон решимости умереть, он хотел, чтобы вся семья с детьми вернулась в тематический парк фэнтези. Но мечта не сбылась из -за возражения его жены о том, что она хотела сделать это после завершения моря плодородия . [ 150 ]

- ^ Мисима, который обращал внимание на обеспокоенное движение Китая, также в 1959 году прокомментировала сопротивление Тибету , как ниже, «молодой герой проблемных времен» ( 風雲児 , фуунджи ) , который погружается и присоединяется к тибетской повстанческой армии Китая против . Не появляется из Японии [ 160 ]

- ^ Существует порешение JSDF ( ( , jieitai nibun ron ) , соединить их с узы чести, хризантемы и меча kizun Eiyo no ) ) о щитовом обществе ( Tatenokai , Tatenokai, Tatenokai ) ) , Японский национальный гвардия: преднамеренный план ( JNG, JNG. Временный план) , JNG Karian (Sokoku Boei-Tai , который нам нужен Национальная гвардия Японии ( силы обороны Отец? ) зачем нам нужны , Собранная в комплексе 34 2003 , Complete35 2003 .